의학교육에서 평가의 신뢰(Credibility)인식에 영향을 미치는 요인(Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2021)

Factors affecting perceived credibility of assessment in medical education: A scoping review (Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2021)

Stephanie Long1 · Charo Rodriguez1 · Christina St‑Onge2 · Pierre‑Paul Tellier1 · Nazi Torabi3 · Meredith Young4,5

도입 Introduction

[평가]는 일반적으로 [학습자의 특정 학습 목표, 목표 또는 역량 달성에 대한 판단]을 내리기 위해, 정보를 [시험, 측정, 수집 및 결합]하는 전략을 포함한다(Harlen, 2007; Norcini et al., 2011). 평가는 일반적으로 의학교육에서 네 가지 방법으로 사용된다(엡스타인, 2007).

Assessments are broadly described as any strategy involving testing, measuring, collecting, and combining information to make judgments about learners’ achievement of specific learning objectives, goals, or competencies (Harlen, 2007; Norcini et al., 2011). Assessments are commonly used in four ways in medical education (Epstein, 2007):

- (i) Practice에 입문하는 사람들이 [역량있음을 보장함으로써 대중을 보호]해야 한다.

- (ii) 고등교육 [지원자 선발의 근거]를 제공하기 위해

- (iii) 교육기관(품질보증)을 위하여 [Trainee의 성과에 대한 피드백] 제공

- (iv) 미래 학습을 지원하고, 방향을 제시한다(엡스타인, 2007; Norcini 등, 2011).

- (i) to protect the public by ensuring those entering practice are competent,

- (ii) to provide a basis for selecting applicants for advanced training,

- (iii) to provide feedback on trainee performance for the institution (i.e., quality assurance), and

- (iv) to support and provide direction for future learning (Epstein, 2007; Norcini et al., 2011).

[미래 학습을 가이드하는 평가]라는 개념은 평가의 [촉매 효과]로 설명되었으며, 이러한 촉매 효과가 달성되려면 학습자가 평가-생성 피드백(즉, 점수, 서술 코멘트)에 참여함으로써, 학습자가 평가 과정에 능동적으로 참여해야 한다(Norcini 등, 2011). 학습자가 향후 성과를 개선하기 위해 평가에서 생성된 피드백에 참여하지 않을 경우 평가의 잠재적인 교육적 이점은 무효화됩니다. 따라서 평가의 교육적, 수행적 이점을 극대화하기 위해서는, 학습자가 평가에서 생성된 피드백에 참여하도록 장려하거나 저해하는 요소를 이해하는 것이 중요합니다.

The notion of assessment guiding future learning has been described as the catalytic effect of assessment, and for this catalytic effect to be achieved, a learner must be an active participant in the assessment process by engaging with assessment-generated feedback (i.e., scores, narrative comments) (Norcini et al., 2011). If learners fail to engage with assessment-generated feedback to improve future performance, the potential educational benefit of assessment is negated. Therefore, it is critical to understand the factors that encourage or discourage, learners from engaging with assessment-generated feedback in order to maximize the educational and performance benefits of assessment.

의료 학습자(학생, 레지던트 또는 동료)가 [평가 과정에 참여]하고 [평가에서 생성된 피드백을 통합]하여 이후 [성과를 개선하는지 여부]에 몇 가지 요소가 기여할 수 있다. 학생의 평가 참여에 기여하는 한 가지 핵심 요소는 특히 평가인에 의존하는 평가 상황에서 [학습자가 평가와 평가자에 대해 인식하는 신뢰도credibility]이다(Bing-You 등, 1997; Watling, 2014; Watling 등, 2013). 여기서, 현재 증거는 신뢰할 수 있다고 간주되는 피드백이 이후의 관행 개선을 지원하는 데 사용될 가능성이 더 높다는 것을 지적한다. 신뢰할 수 없다고 판단된 피드백은 무시될 가능성이 높으므로 교육적 가치가 거의 없다(Watling, 2014; Watling & Lingard, 2012; Watling 등, 2013). 이 작업의 초점은 평가 순간에 수반되는 [피드백 대화]에 맞춰져 있다는 점에 유의해야 합니다. 따라서, 신뢰성 판단은 평가 과정과 평가자 자체에 의해 영향을 받았습니다. [Supervisor의 피드백 중에서 학습자가 신뢰할 수 있다고 판단한 것]만이 학습 형성에 영향을 미칠 수 있다는 얘기다.

