CME와 CPD의 이해와 개선을 위한 새로운 원천으로서의 학습과학(Med Teach, 2018)

Learning science as a potential new source of understanding and improvement for continuing education and continuing professional development

Thomas J. Van Hoofa,b,c and Terrence J. Doyled,e

서론

Introduction

적어도 2009년까지 거슬러 올라간다(커풋 외. 2009), CE/CPD 문헌에서, 학습이 일어날 때 뇌에서 일어나는 일과 관련된 "학습 과학"으로 알려진 새로운 학제간 분야와 관련된 전략에 대한 기사가 계속적으로 나오기 시작했다. 일부 저자들은 "학습 과학"이라는 다른 총체적인 용어를 선호하며, 이를 교수와 학습에 관한 연구 분야로 정의한다(Sawyer 2016). 학습과학이 인지심리학, 신경과학 등 전통적인 분야의 중첩을 반영하는 인위적인 구성인지, 그리고 어떤 용어가 학습과학을 가리키는지 여부는 CE/CPD 리더와 중요한 관련성을 갖는다. 최근 몇 년 동안 적지만 상당히 잘 설계된 연구에도 불구하고, CE/CPD 문헌은 한 가지 주목할 만한 예외를 제외하고 학습 과학과 관련 전략에 대한 명시적인 설명이 부족한 것으로 보인다. Weidman과 Baker(2015)는 "학습의 인지과학"이라는 용어를 사용하여 일반적으로 의학 교육에 적용되는 학습과학의 일부 개념, 이론적 원리 및 실제 적용에 대한 설명을 제공한다. 이 논문은 CE/CPD에 대한 보완책으로, 과학 학습에서 나오는 몇 가지 핵심 전략 및 습관을 설명하고 증거 기반 CE/CPD 속성과 어떻게 일치하는지 설명한다.

At least as far back as 2009 (Kerfoot et al. 2009), articles have begun to appear in the continuing education/continuing professional development (CE/CPD) literature about strategies associated with an emerging interdisciplinary field known as “learning science,” which concerns itself with what happens in the brain when learning occurs. Some authors prefer a different, collective term, that is, “the learning sciences,” and define it as a field of study about teaching and learning (Sawyer 2016). Whether learning science is a distinct field or an artificial construct reflecting an overlap of such traditional fields as cognitive psychology and neuroscience, and whether one refers to learning science by one term or another, the field has significant relevance to CE/CPD leaders. Despite a modest but significant number of well-designed studies in recent years (Larsen et al. 2015; Kerfoot and Baker 2012; Kerfoot et al. 2014; Boespflug et al. 2015; Mallon et al. 2016), the CE/CPD literature appears to lack an explicit description of learning science and its attendant strategies with one noteworthy exception. Using the term “cognitive science of learning,” Weidman and Baker (2015) provide a description of some concepts, theoretical principles and practical applications of learning science as applied to medical education in general. As a complement to that article but more specific to CE/CPD, this article describes some key strategies and/or habits that emanate from learning science and explains how they align with evidence-based CE/CPD attributes.

배움이란 무엇이며 어떻게 이루어지는가?

What is learning and how does it happen?

네 가지 핵심 학습 과학 전략을 설명하기 전에 학습 자체에 대한 간략한 설명이 적절해 보인다. 많은 학습 과학 자원이 훨씬 더 깊고 광범위한 설명을 제공하지만(Doyle and Zakrajsek 2013; Brown et al. 2014; Carey 2014; Oakley 2014), "학습"은 뇌의 뉴런 간 연결, 즉 신경망을 개발하는 산물이다(Doyle and Zakrajsek 2013). 학습에는 지식, 기술, 행동 및 태도와 같은 정보가 신경망을 통해 물리적으로 표현되는 것이 포함된다(Doyle and Zakrajsek 2013). 나중에 사용하기 위해 접근할 가능성이 있는 학습은 단순히 뇌를 사용하는 것이 아니라 말 그대로 뇌를 변화시켜야 한다. 린슨(1999)의 학습 정의는 이러한 변화와 일치한다(이탤릭체는 생략한다.) "학습은… 반복적인 사용을 통해 뇌의 특정 적절하고 바람직한 시냅스를 안정화시키는 것이다."(5페이지)

Before describing four key learning science strategies, a brief explanation of learning itself seems appropriate. While many learning science resources provide a far deeper and broader explanation (Doyle and Zakrajsek 2013; Brown et al. 2014; Carey 2014; Oakley 2014), “learning” is the product of establishing connections between neurons in the brain, that is, developing neural networks (Doyle and Zakrajsek 2013). Learning involves information, such as knowledge, skills, behaviors and attitudes, becoming physically represented through neural networks (Doyle and Zakrajsek 2013). Learning that has the prospect of being accessed for later use must literally change the brain, not merely use it (Leamnson 1999; Doyle and Zakrajsek 2013; Brown et al. 2014). Leamnson’s (1999) definition of learning is consistent with such change (italics omitted): “Learning is … stabilizing, through repeated use, certain appropriate and desirable synapses in the brain” (p. 5).

