임상 교수자의 교육개발 참여의 모순: 활동이론 분석(Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2019)

Contradictions in clinical teachers’ engagement in educational development: an activity theory analysis

Agnes Elmberger1 · Erik Björck2,3 · Matilda Liljedahl1,4 · Juha Nieminen1 · Klara Bolander Laksov1,5

서론

Introduction

보건 전문 교육(HPE) 내에서 전문화된 교육을 실시해야 한다는 요구가 반복적으로 제기됨에 따라, 많은 의과대학은 임상의의 교육 역할을 지원하기 위한 교육 개발 활동을 제공하고 있습니다. 연구는 그러한 활동의 배치, 범위 및 효과와 개별 임상 교사가 이러한 프로그램에 참여하는 이유에 초점을 맞추고 있다. 그러나 임상교사의 [교육개발 참여에 대한 시스템적 영향]에 대해서는 충분히 알려져 있지 않다.

Due to recurrent calls to professionalise teaching practice within health professions education (HPE) (Mclean et al. 2008), many medical universities offer educational development activities to support clinicians in their teaching role. Research has focused on the arrangement, scope and effectiveness of such activities (De Rijdt et al. 2013; Leslie et al. 2013; Steinert et al. 2016; Stes et al. 2010), as well as the reasons why individual clinical teachers participate in these programs (Steinert et al. 2010). However, not enough is known about systemic influences on clinical teachers’ engagement in educational development.

[교육 개발]은 "교수진 자체 또는 교직원과 함께 일하는 다른 사람에 의해 계획되고 실행되는 행동"을 기술한다. 고등교육교사의 이러한 교육개발 참여에 대한 이전의 연구는 [내재적 요소]와 [직업적 동기]의 중요성을 보여주었다. 또한, 의학 교육자들 사이에서 개인, 그룹 및 기관 차원에서 교육 발전의 장벽과 기회를 조사하기 위한 노력이 있었다.

Educational development describes “actions, planned and undertaken by faculty members themselves or by others working with faculty, aimed at enhancing teaching” (Amundsen and Wilson 2012, p. 90). Previous research into higher education teachers’ participation in such educational development has shown the importance of both intrinsic factors and professional motives (Knight et al. 2006). Also, there have been efforts to investigate barriers to and opportunities for educational development at individual, group and institutional levels among medical educators (Stenfors-Hayes et al. 2010).

임상 환경에 있는 교사에 초점을 맞추어, 현재의 문헌은, 개인 및 전문적 개발, 같은 생각을 가진 동료와 만날 기회 등, 교육 개발에 참가하기 위한 [시간 관련 장벽]과 [개인의 동기 요소]에 대한 통찰력을 제공합니다. 단, 주로 [임상 교사 개개인에 중점]을 두고 있지만, 교수자가 소속된 복잡한 임상 환경을 인식하고, 교육 개발에 참여하는 데 있어 [시스템적 관점]을 포함하는 것이 중요하다.

Focusing on teachers situated in clinical environments, the current literature offers insights into time-related barriers and individual motivation factors to participate in educational development, including personal and professional development and opportunities to meet like-minded colleagues (Sorinola et al. 2013; Steinert et al. 2009, 2010; Zibrowski et al. 2008). However, the emphasis has primarily been on individual clinical teachers, while it would be valuable to include a systemic perspective on their engagement in educational development, recognising the complex clinical environment of which they are part (Amundsen and Wilson 2012; O’Sullivan and Irby 2011; Steinert et al. 2006).

[개인과 시스템 사이의 상호작용]에 주목하는 한 이론은 [활동 이론]이다. HPE의 복잡한 문제를 연구하기 위한 도구로 제안되었으며, 이전에는 직장 학습의 다양한 측면을 다루기 위해 적용되었다.

One theory that pays attention to interactions between the individual and the system is activity theory (Engeström et al. 1999; Engeström 1987; Virkkunen and Newnham 2013). It has been proposed as a tool for studying complex issues in HPE (Varpio et al. 2017) and has previously been applied to address different aspects of workplace learning (Reid et al. 2015; de Feijter et al. 2011; Larsen et al. 2017) and group interactions (Kent et al. 2016).

[활동체계(그림1)]는 분석의 기본단위로 간주된다. 이 시스템은 [인간 활동의 객체 지향적인 본질]을 주제로 묘사하고 있습니다. 즉, 분석의 관점으로 선택된 개인 또는 집단이 성과를 도출하는 대상에 대해 작업하는 것이다. 활동의 대상object은 활동을 향한 동기(예: 환자 치료)이지만, 그 결과outcome는 활동의 산물(예: 건강 개선)이다. 그 대상object은 개인적인 동기 부여와 연결된 [개인 수준], 즉 '특정 물체the specific object' 또는 사회적 의미와 연결된 [시스템 수준], 즉 '일반화된 물체the generalized object'에 존재할 수 있습니다.

The activity system (Fig. 1) is seen as the basic unit of analysis. It depicts the object-oriented nature of human activity with a subject, i.e. the individual or group whose viewpoint is chosen as the perspective of analysis, working on an object resulting in outcomes (Engeström and Sannino 2010; Leont’ev 1978; Vygotskij and Cole 1978). While the object of an activity is the motive directing it, e.g. patient care, the outcome is the product of the activity, e g. improved health. The object can be present at the individual level where it is connected to personal motivation, called ‘the specific object’, or at the system level connected to societal meaning, referred to as ‘the generalized object’ (Engeström and Sannino 2010).

활동 시스템은 또한 [주체와 객체subject and object 사이의 상호작용]을 위한 [중재 도구]의 사용, 즉 [객체object의 달성을 위해 도구tool가 어떻게 주체의 작업을 중재mediate하는지]를 묘사합니다. 이러한 도구는 우리의 문화 역사 및 사회 환경에서 비롯되었으며, 일정과 같은 구체적이거나 언어 및 개념과 같은 추상적일 수 있습니다(Nicolini 2012). 이 주체subject는 [규칙이 활동을 규제하고, 분업division of labour이 공동체 내에서 어떻게 일을 분배하는지를 지정]하는 사회 문화 공동체의 일부이다. 모든 요소는 상호 연결되고 함께 주체의 목적 달성을 중재하거나 방해합니다.

The activity system also depicts the use of mediating tools for the interaction between subject and object, or in other words, how tools mediate the subject’s work towards achieving the object (Engeström and Sannino 2010; Leont’ev 1978; Vygotskij and Cole 1978). Such tools originate from our cultural history and social environment and can be concrete, such as a schedule, or abstract, such as language and concepts (Nicolini 2012). The subject is part of a social and cultural community in which rules regulate the activity and where a division of labour specifies how work is divided within the community. All elements interconnect and together mediate, or hinder, the subject’s ability to achieve the object (Engeström and Sannino 2010).

활동 시스템은 다양한 견해, 전통 및 문화를 구성하며, 잘못 정렬되면 인접 활동 시스템 내부 및 사이에 [모순]을 일으킨다. [모순]은 역사적, 시스템적 긴장이며, 이는 활동의 방해로 나타난다. 그것들은 경험적 연구에서 포착하기 어렵지만, 그들의 징후는 개인의 설명과 말과 행동의 구성에서 인식될 수 있다.

Activity systems comprise a multiplicity of views, traditions and cultures which, when misaligned, give rise to contradictions within and between neighbouring activity systems (Engeström 1987). Contradictions are historic and systemic tensions, which manifest as disturbances in the activity. They are challenging to capture in empirical studies, however, their manifestations can be recognised in individuals’ accounts and constructs of words and actions (Engeström and Sannino 2011).

활동 이론은 개인과 시스템 간의 복잡한 상호작용을 이해하기 위한 도구를 제공하며 교육 개발에 참여하는 시스템성의 일부에 대처하는 데 도움을 줄 수 있습니다. 따라서 본 연구의 목적은 활동 이론의 관점을 채택하여 임상 교사가 교육 개발에 참여하는 것이 어떻게 그들이 행동하는 시스템에 의해 영향을 받는지를 탐구하는 것이었다. 구체적인 조사 질문은 다음과 같습니다.

- (1) 임상 교사는 어떤 시스템에 속하며 이러한 시스템의 모순은 무엇입니까? 그리고.

- (2) 교육 시스템에서 모순은 어떻게 드러납니까?

Activity theory affords a tool for understanding complex interactions between individuals and systems and can aid in addressing parts of the systemness of engaging in educational development. Thus, the aim of this study was to employ an activity theory perspective to explore how clinical teachers’ engagement in educational development is affected by the systems they act within. Our specific research questions were:

- (1) what systems are clinical teachers part of and what are the contradictions in these systems? and

- (2) how do the contradictions manifest in the system of education?

