학습이론의 통합된 이론적 프레임워크와 공중보건 CME 연구 및 실천의 가이드(J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2021)

A Unified Theoretical Framework of Learning Theories to Inform and Guide Public Health Continuing Medical Education Research and Practice

Thomas L. Roux, MBChB, MPH, DFPHMI RCPI, FRSPH; Mirjam M. Heinen, BSc, MSc, PGDIp, PhD;

Susan P. Murphy, PhD, MA, BA, PDip; Conor J. Buggy, BA Mod, PhD, PCert, PDip

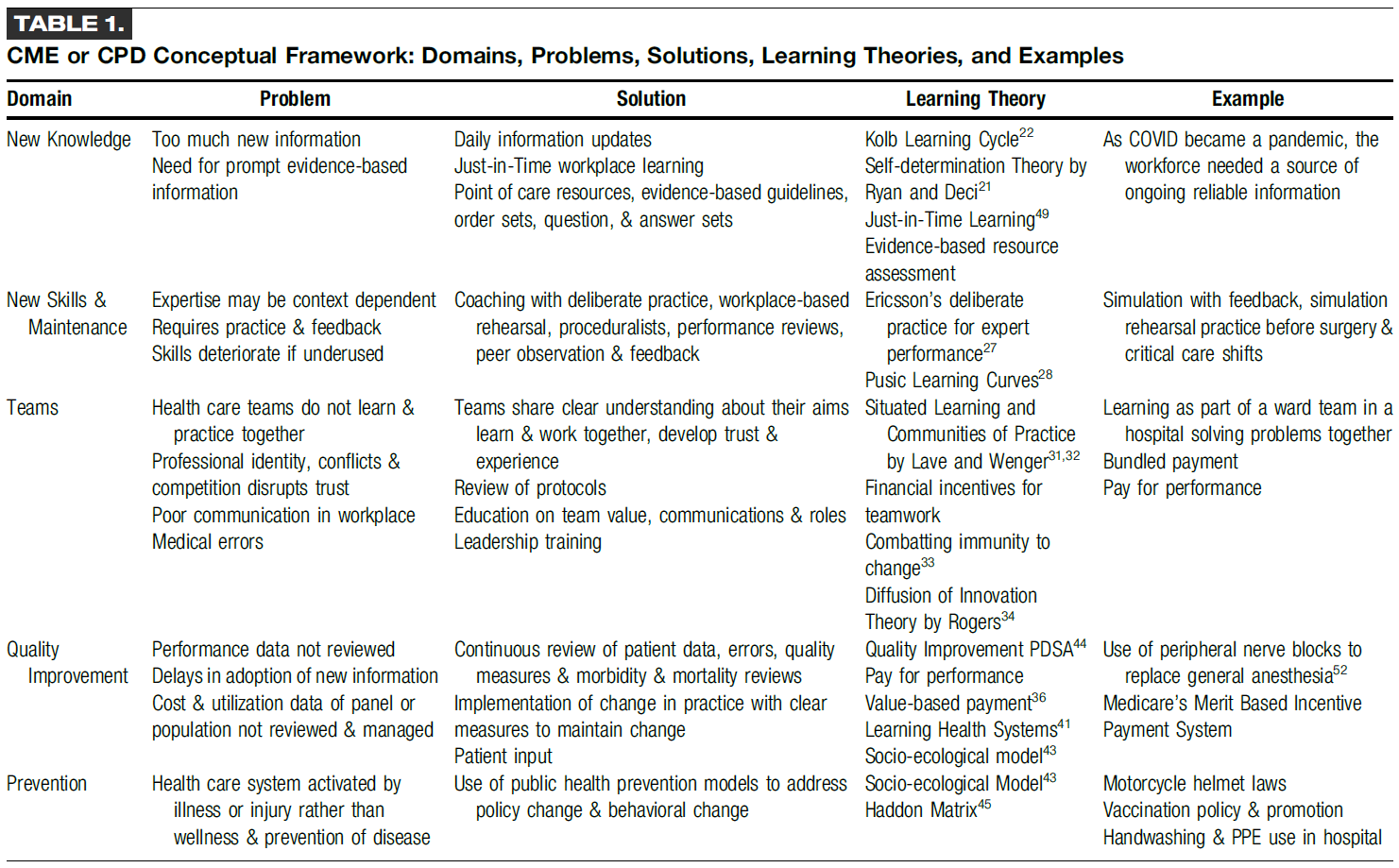

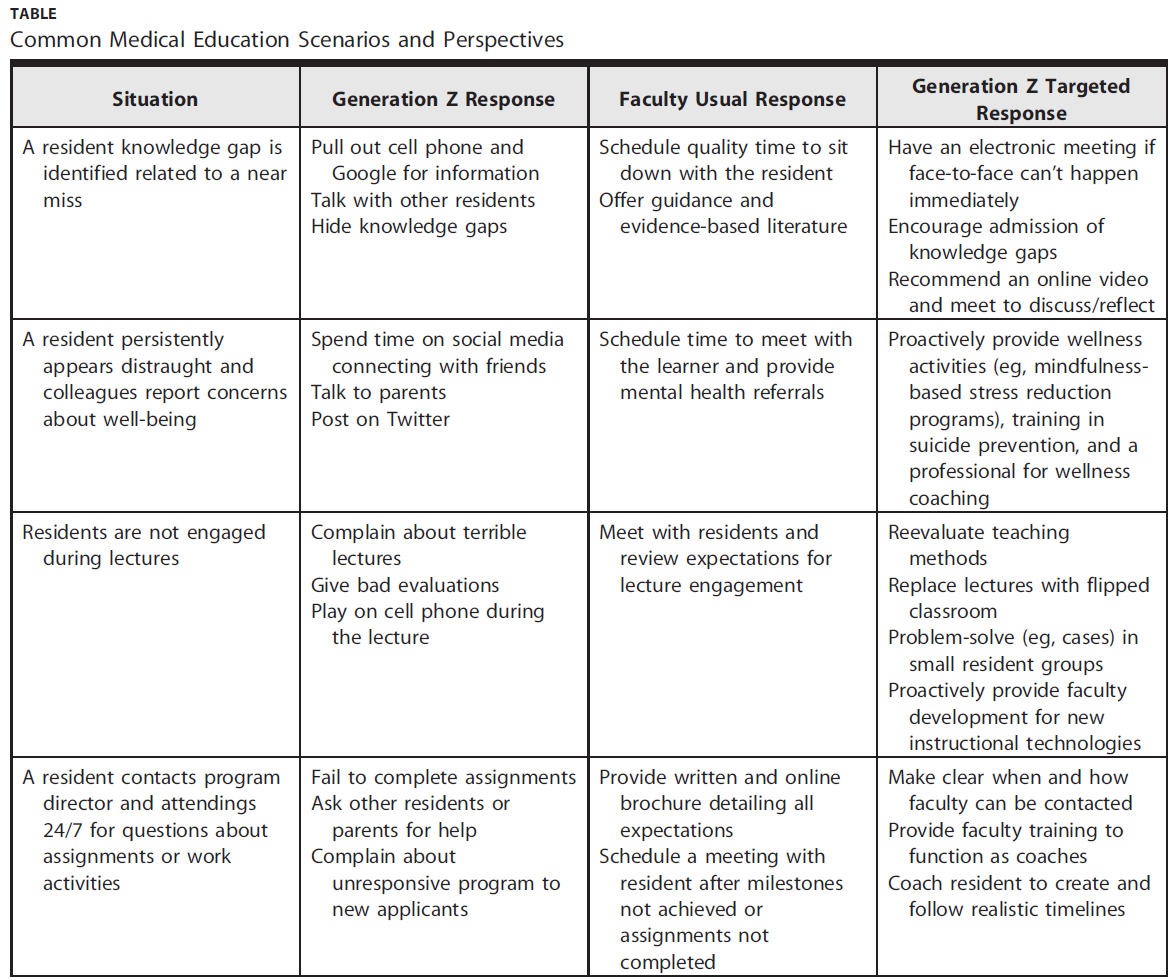

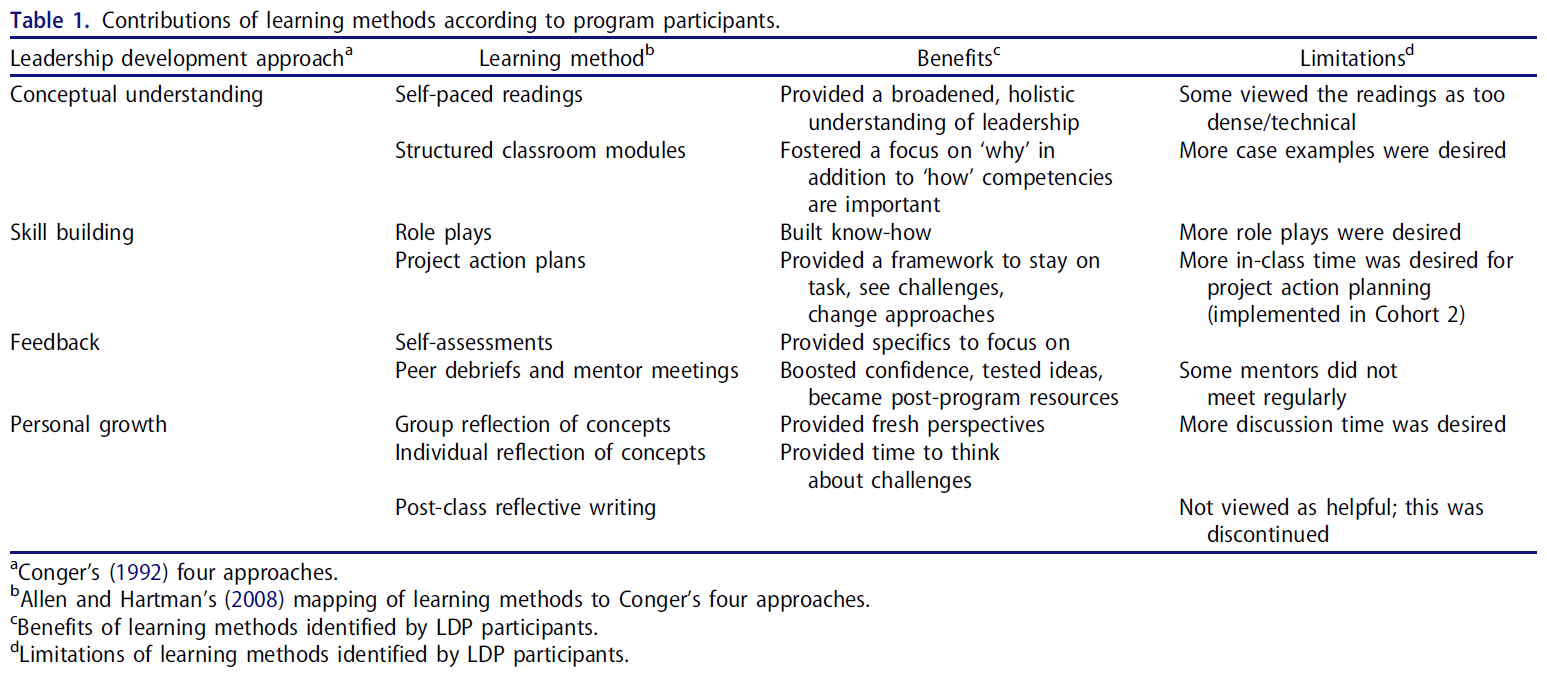

20세기 초 평생 의학 교육(CME)의 등장은 의료 전문가(HCP)들 사이에서 평생 교육의 중요성을 인식하는 전환점이 되었습니다.1 1977년 이후 39건의 체계적 문헌고찰에 따르면 CME가 의료 전문가의 지식을 높이고, 의료 전문가의 행동을 변화시키며, 환자 결과를 개선하는 데 효과적이라는 사실이 밝혀졌습니다.2 그러나 비효율적인 형식(예: 교훈적인 강의 및 컨퍼런스)이 여전히 지배적이며,2 공인된 CME 활동의 80% 이상이 블룸 분류법(인지(표 1), 정서 및 신체운동 영역)에 정의된 더 높은 수준의 학습을 목표로 하지 않는 등 CME가 제대로 발전하지 못하고 있다는 우려가 계속되고 있습니다.3

The advent of continuing medical education (CME) in the early part of the 20th century was a turning point in the recognition of the importance of lifelong education among health care professionals (HCPs).1 Thirty-nine systematic reviews since 1977 reveal that CME is effective in increasing HCP's knowledge, changing HCP's behavior, and to a lesser extent, improving patient outcomes.2 However, there is ongoing concern that CME continues to be poorly developed: ineffective formats (eg, didactic lectures and conferences) continue to dominate,2 with more than 80% of accredited CME activities not targeting higher levels of learning as defined by Bloom taxonomy (cognitive (Table 1), affective, and pyschomotor domain).3

