의학교육에서 장애 역량 훈련(Med Educ Online. 2023)

Disability competency training in medical education (Med Educ Online. 2023)

Danbi Leea,b, Samantha W. Pollackb, Tracy Mroza,b, Bianca K. Frognerb and Susan M. Skillmanb

소개

Introduction

장애인은 건강 상태와 의료 서비스에서 지속적인 격차를 경험합니다. [1,2,3] 적절한 의료 서비스를 가로막는 다단계 장벽의 핵심은 장애인의 다양한 경험과 필요에 대한 의료 서비스 제공자의 인식과 교육 부족, 부정적인 태도와 가정입니다[4,5]. 장애인은 접근하기 어려운 공간 및 장비, 의사소통 부족, 치료 결정 시 기존 장애 또는 기능적 상태를 고려하지 않는 등 의료 제공자의 장애 친화적 진료 부족으로 인해 양질의 의료 서비스를 이용하는 데 어려움을 겪고 있습니다[6-8]. 의사를 포함한 25,000명 이상의 의료 서비스 제공자를 대상으로 한 최근 연구에 따르면 60% 이상이 장애인에 대한 자신의 암묵적인 편견을 인식하지 못하고 있는 것으로 나타났습니다[9]. 그러나 문헌에 따르면 의료 서비스 제공자들은 장애에 대한 부정적인 태도와 특정 임상 및 접근 요구 사항을 포함한 장애인의 광범위한 의료 요구 사항을 다루는 제한된 교육만 받고 있습니다[10-13].

People with disabilities experience persistent disparities in health status and health care. [1, 2,3] Central to the multilevel barriers to adequate health care are the lack of awareness and training among health care providers about the varied experiences and needs of individuals with disabilities, as well as negative attitudes and assumptions [4,5]. People with disabilities continue to experience challenges in accessing quality health care because of lack of disability-competent care by providers such as inaccessible space and equipment, poor communication, and not considering existing disability or functional status in making treatment decisions [6–8]. A recent study of over 25,000 health care providers, including physicians, found that more than 60% were unaware of their own implicit bias against people with disabilities [9]. Yet, literature shows that providers receive only limited training addressing negative attitudes towards disability and the wide range of health care needs of people with disabilities including specific clinical and access needs [10–13].

2017년에 발표된 미국 의과대학 장애 커리큘럼을 검토한 결과, 장애 역량을 통합하는 수준은 여전히 이질적이며 주로 노출에 기반한 것으로 나타났으며 종단적 모델을 제공하는 학교는 소수에 불과했습니다[12]. 여기에는 강의 및 단일 코스와 같은 교훈적인 방법부터 사무직 로테이션 중 표준화된 장애 환자 포함, 6주 통합 사무직 경험, 위의 모든 방식과 4년간의 장애 중심 선택적 사무직에 대한 옵션이 포함된 4년 통합 장애 커리큘럼에 이르기까지 다양합니다. 의학교육에서 장애에 대해 무엇을 가르쳐야 하는지에 대한 합의가 부족하기 때문에 장애 커리큘럼 제공의 다양성은 내용에도 영향을 미칩니다[14].

A review of published U.S. medical school disability curricula in 2017 found that the level of integrating disability competency remained to be heterogeneous and primarily exposure-based with only a few schools providing a longitudinal model [12]. These range from didactic methods like lectures and single courses, to the inclusion of standardized patients with disabilities during clerkship rotations; 6-week integrated clerkship experiences; and 4-year integrated disability curriculum that included all of the above modalities and the option of attending a 4th-year disability-focused elective clerkship. The variability in delivering disability curricula also extends to content as there has been lack of agreement on what to teach about disability in medical education [14].

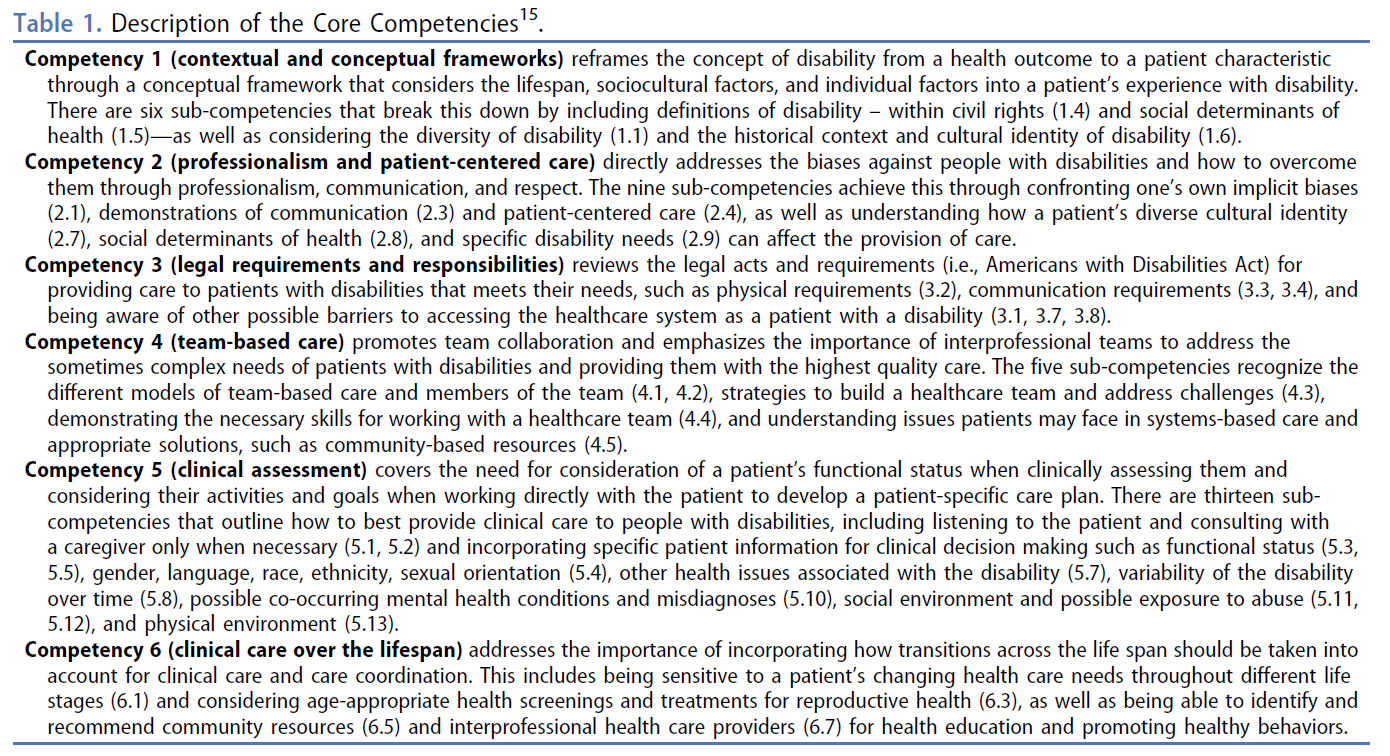

이러한 격차를 인식하고 2019년에 보건의료 교육 장애 연합은 장애 관련 콘텐츠와 경험을 보건의료 교육 및 훈련 프로그램에 통합하는 것을 촉진하기 위해 보건의료 교육 장애에 관한 핵심 역량(핵심 역량)을 발표했습니다[15]. 다양한 보건의료 분야의 보건의료 교육자, 교수진 및 전문가로 구성된 연합 회원들은 역량 초안을 작성하고 140명의 장애 전문가 및 보건교육자로부터 두 차례에 걸친 반복적인 프로세스를 통해 피드백을 받았습니다. 2년에 걸친 이 과정을 통해 장애의 사회적, 환경적, 신체적 측면에 대한 보건의료 교육 표준을 제공하는 6개의 핵심 역량과 49개의 하위 역량(표 1)이 도출되었습니다[14,15]. 이러한 핵심 역량이 의학교육에서 다루어지고 있는지 여부와 그 방법을 조사한 연구는 아직 없습니다. 이 연구는 미국의 의학교육 프로그램에서 핵심역량이 어느 정도 다루어지고 있는지, 그리고 교과과정 통합을 확대하는 데 있어 촉진요인과 장벽이 무엇인지 살펴보는 것을 목표로 했습니다.

