교수자 준비에 테크놀로지 통합을 위한 PICRAT 모델(Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 2020)

The PICRAT Model for Technology Integration in Teacher Preparation

Royce Kimmons, Charles R. Graham, & Richard E. West

교육 테크놀로지 통합을 위해서는 교사 교육자가 다음과 씨름해야 합니다.

- (a) 끊임없이 변화하고 정치적으로 영향을 받는 전문적 요구 사항,

- (b) 지속적으로 진화하는 교육 테크놀로지 리소스,

- (c) 콘텐츠 분야와 맥락에 따른 다양한 요구 사항

교사는 학생들이 미래에 교육용 테크놀로지를 어떻게 사용할지 또는 교직 생활 동안 테크놀로지가 어떻게 변화할지 예측할 수 없습니다. 따라서 학생 교사가 의미 있고 효과적이며 지속 가능한 방식으로 테크놀로지 통합을 실천하도록 교육하는 것은 어려운 과제입니다. 우리는 이러한 요구에 대응하기 위한 이론적 모델인 PICRAT을 제안합니다.

Teaching technology integration requires teacher educators to grapple with

- (a) constantly changing, politically impacted professional requirements,

- (b) continuously evolving educational technology resources, and

- (c) varying needs across content disciplines and contexts.

Teacher educators cannot foresee how their students may be expected to use educational technologies in the future or how technologies will change during their careers. Therefore, training student teachers to practice technology integration in meaningful, effective, and sustainable ways is a daunting challenge. We propose PICRAT, a theoretical model for responding to this need.

현재 학생 교사가 효과적인 테크놀로지 통합을 개념화하는 데 도움이 되는 다양한 이론적 모델이 사용되고 있는데, 여기에는 다음 등이 있다.

- 테크놀로지, 페다고지 및 콘텐츠 지식(TPACK; Koehler & Mishra, 2009),

- 대체-증강-수정-재정의(SAMR; Puentedura, 2003),

- 테크놀로지 통합 계획(TIP; Roblyer & Doering, 2013),

- 테크놀로지 통합 매트릭스(TIM; Harmes, Welsh, & Winkelman, 2016),

- 테크놀로지 수용 모델(TAM; Venkatesh, Morris, Davis, & Davis, 2003),

- 테크놀로지 통합 수준(LoTi; Moersch, 1995),

- 대체 - 증폭 - 변환(RAT; Hughes, Thomas, & Scharber, 2006)

Currently, various theoretical models are used to help student teachers conceptualize effective technology integration, including

- Technology, Pedagogy, and Content Knowledge (TPACK; Koehler & Mishra, 2009),

- Substitution – Augmentation – Modification – Redefinition (SAMR; Puentedura, 2003),

- Technology Integration Planning (TIP; Roblyer & Doering, 2013),

- Technology Integration Matrix (TIM; Harmes, Welsh, & Winkelman, 2016),

- Technology Acceptance Model (TAM; Venkatesh, Morris, Davis, & Davis, 2003),

- Levels of Technology Integration (LoTi; Moersch, 1995), and

- Replacement – Amplification – Transformation (RAT; Hughes, Thomas, & Scharber, 2006).

이러한 모델은 교육 테크놀로지 연구를 위한 방법론적 접근을 정당화하기 위해 문헌 전반에 걸쳐 일반적으로 참조되지만, 교육 테크놀로지 연구를 개선하거나 교육 테크놀로지 통합을 위한 효과성, 정확성 또는 가치를 측정하기 위한 이론적 비판과 최소한의 평가 작업은 거의 찾아볼 수 없습니다(Kimmons, 2015; Kimmons & Hall, 2017). 이러한 모델을 비판적으로 평가하고, 분류 및 비교하고, 지속적인 개발을 지원하고, 모델을 채택하기 위한 가정과 프로세스를 이해하거나, 이 영역에서 무엇이 좋은 이론을 구성하는지 탐구하는 데 노력을 기울인 연구자는 상대적으로 적습니다(Archambault & Barnett, 2010; Archambault & Crippen, 2009; Brantley-Dias & Ertmer, 2013; Graham, 2011; Graham, Henrie, & Gibbons, 2014; Kimmons, 2015; Kimmons & Hall, 2016a, 2016b, 2017).

Though these models are commonly referenced throughout the literature to justify methodological approaches for studying educational technology, little theoretical criticism and minimal evaluative work can be found to gauge their efficacy, accuracy, or value, either for improving educational technology research or for teaching technology integration (Kimmons, 2015; Kimmons & Hall, 2017). Relatively few researchers have devoted effort to critically evaluating these models, categorizing and comparing them, supporting their ongoing development, understanding assumptions and processes for adopting them, or exploring what constitutes good theory in this realm (Archambault & Barnett, 2010; Archambault & Crippen, 2009; Brantley-Dias & Ertmer, 2013; Graham, 2011; Graham, Henrie, & Gibbons, 2014; Kimmons, 2015; Kimmons & Hall, 2016a, 2016b, 2017).

즉, 교육 테크놀로지자들은 경쟁 모델을 비판적으로 평가하고, 그 사용법을 이해하고, 시간이 지남에 따라 발전하는 모델을 탐구하지 않고 쿤(1996)이 "정상적인 과학"이라고 간주한 것에 크게 관여하는 것으로 보입니다. 실용적인 테크놀로지 통합을 형성하는 이론과 현실에 대한 비판적 담론에 참여하지 않는 것은 실무에 심각한 영향을 미치며, Selwyn(2010)이 "지난 25년간의 교육 테크놀로지 장학의 대부분을 관통하는 수사학과 현실 사이의 명백한 불균형"(66쪽)으로 이어져 교육 테크놀로지에 대한 약속을 상대적으로 실현하지 못하는 결과를 초래합니다.

In other words, educational technologists seem to be heavily involved in what Kuhn (1996) considered “normal science” without critically evaluating competing models, understanding their use, and exploring their development over time. Reticence to engage in critical discourse about theory and realities that shape practical technology integration has serious implications for practice, leading to what Selwyn (2010) described as “an obvious disparity between rhetoric and reality [that] runs throughout much of the past 25 years of educational technology scholarship” (p. 66), leaving promises of educational technologies relatively unrealized.

현존하는 모델과 실천의 이론적 토대에 대한 비판적 논의가 필요하기 때문에 우리는 다음 등의 개념적 틀을 제시합니다.

- (a) 이론적 모델이 무엇이며 교육 테크놀로지 통합에 왜 필요한지,

- (b) 시간이 지남에 따라 어떻게 채택되고 개발되는지,

- (c) 무엇이 좋은지 나쁜지,

- (d) 기존 테크놀로지 통합 모델이 교사 준비에 어려움을 일으키는지

이러한 배경을 바탕으로 학생 교사가 테크놀로지 통합 소양을 개발하는 데 도움이 될 수 있는 새로운 이론적 모델, 즉 휴즈 외(2006)의 이전 연구를 기반으로 한 PICRAT을 제안합니다.

Needing a critical discussion of extant models and theoretical underpinnings of practice, we provide a conceptual framework, including

- (a) what theoretical models are and why we need them for teaching technology integration,

- (b) how they are adopted and developed over time,

- (c) what makes them good or bad, and

- (d) how existing models of technology integration cause struggle in teacher preparation.

With this backdrop, we propose a new theoretical model, PICRAT, built on the previous work of Hughes et al. (2006), which can guide student teachers in developing technology integration literacies.

이론적 모델

Theoretical Models

저자들은 종종 모델, 이론, 패러다임, 프레임워크와 같은 용어를 혼용하여 사용합니다(예: 파라데이그마는 그리스어로 패턴, 삽화 또는 모델을 의미함; 참조: Dubin, 1978; Graham et al., 2014; Kimmons & Hall, 2016a; Kimmons & Johnstun, 2019; Whetten, 1989). 그러나 테크놀로지 통합 모델에 대해서는 이론적 모델이라는 용어를 사용하는데, 이는 우리가 논의하는 구성의 개념적, 조직적, 반영적 특성을 함축하고 있기 때문입니다.

Authors frequently use terms such as model, theory, paradigm, and framework interchangeably (e.g., paradeigma is Greek for pattern, illustration, or model; cf. Dubin, 1978; Graham et al., 2014; Kimmons & Hall, 2016a; Kimmons & Johnstun, 2019; Whetten, 1989). However, we rely on the term theoretical model for technology integration models, as it encapsulates the conceptual, organizational, and reflective nature of constructs we discuss.

모델 목적 및 구성 요소

Model Purposes and Components

이론적 모델은 현상을 개념적으로 표현하여 개인이 개별적으로나 상호 작용적으로 자신의 경험을 조직하고 이해할 수 있도록 합니다. 하드 과학과 사회 과학의 모든 학문은 이론적 모델을 활용하며, 전문가들은 본질적으로 질서정연하지 않고 복잡하며 지저분한 자연 및 사회 세계를 이해하기 위해 이러한 모델을 사용합니다. 이론 개발에 관한 Dubin(1978)의 방대한 연구를 요약한 Whetten(1989)은 모든 이론적 모델의 네 가지 필수 요소인 '무엇을, 어떻게, 왜, 누가/어디서/언제'를 설명했습니다.

A theoretical model conceptually represents phenomena, allowing individuals to organize and understand their experiences, both individually and interactively. All disciplines in hard and social sciences utilize theoretical models, and professionals use these models to make sense of natural and social worlds that are inherently unordered, complex, and messy. Summarizing Dubin’s (1978) substantial work on theory development, Whetten (1989) explained four essential elements for all theoretical models: the what, how, why, and who/where/when.

첫째, 모델은 연구된 현상의 내용을 설명하는 충분한 변수, 구조, 개념 및 세부 사항을 포함하여, 이론을 포괄적이면서도 충분히 제한하여 간결성을 유지하고 지나치게 광범위하지 않도록 해야 합니다.

First, models must include sufficient variables, constructs, concepts, and details explaining the what of studied phenomena to make the theories comprehensive but sufficiently limited to allow for parsimony and to prevent overreaching.

둘째, 모델은 구성 요소들이 어떻게 상호 연관되어 있는지를 다루어야 합니다. 즉, 이론가들이 새로운 방식으로 세상을 이해할 수 있도록 하는 모델의 범주화 또는 구조입니다.

Second, models must address how components are interrelated: the categorization or structure of the model allowing theorists to make sense of the world in novel ways.

셋째, 모델은 구성 요소가 제안된 형태로 관련되어 있는 이유를 뒷받침하는 논리와 근거를 제공해야 합니다. 여기에는 일반적으로 모델의 가정이 명시적이든 암시적이든 남아 있으며, 모델의 논증력은 이론가가 모델이 합리적이라는 강력한 사례를 제시할 수 있는 능력에 달려 있습니다.

Third, models must provide logic and rationale to support why components are related in the proposed form. Herein the model’s assumptions generally linger (explicitly or implicitly); its argumentative strength relies on the theorist’s ability to make a strong case that it is reasonable.

넷째, 모델은 누가, 어디서, 언제 적용하는지를 나타내는 컨텍스트에 구속되어야 합니다. 모델은 모든 것에 대한 이론이 아니며, 모델을 특정 맥락(예: 미국 교사 교육)에 한정함으로써 이론가는 순수성을 높이고 비평가에 더 쉽게 대응할 수 있습니다(Dubin, 1978).

Fourth, models must be bounded by a context representing the who, where, and when of its application. Models are not theories of everything; by bounding the model to a specific context (e.g., U.S. teacher education), theorists can increase purity and more readily respond to critics (Dubin, 1978).

테크놀로지 통합 모델의 등장

Emergence of Technology Integration Models

많은 교사 교육자들은 무정부적인 방식으로 또는 진영에 따라 테크놀로지 통합 모델을 채택합니다(Feyerabend, 1975; Kimmons, 2015; Kimmons & Hall, 2016a; Kimmons & Johnstun, 2019). 즉, 경쟁 모델에 대한 정당화나 비교 없이 자체 훈련을 통해 학습된 모델을 사용합니다. 문헌은 모델 비교나 선택의 근거 없이 도구가 만들어지고 연구가 구성되기 때문에 이러한 캠프를 반영합니다(참조: Kimmons, 2015b). 각 진영은 다른 진영을 인정하지도, 그들과의 관계를 인정하지도 않은 채 고유한 언어(TPACK, TIM, TAM, SAMR, LoTi 등)를 사용합니다.

Many teacher educators adopt technology integration models in anarchic ways or according to camps (Feyerabend, 1975; Kimmons, 2015; Kimmons & Hall, 2016a; Kimmons & Johnstun, 2019). That is, they use models enculturated to them via their own training without justification or comparison of competing models. Literature reflects these camps, as instruments are built and studies are framed without comparison of models or rationales for choice (cf. Kimmons, 2015b). Each camp speaks its own language (TPACK, TIM, TAM, SAMR, LoTi, etc.), neither recognizing other camps nor acknowledging relationships to them.

이러한 단절이 이론적 비호환성에서 비롯된 것이든 기회주의에서 비롯된 것이든(Feyerabend, 1975; Kuhn, 1996 참조), 우리는 이론적 다원주의, 즉 "다양한 모델이 서로 다른 맥락에서 적절하고 가치 있다는 것"(Kimmons & Hall, 2016a, 54쪽; Kimmons & Johnstun, 2019)에 대해 조언합니다. 따라서 우리는 "하나의 이론적 관점이나 방법론을 우월한 것으로 확립하려는 패러다임 전쟁"을 수행할 필요성을 느끼지 않으며, 이를 "비생산적인 논쟁"으로 간주합니다(Burkhardt & Schoenfeld, 2003, 9쪽).

