연구-바탕 교육과정 설계에서의 실제성 프레임워크 (TEACHING IN HIGHER EDUCATION, 2017)

A framework for authenticity in designing a research-based curriculum

Navé Wald and Tony Harland

소개

Introduction

저희는 뉴질랜드 오타고 대학교의 학부 생태학 커리큘럼을 살펴보던 중 고등 교육에서 진정성이라는 주제에 관심을 갖게 되었습니다(Harland, Wald, Randhawa, 곧 출간 예정). 이 프로그램에서 학생들은 연구를 통해 학습하며, '진정성'이라는 개념은 오랫동안 학습 활동 설계의 중심이 되어 왔습니다. 기본 아이디어는 학생들이 생태학을 공부할 때마다 어떤 형태로든 진정성 있는 연구에 참여해야 한다는 것입니다. 우리가 진정성이라고 생각하는 것을 달성하기 위해 교사는 전문적인 연구 활동을 사용하여 학생들을 안내합니다. 진정성을 갖추기 위해 교사-학생 관계는 대학원 감독과 호환되는 모델로 전환됩니다. 교육 및 커리큘럼에 대한 이러한 일반적인 접근 방식은 연구자로서 학생을 가르치기 위한 전략 2에서 Jenkins, Healey, Zetter(2007)에 의해 설명되었지만, 이 저자들은 진정성을 주장하지는 않습니다. 생태학에서는 이전에는 '진정성'의 정확한 의미를 고려하지 않았으며, 이 글에서는 이 용어의 사용과 관련된 담론적 수사를 이론 및 교육 실무와 관련하여 살펴볼 것입니다. 그런 다음 이러한 지식을 바탕으로 연구를 통해 교수의 진정성에 대한 프레임워크를 제시합니다.

We became interested in the subject of authenticity in higher education while examining the undergraduate ecology curriculum at the University of Otago, New Zealand (Harland, Wald, and Randhawa forthcoming). In this programme, students learn by doing research and the concept of ‘authenticity’ has long been central to the design of learning activities. The basic idea is that anytime students are studying ecology, they should be engaged in some form of authentic research. In order to achieve what we consider as authenticity, teachers use their professional research activities to guide them. In order to be authentic, the teacher-student relationship shifts towards a model compatible with postgraduate supervision. This general approach to teaching and curriculum has been described by Jenkins, Healey, and Zetter (2007) in their Strategy 2 for teaching students as researchers, although these authors do not claim authenticity. In ecology, we had not previously considered the precise meaning of ‘authenticity’ and in this essay the discursive rhetoric around the use of the term will be examined in relation to theory and teaching practice. We then use this knowledge to offer a framework for authenticity in teaching through research.

우리는 연구자로서 학생들을 가르치는 다양한 모델에서 진정성에 대한 주장을 찾기 시작했지만(Hung and Chen 2007, Laursen 외. 2010, Sadler 외. 2010, Sadler and McKinney 2010), 고등 교육에서도 다양한 맥락에서 진정성이 사용된다는 사실을 발견했습니다. 여기에는 교수 및 학습(Cranton 2001, Cranton과 Carusetta 2004a, 2004b, Herrington과 Herrington 2006, Herrington, Reeves, Oliver 2014), 평가(Frey, Schmitt, and Allen 2012, Gulikers, Bastiaens, Kirschner 2004, Herrington과 Herrington 1998), 성취(Newmann 1996, Newmann과 Archbald 1992) 등이 포함됩니다. 거의 모든 경우에서 '진정성' 또는 '진정성 있는 행동'을 구성하는 요소의 의미는 완전히 설명되지 않았으며, 따라서 여전히 애매한 상태로 남아 있습니다. 고등 교육에서 진정성에 대한 연구는 결코 미지의 영역이 아니지만, 역사적 측면에서 보면 20세기 듀이주의 사상(Petraglia 1998)에 뿌리를 둔 비교적 최근의 아이디어이므로 교육의 진정성에 대한 탐구는 긴 궤적을 가지지 않습니다(Splitter 2009).

Although we set out to find claims to authenticity in various models of teaching students as researchers (Hung and Chen 2007; Laursen et al. 2010; Sadler et al. 2010; Sadler and McKinney 2010), we discovered that it was also used in many different contexts in higher education. These include teaching and learning (Cranton 2001; Cranton and Carusetta 2004a, 2004b; Herrington and Herrington 2006; Herrington, Reeves, and Oliver 2014), assessment (Frey, Schmitt, and Allen 2012; Gulikers, Bastiaens, and Kirschner 2004; Herrington and Herrington 1998), and achievement (Newmann 1996; Newmann and Archbald 1992). In nearly all cases the meaning of what constitutes ‘being authentic’ or ‘doing something authentically’ is not fully explained and thus remains elusive. While the study of authenticity in higher education is by no means uncharted territory (for examples see Carusetta and Cranton 2005; Cranton and Carusetta 2004a, 2004b; Kreber 2013; Kreber et al. 2007), in historical terms it is a relatively recent idea rooted in twentieth-century Deweyan thought (Petraglia 1998), and thus inquiries into educational authenticity do not have a long trajectory (Splitter 2009).

진정성의 복잡성을 이해하기 시작하려면 용어의 다양한 용도와 정의를 살펴보는 것부터 시작할 수 있습니다. 옥스퍼드 영어 사전(1989)은 '진위성'을 명사로, '진품'을 형용사이자 명사로 정의합니다. 주로 이러한 용어는 사람, 문서, 인공물, 아이디어, 행동, 정체성, 프로세스 등 어떤 것을 지칭합니다. - 진짜, 진품, 진실, 원본, 사실, 정확성, 유효성, 권위 등의 고유한 특성을 지닌 것으로 인식되는 것을 의미합니다. 정확한 의미는 구체적인 맥락에 따라 달라집니다. 사회학적 관점에서 '진정성은 존재의 상태가 아니라 과정이나 표현의 객관화, 즉 특정 시간과 장소의 사람들이 이상이나 모범을 대표한다고 동의하게 된 일련의 자질을 의미합니다'(Vannini and Williams 2009, 3). 따라서 진정성은 사회적으로 구성되므로 유동적이고 맥락에 따라 달라지며 논쟁의 대상이 될 수 있습니다. 따라서 진정성의 구성은 권력, 현실성, 권위, 그리고 궁극적으로는 우월성에 대한 내재적이고 암묵적인 아이디어를 암시합니다. 따라서 진정성은 다양한 의미와 가치가 담긴 키워드입니다(Williams 1976).

To begin to appreciate the complexity of authenticity one can start by examining the term’s various uses and definitions.

- The Oxford English Dictionary (1989) defines ‘authenticity’ as a noun and ‘authentic’ as both adjective and noun. Primarily, these terms refer to something – person, document, artefact, idea, behaviour, identity, process, etc. – having the perceived inherent quality of being real, genuine, true, original, factual, accurate, valid, authoritative, and so forth. The exact meaning will depend on the specific context at hand.

- From a sociological perspective, ‘Authenticity is not so much a state of being as it is the objectification of a process or representation, that is, it refers to a set of qualities that people in a particular time and place have come to agree represent an ideal or exemplar’ (Vannini and Williams 2009, 3).

Thus, authenticity is socially constructed and as such is fluid, highly contextual and may be contested. Constructions of authenticity, then, allude to inherent and implicit ideas of power, realness, authority and, ultimately, of superiority. Authenticity is, therefore, a keyword laden with a range of meanings and values (Williams 1976).

연구를 통해 과학을 가르친다는 좁은 맥락에서조차도 실질적으로 다른 교육 모델과 관련하여 진정성에 대한 주장이 제기되는 것은 놀라운 일이 아닙니다. 그런 다음 우리는 '어떤 이유로 사건과 경험이 어떻게 해석되고 해석되어야 하는지에 대해 궁금증을 불러일으킬 때 철학을 해야 한다'고 주장한 맥신 그린(1973, 10)에서 힌트를 얻습니다. 달리 말하면, 그린은 우리가 파편화되고 의미가 거의 없는 그림에서 더 나은 일관성을 추구할 때 추상화로 전환할 것을 촉구합니다. 따라서 이 글에서는 이 용어의 사용과 관련된 담론적 수사를 살펴볼 것입니다. 진정성에 관한 문헌을 읽은 것은 연구를 통한 학습의 원리와 진정성 이론을 연결할 수 있는 중요한 아이디어를 발견하기 위한 목적으로 특별히 수행되었습니다. 본질적으로 우리는 '우리의 작업이 '진정성있다'라는 말을 이해하는 데 도움이 되는 매우 복잡한 현상에서 무엇을 취할 수 있을까'라는 연구 질문을 던졌습니다. 문헌 검토를 통해 새롭게 등장한 연관성을 바탕으로 교육과 학습, 그리고 진정성에 대한 현재의 논쟁에 정보를 제공하기 위해 설계된 프레임워크를 구축했습니다. 그 결과, 우리의 질문과 관련된 진정성을 이해하는 세 가지 방법을 확인할 수 있었습니다:

It is of little surprise then that even within the narrower context of teaching science through research, claims for authenticity are made in relation to substantially different educational models. We then take a cue from Maxine Greene (1973, 10) who argued we ought to ‘philosophize when, for some reason, we are aroused to wonder about how events and experiences are interpreted and should be interpreted’. Put differently, Greene urges us to turn to abstraction when we seek better coherence from a picture otherwise fragmented and of little sense. In this article, therefore, the discursive rhetoric around the use of the term will be examined. Our reading of the literature on authenticity was done specifically with the purpose of discovering significant ideas that might connect the principles of learning through research with the theories of authenticity. Essentially we were asking the research question: ‘what can we take from a highly complex phenomenon that would help us understand our work as authentic?’ After our literature review, emerging associations were used to construct a framework designed to inform both teaching and learning and the current debates around authenticity. We were able to identify three ways of understanding authenticity that were relevant to our inquiry:

- '실제 세계'와 관련된 진정성

Authenticity as relating to the ‘real-world’ - 실존적인 진정한 자아

The existential authentic self - 의미의 정도

A degree of meaning

'현실 세계'와 관련된 진정성

Authenticity as relating to the ‘real world’

진정성을 과학교육과 연결하는 가장 일반적이고 응용적인 관점은 '실제 세계'를 반영하는 교육입니다. 간단히 말해, '진정성 있는 과학은 과학자들이 연구하는 방식과 밀접하게 일치하는 탐구 교육의 변형이며 전통적인 학교 과학 실험실 실습과는 다르다'(크로포드 2015, 113)고 할 수 있으며, 이 개념은 우리가 여기서 다루는 생태 프로그램의 커리큘럼 설계에 큰 지침이 되었습니다. 과학교육의 진정성에 대한 이러한 단순한 개념화는 '상응하는 관점'(Kreber 2013, Splitter 2009)으로도 알려져 있으며, 존 듀이와 진보주의 운동의 실용주의 교육적 신념과 강하게 공명합니다. 듀이는 엘리트주의-이상주의 교육과 직업-도제 교육 사이의 확립된 이분법을 거부했는데, 이는 '아이디어의 궁극적 중요성은 현실 세계에 적용될 때 그 결과에서 찾을 수 있다는 가정에 뿌리를 둔 거부'였습니다(Petraglia 1998, 26). 따라서 페트라글리아(1998)는 듀이가 교육과 '실제 삶' 사이의 벽을 허물고, 이를 통해 진정성에 대한 특정한 수사학을 확립한 영향력 있는 유산을 남겼다고 평가합니다. 듀이는 '학습은 학생들에게 '배울 것'이 아니라 '할 일'이 주어질 때 일어난다'고 믿었으며, 학생들이 하는 일은 '실제 삶'과 관련되어야 하며, 이것이 바로 이러한 접근 방식을 의미 있고 가치 있게 만드는 이유입니다(Greene 1973, 158, 원문에서 강조).