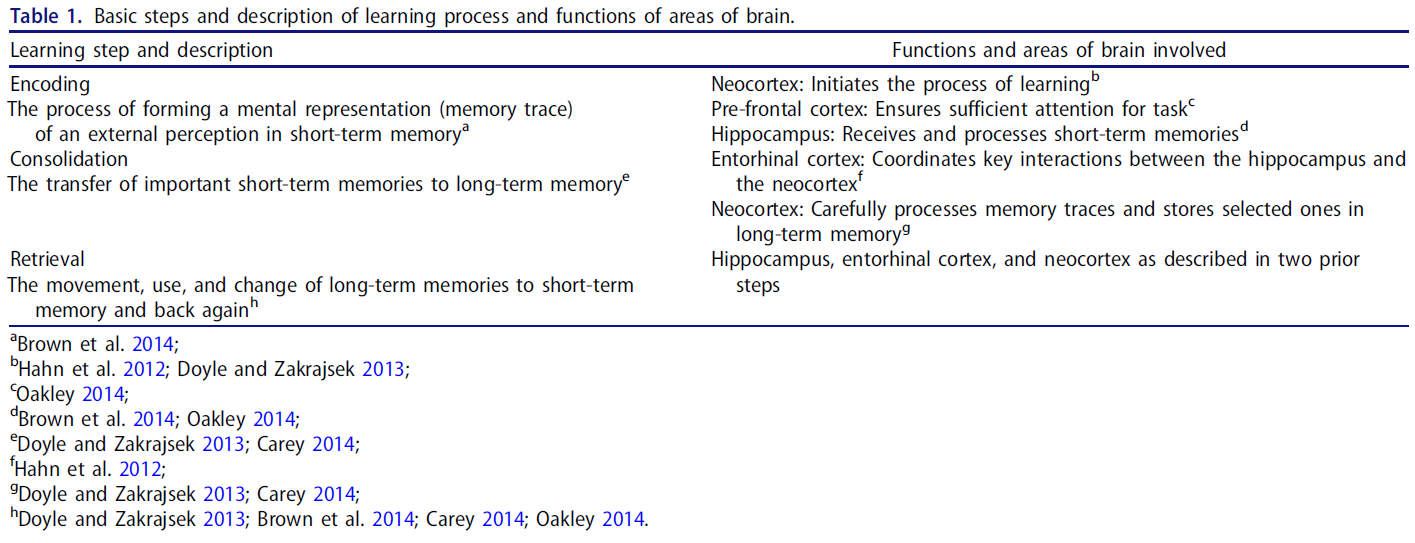

필연적으로, 배우는 것은 힘든 일이다. 노력적 학습effortful learning의 좋은 예는 비지배적 손으로 글을 쓰는 연습이다(Leamnson 1999). 전문성을 유지하고 확장하고자 하지만 간단하고 쉬운 CE/CPD 활동을 찾고 있는 임상의는 학습 프로세스에 대한 Doyle(2008)의 기본 진술을 신중하게 고려해야 합니다. "… 일을 하는 사람이 배움을 한다"(p. 63). 의미 있는 학습에는 빠르고 쉬운 것이 없다. 그럼에도 불구하고, 약 860억 개의 뉴런(허큘라노-호젤과 2005년 사순절)이 150조 개의 연결 또는 시냅스를 만들고, 100만 기가바이트의 디지털 저장 용량을 가진, 적절하게 사용한다면, 평균적인 인간 두뇌의 학습 능력은 정말로 놀랍다. 수천 시간의 연구와 연습을 반영하듯, 학문적이든 아니든 한 분야의 진정한 전문 지식을 구성하는 방대한 신경망은 종종 "청크"(Oakley 2014) 또는 "정신 모델"(Brown et al. 2014)로 설명된다. 정신 모델은 사람이 더 효과적으로 추론하고, 해결하고, 창조할 수 있게 해준다(Brown et al. 2014). 학습자가 전문지식을 개발하는 초보자인지 또는 전문지식을 확장하는 전문가인지에 관계없이 학습은 뇌의 많은 다른 부분을 포함하는 세 가지 기본 단계를 따릅니다(표 1).

Necessarily, learning is hard work. A good example of effortful learning is practicing to write with one’s non-dominant hand (Leamnson 1999). Clinicians who want to maintain and extend their expertise but who are looking for simple and easy CE/CPD activities should carefully consider Doyle’s (2008) foundational statement about the learning process: “… the one who does the work does the learning” (p. 63). There is nothing quick and easy about meaningful learning. Having said this, with roughly 86 billion neurons (Herculano-Houzel and Lent 2005) making 150 trillion connections or synapses (Doyle and Zakrajsek 2013), and with a digital storage capacity of one million gigabytes (Carey 2014), the capacity of the average human brain for learning is truly remarkable, if used appropriately. Reflecting thousands of hours of study and practice, the vast neural networks that constitute true expertise in a field – academic or otherwise - are often described as a “chunk” (Oakley 2014) or a “mental model” (Brown et al. 2014). Mental models allow a person to reason, solve and create more effectively (Brown et al. 2014). Whether a learner is a novice developing expertise or an expert expanding her/his expertise, learning follows three basic steps that involve many different parts of the brain (Table 1).

인코딩

Encoding

학습 과정의 첫 단계인 [인코딩]은 하나 이상의 감각에 의해 인식되는 정보를 뇌로 가져오는 것을 수반하며, 이는 [단기 기억]의 정보를 일시적으로 기억 흔적으로 표현하기 위해 화학적, 전기적 신호를 사용한다(Brown et al. 2014). 새로운 것을 배울 때 형성되는 신경 연결은 뇌가 그 정보에 대한 영구적인 기억을 형성하기 위해 사용할 것과 같은 세트이다. 이와 같이 초기 노출 시점에 새로운 정보(즉, 상세하고 다면적이며 감정적으로 만드는 것)를 더 정교하게 인코딩할수록 나중에 회상할 가능성이 더 높다(Squire 및 Kandel 2000). 인코딩에 관여하는 뇌의 부분은 다음을 포함한다.

- 신피질(학습 프로세스를 시작),

- 전전두피질(과제에 충분한 주의를 기울일 수 있도록 보장)

- 해마(운동 기술과 관련된 것 이외의 의식적인 단기 기억의 위치 및 처리)

The first step in the learning process – encoding – entails bringing information perceived by one or more senses into the brain, which uses chemical and electrical signals to represent the information temporarily in short-term memory as a memory trace (Brown et al. 2014). The neural connections that form when one learns something new are the same set that the brain will use to form a permanent memory for that information. As such, the more elaborately one encodes new information (i.e. making it detailed, multifaceted, and emotional) at the time of initial exposure, the better the chance of later recall (Squire and Kandel 2000). Parts of the brain that are involved in encoding include

- the neocortex (initiates the process of learning) (Hahn et al. 2012; Doyle and Zakrajsek 2013),

- the pre-frontal cortex (ensuring that sufficient attention is available for the task) (Oakley 2014), and

- the hippocampus (location and processing of conscious short term memories other than those involving motor skills) (Brown et al. 2014; Oakley 2014).

이름에서 알 수 있듯, 기억 흔적은 본질적으로 유연하지만(Brown et al. 2014), 초기 인코딩 이벤트의 품질은 장기적인 숙달에 중요하다(Benjamin and Tullis 2010). 인코딩은 한 저자가 '집중 모드 사고'(Oakley 2014)라고 지칭하고 다른 저자가 '노력적 관심'(Brown et al. 2014)이라고 부르는 특별한 유형의 주의를 필요로 한다. 이름과는 상관없이, 새롭고/또는 도전적인 것에 집중하는 데 더 많은 집중력을 쏟을 수 있는 정신적인 에너지가 더 많을수록, 정보는 단기 기억에서 정확하고 완전히 표현될 가능성이 더 높다.

Even though memory traces, as the name implies, are inherently labile (Brown et al. 2014), the quality of the initial encoding event is critical to long-term mastery (Benjamin and Tullis 2010). Encoding requires a special type of attention that one author refers to as ‘focused-mode thinking’ (Oakley 2014) and that others call ‘effortful attention’ (Brown et al. 2014). Regardless of its name, the more undistracted mental energy that one can devote to focusing on something new and/or challenging, the more likely it is that the information will find itself accurately and completely represented in short-term memory.