Whether this disconnect results from theoretical incommensurability or opportunism (cf. Feyerabend, 1975; Kuhn, 1996), we advise theoretical pluralism: “that various models are appropriate and valuable in different contexts” (Kimmons & Hall, 2016a, p. 54; Kimmons & Johnstun, 2019). Thus, we do not perceive a need to conduct “paradigm wars that seek to establish a single theoretical perspective or methodology as superior,” considering such to be an “unproductive disputation” (Burkhardt & Schoenfeld, 2003, p. 9).

그러나 우리는 "어떤 [모델]도 그것이 정의하는 모든 문제를 해결하지 못하며", "어떤 두 [모델]도 동일한 문제를 모두 해결하지 못하기 때문에"(Kuhn, 1996, 110쪽) 이론적 모델의 어포던스, 한계, 모순, 다른 모델과의 관계에 대한 논의가 거의 없이 이 분야에서 이론적 모델을 지속적으로 채택하는 것은 심각한 우려 사항이라고 주장합니다. 이 분야에서 이론적 진영의 어려움은 다원주의가 아니라 진영 간의 상호 이해와 의미있는 상호 의사 소통의 부재와 경쟁 이론의 장단점을 평가하지 않고 교육자들이이를 진지하게 받아들이지 않는다는 것입니다 (Willingham, 2012). 여러 캠프 간에 대화하거나 다양한 캠프를 형성하는 기본 이론을 비판적으로 평가하지 않으려는 태도는 전문적인 사일로를 초래하고 우리 분야가 교육에서 테크놀로지 통합의 다면적인 복잡성과 효과적으로 씨름하는 데 방해가 됩니다.

We contend, however, that the field’s ongoing adoption of theoretical models with little discussion of their affordances, limitations, contradictions, and relationships to others is of serious concern, because “no [model] ever solves all the problems it defines,” and “no two [models] leave all the same problems unsolved” (Kuhn, 1996, p. 110). The difficulty with theoretical camps in this field is not pluralism but absence of mutual understanding and meaningful cross-communication among camps, along with the failure to weigh the advantages and disadvantages of competing theories, revealing that educators do not take them seriously (Willingham, 2012). Unwillingness to dialogue across camps or to evaluate critically the underlying theories shaping diverse camps leads to professional siloing and prevents our field from effectively grappling with the multifaceted complexities of technology integration in teaching.

테크놀로지 통합 교육을 위한 좋은 모델

A Good Model for Teaching Technology Integration

쿤(2013)은 특정 이론적 모델을 우월한 것으로 식별하는 핵심 특성을 가진 채택 모델링 구조를 주장했습니다. 이러한 특성은 분야와 적용 맥락에 따라 다소 다르며, 이 분야의 이론적 모델은 하드 과학 분야의 모델과 다른 용도로 사용되며 교사 교육자는 교육 연구자나 테크놀로지자와는 다른 방식으로 모델을 활용합니다(Gibbons & Bunderson, 2005).

Kuhn (2013) argued for a structure to model adoption, with core characteristics identifying certain theoretical models as superior. These characteristics vary somewhat by field and context of application; theoretical models in this field serve different purposes than do models in the hard sciences, and teacher educators will utilize models differently than will educational researchers or technologists (Gibbons & Bunderson, 2005).

Kimmons와 Hall(2016a)은 "[모델의] 가치 결정은 순전히 자의적인 것이 아니라 입양인의 신념, 필요, 욕구, 의도를 나타내는 구조화된 가치 체계에 기반한다"고 말했습니다(55페이지). 교사 교육 테크놀로지 통합 모델의 품질을 결정하기 위해 여섯 가지 기준이 제안되었습니다(표 1 참조).

- (a) 명확성,

- (b) 호환성,

- (c) 학생 중심,

- (d) 유익성,

- (e) 테크놀로지 역할

- (f) 범위

Kimmons and Hall (2016a) said, “Determinations of [a model’s] value are not purely arbitrary but are rather based in structured value systems representing the beliefs, needs, desires, and intents of adoptees” in a particular context (p. 55). Six criteria have been proposed for determining quality of teacher education technology integration models:

- (a) clarity,

- (b) compatibility,

- (c) student focus,

- (d) fruitfulness,

- (e) technology role, and

- (f) scope (see Table 1).

첫째, 테크놀로지 통합 모델은 혼란과 '숨겨진 복잡성'을 유발하는 설명과 구성을 피하고 "개념적으로나 실제로 이해하기 쉽고 간단해야" 합니다(Graham, 2011, 1955쪽; Kimmons, 2015). 이상적으로 모델은 교사에게 빠르게 설명할 수 있을 만큼 간결하고 실제 수업에 쉽게 적용할 수 있는 직관적이고 실용적이며 가치 평가가 쉬운 것이 좋습니다. 긴 설명이 필요하거나, 너무 많은 구성을 소개하거나, 교사의 일상적인 필요의 중심이 아닌 문제를 다루는 모델은 재평가하거나 단순화하거나 피해야 합니다.

First, technology integration models should be “simple and easy to understand conceptually and in practice” (Kimmons & Hall, 2016a, pp. 61–62), eschewing explanations and constructs that invite confusion and “hidden complexity” (Graham, 2011, p. 1955; Kimmons, 2015). Ideally, a model is concise enough to be quickly explained to teachers and easily applied in their practice — intuitive, practical, and easy to value. Models requiring lengthy explanation, introducing too many constructs, or diving into issues not central to teachers’ everyday needs should be reevaluated, simplified, or avoided.

둘째, "기존의 교육 및 교육적 관행"과의 호환성(즉, 일치성)이 중요합니다. 교사는 제한된 개념적 오버헤드로 일상적인 교실 문제를 해결하는 데 도움이 되는 실용적인 모델을 원합니다. 우리는 이전의 경험적 연구에서 다음과 같은 결론을 내렸습니다:

Second, compatibility (i.e., alignment) with “existing educational and pedagogical practices” (Kimmons & Hall, 2016a, p. 55) is important. Teachers want practical models that help them address everyday classroom issues with limited conceptual overhead. We concluded the following in an earlier empirical study:

교사들은 자신의 성과와 학생의 성과에 대한 외부 요구 사항에 의해 주도되는 세상에 처해 있으며, 테크놀로지가 교육 시스템을 어떻게 변화시키고 있는지에 대한 광범위한 이론적 논의는 그다지 도움이 되지 않습니다..... 전형적인 교사는 교육 기관에서 규정하는 방식으로 자신이 돌보는 지역 학생들의 요구를 해결하는 데 가장 관심이 있는 것 같습니다. (Kimmons & Hall, 2016b, 23쪽)

Teachers find themselves in a world driven by external requirements for their own performance and the performance of their students, and broad, theoretical discussions about how technology is transforming the educational system are not very helpful…. The typical teacher seems to be most concerned with addressing the needs of the local students under their care in the manner prescribed to them by their institutions. (Kimmons & Hall, 2016b, p. 23)

따라서 테크놀로지 통합 모델은 광범위한 개념(예: 사회 변화)이나 비현실적인 테크놀로지 요구 사항(예: 빈곤 지역사회의 교사 대 기기 비율 1:1)보다는 "식별 가능한 영향과 테크놀로지에 대한 현실적인 접근"(24쪽)에 중점을 두어야 합니다.

Thus, technology integration models should emphasize “discernible impact and realistic access to technologies” (p. 24) rather than broad concepts (e.g., social change) or unrealistic technological requirements (e.g., 1:1 teacher–device ratios in poor communities).

셋째, 유익한 모델은 "다양한 목적을 가진 다양한 사용자들 사이에서 채택을 장려하고 학문 분야와 전통적인 실천의 사일로를 가로지르는 가치 있는 결과를 산출"해야 합니다(Kimmons & Hall, 2016a, 58쪽). 우리는 교사를 가르치는 데 사용되는 테크놀로지 통합 모델이 연결과 사려 깊은 질문의 라인을 생성하고, 모델이 없었다면 발생하지 않았을 방식으로 여러 실천 영역으로 확장하고, 모델 구현의 초기 범위를 넘어서는 통찰력을 얻는 등 유익한 사고를 이끌어 내야한다고 의도합니다.

Third, fruitful models should encourage adoption among “a diversity of users for diverse purposes and yield valuable results crossing disciplines and traditional silos of practice” (Kimmons & Hall, 2016a, p. 58). We intend that technology integration models used to teach teachers should elicit fruitful thinking: yielding connections and thoughtful lines of questioning, expanding across multiple areas of practice in ways that would not have occurred without the model, and yielding insights beyond the initial scope of the model’s implementation.

넷째, 테크놀로지의 역할은 그 자체가 목적이 아니라 목적을 위한 수단으로 사용되어야 하며, 테크놀로지 중심적 사고를 피해야 합니다(Papert, 1987, 1990). 테크놀로지 통합 모델이라고도 하지만, 그 목표는 통합을 넘어 페다고지 또는 학습의 개선을 강조하는 것이어야 합니다. 이 모델은 테크놀로지 사용을 정당화할 수 있는 기반 없이 단순히 교육자가 테크놀로지를 사용하도록 안내해서는 안 됩니다. 이러한 수단 지향적 관점에서는 테크놀로지를 원하는 결과에 영향을 미치는 여러 요소 중 하나로 간주해야 합니다.

Fourth, technology’s role should serve as a means to an end, not an end in itself — avoiding technocentric thinking (Papert, 1987, 1990). Though referred to as technology integration models, their goal should go beyond integration to emphasize improved pedagogy or learning. The model should not merely guide educators in using technology without a foundation for justifying its use. This means-oriented view should place technology as one of many factors to influence desired outcomes.

다섯째, 테크놀로지 통합의 대상, 방법, 이유를 실무자에게 안내하기 위해서는 적절한 범위가 필요합니다. 모델은 기존 관행과 호환되는 동시에 교사가 테크놀로지 사용에 대해 더 나은 정보를 바탕으로 선택할 수 있도록 영향을 미쳐야 합니다. Burkhardt와 Schoenfeld(2003)는 다음과 같이 설명했습니다,

Fifth, suitable scope is necessary for guiding practitioners in the what, how, and why of technology integration. While being compatible with existing practices, models should also influence teachers in better-informed choices about technology use. As Burkhardt and Schoenfeld (2003) explained,

교육에 적용된 대부분의 이론은 상당히 광범위합니다. "공학적 힘"이라고 할 수 있는 것이 부족합니다... [또는] 설계를 안내하고, 좋은 아이디어를 취하고, 실제로 작동하도록 하는 데 도움이 되는 구체성이 부족합니다. ... 교육은 이론의 범위와 신뢰성에서 [다른 분야]에 비해 훨씬 뒤쳐져 있습니다. 이론의 힘을 과대평가함으로써 ... 피해가 발생했습니다. ... 국지적 또는 현상학적 이론은 ... 현재 설계에서 더 가치가 있습니다. (p. 10)

Most of the theories that have been applied to education are quite broad. They lack what might be called “engineering power” … [or] the specificity that helps to guide design, to take good ideas and make sure that they work in practice. … Education lags far behind [other fields] in the range and reliability of its theories. By overestimating theories’ strength … damage has been done. … Local or phenomenological theories … are currently more valuable in design. (p. 10)

이런 식으로 "범위와 호환성은 상충되는 것처럼 보일 수 있습니다 ... 호환성이 뛰어난 모델은 현상 유지를 지원하는 것으로 인식 될 수있는 반면, 글로벌 범위를 가진 모델은 광범위한 변화를 지원하는 것으로 인식 될 수 있습니다."(Kimmons & Hall, 2016a, p. 57). 그러나 좋은 모델은 포괄성과 간결함의 균형을 유지하며(Dubin, 1978), 교사를 실질적으로 안내하고 사회 및 교육 문제의 더 큰 배경에 대해 자신의 실천을 비판적으로 평가할 수 있도록 개념적으로 유도합니다. 이러한 모델은 "정확히 한 집단"(137쪽)에 집착하지 않으면서 모든 교육 전문가에게 광범위하게 적용될 수 있도록 노력해야 합니다. 우리의 맥락에서 모델의 범위는 학생 교사에 초점을 맞춰야 하며, 현직 교사와 다른 교사에게도 적용될 수 있어야 합니다.

In this way “scope and compatibility may seem at odds … models that excel in compatibility may be perceived as supporting the status quo, while models with global scope may be perceived as supporting sweeping change” (Kimmons & Hall, 2016a, p. 57). However, a good model balances comprehensiveness and parsimony (Dubin, 1978), both guiding teachers practically and prompting them conceptually in critically evaluating their practice against a larger backdrop of social and educational problems. Any such model should seek to apply to all education professionals broadly while fixating on a “population of exactly one” (p. 137). In our context, a model’s scope should focus squarely on student teachers, with possible applicability to practicing teachers and others as well.