CME 선택은 주로 HCP가 자신의 학습 요구를 정확하게 자가 평가하고 결정할 수 있을 것이라는 기대에 의해 주도됩니다.4 그러나 증거에 따르면 HCP는 자신의 기술 부족을 정확하게 자가 평가할 수 없으며4 종종 자신의 능력을 과대평가하는 경향이 있습니다.5 그 결과, HCP는 이미 역량을 갖춘 익숙한 CME 주제를 선택하는 경향이 있으며, 잠재적으로 중요하고 현대적인 의학 지식의 다른 영역을 무시할 수 있습니다.6

CME selection is predominantly driven by the expectation that HCPs are able to accurately self-assess and determine their own learning needs.4 Evidence suggests, however, that HCPs are unable to accurately self-assess their skill deficit4 and often tend to overestimate their abilities.5 As a result, HCPs are more inclined to select familiar CME topics in which they are already competent, potentially ignoring other areas of important and contemporary medical knowledge.6

의과대학에서 다루는 의학 지식의 범위가 73일마다 두 배씩 증가하는 것으로 추정되는 등 빠르게 변화하는 의학 지식 분야로 인해 CME의 질3 형식2 및 자체 선택6에 대한 이러한 우려는 더욱 심화되고 있습니다.7 이러한 증가된 지식의 초점은 인구 역학 및 의료 요구의 변화에 대한 전 세계적인 인식에 따라 공중보건(PH) 및 양질의 환자 치료와 관련된 문제로 옮겨가고 있습니다.8 또한 보편적 의료에 대한 추진,10 그리고 지역사회에서 예방적 일차 진료의 이점,11은 HCP가 PH 영역의 발전과 지식을 계속 평가할 것을 요구합니다. 현재 환자의 50%만이 적절한 수준의 예방 진료를 받고 있습니다.12 이를 90%까지 높이면 비용 절감과 함께 연간 200만 명의 생명을 추가로 구할 수 있습니다.13 PH의 광범위한 다전문가, 다분야, 다기관 특성으로 인해 임상 영역을 넘나들고 인구의 PH 요구사항에 특화된 CME가 필요합니다.14 HCP는 PH 인력의 필수 구성 요소로 간주되므로, "의료 환경에서 관련 건강 증진 및 질병 예방 서비스를 제공하는 데 필요한 지식과 기술을 갖추도록 보장해야 할 고유한 책임이 있습니다."15(17페이지).

