왜 우리는 교사를 가르쳐야 하는가? 임상감독관의 학습 우선순위 확인(Adv in Health Sci Educ, 2018)

What should we teach the teachers? Identifying the learning priorities of clinical supervisors

Margaret Bearman1 • Joanna Tai1 • Fiona Kent2,3 • Vicki Edouard2 • Debra Nestel4,5 • Elizabeth Molloy6

도입

Introduction

미래 의료 인력을 개발하는 데 있어 경험이 풍부한 임상의의 역할이 중요하며 잘 알려져 있다. '임상 감독'이라는 용어는 [환자 치료]와 [훈련생 개발 활동]에 대한 감독 모두를 포함하기 때문에 종종 사용된다(Fitzpatrick et al. 2012; Strand et al. 2015). 하급 직원의 개발은 효과적인 임상 감독(de Jong et al. 2013; Kilminster and Jolly 2000)과 연계되어 있다. 따라서 임상 감독자가 임상 전문지식 외에도 교수 기술을 보유하는 것이 중요하다. 본 논문은 임상 감독자의 교육 역할에 초점을 맞추고 있으며, 이는 환자 치료와 불가분의 관계에 있음을 인정한다.

The role of experienced clinicians in developing the future health workforce is significant and well recognised. The term ‘clinical supervision’ is often used as the role involves both oversight of patient care and trainee development activities (Fitzpatrick et al. 2012; Strand et al. 2015). Development of junior staff is linked to effective clinical supervision (de Jong et al. 2013; Kilminster and Jolly 2000). It is consequently important that clinical supervisors have skills in teaching in addition to clinical expertise. This paper focusses upon clinical supervisors’ teaching role, with the acknowledgement that this is inextricably linked with patient care.

임상 감독관들에게 있어서 교직 역할은 때때로 불편하다. 2015년 임상 감독자의 정성적 연구에서 한 명의 의사가 지적한 바와 같이(Strand et al. 2015): 나는 교사가 되기 위해 교육을 받은 적도 없고, 교사가 되는 것에 대한 지식과 흥미가 전혀 없다. 가장 중요한 것은, 나는 교육적인 훈련이 전혀 없다는 것이다.

The teaching role is sometimes uncomfortable for clinical supervisors. As one doctor noted in a 2015 qualitative study of clinical supervisors (Strand et al. 2015): I have not been educated to be a teacher, nor do I have any knowledge and interest in being a teacher …Most importantly, I have no pedagogic training at all…

임상 감독관들은 교육 기술 개발을 지원하는 프로그램이 필요하다고 보고한다(Andrews and Ford 2013, Henderson and Eaton 2013, Neville 및 French 1991). 단, 학습하고자 하는 내용에 대한 구체적인 세부 사항은 없다.

Clinical supervisors report the need for programs to assist in their development of education skills (Andrews and Ford 2013; Henderson and Eaton 2013; Neville and French 1991) although without specific detail regarding what they wish to learn.

우리는 임상의의 교육적 숙련도를 개발하는 프로그램을 설명하기 위해 '교수 개발'이라는 용어를 사용한다(O'Sullivan and Irby 2011; Steinert et al. 2006). 짧은 워크숍부터 1년 동안 지속된 펠로우쉽에 이르기까지 다양한 교수개발 프로그램이 있는데, 이 프로그램은 임상 감독관들에게 가르치는 방법을 가르친다. 2016년 체계적인 검토는 관찰된 교육 변화 및 교육에서 독립적인 워크숍이 영향을 미칠 수 있는 몇 가지 증거를 포함하여 이러한 프로그램의 가치를 나타낸다. 이 검토에 포함된 교수진 개발 커리큘럼은 다양하고, [교육 성과, 교수 원리, 특정 교수 기술, 평가, 교육 설계, 리더십 및 학술활동] 등을 다룬다(Steinert et al. 2016).

We use the term ‘faculty development’ to describe programs which develop the educational proficiency of clinicians (O’Sullivan and Irby 2011; Steinert et al. 2006). There is a broad sweep of faculty development programs ranging from the short workshop to year long fellowships, which teach clinical supervisors how to teach. A 2016 systematic review indicates the value of such programs, including observed changes to teaching and some evidence that stand alone workshops in teaching can have an impact. Faculty development curricula included in this review are diverse and cover teaching performance, principles of teaching, specific teaching skills, assessment, educational design, leadership and scholarship (Steinert et al. 2016).

2013년 의료 교수진 개발 프로그램에 대한 체계적인 검토는 "[교육 퍼포먼스]에만 초점을 맞추는 것에서 벗어나라"(Leslie et al. 2013)고 언급했지만, 다른 직종에서는 그렇지 않을 수 있다. 교수진 개발 커리큘럼에 포함된 유형의 주제는 스탠포드 대학교육 프로그램에 의해 잘 설명되며, 여기에는 "학습 분위기, 세션 제어, 목표의 소통, 이해와 유지의 촉진, 평가, 피드백 및 자기주도학습의 촉진"이 포함된다(요한슨 외). 2009).

A 2013 systematic review of medical faculty development programs noted a ‘‘move away from a focus on teaching performance alone’’ (Leslie et al. 2013) but this may not hold true for other professions. The type of topics included within faculty development curricula are well illustrated by the Stanford Faculty Development program, which includes: ‘‘learning climate, control of session, communication of goals, promotion of understanding and retention, evaluation, feedback and promotion of selfdirected learning’’ (Johansson et al. 2009).

