교수 리더십 개발: 시너지적 접근의 사례 연구(Med Teach, 2021)

Faculty leadership development: A case study of a synergistic approach

Ellen Goldman , Nisha Manikoth, Katherine Fox, Rosalyn Jurjus and Raymond Lucas

서론

Introduction

조직이 환경의 변화 속도가 증가하고 무수한 과제에 직면함에 따라 리더십 훈련과 개발이 매우 중요합니다(Yukl 및 Gardner 2020). 이는 특히 교육 및 의료 서비스 제공 개선 및 조직 성과 향상을 위한 이니셔티브를 교직원이 주도할 수 있는 수많은 기회가 있는 Academic Health Center(AHC)에 해당됩니다. 그러나 필요한 리더십 역량을 개발하기 위한 교육을 받은 교직원은 거의 없습니다. 리더십 개발 프로그램(LDP)을 제공하는 AHC가 증가하고 있지만, 평가 방법은 특히 프로그램 설계와 결과를 연결하는 데 있어 엄격하지 않습니다. 교직원의 개발 자원을 효율적으로 활용해야 한다는 압박감이 높아짐에 따라 교직원의 리더십 개발을 극대화하는 프로그램을 설계하는 방법에 대한 더 많은 지식이 필요합니다.

Leadership training and development is critical as organizations face increasing rates of change and a myriad of challenges in their environments (Yukl and Gardner 2020). This is especially true for academic health centers (AHCs), where faculty members have numerous opportunities to lead initiatives to improve education and care delivery, and to enhance organizational performance. However, few faculty members have had training to develop the requisite leadership competencies. While an increasing number of AHCs are offering leadership development programs (LDPs), evaluation methods lack rigor, particularly in linking program design to outcomes (Steinert et al. 2012; Leslie et al. 2013; Straus et al. 2013; Frich et al. 2015; Lucas et al. 2018; Simas et al. 2019). With increasing pressure to use faculty development resources effectively, we need further knowledge about how to design programs that will maximize faculty leadership development.

리더십 개발에 전념하는 자원에도 불구하고 후원 기관들은 프로그램 효과에 대해 계속 의문을 제기하고 있으며(Lacerenza et al. 2017), 관련 연구는 관찰 가능한 결과를 식별하고 다른 환경 세력으로부터 프로그램 효과를 분리하는 것이 어렵기 때문에 어려운 과제이다(Day and Thornton, Yukl and Gardner 2020). 확인된 공식 프로그램의 메타 분석에서는 요구 분석, 대면 현장 세션, 간격 전달, 다중 전달 방법의 사용, 연습 및 피드백이 프로그램 효율성의 중요한 요소로 파악되었습니다(Lacerenza et al. 2017). 이러한 원칙은 지도 학자들의 권고에 부합하며 의학 교육 문헌에서도 공명을 발견한다. 그러나 프로그램 설계를 안내하려면 학습 방법에 대한 자세한 내용이 필요합니다. 어떤 방법이 가장 효과적입니까? 각 방법은 어떻게 리더십을 기르나요?

Despite the resources devoted to leadership development, sponsoring organizations continue to question program effectiveness (Lacerenza et al. 2017) and related research is challenging because identifying observable outcomes and isolating program effects from other environmental forces is difficult (Day and Thornton 2018; Yukl and Gardner 2020). A meta-analysis of formal programs identified needs analysis, face-to-face on-site sessions, spaced delivery, use of multiple delivery methods, practice, and feedback as critical factors for program effectiveness (Lacerenza et al. 2017). These principles are consistent with recommendations from leadership scholars (DeRue and Myers 2014; Day and Thornton 2018; Yukl and Gardner 2020) and also find resonance in the medical education literature (Frich et al. 2015; Lucas et al. 2018; Simas et al. 2019). Yet more specifics regarding learning methods are needed to guide program design: What methods are most effective? How does each method develop leadership?

Allen과 Hartman(2008)이 제안한 학습 방법을 사용한 Conger(1992)의 프로그래밍 접근방식을 활용하여 앞서 언급한 프로그램 효과 원칙(Lacerenza 등 2017)을 포함하도록 설계된 프로그램의 사례 연구를 통해 이러한 질문을 탐색하려고 했다.

We sought to explore these questions through a case study of a program designed to include the aforementioned principles for program effectiveness (Lacerenza et al. 2017), utilizing Conger’s (1992) programming approaches with learning methods suggested by Allen and Hartman (2008).

Conger(1992)의 선구적 리더십 개발 프레임워크는 리더십에 대한 변혁적 접근법(Northouse 2019)을 기반으로 만들어졌으며, 리더십 이론에 대한 경험적 학습의 원칙을 연결하였다. Conger(1992)는 필요한 기술과 능력을 습득할 수 있다고 보고 리더십 개발 프로그래밍에 필요한 4가지 접근법(개념 이해, 스킬 육성, 피드백, 개인 성장)을 확인하였습니다. 앨런과 하트만(2008)은 콩거(1992)의 네 가지 접근법에 매핑된 27가지 학습 방법의 분류법을 만들었다. 이 분류법은 리더십 개발의 필수요소(즉 경험, 지원 네트워크 및 피드백이 리더십 역량을 개발하는 데 중요하다는 것)를 경험적 학습에 관한 문헌에 통합한다(Merriam et al. 2007).

