"어려울 거에요..." 의과대학의 Widening access에 대한 선생님의 역할 인식(Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2021)

“It’s going to be hard you know…” Teachers’ perceived role in widening access to medicine

Kirsty Alexander1 · Sandra Nicholson2 · Jennifer Cleland3

소개

Introduction

전 세계적으로 의료계는 주로 부유한 배경을 가진 사람들로 구성되어 있으며, 평균보다 높은 수준의 교육을 받은 경우가 많습니다(AFMC 2010, 교육훈련부 2019, Milburn 2012). 학교별 격차는 의대 지원에도 반영됩니다. 예를 들어, 영국 의대 지원자의 80%는 영국 고등학교의 20% 출신이며, 최근 몇 년간 의대 지원자를 한 명도 배출하지 않은 학교도 절반에 달합니다(Medical Schools Council 2014a, b); 지원자의 44%는 문법(학업 선택제) 및 독립(학비 납부) 학교 출신인 반면(Mathers 외 2016), 학령 인구의 약 6.5%만이 이러한 학교에 다니고 있습니다(Bolton 2017; ISC 2020).

Globally, the medical profession consists predominantly of individuals from affluent backgrounds, often educated in schools which outperform the average (AFMC 2010; Department of Education and Training 2019; Milburn 2012). School disparities are reflected in medical school applications. For example, 80% of UK medical school applicants come from only 20% of UK high schools, and half of schools have sent no applicants to medicine in recent years (Medical Schools Council 2014a, b); 44% of applicants come from grammar (academically selective) and independent (fee-paying) schools (Mathers et al. 2016), whilst only approximately 6.5% of the school age population attend these schools (Bolton 2017; ISC 2020).

의학 분야의 사회경제적 다양성 부족으로 인해 의과대학이 사회 이동성을 촉진하지 못하거나, 의과대학이 서비스를 제공하는 인구를 돌볼 수 있는 최상의 인력을 창출하지 못할 수 있다는 우려가 제기되고 있습니다(Larkins 외. 2015; Medical Schools Council 2014a; Milburn 2012; O'Connell 외. 2017; Puddey 외. 2017). 독립 및 문법학교 출신 지원자가 주립(무료) 학교 출신 지원자에 비해 의대에 합격할 확률이 약간 더 높기 때문에(Steven 외 2016), 지원자 풀이 전체 인구의 대표성을 높여야 한다는 요구가 강하게 제기되어 왔습니다(Mathers 외 2011; McLachlan 2005; O'Neill 외 2013). 이로 인해 전통적으로 의대 진학을 고려하지 않는 학교 및 지역사회와 협력하여 의대 진학에 대한 인식을 높이고 지원을 지원하는 의과대학의 폭 넓은 접근(WA) 이니셔티브(파이프라인, 멘토링, 아웃리치 또는 학업 강화 프로그램이라고도 함)가 증가하고 있습니다(Medical Schools Council 2014b). WA 이니셔티브는 영국 고등 교육에 참여하는 다양한 인구통계학적 그룹의 학생들 간의 불균형을 줄이기 위한 정부 정책에서 비롯되었습니다(Connell-Smith and Hubble 2018). 이러한 프로그램은 영국(Greenhalgh 외. 2006; Kamali 외. 2005; Ratneswaran 외. 2015; Smith 외. 2013), 미국(Crews 외. 2020; Martos 외. 2017; Navarre 외. 2017; Soto-Greene 외. 1999), 캐나다(Robinson 외. 2017; Rourke 2005), 호주(Bennett 외. 2015; Gale and Parker 2013; Naylor 외. 2013) 전역에서 다양하게 운영되고 있다.

The lack of socioeconomic diversity in medicine has caused concern that medical schools may not be promoting social mobility nor creating the best possible workforces to care for the populations they serve (Larkins et al. 2015; Medical Schools Council 2014a; Milburn 2012; O’Connell et al. 2017; Puddey et al. 2017). As applicants from independent and grammar schools are only slightly more likely to be accepted for a place at medical school in comparison to those applying from state (free to attend) schools (Steven et al. 2016), there have been strong calls for the applicant pool to become more representative of the population as a whole (Mathers et al. 2011; McLachlan 2005; O’Neill et al. 2013). This has caused an increase in medical schools’ widening access (WA) initiatives (otherwise known as pipeline, mentorship, outreach or academic enrichment programmes) which work with schools and communities that may not traditionally consider a career in medicine, to raise awareness about the career and support an application (Medical Schools Council 2014b). WA initiatives stem from governmental policies that aim to reduce discrepancies between the participation of different demographic groups of students in UK higher education (Connell-Smith and Hubble 2018). A wide variety of these programmes run across the UK (Greenhalgh et al. 2006; Kamali et al. 2005; Ratneswaran et al. 2015; Smith et al. 2013), the US (Crews et al. 2020; Martos et al. 2017; Navarre et al. 2017; Soto-Greene et al. 1999), Canada (Robinson et al. 2017; Rourke 2005) and Australia (Bennett et al. 2015; Gale and Parker 2013; Naylor et al. 2013).

학교 교사는 학생들이 의과대학과 의학에 대한 정보와 이니셔티브에 접근하는 주요 경로로 인식되고 있으며(Fleming and Grace 2014; McHarg 외 2007; 의과대학협의회 2016), 교사의 격려가 학생들의 전반적인 학업 성취도와 졸업 후 선택에 긍정적인 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다(Alcott 2017; Gale 외 2010). 따라서 학교 교사들은 게이트키퍼이자 영향력 있는 사람으로서 WA의 성공에 있어 핵심적인 이해관계자로 자리매김하고 있습니다(플레밍과 그레이스 2014; 올리버와 케틀리 2010). 그러나 영국 국공립학교에서 정식으로 교육을 받은 대학생들은 교사의 질 낮은 지도와 격려 부족으로 인해 졸업 후 진로 선택에 어려움을 겪었다고 보고합니다(Mathers and Parry 2009, McHarg 외. 2007, 의과대학협의회 2013, UCAS 2015). 교사의 열악한 지원에 대한 이러한 보고는 미국, 캐나다, 호주 등 소외 계층에 대한 접근성을 확대하는 데 초점을 맞춘 다른 국가의 사례와 유사하지만(Behrendt 외 2012; Fray 외 2019; Gale and Parker 2013; Murray-García와 García 2002; Restoule 외 2013; Tomaszewski 외 2017), 교사가 WA에 미치는 영향에 대한 연구는 제한적입니다. 주립대 의대생들은 교사가 자신의 성공 가능성을 과소평가하고(McHarg 외 2007), 실패할 운명이라는 인상을 주며(Southgate 외 2017), 학교에 기대치가 낮은 반학문적 문화가 존재한다고 주장합니다(Mathers and Parry 2009). 다른 연구에서는 적합한 특성을 가진 학생들 중 상당수가 의사로서의 자신을 상상할 기회가 주어지지 않거나 입학 요건을 적절히 준비할 수 있는 지원이 부족하기 때문에 의대 진학을 미루는 것으로 나타났습니다(Greenhalgh 외. 2004; Southgate 외. 2015).

School teachers are recognised as a key pathway through which pupils access information and initiatives about medical schools and medicine (Fleming and Grace 2014; McHarg et al. 2007; Medical Schools Council 2016) and their encouragement can positively influence pupils’ overall attainment and post-school choices (Alcott 2017; Gale et al. 2010). As such they are positioned as key stakeholders in the success of WA, acting as gatekeepers and influencers (Fleming and Grace 2014; Oliver and Kettley 2010). University students formally educated at UK state schools report, however, that poor quality guidance and lack of encouragement from teachers hindered their ability to make post-school choices (Mathers and Parry 2009; McHarg et al. 2007; Medical Schools Council 2013; UCAS 2015). These reports of poor teacher support parallel those in other countries with a focus on widening access to underrepresented groups, for example, the US, Canada and Australia (Behrendt et al. 2012; Fray et al. 2019; Gale and Parker 2013; Murray-García and García 2002; Restoule et al. 2013; Tomaszewski et al. 2017) however, studies on teachers’ influence on WA are limited. Medical students from state schools claim their teachers underestimated their chances of success (McHarg et al. 2007), gave them the impression they were destined for failure (Southgate et al. 2017), and that there was an anti-academic culture of low expectations in their schools (Mathers and Parry 2009). Other studies suggest that pupils, many of whom do have suitable attributes, may be put off medicine as they are not given the opportunity to imagine themselves as doctors, or lack the support to prepare themselves adequately for admission requirements (Greenhalgh et al. 2004; Southgate et al. 2015).

따라서 의과대학은 불우한 환경의 학교 교사들과 더욱 긴밀히 협력하여(예: 미국의과대학협의회 2018), 이들이 WA 이니셔티브와 전문직의 다양화에 장애가 되지 않도록 해야 합니다(미국의과대학협의회 2014a). 그러나 WA 내에서 영향력 있는 이해관계자로서의 역할에도 불구하고, 학교 교사들의 의학에 대한 WA에 대한 태도는 문헌에서 거의 연구되지 않았습니다. 앞서 언급한 연구들은 학생과 의대생의 관점에서 교사가 학생의 의학에 대한 열망과 선택에 미치는 영향을 고려했지만, Southgate 등(2015)만이 교사(진로 상담사) 자신의 견해를 포함했습니다. 따라서 의과대학이 교사들과 어떻게 가장 잘 소통하고 협력해야 하는지, 왜 현재 의대 지원을 저해하는 관행이 계속되고 있는지에 대한 이해에는 상당한 격차가 있습니다. 교사들의 지원이 없다면 잠재적 지원자들이 불필요하게 의대 진학 경로를 이탈하거나 의대를 떠나고 싶다는 생각을 하게 될 수 있습니다.

Medical schools are thus recommended to work more closely with teachers in disadvantaged schools (e.g., Medical Schools Council 2018) to prevent them becoming a barrier to WA initiatives and thus the diversification of the profession (Medical Schools Council 2014a). However, despite their role as influential stakeholders within WA, schoolteachers’ attitudes towards WA to medicine have been little explored in the literature. Although the aforementioned studies consider the influence of teachers on pupils’ aspirations and choices towards medicine from the point of view of pupils and medical students, only Southgate et al. (2015) included views from teachers (careers advisers) themselves. There is thus a substantial gap in understanding about exactly how medical schools should best engage and work with teachers, and why they may currently continue practices which discourage application to medicine. Without their support, potential applicants may leak out of the WA pipeline unnecessarily or feel encouraged to leave.

따라서 이 연구에서는 지역 의과대학의 WA 이니셔티브에 참여할 자격이 있는 고등학교에서 학생들에게 의학에 대해 조언하는 교사들을 인터뷰하여 그들의 관행과 태도를 알아보고, 그들이 학생들에게 의과대학을 옵션으로 홍보하는 것을 꺼리는 이유와 방법에 대한 통찰력을 구축하고자 했습니다. 우리의 전반적인 목표는 이해를 높이고, 이를 통해 의과대학이 어떻게 하면 교사들을 의대 진학에 대한 옹호자로 더 잘 참여시킬 수 있을지 고려하는 것이었습니다. 그러나 이 연구에는 교사 스스로가 왜 WA 이니셔티브와 그 안에서 자신의 역할에 문제가 있다고 생각하는지, 그렇다면 이것이 실무에 어떤 영향을 미치는지 고려하고자 하는 보다 중요한 목적도 있었습니다. 이는 교육자가 학생의 역량을 개발하여 자신의 미래를 자유롭게 선택할 수 있도록 장려하는 역량 접근법(Walker and Unterhalter 2010)을 통한 결과 해석을 통해 촉진되었습니다. 다음과 같은 연구 질문이 연구를 이끌었습니다: 영국 WA 학교의 교사들은 학생들이 의대를 지망하고 지원서를 준비하도록 격려하는 데 있어 자신의 역할이 무엇이라고 인식하는가?

