라오스의 의학교육(Med Teach, 2019)

Medical education in Laos

Timothy Alan Witticka, Ketsomsouk Bouphavanhb, Vannyda Namvongsac, Amphay Khounthepd and Amy Graye,f,g

소개

Introduction

배경

Background

라오스는 동남아시아의 내륙 산악 국가입니다(그림 1). 인구는 약 700만 명이며 인구의 63%가 농촌 지역에 거주하는 것으로 추정됩니다(세계보건기구 2015). 라오스에는 총 49개의 민족이 공식적으로 인정되고 있으며, 각 민족은 고유한 방언, 관습, 건강 신념을 가지고 있습니다. 라오스의 경제는 노동력의 약 80%를 고용하는 농업에 크게 의존하고 있습니다(라오스 보건부 외. 2014).

Laos is a landlocked, mountainous country in South-East Asia (Figure 1). It has a population of approximately seven million people and it is estimated that 63% of the population live in rural areas (World Health Organisation 2015). A total of 49 ethnic groups are officially recognized in Laos, each having their own dialect, customs, and health beliefs. The economy is heavily based on agriculture, which employs an estimated 80% of the labor force (Ministry of Health Lao PDR et al. 2014).

20세기 이전 라오스가 포함된 지역은 수 세기에 걸쳐 여러 왕국의 통치를 받았습니다(Evans 2002). 1893년부터 1953년 라오스가 독립할 때까지 60년 동안 프랑스는 라오스에 강력한 영향력을 행사했습니다(Sweet 2015). 제2차 인도차이나 전쟁 이후 1975년 신라오학삿(NLHX) 또는 파텟 라오가 라오스의 통치기구로 취임했습니다. 이 시점에 라오스 인민민주주의 공화국(라오스)이 수립되었습니다(Evans 2002). 이후 라오스는 일당 국가로 남아있습니다(아카봉 외. 2014).

Prior to the 20th century, the area encompassed by Laos was governed by multiple kingdoms over a period of many centuries (Evans 2002). From 1893, the French had a strong presence in the country for a period of 60 years until Laos gained independence in 1953 (Sweet 2015). Following the Second Indochina War, in 1975, the Neo Lao Hak Xat (NLHX) or Pathet Lao took over as the country’s governing body. It was at this point that the Lao People’s Democratic Republic (Lao PDR) was established (Evans 2002). Laos has since remained a one-party state (Akkhavong et al. 2014).

의료 시스템 개요

Overview of the healthcare system

사회경제 및 보건 지표가 개선되고 있지만 라오스는 이 지역 최빈국 중 하나이며 인간개발지수에서 188개 국가 및 지역 중 141위에 랭크되어 있습니다(유엔개발계획 2015). 세계보건기구(WHO)에 따르면 라오스인의 평균 기대 수명은 66세이며, 5세 미만 사망률은 1000명당 71명, 모성 사망률은 10만 명당 220명입니다(세계보건기구 2015). 비전염성 질병의 비율이 증가하고 있지만 감염으로 인한 질병 부담은 상당합니다(Akkhavong 외. 2014; 세계보건기구 2015).

Although socioeconomic and health indicators are improving, Laos is one of the least developed countries in the region and ranks as 141 out of 188 countries and territories on the Human Development Index (United Nations Development Programme 2015). The World Health Organization (WHO) reports the average life expectancy for a Lao person to be 66 years, with an under-5 mortality rate of 71 deaths per 1000 live births and maternal mortality ratio of 220 deaths per 100000 live births (World Health Organisation 2015). Infections cause a significant burden of disease although rates of non-communicable diseases are rising (Akkhavong et al. 2014; World Health Organisation 2015).

라오스의 의료 시스템에는 정부 소유의 사용자 부담 시스템과 성장하는 민간 의료 부문이 포함됩니다. 정부 시스템은 중앙, 지방 및 지역 수준에서 운영되며 라오스 의료 종사자 및 자원봉사자들이 근무하고 있습니다(Akkhavong 외. 2014; Yoon 외. 2016). 2011년 라오스에는 인구 1만 명당 약 2.4명의 의사와 7.5명의 간호사가 있었습니다(라오스 보건부 및 세계보건기구 2012). 이는 세계보건기구(WHO)가 권장하는 인구 1만 명당 의사 및 간호사 최소 기준인 23명(세계보건기구 2010)과 비교됩니다.

The healthcare system in Laos includes a government-owned, user pays system along with a growing private healthcare sector. The government system operates at central, provincial and district levels and is staffed by Lao health practitioners and volunteers (Akkhavong et al. 2014; Yoon et al. 2016). In 2011 there were approximately 2.4 doctors and 7.5 nurses per 10000 people in Laos (Ministry of Health Lao PDR and World Health Organisation 2012). This compares with the WHO recommended a minimum threshold of 23 doctors and nurses per 10000 people (World Health Organisation 2010).

기사 목적

Article objectives

이 글은 라오스의 의료 교육 시스템을 설명하는 것을 목표로 합니다. 중요한 역사적 발전, 관리 기관, 이해관계자, 현재 학부 및 대학원 연구 프로그램에 대해 간략히 설명하고 앞으로의 잠재적 방법과 함께 중요한 과제에 대해 논의합니다.

This article aims to describe the medical education system in Laos. We outline important historical developments, the governing bodies, stakeholders, current undergraduate, and postgraduate study programs and we discuss important challenges along with potential ways forward.

국가별 상황

Country in context

라오스 의학교육의 역사

History of medical education in Laos

라오스 의학교육의 역사는 크게 네 시기로 나눌 수 있습니다.