The most common and applied perspective that links authenticity with science education is teaching that mirrors the ‘real world.’ Put simply, ‘Authentic science is a variation of inquiry teaching that aligns closely with how scientists do their work and differs from traditional school science laboratory exercises’ (Crawford 2015, 113), and this concept has largely guided the curriculum design of the ecology programme that we address here. This simple conceptualisation of authenticity in science education, also known as the ‘corresponding view’ (Kreber 2013; Splitter 2009), strongly resonates with the pragmatist pedagogical beliefs of John Dewey and the Progressivist movement. Dewey rejected the established dichotomy between an elitist-idealist education and vocational-apprenticeship training, a rejection that ‘was rooted in the assumption that the ultimate significance of an idea is to be found in its consequences when applied in the real world’ (Petraglia 1998, 26). Thus, Petraglia (1998) attributes to Dewey the influential legacy of dismantling the wall between education and ‘real life,’ by which a particular rhetoric of authenticity was established. Dewey believed that ‘learning takes place when students are given something to do rather than something to learn,’ and what they do should relate to ‘real life,’ which is what renders this approach significant and worthwhile (Greene 1973, 158, emphasis in original).

예를 들어, 헤링턴, 리브스, 올리버(2014, 401)는 '진정성 있는 학습은 학습 과제를 미래의 사용 맥락에 위치시키는 교육학적 접근 방식'이라고 주장합니다. 따라서 진정한 학습의 모델은 지식이 실제 생활에서 그리고 나중에 어떻게 활용될지를 반영하도록 설계됩니다. 이 접근 방식에 따르면 학생들은 졸업 후 자신이 선택한 직업과 분야에서 지식을 창출하고 혁신을 이룰 수 있는 지식과 기술을 습득해야 합니다. 따라서 진정성은 전문적인 환경에서 지식이 어떻게 생산되고 전달되는지를 반영합니다(Herrington 및 Herrington 2006). 이러한 교육적 접근 방식은 지식이 적용될 맥락에서 의미 있는 학습이 설정된다는 Brown, Collins, Duguid(1989)의 상황적 학습 또는 상황적 인지 이론에 뿌리를 두고 있습니다(Herrington, Reeves, Oliver 2010).

Herrington, Reeves, and Oliver (2014, 401), for example, maintain that ‘Authentic learning is a pedagogical approach that situates learning tasks in the context of future use.’ Models of authentic learning are thus designed to reflect how knowledge will be utilised in real life and at a later time. Accoㄴrding to this approach, students should acquire knowledge and skills that would allow them, after graduation, to create knowledge and innovate in their chosen professions and fields. Therefore, authenticity reflects how knowledge is produced and communicated in professional settings (Herrington and Herrington 2006). This pedagogical approach is rooted in Brown, Collins, and Duguid’s (1989) theory of situated learning or cognition in which meaningful learning is set in the context within which the knowledge will be applied (Herrington, Reeves, and Oliver 2010).

그러나 Hung과 Chen(2007)은 학교 공동체와 전문직 공동체 모두 그 자체로 진정성이 있다고 주장합니다. 그들은 이 두 커뮤니티 간의 관계를 맥락-프로세스 프레임워크 내에서 분석해야 한다고 제안합니다. 이 프레임워크에서 진정성에 대한 접근 방식은 주로 유동적이고 다면적인 정체성 개념과 학교 공동체와 전문직 공동체 사이의 전환과 관련된 정체성의 문화화, 형성 및 변화에 초점을 맞추고 있습니다. Hung과 Chen(2007, 162-3)은 '진정성의 문제를 현실 세계의 실천과 학문에만 국한시켜서는 안 되며, 맥락과 과정 차원을 모두 만족시킬 때 진정성 있는 학습이 가능하다'고 말했는데, 여기서 전자는 실천 공동체를, 후자는 정체성 함양과 변형을 의미합니다. 이와는 대조적으로 Splitter(2009, 139)는 '교실 밖의 세계'에서 일어나는 일이 우리가 진정성이 의미하는 바, 또는 의미할 수 있는 바에 대한 표준을 제공한다는 가정에 의문을 제기합니다. 이 저자는 교실에서 이루어지는 일과 '실제 세계'에서 이루어지는 일 사이의 단순한 관계에 반대합니다. 대신, 스플리터에게 진정성은 과업의 의미, 성취도 또는 가치에 뿌리를 두고 있기 때문에 '실제'에 있는 것은 실제보다 덜 중요하다고 말합니다. 이 개념은 진정성에 대한 주장이 이상화된 관행에 대한 주관적인 가치 판단에 근거한다는 것을 의미합니다(Splitter 2009).

However, Hung and Chen (2007) argue that both what they call school community and professional community are authentic in their own right. They propose that the relationships between these two communities should be analysed within a context-process framework. In this framework, approaches to authenticity focus predominantly on the fluid and multi-faceted notion of identity, and its enculturation, formation and transformation within and in relation to the transition between the school community and the professional community. For Hung and Chen (2007, 162-3) ‘the issue of authenticity should not be constrained to real world practices and disciplines, but authentic learning should be possible when we satisfy both context and process dimensions,’ where the former refers to the practice community and the latter to identity enculturation and transformation. In contrast, Splitter (2009, 139) questions ‘the presumption that what happens in “the world beyond the classroom” offers a standard for what we mean, or might mean, by authenticity.’ This author argues against a simple relationship between what is done in the classroom and what is being done in the ‘real world.’ Instead, for Splitter authenticity is rooted in a task’s degree of meaning, fulfilment or worthiness, and therefore what is ‘out there’ is less important than what ought to be. This idea means that assertions of authenticity are based on subjective value judgments about idealised practices (Splitter 2009).

수학적 모델링을 가르치는 맥락에서 Vos(2011)는 '교육-현실 세계'의 연결고리에 대한 다른 관점을 제시합니다. Vos는 진정성의 개념이 사회적으로 구성되는 것으로 인식하고 특정 맥락에서 진정성을 형성하는 데 신중을 기할 것을 촉구합니다.

- 먼저, 진정성이 사본과 시뮬레이션을 지칭할 수 있는지, 아니면 무조건적인 원본을 지칭할 수 있는지 결정해야 합니다.

- 두 번째 고려 사항은 진위가 예/아니오의 이진법인지, 아니면 어느 정도 서수적 품질을 갖는지에 관한 것입니다.

보스는 진위성의 정의는 이분법적이어야 하며 원본만을 지칭해야 한다고 주장합니다. 따라서 교육 과제는 전체적으로 진정성이 있는 것이 아니라, 진정성 있는 측면을 포함할 수 있습니다. 또한 과제에 진정성 요소가 있으려면 학교 밖 전문가가 인증 할 수있는 학교 밖에서 유래 한 널리 인식 할 수있는 품질이 있어야하며, 이는 '실제로 ... 진정성을 구현'해야합니다 (Vos 2011, 720).

Writing within the context of teaching mathematical modelling, Vos (2011) provides a different view on the ‘teaching-real world’ nexus. Vos recognises the concept of authenticity as being socially constructed and urges its formation in a particular context to be done thoughtfully.

- First, a decision should be made as to whether authenticity can refer to copies and simulations or to unconditional originals.

- The second consideration concerns whether authenticity is a yes/no binary or has an ordinal more-or-less quality.

Vos argues that a definition of authenticity should be a binary and refer only to originals. Consequently, an educational task will never be authentic as a whole; rather, it may contain authentic aspects. In addition, for a task to have authentic elements it must have a widely recognisable quality that has an out-of-school origin certifiable by out-of-school experts, which ‘in fact … embody the authenticity’ (Vos 2011, 720).

실존적 진정성 자아

The existential authentic self

교육에서 진정성의 또 다른 중요한 측면은 실존 철학과 자아 및 존재 감각과 관련이 있습니다. 교육 문헌에서는 교사의 행동 및 가치관, 교사-학생 관계와 관련하여 진정성의 이러한 측면을 논의하는 경향이 있지만, 여기서는 연구를 통해 교육이라는 주제와도 연결하고자 합니다.

Another important facet of authenticity in education is linked to existential philosophy and to a sense of self and of being. Whereas the education literature tends to discuss this aspect of authenticity in relation to teachers’ behaviour and values and to teacher-student relations, here we also wish to link it to the theme of teaching through research.

철학적 관점에서 볼 때, 일부 진정성은 '현대 서구 세계의 문화적 구성물이며 ... [그리고] 개인에 대한 서구의 개념과 밀접하게 연관되어 있다'(Handler 1986, 2). 테일러(1991)의 『진정성의 윤리』에서 그는 이러한 개인주의가 현대 사회의 업적이면서 동시에 그 폐해라고 말하며, 개인주의가 사람들의 의미와 존재감에 미친 결과에 대해 우려하고 있습니다. '진정성'이란 사회적 관습과 압력에도 불구하고 자기 자신에 대해 독창적이고 진실한 것을 의미합니다. 트릴링(1972, 93)은 진정성이 '불길한 의미를 지닌 단어'이며, '이 단어가 우리 시대의 도덕적 속어의 일부가 된 것은 타락한 상태의 특이한 본질, 존재와 개인 존재의 신뢰성에 대한 불안을 가리킨다'고 지적합니다. 기든스(1991)도 자아 정체성, 대인 관계, 도덕성 또는 도덕적 지지와 관련하여 진정성에 대해 논의합니다. 그에 따르면 '진정성 있는 사람은 자신을 알고 그 지식을 담론적으로 그리고 행동 영역에서 상대방에게 드러낼 수 있는 사람'입니다(Giddens 1991, 186-7). 따라서 진정성은 사람들 간의 신뢰와 도덕적 지원을 강화하기 위해 자아의 무결성을 활용하는 데 매우 중요합니다.

