공유의사결정을 가르치는 열두가지 팁(Med Teach, 2023)

Twelve Tips for teaching shared decision making

Matthew Zegareka,b, Rebecca Brienzaa,b and Noel Quinnb

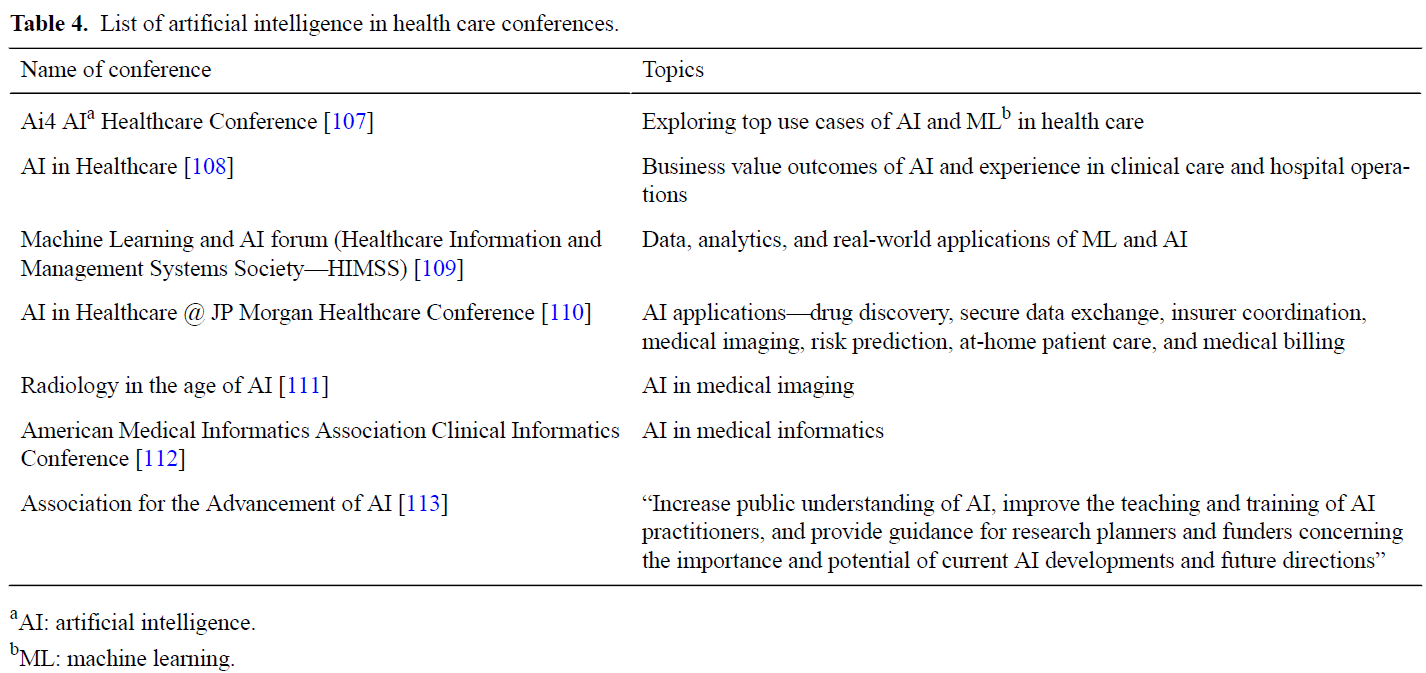

소개

Introduction

환자 치료에서 공유 의사 결정(SDM)을 활용하는 것은 임상 결과를 개선하고 의료 낭비를 줄이며 환자 만족도를 향상시키는 방법으로 제안되어 왔습니다. 환자에게 위험과 이점을 제시하고 결정을 내리도록 요청하는 단순 정보 제공 동의나 의료진이 위험과 이점에 대한 해석을 바탕으로 치료를 추천하는 온정주의적 치료와 달리, SDM은 임상의가 환자의 가치와 선호를 이끌어내 의사 결정에 반영해야 합니다(Elwyn 외. 2017; Spatz 외. 2017). SDM은 환자의 가치관에 대한 환자의 의견뿐만 아니라 환자의 상황과 맥락이 의사 결정에 어떤 영향을 미칠 수 있는지를 강조하는 접근 가능한 방식으로 위험과 이점에 대한 명확한 의사소통이 필요하다는 데 폭넓은 동의가 있습니다. 중요한 것은 SDM이 '선호도에 민감한' 결정이라고도 하는, 옵션 간에 어느 정도 균형이 있는 특정 임상 결정에만 적합하다는 것입니다. 예를 들어, 금연 노력을 약물 요법, 상담 또는 이 두 가지를 결합하여 지원할지 여부에 대한 결정은 공유하는 것이 합리적이지만, 금연 여부에 대한 결정은 공유해서는 안 됩니다. 금연이 건강 결과 개선에 도움이 된다는 명백한 증거가 있으므로 금연을 권장해야 하며, 의료진은 금연을 합리적인 옵션으로 제시하기보다는 환자가 금연을 결정하도록 동기를 부여하는 것을 목표로 삼아야 합니다.

Utilizing shared decision making (SDM) in patient care has been suggested as a way to improve clinical outcomes, reduce healthcare waste, and improve patient satisfaction. In contrast to simple informed consent, in which patients are presented with risks and benefits and asked to make a decision, or paternalistic care, in which the provider recommends a treatment based on their interpretation of the risks and benefits, SDM requires clinicians to elicit and incorporate patient values and preferences into decision making (Elwyn et al. 2017; Spatz et al. 2017). There is broad agreement that SDM requires not only input from patients about their values, but also clear communication of risks and benefits in an accessible way that highlights how patient circumstances and contexts may influence their decision making. Importantly, SDM is appropriate only in certain clinical decisions in which there is some degree of equipoise between options, also known as ‘preference-sensitive’ decisions. For instance, while it is reasonable to share the decision on whether to assist smoking cessation efforts with pharmacotherapy, counseling, or a combination of both, the decision of whether to quit smoking should not be a shared one. There is unequivocal evidence that quitting smoking is beneficial to improve health outcomes and, therefore, it should be recommended — providers should aim to motivate their patients to make the decision to quit smoking, rather than offer not quitting as a reasonable option.

SDM은 여러 그룹에서 의료 결정에 권장되거나 의무화되었습니다. SDM의 역량은 미국 의과대학 협회의 위탁 전문 활동, 여러 전문 분야의 의학전문대학원 교육 인증 위원회의 이정표, 유럽 내과 교육과정 및 미국 전문간호사 학부 조직과 같은 기타 전문 기관의 핵심 역량에 포함되어 있습니다. 이러한 요건을 충족하기 위해서는 수련생에게 SDM에 효과적으로 참여하는 방법에 대한 접근 방식과 전략을 가르쳐야 합니다. 교훈적인 세션, 소그룹 세션, 표준화된 환자, 웹 기반 튜토리얼, 역할극 등 다양한 중재를 사용하여 SDM 교육의 효과를 평가해 왔습니다(Singh Ospina 외. 2020). 아시아, 호주, 유럽, 북미, 남미에서 SDM을 가르치기 위한 중재가 개발되었습니다(Diouf 외. 2016). 이러한 커리큘럼은 확실히 가치가 있고 연수생의 SDM 지식을 향상시키는 것으로 나타났지만, 모든 임상 교육은 SDM의 역량을 통합할 수 있으며(Thériault 외. 2019), 역량 교육 및 평가에 대한 이러한 접근 방식은 개별 커리큘럼보다 연수생의 행동과 임상 결과에 더 지속적인 영향을 미칠 것으로 생각합니다(Touchie와 ten Cate 2016). 대체로 수퍼바이저는 관계 역량(치료 임상의-환자 관계 구축)과 위험 커뮤니케이션 역량을 모두 개발하여 SDM에서 수련의 역량을 구축할 수 있도록 지원해야 합니다(Legare 외. 2013). 이 글에서는 교육생이 이러한 교육 기대치를 충족할 수 있도록 SDM을 가르치기 위한 12가지 전략에 대해 설명합니다. 이 모든 팁이 모든 학습 환경에 적합한 것은 아니지만, 교사는 교육 및 임상 환경에서 이러한 제안 중 적어도 몇 가지를 통합할 수 있습니다.

SDM has been recommended or mandated for healthcare decisions by multiple groups. Competencies in SDM are included in entrustable professional activities from the Association of American Medical Colleges, in milestones from the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education in multiple specialties, and in core competencies from other professional organizations such as the European Curriculum of Internal Medicine and National Organization of Nurse Practitioner Faculties. In order to meet these requirements, trainees need to be taught approaches and strategies for how to engage in SDM effectively. The effect of teaching SDM has been evaluated using a wide variety of interventions including didactic sessions, small group sessions, standardized patients, web-based tutorials, and role playing (Singh Ospina et al. 2020). Interventions to teach SDM have been developed in Asia, Australia, Europe, North America, and South America (Diouf et al. 2016). While these curricula are certainly valuable and have been shown to increase trainee knowledge in SDM, all clinical teaching can integrate competencies in SDM (Thériault et al. 2019) – and we suspect this approach to teaching and assessment of competencies will have a more durable effect on trainee behaviors and clinical outcomes than discrete curricula (Touchie and ten Cate 2016). Broadly, supervisors need to support the development of both relational competencies (building a therapeutic clinician-patient relationship) and risk communication competencies to build trainee competency in SDM (Legare et al. 2013). In this article, we discuss twelve strategies for teaching SDM to assist trainees in meeting these training expectations. While not all of these tips will be appropriate for every learning encounter, teachers can integrate at least some of these suggestions in both didactic and clinical settings.

팁 1 공유 의사 결정의 가치를 강조하고 이를 사용하기에 적합한 임상 상황을 강조하세요.

Tip 1 Emphasize the value of shared decision making and highlight appropriate clinical situations for its use

SDM 역량 개발의 가치에 대해 교육생들의 동의buy-in를 얻는 것이 중요합니다. 일부 교육생은 이미 SDM을 수행하고 있다고 생각하거나 개선의 여지가 없다고 생각할 수 있습니다. 그러나 SDM 행동을 평가하는 연구에 따르면 SDM은 임상 실습에서 일반적이지 않은 것으로 나타났습니다(Legare and Thompson-Leduc 2014). 교육자는 SDM의 가치를 강조함으로써 교육생이 SDM 역량을 개발하도록 동기를 부여할 수 있습니다. SDM은 예를 들어 선호도에 민감한 심장 수술의 비율을 줄임으로써 비용을 절감하는 것으로 나타났습니다(James 2013; Stacey 외. 2017). SDM과 환자 의사결정 보조 도구의 사용은 옵션에 대한 환자의 지식을 향상시키고, 의사결정 갈등을 줄이며, 환자 만족도를 높이고, 정확한 위험 인식을 개선하고, 환자의 선택이 자신의 가치와 일치할 가능성을 높이는 것으로 나타났습니다(Stacey 외 2017). 따라서 SDM은 우수한 환자 중심 진료를 넘어 과학적 정보에 대한 환자의 참여를 높여 증거 기반 진료를 지원합니다(Adams and Drake 2006). 또한 SDM이 치료 순응도를 높이고 천식 중증도와 같은 결과를 개선한다는 증거도 있습니다(Wilson 외. 2010). 또한 저선량 CT 스캔을 통한 폐암 검진, 뇌졸중 예방을 위한 심방세동 환자의 좌심방 부속기 폐쇄술, 미국 내 심부전 환자의 제세동기 시행 등 특정 검사 및 치료에 대한 보험급여를 지급하기 위해 보험사는 SDM 및 환자 의사 결정 보조 도구의 사용을 요구하고 있습니다. 요약하면, SDM은 치료의 질을 개선하고, 비용을 절감하며, 일부 상황에서는 환급이 의무화되어 있습니다. 감독자는 교육생에게 이러한 이점을 강조하고, 환자가 선택할 수 있는 합리적인 옵션이 여러 개 있는 상황을 알려주며, 교육생이 SDM 역량을 실천하도록 장려할 수 있습니다.

It is vital to get buy-in from trainees to value development of SDM competencies. Some trainees may feel like they are already doing SDM, or there is no room for improvement. However, studies that assess SDM behaviors have shown that SDM is not common in clinical practice (Legare and Thompson-Leduc 2014). Educators can motivate trainees to develop competencies in SDM by highlighting its value. SDM has been shown to reduce cost, for example by reducing the rate of preference-sensitive heart surgeries (James 2013; Stacey et al. 2017). Use of SDM and patient decision aids have been shown to improve patient knowledge about options, reduce decisional conflict, increase patient satisfaction, improve accurate risk perception, and increase the likelihood that patients’ choices are consistent with their values (Stacey et al. 2017). Thus, beyond good patient-centered care, SDM supports evidence-based practice by increasing patient engagement with scientific information (Adams and Drake 2006). There is also evidence that SDM increases adherence and improves outcomes such as asthma severity (Wilson et al. 2010). In addition, payors require use of SDM and patient decision aids to reimburse for certain tests and treatments, such as Medicare reimbursement for lung cancer screening with low dose CT scan, left atrial appendage closure in patients with atrial fibrillation for stroke prophylaxis, and implementation of cardioverter-defibrillators in patients with heart failure in the United States. In sum, SDM improves quality of care, reduces cost, and is mandated for reimbursement in some circumstances. Supervisors can highlight these benefits with trainees, alert them to situations in which there are multiple reasonable options for patients to choose from and encourage them to practice SDM competencies.

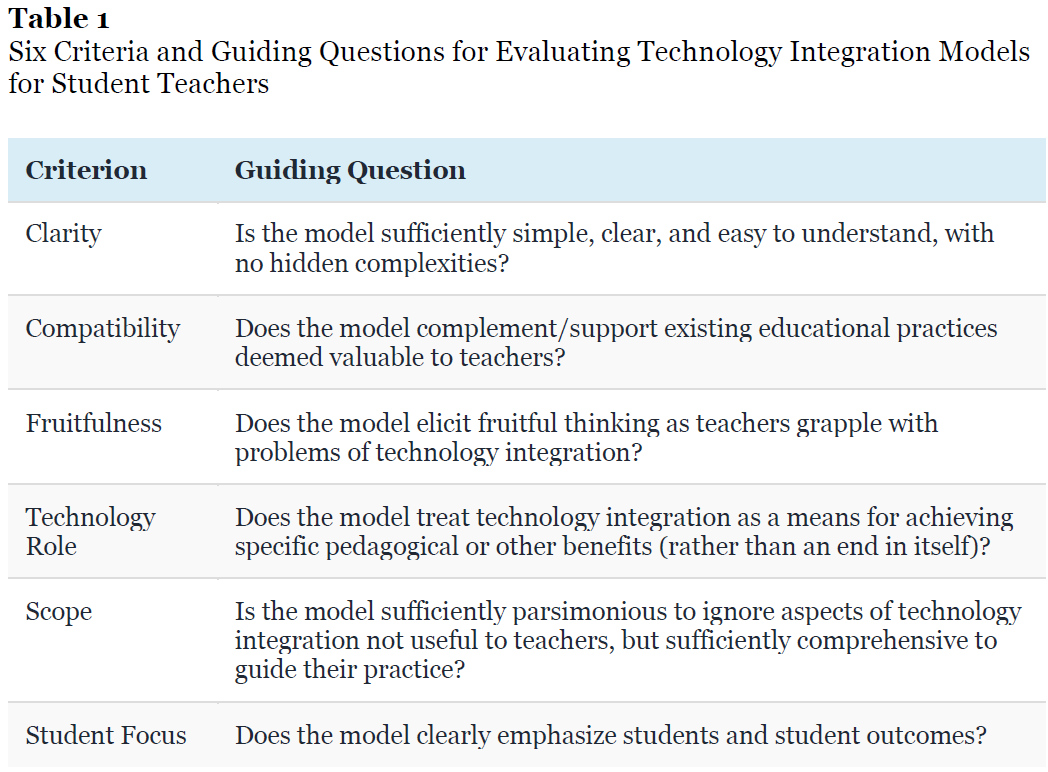

팁 2 프레임워크를 사용하여 교육생이 공유 의사 결정의 구성 요소를 이해하도록 돕습니다.

Tip 2 Use a framework to help trainees understand the components of shared decision making

