임상환경에서 문화가 학습, 실천, 정체성 발달에 영향을 주는 방식에 대한 시야 넓히기(Med Educ, 2021)

Widening how we see the impact of culture on learning, practice and identity development in clinical environments

Dale Sheehan1 | Tim J. Wilkinson2

감각을 개발하고 특히 보는 법을 배우세요. 모든 것이 다른 모든 것과 연결되어 있다는 것을 깨달으십시오. (레오나르도 다빈치)

Develop your senses—especially learn how to see. Realize that everything connects to everything else. (Leonardo Da Vinci)

1 소개

1 INTRODUCTION

세기가 바뀌면서부터 보건 전문 교육 학자들은 임상 학습 환경에 점점 더 많은 관심을 갖게 되었고, 직장 환경에서 무엇이 학습에 도움이 되고 방해가 되는지 이해하기 위한 연구를 진행했습니다. 환경, 사회적, 물리적 측면, 감독자의 역할, 학습자의 주체성 등 직장이 제공하는 어포던스를 파악하는 데 중점을 두었습니다. 이 모든 것은 학습 환경이 제공하는 기회를 극대화하는 데 목적이 있습니다. 사회문화적 관점,1,2 직장 학습 이론,3-5 상황 학습6 및 상황성 이론7의 수용은 이러한 노력을 뒷받침해 왔습니다. 이번 자아, 사회 및 상황에 대한 과학 현황 시리즈의 일환으로, 우리는 상황을 보다 폭넓게 바라보는 방법과 문화가 이에 어떤 영향을 미칠 수 있는지에 초점을 맞춥니다.

Since the turn of the century, health professional education scholars have become increasingly interested in the clinical learning environment, positioning research to understand what helps and hinders learning in workplace settings. The focus has included uncovering the affordances that the workplace offers: the environment, social and physical aspects; the role of the supervisor; and the agency of the learners. These are all aimed at maximising the opportunities the learning environment presents. The embracing of sociocultural perspectives,1, 2 workplace learning theory,3-5 situated learning6 and situativity theory7 have supported these endeavours. As part of this State of the Science series on Self, Society and Situation, we focus on how we might see the situation more broadly and how culture might influence this.

먼저 용어에 대한 몇 가지 설명을 드리겠습니다. '상황'이란 임상 학습 환경을 의미합니다. 임상 학습 환경 자체에 대한 정의는 쉽지 않지만, 저희의 목적상 학습이 이루어지는 모든 임상 업무 환경을 포함하며, 이러한 의도적으로 넓은 관점에는 실무자와 수련의에게 학습 경험을 제공하면서 주로 업무(의료 서비스 제공)에 중점을 두는 환경뿐만 아니라 업무에 중점을 두지 않는 환경도 포함될 수 있습니다. 여기에는 학부 및 대학원 교육뿐만 아니라 지속적인 실습 단계의 교육도 포함됩니다. 또한 모든 의료 전문직을 포함하는 것으로 보고 있습니다. 일부에서는 '일'과 '학습'을 분리하려고 하지만, 저희는 보다 통합적인 관점을 취합니다. 2019년이 되어서야 개인적 요소, 사회적 요소, 조직적 요소(조직 문화 포함), 물리적 공간, 가상 공간을 강조하는 학습 환경의 개념적 틀이 제안되었습니다.8 마찬가지로 문화도 정의에 저항해 왔습니다.9 역량과 마찬가지로 문화는 보건 전문가 교육에서 '신의 용어'가 될 수 있습니다.10 링가드는 '신 용어의 위험은 반복적인 사용과 친숙함을 통해 자연스럽고 보편적이며 필연적인 현실의 질서를 암시하게 된다는 점'이라고 경고합니다.10 이러한 용어를 구분하는 것은 낯설게 만들고, 이를 뒷받침하는 동기를 발굴하며, 적응적이고 유연한 담론을 위한 공간을 여는 작업입니다.10 그러나 이 백서 뒷부분에서 논의하는 최근 연구는 문화의 구성 요소를 명확히 하고 있습니다.

First, some clarification of terms are made. By ‘situation’, we refer to clinical learning environments. The clinical learning environment itself has resisted definition but for our purposes includes any clinical workplace where learning occurs—this deliberately wide view encapsulates environments that primarily focus on work as well as those that are focused on work (the delivery of health care services), while providing learning experiences for practitioners and trainees. It includes undergraduate and postgraduate training as well as ongoing practice stages of training. We also see this as including all health professions. Some try to separate ‘work’ from ‘learning’, but we take a more integrated view. It was not until 2019 that a conceptual framework of the learning environment was proposed, which highlighted a personal component, a social component, an organisational component (including the organisational culture), physical spaces and virtual spaces.8 Likewise, culture has resisted definition.9 Culture, like competence, may have become a ‘God term’ in health professional education.10 Lingard warns us that ‘the danger with God terms is that, through repeated use and familiarity, they become suggestive of a natural, universal and inevitable order of reality.10 Teasing them apart is an exercise in making them unfamiliar, excavating the motivations that underpin them, and opening space for an adaptive and flexible discourse’.10 However recent work, which we discuss later in this paper, has clarified components of culture.

보건 전문 교육자들이 보건 환경에서 일하는 동안 개인이 학습하는 방식에 대한 생각을 어떻게 발전시켜왔는지 요약합니다. 임상 작업장 환경에서의 학습에 관한 새로운 논의를 검토합니다. 최근에 우리는 문화와 학습 환경에 미치는 영향에 관한 다른 사람들의 연구에 경각심을 불러일으킨 관찰 연구를 자체 연구에 포함하기로 결정했습니다. 우리는 우리의 성찰을 공유하고 조직 문화와 문화의 더 넓은 측면이 자주 언급되지만 덜 자주 탐구되는 요소라는 결론을 내리는 예시적인 사례 연구를 제공합니다. 실무와 연구에 대한 시사점을 논의합니다.

We summarise how health professional educators have evolved their thinking about how individuals learn while working in health environments. We review the emerging dialogue concerning learning in clinical workplace environments. Recently, we moved to include observational studies in our own work which has alerted us to the work of others around culture and its impact on learning environments. We share our reflections and offer illustrative case studies concluding that organisational culture and wider aspects of culture are factors that are often mentioned but less often explored. We discuss the implications for practice and research.

