임상교육자를 위한 인센티브: 인센티브의 영향은 복잡하기에 조심해야 한다 (Med Educ, 2020)

Incentives for clinical teachers: On why their complex influences should lead us to proceed with caution

Katherine M. Wisener1 | Erik W. Driessen2 | Cary Cuncic3 | Cassandra L. Hesse4 | Kevin W. Eva5

1 소개

1 INTRODUCTION

의욕적인 임상 교사를 모집하고 유지하는 것은 어려울 수 있다. 교사 수가 부족하거나 임상의가 수업 의욕이 없을 때 의대생과 전공의들의 교육의 질이 떨어질 수 있다. Suboptimal한 해결책은 지도자당 학생 수가 증가하거나 교육자가 소진에 굴복하는 등 Suboptimal한 학습 조건으로 이어진다. 학습자가 교육 의욕이 없는 임상의에게 배정되면 부정적인 역할 모델링이 가능해지고 피드백 대화가 상처가 되거나, 학생들이 동정심 있고 효과적인 간병인이 될 수 있는 모든 범위의 역량을 개발하는데 어려움을 겪을 수 있다. 그렇긴 하지만, 열정적이고 헌신적인 임상 교사들도 동기 부여 문제에 면역이 되지 않는다. 실습, 체계 및 교육 수요가 계속 증가함에 따라 임상의는 일상적인 교육 활동을 통합하는 데 어려움을 겪는 경우가 많습니다.

Recruiting and retaining motivated clinical teachers can be challenging.1, 2 When teacher numbers are insufficient, or when clinicians are not motivated to teach, the quality of education for medical students and residents can suffer. Suboptimal solutions lead to suboptimal learning conditions, such as increases in the number of students per preceptor or leading the educator to succumb to burnout. When learners are assigned to clinicians who are not motivated to teach, negative role modelling becomes likely and feedback conversations can become hurtful or leave students struggling to develop the full range of competencies that will make them compassionate and effective caregivers.3, 4 That said, even enthusiastic and dedicated clinical teachers are not immune to motivational issues. As practice, systemic and educational demands continue to increase, clinicians often struggle with incorporating educational activities into their day to day.

이러한 문제들은 일상적으로 의과대학들이 임상의들의 [교육 노력에 대한 인센티브와 보상]을 제공하는 방법을 찾도록 한다. 이에 따라 프로그램 리더들의 감사를 표시하기 위해 [금전적 보상, 교수상, 감사장 등]이 일반적으로 사용되고 있다. 불행하게도, 최근 리뷰에서, 우리는 인센티브가 종종 역효과를 낼 수 있다는 충분한 증거를 발견했고, 원하는 행동을 장려하기보다는 동기를 감소시켰다. 이러한 현상에 대한 여러 설명이 있으며 각 전경이 인센티브가 영향을 미치는 메커니즘이 다르기 때문에 이론 간 통합은 어렵다. 또한, 요약된 메커니즘은 반드시 상호 배타적이지는 않으므로, 다양한 맥락에서 인센티브가 수행하는 역할을 더 잘 이해하기 위해 [여러 관점을 민감한 개념으로 사용할 필요가 있음]을 시사한다. 예를 들어,

- 심리학의 [인지 평가 이론가]들은 상award과 같은 외적인 인센티브가 그들이 가르치는 것으로부터 받는 즐거움에 의해 본질적으로 추진되는 사람들을 의욕을 잃게 할 수 있다고 주장한다.

- 반면에, 조직 행동의 [형평성 이론가]들은 동기를 감소시키는 불공정에 대한 인식을 촉진하지 않기 위해 [자신이 투입하는 노력]과 비교하여 [적절한 규모의 인센티브]를 설정하는 것의 중요성을 강조한다.

- 동기부여-행동경제학의 [군중이론가]들은 [이타적이라고 느끼는 것으로부터 받는 보상]을 감소시킬 수 있다는 두려움 때문에 자원봉사와 같은 [친사회적 활동에 인센티브를 주는 것에 대해 경고]한다.

These problems routinely lead medical schools to seek ways of providing incentives and rewards for clinicians’ teaching efforts. As a result, financial compensation, teaching awards and letters of appreciation are commonly used to demonstrate program leaders’ gratitude.5 Unfortunately, in a recent review, we found ample evidence that incentives can often backfire, reducing motivation rather than encouraging the desired behaviour.6 There are multiple accounts of this phenomenon and integration across theories is difficult as each foregrounds different mechanisms through which incentives have an influence. Further, the mechanisms outlined are not necessarily mutually exclusive, thereby suggesting the need to use multiple perspectives as sensitising concepts to better understand the role incentives play in divergent contexts.

- Cognitive evaluation theorists from psychology, for example, argue that extrinsic incentives like awards can de-motivate those who are intrinsically driven by the pleasure they receive from teaching.

- Equity theorists from organisational behaviour, in contrast, emphasise the importance of setting appropriately sized incentives in relation to the investment of effort one exerts, so as to not promote perceptions of unfairness that reduce motivations.

- Motivation-Crowding theorists from behavioural economics caution against incentivising prosocial activities such as volunteering out of fear that doing so can reduce the reward one receives from feeling altruistic.

인센티브가 의도하지 않은(그리고 종종 부정적인) 결과를 초래할 수 있는 가변적인 방법을 고려할 때, 보건 전문 교육에서 인센티브의 영향력 메커니즘은 충분히 다루어지지 않았다. 몇몇 연구들은 동기를 탐구했고 다음을 발견했다.

- 임상의는 무엇보다도 내재적인 이유(예: 개인적 만족)로 가르친다.

- 다음으로, 가장 자주 그들은 전문적인 목표를 달성하기 위해 가르친다고 주장한다(예: 경력 향상).

- 대조적으로 목록에서 낮은 것은 외부적인 이유(예: 돈)이다.

그러나 이 연구는, 위에서 언급한 문헌이 [특정 행동에 대한 동기가 straightforward한 일은 거의 없음]을 시사한다는 점을 고려할 때, [복잡한 문제에 대한 필요하지만 충분하지 않은 성찰]일 수 있다. [교육 인센티브에 대한 생각]을 조사하는 경우, [서로 다른 요인들이 상호작용하여 예상치 못한 결과의 가능성을 만들어내는 방법에 대한 뉘앙스를 생각할 기회나 자극 없이 설문에만 기반]했을 때, 복잡성은 쉽게 과소평가될 수 있다. 다른 분야에서 보았던 것처럼 인센티브 사용을 통해 의도치 않게 동기부여가 저하될 위험을 피하기 위해서는 인센티브가 임상교사에게 어떤 영향력을 행사하는지에 대한 더 깊은 이해가 필요하다.

Given the variable ways in which incentives can yield unintended (and often negative) consequences, the mechanism of their influence in health professional education has not been sufficiently addressed. Several studies have explored motivations and found that

- clinicians teach for intrinsic reasons (eg personal satisfaction) first and foremost;

- next, most frequently they claim to teach to meet professional goals (eg career advancement);

- low on the list, in contrast, are extrinsic reasons (eg money).6

This work, however, offers a necessary but perhaps not sufficient reflection of a complex problem given that the literature alluded to above suggests that motivations towards certain behaviours are rarely so straightforward. Complexity can easily be underappreciated when considerations of teaching incentives are based on surveys of what one perceives without opportunity or prompts to reflect on the nuances of how different factors interact to create the possibility of unanticipated consequences. To avoid the risk of unintentionally lowering motivation through the use of incentives, as has been seen in other fields, we need a deeper understanding of how incentives exert their influence on clinical teachers.

현재의 연구는 임상의들이 무엇이 가르치는 것을 유도driving하는지, 그들이 직면한 장벽, 그리고 그들이 과거에 어떻게 교육 인센티브를 인식했는지를 탐구함으로써 이 다음 단계를 제공한다. 우리의 목표는 인센티브가 어떻게 의미 있고 영향력 있는 지원으로 작용하도록 개발될 수 있는지 더 잘 이해하는 것이다. 이 문제를 연구하면서 우리는 다양한 다른 분야의 핵심 테이크아웃 메시지와 역사적으로 동기 부여에 영향을 미치는 인센티브의 불안정한 특성에 의해 안내되었다. 가장 중요한 연구 질문은 다음과 같습니다.

- (a) 임상교사의 관점에서 의학교육에서 경험하는 동기부여와 동기부여의 관계는 어떠한가?; 그리고,

- (b) 임상의들은 교육 동기에 영향을 미치는 인센티브의 역할을 어떻게 생각하는가?

이러한 질문을 해결함에 있어 인센티브와 동기 간의 고유한 상호 작용이 임상 교사에게 어떻게 작용하는지에 대한 새로운 지식을 제공함으로써 임상의가 교육자 및 교육 관리자로서의 역할에서 프로그램 리더로서의 역할을 더 잘 지원할 수 있는 권장 사항을 생성하기를 바란다.

The current study offers this next step by exploring what is driving clinicians to teach, the barriers they face, and how they have perceived teaching incentives in the past. Our aim is to better understand how incentives can be developed to act as meaningful and impactful supports. In studying this issue we were guided by the key takeaway messages from a variety of other disciplines and the precarious nature with which incentives have been historically shown to impact motivation.6 The overarching research questions are:

- (a) How is the relationship between motivation and incentives experienced in medical education from the perspective of clinical teachers?; and,

- (b) How do clinicians view the role of incentives in influencing their motivations to teach?

