졸업후의학교육을 위한 인증 시스템: 다섯 개 국가의 비교(Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2019)

Accreditation systems for Postgraduate Medical Education: a comparison of five countries

Dana Fishbain1,2 · Yehuda L. Danon1 · Rachel Nissanholz‑Gannot1,3

소개

Introduction

졸업후 의학 교육 인증(PGME)은 교육 기관(대학, 프로그램, 학과, 클리닉 등)의 레지던트(수련의/전공의) 교육에 대한 지속적인 질 평가 및 모니터링 프로세스입니다.

- 1910년 플렉스너 보고서는 의학교육의 표준화와 표준이 충족되고 있음을 보장하기 위한 인증 절차 수립의 중요성을 처음으로 강조했으며,

- 2010년 카네기 보고서는 교육과정의 길이와 구조 대신 학습 결과와 일반 역량을 표준화할 것을 강조했습니다(Irby 외. 2010).

국가 인증 시스템은 평가 기준을 개발하고, 바람직한 결과물을 정의하며, 졸업생이 사회적 건강 요구를 충족할 수 있는 적절한 역량을 갖추도록 보장해야 합니다(Frenk 외. 2010). PGME 인증이 필요하다는 데는 폭넓은 공감대가 형성되어 있지만, 이를 달성할 수 있는 보편적인 방법은 없습니다(WHO 2013).

Accreditation of Postgraduate Medical Education (PGME) is an ongoing process of quality evaluation and monitoring of medical resident (doctor in training/postgraduate trainee) training in an institution (a university, program, department, clinic and others). The 1910 Flexner report was the first to highlight the importance of standardizing medical education and establishing accreditation process to assure standards are being met, while the 2010 Carnegie report stressed for standardizing learning outcomes and general competencies instead of length and structure of curriculum (Irby et al. 2010). National accreditation systems are expected to develop criteria for assessment, define desired outputs, and make sure that graduates achieve adequate competencies to meet societal health needs (Frenk et al. 2010). There is a broad consensus that accreditation of PGME is needed, but there is no universal way of accomplishing this (WHO 2013).

2000년대 초, PGME는 특정 시간 내에 레지던트를 수련하는 과정에 초점을 맞춘 시간/과정 기반 모델에서 역량에 대한 조직화된 프레임워크를 사용하여 의학교육 프로그램의 설계, 실행, 평가 및 평가에 대한 결과 기반 접근 방식인 역량 기반 의학교육(CBME)으로 점차 전환되었습니다(Frank 외. 2010). 이는 전공의가 전문의 수준에 도달할 때까지 수련의 각 단계에서 전공의의 개인적 진전을 모니터링하는 것을 기반으로 합니다.

In the early 2000s, a shift gradually emerged in PGME from time/process-based models, which focus on the process of training a resident within a certain time frame, to Competency Based Medical Education (CBME), an outcome-based approach to the design, implementation, assessment and evaluation of medical education programs, using an organizing framework of competencies (Frank et al. 2010). It is based on monitoring residents’ personal progress at each stage of training, until they reach the level of specialist.

전통적인 과정 기반 인증 시스템은 의사를 수련하는 데 필요한 자원과 구조에 초점을 맞추고, 공식적인 교육 과정뿐만 아니라 구조적 매개변수(수술 건수, 선임 의사 수, 시설 목록 등)를 사용했습니다(Nasca 외. 2012). 지난 몇 년 동안 일부 국가에서는 교육의 구조와 과정뿐만 아니라 프로그램과 학습자의 결과도 조사하기 위해 인증 시스템을 개정하기 시작했습니다(Manthous 2014).

Traditional process-based accreditation systems focused on the resources and structure required for training physicians, and used structural parameters (the number of procedures, the number of senior physicians, a list of facilities and others), as well as on the process of formal teaching (Nasca et al. 2012). During the last few years, some countries began revising their accreditation systems in an attempt to examine not only the structure and process of training, but the outcomes of programs and learners, as well (Manthous 2014).

의학교육의 인증 시스템은 국가마다, 때로는 국가 내에서도 다양합니다. 전 세계적으로 인증 과정에는 큰 차이가 존재하며, "인증"이라는 용어가 반드시 "적절한 인증"으로 기대할 수 없는 다른 과정을 지칭하기도 합니다(Karle 2006).

Accreditation systems in medical education vary from country to country and sometimes within countries. Great variation exists in accreditation processes world-wide, sometimes referring the term “accreditation” to different process which would not necessarily be expectable as “proper accreditation” (Karle 2006).

인증 시스템은 환경 조건, 보건 시스템 요구 및 기타 요인에 따라 발전해 왔지만, 세계화로 인해 각국은 다른 국가에 존재하는 모델을 알게 되고 새로운 아이디어를 채택하게 됩니다. 미국과 캐나다의 의학교육에 관한 방대한 문헌이 있지만, PGME 인증에 관한 문헌은 거의 없으며, 다른 국가의 인증에 관한 문헌은 더욱 적습니다. 우리는 지난 20년간의 변화를 고려하여 5가지 인증 시스템을 비교하고자 합니다. 우리의 목표는 의사 결정권자가 새로운 아이디어를 고려하는 데 도움이 될 수 있는 공통 원칙과 차이점을 모두 찾는 것입니다.

Accreditation systems have evolved based on environmental conditions, health system demands and other factors, but due to globalization, countries become acquainted with models existing in other countries and adopt new ideas. A vast body of literature describes medical education in the United States and Canada, but very little is written about accreditation of PGME, and even less is written about it in other countries. We aim to compare five accreditation systems, taking into consideration changes to these systems during the last 20 years. Our goal is to find both common principles and differences, which may help decision makers consider new ideas.

조사 방법

Methods

여러 국가의 5가지 인증 시스템을 중점적으로 검토했습니다: 미국, 캐나다, 영국, 독일, 이스라엘. 오랜 기간 동안 PGME와 그에 수반되는 인증 시스템을 운영해 온 서구 국가를 선정했습니다. 이 기준에 부합하는 모든 국가 중에서 다양한 그룹을 찾기 위해 북미와 유럽 국가, 의사와 레지던트 수가 다른 국가, 의학교육 논의와 문헌을 선도하는 국가(미국, 영국, 캐나다 등), 시스템이 잘 알려지지 않은 기타 국가를 포함시켰습니다. 영어로 된 정보에 대한 접근성(공개되어 있거나 개인적 인맥을 바탕으로 요청 시 제공)도 또 다른 요소였습니다.

We focused our review on five systems of accreditation from different countries: The United States, Canada, The United Kingdom, Germany and Israel. We selected Western countries that have had PGME and accompanying accreditation systems for many years. Of all countries fitting this criteria, we looked for a diverse group, and thus included North American as well as European countries, countries differing in the number of physicians and residents, countries leading in medical education discussion and literature (as USA, UK and Canada), and other countries where the systems are less publicized. Accessible information in English, either published or available on request based on personal connections, was another factor.

세 가지 정보 소스를 기반으로 비교했습니다.

- 첫째, Pub-Med와 Web of Science 검색을 통해 선정된 5개국 중 하나 이상의 국가에 대한 일반적 또는 특정 국가에 대한 PGME 인증 관련 논문을 대상으로 문헌 검토를 실시했습니다.

- 둘째, 5개국의 각 관련 인증 기관 및 기타 보건 당국이 2018년 12월까지 공개적으로 발표한 PGME 인증에 관한 모든 정보 및 문서(입장문, 규정, 프로토콜, 표준, 강의 계획서 및 각 기관의 웹사이트에 게시된 정보 포함)에 대해 온라인 검색을 실시했습니다.

- 마지막으로 캐나다와 독일의 인증 기관에 추가 세부 정보를 요청하는 이메일을 보냈습니다.

We based our comparison on three information sources.

- First, a literature review was conducted, using both Pub-Med and Web of Science searches, for articles concerning accreditation of PGME generally or specifically concerning one or more of the five selected countries.

- Second, an online search was conducted for all information and documents concerning accreditation of PGME publicly published until December 2018 by each relevant accreditation authority and other health authorities in the five countries (including position papers, regulations, protocols, standards, syllabi and information published on each authority’s web site).

- Finally, a request for further details was e-mailed to accreditation authorities in Canada and Germany.

정보 분석을 위해 King(2012)이 설명한 대로 유연성과 직관적인 사용법을 위해 템플릿 분석을 사용했습니다.

- 처음 읽은 인상과 주제에 대한 저자의 인식을 바탕으로 선험적인 주제 목록을 설정했습니다.

- 그런 다음 두 국가(미국, 캐나다)에 관한 문서를 검토하고 선험적 주제 목록과 관련된 문장과 새로 발견된 주제를 코딩하여 초기 템플릿을 구축했습니다.

- 그런 다음 코드는 의미 있는 그룹으로 클러스터링되었고, 각 그룹은 같은 클러스터에 속한 테마 간의 계층적 연결을 가졌습니다. 선험적 목록에 나타난 일부 테마는 예상보다 참조가 적은 것으로 판명되어 초기 템플릿에 포함되지 않았습니다.

- 테마 선정은 조사 대상 국가 중 3개국 이상에서 반복되는 주제를 찾는 방식으로 진행되었습니다.

- 모든 문서를 검토하고 관련 주제에 대한 모든 참조를 표시한 후 최종 템플릿을 작성하여 5개 국가를 모두 비교할 수 있도록 했습니다.

- 분석에서 나타난 주요 주제를 표로 정리했습니다.

For our analysis of the information we used Template Analysis, as described by King (2012), which was chosen for its flexibility and its intuitive use.

- An a priori list of themes was set based on first reading impressions and the authors’ perceptions of the subject.

- An initial template was then constructed by reviewing documents concerning two countries (the United States and Canada), coding statements that related to the a priori list of themes, as well as new themes located.

- The codes were then clustered into meaningful groups, each with hierarchical connections between themes in the same cluster. Some themes that appeared on the a priori list were not included in the initial template, as they proved to have fewer references than anticipated.