마지막으로, 학생 중심은 테크놀로지 통합 모델에 필수적입니다. 윌링햄(2012)이 설명했듯이 "교육 시스템의 변화가 궁극적으로 학생 사고의 변화로 이어지지 않는다면 무의미하다"(155쪽)고 할 수 있습니다. 테크놀로지 통합을 둘러싼 문헌에서는 테크놀로지-페다고지 관계나 수업 개선으로서의 비디오 등 교사 또는 활동 중심의 분석에 치우쳐 학생을 무시하는 경우가 너무 많습니다. "일부 모델은 학생의 결과를 암시할 수 있지만, 테크놀로지 통합 과정에서 이러한 결과를 ... [우선적으로] 제공하지 않을 수 있습니다."(Kimmons & Hall, 2016a, 61쪽) 이는 교사에게 학생을 고려하는 것이 가장 중요하지 않다는 신호를 줄 수 있습니다.

Finally, student focus is vital for a technology integration model. As Willingham (2012) explained, “changes in the educational system are irrelevant if they don’t ultimately lead to changes in student thought” (p. 155). Too often the literature surrounding technology integration ignores students in favor of teacher- or activity-centered analyses of practice: perhaps the technology–pedagogy relationship or video as lesson enhancement. “Though some models may allude to student outcomes, they may not give these outcomes … [primacy] in the technology integration process” (Kimmons & Hall, 2016a, p. 61), which may signal to teachers that student considerations are not of primary importance.

기존 테크놀로지 통합 모델의 약점

Weaknesses of Existing Technology Integration Models

가장 널리 사용되는 테크놀로지 통합 모델에는 각각 장단점이 있습니다. 현장에 더 적합한 모델의 필요성을 정당화하기 위해 이 섹션에서는 학생 교사를 위한 테크놀로지 통합을 지도하는 맥락에서 기존 7가지 모델(LoTi, RAT, SAMR, TAM, TIM, TIP 및 TPACK)에 내재된 주요 제한 사항 또는 어려움을 요약합니다. 이 간략한 요약만으로는 각 모델의 장점을 모두 설명할 수 없습니다. 자세한 내용은 Kimmons and Hall(2016a)을 포함하여 이전에 참조한 출판물에서 얻을 수 있습니다.

Each of the most popular technology integration models has strengths and weaknesses. To justify the need for a model better suited for the field, we summarize in this section the major limitations or difficulties inherent to seven existing models — LoTi, RAT, SAMR, TAM, TIM, TIP, and TPACK — in the context of guiding technology integration for student teachers. This brief summary will not do justice to the benefits of each of these models. Additional detail may be obtained from the previously referenced publications, including Kimmons and Hall (2016a).

우리는 모델에 대한 근거 없는 주장을 제공하거나 모델의 어포던스를 무시했다는 비판을 받을 수도 있지만, 단지 이러한 각 모델이 교사 교육에 한계가 있을 수 있는 영역임을 제안하기 위해 선택했습니다. 이러한 영역 중 일부는 선행 문헌에서 살펴본 것이지만, 다른 영역은 테크놀로지 통합 분야에서 교사 교육자로서의 경험에서 도출한 것으로 표 2에 간략히 요약되어 있습니다. 또한 이러한 비평은 다른 교육 관련 맥락(예: 교육 행정 또는 교육 설계)에는 적용되지 않을 수 있으며 교사 교육에 전적으로 초점을 맞추고 있습니다. 다음 섹션에 나열된 각 주장에 대해 확실한 논거나 증거를 제시하지는 않지만(그렇게 하려면 여러 번의 연구와 책 분량으로 다루어야 합니다), 이러한 불만을 표출하는 것은 이 전문적인 영역의 격차를 해소하고 진행하기 위해 필요합니다. 요약하자면, 우리의 목표는 열거된 각각의 어려움이 논란의 여지가 없는 사실이라고 누구에게나 설득하는 것이 아니라, 단지 우리 자신의 추론과 경험에 대한 투명성을 제공하는 것입니다.

We may be critiqued for providing strawman arguments against models or ignoring their affordances, but we have chosen merely to suggest that these might be areas where each of these models may have limitations for teacher education. Several of these areas have been explored in prior literature, whereas others are drawn from our own experiences as teacher educators in the technology integration space, briefly summarized in Table 2. Additionally, these critiques may not apply in other education-related contexts (e.g., educational administration or instructional design) and are squarely focused on teacher education. Even though we do not provide ironclad arguments or evidence for each claim listed in the subsequent section (doing so would require multiple studies and book-length treatment), voicing these frustrations is necessary for proceeding and for articulating a gap in this professional space. In sum, our goal is not to convince anyone that each enumerated difficulty is incontrovertibly true but merely to provide transparency about our own reasoning and experiences.

명확성. 많은 테크놀로지 통합 모델은 지나치게 이론적이거나, 기만적이거나, 직관적이지 않거나, 혼란스럽기 때문에 교사에게 불분명합니다. 예를 들어, SAMR, TIM, TPACK은 다양한 통합 수준(분류)을 제공하지만 이를 명확하게 정의하거나 다른 수준과 구분하지 않을 수 있습니다. 따라서 학생 교사는 이를 이해하기 어렵거나 부정확하거나 쓸모없는 방식으로 인위적으로 관행을 분류할 수 있습니다. 대부분의 모델에는 교사가 이해하기 어려울 수 있는 특정 개념(예: TPACK의 과녁 영역, TIP의 상대적 우위, SAMR의 대체 대 증강, TIM 및 RAT의 변환)이 포함되어 있어 복잡한 문제를 피상적으로 이해하거나 상대적으로 얕은 테크놀로지 사용에 대한 정교하지 못한 근거를 제시하게 됩니다.

Clarity. Many technology integration models are unclear for teachers, being overly theoretical, deceptive, unintuitive, or confusing. For instance, SAMR, TIM, and TPACK provide a variety of levels (classifications) of integration but may not clearly define them or distinguish them from other levels. Student teachers, thus, may have difficulty understanding them or may artificially classify practices in inaccurate or useless ways. Most models include specific concepts that may be difficult for teachers to comprehend (e.g., the bullseye area in TPACK, relative advantage in TIP, substitution vs. augmentation in SAMR, or transformation in TIM and RAT), leading to superficial understanding of complex issues or to unsophisticated rationales for relatively shallow technology use.

테크놀로지 통합의 맥락적 복잡성을 인식한 미슈라와 쾰러(2007)는 모든 통합 사례는 "사악한 문제"라고 주장했습니다. 이러한 특성화는 정확할 수 있지만, 교사는 이러한 복잡성을 명확하고 직관적으로 파악할 수 있도록 안내하는 모델이 필요합니다.

Recognizing the contextual complexities of technology integration, Mishra and Koehler (2007) argued that every instance of integration is a “wicked problem.” Although this characterization may be accurate, teachers need models to guide them in grappling clearly and intuitively with such complexities.

호환성. 초중고 교사에게 적합하지 않은 것으로 간주되는 모델은 비실용적이거나 교사의 일상적인 필요의 중심이 아닌 구성을 강조합니다. 예를 들어, TAM은 채택에 영향을 미치는 사용자 인식에만 초점을 맞추고 수업 계획 개발, 학생 학습 안내 또는 교실 행동 관리에는 거의 적용되지 않습니다. 교육자를 위해 개발된 모델조차도 교사의 요구와 맞지 않는 활동(예: LoTi의 학생 활동)에 초점을 맞추거나 너무 이론적이어서 교사 실무에 직접 적용하기 어려울 수 있습니다(예: TPACK의 테크놀로지 콘텐츠 지식).

Compatibility. Models we consider incompatible for K–12 teachers emphasize constructs that are impractical or not central to a teacher’s daily needs. TAM, for instance, focuses entirely on user perceptions influencing adoption, with little application for developing lesson plans, guiding student learning, or managing classroom behaviors. Even models developed for educators may focus on activities incompatible with teacher needs (e.g., student activism in LoTi) or be too theoretical to apply directly to teacher practice (e.g., technological content knowledge in TPACK).

결실. 결실이 부족한 모델은 교사로 하여금 의미 있는 성찰을 이끌어내지 못하고 오히려 의미 없는 실천 평가를 내릴 수 있습니다. LoTi, SAMR 및 TIM과 같이 여러 수준의 통합이 있는 모델에서는 각 수준에서 실습을 분류하는 목적이 필요하며, 교사는 실습을 증강 대 수정(SAMR) 또는 인식 대 탐구(LoTi)로 분류하는 것이 왜 의미 있는지를 이해해야 합니다. SAMR은 4단계, LoTi는 6단계, TIM은 두 축(5×5)에 걸쳐 25단계의 통합이 있습니다. 교사의 경우, 특히 비계층적일 경우 가능성이 너무 많으면 자신의 상황에 맞는 목표가 자신의 실제를 빠르게 반영하고 필요에 따라 개선하는 데 도움이 되는 것이라면 모델을 혼란스럽고 번거롭게 만들 수 있습니다.

Fruitfulness. Models that lack fruitfulness do not lead teachers to meaningful reflection, but rather yield unmeaningful evaluations of practice. Models with multiple levels of integration, such as LoTi, SAMR, and TIM, need a purpose for classifying practice at each level; teachers must understand why classifying practice as augmentation versus modification (SAMR) or as awareness versus exploration (LoTi) is meaningful. SAMR has four levels of integration, LoTi has six, and TIM has 25 across two axes (5×5). For teachers, too many possibilities, particularly if nonhierarchical, can make a model confusing and cumbersome if the goal in their context is to help them quickly reflect on their practice and improve as needed.

테크놀로지 역할. 일부 모델은 교육 결과의 수단으로서가 아니라 목표로서의 테크놀로지 사용에 초점을 맞추는 테크놀로지 중심적입니다. 예를 들어, TAM은 특히 교수 및 학습 개선이 아닌 테크놀로지 채택에만 초점을 맞춥니다. 다른 모델은 실천 개선에 초점을 맞출 수 있지만 효과적인 교수법이 등장할 수 있는 공간을 만들기보다는 테크놀로지를 실천 개선으로 보는 테크놀로지 결정론적 관점을 취합니다.

Technology role. Some models are technocentric: focused on technology use as the goal rather than as a means to an educational result. TAM, for instance, particularly focuses only on technology adoption, not on improving teaching and learning. Other models may focus on improving practice but be largely technodeterministic in their view of technology as improving practice rather than creating a space for effective pedagogies to emerge.

범위. 범위가 좋지 않은 모델은 포괄성과 간결성 사이에서 효과적으로 균형을 이루지 못하며, 너무 지시적이거나 너무 광범위하여 의미 있는 적용이 어렵습니다. 예를 들어, TIP은 지나치게 지시적이어서 TPACK 기반 수업 계획 작성에 대한 교수 설계 접근 방식을 모방하지만 너무 좁게 초점을 맞추기 때문에 이를 넘어서지 못합니다. 이와는 대조적으로, 훨씬 더 광범위한 TPACK은 교사에게 구성 요소를 동기화하기 위한 개념적 프레임워크를 제공하지만 이를 실제로 적용하는 구체적인 지침은 제공하지 않습니다. 유용하려면 모델이 교사에게 쉽게 적용되지 않는 테크놀로지 통합의 측면을 무시하고 실습을 안내할 수 있는 충분한 포괄성을 제공해야 합니다.

Scope. Models with poor scope do not balance effectively between comprehensiveness and parsimony, being either too directive or too broad for meaningful application. TIP, for instance, is overly directive, simulating an instructional design approach to creating TPACK-based lesson plans but too narrowly focused to go beyond this. In contrast, the much broader TPACK provides teachers with a conceptual framework for synchronizing component parts but without concrete guidance on putting it into practice. To be useful, models should ignore aspects of technology integration not readily applicable for teachers, but provide sufficient comprehensiveness to guide practice.

학생 중심. 대부분의 테크놀로지 통합 모델은 학생에게 의미 있게 초점을 맞추지 않으며, 학생이 무엇을 하고 배우는지에 대한 명확성보다는 테크놀로지 채택 또는 교사-페다고지 목표에 초점을 맞추고 있습니다. 이러한 모델은 단순히 페다고지적 고려 사항과 함께 학생의 존재를 가정할 수 있지만, 실무자 모델의 중심에 학생을 고려하지 않으면 학생 중심의 실무자 요구와 일치하지 않게 됩니다.

Student focus. Most models of technology integration do not meaningfully focus on students, focusing on technology-adoption or teacher-pedagogy goals rather than clarity on what students do or learn. Models may merely assume student presence with pedagogical considerations, but failure to consider students at the center of practitioner models prevents alignment with student-focused practitioners’ needs.

이론적 모델 요약. 이러한 모델 중 다수는 처음에 더 넓은 대상을 위해 개발되었으며 예비 교사에게 소급 적용되었습니다. 다른 모델들은 실제 실행에 대한 충분한 지침을 제공하지 않고 개념적인 수준에서 교사의 교육적 실천을 위해 개발되었습니다. 많은 모델이 교육 전문가에게 도움이 되지만, 다음의 특징을 갖춘 교사 교육을 위한 이론적 모델이 필요합니다.

- (a) 명확하고, 호환 가능하며, 유익하고,

- (b) 수단으로서 테크놀로지 사용을 강조하고,

- (c) 간결함과 포괄성의 균형을 맞추고,

- (d) 학생에 초점을 맞춘

Summary of theoretical models. Many of these models were initially developed for broader audiences and retroactively applied to preparing teachers. Others were developed for teacher pedagogical practices at a conceptual level without providing sufficient guidance on actual implementation. Although many models benefit education professionals, a theoretical model for teacher education is needed that

- (a) is clear, compatible, and fruitful;

- (b) emphasizes technology use as a means to an end;

- (c) balances parsimony and comprehensiveness; and

- (d) focuses on students.

