졸업후교육 학습자(전공의)의 평가에서 환자참여: 스코핑 리뷰(Med Educ, 2021)

Patient involvement in assessment of postgraduate medical learners: A scoping review

Roy Khalife1 | Manika Gupta1 | Carol Gonsalves1 | Yoon Soo Park2 | Janet Riddle3 | Ara Tekian3 | Tanya Horsley4,5

1 소개

1 INTRODUCTION

역량 기반 의학교육(CBME)이 가져온 광범위한 변화에 대응하여, 졸업후의학교육(PGME) 교육 프로그램(PGME)은 투명하고 사회적으로 책임감 있는 환자 중심 교육을 제공하여 미래의 의사 인력이 사회와 환자의 요구를 충족할 수 있도록 준비시킬 의무가 있습니다.1, 2 PGME가 실제로 이러한 의무를 이행하는 정도는 주로 무감독 실습에 대한 증명을 제공하는 평가 시스템에 의존합니다.3 그러나 졸업후의학교육(PGME) 학습자의 역량과 무감독 실습 준비도를 평가하는 것은 복잡하고 어려운 일입니다.4-6

In response to broad-sweeping changes brought on by competency-based medical education (CBME), postgraduate medical education (PGME) training programmes are mandated to deliver transparent, socially accountable and patient-centred education that prepares the future physician workforce to meet societal and patient needs.1, 2 The extent to which PGME in fact delivers on this mandate relies predominantly on systems of assessment that provide attestation for unsupervised practice.3 However, assessing postgraduate medical learners' competence and readiness for unsupervised practice is complex and challenging.4-6

일반적으로 평가 시스템은 전적으로 의사의 판단에만 의존하며, 최근 21세기 의료,5,7,8 환자 참여형 의료에 대한 졸업후의학교육(PGME) 의료 학습자의 역량에 대한 총체적인 관점을 제공하지 못한다는 비판을 받고 있습니다. 환자를 의료 서비스에서 보다 동등한 파트너로 장려하는 전 세계적인 움직임을 고려할 때 이는 놀라운 일이 아닙니다.9,10 실제로 의과대학 커리큘럼에서 환자 파트너가 입학 위원회 및 자문 그룹에서 필수적인 역할을 하거나 표준화된 환자 및 교사로서 점점 더 많이 등장하고 있습니다.11-14 하지만 왜 환자를 포함해야 할까요? 교육 전반에 걸친 환자 참여는 진정한 환자 중심 의학교육과 사회적 책임성 증대로 이어질 수 있지만,15 역량에 대한 결정을 내리는 평가 노력에서 환자의 목소리는 눈에 띄게 부재하거나 중요하지 않은 것으로 남아 있습니다.16-18

Generally, systems of assessment rely solely on physicians' judgements and have recently been criticised for not providing a holistic view of postgraduate medical learners' competence for 21st century care,5, 7, 8 care that is patient-partnered. This should come as no surprise given a global movement promoting patients as more equal partners in health care.9, 10 In fact, patient partners are increasingly present in medical school curricula with integral roles on admission committees and advisory groups and as standardised patients and teachers.11-14 But why include patients? Patient engagement across the educational spectrum can lead us towards true patient-centred medical education and increased social accountability,15 and yet the patient voice remains conspicuously absent, and inconsequential, from assessment endeavours that inform decisions vis-à-vis competence.16-18

최근의 일부 증거에 따르면

- 행정적 어려움(예: 시간 및 인적 자원 제약, 평가 도구의 부족, 사회문화적 및 조직적 장애물)이 평가에 환자를 포함시키는 데 장애가 되는 것으로 나타났습니다.16 이는 어느 정도 놀라운 일이 아니지만, 새로운 증거는 더 복잡한 그림을 그려줍니다.

- 한편으로 환자들은 역량 기반 평가 관행에 자신의 경험적 전문성을 기여할 의향이 있고, 열의가 있으며, 좋은 위치에 있는 것으로 분류되어 왔습니다.17, 19

- 한편, 평가 시스템의 중심 행위자인 의사들의 관점에서는 환자의 관심, 능력, 전문성 부족, 평가에 대한 잠재적 편견에 대해 불확실성과 우려를 표하는 것으로 보입니다.16

이러한 긴장은 환자가 역량 기반 평가에서 적극적인 역할을 하는 맥락을 불러오는 교육 관행의 발전을 방해할 수 있습니다.

Some recent evidence has positioned

- administrative challenges (e.g. time and human resource constraints, perceived lack of assessment tools and sociocultural and organisational hurdles) as a barrier to patient inclusion in assessment.16 While this is to some extent not surprising, emerging evidence paints a more complex picture.

- On the one hand, patients have been categorised as willing, eager and well-positioned to contribute their experiential expertise to our competency-based assessment practices.17, 19

- Meanwhile, there appears to be misalignment with physicians' perspectives (the central actor in assessment systems) who express uncertainty and concern towards patients' lack of interest, abilities, expertise and potential biases in assessment.16

This tension may impede the development of educational practices that invoke contexts where patients have an active role in competency-based assessment.

평가에 대한 환자의 참여에 대한 다양한 의견과 잠재적으로 관련성이 있는 광범위한 문헌을 고려할 때, 우리는 범위 검토 방법론을 사용하여 환자가 졸업후의학교육(PGME) 의학 학습자 평가에 참여했는지 여부와 그 방법을 탐구하고자 했습니다. 구체적으로, '졸업후의학교육(PGME) 의학 학습자 평가에 대한 환자 참여를 탐구하는 문헌의 범위, 성격 및 범위는 어느 정도인가'라는 질문에 답하고, 이어서 '역량 기반 평가에서 환자 참여에 영향을 미치는 요인(예: 어포던스 및 장벽)은 무엇인가'라는 질문에 답하고자 했습니다.

Given the disparate opinions of patients' involvement in assessment and the breadth of potentially relevant literature, we aimed to explore whether and how patients have partnered in the assessment of postgraduate medical learners using a scoping review methodology. Specifically, we aimed to answer the question ‘What is the extent, nature and range of literature that exists exploring patient involvement in the assessment of postgraduate medical learners?’ and subsequently, ‘what factors influence (e.g., affordances and barriers) patient involvement in competency-based assessment?’

2 방법

2 METHODS

Arksey와 O'Malley의 6단계 방법론 프레임워크가 우리의 범위 검토에 영향을 미쳤습니다.20 우리는 또한 Levac 외와 Thomas 외의 업데이트된 방법론 권고사항도 고려했습니다.21,22 구체적으로, 우리는 Levac 외의 제안대로 선택 과정과 데이터 차트 작성 단계에서 여러 차례 회의와 토론을 진행했으며,21 그리고 Thomas 등이 권고한 대로 대상 집단과 중재의 초점을 좁혔습니다.22 20개 항목으로 구성된 체계적 문헌고찰 및 범위 설정을 위한 메타분석의 선호 보고 항목(PRIMA-Scr)이 연구 보고의 지침이 되었습니다.23

Arksey and O'Malley's six-stage methodological framework informed our scoping review.20 We also considered updated methodological recommendations by Levac et al. and Thomas et al.21, 22 Specifically, we conducted multiple meetings and discussions at the selection process and data charting stages as suggested by Levac et al.,21 and we narrowed the focus of our target population and intervention as recommended by Thomas et al.22 The 20-item, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRIMA-Scr) guided our reporting of our research.23

2.1 1단계: 연구 질문 파악하기

2.1 Stage 1: Identifying the research question

범위 검토 프레임워크의 첫 번째 단계에서 정의한 대로, 4명의 저자(RK, CG, YSP, AT)는 보건 전문직 교육(HPE) 문헌에서 평가자로서의 환자를 광범위하게 논의했습니다. 이러한 논의를 통해 연구 질문에 대한 정보를 얻고 정의했습니다:

As defined by the first step of the scoping review framework, four authors (RK, CG, YSP and AT) broadly discussed patients as assessors within the health professions education (HPE) literature. These discussions informed and defined our research questions:

- 졸업후의학교육(PGME) 학습자 평가에 환자의 참여를 탐구하는 문헌의 범위, 성격 및 범위는 어느 정도인가?

What is the extent, nature and range of literature that exists exploring patient involvement in assessment of postgraduate medical learners? and - 역량 기반 평가에서 환자의 참여에 영향을 미치는 요인(예: 어포던스 및 장벽)은 무엇인가?

What factors appear to influence (e.g. affordances and barriers) patient involvement in competency-based assessment?

