형성적 피드백(Formative Feedback) (Review of Educational Research, 2008)

Focus on Formative Feedback (Review of Educational Research, 2008)

Valerie J. Shute

Florida State University

It is not the horse that draws the cart, but the oats. —Russian proverb

교육적 맥락에서 사용 된 피드백은 일반적으로 지식과 기술 습득을 향상시키는 데 결정적인 역할을한다 (예, Azevedo & Bernard 1995, Bangert-Drowns, Kulik, Kulik, & Morgan, 1991, Corbett & Anderson, 1989; Epstein et al. , 2002, Moreno, 2004, Pridemore & Klein, 1995). 성취에 미치는 영향 외에도 피드백은 학습 동기 부여에 중요한 요소로 묘사됩니다 (예 : Lepper & Chabay, 1985; Narciss & Huth, 2004). 그러나 학습을 위해서는 피드백에 관한 이야기가 너무 장밋빛 또는 단순하지 않습니다.

Feedback used in educational contexts is generally regarded as crucial to improv- ing knowledge and skill acquisition (e.g., Azevedo & Bernard, 1995; Bangert- Drowns, Kulik, Kulik, & Morgan, 1991; Corbett & Anderson, 1989; Epstein et al., 2002; Moreno, 2004; Pridemore & Klein, 1995). In addition to its influence on achievement, feedback is also depicted as a significant factor in motivating learn- ing (e.g., Lepper & Chabay, 1985; Narciss & Huth, 2004). However, for learning, the story on feedback is not quite so rosy or simple.

Cohen (1985)의 의견에 따르면 피드백은 "교육 설계에서 교육적으로 강력하지만, 가장 덜 이해되어있는 특성 중 하나입니다"(33 쪽). 수백 가지의 연구 보고서가 피드백의 주제에 관해 발표되었습니다.

According to Cohen (1985) feedback “is one of the more instructionally pow- erful and least understood features in instructional design” (p. 33). the hundreds of research studies published on the topic of feed- back

이러한 피드백 연구의 큰 범위 내에서 많은 결과가 상충하며 일관된 결과 패턴이 존재하지 않습니다.

Within this large body of feedback research, there are many conflict- ing findings and no consistent pattern of results.

형성적 피드백의 정의

Definition of Formative Feedback

형성 피드백은이 리뷰에서 학습 향상을 목적으로 자신의 생각이나 행동을 수정하려는 의도로 학습자에게 전달 된 정보로 정의됩니다.

Formative feedback is defined in this review as information communicated to the learner that is intended to modify his or her thinking or behavior for the pur- pose of improving learning.

이 분야에서 수행 된 대부분의 연구의 전제는 올바른 피드백이 학습 과정과 결과를 올바르게 개선 할 수 있다는 것입니다. 마지막 3 단어 - "올바르게 전달 된 경우"-이 검토의 요점을 구성합니다.

The premise underlying most of the research conducted in this area is that good feedback can significantly improve learning processes and outcomes, if delivered correctly. Those last three words—“if delivered correctly”—constitute the crux of this review.

Goals and Focus

이 글의 두 가지 목적은 (a) 특징, 기능, 상호 작용 및 학습에 대한 링크를 더 잘 이해하기 위해 피드백에 대한 광범위한 문헌 검토 결과를 제시하고 (b) 문헌 검토에서 발견 한 결과를 적용하는 것이다 형성 피드백과 관련된 일련의 가이드 라인을 작성합니다.

The dual aims of this article are to (a) present findings from an extensive liter- ature review of feedback to gain a better understanding of the features, functions, interactions, and links to learning and (b) apply the findings from the literature review to create a set of guidelines relating to formative feedback.

이 리뷰는 일반적인 요약 피드백과는 달리 작업 수준 피드백(task-level feedback)에 중점을 둡니다. 과제 수준 피드백은 일반적으로 학생들에게 문제에 대한 특정 대응에 대한보다 구체적이고 시기 적절한 (때로는 실시간) 정보를 요약 피드백과 비교하여 제공하며 학생의 현재 이해력 및 능력 수준을 추가로 고려할 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, Struggling student는 숙련 된 학생과 비교하여 형성피드백에서 더 큰 지지와 구조를 요구할 수 있습니다

This review focuses on task-level feedback as opposed to general summary feedback. Task-level feedback typically provides more specific and timely (often real-time) information to the student about a particular response to a problem or task compared to summary feedback and may additionally take into account the student’s current understanding and ability level. For instance, a struggling student may require greater support and structure from a formative feedback message com- pared to a proficient student.

방법

Method

절차

Procedure

Seminal articles in the feedback literature were identified (i.e., from sites that provide indices of importance such as CiteSeer), and then collected. The bibliog- raphy compiled from this initial set of research studies spawned a new collection- review cycle, garnering even more articles, and continuing iteratively throughout the review process.

포함 기준

Inclusion Criteria

The focus of the search was to access full-text documents using various search terms or keywords such as feedback, formative feedback, formative assessment, instruction, learning, computer-assisted/based, tutor, learning, and performance.

문헌 고찰

Literature Review

이 주제에 관한 많은 연구에도 불구하고, 학습에 피드백을 관련시키는 특정 메커니즘은 여전히 거의 없고, (매우 소수의) 일반적인 결론이 있더라도 대부분 애매하다. 피드백 데이터에 대한 메타 분석을 수행하는 어려운 과제를 해결 한 연구원은 피드백 결과를 설명하기 위해 "일관적이지 못한", "모순 된", "매우 가변적 인" 이라고 묘사한다 (Azevedo & Bernard, 1995, Kluger & DeNisi , 1996). 10 년 후 그 기술 어는 여전히 적용됩니다.

Despite the plethora of research on the topic, the specific mechanisms relating feedback to learning are still mostly murky, with very few (if any) general conclusions. Researchers who have tackled the tough task of performing meta-analyses on the feedback data use descriptors such as “inconsistent,” “contradictory,” and “highly variable” to describe the body of feedback findings (Azevedo & Bernard, 1995; Kluger & DeNisi, 1996). Ten years later those descriptors still apply.

피드백은 학습과 수행의 중요한 촉진자로 널리 인용되었지만, 몇몇 연구에서 피드백이 학습에 영향을 미치지 않거나 쇠약하게 만드는 영향을 미친다 고보고했다

Feedback has been widely cited as an important facilitator of learning and per- formance but quite a few studies have reported that feedback has either no effect or debilitating effects on learning

예를 들어, 비판적critical이거나 통제하는controlling 것으로 간주되는 피드백 (Baron, 1993)은 종종 성과를 향상시키기위한 노력을 좌절시킨다 (Fedor, Davis, Maslyn, & Mathieson, 2001). 학습을 방해하는 피드백의 또 다른 특징은 다음과 같다 :

-

동료들에 대한 학생의 입장을 나타내는 점수 또는 전반적인 점수를 제공하고

-

그러한 규범적 피드백을 낮은수준의 특이성 (즉, 모호함)과 결합 시킴 (Butler, 1987; Kluger & DeNisi, 1998; McColskey & Leary, 1985; Wiliam, 2007, Williams, 1997).

For instance, feedback that is con- strued as critical or controlling (Baron, 1993) often thwarts efforts to improve performance (Fedor, Davis, Maslyn, & Mathieson, 2001). Other features of feed- back that tend to impede learning include:

-

providing grades or overall scores indi- cating the student’s standing relative to peers, and

-

coupling such normative feedback with low levels of specificity (i.e., vagueness) (Butler, 1987; Kluger & DeNisi, 1998; McColskey & Leary, 1985; Wiliam, 2007; Williams, 1997).

이 검토의 정의에 따르면 학습에 부정적인 영향을 미치는 피드백은 형성 적이지 않습니다.

In line with the definition in this review, feedback that has negative effects on learning is not formative.

피드백 목적

Feedback Purposes

다양한 형식의 피드백 외에도 다양한 기능이 있습니다. Black and Wiliam (1998)에 따르면 피드백의 두 가지 주요 기능이있다 : 지시directive 및 촉진facilitative.