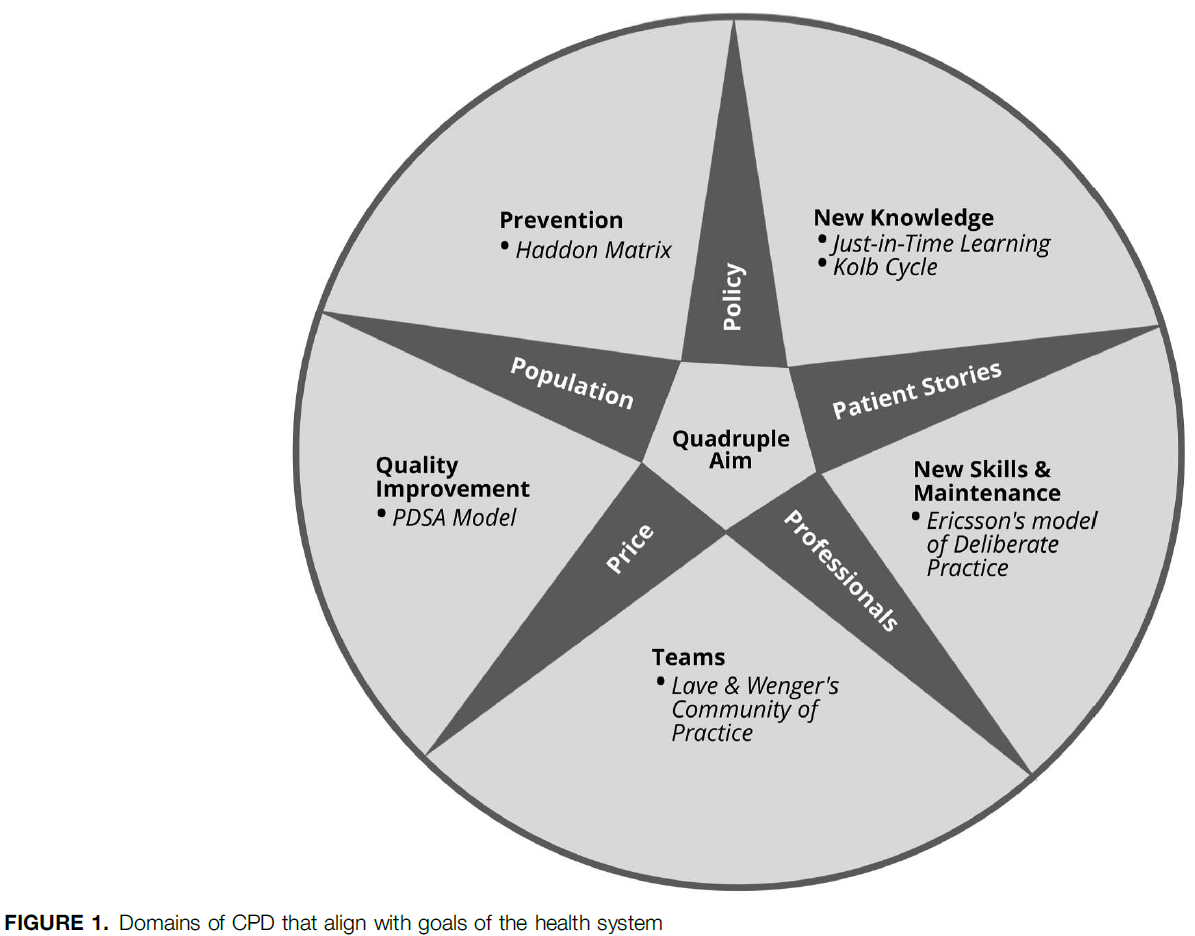

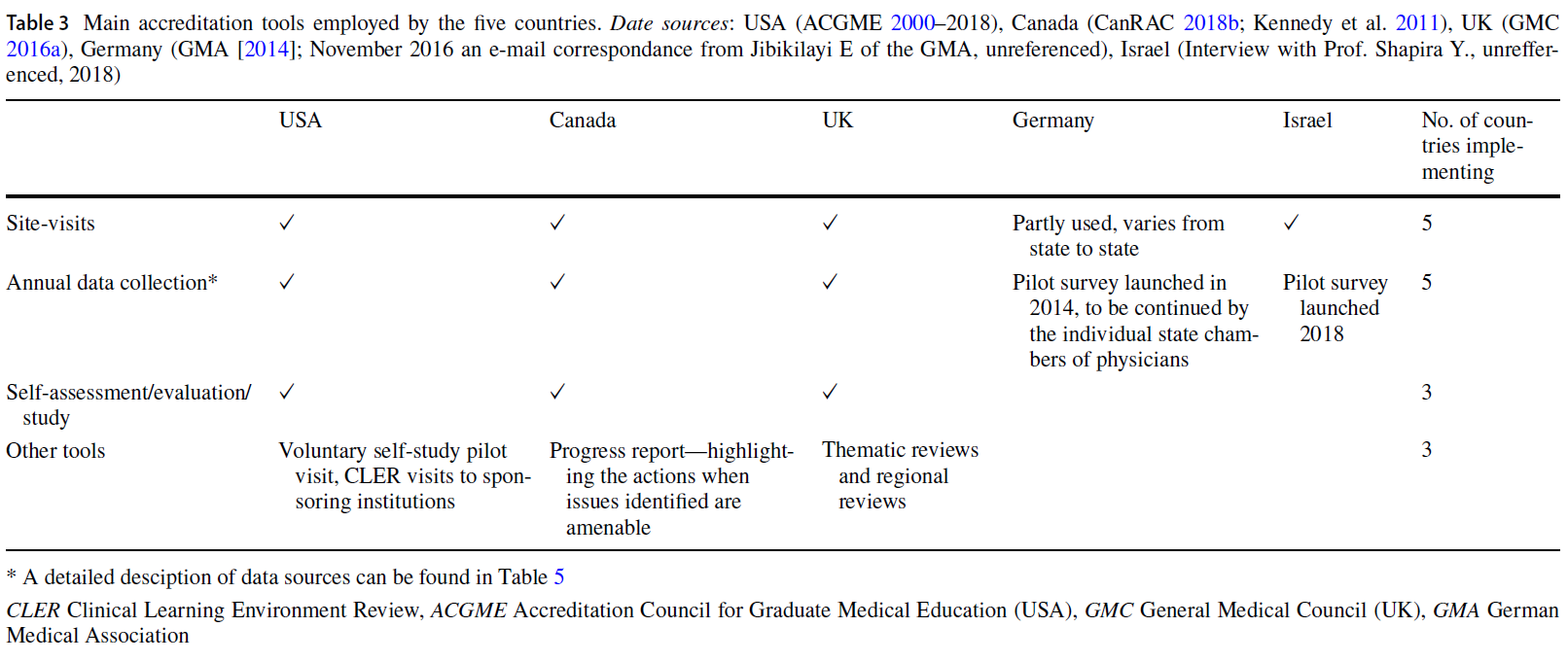

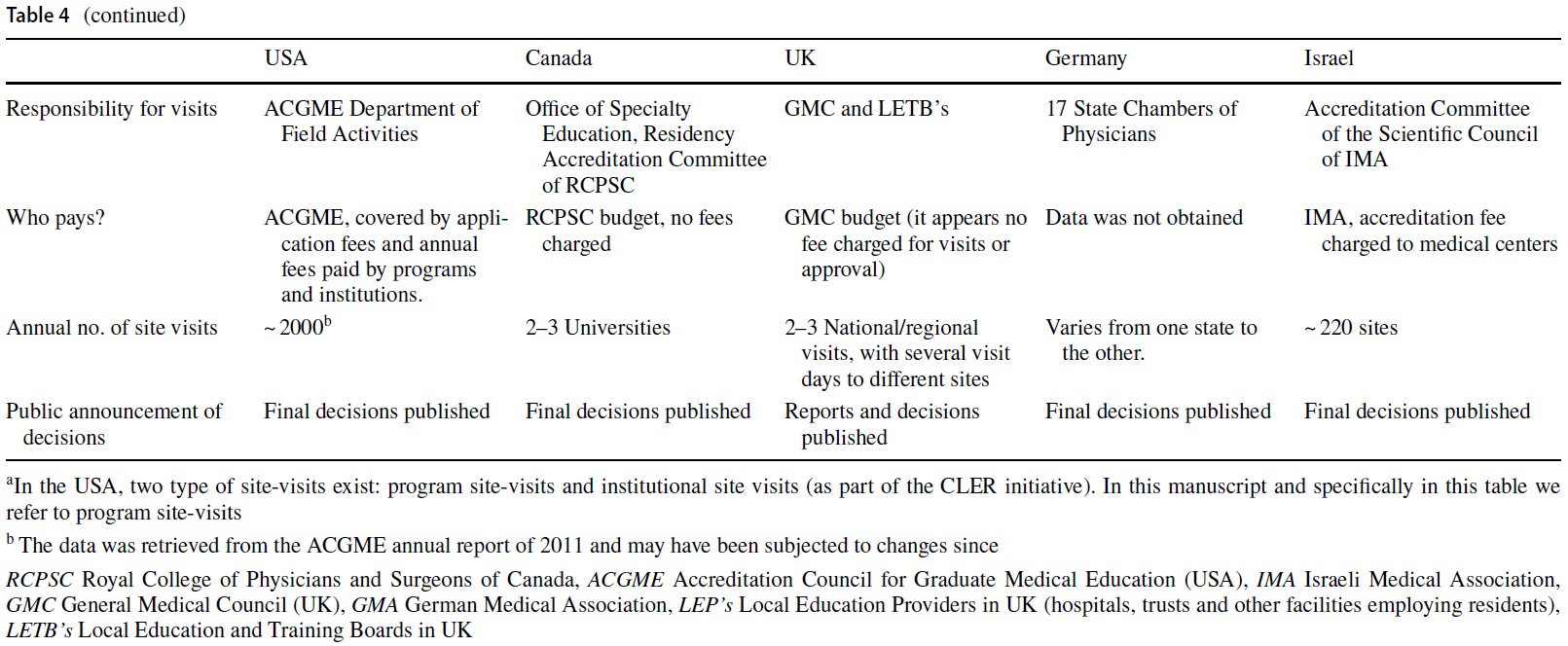

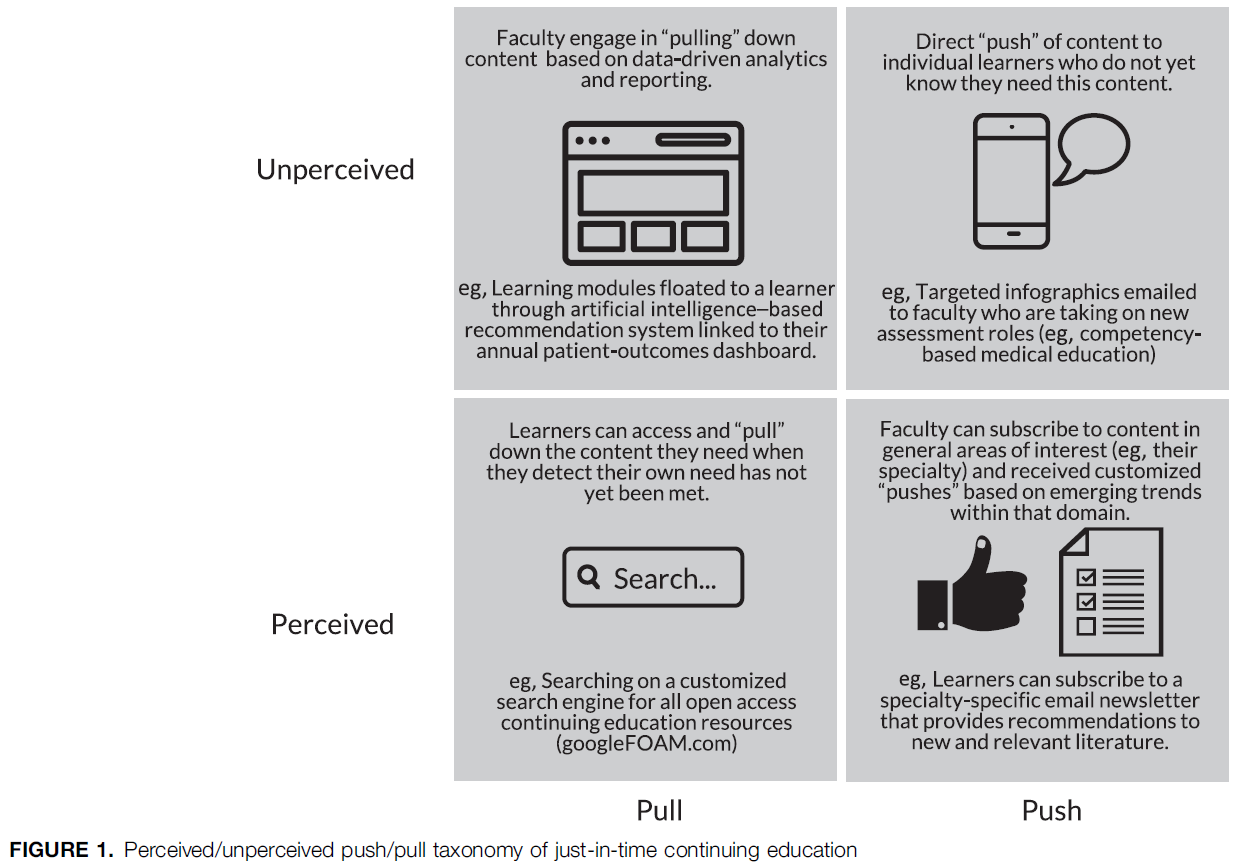

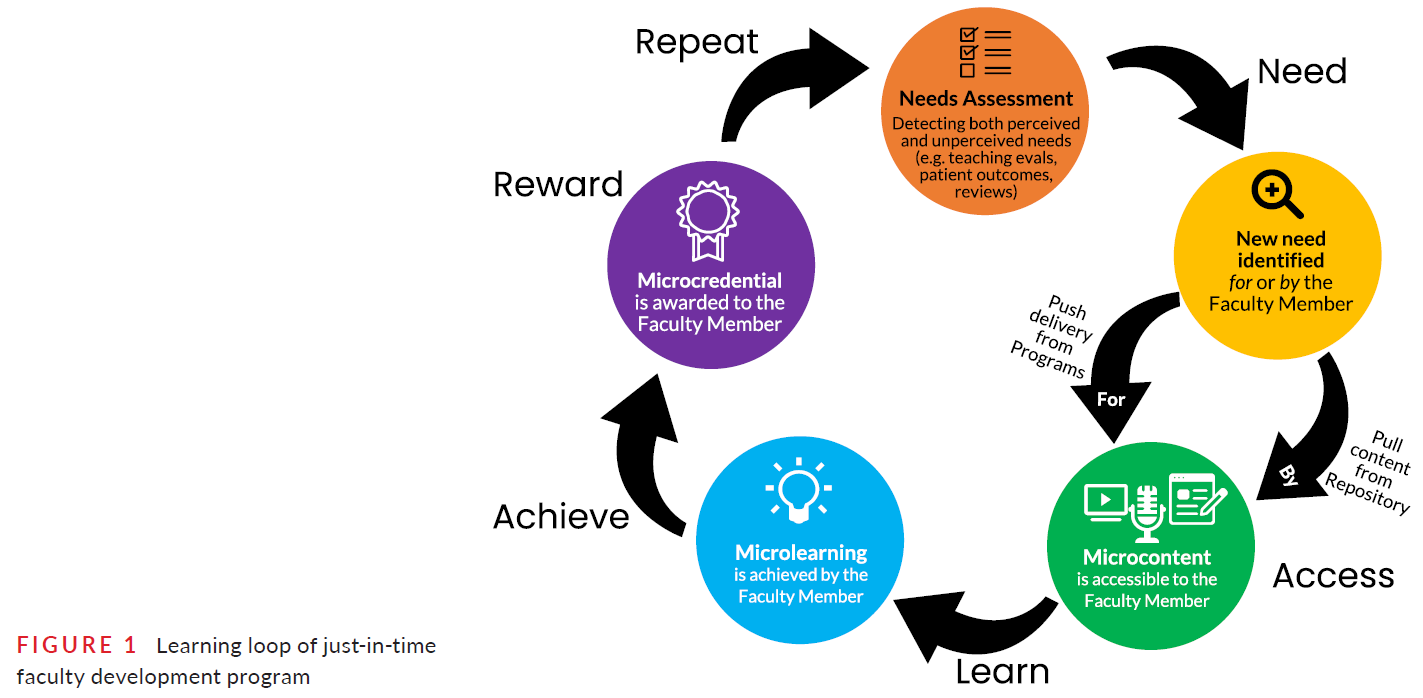

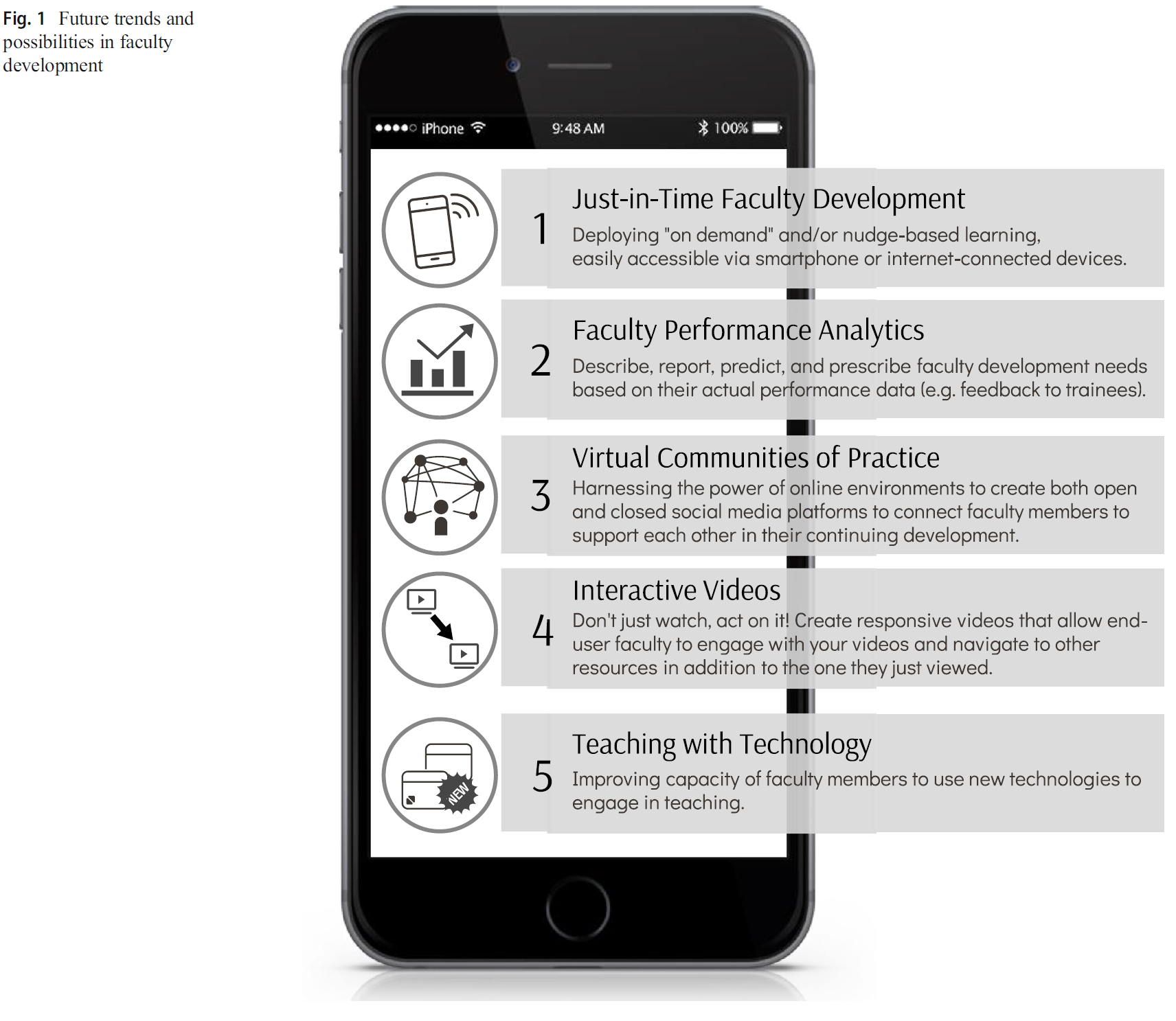

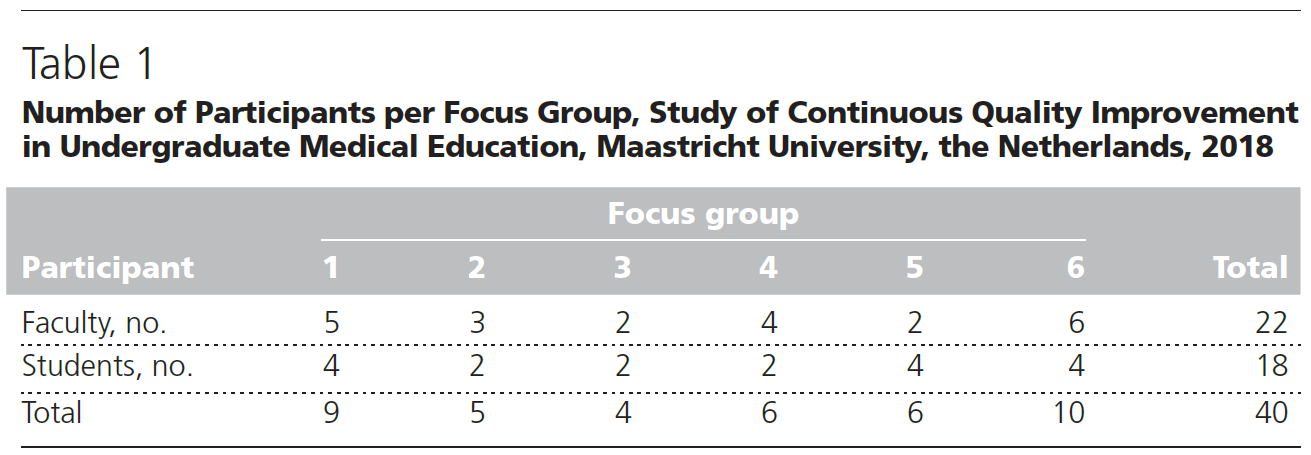

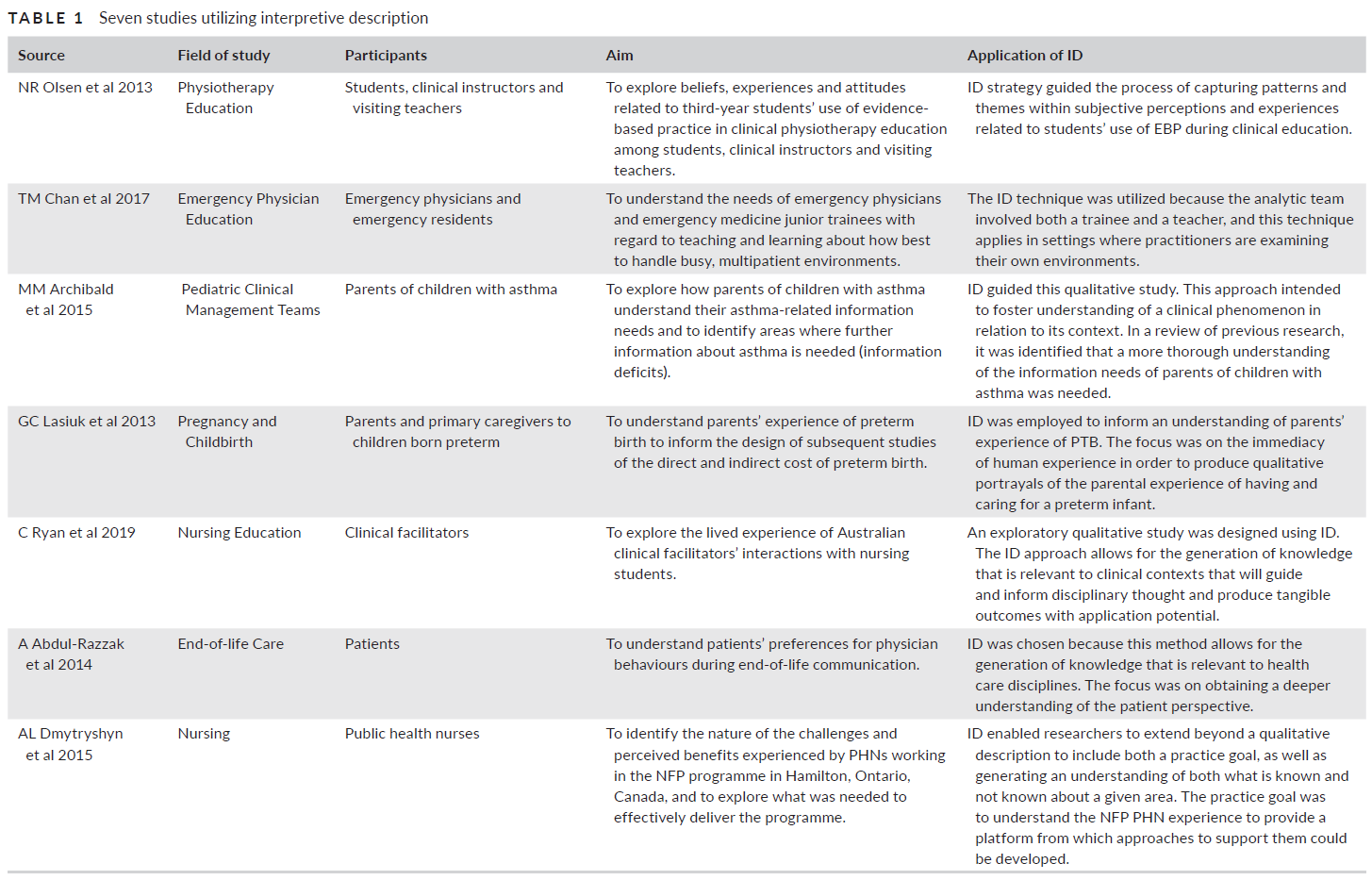

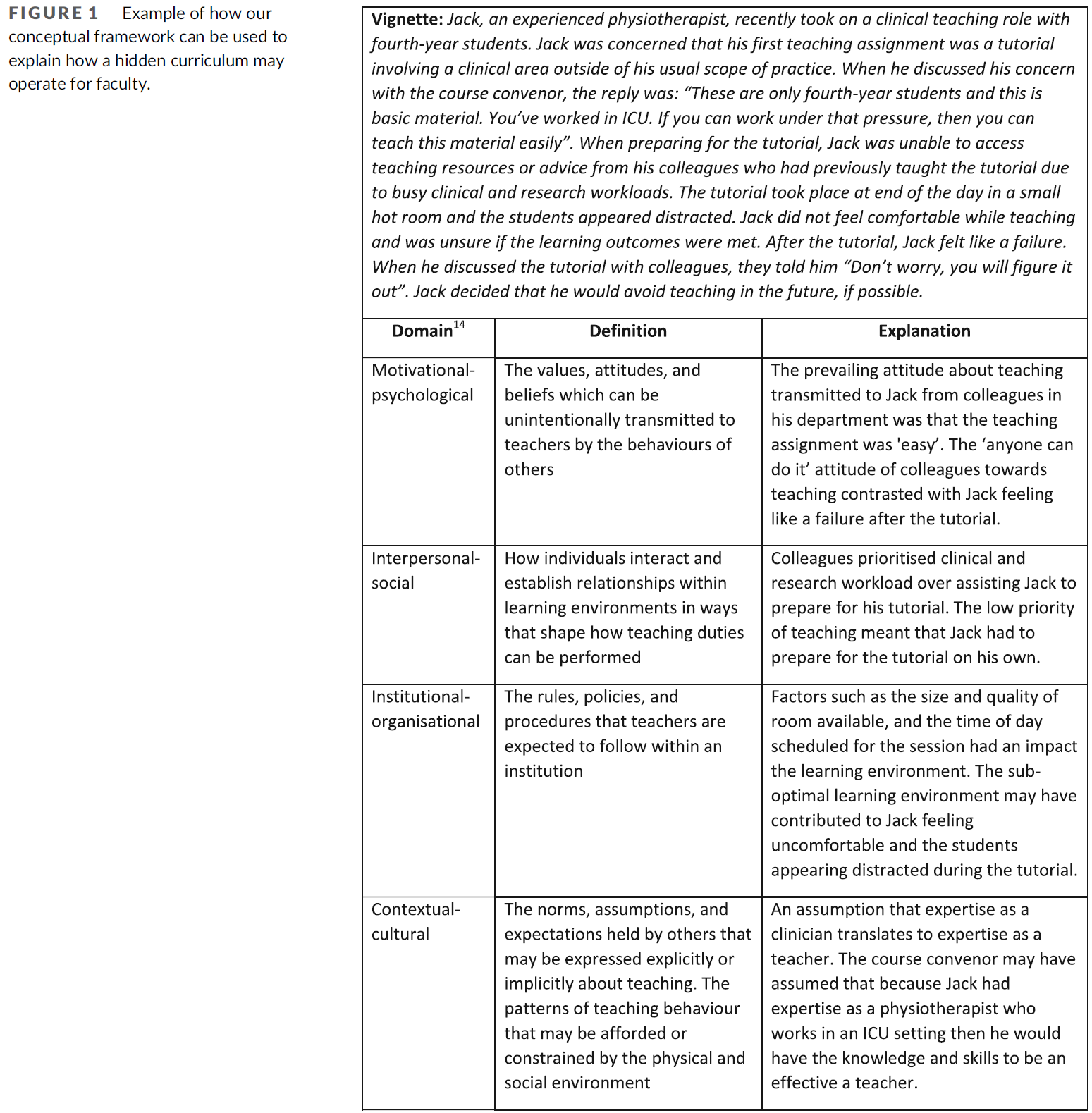

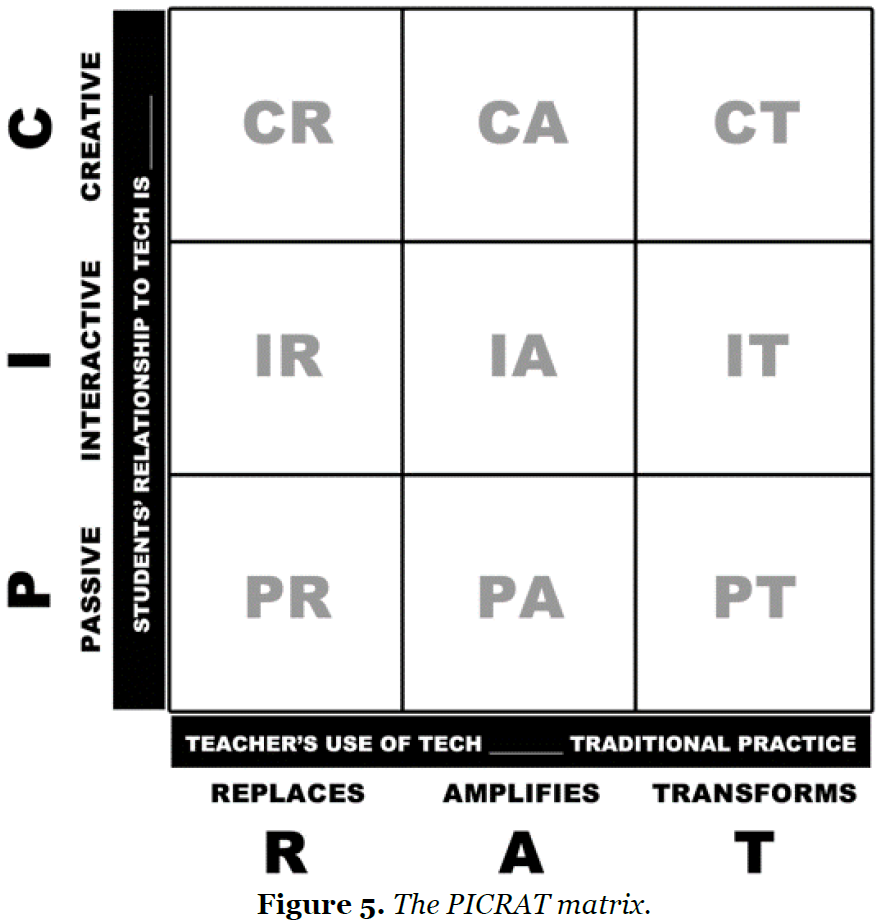

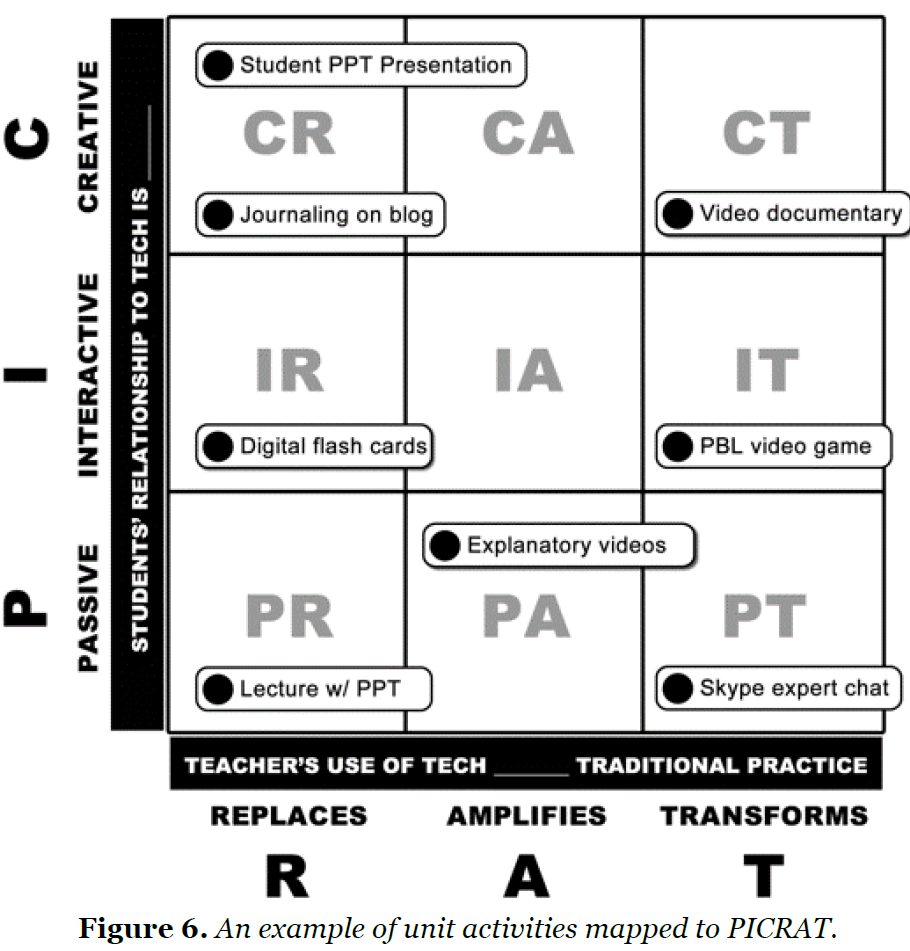

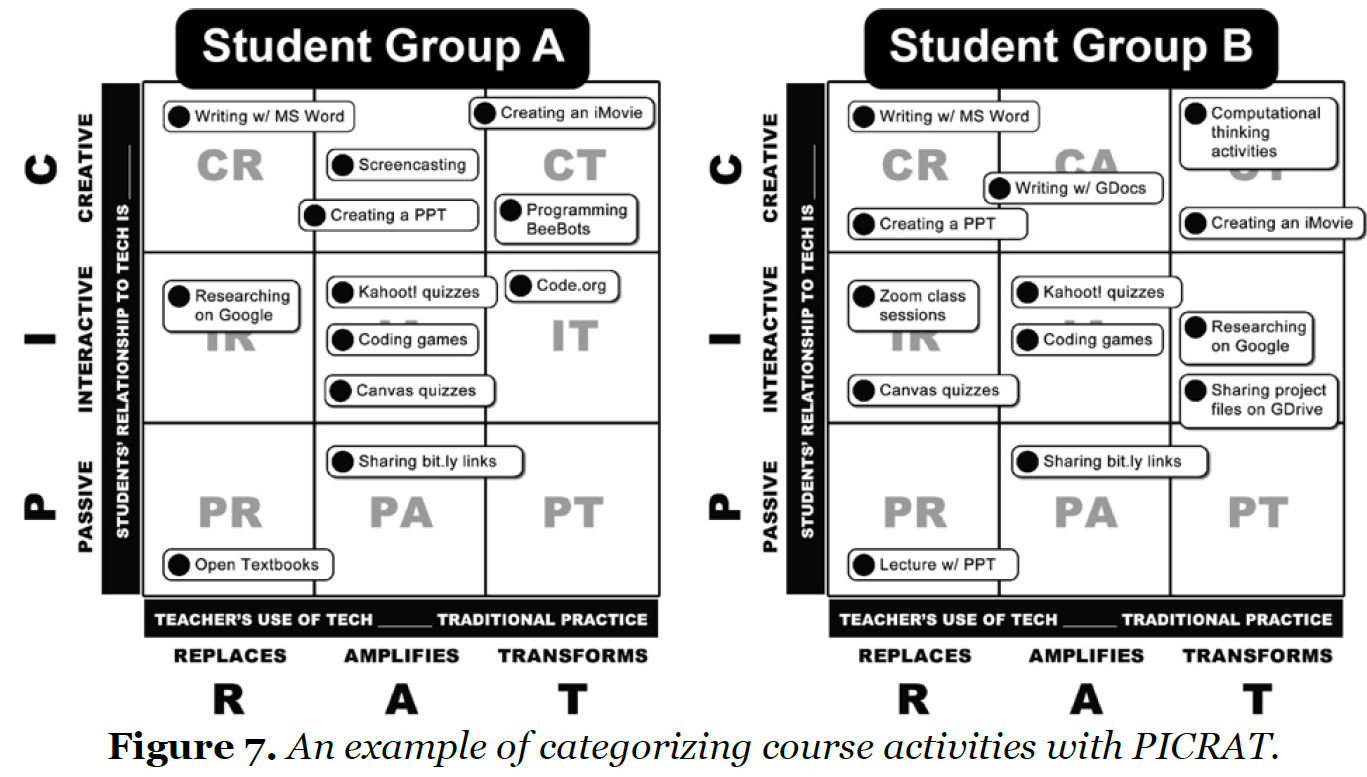

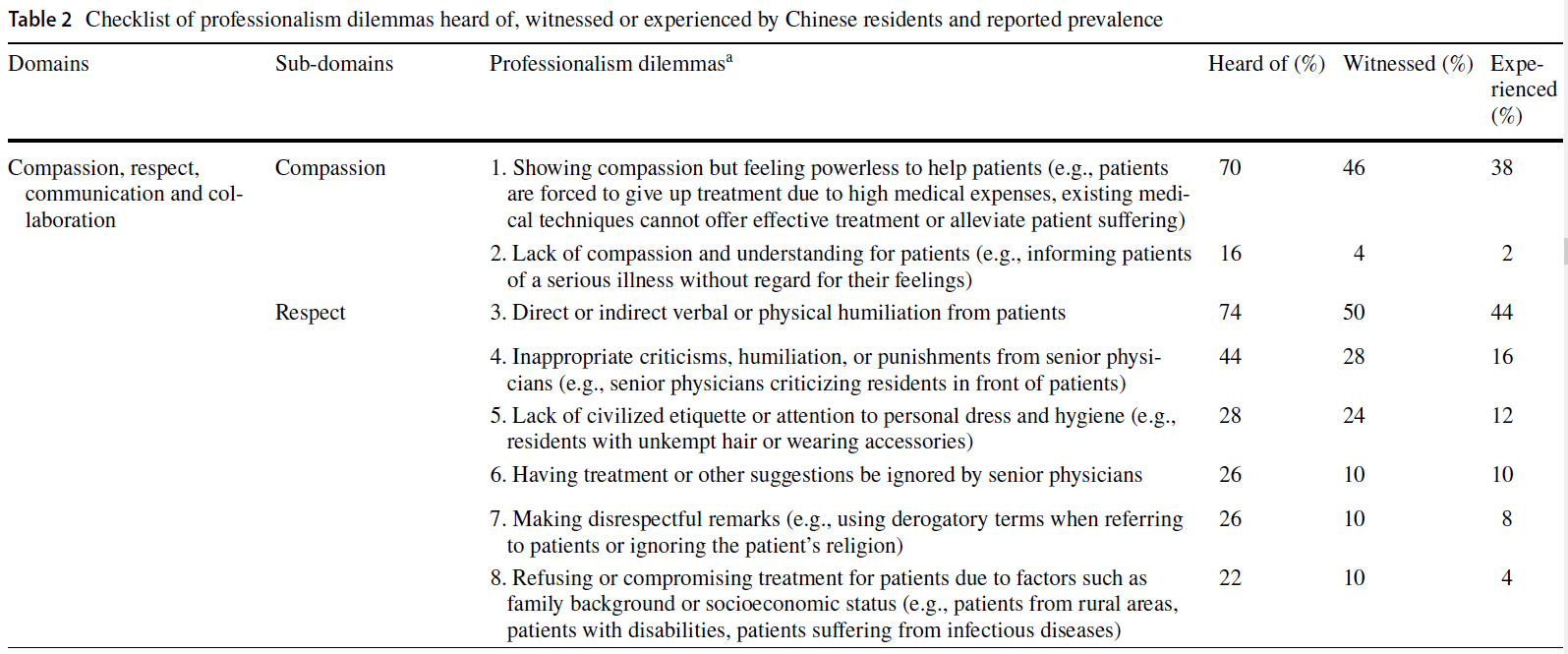

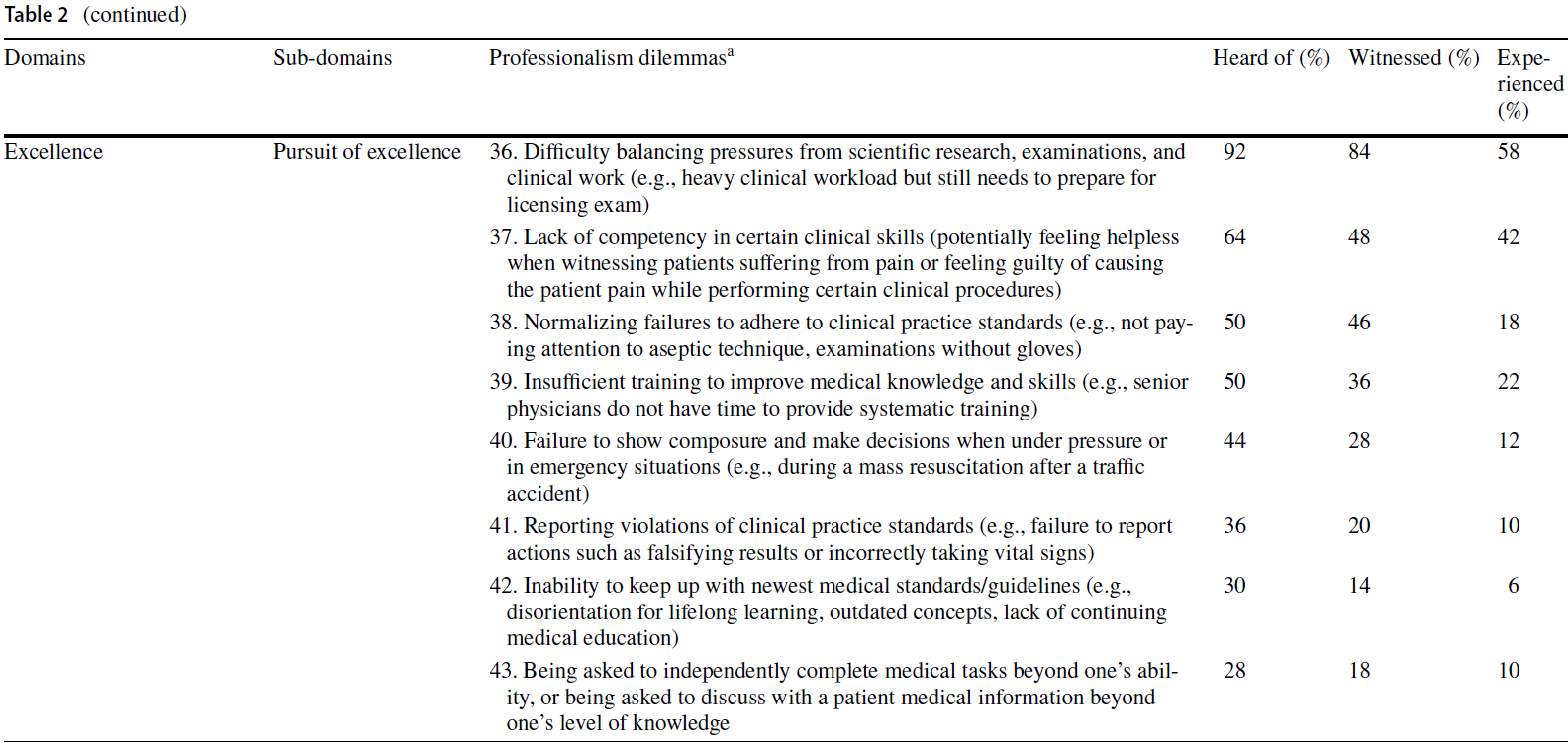

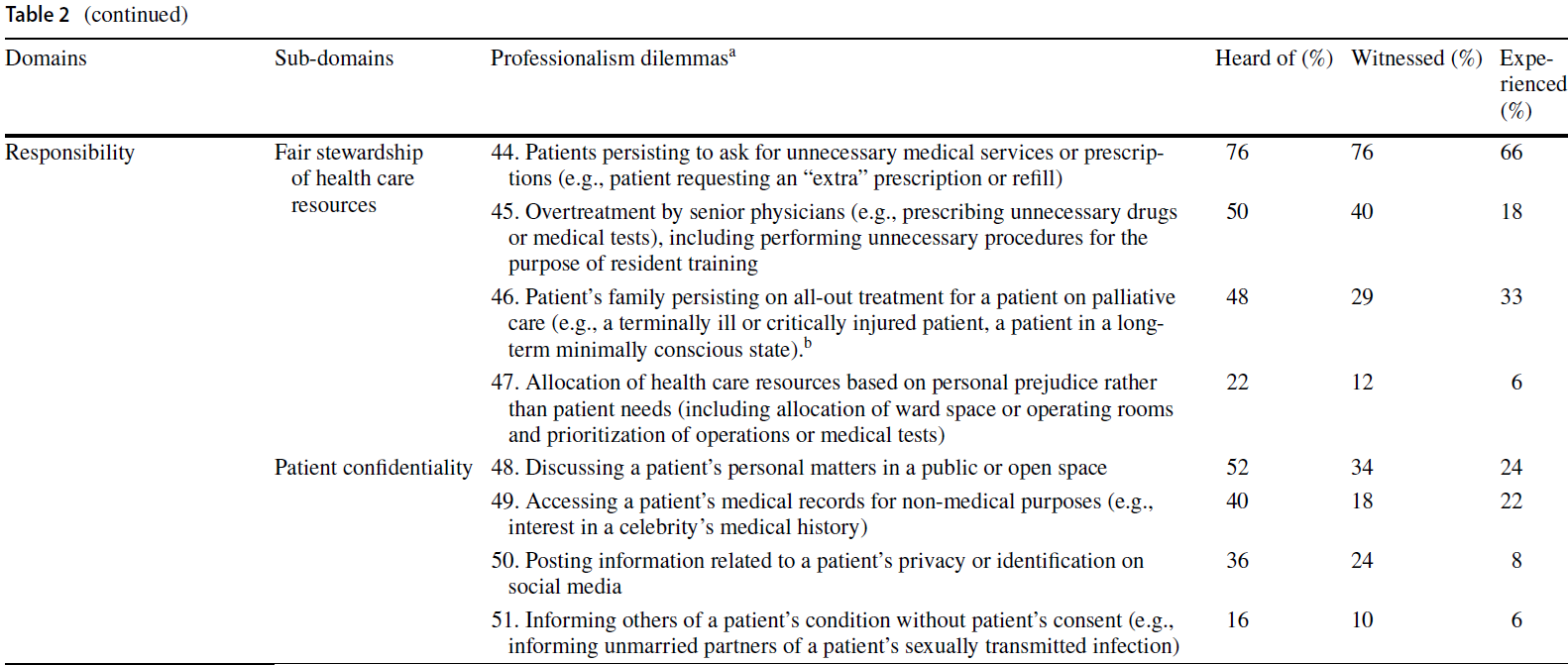

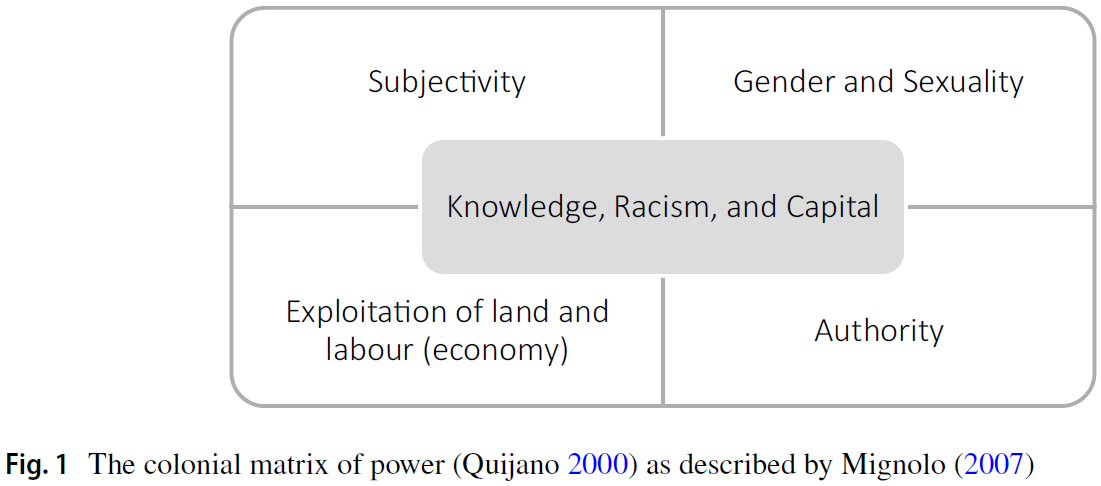

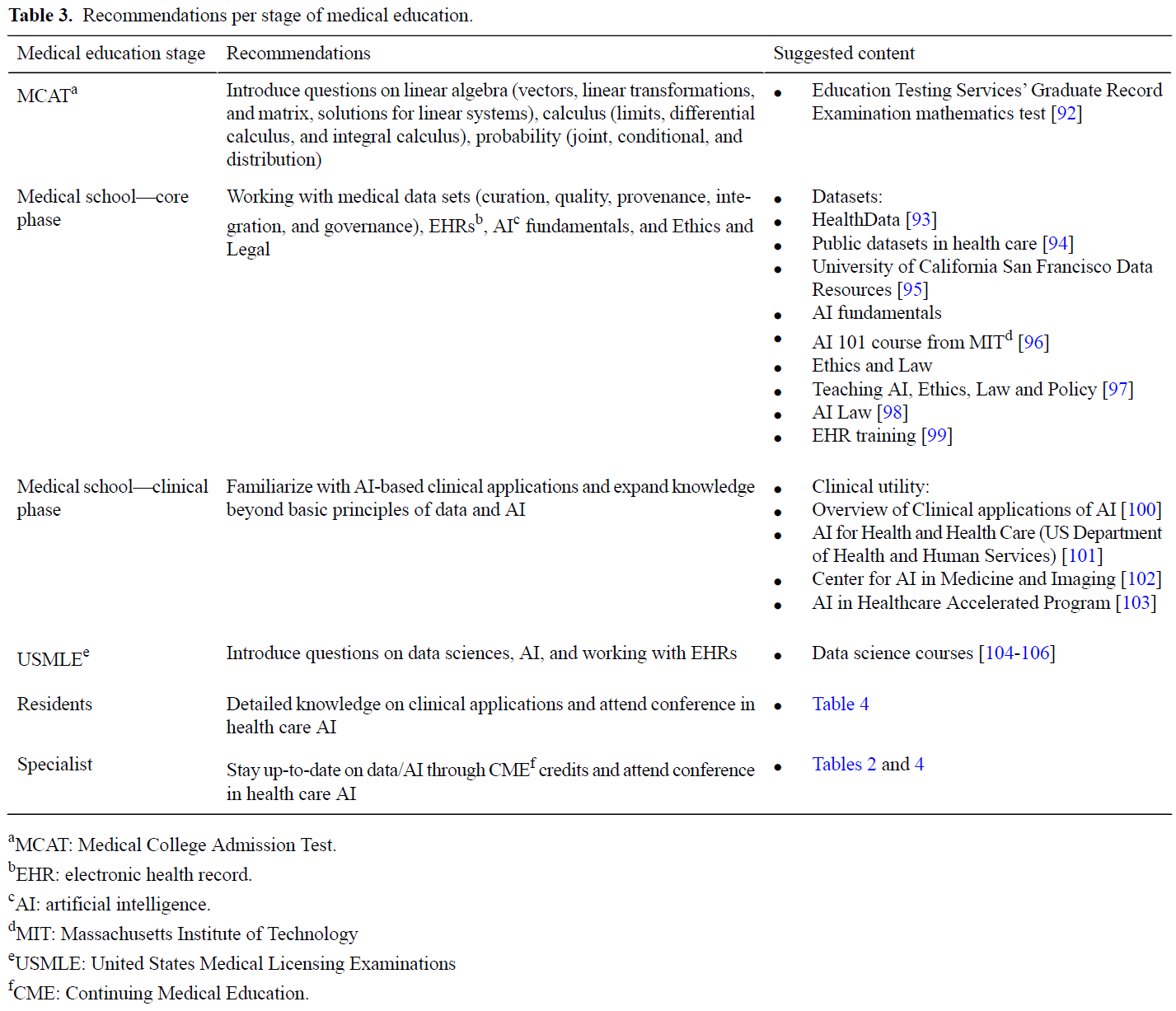

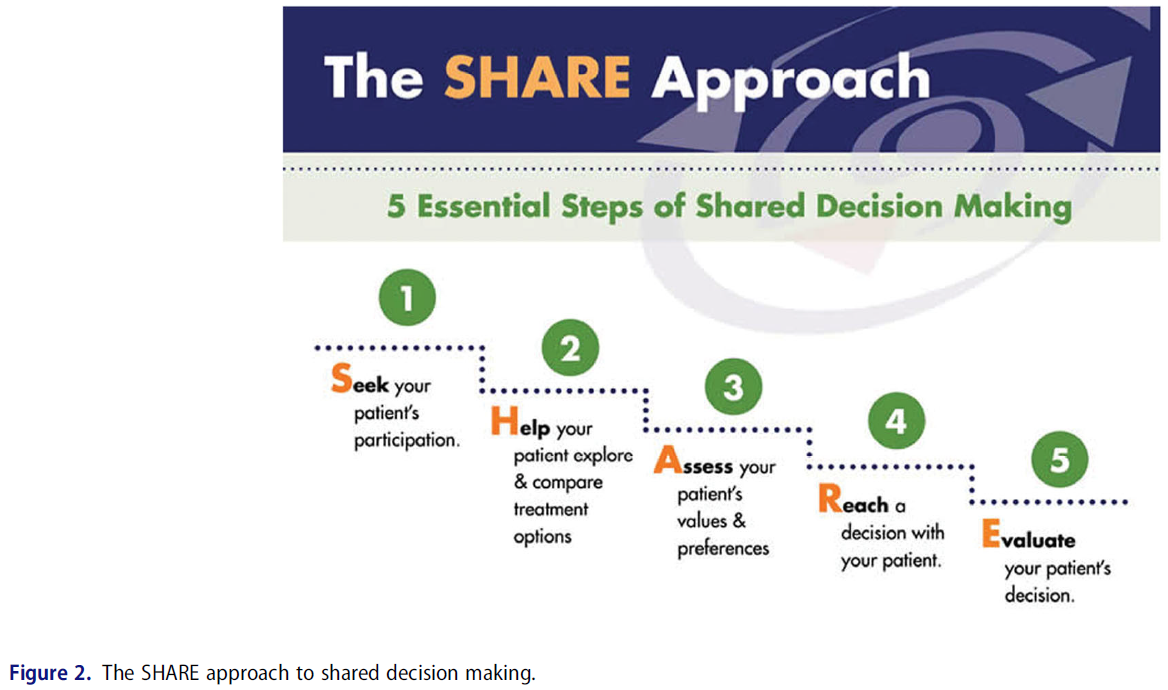