This concern about quality,3 format,2 and self-selection of CME6 is aggravated further by the rapidly changing field of medical knowledge: it is estimated that the extent of medical knowledge covered in medical school doubles every 73 days.7 The focus of this increased knowledge has moved toward matters relating to public health (PH) and quality patient care,8 driven by the global recognition of changing population dynamics and health care needs.9 In addition, the push for universal health care,10 and the benefit of preventive primary care in the community,11 requires that HCPs keep appraised of developments and knowledge within the realm of PH. Currently, only 50% of patients receive the appropriate level of preventive care.12 Increasing this to 90% could save an additional two million lives a year with cost savings.13 Because of the broad multiprofessional, multidisciplinary, and multiagency nature of PH, CME that cuts across clinical domains and is specific to the PH needs of a population is required.14 Because HCPs are considered an integral component of the PH workforce, a unique responsibility exists to ensure they are equipped with the necessary knowledge and skills “to provide relevant health promotion and disease prevention services in the health care setting.”15(pg. 17)

이러한 문제를 해결하기 위해서는 PH CME의 최적화가 필요합니다. 앞서 언급했듯이 CME는 올바르게 제공되고 사용될 때 효과적이지만, 항상 그런 것은 아닙니다. 맥락이 CME 효과에 어떤 역할을 할 수 있는지 이해하는 것이 연구 우선순위로 확인되었습니다.2 실제로 의학교육 내에서 '맥락'은 끊임없이 정의definition를 어렵게 만들고 있으며16, 그 결과 CME 관련 분야에서 맥락을 정의17하고 식별18하려는 관심이 증가하고 있습니다. 베이츠와 엘러웨이16는 어떤 식으로든 컨텍스트를 다룬 62편의 논문을 조사하여 의학교육에서의 컨텍스트에 대한 정의를 개발했습니다:

These issues necessitate the optimization of PH CME. As has been mentioned, CME is effective when offered and used correctly; however, this is not always the case. Understanding what role context may play in CME effectiveness has been identified as a research priority.2 Indeed, within medical education, context continues to elude definition16; as a result, there is increasing interest to define17 and identify18 context in CME-related fields. Bates and Ellaway16 examined 62 articles that addressed context in some way and developed a definition for context in medical education:

"컨텍스트는 환자, 장소, 실무, 교육 및 사회의 기본 패턴과 이러한 패턴 간의 예측할 수 없는 상호 작용에서 나타나는 역동적이고 끊임없이 변화하는 시스템입니다."(814페이지).

“Context is a dynamic and ever-changing system that emerges from underlying patterns of patients, locations, practice, education and society, and from the unpredictable interactions between these patterns.”(p. 814)

이 정의는 저자들이 CME에서 컨텍스트를 이해하는 데 기초가 됩니다.

This definition serves as the basis for the authors' understanding of context in CME.

HCP가 인구의 필요를 충족시킬 수 있는 CME의 잠재력에 대한 인식과 전달 방법 및 맥락에 관한 현재의 한계에 대한 이해가 결합되어 PH CME에서 맥락이 어떤 역할을 하는지에 대한 조사로 이어졌습니다. 이 조사의 일환으로 연구팀은 연구 프로젝트에 정보를 제공하기 위해 이론적 프레임워크를 객관화했습니다. 이러한 프레임워크의 사용은 결과에 대한 이론적 근거를 제공하고19 의학교육 연구 분야를 이론을 시험하고 도전하며 더욱 발전시킬 수 있는 방식으로 발전시킵니다.20 이 글에서는 PH CME와 관련된 학습 이론에 대한 비판적 분석에서 나온 혁신적이고 진보적인 통합 이론적 프레임워크를 제시합니다. 이 통합 프레임워크는 연구팀이 고려한 다른 접근법의 단점을 해결하고 의료 시스템 내 CME 맥락을 이해하는 데 있어 새로운 이론적, 방법론적 통찰력을 제공할 수 있는 잠재력을 제공합니다.

It is the appreciation of CME's potential in equipping HCPs to address population needs, combined with an understanding of its current limitations regarding methods and context of delivery, that has led to an investigation into what role context plays in PH CME. As part of this investigation, the research team has objectified a theoretical framework to inform the research project. The use of such a framework offers a theoretically grounded explanation for results19 and moves the field of medical education research forward in a fashion that allows theory to be tested, challenged, and developed further.20 This article presents an innovative and progressive unified theoretical framework that ensued from a critical analysis of learning theory as it relates to PH CME. This unified framework addresses shortcomings of other approaches considered by the research team and offers the potential for new theoretical and methodological insights into understanding CME context within health care systems.

프레임워크 식별

Identifying a Framework

링스테드 외21는 의학교육 연구의 첫 번째 단계는 이론적 또는 개념적 프레임워크 내에서 문제를 파악하는 것이라고 주장합니다. 의학교육 연구 문헌에서 이러한 프레임워크의 결여는 제출된 논문의 3분의 2에서 출판 거부의 요인으로 지적된 반면, 출판된 모든 의학교육 연구 문헌의 절반만이 이론적 프레임워크를 명시적으로 사용하고 있습니다.22 이는 교육적 장학금을 방해하고 연구 결과의 적용 가능성과 일반화 가능성을 제한하는 요인으로 작용합니다.

Ringsted et al21 argue that the first step in medical education research should be situating the problem within a theoretical or conceptual framework. The deficit of such frameworks within medical education research literature has been noted as a factor in publication rejection in two-thirds of articles submitted, whereas only half of all published medical education research literature makes explicit use of a theoretical framework.22 This hampers educational scholarship and limits applicability and generalizability of findings.

호지스와 쿠퍼23(26쪽)가 지적했듯이, 오늘날 다양한 분야에서 "수백 가지의 이론"이 사용되고 있습니다. 의학교육 연구 영역에서 이러한 이론은 HCP가 기능하고 학습하는 사회문화적 맥락과는 반대로 개인에 초점을 맞추는 경향이 있습니다.24 개인에 초점을 맞추는 것이 Flexner 보고서(1910)의 권고에 따라 의학교육에 유용한 접근법으로 입증되었지만, 의료의 변화하는 모습과 학생들의 학습 방법에 대한 우리의 진화하는 이해는 21세기 빠르게 발전하는 글로벌 사회의 요구를 충족하기 위해 의학교육 발전 방식에 다른 접근법을 요구하고 있습니다.25 HCP는 고립된 채로 기능하는 것이 아니라, 임상팀과 주변 환경, 그리고 HCP가 수행하는 치료의 유형과 표준을 결정하는 국가 보건 정책에 이르기까지 광범위한 의료 시스템의 일부이며, 이는 다시 국제 보건 의제 및 SARS-CoV-2와 같은 새로운 우려의 영향을 받습니다. 사회문화적 학습 이론은 "의학이 학습되고 실행되는 환경 수준에서" 이러한 시스템 전반에서 학습이 어떻게 이루어지는지 살펴볼 수 있는 기회를 제공합니다.23(31페이지) 실제로, 교육 중에 이러한 시스템 복잡성으로부터 HCP를 격리하는 것은 환자 결과를 개선하는 것으로 나타난 전문가 간 능력을 육성하지 못할 가능성이 높습니다.26