In addition to vari- ous formats of feedback, there are different functions. According to Black and Wiliam (1998), there are two main functions of feedback: directive and facilita- tive. Directive feedback is that which tells the student what needs to be fixed or revised. Such feedback tends to be more specific compared to facilitative feedback, which provides comments and suggestions to help guide students in their own revi- sion and conceptualization.

인지 메커니즘과 형성적 피드백

Cognitive Mechanisms and Formative Feedback

형성적인 피드백을 학습자가 사용할 수 있는 몇 가지 인지 메커니즘이 있습니다.

There are several cognitive mechanisms by which formative feedback may be used by a learner.

첫째, 현재 performance 수준과 원하는 수준의 performance 또는 목표 사이의 차이를 나타낼 수 있습니다. 이러한 격차를 해소하면보다 높은 수준의 노력을 위한 동기부여가 될 수있다 (Locke & Latham, 1990; Song & Keller, 2001). 즉, 형성적 피드백은 학생이 과제 수행 능력 (또는 저조한 정도)에 대한 불확실성을 줄일 수있다 (Ashford, 1986; Ashford, Blatt, & VandeWalle, 2003). 불확실성은 그것을 줄이거 나 감당하기위한 전략에 동기를 부여하는 혐오적인 상태이다 (Bordia, Hobman, Jones, Gallois, and Callan, 2004). 불확실성은 종종 불쾌감을 느끼고 업무 성과에서주의를 산만하게하기 때문에 (Kanfer & Ackerman, 1989) 불확실성을 줄이면 더 높은 동기와 더 효율적인 업무 전략으로 이어질 수 있습니다.

First, it can signal a gap between a current level of performance and some desired level of performance or goal. Resolving this gap can motivate higher levels of effort (Locke & Latham, 1990; Song & Keller, 2001). That is, for- mative feedback can reduce uncertainty about how well (or poorly) the student is performing on a task (Ashford, 1986; Ashford, Blatt, & VandeWalle, 2003). Uncertainty is an aversive state that motivates strategies aimed at reducing or man- aging it (Bordia, Hobman, Jones, Gallois, & Callan, 2004). Because uncertainty is often unpleasant and may distract attention away from task performance (Kanfer & Ackerman, 1989), reducing uncertainty may lead to higher motivation and more efficient task strategies.

둘째, 형성 피드백은 학습자, 특히 초보자 또는 고생하는 학생들의 인지적 부하를 효과적으로 줄일 수 있습니다 (예 : Paas, Renkl, & Sweller, 2003; Sweller, Van Merriënboer, & Paas, 1998). 이러한 학생들은 고성능 요구로 인해 학습 중에 압도적으로 압도 될 수 있으므로 인지부하를 줄이기 위해 고안된 supportive 피드백의 이점을 누릴 수 있습니다.

Second, formative feedback can effectively reduce the cognitive load of a learner, especially novice or struggling students (e.g., Paas, Renkl, & Sweller, 2003; Sweller, Van Merriënboer, & Paas, 1998). These students can become cog- nitively overwhelmed during learning due to high performance demands and thus may benefit from supportive feedback designed to decrease the cognitive load.

마지막으로, 피드백은 부적절한 task strategies, 절차상의 오류 또는 오해를 교정하는 데 유용한 정보를 제공 할 수 있습니다 (예 : Ilgen et al., 1979; Mason & Bruning, 2001; Mory, 2004; Narciss & Huth, 2004). 수정 기능 효과는보다 구체적인 피드백에 대해 특히 강력 해 보인다 (Baron, 1988; Goldstein, Emanuel, & Howell, 1968).

Finally, feedback can provide information that may be useful for correcting inappropriate task strategies, procedural errors, or misconceptions (e.g., Ilgen et al., 1979; Mason & Bruning, 2001; Mory, 2004; Narciss & Huth, 2004). The corrective function effects appear to be especially powerful for feedback that is more specific (Baron, 1988; Goldstein, Emanuel, & Howell, 1968),

피드백 구체성

Feedback Specificity

피드백 특이성(Feedback specificity)은 피드백 메시지에 제시된 정보의 레벨로 정의된다 (Goodman, Wood, & Hendrickx, 2004). 즉, 특정 (또는 정교한) 피드백은 특정 응답이나 행동에 대한 정보를 정확도를 넘어 제공하며 촉진적facilitative이기보다는 지시적directive입니다.

Feedback specificity is defined as the level of information presented in feedback messages (Goodman, Wood, & Hendrickx, 2004). In other words, specific (or elaborated) feedback provides information about particular responses or behaviors beyond their accuracy and tends to be more directive than facilitative.

몇몇 연구자들은 학생들의 작업이 올바른지 아닌지를 나타내는 것보다는 답변을 개선하는 방법에 대한 세부 정보를 제공 할 때 피드백이 훨씬 더 효과적이라고보고했습니다 (예 : Bangert-Drowns et al., 1991; Pridemore & Klein, 1995) . 특이성이 결여 된 피드백은 학생들로 하여금 쓸데없는 것, 좌절하는 것, 또는 둘 다로 보게 할 수도 있습니다 (Williams, 1997). 또한 피드백에 어떻게 반응 할 것인가에 대한 불확실성을 야기 할 수 있고 (Fedor, 1991) 의도 된 메시지를 이해하기 위해 학습자가 더 많은 정보 처리 활동을 요구할 수있다 (Bangert-Drowns et al., 1991). 불확실성과인지 부하는 학습 수준을 낮추고 (Kluger & DeNisi, 1996; Sweller et al., 1998), 피드백에 대해 반응respond하려는 동기를 감소시킬 수도있다 (Ashford, 1986, Corno & Snow, 1986).

Several researchers have reported that feedback is significantly more effective when it provides details of how to improve the answer rather than just indicating whether the student’s work is correct or not (e.g., Bangert-Drowns et al., 1991; Pridemore & Klein, 1995). Feedback lacking in specificity may cause students to view it as useless, frustrating, or both (Williams, 1997). It can also lead to uncer- tainty about how to respond to the feedback (Fedor, 1991) and may require greater information-processing activity on the part of the learner to understand the intended message (Bangert-Drowns et al., 1991). Uncertainty and cognitive load can lead to lower levels of learning (Kluger & DeNisi, 1996; Sweller et al., 1998) or even reduced motivation to respond to the feedback (Ashford, 1986; Corno & Snow, 1986).

요약하면, 개념적이고conceptual 절차적인procedural 학습 작업에 대해, 명확하고 명확한 피드백을 제공하는 것이 합리적이고 일반적인 지침입니다. 그러나 이는 학습자의 특성 (예 : 능력 수준, 동기 부여) 및 학습 결과 (예 : 보존 및 전송 작업)와 같은 다른 변수에 따라 달라질 수 있습니다. 또한, 형성 피드백 자체의 특이성 차원은 문헌에서 기술 된 바와 같이 그다지 "특이 적이 지 않다".

In summary, providing feedback that is specific and clear, for conceptual and procedural learning tasks, is a reasonable, general guideline. However, this may depend on other variables, such as learner characteristics (e.g., ability level, moti- vation) and different learning outcomes (e.g., retention vs. transfer tasks). In addi- tion, the specificity dimension of formative feedback itself is not very “specific” as described in the literature.

형성적 피드백의 특징

Features of Formative Feedback

피드백에 대한 훌륭한 역사적 검토에서 Kulhavy and Stock (1989)는 효과적인 피드백이 학습자에게 두 가지 유형의 정보 (검증 및 정교화)를 제공한다고보고했습니다.

-

검증: 대답이 정확한지,

-

정교화: 메시지의 정보적 측면

...에 대한 간단한 판단으로 정의되며, 정확한 답을 얻기 위해 학습자를 안내하는 관련 단서를 제공합니다. 연구원은 효과적인 피드백은 검증과 정교화의 요소를 모두 포함해야 한다는 견해로 수렴하는 것처럼 보인다 (예 : Bangert-Drowns et al., 1991; Mason & Bruning, 2001).

