임상 카데바의 라이프사이클: 실천-기반 민족지학(Teach Learn Med, 2022)

The Lifecycle of a Clinical Cadaver: A Practice-Based Ethnography

Anna MacLeoda , Victoria Luonga , Paula Camerona , George Kovacsb, Molly Fredeena, Lucy Patrickb, Olga Kitsc and Jonathan Tummonsd

소개

Introduction

최근 학자들은 의학교육 탐구에서 보다 명확한 철학적 전환을 요구하며 우리 커뮤니티가 과학 철학을 접하고 "아무도 찾지 못한 문제"를 탐구하도록 장려하고 있습니다.1,2 존재를 다루는 철학의 한 분야인 존재론에 대한 질문은 의학교육 영역에서 중요한 고려 사항으로 제기되었습니다.3 우리는 의학교육에서 가장 복잡한 실습 중 하나인 카데바 기반 시뮬레이션(CBS)을 경험적 및 철학적으로 탐구함으로써 이 요청에 응답했습니다. 이 논문에서는 사람들이 시체를 대면할 때마다 몰입하는 매혹적인 철학적 움직임에 대해 새롭게 조명합니다.

Scholars have recently called for a more explicit philosophical turn in medical education inquiry, encouraging our community to engage with philosophies of science, and to explore “problems no one looked for.”1,2 Questions of ontology, the branch of philosophy that deals with being, have been raised as important considerations in the realm of medical education.3 We responded to this call by both empirically and philosophically exploring one of the most complex practices of medical education: cadaver-based simulation (CBS). In this paper, we shed new light on the fascinating philosophical moves in which people engage each time they find themselves face to face with a cadaver.

시체는 전통적으로 해부학 교육 영역에서 많은 의학교육 프로그램에서 중요한 요소입니다.4,5 의학교육에서 전통적인 시체에 관한 문헌은 해부학 교육에 대한 효과뿐만 아니라,6 시체 사용과 관련된 윤리적7,8 및 전문적9-11 복잡성을 탐구해 왔습니다. 많은 사람들이 논란의 여지가 있는 시체 해부의 역사를 되돌아보면서 한때 "도덕적이지 않고 거의 합법적이지 않은 활동"11(p3)에서 최고 수준의 존중을 요구하는 활동으로 진화했으며, 이는 현재 시체 기반 교육에 관한 윤리 지침 및 법적 규정에 반영되어 있습니다.12 또한 최근의 저자들은 안구 자극부터 불안, 놀라움, 열정에 이르기까지 의료 실습생이 시체 해부와 관련하여 보이는 다양한 신체적, 정신적, 정서적 반응을 탐구했습니다.7,13-17 일반적으로 이러한 연구는 다른 해부학 교육 방법에 비해 시체 기반 학습의 우수성을 입증하고 있으며,6 시체가 학생의 공감과 휴머니스틱 케어에 미칠 수 있는 긍정적인 영향을 입증하고 있습니다.18,19

Cadavers are an important element in many medical education programs, traditionally in the realm of anatomy education.4,5 The literature on traditional cadavers in medical education has explored not only their effectiveness for teaching anatomy,6 but also some of the ethical7,8 and professional9–11 complexities associated with their use. Many have reflected on the controversial history of cadaveric dissection, which has evolved from a once “dubiously moral and barely legal activity” 11(p3) to one demanding the highest standards for respect, which are reflected in current ethical guidelines and legal regulations around cadaver-based education.12 As well, recent authors have explored the various physical and psycho-emotional reactions medical trainees have in relation to cadaveric dissection—ranging from ocular irritation, to anxiety, surprise, and enthusiasm.7,13–17 Generally speaking, these studies attest to the superiority of cadaver-based learning compared to other methods of anatomy education,6 as well as the positive impacts cadavers may have on student empathy and humanstic care.18,19

그러나 맥도날드20와 할람21과 같은 일부 학자들은 시체의 역동적이고 전개되는 특성에 주목하기 위해 인류학 및 민족지학적 접근 방식을 취했습니다. 맥도날드는 학생들이 시체를 어떻게 "습득"하는지를 보여줍니다. "끊임없이 활동하는 미세 관절 과정"에서 학생들은 시간이 지남에 따라 다양한 방식으로 보고, 냄새 맡고, 다루고, 듣는 법을 배웁니다.20(129쪽) 예를 들어, 저자는 학생들이 매뉴얼에 설명된 도표를 눈앞의 시체와 일치시키는 방법을 점차적으로 배우는 과정을 설명하는데, 맥도날드는 이를 "특정한 눈을 획득...보는 법을 배우는 것"으로 묘사하고 있습니다. 또한 할람21은 사후 시신 해부를 "관계적 과정"21(p100)으로 간주하며, 시신은 항상 시신의 조달, 사용 및 추모와 관련된 사회적, 물질적 요소와 관련하여 이해됩니다. 이러한 방식으로 "사후 시신은 인격체로서, 해부학적 지식의 생성 및 전달을 위한 자료로서, 의학 발전을 위한 선물로서 가치가 있다"21(p99).

Some scholars, however, such as McDonald20 and Hallam,21 have taken an anthropological and ethnographic approach to attend to the dynamic and unfolding character of cadavers. McDonald demonstrates how cadavers are “acquired” by students; in an “ever-active process of micro articulation,” students learn to see, smell, handle, and hear in various ways over time.20(p129) For example, the author explains how students gradually learn to match diagrams illustrated in their manuals to the cadavers before them: a process McDonald describes as “acquir[ing] particular eyes…learn[ing] to see.” Moreover, Hallam21 considers the dissection of a body after death a “relational process”21(p100) whereby the cadaver is always understood in relation to the social and material elements involved in their procurement, use, and memorialization. In this manner, “bodies after death are valued as persons, as materials for the generation and communication of anatomical knowledge, and as gifts for the advancement of medical science”21(p99)

최근에는 보존 기술의 발전으로 특히 술기 교육 및 시뮬레이션 영역에서 시체가 새롭게 활용되고 있습니다.22-27 다른 형태의 시뮬레이션과 마찬가지로 CBS는 학습자가 실제와 같은 맥락에서 술기를 연습하고 지식을 적용한다는 아이디어에 기반합니다. 실제 인체보다 인체의 복잡성, 가변성, 특수성을 더 충실하게 재현할 수 있는 마네킹은 없기 때문에 CBS는 특히 고숙련, 저빈도 술기 연습을 위한 유망한 교육 접근법으로 부상하고 있습니다.22-27 이러한 보존 기술은 아직 비교적 새롭기 때문에 임상 사체의 사용을 구체적으로 검토한 연구는 부족합니다. CBS에 관한 기존 문헌은 몇 가지 주목할 만한 예외를 제외하고는 주로 학습에 대한 유효성과 효과를 측정하는 데 중점을 두었습니다.22-28. 예를 들어, 더글러스 존스(Douglas-Jones)29 의 민족지학적 설명은 대만의 추기경 침묵 멘토 프로그램인 메디컬 시뮬레이션 센터에서 사람들이 기증자의 신원을 인정하기 위해 사진을 배치하고 기증자의 삶에 대한 이야기를 들려줌으로써 기증의 문화적 특수성을 자세히 설명합니다.

More recently, advancements in preservation techniques have led to new uses for cadavers, specifically in the realm of procedural skills teaching and simulation.22–27 CBS, like any form of simulation, is based on the idea that learners practice skills and apply knowledge in lifelike contexts. Arguably, no manikin can offer more fidelity in reproducing the complexity, variability, and particularity of the human body than an actual human body; thus, CBS is emerging as a promising approach for teaching, particularly for practicing high-skill, low frequency procedures.22–27 Because these preservation techniques are still relatively new, there is a paucity of research examining the use of clinical cadavers specifically. The limited existing literature on CBS has largely focused on measuring its validity and effectiveness for learning,22–28 with a few notable exceptions. Douglas-Jones’29 ethnographic account, for example, details the cultural specificities of donation in the Taiwanese Tzu Chi Buddhist Silent Mentor program Medical Simulation Center, where people make a deliberate effort to acknowledge the identity of the donor, by positioning photographs and telling stories about the donor’s life.

이러한 시체의 윤리적, 전문적 복잡성은 기존 시체와 크게 다를 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, 전통적인 시신과 비교했을 때 CBS를 위해 준비된 시신은 시각적으로나 촉각적으로 더 생생합니다.

- 딱딱하게 고정된(전통적인) 시신은 포름알데히드라는 화학 물질을 사용하여 방부 처리하는데, 이는 시신 조직의 분해를 지연시킬 뿐만 아니라 시신을 뻣뻣하고 유연하지 않게 만들기도 합니다. 이러한 시신은 신체 조직의 복잡한 형태와 위치를 유지하지만 살아있는 시신과 잘 닮지 않습니다.30

- 반면, 최근에 Thiel,31과 대만,29,32 볼티모어, 핼리팩스의 과학자들이 개발한 소프트 보존(CBS) 시신은 마취된 환자의 모습과 느낌을 그대로 유지합니다. 코백과 동료들은 임상 시체라고 부르는 이러한 실물보다 더 실물 같은 시체를 사용하여27 높은 수준의 충실도로 시술을 연습할 수 있습니다.34

Arguably, the ethical and professional complexities of these cadavers could differ significantly from those of traditional cadavers. For example, compared to traditional cadavers, bodies prepared for CBS are undeniably more lifelike—both visually and tactilely.

- Hard-fixed (traditional) cadavers are embalmed using the chemical formaldehyde, which delays the decomposition of the body’s tissues, but also renders them stiff and unpliable. These cadavers maintain the intricate form and location of bodily tissues but poorly resemble living bodies.30

- In contrast, soft-preserved (CBS) cadavers, such as those more recently developed by Thiel,31 as well as scientists in Taiwan,29,32 Baltimore, and Halifax,27,33 maintain the look and feel of anesthetized patients. Medical learners across the continuum can use these more lifelike cadavers, termed clinical cadavers by Kovacs and colleagues,27 to practice procedures with high degrees of fidelity.34

맥도날드나 할람과 같은 학자들은 시체 해부의 인류학적 및 관계적 차원에 대한 풍부한 통찰력을 제공했으며, '해부' 과정에서 시체가 갖는 다양한 가치와 역할을 암시했습니다.20,21 그러나 이 분야의 학자들은 아직 CBS에 실제와 같은 시체를 사용하는 것과 관련된 근본적인 철학적 및 존재론적 문제를 충분히 검토하지 못했습니다. 또한 일부는 수술 술기 교육을 용이하게 하기 위해 다르게 보존된 시체를 사용하는 프로그램의 문화적 뉘앙스를 설명했지만,29,32 이러한 논문은 아직 CBS에 관련된 사람들이 행정에서 교육에 이르기까지 당면한 다양한 작업을 수행하기 위해 참여해야 하는 개념적 작업에 대해서는 다루지 않았습니다. 이러한 격차를 해소하기 위해 우리는 들뢰즈와 과타리의 창조로서의 존재론 개념을 활용하여 의학교육자들이 시체를 이해하면서 어떻게 진화하는 개념들을 개발하는지를 분석했습니다.35 저자들은 고전적인 저작인 "철학이란 무엇인가?"에서 우리가 세상을 이해하려고 할 때 관여하는 세 가지 주요 행위를 과학, 예술, 철학으로 구분했습니다. 우리는 의학교육자들이 오랫동안 CBS의 과학과 예술을 접해 왔지만, 이 작업의 철학적 측면, 특히 존재론에 대한 질문에는 아직 주의를 기울이지 않았다고 주장합니다.

Scholars such as McDonald and Hallam have given us rich insights into some of the anthropological and relational dimensions of cadaveric dissection, hinting at the multiple values and roles that bodies take on during the process of “anatomisation.”20,21 However, scholars in the field have not yet fulsomely examined the underlying philosophical and ontological questions associated with using lifelike cadavers to engage in CBS. And, while some have described the cultural nuances of programs using cadavers that are differently preserved in order to facilitate surgical skills teaching,29,32 these pieces have not yet addressed the conceptual work in which people involved with CBS must engage to accomplish the variety of tasks at hand—ranging from administrative to educational. In an effort to address this gap, we worked with Deleuze and Guattari’s notion of ontology as creation to analyze how medical educators develop an evolving suite of concepts to make sense of cadavers as they go about their work.35 In their classic work What is Philosophy?,35 the authors distinguished three primary acts in which we engage as we try to make sense of the world: science, art, and philosophy. We argue that medical educators have long engaged with the science and art of CBS; however, we have not yet carefully attuned to the philosophical aspects of this work, and in particular to questions of ontology.

2년에 걸친 실무 기반 36 민족지학적 CBS 연구를 통해 우리는 시체가 존재론적으로 복잡하며 끊임없이 개념이 재창조되는 과정에 있다는 것을 알게 되었습니다. 여기에서는 교육용 시신의 6단계 생애주기를 설명하면서 CBS를 통한 교육 및 학습 작업을 용이하게 하기 위해 각 단계에서 발생해야 하는 존재론적 전환을 설명합니다. 이 백서는 실제와 같은 시체를 다루는 작업의 더 깊고 철학적인 복잡성을 조사하여 현재의 이해를 확장합니다.