주제의 복잡성과 식별할 수 있는 문헌의 폭(환자 중심 문헌과 의료 전문직 교육의 교차점)을 고려하여 검토의 초점을 졸업후의학교육(PGME) 의료 학습자(예: 레지던트 및 펠로우)로 좁혔습니다. 의학 교육은 하나의 연속체이지만, 학부 학습자와 졸업후의학교육(PGME) 학습자는 학습자를 평가하는 이유와 방법이 근본적으로 다릅니다. 이러한 이유로, 우리는 졸업후의학교육(PGME) 학습자만을 분석 단위로 포함하도록 모집단을 합리적으로 분리했습니다. 학부생과 졸업후의학교육(PGME)생이 혼합된 모집단(예: 학부생과 졸업후의학교육(PGME)생 의학 학습자)이 포함된 연구의 경우, 졸업후의학교육(PGME)생 데이터가 별도로 제시된 경우에만 연구에 포함시켰습니다.

Given the complexity of the topic and the breadth of literature that might be identified (intersection of patient-oriented literature and health professions education), we narrowed the focus of our review to postgraduate medical learners (e.g. residents and fellows). Although medical education is a continuum, why and how learners are assessed are fundamentally different between undergraduate and postgraduate learners. For this reason, we rationalised segregating our population to include only postgraduate learners as a unit of analysis. When studies included mixed populations (e.g. undergraduate and postgraduate medical learners), we included studies only when graduate learners data were presented separately.

Thomas 등22 의 영향을 받아 대상 집단(졸업후의학교육(PGME) 의학 학습자)에 초점을 좁혔을 뿐만 아니라, HPE 프로그램의 이질성과 관련된 잠재적인 보급 및 실행 문제를 최소화하기 위해 개입(평가 도구의 환자 완료)의 우선순위를 정하고 집중적으로 포함시켰습니다.

Influenced by Thomas et al.,22 not only did we narrow our focus on a target population (postgraduate medical learners), we prioritised and focused inclusion of the intervention (patient completion of assessment tools) to minimise potential dissemination and implementation challenges related to the heterogeneity of HPE programmes.

2.2 2단계: 관련 연구 식별

2.2 Stage 2: Identifying relevant studies

반복적인 접근 방식과 숙련된 의학 사서의 안내에 따라 날짜 제한 없이 MEDLINE과 EMBASE에 대한 검색 전략을 개발했습니다(부록 S1). 검색의 정확도와 회상률을 높이기 위해 미리 식별된 관련 기록에 대해 검색을 테스트했습니다. 검색은 2019년 11월 18일에 시행되었으며 2021년 2월 25일에 제출하기 전에 업데이트되었습니다. 원래 PubMED©는 진행 중인 기록과 초기 릴리즈 기록을 포착하기 위한 목적으로 검색되었으며, 초기에는 낮은 수율로 인해 후속 검색은 적용되지 않았습니다. 모든 기록은 독점적인 체계적 문헌고찰 소프트웨어 도구로 다운로드되었습니다(Covidence 체계적 문헌고찰 소프트웨어, 베리타스 헬스 이노베이션, 호주 멜버른. http://www.covidence.org 에서 사용 가능). 주제의 복잡성과 검색의 알려진 어려움을 감안하여, 포함된 모든 연구의 참조 목록을 확인하여 원래 검색에서 포착되지 않은 관련 기록을 식별했습니다.24

Using an iterative approach and guided by an experienced medical librarian, we developed a search strategy for MEDLINE and EMBASE without date restrictions (Appendix S1). Searches were tested against pre-identified relevant records as a measure of improving precision and recall of the search. The search was implemented on 18 November 2019 and was updated prior to submission on 25 February 2021. Originally, PubMED© was searched with the intent to capture in-process and early-release records; given the low yield initially, no subsequent searches were applied. All records were downloaded to a proprietary systematic review software tool (Covidence systematic review software, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Available at www.covidence.org). Given the complexity of the topic and known challenges with searching, we checked reference lists of all included studies to identify any relevant records not captured by the original search.24

2.3 3단계: 연구 선택

2.3 Stage 3: Study selection

2.3.1 적격성 기준

2.3.1 Eligibility criteria

검토를 위한 포함 기준을 충족하기 위해, 기록은 (i) 환자를 능동적 평가자로 다루고(예: 완성된 평가 도구), (ii) 졸업후의학교육(PGME) 의학 학습자(예: 레지던트 및 펠로우)를 평가하는 데 초점을 맞추고, (iii) 영어 또는 프랑스어 출판물이어야 하며, (iv) 전체 텍스트 기록으로 제공되어야 합니다. 회색 문헌과 논평, 논문, 사설 또는 의견서는 제외되었습니다.

To meet the threshold of inclusion for our review, records had to (i) address patients as active assessors (e.g. completed assessment tool), (ii) focus on assessing postgraduate medical learners (e.g. residents and fellows), (iii) be English- or French-language publications and (iv) be available as full-text records. Grey literature as well as commentaries, dissertations, editorials or opinion pieces were excluded.

2.3.2 선정 과정

2.3.2 Selection process

정의된 적격성 기준을 사용하여 표준화된 양식을 개발하고 파일럿 테스트를 거쳐 기록의 포함 및 제외 결정을 내리는 데 사용했습니다. 두 명의 저자(RK와 MG)가 검토 소프트웨어 내에서 각 제목과 초록을 독립적으로 검토하고 프로젝트 시작, 중간, 종료 시점에 만나(Levac 외.21의 권고에 따라) 합의점을 논의하고 그에 따라 적격성 결정을 구체화했습니다. 의견 불일치는 각 단계의 적격성 평가 후 토론을 통해 해결했습니다. 다른 복잡한 주제와 마찬가지로, 이는 검토 개념을 구체화하고 졸업후의학교육(PGME) 의학 학습자 또는 환자 자체를 정의할 때 보고가 부실하거나 이질적이기 때문에 발생하는 갈등을 해결하는 데 도움이 되었습니다. 이를 위해 검토자 간의 일치도는 코헨 카파를 사용하여 0.54로 평가되었으며, 이는 중간 수준의 일치도로 해석됩니다.

Using a defined eligibility criterion, we developed and pilot-tested a standardised form that was then used to guide decisions for inclusion and exclusion of records. Two authors (RK and MG) reviewed each title and abstract independently within the review software and met at the project start, midpoint and end (as recommended by Levac et al.21) to discuss agreement and refine eligibility decisions accordingly. Disagreements were resolved by discussion after each level of eligibility assessment. As with any complex topic, this proved helpful in refining review concepts and resolving conflicts, for example, that were due to either poor reporting or heterogeneity in defining postgraduate medical learners or patients themselves. To this end, agreement between reviewers was assessed at 0.54 using a Cohen's kappa, interpreted as a moderate level of agreement.

2.4 4단계: 데이터 차트 만들기

2.4 Stage 4: Charting the data

범위 검토 프레임워크의 4단계에 따라 미리 정의된 데이터 차트 양식을 만들었습니다. 처음에 한 명의 저자(RK)가 기록 수준의 우선순위 항목을 개괄적으로 설명하기 위해 개발한 이 양식은 더 광범위한 팀(RK, CG, YSP 및 AT)의 의견을 수렴하여 검토 및 수정되었습니다. 데이터 차트 항목에는 환자의 특성, 연구 환경, 평가 개입, 사전 지정된 질문에 따른 주요 결과가 포함되었습니다(부록 S2). 그런 다음 양식의 유용성과 포괄성에 대해 파일럿 테스트를 거쳐 팀의 승인을 받았습니다. 한 명의 저자(RK)가 초기 데이터 차트 작성을 수행했고, 두 번째 저자(MG)가 각 대상 연구를 검토하고 차트 작성된 데이터의 정확성을 확인했습니다. Levac 등이 제안한 대로,21 두 저자는 처음 10개의 연구에서 차트화된 데이터에 대해 논의한 후 데이터 차트 양식을 더욱 구체화했습니다. 이 양식에 추가된 항목에는 환자 배제 또는 거부, 환자 익명성 및 기밀성, 환자 참여율, 다중 출처 피드백과 관련된 추가 세부 정보에 관한 데이터가 포함되었습니다. 그런 다음 데이터 차트 작성 프로세스가 끝날 때 저자들이 다시 만나 토론을 통해 모든 이견을 해결했습니다.

