국제 교수개발에서 문화를 이해하고 포용하기(Perspect Med Educ. 2023)

Understanding and Embracing Culture in International Faculty Development

SARA MORTAZ HEJRI, RASHMI VYAS, WILLIAM P. BURDICK, YVONNE STEINERT

소개

Introduction

여러 국가의 보건 전문직 교육자들의 역량 강화를 촉진하기 위해 고안된 국제 교수진 개발 프로그램(IFDP)의 수가 증가하고 있습니다[1, 2]. 프로그램 평가에 따르면 참가자의 지식과 기술이 향상되고 초국가적 커뮤니티가 형성된 것으로 나타났습니다[1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7]. 그러나 프로그램 참가자의 문화적 배경이 다양함에도 불구하고 참가자의 신념, 가치관, 행동이 참여와 학습에 미치는 영향을 조사한 연구[8, 9]는 거의 없습니다. 교육자들은 또한 교수진 개발 문헌에서 '모든 것에 맞는 하나의 크기'라는 개념이 널리 퍼져 있다고 한탄했습니다[10].

The number of international faculty development programs (IFDPs), designed to promote capacity-building among health professions educators across different countries, is growing [1, 2]. Program evaluations have demonstrated increases in participants’ knowledge and skills, and the creation of transnational communities [1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7]. However, despite the diversity of program participants’ cultural backgrounds, very few studies [8, 9] have explored the influence of participants’ beliefs, values, and behaviors on participation and learning. Educators have also lamented that the notion of “one size fits all” prevails in the faculty development literature [10].

IFDP는 전 세계 여러 국가의 참가자를 한데 모으는 프로그램[3, 4, 6, 7]과 한 국가에서 다른 국가로 교수자 개발 프로그램을 이전하는 프로그램[5, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15]의 두 가지 유형을 지칭합니다. IFDP에 대한 24개 보고서를 대상으로 한 범위 검토에 따르면 "이들 보고서의 약 50%가 국가적 맥락이나 문화적 규범 및 신념의 중요성을 인정했지만", IFDP의 문화적 문제는 체계적으로 연구되지 않았습니다[1]. 또한 주요 출판물[3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16]을 검토한 결과, 현재 IFDP 내에서 경험하는 문화적 차이의 유형에 대해 알려진 바가 거의 없는 것으로 나타났습니다. 다른 나라에서 온 참가자들이 IFDP에서 낯선 문화적 가치와 관행에 직면했을 때 어떻게 느끼거나 행동할 수 있는지, 그리고 교수진이 문화적 차이를 어떻게 다루는지에 대해서도 거의 연구되지 않은 상태입니다.

IFDPs refer to two types of programs: those that bring together participants from different countries around the world [3, 4, 6, 7] and those that include the transfer of a faculty development program from one country to another [5, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15]. A scoping review of 24 reports of IFDPs stated that “although close to 50% of these reports acknowledged the importance of national contexts or cultural norms and beliefs”, cultural issues in IFDPs have not been systematically studied [1]. In addition, a review of primary publications [3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16] revealed that little is currently known about the types of cultural differences experienced within an IFDP. How participants from different countries may feel or behave when facing unfamiliar cultural values and practices in an IFDP – and how faculty developers address cultural differences – has also remained largely unexplored.

이 연구의 목표는 IFDP에서 다양한 문화적 가치와 신념이 어떻게 인식되고 경험되는지 탐구하는 것이었습니다. 연구 질문은 다음과 같습니다:

- (1) IFDP에서 문화는 어떻게 인식되었나요?

- (2) 문화가 교육과 학습에 미치는 영향은 무엇인가?

The goal of this study was to explore how different cultural values and beliefs were perceived and experienced in an IFDP. Our research questions addressed the following:

- (1) How was culture perceived in an IFDP?

- (2) What were the influences of culture on teaching and learning?

이 연구를 위해 우리는 다음과 같은 문화의 정의를 선택했습니다: "집단 간에 공유할 수 있고, [사고, 의사소통 스타일, 상호작용 방식, 역할 및 관계에 대한 견해, 가치관, 관행 및 관습을 포함하는] [학습된 신념과 행동]의 통합된 패턴"[17]. 후자는 또한 변혁적 학습 이론(TLT)에 설명된 대로 '마음의 습관'이라고 불리는 것을 지칭할 수도 있습니다[18, 19]. 비판적 성찰과 변증법적 담론의 역할을 포함하는 TLT는 개인이 자신의 신념을 보다 포용적이고 변화에 개방적으로 만들기 위해 가정과 기대를 변화시키는 방법을 설명합니다. 이 이론은 본질적으로 구성주의적이고, 사회적 관점에서 학습을 바라보며, 이문화 교육, 의사소통, 고등교육의 국제화를 연구하는 데 사용되어 왔기 때문에 데이터 분석과 해석에 TLT를 사용했습니다[20, 21].

For this study, we chose the following definition of culture: “An integrated pattern of learned beliefs and behaviours that can be shared among groups and include thoughts, styles of communicating, ways of interacting, views of roles and relationships, values, practices and customs” [17]. The latter can also refer to what has been called “habits of mind”, as described in Transformative Learning Theory (TLT) [18, 19]. TLT, which includes the role of critical reflection and dialectical discourse, describes how individuals transform assumptions and expectations to make their beliefs more inclusive and open to change. We used TLT to inform our data analysis and interpretation as this theory is constructivist in nature, views learning through a social lens, and has been used to study cross-cultural training, communication, and the internationalization of higher education [20, 21].

연구 방법

Methods

우리는 해석적 설명을 사용하여 질적 연구를 수행했습니다 [22, 23]. 해석적 기술(ID)은 "인간 경험의 구성적이고 맥락적인 본질을 인정하는, 해석적 지향에 기반을 둔" 귀납적 접근법입니다[22]. 이러한 설계를 통해 반구조화된 인터뷰를 통해 참가자의 경험과 인식에 대한 심층적인 이해를 확인하고 연구 결과를 교수진 개발의 맥락에서 적용할 수 있는 가시적인 결과로 변환할 수 있었습니다[24]. 이 연구는 맥길 대학교 의학 및 보건과학부 IRB의 윤리 승인을 받았습니다.

We conducted a qualitative study using interpretive description [22, 23]. Interpretive description (ID) is an inductive approach “grounded in an interpretive orientation that acknowledges the constructed and contextual nature of human experience” [22]. This design allowed us to ascertain an in-depth understanding of participants’ experiences and perceptions through semi-structured interviews and translate our findings into tangible outcomes that could be applied in the context of faculty development [24]. Ethics approval was obtained from the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences IRB at McGill University.

연구 설정 및 샘플링

Study Setting and Sampling

연구 환경은 국제 보건 전문직 교육자의 교육 성과 및 리더십 기술 향상을 목표로 2001년에 설립된 미국 기반의 교수진 개발 프로그램인 FAIMER(국제 의학 교육 및 연구 발전 재단) 연구소 펠로우십이었습니다[25]. 이 연구 당시, 변혁적 학습의 원칙[26]에 따라 2년 동안 진행된 이 프로그램은 필라델피아에서 두 차례의 현장 세션과 두 차례의 원격 학습 세션으로 구성되었습니다. 참가자의 소속 기관에서 실행될 교육 프로젝트는 학습의 중심지이자 초국가적 교육자 커뮤니티를 형성하는 매개체였습니다[27]. 40여 개국에서 약 2,000명의 교육자가 FAIMER 인스티튜트에 참여했습니다[25].

The study setting was the FAIMER (Foundation for Advancement of International Medical Education and Research) Institute Fellowship, a US-based faculty development program established in 2001 that aims to improve the teaching performance and leadership skills of international health professions educators [25]. At the time of this study, this two-year program, informed by principles of transformational learning [26], was composed of two onsite sessions in Philadelphia, followed by two distance learning sessions. An education project, to be implemented in participants’ home institutions, was a focal point for learning and a vehicle for creating a transnational community of educators [27]. Almost 2000 educators from over 40 countries have participated in the FAIMER Institutes [25].

저희는 2014년부터 2019년까지 5개 코호트(2014~2019년)의 FAIMER 펠로우와 프로그램에 적극적으로 참여한 FAIMER 교수진 중에서 참가자를 모집했습니다. 적극적인 참여의 기준에는 현장 프로그램 중 최소 한 세션 이상에서 '주임 교수진'으로 간주되는 교수진과 지난 3~5년 동안 FAIMER에서 강의한 경험이 있어 현재 프로그램 콘텐츠와 문화에 익숙한 교수진이 포함되었습니다. FAIMER는 여러 국가에 여러 지역 연구소를 운영하고 있지만, 필라델피아 연구소는 국제적인 코호트를 대표하기 때문에 연구 참가자를 선정했습니다. 연구와 연구팀을 소개하기 위해 WB와 RV는 대상자(72명의 펠로우와 10명의 교수진)에게 이메일을 보냈고, 이어서 SMH와 YS가 동일한 명단에 대한 자세한 이메일 초대장을 보냈습니다. 총 40명의 펠로우와 5명의 교수진이 참여에 동의했으며, 이 중 성별, 국적, 징계 배경, 코호트 연도의 이질성을 보장하기 위해 의도적으로 표본을 추출했습니다. 우리는 새로운 데이터가 새로운 주제나 데이터 해석의 수정으로 이어지지 않을 때 발생하는 정보적 충분성에 도달할 때까지 연구 참가자를 등록했습니다[28].

