인도네시아의 의사국가면허시험: 학생, 교수, 대학의 관점(© 2018 The University of Leeds and Rachmadya Nur Hidayah)

Impact of the national medical licensing examination in Indonesia: perspectives from students, teachers, and medical schools.

Rachmadya Nur Hidayah

3.3 국가 라이선스 시험의 역사

3.3 The history of national licensing examination

이 섹션에서는 북미에서 시작하여 유럽과 아시아로 확장된 NLE의 기원과 발전 과정을 설명합니다. 이 섹션은 인도네시아의 국가면허시험의 배경과 현재 논의 중인 분야를 포함하여 인도네시아의 국가면허시험의 역사를 소개하는 것으로 마무리합니다.

This section will describe the origins and development of the NLE started and developed; starting from North America and extending through Europe and Asia. The section concludes by presenting the history of NLE in Indonesia, including its background and areas of current debate.

북미의 국가 시험

National examination in North America

미국과 캐나다는 의대 졸업생을 대상으로 국가 시험을 최초로 시행한 국가 중 하나입니다. 미국 의사 면허 시험(USMLE)은 남북전쟁(1861~1865년) 이후 의료 종사자에 대한 규제에서 파생되었습니다. 이 시험은 의사들 간의 높은 역량 편차를 줄이기 위한 목적으로 수십 년 동안 시행되었습니다. 미국국립시험위원회(NBME®)는 1915년 미국에서 국가 시험 시스템을 관리하기 위해 설립되었습니다(Melnick et al., 2002). 시험의 구조는 그 이후로 발전해 왔습니다.

- 첫 번째 시험 형식(1916년)은 환자 사례, 구두(구술) 시험, 필기시험을 이용한 복잡한 병상 시험이었습니다.

- 필기 시험은 1922년 주관식 문제로 시작하여 선택형 문제로 발전했으며, 이후 1980년대에는 객관식 문제(MCQ)로 형식이 변경되었습니다(Melnick et al., 2002).

- NBME는 1999년에 임상 술기 시험을 승인하고 2004년에 2단계 임상 술기 평가(CSA)를 시행했습니다. 이러한 결정은 주로 장시간의 구술 시험이 신뢰성이 떨어진다는 비판을 받은 후 임상 술기 평가의 필요성에 의해 주도되었습니다.

The United States of America and Canada were among the first countries that conducted national examinations for their medical graduates. The United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) was derived from regulatory entry for medical practitioners after the Civil War (1861-1865). It served the purpose of reducing the high variation of competence amongst practitioners and was implemented for several decades. The National Board of Medical Examiner (NBME®) was founded in 1915, to administer a national examination system in the United States of America (Melnick et al., 2002). The structure of the examination has evolved since then.

- The first structure of the format (1916) was a complex bedside examination using patient cases, oral (viva) examinations, and written examinations.

- Written examinations started with essay questions in 1922 and evolved to selected-response questions and later, in the 1980s, the format of USMLE was changed to multiple-choice questions (MCQ) (Melnick et al., 2002).

- The NBME approved the clinical skills examination in 1999 and implemented the Step 2 Clinical Skills Assessment (CSA) in 2004. This decision was mainly driven by the need to assess clinical skills after the long case oral examination was criticised for poor reliability.

캐나다 의료 위원회(MCC)는 캐나다에서 의사가 진료할 수 있도록 면허를 부여하는 기관입니다. 자격을 갖춘 후보자를 결정할 때 MCC는 의대생의 학부 과정 중과 종료 시점에 평가 절차를 사용합니다.

- 1970년까지 MCC는 전통적인 에세이 및 구술 시험을 사용했습니다.

- 1980년, MCC 면허증 개발 과정이 완료되자 이 시험은 캐나다의 모든 지역에 적용되었습니다(Dauphinee, 1981).

- 몇 년 후, MCC는 면허 시험으로서의 목표를 검토한 결과 필기 시험으로는 평가할 수 없는 의대 졸업생의 필수 역량이 있다는 결론에 도달했습니다. 여기에는 병력 청취, 신체 검사, 의사소통 능력 등이 포함되었습니다.

- 그 후 MCC는 1980년대 후반에 임상 기술 평가를 위한 파일럿 연구를 실시하기로 결정했습니다.

- 1992년에는 객관적 구조화 임상시험(OSCE)이 면허 시험의 일부가 되었습니다(Reznick et al., 1993).

The Medical Council of Canada (MCC) acts as the authority to grant licentiate for physicians to practice in Canada. In determining eligible candidates, MCC uses assessment procedures during and at the end of medical students’ undergraduate programmes.

- Until 1970, MCC used traditional essay and oral examinations.

- In 1980, when the development process of MCC licentiate was finished, the examination was applied to all regions of Canada (Dauphinee, 1981).

- After a few years of this assessment, MCC reviewed its objectives as a licensing examination and came to the conclusion that there were essential competences for medical graduates that could not be assessed using written examination. These included: history taking, physical examination, and communication skills.

- MCC then decided to conduct a pilot study for clinical skills assessment in the late 1980s.

- In 1992, the Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) became part of the licensing examination (Reznick et al., 1993).

USMLE와 MCCQE는 정기적인 평가와 연구를 바탕으로 잘 정립된 제도로 자리 잡을 수 있는 시간을 가졌습니다. 시험 관리자(NBME 및 MCC)가 수행한 연구는 대부분 시험의 심리측정 측면에 초점을 맞추었습니다. 그러나 지난 10년 동안 NLE가 대학원 학업, 임상 성과 및 환자 치료에 미치는 영향에 대한 연구가 더 많이 진행되었습니다. 이에 대해서는 이 장의 뒷부분에서 설명합니다.

Both USMLE and MCCQE have had the time to become well-established systems based on regular evaluation and research. Studies conducted by test administrators (NBME and MCC) mostly focussed on the psychometric aspects of the test. However, in the last decade, there has been more research on the consequences of the NLE on postgraduate study, clinical performance, and patient care. This will be discussed later in this chapter.

유럽의 국가 시험

National examination in Europe

대서양 횡단 시험에 비해 유럽에서는 지난 10년 동안 국가 또는 유럽 면허 시험에 대해 더 많은 논쟁이 있었습니다. 영국을 포함한 유럽 국가들 사이에서는 국가 또는 대규모 시험 도입 문제에 대한 논의가 계속되고 있습니다. 유럽 국가들은 유럽연합 회원국의 의대 졸업생이 유럽연합(EU) 내에서 활동할 수 있도록 인정했기 때문에 표준화된 의료 교육 및 실습의 질을 확보해야 할 공동의 책임이 있었습니다(Gorsira, 2009). 이 글에서 Gorsira는 제안된 유럽 NLE에 대한 반대 의견을 국가 간 이해, 신뢰, 협력과 같은 주요 이슈와 함께 설명했습니다. 유럽 국가들은 의학교육 시스템이 다양하기 때문에 유럽에서 기대하는 의사 표준을 달성하는 것에 대한 우려가 있었습니다. 그러나 Gorsira(2009)가 지적했듯이, NLE의 잠재적 이점과 함정은 논쟁의 여지를 남겼습니다. 그녀는 유럽 NLE의 즉각적인 시행이 환자의 안전을 보장하지 못할 뿐만 아니라 의학교육에도 해를 끼칠 수 있다고 결론지었습니다(Gorsira, 2009). 의사를 위한 유럽 표준에 동의하는 것은 브렉시트가 시행되면 영국을 포함한 비유럽 졸업생들과 어떻게 조화를 이룰 것인지에 대한 문제를 부각시킵니다.

