평가 프로그램에서 학생의 진급 결정: 임상적 의사결정과 배심원 의사결정을 외삽할 수 있을까? (BMC Med Educ, 2019)

Student progress decision-making in programmatic assessment: can we extrapolate from clinical decision-making and jury decision-making?

Mike Tweed1* and Tim Wilkinson2

배경

Background

평가 의사 결정의 문제점

The problem with decision-making in assessment

학생에 대한 개별 평가에서 생성되는 데이터의 견고성을 확보하기 위해 많은 노력을 기울여 왔습니다. 점수 신뢰도, 청사진 작성, 표준 설정 등 개별 시험 또는 평가 이벤트 수준에서 평가 데이터의 견고성을 확보하는 데 관한 광범위한 문헌이 있습니다[1,2,3]. 이는 특히 수치 데이터[4]에 해당하지만, 텍스트/내러티브 데이터[5]에 대해서도 점점 더 많이 요구되고 있습니다. 그러나 의사 결정은 여러 평가 이벤트의 증거를 종합적으로 고려하여 내리는 경우가 더 많습니다. 이는 평가에 대한 보다 프로그래밍적인 접근 방식을 취함에 따라 점점 더 많아지고 있습니다[6]. 예를 들어, 한 해의 합격 여부에 대한 결정은 연말 시험 합격 여부에 대한 결정이 아니라 한 해 전체의 평가 결과를 종합하여 내리는 결정이 되고 있습니다. 이러한 변화에도 불구하고, 개별 학생에 대한 강력한 결정을 내리기 위해 여러 가지 이질적인 개별 평가의 정보를 종합하는 데 따르는 함정과 개선 방법에 대한 간극이 존재합니다[7].

Much effort has been put into the robustness of data produced by individual assessments of students. There is an extensive literature on achieving robustness of assessment data at the individual test or assessment event level, such as score reliability, blueprinting, and standard setting [1,2,3]. This is especially so for numerical data [4], but increasingly also for text/narrative data [5]. However, decisions are more often made by considering a body of evidence from several assessment events. This is increasingly the case as a more programmatic approach to assessment is taken [6]. For example, the decision on passing a year is becoming less about a decision on passing an end of year examination and more about a decision based on synthesising assessment results from across an entire year. Despite these changes, there is a gap regarding the pitfalls and ways to improve the aggregation of information from multiple and disparate individual assessments in order to produce robust decisions on individual students [7].

이 백서에서는 학생의 진급 의사 결정과 임상 의사 결정 사이의 유사점을 도출한 다음, 그룹이 내리는 의사 결정의 맥락에서 진급 의사 결정과 배심원의 의사 결정 사이의 유사점을 도출할 것입니다. 마지막으로, 이러한 유사점을 살펴봄으로써 진급 의사 결정과 관련된 정책, 실무 및 절차에 대한 실질적인 요점을 제안합니다. 사용할 수 있는 의사결정의 예는 많지만, 의료 교육 기관에 익숙한 임상 의사결정과 집단이 증거를 평가하여 중대한 결정을 내리는 방법과 관련된 사례인 배심원 의사결정을 선택했습니다.

In this paper we draw parallels between student progression decision-making and clinical decision-making, and then within the context of decisions a made by groups, we will draw parallels between progression decision-making and decision-making by juries. Finally, exploration of these parallels leads to suggested practical points for policy, practice and procedure with regard to progression decision-making. There are many examples of decision-making that could be used but we chose clinical decision-making as it is familiar to healthcare education institutions, and jury decision-making as it is a relevant example of how groups weigh evidence to make high-stakes decisions.

진급 의사 결정: 임상 의사 결정의 유사점

Progression decision-making: parallels in clinical decision-making

학생이 진급 진행(합격) 또는 불합격(불합격) 여부에 대한 의사 결정은 환자 진단과 많은 유사점이 있습니다[8].

- 평가 진도 결정과 환자 진단 결정 모두 여러 가지 정보(다양한 수준의 견고성을 가진 수치와 서술/텍스트가 혼합되어 있음)를 종합적으로 고려해야 합니다.

- 환자 진단 결정과 후속 관리 결정은 환자 및/또는 의료기관에 미치는 영향 측면에서 중대한 사안일 수 있습니다.

- 마찬가지로 진급 상황 결정과 그 결과도 학생, 교육 기관, 의료 기관, 환자 및 사회에 큰 영향을 미칩니다.

The decision-making around whether a student is ready to progress (pass) or not (fail) has many parallels with patient diagnosis [8].

- For both assessment progression decisions and patient diagnosis decisions, several pieces of information (a mix of numerical and narrative/text with varying degrees of robustness), need to weighed up and synthesised.

- Patient diagnosis decisions and subsequent decisions on management can be high-stakes in terms of impact on the patient and/or healthcare institution.

- Likewise progression decisions and the consequences carry high-stakes for students, educational institutions, healthcare institutions, patients, and society.

의사 결정을 위한 정보 취합

Aggregating information to make decisions

임상의와 임상팀은 휴리스틱을 사용하여 다양한 정보를 효율적이고 정확하게 결합하지만[9,10,11,12,13,14], 환자 진단에 관한 임상 의사 결정은 편견과 부정확성에 취약할 수 있습니다[12,15,16,17,18]. 이러한 편견과 오류에 대한 메타인지적 인식[15,16]이 임상 의사 결정을 개선하는 것으로 가정되는 것처럼[19,20,21], 평가 정보를 결합할 때 이러한 편견에 대한 인식과 이를 해결하는 방법도 진행 상황 결정의 견고성을 개선할 수 있다고 제안합니다.

Clinicians and clinical teams combine various pieces of information efficiently and accurately using heuristics [9,10,11,12,13,14], however clinical decision-making regarding patient diagnoses can be prone to biases and inaccuracies [12, 15,16,17,18]. Just as metacognitive awareness of such biases and errors [15, 16] is postulated to lead to improved clinical decision-making [19,20,21], we suggest that an awareness of such biases in combining assessment information, and ways to address this, could also improve the robustness of progression decisions.

정보 수집

Gathering information

임상 환경에서 환자 진단에 대한 의사 결정을 내리는 데 사용되는 데이터는 상담 및 관련 조사에서 얻을 수 있습니다. 병력은 거의 전적으로 서술형/텍스트, 임상 검사는 대부분 서술형/텍스트와 일부 수치 데이터, 조사는 서술형/텍스트와 수치 데이터가 혼합된 형태로 이루어집니다. 진단으로 이어지는 임상 의사 결정은 빠르고 효율적일 수 있지만[15], 때로는 더 어렵고 임상의는 더 많은 정보를 얻고, 다양한 옵션을 평가하고, 상충되는 증거를 평가해야 할 수도 있습니다.

In the clinical setting, data used to inform the decision-making of a patient diagnosis may come from the consultation and associated investigations. The history is almost entirely narrative/text, the clinical exam is mostly narrative/text with some numerical data, and investigations are a mixture of narrative/text and numerical data. Clinical decision-making leading to a diagnosis can be quick and efficient [15], but sometimes it is more difficult and the clinician may need to obtain more information, weigh up different options, and/or weigh up conflicting pieces of evidence.

추가 정보를 얻는 과정에는 상담 및 조사 재방문과 같이 데이터 수집을 반복하거나, 일반 방사선 사진을 보완하기 위해 컴퓨터 단층 촬영 스캔을 얻는 등 다른 관점에서 문제에 접근하거나, 생검과 같이 완전히 새롭고 다른 정보 출처를 찾는 것 등이 포함될 수 있습니다[15]. 이러한 추가 정보의 성격은 지금까지 얻은 정보에 따라 달라지며, 이미 알려진 것과 관계없이 모든 환자에게 동일한 추가 검사를 실시하는 것은 좋은 임상 관행이 아닙니다. 또한 제기된 임상적 질문에 답하기 위해 효율성, 위험/편익, 비용 측면에서 가장 적절한 조사를 고려합니다[22, 23].