Recognizing this gap, in 2019, the Alliance for Disability for Health Care Education published Core Competencies on Disability for Health Care Education (Core Competencies) to promote the integration of disability-related content and experiences into health care education and training programs [15]. Members of the alliance composed of health care educators, faculty and professionals across different health care disciplines drafted the competencies and received feedback through a two-wave iterative process from 140 disability experts and health educators. This two-year process resulted in six core competencies and 49 sub-competencies (Table 1) that provide health care education standards on social, environmental, and physical aspects of disability [14,15]. There has yet been a study that examined whether and how these Core Competencies are addressed in medical education. The study aimed to explore the extent the Core Competencies are addressed in medical education programs in the U.S. and the facilitators and barriers to expanding curricular integration.

https://www.adhce.org/Core-Competencies-on-Disability-for-Health-Care-Education

연구 방법

Methods

이 연구는 순차적 혼합 방법 설계를 사용하여 온라인 설문조사에 이어 정성적 인터뷰를 진행했습니다. 문제에 대한 보다 심층적이고 완전한 이해를 제공하기 위해 양적 및 질적 데이터를 모두 수집했습니다[16]. 이 연구는 워싱턴대학교 기관생명윤리심의위원회(IRB# MOD00007591)에서 면제를 결정했습니다.

The study used a sequential mixed-methods design, where an online survey was followed by qualitative interviews. Both quantitative and qualitative data were collected to provide a more in-depth and complete understanding of the problem [16]. This study was determined to be exempt by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board (IRB# MOD00007591).

설문지

Questionnaire

23개 항목으로 구성된 설문지는 장애 연구(DL), 의료 서비스(TM, BF, SS, SP), 의료 인력(DL, TM, BF, SS, SP) 연구 분야의 전문가로 구성된 다학제 프로젝트 팀에 의해 개발되었습니다. 객관식 질문은 현재 커리큘럼에서 어떤 핵심 역량이 다루어지고 있는지, 학교에서 장애 콘텐츠를 커리큘럼에 통합하는 데 있어 어떤 촉진자와 장벽이 있는지, 장애인이 어떻게 참여하고 있는지 파악하기 위해 사용되었습니다. 핵심 역량에 매핑된 학습 활동의 세부 사항(예: 이름, 내용/주제, 형식, 필수/선택 사항, 활동 시기)을 수집하기 위해 개방형 질문이 사용되었습니다. 예비 설문조사 문항은 장애 교육에 전문성을 갖춘 의과대학 교수진과 장애인의 공평한 의료 서비스를 옹호하는 장애인 단체의 장애인 전문가 등 6명의 전문가로 구성된 자문 패널에 의해 파일럿 테스트 및 검토를 거쳤습니다. 이후 이들의 피드백을 바탕으로 설문지를 수정했습니다.

A 23-item questionnaire was developed by a multidisciplinary project team of experts in the research areas of disability studies (DL), health services (TM, BF, SS, SP), and health workforce (DL, TM, BF, SS, SP). Multiple-choice questions were used to identify which Core Competencies are currently addressed in the curriculum; what facilitators and barriers schools experience in to incorporating disability content into the curriculum; and how people with disabilities are involved. Open-ended questions were used to gather details of learning activities mapped to the Core Competencies (i.e., name, content/topic, format, required/optional, and timing of the activity). Preliminary survey questions were pilot-tested and reviewed by an advisory panel of six experts including faculty from medical schools with expertise in disability education and experts with disabilities from disability organizations advocating for equitable health care of people with disabilities. The survey was then revised based on their feedback.

설문조사는 2019학년도 현재 예비 또는 잠정 인증 상태를 유지하고 있는 프로그램을 포함하여 미국의 모든 동종요법 및 정골요법 의과대학(n = 196개)에 배포되었습니다. 2020년 2월부터 6월 사이에 커리큘럼 학장, 학부 교육 학장, 프로그램 디렉터에게 이메일 초대장과 6차례의 리마인더를 보냈습니다. 설문조사 응답의 데이터 수집에는 REDCap(Research Electronic Data Capture)이 사용되었습니다[17].

The survey was distributed to all allopathic and osteopathic medical schools in the U.S. (n = 196), including programs with preliminary or provisional accreditation status as of the 2019 academic year. Email invitations and six reminders were sent to curriculum deans, deans of undergraduate education, and program directors between February and June 2020. Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) was used for data collection of survey responses [17].

질적 인터뷰

Qualitative interviews

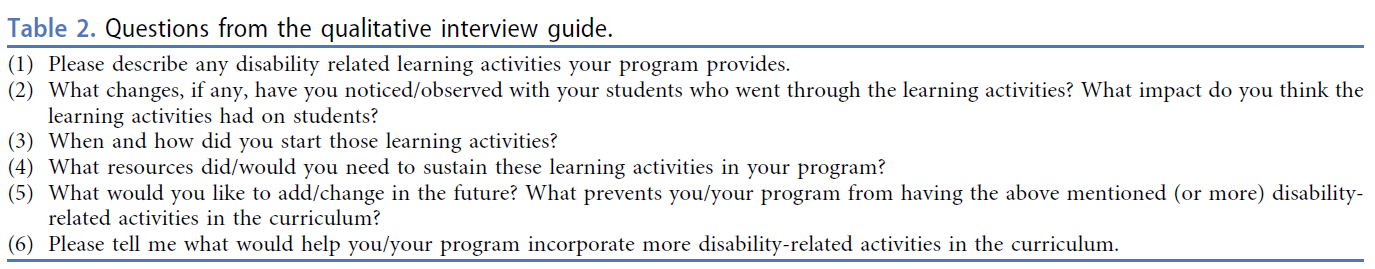

질적 인터뷰 대상자는 설문조사 응답자 중에서 다양한 지역의 의과대학을 대표할 수 있도록 의도적으로 선정되었습니다. 제1저자와 제2저자는 반구조화된 인터뷰 가이드를 사용하여 Zoom을 통해 30~60분간 개별 인터뷰를 진행했습니다. 설문조사 결과를 바탕으로 설문조사에 기술된 학습 활동과 장벽 및 지원 사항을 더 잘 이해할 수 있도록 설계된 인터뷰 가이드(표 2)를 작성했습니다. 인터뷰 가이드는 동일한 다학제 프로젝트 팀에서 개발했습니다. 인터뷰에 앞서 참가자들은 연구 참여에 대한 사전 동의를 제공했습니다. 동의한 참가자에게는 장애 콘텐츠가 포함된 학습 활동과 그것이 학생에게 미치는 영향, 학습 활동을 시작하고 유지하는 데 도움이 되는 요소, 더 많은 통합을 가로막는 장벽에 대해 설명해 달라는 요청을 받았습니다. 인터뷰는 허가를 받아 녹음되었습니다.