좀 더 최근에, Staljmeier 등(2010)은 인지적 도제 이론에서 도출하여 임상적 교수 우수성을 위한 프레임워크를 개발했으며, 이는 평가 도구 역할을 한다. Maastricht 임상 교육 설문지(MCTQ)는 감독자 역할의 7개 범주 내에 24개 항목을 포함하고 있다.

- 적절한 행동 모델링,

- 학생 코칭,

- 개념 비계 제공 ,

- 실천을 설명

- 성찰 장려,

- 목표 및 경계 탐색,

- 학습에 도움이 되는 일반적인 학습 환경을 제공

More recently, Staljmeier et al. (2010) drew from cognitive apprenticeship theories to develop a framework for clinical teaching excellence, which also serves as an assessment instrument. The Maastricht Clinical Teaching Questionnaire (MCTQ) contains 24 items within seven categories of a supervisor’s role:

- modelling appropriate behaviour,

- coaching students,

- scaffolding concepts,

- articulation of practice,

- encouraging reflection,

- exploration of goals and boundaries, and

- providing a general learning climate conducive to learning.

다양한 교육 기관 및 국가 표준이 출판되었습니다. 예를 들어, 의학 교육자 아카데미 (AoME) (2014)가 발행한 의료, 치과 및 수의학 교육자에 대한 전문 표준과 같은 교육자를 위한 다양한 기관 및 국가 표준이 발행되었습니다. 이러한 것들은 교수진 개발 커리큘럼에 대한 암시적이고 명시적인 지침을 제공한다.

various institutional and national standards for educators have been published, such as the professional standards for medical, dental and veterinary educators published by the Academy of Medical Educators (AoME) (2014). These and similar provide implicit and explicit guidance to faculty development curricula.

그러나 이러한 프레임워크는 [가르치기를 열망하지만, 일차적인 초점이 환자 치료이며, 교육 원칙에 대한 훈련이 거의 없을 수 있는] 임상 감독자working clinial supervisor의 우선순위와 요구에 대한 정보는 주지 못한다.

However, these frameworks provide less information about the priorities and needs of the working clinical supervisor, who is keen to teach but whose primary focus is patient care and who may have little training in education principles.

O'Sullivan과 Irby(2011)는 추가 연구를 위한 중요한 영역으로서 임상 감독과 관련된 [작업장workplace의 학습 요구]를 평가할 것을 지적하였다. 교수 개발자들은 임상 감독자들이 어떤 교육 측면에 초점을 맞추고자 하는지 또는 가장 골치 아픈지 알 수 있게 될 것이다. 이는 효과적인 참여와 개발을 위해 [학습자의 환경에 대한 이해]가 필요하다는 것을 시사하는 교육 구성주의적 접근법의 핵심 개념과 일치합니다(Dennick 2012). 감독자의 자기 인식의 강점과 약점을 아는 것은 프로그램 개발에 대한 학습자 중심의 접근을 촉진한다. 또한, 일반적으로 교수 개발 이니셔티브는 단일 세션 워크숍을 구성하므로(Steinert 등. 2006), 교수 개발 프로그램이 가장 필요한 인식 영역을 목표로 학습자를 참여시키는 것이 타당하다.

O’Sullivan and Irby (2011) identify assessing the learning needs of workplaces with respect to clinical supervision as an important area for further research. It would be illuminating for faculty developers to know which facets of teaching that clinical supervisors wish to focus on or find most troublesome. This aligns with the key tenet of constructivist approach to education, which suggests that an understanding of the learners’ circumstances is necessary for effective engagement and development (Dennick 2012). Knowing supervisors’ self-perceived strengths and weaknesses promotes a learner-centred approach to program development. Furthermore, as faculty development initiatives typically constitute a single session workshop (Steinert et al. 2006), it makes sense for faculty development programs to engage learners through targeting perceived areas of greatest need.

우리는 자기보고식 데이터의 한계를 알고 있으며, 특히 실제 사례와 크게 다를 수 있다(Norman 2014). 그러나 자기보고식 데이터는 어떻게 '현장의on the ground' 임상 감독자 자신이 개선 영역의 우선순위를 생각하는지 나타낸다. 이러한 방식으로, 그것은 자기 평가 능력보다는 자기 보고 데이터의 교육 전략 목적과 더 밀접하게 일치한다(Eva 및 Regehr 2008). 더욱이, 자기 평가는 일반적으로 자신을 표준과 비교하는 것과 관련이 있다(Boud and Falchikov 1989). 이 관점에서, 여기서 초점은 성과 표준이 아니고, [상대적 우선순위에 대한 감독자의 인식에 대한 질적 감각]이다.

We are aware of the limitations of self-report data, in particular it can be widely divergent from actual practice (Norman 2014). However, selfreport data indicates how ‘on the ground’ clinical supervisors themselves prioritise areas for improvement. In this way, it is more closely aligned with a pedagogic strategy purpose of self-report data rather than self-assessment ability (Eva and Regehr 2008). Furthermore, self-assessment is generally concerned with comparison of self to a standard (Boud and Falchikov 1989). In this instance, the standard of performance is not the focus here, but a qualitative sense of the supervisors’ perceptions of their relative priorities.

방법 Methods

맥락 Context

참가자들에게 4번째 전문적이고 다기관적인 워크숍 프로그램의 일환으로 MCTQ를 완료할 기회가 주어졌다(ClinSACC)(Tai et al.

