교육자 및 연구자로서 교사를 개발하고 보상하기: 눈부신 진보와 위압적 과제(Med Educ, 2017)

Developing and rewarding teachers as educators and scholars: remarkable progress and daunting challenges

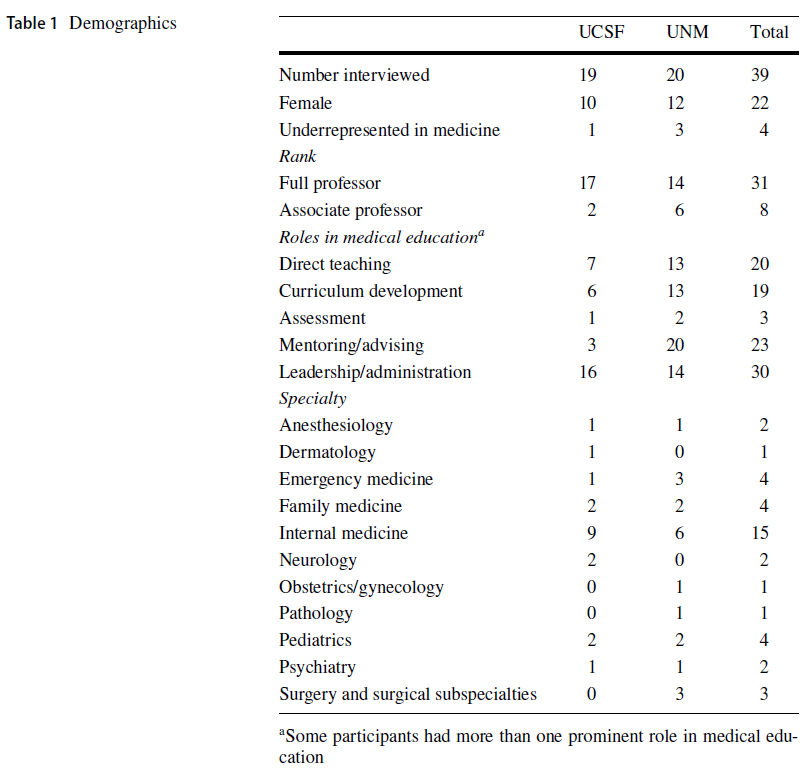

David M Irby & Patricia S O’Sullivan

도입

INTRODUCTION

1988년 세계 의료 교육 회의에서, 참가자들은 전 세계적으로 의료 교육을 개선하기 위해 고안된 의제를 추구할 것을 다짐했다. 알려진 대로 에든버러 선언은 12가지 권고안을 내놨는데, 다섯 번째 권고안은 '교사를 콘텐츠 전문가만이 아닌 교육자로 양성하고, 이 분야의 우수성을 생물 의학 연구나 임상 실습의 우수성만큼 충분히 보상하라'는 글의 초점이다.

At the 1988 World Conference on Medical Education, participants pledged themselves to pursue an agenda designed to improve medical education worldwide. The Edinburgh Declaration,1 as it became known, made 12 recommendations; the fifth recommendation is the focus of this article: ‘Train teachers as educators, not content experts alone, and reward excellence in this field as fully as excellence in biomedical research or clinical practice’.

그러나, 연구는 일반적으로 의학 교육과 고등 교육에서 교육보다 늘 우선순위에 있으며, 그 결과 전문적 만족, 학업 촉진, 연구자와 교육자에 대한 유지 및 보수 비율의 차이를 초래한다.3,4 이러한 차이가 발생하는 맥락에는 성별, 인종, 민족과 같은 다른 형태의 불평등도 포함된다. 이러한 불평등이 지속되는 이유는 무엇입니까?

Yet, research continues to trump teaching in medical education and higher education generally,2 resulting in disparities in rates of professional satisfaction, academic promotions, retention and remuneration for researchers and educators.3,4 The context within which this disparity takes place includes other forms of inequities as well, such as gender, race and ethnicity.5–10 Why do these inequities persist?

교사들을 콘텐츠 전문가만이 아니라 교육자로 양성

TRAIN TEACHERS AS EDUCATORS, NOT CONTENT EXPERTS ALONE

에든버러 선언은 교사들의 컨텐츠 지식의 단순한 향상을 넘어 교육자로서 그들의 기술과 경력을 발전시킬 것을 권고했다. 콘텐츠 지식은 필수적이지만 교수법의 우수성을 위해서는 불충분하다. 교육자들은 교육자로서 직접적인 가르침을 넘어서는 다양한 교육적 역할에 대한 지식, 전문적 실천을 위한 기술, 정체성 형성을 필요로 한다.

The Edinburgh Declaration recommended moving beyond mere improvements in teachers’ content knowledge to advance their skills and careers as educators. Content knowledge is essential but insufficient for excellence in teaching. Educators need knowledge for their various educational roles that may extend beyond direct teaching, skills for professional practice and identity formation as an educator.

교사를 교육자로 육성

Developing teachers as educators

역사적으로, 교수를 위한 전문적 개발professional development은 그들의 컨텐츠 지식이 최신인지 확인하는 데 초점을 맞췄다. 교수진들은 연구에 몰두하고, 국내외 학회에서 연구결과를 발표하며 안식년을 완수하는 등 전문적으로 성장했다. 연구를 수행하던 이 최신 교수들은 훌륭한 연구자와 교사들로 추정되었다. 가르치는 데 특별한 지식이나 기술이 필요하지 않았다.

Historically, professional development for faculty members focused on ensuring that their content knowledge was up to date. Faculty members grew professionally by engaging in research, presenting their work at national and international conferences and completing sabbaticals. These up-to-date professors, who were conducting research, were assumed to be good researchers and teachers. No special knowledge or skills were required for teaching.

Shulman은 이러한 가정에 도전했다. Shulman은 효과적인 가르침을 위해서는 [학습자들이 그들의 발전 수준에서 접근 가능하고 이해할 수 있는 것으로 자신의 콘텐츠 지식을 변화시킬 수 있는 능력]이 필요함을 인식하였다. Shulman은 이러한 독특한 형태의 교사 지식을 '교육적 콘텐츠 지식 또는 PCK'라고 불렀다. 교사들은 PCK, 즉 스크립트를 개발하고, 학생들과 대화를 시작하며, 그들이 내용에 대한 더 깊은 이해를 하도록 도울 방법을 발견함으로써 실제로 이러한 지혜를 심화시킨다.13

Shulman challenged this assumption, recognising that effective teaching requires the ability to transformone’s content knowledge into something that is accessible and understandable to learners at their levels of development.11,12 Shulman called this unique formof teacher knowledge ‘pedagogical content knowledge or PCK’. Teachers develop PCK, or teaching scripts, and deepen this wisdomin practice by entering into dialogue with their students and discovering ways to help themdevelop a deeper understanding of content.13

이러한 관점 하에, 교직원 개발도 변화되었다.

Armed with these perspectives, the development of faculty members as teachers was transformed.