In keeping with Stage 4 of the scoping review framework, we constructed a predefined data-charting form. Initially developed by one author (RK) to outline record-level, priority items, the form was then reviewed and revised with input from the broader team (RK, CG, YSP and AT). Data charting items included the characteristics of patients, study settings, assessment interventions and primary outcomes based on our prespecified questions (Appendix S2). The form was then pilot-tested for usability and comprehensiveness and approved by the team. One author conducted initial data charting (RK), and a second author (MG) reviewed each eligible study and verified the charted data for accuracy. As suggested by Levac et al.,21 both authors met to discuss the charted data from the first 10 studies and then further refined the data-charting form. Items added to the form included data pertaining to patient exclusion or refusal, patient anonymity and confidentiality, patient participation rates and additional details related to multi-source feedback. The authors then met again at the end of the data charting process and resolved all disagreements through discussion.

2.5 5단계: 결과 집계, 요약 및 보고

2.5 Stage 5: Collating, summarising and reporting results

아크시와 오말리의 5단계 접근 방식에 따라, 차트화된 데이터는 엑셀 파일에 간결하게 요약되어 저자 간의 토론과 해석을 알리는 데 사용되었습니다. 연구 설계, 출판 유형, 출판 국가, 개입 세부 사항, 분석 인구 단위(예: 전문 분야) 및 관련 결과 측정값을 포함한 인구통계학적 특성을 보고하기 위해 정량적 서술적 분석을 완료했습니다. 한 명의 저자(RK)가 앞서 언급한 연구 질문에 따라 선택된 모든 연구의 내용을 분류했습니다. 추출된 모든 데이터는 두 번째 저자(MG)가 검토했으며, 두 사람이 만나서 합의점을 논의하고 분류를 수정했습니다. 그런 다음 두 저자는 데이터를 해석하여 연구팀에게 설명적으로 제시했습니다. 그런 다음 연구팀은 가상으로 만나 데이터를 어떻게 제시하고 맥락화할지 논의했습니다. 이후 세 명의 저자(RK, JR, TH)가 세 차례에 걸쳐 만나 해석 분석을 추가로 비교, 대조, 수정했습니다.

In keeping with Step 5 of Arksey and O'Malley's approach, charted data were summarised succinctly within an excel file and used to inform discussions and interpretations between authors. Quantitative descriptive analysis was completed to report on demographic characteristics including study design, publication type, country of publication, intervention details, population unit of analysis (e.g. specialty) and relevant outcome measures. One author (RK) categorised the content of all selected studies based on the aforementioned study questions. All extracted data were reviewed by a second author (MG), and both met to discuss agreement and revise the categorisation. The data were then interpreted by the two authors and presented descriptively to the study team. The team then met virtually to discuss how the data were presented and contextualised. Three authors (RK, JR and TH) then met on three subsequent occasions to further compare, contrast and revise the interpretative analysis.

2.6 6단계: 협의 연습

2.6 Stage 6: Consultative exercise

아크시와 오말리 프레임워크의 6단계(이해관계자 자문)는 '소비자 및 이해관계자가 참여하여 추가 참고 문헌을 제안하고 문헌에 없는 통찰력을 제공할 수 있는 기회'를 제공합니다.20 이 단계는 아크시와 오말리의 프레임워크에서는 선택 사항으로 설명되지만 레박 외의 업데이트에서는 필수 사항으로 간주됩니다.20, 21 이를 고려하여 연구팀은 적절한 연구 윤리 승인 및 자금 지원을 통해 향후 연구를 통해 이 작업을 해결하는 것이 가장 좋다는 결론을 내렸습니다.

Stage 6 of the Arksey and O'Malley framework (consulting stakeholders) provides ‘opportunities for consumer and stakeholder involvement to suggest additional references and provide insights beyond those in the literature’.20 This step is described as optional in Arksey and O'Malley's framework, but deemed essential in Levac et al.'s update.20, 21 Given this, the study team concluded that this work may be best addressed through future research with appropriate research ethics approval and funding.

3 결과

3 RESULTS

검색 결과 821개의 기록이 발견되었습니다. 적격성 평가 결과, 41개의 전체 텍스트 연구가 포함 기준을 충족했습니다. 적격성 평가의 각 단계에 대한 자세한 내용은 그림 1에 나와 있습니다. 포함된 연구의 인구통계학적 특성은 표 1에 요약되어 있습니다. 대부분의 연구는 최근 10년(2010~2020년) 동안 미국 출신 저자에 의해 발표되었으며, 단일 기관에서 수행되었습니다. 포함된 연구는 내과와 가정의학 등 여러 분야에서 발표되었으며, 환자는 여러 임상 환경(대부분 외래 진료소)을 대표하는 경우가 많았습니다(표 1). 부록 S4에는 연구 설계, 출판 국가, 졸업후의학교육(PGME) 학습자의 특성, 환자 평가 횟수, 주요 연구 결과 등 41개 연구 전체에 대한 자세한 설명이 나와 있습니다.

Our search yielded 821 records. Following eligibility assessment, 41 full-text studies met the inclusion criteria. Details outlining each stage of eligibility assessment are depicted in Figure 1. Demographic characteristics of included studies are outlined in Table 1. Most studies were published by authors originating from the United States, during the most recent decade (2010–2020), and form a single institution. Included studies were published within several disciplines, most commonly internal and family medicine, with patients representing multiple clinical settings, most frequently out-patient clinics (Table 1). Appendix S4 provides a detailed description of all 41 studies including study design, country of publication, characteristics of postgraduate learners, number of patient assessments and the main study findings.

3.1 환자 대표성

3.1 How patients are represented

포함된 41개의 연구 중 18개(43.9%)만이 환자의 성별을 보고했습니다.25-27, 37, 41-49, 58, 59, 61-63 부모와 보호자를 대표하는 소아 환자 집단을 대상으로 한 3개의 연구에서 여성은 학습자 평가의 일부로 피드백 수집의 82-87%에 기여했습니다.44, 45, 49 여러 연구에서 인구학적 특성을 보고했지만, 성별이 평가에 미치는 영향을 탐구한 연구는 거의 없었습니다. 외과 레지던트의 의사소통 능력에 대한 다중 소스 피드백(MSF)의 타당성을 조사한 한 연구에서는 성별에 기반한 접근 방식을 사용하여 여성 레지던트가 통계적으로 유의하게 높은 평가를 받은 것으로 보고했습니다.41

Of the 41 included studies, only 18 (43.9%) reported patients' gender.25-27, 37, 41-49, 58, 59, 61-63 In three studies with a paediatric patient population representing parents and guardians, women contributed to 82–87% of feedback collection as part of learners' assessments.44, 45, 49 While several studies reported demographic characteristics, few explored the effect of gender on assessment. One study that explored the feasibility of multi-source feedback (MSF) for surgical residents' communication skills used a gender-based approach to report as women as providing statistically significantly higher ratings of residents.41

환자의 인종과 민족은 13개 연구(31.7%)에서 확인되었습니다. 보고된 용어에 따르면, 환자는 주로 '백인' 또는 '백인'으로 식별되었으며, 13개 연구 중 9개 연구에서 가장 큰 코호트(>50%)를 차지했습니다.25-27, 41, 46, 48, 49, 59, 62 실제로 두 연구에서 '백인' 환자 참가자 비율이 90%까지 보고되었습니다.26, 62 소수 인종 또는 소수 민족의 대표성은 다양했으며 그 이유를 명확하게 파악하기 위한 설명 정보가 거의 없었습니다. 샘플링이 수행된 이유와 대표성을 추구했는지에 대한 이유는 보고되지 않았습니다. 기타 환자 인구통계학적 특성(예: 사회경제적 지위)에 대한 보고는 공통성과 일관성이 부족하여 연구 간 비교가 어려웠습니다.

Patient race and ethnicity were identified in 13 studies (31.7%). Using the reported terminology, patients predominantly identified as ‘White’ or ‘Caucasian’ representing the largest cohort of participants (>50%) in nine of the 13 studies.25-27, 41, 46, 48, 49, 59, 62 In fact, two studies reported rates of ‘White’ patient participants as high as 90%.26, 62 Representation of racial or ethnic minorities was variable, with little explanatory information to succinctly determine why. Reasons for how sampling was carried out, and whether representation was sought, was not reported. Reporting of other patient demographics (e.g. socio-economic status) lacked commonality and consistency making comparisons across studies challenging.

