의료전문직 학술활동: 그것의 등장, 현재상태, 미래(FASEB Bioadv. 2021)

Health professions education scholarship: The emergence, current status, and future of a discipline in its own right

Olle ten Cate

1 의학교육의 역사적 연구

1 THE HISTORICAL OUVERTURE OF SCHOLARSHIP IN MEDICAL EDUCATION

교육 또는 의학 학문에 관여하는 대부분의 생물 의학 과학자는 물론 대부분의 교육 과학자는 현재 "보건 전문직 교육"이라는 더 넓은 용어로 포괄되는 의학 교육 학술활동이라는 교차 영역의 풍부함을 깨닫지 못할 수 있다.

Most educational scientists, as well as most biomedical scientist, involved in educational or medical scholarship, may not realize the richness of the intersecting field of medical education scholarship, currently subsumed under the broader term of “health professions education.”

[인구 건강]과 [인구 교육]은 번영하는 사회의 두 가지 기본 요소이다. 이 둘의 교차점에는 의사 및 보건 전문직이 인구의 건강을 위해 복무하도록 교육하는 기술art가 있다. 의학 교육은 항상 [의사와 교육자]의 헌신적인 관심을 누려왔다. 아폴로와 코로니스의 아들인 최초의 저명한 의대생이자 교육자인 아스클레피오스가 켄타우루스 키론에게 의술을 배웠고, 마법의 막대기와 함께 자신의 회사가 된 뱀으로부터 치유와 부활에 대해 배웠다는 것이 신화의 교훈이다(그림 1). 전 세계 의료협회의 수많은 로고에서 볼 수 있듯이, 막대기와 뱀은 오늘날까지 가장 중요한 의학 상징이 되었고 지금도 남아 있다. 키론과 아스클레피오스가 의학적 지식뿐만 아니라 [교육적 능력]으로도 유명했다는 것을 인정해야 한다.

The intersection of two fundamental pillars of a thriving society—population health and population education—is the art of educating doctors and other health professionals to serve the health of populations. Medical education has always enjoyed the dedicated interest of physicians and educators. Mythology teaches us that the first renown medical student and educator, Asclepius, son of Apollo and Coronis, had been educated himself in the art of medicine by centaur Chiron, and had learned about healing and resurrection from a snake who became his company along with a magical rod (Figure 1). Rod and snake became and remained the most important symbols of medicine throughout the ages until today, as witnessed by the many logos of medical associations around the world. It should be acknowledged that Chiron and Asclepius were not only famous for their medical knowledge, but also known for their educational skill.

21세기에 의학과 생의학은 전문 병원, 실험실, 대학 및 상업 기업을 통해 주요 산업이 되었다. 교육은 여러 세기에 걸쳐서 청소년들을 위한 초등교육과 handcraft에 초점을 맞추었지만, 대부분의 중등교육과 중요한 과학적 토대를 가진 많은 시민들을 위한 3차교육과 함께 지난 세기 동안 산업화된 사회에서 발전해왔다. 교육과학은 20세기에 강하게 발전했다.

In the 21st century, medical and biomedical sciences have become a major industry through specialized hospitals, laboratories, universities, and commercial enterprises. Education, while for many ages focused on primary schooling and handicraft for the youth, has developed in the past century in industrialized societies with secondary education for most and tertiary education for many citizens with important scientific foundations. The science of education has developed strongly in the 20th century.

어느 시대든, 의학 교육 자체는 존경받는 기술respected art이었다. 시대를 통한 유명한 의학 학자들과 교육자들은 히포크라테스, 셀수스, 갤런, 안드레아스 비살리우스, 허먼 보어하브, 윌리엄 오슬러, 그리고 윌리엄 할스테드를 20세기 초까지 주요한 예로 포함한다. 국내적이든 국제적으로든 더 많은 의학 교육자들이 따랐고, 대부분의 의과대학들은 과거에 있었던 교수들에 대하여 초상화 갤러리와 강의실에서 그들의 이름과 얼굴을 기리는 형태로 자부심을 드러낸다.

Medical education itself has been a respected art through the ages. Famous medical scholars and educators through the ages include Hippocrates, Celsus, Galen, Andreas Vesalius, Herman Boerhaave, William Osler, and William Halsted as prime examples until the early 20th century.1-4 Many more medical educators followed, nationally or internationally famous, and most medical schools take pride in some of their own professors of the past, honoring their names and faces in portrait galleries and lecture halls.

오랜 세월 동안 dissection을 통한 [인체 해부학]은 임상 전 교육의 중심이었다. 그림 2는 암스테르담의 와그 해부학 극장에서 공공 해부 강의를 하는 니콜라이스 툴프 교수 (1593–1674)를 보여준다.

For many ages, the anatomy of the human body through dissection was central to preclinical education. Figure 2 shows professor Nicolaes Tulp (1593–1674), delivering a public dissection lecture at the Waag Anatomical Theater in Amsterdam.

2 학문적 연구의 영역으로서 의학 교육의 탄생

2 THE BIRTH OF MEDICAL EDUCATION AS A DOMAIN OF SCHOLARLY STUDY

[의학을 가르치는 기술Art of teaching medicine]이 수 세기에 걸쳐 널리 인정받았지만, 개별 교육자와는 별개로 의학 교육의 방법과 효과에 초점을 맞춘 의학교육 연구는 최근에야 연구의 초점이 되었다. 그 출현은 주로 [20세기 중반]부터 시작된 것으로 간주될 수 있으며, 새로운 방법, 목표 및 내용과 함께 의학 커리큘럼에 대한 새로운 접근법의 개발과 연결된다. 세계적으로 의과대학이 1953년 566개에서 2018년 2881개로 급증하면서 의과대학 학술활동, 이후 보건전문교육에 대한 관심이 눈에 띄게 발전했다.

While the art of teaching medicine became widely acknowledged over the centuries, the study of medical education, with its focus on methods and effectiveness of medical education, independent of individual educators, became a focused domain of study only recently. Its emergence can be considered to have started primarily from mid-20th century, linked to development of new approaches to the medical curriculum, with new methods, objectives, and content. With the rapid increase of medical schools around the world, from 566 in the year 1953 to 2881 in the year 20185 the interest in scholarship of medical and, later, health professional education has developed remarkably.

학문으로서 의학교육 학술활동의 출발점을 어디로 볼 것인가를 논란의 여지없이 정확히 집어내기는 어렵다. 보통 많은 요소들이 함께, 우연히 작동하여, 그러한 출현을 가능하게 한다.

- 의학교육사학자 Ludmerer는 1920년 전후를 미국의 현대 의학 교육의 시작이라고 본다. (비록 유럽에서는 영향력이 작았지만) 이 시기는 미국 학교들을 폐쇄하거나 현대화하도록 강요한 유명하지만 비판적인 1910년 카네기 보고서(플렉스너 보고서) 직후이다.

- Journal of Medical Education 의 첫 호는 1920년에 나왔지만, 솔직히, 학문적 노력으로서 의학 교육 발전과 연구의 시작은 [Western Reserve 대학교가 그들의 의학 교육과정을 현대화하기 위해 위원회를 설립한 1950년 즈음]이라고 보는 것이 더 나을지도 모른다. 이후 콜로라도대학이 이를 따랐고, 이 두 대학의 노력은 철저히 기록되었기에, 그 변화의 움직임의 시작을 정확히 짚어낼 수 있다.

- 조지 밀러, 스티븐 에이브러햄슨, 힐리어드 제이슨, 크리스틴 맥과이어, 그리고 하워드 베로우스 같은 연구자들이 뉴욕, 미시간, 일리노이, 캘리포니아의 여러 대학에서 등장하면서, 대표적인 1세대 의학 교육 학자가 등장했다고 볼 수 있다. 이렇게 약 70년 전에 새로운 학문을 구성하였고, 이 당시 최초로 뚜렷한 교육 연구 유닛들이 의과대학에 설립되었습니다.

- 동시에 1950년대에 의학 교육은 사회과학자들의 연구 대상이 되었다. 그들은 의사가 되는 것이 어떤 의미인지를 연구한 후 영향력 있는 심리학적, 사회학적 보고서를 작성하였다. 미국만이 의학교육을 위한 단위units을 설립한 것은 아니다. 캐나다의 맥마스터 대학, 스코틀랜드의 던디 대학, 네덜란드의 마스트리흐트 대학이 다른 나라에서 의학교육을 위한 학술활동을 가진 최초의 기관이다.

It is difficult to pinpoint an undisputed moment in time that can be qualified as the starting point of medical education scholarship as a discipline. Usually many factors together, operating coincidentally, enable such an emergence.

- Medical education historian Ludmerer rightly qualifies the years around 1920 as the start of modern medical education in the United States,6 shortly after Flexner's famous but critical 1910 Carnegie Report that forced U.S. schools to either close or modernize7—while less influential in Europe.8

- The first issue of the Journal of Medical Education appeared in 1920, but, frankly, the start of medical education development and research as a scholarly endeavor may be better located around 1950, the year that Western Reserve University established a committee to modernize their medical curriculum, followed by the University of Colorado a few years later, two endeavors that were extensively documented,9, 10 and therefore, enabling to pinpoint the start of a movement.

- With George Miller, Stephen Abrahamson, Hilliard Jason, Christine McGuire, and Howard Barrows at universities in New York, Michigan, Illinois, and California, prominent examples of a first generation of medical education scholars emerged, together constituting a new discipline about 70 years ago, when the first distinct units of education research were established in medical schools.11, 12

- In parallel, in the 1950s, medical education became an external object of study by social scientists, who produced influential psychological and sociological reports after studying what it means to become a doctor.13-15 Not only the United States established units for the study of medical education. McMaster University in Canada, University of Dundee in Scotland, and Maastricht University in the Netherlands are among the first institutions with units for scholarship in medical education in other countries.

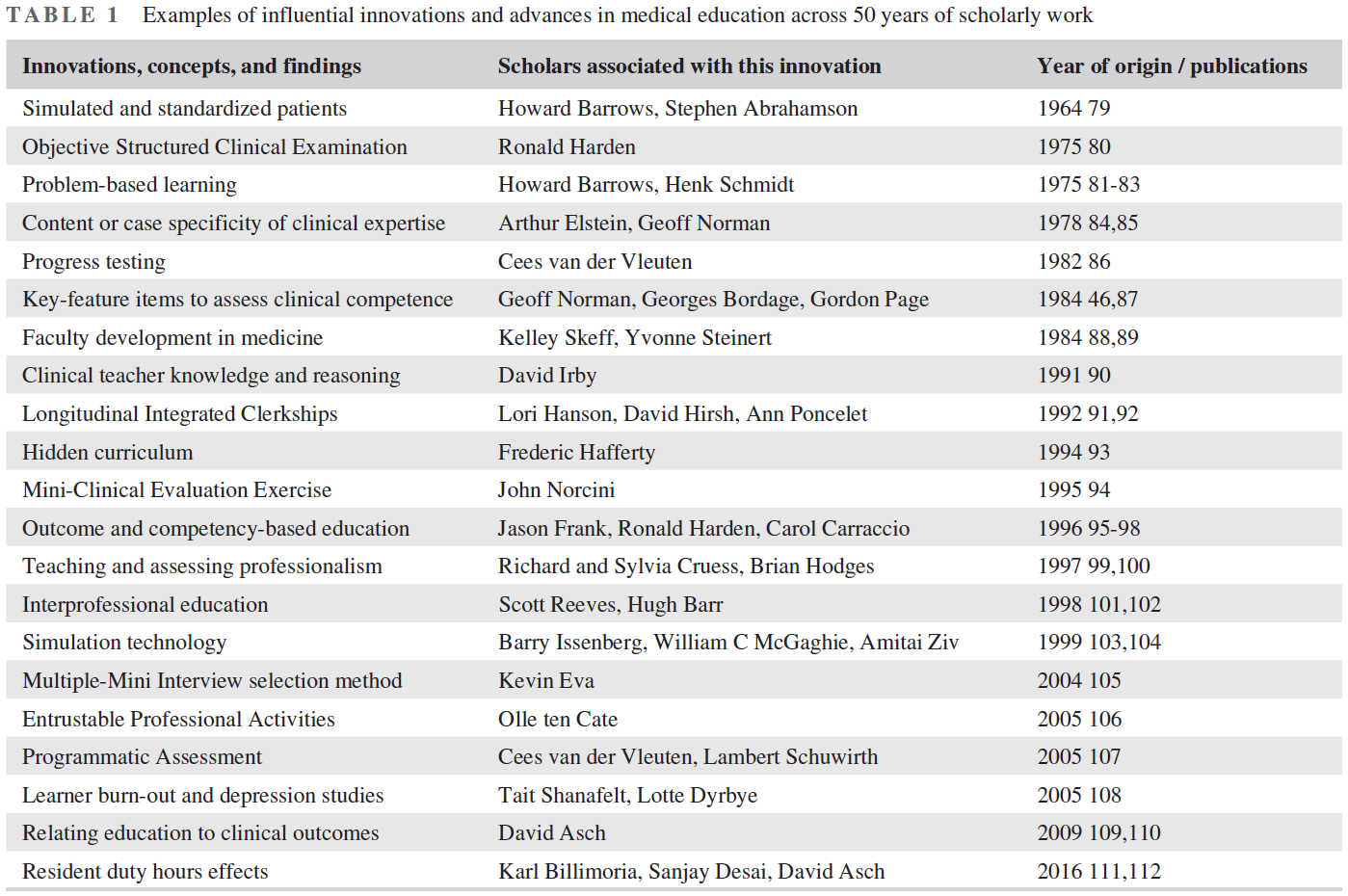

몇몇 개인, 교사, 연구원, 또는 과학적 추구의 특정 영역에 특정한 관심을 가진 센터들은 아직 그 분야를 인정받을 수 있는 학문 영역으로 만들지 못할 수 있다. 그래서 질문은 이것이다. 누군가를 의료 또는 보건 전문직 교육의 학자scholar라고 부르고, 그러한 개인들의 공동체를 "학술적scholarly"이라고 부르려면 무엇이 필요할까? 아자위와 동료들은 연구자 정체성 형성과 협력관계, 연구에 대한 보호시간을 조성하는 환경이 보건직 학술활동을 번창하게 할 수 있다는 것을 발견했다. 학술 공동체는 어니스트 보이어의 널리 인용된 네 가지 기준을 사용하여 정의될 수 있다: 발견, 통합, 응용, 그리고 가르침.17

A few individuals, teachers, researchers, or even centers with a specific interest in a particular domain of scientific pursuit may not yet make the field a recognizable scholarly domain. So the questions is: what would be needed to call someone a medical or health professions education (HPE) scholar1 and to call a community of such individuals scholarly? Ajjawi and colleagues found that an environment fostering researcher identity formation, collaborative relationships, and protected time for research is likely to make health professions education scholarship thrive.16 To create that identity, the scholar should belong to a community with specific characteristics. Scholarly communities may be defined using Ernest Boyer's widely cited four criteria that, together, should determine scholarship: discovery, integration, application, and teaching.17

[디스커버리]란 과학적 호기심을 충족시키기 위해서만 알 가치가 있는 새로운 아이디어와 통찰력의 생산이다. 상당수의 학자들이 적극적인 HPE 연구에 참여하고 영역을 발전시키는 연구 결과를 산출하고 있다는 사실은, 이 준거를 중요하게 만든다.