Participants were given the opportunity to complete the MCTQ as part of a 4 h interprofessional and multi-institutional workshop program, called Clinical Supervision Support across Contexts (ClinSACC) (Tai et al. 2015).

샘플 Sample

호주 대도시 내 광범위한 지리적 지역의 급성 및 지역사회 환경에서 978명의 임상 감독관이 연구에 참여하도록 초청되었다.

978 clinical supervisors from acute and community settings in a broad geographical area within a metropolitan city in Australia were invited to participate in the research.

도구 Instrument

MCTQ는 처음에 학생들의 임상 감독자를 위한 피드백 도구로 사용되었다(Stalmeijer et al. 2010). 각 항목은 1 = 완전 불일치, 5 = 완전 동의)인 5 포인트 라이커트 척도로 평가됩니다. 전체 등급 점수와 열린 텍스트 주석을 위한 공간이 있습니다. 여러 연구에서 MCTQ가 피드백 도구로서 신뢰할 수 있고 유효할 수 있음을 시사하고 있으며(Boerboom et al. 2011a; Stalmeijer et al. 2008, 2010), 이것은 수의학 임상 교사를 위한 자가 평가 도구로 사용되어 왔다(Boerboom et al. 2011b).

The MCTQ was initially used as feedback tool for clinical supervisors from students (Stalmeijer et al. 2010). Each item is assessed with 5-point Likert scale where 1 = fully disagree, 5 = fully agree). There is an overall rating score, and space for open text comments. Several studies suggest the MCTQ may be reliable and valid as a feedback tool (Boerboom et al. 2011a; Stalmeijer et al. 2008, 2010) and it has been used as a selfassessment instrument for veterinary clinical teachers (Boerboom et al. 2011b).

MCTQ는 개인 학습 니즈 분석을 위한 자기보고식, 자기평가도구(수정 또는 mMCTQ)로 만들기 위해 다시 작성되었다. 참가자들의 강점과 개선 분야에 대한 두 가지 개방형 질문이 포함되었다. 또한, mMCTQ는 임상 감독자의 자기 인식 학습 요구에 관한 데이터를 제공하는 연구 목적과 더불어 참가자들에게 성찰적 도구 역할을 하였다.

The MCTQ was reworded to make it a self-report, self-evaluation tool (modified or mMCTQ) intended for a personal learning needs analysis. Two open-ended questions were included, on participants’ perceived strengths, and areas for improvement. In addition, to the research purpose of providing data regarding the self-perceived learning needs of clinical supervisors, the mMCTQ also served as a reflective tool for the participants.

자료 수집

Data collection

워크숍 참가자는 임상 감독의 기본 아이디어에 대한 오리엔테이션과, 성찰적 실천에 대한 짧은 소개를 거쳐, [자신의 학습 요구를 식별하는 성찰 활동]의 일환으로 mMCTQ의 종이 버전을 완성했다.

Workshop participants completed a paper version of the mMCTQ as part of a reflective activity identifying their own learning needs, after orientation to the fundamental ideas of clinical supervision and a short introduction to reflective practice.

자료 분석

Data analysis

임상 감독 강점과 개선 분야에 대한 두 가지 개방형 질문에 대한 응답은 내용 분석 기법(Vaismoradi et al. 2013)을 사용하여 정성적으로 분석되었으며, 다음과 같이 설명되었다. 세 명의 연구자(FK, MB, JT)는 각각 동일한 100개의 응답(강점 45개, 개선 분야 55개)을 유도적으로 코드화하여 진술의 명시적 내용에 기초한 코딩 프레임워크를 개발하였다. 단일 문을 여러 번 코드화할 수 있습니다. 그런 다음 프레임워크를 사용하여 모든 응답(DN, FK, MB, JT)이 코드화되었다. 불확실성에 대해 논의했고 합의(JT, FK, MB)에 의해 최종 프레임워크가 해결되었다.

The responses to the two open-ended questions on clinical supervision strengths and areas for improvement were qualitatively analysed using content analysis techniques (Vaismoradi et al. 2013), described as follows: Three researchers (FK, MB, JT) each inductively coded the same 100 responses (45 strengths; 55 areas of improvement) to develop a coding framework based on the manifest content of the statements. A single statement could be coded multiple times. All responses were then coded (DN, FK, MB, JT) using the framework. Uncertainties were discussed and the final framework resolved by consensus (JT, FK, MB).

윤리

Ethics

결과 Results

총 481명(49%)의 작업장 참가자가 mMCTQ 데이터를 연구에 사용할 것을 동의했습니다. 직업은 표 1에 자세히 설명되어 있습니다. 103명(21%)은 사전 전문적 개발이 없었다고 답한 반면, 203명(43%)은 기본 워크숍이나 실무 교육에 참석했으며, 더 적은 수는 광범위한 비공식 교육(64, 14%) 또는 추가 자격 취득(86, 18%)을 받았다.

A total of 481 (49%) workshop participants consented for their mMCTQ data to be used in the study. Professions are detailed in Table 1. While 103 (21%) reported no prior professional development, 203 (43%) had attended basic workshops or in-service training, with smaller numbers having had extensive informal training (64, 14%) or a further qualification (86, 18%).