- 첫 번째 시기인 1893년부터 1950년까지는 라오스의 프랑스 식민지 시대와 관련이 있습니다. 이 기간 동안 프랑스는 외국 의사들로 구성된 의료 네트워크를 구축했습니다(Sweet 2015). 외국인 의사를 유지하는 데 여러 가지 문제가 발생하자 1900년대 초에 현지 의료 인력 교육이 지원되었습니다. 소수의 라오스 학생들이 하노이로, 이후에는 사이공과 프놈펜으로 보내져 의료 보조원으로 훈련받았습니다. 1940년대 후반부터 라오스 학생들은 프랑스에서 의학 공부를 시작했습니다(Sweet 2015)

- The history of medical education in Laos can be divided into four time periods. The first period, from 1893 to 1950, correlates with the French colonization of Laos. During this time the French established a health network staffed by foreign doctors (Sweet 2015). Having encountered multiple issues retaining foreign practitioners, in the early 1900s local health workforce training was supported. Small cohorts of Lao students were sent to Hanoi then later Saigon and Phnom Penh to train as medical assistants. From the late 1940s, Lao students undertook medical studies in France (Sweet 2015).

- 두 번째 시기인 1950년부터 1975년까지는 라오스가 프랑스로부터 독립한 시기와 관련이 있습니다. 의과 대학 (그림 2)은 1957 년 비엔티안에 설립되었습니다. 세계보건기구와 프랑스 정부가 기술 및 재정 지원을 제공했습니다. 처음에는 프랑스어로 진행되는 4년제 의료 보조 과정을 제공했으며, 1961년 7명의 첫 졸업생이 배출되었습니다(토비수크). 이후 7년 과정의 의학 박사 과정이 개설되어 1969년 25명의 첫 번째 코호트가 이 과정을 시작했습니다. 이 현지 교육 외에도 라오스 학생들은 이 기간 동안 다른 나라에서 의학을 공부할 수 있는 후원을 계속 받았습니다(Sweet 2015).

- The second period, from 1950 to 1975, correlates with Lao independence from France. The School of Medicine (Figure 2) was established in Vientiane in 1957. Technical and financial assistance was provided by WHO and the French Government. It initially offered a four-year medical assistant course taught in French and the first class of seven students graduated in 1961 (Thovisouk). A seven-year Doctor of Medicine course was later established with the first cohort of 25 students commencing this course in 1969. In addition to this local training, Lao students continued to receive sponsorship to study medicine in other countries throughout this period (Sweet 2015).

- 제2차 인도차이나 전쟁의 끝은 1975년부터 1990년까지 지속된 제3차 인도차이나 전쟁의 시작을 알렸습니다. 이 기간 동안 상당수의 교육받은 라오스 전문가들이 라오스를 떠났습니다 (나이팅게일 2011). 프랑스의 존재는 감소한 반면 사회주의 국가의 지원은 상당히 증가했습니다. 1960년대 초부터 1991년까지 17000명 이상의 라오스 학생들이 소련의 대학에서 교육을 받은 것으로 추정되지만, 이들 중 몇 퍼센트가 의학을 공부했는지는 확실하지 않습니다(Sweet 2015). 해외 연수 제도로 인해 교육의 질이 다양하고 라오스 의사들이 귀국 후 공통된 전문 언어가 없는 등 여러 가지 문제가 발생했습니다.

- The end of The Second Indochina War marked the beginning of the third period, which lasted from 1975 to 1990. A significant number of educated Lao professionals left the country during this time (Nightingale 2011). The French presence decreased while support from socialist countries rose considerably. It is estimated that over 17000 Lao students received training at universities in the Soviet Union from the early 1960s until 1991, although it is unclear what proportion of these students studied medicine (Sweet 2015). Multiple issues arose as a result of overseas training schemes including varied quality of education and Lao doctors lacking a common professional language upon their return home.

- 현지 의사 교육도 증가하여 1978년에는 의대생 코호트가 연간 20명 수준에서 100명 이상으로 증가했습니다(Sweet 2015). 이에 따라 교사 수, 교사 자질, 시설, 교육 자료도 함께 증가했습니다. 소련, 베트남, 쿠바 직원들은 1960년대에 설립되어 1970년대 라오스 정부가 지방 간호 교육을 위해 부활시킨 의과대학과 지방 보건대학에 현장 직원과 기술 지원을 제공하면서 이 공백을 메우기 위해 노력했습니다(Sweet 2015).

- Training of doctors locally also increased, with medical student cohorts rising from 20 to over 100 students per year level in 1978 (Sweet 2015). A corresponding increase in teacher numbers, teacher quality, facilities, and educational materials proved challenging. Soviet, Vietnamese, and Cuban staff sought to fill this void, providing both on the ground staff and technical support to the School of Medicine and to provincial health colleges which had been established in the 1960s, and revived by the Lao government in the 1970s to deliver nursing training in the provinces (Sweet 2015).

- 마지막 시기인 1990년부터 현재까지 외국 지원의 성격이 변화하고 의료 교육에 대한 현지 통제가 증가했습니다(Sweet 2015). 문화적, 언어적 유사성뿐만 아니라 근접성과 공동체적 유대감으로 인해 태국의 대학들은 라오스 보건부와 협력 협약을 맺고 대학원 교육 및 지속적인 의학교육 기회를 제공했습니다. 현지에 기반을 둔 대학원 의학 교육도 설립되었습니다. 1990년대 초, 미국의 비정부기구(NGO)인 Health Frontiers는 보건과학대학(UHS)과 협력하여 소아과 대학원 교육 프로그램을 개발하기 시작했습니다. 비슷한 시기에 프랑스 NGO인 라오스 협력 위원회(CCL)는 UHS와 협력하여 수술, 마취 및 공중보건 분야의 현지 기반 대학원 교육을 개발했습니다(Phongsavath and Soukaloun 2014; Sweet 2015).