- Our choice of themes was conducted by looking for reoccurring themes in three or more of the countries examined.

- After reviewing all documents and marking all references to the relevant themes, we assembled our final template, which allowed a comparison among all five countries.

- Major themes emerging from the analysis were tabulated.

결과

Results

우리가 선택한 5개국에서는 PGME 시스템과 보건 시스템의 다양한 특성을 발견할 수 있었습니다(표 1, 2).

Among the five countries we chose, we found diversified characteristics of PGME systems and health systems (Tables 1, 2).

인증은 어떻게 이루어지나요?

How is accreditation performed?

표준에 의한 인증

Accreditation by standards

표준에 의한 인증은 표준의 형식과 사양은 다르지만 대부분의 인증 시스템이 공유하는 기본 원칙입니다. 미국, 캐나다, 영국은 교육기관 또는 교육기관에 대한 일반 표준을 사용하는 반면, 이스라엘에서는 이러한 일반 표준을 대부분 폐지하고 각 전문 분야 및 교육기관 유형에 대한 특정 표준에 중점을 두고 있습니다. 미국과 캐나다에서도 전문 분야별 표준이 사용되고 있으며, 영국과 독일은 트레이너를 위한 특정 표준을 채택하고 있습니다(ACGME 2016, 2000-2018, RCPSC 외. 2007-2013, 2007-2011, GMC 2015, 2016a, Ärztekammer 2014, GMA 2003-2015, IMA 2014). 독일에서는 각 주 의사회에서 표준을 규정하기 때문에 독일 의회에서 채택한 (모델) 전문의 수련 규정을 기반으로 하지만 각 주마다 다를 수 있습니다(Nagel 2012). 다양성은 매우 광범위하여 가정의학 PGME에서와 같이 일부 독일 주에서는 전혀 표준을 적용하지 않는 경우도 있습니다(Egidi 외. 2014).

Accreditation by standards is a basic principle shared by most accreditation systems, though the standards differ in format and specification. The United states, Canada and Britain employ general standards for sites or institutions, while in Israel most of those general standards were canceled, with emphasis put on specific standards for each specialty and type of training site. Specialty specific standards are used in the United states and Canada as well, while Britain and Germany employ specific standards for trainers (ACGME 2016, 2000–2018; RCPSC et al. 2007–2013, 2007–2011; GMC 2015, 2016a; Ärztekammer 2014; GMA 2003–2015; IMA 2014). In Germany, standards are regulated by each state physicians’ chamber and therefore may vary from one to the other though they are all based on the (Model) Specialty Training Regulations, which are adopted by the German Medical Assembly (Nagel 2012). Variation may be so extensive that in some cases, as in Family Medicine PGME, some of the German states employ no standards at all (Egidi et al. 2014).

각기 다른 표준의 내용에는 공통점이 많지만 분명한 차이점도 있습니다. 예를 들어, 미국, 캐나다 및 영국의 표준은 더 정교하고 CBME로의 전환에 따라 결과 기반 표준의 추가 측면이 있으며, 이는 "과정 기반/결과 기반 인증 시스템" 섹션에서 자세히 설명할 것입니다.

Though the content of the different standards has much in common, there are apparent differences as well. Those of the United states, Canada and Britain, for example, are more elaborate and have an additional facet of outcomes-based standards, corresponding with the move to CBME, which will be further explained in the section “Process-based/outcome-based accreditation system”.

인증 도구

Accreditation tools

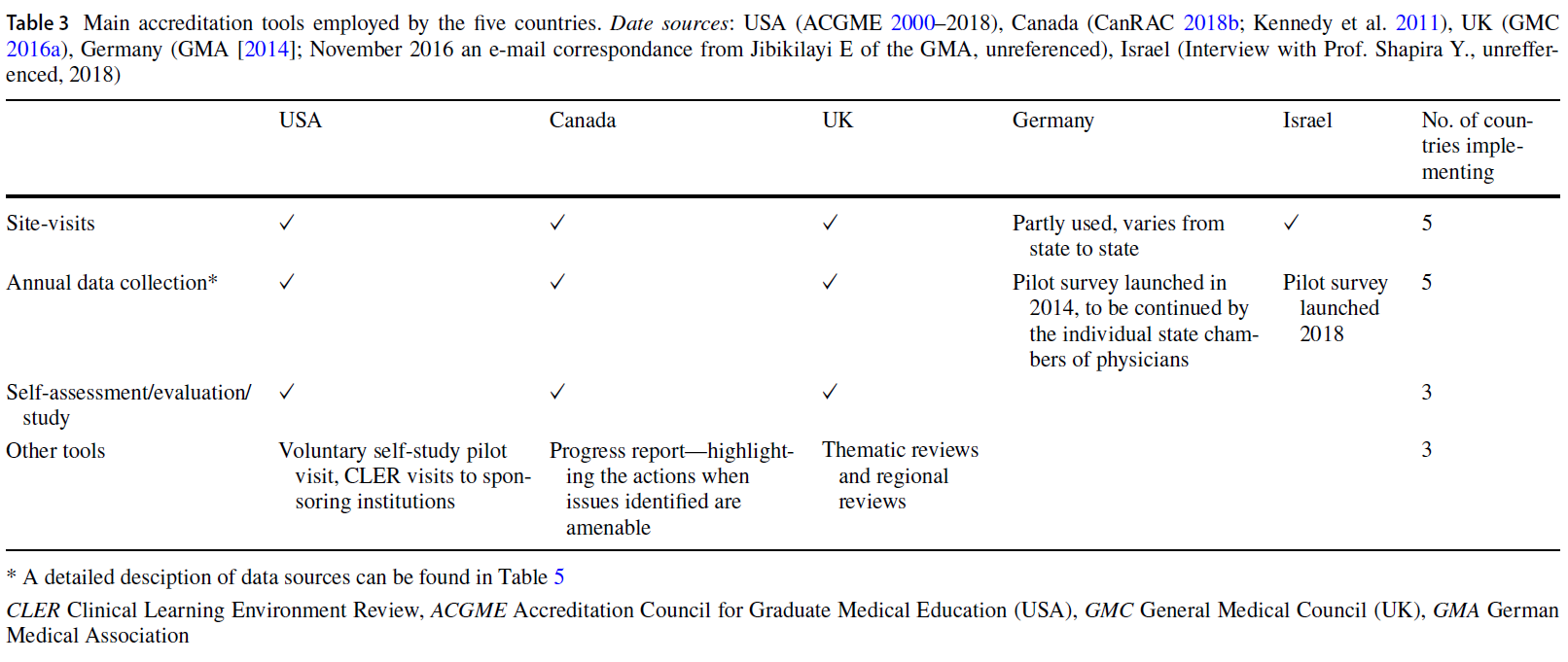

5개국 모두 현장 방문, 연간 데이터 수집, 자체 평가라는 세 가지 주요 인증 도구 중 2~3가지를 적용하여 기준이 충족되고 있는지 검증하는 것으로 나타났습니다(Marsh 외. 2014, Kennedy 외. 2011, GMC 2016a, IMA 2014, 2016년 11월 GMA의 지비킬레이이 E로부터 받은 이메일 서신, 참조하지 않음)(표 3).

We found that all five countries applied between 2 and 3 of the same three main accreditation tools to verify that standards are being met: site-visits, annual data collection and self-evaluations (Marsh et al. 2014; Kennedy et al. 2011; GMC 2016a; IMA 2014; November 2016 an e-mail correspodence from Jibikilayi E of the GMA, unrefferenced) (Table 3).