Conger’s (1992) pioneering leadership development framework built on work underpinning the transformational approach to leadership (Northouse 2019) and connected principles of experiential learning to leadership theory. Seeing the requisite skills and abilities as learnable, Conger (1992) identified four required approaches to leadership development programming: conceptual understanding, skill building, feedback, and personal growth. Allen and Hartman (2008) created a taxonomy of 27 learning methods mapped to Conger’s (1992) four approaches. This taxonomy unites the essence of leadership development—i.e. that experience, supportive networks, and feedback are critical for developing leadership competencies (Yukl and Gardner 2020)—to the literature on experiential learning (Merriam et al. 2007).

[경험]은 (경험에서 의미가 만들어지는) [구성주의적 학습 지향]의 핵심이고, 인지적 지향의 핵심으로서, 여기서 [학습 능력capacity to learn]은 지각, 통찰력 및 의미 창출을 통해 개발된다 (Merriam et al. 2007). 구성주의 및 인지적 성향에 기초한 Kolb의 (2015) 경험적 학습이론에서, [학습]은 [경험, 성찰, 사고 및 행동의 지속적인 발전 과정]이다. 앨런과 하트먼(2008) 분류법의 학습 방법을 결합하면 콜브(2015) 학습 주기의 4단계 모두에서 학습할 수 있는 기회를 제공한다. 이와 같은 [학습 방법과 발달 접근법의 조합]은 [인지적, 경험적 및 사회적 과정을 포함하는 전인적holistic 리더십 개발 경험]을 위한 시너지를 제공합니다.

Experience is

- core to a constructivist orientation to learning, where meaning is made from experience, and

- core to a cognitive orientation, where the capacity to learn is developed through perception, insight, and meaning-making (Merriam et al. 2007).

Drawing on Kolb’s (2015) Experiential Learning Theory, based on both constructivist and cognitive orientations, learning is a continuous developmental process of experience, reflection, thinking, and acting. Combining learning methods from Allen and Hartman’s (2008) taxonomy provides opportunity to learn from all four stages of Kolb’s (2015) learning cycle. The combination of learning methods and development approaches provides the synergy for a holistic leadership development experience that includes cognitive, experiential, and social processes.

AHC의 리더십 개발에 관한 문헌은 만족도와 학습 수준을 넘어서는 경우가 거의 없으며(Lucas 등 2018; Simas 등 2019), 평가 설계 프레임워크가 부족하고 대부분 자체 보고 데이터에 의존한다는 점에 주목하면서 보다 엄격한 평가가 시급하다는 점을 식별한다(Leslie 등 2013). 다중 데이터 소스(Steinert 등 2012) 또는 종적 데이터(Frich 등 2015)를 사용하는 프로그램 평가는 거의 없다. 또한 '리더십 훈련의 어떤 측면이 가장 효과적이고 참가자들에게 가장 유용한 과정'을 학습하기 위해 질적 방법을 사용할 필요성에 대한 공감대가 형성되어 있다. 또, LDP의 설계와 성과를 관련짓는 문헌에는 gap이 있다. 단일 전략(예: 성찰, 멘토링)의 효과는 연구되었지만, 많은 방법을 설계에 체계적으로 통합하는 프로그램의 효과는 평가되지 않았다. 따라서 특정 학습 방법이 프로그램 효율성에 어떻게 기여하는지를 확인하기 위해 LDP에 대한 엄격한 평가가 필요하다.

The literature on leadership development in AHCs identifies an urgent need for more rigorous evaluations, noting that most rarely go beyond levels of satisfaction and learning (Lucas et al. 2018; Simas et al. 2019), lacking a framework for evaluation design and relying mostly on self-reported data (Leslie et al. 2013). Few program evaluations use multiple sources of data (Steinert et al. 2012) or longitudinal data (Frich et al. 2015). There is also consensus on the need for using qualitative methods (Leslie et al. 2013; Straus et al. 2013; Frich et al. 2015) to ‘learn what aspects of leadership training are most effective and what processes are most useful to participants’ (Straus et al. 2013, p. 714). Further, there is a gap in the literature linking design of LDPs to outcomes. The effectiveness of singular strategies (e.g. reflection, mentoring) has been researched, but the effectiveness of a program that systematically integrates many methods into its design has not been evaluated. Thus, there is a need for rigorous evaluations of faculty LDPs to identify how specific learning methods contribute to program effectiveness.

본 연구는 프로그램 결과에 대한 [특정 학습 방법의 효과를 평가]함으로써 문헌의 격차를 해소한다. 한 가지 조사 질문이 연구의 방향을 제시했습니다.

- Conger(1992)의 리더십 개발에 대한 4가지 접근법 및 관련 학습방법(Allen 및 Hartman 2008)은 참가자, 감독자 및 멘토에 의해 보고된 바와 같이 리더십 역량 향상에 어떻게 기여하는가? 다양한 학습 접근법에 맞는 특정 학습 방법이 리더십 역량 향상에 어떻게 기여하는지 연구했다.