As Hodges and Kuper23(p. 26) have pointed out, “there are hundreds of theories” in use today across various disciplines. Within the realm of medical education research, these theories have tended to focus on the individual, as opposed to the sociocultural context in which HCPs function and learn.24 Although focusing on the individual has proved a useful approach to medical education following the recommendations of the Flexner report (1910), the changing face of health care, and our evolving understanding of how students learn, necessitates a different approach in how we advance medical education to meet the needs of a rapidly progressing global society in the 21st century.25 HCPs do not function in isolation; they are part of wider health care systems that stretch from clinical teams, in their immediate environment, to national health policies determining the type and standard of care that HCPs practice, which in turn are influenced by international health agendas and emerging concerns, such as SARS-CoV-2. Sociocultural theories of learning offer opportunities to examine how learning occurs across these systems “at the level of the environment in which medicine is learned and practiced.”23(p. 31) Indeed, isolating HCPs from this system complexity during training is unlikely to foster interprofessional abilities that are shown to improve patient outcomes.26

시스템적 사고는 PH 분야에서 점점 더 인기를 얻고 있으며27,28 오피오이드 남용에 대한 교육적 개입의 영향을 모델링하는 데 유용하다는 것이 입증되었습니다.29 실제로 시스템적 사고의 기본 교리는 인구 결과를 개선하기 위해 새로운 지식이 어떻게 생성, 관리, 전파 및 통합되는지 이해하는 것입니다.30 마찬가지로, 사회 학습 이론은 복잡한 시스템 내에서 사회적 상호 작용을 통해 지식이 생성된다는 것을 인식함으로써 시스템 관점을 가정합니다.31 이러한 공통점은 사회 문화 학습 이론을 사용하여 PH CME를 조사하는 데 유익한 근거를 제공합니다.

Systems thinking is becoming increasingly popular within the field of PH27,28 and has proved useful in modeling impacts of educational interventions on opioid abuse.29 Indeed, a fundamental tenet of systems thinking is understanding how new knowledge is created, managed, disseminated, and integrated across systems to improve population outcomes.30 Similarly, social learning theories assume a systems perspective by recognizing that knowledge is created through social interaction within complex systems.31 These commonalities offer fruitful ground for using sociocultural theories of learning to investigate PH CME.

이를 염두에 두고 저자들은 연구에 정보를 제공하고 근거를 제시할 수 있는 적절한 이론적 틀을 수립하기 시작했습니다. 의학 및 사회과학 분야의 온라인 저널 데이터베이스를 '의학 교육', '학습 이론' 및 관련 동의어를 사용하여 검색했습니다. 이를 의학교육 및 고등교육 교수학습 분야의 교육학 전문가들과 비공식 그룹 토론을 통해 보완했습니다. 이러한 과정을 통해 확인된 리뷰 논문23,25,32,33은 관련 현대 이론을 평가하기 위한 발판으로 사용되었으며, 이를 바탕으로 적절한 참고 문헌이 눈덩이처럼 불어났습니다. 또한, 확인된 이론을 보다 명확하게 설명하기 위해 일부 학술 문헌을 참고했습니다.

With this in mind, the authors set out to establish a suitable theoretical framework to inform and ground their research. A search of online journal databases within the medical and social science fields was performed using terms “medical education,” “learning theory,” and associated synonyms. This was supplemented by informal group discussions with pedagogical experts in the field of medical education and higher education teaching and learning. Review articles identified through these processes23,25,32,33 were used as a springboard to evaluate relevant contemporary theories; from there, snowballing of suitable references took place. In addition, select academic text was consulted to provide deeper clarity on identified theories.

프레임워크 개발에 적합한 이론을 식별하는 데 다음 세 가지 기준이 사용되었습니다:

The following three criteria were used in identifying a suitable theory to inform the framework's development:

- 이론은 개별 학습자 외에도 학습과 관련된 더 넓은 맥락적 요인을 인식해야 합니다.

In addition to the individual learner, the theory needs to be cognizant of the wider contextual factors involved in learning. - 이론은 학습자와 더 넓은 맥락적 요인 간의 상호 작용에 대한 시스템적 이해를 수반해야 합니다.

The theory needs to entail a systems understanding of the interactions between learner and wider contextual factors. - CME에 정보를 제공할 모든 이론은 학습을 단순한 지식 습득이라는 개념을 넘어설 필요가 있습니다.

Any theory that will inform CME needs to move beyond the notion of learning as mere acquisition of knowledge.

또한 선택한 이론의 실제 적용은 연구 프로젝트의 시간 및 리소스 제약 내에서 실현 가능해야 했습니다. 식별된 이론에 대한 1차 평가 후, 10개의 이론을 세부적으로 검토하여 미리 정해진 기준과 연구와의 관련성에 따라 적합성을 평가했습니다(표 2). 10가지 이론 중 어떤 이론도 개별적으로 PH CME의 맥락을 탐구하는 데 충분하지 않다고 판단된 것은 없었습니다.

- 몇몇 이론은 지나치게 개인에 초점을 맞춘 것으로 간주되었고(패스만 인식-준수 모델, 콜브 경험적 학습 주기, 메지로우 변형 학습, 가드너 다중 지능 이론),

- 로저스 혁신 확산 이론은 대규모 변화에 더 적합한 것으로 간주되었습니다.

- 또한, 전기적 학습에서 홀크비스트 '사회적 공간'의 모호한 특성과 라베와 벵거의 실천 커뮤니티에서 PH '마스터'를 식별하는 데 어려움이 있었기 때문에 이 두 이론을 사용할 수 없었습니다.