Several factors may contribute to whether medical learners (students, residents, or fellows) engage with the assessment process and integrate assessment-generated feedback to improve later performance. One key contributing factor to student engagement with assessment is the learner’s perceived credibility of the assessment and of their assessor, particularly in assessor-dependent assessment contexts (Bing-You et al., 1997; Watling, 2014; Watling et al., 2013). Here, current evidence points out that feedback deemed credible is more likely to be used to support later practice improvement. Feedback judged to be not credible is likely to be ignored, and therefore, be of little educational value (Watling, 2014; Watling & Lingard, 2012; Watling et al., 2013). It is important to note that the focus of this work was on the feedback conversation that accompanied an assessment moment. Hence, judgments of credibility were influenced by both the assessment process and the assessor themselves. In other words, only supervisor-provided feedback judged as credible by learners will be influential in shaping learning.

와틀링 외 연구진(2012)에 따르면, 신뢰도 판단은 학습자가 [학습에 통합되어야 할 정보]와 [무시해야 할 정보]를 정리하고, 평가하고, 학습 단서에 가치를 부여할 때 발생한다. Bing-You 외 연구진(1997)에 따르면, Supervisor가 제공한 피드백의 신뢰성에 대한 학습자의 판단은 다음으로부터 영향을 받습니다.

According to Watling et al., (2012), credibility judgments occur when learners organize, weigh, and allocate value to the learning cues presented to them, deciding which information should be integrated into their learning and which should be dismissed. According to Bing-You et al., (1997), learners’ judgments of the credibility of feedback provided by a supervisor are influenced by:

- (i) Supervisor의 특성에 대한 전공의의 인식(예: 신뢰와 존중, 임상 경험)

- (ii) Supervisor의 행동에 대한 전공의의 관찰(예: 대인관계 기술 부족, 관찰 부족),

- (iii) 피드백의 내용(예: 비특정, 자기 표현과 불일치),

- (iv) 피드백 전달 방법(예: 판단적인 것, 그룹 설정에서 발생한 것) (Bing-You 등, 1997).

- (i) residents’ perceptions of supervisor characteristics (e.g., trust and respect, clinical experience),

- (ii) residents’ observations of supervisor behaviour (e.g., lack of interpersonal skills, lack of observation),

- (iii) content of feedback (e.g., non-specific, incongruent with self-perceptions), and

- (iv) method of delivering feedback (e.g., judgmental, occurs in group setting) (Bing-You et al., 1997).

따라서 이 지식 본문은 피드백의 개념을 평가자와 학습자 사이의 대화 또는 토론으로 간주한다(Ajjawi & Regehr, 2019).

This body of knowledge therefore conceives the notion of feedback as a conversation or discussion between an assessor and a learner (Ajjawi & Regehr, 2019).

우리는 교육 동맹의 중요성과 피드백 대화를 신중하게 구성해야 할 필요성을 인정한다(Telio et al., 2015). 하지만 동시에 우리는 평가자 또는 감독자와의 대면 대화(예: 시험 점수, 교육 중 성과 평가, OSCE 점수)와 별개로 학습자는 다양한 출처로부터 자신의 성과에 대한 데이터 또는 정보를 제공받는다고 주장한다. 이 평가 데이터는 학습자에게 피드백을 제공하기 위한 목적으로 작성된 경우가 많습니다 – 컨텐츠의 숙달도를 측정하고, 더 많은 주의나 집중이 필요한 영역을 제안하거나, 학습자가 커리큘럼을 통해 자신의 진행 상황을 추적하도록 지원합니다.