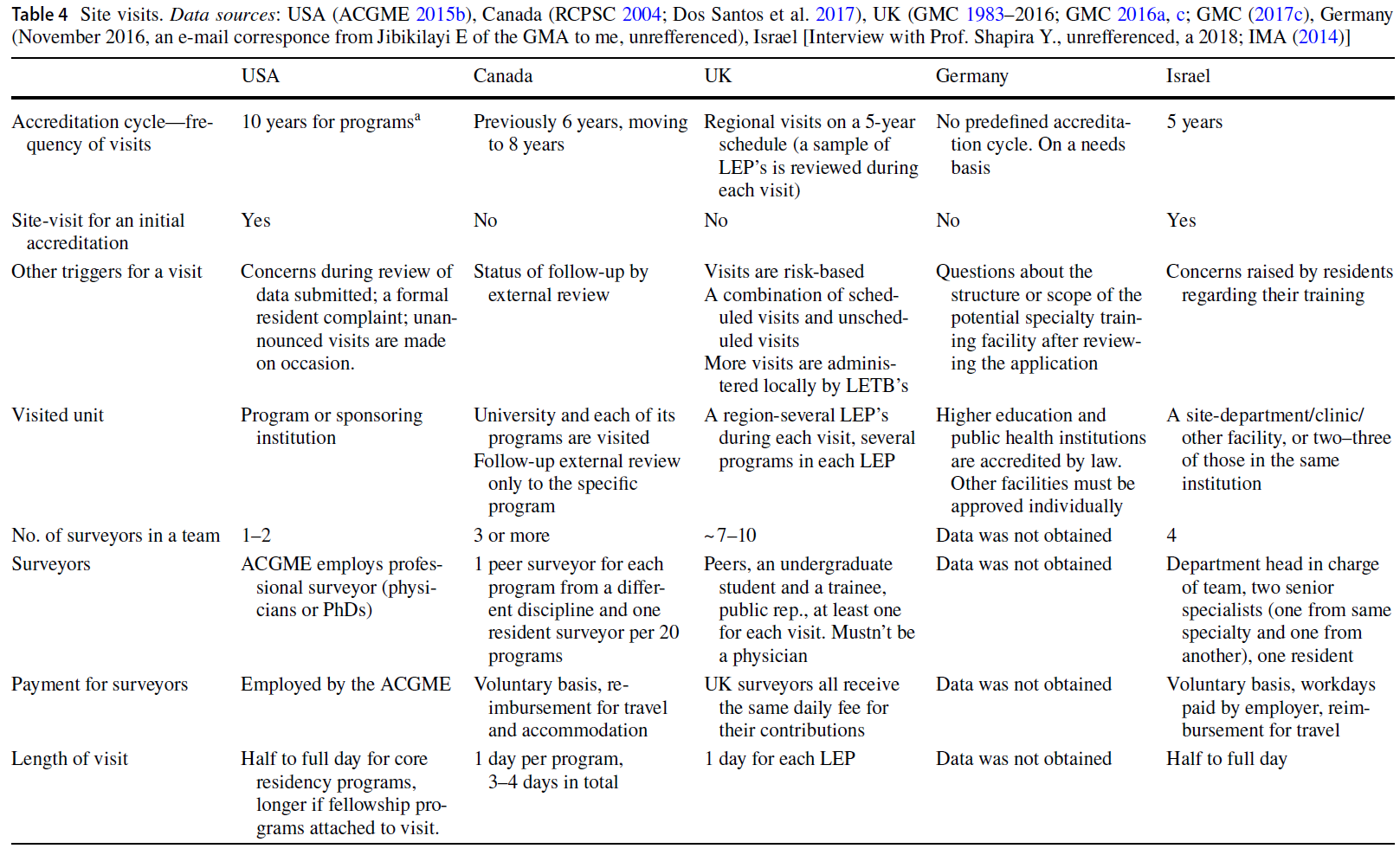

5개국 모두에서 실시된 외부 검토인 현장 방문은 주로 조사팀이 시설을 방문하여 직원을 인터뷰하고 경영진을 만나 조사 결과와 권고 사항을 담은 보고서를 작성하는 방식으로 이루어집니다. 대부분의 국가에서는 사전 정의된 주기에 따라 방문을 실시했지만, 불만이나 우려 사항과 같은 예기치 않은 상황에 의해 방문이 촉발되기도 했습니다(표 4).

- 영국 일반의학회(GMC)는 잉글랜드에서는 지역 검토를, 북아일랜드, 스코틀랜드, 웨일즈에서는 전국 검토를 예정했는데, 독특하게도 학부 및 대학원 의학교육을 모두 같은 방문에 포함하도록 설계했습니다.

- 독일의 현장 방문은 주 의사회에서 필요에 따라 일정을 잡았습니다. 각 주 의사회는 전문과목 수련 시설과 전문과목 수련을 제공하도록 승인된 의사를 품질 보증의 틀 안에서 사례별로 또는 특별한 이유 없이 모니터링할지 여부(모니터링한다면 어느 정도까지)를 결정합니다(2017년 10월, GMA의 O'Leary S가 보낸 이메일 서신, 참조하지 않음).

- 미국에서 ACGME는 크게 두 가지 종류의 현장 방문을 실시합니다:

- 10년 일정으로 운영되는 프로그램 현장 방문과

- 후원 기관을 대상으로 하며 임상 현장에서 레지던트 및 동료 의사가 안전하고 질 높은 환자 치료를 제공하기 위한 학습에 참여하는 방식을 개선하기 위해 고안된 임상 학습 환경 검토(CLER)가 그것입니다. 이 원고에서는 주로 프로그램 현장 방문에 대해 자세히 설명합니다.

A site-visit, an external review performed in all five countries, mainly requires a team of surveyors to visit the facilities, interview the staff, meet with the management and compile a report of their findings and recommendations. Most countries used visits on a predefined cycle, though triggered visits by unexpected circumstances as well, such as complaints or concerns (Table 4).

- The British General Medical Council (GMC), scheduled regional reviews in England and national reviews in Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales, uniquely designed to include both undergraduate and Postgraduate Medical Education at the same visit.

- Site visits in Germany were scheduled on a needs basis by the state chamber of physicians. It is up to the respective State Chambers of Physicians to decide whether (and, if so, to what extent) specialty training facilities and physicians authorized to provide specialty training should be monitored within the framework of quality assurance—either on a case-by-case basis or without a specific reason (October 2017, an e-mail correspondence from O’Leary S of the GMA, unreferenced.).

- In the United States, the ACGME conducts two main kinds of site-visits:

- A program site-visit, run on a 10-year schedule, and

- a Clinical Learning Environment Review (CLER), which is aimed for sponsoring institutions and designed to improve the way clinical sites engage resident and fellow physicians in learning to provide safe, high quality patient care. In this manuscript we mainly elaborate on the program site-visits.

방문 조사원의 수, 조사원의 전문 분야(시니어 의사, 레지던트, 공공 대표, 교육자), 방문 기간에 따라 국가마다 방문 팀이 다릅니다(표 4 참조).

- 캐나다와 이스라엘의 경우, 조사원은 모두 자원봉사 의사로 구성되며, 적어도 한 명은 같은 전문 분야, 다른 한 명은 다른 전문 분야의 의사입니다. 방문은 특정 치료법이 아닌 교육의 과정과 틀에 초점을 맞추기 때문에 다른 전문과목의 조사원이 객관성을 유지하고 전문과목 간 모범 사례를 전파하는 역할을 합니다(Shapira Y. 교수 인터뷰, 미인용, 2018).

- 미국에서는 의학전문대학원교육인증위원회(ACGME)에서 고용한 한 명 이상의 조사위원(의사 또는 관련 분야의 박사)이 각 방문에 참여합니다.

- 영국의 경우, 방문 팀에는 공공 대표, 학부생, 레지던트(수련의) 및 선임 의사가 포함됩니다.

- 독일에서는 방문팀에 관한 정보를 얻지 못했습니다. 그럼에도 불구하고 방문팀의 역할은 모든 출처의 데이터 사용, 경영진과의 회의, 프로그램 책임자, 레지던트, 교수진 및 기타 행정 담당자 인터뷰, 문서 검토, 물리적 시설 견학, 상세한 서면 보고서 작성, 조치를 위한 권고 또는 제안서 작성 등 대부분 일부 또는 전부가 포함된 유사한 것으로 밝혀졌습니다.

Visiting teams vary among countries by the number of surveyors, their expertise (senior physicians, residents, public representatives, educators) and the length of the visit (see Table 4).

- In Canada and Israel, surveyors are all volunteer physicians, at least one of them from the same specialty and another from a different specialty. Since the visit focuses on the processes and framework of education and not on specific treatments, a surveyor from a different specialty serves for objectivity and spreading best practices between specialties (Interview with Prof. Shapira Y., unreferenced, 2018).

- In the United States, one or more surveyors employed by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), either physicians or PhDs in a relevant field, participate in each visit.

- In The United Kingdom, the visiting team includes public representatives, an undergraduate students and a resident (trainee) as well as senior physicians.

- We acquired no information regarding visiting teams in Germany. Visiting team’s roles, nevertheless, were found to be similar and include mostly some or all of the following: using data from all sources, meeting with management, interviewing program director, residents, faculty and other administrative representatives, reviewing documentation, touring physical facilities, writing a detailed written report and compiling recommendations or proposals for action.

영국에서는 팀이 한 지역과 그 지역에 위치한 일부 LEP(Local Education Provider)를 방문하는 반면, 캐나다에서는 각 대학과 모든 프로그램을 방문합니다. 하지만 하나의 프로그램이 여러 LEP에서 제공될 수 있기 때문에 사실상 영국과 캐나다의 방문 샘플링은 거의 차이가 없을 수 있습니다. 미국에서는 모든 펠로우십이 연결된 프로그램을 방문하고, 이스라엘에서는 각 사이트를 방문합니다. 시스템 간의 주요 차이점 중 하나는 연간 방문 횟수입니다. 이는 여러 가지 요인에 의해 영향을 받는데,

- 초기 인증을 요청하는 사이트를 방문하는지 여부(캐나다와 영국은 해당 시점에 서류에만 의존),

- 주기 기간(4년에서 10년 사이),

- 일반적인 조사 정책

- 각 사이트/프로그램을 모두 방문할지(미국 및 이스라엘과 같이) 또는

- 위험이 의심되는 경우(영국과 같이)에 방문할지

- 국가 내 교육 프로그램/사이트의 수

이는 시스템 비용과 효율성에 영향을 미칩니다.

While in The United Kingdom, teams visit a region and some of the LEPs located therein, in Canada visits are made to each university and all of its programs. Nevertheless, since one program might be provided by several LEPs, there may be little difference between the UK and Canada visit sampling de facto. In the United States, visits are made to programs with all the attached fellowships, and in Israel to each site. One major difference among the systems is the number of visits conducted annually. This is influenced by several factors:

- whether a visit is made to a site requesting initial accreditation (Canada and the United Kingdom rely on documentation only at that point);

- the length of the cycle (varying between 4 and 10 years);

- the inspection policy in general, which determines

- whether a visit is conducted to each site/program (as in the United States and Israel); or

- when a risk is suspected (as in the United Kingdom) and

- the number of training programs/sites in the country.

This has implications for system costs and efficiency.