Qualitative interviewees were purposefully selected from survey respondents to represent medical schools from different regions. Thirty to sixty-minute individual interviews were conducted by the first and second authors via Zoom using a semi-structured interview guide. Informed by the survey findings, the interview guide that was designed to better understand the learning activities and barriers and supports described in the survey (Table 2). The interview guide was developed by the same multidisciplinary project team. Prior to the interview, participants provided informed consent to their research participation. Consented participants were asked to describe learning activities with disability content and their impact on students, facilitators to initiating and maintaining learning activities, and barriers to integrating more. Interviews were recorded with permission.

데이터 분석

Data analysis

O'Cathain 외[18]가 제안한 데이터 삼각측량 프로토콜에 따라 데이터를 먼저 개별적으로 분석한 다음 해석 단계에서 통합했습니다. 먼저, 의과대학에서 어떤 핵심역량을 얼마나 많이 다루고 있는지, 장애인이 어떻게 참여하고 있는지, 어떤 지원과 장벽이 존재하는지 파악하기 위해 서술적 통계를 사용하여 설문조사 데이터를 분석했습니다. 개방형 질문에 기술된 학습 활동의 세부 사항(예: 학습 활동의 유형, 초점, 길이, 빈도)을 코딩하고 정성적, 정량적으로 요약했습니다. 그런 다음 개별 인터뷰의 메모와 녹취록을 주제 분석을 사용하여 분석했습니다[19]. 주제는 연구팀과 논의했습니다. 코딩-재코딩, 데이터 삼각측량, 데이터의 두꺼운 기술, 반성성(장애인으로서의 입장에 대한 끊임없는 성찰과 토론)을 통해 신뢰성, 전달성, 확인성을 확보했습니다. 마지막으로 해석의 깊이를 더하기 위해 양적 데이터와 질적 데이터의 결과를 비교하고 수렴성, 상호보완성, 불일치성을 검토했습니다[18].

Following the data triangulation protocol suggested by O’Cathain et al. [18], data were first analyzed separately then integrated at the interpretation stage. First, survey data were analyzed using descriptive statistics to identify which and how many Core Competencies were addressed in medical schools, how people with disabilities are involved, and what supports and barriers exist. Details of the learning activities described in the open-ended questions were coded (e.g., types, focus, length, and frequency of the learning activities) and summarized qualitatively and quantitatively. Then, notes and transcripts from the individual interviews were analyzed using thematic analysis [19]. Themes were discussed with the research team. Credibility, transferability, and confirmability were ensured through coding-recoding, data triangulation, thick description of data, and reflexivity (i.e., constant reflection and discussion regarding positionality as persons without disabilities). Finally, to add depth to the interpretation, results from quantitative and qualitative data were compared and examined for convergence, complementarity, and discrepancy [18].

결과

Results

참가자

Participants

총 14개 프로그램에서 설문조사를 완료했습니다. 대부분의 응답자는 대규모 코호트를 보유한 동종요법 공립 의과대학이었습니다(표 3). 5명의 의과대학 대표가 질적 인터뷰에 참여했습니다. 여기에는 미국의 4개 인구조사 지역을 대표하는 사립 의과대학 1개와 공립 의과대학 4개가 포함되었습니다.

A total of 14 programs completed the survey. Most respondents were allopathic public medical schools with larger cohorts (Table 3). Five medical school representatives participated in the qualitative interview. This included one private and four public medical schools representing four U.S. census regions.

조사 결과

Findings

설문조사와 질적 인터뷰 결과를 통합하여 두 가지 주제 영역으로 분류했습니다:

- 1) 핵심 역량을 다루는 장애 역량 교육 현황,

- 2) 장애 역량 교육을 통합하는 데 있어 장벽과 촉진 요인.

특히 질적 데이터를 통해 다음에 대해 보다 심층적으로 이해할 수 있었습니다.

- 1) 커리큘럼 구조와 시간이 핵심역량 통합에 미치는 영향,

- 2) 자원과 챔피언의 중요한 역할

Integrated, the results from the survey and qualitative interviews were categorized into two topic areas: 1) status of disability competency training addressing the Core Competencies and 2) barriers and facilitators to integrating disability competency training. Qualitative data particularly provided more in-depth understanding on 1) the influence of curricular structure and time on integrating Core Competencies and 2) the crucial role of resources and champions.

핵심 역량을 다루는 장애 역량 교육 현황

Status of disability competency training addressing the Core Competencies

14개 학교 중 11개 학교가 교육과정에서 5~6개의 핵심 역량을 다루고 있다고 응답했습니다(표 4). 대부분의 학교(n=13)는 장애에 대한 맥락 및 개념적 프레임워크와 팀 및 시스템 기반 실무에 대해 다루고 있다고 답했습니다. 법적 의무와 책임에 관한 역량은 가장 적게 다루고 있었습니다(n = 6).

Eleven out of 14 schools reported that their curriculum addresses five to six Core Competencies in their curriculum (Table 4). Most schools (n = 13) said that they address contextual and conceptual frameworks on disability and teams and systems-based practice. Competencies around legal obligations and responsibilities were least addressed (n = 6).

장애 역량 교육의 정도는 다양했습니다. 의과대학의 약 절반은 커리큘럼에 한두 가지 학습 활동이 있다고 답했고, 나머지 절반은 세 가지 이상의 학습 활동이 있다고 답했습니다. 대부분의 학습 활동은 일회성 환자 패널 또는 환자 시뮬레이션과 같이 45분~2시간의 단일 세션으로 제공되었습니다. 일부는 2년 이상의 통합 사례, 1년 이상의 주간 시뮬레이션, 4주간의 임상 로테이션 등 여러 과정과 장기간에 걸쳐 통합된 더 긴 학습 활동도 있었습니다. 고급 배치 또는 임상 로테이션과 같은 연장된 경험은 선택 사항이었지만 대부분의 학습 활동은 필수였습니다. 4학년의 임상 로테이션과 3학년의 몇 가지 환자 대면을 제외하고 보고된 모든 학습 활동은 의학교육의 첫 2년 동안 완료되었습니다.

The extent of disability competency training varied. About half of the medical schools reported one or two learning activities within their curriculum; the other half described three or more learning activities. Most learning activities described were offered in single 45-minute to 2-hour sessions such as one-time patient panels or patient simulations. Some were longer and more integrated across different courses and extended time periods, including integrated cases over 2 years, weekly simulations over a year, and 4-week clinical rotations. The majority of learning activities were required although most of the extended experiences such as advanced placement or clinical rotations were optional. Except for the clinical rotations in year 4 and a few patient encounters in year 3, all learning activities reported were completed during the first two years of medical education.