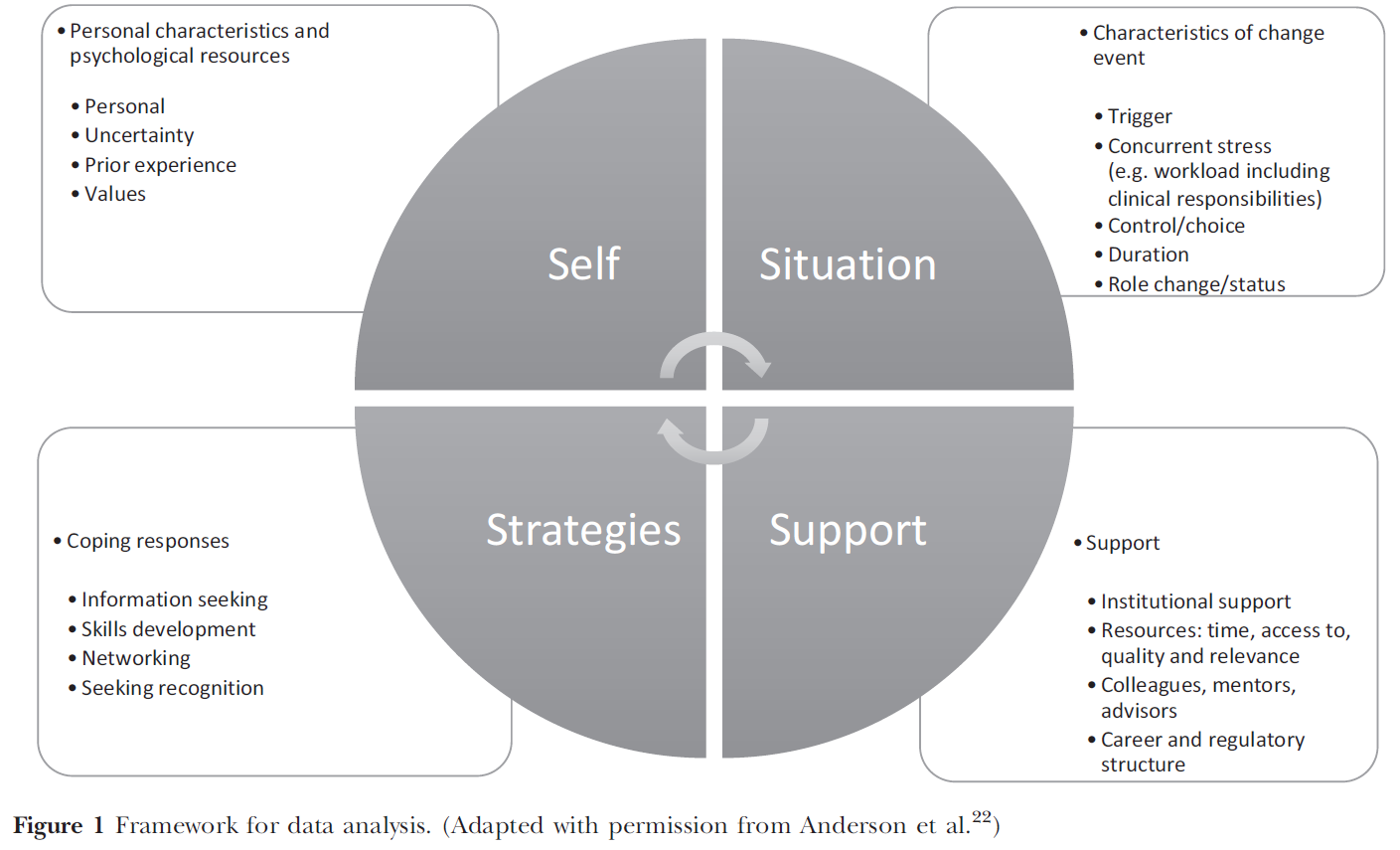

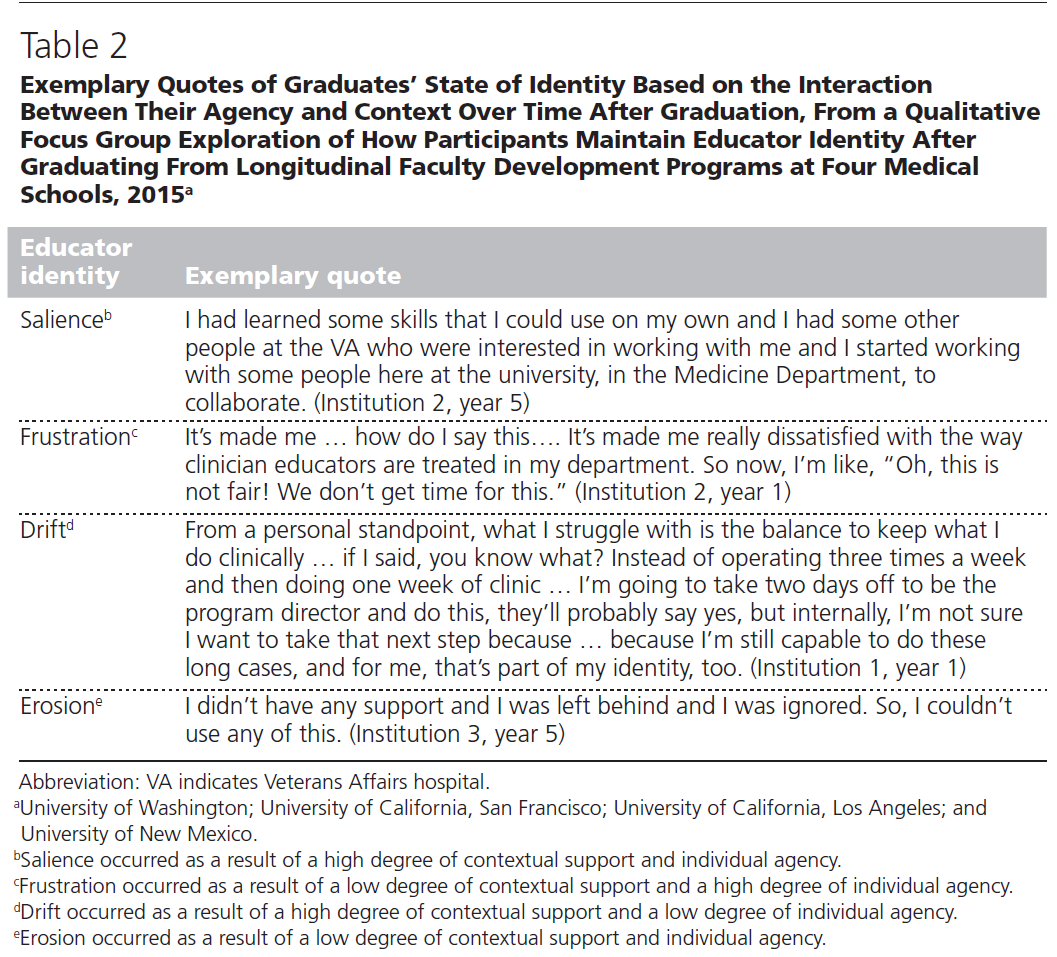

교사들은 직접적인 교육 외에도 다양한 학문적 역할을 수행하며, 추가적인 형태의 지식과 기술을 요구한다. 여기에는 멘토와 조언자, 커리큘럼 개발자, 학습의 평가자, 교육 지도자 및 학자로서의 역할이 포함된다. 또한 교육자는 혁신해야 하며, 새로운 기술을 교육에 적응시키고, 전문가 간 이니셔티브에 참여하며, 보다 광범위한 사회적 이슈(예: 건강상의 차이)에 관심을 가져야한다. 교사는 조직 환경 내에서 교육자로서의 정체성을 공동 구축하면서 개인적, 직업적 정체성의 변화를 겪는다. [교육자 역할을 정체성에 통합시키는 것]은 시간이 지남에 따라 일어나며, 더 많은 교수와 교수진 개발에 참여해야 하는지에 대한 그들의 선택에 영향을 미친다.18–21

Teachers perform a wide variety of other academic roles besides direct instruction, requiring additional forms of knowledge and skills. These include roles as mentors and advisors, curriculum developers, assessors of learning, educational leaders and scholars.17 Educators also innovate, adapt new technologies to instruction, participate in interprofessional initiatives and attend to broader social issues (such as health disparities). Teachers undergo changes in their personal and professional identities, as they co-construct their identities as educators within their organisational environments. Integrating educator roles into their identities occurs over time, influencing their choices about whether to engage in more teaching and in faculty development.18–21

교수진 개발을 통한 교육인적 변화

Transforming educators through development of faculty members

많은 교수진에게 있어 교육에 대한 실무 지식과 교육자의 전문적인 기술과 정체성 형성은 관찰과 연습을 통해 발전한다. 그러나, 모든 교직원은 교수개발에 참여함으로써 이러한 지식, 기술, 정체성 형성을 확장할 수 있다, 16

For many faculty members, the practical knowledge for teaching and the professional skills and identity formation of educators develop through observation and practice. However, all faculty members can expand this knowledge, skill and identity formation by participating in faculty development,16

기초과학이 의학의 학습을 강화할 수 있는 것처럼, 교육학pedagogical contruct은 [가르침과 교육자의 다른 여러 역할]에 대한 배움을 증진시킬 수 있다.