- The final period, from 1990 to the present day, has seen a change in the nature of foreign support and an increase in local control over medical education (Sweet 2015). As a result of cultural and language similarities, as well as proximity and collegial ties, universities in Thailand formed cooperation arrangements with the Lao Ministry of Health to provide postgraduate training and continuing medical education opportunities. Locally based postgraduate medical training was also established. In the early 1990s, an American non-government organization (NGO), Health Frontiers, began working with the University of Health Sciences (UHS) to develop a pediatric postgraduate training program. At a similar time, the French NGO Comité pour la Coopération avec le Laos’ (CCL) partnered with the UHS to develop locally based postgraduate training in surgery, anesthetics and public health (Phongsavath and Soukaloun 2014; Sweet 2015).

- 1990년대 초, 의과 대학(이전에는 "의과 대학"으로 불림)은 의학, 치과, 약학 등 세 개의 학부로 구성되었으며 보건부가 관리했습니다. 1995년에 대학 관리가 교육부로 이관되면서 큰 변화가 일어났습니다. 그 후 라오스 의과 대학은 라오스 국립 대학교에 합병되어 의과학 학부가 설립되었습니다. 2007년에 보건부가 의료 교육 관리를 다시 맡으면서 다시 변화가 일어났고, 이 시점에 UHS가 설립되었습니다.

- In the early 1990s, the University of Medical Science (previously termed “School of Medicine”) consisted of three faculties: medicine, dentistry, and pharmacy and was governed by the Ministry of Health. Significant changes took place in 1995 when administration of the university was transferred to the Ministry of Education. The University of Medical Science was then merged into the National University of Laos, leading to the establishment of the Faculty of Medical Science. Change took place again in 2007 when the Ministry of Health regained administration of medical training and at this point in time the UHS was established.

교육 기관

Training institutions

UHS는 라오스에서 의사가 되기 위한 교육을 제공하는 유일한 기관입니다. 의료 보조원을 양성하는 4개의 주립 보건대학(루앙프라방, 타케크, 사반나켓, 팍세)과 다른 여러 주에 지역 보건 기초 과정을 제공하는 추가 보건대학이 있습니다. UHS, 주립 보건 대학, 보건 학교는 모두 별도의 조직이지만 보건부에서 관리합니다(그림 3).

The UHS is the only institution in Laos providing training to become a medical doctor. There are four provincial health colleges which train medical assistants (in Luang Prabang, Thakhek, Savannakhet, and Pakse) and additional health schools in a number of other provinces, offering basic courses in community health. Whilst the UHS, provincial health colleges, and health schools are all separate organizations they are administered by the Ministry of Health (Figure 3).

최근까지 UHS는 비엔티안의 4개 캠퍼스에 7개 학부가 있었습니다. 여기에는 기초과학부, 의학부, 간호학부, 치의학부, 약학부, 의료기술부, 대학원 학부, 그리고 행정 부서와 교육 개발 센터(EDC)가 포함됩니다. 교육 개발 센터는 2010년에 WHO의 지원으로 설립되었습니다. 이 센터는 WHO 서태평양 지역 대학 교육 개발 센터 네트워크의 일부입니다. 라오스의 EDC는 UHS에 전략적 계획을 지원하고, 학부와 협력하여 교육의 질을 향상시키며, 의학교육 활동에 대한 UHS와 외부 기관 간의 협력을 위한 구심점 역할을 합니다. 2018년에 UHS의 구조가 개정되었습니다. 여러 가지 변화 중에서도 6년간의 학부 의학 교육과 대학원 의학 교육이 모두 의학부 산하로 통합되어 의학 커리큘럼에 대한 보다 통합적인 접근이 가능해졌습니다. 가장 최근의 변화에서 EDC는 연구 및 교육 개발 연구소로서의 역할이 확대되었습니다.

Until recently the UHS had seven faculties located across four campuses in Vientiane. These include the Faculty of Basic Sciences, Medicine, Nursing, Dentistry, Pharmacy, Medical Technology, and the Postgraduate Faculty, in addition to an Administrative Affairs department and the Education Development Centre (EDC). The EDC was established in 2010 with support from WHO. It forms part of a network of education development centers at universities in the WHO Western Pacific Region. The EDC in Laos provides support to the UHS with strategic planning, works with faculties to improve the quality of their education and is a focal point for collaboration between the UHS and external organizations on medical education activities. In 2018 the structure of UHS has been revised. Among a number of changes, all six years of undergraduate medical training, as well as post-graduate medical training have been brought together under the Faculty of Medicine, enabling a more integrated approach to the medical curriculum. In the most recent changes, the EDC has an expanded role as an Institute for Research and Education Development.

학부 과정

Undergraduate studies

입학

Admission

UHS는 의대생을 위한 6년제 학부 커리큘럼을 제공하며, 학생들은 입학 시험을 통해 입학합니다(의학부). 시험은 화학, 생물학, 수학 과목에 대한 객관식 시험 3문항으로 구성되며, 각 시험은 2시간 동안 진행됩니다. 이 과정은 UHS와 보건부(MoH) 직원으로 구성된 위원회에서 감독합니다.

The UHS offers a six-year undergraduate curriculum for medical students to which students are admitted based on entrance examinations (Faculty of Medicine). The examinations consist of three multiple choice question examinations, each two hours in length, covering subject areas of chemistry, biology, and mathematics. The process is overseen by a committee comprising UHS and Ministry of Health (MoH) staff.

학생들은 이 시험의 결과에 따라 순위를 매긴 다음 세 가지 그룹에 따라 선발됩니다.

- 지원자의 70%로 구성된 그룹 1에는 그룹 2 또는 그룹 3 지원 자격이 없는 가장 높은 순위를 받은 학생이 포함됩니다.

- 두 번째 그룹은 군대, 경찰 또는 지방, 주 또는 중앙 병원에서 근무한 경험이 있는 지원자(예: 의료 보조원)로 구성되며, 고용주가 의과 과정 입학 시 특별 배려를 받도록 추천한 지원자들로 구성됩니다.