We recruited participants from five cohorts of FAIMER Fellows (2014–2019) and from FAIMER Faculty who were actively involved in the program. Criteria for active involvement included Faculty who were considered “lead faculty” in at least one session during the onsite program and Faculty who had taught in FAIMER within the last 3–5 years and were, therefore, familiar with the current program content and culture. While FAIMER offers several Regional Institutes in different countries, we selected study participants from the Philadelphia site because it represents an international cohort. To introduce the study and research team, WB and RV sent e-mails to the eligible population (72 Fellows and 10 Faculty); this was followed by a detailed e-mail invitation from SMH and YS to the same list. Altogether, 40 Fellows and 5 Faculty agreed to participate, from which we purposefully sampled participants to ensure heterogeneity in gender, nationality, disciplinary background, and cohort year. We enrolled study participants until we reached informational sufficiency, which occurred when new data did not lead to new themes or modifications of data interpretation [28].

데이터 수집 및 분석

Data Collection and Analysis

FAIMER 연구소와 관련이 없거나 이전에 펠로우들에게 알려지지 않았던 SMH는 2019년 가을과 겨울에 Zoom 또는 Skype를 사용하여 반구조화된 인터뷰를 진행하여 펠로우들의 경험과 인식을 이끌어냈습니다. 처음 두 차례의 인터뷰와 데이터 분석을 통해 얻은 조사자들의 개념 정립에 따라 인터뷰 가이드(온라인 부록 1)를 파일럿 테스트했습니다. 이러한 변경 사항에는 질문의 순서를 바꾸고 도입부를 짧게 하여 주요 질문으로 더 빨리 진입하고 인터뷰 시간에 맞출 수 있도록 했습니다. 또한 필요에 따라 다른 문구를 사용하여 FAIMER 교수진에 대한 인터뷰 가이드를 수정했습니다. 예를 들어, 교수진에게는 "당신의 가르침"을, 펠로우에게는 "당신의 학습"을 사용했습니다. 또한 FAIMER 교수진이 문화적 차이를 고려하기 위해 교육 내용이나 과정을 변경한 적이 있는지 조사했습니다. 차별, 판단, 고정관념을 암시할 수 있는 인터뷰 질문은 의도적으로 피했습니다. 인터뷰는 43분에서 74분 동안 진행되었으며, 오디오로 녹음되었고 외부 전문가가 그대로 필사했습니다. SMH는 모든 녹취록의 정확성을 검토했습니다.

SMH, who was not connected to the FAIMER Institute nor previously known to Fellows, conducted semi-structured interviews in the fall and winter of 2019 using Zoom or Skype to elicit Fellows’ experiences and perceptions. We pilot-tested an interview guide (Online Appendix 1), which was adjusted following the first two interviews and the investigators’ evolving conceptualizations that arose from data analysis. These changes included the order of questions asked and a shorter introduction so that we could dive into the main questions more quickly and accommodate the interview timeframe. We also modified the interview guide for FAIMER Faculty by using different wording, as needed. For example, for Faculty, we used “your teaching;” for Fellows, we used “your learning”. We also probed if FAIMER Faculty had ever changed their teaching content or process to take cultural differences into account. We deliberately avoided interview questions that could suggest discrimination, judgment, or stereotyping. Interviews lasted from 43 to 74 minutes, were audio-recorded, and were transcribed verbatim by an external professional. SMH reviewed all transcripts for accuracy.

데이터 분석은 데이터 수집과 함께 반복적으로 진행되었습니다. 귀납적 기법으로 시작하여 예비 패턴과 공통 스레드를 식별하고, 나중에 데이터를 가장 잘 표현하기 위해 병합했습니다. 지속적인 비교 분석을 통해 유사한 코드와 주제에 대한 전체론적, 교차 사례 분석을 수행했습니다. 또한 각 주제를 설명하는 예시적인 인용문도 적극적으로 찾았습니다. 분석 결과를 이해하기 위해 점차 해석 단계로 나아갔고, 이를 통해 의미 있는 주제에 집중하고 분석 결과의 실제 적용을 정교화할 수 있었습니다. 또한 기존의 이론적 프레임워크[22]를 사용하여 코드를 생성하지 않았기 때문에 데이터 분석은 '상향식'이었지만, 분석과 해석이 발전함에 따라 TLT를 활용하여 참가자 간의 상호 연결된 관계와 교육 및 학습의 맥락에 대한 의미 있는 시각을 제공했습니다[23].

Data analysis was iterative and started alongside data collection. We began with an inductive technique to identify preliminary patterns and common threads which were later merged to best represent the data. By using constant comparative analysis, we conducted a holistic and cross-case analysis of similar codes and themes. We also actively sought out exemplar quotations, illustrating each theme. To make sense of the findings, we gradually progressed to interpretation; this allowed us to focus on meaningful themes and elaborate on the practical application of findings. Moreover, though our data analysis was “bottom-up” as we did not generate codes using a pre-existing theoretical framework [22], we drew upon TLT as the analysis and interpretation evolved, to provide a meaningful lens on the interconnected relationship between participants and the context for teaching and learning [23].

두 명의 저자(SMH와 YS)가 처음 두 번의 인터뷰를 독립적으로 읽고 코딩한 후, 주요 관찰 사항과 예비 조사 결과를 논의했습니다. SMH는 YS의 의견을 바탕으로 나머지 녹취록을 계속 분석하여 패턴과 주제에 대한 합의를 이끌어냈습니다. 펠로우들과의 15개 인터뷰가 모두 코딩되었을 때, SMH는 나머지 FAIMER 교수진과의 인터뷰 5개를 코딩하기 시작했습니다. SMH와 YS는 정기적으로 만나 확인된 코드, 주제별 그룹, 연구 결과의 해석을 다듬고 합의했습니다. RV와 WB는 주제를 검토하고 주제, 예시 인용 및 연구 결과의 적용에 대한 피드백을 제공했습니다.

Two authors (SMH and YS) independently read and coded the first two interviews, after which they discussed key observations and preliminary findings. SMH continued analyzing the remaining transcripts with input from YS, which led to consensus on patterns and themes. When all 15 interviews with Fellows had been coded, SMH started coding the remaining five interviews with FAIMER Faculty. SMH and YS met regularly to refine and agree on identified codes, thematic groupings, and interpretations of the findings. RV and WB reviewed the themes and gave feedback on themes, exemplar quotations, and applications of the findings.

반영성

Reflexivity

저자들은 학문적 배경, 교육적 책임, FAIMER 연구소에서의 참여도 등이 서로 달랐습니다. 저자 중 두 명은 미국 출신으로 FAIMER 펠로우십에 참여했습니다. 다른 두 명의 저자는 캐나다(다양한 문화가 공존하는 프랑스어권 지역) 출신입니다. 모든 저자는 국제 교수진 개발에 참여했습니다. 문화에 대해 묻고 있었기 때문에 우리가 직접 문화적 유사점과 차이점을 어떻게 경험하고 인식했는지에 대해 논의하는 것이 중요했습니다. 우리는 개별적으로 또는 함께 반성하고, 우리의 경험이 인터뷰 질문과 데이터 분석에 어떤 영향을 미칠 수 있는지 논의했습니다. 우리는 우리의 이전 경험이 연구의 질문과 설계를 형성했을 뿐만 아니라 데이터 수집과 분석에도 영향을 미쳤을 수 있다는 것을 알고 있었습니다. 정기적으로 모임을 갖고 지속적인 토론과 성찰의 과정에 깊이 참여함으로써 참가자들의 내러티브를 해석하는 데 있어 다양한 관점의 균형을 맞추는 데 도움이 되었습니다.

The authors differed in their disciplinary backgrounds, educational responsibilities, and involvement in the FAIMER Institute. Two of the authors are from the US and have been involved in the FAIMER Fellowship. The two other authors are from Canada (from a French-speaking province with multiple cultures). All authors have been involved in international faculty development. Since we were asking about culture, it was important for us to discuss how we experienced and perceived cultural similarities and differences ourselves. We reflected individually and together, and we discussed how our experiences could influence the interview questions and data analysis. We were aware that our previous experiences not only shaped the questions and design of the research but might have also impacted data collection and analysis. Meeting regularly and becoming deeply engaged in the process of continuous discussion and reflection further helped us balance diverse perspectives on the interpretation of participants’ narratives.

