행동주의, 인지주의, 구성주의: 교육설계 관점에서 중요특징 비교(Performance Improvement Quarterly, 2013)

Behaviorism, Cognitivism, Constructivism: Comparing Critical Features From an Instructional Design Perspective

Peggy A. Ertmer and Timothy J. Newby

기초학습 연구와 교육 실천 사이에 교량의 필요성이 오랫동안 논의되어 왔다. 이 두 영역 사이의 강한 연관성을 보장하기 위해 듀이(Reigeluth, 1983년 Reigeluth에 인용)는 "연결linking 과학"의 창조와 개발을 요구했다. 타일러(1978)는 "중간자 입장"을 요구했고, 린치(1945)는 이론을 실천으로 번역하는 보조 수단으로 "공학적인 비유"를 채택한 사람이다.

The need for a bridge between basic learning research and educational practice has long been discussed. To ensure a strong connection between these two areas, Dewey (cited in Reigeluth, 1983) called for the creation and development of a “linking science”; Tyler (1978) a “middleman position”; and Lynch (1945) for employing an “engineering analogy” as an aid for translating theory into practice.

교육설계자는 "학습 및 교육의 원칙을 교육자료와 활동의 specification으로 변환"하는 임무를 맡았다(Smith & Ragan, 1993, 페이지 12). 이 목표를 달성하기 위해서는 두 가지 기술과 지식이 필요하다.

Instructional designers have been charged with “translating principles of learning and instruction into specifications for instructional materials and activities” (Smith & Ragan, 1993, p. 12). To achieve this goal, two sets of skills and knowledge are needed.

첫째, 설계자는 반드시 실무자의 입장을 이해해야 한다. 이와 관련하여 다음과 같은 질문이 타당할 것이다. 애플리케이션의 상황적 및 맥락적 제약조건은 무엇인가? 학습자들 사이의 개인차이의 정도는?

First, the designer must understand the position of the practitioner. In this regard, the following questions would be relevant: What are the situational and contextual constraints of the application? What is the degree of individual differences among the learners?

설계자는 실질적인 학습 문제를 진단하고 분석할 수 있어야 한다. 의사가 적절한 진단 없이는 효과적인 치료법을 처방할 수 없듯이, 지침 설계자는 지침 문제에 대한 정확한 분석 없이는 효과적인 규범적 해결책을 적절하게 권고할 수 없다.

the designer must have the ability to diagnose and analyze practical learning problems. Just as a doctor cannot prescribe an effective remedy without a proper diagnosis, the instructional designer cannot properly recommend an effective prescriptive solution without an accurate analysis of the instructional problem.

문제를 이해하고 분석하는 것 외에, 두번째로 해결책의 잠재적 원천(즉, 인간 학습의 이론)을 이해하는 것, 즉 연구와 적용을 "bridge"하거나 "link"하기 위해 지식과 기술이 필요하다. 이러한 이해를 통해서, 적절한 규범적 해결책은 주어진 진단 문제와 일치할 수 있다. 그러므로 결정적 연결고리는 [교육 설계]와 [교육 현상에 관한 지식] 사이에 있는 것이 아니라, [교육 설계 문제]와 [인간 배움의 이론] 사이에 있다.

In addition to understanding and analyzing the problem, a second core of knowledge and skills is needed to “bridge” or “link” application with research—that of understanding the potential sources of solutions (i.e., the theories of human learning). Through this understanding, a proper prescriptive solution can be matched with a given diagnosed problem. the critical link, therefore, is not between the design of instruction and an autonomous body of knowledge about instructional phenomena, but between instructional design issues and the theories of human learning.

왜 이렇게 학습의 이론과 연구에 중점을 두는가?

Why this emphasis on learning theory and research?

첫째, 학습이론은 검증된 교육 전략, 전술, 기법의 원천이다. 주어진 지시 문제를 극복하기 위한 효과적인 처방을 선택하려고 할 때 그러한 전략의 다양한 지식은 매우 중요하다.

First, learning theories are a source of verified instructional strategies, tactics, and techniques. Knowledge of a variety of such strategies is critical when attempting to select an effective prescription for overcoming a given instructional problem.

둘째, 학습이론은 지적이고 합리적인 전략 선택을 위한 기초를 제공한다. 설계자는 적절한 전략의 레퍼토리를 제공해야 하며, 각 전략을 언제, 왜 채택해야 하는지에 대한 지식을 보유해야 한다. 이러한 지식은 학습자를 돕는 지침 전략으로 직무의 요구에 부합하는 설계자의 능력에 달려 있다.

Second, learning theories provide the foundation for intelligent and reasoned strategy selection. Designers must have an adequate repertoire of strategies available, and possess the knowledge of when and why to employ each. this knowledge depends on the designer’s ability to match the demands of the task with an instructional strategy that helps the learner.

셋째, 교육적 맥락 안에서 선택된 전략의 통합이 매우 중요하다. 학습 이론과 연구는 교육 구성 요소와 교육 설계 간의 관계에 대한 정보를 제공함으로써 특정 기술/전략이 특정 맥락 내에서 그리고 특정 학습자와 어떻게 가장 잘 결합될 수 있는지를 지시한다 (Keller, 1979).

third, integration of the selected strategy within the instructional context is of critical importance. Learning theories and research often provide information about relationships among instructional components and the design of instruction, indicating how specific techniques/strategies might best fit within a given context and with specific learners (Keller, 1979).

마지막으로, 이론의 궁극적인 역할은 신뢰할 수 있는 예측을 제공하는 것이다(Richy, 1986). 실제적인 교육 문제에 대한 효과적인 해결책은 종종 제한된 시간과 자원에 의해 제한된다. 선택되고 실행된 전략들이 성공의 가장 높은 기회를 가지는 것이 무엇보다 중요하다. 워리어스(1990년)가 제안한 바와 같이, 강력한 연구에 기초한 선택은 "교육 현상"에 근거한 것보다 훨씬 신뢰성이 있다.

Finally, the ultimate role of a theory is to allow for reliable prediction (Richey, 1986). Effective solutions to practical instructional problems are often constrained by limited time and resources. It is paramount that those strategies selected and implemented have the highest chance for success. As suggested by Warries (1990), a selection based on strong research is much more reliable than one based on “instructional phenomena.”

이 글은 학습 과정의 세 가지 뚜렷한 관점(행동주의, 인지주의, 구성주의)을 제시하며, 각각의 독특한 특징들이 많지만, 각각의 관점들이 여전히 같은 현상(학습)을 기술하고 있다는 것이 우리의 생각이다.

this article presents three distinct perspectives of the learning process (behavioral, cognitive, and constructivist) and although each has many unique features, it is our belief that each still describes the same phenomena (learning).

스넬베커(1983년)가 강조한 바와 같이, 실제 학습 문제를 다루는 개인들은 "자신을 하나의 이론적 위치로 제한하는 사치"를 누릴 수 없다. [그들은] 다음을 재촉받는다. 우선 학습과 연구에 있어서 심리학자들에 의해 개발된 각각의 기본적인 과학 이론을 검토해야 하며, 자신의 특정한 교육 상황에 가치가 있는 원칙과 개념을 선택해야 한다.

as emphasized by Snelbecker (1983), individuals addressing practical learning problems cannot afford the “luxury of restricting themselves to only one theoretical position . . . [they] are urged to examine each of the basic science theories which have been developed by psychologists in the study of learning and to select those principles and conceptions which seem to be of value for one’s particular educational situation” (p. 8).

존슨(1992년)이 보고한 바와 같이, 교육기술의 일반적인 영역에서 대학 커리큘럼에서 제공되는 강좌 중 2% 미만만이 그들의 핵심 개념 중 하나로 "이론"을 강조한다.

As reported by Johnson (1992), less than two percent of the courses offered in university curricula in the general area of educational technology emphasize “theory” as one of their key concepts.

이 논문은 현대 학습 이론에 대한 우리의 지식에 존재하는 "몇 가지 틈새를 채우려는" 시도를 하려는 것이다.

this article is an attempt to “fill in some of the gaps” that may exist in our knowledge of modern learning theories.

핵심은, 만약 우리가 학습 이론의 깊은 원리들 중 일부를 이해한다면, 우리는 필요에 따라 세부 사항들을 추론할 수 있다는 것이다. 브루너(1971년)가 말했듯이, "자연 속의 모든 것을 자연을 알기 위해 마주칠 필요는 없다"(p. 18). 학습 이론에 대한 기본적인 이해는 여러분에게 "아주 약간만 기억하면서도 동시에 많은 것에 대해 많은 것을 알 수 있는 영민한 전략"을 제공할 수 있다.

the idea is that if we understand some of the deep principles of the theories of learning, we can extrapolate to the particulars as needed. As Bruner (1971) states, “You don’t need to encounter everything in nature in order to know nature” (p. 18). A basic understanding of the learning theories can provide you with a “canny strategy whereby you could know a great deal about a lot of things while keeping very little in mind” (p. 18).

학습에 대한 정의

Learning Defined

배움은 많은 다른 이론가, 연구원 그리고 교육 실무자들에 의해 수많은 방법으로 정의되어 왔다. 단일 정의에 대한 보편적 동의는 존재하지 않지만, 많은 정의는 공통 요소를 사용한다. 슈엘(Shueell, 1991년 스컹크가 해석한 바와 같이)의 다음 정의는 다음과 같은 주요 사상을 통합한다: "학습은 행동의 지속적인 변화 또는 주어진 방식으로 행동할 수 있는 능력으로, 연습이나 다른 형태의 경험에서 비롯된다"(p. 2)

Learning has been defined in numerous ways by many different theorists, researchers and educational practitioners. Although universal agreement on any single definition is nonexistent, many definitions employ common elements. the following definition by Shuell (as interpreted by Schunk, 1991) incorporates these main ideas: “Learning is an enduring change in behavior, or in the capacity to behave in a given fashion, which results from practice or other forms of experience” (p. 2).

한 이론과 다른 이론을 구분하는 것은 정의 그 자체가 아니다. 이론들 사이의 주요한 차이점은 정의에서보다 해석에 더 많이 있다. 이러한 차이점들은 궁극적으로 각 이론적 관점에서 소유하는 교육적 처방을 기술하는 많은 핵심 이슈들을 중심으로 나타난다.

it is not the definition itself that separates a given theory from the rest. the major differences among theories lie more in interpretation than they do in definition. these differences revolve around a number of key issues that ultimately delineate the instructional prescriptions that fl ow from each theoretical perspective.

Schunk(1991)는 각 학습 이론을 다른 학습 이론과 구별하는 역할을 하는 다음과 같은 다섯 가지 결정적인 질문을 나열한다.

Schunk (1991) lists five definitive questions that serve to distinguish each learning theory from the others:

(1) How does learning occur?

(2) Which factors influence learning?

(3) What is the role of memory?

(4) How does transfer occur?

(5) What types of learning are best explained by the theory?

우리는 교육 디자이너에게 중요한 두 가지 질문을 추가했다.

we have included two additional questions important to the instructional designer:

(6) What basic assumptions/principles of this theory are relevant to instructional design? and

(7) How should instruction be structured to facilitate learning?

이 글에서 이러한 질문들은 각각 행동주의, 인지주의, 구성주의라는 세 가지 뚜렷한 관점에서 대답된다. 학습이론은 일반적으로 행동과 인지라는 두 개의 범주로 구분되지만, 최근 교육 설계 문헌에 강조되어 있기 때문에 제3의 범주인 구성주의 범주가 여기에 추가된다(예: 베드나르, 커닝햄, 더프 y, & 페리, 1991; Duff y & Jonassen, 1991; Jonassen, 1991, Winn, 1991). 여러 면에서 이러한 관점은 중복되지만, 학습을 이해하고 기술하기 위한 별도의 접근방식으로 취급될 만큼 충분히 독특하다.

In this article, each of these questions is answered from three distinct viewpoints: behaviorism, cognitivism, and constructivism. Although learning theories typically are divided into two categories—behavioral and cognitive—a third category, constructive, is added here because of its recent emphasis in the instructional design literature (e.g., Bednar, Cunningham, Duff y, & Perry, 1991; Duff y & Jonassen, 1991; Jonassen, 1991b; Winn, 1991). In many ways these viewpoints overlap; yet they are distinctive enough to be treated as separate approaches to understanding and describing learning.

