보건의료전문직교육에서 온라인 학습 파트1: 온라인 환경에서의 교수-학습: AMEE Guide No. 161 (Med Teach, 2023)

Online learning in Health Professions Education. Part 1: Teaching and learning in online environments: AMEE Guide No. 161

Heather MacNeilla , Ken Mastersb , Kataryna Nemethyc and Raquel Correiad

소개: 온라인 학습과 팬데믹 교육학을 넘어서기 위한 증거

Introduction: evidence for online learning and moving beyond pandemic pedagogy

'[D] 디지털 테크놀로지은 고등 교육의 중심적인 측면이 되어 학생 경험의 모든 측면에 본질적으로 영향을 미치고 있습니다'(Bond 외. 2020).

‘[D]igital technology has become a central aspect of higher education, inherently affecting all aspects of the student experience’ (Bond et al. 2020).

보건 전문직 교육(HPE)의 온라인 학습은 탄탄한 기반을 갖추고 있으며(Ellaway and Masters 2008; Masters and Ellaway 2008) 소프트웨어, 하드웨어, 학습자 선호도, 커리큘럼 개혁의 발전으로 지난 10년 동안 빠르게 진화해 왔습니다(Schwartzstein and Roberts 2017; Emanuel 2020). 이러한 발전에도 불구하고 HPE는 일반적으로 온라인 학습 채택에 있어 고등 교육보다 뒤처져 있었습니다.

Online learning in Health Professions’ Education (HPE) has a well-established foundation (Ellaway and Masters 2008; Masters and Ellaway 2008) and has been rapidly evolving over the last decade due to advances in software, hardware, learner preferences, and curriculum reform (Schwartzstein and Roberts 2017; Emanuel 2020). Despite these advances, HPE has typically fallen behind higher education in the adoption of online learning.

그러나 코로나19의 출현으로 전 세계적으로 대면(F2F) 교육에서 온라인 긴급 원격 교육(ERT)으로의 전환이 급격하고 가속화되었으며, 학습자가 온라인 시스템에 최대한 중단 없이 신속하게 액세스할 수 있도록 교육 자료를 제공하는 데 중점을 두었습니다(Hodges 외. 2020; Daniel 외. 2021). 이는 종종 온라인 교육 관행, 이론 또는 교수진 개발을 적용할 시간이 거의 없이 사용 가능한 리소스를 사용하여 F2F 활동에 가장 가까운 온라인 활동을 찾는 것을 수반했습니다(Fawns 외. 2020; Stojan 외. 2021). 안타깝게도 이로 인해 많은 사람들이 온라인 학습이 F2F 방법보다 열등하다는 잘못된 가정을 하게 되었습니다.

However, the emergence of COVID-19 led to a sudden and accelerated world-wide shift from face-to-face (F2F) teaching to online Emergency Remote Teaching (ERT) (Hodges et al. 2020) or Pandemic Pedagogy (Schwartzman 2020), with the focus on getting educational materials into online systems accessible to learners quickly, and with as little disruption as possible (Hodges et al. 2020; Daniel et al. 2021). This often entailed finding the closest online equivalent to F2F activities, using available resources, with little time to apply online education practices, theories or faculty development (Fawns et al. 2020; Stojan et al. 2021). Unfortunately, this led many to the incorrect assumption that online learning was inferior to F2F methods.

수십 년에 걸친 연구 결과에 따르면 온라인 학습 결과가 F2F 결과와 유사하며, 의료 맥락에서도 마찬가지입니다(Cook et al. 2008; Pei and Wu 2019). 이러한 결과는 여러 분야에 걸친 수많은 체계적 문헌고찰과 메타분석, 그리고 진화하는 테크놀로지에서 반복되어 왔으며 '유의미한 차이 효과 없음'으로 알려져 있습니다(DETA 2019). 다양한 온라인 방식, 상황, 교사 및 학습자 그룹의 고유한 장점과 과제에도 불구하고 온라인 학습의 핵심은 학습이며, 특히 온라인과 F2F 방식 간의 경계가 계속 모호해짐에 따라 온라인과 F2F 방식을 구분하는 것을 중단해야 할 수도 있습니다.

Decades of research have shown that online learning outcomes are similar to F2F outcomes (U.S. Department of Education, Office of Planning, Evaluation, and Policy Development, Policy and Program Studies Service 2010; Nguyen 2015), including in healthcare contexts (Cook et al. 2008; Pei and Wu 2019). This finding has been repeated in numerous systematic reviews and meta-analyses across multiple disciplines, and evolving technologies, and is known as the ‘no significant difference effect’ (DETA 2019). Despite unique advantages and challenges of different online modalities, contexts, teachers and learner groups, online learning at its core is just learning, and perhaps we should cease making a distinction between online and F2F methods, especially as the lines between the two continue to blur.

그러나 동등성의 문제는 여전히 모호한 측면이 있습니다. 첫째, 온라인 학습은 이질적입니다. 강의, 침상 학습, 문제 기반 학습(PBL), 직장 학습, 저널 클럽과 같은 F2F 방식을 한데 묶어 동일한 학습 결과를 제공하는 것으로 간주하기는 어렵습니다. 마찬가지로 웨비나, 온라인 시뮬레이션, 가상 사례, 팟캐스트, 소셜 미디어 등 다양한 방식이 있습니다. 또한 온라인 비디오와 설문조사 앱은 F2F 강의실에서 자주 사용되며, 온라인 학습에는 F2F 참가자가 포함될 수 있으므로(예: 나중에 설명하는 HyFlex 또는 원격 강의실 제공) 이러한 방식을 구분하는 것이 비현실적이거나 불가능할 수 있습니다.

However, the question of equivalency remains fraught with ambiguity. First, online learning is heterogeneous. It is unlikely we would clump F2F modalities such as lectures, bedside learning, Problem-Based Learning (PBL), workplace learning and journal club together and consider them to provide the same learning outcomes. Similarly, webinars, online simulation, virtual cases, podcasts, and social media, are diverse modalities. In addition, online videos and polling apps are often used in F2F classrooms, and online learning may involve F2F participants (such as in HyFlex or remote classroom delivery discussed later), making the distinction between these modalities impractical or impossible.

따라서 상호작용, 피드백, 반복 및 연습과 같이 온라인 교육에서 성과를 향상시키는 기법이 F2F 환경에서도 동일하다는 것은 놀라운 일이 아닙니다(Cook 외. 2010; Cervero와 Gaines 2015). 또한 분산 연습(시간 간격을 둔 연습) 및 멀티미디어 학습과 같이 F2F 환경에서 더 효과적인 것으로 입증된 학습 설계 전략은 온라인 학습을 통해 촉진될 수 있습니다(Cervero and Gaines 2015; Van Hoof 외. 2021).

Perhaps it is no surprise, then, that the techniques that improve outcomes in online teaching are the same in F2F environments, such as interactivity, feedback, repetition, and practice exercises (Cook et al. 2010; Cervero and Gaines 2015). In addition, learning design strategies that are proven to be more effective in F2F environments, such as distributed practice (spaced over time) and multimedia learning, can be facilitated with online learning (Cervero and Gaines 2015; Van Hoof et al. 2021).

둘째, 대부분의 연구는 만족도, 지식 및 스킬 습득과 같은 학습 결과를 조사했으며 환자 결과는 거의 조사하지 않았습니다. 또한 직업적 정체성 형성, 멘토링, 교사와 학생의 소진, 온라인 학습의 비용 효율성 등 학습에는 추가 조사가 필요한 다른 뉘앙스도 있습니다(Castañeda and Selwyn 2018; Cook 외. 2021; Oducado 외. 2022).

Second, most studies have examined learning outcomes such as satisfaction, knowledge, and skill acquisition and rarely patient outcomes. In addition, there are other nuances to learning such as professional identity formation, mentorship, teacher and student burnout and cost effectiveness of online learning that need further examination (Castañeda and Selwyn 2018; Cook et al. 2021; Oducado et al. 2022).

마지막으로, 온라인 교육이 이루어지는 제도적 및 학습적 맥락은 테크놀로지를 통한 학습과 사용에 영향을 미칠 수 있으므로(Ellaway 외. 2014a,b), 결과, 방법 및 접근 방식의 단순한 이식에 대한 순진한 믿음은 피해야 합니다.

Lastly, institutional and learning contexts in which online education occurs can affect learning with, and usage of, technology (Ellaway et al. 2014a,b), so one should avoid a naïve belief in a simple transplant of outcomes, methods, and approaches.

동등성 문제와 관련하여 가장 흥미롭고 중요한 발견은 혼합 학습(F2F와 온라인 방식을 함께 결합)이 F2F 또는 온라인 학습만 하는 것보다 더 나은 학습 결과를 제공한다는 것입니다(Liu 외. 2016; Vallée 외. 2020). 혼합 학습을 통해 온라인 학습과 F2F 학습의 장점은 활용하면서 바람직하지 않은 효과는 최소화할 수 있기 때문에 이는 놀라운 일이 아닐 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, F2F 구성 요소는 즉각적인 피드백과 사회적 연결을 제공하는 반면, 온라인 구성 요소는 분산되고 편리한 학습에 도움이 될 수 있습니다.

The most exciting and significant finding on the issue of equivalency is that blended learning (combining F2F and online methods together) provides better learning outcomes than either F2F or online learning alone (Liu et al. 2016; Vallée et al. 2020). Perhaps this is not surprising, as blended learning allows us to utilize the best aspects of both online and F2F learning while minimizing undesirable effects. For example, F2F components could provide immediate feedback and social connections, while online components help with dispersed and convenient learning.

여기서는 온라인 HPE에 대한 ERT의 영향에 대한 자세한 강점-약점-기회-위협(SWOT) 분석을 수행하지는 않지만, 이 프레임워크를 느슨하게 사용하여 이 소개의 나머지 부분을 안내하고 ERT가 제기하는 주요 문제 몇 가지를 강조하겠습니다.

Although this is not the place to conduct a detailed Strengths-Weaknesses-Opportunities-Threats (SWOT) Analysis of ERT’s impact on online HPE, we will loosely use this framework to Guide the rest of this introduction, highlighting some of the major issues raised by ERT.

ERT의 주요 강점은 온라인 교수 학습 경험이 없거나 제한적이었던 많은 교사와 학습자가 이제 온라인 교수 학습에 노출되어 그 이점을 확인할 수 있다는 것입니다(Naciri 외. 2021). 또한 인프라 및 조직에 변화를 준 보건 전문 학교 및 기관은 시스템을 더욱 발전시킬 수 있습니다.

The major strengths of ERT are that many teachers and learners who had no or limited experience with online teaching and learning have now had exposure and can see its benefits (Naciri et al. 2021). In addition, those health professions schools and institutions that effected infrastructural and organizational changes are able to develop their systems further.

학습자와 교육자 모두 온라인 학습의 유연성과 접근성, 특히 시간, 거리 또는 직장이나 가족 의무와 같은 경쟁 우선 순위로 인해 교육 활동에 참석할 수 없었을 사람들에게 주는 이점에 주목했습니다(Daniel 외. 2021). 어떤 경우에는 학습 요구가 가장 큰 동영상이나 모듈을 선택해 다시 보거나 퀴즈와 같은 자동화된 개별 피드백을 받을 수 있는 등 학습자 중심의 교육 접근 방식을 장려하기도 했습니다.

Learners and educators alike have noted the benefits of flexibility and accessibility of online learning, particularly for those who otherwise might not have been able to attend educational activities due to time, distance, or competing priorities, such as work or family duties (Daniel et al. 2021). In some cases, the ERT pivot encouraged a learner-centric approach to education, such as being able to choose and revisit videos or modules where learning needs were greatest or receive automated individualized feedback such as quizzes.

이러한 강점을 통해 ERT는 온라인 학습을 처음 접하는 교사에게 큰 잠재력을 약속했으며, 교육학적으로 정보에 입각하고 테크놀로지적으로 변화된 HPE를 통합할 수 있는 강력한 기반을 제공했습니다(Jeffries 외. 2022).

With these strengths, ERT promised great potential for teachers new to online learning and provided a strong grounding on which to incorporate further pedagogically informed and technology-transformed HPE (Jeffries et al. 2022).

ERT의 약점은 이러한 전환을 시도하는 대부분의 보건 전문 학교와 기관이 준비가 제대로 되어 있지 않았고, 많은 교사와 학습자가 부정적인 경험을 했으며, 그 결과 온라인 교육은 제한적이며, 모든 과목을 온라인으로 가르칠 수 없고, 다른 사람과의 소통과 연결에 심각한 제약이 있으며, 온라인 학습은 비상시에만 사용해야 한다는 인식을 갖게 되었다는 점입니다. ERT는 또한 하드웨어, 인터넷, 안전한 학습 공간에 대한 접근이 제한적이거나 전혀 없는 학생들이 경험하는 '디지털 격차'와 테크놀로지 접근의 글로벌 불평등을 강조했습니다(Schwartzman 2020).