From a philosophical standpoint, for some authenticity is ‘a cultural construct of the modern Western world … [and is] closely tied to Western notions of the individual’ (Handler 1986, 2). In Taylor’s (1991) Ethics of Authenticity, this individualism is both an achievement of modern society and its malaise, and he is concerned with the consequences it has had for people’s sense of meaning and being. Being ‘authentic’ means being original and true to one’s self in spite of societal conventions and pressure. Trilling (1972, 93) notes that authenticity ‘is a word of ominous import’ and that this ‘word has become part of the moral slang of our day points to the peculiar nature of our fallen condition, our anxiety over the credibility of existence and of individual existences.’ Giddens (1991) also discusses authenticity in relation to self-identity, interpersonal relationships and morality, or moral support. For him, ‘the authentic person is one who knows herself and is able to reveal that knowledge to the other, discursively and in the behavioural sphere’ (Giddens 1991, 186-7). Authenticity, then, is crucial for harnessing the integrity of the self for enhancing trust and moral support among people.

따라서 진정성은 일반적으로 긍정적인 의미를 지니며, 포터(2010, 6)가 '모성어'라고 부르는 '커뮤니티', '지속 가능성', '자연'과 같은 유사한 강력한 용어 그룹에 속한다고 볼 수 있습니다. 서구 사회는 진정성에 대한 추구에 사로잡혀 있으며, 포터는 현대 생활에서 의미를 찾기 위해 자기 성취와 발견을 추구하는 개인주의적 추구로 이해합니다. 그러나 포터에게 진정성이란 특권의 본질은 누구나 가질 수 있는 것이 아니기 때문에 특권을 구성하는 관계적이고 주관적인 속성인 허구입니다. 따라서 진정성에 대한 열망은 현대 사회의 문제에서 벗어나기보다는 근대 이전의 삶에 대한 잘못된 낭만적 관념을 조장합니다(Potter 2010). 치커링(2006)도 진정성의 일반적인 긍정적 속성과 함께 진정성이 나쁠 수 있는 가능성에 주목합니다. 그에게 진정성은 개념적으로 간단합니다. '진정성이 있다는 것은 보이는 것이 곧 얻는 것임을 의미합니다. 내가 믿는 것, 내가 말하는 것, 내가 행동하는 것이 일관성이 있다는 것입니다'(Chickering 2006, 8). 그러나 내적 일관성은 진정으로 선하거나 악한 사람에게도 똑같이 적용될 수 있습니다.

Thus, authenticity usually carries positive connotations and arguably belongs to a group of similarly powerful terms like ‘community,’ ‘sustainability’ and ‘natural;’ what Potter (2010, 6) calls ‘motherhood words.’ Western society is possessed by a quest for authenticity, which Potter understands as an individualistic pursuit after self-fulfilment and discovery in order to find meaning in modern life. For Potter, however, authenticity is a hoax, a relational and subjective attribute that constructs privilege, because the very nature of privilege is that not everybody can have it. So rather than escaping the malaises of modern society, the aspiration to authenticity promotes ill-informed romantic notions of pre-modern life (Potter 2010). Chickering (2006) also notes the usual positive attribute of authenticity alongside the possibility for authenticity to be bad. For him, authenticity is conceptually straightforward: ‘Being authentic means that what you see is what you get. What I believe, what I say, and what I do are consistent’ (Chickering 2006, 8). Internal consistency, however, can be equally ascribed to someone who is authentically good or evil.

Kreber (2013)와 Kreber 외(2007)가 교육과 학문적 실천에서 진정성을 조사했을 때, 하이데거의 실존철학과 '죽음을 향한 진정한 존재의 존재론적 가능성'과 관련하여 '일상성', '진정성', '비진정성' 사이의 구별에 상당한 주의를 기울였습니다(Heidegger 1962, 304).

- 여기서 일상성이란 자신의 행동과 신념이 타인의 행동과 신념에 의해 지시되는 순응주의를 의미합니다. 이 상태는 '부(un)진정성'으로 간주되는 반면,

- '비(in)진정성'은 사람이 자신의 예정된 죽음을 받아들이거나 깨닫지 못하여 자신의 삶을 비판적으로 검토하지 않는 상태입니다.

- 따라서 진정성은 개인이 자신의 유한한 존재를 인식하고 성찰하는 삶을 살도록 요구합니다. '하이데거의 작업에서 [돌본다는 것은] 세속적인 일과 자신의 존재에 대해 '관심을 갖는 것'을 의미하기 때문에'(Kreber 외, 2007, 32, 원문 강조) 돌봄의 개념은 이러한 성찰적 삶의 핵심입니다.

When Kreber (2013) and Kreber et al. (2007) examined authenticity in teaching and academic practice, considerable attention was paid to Heidegger’s existential philosophy and his distinction between ‘everydayness,’ ‘authenticity,’ and ‘inauthenticity’ in relation to the ‘ontological possibility of an authentic Being-towards-death’ (Heidegger 1962, 304).

- Here, everydayness denotes conformism, where one’s actions and beliefs are directed by those of others. This state is deemed ‘unauthentic,’

- whereas ‘inauthenticity’ is when persons do not come to terms with or realise their own predetermined demise and therefore do not critically examine their lives.

- Authenticity, then, requires individuals to appreciate their finite existence and live examined lives. The notion of care is central to such examined life; for ‘in Heidegger’s work, [to care] means “to be concerned” about worldly affairs and one’s own existence’ (Kreber et al. 2007, 32, emphasis in original).

하이데거의 존재 방식은 무엇보다도 자신의 유한한 경력을 고려하고 이 시기에 무엇을 성취하고 싶은지, 성취해야 하는지를 고민해야 하는 교사의 직업적 삶과 관련이 있습니다.

- 일상성이라는 선택지는 교사가 다른 모든 사람들이 하는 것처럼 보이는 일을 하는 길을 의미합니다.

- 반대로 진정성이란 교육자로서 자신의 제한된 선택지를 인식하는 동시에 가르치는 것에 대해 성찰하고 반성하며, 자신이 가르치는 대상과 영향력에 대해 진정으로 관심을 갖는 것을 의미합니다.

- Kreber 등(2007)에 따르면 비진정성은 가르치기를 꺼려하고 이기적인 이유만으로 가르치는 것을 의미합니다.

이러한 진정성 개념화의 초점은 주로 자기 자신에 맞춰져 있지만, 크레버와 동료들은 개인이 생활하고 행동하는 사회적 맥락의 중요성을 강조한 아도르노(1973)의 비판에도 주목합니다. 개인의 결정, 신념, 행동이 환경의 영향을 받는다는 점에서 아도르노의 진정성에 대한 관점은 보다 구조주의적입니다. 이를 깨닫기 위해서는 비판적 의식이 필요합니다.

Heidegger’s modes of Being are relevant to the professional lives of teachers, who first and foremost should consider their own finite careers and ponder what they wish or ought to achieve in this time.

- The option of everydayness implies a path where a teacher does what everybody else seems to be doing.

- In contrast, being authentic means to be cognisant of one’s limited options as an educator but also to be reflective and reflexive towards teaching, and to genuinely care about one’s subject and impact.

- Inauthenticity, for Kreber et al. (2007), implies being reluctant to teach and doing so only for selfish reasons.

The focus of this conceptualisation of authenticity is devoted primarily to one’s self, but Kreber and colleagues also note Adorno’s (1973) critique that emphasises the importance of the social context within which individuals live and act. Adorno’s view of authenticity is more structuralist as an individual’s decisions, beliefs and actions are influenced by their environment. Realising this requires a critical consciousness.

의식이라는 개념은 실존주의와 진정성에 관한 사르트르의 저술에서도 핵심적인 개념입니다. 사르트르에게 있어 사람의 존재는 본질보다 우선합니다. 이것은 '인간은 무엇보다도 먼저 존재하고, 자신을 만나고, 세계로 솟구쳐 오르고, 그 후에 자신을 정의한다'는 것을 의미합니다(Sartre 2001, 29). 이는 무엇보다도 인간이 되는 데에 미리 정해진 목적이 없으며, 인간은 자신의 실존적 존재를 구성할 책임과 자유가 있다는 것을 의미합니다(카코리 및 후투넨 2012). 그러나 자신의 존재에 의미를 부여하는 자유와 책임은 내면적으로만, 고립적으로만 일어나는 것이 아니라 '존재는 본질에 선행하기 때문에 자신이 무엇이며 타인을 위해 무엇을 하는지에 대해 도덕적으로 책임이 있다. 사람은 자신에 대해서만 책임지는 것이 아니라 모든 인간에 대해 책임을 져야 한다'(카코리와 후투넨 2012, 355). 따라서 자신의 선택에 대한 책임감은 사르트르(1957)의 실존주의 사상의 핵심입니다. 또한, 선택의 자유와 능력은 아무리 제약이 있더라도 '의식의 존재와 그 자체에 대한 의식을 수반한다'(Priest 2001, 107)고 말합니다.

The idea of consciousness is also central in Sartre’s writings on existentialism and authenticity. For Sartre, a person’s existence comes before essence. This means ‘that man first of all exists, encounters himself, surges up in the world – and defines himself afterwards’ (Sartre 2001, 29). This means, inter alia, no predetermined purpose for being human as well as humans’ responsibility and freedom to construct their own existential being (Kakkori and Huttunen 2012). The freedom and responsibility for giving meaning to one’s being, however, does not happen only internally, in isolation; but rather, ‘Because existence precedes essence, one is morally responsible for what one is and what one does for others. One is not responsible for only oneself but instead for all humans’ (Kakkori and Huttunen 2012, 355). This sense of responsibility for one’s own choices, then, is key in Sartre’s (1957) existential ideas. Moreover, one’s freedom and capacity of making choices, however constrained, ‘entails the existence of consciousness, and consciousness of itself’ (Priest 2001, 107).

사르트르의 실존주의는 하이데거의 실존주의에 비해 고등 교육 분야에 덜 영향을 미쳤지만, 존재와 자아에 대한 그의 사상은 어느 정도 구매력이 있었습니다. 예를 들어, Barnett(2007)은 사르트르의 사상을 고등 교육에서 학생들이 (자신의 행동에 대한 책임을 지는 것과 같이) 자신의 존재를 변화시키는 여정과 연결시킵니다. Barnett(2007, 61)은 '고등 교육은 학생이 진정성을 갖게 될 때 정점에 도달한다'고 말하며, 여기서 하이데거의 작품에서도 발견할 수 있는 '소유권'이라는 개념이 중추적인 역할을 한다고 말합니다. 책임감과 소유권이라는 실존적 개념은 개인이 독립적인 학습자가 되는 데 중요하며, 이러한 학습은 답을 찾는 것뿐만 아니라 질문하는 사람이 됨으로써 이루어집니다(Greene 1973).