연구 결과

Results

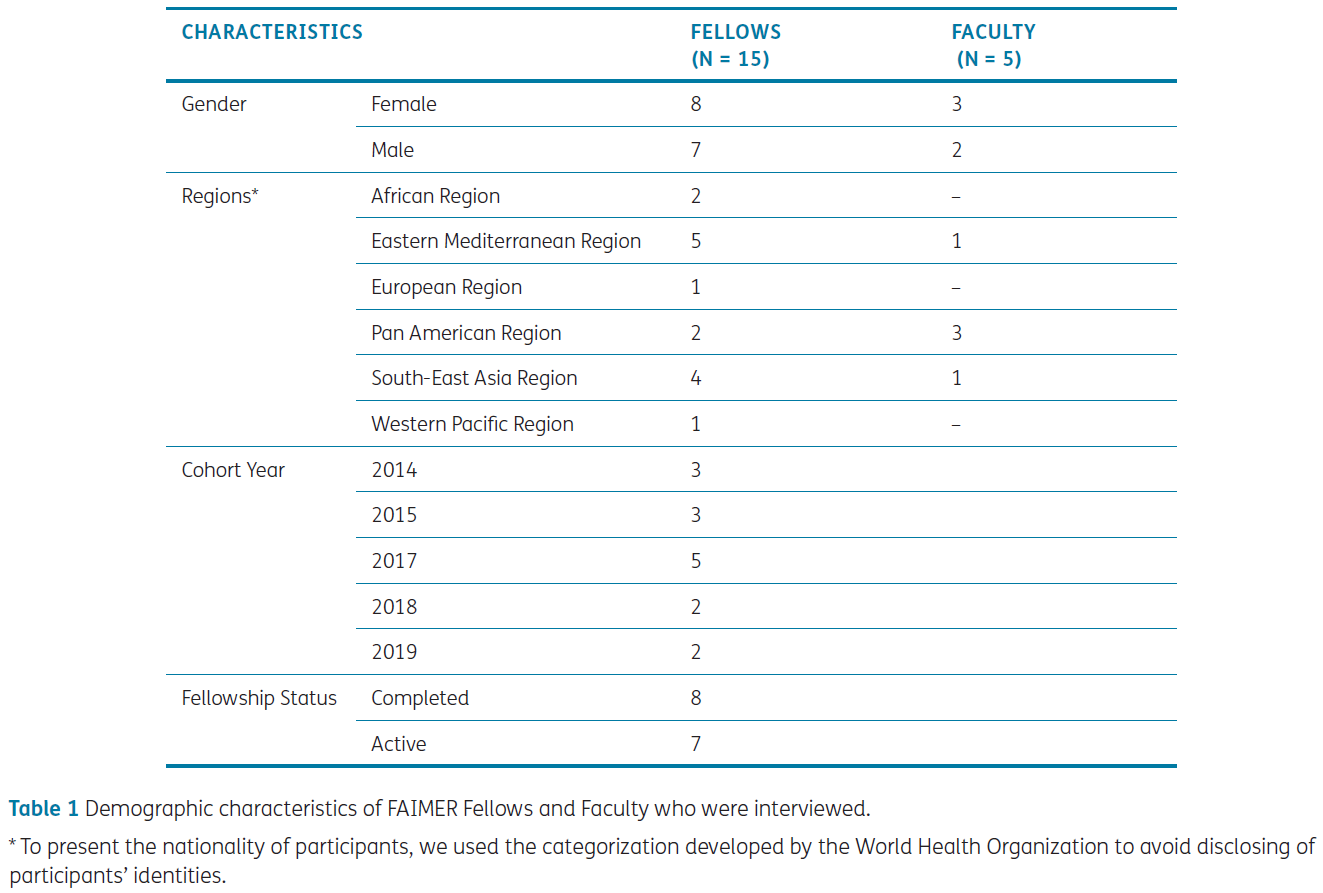

12개국에서 15명의 FAIMER 펠로우와 5명의 FAIMER 교수진이 연구에 참여했습니다(표 1). 아래에서는 두 가지 조사 영역에 따라 연구 결과를 제시합니다. 인용문은 펠로우(F) 또는 FAIMER 교수진(FF)으로 표기했습니다.

Fifteen FAIMER Fellows and five FAIMER Faculty from 12 countries participated in the study (Table 1). Below, we present our findings according to the two areas of inquiry. Quotations are referenced by Fellows (F) or FAIMER Faculty (FF).

1) IFDP에서 문화는 어떻게 인식되었나요?

1) How was culture perceived in an IFDP?

FAIMER 펠로우와 교수진은 위계질서, 협업, 문서화, 자발성과 관련된 가치와 신념뿐만 아니라 특정 행동과 관행(예: 얼굴 표정, 몸짓, 서로를 대하는 방식, 의견 표현, 물리적 거리두기)에서 문화적 유사점과 차이점을 인식했다고 답했습니다.

FAIMER Fellows and Faculty commented that they perceived cultural similarities and differences in terms of specific behaviors and practices (e.g., facial expressions, body gestures, ways of addressing each other, opinion expression, physical distancing) as well as values and beliefs related to hierarchy, collaboration, documentation, and spontaneity.

[X]의 사람들은 여러분과 대화할 때 실제로 여러분을 쳐다보지 않습니다. 그들은 아래를 내려다보거나 어깨 너머로 바라봅니다. 여러분은 서로 마주보고 있고, 여러분은 그들을 바라보고 있지만 그들은 여러분의 얼굴을 보고 있지 않습니다. (F-9)

They in [X] don’t actually look at you when they talk to you. They look down, or they look over your shoulder. You are facing each other, and you are looking at them, but they are not looking at your face. (F-9)우리나라 문화의 특징 중 하나는 상급자에서 하급자로 내려오는 상명하복식 문화입니다. 이는 사람과 사람 사이의 상호작용, 즉 후배와 선배, 젊은이와 나이든 사람 사이의 상호작용과 관련이 있습니다. 이 나라에는 일정한 패턴이 있습니다. (F-6)

One characteristic in the culture in my country, one policy they use, is top-down, from the superior to the subordinate. That’s related to the interaction between people, with junior, with senior, with the younger, with the older ones. There is a certain pattern in this country. (F-6)

일부 문화적 차이는 초창기 FAIMER와의 만남에서 '눈에 보이는' 것으로 여겨졌지만, 일부는 펠로우와 교수진이 함께 시간을 보낸 후에야 분명해졌습니다. 또한 어떤 문화적 차이(예: 의견 표현)는 펠로우들이 온라인 세션을 시작할 때에도 분명했던 반면, 다른 문화적 차이(예: 주도권 잡기, 위계질서 존중)는 펠로우들이 각자의 나라에서 개별 프로젝트를 시작했을 때에 분명해졌습니다.

While some cultural differences were deemed “visible” in the early FAIMER encounters, some were only evident after Fellows and Faculty had spent time together. Also, several cultural differences (e.g., opinion expression) were evident when Fellows started the online sessions, whereas others (e.g., taking initiative; respecting hierarchy) were apparent when Fellows began working on their individual projects in their own countries.

제가 소속된 기관으로 돌아갔을 때, 그곳의 교육 문화는 상당히 달랐습니다. 사람들은 혼자서 가르치고 다른 사람이 옆에 있는 것을 원하지 않기 때문에 교사들 간의 상호 협력은 FAIMER의 독특한 측면이었는데, 저는 여전히 본국 기관에서 이를 구현하는 데 어려움을 겪고 있습니다. (F-2)

When I went back to my institution, there the culture of how to teach is quite different. People teach in isolation; they don’t want any other person to be there, so the kind of mutual collaboration between teachers was a unique aspect of FAIMER, which I am still struggling with in trying to implement it in my home institution. (F-2)

참가자들은 일반화나 지나친 단순화를 피하기 위해 조심스럽게 문화라는 개념에 접근했습니다. 예를 들어, 참가자들은 한 국가 내에서도 서로 다른 문화적 가치관을 가질 수 있기 때문에 같은 나라에서 온 다른 참가자가 자신의 신념을 공유하지 않을 수도 있다는 점을 강조했습니다. 또한 참가자들은 '문화적 습관'으로 인식되는 것이 반드시 문화와 관련이 있는 것이 아니라 성격, 개인의 선택, 조직 구조 또는 직업적 가치관에 기인할 수 있다는 점에 주목했습니다.

Participants approached the notion of culture with caution, trying to avoid generalizations or oversimplification. For example, participants highlighted that another participant from their country might not share their beliefs, as people within a single country could have distinct cultural values. Participants also noted that what was perceived as a “cultural habit” might not necessarily be related to culture; instead, it could be attributed to personality, individual choice, organizational structure, or professional values.