The process of obtaining additional information may include repeating data collection, e.g. revisiting the consultation and investigations; approaching the issue from a different perspective, e.g. obtaining a computerised tomography scan to complement a plain radiograph; and/or looking for an entirely new and different source of information, e.g. getting a biopsy [15]. The nature of this additional information will depend on the information obtained so far, as doing the same extra tests on all patients regardless of what is already known is not good clinical practice. Consideration is also given to the most appropriate investigations in terms of efficiency, risk/benefit, and cost [22, 23], to answer the clinical question posed.

임상 의사 결정에서 진단이 확정된 후에도 데이터를 계속 수집하거나 조사를 수행하는 것은 비효율적이며 때로는 해로울 수 있습니다. 진급 의사결정 측면에서도 이와 유사한 점이 있는데, 진급 의사결정에 필요한 추가 정보를 얻기 위해 충분한 정보가 수집되면 개별 학생에 대한 검사를 중단하는 순차적 검사가 포함될 수 있습니다[24]. 이는 진급 결정의 근거가 될 충분한 정보가 확보되면 평가를 중단하는 평가 프로그램에도 적용될 수 있습니다. 결정의 부담stake은 충분한 정보에 필요한 정보의 강도와 가중치를 알려줄 것입니다. 임상 의사 결정과 마찬가지로, 같은 유형의 평가를 더 많이 한다고 해서 진도 의사 결정이 개선되지 않을 수 있으며, 새로운 관점이나 완전히 새로운 데이터 소스가 필요할 수 있습니다. 학생에게 평가를 반복하도록 요청하는 대신, 필요한 충분한 정보를 제공하기 위해 목표 관찰 기간, 면밀한 감독 또는 다른 평가를 실시하는 것이 더 바람직할 수 있습니다. 필요한 추가 정보의 성격은 개인에 대해 이미 알려진 내용에 따라 달라지며 학생마다 다를 수 있습니다. 결과적으로 가변 평가는 공정성에 대한 우려를 불러일으킬 수 있습니다. 이에 대해 저희는 공정성이란 모든 학생이 동일하게 평가되었는지 여부보다는, 진급 결정의 견고성과 방어 가능성에 더 많이 적용된다고 주장합니다.

In clinical decision-making it is inefficient, and sometimes harmful, to keep collecting data or undertaking investigations once a diagnosis is secure. There are parallels with this, in terms of progression decision-making: obtaining additional information to inform progression decision-making may include sequential testing, whereby testing ceases for an individual student when sufficient information has been gathered [24]. This could be extrapolated to programmes of assessment whereby assessments cease when sufficient information is available on which to base a progress decision. The stakes of the decision would inform the strength and weight of the information required for a sufficiency of information. Just as for clinical decision-making, more of the same type of assessment may not improve progress decision-making, and a new perspective or an entirely new data source may be required. Instead of asking a student to repeat an assessment, a period of targeted observation, closer supervision or different assessments might be preferable to provide the required sufficiency of information. The nature of the extra information required will depend on what is already known about the individual, and may vary between students. The resulting variable assessment may generate concerns over fairness. In response, we would argue that fairness applies more to the robustness and defensibility of the progression decision, than to whether all students have been assessed identically.

상충되는 정보 취합

Aggregating conflicting information

임상 의사 결정에서는 상충되는 증거를 종합적으로 검토해야 하는 경우가 많습니다. 병력, 검사 및 조사에서 수집한 정보를 개별적으로 고려하면 가장 가능성이 높은 진단 목록이 여러 개 생성될 수 있으며, 각 목록은 불확실성을 내포하고 있습니다. 그러나 모든 정보를 종합하면 가장 가능성이 높은 진단 목록이 더 명확해지고 점점 더 확실해집니다[25]. 진도 의사 결정에서도 마찬가지로, 독립적인 평가 이벤트에서 생성된 단일 정보를 고려하면 학생의 진도 준비 상태에 대한 해석이 달라질 수 있지만, 이러한 단일 정보를 종합하면 더 강력한 그림이 구성됩니다.

In clinical decision-making it is often necessary to weigh up conflicting pieces of evidence. Information gathered from history, examination, and investigations might, if considered in isolation, generate different lists of most likely diagnoses, each of which is held with uncertainty. However, when all the information is synthesised, the list of most likely diagnoses becomes clearer, and is held with increasing certainty [25]. Likewise in progression decision-making, considering single pieces of information generated from independent assessment events might generate different interpretations of a student’s readiness to progress, but when these single pieces are synthesised, a more robust picture is constructed.

의료 정책 입안자와 실무자는 여러 출처의 데이터를 종합할 수 있습니다[26,27,28]. 일부 데이터 합성은 개별 임상의보다 기계적으로 또는 알고리즘에 의해 더 잘 수행되지만[29], 빠르고 검소한 휴리스틱을 보험 계리 방법과 결합하면 더 나은 결과를 얻을 수 있습니다[30]. 진행 의사 결정에서 알고리즘을 사용하여 점수를 결합하는 것은 가능하지만[31], 똑같이 그럴듯한 알고리즘도 다른 결과를 초래할 수 있습니다[32, 33]. 검사 결과를 단순히 합산하는 것은 쉬울 수 있지만, 그 결과가 반드시 의사결정 목적에 가장 적합한 정보를 제공하지는 않을 수 있습니다[31].

Synthesising data from multiple sources is possible for healthcare policy makers and practitioners [26,27,28]. Some data synthesis is done better mechanically or by algorithms than by individual clinicians [29], but better results may be achieved if fast and frugal heuristics are combined with actuarial methods [30]. In progression decision-making, combining scores using algorithms is possible [31], but equally plausible algorithms can lead to different outcomes [32, 33]. It may be easy simply to add test results together, but the result may not necessarily contribute the best information for decision-making purposes [31].

임상 의사 결정의 경우, 의사 결정을 개선하기 위한 전략에는 진단 의사 결정 지원의 가용성, 이차 의견, 감사 등 의료 시스템에 대한 고려가 포함됩니다[12]. 확인 및 안전장치가 부족하면 오류가 발생할 수 있습니다[34]. 이를 진행 의사 결정에 적용하면 모든 평가 결과를 맥락에서 고려하고 의사 결정 지원 및 의사 결정 검토 프로세스를 사용해야 합니다.

For clinical decision-making, strategies to improve decision-making include consideration of the health systems, including the availability of diagnostic decision support; second opinions; and audit [12]. A lack of checking and safeguards can contribute to errors [34]. Extrapolating this to progression decision-making, all assessment results should be considered in context, and decision support and decision review processes used.

선별 검사 및 진단 검사

Screening tests and diagnostic tests

임상 진료에서 질병 검사에는 선별 검사와 확진 검사 등 검사를 결합해야 하는 선별 검사 프로그램이 포함될 수 있습니다[35]. 이는 특히 데이터가 희박한 경우[36] 진행 의사 결정으로 추정될 수 있습니다[8]. 일반적으로 임상 검사 및 교육 평가를 통한 의사 결정은 민감도와 검사의 특이도 간의 균형을 유지하여 의사 결정에 도움을 주어야 합니다. 이는 개별 평가의 목적과 평가 검사 프로그램의 목적에 따라 영향을 받습니다[8]. 일반적으로 질병 선별 검사는 특이도가 낮고 민감도가 높으며, 확진 검사는 민감도가 낮고 특이도가 높습니다[35]; 검사의 예측 값은 질병 유병률에 따라 달라집니다. 따라서 겉으로 보기에 민감도와 특이도가 우수하더라도 유병률이 매우 높거나 낮으면 검사 프로그램이 기여도가 없거나 더 심하면 잠재적으로 해로울 수 있습니다[8]. 교육 평가와 관련된 이러한 편견은 나중에 논의합니다.