Sartre’s existentialism has had less impact on the field of higher education, compared with Heidegger’s, but his ideas of being and self did have some purchase. Barnett (2007), for example, links Sartre’s ideas to the journey students undergo in higher education, where they transform their being by, among other things, assuming responsibility for their actions. For Barnett (2007, 61), ‘Higher education achieves its apogee when the student becomes authentic,’ where the idea of ‘ownership,’ which he also finds in Heidegger’s work, is pivotal. These existential ideas of responsibility and ownership are important for individuals’ ability to become independent learners, and this learning happens by means of not only finding answers but also being the ones asking the questions (Greene 1973).

Brook(2009)도 하이데거의 실존 철학과 진정성 개념을 통해 교수법을 검토합니다. 다시 말하지만, 하이데거의 실존적 의미의 진정성은 진정한 인간이 되는 것을 필요로 합니다. 이것은 자기 자신이 되고, 타인을 돌보고, 자신의 필멸성과 따라서 시간성을 깨닫는 것을 포함합니다. 인간은 진정성 있는 존재로 태어나지 않으며, 평생을 진정성 있는 존재가 되지 못한 채 살아갈 수도 있기 때문에 진정성 있는 존재가 되고 변화한다는 개념이 중요합니다. 따라서 인간은 진정한 존재가 될 수 있으며, '하이데거는 교육을 진정한 의미에서 진정성의 형성으로 공식화한다'(Brook 2009, 51, 강조 추가)고 말합니다. 이러한 맥락에서 크레버(2013, 45)는 교사와 학생 모두의 진정성을 증진하는 것이 '고등교육의 주요 목적 또는 보편적 목표가 되어야 한다'고 주장합니다. 그녀에게 고등 교육에서 그리고 고등 교육을 통해 진정성을 형성하는 것은 궁극적으로 사람들이 더 비판적이고, 인식하고, 동정심을 갖고, 연결되는 더 공정하고 풍요로운 세상을 촉진하는 것을 목표로합니다. Jarvis(1992)에 따르면 교사는 관련된 모든 사람의 개인적 발전과 성장을 촉진하려고 노력할 때 진정성 있게 행동합니다. 이 과정에서 학습은 일방적인 것이 아니라 교사와 학생이 대화를 통해 학습하고 상호 성장을 위한 책임을 공유한다는 Paulo Freire(2000)의 아이디어를 따릅니다.

Brook (2009) also turns to Heidegger’s existential philosophy and notions of authenticity for examining teaching. Again, Heidegger’s existential meaning of authenticity necessitates becoming truly human. This constitutes being one’s self, caring for others and realising one’s own mortality and hence temporality. This notion of becoming, of transforming, is key because humans are not born authentic and may live their entire lives without being authentically themselves. Thus, they can become authentic beings, and ‘Heidegger formulates education in its proper sense as the formation of authenticity’ (Brook 2009, 51, emphasis added). In this vein, Kreber (2013, 45) argues that promoting the authenticity of both teachers and students ‘should be a chief purpose or universal aim of higher education.’ For her, the formation of authenticity in and through higher education ultimately aims to promote a fairer and more enriched world, where people are more critical, aware, compassionate and connected. For Jarvis (1992), teachers act authentically when they attempt to nurture the personal development and growth of everybody involved. In this process, learning is not uni-directional; but rather, it follows Paulo Freire’s (2000) ideas around teachers and students learning in dialogue and sharing responsibilities for mutual growth.

프레이레(2000)는 그의 대표작인 '억압받는 자의 교육학'에서 진정성을 언급하거나 '진정성'이라는 용어를 다양한 방식으로 사용했습니다. 주로 '진실성' 또는 '진정성'을 의미하며, 예를 들어 혁명(지도자가 민중과 소통하는 것)과 권위(권력이 위임되고 공유되는 것)와 관련해서도 사용됩니다. 프레이레는 연대, 자유, 진정성을 함께 연결하며, 이러한 결합은 양방향 소통의 교육학에 달려 있습니다. '진정한 교육은 'A'가 'B'를 위해 또는 'A'가 'B'에 대해 수행하는 것이 아니라, 'A'와 'B'가 (세계, 즉 양 당사자에게 감동을 주고 도전하며 그에 대한 견해나 의견을 제시하는) 세계를 매개로 수행됩니다'(Freire 2000, 93, 원문에서 강조 표시). 교사의 사고는 학생의 사고에 의해 인증되어야 하며, 프레이레에 따르면 이는 학생이 자신의 비진정적이고 억압된 존재를 확인하고 그 사고를 해방하기 위해 행동하지 않는 한 일어날 수 없습니다. 이러한 억압을 내면화하는 상태는 본질적으로 하이데거(1962)가 말한 일상성, 즉 현실을 수동적으로 받아들이고 독창적이고 비판적인 사고가 결여된 상태입니다.

In his seminal work Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Freire (2000) refers to authenticity or uses the term ‘authentic’ in various ways. It primarily denotes ‘truthfulness’ or ‘genuineness,’ for instance in relation to revolution (where leaders communicate with the people) and authority (where power is delegated and shared). Freire links together solidarity, freedom and authenticity, whose combination depends on a pedagogy of bidirectional communication, ‘Authentic education is not carried on by “A” for “B” or by “A” about “B,” but rather by “A” with “B,” mediated by the world – a world which impresses and challenges both parties, giving rise to views or opinions about it’ (Freire 2000, 93, emphasis in original). The teacher’s thinking must be authenticated by student thinking and, for Freire, this cannot occur unless the students are able to identify their inauthentic and oppressed being and act to liberate their thought. Such a state of internalising oppression is essentially Heidegger’s (1962) everydayness: a passive acceptance of reality and lack of original and critical thinking.

크레버(2013, 11)는 '진정성은 적어도 세 가지의 광범위한 철학적 전통, 즉 실존주의, 비판주의, 공동체주의에 의해 뒷받침되는 다차원적 개념'이라고 말합니다.

- 실존적 관점에서 진정성은 자신의 가능성과 삶의 목적에 대한 자기 인식과 내면의 견해에 대한 헌신으로 이해됩니다.

- 비판적 관점에서 실존적 진정성을 포함한 진정성은 자신의 지식, 가치, 신념에 대한 반성적 비판을 전제로 합니다. 이러한 비판은 이러한 것들이 어떻게 무비판적으로 동화되어 왔으며, 때로는 당연한 것으로 받아들여졌는지를 고려합니다.

- 공동체주의적 관점은 개인의 진정성에 영향을 미치는 사회적 맥락의 중요성을 지적함으로써 비판적 관점과 관련이 있습니다.

진정성은 종종 자기 자신을 발견하고 진실해지는 것과 관련이 있지만, 사람들은 고립되어 살지 않으며 공동체주의 관점은 관계의 중요성과 사람들의 상호 연결성을 강조합니다.

Kreber (2013, 11) notes that ‘Authenticity is a multidimensional concept underpinned by at least three broad philosophical traditions: the existential, the critical and the communitarian.’

- From an existential perspective authenticity is understood as self-awareness of one’s own possibilities and purpose in life, and commitment to one’s inner views.

- From a critical perspective, authenticity, including existential authenticity, is contingent on reflective critique of one’s own knowledge, values and beliefs. This critique would take account of how these have been uncritically assimilated and, at least sometimes, taken for granted.

- The communitarian perspective is related to the critical by pointing to the importance of social contexts in affecting an individual’s authenticity.

While authenticity is often associated with discovering and being true to one’s self, people do not live in isolation and the communitarian perspective stresses the importance of relationships and people’s interconnectedness.

의미의 정도

A degree of meaning

의미의 정도가 진정성의 가치를 구성한다는 생각은 두 가지 측면이 있습니다.

- 첫째, 서론에서 언급했듯이 진정성이라는 개념은 복잡하고 상황에 따라 달라지지만, 본질적으로 긍정적인 속성을 가지고 있습니다. 이런 의미에서 진정성이 있다고 평가받으려면 사람, 사물, 아이디어 또는 프로세스가 기본적으로 높은 수준의 의미를 가져야 합니다.

- 둘째, 교육학적 관점에서 볼 때 의미의 정도는 실존적 자아뿐만 아니라 해당 관점(Splitter 2009)의 중요한 속성입니다. 따라서 의미 정도라는 개념을 통해 진정성을 이해하는 것은 여기에서 확인된 진정성의 다른 가치에 내재되어 있기 때문에 의문을 제기할 수 있습니다.

그러나 우리는 고등 교육에서 그리고 고등 교육을 통해 진정성을 향상시키는 데 중요하기 때문에 이 아이디어를 별도로 다루었습니다(Kreber 2013 참조). 이를 별개의 가치로 다루는 것은 위에서 설명한 것처럼 의식, 책임, 소유권, 보살핌에 관한 실존적 아이디어의 중요성을 강조하는 데 도움이 됩니다. 이러한 의미에서 우리는 진정한 자아가 다소 개인적인 의미를 지닌 경험('현실 세계'에 해당하거나 그렇지 않은 경험)에 따라 다르게 영향을 받는다고 주장합니다. 개인적 의미를 지닌 경험은 부과된 과제와 필수 지식을 포함하는 교육 시스템에서 항상 제공되는 것은 아니며, 학생들은 학습 과제에서 주인의식과 책임감에 따라 의미를 찾을 가능성이 더 높습니다.

The idea that a degree of meaning constitutes a value of authenticity is twofold.

- First, as noted in the introduction, while the concept of authenticity is complex and context dependent, it has an inherent positive attribute. In this sense, to be regraded authentic, a person, an object, an idea or a process must by default have a high degree of meaning.

- Second, from a pedagogical perspective, a degree of meaning is an important attribute of the corresponding view (Splitter 2009) as well as of the existential self. As such, understanding authenticity through the idea of a degree of meaning could be questioned because it is inherent to the other values of authenticity identified here.

However, we have treated this idea separately because of its importance for enhancing authenticity in and through higher education (see Kreber 2013). Having this as a distinct value serves to emphasise the importance of existential ideas around consciousness, responsibility, ownership and care, as outlined above. In this sense, we argue that the authentic self is influenced differently by experiences (‘real world’ corresponding or otherwise) that have more or less personal meaning. Experiences that have personal meaning are not always available in a system of education that includes imposed tasks and required knowledge, and students are more likely to find meaning in a learning task depending on the sense of ownership and responsibility it animates in them.

학습이 학생에게 의미를 가져야 한다는 생각은 단순히 '암기식 학습'에 반대하여 '의미 있는 학습'을 경험하는 것에 관한 것이 아닙니다(Novak 2002; Ramsden 2003). 또한 의미 있는 지식은 학습자가 이미 알고 있고 할 수 있는 것을 기반으로 구축되어야 한다는 구성주의적 관점도 아닙니다. 여기서 우리가 관심을 두는 것은 학습 경험의 맥락에서 개인적 의미를 개발하는 것입니다(Rawson 2000). Rawson에 따르면, 개인적 의미는 학생이 스스로 지식을 탐색하고, 어느 정도의 자기 결정권과 주제와 맥락을 초월할 수 있는 잠재력을 제공하는 활동에 참여할 때 가장 잘 달성됩니다. 이러한 의미에서 의미 있다는 것은 학생이 중요하거나 가치 있다고 판단하는 경험을 의미하며, 결과적으로 다른 진정성 가치와도 잘 부합합니다. 또한 하이데거와 사르트르에 따르면 학습자 개개인은 항상 더 넓은 사회적 맥락에서 주체이며, 개인의 의미는 더 넓은 커뮤니티의 다른 사람들을 통해 구성되고 그들과 공유된다고 주장합니다.