3.2 환자 포함(및 제외)

3.2 Patient inclusion (and exclusion)

환자 포함 및 제외는 포함된 연구 전반에 걸쳐 다양한 방식으로 나타났습니다. 포함된 연구의 절반 미만(18/41, 43.9%)에서 특정 환자가 학습자 평가에서 제외된 이유를 명확하게 설명했습니다(부록 S5).25, 26, 28-32, 41, 43, 44, 47-50, 59, 61, 62, 64 가장 빈번한 제외 이유는 언어 능력(예: 제한된 영어 능력)이었는데, 이는 발표된 연구의 대부분이 영어 교육이 주를 이루는 국가에서 시작되었음을 고려할 때 놀라운 일이 아닙니다. 평가 도구를 여러 언어로 제공함으로써 평가 도구의 접근성을 보장하기 위한 조치를 고안한 연구는 Tamblyn과 동료들의 연구 한 건에 불과했습니다.58 반대로 환자가 평가에 참여하지 않기로 선택한 경우는 5건(12.8%)에서 보고되었으며, 여기에는 관심 부족, 경쟁 치료 계획, 전반적인 건강(예: 신체적 또는 정신적으로 건강하지 않음) 및 언어 장벽(예: 개인적으로 의사소통이 불가능하다고 느낌)의 예가 포함됩니다(부록 S5).25, 28, 31, 59, 65

Patient inclusion and exclusions were represented in a variety of ways across included studies. Less than half of included studies (18/41, 43.9%) clearly described reasons for why certain patients were excluded from learner assessment (Appendix S5).25, 26, 28-32, 41, 43, 44, 47-50, 59, 61, 62, 64 The most frequent reasons for exclusion was language proficiency (e.g. limited proficiency in English), perhaps unsurprising given the majority of published studies originated in countries where English-language instruction predominates. Only one study by Tamblyn and colleagues devised measures to ensure accessibility of their assessment tool by making it available in multiple languages.58 Conversely, patients' choice to not engage in assessment was reported in five studies (12.8%) and included examples lack of interest, competing care plans, overall well-being (e.g. physically or psychologically unwell) and language barriers (e.g. personally felt unable to communicate) (Appendix S5).25, 28, 31, 59, 65

진행성 암 환자,25 중증 만성 질환을 앓고 있는 환자,62 사회경제적 지위가 낮은 환자,62 교육 수준이 낮은 환자 등 다양한 환자 집단이 대표되었습니다.26, 58 그러나 미성년자, 수감자, 중환자 또는 임종기 환자 등 특정 환자 집단을 체계적으로 배제한 연구는 거의 보고되지 않았습니다.25, 29, 32, 47, 62

There was diverse patient populations represented including those living with advanced-stage cancers,25 suffering from severe chronic diseases,62 from lower socio-economic status,62 and lower educational attainment.26, 58 That said, few studies reported systematically excluding specific patient population such as minors, prisoners or patients critically ill or at the end-of-life.25, 29, 32, 47, 62

3.3 환자 신원 보호(기밀 유지)

3.3 Protecting patient identify (confidentiality)

학습자 평가에 환자를 참여시키는 것은 위험을 수반하는 것으로 인식될 수 있습니다. 학습자가 평가 데이터를 해당 맥락과 연결할 수 없을 때 환자의 평가 및 서술적 의견에 대한 인식에 부정적인 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다.30, 33 이러한 이유로 사용된 절차에 대한 추가 정의 없이 환자 기밀성 및 익명성이 7건(17.9%)의 연구에서만 보고되었습니다.27, 32, 46, 47, 49, 51, 52. 8건(19.5%)의 연구에서는 수집된 환자 설문지가 익명화되었다고 명시했습니다.31, 33-35, 37, 44, 48, 65 비밀이 보장된 피드백 수집을 보장한 9개 연구(23.1%) 중26, 36, 38, 50, 53, 59, 60, 64 Reinders 등만이 특정 환자를 생년월일을 통해 추적할 수 있어 익명성을 보장할 수 없다고 설명했습니다.50 환자의 비밀 유지 및 익명성은 중요한 고려사항이 되며 프로그램의 환자 피드백 요청 목적에 따라 달라질 수 있습니다. 환자-연수생 관계의 유지가 기밀성 및 익명성 보장을 지지하는 주요 논거였습니다.

Involving patients in assessment of learners may be perceived as carrying some risk. There may be a signal that this could adversely influence learners' perceptions of patient ratings and narrative comments when they were unable to link the assessment data to the context in question.30, 33 To this end, patient confidentiality and anonymity were reported in only seven studies (17.9%) without further defining the procedures used.27, 32, 46, 47, 49, 51, 52 Eight studies (19.5%) stated that the collected patient questionnaires were anonymised.31, 33-35, 37, 44, 48, 65 Of the nine studies (23.1%) that assured confidential feedback collection,26, 36, 38, 50, 53, 59, 60, 64 only Reinders et al. explained how they could trace certain patients back through their date of birth and therefore could not guarantee anonymity.50 Maintaining patient confidentiality and/or anonymity becomes an important consideration and dependent on the purpose for which a programme is seeking patients' feedback. Preserving the patient–trainee relationship was the main argument in favour of confidentiality and anonymity.

3.4 환자 평가 수집 방법

3.4 How patient assessments are collected

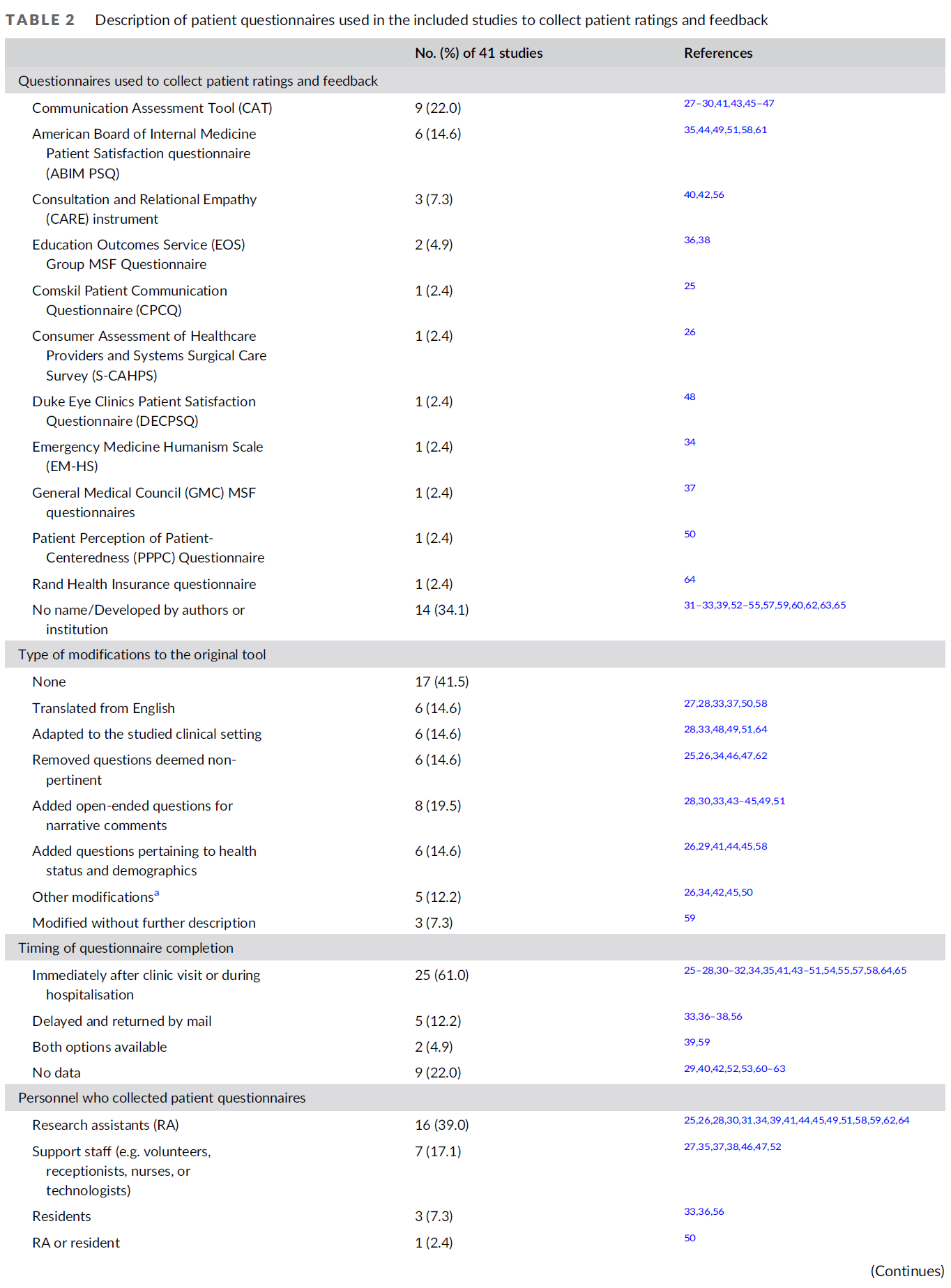

환자 평가는 다양한 심리측정 도구를 통해 수집되었습니다(표 2). 의사소통 평가 도구(CAT)는 지난 10년간 발표된 총 9건의 연구(22.0%)에서 가장 많이 사용되었습니다.27-30, 41, 43, 45-47 환자의 평가 참여는 14건의 연구에서 보고되었습니다.33, 34, 36-39, 44, 49, 51-54, 59, 61 이 연구들 중 MSF 프로세스는 교수진 의사,33, 34, 36, 38, 39, 44, 49, 52-54, 59, 61 간호사,33, 34, 36, 38, 44, 49, 51, 53, 54, 59, 61 수련생/동료,36-39, 53, 54 사무직원,36, 38 연합 보건 전문가53 및 프로그램 디렉터가 중심이 되었습니다.59

