피드백 제공자로서 환자: 의과대학생의 신뢰 판단 탐색(Perspect Med Educ. 2023)

Patients as Feedback Providers: Exploring Medical Students’ Credibility Judgments

M. C. L. EIJKELBOOM R. A. M. DE KLEIJN W. J. M. VAN DIEMEN C. D. N. MALJAARS M. F. VAN DER SCHAAF J. FRENKEL

소개

Introduction

환자가 학생들의 학습에 기여할 수 있다는 사실이 널리 인식되면서 의학교육에 환자를 참여시키는 이니셔티브가 증가하고 있습니다[1, 2]. 환자로부터 배우는 한 가지 방법은 환자의 피드백입니다[3]. 의료 서비스의 사용자로서 환자는 의료 성과에 대한 독특한 관점을 제공할 수 있습니다. 따라서 환자의 피드백은 교수진이나 동료의 피드백을 보완할 수 있습니다. 이는 환자들이 동일한 상담에 대해 학생이나 레지던트를 교수진과 다르게 평가한다는 연구 결과에서 잘 드러납니다 [4]. 환자 피드백이 학생의 학습에 기여하기 위해서는 학생이 피드백에 참여해야 하며, 이는 학생이 피드백을 찾고, 이해하고, 행동으로 옮겨야 한다는 것을 의미합니다[5]. 학생이 피드백에 참여할지 여부는 피드백 제공자의 신뢰성에 대한 판단에 따라 부분적으로 결정됩니다[5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11]. 이에 따라 Baines 등의 연구에 따르면 환자의 피드백이 의사의 성과에 미치는 영향은 환자의 신뢰성에 대한 의사의 판단에 영향을 받는다고 보고했습니다[12]. 그러나 피드백 제공자로서 환자의 신뢰성에 대한 이러한 판단이 어떻게 이루어지고 어떤 논거에 근거하여 이루어지는지에 대해서는 알려진 바가 거의 없습니다.

It is becoming widely recognized that patients can contribute to students’ learning, and the number of initiatives that involve patients in medical education is growing [1, 2]. One way to learn from patients is through their feedback [3]. As the users of healthcare, patients can provide unique perspectives on medical performance. Therefore, their feedback can be complementary to faculty or peer feedback. This is illustrated by studies in which patients rate students or residents differently on the same consultation compared to faculty [4]. In order for patient feedback to contribute to student learning, students need to engage with this feedback, meaning they should seek it, make sense of it, and act upon it [5]. Whether students engage with feedback is partly determined by their judgment of the feedback provider’s credibility [5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11]. In accordance with this, a review by Baines et al. reports that the impact of patient feedback on doctors’ performance was influenced by doctors’ judgments of patients’ credibility [12]. However, little is known about how these judgments regarding patients’ credibility as feedback providers are made and on the basis of which arguments.

Molloy와 Bearman에 따라 우리는 신뢰성을 타인의 판단에 의해 정의되는 개인의 속성으로 간주합니다[13]. 이와 관련하여 신뢰성은 개인이 소유하는 절대적인 특성이 아니라 타인의 인식에 따라 달라집니다. 신뢰는 타인과의 관계 속에서 형성되며 관계에 따라 달라집니다 [7, 14, 15]. 따라서 한 학생은 어떤 환자를 매우 신뢰할 수 있다고 생각하지만, 다른 학생은 같은 환자를 신뢰할 수 없다고 판단할 수 있습니다. 신뢰성 판단은 판단이 이루어지는 맥락, 학습 문화 및 이러한 맥락 내에서 형성되는 관계에 의해 형성됩니다 [7, 16, 17]. 따라서 이론적으로 한 학생이 교실 환경에서는 환자를 매우 신뢰할 수 있다고 판단할 수 있지만, 병원 환경에서는 같은 환자를 신뢰할 수 없다고 판단할 수도 있습니다. 따라서 신뢰성은 역동적이고 대인관계에 따라 달라집니다. 환자가 의대생에게 피드백을 제공할 때, 그 맥락에서 그 환자의 신뢰도는 그 학생의 환자에 대한 판단에 의해 정의됩니다.

In line with Molloy and Bearman, we view credibility as an attribute of an individual, which is defined by judgments of others [13]. In this regard, credibility is not an absolute quality someone possesses, rather it depends on the perceptions of others. It is established in relationships with others and varies between these relationships [7, 14, 15]. So, whereas a patient can be seen as highly credible by one student, another student can judge the same patient as not credible. Credibility judgments are shaped by the context in which the judgment takes place, by its learning culture and the relationships that are formed within these contexts [7, 16, 17]. So, in theory, a student could judge a patient as highly credible in a classroom setting, but this same student might judge the same patient as not so credible in a hospital setting. Thus, credibility is dynamic and interpersonal. When a patient provides feedback to a medical student, this patient’s credibility is defined by that student’s judgment of that patient, in that context.

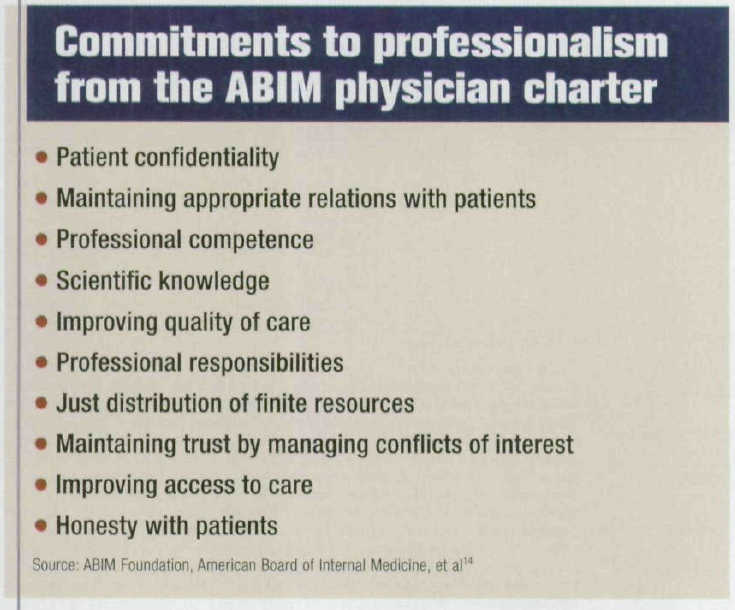

신뢰도를 더 개념화하기 위해 우리는 교사 신뢰도 연구에 일반적으로 적용되는 맥크로스키의 연구를 기반으로 합니다[18, 19]. 맥크로스키는 신뢰성을 역량, 신뢰성, 선의로 구성된 3차원적 구조로 정의하고 운영했습니다[18]. 유능성은 관심 있는 주제에 대한 지식과 전문성을 갖춘 사람을 의미합니다[20]. 신뢰성은 좋은 성품과 정직성을 가진 사람을 의미합니다. 선의는 상대방을 배려하고 좋은 의도를 가지고 있는지를 의미합니다[18]. 따라서 환자-학생 피드백 상호작용에서 이러한 신뢰성의 개념화를 적용하면, 환자의 신뢰성에 대한 학생의 판단은 환자의 유능성, 신뢰성, 선의에 대한 판단으로 구성되어야 합니다.

To further conceptualize credibility we build on the work of McCroskey, which is commonly applied in research on teacher credibility [18, 19]. McCroskey defined and operationalized credibility as a three-dimensional construct consisting of Competence, Trustworthiness, and Goodwill [18]. Competence refers to someone having knowledge of, and expertise in, the subject of interest [20]. Trustworthiness refers to someone being of good character and being honest. Goodwill refers to whether someone cares about the receiver and has good intentions [18]. Thus, using this conceptualization of credibility in patient-student feedback interactions, students’ judgments of patients’ credibility should comprise judgments of patients’ Competence, Trustworthiness and Goodwill.

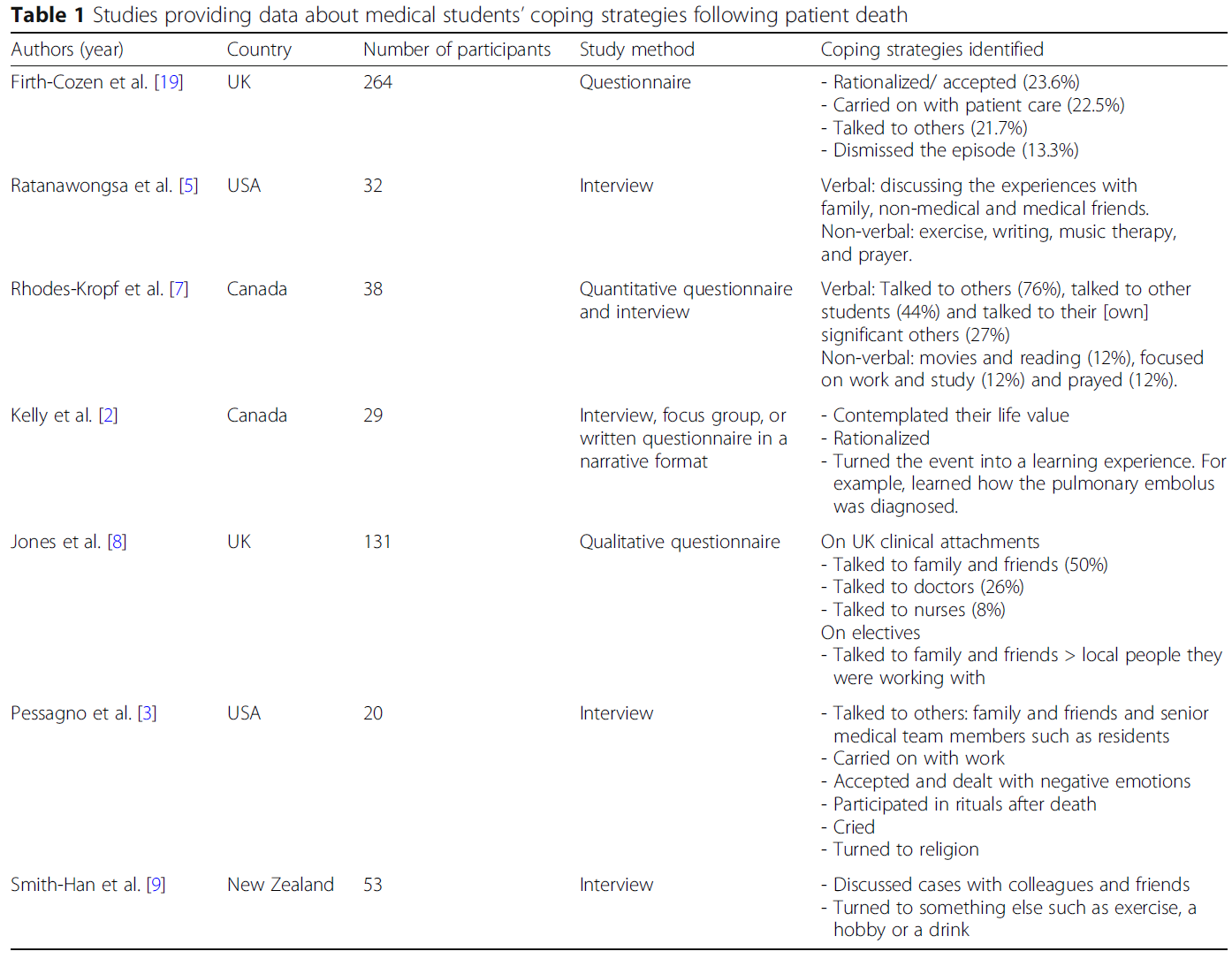

교육 분야, 특히 최근에는 의학교육 분야의 연구에서 학습자의 교사 또는 감독자에 대한 신뢰도 판단이 여러 요소로 구성된다는 사실이 밝혀졌지만, 환자와 (미래의) 의료인 간의 피드백 상호작용에 대한 경험적 연구는 주로 단일 요소의 신뢰도 판단을 보고하고 있습니다 [7, 19]. 일반적으로 학생들은 (잠재적) 피드백 제공자로서 환자에 대해 긍정적인 판단을 내리는 반면[3, 21, 22, 23, 24], 의사는 피드백 제공자로서 환자에 대해 긍정적인 판단과 부정적인 판단을 모두 내리는 것으로 보고됩니다[25, 26, 27].

- 성과를 관찰할 수 있는 능력은 환자의 신뢰도에 긍정적으로 기여하는 요인으로 설명됩니다[26, 28, 29].

- 의사나 학생이 언급하는 신뢰도를 낮추는 요인으로는 의학 지식 부족, 환자의 진정성에 대한 우려, 피드백이 환자의 진단에 영향을 받을 수 있다는 우려 등이 있습니다[8, 24, 27, 30, 31, 32, 33].

Although studies in education, and more recently in medical education, have shown that learners’ credibility judgments of teachers or supervisors are comprised of multiple elements, empirical studies on feedback interactions between patients and (future) healthcare providers mainly report single elements of credibility judgments [7, 19]. In general, students hold positive judgments about patients as (potential) feedback providers [3, 21, 22, 23, 24], whereas doctors report both positive and negative judgments of patients as feedback providers [25, 26, 27].

- The ability to observe performance is described as an argument positively contributing to patients’ credibility [26, 28, 29].

- Arguments for reduced credibility, as mentioned by doctors or students, are: lack of medical knowledge, concerns about the sincerity of patients, and concerns about feedback being influenced by a patient’s diagnosis [8, 24, 27, 30, 31, 32, 33].

의대생은 강의실, 병원, 환자의 집, 지역사회 등 다양한 환경에서 환자와 함께 그리고 환자로부터 학습합니다. 앞서 언급했듯이 신뢰성 판단은 맥락에 의해 형성됩니다[7, 16, 17]. 의대생들이 환자의 피드백에 참여하여 환자로부터 배우기를 원한다면, 학생들이 환자에 대한 신뢰성 판단을 내리는 과정, 이러한 판단의 근거가 되는 논거, 그리고 이러한 판단이 맥락에 의해 어떻게 형성되는지에 대한 더 나은 이해가 필요합니다. 이를 통해 학생들의 환자 피드백에 대한 참여를 개선할 수 있는 기회를 발견할 수 있습니다. 따라서 이 연구는 다음과 같은 연구 질문에 답하는 것을 목표로 합니다: 의대생들은 임상 및 비임상 맥락에서 피드백 제공자로서 환자의 신뢰도를 어떻게 판단할까요?

Medical students learn with and from patients in various contexts, such as the classroom, the hospital, a patient’s home or the community. As previously mentioned, credibility judgments are shaped by the context [7, 16, 17]. If we want medical students to engage with patient feedback, and thereby learn from patients, we need a better understanding of the process by which students make credibility judgments regarding patients, on which arguments they base these judgments, and how this is shaped by the context. This might reveal opportunities to improve students’ engagement with patient feedback. Therefore, this study aims to answer the following research question: How do medical students judge patients’ credibility as feedback providers in a clinical and in a non-clinical context?

방법

Methods

연구 디자인

Study design

피드백 상호작용에서 환자의 신뢰도에 대한 학생들의 판단을 이해하기 위해 후향적 질적 인터뷰 연구를 수행했습니다. 이 연구에 대한 윤리적 승인은 네덜란드 의학교육협회에서 제공했습니다(NVMO, NERB 파일 번호: 2020.5.8 및 NERB 파일 번호 2021.8.8).

We undertook a retrospective qualitative interview study to understand students’ credibility judgments of patients in feedback interactions. Ethical approval of this study was provided by the Dutch Association for Medical Education (NVMO, NERB file number: 2020.5.8 and NERB file number 2021.8.8).

연구 배경 및 참여자

Context and participants

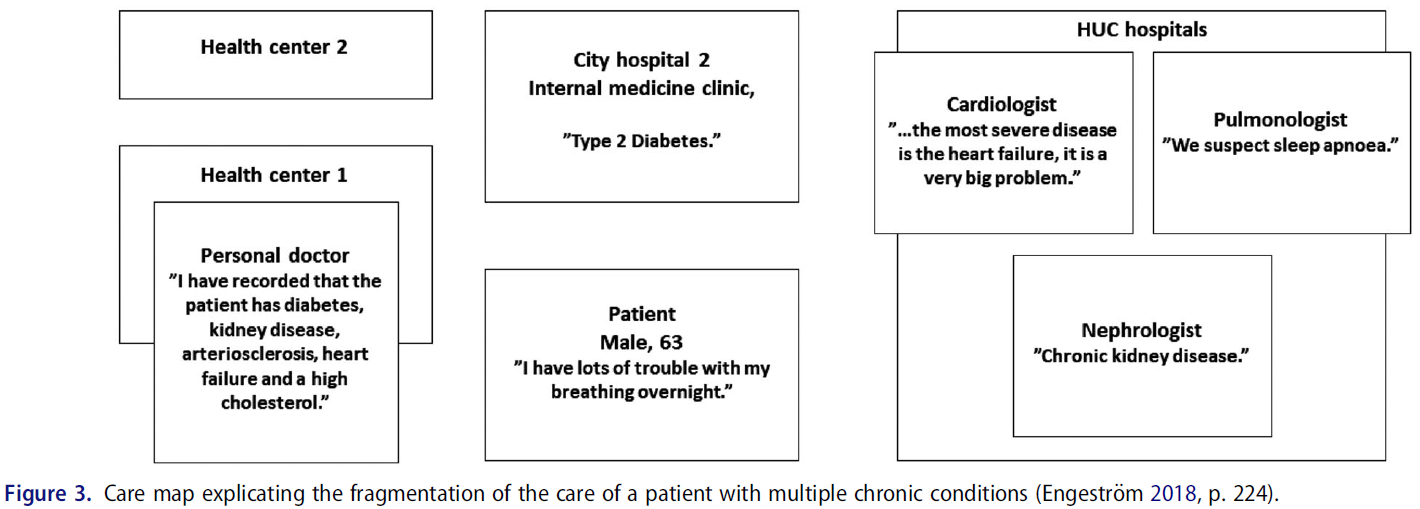

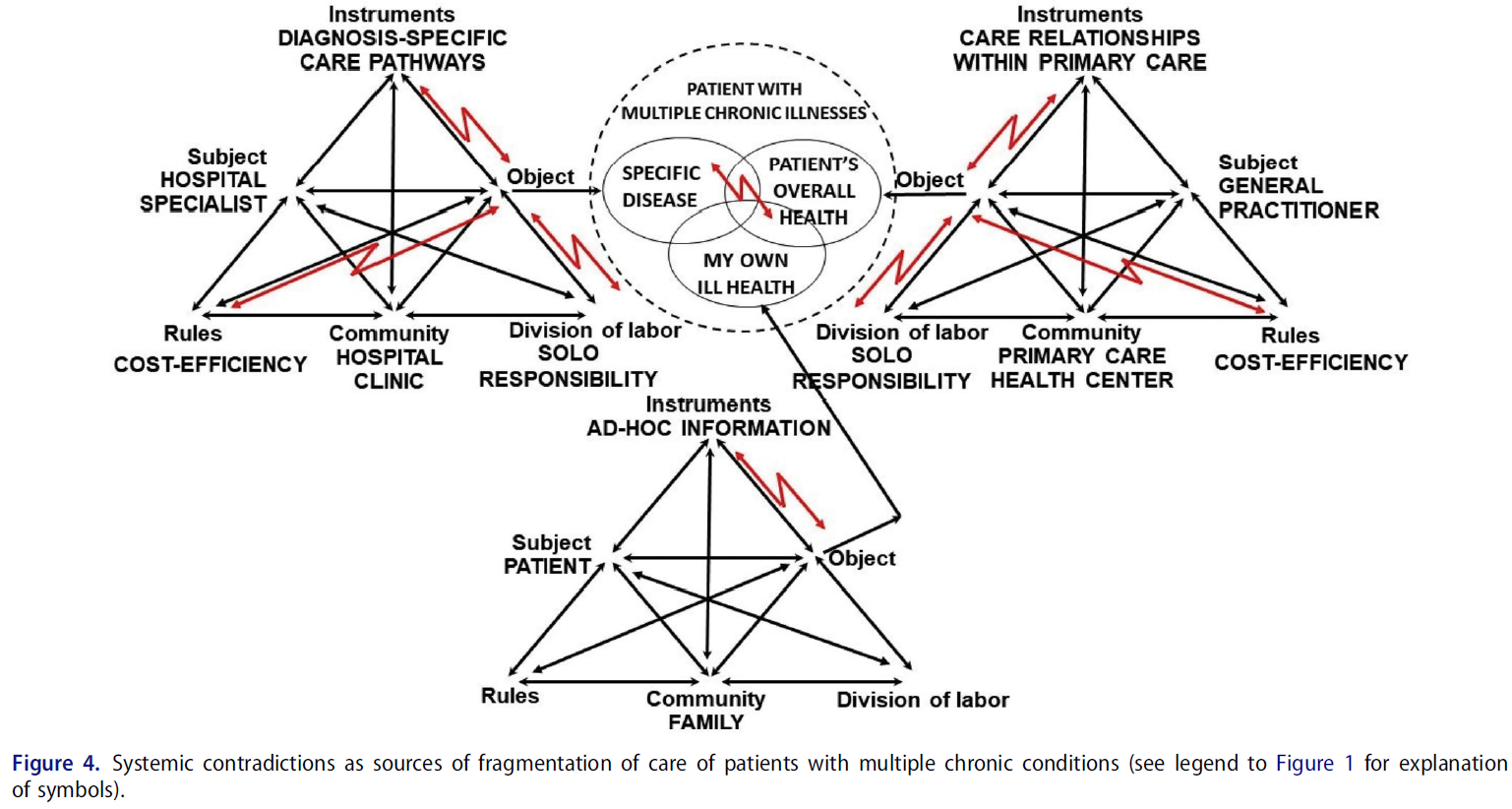

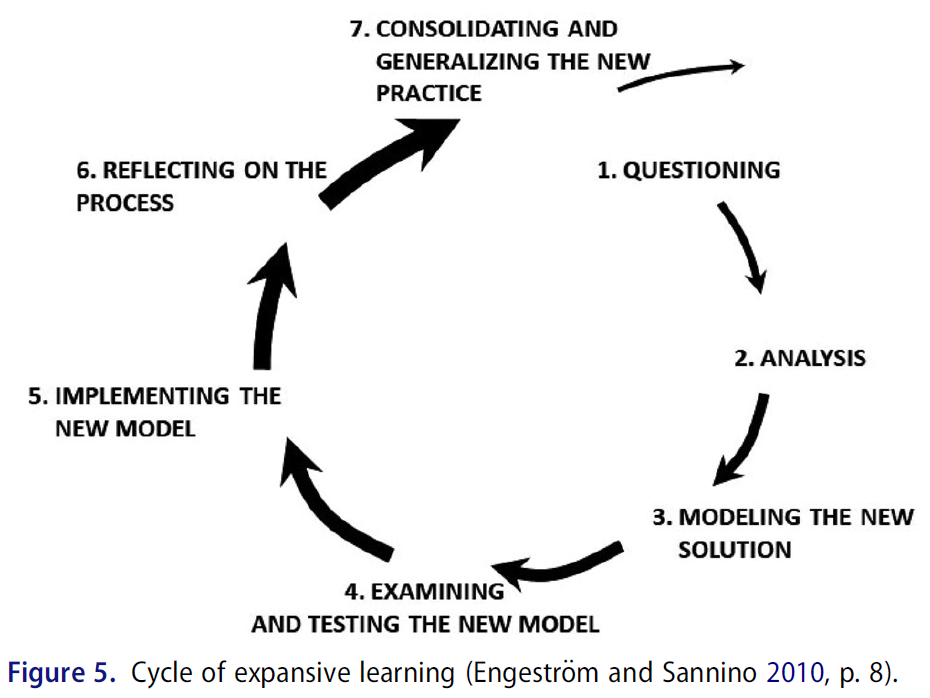

우리는 임상적 맥락과 비임상적 맥락에서 환자에 대한 학생들의 신뢰성 판단을 조사했습니다. 두 상황 모두에서 학생들은 (온라인) 일대일 대화를 통해 환자로부터 피드백을 수집했습니다.

We explored students’ credibility judgments regarding patients in a clinical and a non-clinical context. In both contexts students collected feedback from patients through (online) one-on-one dialogues.