차이는 구분을 명확히 하기 위해 강조된다. 이것은 이러한 관점들 사이에 유사점이 없거나 겹치는 특징이 없다는 것을 암시하는 것이 아니다. 사실, 서로 다른 학습이론도 종종 동일한 상황에 대해 동일한 지침 방법을 규정할 것이다(단, 용어가 다르고 의도가 다를 수 있다).

differences are emphasized in order to make distinctions clear. this is not to suggest that there are no similarities among these viewpoints or that there are no overlapping features. In fact, different learning theories will often prescribe the same instructional methods for the same situations (only with different terminology and possibly with different intentions).

역사적 토대

Historical Foundations

현재의 학습이론은 먼 옛날로 뻗어나가는 뿌리를 가지고 있다. 오늘날의 이론가들과 연구자들이 씨름하고 투쟁하는 문제들은 새로운 것이 아니라 단지 시대를 초월한 주제에 대한 변화일 뿐이다. 지식은 어디서 나오고 사람들은 어떻게 알게 되는가? 지식의 기원에 대한 두 가지 상반되는 입장, 즉 경험주의와 합리주의는 수세기 동안 존재해왔으며 오늘날 학습 이론에서는 여전히 다양한 정도로 명백하다. 행동주의, 인지주의, 구성주의 등의 "현대적" 학습 관점을 비교하기 위한 배경으로 이러한 견해에 대한 간략한 설명이 여기에 포함된다.

Current learning theories have roots that extend far into the past. the problems with which today’s theorists and researchers grapple and struggle are not new but simply variations on a timeless theme: Where does knowledge come from and how do people come to know? Two opposing positions on the origins of knowledge—empiricism and rationalism— have existed for centuries and are still evident, to varying degrees, in the learning theories of today. A brief description of these views is included here as a background for comparing the “modern” learning viewpoints of behaviorism, cognitivism, and constructivism.

경험론은 경험이 지식의 주요 원천이라는 견해이다(Schunk, 1991). 즉, 유기체는 기본적으로 아무런 지식도 없이 태어나고 배운 것은 환경과의 상호 작용과 연관성을 통해 얻어진다. 아리스토텔레스(384–322 B.C)를 시작으로, 경험론자들은 지식은 감각적 인상으로부터 파생된다는 견해를 옹호했다. 그러한 인상은 시간 및/또는 공간에서 연속적으로 연관될 때 복잡한 아이디어를 형성하기 위해 서로 연결될 수 있다.

Empiricism is the view that experience is the primary source of knowledge (Schunk, 1991). Th at is, organisms are born with basically no knowledge and anything learned is gained through interactions and associations with the environment. Beginning with Aristotle (384–322 B.C.), empiricists have espoused the view that knowledge is derived from sensory impressions. Those impressions, when associated contiguously in time and/or space, can be hooked together to form complex ideas.

예를 들어, 허스, 에게트, 디즈(1980년)가 그린 것처럼 '나무'라고 하는 복잡한 사상은 '가지와 잎'이라는 덜 복잡한 사상에서 만들어질 수 있는데, 이것은 다시 '나무와 섬유성'의 사상에서 만들어지고, 이는 '녹색성, 나무 냄새' 등 기본적인 감각으로 만들어지는 것이다.

For example, the complex idea of a tree, as illustrated by Hulse, Egeth, and Deese (1980), can be built from the less complex ideas of branches and leaves, which in turn are built from the ideas of wood and fiber, which are built from basic sensations such as greenness, woody odor, and so forth.

이러한 관점에서 중요한 교육 설계 문제는 [적절한 연관성이 발생할 수 있도록 개선하고 보장하기 위해 환경을 조작하는 방법]에 초점을 맞춘다.

From this perspective, critical instructional design issues focus on how to manipulate the environment in order to improve and ensure the occurrence of proper associations.

Rationalism is the view that knowledge derives from reason without the aid of the senses (Schunk, 1991). this fundamental belief in the distinction between mind and matter originated with Plato (c. 427–347 B.C.), and is reflected in the viewpoint that humans learn by recalling or “discovering” what already exists in the mind.

예를 들어, 일생 동안 나무에 대한 직접적인 경험은 단순히 이미 마음속에 있는 것을 드러내는 역할을 한다. 나무의 "실제" 성질(녹색, 목질, 기타 특성)은 경험을 통해서가 아니라, 주어진 나무의 예에 대한 자신의 생각에 대한 반성을 통해 알려지게 된다. 비록 후기 합리주의자들이 플라톤의 다른 생각들 중 일부에 대해서는 서로 의견이 달랐지만, 중심적 믿음은 그대로 유지되었는데, 그것은 바로 지식은 마음에서 비롯한다는 것이다.

For example, the direct experience with a tree during one’s lifetime simply serves to reveal that which is already in the mind. the “real” nature of the tree (greenness, woodiness, and other characteristics) becomes known, not through the experience, but through a reflection on one’s idea about the given instance of a tree. Although later rationalists differed on some of Plato’s other ideas, the central belief remained the same: that knowledge arises through the mind.

이러한 관점에서, 교육적 설계 문제는 다음의 두 가지를 위해 새로운 정보의 구조를 어떻게 최적화 하는가에 초점을 맞춘다.

From this perspective, instructional design issues focus on how best to structure new information in order to facilitate (1) the learners’ encoding of this new information, as well as (2) the recalling of that which is already known.

교육 이론이 시작될 때 행동주의가 지배적이었기 때문에( 1950년경), 그것과 함께 생겨난 교육 설계(ID) 기술은 당연히 그 기본적인 가정과 특징의 많은 영향을 받았다. ID는 행동 이론에 뿌리를 두고 있기 때문에, 우리가 먼저 행동주의에 주의를 돌리는 것이 적절해 보인다.

Because behaviorism was dominant when instructional theory was initiated (around 1950), the instructional design (ID) technology that arose alongside it was naturally influenced by many of its basic assumptions and characteristics. Since ID has its roots in behavioral theory, it seems appropriate that we turn our attention to behaviorism first.

행동주의

Behaviorism

배움은 어떻게 발생하는가?

How does learning occur?

행동주의는 학습을 [관찰 가능한 수행]의 형태나 빈도의 변화와 동일시한다. 학습은 특정 환경 자극의 제시 후에 적절한 반응을 보일 때 이루어진다.

Behaviorism equates learning with changes in either the form or frequency of observable performance. Learning is accomplished when a proper response is demonstrated following the presentation of a specific environmental stimulus.

예를 들어, "2 + 4 =?" 방정식을 나타내는 수학 플래시 카드를 제시하면, 학습자는 "6"의 대답으로 답한다. 방정식은 자극이고 적절한 대답은 관련 반응이다. 핵심 요소는 자극, 반응, 그리고 둘 사이의 연관성이다. 주된 관심사는 자극과 반응 사이의 연관성이 어떻게 만들어지고, 강화되고, 유지되는가 하는 것이다.

For example, when presented with a math flashcard showing the equation “2 + 4 = ?” the learner replies with the answer of “6.” the equation is the stimulus and the proper answer is the associated response. the key elements are the stimulus, the response, and the association between the two. Of primary concern is how the association between the stimulus and response is made, strengthened, and maintained.

행동주의는 그러한 수행의 결과의 중요성에 초점을 맞추고 있으며, 강화가 따라오는 반응이 미래에 재발할 가능성이 더 높다고 주장한다. 학생의 지식 구조를 결정하거나 어떤 정신적 과정을 그들이 사용하는 것이 필요한지 평가하려는 시도는 없다(Winn, 1990). 학습자는 환경을 발견하는 데 적극적인 역할을 하는 대신 환경의 조건에 반응하는 것이 특징이다.

Behaviorism focuses on the importance of the consequences of those performances and contends that responses that are followed by reinforcement are more likely to recur in the future. No attempt is made to determine the structure of a student’s knowledge nor to assess which mental processes it is necessary for them to use (Winn, 1990). the learner is characterized as being reactive to conditions in the environment as opposed to taking an active role in discovering the environment.

어떤 요인들이 학습에 영향을 줍니까?

Which factors influence learning?

행동주의자들은 학습자와 환경적 요인을 모두 중요하게 생각하지만, 환경 조건이 가장 큰 강조를 받는다. 행동주의자들은 학습자를 평가하여 교육을 시작할 시점과 특정 학생에게 가장 효과적인 강화자를 결정한다. 그러나 가장 중요한 요소는 환경 내에서 자극과 결과의 배열이다.

Although both learner and environmental factors are considered important by behaviorists, environmental conditions receive the greatest emphasis. Behaviorists assess the learners to determine at what point to begin instruction as well as to determine which reinforcers are most effective for a particular student. the most critical factor, however, is the arrangement of stimuli and consequences within the environment.

기억의 역할은 무엇인가?

What is the role of memory?

행동주의자에게 기억은 보통 일반적인 정의처럼 다뤄지지 않는다. "습관"의 취득이 논의되고 있지만, 이러한 습관들이 향후의 사용을 위해 어떻게 저장되거나 회수되는지에 대해서는 거의 관심을 기울이지 않는다. 망각은 시간이 지남에 따라 반응의 "비사용"에 기인한다. 정기적인 연습이나 복습의 사용은 학습자의 반응 준비를 유지하는 역할을 한다(Schunk, 1991).

Memory, as commonly defined by the layman, is not typically addressed by behaviorists. Although the acquisition of “habits” is discussed, little attention is given as to how these habits are stored or recalled for future use. Forgetting is attributed to the “nonuse” of a response over time. the use of periodic practice or review serves to maintain a learner’s readiness to respond (Schunk, 1991).

전이는 어떻게 발생하는가?

How does transfer occur?

전이(transfer)는 [학습된 지식을 새로운 방법이나 상황에 적용하는 것]뿐만 아니라 선행학습이 새로운 학습에 어떻게 영향을 미치는가를 말한다. 행동학습 이론에서, 전이는 일반화의 결과물이다. 동일하거나 유사한 특징들을 포함하는 상황들은 행동들이 공통적인 요소들에 걸쳐 전달될 수 있게 한다.

Transfer refers to the application of learned knowledge in new ways or situations, as well as to how prior learning affects new learning. In behavioral learning theories, transfer is a result of generalization. Situations involving identical or similar features allow behaviors to transfer across common elements.

예를 들어, 느릅나무를 인식하고 분류하는 법을 배운 학생은 같은 과정을 이용하여 단풍나무를 분류할 때 전이를 보여준다. 느릅나무와 단풍나무의 유사성을 통해 학습자는 이전의 느릅나무 분류 학습 경험을 단풍나무 분류 작업에 적용할 수 있다.

For example, the student who has learned to recognize and classify elm trees demonstrates transfer when (s)he classifies maple trees using the same process. the similarities between the elm and maple trees allow the learner to apply the previous elm tree classification learning experience to the maple tree classification task.

어떤 종류의 학습이 이 직책에 의해 가장 잘 설명되는가?

What types of learning are best explained by this position?

행동주의자들은 교육적 단서, 연습 및 보강의 사용을 포함하여 자극-반응 연관성의 구축 및 강화에 가장 유용한 전략을 규정하려고 한다(Win, 1990). 이러한 처방들은 일반적으로 다음...을 포함하는 것이 학습을 촉진하는 데 신뢰할 수 있고 효과적인 것으로 입증되었다.

구별(사실 호출),

일반화(개념 정의 및 설명),

연관성(설명 적용) 및

체이닝(특정 절차를 자동적으로 수행)

Behaviorists attempt to prescribe strategies that are most useful for building and strengthening stimulus-response associations (Winn, 1990), including the use of instructional cues, practice, and reinforcement. these prescriptions have generally been proven reliable and effective in facilitating learning that involves

discriminations (recalling facts),

generalizations (defining and illustrating concepts),

associations (applying explanations), and

chaining (automatically performing a specified procedure).

그러나 행동주의 원리는 상위 수준의 기술이나 보다 심층적인 처리가 필요한 기술(예: 언어 개발, 문제 해결, 추론 생성, 비판적 사고)의 획득을 적절하게 설명할 수 없다는 데 일반적으로 동의한다(Schunk, 1991).

However, it is generally agreed that behavioral principles cannot adequately explain the acquisition of higher level skills or those that require a greater depth of processing (e.g., language development, problem solving, inference generating, critical thinking) (Schunk, 1991).

