의학교육에서 증례-기반 학습: 존재론적 충실성을 위한 요구(Perspect Med Educ. 2023)

Case-Informed Learning in Medical Education: A Call for Ontological Fidelity

ANNA MACLEOD, VICTORIA LUONG, PAULA CAMERON, SARAH BURM, SIMON FIELD, OLGA KITS, STEPHEN MILLER, WENDY A. STEWART

학부 의학교육 커리큘럼에 대한 사례를 작성해 달라는 요청을 받았다고 상상해 보세요: "고혈압에 대한 증례를 작성해 주세요." 이 지시에 따라 일련의 활동을 진행해야 하는데, 질환, 임상 증상, 관련 징후, 치료 옵션 및 예후에 대해 설명할 수 있습니다. 포함된 정보가 정확하고 근거에 기반하며 최신 정보인지 확인하기 위해 문헌을 참고할 수도 있습니다.

Imagine you’ve been asked to write a case for an undergraduate medical education curriculum with the direction: “Please write a case about hypertension.” That instruction sets into place a sequence of activity: you would likely go about describing the condition, its presenting clinical manifestations, relevant signs, treatment options, and prognosis. You might turn to the literature to ensure the information included is accurate, evidence-based, and up to date.

반대로 다음과 같은 지시를 받았다고 상상해 보세요: "고혈압 환자의 이야기를 담은 사례를 작성해 주세요."라는 지시를 받았다고 상상해 보세요. 미묘하지만 분명한 차이가 있습니다. 이 경우 질병과 진단에 대한 이야기를 쓸 때 질병의 본질 또는 생생한 경험을 전달하려는 시도가 다른 초점으로 부각됩니다. 이러한 다른 방향성은 미묘하지만 중요하다고 생각합니다.

In contrast, imagine you received the direction: “Please write a case that tells the story of a person with hypertension.” The difference is subtle, but notable. The path you would take to write this case, in telling the story of an illness and diagnosis, brings to the fore a different focus: an attempt to convey the essence, or lived experience, of the illness. We believe this different orientation, though subtle, matters.

사실 텍스트 기반 사례는 의학 교육의 기본입니다. 사례 기반 학습(문제 기반, 사례 기반, 팀 기반 등 사례를 중심으로 한 다양한 학습 접근 방식을 포괄하는 포괄적인 용어로 사용함)이 이루어지는 주요 메커니즘입니다. 우리는 사례의 형식, 내용, 목적 등 우리가 사례를 작성하고 생각하는 방식이 의학에서 실제라고 보는 정보 유형(사실, 증거, 프로시져 등)에 대한 '사소하지 않은 단서'를 제공한다고 주장합니다.

Text-based cases are, in fact, fundamental to medical education. They are the primary mechanism through which case-informed learning (which we will use as an umbrella term that includes the various approaches to learning with cases at their heart, including problem-based, case-based, team-based and others) occurs. We contend that the way we write and think about cases, including their format, content, and purpose, provides not-so-subtle clues about the types of information medicine takes to be real: fact, evidence, procedure.

교육적 장치로서의 사례는 의학교육 문헌에서 놀라울 정도로 덜 탐구되었지만, 존재하는 기여는 개인의 사회적 상호 작용과 정체성이 임상적 만남과 건강 결과에 영향을 미칠 수 있는 방식보다는 사실적인 의료 정보에 중점을 두었습니다 [1, 2, 3]. 이러한 경우 환자의 목소리가 거의 들리지 않는 것은 악의나 나쁜 의도의 산물이 아니라고 생각합니다. 오히려 학생이 다음 단계의 교육으로 넘어가는 데 필요한 정보, 즉 필수적인 내용을 사례에 가득 채우고자 하는 욕구에서 비롯된 것입니다. 여기에 어떤 정보가 실제로 사례에 포함해야 하는 필수 정보인지 어떻게 결정할 수 있을까요?

While cases as an educational device remain surprisingly under-explored in the medical education literature, those contributions that do exist have noted an emphasis on the factual medical information rather than the way an individual’s social interactions and identity can affect a clinical encounter and health outcome [1, 2, 3]. This largely absent patient voice in cases, we believe, is not a product of ill-will or bad intention. On the contrary, it arises from a desire to ensure that cases are packed full of the essentials, meaning the information a student needs to move onto the next stage of their education. Herein lies the challenge: How do we determine what information is, in fact, essential to include in a case?

여기서 놓치고 있는 부분은 철학적 문제, 더 구체적으로는 존재론적 문제라고 주장합니다. 즉, 우리가 교육에 사용하는 사례는 현실의 본질에 대한 의심할 여지 없는 철학적 가정을 재생산합니다. 과학 철학에서는 의학교육을 포함한 모든 분야는 다음을 포함한 일련의 철학적 원칙을 통해 구성된다고 주장합니다[4].

- 존재론(무엇이 실재하는가),

- 인식론(우리가 무엇을 알 수 있는가),

- 방법론(우리가 어떻게 알 수 있는가),

- 공리론(우리가 무엇에 가치를 두는가)

가장 단순한 형태로 온톨로지는 존재의 과학으로 정의할 수 있습니다. 의학교육의 세계에서 바르피오와 맥레오드[4]는 온톨로지를 한 분야로서 우리가 실재한다고 가정하는 것으로 설명했습니다.

The missing piece here, we contend, is a philosophical issue, and more specifically, an ontological one. In other words, the cases we use for education reproduce unquestioned philosophical assumptions about the nature of reality. The philosophy of science holds that all fields, including medical education, are constituted through a set of philosophical principles, including

- ontology (what is real),

- epistemology (what we can know),

- methodology (how we can know), and

- axiology (what we value) [4].

In its simplest form, ontology can be defined as the science of being. In the world of medical education, Varpio and MacLeod [4] described ontology as what we, as a field, assume to be real.

이 원고에서 우리는 증례는 교육적 인공물이며, 우리가 교육에 사용하는 증례의 목적, 구조 및 내용에는 의학의 존재론적 가정이 존재하거나 존재하지 않는다는 입장을 취합니다. 우리는 존재론적 충실성의 관점에서 증례를 만든다는 것은 무엇을 의미하며, 일상적인 의학 교육에서 이를 수행하는 방법에 대한 제안을 제공한다는 질문을 던집니다.