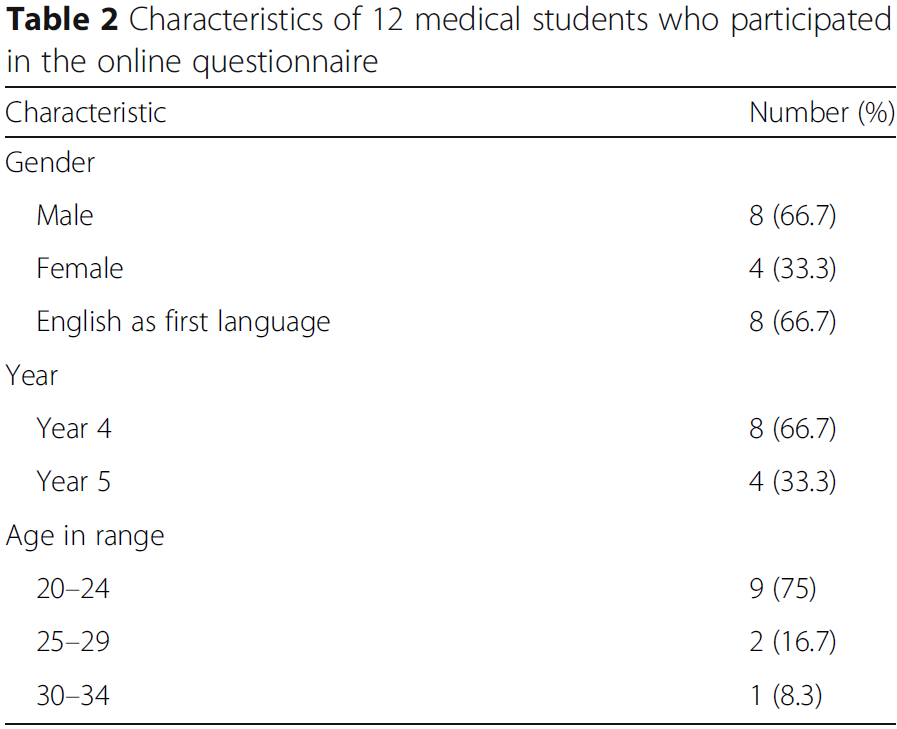

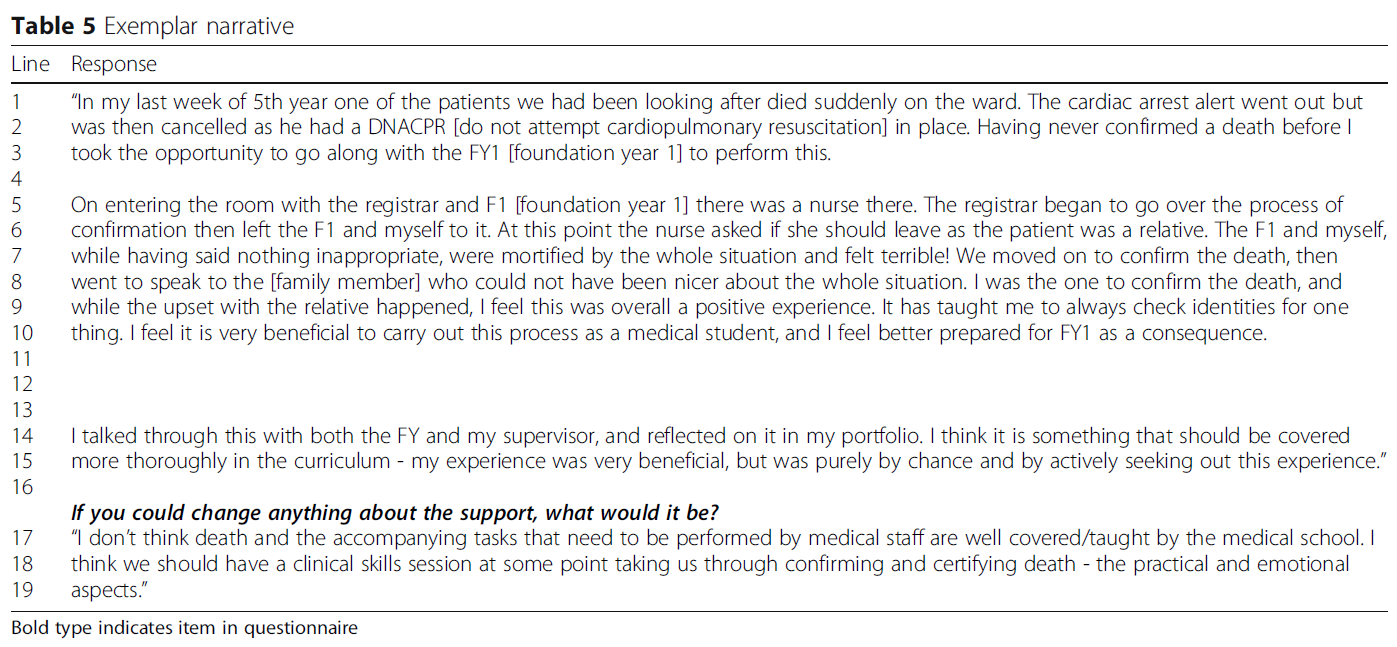

비임상적 맥락에서는 6주간의 선택 과목으로, 6학년 의대생들이 한 조를 이루어 시청각 환자 정보인 지식 클립을 개발했습니다. 지식 클립은 선천성 심장병에 대해 설명하는 짧은 동영상(주로 애니메이션)이었습니다. 학생들은 환자, 그리고 커뮤니케이션 및 정보 과학(CIS) 학생과 협력하여 이러한 지식 클립을 개발했습니다[34]. 의대생의 목표는 환자의 정보 요구를 파악하고, 이해하기 쉬운 정보를 만들고, 환자 및 CIS 학생과 협업하는 방법을 배우는 것이었습니다. 이 과정을 진행하는 동안 두 의대생은 환자와 세 차례 만났습니다. 첫 번째 미팅에서는 의대생과 환자가 서로 친해지고 지식 클립의 주제를 결정했습니다. 2번과 3번 미팅에서 의대생은 지식 클립과 협력 기술에 대한 환자의 피드백을 받았습니다. 의대생 쌍은 시청각 정보 개발 방법에 대한 조언을 제공하고 지식 클립에 대한 피드백을 제공한 CIS 학생과도 세 차례 만났습니다[34]. 2020년 8월, 네덜란드 중심부의 한 대학병원에서 12명의 의대생이 이 선택 과목에 등록했습니다. 이 과정은 코로나19 팬데믹으로 인해 전적으로 온라인으로 진행되었습니다. 이 과정에 등록한 의대생 12명 중 11명이 이 연구에 참여하기 위해 사전 동의를 제공했습니다.

The non-clinical context was a six-week elective course, in which pairs of sixth-year medical students developed audiovisual patient information, a knowledge clip. The knowledge clips were short (often animated) videos, where for instance a congenital heart disease is explained. Students developed these knowledge clips in collaboration with a patient and a Communication and Information Sciences (CIS) student [34]. The goal for medical students was learn how to identify a patient’s information need, create understandable information, and collaborate with a patient and a CIS student. During the course, the pair of medical students met three times with the patient. In meeting 1, the medical students and the patient got acquainted and determined the subject of the knowledge clip. In meetings 2 and 3, medical students received patient feedback on their knowledge clip and cooperation skills. The medical student pair also met three times with the CIS student, who provided advice on how to develop audiovisual information and gave feedback on the knowledge clip [34]. In August 2020, twelve medical students from an academic hospital in the center of the Netherlands enrolled in this elective course. The course was entirely online, due to the COVID pandemic. Eleven out of twelve medical students who signed up for the course enrollees provided informed consent to participate in this study.

임상 상황은 소아과와 산부인과를 결합한 12주간의 임상 실습이었으며, 4학년 의대생들은 의학 커리큘럼의 필수 과정으로 이 실습에 참여했습니다. 실습 기간 동안 학생들은 두 명의 환자에게 피드백을 요청했습니다. 이에 대비하여 학생들은 대화를 통해 적절한 시기에 적절한 피드백을 요청하는 자기 주도적 피드백 과정을 이수했습니다[35]. 임상 실습이 끝날 무렵, 학생들은 의미 파악과 행동 계획에 초점을 맞춘 촉진된 성찰 세션에 참여했습니다[35]. 2022년 6월부터 8월까지 사무원 과정을 마친 학생들은 이 연구에 참여하도록 요청받았습니다. 54명 중 10명의 학생이 사전 동의를 통해 참여에 동의했습니다.

The clinical context was a twelve-week clerkship combining Pediatrics and Gynecology, in which fourth-year medical students participated as a mandatory part of their medical curriculum. During the clerkship, students asked two patients for feedback. In preparation, students completed a self-directed feedback course on asking for relevant feedback, at the right time, through dialogue [35]. At the end of the clerkship, students participated in a facilitated reflection session, which focused on sense-making and action-planning [35]. Students who completed their clerkship between June – August 2022, were asked to participate in this study. Ten students out of 54 provided informed consent to participate.

익명성을 보장하고 명확성을 기하기 위해 이 논문에서 모든 학생은 '그녀'로, 모든 환자는 '그'로 지칭합니다. 간결성을 위해 의대생은 '학생'으로 지칭합니다.

To ensure anonymity, and for the sake of clarity, all students in this paper will be referred to as ‘she’, and all patients will be referred to as ‘he’. For the sake of brevity, medical students will be referred to as students.

데이터 수집

Data collection

비임상 분야의 경우, 신뢰성 문헌을 기반으로 반구조화된 인터뷰 가이드를 개발했습니다. 두 명의 학생을 대상으로 인터뷰 가이드를 시범 운영하여 약간의 조정을 거쳤습니다. 그런 다음, 후속 인터뷰가 유사하고 비교 가능한 방식으로 진행될 수 있도록 CE와 NM이 함께 처음 두 번의 인터뷰를 진행했습니다. 나머지 9번의 면접은 NM과 CE가 나누어 진행했습니다.

For the non-clinical context, we developed a semi-structured interview guide based on credibility literature. We piloted the interview guide with two students, which resulted in minor adjustments. Then, CE and NM conducted the first two interviews together to ensure subsequent interviews were conducted similarly and comparably. The remaining nine interviews were divided between NM and CE.

인터뷰 가이드를 임상 상황에 맞게 조정하고 비임상 상황의 결과를 기반으로 했습니다. 세 번째 연구자(WD)가 임상 맥락에서 대부분의 인터뷰를 수행했습니다. 먼저, CE와 WD가 함께 두 번의 인터뷰를 진행하여 WD가 비임상 상황과 유사한 인터뷰를 수행할 수 있도록 훈련시켰습니다. 그런 다음 나머지 인터뷰는 WD가 진행했습니다.

We adjusted the interview guide to fit the clinical context and build on the results from the non-clinical context. A third researcher (WD) performed most of the interviews from the clinical context. First, CE and WD conducted two interviews together to train WD in performing the interviews comparably to the non-clinical context. Then, WD conducted the remaining interviews.

인터뷰 가이드에는 환자의 신뢰도, 학생과 환자의 관계, 피드백 메시지에 대한 질문이 포함되어 있었습니다(부록 A 참조). 학생들은 선택 과목 또는 임상실습을 마친 후 개별적으로 인터뷰를 진행했습니다. 화상 통화 또는 대면으로 진행된 인터뷰는 음성으로 녹음하고 그대로 필사했습니다. 인터뷰는 약 60분간 진행되었습니다.

The interview guide included questions on patients’ credibility, students’ relationship with the patients and the feedback messages (See Appendix A). Students were interviewed individually after completion of the elective course or clerkship. The interviews, which were conducted via video-call or face-to-face, were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Interviews lasted approximately 60 minutes.

데이터 분석

Data analysis

학생들이 환자의 신뢰도를 판단하는 방법을 이해하기 위해 신뢰도에 대한 학생들의 추론을 분석했습니다. 우리는 주제별 분석의 한 형태인 템플릿 분석을 수행하여 신뢰도 증가 또는 감소에 대한 학생들의 주장을 파악했습니다[36]. 이 방법을 선택한 이유는 이전의 피드백 신뢰도 문헌을 기반으로 구축할 수 있고, 귀납적으로 환자 신뢰도에 관한 새로운 코드를 개발할 수 있는 여지를 남겨두었기 때문입니다. 학생들이 어떻게 판단을 내리는지, 그리고 이것이 맥락적 요소의 영향을 받는지 이해하기 위해 인과적 네트워크 분석을 수행했습니다. 이 방법을 선택한 이유는 프로세스의 변수 간 일관성을 매핑하기 때문인데, 이는 신뢰성 판단과 같은 인지 프로세스에도 적용될 수 있습니다[37]. 학생들이 환자의 신뢰도를 판단하는 추론의 요소를 이 연구에서는 '논증'이라고 부릅니다.

To understand how students make credibility judgments of patients, we analyzed their reasoning about credibility. We performed template analysis, which is form of thematic analysis, to identify students’ arguments for increased or reduced credibility [36]. We chose this method because it allowed for building on previous feedback credibility literature, and left room for inductively developing new codes regarding patient credibility. To understand how students built their judgment and how this was impacted by contextual elements, we performed a causal network analysis. We chose this method because it maps the coherence between variables of a process, which can also be applied to cognitive processes such as making a credibility judgment [37]. The elements in students’ reasoning for determining a patient’s credibility are called ‘arguments’ in this study.

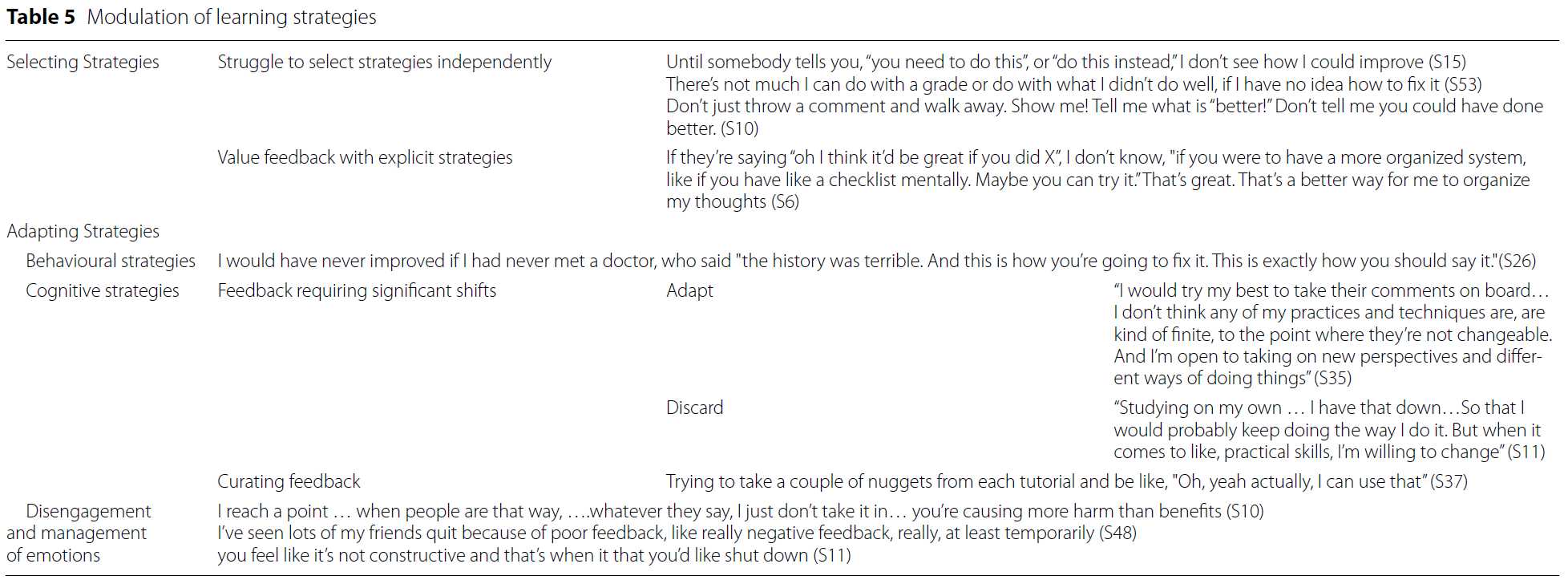

템플릿 분석

Template analysis

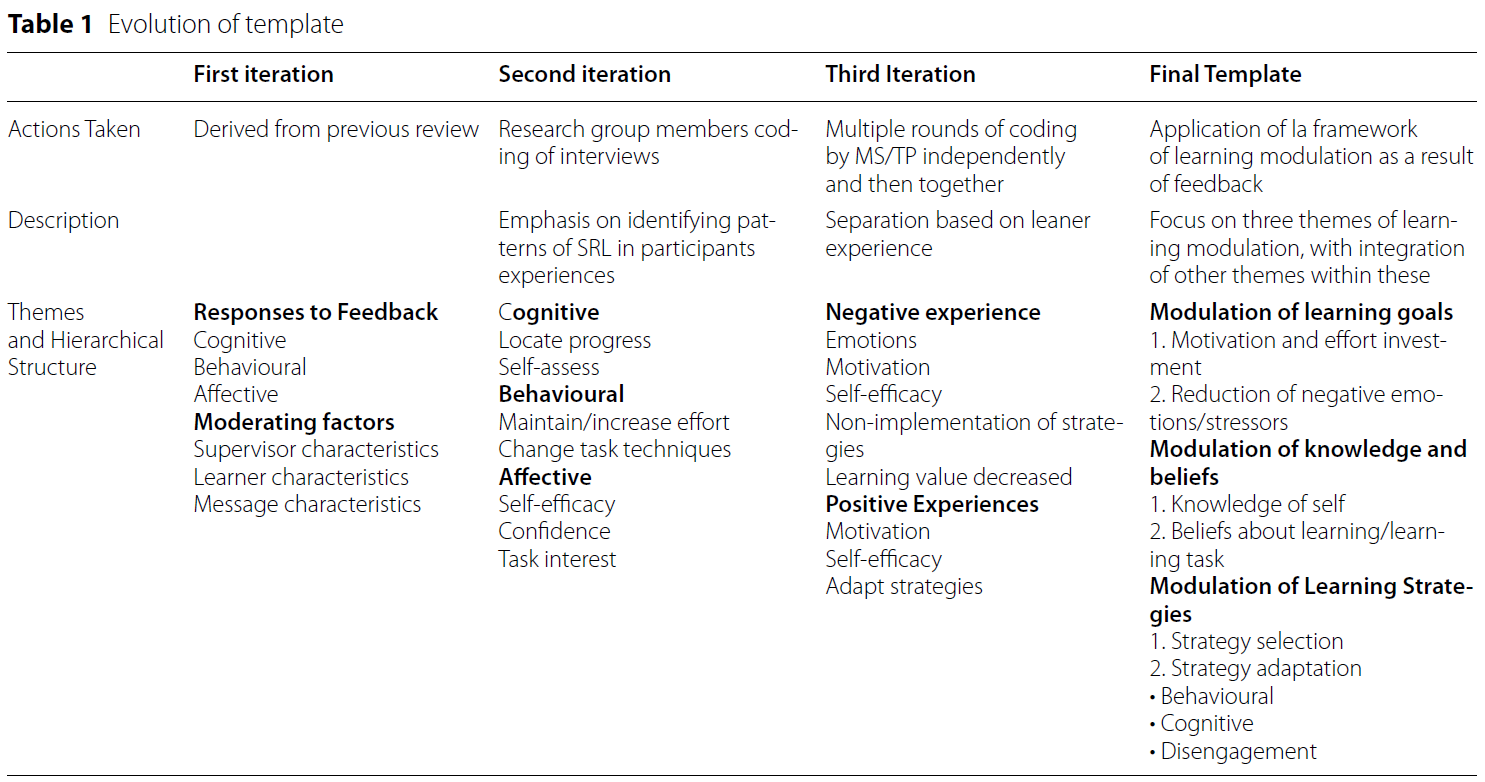

코딩 템플릿은 귀납적 접근법과 연역적 접근법을 모두 사용하여 세 단계로 개발되었습니다.

- 첫째, 신뢰성 판단의 근거가 될 수 있는 문헌에 기술된 논거를 구성하는 선험적 코드를 정의했습니다(부록 B)[6, 10, 11, 14, 15, 18, 19, 38].