우리는 교육의 이론적 모델을 기회주의적으로 바라봅니다(à la Feyerabend, 1975). 모든 상황과 고려 사항에 대해 하나의 모델을 찾기보다는, 교사에게 구체적인 실천에 가장 유용한 모델을 제공해야 할 필요성을 인식하고 있습니다. 이러한 다른 모델도 제자리를 차지하고 있지만(예: TPACK은 코스 전반에 걸쳐 관리 수준에서 테크놀로지를 포함하는 방법을 개념화하는 데 유용함), 교사 교육을 위해 더 잘 조정된 '공학적 힘'이 필요합니다(Burkhardt & Schoenfeld, 2003, 10페이지).

We view theoretical models in education opportunistically (à la Feyerabend, 1975). Rather than seeking one model for all contexts and considerations, we recognize a need to provide teachers with a model that is most useful for their concrete practice. While these other models have a place (e.g., TPACK is great for conceptualizing how to embed technology at an administrative level across courses), something is needed with better-tuned “engineering power” for teacher education (Burkhardt & Schoenfeld, 2003, p. 10).

PICRAT 모델

The PICRAT Model

교사 테크놀로지 통합을 안내하는 이론적 모델인 PICRAT은 교사 교육자가 성찰을 장려하고, 규범적으로 실습을 안내하며, 학생 교사의 작업을 평가할 수 있도록 해줍니다. 어떤 이론적 모델이라도 특정 속성은 잘 설명하고 다른 속성은 소홀히 할 수 있지만, PICRAT은 학생 중심의 페다고지 중심 모델로 교사 교육의 특정 맥락에 효과적이며 테크놀로지 통합을 위해 가장 가치 있는 고려 사항을 안내하기 때문에 교사들이 이해하고 사용할 수 있습니다.

As a theoretical model to guide teacher technology integration, PICRAT enables teacher educators to encourage reflection, prescriptively guide practice, and evaluate student teacher work. Any theoretical model will explain particular attributes well and neglect others, but PICRAT is a student-focused, pedagogy-driven model that can be effective for the specific context of teacher education —comprehensible and usable by teachers as it guides the most worthwhile considerations for technology integration.

저희는 시간 제약, 연수 제한, 교사의 교육에 대한 감성적 관점 등을 고려하여 교사가 교육에 테크놀로지를 사용할 때 가장 중요하게 고려하고 평가해야 할 두 가지 질문을 고려하면서 이 모델을 개발하기 시작했습니다.

- 학생에 초점을 맞춘 모델의 필요성을 강조하는 연구(Wentworth et al., 2009; Wentworth, Graham, & Tripp, 2008)에 근거하여 첫 번째 질문은 "학생들이 테크놀로지를 사용하여 무엇을 하고 있는가?"였습니다.

- 교육적 실천에 대한 교사의 성찰이 중요하다는 점을 인식하여 두 번째 질문은 "이러한 테크놀로지 사용이 교사의 페다고지에 어떤 영향을 미치는가?"였습니다.

We began developing this model by considering the two most important questions a teacher should reflect on and evaluate when using technology in teaching, considering time constraints, training limitations, and their emic perspective on their own teaching.

- Based on research emphasizing the need for models to focus on students (Wentworth et al., 2009; Wentworth, Graham, & Tripp, 2008), our first question was, “What are students doing with the technology?”

- Recognizing the importance of teachers’ reflection on their pedagogical practices, our second question was, “How does this use of technology impact the teacher’s pedagogy?”

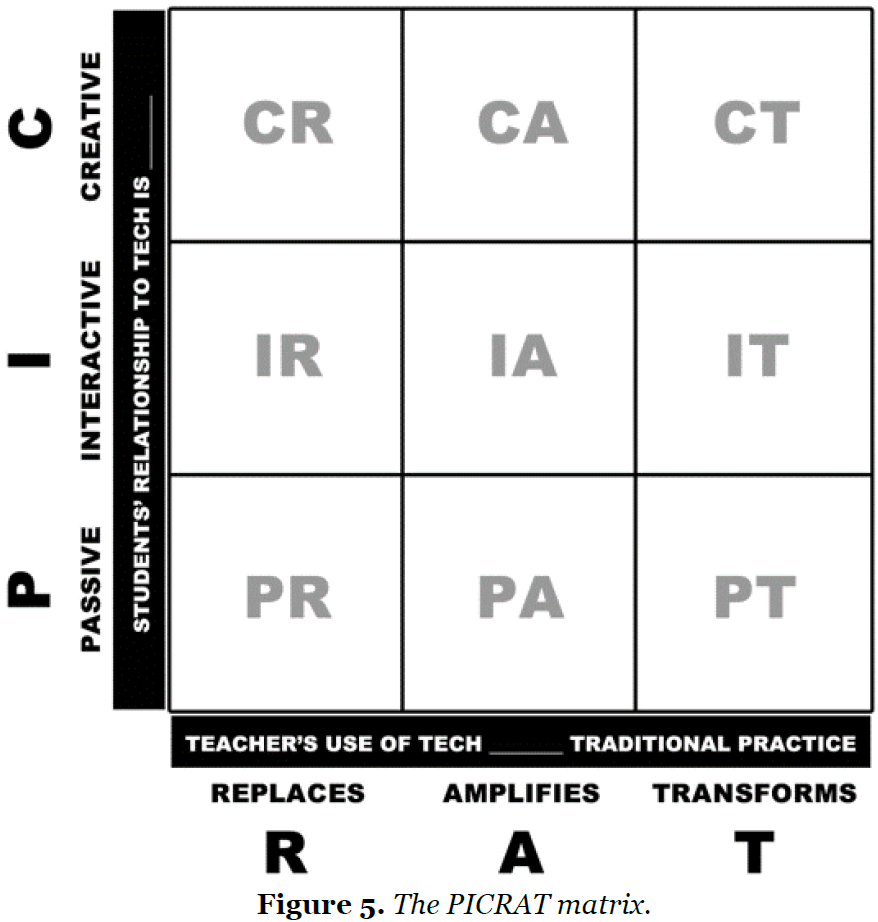

이러한 질문에 대한 교사들의 답변은 3단계 응답 메트릭으로 구성되며, 이를 PICRAT이라고 부릅니다.

- PIC는 첫 번째 질문과 관련된 세 가지 옵션(수동적, 상호작용적, 창의적)을 의미하고,

- RAT는 두 번째 질문에 대한 세 가지 옵션(대체, 증폭, 변형)을 나타냅니다.

Teachers’ answers to these questions on a three-level response metric comprise what we call PICRAT.

- PIC refers to the three options associated with the first question (passive, interactive, and creative); and

- RAT represents the three options for the second (replacement, amplification, and transformation).

PIC: 패시브, 인터랙티브, 크리에이티브

PIC: Passive, Interactive, Creative

첫째, 테크놀로지를 사용할 때 학생의 세 가지 기본 역할을 강조합니다:

- 수동적 학습(콘텐츠를 수동적으로 수용),

- 대화형 학습(콘텐츠 및/또는 다른 학습자와 상호 작용),

- 창의적 학습(인공물 제작을 통한 지식 구성, Papert & Harel, 1991).

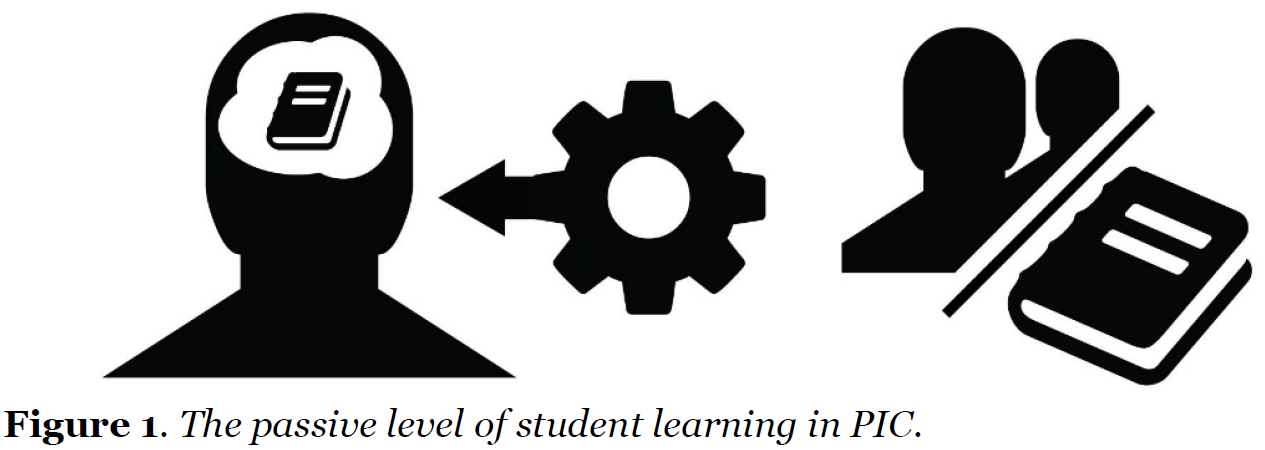

전통적으로 교사는 학생들에게 수동적인 수용자로서 지식을 제공하는 테크놀로지를 통합해 왔습니다(Cuban, 1986). 강의 노트를 PowerPoint 슬라이드로 변환하거나 YouTube 동영상을 보여주는 것은 학생들이 능동적인 참여자로서 참여하기보다는 수동적으로 관찰하거나 듣는 교육에 테크놀로지를 사용합니다(그림 1).

First, we emphasize three basic student roles in using technology:

- passive learning (receiving content passively),

- interactive learning (interacting with content and/or other learners), and

- creative learning (constructing knowledge via the construction of artifacts; Papert & Harel, 1991).

Teachers have traditionally incorporated technologies offering students knowledge as passive recipients (Cuban, 1986). Converting lecture notes to PowerPoint slides or showing YouTube videos uses technology for instruction that students passively observe or listen to rather than engaging with as active participants (Figure 1).

듣기, 관찰, 읽기는 필수적이지만 충분한 학습 스킬은 아닙니다. 우리의 경험에 따르면 테크놀로지를 활용하여 수업을 지원하는 대부분의 교사는 수동적인 수준에서 작업을 시작하며, 이 첫 단계를 넘어설 수 있도록 명시적인 안내가 필요합니다.

Listening, observing, and reading are essential but not sufficient learning skills. Our experiences have shown that most teachers who begin utilizing technology to support instruction work from a passive level, and they must be explicitly guided to move beyond this first step.

학생들이 탐구, 실험, 협업 및 기타 능동적인 행동을 통해 상호 작용적으로 참여할 때만 훨씬 더 지속적이고 영향력 있는 학습이 이루어집니다(Kennewell, Tanner, Jones, & Beauchamp, 2008). 테크놀로지를 통한 학습에는 게임 플레이, 컴퓨터 적응 테스트, 시뮬레이션 조작, 디지털 플래시 카드를 사용한 기억력 지원 등이 포함될 수 있습니다. 이러한 상호작용적 수준의 학생 사용은 학생이 테크놀로지와 직접 상호 작용하고(또는 테크놀로지를 통해 다른 학습자와 상호 작용), 이러한 상호 작용을 통해 학습이 매개된다는 점에서 수동적 사용과는 근본적으로 다릅니다(그림 2).

Much lasting and impactful learning occurs only when students are interactively engaged through exploration, experimentation, collaboration, and other active behaviors (Kennewell, Tanner, Jones, & Beauchamp, 2008). Through technology this learning may involve playing games, taking computerized adaptive tests, manipulating simulations, or using digital flash cards to support recall. This interactive level of student use is fundamentally different from passive uses, as students are directly interacting with the technology (or with other learners through the technology), and their learning is mediated by that interaction (Figure 2).

이 수준에서는 테크놀로지의 특정 어포던스가 필요할 수 있지만 상호 작용의 잠재력만으로는 상호작용형 학습과 동일하지 않습니다. 상호 작용으로 인해 학습이 이루어져야 하며, 상호 작용 기능이 있다는 것만으로는 충분하지 않습니다. 교육용 게임은 최적의 솔루션을 보여주거나 추가 콘텐츠를 제공하기 전에 학생이 문제를 해결하도록 요구할 수 있으며, 이는 학생이 선택하고, 문제를 해결하고, 피드백에 응답함으로써 게임과 상호 작용하여 자신의 학습 측면을 능동적으로 이끌어야 함을 의미합니다. 하지만 상호작용 수준은 여전히 제한적입니다. 테크놀로지와의 반복적인 상호 작용에도 불구하고 학습은 학생보다는 테크놀로지에 의해 주로 구조화되어 이전 학습과의 전이가능성 및 의미 있는 연결이 제한될 수 있습니다.

This level may require certain affordances of the technology, but potential for interaction is not the same as interactive learning. Learning must occur due to the interactivity; the existence of interactive features is not sufficient. An educational game might require students to solve a problem before showing the optimal solution or providing additional content, which means that students must interact with the game by making choices, solving problems, and responding to feedback, thereby actively directing aspects of their own learning. The interactive level is still limited, however. Despite recursive interaction with the technology, learning is largely structured by the technology rather than by the student, which may limit transferability and meaningful connections to previous learning.