Just as basic science constructs can strengthen learning of medicine,22 so pedagogical constructs can advance the learning of teaching and other educator roles.13,23,24

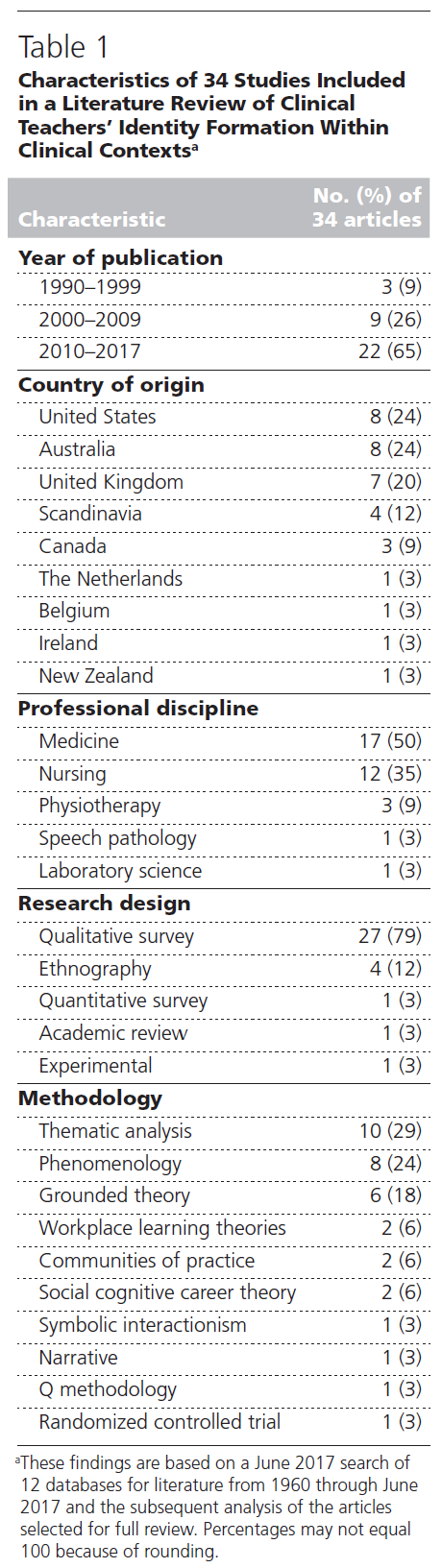

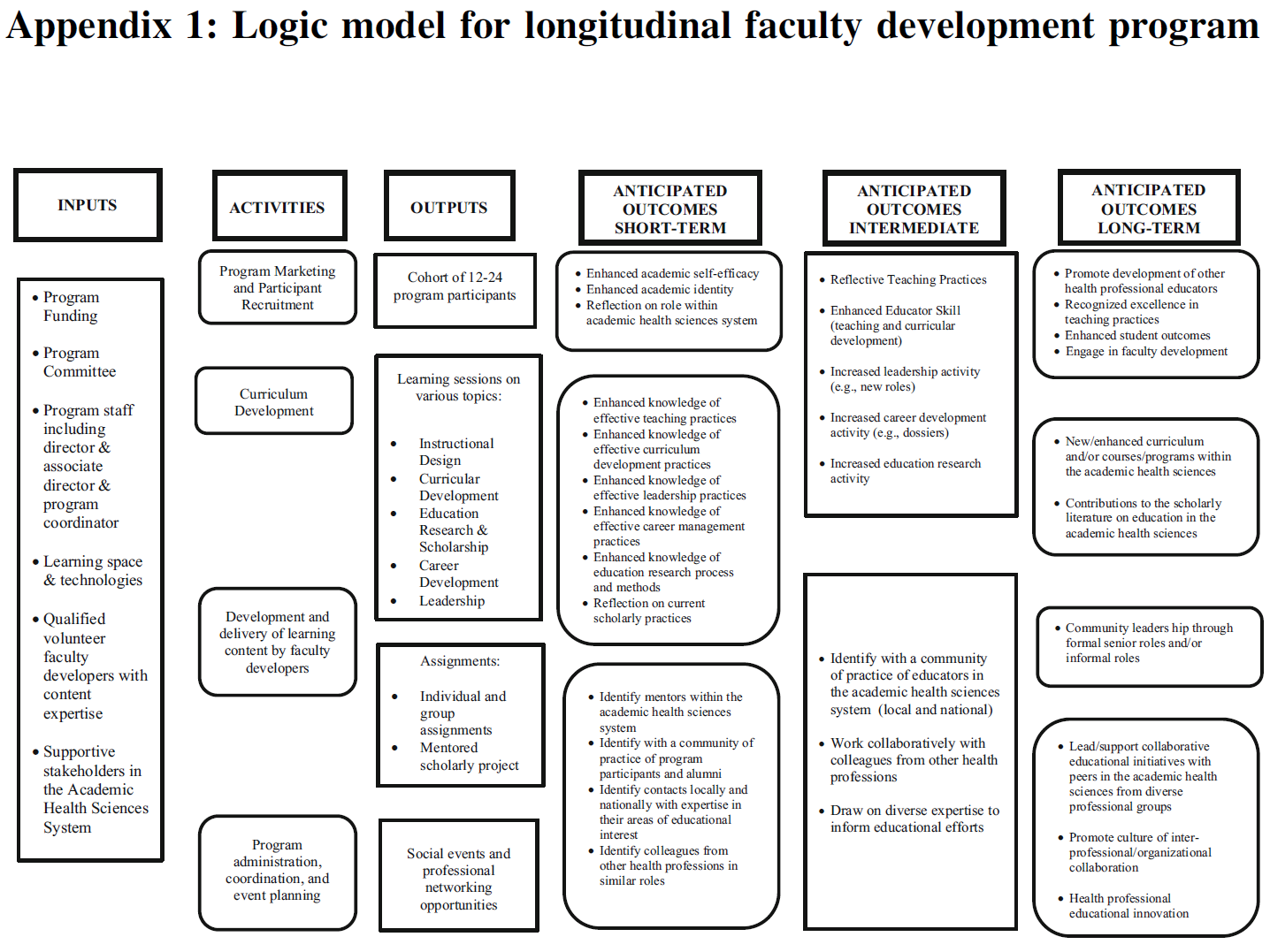

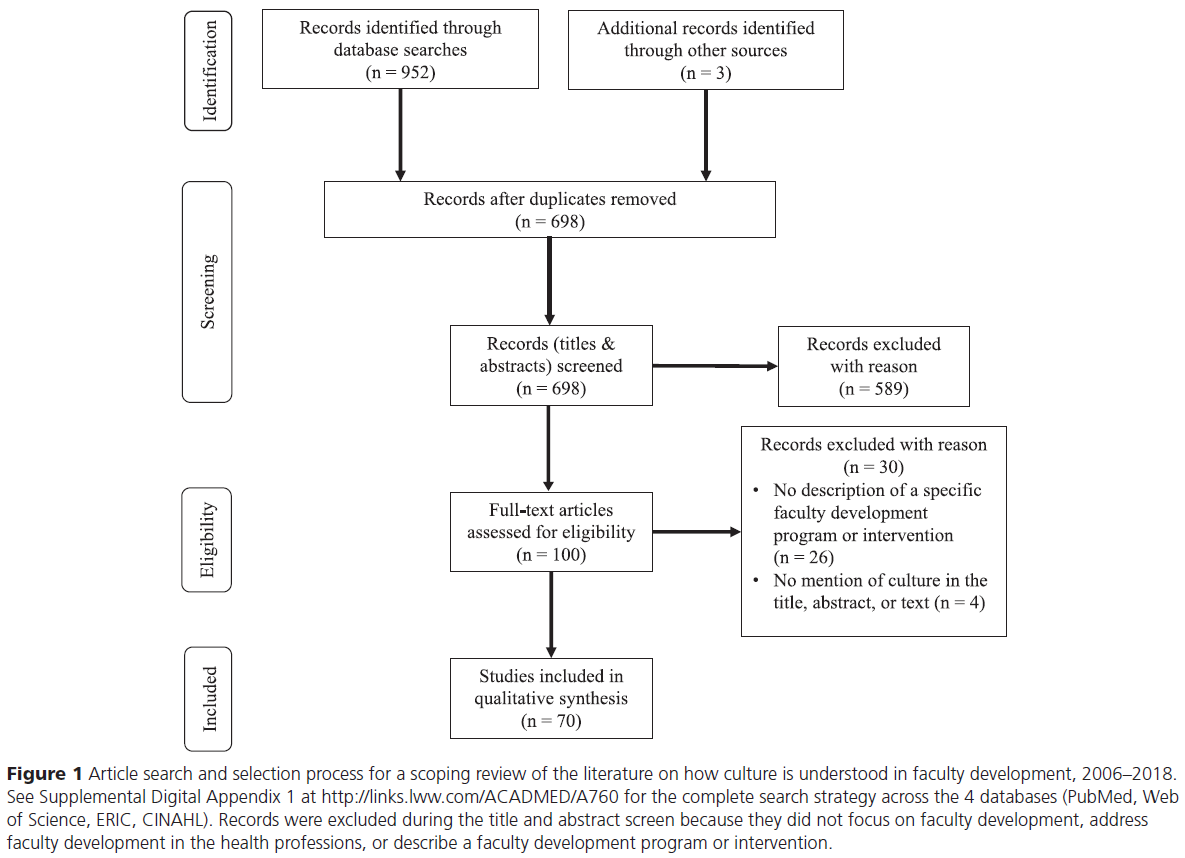

고등 교육에서 교수 개발에 대한 문헌을 검토해보면, 이러한 프로그램이 교수의 가르침과 학생 학습에 미치는 긍정적인 영향을 문서화한다.25-27 보건직업 문헌의 검토는 교육 리더십, 장학금 및 네트워킹을 발전시키는 데 있어 종단적 교수개발 프로그램의 강점을 추가로 강조한다.28,29

Literature reviews of faculty development in higher education document positive impacts of these programmes on faculty members’ teaching and student learning.25–27 Reviews in the health professions literature additionally highlight the strengths of longitudinal faculty development programmes in advancing educational leadership, scholarship and networking.28,29

교수진 개발 프로그램들은 또한 참가자와 근무지 사이에서 실천공동체를 형성한다.32 일부에서는 '교직 공동체teaching commons의 설립'을 요구했고, 다른 일부는 일시적transitory 실천공동체(교실 및 임상 환경에서 교수 개발 워크숍, 종적 프로그램, 주제 지향적 이익 그룹)와 근무지workplace 실천공동체(교실과 임상현장)에 대해 썼다.34

Faculty development programmes also build communities of practice among participants and in the workplace.32 Some have called for the establishment of a ‘teaching commons’33 and others have written about transitory communities of practice (faculty development workshops, longitudinal programmes, topic-oriented interest groups) and workplace communities of practice (in classroom and clinical settings).34

고등교육 교사 인증

Certifying teachers in higher education

많은 국가들과 기관들이 [교사들과 교육자들을 위한 인증 과정]을 실행했다. 이를 통해 모든 교직원이 확립된 전문직 기준을 충족하고 고등교육에서 가르치는 데 필요한 자격 증명을 확보할 수 있습니다. 예를 들어,

- 네덜란드에서 모든 대학교 교직원은 UTQ(University Teaching Qualification) 자격증을 취득해야 합니다.

- 영국에서 Professional Standards Framework는 양질의 교육을 위한 지침과 벤치마크를 제공한다.43

- 스웨덴41과 독일40은 또한 의무적인 고등교육 교사 교육을 요구한다.

- 미국에서는 고등교육에서 교사들의 역량을 정의하기 위한 노력이 44,45건 있었지만, 교사 자격증은 교직원 개발의 자발적인 부분을 계속하고 있다.

many countries and institutions have implemented certification processes for teachers and educators. This ensures, as a matter of policy, that all faculty members meet established professional standards as teachers36–40 and have the necessary credentials to teach in higher education.41,42

- In the Netherlands, for example, all university faculty members must acquire a University Teaching Qualification (UTQ) certificate.

- In the UK, the Professional Standards Framework provides guidelines and benchmarks for quality teaching.43

- Sweden41 and Germany40 also require compulsory higher education teacher training.