Through a two-year practice-based36 ethnographic study of CBS, we learned that cadavers are ontologically complex, and in a process of constant conceptual re-creation. We describe herein a six-step lifecycle of an educational cadaver, delineating the ontological transitions that must occur at each stage to facilitate the work of teaching and learning through CBS. This paper expands our current understanding, probing the deeper, philosophical complexities of working with lifelike cadavers.

방법

Method

이론적 틀

Theoretical frame

본 연구는 실천 이론에 이론적 틀을 두고 있습니다.36 실천 이론은 사회 세계를 "숙련된 인간의 몸과 마음, 사물과 텍스트에 새겨지고 한 수행의 결과가 다른 수행의 자원이 되는 방식으로 함께 매듭지어져 내구성이 있는 방대한 수행의 배열 또는 집합체"로 보는 관점을 제시한다고 할 수 있습니다.37(p20) 실천은 물질적으로 매개되고 사회적이고 관계적인 것과 얽혀 있습니다.36 이 접근법은 사람들이 직장과 기타 일상 환경에서 참여하는 일상 활동의 네트워크를 이해하는 데 중점을 둡니다.37,38

Our study is theoretically framed in Practice Theory.36 Practice theory can be said to present a view of the social world as

- “a vast array or assemblage of performances made durable by being

inscribed in skilled human bodies and minds, objects and texts and

knotted together in such a way

that the results of one performance become the resource for another.”37(p20)

Practices are materially mediated and entangled with the social and relational.36 This approach focuses on understanding the networks of everyday activities in which groups of people engage in their workplaces and other everyday settings.37,38

우리는 시체 업무와 관련된 여러 인간 및 비인간 행위자를 고려하면서 사람(예: 시체 보관소 직원, 관리자, 교사, 학습자)과 사물(도구, 공간, 법률 및 교육 문서)은 물론 한계 공간에 존재하며 어떻게 보면 인간인 동시에 비인간인 시체 자체에 주목했습니다.39 우리는 CBS의 복잡성을 충분히 이해하고 설명하기 위해 일상적이고 당연하게 여겨지는 요소를 세밀하게 연구하는 데 관심이 있었기 때문에 실무 기반 접근법을 선택했습니다. 사체는 인간과 비인간 배열의 일부이며 이러한 네트워크와 관행에서 관련 행위자입니다. "... 사물이 승인, 허용, 여유, 장려, 허용, 제안, 영향, 차단, 가능, 금지 등을 할 수 있기 때문이다."40(p72) 카데바 작업의 관행에 집중함으로써 우리는 이러한 전문적인 환경에서 수행되는 일상적인 활동의 복잡성을 명확하게 표현하고 더 잘 이해할 수 있었습니다.

We considered multiple human and non-human actors associated with cadaver work, taking care to note both people (e.g., cadaver staff, administrators, teachers, learners) and things (tools, spaces, legal and educational documents), as well as the cadaver itself, which exists in a liminal space, and is somehow both human, and non-human.39 We selected a practice-based approach because we were interested in studying, in fine detail, the everyday, taken for granted elements of CBS in order to fulsomely understand and describe its complexities. Cadavers are part of the human and non-human arrangement and are relevant actors in these networks and practices as “… things might authorize, allow, afford, encourage, permit, suggest, influence, block, render possible, forbid, and so on.”40(p72) Focusing on the practices of cadaver work allowed us to articulate, and better understand, the complexities of day-to-day activities performed in these professional settings.

분석과 해석과 관련하여 우리는 '시체'의 개념이 어떻게 진화하는지 이해하기 위해 들뢰즈와 과타리의 '되기'와 '차이'에 대한 아이디어를 활용했습니다. 들뢰즈와 과타리는 차등적 존재론자라고 불리며, 이는 개념이 항상 차이에 기초하여 구성된다는 가정 하에 작업한다는 의미입니다(우리는 사물을 아닌 것으로 식별합니다). 따라서 이러한 관점을 존재론의 문제에 접목하려면 새로운 사고 방식이나 이해 방식을 제시하기 위해 존재에 대한 전통적인 관념을 해체하려는 고의적인 노력이 필요합니다.

With respect to analysis and interpretation, we drew on Deleuze and Guattari’s ideas about becoming and difference to understand how the concept of “cadaver” evolves. Deleuze and Guattari have been referred to as differential ontologists, meaning that they worked with the assumption that concepts are always constituted on the basis of difference (we identify things by what they are not). Folding this perspective into questions of ontology, then, requires a deliberate effort to unravel traditional ideas about being in order to offer new ways of thinking or understanding.

들뢰즈와 과타리는 철학의 목적이 세계가 실제로 어떤 것인지 '발견'하는 것이라고 믿지 않았습니다. 그들에게 이것은 불가능한 목표였습니다. 대신 그들은 철학을 개념의 창조와 동일시했습니다. 철학은 우리가 세상의 무한한 복잡성을 이해하는 데 도움이 되는 틀을 만드는 것입니다. 우리가 일상에서 하는 모든 행위에는 새로운 개념에 영감을 줄 수 있는 잠재력이 있습니다. 따라서 존재는 발견이 아닌 창조의 과정으로 개념화됩니다. 이는 발견해야 할 하나의 이야기나 통일된 진실이 없다는 것을 의미합니다. 오히려 세상을 구성하는 개념을 창조하는 것은 우리의 몫입니다.

Deleuze and Guattari did not believe that the purpose of philosophy was to “discover” what the world is really like. To them, this was an impossible goal. Instead, they equated philosophy to the creation of concepts: philosophy is about creating frameworks that help us make sense of the infinite complexity of the world. Each act in which we engage in our everyday life has the potential to inspire new concepts. Being, then, is conceptualized as a process of creation rather than discovery. This means that there is no one story, or unified truth to be discovered. Rather, it is up to us to create the concepts that structure the world.

우리의 사례와 관련하여, 우리는 인체 기증과 시체 기반 시뮬레이션의 심오한 복잡성을 더 잘 이해하는 데 도움이 되는 일련의 개념을 제시하는 데 관심이 있습니다. 이러한 들뢰즈의 아이디어를 우리의 실무 기반 접근 방식과 연결하면 인체 기증과 시체 기반 시뮬레이션이라는 일상적인 활동이 실제로는 '되기'의 행위로 간주될 수 있음을 알 수 있습니다. 이러한 관점에서 시신은 고정된 정체성이 없으며, 우리가 시신과 상호작용하거나 시신에 무언가를 할 때마다 끊임없이 다른 존재가 됩니다.

Specific to our case, we are interested in putting forth a series of concepts that help us better understand the profound complexity of the practices of human body donation and cadaver-based simulation. Linking these Deluezian ideas to our practice-based approach, we see that the everyday activities of human body donation and cadaver-based simulation can, in fact, be taken as acts of becoming. From this perspective, a cadaver has no fixed identity; it is constantly becoming something different each time we interact with, or do things to, it.

설정

Setting

우리는 Dalhousie 임상 시체 프로그램(CCP)에 대한 실무 기반 민족지학적 조사를 실시했습니다. Dalhousie CCP는 레지던트와 의사가 통제된 환경에서 고도로 전문화되고 종종 생명을 구하는 시술 기술을 연습할 수 있도록 새로 사망한 부드러운 보존 상태의 임상 시체를 제공합니다. Dalhousie CCP는 매년 약 150구의 시신을 수락하는 Dalhousie University 인체 기증 프로그램(HBD)에서 시신을 확보합니다. 두 프로그램이 원활하게 운영될 수 있도록 CCP와 HBD의 관리자와 직원이 함께 협력하고 있습니다.

We conducted a practice-based ethnographic investigation of the Dalhousie Clinical Cadaver Program (CCP). The Dalhousie CCP provides newly deceased, soft-preserved, clinical cadavers that allow residents and physicians to practice highly specialized, often life-saving, procedural skills within a controlled setting. The Dalhousie CCP obtains their bodies from the Dalhousie University Human Body Donation Program (HBD), which accepts approximately 150 bodies per year. Administrators and staff from the CCP and HBD work in concert to ensure that both programs operate smoothly.

방법론

Methodology

민족지학적 몰입은 실천에 기반한 이론적 접근 방식과 일치하여 연구자가 일상적인 활동을 관찰하고 문서화할 수 있습니다. 따라서 우리는 의학 교육에서 시체 작업의 일상적인 관행을 자세히 이해하기 위해 다양한 데이터 수집 전략을 사용했습니다. 니콜리니의 실천 이론 접근법에 따라 카데바 작업의 특정 측면을 '확대'한 다음, 의학교육에서 카데바 작업과 시뮬레이션에 대한 보다 광범위한 사회적 대화에서 이러한 관행을 찾기 위해 '축소'했습니다.38 이를 위해 2년 동안(2018/19-2019/20) 여러 출처에서 데이터를 반복적으로 수집하고 분석했습니다.

Ethnographic immersion is consistent with a practice-based theoretical approach, allowing researchers to observe and document everyday activity. We therefore used a range of data collection strategies in order to develop a detailed understanding of everyday practices of cadaver work in medical education. In accordance with Nicolini’s approach to practice theory, we “zoomed in” on specific facets of cadaver work, and then “zoomed out” to locate these practices in broader societal conversations about cadaver work and simulation in medical education, more broadly.38 In order to do this, we iteratively collected and analyzed data from multiple sources over a two-year period (2018/19–2019/20).

팀 구성 및 반사성

Team composition and reflexivity

우리는 교육 민족지학(AM, PC, OK, VL, JT), 실무 이론(AM, PC, OK, VL, JT), 임상의학(GK, VL, LP), CBS(GK, LP) 등 의학 및 의학교육의 다양한 측면에 전문성을 가진 연구자들로 구성된 팀입니다. 우리는 다양한 전문 분야를 한데 모아 절차적 술기 학습과 임상 시체를 이용한 시뮬레이션에 대한 새로운 질문을 던졌습니다.

We are a team of researchers with expertise in various facets of medicine and medical education including educational ethnography (AM, PC, OK, VL, JT), practice theory (AM, PC, OK, VL, JT), clinical medicine (GK, VL, LP), and CBS (GK, LP). We brought our various areas of expertise together to ask new questions about procedural skills learning and simulation with clinical cadavers.

이 과정에서 임상 시체 프로그램 의료 책임자(GK)와 CBS를 경험한 학습자(LP)의 CBS 프로그램에 대한 내부 지식을 바탕으로 질문을 진행했습니다. 이 팀원들은 인터뷰할 주요 인물과 관찰해야 할 중요한 교육적 노력을 파악하는 데 도움을 주었습니다. 또한 CBS 직원들과의 연결을 용이하게 하여 운송부터 교육에 이르기까지 시체 작업이 이루어지는 공간에 접근할 수 있도록 도와주었습니다.

Throughout the process, we relied on insider knowledge of the CBS program from the Medical Director of the Clinical Cadaver Program (GK) and a learner experienced with CBS (LP) to guide our inquiry. These team members helped us identify key people to interview, as well as important educational endeavors to observe. They also facilitated connections with the workers of CBS, so that we might gain access to spaces in which cadaver work—everything from transportation to education—was taking place.

반성적인 대화와 연구 과정 및 전략의 개선은 우리 작업의 정기적인 부분이었습니다. 다시 말해, 우리의 프로세스는 선형적이지 않았고, 즉흥적인 대화에 반사성이 내재되어 있었습니다. 이는 작업의 초점이 시신에 맞춰져 있고, 시신과 마주치면 당황스럽고 불안할 수 있다는 사실을 고려할 때 특히 중요했습니다.16,20,41 우리는 정기적으로 분석 대화를 나누며 데이터에 대해 토론하고 반영했습니다. 이러한 대화는 데이터에 대한 공동 분석을 발전시키는 데 도움이 되었지만, 동시에 반성하는 연습이기도 했습니다. 우리 팀에게 중요한 훈련 중 하나는 개인으로서 교육 목적으로 시신 기증을 고려할 수 있는지 생각해보는 것이었습니다. 우리는 최근에 관찰한 시나리오나 최근에 인터뷰한 사람에 따라 이 질문에 대한 답이 달라진다는 사실을 발견했습니다.

Reflexive conversations and refinement of our research processes and strategies were a regular part of our work. In other words, our process was not linear, and reflexivity was built into our emergent conversations. This was particularly important given the focus of the work, and the fact that encountering cadavers can be upsetting and unsettling.16,20,41 We held regular analytical conversations to discuss and reflect upon our data. While these conversations served to advance our collaborative analysis of the data, they were also an exercise in reflexivity. One important exercise for our team was to reflect upon whether we, as individuals, would consider donating our bodies for educational purposes. We found that, depending on which scenario we had recently observed, or which person we had recently interviewed, the answer to that question changed.

데이터 수집

Data collection

민족지학적 몰입

Ethnographic immersion

아래에서는 공식적, 비공식적으로 CBS 관련 활동을 관찰한 시간을 보고하지만, 우리의 작업은 근본적으로 민족지학적 연구입니다. 즉, 저희는 CBS와 HBD의 공간과 사람들과 '어울리며' 상당한 시간을 보냈습니다. 우리는 배경 자료를 읽고 영안실, 시뮬레이션실, 시체 준비 및 교육 공간을 방문했습니다. 우리는 HBD 및 CBS 관계자들과 함께 앉아 프로젝트에 대해 논의하고, 시간을 내어 질문에 답하고, 자신을 개방함으로써 신뢰를 쌓고 관계를 구축하기 위해 열심히 노력했습니다. 이를 통해 현장에서 질문하고 시간을 보내며 편안하고 친숙해질 수 있는 기회를 얻을 수 있었습니다.