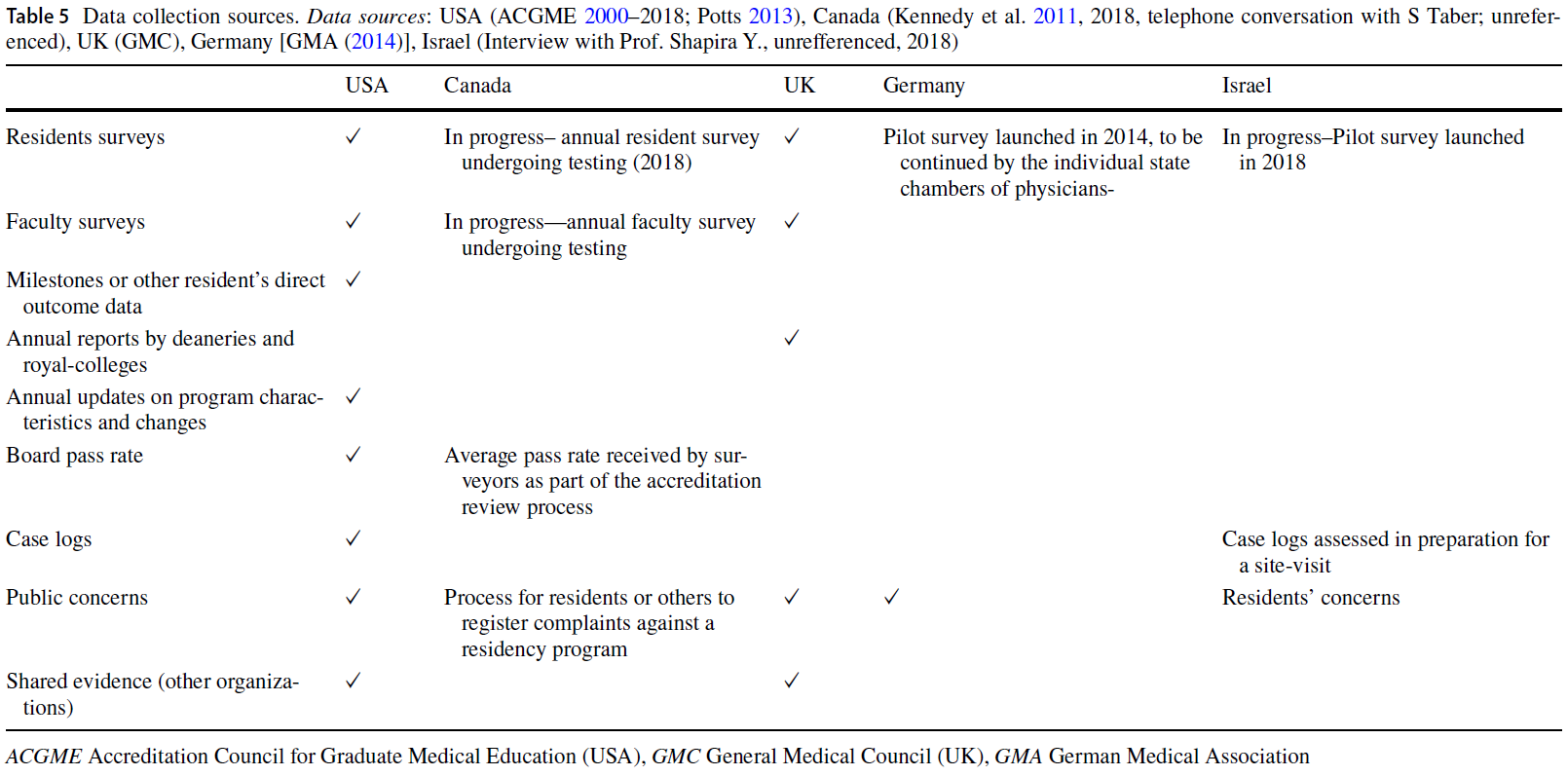

5개국은 현장 방문을 통해 수집한 정보를 넘어 데이터를 보강하기 위해 다양한 데이터 소스를 사용합니다(표 5). 가장 일반적인 방법은 설문조사, 특히 전공의 설문조사입니다.

- 미국과 영국은 일상적으로 설문조사를 통해 정보를 수집하고 있으며, 캐나다, 독일, 이스라엘은 현재 전공의 설문조사를 진행하고 있습니다.

- 독일의 경우, 설문조사가 인증 목적으로 특별히 고안된 것은 아니지만 설문지 자체에 수련 시설 및 수련 활동에 관한 질문이 주로 포함되어 있습니다(GMA 2015).

The five countries employ varied data sources (Table 5) to enrich data beyond the information gathered by site-visits. The most common method is surveys, in particular, resident surveys.

- The United States and the United Kingdom routinely gather information using a survey,

- while Canada, Germany and Israel are currently constructing a resident survey.

- In Germany, surveys were not declared to be specifically designed for accreditation purposes, but the questioner itself contains mainly questions regarding the training facility and training activities (GMA 2015).

미국에서는 레지던트 평가위원회가 매년 연례 업데이트(프로그램 변경 사항, 프로그램 특성, 참여 기관, 교육 환경 등), 레지던트/펠로우 설문조사, 임상 경험, 인증 시험 합격률, 교수진 설문조사, 학술 활동, 반기별 레지던트 평가(나중에 자세히 설명할 마일스톤 포함), 데이터 누락 등 다양한 데이터 소스를 사용하여 프로그램을 검토합니다(Potts 2013).

In the United States, Residency Review Committees review programs annually by using multiple sources of data: annual updates (program changes, program characteristics, participating sites, educational environment and others), resident/fellow survey, clinical experience, certification examinations pass rate, faculty survey, scholarly activity, semi-annual resident evaluation (including milestones which will be further explained later on) and omission of data (Potts 2013).

미국, 캐나다, 영국에서 사용되는 자체 평가는 신청 기관이 현장 방문에 앞서 내부 검토를 수행하고 자체 개선을 촉진하는 보고서를 작성하도록 요구합니다.

Self-evaluation used in the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom, requires the applying institution to conduct an internal review preceding the site visit and compiling a report promoting self-improvement.

인증의 결과

Consequences of accreditation

인증 신청은 다양한 결과를 초래할 수 있습니다(ACGME 2015-2016, Potts 2013, GMA 2003-2015, RCPSC 외. 2012, GMC 2016a, IMA 2014): "최초 인증", "계속 인증", "조건부 인증"("수습" 또는 "경고 포함") 및 "인증 철회". 일부 국가에서는 전체 강의 계획서 요건을 충족할 능력이 부족한 프로그램이 전공의를 다른 곳에서 일정 기간의 교육을 이수하도록 보내 인증을 받을 수 있습니다. 이를 "부분 인증"이라고도 합니다. 대부분의 국가에서는 특정 규칙("통합 사이트", "기관 간 제휴 계약", "컨소시엄", "공동/결합 인증" 또는 기타)에 따라 두 개의 프로그램/기관/사이트가 레지던트 교육을 위한 노력과 자원을 함께 할 수 있도록 허용합니다.

An application for accreditation may result in various outcomes (ACGME 2015–2016; Potts 2013; GMA 2003–2015; RCPSC et al. 2012; GMC 2016a; IMA 2014): “Initial Accreditation”, “Continued Accreditation”, “Conditioned Accreditation” (also called “Probationary” or “With Warning”) and “Withdrawal of Accreditation. In some countries, a program that lacks the ability to support the full syllabus requirements, may receive accreditation by sending its residents to complete certain periods of training elsewhere. This is sometimes referred to as “Partial Accreditation”. Most countries allow for two programs/institutions/sites to join efforts and resources to train residents together under certain rules (“integrated sites”, “Inter-institution affiliation agreements”, “Consortium”, “Conjoint/combined accreditation” or other).

인증 철회는 수치 데이터를 확보할 수 있는 모든 국가에서 신중하게 사용되었습니다. 2016년 이스라엘에서는 5건(전체 인증 사이트의 0.3%), 미국에서는 42건(전체 인증 프로그램의 0.4%), 영국에서는 0건의 인증 철회가 있었습니다. 캐나다에서는 '탈퇴 의사 통지' 항목이 프로그램 개선을 위한 강력한 도구로 사용되기 때문에 탈퇴가 거의 발생하지 않습니다(2018년, S Taber와의 전화 통화, 출처 불명). 이러한 탈퇴 중 일부는 자발적으로 이루어지는 경우가 많기 때문에 사실상 거의 사용되지 않습니다. 결과의 선택권을 실질적으로 확대하고 프로그램/사이트에 개선 동기를 부여하기 위해 일부 국가에서는 더 광범위한 규모의 결과를 사용합니다.

Withdrawal of accreditation was carefully used in all countries for which we could obtain numerical data. In 2016, there were 5 withdrawals in Israel (0.3% of accredited sites), 42 in the United States (0.4% of accredited programs) and 0 in the United Kingdom. In Canada, withdrawal is rare as the “notice of an intent to withdraw” category serves as a powerful tool to enable programs to make improvements (2018, telephone conversation with S Taber; unreferenced). Since some of these withdrawals are voluntary—this consequence is rarely used de-facto. In order to practically expand options for consequences and give programs/sites motivation for improvement, a broader scale of consequences is used in some countries.

과정 기반/결과 기반 인증 시스템

Process-based/outcome-based accreditation system

결과 기반 PGME 모델은 1990년대 후반에 처음 도입되었지만, 호환 가능한 결과 기반 인증 시스템이 개발되는 데는 거의 15년이 걸렸습니다.

Although outcome-based PGME models were first introduced during the late 1990s, it took almost 15 years for compatible outcome-based accreditation systems to be developed.