통합

Consolidation

[통합]으로 알려진 학습의 다음 단계 동안 뇌는 중요한 것으로 플래그가 지정된 기억 흔적을 "빠르지만 용량이 적은 단기 기억 저장소"인 [해마]에서 가져와서 "학습은 가능하지만 용량은 더 큰 장기 기억 저장"인 신피질의 적절한 영역(예: 시각 처리 센터)으로 옮긴다. 이 단계에는 경막피질(해마와 신피질 사이의 주요 상호 작용을 조정하는)이 관여한다(Hahn et al. 2012). 신피질이 적절한 조건(예: 양질의 수면)에 있다면, 기억 흔적은 [신중한 처리]를 거치게 되는데, 그 동안 "뇌는 학습을 재생하거나 리허설을 하며 의미를 부여하고 빈 곳을 채우며 과거의 경험과 이미 장기 기억에 저장되어 있는 다른 지식과 연결시킨다." 이것이 한 과목에 대한 상당한 양의 사전 지식을 가진 사람이 그 과목에 대한 새로운 학습이 더 쉽다고 느끼는 이유이다. 뇌는 연결을 만드는 경험을 많이 가지고 있다.

During the next step of learning known as consolidation, the brain takes memory traces flagged as important (Carey 2014) – based on significant effort or relevance – from the hippocampus, which is the “fast-learning but low-capacity short-term memory store” (Doyle and Zakrajsek 2013, p. 73) and transfers them to the appropriate area (e.g. visual processing center) of the neocortex, which is the “slower-learning but higher-capacity long-term memory store” (Doyle and Zakrajsek 2013, p. 73). The entorhinal cortex (coordinating key interactions between the hippocampus and the neocortex) is involved in this step (Hahn et al. 2012). Under the right conditions (e.g. quality sleep) in the neocortex, the memory traces undergo careful processing, during which time “… the brain replays or rehearses the learning, giving it meaning, filling in blank spots, and making connections to past experiences and to other knowledge already stored in long-term memory” (Brown et al. 2014, p. 73). This is why a person with significant amounts of prior knowledge in a subject finds new learning in that subject to be easier; the brain has many experiences with which to make connections.

수면은 [통합]에 중요할 뿐만 아니라, 수면의 주요 목적이 될 수 있다(Carey 2014). 낮잠이나 다른 인지적 '휴식' 동안 정보를 통합할 수 있지만, 야간 수면은 통합에 가장 좋습니다(Doyle and Zakrajsek 2013). 수면 단계가 다르면 학습 유형이 다르기 때문에 모든 수면 단계를 포함하는 숙면 휴식이 필요하다(Carey 2014). 예를 들어, 빠른 안구 운동(REM) 수면은 패턴 인식 및 창의적 문제 해결과 관련이 있다(Carey 2014). 새로 학습된 정보는 통합 중에 기존 신경망의 일부가 되거나(동조화) 새로운 신경망(수용)을 형성하기 시작한다. 수면은 단기 기억의 공간을 비움으로써 다음날 새로운 학습을 위해 뇌를 준비시키는 추가적인 이점을 제공한다. Oakley(2014)는 인코딩에 대한 [집중 모드 사고]와 달리 통합과 관련된 사고의 유형을 '확산 모드 사고'라고 부른다. 왜냐하면 이 과정은 우리의 의식적인 노력 없이 일어나고, 종종 신피질의 다른 영역을 포함한 뇌의 많은 부분을 포함하기 때문이다.

Not only is sleep critical to consolidation, it may be the primary purpose of sleep (Carey 2014). While one can consolidate information during a nap or other cognitive ‘break,’ nocturnal sleep is best for consolidation (Doyle and Zakrajsek 2013). A good night’s rest that includes all sleep phases is necessary, as different sleep phases are associated with different types of learning (Carey 2014). For example, rapid eye movement (REM) sleep is associated with pattern recognition and creative problem solving, among other things (Carey 2014). During consolidation, newly learned information becomes part of an existing neural network (assimilation) or begins to form a new one (accommodation) (Doyle and Zakrajsek 2013). Sleep offers the additional benefit of preparing the brain for new learning the next day by clearing space in short-term memory (Doyle and Zakrajsek 2013). In contrast to the focused-mode thinking of encoding, Oakley (2014) refers to the type of thinking associated with consolidation as ‘diffuse-mode thinking,’ given that it happens without our conscious effort and involves many parts of the brain, often including different areas of the neocortex.

인출

Retrieval

학습과학 전문가들은 종종 "필요할 때 인출할 수 있을 때 무언가를 배웠다고 한다"(도일 2017). 인출이라는 이름은 이전에 학습된 정보에 접근하는 것을 의미하지만, 메모리로부터 정보를 검색하는 과정 그 자체가 신경망에 관여하는 세포의 시냅스를 안정화시켜 더 강하고 빠르게 만든다(Brown et al. 2014). LTP(Long-term potentiation)라고 알려진 프로세스는 미래에 정보를 리콜할 수 있는 가능성을 의미합니다. 중요한 정보를 검색할 때마다 LTP가 증가합니다. 검색은 또한 뇌가 정보를 다시 사용한 후에 정보를 다시 통합함으로써 이해도를 향상시킬 수 있다(Brown et al. 2014). 학습에 대한 다음 정의에 따르면, [인코딩과 통합]은 "지식과 기술 습득" 부분을 설명하지만, [인출]은 나머지 부분을 설명합니다.

- "[학습이란] 지식과 기술을 습득하고 이를 기억에서 쉽게 얻을 수 있게 하여 미래의 문제와 기회를 이해할 수 있게 하는 것을 의미한다."

earning science experts often say, “You are said to have learned something when you can retrieve it when you need it” (Doyle 2017). While retrieval’s name implies accessing previously learned information, the process of retrieving information from memory makes it stronger and faster by stabilizing the synapses of cells involved in the neural network (Brown et al. 2014). A process known as long-term potentiation (LTP) refers to the potential to recall information in the future; LTP increases each time one retrieves important information (Hebb 1949; Paradiso et al. 2007). Retrieval can also improve understanding by reconsolidating the information after the brain uses it again (Brown et al. 2014). As per the following definition of learning, encoding and consolidation account for the “acquiring knowledge and skills” part, but retrieval accounts for the remainder of the definition:

- “[Learning means] acquiring knowledge and skills and having them readily available from memory so you can make sense of future problems and opportunities” (Brown et al. 2014, p. 2).