While we report below on the hours we spent formally and informally observing CBS related activities, our work is fundamentally ethnographic. This meant that we spent a significant amount of time “hanging around” the spaces and people of CBS and HBD. We read background materials and visited morgues, simulation suites, and cadaver preparation and teaching spaces. We worked hard to build trust and establish relationships with the people involved with HBD and CBS by sitting down to discuss our project with them, making time to answer their questions, and making ourselves available. This, in turn, provided us an opportunity to ask questions and spend time in the field in order to become comfortable and familiar with it.

구체적으로, 우리가 방문한 곳은 캐나다 핼리팩스에 있는 Dalhousie University의 CBS 공간과 장소였습니다. 대서양 연안에 위치한 달하우지 의과대학은 해양 의과대학으로 알려져 있으며, 캐나다 3개 주의 지역사회에 서비스를 제공하고 있습니다: 노바스코샤, 뉴브런즈윅, 프린스 에드워드 아일랜드입니다. Dalhousie 의과대학은 핼리팩스 준비27로 알려진 Thiel 시체 준비 기법의 개선과 이러한 임상 시체를 활용한 지속적인 전문성 개발 기회로 국제적으로 인정받고 있습니다.

Specifically, our field was the spaces and places of CBS at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Canada. Situated on the Atlantic Coast, Dalhousie Medical School is known as the Medical School of the Maritimes, and serves the communities of three Canadian Provinces: Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island. Dalhousie Medical School is internationally recognized for our refinement of the Thiel Cadaver preparation technique, known as the Halifax Preparation27 and our continuing professional development opportunities that make use of these clinical cadavers.

이 기관에서 수년간 의료 교육 분야에서 일해 왔음에도 불구하고 임상의가 아닌 팀원들에게는 이러한 공간 중 많은 부분이 처음이었습니다. 특히 CBS의 업무 대부분은 일화적으로 들어본 적은 있지만 직접 걸어볼 기회는 없었던 일련의 터널로 연결된 지하 공간에서 이루어집니다. 따라서 우리의 민족지학적 작업은 익숙한 장소에서 숨겨진 공간을 발견하는 낯선 과정이었으며, 우리는 비공식적인 대화에서 이를 "지하세계"라고 불렀습니다.

Despite years of working in medical education at this institution, many of these spaces were new to the non-clinician team members. Notably, much of the work of CBS takes place in underground spaces, connected by a series of tunnels that we had heard mentioned anecdotally, but had never had the opportunity to walk through. Thus, our ethnographic work was a strange process of discovering hidden spaces in familiar places, which we referred to in our informal conversations as “the underworld.”

이와는 대조적으로 기증자를 모집하고 기록을 관리하며 교육 목적으로 임상 시체를 준비하는 HBD의 업무는 오피스 타워의 가장 높은 층에서 이루어집니다. 이 공간에는 작은 사무실과 시체 준비 공간, 교육 실습실이 있습니다. 이 공간은 밝고 깨끗하며 위생적입니다. 세탁기와 톱 및 기타 도구가 있다는 것 외에는 이곳에서 시신 준비가 어떻게 이루어지는지에 대한 단서는 거의 없었습니다.

In contrast, the work of HBD, where donors are recruited, records are managed, and clinical cadavers are prepared for educational purposes, takes place on the highest floors of an office tower. The space includes small offices, as well as cadaver preparation spaces and teaching labs. Here, the space is bright, pristine, and hygienic. There were few clues about the cadaver preparation that happens here, except for the presence of washing machines and saws and other types of tools.

일부 팀원들은 지속적인 전문성 개발 과정에 참여하는 학습자 집단에 합류하여 CBS의 활동에 어느 정도 참여할 수 있었습니다. 단순히 그림자처럼 따라 하는 것이 아니라 강의에 참여했고, CBS의 자료를 보고 냄새 맡고 만질 수 있었기 때문에 참여 자체가 감각적인 경험이었습니다.

Some team members were able to participate, to some degree, in the activities of CBS, by joining a cohort of learners participating in a continuing professional development course. Rather than simply shadowing, we were engaged in the lectures, and even our participation was a sensory experience, as we were able see, smell, and touch the materials of CBS.

관찰

Observations

우리 연구팀은 4회의 지속적인 전문성 개발 기도 관리 과정(관찰 40시간 × 관찰자 2~3명/회 = 90시간), 4회의 응급 레지던트 교육 세션(8시간 × 관찰자 1~2명/회 = 10시간), 1회 안치식 및 기증자를 기리는 추모식(5시간 × 관찰자 2명 = 10시간) 등 총 110시간의 공식 관찰을 통해 교육용 카데바 사용의 다양한 측면을 공식적으로 관찰했습니다. 관찰할 교육 활동과 기타 중요한 행사/장소는 전문 팀원과의 협의와 후속 인터뷰 중 참가자들의 조언을 바탕으로 선정했습니다. 현장 노트는 관찰 가이드(부록 A)에 따라 공간, 행위자, 활동, 사물, 행위, 이벤트, 시간, 목표와 관련된 메모와 성찰을 기록했습니다.42 또한 다감각적 참여에 참여하여38 CBS와 관련된 소리, 냄새, 감정을 문서화했습니다.

Our research team formally observed various facets of educational cadaver use including four continuing professional development airway management courses (40 hours of observations × 2–3 observers/session = 90 hours), four emergency resident teaching sessions (8 hours × 1–2 observers/session = 10 hours), as well as one interment and two memorial services honoring donors (5 hours × 2 observers = 10 hours) for a total of 110 hours of formal observation. We identified educational activities and other significant events/locations to observe based on consultation with expert team members, and on advice that emerged from participants during subsequent interviews. Field notes were guided by an observation guide (Appendix A), these recorded notes and reflections surrounding spaces, actors, activities, objects, acts, events, times, and goals.42 We also engaged in multisensory participation,38 documenting the sounds, smells, and emotions involved in CBS.

또한 구조화되지 않은 관찰도 완료했습니다. 이러한 관찰 세션은 반응성 효과를 줄이기 위해 생체 내에서가 아니라 후향적으로 문서화한 다음43 연구팀 간에 논의했습니다. 이를 통해 프로그램에 대한 전반적인 지식과 사체 프로그램의 범위를 파악할 수 있었습니다. 여기에는 HBD 본사(0.5시간 × 연구원 2명 = 1시간), 대학 영안실(2시간 × 연구원 3명 = 6시간), 시체 준비 공간(2시간 × 연구원 3명 = 6시간), 다양한 병원 기반 시뮬레이션 공간(3시간 × 연구원 2명 = 6시간), 지역 해부학 박물관(2시간 × 연구원 4명 = 8시간) 방문이 포함되었습니다. 이렇게 해서 총 27시간의 비정형 관찰이 이루어졌습니다.

We also completed unstructured observations. These were observational sessions which were documented retrospectively rather than in vivo to reduce reactivity effects43 and then discussed amongst the research team. They informed our overall knowledge of the program and the scope of the cadaver program. This included visits to the HBD main office (0.5 hours × 2 researchers = 1 hour), the university morgue (2 hours × 3 researchers = 6 hours), the cadaver preparation space (2 hours × 3 researchers = 6 hours), various hospital-based simulation spaces (3 hours × 2 researchers = 6 hours), and the local anatomy museum (2 hours × 4 researchers = 8 hours). This led to a total of 27 hours of unstructured observations.

총 137시간의 공식적인 관찰 데이터를 수집했습니다.

In total, we gathered 137 hours of formal observational data.

인터뷰

Interviews

관찰과 함께 학습자(지속적인 전문성 개발 학습자 n = 5명, 응급의학과 레지던트 n = 4명), 임상 교사(n = 4명), 과거 기증자의 가족(n = 5명)을 대상으로 24회의 반구조화 인터뷰를 실시했습니다. 또한 인체 기증 직원(n = 6)에는 CCP 프로그램의 행정(예: 기증자 연락, 기록 보관), 법률(예: 시신 수락 및 관리), 기술(예: 시신 준비) 업무에 관여하는 사람들이 포함되었습니다. 저희는 전문가 팀원들의 자문을 바탕으로 인터뷰 대상자를 선정했습니다. 의도적으로 24명을 모집하여 초대를 수락한 모든 사람을 인터뷰했습니다. 인터뷰 가이드는 대화 형식으로 각 참가자의 역할에 맞게 제작되었으며(예시는 부록 B 참조), 연구팀의 여러 구성원이 함께 개발했습니다. 우리는 진화하는 주제에 따라 지속적으로 가이드를 수정했습니다.

Alongside observations, we conducted 24 semi-structured interviews with learners (continuing professional development learners n = 5 & emergency medicine residents n = 4), clinical teachers (n = 4), as well as family members of past donors (n = 5). As well, human body donation staff (n = 6) included those involved in the administrative (e.g., contacting donors, record keeping), legal (e.g., accepting and managing bodies), and technical (e.g., preparing cadavers) tasks of the CCP program. We identified individuals to interview based on consultation with expert team members. We purposively recruited 24 people and interviewed all who accepted the invitation. Our interview guides were conversational in nature and were tailored to each participant’s role (see Appendix B for an example); they were developed by multiple members of the research team. We continuously revised the guides according to evolving themes.

문서 분석

Document analysis

인체 기증 프로그램 및 시신 기반 교육과 관련된 문서도 검토했습니다[n = 22]. 여기에는 시신 기증 및 매장 과정과 관련된 법률 행위 및 보고서, 인체 기증 프로그램 관련 문서, 커리큘럼 자료 및 광고와 같은 교육 자료, 언론 보도 등이 포함되었습니다. 이전에 개발한 문서 검토 양식을 개선하여 이 부분의 분석을 구성했습니다(부록 C).44

Documents related to the Human Body Donation program and cadaver-based education were also reviewed [n = 22]. This included legal acts and reports related to the process of body donation and burial; documents related to the human body donation program; educational material such as curriculum materials and advertisements; and media coverage. We refined our previously developed document review form to structure this piece of the analysis (Appendix C).44

데이터 분석

Data analysis

저희의 분석은 민족지학적 데이터 분석에 대한 울콧의45 3단계 접근 방식인 기술, 분석, 해석과 일치했습니다. 이 접근 방식은 다음의 조합을 사용합니다.

- 순수한 기술(데이터에 근접),

- 체계적 분석(핵심 요소와 관계 파악),

- 해석(데이터 너머로 확장하여 무슨 일이 일어나고 있는지 이해)

울콧은 정성적 데이터를 변환하는 세 가지 방법을 구분하지만, 이 세 가지 방법은 서로 겹치면서 동시에 발생한다는 점을 강조합니다. 따라서 우리는 시신의 개념이 생애주기에 걸쳐 어떻게 변화했는지, 그리고 그 진행과 전환에 기여한 행위자와 자료에 주목하면서 반복적인 분석 접근 방식을 따랐습니다.

Our analysis aligned with Wolcott’s45 three-step approach to the analysis of ethnographic data: description, analysis, and interpretation. This approach uses a combination of

- pure description (staying close to the data),

- systematic analysis (identifying key factors and relationships), and

- interpretation (extending beyond the data, making sense of what is happening).

Although Wolcott distinguishes three ways to transform qualitative data, he emphasizes that they overlap and occur simultaneously. Accordingly, we followed an iterative approach to analysis, attuning to how the concept of the cadaver changed across the lifecycle, as well as the actors and materials contributing to its progression and transitions.

설명 단계에서는 출처별(문서, 관찰, 인터뷰), 유형별(응급 레지던트 또는 지속적인 전문성 개발 과정 참가자 관찰, 학생, 교사, 직원 또는 기증자/기증자 가족 인터뷰) 등 각 데이터 세트를 개별적으로 검토한 다음 이러한 통찰력을 더 넓은 전체의 일부로 재검토하는 작업이 포함되었습니다. 세 명의 연구원(MF, PC, VL)이 안전한 데이터 관리 및 공유를 지원하는 질적 데이터 분석 소프트웨어(ATLAS.ti)를 사용하여 각 데이터 소스를 독립적으로 검토하고 코딩했습니다.

Broadly speaking, the descriptive phase involved reviewing each data set separately, including by source (document, observation, interview) and by type (observation of emergency residents or continuing professional development course participants; interview with student, teacher, staff, or donor/donor’s family), and then reconsidering these insights as part of a broader whole. Three researchers (MF, PC, VL) independently reviewed and coded each data source using qualitative data analysis software (ATLAS.ti) which also assisted with secure data management and sharing.

분석 단계에서는 현장 조사, 인터뷰, 문서 검토를 통해 얻은 아이디어를 적극적으로 번역하고 그룹별로 토론하여 서면으로 표현했습니다. 패턴, 일관성, 불일치를 찾으면서 참가자들이 임상 시체의 모호성을 관리하면서 철학적 작업에 참여하는 방식에 흥미를 갖게 되었습니다. 특히, 기증자/시신/시체가 어떻게 사용되느냐에 따라 시신을 생각하는 방식이 크게 달라진다는 점에 주목했습니다. 이 시점에서 우리는 '라이프사이클'이라고 부르기 시작한 6단계를 식별하고, 특히 다양한 언어 패턴과 작업에 맞게 조정하여 존재론적 전환을 식별할 수 있었습니다.