Testing for disease in clinical practice can include a screening programme which requires combining tests, such as a screening test followed by a confirmatory test [35]. This can be extrapolated to progression decision-making [8], especially when data are sparse [36]. Generally, decision-making from clinical tests and educational assessments has to balance the sensitivity with the specificity of a test to help inform the decision. This is influenced by the purpose of the individual assessment and by the purpose of the assessment testing programme [8]. A screening programme for a disease will generally have a lower specificity and higher sensitivity, and a confirmatory test a lower sensitivity and higher specificity [35]; the predictive value of the test will be dependent on disease prevalence. Hence despite apparently excellent sensitivity and specificity, if the prevalence is very high or low, a testing programme can be non-contributory, or worse still, potentially harmful [8]. Such biases associated with educational assessment are discussed later.

결정과 관련된 위험

Risks associated with decisions

잘못된 임상적 결정 또는 최적의 진료에서 벗어난 결과와 위험은 임상적으로 유의미한 결과가 없는 것부터 사망에 이르기까지 크게 다를 수 있습니다[37]. 최적의 진료에서도 부작용과 위험은 발생할 수 있습니다. 약물은 적절하게 사용하더라도 부작용이 있으며, 때때로 이러한 위험은 임상 진료에서야 드러납니다[38].

The consequence and risk of incorrect clinical decisions, or deviation from optimal practice, can vary significantly from no clinically significant consequence to fatality [37]. Adverse consequences and risks occur even with optimal practice. Drugs have side effects, even when used appropriately, and sometimes these risks only come to light in clinical practice [38].

의료 교육 기관은 학생에 대한 진급 결정을 내릴 때 학생[39]과 사회[40]의 이익을 모두 고려해야 할 주의 의무가 있습니다. 개인뿐만 아니라 사회에도 영향을 미치는 개인을 위한 결정을 내릴 때의 이러한 딜레마는 배심원 의사 결정 섹션에서 자세히 살펴봅니다.

Healthcare educational institutions have a duty of care to take the interests of both students [39] and society [40] into account when making progression decisions on students. This dilemma of making decisions for individuals which have an impact not only on that individual, but also society, is explored further in the section on jury decision-making.

결정이 어려울 때

When the decisions get tough

임상에서 시간에 쫓기는 의사 결정[41] 및 고위험 의사 결정[42]과 같이 상황에 따라 의사 결정이 더 어려워지는 경우도 있습니다. 정답을 알고 있더라도 시간 압박은 의사 결정의 불확실성과 부정확성을 증가시킵니다. 교육 기관은 의사 결정자에게 올바른 결정을 내릴 수 있는 충분한 시간을 제공하는 것이 중요합니다.

Some decisions are made more difficult by the context, such as time-pressured decision-making in clinical practice [41] and high-stakes decision-making [42]. Even when correct answers are known, time-pressure increases uncertainty and inaccuracy in decision-making. It is important that educational institutions provide decision-makers with sufficient time to make robust decisions.

또한 개인이 해결할 수 없는 질문도 있습니다[34]. 결정이 중대한 결과를 초래할 수 있고 최적의 치료를 조언하기 위해 여러 전문 정보 또는 관점을 결합해야 할 수 있기 때문에 진단이 간단하지 않을 수 있습니다. 이러한 상황에서는 2차 소견을 요청할 수 있습니다[12]. 사용 가능한 데이터를 고려하는 사람의 수를 늘리는 것이 실용적이거나 안전하지 않은 경우 사용 가능한 데이터를 늘리는 것보다 더 나은 방법이 될 수 있습니다. 다학제 팀, 다학제 회의, 사례 회의는 여러 사람의 도움을 받아 집계된 정보를 바탕으로 의사 결정을 내림으로써 환자 치료를 개선할 수 있습니다. 특정 상황에서는 이러한 집단 의사 결정이 환자의 치료 결과를 개선하기도 합니다[43].

In addition, there are some questions that are impossible for an individual to resolve [34]. The diagnosis may not be straightforward because decisions may have significant consequences, and multiple specialised pieces of information or perspectives may need to be combined in order to advise optimal care. In these circumstances a second opinion may be requested [12]. Increasing the number of people considering the available data can be a better method than increasing the available data where this is not practical or safe. Multi-disciplinary teams, multi-disciplinary meetings, and case conferences can enhance patient care by using multiple people help to make decisions on aggregated information. In certain situations such group decision-making improves outcomes for patients [43].

의료 전문직 학생에게 가장 중요한 진급 결정 중 하나는 졸업입니다. 교육기관은 개인이 의료 전문직에 진출할 준비가 되었으며, 최소한 유능하고 안전한 의료인이 될 것임을 규제 기관과 사회에 권고해야 합니다. 고려해야 할 정보의 잠재적 위험과 복잡성을 고려할 때, 패널은 종종 프로그램 평가에서 의사 결정의 일부가 됩니다[6]. 패널은 서로 다른 관점을 가지고 있으며, 집단이 구성 요소 개인보다 낫다는 오랜 주장이 있습니다[44].

One of the highest-stakes progression decisions on healthcare professional students is at graduation. The institution needs to recommend to a regulatory authority, and thereby society, that an individual is ready to enter the healthcare profession, and will be at least a minimally competent and safe practitioner. Given the potential high-stakes and complexity of the information to be considered, a panel is often part of decision-making in programmatic assessment [6]. The panellists bring different perspectives, and the longstanding assertion is that the collective is better than the component individuals [44].

개인과 집단의 의사 결정 비교

Comparing decision-making by individuals and groups

정보를 취합할 때, 개인의 추정치가 다양하고 현실과 거리가 멀더라도 많은 개인의 추정치의 평균은 현실에 가까울 수 있습니다[44, 45]. 이러한 '군중의 지혜' 효과가 모든 상황에서 적용되는 것은 아닙니다. 사람들이 개별적으로 일하지 않고 집단적으로 일할 때는 사회적 상호작용과 집단 내에서 인지된 권력 차이가 개인의 추정치에 영향을 미치기 때문에 이 효과가 덜 분명할 수 있습니다. 결과적으로 도출된 합의는 더 이상 정확하지 않지만, 그룹 구성원은 자신이 더 나은 추정을 하고 있다고 인식할 수 있습니다[45]. 또한, 평균이든 중앙값이든 이 효과를 입증하기 위해 평균을 사용하는 것은 이 효과가 서술형 데이터가 아닌 수치 데이터에서 작동하는 방식, 즉 수학적 효과의 강점을 반영합니다[45]. 집단이 개인보다 더 나은 의사 결정을 내린다는 명백한 안심은 예방 조치를 취하지 않는 한 내러티브 데이터나 집단적 의사 결정에 있어서는 잘못된 판단일 수 있습니다.

When aggregating information, the average of many individuals’ estimates can be close to reality, even when those individual estimates may be varied and lie far from it [44, 45]. This ‘wisdom of the crowd’ effect may not be true in all situations. When people work collectively rather than individually, this effect may be less apparent, as social interactions and perceived power differentials within groupings influence individual estimates. The resulting consensus produced is no more accurate, yet group members may perceive that they are making better estimates [45]. Further, the use of average, whether mean or median, to demonstrate this effect reflects the strength of how this effect works for numerical rather than narrative data, it is a mathematical effect [45]. The apparent reassurance that groups make better decisions than individuals may be misplaced when it comes to narrative data or collective decisions, unless precautions are taken.