This study addresses a gap in the literature by evaluating the effectiveness of specific learning methods for program outcomes. One research question guided our study:

- How do Conger’s (1992) four approaches to leadership development and the associated learning methods (Allen and Hartman 2008) contribute to improving leadership competencies as reported by participants, supervisors and mentors? We studied how specific learning methods catering to different learning approaches contributed to improving leadership competencies.

방법들

Methods

사례 연구 설계는 [경계지어진 현상]으로서 LDP의 '집약적이고 전체적인 설명과 분석'(Merriam and Tisdell 2016, 페이지 232)을 제공한다. 사례 연구를 통해 다양한 연구 방법과 여러 데이터 소스를 통해 분석 단위로서 프로그램에 심도 있는 집중을 통해 구축 타당성을 보장할 수 있습니다(2014년 Yin). 사례연구의 구조적 요소는 앞서 언급한 LDP 평가의 엄격성에 대한 요구에 대처한다.

A case study research design provides an ‘intensive, holistic description and analysis’ (Merriam and Tisdell 2016, p. 232) of the LDP as a bounded phenomenon. Case study allows for in-depth focus on the program as a unit of analysis through mixed research methods and multiple data sources to ensure construct validity (Yin 2014). The structural elements of a case study address the aforementioned calls for rigor in LDP evaluation.

프로그램 설명

Program description

George Washington University Medicine and Health Sciences는 리더십 능력 모델을 사용하여 실시한 니즈 평가에 따라 중간 수준의 교직원을 위한 리더십 개발 프로그램인 Fundamentals of Leadership을 설계했습니다(Lucas et al. 2018). 이 프로그램에는 4가지 학습 목표가 있었습니다. 개인 효과, 대인 효과, 팀 성과 및 변경 관리 향상입니다. 참가자들은 학과장의 서포트에 따라 자기 지명을 하고, 실제 프로젝트에 임할 것을 약속했다. 지원자들은 모두 합격했다.

The George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences designed a leadership development program, Fundamentals of Leadership, for mid-level faculty following a needs assessment conducted using a leadership competency model (Lucas et al. 2018). The program had four learning objectives: to enhance personal effectiveness, interpersonal effectiveness, team performance, and change management. Participants self-nominated with chair support and committed to work on a real-life project. All who applied were accepted.

[교실 내 세션]은 8개월 동안 매달 4시간씩 총 32시간 동안 진행되었습니다. 학습 방법은 프로그램 목표와 앨런과 하트먼(2008) 분류법에 기초했다(표 1의 첫 번째 두 열 참조). 비즈니스, 리더십 및 조직 변화에 대한 고급 교육을 받은 교직원은 변경 리더십, 시간 관리, 협상, 팀 구성, 감성 인텔리전스 및 조직 문화에 대한 세션을 촉진했습니다. 참가자들은 실제 [프로젝트 실행을 위한 계획]을 수립하고 세션 내용을 반영하기 위해 매달 업데이트했습니다. 프로젝트 진행 상황은 동료 보고 중에 코호트 구성원과 공유되었다. 각 참가자는 상호 합의에 의해 선택된 [상급 경영자executive 멘토]와 세션과 세션 사이에 만났습니다. [멘토링 툴킷]은 멘토와 멘티의 혜택과 책임, 생산적인 미팅을 위한 팁, 멘토링 계약을 위한 템플릿 등 제공되었습니다.

In-classroom sessions occurred 4 h per month for 8 months, for a total of 32 h. Learning methods were based on program objectives and Allen and Hartman’s (2008) taxonomy (see first two columns of Table 1). Faculty with advanced training in business, leadership, and organizational change facilitated sessions on change leadership, time management, negotiation, team building, emotional intelligence, and organizational culture. Participants developed an action plan for their real-life projects and updated them monthly to reflect session content. Project progress was shared with cohort members during peer debriefs. Each participant met between sessions with a senior executive mentor selected by mutual agreement. A mentoring toolkit was provided, including benefits and responsibilities of mentor and mentee, tips for productive meetings and a template for a mentoring agreement.

리서치 어프로치

Research approach

기관 심사 위원회는 그 연구를 면제한다고 간주했다. 익명의 조사 데이터는 각 세션과 프로그램의 가치에 대한 피드백을 제공했습니다. 프로그램 종료 시 프로젝트 프레젠테이션 및 멘토 설문조사를 통해 프로그램 결과에 대한 정보를 제공했습니다. 프로그램 완료 후 3개월 후 참가자 및 작업 감독관과의 개별 인터뷰를 통해 장기적인 영향에 대한 정보를 얻을 수 있었습니다.

The institutional review board deemed the study exempt. Anonymous survey data provided feedback on the value of each session and the program. Project presentations and mentor surveys at program conclusion provided inputs on program results. Separate interviews with participants and their work supervisors, 3 months after program completion, provided information on longer-term impacts.