The idea that learning should have meaning for a student is not just about experiencing ‘meaningful learning’ as opposed to ‘rote learning’ (Novak 2002; Ramsden 2003). Neither is it about the constructivist view that to have meaning knowledge should be built on what the learner already knows and can do. What we are concerned about here is developing personal meaning in the context of the learning experience (Rawson 2000). According to Rawson, personal meaning is best achieved when students are engaged in their own search for knowledge, an activity that offers a degree of self-determination and the potential to transcend both subject and context. Being meaningful in this sense is about an experience that the student determines to be significant or worthwhile, and as a consequence fits well with other authenticity values. In addition, following Heidegger and Sartre, we also argue that the individual learner is always a subject in a wider social context and that personal meaning is both constructed through, and shared with, others in a wider community.

'진정성 있는' 연구를 통한 학부생 교육

Teaching undergraduate students through ‘authentic’ research

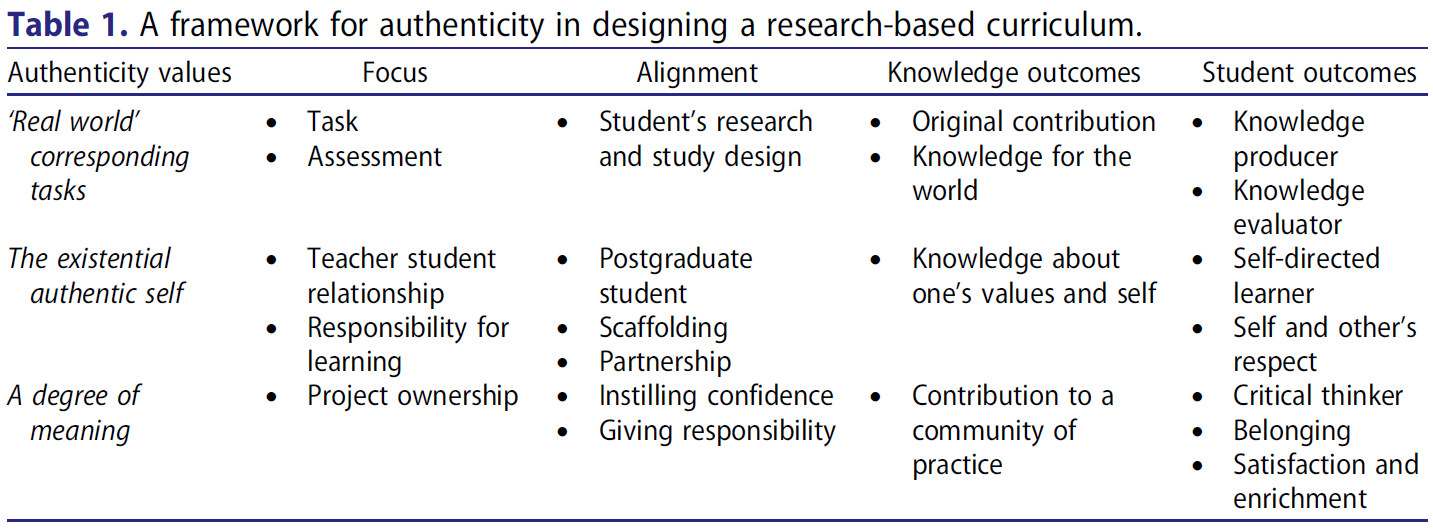

우리는 진정성의 세 가지 렌즈를 사용하여 오타고 대학의 생태학 프로그램에서 진정성 있는 연구에 대한 우리의 주장을 재고했습니다. 이 작업을 돕기 위해 이론적 아이디어를 출발점으로 삼아 각 아이디어를 교육, 커리큘럼, 지식 및 학생 학습 결과에 대한 아이디어와 연결하는 프레임워크가 개발되었습니다. 이를 통해 우리는 생태학 분야의 진정한 학부 연구를 구성하는 요소에 대한 보다 자세한 설명을 만들었습니다(표 1). 이 표에는 생태학 프로그램의 현재 관행 중 일부가 진정성에 대한 요건을 충족한다고 주장할 수 있는 개념이 포함되어 있지만, 더 중요한 것은 이러한 개념이 현상에 대한 이해를 발전시키는 데 도움이 된다는 것입니다. 프레임워크를 설명한 후에는 연구를 통한 다른 형태의 학부 교육이 이 진정성 프레임워크와 어떻게 비교되는지 논의할 것입니다.

Using the three lenses of authenticity we have reconsidered our claim to authentic research in the ecology programme at the University of Otago. To help us in this task a framework was developed that took the theoretical ideas as a starting point and then connected each of these to ideas about teaching, curriculum and outcomes for knowledge and student learning. In doing so we have produced a fuller explanation of what we consider constitutes authentic undergraduate research in ecology (Table 1). The table includes concepts that allow us to claim that parts of the present practices in the ecology programme meet the requirements for authenticity, but more importantly, these concepts assist our developing understanding of the phenomenon. After explaining the framework, we will discuss how other forms of undergraduate teaching through research compare with respect to this framing of authenticity.

이 프레임워크는 특정 맥락에서 진정성의 핵심 가치로 간주되는 것을 통합합니다. 이러한 가치는 커리큘럼을 조정할 때 교사가 집중해야 하는 주요 개념과 일치합니다(Biggs and Tang 2011). 표 1에서 정렬은 커리큘럼 설계, 교수 전략 또는 특정 교수 철학의 채택을 통해 초점 포인트를 적용하는 것을 의미합니다. 따라서 우리는 '실제 세계'에서 과학이 수행되는 방식을 반영하는 보다 응용적 속성과 실존적 자아에 대한 철학적 요소를 함께 가져옵니다. 그러나 결정적으로, 진정성은 맥락에 따라 달라지고 사회적으로 구성되기 때문에 이 프레임워크는 진정성을 주장하는 데 필요한 의미의 정도를 전달합니다. 따라서 연구를 통한 진정성 있는 교육 모델은 학생에게 연구에 대한 주인의식을 고취시켜야 하며, 이는 학생에게 과제에 대한 책임과 동료에 대한 보살핌을 맡기고, 교사는 전문적인 지원을 제공함으로써 달성됩니다. 따라서 이 프레임워크는 이론적 요소뿐만 아니라 실제적 요소도 포함하고 있습니다. 언급된 결과 중 많은 부분이 측정하거나 평가하기 어려운 것은 사실이지만, 더 많은 경험적 테스트가 필요하지만 현재 연구를 통해 다양한 교육 모델과 비교하여 검토할 수 있습니다.

The framework incorporates what we consider the core values of authenticity within our particular context. These values are then matched with the main concepts that teachers would need to focus on when aligning a curriculum (Biggs and Tang 2011). In Table 1 alignment refers to the application of focus points, either through curriculum design, teaching strategies or adopting specific teaching philosophies. As such we bring together the more applied attributes of mirroring how science is done in the ‘real world,’ and philosophical elements of the existential self. But crucially, since authenticity is context dependent and socially constructed, the framework conveys the degree of meaning necessary for claiming authenticity. Thus conceived, an authentic model of teaching through research should promote students’ sense of ownership over the research, which is achieved by entrusting them with the responsibility for the work and care for their peers, while teachers provide expert support. The framework therefore contains theoretical as well as practical elements. It is certainly the case that many of the outcomes noted will be difficult to measure or evaluate, but while more empirical testing is required, it is currently possible to examine it against different models of teaching through research.

이 프레임워크를 뒷받침하기 위해 Chinn과 Malhotra(2002)는 듀이(1938)가 사용한 용어인 '진정한 탐구'와 관련된 인지적 과정에 대한 포괄적인 개요를 제공합니다. 이러한 과정에는 자신의 연구 질문 생성, 복잡한 절차의 발명, 자신의 결과에 대한 의문 제기, 다양한 형태의 논증 사용, 이전 연구의 (때로는 상충되는) 결과의 사용 등이 포함됩니다. 이러한 과제는 학생의 주인의식과 고차원적인 학습 결과로 이어집니다. 그러나 일부 저자는 완전히 다른 패러다임과 관련하여 진정성을 주장하기도 했습니다. 따라서 진정한 탐구 또는 연구, 즉 '진짜 과학을 하는 것'에 대한 단순한 이해는 일반적으로 공유되지만, 우리의 프레임워크에서는 진정성이라는 하나의 가치로만 구성됩니다. 진정성에 대한 유일한 척도를 갖는 것과는 대조적으로, 이 프레임워크를 구성하는 일련의 가치들은 필연적으로 연구를 통해 근본적으로 일관된 형태의 교육을 초래할 것입니다. 이 주장을 받아들인다면, 생태학에 대한 우리의 주장을 포함하여 모든 주장이 그 자체로 진정성이 있을 수 있는지에 대한 의문이 제기됩니다. 우리는 대답은 '아니오'라고 제안하며, 여기에 제시된 프레임워크가 연구 모델을 통한 진정한 교육을 설계하는 데 어느 정도 유연성을 허용하지만, 적절하고 인식 가능한 경계를 설정하기 때문에 충분히 제약적이라는 점에 유의해야 합니다.

In support of the framework, Chinn and Malhotra (2002) provide a comprehensive overview of the cognitive processes implicated in what they call ‘authentic inquiry,’ a term also used by Dewey (1938). These processes include the generation of one’s own research questions, the invention of complex procedures, the questioning of one’s own results, the employment of multiple forms of argument, the use of (sometimes conflicting) results from previous studies, and more. These tasks lead to both ownership and higher-order learning outcomes for students. However, some authors have made claims for authenticity in relation to quite different paradigms. Therefore, while the simple understanding of authentic inquiry or research – namely ‘doing real science’ – is commonly shared, in our framework it constitutes only one value of authenticity. In contrast to having a sole measure for authenticity, the set of values constituting this framework will inevitably result in a fundamentally consistent form of teaching through research. If this argument is accepted, then it brings into question whether all claims can be authentic in their own right (including our own for ecology). We suggest the answer is no, and further note that although the framework offered here allows for some flexibility in designing an authentic teaching through research model, it is also sufficiently constraining because it sets adequate and recognisable boundaries.