This study thus interviewed teachers advising pupils about medicine in high schools that were eligible for local medical schools’ WA initiatives to learn about their practices and attitudes, and to build insight into how and why they may be reluctant to promote medical school as an option to their pupils. Our overall aim was to build understanding and thereby consider how medical schools might better engage teachers as advocates for WA to medicine. However, the study also had a more critical purpose, in that we wished to consider why teachers themselves might find WA initiatives and their role within them problematic, and if so, how this impacted their practice. This was facilitated by the interpretation of results through the capability approach (Walker and Unterhalter 2010) which encourages educators to develop their students’ capability and thus freedom to choose their own future. The following research question guided the work: What do teachers in UK WA schools perceive to be their role in encouraging pupils to aspire to medicine and prepare an application?

방법

Methods

패러다임

Paradigm

이 연구는 참여자들의 다양하고 복합적인 현실을 인정하는 해석학적 존재론에 기반을 두고 있으며, 이는 참여자들의 사회적, 문화적 참조 프레임과 맥락에 따라 구축됩니다(Crotty 2003). 인식론적으로 이 연구는 의미를 연구자와 참여자가 함께 구성하는 것으로 이해하는 사회적 구성주의를 따르며, 연구자는 지식 창출 과정에서 참여자의 경험을 신뢰할 수 있고 공정하게 표현하기 위해 노력합니다(Mann and MacLeod 2015). 이 패러다임은 참가자의 해석과 맥락에 특히 중점을 두어 참가자가 인지한 역할과 경험에 대한 상세하고 주관적인 설명을 수집할 수 있게 해 주었습니다(Bunniss and Kelly 2010).

This study is based within an interpretivist ontology, which acknowledged participants’ diverse and multiple realities, built relative to their social and cultural frames of reference and context (Crotty 2003). Epistemologically, the study follows social constructivism, which understands meaning to be co-constructed between researcher and participant, with the researcher striving to portray a credible and fair representation of participants’ experiences within this process of knowledge creation (Mann and MacLeod 2015). This paradigm allowed us to gather detailed and subjective accounts of participants’ perceived role and experiences, with a particular emphasis on their interpretations and context (Bunniss and Kelly 2010).

이 접근 방식은 연구자가 연구의 구상부터 보급에 이르기까지 연구 과정의 모든 측면에서 주관적이고 능동적인 요소로 이해합니다. 의학교육학 박사 학위를 취득하기 전, KA는 대학 아웃리치 및 WA 이니셔티브를 설계하고 운영한 경력이 있고, JC는 심리학자이며, SN은 임상 학자입니다. 모두 의학교육 연구 분야에서 활발한 활동과 경험을 가지고 있으며, 특히 의료 접근성 확대에 관심이 많고, 저자 중 한 명은 고등교육기관에서 WA를 경험한 바 있습니다. 의미 구성에서 우리의 관점이 참여자의 관점보다 우위에 있지 않도록 하기 위해 우리는 데이터에 대한 우리의 입장과 관계를 지속적이고 비판적으로 고려했습니다. 예를 들어, KA는 WA 실무자로 일한 경험이 있었기 때문에 처음에는 교사를 게이트키퍼로 인식하고, 교사가 학생들의 참여를 긍정적으로 독려하면 이니셔티브의 활용을 촉진하는 데 효과적인 동맹이 되지만 그렇지 않으면 문제가 될 수 있다는 가정을 바탕으로 연구에 접근했습니다. 그러나 데이터 수집과 분석 과정에서 이러한 가정에 의문을 제기하고 교사의 대안적인 역할을 탐색하고 논의하고 정당화했습니다. 그 결과, 이 논문에서는 이러한 초기 가정을 뛰어넘는 더 넓고 미묘한 범위의 가능한 교사 역할을 고려합니다.

This approach understands the researchers to be a subjective and active element in all aspects of the research process, from conception to dissemination. Prior to obtaining a PhD in medical education, KA’s professional background was in designing and running university outreach and WA initiatives; JC is a psychologist; and SN is a clinical academic. All have experience and active roles in medical education research, with a particular interest in widening access to medicine and one author experienced a WA trajectory to higher education. To ensure that our perspectives did not dominate those of participants’ in the meanings constructed, we considered our positions and relationships with the data constantly and critically. For example, KA’s previous experience as a WA practitioner meant that she initially approached the study with assumptions built from this perspective: perceiving teachers as gatekeepers, either effective allies in boosting the uptake of initiatives if they positively encouraged pupils to participate, or problematic if they did not. However, during data collection and analysis, these assumptions were challenged and alternative roles for teachers were explored, discussed and justified. As a result, the paper considers a wider and more nuanced range of possible teacher roles, which go beyond this initial assumption.

데이터 수집

Data collection

학교 및 참여자

Schools and participants

영국 학령기 학생의 93.5%가 공립학교에서 교육을 받고 있습니다(ISC 2020). 고등학교는 11~18세 학생을 대상으로 하는 반면, 6년제 대학은 마지막 학년(16~18/19세)의 학생들만 교육합니다. 아동이 진학할 수 있는 학교는 지역에 따라 크게 제한되며, 따라서 학교는 사회경제적, 사회적으로 분리되어 있는 경우가 많습니다(Jerrim 외, 2017; The Challenge 외, 2017). 이러한 차이는 학교 성과 평가에 반영됩니다(스코틀랜드 정부 2019, 영국 정부 2019). 이번 연구는 다양한 주정부 지원 학교에서 근무하는 교사들의 폭넓은 경험을 수집하는 것을 목표로 했으며, 이들 학교는 지역 의과대학에서도 WA 이니셔티브의 대상이 되는 학교이기도 하였습니다. 이니셔티브의 대상이 되는 학교는 의대 진학률이 평균 이하이거나 사회경제적 빈곤 지역에 위치한 학교였습니다.

93.5% of school-aged pupils in the UK are educated at state-run schools (ISC 2020). High schools take pupils aged 11–18, whereas sixth-form colleges only educate pupils in their final years (16–18/19). The schools available to a child are strongly restricted by their location, and schools are thus often socioeconomically and socially segregated (Jerrim et al. 2017; The Challenge et al. 2017). These differences are reflected in school performance ratings (Scottish Government 2019; UK Government 2019). The current study aimed to capture a breadth of experiences from teachers working in a wide range of state-funded schools, which were also targeted by local medical schools for participation in WA initiatives. To be targeted for initiatives, schools had below average rates of progression to medicine and/or were situated in areas of socioeconomic deprivation.

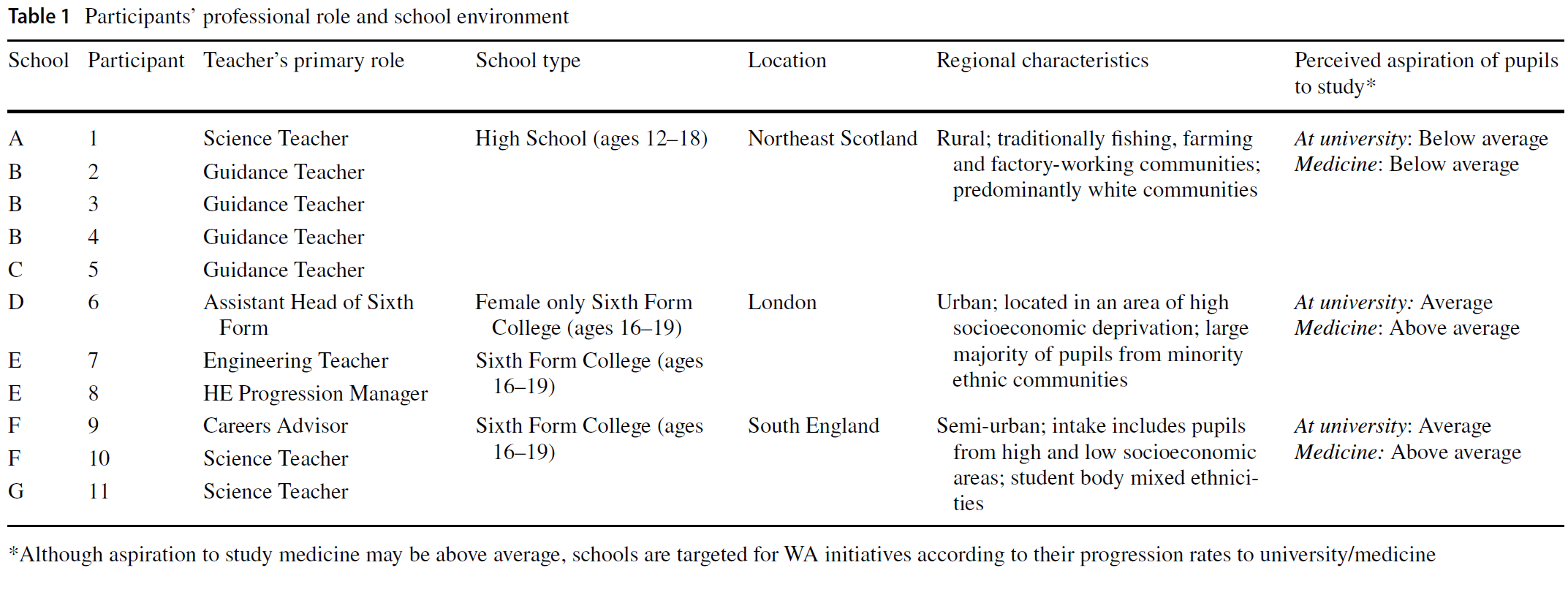

세 곳의 의과대학(각기 다른 지역에 위치)이 이 연구를 승인하고 WA 이니셔티브의 대상 학교 목록을 제공했습니다. 연구팀은 이 목록을 검토한 후 16개 학교로 구성된 소규모 목적 그룹을 선정하여 참여 초대를 보냈습니다. 이 그룹은 대규모 학교부터 소규모 학교까지, 도시부터 시골까지, 그리고 매년 의대에 지원하는 지원자 수가 다양한 학교를 최대한 폭넓게 포함하도록 설계되었습니다(표 1 참조). 이러한 결정은 정부 웹사이트에서 공개적으로 제공되는 데이터를 사용하여 이루어졌습니다.

Three medical schools (each in a different geographical region) approved the study and provided a list of the schools targeted by their WA initiatives. These lists were considered by the research team and a smaller purposive group of sixteen schools were targeted for an invitation to participate. This group was designed to contain the broadest possible diversity of schools: large to small; urban to rural; and with varying numbers of applicants applying to medicine each year (see Table 1). These decisions were informed using data publicly available on government websites.

교장(교감)에게는 연구 정보와 학교의 참여 요청서를 보냈습니다. 연락을 받은 16개 학교 중 8개 학교의 교장(교장)이 자신의 학교에서 연구가 진행되도록 허락했습니다. 거부 사유를 밝힌 교장들은 학생들에게 직접적인 혜택이 없는 활동에 교사가 참여할 수 있는 자원이 부족하다는 이유를 들었습니다. 교장 선생님이 동의한 후, 학생들에게 대학 선택에 대한 조언을 담당하는 교사(의대를 중심으로)에게 편지와 이메일을 통해 참여를 권유하고, 교장 선생님을 통해 또는 연구자가 직접 표준화된 정보 시트를 제공했습니다. 영국 공립학교에서는 특별한 관심을 가진 교사 한 명이 의대 진학 지도교사로 자원하는 것이 일반적이지만, 이들의 실질적인 역할은 매우 다양할 수 있습니다. 지원자들은 연구자에게 이메일로 직접 연락하여 연구의 목적과 실제에 대해 논의하고, 연구자를 소개하고, 궁금한 점을 묻고, 진행에 동의하는 경우 인터뷰 일정을 잡았습니다. 13명의 교사가 관심을 표명했고 11명이 인터뷰 진행을 희망했습니다.