2 우리가 아는 것

2 WHAT WE KNOW

이제는 시대에 뒤떨어진 관점에서는 학습이 가르치는 내용에 의해 통제될 수 있다고 주장했습니다. 이후 학습자의 자율성과 신뢰를 반영하는 학습 성과로 초점이 옮겨졌습니다. 이후 직장에서의 학습이 처음 생각했던 것만큼 예측하기 어렵다는 사실을 깨닫고 감독자의 역할에 더 중점을 두게 되었습니다. 이로 인해 수퍼바이저는 학습 내용을 통제하거나 관리하는 데 도움을 줄 수 있으며, 학습자가 학습을 하지 않는다면 이는 학습자, 수퍼바이저 또는 dyad에게 문제가 있다는 견해로 이어졌습니다. 이후 직업 교육과 사회 학습 패러다임이라는 더 넓은 분야의 영향을 받은 연구에서는 학습 환경과 학습자의 학습 환경에 대한 경험에 주목했습니다. 예를 들어, 우리는 자체 연구와 Stephen Billett과의 협력을 통해 임상 환경에 대한 학습자의 경험과 학습의 필수 요소인 참여를 지원하기 위해 감독자가 할 수 있는 일을 조사했습니다.11 우리는 실무 커뮤니티 내에서 학습이 어떻게 발생하는지 고려하고6 직장이 학습자에게 무엇을 제공하고 이것이 워크플로와 물리적 환경에 의해 어떻게 영향을 받는지 이해하는 데 관심을 갖게 되었습니다.4, 11, 12 이 연구는 모든 역량을 포괄할 수 있도록 학습 결과를 업무 경험에 매핑하려는 시도와 대조적으로 진행됩니다. 당시의 개념은 학습 환경을 둘러싼 문화를 기껏해야 통제할 수 없는 것으로, 최악의 경우 무시해야 할 것으로 간주했습니다. '숨겨진 커리큘럼'이라는 용어는 학습 환경의 부정적 영향과 동의어로 여겨질 정도로 부정적으로 여겨지기도 했습니다.13 집단 따돌림은 이러한 부정적 영향 중 하나에 초점을 맞추었지만, 여기에서도 의대생 괴롭힘 문제를 해결하려면 의사에 초점을 맞춰야 하고, 간호대생 괴롭힘 문제를 해결하려면 간호사에 초점을 맞춰야 한다는 제한적이고 비전문적인 렌즈를 통해 바라보려는 경향을 보였습니다. 실제로 괴롭힘 문화는 환경 문화를 반영하는 것으로, 여러 분야에 걸쳐 발생하는 경우가 많습니다. 예를 들어 의대생은 의사보다 간호사에게 괴롭힘을 당할 가능성이 더 높거나 더 높습니다.14

A now outmoded view contended that learning could be controlled by what is taught. The focus then moved to learning outcomes, reflecting greater agency and trust in the learner. Later developments followed the realisation that learning in workplaces is not as predictable as first thought so there was a greater focus on the role of the supervisor. This led to the view that the supervisor could help control or manage what is learnt and if the trainee was not learning, then somehow it was either a problem with the trainee, the supervisor or the dyad. Influenced by the wider field of vocational education and social learning paradigms, later research turned attention to the learning environment and learners' experiences of those environments. As an example, in our own research and working with Stephen Billett, we investigated learners' experiences of the clinical environment and what supervisors could do to support participation as an essential ingredient for learning.11 We considered how learning occurred within communities of practice6 and became interested in understanding what the workplace afforded learners and how this was influenced by workflows and the physical environment.4, 11, 12 This work contrasts with trying to map learning outcomes to work experiences to ensure that every competency is covered. Conceptualisations at that time came to view the culture surrounding the learning environment as, at best, out of control and, at worst, something to be ignored. It was often seen as negative—adapting the term the ‘hidden curriculum’, which came to be seen as synonymous with the adverse impacts of the learning environment.13 Bullying became a focus of one of these adverse impacts, but even here we tended to view this through a limited, uniprofessional, lens—to fix the bullying of medical students, we need to focus on the doctors; to fix the problems of bullying nursing students, we needed to focus on nurses. In fact, a bullying culture is more a reflection of the environmental culture and often occurs across disciplines—for example, medical students are just as, or more, likely to be bullied by a nurse than by a doctor.14

좋은 견습생, 좋은 감독자, 좋은 학습 환경을 만드는 요인을 탐구한 연구에서 몇 가지 핵심 메시지를 제시했습니다.15-17

As research explored what made a good apprentice, a good supervisor and a good learning, environment it offered some key messages.15-17

- 학습자 참여가 핵심입니다.

- 환경은 학습 기회를 제공함으로써 교육을 수행하지만, 이는 슈퍼바이저가 지원해야 합니다.

- 학습자가 주체성과 발언권을 갖기 위해서는 업무 압박, 인적 요인 및 오류를 유발할 수 있는 기타 영향의 영향을 인정하면서 안전한 환경이 필요합니다.

- 학습 환경을 직접 관찰하면 팀 커뮤니케이션을 이해하여 학습 이벤트가 발생하는 위치를 파악하고 전문가 간 협업이 이루어지는 방식과 장소를 탐색하는 데 도움이 됩니다.

- Learner participation is the key.

- The environment does the teaching by affording opportunities for learning, but this needs to be supported by the supervisor.

- In order for learners to have agency and a voice, they need safe environments while acknowledging the impacts of work pressure, human factors and other influences that could lead to errors.

- Direct observation of learning environments helps gain an understanding of team communication to see where learning events happen and to explore how and where interprofessional collaboration occurs.

이 논문은 사물이 서로 연결되어 있다는 것을 깨닫는 데 도움이 되는 감각을 개발해야 한다는 레오나르도 다빈치의 인용문에서 시작되었습니다. 우리는 더 넓은 기관의 요소를 포용하고, 환자 치료 및 임상 학습 모델에 영향을 미치는 조직의 가치와 문화를 인식하고 인정하여 이를 외면하거나 무시하지 않고 함께 일하며, 성찰과 관찰을 통해 암묵적인 것을 가시화하고 문화에 대한 다양한 관점을 포용할 필요가 있다고 제안합니다.

Our paper started with a quote from Leonardo Da Vinci who suggests we need to develop our senses to help us realise that things connect to each other. We suggest there is a need to embrace the wider institution factors, recognise and acknowledge an organisation's values and culture as they impact on models of patient care and clinical learning in order to work with these, not around them or ignore them, to make what may be tacit visible through reflection and observation and to embrace a range of perspectives on culture.

3 새로운 대화

3 THE EMERGENT DIALOGUE

학습 환경의 개념적 틀은 정책, 리더십 행동, 규제 기관 및 인증의 영향을 포함한 조직 문화의 역할을 강조했습니다.8 이와 함께 질 향상 분야의 저자들은 보건의료 조직 문화를 '의료 서비스 조직의 눈에 잘 띄지 않는 부드러운 측면과 이것이 진료 패턴에서 어떻게 나타나는지'에 대한 은유로 설명했습니다.18 이 연구는 학습 환경 작업의 범위를 넓혀 조직 문화가 보건의료 실무에 미치는 영향과 따라서 특정 학습 환경에서 제공되는 어포던스(또는 그렇지 않은)를 탐구해야 할 필요성을 강조합니다. 두 가지 관점 모두 특히 학습자가 자신의 전문적 정체성을 만들고 창조하기 위해 노력할 때 '문화'가 감독자와 학습자에게 미치는 영향을 상기시켜 줍니다.

A conceptual framework of the learning environment highlighted the role of organisational culture including the impact of policies, leadership actions, regulatory bodies and accreditation.8 Alongside this, authors in quality improvement have described health care organisation culture as a metaphor for ‘the softer less visible aspects of health service organisations and how these become manifest in patterns of care’.18 This work highlights the need to broaden the scope of learning environment work to explore the impact of organisational culture on health care practices and therefore the affordances (or not) offered in specific learning environments. Both perspectives remind us of the impact of ‘culture’ on the supervisor and learner, particularly as learners strive to create and create their professional identities.