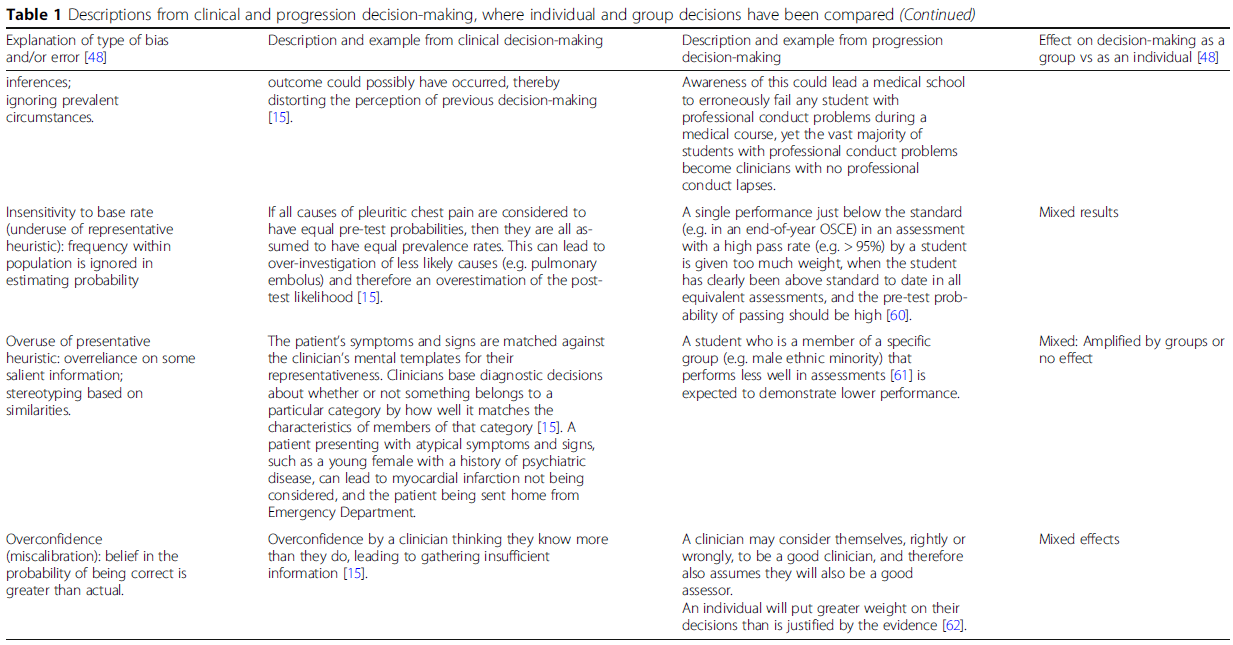

의사 결정의 오류는 지식, 데이터 수집, 정보 처리 및/또는 검증의 결함으로 인해 발생할 수 있습니다 [46]. 개인의 의사 결정에는 편견과 오류가 존재하며[10, 12, 15, 17, 18, 47], 그 중 일부는 집단 의사 결정에서도 나타납니다[48,49,50]. 개인이 내린 의사 결정의 편견과 오류를 집단이 내린 의사 결정과 비교할 때, 일부는 약화되고 일부는 증폭되며 일부는 재생산되며 분류별로 일관된 패턴이 없습니다 [48]. 이러한 편견과 오류는 개인 및 그룹 진급 의사 결정과 관련하여 표 1에 나와 있습니다.

Errors in decision-making can arise due to faults in knowledge, data gathering, information processing, and/or verification [46]. There are biases and errors in individual’s decision-making [10, 12, 15, 17, 18, 47], some of which are also evident in group decision-making [48,49,50]. In comparing biases and errors in decisions made by individuals with those made by groups, some are attenuated, some amplified, and some reproduced, with no consistent pattern by categorisation [48]. These biases and errors, as they relate to individual and group progression decision-making, are shown in Table 1.

개인과 마찬가지로 그룹도 의사결정을 내릴 때 여러 과정을 거칩니다. 개인이 그룹으로 모이는 과정은 정보 회상 및 처리에 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다[48]. 개인이 의사 결정을 내리는 것에 대한 문헌이 훨씬 더 많지만, 의사 결정을 내리는 그룹도 편견에 빠지기 쉬우며[63] 이는 여러 출처에서 발생할 수 있습니다[43]. 진행 의사결정의 맥락에서, 그룹의 초기 선호도는 이용 가능하거나 이후에 공개된 정보에도 불구하고 지속될 수 있으며[64], 이는 진단 의사결정의 조기 종결 편향과 유사합니다[15]. 그룹 구성원은 지배적인 성격의 과도한 비중과 같은 의사 결정 그룹 내 대인 관계를 인식할 수 있으며, 이러한 인식은 개인의 기여와 정보 토론에 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다[48]. 설득과 영향력은 후보자 평가에 대한 토론 중에 발생합니다. 처음에 후보자의 점수를 높게 매긴 이상값은 점수를 낮출 가능성이 높고, 처음에 후보자의 점수를 낮게 매긴 이상값은 점수를 높일 가능성이 낮기 때문에 합의된 토론은 후보자의 점수를 낮추어 합격률을 낮출 가능성이 높습니다[65].

Groups, like individuals, undertake several processes in coming to a decision. The process of individuals gathering into a group can influence information recall and handling [48]. Although there is a significantly greater literature on individuals making decisions, groups making decisions can also be prone to biases [63] and this can arise from many sources [43]. In the context of progression decision-making, a group’s initial preferences can persist despite available or subsequently disclosed information [64], a bias similar to premature closure in diagnostic decision-making [15]. Group members may be aware of interpersonal relationships within the decision group, such as the undue weight of a dominant personality, and these perceptions can influence an individual’s contribution and discussion of information [48]. Persuasion and influence occur during discussion of a candidate assessment. Outliers who initially score candidates higher are more likely to reduce their score, while outliers who initially score the candidates lower are less likely to increase their score, with the result that consensus discussion is likely to lower candidate scores and therefore reduce the pass rate [65].

집단에 의한 고위험 의사 결정의 예로서 배심원단

A jury as an example of high-stakes decision-making by a group

배심원 의사결정은 그룹이 고위험 의사결정을 내리는 예로서[48], 광범위하게 연구되어 왔으므로 진급 의사결정에 대한 통찰력을 제공할 수 있습니다. 배심원 및/또는 배심원의 의사 결정, 편견, 오류에 관한 중요한 문헌[49, 50, 66,67,68,69,70,71, 72,73,74,75,76]이 있으며, 여기에는 요약 리뷰[77]도 포함되어 있습니다. 모든 증거를 고려하는 배심원 그룹의 주된 목적(유죄 또는 무죄라는 이분법적인 평결에 도달하는 것을 목표로 함)과 모든 평가 데이터를 고려하는 의사 결정자 그룹의 주된 목적(합격 또는 불합격이라는 고위험 평결에 도달하는 것을 목표로 함) 사이에는 유사성이 있습니다. 배심원 의사 결정은 진도 의사 결정과 비슷하지만, 앞서 설명한 다른 그룹 의사 결정과 달리 정답이 알려진 문제를 다루지 않습니다[48, 66].

Jury decision-making is an example of a group making a high-stakes decision [48], that has been extensively researched and therefore could offer insights into progression decision-making. There is significant literature on decision-making, biases, and errors by jurors and/or juries [49, 50, 66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76], including a summarising review [77]. There are similarities between the main purpose of the group of jurors considering all the evidence (with the aim of reaching a high-stakes verdict which is often a dichotomous guilty or not guilty verdict) and the main purpose of a group of decision-makers to consider all the assessment data (with the aim of reaching a high-stakes verdict of pass or fail). Jury decision-making, like progression decision-making, but unlike other group decision-making described, does not address a problem with a known correct answer [48, 66].