검색은 [장기 기억(신피질)]에 저장된 정보에 접근하여 정보를 [단기 기억(히포캠퍼스)]으로 불러오는 것을 포함한다. 뇌가 학습된 정보에 접근할 때마다 기억력이 변하며, 최신 맥락을 반영하는 새로운 신호 세트와 연관된다는 점을 고려할 때(Carey 2014) 더 나아진다(Brown et al. 2014) 응답할 수 있는 신호가 많을수록 정보를 떠올릴 가능성이 높아진다. 또한 학습된 정보와 관련된 맥락적 단서가 더 다양할수록 (추가적이고 다른 응용 프로그램을 통해) 정보에 대한 뇌의 이해와 접근성이 향상된다(Brown et al. 2014). 또한 검색은 학습된 정보와 관련된 청크의 크기를 증가시키고 새로운 상황으로의 전송 가능성을 향상시킨다(Oakley 2014).

Retrieval involves accessing information stored as a long-term memory (neocortex) and bringing the information back to short-term memory (hippocampus). Each time the brain accesses learned information, the memory changes (Doyle and Zakrajsek 2013; Carey 2014), and for the better (Carey 2014), given that it becomes associated with a new set of cues reflecting the latest context (Brown et al. 2014). The more cues to which one can respond, the better the chance of recalling the information. In addition, the more diverse the contextual cues associated with learned information, the better the brain’s understanding of (through additional and different applications), and access to, the information (Brown et al. 2014). Retrieval also increases the size of the chunk associated with learned information and improves its transferability to new situations (Oakley 2014).

어떤 전략이 학습에 중요합니까?

What strategies are important to learning?

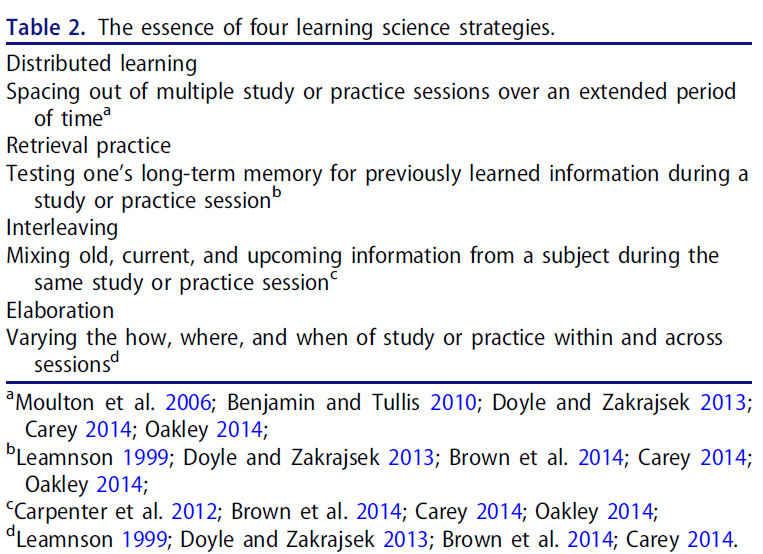

네 가지 보완적 학습 과학 전략은 학습에 대한 간략한 개요(표 2)와 일치하며, 저자들의 의견으로는 CE/CPD에 가장 중요하다. 뚜렷한 전략으로 설명되지는 않았지만, 4대 접근법의 기초가 되는 것은 학습은 학습 의미에서 많은 "실습practice"을 필요로 하는 과정이라는 것이다. 전문가가 되고 전문가로 남으려면 말 그대로 수천 시간의 공부와 훈련이 필요하기 때문에, 실습이 중요하다는 것을 학문과 전문지식을 갖춘 임상의에게 설명할 필요는 거의 없다(Brown et al. 2014). 전문가들 사이에서 우수한 성과를 설명하면서 에릭슨과 풀(2016)은 성과 약점에 초점을 맞추고 피드백을 제공하고 개선을 촉진할 줄 아는 교사나 코치가 지도하는 몇 년간의 공부 또는 연습(일반적으로)을 지칭하기 위해 "의도적 연습"이라는 용어를 사용한다.

Four complementary learning science strategies are consistent with this brief overview of learning (Table 2), and, in the authors’ opinion, most important to CE/CPD. Though not described as a distinct strategy, what underlies the four major approaches is that learning is a process that requires lots of “practice,” in the learning sense. Practice requires little explanation for any clinician with discipline and specialty-specific expertise, as becoming and remaining an expert requires literally thousands of hours of study and training (Brown et al. 2014). Describing superior performance among experts, Ericsson and Pool (2016) use the term “deliberate practice” to refer to the years (typically) of study or practice focused on performance weaknesses and guided by teachers or coaches who know how to provide feedback and to facilitate improvement.

일반적으로 (태도, 역량, 행동 및 수행은 말할 것도 없고) 지식과 기술의 집합이 더 생소하거나 복잡할수록, 그것을 마스터하고 유지하기 위해 더 많은 정보를 가진 공부나 연습이 필요할 것이다. 예를 들어, 무작위 대조 시험에서 쇼 외 연구진(2011)은 CE 회의에 이어 온라인 보충물(정답과 설명이 포함된 객관식 질문)에 참여한 임상의(대부분 의사와 간호사)가 임상 실무 행동의 개선을 자체 보고하였다. 평가를 완료하기 전에만 회의에 참석한 임상의. 끊임없이 변화하는 임상 실습의 특성을 고려할 때, CE/CPD는 이전 교육 및 훈련과 마찬가지로 피드백을 통한 학습에 전념해야 합니다. 그 연습 시간 동안 다양한 접근법을 사용하는 것처럼 중요한 정보를 가지고 상당한 양의 연습이 필요하다. 많은 경쟁적인 관심사와 요구에 직면한 바쁜 임상의는 틀림없이 과학 전략을 학습함으로써 가장 많은 이익을 얻을 것이며, 이는 또한 교육, 공식(학생, 훈련생 및 동료 교사) 및 비공식(환자 상담)에서의 역할을 모두 지원할 것이다.

In general, the more unfamiliar or complex some set of knowledge and skills is (not to mention attitude, competence, behavior and performance), the more informed study or practice will be necessary to master and maintain it. For example, in a randomized controlled trial Shaw et al. (2011) demonstrated that clinicians (mostly physicians and nurse practitioners) who participated in an online supplement (multiple choice questions with correct answers and explanations) following a CE conference self-reported enhanced improvement in clinical practice behaviors compared to clinicians who only attended the conference prior to completing the assessment. Given the ever-changing nature of clinical practice, CE/CPD requires the same devotion to learning with feedback as did prior education and training. A significant amount of practice with important information is necessary, as is using a variety of approaches during that practice time. Busy clinicians, facing many competing interests and demands, would arguably benefit most from learning science strategies, which would also support their roles in education, formal (teaching students, trainees, and colleagues) and informal (counseling patients) alike.