이제 수련자와 슈퍼바이저가 속한 더 넓은 조직의 영향, 이것이 학습에 미치는 영향, 그리고 이것이 보건 서비스, 도시, 지역 및 국가에 따라 어떻게 달라지는지에 대한 관심이 떠오르고 있습니다. 이러한 제도적 요인을 탐구하는 과정에서 의학교육자들에게 '문화를 불러일으키기'를 권유한 Bearman 등의 비판적 검토는 시의적절합니다.19 이들의 연구에 따르면 의학교육자들은 문화에 대해 자주 언급하지만 대개 부정적이거나 중립적인 자세로 언급하는 것으로 나타났습니다. 이들은 '교육자, 학생, 행정가에게 권한을 부여하는 문화에 대한 개념이 현저히 부재'하지만 동시에 사회적 환경과 관행의 영향력을 인정하고 있음을 발견했습니다.19

What is now emerging is an interest in the impact of the wider organisation in which a trainee and a supervisor are situated, how this impacts on learning and how this varies across health services, cities, regions and countries. As part of exploring these institutional factors, a critical review by Bearman et al. is timely in its invitation to medical educators to ‘invoke culture’.19 Their work revealed that medical educators comment on culture frequently but usually negatively or from a neutral stance. They found that there is a ‘notable absence around conceptualisations of culture that allow educators, students and administrators agency’ but at the same time acknowledge the influence of social settings and practices.19

Watling 등은 문화에 대한 세 가지 관점, 즉 조직, 정체성, 실천을 인정하는 프레임워크를 제시합니다.9

- 조직 관점은 조직 내에서 개인을 묶는 공유된 가정과 가치를 강조합니다.9

- 정체성 관점은 개인이 자신을 보는 방식을 형성하는 공동의 내러티브의 힘을 강조합니다.9

- 실천 관점은 활동과 인적-물적 네트워크 또는 배열을 강조합니다.9

Watling et al. offer a framework that recognises three perspectives on culture: organisational, identity and practice.9

- The organisational perspective highlights the shared assumptions and values that bind individuals within an organisation.9

- The identity perspective highlights the power of communal narratives to shape how individuals see themselves.9 T

- The practice perspective highlights activity and human-material networks or arrangements.9

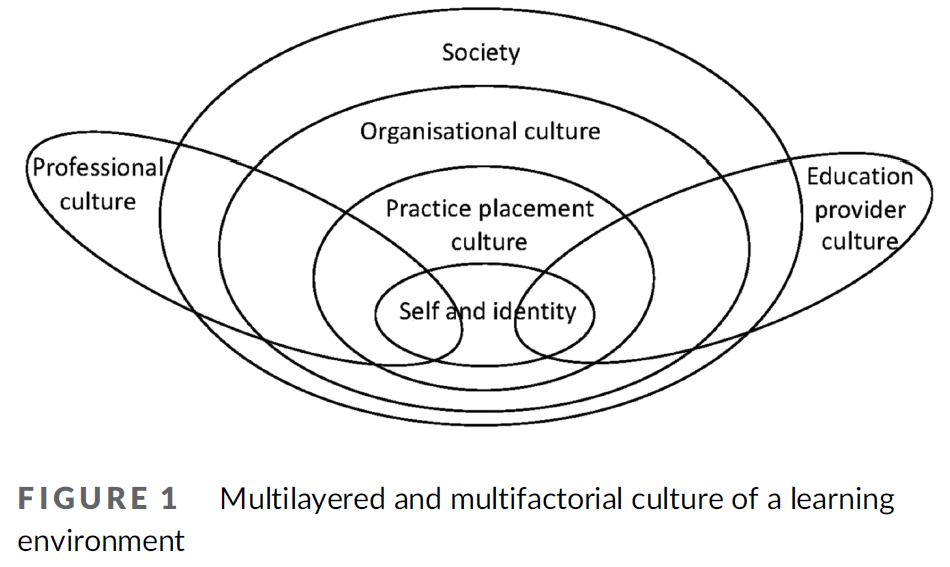

우리는 이러한 관점을 수용하거나 조정했으며, 세 가지 관점 모두에 공통점이 있음을 인식하면서 각각에 대해 예시적인 사례 연구와 잠재적인 탐구 프로그램을 제공합니다. 이러한 관점 내에서 그리고 이러한 관점을 넘나들며 작업하면 다른 연구를 보완하거나 다른 보건 연구자들과 파트너십을 맺고 학제 간 협력자와 함께 혼합 방법 접근법을 설계할 수 있는 기회를 제공할 가능성이 매우 높습니다. 그림 1은 학습 환경의 문화가 다층적이고 다요인적이라는 것을 보여주는 개념적 관점을 제공하는 것을 목표로 합니다. Watling 등의 관점에9 사회, 교육 제공자 및 직업 자체와 관련된 문화를 추가했습니다.

We have embraced or adapted these perspectives, and for each, we offer illustrative case studies and potential programmes of enquiry while recognising there is a common thread across all three. Working within and across these perspectives is very likely to complement other work and or provide opportunities for partnerships with other health researchers and to design mixed-methods approaches with interdisciplinary collaborators. Figure 1 aims to provide a conceptual view illustrating that the culture of a learning environment is multilayered and multifactorial. To Watling et al.'s perspectives,9 we have added the cultures associated with society, the education provider and the profession itself.

개인은 즉각적인 상황의 문화, 일반적으로 진료 배치, 특히 임상 팀의 문화를 가장 잘 알고 있지만 여기에는 물리적 배치, 작업 리듬, 작업 도구 또는 장비(인공물)도 포함됩니다.11 그러나 이러한 배치는 의료 서비스의 조직 문화와 사회 자체의 문화에 영향을 받습니다. 이러한 모든 요소와 상호 작용하는 것은 직업 및 교육 제공자의 문화입니다. 그러나 가장 중요한 것은 이러한 문화가 반드시 일치하는 것은 아니며,20 이러한 문화를 조정하는 것은 개인에게 긴장을 유발할 수 있다는 것입니다.

The individual will be most aware of the culture of the immediate situation, commonly the practice placement, particularly the clinical team, but this also includes the physical layout, the rhythms of work and work tools or equipment (artefacts).11 However such placements will, in turn, be influenced by the organisational culture of the health service and that of society itself. Interacting with all these factors are the cultures of the profession and the education provider. Most importantly however, these cultures will not necessarily be aligned,20 and reconciling such alignments can cause tension for individuals.

4 조직 문화

4 ORGANISATIONAL CULTURE

조직 문화는 사고 방식, 어떤 지식이 가치 있고 일반적으로 받아들여지는지, 지식이 어떻게 사용되는지,21 그리고 의료 환경 내에서 환자 치료가 어떻게 제공되는지에 대한 가정을 형성합니다. 조직의 문화는 비전, 사명, 가치, 리더십 모델, 자금 및 계획 모델, 직무 설계, 성과 관리, 팀워크, 혁신, 갈등 해결 방법, 슈퍼비전, 임상 리더십 및 관리 스타일에 의해 영향을 받습니다.22 베어만 등은 또한 '문화'라는 용어의 기본 개념이 움직일 수 없는 문화에서 사용 가능하고 유연한 문화까지 연속선을 따라 존재한다고 지적했습니다.19 우리는 학습에 있어 후자가 해당된다고 생각하여 조직과 협력하여 학습 문화를 발견, 개발 및 개선할 수 있기를 희망합니다.