A weakness of ERT was that most health professions schools and institutions making this pivot were poorly prepared, and many teachers and learners had negative experiences; as a result, their perception of online education may be that it is limited, that not all subjects can be taught online, that communication and connection with others are severely constrained, and that online learning should be used in emergencies only. ERT also highlighted the ‘digital divide’ that students with limited or no access to hardware, internet, and safe spaces to learn in experienced, and global inequities of technology access (Schwartzman 2020).

이러한 문제는 교수진 개발 부족, 하드웨어, 소프트웨어, 인터넷 접근성의 테크놀로지적 문제, 학습자 및 교육자 오리엔테이션과 디지털 리터러시 부족으로 인해 증폭되는 경우가 많았습니다(Schwartzman 2020; Daniel 외. 2021). 학습자 참여, 학생의 소속감, 경쟁 우선순위, 화면 피로 등의 문제도 영향을 미쳤으며, 네티켓, 동료 협업, 상호 작용, 혼합 접근 방식과 같은 교육적 설계를 통해 해결해야 할 과제입니다(Naciri 외. 2021).

These issues were frequently amplified by a lack of faculty development, technical problems with hardware, software, internet accessibility, and poor learner and educator orientation and digital literacy (Schwartzman 2020; Daniel et al. 2021). Problems with learner engagement, student sense of belonging, competing priorities and screen fatigue also played their part, and still need to be addressed through pedagogical design such as netiquette, peer collaboration, interactivity, and blended approaches (Naciri et al. 2021).

따라서 교사와 학습자가 자신의 경험을 활용하여 단순히 F2F 관행을 대체하는 것을 넘어, 보다 유연한 학습, 자료, 환자 및 활동에 대한 접근성 향상과 같은 이점을 경험하고, 한계와 오류로부터 배우면서, 교육학적으로 정보에 입각한 본격적인 온라인 교육을 개발할 수 있는 기회가 ERT에 의해 촉진될 수 있습니다.

An opportunity fostered by ERT, therefore, exists: that of teachers’ and learners’ using their experience to move beyond merely replacing F2F practices to develop full-blown and pedagogically informed online education, building on benefits experienced, such as more flexible learning and increased accessibility to materials, patients, and activities, while learning from limitations and errors.

그 결과, 우리는 코로나19 이전부터 느리기는 하지만 교육을 재구성해 온 온라인 HPE의 발전(인프라, 리더십, 교수진, 직원, 학습자 역량 포함)을 기반으로 보건 전문직 교육에서 무엇이 효과적인지에 대한 변화하는 이해를 반성할 기회를 갖게 되었습니다(Emanuel 2020; Price and Campbell 2020). 이러한 구조 조정은 수동적인 학습 기회에서 보다 능동적인 학습 기회로 전환하고 교육 관행의 노하우 격차를 좁힐 수 있는 기회를 제공할 수 있습니다. 또한, 온라인 학습을 통해 대규모 강의실을 병상이나 직장으로 가져 오거나 다른 국가를 포함하여 원격으로 학습자를 교육하는 등 F2F 방법으로는 불가능한 기회를 제공할 수 있는 방법을 고려할 수 있습니다(Jiang 외. 2021). 이는 또한 ERT를 넘어 교육학적으로 정보에 입각한 온라인 및 혼합 교육 방식으로 전환하는 데 필요한 교수진 및 직원 개발(FSD)에 투자할 수 있는 기회를 제공합니다.

As a result, we have an opportunity to continue to build on the advances in online HPE that were restructuring education, albeit slowly, long before Covid-19 (including infrastructure, leadership, faculty, staff, and learner competence) to reflect a shifting understanding of what works in health professions education (Emanuel 2020; Price and Campbell 2020). This restructuring may provide an opportunity to move away from passive to more active learning opportunities, and narrow the know-do gap in educational practices. In addition, we can consider ways in which online learning may allow for opportunities that would not be possible with F2F methods, such as bringing large classrooms to the bedside or workplace, or training learners remotely, including in different countries (Jiang et al. 2021). This also provides us with an opportunity to invest in the faculty and staff development (FSD) needed to move beyond ERT into pedagogically informed ways of online and blended education.

ERT의 가장 큰 위협은 아마도 위에서 설명한 약점으로 인한 의구심과 관련하여 온라인 학습을 어떻게 활용하고 탐구해야 하는지에 대한 현재 방향성이 부족하다는 점일 것입니다. 이러한 방향성의 부재는 교사와 학생들이 F2F 교육으로 되돌아가 코로나19 이전의 안전지대에 안주하고 온라인 경험의 가치를 상실하도록 부추길 수 있습니다. 이는 F2F 테크놀로지에 대한 경험, 연구, 개발이 오랜 기간에 걸쳐 이루어진 것과 달리, 지난 2~3년 동안 이러한 새로운 환경에서 수집된 모범 사례에 대한 경험과 연구 기간이 상대적으로 짧았기 때문에 더욱 악화될 수 있습니다. 또한 보건 전문직 교육의 변화를 계속 진전시키기 위해서는 코로나19 위기 상황에서도 전략, 인프라, 교수진 개발 등 제도적 지원을 유지하는 것이 중요합니다(O'Doherty 외. 2018).

Perhaps the greatest threat from ERT was a lack of current direction on how we should be using and exploring online learning, often related to the doubts caused by the weaknesses described above. This lack of direction may encourage teachers and students to revert to F2F education, settle into pre-COVID-19 comfort zones, and lose the value of their online experience. This is exacerbated by the relatively short duration of experience and research in best practices gathered in these new environments over the last two to three years, in contrast to lifetimes of experiencing, researching and/developing comfort levels with F2F techniques. It will also be important to maintain institutional support, including strategy, infrastructure, and faculty development in the absence of the COVID-19 crisis if we are to keep moving forward in our transformation of health professions education (O’Doherty et al. 2018).

이 가이드의 목적은 약점과 위협을 줄이고 온라인 HPE의 강점과 기회를 바탕으로 HPE 온라인 학습에 대한 지침과 방향을 제시하는 것입니다. 이를 위해 본 가이드는 두 부분으로 나누어 서로 정보를 제공합니다.

The aim of this Guide is to provide guidance and direction for HPE online learning, by diminishing the weaknesses and threats, and building on the strengths and opportunities of online HPE. To accomplish this, we have divided this Guide into two Parts that inform one another.

- 첫 번째 파트에서는 학습자 참여, 교수진 개발, 포용성, 접근성, 저작권 및 개인정보 보호와 같은 최근 이슈와 고려 사항을 포함하여 온라인 학습의 증거, 이론, 형식 및 교육 설계에 대한 개요를 제공합니다. 부록에서는 실제 사례와 구현 전략을 제공합니다.

The first Part will provide an overview of evidence, theories, formats and educational design in online learning, including contemporary issues and considerations such as learner engagement, faculty development, inclusivity, accessibility, copyright, and privacy. The Supplemental Appendix provides practical examples and implementation strategies. - 2부에서는 1부에서 논의한 개념의 구현 및 통합을 위한 실제 사례와 함께 특정 테크놀로지 도구 유형에 중점을 두며, 디지털 장학금, 학습 분석 및 신흥 테크놀로지를 다룹니다. 요약하자면, 파트 1은 파트 2에서 소개하는 테크놀로지의 실제 적용에 필요한 기초를 제공하므로 두 파트를 함께 읽어야 합니다.

The second Part focuses on specific technology tool types with practical examples for implementation and integration of the concepts discussed in Part 1, and will include digital scholarship, learning analytics, and emerging technologies. In sum, both Parts should be read together as Part 1 provides the foundation required for the practical application of technology showcased in Part 2.

먼저 온라인 교육의 기본이자 간과하기 쉬운 출발점인 온라인 학습 이론부터 살펴보겠습니다.

We first begin with online learning theories as a fundamental, and often overlooked, starting point for online education.

온라인 학습 프레임워크 및 이론

Online learning frameworks and theories

온라인 학습의 결점은 온라인 고등 교육의 연구 및 커리큘럼 설계에 사용되는 이론이 부족하다는 것입니다(Castañeda and Selwyn 2018; Hew 외. 2019; Bond 외. 2020). 이는 의료 환경에서도 마찬가지입니다(Bajpai 외. 2019). 온라인 교육 연구와 커리큘럼은 종종 건전한 교육적 설계보다는 경험적이고 실용적인 경험을 기반으로 하며, 혁신의 참신성이나 실용적 필요성 때문에 이론에 대한 탄탄한 기반이 필요하지 않다는 개념에 따라 진행되는 것처럼 보입니다.

A deficiency in online learning is the lack of theory employed in the research and curricular design of online higher education (Castañeda and Selwyn 2018; Hew et al. 2019; Bond et al. 2020). This is also true within healthcare settings (Bajpai et al. 2019). Online educational research and curricula are often based on empirical and practical experience rather than sound pedagogical design and appear to be guided by the notion that innovation, because of its novelty or practical need, does not require a sound grounding in theory.

온라인 학습에 이론과 프레임워크를 사용하면 이전 작업을 기반으로 하고, 공통 언어와 학습 방향을 개발하고, 온라인 학습 과정에 대한 이해를 높이고, 결과를 다른 온라인 상황에 일반화하고, 건전한 커리큘럼과 평가를 설계하고, 학습자가 자신의 학습 과정을 이해하는 데 도움을 주어 더 나은 학습 결과를 얻을 수 있습니다(Bajpai 외. 2019; Hew 외. 2019). 궁극적으로 온라인 학습 이론을 사용하면 학생의 참여와 학습 성과를 극대화하는 방식으로 온라인 교육을 제공하는 방식을 재고할 수 있습니다.

The use of theories and frameworks for online learning helps us build on prior work, develops a common language and direction of study, enhances our understanding of online learning processes, allows generalization of results to other online contexts, designs sound curriculum and assessment, and helps learners understand their learning processes, all toward better learning outcomes (Bajpai et al. 2019; Hew et al. 2019). Ultimately, using online learning theories can allow us to rethink the way we provide online education in a way that maximizes student engagement and learning outcomes.

이전의 AMEE 문헌은 일반적인 교육 이론과 프레임워크에 대한 훌륭한 소개를 제공하며(Taylor and Hamdy 2013), 온라인 학습 사례와 함께 교육 이론을 검토합니다(Sandars et al. 2015). 온라인 학습을 위해 특별히 만들어진 프레임워크, 모델 및 이론이 잘 정립되었지만 F2F 환경에서 온라인 환경으로 '가져온' 다른 이론보다 선호되어야 하는지에 대한 논쟁이 있습니다. 적응형 모델의 한 가지 예로 온라인 커리큘럼 개발에 대한 Kern의 6단계 접근법을 들 수 있습니다(Chen 외. 2019). 이 가이드에서는 온라인 학습에 고유한 세 가지 이론을 간략하게 소개하며, 초급(PICRAT 모델), 중급(탐구 커뮤니티 프레임워크) 및 고급(커넥티비즘) 온라인 교육자가 접근할 수 있다고 생각되는 이론을 소개합니다. 온라인 학습에 관한 더 많은 이론, 프레임워크 및 모델이 있으며, 독자들은 이러한 이론과 프레임워크를 더 자세히 살펴볼 것을 권장합니다. 마찬가지로 교육자는 연구 및 커리큘럼 개발 시 각 이론의 고유한 장점, 단점 및 맥락을 고려하여 여러 이론을 고려해야 합니다. 온라인 이론의 실제 적용에 대해서는 이 가이드의 파트 2에서 자세히 설명합니다.

Previous AMEE literature provides an excellent introduction to general educational theories and frameworks (Taylor and Hamdy 2013), as well as a review of educational theories with online learning examples (Sandars et al. 2015). There are arguments about whether frameworks, models, and theories created specifically for online learning should be preferred over other well-established but ‘imported’ theories from F2F environments to the online environment. One example of an adapted model is Kern’s six-step approach to online curriculum development (Chen et al. 2019). This Guide briefly introduces three theories original to online learning, that we feel are accessible to the

- beginner (PICRAT model),

- intermediate (Community of Inquiry Framework) and

- advanced (Connectivism) online educator.

There are many more theories, frameworks, and models of online learning, and readers are encouraged to explore these in more detail. Equally, educators should consider multiple theories in their research and curriculum development, considering the unique advantages, disadvantages, and context of each theory. Practical application of online theories will be further discussed in Part 2 of this Guide.

수동적-대화적-창의적-대체-증폭-변환(PICRAT) 모델

Passive-Interactive-Creative-Replaces-Amplifies-Transforms (PICRAT) model

PICRAT는 테크놀로지 통합의 최신 모델로, 특히 유치원부터 12학년(K-12) 문학에서 인기를 얻고 있습니다. 이 모델은 F2F 학습에서 교사와 학습자의 역할을 고려한 다음 이를 온라인 환경으로 비교하고 확장하는 것으로 시작하기 때문에 온라인 교육 초보자도 쉽게 접근할 수 있고 사용할 수 있습니다. PICRAT은 복잡한 온라인 환경에서 다양한 솔루션을 제공하기 위해 이론적 다원주의를 주장하면서 SAMR 및 RAT와 같은 여러 선행 모델을 기반으로 하고 결합합니다(Kimmons 외. 2020).