배심원과 배심원이 내린 결정에 대한 상대적 기여도는 과제에 따라 다릅니다 [50]. 임상 의사결정의 경우 의사결정의 정확성과 효율성을 향상시킬 수 있는 휴리스틱이 있지만, 이러한 휴리스틱이 정확도가 떨어지거나 효율성이 떨어지는 결과를 낳으면 편견으로 간주됩니다. 시뮬레이션 배심원 및/또는 일부 실제 배심원의 경우 편견과 편향에 대한 취약성이 보고되었으며, 그 요인으로는 [49, 50, 66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77] 등이 있습니다:

The relative contribution to the decision brought about by jurors and juries varies with the task [50]. As for clinical decision-making, there are heuristics which can improve the accuracy and efficiency of decisions, but when these produce less accurate or less efficient results, they are seen as biases. Susceptibility to variation and bias has been reported for simulated jurors and/or for some real juries, with factors that include [49, 50, 66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77]:

- 피고 및/또는 피해자/원고 요인. 여기에는 성별, 인종, 외모, 경제적 배경, 성격, 부상, 재판 전 홍보, 피고인의 전과 기록 공개, 자기 모욕죄로부터의 자유, 개인 또는 법인 여부, 법정 행동과 같은 개인적 요인이 포함됩니다;

Defendant and/or victim/plaintiff factors. This includes personal factors such as gender, race, physical appearance, economic background, personality, injuries, pre-trial publicity, disclosure of defendants prior record, freedom from self-incrimination, being individual or corporation, courtroom behaviour; - 배심원 요인. 여기에는 권위주의, 유죄 또는 무죄 판결에 찬성하는 성향, 나이, 성별, 인종, 사회적 배경, 증거의 기억력, 증거에 대한 이해도, 지시된 정보를 무시하는 정도, 배심원 경험 등이 포함됩니다;

Juror factors. This includes authoritarianism, proneness to be pro-conviction or pro-acquittal, age, gender, race, social background, recall of evidence, understanding of evidence, ignoring information as instructed, prior juror experience; - 대표성 요인. 여기에는 성별, 서면/언어적 표현, 명확성, 스타일 및 프레젠테이션의 효율성과 같은 법적 대표성 요인이 포함됩니다;

Representative factors. This includes legal representation factors such as gender, written/verbal representation, clarity, style and efficiency of presentation; - 증거 요인. 여기에는 증거의 이미지(더 시각적이거나 시각적으로 상상할 수 있는 것), 제시 순서, 증거의 성격이 포함됩니다;

Evidence factors. This includes imagery of evidence (the more visual or more visually imaginable), order of presentation, nature of evidence; - 범죄 요인. 여기에는 범죄의 심각성 또는 유형이 포함됩니다;

Crime factors. This includes the severity or type of crime; - 판사 요인. 여기에는 주어진 지침 또는 안내의 내용이 포함됩니다;

Judge factors. This includes the content of the instructions or guidance given; - 배심원단 구성 요소. 여기에는 사회적 배경 혼합, 인종 혼합과 같은 여러 측면이 포함됩니다.

Jury membership factors. This includes the mix of aspects such as social background mix, racial mix.

이러한 요인 중 일부는 진행 상황 결정과 관련하여 유사점이 있습니다. 스토리 구축의 용이성은 결정과 그 결정의 확실성 모두에 영향을 미치며[71], 이는 가용성 편향과 유사합니다. 첫인상으로 인한 배심원 편향[67, 75, 77]은 앵커링과 유사합니다. 사람들은 비슷한 사람들과 동일시할 수 있으며, "우리와 같은 사람들" 효과가 존재할 수 있습니다[78]. 진급 의사 결정의 경우 이러한 영향 중 일부는 가능한 한 학생을 익명화하여 완화할 수 있습니다.

There are similarities in some of these factors in relation to progression decision-making. The ease of building a story influences both the decisions and the certainty in those decisions [71], akin to the availability bias. The juror bias due to initial impression [67, 75, 77] is akin to anchoring. People may identify with similar people; a “people like us” effect may be present [78]. For progression decision-making some of these effects can be mitigated by anonymisation of students, as far as possible.

배심원과 진도 결정을 내리는 패널의 한 가지 차이점은 배심원은 동료 배심원에게 정보를 제공하지 않는다는 점입니다. 이와는 대조적으로 진급 결정 패널의 구성원은 학생을 관찰하고 정보를 제공할 수 있습니다. 의사 결정권자의 관찰 부족은 편견의 잠재적 원인을 제거하기 때문에 의사 결정에 도움이 될 수 있습니다. 하나의 일화가 강력한 증거와 부적절하게 모순될 수 있기 때문입니다[57]. 또한, 잘못된 증거 회상으로 인한 편견은 심의를 위해 패널에 제출된 증거보다 덜 문제가 됩니다.

One difference between a jury and a panel making a progression decision, is that a juror does not provide information to their co-jurors. In contrast, a member of a progression decision panel might also have observed the student and can provide information. Lack of observation by the decision-makers can be a benefit in decision-making, as it removes a potential source of bias: a single anecdote can inappropriately contradict a robust body of evidence [57]. Additionally, bias produced by incorrect evidential recall is less of an issue than evidence presented to the panel for deliberation.

프로그램 평가 패널은 일반인 및 동료 배심원단보다는 대법원 판사 패널에 더 가까울 수 있지만, 비공개 회의로 진행되는 대법원 판사 패널의 의사 결정 및 심의에 대한 연구는 거의 없습니다.

The programmatic assessment panel may be closer to a Supreme Court panel of judges rather than a jury of lay-people and peers, but there is little research on the decision-making and deliberations of panels of Supreme Court judges, which are conducted in closed-door meetings.

배심원단의 의사 결정 스타일

Jury decision-making style

배심원단의 심의 스타일은 정보 수집을 통한 증거 중심 또는 평결 투표로 시작하는 평결 중심[68]으로 나타났습니다. 증거 중심 심의는 시간이 오래 걸리고 더 많은 합의를 이끌어내는 반면, 평결 중심 심의는 적대적인 방식으로 반대 의견을 이끌어내는 경향이 있습니다. 증거 중심 심의에서 의견이 크게 바뀌는 경우, 이는 판사의 지시에 대한 토론과 관련이 있을 가능성이 높습니다[68]. 결정 규칙이 합의 없이 다수결로 평결을 내릴 수 있도록 허용하는 경우, 작지만 실질적인 효과를 볼 수 있습니다. 배심원단이 필요한 정족수에 도달하면 심의를 중단하는 것입니다 [77]. 평결 투표는 사람들이 투표 순서에 따라 투표를 변경하는 투표 순서와 같은 추가적인 편견의 영향을 받을 수 있습니다[77]. 그룹 토론은 극단적인(보다 정직한) 입장을 도출할 수 있다는 점에서 잠재적인 문제가 없는 것은 아닙니다. 전체 배심원 평결의 90%는 1차 투표 과반수[66]의 방향으로 이루어지지만, 적지 않은 수의 배심원들이 숙의에 의해 흔들립니다. 개인이 개별적인 결정과 근거를 진술하면 그룹 내에서 책임이 분산되어 더 위험한 의견이 진술되고 따라서 더 위험한 결정이 내려질 수 있습니다[66].