이를 '실제 세계'의 가치와 관련하여 설명하기 위해 Laursen 외(2010, 2)에 따르면 '실제 연구란 질문, 방법, 일상적인 작업 방식이 해당 분야에 진정성 있는 연구'라고 합니다. 따라서 학부 연구는 진정성에 대한 해당 관점을 주요 특징으로 삼고, 프로그램의 가치나 효과를 평가할 수 있는 기준으로 삼습니다. 같은 저자들은 또한 진정성이 교직원과 학생 모두에게 유익한 것으로 보고 있으며 다음과 같은 점에 주목합니다:

To illustrate this with reference to the ‘real world’ value, according to Laursen et al. (2010, 2), ‘real research is an investigation whose questions, methods, and everyday ways of working are authentic to the field.’ Undergraduate research, therefore, privileges the corresponding view of authenticity as a key feature, and positions it as a benchmark according to which the value or effectiveness of a programme could be evaluated. The same authors also see authenticity as being beneficial to both staff and students and note that:

지도교수는 답을 알 수 없지만 자신과 자신의 학문에 관심이 있고, 그 답에 기득권을 가지고 있기 때문에 진짜인 연구 질문에서 시작합니다. 그들은 그 질문의 범위를 정의하고, 제한된 시간 내에 초보 연구자에게 적절한 규모의 프로젝트를 제공하는 접근 방식을 고안한 다음, 의도적으로 가르칠 수 있는 순간을 활용합니다. (Laursen 외. 2010, 205)

Advisors begin with a research question that is real because its answer is unknown but of interest to them and their discipline; they have vested interest in its answer. They define the scope of that question and devise approaches to it that offer a right-sized project to a novice researcher with a limited time frame, then purposefully exploits its teachable moments. (Laursen et al. 2010, 205)

그러나 진정성 있는 연구에 대한 이러한 관점에도 문제가 없는 것은 아닙니다. 이러한 연구 프로젝트는 교실을 넘어서는 관련성이 있고 독창적이라는 측면에서 진정성이 있을 수 있지만, 학생들의 독창성, 창의성 및 아이디어와 관련된 측면에서는 그렇지 않을 수 있습니다. 또한 Hung과 Chen(2007)의 말을 빌리자면, 이 모델은 과학자로서의 정체성을 형성하고 교양을 쌓는 진정한 학습의 과정 차원에서는 부적절할 수 있습니다. 마찬가지로, 우리의 프레임워크를 사용하면 이러한 모델이 '실제' '지식 결과' 기준의 일부 요소를 충족할 수 있지만 학생의 기여도를 완전히 인정받지 못할 수도 있습니다. 또한 학생이 연구 설계 및 수행에 대한 책임이 있다는 의미에서 프로젝트를 소유하지 않기 때문에 세 가지 가치 범주에 걸친 학생의 성과가 실현될 가능성이 낮습니다.

This view of authentic research, however, is not without problems. Such a research project could be authentic in terms of having relevance beyond the classroom and being original, but not so much in relation to students’ originality, creativity and ideas. And, borrowing from Hung and Chen (2007), this model may be inadequate for the process dimension of authentic learning, where identity formation and enculturation as scientists are developed. Similarly, using our framework, whereas such a model may satisfy some elements of the ‘real-world’ ‘knowledge outcomes’ criterion, the contribution of the student may not be fully recognised. In addition, student outcomes across the three value categories are unlikely to materialise because the student does not own the project in the sense of having the responsibility for designing and performing the research.

다른 학생 연구 모델도 있으며, 미국에서는 학부생이 기존 과학 연구팀에서 견습생으로 일할 수도 있습니다(Laursen 외. 2010). Grabowski, Healy, Brindley(2008)는 학부생이 교수진의 연구 프로젝트와 매칭되어 구직 지원과 유사한 과정을 거치는 프로그램을 조사했습니다. 오버하우저와 르분(2012)은 학부생이 시민 과학이라는 더 넓은 틀 안에서 연구에 참여하는 약간 다른 사례를 조사합니다. 이 모델에서 학생들은 연구 설계, 프로토콜 테스트, 데이터 수집, 출판물 공동 저술과 같은 다양한 연구 과제를 수행했으며, 이 모든 과제는 진정성 있는 것으로 간주되었습니다. 그러나 이 연구의 대부분이 여름 방학 동안 이루어졌고, 얼마나 많은 학생이 프로젝트에 참여했는지 명확하지 않았으며, 학생들이 다른 실제 하위 과제에 참여했을 수 있기 때문에 전체 연구 과정을 경험했는지 또는 얼마나 많은 학생이 경험했는지는 확실하지 않습니다.

There are other models of student research and in the United States, undergraduates may work as apprentices in an established scientific research team (Laursen et al. 2010). Grabowski, Healy, and Brindley (2008) examine a programme where undergraduate students are matched with faculty members’ research projects in a process that resembles a job application. Oberhauser and LeBuhn (2012) examine a slightly different example whereby undergraduate students engage in research within a broader framework of citizen science. In this model students performed different research tasks such as study design, protocol testing, data collection and co-authoring publications, all of which were deemed authentic. It seems, however, that much of this research was done over summer breaks, it was not clear how many students were involved in the project, and because students may have been involved in different authentic sub-tasks it is not certain if or how many experienced the complete research process.

학부 연구에 대한 접근 방식에 대한 간략한 논의에서 Harvey와 Thompson(2009, 13)은 진정한 학부 연구 경험이란 '발표 및 출판을 목표로 연구를 수행하는 지적 동료로서 한 명 이상의 학생을 참여시키는 교수 주도 프로젝트'라고 주장합니다. 저자들이 인정하듯이 이 접근 방식에는 소수의 선별된 학생만 참여할 수 있고 교수의 연구 관심사에 치우칠 수 있지만, 지속 가능한 모델이 될 수 있습니다. 결정적으로, 학생의 참여는 인지적으로나 인식론적으로 유의미해야 하며, 의미 있는 협업으로 이어져야 하는데, 이는 위에서 언급한 다른 견습 모델보다 더 중요한 요건일 수 있습니다. 그러나 저자들이 이 견습 모델이 지속 가능한 상생 모델이라는 보다 명시적인 주장과 '실제 과학을 하는 것'이라는 암묵적인 주장 외에 왜 이 모델이 진정성 있는 것으로 간주되는지는 명확하지 않습니다.

In their brief discussion of approaches to undergraduate research, Harvey and Thompson (2009, 13) maintain that an authentic undergraduate research experience is ‘a faculty-led project [that] engages one or more students as intellectual colleagues who conduct research directed toward presentation and publication.’ This approach would include, as the authors admit, only a small and selective number of students and would lean towards the teacher’s research interest, but this would make it a sustainable model. Crucially, students’ involvement should be cognitively and epistemically significant, resulting in a meaningful collaboration, a requirement that perhaps goes further than some of the other apprenticeship models mentioned above. It is not entirely clear, however, why this apprenticeship model is deemed authentic by the authors, beyond the more explicit claim that it is a win-win sustainable model and the implicit claim that it is about ‘doing real science.’

연구 견습생 관련 문헌을 검토한 새들러와 맥키니(2010)는 여러 연구에서 이러한 직책을 맡은 학부생이 지식과 기술 수준이 향상되었다는 증거를 발견했다고 언급했습니다. 그러나 이 저자들은 '이러한 경험이 데이터 분석, 질문 제기, 가설 세우기 등 인식론적으로 더 까다로운 관행을 포함하도록 발전하지 않으면 고차원적인 결과에 대한 학습 이득이 제한될 수 있다'는 우려를 표명합니다(Sadler and McKinney 2010, 48). 따라서 학생들이 '실제' 연구에 참여할 수는 있지만, 어떤 역할이나 과제를 수행해야 하는지, 주인의식, 책임감, 관심을 통해 의미를 가질 수 있을 만큼 연구 과정을 충분히 경험할 수 있는지 여부가 항상 명확하지는 않습니다.

In a review of the research apprentice literature, Sadler and McKinney (2010) noted that several studies found evidence that undergraduate students that held such positions improved their level of knowledge and skills. However, these authors express a concern that ‘if these experiences do not evolve to include more epistemically demanding practices, such as data analysis, question posing, and hypothesizing, then learning gains on higher-order outcomes will likely be limited’ (Sadler and McKinney 2010, 48). Thus, students may be involved in ‘real-world’ research but it is not always clear what roles or tasks they are required to perform and whether or not they get to experience enough of the research process for it to have meaning through a sense of ownership, responsibility and care.

또한, 도제식 모델에서 '실제' 연구를 통한 학습이 대중 고등 교육에 적합한 전략인지에 대한 적절한 의문이 제기되고 있습니다. 소수의 재능 있는 학생을 선별하여 연구 기회를 제공하는 것과 모든 능력을 갖춘 다수의 학생이 독창적인 연구를 수행하여 학습하는 것은 결코 같을 수 없기 때문에 이 질문은 중요합니다. 예를 들어, Gardner 등(2015)은 '떠오르는 대학 신입생'(62명)을 포함한 견습생 연구 프로그램을 연구했는데, 그 수는 공개되지 않았지만 8명의 학생이 연구 참여에 동의했습니다. 따라서 이 프로그램은 상대적으로 소수의 뛰어난 능력을 가진 학생들을 대상으로 한 것으로 보입니다. 반면, 우리의 프레임워크는 연구를 통한 진정한 교육을 학급의 모든 학생을 위한 커리큘럼에 통합할 수 있는 지침을 제공하는 것을 목표로 합니다.

Moreover, there is a pertinent question as to whether learning through ‘real-world’ research in an apprenticeship model is a viable strategy for mass higher education. This question is important since selectively identifying a small number of talented students for research opportunities is by no means the same as getting a large number of students of all abilities to learn by carrying out original research. Gardner et al. (2015), for instance, studied an apprenticeship programme of research that included what they describe as ‘rising college freshmen’ (62), and while their number was not disclosed, eight student agreed to take part in the study. It seems, therefore, that this programme was targeted at relatively small number of exceptionally capable students. In contrast, our framework aims to provide guidance for the incorporation of authentic teaching through research into a curriculum for all students in a class.

2000년대 초 오타고 대학교의 생태학 프로그램이 재설계되었을 때 주요 목표 중 하나는 비판적 사고 능력을 개발하는 것이었습니다. 과학자가 되는 법을 배우는 것도 우선 순위가 높았지만 이는 대부분 비판적 사고의 범주에 속했습니다. 그러나 이 두 가지 모두 학생들이 진정한 연구에 참여하게 함으로써 달성할 수 있는 목표였습니다(Spronken-Smith 외. 2011). Spronken-Smith 외(2011, 732)는 '생태학 프로그램의 탐구는 학생에게 새로운 지식을 창출하고 궁극적으로 과학에 새로운 지식을 제공할 수 있는 모든 기회가 있어야 한다는 의미에서 진정성이 있었다'고 말합니다... [프로그램의 3년 동안의] 모든 연구 활동은 생태학자의 작업 측면을 다루기 때문에 이런 의미에서 모두 진정성이 있다'고 설명합니다. 앞서 언급한 '실제 세계'에 상응하는 진정성에 대한 주장은 좀 더 심도 있는 설명이 필요합니다.