Compared to their transatlantic counterparts, there had been wider debate about the national or European licensing examination during the last decade. There is on-going discussion amongst European countries, including the United Kingdom, about the issue of establishing national or large-scale examinations. Since European countries recognised medical graduates from the European Union members to practice within the European Union (EU), there was a shared responsibility to have a standardised quality of medical education and practice (Gorsira, 2009). In her article, Gorsira described the opposing views in response to a proposed European NLE, with key issues such as understanding, trust, and collaboration between countries. European countries varied in their medical education system, thus there was concern about achieving the expected standard of doctors in Europe. However, as Gorsira (2009) pointed out, the potential benefits and pitfalls of the NLE left the debate open. She concluded that immediate implementation of an European NLE would not guarantee patient safety and would also cause harm to medical education (Gorsira, 2009). Agreeing European standards for doctors highlights the issue of how they align with non-European graduates, which will include the UK when Brexit is implemented.

네덜란드와 같이 의학교육에 대한 엄격한 인증과 동질적인 커리큘럼을 갖춘 일부 유럽 국가에서는 국가시험을 우선순위로 여기지 않는다고 말한 van der Vleuten(2013)에 의해 이 논쟁은 더욱 복잡해졌습니다. 일부 학교에서는 이미 커리큘럼의 비교 가능성을 보장하기 위해 집단 진도 테스트를 시행하고 있었습니다(Schuwirth 외., 2010). GMC의 '내일의 의사'를 기반으로 의과대학의 커리큘럼 설계와 실행에 더 큰 자유가 있는 영국의 경우, 의대 졸업생의 역량 비교 가능성에 초점을 맞춰 국가시험이 논의되었습니다(McCrorie and Boursicot, 2009). 객관성, 일관성, 품질 보증, 환자 안전 등의 논거를 고려한 GMC는 최근 국가 면허 시험에 대한 지지를 발표했습니다. 국가 시험을 제안하는 또 다른 이유는 졸업후 교육에 입학하는 학생의 기준을 설정하기 위해서입니다. 졸업후 교육에서 투명한 정량적 선발 메커니즘을 개발해야 한다는 문제도 영국에서 국가 면허 시험의 필요성을 제기했습니다. 미국과 달리 영국의 대학원 교육 선발은 국가시험(예: USMLE)의 순위를 사용하지 않기 때문에 동일한 평가 프로그램에서 해외 의대 졸업생과 영국 졸업생을 비교할 수 없었습니다(Gorelov, 2010).

This debate was further complicated by van der Vleuten (2013), who stated that some European countries that had strict accreditation of medical education and homogenous curricula, e.g. the Netherlands, did not see a national examination as a priority. Some schools already had collective progress testing to ensure the comparability of their curriculum (Schuwirth et al., 2010). In the UK, where there is greater freedom to design and implement medical schools’ curriculum based on the GMC’s Tomorrow’s Doctors, the national examination had been discussed following the focus on comparability of medical graduates’ competences (McCrorie and Boursicot, 2009). Considering the arguments of objectivity, consistency, quality assurance, and patient safety, the GMC recently announced its support for a national licensing examination. Other reasons for proposing national examinations would be to set the standard for students entering postgraduate education. The concern to develop a transparent quantitative mechanism of selection in postgraduate training also raised the need for national licensing examinations in the UK. Unlike the US, postgraduate training selection in the UK does not use the ranks in a national examination (such as USMLE), therefore it could not compare international medical graduates and UK graduates in the same assessment programme (Gorelov, 2010).

다른 유럽 국가에서는 NLE에 대해 보다 긍정적인 접근 방식을 취했습니다. 스위스는 2013년에 국가 면허 시험을 도입했습니다. 연방 면허 시험(FLE)은 학부 의학교육이 끝날 때 지식과 기술을 평가하여 품질 보증을 위한 수단으로 개발되었습니다. 스위스는 자국의 의료 및 의학교육의 높은 수준을 유지하기 위해 FLE를 도입했습니다. 기대되는 질은 졸업생의 역량 수준으로 설명되었습니다. 2010/2011년에 파일럿 시험을 실시한 후, 중앙에서 관리하고 지방에서 시행하는 시험(MCQ 필기시험과 OSCE로 구성)이 실시되었습니다(Guttormsen 외., 2013). 국가 시험으로 OSCE를 도입한 목적은 응용 임상 지식과 실제 임상 기술을 평가하여 졸업생의 수준 높은 수준을 보장하기 위한 것이었습니다.

Other European countres took a more positive approach to NLEs. Switzerland introduced a national licensing examination in 2013. The federal licencing examination (FLE) was developed as a means of quality assurance by assessing knowledge and skills at the end of undergraduate medical education. The reason the FLE was introduced was that Switzerland wanted to maintain the high quality of health care and medical education in their country. The expected quality was described as the level of competence of graduates. After performing a pilot in 2010/2011, the examination (which is centrally-managed and locally administered) was conducted, comprising MCQ written examinations and OSCEs (Guttormsen et al., 2013). The aim of establishing an OSCE as a national examination was to assess applied clinical knowledge and practical clinical skills to ensure a high-quality standard of graduates.

앞서 언급했듯이 EU 국가 내에서 의료 전문가의 이동성은 장점이자 단점으로 여겨져 왔습니다. 예를 들어, 영국에서는 해외 졸업생들이 의사 부족 문제를 해결하는 데 도움이 되었지만 EU 국가 간 교육 격차로 인해 EU에서 교육받은 의사 수가 증가하면서 우려가 제기되었습니다. 2015년 GMC는 2022년까지 영국 내에서 진료하려는 국내, 유럽 및 해외 의사를 대상으로 NLE의 한 형태인 의료 면허 평가(MLA)를 구축하는 프로젝트를 시작했습니다(Gulland, 2015; Archer 외., 2016a; Archer 외., 2016b). MLA는 국제 졸업생을 대상으로 하는 현재의 전문 및 언어 평가 위원회(PLAB) 시험을 대체할 것입니다. PLAB 시험은 임상 실무에서 영어에 대한 이해와 맥락을 테스트합니다. 영국에서 MLA 시범 프로젝트가 아직 진행 중이지만, 다양성에 대한 의문과 NLE가 의과대학의 현재 평가에 잘 맞을지에 대한 의문은 여전히 남아 있습니다(Archer 외., 2016a; Archer 외., 2016b; Stephenson, 2016). NLE를 설계하고 전달하는 '방법'에 대한 이러한 문제는 NLE를 도입하는 국가에서 흔히 발견되며, 이를 자세히 고려하면 그 결과의 잠재적 이점과 단점을 강조할 수 있습니다.