교육생이 SDM 역량을 개발하는 데 도움이 될 수 있는 두 가지 프레임워크는 미국 의료연구품질국(AHRQ)의 SHARE 접근법과 3-토크 모델입니다(The SHARE 접근법, Elwyn 외. 2017). 프레임워크는 학습자가 시각적 연상을 통해 새로운 지식을 공고히 하고, 교사가 향후에 개념을 쉽게 복습하여 기술을 강화하는 데 도움을 줄 수 있다는 점에서 프레임워크 사용의 가치를 강조합니다(Al-Eraky 2012). 이 두 가지 프레임워크는 시각적 다이어그램으로 표시할 수 있습니다(그림 1 및 2 참조). 개념을 시각적으로 표현하는 프레임워크를 가르치면 시각적 학습을 선호하는 학습자의 참여를 높일 수 있습니다(Evans 외. 2016).

Two frameworks that can assist trainees in developing competencies in SDM are the SHARE approach from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and the three-talk model (The SHARE Approach; Elwyn et al. 2017). Gagne’s Nine Events of Instruction highlights the value of using frameworks – they can help learners to solidify new knowledge by making visual associations and allow teachers to easily revisit concepts in the future to help reinforce skills (Al-Eraky 2012). These two frameworks can be displayed as visual diagrams (see Figures 1 and 2). Teaching a framework that offers a visual representation of concepts can better engage learners with preferences for visual learning (Evans et al. 2016).

AHRQ의 SHARE 접근 방식은 5단계로 구성됩니다:

- 환자의 참여 구하기,

- 환자가 치료 옵션을 탐색하고 비교하도록 돕기,

- 환자의 가치와 선호도 평가하기,

- 환자와 함께 결정에 도달하기,

- 환자의 결정 평가하기

이러한 단계는 치료 결정에 대한 논의를 지원하기 위해 선형적인 프로세스로 제시됩니다.

The AHRQ’s SHARE approach consists of five steps:

- Seek your patient’s participation,

- Help your patient explore and compare treatment options,

- Assess your patient’s values and preferences,

- Reach a decision with your patient, and

- Evaluate your patient’s decision.

These steps are presented as a linear process to support discussion around treatment decisions.

