베트남 의학교육의 혁신(BMJ Innov 2021)

Innovations in medical education in Vietnam

David B Duong ,1,2 Tom Phan ,3 Nguyen Quang Trung,4 Bao Ngoc Le,4 Hoa Mai Do,4 Hoang Minh Nguyen,4 Sang Hung Tang,4 Van-Anh Pham,5 Bao Khac Le,6 Linh Cu Le,7 Zarrin Siddiqui,7 Lisa A Cosimi,2,8 Todd Pollack9

소개

Introduction

현재 증거에 따르면 저소득 및 중저소득 국가(LMIC)에서는 진화하는 역학적 질병 패턴, 인구 통계 변화, 새로운 전염병 건강 위협, 기후 변화의 건강 영향 등 현재와 미래의 인구 요구를 충족하기 위해 의료 시스템 개선이 필요합니다.1 의학교육 개혁은 이러한 노력의 필수 요소이며, 양질의 의사 인력을 모집, 교육, 유지 및 분배하는 데 어려움을 겪고 있는 LMIC의 중요한 관심 분야입니다.2 3 2010년, 랜싯 위원회는 '의료 전문 교육을 혁신하는 새로운 세기'를 촉구하며 특히 LMIC의 필요성에 중점을 두었습니다.4 랜싯 보고서는 의료 교육을 개혁하기 위한 프레임워크와 권고 사항을 제공하고 필요한 정치적, 재정적, 리더십 약속을 포함하여 전 세계 의료 교육을 혁신하기 위한 행동 촉구입니다.4 이 야심찬 목표를 달성하려면 정책 입안자와 교육 지도자들이 의학교육의 설계 및 제공에 새롭고 혁신적인 접근법을 찾고 적용해야 합니다.5 6

Current evidence suggests that, in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs), healthcare system improvements are necessary to ensure healthcare services can meet current and future population needs, including evolving epidemiological disease patterns, shifting demographics, new infectious disease health threats and the health impacts of climate change.1 Medical education reform is an integral component of any such effort, and is an area of significant concern for LMICs, which struggle with recruiting, training, retaining and distributing a high-quality physician workforce.2 3 In 2010, a Lancet commission called for ‘a new century of transformative health professional education’, with a particular focus on the needs of LMICs.4 The Lancet report is a call to action to transform healthcare education worldwide by providing a framework and recommendations to reform healthcare education, including much needed political, financial and leadership commitments.4 Achieving this ambitious goal requires policymakers and educational leaders to find and apply novel and innovative approaches to the design and delivery of medical education.5 6