As mentioned earlier, the mobility of healthcare professionals within the EU countries has been seen as both a benefit and drawback. For example, in the UK although international graduates have helped to address the shortage of doctors the difference in training across the EU countries raised concerns when the number of EU-trained doctors increased. In 2015 the GMC initiated a project to establish by 2022 a medical licensing assessment (MLA), a form of NLE, for home, Europe, and international doctors intending to practice within the UK (Gulland, 2015; Archer et al., 2016a; Archer et al., 2016b). The MLA will replace the current Professional and Linguistic Assessment Board (PLAB) examination which is aimed at international graduates. The PLAB examination tests the understanding and context of English in clinial practice. While the pilot project for the MLA in the UK is still ongoing, the questions about diversity and whether the NLE would sit well within medical schools’ current assessment remains (Archer et al., 2016a; Archer et al., 2016b; Stephenson, 2016). This problem of “how” in designing and determining the delivery of NLE is commonly found in countries introducing the NLE; considering this in detail highlights the potential benefits and drawbacks of its consequences.

중동 및 아시아의 국가 시험

National examinations in Middle East and Asia

많은 전문가들은 교육과정의 다양성이 높은 곳에서 NLE가 하나의 옵션이 될 수 있음을 인식하고 있습니다. Van der Vleuten(2013)은 한 국가 또는 지역의 교육 프로그램과 평생교육의 다양성이 NLE의 필요성을 강화한다고 제안했습니다. 대부분의 아시아 국가에서 의과대학은 여전히 커리큘럼과 함께 일하기 위한 '최선의 방법'을 개발하고 있습니다. 학교는 교육 전문가와 협력하여 프로그램과 교육 전략을 개발하여 혁신하고 있습니다. 그들은 평가 시스템과 함께 주기적으로 커리큘럼을 평가하고 변경하여 국가 또는 국제적 요구에 맞게 조정합니다(Telmesani 외., 2011; Lin 외., 2013).

Many experts recognised that NLEs could be an option where there is a high diversity in curriculum implementation. Van der Vleuten (2013) suggested that the diversity of training programs and continuing education in a country or region strengthens the need for NLE. In most Asian countries, medical schools are still developing their ‘best way’ to work with the curriculum. Schools work with educational experts to innovate, developing their programme and educational strategies. They evaluated and changed their curriculum periodically, along with the assessment system, to suit national or international needs (Telmesani et al., 2011; Lin et al., 2013).

중동에서 사우디아라비아는 졸업생의 질을 보장하기 위해 역량 기반 커리큘럼과 NLE를 구축하려고 시도한 국가 중 하나입니다. 이러한 결정은 사우디 아라비아의 의학교육에 대한 변화로 인해 이루어졌습니다. 여기에는 다음이 포함됩니다:

- 1) 의과대학의 수 증가와 각 의과대학이 채택한 다양한 커리큘럼 및 평가 시스템,

- 2) 사우디아라비아에서 진료하기를 원하는 다른 나라 졸업생의 증가,

- 3) 해외에서 의학을 공부하는 사우디 원주민의 증가(Bajammal 외., 2008).

In the Middle East, Saudi Arabia was the one of the countries to attempt to establish a competence-based curriculum and NLEs to ensure the quality of their graduates. This decision was driven by changes to medical education in Saudi Arabia. These included:

- 1) The increasing number of medical schools, and the different curricula and assessment systems they adopted;

- 2) Increasing numbers of graduates from other countries who wanted to practice in Saudi Arabia; and

- 3) The increasing number of Saudi natives who pursued their medical study abroad (Bajammal et al., 2008).

비슷한 이유로 아시아에서는 한국이 2008년에 NLE와 OSCE를 최초로 시범 운영한 국가 중 하나였으며, 대만과 인도네시아가 그 뒤를 이었습니다.

- 한국은 2008년부터 표준화된 환자를 대상으로 한 임상 술기 평가와 마네킹을 이용한 OSCE를 시작했습니다. 한국 국가 OSCE는 임상 교육을 개선하는 것을 목표로 했습니다. 2010년부터는 임상 술기 시험 센터에서 3개월에 걸쳐 12개 스테이션으로 구성된 OSCE를 시행하고 있습니다. OSCE는 표준화된 환자(SP) 평가자와의 환자 대면 상황을 기반으로 한 6개의 스테이션과 의료진 평가자와의 시술 술기를 기반으로 한 6개의 스테이션으로 구성됩니다(Park, 2008). SP 평가자를 활용하고 장기간에 걸쳐 시행되기 때문에 시험의 공정성 및 타당성, 시험 정보 공유/공개와 관련된 여러 가지 문제에 직면했습니다.

- 대만에서 NLE는 필기 시험으로 시작되었습니다. 2008년 말, 대만 당국은 필기 면허 시험의 전제 조건으로 국가 OSCE를 발표했습니다. 2011년과 2013년에 대규모 파일럿 OSCE가 실시되었고, 이후 본격적인 OSCE가 시행되었습니다(Lin et al., 2013).

- 일본과 같은 다른 국가에서는 의대 졸업반 학생을 대상으로 NLE에 대한 필기 평가만 계속 요구하고 있습니다(Kozu, 2006; Suzuki et al., 2008).

For similar reasons, in Asia, South Korea was one of the first countries to pilot their NLE and its OSCE in 2008, followed by Taiwan and Indonesia.

- South Korea started clinical skills assessment in 2008, having a clinical performance examination with standardized patients and an OSCE using manikins. The South Korean national OSCE aimed to improve clinical education. Since 2010, it has been carried out as a 12-station OSCE and administered over the course of three months in clinical skill test centres. The OSCE consists of 6-stations based on a patient encounter with standardised patient (SP) raters and 6-stations based on procedural skills with medical faculty raters (Park, 2008). It faced several challenges related to test fairness and validity of the exam, since it used SP raters and was administered over a long period, which enabled information sharing/ disclosure of exam information.

- In Taiwan, NLE started as a written examination. Later in 2008, Taiwanese authorities announced the national OSCE as a prerequisite for taking the written licencing examination. Large-scale pilot OSCEs were held in 2011 and 2013 before the high-stake OSCE was implemented (Lin et al., 2013).

- Other countries, such as Japan, continue to require only written assessment for the NLE for final year medical students (Kozu, 2006; Suzuki et al., 2008).

동남아시아에서는 10개국 중 4개국만이 NLE를 시행하고 있으며, 각 국가마다 목적과 대상이 다릅니다.

- 태국, 필리핀, 인도네시아, 말레이시아는 MCQ 또는 수정된 에세이 질문(MEQ) 형식을 사용하여 지식 평가를 실시합니다.