방법

Methods

이 연구는 [현실의 구성이 연구자와 연구 대상물 사이의 상호작용을 통해 도출된다는 것]을 인정하는 [해석주의적 접근법]을 채택했다. [활동 이론]을 이론적 틀로 적용하였고, 질적 데이터 수집 방법을 사용하여 다양한 경험을 수집하였다. 연구 그룹은 정성적 방법과 HPE(KBL, ML), 임상 교육(EB, AE) 및 교육 심리학(JN)에 대한 전문 지식을 가진 연구자로 구성되었다. 이를 통해 저자들이 반사적인 데이터 수집과 분석에 관여하는 동적인 논의가 가능해졌다.

The study employed an interpretivist approach, acknowledging that constructions of reality are elicited through interactions between the researcher and the object under study (Bunniss and Kelly 2010). Activity theory (Engeström 1987) was applied as a theoretical framework, and qualitative data collection methods were used to gather various experiences. The research group consisted of researchers with expertise in qualitative methods and HPE (KBL, ML), clinical education (EB, AE) and educational psychology (JN). This enabled a dynamic discussion whereby the authors engaged in reflexive data collection and analysis.

설정

Setting

연구는 스웨덴에 있는 대규모 단일 시설 의과대학에서 수행되었으며, 20개 이상의 학부 HPE 프로그램을 제공했으며, 그 중 일부는 많은 양의 임상실습도 포함하고 있다. 이러한 임상실습은 환자 치료, 연구 및 교육이라는 세 가지 업무를 수행하는 학술 병원에서 이루어집니다. 임상 교사는 다양한 임상 작업을 유지하면서 교육자로서의 역할을 하도록 임명된 임상 의사입니다. 대학에는 의학 교육 센터와 임상 교육 센터가 있으며, 두 센터 모두 임상 교사에게 교육 개발 지원을 제공합니다. 각 보건 분야별 전문 분야별 교육 개발은 별도로 담당한다.

The study was conducted in a large single-faculty medical university in Sweden, offering over 20 undergraduate HPE programmes, several of which include a large amount of clinical clerkships. These clerkships take place in academic hospitals which have the threefold task of patient care, research and education. Clinical teachers are clinicians appointed to roles as educators while maintaining varying amounts of clinical work. The university has a centre for medical education and a centre for clinical education, both of which offer educational development support to clinical teachers. Each health profession discipline is separately in charge of educational development for their professionals.

참가자

Participants

이 연구는 팀 차원에서 교육 개발을 실시하는 것을 제안했던 이전 연구 결과에서 나온 대규모 연구 프로젝트의 일부였습니다. 따라서 임상교사 팀은 자신의 직장에서 교육개발 프로젝트를 추진할 수 있도록 지원하는 것을 목적으로 하는 [교육개발 프로그램]에 참여하도록 초대되었습니다. 5개 팀이 참가했는데, 그 중 3개 팀이 다학문이었다. 연구에 초대된 17명의 참가자 중 한 명은 개인적인 이유로 참석하지 못했다. 16명의 참가자는 2개의 전문병원과 5개의 외과 및 내과 임상과를 대표하며 물리치료사 7명, 의사 4명, 간호사 3명, 작업치료사 1명, 병원 사회복지사 1명으로 구성됐다. 두 명은 남자였고 평균 연령은 45세였다. 교육에 대한 적극적인 참여 기간은 다음과 같다. 5년 이상(8명), 3~5년(5명), 1~2년(2명), 1년(1명).

The study was part of a larger research project in which previous findings had suggested conducting educational development on a team level (Barman et al. 2016; Söderhjelm et al. 2018). Therefore, teams of clinical teachers were invited to participate in an educational development program aiming to support them in pursuing educational development projects in their own workplace. Five teams, of which three were multi-disciplinary, participated in this one-year program. Of the 17 attendees invited to join the study, one was unable to participate for personal reasons. The 16 participants represented two academic hospitals and five clinical departments in surgery and internal medicine, and comprised seven physiotherapists, four physicians, three nurses, one occupational therapist and one hospital social worker. Two were male, and the mean age was 45 years. The duration of active participation in education was: 5+ years (8 participants), 3–5 years (5 participants), 1–2 years (2 participants) and 1 year (1 participant).

3명의 저자가 교육개발 프로그램에서 강의하고 있었기 때문에, 참가자는 다른 저자의 연구(AE)에 초대되어 자발적인 참가이며, 프로그램에서의 성과 평가에 영향을 미치지 않는다는 것을 명확히 알렸습니다. 모든 개별 참가자들로부터 사전 동의를 얻었으며, 스톡홀름 윤리 검토 위원회로부터 윤리적 승인을 받았습니다.

As three of the authors (EB, ML, KBL) were teaching in the educational development program, the participants were invited to the study by another author (AE) and clearly informed that participation was voluntary and would bear no impact on the assessment of their performance in the program. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants, and ethical approval was received from the Stockholm Ethical Review Board (nr: 2016/1425-31).

데이터 수집

Data collection

포커스 그룹은 참여를 촉진하기 위해 프로그램 데이와 함께 개최되었습니다. 인터뷰 가이드는 액티비티 이론을 사용하여 작성되었으며 다음과 같은 세 가지 중점 영역으로 나뉩니다. 개인, 그룹 및 조직. 인터뷰 주제의 예는 다음과 같습니다: 교육 및 교육 발전을 추구하기 위한 원동력, 경영진과 지역사회가 교육 문제에 어떻게 관심을 기울였는지, 그리고 임상 작업장의 교육 구조.

Focus groups were held in conjunction with a programme day to facilitate participation. The interview guide was developed using activity theory and was divided into three focus areas: the individual, the group and the organisation. Examples of topics were: the driving forces for pursuing education and educational development, how management and the community attended to educational matters and the structure of education in the clinical workplace.

3개의 포커스 그룹 각각에 5~6명의 참가자가 있었다. 첫 번째 그룹은 임상 훈련 병동으로 작업하는 두 개의 팀으로 구성되었고, 두 번째 그룹은 서로 다른 병원에 있지만 환자 특성 및 업무 측면에서 유사한 부서의 두 개의 팀으로 구성되었으며, 세 번째 그룹은 하나의 더 큰 팀으로 구성되었다. 각 포커스 그룹에는 진행자(AE, KBL, ML)와 관찰자(JN, EB, 연구 보조 JC)가 있어 후속 질문에서 진행자를 지원했습니다. 약 1시간 동안 진행된 포커스 그룹 인터뷰는 AE에 의해 음성녹음 및 문자 그대로 기록되었으며 모든 개인 데이터는 비식별화되었다.

Each of the three focus groups had five to six participants. The first group consisted of two teams working with clinical training wards, the second group of two teams from similar departments in terms of patient characteristics and tasks, though at different hospitals, and the third group of one larger team. Each focus group had a moderator (AE, KBL, ML) and an observer (JN, EB, research assistant JC) who supported the moderator in asking follow-up questions. The focus group interviews, lasting approximately one hour, were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim by AE, and all personal data were de-identified.

분석.

Analysis

학술 병원의 활동 시스템은 녹취록(AE, EB, KBL)를 읽고 다시 읽고, 잠재적 시스템(AE, EB, KBL)을 식별하며, 새롭게 드러나는emerging 시스템(모든 저자)에 대해 논의함으로써 모색되었다. 그런 다음 [딜레마, 갈등, 비판적 충돌 및 이중 구속]으로 구분될 수 있는 [모순의 담론적 징후]를 조사했다. 딜레마와 갈등은 각각 'but'과 'no'와 같은 언어적 단서로 표현된다. 비판적인 갈등은 감정적인 설명을 포함한 이야기적 스토리를 사용하여 표현되는 반면, 이중 구속은 무력감의 표현으로 표현됩니다. 모순의 징후를 식별하기 위해 언어적 신호와 데이터의 세심한 읽기가 사용되었다. 서로 다른 종류의 징후들이 서로 겹치고 얽혀 있다는 것을 인정하면서 그룹화 되었다.

The activity systems of the academic hospital were sought by reading and re-reading transcripts (AE, EB, KBL), identifying potential systems (AE, EB, KBL), and discussing the emerging systems (all authors). The data were then interrogated for discursive manifestations of contradictions, distinguishable as dilemmas, conflicts, critical conflicts and double binds (Engeström and Sannino 2011). Dilemmas and conflicts are expressed with the linguistic cues ‘but’ and ‘no’, respectively. Critical conflicts are expressed using narrative stories, including emotional accounts, while double binds are represented by expressions of helplessness (Engeström and Sannino 2011). The linguistic cues and a careful reading of the data were used to identify manifestations of contradictions. The different kinds of manifestations were grouped, acknowledging that they overlapped and intertwined.