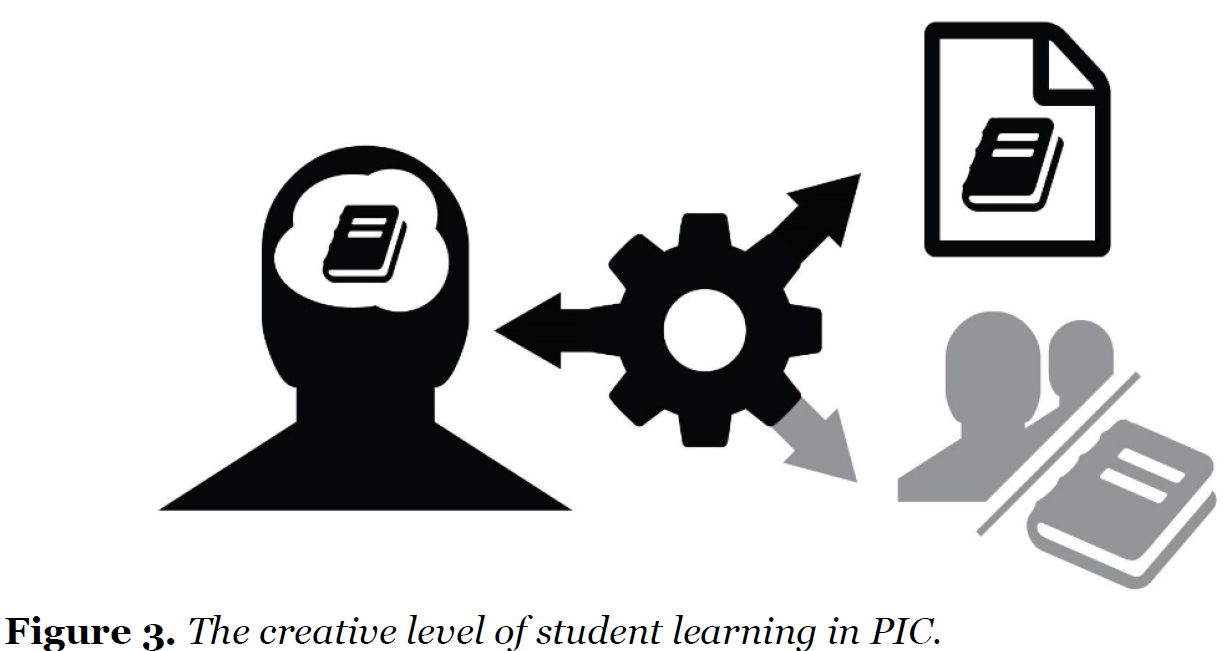

창의적인 수준의 학생 테크놀로지 사용은 학생이 테크놀로지를 학습 숙달을 인스턴스화하는 학습 아티팩트를 구성하는 플랫폼으로 사용하도록 함으로써 이러한 한계를 우회합니다. 지속적이고 의미 있는 학습은 학생들이 문제를 해결하기 위해 실제 또는 디지털 아티팩트를 구성하여 개념과 스킬을 적용할 때 가장 잘 이루어지며(Papert & Harel, 1991), 이는 블룸의 개정된 최고 수준의 학습 분류법(Anderson, Krathwohl, & Bloom, 2001)과도 일치합니다.

The creative level of student technology use bypasses this limitation by having students use the technology as a platform to construct learning artifacts that instantiate learning mastery. Lasting, meaningful learning occurs best as students apply concepts and skills by constructing real-world or digital artifacts to solve problems (Papert & Harel, 1991), aligning with the highest level of Bloom’s revised taxonomy of learning (Anderson, Krathwohl, & Bloom, 2001).

테크놀로지 구축 플랫폼에는 저작 도구, 코딩, 비디오 편집, 사운드 믹싱 및 프레젠테이션 제작이 포함될 수 있으며, 이를 통해 학생들은 개발 중인 지식에 형태를 부여할 수 있습니다(그림 3).

- 코딩의 기초를 배우는 과정에서 학생들은 아바타를 A 지점에서 B 지점으로 이동시키는 프로그램을 만들 수도 있고,

- 다른 사람을 가르치는 동영상을 제작하여 생물학 원리를 배울 수도 있습니다.

Technology construction platforms may include authoring tools, coding, video editing, sound mixing, and presentation creation, allowing students to give form to their developing knowledge (Figure 3).

- In learning the fundamentals of coding, students might create a program that moves an avatar from Point A to Point B, or

- they might learn biology principles by creating a video to teach others.

두 경우 모두 테크놀로지를 통해 학생이 제작 과정에서 다른 학습자 또는 추가 콘텐츠와 상호 작용할 수 있지만, 이러한 상호 작용 없이도 창의적인 활동을 할 수 있습니다. 창의적 학습 활동에서는 학생이 직접 아티팩트를 제작하면서 학습을 주도하고(자신의 개념적 구성에 형태를 부여), 테크놀로지를 적용하여 콘텐츠 이해를 구체화함으로써 문제를 반복적으로 해결할 수 있습니다.

In either instance the technology may also enable the student to interact with other learners or additional content during the creation process, but the activity can be creative without such interaction. In creative learning activities, students may directly drive the learning as they produce artifacts (giving form to their own conceptual constructs) and iteratively solve problems by applying the technology to refine their content understanding.

이 세 가지 수준에 걸쳐 유사한 테크놀로지를 사용하여 학생에게 다양한 학습 경험을 제공할 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, 교사는 PowerPoint와 같은 전자 슬라이드쇼 소프트웨어를 다음과 같이 사용할 수 있습니다.

- 태양계에 대한 강의 노트를 제공하기 위하여 (P),

- 행성에 대한 게임을 제공하기 위하여 (I),

- 다른 학생들에게 태양 복사에 대해 가르치는 대화형 키오스크를 만들기 위한 플랫폼을 제공하기 위하여 (C)

Across these three levels, similar technologies might be used to provide different learning experiences for students. For instance, electronic slideshow software like PowerPoint might be used by a teacher alternatively

- (P) to provide lecture notes about the solar system,

- (I) to offer a game about planets, or

- (C) to provide a platform for creating an interactive kiosk to teach other students about solar radiation.

이 세 가지 애플리케이션에서는 동일한 테크놀로지를 사용하여 동일한 콘텐츠를 가르치지만, 테크놀로지를 통해 학생이 참여하는 활동은 다르며 학습 경험에서 학생의 역할에 따라 학습 내용, 기억에 남는 내용, 다른 상황에 적용할 수 있는 방법이 달라집니다.

Across these three applications, the same technology is used to teach the same content, but the activity engaging the student through the technology differs, and the student’s role in the learning experience influences what is learned, what is retained, and how it can be applied to other situations.

테크놀로지를 통한 학생의 행동에 초점을 맞추면 테크놀로지 중심적 사고(테크놀로지 자체에 교육적 가치를 부여하는 사고)를 피할 수 있으며, 교사는 학생이 제공된 도구를 어떻게 사용하는지 고려하게 됩니다. 세 가지 수준의 PIC 모두 학습 목표와 상황에 따라 적절할 수 있습니다.

This focus on student behaviors through the technology avoids technocentrist thinking (ascribing educational value to the technology itself) and forces teachers to consider how their students are using the tools provided to them. All three levels of PIC might be appropriate for different learning goals and contexts.

RAT: 대체, 증폭, 변형

RAT: Replacement, Amplification, Transformation

테크놀로지 사용이 교사 페다고지에 어떤 영향을 미치는지에 대한 질문을 해결하기 위해 우리는 두 번째 저자가 제안한 활성화, 강화, 변형 모델과 유사한 Hughes 등(2006)이 제안한 RAT 모델을 채택했습니다(Graham & Robison, 2007). RAT의 이론적 토대는 저자들의 초기 컨퍼런스 진행 이외의 문헌에서 탐구되지 않았지만 이전 연구에서 적용했습니다.

- (a) 교사가 기술 통합에 대해 어떻게 생각하는지에 대한 이해를 체계화하기 위해(Amador, Kimmons, Miller, Desjardins, & Hall, 2015; Kimmons, Miller, Amador, Desjardins, & Hall, 2015),

- (b) 평가 모델을 비교하기 위해 (Kimmons & Hall, 2017) 및

- (c) 특정 모델의 강점을 설명하기 위해(Kimmons, 2015; Kimmons & Hall, 2016b).

To address the question of how technology use impacts teacher pedagogy, we adopted the RAT model proposed by Hughes et al. (2006), which has similarities to the enabling, enhancing, and transforming model proposed by our second author (Graham & Robison, 2007). Though the theoretical underpinnings of RAT have not been explored in the literature outside of the authors’ initial conference proceeding, we have applied it in previous studies

- (a) to organize understanding of how teachers think about technology integration (Amador, Kimmons, Miller, Desjardins, & Hall, 2015; Kimmons, Miller, Amador, Desjardins, & Hall, 2015),

- (b) to compare models for evaluation (Kimmons & Hall, 2017), and

- (c) to illustrate particular model strengths (Kimmons, 2015; Kimmons & Hall, 2016b).

PIC와 마찬가지로 약어 RAT는 목표 질문에 대한 세 가지 잠재적 반응을 나타냅니다: 어떤 교육적 맥락에서든 테크놀로지은 교사의 교육적 실천에 대체, 증폭, 변화의 세 가지 효과 중 하나를 가져올 수 있습니다.

Like PIC, the acronym RAT identifies three potential responses to a target question: In any educational context technology may have one of three effects on a teacher’s pedagogical practice: replacement, amplification, or transformation.

저희의 경험에 따르면 테크놀로지를 사용하여 교육을 지원하기 시작한 교사는 종이 플래시카드 대신 디지털 플래시카드를, 오버헤드 프로젝터 대신 전자 슬라이드를, 칠판 대신 대화형 화이트보드를 사용하는 등 이전 관행을 대체하는 데 테크놀로지를 사용하는 경향이 있습니다. 즉, 기존의 교육 관행을 기능적으로 개선하지 않고 새로운 매체로 옮기는 것입니다.

Our experience has shown that teachers who are beginning to use technology to support their teaching tend to use it to replace previous practice, such as digital flashcards for paper flashcards, electronic slides for an overhead projector, or an interactive whiteboard for a chalkboard. That is, they transfer an existing pedagogical practice into a newer medium with no functional improvement to their practice.

다른 모델에서도 비슷한 대체 방식을 찾을 수 있습니다: SAMR의 대체 또는 TIM의 입력. 이 수준의 사용은 반드시 나쁜 관행은 아니지만(예: 디지털 플래시카드가 종이 플래시카드 대신 잘 작동할 수 있음),

- (a) 관행을 개선하거나 지속적인 문제를 해결하기 위해 테크놀로지를 사용하고 있지 않으며

- (b) 테크놀로지를 사용함으로써 학생 학습 결과에 정당한 이점을 얻지 못함을 보여줍니다.

Similar replacements may be found in other models: substitution in SAMR or entry in TIM. This level of use is not necessarily poor practice (e.g., digital flashcards can work well in place of paper flashcards), but it demonstrates that

- (a) technology is not being used to improve practice or address persistent problems and

- (b) no justifiable advantage to student learning outcomes is achieved from using the technology.

교사와 관리자가 대체 수준에 머물러 있는 테크놀로지 이니셔티브를 지원하기 위해 자금을 요청하는 경우, 자금 지원 기관은 한정된 학교 자금과 교사 시간을 신테크놀로지에 투자할 이유가 거의 없다고 (옳은) 판단을 할 것입니다.

If teachers and administrators seek funding to support their technology initiatives for use that remains at the replacement level, funding agencies would (correctly) find little reason to invest limited school funds and teacher time into new technologies.

두 번째 수준인 증폭은 교사가 학습 관행이나 결과를 개선하기 위해 테크놀로지를 사용하는 것을 나타냅니다. 예를 들어, 학생들이 Google 문서 도구의 검토 기능을 사용하여 에세이에 대해 보다 효율적이고 집중적인 피드백을 제공하거나 디지털 프로브를 사용하여 LoggerPro에서 분석할 데이터를 수집함으로써 데이터 관리 및 조작을 개선하는 것이 있습니다.

The second level of RAT, amplification, represents teachers’ use of technology to improve learning practices or outcomes. Examples include using review features of Google Docs for students to provide each other more efficient and focused feedback on essays or using digital probes to collect data for analysis in LoggerPro, thereby improving data management and manipulation.

이러한 증폭 시나리오에서 테크놀로지를 사용하면 교사의 실습이 점진적으로 개선되지만 교육법이 근본적으로 바뀌지는 않습니다. 증폭은 기존 관행을 개선하거나 개선할 수 있지만, 교사가 자신의 관행을 근본적으로 재고하고 변화시킬 수 없다는 점에서 바람직하지 않은 한계에 도달할 수 있습니다.

Using technology in these amplification scenarios incrementally improves teachers’ practice but does not radically change their pedagogy. Amplification improves upon or refines existing practices, but it may reach undesirable limits insofar as it may not allow teachers to fundamentally rethink and transform their practices.