Headteachers (principals) were sent the study information and an invitation for their school to participate. Of the sixteen schools contacted, eight headteachers gave permission for the study to be conducted in their school. Those who gave a reason for refusal, cited a lack of resources to allow teachers to participate in activities which did not directly benefit pupils. After headteachers had provided consent, teachers with responsibility for advising students on university choices (with a focus on medicine) were invited to participate by letter and email, and provided with a standardized information sheet via the headteacher or directly from the researcher. It is common in UK state schools for one teacher with a special interest to volunteer to be the key advisor for medicine, but their substantive roles may be very varied. Volunteers responded directly to the researchers by email to discuss the purpose and practicalities of the study, to be introduced to the researchers, ask any questions and, if happy to proceed, to arrange an interview. Thirteen teachers expressed interest and eleven wished to proceed to interview.

우리의 연구 설계와 목표는 교사들의 인식을 정량화하거나 일반화하지 않고 그 범위와 복잡성을 이해하고 탐구하고자 했기 때문에 소규모 참여자 그룹이 필요했습니다(Crouch와 McKenzie 2006). 소규모 접근 방식은 연구 결과의 전이성을 제한하지만, 교사들의 생생한 경험, 맥락, 내러티브의 개성을 보존하고 그들 사이의 주제적 유사성을 더 충분히 탐구할 수 있게 해줍니다.

Our research design and objectives called for a small participant group, as we sought to understand and explore the range and complexity of these teachers’ perceptions—not to quantify or generalize them (Crouch and McKenzie 2006). Although a small-scale approach limits the transferability of findings, it preserves the individuality of teachers’ lived experiences, contexts and narratives, and allows any thematic similarities between them to be more fully explored.

인터뷰

Interviews

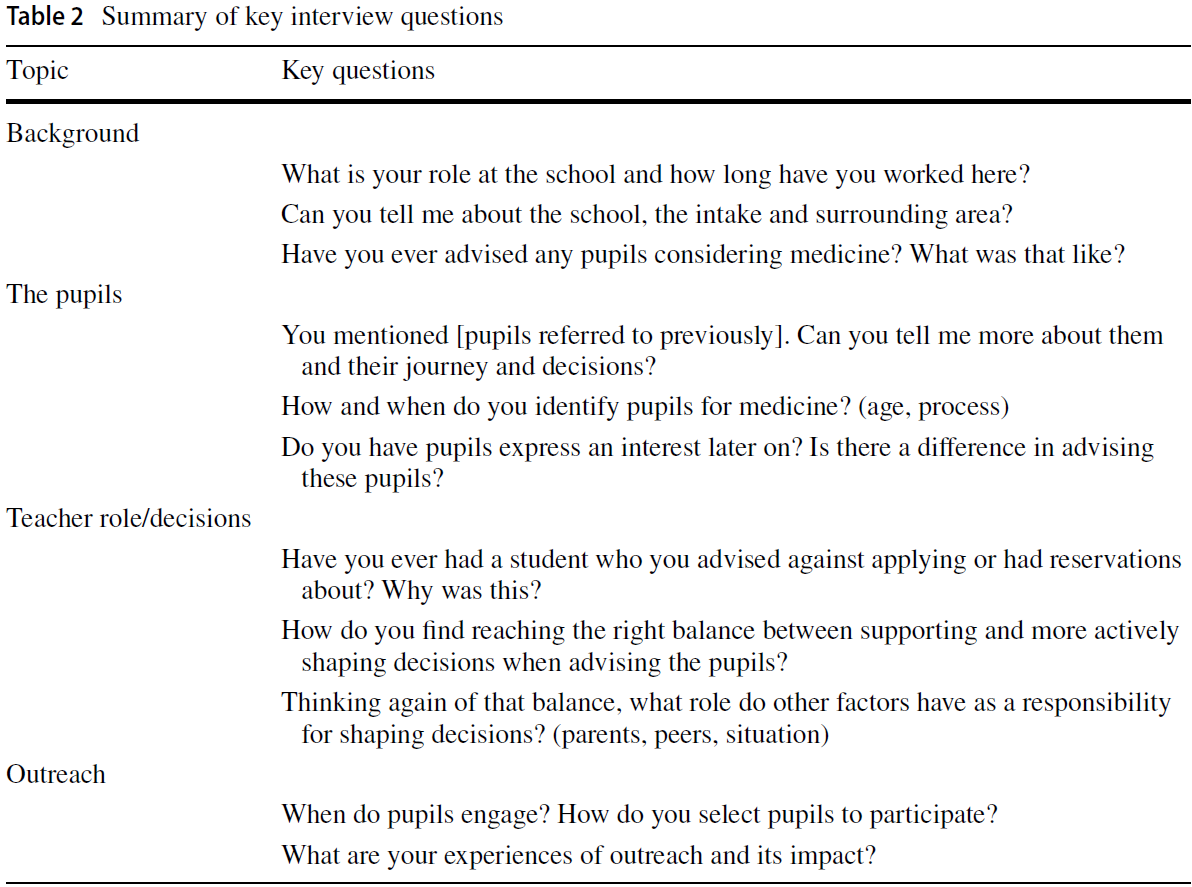

KA는 연구용 인터뷰에 대한 교육을 받은 후 참여자들의 학교에서 반구조화된 인터뷰를 진행했습니다. KA는 자신을 의학교육 박사과정에 재학 중이며, WA 이니셔티브 실행을 전문으로 하는 사람이라고 소개하며 의사나 의대 직원이 아님을 명확히 밝혀 참가자들이 느끼는 권력 불균형을 바로잡고 자유롭게 이야기할 수 있도록 유도했습니다. 참가자들에게 던진 주요 질문의 요약은 표 2에 나와 있습니다. 또한 참가자들은 인터뷰 가이드에서 다루지 않았지만 관련성이 있다고 생각되는 주제를 소개하도록 장려되었습니다.

KA conducted semi-structured interviews at participants’ schools, following training on interviewing for research. KA introduced herself as a PhD student in medical education whose professional background was in the area of implementing WA initiatives, clarifying that she was not a doctor nor medical school staff to calibrate any perceived power imbalance and encourage participants to speak freely. A summary of the main questions for participants are included in Table 2. Participants were also encouraged to introduce topics they perceived to be of relevance which were not covered in the interview guide.

참가자에게는 연구에 대해 질문할 기회가 주어졌으며, 연구 참여는 전적으로 자발적인 것이며 동의를 철회할 수 있음을 알렸습니다. 모든 참가자는 인터뷰 내용을 음성으로 녹음하여 전사하고 인터뷰 중 현장 메모를 작성하는 데 동의하는 서면 동의서를 제출했습니다.

Participants were given the opportunity to ask questions about the study, were made aware that participation was entirely voluntary and that their consent could be withdrawn. All participants gave written consent to participate, for their interview to be audio recorded for transcription and for field notes to be made during interview.

데이터 분석

Data analysis

템플릿 분석(King 2004)은 코딩이 진행됨에 따라 데이터를 주제별로 정리하고 분석하여 주제 간의 관계를 의미 있게 보여주기 위해 사용되었습니다. 템플릿 분석은 해석과 패턴 식별을 개발하는 데 있어 선행 문헌과 경험의 불가피한 영향을 인정하고 통합하지만, 주로 데이터 중심이며, 이는 우리의 탐색적 연구에서 중요했습니다. 하지만 데이터의 하위 집합을 기반으로 구축된 초기 템플릿의 형태로 구조를 조기에 도입한 것은 특정 연구 질문에 초점을 맞추는 데 도움이 되었습니다. 템플릿은 코딩이 진행됨에 따라 개선되고 수정되었으며, 예상치 못한 인사이트가 포함될 수 있도록 유연성을 유지하여 분석 내에서 귀납적 성격을 유지했습니다.

Template analysis (King 2004) was used to organise and analyse data thematically and meaningfully show the relationships between themes as coding progressed. Template analysis acknowledges and incorporates the inevitable influence of prior literature and experience in the development of interpretations and pattern-identification, but remains largely data-driven, which was important within our exploratory study. The early introduction of structure, in the form of an initial template built on a subset of data, was beneficial however as it directed our focus to our specific research question. The template was refined and revised as coding progressed and remained flexible for unexpected insights to be included, thus maintaining an inductive character within the analysis.

인터뷰 녹음은 그대로 전사하고, 익명으로 처리하고, 정확성을 검증한 후 NVivo 11(호주 빅토리아주 돈캐스터에 위치한 QSR International Pty Ltd)로 가져와 데이터 분석을 정리하고 용이하게 했습니다. KA는 초기 코딩을 맡았고, 이후 분석 주기 동안 정기적으로 JC 및 SN과 이 코드에 대해 논의하여 확인 가능성을 보장했습니다. 개발 주제에 대한 신뢰성을 면밀히 검토하고 연구팀 간의 비판적 대화를 통해 도출된 결정에 대해 탐구하고 이의를 제기하며 정당화했습니다.

Interview recordings were transcribed verbatim, anonymized, proofed for accuracy and imported to NVivo 11 (QSR International Pty Ltd, Doncaster, Vic, Australia) to organise and facilitate data analysis. KA undertook initial coding and discussed these codes with JC and SN at regular intervals throughout subsequent analytical cycles to ensure confirmability. Developing themes were scrutinised for trustworthiness and explored through critical conversation amongst the research team to explore, challenge and justify decisions taken.

윤리

Ethics

애버딘 대학교의 예술 및 사회과학, 비즈니스 분야의 연구 윤리 및 거버넌스 위원회에서 연구 수행을 허가했습니다.

Permission to conduct the study was granted by the Committee for Research Ethics and Governance in Arts and Social Sciences and Business at the University of Aberdeen.

연구 결과

Results

11명의 교사가 연구에 참여했습니다. 이들은 영국의 3개 지역에 있는 7개 학교에서 근무했습니다(표 1 참조). 교사들은 평균 10.5년, 최소 4년의 교육 경력을 가지고 있었습니다. 인터뷰는 1:1로 진행되었지만, 교사들의 요청에 따라 두 명의 교사가 함께 인터뷰한 경우도 있었습니다. 인터뷰 시간은 평균 28분(범위: 23~60분)이었습니다.

Eleven teachers participated in the study. They worked in seven schools across three regions of the UK (see Table 1). Collectively, teachers had an average of 10.5 years and a minimum of 4 years teaching experience. Interviews were one-to-one, except in one case, where two teachers were interviewed together at their request. Interview length averaged 28 min (range: 23–60 min).

결과 발표에서는 학생들이 의대를 지망하고 지원서를 준비하도록 격려하는 데 있어 교사들이 자신의 역할을 어떻게 인식하고 있는지 살펴봅니다. 발표는 다음과 관련된 주제를 탐구하는 세 가지 섹션으로 구성됩니다:

The presentation of results explores how these teachers perceived their role in encouraging pupils to aspire to medicine and to prepare an application. It is structured in three sections, which explore themes related to:

1. 의학에 대한 학생들의 열망에 대한 교사의 태도.

1.Teachers’ attitudes towards their pupils’ aspiration to medicine.

2. 학생이 의대 지원서를 준비하는 동안 상황적 장벽을 해결하는 데 있어 교사의 역할에 대한 인식.

2.Teachers’ perceived role in addressing contextual barriers during their pupils’ preparation for a medical school application.

3. 학생의 열망과 지원 결정에 영향을 미치는 교사의 역할에 대한 인식.

3.Teachers’ perceived role in influencing pupils’ aspirations and decisions about application.

뒷부분의 토론에서는 이러한 연구 결과를 학생들의 경험에 관한 광범위한 문헌에 배치하고 역량 접근법의 렌즈를 통해 비판적으로 분석합니다.