In addressing these questions, we hope to contribute new knowledge around how unique interactions between incentives and motivations play out for clinical teachers, thereby generating recommendations that will better support clinicians in their roles as educators and educational administrators in their roles as program leaders.

2 방법

2 METHODS

2.1 설계 연구

2.1 Study design

[해석적 기술 방법론]을 사용하고 COREQ(Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitical Research)를 따랐다. [해석적 기술]은 건강 연구자들이 일반적으로 질문하는 적용된 질문에 대한 탐구를 우선시하기 위해 근거 이론과 현상학의 원칙을 기반으로 하는 비교적 새로운 질적 접근법이다. [구성주의자적 세계관에 기반]한 해석적 서술은, 패턴을 포착하고 연구 중인 문제를 개선하기 위해 이해를 알릴 수 있는 서술을 생성하는 데 사용된다. 따라서 여러 현실이 존재하고, 각각이 개인에 의해 사회적으로 구성되고 문화적, 사회적 맥락에 의해 영향을 받는다는 것을 인정하면서 매우 집중하는 경향이 있다. 즉, 경험의 의미에 대한 이해는 참가자와 연구자가 공동으로 구성한다.

We used interpretive description methodology7 and followed the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ).8 Interpretive description is a relatively new qualitative approach that builds on the principles of grounded theory and phenomenology to prioritise exploration of the applied questions commonly asked by health researchers. Constructivist9 in worldview, interpretive description is used to capture patterns and generate description that can inform understanding for the sake of improving the problem being studied. It tends, therefore, to be very focused while acknowledging that multiple realities exist, each being socially constructed by individuals and influenced by cultural and social context.10 In other words, an understanding of the meaning of experiences is co-constructed by participants and researchers.

2.2 설정

2.2 Setting

브리티시컬럼비아 대학교(UBC)의 MD 프로그램은 2 + 2 (전임상실습 연수 + 임상실습 연수) 구조를 따르는 4년제 졸업생 등록 분산 프로그램이다. 4개의 지역 캠퍼스에서 제공되며, 각각의 캠퍼스는 더 큰 UBC 프로그램의 일부임에도 불구하고 뚜렷한 우선순위, 교수진, 제도적 문화를 가지고 있다. 대다수의 교사들은 임상 교수진으로 임명되어 있으며, 따라서 그들이 얼마나 자주 그리고 어떤 맥락에서 가르치는지에 대해 상당한 유연성을 가지고 있다. 이와 같이 교사들은 그들이 어디서 어떤 학습자를 가르치느냐에 따라 재정적이든 그 밖의 다양한 지원과 교수 인센티브를 받는다. 앨버타주 캘거리에 있는 커밍 의과대학의 한 명 외에 네 곳의 교수진이 모두 포함되었다. 프로그램의 분산 특성을 고려할 때, 인터뷰는 가능할 때 직접 수행되었고(참가자의 요청에 따라 클리닉, 병원 또는 기타 장소에서) 장거리 인터뷰는 전화 또는 화상 회의를 통해 수행되었다.

The MD program at the University of British Columbia (UBC) is a four-year graduate entry distributed program that follows a 2 + 2 (preclerkship years + clerkship years) structure. It is delivered at four regional campuses, each of which has distinct priorities, faculty and institutional culture despite being part of the larger UBC programme.11 A large majority of the teachers have clinical faculty appointments and, thus, have considerable flexibility in how often and in what contexts they teach; clinicians appointed to academic positions are expected to teach, but still often have flexibility with respect to how they contribute educationally. As such, teachers receive a variety of supports and teaching incentives, financial or otherwise, depending on where and which learners they teach. Faculty from all four sites were included in addition to one participant from the nearby Cumming School of Medicine in Calgary, Alberta. Given the distributed nature of the programme, interviews took place in person when possible (in clinic, hospital settings or other locations at the request of participants) and long-distance interviews took place over the phone or via videoconference.

2.3 참가자

2.3 Participants

정보가 풍부한 사례(학부와 대학원 모두에서 다양한 환경에서 강의한 것으로 알려진 임상 교수진)를 식별하기 위해 [목적적 샘플링 전략]이 사용되었다. 우리는 임상적 맥락(예: 입원 환자, 외래 환자)을 넘나들며 다양한 수준의 교육 경험을 가진 임상의를 추구함으로써 이질성을 극대화하기 위해 노력했다. 일부 참가자들은 임상 환경 외에 교실 환경에서도 가르쳤다. 수석 연구원은 알려진 임상의에게 이메일을 통해 임상의 네트워크에 참여 초대장을 배포할 것을 요청했다. 연구원과 접촉한 사람들은 인터뷰를 했다. 주제의 초기 개념화에 이의를 제기할 가능성이 있다고 생각되는 참가자들은 의도적으로 추구되었다. 예를 들어, 초기 응답자들은 교육에 매우 참여하고 유사한 인식을 기술했기 때문에, 관찰된 패턴에 도전하기 위해 교사 역할에서 사임한 임상의를 초대하기 위해 네트워크를 사용했다.

A purposeful sampling strategy was used to identify information-rich cases12 (clinical faculty known to have taught in a variety of settings, both undergraduate and postgraduate). We strove to maximise heterogeneity by pursuing clinicians who have taught across clinical contexts (eg inpatient, outpatient) and who had varying levels of teaching experience. Some participants taught in classroom environments in addition to clinical ones. The lead researcher asked known clinicians to disseminate a participation invitation to their clinician networks via email; those who contacted the researcher were interviewed. Participants thought likely to challenge early conceptualisations of themes were purposely sought. For example, early respondents were highly involved in teaching and described similar perceptions, so networks were used to invite clinicians who had resigned from teaching roles to challenge observed patterns.

2.4 데이터 수집

2.4 Data collection

인터뷰 가이드(부록 S1 참조)는 [동기와 인센티브 사이의 관계에 대한 다양한 관점을 제공하는 문헌 검토를 통해 확인된 다양한 이론을 사용하여 구성]되었다. 그러나 질문은 참가자들을 특정 견해로 유도하지 않기 위해 광범위하게 표현되었다. 또한, [민감 개념]으로 작용하는 이론에 의해 만들어진 가정에 도전하기 위한 노력으로 인터뷰 가이드의 반복적인 수정을 통해 데이터 자체에서 발생한 개념화를 수용하고 탐구했다.

An interview guide (see Appendix S1) was structured using the various theories identified through our literature review that offered different perspectives on the relationship between motivation and incentives.6 Questions, however, were phrased broadly to avoid directing participants to particular views. Further, conceptualisations that arose from the data themselves were embraced and explored through iterative modification of the interview guide in efforts to challenge assumptions made by the theories that served as sensitising concepts.

일반적으로, 인터뷰는 45-90분이 걸렸고 인구 통계와 교육 맥락을 포착하기 위한 몇 가지 질문으로 시작했다. 이어 개인의 교육에 대한 인식, 그들에게 제공되는 인센티브, 그들이 직면한 장벽, 그리고 그들이 교사로서 가치를 느낀다고 느끼는 지를 탐구하는 반구조적 질문을 했다. 인터뷰 가이드가 연구 목적에 효과적으로 부합하는지 여부를 평가하고, 질문이 참가자 풀에 있는 사람들과 어떻게 공명할지 결정하기 위해, 리드 연구자에게 알려진 임상의를 대상으로 두 번의 초기 인터뷰를 실시했다. 이러한 인터뷰에 이어진 디브리핑 토론 후 인터뷰 프로토콜을 약간 수정했을 뿐이므로 이러한 데이터는 분석에 포함되었다. 추가적인 작은 연구 가이드 수정은 연구팀이 녹취록을 검토한 후 인터뷰 내내 반복적으로 발생했고, 참가자들이 구조를 제기했을 때 조사자들이 미래의 참가자들과 함께 더 표적적인 방식으로 질문해야 한다고 생각하는 것에 주목했다. 마찬가지로, 프로빙 질문이 많은 토론을 유발하지 않을 때 변경이 이루어졌다. 인터뷰는 데이터가 포화된 것으로 나타난 후 3명의 참가자가 모집될 때까지 계속되었다(참가자의 교육 경험과 업무 맥락의 차이에 관계없이 연구 질문에 대한 새로운 관점을 밝히는 것을 중단했다).

In general, interviews took 45-90 minutes and began with several questions to capture demographics and teaching contexts. Semi-structured questions were then asked that explored individuals’ perceptions of teaching, incentives provided to them, barriers they face, and whether they felt valued as teachers. Two initial interviews were conducted with clinicians known to the lead researcher to pilot the interview guide, assess whether the guide was effectively aligned with the study purpose, and to determine how the questions would resonate with those in the participant pool. After a debrief discussion following these interviews, only slight modifications to the interview protocol were made, so these data were included in our analysis. Additional minor study guide modifications occurred iteratively throughout interviews after the research team reviewed transcripts and noted when participants raised constructs the investigators thought should be asked in a more targeted way with future participants; similarly, changes were made when probing questions did not yield much discussion. Interviews continued until three participants had been recruited after the data appeared to have saturated (ie stopped revealing novel perspectives on the research questions regardless of differences in participants’ teaching experience and work contexts).

2.5 데이터 분석

2.5 Data analysis

인터뷰 녹취록을 분석하기 위해 [해석적 서술 기법]이 사용되었으며, 여기에는 [데이터 해석, 연구 결과 합성, 패턴 및 관계 이론화]의 반복적인 단계가 포함되었다.