- 세 번째 그룹은 라오스 내 미리 정해진 취약 지역 출신 지원자로 구성됩니다.

- 코스 입학생의 약 15%는 2그룹과 3그룹 지원자 각각에게서 나옵니다. 총 입학 학생 수는 해마다 90명에서 150명 이상까지 다양합니다.

Students are ranked based on their results in these examinations and then selected according to three groupings.

- Group one, which consists of 70% of entrants, includes the students with the highest ranks who are not eligible as group two or three applicants.

- Group two consists of applicants who have worked for the military, police or in district, provincial or central hospitals (for example as a medical assistant) and who have been nominated by their employer to receive special consideration for entry into the medical course.

- The third group consists of applicants who are from a pre-determined list of disadvantaged districts in Laos.

- Approximately 15% of the course intake comes from each of group two and group three applicants. Total student admission numbers have varied from year to year, ranging from 90 to over 150 students.

코스 개요 및 교육 방법

Course outline and teaching methods

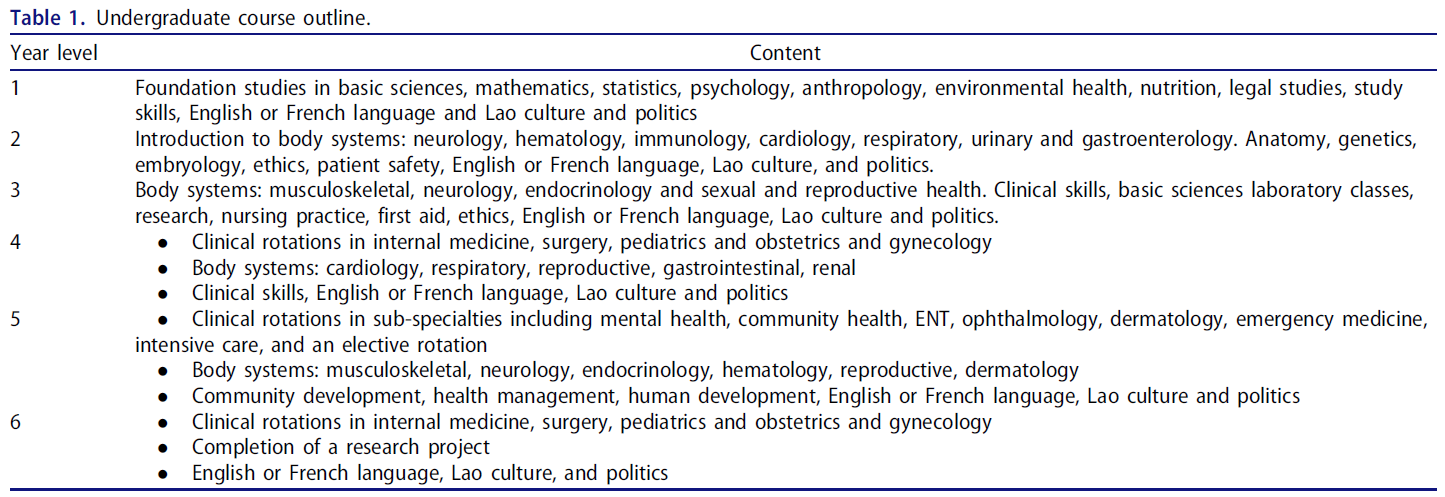

1969년 라오스에 의사 커리큘럼이 개설된 이래로 이 과정은 6~7년 동안 다양하게 진행되었습니다. 가장 최근의 변화는 2003년에 6년 풀타임 과정으로 축소된 것입니다(일본국제협력기구 2010). 2018년까지 1~3학년은 기초과학부에서, 4~6학년은 의학부에서 관리해 왔습니다. 표 1은 각 학년별 수업 내용을 개괄적으로 보여줍니다.

Since the establishment of a medical doctor curriculum in Laos in 1969, the course has varied between six and seven years in length. The most recent change occurred in 2003 when it was reduced to what remains a six-year, full-time course (Japan International Cooperation Agency 2010). Up until 2018, years one to three have been managed by the Faculty of Basic Sciences and years four to six have been managed by the Faculty of Medicine. Table 1 outlines the course content for each year level.

과목은 블록 단위로 진행되며 대부분의 수업은 라오스어로 진행됩니다. 4, 5, 6학년의 임상 로테이션 기간 동안 학생들은 오전에 배치된 병원에 출근하고 오후에는 대학 캠퍼스로 돌아와 교육을 받습니다. 제한된 인원으로 인해 학생들은 주로 대규모 그룹 강의 형식으로 교육을 받습니다. 임상 로테이션에서는 소규모 그룹 학습이 가능하지만 내용과 형식은 개별 현장에 따라 다릅니다. 제한된 교직원 수와 제한된 교육 시설 등 여러 가지 현실적인 문제로 인해 의과대학에서는 학생들이 받는 공식적인 교육과 임상 로테이션에서의 경험을 일치시키는 데 어려움을 겪고 있습니다. 이는 개별 과목 콘텐츠 간의 제한된 통합과 함께 지속적인 과제를 제기합니다.

Subjects are taught in blocks and the majority of teaching is undertaken in the Lao language. During the clinical rotations in years four, five, and six, students attend their placement in the morning and return to the university campus each afternoon for teaching. Limited staff numbers mean that students are predominantly taught in large group, lecture format. Smaller group learning is possible on clinical rotations however the content and format is dependent on individual sites. A number of practical issues, including limited staff numbers and limited teaching facilities, make it challenging for the Faculty of Medicine to align the formal teaching students receive with their experiences on clinical rotations. This, along with the limited integration between individual subject content poses ongoing challenges.