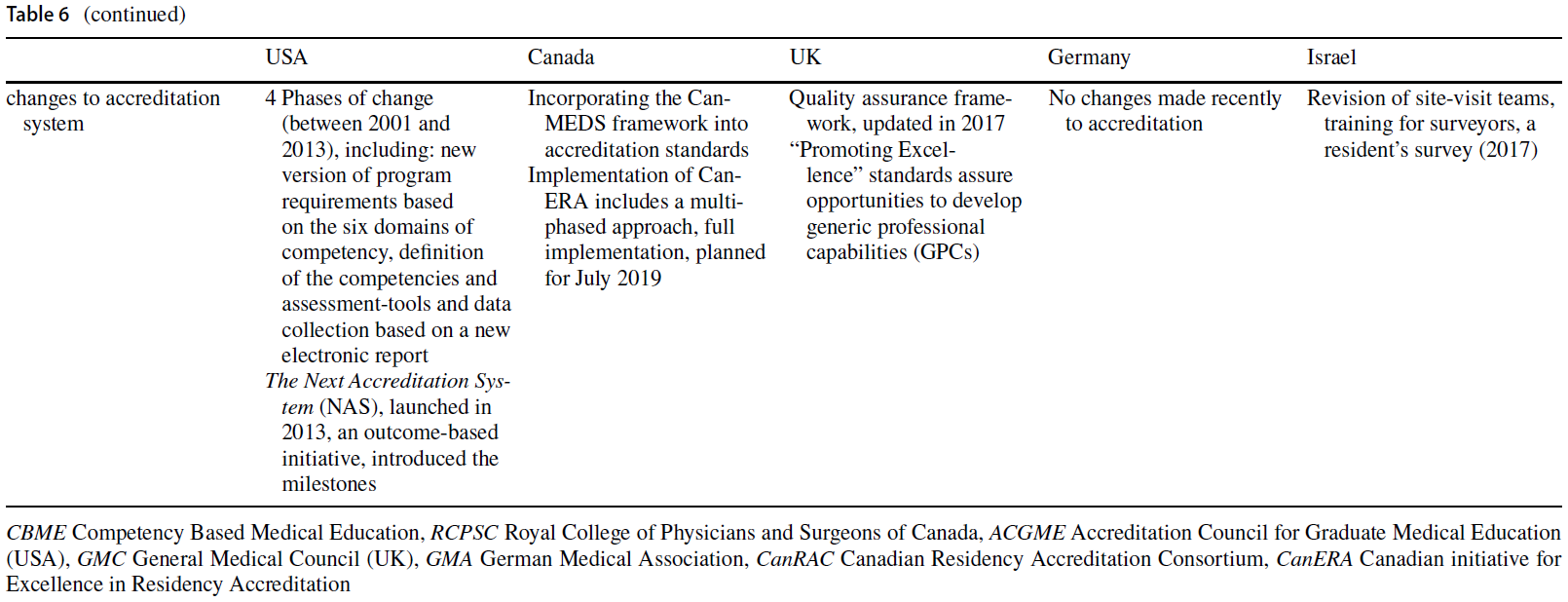

표 6에 명시된 바와 같이, 우리는 지난 20년간 인증 시스템의 변화 과정을 3단계로 나누어 설명할 수 있었습니다.

- 1990년대 후반까지는 시간/과정 기반 레지던트 수련 프레임워크와 일치하는 전통적인 시간/과정 기반 인증 시스템이 우세했습니다. 이러한 시스템은 프로그램 구조를 강조하고, 공식 교육의 양과 질을 높이며, 서비스와 교육 간의 균형을 도모하고, 레지던트 평가와 피드백을 촉진하여 긍정적인 결과를 얻었습니다(Nasca 2012).

Our findings, as specified in Table 6, led us to portray a three-phased process of change in accreditation systems over the last two decades. Traditional time/process-based accreditation systems corresponding with time/process-based residency training frameworks prevailed until the late 1990s. Systems such as these emphasized program structure, increased the amount and quality of formal teaching, fostered a balance between service and education, promoted resident evaluation and feedback and gained positive results (Nasca 2012).

새로운 성과 기반 PGME 프레임워크의 시행으로 일부 국가에서는 인증 시스템을 변경해야 한다는 의견이 제기되었습니다. 이를 위해 각 프로그램의 노력과 자원에 대한 평가를 포함하도록 표준을 개정하여 전공의가 모든 필수 영역에서 역량을 확보할 수 있도록 했습니다. 경우에 따라서는 데이터 수집을 업그레이드하고 정보를 확인하기 위해 현장 방문을 조정하기도 했습니다.

Implementation of new outcome-based PGME frameworks raised, in some countries, the idea of changing accreditation systems. For that purpose, standards were revised to include evaluation of each program’s efforts and resources to allow its residents to gain competencies in all the required domains. In some cases, data collection was upgraded as well and site-visits adapted to verify the information.

예를 들어,

- GMC 표준은 모든 졸업후의학교육 프로그램이 레지던트에게 커리큘럼에서 요구하는 임상 또는 의료 역량(또는 둘 다)을 달성하고 유지할 수 있는 충분한 실무 경험을 제공하도록 요구합니다(GMC 2015). 커리큘럼 설계 및 개발 표준인 "Excellence by Design"과 교육 프로그램의 품질 보증 및 승인 표준인 "Promoting Excellence"는 모두 "우수 의료 행위" 및 "일반 전문 역량"의 결과 기반 프레임워크와 일치합니다(GMC 2015, 2017b).

- 캐나다 표준은 각 프로그램이 임상, 학술 및 학술적 내용, 교육 및 평가 활동, 교수진 개발에서 결과 기반 용어로 목표를 명확하게 정의하는 데 있어 CanMEDS 역량 프레임워크를 기초로 설정합니다(RCPSC 2007a, b 편집 개정판-2013년 6월, 2007년 재인쇄 2011년 1월).

- ACGME는 인증 심사 시 프로그램에 레지던트의 역량을 가르치고 평가하는 방법을 설명하고, 레지던트의 학습 기회를 개선하기 위해 변경된 사항을 보고하도록 요구합니다(Swing 2007). 이 시행 시점의 계획대로, 인증에 결과 데이터를 사용하는 것은 아직 이루어지지 않았기 때문에 인증은 프로그램의 교육 결과가 아닌 역량을 가르치고 평가하는 과정에 초점을 맞추었습니다(Swing 2007).

- GMC standards, for example, require all postgraduate programs to give residents sufficient practical experience to achieve and maintain the clinical or medical competences (or both) required by their curriculum (GMC 2015). Both standards for curricula design and development “Excellence by Design” and standards for quality assurance and approval of training programs “Promoting Excellence” are concurrent with the outcome-based frameworks of “Good Medical Practice” and “General Professional Capabilities” (GMC 2015, 2017b).

- Canadian standards set the CanMEDS roles framework of competencies as the basis for each program in clearly defining objectives in outcome-based terms, in clinical, academic and scholarly content, in teaching and assessment activities and in faculty development (RCPSC 2007a, b Editorial Revision—June 2013, 2007 reprinted January 2011).

- The ACGME requires programs at their accreditation review, to describe how they are teaching and assessing their residents’ competencies and report changes made to improve residents’ learning opportunities (Swing 2007). As planned at this point of implementation, the use of outcome data in accreditation had not occurred yet, and therefore accreditation focused on the processes of teaching and assessing the competencies and not on of programs’ educational outcomes (Swing 2007).

또 다른 변화의 단계는 역량 기반 의학교육과 인증 과정 간의 더 나은 동기화에 대한 필요성이 인식되면서 일어났습니다.

- 미국에서 ACGME는 "성과 프로젝트"의 약속을 실현하고 성과에 대한 공적 책무성을 제공하기 위해 성과에 기반한 프로그램을 인증하는 것을 목표로 선언했습니다(Potts 2013).

- 이러한 목표와 다른 목표에 부응하기 위해 ACGME는 2013년에 인증에서 교육 결과 데이터의 사용 증가를 강조하는 차기 인증 시스템(NAS)을 만들었습니다.

- NAS의 일환으로, ACGME는 전공의가 교육 시작부터 무감독 전문과목 실습에 이르기까지 점진적으로 입증할 수 있는 역량 기반 개발 성과인 마일스톤도 도입했습니다(ACGME 2015a).

- "성과"라는 약속의 결실을 맺을 수 있도록 하는 마일스톤은 프로그램과 기관에서 자체 평가 및 개선을 위해 사용됩니다.

- NAS를 시행하는 모든 프로그램의 레지던트가 달성한 마일스톤 데이터는 ACGME에서 1년에 두 번 수집합니다. 이 데이터는 레지던트 검토 위원회에서 프로그램에 관한 연례 데이터 검토의 일부로, 그리고 집계된 형태로 전문과목별 국가 규범 데이터로 사용되었습니다.

- 마일스톤은 전국적으로 프로그램의 벤치마크 역할을 하도록 설계되었습니다(Potts 2013).

Another phase of change took place when a need for better synchronization between the competency-based medical education and accreditation process was realized.

- In the United States, the ACGME pronounced its goal to accredit programs based on outcomes, to realize the promise of the “Outcomes Project” and to provide public accountability for outcomes (Potts 2013).

- To answer these goals and others, ACGME created in 2013 the Next Accreditation System (NAS) which emphasized an increased use of educational outcome data in accreditation.

- As part of NAS, the ACGME also introduced Milestones, competency-based developmental outcomes that can be demonstrated progressively by residents from the beginning of their education to the unsupervised practice of their specialties (ACGME 2015a).

- The milestones, which were said to permit fruition of the promise of “Outcomes”, are used by programs and institutions for self-evaluation and improvement.

- Data of milestones achieved by residents of all programs implementing NAS has been collected twice a year by ACGME. It has been used by Residency Review Committees as part of annual data review regarding a program and in its aggregated form as a specialty specific national normative data.

- Milestones were designed to serve as a benchmark for programs nationally (Potts 2013).

2017년, 성과 기반 교육에는 성과 기반 인증이 필요하다는 것을 인식한 캐나다의 이니셔티브 CanRAC은 CBME 모델로 전환하는 레지던트 프로그램의 증가를 반영하기 위해 개발된 새로운 인증 시스템인 CanERA를 발표했습니다(CanRAC 2018a).

- 새로운 시스템은 새로운 평가 프레임워크, 새로운 표준, 기관 검토 프로세스, 새로운 결정 범주 및 임계치, 8년 주기 및 데이터 통합, 향상된 인증 심사, 디지털 인증 관리 시스템, 학습 환경 강조, 지속적인 개선 및 평가와 연구 강조 등 새로운 기능을 도입했습니다(CanRAC 2018b).

In 2017, after recognizing that outcomes-based education requires outcomes-based accreditation, the Canadian initiative CanRAC announced a new accreditation system called CanERA, which was developed to reflect the increasing number of residency programs shifting to a CBME model (CanRAC 2018a).