- In the USA, there have been some efforts to define competencies for teachers in higher education44,45 but teacher certification continues to be a voluntary part of faculty development.

여러 기관과 전문 그룹은 전문 개발 활동을 설계하기 위한 프레임워크를 제공하는 [의료 교육자를 위한 역량 표준]을 개발하였다. [필수 교사 자격증]부터 [자발적인 전문성 개발]까지 접근법이 다양하다.48–50

Several organisations and professional groups have developed competency standards for medical educators,38,45–47 which provide a framework for designing professional development activities. Approaches range from mandatory teacher certification to voluntary professional development.48–50

역량 기반 인식 프로그램의 또 다른 예는 임상의사 교육자를 위한 캐나다 왕립 의사 및 외과의사 학위 프로그램이며, 이는 역량 집중 영역에 대한 인증이다.53

Another example of a competency- based recognition programme is the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada Diploma programme for clinician educators, which is certification for a focused area of competence.53

교육의 우수성을 보상합니다.

REWARD EXCELLENCE IN TEACHING

에든버러 선언의 두 번째 부분은 [생물 의학 연구와 임상 실습의 우수성만큼이나 전적으로 가르치는 데 있어 탁월함을 보상하는 것]을 포함한다. 이러한 정책 목표를 달성하기 위해서는 구조적인 변화가 필요하다.

The second part of the Edinburgh Declaration involves rewarding excellence in teaching as fully as excellence in biomedical research and clinical practice. In order to achieve this policy goal, structural changes are required,

학술활동의 재정의

Redefining scholarship

고등교육의 학술활동scholarship은 전통적으로 발견 위주의 연구와만 관련이 있다. 그러나 1990년, Boyer는 학문적 견해의 확대를 위해 연구를 포기하고 논쟁을 재탄생시킨 강력한 사례를 만들었다.57 그는 학술활동이 [발견, 통합, 적용, 보급/교육]의 네 가지 기본적 형태로 존재한다고 주장했다. 이들 각각은 엄격함rigour으로 수행될 수 있고, 동료 검토를 위해 가시화 될 수 있으며, 학술활동의 한 형태로 간주될 수 있다. Boyer의 연구를 바탕으로 Glassick은 [적절한 준비, 명확한 목표, 적절한 방법, 중요한 결과, 효과적인 프레젠테이션 및 성찰적 비평]의 6가지 교육 학술활동 평가를 위한 표준을 제안했다.58,59 이것은 개선과 승진을 위한 교육자들의 기여를 평가하기 위한 투명한 기준을 제공했다.

Scholarship in higher education has traditionally been associated exclusively with discovery-oriented research. However, in 1990 Boyer made a strong case for giving up the research versus teaching debate and reframing the argument in favour of an expanded view of scholarship.57 He argued that scholarship comes in four fundamental forms: discovery, integration, application and dissemination/teaching. Each of these can be performed with rigour, be made visible for peer review and be considered a formof scholarship. Building on Boyer’s work, Glassick proposed six standards for evaluating the scholarship of teaching: adequate preparation, clear goals, appropriate methods, significant results, effective presentation and reflective critique.58,59 This offered a transparent set of criteria to evaluate the contributions of educators for improvement and promotion.