The interpretive description technique was followed to analyse the interview transcripts, which involved iterative phases of interpreting data, synthesising findings, and theorising patterns and relationships.13

처음 3개의 녹취록은 두 명의 조사관(KW, KE)에 의해 독립적으로 검토되었으며 초기 인상은 후속 인터뷰에서 인터뷰 가이드의 변경 사항을 알리는 데 도움이 되었다. 약 10개의 인터뷰가 완료된 후, 4명의 조사관(KW, ED, CC, KE)이 두 개의 대조적인 녹취록을 독립적으로 검토했다. 각각은(교수진 개발자 1명, 임상의 1명, 의료 교육자 2명) 개인적 경험과 맥락이 해석에 어떻게 영향을 미칠 수 있는지 식별하기 위해 [데이터에 대한 자신의 반응]을 문서화했다. 그런 다음 이러한 문서화된 반응을 종합적으로 논의하여 조사자들이 패턴을 식별하고 데이터에서 시사점을 도출하기 위해 유사하고 다양한 인상을 가진 곳을 식별했다. [반사성]에 대한 이러한 노력은 해석적 기술 방법론에 매우 중요하다.

The first three transcripts were reviewed independently by two investigators (KW, KE) and initial impressions helped to inform changes to the interview guide in subsequent interviews. After approximately ten interviews were completed, four investigators (KW, ED, CC, KE) independently reviewed two contrasting transcripts. Each (one faculty developer, one clinician and two medical educators) documented their own reactions to the data with effort to identify how their personal experiences and contexts might influence their interpretation. These documented reactions were then discussed collectively to identify where investigators had similar and divergent impressions for the purpose of identifying patterns and deriving implications from the data. Such efforts at reflexivity are critical to the interpretive description methodology.

그룹 토론에서 수집된 결과는 [초기 주제 구조]를 개발하는 데 사용되었으며, 이 구조는 4명의 조사관 모두가 두 개의 더 많은 녹취록을 코딩하는 데 사용되었다. 이 과정은 대본 코딩이 더 이상 추가 수정을 산출하지 않을 때까지 주제 구조와 인터뷰 가이드에 대한 지속적인 조정을 계속했다.

The collated output of the groups’ discussions was used to develop an initial thematic structure that was then used by all four investigators to code two more transcripts. This process continued with ongoing adjustments to the thematic structure and interview guide until transcript coding no longer yielded additional revisions.

마지막으로, 연구 보조자(CH)는 모든 대본을 읽고 주제 구조에 대해 체계적으로 코드화했다. 주 저자와의 매주 회의를 통해, 코드북을 적용하는 과제가 식별됨에 따라 [주제 구조에 대한 작은 조정]이 이루어졌다(예: 코드화된 데이터가 연구 질문과 관련성을 주장할 만큼 충분히 실질적이지 않은 경우 코드화된 일부 하위 테마가 중복된 것처럼 보이게 하거나 삭제되었을 때 일부 하위 테마가 병합되었다). 연구팀은 모든 코딩이 완료되면, 주제구조 내에서 각 주제로부터 일반적인 메시지를 외삽하는 동시에, 개별 참여자들 간의 주장의 차이를 설명하기 위한 [모순된contradictory 사례와 방법]을 모색했다. 이는 [연구 질문과 관련한 패턴, 불협화음, 경향, 시사점 등을 검토]하여 [주제의 의미를 종합하고 이론화]하기 위한 그룹 회의를 개최하는 등 [주제 설명]과 [예시 인용]을 검토하는 방식으로 진행되었다. [감사 추적]은 본 연구의 분석 단계 전반에 걸쳐 유지되었고, 우리의 분석 과정과 결과는 조사 결과를 개입의 출발점으로 직접 적용할 수 있는 방식으로 완료되었다.

Finally, a research assistant (CH) read through all transcripts and systematically coded each against the thematic structure. Through weekly meetings with the lead author, minor adjustments to the thematic structure were made as challenges applying the codebook were identified (eg some subthemes were merged when coding made them appear redundant or dropped when coded data were not substantive enough to make claims of relevance to the research question). Once all coding was completed, the research team extrapolated the general message from each theme within the thematic structure while also seeking contradictory cases and ways to account for variations in claims between individual participants. This was done by reviewing theme descriptions and example quotes, with group meetings held to synthesise and theorise the meaning of themes through examination of patterns, dissonances, trends and implications in relation to the research questions. An audit trail was kept throughout the analytic phase of this work and the process and product of our analysis was completed in such a way that findings could be directly applied as a starting point for intervention.14

2.6 윤리

2.6 Ethics

윤리적 승인은 UBC의 행동 연구 윤리 위원회(H18-01109)에 의해 제공되었다.

Ethical approval was provided by the UBC’s Behavioural Research Ethics Board (H18-01109).

3 결과

3 RESULTS

16개의 인터뷰가 완료되었다. 참가자의 특기사항, 장소 및 실무연수는 표 1에서 확인할 수 있다.

Sixteen interviews were completed. A summary of participant specialties, locations and years in practice can be seen in Table 1.

인센티브의 영향을 이해하려면 먼저 무엇이 임상의를 교육으로(또는 교육에서 멀어지게) 만드는지 알아야 합니다. 따라서 우리는 교육 인센티브에 대한 참가자의 인식을 설명하기 전에 교육 결정에 영향을 미치는 개인 및 외부 요인에 대한 설명과 함께 그 복잡성(즉, 이러한 요인이 역할을 하는 미묘한 및 가변적인 방식)으로 시작한다.

To understand the impact of incentives, we need to first know what drives clinicians towards (or away from) teaching. We start, therefore, with a description of personal and external factors influencing teaching decisions, along with their complexities (ie the nuanced and variable ways in which these factors play a role), before outlining participants’ perceptions of teaching incentives.

3.1 교수 결정에 영향을 미치는 요인

3.1 Factors influencing decisions to teach

표현된 동기부여 요인은 [개인적 요인(자신과 관련된)]과 [외부 요인(환경/상황과 관련된)]으로 분류되었다. [개인적인 요인]과 관련하여, 많은 사람들이 학생들과 그들의 교육 욕구에 근본적으로 영향을 미친 의학계 전반의 복지에 대해 [이타적unselfish 배려]를 표명했다. 예를 들어, 그들은 'pay it forward'할 의무를 느꼈고 미래의 의사들의 개발을 지원하는 것에 대한 열정이 깊이 뿌리내렸다. 많은 사람들은 또한 그들의 임상 지식의 인맥, 평판 또는 통화를 구축하고자 하는 열망을 표현했다.

Motivators participants expressed were categorised into personal factors (related to the self) and external factors (related to the environment/context). Regarding personal factors, many expressed unselfish regard for the welfare of students and the medical community at large that fundamentally influenced their desire to teach. For example, they felt a duty to ‘pay it forward’ and had deeply rooted passion for supporting the development of future physicians. Many also expressed desire to build connections, reputation or the currency of their clinical knowledge.

[외부 요인]과 관련하여, 많은 참가자들은 [학습자가 환자 치료를 더 효율적으로 할 수 있을 때] 또는 [임상 환경이 교육에 도움이 될 때(예: 학습자를 수용할 수 있는 적절한 물리적 공간이 있는 경우)]에 가르치는 데 더 동기부여가 된다고 공유했다. 시간이 너무 짧거나, 소득 손실이 너무 크거나, 학습자가 안전 위험을 제기하거나, 임상의가 가족의 요구를 균형 있게 해야 하는 필요성과 마찬가지로 동기 부여 장벽을 만들었는지 여부에 대한 선택권이 없다고 느꼈다.

Regarding external factors, many participants shared that they were more motivated to teach when learners could help make patient care more efficient or when their clinical environment was conducive to teaching (eg they had adequate physical space to accommodate learners). Feeling that time was stretched too thin, that income loss was too great, that learners posed safety risks or that the clinician did not have a choice in whether they taught created motivational barriers as did the need to balance family demands.