평가

Assessment

1~3학년 학생들은 각 블록 과목을 이수한 후 시험을 치릅니다. 각 시험의 형식과 내용은 과목 코디네이터가 결정합니다. 각 학년 수료 시 학생의 최종 점수는 개별 과목 시험 결과와 각 과목의 학점 가중치를 합산하여 계산됩니다.

In years one to three, students undertake examinations following the completion of each block subject. The format and content of each exam are decided by the subject coordinator. A student’s final mark at the completion of each year is calculated based on a sum of the individual subject examination results and the credit weighting for each subject.

4~6학년에는 블록 과목과 시험이 이어지며, 임상 로테이션에 참여하는 학생에게는 로그북과 병원 보고서라는 두 가지 추가 평가가 실시됩니다.

- 로그북은 허들 요건이며, 사례 발표, 진행 기록 작성 및 특정 절차를 포함한 역량을 다루며 담당자가 서명합니다.

- 병원 보고서는 각 병원의 의료 교사가 제출하는 평가서로, 교사가 로테이션 기간 동안 학생의 성과를 관찰한 내용을 바탕으로 지식, 태도, 기술 영역을 평가합니다.

In years four to six, students continue to undertake block subjects followed by exams, with two additional assessments for students on clinical rotations – a logbook and a hospital report.

- The logbook is a hurdle requirement and covers competencies including case presentations, progress note writing and specific procedures, on which staff signs off.

- The hospital report is an assessment submitted by medical teachers at each hospital, assessing domains of knowledge, attitudes, and skills, based on the teachers’ observations of student performance throughout the rotation.

최종 시험은 6학년 말에 완료됩니다. 여기에는 객관식(MCQ) 시험, 객관적 구조화 임상 시험(OSCE), 그룹 연구 논문 제출이 포함됩니다. MCQ 시험은 4~6학년의 교과 내용을 다루며, OSCE는 내과, 외과, 소아과, 산부인과 등 각 핵심 전문과목에서 2개씩 총 8개 스테이션으로 구성됩니다. 학위를 받으려면 학생들은 이 두 가지 최종 시험과 연구 논문을 통과하고, 각 과목을 통과해야 하며, 재학 기간 동안 전문성을 입증해야 합니다(의학부, 토비수크).

Final examinations are completed at the end of year six. These include a Multiple Choice Question (MCQ) examination, an Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) and submission of a group research thesis. The MCQ exam covers course content from years four to six, whilst the OSCE includes a total of eight stations, with two stations from each of the core specialties; internal medicine, surgery, pediatrics and obstetrics, and gynecology. To receive their degree students must pass these two final examinations and their research thesis, have passed each of their individual subjects and have demonstrated professionalism during the period of their studies (Faculty of Medicine; Thovisouk).

의학 학위를 마친 후 학생들의 경력 경로는 매우 다양합니다.

- 정부는 일부 졸업생에게 제한된 감독을 받을 수 있는 지역 병원에서 일하도록 배정하는 반면,

- 다른 졸업생은 중앙 또는 지방 병원이나 UHS에서 자원봉사를 하며 유급 취업의 기회를 기다립니다.

- 소수의 졸업생은 비정부기구 또는 민간 부문에 취업합니다(일본국제협력기구 2010).

Following completion of the medical degree, student career paths vary greatly.

- The government assigns some graduates to work in district hospitals, where they may have limited supervision,

- while others volunteer at central or provincial hospitals or at the UHS, waiting for an opportunity for paid employment.

- A small proportion of graduates take up employment with a non-government organization or in the private sector (Japan International Cooperation Agency 2010).

대학원 과정

Postgraduate studies

라오스에서 졸업 후 수련 과정은 비교적 새로운 것입니다. 1997년에 소아과 레지던트가 최초로 개설된 대학원 교육 과정입니다(나이팅게일 2011). 현재 내과, 소아과, 산부인과, 외과, 안과, 방사선과, 마취과, 가정의학과, 응급의학과 등 총 9개의 대학원 레지던트 과정과 2017년에 시작된 공중보건 및 가정의학 석사 과정을 포함한 2개의 의학 석사 프로그램이 운영되고 있습니다. 모든 프로그램의 교육은 주로 라오스에서 2~3년에 걸쳐 이루어지며, 일부 프로그램의 학생들은 태국에서 단기 병원 로테이션을 이수합니다. 교육은 병원과 1차 진료 환경에서 모두 이루어지는 경우가 많으며, 이는 라오스의 인구가 주로 농촌에 기반을 두고 있기 때문에 특히 중요합니다(세계보건기구 2015). 현지에 기반을 둔 대학원 교육의 강점은 현지 보건 전문가를 유지하여 '두뇌 유출'을 최소화하고 현지 보건 시스템에 익숙한 졸업생을 확보할 수 있다는 점입니다. 문제는 다양한 방식으로 이러한 프로그램을 형성한 여러 국제기구의 지원을 받으면서 현지 교육 역량을 장기적으로 개발하는 데 의존해야 한다는 점입니다. 많은 레지던시에서 지원 국제기구는 교육 및 행정 제공을 지원하기 위해 국제 자원 봉사자를 지속적으로 현지에 상주시킵니다(나이팅게일 2011).

Post-graduate training pathways are relatively new in Laos. In 1997 the pediatric residency was the first postgraduate training pathway to be established (Nightingale 2011). There are now a total of nine postgraduate residencies and two medical masters programs including internal medicine, pediatrics, obstetrics and gynecology, surgery, ophthalmology, radiology, anesthetics, family medicine, and emergency medicine which commenced in 2017, along with a Masters in Public Health and Family Medicine. Training in all programs is predominantly completed in Laos over a period of two to three years, with students in some programs completing short hospital rotations in Thailand. Training often takes place in both hospital and primary care settings, which has been particularly important for Laos given its population is predominantly rurally based (World Health Organisation 2015). The strength of the locally based postgraduate education has been to retain local health professionals thereby minimize the “brain drain” and having graduates who are familiar with the local health system. The challenges are that they rely on the long-term development of local teaching capacity whilst receiving support from different international organizations which have shaped these programs in varying ways. In a number of residencies, the supporting international organizations have a continuous presence of international volunteers in-country to support the delivery of teaching and administration (Nightingale 2011).