이 이론의 어떤 기본적인 가정/원칙이 교육적 설계와 관련이 있는가?

What basic assumptions/principles of this theory are relevant to instructional design?

교육 설계와 직접적인 관련이 있는 구체적인 가정이나 원칙은 다음을 포함한다(잠재 가능한 현재 ID 애플리케이션은 나열된 원칙에 따라 괄호[ ]에 열거되어 있다).

Specific assumptions or principles that have direct relevance to instructional design include the following (possible current ID applications are listed in brackets [ ] following the listed principle):

♦ 학생에게 관찰 가능하고 측정 가능한 결과의 생산에 대한 강조[행동 목표, 과제 분석, 기준 참조 평가]

♦ 교육을 시작해야 할 위치를 결정하기 위한 학생 사전 평가 [학습자 분석]

♦ 더 복잡한 수준의 성과로 진행하기 전에 초기 단계를 숙달해야 함을 강조함 [교육 프레젠테이션의 순서, 숙달된 학습]

♦ 성과에 영향을 미치는 강화의 활용 [무형 보상, 정보 피드백]

♦ 강력한 자극 반응 연관성을 보장하기 위한 단서, 형상화 및 실천의 사용 [단순한 것에서 복잡한 것으로 순서, 프롬프트 사용]

♦ An emphasis on producing observable and measurable outcomes in students [behavioral objectives, task analysis, criterion-referenced assessment]

♦ Pre-assessment of students to determine where instruction should begin [learner analysis]

♦ Emphasis on mastering early steps before progressing to more complex levels of performance [sequencing of instructional presentation, mastery learning]

♦ Use of reinforcement to impact performance [tangible rewards, informative feedback]

♦ Use of cues, shaping and practice to ensure a strong stimulus response association [simple to complex sequencing of practice, use of prompts]

교육은 어떻게 구성되어야 하는가?

How should instruction be structured?

행동주의자를 위한 가르침의 목표는 목표 자극이 제시된 학습자로부터 원하는 반응을 이끌어내는 것이다. 이를 달성하기 위해 학습자는 적절한 응답과 적절한 응답을 실행하는 방법을 알고 있어야 한다. 따라서, 교육은 목표 자극의 제시와 학습자가 적절한 대응을 연습할 수 있는 기회 제공을 중심으로 구성된다. 자극-반응 쌍의 연계를 용이하게 하기 위해, 교육에서는 흔히 신호(반응을 보일 것을 자극하는 최초의 것)와 강화(대상 자극이 있는 경우 올바른 대응을 강화한다)를 사용한다.

the goal of instruction for the behaviorist is to elicit the desired response from the learner who is presented with a target stimulus. To accomplish this, the learner must know how to execute the proper response, as well as the conditions under which that response should be made. therefore, instruction is structured around the presentation of the target stimulus and the provision of opportunities for the learner to practice making the proper response. To facilitate the linking of stimulus-response pairs, instruction frequently uses cues (to initially prompt the delivery of the response) and reinforcement (to strengthen correct responding in the presence of the target stimulus).

행동 이론에 따르면 교사/설계자의 일은

(1) 원하는 반응을 이끌어낼 수 있는 단서를 결정하는 것

(2) 프롬프트가 처음에는 유도력이 없지만 "자연" (성능) 환경에서 반응을 이끌어낼 것으로 예상되는 목표 자극과 짝을 이루는 연습 상황을 배치하는 것

(3) 학생들이 목표 자극이 존재하는 상태에서 올바른 반응을 할 수 있도록 환경 조건을 조정하고, 그러한 반응에 대한 강화를 받을 수 있도록 하는 것(Gropper, 1987).

Behavioral theories imply that the job of the teacher/designer is to

(1) determine which cues can elicit the desired responses;

(2) arrange practice situations in which prompts are paired with the target stimuli that initially have no eliciting power but which will be expected to elicit the responses in the “natural” (performance) setting; and

(3) arrange environmental conditions so that students can make the correct responses in the presence of those target stimuli and receive reinforcement for those responses (Gropper, 1987).

인지주의

Cognitivism

1950년대 후반, 학습이론은 행동 모델의 사용에서 인지과학의 학습 이론과 모델에 의존하는 접근으로 전환하기 시작했다. 심리학자와 교육자들은 명백하고 관찰 가능한 행동에 우려를 강조하기 시작했으며 대신 사고, 문제 해결, 언어, 개념 형성 및 정보 처리와 같은 보다 복잡한 인지 과정을 강조했다(Snelbecker, 1983). 지난 10년 동안, 교육 설계 분야의 많은 저자들은 인지 과학에서 도출된 학습에 대한 새로운 심리적 가정들에 호의적으로 ID의 전통적인 행동주의 가정들 중 많은 것들을 공개적으로 그리고 의식적으로 거부해왔다. 개방적인 혁명으로 보든 단순하게 점진적인 진화 과정으로 보든, 인지 이론이 현재의 학습 이론의 최전선으로 이동했다는 일반적인 인식이 있는 것 같다(Bednar et al., 1991).

In the late 1950s, learning theory began to make a shift away from the use of behavioral models to an approach that relied on learning theories and models from the cognitive sciences. Psychologists and educators began to de-emphasize a concern with overt, observable behavior and stressed instead more complex cognitive processes such as thinking, problem solving, language, concept formation and information processing (Snelbecker, 1983). Within the past decade, a number of authors in the field of instructional design have openly and consciously rejected many of ID’s traditional behavioristic assumptions in favor of a new set of psychological assumptions about learning drawn from the cognitive sciences. Whether viewed as an open revolution or simply a gradual evolutionary process, there seems to be the general acknowledgment that cognitive theory has moved to the forefront of current learning theories (Bednar et al., 1991).

배움은 어떻게 발생하는가?

How does learning occur?

인지 이론은 지식과 내부적 정신 구조의 획득을 강조하며, 이와 같이 인식론 연속체의 합리주의적 종말에 더 가깝다(Bower & Hilgard, 1981). 학습은 반응 확률의 변화보다는 지식 상태 간의 이산적 변화와 동일하다. 인지 이론은 학생들의 학습 과정의 개념화에 초점을 맞추고 있으며, 정보가 어떻게 전달, 조직, 저장, 회수되는지에 대한 문제를 다룬다.

Cognitive theories stress the acquisition of knowledge and internal mental structures and, as such, are closer to the rationalist end of the epistemology continuum (Bower & Hilgard, 1981). Learning is equated with discrete changes between states of knowledge rather than with changes in the probability of response. Cognitive theories focus on the conceptualization of students’ learning processes and address the issues of how information is received, organized, stored, and retrieved by the mind.

배움은 학습자가 무엇을 하는지에 대한 것이 아니라, 그들이 무엇을 알고 어떻게 그것을 습득하게 되는지에 대한 것이다(Jonassen, 1991b). 지식 습득은 학습자에 의해 내부 코딩과 구조를 수반하는 정신적 활동으로 설명된다. 학습자는 학습 과정에 매우 적극적인 참여자로 간주된다.

Learning is concerned not so much with what learners do but with what they know and how they come to acquire it (Jonassen, 1991b). Knowledge acquisition is described as a mental activity that entails internal coding and structuring by the learner. the learner is viewed as a very active participant in the learning process.

어떤 요인들이 학습에 영향을 줍니까?

Which factors influence learning?

인지주의는 행동주의와 마찬가지로 환경 조건이 학습을 용이하게 하는 역할을 강조한다. 지침 설명, 데모, 사례, 일치된 비고사례는 모두 학생 학습을 지도하는 데 도움이 되는 것으로 간주된다. 마찬가지로, 교정적 피드백과 함께 실천의 역할에 중점을 둔다. 이 정도까지는 이 두 이론 사이에 거의 차이가 감지되지 않는다.

Cognitivism, like behaviorism, emphasizes the role that environmental conditions play in facilitating learning. Instructional explanations, demonstrations, illustrative examples and matched non-examples are all considered to be instrumental in guiding student learning. Similarly, emphasis is placed on the role of practice with corrective feedback. Up to this point, little difference can be detected between these two theories.

그러나 학습자의 "능동적" 성질은 전혀 다르게 인식된다. 인지적 접근은 반응을 이끌어내는 학습자의 정신 활동에 초점을 맞추고, 정신 계획, 목표 설정 및 조직 전략의 과정을 인정한다(Shueell, 1986). 인지 이론은 환경적 "cue"와 교육적 요소만으로는 교육적 상황에서 발생하는 모든 학습을 설명할 수 없다고 주장한다.

However, the “active” nature of the learner is perceived quite differently. the cognitive approach focuses on the mental activities of the learner that lead up to a response and acknowledges the processes of mental planning, goal-setting, and organizational strategies (Shuell, 1986). Cognitive theories contend that environmental “cues” and instructional components alone cannot account for all the learning that results from an instructional situation.

추가 주요 요소에는 학습자가 정보를 수집, 코드화, 변환, 리허설, 저장 및 검색하는 방법이 포함된다. 학습자의 생각, 신념, 태도, 가치관도 학습 과정에 영향을 미치는 것으로 간주된다(Winne, 1985). 인지적 접근법의 진짜 초점은 적절한 학습 전략을 사용하도록 권장함으로써 학습자를 바꾸는 것이다.

Additional key elements include the way that learners attend to, code, transform, rehearse, store and retrieve information. Learners’ thoughts, beliefs, attitudes, and values are also considered to be influential in the learning process (Winne, 1985). the real focus of the cognitive approach is on changing the learner by encouraging him/her to use appropriate learning strategies.

기억의 역할은 무엇인가?

What is the role of memory?

위에서 설명한 것처럼 기억력은 학습 과정에서 두드러진 역할을 한다. 학습은 정보가 체계적이고 의미 있는 방식으로 메모리에 저장될 때 발생한다. 교사/설계자는 학습자가 최적의 방식으로 정보를 구성할 수 있도록 도울 책임이 있다. 설계자는 학습자가 새로운 정보를 사전 지식에 연결하도록 돕기 위해 고급 계획자, 유사성, 계층적 관계 및 행렬과 같은 기법을 사용한다. 잊어버리는 것은 정보에 접근하는 데 필요한 간섭, 메모리 손실 또는 누락 또는 불충분한 단서 때문에 메모리로부터 정보를 검색할 수 없는 것이다.

As indicated above, memory is given a prominent role in the learning process. Learning results when information is stored in memory in an organized, meaningful manner. Teachers/designers are responsible for assisting learners in organizing that information in some optimal way. Designers use techniques such as advance organizers, analogies, hierarchical relationships, and matrices to help learners relate new information to prior knowledge. Forgetting is the inability to retrieve information from memory because of interference, memory loss, or missing or inadequate cues needed to access information.

이전은 어떻게 발생하는가?

How does transfer occur?

인지 이론에 따르면, 전이(transfer)는 정보가 기억 속에 어떻게 저장되는지의 함수라고 한다(Schunk, 1991). 학습자가 다른 맥락에서 지식을 적용하는 방법을 이해할 때, 전이가 발생한다. 이해라는 것은 규칙, 개념, 구별의 형태로 지식기반을 구성하는 것으로 여겨진다(Duff y & Jonassen, 1991).

According to cognitive theories, transfer is a function of how information is stored in memory (Schunk, 1991). When a learner understands how to apply knowledge in different contexts, then transfer has occurred. Understanding is seen as being composed of a knowledge base in the form of rules, concepts, and discriminations (Duff y & Jonassen, 1991).

사전 지식은 새로운 정보의 유사성과 차이점을 식별하기 위한 경계 제약boundary constraint을 확립하기 위해 사용된다. 지식 그 자체는 기억 속에 저장되어야 할 뿐만 아니라 그 지식의 사용도 저장되어야 한다. 특정 교육적 또는 현실적 이벤트는 특정한 반응을 유발하지만, 학습자는 어떤 지식을 활성화하기 전에, 그 지식이 주어진 상황에서 유용하다고 믿어야 한다.

Prior knowledge is used to establish boundary constraints for identifying the similarities and differences of novel information. Not only must the knowledge itself be stored in memory but the uses of that knowledge as well. Specific instructional or real-world events will trigger particular responses, but the learner must believe that the knowledge is useful in a given situation before he or she will activate it.

어떤 종류의 학습이 이 직책에 의해 가장 잘 설명되는가?