학습 활동에는 강의, 사례 연구, 패널 토론, 소그룹 토론이 포함되었습니다. 많은 학교에서

- 장애에 대한 인식을 높이기 위해 다양한 장애 모델, 능력주의, 암묵적 편견과 같은 주제를 논의하고,

- 장애 에티켓과 임상 평가 또는 다학제 진료에서 장애인과 상호작용하는 방법을 다루었으며,

- 환자 패널을 통해 장애인의 생생한 경험에 대해 배울 수 있는 기회를 제공했습니다.

일부 학교에서는 재활의 맥락에서 의학적 상태로서의 장애에 대해 배우거나(예: 재활 현장 방문, PM&R 임상 로테이션) 의학적 맥락에서 장애 관련 진단(예: 뇌성마비, 치매)을 이해하는 데 중점을 둔 활동을 보고했습니다. 장애인 또는 표준화된 환자와의 일회성 만남 및 시뮬레이션이 더 일반적이었으며, 장애 커뮤니티와의 현장 프로젝트 또는 장애인과의 장기 임상 경험과 같은 몰입형 체험 학습 기회를 제공하는 학교는 더 적었습니다. 핵심 역량과 연계된 학습 활동의 구체적인 예는 표 4에 나와 있습니다.

The learning activities included lectures, case studies, panel discussions, and small group discussions. Many

- discussed topics such as different disability models, ableism, and implicit bias to raise awareness of disability;

- addressed disability etiquette and how to interact with people with disabilities in clinical assessments or in interdisciplinary care; and

- provided opportunities to learn about the lived experiences of people with disabilities through patient panels.

Some schools reported activities focused on learning about disability as a medical condition within the context of rehabilitation (e.g., visiting rehabilitation sites, clinical rotation in PM&R) or understanding disability-related diagnoses (e.g., cerebral palsy, dementia) in a medical context. One-time encounters and simulations with people with disabilities or standardized patients were more common, and less schools offered immersive experiential learning opportunities such as a field project with disability communities or extended clinical experiences with people with disabilities. Specific examples of learning activities linked to the Core Competencies are listed in Table 4.

의과대학 커리큘럼에서 신체적 장애를 가장 많이 다루고 있었으며(n = 13), 감각 장애에 대한 논의는 가장 적었습니다(n = 9). 또한 설문조사 결과에 따르면 장애인은 패널(n = 9) 또는 환자(n = 7)로서 학습 활동에 참여하는 경우가 많았으며, 교육(n = 4) 또는 커리큘럼 활동 계획(n = 4)에 참여하는 역할은 적었습니다. 3개 학교는 장애인이 전혀 참여하지 않았다고 보고했습니다. (표 5 참조)

Most frequently, the medical school curricula addressed physical disability (n = 13) while sensory disabilities were least discussed (n = 9). The survey result also shows that people with disabilities were often engaged in learning activities as panelists (n = 9) or patients (n = 7) with less of a role in teaching (n = 4) or planning curricular activities (n = 4). Three schools reported no involvement of individuals with disabilities. (see Table 5)

설문조사 결과와 유사하게, 주요 정보 제공자들과의 질적 인터뷰에서는 패널과 함께하는 짧은 독립 세션, 시뮬레이션 또는 특정 주제를 다루는 토론과 관련된 학습 활동이 많이 논의되었습니다. 인터뷰 참여자들은 패널과 환자와의 만남이 종종 학생들이 좋아하고 긍정적인 영향을 미친다고 언급했습니다.

Similar to the survey results, in the qualitative interviews with key informants, many learning activities discussed involved short independent sessions with panels, simulations, or discussions that address particular topics. Interviewees noted that panels and patient encounters are often liked by students and have a positive impact.

... 학생들은 이러한 세션이 끝난 후 훨씬 더 자신감이 생겼다고 말했습니다... [장애] 환자와 함께 방에 들어가서 어떻게 행동해야 하는지 알고, 때로는 조금 어색할 수 있지만 괜찮습니다... 에티켓과 H&P(병력 및 신체 검사) 방법에 대해 염두에 두고 환자에게 물어보십시오. (CS1)

… students have voiced that they feel a lot more confident after these sessions … going into the room with a patient with [disabilities], knowing how to act, and kind of owning that sometimes, yeah, you’re going to feel a little awkward, that’s ok … be mindful of etiquette and how you go about an H&P [history and physical examination], you know, ask the patient. (CS1)

그러나 이러한 교육은 일반적으로 커리큘럼 전체에 걸쳐 한 번만 제공되기 때문에 많은 인터뷰 대상자가 충분하지 않다고 설명했습니다. 일부 인터뷰 참여자들은 4년 동안 여러 곳에서 장애에 대해 이야기하는 것이 중요하다고 강조했습니다. '커리큘럼에 장애를 더 많이 포함시키는 더 좋은 방법은 장애인 사례를 곳곳에 배치하는 것이라고 생각합니다...' 몇몇은 다양성 및 건강 격차 논의에 장애 내용을 엮는 방법에 대해 언급했습니다. 한 학교는 3학년과 4학년 가정의학과 및 내과 실습에 다양성 및 의료 격차 스레드의 일부로 장애 관련 학습 이벤트 두 개를 포함했습니다. 또 다른 인터뷰 참여자는 다음과 같이 말했습니다,

However, because they were typically offered only once throughout the curriculum, many interviewees described those as not enough. Some interviewees stressed the importance of talking about disability in multiple places throughout the four years: ‘I think a better way to get more disability into the curriculum would be to put more examples of people with disabilities…peppered throughout…’ A few mentioned how they weave disability content into the diversity and health disparities discussion. One school included two disability-related learning events as part of their diversity and health care disparities thread in their 3rd and 4th year family medicine and internal medicine clerkships. Another interviewee shared,

우리는 ... 자폐증 패널과 모의 환자 만남을 ... 커리큘럼의 일부에서 집단 내 환자에 대해 이야기하고 있습니다 ... 저는 장애가 [건강의 사회적 결정 요인을 이해하는] 이 맥락에서 전적으로 적절하다는 사례를 만들 수 있었습니다... (CS2).

We have … the autism panel and the simulated patient encounter … in a part of the curriculum where they’re talking about patients within populations … I was able to make the case that disability is totally appropriate in this context [of understanding social determinants of health] … (CS2)

처음 2년 동안만 학습 활동을 한 참가자들은 이후 임상에서 정보를 다시 연결시키는 반복적인 경험이 부족하다는 데 동의했습니다: '[T]3년차와 4년차에는 사람들이 반드시 모여서 첫 2년 동안 배운 내용을 되돌아볼 수 있는 기회가 없기 때문에... 완전히 적중하거나 놓치는 경우가 있습니다'(CS5). 또한 프로그램 구조가 장벽이 될 수 있다는 점을 인식했습니다. '[첫 18개월 이후에는] 학생들이 수백 개의 장소에 있기 때문에 교육 단계에서 지식을 쌓는 데 환자 경험을 활용할 수 없다고 생각합니다'(CS4). 하지만 이 참가자는 임상 실습 중에 장애 콘텐츠를 통합하기 위해 필수 온라인 강의를 사용할 수 있는 가능성을 제시했습니다.