When the ecology programme at the University of Otago was redesigned in the early 2000s one of the main aims was to develop critical thinking skills. Learning to be a scientist also featured high as a priority, but this largely fell within the parameters of critical thinking. Both, however, were to be achieved through getting students engaged in authentic research (Spronken-Smith et al. 2011). Spronken-Smith et al. (2011, 732) note that ‘the inquiry in the ecology programme was authentic in the sense that there had to be every chance of new knowledge being created for the student and eventually new knowledge to science … All research activities [over three-years of the programme] cover aspects of an ecologist’s work so, in this sense, they are all authentic.’ This earlier claim to ‘real world’ corresponding authenticity requires some more in-depth explanation.

커리큘럼은 모든 학생이 대학에 처음 입학할 때부터 연구자로서의 훈련을 받도록 설계되어 3년 동안의 경험 중 일부는 연구를 통해 배우는 데 중점을 두어 연구를 수행하도록 합니다. 연구 활동은 학생들의 현재 능력에 맞게 조정되며, 프로그램이 진행됨에 따라 기대되는 연구 수준이 높아져 결국에는 고급 대학원생이나 심지어 학부 교사의 작업과 비슷해집니다(Harland 2016). 이 프로그램은 학생들이 완전히 설계하고 주도하는 캡스톤 연구 프로젝트로 마무리됩니다. 이 연구 프로젝트의 준비는 프로그램에 참여한 교사들이 연구를 수행하는 방식을 면밀히 따릅니다. 학생들은 짝을 이루어 2학년 때 짧은 현장 학습을 통해 다양한 생태계를 탐험한 후, 3학년 프로젝트에 대한 연구 제안서와 함께 보조금 신청서를 작성합니다. 이 보조금 신청서는 교직원과 학생이 모두 참여하는 이중 맹검 동료 검토 과정을 거치며, 피드백은 연구 설계를 개선하는 데 사용됩니다. 프로그램 3년차에는 학생들이 연구 프로젝트를 수행하고 보고서를 작성합니다. 이러한 프로젝트에서 생성된 지식은 해당 분야에 새로운 지식일 가능성이 높으며, 지난 몇 년 동안 일부는 기존 학술지(Harland, Wald, Randhawa 곧 출간 예정)에 연구를 발표하기도 했습니다. 그러나 이 프로그램은 미래의 학자를 양성하는 것이 목적이 아니라 학생 연구자로서의 작업을 통해 모든 학생의 개인적 성장을 촉진하고자 합니다(Harland 2016).

The curriculum is designed so that all students are trained as researchers from when they first start at university so that a part of their experiences over three years focuses on learning through research by learning to do research. Research activities are aligned to students’ current abilities and as they progress in the programme, the expected level of research increases so that eventually their work resembles that of more advanced postgraduate students or even of their academic teachers (Harland 2016). The programme concludes with a capstone research project that is fully designed and led by the students. The preparation of this research project follows closely how the teachers in the programme do research. Working in pairs, and following a short fieldtrip in second-year where students explore a number of different ecosystems, students write a grant application with a research proposal for the third-year project. This grant application goes through a double-blind peer-review process involving both staff and students, and the feedback is then used to improve the research design. In the third year of the programme, students conduct their research projects and write their reports. The knowledge generated in these projects has every chance of being new to the discipline and in past years some have published their research in established journals (Harland, Wald, and Randhawa forthcoming). The programme, however, does not aim to train future academics; instead, it wishes to promote the personal growth of all students through their work as student-researchers (Harland 2016).

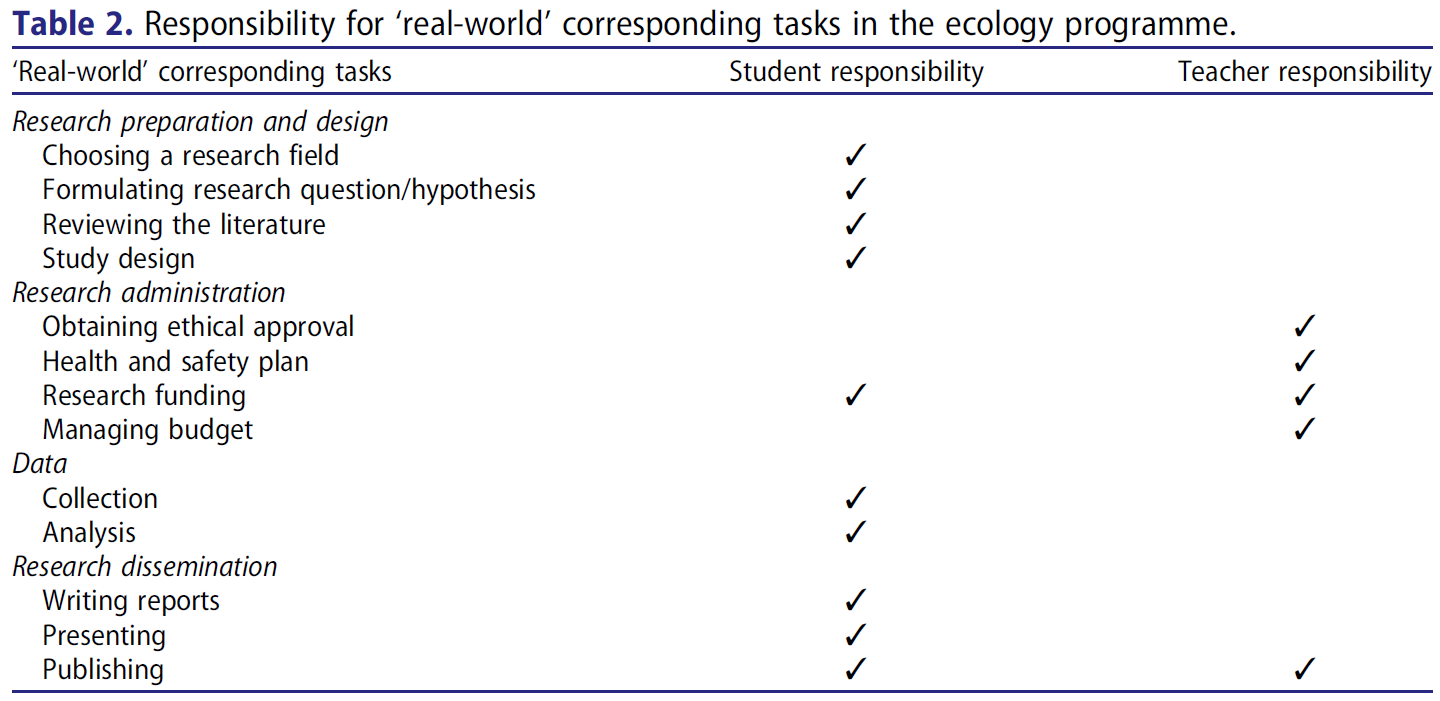

이 모델에는 '실제 과학 수행'이라는 익숙한 형태로 '실제 세계'와의 대응이 포함될 수 있지만, 우리는 더 이상 이것만으로는 '진짜authentic'라고 부르기에 충분하다고 주장하지 않습니다. 오히려 연구를 통한 교육이 진정성을 가지려면 학생들이 자신이 선택한 학문 분야에서 학습자이자 연구자로서, 그리고 교실 밖에서도 자아를 긍정적이고 의미 있게 발전시킬 수 있어야 한다는 것이 우리의 견해입니다. 진정성 있는 학습자는 자신의 가치와 행동에 대한 지식을 얻고 이것이 자신과 타인에게 어떤 영향을 미치는지 알게 됩니다. 학생들의 의식에 대한 이러한 실존적 효과는 학생들이 더 큰 책임감을 갖도록 장려하고 연구를 결정할 수 있는 더 많은 자유를 부여하는 커리큘럼을 통해 달성됩니다. 이 주장을 받아들인다면, 이러한 교육 모델에서 연구는 독창적일 뿐만 아니라 대부분 학생이 주도해야 한다는 결론이 나옵니다. 표 2는 생태학 프로그램의 캡스톤 프로젝트에서 학생과 교사가 책임져야 하는 '실제' 과제를 세분화하여 보여줍니다.

The ‘real-world’ correspondence may be embedded in this model in the familiar form of ‘doing real science,’ but we would no longer claim that this in itself is sufficient for calling it ‘authentic.’ Rather, it is our view that for teaching through research to be authentic, it should positively and meaningfully enable students to develop their sense of self, both within their chosen discipline as learners and researchers, and beyond the classroom. The authentic learner gains knowledge about his or her values and actions and how these impact on self and others. This existential effect on students’ consciousness is achieved by a curriculum that encourages them to assume greater responsibility and that gives them more freedom to determine their research. If this argument is accepted, then it follows that in such a pedagogical model research should be not only original but also largely student-led. Table 2 breaks down ‘real-world’ corresponding tasks and shows what students and teachers assume responsibility for in the capstone project of the ecology programme.

이러한 책임은 진정한 자아의 일부이지만, 이것이 프로젝트 주인의식을 전제로 하는 개인적으로 의미 있는 경험과 어떻게 관련될지 예측하기는 더 어려워 보입니다. 학생에게 책임감을 부여하고 프로젝트를 설계하도록 요구할 수는 있지만, 진정성에 대한 우리의 관점에서 진정으로 느껴야 하는 소유권을 부여할 수는 없습니다(Barnett 2007). 지금까지는 코스 평가에서 주인의식이 특히 학습자이자 연구자로서 자신감을 키우는 데 매우 중요하다는 사실이 일관되게 밝혀졌다는 사실 외에 이러한 경험이 학생들에게 어떤 의미를 갖는지는 명확하지 않았습니다. 진정성의 맥락에서 우리는 진정성 있는 학습 경험에 어느 정도의 개인적 의미가 필요한지 묻고 있습니다. 우리가 결정해야 할 것은 의미가 학습자이자 생태학자가 되는 데, 그리고 궁극적으로 한 사람의 존재와 자아가 되는 데 어떤 영향을 미치는지입니다(Barnett 2007). 그런 다음 이것이 공동 연구 커뮤니티 내에서 일하는 것과 어떤 관련이 있는지, 그리고 나중에 학생들이 사회에 더 광범위하게 기여하는 방법과 어떤 관련이 있는지 확인해야 합니다.

Such responsibility is part of the authentic-self but it seems more difficult to predict how this might relate to personally meaningful experiences that are predicated on the idea of project ownership. Students may be given responsibility and be required to design a project, but they cannot be given ownership, which has to be genuinely felt (Barnett 2007) in our view of authenticity. To date it has not been clear what the experiences have meant to students, beyond the fact that course evaluations have consistently shown that ownership has been very important, particularly with respect to students growing in confidence as both learners and developing researchers. In the context of authenticity we are asking what degree of personal meaning is required for an authentic learning experience. What we need to determine is how meaning impacts on becoming a learner and an ecologist, and ultimately on being and becoming one’s own person (Barnett 2007). We then need to ascertain how this relates to working within a collaborative research community and perhaps later how students contribute to society more broadly.