개별 mMCTQ 항목 평균은 3.50에서 4.64까지 다양하며 mMTCQ에서 자체 보고한 가장 빈번한 것부터 가장 적게 수행되는 것까지 표 2에 제시되어 있다.

Individual mMCTQ item means ranged from 3.50 to 4.64 and are presented in Table 2 from most frequently to least frequently performed as self-reported on the mMTCQ.

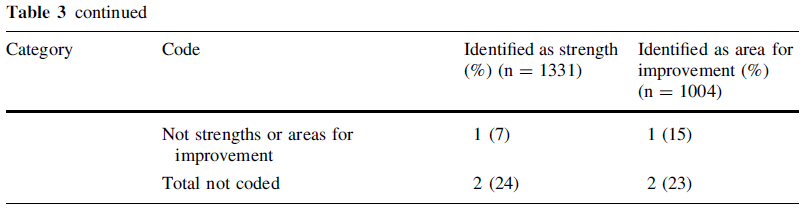

자유 텍스트 데이터의 정성적 분석을 위한 코딩 프레임워크, 코드 및 빈도수는 표 3에 제시되어 있다. 가장 많이 보고된 강점은 224건의 응답으로 '관계 수립' 카테고리로 공감대 형성, 접근성, 친근감 등이 포함됐다. '평가'는 가장 적게 인용된 강점으로 응답자가 식별하지 않은 유일한 범주였다. 가장 자주 보고되는 다섯 가지 강점을 설명하는 실례 인용문은 표 4에 제시되어 있다.

The coding framework, codes and frequency counts for the qualitative analysis of the free text data are provided in Table 3. The most reported strength, with 224 responses, was the category of ‘establishing relationships’, which included rapport building, approachability and friendliness. ‘Assessment’ was the least cited strength and the only category not identified by any respondent. Illustrative quotes describing the five most frequently reported strengths are provided in Table 4.

151개의 응답으로 가장 많이 개선이 필요한 것으로 보고된 분야는 '피드백'이었다. 가장 적게 보고된 분야는 '존중하다'는 주제였는데, 이는 어떤 응답자도 확인되지 않았다. 개선을 위해 가장 자주 보고되는 영역을 설명하는 예시적인 인용문은 표 5에 제시되어 있다.

The most reported area for improvement, with 151 responses, was ‘feedback’. The least reported area for improvement was the theme of being ‘respectful,’ which was not identified by any respondent. Illustrative quotes describing the most frequently reported areas for improvement are provided in Table 5.

고찰 Discussion

임상 감독자의 자체 평가된 장단점에 대한 이 대규모 조사는 작업장 학습 요구workplace learning needs에 대한 연구의 필요성을 보여준다(O'Sullivan and Irby 2011).

- mMCTQ에서 확인된 임상 교육의 세 가지 가장 빈번한 측면은 [존중이나 관심을 보이거나 안전한 환경을 조성하는 것]과 같은 [대인 관계 기술 또는 속성]이었다. mMCTQ에서 가장 자주 식별되는 네 번째와 다섯 번째 측면은 [질문을 하거나] [새로운 것을 배우도록 장려하는 것]과 관련이 있다.

- 질적 데이터에서 확인된 5가지 강점은 [관계 설정, 임상 전문 지식, 커뮤니케이션 기술, 열정, 정직이나 재치와 같은 기타 개별 속성]이었다. 전체적으로 참여자의 54%가 대인관계 능력이나 속성을 강점으로, 17%의 자유 텍스트 코멘트가 관계 구축을 핵심 강점으로 구체적으로 지목했다.

This large scale investigation of clinical supervisors’ self-assessed strengths and weaknesses addresses calls for research into workplace learning needs (O’Sullivan and Irby 2011).

- The three most frequently performed aspects of clinical teaching identified in the mMCTQ were largely interpersonal skills or attributes, such as showing respect or interest or creating a safe environment. The four and fifth aspects most frequently identified in the mMCTQ concerned encouragement to ask questions or learn new things.

- The top five strengths identified in the qualitative data were: establishing relationships, clinical expertise, communication skills, enthusiasm and other individual attributes such as honesty or tact. Overall, 54% of participants nominated interpersonal skills or attributes as their strengths and 17% of free text comments specifically identified relationship building as a key strength.

mMCTQ에서 확인된 가장 수행 빈도가 낮은 5개 영역 중 4개는 [학습자가 자신의 강점, 약점 및 학습 목표를 식별하고 탐구하도록 유도하는 것]이었다. 또한, 응답자들은 '충분한 시간 소요'를 상대적 약점 분야로 지정했다. 질적 데이터에서 확인된 상위 3개 개선 분야는 [피드백 제공, 성찰 및 통찰력 증진, 다양한 교육 전략 개발]이었다. 그 밖에 확인된 개선 분야로는 추가적인 기술 개발을 수행하고 교육 세션의 구조와 구성을 고려하는 것이 포함되었다. 전체적으로 참여자의 49%가 개선 분야로 [어떤 형태의 교육 전략]을 지명했고 15%는 [피드백]을 중점 분야로 구체적으로 지목했다.

Four of the five least frequently performed areas identified in the mMCTQ were prompting learners to identify and explore their strengths, weaknesses and learning goals. In addition, respondents nominated ‘taking sufficient time’ as an area of relative weakness. The top three areas for improvement identified in the qualitative data included: giving feedback, promoting reflection and insight, and developing a range of teaching strategies. Other identified areas for improvement included undertaking further skills development and considering the structure and organization of the teaching session. Overall, 49% of participants nominated some form of teaching strategy as an area for improvement and 15% specifically identified feedback as an area of focus.