PICRAT is a newer model of technology integration, gaining popularity particularly in the kindergarten to grade 12 (K-12) literature. It is accessible and easy to use for the beginner online educator, as it starts with considering teacher and learner roles in F2F learning and then comparing and extending this to the online environment. PICRAT builds upon and combines several prior models such as the SAMR and RAT, arguing for theoretical pluralism to enable different solutions in these complex online environments (Kimmons et al. 2020).

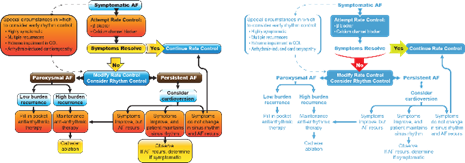

PICRAT 모델은 학생들이 테크놀로지와 상호작용하는 방식과 교사가 교육에서 테크놀로지를 사용하는 방식이라는 두 가지 주요 질문을 살펴봅니다. PICRAT의 요소는 매트릭스를 형성하며, 한 축(PIC - 수동적, 상호작용적, 창의적)은 학습자의 사용을, 다른 축(RAT - 대체, 증폭, 변형)은 교사의 사용을 살펴봅니다(그림 1(a)). 목표는 '테크놀로지의 역할은 그 자체가 목적이 아니라 목적을 위한 수단으로 사용되어야 하며, 테크놀로지 중심적 사고를 피해야 한다'는 것입니다(Kimmons 외. 2020).

The PICRAT model looks at two main questions: how students interact with technology, and how teachers use technology in their pedagogy. The elements of PICRAT form a matrix,

- with one axis (PIC – Passive, Interactive, Creative) examining learners’ use and

- the other axis (RAT – Replacement, Amplification, Transformation) examining teachers’ use (Figure 1(a)).

The goal is that ‘technology’s role should serve as a means to an end, not an end in itself – avoiding technocentric thinking’ (Kimmons et al. 2020).

Kimmons는 e-모듈이나 온라인 퀴즈와 같은 테크놀로지가 학생의 상호작용을 유도할 수 있지만, 이러한 규범적 학습은 '이전 학습과의 전달성과 의미 있는 연결을 제한'할 수 있지만, 창의적 학습(학습자가 동영상이나 협업 블로그와 같은 아티팩트를 만드는 것)은 창의적인 문제 해결과 더 깊이 있고 맥락화된 학습을 유발하므로, 수동적 학습은 물론이고 심지어 상호작용적 학습보다도 (창의적 학습이) 선호될 수 있다고 주장합니다(Kimmons 외., 2020).

Kimmons argues that, while technology such as e-modules or online quizzes can drive student interactivity, this prescriptive learning may ‘limit transferability and meaningful connections to previous learning’, but creative learning (where learners create artifacts such as videos and collaborative blogs) causes creative problem solving and deeper, contextualized learning, and therefore may be preferred over passive and even interactive learning (Kimmons et al. 2020).

교사가 테크놀로지를 사용하는 방법을 조사할 때 매트릭스의 'RAT' 축을 고려합니다. ERT와 마찬가지로, 테크놀로지를 사용하기 시작하는 교사들은 교육적 관행에 대한 개선 없이 F2F 교육을 대체하는 용도로 테크놀로지를 사용하는 경우가 많습니다. 그러나 더 많은 편안함과 스킬을 갖추면 테크놀로지를 사용하여 교육적 접근 방식을 증폭(근본적으로 바꾸지는 않지만 개선)하거나 심지어 변형(비테크놀로지적 수단으로는 달성할 수 없는 학습을 가능하게 함)할 수도 있습니다.

When examining how teachers use technology, we consider the ‘RAT’ axis of the matrix. Like ERT, teachers starting to use technology will often use it as a replacement to F2F teaching with no improvement to their pedagogical practice. However, with more comfort and skills, technology can be used to amplify (improve, but not radically alter) or even transform (enable learning not achievable through non-technological means) pedagogical approaches.

PICRAT은 직관적으로 사용하기 쉬우며 교육 테크놀로지의 복잡한 사회문화적 사용에 관한 대화를 촉진하는 데 도움이 됩니다. 이 도구는 테크놀로지를 사용하는 유일한 '올바른' 방법은 없으며(본질적으로 나쁘거나 좋은 매트릭스 사각형은 없으며 각각 고유한 이점이 있음), 상황에 따라 서로 다른 창의적인 솔루션이 필요하다는 점을 인정합니다.

PICRAT is intuitively easy to use and helps to facilitate conversations around complex sociocultural use of educational technology. It acknowledges that there is often no one ‘right’ way to use technology (no matrix square is inherently bad or good and each has its own benefits), and that different contexts require different creative solutions.

탐구 커뮤니티 모델

The Community of Inquiry model

탐구 커뮤니티(CoI) 모델은 가장 널리 사용되고 연구된 온라인 학습 모델 중 하나이며 중급 온라인 교육자에게 적합합니다(Garrison 외. 1999). 사회적 현존감(SP), 인지적 현존감(CP), 교수적 현존감(TP)의 세 가지 상호 연결 현존감은 온라인 학습을 설계하고 연구할 때 고려해야 할 사항에 대한 대화를 시작할 수 있는 중첩된 영역을 만듭니다(그림 1(b)).

The Community of Inquiry (CoI) model is one of the most widely used and studied online learning models and is well suited for intermediate online educators (Garrison et al. 1999). Three interconnecting presences: social presence (SP), cognitive presence (CP), and teaching presence (TP), create overlapping domains from which to start conversations around considerations in designing and researching online learning (Figure 1(b)).

- 사회적 존재감이란 학습자로서 자신을 가상 학습 환경에 투영하고 다른 사람들과 관계를 형성하는 능력을 말합니다. 이는 인지 및 TP 형성의 구성 요소로 간주됩니다(예: 안전한 학습 환경을 협상하거나 학습자가 연결할 수 있는 기회를 제공하는 것).

Social presence refers to the ability to project oneself as a learner into the virtual learning environment and form connections with others. It is thought of as the building block to cognitive and TP formation (e.g. negotiating a safe learning environment or providing opportunities for learners to connect). - 교수적 존재감은 교수 설계(ID), 조직 및 학습 촉진입니다. 이는 학생 만족도와 인지된 학습에 중요한 요소인 것으로 밝혀졌습니다(예: 과제에 대한 온라인 루브릭 사용 또는 교수자의 비디오 발표).

Teaching presence is the Instructional Design (ID), organization, and facilitation of learning. It is found to be a significant factor in student satisfaction and perceived learning (e.g. use of online rubrics for assignments or instructor video announcements). - 인지적 존재감은 학습자가 학습과 인지적으로 연결되는 방식을 말하며, 보통 4단계(이벤트 유발, 탐색, 통합, 해결)의 주기적 반복을 통해 이루어집니다. 여기에는 다양한 관점에서 지식을 사회적으로 구성하고 적용하기 위한 그룹 협업과 개인적 성찰, 보유, 정보 해석(예: 온라인 시뮬레이션 또는 소그룹 토론)이 포함됩니다.

Cognitive presence refers to how learners cognitively connect with the learning, often through cyclical iterations of four stages (triggering event, exploration, integration, and resolution). It involves group collaboration to socially construct and apply knowledge from different perspectives, as well as personal reflection, retention, and interpretation of information (e.g. online simulation or small group discussions).

본질적으로 'SP가 만들어내는 그룹 응집력과 열린 소통, 그리고 TP와 관련된 구조, 조직, 리더십은 고차 학습과 관련된 가장 중요한 요소로 간주되는 CP가 번성할 수 있는 환경을 조성하는 토대가 됩니다'(Shea 외. 2014).

In essence, ‘the group cohesion and open communication created by SP and the structure, organization, and leadership associated with TP lay the foundation to create the environment where CP, which is considered to be the most important element associated with higher-order learning, can flourish’ (Shea et al. 2014).

연결주의

Connectivism

커넥티비즘은 보다 발전된 이론으로, 교육자들이 테크놀로지가 단순히 교사와 학습자 간의 정보 전달을 허용하는 교육 시스템에서 연결을 통해 학습을 변화시키는 시스템과 네트워크로 교육 시스템을 변화시키는 데 어떻게 도움이 될 수 있는지 고려하도록 유도합니다. 연결주의는 '카오스, 네트워크, 복잡성 및 자기 조직화 이론에서 탐구하는 원리의 통합'과 함께 네트워크를 통해 '우리의 역량을 연결 형성에서 도출'한다고 가정합니다(Siemens 2005). 이러한 복잡한 지식 네트워크는 연결, 다양성, 멘토링을 통해 형성되고 유지되며, 21세기 헬스케어에서는 잊혀지거나 금방 쓸모없어질 수 있는 개별 지식보다 더 중요합니다. 커넥티비즘의 몇 가지 실제 사례로는 대규모 공개 온라인 강좌(MOOC), 소셜 미디어 또는 실무 커뮤니티 토론 게시판이 있습니다(온라인 교육에서 배우는 것 2012).

Connectivism is a more advanced theory, which prompts educators to consider how technology may assist in changing education systems from those that merely allow transmission of information from teacher to learner, to systems and networks that transform learning through connections. Connectivism assumes that we ‘derive our competence from forming connections’ through networks, with ‘integration of principles explored by chaos, network, and complexity and self-organization theories’ (Siemens 2005). These complex knowledge networks are formed and maintained through connections, diversity, and mentorship, and are more important than individual knowledge, which can be forgotten or quickly obsolete in twenty-first century healthcare. Some practical examples of connectivism include Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs), social media or community of practice discussion boards (What We’re Learning From Online Education 2012).

일상적인 커넥티비즘 교육에서는 학습자가 인터넷에서 제공하는 정보를 사용하여 검증되지 않은 아이디어를 조사하고, 전자 형식의 자료를 만들고, 공동 작업하며, 심지어 코스 커리큘럼에 영향을 미치는 것을 목표로 합니다. 이러한 철학이 실천으로 옮겨지는 과정은 처음에는 HPE MOOC(Masters 2011)의 핵심으로 여겨지던 커넥티비스트 MOOC(cMOOC)(Downes 2010; Siemens 2012)에서 잘 드러납니다. 본 가이드의 2부에서는 HPE MOOC의 개발 및 유형에 대해 자세히 설명하지만, 현재로서는 커넥티비즘의 철학적 요소가 심도 있는 학습을 촉진하고 학생들이 핵심 강의 계획서 이외의 자료에 접근하고 협업하도록 장려하기 위해 코스에 포함될 수 있지만, 전통적인 코스 구조에서 벗어나야 할 수도 있다는 점에 유의하시기 바랍니다.

In day-to-day Connectivist education, the aim is for learners to use the information afforded by the Internet to investigate untested ideas, create, and collaborate on material in electronic format, and even influence the course curriculum. The translation of this philosophy into practice is well-illustrated in what has become known as Connectivist MOOCs (cMOOCs) (Downes 2010; Siemens 2012) which were initially seen as central to HPE MOOCs (Masters 2011). The development and types of MOOCs in HPE will be discussed in more detail in Part 2 of this Guide, but for now, note that the philosophical elements of Connectivism can promote deeper learning and be embedded into courses to encourage students to collaborate and access materials beyond the core syllabus, although may require a departure from traditional course structures.

이제 다양한 온라인 교육 형식을 살펴보겠습니다. 그러나 독자들은 잠시 시간을 내어 온라인 HPE가 경험적 연구와 커리큘럼 설계에서 이론적 접근 방식에 기반을 두는 것으로 전환하여 해당 분야의 학문을 향상시키고 교육을 더욱 견고하고 이전 가능하게 하는 것의 중요성에 대해 생각해 보아야 합니다.

We now turn to examining different online educational formats. Readers should, however, take a moment to reflect on the importance of online HPE’s shifting from empirical research and curriculum design to being grounded in theoretical approaches, so that scholarship in the field is enhanced and education more robust and transferable.

온라인 교육 형식

Online educational formats

온라인 학습의 정의와 형식은 다양하고 지속적으로 진화하고 있습니다(Regmi and Jones 2020). 각 형식은 각기 다른 교사와 학습자에게 어필할 수 있고, 구현에 어려움이 있을 수 있으며, 다양한 맥락의 영향을 받을 수 있습니다. 아래에서는 동기식 및 비동기식 온라인 학습과 혼합식 및 하이브리드 유연 방식과 같은 다른 변형에 대해 살펴봅니다. 여기서는 이러한 형식을 단순히 동기식 및 비동기식 학습으로 지칭하며, F2F 형식에도 동기식(예: 강의) 및 비동기식(예: 읽기) 구성 요소가 있다는 점을 인정합니다(그림 2 참조).

Online learning definitions and formats are diverse and continually evolving (Regmi and Jones 2020). Each format will appeal to different teachers and learners, will have its implementation difficulties, and will be influenced by different contexts. Below, we explore synchronous and asynchronous online learning as well as other variations such as blended and Hybrid-Flexible methods. We will refer to these formats as simply synchronous and asynchronous learning, acknowledging F2F formats also have synchronous (e.g. lecture) and asynchronous (e.g. reading) components (see Figure 2).