In an excellent historical review on feedback, Kulhavy and Stock (1989) reported that effective feedback provides the learner with two types of information: verifi- cation and elaboration. Verification is defined as the simple judgment of whether an answer is correct, and elaboration is the informational aspect of the message, pro- viding relevant cues to guide the learner toward a correct answer. Researchers appear to be converging toward the view that effective feedback should include ele- ments of both verification and elaboration (e.g., Bangert-Drowns et al., 1991; Mason & Bruning, 2001).

확인 Verification

가장 일반적인 방법은 간단히 "정확함"또는 "부정확함"을 말합니다.보다 유익한 옵션이 있습니다

The most common way involves simply stating “correct” or “incor-rect.” More informative options exist

명시적 검증 중에서 응답 정확도를 나타 내기 위해 응답을 강조 표시하거나 마킹하면 (예 : 체크 표시와 함께) 정보를 전달할 수 있습니다. 암시 적 검증은 예를 들어 학생의 응답이 예기치 않은 결과 (예 : 시뮬레이션 내)를 초래할 때 발생할 수 있습니다.

Among explicit verifications, highlighting or otherwise marking a response to indicate its correctness (e.g., with a checkmark) can convey the infor- mation. Implicit verification can occur when, for instance, a student’s response yields expected or unexpected results (e.g., within a simulation).

정교화 Elaboration

피드백 정교화는 검증보다 훨씬 다양합니다. 예를 들어 (a) 주제를 다룰 때, (b) 응답을 할 때, (c) 특정 오류를 토론 할 때, (d) 예제를 제공 할 때, (e) 온화한 안내를 할 수 있습니다.

Feedback elaboration has even more variations than verification. For instance, elaboration can (a) address the topic, (b) address the response, (c) discuss the par- ticular error(s), (d) provide worked examples, or (e) give gentle guidance.

정교한 피드백(Elaborated feedback)은 일반적으로 정답을 다루고, 선택된 응답이 왜 틀린 지 설명 할 수 있으며, 정답이 무엇인지 나타낼 수 있습니다. 한 가지 유형의 정교화, 즉 반응-관련 피드백이 단순한 검증이나 "정확한 때까지의 대답"과 같은 다른 유형의 피드백보다 학생들의 성취, 특히 학습 효율성을 향상시키는 것처럼 보입니다 (예 : Corbett & Anderson , 2001, Gilman, 1969, Mory, 2004, Shute, Hansen, & Almond, 2007).

Elaborated feedback usually addresses the correct answer, may explain why the selected response is wrong, and may indicate what the correct answer should be. There seems to be growing consensus that one type of elaboration, response- specific feedback, appears to enhance student achievement, particularly learning efficiency, more than other types of feedback, such as simple verification or “answer until correct” (e.g., Corbett & Anderson, 2001; Gilman, 1969; Mory, 2004; Shute, Hansen, & Almond, 2007).

피드백의 복잡성과 길이

Feedback Complexity and Length

특정 피드백 하에서보다 구체적인 피드백이 일반적으로 덜 구체적인 피드백보다 좋을지라도 고려해야 할 관련 차원은 정보의 길이 또는 복잡성입니다. 예를 들어, 피드백이 너무 길거나 너무 복잡하면 많은 학습자가 주의를 기울이지 않아 사용하지 않게됩니다. 긴 피드백은 또한 메시지를 확산 시키거나 희석시킬 수 있습니다.

Although more specific feedback may be generally better than less specific feedback (at least under certain conditions), a related dimension to consider is length or complexity of the information. For example, if feedback is too long or too complicated, many learners will simply not pay attention to it, rendering it use- less. Lengthy feedback can also diffuse or dilute the message.

많은 연구 논문들이 피드백 복잡성에 대해 다루었지만 복잡성의 차원에서 주요 변수를 배열하려고 시도한 것은 소수다 (Dempsey, Driscoll, & Swindell, 1993; Mason & Bruning, 2001; Narciss & Huth, 2004). 각 목록의 정보를 하나의 컴파일로 집계했습니다 (표 1 참조).

Many research articles have addressed feedback complexity, but only a few have attempted to array the major variables along a dimension of complexity (albeit, see Dempsey, Driscoll, & Swindell, 1993; Mason & Bruning, 2001; Narciss & Huth, 2004). I have aggregated information from their respective lists into a single compilation (see Table 1),

형성적 피드백이 교정 기능을 제공하는 것이라면 가장 단순한 형태로도 (a) 학생의 대답이 옳은지 또는 틀린지를 확인하고 (b) 정확한 응답 (지시 또는 촉진)에 대한 정보를 학습자에게 제공해야합니다. .

If formative feedback is to serve a corrective function, even in its simplest form it should (a) verify whether the student’s answer is right or wrong and (b) provide information to the learner about the correct response (either directive or facilita- tive).

피드백 복잡성은 영향이 없다

No Effect of Feedback Complexity

정보의 양(=피드백 복잡성)은 피드백 효과와 유의한 관계가 없다.

Schimmel (1983) found that the amount of information (i.e., feedback complexity) was not significantly related to feedback effects.

TABLE 1 Feedback types arrayed loosely by complexity

피드백 복잡성의 부정적 영향

Negative Effects of Feedback Complexity

피드백 복잡성은 다양했습니다. 가장 낮은 수준은 단순히 정답이었으며, 가장 복잡한 피드백에는 검증, 정답 및 해답이 잘못 된 텍스트 통로의 관련 부분에 대한 포인터가 잘못된 이유에 대한 설명이 포함되었습니다. .

Feedback complexity was systematically varied. The lowest level was simply correct answer feedback, and the most complex feedback included a com- bination of verification, correct answer, and an explanation about why the incorrect answer was wrong with a pointer to the relevant part of the text passage where the answer resided.

요약하면, 피드백 복잡성에 대한 inconclusive한 발견은 형식적 피드백과 학습 간의 관계에 관련된 다른 중개 요인이있을 수 있음을 시사한다. 예를 들어, 피드백 복잡성보다 피드백의 더 중요한 측면은 학습 목표에 관한 정보 제공과 이를 달성하는 방법과 같은 컨텐츠의 특성과 품질 일 수 있습니다.

In summary, the inconclusive findings on feedback complexity suggest that there may be other mediating factors involved in the relationship between forma- tive feedback and learning. For instance, instead of feedback complexity, a more salient facet of feedback may be the nature and quality of the content, such as pro- viding information about learning goals and how to attain them.

목표-지향적 피드백과 동기부여

Goal-Directed Feedback and Motivation

목표 지향 피드백은 개별 응답 (즉, 개별 작업에 대한 응답)에 대한 피드백을 제공하기보다는 학습자가 원하는 목표 (또는 목표 집합)에 대한 진행 상황에 대한 정보를 제공합니다. 연구 결과에 따르면 학습자가 동기를 부여 받고 참여하게하려면 학습자의 목표와 이러한 목표를 달성 할 수 있다는 자신의 기대치가 밀접하게 일치해야 합니다 (Fisher & Ford, 1998, Ford, Smith, Weissbein, Gully, & Salas, 1998). 목표를 달성 할 수 없을 정도로 높게 설정하면 학습자는 실패를 경험하고 낙담하게됩니다. 목표가 너무 낮아 달성이 확실하지 않을 경우 성공은 더 많은 노력을 촉진 할 수있는 힘을 잃습니다 (Birney, Burdick, & Teevan, 1969).

Goal-directed feedback provides learners with information about their progress toward a desired goal (or set of goals) rather than providing feedback on discrete responses (i.e., responses to individual tasks). Research has shown that for a learner to remain motivated and engaged depends on a close match between a learner’s goals and his or her expectations that these goals can be met (Fisher & Ford, 1998; Ford, Smith, Weissbein, Gully, & Salas, 1998). If goals are set so high that they are unattainable, the learner will likely experience failure and become discouraged. When goals are set so low that their attainment is certain, success loses its power to promote further effort (Birney, Burdick, & Teevan, 1969).