본 연구는 임상 감독자의 '현장' 관점과 우선 순위를 조명하기 위한 것이었다. mMCTQ와 자유 텍스트 데이터는 모두 [대인관계 기술과 속성]을 상대적 강점으로 인지함을 강조한다. 응답자들이 임상 교육에서 관계 구축 기술의 중요성을 인식한 것은 고무적이다. 킬민스터와 졸리(2000년)는 이러한 유형의 기술이나 자질이 효과적인 감독에 기여한다고 밝혔다. 임상 교육의 프레임워크는 종종 대인관계를 포괄한다.

- 예를 들어, 헤스케 외 연구진(2001)의 모델에는 "열정", "학습자에 대한 공감 및 관심", "학생에 대한 존중"과 같은 학습 결과가 포함되며

- MCCS는 "상사와 임상 사례 작업 중에 접한 민감한 문제에 대해 논의할 수 있다"(윈스턴리 및 화이트 2011)와 같은 항목을 제시한다.

이는 앞서 언급한 (Clement et al. 2016) 임상 교육에 있어 대인관계의 중요성이며 임상 감독에 대한 관계적 접근 방식의 강점과 한계를 논의하는 데 있어 귀중한 명시적 포인트가 될 수 있음을 시사한다.

This research was intended to illuminate ‘on the ground’ perspectives and priorities of clinical supervisors. The mMCTQ and the free-text data both highlight self-perceived relative strengths in interpersonal skills and attributes. It is heartening that respondents recognized the significance of relationship building skills in their clinical teaching. Kilminster and Jolly (2000) identified these type of skills or qualities as contributing to effective supervision. Frameworks in clinical education often encompass the interpersonal dimension.

- For example, Hesketh et al’s model (2001) includes learning outcomes such as ‘‘enthusiasm’’, ‘‘empathy and interest in learners’’ and ‘‘respect for student’’ and

- the MCCS presents items such as: ‘‘I can discuss sensitive issues encountered during my clinical casework with my supervisor’’ (Winstanley and White 2011).

This suggests that the importance of the interpersonal relationship in clinical education, noted previously (Clement et al. 2016) and may well be a valuable explicit point for discussing strengths and limitations of a relational approach to clinical supervision.

대인 관계 기술 또한 효과적이고 전문적인 임상 행위의 특징이다. 대인적인 측면이 아닌 것 중에 한 가지 인식된 강점은 '임상 전문 지식'이었다. 종합해보면, 우리는 응답자들이 건강 전문가로서의 주요 역할의 일부로 매일 연습하는 기술에 대해 가장 자신 있다고 제안한다. 한 가지 전문지식을 바탕으로 다른 기술을 구축하는 것이 이치에 맞는다. 교수진 개발 프로그램은 임상 감독관이 이 두 가지 독특한 역할, 즉 임상 실습과 교수 실습, 그리고 그것들이 어떻게 겹치거나 갈라지는지를 탐구할 수 있도록 하는 데 가치를 찾을 수 있다.

Interpersonal skills are also hallmarks of effective and professional clinical practice. One perceived strength which did not have an interpersonal aspect was ‘clinical expertise’. Taken together, we suggest that respondents are most confident in skills that they practice daily as part of their primary role as a health professional. It makes sense to draw fromone form of expertise to build another. Faculty development programs may find value in allowing clinical supervisors exploring these two distinctive roles—clinical practice and teaching practice—and how they overlap or diverge.

임상 감독관이 응답한 개선이 필요한 우선 순위는 수렴하였다. mMCTQ와 자유 텍스트 데이터는 개선을 위한 세 가지 광범위한 영역,

- (1) 피드백

- (2) 장단점에 대한 학습자의 탐색 촉진

- (3) 시간 관리 및 계획과 같은 물류 문제

이것들은 차례대로 논의될 것이다.

Clinical supervisors also described convergent priorities for development. The mMCTQ and free-text data identifies three broad areas for improvement:

- (1) feedback

- (2) promoting learners’ explorations of their own strengths and weaknesses and

- (3) logistical issues such as time management and planning.

These will be discussed in turn.

많은 사람들이 '건설적' 또는 '부정적' 메시지의 전달을 개선하고자 하는 가운데, 임상 감독관이 자신의 피드백 관행을 개발하고자 하는 것은 놀라운 일이 아니다. 피드백 만남의 일환으로 학습자 결손을 드러내는 이러한 불편함은 감독자들이 학습자의 감정을 보호하기 위해 불완전하거나 '소멸vanishing'(1983년 말)과 같은 회피적 행동을 할 때 흔히 나타난다. 교육 피드백 기술은 일반적으로 커리큘럼에 존재하며 대부분의 전문가 프레임워크는 '피드백'(의학 교육자 아카데미 2014; Stalmeijer 외 2010) 또는 '상담'(Hesketh et al. 2001) 또는 '가이드'(Winstanley and White 2011)와 같은 관련을 언급한다. 여기에 유용한 세 가지 포인트가 있습니다.