Discovery is the production of new ideas and insights, things that are worth knowing, if only to satisfy scientific curiosity. A significant number of scholars should engage in active HPE research and yield research findings that advance the domain, to give this criterion weight.

[통합]은 고립된 사실에 의미를 부여하고 새로운 발견과 이미 알려진 것을 연결하는 것이다. 학술활동은 응집력coherence를 갖추어야 하고, 그러기 위해서는 [사회 및 기타 과학과 관련을 짓거나, 다양한 연구 합성 노력]을 해야 한다. 이렇게 해야만 "바퀴의 재발명"을 피할 수 있다. [수용될 지식체body of accepted knowledge]는 통합을 통해 구축된다.

Integration is giving meaning to isolated facts and connecting new findings with what is already known, within and across disciplines. Coherence must be established, by relating to or involving social and other sciences and by various research synthesis efforts, if only to avoid wheels being reinvented. A body of accepted knowledge is to be built through integration.

[응용]은 문제를 해결하기 위한 발견의 유용성과 관련이 있습니다. 학술활동은 "그 자체로서가 아니라, 사회에 대한 복무를 통하여 가치를 입증해야 한다."(보이어, 23페이지) 실무적으로 개선된 의료 및 보건직 교육 커리큘럼을 통해, 졸업생들의 역량 향상을 통해, 궁극적으로는 더 나은 의료 서비스를 통해 보여야 한다.

Application relates to the usefulness of findings to solve problems. Scholarship must "prove its worth not on its own terms but by service [to society]"(Boyer, page 23). It should be visible through improved medical and health professions education curricula in practice, through improved competence of graduates and, ultimately, through better health care.

[가르치는 것]은 "가장 높은 형태의 이해"이다. 여기에는 [과학적 의사소통]과 [미래 학자를 위한 교육]을 포함한다. 보이어는 학생과 개인의 상호작용을 염두에 두고 있었지만, 강의는 회의, 책, 논문, 현대 미디어를 통해서도 이루어질 수 있다. 더 넓은 의미에서 Teaching이란 [차세대 학자들의 충분하고 지속적인 훈련]과 [충분한 출판물, 회의, 협회]로 특징지어지며, 이는 [진정한 상호작용적 학문 공동체의 존재]를 의미한다.

Teaching, as "the highest form of understanding" (Boyer, page 23), involves scientific communications and the education of future scholars. While Boyer had students and individual interactions in mind, teaching can also be done through conferences, publication of books, papers, and modern media. Teaching in its broader sense, would be characterized by the sufficient and sustained training of next generation scholars and sufficient publications, conferences, associations that would characterize the existence of a true interactive scholarly community.

글래식18과 오브라이언 외 19는 보이어의 기준을 건강 직업 교육 학술활동 단위의 개별 학자들뿐만 아니라 더 자세히 설명했다.

Glassick18 and O'Brien et al19 have elaborated Boyer's criteria not only for individual scholars in health professions education scholarship units.

보건 전문직 교육HPE은 학술적 영역이나 학문으로서 적합한가?

3 DOES HEALTH PROFESSIONS EDUCATION QUALIFY AS A SCHOLARLY DOMAIN OR DISCIPLINE?

학문 분야와 하위학문 분야가 명확하게 정의된 것은 아니다. 그것들은 보통 대학들에 의해 인정되고, 때로는 과학 학회에 의해, 때로는 법에 의해, 면허와 특권이 제한될 때, 교수진, 학과, 학술 과정에 분류된다. 그러나 공식적인 제도적 진술을 넘어, [학문적 공동체나 학문이 무엇인지를 결정하는 것]은 [학문적 개인들 간의 상호작용과 활동]이다. [사회 정체성 이론Social Identity Theory] 은 개인에게 정체성을 제공하는 집단에 속하는 것이 중요하다고 가정한다. 사회적 정체성은 자존감과 집단 행동을 서포트하는데, 이는 사람들이 자신의 존재를 알고 자부심을 느끼고, 다른 사람들에게 그것을 설명하고, (명함이나 문구처럼) 쓸모 없어 보이는 목적을 위해 사용할 수 있고, 또한 마음이 비슷한 다른 사람들과 연결되기 위해서이다. 학문적 공동체에서 정의된 정체성은 [조직 내에서의 승진]과 심지어 [연구 자금]에도 영향을 미칠 수 있다. 분야를 정의하는 것은 사소하지 않다.

Academic disciplines and subdisciplines are not unequivocally defined. They are usually acknowledged by universities and categorized in faculties, departments, and academic courses, sometimes by scientific societies and sometimes by law, when licensing and privileging is restricted. But beyond formal, institutional statements, it is the dynamics among scholarly individuals, with their interactions and activities, that determines what a scholarly community or discipline is. Social Identity Theory posits that for individuals it is important to belong to a group that provides them with identity.20 Social identification supports self-esteem and group behavior,21 as people like to know and take pride in what they are, be able to explain that to others, use it for purposes as seemingly futile as business cards and stationary, and also to connect with likeminded others. A defined identity in a scholarly community can also affect promotions in an organization, and even funding of research. Defining a discipline is not trivial.

3.1 검색

3.1 Discovery

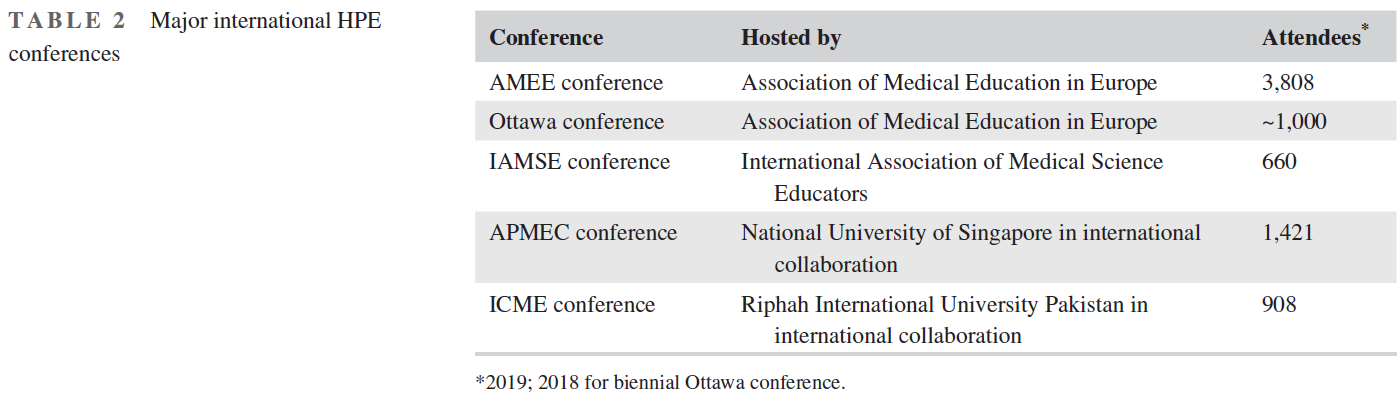

(학문분야로서) Discovery 기준을 충족시키려면 현재 발견자 역할을 하는 충분한 연구자가 있어야 한다. 2021년에 세계적으로 얼마나 많은 HPE 연구원들이 활동하고 있는지 정확히 알 수 없다. 그러나 1950년 이후 그 수가 증가했다는 몇 가지 대리 지표가 있다. 만약 활동적인 연구원이 10년이라는 기간 동안 매년 적어도 한 편의 저널 기사를 발표하는 사람이고, 발견이 건강 직업 교육의 지식의 본체에 사실이나 통찰력의 추가라고 정의된다면, 시간에 따라 발표된 논문의 수와 저자들을 볼 가치가 있다.

To meet the Discovery criterion, there must be sufficient researchers who are active discoverers. We do not know how many HPE researchers exactly are active worldwide, in 2021. However, there are some proxy indicators of growth in volume since 1950. If an active researcher would be someone who publishes at least one journal article per year over a sustained period of time, say 10 years, and discovery would be defined as the addition of a fact or insight to the body of knowledge of health professions education, it is worth looking at number of published papers and their authors at different moments in time.