데이터 수집 및 분석은 프로그램 설계 또는 제공에 관여하지 않은 작성자(NM, KF, RJ)에 의해 완료되었습니다. 복수의 근거 소스(예: 인터뷰, 세션 및 프로그램 평가, 조사)와 수렴하는 조사 라인(예: 참가자, 감독자, 멘토)이 결과를 삼각측량하여 'rigor, 폭, 복잡성, 풍부성 및 깊이'를 추가했다. 데이터 분석은 테마를 식별하기 위해 개방형 코딩과 지속적인 비교 방법(Merriam과 Tisdell 2016)을 사용했으며, 콩거 프레임워크와 앨런과 하트만 분류법(2008)의 이론적 코드를 사용한 두 번째 코딩 주기(2014년 Yin 2014)를 사용했다. 코딩과 주제에 대한 합의는 토론을 통해 이루어졌다.

Data collection and analysis were completed by authors not involved in the program design or delivery (NM, KF, RJ). Multiple sources of evidence (i.e. interviews, session and program evaluations, surveys) and converging lines of inquiry (i.e. participants, supervisors, mentors) triangulated the results, adding ‘rigor, breadth, complexity, richness and depth’ (Denzin and Lincoln 2013, p. 10). Data analysis utilized open coding and constant comparative methods to identify themes (Merriam and Tisdell 2016), followed by a second coding cycle (Yin 2014) with theoretical codes from the Conger (1992) framework and the Allen and Hartman (2008) taxonomy. Consensus on coding and themes was reached through discussions.

결과.

Results

조사 참가자는 프로그램을 완료한 최초 두 개 코호트 멤버 21명, 참가자의 작업 감독자 15명 중 11명, 시니어 이그제큐티브 멘토 12명(15명 중 12명)을 포함했다. 코호트 구성원은 피부과, 응급의학, 일반 및 전문 소아과, 내과, 실험실 과학, 신경외과, 신경외과, 병리학, 약리학, 의사 보조, 정신과, 종양학 및 외과 조교, 새로운 프로그램, 클리닉, 센터 및 외과와 관련된 프로젝트를 포함했다. 시스템 개선. 모든 프로젝트에는 복수의 부서가 관여하고 있으며, 커뮤니티 파트너도 있었습니다.

Study participants included all 21 members of the first 2 cohorts who completed the program, 11 (of 15) participants’ work supervisors, and 12 (of 15) of the senior executive mentors. Cohort members included assistant and associate professors in departments of dermatology, emergency medicine, general and specialty pediatrics, internal medicine, laboratory science, neurology, neurosurgery, pathology, pharmacology, physician assistant, psychiatry, oncology, and surgery, with projects concerning new programs, clinics, centers, and system improvements. All projects involved multiple departments; some had community partners.

표 1의 세 번째 열은 리더십 개발에 대한 네 가지 접근법 각각(Conger 1992)과 관련 학습 방법이 리더십 역량 향상에 어떻게 기여했는지 요약한다. 자세한 내용은 아래 설명과 함께 Kirkpatrick 및 Kirkpatrick의 (2016) 평가 수준을 사용하여 프로그램 전반에 대해 논의합니다. 만족, 학습, 행동 및 결과. 인용구 출처는 코호트('C') 1 또는 2의 프로그램 참가자('P'), 감독자('S') 또는 멘토('M')입니다.

The third column of Table 1 summarizes how each of the four approaches to leadership development (Conger 1992) and associated learning methods (Allen and Hartman 2008) contributed to improving leadership competencies. Further description is provided below, followed by a discussion of the program overall using Kirkpatrick and Kirkpatrick’s (2016) evaluation levels: satisfaction, learning, behavior and results. Quote sources are program participants (‘P’), supervisors (‘S’), or mentors (‘M’) from cohort (‘C’) 1 or 2.

개념적 이해

Conceptual understanding

리더십 개발에 대한 이러한 접근방식은 리더십 개념에 대한 [인지적 이해]를 구축한다(Conger 1992). 참가자들은 수업 전 독서, 과제 및 강의실 세션에서 다음과 같은 주제를 인용하여 새로운 개념을 제시했습니다.

This approach to leadership development builds cognitive understanding of leadership concepts (Conger 1992). The participants cited the following topics from the pre-class readings, assignments and classroom sessions that offered them new concepts:

[세션]을 통해 리더쉽 스킬에 대해 생각해 볼 수 있는 훌륭한 구성을 얻을 수 있었습니다. 회의 리드하기, 프로젝트 아이디어의 개발, 팀의 동기 부여 등입니다. (P9C1)

[The session] gave me nice constructs to think about my leadership skills … leading a meeting, developing project ideas, motivating my team. (P9C1)

정말로 공명하고 있는 것은, 시간 관리의 그리드입니다.(P3C2 )

What really resonated with me is the grid of (how to achieve) time management. (P3C2)

감성 인텔리전스 세션은 사람들이 어디에서 오는지를 듣고 이해하는 데 매우 적극적인 역할을 할 수 있게 해주었습니다. (P6C1)

The emotional intelligence session allowed me to take a very active role in listening and understanding where people are coming from. (P6C1)

문화에 대해 배우는 것은 매우 중요했습니다.그것을 바꾸는 것은 얼마나 어려운 일입니까.필요한 일을 해야 합니다.(P4C2)

It was really important to learn about culture … how difficult it is to change that …what you might need to do. (P4C2)

다른 이들은 참여 강화(P3C1, P5C1), 의사결정 개선(P6C1), 적절한 위임(P3C2, P7C1) 및 좋은 평가를 받는 피드백(P6C2, P7C1)을 위한 리더십 스타일과 팀 개발 원칙을 이해하는 것의 가치에 주목했다. 한계(표 1 열 4 참조)에는 읽기 자료의 과밀함denseness에 대한 불만과 더 많은 사례 사례에 대한 욕구가 포함되었다.