- 말레이시아는 해외 졸업생만 평가하고 나머지 3개 국가는 국내 및 해외 졸업생을 평가합니다.

- 필리핀을 제외한 나머지 3개 국가는 OSCE 형식을 사용하여 임상 기술을 평가합니다.

- 베트남과 라오스는 NLE를 개발 중이며

- 브루나이, 싱가포르, 캄보디아, 미얀마는 NLE가 없습니다.

동남아시아에서 NLE에 대한 논의는 이 지역의 다른 국가에서 의술을 펼칠 수 있도록 의료 전문가의 자유로운 이동을 장려하는 아세안1 경제 공동체(AEC)에도 과제를 안겨주고 있습니다(Kittrakulrat 외., 2014).

In South East Asia, only four out of ten countries have implemented NLEs and each have different purposes/ targets.

- Thailand, Phillipines, Indonesia, and Malaysia, have knowledge assessment using the MCQ or modified essay questions (MEQ) formats.

- Malaysia assesses international graduates only, while the other three assess home and international graduates.

- Aside from the Phillipines, the other three countries assess clinical skills using OSCE formats.

- Vietnam and Lao are in the process of developing NLEs, while

- Brunei, Singapore, Cambodia, and Myanmar do not have one.

The discussion of NLEs in South East Asia also brings challenges to the ASEAN1 Economic Community (AEC) which promotes for the free movement of medical professions to practice medicine in another country in this region (Kittrakulrat et al., 2014).

인도네시아 국가 시험

National examination in Indonesia

인도네시아에서 NLE의 발전은 21세기 초 고품질 의료 전문가에 대한 필요성 증가에 뿌리를 두고 있습니다. 2007년 보건부 보고서에 따르면, 지역사회의 의료 접근성은 향상되었지만 의료 서비스 결과는 약간만 개선되었습니다. 2010년 세계보건기구(WHO) 보고서에 따르면 인도네시아의 의사 밀도는 인구 1,000명당 0.15명으로 예상 표준 비율에 미치지 못했습니다. 또한 도시와 농촌 지역에 의료 전문가가 고르지 않게 분포되어 있었습니다. 2006년에 의사의 17%만이 의료 서비스가 부족한 지역에서 근무한 반면, 83%는 인구 밀도가 높은 지역에서 근무했습니다(WHOSEARO, 2011). WHO와 인도네시아 정부는 네 가지 전략을 강조하여 보건 인적 자원을 개발하고 역량을 강화하는 것을 목표로 삼았습니다: 1) 계획 강화, 2) 공급/생산 증가, 3) 관리(유통 및 활용) 개선, 4) 품질 감독 및 관리 강화입니다(WHOSEARO, 2011).

The development of the NLE in Indonesia was rooted in the increasing need for high quality health care professionals at the beginning of 21st century. According to the report from the Ministry of Health in 2007, whilst communities had better access to health care, there were only slight improvements in health care outcomes. According to a World Health Organisation (WHO) report in 2010, Indonesia had a physician density of 0.15 per 1,000 population, which was less than the expected standard ratio. Moreover, there was uneven distribution of healthcare professionals in urban and rural areas. In 2006, only 17% of physicians worked in underserved areas, while 83% worked in highly populated areas (WHOSEARO, 2011). WHO and the Indonesian Government aimed to develop and empower human resources for health by emphasizing four strategies: 1) strengthening planning, 2) increasing supply/ production, 3) improving management (distribution and utilization), and 4) strengthening supervision and control of quality (WHOSEARO, 2011).

이러한 틀 안에서 정부는 이러한 목표를 달성하기 위해 설계된 보건의료 및 보건 전문직 교육 정책을 지속적으로 시행했습니다. 몇 년 전부터 정부가 보건 전문직 교육 법안을 제정하면서 변화가 시작되었습니다: 2003년에는 국가 교육 시스템 법안, 2004년에는 의료 실무 법안이 제정되었습니다. 이 법안들은 2006년에 인도네시아 의료 위원회의 설립을 촉구했습니다. 이 법안은 또한 교육부가 학부 의학교육 커리큘럼을 개선하는 데 촉매제 역할을 했습니다. 역량 기반 커리큘럼이 시행되었고, 커리큘럼의 참고 자료로 인도네시아 의사 역량 표준(인도네시아 의사 역량 표준 - SKDI)이 만들어졌습니다.

Within this framework, the Government continued to implement policies in health care and health professions education designed to achieve these aims. Changes had begun a few years before, when the government established health profession education bills: The National Education System Bill in 2003 and Medical Practice Bill in 2004. The Bills urged the establishment of the Indonesian Medical Council in 2006. The Bills also acted as a catalyst for the Ministry of Education to improve the undergraduate medical education curriculum. Competence-based curricula were implemented and the Standard of Competence for Indonesian Medical Doctors (Standar Kompetensi Dokter Indonesia – SKDI) created as a reference for curricula.

역량 기반 커리큘럼 구현은 세계은행이 후원하는 교육부의 보건 전문가 교육 품질 프로젝트의 감독하에 진행되었습니다. NLE 설립에 앞서 인도네시아 의과대학 간 벤치마킹 테스트가 진행되었습니다. 자바섬(본섬)과 수마트라섬(외딴 지역)의 공립대학을 대상으로 한 벤치마킹 테스트 결과, 인도네시아 의과대학의 질에 차이가 있는 것으로 나타났습니다(Agustian and Panigoro, 2005). 위원회가 각 학교를 지속적으로 방문한 결과, 의학교육의 질을 보장하기 위해 의과대학의 '역량과 능력'을 개선할 필요가 있다는 사실이 밝혀졌습니다. '역량과 역량'이라는 용어는 자원에만 국한된 것이 아니라 교육 기관 내부의 학습 과정도 포함했습니다.

The competence-based curriculum implementation was conducted under the supervision of the Ministry of Education’s Health Professionals Education Quality project sponsored by the World Bank. Prior to the establishment of the NLE, a series of benchmarking tests among medical schools in Indonesia took place. A benchmarking test between a public university in Java (the main island) and in Sumatera (a more remote area) shows that there were gaps among medical schools’ quality in Indonesia (Agustian and Panigoro, 2005). A continuous visit to each school by the committee revealed the need to improve the ‘capacity and capability’ of medical schools to ensure the quality of medical education in the institution. The term ‘capacity and capability’ was not only limited to resources but also included the learning process inside the institution.

세계보건기구에 따르면 2008년 인도네시아 의과대학을 졸업한 의사는 4325명이었습니다(WHO, 2011). 2013년에는 이 숫자가 거의 두 배로 증가하여 7047명이 졸업했습니다. 2008년 이후 20개 이상의 의과대학이 새로 설립되어 인도네시아의 의대생 수가 크게 증가했습니다. 일부 신설 학교는 기존 학교보다 더 많은 학생을 수용하기도 했는데, 예를 들어 C-인증을 받은 한 신설 학교는 연간 400명의 신입생을 수용했습니다(HPEQ, 2013). 2013년 이전에는 의과대학에 대한 학생 정원 규제가 없었기 때문에 이런 일이 가능했습니다. 각 대학(사립 또는 공립)의 내부 정책에 따랐을 뿐입니다. 현재 인도네시아의 의과대학은 매년 약 7,000~8,000명의 졸업생을 배출하고 있습니다. 인도네시아의 의료 수요를 충족하기 위해 이 숫자는 앞으로 크게 증가할 수 있습니다. 이처럼 의사 수가 크게 증가함에 따라 의학교육의 질을 보장하는 데 어려움이 있습니다.