At the analytic phase, ideas borne from our field work, interviews, and document review were actively translated, discussed as a group, and represented in written form. As we searched for patterns, consistencies, and inconsistencies, we became intrigued by the way in which participants were engaging in philosophical work as they managed the ambiguity of clinical cadavers. In particular, we noted that the ways in which donors/bodies/cadavers were conceived evolved significantly, depending on how they were being used. At this point, we identified the six stages of what we began to refer to as a “lifecycle,” and specifically attuned to different language patterns and tasks which in turn allowed us to identify ontological transitions.

해석 작업에 참여하면서 우리는 개념적 전환이 시체가 생애주기를 어떻게 통과할 수 있게 했는지에 초점을 맞춰 들뢰즈적 관점에서 실무에서 얻은 통찰력을 고려했습니다. 이 해석 작업에는 시체가 어떻게 끊임없이 변화하는 상태에 있는지 탐구하고, 각 단계에서 참가자들이 다양한 유형의 작업에 참여하면서 눈앞의 시체를 이해하기 위해 어떻게 적극적으로 새로운 개념을 만들어냈는지 묘사하는 것이 포함되었습니다.

As we then engaged in interpretive work, we considered our practice-generated insights from a Deleuzian perspective, focusing on how the conceptual shifts allowed the cadaver to move through the lifecycle. This interpretive work involved exploring how the cadaver was in a constant state of becoming, and delineating how, at each stage, participants actively created new concepts to make sense of the body in front of them, as they engaged in various types of work.

윤리적 고려 사항

Ethical considerations

노바스코샤 보건연구윤리위원회는 이 연구를 승인했습니다(REB 파일 번호: 1023958). 인체 기증자의 기밀을 유지하기 위해 관찰 내용을 식별할 수 있는 사진, 비디오 또는 오디오 녹음을 하지 않았습니다.

The Nova Scotia Health Research Ethics Board approved this study (REB FILE#: 1023958). No identifying photographs, videos, or audio-recordings of observations were taken in order to preserve the confidentiality of human donors.

결과

Results

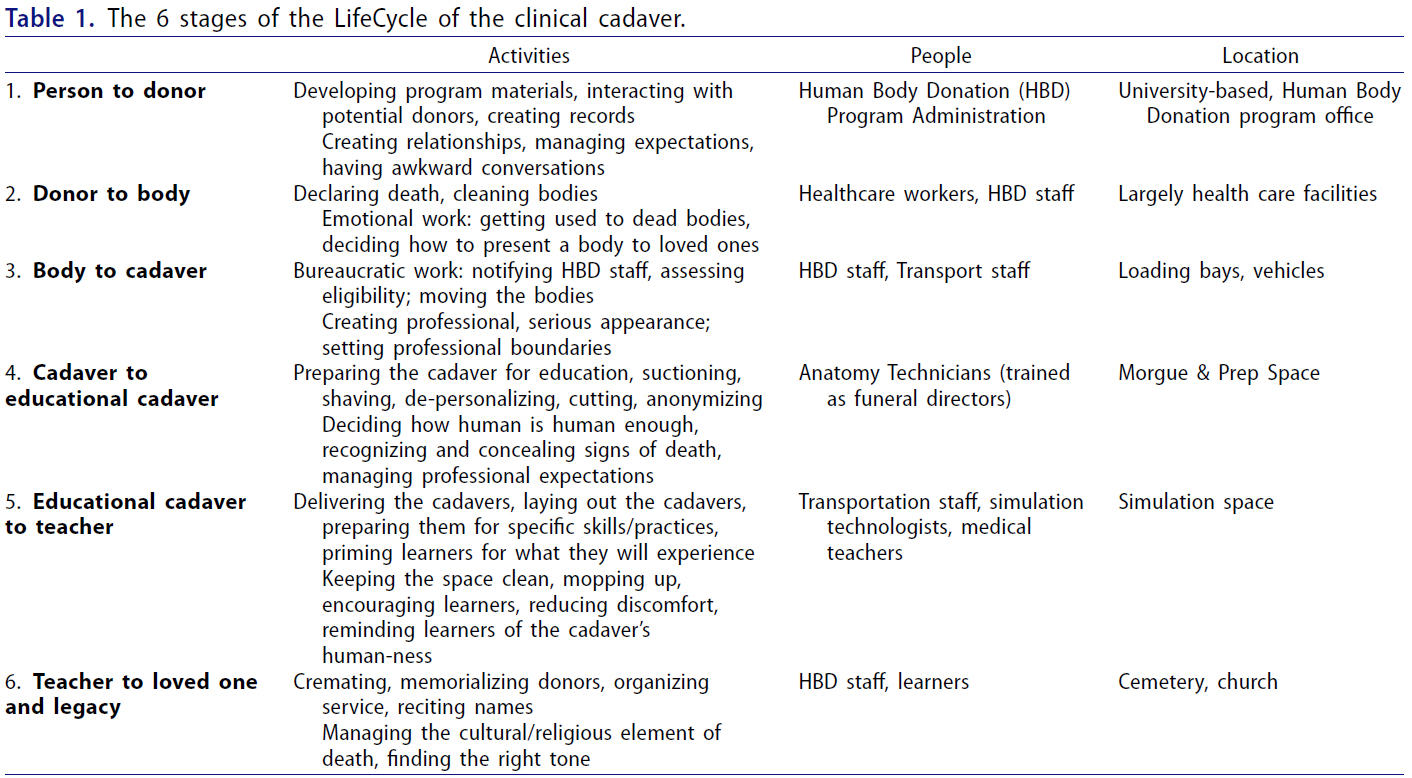

인체 기증(HBD)과 CBS를 통해 사망한 사람은 자신의 신체가 살아있는 환자를 위해 "대신" 살아 있는 "사후의 삶"에 참여했습니다. 여기에서는 기증자 등록부터 최종 안치까지 이 주기와 각 단계의 관련 존재론적 전환에 대해 설명합니다(표 1). 우리가 설명하는 요소는 우리가 연구한 HBD 프로그램에 한정된 것이지만, 이러한 전환 자체는 다른 상황에도 적용될 수 있다고 생각합니다.

Through Human Body Donation (HBD) and CBS, a deceased person participated in a “life after death” where their body “stood in” for a living patient. We describe herein this cycle, from donor enrollment to eventual interment, and the associated ontological transitions at each stage (Table 1). While the elements we describe are specific to the HBD program we studied, we believe the transitions, themselves, are transferable to other contexts.

온톨로지는 "존재"에 대한 질문, 즉 "무엇이 있는가"에 초점을 맞춥니다. 교육용 시신과 관련해서는 존재론적 질문이 중요했습니다: 이것은 사람인가? 이것은 교육용 도구인가? 무엇이 사람을 사람답게 만드는가? 우리는 기증자의 시신이 HBD 프로그램을 통해 진행됨에 따라 연구 참여자들이 시신을 개념화하는 방식이 크게 바뀌는 것을 발견했으며, 이러한 개념 변화를 존재론적 전환이라고 부릅니다. 이러한 전환은 참가자들이 언어를 사용하는 방식에서도 분명하게 나타났습니다. 예를 들어 직원, 교사, 학습자, 연구자 모두 시신을 사람, '사람이 아닌 것', 환자, 표본, 이 사람/저 사람, 신체, 그/그녀, 교육 도구 등으로 혼용하여 불렀습니다. 이러한 변화하는 온톨로지는 참가자들이 시신을 다루는 방식에서도 분명하게 드러났습니다. 때때로 참가자들은 살아있는 생명체에게는 하지 않는 방식으로 몸을 연습하기도 하고, 무생물에게는 절대 보여주지 않을 것 같은 부드러움과 존중으로 몸을 대하기도 했습니다. 이러한 방식으로 참가자들은 시체를 완전한 사람이 아닌 사물 이상의 존재로 생각했습니다.

Ontology focuses on questions of “being”—in other words, “what is.” With respect to educational cadavers, the ontological questions were significant: Is this a person? Is this an educational tool? What makes something human? We noted that as a donor’s body progressed through the HBD program, the ways in which study participants conceptualized the body changed significantly, and we refer to these changing concepts as ontological transitions. These transitions were apparent in the way participants used language. For example, staff, teachers, learners, and researchers alike interchangeably referred to the cadaver as a person, a “not-a-person”, a patient, a specimen, this/that “guy”, a body, a him/her, and an educational tool. These shifting ontologies were also apparent in the way participants handled the bodies. At times, they practiced on the body in ways that they would not on a living being; at others, they treated the body with a tenderness and respect that they likely would never show an inanimate object. In this manner, participants conceived of cadavers as not fully people, but also as much more than things.

시신과 관련하여 관찰한 존재론적 복잡성에는 사람, 인체, 시신, 교육 도구 사이의 불확실하고 변화하는 경계가 포함되었습니다. 시체를 이해하는 방식은 공간과 시간에 따라 지속적으로 변화했으며, 때로는 예측 가능하지만 때로는 예측할 수 없는 방식으로 변동하고 진화했습니다. 다음 섹션에서는 전문적인 관행을 통한 이러한 철학적 작업이 기증자, 시신, 시신, 교육용 시신, 교사, 사랑하는 사람/유산의 '생애주기'를 따라 시신을 어떻게 이끌어 가는지 설명합니다.

The ontological complexity we observed in relation to the cadaver involved uncertain and shifting boundaries between person, human body, cadaver, and educational tool. How the cadaver was understood changed continuously over space and time, fluctuating and evolving in sometimes predictable, but sometimes, unpredictable ways. The following sections illustrate how this philosophical work brought about through professional practices drives the cadaver along its “lifecycle” from person to donor, body, cadaver, educational cadaver, teacher, and loved one/legacy.

우리가 설명하는 단계는 "깔끔한" 단계가 아니며 개별적인 단계도 아니라는 점을 분명히 말씀드리고 싶습니다. 가독성을 높이고 존재론적 전환을 명확히 하기 위해 단순화했지만, 실제로 이러한 단계는 명확하게 정의되어 있지도 않고 정적인 것도 아닙니다. 사람/시체/시신은 끊임없이 변화하는 상태이며, 다양한 단계에 대한 설명은 특정 시점의 CBS 및 HBD와 관련된 관행에 초점을 맞추기 위해 확대한 시점을 나타내는 '스냅샷'일 뿐이라는 것이 저희의 관점입니다.

We want to state clearly that the stages we describe are not “neat,” nor are they discrete. We have simplified, in order to increase readability and clarify the ontological transitions, but in reality, these stages are not clearly defined nor are they static. Our perspective is that people/bodies/cadavers are in a perpetual state of becoming, and our description of the various stages are only “snapshots” representing points in time, when we zoomed in to focus on the practices associated with CBS and HBD at a given moment.

저희는 의도적으로 사망 시점부터 유산에 이르기까지 시신의 생애주기를 따라가려고 한 것이 아닙니다. 사실 이 작업을 시작할 당시에는 공동 기술, 분석 및 해석을 통해 개발하게 될 라이프사이클에 대한 개념이 없었습니다. 대신 우리는 민족지학적 몰입을 통해 CBS와 HBD의 프로세스와 활동에 대해 배웠습니다. 즉, HBD 및 CBS의 사람들과 함께하고 관계를 구축함으로써 우리는 공식적으로 관찰할 사건/시나리오를 식별하고 결정할 수 있었습니다.

We did not set out to deliberately follow a cadaver from point of death to legacy, through the lifecycle we described. In fact, when we began this work, we had no concept of the lifecycle which we would eventually develop through collaborative description, analysis, and interpretation. Instead, we learned about the processes and activities of CBS and HBD through ethnographic immersion. In other words, by being present and building relationships with the people of HBD and CBS, we were able to identify and decide upon events/scenarios to formally observe.

사람에서 기증자로

Person to donor

한 사람이 기증자가 된 것은 공동의 의사 결정, 관료적 업무, 윤리적 문제에 대한 신중한 고려의 (때로는 긴) 과정을 거친 후입니다. 저희가 인터뷰한 기증자 가족에 따르면, 대부분의 사람들이 이타적인 이유로 기증자가 되기를 희망했습니다. 많은 사람들이 잘 알려지지 않은 질병으로 고통받고 있었기 때문에, '과학에 기여하고 싶다', 즉 미래 세대가 질병에 대한 더 많은 이해를 통해 혜택을 받을 수 있도록 돕고 싶다는 소망이 대화에 스며들었습니다. 기증자와 가족들의 이러한 바람은 HBD 프로그램의 일부 종사자들에게 긴장감을 주기도 했습니다. HBD 직원들은 참가자들이 종종 자신의 기부가 표적이 될 것이라는 생각을 가지고 있다고 지적했습니다. 한 사람은 다음과 같이 말했습니다.