다음으로, 주제적 접근방식을 적용하였다. 즉, 발현 부호화(AE), 주제별 코드 대조(AE, KBL, ML), 새로운 주제 검토(모든 저자)이다. 분석의 이 단계에서는 모순 분석 중에 나타난 요소와 시스템 간의 중재도 고려했다.

Next, a thematic approach (Braun and Clarke 2006) was applied as follows: coding of manifestations (AE), collating codes into themes (AE, KBL, ML), and reviewing the emerging themes (all authors). At this stage of the analysis, we also considered the mediations between elements and systems that emerged during the analysis of contradictions.

우리는 교육 개발 프로그램에 대한 저자의 일부(EB, ML, KBL) 관여가 분석에 영향을 미쳤을 수 있음을 인정한다. 따라서 우리는 [데이터에 의해 뒷받침되지 않는 가정]에 지속적으로 이의를 제기하면서, 합의에 도달할 때까지 진행 중인 분석에 대해 반복적으로 논의했다. 또한 주 작성자(AE)는 의사결정과 진행 중인 분석에 대한 [반성을 문서화]하여 성찰 로그를 작성하였다.

We recognise that some of the authors’ (EB, ML, KBL) involvement in the educational development program might have influenced the analysis. Therefore, we iteratively discussed the ongoing analysis until consensus was reached, continuously challenging any assumptions not supported by the data. Also, the main author (AE) kept a reflective log, documenting decisions and reflections on the ongoing analysis.

결과.

Results

학술병원 활동체계: 환자진료, 연구 및 교육

Activity systems of the academic hospital: patient care, research and education

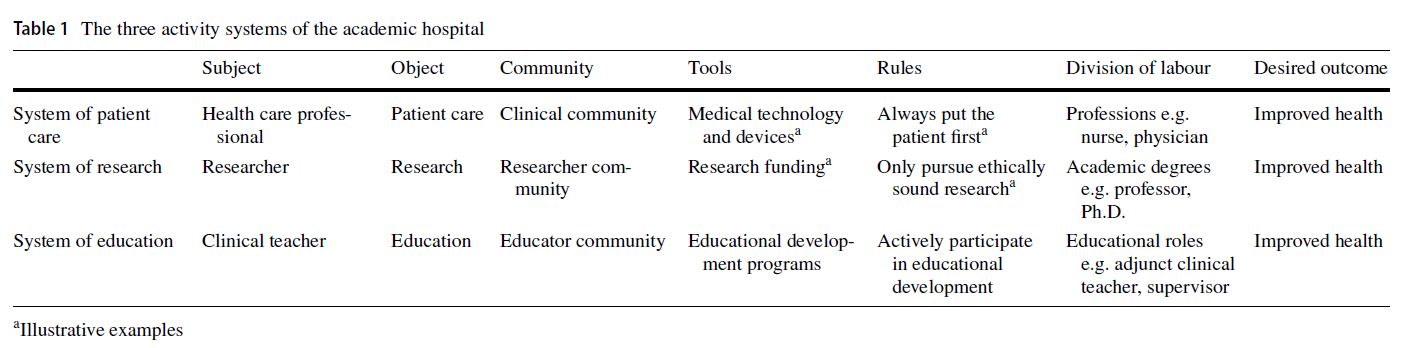

활동 이론에 따라 학술 병원의 활동을 환자 진료, 연구 및 교육 대상이 각각 지시하는 [세 가지 활동 시스템]으로 나누었다(표 1). 이러한 활동은 학술병원이 원하는 "건강의 향상"이라는 결과를 얻기 위해 결합된다. 임상 교사는 이 세 가지 시스템 중 몇 가지 또는 모두 대상이었지만 역할과 책임은 달랐다. 이하에서는, 이러한 시스템간의 모순에 대해, 그 모순과 중재자가 교육 활동에 어떻게 나타나는지에 대해 논의한다.

In keeping with activity theory, we divided the activity of the academic hospital into three activity systems directed by the objects of patient care, research and education respectively (Table 1). These activities join together in the desired outcome of the academic hospital: improved health. The clinical teachers were subjects in several or all of these three systems, yet with different roles and responsibilities. In the section below, the contradictions between these systems will be described followed by a discussion of how the contradictions, as well as mediators, manifested in the activity of education.

학술병원 시스템 간의 모순되는 대상

Contradicting objects between the systems of the academic hospital

세 가지 활동 시스템은, 학술 병원의 성과를 달성하기 위해 함께 협력해야 했기 때문에, 밀접하게 상호 연결되었지만, 환자 치료, 연구 및 교육의 대상이 일치하지 않음에 따라 시스템 간에 모순이 발생한 것이 분명했다(그림 2, 1행 #1). 시간이 끊임없이 부족했기 때문에, 일부 활동이 다른 활동보다 우선시되었고, 시스템 간의 모순을 드러내었으며, 여러 활동이 학술 병원의 업무에서 지니는 가치가 얼마나 불평등한지를 반영하였다.

The three activity systems were closely interconnected as they had to work together to achieve the outcome of the academic hospital, however it was evident that contradictions arose between the systems as their objects of patient care, research and education were not aligned (Fig. 2, line #1). As time was constantly scarce, some activities were prioritized over others, manifesting the contradiction between the systems and reflecting how activities held unequal value in the work of an academic hospital.

우리 과는 스트레스를 받고 압박이 가해지면 바로 교육을 중단합니다. (참가자1, 초점그룹3)

Our department drops education as soon as it gets stressed and the pressure is on, then it’s the patient first and education last. (Participant 1, Focus group 3)

이러한 모순으로 인해 개별 교사는 [여러 활동 시스템의 일부]가 되는 데 어려움을 겪었습니다. 활동들 사이에 시간이 나뉘어야 했습니다. 그래서 교사들은 서로 다른 역할과 정체성 사이에서 고민하고 있었습니다. 교육에 종사하는 것과 동료이자 임상의가 되는 것, 그리고 때로는 연구원이 되는 것 사이에서 협상을 해야 했습니다.

This contradiction left the individual teacher struggling with being part of several activity systems where time had to be divided between activities. Hence, the teachers were torn between conflicting roles and identities where they had to negotiate between engaging in education and being a colleague and clinician, and sometimes also a researcher.

우리는 동료들이 교육 업무에 시간을 들여야 할 때 그들이 필요로 하는 지원을 받지 못하기 때문에 부담을 느낍니다. 만약 우리가 거기에 착륙해서 우리가 필요로 하는 며칠 반의 시간을 가질 수 있다면, 우리는 지금과 같은 부담 없이 교육 업무를 더 잘 추진할 수 있을 것입니다. […] 교육 업무를 위해 하루를 예약한 경우, 누군가 일정과 함께 앉아 있는 경우:

"아니, 교육 업무 때문에 하루 종일 필요하니?" "한나절 클리닉을 할 수 있니?" "적어도 몇 시간 정도는 일할 수 있니?"

그리고 나서 너무 분명해져서 내가 스스로 자수하려고 노력하지 않으면 내 동료들은 많은 환자와 높은 처리량을 가진 거대한 일을 하게 될 거야. […] 시스템에 공간이 거의 없는 것이 가장 번거롭습니다.(P5, FG 3)

We feel pressured because our colleagues don’t get the back-up they need when we need to take time for educational work and if we could just land in that and be able to take those days and half days that we need to take, then we could pursue the educational work even better, without feeling pressured like we are now. […] If you have reserved a day for educational work and someone is sitting with the schedule:

‘No, do you need the whole day for educational work?’ ‘Can you do clinic half a day?’ ‘Can you at least work some hours?’ and then it becomes so clear that if I don’t try to turn myself inside out, my colleagues will have a huge job with lots of patients and a high throughput. […] That’s the most troublesome, that there is hardly any space in the system at all. (P5, FG 3)

이러한 대학병원의 활동간의 끊임없는 교섭에 의해, 교사는 일반적인 교육 업무에 거의 시간을 할애할 수 없게 되어, 결과적으로, 교육 활동과 본질적으로 연계된 활동인 교육 개발educational development에도 거의 시간을 할애할 수 없게 되었다.

This constant negotiation between the activities of the academic hospital left the teachers with little time for educational work in general, and consequently also little time for educational development which was an activity intrinsically interconnected to the activity of education.