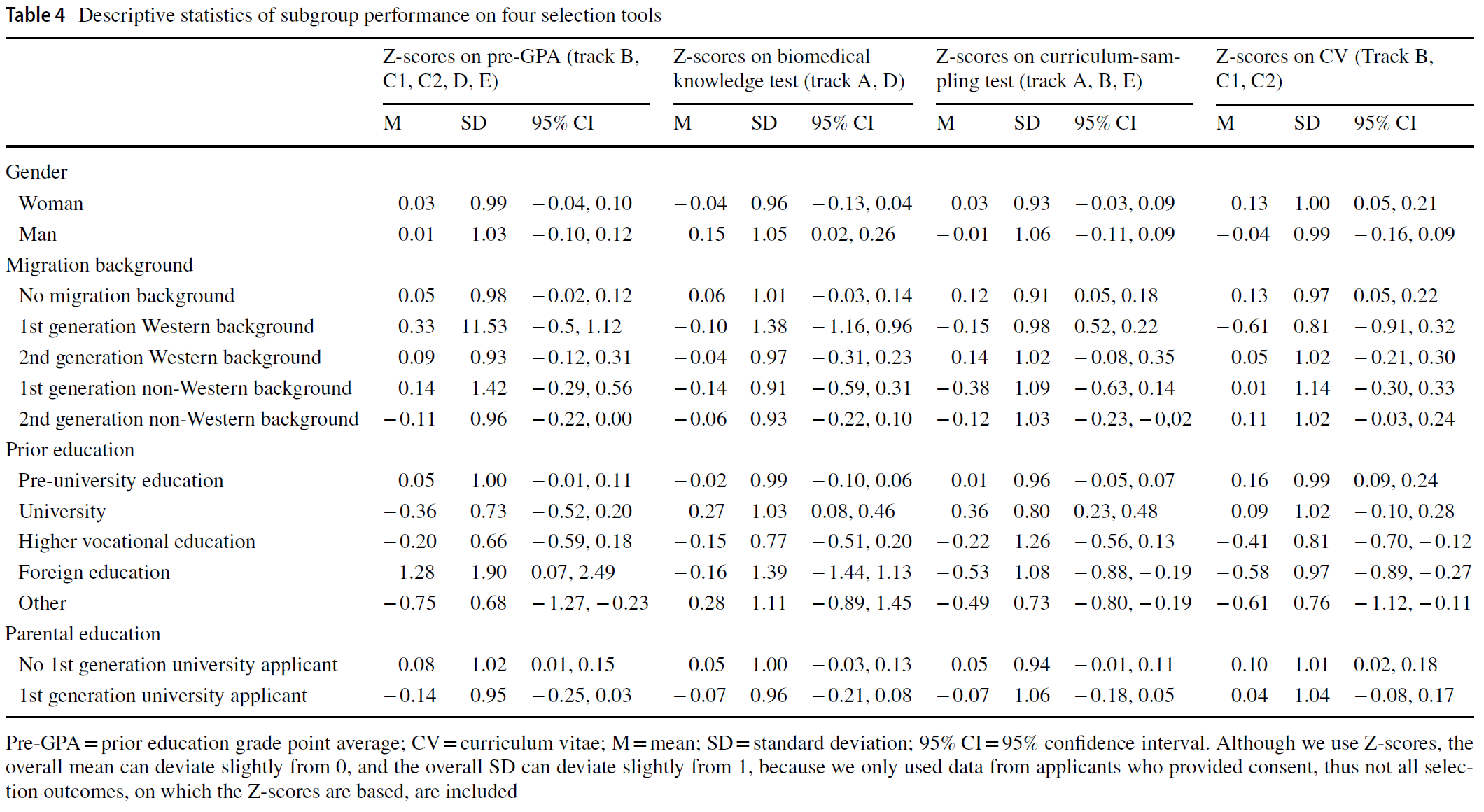

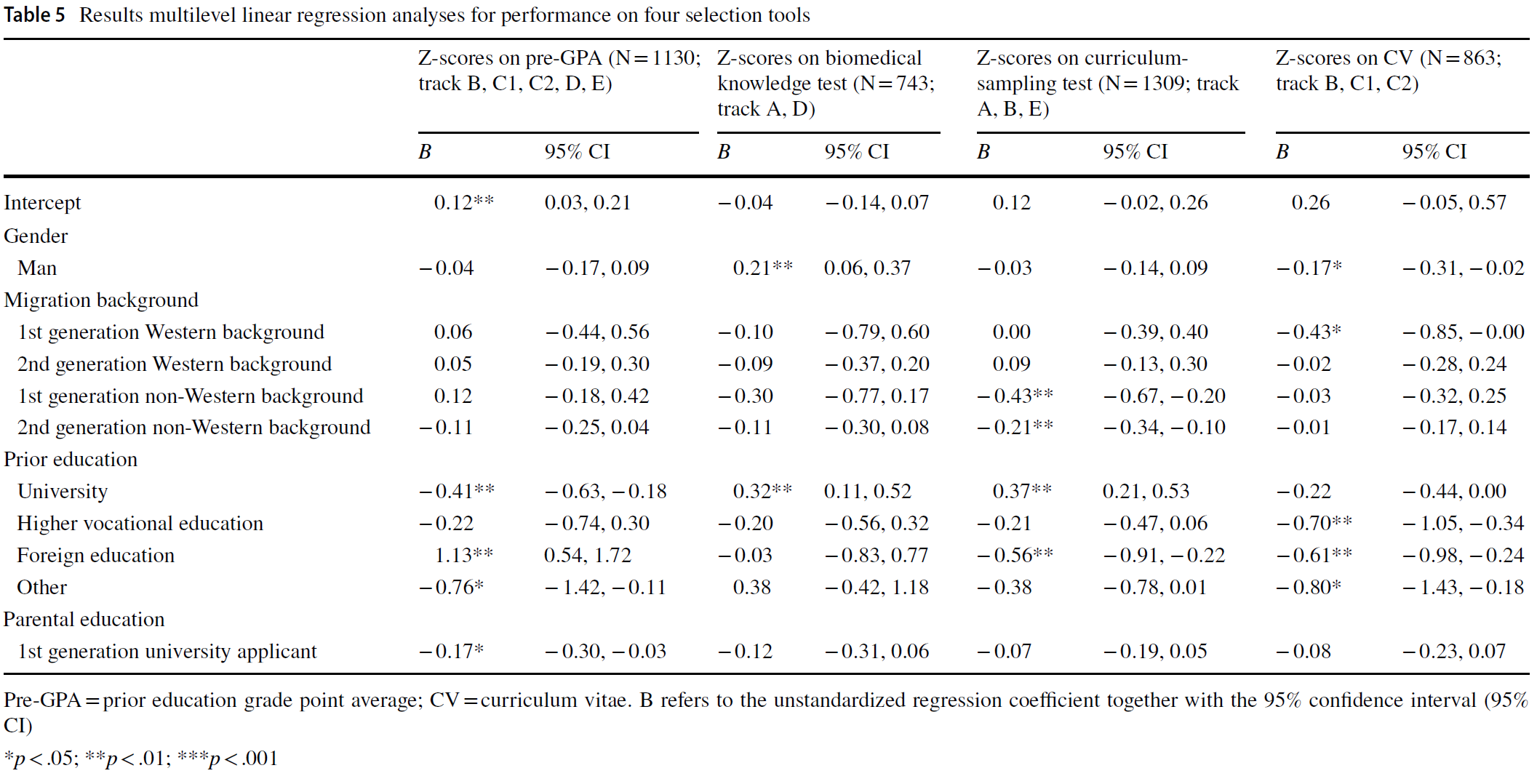

- 둘째, 초기 코딩 템플릿을 구성하기 위해 비임상 맥락의 인터뷰를 사용했습니다. CE와 NM은 코딩 템플릿을 인터뷰에 반복적으로 적용하면서 새로운 코드를 추가하고 기존 코드를 개선했습니다. 코드를 더욱 세분화하고 구조화하기 위해 이들은 1-3차, 4-5차 인터뷰 코딩 후, 그리고 5-12차 인터뷰 후 코딩 템플릿에 대해 RK와 논의했습니다. 코드는 세 가지 신뢰성 차원에 따라 구조화되었습니다: 역량, 신뢰성, 선의의 세 가지 차원에 따라 코드를 구조화했습니다[18]. 몇몇 코드는 신뢰성 차원에 맞지 않았습니다. 여기에는 맥락의 요소와 두 가지 새로운 주제, 즉 피드백 메시지와 환자 피드백에 대한 이전 경험이 포함되었습니다.

- 셋째, CE와 WD는 초기 코딩 템플릿을 임상적 맥락에서 처음 6개의 인터뷰에 적용하고 새로운 코드를 추가하고 기존 코드를 재정의하여 템플릿을 수정했습니다. 이러한 수정 사항은 최종 코딩 템플릿을 정의하기 위해 RK와 논의했습니다.

- 마지막으로 CE는 최종 코딩 템플릿을 전체 데이터 세트에 적용하고 최종 해석에 대한 합의에 도달할 때까지 전체 연구팀과 결과를 논의했습니다.

The coding template was developed in three steps, using both an inductive and deductive approach.

- First, a priori codes were defined constituting arguments described in literature on which credibility judgments can be based (Appendix B) [6, 10, 11, 14, 15, 18, 19, 38].

- Second, interviews from the non-clinical context were used to construct the initial coding template. CE and NM iteratively applied the coding template to the interviews, whilst adding new codes and refining existing codes. To further refine and structure the codes, they discussed the coding template with RK after coding interviews 1–3, 4–5, and after interviews 5–12. Codes were structured according to the three credibility dimensions: Competence, Trustworthiness, and Goodwill [18]. Several codes did not fit the credibility dimensions. These included elements of the context and two emergent themes: the feedback message and previous experiences with patient feedback.

- Third, CE and WD applied the initial coding template to the first six interviews from the clinical context and modified the template by adding new codes and redefining existing codes. The modifications were discussed with RK to define the final coding template.

- Lastly, CE applied the final coding template to the full dataset and findings were discussed with the entire research team until consensus was reached about the final interpretation.

인과 관계 네트워크 분석

Causal network analysis

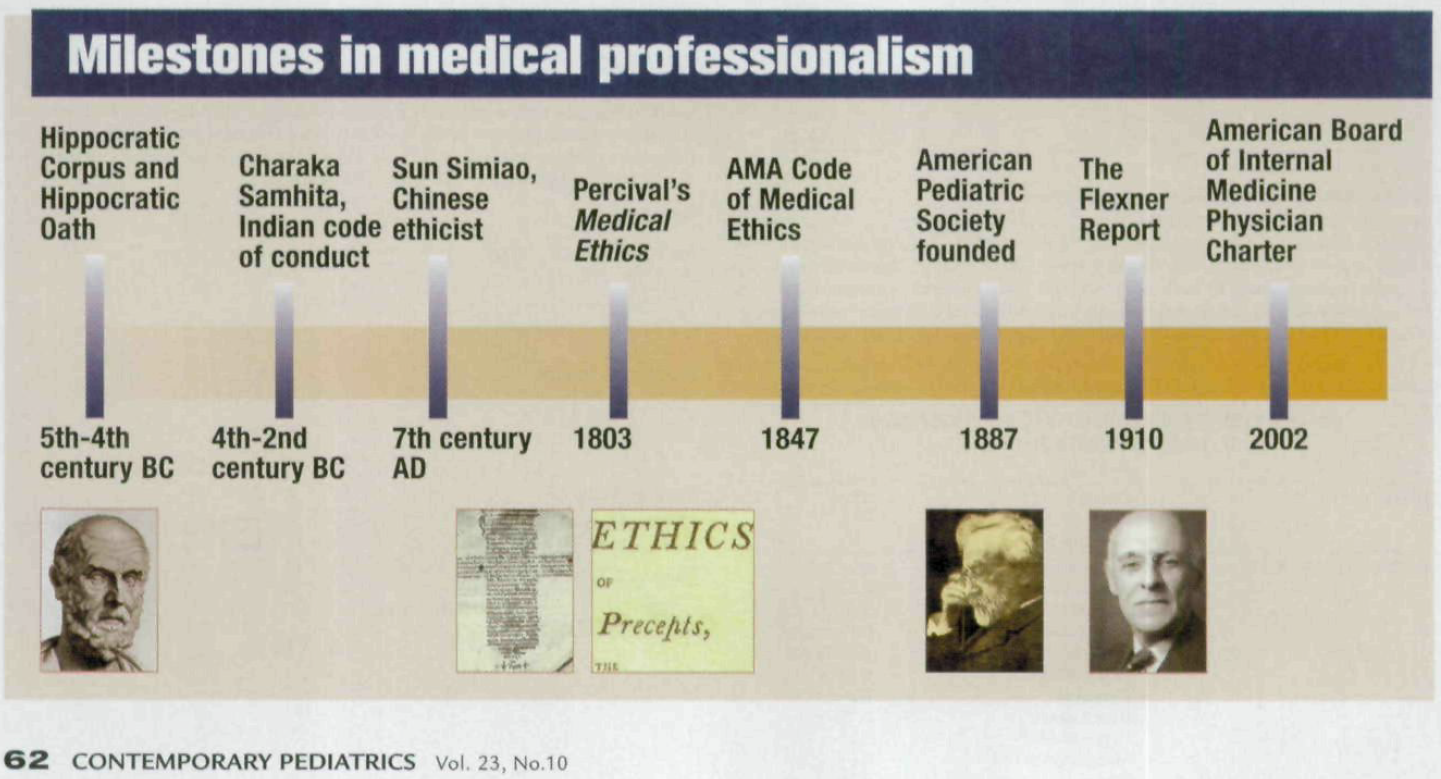

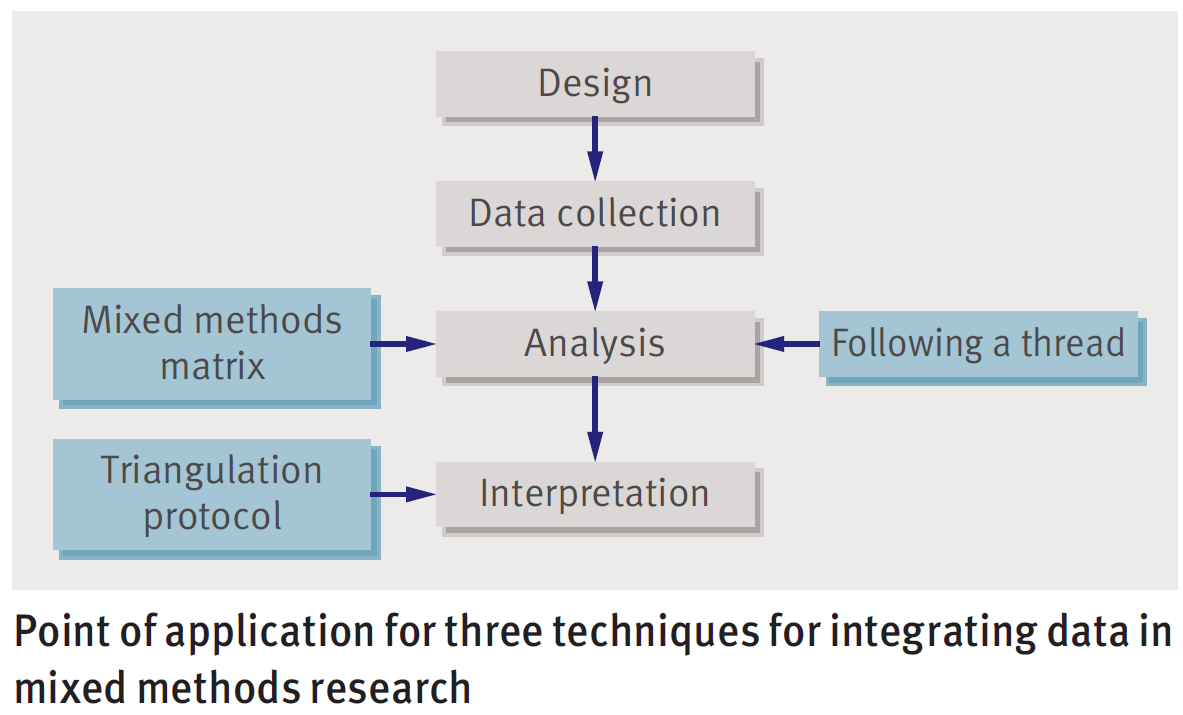

판단이 어떻게 만들어지고 주장이 어떻게 연관되어 있는지 살펴보기 위해 사례 간 인과 네트워크 분석을 수행했습니다[37].

- 먼저, 학생들이 신뢰성 판단의 근거로 삼은 모든 주장의 목록을 작성했습니다. 이 목록은 템플릿 분석에서 도출된 것으로, 이 코드북의 각 코드는 하나의 논증과 유사했습니다.

- 둘째, 학생 한 명당 하나씩 21개의 인과 네트워크를 구성하여 이러한 주장과 그 관계를 표시했습니다. 관계를 다음을 통해 식별했습니다.

- 학생들이 서로 조합하여 언급한 논증(텍스트 조각이 서로 겹치거나 이어지는 것을 의미),

- 신호어 분석(예: 그렇다면, 그러므로, 그래서, 왜냐하면),

- 시간성 분석(한 논증이 다른 논증에 영향을 미치는 경우 이 논증이 학생들의 추론에서 먼저 발생해야 함)