According to WHO, in 2008, 4325 doctors graduated from medical schools in Indonesia (WHOSEARO, 2011). In 2013, this number almost doubled, with 7047 graduates. Since 2008 more than 20 new medical schools were established, which significantly increased the number of medical students in Indonesia. Some new schools even accepted more students than the established schools; for example a new and C-accredited school accepted 400 new students per year (HPEQ, 2013). This was possible because, before 2013, there was no regulation of student quota for medical schools. It was only based on each university’s (private or public) internal policy. Nowadays, medical schools in Indonesia produce roughly around 7,000-8,000 graduates per year. This number could increase in the future significantly to meet health care needs in Indonesia. Such a significant increase in the number of medical doctors creates a challenge in assuring the quality of their medical education.

이에 보건부는 인도네시아 의대 졸업생들이 SKDI의 역량을 기반으로 특정 기준을 충족할 수 있도록 NLE를 설립하여 그 질을 높이기로 결정했습니다. 이 시험은 의과대학 내 역량 강화 및 개선을 유도하기 위한 목적도 있었습니다. 인도네시아 보건부와 인도네시아 의사회가 공동 주관하는 위원회에서 관리하는 NLE는 2007년에 설립되었습니다. 시험은 MCQ를 이용한 지식 평가로 시작되었습니다. 임상 술기 역량에 대한 논의가 시작되기 전까지는 지식 평가로 졸업생의 임상 분야 역량을 평가하는 것으로 충분하다고 여겨졌습니다. 2011년, 의사면허시험을 주관하는 인도네시아 국가역량시험 공동위원회(Komite Bersama Uji Kompetensi Dokter Indonesia - KBUKDI)는 MCQ로 평가할 수 없는 임상 술기를 평가하기 위해 OSCE를 개발하기로 결정했습니다(의사면허시험 공동위원회, 2013a). OSCE 시행 준비 과정은 다음과 같이 구분되었습니다:

- 1) 청사진 설계,

- 2) 문항 은행 및 지침 개발,

- 3) 시험 속성 구성(도구, 인쇄된 루브릭, 컴퓨터 기반 채점),

- 4) 2011-2012년 연 4회 시범 실시,

- 5) 시범 실시 평가,

- 6) 2013년 시행, 처음에는 두 번의 시험 기간에 형성 평가로, 다음 시험 기간에 종합 평가로 실시.

The MoHER then decided to lever the quality of Indonesian medical graduates to meet certain standards, based on competences in SKDI, by establishing a NLE. This examination was also intended to drive improvement or capacity building within medical schools. Managed by a committee coordinated by the MoHER and the Indonesian Medical Council, a NLE was established in 2007. The examination started with an assessment of knowledge using MCQ. Until the discussion of clinical skills competence came up, it was considered sufficient to assess graduate competence in the clinical area by assessing their knowledge. In 2011, the Joint Committee of Indonesia National Competency Examination (Komite Bersama Uji Kompetensi Dokter Indonesia – KBUKDI), who act as an executive for the licensure, decided to develop an OSCE to assess clinical skills which could not be assessed using MCQ (Joint Committee on Medical Doctor Licensing Examination, 2013a). The process of preparing OSCE implementation was divided into:

- 1) Designing the blueprint;

- 2) Developing an item bank and guidelines;

- 3) Organizing exam attributes (tools, printed rubrics, computer-based scoring);

- 4) Piloting four times a year within 2011-2012;

- 5) Evaluation of pilots;

- 6) Implementation in 2013, initially as a formative assessment in two examination periods and summative in the next ones.

OSCE는 15분 분량의 12개 스테이션으로 구성되었습니다. 12개 스테이션은 12개 신체 시스템을 대표하며, 2012년 SKDI를 청사진으로 삼았습니다. 각 스테이션에서는 외래 진료실, 응급실, 수술실, 수술실로 설정된 공간에서 시뮬레이션된 임상 시나리오를 사용했습니다. 표준화된 환자 발생 사례와 마네킹을 이용한 시뮬레이션이 있었습니다. 수험생들은 로테이션을 위해 부저 소리로 안내를 받았습니다. 시험관들은 루브릭으로 학생들을 평가하고, 해당 스테이션의 케이스에 대한 임상 정보에 대한 가이드라인을 제공했습니다.

The OSCE comprised of twelve 15-minute stations. The twelve stations represented 12 body systems, referring to the 2012 SKDI as the blueprint. The stations used simulated clinical scenarios in rooms set as outpatient clinics, emergency room, and operation/ surgical room. There were standardised patient encounter cases as well as simulation using manikins. Examinees were guided by buzzer sounds for the rotation. Examiners assessed students with rubrics; provided with guidelines for clinical information regarding the case in the particular station.

2011년 8월부터 6차례의 시범 운영이 실시되었으며, 초기에는 1개 의과대학이 참여하여 2012년 말에는 44개 의과대학이 참여했습니다. 시험 센터에서 2단계(임상술기 평가)를 실시하는 미국과 달리, 인도네시아에서는 각 의과대학이 해당 시험 기간에 의대 졸업생을 배출한 경우 시험 센터가 되어야 합니다. 즉, 의과대학은 시험에 필요한 시험관, 직원, 시설 및 자원을 갖추어야 합니다. 시험 시행에 필요한 자원은 졸업생 수에 맞게 충분해야 합니다.

Six pilots were conducted from August 2011, involving one medical school at the beginning to 44 medical schools at the end of 2012. Unlike in the US where the Step 2 (the clinical skills assessment) is conducted in test centres; in Indonesia, each medical school must be a test centre if they had medical graduates in that current period of examination. This means that medical schools must have the examiners, staff, facilities, and resources needed for the examination. The resources needed to deliver the examination should be sufficient to suit the number of graduates.