교육자 역할 구체화

Specifying educator roles

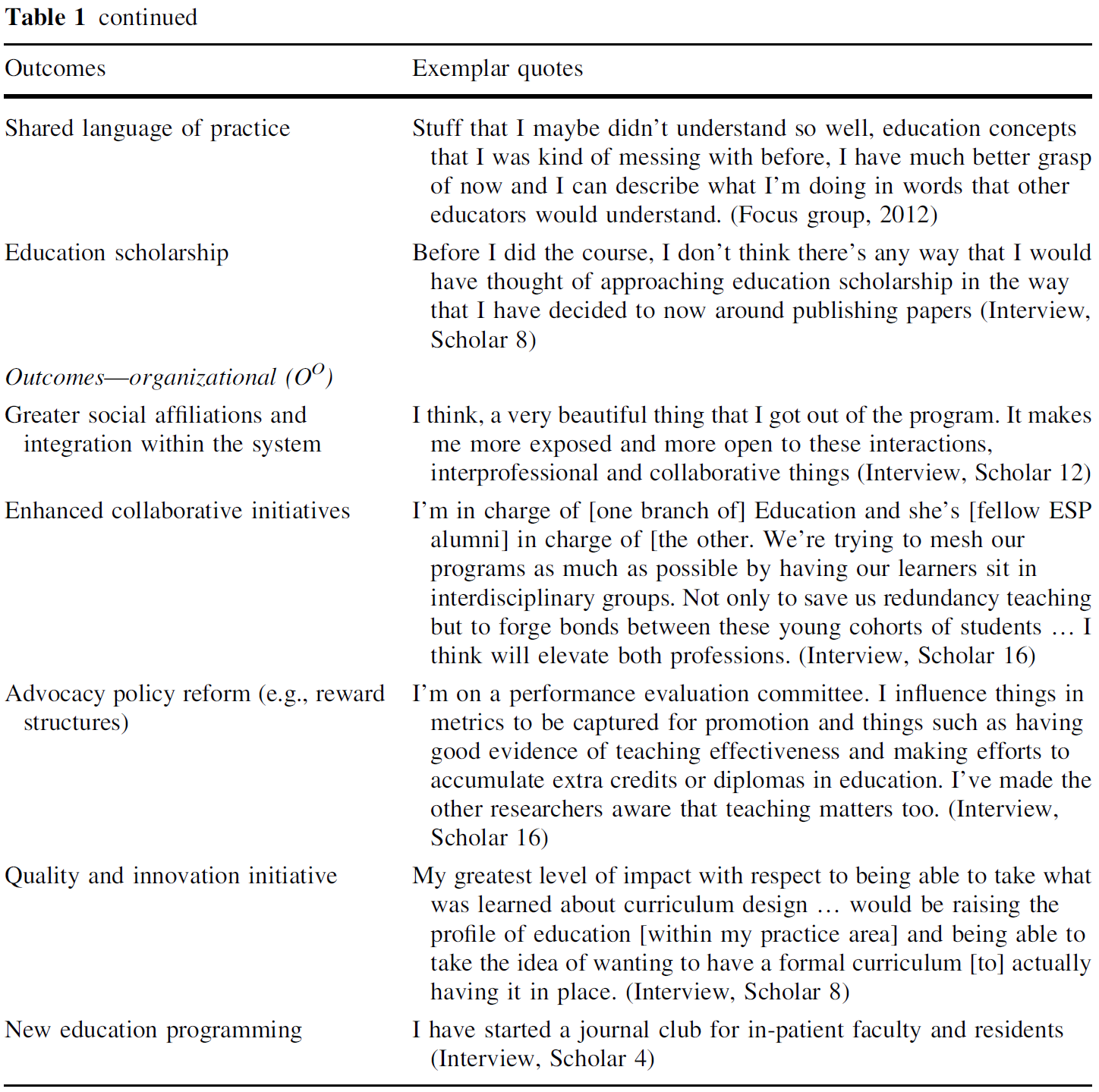

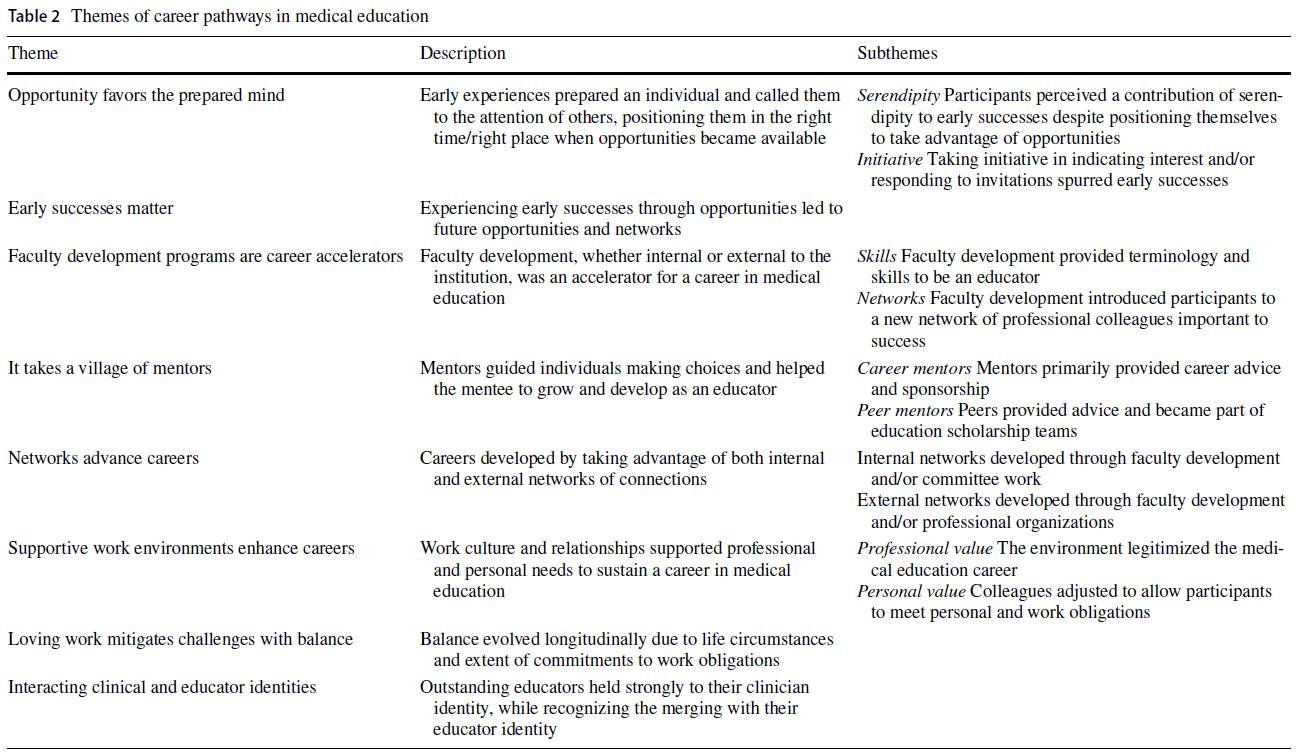

2006년 미국 의과대학연합회(AAMC)는 교육장학회의(교육장학회의)를 소집하여 [교육, 커리큘럼 개발, 조언과 멘토링, 교육 리더십과 행정, 학습자 평가] 등 5대 핵심 교육자 역할을 확정했다. 이 보고서는 또한 다음을 구분했다.

- '교육적 수월성' 퀄리티의 측정을 수반함.

- '학술적 교육' 다른 사람의 업무(최상의 증거와 모범 사례)를 기반으로 함

- '교수학습의 학술' 다른 사람들이 그것을 기반으로 할 수 있도록 보급을 추가로 필요로 함

In 2006, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) convened a consensus conference on educational scholarship that identified five core educator roles: teaching, curriculum development, advising and mentoring, education leadership and administration, and learner assessment.17 The report also distinguished between

- ‘excellence in teaching’ that involves measures of quality,

- ‘scholarly teaching’ that builds on the work of others (best evidence and best practice), and

- the ‘scholarship of teaching and learning’ that additionally requires dissemination so that others can build on it.