전반적으로, 그리고 보다 실용적인 측면에서 볼 때, 연구를 통한 진정한 교육 모델은 대학원 및 학부 연구자들이 지식을 학습하고 생성하는 방식을 최대한 가깝게 따르는 모델이며, 여기에는 여러 가지 기술적 작업뿐만 아니라 연구에 만연한 복잡성, 불확실성, 정치성을 다루어야 하는 것도 포함됩니다. 이 개념에서 학부생은 마치 대학원생처럼 일하기 때문에 일반적으로 이 수준에서 기대할 수 있는 것보다 훨씬 더 큰 학습 책임을 지는 동시에 교수와 훨씬 더 긴밀하고 협력적인 관계를 구축합니다(Harland 2016). 이러한 새로운 관계는 고차원적인 학습 성과와 인식론적으로 까다로운 관행에 대한 요구의 결과입니다. 우리 중 한 명은 수년 동안 이 프로그램에 참여해 왔고 오랫동안 학생들을 연구자로 가르치는 것을 지지해 왔지만, 연구를 통한 교육에서 진정성을 위한 프레임워크의 정교화는 프로그램 개발에서 거의 고려되지 않았던 기술적 과제와 가치를 모두 강조했습니다. 이는 대부분 실존적인 진정한 자아와 의미의 정도와 관련이 있습니다. 이 프레임워크를 통해 우리는 이러한 형태의 교육학, 무엇에 집중해야 하는지, 우리의 가치를 실천과 어떻게 일치시킬 수 있는지 재고할 수 있었습니다. '현실 세계'에 해당하는 과제는 비교적 쉽게 연계할 수 있는 것처럼 보이지만, '존중', '소속감', '풍요로움'과 같은 가치는 학생의 학습 결과에 대한 광범위한 토론에서 거의 주목을 받지 못했으며, Barnett(2007)의 '되기'는 더더욱 그러했습니다. 그러나 우리는 이러한 요소들이 모두 진정한 연구를 통해 학습의 필수적인 부분이라고 주장할 수 있습니다.

Overall, and in more pragmatic terms, an authentic model of teaching through research is one that follows as closely as possible how postgraduate and academic researchers learn and generate knowledge, which includes a number of technical tasks as well as having to deal with the complexities, uncertainties and politics that are omnipresent in research. In this conception, undergraduate students work as if they were postgraduate students and so have a far greater responsibility over their learning than might typically be expected at this level, while establishing a much closer and more collaborative relationship with their teachers (Harland 2016). These new relationships are a consequence of the drive for higher-order learning outcomes and epistemologically demanding practises. Although one of us has been involved in this programme for many years, and has long been an advocate of teaching students to be researchers, the elaboration of a framework for authenticity in teaching though research has highlighted both technical challenges and values that have received little consideration in the development of the programme. These are mostly related to the existential authentic self and degree of meaning. The framework has allowed us to reconsider this form of pedagogy, what to focus on and how to align our values with practice. Although the ‘real world’ corresponding tasks seem relatively straightforward to align, values such as ‘respect’, ‘belonging’ and ‘enrichment’ have received little attention in wider debates on student learning outcomes; Barnett’s (2007) ‘Becoming,’ even less so. Yet we would argue that they are all an essential part of learning through authentic research.

결론

Conclusions

이 논문은 학부 생태학 프로그램에서 연구를 통한 교육과 관련하여 무엇이 진정성을 구성하는지에 대한 논의에서 시작되었습니다. 과학 교육에서 진정성이란 일반적으로 과학자들이 교실에서 생각하고 작업하는 방식을 그대로 재현하는 것을 의미합니다(Crawford 2015). 그러나 우리의 토론은 진정성에 대해 더 미묘하고 정보에 입각 한 조사를 수행하도록 자극하는 여러 가지 질문을 제기했습니다. 학부생들이 독창적인 연구를 통해 새로운 지식을 창출하는 데 참여하도록 하는 아이디어는 연구를 통한 교수법에서 중추적인 역할을 하며, 진정성은 일반적으로 소위 '실제 세계'와 '대응하는 관점'으로 알려진 것과 관련하여 프레임워크가 구성됩니다(Splitter 2009).

This paper was conceived out of a discussion about what constitutes authenticity in relation to teaching through research in an undergraduate ecology programme. The common use of authenticity in science teaching refers to replicating the way in which scientists think and work in the classroom (Crawford 2015). Our discussion, however, raised a number of questions that prompted us to carry out a more nuanced and informed inquiry into authenticity. The idea of getting undergraduate students involved in generating new knowledge through original research is pivotal in pedagogies of teaching through research and authenticity is commonly framed in relation to the so-called ‘real world,’ and what has become known as the ‘corresponding view’ (Splitter 2009).

그러나 여기에 제시된 진정성에 대한 제안된 프레임워크는 연구를 통한 교육에서 진정성을 구성하는 요소에 대한 보다 복잡한 이해를 제공합니다. 이는 일반적으로 사용되는 '현실 세계'에 해당하는 관점에 진정성의 다른 두 가지 핵심 가치, 즉 실존적 진정한 자아와 의미의 정도를 추가함으로써 그렇게합니다. 하이데거, 아도르노, 사르트르와 같은 실존 철학자들의 연구, 특히 의식, 책임, 소유권, 보살핌과 관련된 진정성에 대한 그들의 분석은 고등 교육 분야의 학자들에 의해 확인되고 사용되어 왔습니다. 그러나 여기서 우리의 주요 기여는 이러한 아이디어를 연구를 통해 교육 맥락에서 '현실 세계'에 대한 상대적으로 더 일반적인 아이디어와 결합하는 것입니다. 실존주의와 밀접한 관련이 있는 의미의 정도는 진정성과 관련된 주로 긍정적인 의미를 반영하며, 이는 다시 우수한 모범의 표현이라는 개념의 더 일반적인 의미를 반영합니다. 이러한 가치들을 종합하면 교사가 주요 초점 포인트와 이러한 포인트가 다양한 결과와 어떻게 연계되는지를 안내하는 프레임워크가 구성됩니다. 이 프레임워크는 커리큘럼을 설계할 때 어느 정도 유연성을 허용하는 동시에 연구를 통해 과학 교육의 맥락에서 우리가 진정성이 있다고 인식하는 것에 대한 명확한 지침과 경계를 제공합니다.

The proposed framework for authenticity presented here, however, offers a more complex understanding of what constitutes authenticity in teaching through research. It does so by adding to the commonly used ‘real world’ corresponding view two other core values of authenticity; namely, the existential authentic self and a degree of meaning. The work of existential philosophers such as Heidegger, Adorno and Sartre, and more specifically their analyses of authenticity in relation to consciousness, responsibility, ownership and care, have been identified and used by scholars in higher education. But our main contribution here is joining these ideas together with the relatively more common ideas about the ‘real world’ within the context of teaching through research. A degree of meaning, which is also closely related to existentialism, reflects the predominantly positive connotation associated with authenticity, which in turn echoes the concept’s more common meanings as a representation of a superior exemplar. Put together, these values constitute a framework that directs teachers towards key focus points and how these align with different outcomes. It allows for some flexibility in designing a curriculum while at the same time provides clearer guidance and boundaries for what we perceive to be authentic in the context of science teaching through research.

따라서 제안된 프레임워크는 주로 연구를 통한 진정한 교육 모델이 어떻게 학생들의 개인적, 심지어 직업적 발달에 긍정적이고 의미 있으며 장기적인 효과를 가져올 수 있는지에 초점을 맞추고 있습니다. 프레임워크의 '학생'과 '지식 결과'에는 교육자로서 학생들이 갖추기를 바라는 몇 가지 핵심 가치와 기술이 포함되어 있습니다. 프레임워크의 '초점' 및 '정렬' 구성 요소는 커리큘럼이 이러한 가치와 기타 결과를 심어줄 수 있는 방법에 대한 지침 역할을 합니다. 원하는 결과를 달성하기 위한 이러한 수단은 주로 학생이 주도하고 책임감, 주인의식, 파트너십 및 배려의 개념을 키우는 학습 환경에 의해 조정되는 '실제 세계'에 해당하는 과제에 달려 있습니다. 하지만 이 프레임워크 내에서 '실제 세계' 측면에 대한 몇 가지 좋은 증거가 있지만, 실존과 의미 속성에 대해서는 더 많은 조사가 필요합니다.

The proposed framework is thus mainly concerned with how an authentic model of teaching through research could lead to positive, meaningful and long-lasting effects on the personal, and perhaps even professional, development of students. The ‘student’ and ‘knowledge outcomes’ in the framework include some key values and skills that we as educators wish our students to have. The ‘focus’ and ‘alignment’ components in the framework serve as guidance for ways in which a curriculum could instil those values and other outcomes. These means for achieving the desired outcomes predominantly rests on ‘real world’ corresponding tasks that are student-led and moderated by a learning environment that fosters notions of responsibility, ownership, partnership and care. And yet, while we have some good evidence for the ‘real world’ aspects within this framework, the existential and meaning attributes require further inquiry.

ABSTRACT

This conceptual paper is concerned with the discursive and applied attributes of ‘authenticity’ in higher education, with a particular focus on teaching science through student research. Authenticity has been mentioned in passing, claimed or discussed by scholars in relation to different aspects of higher education, including teaching, learning, assessment and achievement. However, it is our position that in spite of the growing appeal of authenticity, the use of the term is often vague and uncritical. The notion of authenticity is complex, has a range of meanings and is sometimes contested. Therefore, we propose here a practice-oriented and theoretically-informed framework for what constitutes authenticity within the context of teaching through research. This framework brings together aspects of the ‘real world,’ existential self, and embedded meaning, and aligns them with different outcomes relating to knowledge and to students. Different models of teaching through research with conflicting claims to authenticity are used to illustrate the framework.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 교육과정 개발&평가' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 의학교육에서 장애 표용: 질향상 접근을 향하여 (Med Educ, 2022) (0) | 2023.08.31 |

|---|---|

| 의학교육에서 장애 역량 훈련(Med Educ Online. 2023) (0) | 2023.08.31 |

| 연구-바탕 학습이 효과적인가? 사회과학에서 사전-사후 분석(STUDIES IN HIGHER EDUCATION, 2021) (0) | 2023.08.03 |

| 의학교육커리큘럼에서 인공지능의 필요성, 도전, 적용(JMIR Med Educ. 2022) (0) | 2023.07.26 |

| 의학교육에서 인공지능 훈련 도입하기 (JMIR Med Educ. 2019) (0) | 2023.07.26 |