레지던트 프로그램마다 입학 절차는 다르지만, 일반적으로 예비 학생들은 입학 시험을 치르고 선배 동료의 공식적인 추천을 받아 프로그램에 입학해야 합니다. 레지던트는 임상 책임을 맡게 되며 병상 튜토리얼, 강의, 저널 클럽, 케이스 토론, 임상 회의 참여 등을 통해 교육을 진행합니다. 일지, 연구 논문을 제출하고 최종 MCQ 및 OSCE 시험을 통과해야 하는 등 총체적이고 형성적인 평가가 사용됩니다.

There are differing admission processes for each residency program, however, in general, prospective students are required to sit an entrance examination and have a senior colleague formally recommend them for admission into the program. Residents assume clinical responsibilities and teaching is delivered through bedside tutorials, lectures, journal clubs, case discussions, and participation in clinical meetings. Summative and formative assessments are used, including the requirement to submit a logbook, research thesis and pass final MCQ and OSCE examinations.

레지던트 수련 프로그램을 마친 후 졸업생은 대부분 중앙, 주 또는 지역 단위의 공중보건 시스템에서 근무하며, 대부분의 경우 채용된 병원으로 복귀해야 합니다. 일부 졸업생에게는 국제 펠로우십의 형태로 라오스에서 제공되지 않는 추가 하위 전문 교육을 이수할 수 있는 기회가 제공됩니다(나이팅게일 2011). 이 펠로우십은 국제 기부자들의 재정적 지원을 받으며 일반적으로 태국에서 수료합니다.

Following completion of a residency training program, graduates most commonly work in the public health system, at a central, provincial or district level, and in most instances are required to return to the hospital from which they were recruited. A select number of graduates are offered the opportunity to complete further sub-specialty training which is not available in Laos, in the form of an international fellowship (Nightingale 2011). These fellowships are supported financially by international donors and are commonly completed in Thailand.

지속적인 전문성 개발

Continuing professional development

라오스에서 일하는 의사 및 기타 의료 전문가를 위한 면허 시스템이 현재 개발 중입니다(Sonoda 외. 2017). 이 단계에서는 지속적인 전문성 개발(CPD)에 대한 의무 요건은 없습니다. 그러나 CPD를 취득할 수 있는 방법은 여러 가지가 있습니다.

- 레지던트 프로그램 졸업생의 요구를 충족하기 위해 현지에서 운영되고 조직된 의학 컨퍼런스가 성장하고 있습니다.

- 보건부와 기부자를 통해 지원되는 프로그램을 통해 지역 및 지방 병원의 의사들이 단기 또는 중기적으로 상급 시설에 배치되어 특정 분야에 대한 전문성을 향상시킬 수 있습니다.

- 또한 아동 질병 통합 관리(IMCI), WHO 아동 병원 진료 포켓북, 조기 필수 신생아 치료 및 응급 산과 치료와 같은 국가 보건 프로그램과 기타 기부자 프로그램을 통해서도 CPD가 제공됩니다.

A licensing system for medical doctors and other health professionals working in Laos is currently being developed (Sonoda et al. 2017). At this stage, there is no mandatory requirement for continuing professional development (CPD). There are, however, a number of avenues through which CPD is obtained.

- Locally run and organized medical conferences have grown to meet the needs of graduates of residency programs.

- Programs supported through the Ministry of Health and donors facilitate short to medium term placement of doctors from district and provincial hospitals in higher level facilities to upskill these staff in particular areas.

- CPD is also provided through national health programs such as the Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI), the WHO Pocketbook of Hospital Care for Children, Early Essential Newborn Care and Emergency Obstetric Care, as well as other donor programs.

CPD 참여는 출석을 지원하고 의료 전문가의 상대적으로 낮은 임금을 보충하기 위해 일당제 문화에 크게 의존합니다(Vian 외. 2013). 이는 지속 가능성에 영향을 미치며, 때때로 교육의 초점이 현지의 필요보다는 기부자의 의제에 의해 주도되고 보수에 의해 동기가 부여될 수 있음을 의미합니다. 그러나 일부 지역 컨퍼런스가 참가비를 부과하고 일당을 제공하지 않는 다른 프로그램이 제공하는 가치에 비해 참석률이 저조한 것으로 나타나면서 기대치가 변화하고 있습니다. Participation in CPD relies largely on a culture of per diems to support attendance and to supplement the relatively low wages of health care professionals (Vian et al. 2013). This impacts on sustainability and means the focus of education can at times be driven by donor agendas and be motivated by remuneration, rather than the local need. Expectations are however shifting with some local conferences charging attendance fees and other programs not offering per diems being well attended because of the value they offer.

강점과 과제

Strengths and challenges

현재 UHS의 강점은 의학교육의 격차를 해소해야 한다는 명확한 인식이 있다는 점입니다. 세계의학교육연맹의 세계 의학교육 질 향상 표준(2015)에 따라 의학 커리큘럼의 개혁을 평가하고, 질 표준을 시행하는 면허 시험을 개발하는 프로세스가 마련되어 있습니다. 또한 국제 파트너와의 장기적인 관계를 통해 교육 개혁을 위한 기술 지원과 함께 일하는 현지 직원의 역량을 강화할 수 있는 기반을 마련했습니다. UHS에 교육 개발 센터를 설립한 것은 이러한 환경에서 교육 역량 강화가 절실히 필요했기 때문이며, 외부 파트너가 노력을 조정할 수 있는 구심점을 제공합니다. 마지막으로, 많은 개발도상국이 두뇌 유출로 어려움을 겪고 있지만(Lofters 2012), 지난 20년 동안 라오스는 다른 나라에서 라오스 의학 학위를 인정하지 않았고, 졸업생이 필요한 특정 분야에서 일하도록 요구하는 현지에서 운영하는 레지던트 프로그램의 존재로 인해 상대적으로 두뇌 유출에서 벗어날 수 있었습니다.