In this manuscript, we take the position that cases are educational artefacts, and that the ontological assumptions of medicine are present (or not) in the purpose, structure, and content of the cases we use for teaching. We ask the question: what would it mean to create cases from a position of ontological fidelity and provide suggestions for how to do this in everyday medical education?

철학이 중요한 이유는 무엇일까요?

Why does philosophy matter?

의학교육은 모든 관련 분야와 마찬가지로 철학의 영향을 많이 받습니다. 그러나 철학적 탐구는 아직 의과대학의 일상적인 업무에 적용되지 못하고 있습니다. 의학의 철학과 의학교육 시리즈[5], 아카데믹 메디슨의 과학철학 시리즈[4], 최근 출간된 보건 전문직 교육을 위한 응용철학[6] 등 학문 영역에서 철학적 아이디어를 통합하는 데 대한 관심이 높아지고 있음에도 불구하고 말입니다. 물론 의학교육은 철학의 도구를 활용하여 새로운 관점을 통해 의학의 오랜 과제를 해결함으로써 이점을 얻을 수 있습니다[5]. 빈과 시안치올로[5]는 "철학은 복잡하고 불확실할 때 잠시 멈춰서 명백해 보이는 관행에 대해 기본적인 질문을 던져 새로운 방식으로 사물을 보고 행동할 수 있도록 하는 근본적인 접근 방식으로 볼 수 있다"고 말합니다[5 p337].

Medical education, along with all related fields, is steeped in philosophy. Yet, philosophical inquiry has yet to find its way to the everyday practices of our medical schools. This is despite increasing interest in integrating philosophical ideas in the academic realm, notably within Teaching and Learning in Medicine’s Philosophy and Medical Education series [5], Academic Medicine’s Philosophy of Science series [4], and the recent book Applied Philosophy for Health Professions Education [6]. Certainly, medical education can benefit from turning to the tools of philosophy to address medicine’s long-standing challenges through a fresh perspective [5]. As Veen and Cianciolo [5] remind us, “philosophy can be seen as the fundamental approach to pausing at times of complexity and uncertainty to ask basic questions about seemingly obvious practices so that we can see (and do) things in new ways” [5 p337].

전통적으로 의학 및 의학교육은 합리성, 객관성, 중립성에 대한 실증주의적 이상을 수용해 왔습니다[7]. 근거 기반 의학 및 비판적 평가와 같이 불확실성을 최소화하기 위해 고안된 체계적인 관행은 역사적으로 의학 및 의학교육 내에서 특권의 지위를 유지해 왔습니다[8]. 그러나 객관성과 중립성이라는 개념은 복잡하고 모순적이며 종종 예측할 수 없는 인간 활동의 본질을 가리고 있습니다[9]. 연구 맥락에서, 의학교육의 세계는 지식이 발견을 기다리는 객관적인 '사실'로 존재하는 것이 아니라 사회적 산물이며 제작자의 주관성이 반영된 증거라는 구성주의적 관점의 혜택을 받았습니다[10, 11](그림 1 참조). 트위터는 학술적 작업에서 다양한 온톨로지를 위한 공간을 마련하고 있으며, 최근 우이 저널과 컨퍼런스에서 비판 지향적이고 이론적 정보를 바탕으로 한 사회과학적 관점의 기고문을 발표하고 있습니다[1, 12, 13]. 그러나 흥미롭게도 사례 기반 학습을 포함한 교육 관행에서 동일한 공간을 만드는 것은 그다지 성공적이지 않았습니다.

Traditionally, medicine and medical education have embraced positivist ideals around rationality, objectivity, and neutrality [7]. Systematic practices designed to minimize uncertainty like evidence-based medicine and critical appraisal have historically maintained a position of privilege within medicine and medical education [8]. However, notions of objectivity and neutrality disguise the complex, contradictory, and often unpredictable nature of human activity [9]. In the context of research, the world of medical education has benefited from constructivist perspectives that knowledge does not exist as an objective “fact” awaiting discovery; rather, it is a social product, a testament to the subjectivities of its creators [10, 11] (See Figure 1). We make room for multiple ontologies in our scholarly work, with recent contributions of critically oriented, theoretically informed social science perspectives in our journals and conferences [1, 12, 13]. Interestingly, however, creating the same space in our educational practices, including case-informed learning, has not been quite as successful.

그림 1 사례 기반 학습에 대한 실증주의 및 구성주의 접근 방식.

Figure 1 Positivist and Constructivist Approaches to Case-Based Learning.

사례 기반 학습

Case-Informed Learning

사례 기반 학습은 학습자가 가장 먼저 접하게 되는 교육적 접근 방식 중 하나입니다. 이 접근 방식은 원래 1960년대 중반 Barrows와 Tamblyn에 의해 문제 기반 학습(PBL)으로 개념화되고 구현되었으며[14], 학생들이 교수진 또는 튜터와 함께 소그룹으로 작업하여 실제 임상 상황을 시뮬레이션하는 임상 '문제'(즉, 사례)를 해결하도록 합니다[15]. 목표는 "지식의 단편화와 무의미한 사실의 습득을 줄이고, 호기심과 팀워크를 촉진하며, 질병 모델이 아닌 환자를 제시하는 것"입니다[16 p868]. 즉, 학습자가 당면한 사례를 공동으로 조사하면서 정보를 찾고 문제를 해결하는 기술을 개발하여 추후 전문 실무에 적용할 수 있습니다[15].

Case-informed learning is one of the first pedagogical approaches learners will encounter. This approach, originally conceptualized and implemented as Problem-Based Learning (PBL) by Barrows and Tamblyn in the mid 1960s [14], involves students working in small groups with a faculty facilitator or tutor to solve a clinical “problem” (i.e., a case) that simulates a real-life clinical situation [15]. The goal is to “reduce fragmentation of knowledge and acquisition of meaningless facts, to promote curiosity and teamwork, and to present a patient rather than a disease model” [16 p868]. In other words, as learners collaboratively investigate the case at hand, they develop the skills to find information and solve problems they can subsequently apply to their professional practice [15].

사례 기반 학습 접근법은 사실 존재론적 인공물입니다. 이는 의견과 행동이 감정이나 감각적 경험보다는 이성과 지식(예: 수학적 지식)에 근거해야 한다는 합리주의 이론에서 그 기원을 찾을 수 있으며, 인지 심리학[17]과 듀이[18]의 독립적이고 경험적인 학습 장려[15]의 영향을 강하게 받습니다. 시뮬레이션된 사례 또는 문제에서 학습한다는 개념은 듀이가 '실제 생활'과 함께 맥락과 학습을 매우 중요하게 여겼기 때문에 그의 공로를 인정받을 수 있습니다.