동기식 학습

Synchronous learning

동기식 학습은 학습자가 동시에 학습할 때 발생합니다(데이터가 실시간으로 송수신됨). 자주 사용되는 동기식 테크놀로지로는 Zoom, Microsoft Teams, Google Meet 등이 있습니다. 또한 학습자가 가상 환경에서 자유롭게 이동하고 상호 작용할 수 있는 Gather.Town, SpatialChat, Wonder.me와 같은 보다 몰입도 높은 도구가 등장하고 있으며, 세컨드 라이프와 같은 아바타 기반의 가상 세계도 한동안 의료 교육에 사용되어 왔습니다(Ghanbarzadeh 외. 2014).

Synchronous learning occurs when learners are learning at the same time (data are sent and received in real time). Frequently used synchronous technologies include Zoom (https://zoom.us/), Microsoft Teams (https://teams.microsoft.com/edustart), and Google Meet (https://apps.google.com/meet/). In addition, other more immersive tools, such as Gather.Town (https://www.gather.town/), SpatialChat (https://www.spatial.chat/), and Wonder.me (https://www.wonder.me/), which allow learners to move freely and interact in a virtual environment, are emerging, and other virtual, avatar-based worlds such as Second Life (https://secondlife.com/) have been used in healthcare education for some time (Ghanbarzadeh et al. 2014).

동기식 학습은 F2F 교실을 가장 유사하게 반영하기 때문에 팬데믹 상황에서 더 쉽게 채택되었습니다(Stojan 외. 2021). 동기식 HPE에 대한 체계적인 검토 및 메타 분석에 따르면 지식 및 스킬 습득에 있어 기존 학습 환경과 비슷한 결과를 보였으며 학습자들이 선호하는 것으로 나타났습니다(He 외. 2021).

As synchronous learning most closely mirrors F2F classrooms, it was more readily adopted in the pandemic (Stojan et al. 2021). A systematic review and meta-analysis of synchronous HPE showed comparable outcomes to traditional learning environments for knowledge and skill acquisition and was preferred by learners (He et al. 2021).

동기식 학습 소프트웨어의 일반적인 기능으로는 화면 공유, 채팅, 오디오/비디오 공유, 비언어적 반응/이모티콘 등이 있습니다. 다른 기능으로는 설문 조사, 주석, 화이트보드 및 소회의실 등이 있습니다. 그러나 이러한 기능을 사용할 수 없는 경우 설문조사 소프트웨어(예: Poll Everywhere 또는 Kahoot!) 또는 화이트보드 소프트웨어(예: Google Jamboard 또는 Miro)와 같은 추가 소프트웨어를 사용하여 이러한 기능을 쉽게 가져올 수 있습니다. 또한 Nearpod, Mmhmm, Prezi와 같이 동기식 프레젠테이션을 더욱 인터랙티브하게 만드는 데 도움이 되는 도구도 많이 있습니다.

Typical features of synchronous learning software include screen sharing, chat, and audio/video sharing and nonverbal reactions/emojis. Other features may include polling, annotation, whiteboard, and breakout rooms. However, if these features are not available, they can easily be imported by using additional software such as polling software (e.g. Poll Everywhere https://www.polleverywhere.com or Kahoot! https://kahoot.com) or whiteboard software (e.g. Google Jamboard https://workspace.google.com/products/jamboard or Miro https://miro.com). In addition, there are many tools that can assist with making synchronous presentations more interactive such as Nearpod https://nearpod.com, Mmhmm https://www.mmhmm.app/home, and Prezi https://prezi.com.

상호 작용은 동기식 학습의 핵심입니다. 상호작용이 없다면 녹화된 강의가 더 효율적이고(1.5배속으로 시청), 편리하며(언제든지 시청), 세련된(동기식 테크놀로지 결함 없이) 강의가 될 수 있습니다. 그럼에도 불구하고 학습자 참여는 동기식 학습의 가장 어려운 측면 중 하나로 보고되고 있습니다. 온라인 환경에서 학습자 상호 작용과 참여가 학습자의 성과, 동기 부여 및 만족도와 상관관계가 있다는 점을 고려할 때 이는 우려스러운 부분입니다 (Cook 외. 2010; MacNeill 외. 2014; Bond 외. 2020; Händel 외. 2022).

Interactivity is the key to synchronous learning. Without interactivity, a recorded lecture could be more efficient (watching at 1.5× speed), convenient (at any time), and polished (without synchronous technological glitches). Despite this, learner engagement has been reported as one of the most challenging aspects of synchronous learning. This is concerning, given the correlation between learner interactivity and engagement with learner performance, motivation, and satisfaction in online environments (Cook et al. 2010; MacNeill et al. 2014; Bond et al. 2020; Händel et al. 2022).

이러한 환경에서 상호 작용할 때는 형평성, 특히 참여 형평성을 고려하는 것이 중요합니다(Reinholz 외. 2020). 모든 학습자가 온라인 학습에 완전히 참여할 수 있는 하드웨어, 대역폭 또는 안전한 학습 공간에 액세스할 수 있는 것은 아닙니다. 익명(설문조사) 또는 비언어적(채팅) 방식으로 공유하는 것이 더 편한 사람도 있을 수 있습니다. 다섯 손을 들 때까지 기다리거나 채팅 모니터 또는 테크놀로지 도우미 등의 역할을 할당할 때 온라인 무작위 이름 생성기를 사용하는 등 동등한 참여를 보장하는 방법을 고려하세요(Reinholz 외. 2020). 그러나 웹캠 미사용에는 접근성 및 개인정보 보호 문제 외에도 많은 다른 요인이 있습니다(Händel 외. 2022; Masters 외. 2022).

Equity, particularly participatory equity, is important to consider when interacting in these environments (Reinholz et al. 2020). Not all learners have access to hardware, bandwidth, or safe learning spaces to fully participate in online learning. Others may feel more comfortable sharing in anonymous (polls) or non-verbal (chat) ways. Consider ways to ensure equal participation, such as waiting for five hands to be raised or online random name generators for assigning roles such as chat monitor or tech assistant (Reinholz et al. 2020). However, webcam non-usage involves many other factors than accessibility and privacy issues (Händel et al. 2022; Masters et al. 2022).

이러한 문제 중 하나는 컴퓨터 매개 커뮤니케이션 피로의 구성 요소인 화상 회의 피로입니다(Oducado 외. 2022). 2차원적이고 제한된 비언어적 단서를 해석하는 것, '거울 피로', 물리적으로 갇혀 있다는 느낌, 가상의 환경에 자신을 투영하는 것에 대한 불안감 등 동기식 환경에서의 커뮤니케이션이 더 피곤하게 느껴지는 이유에 대한 가설은 많습니다. 이러한 문제에 대한 몇 가지 해결책으로는 다음과 같은 방법이 있습니다.

- 카메라의 셀프 뷰를 끄거나(카메라는 켜져 있는 동안),

- 참가자의 비디오를 작게 만들거나,

- 시각적 휴식을 취하거나 오디오를 일시적으로만 사용하거나,

- 세션 중에 시각적 자료가 필요하지 않을 때 산책을 하는

이전 연구에 따르면 화상 회의에 대한 태도가 화상 회의 피로를 가장 강력하게 예측하는 것으로 나타났으며, 경험, 지원, 능동적 학습 기법을 통해 피로를 줄일 수 있습니다(de Oliveira Kubrusly Sobral 외. 2022; Oducado 외. 2022). 화상회의의 빈도와 지속 시간도 피로와 관련이 있으며, 온라인 학습에서 더 짧은 시간, 더 자주 휴식, 혼합 방법 및 멀티미디어 사용의 모범 사례를 지적합니다(Oducado 외. 2022).

One such issue is videoconferencing fatigue, a component of computer-mediated communication exhaustion (Oducado et al. 2022). There are many hypotheses as to why communication in synchronous environments feels more exhausting, including interpreting two-dimensional and limited non-verbal cues, ‘mirror fatigue’, feeling physically trapped, and anxiety of projecting oneself into the virtual, sometimes recorded, environment. Some solutions to these issues are to

- turn off the self-view of your camera (while your camera remains on),

- make videos of participants smaller,

- take visual breaks/use audio only temporarily, or

- go for a walk during sessions when visuals are not required.

Prior research has found attitudes toward videoconferencing was the strongest predictor of videoconference fatigue, and may be lessened by experience, support and active learning techniques (de Oliveira Kubrusly Sobral et al. 2022; Oducado et al. 2022). Frequency and duration of videoconferencing is also associated with fatigue, and points to best practices of shorter duration, more frequent breaks and use of blended methods and multimedia in online learning (Oducado et al. 2022).

반면, 다음처럼 교육 세션 중에 카메라를 켜는 것을 권장하는 교육적 이유는 많습니다.

- 참여와 정서적 반응에 대한 시각적 피드백,

- 사회적 상호 작용,

- 학습자 및 발표자의 동기 부여와 참여에 미치는 영향

여러 연구에 따르면 [웹캠 미사용/저사용]은 학생의 코스 성과 및 참여도 저하, 교사의 좌절감 및 불안감과 관련이 있는 반면, [웹캠 사용]은 수업 중 학생의 언어적 참여도 증가와 관련이 있는 것으로 나타났습니다(Händel 외. 2022). 긍정적인 웹캠 사용과 관련된 요인으로는 소규모 수업 또는 소규모 회의실, 강사의 격려, 열린 커뮤니케이션 분위기, 그리고 가장 중요한 동료의 웹캠 사용 등이 있습니다(Händel 외. 2022). 형평성과 포용성을 증진하면서 웹캠 사용을 개선하기 위한 권장 사항에는 산만함을 해소하고 능동적인 학습 전략을 채택하는 것(Castelli 및 Sarvary 2021), 네티켓을 확립하는 것(Kempenaar 외. 2021; Thomson 외. 2022) 등이 있습니다. 네티켓 고려 사항은 부록 1에 나열되어 있습니다.

On the other hand, there are many pedagogical reasons to encourage cameras to be on during teaching sessions, including

- visual feedback for engagement and emotional response,

- social interactivity, and

- effect on learner and presenter motivation and engagement.

Several studies have shown that lack of webcam use is associated with poorer student course performance and involvement, and teacher frustration and insecurity, whereas webcam use has been associated with increased student verbal engagement in class (Händel et al. 2022). Factors related to positive webcam use have included smaller classes or breakout rooms, lecturer encouragement, a sense of open communication, and most importantly, peer use of webcams (Händel et al. 2022). Recommendations for improving webcam usage while still promoting equity and inclusion include addressing distractions and employing active learning strategies (Castelli and Sarvary 2021) and establishing netiquette (Kempenaar et al. 2021; Thomson et al. 2022). Netiquette considerations are listed in Supplementary Appendix 1.

- 카메라를 사용하면 학습 효과는 향상되지만 화상 회의의 피로도가 높아집니다. 일부 학습자는 대역폭 또는 병원 개인정보 보호 문제로 인해 카메라를 사용할 수 없을 수도 있습니다. 이 학습 그룹의 경우 카메라를 켜두는 데 이상적인 시간은 어느 정도일까요? 피드백 및 상호 작용을 위해 카메라를 항상 켜 두어야 하나요, 항상 꺼 두어야 하나요, 아니면 50~75%만 켜 두어야 하나요?

Camera use leads to improved learning but also videoconferencing fatigue. Some learners may not be able to use a camera due to bandwidth or hospital privacy issues. For this learning group, what is the ideal amount of time to have your camera on? Should cameras be always on, always off, or on for 50-75% to allow feedback and interactivity? - 카메라(또는 오디오)를 켤 수 없는 학습자를 그룹에 가장 잘 포함시키고 지원할 수 있는 방법은 무엇인가요?

How can the group best include and support learners who cannot have their camera (or audio) on? - 휴식 시간은 얼마나 자주, 얼마나 길게 가져야 하나요?

How frequent and long should breaks be? - 얼마나 자주 동시에 만나야 하나요? 학습자가 온라인 그룹 작업을 위해 정해진 시간을 선호하나요, 아니면 스스로 시간을 정하는 것을 선호하나요? 학습자는 교훈적인 강의/자료에 대해 동기식 미팅을 선호하나요, 아니면 비동기식 녹화를 선호하나요?

How often should we meet synchronously? Do learners prefer set times for online group work, or prefer to arrange this themselves? Do learners prefer synchronous meetings or asynchronous recordings for didactic lectures/material? - 학습자가 화면에 갇혀 있다고 느끼지 않고 자유롭게 이동할 수 있는 교실을 조성하려면 어떻게 해야 할까요? 학습자가 여전히 수업에 적극적으로 참여할 수 있다면 수업 중에 산책을 하거나 러닝머신을 사용하거나 서 있어도 괜찮나요?