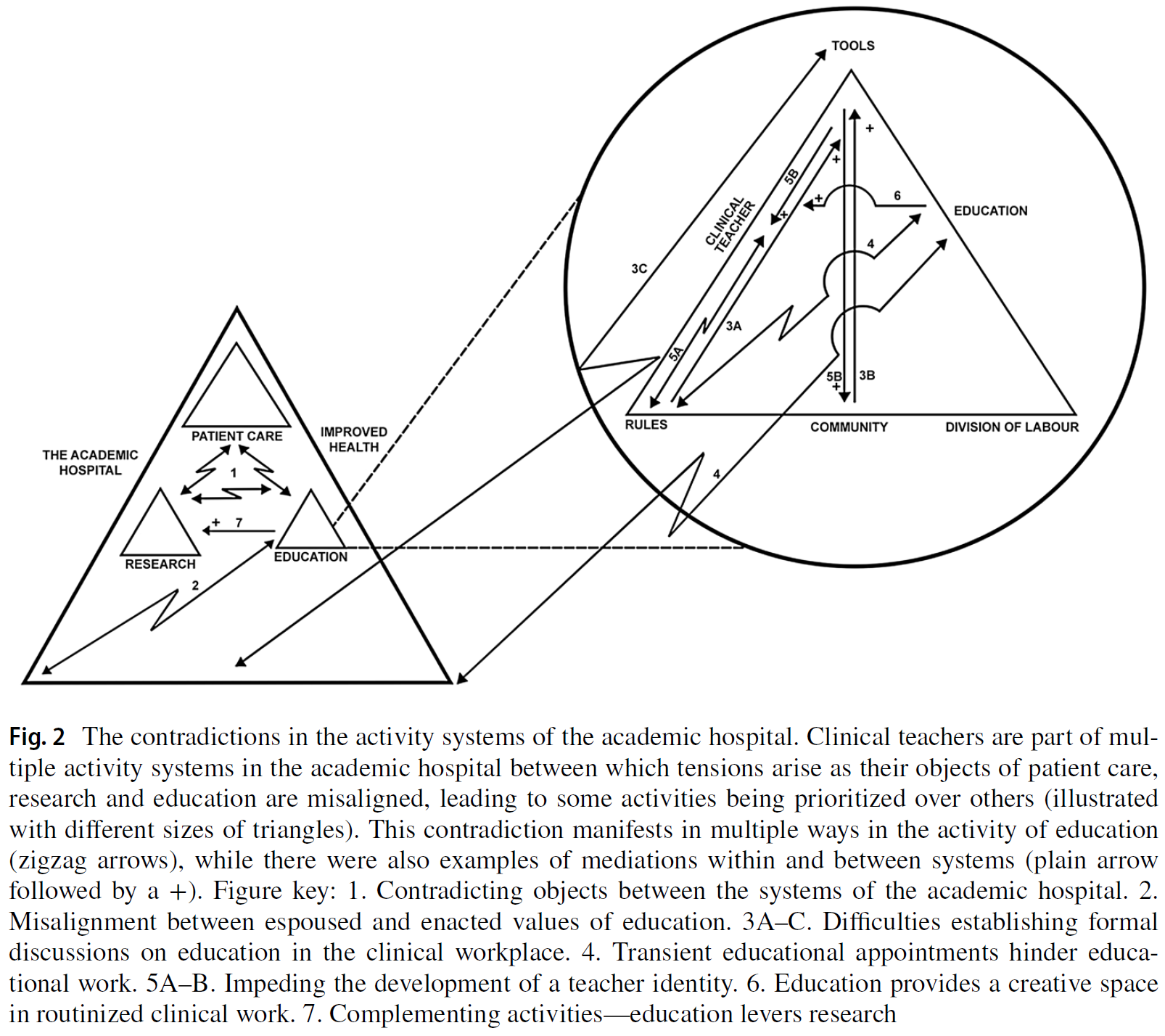

- 마지막으로, 활동 시스템 수준에서 엥스트롬의 확장적 학습 이론을 적용하는 데 내재된 복잡성은 너무 많은 시간과 자원이 소요되는 것으로 간주되었습니다.

In addition, practical application of any theory selected had to be feasible within the time and resource constraints of the research project. After an initial evaluation of identified theories, 10 theories were subsequently examined in detail to evaluate their suitability based on the prespecified criteria and relevance to the research (Table 2). None of the 10 theories individually was deemed sufficient for the purpose of exploring context in PH CME.

- Several were considered to be too overtly focused on the individual (Pathman awareness-to-adherence model, Kolb experiential learning cycle, Mezirow transformative learning, and Gardner theory of multiple intelligences) while

- Rogers diffusion of innovations theory was deemed more appropriate for making large-scale changes.

- Furthermore, the nebulous nature of Hallqvist “social space” in biographical learning and the challenge in identifying a PH “master” in Lave and Wenger communities of practice precluded the use of these two theories.

- Finally, the complexity inherent in applying Engström expansive learning theory at the level of activity systems was considered too time and resource intensive.

그러나 이러한 문제를 피할 수 있고 비판적 평가를 통해 각 관점의 개별적인 단점을 보완하면서 맥락 문제에 대한 이해를 심화할 수 있는 두 가지 이론적 관점이 등장했습니다. 바로 빅스의 건설적 조정 원리34와 브론펜브레너35의 생물생태학적 인간 발달 모델입니다.

- 빅스 원리는 학습 환경 내에서 개별 학습자가 경험하는 학습 과정에 대한 이론적 명확성을 제공하는 반면,

- 브론펜브레너 모델은 학습이 다양한 시스템과의 상호작용을 통해 어떻게 영향을 받는지를 설명함으로써 이를 확장합니다.

Two theoretical perspectives, however, did emerge that avoided these challenges and, on critical assessment, could be combined to deepen understanding of the issue of context while complementing individual shortfalls of each perspective in isolation. These were Biggs principle of constructive alignment34 and Bronfenbrenner35 bioecological model of human development.

- Biggs principle offers theoretical clarity around the learning process as experienced by individual learners within the learning environment, whereas

- Bronfenbrenner model expands on this by describing how learning is influenced through interactions with various systems.

건설적 정렬의 빅스 원리

Biggs Principle of Constructive Alignment

빅스의 구성적 연계의 원리는 구성주의 학습 이론, 즉 학습은 개인적 경험과 사회적 상호작용에 기반한 지식의 구성을 통해 발생한다는 학파에 속합니다.34 빅스는 이를 기반으로 교육과정의 연계 개념을 통해 성과, 교수/학습 활동 및 과제 평가의 연계가 추가적인 교육적 혜택을 부여합니다.34 빅스가 이 이론을 고등교육에 적용하여 의도한 결과는 고등교육을 졸업할 때 선언적 지식뿐만 아니라 직업적 맥락에서 학습을 실천하는 데 필요한 기능적 지식을 갖춘 "깊은" 자기 주도적 학습자를 개발하는 것이 었습니다. 증거에 따르면 고등 교육에서 빅스의 건설적 연계 원칙을 적용하면 개인이 선호하는 학습 스타일에 관계없이 실제로 "심층적인" 상황 학습 접근법이 가능하다고 합니다.36 이는 특히 자기주도적 학습을 통해 직업 경력 전반에 걸쳐 지식과 기술을 지속적으로 업데이트해야 하는 HCP와 관련이 있습니다.

Biggs principle of constructive alignment lies within the school of constructivist learning theory, that is, learning occurs through construction of knowledge based on personal experiences and social interactions.34 Biggs builds on this through the curricular concept of alignment, whereby alignment of outcomes, teaching/learning activities, and task assessment confers additional educational benefits.34 Biggs' intended outcome of applying this theory in higher education was to develop “deep” self-directed learners who leave tertiary education not only with declarative knowledge but also with functioning knowledge needed to put learning into practice in a professional context. Evidence suggests that applying Biggs principle of constructive alignment in higher education does indeed result in a “deep” situational learning approach, regardless of individuals' preferred learning styles.36 This is particularly relevant to HCPs, who must constantly update their knowledge and skills throughout their professional career through self-directed learning.

빅스 원칙에는 시스템적 특성이 내재되어 있습니다. 그의 초기 3P 모델(사전-과정-결과)37은 한 구성 요소의 변화가 다른 구성 요소에 어떤 영향을 미칠 수 있는지에 대한 인식을 통해 이를 명확하게 표현합니다. 실제로 빅스는 교육을 여러 개의 중첩된 "상호 작용하는 생태계"로 구성된다고 설명합니다.37(74페이지) 학습 활동과 교육기관 수준 간의 연계성을 고려하여 기능적 지식을 개발하는 것을 목표로 하는 CME에 가능성을 제공하는 것은 바로 이러한 상호 작용하는 시스템의 특성입니다.

There is an inherent systems nature evident in Biggs principle. His initial 3P model (Presage-Process-Product)37 clearly expresses this through its recognition of how changes in one component can impact the other. Indeed, Biggs describes education as consisting of several nested “interacting ecosystems.”37(p. 74) It is this interactive systems nature that offers promise for CME, aiming to develop functioning knowledge by considering alignment across learning activities and institute levels.

빅스는 고등교육에 내재된 다양한 수준(프로그램, 대학, 전문대학)이 연계될 수 있음을 인정하지만, 이 원칙을 고등교육 이외의 환경에 적용하는 것은 복잡합니다. 특히 CME 내에는 개발 및 제공에 중요한 역할을 하는 수많은 요소와 이해관계자가 있습니다.38 Freeth와 Reeves39는 전문직 간 직장에서의 학습 기회에 대한 이러한 광범위한 영향을 파악하기 위해 빅스 3P 모델을 채택했습니다. 이 모델은 전문직 간 교육에 대한 체계적인 검토에서 결과를 종합하는 분석 도구로 효과적임이 입증되었습니다.40,41 그러나 빅스 모델은 맥락을 하나의 선행 요인으로 통합하기 때문에 시스템 전반에서 학습에 미치는 맥락의 영향을 탐색할 수 없습니다. 앞서 언급했듯이, 시스템 전반에서 지식이 어떻게 생성되는지 이해하는 것은 PH 및 사회 학습 이론에서 시스템 사고의 기본 측면입니다. 바로 이 지점에서 브론펜브레너의 인간 발달 생물생태학적 모델35은 빅스 모델 내에서 여러 시스템에서 지식이 어떻게 생성되는지 더 잘 이해할 수 있는 기회를 제공합니다.