Case-informed learning approaches are, in fact, ontological artefacts. They can be traced to theories of rationalism, which refer to the idea that opinions and action should be based on reason and knowledge (e.g., mathematical knowledge) rather than on emotions or sensory experience, and are strongly influenced by cognitive psychology [17] as well as Dewey’s [18] encouragement of independent and experiential learning [15]. The notion of learning from a simulated case, or problem, can also be credited to Dewey, as he considered context and learning in concert with “real life” critically important.

사례 기반 학습은 시간이 지남에 따라 사례 및 팀 기반 학습과 같은 변형이 인기를 얻으면서 발전해 왔지만, 질문의 중심이 되는 내러티브 사례 이야기는 일관되게 유지되고 있습니다. 텍스트 기반 커리큘럼 모델로서 사례 기반 접근 방식은 의료 현장의 이야기를 포용할 수 있는 잠재력을 가지고 있습니다. 그러나 실제로는 기술적, 과학적, 전문적인 접근 방식인 '의학의 목소리'가 질병 이야기를 지배해 왔으며, 환자의 '삶의 목소리', 즉 환자의 삶의 사건과 문제에 대한 생생한 경험은 희생되어 왔습니다[19, 20]. 따라서 실제로 우리가 더 자주 보게 되는 것은 Coulehan이 설명한 것과 같은 의료 중심의 '병원 이야기'입니다[21]:

While case-informed learning has evolved over time, with variations like case- and team-based learning gaining popularity, the narrative case story at the heart of the inquiry remains consistent. As a text-based curricular model, case-informed approaches have the potential to embrace the stories of medical practice. In reality, however, the “voice of medicine”—a technical, scientific, and professional approach—has dominated illness stories, at the expense of the patient’s “voice-of-the-life-world”: the patient’s lived experiences of events and problems in their life [19, 20]. What we therefore see more often in practice are the medical-centric “hospital stories,” such as those described by Coulehan [21]:

병원 정신에 스며든 이야기에는 일반적으로 환자가 주인공으로 등장하지 않으며, 심지어 인간적인 역할을 하는 부수적인 인물로 등장하지 않는 경우가 많습니다. 오히려 환자는 이야기의 진행을 방해하는 장애물이나 도전과 같이 영리하거나 좌절감을 주는 플롯 장치로 등장하거나, 때로는 이야기의 성공적인 해결을 촉진하는 예상치 못한 선물과 같은 긍정적인 플롯 장치로 등장하기도 합니다[21 p109].

The stories that permeate the hospital ethos don’t usually have patients as their protagonists, and often not even as ancillary characters that play human roles. Rather, patients quite frequently serve as clever or frustrating plot devices—obstacles or challenges that impair the story’s progress; or sometimes they may serve as positive plot devices, unexpected gifts that facilitate the story’s successful resolution [21 p109].

Coulehan과 다른 내러티브 학자들[22]은 이야기를 통해 성취되는 작업에 주목할 것을 권장했습니다. 내러티브 의학[23, 24, 25]은 내러티브 역량을 키우기 위한 의미 있는 수단으로 번창했습니다: "질병에 대한 이야기를 인식하고, 흡수하고, 대사하고, 해석하고, 감동할 수 있는 능력"[23 p1265]. 의학교육 연구와 의학 인문학 커리큘럼에서 환자의 주관적인 질병 경험을 묘사함으로써 "(재)인간화 의학"[26 p113]을 통해 생생한 경험이 지식으로 정당화되고 환자가 자신의 이야기를 서술하는 화자로서 주체성을 갖게 됩니다[26]. 하지만 흥미롭게도 미래의 의사를 가르치는 데 사용하는 이야기에 대한 관심은 현저히 떨어집니다.

Coulehan, and other scholars of narrative [22], have encouraged us to pay attention to the work that is accomplished through stories. Narrative medicine [23, 24, 25] has flourished as a meaningful avenue for fostering narrative competence: “the capacity to recognize, absorb, metabolize, interpret, and be moved by stories of illness” [23 p1265]. By “(re)humanizing medicine” through portrayals of patients’ subjective experience of illness in medical education research and medical humanities curriculum [26 p113], lived experience becomes legitimized as knowledge and provides patient agency as narrator of their own story [26]. Interestingly, though, the stories that we use for teaching future physicians have received significantly less attention.

사례는 어떻습니까?

What about the case?

다양한 사례 기반 학습 접근법을 다루는 수십 년간의 연구에도 불구하고, 놀랍게도 전통적인 사례 형식에 이의를 제기한 연구는 거의 없습니다[2, 27, 28, 29]. Kenny와 Beagan[30]은 전형적인 사례 구성은 "환자의 목소리를 배제하고 의사의 목소리에 궁극적인 권위를 부여한다"고 지적했습니다. 이는 의학적 관찰과 해석을 논쟁의 여지가 없는 사실로 구성하는 반면 환자의 관찰은 주관적이고 오류 가능성이 있는 것으로 평가 절하합니다."(30페이지 1073). 이러한 방식으로 학생들은 환자를 해결해야 할 문제로 여기고 스스로를 문제 해결자로 여기는 데 길들여질 수 있습니다[1].

Despite decades of research addressing various case-informed learning approaches, surprisingly few studies have contested the traditional format of cases [2, 27, 28, 29]. Kenny and Beagan [30] noted that the typical construction of cases “grants ultimate authority to the voice of the doctor, excluding the voice of the patient. It constructs medical observations and interpretations as incontestable facts while devaluing patient observations as subjective and fallible” (30 p1073). In this manner, students may be accultured to view patients as problems to be solved, and themselves as problem-solvers [1].

물론 사례는 학생들에게 특정 진단 이상의 것을 교육합니다. 증례를 통해 재조명되는 의학의 존재론적(그리고 이와 관련된 공리론적, 즉 우리가 중요하게 여기는 것) 토대는 학생들에게

- 주의해야 할 것과

- 무시해도 되는 것에 대해 암묵적으로 가르칩니다. 이는 다시 학생들이

- 무엇을, 어떻게 생각해야 하는지뿐만 아니라

- 무엇을, 어떻게 느껴야 하는지, 그리고 이러한 영역에

- 어떻게 중요성을 부여하고 우선순위를 정해야 하는지도 결정합니다.