베트남의 의학교육

Medical education in Vietnam

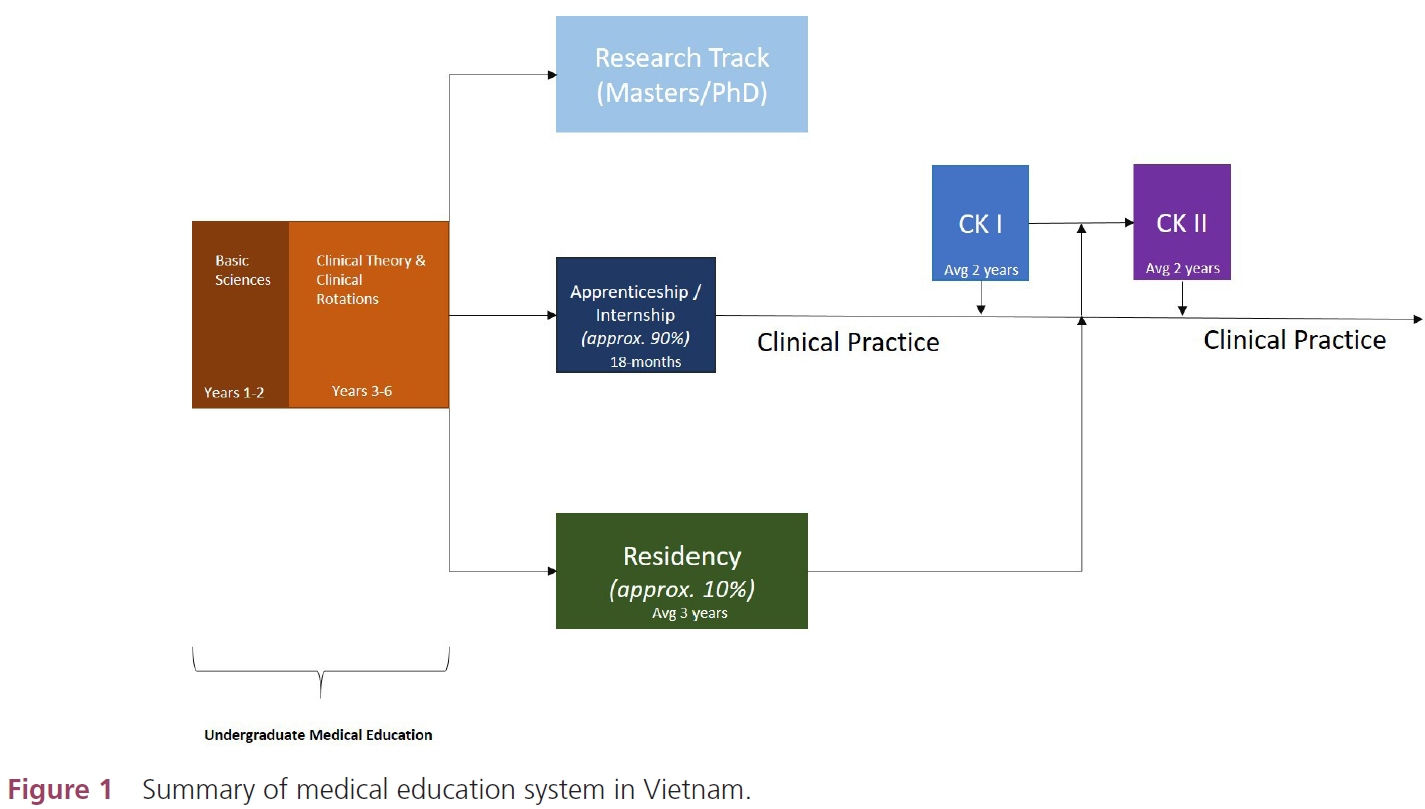

동남아시아의 LMIC인 베트남의 의학교육 시스템(그림 1)은 최근까지 사회 대부분의 다른 부분과 환자의 건강 요구가 크게 발전했음에도 불구하고 거의 변하지 않았습니다.7 이전의 의학교육 개혁 노력은 산발적이고 특정 학과의 단일 의과대학에 국한되어 있었으며 포괄적이거나 광범위하지 않았습니다.8 1999년부터 베트남 전역의 의학교육자들은 학부 의학교육(UME)에 대한 지역사회 지향성을 촉진하기 위해 협력하여 의과대학 졸업생에게 기대되는 지식, 태도 및 기술의 형태로 학습 목표와 결과를 확인했습니다.9 10 이는 보건부(MOH)가 2015년에 일반 의사를 위한 최초의 표준 역량 세트를 발표할 수 있는 토대가 되었습니다. 그러나 그 실행은 제한적이었습니다.8

Vietnam, an LMIC in Southeast Asia, has a medical education system (figure 1) which, until recently, had changed little despite substantial advancement in most other parts of society and in the health needs of patients.7 Previous medical education reform efforts have been sporadic and limited to single medical universities in specific departments, and not comprehensive or widespread.8 Starting in 1999, medical educators across Vietnam collaborated to promote a community orientation to undergraduate medical education (UME), and identified learning objectives and outcomes in the form of the knowledge, attitude and skills expected of a medical school graduate.9 10 This was the groundwork for the Ministry of Health (MOH) to issue the first set of standard competencies for general doctors in 2015. However, their implementation has been limited.8

현재 베트남에는 29개의 의과대학이 있으며, 각 학교당 연평균 400~600명의 의대생이 입학하고 있습니다.11 UME는 중등교육 이수 후 4~6년 과정으로 운영됩니다.7 대부분의 프로그램은 6년 과정으로, 초기 임상 노출을 최소화한 기초과학 2년과 나머지 4년 동안 임상 이론과 국립 및 지방 병원을 통한 병원 로테이션이라는 전통적인 형식으로 구성됩니다.7 UME를 수료하면 졸업생은 크게 두 가지 경로로 진로를 선택할 수 있습니다.

- 첫 번째는 프랑스의 경쟁형 인턴 제도를 모델로 한 레지던트 트랙입니다.12 레지던트 트랙은 주요 학술 의료 센터에서 진행되며 전문과목과 하위 전문과목 프로그램이 모두 포함됩니다. 현재 베트남에서는 졸업생의 약 10%가 레지던트 트랙에 입학합니다.

- 나머지 졸업생들은 다양한 병원에서 스스로 일자리를 찾아 18개월 동안 도제식 인턴십에 들어가며, 그 후 지방 보건부에 의사 면허를 등록할 수 있습니다.

인턴십을 마치고 의사 면허를 취득한 의사는 수련 분야에서 진료를 하거나 즉시 추가 전문의 수준('추옌 코아'(CK)) 교육(전문의 레벨 1 또는 CK I)을 받은 후 세부 전문의 교육(전문의 레벨 2 또는 CK II)을 더 받을 수 있습니다. CK I과 CK II 모두 완료하는 데 평균 2년이 걸립니다. 레지던트 과정을 마친 의사는 의사 면허를 취득한 후 진료를 하거나 바로 CK II 교육에 들어갈 수 있습니다. 현재 면허 취득 전 국가 시험은 없지만 가까운 시일 내에 시행할 계획이 수립되어 있습니다.7

Currently, there are 29 medical universities in Vietnam, with an average of 400–600 medical students matriculating per year at each school.11 UME is a programme of 4–6 years following the completion of secondary education.7 Most programmes are 6 years in duration and are organised in a traditional format of 2 years of basic science with minimal early clinical exposure, followed by clinical theory and hospital rotations through national and provincial hospitals in the remaining 4 years.7 On completion of UME, there are two major pathways for graduates.

- The first is the residency track, modelled after the French competitive interne des hôpitaux system.12 These take place at major academic medical centres and include both specialty and subspecialty programmes. Currently, approximately 10% of graduates enter the residency track in Vietnam.

- The remaining graduates find their own placement at various hospitals and enter apprenticeship-style internships for 18 months, after which they are eligible to register for a medical licence from a provincial department of health.

After completing internship and attaining a medical license, physicians can practice in the area of their training or immediately pursue further specialist-level ('chuyên khoa' (CK)) training (specialist level 1 or CK I) and then further subspecialist training (specialist level 2 or CK II). Both CK I and CK II take an average of 2 years to complete. Physicians completing residency are able to either practice after obtaining a medical licence or enter CK II training directly. Currently, there is no national examination prior to licensing, although a plan has been set for its establishment in the near future.7

현재 베트남의 정책 입안자들 사이에서는 비전염성 질병, 신종 전염병, 글로벌 기후 위기로 인한 보건 문제, 불평등 심화로 인해 베트남의 교육 시스템을 개혁하고 현대화할 필요성에 대한 광범위한 공감대가 형성되어 있습니다.10 13 14 특히 학부와 대학원 모두에서 의학교육의 커리큘럼 개혁이 우선순위에 놓여 있습니다.7 9 15 보건부는 국제 의료계와의 통합을 향한 비전과 함께 투자와 정책 변화를 통해 개혁 노력을 촉진했습니다.8 이러한 국가 차원의 노력은 교육자들이 혁신을 개발하고 공유할 수 있는 환경을 조성했습니다. 현재 호치민시 의약대학(UMP), 후에 의약대학, 타이빈 의약대학, 하이퐁 의약대학, 타이응우옌 의약대학 등 5개 공립 의과대학에서 UME 커리큘럼 개혁이 진행 중입니다. 현재 호치민에서는 대학원 의학교육(GME) 개혁이 진행 중입니다. 또한 베트남 의료 전문가의 질을 높이기 위한 노력의 일환으로 최근 비영리 사립 보건과학 대학인 빈대학교(VinUni)가 새롭게 출범했습니다.