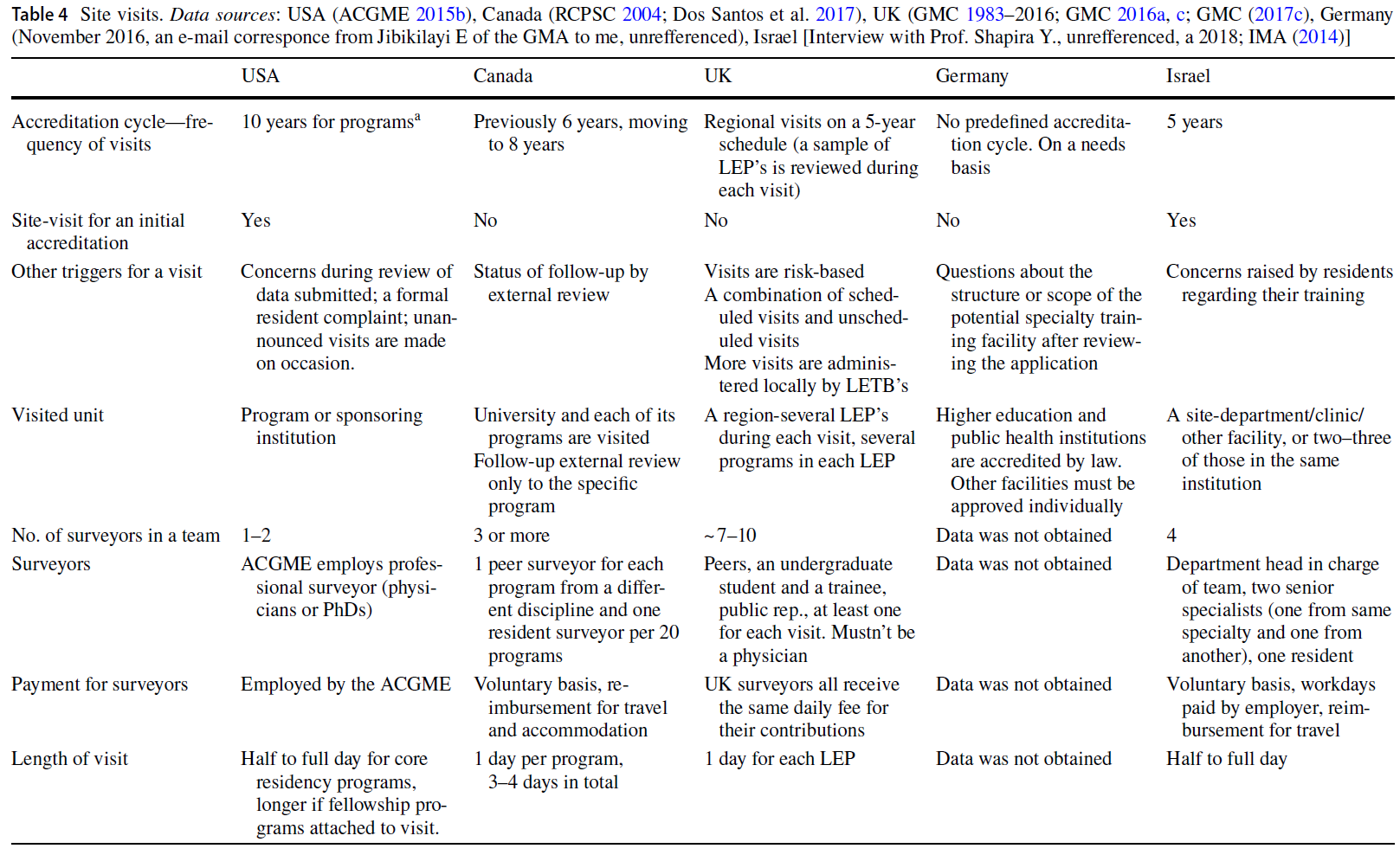

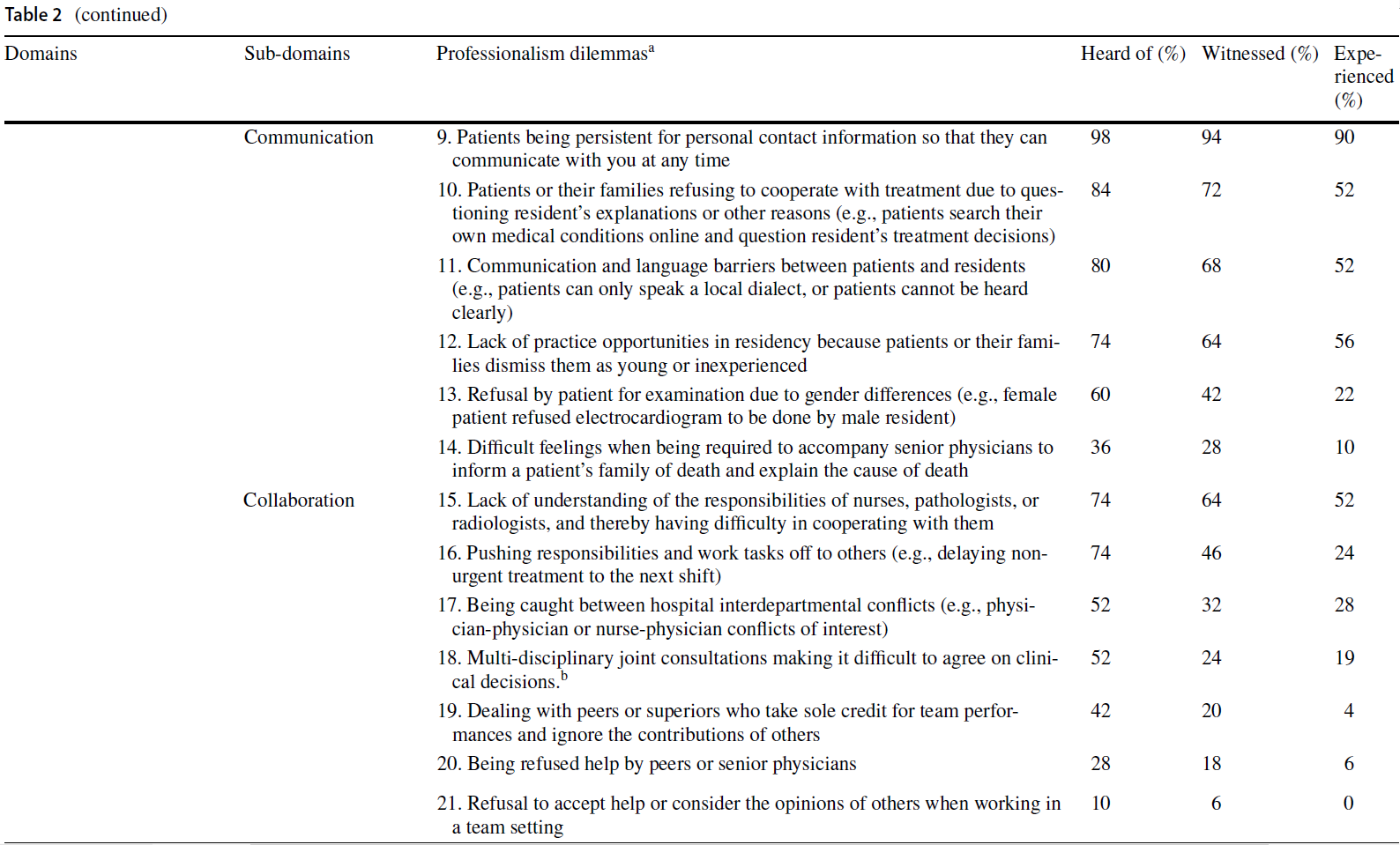

SDM을 위한 3-토크 모델은 보다 유동적인 접근 방식으로 제시됩니다. 이 모델은 팀 토크, 옵션 토크, 결정 토크의 세 단계로 구성됩니다.

- '팀 대화'는 의료진이 환자와 협력하고, 지원을 제공하고, 선호도와 목표에 대해 논의할 의사가 있음을 표시함으로써 이루어집니다. 환자가 혼자서 결정을 내리도록 내버려두지 않을 것임을 명시적으로 강조하는 것이 도움이 될 수 있습니다.

- '옵션 대화'는 옵션의 존재를 강조하고 위험 커뮤니케이션 원칙을 사용하여 옵션에 대해 논의하는 것을 포함합니다.

- '결정 대화'는 '당신에게 가장 중요한 것은 무엇입니까'와 같은 문구를 사용하여 환자가 정보에 입각한 선호도를 바탕으로 옵션을 선택하도록 안내하는 것을 말합니다(Elwyn 외. 2016).

이 세 단계는 반드시 이 순서대로 수행할 필요는 없습니다. 세 단계 모두에서 적극적인 경청과 숙고가 핵심적인 역할을 합니다(Elwyn 외. 2017). 따라서 관계 역량은 세 단계 모두에서 중요하지만, 위험-편익 의사소통 역량은 '옵션 대화' 단계에서 가장 핵심적입니다.

The three-talk model for SDM is presented as a more fluid approach. It consists of three stages: team talk, option talk, and decision talk.

- ‘Team talk’ is accomplished by providers indicating that they intend to work collaboratively with a patient, provide support, and discuss preferences and goals. It can be helpful to highlight explicitly that patients will not be abandoned to make decisions alone.

- ‘Option talk’ involves highlighting the presence of options and discussing them using risk communication principles.

- ‘Decision talk’ refers to guiding the patient to select an option using informed preferences, using phrases such as ‘what matters most to you?’ (Elwyn et al. 2016).

These three stages need not be done in this order. In all three stages, active listening and deliberation play a central role (Elwyn et al. 2017). Thus, relational competencies are important in all three stages, though risk-benefit communication competencies are most central to the ‘Option talk’ stage.

경험상 수련 초기의 학생과 레지던트는 SHARE 모델의 보다 체계적이고 선형적인 지도가 가장 도움이 되는 반면, 시니어 레지던트는 실습 경험과 자신감이 쌓일수록 3-토크 모델이 더 도움이 된다는 것을 알게 됩니다.

In our experience, students and residents earlier in their training find the more structured and linear guidance of the SHARE model to be most helpful, while senior residents find that the three-talk model is more helpful as they build experience and confidence in their practice.

팁 3 공유 의사결정 대화를 맞춤화하기 위해 환자 개개인의 요인, 가치관, 선호도를 고려하도록 수련의를 안내합니다.

Tip 3 Guide trainees in considering individual patient factors, values, and preferences in order to tailor shared decision-making conversations

환자들은 자신의 건강에 대한 결정을 내리는 방식에 있어 서로 다른 선호도를 가지고 있습니다(Levinson 외. 2005). 이러한 선호도는 가치관, 문화, 종교 및 영적 신념, 교육, 감정 상태 등 다양한 환자 특성에 의해 영향을 받습니다. 환자와 의료진의 파트너십을 돕기 위해 임상의는 먼저 환자의 치료 결정에 대한 욕구를 평가해야 합니다. 따라서 처음에는 SDM 프로세스에 적극적으로 참여하는 환자가 있는 반면, 의료진의 의견을 따르는 것을 선호하는 환자도 있을 수 있습니다. 평균적으로 젊은 환자, 교육 수준이 높은 환자, 여성은 의료진과 함께 의사 결정에 더 적극적으로 참여하는 것을 선호할 수 있습니다(Arora and McHorney 2000). 문화는 원하는 가족의 참여 정도와 환자-임상의 관계에서 역할에 대한 기대치를 포함하여 의사 결정 스타일에 대한 선호도에 상당한 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다(Charles 외. 2006; Sepucha와 Mulley 2009; Keij 외. 2021). 예를 들어, 많은 문화권에서 환자 자율성의 가치는 우선순위가 높지 않으며, 환자가 아닌 가족이 주요 의사 결정권자가 될 것으로 기대할 수 있습니다(Charles 외. 2006). 동양 문화권의 환자가 가족 참여에 대한 욕구가 더 높다고 보고되는 경우가 많지만, 이는 서양과 동양 모두에서 나타나는 현상이므로 임상의는 가족 참여에 대한 욕구를 가정하지 않아야 합니다(Alden 외. 2018). 임상의, 환자, 동반자가 모두 중요한 역할을 하는 삼자간 의사 결정은 가족의 의견을 중시하는 환자와 인지 장애가 있는 환자처럼 환자의 의사 결정이 손상된 상황에 더 적합한 프레임워크입니다(Laidsaar-Powell 외. 2013).

Patients have different preferences in how they make decisions about their health (Levinson et al. 2005). These preferences are informed by a vast array of patient characteristics including values, culture, religious and spiritual beliefs, education, and emotional states. To assist in the patient-provider partnership, clinicians must first assess a patient’s desire to make decisions in their care. As such, there will be patients who are initially highly engaged in the SDM process, while others would prefer to default to the provider’s opinion. On average, younger patients, those with more education, and women may prefer to take a more active role in decision making with their clinicians (Arora and McHorney 2000). Culture can significantly influence preferences for the style of decision making, including the degree of desired family involvement and the expectations for roles in the patient-clinician relationship (Charles et al. 2006; Sepucha and Mulley 2009; Keij et al. 2021). For example, the value of patient autonomy is not as prioritized in many cultures, and family members may be expected to be the primary decision maker rather than the patient (Charles et al. 2006). While it is often reported that patients from Eastern cultures have higher desire for family involvement, clinicians should avoid making assumptions about desire for family involvement since this falls along a spectrum in both Western and Eastern countries (Alden et al. 2018). Triadic decision-making, in which the clinician, patient, and a companion all play important roles, is a more appropriate framework for patients that value input of the family and for situations in which the patient’s decision making is compromised, such as in patients with cognitive impairment (Laidsaar-Powell et al. 2013).

학습자에게 환자의 의사 결정 욕구의 연속성에 대해 가르치면 환자와 의료진 모두의 좌절감을 줄일 수 있습니다. 이러한 평가는 SDM 참여 방법을 결정하는 데 매우 중요하지만, SDM에 대한 환자의 관심은 정적인 것이 아니며, 환자는 의사 결정에 보다 적극적인 역할을 하도록 동기를 부여받을 수 있습니다(Sepucha and Mulley 2009). 실제로 대부분의 환자가 자신의 건강 상태에 대해 더 많은 정보를 원하고 자신의 건강과 관련된 의사 결정에서 더 적극적인 역할을 선호한다는 증거가 있습니다. 가장 취약한 환자들은 처음에는 SDM에 참여하기를 꺼려할 수 있지만, 교육생들이 이러한 환자들을 의사 결정에 참여하도록 유도하기 위해 접근 방식을 조정하도록 장려해야 합니다(Legare and Thompson-Leduc 2014). 가장 중요한 것은 학습자에게 환자 선호도를 평가하는 방법을 교육하는 것은 라뽀와 임상의의 신뢰를 바탕으로 구축된다는 점입니다. 이러한 관계적 역량은 SDM 대화의 토대이며 의학적 결정이 일상생활에 미치는 영향에 대한 토론을 위한 도구입니다(Legare 외. 2013).

Teaching learners about the continuum of patient desire to make decisions can result in less frustration for both patient and provider. While making this assessment is vital to determine how to engage in SDM, patient interest in SDM is not static, and patients can be motivated to take a more active role in decision making (Sepucha and Mulley 2009). In fact, evidence suggests that most patients desire more information about their health conditions and would prefer a more active role in decisions concerning their health. Our most vulnerable patients may initially express reticence to engage in SDM, but we must encourage trainees to adjust their approach to invite these patients to share in decision making (Legare and Thompson-Leduc 2014). Most importantly, training learners on how to assess patient preferences is built from a foundation of rapport and clinician trust. These relational competencies are the bedrock of SDM conversations and instrumental for discussions about the impact of medical decisions on daily life (Legare et al. 2013).

학습자에게 SDM에 대한 관심을 평가하고 환자의 의사 결정에 영향을 미치는 가치와 선호도를 이끌어내는 방법을 가르칠 때는 의제 설정, 개방형 질문 및 성찰 사용과 같이 접근성이 높은 기술을 보여주는 것이 좋습니다. 학습자는 의제 설정으로 시작하여 환자에게 임상적 상호작용에서 시간을 어떻게 사용할 것인지에 대해 협력하도록 유도합니다. '유도-제공-유도' 및 '묻고-말하기'와 같은 프레임워크는 환자가 현재 내려야 하는 결정에 대해 무엇을 알고 있는지 평가하는 것으로 시작하여, 정보를 제공하고, 논의된 내용에 대해 궁금한 점을 질문하는 것으로 이어진다. 학습자는 해당 결정이 환자의 일상 생활(또는 가족 생활, 영적 생활, 여가 활동)에 어떤 영향을 미칠지, 그리고 환자에게 가장 중요한 것이 무엇인지에 대해 개방형 질문을 하도록 권장합니다. 상담을 시작할 때 caregiver가 의사 결정에서 담당할 역할을 명확히 하고 동의하면 교육생이 상담 구조와 방문에 대한 기대치를 조정할 수 있습니다(Laidsaar-Powell 외. 2013). 환자 결정 보조 도구는 학습자가 개별 결정과 관련된 환자의 가치와 선호도를 이끌어내는 데 도움을 줄 수 있지만, 환자와 관련된 모든 가치와 선호도를 평가하지는 못할 수 있으며, 특히 비 서구 문화적 배경을 가진 환자에게는 더욱 그렇습니다(Charles 외. 2006). 수련의에게 자신과 가족이 의사 결정에 참여하는 방식에 대한 환자 선호도를 묻고 이를 의사 결정 스타일에 반영하도록 교육하는 등 다문화 진료에 대한 수련의 교육은 수련의가 문화적으로 적절한 방식으로 의사 결정을 보다 효과적으로 공유할 수 있도록 할 수 있습니다(Blumenthal-Barby 2017). 이러한 핵심 전략(규정된 단계와 비교)을 종합하면 학습자는 환자의 특성, 가치, 선호도를 평가할 수 있습니다.

When teaching learners to assess interest in SDM and to elicit values and preferences that influence a patient’s decision making, we recommend showcasing skills that are highly approachable, such as agenda-setting and the use of open-ended questions and reflections. By starting off with an agenda, the learner invites the patient to collaborate on how time will be spent in the clinical interaction. Frameworks like ‘elicit-provide-elicit’ and ‘ask-tell-ask’ start by assessing what the patient currently knows about the decision that needs to be made, provides information, and queries for questions about the material discussed. Learners are encouraged to ask open ended questions about how the decision will impact the patient’s daily life (or family life, spiritual life, leisure activities) and what matters most to them. Clarifying and agreeing on the roles that caregivers will have in decision-making at the start of the consultation can allow trainees to adjust how they structure their counseling and expectations for the visit (Laidsaar-Powell et al. 2013). Patient decision aids can also assist learners in eliciting patient values and preferences as they pertain to individual decisions, though these may not evaluate all values and preferences that are relevant to patients, perhaps especially for those with non-Western cultural backgrounds (Charles et al. 2006). Trainee education in cross-cultural care, including teaching trainees to ask about patient preferences for how they want themselves and their families to be involved in decision-making and then incorporating this into their decision-making style, can enable trainees to be more effectively share decisions in a culturally appropriate way (Blumenthal-Barby 2017). Taken together, these core strategies (versus prescribed steps) enable learners to assess patient characteristics, values, and preferences.

팁 4 교육생이 공동 의사 결정에 참여하기에 적절한 시간과 장소를 결정하도록 돕기

Tip 4 Help trainees determine the right time and place to engage in shared decision making

각 임상 상황에 대한 요구 사항이 이미 상당하기 때문에 SDM이 어렵게 느껴질 수 있습니다. 실제로 임상의와 환자 모두 SDM의 가장 큰 장애물로 가장 많이 언급하는 것은 시간입니다(Pieterse 외. 2019). 수련의가 이러한 요구에 직면하고 부담을 느낄 때, 수퍼바이저는 두 가지 원칙을 강조하여 수련의를 도울 수 있습니다.

SDM can feel challenging due to the already significant demands on each clinical encounter. Indeed, the most commonly cited barrier to SDM by both clinicians and patients is time (Pieterse et al. 2019). As trainees inevitably encounter and feel burdened by these demands, supervisors can assist them by highlighting two principles.

- 첫째, SDM은 종종 '분산된' 방식으로 여러 차례 방문에 걸쳐 진행될 수 있습니다(Rapley 2008). 환자는 종종 새로운 정보를 처리하고 자신의 선호도와 가치관을 명확히 하기 위해 사랑하는 사람들과 논의할 시간이 필요합니다. 마찬가지로 임상의사도 이러한 가치를 이해하기 위해 여러 번의 만남이 필요할 수 있습니다. 선호도에 민감한 많은 의사 결정의 경우, 임상의와 환자 모두 해당 결정이 자신의 가치관에 부합한다는 확신을 가질 수 있도록 의사 결정 과정에서 한 번 이상의 만남을 갖는 것이 임상적으로 허용되며, 또한 바람직합니다. 이러한 시간을 허용하는 것은 SDM의 기초가 되는 관계적 역량을 구축하는 것으로, 임상의는 다양한 환자의 고유한 의사결정 스타일을 존중하고 의사소통에 대한 접근 방식을 유연하게 가져야 합니다(Kiesler and Auerbach 2006; Legare 외. 2013).