A strength the current situation for UHS is that there is clear recognition of the gaps in medical education which must be bridged. Processes are in place to assess the reform of the medical curriculum against World Federation for Medical Education Global Standards for Quality Improvement (World Federation for Medical Education 2015) and develop a licensing examination which enforces quality standards. Furthermore, long-term relationships with international partners have provided a foundation for technical support for educational reform and to build the capacity of local staff with whom these partners work. The creation of the Education Development Centre at UHS was born out of the critical need for education capacity building in this setting and provides a focal point through which external partners can coordinate efforts. Finally, while many developing countries suffer brain drain (Lofters 2012), in the last two decades Laos has been relatively spared, as a result of the lack of recognition of the Lao medical degree in other countries and the presence of locally run residency programs which require graduates to work in specific areas of need.

하지만 여전히 많은 과제가 남아 있습니다. 가장 큰 문제 중 하나는 아마도 영어(또는 기타 외국어) 능력일 것입니다. 라오스는 의료와 문화 전반에서 독서 문화가 제한되어 있습니다(Duerden 2017). 이러한 상황은 변화하고 있지만 라오스어로 된 의학 텍스트와 지침은 거의 존재하지 않으며, 존재한다고 하더라도 통화, 수, 배포 및 개인 접근성에 제한이 있습니다(Gray 외. 2017). 라오스어와 태국어의 유사성으로 인해 태국어 교과서가 사용되지만 이 솔루션은 불완전합니다. 수도와 주요 도시 외곽에서는 인터넷 접속이 어려울 수 있으며, 접속이 가능하더라도 속도가 느리고 비용이 많이 들 수 있습니다. 라오스 언어 리소스가 없는 경우 온라인 학습은 검색, 필터링 및 검색된 내용을 이해하기 위한 충분한 언어 능력에 의존하며, 많은 경우 불가능하지는 않더라도 매우 어려운 일입니다. 이러한 기술을 가진 사람들은 종종 젊은 세대의 학생과 의사이며, 이러한 젊은 학습자와 나이든 교사 사이에 지식의 불균형이 발생하고 있으며, 학습자들은 점점 더 이를 인식하고 있습니다.

Many challenges do however remain. One of the greatest is perhaps English (or other foreign) language capacity. Both in medicine and the broader culture, Laos has had a limited reading culture (Duerden 2017). While this is changing, few Lao language medical texts and guidelines exist and many which do are limited in their currency, number, distribution, and accessibility to individuals (Gray et al. 2017). Thai textbooks are used due to the similarity between Lao and Thai but this solution is imperfect. Internet access can be challenging outside of the capital and major cities, but even when available it can be slow and costly. In the absence of Lao language resources, online learning is reliant on sufficient language skills to search, filter and understand what is found, and for many, this is highly challenging if not impossible. Those with these skills are often the younger generation of students and doctors, creating an imbalance in the currency of knowledge between these younger learners and old teachers, of which learners are increasingly aware.

또 다른 큰 문제는 교육 역량입니다. 교사 수가 부족하기 때문에 UHS는 이전에 문제 기반 학습 커리큘럼을 구현하기 위해 분류했지만 실현 불가능한 교사 대 학습자 비율로 인해 실현되지 못했습니다. 같은 문제가 실질적인 임상 술기 교육 제공을 방해하고 있습니다. 기존 직원의 경우 열악한 보수, 경쟁적인 요구, 불명확한 책임, 자신의 한계에 대한 인식이 교육에 대한 몰입도에 영향을 미칩니다. 초등학교에서 이루어지는 기초 교육을 포함한 교육은 전통적으로 의학에서 중요한 비판적 사고와 개념 이해보다는 지식 습득, 교훈적 방법, 권위자로서의 교사에 대한 존경에 중점을 두어 왔습니다. 새로운 방식으로 가르칠 수 있는 역량을 개발하려면 시간과 노력, 의지가 필요하며 무엇보다도 문화의 변화가 필요합니다.

The other great challenge is the teaching capacity. Teacher numbers are insufficient, so whilst UHS previously sort to implement a problem-based learning curriculum, it was not realized due to infeasible teacher-to-learner ratios. The same issue impedes delivery of practical clinical skills training. For existing staff, poor remuneration, competing demands, unclear responsibilities and the awareness of their own limitations impact on the engagement with teaching. Education, including the foundation laid in primary schools, has traditionally focused on knowledge acquisition, didactic methods and respect for the teacher as an authority, rather than on critical thinking and conceptual understanding which are critical in medicine. Developing the capacity to teach in new ways requires time, effort, willingness, and above all, culture change.

앞으로 나아갈 길

The way forward

라오스의 의학교육 상황은 여러 가지 도전 과제에도 불구하고 매우 낙관적인 이야기입니다. 라오스의 교육 개발 리더들은 극복해야 할 장애물을 인식하고 변화와 혁신을 기꺼이 시도하고 있습니다. 최근 라오스에서는 콘텐츠, 교육 및 평가 방법을 조정하고 커리큘럼을 통합하기 위해 의과대학의 6년 과정을 모두 의과대학 산하로 통합하는 변화가 있었습니다. 다른 의과대학의 발전 경로를 따라가는 것도 쉽지만, UHS는 이전에 해왔던 것에서 '도약'해야 할 필요성을 인식했습니다. 10년 이상 걸릴 수 있는 자체 커리큘럼으로 파트너 기관이 지금 하고 있는 것을 모방하려고 하는 대신, UHS는 5년 후 이들 기관에서 의학교육이 어떤 모습일지 생각하고 이를 목표로 삼아야 합니다. 예를 들어, 팀 기반 학습은 현재의 교직원 대 학생 비율로 실현 가능한 교육 방법으로서 잠재력이 있습니다(Punja 외. 2014).