There is currently wide consensus among policymakers in Vietnam on the need to reform and modernise the country’s educational system due to increasing incidence of non-communicable disease, emergent infectious diseases, health challenges arising from the global climate crisis and widening inequalities.10 13 14 In particular, curricular reform in medical education, both undergraduate and graduate, has been prioritised.7 9 15 The MOH has catalysed reform efforts through investments and policy changes with a vision towards integration with the international medical community.8 Such national-level commitment has created an enabling environment for educators to develop and share innovations. UME curriculum reform is currently under way at five public medical universities, including the University of Medicine and Pharmacy (UMP) at Ho Chi Minh City (HCMC), Hue UMP, Thai Binh UMP, Hai Phong UMP and Thai Nguyen UMP. Graduate medical education (GME) reform is currently under way in HCMC. Additionally, a new private not-for-profit health sciences college at VinUniversity (VinUni), has recently launched in efforts to increase the quality of healthcare professionals in Vietnam.

이 글에서는 베트남의 의료 교육 혁신의 두 가지 영역(커리큘럼과 기술)에 대해 설명하고, 파트너십과 정책 변화를 통해 이러한 혁신이 어떻게 가능했는지 살펴봅니다. 이러한 혁신은 베트남 내에서 새롭게 발생했거나 다른 국가의 관행을 베트남에 맞게 변형한 것이지만 베트남의 상황에 맞게 새로운 것으로 간주됩니다. 이러한 혁신은 베트남 의과대학이 직면한 문제를 해결합니다. 우리의 검토는 이 원고에 대한 저자들의 집단적 경험과 지식뿐만 아니라 출판된 문헌과 회색문헌을 기반으로 합니다.

In this article, we describe two areas of innovation in medical training in Vietnam (curriculum and technology) and we review how these innovations were enabled through partnerships and policy changes. These innovations are de novo (arising within Vietnam) or they are Vietnamese adaptations of practices from other countries but are considered new for the Vietnamese context. They address challenges experienced by medical universities in Vietnam. Our review is based on the published and grey literature, as well as the collective experience and knowledge of the authors on this manuscript.

커리큘럼 혁신

Curricular innovations

전 세계의 많은 교육기관과 마찬가지로 베트남의 교육기관도 인구 보건 수요를 충족할 수 있는 의사를 양성하기 위한 커리큘럼 개혁에 착수하고 있습니다. 5개의 공립 UMP가 UME 프로그램을 역량 기반 커리큘럼으로 전환하고 있습니다. 역량 기반 의학교육(CBME)은 성과에 초점을 맞추고 지식과 실습의 적용을 강조하며 학습자 중심주의를 촉진합니다.16-18 2015년 베트남 보건부는 베트남의 인구 보건 요구사항을 기반으로 표준 UME 역량을 만들었습니다.19 이러한 역량을 기반으로 새로운 커리큘럼을 개발하기 위해 UMP 교수진은 백워드 코스 설계 원칙을 사용하여 각 역량에 대한 하위 구성 요소를 정의하고, 이정표를 만들고, 적절한 평가 도구와 전략을 선택하고, 마지막으로 교육 활동과 교수법을 설계했습니다.20 UME 커리큘럼에서 이정표를 적용하는 것은 새로운 접근 방식입니다. 개발 마일스톤은 다양한 GME 프로그램에서 적용되어 왔지만, UME 맥락에서의 적용은 비교적 새롭고 전 세계적으로 다양합니다.21 22 마일스톤은 학습자가 역량을 향한 경로를 따라 특정 시점에 달성해야 하는 최소 기준을 정의하므로 학습자와 교수진 모두에게 투명성을 높여줍니다.23

Like many institutions around the world, those in Vietnam are embarking on curricular reforms aiming to train physicians better prepared to meet population health needs. Five public UMPs are transforming their UME programmes to a competency-based curriculum. Competency-based medical education (CBME) focuses on outcomes, emphasises application of knowledge and practice, and promotes greater learner-centredness.16–18 In 2015, the Vietnam MOH created standard UME competencies based on the population health needs of Vietnam.19 To develop the new curriculum based on these competencies, UMP faculty used the principles of backward course design, defining subcomponents for each competency, creating milestones, selecting appropriate assessment tools and strategies, and finally designing educational activities and teaching methods.20 The application of milestones in the UME curriculum is a novel approach. Developmental milestones have been applied in various GME programmes; however, its implementation in the UME context is relatively new and varies globally.21 22 Milestones increase transparency for both the learner and faculty as they define the minimum standard that learners need to accomplish at a point of time along their pathway towards competency.23

개혁된 커리큘럼은 기대되는 학습 결과의 달성에 건설적으로 연계된 쌍방향 교수 및 학습 활동이 특징입니다. 커리큘럼을 제공함에 있어 개혁 노력은 수동적인 강의 시간을 줄이고 능동적인 교육적 접근 방식을 구현하는 데 중점을 두었습니다. 수동적인 학습 접근 방식은 학생의 이해에 부정적인 영향을 미치고 문제 해결, 자기 주도적 학습 및 의료 전문가에게 필요한 기타 핵심 기술을 저해하는 것으로 나타났습니다.24-26 이는 대규모 학급 규모(UMP당 연간 400~600명의 의대생)와 낮은 교수 대 학생 비율로 인해 베트남 상황에서 특히 어려운 문제입니다. 이러한 문제를 극복하기 위해 교수진은 다른 환경에서 사용되는 교육적 접근 방식을 검토하고 베트남 강의실의 필요에 맞게 반복하여 적용했습니다. 소그룹 학습이 바람직하지만, 학급 규모가 크기 때문에 대규모 그룹 환경에서 활발한 학습을 유도하기 위한 전략이 필요합니다.