Organisational culture shapes assumptions about ways of thinking, what knowledge is worthwhile and commonly accepted, how knowledge will be used,21 and within health care settings, how patient care is delivered. An organisation's culture is influenced by its vision, mission, values, leadership models, funding and planning models, job design, performance management, teamwork, innovation, methods for conflict resolution, supervision, clinical leadership and managerial styles.22 Bearman et al. also noted that the underlying conceptions of the term ‘culture’ sit along a continuum: from culture as immoveable to culture as usable and malleable.19 We would like to think that the latter is true for learning so that we could partner with organisations to uncover, develop and improve its learning culture.

학부 및 대학원 프로그램에 소속된 임상 교육자만이 근로자의 주체성을 개발하기 위해 노력하는 것은 아닙니다. 교육에 주로 관여하지 않는 조직에서도 문화가 지식 공유 행동23 및 지식 관리와 밀접한 관련이 있다는 몇 가지 증거를 확인한 것은 고무적입니다.21, 24 조직은 안전한 환자 치료를 보장하고 신기술과 새로운 기술을 수용하기를 원합니다. 또한 역량과 역량을 위한 기술을 구축하고 전문가 간 이해를 발전시키기를 원합니다. 교육 기관과 의료 서비스 사이에 공생이 가능하다는 생각은 새로운 것은 아니지만,25 학습 환경에서 시너지 효과를 확인하고 숨겨진 커리큘럼에 반하는 것이 아니라 협력할 수 있는 미충족 기회가 있다는 것을 시사합니다. 이는 의료 서비스를 지식 개발의 파트너, 전문가 간 치료 및 협력 진료의 협력자, 모두를 위한 안전하고 건강한 환경을 보장하는 파트너, 환자 치료 결과를 개선하는 파트너로 포용하는 것입니다.

Clinical educators attached to undergraduate and postgraduate programmes are not the only ones working to develop agency in workers. Here it is encouraging to see some evidence that, even for organisations not primarily involved in education, culture is strongly associated with knowledge-sharing behaviour23 and with knowledge management.21, 24 Organisations want to ensure safe patient care and to embrace new technology and new skills. They want to build skills for competence and capability and develop interprofessional understandings. The idea that there could be symbiosis between an education organisation and a health service is not new,25 but it does suggest there are unmet opportunities to identify synergies in learning environments; to work with and not against the hidden curriculum. This would embrace health services as partners in knowledge development, a collaborator for interprofessional care and collaborative practice, a partner in ensuring safe and healthy environments for all, and a partner to improve patient outcomes.

각 조직은 서로 다른 기회를 제공할 가능성이 높으며, 이러한 기회를 설명하고 이해하면 기회를 더 잘 활용할 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, 의료 서비스 기관은 스스로를 학습하는 조직이라고 설명하는 경우가 많으며 품질 개선 전문가, 전문 개발 직원, 웰빙 실무자 등 관련 팀을 보유하고 있습니다. 이러한 팀은 '공식적인' 교육의 목표에 부합하는 학습 및 업무 문화 목표를 구현하는 임무를 맡고 있습니다. 더 넓은 렌즈를 사용하여 사물이 서로 어떻게 연결되어 있는지 파악하는 것이 업무 환경 분석에서 포착되어야 합니다.

Each organisation is likely to offer different opportunities; describing and understanding those opportunities could help us make better use of them. For example, health service organisations often describe themselves as learning organisations and have relevant teams, such as quality improvement specialists, professional development staff, and well-being practitioners. These teams are tasked with implementing goals for learning and work culture that align to those of ‘formal’ education. Using a wider lens and seeing how things connect to each other should be captured in our analyses of workplace environments.

조직 문화를 설명하는 사례 연구

Case study to illustrate the organisational culture

영국에서 파운데이션 수련의의 처방 오류 원인에 대한 심층 조사를 실시한 결과,26 뉴질랜드의 두 보건 서비스에서도 비슷한 문제를 인식했습니다. 약사가 처방 오류를 발견했지만 전문가 간 협업 문화가 없었기 때문에 의사-약사 협업을 통해 이러한 오류를 예방할 수 없었습니다. 두 의료 서비스의 교육 부서는 질 향상 약사와 협력하여 일상적인 상호작용에서 의사와 약사 간의 전문직 간 협업을 활용하여 효과적인 처방을 촉진하는 방법을 모색했습니다.27-29 약사는 질 향상 전문 지식을, 교육 부서는 직장 학습 및 전문직 간 교육에 대한 전문 지식을 가져와 문제를 해결했습니다. 서로 협력한 결과 오류 감소뿐만 아니라 협업 문화도 개선되었습니다.27-29

In response to an in-depth investigation in the United Kingdom into causes of prescribing errors by foundation trainees,26 two health services in New Zealand recognised a similar problem. Prescribing errors were detected by pharmacists, but there was not a culture of interprofessional collaboration, so preempting such errors through doctor–pharmacist collaboration did not occur. The education units of both health services partnered with quality improvement pharmacists and explored ways to leverage the interprofessional collaboration between doctors and pharmacists in their everyday interactions to promote effective prescribing practice.27-29 The pharmacists brought their quality improvement expertise, and the education units brought expertise in workplace learning and interprofessional education to address the problem. They partnered with each other and found not only a reduction in errors but also an improvement in collaborative culture.27-29

한 사이트는 다른 사이트에 비해 더 큰 영향을 미쳤습니다.28 학습자와 교육자의 질적 인터뷰 데이터는 그 이유에 대한 통찰력을 제공하고 전수 가능성 및 조직 문화에 관한 귀중한 교훈을 제공했습니다. 효과가 가장 컸던 현장에는 시뮬레이션에 대한 높은 수준의 지원을 제공하는 시뮬레이션 유닛이 있었고, 병동 기반 전문가 간 코칭에 대한 사전 경험이 있었습니다. 공유된 임상 리더십과 의료 서비스 코드 설계 및 개선 학습에 대한 헌신은 조직의 목표였습니다. 따라서 두 서비스 간의 강력한 협업 문화와 함께 프로그램을 수행하기 위한 전제 조건이 있는 직장 환경과 문화를 갖추고 있었습니다. 다른 사이트는 그 효과가 적었고, 돌이켜보면 시행 전에 더 많은 교육과 브리핑이 필요하다는 것을 깨달았습니다.

There was greater impact at one site compared with the other.28 The qualitative interview data from learners and educators provided insight into why and offered a valuable lesson regarding transferability and organisational culture. The site with the greatest effect had a simulation unit that provided a high level of support for the simulations, as well as prior experience of interprofessional ward-based coaching. Shared clinical leadership and a commitment to codesign of health services and improvement learning were espoused organisational goals. It therefore had a workplace environment and culture with prerequisites for undertaking the programme with a strong culture of collaboration between the two services. The other site had a lesser effect and retrospectively we realised that it needed to undertake more training and briefing prior to implementation.

이중 사이트 구현을 통해 업무 환경과 문화적 요인이 사이트마다 다를 수 있으며, 광범위하게 구현하려면 이를 예상해야 한다는 사실을 깨닫게 되었습니다. 모든 사이트에는 고유한 실행 강점과 과제가 있습니다.