Later on, in the Discussion, these findings are situated within the wider literature on the experiences of pupils and critically analysed through the lens of the capability approach.

섹션 1: 의학에 대한 학생들의 열망에 대한 태도

Section 1: Attitudes towards pupils’ aspiration to medicine

전반적으로 교사들은 의학을 권위 있고 가치 있는 직업으로 긍정적으로 인식하고 있었습니다. 그들은 의대에 진학한 제자들에 대해 따뜻하고 자랑스럽게 이야기했습니다. 그러나 이러한 대체로 긍정적인 시각에도 불구하고 교사들은 제자들이 의사를 지망하는 것에 대해 문제가 있거나 위험한 열망으로 묘사하며 주저하는 모습을 보이기도 했습니다. 그 이유는 상황에 따라 크게 달라졌지만, 아래에서 살펴보는 세 가지 주요 주제에 집중되어 있었습니다:

Overall, teachers expressed a positive perception of medicine as a prestigious and worthwhile career. They talked warmly and proudly of former pupils who had entered medical school. Despite this generally positive view, however, teachers also communicated hesitations about their pupils aspiring to medicine, portraying this as a problematic or risky aspiration. Reasons for this were strongly context dependent but clustered around three main themes, explored below:

가족의 압력으로 인한 열망

Aspiration due to family pressure

의대에 대한 열망이 보통에서 높은 수준인 학교(표 1 참조)의 교사들은 일부 가정에서 의대를 자녀의 성공의 중요한 지표로 삼는다고 인식했습니다. 교사들은 적어도 처음에는 "누가 시켜서 의대를 선택한"(참가자 7, 런던) 학생들이 많다고 설명했습니다.

In schools where aspiration to medicine was moderate to high (see Table 1), teachers perceived that medicine was strongly prioritised by some families as an important marker of a child’s success. Teachers described numerous pupils who, at least initially, “choose medicine because they are told to” (Participant 7, London).

부모의 압력이 전적으로 해롭다고 볼 수는 없지만(교사들은 그것이 학생들에게 긍정적인 동기를 부여할 수도 있다고 생각했습니다), 모든 교사들은 의학이라는 직업에 대한 진정한 관심이 필수적이라고 강하게 강조했습니다. 따라서 그들은 학생이 의학에 대한 열망이 단지 가족의 바람을 반영한 것이라고 느낄 때 깊은 우려를 표명하고 이를 경계해야 한다고 생각했습니다.

Although parental pressure was not seen as entirely detrimental (teachers reasoned it could also positively motivate pupils), all teachers strongly emphasised that they felt a genuine interest in the career of medicine was essential. They thus expressed deep concern when they felt a pupil’s aspiration to medicine was solely a reflection of their family’s wishes and were alert to watch out for this.

교사들은 또한 의학에 대한 가족의 강한 열망이 학생들이 더 성취감이 있거나 개인적으로 보람을 느낄 수 있는 다른 직업을 고려하는 것을 방해할 수 있다고 인식했습니다:

Teachers also perceived that a strong familial aspiration to medicine could prevent pupils from considering a range of other careers, including those that were more achievable or personally rewarding:

두 가지 문제는... 열망이 항상 실제 전망과 일치하는 것은 아니며, 학생과 가족이 신중하지 않으면 다른 기회, 다른 경로를 차단하는 효과를 가져올 수 있다는 것입니다. (참가자 8, 런던)

the two-fold challenge is that… not always does the aspiration meet real prospects, and that it can have the effect of shutting down other opportunities, other routes if students and their families are not careful. (Participant 8, London)

부적절하거나 정보에 근거하지 않은 동기 부여

Unsuitable or uninformed motivations

교사들은 학업 능력이 있는 학생에게 의학은 분명한 선택지이며, 따라서 학생들이 이 진로를 선택하지 않는다면 그 가능성을 인식하지 못했기 때문이 아니라고 답했습니다. 교사들은 학생들이 어렸을 때부터 이 직업에 대해 알고 있었고, 사람들을 돕는다는 점 등 몇 가지 매력적인 측면을 인식하고 있었다고 느꼈습니다.

Teachers reported that medicine was an obvious option for academically able pupils, and therefore if pupils chose not to pursue this career, it was not because they were unaware of it as a possibility. They felt that pupils were aware of the career from a young age and perceived some aspects to be appealing (e.g. the idea of helping people).

교사들은 일부 학생의 경우 의학 공부에 대한 열망에 동기가 부여되었지만, 다른 학생의 경우 이러한 열망이 순진하거나 획일화될 수 있으며, 의료 과목 내에 만연한 위계질서로 인해 의학에 대한 열망이 악화될 수 있다고 보고했습니다:

Teachers reported that, for some pupils the aspiration to study medicine was well motivated, however, that for others, these aspirations could be naïve or uniformed, and that the draw to medicine could be exacerbated by a pervasive hierarchy within healthcare subjects:

...학생들과 이야기를 나누다 보면 그들은 실패하고 싶지 않고 의학을 정점으로 여기는 것 같아요. (참가자 9, 남부 잉글랜드)

…talking to the students and it’s just, they kind of don’t want to fail and they see that as the thing, they see that as the pinnacle, medicine. (Participant 9, South England)

그 결과, 교사들은 소수의 학생들이 의학이라는 과목이나 직업에 매력을 느껴서라기보다는 자신이 높은 성취도를 가진 학생임을 증명하기 위해 의학을 지망한다고 인식했습니다. 교사들은 이러한 동기가 의학과 같은 직업에 대한 즐거움, 탁월함, 인내심 측면에서 부적합하다고 생각했습니다.

As result, teachers perceived that a minority of pupils aspired to medicine, not because the subject matter or career appealed, but rather to prove themselves as a high achieving student. Teachers saw this motivation as unsuitable, believing it to be untenable in terms of enjoying, excelling and persevering in a vocational career such as medicine.

'성적 미달'에 대한 두려움

Fear of not ‘making the grade’

교사들은 많은 학생들이 의대 과정과 직업에서 성공할 수 있는 충분한 학업 능력과 적합한 개인적 자질을 갖추고 있다고 확신했습니다. 그러나 그들은 학교와 학생의 가정 생활의 맥락적 요인을 고려할 때 학업 성취도가 높은 학생들도 입학 요건을 달성하는 데 어려움을 겪을 것이라고 믿었습니다('방법' 섹션 참조).

Teachers were confident that many of their pupils had ample academic ability and suitable personal qualities to be successful in a medical course and career. However, they believed that even their high-fliers would struggle to achieve the academic entry requirements given the contextual factors in their schools and pupils’ home lives (see section “Methods”).

저에게 찾아오는 학생들 중에는 절대 성적을 올릴 수 없다는 것을 알고 있는 학생들도 있습니다(참가자 10, 남부 잉글랜드).

I do have students who come to me and I know they are never going to make the grade (Participant 10, South England)

따라서 많은 학생들이 의대에 대한 열망은 학생들이 그 직업을 가질 능력이 없어서라기보다는 입학 경쟁률과 성적 요건 때문에 비현실적인 것으로 암시되었습니다.

Aspiration to medicine was thus implied to be unrealistic for many pupils because of the competitiveness of entry and the grade requirement, rather than because pupils were not capable of the career.

섹션 2: 의대를 위한 준비

Section 2: Preparation for medicine

이 섹션에서는 교사들이 학생들이 의학에 대한 열망을 키우고 지원서를 준비하는 데 어떻게 도움을 주었는지 살펴봅니다. 전반적으로 교사들은 일반적으로 의대 지원 과정을 벅차고, 길고, 감정적으로 어렵다고 생각했습니다. 치열한 입시 경쟁과 낮은 합격률로 인해 교사들은 학생들이 상당한 시간, 에너지, 정서적 헌신을 해야 하는 만큼 위험 부담이 큰 투자라고 생각했습니다:

This section explores how teachers helped pupils develop an aspiration for medicine and prepare for an application. Overall, teachers generally regarded the application process to medicine as daunting, long and emotionally difficult. The intense competition for places and the schools historic acceptance rates, meant that teachers framed the substantial time, energy and emotional commitment pupils required as a high-risk investment:

...하지만 제가 다른 학생들과 공유할 수 있는 것은 이것은 긴 과정이라는 것입니다. 정말 하고 싶다면 인내심을 가져야 하고, 긴 과정이 될 것입니다. (참가자 7, 런던)

…but that’s something I can share with the other students, this is a long process: if you really want to do it, you are going to have to hang in there, it’s going to be a long process. (Participant 7, London)

학교의 물질적 제약

Material constraints in schools

교사들은 학생들이 의학에 대한 학문적, 비학문적 요구 사항을 인식하도록 하는 것이 자신의 역할이라고 답했습니다. 그러나 그들은 학생들이 이러한 입학 요건을 충족하기 위해서는 정보 외에도 적극적인 지원이 필요하다는 점을 인정했습니다. 많은 참여 교사들이 자발적으로 학생들을 지원하기 위해 추가 세션을 운영했지만, 의대 입학 시험 준비 지원 부족, 수업 시간 단축, 제한된 과목 선택, 인력 부족 등 학생들에게 부과된 제약을 해결할 수 있는 능력에 대해 여전히 좌절감을 느끼고 때때로 무력감을 느꼈습니다:

Teachers reported that it was their role to ensure pupils were aware of the academic and non-academic requirements for medicine. They acknowledged, however, that in addition to information, pupils required active support if they were to meet these entry requirements. Although many of the participating teachers voluntarily ran extra sessions to help support their pupils, they still expressed frustration and occasionally a sense of powerlessness about their ability to address the constraints imposed on pupils, for example: lack of support to prepare for the compulsory medical admissions tests; reduced teaching hours; limited subject choices; and staff shortages:

... 화학 선생님이 떠나고, 생물 선생님이 떠나고, 물리학 선생님이 떠나고, [학생들은] 결국 시간이 거의 없는 부교사나 부장 선생님이 가르치게 되었습니다... 학생 스스로 많은 것을 해야 한다는 것은 알지만, 선생님의 도움이 필요합니다. 결과적으로 [의대 지망학생은] 의대를 지원하지 않고 마지막 순간에 그만뒀어요. (참가자 5, 스코틀랜드 북동부)

…the Chemistry teacher left, the Biology teacher left, the Physics teacher left, and [the pupils] ended up being taught by a deputy or the Head of Department who had practically no time… I know you’re supposed to do a lot of it yourself, but you do need some teacher input. Consequently, [our aspiring medic] didn’t apply for medicine, he pulled out at the last minute. (Participant 5, Northeast Scotland)

학교는 특히 과학 분야에서 직원, 시설, 장비가 부족한 경우가 많았습니다. 일부 학교에서는 수업 시간을 해당 과목의 권장 수업 시간의 절반 이하로 제한하거나, 자격 수준이 다른 학생들을 함께 가르치는 등의 방법을 통해 부족한 인력을 확보했습니다. 시골 학교들은 학생과 교직원을 한데 모아 한 곳에서 마지막 학년 과학을 가르치기 위해 힘을 합쳤습니다. 한 교사는 이러한 접근 방식이 성적이 우수한 학생들이 '같은 생각을 가진 다른 학생들'과 어울리며 자신감을 키울 수 있게 해준다고 칭찬했습니다(참가자 1, 스코틀랜드 북동부). 특히 많은 시골 학생들이 대학 진학을 위해 집을 떠나는 것에 대해 불안해하는 상황에서 이러한 접근 방식은 많은 시골 학생들에게 의대 진학을 막는 장애물이었습니다. 그러나 또 다른 학생은 일주일에 여러 번 다른 도시로 통학해야 하는 상황을 지적했습니다: "피곤하죠. 좋지 않아요."(참가자 5, 스코틀랜드 북동부).