What types of learning are best explained by this position?

정신 구조에 대한 강조 때문에 인지 이론은 일반적으로 더 행동적인 관점보다 복잡한 형태의 학습(이성, 문제 해결, 정보 처리)을 설명하는데 더 적합한 것으로 간주된다(Schunk, 1991). 그러나, 이 시점에서 이러한 두 가지 관점에 대한 강의의 실제 목표가 종종 동일하다는 것을 나타내는 것이 중요하다: 가능한 한 가장 효율적이고 효과적인 방법으로 학생들에게 지식을 전달하거나 소통하는 것이다(Bednar et al., 1991).

Because of the emphasis on mental structures, cognitive theories are usually considered more appropriate for explaining complex forms of learning (reasoning, problem-solving, information-processing) than are those of a more behavioral perspective (Schunk, 1991). However, it is important to indicate at this point that the actual goal of instruction for both of these viewpoints is often the same: to communicate or transfer knowledge to the students in the most efficient, effective manner possible (Bednar et al., 1991).

지식 전달의 이러한 효과와 효율성을 달성하는데 양 진영에서 사용하는 두 가지 기술은 단순화와 표준화다. 즉, 지식은 분석, 분해, 그리고 기본적인 구성 요소로 단순화할 수 있다. 관련 없는 정보가 제거되면 지식 전달이 빨라진다.

Two techniques used by both camps in achieving this effectiveness and efficiency of knowledge transfer are simplification and standardization. Th at is, knowledge can be analyzed, decomposed, and simplified into basic building blocks. Knowledge transfer is expedited if irrelevant information is eliminated.

예를 들어 워크숍에 참석하는 연습생에게는 가능한 한 빠르고 쉽게 새로운 정보를 동화 및/또는 수용할 수 있는 방법으로 "sized"와 "chunked"의 정보가 제공될 것이다.

For example, trainees attending a workshop would be presented with information that is “sized” and “chunked” in such a way that they can assimilate and/or accommodate the new information as quickly and as easily as possible.

행동주의자들은 그러한 전달을 최적화하기 위한 환경 설계에 초점을 맞추고, 인지주의자들은 효율적인 처리 전략을 강조할 것이다

Behaviorists would focus on the design of the environment to optimize that transfer, while cognitivists would stress efficient processing strategies.

이 이론의 어떤 기본적인 가정/원칙이 교육적 설계와 관련이 있는가?

What basic assumptions/principles of this theory are relevant to instructional design?

인지학자들이 옹호하고 활용하는 많은 교육 전략들 또한 행동주의자들에 의해 강조되지만, 대개는 다른 이유로 강조된다. 분명한 공통점은 피드백의 사용이다.

행동주의자는 피드백(강화)을 사용하여 원하는 방향으로 행동을 수정하는 반면,

인지주의자는 피드백(결과 지식)을 활용하여 정확한 정신연계를 안내하고 지원한다(Thompson, Simonson & Hargrave, 1992).

Many of the instructional strategies advocated and utilized by cognitivists are also emphasized by behaviorists, yet usually for different reasons. An obvious commonality is the use of feedback. A behaviorist uses feedback (reinforcement) to modify behavior in the desired direction, while cognitivists make use of feedback (knowledge of results) to guide and support accurate mental connections (Thompson, Simonson, & Hargrave, 1992).

학습자와 과제 분석은 또한 인식론자와 행동론자 모두에게 매우 중요하지만, 다른 이유로 다시 한 번 더 중요하다.

인지학자들은 학습자의 학습 성향을 판단하기 위해 학습자를 본다. (즉, 학습자가 어떻게 학습을 활성화, 유지 및 지시하는가?) (Th 옴슨 외, 1992). 또한, 인지학자들은 학습자가 쉽게 동화될 수 있도록 교육을 설계하는 방법을 결정하기 위해 학습자를 검사한다(즉, 학습자의 기존 정신 구조는 무엇인가?).

Learner and task analyses are also critical to both cognitivists and behaviorists, but once again, for different reasons. Cognitivists look at the learner to determine his/her predisposition to learning, (i.e., How does the learner activate, maintain, and direct his/her learning?) (Th ompson et al., 1992). Additionally, cognitivists examine the learner to determine how to design instruction so that it can be readily assimilated (i.e., What are the learner’s existing mental structures?).

In contrast, the behaviorists look at learners to determine where the lesson should begin (i.e., At what level are they currently performing successfully?) and which reinforcers should be most effective (i.e., What consequences are most desired by the learner?).

지침 설계와 직접적인 관련이 있는 구체적인 가정 또는 원칙은 다음을 포함한다.

Specific assumptions or principles that have direct relevance to instructional design include the following

♦ 학습 과정의 학습자의 적극적인 참여 강조 [학습자 제어, 인지 훈련(예: 자기 계획, 모니터링 및 수정 기법)]

♦ 선행 조건 관계를 식별하고 설명하기 위한 계층 분석의 사용 [인식 작업 분석 절차]

♦ 최적 처리를 위한 정보의 구조화, 정리, 배열 등에 대한 강조[개요, 요약, 합성기, 사전 기획자 등 인지 전략의 활용]

♦ 학생들이 이전에 학습한 자료와 연결할 수 있도록 하고 권장하는 학습 환경 조성 [필수 조건 기술 회수; 관련 예제 사용, 유사 자료 사용]

♦ Emphasis on the active involvement of the learner in the learning process [learner control, metacognitive training (e.g., self-planning, monitoring, and revising techniques)]

♦ Use of hierarchical analyses to identify and illustrate prerequisite relationships [cognitive task analysis procedures]

♦ Emphasis on structuring, organizing, and sequencing information to facilitate optimal processing [use of cognitive strategies such as outlining, summaries, synthesizers, advance organizers, etc.]

♦ Creation of learning environments that allow and encourage students to make connections with previously learned material [recall of prerequisite skills; use of relevant examples, analogies]

교육은 어떻게 구성되어야 하는가?

How should instruction be structured?

지도는 학생의 기존 정신 구조, 즉 스키마를 기반으로 해야 효과적이다. 그것은 학습자가 새로운 정보를 어떤 의미 있는 방법으로 기존 지식과 연결할 수 있도록 정보를 구성해야 한다. 비유와 은유는 이러한 유형의 인지 전략의 예들이다.

Behavioral theories imply that teachers ought to arrange environmental conditions so that students respond properly to presented stimuli. Cognitive theories emphasize making knowledge meaningful and helping learners organize and relate new information to existing knowledge in memory. Instruction must be based on a student’s existing mental structures, or schema, to be effective. It should organize information in such a manner that learners are able to connect new information with existing knowledge in some meaningful way. Analogies and metaphors are examples of this type of cognitive strategy.

다른 인지 전략에는 프레임 사용, 개요, 니모닉 사용, 개념 매핑, 사전 계획자 등이 포함될 수 있다(West, Farmer, 1991).

Other cognitive strategies may include the use of framing, outlining, mnemonics, concept mapping, advance organizers, and so forth (West, Farmer, & Wolff , 1991).

이러한 인지적 강조는 교사/설계자의 주요 업무가 다음을 포함한다는 것을 의미한다.

(1) 개인은 학습 상황에 다양한 학습 경험을 가져오며, 이것이 학습 결과에 영향을 미칠 수 있다는 이해

(2) 이전에 습득한 지식, 능력 및 경험을 활용하기 위해 새로운 정보를 구성하고 구성하는 가장 효과적인 방법 결정

(3) 새로운 정보가 효과적이고 효율적으로 동화 및/또는 학습자의 인지 구조 내에서 수용될 수 있도록 피드백을 통해 실천을 정돈한다(Stepich & Newby, 1988).

Such cognitive emphases imply that major tasks of the teacher/designer include

(1) understanding that individuals bring various learning experiences to the learning situation which can impact learning outcomes;

(2) determining the most effective manner in which to organize and structure new information to tap the learners’ previously acquired knowledge, abilities, and experiences; and

(3) arranging practice with feedback so that the new information is effectively and efficiently assimilated and/or accommodated within the learners’ cognitive structure (Stepich & Newby, 1988).

인지적 접근법을 활용하는 학습 상황의 다음 예를 고려해보자: 대기업 교육부의 한 관리자가 새로운 인턴에게 다가오는 개발 프로젝트를 위해 비용-편익 분석을 완료하도록 가르쳐 달라고 요청 받았다. 이 경우, 사업 환경에서 비용 편익 분석에 대한 경험이 없는 것으로 가정한다. 그러나, 이 새로운 작업을 인턴이 더 많은 경험을 가진 매우 유사한 절차와 연관시킴으로써, 관리자는 이 새로운 절차의 원활하고 효율적인 기억으로의 동화를 촉진할 수 있다. 이러한 익숙한 절차에는 개인이 자신의 월 급여 수표를 배분하는 과정, 사치품 구매와 관련하여 구매/무구매 결정을 내리는 방법, 심지어 주말 지출 활동이 어떻게 결정되고 우선 순위가 매겨지는지 등이 포함될 수 있다. 그러한 활동에 대한 절차는 비용-효익 분석의 절차와 정확히 일치하지 않을 수 있지만, 활동 사이의 유사성은 익숙하지 않은 맥락 안에 낯선 정보를 넣을 수 있게 한다. 당사에서는 처리 요건이 감소하고 회수 신호의 잠재적 효과성이 증가한다.

Consider the following example of a learning situation utilizing a cognitive approach: A manager in the training department of a large corporation had been asked to teach a new intern to complete a cost-benefi t analysis for an upcoming development project. In this case, it is assumed that the intern has no previous experience with cost-benefit analysis in a business setting. However, by relating this new task to highly similar procedures with which the intern has had more experience, the manager can facilitate a smooth and efficient assimilation of this new procedure into memory. these familiar procedures may include the process by which the individual allocates his monthly pay check, how (s)he makes a buy/ no-buy decision regarding the purchase of a luxury item, or even how one’s weekend spending activities might be determined and prioritized. the procedures for such activities may not exactly match those of the cost-benefit analysis, but the similarity between the activities allows for the unfamiliar information to be put within a familiar context. Th us, processing requirements are reduced and the potential effectiveness of recall cues is increased.

구성주의

Constructivism

행동 이론과 인지 이론 둘 다에 기초하는 철학적인 가정들은 주로 객관성이다; 즉 세상은 실제적이고 학습자에게 외재적이다. 교육의 목표는 세계의 구조를 학습자에게 매핑하는 것이다(Jonassen, 1991b).

the philosophical assumptions underlying both the behavioral and cognitive theories are primarily objectivistic; that is: the world is real, external to the learner. the goal of instruction is to map the structure of the world onto the learner (Jonassen, 1991b).

많은 현대의 인지 이론가들은 이러한 기본적인 객관적 가정에 의문을 갖기 시작했고 학습과 이해에 대해 보다 구성주의적인 접근법을 채택하기 시작하고 있다: 지식은 "개인이 자신의 경험으로부터 어떻게 의미를 창조하는가에 대한 함수이다" (p. 10).

A number of contemporary cognitive theorists have begun to question this basic objectivistic assumption and are starting to adopt a more constructivist approach to learning and understanding: knowledge “is a function of how the individual creates meaning from his or her own experiences” (p. 10).

구성주의는 완전히 새로운 학습 방식이 아니다. 대부분의 다른 학습 이론과 마찬가지로, 구성주의는 특히 피아제, 브루너, 굿맨(Perkins, 1991년)의 작품에서 금세기 철학적, 심리적 관점에 복수의 뿌리를 두고 있다.

Constructivism is not a totally new approach to learning. Like most other learning theories, constructivism has multiple roots in the philosophical and psychological viewpoints of this century, specifically in the works of Piaget, Bruner, and Goodman (Perkins, 1991).

배움은 어떻게 발생하는가?

How does learning occur?

구성주의는 학습을 경험으로부터 의미를 창조하는 것과 동일시하는 이론이다(Bednar et al., 1991). 구성주의는 인지주의의 한 분야(두 가지 모두 정신적 활동으로 학문을 인식하는 것)로 간주되지만, 여러 가지 면에서 전통적인 인지 이론과 구별된다.