Dual-site implementation reminds us that workplace contextual and cultural factors will vary across sites and any widespread implementation needs to anticipate this. All sites have their own implementation strengths and challenges.

5 실천 문화

5 PRACTICE CULTURE

실천 문화는 종종 의료팀 수준에서 나타납니다. 한 팀에서 받아들일 수 있는 규범, 기대치, 일반적인 관행이 다른 팀에서는 받아들여지지 않을 수 있습니다.30 이는 때때로 '여기는 이렇게 한다'라는 문구로 요약됩니다. 이러한 문화는 대개 팀의 선임 간호사나 선임 의사와 같은 선임 멤버에 의해 설정됩니다. 각 팀마다 고유한 특성과 프로토콜이 있으며, 모든 프로토콜이 명시적이거나 팀원들이 명확히 알 수 있는 것은 아닙니다. 이러한 특수성을 이해하고 이를 명시하는 것이 효과적인 슈퍼비전의 중요한 전제 조건인 것으로 밝혀졌습니다.30 또한 이러한 특수성은 직장이 제공하는 어포던스, 즉 학습할 수 있는 내용을 형성합니다. 마찬가지로 물리적 배치, 사용 가능한 장비, 자연스러운 업무 리듬은 모두 학습에 영향을 미치지만 장소마다 상당히 다릅니다.11 이러한 차이가 존재하지 않는다고 가정하기보다는 이러한 차이를 더 명확하게 만들어서 어떻게 작용하는지 이해할 수 있는 방법을 찾아야 합니다. 이는 교육 프로그램을 확장하거나 다른 센터에 프로그램을 배포할 때 특히 중요합니다.

Practice culture is often manifest at the health care team level. Trainees often notice this—the norms, expectations and common practices that are acceptable in one team may be less acceptable in another.30 This is sometimes encapsulated in the phrase ‘this is how we do things here’. Such a culture is often set by a senior member of the team—a senior nurse or senior doctor. Each team has its idiosyncrasies and protocols—not all of which are explicit or even able to be enunciated by the team members. Understanding these idiosyncrasies and making them explicit has been found to be an important prerequisite to effective supervision.30 They also shape what affordances the workplace offers and therefore what can be learnt. Likewise the physical layout, the equipment that is available and the natural rhythm of workplace practices are all influential on learning yet vary considerably from place to place.11 Rather than pretend these variations do not exist, we need to find ways to make them more explicit so that we can then understand how they act. This is particularly important when scaling up an education programme or rolling out a programme to other centres.

실습 환경을 설명하는 사례 연구

Case studies to illustrate the practice environment

- 수퍼바이저 트레이너인 저자 중 한 명(박사)은 수퍼바이저 교육 과정 중 참가자들이 자신의 학습 환경을 감사하도록 요청받은 실습을 감독했습니다. 참가자들은 한 발 물러서서 학습 환경으로서 자신의 직장을 관찰하고 성찰하여 배치의 학습 기회를 파악하도록 요청받았습니다. 이는 직장 커리큘럼 매핑4의 개념에서 파생된 활동이었지만 보다 미시적인 수준에서 수행되었습니다. 교육에 참여한 감독자들은 익숙한 환경을 새로운 시각으로 바라보는 것의 가치를 높이 평가하면서 이 활동이 도움이 되고 눈을 뜨게 하는 활동이라고 보고했습니다. 수업 시간에는 장애물을 공유하고 해결책을 찾기 위해 노력했습니다.

As a trainer of supervisors one of the authors (D. S.) oversaw an exercise within a supervisor training course where participants were asked to audit their learning environment. They were asked to step back, observe and reflect on their workplace as a learning environment to identify the learning opportunities of the placement. This was an activity drawn from the concept of mapping the workplace curriculum4 but undertaken at a more microlevel. Supervisors in training reported this as a helpful and an eye-opening activity, appreciating the value of looking at a familiar environment through a change of lens. In class they shared barriers and worked on solutions for workarounds. - 학습 환경을 직접 관찰한 결과 학습은 종종 '한입 크기'(한 번에 1분 미만)로 이루어졌으며, 업무의 성격과 리듬으로 인해 특정 장소와 특정 시간에 발생할 가능성이 더 높았습니다.11

Direct observation of a learning environment uncovered learning often occurred in ‘bite-sized’ pieces (<1 min at a time) and were more likely to occur in specified places and at particular times due to the nature and rhythm of work.11 - 조산사 배치 현장 두 곳의 경험 경로와 교육적 특성을 매핑하여 조산사 커리큘럼이 프로그램의 의도된 학습 결과를 실현하는 특정 교육적 관행에 의해 어떻게 주문되고 보강될 수 있는지 파악했습니다.12 두 가지 실습 기반 경험은 학생들에게 뚜렷한 학습 결과를 만들어 냈습니다.

The pathways of experiences and pedagogic properties of two midwifery placement sites were mapped to identify how the midwifery curriculum could be ordered and augmented by particular pedagogic practices that realise the program's intended learning outcomes.12 The two different practice-based experiences generated distinct learning outcomes for the students.

수퍼바이저는 조직의 문화에 영향을 받기도 하고 기여하기도 하며, 종종 순환적이고 상호 의존적인 방식으로 영향을 주고받습니다. 수퍼바이저는 현지 문화에 몰입되어 있기 때문에 수퍼비전에 대한 암묵적 신념과 수퍼바이저로서의 정체성에 어떤 영향을 미치는지 인식하지 못할 수 있습니다.31, 32 칸틸롱 등은 교수진 개발이 수퍼바이저로서의 정체성, 신념 및 관행을 강화하는 환경적 요인에 대한 교사의 마음챙김을 증가시키도록 시도해야 한다고 제안합니다.32 이는 신규 수퍼바이저가 적절한 성향(예: '교수법'을 식별하는 동기 개발)을 갖는 것에서 적절한 성향(예: '교수법'을 실행하는 것)을 실행하는 것(예: 사회 및 문화적 맥락에 관여하고 대응하는 것)으로 이동할 수 있도록 지원할 필요성을 강조하는 수퍼바이저 교육에 시사점을 줍니다."32

Supervisors are both influenced by, and contributors to, their organisation's culture, often in a cyclical, interdependent way. Because of their immersion in the local culture, they may not be aware of how it is impacting on their tacit beliefs about supervision and their identity as a supervisor.31, 32 Cantillon et al. suggests faculty development should attempt to increase teacher's mindfulness of the environmental factors that sharpen their identities, beliefs and practices as supervisors.32 This has implications for supervisor training highlighting a need to assist new supervisors to move from having the appropriate disposition (e.g., developing the motivation to identify ‘teaching work arounds’) to enacting the appropriate disposition (e.g., implementing the ‘teaching work arounds'…. as they engage with and respond to social and cultural contexts.’32

수퍼바이저는 긍정적이든 부정적이든 조직의 문화적 힘에 관여하고 이에 대응할 때 자신의 가정(예: 위계 업무량 또는 교육 대 환자 치료의 긴장 관계에서 우선순위)에 대해 의도적으로 성찰할 기회를 제공받는 것이 도움이 될 수 있습니다. 수퍼바이저의 정체성, 역할에 대한 암묵적 신념과 이해는 조직 전체의 관점에 영향을 받을 가능성이 높습니다.