NLE의 일부로 OSCE를 시행하는 것은 2013년 고등교육부 고등교육국장의 법령에 명시되어 있습니다. 이 법령에 따르면 NLE는 컴퓨터 기반 MCQ와 OSCE로 구성되며, NLE는 학부 교육이 끝날 때 졸업 시험의 역할을 합니다. 처음 두 차례(2013년 2월과 5월)에 걸쳐 실시된 OSCE는 교육적 목적의 평가였습니다. 2013년 8월부터 OSCE는 필기 시험과 함께 종합적인 목적으로 사용되었습니다. 의대생은 두 시험을 모두 통과해야 의과대학을 졸업할 수 있습니다. 시험에 합격한 학생은 인도네시아 의학위원회로부터 역량 인증서를 받고 의과대학을 졸업할 수 있습니다. 이 증명서는 인도네시아 보건부로부터 의사 면허를 취득하는 데 필요합니다. 시험에 불합격한 학생은 재시험에 응시해야 하며, 의과대학은 이들을 위한 재교육 프로그램을 제공해야 합니다. 2014년 1월부터 보건부 고등교육국장은 의과대학의 NLE 합격률과 인증을 규제하는 법령을 제정하여 다음 학년도 신입생 최대 정원을 결정했습니다. 이 법령은 전임상 및 임상 교육 단계의 교사와 학생 비율의 균형을 맞추기 위한 것이었습니다. 이 법령은 일부 의과대학의 행태로 인해 촉발되었습니다. 예를 들어, C-인증을 받은 한 학교는 교사가 100명 미만인데도 연간 400명의 학생을 수용했습니다(HPEQ, 2013).

The implementation of the OSCE as part of the NLE was described in the 2013 decree by Higher Education General Director of the MoHER. It stated that the NLE consists of computer-based MCQ and an OSCE; and the NLE serves as an exit exam at the end of undergraduate education. In the first two periods of the OSCE as the NLE (February and May 2013), the assessment was for formative purposes. Starting in August 2013, the OSCE served summative purposes, alongside the written examination. Medical students must pass both examinations before they can graduate from medical school. Students who pass the examination gain a certificate of competence from the Indonesian Medical Council and graduate from medical schools. This certificate is required for a licence of practice from the MoH. Students who fail the examination must retake the examination and medical schools must provide remediation programmes for them. Starting in January 2014, the Higher Education General Director under the MoHER established a decree that regulates the passing rate of medical schools in NLE and their accreditation to determine the maximum quota for new students in the next academic year. This decree was meant to balance the ratio of teachers and students in preclinical and clinical phases of education. This decree was precipitated by the behaviour of some medical schools. For example, a C-accredited school accepted 400 students per year when they had less than 100 teachers (HPEQ, 2013).

이로 인해 합격률이 낮고 인증 수준이 낮은 의과대학들 사이에서 우려의 목소리가 높았습니다. A 인증 의과대학은 NLE 합격률이 90% 이상인 경우 최대 250명의 학생을 수용할 수 있었습니다. 반면, C 인증 의과대학은 NLE 합격률이 90% 이상인 경우 100명, 50% 미만인 경우 50명의 학생만 수용할 수 있었습니다. 이 규칙을 위반하는 의과대학(또는 대학)에 대해서는 보건복지부가 제재를 가하고 있습니다. 학생들의 등록금이 주 수입원인 사립학교의 경우, 이는 심각한 문제를 야기할 수 있습니다.

This caused worries among medical schools that had lower passing rates and low levels of accreditation. The A-accredited medical schools could have a maximum of 250 students if they had a 90%+ passing rate in the NLE. Meanwhile, the C-accredited schools could only accept 100 students if they had a 90%+ passing rate in the NLE, and 50 students if they had less than 50%. There are sanctions from the MoHER for medical schools (or universities) that violate this rule. For private schools, whose main income is student’s tuition fees, this might raise significant problems.

인도네시아에서 NLE를 도입하고 그 일환으로 OSCE를 시행하는 것은 NLE를 시행한 다른 국가들의 경우와 마찬가지로 의학교육에 상당한 영향을 미칠 것으로 보입니다.

In Indonesia, the introduction of the NLE and the implementation of the OSCE as part of it, are likely to generate a significant impact on medical education, as has been the case for other countries that have implemented the NLE.

3.4 NLE의 결과: 현재의 논쟁

3.4 The consequences of the NLE: current debate

Kane(2014)이 제안한 평가의 타당성에는 결과 영역이 포함됩니다. 즉, 시험 점수의 해석을 뒷받침하는 증거가 있어야 하며, 평가의 결과에 대한 증거가 있어야 합니다. 평가의 타당성 정도는 개입으로서의 영향에 대한 증거를 포함하여 증거가 얼마나 강력한지에 따라 달라집니다(Kane, 2014). 면허 시험은 실무에 필요한 지식, 기술, 판단력을 갖춘 응시자만이 시험에 합격할 수 있도록 함으로써 대중을 보호하는 역할을 합니다. 시험 점수가 향후 업무 수행 능력과 상관관계가 있다고 가정하면 시험 점수가 낮은 수험생이 공공에 위협이 될 수 있다고 생각할 수 있습니다. 그러나 시험 점수가 높다고 해서 반드시 좋은 실무자가 되는 것은 아닙니다. NLE의 타당성은 시험 점수에만 의존하는 것이 아니라 이해관계자에게 미치는 영향도 고려해야 합니다.

The validity of assessment, as proposed by Kane (2014), includes the consequences domain: there should be evidence that supports the interpretation of test scores; meaning there must be evidence of the consequences of the assessment. The degree of any assessment’s validity depends on how strong is the evidence, including the evidence of its impact as an intervention (Kane, 2014). The licensing examination works as a protection to the public by ensuring that only candidates who have the necessary knowledge, skills, and judgement for practice, pass the test. It could be assumed that the test score correlates with future performance, so that students with low test scores could pose a threat to public. However, it does not necessarily mean that those who have higher test scores will be good practitioners. The validity of the NLE does not solely rely on test scores, but also its consequences for stakeholders.

다우닝의 프레임워크를 사용하여 체계적 문헌고찰을 수행한 Archer 등(2016)이 설명한 바와 같이, NLE의 결과는 참가자, 의과대학, 규제기관, 정책 입안자 또는 더 넓은 사회에 미칠 수 있으며, 의도적이거나 의도하지 않았거나, 유익하거나 해로울 수 있습니다(Archer 등, 2016a). NLE의 영향은 의료 시스템에만 국한되지 않고 의학교육 시스템에도 영향을 미친다는 점에 유의하는 것이 중요합니다. NLE의 결과에 대한 몇 가지 연구가 있었지만 이 분야에 대한 지식은 제한적입니다. Archer 등이 GMC(2016)를 대상으로 실시한 체계적 문헌고찰에서는 수험생의 과거 및 미래 성과, 환자 결과 및 불만과의 관계, 국내 졸업생과 해외 졸업생 간의 성과 차이 등 세 가지 영역의 결과를 조사했습니다.

As described by Archer, et al. (2016), who used Downing’s framework to conduct a systematic review, the consequences of NLEs may fall on participants, medical schools, regulators, policy makers, or wider society; and they can be intended or unintended, beneficial or harmful (Archer et al., 2016a). It is important to note that the impact of NLEs will not be limited to the healthcare system, but also to the medical education system. There have been some studies of the consequence of NLEs but knowledge in this area is limited. The systematic review conducted by Archer et al. for the GMC (2016) looked into three areas of consequences: prior and future performance by examinees, relationship to patient outcomes and complaints, and variation in performance between home and international graduates.