It is not surprising that clinical supervisors wish to develop their feedback practices, with many wanting to improve delivery of ‘constructive’ or ‘negative’ messages. This discomfort in revealing learner deficits as part of the feedback encounter is commonly noted with supervisors undertaking avoidant behaviours such as incomplete or ‘vanishing’ (Ende 1983) performance information to protect the feelings of the learner. Teaching feedback skills is generally present in curricula and most expert frameworks mention ‘feedback’ (Academy of Medical Educators 2014; Stalmeijer et al. 2010) or related such as ‘counsel’ (Hesketh et al. 2001) or ‘guidance’ (Winstanley and White 2011). There are three points that are useful here.

- 첫째, 피드백을 특별히 목표로 하는 교수진 개발은 바쁜 의료 전문가들에게 동기를 부여하고 참여시키는 방법이 될 수 있다.

- 둘째로, 어려운 상황에서 피드백을 제공하는 것은 인지된 인문학적 및 대인관계적 강점과 불일치를 일으킬 수 있으며, 이는 명시적으로 탐구할 가치가 있을 수 있다.

- 마지막으로, 피드백의 일반적인 개념은 지난 5년 정도 동안 정보 제공에서 학습자의 성찰과 통찰력을 용이하게 하는 대화식 접근으로 크게 이동했다(Ajjawi 및 Boud 2015).

교육 피드백 기술은 이제 성능 격차에 대한 정보를 제공하는 것 이상으로 발전했습니다(1983년 Ende). 교육 피드백 기술은 그 자체로 중요한 교육 전략이 되었습니다(Boud and Molloy 2013년).

- Firstly, faculty development which specifically targets feedback may be a way of motivating and engaging busy health care professionals.

- Secondly, providing feedback in challenging situations may cause dissonance with the perceived humanistic and interpersonal strengths, and this may be worth explicit exploration.

- Finally, general conceptions of feedback have shifted enormously in the last 5 years or so, from information provision to a dialogic approach which facilitates learner reflection and insight (Ajjawi and Boud 2015).

Teaching feedback skills has now developed beyond providing information on performance gaps (Ende 1983), it has become a significant teaching strategy in its own right (Boud and Molloy 2013).

mMCTQ와 자유 텍스트 데이터는 임상 감독자들이 [성찰적 실천(이나 유사한 활동)을 촉진할 수 있는 능력]이 가장 적다고 느낀다는 것을 나타냈다. 대인관계 기술의 자기 식별된 강점과 대조적으로, 성찰적 실천은 많은 임상적 역할과 잘 맞지 않는다. 이는 [학생들이 자신의 학습에 대한 책임을 지도록 하는 것]에 임상 감독자들이 어려움을 겪는다는 것을 의미할 수 있다.

The mMCTQ and the free-text data indicated that clinical supervisors felt they had least capacity around promoting reflective practice or similar activities. In contrast to the selfidentified strengths of interpersonal skills, prompting reflective practice does not align well with many clinical roles. This may mean that the clinical supervisors are challenged by letting students take responsibility for their own learning.

이는 mMCTQ에서 가장 자주 수행되는 항목을 비교함으로써 설명된다.

- "학생들에게 경의를 표합니다."

- "나는 진정으로 학생들에게 관심이 있다" 그리고

- "안전한 학습 환경을 조성합니다."—

반면 아래 응답은 빈도가 낮다.

- "나는 학생들이 그들의 장점과 단점을 탐구하도록 자극한다."

- "나는 학생들이 그들의 장점과 단점을 어떻게 개선할 수 있는지 고려하도록 자극한다."

- "나는 학생들이 학습 목표를 수립하도록 장려한다."

전자는 교육자를 존경과 흥미와 안전을 가르치는 선생님으로 임명한다.

후자는 학습자가 자신의 학습에 대한 책임을 지도록 배치한다.

This is illustrated by comparing the most frequently performed items of the mMCTQ—

- ‘‘I show respect to the students’’,

- ‘‘I am genuinely interested in the students’’ and

- ‘‘I create a safe learning environment’’—

with the least frequently =

- ‘‘I stimulate students to explore their strengths and weaknesses’’,

- ‘‘I stimulate students to consider howthey could improve their strengths and weaknesses’’ and

- ‘‘I encourage students to formulate learning goals’’.

The former positions the educator as the teacher who bestows respect, interest and safety,

while the latter positions the learners as responsible for their own learning.

독립적 학습을 촉진하려면 피드백을 포함한 특정 교육 전략의 도구 상자가 필요하다. 이는 (이를 개선 분야로 지정한 49%가 지적한 바와 같이) 임상의에게는 낯설게 느껴질 수 있습니다. 이러한 편안함 부족은 '똑같은 것을 한번 더 하는 것'을 일반적인 재교육 전략으로 사용한 임상 교육자에 관한 이전 연구에서도 뒷받침된다(Bearman et al. 2013; Cleland et al. 2013). 우리의 샘플 중 극소수만이 '스캐폴딩'과 '관찰'과 같은 특정 교육 전략에 강점을 보고했으며 이러한 것들은 교사 중심적인 경향이 있었다. 대화식 피드백, 동료 학습, 역할 놀이, 자기 또는 동료 평가와 같은 다른 학습자 중심의 기술은 확인되지 않았다. 프레임워크와 커리큘럼은 성찰적 실천(Academy of Medical Educators 2014, Winstanley and White 2011) 또는 자기주도적 학습(Johansson et al. 2009)는 교수진 개발 커리큘럼에서 어떤 학습자 중심의 교육 전략이 제공되는지 알 수 없다. 이 연구는 실제 학습자 중심의 기술에 대한 특정 초점이 임상 감독자에게 매우 유용할 수 있음을 시사한다.