Malone (1981)에 따르면 학습자가 목표를 달성하는 데 필요한 몇 가지 특징이 있습니다. 예를 들어, 목표는 개인적으로 의미 있고 쉽게 생성되어야하며 학습자는 목표 달성 여부에 관한 성과 피드백을 받아야합니다. Hoska (1993)는 목표를 두 가지 유형, 즉

According to Malone (1981), there are certain features that goals must have to make them challenging for the learner. For example, goals must be personally meaningful and easily generated, and the learner must receive performance feed- back about whether the goals are being attained. Hoska (1993) classified goals as being of two types: acquisition (i.e., to help the learner acquire something desirable) and avoidance (i.e., to help the learner avoid something undesirable).

동기 부여는 학습자의 성취에 중요한 중재 요소로 나타 났으며 (Covington & Omelich, 1984), 피드백은 목표 중심의 노력에 응답하여 전달 될 때 강력한 동기가 될 수 있습니다.

Motivation has been shown to be an important mediating factor in learners’ per- formance (Covington & Omelich, 1984), and feedback can be a powerful motiva- tor when delivered in response to goal-driven efforts.

목표-지향성은 사람들이 다른 종류의 목표를 향해 노력하도록 동기 부여되는 방식을 설명합니다. 개인은 과제에 대해 학습learning 또는 성과performance 지향적 태도를 취하는 것으로 생각합니다 (예 : Dweck, 1986).

-

learning orientation 은 새로운 기술을 개발하고 지능은 가단성이 있다는 신념을 바탕으로 새로운 상황을 마스터함으로써 자신의 능력을 향상시키려는 욕망을 특징으로합니다.

-

performance orientation은 자신의 능력을 다른 사람에게 보여주고, 다른 사람에게 좋은 평가를 받으며, 지능은 타고난 것이라고 믿는 바램을 반영합니다 (Farr, Hofmann, & Ringenbach, 1993).

Goal orientation describes the manner in which people are motivated to work toward different kinds of goals. The idea is that individuals hold either a learning or a performance orientation toward tasks (e.g., Dweck, 1986). A learning orientation is characterized by a desire to increase one’s competence by developing new skills and mastering new situations with the belief that intelligence is malleable. In contrast, performance orientation reflects a desire to demonstrate one’s competence to others and to be positively evaluated by others, with the belief that intelligence is innate (Farr, Hofmann, & Ringenbach, 1993).

연구에 따르면 두 가지 유형의 목표 지향이 개인이 과제 난이도와 실패에 어떻게 반응하는지에 차별적으로 영향을 미치는 것으로 나타났습니다 (Dweck & Leggett, 1988).

-

학습 지향learning orientation은 실패 직면의 지속성,보다 복잡한 학습 전략의 사용, 도전적인 자료 및 과제의 추구로 특징 지워집니다.

-

성과 지향performance orientation은 업무 (특히 실패의 직면)에서 벗어나고, 어려운 업무에 대한 관심이 적으며, 성공할 가능성이 적은 도전 과제 및 과제를 찾는 경향이 특징입니다.

이러한 연구 결과에 따르면 연구 결과는 일반적으로 학습 지향은 긍정적 인 결과와 관련이 있으며 성과 지향은 모호하거나 부정적 결과와 관련이 있음을 보여 주었다 (Button, Mathieu, & Zajac, 1996, Fisher & Ford, 1998, VandeWalle , Brown, Cron, & Slocum, 1999).

Research has shown that the two types of goal orientation differentially influ- ence how individuals respond to task difficulty and failure (Dweck & Leggett, 1988). That is, learning orientation is characterized by persistence in the face of failure, the use of more complex learning strategies, and the pursuit of challenging material and tasks. Performance orientation is characterized by a tendency to with- draw from tasks (especially in the face of failure), less interest in difficult tasks, and the tendency to seek less challenging material and tasks on which success is likely. Consistent with these labels, research has generally shown that learning ori- entation is associated with more positive outcomes and performance orientation is related to either equivocal or negative outcomes (e.g., Button, Mathieu, & Zajac, 1996; Fisher & Ford, 1998; VandeWalle, Brown, Cron, & Slocum, 1999).

학습자의 목표-지향성에 영향을 미치는 한 가지 방법 (예 : 수행 강조에 초점을 학습에 중점을 두는 것)은 형성적 피드백을 통해 이루어집니다.

One way to influence a learner’s goal orientation (e.g., to shift from a focus on performing to an emphasis on learning) is via formative feedback.

스캐폴딩으로서 형성적 피드백

Formative Feedback as Scaffolding

훈련 바퀴와 마찬가지로 스캐폴딩은 학습자가보다 advanced 활동을 할 수있게 해주 며, 그러한 도움없이 할 수있는 것보다 더 진보 된 사고와 문제 해결에 참여할 수있게 해줍니다.

Like training wheels, scaffolding enables learners to do more advanced activi- ties and to engage in more advanced thinking and problem solving than they could without such help.

기존에는 촉진적 피드백 (지침 및 단서 제공)이 지침 피드백 (교정 정보 제공)보다 학습을 향상시킬 수 있다고 제안하지만, 반드시 그런 것은 아닙니다. 사실, 일부 연구는 Directive 피드백이 실제로 주제 나 내용 영역을 학습하는 학습자 (특히 Knoblauch & Brannon, 1981; Moreno, 2004)의 경우보다 실질적으로 도움이 될 수 있음을 보여주었습니다. 스캐 폴딩은 학습 과정에서 학습자가 명시 적으로 지원하는 것과 관련되어 있기 때문에 교육적 측면에서 모델, 단서, 프롬프트, 힌트, 부분 해법 및 직접 교육 (Hartman, 2002)이 포함될 수 있습니다. 스캐폴딩은 학생들이 인지적 발판을 얻음에 따라 점차적으로 제거됩니다. 따라서 Directive 피드백은 학습 초기 단계에서 가장 유용 할 수 있습니다. 촉진 적 피드백은 나중에 도움이 될 수 있으며, 관련된 질문은 "언제입니까?"이다.

Vygotsky (1987)에 따르면, 학습자가, 외부 스캐폴딩은 기존의 지식 시스템이 새로운 학습을 위한 스캐폴딩의 일부가 되는, 보다 정교한 인지 시스템을 개발할 때 제거 될 수 있습니다. 피드백 타이밍 문제는 이제 더 자세히 논의됩니다.

Conventional wisdom suggests that facilitative feedback (providing guidance and cues, as illustrated in the research cited previously) would enhance learning more than directive feedback (providing corrective information), yet this is not nec- essarily the case. In fact, some research has shown that directive feedback may actu- ally be more helpful than facilitative—particularly for learners who are just learning a topic or content area (e.g., Knoblauch & Brannon, 1981; Moreno, 2004). Because scaffolding relates to the explicit support of learners during the learning process, in an educational setting, scaffolded feedback may include models, cues, prompts, hints, partial solutions, and direct instruction (Hartman, 2002). Scaffolding is grad- ually removed as students gain their cognitive footing; thus, directive feedback may be most helpful during the early stages of learning. Facilitative feedback may be more helpful later, and the question is: When? According to Vygotsky (1987), exter- nal scaffolds can be removed when the learner develops more sophisticated cogni- tive systems, where the system of knowledge itself becomes part of the scaffold for new learning. The issue of feedback timing is now discussed in more detail.

시기

Timing

It was my teacher’s genius, her quick sympathy, her loving tact which made the first years of my education so beautiful. It was because she seized the right moment to impart knowledge that made it so pleasant and acceptable to me. —Helen Keller

앞서 언급 한 피드백 변수 (예 : 복잡성 및 특이성)와 마찬가지로 피드백시기와 학습 결과 및 효율성에 미치는 영향에 관한 문헌에서 상충되는 결과가 있습니다.

Similar to the previously mentioned feedback variables (e.g., complexity and specificity), there are also conflicting results in the literature relating to the timing of feedback and the effects on learning outcome and efficiency.