Supervisors may benefit from being provided with opportunities to deliberately reflect on their assumptions (e.g., about hierarchy workload or priorities in the teaching vs. patient care tension) as they engage with, and respond to, cultural forces in their organisation, both positive and negative. The identity of the supervisor, the tacit beliefs and understandings they have about the role are likely influenced by the organisation wide view.

6 정체성

6 IDENTITY

직업적 정체성을 개발하는 것은 독립적인 의료 전문가가 되기 위한 과제 중 하나입니다. 학습 환경과 문화도 정체성 형성에 영향을 미치며, 이는 다시 수련 단계에 따라 달라집니다.

- 학부 수준에서 학습 환경은 임상 경험의 원천으로 여겨지는 경우가 가장 많습니다.33

- 이후 신규 졸업생의 경우, 학습 환경은 직업적 정체성을 형성하고 진로 결정을 내리고 취업하는 장소로 여겨집니다.

- 의료 전문가가 더 고위직이 되어 업무 환경에 완전히 몰입할 때 비로소 이러한 환경이 보다 일관되고 예측 가능하게 됩니다.

그러나 실무자가 환경 문화를 형성하는 데 있어 더 큰 권한을 갖는 것은 바로 이 고위급 수준에서입니다. 인턴십은 정체성 형성의 시기로 볼 수 있으며, '의사 되기'라는 자기 결정적 능동적 과정으로서 이 중요한 전환을 이해하려면 문화 또는 사회화 이론보다 더 넓은 관점이 필요합니다.34 예를 들어, 경영학 문헌의 모델을 사용하여 인턴 교육을 시간이 지남에 따라 자아의 전개와 변화라는 되기 과정으로 설명할 수 있습니다.34

Developing a professional identity is one of the tasks of becoming an independent health professional. The learning environment and its culture also impact on identity formation which, in turn, depends on the stage of training.

- At an undergraduate level, the learning environment is most often seen as a source of clinical experiences.33

- Later, as new graduates, it is seen as a place to shape professional identity, to shape career decisions and to be employed.

- It is only when health professionals become more senior and fully immersed in the work environment that such environments become more consistent and predictable.

It is at this more senior level however that practitioners have greater agency in shaping the environment culture. An internship can be viewed as a period of identity formation and, as a self-determined active process of ‘becoming a doctor’, requires a wider perspective than enculturation or socialisation theories to understand this significant transition.34 For example, a model from management literature could be used to describe intern education as a process of becoming: as an unfolding and as a transformation of the self over time.34

전문가 간 팀의 일원이 되는 법을 배우는 것은 전문가 정체성에 대한 또 다른 도전이며, 이는 관점의 균형을 맞추고 자신의 전문적 역할과 팀 역할의 균형을 맞춰야 합니다. 의료팀 과제와 같은 활동은 학생과 인턴이 서로의 직업과 역할에 대한 이해를 높이고 직장에서 서로를 인정하는 데 도움이 됩니다.35

Learning to be part of an interprofessional team is another challenge to professional identity that requires balancing perspectives and juggling one's own professional roles with team roles. Activities such as health care team challenges have increased students' and interns' understanding of each other's professions and roles and lead to recognition of each other in workplaces.35

신규 의사의 경우, 많은 경우 자신의 가치관이나 의료인으로서의 역할에 대한 인식과 상충되는 환경에서 일하고 전문직으로 전환하는 과정에서 정체성을 확립하는 데 많은 노력을 기울여야 합니다. 최근 의료계에서 원주민(마오리족)36 및 태평양계37 졸업생 의사가 크게 증가한 뉴질랜드에서 개인이 업무 환경에 적응하는 과정이 잘 드러납니다. 수상 경력에 빛나는 팟캐스트에서 마오리족 의사를 갓 졸업한 엠마 에스피너의 관점에서 바라본 다음 사례 연구는 비 마오리족이 주류를 이루는 의료 직장 문화와 마오리족의 불평등한 건강 결과와 관련된 의료 시스템 내에서 마오리족 의대생으로서 정체성을 관리하는 데 따르는 어려움을 보여줍니다.

For new practitioners, there is much identity work to undertake in the challenge of moving into a profession and working in an environment that for many is at odds with their values and perception of their role as a health professional. The enculturation of the individual into a work environment has been well illustrated recently in New Zealand where the medical workforce has seen a substantial increase in indigenous (Māori)36 and Pacific37 graduating doctors. The following case study taken from the perspective of Emma Espiner, a newly graduated Māori doctor, in an award winning podcast, demonstrates the challenges of managing identity as a Māori medical student within a health workplace culture that is predominantly non-Māori and within a health care system associated with unequal health outcomes for Maori.

개인 문화와 조직 문화의 조화를 보여주는 사례 연구

Case study illustrating reconciling personal culture with organisational culture

팟캐스트 시리즈에서 마오리족 의대생인 엠마 에스피너는 마오리족을 차별하는 의료 시스템에서 일하는 것이 어떤 것인지 설명합니다. '불평등한 결과란 마오리족인 경우 사망 확률이 높다는 뜻입니다."38 그녀는 의과대학에서 마오리족 건강 통계에 대해 배우는 것과 '실제 사람들, 즉 와나우(대가족)와 함께 실시간으로 플레이하는 것'이 어떻게 다른지에 대해 이야기합니다.38

In a podcast series, a Māori medical student Emma Espiner describes what it is it like working in a health system that discriminates against your people. ‘Unequal outcomes is jargon for a better chance of dying if you are Māori.’38 She discusses how it is one thing to learn about Māori health statistics at medical school and another to see this ‘Playing out in real time with real people, your whānau [extended family]’.38

그녀는 마오리 의료 서비스 제공자(키아 오라 응아티와이)의 의사로 일하는 한 일반의(GP)의 경험을 설명합니다38:

She describes the experience of a general practitioner (GP) working as a doctor for a Māori health provider (Ki A Ora Ngātiwai)38:

'한 번은 지역사회의 건강에 깊이 관여하고 있는 사람에게 제 깨달음을 설명한 적이 있습니다. 내가 웰빙(오라)의 개념에 대해 설명하기 시작하자 그녀는 코웃음을 치며 마오리족에게 오라는 개인의 웰빙이 아니라 집단주의에서 비롯된 웰빙이라고 말했다...... 지역사회 거버넌스와 소유권이 키아 오라 응아티와이의 특징이지만 그렇다고 해서 키아 오라 응아티와이가 서비스를 제공하는 지역사회에 대한 의료 제공을 통제할 수 있는 권한이 있다는 의미로 해석되지는 않는다. 모든 마오리족 의료 제공자와 마찬가지로 자금 조달 메커니즘, 계약 보고 요건 및 성공 척도는 마오리족이 아닌 세계를 반영하는 구조와 시스템에 의해 결정되고 이에 따라 정의됩니다. 이러한 환경은 마오리족 의료 서비스 제공자들을 더욱 구별 짓는 요소이며, 자결권을 위한 지속적인 정치적 투쟁이 바로 제가 일하는 세계입니다.