RAT의 혁신 수준은 테크놀로지를 사용하여 제정된 교육적 관행을 단순히 강화하는 것이 아니라 가능하게 합니다. 테크놀로지의 어포던스가 페다고지의 기회를 창출하고 페다고지와 얽혀 있기 때문에 테크놀로지를 제거하면 이러한 페다고지적 전략이 사라지게 됩니다(Kozma, 1991). 예를 들어,

- 학생들은 모바일 장치에서 GPS 검색을 통해 지역 사회에 대한 정보를 수집하거나,

- 온라인 시뮬레이션을 사용하여 지진 데이터를 분석하거나,

- Zoom과 같은 웹 화상 회의 서비스를 사용하여 원격 대학의 고생물학 전문가와 인터뷰할 수 있습니다.

The transformation level of RAT uses technology to enable, not merely strengthen, the pedagogical practices enacted. Taking away the technology would eliminate that pedagogical strategy, as technology’s affordances create the opportunity for the pedagogy and intertwines with it (Kozma, 1991). For example,

- students might gather information about their local communities through GPS searches on mobile devices,

- analyze seismographic data using an online simulation, or

- interview a paleontological expert at a remote university using a Web video conferencing service such as Zoom (https://zoom.us).

이러한 경험은 다른 저테크놀로지 수단으로는 불가능했을 것입니다.

None of these experiences could have occurred via alternative, lower tech means.

테크놀로지가 학습에 변혁적인 영향을 미칠 수 있는지에 대한 오랜 논쟁을 반영하기 때문에 PICRAT의 영향을 받는 모든 프로세스 중에서 변혁이 가장 문제가 될 수 있습니다(예: Clark, 1994). 다양한 저널 기사와 책에서 이 문제를 다루고 있지만, 이 글에서는 이 논쟁을 모두 다룰 수는 없습니다. 많은 연구자와 실무자들은 학습을 위한 테크놀로지의 혁신적 사용은 기존 관행의 기능적 개선 또는 효율성 향상만을 의미할 수 있다고 지적해 왔습니다. 그러나 효율성이 크게 향상되어 더 이상 효율성만으로는 새로운 관행과 기존 관행을 구분할 수 없게 되는 티핑 포인트가 존재합니다.

Of all the processes affected by PICRAT, transformation is likely the most problematic, because it reflects a longstanding debate on whether technology can ever have a transformative effect on learning (e.g., Clark, 1994). Various journal articles and books have tackled this issue, and this article cannot do justice to the debate. Many researchers and practitioners have noted that transformative uses of technology for learning may only refer to functional improvements on existing practices or greater efficiency. A tipping point exists, however, where greater efficiency becomes so drastic that new practices can no longer be distinguished from old in terms of efficiencies alone.

백열전구의 탄생을 생각해 보십시오. 이전에는 가정 및 산업용 조명이 주로 촛불과 램프에 의해 제공되었기 때문에 해가 지면 경제 및 사회 활동이 결정적으로 변화했습니다. 백열전구가 촛불보다 더 효율적인 것은 틀림없지만, 효율성의 향상은 노동자의 노동 시간, 산업의 생산 잠재력, 대중의 사회적 상호 작용을 증가시키는 등 사회에 변혁적인 영향을 미치기에 충분할 정도로 획기적이었습니다. 기능적으로는 촛불과 동일하지만 전구의 효율성은 촛불을 켜고 살던 사람들의 삶에 혁신적인 영향을 미쳤습니다. 마찬가지로, 페다고지를 변화시키는 테크놀로지의 사용은 기능적 개선으로 인한 변화라고 하더라도 단순히 효율성을 개선하는 것과는 다르게 보아야 합니다.

Consider the creation of the incandescent light bulb. Previously, domestic and industrial light had been provided primarily by candles and lamps, a high-cost source of low-level light, meaning that economic and social activities changed decisively when the sun set. Arguably the incandescent light bulb was a more efficient version of a candle, but the improvements in efficiency were sufficiently drastic to have a transformative effect on society: increasing the work day of laborers, the manufacturing potential of industry, and the social interaction of the public. Though functionally equivalent to the candle, the light bulb’s efficiencies had a transformative effect on candlelit lives. Similarly, uses of technology that transform pedagogy should be viewed differently than those that merely improve efficiencies, even if the transformation results from functional improvement.

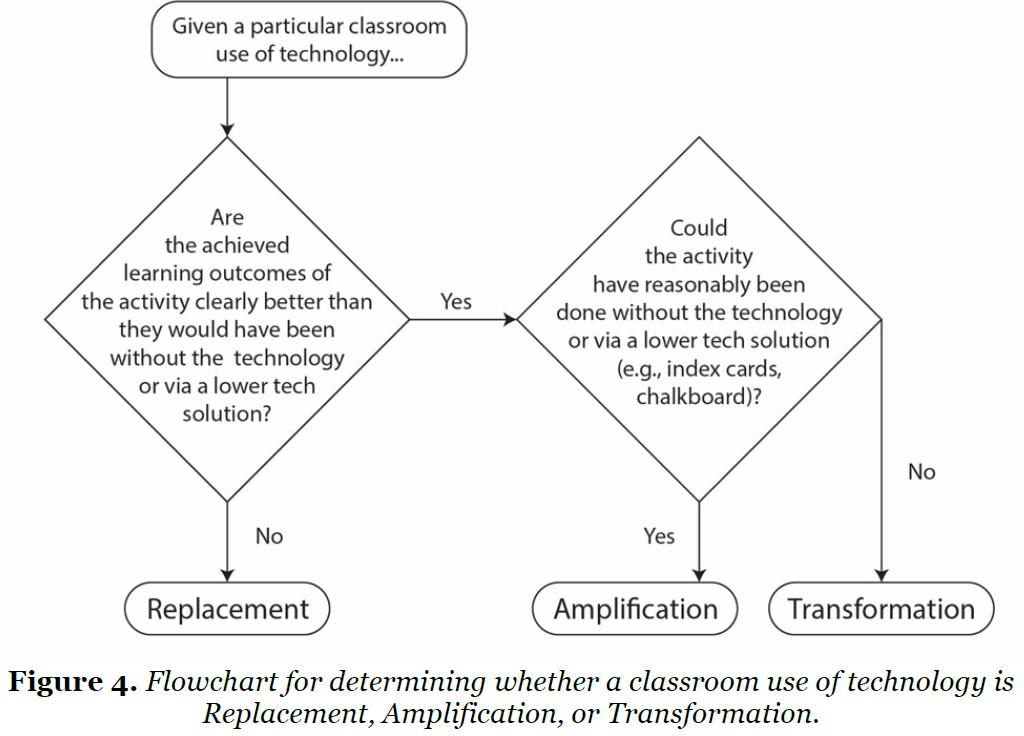

교사들이 RAT에 따라 자신의 관행을 분류하는 데 도움을 주기 위해 이전 연구(Kimmons et al., 2015)에서 수정한 일련의 운영화된 평가 질문(그림 4)을 교사들에게 묻습니다. 이러한 질문을 사용하여 교사는 먼저 해당 사용이 단순한 대체인지 아니면 학생의 학습을 향상시키는지 판단해야 합니다. 만약 사용이 개선을 가져온다면, 더 낮은 테크놀로지 수단을 통해 달성할 수 있는지 판단하여 증폭이 될 수 있는지, 그렇지 않다면 변형이 될 수 있는지 판단해야 합니다.

To help teachers classify their practices according to RAT, we ask them a series of operationalized evaluation questions (Figure 4), modified from a previous study (Kimmons et al., 2015). Using these questions, teachers must first determine if the use is merely replacement or if it improves student learning. If the use brings improvement, they must determine whether it could be accomplished via lower tech means, making it amplification; if it could not, then it would be transformation.

PICRAT 매트릭스

PICRAT Matrix

각 질문에 대한 세 가지 답변 수준을 사용하여 학생 교사가 모든 테크놀로지 통합 시나리오를 평가할 수 있는 9가지 가능성을 보여주는 매트릭스를 구성합니다. PIC를 Y축으로, RAT를 X축으로 사용하는 계층적 행렬(왼쪽 아래에서 오른쪽 위로 진행)을 PICRAT라고 지정하여 이론적 모델이 새롭고 유익한 행동에 대한 제안을 제공한다는 Kuhn(2013)의 요구를 충족하려고 시도합니다(그림 5). 이 매트릭스를 사용하면 교사는 모든 테크놀로지 사용에 대해 두 가지 기본 질문을 하고 각 수업 계획, 활동 또는 교육 실습을 9개의 셀 중 하나에 배치할 수 있습니다.

With the three answer levels for each question, we construct a matrix showing nine possibilities for a student teacher to evaluate any technology integration scenario. Using PIC as the y-axis and RAT as the x-axis, the hierarchical matrix (progressing from bottom-left to top-right), which we designate as PICRAT, attempts to fulfill Kuhn’s (2013) call that theoretical models provide suggestions for new and fruitful actions (Figure 5). With this matrix, a teacher can ask the two guiding questions of any technology use and place each lesson plan, activity, or instructional practice into one of the nine cells.

경험상 테크놀로지 통합을 시작하는 대부분의 교사는 왼쪽 하단에 가까운 사용 방법(즉, 수동적 대체)을 채택하는 경향이 있습니다. 따라서 이 매트릭스를 사용하여

- (a) 교사들이 자신과 다른 교사들이 접하는 관행을 비판적으로 고려하도록 장려하고,

- (b) 오른쪽 상단에 더 가까운 관행(즉, 창의적 혁신)으로 나아갈 때 고려할 수 있는 경로를 제시합니다.

In our experience, most teachers beginning to integrate technology tend to adopt uses closer to the bottom left (i.e., passive replacement). Therefore, we use this matrix

- (a) to encourage them to critically consider their own and other practices they encounter and

- (b) to give them a suggested path for considering in moving their practices toward better practices closer to the top right (i.e., creative transformation).

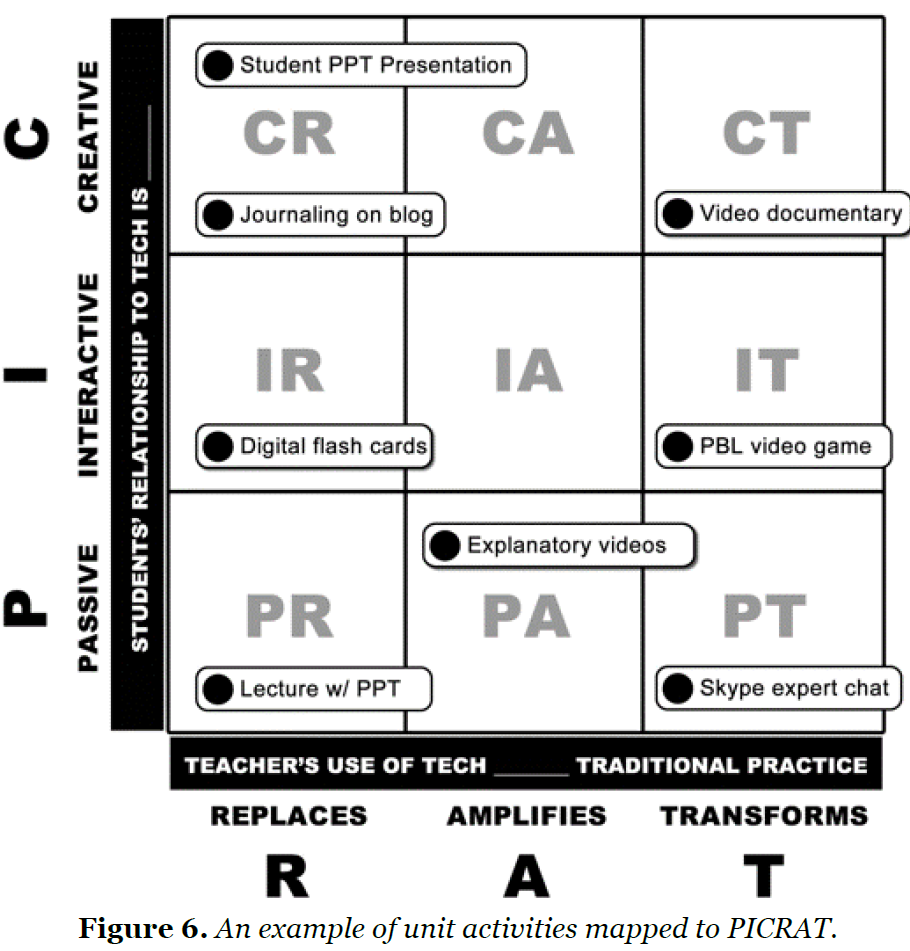

이 매트릭스는 교사 또는 코스 수준이 아닌 활동 수준에서만 사용합니다. 개인 또는 학급의 전반적인 테크놀로지 사용을 분류하는 이전의 특정 모델(예: SAMR, TIM)과 달리, 이 모델은 교사가 효과적이기 위해서는 다양한 테크놀로지를 사용해야 하며, 사용에는 전체 매트릭스에 걸친 활동이 포함되어야 한다는 점을 인식하고 있습니다. 예를 들어, 그림 6은 교사가 특정 단원에 대해 잠재적인 모든 테크놀로지 활동을 매핑하는 방법의 예를 보여줍니다.

We use this matrix only at the activity level, not at the teacher or course level. Unlike certain previous models that claim to classify an individual’s or a classroom’s overall technology use (e.g., SAMR, TIM), this model recognizes that teachers need to use a variety of technologies to be effective, and use should include activities that span the entire matrix. For instance, Figure 6 provides an example of how teachers might map all of their potential technology activities for a specific unit.