The schools often lacked staff, facilities and equipment, especially in science. Some schools resorted to restricting teaching hours to less than half those recommended for the course, or teaching pupils at different qualification levels together, to ensure provision. Rural schools banded together to collectively pool pupils and teaching staff to provide final year science in a central location. This approach was praised by one the teacher as it allowed high-achieving pupils to socialise with “like-minded others” and build their confidence (Participant 1, Northeast Scotland) especially as many pupils in the school were nervous about leaving home to attend university, an anxiety that precluded medical school for many rural pupils. However, as another pointed out, traveling several times a week to another town to attend class: “That’s tiring. You know, it’s not good” (Participant 5, Northeast Scotland).

모든 교사는 가능한 경우 학교 및 지역 대학에서 학생들을 지원받을 수 있는 곳으로 안내했습니다. 잠재적 지원자가 많은 6학년 대학(16~19세 학생만 받는 대규모 학교-표 1 참조)에서는 교사들이 의대 및 유사 학과(예: 옥스브리지, 법학)를 지망하는 학생들을 위한 또래 그룹이나 준비 프로그램을 만들고 운영했습니다. 한 교사는 이 프로그램을 특권층 학생들 사이에서 자연스럽게 일어나는 것과 같은 수준으로 학생들의 기술과 문화적 인식을 개발하기 위한 도구라고 설명했습니다:

All teachers directed pupils to sources of support where available, either in school and/or by local universities. In sixth-form colleges (large schools which take pupils aged 16-19 only—see Table 1), where there were greater numbers of potential applicants, teachers created and ran peer groups or preparation programmes for pupils aspiring to medicine and similarly classified subjects (e.g. Oxbridge, Law). One teacher described their programme as a tool to try to develop pupils’ skills and cultural awareness to the same level as happens naturally for more privileged pupils:

이것은 수업에서 가르치는 것이 아닙니다... 이것은 동화되는 것이며, 우리는 이러한 [특권층] 지원자 대부분이 종종 접할 수 있는 문화 등을 포함하여 개인적, 학문적 발전의 거의 자연스러운 과정인 것과 일치하는 메커니즘을 찾아야 합니다. (참가자 8, 런던)

This is not something that you’re taught in a lesson… this is something that’s assimilated, and we’ve got to find mechanisms to kind of match what for most of these [more privileged] applicants will be almost a natural process of personal and academic development, including all those wider enrichments of culture and so forth that they often have access to. (Participant 8, London)

교사들은 자신의 시간과 학교 자원이 제한적이라는 점을 인정하면서도 이러한 그룹을 학생들이 감정적으로 힘들고, 고된 의대 선택 과정에서 서로를 지원할 수 있는 기회로 인식했습니다:

Acknowledging that their own time and school resources were limited, teachers also recognised these groups as an opportunity for pupils to provide each other with mutual support during the emotional and arduous selection process for medicine:

제 가장 큰 임무 중 하나는 학생들이 인생에서 처음 겪게 될지도 모를, 정말 큰 거절에 대비하는 것이며, 그것은 연이은 거절일 수도 있습니다. 그리고 높은 점수를 받은 학생의 경우... 대부분 한 번도 해본 적이 없기 때문에 대처하기가 매우 어렵습니다. 그리고 그것은 정말 모든 학생들의 자신감을 무너뜨리고, 모든 학생들의 자신감을 무너뜨립니다. 그래서 우리는 [프로그램] 내에서 많은 공유와 토론, 상호 지원 그룹이 진행되고 있으며, 사람들이 직면하고 있는 문제와 이슈에 대해 이야기하는 매우 개방적인 세션입니다. (참가자 7, 런던)

One of my biggest jobs is preparing them for possibly their first rejection in their lives, and really big rejection, and it could be serial rejections as well. And for high flying students… that is such a difficult thing to cope with… most of them haven’t done it before. And that really does knock back the confidence in all, well in all of them, it knocks them back. And so we have an awful lot of sharing and discussions and mutual support groups going on within [the programme], it’s a very, very open session, where people talk about the issues and the problems they are facing. (Participant 7, London)

의료진 지망생이 적은 학교일수록 대학의 지원 프로그램에 더 많이 의존하여 맞춤형 준비를 제공했습니다. 시골에 있는 교사들은 학생들이 버스비를 감당하지 못하거나 대학까지 가는 여정에서 포기할까 봐 걱정하여, 한 교사는 자신의 차로 학생들을 행사장에 데려다 주었다고 설명했습니다. 참가자들의 이야기는 의료진 지망생을 지원하기 위한 개별 교사들의 헌신적인 노력을 보여주었지만, 이미 축소되거나 중단된 제도의 사례도 보고했습니다. 따라서 이러한 관행은 제도화된 관행이라기보다는 헌신적인 개인들의 전유물로 보였으며, 교사의 은퇴 또는 이러한 프로그램에 할당된 시간과 자원의 철수는 이러한 프로그램의 지속을 끊임없이 위협하는 요소로 작용했습니다.

Schools with small numbers of aspiring medics relied more heavily on universities’ outreach programmes to provide targeted preparation. Rural teachers were concerned pupils might be unable to afford the bus fare or be put off by the journey to the university, so one teacher described how she transported pupils to events in her own car. Participants’ accounts revealed the dedication of individual teachers to supporting aspiring medics, however, they also reported examples of schemes that had already been curtailed or discontinued. These practices thus appeared to be largely the preserve of committed individuals rather than institutionalised practices, and the prospect of a teacher’s retirement or the withdrawal of allocated time and resources to these programmes was a constant threat to their continuation.

이러한 장벽을 고려할 때 교사들은 뛰어난 추진력, 결단력, 적극적인 태도를 의료 지망생에게 필수적인 특성으로 꼽았습니다.

Given these barriers, teachers considered exceptional drive, determination and a proactive attitude to be essential characteristics for medical aspirants.

낮은 자신감으로 인한 장벽

Low confidence as a barrier

교사들은 학생들이 저소득층 가정에서 생활하는 것과 관련된 어려움과 스트레스 요인을 자주 경험한다고 보고했습니다(예: "과밀, 부모님 또는 조부모님이 몸이 좋지 않으세요"(참가자 6, 런던)). 따라서 교사들은 학생들이 "다른 지역의 많은 또래들이 겪지 않는 엄청난 장애물과 도전에도 불구하고"(참가자 8, 런던) 학업 성취도를 높이고 침착함을 유지하며 동기를 유지하는 놀라운 회복탄력성을 보인다는 사실을 발견했습니다. 그러나 그들은 또한 많은 학생들이 잠재적 의료인으로서 자신을 상상할 때 '사기꾼 증후군'(Clance 1985)을 경험하여 지원서에서 자신의 강점, 경험 및 회복탄력성을 의료계에서 바람직한 특성으로 인식하고 논의하는 데 어려움을 겪었다고 보고했습니다.

Teachers reported that their pupils often experienced difficulties and stressors related to living in low-income households (e.g. “overcrowding, parents perhaps, or grandparents, are unwell” (Participant 6, London)). Teachers thus found that their pupils demonstrated admirable resilience to achieve academically, keep calm and stay motivated “often despite incredible obstacles and challenges, not necessarily face by many of their peers in other areas” (Participant 8, London). They also reported, however, that many pupils experienced ‘imposter syndrome’ (Clance 1985) when imagining themselves as a potential medic and thus struggled to recognise and discuss their strengths, experiences and resilience as desirable traits for the career in their applications.

의학에 대한 열망이 일반적이지 않은 학교의 교사들은 자신감이 낮기 때문에 학생들이 공개적으로 의대 지원을 결심하고 준비하는 데 방해가 된다고 보고했습니다. 그 결과, 교사들은 때때로 학생이 의대에 관심이 있다는 사실을 인지하지 못해 적절한 정보나 지원을 제공하지 못하는 경우가 있었습니다: "우리가 완전히 놓친 한 여학생은 정말 끔찍했습니다."(참가자 5, 스코틀랜드 북동부).

In schools where aspiration to medicine was not common, teachers reported that low confidence deterred pupils from openly committing to, and preparing for, a medical application. As a result, teachers were sometimes not aware that a pupil was interested, and thus did not know to offer them targeted information or support: “one girl we completely missed which was terrible” (Participant 5, Northeast Scotland).

한 교사는 학생들이 의학에 관심을 보인 것에 대해 "거의 사과할 뻔했다"고 말했는데, 그 이유는 학생들이 "충분히 잘할 수 있을 것"이라고 믿지 않았기 때문입니다(참가자 4, 스코틀랜드 북동부). 또 다른 학생은 학급 앞에서 의학에 대한 열망을 드러내면 또래 집단으로부터 조롱을 받을 수 있다고 말했습니다:

One teacher reported pupils were “almost apologetic” for their interest in medicine, because they didn’t believe they would “be good enough” (Participant 4, Northeast Scotland). Another suggested revealing an aspiration for medicine in front of the class would invite ridicule from the peer group:

친구들이 비웃을 것이기 때문에 '나는 정말 의사가 되고 싶고, A를 5개나 받기로 결심했다'고 말할 수 있을 만큼 자신감이 있는 것은 아닙니다. 농담일 수도 있고 농담일 수도 있지만, 그런 농담에 대해 '그래, 넌 어떻게 할 건데'라고 대답할 수 있을 만큼 튼튼하지 못합니다."(참가자 3, 스코틀랜드 북동부).

They’re not always confident enough to say: ‘I really want to do medicine, I’m determined to get these five As’ you know, because their mates will have a pop at them. Maybe just banter, maybe just jokes, but they’re not sturdy enough to handle that kind of banter, to have a response and say: ‘Yeah I am, what are you going to do?’ (Participant 3, Northeast Scotland).

이 학교의 지도 교사들은 학생들과 일대일로 진로 선택에 대해 논의할 수 있는 시간을 어느 정도 보장받았지만, 이는 일반적으로 연간 10분으로 제한되었습니다. 따라서 교사들은 진로에 대한 열망과 조언을 제공하기 위해 공식적인 구조보다는 학생과 과목 교사 간의 비공식적인 대화에 크게 의존하고 있었습니다.

Guidance teachers in these schools did have some protected time to discuss career choices with pupils one-to-one, however, this was typically limited to an annual ten-minute appointment. Teachers thus heavily relied upon informal conversations between pupils and subject teachers to provide careers aspiration and advice, rather than formal structures.

섹션 3: 학생의 결정에 영향력 행사하기

Section 3: Influencing pupils’ decisions

이 섹션에서는 교사가 의학에 대한 열망에 영향을 미치기 위해 사용한 전략과 지원 여부에 대해 학생들에게 조언하는 접근 방식에 대해 설명합니다. 이를 통해 조언자로서의 의무와 역할의 경계에 대한 참가자들의 인식을 살펴봅니다.

This section discusses the strategies teachers employed to influence aspiration to medicine, and their approaches to advising pupils on whether or not to apply. In so doing, it explores our participants’ perception of the duties and boundaries of their role as an advisor.