따뜻하고 외향적이며 사람들과 대화하는 것을 좋아하는 사람과 사람들과 교류하기 싫어하고 목이 뻣뻣한 사람은 다르게 행동할 수 있습니다. 하지만 이는 모든 문화에 존재합니다. 그게 바로 개성이죠. 저는 그것을 문화와 연결시킬 수 없다고 생각합니다. (F-9)

If you are warm and outgoing and you like to talk to people, if you are a stiff-necked person who doesn’t want to engage with people, you behave differently. But that’s in every culture. That’s personality. I don’t think I can connect it to culture. (F-9)"제가 다니는 대학은 65년 정도 된 곳인데 [...] 변화에 대한 저항이 엄청나지만, 문화를 그 원인으로 돌리지는 않겠습니다." (F-14)

“My university is about sixty-five-years old […] the resistance to change is enormous, but I’m not going to attribute culture to this.” (F-14)

2) 문화적 다양성이 교수와 학습에 미치는 영향은 무엇인가요?

2) What were the influences of cultural diversity on teaching and learning?

IFDP에서 문화적 차이가 교수와 학습에 미치는 영향과 관련된 세 가지 주제를 확인했습니다.

We identified three themes related to the influences of cultural differences on teaching and learning in an IFDP.

배움의 장벽이 아니라, 문화 인식과 네트워크 구축의 가교 역할

Not a barrier to learning, but a bridge to cultural awareness and network-building

펠로우들은 연수 프로그램에서 경험한 문화적 차이가 대부분 학습에 방해가 되지 않는다고 생각했습니다. 이들은 펠로우십을 최대한 활용하려는 의욕과 열정이 강했으며, 새로운 규칙과 경험을 이해하고 존중하며 수용하는 데 도움이 되는 새로운 '마음가짐'을 가지고 프로그램에 참여했습니다. 또한 자신의 생각에 의문을 제기하고 자신의 신념과 가정을 평가할 수 있는 기회도 소중하게 여겼습니다.

Fellows believed that the cultural differences they experienced during the Institute program did not, for the most part, impede learning. They were highly motivated and passionate about making the most out of the Fellowship, and they came to the program with a fresh “mindset” that helped them understand, respect, and embrace new rules and experiences. They also valued the opportunity to question their thinking and assess some of their beliefs and assumptions.

몇 가지 사소한 것들이 눈에 띄지만 학습에 큰 영향을 미치지는 않는다고 생각합니다. 이런 것들은 우리가 주의해야 할 작은 문화적인 것들일 뿐이고... 저는 그 문화가 무엇이든 배우고 싶었습니다. (F-10)

You can see there are some small things, but I don’t think that they would drastically affect our learning. These are just small cultural things that we have to be careful about… and I wanted to learn whatever the culture was. (F-10)

또한 문화적 차이로 인해 펠로우들이 "다양성에 대한 학습"과 "네트워크 구축"과 같은 프로그램 목표 이상의 성과를 달성할 수 있었다는 점도 주목했습니다. 많은 참가자가 문화적 다양성의 존재를 높이 평가했으며, 한 펠로우는 이를 "삶의 아름다움"이라고 표현했습니다. 참가자들은 다른 문화에 대해 배우는 것 외에도 비판적 성찰과 변증법적 담론의 중요한 측면인 잘못된 가정을 바로잡을 수 있는 기회를 가졌다고 보고했습니다. 다양성은 참가자들이 자신이 "세계를 대표하지 않는다"는 것과 자신이 실천하는 것이 반드시 "유일한 것 또는 최선의 것"은 아니라는 것을 이해하는 데 도움이 되었습니다. 또한 다양한 문화에 대한 노출은 참가자들이 문화적으로 다양한 환경에서 일하는 데 더 유능해졌다고 느끼면서 전문성 개발에 도움이 되었습니다. 한 펠로우는 이 새로운 인사이트가 "눈을 뜨게 해줬다"고 말했는데, 펠로우십 이전에는 "비슷한 특성을 공유하는 특정 인구가 있는 특정 환경에 갇혀 있었기 때문에" "이야기의 다른 측면을 보지 못했다"고 합니다.

We also noted that cultural differences enabled Fellows to achieve outcomes beyond the program objectives, including “learning about diversity” and “network building.” Many participants appreciated the existence of cultural diversity, which one Fellow described as the “beauty of life.” In addition to learning about other cultures, participants reported having an opportunity to correct false assumptions, an important aspect of critical reflection and dialectical discourse. Diversity helped participants understand that they did “not represent the world” and that what they practiced was not necessarily “the only thing or the best thing.” Additionally, exposure to different cultures helped participants with their professional development, as they felt that they had become more competent working in culturally diverse settings. One Fellow called this new insight an “eye-opener,” as before the Fellowship, she was “confined to a certain environment with a certain population sharing similar characteristics” that prevented her from “seeing other aspects of stories.”

다양한 문화를 접하고 이러한 규칙을 배우면서 지난번에 무슨 일이 있었는지 기억하기 때문에 매번 더 효과적으로 대처할 수 있다고 느낍니다. 그래서 저는 바로 제 규칙을 적용하지 않습니다. 대신 한 발 물러서서 관찰만 하고 판단하지 않으려고 노력합니다. (FF-3)

As I encounter different cultures and learn these rules, I feel that I’m able to be more effective each time because I remember what happened last time. So, I don’t immediately jump to my set of rules. Instead, I try to stay back, just observe, and not judge. (FF-3)

몇몇 참가자들은 펠로우십을 마친 후에도 다른 펠로우들과 돈독한 관계를 맺었고, 문화적 이질감이 네트워크 구축의 장애물이 되지 않았다고 말했으며, 오히려 공통의 관심사와 공동의 목표를 가진 개인들의 네트워크에 대한 설명은 팀워크와 자원에 대한 접근 기회를 제공하는 실천 커뮤니티[29]의 정의와 일치한다고 말했습니다. 일부 펠로우들은 여러 면에서 다른 사람들과 "이렇게 오래 지속되는 관계를 구축"하거나 "개인적인 생각과 이야기를 공유"할 수 있을 거라고는 예상하지 못했기 때문에 네트워크 구축이 놀랍게 다가왔습니다. 한 펠로우는 국제 프로그램은 물론이고 좀 더 동질적인 환경에서 "매우 특별한 수준의 신뢰"를 쌓은 경험이 없었다고 설명하며, 과거의 경험에 대해 비판적으로 생각할 수 있는 기회를 소중히 여겼습니다.

Several participants stated that they developed strong relationships with other Fellows that continued after completing the Fellowship, and that cultural dissimilarities were not experienced as barriers to network building; rather, their description of a network of individuals with common interests and shared goals was consistent with the definition of a community of practice [29], offering opportunities for teamwork and access to resources. Network-building came as a surprise to some Fellows, as they did not expect to “build such long-lasting relationships” or “share their personal thoughts and stories” with people who were different in many aspects. One Fellow explained that she had not previously experienced building “trust at a very special level” in more homogenous settings, let alone in an international program, and she valued the opportunity to think critically about past experiences.

우리는 서로 다른 환경, 다른 수준의 발전, [다른] 교육 분야에서 왔습니다. 그래서 우리는 서로에게서 배우고, 경험을 공유하고, 협력할 수 있는 기회를 가졌습니다. 저는 직장에서 어려운 일이 생기면 "여러분, 저에게 이런 문제가 있습니다. 어떻게 하면 좋을까요?"라고 묻습니다. (F-1)

We came from different environments, different levels of advancement, [different] education fields. So, we had the chance to learn from each other, to share our experiences, to collaborate. If I have some challenges at work, I just write a message asking, “Guys, I have this issue. What do you advise me?” (F-1)

적응, 수정, 중재로 이어지는 불안과 불확실성

Unease and uncertainty leading to adaptation, modification, and mediation

인터뷰 결과, 특정 문화적 차이는 때때로 불안감이나 불확실성을 야기하는 미묘한 도전으로 경험되는 것으로 나타났습니다.

The interviews revealed that certain cultural differences were experienced as subtle challenges which, at times, created uneasiness or uncertainty.

위에서 강조한 바와 같이 프로그램 진행 중 문제가 되었던 문화적 행동의 예로는 다음 등이 있었습니다.