대부분의 연구에 따르면 학교 평가에서 우수한 학생은 NLE에서도 우수한 성적을 거둘 수 있으며(Hecker and Violato, 2008), NLE 결과는 대학원 평가에서 더 나은 성과를 예측하는 것으로 나타났습니다(Thundiyil 외., 2010; Miller 외., 2014; Yousem 외., 2016). 그러나 Archer 등이 지적했듯이 의과대학의 의학교육에 대한 다른 접근 방식이 결과에 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다(Archer 등, 2016a). 그의 검토에 따르면 NLE의 결과로 환자 예후가 개선되었다는 증거가 부족하다고 합니다. NLE의 개입이 더 나은 환자 치료로 이어질 수 있다는 명확한 증거는 없습니다. 연구에 따르면 NLE의 성과와 환자의 불만 비율 사이에는 상관관계가 있는 것으로 나타났습니다(Tamblyn 외., 2007). 이는 인과관계를 설명하는 것이 아니라 환자 치료에 대한 NLE의 예측 가치가 있음을 보여줄 뿐이었습니다. 그러나 Archer의 검토에서는 이러한 연구가 NLE를 지지하는 강력한 논거를 제공한다는 점을 인정했습니다(Archer et al., 2016a).

Most of the studies found that students who excelled in schools’ assessment would do well in NLEs (Hecker and Violato, 2008) and the NLE results predicted better performance in postgraduate assessment (Thundiyil et al., 2010; Miller et al., 2014; Yousem et al., 2016). However, as Archer et al. pointed out, the different approach to medical education in the medical schools might affect the results (Archer et al., 2016a). His review also revealed that there is the lack of evidence for the improvement of patient outcome as an NLE consequence. There is no clear evidence that the intervention of NLEs could lead to better patient care. The studies showed there was a correlation between performance in the NLE and rate of complaints made by patients (Tamblyn et al., 2007). This did not explain the causation; it only showed that there is a predictive value of the NLE on patient care. However, it was acknowledged in Archer’s review that these studies provided a strong argument in favour of NLEs (Archer et al., 2016a).

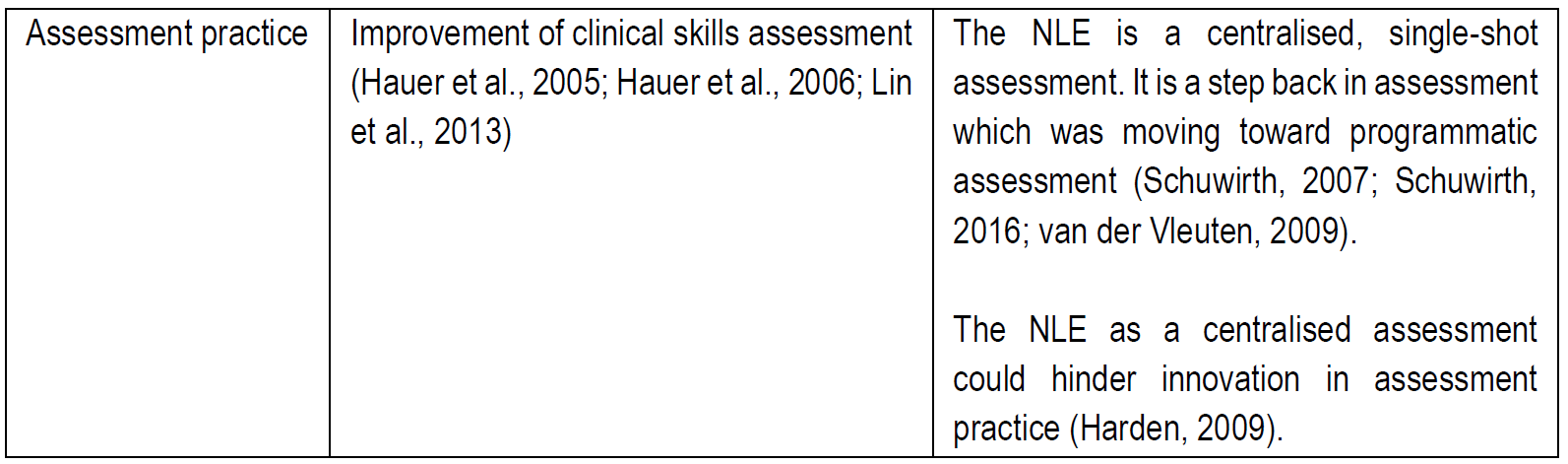

NLE의 타당성에 기여하는 NLE의 영향은 환자 치료와 의사의 임상 성과 영역에만 국한되지 않습니다. NLE가 교육에 미치는 영향도 중요하지만, 이 영역에 대한 증거는 매우 제한적입니다. 대부분의 연구는 임상 술기 평가의 NLE 구성 요소로 인한 임상 술기 커리큘럼 및 평가의 변화를 설명했습니다. 미국에서는 USMLE의 2단계 CSA가 임상 술기 교육의 변화를 주도했습니다. 의학 커리큘럼, 특히 자체 임상 술기 평가에 미치는 영향은 많은 학교가 의학교육에서 임상 술기의 중요성을 바라보는 시각을 바꾼 것으로 나타났습니다(Hauer 외, 2005; Hauer 외, 2006). 대부분의 학교는 의사소통 능력에 중점을 두고 종합적인 임상 술기 평가를 실시합니다(Hauer et al., 2005). Archer 등(2016)은 미국과 캐나다와 같은 기존 시스템에서는 임상 술기의 중요성이 부각되면서 의과대학의 임상 술기 교육에 집중하여 전국적으로 덜 자주 가르치는 특정 술기에 대한 필요성을 해결하고 있다고 강조했습니다.

The impact of the NLE, which contributes to its validity, is not limited to the area of patient care and clinical performance of a doctor. NLEs’ consequences on education are also important, however, the evidence in this area is very limited. Most of the studies described changes in clinical skills curricula and assessment as a result of the NLEs’ component of clinical skills assessment. In the US, the Step 2 CSA of USMLE drove changes in clinical skills education. The impact on medical curricula, especially in-house clinical skills assessments, showed that many schools changed how they viewed the importance of clinical skills in medical education (Hauer et al., 2005; Hauer et al., 2006). Most schools conduct comprehensive clinical skills assessment with an emphasis on communication skills (Hauer et al., 2005). Archer et al. (2016) highlighted that in the established system, like the USA and Canada, the emerging importance of clinical skills was used to focus medical schools’ clinical skills teaching to address the need for specific skills which were less frequently taught nationwide.