교육 개발 작업을 할 여유는 없고, 가능한 한 좋은 품질로 해야 할 최소한의 일에 집중합니다. 그러나 당신은 교육을 더 발전시키고 싶기 때문에 여가 시간에 하지 않으면 그럴 시간이 없습니다.(P2, FG 3)

There is no extra time to carry out educational development work, and instead, you focus on the minimum that needs to be done with as good quality as possible. But you would like to develop the education further, and you don’t have the time for that if you don’t do it in your spare time. (P2, FG 3)

교육 활동 시스템의 모순과 중재자의 표현

Manifestations of contradictions and mediators in the activity system of education

교육의 가치관과 제정된 가치관의 불일치

Misalignment between espoused and enacted values of education

대학병원의 상반된 대상들 사이의 모순은 교육활동에서 여러 가지 방법으로 나타나서 활동과 그 요소들을 형성하였다. 이러한 표현들 중 하나는 학술병원이 [지지하는espoused 가치들(병원이 주장하는 가치들)]과 [집행되는enacted 가치들(병원이 실제로 하는 일을 통해 암시하는 가치들)] 사이의 불일치에 관한 것이었다.

The contradiction between the conflicting objects of the academic hospital manifested in the activity of education in several ways, thus shaping the activity and its elements. One of these manifestations concerned the misalignment between the espoused values of the academic hospital (what the hospital says it values) and its enacted values (what the hospital implies it values through what it actually does).

Espoused values: education as an integral part of working in an academic hospital

학원에서 일하는 데 있어서 공식적인 의무이자 필수적인 부분으로서 교육에 대한 가치관과 규범이 있는 것 같았고, 단지 교육적인 역할을 하는 사람들에게만 국한된 책임이 아니었다. 또한, 참가자들은 교육에 대한 경영진의 접근법이 의료계의 교육에 대한 일반적인 접근법에 어떻게 영향을 미칠 수 있는지 설명했으며, 일부 참가자들은 명확한 교육 초점을 가진 경영진을 묘사했다.

There seemed to be espoused values and norms about education as an official obligation and integral part of working in an academic hospital and not just a responsibility limited to those with an appointed educational role. Further, the participants described how management’s approach towards education could impact the general approach towards education in the clinical community where some participants described having a management with an articulated educational focus.

그것 [경영]은 큰 영향을 끼친다. 이것은 교육이 공간을 차지할 수 있다는 것을 보여주는 하나의 방법입니다. 그들이 말하는 것처럼, 뿐만 아니라, 뭔가 일어나고 있다는 것을 의미하기도 합니다. 그들이 교육과 함께 일하고 싶어한다는 것입니다. 그래서 경영진은 이해관계가 있는지 없는지, 무관심하다는 의사를 전달하고, 이를 직원들 사이에서 반영하고 있다고 생각합니다.(P4, FG 2)

It [management] has a huge impact. It’s a way of signalling that education is allowed to take space, not only as they say, but also that something happens, that they want to work with it [education]. So I think that management communicates either that they have an interest or that they don’t care, and this is reflected [among the staff]. (P4, FG 2)

Enacted values: lacking support and formal acknowledgment for education

이러한 [지지된 가치]들이 병원의 [집행된 가치]들과 맞지 않는 것처럼 보였다. 예를 들면, 교육 업무에 대한 경영진의 지원이나 참여buy-in의 결여에 반영되어 교육 활동을 규제하는 룰을 형성하고 있다(그림 2의 2행).

These espoused values seemed to misalign with the enacted values of the hospital. For example, the misalignment was reflected in the lack of support and buy-in from management for educational work and as such, this misalignment shaped the rules that regulated the activity of education (Fig. 2, line #2).

제가 원하던 피드백을 받지 못했습니다. 그들은 학생 병동wards를 원하고, 우리가 감독하기를 원하지만, 그에 대한 자원을 얻지 못하기 때문에 어렵다. 물론 힘든 싸움을 하는 것과 같죠. 대학에서는 임상학과와 계약하기를 원하지만, (학과장 책상에) 아직 계약하지 않고 있습니다.[…] 물론 긍정적인 응원은 있지만, 때로는 매우 소모적인 때가 있습니다. (P6, FG 1)

I haven’t really gotten the feedback that I wanted. It’s difficult because at the same time as they say that they want student wards and want us to supervise, we don’t get the resources for it. It’s like fighting an uphill battle, of course. The university wants us to sign a contract with the clinical department, which I have done, but it’s still lying there [at the department head’s desk], I haven’t got it signed […] But of course, there is positive cheering, but sometimes it’s backbreaking. (P6, FG 1)

또, 일부의 참가자는, 학과 이사회에 교육 대표가 없거나, 경영진이 교육 논의에 거의 참가하지 않았다고 이야기했다. 한 가지 경우, 경영진은 교육 문제에 대한 [책임을 임상 교사에게 완전히 위임한 것]으로 묘사되었다. 이는 경영진의 지원과 참여buy-in 부족이 강조되었으며, 환자 관리, 연구 및 교육 간의 노동 분담이 교육에 대한 책임을 교육적 역할을 가진 사람들에게 전가한 반면, 교육적 대표자는 결정이 내려진 포럼 밖에 남겨둔 것을 반영했다.

Further, some participants related that educational representatives were missing from the department’s board of directors or that management rarely took part in educational discussions. In one case, management was described as having delegated the responsibility for educational matters fully to the clinical teachers. This highlighted the lack of support and buy-in from management and reflected how the division of labour between patient care, research and education had shifted the responsibility for education to those with educational roles, while leaving educational representatives outside the forums in which decisions were made.

P1: 음, 만약 당신이 임시 교사와 몇몇 임상 교사를 가지고 있다면, 당신은 관리자로서 교육에 대해 신경 쓸 필요가 없다는 것이 항상 느껴져 왔다. […] 그러면 담당자가 있기 때문입니다. […] 그래서 저는 (매니저들이) 그들도 이 일에 관여해야 한다는 것을 이해하려고 노력했다고 생각합니다.

P1: Well, the feeling has always been that if you have an adjunct teacher and some clinical teachers then you as a manager don’t need to care about education. […] Because then you have people that are supposed to take care of it. […] And that’s where I feel I might have struggled a bit, trying to get them [the managers] to understand that they must also be involved in it.인터뷰 담당자: 당신은 그들이 어떻게 관여해야 한다고 생각합니까?

Interviewer: How do you think they should be involved?P1: 음, 당신은 학생들이 있다는 것을 알아야 합니다. 아니요, 하지만 우리는 이것에 대해 많은 시간을 가지고 이야기했습니다. 그래서 누군가는 학생 기간 동안 스케줄을 짜고 학생과 가르치는 데 실제로 얼마나 많은 시간이 걸리는지 이해합니다. 이제 임상 일을 하면서 회복하려고 노력해야 해

P1: Well, you should know that you have students [laughs]. No, but we’ve talked a lot about this with time, so who does the scheduling during the student period and understands how much time it actually takes with students and teaching. Now you have to try to pull through while doing your clinical job at the same time.P5: 네, 좋은 설명이었습니다. 예를 들어, 교육은 항상 환자가 먼저이기 때문에 시간을 끌 수 없습니다.

P5: Yes that was a good description. Like, [education] cannot take any time because it’s always the patient first.P1: 그리고 그건 그들이 (관리자들이) 그게 뭔지 모르기 때문이라고 생각해요. […] 매니저들은 '그건 네가 알아서 할 거야'라고 말합니다.(FG3)

P1: And I think it’s because they [the managers] don’t understand how it is. […] They [the managers] have like ‘well you’ll take care of that’. (FG3)

또 다른 가치관과 제정된 가치관의 불일치의 징후는 많은 교사들이 [교육 업무에 대한 공식적인 인정이 부족하다는 것]을 경험했다는 것이다. 이러한 공식적인 인정의 부족은 예를 들어 교육에 종사하는 임상의에 대한 강의의 부족을 포함하였고, 이러한 인정의 부족이 어떻게 교육자의 진로를 이탈하게 되었는지에 대해 논의하였다.

Another manifestation of the misalignment between the espoused and enacted values was that many teachers experienced a lack of formal acknowledgment for educational work, despite the espoused values of education as integral to academic hospitals. This lack of formal acknowledgment included for example the lack of lectureships for clinicians engaged in education and some discussed how this lack of formal acknowledgment might have led to others leaving the educator career path.