Jury deliberation styles have been shown to be either evidence-driven, with pooling of information, or verdict-driven, which start with a verdict vote [68]. Evidence-driven deliberations take longer and lead to more consensus; verdict-driven deliberations tend to bring out opposing views in an adversarial way. When evidence-driven deliberations lead to a significant change of opinion, it is more likely to be related to a discussion of judge’s instructions [68]. If the decision rules allow a majority vote verdict without consensus, a small but real effect is seen [77]: juries will stop deliberating once the required quorum is reached. Verdict voting can be subject to additional biases such as voting order where people alter their vote depending on the votes given to that point [77]. Group discussions are not without potential problems, in that they can generate extreme (more honest) positions. Ninety percent of all jury verdicts are in the direction of the first ballot majority [66], but a small and not insignificant number are swayed by deliberation. Once individuals state their individual decisions and rationales, diffusion of responsibility within a group may lead to riskier opinions being stated, and therefore riskier decisions being made [66].

이를 진급 의사 결정의 맥락으로 확장하면, 최적의 접근 방식은 정책과 프로세스의 규칙과 실행에 주의를 기울이면서, 증거에 기반하는 합의 결정입니다.

Extrapolating this to the context of progression decision-making, an optimal approach is consensus decisions that are based on evidence, whilst attending to the rules and implementation of policy and process.

배심원 리더십

Jury leadership

배심원 의사결정 프로세스에 대해 우리가 알고 있는 바에 따르면, 평가 진행 패널 위원장에 해당하는 배심원 단장은 의사결정에서 좋은 프로세스를 유지하면서 열린 담론을 보존할 수 있는 기술이 필요합니다. 배심원단장은 영향력이 있을 수 있으며[77], 개별 배심원들은 극단적인 견해를 가질 수 있지만, 배심원단 선정 과정이 일반적으로 극단적인 견해를 가진 사람들의 선정 가능성을 낮춰준다[66].

Based on what we know about jury decision-making processes, the jury foreperson, the equivalent of the assessment progress panel chair, needs the skills to preserve open discourse, whilst maintaining good process in decision-making. The jury foreperson can be influential [77], and individual jurors can hold extreme views, though the process of jury selection usually mitigates against the selection of people with extreme views [66].

진행 의사결정자를 선정할 때는 임상 진료와 관련된 기술 및 지식보다는, 정보를 종합하여 중대한 결정을 내리는 데 필요한 기술을 고려해야 합니다.

In choosing progress decision-makers, consideration should be given to the skills that are required to make high-stakes decisions based on aggregating information, rather than skills and knowledge relating to clinical practice.

배심원단의 관용과 실패하지 않기

Jury leniency and failure to fail

피고인에 대한 관용과 failure to fail 현상 사이에 유사점이 있습니까[55]? 배심원단은 무죄를 추정하도록 지시받습니다[67]: 평결에 오류가 있을 경우 관용을 베푸는 것이 바람직합니다[79]. 법적 의사 결정에는 결정을 지지할 확률과 해당 결정을 지지하는 데 필요한 임계값이라는 두 가지 요소가 있습니다[66]. 결정을 지지하면서도 어느 정도의 의심은 남아있을 수 있습니다. 배심원 및 배심원 결과에 요구되는 증명 기준(합리적 의심)의 영향은 상당합니다[69, 77]. 의심스러운 경우 배심원은 무죄를 선호합니다[48, 63]. 배심원단의 심의는 관용을 베푸는 경향이 있으며[72, 75], 대부분의 관용은 증명 기준의 요건에 의해 설명됩니다[72].

Is there a parallel between leniency towards the defendant and the failure to fail phenomenon [55]? Juries are instructed to presume innocence [67]: if one is to err in a verdict, leniency is preferred [79]. Legal decision-making has two components: the probability of supporting a decision, and threshold required to support that decision [66]. It is possible to support a decision but still retain a degree of doubt. The effect of standard of proof (reasonable doubt) required on juror and jury outcomes is significant [69, 77]. If in doubt, a jury will favour acquittal [48, 63]. Jury deliberations tend towards leniency [72, 75], with most leniency is accounted for by the requirement of standard of proof [72].

진급 의사 결정에서도 비슷한 효과가 관찰되었는데, 의심스러운 경우 일반적으로 학생을 합격시키는 결정을 내립니다[55]. 유죄가 입증되지 않는 한 무죄를 추정할 책임은 배심원단에게 있지만, 학생의 유능함을 입증할 책임은 진행 패널에게 있습니까? 이 책임은 무능력이 입증되지 않는 한 능력이 있다고 추정하는 것으로 잘못 해석되는 경우가 너무 많습니다. 이는 능력이 아직 입증되지 않았음을 시사하는 여러 가지 작은 증거를 무시하는 것으로 나타날 수 있습니다[36].

A similar effect has been observed in progression decision-making where, if in doubt, the decision is usually to pass the student [55]. The onus is on the jury to presume innocence unless finding guilt proven, but is the onus on the progress panel to find student competent proven? Too often this onus is erroneously misinterpreted as presuming competence unless finding incompetence proven. This can manifest as a discounting of multiple small pieces of evidence suggesting that competence has not yet been demonstrated [36].

학생 진급과 관련된 의사 결정의 견고성을 높이기 위해 주의해야 할 제안 사항

Suggestions to attend to in order to promote robustness of decisions made relating to student progression

이제 진급 결정권자가 사용할 수 있는 몇 가지 모범 사례 팁과 원칙을 제안합니다. 이는 앞서 설명한 임상 의사 결정 및 배심원단 의사 결정의 증거와 추가 관련 문헌에 근거한 것입니다.

We now propose some good practice tips and principles that could be used by progression decision-makers. These are based on the previously outlined evidence from clinical decision-making and jury decision-making, and from additional relevant literature.

교육 기관, 의사 결정 패널, 패널리스트는 진행 상황 결정에 편견과 오류가 있을 수 있음을 인지해야 합니다.

Educational institutions, decision-making panels, and panellists should be aware of the potential for bias and error in progression decisions

편견의 가능성을 의식적으로 인식하는 것이 편견을 완화하기 위한 첫 번째 단계입니다[19,20,21]. 이러한 편향은 의사 결정을 내리는 개인과 의사 결정을 내리는 집단 모두에서 발생할 수 있습니다. 임상 의사 결정에서 추론해 보면, 의사 결정자의 오류 가능성에 대한 인식을 높이는 것이 과제입니다[12]. 임상의가 임상 의사 결정에서 불확실성을 인식하고 공개하지 않는 것은 심각한 문제입니다 [47, 80]. 그러나 학생 성과에 대한 불확실성이 있더라도 의사 결정 패널은 여전히 결정을 내려야 합니다.

Being consciously aware of the possibility of bias is the first step to mitigate against it [19,20,21]. Such biases can occur both for individuals making decisions and for groups making decisions. Extrapolating from clinical decision-making, the challenge is raising awareness of the possibility of error by decision-makers [12]. Clinicians failing to recognise and disclose uncertainty in clinical decision-making is a significant problem [47, 80]. However, even when there is uncertainty over student performance, decision panels still need to make a decision.

의사 결정은 적절하게 선정된 의사 결정 패널에 의해 이루어져야 합니다.

Decisions should be made by appropriately selected decision-making panels

임상 의사 결정에서 추론해 볼 때, 개인의 의사 결정을 개선하기 위한 전략에는 전문 지식과 메타인지 연습을 증진하는 것이 포함됩니다. 전문성 부족은 오류의 원인이 될 수 있으므로[34], 평가 내용보다는 학생 결과 의사결정에 대한 적절한 전문성을 갖춘 패널을 선정해야 하며, 의사결정의 질에 대한 반영에는 의사결정에 대한 피드백 및 의사결정 훈련 방식의 질 보증이 포함되어야 합니다. 따라서 패널은 지위/연공서열, 평가 내용에 대한 친숙도 또는 학생과의 친밀도보다는 편견을 인식하는 메타인지 능력을 기준으로 선정해야 합니다.