Constructivism is a theory that equates learning with creating meaning from experience (Bednar et al., 1991). Even though constructivism is considered to be a branch of cognitivism (both conceive of learning as a mental activity), it distinguishes itself from traditional cognitive theories in a number of ways. Most cognitive psychologists think of the mind as a reference tool to the real world; constructivists believe that the mind filters input from the world to produce its own unique reality (Jonassen, 1991a).

플라톤 시대의 합리주의자들과 마찬가지로 정신은 모든 의미의 근원으로 믿어지고 있지만, 경험주의자들처럼 개인적이고 직접적인 환경 경험도 중요하다고 여긴다. 구성주의는 이 두 변수 사이의 상호작용을 강조함으로써 두 범주를 넘나든다.

As with the rationalists of Plato’s time, the mind is believed to be the source of all meaning, yet like the empiricists, individual, direct experiences with the environment are considered critical. Constructivism crosses both categories by emphasizing the interaction between these two variables.

구성주의자들은 (인지주의자나 행동주의자들과) 지식이 정신에 의존하고 학습자에게 "매핑"될 수 있다는 믿음을 공유하지 않는다. 구조주의자들은 현실 세계의 존재를 부정하는 것이 아니라 우리가 세계에 대해 알고 있는 것은 우리의 경험에 대한 우리 자신의 해석에서 비롯된다고 주장한다. 인간은 그것을 획득하는 것과 반대로 의미를 창조한다. 어떤 경험으로부터든 얻을 수 있는 많은 의미들이 있기 때문에, 우리는 미리 정해진 "올바른" 의미를 달성할 수 없다.

Constructivists do not share with cognitivists and behaviorists the belief that knowledge is mind-independent and can be “mapped” onto a learner. Constructivists do not deny the existence of the real world but contend that what we know of the world stems from our own interpretations of our experiences. Humans create meaning as opposed to acquiring it. Since there are many possible meanings to glean from any experience, we cannot achieve a predetermined, “correct” meaning.

학습자는 외부 세계로부터 얻은 지식을 기억으로 전달하지 않고, 오히려 개인의 경험과 상호작용을 바탕으로 세계에 대한 개인적 해석을 구축한다. 우리보다 지식의 내면적 표현은 끊임없이 변화에 열려있다; 학습자가 알기 위해 노력하는 객관적인 현실은 없다. 지식은 그것이 관련된 맥락에서 나타난다. 따라서, 개인 내에서 일어난 학습을 이해하기 위해서는 실제 경험을 조사해야 한다(Bednar et al., 1991).

Learners do not transfer knowledge from the external world into their memories; rather they build personal interpretations of the world based on individual experiences and interactions. Th us, the internal representation of knowledge is constantly open to change; there is not an objective reality that learners strive to know. Knowledge emerges in contexts within which it is relevant. therefore, in order to understand the learning which has taken place within an individual, the actual experience must be examined (Bednar et al., 1991).

어떤 요인들이 학습에 영향을 줍니까?

Which factors influence learning?

학습자와 환경적 요인은 모두 구성주의자에게 매우 중요하다. 왜냐하면 지식을 창출하는 것은 두 변수 사이의 특정한 상호 작용이기 때문이다. 구성주의자들은 행동이 상황적으로 결정된다고 주장한다(Jonassen, 1991a). 새로운 어휘 단어의 학습이 (사전으로부터 그 의미를 배우는 것과는 반대로) 문맥에서의 그러한 단어들과의 노출과 그 후의 상호작용에 의해 향상되는 것과 마찬가지로, 내용 지식도 그것이 사용되는 상황에 내재하는 것이 필수적이다.

Both learner and environmental factors are critical to the constructivist, as it is the specific interaction between these two variables that creates knowledge. Constructivists argue that behavior is situationally determined (Jonassen, 1991a). Just as the learning of new vocabulary words is enhanced by exposure and subsequent interaction with those words in context (as opposed to learning their meanings from a dictionary), likewise it is essential that content knowledge be embedded in the situation in which it is used.

브라운, 콜린스, 듀기드(1989)는 상황이 실제로 활동을 통해 (인식과 함께) 지식을 공동 생산한다고 제안한다. 모든 행동은 "이전 상호작용의 전체 역사를 바탕으로 한 현재 상황에 대한 해석"으로 본다(Clancey, 1986). 주어진 단어의 의미들의 그림자들이 단어에 대한 학습자의 "현재" 이해를 끊임없이 변화시키고 있는 것처럼, 개념들 또한 계속해서 새로운 용도를 발전시킬 것이다. 이러한 이유로, 학습은 현실적인 환경에서 발생하며, 학습과제는 학생들의 생생한 경험과 관련이 있는 것이 중요하다.

Brown, Collins, and Duguid (1989) suggest that situations actually co-produce knowledge (along with cognition) through activity. Every action is viewed as “an interpretation of the current situation based on an entire history of previous interactions” (Clancey, 1986). Just as shades of meanings of given words are constantly changing a learner’s “current” understanding of a word, so too will concepts continually evolve witheach new use. For this reason, it is critical that learning occur in realistic settings and that the selected learning tasks be relevant to the students’ lived experiences.

기억의 역할은 무엇인가?

What is the role of memory?

교육의 목표는 개인이 특정한 사실을 확실히 아는 것이 아니라 정보에 대해 상세히 설명하고elaborate 해석하는interpret 것이다. "'이해'는 지속적, 상황적 사용을 통해 개발되며, 기억에서 불러올 수 있는 범주형categorical 정의로 결정되지 않는다(Brown et al., 1989, 페이지 33). 앞에서 언급한 바와 같이, 개념은 각각의 새로운 용도에 따라 계속 진화할 것이다.

the goal of instruction is not to ensure that individuals know particular facts but rather that they elaborate on and interpret information. “Understanding is developed through continued, situated use . . . and does not crystallize into a categorical definition” that can be called up from memory (Brown et al., 1989, p. 33). As mentioned earlier, a concept will continue to evolve with each new use

따라서 "기억"은 상호 작용의 누적 이력으로서, 늘 구성construction 중에 있다. 경험의 표현은 공식화되거나 선언적 지식의 한 조각으로 구조화되고 다음 머리에 저장되는 것이 아니다. 강조점은 온전한intact 지식 구조를 인출retrieve하는 것이 아니라, 당면한 문제에 적합한 다양한 출처에서 사전 지식을 "조립"함으로써 학습자에게 새롭고 상황별 이해를 창출할 수 있는 수단을 제공하는 것이다.

therefore, “memory” is always under construction as a cumulative history of interactions. Representations of experiences are not formalized or structured into a single piece of declarative knowledge and then stored in the head. the emphasis is not on retrieving intact knowledge structures, but on providing learners with the means to create novel and situation-specific understandings by “assembling” prior knowledge from diverse sources appropriate to the problem at hand.

구성주의자들은 미리 포장된 스키마의 인출보다는 기존의 지식의 유연한 사용을 강조한다(Spiro, Feltovich, Jacobson, 1991). 과제 수행을 통해 개발된 정신적 표현은 환경의 일부가 동일하게 유지되는 한 후속 작업이 수행되는 효율성을 증가시킬 가능성이 있다. "환경의 특징을 복구하는 것은 행동 순서를 재반복하게 만들 수 있다." (브라운 등, 페이지 37).기억은 맥락-독립적인 과정이 아니다.

Constructivists emphasize the flexible use of preexisting knowledge rather than the recall of prepackaged schemas (Spiro, Feltovich, Jacobson, & Coulson, 1991). Mental representations developed through task-engagement are likely to increase the efficiency with which subsequent tasks are performed to the extent that parts of the environment remain the same: “Recurring features of the environment may thus afford recurring sequences of actions” (Brown et al., p. 37). Memory is not a context-independent process.

분명히 구성주의의 초점은 그들이 사용되는 문화의 지혜와 개인의 통찰력과 경험을 재조명하는 인지적 도구를 만드는 데 있다.

Clearly the focus of constructivism is on creating cognitive tools which reflect the wisdom of the culture in which they are used as well as the insights and experiences of individuals.

성공하고, 의미 있고, 지속적이 되려면, 학습은 활동(실무), 개념(지식), 문화(컨텍스트)의 세 가지 중요한 요소를 모두 포함해야 한다(Brown et al., 1989).

To be successful, meaningful, and lasting, learning must include all three of these crucial factors:

전이는 어떻게 발생하는가?

How does transfer occur?

구성주의적 입장에서는 의미 있는 맥락에 anchor되어 있는 authentic task에 참여함으로써 전이를 촉진할 수 있다고 가정한다. 이해는 경험에 의해 "색인화"되기 때문에(단어의 의미가 특정 사용 사례와 연관되어 있는 것처럼), 경험의 authenticity는 개인의 아이디어 사용 능력에 매우 중요해진다(Brown et al., 1989). 구성주의자의 관점에 있어서 본질적인 개념은 학습은 항상 특정 맥락에서 일어나고 그 맥락은 그것에 내재된 지식과 분리할 수 없는 연관성을 형성한다는 것이다(Bednar et al., 1991).

the constructivist position assumes that transfer can be facilitated by involvement in authentic tasks anchored in meaningful contexts. Since understanding is “indexed” by experience (just as word meanings are tied to specific instances of use), the authenticity of the experience becomes critical to the individual’s ability to use ideas (Brown et al., 1989). An essential concept in the constructivist view is that learning always takes place in a context and that the context forms an inexorable link with the knowledge embedded in it (Bednar et al., 1991).

따라서, 교육의 목표는 과제를 정확하게 묘사portray하는 것이지, 과제를 달성하는 데 필요한 학습의 구조structure of learning를 정의하는 것은 아니다. 학습에서 맥락이 제거된다면 전이가 일어날 가망은 거의 없다.

therefore, the goal of instruction is to accurately portray tasks, not to define the structure of learning required to achieve a task. If learning is decontextualized, there is little hope for transfer to occur.

사람은 단순히 규칙 목록을 따르는 방식으로 도구 세트를 사용하는 것을 배우지 않는다. 적절하고 효과적인 사용은 학습자가 실제 상황에서 도구를 실제 사용하게 함으로써 발생한다. 따라서, 학습의 궁극적인 척도는 학습자의 지식 구조가 [도구가 사용되는 시스템 내에서] 사고와 수행을 촉진하는 데 얼마나 효과적인가에 기초한다.

One does not learn to use a set of tools simply by following a list of rules. Appropriate and effective use comes from engaging the learner in the actual use of the tools in real-world situations. Thus, the ultimate measure of learning is based on how effective the learner’s knowledge structure is in facilitating thinking and performing in the system in which those tools are used.

어떤 종류의 학습이 이 직책에 의해 가장 잘 설명되는가?

What types of learning are best explained by this position?

구성주의적 견해는 학습의 유형이 내용 및 학습의 맥락과 무관하게 identify될 수 있다는 가정을 수용하지 않는다(Bednar et al., 1991). 구조주의자들은 관계의 계층적 분석에 따라 지식 영역을 나누는 것은 불가능하다고 믿는다.

the constructivist view does not accept the assumption that types of learning can be identified independent of the content and the context of learning (Bednar et al., 1991). Constructivists believe that it is impossible to divide up knowledge domains according to a hierarchical analysis of relationships.

비록 성과와 가르침에 대한 강조가 상대적으로 구조화된 지식 영역에서 기본적인 기술을 가르치는 데 효과적이라는 것이 입증되었지만, 많은 교육내용들은 구조화되지 않은 영역의 고급 지식을 포함한다. 요나센(1991a)은 지식 습득의 3단계(내부, 고급, 전문가)를 기술하고 있으며, 구성주의적 학습 환경이 고급 지식 습득의 단계에 가장 효과적이라고 주장한다.

Although the emphasis on performance and instruction has proven effective in teaching basic skills in relatively structured knowledge domains, much of what needs be learned involves advanced knowledge in ill-structured domains. Jonassen (1991a) has described three stages of knowledge acquisition(introductory, advanced, and expert) and argues that constructive learn-ing environments are most effective for the stage of advanced knowledge acquisition

Jonassen은 입문적 지식 습득은 더 객관적 접근법(행동적 및/또는 인지적)에 의해 더 잘 뒷받침된다는 것에 동의하지만, 학습자가 복잡하고 잘못된 구조적인 문제를 다루는 데 필요한 개념적 힘을 제공하는 더 많은 지식을 습득함에 따라 구성주의적 접근법으로의 전환을 제안한다.