- 학습자의 반응을 중시하는 강사에게 특히 어려운 수업 중 무표정, 눈 맞춤 부족, 의견 보류,

- 잘못 해석을 하기도 하고, 무슨 일이 일어나고 있는지 파악하기 위한 '속앓이inner talk'로 이어질 수 있는 몸짓,

- '너무 친밀하다' 또는 '조금 무섭다'고 인식될 수 있는 물리적 거리,

- 수업 기능이나 그룹 작업을 방해할 수 있는 시간에 대한 다른 태도, 프로그램 일정을 변경해야 하는 특정 종교 의식

Examples of cultural behaviors that were challenging during the program, as highlighted above, included:

- a flat facial expression, a lack of eye contact, and holding back opinions in class, which was especially challenging for instructors who valued learners’ reactions;

- body gestures that might be interpreted incorrectly and lead to an “inner talk” to figure out what was happening;

- physical distance that might be perceived as “too intimate” or “a little frightening”;

- different attitudes towards time that could interrupt class function or group work; and

- certain religious rituals that would require program rescheduling.

제가 질문을 했더니 그녀는 저를 붙잡고 제 귀에 대고 말하기 시작했습니다. [...] 그 순간 저는 배우고 이야기하는 것보다 그녀에게서 도망치는 데 더 관심이 있었습니다. [X의 문화는 상당히 개방적이고 매우 친밀합니다... 그리고 저는 포옹, 특히 이성과의 포옹을 좋아하지 않습니다(웃음) 포옹은 종교적인 것에 가깝기 때문입니다. 그래서 아마 그녀는 몰랐을 것이고 그것은 그녀의 사랑의 제스처 였지만 그 사랑의 제스처는 저에게 효과가 없었습니다. (F-10)

I asked her a question, and she just grabbed me and started talking in my ear. […] At that moment, I was more interested in getting away from her, instead of learning and talking. [X’s] culture is quite open, very intimate… And, I am not into hugging, especially with the opposite gender (laughs), because it’s more of a religious thing. So, probably she didn’t realize, and it was her gesture of love, but that gesture of love did not work for me. (F-10)

펠로우들은 고국으로 돌아간 후에도 문화적 차이로 인해 어려움을 겪었다고 말했습니다. 거의 모든 펠로우가 자신의 교육기관에서 FAIMER의 대화형 교수법을 사용하려고 했지만, 일부 펠로우들은 새로운 이니셔티브를 성공적으로 실행하지 못했습니다. 한 펠로우는 자신이 "위험을 감수하고 비판적 사고와 사회적 상호작용을 촉진하기 위해 비학문적 개인적 문제에 대해 성찰하고 이야기하는 데 보호된 시간을 할애하는 '학습 서클'과 같은 활동을 설계할 용기가 있는지 확신할 수 없었다"고 말했습니다. 참가자들은 또한 위계 존중, 협업, 문서화와 같은 문화적 관행이 각자의 가정 환경에서 프로젝트의 성공과 지속 가능성에 영향을 미칠 수 있다고 믿었습니다.

Fellows also indicated some challenging cultural differences once they returned to their home countries. While almost all Fellows intended to use FAIMER’s interactive teaching methods in their own institutions, some were not able to successfully implement new initiatives. One Fellow specified that he was not sure he had “the courage to take a risk” and design an activity like “learning circles,” in which protected time was devoted to reflection and talking about non-academic personal issues to promote critical thinking and social interactions. Participants also believed that cultural practices, such as respecting hierarchy, collaboration, and documentation, could influence their projects’ success and sustainability in their home settings.

우리는 매우 즉흥적입니다. 아이디어가 떠오르면 이렇게 말합니다: "해보자. 멋지네요!" (웃음). 그리고 프로그램은 포기되거나 전혀 개발되지 않습니다. 사람들이 준비와 생각 없이 잘못된 방식으로 시작했기 때문입니다. (F-7)

We are very spontaneous. We have just the idea, and we are like: “let’s do it. It’s great!” (laughs). And programs are abandoned or not developed at all. Because people started in the wrong way without preparing and thinking. (F-7)

펠로우와 교수진은 문화적 이질감을 해소하기 위해 세 가지 접근 방식을 사용한다고 보고했습니다:

Fellows and Faculty reported using three different approaches to address cultural dissimilarities:

적응: 몇몇 참가자들은 서로 다른 억양을 사용하거나 서로 이름을 부르는 등 특정 문화적 차이를 다루는 것이 "처음에는 조금 힘들었다"고 말했습니다. 하지만 곧 새로운 상황에 익숙해졌고 큰 어려움 없이 적응할 수 있는 방법을 찾았습니다.

Adaptation: Several participants observed that it was a “bit tough in the beginning” to deal with certain cultural variations, including different accents or addressing each other by first names. However, they quickly became accustomed to the new situation and found ways to adapt without much trouble.

교수님이나 상대방의 이름을 불러야 한다는 사실 자체가 첫날에는 저에게 충격이었습니다. 적응하는 데 시간이 좀 걸렸어요. (F-11)

The fact that we had to speak to our professors or whoever they were by their first name itself was a shock for me on the first day. It took some time to adjust to that. (F-11)

한 FAIMER 교수진이 FAIMER에서 펠로우십을 시작했을 때의 이야기를 들려주었습니다. 그는 펠로우들이 팀 빌딩 연습을 위해 외부로 끌려갔을 때 "문화적 충격"이라고 표현한 "약간 굴욕적인" 경험 때문에 첫날 프로그램을 그만두기로 결심했습니다. 하지만 그는 "며칠 동안 머물면서 프로그램의 좋은 점들을 하나씩 알아가기 시작했고, 마침내 프로그램의 가치에 대해 확신을 갖게 되었다"고 합니다.

A FAIMER Faculty shared a story of the time when he started his Fellowship in FAIMER. He had decided to quit the program on the first day, because of a “little bit humiliating” experience that he described as a “cultural shock” when the Fellows were taken outside for a team-building exercise. But then, he “stayed for a few days, started to pick up the nice things in the program, and finally, was convinced about the program’s value”.

수정: 대부분의 경우, 참가자들은 불안감이나 불확실성에 대응하여 평소의 관행을 수정하고 해결책을 찾았습니다. 예를 들어, 펠로우가 자원봉사를 하거나 의견을 표현하는 것이 어렵다고 느꼈을 때, FAIMER 교수진은 펠로우에게 직접 말하거나 펠로우가 게시판에 질문을 적어두면 나중에 교사가 익명으로 답변하는 형식인 '주차장'을 사용하는 등 다른 접근 방식을 사용했습니다. 다른 예로는 더 천천히 말하기, 종교적 관습에 맞춰 프로그램 일정 변경하기, 교육 내용 수정하기 등이 있습니다.

Modification: In most cases, participants modified their usual practices and found solutions in response to unease or uncertainty. For instance, when Fellows found it difficult to volunteer or express their opinions, FAIMER Faculty used alternative approaches, such as addressing the Fellow directly or using “parking lots”, a format in which Fellows noted their questions on a board for teachers to address anonymously later. Other examples included speaking more slowly, shifting program schedules to accommodate religious practices, and modifying educational content.

저는 첫해에 피드백을 바탕으로 리더십 커리큘럼을 변경했습니다. 우리는 상당히 전통적인 하버드 비즈니스 스쿨의 리더십을 가르치고 있었는데, [X]의 일부 학생들에게는 공감을 얻지 못했습니다... 우리는 조정하고, 국제적인 그룹을 구성하고, 리더십 커리큘럼을 다시 만들었습니다. (FF-4)

I changed the leadership curriculum based on feedback in the first year. We were teaching fairly traditional Harvard Business School leadership, and it was not resonating with some from [X]… We adjusted, put together an international group, and redid the leadership curriculum. (FF-4)

중재: 중재는 덜 일반적이지만 그럼에도 불구하고 효과적인 접근법으로, 다른 사람이 상호 이해와 합의를 이끌어내기 위해 옹호자 역할을 하는 것입니다. 어떤 상황에서는 대화에 참여한 두 사람이 문화적 차이의 존재를 인식하지 못하고 있을 때, 제3의 사람이 오해가 있음을 깨닫고 도움을 주기 위해 나섰습니다. 다른 상황에서도 펠로우들은 인식된 차이를 숨기고 싶지 않았지만 직접 개입하는 대신 다른 사람에게 옹호해 달라고 요청하는 것을 선호했습니다.

Mediation: Mediation was a less common but nonetheless effective approach in which another person acted as an advocate to bring about mutual understanding and agreement. In one situation, while two individuals involved in a conversation were not aware of the existence of a cultural disparity, a third person realized that there was a misunderstanding and stepped forward to help. In other situations, Fellows did not want to hide a perceived difference but preferred to ask someone else to advocate for them instead of getting involved directly.