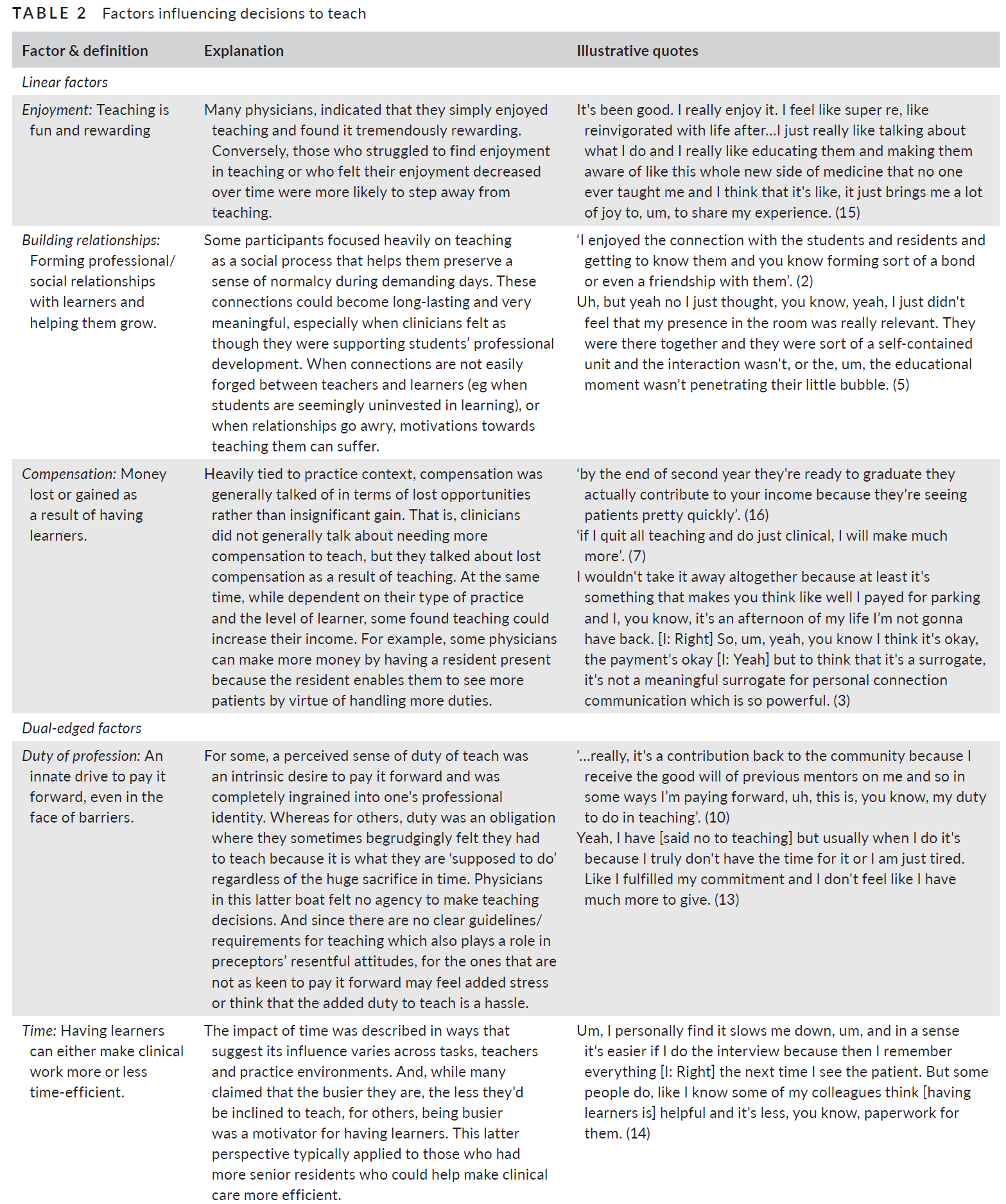

이러한 요인들은 시간이 지남에 따라 또는 환경 전반에 걸쳐 [정적인 것이 아니라], 경력과 삶의 단계를 통해 진화한 [역동적인 방식]으로 개인들에 의해 가중치가 부여되었다. 또한, 일부 요인들은 상당히 [선형적인 영향력]을 가지고 작동하는 것으로 설명되었지만(예: 더 많이 가르치는 것을 좋아할수록 더 많이 할 가능성이 더 높다), 동기 부여자의 존재가 항상 더 많은 교육으로 이어지지 않고 장벽의 존재가 항상 더 적게 작동하지 않는다는 점에서, 많은 요인들이 더 복잡한 방식으로 작동하는 것으로 보였다. 예를 들어, 어떤 요인들은 그들의 존재가 때로는 동기부여로 묘사되고 때로는 동기부여를 감소시키는 부정적인 요소들을 만들었다는 의미에서 [양날의 것]이었다. 예를 들어, 다른 요인에 따라, 임상의가 가르치는 의무감은 [어떤 순간에는 특권처럼 느껴지고, 다른 순간에는 부끄러운 의무처럼 느껴질 수] 있다. 여전히 다른 요인들은 [역전된 U자형 함수]로 더 잘 설명되어, 감소를 야기하기 전에 어느 정도 동기를 증가시키는 것처럼 보였다. 예를 들어, 한 사람의 지식이 시대에 뒤떨어지는 것에 대한 걱정은 참가자들의 교육 욕구를 증가시켰지만(학습자가 임상의를 최신 상태로 유지하는 데 도움을 줄 수 있기 때문에), 단지 어느 정도만; 그들의 전문 지식과 너무 동떨어진 느낌은 임상의가 가르치는 것을 단념시켰다. 표 2는 포괄적이지는 않지만 선형, 양날 및 U자형 요인에 대한 설명과 대표적인 인용문을 제공함으로써, 교육에 동기를 부여하거나 장벽을 만드는 요인을 단순히 나열하는 것의 부적절성을 보여준다.

These factors were not static over time or across environment, but were weighed by individuals in a dynamic manner that evolved throughout their career and life phases.

- Further, while some factors were described as operating with a fairly linear influence (eg the more one likes to teach the more likely they are to do it), many factors appeared to operate in a more complex manner in that the presence of a motivator did not always lead to more teaching and nor did the presence of a barrier always lead to less.

- To illustrate, some factors were dual-edged in the sense that their presence was sometimes described as motivating and sometimes created negatives that reduced motivation. For example, dependent on other factors, a clinician's sense of duty to teach could feel like a privilege in some moments and a begrudging obligation in others.

- Still other factors seemed better described as an inverted U-shape function, increasing motivation to a point before causing a decline. For example, worry about one's knowledge being out of date increased participants’ desire to teach (because learners can help clinicians stay up to date), but only to a point; feeling too far from their expertise deterred clinicians from teaching.

Table 2, while not comprehensive, illustrates the inadequacy of simply listing factors that motivate or create barriers to teaching by providing descriptions and representative quotes of linear, dual-edged and U-shaped factors.

더욱 복잡해짐에 따라, 참가자들은 종종 [그들이 가르치는 것으로부터 얻는 이익]에 초점을 맞추어 특정 장벽을 제거했다. 보상에 대한 그들의 관점은 좋은 예를 제공한다. 참가자들은 대부분의 경우 가르치는 것이 수입을 잃는 결과를 가져온다는 것을 일반적으로 인정했지만, 'pay it forward'에 대한 의무감이 너무 강해서 많은 사람들은 가르치는 기회가 돈보다 더 가치 있는 'currency'와 동등하다고 묘사했다.

Adding further complexity, participants frequently rationalised certain barriers away by focusing on the benefits they derived from teaching. Their perspective on compensation provides a good example. While participants generally acknowledged that in most cases teaching results in a loss of income, the sense of duty to ‘pay it forward’ can be so strong that the opportunity to teach was described by many as equivalent to a ‘currency’ they valued more than money:

거기가 나를 위한 돈이 있는 곳이다. 그것은 제가 이 사람에게 무언가를 가르쳤고, 그 사람은 이제 다른 사람에게 그것을 가르치거나 무언가를 진단하고 변화를 일으켜 누군가의 삶에 영향을 미칠 것이라는 것을 아는 것입니다. 나에게는 풍요로움이 있다. (참가자 2)

That’s where the money is for me. It’s knowing that I’ve taught this person something and that person’s now going to either teach it to somebody else or maybe diagnose something and make a difference and have an impact in somebody’s life. To me that’s where the richness is. (Participant 2)

그러한 정당성은 단기적으로 효과가 있었지만, 참가자들은 장벽의 축적이 그들의 교육 능력이나 의지에 어떻게 영향을 미치는지 설명했기 때문에 동기부여는 역동적이었다. 그 결과, 개인의 영향력이 임상의에게 각기 다른 시점에서 영향을 미치기 때문에 [언제나 교수 감소teaching attrition를 초래하는 특정 요인]은 식별할 수 없었다. 일부 임상의들은 그들이 충분히 양보했다고 느꼈기 때문에 가르치는 것을 중단했지만, '티핑 포인트'는 대개 부정적인 경험이나 별개의 삶이나 경력 단계로 접어들면서 촉발되었다.

While such justifications worked in the short-term, motivations were dynamic as participants described how the accumulation of barriers impacted their ability or willingness to teach. As a result, it was not possible to identify particular factors that always led to teaching attrition as their individual influence affected clinicians differently and at different points in time. Some clinicians stopped teaching because they felt like they had given enough (ie it was time to take a step back), but the ‘tipping point’ was usually triggered by a negative experience or by entering a separate life or career stage:

나는 서비스 클리닉 비용이 있고 환자가 많다는 이유만으로 빨리 환자를 봐야 한다는 압박을 받을 때 특별히 가르치는 것을 좋아하지 않는다.

I don’t particularly like teaching when I have a fee for service clinic and I’m pressured to see patients quickly just because I have a lot of patients and because I need to get home to children and, like, motherhood and stuff. (15)

예를 들어, 그들이 직면한 장벽에도 불구하고 강의를 계속한 임상의들은 바쁜 가족 생활의 누적된 영향과 바쁜 임상 실습이 결국 교수직을 사임하게 될 것이라고 암시했다.

Those clinicians who continued to teach despite barriers they faced hinted that the cumulative impact of a busy family life in combination with a busy clinical practice, for example, would eventually lead to resigning from teaching commitments:

전반적으로 우리는 삶에 만족하고 있지만, 우리는 긴장하고 있다고 생각해요. 그리고 우리는 이것을 지탱할 수 없는 벼랑 끝에 와 있는 것처럼 느끼고 있다. (16)

I think overall, I think overall we’re, uh, happy with our lives but I think we’re feeling stretched…And we’re feeling like we’re on the brink where we can’t sustain this. (16)

이러한 복잡한 현실 앞에서 우리는 교육 인센티브가 어떻게 인식되고 궁극적인 소진과 교육 감소를 완화하는 데 사용될 수 있는지 고려해야 한다.

It is in the face of such complex realities that we must consider how teaching incentives are perceived and might be used to mitigate against eventual burnout and teaching attrition.