How can we encourage a classroom where learners can freely move around and not feel trapped on screen? Is it OK to go for a walk/ use treadmill/ stand during class if learners can still actively engage with the class? - 학습자가 자리를 비워야 하는 경우 어떻게 알 수 있나요? (예: 환자와 관련된 전화를 받거나 화장실에 가기 위해)

How will learners indicate if they need to step away? (For example, to answer a patient related call or go to the bathroom) - 상호 작용이 더 나은 학습 성과와 온라인 피로 감소로 이어진다는 점을 고려할 때, 학습자가 온라인에서 가장 참여하기를 좋아하는 방식은 무엇인가요? (채팅, 설문 조사, 오픈 마이크, 주석 달기, 브레이크아웃 등)

Given that interactivity leads to better learning outcomes and less online fatigue, how do learners like to be engaged best online? (Chat, polls, open mic, annotation, breakouts, etc.) - 편견 없이 질문하거나 응답할 수 있는 안전한 환경을 조성하고, 질문하는 사람을 인정하고 존중하는 가장 좋은 방법은 무엇인가요?

How can we best create a safe environment to non-judgmentally ask or respond to questions and acknowledge/value those who do? - 발표자/교사의 학습을 어떻게 지원할 수 있나요?

How can we support the presenter(s)/teachers in our learning? - 채팅을 모니터링하고 기술적 문제를 지원할 그룹 구성원을 지정할 수 있나요? 이러한 역할을 돌아가면서 맡아야 하나요?

Can we assign group members to monitor the chat and assist with technical issues? Should we rotate these roles? - 이 자료가 본인/경력에 얼마나 중요하다고 생각하나요? 이것이 여러분의 참여에 어떤 영향을 미치나요?

How important do you feel this material is to you/ your career? How will this influence your participation? - 이 세션에 적극적으로 참여할 수 있나요? 병원 내 조용한 공간에서 컴퓨터를 찾거나 마이크가 아닌 채팅으로 참여하는 등 적극적인 참여를 촉진하기 위해 할 수 있는 일이 있습니까?

Are you able to actively participate in these sessions? Is there anything that can be done to facilitate your active engagement such as finding a computer in the hospital in a quiet space or participating by chat rather than by microphone? - 이러한 세션에 수동적으로 듣기를 원하십니까, 아니면 적극적으로 참여하기를 원하십니까? (아래에서 주석을 사용하여 청중을 대상으로 참여 선호도를 익명으로 빠르게 조사할 수 있는 방법을 예로 참조하세요.)

Would you rather passively listen or be actively engaged in these sessions? (See below as an example of using annotation to create a quick and anonymous way to poll your audience for engagement preferences)

궁극적으로 동기식 학습의 핵심은 웹캠 사용이 아닌 참여와 상호 작용이며, 대역폭, 개인 정보 보호 또는 형평성 문제로 인해 비디오를 사용할 수 없는 경우 이를 달성할 수 있는 다른 많은 방법이 있습니다(MacNeill 2020; Khan 외. 2021). 동기식 HPE에 대한 실용적인 팁을 요약한 많은 기사(Khan 외. 2021; Nunneley 외. 2021), 비디오(MacNeill 2020) 및 온라인 핸드북(Hyder 외. 2007)이 있으며, 부록 2에 요약되어 있습니다.

Ultimately, engagement and interactivity, not webcam use, are key to synchronous learning, and there are many other ways to achieve this when videos are not an option due to bandwidth, privacy, or equity issues (MacNeill 2020; Khan et al. 2021). There are many articles (Khan et al. 2021; Nunneley et al. 2021), videos (MacNeill 2020), and online handbooks (Hyder et al. 2007) summarizing practical tips for synchronous HPE, which are summarized in Supplementary Appendix 2.

- 동기식 환경에서는 교육 시간이 더 오래 걸립니다. 기술 문제, 온라인 그룹 형성 및 오디오 지연으로 인해 온라인 그룹 상호 작용이 지연될 수 있습니다.(Hanna 외. 2013) 그러나 이는 콘텐츠를 필수적인 내용으로 줄이고(F2F 콘텐츠의 50% 목표), 상호 작용 시간을 늘리고, 필요에 따라 보충 콘텐츠 및 리소스에 대한 링크를 제공할 수 있는 기회를 제공합니다.

Teaching in synchronous environments takes longer. Technology problems, online group formation and audio lags will cause delays in online group interactivity.(Hanna et al. 2013) However, this provides us with an opportunity to shorten our content to what is essential (aim for 50% of F2F content), increase time on interactivity, and provide links to supplemental content and resources as needed. - 대화형 요소(설문조사, 채팅, 오픈 마이크)를 일찍 자주(5~10분마다) 포함시키고 휴식 시간을 자주 주어 화면 피로와 이메일 확인과 같은 온라인 멀티태스킹을 방지하세요. 이상적인 동기식 학습은 혼합형 학습 커리큘럼의 일부로 이루어져야 하며, 최상의 학습 결과를 위해 플립형 강의실, 멀티미디어 디자인, 여러 번의 노출을 통한 다양한 방법과 같은 접근 방식을 활용해야 합니다. 교훈적인 구성 요소는 대화형 동기식 세션 전에 시청하는 마이크로 강의 또는 비디오에서 더 잘 전달될 수 있습니다.

Try to include interactive components (polls, chat, open mic) early and often (every 5-10 mins), and frequent breaks, to avoid screen fatigue and online multitasking such as checking email. Ideally synchronous learning should be part of a blended learning curriculum, utilizing approaches such as flipped classroom, multimedia design, and multiple methods over multiple exposures for the best learning outcomes. Didactic components may be better delivered in micro-lectures or videos that are viewed before the interactive synchronous session. - 가능하면 공동 진행자를 활용합니다. 콘텐츠, 그룹 역학, 채팅 및 상호 작용을 관리하는 것은 한 사람이 관리하기에는 너무 많은 양입니다. 공동 진행자를 둘 여건이 되지 않는다면 학습자 지원자에게 채팅을 모니터링하여 질문이나 주제를 파악하도록 요청하는 것이 좋습니다.

Use a co-facilitator whenever possible. Managing the content, group dynamics, chat, and interactivity is too much for any one person to manage. If you do not have the luxury of a co-facilitator, consider asking for learner volunteers to monitor the chat for questions or themes. - 두 개의 화면(이상적으로는 두 대의 컴퓨터)을 사용합니다. 두 개의 화면을 사용하여 학습자, 채팅, 공유 화면, 설문 조사 등을 볼 수 있도록 가능한 한 많은 시각적 '공간'을 확보해야 합니다. 두 대의 컴퓨터(한 대는 발표자 보기, 다른 한 대는 참가자 보기)를 사용하면 "지금 내 화면이 보여요?"라고 묻지 않고도 학습자가 무엇을 보고 있는지 확인할 수 있고 기술 문제를 더 빨리 해결할 수 있습니다.

Use two screens (and ideally two computers). You should give yourself as much visual “real estate” as possible, to see learners, chat, shared screen, polls, etc. by using two screens. Using two computers (one in presenter view and other in participant view) allows you to see what your learners are seeing without needing to ask, “can you see my screen now?” and solve technology problems quicker. - 더 명확하게 설명하세요. 지침은 F2F 환경보다 더 명확해야 하며, 채팅에 게시하는 것이 가장 이상적입니다. 문제가 발생할 때마다 학습자에게 말로 설명하여 어색한 침묵을 피하고 청중의 참여를 유지하세요.

Be more explicit. Instructions need to be clearer than in F2F environments, and ideally posted to chat. Verbalize to learners anytime you are experiencing problems to avoid awkward silences and keep the audience engaged.

동기식 강의는 비동기식 녹화 강의와 비슷한 결과를 가져옵니다(Brockfeld 외. 2018). 그러나 동기식 학습에는 학습을 위한 구조화된 시간을 위하여 캘린더에 일정표시를 제공하는 것, 소셜 학습, 실시간 피드백 및 상호 작용 등의 장점이 있습니다(Ranasinghe와 Wright 2019). 많은 도구와 기법을 동기식 및 비동기식으로 모두 사용할 수 있으며, 최적의 학습은 동기식 강의와 강의 후 비동기식 녹화를 제공하는 것과 같이 두 가지 방법을 모두 결합하는 것입니다(Ranasinghe와 Wright 2019).

Synchronous lectures have similar outcomes to asynchronous recorded lectures (Brockfeld et al. 2018). However, there are advantages to synchronous learning, including providing a placeholder in calendars to allow structured time for learning, social learning, real-time feedback, and interactivity (Ranasinghe and Wright 2019). Many tools and techniques can be used both synchronously and asynchronously, and optimal learning likely involves combining both methods such as providing synchronous lectures in addition to asynchronous recordings after the lecture (Ranasinghe and Wright 2019).

이제 비동기식 학습에 대해 살펴보았지만, 독자는 습관, 편안함, 스킬 수준 또는 실시간 상호작용 및 학습자 참여와 같은 교육적 이유인지 판단하여 비동기식 또는 혼합 방식 대신 동기식 학습을 선택하는 이유를 생각해 볼 것을 권장합니다.

We now turn our attention to asynchronous learning, but the reader is encouraged to reflect on why they may choose synchronous learning over asynchronous or mixed methods, decerning whether it is for habit, comfort, skill level, or pedagogical reasons, such as real-time interactivity and learner engagement.

비동기 학습

Asynchronous learning

비동기 학습은 학습자가 언제 어디서나 참여할 수 있을 때 발생합니다. 일반적인 비동기 학습 유형에는 게시글 또는 공유 파일을 통해 배포되는 모듈, MOOC, 토론 게시판, 비디오, 오디오 녹음 및 기타 학습 자료가 포함됩니다. 비동기식 공동 작업은 토론 포럼과 같은 학습 관리 시스템(LMS)의 동료 및 교수자 상호 작용을 위한 기본 제공 도구를 통해 이루어지거나 Slack, Twitter 또는 Flip과 같은 플랫폼, 공동 작업 도구(예: Google 문서, Miro 또는 Trello), 이메일, 가상 근무 시간 및 오디오 메시징을 통한 교사/학습자 지원을 통해 LMS 외부에서 이루어질 수 있습니다.

Asynchronous learning occurs when learners can participate from anywhere at any time. Common types of asynchronous learning include emodules, MOOCs, discussion boards, video, audio recordings, and other study material distributed via postings or shared files. Asynchronous collaboration can happen through built-in tools for peer and instructor interaction in the Learning Management System (LMS) such as discussion forums, or outside of the LMS via platforms such as Slack (https://slack.com), Twitter (https://twitter.com), or Flip (https://info.flip.com/), collaboration tools (such as Google docs https://workspace.google.com/products/docs, Miro, or Trello https://trello.com), or teacher/learner support through email, virtual office hours, and audio messaging.

대역폭, 하드웨어, 소프트웨어와 같은 테크놀로지적 요구 사항이 적기 때문에 비동기 학습은 HPE에서 온라인 학습의 첫 번째 형태 중 하나였습니다. 전통적으로 블렌디드 러닝은 대면 강의실 학습과 온라인 읽기 또는 토론 게시판과 같은 비동기식 숙제를 포함했습니다. 이는 교실에서 F2F를 실제로 적용하기 전에 일반적으로 모듈과 비디오를 통해 비동기식 자료로 콘텐츠를 제공했던 플립형 교실 학습과는 달랐습니다(Schwartzstein and Roberts 2017, Phillips and Wiesbauer 2022).

Due to fewer technological requirements (such as bandwidth, hardware, and software), asynchronous learning was among the first forms of online learning in HPE. Traditionally, blended learning involved in-person classroom learning with asynchronous homework, such as online readings or discussion boards. This differed from flipped classroom learning, where asynchronous materials provided content, typically through emodules and videos, prior to F2F practical application in the classroom (Schwartzstein and Roberts 2017; Phillips and Wiesbauer 2022).

비동기식 교육은 교육기관의 디지털 도달 범위를 가속화하고, 콘텐츠의 잠재적 수익화를 가능하게 하며, 국제적인 영향력을 가진 디지털 장학금을 촉진한다는 점에서 고등 교육에도 매력적입니다. 행정 효율성과 확장성을 통해 방대한 학생 코호트를 교육하고, 보다 유연한 학습을 통해 학습자 등록을 늘리고, 학문적 도달 범위를 확대할 수 있다는 점은 비동기식 교육에 대한 투자를 유도하는 매력적인 논거가 될 수 있습니다.

Asynchronous education is also attractive to higher education, as it accelerates institutions’ digital reach, allows potential monetization of content, and promotes digital scholarship with international impact. The promise of teaching vast student cohorts through administrative efficiency and scalability, greater learner enrolment through more flexible learning, and expanding academic reach can be an enticing argument toward investment in asynchronous education.