‘Once I described my epiphany to someone who was heavily involved with the health of her community. She snorted when I started to expound on my conceptualisation of wellness (ora) and [said] in not so many words, that for Māori ora is not individual wellness but is instead the wellness arising from collectivism.… While community governance and ownership are defining features of Ki A Ora Ngātiwai this does not translate into having control over the delivery of health care into the communities that Ki A Ora Ngātiwai services. Like all Māori health providers the funding mechanisms, contract reporting requirements and measures of success are dictated by, and defined by, structures and systems that reflect a non-Māori world. It is this environment that further distinguishes Māori health providers — the ongoing political struggle for self-determination — and it is in this world that I work.’

이 사례는 마오리족 의료 종사자들이 현재 시스템 내에서 최선을 다하면서 변화를 옹호해야 하는 어려움이 있음을 반영합니다. '새로운 세상을 설계하면서 반창고를 붙이는 동시에 동의하지 않는 사람들과 싸우고 있습니다.'38

This example reflects that the challenge for Māori health practitioners is that they are advocating for change while having to do their best within the current system. ‘You are putting on the band aid on while designing the new world and all the while fighting those who do not agree with you.’38

이 사례 연구는 사회 문화가 조직에 미치는 영향과 의료 서비스 제공 방식을 보여줍니다. 또한 지배적인 문화가 어떻게 불평등을 지속시킬 수 있는지도 보여줍니다. 또한 이러한 영향이 개인 수준에서 어떻게 나타날 수 있는지, 한 문화권의 의료진이 자신의 가치와 신념을 조직의 가치와 신념과 조화시키는 데 어려움을 겪을 수 있음을 보여줍니다. 또한 조직 문화에 맞추기 위해 항상 개인이 변화해야 하는 것은 아니며, 오히려 개인이 더 넓은 범위의 시스템적 변화를 옹호할 수 있음을 보여줍니다.

This case study illustrates the impact of society culture on an organisation and how health services are provided. It also illustrates how a dominant culture can perpetuate inequities. Furthermore, it shows how these effects can be manifest at the individual level where a practitioner from one culture may find it hard to reconcile their values and beliefs with those of the organisation. It further illustrates that it should not always be the individual who has to change to fit within the organisation's culture—rather individuals can advocate for wider systemic changes.

7 문화 드러내기

7 REVEALING CULTURE

문화의 이러한 영향을 더 잘 이해하려면 어떻게 인식해야 할까요? 문화는 그 문화에 몰입한 사람에게는 보이지 않는 경우가 많지만 규범과 가치에 주목하면 인식할 수 있습니다. 이러한 보이지 않는 규범을 발견하기 위한 몇 가지 질문은 다음과 같습니다.

If we are to understand better these effects of culture, how might we recognise them? Culture is often unseen by those immersed in it but can be recognised by noting norms and values. Some questions to uncover these unseen norms might be to ask

- 우리는 서로의 관행을 관찰하고 있으며 이러한 관행은 어떻게 제정되었는가? 서로의 학습을 돕는 방식으로 간주되는가, 아니면 판단을 내리기 위한 것인가?

Do we observe each other's practice and how is this enacted? Is it seen as a way of helping each learn or is it to make judgements? - 기관은 서로에게 어떻게 피드백을 제공하나요? 의료 서비스는 교육 기관에 어떻게 피드백하고, 교육 기관은 의료 서비스에 어떻게 피드백하나요? 피드백에 대한 응답으로 어떤 일이 일어나나요?

How do institutions feedback to each other? How does the health service feed back to a training institution and how does a training institution feed back to a health service? What happens as a response to that feedback? - 오피니언 리더와 변화 옹호자들은 어떻게 인식하고 있으며 어떤 장벽과 조력자를 만나게 되나요?

How are opinion leaders and change advocates perceived and what barriers and enablers do they encounter? - 직원들이 학습할 수 있는 시간을 어떻게 확보할 수 있을까요?

How do we make time for our employees to learn? - 품질 개선을 위한 의견을 말하고 아이디어를 제안하는 것이 안전하다고 느끼나요? 누가 이런 일을 할 수 있는 권한을 가지고 있나요?

Do we feel safe to speak up and offer ideas for quality improvement? Who has the power to do this? - 직원들이 만나는 중요한 시간과 장소는 어디이며 회의에서 논의되는 내용은 무엇인가요?

What are the critical times and places that staff meet and what is discussed at those meetings? - 연습의 어떤 측면에 엄격한 프로토콜이 있으며 '여기서 하는 방식'으로 간주되는가?

What aspects of practice have strict protocols and are seen as ‘how we do things here’? - 학습자가 하지 말아야 하는 활동에는 어떤 것이 있나요?

What activities are learners discouraged from? - 여기서 배우기 쉬운 것은 무엇이고 어려운 것은 무엇인가요?

What is easy to learn here and what is more difficult? - 전문가 간 견해가 의사 결정에 어떻게 통합되나요?

How are interprofessional views integrated into decisions? - 다른 조직에서 온 신입 연수생에게 문화가 어떻게 고통을 줄 수 있나요?

How might culture cause distress to a new trainee from another organisation? - 수련의가 직장에서 '인상적'이 되게 하는 원동력은 무엇이며, 어떤 행동이 '인상적'으로 여겨지는가39?

What drives students to ‘impress’ in the workplace and what behaviours are seen as ‘impressive’39? - 어떤 임상 환경이 다른 임상 환경보다 다양성을 더 지지하는 것으로 여겨지는 이유는 무엇인가요?

Why are some clinical environments seen as more supportive of diversity than others? - 형평성 문제는 어떻게 해결됩니까?

How are issues of equity addressed? - 사람들은 형평성이나 직원 복지와 관련된 문제를 발견했을 때 안전하게 말할 수 있다고 느끼나요?

Do people feel safe to speak up when they see problems with equity or staff wellbeing?

8 앞으로 나아갈 길

8 THE WAY FORWARD

보건 기관과 협력하여 실습 학습 문화를 파악하는 것이 유익한 출발점이 될 수 있다고 생각합니다. 조직에서 가장 많이 사용하는 두 가지 평가는 참여도 설문조사와 문화 설문조사입니다.21, 24 문화 설문조사를 더 많이 활용하는 것이 앞으로 나아갈 수 있는 방법일 것입니다. 보건 전문가 교육에서는 학습자의 배치 경험을 파악하기 위해 설문조사를 실시하는 것이 일반적입니다. 조직은 직원의 역할, 책임, 업무량, 관리자 및 동료와의 관계, 의사소통 및 협력, 직무 스트레스 등 직원의 개인적인 업무 경험을 파악하기 위해 참여도 설문조사를 실시합니다. 이 두 가지 모두 배치에 대한 학습자 평가와 마찬가지로 '나'의 관점을 다룹니다. 이와는 대조적으로 문화 설문조사 응답은 사람들이 적응하기 위해 필요하다고 생각하는 행동과 규범의 관점에서 직원들이 현재 문화를 어떻게 인식하고 있는지를 알려줍니다. 문화 설문조사는 '우리'의 관점을 다룹니다. 예를 들어, 한국의 한 연구에 따르면 씨족 문화와 옹호 문화는 조직 학습과 매우 긍정적인 관계가 있는 반면, 시장 문화와 위계 문화는 그러한 관계가 없는 것으로 나타났습니다.40 이러한 설문조사의 결과는 해석의 여지가 있고 그 유용성에 의문이 제기될 수 있지만, 그에 따른 토론과 대화는 유익한 정보를 제공할 수 있습니다.