지원 동기와 적합성을 테스트할 수 있는 기회 제공

Promoting opportunities to test motivations and suitability

모든 학교에서 교사가 학생에게 의대 진학을 구체적으로 제안하기보다는 학생이 자발적으로 의대 진학을 희망한다고 답했습니다. 또한, 한 학교를 제외한 모든 학교에서 교사들은 학생들이 의학에 대한 열망을 드러냈을 때 이를 긍정적인 진로 선택으로 인정하는 동시에 "가능한 한 창의적으로 생각하라"(참가자 11, 남부 잉글랜드), "네가 가지고 있고 할 수 있는 모든 것을 생각하라"(참가자 9, 남부 잉글랜드)고 격려했다고 보고했습니다. 이러한 전략은 다른 직업도 똑같이 가치 있고 흥미로운 것으로 제시하고, 가족의 압력이나 의학이 최고 또는 유일한 직업으로 인식되는 위계질서에 맞서기 위한 것이었습니다:

Across all schools, teachers reported that their pupils usually volunteered an aspiration for medicine, rather than teachers suggesting this specifically to pupils. Moreover, in all but one school, teachers reported that when pupils revealed an aspiration to medicine, they acknowledged this as a positive career choice, but also simultaneously encouraged them to “think as creatively as possible” (Participant 11, South England) and “think of all you have and could possibly do” (Participant 9, South England). This strategy was intended to present other careers as equally valuable and interesting, and to combat familial pressure or the perceived hierarchy of medicine as the best or only career choice:

저는 학교 내에서 과학을 장려하고 학생들에게 의학, 생물 의학 같은 것을 홍보하는 데 많은 노력을 기울이고 있습니다. (참가자 1, 스코틀랜드 북동부)

I’m heavily involved in trying to help promote sciences within the school and promote medical, biomedical sort of things to pupils. (Participant 1, Northeast Scotland)

교사들은 학생들이 의사라는 직업의 현실에 대해 더 많이 배우고, 순진하거나 부적절한 동기를 없애고, 이 직업이 즐겁고 보람을 느낄 수 있는지 알아볼 수 있는 기회를 제공하는 것이 중요하다고 생각했습니다. 또한 의학에 대한 이해와 대안 직업에 대한 인식이 높아지면 학생들이 부모의 뜻을 거스르고 자신의 뜻을 관철할 수 있는 자신감을 키우는 데 도움이 될 수 있다고 생각하는 교사들도 있었습니다.

Teachers considered it important to guide pupils to opportunities in which they could learn more about the realities of a medical career, to dispel naïve or inappropriate motivations and discover whether they would find the career enjoyable and rewarding. Some also felt a better understanding of medicine, and awareness of alternative careers, could help pupils build up enough confidence to resist parents’ wishes in favour of their own.

교사들은 학생들이 자기소개서와 면접 기술을 준비할 수 있도록 지원하는 데 중점을 두었는데, 이는 부분적으로는 높은 수준의 성과를 내기 위한 것이지만, 학생들이 자신에게 적합한 기술과 동기를 가지고 있는지 스스로 탐구하고 질문하도록 격려하기 위해서이기도 했습니다. 입학 시험(예: UKCAT, BMAT)에 익숙해지는 것은 가장 적은 관심을 받았습니다.

Teachers focussed their own support on helping pupils prepare their personal statement and interview skills: partly to produce a high-quality performance, but also further encourage pupils to explore and question whether they possessed the right skills and motivations. Familiarization with admissions tests (e.g. UKCAT, BMAT) were given the least attention.

선택의 자유 보장

Preserving a freedom to choose

위에 제시된 이유로 교사들은 학생의 진로 결정에 지나치게 많은 영향력을 행사하는 것에 대해 조심스러워하는 것으로 나타났습니다. 따라서 진로에 대해 조언할 때는 사실에 입각한 조언을 하려고 노력했으며, 학생의 장래 희망을 유도하려는 경우 일반적으로 의학보다는 과학이나 보건 과목과 같은 특정 과목에 대한 조언을 주로 했습니다:

For the reasons given above, teachers appeared cautious about exerting too much influence in a pupil’s decision about medicine. When advising about the career they thus tried to appear factual and if they did try to direct pupils’ aspirations, this was generally towards a group of subjects (e.g. the sciences or healthcare subjects) rather than medicine in particular:

저는 모든 것을 매우 사실적으로 설명하는 편입니다. '이 일을 하려면 이런 기술이 필요하고, 이런 종류의 기술을 찾고 있다'고 설명하면 학생들이 알아서 결정하도록 하는 편입니다. 저는 영향을 미치려 한다기보다는 정보를 제공하려고 노력하는 것 같아요. (참가자 4, 스코틀랜드 북동부)

I just tend to keep it all very factual: ‘this what you’ll need to do, this is the kind of skills they’re looking for’ and then they go away and make up their minds kind of thing. I don’t think I try and influence, I think I just try and inform. (Participant 4, Northeast Scotland)

마찬가지로, 학생이 의학에 관심을 갖지 않기로 결정한 경우에도 대개는 문제 삼지 않고 받아들여졌습니다:

Likewise, if a pupil decided not to pursue an interest in medicine, this was also usually accepted without a challenge:

그녀의 지도 선생님은... '이봐, 넌 그냥 한 번 해보고 이런 것들을 시도해봐야 해'라고 말했지만, 그녀는 와서 아니요, 나는 그것을하고 싶지 않다고 말했습니다. 그래서 그게 끝이었죠. 그래서 우리는 그들을 강요할 수 없습니다. (참가자 6, 스코틀랜드 북동부)

Her Guidance teacher… he kind of said: ‘look, you should just give it a go and try these things’, but she came and she said, no, I don’t want to do it. So, that was that. So, you know, we can’t make them do it. (Participant 6, Northeast Scotland)

학생들은 다양한 이유로 의대를 지원하지 않기로 결정했지만, 가장 흔한 이유는 성적이 충분히 높지 않거나 높을 것으로 예상되지 않았기 때문이었습니다. 교사들은 대개 학생들이 스스로 이러한 결정을 내렸으며 교사의 개입이 필요 없었다고 보고했습니다.

Although pupils decided against applying for medicine for a variety of reasons, most commonly this was because they had not achieved, or were not predicted to achieve, high enough grades. Teachers reported that pupils usually came to this decision by themselves, and with no need for teacher intervention.

그러나 입학 요건을 갖추지 못한 학생이 지원하기로 결정한 경우, 교사들은 학생들이 현실적인 기회를 알 수 있도록 하는 것이 의무라고 생각했습니다: "학생들이 자신에게 불리한 확률이 있다는 것을 알 수 있도록요."(참가자 11, 남부 잉글랜드). 그들은 자신의 역할에서 이 부분이 어렵다고 느꼈습니다: "학생들이 받아들일 수 있는 적절한 시기에 현실감을 주는 것이 때때로 어려운 일이라고 생각합니다."(참가자 9, 남부 잉글랜드).

When pupils were determined to apply without possessing the entry requirements, teachers felt, however, that it was their duty to ensure pupils knew their realistic chances: “so they can see that, you know, the odds are stacked against them” (Participant 11, South England). They found this part of their role challenging: “getting the realism at the right time when they can take it I suppose, I think, is the challenge sometimes” (Participant 9, South England).

그럼에도 불구하고 교사들은 "궁극적으로는 학생이 결정해야 한다"(참가자 11, 남부 잉글랜드), "나는 학생을 설득하지 않는다"(참가자 7, 런던)고 강력하게 답했습니다. 오히려 교사는 학생들이 정보에 입각한 현실적인 방식으로 스스로 결정을 내릴 수 있도록 돕는 것이 자신의 역할이라고 생각했습니다. 교사들은 이로 인해 더 적은 수의 후보자가 지원하지만 더 많은 후보자가 지원하게 될 것이라고 답했으며, 이는 긍정적으로 인식되었습니다.

Nonetheless, teachers strongly reported that “ultimately it has to be the student’s decision” (Participant 11, South England) and “I don’t dissuade them” (Participant 7, London). Rather, teachers saw their role as aiming to ensure pupils made their own decisions in an informed and realistic way. Teachers reported that this meant fewer, but stronger, candidates would apply, which was perceived positively.

토론

Discussion

의과대학에 대한 접근성을 확대하고 코호트를 다양화해야 한다는 압력이 증가하고 있는 가운데(Mathers 외. 2011; McLachlan 2005; O'Neill 외. 2013), 이 연구는 접근성 확대(WA) 학교의 교사들이 의학 홍보를 꺼리는 것으로 보고된 이유에 대한 상당한 지식 격차를 다루고 있습니다(Mathers and Parry 2009; McHarg 외. 2007; Medical Schools Council 2013; UCAS 2015).

Against a backdrop of increasing pressure on medical schools to widen access and diversify their cohorts (Mathers et al. 2011; McLachlan 2005; O’Neill et al. 2013) this study addresses a significant knowledge gap about why teachers in widening access (WA) schools have been reported as reluctant to promote medicine (Mathers and Parry 2009; McHarg et al. 2007; Medical Schools Council 2013; UCAS 2015).

저희는 학생들이 의대 진학을 꿈꾸고 준비하도록 격려하는 데 있어 교사들의 역할을 더 잘 이해하기 위해 다양한 영국 고등학교와 6년제 대학에 소속된 11명의 교사를 인터뷰했습니다. 연구 결과에 따르면 교사들은 이전 연구에서 학생 및 이전 학생들과 동일한 행동을 많이 보고했습니다. 여기에는 다음 등이 포함되었습니다.

- 의학에 지원하는 것이 어려울 것이라고 학생들에게 경고하는 것(Mathers and Parry 2009),

- 합격하는 학생이 거의 없을 것이라고 믿는 것(Southgate 외 2017),

- 학교 내 물질적 제약으로 인해 교사들이 충분한 지원을 제공할 수 없다는 것(Mathers and Parry 2009; Robb 외 2007; Southgate 외 2015)

그러나 중요한 것은 연구 참여자들이 학생들의 의과대학 지원으로부터 막으려는 의도가 없었다는 점입니다. 대신, 교사들은 학생들이 의학의 현실에 대한 지식을 향상시키고 대안적인 직업을 연구하며 지원 여부를 스스로 결정할 수 있는 역량을 키울 수 있도록 안내하는 것, 즉 영향을 주는 것이 아니라 정보를 제공하는 것이 자신의 역할이라고 답했습니다.

We interviewed eleven teachers in a diverse range of UK high schools and sixth-form colleges targeted by WA initiatives, to better understand their perceived role in encouraging pupils to aspire to, and prepare, an application to medicine. Our findings show that teachers reported many of the same behaviours as pupils, and former pupils, have in previous studies. These included:

- warning pupils that it was going to be tough to apply to medicine (Mathers and Parry 2009);

- a belief that few pupils would be accepted (Southgate et al. 2017); and

- that teachers were unable to provide sufficient support because of material restraints within their schools (Mathers and Parry 2009; Robb et al. 2007; Southgate et al. 2015).

Importantly, however, we found that our participants did not intend their actions to deter pupils from medicine. Instead, teachers reported that it was their role to guide pupils to improve their knowledge about the realities of medicine, as well as research alternative careers, and to build their capacity to make their own decisions about whether to apply: i.e. to inform, not influence.

접근성 확대를 위한 옹호자로서의 교사들

Teachers as advocates for widening access

무엇보다도 이번 연구는 교사들이 왜 이러한 인식을 갖고 있는지에 대한 인사이트를 제공합니다. 일부 참가자들은 학생들의 의대 진학 준비를 지원하기 위해 상당한 시간, 에너지, 헌신을 쏟았음에도 불구하고, 특권privileged 교육기관이나 가정에서 제공하는 혜택과 경쟁하기에는 학교의 역량이 제한적이라는 점을 기꺼이 인정했습니다. 교사들은 가장 강하고 회복탄력성이 뛰어나며 헌신적인 지원자들이 의대 지원에서 성공할 수 있는 학교 환경(그리고 이후 의사로서의 경력)을 묘사한하면서도, 대다수의 지원자들은 지원 전 포기하게 되는 학교 환경을 설명했습니다.

Vitally, our study offers insight into why teachers held these perceptions. Despite the substantial time, energy and commitment some of our participants dedicated to supporting their pupils prepare for medicine, they readily acknowledged the limited capacity of their schools to compete with the advantages provided by more privileged institutions and families. Teachers described school environments in which the strongest, most resilient and dedicated applicants could succeed in their medical applications (and subsequently in their careers as doctors) whereas the majority would bow out pre-application.