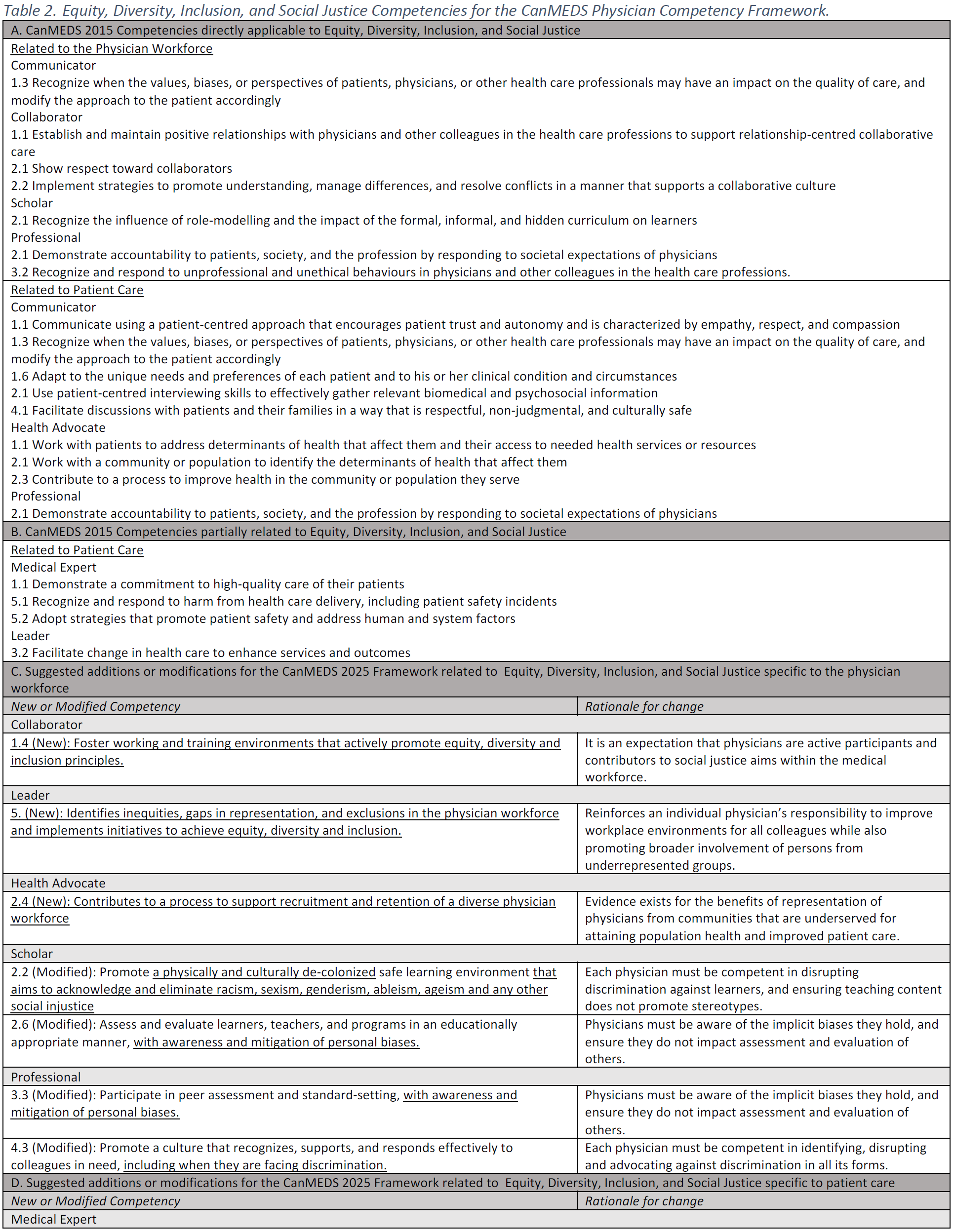

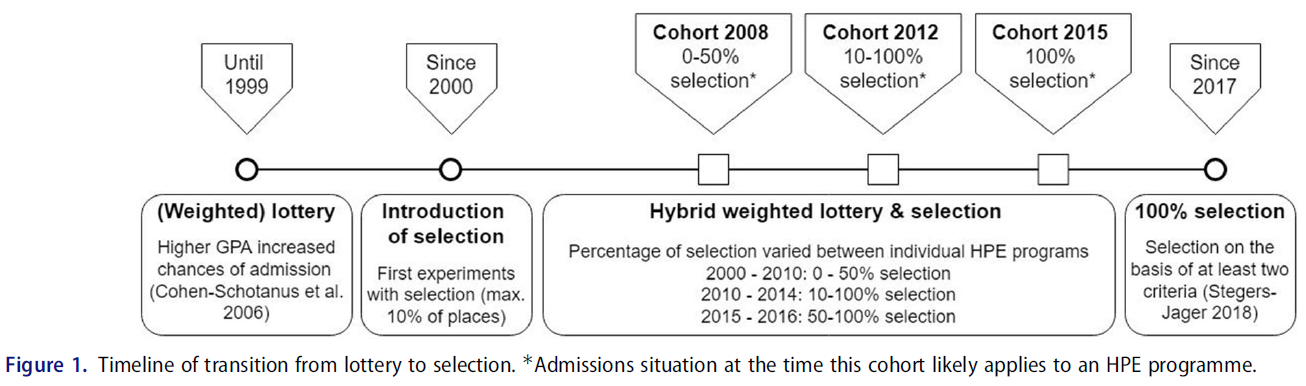

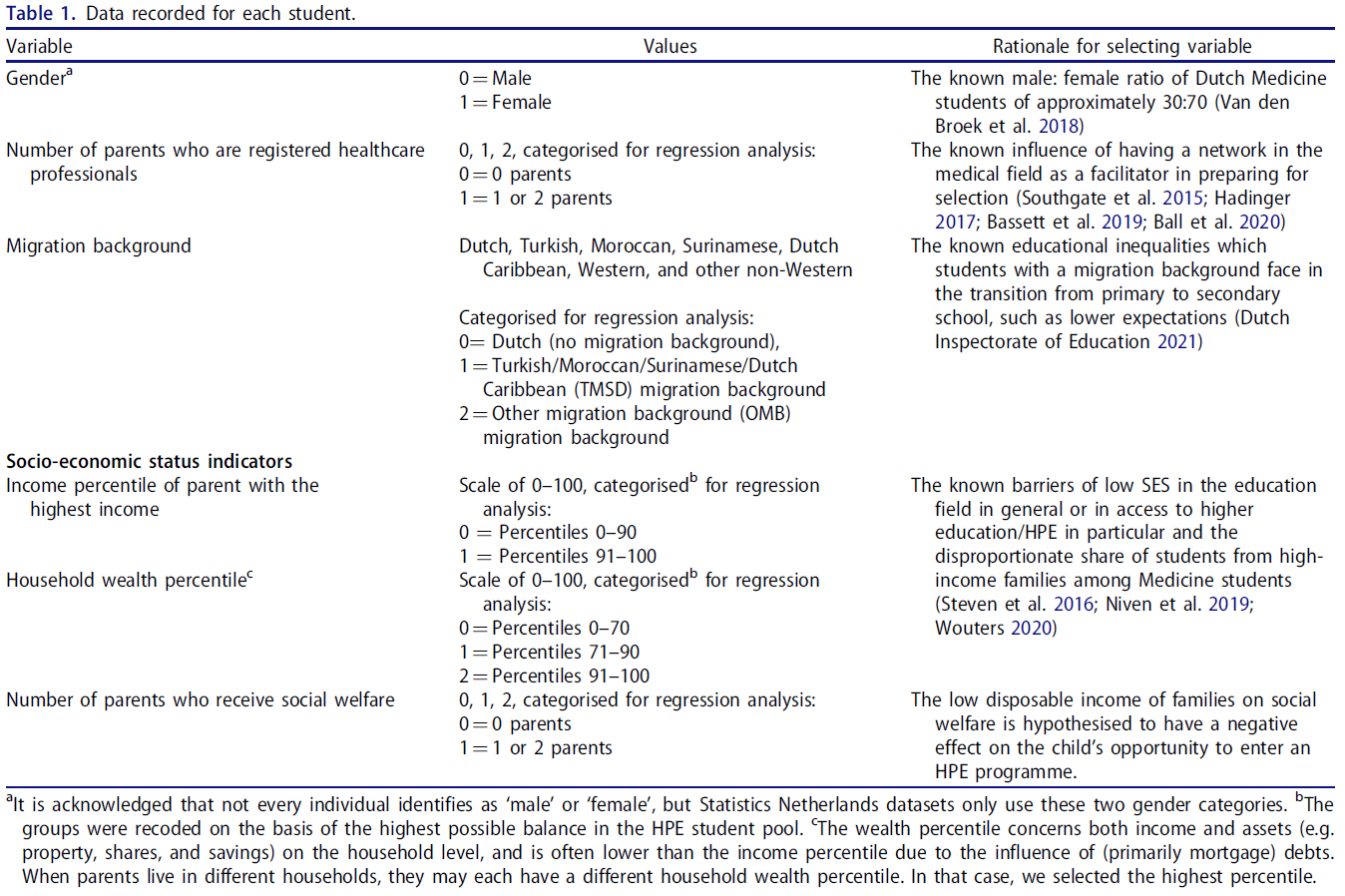

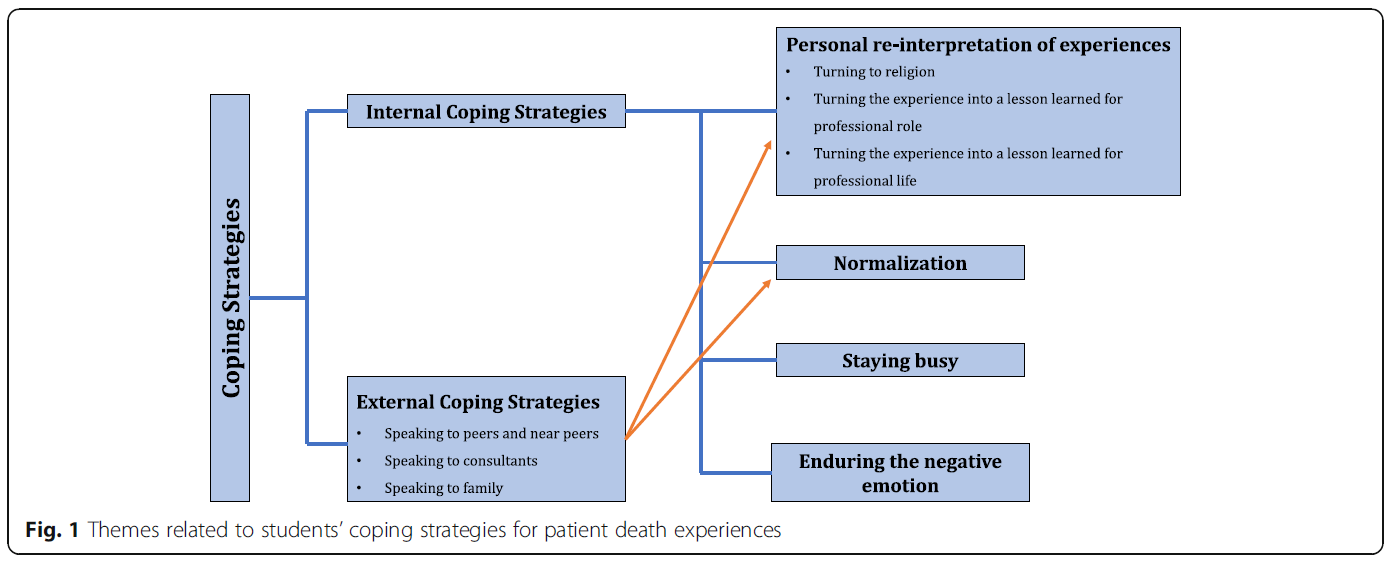

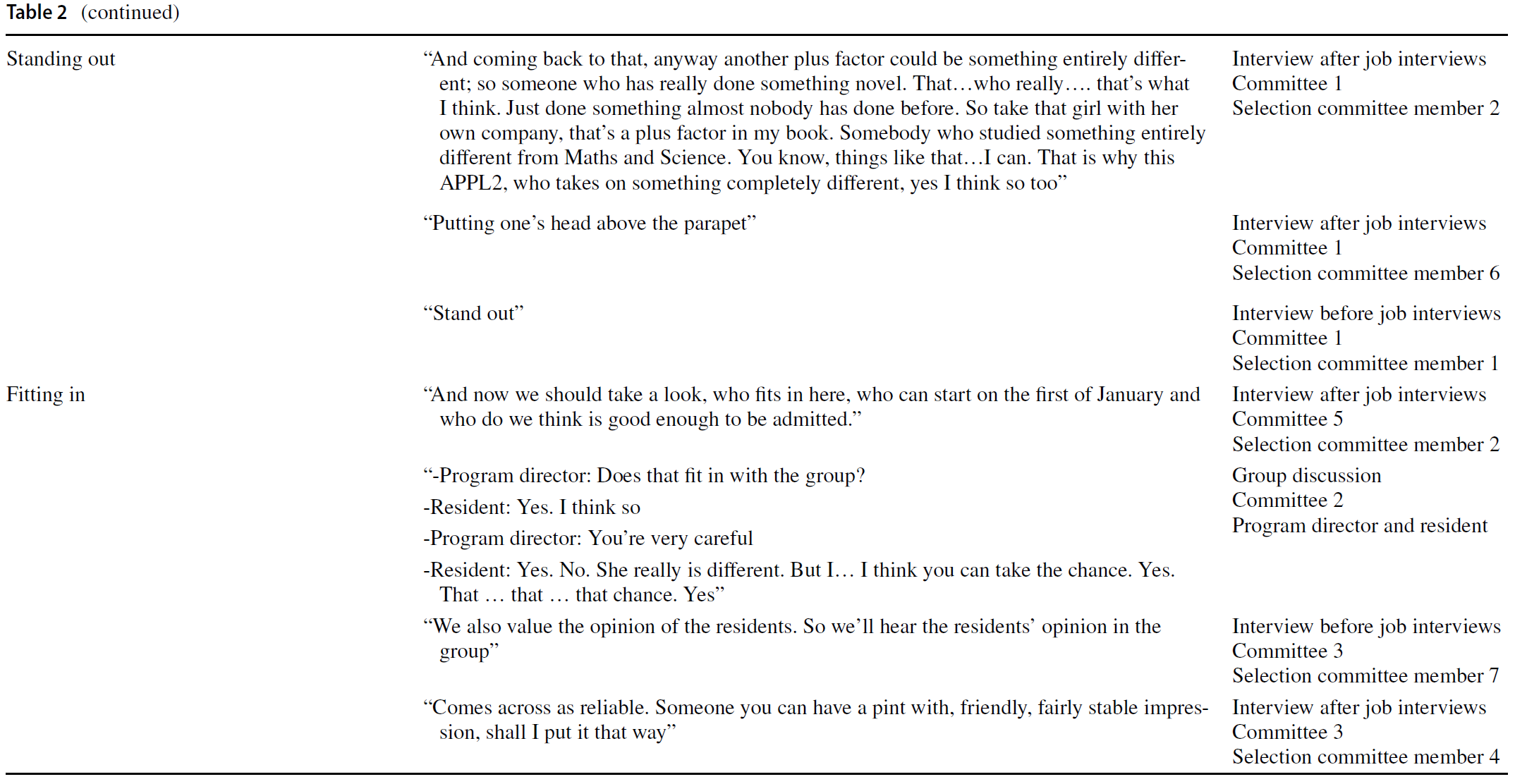

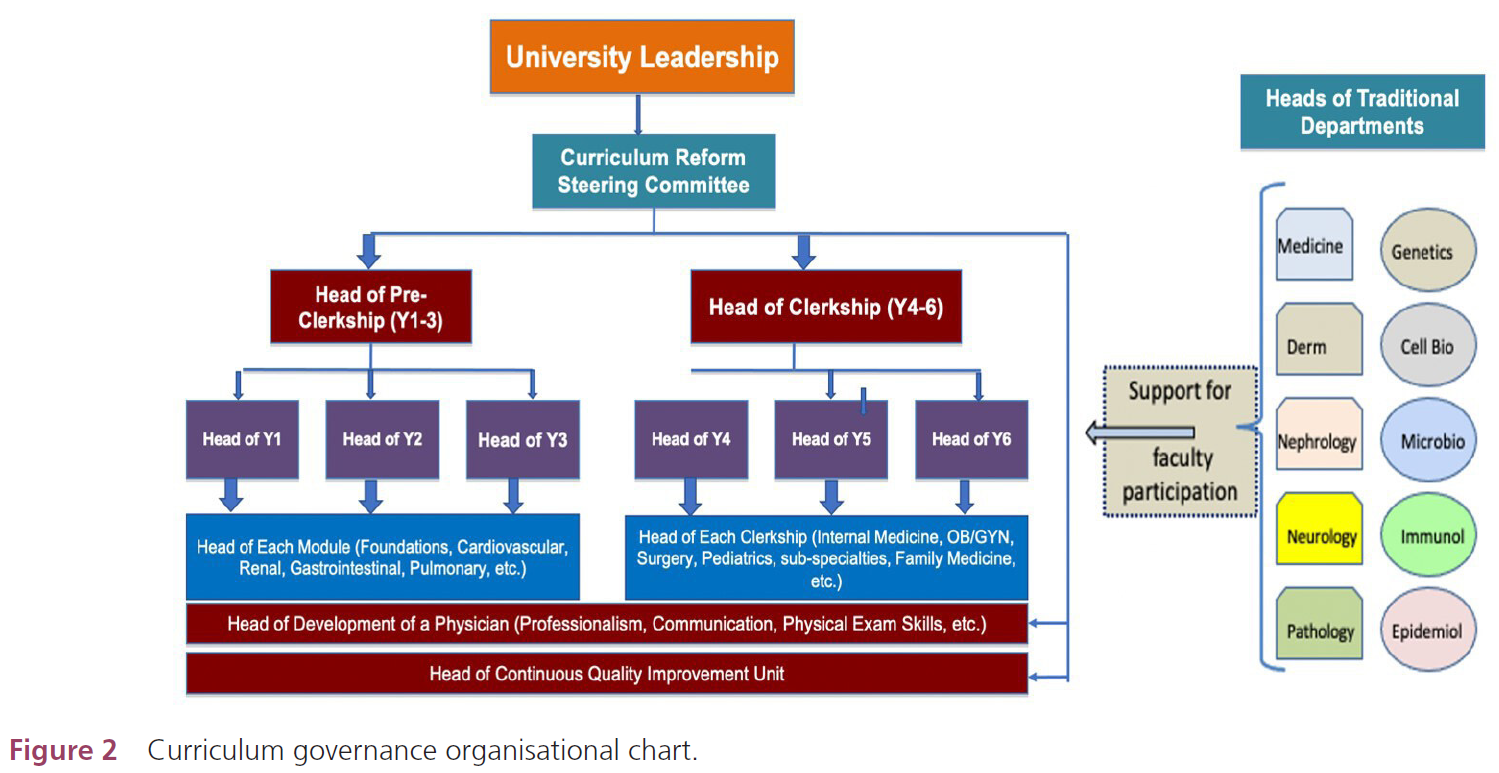

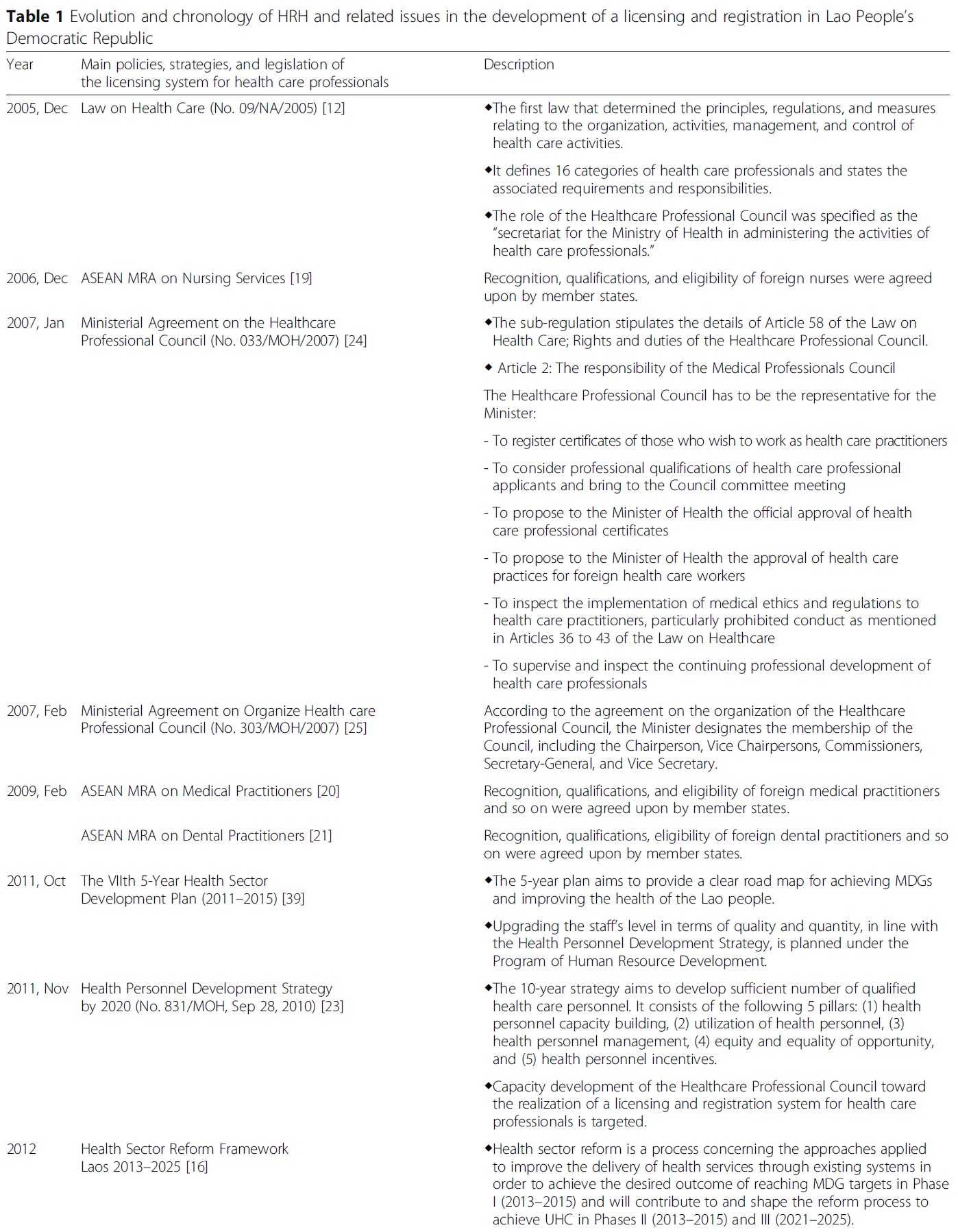

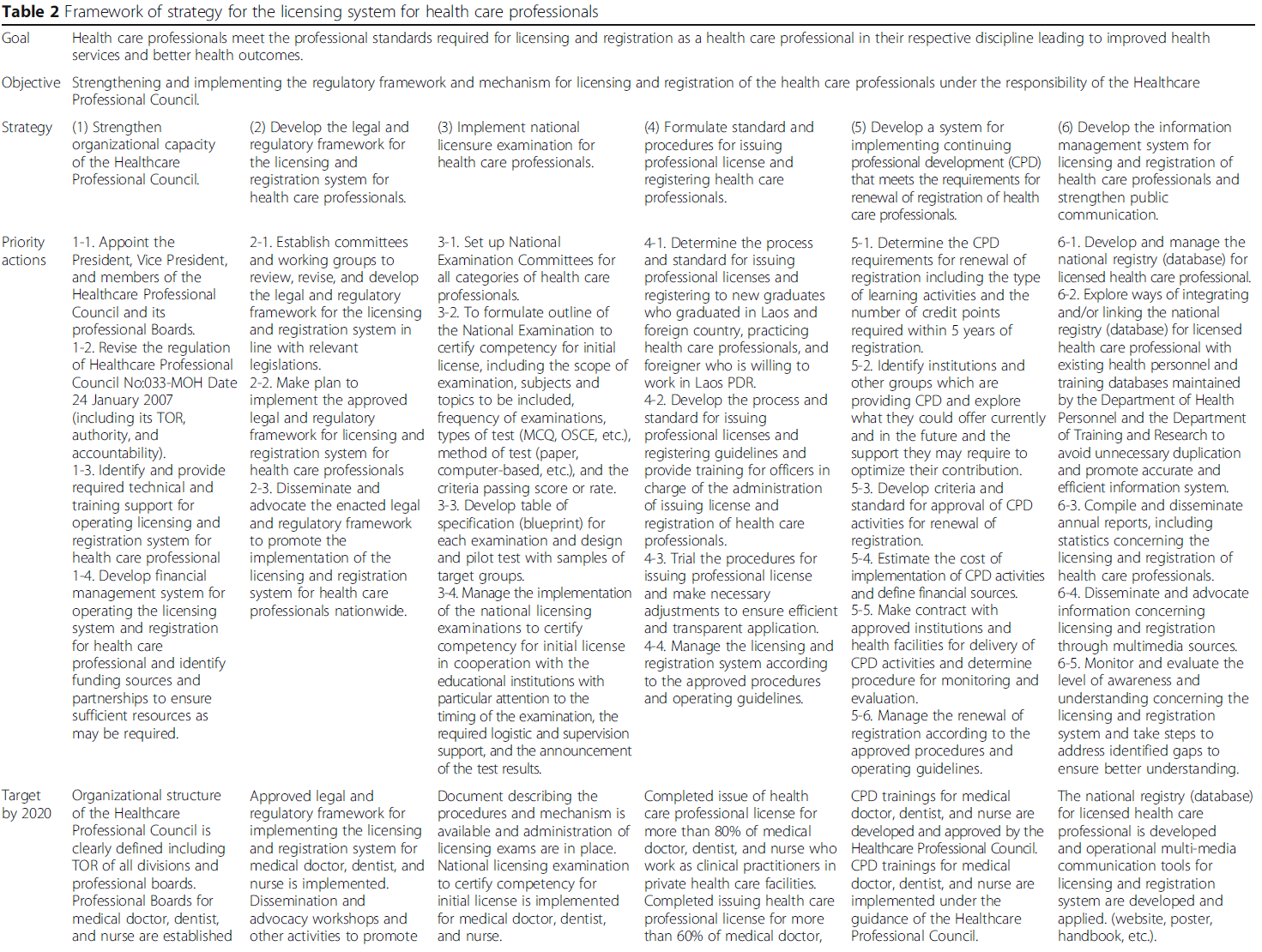

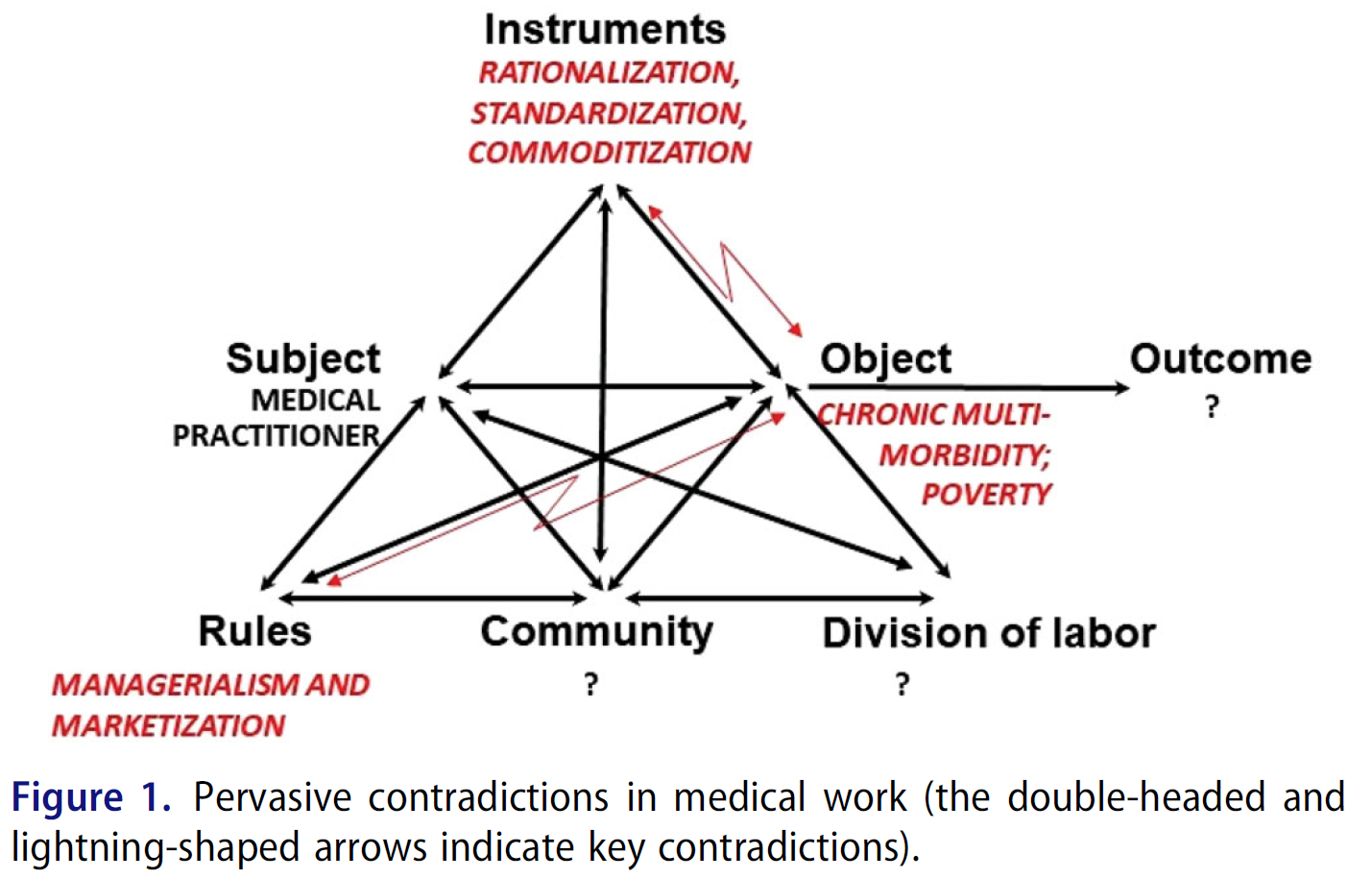

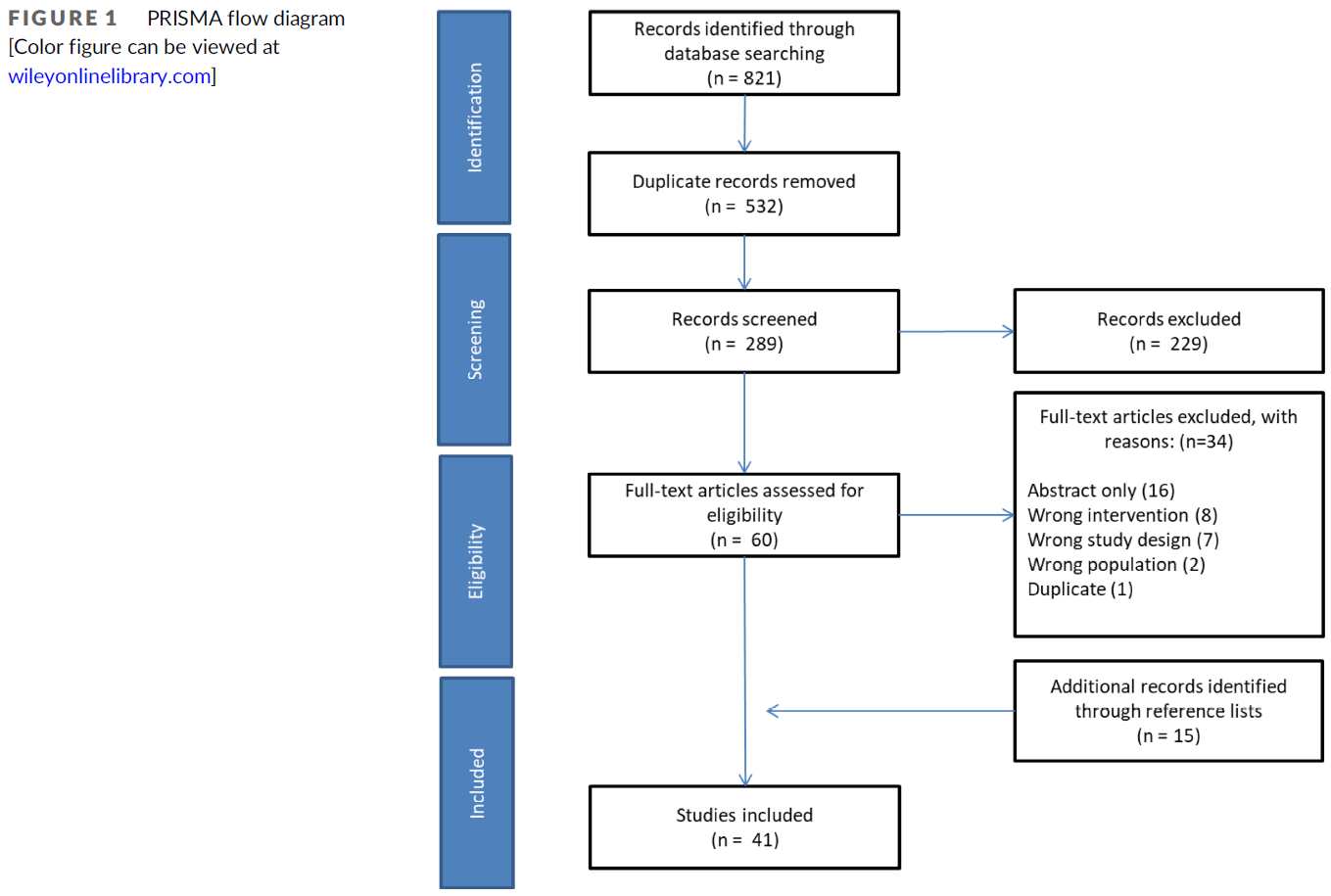

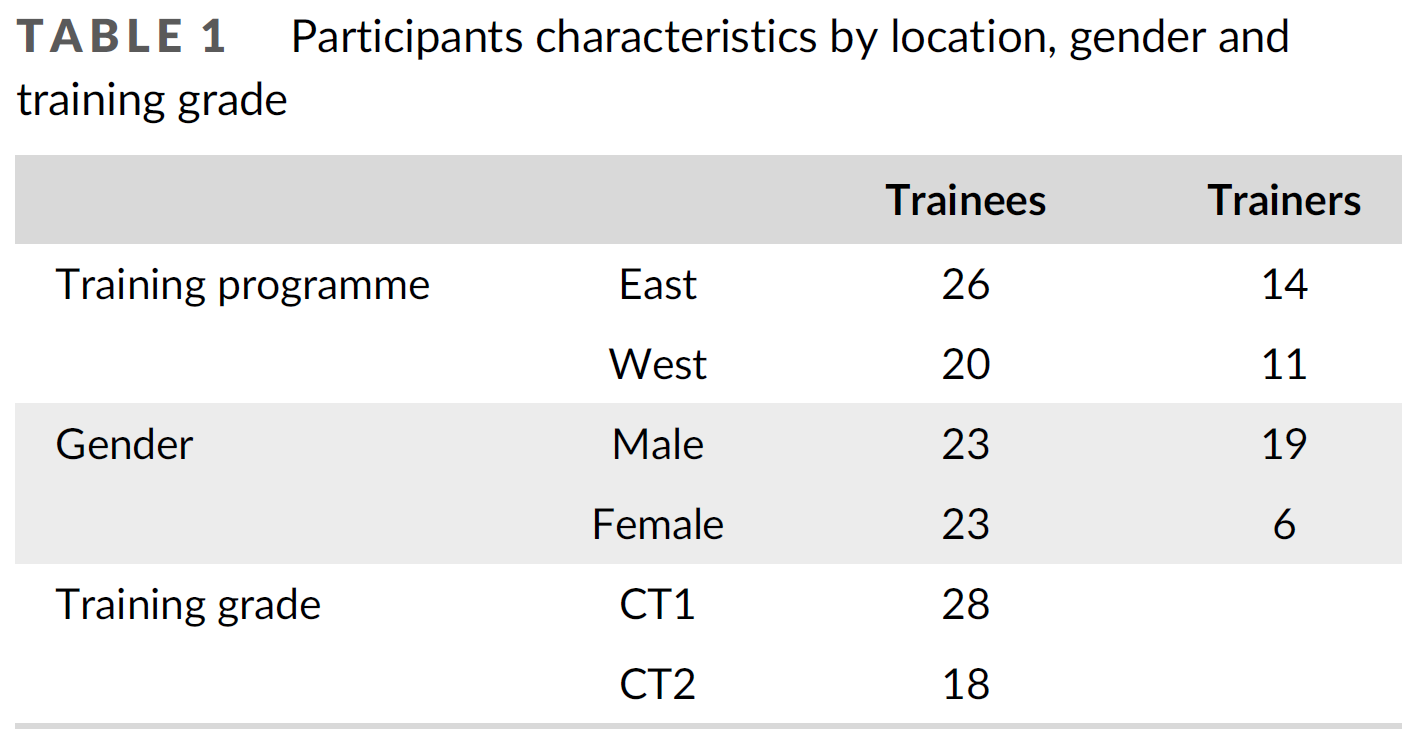

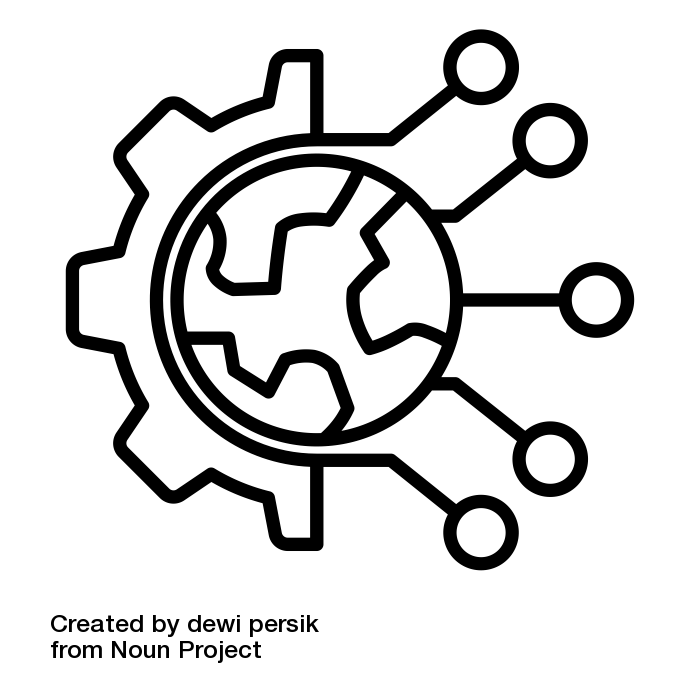

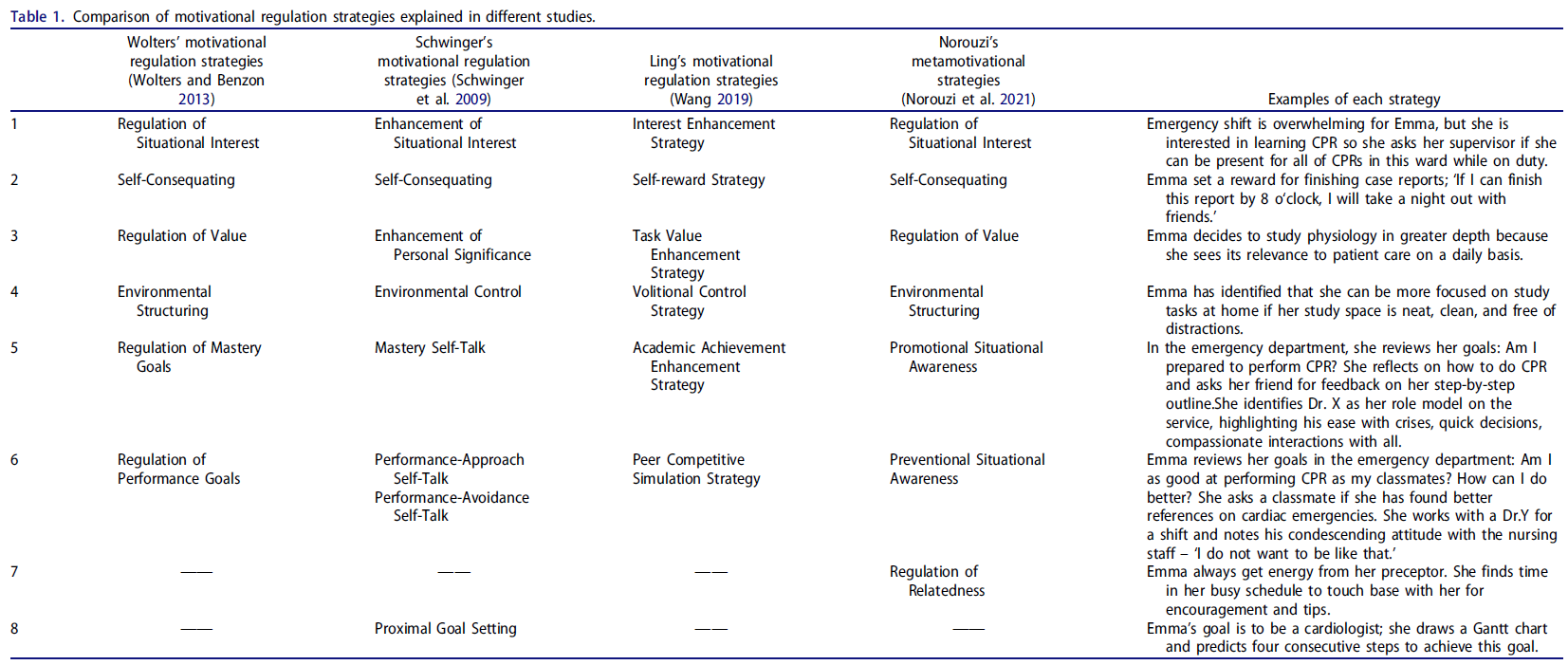

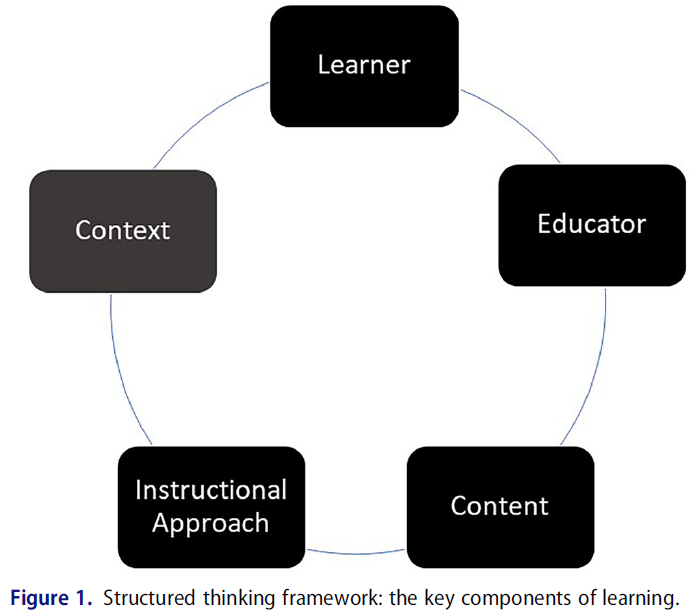

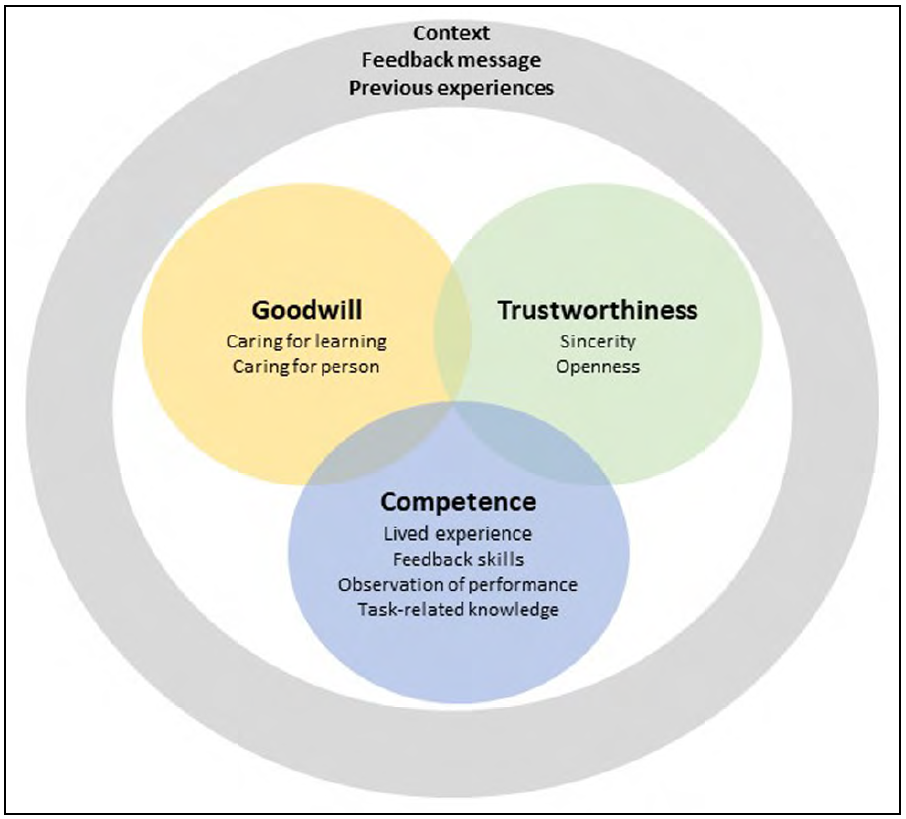

- 셋째, 21개의 개별 인과 네트워크는 개별 논증 간의 모든 상호작용을 포함하는 전체 네트워크로 결합되었습니다. 이 네트워크를 이해하기 쉽게 하기 위해 신뢰도 차원과 맥락, 피드백 메시지, 이전 경험의 요소 간의 상호작용만 설명하여 네트워크를 단순화했으며, 그 결과 그림 1과 같이 나타났습니다.

To explore how judgments were built, and how arguments were related, we performed cross-case causal network analyses [37].

- First, we constructed a list of all arguments on which students based their credibility judgments. This list was derived from the template analysis, each code of this codebook resembled an argument.

- Second, we constructed 21 causal networks, one for each individual student, in which we displayed these arguments and their relations. Relations were identified

- by selecting arguments that students mentioned in combination with each other (meaning text-fragments overlapped or followed-up on each other),

- by analyzing signal words (for instance: then, therefore, so, because), and

- by analyzing temporality (if one argument affects the other, this argument must happen first in students’ reasoning).

- Third, the 21 individual causal networks were combined in an overarching network, that comprised all interactions between individual arguments. To make this network comprehensible, we simplified the network by only illustrating the interactions between dimensions of credibility and the elements of the context, the feedback message, and previous experiences, which resulted in Figure 1.

이 그림은 피드백 제공자인 환자에 대한 학생들의 신뢰도 판단을 시각화한 것입니다. 학생들의 신뢰도 판단은 환자의 선의, 신뢰성 및 역량에 관한 여러 가지 논증으로 구성되었습니다. 각 차원 내 및 차원 간의 논증은 서로 상호작용했습니다. 또한 학생들의 신뢰도 판단은 회색 원으로 표시된 것처럼 맥락, 피드백 메시지, 이전 경험 등의 요소에 의해 영향을 받았습니다. 이러한 요소는 환자의 선의, 신뢰성 및 역량에 관한 논쟁에 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다.