Jonassen agrees that introductory knowledge acquisition is better supported by more objectivistic approaches (behavioral and/or cognitive) but suggests a transition to constructivistic approaches as learners acquire more knowledge which provides them with the conceptual power needed to deal with complex and ill-structured problems.

이 이론의 어떤 기본적인 가정/원칙이 교육적 설계와 관련이 있는가?

What basic assumptions/principles of this theory are relevant to instructional design?

구성주의 설계자는 학습자가 복잡한 주제/환경에 대해 능동적으로 탐구할 수 있도록 돕고, 해당 영역의 전문가가 생각하는 식의 사고방식으로 이들을 이동시키는 교육 방법을 specify한다.

the constructivist designer specifies instructional methods that will assist learners in actively exploring complex topics/environments and that will move them into thinking in a given content area as an expert user of that domain might think.

지식은 추상적이지는 않으며, 학습중인 맥락과 참여자들이 맥락에 가져오는 경험과 연관되어 있다. 이와 같이, 학습자들은 그들 자신의 이해를 형성하고 사회적 협상을 통해 이러한 새로운 관점을 검증하도록 권장된다. 콘텐츠는 미리 지정되어 있지 않다. 많은 출처의 정보가는 필수적이다.

Knowledge is not abstract but is linked to the context under study and to the experiences that the participants bring to the context. As such, learners are encouraged to construct their own understandings and then to validate, through social negotiation, these new perspectives. Content is not pre-specified; information from many sources is essential.

예를 들어, 전형적인 구성주의자의 목표는 초보 ID 학생들에게 교육 설계에 대한 사실을 똑바로 가르쳐 주는 것이 아니라, 학생들이 교육 설계자로서 ID 사실을 사용할 수 있도록 준비하는 것이다. 이와 같이 성과목표는 건설과정에 관한 것만큼 콘텐츠와 크게 관련되지 않는다.

For example, a typical constructivist’s goal would not be to teach novice ID students straight facts about instructional design, but to prepare students to use ID facts as an instructional designer might use them. As such, performance objectives are not related so much to the content as they are to the processes of construction.

구성주의자가 활용하는 구체적인 전략의 일부는 다음과 같다.

과제를 현실 세계의 상황에 situate시킨다,

인지적 도제 사용(전문가 성과에 대한 학생 모델링 및 지도)

다양한 관점 제시(대체 관점을 개발하고 공유하기 위한 협력적 학습)

사회적 협상(논의, 토론, 증거 제공)

"삶의 한 조각"과 같은 실제 사례 활용

성찰적 인식

구성주의적 프로세스의 사용에 대한 상당한 가이드 제공

Some of the specific strategies utilized by constructivists include

situating tasks in real world contexts,

use of cognitive apprenticeships (modeling and coaching a student toward expert performance),

presentation of multiple perspectives (collaborative learning to develop and share alternative views),

social negotiation (debate, discussion, evidence-giving),

use of examples as real “slices of life,”

reflective awareness, and

providing considerable guidance on the use of constructive processes.

다음은 구성주의자 입장에서 본 몇 가지 구체적인 가정이나 원칙이다.

the following are several specific assumptions or principles from the constructivist position

♦ 기술을 습득하고 그 후에 적용할 맥락의 식별에 대한 강조[의미있는 문맥으로 학습 집중]

♦ 학습자 통제와 학습자가 정보를 조작할 수 있는 능력에 대한 강조 [학습한 내용을 능동적으로 사용]

♦ 다양한 방법으로 정보를 제시할 필요성 [다양한 시간, 재배치된 상황, 다른 목적, 다른 개념적 관점 등].

♦ 학습자가 "주어진 정보 이상"으로 갈 수 있도록 하는 문제 해결 스킬의 활용 지원[패턴 인식 스킬을 개발하고, 문제를 표현하는 다른 방법을 제시한다].

♦ 지식과 기술의 전이에 초점을 맞춘 평가 [초기 지시 조건과 다른 새로운 문제와 상황 제시]

♦ An emphasis on the identification of the context in which the skills will be learned and subsequently applied [anchoring learning in meaningful contexts].

♦ An emphasis on learner control and the capability of the learner to manipulate information [actively using what is learned].

♦ the need for information to be presented in a variety of different ways [revisiting content at different times, in rearranged contexts, for different purposes, and from different conceptual perspectives].

♦ Supporting the use of problem solving skills that allow learners to go “beyond the information given” [developing pattern-recognition skills, presenting alternative ways of representing problems].

♦ Assessment focused on transfer of knowledge and skills [presenting new problems and situations that differ from the conditions of the initial instruction].

교육은 어떻게 구성되어야 하는가?

How should instruction be structured?

행동주의자-인지주의-구성주의 연속체를 따라 움직일 때, 가르침의 초점은 가르침에서 배움으로, 사실과 루틴의 수동적인 전달에서 문제에 대한 아이디어의 능동적인 적용으로 옮겨간다.

As one moves along the behaviorist—cognitivist—constructivist continuum, the focus of instruction shifts from teaching to learning, from the passive transfer of facts and routines to the active application of ideas to problems.

인식론자와 구성론자 모두 학습자가 학습 과정에 적극적으로 참여하는 것으로 간주하지만, 구성주의자는 학습자를 단순한 정보 처리자 이상의 능동적 프로세서로 본다. 학습자는 주어진 정보에 대해 상세히 설명하고 해석한다(Duff y & Jonassen, 1991). 의미는 학습자에 의해 만들어진다: 학습 목표는 미리 지정되지 않거나, 학습 목표가 미리 지정되지 않는다.

Both cognitivists and constructivists view the learner as being actively involved in the learning process, yet the constructivists look at the learner as more than just an active processor of information; the learner elaborates upon and interprets the given information (Duff y & Jonassen, 1991). Meaning is created by the learner: learning objectives are not pre-specified nor is instruction predesigned.

"구성주의자의 관점에 있어서의 가르침의 역할은

학생들에게 지식을 구성하는 방법을 보여주고,

다른 사람들과의 협력을 촉진하여 특정한 문제를 다룰 수 있는 여러 가지 관점을 보여주며,

자신이 동의하지 않는 다른 관점들의 토대를 인식하면서, 동시에 스스로 선택한 입장을 정하고, 거기에 헌신하도록 하는 것이다" (Cunningham, Cunningham).

“the role of instruction in the constructivist view is

to show students how to construct knowledge,

to promote collaboration with others to show the multiple perspectives that can be brought to bear on a particular problem, and

to arrive at self-chosen positions to which they can commit themselves, while realizing the basis of other views with which they may disagree” (Cunningham, 1991, p. 14).

학습자 구성에 중점을 두고 있음에도 불구하고, 교육 디자이너/교사의 역할은 여전히 중요하다(Reigeluth, 1989). 설계자의 과제는 두 가지로 구분된다.

(1) 학생들에게 의미 구성 방법과 이러한 구조를 효과적으로 모니터링, 평가 및 업데이트하는 방법을 가이드하는 것,

(2) 학습자를 위한 경험을 align하고 설계하여 authentic, relevant 맥락을 경험할 수 있도록 한다.

Even though the emphasis is on learner construction, the instructional designer/teacher’s role is still critical (Reigeluth, 1989). Here thetasks of the designer are two-fold:

(1) to instruct the student on how to construct meaning, as well as how to effectively monitor, evaluate, and update those constructions; and

(2) to align and design experiences for the learner so that authentic, relevant contexts can be experienced.

구성주의자의 손에 맡겨진 학생은 "도제" 경험에 몰입할 가능성이 높다.

a student placed in the hands of a constructivist would likely be immersed in an “apprenticeship” experience.

예를 들어, 요구 평가에 대해 배우기를 원하는 초보 교육 설계 학생은 그러한 평가가 완료되어야 하는 상황에 놓일 것이다.

실제 사례에 관련된 전문가의 모델링과 코칭을 통해, 초보 설계자는 실제 문제 상황의 진정한 맥락에 내재된 과정을 경험하게 된다.

시간이 지남에 따라 학생은 몇 가지 추가 상황을 경험하게 될 것이며, 이 모든 상황은 유사한 필요성 평가 능력을 필요로 한다.

각각의 경험은 이전에 경험하고 건설된 것을 기반으로 하고 적응하는 역할을 할 것이다.

그 학생이 더 많은 자신감과 경험을 얻었을 때, 그는 토론이 중요해지는 학습의 협력적인 단계로 나아갈 것이다.

다른 사람들(피어, 고급 학생, 교수, 디자이너)과 대화함으로써, 학생들은 필요성 평가 과정에 대한 그들 자신의 기준을 더 잘 표현할 수 있게 된다.

순진한 이론을 들추어내면서, 그들은 그러한 활동을 새로운 시각으로 보기 시작하는데, 이것이 그들을 개념적 리프레밍(학습)으로 인도한다.

학생들은 복잡한 상황에서 분석과 행동에 익숙해져 결과적으로 그들의 시야를 넓히기 시작한다.

관련 서적을 접하고, 컨퍼런스 및 세미나에 참석하며, 다른 학생들과 이슈를 논의하며, 지식을 활용하여 주변의 수많은 상황을 해석한다(특정 설계 문제뿐만 아니라).

초보에서 '예산 전문가'로 옮겨가면서 학습자가 서로 다른 유형의 학습에 관여했을 뿐 아니라 학습 과정의 성격도 달라졌다.

For example, a novice instructional design student who desires to learn about needs assessment would be placed in a situation that requires such an assessment to be completed. Through the modeling and coaching of experts involved in authentic cases, the novice designer would experience the process embedded in the true context of an actual problem situation. Over time, several additional situations would be experienced by the student, all requiring similar needs assessment abilities. Each experience would serve to build on and adapt that which has been previously experienced and constructed. As the student gained more confidence and experience, (s)he would move into a collaborative phase of learning where discussion becomes crucial. By talking with others (peers, advanced students, professors, and designers), students become better able to articulate their own under-standings of the needs assessment process. As they uncover their naive theories, they begin to see such activities in a new light, which guides them towards conceptual reframing (learning). Students gain familiarity with analysis and action in complex situations and consequently begin to expand their horizons. They encounter relevant books, attend conferences and seminars, discuss issues with other students, and use their knowledge to interpret numerous situations around them (not only related to specific design issues). Not only have the learners been involved in different types of learning as they moved from being novices to “bud-ding experts,” but the nature of the learning process has changed as well.

일반 고찰

General Discussion

이는 강사/설계자가 다음 두 가지 중요한 질문을 하도록 유도한다. 하나의 "최상의" 접근방식이 있고 한 접근방식이 다른 접근방식에 비해 더 효율적인가?

this leads instructors/designers to ask two significant questions: Is there a single “best” approach and is one approach more efficient than the others?

아마도 이 질문들에 대한 가장 좋은 대답은 "그때그때 다르다"이다. 학습은 많은 출처의 많은 요인에 의해 영향을 받기 때문에 학습 과정 자체는 진행됨에 따라 자연과 다양성 모두에서 끊임없이 변화하고 있다(Shueell, 1990).

perhaps the best answer to these questions is “it depends.” Because learning is influenced by many factors from many sources, the learning process itself is constantly changing, both in nature and diversity, as it progresses (Shuell, 1990).

[복잡한 지식의 본체를 처음 접하는 초보 학습자에게 가장 효과적일 수 있는 것]은 [내용에 더 친숙한 학습자]에게 효과적이고 효율적이거나 자극적이지 않을 것이다. 채택된 교육 전략과 (깊이 및 넓이 모두에서) 다루는 내용은 학습자의 수준에 따라 달라질 수 있다.

What might be most effective for novice learners encountering a complex body of knowledge for the first time, would not be effective, efficient or stimulating for a learner who is more familiar with the content. Both the instructional strategies employed and the content addressed (in both depth and breadth) would vary based on the level of the learners.

우선 주어진 내용에 더 익숙해짐에 따라 학습자의 지식이 어떻게 변하는지 생각해 보자. 사람들은 주어진 내용에 대해 더 많은 경험을 쌓을수록, 지식의 하위부터 상위까지 연속체를 따라 발달한다.

1) 직업의 표준 규칙, 사실 및 운영을 인식하고 적용할 수 있는 능력(knowing what)

2) 이러한 일반적인 규칙에서 구체적인, 문제가 있는 경우로 추론하기 위해 전문가처럼 생각하는 것(knowing how)

3) 익숙한 범주와 사고방식이 실패할 때 새로운 형태의 이해와 행동을 개발하고 시험하는 것(RIA) (Schon, 1987).