- 이러한 전략 중 하나는 토론과 동료 학습을 유도하기 위해 생각-쌍-공유 접근 방식과 함께 청중 응답 시스템(ARS)을 사용하는 것입니다.27 28 그러나 교수진은 값비싼 기술 기반 ARS 대신 빠르게 확장하고 구현할 수 있는 색상으로 구분된 종이 기반 시스템을 개발했습니다.

- 두 번째 전략은 팀 기반 학습(TBL)을 사용하는 것입니다. TBL은 학습자 중심성을 높이고 동료와의 능동적인 학습을 촉진하며 기존의 문제 기반 학습 접근 방식과 달리 교수 대 학생 비율이 낮은 환경에서도 구현할 수 있습니다.29 베트남에서 이 접근 방식을 채택한 경우, 약 40명의 학생에게 5~8명의 학생으로 구성된 팀과 교류하는 교수 촉진자가 제공됩니다. 학생 팀은 (1) 대면 세션 전 준비 과제, (2) 준비 과제에 초점을 맞춘 객관식 문제로 구성된 개인 및 그룹 준비도 확인 시험, (3) 준비 과제의 자료를 '실제' 시나리오에 적용해야 하는 그룹 적용 활동의 세 단계에 걸쳐 함께 작업하고 서로에게 책임을 집니다.29 이 접근 방식은 학습에 대한 문제 기반 접근 방식을 허용하고, 동료 간 학습과 책임감을 부여하며, 팀워크를 촉진하고, 다른 소그룹 학습 방법보다 적은 교수진 자원으로 구현할 수 있기 때문에 베트남에서 성공적이었습니다.

The reformed curriculum is characterised by interactive teaching and learning activities constructively aligned to the achievement of the expected learning outcomes. In delivering the curriculum, reform efforts have focused on implementing active pedagogical approaches, reducing time spent in passive lectures. Passive learning approaches have been shown to negatively affect student understanding and discourage problem-solving, self-directed learning and other critical skills needed for healthcare professionals.24–26 This is a particular challenge in the Vietnam context due to large class sizes (400–600 medical students per year per UMP) and low faculty-to-student ratios. To overcome these challenges, faculty reviewed pedagogical approaches used in other settings and iterated and adapted them to fit the needs of Vietnamese classrooms. While small group learning is desired, the large class size necessitates strategies for bringing active learning to a large group setting.

- One such strategy is the use of an audience response system (ARS) with think–pair–share approach to generate discussion and peer learning.27 28 However, in lieu of expensive technology-based ARSs, faculty developed a colour-coded paper-based system which could be quickly scaled up and implemented.

- A second strategy is the use of team-based learning (TBL). TBL increases learner-centredness, promotes active learning with peers and, unlike more traditional problem-based learning approaches, can be implemented in settings with low faculty-to-student ratios.29 In the Vietnamese adaptation of this approach, approximately 40 students are provided a faculty facilitator who engages with teams of five to eight students. Student teams work together and are held accountable to one another in the three distinct phases of TBL: (1) a preparation assignment prior to the in-person session, (2) individual and group readiness assurance tests consisting of multiple choice questions focused on the preparation assignment, and (3) a group application activity that requires students to apply the material from the preparation assignment to a ‘real-world’ scenario.29 The approach has been successful in Vietnam because it allows for a problem-based approach to learning, enables peer-to-peer learning and accountability, promotes teamwork and can be implemented with fewer faculty resources than other small group learning methods.

베트남의 UME 역량에는 팀워크와 전문가 간 협업이 포함됩니다. 전문직 간 협업은 의학전문대학원 교육 인증위원회와 캐나다 왕립 의사 및 외과의사 대학을 비롯한 많은 국가의 의학교육 프레임워크에서 핵심 역량이지만,30 진정한 전문직 간 교육 모델은 자원이 풍부한 환경에서도 여전히 제한적입니다.31 32 CBME 개혁 이전 베트남의 의대생들은 시뮬레이션과 병동 실습을 통해 간호 기술을 배웠습니다. 학생들은 간호 교수진으로부터 교육을 받고, 병동에서 간호사를 관찰하고, 간호사의 감독 하에 환자 간호에 참여하여 실습 로테이션에 들어갑니다. 이 새로운 직종 간 교육 모델은 새로운 커리큘럼에서도 유지되었습니다.

- 전문직 간 교육을 더욱 촉진하기 위해 호치민 UMP는 2019년 9월 의학, 약학, 간호학 및 재활학 학생들을 위한 새로운 과정을 도입했습니다. 여러 분야의 교수진이 협력하여 학생들의 협업을 촉진하고 (1) 전문직 간 진료의 가치 이해, (2) 효과적인 의사소통, (3) 전문성, (4) 팀 리더십 기술 등 전문직 간 진료와 관련된 기술을 배양하는 과정을 설계했습니다. 이 과정은 베트남에서 전문직 간 교수진이 전문직 간 학생 그룹을 대상으로 가르치는 최초의 과정입니다.

UME competencies in Vietnam include teamwork and interprofessional collaboration. Although interprofessional collaboration is a core competency in many countries’ medical education frameworks, including those from the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education and the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada,30 models for authentic interprofessional education are still limited, even in high-resourced settings.31 32 Prior to CBME reforms, medical students in Vietnam learnt nursing skills through both simulation and practice on the wards. Students are taught by nursing faculty, observe nurses on the wards and participate in patient care under the supervision of nurses, prior to entering clerkship rotations. This novel interprofessional education model was maintained in the new curriculum.

- To further promote interprofessional education, UMP at HCMC introduced a new course in September 2019 for medicine, pharmacy, nursing and rehabilitation students. Faculty members from the different disciplines cooperated to design a course which promotes student collaboration and foster skills related to interprofessional practice including: (1) understanding the value of interprofessional care, (2) effective communication, (3) professionalism, and (4) team leadership skills. This is the first course in Vietnam taught to an interprofessional group of students by an interprofessional faculty.