의학교육의 변화가 비교적 최근이고 OSCE가 비교적 새로운 아시아 국가에서는 NLE의 일부로 도입하는 것이 어려운 도전이 될 수 있습니다. 대만의 경우, Lin 등(2013)이 설명한 바와 같이 임상시험의 난이도가 높아지면서 임상술기 평가의 사용이 증가하고 병원 내 임상술기 교육 시설이 개선되었습니다. 이 연구진은 설문지를 통해 OSCE 프로그램이 활성화된 교육 병원을 조사하여 OSCE 시행과 그 구성 요소에 대한 정보를 얻었습니다. 그 결과 교육 및 시험실, 모의 환자(SP), 임상 술기 평가를 위한 케이스 개발 수가 모두 증가했다는 사실을 발견했습니다. 그러나 교육이나 평가에 사용되는 병원 공간, 직원, SP 등의 한계도 확인했으며, 시험 시행에 필요한 자원이 충분한지에 대한 우려도 제기했습니다. 이러한 문제에도 불구하고 이 연구는 의료 수련 기관에서 NLE에 대한 강력한 지지를 나타냈습니다(Lin et al., 2013). 마찬가지로 한국에서도 OSCE 도입으로 임상술기 교육 커리큘럼, 평가, 시설 등이 개선되었다는 연구 결과가 있었습니다(Kim, 2010; Park, 2012; Ahn, 2014).

In Asian countries, where changes in medical education are more recent and the OSCE is relatively new, its introduction as part of the NLE can be a daunting challenge. For Taiwan, as explained by Lin et al. (2013), the high stakes clinical examination drove the increasing use of clinical skills assessments and the improvement of clinical skills teaching facilities in hospitals. They investigated teaching hospitals with active OSCE programs using questionnaires to gain information about OSCE implementation and its components. They found that the number of rooms for training and examination, simulated patients (SP), and case development for clinical skills assessment all increased. However, they also identified limitations: hospital spaces used for teaching or assessment, staff, and SPs, raising the concern of whether there were sufficient resources to establish the examination. Despite these issues, the study indicated strong support from medical training institutes toward a NLE (Lin et al., 2013). Similarly, studies in South Korea also indicated that the introduction of OSCE drove improvement in clinical skills teaching curricula, assessment, and facilities (Kim, 2010; Park, 2012; Ahn, 2014).

문헌에 나타난 NLE의 긍정적인 결과와 부정적인 결과로 요약되는 이러한 상반된 의견은 아래 표에 요약되어 있습니다: These contrasting opinions, summarised as positive and negative consequences of the NLE from the literature are summarised in the table below:

지난 10년 동안 추가 연구가 수행되었는데, 대부분 의학교육과 의료 시스템이 인도네시아와 같은 개발도상국과 다른 선진국에서 데이터를 가져왔습니다. Archer 등(2016)이 GMC에 대한 검토에서 언급했듯이, 곧 도입될 영국의 MLA는 영국과 유사한 특성을 공유하는 다른 국가의 NLE(인간개발지수가 높고 의학교육 및 보건의료 시스템이 유사한 선진국)와 비교할 수 있습니다. 이를 통해 NLE를 둘러싼 담론에서 개발도상국에서의 실행 및 영향과 관련된 격차가 있음을 확인할 수 있습니다.

Further studies have been conducted in the last decade, most of which draw their data from developed countries, where both medical education and the health care system differs from those in developing countries such as Indonesia. As Archer, et al. (2016) stated in his review for the GMC, the upcoming MLA in the UK could be compared with NLEs in other countries sharing similar characteristics with the UK: highly developed countries with a high human development index, similar systems of medical education and health care. This confirms gaps in the discourse surrounding the NLE to do with its implementation and impact in developing countries.

인도네시아에서는 2007년부터 SKDI를 '표준'으로 도입하고 NLE를 통해 커리큘럼을 변화시켜 역량 기반 커리큘럼으로 이끌었습니다. 이러한 혁신에 대한 연구는 제한적이며 대부분의 문헌은 인도네시아 문화와 이해관계자의 고유한 특성을 다루지 않았습니다. 국가 위원회에서 수행한 연구는 시험의 타당도와 신뢰성 요소에 초점을 맞추었습니다.

In Indonesia, the introduction of SKDI as the “standard” and the NLE drove curriculum changes from 2007 leading to the competence-based curriculum. There is limited research on these innovations and most of the literature has not covered the unique characteristics of Indonesian culture and stakeholders. The studies carried out by the national committee focussed on the validity and reliability component of the examination.

인도네시아의 의학교육과 의료 시스템 이해당사자들에게 NLE가 미친 영향에 대해서는 알려진 바가 거의 없습니다. 소규모 연구에 따르면 NLE가 학생 학습의 질과 학생의 메타인지 조절에 영향을 미쳤다고 합니다(Firmansyah 외., 2015). 그러나 교사는 교육의 예상 결과를 학습 목표로 해석하여 학생들에게 전달해야 하므로 NLE는 교사의 수업과 평가를 수정할 수 있는 잠재력을 가지고 있습니다. 마찬가지로, 이는 학생들이 시험과 관련된 방식에 영향을 미치고 의과대학이 정책 및 교육 관행에 필요한 변화를 파악하도록 유도할 수 있습니다. 그러나 NLE를 경험한 사람들에게 이러한 영향이 구체적으로 어떤 영향을 미쳤는지에 대해서는 알려진 바가 거의 없습니다. 따라서 인도네시아의 매우 다양한 의과대학 시스템에서 NLE가 학생의 학습, 교사의 개발, 의과대학의 정책에 어떤 영향을 미쳤는지 이해하는 것이 중요합니다.

Little is known about the consequences of the NLE on medical education in Indonesia and the stakeholders in the health care system. A small scale study proposed that the NLE affected the quality of student learning and students’ metacognitive regulation (Firmansyah et al., 2015). However, as teachers have to interpret the expected outcome of education into learning objectives and deliver it to students the NLE has the potential to modify their teaching and assessment. Similarly, this would affect how students relate to the examination and lead medical schools to identify changes needed in their policy and educational practice. However, very little is known about the details of this impact on those who experienced the NLE. It is, therefore, important to understand how the NLE affected students’ learning, teachers’ development, and medical schools’ policy in the very diverse system of medical schools in Indonesia.

- 따라서 이 연구는 인도네시아의 문화와 이해관계자 및 그들의 특성이 NLE 시행의 결과에 어떤 영향을 미칠 수 있는지 인식하면서 인도네시아에서 NLE의 영향을 이해하는 데 중점을 두었습니다.

Consequently, this study focussed on understanding the impact of the NLE in Indonesia, recognising how the culture and the stakeholders and their characteristics might affect the consequences of implementing the NLE.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 세계화, 다양한 국가' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 졸업후의학교육을 위한 인증 시스템: 다섯 개 국가의 비교(Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2019) (0) | 2023.12.17 |

|---|---|

| 중국의 2021년 의료전문직 면허법 수정: 코멘터리(Health Syst Reform. 2022) (0) | 2023.11.19 |

| 베트남의 의사면허시험에 대한 코멘터리(MedEdPublish, 2023) (0) | 2023.11.19 |

| 베트남 의학교육의 혁신(BMJ Innov 2021) (0) | 2023.11.19 |

| 동남아시아의 면허시험: 교육정책의 변화에서 찾아낸 교훈( Asia Pacific Sch, 2019) (0) | 2023.11.19 |