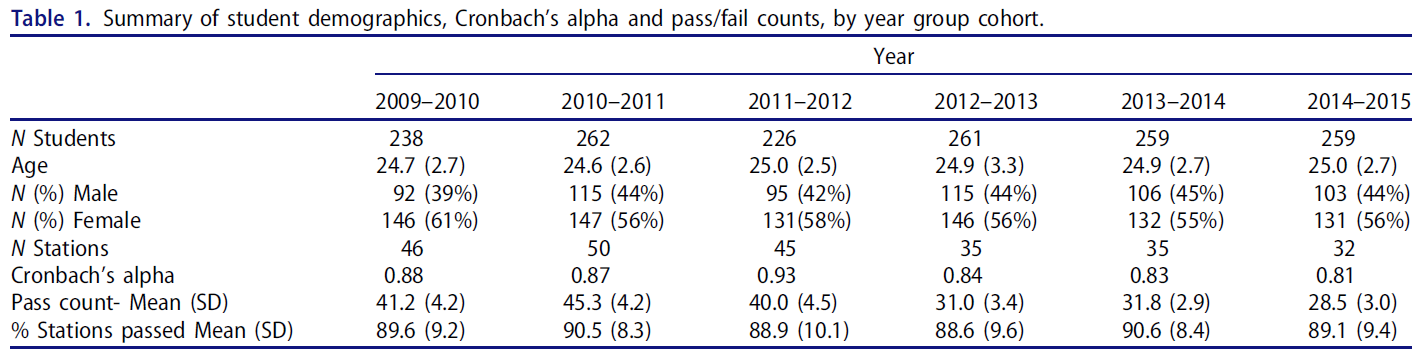

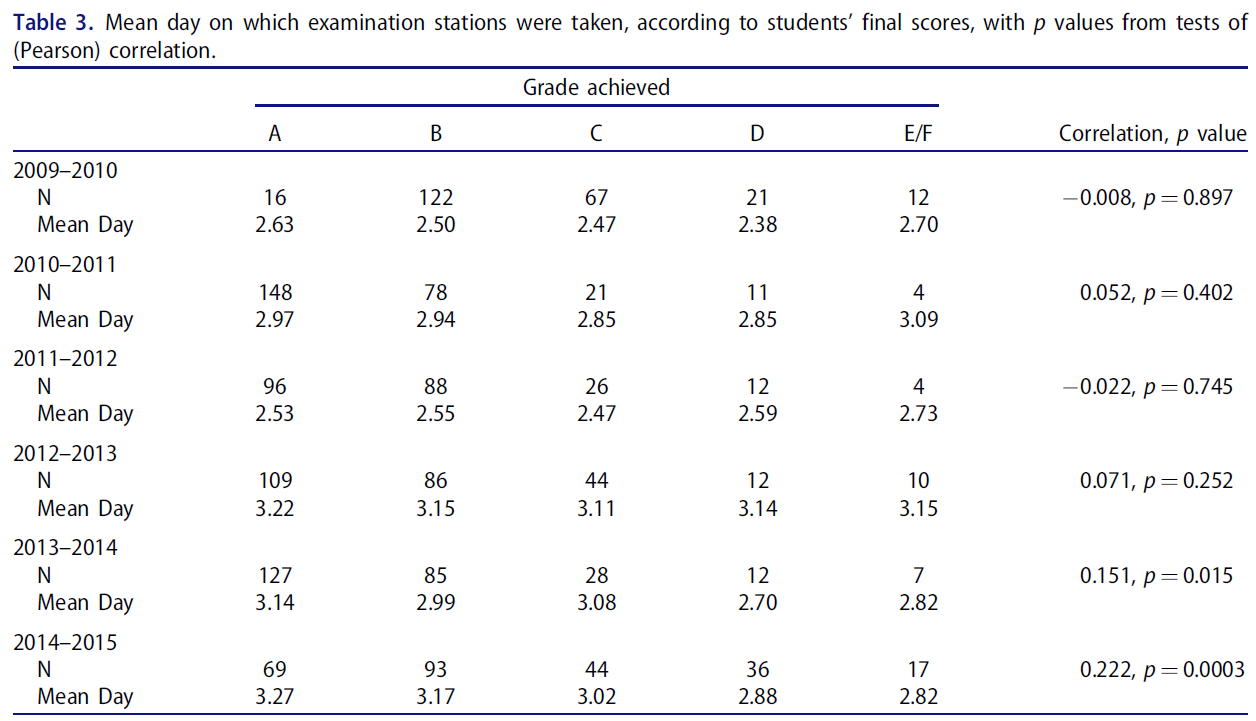

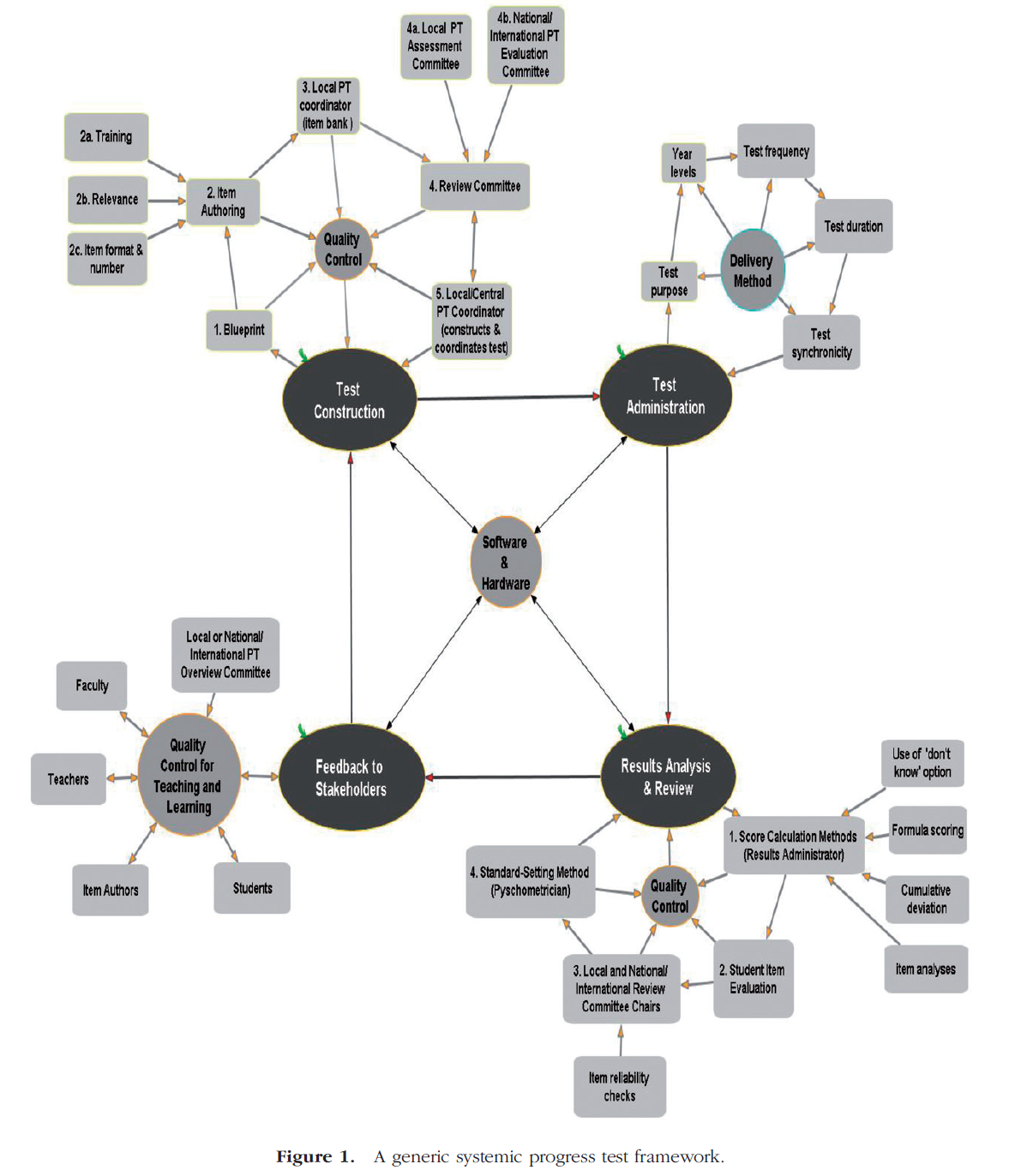

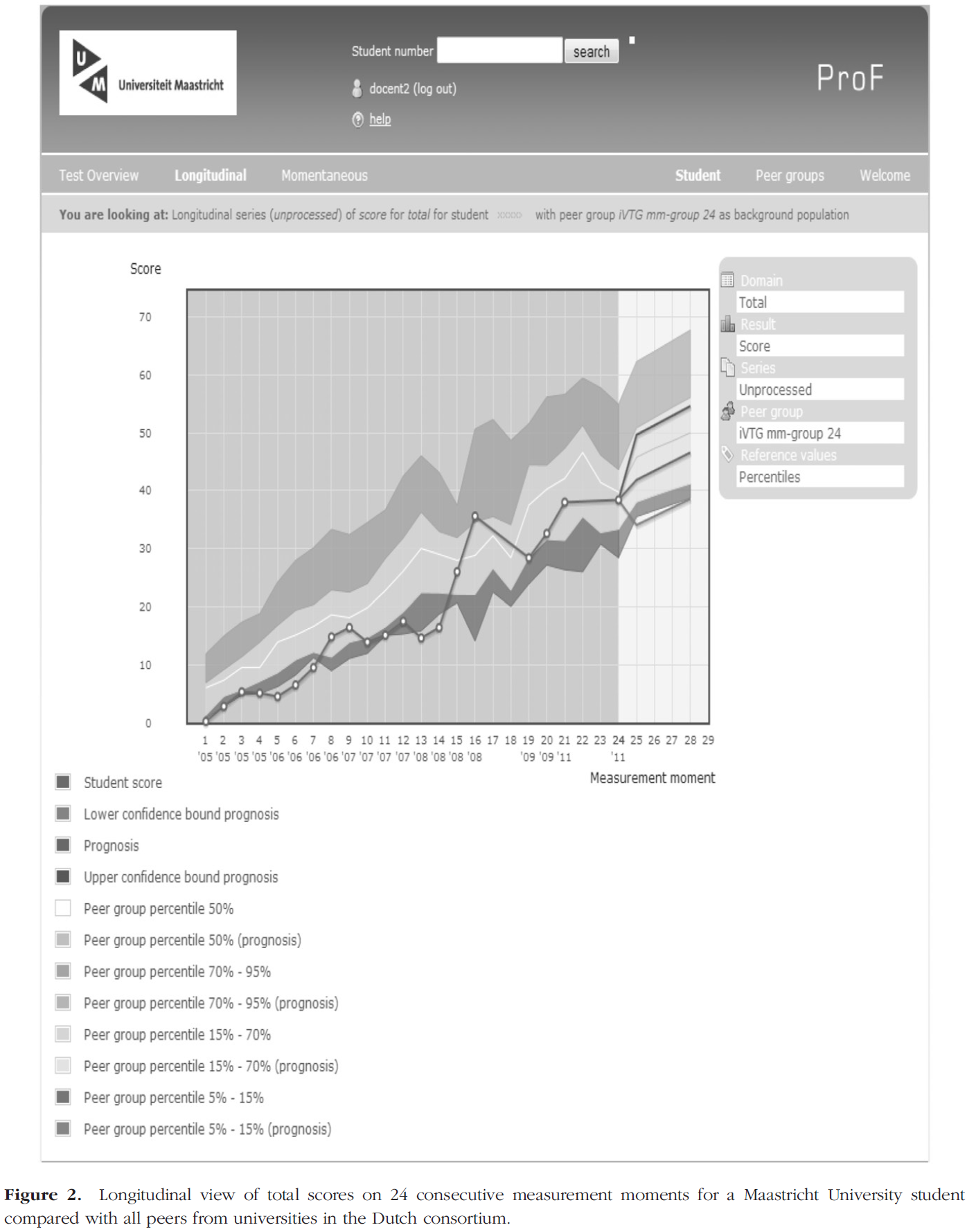

1980년에는 의학 교육 저널(현재의 학술 의학 저널), 영국 의학 교육 저널(현재의 의학 교육 저널), 그리고 의학 교사(Medical Teacher)의 세 개의 의학 교육 전문 저널이 있었다. 가장 오래된 것(의학교육저널)에는 1980년 한 해 동안(12호)에 걸쳐 450여 명의 저자가 등장했는데, 여기에는 비연구자뿐 아니라 두 번 이상 출판한 작가도 포함됐다. 2020년에, 이 저널의 12개 호에 기고하는 추정 저자의 수는 약 3배가 되었다. 2018년에 제이슨이 제시한 그래프와 비교할 수 있는 다른 성장 대용치가 그림 3에 나와 있다. 저널 기사 제목에 있는 "의료"와 "교육"이라는 단어의 조합은 50년 이내에 10배 증가를 보여준다. 게다가, 그 40년 동안, 국제 의학교육 저널의 수는 (해부학, 생리학, 생화학, 수술, 시뮬레이션, 그리고 많은 국가에서 의학 교육을 위한 국가 협회의 저널과 같은 전문 분야의 전용 교육 저널을 제외하고도) 3개에서 약 35개로 꾸준히 증가하였다

In 1980, there were three dedicated medical education journals:

- the Journal of Medical Education (now called Academic Medicine),

- The British Journal of Medical Education (now called Medical Education), and

- Medical Teacher.

The oldest one (the Journal of Medical Education) featured about 450 authors across the year of 1980 (12 issues), including non-researchers, but also some authors who published more than once. In 2020, the estimated number of authors contributing to the 12 issues of this same journal has about tripled. A different proxy of growth is shown in Figure 3, comparable to graphs presented by Jason in 2018.22 The combined words "medical" and "education" in journal article titles shows a 10-fold increase in less than 50 year (data from Google Scholar; and note that such titles only cover a small minority of articles in the domain). In addition, in those 40 years the number of international peer reviewed medical education journals has steadily grown from three to about 35, excluding dedicated education journals in specialty areas such as anatomy, physiology, biochemistry, surgery, simulation, and journals of national associations for medical education in many countries, not counting education journals in other health professions than medicine.

HPE에 관한 학술지의 총 목록은 주로 약 90개에 달한다. 만약 이들 각각이 연간 100명의 저자를 배출하고 모든 학자가 매년 하나의 학술 논문을 낸다면(둘 다 매우 보수적인 추정치이다), 이 영역은 거의 100,000명의 저자를 보유하게 될 것이다. 로건스는 2010년 최근 12년간 가장 많이 발간된 6개 의학교육전문지에 1만건의 기사가 실렸다고 추산했다. 논문 한 편당 평균 3명의 저자를 취해서 현재 양질의 학술지 수가 늘어난 것에 대해 3을 곱하면 비슷한 수치로 이어진다. 수많은 의학 교육 저널 기사의 질은 학문적 기준을 모두 충족시키지 못할 수도 있지만, 만약 20%만이 진정으로 학문적scholarly인 것으로 잡더라도, (보수적으로 추정해도) 연구와 개발에 적극적으로 참여하는 HPE 학자들은 최소한 20,000명에 이르는 구성된 공동체를 구성한다. 공동체의 기준으로서의 [임계질량]은, 논쟁의 여지 없이 충분히 충족된 것으로 보인다.

The total list of journals predominantly publishing on health professional education approaches about ninety2. If these each would feature only 100 authors per year and every scholar would produce one scholarly paper per year (both are very conservative estimates), the domain would have close to 100,000 authors. Rotgans estimated in 2010 that 10,000 articles had appeared in the six most common medical education journals in the past 12 years.23 Taking an average number of three authors per paper and multiplying by three for the increased number of current quality journals leads to a similar figure. The quality of the numerous medical education journal articles may not all meet scholarly standards,24 but if only 20% would be regarded as truly scholarly, the combined authors would establish a community of at least 20,000 true health professions education scholars, educators actively involved in research and development, which again is probably a conservative estimate. The critical mass for a scholarly community as criterion seems, arguably, amply met.

다음으로, 일반적으로 인정된 도메인의 발전은 발견을 지원해야 합니다. 의학교육이 70년 전보다 '더 나아지지' 않는다면 보이어의 발견 기준은 아마도 충족되지 않을 것이다. 그래서 문제는, 우리가 이 개선을 확인할 수 있을까 하는 것입니다. 이 기준은 측정하거나 추정하기가 훨씬 더 어렵다. [2020년 의대 졸업자]들이 [1950년 졸업자]보다 의료행위에 더 적합한지 여부를 확인할 수 있는 측정 수단이 전혀 없다.

Next, generally acknowledged advances in the domain should support discovery. If medical education would not be “better” than 70 years ago, then, the Boyer's discovery criterion would probably not be met. So the question is, can we confirm this improvement? This criterion is much more difficult to measure or estimate. There is simply no measurement instrument to establish whether the 2020 medical graduates are better equipped for clinical practice than in 1950.

교육 연구의 진보와 발견은 종종 [근거 기반의 교육적 진보]가 아닌 [새로운 이론과 연구 방법]에 초점을 맞추는데, 이는 단계적이고 부정할 수 없이 더 나은 교육 결과를 보여준다. 물리, 화학, 의학 등의 분야에서 이론과 실천에 기반을 두고 새로운 사실들이 만들어 질 수 있지만, 이는 교육 연구에서 드물다. 소이어는 "교육에 대한 과학적 접근의 역사는 유망하지 않다"고 주장하며, [교육이 과학인지 예술인지에 대한 계속되는 논쟁]을 인용한다. 그러나 다른 이들은 학습과 지도에 대한 증거 기반 원칙을 확립했다. 새로운 절차나 치료법이 적절히 적용될 때마다 '작동할 것work'을 기대할 수 있는 생물의학이나 공학의 발전과는 달리, 교육원리의 효과는 예측 가능성이 낮다. 종종 통제할 수 없는 많은 변수들이 교육의 결과를 방해할 뿐만 아니라, "교육 시스템" 자체가 복잡하고 적응적이다.

Advances and discoveries in educational research often focus on new theories and research methods, rather than evidence-based education advances, that stepwise and undeniably show better and better education outcomes. New, undisputed facts on which theories and practice can build, such as in physics, chemistry, and medicine, are rare in educational research.25, 26 Sawyer contends that "the history of scientific approaches to [general] education is not promising" and cites the ongoing debate about whether education is a science or an art.27 Others, however, have established evidence-based principles of learning and instruction.28-30 Different from biomedical or engineering advances that may be expected to “work” every time new procedures or therapies are applied appropriately, the effects of educational principles are less predictable. Not only do many variables, often not controllable, interfere with outcomes of education, the "system of education" itself is complex and adaptive.

[복잡한 적응 시스템]은 변수가 바뀌면 자신의 방식대로 반응한다. 새롭고 "증명된" 교육 방법은, 그것이 적용되었을 때, 학생들의 감정적, 동기적, 지적 반응을 불러일으킬 것이다. 의사가 되고자 고도로 동기부여를 받은 학생들은 어떤 교육적 방법과 요구 사항이 적용되든지 간에 목표에 도달하기 위해 그들이 필요하다고 느끼는 모든 것을 할 것이다. 학생은 블랙박스나, [조작이 가능한 수동적인 대상]이 아니라, 어느 정도 학습 경로를 스스로 형성하려는 자유의지가 있다. 예를 들어, 우수한 강의는 자기주도적인 학습 성향을 감소시킬 수 있으며, 시험에서는 이러한 우수한 교사 수행에 참석하지 않은 학생들보다 더 나쁜 성적을 낼 수 있고, 내용물의 복잡성을 스스로 알아내야 한다고 느꼈을 수도 있다.

Complex adaptive systems react in their own way when variables change. A new, "proven" teaching method will, when applied, evoke emotions, motivations, and intelligent responses by students. Students, highly motivated to become doctors, will simply do whatever they feel is needed to reach their target, no matter which curricular methods and demands apply. They are not a black box, or a passive object that can be manipulated, but have a free will to shape their learning pathway to some extent.31, 32

- For instance, excellent lectures may decrease the students' inclination to self-directed study, to the point that on tests they may perform worse than students who did not attend these superb teacher performances, and who may have felt forced to figure out the complexities of the content matter themselves.33

교육 연구를 더욱 복잡하게 만드는 것은 교육 개입의 결과 척도를 결정하기 어렵다는 것이다. 시험에서 증명된 지식과 기술이 그러한 결과로 간주될 수 있지만, 의학에서와 같은 교육의 진정한 목적은 실습에서의 효과적인 성과와 개선된 임상 결과이며, 이는 종종 우수한 개인 기술에 의해서만 결정되는 것이 아니라 생물 의학 및 기술 발전, 맥락 및 팀워크에 의해 결정된다.