이 문화에서는 권위에 의문을 제기하는 것처럼 보일 수 있는 질문을 할 때 그 질문과 관련된 개인적인 이야기를 들려주어 부드럽게 만듭니다. 그래서 그는 자신의 이야기를 늘어놓았는데, 저는 그가 왜 그런 이야기를 하는지 이해하지 못했고, 그가 저에게 질문하는 것도 이해하지 못했습니다. 하지만 그곳의 문화를 잘 아는 몇몇 교직원이 저에게 와서 "상사와 마주치는 것이 걱정되나 봐요"라고 말했고, 저는 "네, 맞아요!"라고 대답했습니다. 그렇게 해서 그 문제를 해결할 수 있었습니다. (FF-4)

In their culture, when you are asking a question that might look like you’re questioning authority, you tell a personal story around the question to soften it. So, he told a whole story, and I didn’t understand why he was telling the story, and I didn’t understand that he was asking me a question. But there were some faculty members there who knew the culture and were able to come over to me and say,” He is worried about confronting his boss,” and I said, “Oh, yes, yes!” Then, I was able to address the question. (FF-4)

프로그램 및 직업 문화에 따른 완화

Mitigation by program and professional cultures

FAIMER 교수진과 펠로우는 맥락의 중요성에 주목하고, 문화적 차이가 교육과 학습에 미치는 영향이 프로그램의 문화(즉, 가치, 규범, 신념)와 참가자들의 공통된 직업적 배경 및 보건 전문직 교육자로서의 경험에 의해 완화되는 것을 관찰했습니다.

FAIMER Faculty and Fellows noted the importance of context and observed that the influences of cultural differences on teaching and learning were mitigated by the program’s culture (i.e., values, norms, and beliefs) and participants’ common professional backgrounds and experiences as health professions educators.

프로그램 문화: 펠로우들은 주최자가 존중하는 의사소통에 대한 기본 규칙을 정하고, 펠로우들이 문화에 대해 명시적으로 이야기하도록 장려하며, 개인적인 이야기를 나눌 수 있는 보호된 시간을 마련함으로써 문화적 차이에 대한 인식을 보여주는 문화적으로 민감한 프로그램에 참가했다고 긍정했습니다. 또한 교수진은 팀워크를 위해 이질적인 그룹을 구성하는 것도 활용했습니다. 종교 의식을 위한 특별한 장소를 제공하고 다양한 식사를 제공하는 것도 문화적 다양성을 지원하는 또 다른 예입니다. 펠로우들은 FAIMER에서 자신들의 문화가 "놀라울 정도로 인정"되고 "대표"되고 있다고 믿었습니다. 두 명의 교수진은 FAIMER가 문화적 차이를 파악하고 해결하는 과정을 지속적으로 수행함으로써 안전하고 편견 없는 환경을 조성했다고 덧붙였습니다.

Program culture: Fellows affirmed that they had entered a culturally sensitive program where organizers showed awareness to cultural differences by setting ground rules about respectful communications, encouraging Fellows to talk explicitly about culture, and scheduling protected time for sharing personal stories. Faculty also took advantage of forming heterogeneous groups for teamwork. Providing special places for religious rituals and making different meals available were other examples of how cultural diversity was supported. Fellows believed that their cultures were “amazingly acknowledged” and “represented” in FAIMER. Two Faculty added that FAIMER created a safe, non-judgmental environment by undertaking a continuous process of identifying and addressing cultural differences.

우리가 가장 먼저 하는 일 중 하나는 이 기본 규칙 세션에서 우리가 여기서 배우려고 하는 것에 동의하는 것입니다. 존중, 경청, 다양성 존중, 외부 호칭, 기밀 유지 등이 우리가 가장 먼저 합의한 사항입니다. (FF-1)

One of the first things that we have is this ground rules session to agree that here we are trying to learn. These are the first things that we agree on: respect, listen, diversity is good, titles outside, and confidentiality. (FF-1)

프로페셔널 문화: 모든 FAIMER 펠로우와 교수진은 광범위한 보건 전문직 교육자 커뮤니티의 일원으로서 비슷한 관심사와 가치관, 익숙한 경험과 관행을 공유했습니다. 한 펠로우는 "변화에 대한 교수진의 저항"이 자국만의 문화적 문제가 아니라 전 세계 어디에서나 일어날 수 있는 일이라는 것을 깨달았을 때가 "펠로우십 기간 중 가장 만족스러운 순간"이었다고 말했습니다. 참가자들은 다양한 방식으로 보건 전문직 교육과 관련된 '공통점'을 찾아내어 차이점을 최소화하고 각국의 직업 문화에 반영된 유사점에 집중할 수 있었습니다.

Professional culture: All FAIMER Fellows and Faculty were members of the broader community of health professions educators and shared similar interests and values as well as familiar experiences and practices. One Fellow said that it was “the most satisfying moment during the Fellowship” when he realized that the “resistance of faculty members toward change” was not a cultural problem specific to his country but could happen anywhere around the world. In diverse ways, participants identified a “common ground” related to health professions education that enabled them to minimize differences and focus on similarities reflected in their professional culture.

교수진 부족, 자원 부족, 학생 수 과다, 전통적인 교육 및 학습 방식, 연구에 대한 높은 관심 등 보건 과학 교육은 어디를 가나 동일한 문제를 공유하고 있습니다. 이러한 문제는 거의 모든 사람이 공유하고 있습니다. (F-14)

Health science education is the same everywhere you go, we share the same problems: lack of faculty, lack of resources, too many students, a traditional way of teaching and learning, high interest in research. Those were shared by almost everyone. (F-14)

토론

Discussion

이 연구는 보건 전문직의 교수진 개발에서 자주 간과되는 측면, 즉 문화가 IFDP에 미치는 영향을 프로그램 참가자와 교수진의 시각에서 살펴봤습니다. 문화적 다양성이 교수와 학습에 미치는 영향을 살펴본 결과, 문화적 차이가 학습에 장애가 되는 것이 아니라 오히려 문화를 배우고 네트워크를 구축할 수 있는 기회로 작용한다는 사실을 발견했습니다. 동시에 특정 문화적 차이는 불안감과 불확실성을 야기하여 적응, 수정, 중재라는 세 가지 건설적인 반응으로 이어졌습니다. 참가자들의 관점은 프로그램 문화와 직업 문화의 영향을 받았기 때문에 맥락도 중요했습니다.

This study explored a frequently overlooked aspect of faculty development in the health professions – the influence of culture on IFDPs – from the lens of program participants and faculty. Exploring the influences of cultural diversity on teaching and learning, we found that cultural differences were not a barrier to learning; rather, they acted as an opportunity to learn about culture and build networks. At the same time, certain cultural dissimilarities produced a sense of unease and uncertainty, which led to three constructive responses: adaptation, modification, or mediation. Context also mattered, as participants’ perspectives were affected by the program culture as well as their professional culture.

첫 번째 주제는 문화적 차이가 학습에 방해가 되지 않는다는 것을 보여주었습니다. 펠로우들은 FAIMER의 콘텐츠와 학습자 중심의 다양한 접근 방식에 대해 매우 높이 평가했습니다. 이들은 소그룹 토론에 적극적으로 참여하고 프로젝트를 완성했으며, 본국에서도 유사한 방법을 적용할 수 있도록 영감을 받았습니다. 이러한 결과는 TLT의 중요한 구성 요소인 관점을 바꾸고 변화의 주체가 되려는 참가자들의 의지를 강조했습니다[25]. 또한 비판적 성찰, 변증법적 담론, '안전한' 환경에서 변화할 수 있는 능력의 가치를 강조했습니다. 위에서 보고한 바와 같이, 이러한 변화 과정의 예로는 다른 문화권 동료의 행동에 대한 성찰, 개인의 가정과 행동을 더 잘 이해하기 위해 해당 문화에 익숙한 동료 및 교수진과의 토론 등이 있습니다. 이전의 여러 연구에서 위계질서에 대한 복종과 연공서열에 대한 존중과 같은 특정 문화적 측면이 참가자의 학습에 영향을 미쳤다고 보고한 바 있지만[30, 31, 32], 본 연구 결과는 다양한 국가에서 실시된 미국 기반의 IFDP에 대한 보고서[33, 34, 35, 36]와 일치하며 성공적인 결과를 도출했습니다. 우리의 연구 결과는 성취 성과를 개인의 기대 관련 신념 및 과제 가치 신념과 연결시키는 기대 가치 이론으로도 설명할 수 있습니다[37]. 우리 연구에서 펠로우들은 명성이 높은 미국의 명문 프로그램에서 "가치 있는 결과를 기대"하고 있었을 가능성이 높습니다. 또한 펠로우들은 이 프로그램이 자기계발에 대한 내적 신념(내재적 가치)에 부합할 뿐만 아니라 본국에서의 잠재적 경력 발전과 같은 외적 혜택(효용적 가치)의 가능성을 높이는 등 자신의 직업적 성장에 기여할 것이라고 믿었을 가능성도 있습니다. 다양한 방식으로, 펠로우들의 학습 동기는 인식된 문화적 격차와 관련된 문제보다 우선시되었을 수 있습니다.