Participants who only had learning activities in their first two years agreed that an iterative experience tying back the information in later clinical years is missing: ‘[T]here’s nothing in the third and fourth year where people necessarily come together to think back on what they learned in the first two years … So it’s completely hit or miss what they get’ (CS5). They also recognized that program structure could be a barrier: ‘[after the first 18 months] I don’t think there is a capitalization on the patient experience to build their knowledge in their phases of training because [students] are in hundreds of locations’ (CS4). This participant yet expressed the potential of using required online lectures to integrate disability content during clerkships.

장애 역량 교육 통합의 장벽 및 촉진 요인

Barriers and facilitators to integrating disability competency training

표 6에서 볼 수 있듯이, 장애 역량 교육을 커리큘럼에 통합하는 데 가장 자주 확인된 촉진제는 교수진의 지지자(n = 11)였으며, 학술적 리더십의 지원(n = 8), 지역사회 기반 장애 단체와의 파트너십(n = 7)이 그 뒤를 이었습니다. 장애 학생, 교수진 또는 교직원이 프로그램에 참여하는 것도 장애 역량 교육의 통합에 긍정적인 영향을 미치는 것으로 보입니다. 가장 큰 장벽은 커리큘럼에 새로운 콘텐츠를 추가할 시간이 부족하다는 점(n = 10)이었으며, 리소스 부족(n = 5)이 그 뒤를 이었습니다. 일부 응답자는 촉진 요인(예: 교수진의 지지자, 장애인 단체와의 관계)의 부족도 장벽으로 보고했습니다.

As seen in Table 6, the most frequently identified facilitator to incorporating disability competency training into curriculum was having a faculty champion (n = 11) followed by support of academic leadership (n = 8) and partnership with community-based disabilities organizations (n = 7). Having students, faculty, or staff with disabilities in the program also seems to positive affect the integration of disability competency training. An overwhelming barrier was lack oftime in the curriculum to add new content (n = 10), followed by inadequate resources (n = 5). Lack of factors identified as facilitators (e.g., faculty champion, relationship with disability organizations) was also reported as barriers by some respondents.

설문조사 결과와 일관되게, 모든 주요 정보 제공자들은 제한된 커리큘럼 시간을 확보하기 위한 경쟁이 더 많은 장애 역량 콘텐츠를 통합하는 데 가장 큰 어려움이라는 데 동의했습니다. 한 인터뷰 참여자는 '커리큘럼에서 발판을 마련하는 것이 정말 어렵습니다. 정말 어렵죠. 두 시간을 위해 싸워야 합니다. (CS5). 인터뷰에서는 장애 역량 교육을 커리큘럼에 통합하는 데 있어 교수진 또는 학생 챔피언이 있다는 점도 분명하게 드러났습니다. 챔피언은 대개 이 주제에 관심을 갖고 강의 자료를 개발하고 실행한 교수진이었습니다. 한 프로그램에서는 장애 형제가 있는 학생 챔피언이 학생들이 장애인 환자, 간병인 및 장애인과 함께 일하는 다른 의료 종사자들과 교류할 수 있는 선택 과목을 개설했습니다. 한 인터뷰 참여자는 휠체어를 사용하는 의사인 코스 디렉터가 의사로서 자신의 장애 경험에 대해 이야기해주기 때문에 '훌륭한 자산'이 되었다고 설명했습니다(CS1).

Consistent with the survey result, all key informants agreed that competition for limited curriculum time is the biggest challenge to integrating more disability competency content. One interviewee said, ‘finding a foothold in the curriculum is huge. It’s really hard. You fight for your two hours.’ (CS5). In the interviews, it was also clear that having a faculty or student champion has been a force in integrating disability competency training into the curriculum. The champions were usually faculty members who were invested in this topic and who developed and carried out course materials. In one program, a student champion who has a sibling with a disability initiated an elective course where students have chances to interact with patients with disabilities, their caregivers, and other health care workers that work with people with disabilities. One interviewee described that having a course director who is a physician using a wheelchair has been a ‘wonderful asset’ because he would talk about his own disability experience as a physician (CS1).

질적 인터뷰를 통해 이러한 챔피언에 대한 지나친 의존이 얼마나 취약한지를 알 수 있었습니다. 휠체어 사용자인 의사의 은퇴가 다가오면 학생들이 그와 교류하고 배울 기회를 잃게 될 것이기 때문에 인터뷰 대상자는 이를 우려했습니다(CS1). 다른 사람들도 이러한 의견을 제시했습니다. 한 사람은 '[교수 챔피언이] 떠났을 때 재활의학과에 있는 누구와도 연결이 되지 않았습니다. 연락이 끊겼어요. (CS4). 한 인터뷰 대상자는 챔피언이 촉진자로 여겨지는 반면, 장애 역량 교육의 약점이라고 지적했습니다: 장애인 역량 교육 접근 방식이 항상 챔피언에 의존해 왔다는 점이 이 노력의 큰 약점이라고 생각합니다. 저는 그들[챔피언]이 할 수 있는 일에 대해 존경심을 가지고 있습니다... 하지만 지속 가능하지도 않고 확장 가능하지도 않습니다... 챔피언이 은퇴하자마자 콘텐츠와 커리큘럼에 판매 기한이 정해져 있는 것과 같습니다. 커리큘럼에 대한 수요의 힘을 견딜 수 없습니다. (CS2)

The qualitative interviews also revealed the fragility of too much reliance on these champions. The upcoming retirement of the physician who is a wheelchair user was a concern of the interviewee because students would lose the opportunity to interact with and learn from him (CS1). This sentiment was also presented by others. One person said, ‘When [the faculty champion] left, I didn’t have a connection with anyone in rehabilitation. I lost those contacts.’ (CS4). While having a champion was seen as a facilitator, one interviewee pointed out how that is a weakness of disability competency training: I think that’s a huge weakness in this effort, that the disability training approach has always relied on champions. I have so much respect for what they [champions] are able to do … But, it’s not sustainable, and it’s not scalable … [A]s soon as the champion retires, there’s like a sell-by date on the content and the curriculum. It just cannot withstand the forces of the demands on the curriculum. (CS2)

인터뷰 참여자들은 또한 커리큘럼에 장애 콘텐츠를 통합하는 데 있어 기관의 지원과 리소스가 중요한 역할을 한다고 지적했습니다. 그들은 어떤 특정 리소스를 이용할 수 있고 어떻게 활용했는지에 대한 자세한 정보를 제공했습니다. 이러한 자원에는 다음 등이 포함되었습니다.

- 콘텐츠 개발을 위한 보호된 시간,

- 패널 또는 환자와의 만남 세션을 조정할 전담 직원,

- 패널 또는 표준화된 환자와 가족에게 지급할 자금,

- 환자 자원봉사자 모집을 위한 장애인 단체와의 연결

Interviewees also pointed to the critical role of institutional supports and resources in integrating disability content in the curriculum. They provided more information on what specific resources they had access to and how they utilized those. These resources included

- protected time to develop content,

- designated staff to coordinate panel or patient encounter sessions,

- funds to pay panelists or standardized patients and families, and

- connection to disability organizations to recruit patient volunteers.

환자와의 만남과 패널을 실행하는 데 필요한 리소스가 자주 지적되었습니다. 한 프로그램에서는 참가자의 접근성을 보장하기 위해 패널/시뮬레이션 세션을 지원하는 데 많은 직원이 참여했습니다(예: 자폐증 환자에게 적합한 환경, 시각 장애가 있는 환자 안내)(CS3). 일부의 경우, 리소스 부족으로 인해 모범 사례라고 생각했던 활동을 하지 못했습니다. '[문제 기반 학습]을 위해 퍼실리테이터를 위해 [장애인] 사람들을 모았는데...[제한된 리소스 때문에] 그 이후로 하지 못했습니다.'(CS5). (CS5).