- The new systems introduced new features, among them a new evaluation framework, new standards, institution review process, new decision categories and thresholds, 8 years cycle and data integration, enhanced accreditation review, digital accreditation management system, emphasis on learning environment, emphasis on continuous improvement and evaluation and research (CanRAC 2018b)

인증 프로세스를 성과 기반 프로세스로 전환하는 것은 점진적으로 이루어졌으며, 한 번에 몇 개의 대학(캐나다) 또는 한 번에 몇 개의 전문 분야(영국, 미국)를 대상으로 이루어졌습니다. 예를 들어, 2019년 7월 1일로 예정된 전체 시행에 앞서 여러 대학에서 3단계의 프로토타입 테스트 단계를 포함하는 다단계 접근 방식을 통해 CanERA를 시행하고 있습니다(CanRAC 2018c).

Adaptation of the accreditation process to outcome-based process was gradual, concerning few universities at a time (Canada) or few specialties at a time (UK, USA). The implementation of CanERA, for example, includes a multi-phased approach containing 3 prototype testing phases in several universities prior to full implementation, which is planned for July 1, 2019 (CanRAC 2018c).

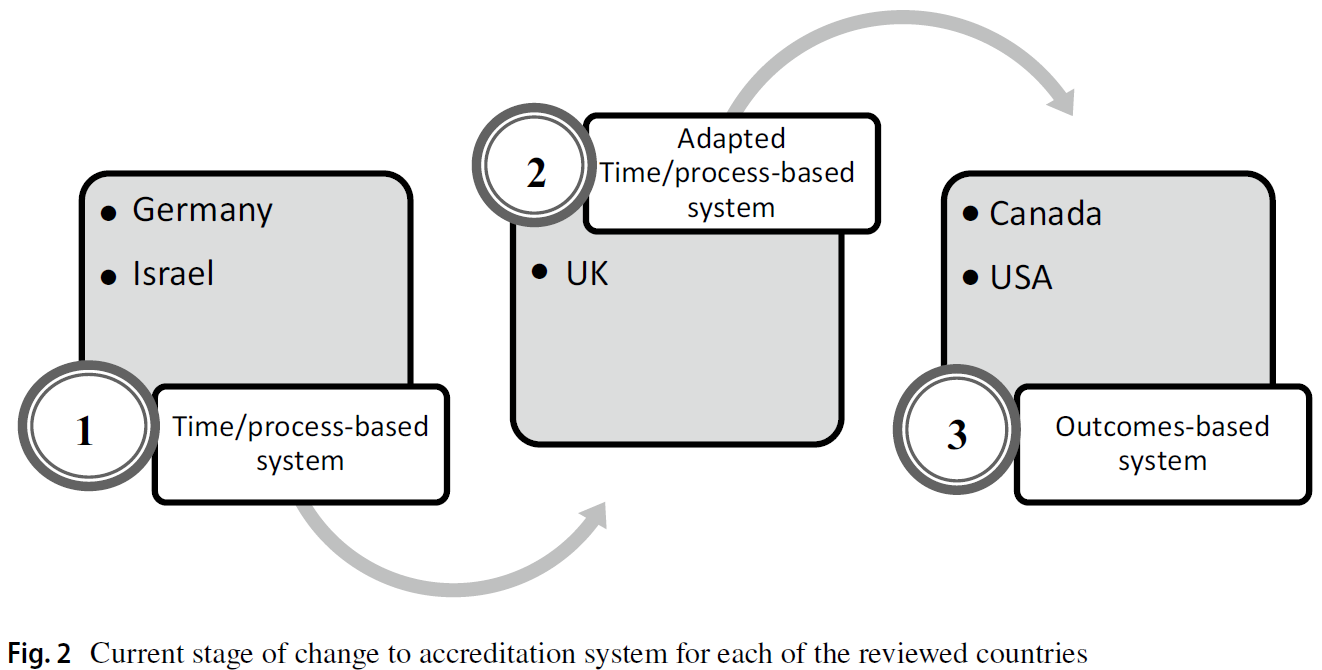

그림 1은 변화의 과정을 요약하고, 그림 2는 검토 대상 5개 국가별로 현재 변화의 단계를 설명합니다.

Figure 1 summarizes the process of change and Fig. 2 describes the current stage of change for each of the five reviewed countries.

토론

Discussion

현장 방문, 정보 수집, 자체 평가를 통해 표준을 정의하고 그 이행 여부를 검증하는 여러 국가의 PGME 인증 방식에서 유사한 원칙을 많이 발견했습니다. 적용 세부사항을 보면 지역 보건 시스템의 구조와 복잡성, 문화와 맥락에서 비롯된 차이점이 드러납니다(Saltman 2009, Segouin과 Hodges 2005).

We found many similar principles in the way different countries accredit PGME-defining standards and verifying their fulfillment by site visits, information gathering and self-evaluations. The application details reveal differences originating from the structure and complexity of the local health system, as well as from culture and context (Saltman 2009; Segouin and Hodges 2005).

현장 방문은 5개국 모두에서 어느 정도 적용되는 대표적인 도구 중 하나이지만 빈도, 계기, 방문 팀, 방문 단위 및 기타 요인에서 차이가 발견되었습니다.

- 캐나다와 이스라엘의 조사원은 대부분 무보수로 활동하는 의사인 반면, 영국에서는 전문의와 수련의, 공공 대표로 구성된 팀이 모두 동일한 일당을 지급받습니다.

- 동료 조사원은 인증 당국뿐만 아니라 조사원의 의견(도스 산토스 외 2017)에 따르면 혁신과 모범 사례의 수정 및 확산(케네디 외 2011)과 내부의 눈이 보지 못하는 것을 볼 수 있는 능력에서 유리한 것으로 나타났습니다. 그럼에도 불구하고 의사들은 설문조사 및 조사원의 기술 개발에 투자할 시간이 충분하지 않을 수 있습니다.

- 또한, 자원자가 감소하는 시기에 동료 검토자를 유지하는 데 어려움이 있습니다(Kennedy 외, 2011). 미국에서 사용되는 전문 조사원과 동료 조사원의 조합은 비용이 증가하지만 프로세스에 전문성을 더하는 방법으로 제안되었습니다(Dos Santos 외. 2017).

- 다른 국가에서는 아직 영국의 GMC처럼 조사팀에 공공 대표를 임명하지 않았지만, PGME 결과에 대한 이해관계자로서 의료 소비자를 참여시키는 방안에 대해 더 논의할 필요가 있습니다.

Site visits are one prominent tool applied to some extent by all five countries, but variations were found in their frequency, triggers, visiting teams, visited units and other factors.

- In Canada and Israel, surveyors are physicians, mostly unpaid for their work, while in The United Kingdom teams include specialists as well as trainees and public representatives, all paid the same daily fee.

- Peer-surveyors were seen to be advantageous by accrediting authorities, as well as in the surveyors’ opinion (Dos Santos et al. 2017) for fertilization and diffusion of innovations and best practices (Kennedy et al. 2011) and the ability to see what internal eyes may not notice. Nevertheless, physicians may not have enough time to devote to surveying and developing surveyors’ skills.

- Moreover, there is a challenge in maintaining peer-reviewers in a time of decline in volunteers (Kennedy et al. 2011). A combination of professional surveyors (as used in the United States) and peer-surveyors was suggested as a way of adding expertise to the process (Dos Santos et al. 2017), although it would increase costs.

- None of the other countries has yet appointed public representatives to the surveying teams as did the GMC in UK, though the idea deserves further discussion regarding the involvement of the consumers of health care as stakeholders in the results of PGME.

자체 평가는 3개국에서 사용되며 일부 국가에서는 비교적 새로운 방식입니다(Guralnick 외. 2015). 일부 규제기관에서는 자체평가를 품질 보증 강화 접근법의 핵심으로 인식하는 반면, 다른 규제기관에서는 신뢰할 수 없다는 의견을 제시하고 있습니다(Colin Wright Associates Ltd 2012). 자체 평가는 PGME를 제공하는 기관에 대한 더 많은 신뢰를 바탕으로 지역 수준에서 품질 개선에 대한 강조를 증가시킬 수 있습니다(Akdemir 외. 2017). 자체평가 방법이 교육 지도자들이 프로그램을 개선하기 위해 행동에 옮길 수 있는 의미 있는 정보를 제공하는지 알아보기 위해서는 더 많은 연구가 필요합니다.

Self-evaluation is used by three countries and is relatively new to some of them (Guralnick et al. 2015). It is perceived by some regulators as the heart of the enhancement approach to quality assurance, while others suggest that it is unreliable (Colin Wright Associates Ltd 2012). Self-evaluation may increase emphasis on quality improvement at the local level, based on more trust in the institutions providing PGME (Akdemir et al. 2017). More research is needed to learn whether self-evaluation methods provide meaningful information that educational leaders can act on to improve their programs.

모든 인증 당국은 각 기관의 교육 품질에 관한 최신의 정확한 정보를 유지하기를 원합니다. 이러한 정보의 축적은 주로 몇 년에 한 번씩 현장을 방문하여 보고된 정보를 기반으로 이루어졌습니다. 여러 국가에서 설문조사, 연례 보고서 또는 온라인 플랫폼을 통해 수집한 데이터, 전공의의 우려 사항, 보건 기관의 정보 등 다양한 출처를 사용하여 '실시간'으로 지속적인 데이터를 수집하는 방식으로의 전환이 진행되고 있습니다.

All accreditation authorities wish to maintain updated, accurate information regarding the quality of training in each institution. Accumulation of this information was once primarily based on information reported by a site visit once every few years. A shift to ongoing data collection in “real time” is advancing in several countries, using a variety of sources including surveys, annual reports or data collected through on-line platforms, concerns from residents of others and information from other health organizations.