Our first theme showed that cultural differences did not impede learning. Fellows were very appreciative of the FAIMER content and variety of learner-centered approaches. They actively participated in small group discussions, completed their projects, and were inspired to apply similar methods in their home countries. This finding highlighted participants’ willingness to change perspectives and become change agents, important components of TLT [25]. It also underscored the value of critical reflection, dialectical discourse, and the ability to change in a “safe” environment. As reported above, examples of this transformative process included reflections on the behaviors of colleagues from other cultures and discussions with colleagues and faculty members familiar with that culture to better understand personal assumptions and behaviors. While several previous studies have reported that specific cultural aspects, like obedience to hierarchy and respect for seniority, influenced participants’ learning (and at times a tendency to prefer a more traditional lecture-dominated program) [30, 31, 32], our findings are consistent with reports on an established US-based IFDP which was delivered across a variety of countries [33, 34, 35, 36], with successful results. Our findings might also be explained by expectancy-value theory, which links achievement performance to individuals’ expectancy-related and task-value beliefs [37]. It is likely that in our study, Fellows were “expecting valuable outcomes” from a prestigious American program with a strong reputation. It is also possible that Fellows believed that this program would contribute to their professional growth, which not only resonated with their internal beliefs about self-improvement (intrinsic value) but would also increase the probability of external benefits such as potential career advancement in their home countries (utility value). In diverse ways, Fellows’ motivation to learn may have overridden challenges related to perceived cultural disparities.

두 번째 주제에서 언급했듯이, 일부 FAIMER 펠로우들은 주로 서로 다른 대인 커뮤니케이션 스타일에서 비롯된 특정 문화적 차이로 인해 불안과 불확실성을 경험했습니다. 다른 나라로 이전한 미국 기반 프로그램에서 참가자들의 정서적 자제력, 침묵, 직접적인 눈맞춤 회피로 인한 어려움에 직면했을 때도 비슷한 결과가 보고되었습니다[13]. 이번 연구에서는 이러한 문제에 대한 세 가지 건설적인 반응(적응, 수정, 중재)을 확인함으로써 이러한 증거를 추가했습니다.

- 적응은 펠로우가 더 자주 언급하는 반면,

- 수정은 FAIMER 교수진이 더 많이 사용했으며,

- 제3자의 중재는 펠로우와 교수진 모두 긴장을 해소하거나 문화적 충돌을 피하기 위한 효과적인 전략으로 확인되었습니다.

TLT[25]는 사람들이 글로벌 인식과 역량을 개발하는 방법을 설명하는 데 유용성이 있는 것으로 나타났는데[21], 개인이 자신에게 익숙하지 않은 상황에 처하게 되면 이를 거부하거나 대부분의 경우 적응한다고 주장하며, 본 연구에서도 볼 수 있습니다. 비판적 성찰과 변증법적 담론도 이러한 변화 과정에 도움이 되었습니다.

As noted in our second theme, some FAIMER Fellows experienced unease and uncertainty due to certain cultural differences, primarily those emanating from different interpersonal communication styles. A similar finding was reported when a US-based program, transferred to another country, encountered challenges resulting from participants’ emotional self-control, silence, and avoidance of direct eye contact [13]. Our study adds to this evidence by identifying three constructive responses (adaptation, modification, and mediation) to these possible challenges.

- While adaptation was mentioned more frequently by Fellows,

- modification was used more by FAIMER Faculty, and

- mediation by a third person was identified as an effective strategy for both Fellows and Faculty to resolve tensions or avoid cultural confrontation.

TLT [25], which has been shown to have utility in describing how people develop global awareness and competence [21], asserts that when an individual is involved in a situation that is unfamiliar to them, they will either reject it or, in most cases, adapt, as seen in our study. Critical reflection and dialectical discourse also helped this transformative process.

또한 연구 결과가 특정 프로그램과 직업 문화 속에서 이루어졌다는 점에 주목했습니다. FAIMER는 TLT의 원칙에 따라 신중하게 설계된 커리큘럼, 문화적으로 민감한 환경, 반응이 빠른 교수진, 동기 부여가 높은 학습자가 특징입니다. 이러한 (그리고 다른) 노력들이 문화적 차이에 대한 네트워크 구축과 솔루션 지향적 대응뿐만 아니라 혁신적인 학습을 가능하게 하여 일부 연구 결과에 기여한 것으로 보입니다. 또한 참가자들이 모두 보건 전문직 교육자였기 때문에 그들의 직업 문화가 문화적 차이를 인식하고 해결하는 방식에 영향을 미쳤을 수 있습니다. 우리는 다른 연구에서도 보건 전문직 교육자들이 학문적 배경, 경험, 가치, 신념, 요구 측면에서 공통점을 발견했으며, 다른 연구에서도 이를 보고한 바 있습니다[3, 33, 35]. 많은 대학이 커리큘럼 개혁을 수행하고 학생 중심 방식으로 전환하고 있고[16, 35], 글로벌 표준 및 인증 프로세스가 점점 더 인정받고 수용되고 있기 때문에[38], 교육 설계 및 전달의 원칙이 일반적으로 잘 받아들여지는 것은 놀라운 일이 아닙니다[16, 38]. 참가자들의 전문적 배경과 '공통점'을 찾고 행동에 전념하려는 열망은 비판적 성찰과 변증법적 담론에 대한 프로그램의 강조와 함께 문화적 차이를 초월하는 데 도움이 되었을 수 있으며[18], 이는 결과적으로 향후 긍정적인 행동과 의미 있는 관계로 이어질 수 있습니다[19].

We also noted that our findings were situated in a specific program and professional culture. FAIMER is informed by principles of TLT and characterized by a carefully designed curriculum, a culturally sensitive environment, responsive Faculty, and highly motivated learners. It is likely that these (and other) efforts contributed to some of our findings, enabling transformative learning as well as network building and solution-oriented responses toward cultural differences. Furthermore, since our participants were all health professions educators, their professional culture might have influenced how they perceived and addressed cultural differences. We found, and other studies have also reported, commonalities among health professions educators in terms of disciplinary backgrounds, experiences, values, beliefs, and needs [3, 33, 35]. As many universities are conducting curricular reforms and moving toward student-centered methods [16, 35], and global standards and accreditation processes are increasingly recognized and accepted [38], it is not surprising that principles of instructional design and delivery are generally well-received [16, 38]. Participants’ professional backgrounds and desires to seek “common ground” and commit to action, together with the program’s emphasis on critical reflection and dialectical discourse, may have helped to transcend cultural differences [18], which in turn, can lead to positive future action and meaningful relationships [19].

강점과 한계

Strengths and Limitations

우리가 FAIMER 펠로우십을 선택한 이유는 다양한 국가의 펠로우와 교수진으로 구성된 다문화 환경을 제공하고, 종단적 프로그램 내에서 현장 및 온라인 교육으로 구성되어 있어 다양한 교육 방법을 탐색할 수 있었기 때문입니다. FAIMER 교수진, 현재 펠로우, 이전에 펠로우십을 수료한 펠로우를 인터뷰하여 데이터 출처를 삼각 측량하고 신뢰도를 높일 수 있었습니다. 하지만 이 연구는 하나의 IFDP만 조사했고 참여가 자발적으로 이루어졌기 때문에 연구 결과를 다른 환경에 그대로 적용하기는 어려울 수 있습니다. 참가자들에게 과거에 있었던 경험을 회상하도록 요청했기 때문에 회상 편향도 또 다른 문제였습니다. 마지막으로, 교육과 학습의 일부 측면은 펠로우십 기간 동안 상호작용을 관찰했더라면 더 잘 이해할 수 있었을 것입니다.

We chose the FAIMER Fellowship because it offered a multicultural environment with Fellows and Faculty from different countries and was composed of onsite and online training within a longitudinal program, thus enabling the exploration of diverse instructional methods. As we interviewed FAIMER Faculty, current Fellows, and Fellows who had previously completed their Fellowship, we were able to triangulate our data sources and enhance trustworthiness. However, this study investigated only one IFDP, and participation was voluntary; hence, findings might not be transferable to other settings. Recall bias was another challenge, since we asked participants to recall experiences that had occurred in the past. Lastly, some aspects of teaching and learning might have been better understood by observing interactions during the Fellowship.

교육 및 연구에 대한 시사점

Implications for Education and Research

본 연구의 결과는 문화가 IFDP에 미치는 영향에 대한 이해를 증진하고 교수진 개발 활동을 개선하고 향후 연구 방향을 제시할 수 있는 제안을 가능하게 합니다.

The findings of this study advance our understanding of the influence of culture on IFDPs and enable us to make suggestions for enhancing faculty development activities and recommending future research directions.