일부 연구자들은 오류가 메모리에 인코딩되는 것을 방지하기위한 수단으로 즉각적인 피드백을 주장했지만, 지연된 피드백은 사전 간섭을 줄여 초기 오류를 잊어 버리고 올바른 정보를 간섭없이 인코딩 할 수 있다고 주장했습니다

Some researchers have argued for immediate feedback as a means to prevent errors being encoded into memory, whereas others have argued that delayed feedback reduces proactive interference, thus allowing the initial error to be forgotten and the cor- rect information to be encoded with no interference

지연된 피드백

Support for Delayed Feedback

즉각적 피드백

Support for Immediate Feedback

피드백 타이밍과 연결

Conjoining Feedback Timing Findings

문헌에서보고 된 이러한 상호 작용 중 하나는 피드백 타이밍과 작업난이도와의 관련성이 있다.

이것은 이전에 Scaffolding으로 Formative Feedback 하위 섹션에서 제시 한 아이디어와 유사합니다.

One such interaction reported in the literature concerns feedback timing and task difficulty. That is, if the task is difficult, then immediate feedback is beneficial, but if the task is easy, then delayed feedback may be preferable (Clariana, 1999). This is similar to the ideas presented earlier in the Formative Feedback as Scaffolding subsection.

피드백 타이밍 요약

Summary of Feedback Timing Results

피드백 타이밍과 학습 및 성과 간의 관계를 조사한 연구는 일관되지 않는 결과를 나타냅니다. 하나의 흥미로운 관찰은 많은 현장 연구가 즉각적인 피드백 (Kulik & Kulik, 1988 참조)의 가치를 입증하는 반면, 많은 실험실 연구는 지연된 피드백의 긍정적 인 효과를 나타내는 반면 Schmidt & Bjork (1992; Schmidt et al.)

불일치를 해결할 수있는 한 가지 방법은 즉각적인 피드백으로 긍정적 인 학습 결과와 부정적인 학습 효과가 모두 활성화 될 수 있다는 점입니다. 예를 들어 즉각적인 피드백의 긍정적 인 효과는 의사 결정을 촉진하거나 실행 동기와 원인에 대한 결과의 명확한 연관성을 제공하는 것으로 볼 수 있습니다. 즉각적인 피드백의 부정적인 영향은 전송하는 동안 사용할 수 없는 정보에 대한 의존을 촉진하고 덜 신중하거나 주의 깊은 행동을 조장 할 수 있습니다. 이 가정이 사실이라면 즉각적인 피드백의 긍정적이고 부정적인 영향은 서로 상쇄 될 수 있습니다. 양자 택일로, 긍정적 인 영향이나 부정적인 영향이 실험적 맥락에 따라 전면에 나타날 수있다.

학습에 대한 지연된 피드백 효과에 대해서도 비슷한 주장이 제기 될 수있다. 예를 들어, 긍정적인면에서 피드백 지연은 학습자가 능동적인 인지 및 메타인지 과정에 참여하도록 유도하여 자율감을 고취시킨다. 그러나 부정적인 측면에서 struggling하고 덜 동기 부여 된 학습자에 대한 피드백을 지연시키는 것은 지식과 기술 습득에 실망스럽고 해로운 것으로 판명 될 수 있습니다.

Research investigating the relationship of feedback timing to learning and per- formance reveals inconsistent findings. One interesting observation is that many field studies demonstrate the value of immediate feedback (see Kulik & Kulik, 1988), whereas many laboratory studies show positive effects of delayed feedback (see Schmidt & Bjork, 1992; Schmidt et al. 1989). One way to resolve the inconsis- tency is by considering that immediate feedback may activate both positive and neg- ative learning effects. For instance, the positive effects of immediate feedback can be seen as facilitating the decision or motivation to practice and providing the explicit association of outcomes to causes. The negative effects of immediate feed- back may facilitate reliance on information that is not available during transfer and promote less careful or mindful behavior. If this supposition is true, the positive and negative effects of immediate feedback could cancel each other out. Alternatively, either the positive or negative effects may come to the fore, depending on the exper- imental context. A similar argument could be made for delayed feedback effects on learning. For example, on the positive side, delayed feedback may encourage learn- ers’ engagement in active cognitive and metacognitive processing, thus engender- ing a sense of autonomy (and perhaps improved self-efficacy). But on the negative side, delaying feedback for struggling and less motivated learners may prove to be frustrating and detrimental to their knowledge and skill acquisition.

피드백과 다른 변인과의 관계

Feedback and Other Variables

학습자 수준

Learner Level

이 리뷰의 Timing Subsection에서 언급했듯이, 성취도가 낮은 학생들은 즉각적인 피드백으로 이익을 얻는 반면, 성취도가 높은 학생은 지연된 피드백을 선호하거나 이익을 얻을 수 있다고 제안했습니다. (Gaynor, 1981; Roper, 1977). 게다가 다양한 유형의 피드백을 테스트 할 때, Clariana (1990)는 능력이 부족한 학생들이 try-again feedback보다 correct response feedback을받는 것으로 이익을 얻는다 고 주장했습니다. Hanna (1976)는 또한 다양한 피드백 조건과 관련하여 학생의 수행 능력을 검증했다. 검증, 정교화, 피드백 없음.

-

Verification피드백 조건은 우수한 학생의 경우 가장 높은 점수를,

-

Elaborated 피드백은 낮은 학생의 경우 가장 높은 점수를 받았습니다.

-

중상위 학생들을위한 검증과 정교한 피드백 간에는 유의미한 차이가 없었지만 이러한 피드백 유형 모두는 피드백이없는 것보다 우위에있었습니다.

As alluded to in the Timing subsection of this review, some research has sug- gested that low-achieving students may benefit from immediate feedback, whereas high-achieving students may prefer or benefit from delayed feedback (Gaynor, 1981; Roper, 1977). Furthermore, when testing different types of feedback, Clariana (1990) has argued that low-ability students benefit from receipt of correct response feedback more than from try again feedback. Hanna (1976) also examined student performance in relation to different feedback conditions: verification, elaboration, and no feedback. The verification feedback condition produced the highest scores for high-ability students and elaborated feedback produced the highest scores for low-ability students. There were no significant differences between verification and elaborated feedback for middle-ability students, but both of these types of feedback were superior to no feedback.

정답에 대한 확신

Response Certitude

Kulhavy and Stock (1989)는 정보 처리의 관점에서 피드백과 응답 증명 문제를 조사했다. 즉 학생들은 다양한 과제에 대한 각 답변에 따라 자신감 평가 ( "응답 성"등급)를 제공하게했습니다. 그들은 학생들이 스스로 답이 정확하다고 확신 할 때 피드백을 분석하는 데 더 적은 시간을 할애하고, 학생들이 스스로 답이 정확하지 않다고 생각할 때 피드백을 검토하는 데 더 많은 시간을 할애 할 것이라고 가설을 세웠습니다. 이것의 암시는 간단합니다. 즉, 자신의 대답이 틀렸다고 확신하는 학생들에게보다 Elaborated 피드백을 제공하고 정답의 정확성이 높은 사람들에게 더 Constrained 피드백을 제공합니다.

Kulhavy and Stock (1989) examined feedback and response certitude issues from an information-processing perspective. That is, they had students provide confidence judgments (“response certitude” ratings) following each response to various tasks. They hypothesized that when students are certain their answer is cor- rect, they will spend little time analyzing feedback, and when students are certain their answer is incorrect, they will spend more time reviewing feedback. The impli- cations of this are straightforward; that is, provide more elaborated feedback for students who are more certain that their answer is wrong and deliver more con- strained feedback for those with high certitude of correct answers.

목표 지향성

Goal Orientation

Davis, Carson, Ammeter, and Treadway (2005)는 learning orientation 이 낮은 사람들한테는 피드백 특이성 (저, 중등도, 고레벨)이 유의한 영향을 미친다는 것을 발견했다. 이 연구 결과는 피드백 활동의 전반적인 긍정적 효과를 뒷받침하며, 학습자가 high-performance 또는 low-learning 지향성을 가질 때 more specific 피드백을 사용할 것을 제안합니다.

Davis, Carson, Ammeter, and Treadway (2005) found that feedback specificity (low, moderate, and high levels) had a significant influence on performance for individuals who were low on learning orientation (i.e., high feedback specificity was better for learners with low learning orientation). They also reported a significant influence of feedback specificity on performance forpersons high in performance orientation (i.e., this group also benefited from more specific feedback). The findings support the general positive effects of feedback on performance and suggest the use of more specific feedback for learners with either high-performance or low-learning goal orientations.