검토 대상 국가 중 일부는 다른 변화 중에서도 기관의 관점을 더 강조하게 되었습니다. ACGME는 새로운 기관 요건, 기관 자체 학습 방문 및 CLER(임상 학습 환경 검토) 방문을 도입했습니다. RCPSC는 새로운 CanERA의 요소로 기관 검토 프로세스를 도입했습니다. GMC의 의학 교육 및 훈련에 대한 " Promoting excellence" 표준은 영국의 의대생과 의사를 교육하고 훈련하는 기관이 표준을 충족할 책임을 져야 한다고 명시하고 있습니다

Some of the reviewed countries came to put more emphasis on the institutional perspective among other changes. The ACGME introduced New Institutional Requirements, Institutional self-study visits and CLER (Clinical Learning Environment Review) visits. The RCPSC introduced an institution review process as an element of the new CanERA. The GMC’s standards for medical education and training “Promoting excellence” declare an expectation for organizations for educating and training medical students and doctors in the UK to take responsibility for meeting the standards.

우리가 검토한 국가 중 일부는 성과 기반 PGME로 전환하면서 앞서 설명한 대로 인증 시스템의 조정이 필요하다는 것을 깨달았습니다. 미국과 캐나다는 성과에 기반한 인증 시스템을 구현함으로써 한 걸음 더 나아갔습니다. 앞서 언급했듯이 마일스톤은 차세대 인증 시스템의 핵심 구성 요소입니다. 차세대 인증 시스템에서는 의도적으로 단일 프로그램을 레지던트의 마일스톤 기록까지 측정하지는 않지만, 집계된 수준에서의 마일스톤을 사용합니다. 마일스톤의 초기 유효성 증거(Su-Ting 2017)와 함께, 효과적인 교육을 입증해야 하는 프로그램의 요구가 수련의에게 기대되는 점수를 부여하는 경향으로 인해 측정에 영향을 미치고 있다는 우려가 제기되었습니다(Witteles 2016). ACGME는 레지던트 또는 프로그램에 관한 중대한 결정에 마일스톤이 사용될 경우 레지던트의 마일스톤 평가 데이터가 인위적으로 부풀려질 수 있다는 우려를 표명하고(ACGME, 2018b), 적어도 초기 단계에서는 검토위원회가 각 레지던트/펠로우에 대해 평가된 수준을 기준으로 프로그램을 판단하지 않을 것이라고 명시하고 있습니다(ACGME 2018a).

Some of the countries we reviewed made the transition to an outcome-based PGME and realized it requires an adaptation of the accreditation system, as described earlier. The United States and Canada have taken another step by implementing an accreditation system based on outcomes. As mentioned earlier, milestones are a central component of the Next Accreditation System. Though the Next Accreditation System intentionally does not measure a single program up to its resident’s milestones records, it uses the milestones on an aggregated level. Alongside initial validity evidence of the milestones (Su-Ting 2017), some concerns were raised that programs’ needs to demonstrate effective education are influencing the measurement by the tendency to give trainees the scores they are expected to have (Witteles 2016). The ACGME itself declares its concern that programs may artificially inflate residents’ milestones assessment data if the milestones are used for high stakes decisions regarding residents or programs (ACGME, 2018b) and states that Review Committees will not judge a program based on the level assessed for each resident/fellow (ACGME 2018a), at least at the early phase.

RCPSC는 CanMeds 2015 프레임워크의 일부로 마일스톤을 도입했지만 인증 제안을 위해 학습자의 데이터를 통합하지는 않습니다. RCPSC는 중요한 절차적 요건과 구조적 요건, 그리고 결과 측정 간의 적절한 균형을 찾고 있습니다(2018년, S Taber와의 전화 통화, 미참조).

The RCPSC has introduced milestones as part of the CanMeds 2015 framework, but does not integrate learner’s data for accreditation proposes. The RCPSC is looking for the right balance between the important procedural and structural requirements with any measurement of outcomes (2018, telephone conversation with S Taber; unreferenced).

의학전문대학원 교육 개선의 궁극적인 목표는 환자 치료의 질적 향상이므로, 향후 인증 과정의 목표는 인증 결정을 위한 또 다른 데이터 소스로서 환자 치료 결과를 측정하는 것일 수 있습니다. 10여 년 전, ACGME는 환자 진료의 질과 역량 교육을 연계하는 아웃컴 프로젝트의 또 다른 단계에 대한 비전을 선언했는데, 이는 역량 교육을 효과적으로 실시하는 레지던트 프로그램이 환자에게 더 나은 진료를 제공한다는 것을 입증하기 위한 시도였습니다(Batalden 외. 2002; Swing 2007). 환자 치료 결과와 교육적 개입을 연계하는 것은 더 많은 시간과 노력을 투자해야 하는 어려운 작업입니다.

Since an ultimate goal of any improvement to Postgraduate Medical Education is quality improvement of patient care, a future aspiration of accreditation processes may be measurement of patient care outcomes as another data source for accreditation decisions. More than a decade ago, the ACGME declared a vision of another phase to its Outcome Project, linking patient care quality and education in the competencies, in an attempt to establish that residency programs that have effective education in the competencies, give better care to their patients (Batalden et al. 2002; Swing 2007). Linking patient outcomes with educational interventions is a challenging task which would probably take more time and effort investment.

PGME 인증 거버넌스의 중앙집권화 수준은 국가와 지방 당국 간의 역할 분담, 인증 기관이 관리하는 기타 PGME 측면(예: 강의 계획서, 보드 시험)의 수에 따라 국가마다 다릅니다.

- 중앙집권형 척도의 한쪽 끝에는 캐나다와 이스라엘이 있는데, 한 국가 기관이 PGME의 세 가지 측면을 모두 책임지고 있으며(다른 보건 부문 기관과 협력하여),

- 분산형 척도에서는 독일이 있는데, 17개 주정부가 모든 PGME 업무를 매우 다양하게 수행하고 있습니다.

- 독일 연방 구조상 주 의사회에 의사의 전문 업무에 관한 광범위한 자율 규제 권한이 부여되어 있기 때문에 독일 제도의 분권적 특성이 제도의 기능에 영향을 미치는 주요 요인으로 작용하는 것으로 나타났습니다.

- 독일 전역에 걸쳐 전문의 수련 규정의 통일성을 높이기 위해 독일 의회의(독일 의사협회 연례 총회)는 주 의회의 모범이 될 권장(모델) 전문의 수련 규정을 채택했습니다. 그러나 각 주 의회가 항상 권고한 대로 정확하게 이행하는 것은 아닙니다(Nagel 2012).

- 독일 의학교육학회 의학전문대학원 교육위원회는 2013년에 발표한 입장문(David 외 2013)에서 투명하고 국가적으로 표준화된 질 보증 절차를 수립할 필요성을 강조하면서 독일 내 의학전문대학원 교육의 구조, 과정, 산출물, 결과 및 영향을 평가할 수 있는 역량을 갖춘 단일 국가 질 보증 기관을 설립할 것을 권고했습니다. 이 기관은 의학 대학원 교육 프로그램 실행을 위한 지침을 제공하고 품질 보증 프로그램, 감사 및 동료 검토를 시작해야 합니다. 저자가 아는 한, 이러한 기관은 아직 설립되지 않았습니다.

The level of centralization in PGME accreditation governance varies between countries: the division of roles between national and local authorities and the number of other PGME aspects governed by the accrediting authority (i.e., syllabi, board examinations).

- On one end of this centralization scale we found Canada and Israel, where one national authority is responsible for all three aspects of PGME (in collaboration with other health sector authorities),

- while on the decentralized end we found Germany, in which all PGME tasks are performed by the 17 state chambers with much variation.

- We found the decentralized nature of the German system to be a dominant factor influencing its functioning, as the federal structure of Germany has granted the state chambers of physicians far reaching self-regulation powers concerning the professional practice of physicians.

- To increase uniformity of specialty training regulations across the entire country, the German Medical Assembly (annual assembly of the German Medical Association) has adopted the recommended (Model) Specialty Training Regulations to serve as a template for the state chambers. However, these are not always implemented by the chambers exactly as advised (Nagel 2012).

- In a position paper published on 2013 (David et al. 2013), the German committee on graduate medical education of the Society for Medical Education has emphasized the need to establish a transparent and nationally standardized quality assurance procedure and therefore recommended the foundation of a single national quality assurance institution with capacities to evaluate structure, process, outputs, outcome and impact of graduate medical education in Germany. The institution should provide guidelines for implementing graduate medical training programs and initiate quality assurance programs, audits and peer-reviews. To the best of the authors knowledge, an institution as such has not yet been founded.

영국에서는 GMC가 국가 기관이지만 지역 이사회와 학장에 의존하고 실행 권한의 상당 부분을 위임하여, GMC 자체는 주로 품질 보증 및 승인 모니터링에 집중할 수 있습니다.

- 학부 의학교육과 대학원 의학교육에 대한 GMC의 권한은 표준과 절차를 간소화하고 의학교육의 여러 단계 간에 자원을 효과적으로 할당하는 데 긍정적인 기여를 할 수 있는 또 다른 독특하고 흥미로운 특징입니다.

- GMC의 또 다른 역할은 모든 전문분야에서 국가 교육과정을 승인하는 것으로, 2017년에는 인증 기준의 기본 원칙에 따라 교육과정을 설계하고 개발하는 기준을 설정하는 " excellence by design"(GMC 2017b)이라는 새로운 표준 프레임워크를 도입했습니다(GMC 2015).

- 단일 기관이 넓은 관할권을 포괄하기는 쉽지 않지만, 모든 역할을 한 기관에 통합하면 PGME의 모든 측면을 더 쉽게 동기화하고 성과 기반 의학교육으로의 전환과 같은 개혁을 촉진할 수 있다고 믿습니다.

In the United Kingdom, though being a national authority, the GMC relies on the local boards and deaneries, and delegates much of its power of execution, allowing GMC itself to focus mainly on monitoring quality assurance and approvals.

- GMC’s mandate over undergraduate medical education as well as on Postgraduate Medical Education, is another unique and interesting characteristic which may have a positive contribution to streamlining standards and processes as well as effectively allocating resources between the different stages of medical education.