Extrapolating from clinical decision-making, strategies to improve individual decision-making include promotion of expertise and metacognitive practice. A lack of expertise can contribute to errors [34], hence panel members should be selected with appropriate expertise in student outcome decision-making, rather than assessment content, and reflections on decision quality should include quality assurance in the way of feedback on decisions and training for decision-making. As such, the panel should be chosen on the basis of its ability to show metacognition in recognising bias, rather than status/seniority, familiarity with assessment content, or familiarity with the students.

숙련된 의사결정자들로 구성된 패널도 편견의 가능성이 없는 것은 아니지만[81], 정책, 절차 및 실무 수준에서 구현할 수 있는 가능한 해결책이 있습니다. 학생과 교직원 간의 직업적, 사회적 상호 작용의 가능성을 고려할 때 잠재적 이해 상충에 대한 정책, 절차 및 실무 문서가 있어야 합니다. 의사 결정자가 한 명 이상의 학생과 이해관계가 충돌하는 경우 의사 결정에서 물러나야 합니다. 잠재적 이해 상충은 개별 의사 결정자 및 개별 학생과 관련될 가능성이 훨씬 높으므로 적절한 정책에 따라 사례별로 처리해야 합니다. 갈등의 예로는 가족 구성원과의 보다 명백한 관계뿐만 아니라 멘토/멘티, 학생과 복지 역할을 하는 사람과의 관계도 포함될 수 있습니다.

Even a panel of experienced decision-makers is not without the potential for bias [81], but there are possible solutions that can be implemented at the policy, procedure and practice levels. Given the potential for professional and social interactions between students and staff, there should be policy, procedure, and practice documentation for potential conflicts of interest. If a decision-maker is conflicted for one or more students, then they should withdraw from decision-making. Potential conflicts of interest are far more likely to relate to individual decision-makers and individual students, and should be dealt with on a case-by-case basis guided by an appropriate policy. Examples of conflict might include more obvious relationships with family members, but also with mentors/mentees and those with a welfare role with students.

교육 기관은 평가 이벤트 및 관련 의사 결정과 관련된 정책, 절차 및 실무 문서를 공개적으로 이용할 수 있어야 합니다.

Educational institutions should have publicly available policies, procedures, and practice documentation related to assessment events and the associated decision-making

배심원단의 성과를 개선하는 것은 절차적 문제를 개선함으로써 달성할 수 있습니다[77]. 여기에는 다음 등이 포함되고 다른 것도 있을 수 있습니다.

- 증거 사실에 대한 철저한 검토,

- 판사의 지시에 대한 배심원단의 정확한 이해,

- 모든 배심원의 적극적인 참여,

- 규범적 압력이 아닌 토론을 통한 이견 해소,

- 다양한 평결 옵션의 요건에 대한 사건 사실의 체계적 일치

마찬가지로 진행 패널 결정의 관점에서 보면, 이는 다음에 해당합니다.

- 제공된 정보의 철저한 검토,

- 정책에 대한 정확한 이해,

- 모든 패널 구성원의 적극적인 참여,

- 토론과 합의를 통한 이견 해소,

- 평가 목적 및 결과에 대한 요건에 대한 정보의 체계적 매칭

이러한 요소들이 이미 많은 의사결정 과정에 내재되어 있다고 주장하는 사람들도 있지만, 이러한 요소들을 보다 명시적으로 만들면 의사결정의 질이 향상될 수 있습니다.

Improving jury performance can be achieved through improving procedural issues [77]. These include, but are not necessarily limited to, the following:

- a thorough review of the facts in evidence,

- accurate jury-level comprehension of the judge’s instructions,

- active participation by all jurors,

- resolution of differences through discussion as opposed to normative pressure, and

- systematic matching of case facts to the requirements for the various verdict options.

Likewise, from the perspective of a progression panel decision, these would equate to:

- a thorough review of the information provided,

- accurate comprehension of the policy,

- active participation by all panel members,

- resolution of differences through discussion and consensus, and

- systematic matching of information to the requirements for the assessment purpose and outcomes.

While some might argue that these components are already implicit in many decision-making processes, the quality of decision-making may be improved if such components are made more explicit.

패널과 토론자에게 필요한 의사결정을 위한 충분한 정보를 제공해야 합니다.

Panels and panellists should be provided with sufficient information for the decision required

그룹 토론은 정보 기억력을 향상시킬 수 있으며[48], jurors과 달리 juries의 이점 중 일부는 개인에 비해 그룹이 기억력을 향상시키는 것과 관련이 있습니다[66, 67, 74]. 다수의 배심원은 개별 배심원보다 덜 완전하지만 더 정확한 보고서를 작성합니다[66].

Group discussions can improve recall of information [48], and some of the benefit of juries, as opposed to jurors, relates to improved recall by a group compared to individuals [66, 67, 74]. Multiple jurors produce less complete but more accurate reports than individual jurors [66].

진급 의사 결정에서 패널리스트가 결정을 내릴 때 정보 또는 정책의 세부 사항에 대한 회상에 의존해야 할 가능성은 낮지만, 패널은 개별 학생에 대한 결정에 도달하기 위해 충분한 정보(질과 양)를 가지고 있는지 결정해야 할 것입니다. 정보가 불충분하지만 더 많은 정보가 입수될 수 있는 경우, 이를 구체적으로 구하고[36] 결정을 연기해야 합니다. 추가 정보가 제공되지 않을 경우, 입증 책임이 어디에 있는지에 대한 질문으로 전환해야 합니다.

In progression decision-making, it is unlikely that panellists will have to rely on recall for specifics of information or policy when making decisions, but the panel will need to decide if they have sufficient information (quality and quantity) in order to reach a decision for an individual student. Where there is insufficient information, but more may become available, this should be specifically sought [36], and a decision deferred. Where further information will not become available, the question should then turn to where the onus of the burden of proof lies.

패널과 토론자는 정보 종합을 최적화하고 편견을 줄이기 위해 노력해야 합니다.

Panels and panellists should work to optimise their information synthesis and reduce bias

표 1에 요약된 바와 같이 그룹 내 심의 및 토론 행위는 개인의 많은 편견과 오류를 줄여줍니다[48]. 증거 외 편향과 같은 일부 편향은 그룹 의사 결정에서 증폭될 수 있으며, 일화 제공이 그룹의 결정에 부당하게 영향을 미칠 수 있는 경우를 예로 들 수 있습니다[57].

The act of deliberation and discussion within groups attenuates many of the biases and errors of individuals [48], as outlined in Table 1. Some biases, such as extra-evidentiary bias, can be amplified in group decision-making, an example being where provision of an anecdote could unduly influence a group’s decision [57].

의사 결정은 의사 결정 지원 및 의사 결정 검토와 함께 모든 정보와 맥락을 고려해야 합니다. 외부 검토는 단순히 의사 결정에 대한 검토를 넘어 기본 패널 프로세스, 절차 및 관행에 대한 외부 검토로 확장될 수 있습니다. 모든 패널 토론에 외부 검토가 필요한 것은 아니지만, 정기적인 외부 참관과 관련된 정책 검토는 적절할 수 있습니다.

Progression decision-making requires consideration of all information and the context, with decision support and decision review. External review might extend beyond just reviewing the decisions, to an external review of the underlying panel process, procedures, and practices. Not every panel discussion needs external review, but policy review associated with regular external observation would be appropriate.

패널은 합의를 통해 결정에 도달해야 합니다.