Although Biggs recognizes various levels inherent in tertiary education that could align (program, college, and university), applying this principle to settings outside of tertiary education is complicated. Particularly within CME, there are numerous factors and stakeholders that play important roles in its development and delivery.38 Freeth and Reeves39 adapted Biggs 3P model in an attempt to identify these wider influences on learning opportunities within interprofessional workplaces. Their adaptation has proven effective as an analytical tool for synthesizing results in systematic reviews of interprofessional education.40,41 However, Biggs model does not allow the exploration of the effect of context on learning across systems because it aggregates them into a single presage factor. As previously mentioned, understanding how knowledge is created across systems is a fundamental aspect of both systems thinking within PH and social learning theories. It is on this point that Bronfenbrenner bioecological model of human development35 offers opportunity for greater understanding of how knowledge is created across systems within Biggs model.

브론펜브레너의 생물생태학적 인간 발달 모델

Bronfenbrenner Bioecological Model of Human Development

브론펜브레너35는 학습이 개인과 개인이 작동하고 생활하는 시스템 간의 점점 더 복잡한 상호작용, 그리고 이러한 시스템 간의 관련 상호작용에서 비롯된다고 보았습니다. 이를 바탕으로 브론펜브레너는 교육 환경의 생태학적 구조를 구성하는 네 가지 초기 수준, 즉 미시체계, 중체계, 외체계, 거시체계를 정의했습니다(표 3).

Bronfenbrenner35 viewed learning as arising from increasingly complex interactions between individuals and the systems in which they operate and live and the associated interactions between these systems. From this, Bronfenbrenner defined four initial levels that make up educational environment's ecological structure, namely the

- microsystem,

- mesosystem,

- exosystem, and

- macrosystem (Table 3).

이러한 수준 정의는 개인과의 상호 작용 정도에 따라 각 시스템 내의 주요 이해관계자에 대한 구체적인 설명을 제공합니다. 이러한 브론펜브레너의 연구를 통해 빅스 모델의 구성 요소를 확장하여 시스템 내 및 시스템 간 학습에 영향을 미치는 맥락적 요인을 더욱 세밀하게 파악할 수 있습니다. 브론펜브레너 모델을 적용하면 빅스 이론을 단독으로 사용할 때의 잠재적인 단점을 해결할 수 있습니다.

These level definitions offer concrete descriptions of key stakeholders within each system based on their degree of interaction with the individual. Such a reading of Bronfenbrenner's work allows for the possible expansion of components of Biggs model to provide further granularity of contextual factors that influence learning within and across systems. Applying Bronfenbrenner model addresses the potential shortcoming of using Biggs theory in isolation.

브론펜브레너 모델 사용에 대한 비판은 초기 네 가지 시스템 수준의 생태학적 프레임워크의 성공으로 인해 모델의 후속 반복을 인정하거나 사용하지 않았다는 점과 관련이 있습니다.42 로사와 터지(Rosa)43 는 이 초기 모델이 두 번의 반복을 더 거쳤다고 지적합니다.

- 두 번째 반복은 자신의 개발에서 개인의 역할에 초점을 맞추었습니다.

- 세 번째이자 마지막 반복은 과정-사람-상황-시간(PPCT) 모델로서, 브론펜브레너가 개인과 주변 환경 간의 복잡한 상호작용(발달의 근위 과정)과 종적 및 역사적 시간이 발달에 미치는 영향에 대해 강조한 것을 강조했습니다.

그 결과, 브론펜브레너가 크로노시스템이라고 명명한 다섯 번째 체계43가 모델에 추가되었습니다. 이 모델은 발달이 삶의 과정과 과거, 현재, 미래의 역사적 시간을 통해 형성된다고 가정합니다. 이는 의료의 변화로 인해 HCP가 역량을 유지하고 전문적으로 발전하는 방식에 변화가 필요하기 때문에 CME와 매우 관련이 있습니다.44

Criticism of the use of Bronfenbrenner model revolves around the lack of acknowledging or using subsequent iterations of the model due to the success of its initial four system-level ecological framework.42 Rosa and Tudge43 point out that this initial model underwent a further two iterations.

- The second iteration focused on the role of the individual in their own development.

- The third and final iteration, referred to as the Process-Person-Context-Time (PPCT) model, highlighted the importance Bronfenbrenner placed on complex interactions between the individual and their immediate surroundings (proximal processes of development), and the influence of time, both longitudinal and historical, on that development.

As a result, the fifth system, termed chronosystem by Bronfenbrenner,43 was added to the model. It posits that development is shaped across the life course and through historical time past, present, and future. This is highly relevant in CME because the changing face of health care requires changes in the way HCPs maintain competency and develop professionally.44

위에서 설명한 두 모델 사이에는 상호보완성과 호환성이라는 큰 요소가 있습니다. 두 모델 모두 학습 과정을 결과의 필수 요소로 간주하지만, 접근 방식은 정반대입니다:

- 빅스는 결과에서 출발하여 학습 과정을 이 결과에 맞추는 반면,

- 브론펜브레너는 학습 과정이 어떻게 결과(발달)로 이어지는지를 관찰합니다.

두 이론 모두 개인을 이론의 중심에 두고 있습니다:

- 빅스는 "학생이 무엇을 하고 그것이 교육과 어떻게 관련되는가"에 초점을 맞추는 3단계 교육에 대해 이야기합니다.34(20쪽);

- 브론펜브레너에게 개인은 매우 중요했기 때문에 그들의 두 번째 작업은 전적으로 개인의 발달에 있어 개인의 역할에 초점을 맞췄습니다.43

마지막으로, 빅스는 자신의 모델에서 브론펜브레너 크로노시스템과 같은 정도로 시간을 명시적으로 다루지는 않지만 학습이 "일회성 과정이 아니라 지속적인 행동 학습 주기"라고 지적합니다.34(281쪽) 이는 평가에 미치는 영향과는 별개로 움직이는 시간 개념을 의미하지만 빅스 원칙의 주요 구성 요소는 아닙니다.

There is a large component of complementarity and compatibility between the two models described above. Both view the process of learning as an integral component of the outcome, although the models approach this from opposite ends:

- Biggs starts with the outcome, and then aligns the learning process to this outcome, whereas

- Bronfenbrenner observes how the learning process leads to the outcome (development).

Both place the individual at the heart of the theory:

- Biggs talks about level 3 teaching, where the focus is on “what the student does and how that relates to teaching”34(p. 20);

- the importance of the individual to Bronfenbrenner was so great that the second iteration of their work focused wholly on the role of the individual in their own development.43

Finally, although Biggs does not explicitly address time in their own model to the same extent as Bronfenbrenner chronosystem, it does point out that learning is not “a one-off process but a continuing action learning cycle”.34(p. 281) This implies a concept of time in motion, although apart from its influence on evaluation, is not a major component of Biggs principle.