One place we believe it can be fruitful to start is to partner with health organisations to unpack the practice learning culture. Two of the most popular assessments that organisations use are engagement surveys and culture surveys.21, 24 Perhaps making more use of culture surveys is a way forward. In health professional education, it is common to survey learners to understand their experience of a placement. Organisations undertake engagement surveys to understand the employees' personal experience of work: how they feel about their roles, responsibilities, workload, relationships with managers and colleagues, communication and cooperation, and job stress. Both of these address the ‘I’ perspective much as learner evaluations of placements do. In contrast, culture surveys responses tell us how the workforce perceives the current culture in terms of the behaviours and norms that people believe are required to fit within. Cultural surveys address the ‘we’ perspective. For example, a Korean study found that clan and advocacy cultures had strong positive relationships with organisational learning, while market and hierarchy cultures showed no such relationships.40 While the results of such surveys may be open to interpretation and their usefulness challenged, the discussion and conversations that ensue could be informative.

의료 전문가 학습자가 처한 상황을 완전히 이해하려면 이론적 접근 방식과 연구 방법의 폭을 넓혀야 할 수도 있습니다. 지금까지 유익한 정보를 제공한 연구는 종종 민족지학과 직접 관찰을 사용했는데,11 이는 암묵적인 지식과 관행뿐만 아니라 우리가 자란 사회, 인종, 성별에서 비롯된 뿌리 깊은 신념 등 당연한 것으로 받아들여지고 보이지 않는 것을 발견하는 데 도움이 될 수 있기 때문입니다. 이는 우리의 직업 문화, 교육 문화, 우리가 몸담고 있는 조직의 교차점을 탐구하는 데 도움이 될 수 있습니다. 우리는 교육, 민족지학, 질 개선 및 실행 과학 간의 연구 시너지를 창출하기 위해 수련생, 수퍼바이저, 환자라는 삼위일체를 넘어선 공동 연구를 모색해야 합니다. 베어먼은 '학습 문화와 문화적 반성성에 관한 다른 문헌들은 대부분 간과되는 영역, 즉 사람들이 사회가 가하는 강력한 힘을 인식하면서 어떻게 문화에 효과적으로 영향을 미칠 수 있는지 탐구하는 데 도움이 될 수 있다'고 제안합니다.19

If we are to understand fully the situation in which we place health professional learners, we may also need to broaden our theoretical approach and with it our research methods. Research to date that has been informative has often used ethnography and direct observation,11 possibly as it assists in uncovering that which is accepted, unseen taken for granted, not just our tacit knowledge and practice but our deeply ingrained beliefs taken from the society in which we grew up, our race, gender. It can help explore the intersection of our professional culture, our educational culture and the organisations we practice in. We should explore collaborative research that extends beyond the triad of trainee, supervisor and patient to create research synergies among education, ethnography, quality improvement and implementation science. Bearman suggests that ‘Other literature on learning cultures and cultural reflexivity may help explore a territory which is mostly overlooked: how people can effectively influence a culture whilst recognising the strong forces exerted by the social’.19

9 결론

9 CONCLUSIONS

우리는 관점을 재구성하고 학습 환경의 '지저분함'을 포용해야 할 구성 요소로 볼 필요가 있다고 제안합니다. 안전하고 효과적인 환자 치료라는 우리 모두가 열망하는 목표를 달성하기 위해 보건 및 환자 단체와 협력할 수 있는 기회를 제공하는 요소입니다. 환자 치료는 사회에 대한 우리의 의무이며, 이 과학의 상태 시리즈에서 자아, 상황, 사회라는 삼위일체를 완성합니다.

We suggest we need to reframe our views and see the ‘messiness’ of the learning environment as a component to be embraced. A component that provides opportunities for partnering with health and patient organisations to achieve the goal we all aspire to – safe and effective patient care. Patient care is our obligation to society and completes the triad within this State of the Science series of self, situation and society.

또한, 우리는 이제 막 학습 환경의 의미를 파악하기 시작했을 뿐이라고 생각합니다.

- 학습 환경은 수행해야 할 작업 그 이상이며 연수생과 감독자 관계 그 이상입니다.

- 학습 환경은 전문가 간, 제도적, 물리적, 문화적, 일상화되고 체계적인 것입니다.

- 학습은 수련의가 배우고자 하는 내용, 감독 방법, 수행해야 하는 업무뿐만 아니라 물리적 환경, 다른 의료 전문가들의 상호작용과 행동, 치료를 안내하기 위해 마련된 시스템에 의해 형성됩니다.

- 마지막으로, 학습은 우리가 서로에게서 배울 수 있는지 여부, 일과 학습의 우선순위, 지식을 '보유'하는 주체를 중요하게 여기는 문화적 규범의 영향을 받습니다.

- 우리는 보는 것을 넓혀야 할 뿐만 아니라 그것을 보는 (연구) 방법과 함께 일하는 협력자를 넓혀야 합니다.

Furthermore, we suggest that we have only just begun to see what we mean by the learning environment.

- It is more than the work that needs to be done and it is more than the trainee-supervisor relationship.

- It is interprofessional, institutional, physical, cultural, routinised and systemic.

- Learning is shaped not only by what we intend trainees to learn, how we supervise and the work that has to be done, but is shaped by the physical environment, the interactions and behaviours of other health professionals and the systems in place to guide care.

- Finally, learning is influenced by the cultural norms that value (or not) whether we can learn from each other, how work and learning are prioritised, and who ‘holds’ knowledge.

- Not only do we need to broaden what we see, but we should broaden the (research) methods by which we see it and the collaborators with whom we work.

Widening how we see the impact of culture on learning, practice and identity development in clinical environments

PMID: 34433232

DOI: 10.1111/medu.14630

Abstract

As part of this State of the Science series on Self, Society and Situation, we focus on how we might see the situation of the workplace as a learning environment in the future. Research to date into how health professionals learn while working in clinical workplace environments has mostly focused on the supervisor-trainee relationship or on the interaction between the affordances of a workplace and the receptiveness of trainees. However, the wider environment has not received as much focus-though frequently mentioned, it is seldom investigated. We suggest there is a need to embrace the wider institution factors, recognise and acknowledge an organisation's values and culture as they impact on clinical learning in order to work with these, not around them or ignore them, to make what may be tacit visible through reflection and observation and to embrace a range of perspectives on culture.

© 2021 Association for the Study of Medical Education and John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 임상교육(Clerkship & Residency)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 보건의료 업무를 통한 학습: 전제, 기여, 실천(Med Educ, 2016) (0) | 2023.11.12 |

|---|---|

| 어떻게 근무현장-기반 평가가 졸업후교육에서 학습을 가이드하는가: 스코핑 리뷰 (Med Educ, 2023) (0) | 2023.11.10 |

| 키워드 특이적 알고리듬으로 발전 문제가 있는 전공의 찾아내기 (J Grad Med Educ. 2019) (0) | 2023.07.16 |

| 임상진료상황에서 능숙한 의사소통가의 특징 식별하기(Med Educ, 2022) (0) | 2023.06.30 |

| 가능성과 불가피성: AI-관련 임상역량의 격차와 그것을 채울 필요성(Med Sci Educ. 2021) (0) | 2023.05.27 |