Patient assessments were captured by a variety of psychometric tools (Table 2). The Communication Assessment Tool (CAT) was most frequently used in a total of nine studies (22.0%) published within the last decade.27-30, 41, 43, 45-47 Patients' engagement in assessment as a component of MSF was reported in 14 studies.33, 34, 36-39, 44, 49, 51-54, 59, 61 Of these studies, the MSF process centred on faculty physicians,33, 34, 36, 38, 39, 44, 49, 52-54, 59, 61 nurses,33, 34, 36, 38, 44, 49, 51, 53, 54, 59, 61 trainees/peers,36-39, 53, 54 office staff,36, 38 allied health professionals53 and programme directors.59

23개 연구(51.2%)에서 환자 참여 또는 작업장 상황을 지원하기 위해 원래 도구를 수정한 것으로 보고되었으며 표 2.25-28, 30, 33, 34, 37, 41, 42, 45-51, 58, 59, 62, 64 두 연구에서 수정된 도구를 시행하기 전에 시범적으로 사용했다고 보고했습니다.34, 43 양적 및 질적 평가 접근법이 포함된 연구들에서 모두 보고되었습니다. 환자가 질적 의견을 제공하는 기능은 11개 연구에서 보고되었으며, 일반적으로 환자에게 전반적인 의견(예: '이 레지던트의 의사소통에 대해 어떤 점이 좋았습니까?'30 또는 '레지던트가 제공하는 진료에 대해 무엇을 바꾸겠습니까?'51)을 묻거나 레지던트의 성과와 관련하여 인지된 강점 및 개선할 부분에 대해 구체적으로 언급하도록 요청했습니다.26, 28, 30, 32, 33, 43, 44, 49, 51, 52, 54

Modifications to adapt the original tool to support patient involvement or the workplace context were reported in 23 studies (51.2%) and listed in Table 2.25-28, 30, 33, 34, 37, 41, 42, 45-51, 58, 59, 62, 64 Two studies reported piloting their modified tool prior to its implementation.34, 43 Both quantitative and qualitative assessment approaches were reported across the included studies. The ability for patients to provide qualitative comments was reported in 11 studies and generally asked patients for either global comments (e.g. ‘what did you like about this resident's communication?’30 or ‘what they would change about the care provided by the residents?’51) or to comment specifically on perceived strengths and areas for improvement in relation to resident's performance.26, 28, 30, 32, 33, 43, 44, 49, 51, 52, 54

3.5 환자 모집 방법

3.5 How patients are recruited

환자는 주로 연구 조교에 의해 모집되었습니다(16/41, 39.0%).25, 26, 28, 30, 31, 34, 39, 41, 44, 45, 49, 51, 58, 59, 62, 64 대상 연구의 거의 1/3에서 수련의의 이름과 사진 신분증이 사용되었습니다.26, 28, 30-32, 34, 39, 41, 44, 45, 49, 51, 54, 59 이 방법을 사용한 환자들은 88%의 비율로 훈련생을 인식했습니다.26 표 3은 환자 설문지를 수집하는 데 사용된 다른 방법에 대한 추가 세부 정보를 제공합니다. 프로그램 관리자, 사무 직원 또는 병원 자원봉사자와 같은 제3자를 통해 환자 참여를 요청하면 보고된 교육생들의 불편함과 환자 선택에 대한 편견을 최소화할 수 있습니다.30

Patients were recruited primarily by research assistants in our sample of studies (16/41, 39.0%).25, 26, 28, 30, 31, 34, 39, 41, 44, 45, 49, 51, 58, 59, 62, 64 Trainees' name and photo identification were used in nearly one-third of eligible studies.26, 28, 30-32, 34, 39, 41, 44, 45, 49, 51, 54, 59 Using this method, patients recognised trainees at rates of 88% as shown by McKinley et al.26 Table 3 provides additional details on other methods used to collect patient questionnaires. Soliciting patient participation through a third party, such as programme administrators, clerical staff or hospital volunteers, may minimise reported trainees' discomfort and bias in patient selection.30

환자 피드백을 수집하는 데 필요한 평균 시간은 4개의 연구에서 몇 분(1~10 범위)에서31, 32, 43, 52, 한 연구에서는 25분 이상까지 다양했습니다.28 인적 자원 필요성은 6개의 연구에서만 기술되었습니다.28, 34, 52, 55, 59, 65 Mahoney 등은 12개의 환자 설문지를 수집하는 데 입원 환자의 경우 평균 6.36시간, 외래 환자의 경우 10.14시간의 연구 보조(RA) 시간을 보고했습니다.28 울리스크로프트의 연구에서는 8명의 RA가 20개월 동안 70명의 레지던트를 위해 625명의 환자로부터 피드백을 수집하는 데 도움을 주었습니다.59 Wood 등은 지원 직원(유방 영상 기술자)의 업무량이 증가하지는 않았지만 레지던트가 시술을 수행할 것이라는 사실을 미리 알지 못한 경우 환자에게 평가 양식을 배포하는 것을 잊는 경향이 있었다고 보고했습니다.52

The average time commitment required to collect patient feedback varied from a few minutes (range 1–10) in four studies,31, 32, 43, 52 to over 25 minutes in one study.28 Human resource needs were described in only six studies.28, 34, 52, 55, 59, 65 Mahoney et al. reported an average research assistant (RA) time of 6.36 hours for in-patients and 10.14 hours for out-patients to collect 12 patient-questionnaires.28 In Woolliscroft's study, eight RAs helped collect feedback from 625 patients for 70 residents over a 20-month period.59 Wood et al. reported no increased workload for support staff (technologist in breast imaging), but they tended to forget distribution of the evaluation form to patients if they did not know ahead of time that residents will be performing the procedures.52

환자 설문지 수집 기회를 놓치는 데 기여한 몇 가지 물류 문제를 논의한 연구는 거의 없습니다. Tamblyn 등은 시간 제약으로 인해 외래 환자의 11.1%가 모집되지 않았다고 보고했습니다.58 입원 환자의 경우, Dine 등과 Mahoney 등의 두 연구에 따르면 레지던트를 인식하지 못하는 것이 설문지 미작성 이유의 각각 8%와 13%를 설명했습니다.28, 31 Jagadeesan 등은 설문지 관리를 담당하는 사람이 한 명뿐이어서 적격 환자의 36%는 모집되지 않았다고 설명했습니다.48

Few studies discussed some of the logistical issues that contributed to missed opportunities for the collection of patient questionnaires. Tamblyn et al. reported that 11.1% of their out-patients were not recruited due to time constraints.58 In the in-patient context, two studies by Dine et al. and Mahoney et al. showed that the inability of recognising residents explained 8% and 13% of patients' reasons for non-completion of questionnaires, respectively.28, 31 Jagadeesan et al. explained that 36% of eligible patients were not recruited since only one person was responsible for the administration of their questionnaire.48