분산 학습

Distributed learning

"공간 효과"라고 하는 이점을 가진 "분산 실습"이라고도 하는 분산 학습은 효과적인 학습 과학 전략입니다(Carey 2014). 분산형(Distributed)은 장기간에 걸쳐 여러 스터디 또는 연습 세션에서 간격을 두는 것을 의미합니다(Benjamin 및 Tullis 2010). Oakley(2014)는 최초 노출 후 24시간 이내에 새로 학습한 정보로 돌아갈 것을 권고한다. 정보가 이해되면, 연구 세션 사이의 간격을 일, 주, 그리고 몇 개월로 점차 늘려 장기간에 걸쳐 확실하게 기억해야 한다(Doyle and Zakrajsek 2013; Oakley 2014). 한 세션 동안 주제를 공부하거나 기술을 연습하는 데 상당한 시간을 소비하는 것은 효율적으로 보일지도 모른다. 이를 "대집합 연습" 또는 보다 구어체로 "벼락치기"라고 한다. 하지만 단일 세션에서 보내는 시간이 많을수록, 그 시간은 덜 효과적이게 된다.

Distributed learning, also known as “distributed practice” with benefits referred to as the “spacing effect,” is an effective learning science strategy (Carey 2014). “Distributed” refers to the spacing out of multiple study or practice sessions over an extended period of time (Benjamin and Tullis 2010). Oakley (2014) recommends that one should return to newly learned information within 24 hours of initial exposure. Once the information is understood, one should gradually increase the spacing between study sessions from days, to weeks, and then to months in order to reliably remember it for extended periods (Doyle and Zakrajsek 2013; Oakley 2014). As efficient as it may seem to spend a significant amount of time studying a topic or practicing a skill during a single session – what is known as “massed practice” or more colloquially as “cramming” – the more time that participants spend in a single session, the less effective that time becomes.

과도한 반복은 뇌를 지루하게 만든다(Carey 2014). 대규모 연습massed practice을 통해 단기 기억에서 정보를 반복적으로 작업하지만, 학습에 결정적인 것은 장기 기억으로 작업하는 것이다(Carey 2014). 숙달을 위해 뇌는 자신이 연습한 것을 처리하고, 수면 시간으로 분리된 다른 시간에 다시 돌아올 시간이 필요하다(도일과 Zakrajsek 2013). CE/CPD에 특유하고 분산된 관행만 있는 예가 결여된 상태에서, 미세혈관 문합법을 배우는 외과 레지던트들의 무작위 대조 실험은 프로시저를 [4주 동안] 배운 레지던트들이 [단일 집중 세션]에서 배운 레지던트들보다 훨씬 더 나은 성과를 보였으나, 후자의 방식이 CE/CPD에서 흔하다(Moulton et al. 2006). 시험과 같이 알려진 종착점이 주어졌을 때 언제 공부해야 하는지, 간격을 고정 또는 확장해야 하는지에 대해 많은 것이 쓰여져 있지만(Carpenter et al. 2012), 가장 중요한 것은 오랜 기간에 걸쳐 학습을 분산시키는 것이다.

The brain becomes bored with excessive repetition (Carey 2014). With massed practice, one is working with the information repeatedly in short-term memory, but working with long-term memory is what is critical to learning (Carey 2014). For mastery, the brain needs time to process what one has practiced and to come back to it at different times separated by periods of sleep (Doyle and Zakrajsek 2013). Lacking an example that is CE/CPD-specific and distributed practice only, a randomized controlled trial of surgical residents learning microvascular anastomosis revealed that residents who learned the procedure over four weekly sessions performed significantly better than those who learned it during a single intensive session, the latter being common in CE/CPD (Moulton et al. 2006). While much has been written about when to study given a known end point, such as an exam, and whether the spacing should be fixed or expanding (Carpenter et al. 2012), what is most important is that one distributes her/his learning over an extended period of time.

인출 연습

Retrieval practice

"언제"(분산 학습)와 대조적으로, 학습하는 동안 "어떻게" 시간을 보내는가는 검색 실습 또는 "리콜"로 알려진 학습 과학 전략과 관련이 있으며, 그 이점은 "테스트 효과" 또는 "생성 효과"로 알려져 있다(Oakley 2014). 검색 연습은 재독과 같은 수동적인 학습 수단에 비해 중요한 정보에 대한 기억력을 향상시킬 수 있다(Carey 2014). 장기 기억에서 정보를 검색하려면 단순히 정보를 다시 리뷰하는 것보다 더 많은 노력이 필요하며, 정보를 복원하면 다시 편집되었다는 점에서 새로운 연결 또는 다른 연결(Carey 2014)이 발생합니다. 린슨(1999)이 설명하듯이, "강도의 집중은, 약간의 압박 하에서, 언어와 씨름하는 동안, 뇌에 무언가를 하지 않을 수 없다." 중요한 정보를 이해하기 위해 초기 학습 세션 동안 집중 모드 사고(Oakley 2014)를 사용한 후, 검색 연습은 학습자가 정보를 설명하기 위해 장기 기억을 검색하도록 강요하며, 이상적으로는 완전한 문장으로, 자신만의 단어로, 말하기 또는 쓰기를 하게 된다(Leamnson 1999).

In contrast to “when” (distributed learning), “how” one spends time while learning is relevant to the learning science strategy known as retrieval practice or “recall,” the benefits of which are known as the “testing effect” or the “generation effect” (Oakley 2014). Retrieval practice can improve memory for important information compared to passive means of study, such as rereading (Carey 2014). Retrieving information from long-term memory requires more effort than simply reviewing the information again, and restoring the information results in new or different connections (Carey 2014) given that it has been re-edited (Doyle and Zakrajsek 2013). As Leamnson (1999) explains, “Intense concentration, under a little pressure, while wrestling with language, cannot but do something to the brain (p. 111).” After using focused-mode thinking (Oakley 2014) during an initial learning session or two to understand important information, retrieval practice forces the learner to search her or his long-term memory to explain the information, ideally using her or his own spoken or written words in complete sentences (Leamnson 1999).