3.2 교수 인센티브에 대한 인식과 교사의 가치관 형성에 미치는 영향

3.2 Perceptions of teaching incentives and their impact on making teachers feel valued

모든 참가자들은 [학생들의 평가]가 특히 중요한 인센티브를 창출했다고 지적했다. 또한, 그들은 특정 인센티브와 보상(예: 감사 편지, 교수 상, 선물 및 피드백)이 어떻게 그들이 교사로서 가치가 있다는 인식을 형성하는지 설명했는데, 이것이 그들의 가르치는 동기의 주요 동인으로 보였다. 그렇게 함으로써, 그들은 인정, 감사, 연결, 관계와 같은 구조를 중심으로 말하는 경향이 있었다. 그러나 참가자들이 이러한 인센티브를 설명하는 방식은 다시 미묘한 차이를 보이며 매우 가변적이었다. 예를 들어, 어떤 이들은 상을 원하지 않는다고 주장했고, 어떤 이들은 그들이 받은 상이 특히 의미 있는 것이라고 언급했다. 선생님으로서 가치를 느낀 사람들은 무엇이 그들을 그렇게 느끼게 하는지 명확하게 표현하는 데 어려움을 겪었고, 다른 사람들은 그들이 의대로부터 가치있게 여겨졌다고 느꼈는지조차 고려하지 않았다.

All participants indicated that students’ appreciation created particularly important incentivisation. In addition, they described how certain incentives and rewards (eg thank you letters, teaching awards, gifts and feedback) built perception that they were valued as a teacher, which appeared to be the primary driver of their motivation to teach. In doing so, they tended to speak around constructs like recognition, appreciation, connectedness and relationships. However, the way in which participants described these incentives were again nuanced and highly variable. For example, some insisted they did not want awards and some referenced the awards they received as being particularly meaningful. Some who felt valued as teachers had difficulties articulating what made them feel that way; others had not even considered whether they felt valued by the medical school.

이러한 변동성과 관계없이, 모든 참여자들은 [인센티브의 개념]과 [인센티브의 실행]을 구별하여, [선의의 인센티브조차도 역효과를 가져올 수 있음]을 나타냈다. 즉, 인정이 해를 끼치는 것보다 더 많은 이익을 주는 것이라면 인센티브의 전달이 인센티브 자체보다 더 중요했다. [긍정적으로 설계된 인센티브의 부정적인 영향]은 참가자들의 기억에서 두드러졌고, 몇몇 참가자들은 그들이 저평가되었다고 느낄 때 감정적이 되었다. 이러한 [의도하지 않은 결과]는 [사기]에 전반적으로 영향을 미쳤고, 참가자들의 [감사하는 마음과 유대감]을 감소시키는 동시에, 그들에게 [의미 있는 관계]를 위협했다. 인센티브는 일반적으로 [비인격적이거나, 불평등하거나, 비효율적이거나, 적절한 프레임 구성이 부족할 때] 의도하지 않은 결과를 이끌어내는 것처럼 보였다.

Regardless of this variability, all participants made a distinction between the notion of an incentive and its implementation, indicating that even well-intentioned incentives could backfire. That is, the delivery of an incentive was just as, if not more, important than the incentive itself if the acknowledgement was to do more good than harm. Negative impacts of incentives that were designed to be positive were prominent in participants’ recollections with several participants becoming emotional when discussing times they felt undervalued. Such unintended consequences impacted morale quite generally, reducing participants’ sense of appreciation and connection while threatening relationships that were meaningful to them. Incentives generally seemed to elicit unintended consequences when they were impersonal, inequitable, inefficient or lacked appropriate framing.

[비개인적]이라는 라벨은 참가자들이 그들의 교육 노력에 대한 인정을 받는 것에 감사했지만, 그들이 [구체적일 때]만 감사했다는 관찰을 반영한다. 개인적 속성이 부족한 감사 이메일이나 감사 편지는 적극적으로 받아들여지지 않았습니다.

The label of impersonal reflects observations that participants were grateful to receive acknowledgements of their teaching efforts, but only when they were specific. Thank you emails or appreciation letters that lacked personal attributes were not enthusiastically accepted:

당신은 이 무작위 이메일처럼 되고 그것에 첨부된 이름이나 어떤 것도 없지만, 그것은 '오 선생님이 되어주셔서 감사합니다'와 같습니다… (6)

you get like this random email and there’s no names attached to it or anything but it’s like 'oh thank you for being a teacher'… (6)형식적인 편지라서 이름만 바꾸고 박사님이나 박사님도 바꾸고 있어요. 사실 마음에 안 들어요. 그냥 쓰레기통에 버립니다. 왜냐하면 저는 그것들이 정말로 아무 의미가 없다고 생각하기 때문입니다. (9

it’s a form letter so they’re just changing your name and Dr so and so or Dr so and so … I actually don’t like those. I just throw them in the trash bin … because I don’t think they really mean anything. (9)

극명하게 대조적으로, 의대로부터 '나는 그저 다른 원숭이로 대체할 수 있는 또 다른 원숭이처럼 느껴진다'고 말하면서 아무런 감사를 느끼지 못했던 한 의사는 [학생들의 몸짓에 깊은 감동을 받았고 그것이 그들이 그녀를 교육자로서 소중히 여기는 것을 보여주는 그들의 방식]이라고 느꼈다.

In stark contrast, one physician who felt no appreciation from the medical school, stating ‘I feel like just another monkey that's replaceable with a different monkey’, was deeply touched by a gesture from her students and felt that it was their way of showing they valued her as an educator:

수업이 끝날 무렵 나는 내 사무실로 갔고, 알다시피, 내가 가르쳤던 그룹의 감사 카드와 함께 [음료] 네 팩이 있었다. (13)

at the end of a course I went up to my office and there was, you know, a four pack of [drink] with a little thank you card from the group that I had taught. (13)

[임상 교사들에 대한 인정의 불평등]은 일부 감정을 간과하고 그들의 노력을 간과하게 만들었다. 이것은 승진, 지급, 직함, 그리고 상에 대해 논의할 때, 특히 다른 사람들이 그들이 덜 받을 자격이 있다고 여겨지는 것을 받는 것을 볼 때 나타났다. 예를 들어, 두 명의 참가자는 [의대가 승진을 할당하는 방법에 대한 공정성의 결여]에 대해 논의할 때 마지못해 고통을 표현했다.

Inequities in the acknowledgement of clinical teachers left some feeling overlooked and their efforts unnoticed. This came up when discussing promotions, payments, titles and awards, especially when others were seen to receive something for which they were perceived as less deserving. For example, two participants reluctantly expressed anguish when discussing the lack of fairness in how the medical school allocates promotions:

나는 이것에 대해 매우 구체적으로 말하고 싶지는 않지만, 가끔 당신이 프로그램에서 수년간 당신의 심혈을 기울이고 있었는데, 갑자기 전혀 기여한 바가 없는 사람이 특정한 지위, 특정한 신용 또는 특정한 [인정]을 얻는 일이 생긴다. 아마도 사람들은 단지 변화를 원하지만, 때때로 내가 과소평가된다고 느낀다. (16)

I don’t want to be very specific about this but sometimes in the program you put your heart and soul for so many years … and then someone who hasn’t contributed suddenly might get a particular position or a particular credit or a particular [acknowledgement] … maybe people just want change but sometimes you feel undervalued… (16)나는 어떤 종류의 상도 바라지 않아, 정말로 그렇지 않아. 사실은 원하지 않아요. 하지만 당신이 그것에 대해 약간 냉소적이 된다는 것은 웃기는 일입니다, 음, 알다시피, 나는 이 상을 받은 사람이 학생들을 수치스럽게 하는 교육방식으로 학생들로부터 비난을 받았다는 것을 알고 있습니다. (8)

I’m not looking for an award of any kind, really I’m not. I don’t want it in fact. But it’s funny that then you get a bit cynical about it, like mmm, you know, I know that this person specifically that got an award has been criticized by students for teaching by shame. (8)

[행정절차의 비효율성]은 인센티브 자체에서 의미를 빼앗는 경향이 있었다. 이와 관련해 교수비 지급, 승진 검토 서류 요건, 지연된 피드백 과정 등이 여러 차례 제기돼 교사가 요구하는 노력이 때로는 보상받을 가치가 없는 경우도 있음을 시사했다. 비효율성으로 인해 시간이 많이 걸리는 다른 단계를 일정에 추가함으로써 좌절감을 초래했습니다.

Inefficiency with administrative procedures tended to take meaning away from the incentive itself. In this regard, payments for teaching, paperwork requirements for promotion reviews and delayed feedback processes were brought up multiple times, suggesting the effort required by the teacher was sometimes not worth the reward. Inefficiency caused frustration by adding another time-consuming step to schedules that are thinly stretched:

시간당 90달러를 받기 위해 백만 달러 상당의 서류 작업을 해야 한다고 의료진에게 요구하지 마세요. 사람들이 무엇을 얻을지 알고, 무엇을 할 것인지 알고, 무엇을 할 것인지 알고, 어떤 보상을 받을 것인지 알 수 있도록 잘 작동하고, 쉽게 작동하는 시스템을 만들기 위해 충분한 사람들을 고용하십시오. (12)

don’t ask clinical faculty to have to like do a million dollars’ worth of paperwork to get their $90.00 an hour or whatever it is. Have enough people hired to make a system that works and works well and works easily so that when people teach they know what they’re gonna get, they know what they’re committing to and they know what the rewards are gonna be. (12)6개월 전에 레지던트들을 가르쳤기 때문에 피드백을 받을 수도 있지만, 피드백이 무엇을 기반으로 한 것인지, 아니면 우리가 어떤 주를 보내고 있었는지 전혀 모르겠습니다. (11)

I might get feedback now from teaching residents six months ago and I’m like well I have no idea [I: What that was …] what they’re basing that on [I: Right] or what kind of weeks we were having or … (11)

마지막으로, 보상금을 교육에 대한 'payment'로 규정하는 것은 단순히 '양동이의 물방울 하나'이라는 점에서 일부 사람들에게는 모욕적이었다. 참가자들은 더 많은 돈을 원하지 않았지만, 재정적인 인센티브의 틀이 실제로 무엇인지 더 잘 반영하도록 조정될 수 있다고 생각했다. 즉, 급여, 제스처 또는 감사의 상징적 표시입니다. 어쨌든, 급여는 교육에 필요하지만 충분하지 않은 인센티브로 보였고 개인적인 의사소통과 감사와 가장 잘 결합되었다고 느꼈습니다.