This figure visualizes students’ credibility judgments of patients as feedback providers. Students’ credibility judgments consisted of multiple arguments regarding a patient’s Goodwill, Trustworthiness and Competence. Arguments within and between the dimensions interacted with each other. Moreover, students’ credibility judgments were influenced by elements of the context, the feedback message and previous experiences, which is depicted by the gray circle. These elements could affect arguments regarding a patient’s Goodwill, Trustworthiness, and Competence.

반사성

Reflexivity

연구팀은 의사(CE, JF), 교육 과학자(RK, MS), 학생(WD, NM)으로 구성되었습니다. 연구팀의 다양한 배경과 역할은 데이터에 대한 다양한 관점을 제공했습니다. 우리 팀은 환자를 학습의 중요한 파트너이자 정당한 피드백 제공자라는 관점을 가지고 있습니다. 우리의 관점이 연구 참여자에게 전달되는 것을 제한하고 학생들이 자신의 관점을 공유할 수 있도록 인터뷰 질문을 신중하게 구성했습니다. 일부 저자는 비임상 과정(CE, JF)과 임상 맥락에서의 피드백 교육(CE, JF, RK) 개발에 참여했습니다. 연구 기간 동안 이들은 이러한 교육에 강사로 참여하지 않았습니다.

The research team consisted of medical doctors (CE, JF), educational scientists (RK, MS), and students (WD, NM). The varied backgrounds and roles of our team provided multiple perspectives on our data. Our team has the viewpoint of patients being important partners in learning, and being legitimate feedback providers. To limit transferring our viewpoint to the study participants, and facilitate students in sharing their own viewpoints, we carefully formulated the interview questions. Some authors were involved in the development of the non-clinical course (CE, JF) and the feedback training in the clinical context (CE, JF, RK). During the study period they did not participate as teachers in these trainings.

또한 데이터 수집 및 분석 기간 동안 반사성을 높이기 위해 격주로 연구 회의를 개최하여 데이터 해석과 기본 가정을 논의했습니다.

Furthermore, to enhance reflexivity biweekly research meetings were held during data collection and analysis, in which interpretation of the data and underlying assumptions were discussed.

결과

Results

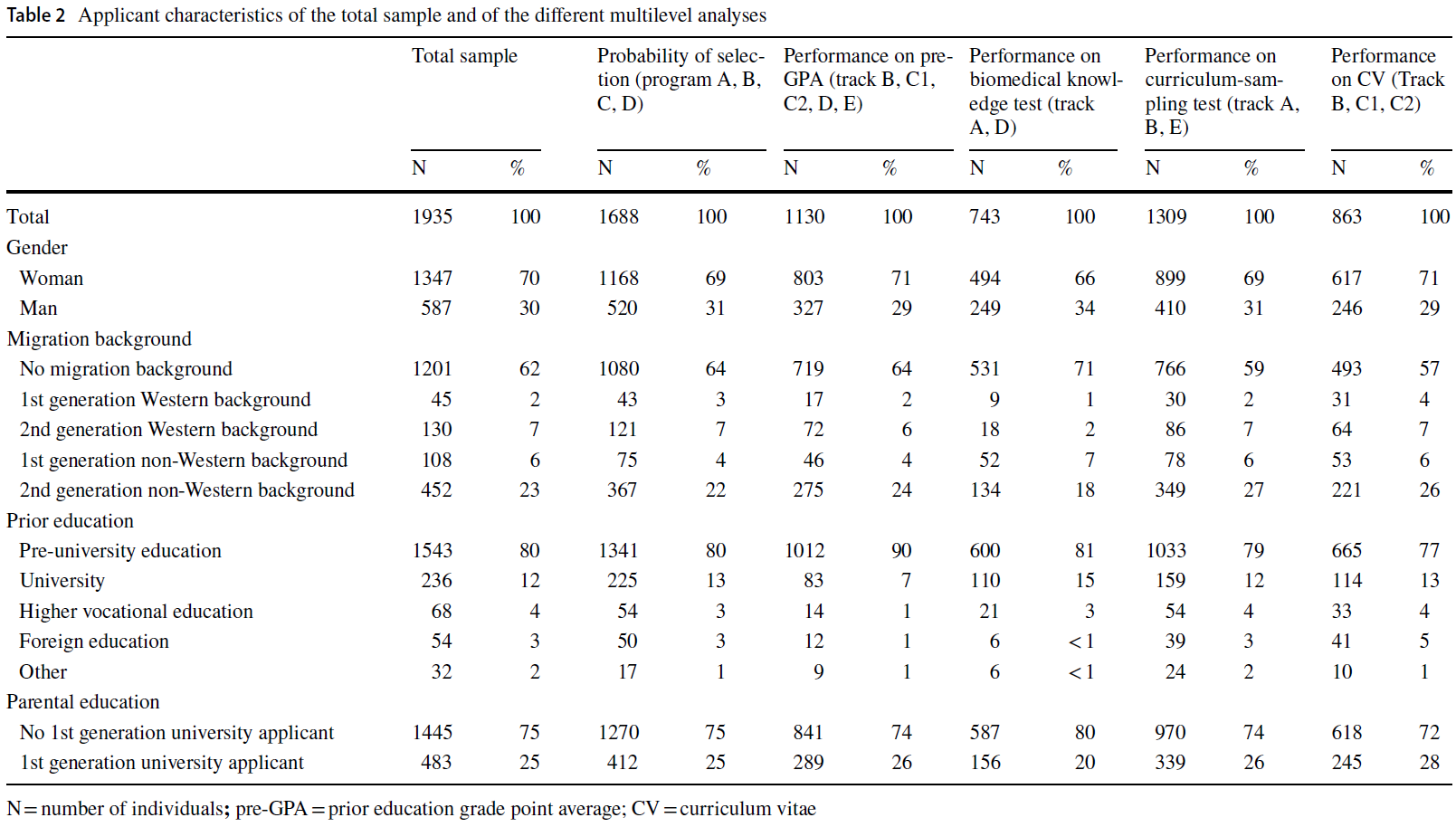

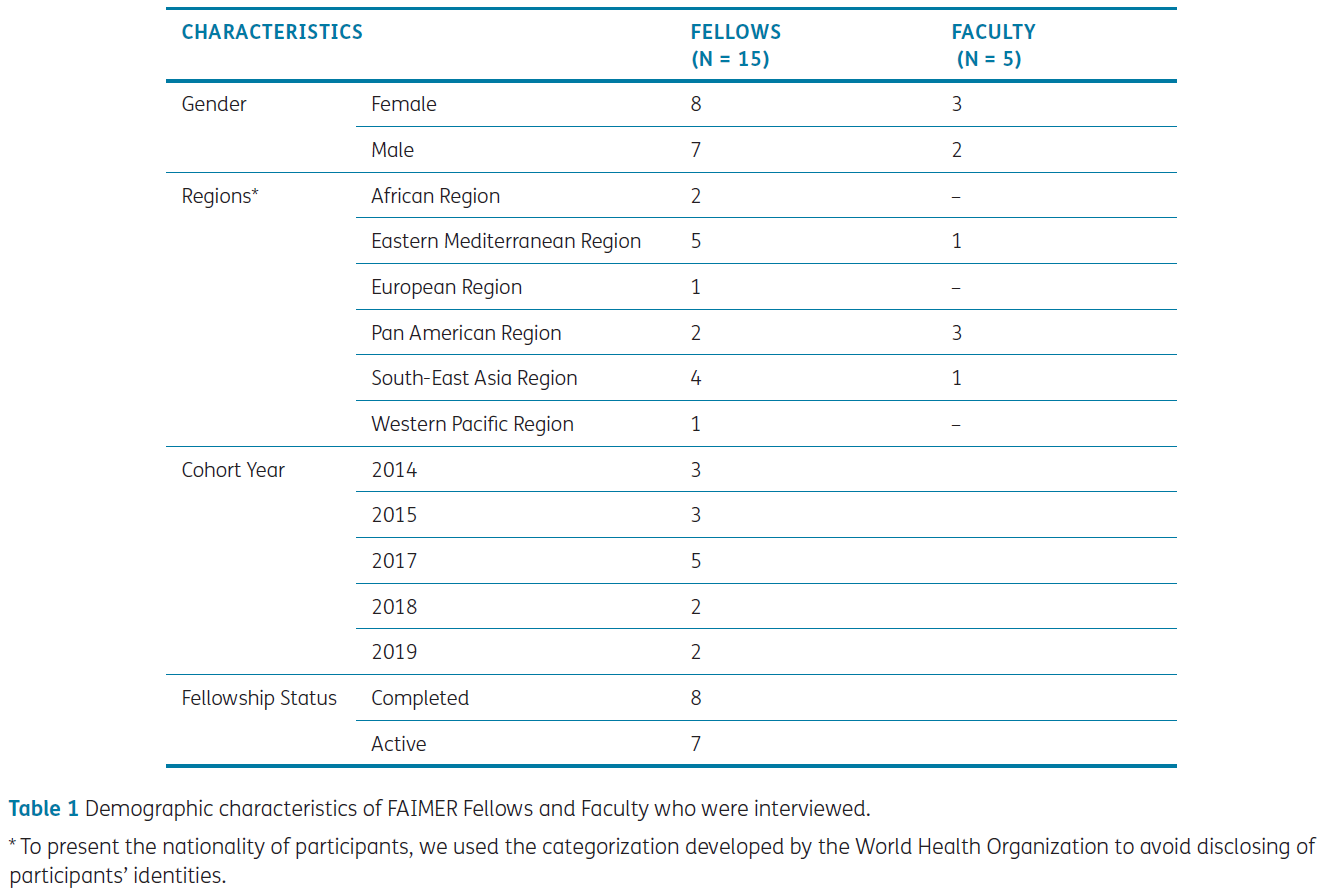

21명의 학생을 인터뷰했으며, 이 중 비임상 환경의 학생은 11명, 임상 환경의 학생은 10명이었습니다. 학생들은 신뢰성의 세 가지 차원을 모두 포함하는 여러 논거를 바탕으로 환자의 신뢰성을 판단했습니다[18]. 학생들은 환자의 신뢰도를 평가할 때 환자의 능력, 신뢰성, 선의에 대해 추론했습니다. 학생들의 추론은 맥락의 지각된 요소에 의해 판단이 형성된다는 것을 보여주었습니다. 맥락적 요소 외에도 지각된 피드백 메시지와 학생의 이전 환자 피드백 경험도 신뢰성 판단에 영향을 미쳤습니다.

Twenty-one students were interviewed, out of which 11 students in the non-clinical and 10 in the clinical setting. Students based their credibility judgments of patients on multiple arguments, comprising all three dimensions of credibility [18]. In estimating a patient’s credibility, students reasoned about his Competence, Trustworthiness, and Goodwill. Students’ reasoning showed that their judgments were shaped by perceived elements of the context. Besides contextual elements, the perceived feedback message and student’s previous experiences with patient feedback also impacted their credibility judgments.