임상 작업장에서 교육에 대한 공식적인 논의를 확립하는 데 어려움

Difficulties establishing formal discussions on education in the clinical workplace

참가자들은 [교육에 종사하는 동료들과의 교육 토론]이 어떻게 그들의 참여를 촉진하고 그들의 교육 역할을 지원함으로써 교육 활동 시스템의 도구 역할을 수행했는지에 대해 설명했다. 이러한 논의는 부분적으로 [비공식적인 장소]에서 이루어졌으며, 여기서 교사와 동료들은 근무일 동안 교육적인 대화를 나누었다. 이러한 비공식 모임에서 실제로 모이는 것은 일정이나 점심 습관 등의 일상과 시설, 교육에 관심이 있는 동료가 근처에 있고, 이러한 논의가 이루어질 수 있는 장소에 접근할 수 있는 것에 의해 중재mediate되었다(그림 2, 3a).

The participants described how educational discussions with peers also engaged in education nurtured their engagement and supported them in their teaching role, thus acting as a tool in the education activity system. These discussions partly occurred in informal arenas, where teachers and peers had educational conversations during the working day. The actual coming together in these informal gatherings was mediated by routines and facilities such as schedules and lunch habits, having educationally interested peers nearby as well as having access to meeting places where these discussions could take place (Fig. 2, line #3a).

만약 이 사람들이 교육에도 관심이 있다는 것을 안다면, 여러분 자신이 있는 상황에서 소규모 그룹에 속해 있는 것이 매우 고무적이라고 생각합니다. 교육 개발 코스는 기초를 형성하지만 그 후에 시행되어야 하고, 그리고 나서 여러분은 영감을 주고, 지원하고, 함께 발전시킬 수 있는 팀을 만들기 위해 '지금 여기서 우리가 어떻게 나아갈 수 있을까?'라고 함께 생각하는 몇몇 친구들이 필요합니다.(P4, FG 2)

I find it very inspiring to be in smaller groups if you know that these people are also interested in education, in a context where you yourself are situated. Educational development courses form a base but then it’s supposed to be implemented, and then you need some friends who think together ‘how can we proceed here and now?’ so that you have a team where you can inspire and support and develop together. (P4, FG 2)

또한, 교육적 논의는 [교육에 할당된 일정일scheduled day] 등 [공식적인 장소에 대한 접근]으로 중재되었다. 여기서 임상 교사는 병원의 다른 교사들과 만나 교육 문제를 논의한다. 그러나, 이러한 공식 경기장은 종종 외부로 나가 대학에 의해 시작되었으며, 매우 드물었다(보통 1년에 한두 번). 일부 사업장에서는 교육계의 챔피언이 부문 차원의 교육 논의를 공식화하기 위한 노력을 기울였다(그림2 3b). 다른 경우, 참가자들은 [임상 커뮤니티에서 공식 또는 체계적인 교육 토론의 기회를 거의 또는 전혀 경험하지 못했으며], 교육은 학술 병원에서 커뮤니티의 공통 의제에서 누락되었다(그림 2, 3c행). 이는 직장 내 특정 토론을 다른 커뮤니티가 허용하거나 허용하지 않는 방법을 나타내어 교사들이 교육에 대해 논의하기 위해 모이는 방식을 형성했다.

Further, educational discussions were also mediated by access to formal arenas such as scheduled days assigned for education, where clinical teachers would meet with other teachers in the hospital as well as with representatives from the university to discuss educational matters. However, these formal arenas were often off-site and initiated by the university, as well as being quite infrequent (usually one or two times a year). In some workplaces, champions in the educator community had made efforts to formalize educational discussions at a departmental level (Fig. 2, line #3b). In other cases, participants experienced few or no opportunities for formal or structured educational discussions in the clinical community, with education apparently missing from the common agenda of the community in the academic hospital (Fig. 2, line #3c). This indicated how different communities either allowed or disallowed certain discussions in the workplace and thus shaped the way in which teachers gathered to discuss education.

직장에서 다른 일을 하려고 하는 것은 주로 나와 교수[전임상교사]이다.

실제로 회의의 구조나 정례는 없습니다. 한 학기에 한 번이지만, 뭐랄까, 명확한 계획이 없습니다.(P4, FG2)

In the workplace, then it’s mostly me and the professor [the former clinical teacher] that tries to carry out different things and we don’t have any real structure or regularity for meetings actually, it’s once a semester but without, what shall I say, any clear plan. (P4, FG2)

임시 교육 임용으로 교육 업무에 지장을 초래하다

Transient educational appointments hinder educational work

대학병원의 [분업division of labour]은 [교육활동의 규칙]을 형성해, 교사의 교육목표를 향한 업무에 방해가 되는 것 같다(그림2의 4행). 부분적으로, 이것은 [교육적 역할의 직원 배치 방식]과 관련이 있었다. 일부 참가자들은 특별히 교사직에 지원했지만, 그들 중 [다수는 커리어 궤적에서 의도적으로 교사직을 추구하지 않았다]. 대신, 임상 교사의 임명은 종종 임상 커뮤니티의 구성원들에게 [교육적 역할을 할당함]으로써 수행되었다. 예를 들어, 한 부서는 레지던트 프로그램의 일환으로 [레지던트들을 임상 교사로 로테이션 시킬 것]을 계획했습니다.

The division of labour in the academic hospital shaped the rules of the activity of education, and appeared to impede teachers in their work towards their object of education (Fig. 2, line #4). Partly, this had to do with how educational roles were staffed. While some participants had specifically applied for a teaching position, many of them had not intentionally sought the teaching position as part of a career trajectory. Instead, the appointment of clinical teachers was often carried out by allocating educational roles to members of the clinical community. As an example of this, one department was planning for residents to rotate as clinical teacher as part of their residency.

제가 부탁받았거나 교수님과 학과장이 제게 임상 선생님이 되는 것에 관심이 있냐고 물었고, 그 때쯤에는 뭐가 수반되는지는 몰랐습니다만, 그 느낌이나, 재미있었던 것 같습니다. 그리고 생각해볼 틈도 없이 '네'라고 대답했기 때문에 교육에도 관심을 갖게 된 것은 그 과정에서였습니다.(P1, FG1)

I was asked to do it, or our professor and our head of department asked me if I was interested in being a clinical teacher […] and by then I didn’t know what it entailed, but it felt, or it sounded fun. And I said yes without having had the time to reflect on it so it was during the process that I also became interested in education. (P1, FG 1)

게다가, 교사로서의 고용은 종종 1년 또는 2년으로 제한되었고, 이것은 (교육적) 역할이 종종 개인들 사이에서 순환한다는 것을 의미했다. 이는 [지속성을 저해]하기 때문에 장기적인 관점에서 교육 업무와 교육 발전의 기회를 제한하는 것으로 경험되었다.

Moreover, the employment as teacher was often limited to one or two years which meant that the role often shifted between individuals. This was experienced as limiting the opportunities for educational work and educational development in a longer-term perspective as it hindered continuity.

P3: 2년간 과제가 있고, 이직률이 상당히 높기 때문에 (교사로서) 교육을 받지 않았기 때문에 이 직책을 익히려면 시간이 좀 걸리고, 그리고 나서 정말로 그만둘 때가 되었습니다.

P3: We have our assignments for two years, and it’s a pretty high turnover, and as we don’t have any education [as teachers], it takes some time to acquaint oneself with the position, and then it’s time to quit really.P4: 교육적인 개발 작업을 하고 싶은 경우는 곤란합니다. 그러면 갑자기 새로운 동료가 소개되어야 하기 때문입니다.(FG 3)

P4: And that makes it difficult if you want to carry out some [educational] development work because then, all of a sudden, there’s a new co-worker who needs to be introduced. (FG 3)

교사 정체성 개발 방해

Impeding the development of a teacher identity

참가자들은 공식적인 교육훈련과 교육지식이 부족했기 때문에 [교육자로서의 역할에 완전히 공감하지 못하는 듯] 보였다.

The participants did not seem to identify fully with the role as educator as they lacked formal training and knowledge within education.

하지만 교육훈련이 없기 때문에 내가 알고 있는 아주 작은 것 이상의 것이 있다는 것을 깨달았을 뿐이다. 우리는 교사teacher가 아니다.(P3, FG 3)

But you just realise that there is much more than the tiny, tiny bit that I know because we don’t have any educational training; we’re not teachers. (P3, FG 3)

이와 같이, 교육 제도의 룰이나 규범 중 하나가, 교육자 커뮤니티의 적법한 멤버가 되어, 교육자의 역할과 자신을 동일시하기 위해서, 정식적인 교육 훈련이 필요하다고 생각되었다(그림 2의 5a행). 그 때문에, 참가자는, 정식 연수를 실시하는 툴로서 교육 개발 활동을 일부 요구하고 있어, 교육 개발은 교사로서의 정체성의 확립과 교육자의 커뮤니티에의 소속감을 중개할 수 있다(그림 2 제5 b항).