교육 학술활동 문서화 및 평가

Documenting and assessing educational scholarship

교직원의 교육장학금의 장점을 판단하기 위해, 교직원은 동료의 검토를 위해 그러한 기여가 가시화될 수 있는 장치가 필요했다. 교육자 포트폴리오(EP)는 교사들이 관련 교육자 역할에 대한 성과를 제시할 수 있도록 함으로써 이 공백을 메웠다. 또한 EP는 경력 개발, 멘토링 및 교수진 개발을 위한 도구 역할을 할 수 있습니다. EP는 K-12 교육 및 고등 교육에서 널리 사용되고 있습니다.63–66 영국 품질보증국에 의해 사용됩니다.63 의학 내에서, 교수진은 학술적 홍보와 의학 교육자 아카데미(AME)에 대한 응용을 위해 EP를 사용합니다.

To judge the merits of a faculty member’s educational scholarship, faculty members needed a mechanismto make those contributions visible for peer review. The educator portfolio (EP) filled this void by allowing teachers to present their accomplishments in relevant educator roles. EPs can also serve as a tool for career development, mentoring and faculty development. The EP is in widespread practice in K-12 education62 and higher education.63–66 It is used in the UK by the Quality Assurance Agency.63 Within medicine, faculty members use EPs for academic promotions and for applications to academies of medical educators (AMEs).

그러나 EP는 variability과 길이, 평가에 대한 부정확한 지침 및 제도적 학술 진흥 절차에 포함되지 않기 때문에 기대 편익benefits을 산출하지 못하는 경우가 많다.69–71 또한, 여러가지 교육자 역할(예: 직접 교육, 멘토링, 커리큘럼 개발, 학습자 평가 및 리더십) 사이의 구별이 항상 명확한 것은 아니며, 이러한 역할이 학습자에게 미치는 영향에 대한 정보는 종종 제공되지 않는다. 이러한 문제들 때문에, EP들은 전통적으로 품질을 평가하기가 어려웠으며, 종종 위원회는 학술 홍보 과정 중에 그것들을 간과했다.

However, EPs often fail to produce anticipated benefits because of their variability and length, imprecise guidelines for evaluation and lack of inclusion in institutional academic promotion procedures.69–71 Furthermore, distinctions are not always made among the multiple educator roles (e.g. direct teaching, mentoring, curriculumdevelopment, learner assessment and leadership) and information is often not provided on the impact of these roles on learners. Because of these problems, EPs have traditionally been difficult to evaluate for quality and often committees overlooked themduring the academic promotions process.

교육자를 위한 서포트

Supporting educators

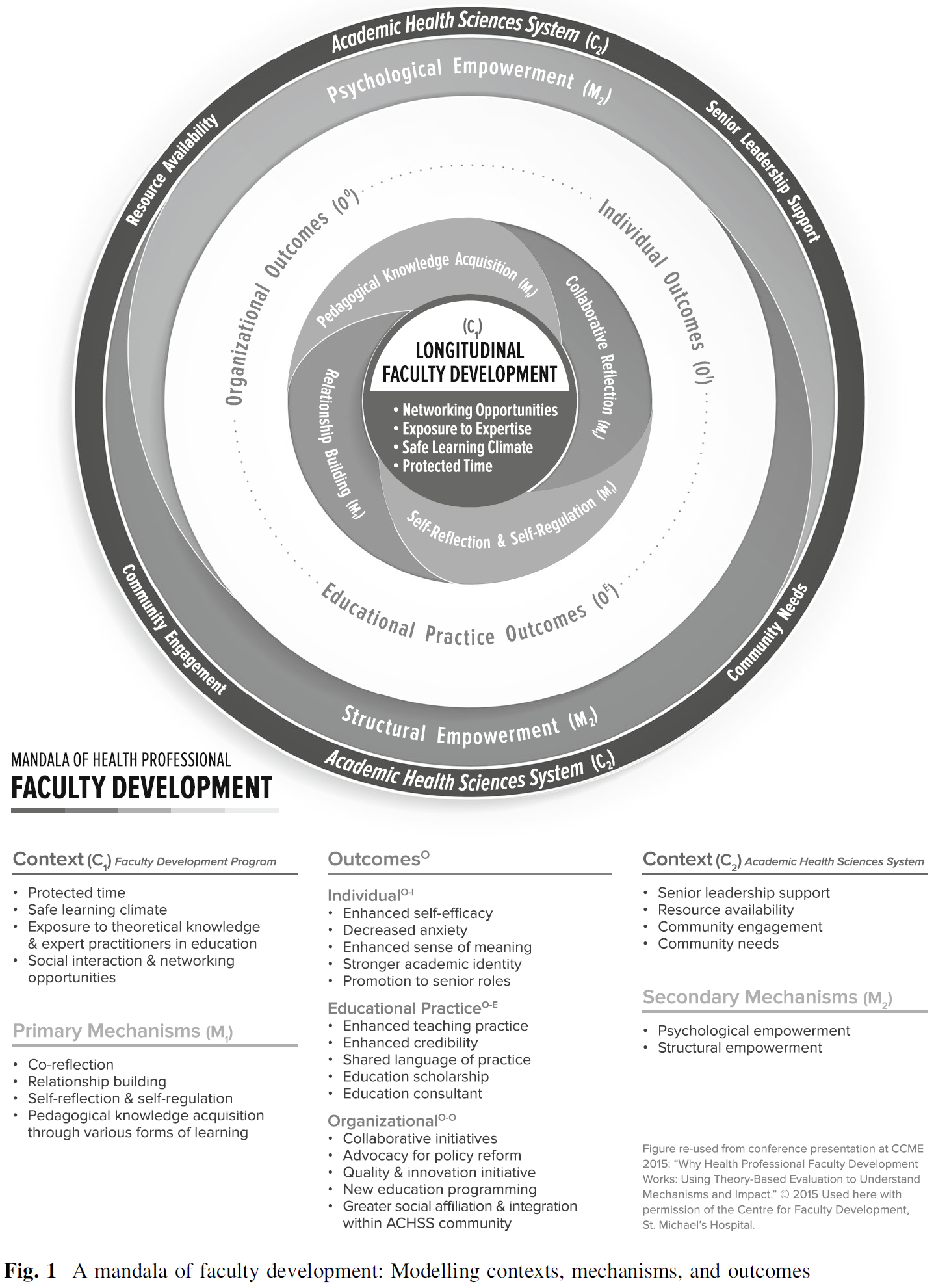

보건 전문 기관들은 교육적 학술활동을 강화하고 교직원을 교육자로 인식하고 보상하기 위해 두 가지 구조 전략을 채택했다: 건강 전문 교육 장학금(HPESU) 및 의료 교육 기관 아카데미. 67

Health professions institutions have employed two structural strategies to strengthen educational scholarship and to recognise and reward their faculty members as educators: health professions education scholarship units (HPESU)72–75 and academies of medical educators.67

HPESU는 전 세계적으로 상당히 다양하지만, [보건직업 교육과 관련된 학술활동에 종사하는, 기관 내에서 인식 가능하고 일관성 있는 조직적 실체]로 정의된다. 이들 조직은 교직원에 대하여 [멘토링, 교수개발, 협업연구, 상담]을 통해 교육적 학술활동을 지원한다. HPESU는 [교육적 사명]을 옹호하며 프로그램 평가, 교육테크놀로지, 교수개발과 같은 [행정 기능]을 종종 가지고 있다. 또한, 이러한 단위는 종종 [교육과정 개발과 수행평가를 지도할 수 있는 최고의 증거]를 학술 지도자들에게 제공한다.76 이 조직은 학자로서의 교육자를 인정하고 지원하는 강력한 힘이다.