학생들이 신뢰성 판단을 위해 제공한 논거와 이러한 논거가 맥락에 의해 어떻게 형성되었는지, 그리고 이러한 논거가 피드백 메시지와 이전 경험에 의해 어떻게 영향을 받았는지에 대해 자세히 설명함으로써 학생들이 신뢰성 판단을 어떻게 구축했는지에 대해 논의할 것입니다.

We will discuss how students built their credibility judgments by elaborating on the arguments that students provided for their credibility judgments, how these were shaped by the context, and how these were affected by the feedback message and their previous experiences.

학생이 신뢰도 판단의 근거로 삼은 논거

Arguments on which students based their credibility judgments

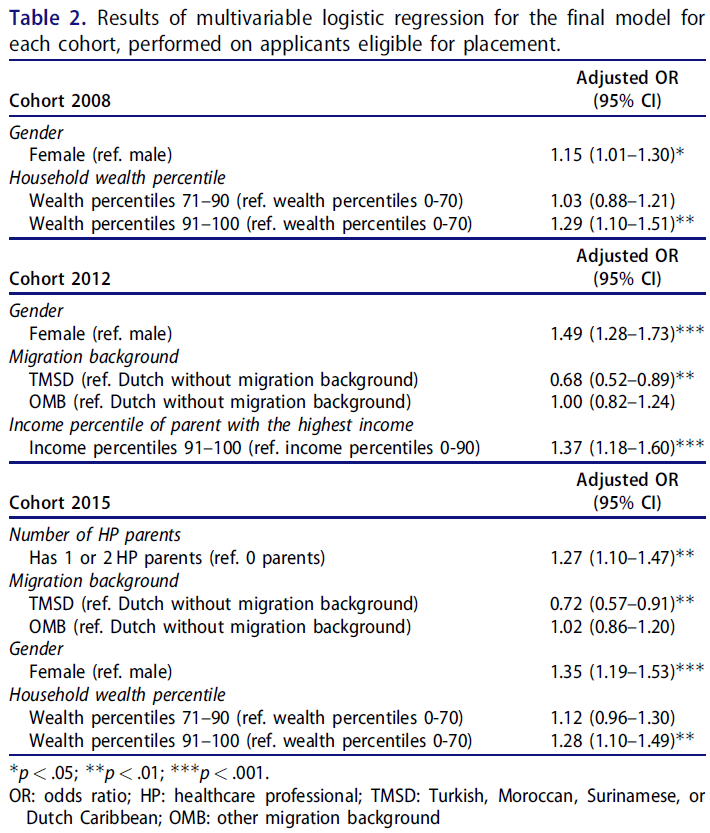

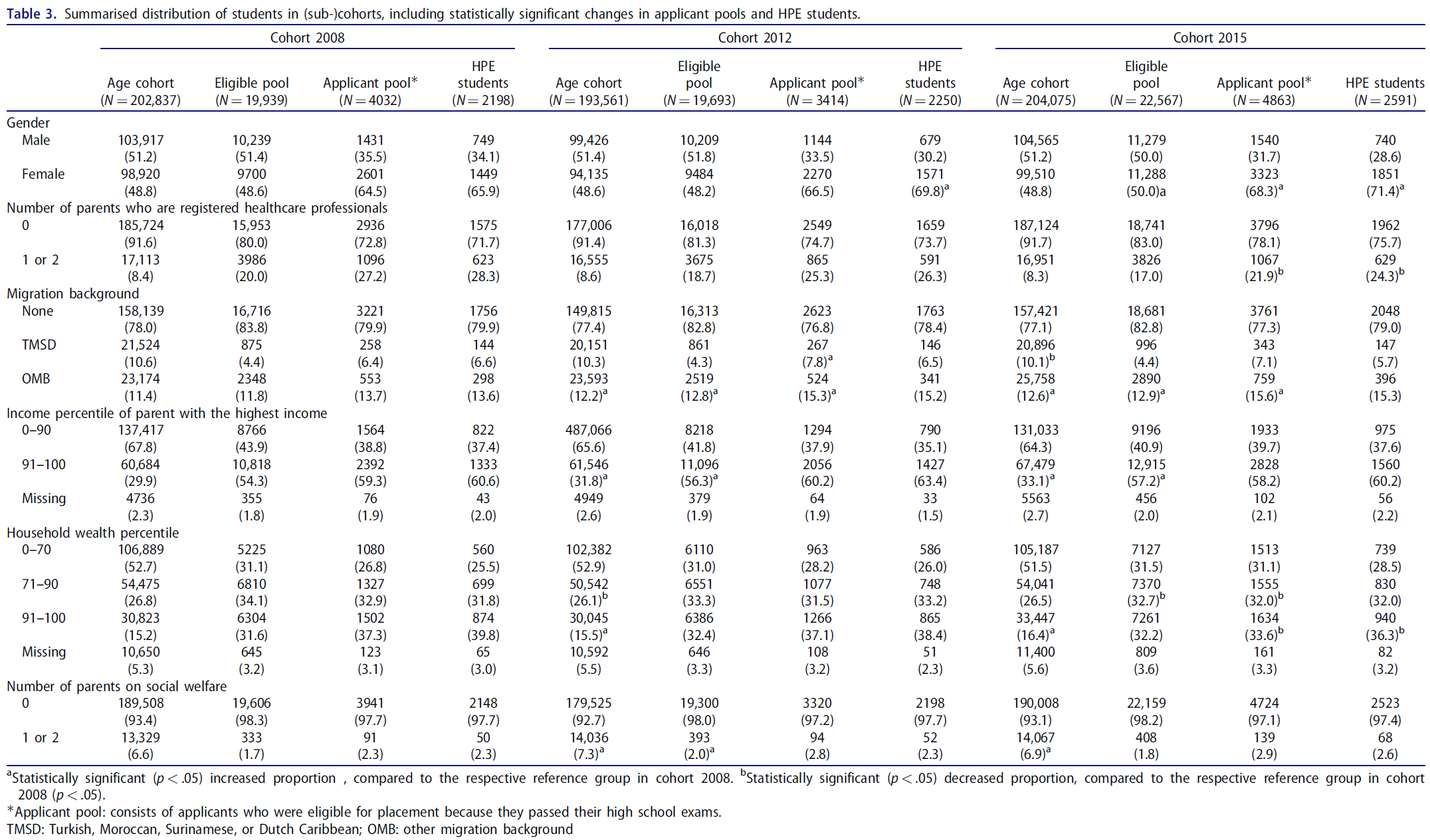

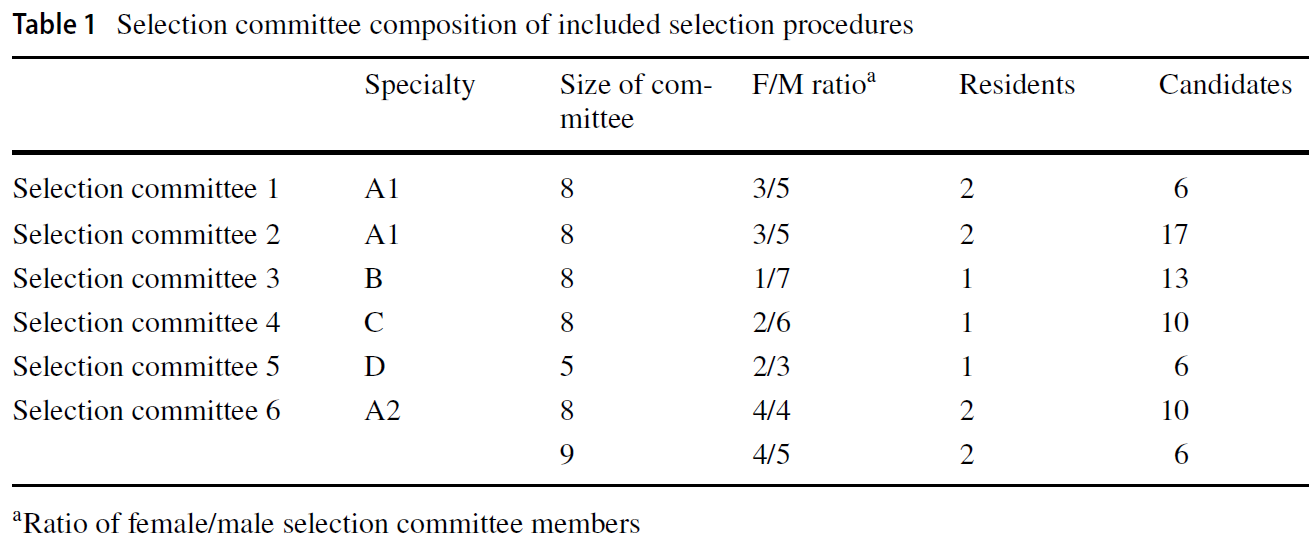

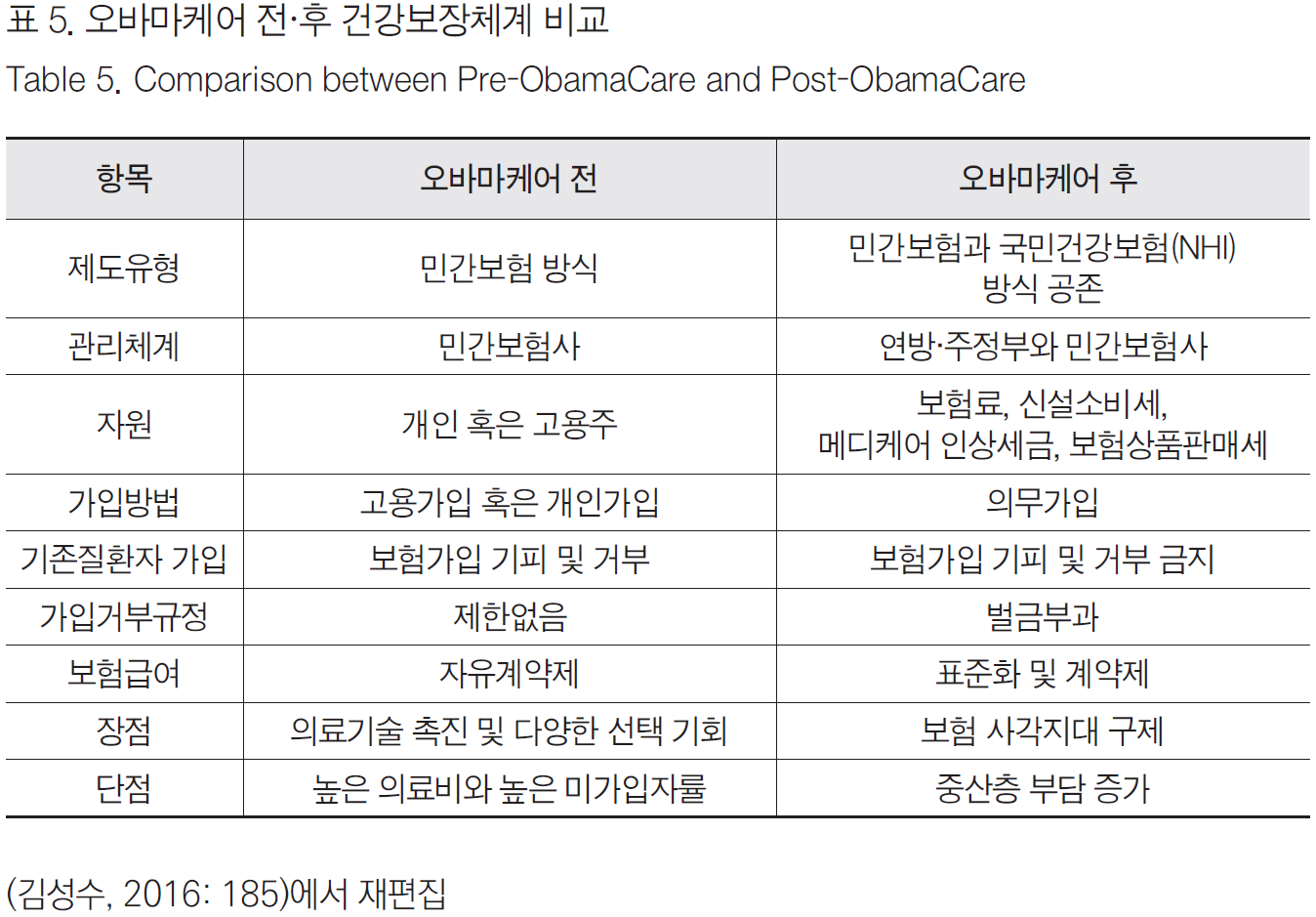

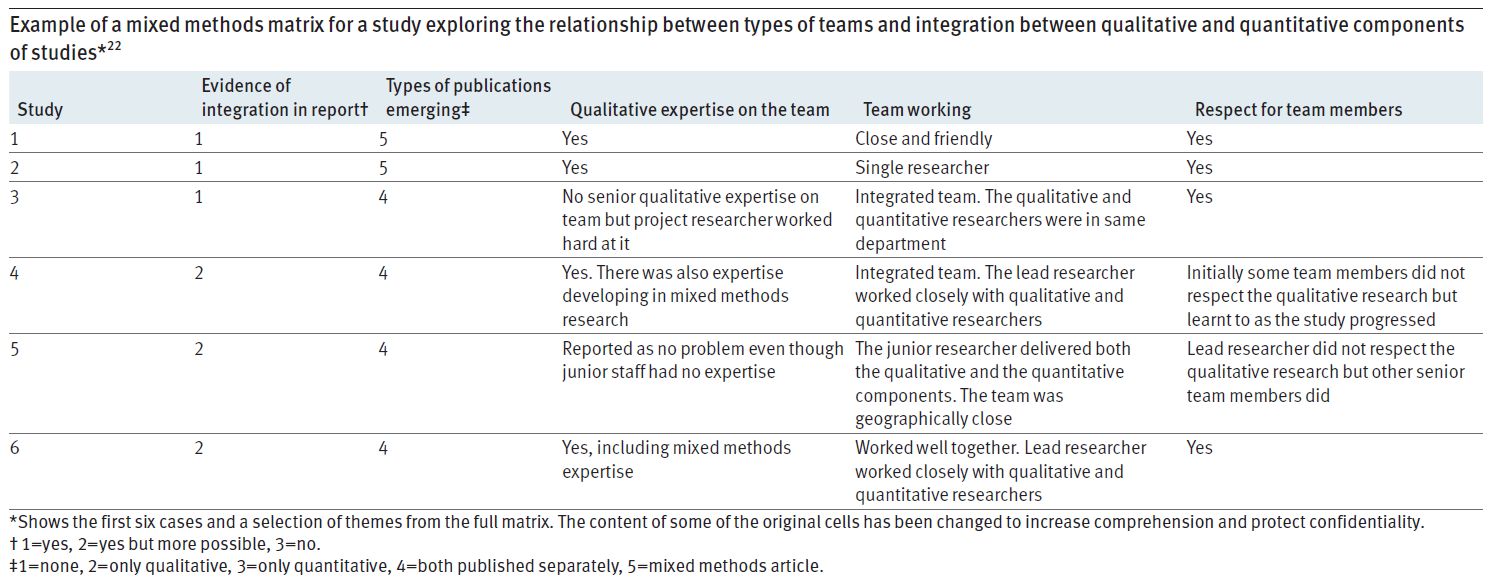

환자의 신뢰성에 대한 학생들의 판단에는 환자의 역량, 신뢰성, 선의에 관한 여러 논거가 포함되었습니다(표 1 참조). 학생들은 네 가지 논거를 바탕으로 환자의 유능성을 판단했습니다.

- 첫째, 학생들은 특정 과제에 대한 지식을 평가했습니다. 비임상적 맥락에서는 시청각적 의사소통에 대한 지식이 될 수 있습니다. 임상적 맥락에서는 의학 지식이 될 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, 학생들은 환자가 의료계에 종사할 때 더 유능하다고 판단했습니다.

- 둘째, 학생들은 예를 들어 환자가 직접 관찰을 통해 얻을 수 있는 학생의 수행 방식에 대한 지식을 추정했습니다.

- 셋째, 학생들은 환자가 피드백을 제공하는 데 경험이 많고 숙련되어 있는지를 평가했습니다.

- 마지막으로 학생들은 환자의 실제 경험을 추정했습니다.

- 대부분의 학생들은 환자가 경험적 지식이 많을수록 더 유능하다고 생각했습니다.

- 반대로, 일부 학생들은 '새로운' 환자가 새로운 관점을 가지고 있기 때문에 더 신뢰할 수 있다고 생각했습니다.

Students’ judgments about a patient’s credibility contained multiple arguments regarding a patient’s Competence, Trustworthiness, and Goodwill, see Table 1. Students judged patients’ Competence based on four arguments.

- First, they estimated their knowledge of the specific task. In the non-clinical context, this could be knowledge about audiovisual communication. In the clinical context, this could regard medical knowledge. For instance, students judged patients as more competent when they were in the medical profession.

- Second, students estimated patients’ knowledge of how the student performed, which patients for instance could have gained through direct observation.

- Third, students estimated whether patients were experienced and skilled in providing feedback.

- Lastly, students estimated patients’ lived experience.

- Most students regarded patients as more competent when they possessed more experiential knowledge.

- Conversely, some students reasoned that their ‘new’ patient was actually very credible because he had a fresh perspective.

"그는 병원에 대해 잘 몰랐고 어떻게 운영되는지 등에 대해 잘 몰랐습니다. 그래서 오히려 그의 말이 더 진솔하게 들렸던 것 같아요. 또한 무지에서 비롯된 무지에서 그는 '이건 이해가 안 된다, 저건 이해가 안 된다'는 식의 질문을 많이 했어요. 그렇지만 그는 자신이 느끼는 것을 그대로 말한다는 것을 의미했고, 그래서 더 신뢰가 갔습니다." - St4clinical(실제 경험)

“He was not familiar with the hospital and didn’t know about how things worked and so on. And I think that actually ensured that what he said came out really sincere. Also from this ignorance, he asked many questions like we don’t understand this, or we don’t understand that. That did mean that he really just says what he feels, … I found him more credible because of it.” – St4clinical (Lived experience)

학생들은 두 가지 논거를 바탕으로 환자의 신뢰도를 판단했습니다.

- 첫째, 학생들은 환자가 피드백에 성실하고 정직한지 여부를 평가했습니다.

- 둘째, 학생들은 환자의 개방성과 개선할 점을 과감하게 언급하는지 여부를 평가했습니다.

Students judged patients’ Trustworthiness on two arguments.

- First, students estimated whether a patient was sincere and honest in his feedback.

- Second, students estimated a patient’s openness and whether he dared to mention points for improvement.

"[협업에 대한 피드백]의 경우, 환자의 피드백이 대부분 긍정적이었고 100% 정직했는지는 잘 모르겠기 때문에 조금 낮게 평가했습니다. 추정하기 어렵습니다. 그래서 저는 그가 저에게 피드백을 주는 것에 대해 개인적으로 특별히 신뢰할 수 없다고 생각합니다. 그가 피드백에 완전히 정직하게 임하고 있는지 잘 모르겠어요." -St6비임상(성실성)

“In terms of [feedback on] our collaboration, it’s a bit lower, because his feedback was mostly positive and I am not sure if he was being 100% honest. I find that hard to estimate. And that’s why I don’t find him particularly credible, as a person, to give me feedback. I can’t quite sense whether he is being completely honest in his feedback.” –St6nonclinical (Sincerity)

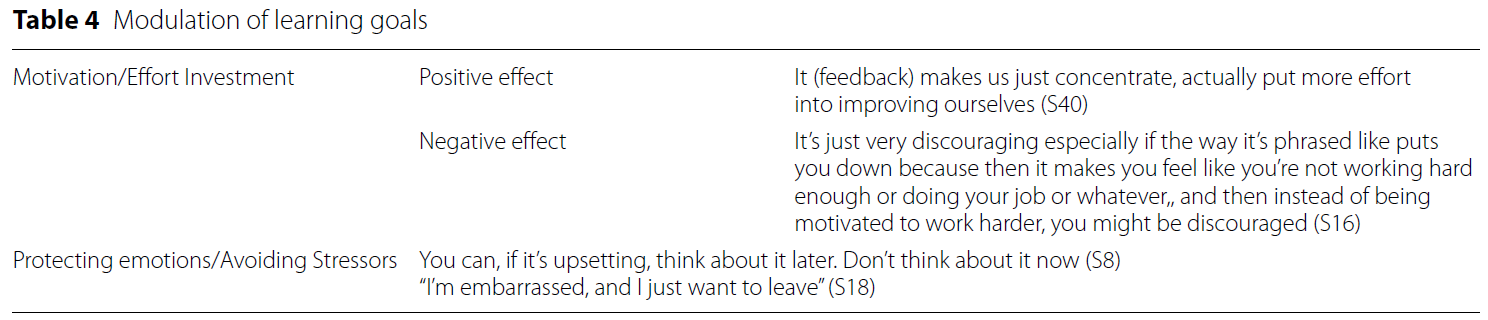

학생들은 두 가지 논거를 바탕으로 환자의 선의를 판단했습니다.

- 첫째, 학생들은 환자가 시간을 내어 피드백을 제공하고 교육 프로젝트에 참여하는 등 학생의 학습을 돕고자 하는 의지가 있는지를 평가했습니다.

- 둘째, 학생들은 환자가 학생의 사생활에 관심을 보이고 학생의 존재에 감사를 표하는 등 학생을 인격적으로 돌보는지 여부를 평가했습니다. 후자는 신뢰도를 높이거나 낮출 수 있습니다. 어떤 학생들은 환자가 학생의 감정을 상하게 하지 않기 위해 비판을 피할 것이라고 추론했습니다.

Students judged patients’ Goodwill on two arguments.

- First, they estimated whether the patient had the intention to help the student learn, for instance by taking time to provide feedback and by being engaged in the educational project.

- Second, students estimated whether the patient cared for the student as a person, for instance by showing interest in the student’s personal life and by expressing gratefulness for the student’s presence. The latter could both increase and decrease credibility. Some students reasoned that a patient would avoid criticism to avoid hurting the student’s feelings.

"글쎄요, '그냥 학생일 뿐인데 상처 주고 싶지 않아요'라고 생각할 수도 있죠. 네, 그리고 그 학생도 최선을 다하고 있을 뿐이죠. 부정적인 말을 해서 저에게 상처를 주고 싶지 않을 수도 있죠." -St4clinical(돌보는 사람)

“Well, he might think ‘she’s just a student, I don’t really want to hurt her. Yes, and she’s also just trying to do the best she can.’ He may not want to hurt me by saying anything negative.” –St4clinical (Caring for person)

인과 관계 네트워크 분석 결과, 학생들은 여러 주장에 무게를 두어 판단을 내리는 것으로 나타났습니다. 서로 다른 차원의 주장이 서로 상호작용했습니다(그림 1 참조). 예를 들어, 한 학생은 환자가 자신의 학습에 관심을 갖고 있다고 가정했기 때문에(선의) 환자가 성실하고 개방적이라고 추론했습니다(신뢰성). 연구 결과에 따르면 학생들의 환자의 신뢰도에 대한 판단은 '전부 아니면 전무'의 판단이 아니었습니다. 오히려 학생들은 신뢰도에 기여하는 논거와 신뢰도를 떨어뜨리는 논거를 고려하여 환자에게 어느 정도의 신뢰도를 부여했습니다.

Causal network analysis showed that students built their judgments by weighing multiple arguments. Arguments of different dimensions interacted with each other (See Figure 1). For instance, a student reasoned that the patient was sincere and open (Trustworthiness), since she assumed that the patient cared for her learning (Goodwill). Our results suggest that students’ judgments of a patient’s credibility were not ‘all or nothing’ judgments. Rather, students assigned a certain degree of credibility to a patient, taking into consideration arguments that contributed to credibility, and arguments that reduced credibility.