비동기식 학습과 관련하여 학습자들이 보고한 장점으로는 자신의 속도에 맞춰 학습할 수 있고, 일정 충돌을 피할 수 있으며, 생산성이 향상된다는 점 등이 있습니다(Gillingham and Molinari 2012; Regmi and Jones 2020). 젊은 학습자가 온라인 학습을 선호한다는 일반적인 생각과는 달리 비동기식 학습은 특히 시간 관리, 주체성, 동기 부여에 더 능숙한 것으로 보이는 성숙한 성인 학습자, 특히 다른 삶의 약속을 가진 학습자에게 더 매력적으로 보입니다(Harris and Martin 2012). 비동기식 학습자는 또한 자신의 학습을 맞춤화할 수 있으며, 이미 숙달된 주제에 더 많은 시간을 할애하고 관심 있거나 필요한 주제에 더 적은 시간을 할애할 수 있습니다(Phillips and Wiesbauer 2022). 이는 특히 다양한 전문 분야 또는 전문직 간 HPE 배경을 가진 대학원생 또는 평생 전문 개발(CPD) 학습자에게 유용할 수 있습니다(MacNeill 외. 2010; Chang 외. 2014). 비동기식 학습은 또한 추적(자료 참여, 평가 점수), 컴퓨터화된 피드백 및 개인화된 학습(학습자 요구 또는 평가에 기반)을 활용하는 적응형 학습(Ruiz 외. 2006)을 가능하게 합니다. 이는 효율적이고 평생에 걸친 역량 기반 학습에 도움이 될 수 있습니다.

Benefits reported by learners regarding asynchronous learning include studying at their own pace, avoiding scheduling conflicts and increased productivity (Gillingham and Molinari 2012; Regmi and Jones 2020) Contrary to popular belief that younger learners prefer online learning, asynchronous learning seems to appeal especially to mature adult learners, particularly those with other life commitments, who appear to be better at time-management, agency and motivation (Harris and Martin 2012). Asynchronous learners are also able to tailor their learning, devoting more time to topics of interest or need and less to those already mastered (Phillips and Wiesbauer 2022). This may be particularly helpful for postgraduate or Continuing Professional Development (CPD) learners coming from different specialties or interprofessional HPE backgrounds (MacNeill et al. 2010; Chang et al. 2014). Asynchronous learning also allows for adaptive learning (Ruiz et al. 2006), utilizing tracking (engagement with material, assessment scores), computerized feedback and personalized learning (based on learner needs or assessment). This may help with efficient, lifelong, and competency-based learning.

비동기식 학습의 '언제 어디서나' 학습할 수 있다는 장점은 임상 업무의 변동, 교대근무, 교대 감독자 교대 등 임상 순환 근무 중(Wittich 외. 2017), 전문가 간 교육과 같은 일정 문제(MacNeill 외. 2010), 분산된 CPD 학습자 수용(Chan 외. 2018) 등 동기식으로 준비하기 어려운 HPE 커리큘럼으로 확장할 수 있습니다. 비동기식 학습은 또한 교육 또는 환자 대면 직전 또는 직후에 독립적인 학습이 가능하므로 적시 교수진 개발(Orner 외. 2022)과 교육/훈련(JITT) 또는 현장 학습(Kuhlman 외. 2021)을 가능하게 해줍니다. 달성 가능하고 '한입 크기'의 접근 가능한 비동기식 학습은 단계별 디지털 배지 완료를 통해 CPD 마이크로 자격 증명 및 역량 기반 교육을 가능하게 할 수도 있습니다(2022 EDUCAUSE Horizon Report 2022).

The ‘anytime, anywhere’ advantages of asynchronous learning extend to HPE curricula that are difficult to arrange synchronously, such as during clinical rotations that involve fluctuating clinical duties, shift work, and rotating supervisors (Wittich et al. 2017), scheduling challenges such as interprofessional education (MacNeill et al. 2010), and accommodating dispersed CPD learners (Chan et al. 2018). Asynchronous learning also allows for just-in-time faculty development (Orner et al. 2022) and teaching/training (JITT) or point of care learning (Kuhlman et al. 2021), as it allows independent learning immediately before or after a teaching or patient encounter. Achievable, ‘bite-sized’ and accessible asynchronous learning can also enable CPD micro-credentialing and competency-based education through stepwise digital badge completion (2022 EDUCAUSE Horizon Report 2022).

비동기식 학습은 인터리빙 및 간격 반복(또는 분산 실습)과 같은 증거 기반의 학습 과학 전략과 연관되어 있습니다. 분산 연습은 학습이 여러 시점에 걸쳐 이루어질 때 발생합니다. 학습 사이의 이러한 시간적 간격은 성찰, 다양한 맥락에서의 학습 통합(인터리빙), 반복적인 검색 연습(예: 퀴즈 또는 요약 토론 게시판)을 가능하게 하며, 모두 학습을 개선하는 것으로 나타났습니다(Maheshwari 외. 2021; Van Hoof 외. 2021). 인터리빙을 사용하면 학습자가 개념, 컨텍스트 및 스킬을 순차적으로 이동하지 않고 앞뒤로 이동하여 중복 및 구별되는 영역을 검토하고 고립된 숙달이 아닌 비판적인 비교를 할 수 있습니다. 인터리빙은 블록형 학습에 비해 복잡한 문제 해결력과 정보 유지력을 향상시킵니다. 비동기식 학습은 다양한 임상 상황에서 자료 재방문 및 퀴즈/시뮬레이션/피드백, 보충 관련 자료 링크 액세스, 일반적인 코호트 외부의 학습자와 함께 학습을 통해 이러한 유형의 다양하고 무작위적인 연습을 촉진할 수 있습니다(Van Hoof 외. 2022).

Asynchronous learning has been associated with evidence-based, learning science strategies such as interleaving and spaced repetition (or distributed practice). Distributed practice occurs when learning occurs over multiple points in time. This time between learning allows for reflection, consolidation of learning in different contexts (interleaving), and the use of repetitive retrieval practice (such as quizzes or summary discussion boards) which have all been shown to improve learning (Maheshwari et al. 2021; Van Hoof et al. 2021). Interleaving allows learners to move back and forth, rather than sequentially, through concepts, contexts, and skills, to examine areas of overlap and distinction, making critical comparisons, rather than siloed mastery. Interleaving leads to improved complex problem solving and retention of information compared to blocked learning. Asynchronous learning can foster this type of varied and random practice through revisiting materials and quizzing/simulation/feedback in different clinical contexts, accessing links to supplemental related materials, and learning together with learners outside of their typical cohort (Van Hoof et al. 2022).

또한 비동기 온라인 학습은 한계가 있을 수 있지만, 특히 대역폭이 제한적이거나 예측할 수 없는 저소득 및 중간 소득 국가(가찬자 외. 2021) 또는 농촌 지역(고소득 국가 포함)에서 접근성, 형평성 및 포용성을 개선하는 데 유용합니다. 교실 필요성 감소, 행정 일정 지원, 출장 비용 등 비용 절감 효과가 있을 수 있습니다(Ruiz 외. 2006). 또한 서로 다른 시간대에 있는 학습자와 교사가 협업할 수 있어 글로벌 학습 네트워크를 강화할 수 있습니다(Chan et al. 2018).

Furthermore, although there may be limitations, asynchronous online learning is beneficial in improving access, equity, and inclusion, especially in low- and medium-income countries (Gachanja et al. 2021), or in rural areas (including in high-income countries), where bandwidth may be limited or unpredictable. There may be cost savings, including reduced need for classrooms, administrative scheduling support, and travel costs (Ruiz et al. 2006). It also allows learners and teachers in different time zones to collaborate, enriching global learning networks (Chan et al. 2018).

그러나 비동기식 학습은 주의 산만, 학습 지연, 즉각적인 피드백 부족, 사회적 상호 작용 부족으로 인한 학습자 이탈의 경향이 있습니다(Nguyen et al. 2021). 비동기 학습이 핵심 F2F 또는 동기 학습에 대한 선택적이거나 보충적인 경우, 특히 임상 업무량이 많고 삶의 우선순위가 경쟁적인 상황에서 비동기 학습은 덜 중요한 것으로 간주될 수 있습니다.

However, asynchronous learning has a propensity for distractions, delayed learning, lack of immediate feedback, and learner disengagement due to the lack of social interaction (Nguyen et al. 2021). If asynchronous learning is optional or supplementary to core F2F or synchronous learning, asynchronous learning may be seen as less important, especially in the context of heavy clinical workloads and competing life priorities.

학습자의 자료 참여도(예: 소요 시간 또는 게시물 수)를 모니터링하는 것은 학습을 반영하지 못할 수 있으며, 학습자-교수자 간 즉각적인 피드백을 제공할 기회가 적습니다. 학습자가 플랫폼에서 단순히 과제를 '완료'로 체크하는 것으로 전락할 위험이 있습니다. 그러나 AI 분석을 사용하여 여러 형성형 및 자동화된 퀴즈와 동료 피드백을 사용하는 등 '위험에 처한 학습자'를 추적함으로써 이러한 문제를 완화할 수 있습니다(온라인 교육에서 배우는 것 2012).

Monitoring learner engagement with material (such as time spent or number of posts) may not be reflective of learning, and there is less opportunity for learner-instructor immediate feedback. There is the danger that it may devolve to learners’ simply ticking tasks as ‘completed’ on a platform. However, this may be moderated by using AI analytics to track for ‘learners at risk’ such as employing multiple formative and automated quizzes and peer feedback (What We’re Learning From Online Education 2012).

비동기식 환경에서의 교육은 강력한 멀티미디어를 제작하는 데 시간이나 비용의 제약이 있을 수 있지만, 한 번 제작하면 재사용할 수 있어 시간을 절약하고 교육 비용을 절감할 수 있습니다(Ruiz 외. 2006; Phillips and Wiesbauer 2022). 또한 토론 게시판은 읽고, 응답하고, 채점하는 데 시간이 많이 소요될 수 있지만 자동화, 동료 검토 및 좋아요 투표를 통해 촉진할 수 있습니다. 마지막으로, 비동기식 환경에서는 비언어적 단서와 즉각적인 피드백이 없고, 오해의 위험이 있기 때문에 교사는 그룹 규범, 목표 및 과제와 같은 사회적 학습 및 학습 기대치를 조성하기 위해 훨씬 더 명확하게 설명해야 합니다(Maheshwari 외. 2021). 비동기 환경에서 소셜 및 협업 학습을 촉진하는 방법에 대한 실용적인 팁은 부록 3을 참조하세요.

Teaching in asynchronous environments can have up front time or cost constraints to create robust multimedia, but, once created, has the potential to be reused, freeing up time and reducing teaching costs (Ruiz et al. 2006; Phillips and Wiesbauer 2022). Furthermore, discussion boards can be time-consuming to read, respond and grade, but can be facilitated through automation, peer reviewing, and up-voting. Lastly, teachers must be much more explicit in asynchronous environments to foster social learning and learning expectations, such as group norms, objectives, and assignments, due to the lack of non-verbal cues, immediate feedback, and risk of misinterpretation (Maheshwari et al. 2021). Please refer to Supplementary Appendix 3 for practical tips on how to foster social and collaborative learning in asynchronous environments.

1. 비동기식 환경에서는 기대치, 루브릭, 예시 과제 및 자세한 코스 개요를 게시하는 등 명확성을 유지합니다. 가상 근무 시간, 동료 토론 게시판 등 학습자가 교수자 및 동료에게 연락하여 기대치 및 과제를 명확히 확인할 수 있는 방법을 마련합니다.

1. Be clear in asynchronous environments such as posting expectations, rubrics, exemplar assignments, and detailed course outlines. Have ways learners can contact you and their peers for clarification of expectations and assignments such as virtual office hours, and peer discussion board.

2. 학습자와 함께 코스 기대치에 대한 '네티켓' 또는 온라인 학습 규칙을 개발하는 것을 고려합니다.

2. Consider developing “netiquette” or online learning rules with your learners for course expectations.

3. 참여를 통한 교사와 다른 학습자 간의 상호 작용이 학습과 향후 관계에 어떤 긍정적인 영향을 미치는지 명시적으로 설명합니다. 동료 피드백의 중요성과 모든 사람의 학습을 보장하기 위한 그룹의 책임에 대해 논의합니다.

3. Be explicit about how interactions teachers and other learners through participation positively affects learning and future connections. Discuss the importance of peer feedback and the group’s responsibility to ensure everyone’s learning.

4. 학습자가 개인 정보를 공유할 수 있도록 허용하는 아이스 브레이커 활동(예: "우리가 모르는 한 가지를 알려주세요" 또는 "좋아하는 음식이나 문화/유산의 레시피를 게시하세요")을 고려합니다.

4. Consider ice-breaker activities that give permission for learners to share personal information, such as “tell us one thing we might not know about you” or “post your favorite food or recipe from your culture/heritage”

5. 정기적으로 토론 게시판을 방문하고, 양질의 게시물을 인정하고, 공평한 기여를 장려하고, 오해를 바로잡고, 생각을 자극하고, 요약하거나 개인적으로 성찰하는 게시물 또는 추가 리소스에 대한 링크를 제공하는 등 효과적인 비동기식 커뮤니케이션을 모델링합니다.

5. Model effective asynchronous communication such as regularly visiting discussion boards, acknowledging quality posts, encouraging equitable contributions, correcting misconceptions, contributing thought provoking, summarizing or personally reflective posts or links to further resources.