As such, it seemed as if one of the rules or norms of the education system was that formal training in education was required to become a legitimate member of the educator community and to identify oneself with the educator role (Fig. 2, line #5a). Therefore, the participants partly sought out educational development activities as a tool offering formal training and thus, educational development could mediate the establishment of an identity as teacher and the sense of belonging to the community of educators (Fig. 2, line #5b).

저는 실제로 변화를 주러 온 것이 아닙니다. 모든 것에 익숙하지 않기 때문에 배우러 온 것입니다. 교수-학습은 새로운 것입니다.그러므로, 이 [교육 개발 프로그램]은 과학이나 여러분이 다루는 것으로서 [교육]에 들어가는 방법입니다. (P2, FG 1 )

I’m not really here to change so much, I’m here to learn because I’m so new in everything, teaching and learning is new […] So this [the educational development program] is a way of entering it [education] as a science or something you work with. (P2, FG 1)

교육은 임상 업무에서 창조적인 공간을 매개한다.

Education mediates a creative space in routinized clinical work

교육이 [시스템 수준]에서 [일반화된 대상generalized object]이었던 교육 활동 시스템은, 참가자들에게 [개별 수준]에서 몇 가지 [잠재적 결과]를 제공했다. 부분적으로 이러한 성과는 교육이 개인 및 전문적 개발을 매개하는 교육에 대한 개인적인 관심에 관한 것이다(그림2의 6행). 또한, 많은 선생님들은 [환자 진료 활동의 창의성을 위한 공간]에 만족하지 못했고 [일상화된 임상 작업]에 충분히 자극을 받지 못했다. 따라서, [교육적 역할]은 manoeuvre을 하고, 자기주도할 수 있는 자유로, 창조적인 공간을 [매개]하고, 기존의 임상 업무와는 질적으로 다른 작업 방식을 수반하는 것으로 끌렸다.

The activity system of education, in which education was the generalized object on the system level, provided the participants with several potential outcomes on an individual level. Partly, these outcomes related to a personal interest in teaching where education mediated personal and professional development (Fig. 2, line #6). Also, many of the teachers were unsatisfied with the space for creativity within the activity of patient care and felt insufficiently stimulated by clinical work which had become routine. Therefore, the educational role attracted as it mediated a creative space with a freedom to manoeuvre and to be self-directed, and entailed a qualitatively different way of working than traditional clinical work.

그것은 자유입니다. 대학병원에는 많은 것들이 통제되고 있습니다. 그리고 이 역할에서는, 제 모든 아이디어의 배출구가 생깁니다.[…] 그러니까, 즐겁고, 일이 일어나기 때문에, 제 자유는 거기에 있습니다. (P3, FG 3)

It’s the freedom. There is so much that is controlled in an academic hospital, and in this role, I get an outlet for all my ideas, […] I mean, it’s fun, things happen, so it’s where my freedom is. (P3, FG 3)

활동 보완 - 교육 레버 리서치

Complementing activities—education levers research

위에서 설명한 바와 같이, 교사들은 교육 업무에 대한 공식적인 인정의 부족을 경험했다. 그러나 일부 부서에서는 예를 들어 연구에 시간과 자금을 제공하는 등 교사들의 작업에 대한 보상을 하려는 노력이 있었다.

As described above, the teachers experienced a lack of formal acknowledgement for educational work. However, there were efforts in some departments to remunerate teachers for their work, for example by offering time and funding for research.

임상교사는 자신의 시간의 33%를 교육용으로 남겨두고 있다. […] 저희 부서에서는 교직이 연구에 33%의 시간을 더 벌어들이고 있습니다[…] 예산은 이 33%의 연구비를 지원하는 특정 예산에서 나옵니다.(P1, FG 1)

The clinical teacher has 33% of his or her time reserved for education. […] In our department, the teaching role generates an additional 33% time for research […] money comes from a specific budget that funds this 33% [time] for research. (P1, FG 1)

또, 교육은 아카데믹 커리어 내의 자격으로서 인식되고 있기 때문에, 교육에 임하는 것은 연구 활동에 한층 더 지렛대를 제공한다(그림 2의 7행).

Also, as education was perceived as a qualification within an academic career, engaging in education offered further leverage in the activity of research (Fig. 2, line #7).

우리 과에서 가르치고 싶은 의욕을 갖게 하는 또 다른 점은 연구가 많다는 것입니다. 그리고 특히 임상 교사로서 의대생들을 가르치는 것은 연구에 매우 가치가 있습니다. 그래서 그 때문에 가르치려는 많은 사람들이 있습니다. (P1, FG 1)

Another thing that makes people motivated to teach in our department is that we have a lot of research. And teaching, especially on that level [as clinical teacher], teaching medical students, is very meriting in research, so there are lots of people [in the department] who want to teach because of that. (P1, FG 1)

논의

Discussion

본 연구에서는 활동 이론의 관점을 사용하여, [임상 교사가 교육 개발에 참여하는 것]이 어떻게 그들이 활동하는 [시스템에 의해 영향]을 받는지 조사했다. 임상 교사는 학술 병원의 세 가지 상호작용 활동 시스템인 [환자 치료, 연구, 교육 시스템]의 일부라는 것을 발견했습니다. 이 세 가지 활동은 서로 다른 대상을 가지고 있기 때문에 모순이 발생하여 일부 활동이 다른 활동보다 우선시되었다. 교사의 우선순위는 학술 병원의 우선순위와 상호 작용하여 협상되는 것처럼 보이기 때문에 이는 교육 및 교육 발전에 여러 가지 영향을 미칩니다.

In this study, we employed an activity theory perspective to explore how clinical teachers’ engagement in educational development was affected by the systems they act within. We found that the clinical teachers were part of three interacting activity systems of the academic hospital: the systems of patient care, research and education. Contradictions arose between these three activities as they had differing objects, resulting in some activities being prioritised over others. This has multiple implications for education and educational development, as teachers’ priorities seem to be negotiated in interaction with the priorities of the academic hospital.

우리의 연구결과는 [교육이 (공동체가 특정 활동을 허용하거나 허용하지 않는) 학술병원의 소외된 활동임]을 시사한다. 우리의 연구에서, 이것은 참여 임상 교사에 의해 논의된 많은 예에서 드러났습니다. 예를 들면 다음과 같습니다.

- 학술병원이 지지하는 가치와 제정된 가치 사이의 불일치

- 임상 작업장에서 공식적인 교육 논의를 할 수 있는 제한된 기회

- 의사결정이 내려지는 포럼(회의)에 교육 대표자가 부족함

- 일정과 작업 부하에 의해 교사에게 부과되는 교육과 환자 치료 간의 지속적인 협상

결국, 대학병원의 [상충하는 목적]은 [임상교수자들이 끊임없이 다른 방향으로 끌려간다는 것]을 의미했다.

Our findings suggest that education is a marginalised activity of the academic hospital where the community allows or disallows certain activities. In our study, this manifested in a number of examples discussed by the participating clinical teachers, including

- the mismatch between the espoused and enacted values of the academic hospital,

- the limited opportunities for formal educational discussions in the clinical workplace,

- the lack of educational representatives in the forums in which decisions were made, and

- the constant negotiation between education and patient care imposed on the teachers by scheduling and workloads.

Thus, the competing objects of the academic hospital meant that the teachers were constantly pulled in different directions.

병원의 환자 진료든, 대학의 연구든, [교육과 조직의 다른 업무 간의 이러한 긴장감]은 [교육 변화와 교육 개발을 수행할 수 있는 교사들의 가능성을 저해하는 것]으로 묘사되어 왔다. 이는 교육 수준이 낮은 병원에서는 교사 기관과 교육 관행을 개발할 기회가 줄어드는 조직의 리더십과 문화와 관련이 있다고 제안되어 왔다. 이와 같이, 교사의 우선 순위는 학술 병원의 가치나 실천과 밀접하게 관련되어 있는 것 같습니다. 또, 본 연구에서는, 교육과 환자 진료의 모순이, 교사의 교육 개발이나 변화를 추구할 기회를 제한할 가능성이 있는 것을 시사하고 있습니다.

This tension between education and other tasks of an organisation, whether it is patient care in hospitals or research in universities, has been described as impeding teachers’ possibilities to carry out educational change and educational development (Cantillon et al. 2016; Jääskelä et al. 2017; Stenfors-Hayes et al. 2010; Zibrowski et al. 2008). It has been suggested that this relates to leadership and culture in an organisation (Jääskelä et al. 2017; O’Sullivan and Irby 2011), where teachers’ agency and their opportunities to develop educational practices is decreased in hospitals where education has low status (Cantillon et al. 2016). As such, teachers’ priorities seem to closely interact with the values and practices of the academic hospital, and our study suggest that the contradictions between education and patient care may restrict teachers’ opportunities to pursue educational development and change.