- 둘째, SDM에 참여하는 데 걸리는 시간이 실제보다 더 길다고 인식될 가능성이 높습니다. 일반적인 진료에 비해 의사결정 보조 도구를 사용하면 평균적으로 진료 시간이 2.6분 연장되었습니다(Stacey 외. 2017). 일부 환자 의사결정 보조 도구는 최초 의료진 방문 전후에 환자에게 제공되어 사용할 수 있으며, 이후 후속 방문 시 검토 및 추가 논의가 이루어질 수 있습니다. 간호 및 심리학과 같은 다른 전문 분야와 협력하여 환자를 지원하고 환자의 목표와 선호도를 명확히 하는 데 도움을 주면 임상의가 SDM에 소요되는 시간을 더욱 줄일 수 있습니다.

- First, SDM can often take place over multiple visits, in a ‘distributed’ fashion (Rapley 2008). Patients often need time to process new information and discuss with their loved ones to help clarify their preferences and values. Similarly, clinicians may need multiple encounters to understand these values. For many preference-sensitive decisions, it is clinically acceptable (and preferable) for the decision-making process to take more than one encounter, so that both the clinician and patient are confident that the decision is in line with their values. Allowing for this time builds on the relational competencies that are foundational for SDM – requiring clinicians to respect the unique decision-making style of different patients and be flexible in their approach to communication (Kiesler and Auerbach 2006; Legare et al. 2013).

- Second, the time it takes to engage in SDM is likely perceived to be longer than in reality. Use of a decision aid compared to usual care extended a visit by 2.6 min on average (Stacey et al. 2017). Some patient decision aids can be given to patients to use before or after the initial clinician visit, and then can be reviewed and further discussed at a follow-up visit. Collaborating with other professions, such as nursing and psychology, to support the patient and assist them in clarifying their goals and preferences can enable clinicians to engage in SDM by further reducing the demands of time.

팁 5 교육생에게 적절한 환자 의사결정 보조 도구를 안내하고 사용법을 교육합니다.

Tip 5 Guide trainees to appropriate patient decision aids and instruct on how to use them

환자 의사 결정 보조 도구(PDA)는 환자가 선호도에 기반한 결정을 내리는 데 도움을 주기 위해 고안된 근거 기반 도구입니다.

- PDA는 결정 사항을 명시하고, 혜택, 위험, 확률, 불확실성에 대한 정보를 제공하며, 환자의 가치와 선호도가 결정에 어떤 영향을 미치는지 강조해야 합니다.

- 일반적인 건강 교육 자료와는 달리, PDA는 환자가 의사 결정에 직접 참여할 수 있도록 도와줍니다. 위에서 설명한 바와 같이, 환자의 만족도, 선택지에 대한 이해도, 선택이 가치관과 일치할 가능성을 향상시키는 것으로 나타났습니다(Stacey 외. 2017).

Patient decision aids (PDAs) are evidence-based tools designed to assist patients in making preference-based decisions.

- PDAs should explicitly state the decision, provide information about benefits, harms, probabilities, and uncertainties, and highlight how patient values and preferences impact the decision.

- As opposed to general health education materials, PDAs directly assist patients in participating in decision making. As discussed above, they have been shown to improve patient satisfaction, understanding of their options, and the likelihood that their choice is consistent with their values (Stacey et al. 2017).

감독자는 환자 의사결정 보조 도구가 도움이 될 수 있는 임상 시나리오를 파악하여 교육생이 이를 사용할 수 있도록 지원할 수 있습니다. 환자가 선호도에 민감한 결정에 직면해 있다는 점을 강조한 후, 감독자와 교육생은 오타와 병원 연구소에서 수집한 A to Z 목록과 같은 데이터베이스를 사용하여 적절한 PDA를 검색할 수 있습니다(https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/AZlist.html(환자 의사 결정 보조 도구)). 빈번하게 사용되는 PDA는 작업실에 쉽게 접근할 수 있도록 보관할 수 있습니다. PDA가 SDM에 도움을 줄 수는 있지만, SDM에 필요한 복잡한 커뮤니케이션 역량을 대체할 수는 없다는 점을 강조하는 것이 중요합니다. 특히, PDA에서 평가되지 않는 문화적 가치와 선호도를 가진 환자에게는 더 적합하지 않을 수 있습니다(Charles 외, 2006). 환자에게 가장 중요한 가치를 정의하도록 요청하는 오타와 개인 의사결정 가이드(https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/decguide.html)와 같은 개방형 PDA는 이러한 상황에 더 적합할 수 있습니다(환자 의사결정 보조 도구). 따라서 임상 진료 중 또는 진료 전후에 PDA를 도구로 사용할 수 있지만, 수련의는 의사 결정 과정에 전적으로 의존하기보다는 이를 진료에 통합할 수 있도록 지도받아야 합니다(Legare and Thompson-Leduc 2014).

Supervisors can assist trainees in their use by identifying clinical scenarios in which a patient decision aid would be helpful. After highlighting that a patient faces a preference-sensitive decision, supervisors and trainees can search for appropriate PDAs using databases such as the A to Z inventory collated by the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, available at https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/AZlist.html (Patient Decision Aids). Commonly used PDAs can be kept readily accessible in workrooms. While PDAs can assist in SDM, it is important to emphasize that they are not a replacement for the complex set of communication competencies that are required in SDM. In particular, they may not be less well suited to patients with cultural values and preferences that are not assessed in the PDA (Charles et al. 2006). Open-ended PDAs, such as the Ottawa Personal Decision Guide available at https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/decguide.html, which ask patients to define the values that are most important to them, may be better suited to these situations (Patient Decision Aids). Thus, PDAs can be used as a tool during or around clinical encounters, but trainees should be coached to incorporate them into their care rather than rely on them entirely for the decision-making process (Legare and Thompson-Leduc 2014).

팁 6 수련의가 환자 의사결정 지원 도구의 질을 평가할 수 있도록 지원합니다.

Tip 6 Assist trainees in evaluating the quality of patient decision aids

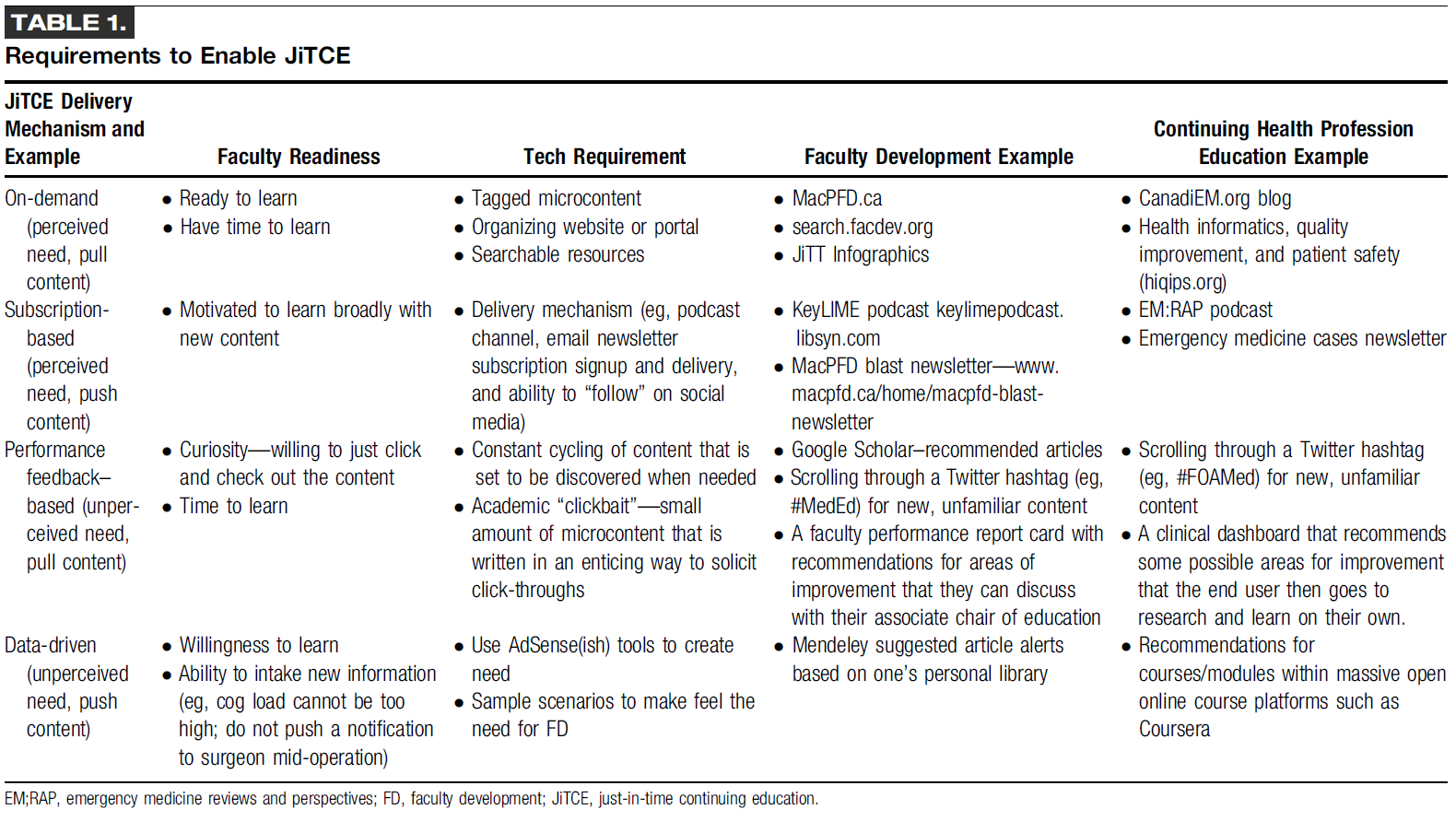

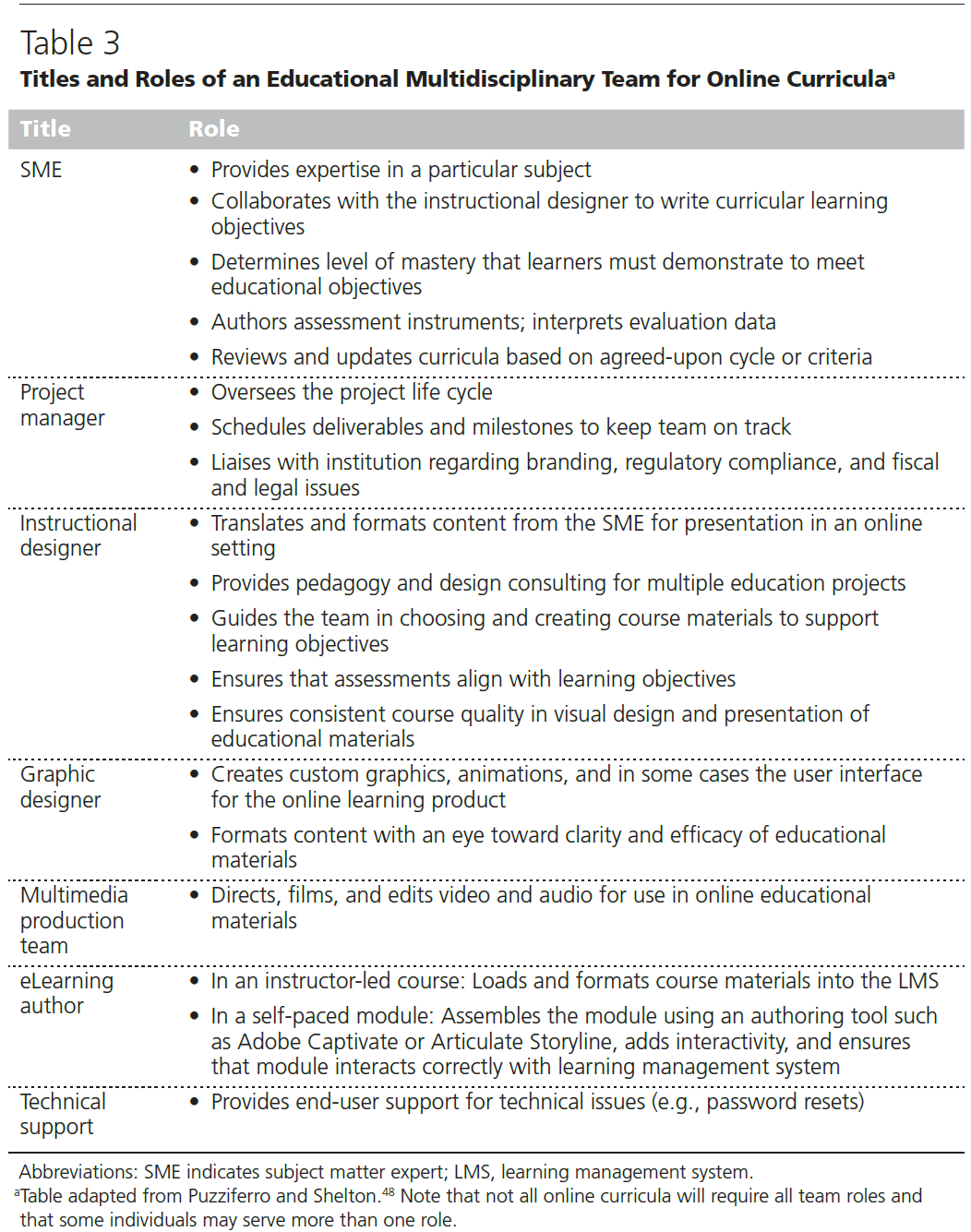

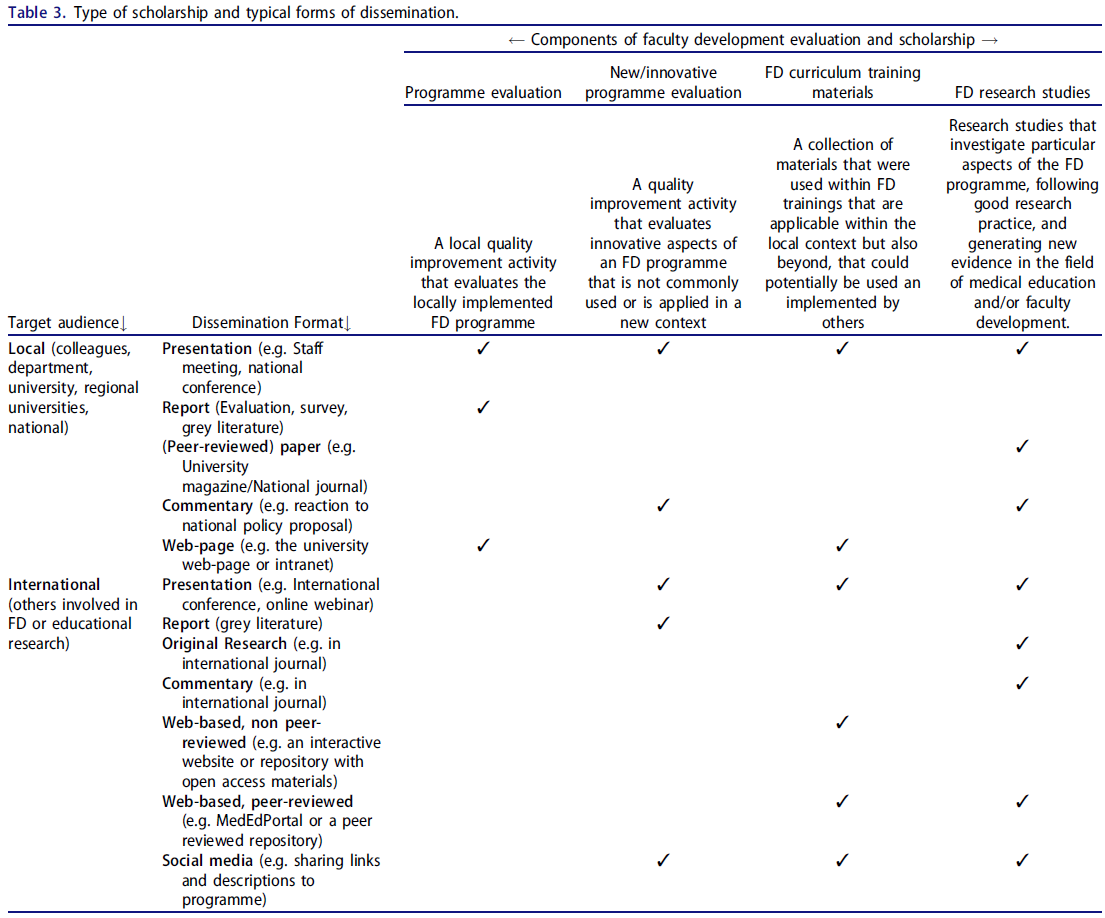

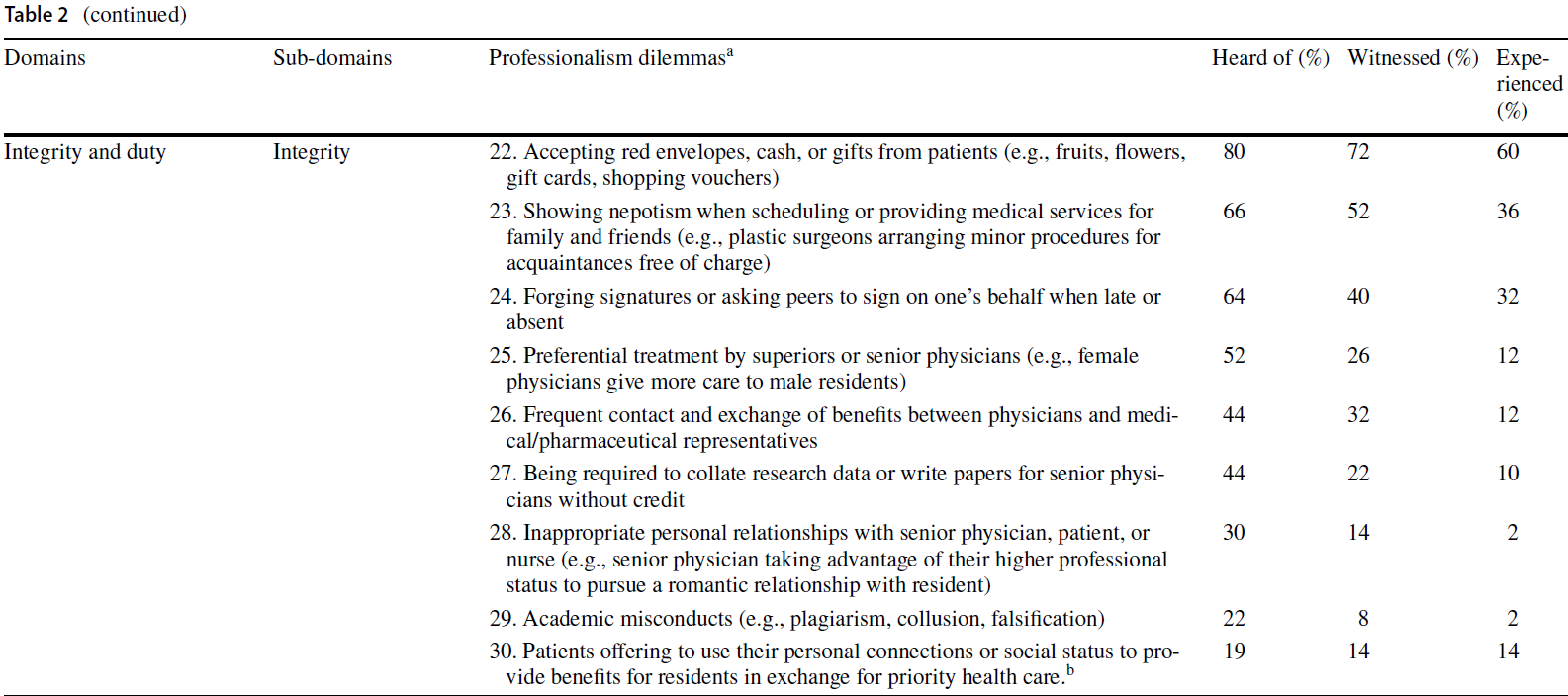

국제 환자 의사결정 지원 표준(IPDAS) 협력체에서 PDA 품질 평가 기준을 발표했습니다. PDA마다 이러한 기준을 충족하는 정도가 다르기 때문에 수련의는 특정 도구의 품질이 우수하고 임상 실습에 사용할 가치가 있는지를 파악하는 것이 중요합니다. 오타와 병원 연구소의 인벤토리는 이러한 기준(환자 의사 결정 보조 도구)에 따라 PDA를 평가하는 데 도움이 됩니다. 이 기준은 다음과 같은 차원으로 요약할 수 있습니다:

- 정보(예: 결정 사항을 명시하고 옵션의 긍정적, 부정적 특징을 편견 없이 설명),

- 확률(예: 옵션의 위험 및 이득 가능성을 포함하며, 이상적으로는 동일한 기간과 분모를 사용하고, 다양한 방법으로 확률을 볼 수 있음),

- 가치(예. 예: 환자에게 가장 중요한 것이 무엇인지 고려하도록 장려),

- 지침(예: 결정을 내리기 위한 구조 제공),

- 개발(예: 환자와의 요구 평가, 현장 테스트 수행),

- 근거(예: 근거의 출처 및 품질 설명),

- 공개(예: 연구비 지원 및 저자 관련),

- 평이한 언어 사용(Joseph-Williams 외. 2014)

연수생이 품질을 평가하는 역량을 키우기 위해 동일한 의사결정에 대해 여러 개의 PDA를 비교하는 것이 도움이 될 수 있습니다.