Panellists should reach decisions by consensus

투표가 아닌 합의에 의한 의사결정은 적대적인 의사결정을 피할 수 있습니다. 법정에서는 공정성을 확보하기 위해 사실관계가 적대적인 방식으로 밝혀지고 제시되며, 반대 측 법률 대리인이 정보를 문제 삼습니다[67]. 그 결과 증거의 신뢰성이 떨어지고 논쟁의 여지가 있는 것처럼 보입니다. 마찬가지로, 적대적인 방식으로 제시된 정보에 직면한 경우, 진급 의사결정 패널은 해당 정보의 신뢰성이 떨어지고 따라서 확고한 결정을 내리기에는 불충분하다고 생각할 수 있습니다.

Consensus decision-making rather than voting avoids adversarial decision-making. In an attempt to produce fairness within a courtroom, facts are uncovered and presented in an adversarial manner, with information being questioned by opposing legal representation [67]. This results in the appearance of evidential unreliability and contentiousness. Similarly, when faced with information presented in an adversarial way, progression decision-making panels might view the information as being less reliable, and therefore insufficient to make a robust decision.

입증 책임은 입증된 역량 입증자에게 있어야 합니다.

The burden of proof should lie with a proven demonstration of competence

합격/불합격이 중요한 의사 결정의 경우, 입증 기준은 학생의 역량이 진도에 만족할 만한 수준이라는 것을 증명하는 것이어야 합니다. 그렇지 않다는 것이 증명되기 전까지는 학생이 유능하다고 가정하는 경우가 많습니다. "유죄가 입증될 때까지 무죄"와는 대조적으로, 우리는 보건의료 교육 기관이 사회를 보호해야 할 의무를 반영하여 유능한 것으로 입증될 때까지 학생을 무능력한 것으로 간주해야 한다고 제안합니다[40].

For high-stakes pass/fail decision-making, the standard of proof should be proof that the student’s competence is at a satisfactory standard to progress. The assumption is often that the student is competent, until proved otherwise. In contrast to “innocent until proven guilty”, we suggest students should be regarded as incompetent until proven competent, reflecting the duty for healthcare educational institutions to protect society [40].

검사 결과의 예측값은 민감도와 특이도는 변하지 않더라도 검사 전 확률 또는 유병률의 영향을 받습니다. 이 시험 전 합격 확률 또는 유병률은 코호트가 과정을 진행하면서 능력이 떨어지는 학생이 제거됨에 따라 증가해야 합니다. 따라서 잘못된 합격/불합격 결정은 잘못된 합격(진정한 불합격)보다 잘못된 불합격(진정한 합격)일 가능성이 상대적으로 더 높으며, 평가가 모호한 경우에는 학생이 괜찮을satisfactory 가능성이 안괜찮을 가능성보다 더 높습니다. 그러나 학생이 코스를 진행하면서 추가 평가의 기회가 줄어듭니다. 졸업이 가까워질수록 잘못된 합격/불합격 결정의 위험과 영향이 커집니다. 시험 전 확률이나 유병률을 고려하면 학생의 pass할 가능성이 높아질테지만, 사회의 요구와 기대를 충족해야 하는 교육기관의 의무가 이를 우선시해야 합니다.

The predictive value of a test result is affected by the pre-test probability or prevalence, even though sensitivity and specificity may not change. This pre-test probability or prevalence of passing should increase as a cohort progresses through the course, as less able students are removed. Therefore, incorrect pass/fail decisions are relatively more likely to be false fails (true passes) than false passes (true fails), and when an assessment is equivocal, it is more likely that the student is satisfactory than not. However, as a student progresses through the course and the opportunities for further assessment are reduced. As graduation nears, the stakes and impact of an incorrect pass/fail decision increases. Although pre-test probability or prevalence considerations would favour passing the student, the duty of the institution to meet the needs and expectations of society should override this.

결론

Conclusion

우리는 진급 의사 결정에 메타인지를 요구합니다. 우리는 학생에 대한 정확한 그림을 구성하기 위해 여러 정보를 결합하는 것의 강점을 염두에 두어야 하지만, 결정을 내릴 때 편견의 근원에 대해서도 염두에 두어야 합니다. 많은 교육기관이 이미 모범 사례를 보여주고 있다는 점을 인정하지만, 편견에 대한 인식과 이 백서에 요약된 제안 프로세스는 숨겨진 편견과 의사 결정 오류를 최소화하기 위한 품질 보증 체크리스트의 일부로 활용될 수 있습니다. 임상 의사결정 경험과 배심원단의 의사결정에 대한 이해가 도움이 될 수 있습니다.

We provide a call for metacognition in progression decision–making. We should be mindful of the strengths of combining several pieces of information to construct an accurate picture of a student, but should also be mindful of the sources of bias in making decisions. While we acknowledge that many institutions may already be demonstrating good practice, awareness of biases and the suggested process outlined in this paper can serve as part of a quality assurance checklist to ensure hidden biases and decision-making errors are minimised. Drawing on one’s experience of clinical decision-making and an understanding of jury decision-making can assist in this.

Student progress decision-making in programmatic assessment: can we extrapolate from clinical decision-making and jury decision-making?

PMID: 31146714

PMCID: PMC6543577

DOI: 10.1186/s12909-019-1583-1

Free PMC article

Abstract

Background: Despite much effort in the development of robustness of information provided by individual assessment events, there is less literature on the aggregation of this information to make progression decisions on individual students. With the development of programmatic assessment, aggregation of information from multiple sources is required, and needs to be completed in a robust manner. The issues raised by this progression decision-making have parallels with similar issues in clinical decision-making and jury decision-making.

Main body: Clinical decision-making is used to draw parallels with progression decision-making, in particular the need to aggregate information and the considerations to be made when additional information is needed to make robust decisions. In clinical decision-making, diagnoses can be based on screening tests and diagnostic tests, and the balance of sensitivity and specificity can be applied to progression decision-making. There are risks and consequences associated with clinical decisions, and likewise with progression decisions. Both clinical decision-making and progression decision-making can be tough. Tough and complex clinical decisions can be improved by making decisions as a group. The biases associated with decision-making can be amplified or attenuated by group processes, and have similar biases to those seen in clinical and progression decision-making. Jury decision-making is an example of a group making high-stakes decisions when the correct answer is not known, much like progression decision panels. The leadership of both jury and progression panels is important for robust decision-making. Finally, the parallel between a jury's leniency towards the defendant and the failure to fail phenomenon is considered.

Conclusion: It is suggested that decisions should be made by appropriately selected decision-making panels; educational institutions should have policies, procedures, and practice documentation related to progression decision-making; panels and panellists should be provided with sufficient information; panels and panellists should work to optimise their information synthesis and reduce bias; panellists should reach decisions by consensus; and that the standard of proof should be that student competence needs to be demonstrated.

Keywords: Decision-making; Policy; Programmatic assessment.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 평가법 (Portfolio 등)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 사례 기반 다지선다형 문항 작성을 위한 ChatGPT 프롬프트(Spanish Journal of Medical Education, 2023) (0) | 2023.11.19 |

|---|---|

| 졸업후교육 학습자(전공의)의 평가에서 환자참여: 스코핑 리뷰(Med Educ, 2021) (0) | 2023.11.10 |

| 평가에 대한 메타포의 사용과 남용(Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2023) (0) | 2023.11.05 |

| 사회문화적 학습이론과 학습을 위한 평가 (Med Educ, 2023) (0) | 2023.11.05 |

| 작은 코호트 OSCE에서 방어가능한 합격선 설정하기: 언제 경계선 회귀방법이 효과적인지 이해하기(Med Teach, 2020) (0) | 2023.09.08 |