[임상교사가 어떻게 학술병원에서 모순되는 대상과의 활동 사이에서 끌려가는지pulled]를 보여주는 이 연구에 비추어 볼 때, 어떻게 하면 이러한 교사들이 교육 개발에 참여할 수 있을지에 대한 불타는 의문은 여전히 남아 있다. 이 복잡한 문제를 해결할 수 있는 몇 가지 가능한 방법은 본 연구에서 제시한 중재 사례이며, 그 중 하나는 교육적인 토론educational discussions였다. 이러한 [토론]은 교사들의 교육적 역할을 지원하고 교육자들의 커뮤니티를 형성할 수 있게 해주었기 때문에 [교육 활동에서 중요한 도구]로 떠올랐다. 이는 교사 커뮤니티가 교사들의 교육에 대한 이해를 집단적으로 증진시키고, 직장이 가치 있는 학습의 근원으로 부각되는 이전 조사 결과를 고려할 때, 특히 중요한 것으로 보인다. 따라서, 직장에서 [교육적 토론을 가능하게 하는 경기장arenas]을 조성하는 것이, 전문 병원의 교육 개발자나 관리자에게 있어서 중요한 과제로 부상한다. 이는 교육자 공동체를 촉진·유지해, 임상 직장에서의 학습·교육 발전을 가능하게 하고 있다.

In the light of the present study illustrating how clinical teachers are pulled between activities with contradicting objects in the academic hospital, the burning question remains how to enable these teachers to engage in educational development. Some possible ways to address this complex question were those instances of mediation suggested by this study, one of which was educational discussions. These discussions emerged as a crucial tool in the activity of education as they supported teachers in their educational role and enabled the creation of communities of educators. This appears especially important considering previous findings where communities of teachers have been found to collectively advance teachers understanding of education, with the workplace being highlighted as a valuable source of learning (Jääskelä et al. 2017; Knight et al. 2006; O’Sullivan and Irby 2011; Roxå and Mårtensson 2009). Therefore, creating arenas allowing educational discussions in the workplace emerges as an important task for educational developers and managers in academic hospitals, thus promoting and sustaining communities of educators and enabling learning and educational development in the clinical workplace.

위의 내용은 교육발전을 위한 직장학습과 교육자 커뮤니티의 중요성을 강조하지만, 이 연구의 일부 참가자들은 공식적인 교육훈련이 부족했기 때문에 스스로를 교수자라고 생각하지 않았다. 따라서, 교육 제도의 ['규칙'] 중 하나는 교육 공동체의 합법적인 구성원이 되기 위해서는 공식적인 훈련이 필요하다는 것으로 보였다. 이것은, 여기나 그 외의 장소에서 설명되고 있는 것과 같이, 교육에 있어서의 지식과 스킬을 높이기 위해서, 교육 개발 활동에 종사하는 인센티브와 관련됩니다. 참여자들이 교사의 정체성을 개발하고 교육 공동체의 합법적인 구성원이 될 수 있는 기회를 제한시키는 또 다른 요인은 [교육적 역할의 일시성transience]이었다. 교육적 역할은 종종 [능동적으로 추구]되기 보다는 [수동적으로 할당]되었다. 이전의 연구는 교사 정체성이 직장 문화와 관련하여 협상된다는 것을 시사하고 있으며, 이는 우리 연구에서 학술 병원의 가치와 실천이 참가자들의 교사로서의 의식을 더욱 저해하는 이유를 설명할 수 있다. 우리의 연구결과는 교육개발이 임상의의 교사 정체성 형성과 교육자 커뮤니티에서의 정당한 멤버십을 매개하는 도구로서 기능할 가능성을 시사한다. 이와 같이, 교육개발은 직장에서 경험하는 모순된 가치관을 극복하는 데 중심적인 역할을 할 수 있다. 따라서 우리는 교육개발에 있어서 [교수자의 정체성]에 초점을 맞추자는 이전의 제안에 동의한다.

While the above underscores the importance of workplace learning and communities of educators for educational development, some of the participants in this study did not percieve themselves as teachers as they lacked formal training in education. Accordingly, one of the ‘rules’ of the education system seemed to be that one needs formal training to become a legitimate member of the educator community. This relates to the incentive to engage in educational development activities to increase knowledge and skills within teaching as described here and elsewhere (Bouwma-Gearhart 2012; Steinert et al. 2010; Stenfors-Hayes et al. 2010). Another factor that might have limited participants’ opportunities to develop teacher identities and become legitimate members of the educator community was the transience of educational roles, which were often allocated rather than sought out. Previous research suggests that teacher identity is negotiated in relation to the culture of the workplace (Cantillon et al. 2016), which could explain why the values and practices of the academic hospital in our study might have further impeded the participants’ sense of being teachers. Our findings suggest that educational development have the potential to function as a tool mediating the formation of clinicians’ teacher identity and their legitimate membership in the educator community. As such, educational development may have a central role to play in overcoming some of the contradicting values experienced in the workplace. We therefore agree with previous suggestions to focus on teacher identity in educational development (Steinert and MacDonald 2015; Stone et al. 2002).

본 연구결과는 [임상교사가 참여하는 시스템]이 [교육실천을 발전시키고, 임상직장의 교육변화를 실시conduct하며, 교사로서의 정체성을 발전시킬 기회가 있는지 여부]를 판단하는 데 중요하다는 것을 시사하기에 교육발전에 대한 함의가 있다. 이러한 이유로, 교육 개발자는, [개별 교사]에 초점을 두기 보다는, [고유의 규칙, 분업, 커뮤니티에의 대처에 의해서 활동 시스템의 개발]로 초점을 옮겨야 한다고 생각한다. 따라서 우리는 다른 사람들과 동의하며 향후 교육 개발 활동에서 [임상교사가 일하는 상황]을 고려하는 것이 필수적이라고 생각한다. 또, [의료 현장의 권력자(경영진 등)]도, 교육 개발 활동에 참가할 필요가 있습니다. 그래야만, 직장의 교육 리더십을 확립해, 교육의 진보를 인정받아 가치 있는 임상 작업장을 만들 수 있습니다. 또, 특히, 항상 그렇지만은 않았던 것을 고려하면, 임상교수자나 그 외 교육 담당자를 임상 부문의 의사결정조직decision making bodies에 포함시키는 것을 강하게 지지한다. 상기의 개입은, 의사결정에 있어서의 교육적인 관점을 촉진하는 것 뿐만이 아니라, 대학병원의 활동을 보다 제휴시켜, 임상 교사가 교육 개발에 임하는 것을 서포트하는 것이 바람직하다.

The findings of the present study have implications for educational development in suggesting that the systems clinical teachers participate in are important in determining whether or not they have opportunities to develop their teaching practice, to conduct educational change in the clinical workplace, and to develop their identities as teachers. For these reasons, we believe that educational developers should shift focus from individual teachers to also developing activity systems by addressing the inherent rules, division of labour and communities. We therefore concur with others and regard it as imperative that the context in which clinical teachers work is taken into account in future educational development activities (Jääskelä et al. 2017; O’Sullivan and Irby 2011). Moreover, we suggest that those with power in the clinical workplace, such as management, also need to take part in educational development activities as it would enable us to establish educational leadership in the workplace (Bolander Laksov and Tomson 2017) and to create clinical workplaces in which the advancement of teaching is recognised and valued (Knight et al. 2006). Also, we strongly support the inclusion of clinical teachers or other educational representatives in the decision-making bodies of clinical departments, especially considering the finding that this was not always the case. The above interventions taken together would not only promote an educational perspective in decision-making but would hopefully also help us to better align the activities of the academic hospital, thus supporting clinical teachers in engaging in educational development.

게다가 임상 교육자로서의 진로를 추구할 수 있는 가능성을 확대하는 것을 시사하고 있습니다. 이를 위해서는 교육적 역할을 임상의에게 할당하거나 임명하는 것에서 벗어나야 하는 교육에서의 채용 관행에서 출발하여 교육이 적합한 교육적 진로가 필요합니다. 대신, 이러한 임명은 명확하고 집중적인 직무 기술 및 보상 체계 구축을 통해 매력적으로 만들어져야 한다. 조사결과에서 지적된 바와 같이, 이러한 보상구조 중 하나는 교육강연회나 이와 유사한 역할을 하는 것이 될 수 있으며, 이는 임상의의 교육경로를 가시화하고 매력적으로 만드는 데 기여할 수 있다.