A person became a donor after a (sometimes long) process of shared decision-making, bureaucratic work, and careful consideration of ethical concerns. According to the family members we interviewed, most people wished to become donors for altruistic reasons. As many suffered from illnesses that were poorly understood, an overarching wish to contribute “to science”—as in, to help future generations benefit from a greater understanding of their illness— permeated our conversations. This wish of donors and family members, we observed, presented a tension for some workers in the HBD program. HBD workers noted that participants often have the idea that their donation will be targeted. One person noted

'남편이 파킨슨병으로 돌아가셨기 때문에 파킨슨병 연구에 도움이 될 수 있는 일이라면 무엇이든 하고 싶어요. 저는 [우리 프로그램이] 매우 정직하다고 생각합니다. 시신 기증자와 가족들에게 시신은 연구용으로 사용하는 것이 아니라 교육용으로 사용한다고 말합니다. [대부분의 기증자들은 '아, 그것도 괜찮아요'라고 말합니다. 하지만 저는 항상 약간의 단절이 있는 것이 걱정됩니다. (HBD 직원)

‘You know, my husband died of Parkinson’s disease, so whatever I can do to help Parkinson’s research.’ I think [our program] is very honest. We [tell donors and families that we] don’t really use the bodies for that, we use them for teaching. [Most donors say] ‘oh, well, you know, that’s fine too.’ But, I always worry that there’s a little disconnect. (HBD Staff)

다른 기부자들은 의대생들이 "책으로는 배울 수 없는" "실전 학습"을 할 수 있도록 돕고 싶다고 분명히 밝히거나, 한 기부자의 말처럼 "누군가의 학업을 발전시킬 수 있다면 좋은 생각이라고 생각했다"고 말했습니다. 대개 이 프로그램에 대해 알고 있는 가족이나 친구를 통해 이 프로그램에 대해 알게 된 기부자 또는 그 가족은 프로그램에 연락하여 동의서를 제출하는 서류 작업을 시작했습니다.

Others clearly articulated that they wanted to help medical students gain “hands-on learning” that they simply “can’t learn in a book” or, as one donor noted, “we just thought it was a good idea if we could further somebody’s studies.” After finding out about the program (usually through family or friends who knew about the program), these individuals or their loved ones reached out to the program and initiated the paperwork involved in providing consent.

이 첫 접촉 이후, HBD 직원은 기부가 이루어지기 위해 몇 가지 작업을 수행해야 했습니다. 이 작업의 대부분은 프로그램 자료(예: 웹사이트, 정보 팜플렛, 동의서) 개발과 기록 보관 등 문서 제작과 관련된 것이었습니다. 우리의 현장 기록46은 개인에서 기증자로의 전환과 관련된 행정 업무의 진화하는 특성을 문서화하는 데 핵심적인 관행을 형성했습니다. 민족지학적 몰입은 1900년대 초로 거슬러 올라가는 원본 장부를 검토할 수 있는 기회를 제공했으며, 이 장부에는 기부자의 이름이 자필로 기재되어 있습니다. 잠재적 기부자에게 정보를 제공하기 위해 고안된 문서에는 "차분하다"고 표현할 수 있는 신중하게 선택된 언어가 사용되었습니다. 프로그램 문서를 분석한 결과, "기부 프로그램은 쉽게 접근할 수 있고, 정중하며, 부드러우면서도 규정이 엄격하다는 것을 알 수 있었습니다. 사용된 언어는 존중과 지속적인 추모(예: "지속적인 유산")를 의미합니다."

After this initial contact, HBD staff needed to accomplish several tasks in order for donation to occur. Much of this work was bound up in the production of texts: developing program materials (e.g., website, information pamphlets, consent forms) and recording-keeping. Our field noting46 formed a key practice in documenting the evolving nature of administrative work associated with the transition from person to donor. Our ethnographic immersion provided the opportunity for us to review original ledgers, dating back to the early 1900s, listing the names of donors in handwriting. The documents designed to provide information for potential donors used carefully chosen language, that we described as “calm.” Through our analysis of program documents, we noted that “the donation program is easily accessible, respectful, gentle, but firm on its regulations. The language used implies respect and ongoing remembrance (i.e. “lasting legacy”).”

비공식적으로 직원들은 기증자 및 그 가족들과 신뢰 관계를 형성하고, 기증에 대한 기대치를 관리하며, 시신이 존중받을 것이라는 확신을 주어야 했습니다.

More informally, staff also needed to create trusting relationships with donors and their families, manage expectations around donation, and give them the confidence that the body would be treated with respect.

또한 직원들은 사전 동의와 같은 시신 기증과 관련된 윤리적 문제와도 씨름해야 했습니다. 무엇보다도 HBD 프로그램은 사전 동의를 "모든 일의 주춧돌"이라고 생각했습니다. 하지만 기증자가 사망하기 30년 전에 동의하고 그 이후로 프로그램에 연락하지 않았다면 어떻게 해야 할까요? 가족이 반대했다면 어떻게 해야 할까요? 이러한 질문은 프로그램에서 심각하게 고려한 질문입니다:

Further, staff grappled with the ethical challenges associated with body donation, such as informed consent. Chiefly, the HBD program considered informed consent “the pillar stone of everything [they] ever do”. But what if the donor consented 30 years prior to their death and had not contacted the program since? What if the family was opposed? These are questions the program took seriously:

아버지, 어머니, 형제 또는 자매가 여기 있을지도 모른다는 사실에 겁에 질린 누군가를 그런 상황에 처하게 하고 싶지 않으니까요. 가족에게 이런 말을 하기는 어렵고 저도 절대 하지 않겠지만, 결국에는 죽은 사람은 알 수 없기 때문에 그 사람이 그 사실을 알 수 있는지 여부에 영향을 미쳐야 한다고 생각해요. (시신 직원)

Because you don’t want to put someone in that situation where they’re just horrified by the fact that, you know, their father, mother, brother or sister or whatever would be here. And I think…that that should play a part in whether or not the person…because at the end of the day—it’s hard to say this to a family and I never would—but at the end of the day, the person who’s dead is not going to know. (Cadaver staff)

따라서 기증자 본인과 가족, HBD 프로그램 직원을 포함한 여러 사람이 중요한 결정을 내리고, 행정 업무와 기록 보관에 참여하고, 구체적인 조치를 취하고, 불가피한 협상에 참여한 후에야 한 사람이 기증자가 될 수 있습니다.

A person thus became a donor only after multiple people—including the donors themselves, their families, and staff from the HBD program—made important decisions, engaged in administrative work and record keeping, took concrete actions, and engaged in inevitable negotiations.

시신 기증자

Donor to body

죽음은 기증자에서 시신으로 전환되는 가장 확실한 신호입니다. 한 학습자가 설명한 것처럼, 살아 숨 쉬는 사람(누군가)과 생명이 없는 시신(무언가)의 차이는 명확하게 느껴졌습니다:

Death is the most obvious marker of the transition from donor to body. As one learner illustrated, the difference between a living, breathing person (a somebody) and a still, lifeless body (a something) felt unambiguous:

이불 속에서 얕은 숨을 쉬며 잠들어 있는 89세 노인과 문밖에서 바라보고 있는 사람 사이에는 큰 차이가 있습니다. 하지만 그분들이 살아있다는 것을 알 수 있는 무언가가 있습니다. 그리고 그들이 죽으면 사라져 버리죠. 그게 뭔지 모르겠어요. 하지만 시체는 그냥 가구가 되죠. 침대, 의자, TV, 그리고 죽은 사람이 있는 것과 같죠. 침대, TV, 의자가 있고 거기서 자고 있는 사람이 있는 것과는 많이 다르죠. (응급 의학 학습자)

There’s a huge difference between the 89-year-old who’s under the covers asleep, breathing shallowly, and you’re just looking in from the door. But there’s something there that you just know they’re alive. And when they die, it’s gone. And I don’t know what it is. But bodies just become furniture. You know, it’s like there’s a bed, a chair, a TV, and a dead person. Which is much different than there’s a bed, a TV, a chair, and there’s somebody sleeping in there. (Emergency Medicine Learner)

동시에 기증자가 시신이 된 정확한 순간은 기증자가 사망한 순간이 아니었습니다. 오히려 주변 사람들이 기증자의 죽음을 알게 되는 순간이었습니다. 시신의 맥박, 동공 및 촉각 반응, 자발 호흡 등 생명 징후를 검사하고 사망을 선언하고 사망 진단서에 서명함으로써 사망을 '공식화'하는 것은 담당 의사의 재량에 달려 있었습니다.

At the same time, the exact moment that the donor became a body was arguably not the moment the donor died. Rather, it was the moment those around them become aware of their death. This moment was up to the discretion of the doctor in charge who made the death “official” by examining the body for signs of life (e.g., pulse, pupil and tactile response, spontaneous respiration), declaring death, and signing a death certificate.

사망 선언을 통해 일련의 일상적인 이벤트가 동원되어 결국 임상 시체가 만들어졌습니다. '사망 시'에 어떤 일이 일어나는지 설명하기 위해 설계된 프로그램 문서를 분석한 결과, 기증자에서 시신으로 개념이 바뀌는 것을 확인할 수 있었습니다. 이러한 자료는 사망이 발생한 장소에 따라 어떻게 진행해야 하는지에 대한 지침을 포함하여 물류에 중점을 두었습니다. 이 문서에는 시신의 프로그램 수용 여부를 최종적으로 결정하는 '해부 검사관'의 역할에 대한 언급도 처음 포함되었습니다.

The declaration of death mobilized a routine set of events that eventually led to the creation of a clinical cadaver. Through our analysis of programmatic documentation designed to delineate what happens “at the time of death”, we saw the conceptual shift beginning from a donor to a body. These materials focused on logistics, including instructions on how to proceed, depending on where the death occurred. These documents also included the first mention of the role of the “Inspector of Anatomy,” who ultimately determined whether a body would be accepted into the program.

기증자가 병원에서 사망하면 간호 직원은 시신에서 심장 및 산소 모니터, 삽관 튜브, 중심정맥관, 정맥주사, 바디 테이프 및 기타 모든 의료 장비를 제거하는 작업을 수행했습니다. 또한 피부에서 혈액과 기타 물질을 닦아내고 담요를 교체하고 눈을 감겼습니다. 이러한 활동은 기증자가 병원 밖에서 사망했을 때 특히 중요했습니다. 이러한 경우 시신을 청소한다는 것은 죽음에 대한 공포를 완화하는 것을 의미하는데, 대부분의 경우 새로 죽은 시신의 모습은 정말 불안할 수 있기 때문입니다:

When a donor died in-hospital, nursing staff attended to removing heart and oxygen monitors, intubation tubes, central lines, IVs, body tape, and all other medical equipment from the body. They wiped blood and other substances from the skin, replaced blankets, and closed the eyes. These activities were especially important when a donor died outside of the hospital. In these cases, cleaning the body meant attenuating the horror of death because, in many cases, the appearance of newly dead bodies could be truly unsettling:

처음 가서 시체를 수습할 때요. 입이 열려 있고, 때로는 눈이 열려 있고, 입에서 토사물이 나올 수도 있고... 그냥 깨끗하지 않은 상태의 시신을 보게 될 겁니다. 그리고 궤양이 생기기도 하고... 토사물에 질식하기도 하고... (시체 직원)

The first time you go and pick up a dead body. Their mouths’ open, sometimes their eyes are open, there could be purge coming out of their mouth…you’ll get people in a state where they’re just, they’re not clean. And you’re going to get some ulcers…if they soil themselves…they choke on their vomit… (Cadaver staff)

이러한 활동의 목적은 시신을 외부 세계에 '보기 좋게' 보이게 하여 가족들이 시신을 인식하고 반응하는 방식을 바꾸고, 시신을 보려는 사람들의 충격을 완화하는 데 있습니다.

The purpose of these activities was to make the body look “presentable” to the outside world, transforming the way the family will perceive and react to the body, and serving to soften the blow for those who wish to view it.

시신에서 시신으로

Body to cadaver

의료진과 HBD 직원이 시신에서 질병(예: 산소 모니터, 삽관 튜브)과 사망(예: 혈액, 체액 분비물)의 가장 명백한 징후를 제거한 후 시신body은 시신cadaver이 될 준비가 되었습니다. HBD 직원들의 일련의 전문적이고 관료적인 활동은 이러한 전환을 완료하는 데 도움이 되었습니다.

After healthcare workers and HBD staff removed the most obvious signs of illness (e.g., oxygen monitors and intubation tubes) and death (e.g., blood, bodily secretions) from the body, it was ready to become a cadaver. A series of specialized, bureaucratic activities from the part of HBD staff served to complete this transition.

기증자가 사망한 장소와 관계없이 의료진은 사망 진단서를 받자마자 해부 검사관(IoA)에게 연락하여 알렸습니다. 보건부 장관이 임명하는 해부조사관은 HBD 프로그램에 대한 첫 번째 연락 창구였습니다. 이 담당자는 시신을 프로그램에 수용할지 여부(즉, 시신으로 인정할지 여부)를 결정하기 위해 치료를 담당한 의료진, 가족, HBD 직원과 소통합니다. 특히, IoA는 시신에 특정 금기 사항(예: 전염병 위험, 이전 부검, 병적 비만, 주요 절단)이 없는지 확인하고 기증자 가족에게 연락하여 지속적인 동의 여부를 확인합니다. 의심스러운 사망 상황에서는 검시관도 관여했을 수 있으며, 부검이 필요한 경우 시신은 프로그램에서 제외되었습니다. 대학 영안실은 특정 수의 시신만 보관할 수 있고, HBD 프로그램은 특정 목적에 따라 특정 유형의 시신을 수시로 필요로 했기 때문에 임상 시신 담당 직원은 시신이 현재 요구 사항을 얼마나 잘 충족하는지 평가하는 데 IoA를 지원했습니다.