3.6 환자 참여 및 평가 횟수

3.6 Patient participation and number of assessments

환자의 참여율은 14개 연구에서 보고되었으며, 두 연구를 제외한 모든 연구에서 60% 이상의 참여율을 보였다.25, 26, 28, 31, 36-38, 41, 48, 49, 58, 59, 63, 64 Mahoney등과 McKinley등은 모두 레지던트 교육에 대한 환자의 의견에 대한 기관의 관심과 과정에 만족하는 경향이 있다고 보고하였다.26, 28 Olsson의 연구는 가정의학과 전공의를 대상으로 6개월 동안 평가를 수집한 외래 환자의 경우 25%로 가장 낮은 참여율을 보였다고 보고하였다.37 Newcomb 등은 일반외과 레지던트를 대상으로 12개월 동안 환자 피드백을 수집한 결과 입원 환자의 참여율은 28%, 외래 환자의 참여율은 72%로 보고했습니다.41 다중 소스 피드백(MSF) 도구의 심리측정 특성을 평가하기 위해 유사한 설계를 적용한 두 연구에서는 모든 참가자의 참여율이 100%로 보고되었습니다.36, 38

Patients' participation rates were reported in 14 studies with rates over 60% in all but two studies.25, 26, 28, 31, 36-38, 41, 48, 49, 58, 59, 63, 64 Mahoney et al. and McKinley et al. both showed that patients tend to be satisfied with the process and the institution's interest in their input towards residents' education.26, 28 Olsson's study reported the lowest participation rate at 25% for out-patients over a 6-month period of assessment collection for family medicine residents.37 Newcomb et al. reported a 28% participation rate for in-patients compared with 72% for out-patients over a 12-month period of collected patient feedback for general surgery residents.41 Two studies with similar designs to assess the psychometric properties of a multi-source feedback (MSF) tool reported 100% participation rates from all participants.36, 38

4건의 연구에 따르면 수용 가능한 평가자 간 신뢰도를 달성하기 위해서는 많은 수의 환자를 모집해야 합니다.31, 56, 58, 59 집계된 EVGP 도구를 사용하여 Tamblyn 등은 0.75에서 0.80 사이의 신뢰도를 위해 30-40명의 환자를 제안했습니다.58 Murphy 등은 CARE 도구의 신뢰도 0.80을 위해 40명 이상의 환자를 추천했습니다.56 반면, 연구 저자들이 개발한 설문지의 경우 울리스크로프트 등은 100명 이상의 환자를, 다인 등은 이상적인 평가자 간 신뢰도 수준인 0.80을 위해 165명의 환자 평가를 권고했습니다.31,59 한편, 소아과 입원실에 입원한 아동의 보호자를 대상으로 ABIM 환자 만족도 설문지를 사용한 Byrd 등은 레지던트 1인당 7명의 환자 피드백에 대해 0.97의 Cronbach α 계수로 높은 수준의 내적 신뢰도를 보고했습니다.44

Recruitment of a high number of patients is required to achieve acceptable inter-rater reliability based on four studies.31, 56, 58, 59 Using the aggregated EVGP instrument, Tamblyn et al. suggested 30–40 patients for reliability between 0.75 and 0.80.58 Murphy et al. recommended over 40 patients for a reliability of 0.80 with the CARE instrument.56 On the other hand, for questionnaires developed by the study authors, Woolliscroft et al. proposed over 100 patients, and Dine et al. advised for 165 patient-ratings for an ideal inter-rater reliability level of 0.80.31, 59 On the other hand, using the ABIM Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire with caregivers of children admitted on paediatric in-patient units, Byrd et al. reported high degree of internal reliability with a Cronbach α coefficient of 0.97 for seven patient feedback per resident.44

3.7 환자가 학습자를 평가하고 피드백을 제공하는 방법

3.7 How patients rate and give feedback to learners

학습자를 평가하는 것은 일반적으로 환자에게 새로운 경험입니다. 24개 연구(58.5%)에서 보고된 바와 같이 환자들은 학습자를 높게 평가했습니다.26-29, 31, 34-38, 41, 43-49, 56-59, 63, 64 그러나 환자에게 선험적 지침을 제공하면 평가 점수의 변동이 개선되고 높은 평가의 비율이 낮아졌습니다.41 MSF 기반 도구를 사용한 연구에서 레지던트에 대한 환자의 평가는 다른 환자의 평가와 잘 일치했지만 의사와는 일치하지 않았습니다44, 53, 61; 두 평가자에게 동일한 도구를 사용한 경우는 Byrd 등이 유일했습니다.44

Rating learners is generally a new experience for patients. Patients were described as rating learners highly as reported in 24 studies (58.5%).26-29, 31, 34-38, 41, 43-49, 56-59, 63, 64 However, providing patients with a priori instructions improved variation in rating scores and lowered the proportion of high ratings.41 In studies using MSF-based instruments, patient ratings of residents correlated well with those of other patients but not with physicians44, 53, 61; only Byrd et al. used the same instrument for both raters.44

그들의 피드백에서 환자 또는 간병인은 관찰된 전문적 행동, 옹호 및 의사소통 기술을 중요시하고 집중하는 것으로 보고되었습니다.33, 40, 49, 62 이에 비해 의사는 의학 지식을 우선시했으며33, 49 간호사는 리더십, 협업 및 의사소통에 대해 보고했습니다.33 가정의학 프로그램의 후향적 데이터를 사용하여 환자 평가는 면허 시험 성적 및 어려움에 처한 레지던트의 수련 연장과 상관관계가 있습니다.42 마지막으로, 맥킨리는 환자 평가가 실제로 주니어와 시니어 레지던트를 차별할 수 있음을 입증했습니다.26 그러나 이러한 결과는 포함된 다른 연구들에서 반복되지 않았습니다.32, 35, 44-46, 63

In their feedback, it was reported that patients and/or caregivers valued and focused on the observed professional behaviours, advocacy and communication skills.33, 40, 49, 62 In comparison, physicians prioritised medical knowledge,33, 49 and nurses reported on leadership, collaboration and communication.33 Using retrospective data from a family medicine programme, patient ratings correlate with performance on licensing examinations and extensions of training for residents in difficulty.42 Lastly, McKinley demonstrated that patient ratings could in fact discriminate between junior and senior residents.26 These findings were not replicated however across other included studies.32, 35, 44-46, 63

3.8 환자 평가의 인식 및 수용 방법

3.8 How patient assessments are perceived and received

13개 연구에서 수집된 환자 평가와 피드백이 학습자에게 제공되었습니다(부록 S6).30, 32, 33, 36, 39, 45, 47, 51, 52, 54, 60, 64, 65 졸업후의학교육(PGME) 학습자들은 일반적으로 환자 평가가 자신의 행동과 술기가 환자 치료에 미치는 영향을 더 잘 이해하는 데 도움이 되고, 수용 가능하며, 유용하다고 인식했습니다.30, 33, 44, 52, 56, 65 두 연구에서 일부 수련의는 환자 피드백을 받아들이는 데 어려움을 겪었으며, 심지어 스스로 인지한 역량과 일치하지 않거나 피드백을 환자 또는 임상 상황과 연관시킬 수 없는 경우 무효화하기도 했습니다.30, 33 몇몇 연구에서는 수련의에게 수집된 환자 피드백에 대해 토론할 기회를 제공했습니다. 이러한 연구에서는 프로그램 디렉터,47, 51, 54, 64 다른 교수진 의사,39, 45, 52 수련의가 선택한 의학 교육자33 또는 행동 과학에 대한 전문적 배경을 가진 비의사가 레지던트를 위한 코치 역할을 수행했습니다.65

Collated patient ratings and feedback was provided to learners in thirteen studies (Appendix S6).30, 32, 33, 36, 39, 45, 47, 51, 52, 54, 60, 64, 65 Graduate medical learners generally perceived patient assessments as helpful, acceptable and useful to better understand how their behaviours and skills influence patient care.30, 33, 44, 52, 56, 65 In two studies, some trainees struggled to accept and even invalidated patient feedback if not aligned with self-perceived competence, or if they could not associate the feedback with the patient or clinical context.30, 33 Several studies offered trainees the opportunity to discuss collated patient feedback. In these studies, programme directors,47, 51, 54, 64 other faculty physicians,39, 45, 52 a medical educator chosen by the trainee33 or a non-physician with a professional background in behavioural science served as coach for residents.65