테크놀로지 혁신

Technological innovation

테크놀로지를 의학 커리큘럼에 통합하면 성인 학습 이론을 의학 교육에 적용하고 학습 환경을 단순히 콘텐츠와 지식을 전달하는 공간에서 학습 과정과 학습자 평가를 촉진하는 공간으로 전환할 수 있습니다.33 이를 통해 학습 환경은 교실, 강의실, 도서관의 전통적인 영역을 넘어 가상 공간으로 확장될 수 있습니다. 베트남 의과대학 개혁의 핵심은 새로운 학습 테크놀로지를 도입하고 이를 적용할 수 있는 네트워크 인프라에 투자하는 것이었습니다.

Integration of technology into medical curricula can catalyse the application of adult learning theory in medical education and help to transform the learning environment from solely a distributor of content and knowledge into a space which facilitates the learning process and the assessment of the learner.33 In doing so, learning environments can be expanded beyond the traditional domains of classrooms, lecture halls and libraries into virtual spaces. A key pillar of the reform at medical universities in Vietnam has been to adapt new learning technologies and invest in network infrastructure to enable their application.

베트남의 의과 교육 프로그램은 공립 대학의 경우 Moodle과 같은 무료 오픈 소스 학습 관리 시스템(LMS)을 사용하고 맞춤화하여 가상 공간을 확장했으며, 사립 대학의 경우 Canvas 및 One45와 같은 구독 서비스 LMS를 사용했습니다. 일부 교육기관에서는 LMS를 수업 자료를 업로드하고 다운로드하는 플랫폼으로만 사용하기도 하지만, 학생과 교수진의 피드백 수집, 게시판 및 토론 포럼 생성, 평가 관리, 온라인 리소스 센터 또는 라이브러리 개발, 온라인 학습 과정 구현과 같은 고급 기능을 사용할 수 있도록 LMS를 커스터마이즈한 교육기관도 있습니다. 예를 들어,

- 미국 외과 대학원 프로그램을 위한 표준화된 역량 기반 온라인 커리큘럼을 만든 미국 컨소시엄인 외과 레지던트 교육 위원회(SCORE)와 협력하여 호치민 UMP의 일반외과 레지던트 프로그램에 사용할 수 있도록 SCORE 포털을 도입하고 맞춤화했으며, VinUni도 GME 프로그램의 일부로 SCORE 프레임워크를 사용하고 있습니다.

- 아직 파일럿 단계에 있지만 역량 기반 온라인 교육 자료를 적용하면 모든 일반외과 레지던트가 공통 커리큘럼을 받고 공통 지식 기반을 개발할 수 있습니다. 이는 베트남 GME의 새로운 접근 방식으로, 일반적인 교사 중심 접근 방식에서 벗어나 학습자가 자신의 시간에 온라인 모듈에 액세스하여 자신의 속도에 맞춰 진행할 수 있는 학습자 중심 접근 방식으로 커리큘럼을 재조정하는 데 도움이 됩니다.

Medical education programmes in Vietnam have expanded their virtual footprint through the use and customisation of free, open-source learning management systems (LMS) such as Moodle for public universities, and subscription-service LMS such as Canvas and One45 for private universities such as VinUni. While some institutions have used the LMS solely as a platform to upload and download class materials, others have customised the LMS to allow for more advanced features, such as collecting feedback from students and faculty, creating message boards and discussion forums, administering assessments, developing online resource centres or libraries and implementing online learning courses. For example,

- in collaboration with the Surgical Council on Resident Education (SCORE), a US consortium that created a standardised competency-based online curriculum for US surgical graduate programmes, the SCORE Portal was introduced and tailored for use in the general surgery residency programme at UMP at HCMC; VinUni also uses the SCORE framework as part of their GME programme.

- While still in a pilot phase, the application of competency-based on-line training materials ensures that all general surgery residents can receive a common curriculum and develop a common knowledge base. This is a novel approach for GME in Vietnam, helping to reorient the curriculum away from the more typical teacher-centred approach to a learner-centred approach in which learners can access online modules on their own time and proceed at their own pace.

앞서 설명한 LMS 구현과 같은 테크놀로지에 대한 투자와 혁신 덕분에 베트남의 대학들은 2020년 2월 코로나19 팬데믹이 시작되었을 때 온라인 학습으로 빠르게 전환할 수 있었습니다. 교직원과 학생들은 이미 Zoom, Microsoft Teams, Google 행아웃과 같은 LMS 및 온라인 학습 플랫폼에 익숙해져 있었습니다. 그 결과 사회적 거리두기 조치가 시행되었을 때 프로그램 중단을 최소화할 수 있었습니다. 또한 온라인 교육 및 학습을 위한 역량을 갖추면 신종 SARS-CoV-2 바이러스에 대한 지식을 전파하는 데 도움이 되었습니다. UMP는 기존 인프라를 활용하여 의대생들을 위한 가상 코로나19 교육 프로그램을 신속하게 출시했습니다. 학생들은 혼합 접근 방식을 사용하여 접촉자 추적, 분류 및 검사를 포함한 SARS-CoV-2의 역학 및 예방에 대한 교육을 받았습니다. 현재까지 720명 이상의 의대생이 베트남의 코로나19 대응에 투입되었습니다.34 35 교수진과 학생들이 가상 교육 및 학습에 익숙해지면서 일부 교육기관은 코로나19 팬데믹 이후에도 커리큘럼의 20%를 가상으로 제공할 계획을 세웠습니다.