What further complicates educational research is that outcome measures of educational interventions are difficult to determine. While knowledge and skills demonstrated at exams may be considered such outcomes, the true purpose of education, such as in medicine, is effective performance in practice and improved clinical outcomes, which are often determined by biomedical and technical advances, context and teamwork, not only by superior individual skills.34, 35

그러나 이러한 어려움에도 불구하고, 현재 HPE의 학자들은 많은 발전이 분명히 이루어졌고, 이러한 발전이 교육 관행으로 확립되어왔다는 것에 동의할 가능성이 높다. 의학 교육에서 "발견"은 [일반화된 이론적 진리를 뒷받침하는 발견]보다는 [새로운 교육 또는 평가 방법]인 경우가 더 많다. 성공이 보장된 교육 혁신에 대한 논란의 여지가 없는 증거는 확립하기 어렵지만, 신뢰할 수 있는 이론에 기초한 의학의 몇 가지 변화는 지난 50년 동안 의료 커리큘럼에 깊은 영향을 미쳤으며 현재 권장 접근법으로 간주되고 있다. [이론의 여지가 없는 증거 기반]이라기보다는, 엄격한 최선의 근거에 기반한 의학교육 BEME 문헌 리뷰가 의료 교육자들에게 인기 있는 자료였다. 지난 20년 동안 60개 이상의 BEME 리뷰가 출판되었으며, 건강 직업 교육에서 많은 다른 지식 합성도 이루어졌다.

Despite these difficulties, however, current scholars in HPE would likely agree that many advances have certainly been made and turned into established educational practices in the health care domain. "Discoveries" in medical education are more often new educational or assessment methods, rather than findings supporting generalized theoretical truths. While undisputable evidence of educational innovations with guaranteed success is hard to establish,36 several changes in medical education, based on credible theory, have had profound influence on medical curricula in the past 50 years and would now be viewed as recommended approaches. Rather than suggesting to be unequivocally evidence based, rigorous best-evidence medical education (BEME) literature reviews have been popular resources for medical educators.37 Over 60 BEME reviews have been published in the past 20 years, in addition to many other knowledge syntheses in health professions education.