Promoting independent learning requires a toolbox of specific teaching strategies, including feedback. These may feel foreign to working clinicians, as is indicated by the 49%who nominated this as an area for improvement. This lack of comfort is supported by previous studies of clinical educators working with underperforming learners where ‘more of the same’ is a common remediation strategy (Bearman et al. 2013; Cleland et al. 2013). Only a very few of our sample reported strengths in specific teaching strategies, such as ‘scaffolding’ and ‘observation’ and these tended to be teacher-driven. Other more learnercentred techniques—such as dialogic feedback, peer learning, role-play and self or peer assessment—were unidentified. While frameworks and curricula acknowledge the importance of reflective practice (Academy of Medical Educators 2014; Winstanley and White 2011) or self-directed learning (Johansson et al. 2009), it is unknown what learnercentred teaching strategies are provided within faculty development curricula. This study suggests that specific focus on practical learner-centred techniques may be very beneficial to clinical supervisors.

보고된 로지스틱스의 문제는 교수개발 프로그램과 전문가 프레임워크 모두에 시사하는 바가 있는 핵심 발견이다.

- 어떤 프레임워크는 이러한 상축적 요구를 탐색할 수 있는 능력을 목표로 하지 않으며(Hesketh 등. 2001),

- 다른 프레임워크는 이를 암시적으로 언급하고(Academy of Medical Educators 2014, Stalmeijer 등. 2010)

- 다른 프레임워크는 여기에 (명확히) 초점을 맞춘다(Winstanley 및 White 2011).

The reported challenge of logistics is a key finding with implications for both faculty development programs and expert frameworks.

- Some frameworks do not specifically target the capacity to navigate these types of competing demands (Hesketh et al. 2001),

- others make implicit mention of it (Academy of Medical Educators 2014; Stalmeijer et al. 2010) and

- others focus on it (Winstanley and White 2011).

(배치 구조화, 강의 시간 할당 및 배치 환경에 대한 방향 지정과 같은) 로지스틱스 문제는 개선을 위한 영역을 설명하는 자유 텍스트 코멘트의 14%를 구성했다. 마찬가지로 '교육에 시간을 쏟는다'는 역량이 가장 적은 분야로 평가되었다. 교육과 관련 없는 문제로 치부하기 쉬워 보일 수 있지만, 이는 복잡한 서비스 역할은 물론 교직 업무를 저글링하는 임상 감독자들이 직면하는 실제 과제를 고려하지 않는다. 스타이너트 외 연구진(2016)이 최근 리뷰에서 언급했듯이, "대부분의 교수 개발 개입은 개업 임상의사를 목표로 했다." 모든 연구 결과 중, 이것은 전문가 프레임워크와 임상 감독자의 견해 사이의 가장 큰 차이를 나타내며, '현장의on the ground' 우선 순위가 전문가 프레임워크와 현저하게 다를 수 있다는 것을 상기시켜 주는 유용한 정보이다.

Logistical concerns such as structuring a placement, allocation of teaching time and orientation to the placement environment together comprised 14%of free-text comments describing areas for improvement. Similarly ‘taking time to teach’ was rated as an area of least capability. While it may seem easy to brush off as a problem that is not related to education, this does not take account of the real challenges faced by clinical supervisors juggling complex service roles as well as teaching duties. As Steinert et al. (2016) note in their recent review, ‘‘the majority of faculty development interventions targeted practicing clinicians’’. Of all the findings, this indicates the biggest gap between expert frameworks and the views of clinical supervisors and is a useful reminder that ‘on the ground’ priorities can markedly differ from expert ones.

[제한된 시간 내에 상충하는 요구를 다루기] 같은 복잡한 상황을 관리하는 데 있어 쉬운 답이 없는 경우가 많습니다. 교수진 개발 워크숍은 부서 및 기관의 제약으로 인해 발생하는 과제를 인식할 수 있습니다. 임상 감독관이 자신의 로지스틱스에 대해 구체적으로 언급하도록 유도하는 것이 도움이 될 수 있다. 이것은 대인관계 교류의 미시적 기술에만 초점을 맞추기 보다는, 전체적으로 배치placement에 대해 생각하는 방식으로의 전환을 필요로 한다. 예를 들어, 임상 감독관이 배치 시작 시(즉, 프로세스의 이면 목적)에 대한 기대치를 설정하고 표현하도록 학습자를 준비시키는 경우, 이는 사용 가능한 시간의 사용을 최적화하는 데 도움이 될 수 있다.

There are often no easy answers in managing complex situations such as competing demands within limited time. Faculty development workshops can acknowledge the challenges presented by departmental and institutional constraints. Prompting clinical supervisors to specifically address their logistics may be beneficial. This may require orientation to thinking about placements as a whole, rather than only focusing on the micro-skills of the interpersonal exchange. For example, if clinical supervisors prepare learners in establishing and articulating expectations at the beginning of the placement (i.e. the purpose behind processes), then this may assist in optimizing use of available time.