Investments and innovations in technology, such as the implementation of LMS described previously, enabled universities in Vietnam to rapidly transition to online learning when the COVID-19 pandemic began in February 2020. Faculty and students were already familiar with LMS and online learning platforms, such as Zoom, Microsoft Teams and Google Hangout. As a result, disruption to the programme was minimised when social distancing measures were enforced. In addition, having capacity for online teaching and learning was beneficial for disseminating knowledge about the novel SARS-CoV-2 virus. The UMPs used their existing infrastructure to quickly roll out a virtual COVID-19 training programme for senior medical students. Students were trained, using a blended approach, on the epidemiology and prevention of SARS-CoV-2, including contact tracing, triage and testing. To date, over 720 medical students have been deployed in Vietnam’s COVID-19 response.34 35 As faculty and students become more familiar with virtual teaching and learning, some institutions have planned for 20% of the curriculum to be delivered virtually beyond the COVID-19 pandemic.

파트너십 활성화

Enabling partnerships

여러 새로운 파트너십이 베트남 의학교육의 혁신을 가능하게 하고 촉진하는 데 도움이 되었습니다. 산업계와 국제 기관 간의 파트너십은 혁신이 번창할 수 있는 생태계를 조성합니다.36-38 특히 국제 학술 파트너십은 혁신의 원천이 될 수 있습니다. 예를 들어,

- 하버드 의과 대학(HMS)은 베트남 보건부의 보건 시스템 개혁을 위한 보건 전문가 교육 및 훈련 프로젝트 및 베트남 의과대학과 협력하여 의학교육 및 신흥 질병에 대한 접근성, 커리큘럼 및 교육 개선(IMPACT MED) 연합을 구성했습니다.39 미국 국제개발처의 자금 지원으로 IMPACT MED 연합은 커리큘럼 설계, 개발 및 실행에 대한 기술 지원 및 지식 이전을 제공하여 5개 의과대학의 UME 커리큘럼 개혁을 지원하고 있습니다.

- 이와 유사하게, VinUni는 커리큘럼 개발 및 실행에 대한 기술 지원과 서비스 제공 및 환자 치료 개선을 통해 의료 전문가 교육을 혁신하는 것을 목표로 펜실베니아 대학교와 전략적 제휴 계약을 체결했습니다.40 이 두 가지 학술 파트너십에는 학생 및 교수진 교류와 연구 협력도 포함됩니다. 이러한 파트너십을 통해 새로운 개념과 접근 방식이 도입되면 지역 전문가와 이해관계자가 적응, 계획 및 실행 작업을 주도하여 혁신이 상황과 문화에 적합하도록 보장합니다.

A number of novel partnerships have helped to enable and catalyse innovations in medical education in Vietnam. Partnerships between industry and international institutions create an enabling ecosystem for innovation to thrive.36–38 In particular, international academic partnerships can provide a source of innovation. For example,

- Harvard Medical School (HMS) has partnered with the Vietnam MOH’s Health Professionals Education and Training for Health System Reforms Project and medical universities in Vietnam as part of the Improving Access, Curriculum and Teaching in Medical Education and Emerging Diseases (IMPACT MED) Alliance.39 With funding from the United States Agency for International Development, the IMPACT MED Alliance supports UME curricular reform at five medical universities through provision of technical assistance and knowledge transfer on curriculum design, development and implementation.

- Similarly, VinUni has a strategic alliance agreement with the University of Pennsylvania with a goal of innovating health professional education through technical support on curriculum development and implementation, and by improving service delivery and patient care.40 Both of these academic partnerships also involve student and faculty exchanges, and promote research collaborations. As novel concepts and approaches are introduced through these partnerships, local experts and stakeholders lead the work of adapting, planning and implementing, ensuring that innovations are contextually and culturally appropriate.

두 번째 사례는 Microsoft와 공공 UMP 간의 공공-민간 파트너십으로, 처음에는 참여 UMP의 모든 대학생, 교수진 및 직원에게 Microsoft Office 365 제품군에 대한 무료 온라인 액세스를 제공한 IMPACT MED 얼라이언스가 촉진한 것입니다. Microsoft의 기술 지원을 통해 Microsoft Office 365 제품군의 전체 기능을 도입하고 대학 운영에 통합하여 할인된 전체 액세스 구독으로 전환했습니다. Microsoft Office 365 제품군 사용은 기관의 커뮤니케이션 및 관리 기능을 간소화하는 데 도움이 되었습니다. 대학 관리자와 경영진은 대학 커뮤니티의 모든 구성원과 쉽게 소통할 수 있고, 학생들은 가상 코스워크와 LMS 액세스를 위한 단일 진입 지점을 갖게 되었으며, 인사 관리와 같은 대학 행정 기능이 공통 시스템으로 통합되었습니다. 그 전에는 종이 기반 시스템을 사용했고, 교수진은 다양한 소셜 미디어 플랫폼을 통해 학생들과 소통했으며, 커뮤니케이션은 종이 기반 또는 개인 이메일 주소와 휴대전화를 통해 이루어졌습니다. 이 사례는 기술 솔루션 도입 및 유지를 위한 적절한 자금 조달 메커니즘과 함께 기술 및 기술 이전을 위한 민관 파트너십의 중요성을 보여줍니다.

A second example is a public–private partnership between Microsoft and public UMPs, facilitated by the IMPACT MED Alliance, which initially provided free online access to the Microsoft Office 365 Suite for all university students, faculty and staff at the participating UMPs. With technical assistance from Microsoft, the full functionality of the Microsoft Office 365 Suite was introduced and incorporated into university operations, leading to transition to a discounted, full-access subscription. Using the Microsoft Office 365 Suite has helped to streamline the institutions’ communication and administrative functions. University administrators and leadership can easily communicate with all members of the university community; students have a single point of entry for virtual coursework and LMS access; and university administrative functions such as human resources management have been integrated into a common system. Prior to this, paper-based systems were employed; faculty communicated with students through various social media platforms; and communication was paper-based or via personal email addresses and mobile phones. This example demonstrates the importance of public–private partnerships with technology and technical skills transfer combined with appropriate financing mechanisms for introducing and sustaining technological solutions.