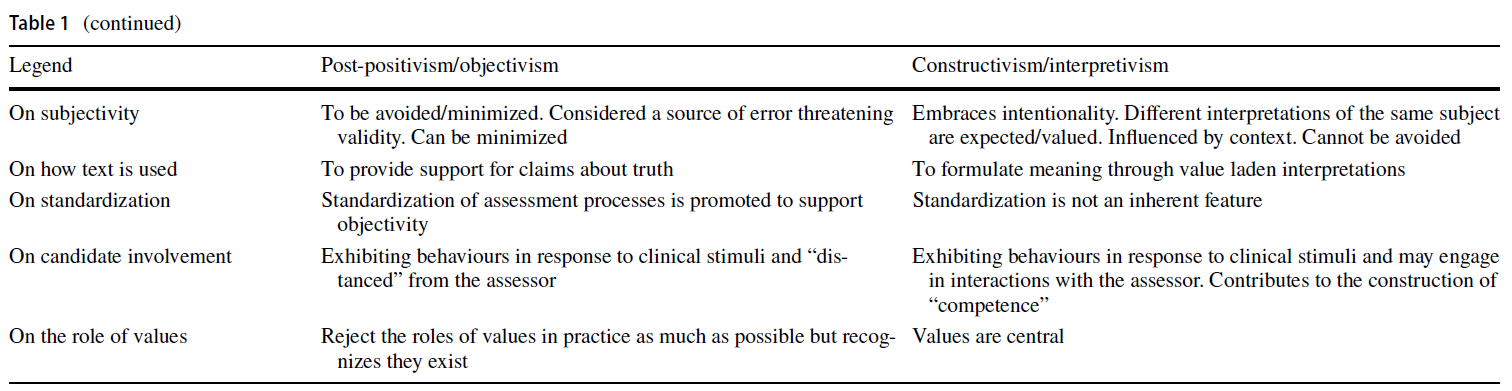

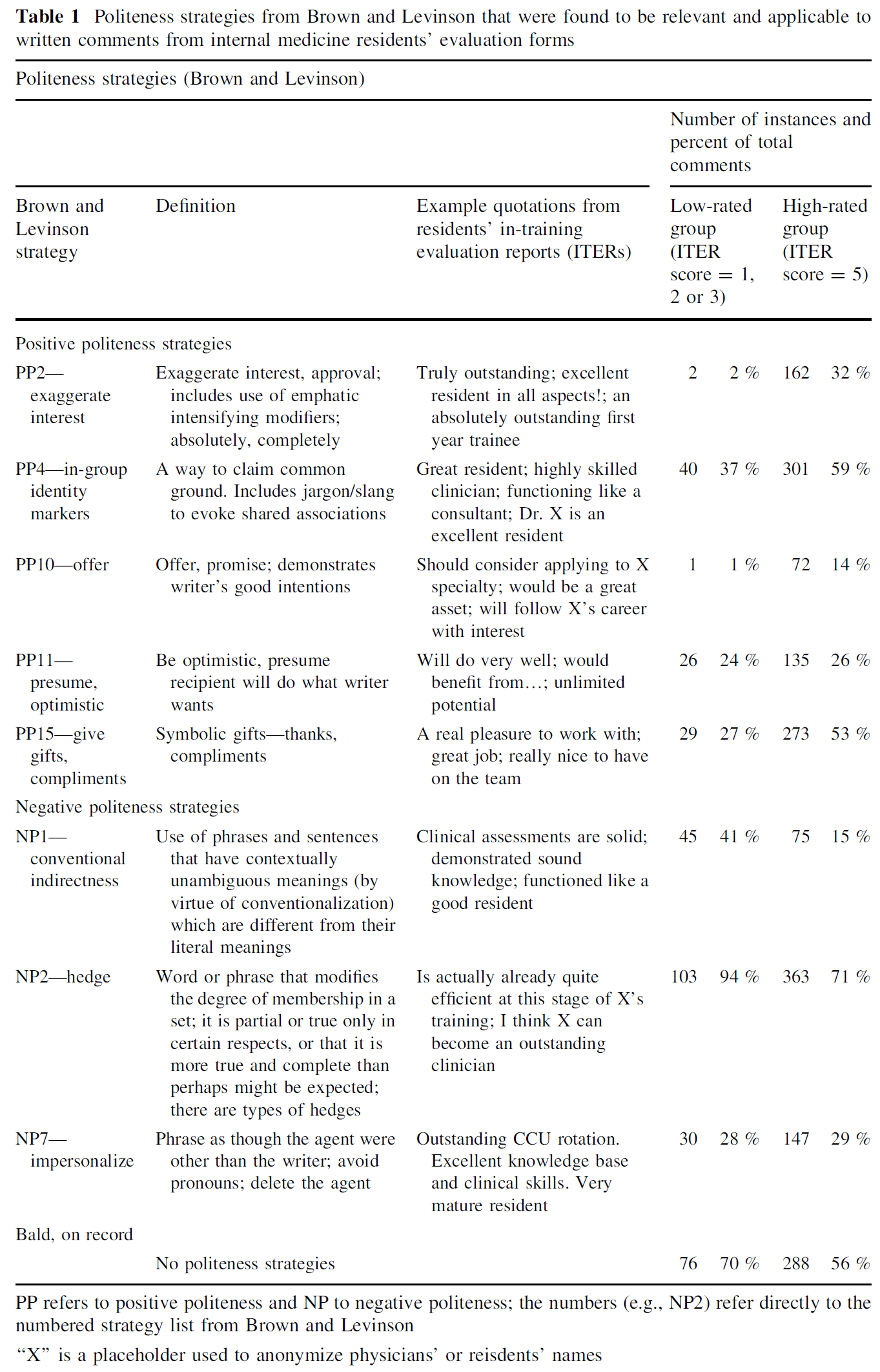

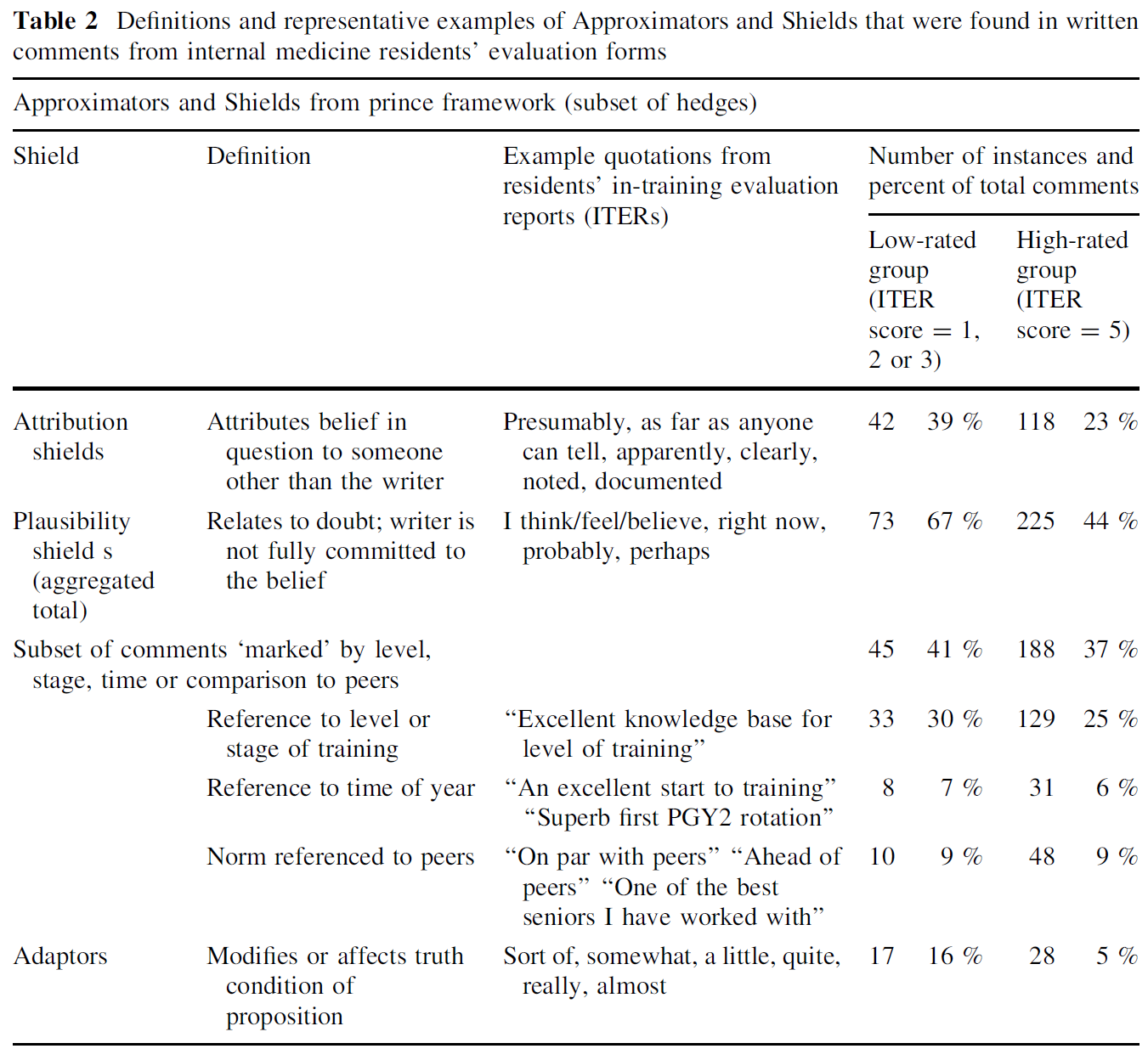

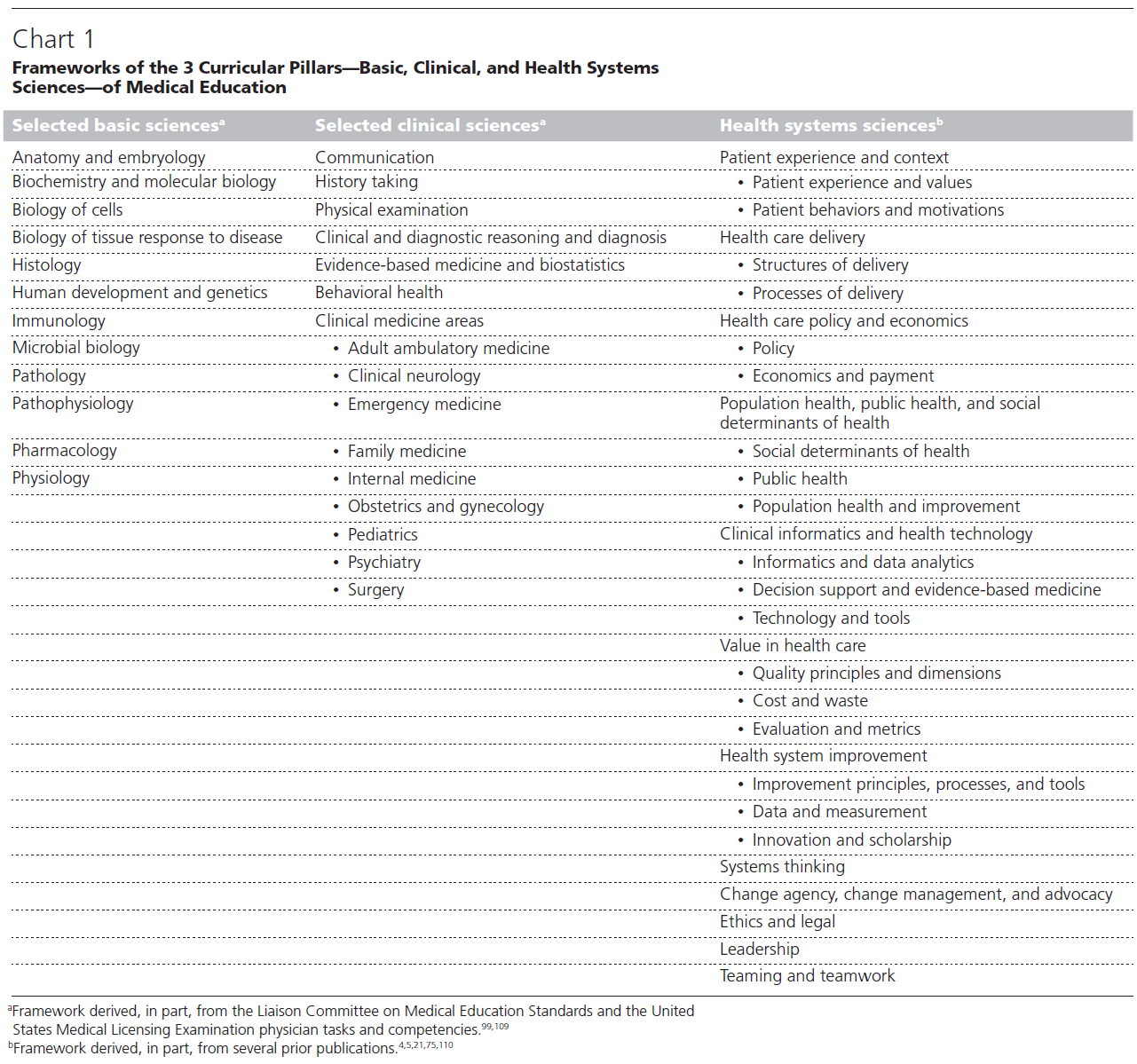

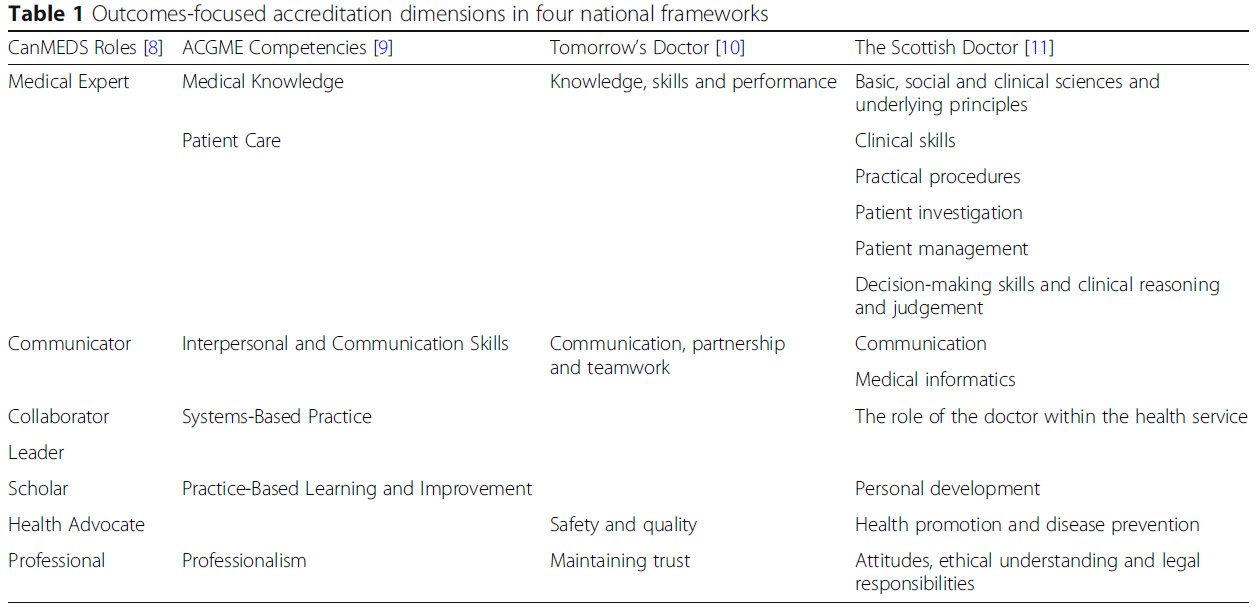

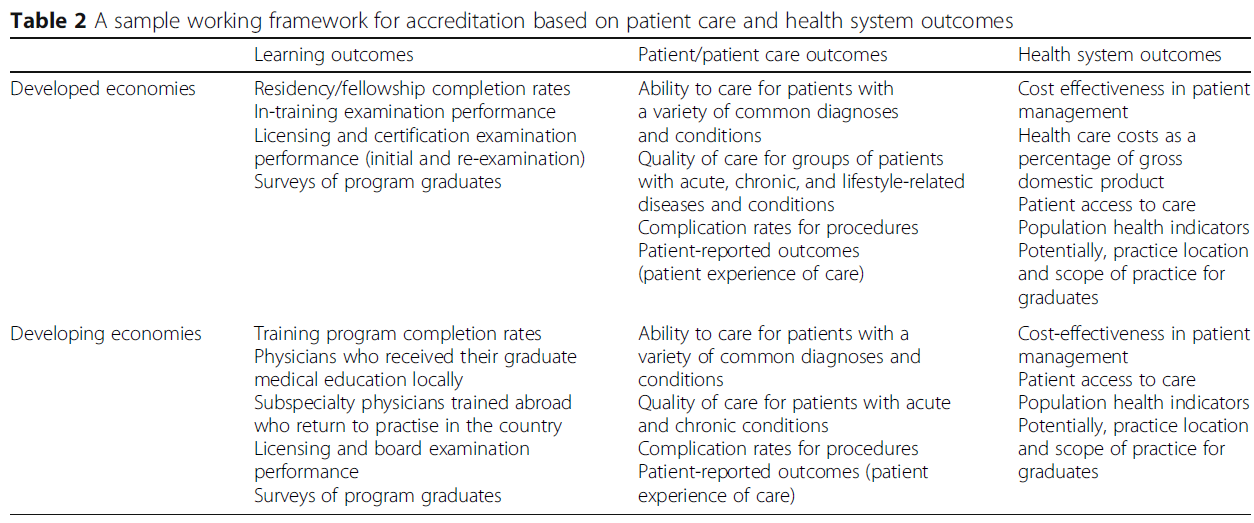

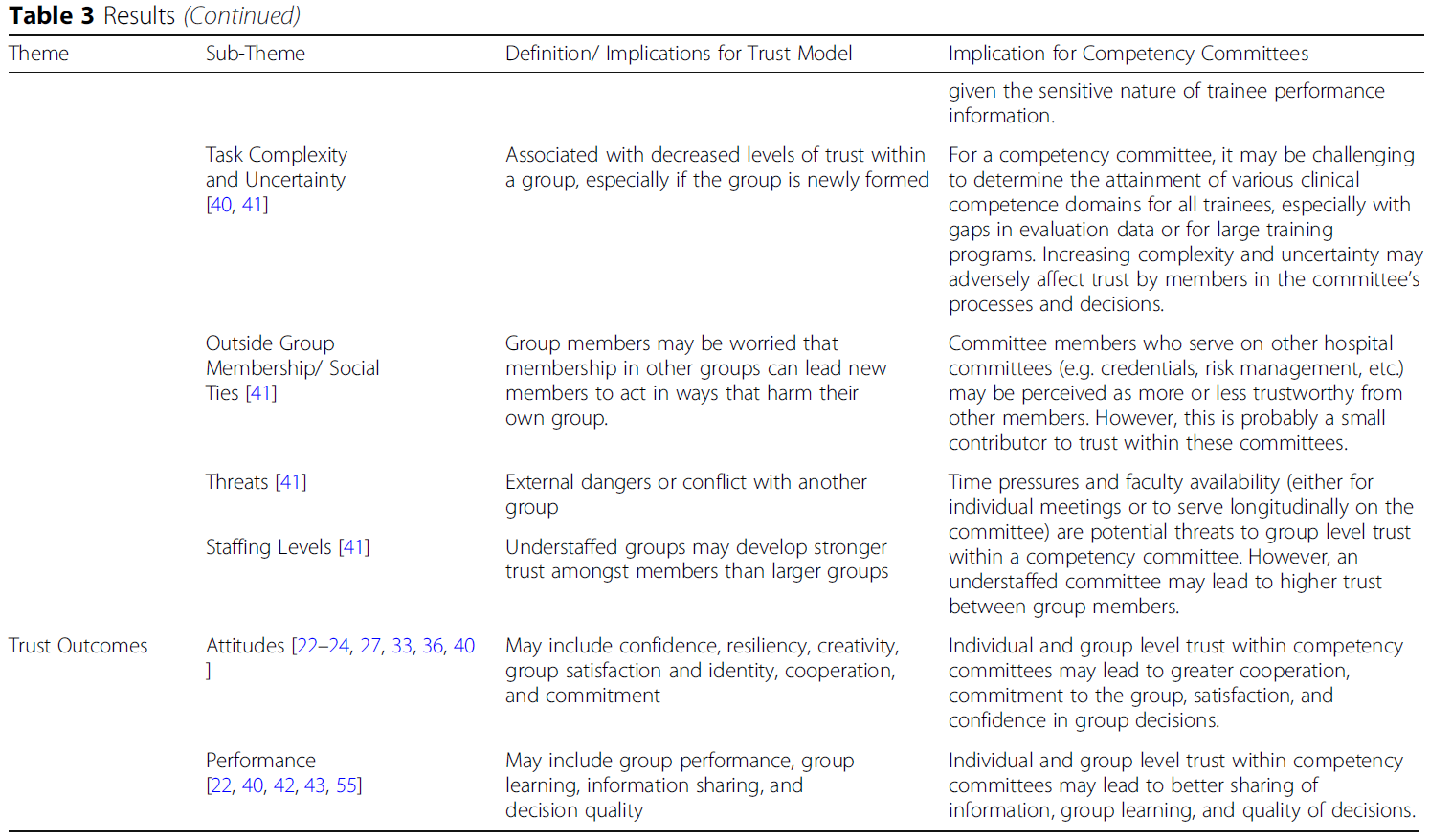

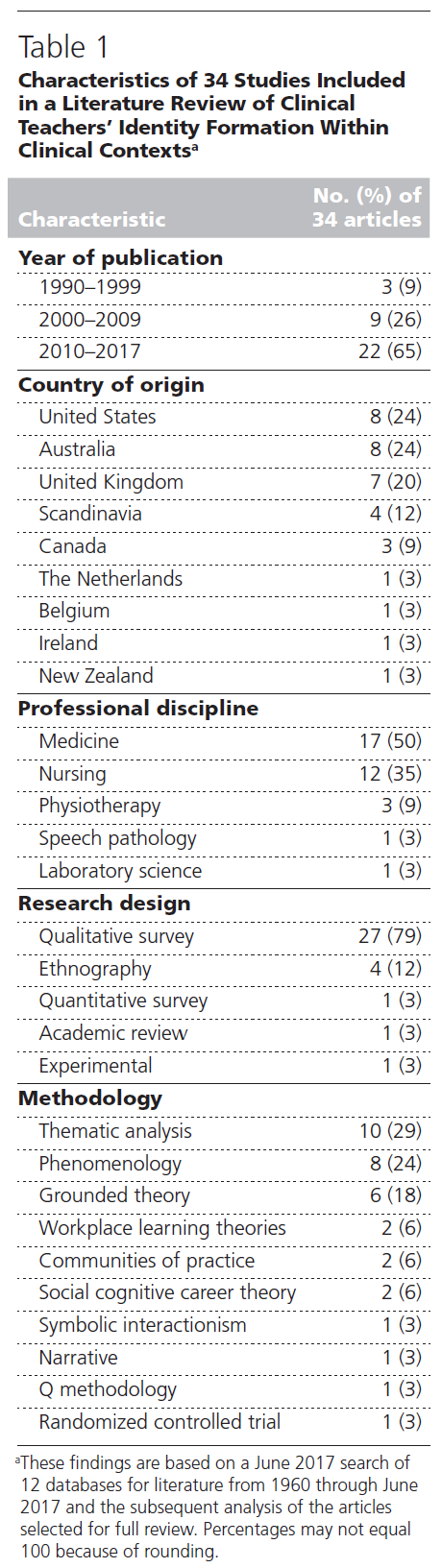

표 1은 50년 동안 의학에 대한 발견과 교육 발전의 예를 보여주는데, 이는 보건 직업 교육 분야의 학자들 덕분이라고 할 수 있다. 표의 한계는 단일 식별 가능한 개념, 발견 또는 혁신과 관련되지 않은 많은 의학 교육자들의 중요한 학문적 작업을 공정하게 수행하지 못한다는 것이다. 아래의 모두든 것들이 어느 정도 의료 훈련을 개선했다. 한편 다른 학자들은 (혁신을 제시하거나 시도하기보다는), 의학교육에 대한 [신화를 폭로]하거나 [의학교육의 강점과 약점에 대한 주요 개요를 제공]하고, [개혁을 촉구]함으로써 이 분야를 더 예리하게 하는 데 도움을 주었다.

Table 1 shows examples across a 50-year period of findings and educational advances in medicine, “discoveries” if you will, that can be attributed to scholars in the field of health professions education. A limitation of the table is that does not do justice to the important scholarly work of many medical educators not associated with single identifiable concepts, findings, or innovations.

- Applying advanced skills training and advanced assessment techniques,

- deliberate practice,

- mastery learning,

- clinical reasoning tests,

- instruments to measure clinical learning environments,

- physical space for education,

- studies to correlate lapses in professional behavior with later adverse practice events,

- studies on theories of workplace learning,

- motivation,

- cognitive load in medical education,

- conditions for interprofessional education,

- studies on burn-out and depression, and

- many other findings or innovations that were tried on smaller scale

all have improved medical training to some extent.

Still other scholars, rather than presenting or trying an innovation, have helped sharpen the mind by

- debunking myths about medical education,38-41 or

- provided major overviews of strengths and weaknesses in medical education, and urged for reform.42, 43

의학 교육, 그리고 어느 정도 다른 건강 직업 교육은 오늘날 우리가 알고 있는 바와 같이 이러한 진보가 없었다면 분명히 달라졌을 것이다.

Medical education, and to some extent other health professions education, as we know it today would be definitely different without these advances.