Regardless of where the donor died, healthcare workers would contact and inform the Inspector of Anatomy (IoA) as soon as they received the death certificate. Appointed by the Minister of Health, the IoA was the first point of contact to the HBD program. This individual would communicate with medical personnel in charge of their care, the family, and HBD staff in order to decide whether or not the body should be accepted into the program (i.e., to become a cadaver). Specifically, the IoA verified that the body lacked specific contraindications (e.g., risk of infectious disease, previous autopsy, morbid obesity, major amputations) and contacted the donor’s family to ensure their ongoing consent. In circumstances of suspicious death, the medical examiner may have also been involved; need for an autopsy excluded the body from the program. Because the university morgue was only able to hold a certain number of cadavers and the HBD program required certain types of bodies for specific purposes at any given time, clinical cadaver staff aided the IoA in assessing how well the body met their current needs.

이 단계에 참여한 HBD 직원들은 프로그램의 요구와 고통에 처한 가족의 요구 사이의 균형을 맞추는 데 주력했습니다. 한 참가자는 시신을 프로그램에 받아들이는 데 관련된 관료적 업무를 관리하는 데 어려움을 겪었다고 설명했습니다.

HBD workers involved at this stage were engaged in balancing the needs of the program with the needs of a family in distress. One participant described the challenges of managing the bureaucratic work involved in accepting a body into the program.

사망 진단서 없이는 행동할 수 없습니다. ... 집에서 누군가 사망하면 전화를 받습니다... 시신을 기증하고 싶다고 하는데... 사망 진단서가 없으면 아무것도 할 수 없습니다. 따라서 시신은 사망 장소에 머물거나 가족이 비용을 부담해야하며, 수락 여부에 대한 결정이 내려질 때까지 저온 보관소가있는 장례식장으로 가져 가야합니다. (HBD 직원)

I can’t act without a death certificate. … So, if someone dies at home, I get a call… The person wishes to donate their body …but without a death certificate, I can’t do anything. And so, the body has to either stay at the place of death or at the family’s expense, needs to be taken to a funeral home which has cold storage until a decision can be made about acceptance. (HBD Staff)

프로그램에 접수된 시신은 병원이나 지역 공공 영안실에 임시로 보관되는 경우가 많았습니다. 공간이 확보되면 HBD 프로그램은 운송 직원을 고용하여 시신을 대학 영안실로 가져왔습니다. 보관 공간의 중요성은 프로그램 전반에 걸쳐 중요한 고려 사항이었으며, 시신을 관리해야 할 대상으로 인식하는 데 중요한 역할을 했습니다. HBD 참가자들은 기증자를 위한 '공간'이 필요하며, 공간의 물리적 용량 내에서 작업해야 한다고 자주 설명했습니다. 몰입과 관찰을 통해 시설의 물리적 현실과 관련 보관에 대해 참가자들이 설명한 어려움은 분명해졌습니다. 한 연구자는 다음과 같이 언급했습니다:

Once accepted by the program, the cadaver was often temporarily stored in the hospital or local public morgue. When space became available, the HBD program hired transportation staff to bring the cadavers to the university morgue. The importance of storage space was a key consideration throughout and pointed to a conception of the body as a thing to be managed. Participants from the HBD frequently described having “room” for a donor, and a need to operate within the physical capacity of the space. Through immersion and observation, the physical realities of the facilities, and related storage, challenges participants described were made plain. One researcher noted:

[뇌가 가득 담긴 양동이와 시신으로 가득 찬 냉장고가 선반에 쌓여 있었습니다. 화장터로 가는 복도에는 관 모양의 골판지 상자가 줄지어 있었습니다. 그리고 그 한가운데에는 지게차가 있었습니다. (현장 노트)

[there were] buckets full of brains and a fridge full of bodies—stacked up on shelves. The hallways were lined with coffin-shaped cardboard boxes on their way to the crematorium. And in the middle of it all, there was a forklift. (Fieldnote)

이러한 물리적, 물류적 보관 문제에도 불구하고 각 장소에서는 시신 처리에 신중을 기했습니다. 대학 영안실의 일반적인 파란색 또는 흰색 비닐 봉투 대신 부드러운 자수가 놓인 천으로 된 봉투에 시신을 옮겼습니다. HBD 프로그램과는 별개로 진행되었지만, 운송 직원들은 시신을 픽업하고 내려놓기 위해 정장 차림으로 한 번도 빠짐없이 도착했습니다.

Despite these physical and logistical storage challenges, in each of these locations, handling of the cadavers was taken seriously. Rather than the typical blue or white plastic bags of the university morgue, cadavers were transferred at this moment to bags of soft embroidered fabric. Despite being independent from the HBD program, transportation staff never failed to arrive fully dressed in formal suits to pick up and drop off the bodies.

시신에서 교육용 시신으로

Cadaver to educational cadaver

시신이 대학 시체 안치소에 도착하면 HBD 직원들은 시신을 교육용으로 준비하기 시작했습니다. 이들은 분비물을 제거하고 체액이 계속 고여 있는 목과 위를 석션하고 대변이 더 이상 배출되지 않도록 청소했습니다. 때로는 기관과 식도 등 신체의 특정 부위를 잘라 체액이 더 이상 축적되는 것을 막기도 했습니다. 그런 다음 시신을 방부 처리하고 냉동 보관했습니다. 가능한 한 익명을 보장하기 위해 머리를 밀었고, 이후 각 시신을 식별하기 위해 발가락에 장부에 있는 번호에 해당하는 태그를 붙였습니다. 각 CBS 세션 전에 스태프들은 시신을 얼리지 않고 깨끗이 씻고 석션한 다음 눈은 수술용 모자로, 나머지 신체 부위는 파란색 수술용 천으로 덮었습니다. 한 연구원이 지적했듯이 눈과 머리 윗부분을 덮는 것이 특히 중요했습니다:

Once cadavers arrived at the university morgue, HBD staff began preparing them for their educational purposes. These individuals further cleaned the body of its secretions, suctioning the throat and stomach which had continued to build up fluids, and cleaned any further release of feces. They sometimes cut certain parts of the body, such as the trachea and esophagus, to halt further build-up of fluids. They then embalmed and froze the bodies. To make them as anonymous as possible, they shaved their heads; to identify each body thereafter, they attached tags to their toes with a number corresponding to one in a ledger book. Before each CBS session, staff unfroze these bodies, freshly cleaned and suctioned them, then covered their eyes with surgical caps and the rest of their bodies in blue surgical drapes. The covering of eyes and the top of the head were particularly significant, as one researcher noted:

하지만 한 번은 시체의 얼굴 덮개가 벗겨져 은빛 눈동자, 아가페 입, 두개골을 가로지르는 넓은 상처가 거칠게 꿰매진 것을 볼 수 있었습니다. 이런 디테일은 저를 괴롭혔습니다. 그렇지 않으면 수면 중인 환자와 시체 사이의 차이를 최소화하기 위해 전략적으로 덮는 것이 트릭을 수행하는 것 같았습니다. (현장 노트)

Once, though, a cadaver’s face covering slipped, and I could see blank silver eyes, mouth agape and a broad gash roughly stitched across its skull. These details [bothered me]. Otherwise, strategic covering seemed to do the trick to minimize the difference between a sleeping patient and cadaver. (Fieldnote)

교육용 시신을 준비하기 위해 HBD 직원이 사용한 위에서 설명한 절차는 전통적인 방부 처리사나 장례 전문가가 장례식을 위해 시신을 준비할 때 사용하는 절차와는 크게 달랐습니다. 예를 들어, 장례식을 위해 준비된 시신은 순전히 미적인 목적으로 세척하고 옷을 입히며, 이 경우 기관과 식도를 절단하거나 폐를 보기 위해 가슴을 열 이유가 없습니다. 따라서 시신 준비에 관여하지 않은 방부처리사나 장의사는 이러한 행위를 시신 훼손으로 간주하는 경우가 많았습니다:

The procedures described above, which HBD staff used to prepare an educational cadaver, differed markedly from those traditional embalmers and funeral professionals use to prepare bodies for a funeral service. For instance, bodies prepared for a funeral service are cleaned and dressed for purely esthetic purposes; there is no reason, in these cases, to sever the trachea and esophagus or cut open the chest to help visualize the lungs. Consequently, embalmers and funeral directors who were not involved in cadaver preparation often saw these acts as mutilation:

장례식장에서는 장례식장 방부사가 준수해야 하는 기준이 정해져 있습니다. 반면에 아주 사소한 일탈도 하지 말아야 할 일을 하는 것으로 간주됩니다. (HBD 직원)

In a funeral home, I mean everything is, there’s a set kind of standard that funeral embalmers should adhere to. Whereas even the smallest diversion [is considered] doing something that you shouldn’t. (HBD staff)

참가자들은 시신을 사용하여 의미 있는 교육적 경험을 제공한다는 목표를 향해 일하고 있다는 점을 염두에 두고 작업에 집중함으로써 이러한 복잡성을 헤쳐 나간다고 설명했습니다.

Participants described navigating this complexity by focusing on the work and keeping in mind that they were working toward a goal: using the cadaver to generate a meaningful educational experience.

작업에 집중할 수 있을수록 더 좋은 결과를 얻을 수 있습니다. ... 제가 제 일을 제대로 잘하면 [학습자에게] 도움이 될 것입니다. ... 여기서도 동일한 자부심과 동일한 관심을 가지고 학생들을 위한 교재를 제작합니다. (HBD 직원)

I find that the more I can concentrate on the task [the better]. … If I do my job properly well that’s going to help [learners]. … Here again the same pride and the same attention is to create those teaching materials for the students. (HBD staff)

따라서 시신 담당 직원들의 전문적인 (때로는 논란의 여지가 있는) 작업은 전통적인 장례 관행에서 벗어나 시신을 시신과는 다른, 즉 임상 도구로 탈바꿈시키는 과정이었습니다.

Hence, the specialized—and sometimes controversial—work of cadaver staff deviated from traditional funeral practices and transformed the cadaver into something different from a dead body: it was in the process of becoming a clinical tool.

교육용 카데바에서 교사로

Educational cadaver to teacher

시뮬레이션 실습실에서 전담 직원은 촉촉하고 노랗게 얼룩진 흰색 시트와 깨끗한 파란색 커튼으로 겹겹이 덮인 금속 테이블 위에 시체를 놓았습니다. 짧은 세션 동안에는 시신을 시신 가방에 넣어 지퍼를 다시 닫아 냉장고에 보관하기도 했습니다. 그들은 수술 도구, 기계, 스크린을 사이드 테이블과 이동식 카트 위에 조심스럽게 배치했습니다.

In the simulation lab, dedicated staff placed cadavers on metal tables, covered in layers of moist, yellow-stained white sheets and clean, blue drapes. For short sessions, they often kept the cadavers in their body bags, ready to be zipped back up and returned to their refrigerators. They carefully arranged surgical instruments, machines, and screens throughout the room on side tables and mobile carts.

시뮬레이션 세션이 시작되자 노란색 가운과 파란색 장갑을 착용한 교사와 학습자들이 시신을 둘러싸고 있었습니다. 최적의 학습 환경을 제공하기 위해 교사, 학습자, 시체 보관소 직원들이 분주하게 움직였습니다. 한 연구자는 공간의 분주함을 다음과 같이 설명했습니다,

When the simulation sessions began, teachers and learners, dressed in yellow gowns and blue gloves, encircled the cadavers. The room would be busy as teachers, learners, and cadaver staff worked to provide an optimal learning environment. One researcher described the busyness of the space, noting,

사람들이 서로 다른 도구나 공간으로 이동하기 위해 서로를 피해야 하는 모습은 마치 콘서트장의 관중을 헤쳐나가는 것 같았고, 서로 부딪히지 않으려고 애쓰는 모습이 떠올랐습니다. (현장 노트)

The way people have to duck around each other to get to different tools or spaces makes me think of navigating a concert crowd – lots of shuffling and trying not to bump anything. (Fieldnote)

여기저기서 흡입하는 소리와 흥분된 목소리가 들려왔고, 방부액과 체액 분비물이 섞인 다양한 냄새가 방 안 구석구석에 스며들었습니다. 가만히 들여다보면 아이러니가 무르익어 있었습니다. 시신의 눈을 가리는 수술용 보닛은 종종 알록달록한 행복한 얼굴이나 곰 인형으로 장식되어 있었습니다. 한 번은 심지 3개짜리 양초가 배경에서 천천히 타오르면서 방에 "설탕을 넣은 스니커 낙서" 냄새가 났던 적도 있습니다.

The sounds of suctioning and excited voices arose from huddles, and various smells—mostly embalming fluid mixed with bodily secretions—infiltrated all corners of the room. When one attended to it, irony was ripe in this environment. The surgical bonnets that covered the eyes of the cadavers were often decorated with colorful happy faces or teddy bears. On one occasion, a 3-wick candle burned slowly in the background, making the room smell of “sugared snicker doodle.”