Certainly, cases educate students about more than a particular diagnosis. The ontological (and relatedly, axiological, i.e., what we value) foundations of medicine, reinscribed through the case, implicitly teach students about

- what they need to concern themselves with, and

- what they can ignore. This, in turn, dictates not only

- what and how they should think, but also

- what and how they should feel, and

- how they ascribe and prioritize importance to these areas.

의학교육 문헌에 일관되게 기술된 사례 기반 접근법의 주요 특징은 '실제 삶'을 시뮬레이션한다는 점입니다[3, 14, 17, 27, 31, 32, 33, 34]. 의학교육자로서 우리는 잠시 멈춰서 스스로에게 질문해야 합니다. 이 사례를 통해 어떤 유형의 진료를 시뮬레이션할 수 있기를 바라는가?

A key feature of case informed approaches consistently described in the medical education literature is their simulation of “real life” [3, 14, 17, 27, 31, 32, 33, 34]. As medical educators, we must pause to ask ourselves: what type of practice do we hope this case will simulate?

사례, 시뮬레이션 및 온톨로지 충실도

Case, Simulation, and Ontological Fidelity

흥미롭게도 사례 기반 학습이 사실 시뮬레이션의 한 유형이라는 것을 알고 있지만, 우리 분야에서는 아직 사례와 충실도 개념을 명확하게 연결 짓지 못했습니다. 시뮬레이션 기반 의학 교육의 맥락에서 충실도는 우리가 기대하는 현실감의 정도 또는 시뮬레이션이 현실을 재현하는 정확성의 정도를 의미합니다[35, 36, 37]. 의료 교육자는 일반적으로 두 가지 유형의 충실도에 중점을 둡니다[35, 38].

- 물리적(즉, 시뮬레이터의 모양과 느낌의 유사성)과

- 기능적(즉, 시뮬레이터가 조작 또는 개입에 반응하는 방식의 유사성)이라는

기본 철학적 가정으로 돌아가서, 이러한 충실도에 대한 접근 방식은 실증주의적 방향에 기반하며, 이러한 시뮬레이션이 "실제" 임상 실습과 일치하는 객관적이고 측정 가능한 방식에 관심을 기울입니다[37].

Interestingly, while we recognize that case-informed learning is, in fact, a type of simulation, our field has not yet made a clear connection between cases and the concept of fidelity. In the context of simulation-based medical education, fidelity refers to the degree of realism we should expect, or the degree of exactness with which the simulation reproduces reality [35, 36, 37]. Medical educators generally focus on two types of fidelity:

- physical (i.e., similarity in the look and feel of the simulator) and

- functional (i.e., similarity in how the simulator responds to manipulation or intervention) [35, 38].

Returning to our underlying philosophical assumptions, these approaches to fidelity draw on positivistic orientations, concerned with objective, measurable ways these simulations align with “real” clinical practice [37].

또 다른 연구에서는 신중하게 고려할 가치가 있는 추가적인 충실도 유형으로 존재론적 충실도 개념을 제시했습니다[12]. 이 연구에서 우리는 학습자가 마네킹이 아닌 카데바에서 프로시져를 연습할 때와 시체에서 프로시져를 연습할 때 매우 다르게 참여하는 것을 발견했습니다. 간단히 말해서 시체는 실제와 다름없기 때문입니다. 카데바는 사연과 역사가 있는 살아있는 사람이었고, 그 이전의 삶이 교육 세션에 스며들었습니다[12, 39]. 간단히 말해, 존재론적 충실도는 시뮬레이터가 실제 환자와 얼마나 일치하는지, 즉 실제 인간과 얼마나 일치하는지를 의미합니다. 카데바의 존재론적 충실도는 가장 큰 강점이며 매우 다른 유형의 실습에 영감을 주었습니다. 최선의 노력에도 불구하고 아무리 기술을 발전시켜도 그 리얼리티를 재현할 수는 없었습니다.

In another study, we brought forward the concept of ontological fidelity as an additional type of fidelity that merits our careful consideration [12]. In that work, we noticed that learners engaged very differently when they practiced procedures on a cadaver as opposed to a manikin because, to simplify, the cadaver was real—and unmistakably so. The cadaver had been a living person with a story and a history, and that former life permeated the teaching sessions [12, 39]. Stated simply, then, ontological fidelity refers to the degree to which a simulator matches what a patient is: a real, human person. The ontological fidelity of cadavers was their greatest strength and inspired a very different type of practice. Despite our best efforts, no amount of technological advancement could reproduce that realness.

존재론적 충실도의 개념을 사례 기반 학습으로 확장하여, 우리는 내러티브 실천으로서의 의학이 실제로 이야기를 통해 구성된다고 믿습니다. 물론 의학에는 설득력 있고 실제적인 사례를 만들 수 있는 실화가 충분히 많지만, 이는 우리가 내러티브 실천에 동의하고 사례에서 의학에 대한 인간적 경험을 위한 공간을 확보하는 경우에만 가능합니다.

Extending the concept of ontological fidelity to case-informed learning, we believe that medicine, as a narrative practice, is in fact constructed through story. Certainly, there are enough true stories in medicine that we can create a compelling, and real, case—but only if we agree to engage in narrative practice, and only if we make space for the human experience of medicine in our cases.

사례 기반 학습으로 돌아가서, 우리는 일련의 철학적 질문에 직면하게 됩니다:

- 무엇이 진짜인가?

- 또는 더 정확하게는 사례를 통해 무엇을(그리고 누구의) 현실을 시뮬레이션하고자 하는가?

- 실제처럼 느끼게 하는 사례의 필수 요소는 무엇일까요?

- 사례 형식으로 재현하고자 하는 임상 스토리는 무엇인가요?

Returning to case-informed learning, we are faced with a set of philosophical questions:

- What is real? Or, perhaps more accurately,

- what (and whose) reality do we want to simulate through cases?

- What are the essential elements of a case that make it feel real?

- What is the clinical story we want to reproduce in case format?