따라서 교사의 관행과 태도는 그들이 일하는 구조에 맞춰져 있으며, 낮은 기대치를 설정한 교사에게 책임을 돌리는 것은 학교의 자원 부족과 특정 지역이 경험하는 박탈감의 수준을 더 악화시킨다는 주장이 제기될 수 있습니다. 직업에 대한 공정한 접근에 관한 패널의 최종 보고서에 따르면:

It can thus be argued that teachers’ practices and attitudes are adapted to the structures they work within, and that an individualisation of blame onto teachers for setting low expectations detracts from the wider under-resourcing of schools and levels of deprivation experienced by certain neighbourhoods. As the Final Report of the Panel on Fair Access to the Professions states:

현재 많은 진로 상담이 전문 상담사가 아닌 정규직 교사에 의해 제공되고 있습니다. 젊은이들의 미래가 교사의 정상적인 교육 의무를 넘어선 조언과 지원에 의존하는 것은 용납될 수 없습니다. 많은 교사들이 선의의 의도를 가지고 청소년의 사회 진출을 돕기 위해 헌신하고 있지만, 진로 상담은 전문적이고 전문적인 서비스이므로 이를 바탕으로 운영되어야 합니다(2009 직업에 대한 공정한 접근에 관한 패널).

much careers advice is currently provided by staff who are full-time teachers, rather than professional advisers. It is not acceptable that the futures of young people rely on teachers having to provide advice and support above and beyond their normal teaching duties. While many teachers are well-meaning and dedicated to helping young people get on in life, careers advice is a professional and specialist service and should be operated on that basis (Panel on Fair Access to the Professions 2009)

따라서 우리는 누가 의사를 지망할 수 있는지에 대한 문화적 변화[더 이상 부유층과 중산층의 전유물로 여겨지지 않음(Alexander 외 2019)]가 있었음에도 불구하고, 중등 또는 고등 교육에서 자원이 부족한 지망생이 더 특권을 누리는 동료들과 실제로 의학에 들어갈 수 있는 동일한 기회를 가질 수 있도록 구조적 변화가 수반되지 않았다고 제안합니다.

We thus suggest that although there has been a cultural shift in terms of who can aspire to medicine [it is no longer seen as the sole preserve of the affluent and middle-class (Alexander et al. 2019)], there has not been an accompanying structural shift in secondary or tertiary education to allow less well-resourced aspirants the same opportunities to actually enter medicine as their more privileged peers.

이러한 상황을 고려할 때, 교사가 의학의 옹호자가 되어야 하는지에 대해서도 의문을 제기할 수 있습니다. 이해관계자들이 젊은이들이 전통적으로 지역사회에서 고려되지 않았던 직업에 도전하도록 격려하는 것은 대학 WA 이니셔티브의 핵심입니다(Milburn 2012). 그러나 이 연구에 참여한 교사들은 오히려 학생들이 성취하고 시야를 넓히도록 격려하는 역할에 치우쳐 있었으며, 특정 이니셔티브를 강력하게 지시하거나 영감을 주거나 진로 선택에 대한 가치 판단을 내리는 것을 원하지 않았습니다. 교사들은 손을 떼는 접근 방식을 통해, 학생들이 더 많은 정보를 얻고 정보에 입각한 결정을 내릴 수 있지만, 결정에 대한 주도권은 여전히 학생 스스로 행사할 수 있다고 암시했습니다. 이는 교육의 핵심 목표가 학생에게 스스로 합리적인 결정을 내릴 수 있는 능력과 자유를 제공하는 것이어야 한다고 주장하는 능력 접근법과 일맥상통합니다(Walker 2005). 이 이론은 사회 정의와 교육 간의 관계를 탐구하고(Gale and Molla 2015, Walker and Unterhalter 2010, Wilson-Strydom 2015), WA의 개입을 평가하는 데 점점 더 많이 사용되고 있습니다(Hart 2012, Walker 2008, Watts and Bridges 2006, Wilson-Strydom 2017). 또한, 젊은 세대가 성인이 되어 살아갈 환경이 매우 불확실하고 급변하는 상황에서 성인이 젊은 세대에게 '좋은' 미래나 직업에 대한 특정한 비전을 제시하는 것은 도덕적으로나 실질적으로 문제가 있다고 주장할 수 있습니다(Facer 2016).

Given these circumstances, we can also question whether teachers should be expected to be advocates for medicine. Encouraging stakeholders to challenge young people to aspire to careers not traditionally considered within their communities is at the heart of universities’ WA initiatives (Milburn 2012). The teachers in this study, however, rather erred towards a role in which they encouraged pupils to achieve and to broaden their horizons but did not wish to strongly direct or inspire them to any particular initiative or impart value-judgement on career choices. Teachers implied that their hands-off approach allowed pupils to be more informed and thus more capable of making an informed decision, but to still exert their own agency over decisions. This chimes with the capability approach, which argues a key goal of education should be to provide pupils with the capability and freedom to make rational decisions for themselves (Walker 2005). This theory is increasingly used to explore the relationship between social justice and education (Gale and Molla 2015; Walker and Unterhalter 2010; Wilson-Strydom 2015) and to evaluate WA interventions (Hart 2012; Walker 2008; Watts and Bridges 2006; Wilson-Strydom 2017). Moreover, it can be argued that it is morally and practically problematic for adults to ascribe particular visions of a ‘good’ future or career on younger generations, given the vast uncertainty and rapidly changing environment in which these generations will live as adults (Facer 2016).

그러나 학생의 진로 선택에 전적인 자유를 허용하는 것에 대한 정당한 비판도 존재합니다. 예를 들어, 학생들이 자신의 열망을 드러내고(Hart 2012), 높은 요구 사항을 달성하고, 의학과 같이 도전적이고 생소한 직업을 선택할 수 있도록 자신감과 기회를 주기 위해서는 보다 개입주의적인 자세가 필요할 수 있습니다(Donnelly 2015; Oliver and Kettley 2010). 따라서 '손을 떼는' 접근 방식은 사회적 정체를 초래할 위험이 있으며, 불이익disadvantage이 (문제가 제기되기보다는) 세대를 거쳐 재생산될 수 있습니다. 역량 접근법 내에서 개념화된 교사들의 설명에 따르면, 교사들은 WA 이니셔티브를 학생들의 열망 자체를 변화시키기보다는 학생들이 역량(예: 기술, 지식, 지원 시스템, 열망, 자신감)을 구축하여 자신의 삶과 진로 목표를 실현할 수 있는 더 나은 위치에 서기 위한 추가 자원으로 주로 인식하고 있었다. 또한 교사들의 설명에 따르면, 교사들은 학생들에게 이러한 (그리고 다른) 리소스를 안내하는 것이 자신의 역할이지 참석이나 참여를 강요하는 것이 아니라고 인식하고 있었습니다. 즉, 자원을 역량으로 전환할지 여부는 주로 학생 개개인의 선택에 맡겨져 있었습니다. 따라서 열망하는 역량은 자원을 통해 구축되지만, 학생들이 이용할 수 있는 자원을 다양한 잠재적 열망으로 전환하도록 장려하지 않으면 이미 보유하고 있는 자원을 고수할 가능성이 높다는 문제가 발생합니다.

There are, however, also legitimate criticisms of allowing pupils total freedom in their choice of career. For example, a more interventionist stance may be necessary to give pupils the confidence and opportunity to reveal their aspirations (Hart 2012), achieve the high requirements, and select a challenging and unfamiliar career such as medicine (Donnelly 2015; Oliver and Kettley 2010). A ‘hands off’ approach thus risks social stasis and allows disadvantage to be reproduced through the generations rather than challenged. Conceptualised within the capability approach, teachers’ accounts suggest that they saw WA initiatives primarily as additional resources for pupils to build their capability (i.e. skills, knowledge, support systems, aspiration, confidence) and thus be better positioned to realise their life and career goals; rather than to change the pupils’ aspirations per se. Teachers’ accounts also suggest they perceived it to be their role to be to direct pupils to these (and other) resources but not to push them to attend or engage. In other words, the choice whether to convert the resource to capability was largely left to the choice of the individual pupil. A problem thus arises, in that the capability to aspire is built out of resources, but if pupils are not encouraged to convert the resources available to them into a range of potential aspirations, they are instead likely to stick with those they already possess.

따라서 이 연구는 WA 정책의 목표와 교사들의 우선순위 사이에 잠재적인 긴장이 있음을 드러냅니다. 교사들은 일반적으로 WA 이니셔티브와 의학을 지지했지만, 사회적 이동성을 높이기 위한 교육 정책의 추진보다 학생들이 자신의 열망과 기회를 넓힐 수 있는 선택의 자유를 우선시했습니다.

This study thus exposes a potential tension between the objectives of WA policy and the priorities of teachers. Although teachers were supportive of WA initiatives and medicine in general, they prioritised pupils’ freedom to choose whether to broaden their aspiration and opportunity set over the promotion of educational policies to increase social mobility.

강점과 한계

Strengths and limitations

저희는 의도적으로 다양한 상황, 학교 유형, 교사 역할을 가진 교사들을 인터뷰하여 폭넓은 관점을 포함하고자 했습니다. 이를 통해 유사점과 공통 주제를 탐색하고 개별 경험의 세분성을 보존할 수 있었습니다. 연구 목적에는 유용했지만, 상황적 차이와 소규모 참여자 그룹은 연구 결과의 적용 가능성에 상당한 제한을 가했습니다. 우리는 대학 연구자에게 의학에 대한 비판적 견해를 표현하는 것에 대한 교사들의 주저함을 줄이기 위해 연구 설계에 조치를 취했지만, 그럼에도 불구하고 일부 참가자들은 연구 목적을 고려할 때 의학에 대해 부정적으로 말하는 것에 주저함을 느꼈을 수 있음을 인정합니다. 또한, 참여도가 낮은 교사나 의학에 대해 덜 긍정적인 견해를 가진 교사의 경우 참여 의향이 낮았을 것으로 합리적으로 예상할 수 있습니다. 교직원의 참여를 허락하지 않은 교장(교감)은 자원 부족을 가장 큰 이유로 꼽았는데, 이는 이러한 상황에 처한 학교가 조사 대상에 포함될 가능성이 낮다는 것을 의미할 수 있습니다.

We purposely interviewed teachers in a range of contexts, school types and teaching roles to include a wide breadth of perspectives. This allowed us to explore similarities and shared themes, as well as preserve the granularity of individual experiences. Although useful for our study purpose, the contextual differences and the small participant group add substantial limitations to the transferability of findings. We built measures into the research design to lessen teachers’ inhibitions about expressing critical views of medicine to a university researcher but acknowledge some participants may nevertheless have felt inhibited about speaking negatively about medicine given the study’s aims. Moreover, we can reasonably expect that less engaged teachers and those with a less positive view of medicine may have been less inclined to participate. Headteachers (principals) who declined to permission for their staff to participate cited under-resourcing as the major reason, which may mean schools in this situation were also less likely to be included.

교사들의 바쁜 일정이나 갑작스럽게 학생들을 돌봐야 하는 상황으로 인해 일부 인터뷰는 짧게 진행되었으며, 이는 데이터의 양에 영향을 미쳤습니다. 두 명의 교사를 함께 인터뷰한 경우, 상대방의 판단을 두려워하여 자신의 경험을 충분히 설명하지 못했을 수 있습니다. 반면에 함께 인터뷰하는 것은 그들의 선택이었기 때문에 상황을 더 편안하게 만들어서 두 사람 모두로부터 더 깊고 미묘한 기여를 이끌어 냈을 수도 있습니다(Finch 외. 2014).

Due to the restrictions of teachers’ busy schedules and/or the need to suddenly attend to pupils, some interviews were cut short, with implications for the quantity of data. Two teachers were interviewed together, which may have inhibited their willingness to give a full account of their experiences, fearing the judgement of the other. On the other hand, being interviewed together was their choice, which might have made the situation more comfortable and hence generated deeper and more nuanced contributions from both (Finch et al. 2014).