3.2 통합

3.2 Integration

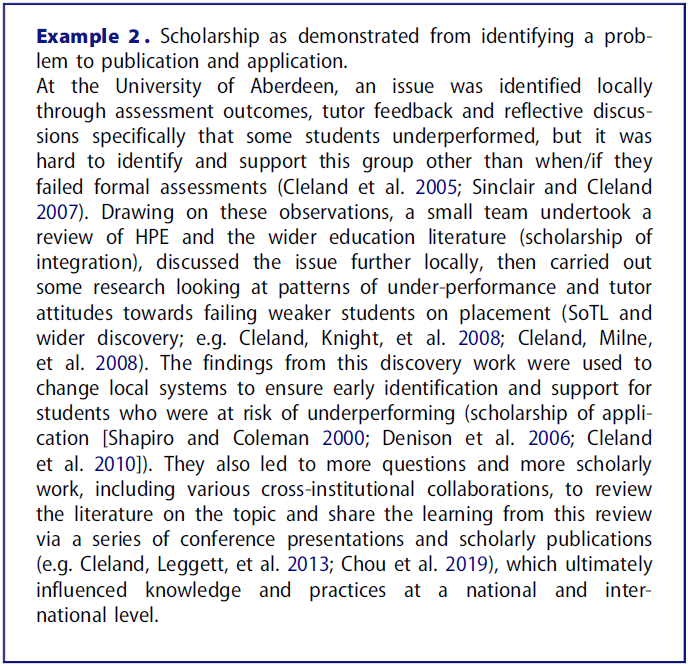

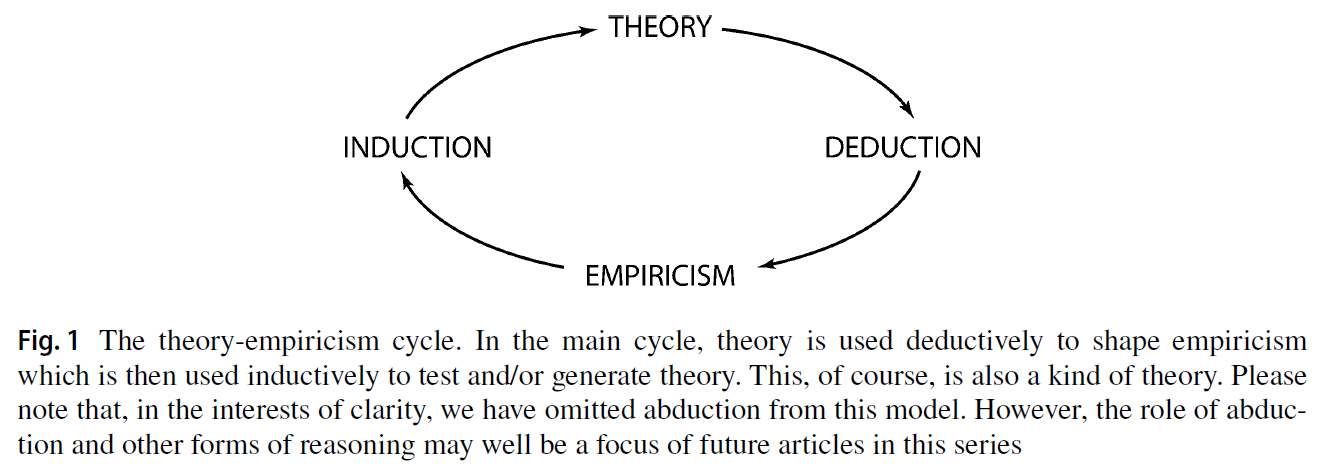

[통합]은 [분야 내부에서의 통합] 및 [분야 간 새로운 발견의 통합]과 관련이 있습니다. 표 1에 나타난 모범적인 발전은 특히 보건 직업 교육을 위해 개발되었으며, 많은 것들이 문제 기반 학습과 같은 의료 교육이나 보건 직업보다 더 넓은 지역사회에서 상당한 영향을 미쳤다. 일부 발전은 연구가 불충분한 것으로 밝혀진 후 포기되고 새로운 방법으로 대체되었다. 예를 들면 임상 추론 기술(크리스틴 맥과이어와 동료들에 의한) 평가를 위한 환자 관리 문제의PMP 도입이 그러하다. 그러나 PMP의 후계자라고 할 수 있는 Key-Feature 항목은 선구적인 근거가 없었더라면 결코 도입되지 않았을 것이다. 이러한 통합consolidation의 예는 의학 교육이 스스로 발전하는 학문적 전통으로 자리잡아간다는 증거이다.

Integration pertains to the consolidation of new findings within and across disciplines. The exemplary advances shown in Table 1 have specifically been developed for health professions education, and many had significant impact in a wider community than only medical education or the health professions, such as problem-based learning.44 Some advances, such as the introduction of Patient Management Problems for the assessment of clinical reasoning skill (by Christine McGuire and colleagues) were abandoned45 and replaced by newer methods after research had revealed inadequacies. But Key-Feature items (more or less their successor)46 would have never been introduced without its precursory grounding. This example of consolidation is a testimony of a self-developing scholarly tradition in medical education.

통합은, 연구의 전통을 구축하는, HPE를 전담하는 학술활동 단위가 꾸준히 확산되는 것으로 해석되었다. 1980년대 북미와 유럽에서는 이런 유닛이 적었지만 2000년 북미에는 61개가 생겼고, 2020년에는 전 세계 여러 나라에 셀 수 없이 많은 유닛이 있다. 의학교육연구회에는 현재 78명의 회원이 등록되어 있으며, 많은 이사들은 SDRME 회원이 아니다. 이 부서들은 일반적으로 연구, 교수 개발(교육) 및 봉사에 관여하는 과학자, 학술 교육자 및 행정 지도자를 고용한다.

Consolidation has translated in the establishment of a steady proliferation of dedicated health professions education scholarship units that build a tradition of research.47 In the 1980s, such units were just few in North America and Europe, but in 2000 North America had 61 units48 and 2020 there are countless units in several countries worldwide. The Society of Directors of Medical Education Research currently lists 78 members directing such units, and many directors are not SDRME members. These units typically employ scientists, scholarly educators, and administrative leaders, involved in research, faculty development (teaching), and service.49, 50

통합은 또한 [다양한 과학 영역의 이종교배cross-fertilization]를 의미한다. 보건직 학술활동은 사회과학의 혜택을 많이 받았다. 노먼은 심리학, 사회학자, 심리학자, 심리학자 등 건강 직업 분야에서 비의료적 배경을 가진 학자들의 공헌을 인정하였다. 1980년대와 1990년대에는 사회과학 학자들이 HPE분야에 자신들의 기술을 적응시키는 물결이 거세었다. 이들 중 소수만이 외부 관찰자로 남아 인류학자가 하듯이 HPE를 연구 주제로서 연구하였다. 오히려, 많은 사회과학자들은 의과대학에 고용되어, 의학 및 생물의학 전문가들과 긴밀히 협력하여, 교육의 질적인 발전을 지원하면서, 의학교육 학술공동체에 통합되었다. 이는 보건 직업 교육의 발전과 실천에 학습, 교육, 심리학 이론의 통합을 상당히 자극했다.

Integration also speaks to the cross-fertilization of different domains of sciences. Health professions scholarship has hugely benefited from the social sciences. Norman has qualified the contributions made by scholars with a nonmedical background as made by “immigrants” in the health professions domain: psychologists, sociologists, and psychometricians. He saw a strong wave of these scholars in the 1980 s and 1990s,45 adapting their skills to serve HPE. Only few of these remained outside observers, studying HPE as a topic of research, as would an anthropologist do, without becoming part of it. Rather, PhD level social scientists were hired by medical schools, and integrated in their communities, to support the quality development of their education, in close collaboration with medical and biomedical experts. This has significantly stimulated the integration of theories of learning, education, and psychology in the development and practice of health professions education.

"의료", "교육", "이론"을 결합한 저널 기사 제목은 1960년 이후 60년 동안 기하급수적으로 증가했다. 이 통합은 Norman이 "3세대" 학자라고 부른 이들을 향해 한 걸음 더 나아갔다. 이들은 이민자가 아니라 의학적으로 훈련받은 사람으로서, HPE 석사와 박사과정 고유의 전통 속에서 HPE 학술활동을 훈련받으며 보완해나간 사람들이다. 3세대 학자들은 장점(상아탑 스탠스 없이 고도로 전문화된)과 단점(다른 학문분야에서 경험과 배경지식의 깊이가 얕은)이 있었다. 또 다른 중요한 영향은 연구의 방법론에 관한 것이다. HPE 연구는 통제된 실험의 한계에 대한 인식을 반영하듯, [질적 연구]의 상당한 증가를 보였다.

The number of journal article titles combining "medical," "education," and "theory" has exponentially grown across the six decades since 1960 (from 3, via 7, 11, 31, 96, to 195 in 2020) (Google Scholar). The integration made a further step in what Norman called “third generation” scholars, not immigrants but medically trained, and supplemented with HPE scholarship training in an own tradition of dedicated HPE Masters and PhD education, with its pros (being highly specialized without an ivory tower stance) and cons (with less depth of experience and background in other disciplines).45 Another important influence regards the methodology of research. HPE research has seen a significant increase of qualitative studies,51, 52 reflecting the awareness of the limitations of controlled experiments.36, 53

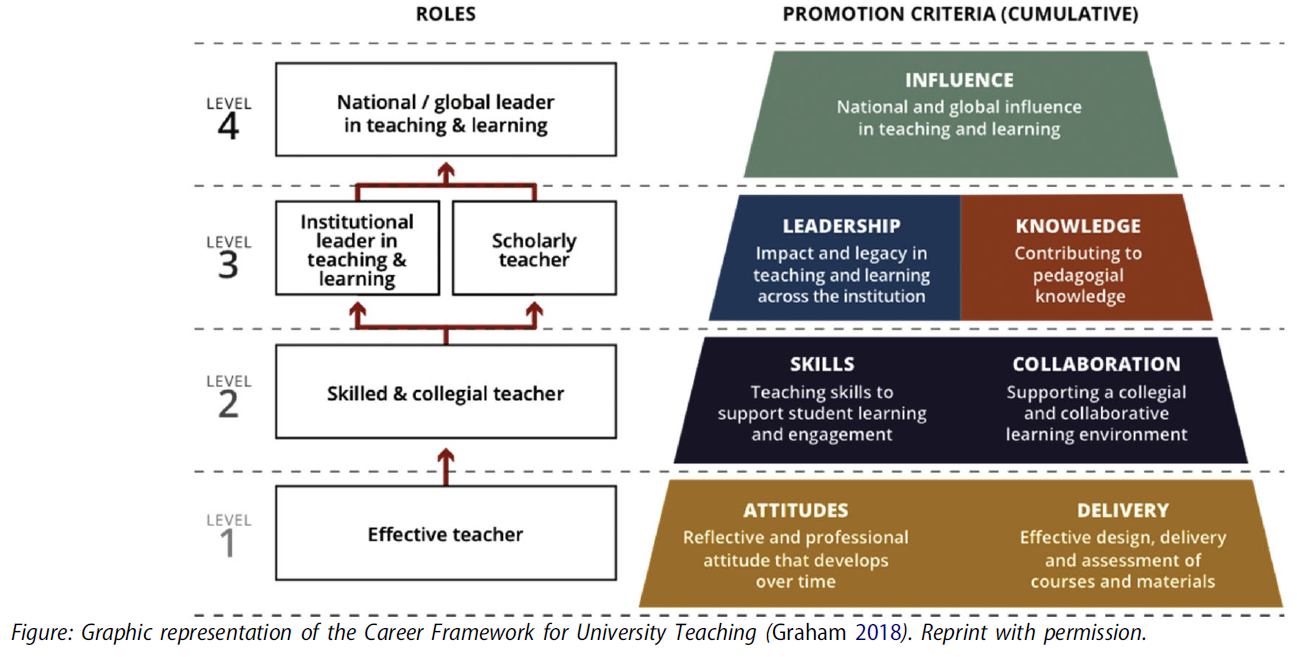

HPE분야의 학술활동은, 보이어가 이야기한 통합이라는 용어에 비추어볼 때 한계가 있는가? 전문 영역으로 성숙되어갈 때 나타나는 특징 중 하나는, 전문 학술지가 만들어지며, 역설적으로 다른 학문과 통합하는 것을 주저하는 모습니다. 사회과학 저널에 게재된 HPE 연구의 양은 비교적 적다. 그것은 HPE 학자들이 어떻게 이러한 저널을 읽고 출판하는 것을 덜 선호하는지, 그리고 이러한 저널의 독자들이 HPE에 대한 관심을 덜 가질 수 있는지를 보여준다. 가장 큰 교육 학자 집단은 거의 틀림없이 미국 교육 연구 협회(AERA)이며, 매년 10,000~15,000명의 학자들이 모인다. HPE 학자들은 AERA에 속하지만, HPE 학자들이 지배하는 "The Profession"의 한 분과 내에서 주로 교류한다. 대조적으로, 일부 주제는 다른 교육 문헌보다 HPE 문헌에서 단순히 더 잘 표현될 수 있다. 예를 들어, Van Dijk 등은 대학교에서의 Teaching task의 프레임워크를 검색한 결과, 광범위한 문헌 리뷰에서 46개를 확인했는데, 그 중 18개는 의학 교수진, 6개는 간호, 치과, 약국 및 조산사를 포함한 다른 보건 직종에 관한 것이었다.

Are there limitations of Boyer's sense of integration with regards to health professions education scholarship? One hallmark of maturation of a professional domain, the establishment of specialized journals, paradoxically shows a hesitation to integrate with other disciplines. Comparatively very little about health professions education is published in journals of the social sciences. It shows how HPE scholars may be less inclined to read and publish in these journals, and how readers of these journal may be less interested in HPE. The largest community of educational scholars is arguably the American Educational Research Association (AERA), with an annual meeting that brings together 10,000–15,000 scholars. HPE scholars are represented in AERA, but interact largely within one division of it, that of “The Professions”, dominated by HPE scholars. In contrast, some topics may simply be better represented in the HPE literature than in other educational literature. As an example, Van Dijk et al., searching for frameworks of university teaching tasks identified 46 in an extensive literature review, 18 of which pertained to medical faculty and 6 more to other health professions including nursing, dentistry, pharmacy, and midwifery.54

결론적으로, 통합은 혁신과 발견의 통합을 통해 [내부적]으로 이루어졌지만, 다른 분야와의 통합(외부적)은 제한적이었다.

To conclude, integration has happened internally, through consolidation of innovations and findings, but integration with other disciplines has been limited.

3.3 적용

3.3 Application

HPE학술활동에서는 연구와 개발이 함께 진행된다. 응용은 이 분야의 핵심적 특성이다. HPE 연구에 관여하는 대부분의 학자들은 임상의, 교사, 또는 둘 다, 교육 과정이나 프로그램 책임자, 부학장과 같은 행정 담당자로서 교육에 대한 역할을 한다. 대학 사회과학부의 교육과학자들이 초중고교 교사가 아니었을 수도 있고 상아탑과학에 대해 비판받을 수도 있는 반면, 매우 많은 경우, HPE 연구자들은 활동적인 교사들, 활동적인 교수 개발자들, 활동적인 교육과정 및 과목 개발자로서, 임상 또는 생의학 연구경험을 가지고 있다. 많은 학구적인 HP 교육자들은 초기에 환자 진료 또는 기초 과학 분야에서 경력을 쌓았고, 이후 단계에서 [두 번째 직업]으로 학문 교육자로 발전했다.

In health professions education scholarship, research and development go hand-in-hand. Application is a core characteristic. The vast majority of scholars involved in HPE research have roles in education, either as clinicians, as teachers, or both; as course or program directors or as administrative officers, such as associate deans. While educational scientists in university faculties of social science, may never have been primary or secondary school teachers (even if that is their domain of study) and may be criticized for ivory tower science, HPE researchers are very often active teachers, active faculty developers, active curriculum and course developers with clinical or biomedical research experience. Many scholarly HP educators have initially built a career in patient care or the basic sciences and developed as scholarly educators only at a later stage, as a second career.

HPE의 학술활동 적용 기준이 다른 고등교육 영역보다 더 강력한 이유는 [양질의 의료 서비스에 대한 명확한 사회적 욕구] 때문이다. 의료는 모든 사람에게 영향을 미치며, [사회적 신뢰]를 필요로 하는데, 이는 주로 [의료 제공자와 그들이 제공할 것으로 추정되는 교육]에 초점을 맞춘 신뢰이다. 수십 년에 걸친 의학 훈련의 개선을 옹호하는 많은 보고서들은 크리스타키스가 1995년에 그들 모두가 다음과 같은 결론을 내리고 있다고 정리했다.