이러한 공간에서 시체는 이야기하고, 기대고, 만지고, 찌르고, 자르는 대상이 되었습니다. 시신은 온전하게 보존되어 있었지만 학습자가 살펴보고 조작할 수 있는 분리된 부위(무릎, 턱, 가슴 창)의 집합으로 개념화되었습니다. 학습자들은 시체 주위에 모여들면서 각 학습자가 당분간 작업할 신체 부위를 '소유'하고, 작업이 끝나면 다른 학습자가 그 자리를 차지하도록 했습니다. 교사가 다양한 기술을 시연할 수 있었기 때문에 교육 도구로서 시체의 어포던스는 분명했습니다:

In these spaces, cadavers became things that were talked about, leaned on, touched, prodded, and cut. While the cadavers remained fully intact, they were conceptualized as a collection of isolated parts (a knee, a jaw, a chest window) that learners examined and manipulated. As they crowded around the body, each learner “claimed” a body part to work on for the time being, letting another learner take their place when they were finished. The affordances of the cadaver as an educational tool were clear, as teachers were able to demonstrate different techniques:

첫 번째 그룹을 관찰하기 위해 멈춰선 교사는 기도 시술에서 흔히 사용하는 '스니핑' 자세에 대한 대안적인 머리 자세를 설명하고 있었습니다. 그는 참가자들에게 바에서 테이블로 걸어갈 때 맥주 윗부분을 홀짝이는 자세인 '홀짝이기' 자세를 시도해 보라고 권유했습니다. 이 설명에 주위에 모인 참가자들은 잔잔한 웃음을 터뜨렸습니다. (현장 노트)

The first group I stopped to observe: the teacher was describing an alternative head position to the “sniffing” position often advocated for in airway procedures. He encouraged participants to try the “sipping” position: how you might sip the top of a beer as you walk from the bar to your table. This description was met with gentle laughter in the cluster of participants gathered around him. (Fieldnote)

시체 위와 다리 사이에 장비가 쌓이기 시작했습니다. 많은 교사와 학습자에게 이 순간 시체는 임상 도구였습니다:

Equipment would begin piling up on the cadaver and between its legs. For many teachers and learners, the cadaver was, at this moment, a clinical tool:

시체가 그곳에 있을 때 저에게는 그저... 교육 도구일 뿐입니다. 무례하다는 뜻이 아닙니다. 제 말은 그것들이 거기에 있지만, 저는 그것들을 예전과 같은 것으로 생각하지 않는다는 것입니다. (교사)

To me when they’re there, they’re just a…teaching tool. And I don’t mean that in a disrespectful way. I mean they’re there, I just don’t think of them as what they were. (Teacher)

제 생각에는 인지적으로 우리는 이 사람이 사람이었다는 사실을 정말 분리해서 생각하는 것 같아요. 우리는 그들을 존중하지만 또한... 우리가 [시신 준비 실험실]에있을 때 우리 중 많은 사람들이이 사람이 살아 있었을 때 어떤 사람이었을지 생각하지 않는 것 같아요. 그것은 우리 모두가 가지고 있는 일종의 인지적 분리라고 생각합니다. (학습자)

I think part of it is like the, cognitively, we really separate the fact that… We really keep the fact that this was a person kind of separate. We treat them with respect, but we also… I don’t think when we’re in [the body preparation lab], I don’t think very many of us are thinking like about who this person might have been when they were alive or something. I think that that’s just sort of a cognitive separation thing that we all have. (Learner)

교사와 학습자 모두 세션이 진행되는 동안 눈과 몸에서 흘러내린 보닛과 커튼을 계속 교체했습니다. 시신을 덮어두는 것은 환자의 존엄성을 지키기 위한 목적도 있지만, 시신을 사람으로 보지 않는 '분리감'을 강화하는 역할도 했습니다:

Both teachers and learners continuously replaced bonnets and drapes that slipped off the eyes and body during the course of the session. While keeping the body covered primarily aimed to preserve the patient’s dignity, it also served to reinforce a “detachment” from viewing the cadaver as a person:

우리는 시신을 최대한 가린 상태로 유지하려고 노력합니다... 시간이 지남에 따라 학생들은 시신의 손이나 발을 노출하면 보는 것이 부담스러워진다는 것을 알고 있다고 설명하는 것을 보았습니다. 그리고 시체를 교육 자료로 사용하는 데 있어 학생들이 편안함을 느끼는 부분 중 하나는 이것이 사람이었다는 사실에 대해 조금은 거부감을 느낄 수 있다는 것입니다. 조금만 분리할 수 있다면 침습적인 시술을 반복해서 하는 것이 조금 더 쉬워질 수 있습니다. (교사)

We try to keep the cadaver as covered up as possible…I’ve seen over time, students describe like you know they get bothered by seeing—if you expose a cadaver’s hands or feet. And I think…part of their comfort level in working with a cadaver as a teaching resource is that they may disconnect a little bit from saying this was a person. Where it’s a little easier to do some invasive procedures over and over again if you can disconnect a little bit from that. (Teacher)

시체 실습에서 학습자의 불편함을 줄이는 중요한 작업을 수행했음에도 불구하고 교사와 선임 학습자는 시체가 (전) 사람이라는 생각을 강화하고 학습자에게 시체를 존중하는 태도로 대할 것을 상기시켰습니다:

Despite accomplishing the important work of reducing learners’ discomfort in the cadaver lab, teachers and senior learners also reinforced the idea that the cadaver was a (former) person, and reminded learners to treat the body with respect:

우리는 학생들에게 시체가 사람이라는 사실을 상기시키는 데 큰 중점을 둡니다. 그들은 환자입니다. 우리는 모두 다른 연설을 합니다. 저는 기본적으로 시신을 환자와 가족들이 들을 수 있는 사람처럼 대하는 것을 기본 원칙으로 삼고 있습니다. 그리고 다른 환자처럼 대하세요. (교사)

We make a big point…to remind students that they are people. They are patients. We all have different speeches. Mine is basically about, you know, you treat the cadaver as if it’s a patient who can hear you and their family members can hear you. And treat them as if they’re any other patient. (Teacher)

저는 여전히 최소한의 손상을 입히는 데 집중하고 있습니다... 실제 환자에게도 하지 않을 일을 하고 싶지 않아요. (시니어 학습자)

I’m still focusing on causing minimal damage…I wouldn’t want to do something that I wouldn’t do in real life with a real patient. (Senior learner)

몇몇 학습자는 시체 교사를 복제할 수 없는 자원으로, 심지어 생명의 은인이나 영웅으로 개념화했습니다. 한 참가자는 이렇게 말했습니다:

Several learners conceptualized the cadaver teacher as an irreplicable resource, and even a lifesaver, or hero. One participant noted:

가장 큰 차이점은 [CBS]에서 하는 것과 외상실에서 하는 것은 사실상 같은 일이기 때문에 차이가 거의 없다고 생각합니다... 말 그대로 일주일 후에 삽관하는 다음 환자는 이완, 해부학적인 측면에서 매우 유사했습니다... 선생님은 그냥 거기에 계셨던 것입니다. (학습자)

I think that the biggest difference is going from what you’re doing in [CBS] to the trauma room is so small because it’s effectively the same thing … literally the next patient I was intubating like a week later was very similar in terms of their relaxation, the anatomy… you were just there. (Learner)

사랑하는 사람에 대한 스승이자 유산

Teacher to loved one and legacy

시신이 교육 도구로서의 역할을 마친 후, HBD 프로그램은 가족에게 연락하여 시신을 돌려주거나 화장 또는 대학 전용 묘지에 안장할 준비를 했습니다. 기증자의 가족은 매년 봄에 열리는 안장식 및 추모식에 초대되었습니다.

Once the cadaver completed its intended role as an educational tool, the HBD program contacted the family and made arrangements to either return the body to them or to prepare it for cremation and/or burial in the university’s dedicated cemetery. Family members of the donors were invited to an annual interment and memorial service in the Spring.

안장식은 공동묘지에서 진행되었습니다. 기증자의 유골이나 유골함은 천막 아래에 놓여 있었고 그 위에 기증자의 이름이 적힌 명판이 놓여 있었습니다. 참석자들은 그 옆에 꽃과 기념품을 놓았습니다. 파이퍼가 연주하고, 성직자들이 연설하고, 비둘기가 날아갔으며, HBD 프로그램 대표가 150여 명의 기부자 이름을 큰 소리로 읽었습니다. 이 행사는 공동체적이면서도 매우 개인적인 행사였습니다.

The interment ceremony happened at a cemetery. The ashes or urns of the donors were set out under a tent with plaques placed on top indicating their names. Attendees placed flowers and keepsakes beside them. A piper played, members of the clergy spoke, doves were released, and a representative from the HBD program read the names of more than 150 donors out loud. The event was both communal and deeply personal.

추모식은 웅장한 가톨릭 교회에서 열렸습니다. HBD 직원, 교수진, 학생들은 모두 정장 차림으로 장례식장을 가득 메운 기부자 가족들과 함께했습니다. 학생들은 물망초 씨앗을 깔끔하게 꽂은 안내 책자를 나눠주며 기부에 동참했습니다. 성직자, HBD 프로그램 회원, 교사, 학습자 등 다양한 사람들이 연설했습니다. 그들은 감사, 슬픔, 관대함, 인간관계에 대해 이야기했습니다:

The memorial service happened in a grand Catholic church. HBD staff, faculty, and students—all formally dressed in funeral wear—joined the families of donors as they filled into the pews. Students contributed by handing out information booklets with forget-me-not seeds tucked neatly inside them. A number of people spoke: clergy, members of the HBD program, teachers, and learners. They spoke of gratitude, grief, generosity, and human connection:

다양한 의료 직종에 종사하는 많은 학습자가 강단에 올라 이 프로그램을 통해 어떤 혜택을 받았는지 이야기했습니다. 대부분 교과서적인 내용입니다. 충분히 사려 깊고 친절하지만 여러분이 기대할 수 있는 그런 내용입니다. 하지만 가장 아름답고 의미 있는 연설을 하는 사람이 한 명 있습니다. 그 연설이 감동적이었던 이유는 그가 인간으로서 우리를 연결하는 요소에 초점을 맞추었기 때문이라고 생각해요. 그는 우리가 누군가를 알 수 있는 모든 방법, 학습자가 함께 일하는 (전?) 사람들을 친밀하게 알게 되는 방법에 대해 이야기했습니다. 그리고 이것이 어떻게 그가 남겨진 사람들과 공유하는 유대감인지에 대해 이야기했습니다. 교육, 슬픔, 희망을 연결하는 방법, 즉 예상했던 것을 미묘하게 재조정하는 것이죠. 완벽했습니다. (현장 노트)

A number of learners from the various health professions come to the lectern to speak about how they’ve benefited from the program. For the most part, they’re pretty textbook remarks. Thoughtful and kind enough, but the kind of thing you’d expect. But there’s one guy who gives the most beautiful, meaningful speech. And, I’ve thought about this—I think the thing that made it so poignant was the fact that he focused on what connects us as humans. He talked about all the ways we can know someone, how learners come to intimately know the (former?) people they work on. How this is a bond that he shares with the people who were left behind. It’s a subtle reorientation of the expected—a way to connect education, grief, and hopefulness. It was perfect. (Fieldnote)

따라서 안장식과 추모식은 고인에 대한 감사와 추모에 전념했습니다. 이렇게 교구로서의 시신은 배경으로 사라졌습니다. 그 대신 시신을 기증한 관대한 '영웅'을 추모하고 참석자들은 다음 현장 노트에서 볼 수 있듯이 그들이 제공한 모든 것에 대해 감사를 표했습니다:

The interment and memorial service was thus dedicated to thanking and commemorating the dead. In this manner, the cadaver-as-teaching-tool faded to the background. In its place, all celebrated the memory of the generous “hero” who donated their body and attendees appreciated them for all that they have offered, as illustrated in the following field note:

연사 중 한 명이 부모님을 축하하기 위해 이 자리에 모인 모든 사람을 먼저 기립시키고, 그 다음에는 형제자매를 축하하는 사람, 사랑하는 사람, 사랑하는 사람의 기증으로 혜택을 받은 모든 사람이 기립하도록 요청하는 특별한 순간이 있었는데, 연사가 "이것이 바로 영향력이고, 이것이 바로 사랑이며, 이것이 우리가 여기 있는 이유"라고 말하며 마지막에 모든 사람이 기립한 모습은 정말 놀라웠습니다. 고인의 시신뿐만 아니라 고인이 나눈 사랑과 고인이 감동한 삶이 무대 위의 디스플레이로는 결코 담아낼 수 없는 거대하고 강력한 에너지와 결합되어 있다는 사실이 갑자기 이해가 되었습니다.

There is an exceptional moment when one of the speakers asks first everyone who is here to celebrate their parent to stand, then those celebrating their sibling, then their loved one, then anyone who’s benefitted from the loved ones’ donation—everyone at the end of it was standing and the speaker said “this is the impact, this is the love, this is why we are here” and it was stunning. All of a sudden, the relatively small candle memorial makes sense—it’s not just about the person’s body but about the love they shared and the lives they’ve touched, all combined a massive and powerful energy that could never be captured by a display on a stage.

토론

Discussion

시체 작업의 복잡성의 핵심은 존재론적 모호함, 즉 시체를 사람 또는 사물, 인간 또는 인간이 아닌 것, 교사 또는 도구로 규정할 수 없다는 것입니다. 이러한 구분은 시체를 산 자와 구별할 수 없게 만드는 새로운 보존 기술의 발달로 인해 더욱 모호해지고 있습니다. 우리가 설명하는 수명 주기의 일부 단계가 반드시 임상 시신에만 적용되는 것은 아니라는 점을 잘 알고 있습니다. 물론 기존의 고정된 시신은 다양한 맥락에서 다르게 사용됨에 따라 변형됩니다. 그러나 우리는 시체가 딱딱하고 회색일 때, 즉 인간성을 간과하기 쉬울 때 철학적 작업이 덜 어려울 수 있다고 믿습니다. 임상 사체의 존재론적 충실성은 생애주기의 각 단계에서 특정 관행에 영감을 주며, 우리는 사람들이 말하고 행동하는 방식을 주목하고 분류하는 과정에서 이를 확인했습니다. 이러한 말과 행동36은 임상 시체의 모호하지만 부인할 수 없는 인간성의 산물입니다.