규범적(서로 비교하는) 피드백

Normative Feedback

McColskey와 Leary (1985)는 실패가 self-referenced 된 용어로 표현 될 때, 즉 다른 측정에 의해 평가 된 학습자의 알려진 수준의 능력과 관련하여 실패의 해로운 영향이 줄어들 수도 있다는 가설을 조사했다. 그들은 norm-referenced feedback에 비해 self-referenced feedback은 미래 성과에 대한 기대치롤 높여주고 노력에 대한 기여도가 증가한다는 것을 발견했다. (예를 들어, "나는 정말로 열심히했기 때문에 성공했다.") 능력에 대한 기여 (예 : '나 때문에 성공했습니다.')는 영향을받지 않았습니다. 주된 의미는 성취도가 낮은 학생들은 규범적 피드백이 아니라 자기 참조 된 피드백을 받음으로써, 자신의 progress에 주의를 집중할 수 있다는 것이다.

McColskey and Leary (1985) examined the hypothesis that the harmful effects of failure might be lessened when failure is expressed in self-referenced terms—that is, relative to the learner’s known level of ability as assessed by other measures. They found that, compared to norm-referenced feed-back, self-referenced feedback resulted in higher expectancies regarding future performance and increased attributions to effort (e.g., “I succeeded becauseI worked really hard”). Attributions to ability (e.g., “I succeeded because I’msmart”) were not affected. The main implication is that low-achieving students should not receive normative feedback but should instead receive self-referenced feedback—focusing their attention on their own progress.

형성적 피드백의 프레임워크

Toward a Framework of Formative Feedback

To understand the world, one must not be worrying about one’s self. —Albert Einstein

Kluger and DeNisi (1996)

Kluger와 DeNisi (1996)는 피드백 개입 (FI)이 다양한 시각에서 성과에 미치는 영향을 조사하고 1900 년대 초 Thorndike의 고전적 연구에 이르기까지 수십 년간의 연구를 조사했다. 그들의 예비 피드백 개입 이론 (FIT)은 FI 효과를 조사하는 광범위한 접근법을 제공하며,

Kluger and DeNisi (1996) examined and reported on the effects of feedback interventions (FIs) on performance from multiple perspectives and spanning decades of research—back to Thorndike’s classic research in the early 1900s. Their preliminary feedback intervention theory (FIT) offers a broad approach to investigating FI effects,

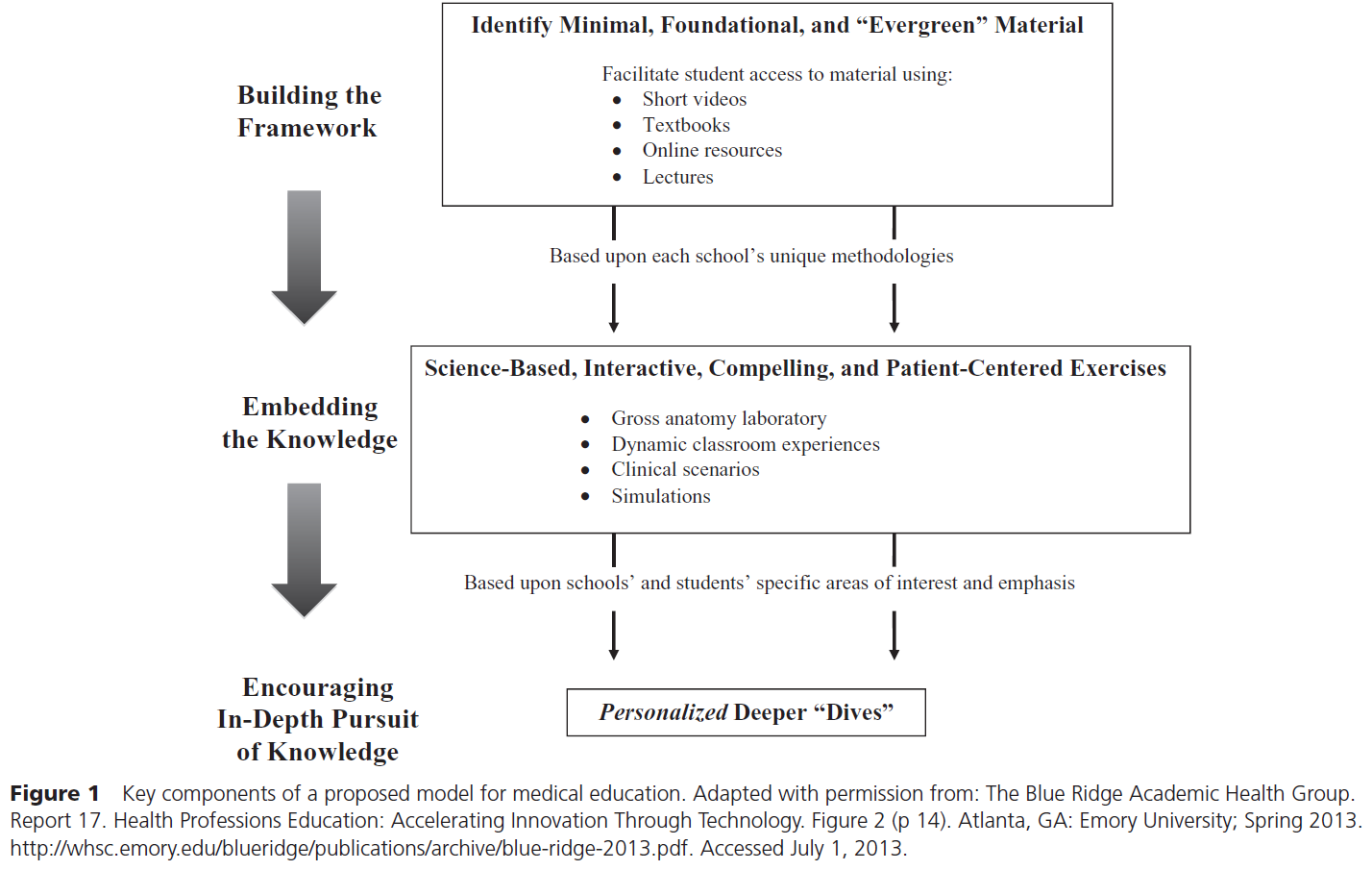

FIT의 기본 전제는 FI가 세 가지 수준의 제어 (a) 작업 학습, (b) 작업 동기 부여, (c) 메타 태스킹 프로세스 (그림 1 참조) 사이에서 학습자의 관심의 위치를 변경한다는 것입니다.

The basic premise underlying FIT is that FIs change the locus of a learner’s attention among three levels of control: (a) task learning, (b) task motivation, and (c) metatask processes (see Figure 1).

FI가 유도한 관심 영역의 위계가 낮을수록 FI에 따른 performance에 이득이 향상된다는 장점이 있습니다. 즉, 학습자가 과제의 측면 (즉, 그림 1의 아래 부분)에 초점을 두는 형성 피드백은 자기 자신에게주의를 환기시키는 FI (즉, 그림 1의 상단 상자)에 비해 학습 및 성취를 촉진합니다. , 이는 학습을 방해 할 수 있습니다.

The lower in the hier- archy the FI-induced locus of attention is, the stronger is the benefit of an FI for performance. In other words, formative feedback that focuses the learner on aspects of the task (i.e., the lower part of Figure 1) promotes learning and achieve- ment compared to FIs that draw attention to the self (i.e., the upper box in Figure 1), which can impede learning.

FIT는 다섯 가지 기본 논점으로 구성된다 :

(a) 행동은 목표 나 표준에 대한 피드백의 비교에 의해 규제된다.

(b) 목표 또는 표준은 계층 적으로 조직된다.

(c)주의는 제한적이므로 피드백 표준 갭 주의력을 행동 규칙에 적극적으로 참여시키는

(d)주의는 일반적으로 계층 구조의 중간 수준으로 향한다. 그리고

(e) FI는 관심의 장소를 바꾸어 행동에 영향을 미친다.