Consider, first of all, how learners’ knowledge changes as they become more familiar with a given content. As people acquire more experience with a given content, they progress along a low-to-high knowledge continuum from

1) being able to recognize and apply the standard rules, facts, and operations of a profession (knowing what), to

2) thinking like a professional to extrapolate from these general rules to particular, problematic cases (knowing how), to

3) developing and testing new forms of understanding and actions when familiar categories and ways of thinking fail (reflection-in-action) (Schon, 1987).

학습자가 자신의 직업적 지식의 발달(무엇을 알고 vs. 반성을 어떻게 하는지 아는 것) 측면에서 연속체에 "sit"한 위치에 따라, 가장 적절한 교육적 접근방식은 연속체에 대한 그 점에 해당하는 이론이 주장하는 것이 될 것이다. 그것은

행동 접근법: 직업의 내용을 효과적으로 숙지하도록 할 때(knowing what).

인지 전략: [정의된 사실과 규칙]을 낯선 상황에서 적용할 문제 해결 전략을 가르칠 때 (knowing how)

구성주의 전략: 특히 RIA를 통해 정의되지 않은 문제를 다룰 때

Depending on where the learners “sit” on the continuum in terms of the development of their professional knowledge (knowing what vs. knowing how vs. reflection-in-action), the most appropriate instructional approach would be the one advocated by the theory that corresponds to that point on the continuum. Th at is,

a behavioral approach can effectively facilitate mastery of the content of a profession (knowing what);

cognitive strategies are useful in teaching problem-solving tactics where defined facts and rules are applied in unfamiliar situations (knowing how); and

constructivist strategies are especially suited to dealing with ill-defined problems through reflection-in-action.

두 번째 고려사항은 학습해야 할 과제의 요건에 따라 달라진다. 필요한 인지 처리 수준에 근거하여, 다른 이론적 관점에서의 전략이 필요할 수 있다.

A second consideration depends upon the requirements of the task to be learned. Based on the level of cognitive processing required, strategies from different theoretical perspectives may be needed.

예를 들어

낮은 수준의 처리가 필요한 과제(예: 기본 쌍체 연관성, 차별성, 로트 암기)는 행동주의적 관점(예: 자극-반응, 피드백/강화)과 가장 빈번하게 관련된 전략에 의해 촉진되는 것으로 보인다.

For example, tasks requiring a low degree of processing (e.g., basic paired associations, discriminations, rote memorization) seem to be facilitated by strategies most frequently associated with a behavioral outlook (e.g., stimulus-response, contiguity of feedback/reinforcement).

Tasks requiring an increased level of processing (e.g., classifications, rule or procedural executions) are primarily associated with strategies having a stronger cognitive emphasis (e.g., schematic organization, analogical reasoning, algorithmic problem solving).

높은 수준의 처리를 요구하는 과제(예: 경험적 문제 해결, 개인 선택 및 인지 전략 모니터링)는 구성주의자의 관점(예: 위치 학습, 인지 견습, 사회적 협상)에 의해 진전된 전략을 통해 가장 잘 학습된다.

Tasks demanding high levels of processing (e.g., heuristic problem solving, personal selection and monitoring of cognitive strategies) are frequently best learned with strategies advanced by the constructivist perspective (e.g., situated learning, cognitive apprenticeships, social negotiation).

우리는 "어느 이론이 가장 좋은가?"가 아니라 "어떤 이론이 특정한 학습자들에 의한 특정 과제에 대한 숙달성을 육성하는데 가장 효과적인가?"라고 질문 설계자들이 질문해야 한다고 믿는다. 전략을 선택하기 전에 학습자와 과제를 모두 고려해야 한다.

We believe that the critical question instructional designers must ask is not “Which is the best theory?” but “Which theory is the most effective in fostering mastery of specific tasks by specific learners?” Prior to strategy(ies) selection, consideration must be made of both the learners and the task.