Although HPESUs vary considerably around the world, they are defined as being a recognisable, coherent, organisational entity within the institution that is engaged in scholarship related to health professions education.73 These units offer faculty members support for their educational scholarship through mentoring, faculty development, collaborative research and consultation. HPESUs advocate for the educational mission and often have administrative functions such as programme evaluation, educational technology and faculty development. In addition, these units often provide academic leaders with best evidence to guide curriculum development and performance assessment.76 They are a powerful force for recognising and supporting educators as scholars.

교육 및 보상 교육 개선을 위한 두 번째 구조적 또는 사회문화적 접근방식은 [의료 교육자 아카데미]에 의해 제공된다. 이것은 다음과 같은 교육 수월성을 인정하고 보상하기 위한 조직 구조입니다.

- 교육자 옹호,

- 교수 개발 촉진,

- 교육 혁신 및 장학금 장려,

- 교육자의 경력 개발 및 학업 증진

The second structural or socio-cultural approach to improving teaching and rewarding educators is provided by academies of medical educators. They are organisational structures for recognising and rewarding excellence in teaching:

- advocating for educators,

- fostering faculty development,

- stimulating educational innovation and scholarship, and

- promoting career development and academic advancement of educators.67,68,77

이러한 유형의 아카데미는 학교, 대학, 국가 차원에서 조직된다. 아카데미에 들어가는 것은 지원자에 대한 엄격한 동료 평가에서부터, 단순히 아카데미가 제공하는 활동에 참여하는 것까지 다양하다. 아카데미는 동료 교육자들 사이에 중요한 공동체 의식을 형성한다. 많은 아카데미는 직업교육에서 창의성과 장학금을 육성하기 위해 혁신 기금을 제공하고 있으며, 일반적으로 교육 관련 학술 작품을 발표하는 행사로 교육의 날education day을 스폰서한다. 교육 실천의 공동체를 대표하는 아카데미들은 [교육자들을 더 드러나게 하고visibility과 지원을 제공함으로써] academic health science school의 문화를 변화시키려 한다.

Academies are organised at the level of schools, universities and nations.78 Entry into academies varies from rigorous peer review of applicants to simply participating in activities offered by the academy. Academies create an important sense of community among fellow educators. Many academies offer innovation funding to foster creativity and scholarship in professions education and they typically sponsor education days for presentation of education-related scholarly works. Representing communities of teaching practice, academies seek to transform the culture of academic health science schools by providing visibility and support to educators.

개혁 없는 변화

HANGE WITHOUT REFORM

그러나, 학문적 가치는 학문적 보상, 보수, 지위 및 승진에서 가르치는 것에 대한 특권을 계속 부여하고 있으며, 그 결과 지속적인 개혁 요구를 낳았다.79–81 연구자로서의 우수성과 교사로서의 우수성 사이의 연관성은 없다는 연구결과에도 불구하고 이러한 현상이 나타난다.82

Yet, academic values continue to privilege research over teaching in academic rewards, remuneration, status and promotions,2 resulting in continuing calls for reform.79–81 This happens despite research showing no association between excellence as a researcher and excellence as a teacher.82

학문적 진흥에 있어서 [제도적 관성]의 이유는 (대학 문화와 정책에 강하게 내재된) 교육보다 학술연구에 우선 순위를 두는 것에서 비롯되며, 그 결과 대학의 많은 사람들이 [연구가 다른 모든 임무보다 더 많이 보상받아야 한다]고 믿게 된다. 결국, 연구는 그 기관에 지위와 자원을 가져다 주었지만, 양질의 교육 프로그램과 교육 장학금은 거의 그렇지 않게 되었다. [연구-교육 사이의 reward 균형을 변화시키기 위한 간헐적 이니셔티브]는 진정한 개혁의 결과를 거의 초래하지 않는 것으로 인식된다. 그러나, 교사-학자들은 대학의 교육 사명을 충족시키기 위해 요구되고 정책 입안자들은 연구뿐만 아니라 교육 및 장학금 보상의 의무들을 재정립할 필요가 있다. 그러한 행동은 대학들이 가르치는 것에 대한 수사적인 찬사를 넘어 다양한 방법으로 교사들에게 실제로 보상을 주는 문화와 정책으로 옮겨갈 것이다.

The reason for institutional inertia in academic promotions derives from the century-old primacy of research and publishing scholarly work over teaching that is strongly embedded in university culture and policies, resulting in many in the university believing that research should be rewarded over all other missions.2 After all, research brings status and resources to the institution, whereas quality educational programmes and educational scholarship rarely do. Episodic initiatives to change the research–teaching balance of rewards are perceived as rarely resulting in true reform. Yet, teacher-scholars are required to meet the educational mission of universities and policymakers need to realign imperatives for rewarding teaching and educational scholarship as well as research. Such action would move universities beyond rhetorical praise for teaching toward a culture and set of policies that actually reward teachers in a variety of ways.

미래 방향

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

교육자를 모집, 개발, 보상 및 유지하려면 개혁에 대한 전체적인 접근이 필요합니다. 이 작업에는 다음이 필요합니다.

- 학업 정책 및 성과 기대치에 변화를 조성

- 교육자에게 명확한 경력 궤적과 정체성을 제공

- 교수진 개발 프로그램 확대

- HPESU 및 AoME 지원

- 모든 교육자에게 높은 기준을 보장하는 메커니즘 생성

To recruit, develop, reward and retain educators, a holistic approach to reform is needed going forward. This will require

- creating changes in academic policies and performance expectations,

- providing a clear career trajectory and identity for educators,

- expanding faculty development programmes,

- supporting health professions education scholarship units and academies of medical educators, and

- creating mechanisms to ensure high standards for all educators.

예를 들어, 임상 교사는 종종 (임상 교육을 함으로써 생기는 생산성 저하를 적절히 설명하지 못하는) [높은 임상 생산성 기준]에 압도당한다.

For example, clinical teachers are often overwhelmed by high clinical productivity standards that do not adequately account for decreased productivity when teaching learners in clinical settings.

[생산성 기대치]는 교육 및 학습을 지원하도록 조정되어야 하며, 따라서 교사의 만족도, 정체성, 유지 및 전문적 성취도를 향상시켜야 한다.

productivity expectations need to be adjusted to support teaching and learning, thereby improving teachers’ satisfaction, identity, retention and professional fulfillment.

[학문적 보상 시스템]을 개혁하기 위해, 구현 과학implementation science에서 배운 교훈은 구조적 변혁을 위한 지침으로서 도움이 될 수 있다: 핵심 이해 당사자들과 참여시키고, 효과 연구를 수행하고, 연구 종합물을 광범위하게 보급한다.83

To reform academic reward systems, lessons learned from implementation science may be instructive as a guide for structural transformation: engage key stakeholders, conduct effectiveness studies and broadly disseminate research syntheses.83

'의료교육에서 새로운 프로그램과 아이디어를 성공적으로 보급하려면 적극적인 교육 리더십, 개인적 접촉, 헌신, 노력, 엄격한 측정 및 구현과학 원리에 대한 관심이 필요합니다.' 우리는 역사, 문화, 제도적 정책 및 관행을 극복하기 위해 강력하고 끈질긴 옹호가 요구될 것이라는 데 동의한다.

‘Successful dissemination of new programs and ideas in medical education takes active educational leadership, personal contacts, dedication, hard work, rigorous measurement, and attention to implementation science principles.’84 We concur that strong and persistent advocacy will be required to overcome historical, cultural and institutional policies and practices.