The International Patient Decision Aids Standards (IPDAS) Collaboration has published criteria to evaluate PDA quality. Since PDAs vary in meeting these criteria, it is important for trainees to have a grasp of whether a particular tool is of high quality and worthwhile to use in their clinical practice. The Ottawa Hospital Research Institute inventory helpfully assesses PDAs based on these criteria (Patient Decision Aids). The criteria can be summarized into the following dimensions:

- information (e.g. explicitly stating the decision and describing positive and negative features of their options in an unbiased fashion),

- probabilities (e.g. includes likelihood of risks and benefits of the options, ideally using the same time period and denominator, with multiple ways of viewing the probabilities),

- values (e.g. encouraging patients to consider what matters most to them), guidance (e.g. providing a structure to come to a decision),

- development (e.g. using a needs assessment with patients, conducting field testing),

- evidence (e.g. describes sources and quality of evidence),

- disclosure (e.g. regarding funding and authors), and

- use of plain language (Joseph-Williams et al. 2014).

It can be helpful for trainees to compare multiple PDAs for the same decision to develop competencies in assessing their quality.

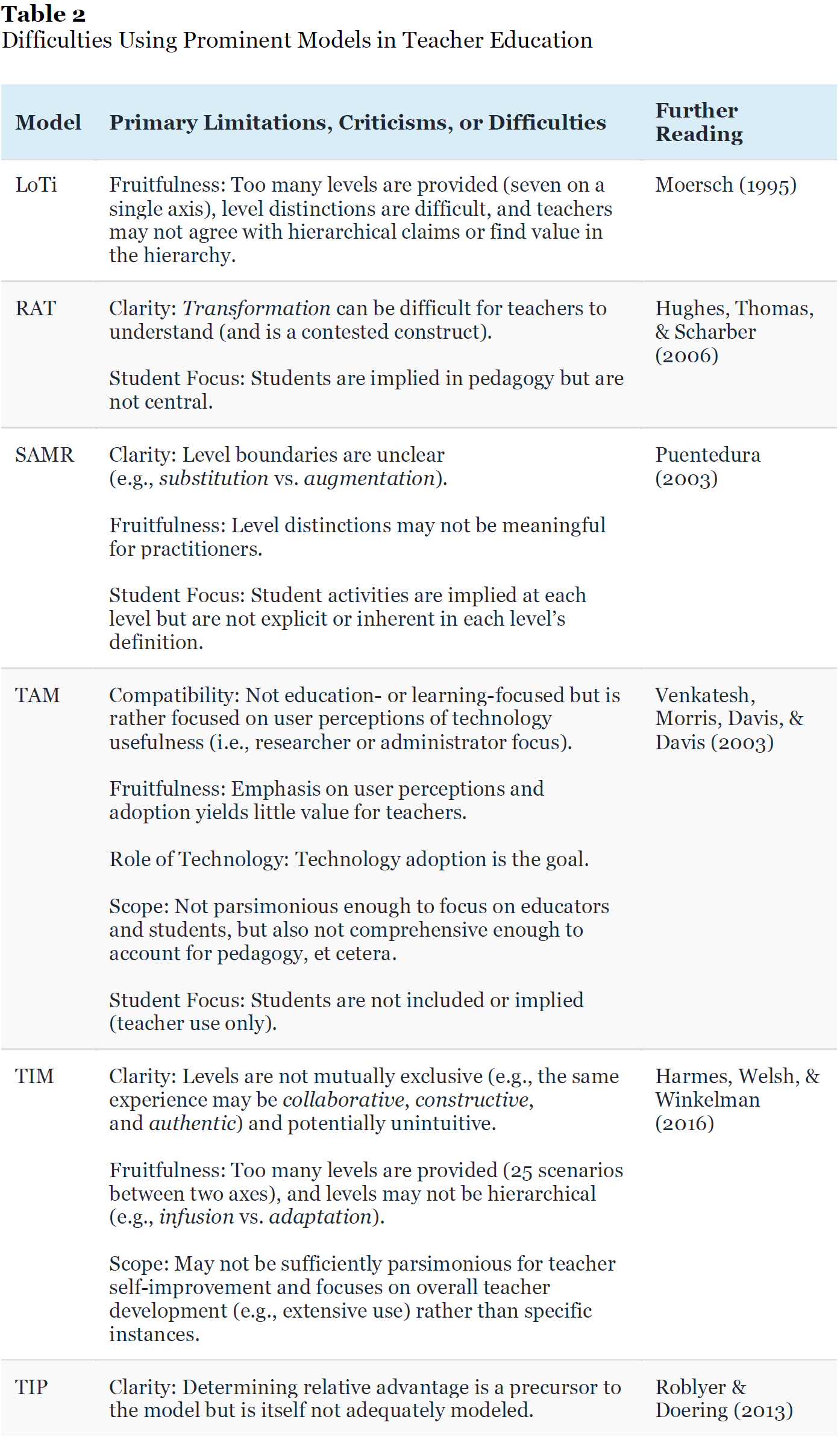

팁 7 교육생이 전문가 간 팀원들과 협업하도록 장려하기

Tip 7 Encourage trainees to collaborate with interprofessional team members

대부분의 SDM 모델은 임상의-환자 DYAD에 초점을 맞추고 있습니다. 그러나 레가레와 동료들이 개발한 전문직 간 SDM 모델은 다른 의료 분야의 팀원이 중요한 역할을 할 수 있다는 점을 강조합니다(레가레 외, 2011). 이 모델에 포함된 팀원은 일반적으로 기존 모델에 포함된 임상의와 환자를 제외한 '첫 번째 접촉자', 의사 결정 코치, 가족 및 기타 의료 전문가입니다. 의대생과 간호대생을 대상으로 한 롤플레잉 워크숍과 같이 공유 의사결정 역량을 개발하기 위해 고안된 일부 커리큘럼에서는 전문가 간 모델을 성공적으로 활용하고 있습니다(Grey 외. 2017).

Most models for SDM are focused on the clinician-patient dyad. However, the interprofessional SDM model developed by Legare and colleagues highlights that team members from other health care disciplines can play crucial roles (Legare et al. 2011). Team members included in this model are the ‘first contact,’ decision coach, family, and other healthcare professionals apart from the clinician and patient typically included in traditional models. Some curricula designed to develop competencies in shared decision making have successfully utilized an interprofessional model, such as in a role-playing workshop for medical and nursing students (Grey et al. 2017).

교육생이 선호도에 민감한 결정을 위해 환자를 공동 의사 결정에 참여시키는 옵션을 고려할 때, 교육자는 교육생이 팀원을 참여시킬 수 있는 방법을 고려하도록 유도할 수 있습니다. 전문가 간 팀과의 협업은 환자 의사결정 지원 도구의 사용을 장려할 때 특히 도움이 될 수 있습니다. 모든 직원 간의 '응집성coherence'은 환자 의사결정 지원 도구를 옹호하고 채택을 지원하는 데 도움이 될 수 있습니다(Joseph-Williams 외. 2021). 예를 들어,

- 수련의가 환자와 전립선암 검진에 대해 논의할 준비를 하는 경우, 의료 보조원은 방문 전에 환자에게 연락하여 수련의와 논의할 환자 의사결정 보조 도구를 공유하여 환자가 치료 결정에 참여할 수 있는 계기를 마련할 수 있습니다.

- 결정을 내리기 전에 환자의 가치관과 선호도에 대한 추가 설명이 필요한 경우, 교육생은 환자(및 가족)가 의사 결정 코치 역할을 통해 환자를 지원할 수 있는 팀 간호사, 사회 복지사 또는 심리학자와 후속 조치를 취하도록 권장할 수 있습니다.

교육생은 전문가 간 모델에 참여함으로써, 시간이 너무 많이 소요될 것이라는 믿음과 같은 공동 의사 결정의 장벽을 극복할 수 있습니다.

As a trainee considers options to engage a patient in shared decision making for a preference-sensitive decision, educators can prompt trainees to consider ways to involve team members. Collaborating with an interprofessional team can be particularly helpful when trying to encourage use of a patient decision aid – ‘coherence’ among all staff can help to champion a patient decision aid and assist in its adoption (Joseph-Williams et al. 2021). For example,

- if a trainee is preparing to discuss prostate cancer screening with a patient, the medical assistant could contact the patient in advance of the visit to share a patient decision aid that will be discussed with the trainee in order to set the stage for participation in treatment decisions.

- If the patient’s values and preferences need further clarification prior to making a decision, the trainee can encourage the patient (and family members) to follow up with the team nurse, social worker, or psychologist who can support a patient by acting as a decision coach.

By engaging in an interprofessional model, trainees can overcome barriers to shared decision making, such as the belief that it will take too much of their time.

팁 8 교육생에게 위험과 이익을 설명할 때 정량적 언어를 사용하도록 권장하세요.

Tip 8 Recommend trainees use quantitative language to describe risk and benefit

SDM은 근거 기반 의학에서 파생된 환자와의 명확한 위험 및 혜택 커뮤니케이션을 필요로 합니다(호프만 외. 2014). 임상의는 환자가 의사 결정에 반영하기 위해 이러한 요소의 규모를 이해할 수 있도록 의사소통을 할 수 있어야 합니다. 따라서 위험과 이점에 대한 모호한 정성적 설명은 일반적으로 SDM에 부적합합니다. 실제로 위험에 대한 정성적 설명은 정량적 위험 설명보다 정확도, 만족도가 낮고 위험 인식이 높은 것으로 나타났습니다(Zipkin 외. 2014).

SDM requires clear communication of risks and benefits with patients, which is derived from evidence-based medicine (Hoffmann et al. 2014). Clinicians must be able to communicate so that patients can appreciate the magnitude of these factors in order to incorporate them into decision making. Thus, vague qualitative statements about risks and benefits are generally inadequate for SDM. In fact, qualitative descriptions of risk have been shown to have lower accuracy, satisfaction, and higher risk perception than quantitative risk descriptions (Zipkin et al. 2014).

교육생은 정량적 위험 설명에 대한 모범 사례를 사용하도록 지도받을 수 있습니다. 여기에는 상대적 위험 감소 또는 치료에 필요한 수보다는 절대적 위험 감소를 사용하고 위험과 이점을 맥락에 맞게 배치하는 것이 포함됩니다. 절대적 위험 감소는 상대적 위험 감소나 치료에 필요한 횟수보다 이해의 정확도를 높입니다. 임상의는 환자가 더 흔히 접하는 다른 빈도(예: 가정 내 사고로 인한 연간 사망 위험 1만 명 중 1명)와 비교하여 위험과 이득을 맥락에 맞게 배치할 수 있습니다.

Trainees can be coached to use best practices for quantitative risk description. These include use of absolute risk reduction rather than relative risk reduction or number needed to treat and placing risks and benefits in context. Absolute risk reduction leads to greater accuracy of understanding than either relative risk reduction or number needed to treat. Clinicians can place risk and benefit in context by comparing them to other frequencies that patients more commonly encounter – for example, the 1 in 10,000 annual risk of death from accidents in the home.

또한 교육생은 위험과 이득에 대한 의사소통에 참여할 때 환자의 수리력을 평가하도록 권장해야 합니다. 수리 능력이 낮은 환자의 경우, 의사 결정에 가장 중요한 정보('적은 것이 더 많다')만 제공하여 계산의 필요성을 줄이도록 교육생에게 권장할 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, 위험이나 이득에 대해 동일한 분모를 사용하면 환자가 더 쉽게 비교할 수 있습니다(예: 100분의 7과 100분의 2는 50분의 1과 100분의 7보다 더 명확합니다). 다음 팁에서 설명하듯이 시각적 표시는 모든 환자, 특히 수리 능력이 낮은 환자에게도 도움이 될 수 있습니다(Peters 외. 2007).

Trainees also need to be encouraged to assess patient numeracy when engaging in communication about risk and benefit. For patients who have lower numeracy skills, trainees can be encouraged to provide only the most crucial information (‘less is more’) to make the decision and to reduce the need for calculations. For example, using the same denominator for risks or benefits allows patients to more easily compare them (e.g. 2 in 100 compared to 7 in 100 is clearer than 1 in 50 compared to 7 in 100). As discussed in the next tip, visual displays can also be helpful for all patients, especially those with lower numeracy skills (Peters et al. 2007).

팁 9 수련의가 환자와 상담할 때 위험과 이득을 시각적으로 표시하도록 권장합니다.

Tip 9 Encourage trainees to use visual displays of risk and benefit to counsel patients

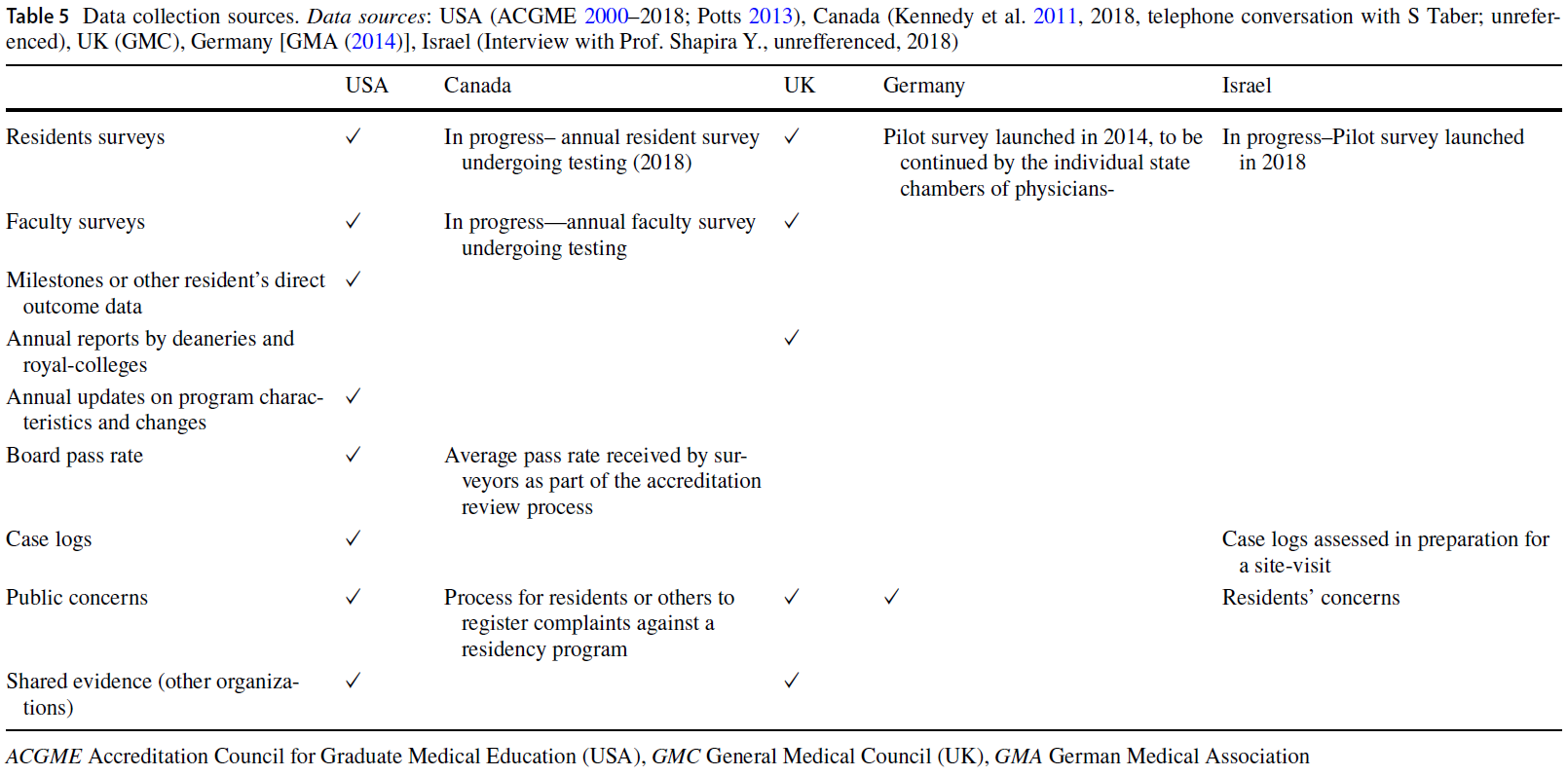

데이터를 시각적으로 표시하면 환자가 위험과 이득에 대한 수치적 질문에 답하는 능력이 향상되고 위험과 이득이 어떻게 비교되는지에 대한 전반적인 이해도가 높아집니다(Zipkin 외. 2014). 근거 기반 의학에서 비롯된 이러한 이해는 SDM에 필수적입니다(Hoffmann 외. 2014). 교사는 교육생에게 시각적 디스플레이의 품질을 평가하는 방법과 SDM 대화에 포함되는 시각적 디스플레이의 가치를 평가하는 방법을 가르칠 수 있습니다.