이 시도가 아무리 성공적이더라도, 학습자는 [신뢰할 수 있는 출처와 비교함으로써, 이해의 정확성과 완전성을 점검]해야 하며, 후속 학습 세션에서 초점을 맞출 개선 기회를 노려야 한다(Brown et al. 2014). 따라서 검색 시도는 정보에 대한 일부 어려움을 겪은 후 학습자에게 [피드백]을 제공한다(Oakley 2014). 게다가, 검색 연습은 단기 기억과 장기 기억 사이에서 정보의 이동을 강요하며, 매번 이해력과 기억력을 향상시킨다. 예를 들어, Larsen 외 연구진(2015)은 연례 회의 참석에 따른 반복 퀴즈를 통해 반복 학습에 비해 습득한 지식의 장기 보존이 향상(거의 두 배)되었음을 입증했다. 인출 연습이 이해를 테스트하는 것으로서도 잘 작동하지만, 리콜은 효과적인 사전 테스트pretest이기도 합니다(Carey 2014). 사전 테스트는 학습자가 종종 자신의 필요를 잘 판단하지 못하기 때문에 지식과 이해에서 [학습자의 격차를 명시함]으로써, 뇌가 [학습할 수 있도록 준비]한다(Brown et al. 2014). 일단 이렇게 작동하면, 뇌는 잠재의식적으로 필요한 정보를 찾기 시작할 것이고, 이 상태는 Carey (2014)가 '사냥하는 뇌'라고 부르는 상태입니다 (p.213).

Following the attempt, however successful, the learner should check the accuracy and completeness of her/his understanding against a credible source, noting opportunities for improvement on which to focus in subsequent study sessions (Brown et al. 2014). Retrieval attempts thus provide feedback to the learner following some struggle with the information (Oakley 2014). Moreover, retrieval practice forces the movement of information between short-term and long-term memory, each time improving comprehension and memory. For example, Larsen et al. (2015) demonstrated that repeating quizzing following attendance at an annual conference improved (nearly doubled) long-term retention of knowledge acquired compared to repeat studying. While retrieval practice works well as a test of understanding, recall is also an effective pretest (Carey 2014). Pre-testing prepares the brain to learn by making explicit for the learner gaps in knowledge and understanding, for learners are often a poor judge of their own needs (Brown et al. 2014). Once realized, the brain will subconsciously begin to look for needed information, a state that Carey (2014) calls the ‘foraging brain’ (p. 213).

인터리빙

Interleaving

인터리빙은 공부나 연습 시간을 보내는 방법과 관련된 또 다른 학습 과학 전략이다. 인터리빙(Interleaving)은 "학습 중에 관련되지만 구분되는 자료를 혼합하는 것"을 의미하며(Carey 2014, p. 163) 학습자가 원칙, 개념 및 절차와 같이 이전에 학습한 정보를 동일한 학습 활동에서 더 최근의 정보와 심지어 향후의 정보와 조화시키도록 강제한다. 학습자는 특정 학습 시간 동안 단일 영역에 비례적으로 더 많은 시간을 할애할 수 있지만, 예를 들어 다가오는 교육 회의에서 논의될 어려운 사례를 고려하는데 30분을 할애할 수 있지만, 사례에만 시간을 할애하지는 않을 것이다. 또한 학습자는 비교적 먼 세션에서 논의된 최근 가이드라인 업데이트에 대해 10분 동안 질문을 하고, 20분 동안 가장 최근 세션에서 해결되지 않은 질문에 대한 가능한 답을 조사합니다. 뇌는 새로운 학습과 이전 학습 사이의 연관성을 찾는 패턴 탐색 장치이기 때문에(Ratey 2001), 학습자의 뇌는 과정이나 활동에서 오래된 자료, 현재 자료, 미래 자료를 동시에 연구함으로써 주제나 주제에 대한 확실한 이해에 따라 발전 및/또는 확장될 가능성이 더 높다(Oakley 2014).

Interleaving is another learning science strategy that relates to how one spends study or practice time. Interleaving means “… mixing related but distinct material during study” (Carey 2014, p. 163), forcing the learner to reconcile previously learned information, such as principles, concepts, and procedures, with more recent and even upcoming information in the same learning activity (Brown et al. 2014; Oakley 2014). While a learner may spend proportionately more time on a single area during a particular study session, for example, spending 30 minutes considering a challenging case to be discussed at an upcoming educational meeting, s/he would not spend time exclusively on the case. The learner might also spend 10 minutes quizzing her/himself on recent guideline updates discussed at a relatively distant session and 20 minutes researching possible answers to unresolved questions from the most recent session. Because the brain is a pattern-seeking device that looks for connections between new and previous learning (Ratey 2001), by studying old, present, and future material in a course or activity at the same time, the brain of the learner will more likely develop and/or expand upon a solid grasp of a topic or subject (Oakley 2014).

정보를 "청킹" 하는 것(앞서 설명한 명사 "청킹"을 동사로 사용함)은 학습자가 관련 부분들 사이에 더 많은 연결고리를 만들기 때문에 주어가 더 응집력 있고 기억에 남도록 만든다(Oakley 2014). 인터리빙의 이점 중 하나는 학습을 분산시킨다는 것이다(Brown et al. 2014). 그러나, 특히 문제 해결이나 사례 전개에 적용할 때, 인터리빙은 학습자가 다양하고 예기치 않은 상황에서 지식과 기술을 사용하는 "언제"와 "어떻게"를 이해하도록 강요한다는 점이며, 이는 임상 실무에서 매우 일반적인 것이다(Carpenter et al. 2012; Oakley 2014). 즉, 학습자는 정보를 다른 맥락으로 '전이transfer'할 수 있는 가능성이 높아집니다(Carey 2014). 저자들은 CE/CPD 문헌에서 인터리빙의 예를 찾을 수 없었지만, Birnbaum et al. (2013)은 생물학 수업에서 서로 다른 범주를 병치(즉, 인터리빙)하는 것이 이러한 동일한 범주의 차단된(대량) 연습에 비해 우수한 학습 방법임을 입증했다. 인터리빙은 종종 학습자에게 느리거나 비효율적으로 느껴지지만, 연구는 인터리빙을 통해 학습된 정보에 대한 이해와 기억이 대규모 연습을 통해 학습하는 것보다 낫다는 것을 보여준다(Brown et al. 2014).

“Chunking” information (using the previously described noun – “chunk” – as a verb) makes a subject more cohesive and memorable, as the learner is creating more connections between related parts (Oakley 2014). One of the benefits of interleaving is that it distributes learning (Brown et al. 2014); however, a distinct benefit – especially when applied to solving problems or unfolding cases – is that interleaving forces the learner to understand “when” and “how” to use knowledge and skill in varying and unexpected circumstances (Carpenter et al. 2012; Oakley 2014), which are quite common in clinical practice. In other words, the learner will be more likely to be able to ‘transfer’ information to other contexts (Carey 2014). While the authors were unable to find any examples of interleaving in the CE/CPD literature, Birnbaum et al. (2013) demonstrated that juxtaposing (i.e. interleaving) different categories in a biology lesson was a superior method of learning compared to blocked (massed) practice of these same categories. While interleaving often feels slower or inefficient to the learner, research demonstrates that understanding and memory for information learned through interleaving is better than through massed practice (Brown et al. 2014).