"놀랄 정도로 일관되게, [의료 전문직의 특정한 사회적 비전]을 제시하고 있으며, 여기에서 의과대학은 다음을 달성하기 위하여 사회에 복무하는 것으로 여겨진다.

- [공공의 이익]에 더 잘 봉사하기 위해

- [의료 인력 수요]를 해결하기 위해

- [급성장하는 의학 지식에 대처]하기 위해

- [일반주의를 강조]하기 위해

다음의 권고사항은 1910년 이후로 거의 지속적으로 등장해 왔다

- 일반의 교육을 늘린다.

- 외래 진료 노출을 증가시킨다.

- 사회과학 강좌를 제공한다.

- 평생 및 자기 학습 기술을 가르친다.

- 교육활동에 보상한다,

- 학교 사명을 명확히 하고

- 교육 과정을 중앙 집중식으로 관리하다

The reason why the application criterion of scholarship in HPE may be stronger than in other higher education domains is a clear societal desire for high-quality health care. Health care affects everyone, and requires societal trust to operate, a trust that primarily focuses on care providers and their presumed education. The many reports, across several decades, advocating for improvement of medical training led Christakis to conclude in 1995 that they all

"articulate a specifically social vision of the medical profession, in which medical schools are seen as serving society [..] with a remarkable consistency, [..]

- to better serve the public interest,

- to address physician workforce needs,

- to cope with burgeoning medical knowledge, and

- to increase the emphasis on generalism.

[Recommendations to]

- increase generalist training,

- increase ambulatory care exposure,

- provide social science courses,

- teach lifelong and self-learning skills,

- reward teaching,

- clarify the school mission, and

- centralize curriculum control

have appeared almost continuously since 1910",55

이러한 결론은 1995년 이래로, 의학 교육 개혁에 대한 후속 요구로 쉽게 확장된다.

conclusions that easily extend to subsequent calls for medical education reforms after 1995.42, 43, 56

보건직업 교육학술활동은 응용과학의 전형이며, 응용에 지속적으로 치중하기 때문에 순수과학으로 볼 수 없다. 현재 주요 HPE 저널에 게재된 모든 간행물 중 대다수는 연구 보고서가 아니라 관점의 기사, 지침, 리뷰이다. 그것들은 교육을 발전시키고 매우 유용하며, 응용이 HPE 학문 영역의 중심이라는 것을 보여준다.

Health professions education scholarship is an exemplar of an applied science and cannot be viewed as a pure science, because of its continuous focus on application. Of all current publications in the major HPE journals, the majority are not research reports, but perspective articles, guidelines, and reviews. They serve to advance education and are highly useful, and show that application is central to the HPE scholarly domain.

3.4 교육 및 학술 커뮤니케이션

3.4 Teaching and scholarly communication

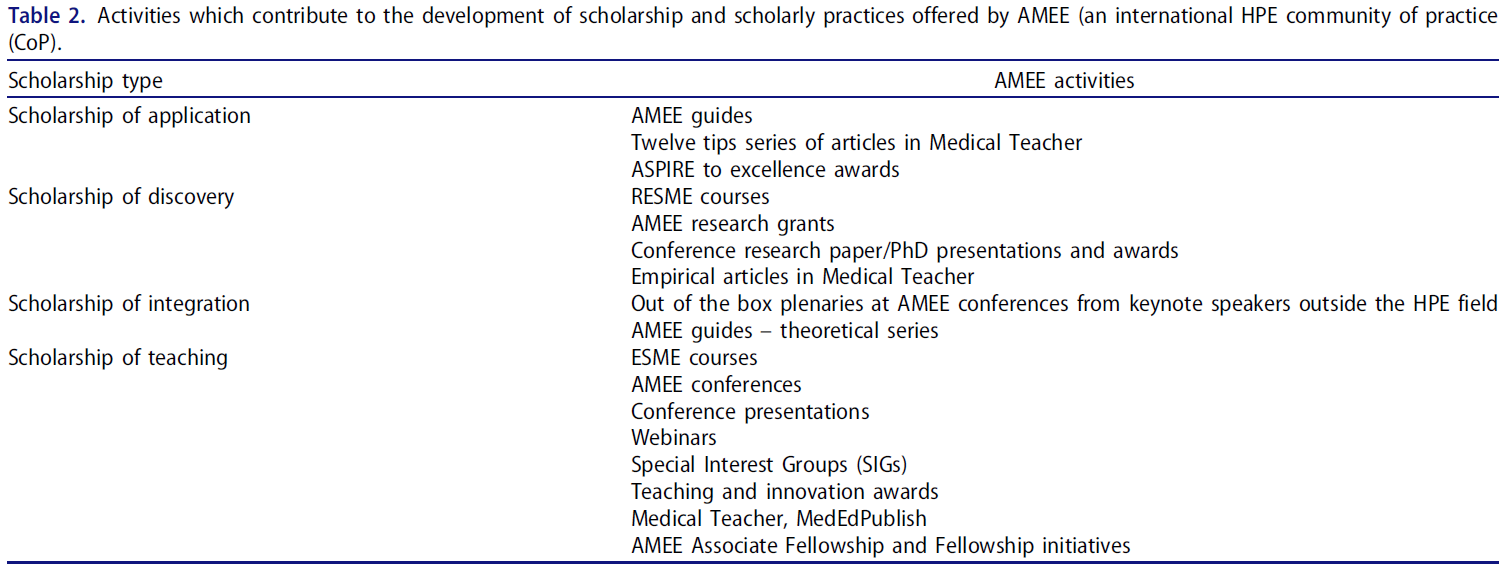

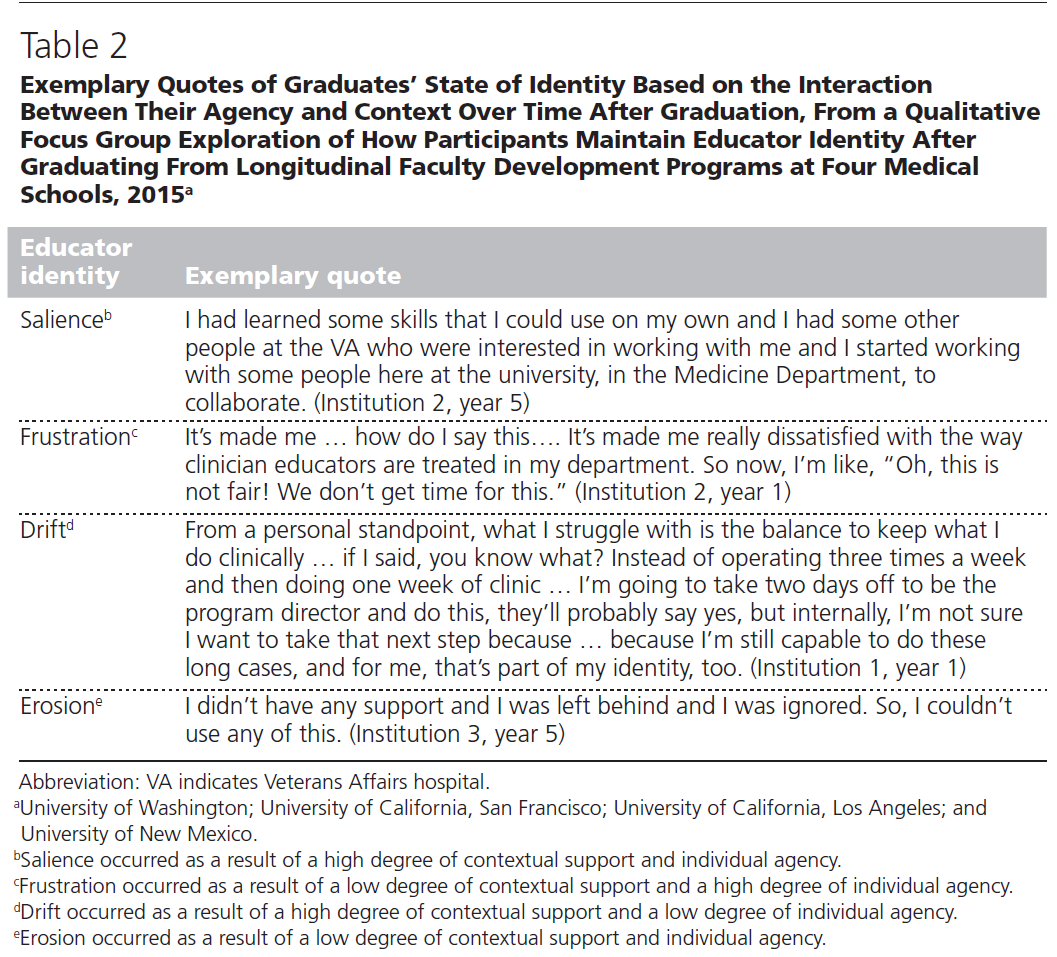

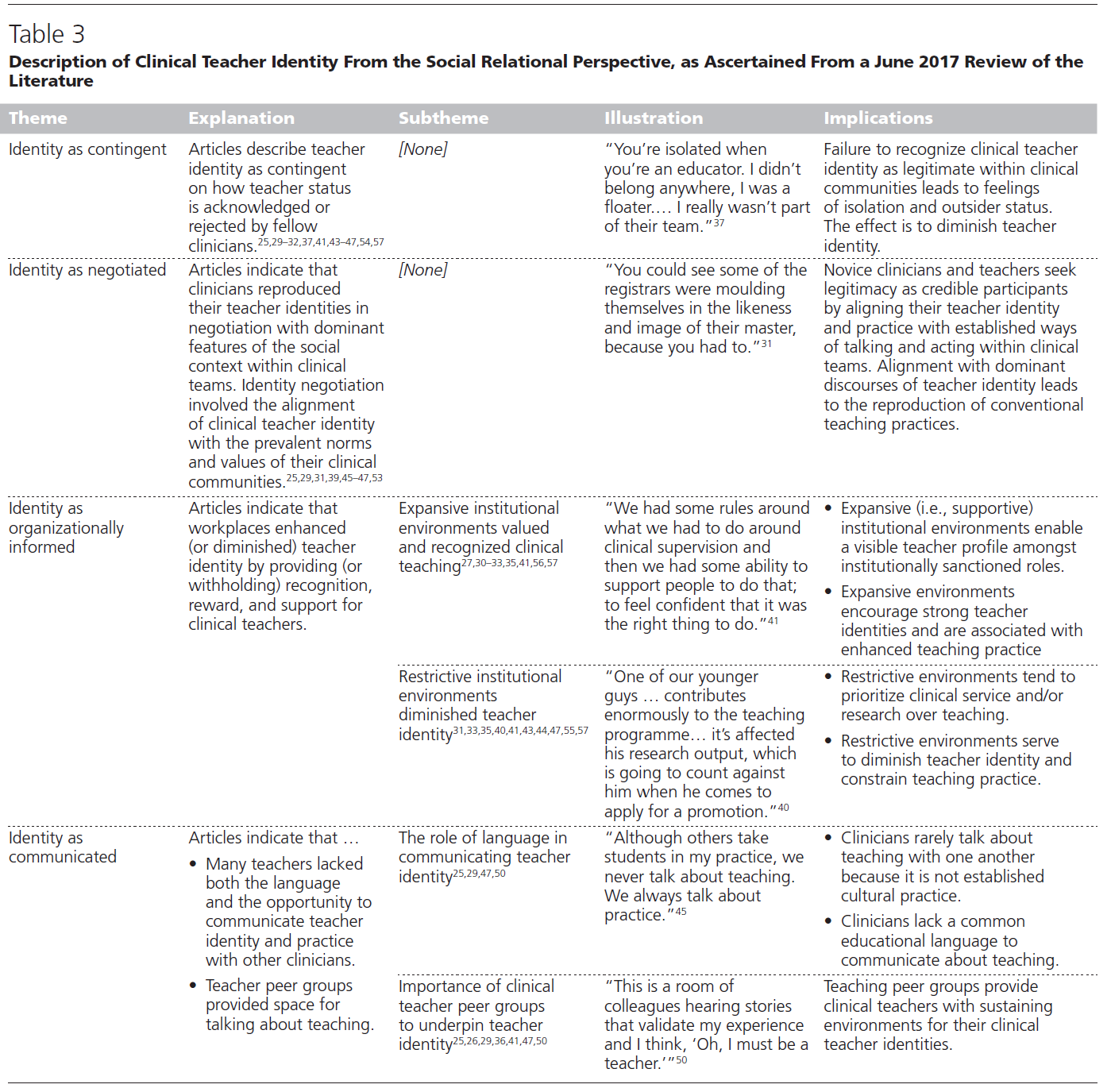

네 번째 기준은 Teaching이며, 더 넓게 해석하자면 지식, 통찰력, 발견을 커뮤니케이션함으로써 공동체와 후배 학자들에게 가르치는 것이다. 1970년 이전에는 사실상 존재하지 않았던 의학 교육에 대한 지역, 국가 및 국제 회의는 수와 규모가 급격히 증가했다(표 2)

Boyer's fourth criterion of scholarship is Teaching, or, interpreted more broadly, the communication of knowledge, insight, and discovery, to the community at large and to junior generations of scholars. Not only the number of journals and publications increased significantly; local, national, and international conferences in medical education––virtually nonexistent before 1970, increased rapidly in number and size (Table 2).

회원들과 회의 참석자들에 의해 가장 큰 국제 HPE 협회는 유럽 의학교육협회이다. 1973년 창설된 이래 매년 열리는 이 회의는 유럽 밖에서 온 대다수의 참석자들이 참석하는 글로벌 회의로 성장했다. AMEE는 의료 및 보건 직업 교육의 질을 높이기 위한 다양한 다른 서비스(여행, 웨비나, 자격증 과정, 지침 및 리뷰를 포함한 자원, 상, 상금, 소액 보조금, 펠로우 멤버 옵션)를 제공합니다. 그들의 웹사이트에는 의료 또는 보건 직업 교육을 위한 37개의 소규모 활동적인 국내 및 국제 사회와 협회가 나열되어 있다. 이들 중 다수는 매년 국가 또는 지역 컨퍼런스를 개최하기도 하며, 일부 국가 HPE 컨퍼런스는 국제 컨퍼런스를 능가한다. 미국 의과대학협회는 2019년 연례 회의에서 4490명의 참가자를 받아들였지만, 교육 연구는 AAMC 회의에서 덜 강조되었다. 네덜란드 연례 HPE 컨퍼런스는 지난 10년 동안 매년 900~1000명의 참가자를 안정적으로 받고 있다.