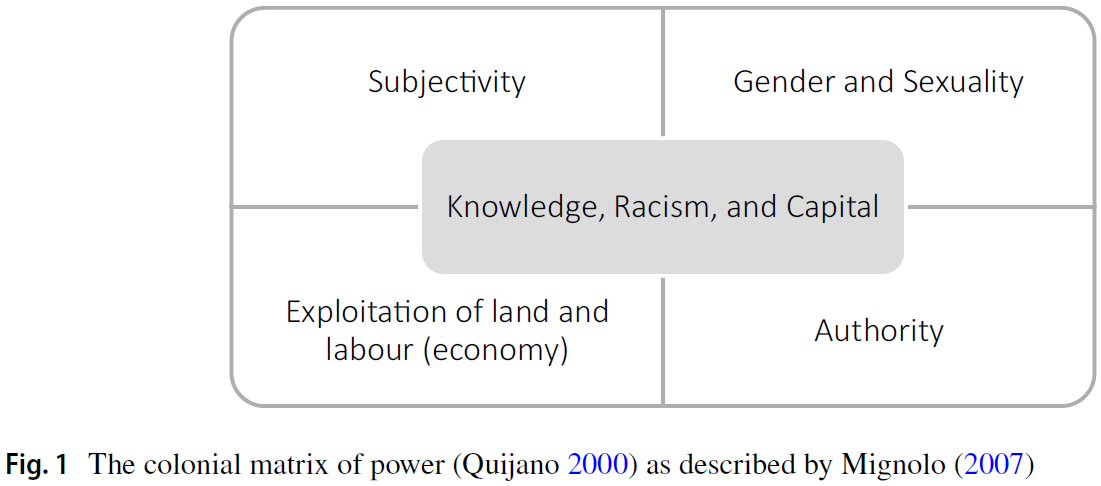

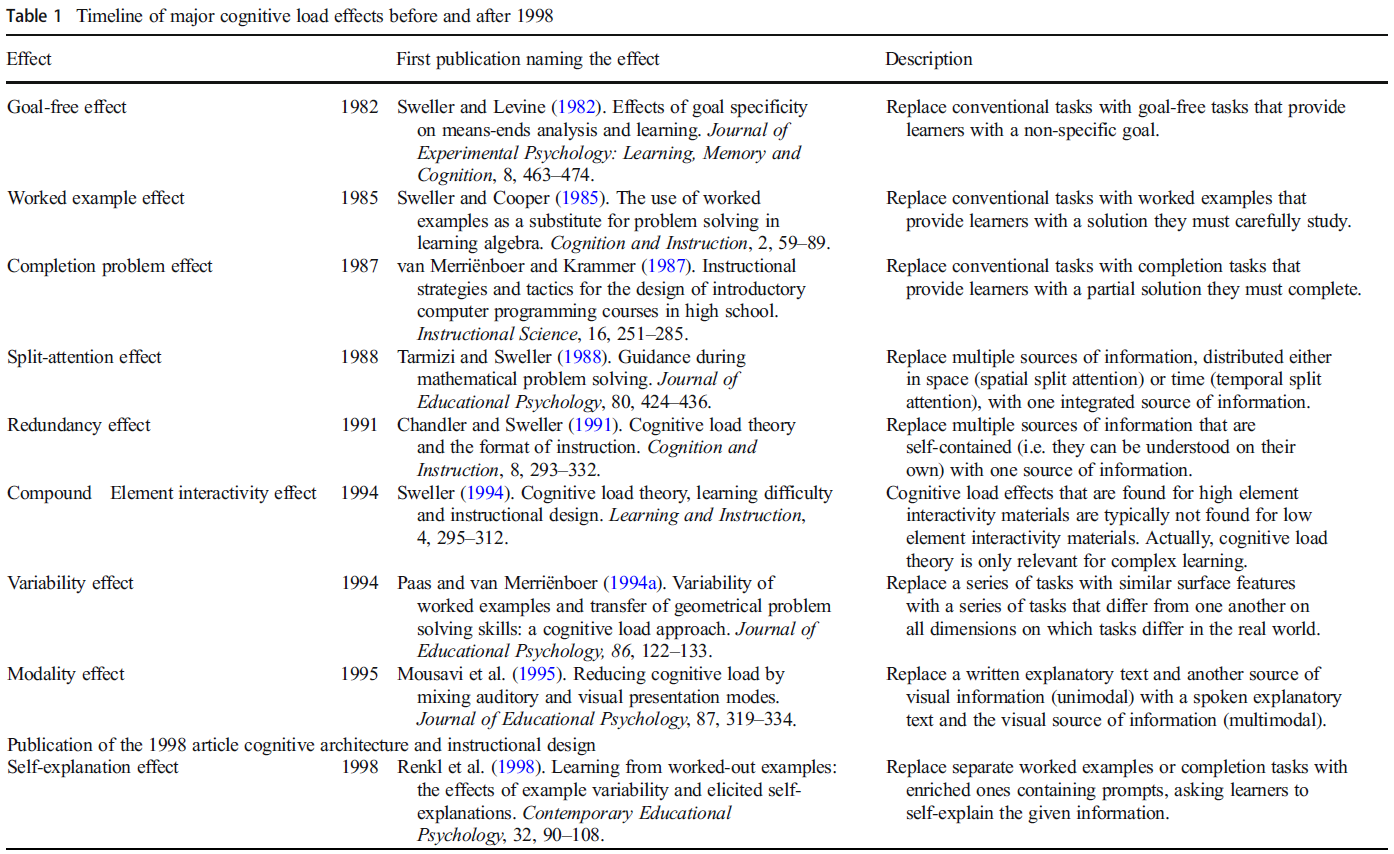

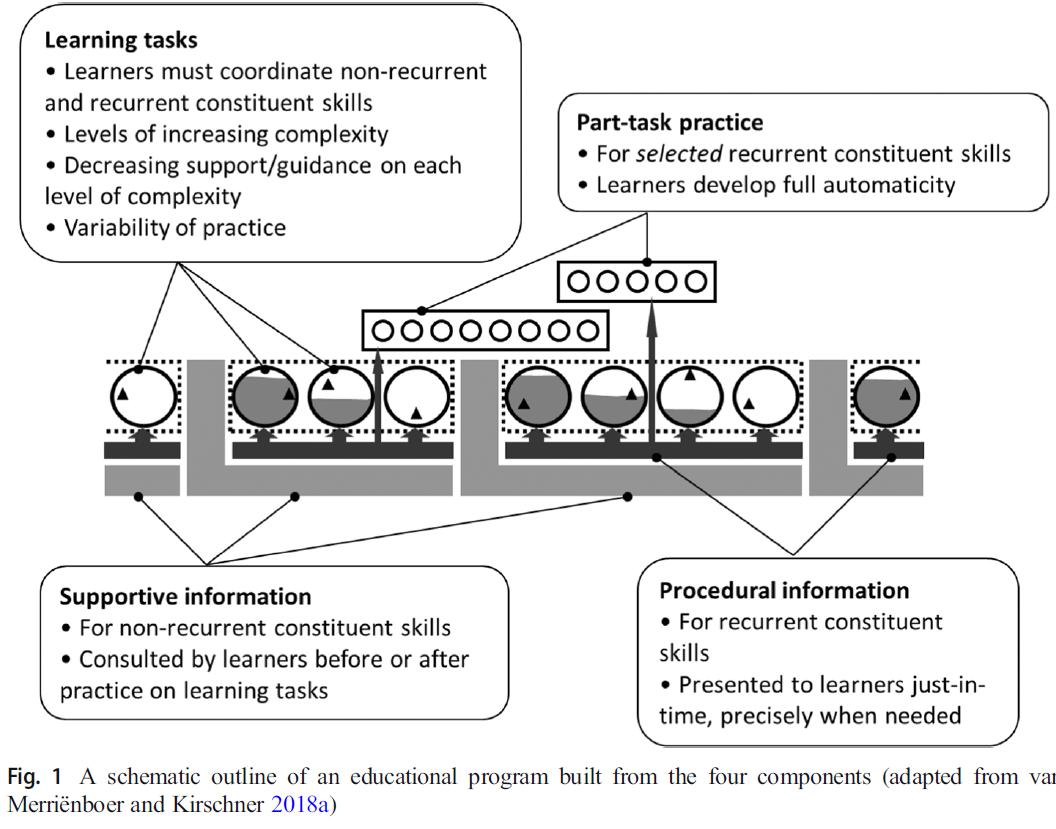

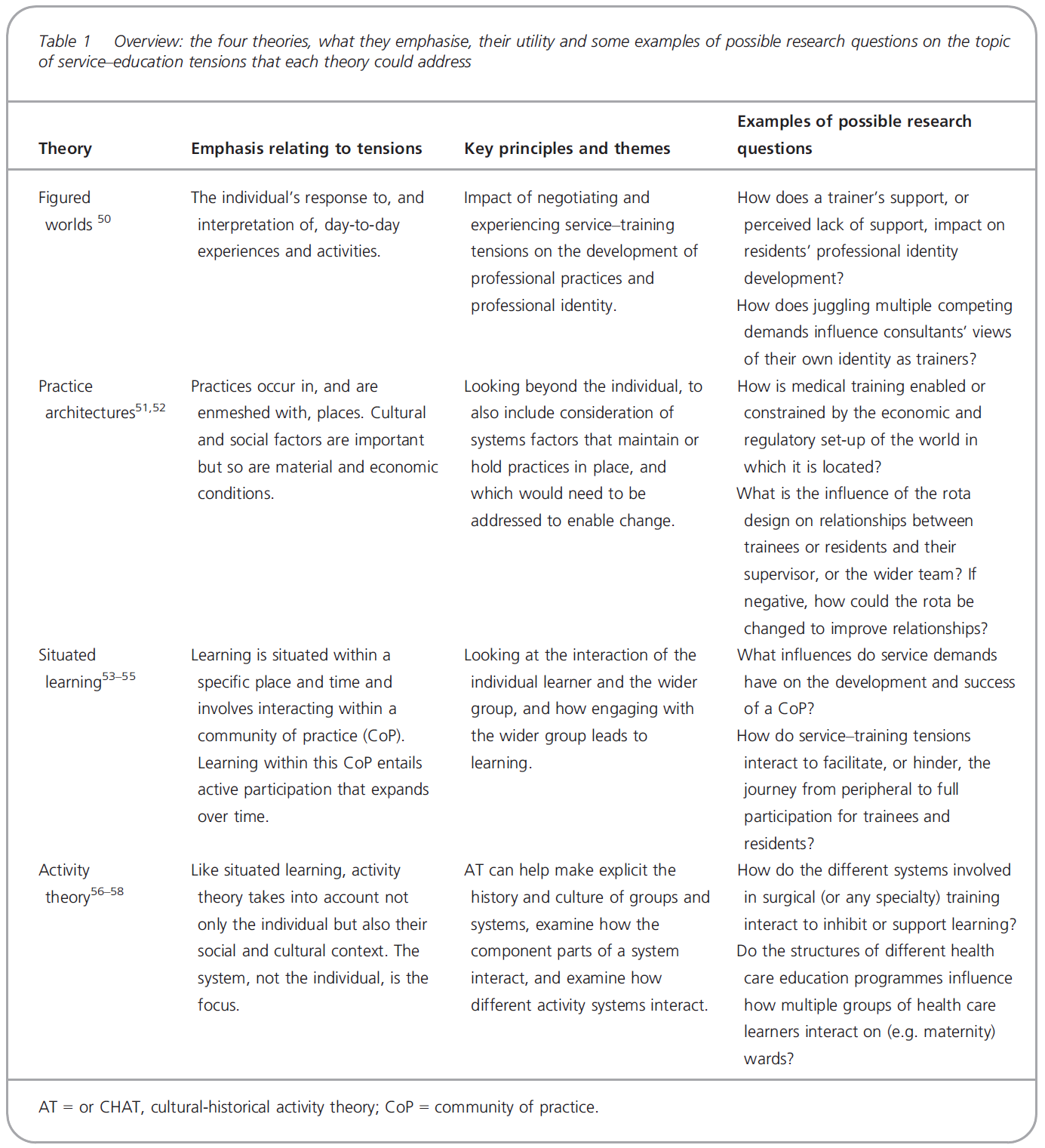

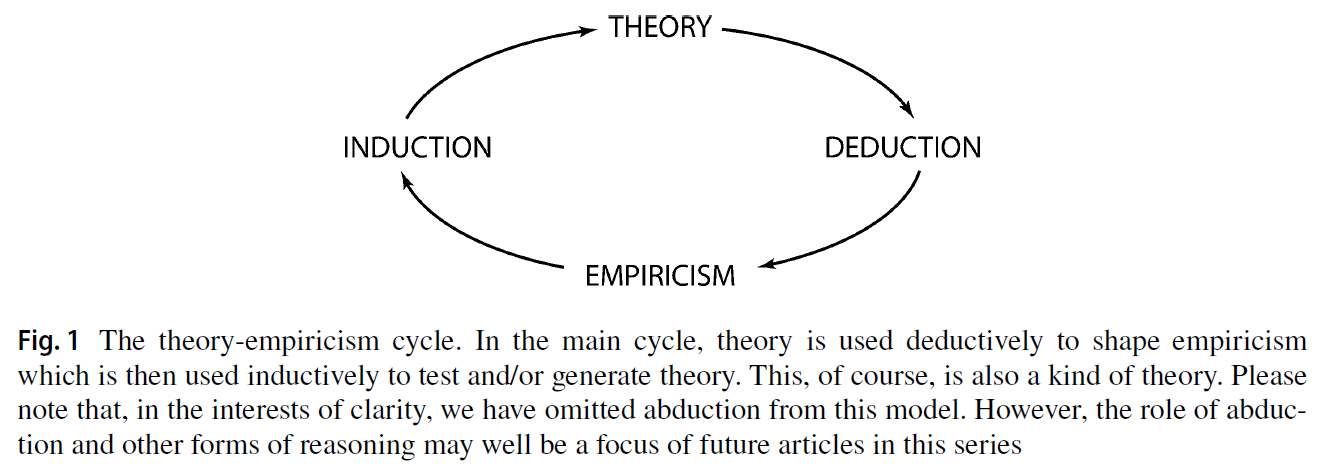

그림 1에서 이 두 연속체(학습자의 지식 수준 및 인지 처리 요구)를 묘사하고 각 이론적 관점에 의해 제공되는 전략이 적용 가능한 정도를 설명하려고 시도한다. 그림은 다음의 것을 보여준다.

An attempt is made in Figure 1 to depict these two continua (learners’ level of knowledge and cognitive processing demands) and to illustrate the degree to which strategies offered by each of the theoretical perspectives appear applicable. the figure is useful in demonstrating: (a) that the strategies promoted by the different perspectives overlap in certain instances , and (b) that strategies are concentrated along different points of the continua due to the unique focus of each of the learning theories.

이는 어떤 전략을 교육 설계 프로세스에 통합할 때, 한 접근방식을 다른 접근방식보다 선택하기 전에 학습 과제의 특성과 관련 학습자의 숙련도 수준을 모두 고려해야 한다는 것을 의미한다.

this means that when integrating any strategies into the instructional design process, the nature of the learning task and the proficiency level of the learners involved must both be considered before selecting one approach over another.

실제로 성공적인 교육 관행은 사실상 세 가지 관점(예: 적극적인 참여와 상호작용, 실천과 피드백)에 의해 뒷받침되는 특징을 가지고 있다.

In fact, successful instructional practices have features that are supported by virtually all three perspectives (e.g., active participation and interaction, practice and feedback).

이러한 이유로, 우리는 의식적으로 하나의 이론을 다른 이론보다 옹호하는 것이 아니라, 대신 각각의 이론에 익숙해지는 유용성을 강조하기로 결정했다. 그 상황에서 최적의 교육적 결과를 얻기 위한 적절한 방법을 지능적으로 선택할 수 있어야 한다.

For this reason, we have consciously chosen not to advocate one theory over the others, but to stress instead the usefulness of being wellversed in each. one must be able to intelligently choose, the appropriate methods for achieving optimal instructional outcomes in that situation.

Smith and Ragan(1993, p. Viiii)에 의해 언급된 바와 같이: "reasoned and validated 이론적 다양성은, [전체 설계 프로세스에 대해 완전한 규범적 원칙을 제공하는 단일 이론적 기반이 없기 때문에] 우리 분야의 핵심 강점이었습니다."

As stated by Smith and Ragan (1993, p. viii): “Reasoned and validated theoretical eclecticism has been a key strength of our field because no single theoretical base provides complete prescriptive principles for the entire design process.”

가장 중요한 설계 과제 중 일부는 어떤 전략을 사용할지, 어떤 내용을 사용할지, 어떤 학생을 위해 그리고 어떤 시점에 사용할지를 결정할 수 있어야 한다.

Some of the most crucial design tasks involve being able to decide which strategy to use, for what content, for which students, and at what point during the instruction.

그러나 각양각색의 이론이 되려면 결합되고 있는 이론에 대해 적지 않은 것을 알아야 한다. 위에 제시된 학습 이론에 대한 철저한 이해는 어떤 설계 모델도 정확한 규칙을 제공하지 않는 결정을 지속적으로 내려야 하는 전문 설계자들에게 필수적인 것으로 보인다.

It should be noted however, that to be an eclectic, one must know a lot, not a little, about the theories being combined. A thorough understanding of the learning theories presented above seems to be essential for professional designers who must constantly make decisions for which no design model provides precise rules.

실무자는 실제적인 의미를 제공할 수 있는 어떤 이론도 무시할 수 없다. 수많은 잠재적 설계 상황을 고려할 때, 설계자의 "최상의" 접근방식은 이전 접근방식과 동일하지 않을 수 있지만, 진정으로 "맥락에 따라 달라지게 될 것이다. 이러한 유형의 교육적 "체리피킹"는 "체계적 다양성주의"라고 불리며, 교육적 설계 문헌에서 많은 지지를 받았다(Snelbecker, 1989).

the practitioner cannot afford to ignore any theories that might provide practical implications. Given the myriad of potential design situations, the designer’s “best” approach may not ever be identical to any previous approach, but will truly “depend upon the context.” this type of instructional “cherry-picking” has been termed “systematic eclecticism” and has had a great deal of support in the instructional design literature (Snelbecker, 1989).

마지막으로, 우리는 P. B. Drucker의 인용구를 확장하고 싶다. (Snelbecker, 1983년 Snelbecker에 인용) "이들의 오래된 논쟁은 내내 거짓이었습니다.

우리는 학습과 기억을 확대하기 위해 행동주의자의 3가지 연습/강화/피드백을 필요로 한다.

우리는 목적, 결정, 가치, 이해가 필요하다(인지적 카테고리). 학습이 행동action보다는 단순한 behavioral activity이면 안되기 때문이다." (p. 203)

In closing, we would like to expand on a quote by P. B. Drucker, (cited in Snelbecker, 1983): “these old controversies have been phonies all along. We need the behaviorist’s triad of practice/reinforcement/feedback to enlarge learning and memory. We need purpose, decision, values, understanding—the cognitive categories—lest learning be mere behavioral activities rather than action” (p. 203).

그리고 여기에 우리는

최적의 조건이 존재하지 않을 때, 상황이 예측 불가능할 때, 그리고 과제가 변화할 때, 문제가 지저분하고 잘못된 형태일 때, 그리고 해결책이 창의성, 즉흥성, 토론, 사회적 협상에 달려 있을 때, 잘 기능할 수 있는 적응적 학습자가 필요하다는 것을 덧붙일 것이다.

And to this we would add that we also need adaptive learners who are able to function well when optimal conditions do not exist, when situations are unpredictable and task demands change, when the problems are messy and ill-formed and the solutions depend on inventiveness, improvisation, discussion, and social negotiation.

Abstract

The way we define learning and what we believe about the way learning occurs has important implications for situations in which we want to facilitate changes in what people know and/or do. Learning theories provide instructional designers with verified instructional strategies and techniques for facilitating learning as well as a foundation for intelligent strategy selection. Yet many designers are operating under the constraints of a limited theoretical background. This paper is an attempt to familiarize designers with three relevant positions on learning (behavioral, cognitive, and constructivist) which provide structured foundations for planning and conducting instructional design activities. Each learning perspective is discussed in terms of its specific interpretation of the learning process and the resulting implications for instructional designers and educational practitioners. The information presented here provides the reader with a comparison of these three different viewpoints and illustrates how these differences might be translated into practical applications in instructional situations.