Resource needs for implementing patient encounters and panels have been frequently noted. One program had many of their staff involved in supporting the panel/simulation session to ensure accessibility of participants (e.g., appropriate environment for patients with autism, guiding patients with visual impairment) (CS3). For some, the lack of resources prevented activities they believed to be best practice: ‘I brought people [with disabilities] together for the facilitators for [problem-based learning]…[H]aven’t done it since because of limited resources.’ (CS5).

기대하는 효과에 적합한 패널리스트를 찾는 것은 때때로 어려운 일이었습니다. 일부 패널은 전달하고자 하는 다른 메시지(예: 총기 규제)를 가지고 있었기 때문에 한 참가자(CS4)는 '그들이 무슨 말을 할 지 모르겠다'고 말했습니다. 팬데믹으로 인해 패널 세션을 계획하는 데 시간을 내기가 어려워지자, 이 프로그램은 학생들이 장애인과 장애인 권리 운동의 생생한 경험을 접할 수 있는 방법으로 '크립 캠프' 다큐멘터리를 시청하고 성찰하는 것으로 대체했습니다. 인터뷰 대상자는 '잘 만들어진 영화가 메시지를 전달하는 데 더 효과적일 것 같다'고 말했습니다.

Finding the right panelists for the hoped impact was sometimes a challenge. ‘I don’t know what they are going to say’ said one participant (CS4) as some panelists had other messages they wanted to communicate (e.g., gun control). When finding time for planning a panel session became a challenge due to the pandemic, this program replaced it with watching and reflecting on the ‘Crip Camp’ documentary, as a way to expose students to the lived experience of people with disabilities and the disability rights movement. The interviewee shared, ‘maybe a very well-done film will be more effective in bringing across the messages.’

일부 인터뷰 대상자는 장애인 단체 또는 다른 분야의 콘텐츠 전문가(예: 언어 병리학 및 물리 치료 교수진)와의 파트너십이 중요하다고 언급했는데, 이는 자신들이 이 주제에 대한 전문성을 갖추지 못했기 때문입니다. 그래서 그들[사무국장]은 그것[장애 콘텐츠]이 중요하다고 느꼈고... 아마도 [장애 단체]가 전문가이기 때문에 그들의 편에 서 있다는 것을 알고 훨씬 더 자신감을 느꼈을 것입니다. (CS1)

Some interviewees mentioned the importance of having partnership with a disability organization or content experts from different disciplines (e.g., faculty from speech language pathology and physical therapy), as they did not have expertise in this topic. So they [clerkship directors] felt like it [disability content] was important and … probably felt a lot more confident knowing that [the disability organization] was in their corner, because they’re the experts. (CS1)

새로운 콘텐츠를 개발하기 위한 시간과 자원을 확보하기 위한 또 다른 방법으로 한 인터뷰 참여자는 외부 자금을 적극적으로 모색했습니다. 이 사람은 외부 지원금이 '첫 발을 내딛는 데' 도움이 된다고 말했습니다. 이 인터뷰 참여자는 콘텐츠가 개발되면 일반적으로 학생들에게 인기가 있고 보조금이 끝난 후에도 계속되는 경향이 있지만, 외부 자금이 없었다면 애초에 이러한 활동은 일어나지 않았을 것이라고 말했습니다: '큰 금액은 아니더라도 보조금을 제공하는 것은 의과대학의 협조를 구하는 측면과 실제로 콘텐츠를 개발하고 실행하는 측면에서 밤낮으로 힘든 일입니다.' (CS2)

As another way to secure time and resources to develop new content, one interviewee actively sought external funding. This person reported that external grant helps ‘get a foot in the door.’ Once content is developed, those activities are typically popular with students and tend to continue after the grant ends, said this interviewee, but they would not happen in the first place without external funding: ‘Offering grants, even if it’s not a huge amount of money, is night and day in terms of getting cooperation from the medical school, and in terms of actually developing content and implementing.’ (CS2)

한 인터뷰 참여자는 핵심 역량을 의학교육 연락위원회(LCME) 인증 기준에 포함시키면 챔피언이나 자원이 없어도 장애 콘텐츠를 적극적으로 통합할 수 있다고 제안했습니다.

One interviewee suggested that embedding the Core Competencies into the Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) accreditation standards may lead to proactive integration of disability content even without a champion or resources.

토론

Discussion

이 연구에서는 의과대학이 커리큘럼에 핵심역량을 통합하는 정도와 통합을 방해하는 장벽 및 촉진 요인을 조사했습니다. 설문조사 응답에서 많은 학교가 대부분의 핵심 역량을 다루고 있다고 답했습니다. 장애 역량 교육의 정도는 의과대학 프로그램마다 차이가 있었으며, 대부분 장애에 대한 심도 있는 이해의 기회가 제한적인 것으로 나타났습니다. 대부분의 학교는 제한적이기는 하지만 장애인과 어느 정도 교류하고 있었습니다. 가장 빈번한 촉진자는 교수진이었으며, 더 많은 학습 활동을 통합하는 데 가장 큰 장벽은 커리큘럼 내 시간 부족이었습니다. 질적 인터뷰는 커리큘럼 구조와 시간의 영향, 교수진 챔피언과 자원의 중요성에 대한 더 많은 통찰력을 제공했습니다.

The study explored the extent medical schools integrate the Core Competencies in their curriculum and the barriers and facilitators to the integration. In survey responses, many schools reported addressing most of the Core Competencies. The extent of disability competency training varied across medical programs with the majority showing limited opportunities for in-depth understanding of disability. Most schools had some, although limited, engagement with people with disabilities. Having faculty champions was the most frequent facilitator and lack of time in the curriculum was the most significant barrier to integrating more learning activities. Qualitative interviews provided more insight on the influence of the curricular structure and time and the importance of faculty champion and resources.

이전 문헌[11,12]과 일관되게, 의과대학에서 장애 역량 학습 활동의 형식과 기간은 다양했습니다. 이 연구에 참여한 대부분의 참가자들은 커리큘럼에서 여러 핵심 역량을 다루고 있다고 답했지만, 대부분의 역량이 한두 가지 학습 활동에서 다루어져 관련 주제에 대한 심도 있는 이해를 제공하지 못할 가능성이 높았습니다. 일회성 패널이나 환자와의 만남은 장애인과의 상호작용에 대한 학생의 자신감과 장애 경험에 대한 이해에 영향을 미칠 수 있지만, 이전 연구에 따르면 이러한 영향은 단기적이며[11,20] 장기적으로 장애인을 위한 임상 치료의 질 향상으로 이어지지는 않는 것으로 나타났습니다[16]. 특히 의료진의 암묵적인 편견이 장애인의 평등하고 질 높은 의료 서비스를 저해하는 요인이 될 수 있으므로 장애 문제에 대해 성찰하고 이를 접할 수 있는 기회를 자주 갖는 것이 중요합니다[9]. 또한 설문조사에 따르면 대부분의 활동이 첫 2년 동안 완료된 것으로 나타났습니다. 장애 관련 콘텐츠가 조기에 도입된 것은 긍정적이지만, 임상 진료와 관련된 역량은 학생들이 임상 상황에서 지식을 적용해야 하기 때문에 후반기에 주로 발생합니다.