Finally, framing compensation as ‘payment’ for teaching was insulting to some given that it was simply a ‘drop in the bucket’. Participants did not want more money, but thought the framing of financial incentives could be adjusted to better reflect what it is in actuality—a stipend, a gesture or symbolic token of thanks. In any case, payment seemed to be a necessary but not sufficient incentive for teaching and was felt best combined with personal communication and appreciation:

사실, 그들은 그것을 보상compensation이라고 부르면 안 된다. 포기하는 비용을 지불하는 데 도움이 되는 제스처일 수도 있습니다. 사실은 돈이 들어가는 일이다. 이것은 감사의 표시입니다. 그리고 비용의 그저 일부를 갚아주기 위한 것입니다. 개인적으로 그렇게 표현하는 게 좋을 것 같아요 (9)

In fact, they shouldn’t even call it compensation. It could be, uh, a gesture to help defray the cost … that you’re giving up…It’s costing you money. This is a little gesture to thank you and just to help you defray some of the, some of the cost. [I: Right] I think that would be a better way to put it personally. (9)

4 토론

4 DISCUSSION

본 연구는 임상교사가 교사로서의 역할을 어떻게 보고 있는지, 교사가 직면하는 동기와 장벽, 인센티브가 교수동기에 어떤 영향을 미치는지에 대한 관점에 대한 심층적인 탐구를 통해 의료교육에서 동기와 동기의 불안정한 관계가 어떻게 형성되는지를 강조한다. 특히, 우리는 복잡하고 역동적인 방법으로 교수 동기를 가능하게 하고 억제하는 몇 가지 [개인적 요인과 환경적 요인]을 발견했다. 우리는 또한 인센티브가 종종 선의의 것이기는 하지만, 교사들의 [동기를 손상시키는 의도하지 않은 결과]를 초래할 수 있다는 것을 발견했다. 이러한 발견은 교육에 대한 임상의의 동기를 구축하고 유지하기 위한 인센티브 제도를 고려하고 있는 의대와 교육 지도자들에게 중요한 의미를 갖는다.

This study highlights how the precarious relationship between motivation and incentives is enacted in medical education through an in-depth exploration of how clinician teachers view their roles as teachers, the motivations and barriers they face, and their perspective on how incentives influence their motivations to teach. In particular, we found several personal and environmental factors that enable and inhibit teaching motivations in complex and dynamic ways. We also found that incentives, while often well-intentioned, can have unintended consequences that undermine teachers’ motivations. These findings have important implications for medical schools and educational leaders who are considering incentive schemes to build and sustain clinicians’ motivations towards teaching.

4.1 이론적 함의

4.1 Theoretical implications

서론에서 언급한 바와 같이, 보건 전문 교육 내의 인센티브에 대한 이전 연구는 대체로 이론적이었으며, 임상의가 교육에 대한 동기에 영향을 미치는 촉진자와 장애요인을 나열하는 데 초점을 맞추고 있다. 우리의 데이터는 이 접근법의 불충분함을 강조한다. 우리의 참가자들이 그들의 동기에 영향을 미치는 것으로 이름 붙인 많은 요소들은 다른 사람들에 의해 식별된 것들과 비슷했지만, 우리의 데이터는 [인센티브가 (단순한 목록이 제시하는 것보다) 어떻게 더 미묘한 차이와 가변성을 가질 수 있음]을 제시한다.

- 하나의 요인이 맥락/개인에 따라 동기 부여 요인으로도 또는 장벽으로도 나타날 수 있다(표 2의 양날 패턴).

- 어떤 요인은 어떤 지점까지 동기부여자 역할을 하지만, 일단 역치에 도달하면 장벽이 된다(역 U자형 패턴).

As noted in the introduction, previous research on incentives from within health professional education has been largely atheoretical, focused on listing facilitators and barriers clinicians perceive to influence their motivation towards teaching.6 Our data highlight the insufficiency of this approach. Many factors our participants named as influencing their motivations were similar to those identified by others, but our data suggest the way in which they have their influence to be more nuanced and variable than a simple list would suggest.

- One factor can present itself as a motivator or as a barrier dependent on context/individual (the dual-edged pattern in Table 2);

- some act as motivators up to a point, but then become barriers once a threshold is reached (the inverted U-shaped pattern).

따라서, 그들의 영향력은 그들의 상호작용과 주어진 맥락 내에서 요소들이 어떻게 경험되는지에 따라 달라질 것이기 때문에, 교육에 대한 동기부여나 장벽이 될 어떤 특정한 요소를 가정하는 것은 신중해야 한다. 이것이 와이즈너와 에바가 요약하고 서론에서 강조한 것처럼 [보건 전문 교육 외부에서 발견되는 다양한 이론적 관점을 완전히 통합하는 것이 어려운 이유]일 수 있다. [인센티브가 동기 부여에 어떻게 영향을 미치는지에 대한 설명의 가변성variability]은 경쟁적이거나 모순된 개념을 반영하기보다는, 맥락마다 다른 요소가 어떻게 적절히 전면에 나타나는지를 보여주는 것일 수 있다.

As such, it appears prudent to be cautious in presuming any particular factor to be a motivator or barrier to teaching as their influence will depend on their interplay and how factors are experienced within a given context. This may be why it is so hard to fully integrate the different theoretical perspectives that are found outside of health professional education, summarised by Wisener and Eva and highlighted in the introduction.6 Variability in accounts of how incentives influence motivation may represent context appropriate foregrounding of different factors rather than reflecting competing or contradictory notions.

이전 검토에서 발견된 이론 관련 개념을 살펴보면, 우리의 데이터에서 특히 두드러졌던 것은 [형평성]이었다. 우리의 보건 전문 교육 맥락의 참가자들은 다음과의 [차이와 비교 측면]에서 (급여, 승진, 직함 및 상과 같은) 교수 인센티브에 대해 가장 자주 논의했다.

- 다른 사람들이 받은 것,

- 자신이 노력한 양

- 다른 방식으로 얼마나 많은 수입을 올릴 수 있는지

그들은 재정적 인센티브의 절대적인 양에 대해서는 덜 논의했다. 이러한 성찰은 [개인이 투입(예: 노력, 시간 등)]이 [자신의 성과(예: 급여, 인식)]와 일치하지 않는다고 생각하면 고통을 느낄 것이라고 가정하는 [형평성 이론]이 특히 보건 전문 교육과 관련이 있음을 시사한다. 임상 교사들은 비교 가능한 상황에 있는 다른 사람들이 적은 노력으로 더 많은 것을 받는다고 느낄 수도 있고, 또는 그들은 가장 중요한 시스템(예: 의대)이 그러한 투입과 산출을 부당하게 결정한다고 느낄 수도 있다. 다시 말하지만, 이것은 인센티브화는 어떤 보상이 '좋은' 것인지 '나쁜' 것인지에 대한 것이 아니라, 보상이 [공정하고, 형평하며, 투명한지에 대한 것임]을 시사한다. 시스템 내(예: 특정 의대의 현장 또는 개인 간) 또는 시스템 간(예: 매우 다른 맥락에서 일하는 사람들과 관련하여)에서 그러한 비교가 이루어지는 정도는 두고 봐야 한다.

Looking across the theory-related concepts uncovered in that previous review,6 one that was particularly prominent in our data was that of equity. Participants in our health professional education context most often discussed teaching incentives such as payments, promotions, titles and awards in terms of disparities and comparisons

- to what others received,

- to the amount of effort exerted, or

- to how much income they could be making in other ways.

They discussed the absolute amount of financial incentives to a lesser extent. These reflections suggest that Equity Theory,14 which posits that individuals will feel distressed if they deem their inputs (eg effort, time, etc) to be misaligned with their outcomes (eg salary, recognition), is a particularly relevant theory for health professional education. Clinician teachers may feel that others in comparable situations receive more for putting in less effort, or they may feel that the overarching system (eg the medical school) unfairly determines those inputs and outputs.15 Again, this suggests incentivisation is less about which rewards are ‘good’ or ‘bad’ and more about whether they are fair, equitable and transparent. The extent to which such comparisons are made within a system (eg across sites or individuals at a particular medical school) or across systems (eg in relation to those working in a highly different context) remains to be seen.