Central to the complexity of cadaver work is what we refer to as its ontological ambiguity: the inability to qualify the cadaver as either a person or a thing; human or not human; or as a teacher or a tool. This distinction is becoming ever more ambiguous with the development of novel preservation techniques that render cadavers less and less distinguishable from the living. We recognize that some of the stages of the lifecycle we describe are not necessarily unique to clinical cadavers. Certainly, a traditional hard-fixed cadaver is transformed as it is used differently, in different contexts. We believe, however, that the philosophical work may be less troubling when the cadaver is rigid and gray—its humanity is perhaps easier to overlook. The ontological fidelity of clinical cadavers inspires specific practices at each stage of the lifecycle, which we identified in noting, and classifying, the ways in which people speak and act. These sayings and doings36 are a product of the nebulous, but undeniable, humanness of clinical cadavers.

CBS는 시체 해부에는 예술과 과학이 모두 존재한다는 것을 관찰했습니다.

- 예술적 측면에서는 시체를 준비하고 전시하는 방식이 예술적이었으며, 작업자들은 실제 임상 사례에 가까운 상호작용을 장려하는 실제와 같은 표본을 제시하는 데 자부심을 가지고 있었습니다.

- 과학과 관련해서는 보존 기술의 혁신, 정교한 기술, 도구 및 장치 테스트에 주목했습니다.

하지만 카데바 기반 시뮬레이션의 철학은 좀 더 모호했습니다. 하지만 철학적 작업이 사실 CBS의 근간을 이루고 있다는 사실을 알게 되었습니다.

We observed that there is both an art, and a science, to CBS.

- With respect to art, the ways in which cadavers are prepared and presented was artful, with workers taking pride in presenting lifelike specimens that encouraged an interaction closer to a real clinical encounter.

- With respect to science, we noted the innovations in preservation techniques, the refined skill, the testing of tools and devices.

The philosophy of cadaver-based simulation, however, was more nebulous to identify. Yet, once we attuned to it, it became clear that philosophical work was, in fact, foundational to CBS.

들뢰즈적 관점에서 보면 CBS에 종사하는 사람들은 철학을 하고 있는 셈입니다.47 여기에는 사체가 생애주기를 거치면서 존재론적 모호성을 관리하는 개념적, 정서적, 윤리적, 기술적 작업이 포함되며 전문적인 관행에 의해 능동적으로 형성됩니다. 해부학적 대상으로서의 교육용 시체를 제작하고 재제작하는 것은 중요한 고려 사항이며20, 시체 기반 교육학의 관계적/사회적 요소21는 교육용 시체 작업의 복잡성에 대한 이해를 넓혀주었지만, 시체의 생애주기에 걸친 철학적 전환에 조율하는 것은 미묘한 요소를 추가합니다.

- 당사자에서 기증자로의 전환을 통해 참가자들은 사후에 시신이 어떻게 사용될지 계획하고 조직할 수 있었습니다.

- 사망 시 발생하는 기증자에서 시신으로의 존재론적 전환은 미래의 생명을 구하기 위한 시신 기반 교육의 실제 실습을 위한 프로세스를 시작할 수 있게 했습니다.

- 시신에서 시체로 전환된다는 것은 참가자들이 특정 상황에서 특정 시신으로 무엇을 할 것인지에 대한 결정을 내릴 수 있다는 것을 의미했습니다.

- 시신에서 교육용 시신으로 전환하면서 참가자들은 '더 큰 선', 즉 자신의 치료가 필요할 미래의 상상 속 환자에 초점을 맞추면서 시신을 비인격화할 수 있었습니다.

- 교육용 시신에서 교사로 전환한 참가자들은 시신에 직접 손을 대고 임상 술기와 절차를 연습할 수 있었습니다.

- 마지막으로, 교사에서 유산으로의 전환을 통해 참가자들은 자신이 참여하는 복잡한 작업에 대해 성찰하고, 기증자를 기리는 공간을 제공하며, 시신을 기증한 사람들의 인격을 기억하는 생애주기의 시작점으로 돌아갈 수 있었습니다.

From a Deleuzian perspective, then, people engaged in CBS are doing philosophy.47 This involves the conceptual, emotional, ethical, and technical work of managing ontological ambiguities as the cadaver passes through the lifecycle and is actively shaped by professional practices. While the making and remaking of teaching cadavers as anatomical objects is an important consideration20 and the relational/social elements of cadaver-based pedagogy21 have broadened our understanding of the complexity of educational cadaver work, attuning to the philosophical transitions across the lifecycle of a cadaver adds a nuanced element to the conversation.

- The transition from person to donor allowed participants to plan and organize for how a body will be used after death.

- The ontological transition from donor to body that occurred at death allowed the process to be set in motion for the actual hands-on work of cadaver-based education, which is intended to save future lives.

- The transition from body to cadaver meant that participants were able to make decisions about what to do with a particular body, in a particular set of circumstances.

- The transition from cadaver to educational cadaver allowed participants to depersonalize the cadaver as they focused on “the greater good”: future, imagined patients who will need their care.

- The transition from educational cadaver to teacher allowed participants to do things to the cadaver, practicing clinical skills and procedures.

- Finally, the transition from teacher to legacy allowed participants to reflect on the complex work in which they engage, providing space to honor donors, and returning us to the start of the lifecycle where we remember the personhood of those who gave the gift of their body.

이러한 존재론적 전환에 대한 철학적 작업은 라이프사이클의 각 단계에서 수행해야 하는 작업의 기초가 됩니다. 예를 들어, 우리가 신체를 사람으로 생각하기를 멈추지 않는다면, 해부학적 구조를 관찰하기 위해 신체를 절단하는 것은 상상하기 어렵습니다. 우리는 이 철학적 작업이 사실 "사전 경험적"이라고 믿습니다."35 이는 우리가 시체 기반 교육의 예술이나 과학에 참여하기 전에 먼저 들뢰즈와 과타리가 "개념을 형성, 발명, 조작하는 것"으로 정의한 철학에 참여해야 한다는 것을 의미합니다. 35(p2) 참가자들이 눈앞의 신체를 이해하기 위해 만들어낸 개념은 CBS의 전문적 관행과 분리할 수 없습니다.

This philosophical work of ontological transitions is foundational to the tasks that must occur at each stage of the lifecycle. It is difficult to imagine, for example, cutting into a body to observe its anatomical structures had we never stopped thinking about that body as a person. We believe this philosophical work is, in fact, “pre-empirical.”35 This means that before we can engage in the art or science of cadaver-based education, we must first engage in philosophy, which Deleuze and Guattari defined as “forming, inventing, and fabricating concepts.” 35(p2) The concepts which participants created in order to make sense of the body before them are inseparable from the professional practices of CBS.

온톨로지 충실도

Ontological fidelity

CBS에 관한 문헌은 주로 시뮬레이터의 효과성 문제에 초점을 맞추고 있습니다. 22,27,34 특히, 현실을 재현하는 사실감의 정도 또는 정확성으로 정의되는 높은 충실도 때문에 의학교육자들에게 CBS는 매력적입니다.48 의학교육자들은 일반적으로 두 가지 유형의 충실도를 인식합니다.49

- 물리적(즉, 시뮬레이터의 모양과 느낌의 유사성)

- 기능적(즉, 시뮬레이터가 조작 또는 개입에 반응하는 방식의 유사성)

그러나 CBS에 대한 우리의 연구는 물리적 및 기능적 충실도보다 더 많은 것이 있음을 시사합니다. 특히, 저희는 세 번째 관련 충실도 유형인 존재론적 충실도가 있다고 주장합니다.

The literature on CBS has primarily been focused on issues of simulator effectiveness. 22,27,34 In particular, CBS is appealing to medical educators because of its high fidelity, defined as the degree of realism, or exactness with which it reproduces reality.48 Medical educators generally recognize two types of fidelity:

- physical (i.e., similarity in the look and feel of the simulator) and

- functional (i.e., similarity in how the simulator responds to manipulation or intervention).49

Our study of CBS suggests, however, that there is more to fidelity than physical and functional. Specifically, we argue that there is a third relevant type of fidelity: ontological fidelity.

존재론적 충실도가 중요하다는 것은 부인할 수 없는 사실입니다. 기존의 딱딱하게 고정된 시신과 달리 임상 시신에는 마네킹 시뮬레이터 및 실제 신체와 구별되는 본질적인 고유성이 있습니다. 카데바는 사람이므로 부드러움과 존중을 가지고 다뤄야 합니다. 그러나 카데바는 살아있는 사람이 아니므로 교육용 도구처럼 자르고, 찌르고, 조작할 수 있습니다. 시체에는 냄새, 촉감, 이야기가 있습니다. 교육생이 CBS에 접근하는 진지함은 다른 어떤 학습 활동과도 비교할 수 없습니다. 따라서 우리의 연구는 시체가 무엇인지에 대한 질문이 CBS 실습에 중요하며 대체할 수 없는 고유한 실습이라는 것을 보여주었습니다. 아무리 기술적으로 진보된 고충실도 마네킹이라도 '인간됨'을 속일 수는 없기 때문에 실제 인체를 대체할 수는 없을 것입니다.

It is undeniable that ontological fidelity matters. In contrast to traditional, hard-fixed cadavers, there is something inherently unique to the clinical cadaver that makes it distinct from both the manikin simulator and the living body. The cadaver is human, and therefore needs to be treated with tenderness and respect. The cadaver is not, however, a living person, and therefore can be cut, prodded, and manipulated like an educational tool. The cadaver has a smell, a feel, and a story. The seriousness with which trainees approach CBS is incomparable to any other learning activity. Our study thus demonstrated that the question of being—what a cadaver is—matters to the practice of CBS, and makes it a unique and irreplaceable practice. Arguably, the most technologically advanced, high-fidelity manikin will never replace a real human body, because you simply cannot fake “human.”

우리는 존재론적 충실도가 들뢰즈와 과타리의 세 가지 사고 방식(예술, 과학, 철학)과 관련하여 빠진 조각일 수 있다고 생각합니다.35 예술이 개념의 감각적, 지각적 측면을 표현하고 과학이 그 기능을 설명하고 조작할 수 있게 해 준다면 철학은 새로운 개념을 묘사하고 창조할 수 있게 해 줍니다. 충실도를 물리적, 기능적, 존재론적 개념으로 개념화하면 CBS를 예술적, 과학적, 철학적으로 표현하는 데 도움이 될 수 있습니다.

We believe ontological fidelity may be the missing piece related to Deleuze and Guattari’s three modes of thought (art, science, and philosophy).35 If art allows us to represent the sensory and perceptual aspects of a concept; science allows us to explain and manipulate its functions; then philosophy allows us to delineate and create new concepts. Conceptualizing fidelity as physical, functional, and ontological can help us represent CBS artistically, scientifically, and philosophically.

시체의 존재론적 충실도 개념은 결과적인 개념입니다. 더글러스-존스가 설명한 "침묵의 멘토"와 함께 작업할 때의 감정적 요소와 함께,29 이는 대면 시체 작업을 없애는 것에 반대하는 중요한 논거를 제공합니다. 현대에는 시체가 더 이상 필요하지 않다는 주장도 있습니다. 특히 코로나19 팬데믹 기간 동안 해부학 학습을 위한 가상 기술의 괄목할 만한 발전으로 값비싸고 자원 집약적인 임상 시체 프로그램이 필요하지 않게 되었습니다.50 그러나 우리의 연구에 따르면 화면을 통해 전달하기 훨씬 더 어려운 시체의 인간성 수준이 중요하다는 것을 알 수 있습니다.39

The concept of ontological fidelity of cadavers is a consequential one. Along with the emotional elements of working with “silent mentors” as described by Douglas-Jones,29 it provides an important argument against eliminating in-person cadaver work. There has been some argument that cadavers are no longer necessary in the modern era. Particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, there have been notable advancements in virtual technologies for anatomy learning that could eliminate the need for expensive and resource-intensive clinical cadaver programs.50 However, our research suggests that the level of humanness of the cadaver—something much more difficult to convey through a screen—matters.39

올레자즈41 는 해부 실습실을 도덕적 실험실, 윤리 교육을 실제로 이해할 수 있는 공간, 해부에 사용되는 인체의 모호함에 대처하는 방법을 기증자로부터 배울 수 있는 공간으로 묘사하고 있습니다. 마찬가지로 CBS와 관련된 교육 공간은 도덕적 교육 역할을 합니다. 이 독특한 환경에서 의학교육의 연속선상에 있는 학습자들은 눈앞에 놓인 시체의 물질적 형태와 씨름하며 새로운 개념을 만들어내고, 이를 통해 수행해야 하는 과제를 용이하게 수행할 수 있습니다. 절차적 술기를 가르칠 수 있는 마네킹이나 기타 시뮬레이터 형태의 다른 교육 도구도 분명 존재하지만, 시체의 존재론적 충실도와 그 사용과 관련된 철학적 작업은 대체할 수 없다고 생각합니다.