6. 콘텐츠와 관련이 없는 토론 게시글을 생성하여 "흥미로운 발견" 또는 "오늘 기분이 어떠세요?" 체크인을 허용합니다(예: 오늘 이 코스에서 기분을 가장 잘 설명하는 사진 선택). 토론 게시판은 LMS에 내장되거나 Slack(https://slack.com) 또는 WhatsApp(https://www.whatsapp.com) 그룹과 같은 외부 소프트웨어로 구축될 수 있습니다.

6. Create non content related discussion posts that allow for “interesting finds” or “how are you feeling today” check-ins (e.g., select a picture that best describes your mood in this course today). Discussion boards may be built into your LMS or as external software such as Slack (https://slack.com) or WhatsApp (https://www.whatsapp.com) group.

7. 학습자의 중간 반성 게시물 또는 교수자의 주간 주제 소개와 같은 1~2분 길이의 비디오 또는 오디오 게시물을 사용하는 것이 좋습니다. 비디오를 공유하면 동료, 학습자 및 교사 간에 텍스트가 제공할 수 있는 것 이상의 사회적 연결이 가능합니다. Flip(https://info.flip.com)과 같은 비디오 블로그 플랫폼, Camtasia(https://www.techsmith.com/video-editor.html), Zoom 녹화(https://zoom.us)와 같은 즉시 사용 가능한 비디오 제작 소프트웨어, 또는 스마트폰에서 MP4 또는 MP3 또는 wav 파일을 녹화하는 것만으로도 이러한 작업을 수행할 수 있습니다.

7. Consider using 1-2 min video or audio postings, such as midterm reflection posts by learners or weekly instructor topic introductions. Sharing videos allows social connection between peers, learners and teachers beyond what text can afford. This may be accomplished by video blog platforms such as Flip (https://info.flip.com), out of the box video creation software such as Camtasia (https://www.techsmith.com/video-editor.html), Zoom recordings (https://zoom.us), or simply by recording an MP4 or MP3 or wav file from your smart phone.

8. 학습자에게 게시글과 링크된 자신의 사진(또는 아바타)을 게시하도록 권장합니다. 학습자가 그날의 기분에 따라 아바타를 변경하도록 하여 감정적인 체크인을 할 수도 있습니다.

8. Encourage learners to post a picture (or avatar) of themselves that is linked with their posts. You can also have learners change their avatar to how they are feeling that day as an emotional check in.

9. 동기식 모임 기회 또는 비동기식 공동 작업 도구를 설정하는 등 학습자가 프로젝트에서 공동 작업할 수 있는 기회를 허용합니다. 개인이 마감일이 지정된 그룹 과제의 여러 구성 요소에 등록하여 책임을 질 수 있는 루브릭을 포함하여 그룹 과제에 대한 명확한 기대치를 설정합니다. 그룹 프로젝트에 대해 자가 보고 및/또는 동료 평가 참여 점수를 부여하는 것을 고려하세요.

9. Allow opportunities for learners to collaborate on projects, such as setting up synchronous meeting opportunities, or asynchronous collaboration tools. Establish clear expectations of group work, including rubrics where individuals can sign up for different components of the group work with assigned due dates to remain accountable. Consider having self-reported and/or peer assessed participation marks for group projects.

10. 한 주 동안의 토론 게시판 스레드를 이끌거나, 한 주 동안 읽은 내용을 소개하는 비디오를 만들거나, 관련 보충 콘텐츠를 찾아 게시하는 등 학습자 리더십 역할을 수행할 기회를 설정합니다.

10. Set-up opportunities for learner leadership roles such as leading a discussion board thread for the week, creating a video introduction to the readings for the week, or finding/posting related supplemental content.

11. 학급을 팀으로 나누어 점수를 모으거나, 좋아하는 개별 토론 게시판 게시글 또는 그룹 과제(예: 팟캐스트 제작)에 대해 학급에서 업보팅을 하는 등 공동 작업을 재미있고 인정받도록 합니다. 모든 참가자를 축하합니다(예: 모의 시상식, 기억에 남는 게시글의 비디오 몽타주 등).

11. Make collaboration fun and recognized, such as dividing the class into teams and collecting points, or class upvoting on favorite individual discussion board posts or group assignments (e.g., Podcast creations). Celebrate all participants (e.g., Mock awards, video montage of memorable postings, etc.)

12. 동료 피드백 기회를 장려합니다(예: VoiceThread(https://voicethread.com)와 같은 비디오 피드백 소프트웨어 사용). 12. Promote opportunities for peer feedback (for example using video feedback software such as VoiceThread https://voicethread.com)

결론적으로, 비동기식 학습은 성숙하고 자기 주도적인 학습자에게 가장 적합합니다. 비동기식 학습은 유연하고 접근 가능하며 맞춤화된 교육을 가능하게 하지만 즉각적인 피드백이 부족하고 비언어적 단서가 부족하기 때문에 구조와 지원을 통해 신중하게 중재해야 합니다. 이러한 위협은 다음에 설명하는 다중 모드 학습을 활용하여 최소화할 수도 있습니다.

In conclusion, asynchronous learning is best suited for mature and self-directed learners. Although asynchronous learning allows for flexible, accessible, and tailored education, the lack of immediate feedback and non-verbal cues need to be carefully mediated by structure, and support. These threats may also be minimized by utilizing multi-modal learning as discussed next.

다중 모드 학습: 혼합형, 하이브리드 및 HyFlex

Multi-modal learning: blended, hybrid, and HyFlex

온라인 학습의 주요 이점 중 하나는 다양한 학습 목표와 학습자의 요구를 충족할 수 있는 멀티모달 방식을 제공할 수 있다는 점입니다. 그림 2는 이러한 중첩 학습 방법의 개념과 그 교차점에서 발생하는 다양한 형태의 학습을 보여줍니다.

One of the major benefits of online learning is the ability to provide multi-modal methods to meet diverse learning objectives and learner needs. Figure 2 depicts this concept of overlapping learning methods and the various forms of learning that occur at its intersections.

이 가이드의 앞부분에서 설명한 바와 같이 멀티모달 전달, 분산 실습 및 혼합의 이점을 고려할 때, F2F 학습과 온라인 학습을 결합한 혼합 학습이 F2F 또는 온라인 방식만 사용하는 것보다 더 나은 학습 결과를 가져오는 것으로 입증된 것은 놀라운 일이 아닙니다(Liu 외. 2016; Vallée 외. 2020). 또한 학습자는 다양한 학습 양식을 사용할 때 더 높은 만족도를 보고합니다(Nguyen et al. 2021). 그렇다면 블렌디드 학습 기회를 제공하지 않는다면 실제로 차선의 학습 경험을 제공하고 있는 것일까요? 이 질문은 커리큘럼 및 교육기관 계획에서 최소한 타당하게 고려할 가치가 있습니다.

Building on the benefits of multimodal delivery, distributed practice and interleaving, as discussed earlier in this guide, it is perhaps no surprise that blended learning, which combines F2F learning with online learning, has been proven to have better learning outcomes than either F2F or online modalities alone (Liu et al. 2016; Vallée et al. 2020). Also, learners report higher satisfaction when a greater diversity of learning modalities are used (Nguyen et al. 2021). Therefore, if we are not providing blended learning opportunities, are we in fact providing suboptimal learning experiences? This question deserves at least some valid consideration in curriculum and institutional planning.

하이브리드 학습은 블렌디드 학습과 유사하지만 온라인 학습이 주요 전달 방식이며, F2F 구성 요소로 보완됩니다(대면 및 온라인 학습 통합을 위한 개념 및 용어 2022). 그러나 '하이브리드 학습'이라는 용어는 학습자가 직접 또는 온라인으로 참석할 수 있는 동기식 학습을 설명하기 위해 문헌(특히 CPD)에서도 사용되었습니다.

Hybrid learning is similar to blended learning, but with online learning as the main mode of delivery, supplemented with F2F components (Concepts and Terminology for Integrating In-Person and Online Learning 2022). However, the term ‘hybrid learning’ has also been used in the literature (particularly in CPD) to describe synchronous learning where learners can attend either in person or online.

이에 대한 또 다른 용어는 하이브리드 플렉서블(HyFlex)로, 여기서는 학습자마다 다른 학습 방식을 수용하는 온라인 학습을 설명하는 데 사용합니다. HyFlex 학습에는 일반적으로 F2F 교육과 하나 이상의 다른 온라인 전달 모드(예: 동기식 또는 비동기식 또는 둘 다)가 포함되며, 학습자가 참여 형식을 선택합니다. 연구에 따르면 대부분의 학습자는 F2F 전달 방식을 선호하지만, 복잡한 생활 환경이 유연한 온라인 옵션에 대한 전달 방식 선택에 더 많은 영향을 미칩니다(Malczyk 2019; Rhoads 2020). 고등 교육 전문가들은 2025년까지 소수의 학습자만이 완전한 F2F 또는 완전한 온라인 수업에 참여할 것이며, 대다수는 블렌디드 및 HyFlex 형식으로 참여할 것이라는 데 동의합니다(2022 EDUCAUSE Horizon Report 2022).

Another term for this is Hybrid Flexible (HyFlex), which we will use here to describe online learning that accommodates different learning modalities for different learners. HyFlex learning typically involves (frequently simultaneous) F2F teaching and at least one other online mode of delivery (such as synchronous or asynchronous or both), where learners choose their format of participation. While research suggests that most learners prefer F2F modes of delivery, complex life circumstances affect their choice of delivery method to flexible online options more (Malczyk 2019; Rhoads 2020). Higher education experts agree that by 2025, only a minority of learners will be either fully F2F or fully online, with the majority attending in blended and HyFlex formats (2022 EDUCAUSE Horizon Report 2022).

HyFlex는 브라이언 비티가 처음 제안했으며 듀얼 딜리버리(네덜란드 2022), 동기식 하이브리드(팔머 외. 2022), 혼합 동기식 학습(라포룬과 라칼 2019), 코모달(고베일-프룰스 2019) 등 많은 동의어가 있지만 학습자가 학습 양식 간에 이동할 수 있는 유연성이 부족하다는 등의 미묘한 차이점도 있습니다.

HyFlex was initially proposed by Brian Beatty and has many synonymous terms which include Dual Delivery (Holland 2022), Synchronous Hybrid (Palmer et al. 2022), Blended Synchronous Learning (Laforune and Lakhal 2019), and Comodal (Gobeil-Proulx 2019) although some have subtle differences, such as lack of learner flexibility to move between learning modalities.

HyFlex 모델은 네 가지 원칙을 기반으로 합니다:

- 학생 선택/학습자 통제,

- 동등한 학습,

- 재사용 가능성

- 접근성(Beatty 2019).

학습자는 자신의 필요에 가장 적합한 경로와 속도를 선택할 수 있으므로 학습의 유연성에 대한 인식이 높아지고 교사의 지원을 받는다는 느낌을 받을 수 있습니다(Beatty 2019, Gobeil-Proulx 2019, Rhoads 2020, Lakhal 외. 2021). 학습자는 F2F 수업에 참석한 후 혼란스러운 자료를 다시 보거나 빠른 재생 속도를 사용하여 이미 알고 있는 자료를 스캔함으로써 학습 속도를 선택할 수 있습니다.

The HyFlex model is based on four principles:

- Student Choice/Learner Control,

- Equivalent Learning,

- Reusability, and

- Accessibility (Beatty 2019).

Learners have the ability to choose which path and pace best suits their needs, leading to increased appreciation for the flexibility of their learning and feeling supported by their teachers (Beatty 2019; Gobeil-Proulx 2019; Rhoads 2020; Lakhal et al. 2021). Learners can choose the speed of their learning by attending a F2F class and then revisiting materials that remain confusing or using fast playback speeds to scan material they already know.

학습자 제어는 장점이자 단점이 될 수 있습니다. F2F 교실에서는 학습자가 교사의 통제를 받으며 선형적 학습 순서를 따르지만, 온라인 환경에서는 링크, 토론, 소셜 미디어 피드를 통해 비선형/분기 경로를 따라갈 수 있습니다. 이는 학습자가 자신의 편의에 따라 자신의 학습 경로를 관리하는 데 있어 학습자의 '동의'와 동기를 부여할 수 있지만, 특히 좋은 학습 습관을 기르지 못했거나 자기 주도적 발견을 시작할 수 있는 지식 기반이 거의 없는 젊은 학부 학습자에게는 (직접적인 피드백과 학습에 대한 추가적인 책임감 없이는) 학습자가 부담을 느낄 수 있습니다(Lin and Hsieh 2001). 구조, 피드백(LMS, 교사 또는 동료에 의한) 및 자기 조절을 지원하는 기능이 이를 도울 수 있습니다(Rhoads 2020; Thomson 외. 2022). HyFlex 학습을 통해 학습자는 온라인 학습의 편리함과 통제력을 F2F 학습의 사회적 연결, 피드백 및 동기 부여와 균형을 맞출 수 있습니다(Butz and Stupnisky 2016).