정교화

Elaboration

정교화는 검색 연습과 인터리빙과 마찬가지로 학습자가 어떻게how 공부나 연습 시간을 보내는지에 관한 것이다. Doyle과 Zakrajsek(2013)에 따르면, 간단히 말해 정교화는 "정보에 대한 여러 경로를 만드는 과정"이다(52페이지). 기억을 논하면서, Schacter(2001)는 기억 형성에 정교화가 얼마나 필수적인지를 강조한다. 일반적으로 같은 시간, 같은 장소에서, 그리고 매번 같은 방식으로 공부하는 것에 비해, 정교함은 학습과 기억에서 훨씬 더 효과적인 전략이다. 정교화는 학습자가 다양한 감각을 포함하는 다양한 상황적 단서와 정보를 점진적으로 연관시킬 수 있도록 학습자가 가능한 한 어떻게, 어디서, 그리고 언제 공부하거나 연습할 수 있도록 장려한다. CE/CPD의 맥락에서, Shaw et al. (2011)은 3일간의 대면 컨퍼런스의 중요한 내용을 반영하는 간격 검색 관행(즉, 이메일을 통해 설명이 포함된 MCQ에 반복적으로 노출)이 자체 보고 임상 행동을 개선하는 효과적인 메커니즘임을 입증했다. Doyle과 Zakrajsek (2013)에 따르면, "(듣기, 말하기, 읽기, 쓰기, 복습 또는 자료나 기술에 대해 생각하는 것 등등) 학습에 더 많이 참여할수록 뇌의 연결이 더 강해지고 새로운 학습이 더 영구적인 기억이 될 가능성이 높아진다." (p.7) 그림이나 이미지를 만드는 것은 "이미지 큐 메모리"와 같이 학습하는 데 특히 효과적인 방법이다. 정보를 설명하기 위해 여러분 자신의 단어와 아이디어를 사용하는 것 – 바꿔말하기 – 또한 효과적인 정교함의 한 형태이다.

Elaboration (Doyle and Zakrajsek 2013; Brown et al. 2014), like retrieval practice and interleaving, concerns how a learner spends her/his study or practice time. According to Doyle and Zakrajsek (2013), elaboration is simply “[the] process of creating multiple paths to information” (p. 52). In discussing memory, Schacter (2001) emphasizes how essential elaboration is to memory formation. Compared to generally studying at the same time, in the same place, and in the same way each time, elaboration is a much more effective strategy for learning and memory. Elaboration encourages a learner to vary, as much as possible, how, where, and when s/he studies or practices so that the learner gradually associates information with a wide variety of contextual cues involving multiple senses (Doyle and Zakrajsek 2013; Carey 2014). In the context of CE/CPD, Shaw et al. (2011) demonstrated that the spaced retrieval practice (i.e. repeated exposure to emailed multiple-choice questions with explanations) reflecting important content from a three-day, face-to-face conference was an effective mechanism to improve self-reported clinical behaviors. According to Doyle and Zakrajsek (2013), “[the] more you engage with something that you are learning – such as listening, talking, reading, writing, reviewing, or thinking about the material or skill – the stronger the connections in your brain become and the more likely the new learning will become a more permanent memory” (p. 7). Creating pictures or images is an especially powerful way to learn (Doyle and Zakrajsek 2013), as “[images] cue memories” (Brown et al. 2014, p. 187). Using your own words and ideas to explain information – paraphrasing - is also an effective form of elaboration (Leamnson 1999; Brown et al. 2014).

과학 학습이 지속적인 교육에 대한 체계적인 리뷰의 최신 통합과 어떻게 일치합니까?

How does learning science align with the latest synthesis of systematic reviews about continuing education?

체계적 검토의 최신 종합(Cervero and Gaines 2015)은 주로 임상의와 CE/CPD보다는 의사와 지속적인 의료 교육(CME)에 초점을 맞추고 있지만, 그 연구 결과는 적어도 이 논의의 목적을 위해 모든 임상의와 일반적으로 CE/CPD에 합리적인 대리인 역할을 할 수 있다. 합성은 연습을 위해 다음과 같은 중요한 교훈을 제공한다.

- "CME가 더 상호작용적이고, 더 많은 방법을 사용하고, 여러 노출을 수반하며, 더 길고, 의사가 중요하게 여기는 결과에 초점을 맞춘다면, 의사 성과와 환자 결과에서 더 큰 향상으로 이어질 것이다."

While the latest synthesis of systematic reviews (Cervero and Gaines 2015) focuses primarily on physicians and continuing medical education (CME) rather than (more broadly) on clinicians and CE/CPD, its findings may serve as a reasonable proxy for all clinicians and for CE/CPD in general, at least for the purposes of this discussion. The synthesis offers the following important lesson for practice:

- “CME leads to greater improvement in physician performance and patient outcomes if it is more interactive, uses more methods, involves multiple exposures, is longer, and is focused on outcomes that are considered important by physicians” (Cervero and Gaines 2015, p. 136).

이러한 일반적인 발견은 이 글에서 간략하게 설명한 학습에 대한 학습 과학 설명과 일치한다. 인터랙티브 세션은 상호 작용의 중요성으로 시작하여, 특히 참가자가 세션 중에 주요 정보를 여러 번 고려하는 경우 단기 메모리에 견고하게 인코딩되는 정보를 촉진한다는 점에서 더 효과적일 가능성이 높다. 더 많은 방법을 사용하는 CME 활동은 더 많은 감각을 참여시키고, 따라서 단기 기억에서 정보를 더 잘 인코딩하는 결과를 가져온다는 점에서 더 효과적일 가능성이 높다. 종단적 프로그램을 통해 여러 번 노출되면 뇌가 여러 번 정보를 검색해야 하기 때문에 여러 번 노출되고 더 긴 CME 활동이 더 효과적일 수 있다. 따라서 [암호화, 통합 및 검색의 반복적 사이클]이 발생하며, 세션 간에 통합(초기 노출 후) 및 재통합(후기 노출 후)을 지원할 수 있는 충분한 수면 시간이 제공됩니다. 마지막으로, [중요한 성과에 초점을 맞춘 활동]이 참가자를 더 잘 참여시킬 수 있다는 점에서, 그 활동이 참가자에게 인식된 중요성을 고려할 때 정보를 견고하게 인코딩하고 후속적으로 처리(연결)할 가능성이 더 높다는 것을 발견했다.