FIT consists of five basic arguments:

-

(a) behavior is regulated by comparisons of feedback to goals or standards,

-

(b) goals or standards are organized hierarchi- cally,

-

(c) attention is limited and therefore only feedback–standard gaps (i.e., dis- crepancies between actual and desired performance) that receive attention actively participate in behavior regulation,

-

(d) attention is normally directed to a moderate level of the hierarchy; and

-

(e) FIs change the locus of attention and therefore affect behavior.

Figure 2 summarizes the main findings.

이러한 결과의 한 가지 중요한 발견은 자기주의의 모델 (Baumeister, Hutton, & Cairns, 1990), 노력의 속성 ( Butler, 1987) 및 통제 이론 (Waldersee & Luthans, 1994).

One important finding from these results concerns the attenuating effect of praise on learning and performance, although this has been described elsewhere in the literature in terms of a model of self-attention (Baumeister, Hutton, & Cairns, 1990), attributions of effort (Butler, 1987), and control theory (Waldersee & Luthans, 1994).

Bangert-Drowns et al. (1991)

행동을 유도하기 위해서는, 학습자는 행동에 의해 초래 된 신체적 변화를 모니터링 할 수 있어야합니다. 즉, 학습자는 새로운 정보에 적응시키고 performance에 대한 자신의 기대치와 일치시킴으로써인지 조작 및 이에 따른 활동을 변경합니다.

The basic idea is that to direct behavior, a learner needs to be able to monitor physical changes brought about by the behavior. That is, learners change cognitive operations and thus activity by adapting it to new information and matching it with their own expectations about performance.

Bangert-Drowns et al. (1991)의 대부분의 변수는 텍스트 기반 피드백을 분석하여 5 단계 모델로 구성했습니다. 이 모델은 학습자가 피드백주기를 통해 움직이고 mindfulness의 구조를 강조하면서 학습자의 상태를 설명합니다 (Salomon & Globerson, 1987). Mindfulness는 "학습자가 상황 별 단서와 관련된 과제에 관련된 근본적인 의미를 탐구하는 반사적 과정"입니다 (Dempsey 외, 1993, 38 페이지).

Most of the variables Bangert-Drowns et al. (1991) analyzed comprised text- based feedback, which they organized into a five-stage model. This model describes the state of learners as they move through a feedback cycle and emphasizes the construct of mindfulness (Salomon & Globerson, 1987). Mindfulness is “a reflec- tive process in which the learner explores situational cues and underlying mean- ings relevant to the task involved” (Dempsey et al., 1993, p. 38).

5 단계는 그림 3에 묘사되어 있으며, 특히 성찰의 중요성과 연관된 다른 학습주기 (예 : Gibbs, 1988, Kolb, 1984)와 유사합니다.

The five stages are depicted in Figure 3 and are similar to other learning cycles (e.g., Gibbs, 1988; Kolb, 1984), particularly in relation to the importance of reflection.

1. 학습자의 초기 또는 현재 상태. 이것은 관심의 정도, 목표 지향성, 자기 효능감 정도 및 이전의 관련 지식에 의해 특징 지어진다.

1. The initial or current state of the learner. This is characterized by the degree of interest, goal orientation, degree of self-efficacy, and prior relevant knowledge.

2. 검색 및 검색 전략. 이러한 인식 메커니즘은 질문에 의해 활성화됩니다. 정교화의 맥락에서 저장된 정보는 정보에 대한 액세스를 제공하는 경로가 더 많기 때문에 메모리에서 찾기가 더 쉽습니다.

2. Search and retrieval strategies. These cognitive mechanisms are activated by a question. Information stored in the context of elaborations would be easier to locate in memory because of more pathways providing access to the information.

3. 학습자가 질문에 응답합니다. 또한, 학습자는 (자신의) 대답에 대해 어느 정도 확신을 갖고 있기 때문에, 피드백에 대해 기대하는 바가 있습니다.

3. The learner makes a response to the question. In addition, the learner feels some degree of certainty about the response and thus has some expectation about what the feedback will indicate.

4. 학습자는 피드백의 정보를 고려하여 응답을 평가합니다. 평가의 성격은 피드백에 대한 학습자의 기대에 달려 있습니다. 예를 들어,

-

학습자가 자신의 응답을 확신하는데다가 피드백이 (그 응답이) 정확하다는 것을 확인해주면 검색 경로retrieval pathway가 강화되거나 변경되지 않을 수 있습니다.

-

학습자가 응답을 확신하고 피드백이 정확하지 않다는 것을 나타내면 학습자는 부조화를 이해하려고 노력할 수 있습니다.

-

피드백 확인 또는 disconfirmation에 대한 응답에 대한 불확실성은 학습자가 수업 내용을 획득하는 데 관심이 없다면 심층 성찰을 시뮬레이트 할 가능성이 적습니다.

4. The learner evaluates the response in light of information from the feedback. The nature of the evaluation depends on the learner’s expectations about feedback. For instance, if the learner was sure of his or her response and the feedback confirmed its correctness, the retrieval pathway may be strength- ened or unaltered. If the learner was sure of the response and feedback indi- cated its incorrectness, the learner may seek to understand the incongruity. Uncertainty about a response with feedback confirmation or disconfirmation is less likely to simulate deep reflection unless the learner was interested in acquiring the instructional content.

5. 응답 평가 결과 관련 지식, 자기 효능감, 관심사 및 목표를 조정합니다. 이러한 조정 된 상태는 이후의 경험과 함께 다음 "현재"상태를 결정합니다.

5. Adjustments are made to relevant knowledge, self-efficacy, interests, and goals as a result of the response evaluation. These adjusted states, with sub- sequent experiences, determine the next “current” state.

Bangert-Drowns et al. (1991)의 메타 분석과 후속 5 사이클 모델의 주된 결론은 피드백이 주의 깊게 받아 들여지면 피드백이 학습을 촉진 할 수 있다는 것이다. 반대로 피드백은 학습자가 자신의 기억 검색을 시작하기 전에 응답이 가능 해지거나 피드백 메시지가 학생들의 인지적 요구 (예 : 너무 쉽거나, 너무 복잡하거나, 너무 모호한 경우)와 일치하지 않는 경우와 같이 어리석은 행동mindlessness을 조장 할 경우 학습을 방해 할 수 있습니다.

The main conclusion from Bangert-Drowns et al.’s (1991) meta-analysis and subsequent five-cycle model is that feedback can promote learning if it is received mindfully. Conversely, feedback can inhibit learning if it encourages mindlessness, as when the answers are made available before learners begin their memory search, or if the feedback message does not match students’ cognitive needs (e.g., too easy, too complex, too vague).

Narciss and Huth (2004)

일반적으로 Narciss and Huth (2004)는 효과적인 형성 피드백을 설계하고 개발하는 것은 복잡한 학습 과제에 효과적인 피드백을 제공하기 위해 학습자의 특성뿐만 아니라 학습 내용(instructional context)을 고려할 필요가 있다고 주장했다. 형성 피드백의 설계를위한 개념적 틀은 그림 4에 묘사되어있다.

In general, Narciss and Huth (2004) asserted that designing and developing effective formative feedback needs to take into consideration instructional context as well as characteristics of the learner to provide effective feedback for complex learning tasks. The conceptual framework for the design of formative feedback is depicted in Figure 4 (modified from the original).

1. 지시. 학습 요소 또는 문맥은

(a) 학습 목표 (예 : 학습 목표 또는 일부 교과 과정과 관련된 표준),

(b) 학습 과제 (예 : 지식 항목,인지 행동, 메타인지 기술), 그리고

(c) 오류 및 장애 (예 : 일반적인 오류, 잘못된 전략, 오류의 출처).

1. Instruction. The instructional factor or context consists of three main elements: (a) the instructional objectives (e.g., learning goals or standards relating to some curriculum), (b) the learning tasks (e.g., knowledge items, cognitive operations, metacognitive skills), and (c) errors and obstacles (e.g., typical errors, incorrect strategies, sources of errors).