Others noted the value of understanding leadership styles and team development principles to enhance engagement (P3C1, P5C1), improve decision-making (P6C1), delegate appropriately (P3C2, P7C1), and provide well-received feedback (P6C2, P7C1). Limitations (see Table 1 column 4) included complaints about the denseness of the reading material and desire for more case examples.

스킬 육성

Skill building

리더십 개발에 대한 이러한 접근방식은 실천을 제공한다(Conger 1992). 참가자들은 [강의실 내 역할극과 프로젝트 실행 ]계획 제정이 새로운 스킬을 구축하는 데 도움이 된다고 확인했습니다. 한 사람이 지적했듯이, '클래스는 단순히 '개념이 여기에 있다'는 것이 아니었다. 읽어보세요」라고 끝나지 않았고, 「이 문제에 대처하는 방법의 예는 무엇입니까」…실제 롤플레잉(P3C1)을 했다.

This approach to leadership development provides practice (Conger 1992). The participants identified in-class role plays and enactment of project action plans as helping them build new skills. As one noted: ‘Class was not just “here’s the concept. Go read about it,” but … “what’s an example of how you would deal with this?’ … actual role-playing’ (P3C1).

[프로젝트 실행 계획]은 스킬을 쌓기 위해 가장 자주 인용되는 도구였습니다.

The project action plan was the tool most often cited for building skills:

드릴다운, 목적 설명 작성, 측정 기준 작성, 목표가 부서와 일치하는지 확인하는 것이 중요했습니다.(P3C2)

It was important to drill down … create a purpose statement … metrics … recognize if your goals were in line with your department. (P3C2)

[이 계획]은 매우 집중적이고 구체적이어서 도움이 됩니다.언제 대처해야 할 것을 특정합니다.우선순위의 변경에 따라 손실될 가능성이 있는 것을 추적합니다.(P4C2)

[The plan] helped by being very focused and concrete … identify what to tackle when … keep track of things that might get lost as priorities change. (P4C2)

이 계획을 통해 리더로서 큰 시야를 갖게 되었습니다.중요한 목표를 향해 한 발짝 물러서는 것.현재 진행 상황을 눈으로 확인할 수 있습니다.또, 뛰어난 과제도 볼 수 있습니다. … 그것은 매우 귀중한 것이었습니다.(P1C1)

The plan helped me as a leader have that big-picture view … take a step back at its overarching goals … visually see the progress you’re making … as well as outstanding challenges. … That was incredibly valuable. (P1C1)

그 계획은 구체적인 틀을 만들었다. … 매달 그것에 대해 질문을 받는 것은 당신을 긴장하게 한다. (P5C1)

[The plan] created a tangible framework. … Being asked about it on a monthly basis keeps you on your toes. (P5C1)

매월 계획을 갱신하는 것으로, 시간 관리가 향상되었습니다. 「실제로 필요한 것에 주의를 기울이는 한편, 불필요한 것은 무시하거나, 그 시간을 재할당하거나 합니다」(P5C2) 상사들은 향상된 능력을 알아차렸다: '그의 조직력은 향상되었다. … 그는 이해관계자들을 모아 프로젝트를 완료하기 위해 필요한 것을 지지하고 사람들에게 책임을 물을 수 있었습니다(S6C2). 다른 연구진은 부하 직원의 프로젝트 리더십(S1C2, S4C1, S6C1, S9C1, S9C2)에 대한 자신감, 주장성 및 편안함을 증가시켰다.

Updating the plans monthly improved time management: ‘[I’m] paying attention to the things I actually really need to do and ignoring what I don’t … or reallocating that time’ (P5C2). Supervisors noticed enhanced abilities: ‘His organizational skills improved. … He was able to bring stakeholders together … advocate for what was needed to finish the project … hold people accountable’ (S6C2). Others observed increased confidence, assertiveness, and comfort in their subordinates’ project leadership (S1C2, S4C1, S6C1, S9C1, S9C2).

피드백

Feedback

리더십 개발에 대한 이러한 접근방식은 [비판적 평가 및 측정 도구]를 사용하여 피드백을 제공합니다(Conger 1992). 참가자가 실시한 자기 평가에서는, 「의심했던 점 뿐만이 아니라, 장점과 단점에 대한 통찰력 향상에 도움이 되지 않았던 점이 강조되었습니다」(P4C2).

This approach to leadership development provides feedback using critical assessment and measurement tools (Conger 1992). Self-assessments completed by the participants ‘highlighted the things I suspected … as well as ones I did not to help improve [my] insight into [my] strengths and weaknesses’ (P4C2).