두 모델 모두 서로를 보완하지만, 브론펜브레너 모델이 더 넓은 맥락 변수를 탐색하는 데 있어 더 깊이 있는 정보를 제공하는 것으로 보입니다. 그러나 PH CME에서 맥락적 요인을 조사하기 위한 목적으로 브론펜브레너 모델을 단독으로 사용하기에는 몇 가지 단점이 있었습니다. 첫째, 브론펜브레너 모델의 근본적인 초점은 아동 발달이었습니다. 발달은 전 생애에 걸쳐 비슷한 방식으로 일어난다고 했지만, 직업 경력에서 발생하는 "점진적으로 더 복잡한 상호 작용"43(252쪽)은 아동에서 조사된 것보다 훨씬 더 복잡할 가능성이 높습니다. 또한 환경, 그리고 그 환경 내의 사물과 사람들도 아동과 전문가 사이에 크게 다를 가능성이 높습니다.

Although both models complement each other, it would seem Bronfenbrenner model offers more depth regarding exploring wider contextual variables. However, for the purpose of examining contextual factors in PH CME, there were several shortcomings with Bronfenbrenner model that precluded its sole use. First, the underlying focus of Bronfenbrenner model was child development. Although it stated that development occurs in a similar fashion throughout life, the “progressively more complex reciprocal interaction”43(p. 252) that occurs over a professional career is likely to be far more complex than those examined in children. In addition, the environments, and the objects and persons within those environments, are also likely to be vastly different between children and professionals.

둘째, 브론펜브레너 모델의 탐구 방향, 즉 과정이 결과에 미치는 영향은 이미 CME 분야에서 잘 연구되어 있습니다.2 이제 관심의 대상은 상호 작용하는 맥락적 요인을 평가하여 이러한 과정, 즉 집단 결과를 어떻게 개선할 수 있는지에 대한 것입니다. 목적을 염두에 두고 시작하는 것이 CME를 통해 이를 달성하기 위한 수단으로 제안되었습니다.45,46 따라서 의도된 결과에서 시작하는 빅스의 건설적 정렬 원칙은 이 점에 대한 학습 이론의 보다 적절한 적용입니다.

Second, the direction of enquiry within Bronfenbrenner model, namely how process affects outcome, is already well studied within the field of CME.2 What is now of interest is how to improve these processes, and thus population outcomes, by evaluating interacting contextual factors that play a role. Beginning with the end in mind has been proposed as a means of achieving this with CME.45,46 Thus, Biggs principle of constructive alignment that starts with the intended outcome is a more suitable application of learning theory on this point.

학습에 대한 통합된 이론적 프레임워크

A Unified Theoretical Framework of Learning

그림 1은 이 두 가지 모델을 융합하여 학습에 대한 고유한 통합 이론적 프레임워크를 제시합니다. 이 프레임워크는 저자들의 현재 연구에 정보를 제공하며, 향후 전문적 학습을 탐구하는 모든 연구의 이론적 토대가 될 수 있는 잠재력을 가지고 있습니다.

Figure 1 presents a fusion of these two models to create a unique unified theoretical framework of learning. This framework will inform the authors' current study and has the potential to serve as a theoretical foundation for any future study exploring professional learning.

Biggs 3P 모델의 원래 표현은 세 가지 영역(사전-과정-결과) 모두에 걸쳐 여러 생태계에 걸친 상호작용을 포함하도록 확장되었습니다. 이는 빅스의 원래 모델에서 제안한 학생과 교사 간의 상호작용을 넘어 다양한 수준에서 CME에서 역할을 하는 잠재적인 맥락적 요인에 대한 검토를 가능하게 합니다. 또한, 브론펜브레너 모델을 포함함으로써 각 시스템 내에서 중요한 이해관계자를 식별하는 데 도움이 되는 명시적인 정의를 제공합니다(표 3). 브론펜브레너가 정의한 각 단계의 주요 특성을 나타내기 위해 각 단계에 제목을 부여했습니다.

- 미시 시스템 수준에는 개인과 이들이 정기적으로 참여하는 환경이 있습니다.

- 중간 시스템 수준에는 미시 시스템을 하나로 모으는 조직인 중개자가 있습니다. 브론펜브레너의 초기 모델에서는 이를 마이크로시스템 주변의 단순한 계층으로 표시했습니다. 저자들은 이 수준에서 발생할 수 있는 풍부한 상호작용을 적절하게 표현하지 못한다는 로사와 터지43의 의견에 동의하며, 따라서 이 프레임워크는 빅스 모델의 모든 구성 요소를 포함하도록 확장했습니다.

- 다이어그램의 미시체계 아래에는 인플루언서라고 불리는 외체계Exosystem가 있으며, 이는 미시체계와 직접적으로 관련되지는 않지만 개인에게 (긍정적이든 부정적이든) 영향력을 행사하는 "사회적 구조"35를 의미합니다.

- 마지막으로, 거시 시스템은 이데올로기라고 하는데, 이는 모든 시스템이 작동하는 전반적인 문화를 형성하는 이데올로기를 가진 조직을 포괄합니다.

The original representation of Biggs 3P model has been expanded to include interactions across multiple ecological systems over all three domains (Presage-Process-Product). This countenances examination of potential contextual factors that play a role in CME at multiple levels beyond the student–teacher interaction as proposed within Biggs original model. In addition, the inclusion of Bronfenbrenner model offers explicit definitions to aid in the identification of critical stakeholders within each system (Table 3). Titles were assigned to each level to represent the key characteristics of each as defined by Bronfenbrenner.

- At the microsystem level is the individual and the settings in which they engage on a regular basis.

- At the mesosystem level are the intermediaries, those organizations that bring the microsystems together. In Bronfenbrenner initial model, this was displayed as a simple layer around the microsystem. The authors are in agreement with Rosa and Tudge43 that this does not adequately represent the richness of interactions that can arise at this level, and therefore, the framework expands it to include all components of Biggs model.

- Below the mesosystem in the diagram is the exosystem, termed influencers, those “social structures”35 that are not directly involved with the microsystem, but nevertheless exert influence (both positive and negative) on the individual.

- Finally, the macrosystem is termed ideologues, as it encapsulates those organizations whose ideologies shape the overall culture in which all systems function.

이론적 관점에서 이 두 모델을 결합한 혼합 프레임워크를 정교화하면 시스템 전반과 시스템 간에 발생하는 상호 작용에 대한 이해의 깊이와 풍부함을 높일 수 있습니다. 이러한 상호 작용은 프레임워크 오른쪽의 십자 화살표 방향으로 표시됩니다. 실제 적용 관점에서 이 프레임워크는 명확한 정의와 이론적 프로세스를 제공하여 연구 탐구를 안내합니다. 또한 추가 세부 사항을 통해 빅스의 정렬 이론을 적용하여 각 시스템의 의도가 시스템 내부 및 시스템 간에 정렬되는지 조사할 수 있습니다. 가로 화살표로 표시된 고등교육 내 커리큘럼 정렬은 '심층적인' 자기주도적 학습을 장려하는 것으로 나타났으며36, 세로 화살표로 표시된 시스템 간 정렬도 동일한 결과를 기대할 수 있습니다.

From a theoretical perspective, elaboration of a blended framework that combines these two models increases the depth and richness of understanding of interactions that occur across and between systems. These interactions are indicated by the cross-arrow directions to the right of the framework. From a practical application perspective, it offers clear definitions and theoretical processes to guide research enquiry. The additional detail also permits applying Biggs theory of alignment to investigate whether the intent of each system is aligned within and across the systems. Curricular alignment within higher education, represented by the horizontal arrow, has been shown to encourage ‘deep’ self-directed learning36; the same outcome might be expected when alignment occurs across systems, represented by the vertical arrow.