기술 및 기술 이전으로 이어진 민간 부문 파트너십의 또 다른 사례는 삼성과 UMP 간의 파트너십입니다. 삼성은 두 개의 UMP에 두 개의 시범 '스마트 교실'에 투자했습니다. 스마트 교실은 그룹 학습을 촉진하기 위해 설계되었으며 인터넷을 통해 쉽게 액세스하고 공유할 수 있는 기술이 적용되었습니다. 교실 인프라와 기술을 커리큘럼 설계 및 교육 방식에 맞추는 것은 새로운 커리큘럼의 성공과 지속 가능성을 위해 매우 중요합니다. 시범 교실을 시범 운영한 결과 학생, 교수진, 경영진 모두 이러한 연계의 가치를 인정하여 5개 UMP 모두에서 강의실 재설계에 대한 대학 투자로 이어졌습니다.

Another example of a private sector partnership which resulted in technology and technical skills transfer is between Samsung and the UMPs. Samsung invested in two demonstration ‘smart classrooms’ at two UMPs. The smart- classrooms were designed to promote group learning and are technology-enabled to facilitate access and sharing across the internet. Aligning classroom infrastructure and technology with the curriculum design and pedagogical method is vital to the success and sustainability of the new curriculum. Following a trial of the demonstration classrooms, students, faculty and leadership all recognised the value of this alignment, leading to university investment in classroom redesigns at all five UMPs.

정책 활성화

Enabling policies

정책 변화는 의료 교육 기관이 혁신을 적응하고 실행하며 지속할 수 있도록 하기 때문에 개혁을 추진하고 유지하기 위해 종종 필요합니다. 베트남 정부는 2014년에 대학 자율성과 관련된 국가 정책을 시행하여 교육 혁신을 위한 환경을 조성했습니다.41-44 이러한 정책은 공립대학이 재정적으로 독립하도록 장려하고 자체 운영, 인적 자원 및 성장 전략을 관리하도록 장려합니다. 새로운 프레임워크는 공공기관이 민간 부문 및 국제 학술 기관과의 파트너십을 모색하여 테크놀로지에 대한 투자 우선순위를 정하고 새로운 커리큘럼, 교육학 및 교육 접근법을 촉진할 수 있도록 지원합니다. 또한 기관은 관리 및 행정 구조를 재설계할 수 있는 권한을 부여받습니다. 이러한 구조 개편은 UMP에서 보다 통합된 CBME 커리큘럼을 개발하는 데 중요한 역할을 했습니다.45 기존 모델에서는 학과장이 교육 내용에 대한 의사 결정 권한을 가졌기 때문에 특정 학과를 중심으로 커리큘럼이 구성되는 결과를 낳았습니다. 보다 통합적인 커리큘럼을 개발하기 위해서는 이러한 거버넌스 구조를 세분화하고 다학제 교수진으로 구성된 커리큘럼 위원회에 권한을 부여할 필요가 있었습니다(그림 2). 위원회 리더는 각 모듈에 무엇이 포함될지, 어떤 교수진이 가르칠지, 커리큘럼 품질 개선 프로그램의 일부로 어떤 조정을 해야 할지 결정합니다.

Policy changes are often necessary to drive and sustain reform, as they can enable medical education institutions to adapt, implement and continue innovations. The Vietnamese government created an enabling environment for innovation in education through the implementation of national policies related to university autonomy in 2014.41–44 These policies promote public universities to become financially independent and encourage them to manage their own operations, human resources and strategies for growth. The new framework enables public institutions to seek partnerships with the private sector and international academic institutions, helping to prioritise investments in technology and to promote new curricula, pedagogy and educational approaches. In addition, institutions are empowered to redesign their management and administration structures. Such restructuring was important to the development of a more integrated CBME curriculum at the UMPs.45 In the traditional model, department chairs held decision-making authority over the teaching content, resulting in a curriculum organised around specific disciplines. To develop a more integrated curriculum, it was necessary to break down this governance structure and to provide authority to curriculum committees consisting of multidisciplinary teaching faculty (figure 2). Committee leaders decide what is included in each module, which faculty should teach and what adjustments should be made as part of the curriculum quality improvement programme.

대학 차원의 또 다른 정책적 지원은 커리큘럼의 지속적인 품질 개선(CQI)을 위한 시스템 개발과 그 실행입니다. 대학 내에 새로 구성된 부서는 학생의 요구에 맞게 커리큘럼과 교육을 지속적으로 개선하기 위해 학생 피드백, 교수진 및 학생 평가 데이터를 일상적으로 수집하고 사용하는 메커니즘을 만들어 CQI 프로세스를 주도하고 있습니다. 데이터는 커리큘럼 위원회와 대학 경영진에게 공유되며 향후 프로그램 조정에 관한 결정을 내리는 데 사용됩니다. 또한 이 시스템은 교수진과 관리자에게 새로운 접근 방식과 혁신의 채택에 대한 데이터를 제공하여 지속적으로 반복하고 개선하며 특정 상황에 맞게 조정할 수 있도록 합니다. 또한 이러한 단위는 향후 인증 프로세스를 위한 지원 데이터도 생성합니다.

Another policy enabler at the university level has been the development of a system for continuous quality improvement (CQI) of the curriculum and its implementation. Newly formed units within the university lead the CQI process by creating mechanisms for routine collection and use of student feedback and faculty and student evaluation data with a goal of continually improving the curriculum and teaching to match student needs. Data are shared to curriculum committees and university leadership and are used to make decisions regarding future adjustments to the programme. This system also provides data to faculty and administrators on the adoption of novel approaches and innovations, allowing them to continually iterate, improve and tailor for specific contexts. These units also generate supporting data for future accreditation processes.

제한 사항

Limitations

이 리뷰는 최근 베트남 의학교육의 몇 가지 혁신을 강조합니다. 현재 진행 중인 의료 전문가 교육 시스템이나 커리큘럼 개혁에 대한 포괄적인 검토를 목적으로 하는 것은 아닙니다. 이 리뷰는 주로 공동 저자들의 지식과 경험, 그리고 영어 문헌에 발표된 내용을 바탕으로 작성되었습니다. 여기에 설명된 혁신은 베트남 내외의 다른 환경에도 적용될 수 있지만, 이러한 접근법을 성공적으로 도입하는 데 장벽이 존재할 수 있음을 인지하고 있습니다.