환자 참여가 행동 변화에 기여했는지 또는 환자 결과에 영향을 미쳤는지 평가한 연구는 거의 없습니다(7/39; 15.4%).25, 33, 39, 45, 51, 54, 64 MSF와 기존의 교수진만 평가하는 무작위 연구에서 환자 평가자로부터 피드백을 받은 레지던트는 대인관계 및 의사소통 기술이 크게 향상되는 것으로 나타났습니다.54 Bylund 등은 종양학 학습자를 위한 의사소통 기술 프로그램을 연구하고 프로그램 완료 전후에 환자 피드백을 수집한 결과, 기준 점수가 낮은 학습자에서 유의미한 개선이 나타났지만 의사소통 기술에는 큰 변화가 없는 것으로 나타났습니다.25 마찬가지로, Cope 등은 기준 점수가 낮고 코칭 피드백을 받은 학습자가 시간이 지남에 따라 개선되어 이후 약간 더 나은 환자 평가를 받았음을 보여주었습니다.64 그러나 다른 4개의 연구에서는 환자 설문조사에서 수집된 피드백을 기반으로 학습자를 코칭하는 것이 레지던트의 성과에 대한 후속 환자 평가에 영향을 주지 않았습니다.39, 45, 51, 64 그럼에도 불구하고 환자 피드백을 반영하고 맥락화하는 코칭은 학습자의 신뢰를 방해하지 않고 수용을 향상시키는 데 도움이 되었습니다.45, 51

Few studies (7/39; 15.4%) evaluated whether patient involvement contributed to changes in behaviours or impacted patient outcomes.25, 33, 39, 45, 51, 54, 64 In a randomised study comparing MSF and traditional faculty-only evaluations, residents who received feedback from patient raters showed significant improvement in interpersonal and communication skills.54 Bylund et al. studied a communication skills programme for oncology learners and collected patient feedback before and after completion of the programme showing no significant change in communication skills, although there was significant improvement seen in learners with lower baseline scores.25 Similarly, Cope et al. demonstrated that learners who had low baseline scores and who received coaching feedback improved over time with subsequent slightly better patient ratings.64 However, in four other studies, coaching learners based on collated feedback from patient surveys did not influence subsequent patient ratings of resident's performance.39, 45, 51, 64 Nevertheless, coaching to reflect on and contextualise patient feedback helped improve its acceptance without hindering their learners' confidence.45, 51

4 토론

4 DISCUSSION

우리의 범위 검토는 졸업후의학교육(PGME) 학습자 평가에 환자의 참여를 최대한 촉진하고, 종종 환자 참여의 장애물로 언급되는 행정적 부담이 실제로는 극복할 수 없는 것이 아니라는 다른 학자5,66의 의견과 일치합니다. 환자는 여러 전문 교육 분야, 임상 환경 및 환자 집단에 걸쳐 효율적으로 참여할 수 있으며, 환자의 참여는 사용 가능한 행정 자원에 달려 있습니다. 환자 모집은 일반적으로 큰 어려움이 없는 것으로 보이며, 다른 연구에서 설명한 바와 같이 적극적으로 참여하고 경험을 공유하려는 환자의 의지와 관련이 있을 수 있습니다12, 17, 19; 대부분의 연구에서 상대적으로 높은 참여율이 보고되었습니다. 환자는 전공의의 대인관계 기술 및 행동 수행과 밀접하게 연관되어 있기 때문에 전통적인 평가 접근법을 보강하고 의사소통, 옹호, 전문성 등 잘 드러나지 않는 역량을 조명할 수 있는 잠재력을 가지고 있으며,19, 66 따라서 학습자의 역량에 대한 보다 전체적인 그림을 제공합니다.5 다양성과 포용성을 보장하고 이러한 요소가 환자의 평가와 의견, 학습자의 환자 중심 진료에 대한 수용에 미치는 영향에 대한 이해를 더욱 향상시키기 위해 모국어 및 기타 사회 문화적 고려사항과 평가를 일치시키는 데 더 많은 주의가 필요합니다.

Our scoping review highlights, and aligns with other scholars,5, 66 that promote patient involvement in postgraduate learner assessment as possible and that administrative burdens, often cited as barriers to patient involvement, are in fact not insurmountable. Patients can be engaged efficiently across a number of specialty training areas, clinical settings and patient populations and their involvement hinges on available administrative resources. Patient recruitment appeared to be generally without major challenges and may tie into patients' willingness to actively participate and share their experiences as described in other studies12, 17, 19; relatively high participation rates were reported in most studies. By virtue of being intimately coupled to performances of residents' interpersonal skills and behaviours, patients hold the potential to augment traditional assessment approaches and shed light on less represented competencies such as communication, advocacy and professionalism,19, 66 thus provide a more holistic picture of learners' competence.5 Greater attention is required to align assessments with native language and other sociocultural considerations to ensure diversity and inclusion and further improve our understanding of how these factors influence patient ratings and comments and learners' uptake into their patient-centred practice.

환자 참여의 본질은 다양한 형태로 나타날 수 있습니다. 우리의 종합 결과, 환자는 개별 작업장 기반 평가뿐만 아니라 다중 소스 피드백 프로세스(의사가 풍부한 평가 데이터를 받아 정기적으로 상호 작용하는 다양한 개인 그룹으로부터 얻은 평가와 비교하여 환자 치료를 개선할 수 있는 핵심 역량을 알려주는 방법)의 구성 요소에도 관여하는 것으로 확인되었습니다.67, 68 환자의 평가와 의견을 수집하기 위해 다양한 구성을 측정하는 여러 평가 도구가 연구되었습니다. 그러나 이러한 도구에 대한 타당성 증거는 주로 신뢰도 측정에 초점을 맞추었으며, 신뢰도 높은 판단을 위해 필요한 환자 평가 횟수에 대한 권장 사항은 대부분 가변적이었습니다. 그러나 CBME 프레임워크에서 '학습을 위한 평가'에 대한 강조가 증가함에 따라,69 환자 평가의 유용성은 학습자의 역량 달성 및 전문성 개발에 정보를 제공하고 혜택을 주는 방법에 따라 결정되어야 합니다.5 따라서 다른 평가 방법과 결합할 경우 많은 수의 환자 평가를 수집하는 것이 필요하지 않을 수도 있습니다.

The nature of patient involvement can take many forms. Our synthesis identified patients have been involved in individual workplace-based assessments as well as a component of a multi-source feedback process (a method by which physicians receive rich assessment data to compare self-assessment to those obtained from different groups of individuals with whom they interact regularly and thereby inform on key competencies that can improve patient care).67, 68 Several assessment tools measuring various constructs have been studied to capture patients' ratings and comments. However, validity evidence for these tools focused primarily on reliability measures with largely variable recommendations in the number of patient assessments needed for highly reliable judgements. However, with the increased emphasis towards ‘assessment for learning’ in CBME frameworks,69 utility of patient assessments need to be driven by how it informs and benefits learners' competency attainment and professional development.5 Therefore, collecting a high number of patient assessments may arguably not be necessary when coupled with other assessment methods.

샘플 조사에서 코칭과 성찰을 통한 피드백 촉진이 환자 평가 데이터의 수용과 이해를 개선하는 것으로 나타났습니다. 그러나 코칭 피드백 개입 후의 결과는 역량 달성에 가장 큰 혜택을 경험한 것으로 보이는 낮은 등급의 학습자를 제외하고는 모호한 결과를 보여주었습니다. MSF 문헌은 코치 또는 동료와의 성찰과 대화가 임상 실습에서 의미 있는 변화를 채택하는 데 중요한 역할을 한다고 제안합니다.70, 71 코치의 지도 아래 수련생이 받은 피드백을 분석하고 반영하여 목표를 파악하고 목표 달성을 위한 계획을 개발하는 코칭 피드백은 의학 교육에서 점점 더 많이 사용되고 있지만,72 종단 데이터가 부족하여 환자 평가와 관련된 연구는 미흡한 실정입니다. 환자의 의견을 바탕으로 한 코칭 피드백이 어떻게 학습, 전문성 개발 및 진료 변화를 유도하여 궁극적으로 환자 치료와 결과를 개선할 수 있는지에 대한 보다 완전한 이해는 앞으로의 과제입니다.

In our sample, we found that feedback facilitation through coaching and reflection improved acceptance and understanding of patient assessment data. However, outcomes following coaching feedback interventions demonstrated equivocal results except for learners with lower ratings who seemed to experience the most benefit to competency attainment. The MSF literature does suggest an important role for reflection and conversations with a coach or peer to adopt meaningful changes in one's clinical practice.70, 71 Coaching feedback whereby trainees analyse and reflect on the received feedback to identify goals and develop a plan to reach them under the guidance of a coach is increasingly used in medical education,72 but under-studied in relation to patient assessments with lack of longitudinal data. Understanding more fully how coaching feedback based on patient input can drive learning, professional development and practice changes that ultimately improve patient care and outcomes is an area of future.