맥락의 요소가 신뢰도 판단에 미치는 영향

How elements of the context affect credibility judgments

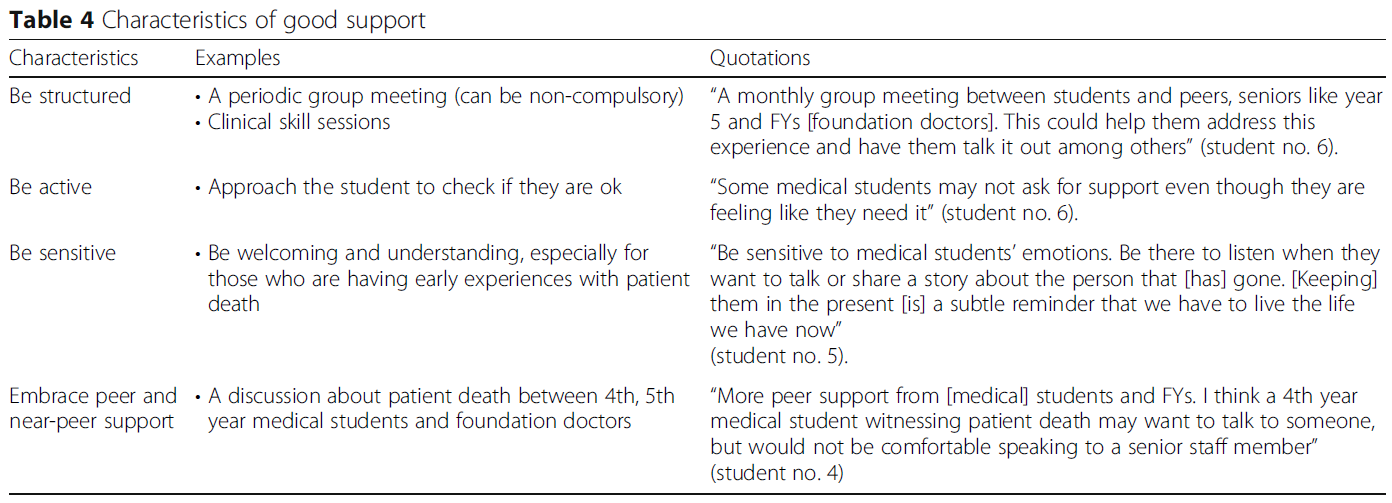

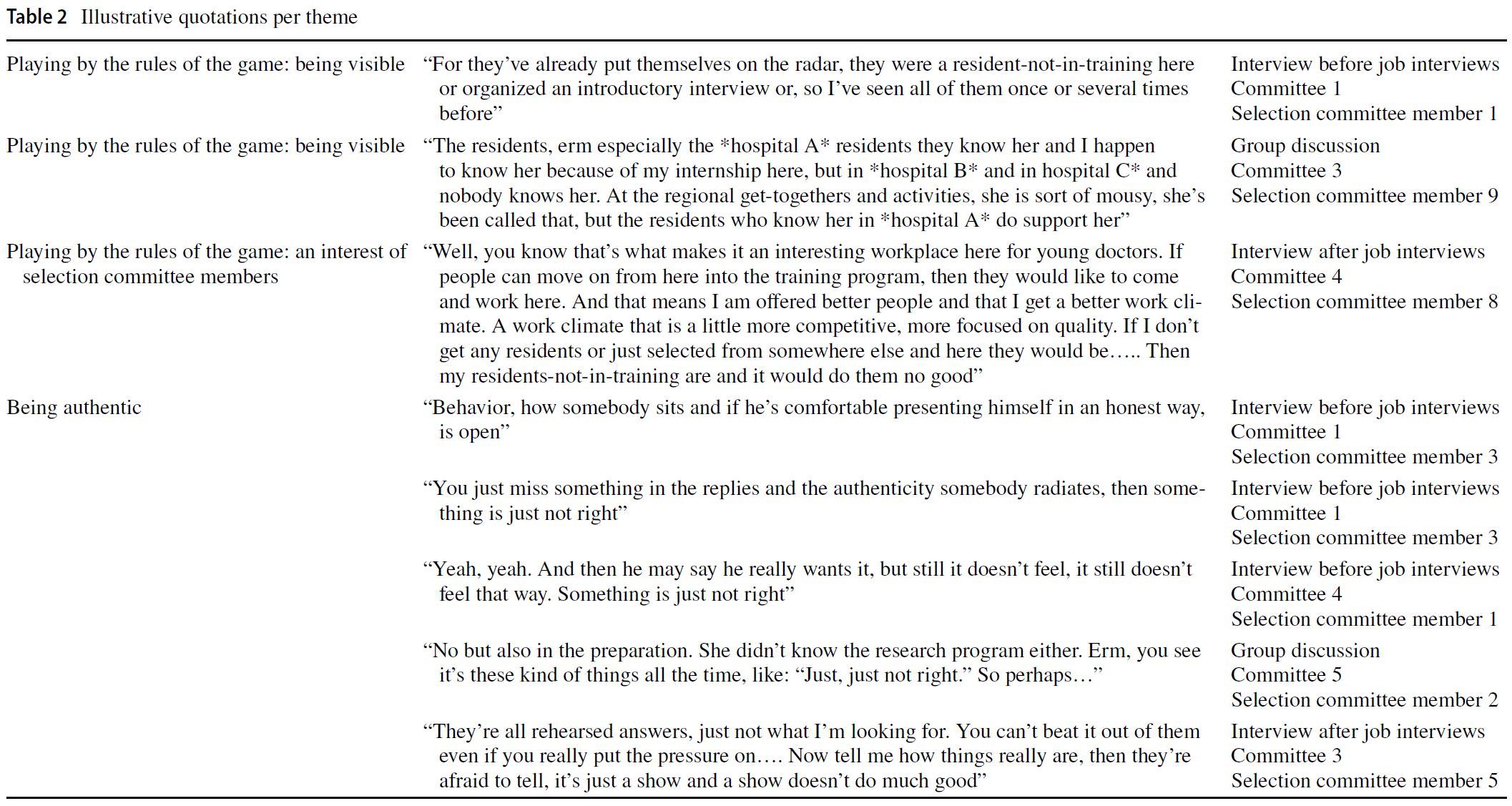

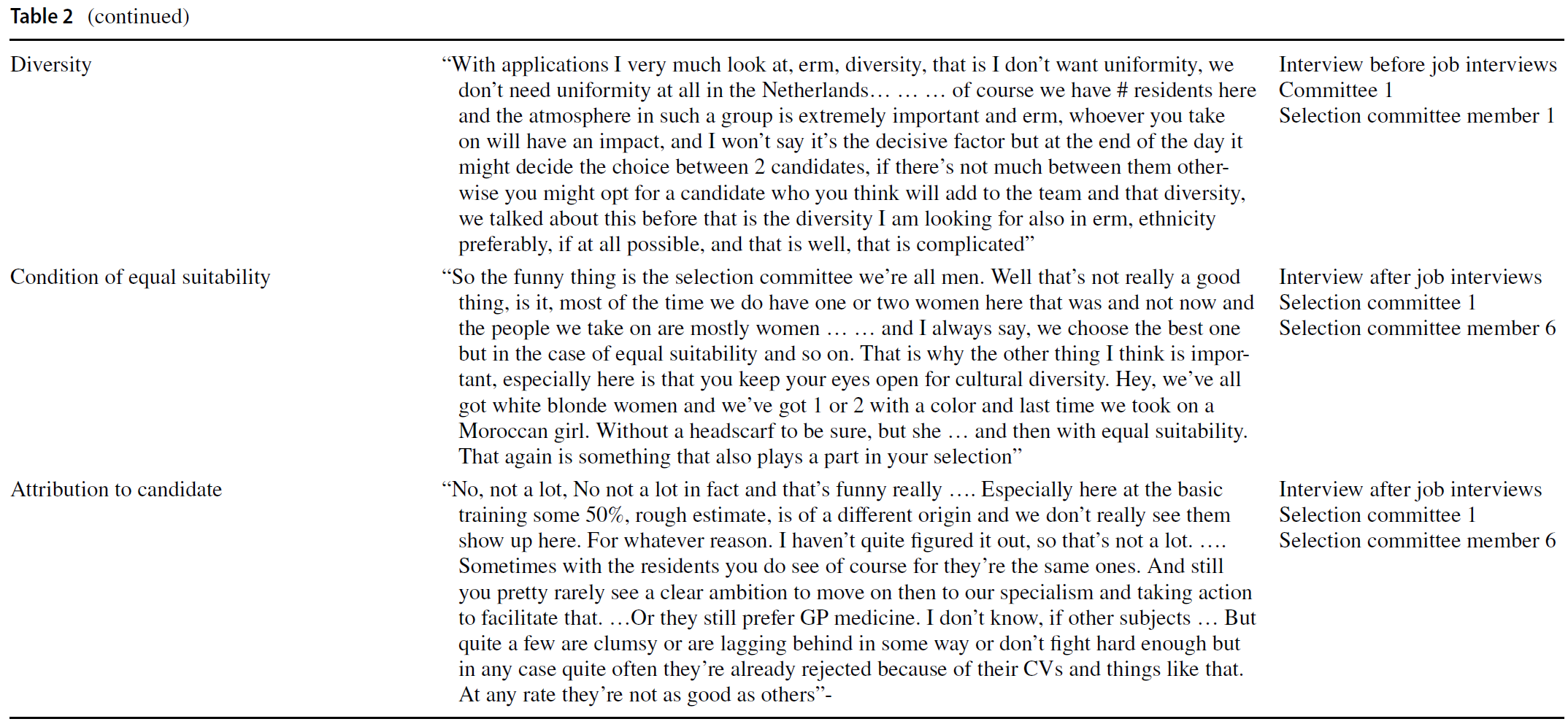

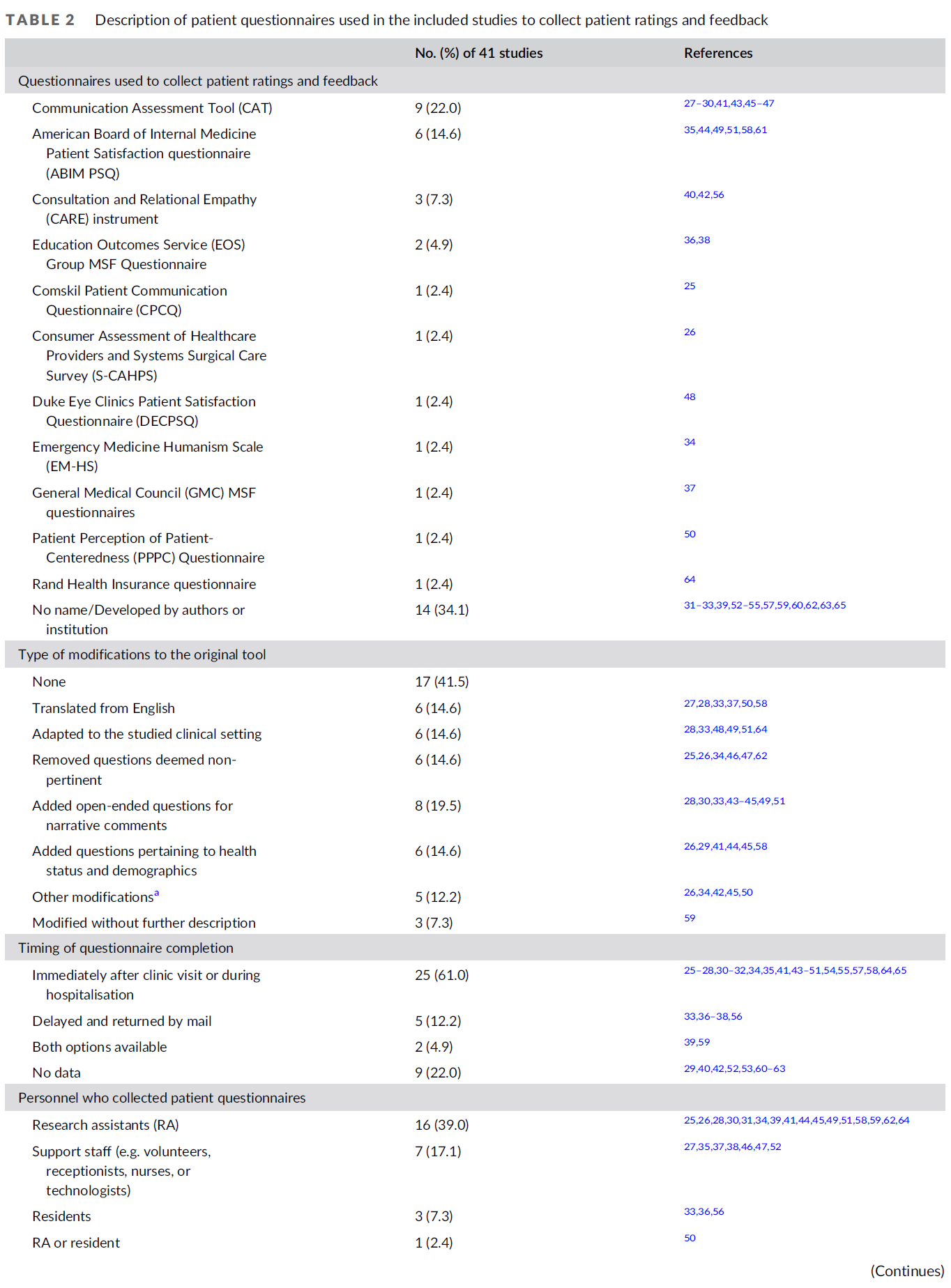

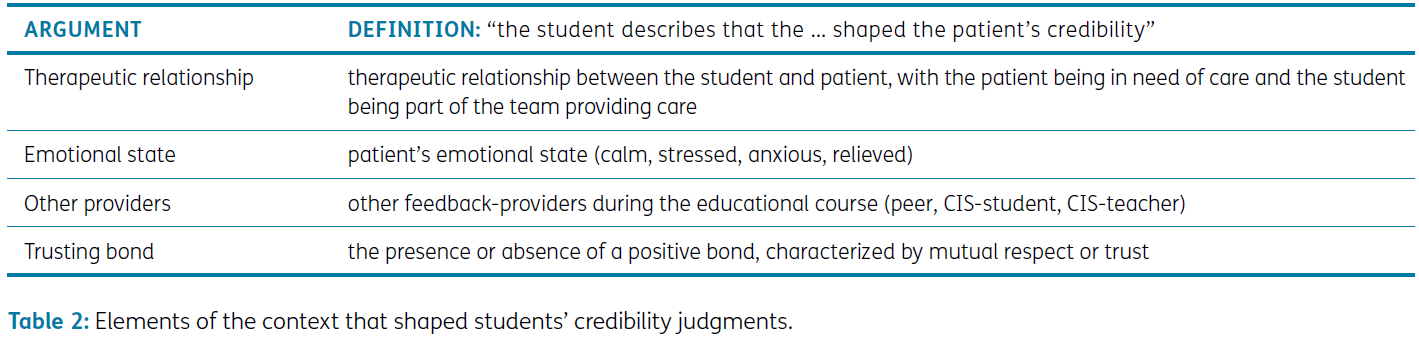

학생들은 신뢰도 판단에 영향을 미치는 네 가지 맥락적 요소를 언급했습니다(표 2 참조).

Students mentioned four contextual elements that affected their credibility judgments (See Table 2).

세 가지 맥락 요소는 임상적 맥락에서 학생들이 언급했거나 비임상적 맥락에서 학생들이 언급했습니다.

Three contextual elements were either mentioned by students in the clinical context, or by students in the non-clinical context.

첫째, 임상적 맥락에서 학생들은 자신과 환자 사이에 치료적 관계가 있다고 언급했는데, 환자는 치료가 필요한 상태이고 학생은 치료를 제공하는 팀의 일원이었습니다. 학생들은 환자가 힘의 불균형을 인식하고 자신에게 의존한다고 느낄 수 있기 때문에 피드백 과정에 방해가 될 수 있다고 추론했습니다. 따라서 환자들이 감히 개방적이고 솔직하게 말하지 못해(신뢰성) 신뢰도가 낮아질 수 있다는 것이었습니다.

First, in the clinical context, students mentioned that there was a therapeutic relationship between them and the patient, with the patient being in need of care and the student being part of the team that provides care. Students reasoned that this could have hindered the feedback process, since patients could perceive a power imbalance and feel dependent on them. Therefore, patients might not dare to be open and honest (Trustworthiness), which lowered their credibility.

"나중에 그 환자도 우리에게 의존하고 있기 때문에 치료 관계를 유지하고 싶다고 말했습니다. 그리고 그도 마음 한구석에 우리와 우호적인 관계를 유지해야 한다는 생각을 가지고 있었기 때문에 너무 비판적으로 대하고 싶지 않았던 것 같습니다."-St4clinical

“He said that later on too, that he wants to maintain the treatment relationship, because he does depend on us as well. And I think that’s why he also has in the back of his mind that he has to remain friendly with us, which is perhaps why he didn’t want to be too critical.”-St4clinical

흥미롭게도 한 학생은 시간이 지남에 따라 환자가 학습자로서의 자신의 역할을 더 잘 인식하게 되었고, 이로 인해 치료 관계는 더 뒷전으로 밀려났으며 학습을 돕고자 하는 환자의 의지가 높아졌다고 말했습니다(Goodwill).

Interestingly, one student mentioned that over time the patient became more aware of her role as a learner, which had put the therapeutic relationship more to the background, and increased the patient’s willingness to help the student learn (Goodwill).

"그 덕분에 그는 인턴이 무엇을 수반하는지 더 잘 알았던 것 같아요. 그리고 실제로 더 나은 피드백을 줄 수 있었던 것 같아요. '당신은 정말 배우러 왔고 내 의사가 아니기 때문에 내 치료 계획을 세우지 않을 거야'라고 생각했기 때문이죠. 그래서 저는 그 부분(즉, 학습)을 도와드리고 싶습니다."-St7clinical

“because of that, I think he knew more what an intern entailed. And I think that actually allowed him to give better feedback, because he was more like okay, so you’re really here to learn and you’re not my doctor, so you’re not going to set my treatment plan. So I want to help you with that [ i.e. learning].”-St7clinical

둘째, 임상 맥락에서 학생들은 환자의 감정 상태가 신뢰도에 영향을 미친다고 언급했습니다. 학생들은 피드백 메시지가 환자의 감정에 의해 형성된다고 추론했습니다. 예를 들어 환자가 좋은 소식을 듣고 행복하거나 안심한 상태라면 피드백이 더 긍정적일 것이고, 그 반대의 경우도 마찬가지입니다. 또한, 학생들은 환자가 낯선 환경에 처해 있거나 매우 아프다는 등의 이유로 취약하다고 느끼면 감히 비판적인 피드백(신뢰성)을 제공하지 않을 것이라고 추론했습니다. 또한 학생들은 스트레스를 받거나 긴장한 환자에 비해 차분하고 편안해 보이는 환자를 더 신뢰할 수 있다고 답했는데, 그 이유는 후자의 경우 학생의 학습에 관심을 갖거나(선의) 학생을 관찰하고 수행 능력을 판단할 수 있는 적절한 마음 상태가 아닐 수 있기 때문입니다(유능성).

Second, in the clinical context, students mentioned that the patient’s emotional state impacted his credibility. Students reasoned that feedback messages were shaped by patients’ emotions. For example, if a patient was happy or relieved due to receiving good news, then his feedback would be more positive, and vice versa. Moreover, students reasoned that patients would not dare to provide critical feedback (Trustworthiness) if they felt vulnerable, for instance because they were in an unknown environment or were very sick. Besides, students mentioned that patients who appeared calm and at ease where more credible compared to patients who were stressed or nervous, because the latter might not be in the right state of mind to care about students’ learning (Goodwill) or observe the student and make judgments about her performance (Competence).

"네, [이 환자는] 따라서 덜 긴장하고 덜 감정적이었으며, 이 업무 환경에서 [내가] 어떻게 하고 있는지 생각할 수 있는 여유가 더 많았습니다. 따라서 자신에게 너무 집중하는 대신 상대방을 바라볼 수 있는 여유도 생겼습니다. 제 생각에 그는 더 나은 피드백을 줄 수 있었고 더 신뢰할 수 있었습니다. 그리고 그는 좀 더 객관적이었던 것 같아요." - St6clinical

“Yes [this patient was] therefore less nervous, and therefore less emotional, with more space to think about how [I am] doing in this work environment. There is therefore also more space to look at the other person instead of focusing too much on yourself. In my opinion, he could therefore give better feedback and was more credible. And he was a bit more objective as well, I think.” – St6clinical

셋째, 비임상 환경의 학생들은 시청각 환자 정보(지식 클립)에 대한 다른 제공자의 피드백 메시지가 환자의 신뢰도에 영향을 미친다고 언급했습니다. 교육 과정에서도 학생들은 의료 전문가와 동료로부터 지식 클립에 대한 피드백을 받았습니다. 환자의 피드백이 의료 전문가나 동료의 피드백에 추가되거나 그에 부합하는 경우, 환자는 더 신뢰할 수 있는 것으로 간주되었습니다.

Third, students in the non-clinical context mentioned that feedback messages of other providers on their audiovisual patient information (the knowledge clip) affected the patient’s credibility. In the educational course, students also received feedback on their knowledge clip from healthcare professionals and peers. When the patient’s feedback added to, or was in accordance with, feedback from healthcare professionals or peers, the patient was seen as more credible.

"실제로 [심리학자]가 제공한 조언은 [환자]의 조언과 완전히 같거나 거의 똑같았습니다. 그래서 항상 매우 비슷했습니다. ... 그래서 [그의] 신뢰성이 강화되었습니다." -St9비임상

“Actually, the tips given by [a psychologist] were exactly the same, or almost exactly the same as [the patient’s]. So that was always very similar. … which did reinforce [his credibility].” -St9nonclinical

맥락의 한 가지 요소인 '신뢰 관계'는 두 맥락 모두에서 학생들이 언급했습니다. 상호 존중과 신뢰로 특징지어지는 유대감은 신뢰도를 높이거나 낮출 수 있습니다.

- 일부 학생들은 긍정적인 유대감으로 인해 환자가 학습에 더 많은 관심을 갖게 되고(선의), 더 개방적으로 행동하게 된다고 추론했습니다(신뢰성).

- 그러나 다른 학생들은 긍정적인 유대감 때문에 환자들이 관계의 손상을 두려워하여 개선해야 할 점에 대해 덜 솔직해졌다고 추론했습니다(신뢰성).

One element of the context, ‘trusting bond’, was mentioned by students in both contexts. A bond, characterized by mutual respect and trust, could both increase or decrease credibility.

- Some students reasoned that their positive bond made patients care more about their learning (Goodwill) and made them dare to be more open (Trustworthiness).

- However, other students reasoned that their positive bond made patients less open about points for improvement (Trustworthiness), because they feared damaging the relationship.