- 첫째, 제도 개혁을 위해서는 국가 및 기관 차원에서 미래 지향적이고 강력한 리더십이 필요합니다. 이러한 리더십이 부족하면 혁신적인 접근법을 활성화하고 채택하는 데 한계가 있을 수 있습니다.

- 둘째, 자원(인적, 재정적, 인프라적)은 특히 자원이 제한된 환경에서 변화를 가로막는 중요한 장벽이 될 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, 기술 기반 개혁에는 안정적인 인터넷 연결이 필요하며, 이는 자원이 제한된 많은 환경에서 중요한 장벽이 될 수 있습니다. 이는 필요한 자원을 동원하기 위한 강력한 리더십의 헌신과 새로운 파트너십의 중요성을 더욱 강조합니다.

- 셋째, 기관의 문화는 혁신의 창출과 적응에 있어 중요한 요소입니다. 새로운 아이디어를 기꺼이 수용하고 위험을 감수하고 실패할 수 있는 의지가 없다면 혁신은 불가능할 것입니다.

- 마지막으로, 모든 변화가 개선으로 이어지는 것은 아닙니다. 지금까지 성공적인 것으로 입증된 혁신에 대해 설명했지만, 그렇지 않은 혁신도 있을 수 있습니다. 성공하지 못한 개혁에서도 배울 점이 많지만, 이번 리뷰에서는 이에 초점을 맞추지 않았습니다.

This review highlights several recent innovations in medical education in Vietnam. It is not intended to be a comprehensive review of the health professional education system or the curriculum reforms currently under way. Our review is shaped primarily by the coauthors’ knowledge and experience and to what is published in the English language literature. While the innovations described here may apply to other settings within and outside Vietnam, we recognise that barriers may exist to the successful uptake of these approaches. First, institutional reform requires forward-thinking and robust leadership at both the national and institutional levels. A lack of such leadership can limit the ability to enable and adopt innovative approaches. Second, resources (human, financial and infrastructural) can be a significant barrier to change, particularly in the resource-limited setting. For example, technology-enabled reforms require reliable internet connectivity, which may be a significant barrier in many resource-limited settings. This further highlights the importance of strong leadership commitment and novel partnerships to mobilise necessary resources. Third, the culture of an institution is a crucial factor in the creation and adaptation of innovations. Without a willingness to embrace new ideas and to take risks and fail, innovation would not be possible. Lastly, not all change leads to improvement. We have described innovations that proved successful, but others may have been less so. While there is still much to learn from less successful reforms, that was not our focus in this review.

결론

Conclusion

플렉스너 보고서가 의학교육의 변화에 영감을 준 지 100년이 넘었습니다.46 오늘날 전 세계적으로 심각한 보건 인력 문제에 직면하여 전문 보건 교육에 대한 접근 방식을 다시 한 번 재고할 필요가 있습니다.4 특히 LMIC에서 의학교육의 혁신과 개혁이 필요합니다. 이 리뷰에서는 커리큘럼 설계, 교육학 및 기술 적용 분야를 포함하여 현재 베트남의 의학교육 개혁의 일환으로 개발된 혁신 사례를 공유했습니다. 또한 파트너십과 정책 변화가 어떻게 혁신을 가능하게 하고, 장려하며, 지속시킬 수 있는지에 대해서도 설명했습니다. 모든 의료 시스템에는 고유한 과제가 있지만, 베트남의 이러한 사례가 미래의 의학교육 혁신에 영감을 줄 수 있기를 바랍니다.

It has been more than 100 years since the Flexner report inspired a transformation of medical education.46 Today, in the face of significant global health workforce challenges, there is again a need to rethink our approach to professional health education.4 Innovation and reform in medical education are needed, particularly in LMICs. In this review, we have shared examples of innovations developed as part of Vietnam’s current medical education reform, including those in the areas of curriculum design, pedagogy and application of technology. We have also described how partnerships and policy changes can enable, encourage and sustain innovation. While every healthcare system has unique challenges, we hope these examples from Vietnam can inspire future innovations in medical education.

Medical education reforms are a crucial component to ensuring healthcare systems can meet current and future population needs. In 2010, a Lancet commission called for ‘a new century of transformative health professional education’, with a particular focus on the needs of low-income and-middle-income countries (LMICs), such as Vietnam. This requires policymakers and educational leaders to find and apply novel and innovative approaches to the design and delivery of medical education. This review describes the current state of physician training in Vietnam and how innovations in medical education curriculum, pedagogy and technology are helping to transform medical education at the undergraduate and graduate levels. It also examines enabling factors, including novel partnerships and new education policies which catalysed and sustained these innovations. Our review focused on the experience of five public universities of medicine and pharmacy currently undergoing medical education reform, along with a newly established private university. Research in the area of medical education innovation is needed. Future work should look at the outcomes of these innovations on medical education and the quality of medical graduates. Nonetheless, this review aims to inspire future innovations in medical education in Vietnam and in other LMICs.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 세계화, 다양한 국가' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 인도네시아의 의사국가면허시험: 학생, 교수, 대학의 관점(© 2018 The University of Leeds and Rachmadya Nur Hidayah) (0) | 2023.11.19 |

|---|---|

| 베트남의 의사면허시험에 대한 코멘터리(MedEdPublish, 2023) (0) | 2023.11.19 |

| 동남아시아의 면허시험: 교육정책의 변화에서 찾아낸 교훈( Asia Pacific Sch, 2019) (0) | 2023.11.19 |

| 말레이시아의 의학교육: 질 vs 양 (Perspect Med Educ, 2017) (0) | 2023.11.19 |

| 말레이시아 의사면허시험: 이것이 나아갈 길인가?(Education in Medicine Journal. 2017) (0) | 2023.11.19 |