도표 상단의 화살표는 결과에서 과정으로 이어지는 CME 개발의 방향을 나타내는데, 이는 빅스의 이론적 관점과 일치합니다.34 이는 또한 CME 개발에 관한 현재의 실용적 사고("끝을 염두에 두고 시작하라"46(6페이지))와도 일치합니다. CME 개발은 결과에서 시작되지만, 도표 아래 화살표로 표시된 학습의 방향은 시간이 지남에 따라 왼쪽에서 오른쪽으로 자연스럽게 발생하는데, 이는 개인과 개인이 속한 시스템의 프레젠테이션 요인이 이러한 시스템 내에서 학습과 지식 전파 과정에 영향을 미치기 때문입니다. 이는 위에서 설명한 두 모델의 이론적 관점에 의해 뒷받침됩니다. 이러한 종적 시간의 실질적인 의미는 학습이 지속적이고 지속적인 과정이라는 것을 의미합니다. 효과적인 학습을 위해서는 CME를 한 시점에 단 한 번의 상호작용으로 개발할 수 없습니다. 실제로 경험적 증거는 여러 번 노출되는 CME가 단일 노출 활동보다 더 효과적이라는 개념을 뒷받침합니다.2

The arrow at the diagram's top indicating direction of CME development, from outcome to process, is in keeping with Biggs' theoretical perspective.34 This also aligns with current practical thinking regarding CME development (“start with the end in mind”46(p. 6)). Although CME development originates with the outcome, the direction of learning, represented by the arrow below the diagram, naturally occurs from left to right over time—presage factors of the individual and the systems they reside in influence the process of learning and knowledge dissemination within these systems. This is supported by the theoretical perspectives of both models as described above. The practical implication of this longitudinal time implies learning is a continuous, ongoing process. To be effective, CME cannot be developed as a single interaction at a point in time. Indeed, empirical evidence supports the notion that multiple-exposure CME is more effective than single-exposure activities.2

마지막으로, 브론펜브레너의 시간 개념화는 학습의 과정과 체계가 존재하는 캡슐화된 크로노시스템으로 표현됩니다. 이는 개인의 학습이 그들이 살아가고 성장하는 역사적 시대에 발생하는 변화에 의해 형성된다는 것을 인정하며,43 연구자들이 지난 수십 년 동안 의학교육의 유사한 변화를 인식할 것을 요구합니다.47 이러한 변화는 기술이 의료 교육48 및 실무에 계속 영향을 미치면서 더 자주 발생할 것입니다.49 따라서 CME 활동을 수행하는 HCP 사이에 여러 세대의 다양한 교육적 학습 전략이 존재할 것입니다.50 이러한 학습 시대가 개인이 선호하는 학습 과정에 미치는 영향을 인정하지 않으면 CME의 효과와 잠재적 영향에 제한이 있을 수 있습니다.

Finally, Bronfenbrenner's conceptualization of time is represented by the encapsulating chronosystem in which processes and systems of learning reside. This acknowledges that an individual's learning is shaped by changes arising in the historical era through which they live and develop,43 and requires researchers to be cognizant of similar changes in medical education over the past decades.47 These changes will occur more frequently as technology continues to impact health care education48 and practice.49 Thus, several generations of various pedagogical learning strategies will be present among HCPs undertaking any CME activity.50 Failure to acknowledge the impact of these learning eras on the individual's preferred learning process may limit the effectiveness and potential impact of CME.

결론

CONCLUSION

저자들은 PH CME에서 맥락적 요인의 역할에 대한 이해를 발전시키기 위해 이 새로운 통합 이론적 틀을 발전시켰습니다. 이 프레임워크에 적용된 모델은 서로를 보완하며, 각 모델을 단독으로 사용할 때보다 더 명확하게 CME의 전문적 학습 현상을 탐구할 수 있는 기회를 제공합니다. 이 분석에서 나온 통합된 이론적 프레임워크는 CME 연구에 사용할 수 있는 구조화된 이론 기반 접근법을 제공합니다. 이 통합 이론적 프레임워크는 문헌51을 종합하여 "가장 적합한" 프레임워크를 위한 선험적 프레임워크를 형성하여 PH CME에서 역할을 하는 맥락적 요인의 개념적 틀을 개발할 것입니다. 입증된 근거를 가진 이론을 바탕으로 만들어진 이 통합된 이론적 프레임워크의 발전은 향후 개념적 프레임워크를 사용한 연구 결과의 신뢰성을 향상시킬 뿐만 아니라 의학교육 연구 분야의 학문을 발전시킬 것입니다.

The authors have advanced this novel unified theoretical framework to evolve understanding into the role of contextual factors in PH CME. The models applied in this framework complement each other and provide opportunity to explore the phenomenon of professional learning in CME with greater clarity than either model on its own. The unified theoretical framework that has emerged from this analysis offers a structured, theory based approach for use in CME research. This unified theoretical framework will form the a priori framework for a “best fit” framework synthesis of the literature51 to develop a conceptual framework of contextual factors that play a role in PH CME. The evolution of this unified theoretical framework created from theories with a proven evidence base not only enhances the reliability of findings using the future conceptual framework but also progresses scholarship within medical education research.

A Unified Theoretical Framework of Learning Theories to Inform and Guide Public Health Continuing Medical Education Research and Practice

PMID: 34057910

PMCID: PMC8168933

DOI: 10.1097/CEH.0000000000000339

Free PMC article

Abstract

Continuing medical education (CME) emerged at the start of the 20th century as a means of maintaining clinical competence among health care practitioners. However, evidence indicates that CME is often poorly developed and inappropriately used. Consequently, there has been increasing interest in the literature in evaluating wider contexts at play in CME development and delivery. In this article, the authors present a unified theoretical framework, grounded in learning theories, to explore the role of contextual factors in public health CME for health care practitioners. Discussion with pedagogical experts together with a narrative review of learning theories within medical and social science literature informed the framework's development. The need to consider sociocultural theories of learning within medical education restricted suitable theories to those that recognized contexts beyond the individual learner; adopted a systems approach to evaluate interactions between contexts and learner; and considered learning as more than mere acquisition of knowledge. Through a process of rigorous critical analysis, two theoretical models emerged as contextually appropriate: Biggs principle of constructive alignment and Bronfenbrenner bioecological model of human development. Biggs principle offers theoretical clarity surrounding interactive factors that encourage lifelong learning, whereas the Bronfenbrenner model expands on these factor's roles across multiple system levels. The authors explore how unification into a single framework complements each model while elaborating on its fundamental and practical applications. The unified theoretical framework presented in this article addresses the limitations of isolated frameworks and allows for the exploration of the applicability of wider learning theories in CME research.

Copyright © 2021 The Author(s). Published by Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. on behalf of The Alliance for Continuing Education in the Health Professions, the Association for Hospital Medical Education, and the Society for Academic Continuing Medical Education.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 교수개발(Faculty Development)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 공식화된, 평생 의사 커리어 개발의 중요성: 패러다임 변화를 위한 주장(Acad Med, 2021) (1) | 2023.12.18 |

|---|---|

| CPD의 개념적 프레임워크의 다섯 도메인 (J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2023) (0) | 2023.12.18 |

| 의학교육자를 위한 교수개발의 실재주의 평가: 무엇이 누구를 위하여 왜 효과가 있는가 (Med Teach, 2017) (0) | 2023.12.18 |

| 교수개발: 루비에서 오크까지 (Med Teach, 2020) (0) | 2023.12.18 |

| 교수자 개발을 위한 적시교육 인포그래픽 앱 (J Grad Med Educ. 2022) (0) | 2023.12.17 |