교사는 매트릭스를 사용하여 낮은 수준의 사용(예: 디지털 플래시카드 또는 전자 슬라이드쇼를 사용한 강의)을 어떻게 높은 수준의 사용(예: 문제 기반 학습 비디오 게임 또는 전문가와의 Skype 화상 채팅)으로 전환할 수 있는지 생각해 보도록 권장합니다. RAT는 교사의 사전 테크놀로지 관행에 따라 달라집니다: 이전의 교육 맥락과 관행이 RAT 평가 결과를 좌우합니다.

Using the matrix we would encourage the teacher to think about how lower level uses (e.g., digital flashcards or lecturing with an electronic slideshow) could be shifted to higher level uses (e.g., problem-based learning video games or Skype video chats with experts). RAT depends on the teacher’s pretechnology practices: Previous teaching context and practices dictate the results of RAT evaluation.

교사가 PICRAT 매핑에 참여할 때 자신의 수업 관행과 PICRAT 모델이 제안할 수 있는 새로운 전략 및 접근 방식에 대해 생각해 볼 것을 권장합니다. 또한 PICRAT 모델을 소개하고 교사에게 이러한 사고 방식을 안내하기 위해 애니메이션 교육용 비디오를 제작했습니다(비디오 1).

As our teachers engage in PICRAT mapping, we encourage reflecting on their practices and on new strategies and approaches the PICRAT model can suggest. We have also created an animated instructional video to introduce the PICRAT model and to orient teachers to this way of thinking (Video 1).

- 비디오 1. 교육에서 효과적인 테크놀로지 통합을 위한 PICRAT

Video 1. PICRAT for Effective Technology Integration in Teaching (https://youtu.be/bfvuG620Bto)

그림 7은 교사 교육 과정을 분석하기 위해 PICRAT을 어떻게 사용했는지 보여주는 예입니다. 공동 작업을 위해 Google 드로잉을 사용하여 동일한 테크놀로지 통합 과정의 각 섹션에 있는 학생들이 코스 순서에서 사용한 모든 테크놀로지 사용을 매핑하도록 했습니다. 그림에서 볼 수 있듯이 학생들은 특정 테크놀로지와 활동을 매핑하는 방법(예: PowerPoint를 PR, CR 또는 CA로 매핑)에 대해 서로 동의하지 않는 경우가 있지만, 이 연습을 통해 이러한 테크놀로지를 사용하여 수행되는 활동의 특성, 동일한 테크놀로지를 서로 다르게 사용하는 이유 등에 대해 귀중한 대화를 나눌 수 있습니다.

Figure 7 provides an example of how we have used PICRAT to analyze our teacher education courses. Using Google Drawings (https://docs.google.com/drawings/) for collaboration, we have students in each section of the same technology integration course map all of the uses of technology that they have used in their course sequence. As is visible from the figure, students sometimes disagree with one another on how particular technologies and activities should be mapped (e.g., PowerPoint as PR, CR, or CA), but this exercise yields valuable conversations about the nature of activities being undertaken with these technologies, what makes different uses of the same technologies of differential value, and so forth.

마찬가지로, 학생이 테크놀로지를 접목한 수업 계획서 작성과 같은 테크놀로지 통합 과제를 완료하면, PICRAT을 평가용 루브릭으로 변환하여 기본 합격 수준에서는 낮은 수준의 사용(예: PR)을, 숙련자 또는 우수 수준에서는 높은 수준의 사용(예: CT)을 평가합니다. 이 접근 방식은 학생들이 테크놀로지가 다양한 방식으로 사용될 수 있으며 모든 수준이 유용할 수 있지만 일부는 다른 수준보다 더 우수하다는 것을 이해하는 데 도움이 됩니다.

Similarly, when students complete technology integration assignments, such as creating a technology-infused lesson plan, we convert PICRAT to a rubric for evaluating their products, evaluating lower level uses (e.g., PR) at the basic passing level and higher level uses (e.g., CT) at proficient or distinguished levels. This approach helps students understand that technology can be used in a variety of ways and that, though all levels may be useful, some are better than others.

PICRAT의 장점

Benefits of PICRAT

이 논문에서는 PICRAT 모델의 이론적 근거를 제시했지만, 모델에 대한 연구가 완료될 때까지는 모델의 장점이나 단점을 단정적으로 주장할 수 없음을 인정합니다. 모델을 검증하는 연구는 일반적으로 초기 모델이 발표된 이후에 이루어집니다. 다음은 이 모델의 장점과 향후 연구에서 이 모델의 유용성을 조사해야 하는 이유입니다.

In this paper, we have presented the theoretical rationale for the PICRAT model but acknowledge that we cannot definitively claim any of its benefits or negatives until research on the model is completed. Research validating a model typically comes (if it comes at all) after the initial model has been published. Following are the benefits of this model and reasons future research should investigate its utility.

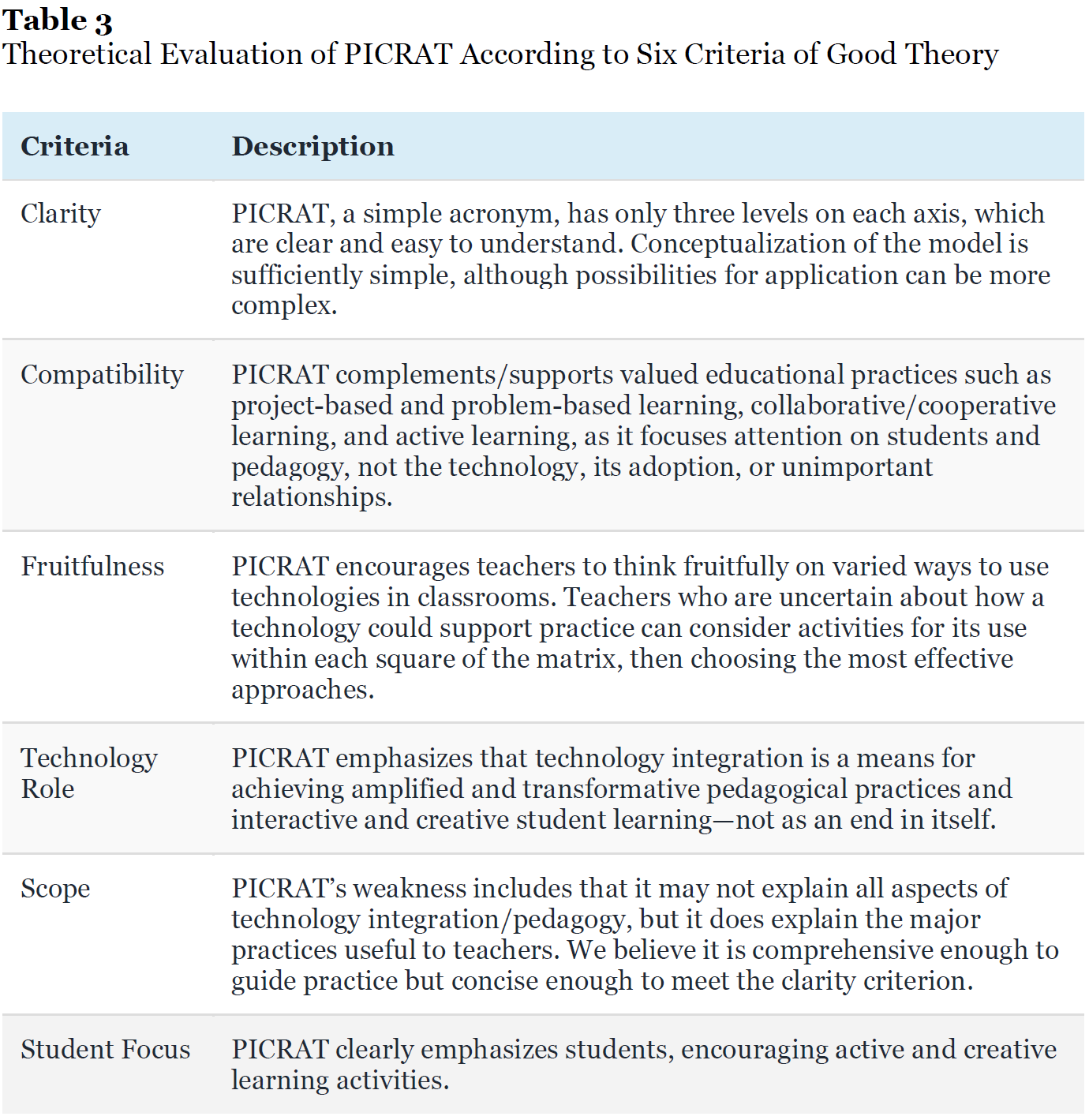

PICRAT 모델은 완벽하거나 완전히 포괄적이지는 않지만, 표 3의 기준과 관련하여 교사 교육을 위한 경쟁 모델에 비해 몇 가지 장점이 있습니다. 우리 교육기관은 테크놀로지 통합 과정의 세 가지 과정을 모두 PICRAT를 중심으로 구성했으며, 학생들은 이 모델이 이해하기 쉽고 테크놀로지 통합 전략을 개념화하는 데 도움이 된다는 것을 알게 되었습니다. 일반적으로 수업 시간 5분 정도에 안내 질문과 수준을 제시하여 모델을 소개한 다음, 학생들에게 교실에서 접할 수 있는 구체적인 활동과 테크놀로지 사례를 매트릭스에 배치하도록 요청합니다. 그런 다음 이 모델을 코스 루브릭의 개념적 프레임으로 사용하여 모델에서 학생의 수행 위치에 따라 성적을 할당합니다.

Though the PICRAT model is not perfect or completely comprehensive, it has several benefits over competing models for teacher education with regard to the criteria in Table 3. Our institution has structured all three courses in its technology integration sequence around PICRAT, and students have found the model easy to understand and helpful for conceptualizing technology integration strategies. We generally introduce the model by taking about 5 minutes of class time to present the guiding questions and levels, then ask students to place on the matrix specific activities and technology practices they might have encountered in classrooms. We subsequently use the model as a conceptual frame for course rubrics, assigning grades based on the position of the student’s performance on the model.

이 모델에 대해 지속적으로 받는 피드백 중 하나는 명확성에 대한 칭찬입니다. 두 개의 질문과 아홉 개의 셀은 비교적 기억하기 쉽고, 이해하기 쉬우며, 어떤 상황에서도 적용하기 쉽습니다. 명확성 외에도 이 모델의 범위는 교실 교사에게 실질적으로 유용할 정도로 충분히 포괄적인 사례의 균형을 효과적으로 맞추고 있으며, 통합의 본질에 대해 이야기할 때 공통적으로 사용할 수 있는 어휘를 제공합니다.

One item of feedback that we consistently receive about the model is praise for its clarity. The two questions and nine cells are relatively easy to remember, to understand, and to apply in any situation. In addition to clarity, the model’s scope effectively balances a sufficiently comprehensive range of practices to make it practically useful for classroom teachers and provides a common, usable vocabulary for talking about the nature of the integration.

명확한 모델에 대한 주요 우려는 테크놀로지 통합의 중요한 측면을 지나치게 단순화하고 중요한 뉘앙스를 무시할 수 있다는 것입니다. 그러나 교사들은 지시적 단순성과 미묘한 복잡성 사이의 적절한 균형을 유지하면서, 지시적 지침과 자기 반성적 비판적 사고의 기회를 모두 제공하는 PICRAT을 사용하여 자신의 실제를 조사하고 있습니다.

The major concern with any clear model is that it may oversimplify important aspects of technology integration and ignore important nuances. However, teachers are using PICRAT to interrogate their practice with a suitable balance between directive simplicity and nuanced complexity, with opportunities for both directive guidance and self-reflective critical thinking.

또한 PICRAT 모델은 강력한 페다고지를 뒷받침하는 테크놀로지를 강조하기 때문에 다른 양질의 교육 관행과도 호환성이 높습니다. PICRAT은 혁신적인 교육과 지속적으로 진화하는 페다고지를 촉진하여 혁신적인 관행을 향해 나아갑니다. 이 모델의 학생 중심(PIC를 통한)은 학생의 참여와 능동적/창의적 학습을 강조하며, 자연스럽게 테크놀로지를 사용하여 학생이 스스로 학습을 주도하도록 하는 교사 관행을 장려하고, 테크놀로지를 이러한 목적을 달성하기 위한 수단으로만 취급하지 않습니다.

Furthermore, the PICRAT model is highly compatible with other quality educational practices, because it emphasizes technology as supporting strong pedagogy. PICRAT promotes innovative teaching and continually evolving pedagogy, progressing toward transformative practices. The model’s student focus (via PIC) emphasizes student engagement and active/creative learning, naturally encouraging teacher practices that use technology to put students in charge of their own learning, never treating technology as more than a means for achieving this end.

아마도 우리가 발견한 가장 강력한 이점은 교사의 테크놀로지 사용에 대한 의미 있는 대화와 자기 대화를 장려함으로써 PICRAT이 결실 기준을 충족해야 한다는 점일 것입니다(Wentworth 외., 2008). 매트릭스의 각 사각형은 긍정적인 테크놀로지 적용이지만, 계층적 관점의 수준은 교사의 관행을 변화시키는 창의적 학습에 초점을 맞추는 오른쪽 상단 모서리로 이동하는 관행으로 교사를 안내합니다. 매트릭스의 이러한 명시적인 셀은 테크놀로지 사용에 대한 교사의 자기 대화와 토론을 효과적으로 유도합니다. 예를 들어, 새로운 테크놀로지를 사용하여 대화형 학습을 강화하거나 혁신적인 창의적 학습을 지원할 수 있는 방법을 스스로에게 물어볼 수 있습니다. 그렇게 함으로써 각 사각형은 잠재적인 교사 관행에 대한 깊은 성찰을 유도하고 테크놀로지 자체에 대한 강조점을 전환합니다.