어쨌든, 참가자들이 종종 [장애물을 합리화한다는 것, 그리고 단점에도 불구하고 계속해서 가르친다는 것]은 우리에게 인식 불협화음의 힘, 즉 자신의 태도와 행동이 모순되는 상태를 상기시킨다. [인지 부조화 이론가]는 개인들이 주어진 행동에 대해 어떻게 느끼는지에 따라 행동할 필요가 있으며, 그들의 [행동을 바꾸기보다는 그들의 행동에 맞춰 태도를 바꿀 가능성이 더 높다]고 제안한다. 이 이론은 임상의가 그들의 [행동을 바꾸기 전]에(예: 재정적인 피해 때문에 가르치는 것을 그만두는 것) 자신의 [태도를 재구성]한 이유(예를 들어, 그들이 가르치는 것으로 돈을 잃지만 다른 사람들의 성공을 돕는 것으로 부자가 된다고 주장하는 것)을 설명한다.

In any case, that participants often rationalised away barriers and continued to teach despite the drawbacks remind us of the power of cognitive dissonance, the state of one's attitudes and behaviours contradicting. Cognitive dissonance theorists16 suggest individuals have a strong need to act in accordance with how they feel towards a given behaviour and are more likely to change their attitude to match their behaviour than to change their behaviour. This theory offers an explanation as to why clinicians reframed their attitudes (eg saying that they lose money by teaching but arguing they gain richness in helping others succeed) before changing their behaviour (eg quitting teaching because of the financial toll).

우리는 [장벽을 극복하기 위한 메커니즘]으로, 임상의들의 [자체적인 불협화음 협상]에 의존할 수도 있지만, 장벽은 결국 (교육을 정당화하는 것이 더 이상 비용 가치가 없을 정도에 이를 수 있는) [누적적 효과]를 갖는 것으로 보이기 때문에 한계가 있다. 이것은 [불평등에 대한 인식과 교육 동기 부족을 완화하기 위해 실질적인 수준에서 무엇을 할 수 있는지에 대한 통찰력을 개발하는 것의 중요성]을 강화한다.

While we may be able to rely on clinicians’ negotiating their own dissonance as a mechanism to overcome barriers, there is a limit as barriers appear to have a cumulative effect that can eventually tip the scales to the point where justifying teaching is no longer worth the cost. This reinforces the importance of developing insights regarding what can be done on a practical level to mitigate perceptions of inequity and a lack of motivation to teach.

4.2 실천적 함의

4.2 Practical implications

[학습자와의 관계가 임상 교육자에게 중요한 동기 부여 요인을 만든다]는 주장만큼 우리 데이터에 만연한 감정은 거의 없었다. 이와 같이, 이러한 연구 결과가 시사하는 실질적인 변화 중 하나는 지도부나 기관에 의해 인센티브가 전달되는 하향식 과정으로 의학 교사에게 인센티브를 주는 것을 중단하는 것이다. 오히려 모든 참가자가 [학습자가 교수자를 어떻게 인식하는지]를 중요시한다는 점을 고려할 때, [어떻게 임상의가 학습자에게 긍정적인 영향을 주었는지에 대한 정보]를 받을 수 있는 적절한 메커니즘을 확보하는 것이 매우 유익한 노력이 될 수 있다. 학생들로 하여금 [학생을 가르치는 교수들이 들이는 노력을 장려하고 가능하게 만드는 학생의 역할을 충분히 인식하도록 돕는 것]은 임상의들이 그들의 교육 활동에서 보람을 느끼게 하는 [의미 있는 교사-학습자 관계]를 형성하는 데 특히 영향을 미칠 수 있다. 이러한 관계가 학습자를 효과적인 피드백 과정에 참여시키는 데 중요한 것으로 나타났다는 점을 고려할 때, 이러한 관계는 또한 교사에게 영향력 있는 방식으로 건설적인 피드백을 전달할 수 있을 것으로 기대할 수 있다. 교사-학습자 관계에 대한 대부분의 연구는 교사가 학습자의 이익을 위해 관계를 발전시키는 방법에 초점을 맞추고 있지만, 강사의 지속적인 교육 노력에 대한 학습자의 기여가 최적화되려면, [어떻게 피드백 프로세스의 진정성을 유지하는 학습자를 위한 가이드라인을 만들 것인가]가 추가 연구의 중요한 영역이다.

Very few sentiments were as prevalent in our data as claims that relationships with learners create important motivational drivers for clinician educators. As such, one practical change these findings suggest is to stop conceiving of incentivising medical teachers as a top-down process in which incentives are delivered by leadership or the institution. Rather, given that all participants valued how their learners perceive them, ensuring appropriate mechanisms are in place for clinicians to receive information indicating how they have positively impacted their learners could be a highly fruitful endeavour. Helping students appreciate their role in encouraging and enabling effort to be put forth by their faculty may be particularly impactful for generating the meaningful teacher-learner relationships that make clinicians feel rewarded in their educational activity. Given that such relationships have been shown important for engaging learners in effective feedback processes, they may be expected also to enable constructive feedback to be delivered to teachers when needed in a manner that is impactful rather than de-motivating. While most research on teacher-learner relationships focuses on how teachers might develop relationships for their learners’ benefit,17 how guidelines for learners might be generated that maintain the authenticity of feedback processes is an important area for further research if learners’ contributions to preceptors’ ongoing teaching efforts are to be optimised.

우리는 또한 [교사 지원teacher support]을 관리자의 특정한 행위라기보다는 활동의 프로그램으로 전략적으로 생각하는 것을 추천한다. 동기부여의 동적 특성은 어떤 개인에게든 항상 하나의 인센티브 제도로는 충분할 것 같지 않게 만들고, 따라서 모든 개인에게 동기부여가 되는 'one size fits all' 전략이 만들어질 수 있다고 상상하기 어렵다. [요인, 시간 및 맥락] 사이의 복잡한 상호작용 특성은 인센티브를 제공하여 동기를 형성하려고 할 때 특이하고 뉘앙스 있게 생각할 필요가 있음을 시사한다. 무엇이 사람들에게 동기를 부여하는지에 관한 일반적인 원칙에 주의를 기울이고(자기 결정 이론에 요약된 역량, 연결 및 자율성의 감정을 포함한다), 그러한 가치에 부합하는 지원과 인센티브를 개발하는 것이 가치 있다. 그러나 그렇게 하는 것은 임상 교사들이 [어설프게 구현된 인센티브 제도에 의해 의욕이 꺾이는 것]을 피하기 위한 일련의 전략을 필요로 할 가능성이 높다.

- 학술 기관의 일원처럼 느끼고 싶은 임상의들에게, 교육 기관에 가입하거나 대학 자원에 접근할 수 있는 기회가 가장 큰 영향을 미칠 수 있다.

- 연결을 구축하고자 하는 다른 사람들에게는 네트워킹과 지역사회 구축 기회가 특히 유익할 수 있다.

- 다른 사람들은 여전히 어려운 학습자와의 만남에 직면하여 탄력성을 구축하는 지원을 요구할 수 있으며, 이는 교사들 사이에서 교사 정체성을 육성하고 실천의 공동체를 구축하는 데 초점을 맞춘 교수진 개발 제안이 가치를 증명할 수 있음을 시사한다.

We also recommend thinking of teacher support strategically, as a programme of activity rather than as a particular act on the part of an administrator. The dynamic nature of motivation makes it unlikely that one incentive scheme will always be sufficient for a given individual and, thereby, makes it foolhardy to imagine that a ‘one size fits all’ strategy could be created that would motivate all individuals. The complex nature of the interaction between factors, time and context suggests a need to think idiosyncratically and with nuance when trying to build motivation by offering incentives. It is valuable to pay heed to general principles regarding what motivates people (including feelings of competence, connection and autonomy, as outlined in self-determination theory 6) and to develop supports and incentives aligned with those values. Doing so, however, is likely to require an array of strategies to avoid clinician teachers feeling de-motivated by poorly implemented incentivation schemes.

- For clinicians who want to feel like part of an academic institution, the opportunity to join teaching academies or access university resources might be most impactful.

- For others who want to build connections, networking and community building opportunities might be particularly beneficial.

- Others still may require support building resilience in the face of difficult learner encounters, suggesting that faculty development offerings focused on nurturing teaching identities and building communities of practice among preceptors could prove valuable.18, 19

어떤 전략(또는 이상적으로는 전략)을 채택하든 간에 [선의의 인센티브 제도의 의도하지 않은 결과]는 인센티브가 어떻게 조작되고 제공되는지에 대해 신중하게 생각할 필요가 있음을 시사한다. 임상의의 [동기를 훼손하는 방식의 인센티브 제공]은 지속적인 결과를 초래하고 냉소주의를 구축할 수 있다. [Generic하고 템플릿 기반의 서포트 레터]는 수신자가 개인 편지를 작성하는 데 걸리는 시간을 낭비할 가치가 없다는 신호를 보낼 수 있습니다. 동시에 교사 채용 문제가 인센티브 제공이 만병통치약을 제공하는 동기부여 문제로만 프레임되어서는 안 된다는 점을 인식해야 한다. 특정한 실무 환경이 다른 환경보다 더 많은 장벽을 만들 수 있다는 것을 인정하는 것은 중요하다. 비슷하게 어린 아이들을 갖는 것은 사무실에서 많은 시간을 보내는 것을 막을 수 있지만, 시간이 장애요인이 되는 정도는 가르치는 것에 대한 자신감과 학습자와의 개인적인 연결에 의해 영향을 받을 수 있다. 해결하기 쉬운 과제는 아니지만, 동기 부여를 찾기 위해 고군분투하는 사람들을 위해 장벽을 줄이기 위해 추가적인 노력을 투자할 가치가 있을 것이며, 임상의나 맥락에 대한 포괄적인 진술은 교육이 인식되는 방법에 영향을 미치는 많은 개별 현실을 간과한다는 것을 인식한다.