마지막으로, '학습의 평가assessment of learning'가 거의 언급되지 않았다는 점에 주목할 필요가 있다. 이는 MCTQ가 제공하는 오리엔테이션에 대한 응답일 수 있지만, 임상 감독자, 교수 개발자 및 의료 교육 전문가들이 평가와 학습 촉진을 별개의 노력으로 보는지는 의문이다. 확실히 그들은 종종 별도의 도메인으로 표시된다(Academy of Medical Educators 2014). 그러나, [학생들의 작업에 대한 평가 또는 판단을 하는 것]은 종종 피드백과 불가분의 관계에 있어 학습을 촉진한다. 학습 내에서 작업에 대한 판단을 촉진하는 것이 '학습을 위한 평가assessment for learning'를 도입하는 실질적인 수단일 수 있음을 제안한다(Schuwirth and van der Vleuten 2011).

Finally, it is worth noting ‘assessment of learning’ was barely mentioned. This may be a response to the orientation provided by the MCTQ, however we wonder if clinical supervisors, faculty developers and medical education experts see assessment and facilitating learning as being separate endeavors. Certainly they are frequently indicated as separate domains (Academy of Medical Educators 2014). However, we suggest that assessment, or making judgements about students’ work is often inextricably linked to feedback and hence facilitating learning. We suggest that promoting judgements about work within learning may be a practical means of introducing ‘assessment for learning’ (Schuwirth and van der Vleuten 2011).

결론

Conclusions

Academy of Medical Educators, Professional Standards. (2014). http://www.medicaleducators.

org/write/MediaManager/AOME_Professional_Standards_2014.pdf. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

Ajjawi, R., & Boud, D. (2015). Researching feedback dialogue: An interactional analysis approach. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2015.1102863. XXXBoud, D., & Molloy, E. (2013). Rethinking models of feedback for learning: The challenge of design. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 38, 698–712. doi:10.1080/02602938.2012.691462.

Strand, P., Edgren, G., Borna, P., Lindgren, S., Wichmann-Hansen, G., &Stalmeijer, R. (2015). Conceptions of how a learning or teaching curriculum, workplace culture and agency of individuals shape medical student learning and supervisory practices in the clinical workplace. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 20, 531–557. doi:10.1007/s10459-014-9546-0. XXX

Tai, J., Bearman, M., Edouard, V., Kent, F., Nestel, D., & Molloy, E. (2015). Clinical supervision training across contexts. The Clinical Teacher. doi:10.1111/tct.12432. XXXVaismoradi, M., Turunen, H., &Bondas, T. (2013). Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nursing and Health Sciences, 15, 398–405. doi:10.1111/ nhs.12048.

Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract

. 2018 Mar;23(1):29-41.

doi: 10.1007/s10459-017-9772-3. Epub 2017 Mar 17.

What should we teach the teachers? Identifying the learning priorities of clinical supervisors

Margaret Bearman 1, Joanna Tai 2, Fiona Kent 3 4, Vicki Edouard 3, Debra Nestel 5 6, Elizabeth Molloy 7

Affiliations collapse

Affiliations

-

1Centre for Research into Assessment and Digital Learning (CRADLE), Deakin University, Geelong, Australia. margaret.bearman@deakin.edu.au.

-

2Centre for Research into Assessment and Digital Learning (CRADLE), Deakin University, Geelong, Australia.

-

3Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia.

-

4WISER Unit, Monash Health, Melbourne, Australia.

-

5Department of Surgery, Melbourne Medical School, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia.

-

6Monash Institute of Health and Clinical Education, Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia.

-

7Department of Medical Education, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia.

-

PMID: 28315114

Abstract

Clinicians who teach are essential for the health workforce but require faculty development to improve their educational skills. Curricula for faculty development programs are often based on expert frameworks without consideration of the learning priorities as defined by clinical supervisors themselves. We sought to inform these curricula by highlighting clinical supervisors own requirements through answering the research question: what do clinical supervisors identify as relative strengths and areas for improvement in their teaching practice? This mixed methods study employed a modified version of the Maastricht Clinical Teaching Questionnaire (mMCTQ) which included free-text reflections. Descriptive statistics were calculated and content analysis was conducted on textual comments. 481 (49%) of 978 clinical supervisors submitted their mMCTQs and associated reflections for the research study. Clinical supervisors self-identified relatively strong capability with interpersonal skills or attributes and indicated least capability with assisting learners to explore strengths, weaknesses and learning goals. The qualitative category 'establishing relationships' was the most reported strength with 224 responses. The qualitative category 'feedback' was the most reported area for improvement, with 151 responses. Key areas for curricular focus include: improving feedback practices; stimulating reflective and agentic learning; and managing the logistics of a clinical education environment. Clinical supervisors' self-identified needs provide a foundation for designing engaging and relevant faculty development programs.

Keywords: Clinical education frameworks; Clinical supervision; Clinical teaching; Faculty development; Health professional education.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 교수개발(Faculty Development)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 보건전문직 교수개발에서 어떻게 문화가 이해되는가: 스코핑 리뷰(Acad Med, 2020) (0) | 2021.02.07 |

|---|---|

| 임상교육자에서 교육적 학자, 그리고 리더: HPE분야에서 커리어 개발(Clin Teach, 2020) (0) | 2021.02.07 |

| 걸출한 교육자 되기: 성공에 대하여 뭐라고 말하는가? (Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract, 2020) (0) | 2021.02.05 |

| HPE 교육과 실천에서 앎과 함 단절(Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract, 2020) (0) | 2020.07.16 |

| 교육적 타당도: 다양한 형태의 '좋은' 가르침을 이해하는 핵심(Med Teach, 2019) (0) | 2020.03.20 |