Perhaps the strongest benefit we have found is how PICRAT should meet the fruitfulness criterion by encouraging meaningful conversations and self-talk around teachers’ technology use (Wentworth et al., 2008). Although each square in the matrix is a positive technology application, our hierarchical view of the levels guides teachers to practices that move toward the upper-right corner: the focus on creative learning that transforms teacher practices. These explicit cells in the matrix effectively initiate teacher self-talk and discussions about technology use. For instance, we might ask ourselves how a new technology could be used to amplify interactive learning or support transformative creative learning. As we do so, each square prompts deep reflection about potential teacher practices and shifts emphasis away from the technology itself.

PICRAT의 한계 또는 어려움

Limitations or Difficulties of PICRAT

이 모델에 관심이 있는 교사 교육자는 최소한 5가지 어려움을 고려해야 합니다. 일부는 RAT에서 계승된 것이고, 일부는 PICRAT만의 고유한 문제입니다. 다음은 주목할 만한 사항입니다:

- (a) 창의적 활용에 대한 혼란,

- (b) 변혁적 실천에 대한 혼란,

- (c) 다른 교육 상황에의 적용 가능성,

- (d) 활동 수준을 넘어서는 평가,

- (e) 학생 결과와의 단절.

- 다음은 각 과제에 대한 설명과 이를 해결하기 위한 지침입니다.

At least five difficulties should be considered by teacher educators interested in this model. Some are inherited from RAT; others are unique to PICRAT. The following are noted:

- (a) confusion regarding creative use,

- (b) confusion regarding transformative practice,

- (c) applicability to other educational contexts,

- (d) evaluations beyond activity level, and

- (e) disconnects with student outcomes.

- Following is an explanation of each challenge and guidance on addressing it.

첫째, 창의적이라는 용어는 최고의 테크놀로지 사용이 예술적이거나 표현적이라는 의미를 내포할 수 있으므로 주의 깊게 설명하지 않으면 학생 교사에게 혼란을 줄 수 있습니다. PICRAT에서 크리에이티브는 아티팩트 창조, 생성 또는 구성으로 작동합니다. 창작된 인공물이 예술적이지 않을 수도 있으며, 모든 형태의 예술적 표현이 가치 있는 인공물을 만들어내는 것은 아닙니다. 우리는 학생 교사들에게 창의적인 것과 예술적인 것은 같지 않으며, 오히려 학생들이 테크놀로지를 지식 인공물을 생성하거나 건설하는 도구로 사용해야 한다는 점을 주의 깊게 가르칩니다.

First, the term creative can be confusing for student teachers if not carefully explained, as it might imply that the best technology use is artistic or expressive. In PICRAT, creative is operationalized as artifact creation, generation, or construction. Created artifacts may not be artistic, and not all forms of artistic expression produce worthwhile artifacts. We carefully teach our student teachers that creative is not the same as artistic, but rather that their students should be using technology as a generative or constructive tool for knowledge artifacts.

둘째, 혁신적 실천은 주관적이고 맥락에 따라 달라질 수 있기 때문에 교사에게 문제가 될 수 있으며, 이는 클라크-코즈마 토론에서 언급된 RAT의 어려움과 동일합니다. 우리는 증폭과 변혁을 구분하는 데 도움이 되는 의사 결정 프로세스를 제공하거나 질문을 안내함으로써 변혁을 운영화하려고 노력해 왔습니다. 변환은 문헌에서 논쟁의 여지가 있기 때문에 이렇게 한다고 해서 이 문제가 완전히 해결되는 것은 아니지만, 교사의 테크놀로지 사용을 평가할 수 있는 프로세스를 제공할 수 있습니다.

Second, transformative practice can seem problematic for teachers, a difficulty shared with RAT, mentioned in the Clark–Kozma debate, because such an identification may be subjective and contextual. We have sought to operationalize transformationby providing decision processes or guiding questions to help distinguish amplification from transformation. Doing so does not completely resolve this issue, because transformation is contentious in the literature, but it does provide a process for evaluating teachers’ technology use.

모든 사례에서 증폭과 변형을 정확하게 구분하는 것은 다양한 테크놀로지 통합 사례가 교사의 수업에 미치는 영향을 고려하는 자기 성찰에 참여하는 것보다 덜 중요하다고 생각합니다. 따라서 학생의 과제를 채점할 때 테크놀로지 사용을 혁신과 증폭으로 분류하는 근거를 제시하도록 요청하여 학생들의 암묵적 추론과 그에 따른 오해 또는 성장을 파악할 수 있도록 합니다.

We consider accurately differentiating amplification from transformation in every case to be less important than engaging in self-reflection that considers effects of various instances of technology integration on a teacher’s practice. In grading our students’ work, then, we ask them to provide rationales for labeling technology uses as transformative versus amplifying, allowing us to see their tacit reasoning and, thereby, perceiving misconceptions or growth.

셋째, 이 글에서 PICRAT의 의도된 범위는 교사 준비에 국한되어 있으며, 우리의 주장은 이러한 맥락에서 이해되어야 합니다. PICRAT는 다른 맥락(예: 프로그램 평가 또는 교육 행정)에도 적용될 수 있지만, 이러한 적용은 특정 맥락에 대한 주장과는 별도로 고려해야 합니다.

Third, the intended scope of PICRAT has been carefully limited in this article to teacher preparation; our claims should be understood within that context. PICRAT may be applicable to other contexts (e.g., program evaluation or educational administration), but such applications should be considered separately from arguments made for our specific context.

넷째, 단원, 코스 또는 교사 수준의 평가에 대한 PICRAT의 완전한 확장이 완료되지 않았으며, 수업 계획 수준에서도 관련 문제가 분명합니다. 교사는 사소하지만 혁신적인 방식으로 테크놀로지를 사용하여 수업을 계획한 다음(예: 예상 세트에 대한 5분 활동), 수업을 계속 진행하면서 테크놀로지를 대체 수단으로 사용할 수 있습니다. 이 수업 계획은 혁신적이라고 평가해야 할까요, 대체라고 평가해야 할까요, 아니면 좀 더 미묘한 것으로 평가해야 할까요?

Fourth, full scaling up of PICRAT to unit-, course-, or teacher-level evaluations has not been completed; related problems are apparent even at the lesson plan level. A teacher might plan a lesson using technology in a minor but transformative way (e.g., a 5-minute activity for an anticipatory set), and then use technology as replacement as the lesson continues. Should this lesson plan be evaluated as transformative, as replacement, or as something more nuanced?

저희의 대답은 평가자의 목표에 따라 평가가 달라진다는 것입니다. 우리는 일반적으로 교사가 혁신적인 방식으로 사고하고 전체 수업에 테크놀로지를 접목하도록 유도하여 분석 수준을 수업 계획으로 삼으려고 노력합니다. 따라서 짧고 단절된 활동이나 일회성 활동은 PICRAT 평가에 부적절하다고 보고 대신 수업의 전체적인 흐름에 초점을 맞추고 있습니다. 그러나 다양한 수준의 분석에 PICRAT을 사용하려는 경우 적절한 항목 수준에서 이 문제를 고려해야 할 수 있습니다.

Our response is that the evaluation depends on the goal of the evaluator. We typically try to push our teachers to think in transformative ways and to entwine technology throughout an entire lesson, making our level of analysis the lesson plan. Thus, we would likely view short, disjointed, or one-off activities as inappropriate for PICRAT evaluation, focusing instead on the overall tenor of the lesson. Those seeking to use PICRAT for various levels of analysis, however, may need to consider this issue at the appropriate item level.

마지막으로, PICRAT에서 학생의 역할은 학생 활동과 이를 가능하게 하는 테크놀로지의 관계에 중점을 둡니다. 교사가 테크놀로지 통합 관행을 측정 가능한 학생 결과와 연결하도록 명시적으로 안내하지는 않습니다. 설명된 모든 모델(TIP을 제외하면)은 이러한 종류의 한계를 가지고 있는 것으로 보이며, PICRAT에 설명된 고차원적인 원칙이 이론적으로는 더 나은 학습으로 이어져야 하지만 그러한 학습에 대한 증거는 콘텐츠, 맥락 및 평가 측정에 따라 달라집니다.

Finally, the student role in PICRAT focuses on relationships of student activities to the technologies that enable them. It does not explicitly guide teachers to connect technology integration practices to measurable student outcomes. All models described (with the possible exception of TIP) seem to suffer from limitations of this sort, and though the higher order principles illustrated in PICRAT should theoretically lead to better learning, evidence for such learning depends on content, context, and evaluation measures.

PICRAT 자체는 학습에 대한 비테크놀로지 중심주의적 가정을 기반으로 하며, 테크놀로지를 "학습이 무엇인지 다시 생각해 볼 수 있는 기회"로 간주합니다(Papert, 1990, 5항). 따라서 교사 교육자는 학생 교사가 PICRAT을 지침으로만 사용한다고 해서 측정 가능한 학생의 성과가 급격히 향상되는 것은 아니며, 오히려 테크놀로지를 교수의 지속적인 문제를 재고하는 도구로 사용할 수 있으므로 더 깊은 학습이 이루어질 수 있는 상황을 만들 수 있다는 점을 인식할 수 있도록 도와야 합니다.

PICRAT itself is built on nontechnocentrist assumptions about learning, treating technology as an “opportunity offered us … to rethink what learning is all about” (Papert, 1990, para. 5). For this reason, teacher educators should help student teachers to recognize that using PICRAT only as a guide may not ensure drastic improvements in measurable student outcomes but may, rather, create situations in which deeper learning can occur as technology can be used as a tool for rethinking some of the persistent problems of teaching.

결론

Conclusion

먼저 교육 테크놀로지에서 이론적 모델의 역할을 살펴보고, 특히 테크놀로지 통합과 관련된 교사 준비에 중점을 두었습니다. 그런 다음 이 분야의 기존 이론적 모델을 평가하기 위한 몇 가지 지침을 제시하고 교사 준비 상황의 요구와 이러한 요구 사항을 해결하는 데 있어 기존 모델의 한계에 대한 새로운 해답으로 PICRAT 모델을 제시했습니다.

We first explored the roles of theoretical models in educational technology, placing particular emphasis upon teacher preparation surrounding technology integration. We then offered several guidelines for evaluating existing theoretical models in this area and offered the PICRAT model as an emergent answer to the needs of our teacher preparation context and the limitations of prior models in addressing those needs.

PICRAT은 포괄성과 간결함의 균형을 유지하여 교사에게 명확하고 유익하며 기존의 관행과 기대에 부합하는 개념적 도구를 제공하는 동시에 테크놀로지 중심적 사고를 피합니다. 우리는 PICRAT 모델에서 네 가지 한계 또는 어려움을 확인했지만, 끊임없이 변화하고 정치적으로 영향을 받으며 맥락적 특성이 강한 이 과제의 특성에도 불구하고 교사 교육자가 테크놀로지를 효과적으로 통합하도록 교사를 훈련하는 데 사용할 수 있는 교육 및 자기 성찰 도구로서 이 모델의 강점을 강조합니다. 향후 연구에는 다양한 관행과 환경에서 PICRAT 모델을 적용하는 동시에 교사의 실천, 성찰, 교육적 변화를 얼마나 효과적으로 안내할 수 있는지 연구하는 것이 포함되어야 합니다.

PICRAT balances comprehensiveness and parsimony to provide teachers a conceptual tool that is clear, fruitful, and compatible with existing practices and expectations, while avoiding technocentrist thinking. Although we identified four limitations or difficulties with the PICRAT model, we emphasize its strengths as a teaching and self-reflection tool that teacher educators can use in training teachers to integrate technology effectively despite the constantly changing, politically influenced, and intensely contextual nature of this challenge. Future work should include employing the PICRAT model in various practices and settings, while studying how effectively it can guide teacher practices, reflection, and pedagogical change.

Technology integration models are theoretical constructs that guide researchers, educators, and other stakeholders in conceptualizing the messy, complex, and unstructured phenomenon of technology integration. Building on critiques and theoretical work in this area, the authors report on their analysis of the needs, benefits, and limitations of technology integration models in teacher preparation and propose a new model: PICRAT. PIC (passive, interactive, creative) refers to the student's relationship to a technology in a particular educational scenario. RAT (replacement, amplification, transformation) describes the impact of the technology on a teacher's previous practice. PICRAT can be a useful model for teaching technology integration, because it (a) is clear, compatible, and fruitful, (b) emphasizes technology as a means to an end, (c) balances parsimony and comprehensiveness, and (d) focuses on students.

Descriptors: Models, Technology Integration, Preservice Teacher Education, Educational Benefits, Influence of Technology, Student Centered Learning, Preservice Teachers, Teaching Methods, Transformative Learning

Society for Information Technology and Teacher Education. P.O. Box 719, Waynesville, NC 28786. Fax: 828-246-9557; Web site: http://www.citejournal.org/