Consistent with previous literature [11,12], the format and length of disability competency learning activities in medical schools varied. Although most participants in this study reported that their curriculum addresses multiple Core Competencies, most competencies were addressed in one or two learning activities that is likely not providing an in-depth understanding of the related topics. While one-time panels or patient encounters can have an impact on student confidence in interacting with people with disabilities and their understanding of disability experiences, previous research found that this impact is short term [11,20] and does not translate into improved quality of clinical care for people with disabilities long term [16]. Especially, with health care provider’s implicit bias being a contributor to equal and quality healthcare for people with disabilities, frequent opportunities to reflect on and be exposed to disability issues are critical [9]. The survey also showed that most activities were completed in the first two years. It is positive that disability content was introduced early; however, competencies related to clinical care would require students to apply their knowledge in clinical context, which often occur in later years.

연구 참여자와 문헌에서 제안한 바와 같이, 오래 지속되는 혁신적 경험을 촉진하기 위해 의료 프로그램은 커리큘럼 전반에 걸쳐 종적, 반복적, 통합적 학습 활동을 고려해야 합니다[8,13,20]. 강의, 패널, 토론과 함께 몰입형 체험 학습 활동이 이상적입니다[8,21]. 그러나 제한된 자원과 시간 제약을 고려할 때, 기존 커리큘럼에 콘텐츠를 엮고 커리큘럼의 기존 사례를 수정하는 것이 장애 관련 내용을 전체적으로 통합하고 학생들의 장애 관련 임상 치료 역량을 촉진하는 데 더 현실적이고 효과적인 변화일 수 있습니다[20]. 사례 전반에 걸쳐 장애를 대표하고 다양성과 문화적 겸손의 맥락에서 장애에 대해 이야기하는 것을 일상화하면 미래의 의사들이 장애인과 함께 일할 때 명시적 및 암묵적 편견을 적극적으로 성찰하고 제거하는 데 도움이 될 수 있습니다[22]. 다양성 및 문화적 역량 논의에서 장애는 종종 누락됩니다[22]. 의학 프로그램이 장애 역량을 의학교육의 필수적인 부분으로 간주하고 커리큘럼 개선을 위한 투자를 하려면 LCME 표준에 장애를 문화적 역량의 일부로 명시적으로 포함하는 등 더 나은 제도화가 이루어져야 합니다[22].

As suggested by the study participants and literature, to promote long-lasting transformative experiences, medical programs should consider longitudinal, iterative, and integrated learning activities woven throughout the curriculum [8,13,20]. Along with lectures, panels, and discussions, immersive experiential learning activities would be ideal [8,21]. However, considering limited resources and time constraints, weaving content into existing curriculum and modifying existing cases in the curriculum may be more realistic and effective changes to make to integrate disability content throughout and to facilitate students’ competency in disability related clinical care [20]. Having disability representation throughout cases and normalizing talking about disability in context of diversity and cultural humility could help future physicians actively reflect on and work towards eliminating their explicit and implicit biases when working with people with disabilities [22]. Disability is often omitted from diversity and cultural competency discussions [22]. Better systemization, such as explicitly including disability as part the cultural competency in LCME standards, needs to be made for medical programs to view disability competency as an essential part of medical education and make the investment for improving curricular [22].

이 연구와 이전 출판물에서는 장애 역량 교육을 의학교육에 통합하기 위해 챔피언을 발굴해야 할 필요성을 강조했습니다[8,13]. 챔피언에 대한 의존도는 의과대학 전반에서 장애 교육의 다양성에 기여하는 요인으로 확인되었습니다[14]. 의과대학 전반에 걸쳐 장애학 전문 지식이나 실무 경험을 갖춘 교수진이 부족하다는 것은 강화된 LCME 표준이 적용되더라도 장애 역량을 가르치는 능력은 다양할 수 있기 때문에 문제가 됩니다. 비전문가도 쉽게 실행할 수 있는 수업 계획이나 리소스를 만들고 공유하는 데 더 많은 노력을 기울이면 이러한 다양성을 줄일 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, Borowsky 등은 능력주의, 장애의 사회적 모델, 장애의 역사와 문화, 건강 격차에 대해 논의하는 2시간짜리 참여형 수업 계획을 발표했습니다[23]. 필요한 모든 자료가 포함된 이 계획과 가이드는 지식이나 경험이 적은 사람들도 쉽게 실행할 수 있습니다. 그러나 가장 중요한 것은 장애 주제에 대한 대다수 교육자의 무능력과 옹호자의 부족은 장애인이 의료 교육과 진료에 더 쉽게 접근하고 포용할 수 있도록 인력을 다양화할 필요가 있음을 요구한다[22].

This study and previous publications have highlighted the need for identifying a champion to integrate disability competency training into medical education [8,13]. The dependency on champions has been identified as a contributor to variability in disability training across medical schools [14]. The lack of faculty with disability studies expertise or lived experiences across medical schools is problematic because even with a strengthened LCME standard, the ability to teach disability competency will vary. The variability may be reduced with more efforts in creating and sharing lesson plans or resources that can be easily implemented by non-experts. For example, Borowsky et al. published a participatory 2-hour lesson plan that discusses ableism, the social model of disability, disability history and culture, and health disparities [23]. With all materials needed, these plans and guides may be easy to implement for those with less knowledge or experience. Yet, most importantly, the incompetency of majority of educators in the topic of disability and lack of champions call for the critical need for diversifying the workforce by making medical education and practice more accessible and inclusive for individuals with disabilities [22].

이 연구에서 장애인은 주로 자문위원이나 강사가 아닌 패널리스트 또는 표준화 환자로 참여했습니다. 환자와의 만남은 표준화된 행위자보다 장애인과 그 가족을 통해 이루어지는 경우가 더 많았는데, 이는 장애인 커뮤니티에서 비판받는 접근 방식입니다[21]. 그러나 장애인 또는 장애인 커뮤니티의 참여에는 시간과 금전적, 인적 자원이 필요하기 때문에 종종 부담으로 인식되는 것으로 나타났습니다. 또한 지역 장애 커뮤니티와의 연결이 항상 챔피언 없이 구축되는 것은 아닙니다. 이 연구에 참여한 한 학교가 공유한 것처럼, 장애인의 직접적인 참여를 조정할 자원이 부족한 프로그램에서는 장애인 권리와 문화에 관한 다큐멘터리나 회고록을 활용하는 것이 좋은 대안이 될 수 있습니다[21]. 비전문가가 관계를 시작하는 데 관심이 있는 경우 장애 콘텐츠를 기획하고 가르치기 위해 지역 장애 단체를 찾고 참여하는 방법에 대한 자료도 출판되어 있습니다[24].

In this study, people with disabilities were primarily involved as panelists or standardized patients rather than advisory members or instructors. Patient encounters were more often completed with individuals with disabilities and their families than with standardized actors, an approach criticized by disability communities [21]. However, we found that engaging people with disabilities or the disability community requires time and monetary and human resources and thus is often perceived as burden. In addition, connections with local disability communities are not always established without a champion. Like one school in this study shared, using documentaries or memoirs about disability rights and culture could be good alternatives for programs lacking the resources to coordinate direct involvement of people with disabilities [21]. There are also published materials on how to find and engage with local disability organizations to plan and teach disability content if a non-expert is interested in initiating a relationship [24].