교육자를 학업에 참여시키기 위해, 훈련 중에 정체성이 형성되는 학생과 전공의에게 [명확한 직업 경로를 보여줄 필요]가 있다. 일부 학교는 학생 및 전공의를 위한 [의학교육 또는 보건전문직교육에 대한 scholarly concentration]을 통해 이러한 진로선택을 투명하게 한다.85,86 교직원 수준에서도 유사한 과정이 필요하다. 많은 학교들은 교직원들을 위한 [교수개발 인증 프로그램]과 보건직 교육학자들을 위한 [종단적 교육 프로그램]을 제공한다.28,87

To recruit educators into academic careers, a clear career pathway needs to be shown to students and residents whose identities are being formed during training. Some schools make this career option transparent through scholarly concentration on medical or health professions education for students and residents.85,86 At the faculty member level a similar process is required. Many schools offer development certification programmes for faculty members, as well as longitudinal teaching programmes for health professions education scholars.28,87

교육지도자 역할을 맡기를 원하는 교직원을 위해 [보건직업교육 석사학위, 보건직업교육 박사학위] 등이 교수-학습의 학술활동 증진을 원하는 교직원을 위해 존재한다.49

For those faculty members who wish to take on educational leadership roles, masters degrees in health professions education are widely available50 and doctoral programmes in health professions education exist for those who wish to advance the scholarship of teaching and learning.49

학술적 교육자scholary educator를 배출하는 핵심 요소인 [교수개발]은 포괄적으로 이루어져야 할 것이다. 교육학적 지식과 기술을 지속적으로 제공하면서 프로그램은 커리큘럼 개발, 평가, 멘토링, 리더십, 장학금 등 다른 교육자 역할도 다룰 필요가 있을 것이다. 게다가, 교직원들은 자신들이 과거에 학생이나 전공의일 때 한번도 배운 적 없는 성찰적 관행뿐만 아니라 퀄리티와 안전, 탐구와 학술활동 등도 가르쳐야 한다. 따라서, 교수개발은 이러한 새로운 기술에 대해 교수진에게 교육하기 위해 보건 시스템뿐만 아니라 학부, 대학원 및 지속적인 보건 전문가 교육과 함께 협력하고 있습니다. 따라서, 교수개발 프로그램은 [교육기술]뿐만 아니라 [기본 콘텐츠]로 돌아가, PCK를 향상시키기 위해 이 둘을 자꾸 결합하는 완전한 동그라미full circle가 되어야 한다.

Faculty development, a key component of producing scholarly educators, will need to become comprehensive. While continuing to offer pedagogical knowledge and skills, programmes will also need to address other educator roles, including curriculum development, assessment, mentoring, leadership and scholarship. In addition, faculty members are now expected to teach quality and safety, inquiry and scholarship, as well as reflective practice, none of which were taught to them when they were students and residents. Faculty development is therefore teaming up with health systems as well as undergraduate, graduate and continuing health professions education to educate faculty members on these new skills. Thus, faculty development programmes have come full circle in returning to teaching basic content as well as educator skills and frequently combining the two to improve pedagogical content knowledge.

이와 함께 교직원 육성프로그램은 스스로 학습하고 스스로 조직화하는 [(임상현장workplace에서의) 교육 실천 공동체]를 위한 새로운 방안을 모색할 필요가 있을 것으로 보인다. 이들은 다음을 중심으로 형성되는 비공식 학습 공동체이다.3

- 공유된 책임(예: 코스 감독, 임상실습 감독 및 레지던시 프로그램 감독),

- 교육 장소(예: 강의실, 임상 및 전문가 간 팀 실습)

- 관심 교육 분야(예: 시뮬레이션, 기술 및 팀 기반 학습)2

In addition, faculty development programmes will need to find new ways to foster the development of self-teaching and self-organising communities of teaching practice in the workplace. These are informal learning communities that can form around

- shared responsibilities (e.g. course directors, clerkship directors and residency programme directors),

- locations of instruction (e.g. classroom, clinical and interprofessional team practice) and

- pedagogical areas of interest (e.g. simulations, technology and team-based learning).32

모든 교육자들이 가르치는 데 필수적인 지식과 기술을 받도록 하는 것이 정책 우선순위가 되어야 한다. 실천 공동체로서, 그 목표를 달성하는 방법은 명확하지 않다. 일부 유럽 국가에서는 이미 [고등교육 교사 자격증]이 일반적이며, 다른 학교에서는 전임자 임용 전이나 그 이후 곧 교수진 개발을 요구하는 곳도 있다. 만약 교육자들이 교사 인증의 일환으로 장학금에 참여할 것으로 기대된다면, 교육 장학금을 지원하는 새로운 메커니즘이 필요할 것이다.

Ensuring that all educators receive the essential knowledge and skills for teaching should be a policy priority. As a community of practice, how to achieve that goal is less clear. Teacher certification in higher education is already the norm in some European countries and some schools elsewhere require faculty development prior to full-time academic appointment or soon thereafter. If educators are expected to engage in scholarship as part of their teacher certification, then new mechanisms of support for educational scholarship will be needed.

16 Irby DM. Excellence in clinical teaching: knowledge transformation and development required. Med Educ 2014;48(8):776–84. 24 Gusic ME, Baldwin CD, Chandran L, Rose S, Simpson D, Strobel HW, Timm C, Fincher RM. Evaluating educators using a novel toolbox: applying rigorous criteria flexibly across institutions. Acad Med 2014;89 (7):1006–11. 45 Srinivasan M, Li S, Meyers F, Pratt D, Collins J, Braddock C, Skeff KM, West DC, Henderson M, Hales RE, Hilty DM. “Teaching as a competency”: competencies for medical educators. Acad Med 2011;86:1211–20.

31 ASPIRE. ASPIRE to excellence in faculty development AMEE Website: Association for Medical Education in Europe; 2016 http://aspire-to-excellence.org/ 47 Sherbino J, Frank J, Snell L. Defining the key roles and competencies of the clinician-educator of the 21st century: a national mixed-methods study. Acad Med 2014;89 (5):783–9.

Med Educ. 2018 Jan;52(1):58-67.

doi: 10.1111/medu.13379. Epub 2017 Aug 3.

Developing and rewarding teachers as educators and scholars: remarkable progress and daunting challenges

David M Irby 1, Patricia S O'Sullivan 1

Affiliations collapse

Affiliation

-

1Department of Medicine, UCSF, San Francisco, California, USA.

-

PMID: 28771776

-

DOI: 10.1111/medu.13379

Abstract

Context: This article describes the scholarly work that has addressed the fifth recommendation of the 1988 World Conference on Medical Education: 'Train teachers as educators, not content experts alone, and reward excellence in this field as fully as excellence in biomedical research or clinical practice'.

Progress: Over the past 30 years, scholars have defined the preparation needed for teaching and other educator roles, and created faculty development delivery systems to train teachers as educators. To reward the excellence of educators, scholars have expanded definitions of scholarship, defined educator roles and criteria for judging excellence, and developed educator portfolios to make achievements visible for peer review. Despite these efforts, the scholarship of discovery continues to be more highly prized and rewarded than the scholarship of teaching. These values are deeply embedded in university culture and policies.

Challenges: To remedy the structural inequalities between researchers and educators, a holistic approach to rewarding the broad range of educational roles and educational scholarship is needed. This requires strong advocacy to create changes in academic rewards and support policies, provide a clear career trajectory for educators using learning analytics, expand programmes for faculty development, support health professions education scholarship units and academies of medical educators, and create mechanisms to ensure high standards for all educators.

© 2017 John Wiley & Sons Ltd and The Association for the Study of Medical Education.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 교수개발(Faculty Development)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 미래의 CPD: 질개선과 역량기반교육의 파트너십(Med Educ, 2017) (0) | 2021.03.13 |

|---|---|

| 무역량의 기준을 높이기: 의사의 자기평가가 임포스터 신드롬에 대하여 드려내어주는 것(Acad Med, 2018) (0) | 2021.03.10 |

| 의학교육으로 도약하기: 의학교육자의 경험에 대한 질적 연구(Med Educ, 2017) (0) | 2021.03.10 |

| 2025년 의학교육자의 직무 역할(J Grad Med Educ, 2018) (0) | 2021.02.23 |

| 교수개발을 통해서 교사의 전문직 정체성 강화하기(Acad Med, 2019) (0) | 2021.02.10 |