Visual displays of data increase the ability of patients to answer numerical questions about risk and benefit and increase their general understanding of how risks and benefits compare (Zipkin et al. 2014). This understanding that comes from evidence based medicine is vital for SDM (Hoffmann et al. 2014). Teachers can instruct trainees how to assess the quality of visual displays and to value their inclusion in SDM conversations.

환자 의사결정 지원 자료에서 가장 많이 사용되는 시각적 데이터 표시는 막대 그래프와 아이콘 배열 또는 픽토그램입니다. 연구 결과에 따르면 두 형식 모두 환자의 이해도에는 차이가 없는 것으로 나타났습니다. 그러나 일부 연구에 따르면 아이콘 배열이 환자에게 더 유용하고 효과적이라고 여겨지는 것으로 나타났습니다. 아이콘 배열은 분자가 작은 위험이나 이점에 더 적합하고 막대 그래프는 분자가 중간 또는 큰 위험이나 이점에 더 적합할 수 있습니다(McCaffery 외. 2012; Zipkin 외. 2014). 또한 연구에 따르면 두 가지 관련 위험(예: 스타틴을 사용할 때와 사용하지 않을 때의 심장마비 위험)을 동일한 아이콘 배열에 표시할 경우 위험 인식과 걱정이 줄어든다고 합니다. 따라서 교사는 환자의 의사 결정 보조 도구를 선택할 때 막대 그래프와 아이콘 배열을 사용하는 것의 가치를 강조할 것을 권장합니다.

The most used visual displays of data in patient decision aids are bar graphs and icon arrays or pictographs. Studies show no difference in patient understanding with either format. However, some studies have found that icon arrays are viewed as more helpful and effective by patients. Icon arrays may be better suited to risks or benefits with smaller numerators while bar graphs may be better suited to risks or benefits with medium or larger numerators (McCaffery et al. 2012; Zipkin et al. 2014). Studies also show that risk perception and worry are reduced when two related risks (e.g. risk of heart attack with and without use of a statin) are displayed on the same icon array. Thus, we recommend that teachers highlight the value of using bar graphs and icon arrays when selecting a patient decision aid.

팁 10 수련의가 임상 의사 결정에서 불확실성을 받아들이도록 돕고 환자에게 불확실성의 존재에 대해 상담할 수 있도록 지도합니다.

Tip 10 Help trainees to accept uncertainty in clinical decision making and coach them in counseling patients about its presence

불확실성은 임상의학에 내재되어 있습니다.

- 추계적 불확실성은 특정 환자에 대한 알 수 없는 결과(예: 환자가 개인적으로 암에 걸릴지 여부)를,

- 개연적 불확실성은 경험적 데이터가 부족하거나 상충되는 경우(예: 암 검진의 혜택 정도)를,

- 정보적 불확실성은 특정 임상 상황에 대한 유용한 정보의 부족(예: 석면 노출에 따라 내 환자의 폐암 위험이 이 시험에 참여한 평균 사람보다 얼마나 큰가?)을 의미합니다.

Uncertainty is intrinsic to clinical medicine.

- Stochastic uncertainty refers to unknown outcomes for a particular patient (e.g. whether or not they personally will develop cancer),

- probabilistic uncertainty refers to lack of or conflicting empirical data (e.g. the degree of benefit of cancer screening), while

- informational uncertainty refers to lack of usable information for a particular clinical situation (e.g. how much greater is my patient’s risk for lung cancer than the average person in this trial based on her asbestos exposure?).

일부 데이터에 따르면 환자 의사 결정 보조 도구를 사용하면 환자의 의사 결정에 대한 불확실성을 줄일 수 있으며, 이는 SDM의 목표입니다. 그러나 어느 정도의 불확실성은 수정할 수 없습니다(Politi 외. 2016). 이러한 모든 형태의 불확실성은 의사 결정에 영향을 미칠 수 있으며, 많은 사람들이 환자에게 불확실성을 명시적으로 인정할 것을 권장합니다(Politi and Street 2011; Berger 2015). 그러나 임상에서 불확실성은 거의 논의되지 않는데, 이는 많은 레지던트가 자신감을 표현하도록 훈련받았고 불확실성에 대해 논의하는 것이 환자의 혼란과 불안으로 이어질 것을 우려하기 때문일 수 있습니다(Politi and Street 2011).

Some data suggests that use of patient decision aids can reduce patient uncertainty in their decision making, which is a goal of SDM. However, some degree of uncertainty is not modifiable (Politi et al. 2016). All of these forms of uncertainty may affect decision making, and many recommend that uncertainty is explicitly acknowledged with patients (Politi and Street 2011; Berger 2015). However, uncertainty is rarely discussed in clinical practice, perhaps because many residents are trained to display confidence and are worried that discussing uncertainty will lead to patient confusion and anxiety (Politi and Street 2011).

레지던트들은 경험이 많은 주치의에 비해 불확실성을 전달할 때 불안감을 더 많이 느낍니다(Politi and Legare 2010). 이러한 불안을 직접적으로 인정하고 불확실성을 논의하는 접근 방식을 제안하고 롤모델을 제시할 수 있습니다. 버거는 환자와의 불확실성을 해결하기 위한 전략의 '툴킷'을 제시합니다(Berger 2015).

- 불확실성의 존재에 대한 정직함과 개방성,

- (예측할 수 없는 질병의 특성에도 불구하고 긍정적인 결과에 대한) 희망,

- (환자의 임상 상황이나 새로운 임상시험 데이터에 대한) 새로운 정보가 입수되면 기꺼이 결정을 재검토하겠다는 의지

불확실성에 대한 솔직한 표현은 많은 수련의들이 생각하는 것처럼 불안과 실망으로 이어지기보다는 환자 만족도를 향상시킬 수 있다는 점에 주목할 필요가 있습니다(Gordon 외. 2000). 수련의는 환자가 기대한 대로 혜택을 받고 있는지 확인하기 위해 언제 결정을 재검토할 것인지에 대한 계획을 세우도록 권장해야 합니다(Politi and Street 2011).

Residents have increased anxiety in communicating uncertainty when compared to experienced attending physicians (Politi and Legare 2010). This anxiety can be directly acknowledged and approaches to discussing uncertainty can be suggested and role modeled. Berger offers a ‘toolkit’ of strategies to address uncertainty with patients, including

- using honesty and openness about the presence of uncertainty,

- hope (for positive outcomes despite unpredictable nature of disease), and

- a willingness to readdress the decision as new information is obtained (about the patient’s clinical situation or new trial data) (Berger 2015).

It is notable that honest expressions of uncertainty can improve patient satisfaction (Gordon et al. 2000), rather than lead to anxiety and disappointment, as many trainees assume. Trainees should be encouraged to make a plan for when to readdress the decision to see if the patient is benefiting as hoped (Politi and Street 2011).

팁 11 표준화 환자를 사용하여 공동 의사 결정 역량 개발하기

Tip 11 Use standardized patients to develop competencies in shared decision making

표준화 환자(SP)를 사용하면 교육생의 평가 및 평가에 도움이 될 뿐만 아니라 SDM의 역량을 개발하는 데도 도움이 됩니다(Elwyn 외. 2016). SDM을 가르치기 위해 출판된 교육 프로그램의 약 절반이 어떤 형태로든 표준화 환자를 활용합니다(Singh Ospina 외. 2020). 표준화 환자를 교육자로 활용하면 학습자의 지식, 역량, 태도에 긍정적인 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다. SDM의 경우, SP를 사용하면 핵심 커뮤니케이션 역량의 채택이 증가하고 SDM에 대한 태도가 개선되었습니다(Rusiecki 외. 2018; Amell 외. 2022). SP를 사용하면 학습자는 SDM 역량을 실천에 옮기고 이를 실제 환자와의 업무에 적용할 수 있는 능력에 대한 자신감을 키울 수 있습니다. 우리는 교육자들이 새로운 역량 개발에 필수적인 이러한 경험을 개발할 때 학습 환경을 조성하는 데 특히 주의를 기울일 것을 권장합니다(Knowles 1975). 학습자가 언어를 '가지고 놀면서' 자신의 개인적 및 실무적 선호도에 맞는 것이 무엇인지 확인할 수 있도록 연습이 설계되었다는 점을 인정하면, 특히 학습자가 그룹으로 연습하는 경우 위험을 감수하는 것을 정상화normalize하는 데 도움이 됩니다.

Use of standardized patients (SPs) can assist not only in the assessment and evaluation of trainees, but also serves to develop competencies in SDM (Elwyn et al. 2016). Approximately half of published educational programs to teach SDM utilize standardized patients in some form (Singh Ospina et al. 2020). When SPs are used as educators, they can positively impact learner knowledge, competencies, and attitudes. In the case of SDM, use of SPs has led to increased adoption of core communication competencies and improved attitudes towards SDM (Rusiecki et al. 2018; Amell et al. 2022). Use of SPs allows learners to put SDM competencies into practice and build confidence in their ability to apply this to their work with real patients. We encourage educators to pay particular attention to setting the learning climate when developing these experiences, which is essential for new competency development (Knowles 1975). Acknowledging that exercises are designed for learners to ‘play with’ language to see what fits their personal and practice preferences helps normalize risk-taking, especially if learners are in groups.

팁 12 교육생과 협력하여 공동 의사 결정을 관찰하고 행동 체크리스트를 사용하여 목표를 개발하고 피드백을 제공하세요.

Tip 12 Partner with trainees to observe shared decision making and consider using behavior checklists to develop goals and provide feedback

교육생과 교육자가 공동 의사 결정 역량을 키우겠다는 목표를 공유하는 경우, 구체적인 피드백을 제공하려면 직접 관찰하는 것이 중요합니다. 관찰에 앞서 교육생과 교육자는 SDM 교육생이 집중하고 싶은 측면을 정의하는 목표를 설정하는 데 협력할 수 있습니다(Ajjawi와 Regehr 2019). 피드백은 협력적이고 공동 건설적인 과정으로 유지하는 것이 중요하지만, 교육자는 OPTION 척도(Elwyn 외. 2003, 2013) 및 SHARE 모델(Hargraves 외. 2020)과 같은 행동 체크리스트를 사용하여 구체적이고 행동적인 피드백을 제공할 수 있습니다. 추가 도구로는 환자가 교육생에게 피드백을 제공할 수 있는 이원적 OPTION 도구가 있습니다(Melbourne 외. 2010). 교육자는 SHARE 또는 '세 가지 대화' 프레임워크와 이러한 행동 체크리스트를 함께 검토하여 교육생이 SDM 역량 개발을 위한 목표를 개발하는 데 도움을 줄 수 있습니다. 이를 통해 교육생과 교육자는 피드백을 위한 공유 계획을 가지고 관찰에 들어갈 수 있습니다.

When trainees and educators share a goal of building competencies in shared decision making, direct observation is vital to providing specific feedback. In advance of observation, trainees and educators can collaborate on constructing goals that define what aspect of SDM trainees want to focus on (Ajjawi and Regehr 2019). While it is important that feedback remain a collaborative and co-constructive process, educators can use behavior checklists such as the OPTION scale (Elwyn et al. 2003; 2013) and SHARE model (Hargraves et al. 2020) to assist in giving specific and behavioral feedback. An additional tool is the dyadic OPTION instrument, which allows patients to provide feedback to the trainee (Melbourne et al. 2010). Educators can assist trainees in developing goals for developing competencies in SDM by reviewing the SHARE or ‘three-talk’ frameworks and these behavior checklists together. This allows trainees and educators to go into observation with a shared plan for feedback

결론

Conclusions

SDM은 접근 가능한 방식으로 위험과 이득을 논의하고 관계를 구축하는 역량이 필요한 복잡한 프로세스입니다. 시간과 교육생 참여 등 SDM을 가르치는 데는 여러 가지 장벽이 있지만, 이 팁이 모든 형태의 임상 교육에 통합할 수 있는 전략을 제공할 수 있기를 바랍니다. SDM의 가치와 참여 기회, 가장 효과적인 방법을 강조함으로써 교사는 학생들이 수련 프로그램의 목표를 달성하고 환자 중심의 고가치 진료를 제공할 수 있는 능력을 향상하도록 도울 수 있습니다.

SDM is a complex process that requires competencies in relationship-building and discussion of risk and benefit in an accessible way. While there are a number of barriers to teaching SDM including time and trainee engagement, we hope that these tips provide strategies that can be integrated into all forms of clinical teaching. By highlighting the value of SDM, opportunities to engage in it, and ways to do so most effectively, teachers can help students meet the goals of their training program and enhance their ability to provide patient-centered and high-value care.

Twelve Tips for teaching shared decision making

Affiliations collapse

PMID: 35793200

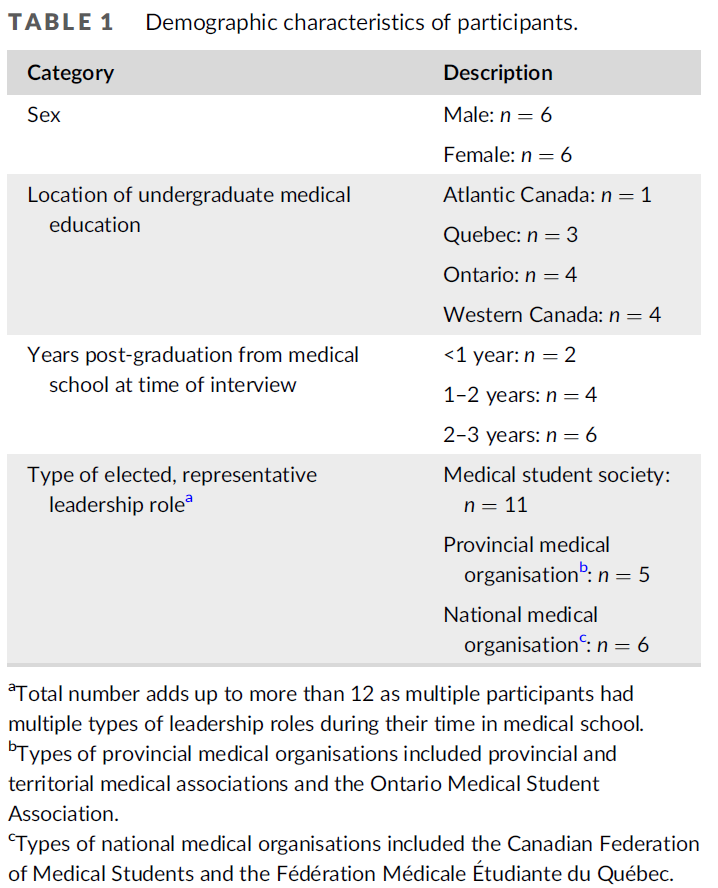

Abstract

Shared decision making (SDM) is a process in which preference-sensitive decisions are discussed with patients in a collaborative and accessible format so that patients can select an option that integrates their values and preferences into the context of evidence-based medicine. While SDM has been shown to improve some metrics of quality of care and is now included in many competencies developed by accreditation bodies, it can be challenging to successfully incorporate competencies in SDM into clinical teaching. Multiple interventions and curricula that build competency in SDM have been published, but here we aim to suggest ways to integrate teaching competencies in SDM into all forms of clinical teaching. These twelve tips provide strategies to foster trainee development of the relational and risk-benefit communication competencies that are required for successful shared decision making.

Keywords: Decision-making; PDAs; communication skills.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 임상교육(Clerkship & Residency)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 근거중심의학과 공유의사결정의 연결(JAMA, 2014) (0) | 2024.01.02 |

|---|---|

| 복잡성 보기: 공유의사결정의 렌즈로서 문화-역사적 활동이론(CHAT) (Acad Med, 2021) (0) | 2024.01.02 |

| 내과의 종단적 코칭 프로그램에서 목표의 공동구성 및 대화(Med Educ, 2022) (0) | 2023.11.14 |

| 보건의료 업무를 통한 학습: 전제, 기여, 실천(Med Educ, 2016) (0) | 2023.11.12 |

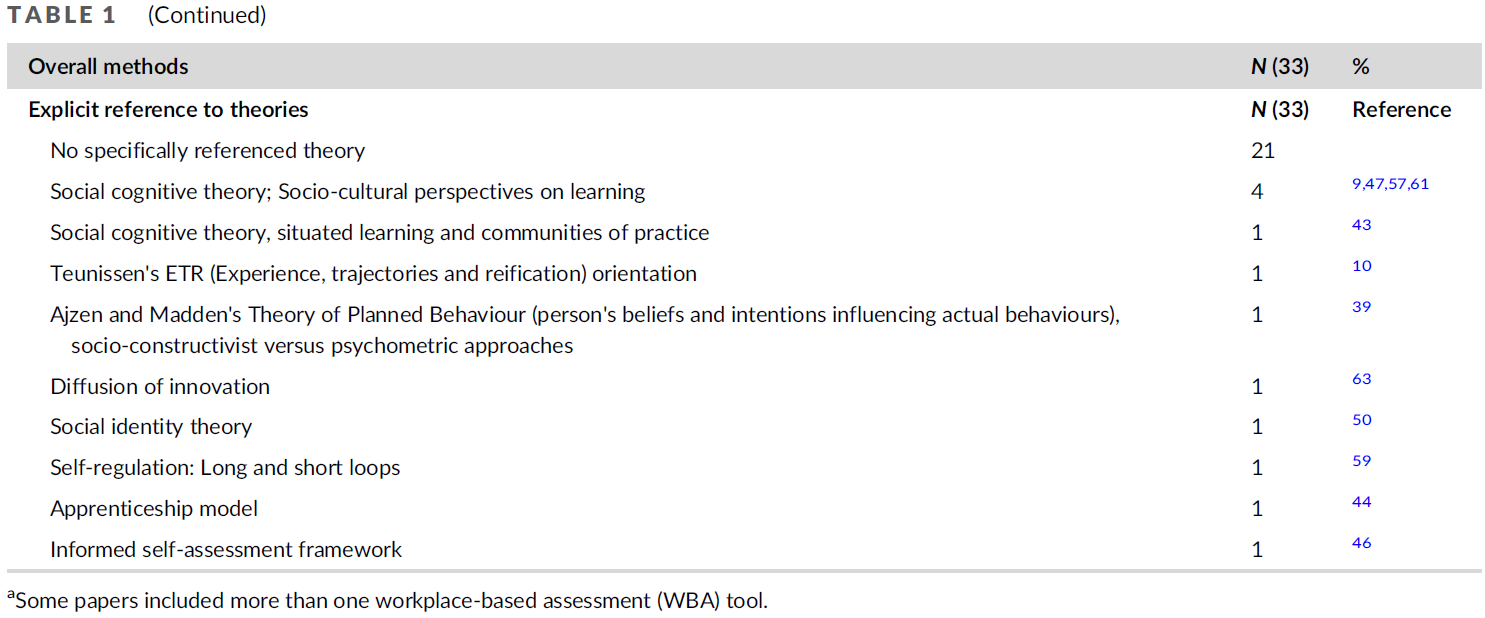

| 어떻게 근무현장-기반 평가가 졸업후교육에서 학습을 가이드하는가: 스코핑 리뷰 (Med Educ, 2023) (0) | 2023.11.10 |