장애인이 자문위원이나 강사로 활동하는 학교는 소수에 불과했습니다. 전반적으로 교수진, 학생 및 자문위원의 장애 대표성을 개선하면 커리큘럼 결정에 장애인의 목소리가 반영될 수 있습니다[10]. 이는 의학계에서 장애를 가진 의사가 3.1%에 불과하고[25], 의대생의 4.5%만이 장애를 가지고 있다고 밝힌[26] 최근 연구 결과와도 일치합니다. 장애 역량 교육에 대한 많은 장벽과 필요성은 더 많은 학생, 교수진, 장애를 가진 의사가 현장에 투입되면 해결될 수 있습니다. 장애를 가진 사람들이 많아지면 더 많은 챔피언이 나올 것입니다. 또한 임상 환경에서 환자가 아닌 동료, 동료, 교사, 멘토로서 장애인을 대할 때 교수진과 학생은 장애가 아닌 그 사람을 바라보고 부정확한 가정과 불편함을 해소할 수 있습니다[27]. 이러한 변화는 의학교육의 정책과 관행에서 장벽을 제거하고 접근성과 포용성을 증진하려는 의도적인 노력을 통해서만 달성할 수 있습니다[22,28].

Only a few schools had a person with a disability serving as an advisory member or instructor. Overall, improving disability representation among faculty, students, and advisory members will ensure that curricular decisions reflect their voices [10]. This is consistent with recent studies that confirmed the underrepresentation of disability in Medicine as having only 3.1% of physicians [25] and 4.5% of medical students identify as disabled [26]. Many barriers and needs to disability competency training could be mended with more students, faculty, and physicians with disabilities in the field. With more individuals with disabilities, there will be more champions. In addition, the interaction with someone with a disability as a peer, colleague, teacher, and mentor, and not as a patient in a clinical setting, will allow faculty and students to see the person and not their disability and debunk inaccurate assumptions and discomfort [27]. These changes can only be achieved with intentional efforts to remove barriers and promote access and inclusion in policies and practices in medical education [22,28].

이 연구에는 몇 가지 한계가 있습니다. 모집 노력에도 불구하고 설문조사 응답률이 낮았던 것은 연구 기간 동안 의과대학과 의과대학장에게 영향을 미친 코로나19 팬데믹의 영향일 가능성이 높습니다. 이 주제에 더 많은 투자와 관심이 있는 학교일수록 설문조사에 응답할 가능성이 더 높았을 것입니다. 또한 이러한 역량을 직접적으로 다루지 않는 학교는 이러한 부족함을 드러내려고 하지 않았을 수도 있습니다. 따라서 이 연구 결과는 일반적으로 의과대학이 커리큘럼에서 장애 역량을 다루는 방식을 대표하지 않을 수 있습니다.

This study has a few limitations. Despite efforts to recruit, the low response rate to the survey was likely influenced by the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, which affected medical schools and directors during the study period. Schools who are more invested and interested in this topic may have been more likely to respond to the survey. In addition, schools that are not directly addressing these competencies may not have been as willing to reveal this deficit. Therefore, the study results may not represent how medical schools in general address disability competency in the curricula.

이러한 한계에도 불구하고 이번 연구 결과를 통해 시간이 제한된 의학교육 내에서 장애 역량 교육을 통합하기 위한 노력과 잠재력을 파악할 수 있었습니다. 또한 모든 의과대학에 이 연구에서 설명한 것과 같은 제도적 지원과 지지자가 있는 것은 아니라는 점도 중요합니다. 인터뷰 참여자 중 한 명이 권고한 바와 같이, 의과대학이 이 중요한 주제를 교육에 통합하도록 장려하기 위해 핵심역량을 LCME 인증 기준에 명시적으로 통합하는 것을 추가로 고려할 필요가 있으며, 이는 가능한 옹호자, 자원 및 지원과 관계없이 의과대학에 인센티브를 제공할 수 있습니다. 모든 의사가 장애인과 함께 일할 수 있도록 교육을 받도록 하는 것은 장애인의 건강 및 의료 서비스 격차를 줄이기 위한 중요한 단계가 될 것입니다.

Despite these limitations, the findings allowed for an understanding of efforts made and the potential for integrating disability competency training within time-restricted medical education. It is also important to note that not all medical schools have the institutional support and champions that this study described. As recommended by one of the interviewees, further consideration of explicitly integrating the Core Competencies into LCME accreditation standards may be needed so medical schools are incentivized to integrate this important topic in their education regardless of available champions, resources, and supports. Ensuring that all physicians are trained to work with people with disabilities would be a critical step towards reducing disparities in health care for and the health of people with disabilities.

Disability competency training in medical education

PMID: 37148284

PMCID: PMC10167870

DOI: 10.1080/10872981.2023.2207773

Free PMC article

Abstract

Purpose: Lack of health care providers' knowledge about the experience and needs of individuals with disabilities contribute to health care disparities experienced by people with disabilities. Using the Core Competencies on Disability for Health Care Education, this mixed methods study aimed to explore the extent the Core Competencies are addressed in medical education programs and the facilitators and barriers to expanding curricular integration.

Method: Mixed-methods design with an online survey and individual qualitative interviews was used. An online survey was distributed to U.S. medical schools. Semi-structured qualitative interviews were conducted via Zoom with five key informants. Survey data were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Qualitative data were analyzed using thematic analysis.

Results: Fourteen medical schools responded to the survey. Many schools reported addressing most of the Core Competencies. The extent of disability competency training varied across medical programs with the majority showing limited opportunities for in depth understanding of disability. Most schools had some, although limited, engagement with people with disabilities. Having faculty champions was the most frequent facilitator and lack of time in the curriculum was the most significant barrier to integrating more learning activities. Qualitative interviews provided more insight on the influence of the curricular structure and time and the importance of faculty champion and resources.

Conclusions: Findings support the need for better integration of disability competency training woven throughout medical school curriculum to encourage in-depth understanding about disability. Formal inclusion of the Core Competencies into the Liaison Committee on Medical Education standards can help ensure that disability competency training does not rely on champions or resources.

Keywords: Disability competency; disability; diversity; health care education; medical education.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 교육과정 개발&평가' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 미국 의과대학생의 장애, 프로그램 접근성, 공감, 번아웃: 전국단위 연구(Med Educ, 2022) (0) | 2023.09.04 |

|---|---|

| 의학교육에서 장애 표용: 질향상 접근을 향하여 (Med Educ, 2022) (0) | 2023.08.31 |

| 연구-바탕 교육과정 설계에서의 실제성/진정성 프레임워크 (TEACHING IN HIGHER EDUCATION, 2017) (0) | 2023.08.03 |

| 연구-바탕 학습이 효과적인가? 사회과학에서 사전-사후 분석(STUDIES IN HIGHER EDUCATION, 2021) (0) | 2023.08.03 |

| 의학교육커리큘럼에서 인공지능의 필요성, 도전, 적용(JMIR Med Educ. 2022) (0) | 2023.07.26 |