멘토 피드백 또한 가치 있었다: '나의 멘토가 나에게 좋은 조언을 해주었다. 계속 만날 수 있는지 물어볼게요.(P2C2) 멘토는 멘티가 역할극 시나리오나 어려운 대화(M1C2, M3C2, M5C2)에 대한 '연습 실행' 역할을 하는 등, 이러한 활동이 사운드보드와 격려의 원천이 되고 있음을 확인했습니다.

Mentor feedback was also valuable: ‘My mentor gave me good advice. I’m going to ask if we could continue meeting’ (P2C2). Mentors confirmed they served as sounding boards and sources of encouragement, with several serving as ‘practice runs’ for their mentee to role-play scenarios or difficult conversations (M1C2, M3C2, M5C2).

[동료 디브리핑] 중에 코호트 구성원으로부터도 귀중한 피드백을 받았다.

Valuable feedback also came from cohort members during peer debriefs:

우리는 모두 두려움, 문제, 뭐 그런 것들을 끄집어내다가 서로에게 이렇게 말하곤 했다. '나도 비슷한 일을 겪었어. 난 이렇게 해왔어. 도움이 되는지 확인해 주세요.(P7C1)

We were all bringing up our fears, problems, whatever … and then we would tell each other: ‘I had similar things. I’ve done it this way. See if that helps.’ (P7C1)

칭찬하든 비판하든, 동료의 피드백은 다른 태도, 경험, 배경을 가진 개인들로부터 나왔기 때문에 특히 도움이 되었습니다. (P1C2)

Whether they praise it or criticize it, [peer feedback] was particularly helpful because it came from [individuals with] different attitudes, different experiences, different backgrounds. (P1C2)

동료와 멘토들의 격려로 프로젝트 리더쉽 이상의 자신감을 얻었습니다.다른 사람의 견해와 피드백을 얻음으로써 자신감을 얻을 수 있었습니다.(P1C1).

Encouragement from peers and mentors provided confidence beyond project leadership: ‘Having other people’s perspective and feedback … gave me more confidence’ (P1C1).

개인의 성장

Personal growth

리더십 개발에 대한 이러한 접근방식은 행동, 가치 및 욕구의 반영을 유도한다(Conger 1992). 참가자들은 수업 시간을 프로젝트 계획을 갱신하고 위에서 논의한 피드백을 받는 것이 개인 및 그룹의 성찰을 촉진하는 것이라고 생각했습니다.'수업에 도움이 된 것은 성찰 시간……프로젝트나 목적지에 대해서만 생각하는 30분 이었다'(P5C2). 그룹 성찰에 참여하는 것은 또 다른 가치를 제공했습니다. '다른 사람이 자신의 문제를 해결할 수 있도록 도와주면서 자신의 프로젝트에 가져올 수 있는 리더십의 자질을 명확히 했습니다.' (P3C2) P6C1은 이 시간의 중요성을 '한 달 동안 당신이 어떻게 진화했는지 볼 수 있도록 하고, 내가 어떻게 발전하고 있는지 생각해 보고, 내가 앞으로 개선할 수 있는 것은 무엇인가'로 요약했습니다.

This approach to leadership development induces reflection of behaviors, values and desires (Conger 1992). Participants identified class time updating project plans and getting the feedback discussed above as promoting personal and group reflection: ‘The thing that helped me were the class reflects … 30 minutes just to think about my project and where I wanted it to go’ (P5C2). Participating in group reflection provided another value: ‘In helping others work through their problems, it clarified … leadership qualities that I could bring to my own project’ (P3C2). P6C1 summarized the significance of the time as ‘allowing you to look at how you evolved over the month … think about how I am improving … what I can improve moving forward.’

전체적인 평가

Overall evaluation

만족도(1단계), 학습(2단계), 행동(3단계), 결과(4단계)를 평가했다(Kirkpatrick 2016).

- 참가자들은 내용, 자료, 진행자 및 학습 환경에 대한 만족도가 높다고 보고했다(1 = 강하게 동의하지 않음 ~ 4 = 강하게 동의함).

- 학습 내용은 표 1에 기재되어 있습니다. 초월 세션 콘텐츠 학습: 「[프로그램]은, 사물을 보다 선명하게 볼 수 있도록 했습니다…… 내가 무엇을 완수하는지, 어떻게 정리하는지…… 스스로 페이스 업 하는 것에 대해, 훨씬 더 신중해졌습니다」(P9C1)

- 리더쉽 행동에 대한 자기 인식적인 변화가 설명되었습니다. '내 직감을 따르기 전에' … 이제 "좋습니다. 여기서 어떤 접근 방식이 작동할까요?"(P3C1)가 되었습니다. P7C1은 병원 경영진과 전략적인 월례 회의를 시작했고 P6C1은 운영을 개선하기 위해 간호 리더십에 접근했습니다.