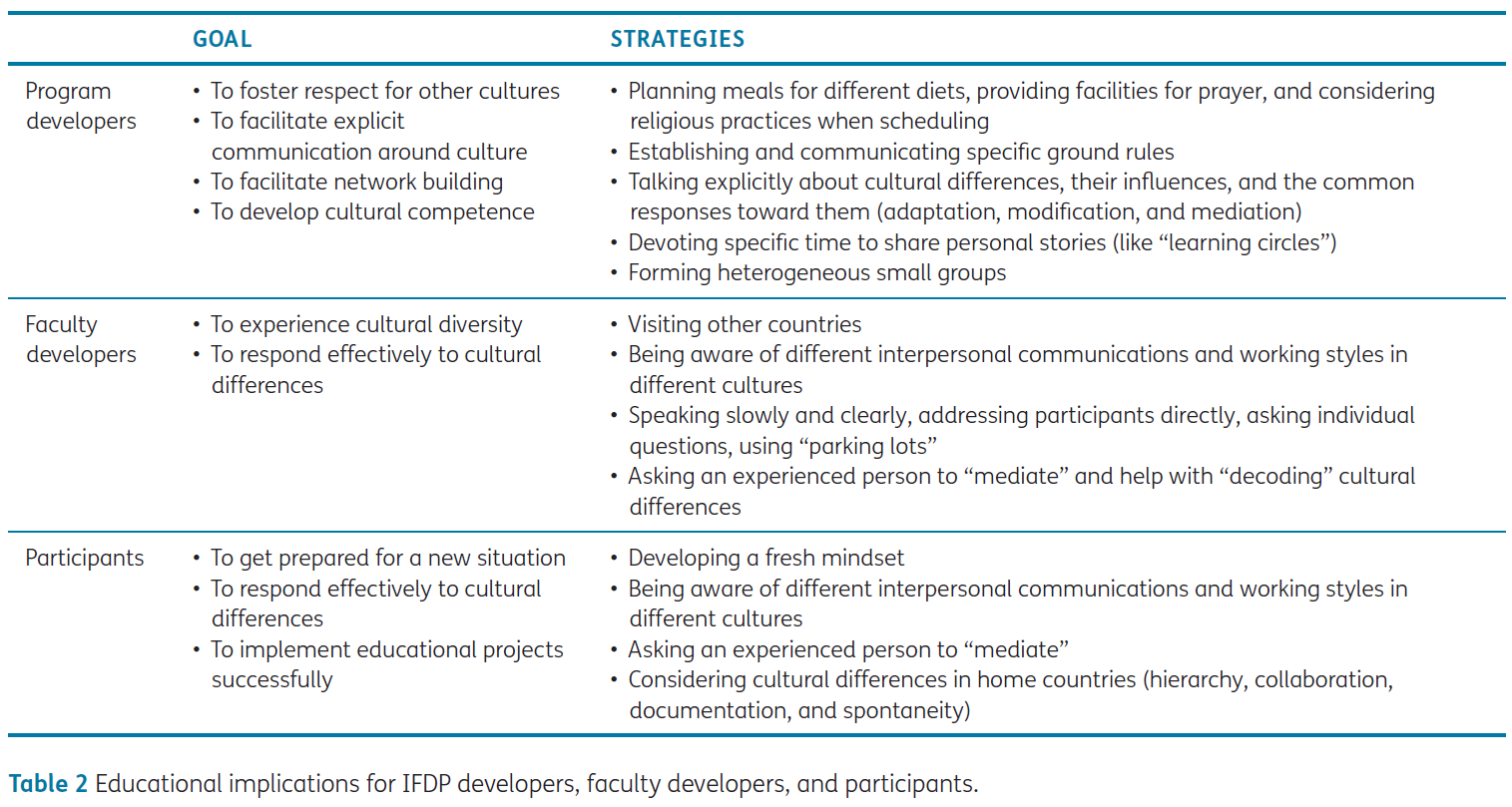

교수진 개발자와 IFDP 참가자를 위한 교육적 시사점을 표 2에 요약했습니다. 연구적 관점에서 볼 때, 교육자들은 다양한 지역의 IFDP를 조사해 볼 것을 권장합니다. 예를 들어, FAIMER 지역 연구소는 'home' 환경에서 문화의 영향력을 탐구하는 데 유용한 데이터 소스가 될 수 있습니다. 또한 민족지학과 같은 다른 방법을 사용하면 전문직 및 프로그램 문화의 영향과 상호 작용에 초점을 맞추어 IFDP에서 문화가 교수와 학습에 미치는 영향에 대해 더 많은 통찰력을 얻을 수 있습니다. TLT의 렌즈를 통해 교수진 개발에 대한 추가 탐구도 가치가 있을 것입니다.

We have summarized the educational implications for faculty developers and participants in IFDPs in Table 2. From a research perspective, we encourage educators to examine IFDPs in different locations; for example, FAIMER Regional Institutes could be a valuable data source for exploring the influence of culture in “home” settings. Additionally, using other methods such as ethnography could provide more insights into the influence of culture on teaching and learning in IFDPs, with a focus on the influence – and interaction – of professional and program cultures as well. Further exploration of faculty development through the lens of TLT would also be worthwhile.

결론

Conclusion

IFDP에서 보건 전문직 교육자의 문화적 다양성은 학습에 장애가 되지 않는 것으로 보입니다. 인식되는 특정 문화적 차이는 미묘한 문제를 야기할 수 있지만, 긴장을 피하기 위해 건설적으로 관리되는 경우가 많습니다. 프로그램 문화와 직업 문화는 때때로 문화적 신념, 가치, 규범보다 우선할 수 있습니다.

The cultural diversity of health professions educators in an IFDP does not seem to be a barrier to learning. Certain perceived cultural differences may cause subtle challenges, but they are often managed constructively to avoid tension. Program culture and professional culture may, at times, override cultural beliefs, values and norms.

인간 본성은 같지만 우리는 문화에 따라 적응합니다. 우리는 그것을 우리에게 두른 다음 특정 문화에 가장 적합한 방식으로 행동하려고 노력합니다. 인간 본성의 개념, 치료자의 개념, 스승의 개념 등 많은 유사점이 있습니다. 이것들은 보편적인 것들 중 일부입니다. (F-10)

We have that same human nature, but then we adapt according to the culture. We wrap it around ourselves, and then we try to act accordingly what is most suitable in that specific culture. There are so many similarities, the concept of human nature, the concept of healer, the concept of teacher. These are some of the universal things. (F-10)

Understanding and Embracing Culture in International Faculty Development

PMID: 36908745

PMCID: PMC9997115

DOI: 10.5334/pme.31

Free PMC article

Abstract

Introduction: Research on international faculty development programs (IFDPs) has demonstrated many positive outcomes; however, participants' cultural backgrounds, beliefs, and behaviors have often been overlooked in these investigations. The goal of this study was to explore the influences of culture on teaching and learning in an IFDP.

Method: Using interpretive description as the qualitative methodology, the authors conducted semi-structured interviews with 15 Fellows and 5 Faculty of a US-based IFDP. The authors iteratively performed a constant comparative analysis to identify similar patterns and themes. Transformative Learning Theory informed the analysis and interpretation of the results.

Results: This research identified three themes related to the influences of culture on teaching and learning. First, cultural differences were not seen as a barrier to learning; instead, they tended to act as a bridge to cultural awareness and network building. Second, some cultural differences produced a sense of unease and uncertainty, which led to adaptations, modifications, or mediation. Third, context mattered, as participants' perspectives were also influenced by the program culture and their professional backgrounds and experiences.

Discussion: The cultural diversity of health professions educators in an IFDP did not impede learning. A commitment to future action, together with the ability to reflect critically and engage in dialectical discourse, enabled participants to find constructive solutions to subtle challenges. Implications for faculty development included the value of enhanced cultural awareness and respect, explicit communication about norms and expectations, and building on shared professional goals and experiences.

Keywords: Faculty development; cultural diversity; culture; transformative learning theory.

Copyright: © 2023 The Author(s).

'Articles (Medical Education) > 교수개발(Faculty Development)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 학습 고리: 적시 교수개발 개념화(AEM Educ Train. 2022) (0) | 2023.12.15 |

|---|---|

| 테크놀로지-강화 교수개발: 미래의 트렌드와 가능성(Med Sci Educ. 2020) (0) | 2023.12.15 |

| ASPIRE 준거를 활용한 교수개발 및 학술활동의 프로그램적 접근 개발: AMEE Guide No. 165 (Med Teach, 2023) (0) | 2023.10.10 |

| 임상실습의 수월성: 재능 분류하기가 아닌 재능 개발하기 (Perspect Med Educ, 2021) (0) | 2023.02.18 |

| 비서구 지역에서 의학 교수자의 전문직정체성형성(Med Teach, 2021) (0) | 2023.01.28 |