These general findings are consistent with the learning science explanation of learning briefly described in this article. Starting with the importance of interaction, an interactive session is more likely to be effective given that it promotes information being encoded solidly in short-term memory, especially if participants are considering key information many times during a session. CME activities that use more methods are more likely to be effective given that they engage more senses, and, as such, will result in better encoding of information in short-term memory. CME activities that involve multiple exposures and are longer are more likely to be effective given that multiple exposures throughout a longitudinal program will require the brain to retrieve the information multiple times, resulting in iterative cycles of encoding, consolidation, and retrieval, with adequate sleep between sessions to support consolidation (after the initial exposure) and reconsolidation (after each of subsequent exposures). Finally, the synthesis’ finding that activities focused on outcomes that are considered important are more likely to be effective given that the activities will better engage participants, resulting in information being solidly encoded and more likely to be subsequently processed (consolidated) given its perceived importance to participants.

최근 체계적 검토의 종합에 대한 일반적인 결과는 네 가지 학습 과학 전략과도 일치한다.

- 대화형 CME 활동은 참가자들이 자신이 알고 있거나 믿는 것을 반성하고 (이상적으로) 자신이 할 수 있는 일에 대한 피드백을 받을 것을 요구합니다. 이러한 유형의 상호작용은 중요한 교육 성과에서 개선의 기회를 밝힐 수 있는 인출 연습 전략과 매우 일치한다.

- 더 많은 (다른) 방법을 사용하는 것은 정교화 전략에 내재된 한 가지 유형의 변형이다. 다른 변형으로는 활동의 위치와 시간을 바꾸는 것이 있다.

- 더 긴 기간에 걸쳐 여러 번 노출을 수반하는 활동은 분산 학습의 주요 원칙을 충족한다.

- 활동에 특정 전문분야의 구별되지만 관련된 정보가 혼재되어 있는 경우, 시간 경과에 따른 다중 노출은 인터리빙과도 일치할 수 있다.

- 마지막으로, 참가자들이 중요한 결과에 주의를 집중하는 한 가지 방법은 인출 연습을 통해 상대적인 약점을 인식하도록 하는 것이다. 충분한 숙달력이 부족하다는 것을 알게 된 참가자는 추가 공부나 연습의 높은 우선순위로 간주할 가능성이 높다.

The general findings of the latest synthesis of systematic reviews (Cervero and Gaines 2015) are also consistent with the four learning science strategies.

- Interactive CME activities require participants to reflect on what they know or believe and (ideally) to receive feedback on what they can do. Interaction of this type is very consistent with the strategy of retrieval practice, which can reveal opportunities for improvement in important educational outcomes.

- Using more (different) methods is one type of variation inherent to the strategy of elaboration; other variation may involve the location and time of activities.

- Activities that involve multiple exposures over a longer duration satisfy the major tenets of distributed learning.

- Multiple exposures over time may be consistent with interleaving too, if the activities involve a mix of distinct but related information of a specialty.

- Finally, one way to focus participants’ attention on important outcomes would be to make them aware of relative weaknesses through retrieval practice. A participant who becomes aware that s/he lacks sufficient mastery will likely consider it a high-priority for additional study or practice.

결론들

Conclusions

학습과학은 CE/CPD에 중요한 통찰력을 제공하여 교육자가 자신의 작업을 더 잘 이해하고 교육자가 제공하는 활동의 효과를 향상시킬 수 있도록 하는 신흥 분야입니다. 인간의 뇌에서 학습하는 것이 완전히 이해되지는 않지만, 인코딩, 통합, 검색과 같은 기본적인 단계들은 개념적으로 중요한 것으로 알려져 있으며 해마, 회음부, 신피질 등과 같은 특정 뇌 구조와 점점 더 연관되어 있다. 또한, 실무에 기반을 둔 학습 과학은 분산 학습, 검색 실습, 인터리빙 및 정교화를 포함한 몇 가지 실용적인 전략을 제공하며, 이는 교육자가 가장 중요한 결과, 즉 임상의 성과 및 환자 결과를 달성하는 것을 지원하기 위해 특정 CE/CPD 형식을 조정하는 데 도움이 될 수 있다. 마지막으로, 단계와 전략에 대한 학습 과학 설명은 가장 최근의 체계적인 검토 합성에 반영된 증거 기반 CE/CPD 속성과 일치한다.

Learning science is an emerging field that stands to offer CE/CPD important insights that may allow educators to understand better their work and to improve the effectiveness of the activities that educators offer. While learning within the human brain is not completely understood, some basic steps, such as encoding, consolidation and retrieval are known to be conceptually important and are increasingly linked to specific brain structures, such as the hippocampus, cingulate gyrus, and neocortex. Additionally, grounded in practice, learning science offers some practical strategies, including distributed learning, retrieval practice, interleaving and elaboration, which may help educators to adjust specific CE/CPD formats in support of achieving the most important outcomes, that is, clinician performance and patient outcomes. Finally, learning-science explanations about steps and strategies align with evidence-based CE/CPD attributes reflected in the most recent synthesis of systematic reviews.

Med Teach. 2018 Sep;40(9):880-885. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1425546. Epub 2018 Jan 15.

Learninㅁg science as a potential new source of understanding and improvement for continuing education and continuing professional development

PMID: 29334306

Abstract

Learning science is an emerging interdisciplinary field that offers educators key insights about what happens in the brain when learning occurs. In addition to explanations about the learning process, which includes memory and involves different parts of the brain, learning science offers effective strategies to inform the planning and implementation of activities and programs in continuing education and continuing professional development. This article provides a brief description of learning, including the three key steps of encoding, consolidation and retrieval. The article also introduces four major learning-science strategies, known as distributed learning, retrieval practice, interleaving, and elaboration, which share the importance of considerable practice. Finally, the article describes how learning science aligns with the general findings from the most recent synthesis of systematic reviews about the effectiveness of continuing medical education.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 교수개발(Faculty Development)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 교수개발을 조직적 관점에서 바라보기: 교훈 공유 (Med Teach, 2021) (0) | 2022.09.24 |

|---|---|

| 의학교육으로 뛰어넘기: 의학교육자의 경험에 대한 질적 연구 (Med Educ, 2018) (0) | 2022.09.17 |

| 보건의료전문직 교육에서 근거의 사용: 태도, 실천, 장애, 지원 (Med Teach, 2019) (0) | 2022.08.17 |

| 임상 교수자의 교육개발 참여의 모순: 활동이론 분석(Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2019) (0) | 2022.04.03 |

| 프로포절 준비 프로그램: NIH 연구비 지원 촉진을 위한 그룹 멘토링, 교수개발 모델(Acad Med, 2022) (0) | 2022.03.26 |