"아마도 그 때문에 왠지 신뢰도가 조금 떨어졌을 것 같아요... 우리는 아주 좋은 관계를 유지하고 있는데, 그가 여전히 감히 엄격할 수 있을까, 말하자면 여전히 감히 팁을 제시할 수 있을까 하는 생각이 들었어요." -St3비임상

“Maybe that somehow made him a little less credible, that I thought … we have a very good relationship, does he still dares to be strict, so to speak, does he still dare to come up with tips.” –St3nonclinical

피드백 메시지와 이전 경험이 신뢰도 판단에 미치는 영향

How the feedback message and previous experiences affect credibility judgments

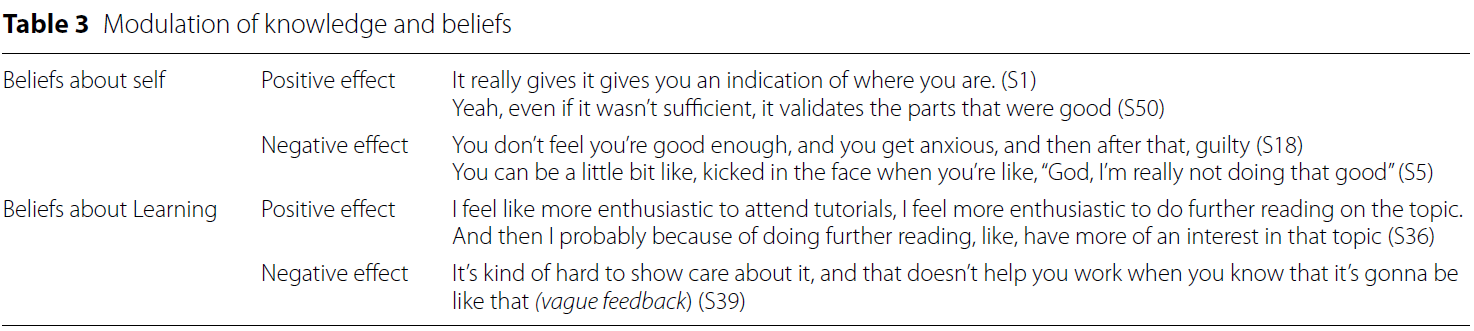

맥락의 요소 외에도 피드백 메시지와 환자의 피드백에 대한 이전 경험도 학생들의 신뢰성 판단에 영향을 미치는 것으로 나타났습니다. 피드백 메시지와 관련하여, 학생들은 피드백 메시지가 구체적이고 광범위하며 긍정적인 피드백과 개선점을 모두 포함하고 있다고 인식할 때 환자가 자신의 학습에 관심을 갖고(선의), 개방적이고 정직하며(신뢰성), 피드백 제공에 능숙하다고(유능함) 추론했습니다. 이는 그 반대의 경우도 마찬가지였습니다:

Besides elements of the context, students reasoning also showed that the feedback message, and previous experiences with patient feedback, affected students’ credibility judgments. With regard to the feedback message, when students perceived the feedback message as specific, extensive, and containing both positive feedback and points for improvement, they reasoned that the patient cared for their learning (Goodwill), was open and honest (Trustworthiness), and that he was skilled in providing feedback (Competence). This also worked vice versa:

"그의 피드백은 대부분 긍정적이었지만 그가 100% 정직했는지는 잘 모르겠습니다. 평가하기 어렵습니다. 그래서 저는 그가 저에게 피드백을 주는 것에 대해 인간으로서 특별히 신뢰할 수 없다고 생각합니다. 그가 피드백에 대해 완전히 정직한지 잘 모르겠습니다."-St6nonclinical(성실성)

“his feedback was mostly positive and I am not sure if he was being 100% honest. I find that hard to estimate. And that’s why I don’t find him particularly credible, as a person, to give me feedback. I can’t quite sense whether he is being completely honest in his feedback.”–St6nonclinical (Sincerity)

개인적 특성과 관련하여 비임상 환경의 일부 학생들은 과거에 환자 피드백에 대한 긍정적인 경험을 가지고 있었습니다. 이 때문에 환자 피드백의 가치를 더 잘 인식하게 되었고, 따라서 환자를 더 신뢰할 수 있다고 판단했습니다.

With regard to personal characteristics, some students in the non-clinical context had positive past experiences with patient feedback. This made them more aware of the value of patient feedback, and therefore judge patients as more credible.

"환자의 피드백은 궁극적으로 메시지를 전달하고 싶거나 안심시키고 싶은 사람이기 때문에 환자의 피드백에 많은 가치가 있다는 것을 이전의 경험을 통해 알게 된 것 같습니다. 목표를 달성하고자 하는 사람이 바로 환자이기 때문에 목표를 달성했는지 여부와 그 이유 또는 그렇지 않은 이유에 대해 가장 좋은 피드백을 줄 수 있는 사람이기도 합니다." -St1비임상

“I do think I have learnt through that earlier experience that there is a lot of value in the patient’s feedback, because the patient is ultimately the person you either do want to convey a message to or you want to reassure. That’s the person you want to achieve your objective with, so that’s also the person who can actually give you the best feedback on whether you achieved that goal and why or why not.” –St1nonclinical

신뢰성에 대한 학생들의 추론을 분석한 결과, 환자에 대한 신뢰성 판단은 여러 가지 상호 작용하는 논거를 종합적으로 고려한다는 사실이 명확해졌습니다. 이러한 주장은 맥락, 피드백 메시지 및 이전 경험에 의해 형성됩니다(그림 1 참조). 부록 C에는 한 학생의 인과 네트워크가 표시되어 있는데, 이 학생은 환자에 대한 신뢰성 판단을 어떻게 구축했는지 보여줍니다.

Analysis of students’ reasoning about credibility clarified that their credibility judgments regarding patients is a weighing of multiple interacting arguments. These arguments are shaped by the context, the feedback message and previous experiences (See Figure 1). Appendix C displays the causal network of a student, which shows how she built her credibility judgment of a patient.

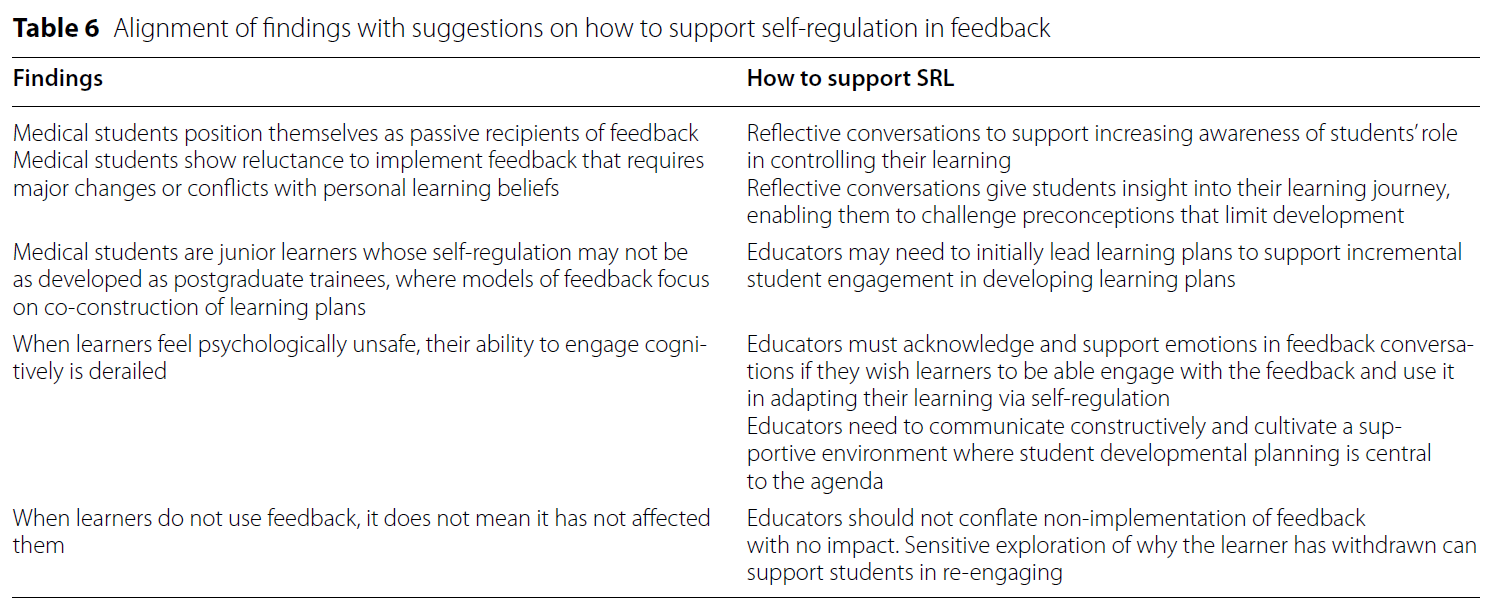

토론

Discussion

이 인터뷰 연구에서는 임상 및 비임상 맥락에서 피드백 제공자로서 환자에 대한 의대생의 신뢰성 판단을 살펴보았습니다. 학생들은 맥락, 피드백 메시지 및 개인적 특성의 영향을 받는 여러 가지 상호 작용하는 논거를 바탕으로 환자에 대한 신뢰도 판단을 내렸습니다. 연구 결과가 문헌에 어떻게 기여하는지, 그리고 그 교육적 함의에 대해 논의합니다.

In this interview study, we explored medical students’ credibility judgments of patients as feedback providers in a clinical and non-clinical context. Students based their credibility judgments of patients on multiple interacting arguments, which were affected by elements of the context, the feedback message and personal characteristics. We will discuss how our results contribute to the literature and we discuss their educational implications

연구 결과에 따르면 학생들의 환자 신뢰도 판단은 맥크로스키의 3차원 신뢰도 모델[18]과 일치하는 것으로 나타났습니다. 학생들은 신뢰도를 판단할 때 환자의 역량, 신뢰성, 학생에 대한 선의 등 다양한 측면을 평가하는 것으로 나타났습니다. 흥미롭게도 '생생한 경험'과 관련하여 학생들이 원하는 피드백이 무엇인지에 따라 생생한 경험의 유무가 신뢰도에 영향을 미칠 수 있었습니다. 많은 학생들은 오랜 병력이 신뢰도에 기여한다고 추론했는데, 그 이유는 경험적 지식을 통해 환자들이 다른 병원 방문과 비교하여 학생의 성과를 판단할 수 있기 때문입니다. 그러나 다른 학생들은 새로운 환자가 치료에 대한 새로운 관점을 제공할 수 있기 때문에 실제로 더 신뢰할 수 있다고 추론했습니다. 따라서 학생과 레지던트 간의 상호작용과 마찬가지로, 연구 결과는 환자의 신뢰도에 대한 결정이 내용에 따라, 즉 학생들이 원하는 피드백 메시지에 따라 달라진다는 것을 시사합니다[7].

Our findings indicate that students’ credibility judgments of patients align with McCroskey’s three-dimensional credibility model [18]. We found that in determining credibility, students estimated various aspects of a patient’s Competence, Trustworthiness, and Goodwill towards the student. Interestingly, regarding the argument ‘lived experience’, depending on what feedback students were looking for, presence or absence of lived experience could both contribute to credibility. Many students reasoned that a prolonged medical history contributed to credibility, because experiential knowledge allowed patients to judge a student’s performance in comparison to other hospital visits. However, other students reasoned that new patients were actually more credible, because they could provide a fresh perspective on care. Similar to student-resident interactions, our results therefore suggest that decisions about patient credibility were content specific, meaning dependent on the feedback message that students were seeking [7].

교육 실습의 경우, 맥크로스키의 3차원 신뢰도 모델을 사용하여 학생들과 신뢰도 판단에 대해 토론하고 학생들이 자신의 주장을 정리하고 이해하는 데 도움을 줄 수 있습니다. 신뢰성에 대한 학생들의 추론에 대한 통찰력은 학생들이 어떤 종류의 학생이 어떤 종류의 피드백을 제공할 수 있는지에 대해 더 많은 피드백을 이해하는 데 도움이 될 수 있습니다. 향후 연구에서는 학생들과 신뢰도 판단에 대해 토론하면 학생들이 환자로부터 피드백 정보를 더 신중하게 찾고 사용할 수 있는지 살펴볼 것을 권장합니다.

For educational practice, McCroskey’s three-dimensional credibility model can be used to discuss credibility judgments with students, and to help them organize and understand their arguments. Insight into their reasoning about credibility might help students to become more feedback literate in terms of which kinds of patients can provide which kinds of feedback. We encourage future research to explore whether discussing credibility judgments with students will enable them to seek and use feedback information from patients more deliberately.

이번 연구 결과는 맥락이 신뢰성 판단을 어떻게 형성하는지 보여줍니다. 학생과 환자의 역할이 다른 임상적 맥락과 비임상적 맥락을 모두 살펴본 결과, 두 관계의 측면이 신뢰도에 어떤 영향을 미치는지 강조되었습니다. 흥미롭게도, 우리의 결과는 슈퍼바이저와 수련의 관계를 설명하고 피드백 과정이 그들의 관계에 의해 어떻게 영향을 받는지 이해하는 데 사용되는 교육적 제휴 프레임워크[39]와 공명하는 것 같습니다[7, 40]. 연구 결과에 따르면 이 프레임워크는 학생-환자 상호작용에도 적용되는데, 두 맥락 모두에서 학생들은 자신과 환자 사이의 교육적 동맹의 요소를 설명했으며, 이는 신뢰성 판단에 영향을 미쳤습니다[39]. 수퍼바이저-레지던트 상호작용에서 볼 수 있듯이, 피드백 제공자(즉, 환자)가 학생에게 인격체로서 관심을 보이고 학생의 학습 과정에 기여하고 싶다는 것을 보여줄 때 신뢰도가 증가했습니다[7]. 그러나 감독자와 레지던트 간의 상호작용과는 달리, 신뢰 관계는 신뢰도를 높이거나 낮출 수 있습니다[7]. 일부 학생들은 환자가 자신의 마음을 자유롭게 말할 것이라고 추론한 반면, 다른 학생들은 환자가 학생의 감정을 상하게 하지 않고 긍정적인 관계를 유지하기 위해 비판적인 피드백을 보류할 수 있다고 추론했습니다. 아마도 이 학생들은 동료 피드백에서 볼 수 있는 현상인 우정 점수 매기기(친구나 동료를 너무 가혹하게 평가하는 것을 불편해하여 과도한 점수 매기기로 이어지는 현상)를 두려워했을 수 있습니다[41].

Our results illustrate how context shapes credibility judgments. Exploring both a clinical and non-clinical context, with different roles for students and patients, highlighted how aspects of their relationship affected credibility. Interestingly, our results seem to resonate with the Educational Alliance Framework [39], which is used to describe the supervisor and trainee relationship and to understand how the feedback process is affected by their relationship [7, 40]. Our results suggest that this Framework also applies to student-patient interactions: in both contexts students described elements of an educational alliance between them and the patient, which affected their credibility judgment [39]. As seen in supervisor-resident interactions, credibility increased when the feedback provider (i.e. the patient) showed interest in the student as a person and demonstrated that they wanted to contribute to the student’s learning process [7]. However, in contrast to supervisor-resident interactions, a bond of trust could both increase and decrease credibility [7]. Whereas some students reasoned that patients would feel free to speak their mind, other students reasoned that patients might withhold critical feedback in order to avoid hurting the student’s feelings, and preserve the positive relationship. Possibly, these students feared so called friendship-marking, a phenomenon seen in peer feedback, in which students find it uncomfortable to grade friends or peers too harshly, which leads to over-marking [41].

임상 상황은 비임상 상황과 달랐는데, 학생은 학습자일 뿐만 아니라 의료 제공자이기도 하고 환자가 직접 치료를 필요로 하는 상황이었기 때문입니다. 따라서 학생들은 교육적 동맹 외에도 치료적 동맹도 인정했습니다[42]. 결과적으로 학생과 환자 관계의 주요 목표가 학생의 학습 과정에서 환자의 치료로 바뀌면서 권력의 이동이 감지되었습니다. 이러한 목표와 권력의 변화는 종종 환자의 신뢰도 저하로 이어졌습니다. 학생들은 환자가 자신의 학습을 돕고자 하는 선의를 가지고 있다고 믿었지만, 환자가 향후 의료 서비스에 부정적인 영향을 미칠까 봐 개선할 점에 대해 감히 솔직하게 말하지 못할 것이라고 생각하여 환자의 신뢰성에 의문을 제기했습니다[31].

The clinical context differed from the non-clinical context, since as well as being learners, students were also healthcare providers and patients were in the direct need of care. Thus, in addition to an educational alliance, students also acknowledged a therapeutic alliance [42]. Consequently, the primary goal of the student-patient relationship shifted from the student’s learning process to the patient’s care, which created a perceived shift in power. This perceived shift of goals and power often led to reduced patient credibility: although students believed patients were of goodwill since they wanted to help them learn, students questioned patients’ trustworthiness since they reasoned that patients might not dare to be open about points for improvement, out of fear of negatively impacting their future healthcare [31].

연구 결과는 신뢰성 판단이 단순한 것이 아니라 관계와 관련 목표의 맥락에서 여러 요소를 복합적으로 고려한 결과라는 것을 보여줍니다. 임상 맥락에서 학생들은 치료 동맹의 목표(돌봄)와 교육 동맹의 목표(학습) 사이의 상충을 언급했습니다. 한 학생의 사례에서 알 수 있듯이, 학생과 환자 간의 역할 설명과 목표 대화는 열린 피드백 대화의 장을 마련할 수 있습니다[40]. 향후 연구에서는 피드백 대화에서 환자의 역할에 대한 다양한 환자의 관점을 존중하면서 학생-환자 관계에서 목표와 역할을 논의하는 방법과 이것이 신뢰성 판단에 어떤 영향을 미치는지 탐구해야 합니다[43].

Our results illustrate that credibility judgments are not straightforward, but are the result of a complex weighing of multiple factors, within the context of relationships and their associated goals. In the clinical context, students mentioned a conflict between goals of the therapeutical alliance (caring) and goals of the educational alliance (learning). As shown by a student, role clarifications and goal conversations between students and patients can set the stage for open feedback conversations [40]. Future research should explore how goals and roles can be discussed in student-patient relationships, while respecting different patient perspectives on their role in feedback conversations and how this affects credibility judgments [43].

마지막으로, 피드백 메시지에 대한 인식이 신뢰성 판단에 영향을 미친다는 사실을 발견했습니다. 학생들은 피드백 메시지가 정보가 없거나, 구체적이지 않거나, 주로 긍정적인 피드백을 담고 있다고 생각하면 환자를 덜 신뢰할 수 있다고 판단했고, 그 반대의 경우도 마찬가지였습니다. 피드백 메시지와 피드백 제공자의 신뢰도 사이의 연관성은 일반적으로 피드백 제공자의 신뢰도가 메시지의 신뢰도에 영향을 미치는 것으로 설명됩니다[7, 44, 45]. 그러나 우리의 결과는 이것이 고리loop 형태임을 시사합니다. 따라서 우리는 제공자의 신뢰도를 피드백 메시지 참여의 전제 조건으로만 볼 것이 아니라, 피드백 메시지 참여의 결과로도 간주해야 합니다.

Lastly, we found that perceptions of feedback messages impacted credibility judgments. Students judged patients as less credible when they considered the feedback message uninformative, nonspecific, or containing mainly positive feedback, and vice versa. Associations between the feedback message and the feedback provider’s credibility are usually described as the credibility of the provider influencing the credibility of the message [7, 44, 45]. Our results, however, suggest that it is a loop. Consequently, we should not only view provider credibility as a prerequisite for engagement with feedback messages, but also as a consequence of engagement with feedback messages.

실제로 환자 피드백에 대한 학생의 참여를 높이기 위해서는 환자로부터 유익한 피드백을 수집하는 방법을 교육하여 피드백 메시지의 품질을 높이기 위해 노력해야 합니다. 환자로부터 비특이적이고 주로 긍정적인 피드백을 받는 경우가 종종 보고되므로[23, 46, 47, 48], 구체적인 질문을 구성하고 대화에 참여하여 유익한 피드백을 요청하는 데 이 교육의 초점을 맞출 것을 제안합니다[35, 49]. 또한 환자를 위한 자발적인 피드백 교육과 설문지와 같은 피드백 도구가 이 과정을 지원할 수 있습니다[46, 50, 51]. 향후 연구에서는 이러한 교육 활동이 신뢰성 판단에 어떤 영향을 미치는지 살펴볼 수 있습니다.

In practice, to enhance student engagement with patient feedback, we should strive to increase the quality of patients’ feedback messages by training students to collect informative feedback from patients. Since receiving non-specific and mainly positive feedback from patients is often reported [23, 46, 47, 48], we suggest focusing this training on asking for informative feedback, by formulating specific questions and engaging in a dialogue [35, 49]. Moreover, voluntary feedback training for patients, and feedback tools like questionnaires, could support the process [46, 50, 51]. Future research could explore how these training activities affect credibility judgments.

향후 연구를 위한 제한점 및 제안

Limitations and suggestions for future research

이 연구에서는 학생들의 신뢰도 판단에 대한 인식에 초점을 맞추었기 때문에 필연적으로 한계가 있습니다. 연구 데이터는 회상에 기반한 것이기 때문에 신뢰성에 대한 논거가 숨겨져 있을 가능성이 남아있습니다. 또한 지각을 연구했기 때문에 제도적 문화와 같이 신뢰성 판단에 영향을 줄 수 있는 외적, 무의식적 측면도 숨겨져 있었을 수 있습니다[52, 53]. 이러한 측면을 수정하고 통제하는 실험 설계를 통해 신뢰도 판단에 미치는 영향을 밝힐 수 있습니다.

In this study we focused on students’ perceptions of their credibility judgments, which inevitably brings limitations. The study data is based on recall, which leaves the possibility that arguments for credibility remained hidden. Moreover, since we studied perceptions, external and subconscious aspects that can influence credibility judgments, like institutional culture, might also have remained hidden [52, 53]. Experimental designs that modify and control these aspects could reveal their impact on credibility judgments.

또한, 연구 대상 집단이 숙련된 의료 전문가로 제한되어 있어 데이터의 전달성이 제한될 수 있습니다. 임상 현장에 있는 대부분의 학생들에게는 환자에게 피드백을 요청하는 것이 처음이었기 때문입니다. 연구 결과에 따르면 신뢰성 판단은 피드백을 받는 사람의 과거 경험에 의해 부분적으로 형성됩니다. 따라서 숙련된 의료진은 환자의 신뢰도를 다르게 판단할 수 있습니다. 그러나 우리의 목적은 학생의 환자에 대한 신뢰도 판단에 대해 심층적으로 탐구하는 것이었습니다. 따라서 우리의 연구 결과는 (미래의) 의료 전문가가 환자에 대한 신뢰성 판단을 내리는 복잡한 과정을 밝히기 위한 향후 연구의 출발점이 될 수 있습니다.

Moreover, our study population might limit the transferability of our data to experienced healthcare professionals. For most students in the clinical context, it was their first time asking patients for feedback. Our results show that credibility judgments are partly shaped by past experiences of the feedback receiver. Therefore, experienced healthcare professionals might judge a patient’s credibility differently. However, our purpose was to conduct an in-depth exploration of students’ credibility judgments regarding patients. Our results therefore serve as a starting point on which future studies can build, to further unravel the complex process by which credibility judgments regarding patients are made by (future) healthcare professionals.

결론적으로, 의대생들은 환자의 역량, 신뢰성, 선의의 측면을 판단하여 환자가 신뢰할 수 있는 피드백 제공자인지 여부를 결정합니다[18]. 학생들의 판단은 관계와 관련 목표라는 맥락에서 여러 가지, 때로는 상충되는 요소들을 종합적으로 고려하여 이루어집니다. 임상적 맥락에서 학생-환자 관계의 치료 목표와 교육 목표 사이에 인식되는 긴장은 신뢰성을 떨어뜨릴 수 있습니다. 향후 연구에서는 학생과 환자 간에 목표와 역할을 논의하여 열린 피드백 대화의 장을 마련할 수 있는 방법을 모색해야 합니다.

In conclusion, medical students judge aspects of patients’ Competence, Trustworthiness and Goodwill to determine whether they are credible feedback providers [18]. Students’ judgments are a weighing of multiple and sometimes conflicting factors, within the context of relationships and their associated goals. In the clinical context, perceived tensions between therapeutic goals and educational goals of the student-patient relationship can diminish credibility. Future research should explore how goals and roles can be discussed between students and patients to set the stage for open feedback conversations.

Patients as Feedback Providers: Exploring Medical Students' Credibility Judgments

PMID: 37064270

PMCID: PMC10103723

DOI: 10.5334/pme.842

Free PMC article

Abstract

Introduction: Patient feedback is becoming ever more important in medical education. Whether students engage with feedback is partly determined by how credible they think the feedback provider is. Despite its importance for feedback engagement, little is known about how medical students judge the credibility of patients. The purpose of this study was therefore to explore how medical students make credibility judgments regarding patients as feedback providers.

Methods: This qualitative study builds upon McCroskey's conceptualization of credibility as a three-dimensional construct comprising: competence, trustworthiness, and goodwill. Since credibility judgments are shaped by the context, we studied students' credibility judgments in both a clinical and non-clinical context. Medical students were interviewed after receiving feedback from patients. Interviews were analyzed through template and causal network analysis.

Results: Students based their credibility judgments of patients on multiple interacting arguments comprising all three dimensions of credibility. In estimating a patient's credibility, students reasoned about aspects of the patient's competence, trustworthiness, and goodwill. In both contexts students perceived elements of an educational alliance between themselves and patients, which could increase credibility. Yet, in the clinical context students reasoned that therapeutic goals of the relationship with patients might impede educational goals of the feedback interaction, which lowered credibility.

Discussion: Students' credibility judgments of patients were a weighing of multiple sometimes conflicting factors, within the context of relationships and their associated goals. Future research should explore how goals and roles can be discussed between students and patients to set the stage for open feedback conversations.

Copyright: © 2023 The Author(s).