- As another role of the GMC is the approval of national curricula in all specialties, it has introduced during 2017 a new framework of standards called “excellence by design” (GMC 2017b) which sets standards for designing and developing of curricula in accordance with the fundamental principles underlining the accreditation standards as well (GMC 2015).

- Though a single authority may not easily cover a large jurisdiction, we do believe that integration of all roles in the hands of one authority makes synchronization of all aspects of PGME easier and may facilitate a reform such as the move to outcome-based medical education.

인증 절차는 레지던트 교육 비용 외에도 인증 기관과 기관 모두에게 복잡하고 유지 비용이 많이 듭니다(Regenstein 외, 2016). 이러한 부담(예: 시간 및 자원)을 간소화하는 것이 중요하며, 프로그램 리더십의 소진을 예방할 수 있습니다(Dos Santos 외. 2017; Yager와 Katzman 2015). 검토 대상 국가 중 일부는 보다 효율적인 인증 절차를 모색하고 있으며 규제 부담을 줄이고 있습니다. 도스 산토스 외(2017)는 인증 당국이 구조와 프로세스(예: 필요한 문서, 준비 시간)와 인적 자원(예: 조사원 교육, 조사원의 업무와 노력에 대한 인정) 사이에 투자된 자원의 균형에 주의를 기울일 것을 권고합니다. 시스템이 더욱 정교해지고 까다로워질 때마다 증가하는 것으로 보이는 인증 시스템과 관련된 재정적, 관료적 부담이 프로세스의 이점과 균형을 이루고 있는지는 아직 불분명합니다(Yager and Katzman 2015).

Accreditation procedures are complex and costly to maintain, in addition to the cost of residency training (Regenstein et al. 2016), both for the accrediting authority and institutions. Streamlining burden (e.g., time and resources) is important and may as well prevent a contribution to program leadership burnout (Dos Santos et al. 2017; Yager and Katzman 2015). Some of the reviewed countries are looking for more efficient accreditation procedures and are cutting down regulatory burden. Dos Santos et al. (2017) recommend accreditation authorities pay attention to the balance of invested resources between structure and process (i.e., required documentation, time for preparations), and human resources (i.e., training surveyors, recognition of surveyors work and efforts). It is yet unclear whether the financial and bureaucratic burden related to accreditation systems, which seems to increase whenever systems become more elaborate and demanding (Yager and Katzman 2015), is balanced against the benefit of the process.

결론

Conclusions

5개국 모두 혁신을 통해 시스템에 도전했습니다. 다른 국가들도 변화를 계획하고 있을 가능성이 높습니다. 조사 대상 5개국의 비교를 바탕으로 인증 기관이 고려해야 할 몇 가지 권장 사항을 제시합니다:

All five countries have challenged their systems with innovation. It is probable that other countries are planning changes as well. Based on the comparison of the five countries examined, we point out some recommendations for accrediting authorities to consider:

- 1. 결과의 규모 '인증 철회'의 사용은 후원 기관, 전공의는 물론 해당 전공의가 돌보는 환자에게도 심각한 결과를 초래합니다. "경고를 수반한 인증" 및 다음 심사까지 제한된 시간 등 일부 국가에서 강조한 추가 옵션은 다른 국가에서도 인증 철회가 더 극단적인 상황에서만 사용되도록 고려하는 데 도움이 될 수 있습니다.

1.Scale of consequences The use of “Withdrawal of Accreditation” has severe consequences for the sponsoring institution, the residents, as well as to the patients cared for by those residents. Additional options used in some countries which we have highlighted, such as “Accreditation with Warning” and a limited time until the next review, may be helpful for others to consider so that withdrawal of accreditation is reserved for use in more extreme circumstances. - 2. 사이트 방문 정책 방문 빈도 및 방문 트리거를 신중하게 고려해야 합니다. 이 문서에 제시된 사례는 실현 가능성, 비용 효율성 및 교육적 영향을 고려하여 내부 논의를 촉진할 수 있습니다. 더 많은 연구가 진행되면 의사 결정권자가 대안의 이점과 비용을 평가하는 데 도움이 될 수 있습니다.

2.Policy for site visits Frequency of visits and their triggers should be carefully considered. The examples shown in this article may facilitate an internal discussion, taking into account feasibility, cost effectiveness and educational impact. More research may help decision makers evaluate benefits and costs of alternatives. - 3."실시간" 데이터 수집을 위한 여러 출처는 인증 주기를 연장할 뿐만 아니라 위험 기반 접근 방식을 위한 수단으로 사용될 수 있습니다. 그럼에도 불구하고 여기에도 타당성과 비용에 대한 고려가 적용되어야 합니다.

3.Multiple sources for “real time” data collection may serve as means for a risk-based approach as well as for lengthening the accreditation cycle. Nevertheless, considerations of feasibility and costs should be applied here, as well. - 4.결과 기반 PGME로 전환하려면 그에 따라 인증 시스템을 조정해야 합니다. 이러한 적응은 앞서 설명한 3단계 모델에서와 같이 점진적으로 전환하는 것이 도움이 될 수 있습니다. 의심할 여지없이, 다른 나라에서의 시행에서 배울 점이 많습니다.

4.A move to an outcome-based PGME requires adaptation of the accreditation system accordingly. This adaptation may benefit from a gradual transition as depicted earlier and in our three-phased model. No doubt, there is much to learn from its implementation in other countries. - 5. 변화를 계획할 때 국가와 지방 당국 간의 역할 분담과 인증 기관이 관리하는 기타 PGME 측면을 고려해야 합니다.

5.Division of roles between national and local authorities and other PGME aspects governed by the accrediting authority should be considered when planning a change.

우리는 각 국가가 새로운 시스템, 아이디어 또는 도구를 채택하기 전에 현지 상황과 문화에 맞는 적절한 준비를 해야 한다는 점을 강조하고 싶습니다. 인증 당국이 직면한 도전 과제의 공통분모는 각국의 경험을 상호 학습하는 데 도움이 될 것입니다. 따라서 의사 결정권자는 지속적인 혁신과 개선을 위한 원동력으로 다른 관련 국가의 인증 발전 상황을 지속적으로 검토해야 합니다.

We would stress that each country may need to make the suitable preparations accommodating for local context and culture before trying to adopt a new system, idea or tool. The common denominator of the challenges occupying the accreditation authorities would facilitate mutual learning of each country’s experience. Therefore, decision makers should constantly examine developments in accreditation in other relevant countries as an impetus for ongoing innovation and improvement.

실험/준실험 모델, 논리 모델, 커크패트릭의 4단계 모델 또는 CIPP 모델과 같은 일부 최근 평가 모델은 인증 시스템의 생성 및 개선에 대한 이론적 배경이 될 수 있습니다(Frey and Hemmer 2012). 저자들은 구조와 복잡성, 맥락 및 문화적 차이를 고려한 CIPP 모델이 인증 의사결정권자의 변화 관리 및 개선 노력에 도움을 줄 수 있다고 생각하지만, 의사결정권자는 다양한 모델을 숙지하는 것이 좋습니다.

Some recent evaluation models such as the experimental/quasi-experimental models, the Logic model, Kirkpatrick’s 4-level model or the CIPP model, may serve as a theoretical background for the creation and improvement of accreditation systems (Frey and Hemmer 2012). In the authors minds, the CIPP model which takes the structure and complexity, context and culture differences into account may offer support for accreditation decision makers in their efforts for change management and improvement, though decision makers are encouraged to familiarize themselves with different models.

방법의 한계

Limitations of methods

본 검토는 주로 문헌과 공개된 문서에 의존했기 때문에 공개되지 않은 세부 정보가 부족할 수 있습니다. 일부 국가에서는 정보가 풍부했지만 다른 국가에서는 정보가 부족했습니다. 추가 정보를 얻기 위해 관련 당국에 연락을 취했지만 일부 세부 정보는 여전히 불완전한 상태였습니다.

Our review relied mostly on literature and published documents and therefore may lack details that were not made public. Information was abundant for some countries but lacking for others. Efforts were made to contact relevant authorities for further information but some details remained incomplete.

Accreditation systems for Postgraduate Medical Education: a comparison of five countries

PMID: 30915642

Abstract

There is a widespread consensus about the need for accreditation systems for evaluating post-graduate medical education programs, but accreditation systems differ substantially across countries. A cross-country comparison of accreditation systems could provide valuable input into policy development processes. We reviewed the accreditation systems of five countries: The United States, Canada, The United Kingdom, Germany and Israel. We used three information sources: a literature review, an online search for published information and applications to some accreditation authorities. We used template analysis for coding and identification of major themes. All five systems accredit according to standards, and basically apply the same accreditation tools: site-visits, annual data collection and self-evaluations. Differences were found in format of standards and specifications, the application of tools and accreditation consequences. Over a 20-year period, the review identified a three-phased process of evolution-from a process-based accreditation system, through an adaptation phase, until the employment of an outcome-based accreditation system. Based on the five-system comparison, we recommend that accrediting authorities: broaden the consequences scale; reconsider the site-visit policy; use multiple data sources; learn from other countries' experiences with the move to an outcome-based system and take the division of roles into account.

Keywords: Accreditation; Outcome-based medical education; Postgraduate Medical Education; Residency.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 세계화, 다양한 국가' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 중국의 2021년 의료전문직 면허법 수정: 코멘터리(Health Syst Reform. 2022) (0) | 2023.11.19 |

|---|---|

| 인도네시아의 의사국가면허시험: 학생, 교수, 대학의 관점(© 2018 The University of Leeds and Rachmadya Nur Hidayah) (0) | 2023.11.19 |

| 베트남의 의사면허시험에 대한 코멘터리(MedEdPublish, 2023) (0) | 2023.11.19 |

| 베트남 의학교육의 혁신(BMJ Innov 2021) (0) | 2023.11.19 |

| 동남아시아의 면허시험: 교육정책의 변화에서 찾아낸 교훈( Asia Pacific Sch, 2019) (0) | 2023.11.19 |