For all of its challenges, the situation for medical education in Laos is a story of great optimism. The leaders of education development in the country recognize the hurdles to be overcome and are willing to change and innovate. There has been a recent change to bring all six years of the medical course under the Faculty of Medicine in order to align content, teaching and assessment methods and to enable curriculum integration. While it would be easy to follow the path of development of other medical schools, UHS have recognized the need to “leapfrog” over what has been done before. Instead of trying to emulate what it’s partner institutions are doing now with their own curricula which could take a decade or more to achieve, UHS must think instead about what medical education may look like in these institutions five years from now and aim for that instead. For instance, potential exists in team-based learning as an educational method which is feasible with current staff to student ratios (Punja et al. 2014).

교육과 학습을 위한 라오스어 의료 자료는 매우 중요합니다. 교사와 학습자의 요구를 충족하기 위해 이러한 자료를 만드는 데는 엄청난 잠재력과 함께 큰 어려움이 있습니다. 의학 텍스트를 완전히 번역하려면 귀중한 시간과 자원이 소모되며 금방 구식이 될 것입니다. 또한 이 작업을 완료하기에 충분한 외국어 및 라오스어 능력을 갖춘 사람의 수도 제한되어 있습니다. 그러나 커리큘럼 콘텐츠는 시간이 지남에 따라 전략적으로 구축할 수 있습니다. 교육 역량이 부족하고 온라인 리소스를 찾는 학습자가 증가하는 상황에서 멀티미디어 리소스와 블로그와 같은 기타 정보 공유 수단을 집중적으로 개발하면 시간이 지남에 따라 조정할 수 있는 콘텐츠를 적시에 제공할 수 있는 잠재력을 제공할 수 있습니다. 이러한 리소스는 콘텐츠의 표준화를 가능하게 하고, 교사와 학습자 모두에게 성과에 대한 표준을 설정하며, 액세스되는 학습 자료의 품질을 모니터링하는 수단을 제공할 수 있습니다.

Lao language medical resources for teaching and learning are crucial. There is both enormous potential and great challenges in creating these to meet the needs of teachers and learners. Complete translation of medical texts consumes both valuable time and resources and will quickly become outdated. Furthermore, the number of individuals with sufficient foreign and Lao language skills to complete this task is limited. Curriculum content could, however, be strategically built over time. With a lack of teaching capacity and a growing number of learners seeking online resources, targeted development of multimedia resources and other means of sharing information such as blogs offer potential to make content available in a timely way which is able to be adapted over time. These resources could enable standardization of content, set a standard for performance for both teachers and learners and provide a means of monitoring the quality of learning material which is being accessed.

라오스의 의료 교육에는 오랜 기간 동안 외국 이해관계자들이 참여해 왔으며, 이들은 각자의 관점, 의료 전통 및 관심사를 가지고 있습니다. 이들은 다양한 도전을 통해 라오스의 의학교육을 지원해 왔지만, 그 자체로 상충되는 메시지와 접근 방식을 가지고 있습니다. UHS와 라오스는 신뢰할 수 있는 파트너의 장기적인 지원을 계속 필요로 할 것입니다. 이러한 노력은 기부자 주기나 우선순위에 의존하지 않고 명확한 현지 전략에 따라 추진되는 안전하고 일관된 자금 기반에 의해 지원될 때 가장 효과적일 것입니다.

Medical Education in Laos has a long history of involvement from foreign stakeholders, who bring with them their own perspectives on practice, medical traditions, and interests. While they have supported medical education in Laos through various challenges, they themselves bring conflicting messages and approaches. The UHS and Laos will continue to require long-term support from trusted partners. These efforts would be most effective if supported by a secure and consistent funding base, which is not dependent on donor cycles or priorities but driven by a clear local strategy.

Medical education in Laos

PMID: 30707856

Abstract

Medical education in Laos has undergone significant developments over the last century. A transition from a foreign to locally trained medical workforce has taken place, with international partners having an ongoing presence. Undergraduate and postgraduate medical education in Laos is now delivered by a single, government administered university. The transition to locally based training has had many flow-on benefits, including the retention of Lao doctors in the country and having graduates who are familiar with the local health system. A number of challenges do however exist. Medical resources in the Lao language are limited, teacher numbers and capacity are lacking and complex factors have led to a lack of uniformity in graduate competencies. Despite these challenges, the situation for medical education in Laos is a story of great optimism. Local staff has recognized the need for simple yet innovative solutions and processes are in place for the establishment of a licensing system for medical doctors and reforming existing curricula. Sustained, long-term relationships with partner organizations along with constructive use of technology are likely to be important factors affecting the future direction of medical education in Laos.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 세계화, 다양한 국가' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 말레이시아 의사면허시험: 이것이 나아갈 길인가?(Education in Medicine Journal. 2017) (0) | 2023.11.19 |

|---|---|

| 보건의료전문직 국가면허시스템의 진화: 라오스의 질적기술사례연구 ( Hum Resour Health. 2017) (0) | 2023.11.19 |

| 정서적 학습과 정체성 발달: 대만과 네덜란드 의대생의 문화간 질적 비교 연구(Acad Med, 2017) (0) | 2023.09.15 |

| 이타주의인가, 국가주의인가? 의과대학 규제에 대한 글로벌 담론 살펴보기 (Med Educ, 2022) (0) | 2023.05.04 |

| 일반의 진료와 의사면허시험 (British Journal of General Practice 2022) (0) | 2022.11.09 |