4.1 격차 및 향후 연구에 대한 시사점

4.1 Gaps and implication for future research

양질의 진료와 환자 중심주의는 CBME 프레임워크의 중요한 결과이므로,1, 7 역량 기반 평가에서 환자가 더 큰 역할을 할 수 있도록 평가 대화를 전환하는 것이 우선순위가 됩니다.5, 66 우리의 연구 결과는 환자가 효과적인 평가자가 될 수 있음을 시사합니다. 그러나 수집된 데이터를 역량 성취와 관련된 결정을 위해 요약 수준에서 어떻게 사용할 수 있는지에 대해서는 표본에서 논의되지 않았으며, 이는 역량 기반 평가의 중요한 요소로서 학술적 관심이 필요합니다.

Since quality care and patient-centeredness are important outcomes to CBME frameworks,1, 7 shifting our assessment conversations to provide patients a larger role in competency-based assessment becomes a priority.5, 66 Our findings suggest that patients can be effective assessors. However, how their collated data may be used at a summative level for decisions related to competency attainment was not discussed in our sample and is an important element of competency-based assessment in need of scholarly attention.

환자의 피드백이 교육생의 성과 및 행동 변화에 미치는 영향은 여전히 모호하며, 이를 해결하기는 어렵지만 불가능하지는 않습니다. 수련의에 대한 환자 평가를 조사한 다른 리뷰에서도 비슷한 결론에 도달했습니다.50, 73 교육 성과 측정과 연결된 환자 보고 성과 척도(PROM)는 평가 시스템에서 교육적 역할로 인해 PGME에서 주목받고 있습니다.74-76 PROM과 연결된 환자 피드백이 성과 평가에 정보를 제공하고 추가하는 방법을 탐구하면 교육 개입, 의미 있는 진료 변화, 진료의 질, 환자 결과 사이의 격차를 해소하는 데 유용할 수 있습니다.

The effect of patient feedback on trainees' performance and behavioural changes remains equivocal and will be challenging, but not impossible, to address. Other reviews investigating patient assessments of practicing physicians reached similar conclusions.50, 73 Patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) linked to educational outcome measures are gaining attention in PGME for their educational role in our systems of assessment.74-76 Exploring how patient feedback tied to PROMs informs and adds to performance assessment may prove useful to bridge the gap between education interventions, meaningful practice change, quality of care and patient outcomes.

PGME 프로그램이 점점 더 어려워지는 경제적 제약 속에서 유능한 의사를 졸업시키기 위해 노력함에 따라,77,78 환자 참여, 평가 데이터 수집 및 학습자 전달의 경제적 영향을 다루는 비용 효과성 연구는 우리가 선택한 연구에는 없었지만 많은 PGME 프로그램이 직면한 중요한 장벽이 될 수 있으므로 추가로 고려할 필요가 있습니다.

As PGME programmes strive to graduate competent physicians in ever-growing economical restrictions,77, 78 cost-effectiveness studies that address the economic implications of patient involvement, assessment data collection and delivery to learners need to be further considered as this was absent from our selected studies yet may be a critical barrier facing many PGME programmes.

마지막으로, 더 중요한 것은 유능한 의사에 대한 총체적인 관점에 기여하고 안전하고 효과적인 환자 중심 진료로 나아가는 데 기여할 수 있는 환자의 목소리를 방해하는 PGME의 사회문화적 및 제도적 장애물을 즉시 해결해야 한다는 점입니다.7, 66

Lastly, and perhaps more importantly, we need to promptly address the sociocultural and institutional roadblocks in PGME that impede the patient voice which can contribute to a holistic view of the competent physician and drive us towards safe, effective patient-centred care.7, 66

4.2 제한점

4.2 Limitations

검색을 위해 포괄적으로 검색하고 숙련된 사서와 협력했지만, 보건 전문직 교육은 검색이 어려운 것으로 확인되었습니다.79 관련 연구가 확인되지 않았을 가능성이 있습니다. 모든 전자 데이터베이스를 검색하지는 않았으며 영어 또는 프랑스어가 아닌 언어는 제외했습니다. 또한 '환자'라는 검색어는 의료 분야에서 모호하지 않기 때문에 포함시켰으며, 고려할 수 있었던 다른 용어로는 '사용자', '소비자', '클라이언트'가 있으며, 이는 앞서 언급한 문헌 검토의 복잡성을 반영한 것입니다.12 검토의 맥락이 레지던트에 대한 평가임을 감안하여 이러한 용어가 '환자'보다 우선순위가 높지 않을 것이라는 가설을 세웠지만 이 가설을 테스트하지 않았습니다.

Although we searched comprehensively and collaborated with an experienced librarian for our search, health professions education is identified as difficult to search.79 It is possible that relevant studies were not identified. We did not search all electronic databases and excluded non-English or French languages. We also included the search term ‘patients’ as it is unambiguous for the medical field; other terms that could have been considered include ‘user’, ‘consumer’ and ‘client’ and speaks to the previously documented complexities in reviewing this literature.12 Given the context of the review was assessment of residents, we hypothesised that these terms were unlikely to be prioritised over ‘patient’ in this context but we did not test this hypothesis.

5 결론

5 CONCLUSION

전공의에 대한 보다 총체적인 관점을 확보하려면 평가에 다양한 관점, 특히 환자를 포함시키는 것이 도움이 될 수 있습니다. 검토 결과, 평가에 환자의 참여는 여러 학문 분야와 임상 환경에서 가능한 것으로 나타났습니다. 또한, 환자는 평가에서 의사 중심의 전통적인 관점을 보완할 수 있는 다양한 관점과 전문성(예: 경험적 관점)을 제공합니다. 학습자의 전문성 개발과 환자 중심 관행을 알리기 위해 환자 수준의 데이터를 가장 잘 활용할 수 있는 방법, 특히 평가 시스템에 대한 환자의 참여가 사회적 요구에 더 많이 기여할 준비가 된 의사를 배출하는 데 의미 있게 기여하는지 여부와 그 방법에 대해서는 향후 연구가 필요합니다. 이를 위해 환자가 의학교육 전반과 특히 평가에 점점 더 많이 참여함에 따라, 총체적인 평가가 완전히 실현될 수 있도록 공평하고 다양한 참여를 보장하는 것이 우선시되어야 합니다.

Achieving a more holistic view of postgraduate learners may benefit from including diverse perspectives in their assessments and specifically patients. In our review, patient engagement in assessments was viewed as feasible across multiple disciplines and clinical settings. Further, patients contribute different perspectives and expertise (e.g. experiential) that can augment more traditional, physician-focused, perspectives in assessments. How patient-level data can best be used to inform learners' professional development and patient-centred practices remains in need of future research, in particular if and how patient involvement in assessment systems contribute meaningfully to producing physicians that are ready to contribute more fully to societal needs. To this end, as patients increasingly engage in medical education generally and assessment specifically, ensuring equitable, diverse inclusion should be prioritised to ensure holistic assessments are to be fully realised.

Patient involvement in assessment of postgraduate medical learners: A scoping review

PMID: 34981565

DOI: 10.1111/medu.14726

Abstract

Context: Competency-based assessment of learners may benefit from a more holistic, inclusive, approach for determining readiness for unsupervised practice. However, despite movements towards greater patient partnership in health care generally, inclusion of patients in postgraduate medical learners' assessment is largely absent.

Methods: We conducted a scoping review to map the nature, extent and range of literature examining the inclusion (or exclusion) of patients within the assessment of postgraduate medical learners. Guided by Arskey and O'Malley's framework and informed by Levac et al. and Thomas et al., we searched two databases (MEDLINE® and Embase®) from inception until February 2021 using subheadings related to assessment, patients and postgraduate learners. Data analysis examined characteristics regarding the nature and factor influencing patient involvement in assessment.

Results: We identified 41 papers spanning four decades. Some literature suggests patients are willing to be engaged in assessment, however choose not to engage when, for example, language barriers may exist. When stratified by specialty or clinical setting, the influence of factors such as gender, race, ethnicity or medical condition seems to remain consistent. Patients may participate in assessment as a stand-alone group or part of a multi-source feedback process. Patients generally provided high ratings but commented on the observed professional behaviours and communication skills in comparison with physicians who focused on medical expertise.

Conclusion: Factors that influence patient involvement in assessment are multifactorial including patients' willingness themselves, language and reading-comprehension challenges and available resources for training programmes to facilitate the integration of patient assessments. These barriers however are not insurmountable. While understudied, research examining patient involvement in assessment is increasing; however, our review suggests that the extent which the unique insights will be taken up in postgraduate medical education may be dependent on assessment systems readiness and, in particular, physician readiness to partner with patients in this way.

© 2022 Association for the Study of Medical Education and John Wiley & Sons Ltd.