- 결과는 주목할 만하다. 거의 모든 참가자가 프로젝트의 주요 컴포넌트를 구현했습니다. 새로운 임상 센터, 학위 프로그램, 연구 시험, 지역사회 관계 확대. 슈퍼바이저는, 많은 참가자가, 부서내 또는 전문 조직내의 리더로서의 역할과 책임을 한층 더 가지고 있는 것에 주목했습니다.

Satisfaction (level 1), learning (level 2), behavior (level 3), and results (level 4) were evaluated (Kirkpatrick and Kirkpatrick 2016).

Participants reported high satisfaction with the content, materials, facilitators, and learning environment (3.14–3.87 on an agreement scale of 1 = Strongly Disagree to 4 = Strongly Agree.

Learning is noted in Table 1. Learning transcended session content: ‘[The program] made me see things a lot crisper … be much more intentional about what I take on, how I organize … pace myself’ (P9C1).

Self-perceived changes to leadership behaviors were described: ‘Before I would go with my gut. … Now it’s “all right, what approach is going to work here?”’ (P3C1). P7C1 started strategic monthly meetings with a hospital executive, and P6C1 approached nursing leadership to improve operations.

Results are notable. Nearly all participants implemented major components of their projects: new clinical centers, degree programs, research trials, expanded community relationships. Supervisors noted many participants had additional leadership roles and responsibilities—either within their departments or with professional organizations.

논의

Discussion

이 연구는 중간 수준의 AHC 교직원을 위한 리더십 개발 프로그램에 평가 엄격성을 적용하고 네 가지 리더십 개발 접근법과 관련된 학습 방법의 이점을 미묘한 이해도를 얻었다(Conger 1992).

- 개념적 이해 접근방식은 참가자가 새로운 리더십 개념을 인식하는 데 도움이 되었습니다.

- 스킬 육성 접근방식은 참가자가 새로운 스킬을 연습하는 데 도움이 되었습니다.

- 피드백 접근방식은 강점과 개발 영역에 대한 인식을 높였습니다.

- 또한 개인 성장 접근방식은 성찰과 전체적으로 성장하기 위한 자극을 촉진했습니다.

중요한 것은 이러한 접근방식의 조합으로 새로운 프로그램, 클리닉, 센터 및 시스템 개선의 형태로 조직 수준(Kirkpatrick 및 Kirkpatrick 2016)에서 이점을 볼 수 있게 되었다는 점입니다.

This study applied evaluation rigor to a leadership development program for mid-level AHC faculty members and obtained a nuanced understanding of the benefits of learning methods associated with four leadership development approaches (Conger 1992).

- The conceptual understanding approach helped participants become aware of new leadership concepts;

- the skill-building approach helped them practice new skills;

- the feedback approach generated greater awareness about strengths and areas for development; and

- the personal growth approach fostered reflection and the impetus to grow holistically as leaders.

Importantly, the combination of these approaches made it possible to see benefits at the organizational level (Kirkpatrick and Kirkpatrick 2016) in the form of new programs, clinics, centers and system improvements.

다양한 방법들이 체험 학습 주기를 육성하였다(Kolb 2015).

- 독서 및 강의실 모듈은 학습자를 추상 개념화 과정을 거치게 했다.

- 역할극 및 사례연구는 구체적인 경험을 제공한다.

- 동료 및 멘토로부터 받은 자기 평가와 피드백이 성찰 관찰에 기여한다.

- 프로젝트 실행 계획은 활발한 실험을 위한 추진력을 제공했습니다.

The various methods fostered the experiential learning cycle (Kolb 2015):

- readings and classroom modules took learners through abstract conceptualization;

- role plays and case studies offered concrete experience;

- self-assessments and feedback from peers and mentors contributed to reflective observation; and

- project action plans provided the impetus for active experimentation.

이러한 학습 방법의 통합은 학습자가 '행위자마다, 그리고 특정 참여에서 일반 분석 분리까지 다양한 정도'를 취하여(Kolb 2015, 페이지 42), 인지적, 경험적, 사회적 과정을 통해 학습 기회를 제공했다.

The integration of these learning methods took the learners ‘in varying degrees from actor to observer, and from specific involvement to general analytic detachment’ (Kolb 2015, p. 42), providing learning opportunities through cognitive, experiential, and social processes.

이 리더십 개발 프로그램의 진정한 가치는 실제 프로젝트에 초점을 맞추기 위해 다양한 학습 방법이 연결되고 서로 연계된 방식입니다.

- 구조화된 강의실 토론은 참가자들이 자신의 프로젝트에 개념을 적용하도록 장려합니다.

- 프로젝트 액션 플랜은 작업을 계속하고 과제를 극복할 수 있는 도구를 제공했습니다.

- 멘토 피드백은 참가자의 프로젝트 성공을 지원하는 데 초점을 두었다.

- 동료 디브리핑는 장애물을 극복하고 새로운 솔루션을 찾기 위한 지원 그룹을 개발했습니다.

- 개인 및 그룹의 성찰은 개념을 명확히 하고 이를 프로젝트에 적용하는 방법에 도움이 되었습니다.