사례 기반 학습에 온톨로지적 충실도 제공

Bringing Ontological Fidelity to Case-Informed Learning

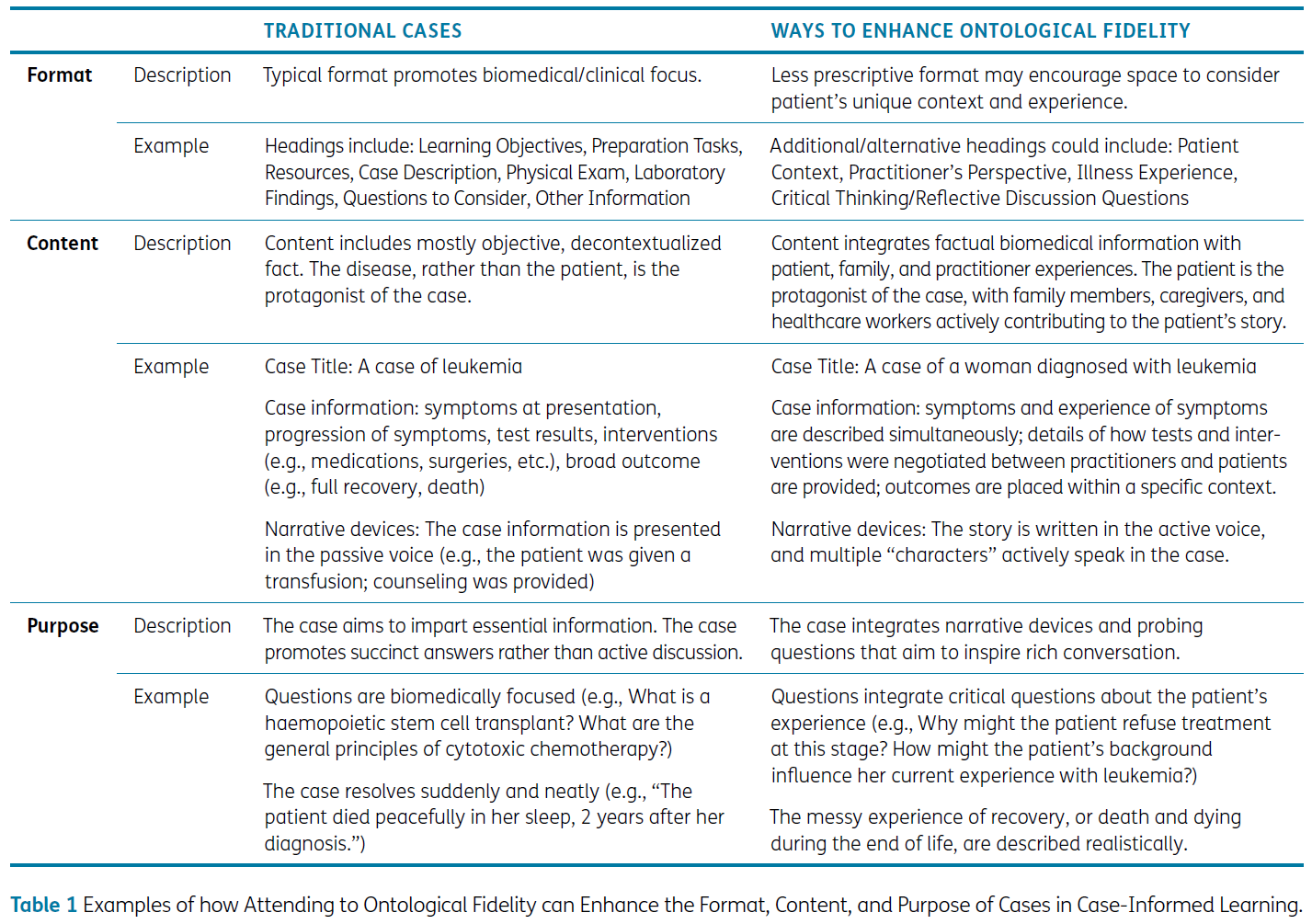

현재 사례 기반 학습에 대해 우리가 알고 있는 것은 환자의 이야기, 감정, 경험보다는 객관적인 사실이 사례의 실체를 구성해야 한다는 실증주의적 존재론적 입장을 강화하는 방식으로 사례 자체가 계속 당연시되고 있다는 것입니다. 우리는 존재론적 충실성에 주의를 기울이면 더 의미 있는 사례로 이어질 것이라고 제안합니다. 이를 위해 교육자들은 잠시 멈춰서 무엇이 실제인지에 대한 가정과 이러한 가정이 사례의 세 가지 요소인 형식, 내용, 목적에 어떻게 적용되는지 신중하게 검토할 것을 권장합니다(표 1 참조).

What we currently know about case-informed learning is that cases themselves continue to be taken-for-granted in ways that reinforce the positivist ontological position that objective fact, rather than patients’ stories, emotions, and experiences should constitute the substance of the case. We propose that attending to ontological fidelity will lead to more meaningful cases. To do that, we encourage educators to pause and deliberately examine their assumptions about what is real, and how those assumptions translate into three elements of cases: format, content, and purpose (See Table 1).

형식

Format

텍스트 기반 증례의 형식은 꾸준히 도전받지 않고 있습니다. 기관마다 차이가 있을 수 있지만, 일반적으로 사례는 간결하게 작성되고 사례의 임상적 초점을 강조하는 전통적인 구조를 따르는 것이 일반적입니다. 일반적으로 증상, 조사 및 치료법이 나열된 환자 시나리오에 대한 설명, 일련의 학습 목표 및 리소스, 몇 가지 안내 질문이 포함됩니다.

The format of text-based cases remains consistently unchallenged. While there might be variation between institutions, we have generally come to expect cases that are written concisely, and offer a traditional structure that highlights the clinical focus of the case. They generally include a description of the patient scenario where symptoms, investigations, and treatments are listed; a set of learning objectives and resources; and some guiding questions.

각 사례마다 등장하는 환자의 이름과 상태는 다르지만 사례의 틀 자체는 몇 번이고 반복해서 재현됩니다. 학생들은 이를 다소 지루하게 느낄 수 있으며, 이는 "PBL 피로감"[40]의 원인이 될 수 있습니다. 또한 이러한 유사한 구조의 사례는 각 모의 임상 상황을 다소 '동일'하게 제시하여 각 환자의 고유성과 복잡성을 떨어뜨리고, 환자 및 동료와의 임상 상황(예: 구두 사례 인계 시)에서 경험할 수 있는 구술 방식에서 벗어날 수 있습니다. 또한 텍스트가 많은 문서는 난독증과 같은 학습 장애를 가진 학습자를 포함하여 다양한 학습 프로필을 가진 학습자의 접근성에 장벽이 될 수 있습니다.