소규모 참가자 그룹 내에서는 일부 목소리가 해석에 불균형적으로 영향을 미치는 경향이 더 클 수 있습니다. 이러한 가능성을 해결하기 위해, 우리는 각 참가자의 경험과 웅변력 수준은 다르지만 분석과 글쓰기에서 각 참가자의 설명에 동등한 비중을 부여하기 위해 의식적으로 노력했습니다. 참여자 검증을 포함했다면 작업의 신뢰도를 더욱 높일 수 있었겠지만, 교사들의 업무량을 가중시키지 않고 반복적인 접촉이 모집에 걸림돌이 될 수 있다고 판단하여 이를 배제하기로 결정했습니다.

There may be a greater tendency within a small participant group for some voices to disproportionately influence interpretations. To address this possibility, we made a conscious effort to give equal weight to each participant’s account in analysis and write-up, despite their different levels of experience and eloquence. The inclusion of participant validation may have further boosted the credibility of the work, however, we decided against this, primarily to not add more to teachers’ workload and because we thought the commitment to repeated contact might be a barrier to recruitment.

연구자 편향 가능성을 최소화하기 위해 연구 방법에서 설명한 대로 반성적 사고와 연구팀 간의 비판적 토론을 실천했습니다. 팀원들이 서로 다른 관점에서 데이터와 주제에 접근했기 때문에 팀 내 다양한 직업적 배경이 강점이었습니다. 하지만 모든 연구원이 여성, 백인, 중산층으로 구성되어 있어 이 분야의 의학교육 연구자라면 흔히 볼 수 있는 다양성에는 한계가 있었습니다.

Practicing reflexivity, as described in the methods, as well as critical discussions amongst the research team were used to minimize potential researcher bias. The diverse professional backgrounds within the team was a strength in this regard, as members approached the data and topic from differing perspectives. There were limits to this diversity however, as all researchers now identity as female, white and middle-class, which is typical for medical education researchers in this area.

연구 및 실무에 대한 시사점

Implications for research and practice

다양한 학교(공립학교와 사립학교, 그리고 참여도가 낮은 WA 대상 주립학교 포함)의 교사들의 인식과 전략을 조사하는 비교 연구는 다양한 맥락에서 교사들의 접근 방식과 역할 인식에 대한 흥미로운 통찰력을 제공할 수 있을 것입니다. 또한, 영국과 다른 국가들에서 교사들이 비슷한 자원 부족 환경에서 일하고 의학에 대해 비슷하게 보수적인 메시지를 홍보하는 유사점을 고려할 때(Southgate 외. 2015), 이 연구의 목적과 결과는 다른 맥락에서 추가 조사가 필요할 수 있습니다. 교사와 학생의 목소리를 모두 포함하는 비교 연구도 도움이 될 것입니다. 이 연구에서는 교사의 설명에 대한 탐구로 제한되어 있으며 학생의 행동에 대한 해석에 대해서는 언급할 수 없습니다.

Comparison studies to investigate the perceptions and strategies of teachers from a variety of schools (including grammar and independent, as well as less-engaged WA eligible state schools) would offer interesting insight into teachers’ approaches and perception of role in different contexts. Furthermore, given the parallels between the UK and other countries, where teachers work in similarly under-resourced environments and promote similarly conservative messages about medicine (Southgate et al. 2015), the study aims and findings may warrant further investigation in other contexts. Comparison studies that include both teacher and their pupils’ voices would also be beneficial: in this study we are limited to the exploration of teachers’ accounts and cannot comment on pupils’ interpretation of their behaviour.

위에서 설명한 바와 같이, 교사는 자신의 역할을 그 자체로 자원이라기보다는 학생들이 의학 자원에 대한 WA 접근을 용이하게 하는 것으로 개념화하는 것으로 나타났습니다. 이는 위에서 인용한 전문직에 대한 접근성 보고서와 일치하는 것으로, 기본적으로 과학 교사가 의학에 대한 전문적 조언자 역할까지 해야 하는 것은 적절하지 않다고 주장합니다. 그러나 우리의 연구는 이러한 경계가 종종 모호해짐을 보여줍니다. 부족한 자원을 보충해야 한다는 압박감 때문에 헌신적인 교사들이 스스로 준비 프로그램을 만들고 목회적pastoral 지원을 제공하게 되는 것입니다. 따라서 우리는 WA 이해관계자 간에 공개적인 논의를 통해 이해관계자의 역할을 명확하게 조정하고 구분하는 데 합의할 것을 제안합니다. 합의가 이루어지면 의과대학은 개선된 커뮤니케이션과 정보 공유 네트워크를 통해 교사들이 전문 자원에 쉽게 접근할 수 있도록 지원하고, 의과대학은 이러한 전문 자원을 제공하는 데 집중할 수 있습니다.

As described above, teachers appeared to conceptualise their role as facilitating pupils’ access to WA to medicine resources, rather than as a resource themselves. This concurs with the Access to the Professions report (quoted above), which essentially argues it is not appropriate to require a science teacher to also be an expert advisor on medicine. Our study reveals how these lines are often blurred however: pressure to compensate for lacking resources results in dedicated teachers taking it upon themselves to create preparation programmes and provide pastoral support. As a result, we suggest open discussions between WA stakeholders to agree a clear alignment and delimitation of stakeholder roles. If agreed, medical schools might then focus on supporting teachers to facilitate access to expert resources through improved communication and information sharing networks; whilst medical schools provide this expert resource.

또한 의과대학은 교사들을 지원하여 [더 많은 학생들이 가용한 자원에 참여할 수 있도록 보다 적극적으로 장려하여 새로운 포부와 기회가 창출될 수 있도록] 하고자 할 수 있습니다. 따라서 의과대학과 정책 입안자들은 의대 진학이 교사들에게 덜 위험한 선택으로 보이도록 시스템을 재조정할 수 있는 방법을 고려할 것을 제안합니다. 의과대학은 학생들이 지원서에서 자신의 강점(예: 지적 능력, 헌신, 회복탄력성)을 강조할 수 있도록 가장 잘 지원할 수 있는 방법에 대한 대화에 교사들을 참여시키고, 의대 지원의 일부 현실(예: 합격률 및 재지원 관련)에 대해 교사들에게 알리고 안심시키는 신화를 깨는 과정을 고려할 수 있습니다. 이는 파운데이션 프로그램과 게이트웨이 과정 등 의학의 대안적 진로에 대한 교사들의 인식을 높이는 것과 결합될 수 있습니다. 보다 근본적으로 의과대학은 교사 전문성 개발 및 교육 팀과 협력하여 교사들이 학생의 개별적인 선택에 우선순위를 두는 선의의 신념의 제약을 인식하도록 도울 수 있는 방법에 대한 전문가의 조언을 받는 것도 고려할 수 있습니다.

Medical schools may also wish to support teachers to be more proactive in encouraging a wider range of pupils to engage with the resources that are available, to enable the possibility of new aspirations, as well as opportunities, to be built. We suggest that medical schools and policy makers thus consider ways in which they can realign systems to make promoting medicine appear a less risky choice to teachers. Medical schools could consider how to engage teachers in a dialogue about how they can best support pupils to highlight their strengths (e.g. intellectual ability, commitment, resilience) in an application, as well as inform and reassure teachers about some of the realities of medical application (e.g. around acceptance rates and re-application) in a process of myth-busting. This could be combined with heightening teachers’ awareness of alternative paths to medicine, including foundation programmes and gateway courses. More fundamentally, medical schools might also consider working with teacher professional development and training teams, to receive expert advice on how they might help teachers recognise the constraints of a well-intentioned belief in prioritising a pupil’s individual choices.

결론

Conclusions

전반적으로 이 연구는 호주 학교에서 매일 존재하는 상황적 장벽을 재확인하고, 이러한 장벽이 교사의 역할에 대한 인식에 어떤 영향을 미칠 수 있는지에 대한 독창적인 통찰력을 보여줍니다. 또한 학생들이 스스로 진로를 선택하는 데 있어 교사의 우선순위를 강조하고 있습니다. 저희는 WA 학교의 교사들이 의학을 옹호하는 것이 단독으로 이루어질 수 없으며, 이를 위해서는 다른 이해관계자들의 지원, 정책 및 시스템이 연계되어 학생들이 자신의 역량을 개발할 수 있는 기회를 제공하고 실제로 그 자리를 차지할 수 있는 더 나은 기회를 제공해야 한다고 제안합니다(Alexander and Cleland 2018; Gorman 2018). 교사의 우려를 인정하고 이해하며 더 나은 파트너십을 구축하고 의대를 향한 여정에 대해 더 긍정적인 시각을 갖도록 협력하는 것이 가시적인 시작이 될 수 있습니다(Greany 외. 2014).

Overall, this study reaffirms the contextual barriers present daily in WA schools, and reveals original insight into how these may influence teachers’ perceptions of their role. It also highlights these teachers’ prioritisation of pupils making their own choice of career. We suggest that the expectation for teachers in WA schools to advocate medicine cannot happen in isolation and instead that this requires the support of other stakeholders, policies and systems aligning to provide their pupils with opportunities to develop their capability, as well as better chances of actually achieving a place (Alexander and Cleland 2018; Gorman 2018). Acknowledging and understanding teachers’ concerns and working with them to construct better partnerships and a more positive view of the journey to medicine, might be a tangible start (Greany et al. 2014).

Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2021 Mar;26(1):277-296. doi: 10.1007/s10459-020-09984-9. Epub 2020 Jul 25.

"It's going to be hard you know…" Teachers' perceived role in widening access to medicine

PMID: 32712931

PMCID: PMC7900090

DOI: 10.1007/s10459-020-09984-9

Free PMC article

Abstract

Medical schools worldwide undertake widening access (WA) initiatives (e.g. pipeline, outreach and academic enrichment programmes) to support pupils from high schools which do not traditionally send high numbers of applicants to medicine. UK literature indicates that pupils in these schools feel that their teachers are ill-equipped, cautious or even discouraging towards their aspiration and/or application to medicine. This study aimed to explore teachers' perspectives and practices to include their voice in discussions and consider how medical schools might best engage with them to facilitate WA. Interviews were conducted with high school teachers in three UK regions, working in schools targeted by WA initiatives. Data were analysed thematically using template analysis, using a largely data-driven approach. Findings showed that although medicine was largely seen as a prestigious and worthwhile career, teachers held reservations about advocating this above other choices. Teachers saw it as their role to encourage pupils to educate themselves about medicine, but to ultimately allow pupils to make their own decisions. Their attitudes were influenced by material constraints in their schools, and the perception of daunting, long and emotionally difficult admissions requirements, with low chances of success. Medical schools may wish to work with teachers to understand their hesitations and help them develop the mindset required to advocate a challenging and unfamiliar career, emphasising that this encouragement can further the shared goal of empowering and preparing pupils to feel capable of choosing medicine. Reciprocally, medical schools should ensure pupils have fair opportunities for access, should they choose to apply.

Keywords: Barriers; Diversity; High school; Interviews; Medical school; Teachers; Widening access; Widening participation.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 입학, 선발(Admission and Selection)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 의과대학의 운동선수: 운동 유경험자의 수행능력에 대한 체계적 문헌고찰(Med Educ, 2023) (1) | 2023.12.23 |

|---|---|

| 보건의료전문직교육을 위한 선발 방법에 대한 지원자 인식: 논리와 하위그룹별 차이 (Med Educ, 2023) (0) | 2023.12.23 |

| 전공의 선발 게임 파헤치기(Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2021) (0) | 2023.12.06 |

| 지나칠 정도로(Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2023) (0) | 2023.06.30 |

| 성형외과 전공의 선발 인터뷰 중 금지된 질문의 사용빈도(Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2023) (0) | 2023.06.28 |