The largest international HPE society by members and conference attendees is the Association of Medical Education in Europe (AMEE). Its annual conference has grown since its inception in 1973 into a global conference with a majority of attendees from outside Europe.57 AMEE offers a variety of other services to foster the quality of medical and health professions education (journals, webinars, certificate courses, resources including guidelines and reviews, awards, prizes, and small grants, fellowship member options). Their website lists 37 smaller active national and international societies and associations for medical or health professions education (www.AMEE.org). Many of these also hold annual national or regional conferences. Some national HPE conferences exceed international conferences. The Association of American Medical Colleges received 4490 participants at their 2019 annual meeting, but educational research has less emphasis at AAMC meetings; the Dutch annual 2-day HPE conference has received a stable number of 900–1000 participants annually across the past decade.

Teaching이란, 좀 더 구체적으로 말하면, 특정 영역에서 [미래 세대를 교육하는 것]이다. 교육학술활동의 목적은 가르치는 것을 포함하지만, [새로운 세대의 학자들을 가르치는 것]은 뭔가 다르다. 그래서 문제는 HPE 공동체가 HPE 학술활동의 내용과 방법을 가르치는데 어느 정도 투자를 했는가 하는 것입니다. [의학적 배경을 가진 1세대 HPE 학자들]은 교육학과 또는 사회과학 분야에서 석박사 학위를 취득하기 위해 교육 방법을 스스로 훈련하거나 시간을 보냈다. 이러한 모습은 1990년대에 HPE 학술활동 단위에서 [자체적인 HPE 석박사 프로그램]이 제공되기 시작하고, 의과대학에서 teacher career에 대한 진지한 관심이 등장하면서 바뀌었다.58 HPE에서

- [전담dedicated 교수] 및 [부교수associated 직책]의 설립,

- [임상 및 비임상 교수진]을 위한 대안적 커리어 기회 제공,

- 의과대학 내 교육 커뮤니티로서 [아카데미Academies의 설립]

...은 이러한 흐름을 더 촉진하였다.

Teaching, more specifically, involves educating future generations in a specific domain. While the object of educational scholarship includes teaching, teaching new generations of scholars is something different. So the question is: to what extent has the HPE community invested in teaching the content and methods of HPE scholarship? The first generations of HPE scholars with a medical background have trained themselves in educational methods or spent time to obtain an advanced degree in schools of educational or social sciences. This has shifted in the 1990s, when advanced academic degree programs began to be offered by units of health professions education scholarship, and serious attention for teacher careers in medical schools emerged.58

- The establishment of dedicated professor and associate professor positions in health professions education,

- providing an alternative career opportunity for clinical and nonclinical faculty members,59 and

- the establishment of Academies as educational communities within medical schools for early career or distinguished educators60

has further fostered this.

석사와 박사 프로그램은 이러한 지속적인 학문의 전문적 발전을 가능하게 하였다. HPE의 석사급 프로그램은 1996년 7개에서 2012년 76개, 2020년 139개로 증가했으며, 구조화된 박사급 프로그램은 2014년 24개, 2020년 26개로 집계됐다. 여기서 훈련받은 학생 수도 크게 늘었다. 일례로 마스트리히트대 보건전문대학원(School of Health Professional Education)에서 활동 중인 박사과정 학생의 수가 지난 10년간 25명에서 100명으로 증가했다. 확장된 국제 협력은 프로그램이 한 곳에 점점 덜 제한됨에 따라 그러한 증가를 촉진한다. 몇몇 국가들은 이 운동에서 지도력이 뛰어났다. 1960년 이후 영국, 캐나다, 미국에 이어 네덜란드, 호주까지 건강 직업 교육에서 학술활동을 장려해 왔다. 의과대학별 생산성으로 측정했을 때, 즉, 지난 10년 반 동안 캐나다와 네덜란드는 가장 높은 상대적 HPE 연구 생산성을 보여주었으며, 학술지 기사에 대한 선임 저자 자격을 종종 제공했으며(표 4), 국제 연구 멘토십의 표시로 해석된다

Masters and PhD programs enable this continued professional development in scholarship. The number of masters level programs in HPE increased from 7 in the year 1996 to 76 in the year 201261 and 139 in the year 2020 (www.faimer.org) and the number of structured doctoral programs was calculated to be 24 in the year 201462 and 26 in the year 2020 (www.faimer.org). The numbers of students trained in these units also expanded significantly. As an example, the number of active PhD students in Maastricht University's School of Health Professions Education increased in the past decade from 25 to 100.63 Expanded international collaborations foster such increases as programs become less and less confined to one location.64 A few countries have excelled in leadership in this movement. Since 1960 the United Kingdom, Canada, and the USA, followed by the Netherlands and Australia have promoted scholarship in health professions education. Measured by productivity per medical school, that is, considering the size of the country, Canada and the Netherlands have shown the highest relative HPE research productivity across the past decade and a half, and often provided senior authorships on journal articles (Table 4), to be interpreted as a sign of international research mentorship (Table 3).

[네덜란드]와 같은 일부 국가에서는 교수직은 박사과정 학생들을 개별적으로 또는 구조화된 프로그램에서 감독할 수 있는 공식적인 권리와 기대를 포함한다. 보건직 교육에서 이러한 의자의 증가는 HPE 박사과정 학생 수의 증가로 인한 촉매 효과를 가져왔다. 박사 학위 졸업에 기초한 대학 연구의 정부 자금과 결합하면, 이것은 네덜란드에서 건강 직업 교육 연구의 다작 생산을 설명할 수 있을 것이다.

In some countries, such as the Netherlands, professor positions include the formal right and expectation to supervise doctoral students in their domain of expertise, individually or in structured programs. In health professions education, the increase of such chairs has had the catalytic effect of increased numbers of PhD students in HPE which. Combined with government funding of university research based on PhD graduations, this may explain the prolific production of health professions education research in the Netherlands.65

의심할 여지 없이, 보이어의 Teaching 기준은 개별 국가 수준 뿐만 아니라, 국제적인 수준에서도 충족되었다.

Boyer's teaching criterion, no doubt, has been met, not only locally, but also at the international level.

4 결론 및 전망

4 CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOK

HPE 학술활동의 발전과 현황을 분석해보았을 때, 보이어의 성숙한 학문 규율 기준을 모두 충족한다는 것을 부인할 수 없다. HPE 학문 단위는 학문적 단위가 될 수 있으며, 따라서 이어져야 하는 질문은 그러한 학과 또는 단위가 대학에서 어디에 속하느냐이다. 지금까지는 사회과학이나 교육과학의 학부나 학과보다는, 보건전문직 대학들이 이러한 단위를 설립하고 주최해왔으며, 이를 유치해야 했다. (사회과학의 통찰력과 결합하여) [보건의료행위가 이뤄지는 곳과 근접하게 자리하는 것]이 이러한 단위가 번창하기 위한 중요한 조건이었던 것으로 보인다. 66 HPE 연구는 의사, 간호사 또는 다른 건강 전문가처럼 생각하고 행동하고 느끼는 것이 무엇인지 이해하는 사고방식을 가진 학자들에 의해 가장 잘 수행되어야 한다. 즉, 의료 분야에서 [전문지업적 정체성]을 소유하거나, 적어도 공감하기 위한 것이다.

The analysis of the development and current status of health professional education scholarship would undeniably qualify it as meeting all of Ernest Boyer's criteria of mature scholarly discipline. HPE scholarly units can become academic departments and a relevant question is then where in universities such departments or units belong.50 Rather than in faculties or departments of social or educational sciences, schools in the health professions have established and hosted such units and should host them. Situated in close vicinity to the practice of health care seems to have been a critical condition for these units to flourish, combined with the insights of the social sciences.66 HPE research should be best conducted by scholars with a mindset to understand what it is to think, act, and feel like a physician, nurse, or other health professional, in other words to possess, or at least sympathize, with professional identities in health care.67

20세기 중반 이후 HPE 학술활동 활동에 대한 관심의 성장은 다른 고등 교육 분야에서도 유사한 발전을 앞질렀다. 잘 준비된 의료 전문가를 위한 최적의 의료 서비스에 대한 추구는 사회적 영향, 전문적인 존중, 직업의 명확성과 70년 전에는 부족했던 교육 이론 및 연구 방법론의 통찰력을 결합한 명확한 교육적 집중으로부터 이익을 얻었을 수 있다.

The growth of health professions education scholarship activities and interest since mid-20th century (journals, publications, conferences, HPE research, and development centers, scholars) has out-paced similar developments in other higher education domains. The quest for optimal health care, and consequently, for well-prepared health care professionals may have benefited from a clear educational focus that combines societal impact, professional esteem, and clarity of occupations with insights from educational theory and research methodology that lacked 70 years ago.

초기 수십 년 동안 몇몇 계몽된 사람들이 HPE 학술활동의 성장과 방향에 큰 영향을 미쳤지만, 현재 학자들의 숫자는 오랫동안 지속 가능한 영역을 유지하는데 중심적인 임계 질량을 넘어섰다.

While during the early decades a few enlightened individuals had a major impact on the growth and direction of HPE scholarship, the number of scholars now has likely passed the pivotal critical mass to keep the domain sustainable for a long time.

스털리 외 연구진(222-225페이지)은 의료 교육의 미래에 대한 분석에서 의료 교육 연구의 개선을 위한 5가지 주요 의제를 상세히 설명한다.

In their analysis of the future of medical education,77 Bleakley et al. (page 222–225) elaborate a five-point agenda for improvement of medical education research (slightly amended):

(1) [개념적 질문 및 명확화]에 초점을 맞추고, 증거로서 무엇이 중요한지 결정한다.

(1) a focus on conceptual questions and clarifications and deciding on what counts as evidence,

(2) 기회주의적 연구보다는 [체계적인 연구]의 프로그램 구축

(2) building programs of systematic research rather than conducting just opportunistic studies,

(3) 보다 엄격한 [성과-기반 연구],

(3) more rigorous outcome-based research,

(4) 질적 및 정량적 (혼합된 방법) 연구에 대한 더 나은 전문지식을 구축하고,

(4) building better expertise in combined qualitative and quantitative (mixed methods) research, and

(5) 학술계와 임상계 사이에 생산적인 대화를 창출한다.

(5) creating a productive dialog between the academic and clinical communities.77

아스클레피오스는 히포크라테스의 선서에 포함된 건강 전문가들의 고유 임무인 뱀과 막대기에 대한 자신의 상징이 어떻게 수천 년 후에 활발한 학문 교육자 공동체로 이어졌는지 알면 놀랄 것이다. 그때나 지금이나, 최고의 자격을 갖춘 의료 전문가를 양성한다는 일반적인 목적은 변하지 않았습니다. 연구자와 학자들은 [유능한 의료 인력이라는 궁극적인 목표]가 달성가능하며, [이 목표가 의료 교육의 지속적인 혁신에 기름을 부을 것]이라는 비전을 만들지만, 학술활동을 특징짓는 것은 달성 가능한 종점이 아니라 거기에 이르는 과정pathway일 수 있다. 최적의 교육을 통해 만들어진 '역량있는 전문직'은 마치 성배Holy Grail처럼 보일지 모르지만, 이를 달성하려면 보이어의 기준에 따른 학술활동이 필요하다. 이 과정에는 부침이 있으며, [역량있는 의료인력]에 대한 [학교, 병원 및 규제 기관의 관심]은 [자금 조달, 효율성, 법적인 제약]이라는 "의도하지 않은 결과"로 이어졌다. 이러한 결과를 분별하고 이를 극복할 수 있는 방법을 제시하는 학자들이 필요하다. 이러한 역학의 혼합은 미래의 학자들이 학습자, 임상의, 환자 및 사회를 위해 건강 직업 교육의 지속적인 혁신을 만들고 시험하도록 계속 도전하게 될 것이다.

Asclepius would be surprised to know how his symbols of snake and rod as well as the obligation to teach—an inherent task of health professionals, incorporated in Hippocrates' oath—have led to a lively community of scholarly educators several millennia later. The common pursuit, then and now, for the best qualified health professionals has not changed. While researchers and scholars develop visions that suggest that the ultimate goal of a competent health care workforce may be attainable and fuel the continued innovation in medical education, it may be the pathway rather than an attainable endpoint that characterizes scholarship. While "the competent health professional," molded by optimal education, may seem a Holy Grail, the quest for it is served by scholarship according to Boyer's criteria. The pathway shows ups and downs,78 and the interest of schools, hospitals, and regulatory bodies in this competent workforce, has led, in the words of Woolliscroft, to "unintended consequences" of financing, efficiency, and legal constraints.69 Scholars are needed to discern these consequences and recommend routes to overcome them. This amalgam of dynamics is bound to keep challenging future scholars to create and test ongoing innovations in health professions education, to the benefit of learners, clinicians, patients, and society.

FASEB Bioadv. 2021 Mar 29;3(7):510-522.

doi: 10.1096/fba.2021-00011. eCollection 2021 Jul.

Health professions education scholarship: The emergence, current status, and future of a discipline in its own right

PMID: 34258520

PMCID: PMC8255850

Free PMC article

Abstract

Medical education, as a domain of scholarly pursuit, has enjoyed a remarkably rapid development in the past 70 years and is now more commonly known as health professions education (HPE) scholarship. Evidenced by a solid increase of publications, numbers of specialized journals, professional associations, national and international conferences, academies for medical educators, masters and doctoral courses, and the establishment of many units of HPE scholarship, the domain of HPE education scholarship has matured into a scholarly discipline in its own right. In this contribution, the author reviews the developments of the field from Boyer's four criteria that determine scholarship: discovery, integration, application, and teaching. Born mid-20th century, and in the first decades developed in the predominant area of physician education, HPE scholarship has matured, with increasing breadth, depth, and volume of scholars, publications, conferences, and dedicated centers for research and development. The author concludes that, given the infrastructure that has emerged, HPE can arguably be considered a discipline in its own right. This academic question may not matter hugely for practices of scholarly work in this domain, and any stance in this academic debate inevitably reflects a personal view, but the author would support the view of health professions scholarship as being a unique niche, with inherent dependence on both medical and other health professional sciences, on the one hand, and social sciences, including educational sciences, on the other hand.

Keywords: History; conferences; health professions education; medical education; publications; scholarship.

© 2021 The Authors. FASEB BioAdvances published by the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 의학교육연구(Research)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 질적연구의 일반화가능성: 오해, 기회, 권고(Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 2018) (1) | 2021.11.23 |

|---|---|

| 질적연구에서 포화: 개념과 조작화 탐색(Qual Quant, 2018) (0) | 2021.11.19 |

| When I say … 리커트 문항(Med Educ, 2021) (0) | 2021.11.02 |

| 정답은 하나? (성찰적) 주제분석의 옳바른 실천은 무엇인가? (Qualitative Research in Psychology, 2021) (0) | 2021.10.22 |

| 다중 비교에 관한 팩트와 픽션(J Grad Med Educ, 2021) (0) | 2021.10.22 |