Further, the findings suggest expanding the possibilities to pursue a career as clinical educator. This would require distinct educational career paths where education is meriting, starting with the hiring practices in education where we should move away from allocating or appointing educational roles to clinicians. Instead, these appointments must be made attractive by having a clear and focused job description, and also through the establishment of reward structures. As pointed out in the findings, one such reward structure could be to create educational lectureships or similar roles, as this would contribute to making the educational career path for clinicians visible and appealing.

마지막으로, 본 연구에서 강조된 바와 같이, [학술 병원의 활동 시스템 간의 모순]으로 인해, [단순히 시간을 추가하는 것]만으로는 임상 교사의 교육 개발 참여를 지원하는 데 충분하지 않으며, 그 시간이 다시 환자 진료, 연구 및 교육 간에 불균등하게 분배될 위험이 있다고 생각합니다. 대신, 한 가지 해결책은 임상 교사에게 [교육적 개발이 요구되는 시스템을 구축하는 것]이며, 워크샵과 강좌에 참석하거나 교육 회의에 참석하거나 자신의 직장에서 교육 개발을 추구하거나 그러한 활동에 시간을 할당하는 것이다. 이를 위해서는 대학 내 병원과 교수진 개발 단위 간의 지속적인 대화가 요구되며, 여기서 지원은 교육 활동 시스템뿐만 아니라 개별 임상 교사의 요구에 맞춰 조정된다.

Lastly, due to the contradictions between the activity systems of the academic hospital as highlighted in this study, we believe that simply adding more time is insufficient in supporting clinical teachers engagement in educational development, risking that time is again distributed unevenly between patient care, research and education. Instead, one solution could be to establish a system in which educational development is required of clinical teachers, with time earmarked for such activities whether it be attending workshops and courses, partaking in educational conferences or pursuing educational development in the own workplace. This would call for a continuous dialogue between the hospital and faculty development units in the university, where the support is tailored to the needs of the individual clinical teacher, as well as to the activity system of education.

한계 및 향후 연구

Limitations and future research

이 연구는 오직 한 개의 의과대학만을 포함하고 있으며, 참가자들은 한 개의 교육 개발 프로그램에서 추출한 것이기 때문에, 결과의 전달 가능성은 제한적일 수 있다. 그러나 여러 직업과 임상 환경이 제시되어 교육 개발에 참여한 다양한 배경과 다양한 경험을 제시하였다.

Given that this study only included one faculty of medicine, with participants drawn from one educational development program, the transferability of findings might be limited. However, several professions and clinical environments were represented, indicating diverse backgrounds and various experiences of engaging in educational development.

흥미롭게도, 이 연구 결과는 장점, 자금, 시간을 제공함으로써 연구 활동을 활용하는 교육을 제안합니다. 효과가 반대 방향으로도 진행되는지, 아니면 이것이 이러한 활동을 조정하는 방법이 될 수 있는지, 그리고 이것이 왜 더 탐구할 가치가 있는지 알 수 없다. 또, 이 연구에는 다른 건강 직업의 참가자가 포함되었지만, 교육 발전의 기회에 관한 직업간의 차이에는 초점을 맞추지 않았다.

Interestingly, the findings suggest education to lever the activity of research by providing merits, funding and time. We do not know if the effect goes also in the opposite direction, or if this might serve as a way of aligning these activities, why this could merit further exploration. Also, while this study included participants from different health professions, it did not focus on differences between professions regarding the opportunities for educational development, a question requiring further studies.

마지막으로, 이 연구는 정규 교육 개발에 참여하는 교사들의 참여에 대한 통찰력을 제공하지만, 그러한 활동에 참여하지 않는 교사들과 그들이 직면할 수 있는 장벽에 대한 해답은 아직 남아 있다.

Lastly, while this study offers insight into the engagement of teachers who do participate in formal educational development, there are still unanswered questions about teachers who do not participate in such activities and the possible barriers that they encounter.

결론

Conclusion

본 연구에서는 활동 이론의 관점을 사용하여 임상 교사가 교육 개발에 참여하는 것이 어떻게 그들이 행동하는 시스템에 의해 영향을 받는지 조사했다. 우리의 결과는 임상 교사를 환자 치료, 연구 및 교육 시스템이 공존하고 상호작용하는 학술 병원의 일부로 배치하고, 이러한 시스템 간에 대상이 잘못 정렬됨에 따라 모순이 발생함을 시사합니다. 또한, 연구결과는 [임상교사의 우선순위]가 [학술병원의 우선순위]와 상호 작용하여 협상된다는 것을 시사한다. 학술병원의 우선순위에서 교육활동의 가치가 떨어지고 우선순위가 낮은 것으로 보이는 경우, 교육발전의 기회를 제한한다.

In this study, we employed an activity theory perspective to explore how clinical teachers’ engagement in educational development was affected by the systems they act within. Our results situate clinical teachers as part of an academic hospital where the systems of patient care, research and education co-exist and interact, and suggest that contradictions arise between these systems as their objects are misaligned. Further, the findings suggest that the priorities of clinical teachers are negotiated in interaction with the priorities of the academic hospital, where the activity of education appears to be less valued and prioritised, thus limiting the opportunities for educational development.

따라서 임상교사 개개인의 지원·육성을 위해서는 교육개발활동도 중요하지만, 교육의 진보를 촉진하고 중시하는 제도 정비에 중점을 두어 임상교사의 교육개발에 대한 관여를 중개해야 한다. 이에 따라 교육발전에 있어 학술병원의 경영진과 리더를 포함한 병원 내 의사결정기관에 교육대표를 포함시키고, 직장에서의 교육발전을 촉진하기 위한 교육자 커뮤니티 형성을 지원하고 싶다. 마찬가지로, 예를 들어 명확한 보상 구조를 가진 뚜렷한 교육 진로 확립을 통해 교육의 가치 및 보상 방식을 바꾸는 것은 임상 교사들과 그들의 교육 관행 개선을 위한 추구를 지원하는 데 도움이 될 수 있습니다.

Therefore, while educational development activities are important in supporting and developing individual clinical teachers, we must also focus on developing systems where the advancement of education is promoted and valued, thus mediating clinical teachers’ engagement in educational development. Accordingly, we would like to suggest including educational representatives in decision-making bodies in the hospital, including management and leaders of academic hospitals in educational development, as well as supporting the creation of communities of educators to better enable educational development in the workplace. Similarly, changing the way in which teaching is valued and rewarded, for example by establishing distinct educational career paths with clear reward structures, might hopefully serve to support clinical teachers and their pursuit of improving their teaching practice.

Contradictions in clinical teachers' engagement in educational development: an activity theory analysis

PMID: 30284068

PMCID: PMC6373255

DOI: 10.1007/s10459-018-9853-y

Free PMC article

Abstract

Many medical universities offer educational development activities to support clinical teachers in their teaching role. Research has focused on the scope and effectiveness of such activities and on why individual teachers attend. However, systemic perspectives that go beyond a focus on individual participants are scarce in the existing literature. Employing activity theory, we explored how clinical teachers' engagement in educational development was affected by the systems they act within. Three focus groups were held with clinical teachers from different professions. A thematic analysis was used to map the contradictions between the systems that the participants were part of and the manifestations of these contradictions in the system of education. In our model, clinical teachers were part of three activity systems directed by the objects of patient care, research and education respectively. Contradictions arose between these systems as their objects were not aligned. This manifested through the enacted values of the academic hospital, difficulties establishing educational discussions in the clinical workplace, the transient nature of educational employments, and impediments to developing a teacher identity. These findings offer insights into the complexities of engaging in educational development as clinical teachers' priorities interact with the practices and values of the academic hospital, suggesting that attention needs to shift from individual teachers to developing the systems in which they work.

Keywords: Activity theory; Clinical teacher; Contradictions; Educational development; Faculty development; Health personnel; Qualitative research; Undergraduate medical education.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 교수개발(Faculty Development)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| CME와 CPD의 이해와 개선을 위한 새로운 원천으로서의 학습과학(Med Teach, 2018) (0) | 2022.08.17 |

|---|---|

| 보건의료전문직 교육에서 근거의 사용: 태도, 실천, 장애, 지원 (Med Teach, 2019) (0) | 2022.08.17 |

| 프로포절 준비 프로그램: NIH 연구비 지원 촉진을 위한 그룹 멘토링, 교수개발 모델(Acad Med, 2022) (0) | 2022.03.26 |

| 편향되지 않고, 신뢰할 수 있고, 타당한 학생강의평가도 여전히 불공정할 수 있다 (Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 2020) (0) | 2022.03.19 |

| 교수 리더십 개발: 시너지적 접근의 사례 연구(Med Teach, 2021) (0) | 2022.03.18 |