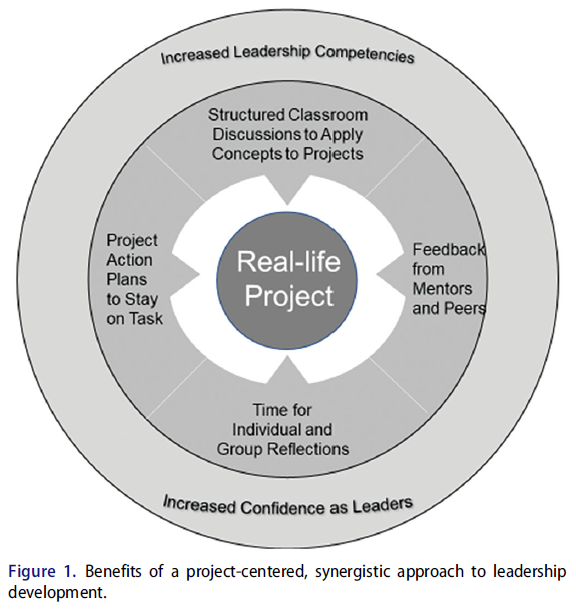

The true value of this leadership development program is in the way different learning methods were connected and interwoven to focus on a real-life project:

- structured classroom discussions encouraged participants to apply concepts to their projects;

- project action plans provided a tool to stay on task and overcome challenges;

- mentor feedback focused on helping participants succeed in their projects;

- peer debriefs developed a support group to overcome obstacles and find new solutions;

- individual and group reflections helped clarify concepts and how to apply them to the project.

프로젝트의 중심성은 개인적이고 경험적인 방식으로 리더십 개념의 의미를 만드는 것을 촉진했습니다. 다양한 리더십 육성 어프로치와 학습 방법의 통합에 의해 달성된 시너지는 리더십 역량 개발에 기여했을 뿐만 아니라 참가자, 감독자, 멘토 입장에서 리더로서의 자신감을 형성했다(그림 1).

The centrality of the project facilitated meaning-making of leadership concepts in a personal, experiential way. The synergy achieved through the integration of different leadership development approaches and learning methods not only contributed to leadership competency development but also built participants’ confidence as leaders from the participants’, supervisors’ and mentors’ perspectives (Figure 1).

제한 사항

Limitations

다른 케이스 스터디와 마찬가지로 이러한 결과는 특정 설정에서 제공되는1개의 LDP를 반영합니다. 또한, 이 결과는 우리 프로그램에서 사용된 특정 학습 방법을 반영합니다. 다른 방법은 다른 결과를 제공할 수 있습니다. 마지막으로 프로그램의 장기적인 영향에 대해 알아보는 것이 도움이 될 것입니다.

As with any case study, these results reflect one LDP offered in a specific setting. In addition, the results reflect the specific learning methods used in our program; other methods might provide different results. Finally, it would be helpful to study the program’s long-term impact.

결론

Conclusion

우리의 연구는 자민당에 대한 엄격한 평가의 예를 제공함으로써 문헌을 추가한다. 특정 학습 방법이 리더십 개발에 어떻게 기여했는지를 파악하여 Conger의 리더십 개발 프레임워크, Allen과 Hartman의 학습 방법 분류법 및 경험적 학습 문헌을 더욱 연결한다. 또한 실제 프로젝트를 중심으로 학습 앵커링의 시너지 효과를 설명하고 개인과 조직에 긍정적이고 의미 있는 결과를 보여줍니다.

Our study adds to the literature by providing an example of rigorous evaluation of an LDP. It identifies how specific learning methods contributed to leadership development, further connecting Conger’s (1992) leadership development framework, Allen and Hartman’s (2008) taxonomy of learning methods, and the experiential learning literature. Moreover, we illustrate the synergistic effect of anchoring learning around a real-life project, and show positive and meaningful outcomes for individuals as well as the organization.

Med Teach. 2021 Aug;43(8):889-893.

doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2021.1931079. Epub 2021 Jun 2.

Faculty leadership development: A case study of a synergistic approach

PMID: 34078213

Abstract

Introduction: Ongoing leadership development is essential for academic health center faculty members to respond to increasing environmental complexity. At the George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences, an 8-month program, based on Conger's leadership development approach emphasizing conceptual understanding, skill building, feedback and personal growth was offered to mid-level faculty charged with developing educational programs, clinical services, and/or research initiatives. We studied how specific learning methods catering to different learning approaches contributed to improving leadership competencies.

Methods: Session and program evaluations, participant interviews, mentor surveys, and supervisor interviews were used for data collection. Themes were identified through open coding with use of constant comparative methods to help find patterns in the data.

Results: Readings and classroom modules provided a broadened, holistic understanding of leadership; role plays and action plans helped participants apply and practice leadership skills; self-assessments and feedback from peers and mentors provided specifics for focusing development efforts; and personal growth exercises provided opportunities to reflect and consider fresh perspectives. Anchoring learning methods around a real-time project led to improved leadership competencies and personal confidence as reported by participants, supervisors and mentors.

Conclusion: A faculty leadership development program that integrates understanding, skill building, feedback and personal growth and connects multiple learning methods can provide the synergy to facilitate behavior change and organizational growth.

Keywords: Leadership development; faculty development; learning process.