Although each case is unique in terms of the names and conditions of the patients represented, the framework for the case, itself, is reproduced again and again. Students can begin to find this rather boring, contributing to what has been referred to as “PBL fatigue” [40]. Additionally, these similarly structured cases present each simulated clinical encounter as more or less “the same,” detracting from the uniqueness and complexity of each patient, and deviating from the ways that spoken speech may be experienced in clinical encounters with patients and colleagues (e.g., during oral case handovers). Further, text-dense documents may pose barriers to accessibility for learners with diverse learning profiles, including those with learning differences such as dyslexia.

표준화된 판례 형식을 재현하는 것은 오랜 관행으로 보입니다. 예를 들어, 1993년 굿과 굿은 "사례 구성 방식(사회적, 개인적 특성은 최소화되고, 생리적 세부 사항은 매우 많음)과 환자가 사례로 재구성되는 방식에 대해 명시적인 주의를 기울이지 않는다"고 관찰했습니다. [41 p94].

The reproduction of a standardized case format appears to be a long-standing practice. For example, in 1993, Good and Good observed, “No explicit attention is paid to how cases are constructed (with minimal social and personal characteristics and great physiological detail) and how sufferers are reconstructed as cases….” [41 p94].

존재론적 충실성을 고려하기 위해 사례 형식을 재구상한다면, 사례 구조화에 대한 규정된 접근 방식을 재고할 수 있습니다. 템플릿은 포함해야 하는 모든 세부 사항을 처리한다는 측면에서 의심할 여지 없이 유용하지만, 템플릿은 모든 사례가 동일하게 보이고, 따라서 동일한 방식으로 관리될 수 있다는 기대를 강화하는 역할을 하기도 합니다. 각 사례와 그 사례에서 영감을 얻거나 필요로 하는 관련 활동이 고유하도록 정보의 순서를 변경할 수 있습니다. 어떤 사례에는 환자의 이야기(글 또는 동영상)가 포함될 수 있고, 어떤 사례에는 의료진의 반성적 의견이 포함될 수도 있습니다. 유도 질문은 특정 정보를 이끌어내기 위해 고안된 것이 아니라 더 높은 수준의 토론, 비판적 사고 및 공감을 불러일으키기 위해 방향을 바꿀 수 있습니다.

Were we to reimagine case format to attend to ontological fidelity, we might reconsider the prescribed approach to structuring cases. While templates are undoubtedly helpful in terms of attending to all the details that need to be included, templates also serve to reinforce the expectation that all cases look the same, and relatedly, can be managed in the same way. The order of information might be changed so that each case, and the related activities it inspires/requires, is unique. Sometimes cases may feature stories from patients (which could be written or video), and in others they might include reflective comments from practitioners. Guiding questions, rather than being designed to draw out specific bits of information, might be reoriented to inspire higher level discussion, critical thinking, and empathy.

콘텐츠

Content

사례 기반 접근법은 흔히 '환자 중심'의 교육적 접근법으로 설명됩니다[14, 16, 27, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47]. 각 사례에는 환자가 등장하는데, 그 외에 다른 무엇이 있을 수 있을까요?

Case-informed approaches are frequently described as a “patient-centred” pedagogical approach [14, 16, 27, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47]. Each case features a patient—how could they be anything else?

그러나 우리는 단순히 각 사례에 이름이 지정된 환자가 있는 것만으로는 존재론적 충실성에 필요한 환자 관점을 제공하지 못한다고 생각합니다. 교육 사례에서 환자는 종종 내러티브 장치, 즉 생물의학 또는 임상 정보를 전달하는 2차원적인 수단으로 쓰입니다. 이러한 환자들은 이름과 직업이 부여된 증상 목록으로 제시됩니다.

- 환자의 목소리를 직접 듣는 경우는 거의 없습니다[2].

- 해당 사례의 감정적 요소에 대해 배우거나 고려하는 경우는 거의 없습니다.

- 개별 환자에게 진단이 얼마나 큰 영향을 미치는지, 진단을 받은 환자의 삶이 어떻게 변할지를 거의 다루지 않습니다. 특히 몇 주에서 몇 달에 걸친 긴 검사와 진료 예약을 거치는 동안의 삶은 서류상 한두 단락과 동일시할 수 없다.

- 환자의 사회적 위치에 따라 질병이 다르게 경험된다는 진단의 사회적 현실을 다루는 사례는 거의 없습니다.

대신, 사례는 일반적으로 환자의 구체화된 경험, 주체성, 인간성의 윤곽이 결여되어, 평면적이고, 정돈되고, 질서정연합니다. 이러한 평면성은 어떤 악의적인 의도에서 비롯된 것은 아니지만, 그 결과는 심각합니다.

We believe, however, that simply having a named patient in each case does not offer the patient perspectives necessary for ontological fidelity. The patient in an educational case is often written as a narrative device: a two-dimensional vehicle for relaying biomedical or clinical information.

- They are presented as a list of symptoms assigned a name and, in some instances, a job.

- Rarely do we hear from a patient in their own voice in cases [2].

- Rarely do we learn about, or even consider, the emotional elements of the case in question.

- Rarely do cases engage with the magnitude of the diagnosis for individual patients and what life will look like for those who have been diagnosed, particularly as they wade through lengthy weeks and months of testing and appointments, which does not equate to a paragraph or two on paper.

- Rarely do cases address the social realities of a diagnosis: that an illness is experienced differently depending on social location of the patient.

Instead, cases are generally flat, tidy, and orderly—lacking the contours of a patient’s embodied experience, agency, and humanness. While this flatness does not arise from any ill intent, it is consequential.

존재론적 충실성을 고려하기 위해 사례 콘텐츠를 재구상한다는 것은 관련 임상 정보뿐만 아니라 임상적 만남의 다른 인간적 차원에도 주의를 기울이는 것을 의미할 수 있습니다. 환자는 종종 신뢰할 수 없는 정보 출처로 고정관념화되어 지식 생성에 기여할 수 있는 능력을 부정당하는 등 인식론적 불공평으로 인해 환자의 목소리는 역사적으로 배제되어 왔습니다[48]. 사례 작성 과정에서 실제 환자(뿐만 아니라 의사 및 기타 의료 서비스 제공자)를 초대하여 일상적인 임상 이야기를 공유함으로써 환자-의사 상호작용의 내러티브 특성을 더욱 부각시킬 수 있습니다.