2. 학습자. 피드백 설계와 관련된 학습자에 관한 정보는

(a) 학습 목표 및 목표;

(b) 사전 지식, 기술 및 능력 (예 : 콘텐츠 지식과 같은 도메인 종속적, 메타인지 기술과 같은 도메인 독립적)

(c) 학업 동기 (예 : 학업 성취도, 학업 자기 효능감, 그리고 metamotivational 기술).

2. Learner. Information concerning the learner that is relevant to feedback design includes (a) learning objectives and goals; (b) prior knowledge, skills, and abilities (e.g., domain dependent, such as content knowledge, and domain independent, such as metacognitive skills); and (c) academic moti- vation (e.g., one’s need for academic achievement, academic self-efficacy, and metamotivational skills).

3. 피드백. 피드백 요소는 3 가지 주요 요소로 구성된다 :

(a) 피드백의 내용 (즉, 검증과 같은 평가 측면과 힌트, 큐, 유추, 설명 및 실제 예제와 같은 정보 측면) ),

(b) 피드백의 기능 (즉,인지, 메타인지 및 동기 부여),

(c) 피드백 요소의 제시 (예 : 타이밍, 일정 및 적응성 고려 사항).

3. Feedback. The feedback factor consists of three main elements: (a) the con- tent of the feedback (i.e., evaluative aspects, such as verification, and infor- mative aspects, such as hints, cues, analogies, explanations, and worked-out examples), (b) the function of the feedback (i.e., cognitive, metacognitive, and motivational), and (c) the presentation of the feedback components (i.e., timing, schedule, and perhaps adaptivity considerations).

Mason and Bruning (2001)

Mason and Bruning’s theoretical framework, depicted in Figure 5,

프레임 워크에서 가져온 일반적인 권장 사항은 간단한 (낮은 수준) 또는 복잡한 (높은 수준) 작업의 맥락에서

The general rec- ommendation they have drawn from the framework is that immediate feedback for students with low achievement levels in the context of either simple (lower level) or complex (higher level) tasks is superior to delayed feedback, whereas delayed feedback is suggested for students with high achievement levels, especially for complex tasks.

Summary and Discussion

Recommendations and Guidelines for Formative Feedback

Tables 2, 3, 4, and 5 present suggestions or prescriptions based on the current review of the formative feedback literature.

사실, 비고츠키 (Vygotsky, 1987)는 지성이 동기 부여와 정서적 (또는 정서적 인) 측면에서 분리 됨으로써 심리학의 연구가 손상되었다고 지적했다. 이것은 정서적 혼란이 정신 활동 (예, 불안, 화가)을 저해 할 수 있다고 주장한 연구자들 (Goleman, 1995; Mayer & Salovey, 1993, 1997, Picard et al., 2004) , 우울한 학생들은 배우지 않습니다). 따라서 미래 연구의 한 가지 흥미로운 영역은 피드백과 결과 성과에서 정서적 인 요소들 간의 관계를 체계적으로 조사하는 것입니다.

In fact, Vygotsky (1987) noted that the study of psychology had been damaged by the separation of the intellectual from the motivational and emotional (or affective) aspects of thinking. This seems to be supported by a growing number of researchers (e.g., Goleman, 1995; Mayer & Salovey, 1993, 1997; Picard et al., 2004) who have argued that emotional upsets can interfere with mental activities (e.g., anxious, angry, or depressed students do not learn). Thus, one intriguing area of future research is to systematically examine the relationship(s) between affective components in feedback and outcome performance.

TABLE 2 Formative feedback guidelines to enhance learning (things to do)

-

학습자가 아닌 과제에 집중하십시오.

-

학습 향상을 위해 정교한 피드백을 제공하십시오.

-

정교한 피드백을 다루기 쉬운 단위로 제시하십시오.

-

피드백 메시지로 구체적이고 명확하게 작성하십시오.

-

피드백을 가능한 한 간단하지만 (학습자의 요구와 교육 제약에 따라) 단순하게하지 마십시오.

-

성과와 목표 사이의 불확실성을 줄입니다.

-

서면 또는 컴퓨터를 통해 공정하고 객관적인 피드백을 제공하십시오. 피드백을 통해 "학습"목표 오리엔테이션을 추진하십시오.

-

학습자가 솔루션을 시도한 후에 피드백을 제공하십시오.

Focus feedback on the task, not the learner.

Provide elaborated feedback to enhance learning.

Present elaborated feedback in manageable units.

Be specific and clear with feedback message.

Keep feedback as simple as possible but no simpler (based on learner needs and instructional constraints).

Reduce uncertainty between performance and goals.

Give unbiased, objective feedback, written or via computer. Promote a “learning” goal orientation via feedback.

Provide feedback after learners have attempted a solution.

TABLE 3 Formative feedback guidelines to enhance learning (things to avoid)

-

규범적인 비교를하지 마십시오. 전반적인 성적 제공에 대해서는 신중해야합니다.

-

학습자를 낙담 시키거나 학습자의 자존심을 위협하는 피드백을 제공하지 마십시오.

-

'칭찬'은 아끼십시오

-

구두로 피드백을 제공하지 않도록하십시오.

-

학습자가 적극적으로 참여하는 경우 피드백을 통해 학습자를 방해하지 마십시오.

-

항상 정답으로 끝나는 점진적인 힌트를 사용하지 마십시오.

-

피드백 프리젠 테이션 모드를 텍스트로 제한하지 마십시오.

-

광범위한 오류 분석 및 진단의 사용을 최소화하십시오.

Do not give normative comparisons. Be cautious about providing overall grades.

Do not present feedback that discourages the learner or threatens the learner’s self- esteem.

Use “praise” sparingly, if at all.

Try to avoid delivering feedback orally.

Do not interrupt learner with feedback if the learner is actively engaged.

Avoid using progressive hints that always terminate with the correct answer.

Do not limit the mode of feedback presentation to text.

Minimize use of extensive error analyses and diagnosis.

TABLE 4 Formative feedback guidelines in relation to timing issues

-

원하는 결과와 일치하도록 피드백 타이밍을 설계하십시오.

-

어려운 작업의 경우 즉각적인 피드백을 사용하십시오.

-

상대적으로 간단한 작업의 경우 지연된 피드백을 사용하십시오.

-

절차 적 또는 개념적 지식을 유지하려면 즉각적인 피드백을 사용하십시오.

-

학습 이전을 촉진하려면 지연된 피드백 사용을 고려하십시오.

Design timing of feedback to align with desired outcome.

For difficult tasks, use immediate feedback.

For relatively simple tasks, use delayed feedback.

For retention of procedural or conceptual knowledge, use immediate feedback.

To promote transfer of learning, consider using delayed feedback.

TABLE 5 Formative feedback guidelines in relation to learner characteristics

-

학습성이 높은 학습자에게는 지연된 피드백 사용을 고려하십시오.

-

저조한 학습자에게는 즉각적인 피드백을 사용하십시오.

-

학습 성이 낮은 학습자의 경우 지시 (또는 정정) 피드백을 사용하십시오.

-

학습성이 높은 학습자에게는 촉진 적 피드백을 사용하십시오. 저학년 학습자의 경우 스캐 폴딩을 사용하십시오.

-

학습성이 높은 학습자에게는 검증 피드백으로 충분할 수 있습니다.

-

저학년 학습자의 경우 올바른 응답과 정교한 피드백을 사용하십시오.

-

낮은 학습 지향 (또는 높은 성취 지향)을 가진 학습자에게 구체적인 피드백을 제공하십시오.

For high- achieving learners, consider using delayed feedback.

For low-achieving learners, use immediate feedback.

For low-achieving learners, use directive (or corrective) feedback.

For high- achieving learners, use facilitative feedback. For low-achieving learners, use scaffolding.

For high- achieving learners, verification feedback may be sufficient.

For low-achieving learners, use correct response and some kind of elaboration feedback.

For learners with low learning orientation (or high performance orientation), give specific feedback.

The general question is: What level of feedback complexity yields the most bang for the buck?

Focus on Formative Feedback

First Published March 1, 2008 research-article