Regardless of what strategy (or, ideally, strategies) one adopts, the unintended consequences of well-intentioned incentive schemes suggest we need to think carefully about how incentives are crafted and delivered. Offering incentives in ways that undermine clinicians’ motivations can have lasting consequences and build cynicism. Generic and template-based letters of support can signal that the recipient is not worth the time it takes to craft a personal letter. At the same time, it must be recognised that teacher recruitment issues should not be solely framed as a motivation problem for which offering incentives provides a panacea. Acknowledging that certain practice environments (eg fee for service roles) can create more barriers than others (eg salaried clinicians working where residents can take some of the patient load) is important.20 Having young children, similarly, may prevent one from spending copious amounts of extra time in the office, but the extent to which time creates a barrier might be influenced by building confidence in teaching and personal connections with learners. While not an easy task to address, it is likely worth investing additional effort to reduce barriers for those who are struggling to find motivation, while recognising that blanket statements about clinicians or contexts overlook many of the individual realities influencing how teaching is perceived.

4.3 제한사항

4.3 Limitations

본 연구는 임상교사의 관점을 의도적으로 모색하였는데, 이는 임상교사가 기초과학자 및 사회과학자보다 학문적 의학을 떠날 가능성이 높기 때문이다. 이와 같이, 이 연구 결과는 더 보호된 수업 시간을 가질 수 있는 다른 유형의 교사들에게는 덜 관련이 있을 수 있다. 그들은 또한 개인이 교육적으로 기여하는지 또는 어떻게 기여하는지에 대한 통제력이 낮은 상황에서 덜 관련이 있을 수 있다. 그렇긴 하지만, 우리는 동기 부여를 위한 자율성의 중요성이 충분히 크다고 주장할 것이다. 일반적으로 교육의 질이 유지되려면 인센티브와 다른 형태의 지원의 영향을 고려하는 것이 중요할 것이다. 물론, 다양한 형태의 인센티브를 제공할 수 있는 능력은 사용 가능한 자원에 더 일반적으로 의존할 것이다. 참가자를 모집한 두 기관이 모두 고소득 국가에 존재한다는 점을 고려할 때, 식별된 일반 원칙이 주목할 가치가 있다고 예상하는 동안에도 참가자의 특정 경험은 저소득 환경으로 이전할 수 없을 수 있다. 마찬가지로, 우리의 연구 결과를 다른 기관에 적용하려는 사람들은 이러한 결과의 이전 가능성에 영향을 미칠 수 있는 다양한 교육 구조, 문화 및 보상 배치의 잠재력을 고려해야 한다. 현재 연구의 많은 참가자들은 다른 기관에서 일하고 가르쳤으며, 그들의 관점이 UBC의 맥락에 특정된다는 것을 거의 나타내지 않았지만, 그들 중 경제적 취약 지역에서 가르친 경험이 있는 사람은 거의 없을 것이다. 마지막으로, 교육을 그만두거나 교육 기회를 거절한 사람들을 참여자 풀에 포함시킴으로써 다양한 관점을 포착할 수 있었지만, 모집할 수 없었던 개인(예: 교육에 전혀 참여하지 않은 임상의)은 현재 연구에 반영되지 않은 더 강력한 관점을 가질 수 있다.

This study purposely sought out the perspectives of clinician teachers because they are more likely to leave academic medicine than are basic and social scientists.21, 22 As such, the findings may be less pertinent to other types of teachers who may have more protected teaching time. They may also be less pertinent in contexts where individuals have less control over whether or how they contribute educationally. That said, we would argue that the importance of autonomy for motivation is sufficiently great, as a rule,6 that it will remain important to consider the influence of incentives and other forms of support any setting if teaching quality is to be maintained. Of course, the capacity to provide different forms of incentives will depend more generally on the resources available. Given that both institutions from which participants were recruited exist in high income countries, their particular experiences may not be transferable to lower income settings even while we anticipate that the general principles identified are worth heeding. Similarly, those attempting to apply our findings to other institutions should consider the potential for different teaching structures, cultures and compensation arrangements to impact on the transferability of these results. Many participants in the current study had worked and taught at other institutions and rarely did they indicate that their perspectives were specific to UBC’s context, but few of them are likely to have experience teaching in less economically privileged parts of the world. Finally, while we were able to capture multiple perspectives by including those who either quit teaching or who had turned down teaching opportunities within the participant pool, individuals who could not be recruited (eg clinicians who never engaged in teaching) may have stronger perspectives that are not reflected in the current study.

5 결론

5 CONCLUSIONS

요약하자면, 교육을 둘러싼 동기와 인센티브 사이의 복잡한 관계를 반복적으로 탐구하고 놀리려는 우리의 의도적인 노력은 임상 교사들에게 최상의 인센티브를 주는 방법에 대한 간단한 '레시피'를 밝히지 않았지만, 세 가지 핵심 메시지는 매우 중요해 보인다.

- (1) 개인에게 고유한 방식으로 경험되며 시간이 지남에 따라 상황에 따라 변화할 수 있는 다양한 요인이 작용한다.

- (2) 임상 교사들은 일반적으로 아래와 같이 느낄 때 가치있게 여겨진다고 느끼고, 따라서, 가르치는 것에 동기를 부여받는다.

- (a) 그들의 교육 노력에 대해 인정받고 감사받는 것

- (b) 학습자, 동료, 리더십 또는 의료 교육 커뮤니티와 연결되는 것

- (c) 그들은 의미 있는 교수자-학습자 관계를 맺는 것. 다른 임상의들은 다른 관계를 우선시할 수 있지만, [학습자들에 의한 인정과 감사]는 특히 영향을 미치는 것으로 보인다.

- (a) 그들의 교육 노력에 대해 인정받고 감사받는 것

- (3) 해로운 것과 반대로 도움이 되기 위해서, 교수 인센티브는 [개인적이고, 공평하고, 효율적으로 제공]되고 주의를 기울이는 방식으로 설계되고 전달되어야 한다.

In sum, while our deliberate efforts to iteratively explore and tease apart the intricate relationships between motivation and incentives surrounding teaching have not revealed a straightforward ‘recipe’ for how to best incentivise clinical teachers, three key messages appear critical:

- (1) There are a variety of factors at play that are experienced in ways that are unique to individuals and are subject to change over time and across contexts;

- (2) Clinical teachers generally feel valued and, hence, motivated to teach, when they feel

- (a) recognised and appreciated for their teaching efforts,

- (b) connected to their learners, peers, leadership or the medical education community and

- (c) they have meaningful teacher-learner relationships. While different clinicians may prioritise different relationships, recognition by and appreciation of learners appears particularly impactful;

- (3) To be supportive as opposed to harmful, teaching incentives should be designed and delivered in ways that are personal, equitable, efficiently provided and framed with care.

Incentives for clinical teachers: On why their complex influences should lead us to proceed with caution

PMID: 33222291

DOI: 10.1111/medu.14422

Abstract

Introduction: When medical education programs have difficulties recruiting or retaining clinical teachers, they often introduce incentives to help improve motivation. Previous research, however, has shown incentives can unfortunately have unintended consequences. When and why that is the case in the context of incentivizing clinical teachers remains unclear. The purposes of this study, therefore, were to understand what values and motivations influence teaching decisions; and to delve deeper into how teaching incentives have been perceived.

Methods: An interpretive description methodology was used to improve understanding of the development and delivery of teaching incentives. A purposeful sampling strategy identified a heterogenous sample of clinical faculty teaching in undergraduate and postgraduate contexts. Sixteen semi-structured interviews were conducted and transcripts were analyzed using an iterative process to develop a thematic structure that accounts for general trends and individual variations.

Results: Clinicians articulated interrelated and dynamic personal and environmental factors that had linear, dual-edged and inverted U-shaped impacts on their motivations towards teaching. Barriers were frequently rationalized away, but cumulative barriers often led to teaching attrition. Clinical teachers were motivated when they felt valued and connected to their learners, peers, leadership, and/or the medical education community. While incentives aimed at producing these connections could be perceived as supportive, they could also negatively impact motivation if they were impersonal, inequitable, inefficient, or poorly framed.

Discussion/conclusion: These findings reinforce the literature suggesting that it is necessary to proceed with caution when labeling any particular factor as a motivator or barrier to teaching. They take us deeper, however, towards understanding how and why clinical teachers' perceptions are unique, dynamic and fluid. Incentive schemes can be beneficial for teacher recruitment and retention, but must be designed with nuance that takes into account what makes clinicians feel valued if the strategy is to do more good than harm.

© 2020 John Wiley & Sons Ltd and The Association for the Study of Medical Education.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 교수개발(Faculty Development)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 의학교육은 Z세대에 준비되었는가? (J Grad Med Educ. 2018) (0) | 2023.01.13 |

|---|---|

| 아이들은 문제 없다: 교육자의 새로운 세대 (Med Sci Educ. 2022) (0) | 2023.01.10 |

| 의대 교수자들에게 인센티브 주기: 동기부여에 영향을 주는 인센티브의 역할 탐색 (Acad Med, 2018) (0) | 2022.11.20 |

| 보건의료시스템과학을 위한 새로운 교육자 역할: 미국 의과대학에 새로운 의사 역량이 가지는 함의(Acad Med, 2019) (0) | 2022.11.09 |

| 교수개발을 조직적 관점에서 바라보기: 교훈 공유 (Med Teach, 2021) (0) | 2022.09.24 |