Reimagining case content to attend to ontological fidelity might mean attending not only to the relevant clinical information, but also to the other human dimensions of a clinical encounter. The patient voice has historically been excluded, in part, due to epistemic injustice: patients are often stereotyped as unreliable sources of information and are therefore denied the capacity to contribute to knowledge generation [48]. The narrative nature of any patient-physician interaction would be made more present by inviting real patients (as well as physicians and other health care providers) to share everyday clinical stories in the case writing process.

우리는 (임상의, 환자 및 당면한 시나리오와 관련된 다른 사람들의) 목소리를 들을 수 있습니다. 사용된 단어, 표현된 감정, 묘사된 반응은 진솔할 것이며, 이야기는 깔끔하거나 논리적인 타임라인을 따르지 않을 수도 있고, 심지어 약간 지저분할 수도 있습니다! 학습자가 커리큘럼을 진행하면서 기술, 지식 및 자신감을 얻게 되면 의료 행위를 포함한 인간 경험의 특징인 불확실성과 모호함에 대한 편안함을 키우기 위해 노력하면서 사례가 점차 더 지저분해질 여지가 있을 수도 있습니다.

We would hear voices—of clinicians, of patients, and of others relevant to the scenario at hand. The words used, the feelings expressed, and the reactions described would be authentic, and the story might not follow a neat or logical timeline—it might even be a bit messy! There may even be room for cases to become progressively messier as learners move through the curriculum and gain skill, knowledge, and confidence, working toward fostering comfort with uncertainty and ambiguity that characterizes human experience, including medical practice.

목적

Purpose

풍부한 대화를 유도하고 깊은 사고를 불러일으키는 사례를 작성하기 위해 최선을 다하고 있지만, 일반적으로 커리큘럼을 구성하는 사례는 주로 필수 정보를 전달하는 것을 목표로 합니다. 따라서 사례는 일종의 체크리스트 역할을 하는 경우가 많습니다.

Despite our best efforts to write cases that lead to rich conversation and inspire deep thinking, the cases that commonly structure our curriculum aim primarily to impart essential information. Consequently, cases often come to serve as a type of checklist.

사례의 의식화된 목적은 학생들이 기대하는 일련의 규정된 소그룹 학습 관행을 불러일으키며, 강렬하고 스트레스가 많은 업무량[49]으로 인해 '일단 해치우자'는 태도로 접근하는 경우가 많습니다[2]. 사례에 접근하는 방식을 사례에 대입하면, 사례는 종종 세부 사항이 제한되어 간결하게 작성되고[33], 복잡한 아이디어를 암기하기 쉬운 단계나 범주로 단순화하며, 다가오는 시험에서 평가될 수 있는 자료를 간소화하는 데 중점을 두는 경우가 많다는 것을 의미합니다.

The ritualized purpose of a case invokes a set of prescribed small-group learning practices that students have come to expect, and—motivated by a workload that is intense and stressful [49]—these are often approached with a ‘let’s get this done’ attitude [2]. Translated into how we approach cases, this means that they are often anticipated to be succinct with limited detail [33]; they simplify complex ideas into easy-to-memorize steps or categories; and they focus on streamlining material that might be assessed on an upcoming exam.

마찬가지로 사례는 일상적인 방식으로 전개될 것으로 예상됩니다. 부정적(예: 환자의 사망으로 끝나는 경우)이든 긍정적(예: 환자의 회복과 번영으로 끝나는 경우)이든 학습자는 일반적으로 사례가 구체적인 해결책으로 마무리될 것으로 기대합니다. 그러나 사례의 목적이 학생이 맥락에서 학습할 수 있는 메커니즘을 제공하는 것이라면 사례는 다층적이고 복잡한[14, 17, 30] 실제 의료 행위의 맥락을 시뮬레이션해야 합니다[50]. 반응과 풍부한 대화를 유도하기 위해 사례는 다소 복잡할 것이라고 예상할 수 있습니다.

Likewise, cases are expected to unfold in a routine way. Whether negative (ending with the patient’s death, perhaps) or positive (ending with the patient recovering and thriving, for example), learners generally expect the cases to conclude with a concrete resolution. However, if the purpose of cases is to provide a mechanism for students to learn in context, cases ought to simulate the context of real-life medical practice [14, 17, 30], which is multi-layered and complex [50]. One might expect that cases would be somewhat convoluted, in order to inspire reaction and rich conversation.

존재론적 충실도를 고려하기 위해 사례를 재구성한다면, 의료 행위를 구성하는 스토리를 위한 공간을 확보할 수 있도록 사례를 재구성할 수 있습니다. 사례는 복잡한 상황이나 일상에서 벗어나 쉽게 해결되지 않을 수 있는 상황을 제시할 수 있습니다. 이러한 사례는 의사들이 실제 진료에서 직면하게 될 문제 유형에 대해 더 깊은 사고와 성찰, 분석을 촉진할 수 있습니다.

If we were to reimagine cases to attend to ontological fidelity, we might reorient cases so that they make space for the stories that constitute medical practice. Cases might present a complicated situation, or one that moves away from the routine and might not be easily resolved. This could foster deeper thinking, introspection, and analysis of the types of challenges they will face moving forward in practice.

"실제 생활"에서의 온톨로지 충실도

Ontological Fidelity in “Real Life”

의심할 여지 없이 증거에 기반한 과학적, 임상적 접근 방식이 치료에 반드시 존재해야 하지만, 이것만이 중요한 것은 아닙니다. 사례에 철학적 관점을 통합하는 것이 복잡해 보일 수 있지만, 실제로 사례는 이미 의학 분야에서 존재론적 지향의 인공물로서 존재합니다. 우리가 할 일은 단순히 우리가 실제적이고 중요한 것으로 표현하고자 하는 것을 반영하는 것입니다.

Without a doubt, evidence-based scientific and clinical approaches must be present in cases—but these are certainly not the only things that matter. While the integration of a philosophical perspective to cases may seem complicated, in reality, cases already exist as an artefact of our ontological orientation in the field of medicine. Our job is simply to reflect on what we want to represent as real and important.