Learner control can be both an advantage and a disadvantage. In F2F classrooms, learners follow a linear sequence of learning, controlled by the teacher; however, in online environments, learners can follow non-linear/branching paths through links, discussions, and social media feeds. This allows learner ‘buy-in’ and motivation in managing their own learning path at their own convenience, but may leave the learner feeling overwhelmed without direct feedback and added responsibility for their learning (Lin and Hsieh 2001), especially with younger undergraduate learners who may not have developed good study habits or have little knowledge base from where to start self-directed discovery (Bond et al. 2020). Structure, feedback (by LMS, teacher or peers) and features that support self-regulation can help with this (Rhoads 2020; Thomson et al. 2022). HyFlex learning allows learners to balance the convenience and control of online learning with the social connection, feedback, and motivation of F2F learning (Butz and Stupnisky 2016).

HyFlex 학습의 두 번째 원칙은 동등성이며, 이는 반드시 동등하지는 않지만 동등한 학습 경험을 제공하는 것을 의미합니다. F2F 수업을 개최하고 비동기식 보기를 위해 녹화본을 온라인에 게시하는 것은 HyFlex 설계의 예가 아닙니다.

The second principle of HyFlex learning is equivalency, which refers to providing an equivalent, but not necessarily equal, learning experience. Note that holding a F2F class and posting the recording online for asynchronous viewing is not an example of a HyFlex design.

교육 설계는 온라인 방식과 상호 작용이 F2F 학습보다 열등해지지 않도록 해야 하며, 각 방식마다 고유한 교육적 고려 사항이 있어야 합니다. 계획은 모든 강의실 참가자의 인식, 포용성, 참여를 포함하여 모든 전달 방식에 걸쳐 콘텐츠, 상호 작용, 커뮤니케이션/지원, 평가를 고려해야 합니다. 예를 들어 응급실에서 여러 교대 근무자와 감독자가 있는 바쁜 임상 로테이션에서 학부 학습자를 교육한다고 가정해 보겠습니다. 부록 4에서는 감독자가 여러 학습자와 감독자 간의 동료 학습 및 연결을 유지하면서 여러 프로그램 현장 및 교대 근무에 걸쳐 학습자를 가르칠 수 있는 방법을 설명합니다.

Instructional design must ensure that online modalities and interactivity do not become inferior to F2F learning, and that each mode has its own pedagogical considerations. Planning should consider content, interactivity, communication/support, and assessment across all modes of delivery, including recognition, inclusiveness, and participation of all classroom participants. Take, for example, training undergraduate learners in a busy clinical rotation in the emergency department, with multiple shifts and supervisors. Supplementary Appendix 4 depicts how supervisors can teach to learners across different program sites and shifts, while still maintaining peer learning and connections between multiple learners and supervisors.

세 번째 원칙인 재사용성의 실제 예는 온라인 참가자의 비동기식 게시물을 다음 주 F2F 및 동기식 수업 토론에 통합하여 그룹과 세션 간에 학습의 연속성을 제공하는 것으로 부록 4에 나와 있습니다. 비동기 학습자는 F2F 수업 녹화에서 자신의 게시물을 보고 다른 학습자와의 결속력과 인정을 느낄 수 있으며, F2F 및 동기 학습자는 비동기 토론 게시판을 읽고 참여하라는 메시지를 받을 수 있습니다. 또한 재사용성을 통해 여러 양식에 걸쳐 학습을 확장하고 표준화할 수 있습니다.

A practical example of the third principle, reusability, is shown in Supplementary Appendix 4 by incorporating an asynchronous posting from an online participant into the F2F and synchronous class discussions the next week, thereby providing continuity of learning between groups and sessions. The asynchronous learner may see their posting in the F2F class recording and feel cohesion and recognition with other learners, while the F2F and synchronous learners might be prompted to read and participate in the asynchronous discussion board. Reusability also allows scaling and standardization of learning across modalities.

마지막으로, 네 번째 원칙인 접근성은 이 가이드의 뒷부분에서 살펴볼 유니버설 학습 디자인(UDL)을 기반으로 합니다.

Lastly, accessibility as a fourth principle, builds on Universal Design for Learning (UDL) which will be explored later in this Guide.

HyFlex 설계는 비교적 새로운 온라인 제공 모델로, HPE에서 축적된 증거가 거의 없습니다(Laforune 및 Lakhal 2019; Malczyk 2019; Zehler 외. 2021; Palmer 외. 2022). HPE가 아닌 분야에 대한 제한적인 연구에서도 F2F 수업과 비교하거나 다른 전달 방식 간에 학습 결과의 차이가 없는 것으로 나타났습니다(Raes 외. 2020; Rhoads 2020). 온라인과 F2F 방식 간에 '유의미한 차이가 없다'는 결과와 대부분의 학습자가 HyFlex 과정 동안 한 가지 학습 방법(F2F 또는 온라인)을 고수한다는 점을 고려하면 이는 놀라운 일이 아닙니다(Gobeil-Proulx 2019). 지금까지의 대부분의 연구는 학습자의 경험과 실행을 기반으로 한 탐색적 연구였습니다(Raes et al. 2020).

HyFlex design is a relatively new model of online delivery, with very little evidence accumulated in HPE (Laforune and Lakhal 2019; Malczyk 2019; Zehler et al. 2021; Palmer et al. 2022). Limited research in non-HPE fields has often shown no difference in learning outcomes compared to F2F classes or between the different delivery modalities (Raes et al. 2020; Rhoads 2020). This is not surprising given the ‘no significant difference’ effect between online and F2F methods and that most learners stick to one learning method (F2F or online) during HyFlex courses (Gobeil-Proulx 2019). Most research to date has been exploratory and based on learner experiences, and implementation (Raes et al. 2020).

교육기관과 교사의 입장에서는 HyFlex 학습을 통해 '오프라인' 강의실과 복잡한 일정 조정을 줄일 수 있어 비용을 절감할 수 있습니다. 그러나 학습자가 언제든지 전달 방식을 변경하여 그룹 구성과 상호 작용에 영향을 미칠 수 있으므로 교수진은 불확실성과 '동적 유연성'에 익숙해져야 합니다(Beatty 2019). 이러한 새로운 전달 방식에 대한 교수진의 개발과 지원은 이러한 다각적인 전달 방식을 구축하고 촉진하기 위한 인식과 마찬가지로 중요합니다(Rhoads 2020; Lakhal 외. 2021). HyFlex 교육은 어렵기 때문에 교수진은 일반적으로 비동기식 수업의 '백본'으로 시작하여 F2F 또는 동기식 구성 요소를 추가하여 온라인 교육을 '시도'하는 소규모로 시작할 수 있습니다. 마지막으로, HyFlex 전달 방법을 개발하면 필요한 경우 완전한 온라인 학습으로 신속하게 전환할 수 있는 교육학적으로 건전한 코스 개발 시간을 확보할 수 있으므로 향후 (팬데믹, 자연재해 또는 대중교통 문제로 인한) ERT를 피할 수 있습니다(Beatty 2019).

For institutions and teachers, HyFlex learning also requires fewer ‘brick and mortar’ lecture halls and complex scheduling arrangements, at possible cost savings. However, faculty need to be comfortable with uncertainty and ‘dynamic flexibility,’ since learners may change their mode of delivery at any time, affecting group composition and interactivity (Beatty 2019). Faculty development and support for these new delivery methods is important (Rhoads 2020; Lakhal et al. 2021), as is recognition to build and facilitate these multifaceted delivery modes. HyFlex teaching is difficult, and faculty may want to start small to ‘try out’ online teaching – typically with the ‘backbone’ of an asynchronous class and adding on either F2F or synchronous components. Lastly, developing HyFlex delivery methods allows the time for pedagogically sound course development with the ability to quickly pivot to fully online learning if required, avoiding future ERT (caused by pandemics, natural disasters, or public transportation issues) (Beatty 2019).

HyFlex 설계에는 일반적으로 추가 소프트웨어, 하드웨어(다중 모니터, 마이크, 양방향 카메라, 테크놀로지 지원) 및 강의실 재구성을 제공하기 위한 기관의 지원이 필요합니다(Lakhal 외. 2021). 또한 학습자는 이러한 새로운 학습 환경에 완전히 참여할 수 있도록 하드웨어, 소프트웨어 및 스킬을 지원받아야 합니다. 그러나 이러한 지원을 받는 것이 어렵거나 불가능해 보이는 경우, 더 낮은 수준의 테크놀로지 옵션도 가능합니다(예: 보충 부록 4 참조).

HyFlex design typically requires institutional support to provide additional software, hardware (multiple monitors, microphones, two-way cameras, and technical support) and classroom reconfiguration (Lakhal et al. 2021). Learners also need to be supported with the hardware, software, and skills to participate fully in these new learning environments. However, if obtaining this support seems daunting or not feasible, lower tech options are also possible (see for example Supplementary Appendix 4).

특히 처음 시작할 때는 이러한 복잡한 환경에서 상호 작용, 카메라 선택 및 테크놀로지 지원을 안내하고 F2F 참가자와 온라인 참가자 간의 동등한 참여를 보장하기 위해 온라인 공동 진행자 또는 수업 내 테크놀로지 지원/룸 코디네이터가 필수적입니다(Lakhal 외. 2021; Thomson 외. 2022).

Online co-facilitation or an in-class technical support/room coordinator is essential, especially when first starting out, to help Guide interactivity, camera selection and technical support in these complex environments and ensure equal participation between F2F and online participants (Lakhal et al. 2021; Thomson et al. 2022).

HyFlex는 캠퍼스와 교육 장소가 분산된 HPE 교육 프로그램(레지던트 프로그램 등)이나 F2F 및 원격 참석 방식이 포함된 CPD 제공에 특히 중요할 수 있습니다. 또 다른 이점은 원격 참여로 수업 규모를 확장하는 데 테크놀로지가 도움이 될 수 있는 소규모 F2F 인원만 허용하는 교육(예: 수술실 또는 시뮬레이션실(Zehler 외, 2021), 병리학 실험실 또는 환자 노출)에도 유용합니다. HyFlex는 많은 장점을 가지고 있고 완전한 온라인 학습이 직면한 많은 문제를 해결하는 데 도움이 될 수 있지만, 복잡성, 지원, 변화를 수용하려는 의지 등을 고려할 때 모든 수업, 강사 또는 교육기관에 적합하지 않을 수 있습니다. 그러나 얼마 전까지만 해도 동기식 환경에서의 교육에 대해서도 마찬가지였으며, 이제는 일반적이고 친숙한 환경이 되었습니다.

HyFlex may be particularly important for HPE training programs with dispersed campuses and training locations (such as residency programs), or CPD offerings that involve F2F and remote ways to attend. Another benefit is for training that allows only small F2F numbers (e.g. operating or simulation rooms (Zehler et al. 2021), pathology labs, or patient exposures) where technology can help expand class size with remote participation. While HyFlex has numerous advantages and may help to negate many of the challenges faced with fully online learning, it may not be suited for all classes, instructors or institutions given the complexity, support, and willingness to embrace the change that HyFlex requires. However, it was not so long ago that the same was true about teaching in synchronous environments, which has now become commonplace and familiar.

HyFlex와 모든 온라인 환경에서 성공적인 온라인 학습을 위해서는 교수진의 개발과 경험이 필수적입니다. 다음 섹션에서는 효과적인 온라인 커리큘럼 개발을 위한 단계와 지침을 안내하는 온라인 교육 설계 섹션의 기초로서 교수자 개발의 중요성에 대해 논의합니다(그림 3).

In HyFlex and all online contexts, faculty development and experience are essential for successful online learning. Next, we discuss the importance of faculty development as a foundation for the next section on online educational design, which will guide readers through steps and guidelines for effective online curriculum development (Figure 3).

온라인 교육 설계

Online educational design

온라인 교육 설계는 온라인 HPE에서 FSD의 중요성을 먼저 강조하지 않고는 논의할 수 없습니다. FSD는 HP 교육자로서 현대적 역량을 개발하는 데 필수적이며, 교수진이 다음을 하게 해준다.

- 자신의 역할을 비판적으로 재고하고,

- 교육에서 '큰 가정'에 도전하며,

- 교육학적으로 정보에 입각한 교육 관행을 가능하게 하고,

- '모든 것에 맞는 한 가지' 교육 관행에서 벗어나 교육 과정을 재설계한다.

일부에서는 온라인 교육 역량에 대한 온라인 FSD가 교육기관과 HP 교육자의 현대적 표준이자 책임이 되어야 한다고 주장합니다.

Online educational design cannot be discussed without first highlighting the importance of FSD in online HPE. FSD is essential to the development of contemporary competencies as a HP educator, and allows faculty to

- critically rethink their roles,

- challenge ‘big assumptions’ in education,

- enable pedagogically informed teaching practices, and

- redesign curriculum outside ‘one size fits all’ teaching practices (Mohr and Shelton 2017).

Some argue that online FSD of online teaching competencies should be a contemporary standard and responsibility of institutions and HP educators.