우리는 미래의 실제 시나리오를 시뮬레이션하려는 모든 교육 전략과 마찬가지로 사례도 충실도의 문제를 고려해야 한다고 믿습니다. 그러나 물리적 또는 기능적 충실도보다는 모든 사례의 핵심은 존재론적 충실도입니다. 존재론적 충실도를 제공하는 가장 간단한 방법, 즉 학생들이 사례를 실제처럼 느낄 수 있도록 하는 방법은 실제 인물을 바탕으로 사례를 만들고 이를 학생들에게 전달하는 것입니다. 그러나 문학 작품을 읽거나 영화를 본 사람이라면 누구나 알 수 있듯이, 이야기가 사실적이어야만 현실감을 느낄 수 있는 것은 아닙니다. 사례를 신중하게 구성하면 현실에 깊이 뿌리박고 있는 보편적인 진리를 우리가 인식하는 방식으로 전달할 수 있습니다. 이러한 방식으로, 이전 연구에서 학생들이 현실감 때문에 마네킹에 비해 시체에 다르게 참여했던 것처럼[12], 사실적인 느낌의 사례를 만들면 학생들이 사례 기반 학습에 참여하는 방식이 달라질 수 있습니다.

We believe that, like all education strategies that attempt to simulate future real-life scenarios, cases should attend to the question of fidelity. But, rather than physical or functional fidelity, it is ontological fidelity that lies at the heart of every case. Perhaps the simplest way to provide ontological fidelity—to make the cases feel real to students—is to base these cases on real people and communicate that to students. However, as any reader of literature or movie-goer can attest, we do not need stories to be true in order for them to feel real. When cases are thoughtfully constructed, they convey universal truths in ways that we recognize to be deeply rooted in reality. In this manner, just as the students in our previous study engaged differently with cadavers compared to manikins because of their realness [12], creating cases that feel authentic may change the way students engage with case-informed learning.

우리가 의학 교육에 사용하는 사례는 현실의 본질에 대한 의심할 여지 없는 철학적 가정을 재현합니다. 정해진 공식을 고수하는 사례는 튜토리얼과 사례가 어떤 모습이어야 하고 무엇을 할 수 있는지에 대한 협소한 구성을 강화하는 데 도움이 됩니다. 존재론적 충실성이라는 개념에 초점을 맞추면서 교육자가 사례의 가능성과 사례의 필수 요소에 대한 생각을 넓힐 것을 권장합니다. 이는 사례의 형식, 내용, 목적을 재검토하는 것을 의미할 뿐만 아니라 스토리, 환자의 목소리, 감정, 문화, 경험 등 '삶의 세계'를 진정성 있게 통합하려는 공동의 노력도 포함합니다. 교육 관리자와 사례 작성자는 현실의 본질과 관련된 존재론적 질문에 귀를 기울이면서 점진적이고 협력적으로 사례 작성에 접근함으로써 얻을 수 있는 것이 무엇인지 고려할 것을 권장합니다. 사례 작성 과정에서 실제 환자, 의사 및 기타 의료 서비스 제공자와 상담하거나 초대하여 일상적인 임상 사례를 공유하는 것도 좋은 방법이 될 수 있습니다.

The cases we use for medical education reproduce unquestioned philosophical assumptions about the nature of reality. Cases that stick to a prescribed formula help to reinforce a narrow construction of what tutorials and cases should look like and what they can do. As we focus on the idea of ontological fidelity, we encourage educators to broaden their ideas about what cases not only could be, but also what they should be. This means re-examining case format, content, and purpose, but also involves a concerted effort to authentically integrate the “lifeworld,” including story, patient voice, emotion, culture, and experience. We encourage educational administrators and case writers to consider what might be gained by approaching case writing progressively and collaboratively, while attuning to ontological questions relating to the nature of reality. Consulting with, and even inviting real patients, physicians, and other health care providers to share everyday clinical stories in the case writing process would be a good way forward.

Case-Informed Learning in Medical Education: A Call for Ontological Fidelity

PMID: 37063601

PMCID: PMC10103732

DOI: 10.5334/pme.47

Free PMC article

Abstract

Case-informed learning is an umbrella term we use to classify pedagogical approaches that use text-based cases for learning. Examples include Problem-Based, Case-Based, and Team-Based approaches, amongst others. We contend that the cases at the heart of case-informed learning are philosophical artefacts that reveal traditional positivist orientations of medical education and medicine, more broadly, through their centering scientific knowledge and objective fact. This positivist orientation, however, leads to an absence of the human experience of medicine in most cases. One of the rationales for using cases is that they allow for learning in context, representing aspects of real-life medical practice in controlled environments. Cases are, therefore, a form of simulation. Yet issues of fidelity, widely discussed in the broader simulation literature, have yet to enter discussions of case-informed learning. We propose the concept of ontological fidelity as a way to approach ontological questions (i.e., questions regarding what we assume to be real), so that they might centre narrative and experiential elements of medicine. Ontological fidelity can help medical educators grapple with what information should be included in a case by encouraging an exploration of the philosophical questions: What is real? Which (and whose) reality do we want to simulate through cases? What are the essential elements of a case that make it feel real? What is the clinical story we want to reproduce in case format? In this Eye-Opener, we explore what it would mean to create cases from a position of ontological fidelity and provide suggestions for how to do this in everyday medical education.

Copyright: © 2023 The Author(s).

'Articles (Medical Education) > 교수법 (소그룹, TBL, PBL 등)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 의료 윤리학을 가르치기 위한 임상 사례활용의 열두가지 팁(Med Teach, 2018) (0) | 2023.09.19 |

|---|---|

| 성공적으로 메디컬 인포그래픽을 만드는 열두 가지 팁(Med Teach, 2021) (0) | 2023.09.19 |

| 임상 카데바의 라이프사이클: 실천-기반 민족지학(Teach Learn Med, 2022) (0) | 2023.08.19 |

| 프로젝트 기반 학습과 연구 기반 학습(Higher Education Faculty Career Orientation and Advancement, Ch 8) (0) | 2023.08.04 |

| 자연어처리와 전공의 피드백 퀄리티의 질 평가 (J Surg Educ. 2021) (0) | 2023.07.19 |