While we acknowledge the importance of the educational alliance (Telio et al., 2015) and the need to carefully construct feedback conversations (Henderson et al., 2019; Watling, 2014), we argue that learners receive data or information about their performance from a variety of sources that are disconnected from face-to-face conversations with an assessor or supervisor (e.g., examination scores, in-training performance evaluations, OSCE scores). This assessment-generated data is often intended to function as feedback to the learners – to gauge mastery of content, to suggest areas that require more attention or focus, or to help a learner track their progress through a curriculum.

이러한 평가-생성 피드백assessment-generated feedback의 교육적 가치를 지원하기 위해 평가(평가 데이터를 생성하는 대상) 및 평가-생성 피드백(평가로 생성된 데이터 및 학습자와 공유되는 데이터)의 인식된 신뢰도perceived credibility에 영향을 미치는 요인을 조사하기 시작했다.

To support the educational value of this assessment-generated feedback, we set out to explore the factors that influence the perceived credibility of assessment (the objects that generate assessment data) and assessment-generated feedback (the data generated by assessments and shared with learners).

방법 Methods

의학 교육에서 평가 및 평가-생성 데이터의 신뢰성에 대한 학습자 인식에 대한 현재 문헌은 이질적이고 방법론과 집중도가 매우 다양한 논문으로 구성되어 있다. 이러한 가변성은 우리의 초점 영역이 의학 교육 내에서 새로운 연구 영역이라는 인식과 결합하여 범위 검토 방법론을 우리의 연구 맥락에서 현재 연구에 가장 적합한 접근방식으로 만든다. Scoping review에 대한 몇 가지 접근방식이 있지만, 우리는 Arcsey와 O'Malley(2005) 5단계 프레임워크에 의존했다. 범위 지정 검토에는 선택 사항인 6단계( 이해관계자와의 협의)가 포함될 수 있지만(Arcsey & O'Malley, 2005) 포함되지 않았다.

Current literature on learner perceptions of credibility of assessment and assessment-generated data in medical education is disparate and comprised of articles that are highly variable in methodology and focus. This variability, in combination with the recognition that our area of focus is an emerging area of research within medical education, makes a scoping review methodology the most appropriate approach for the present study in our research context. While there are several approaches to scoping reviews (Arksey & O'Malley, 2005; Levac et al., 2010), we relied on the Arksey and O'Malley (2005) 5-stage framework. Scoping reviews can include an optional 6th step (consultation with stakeholders) (Arksey & O'Malley, 2005), which was not included.

1단계: 연구 질문 식별

Step one: Identify research question

이 검토는 "의학교육 문헌에 문서화된 평가 및 평가-생성 피드백의 인식 신뢰성에 영향을 미치는 요인은 무엇인가?"라는 연구 질문에 의해 유도되었다.

This review was guided by the research question, “What are the factors that affect the perceived credibility of assessment and assessment-generated feedback documented in the medical education literature?”.

2단계: 관련 연구 확인

Step two: Identifying relevant studies

의료 사서(NT)와 협력하여 통제된 어휘(예: MeSH)와 키워드를 사용하여 관련 문헌을 식별하기 위한 검색 전략을 개발하고 실행했다. 검색 전략은 MEDLINE(Ovid), PsycInfo(Ovid), Scopus, EMBASE(Ovid), EBSCO(EBSCO)에서 채택 및 구현되었다. 검색을 2000년에서 2020년 11월 16일 사이에 발표된 연구로 제한했다.(2017년 6월 17일에 처음 실행되어 2020년에 업데이트됨) 이것이 보건 직업 교육에서 [평가의 교육적 가치에 대해 논의하는 쪽]으로 문헌의 변화를 나타냈기 때문에 우리는 2000년에 닻을 내렸다(Frank 등, 2010). 보다 구체적으로, 이것은 학습과 평가의 성과(즉, 역량)에 초점을 맞춘 의료 교육 개혁으로 향하는 전환점을 나타냈다(Frank et al., 2010).

In collaboration with a medical librarian (NT), a search strategy was developed and executed to identify relevant literature, using controlled vocabularies (e.g., MeSHs) and keywords. The search strategy was adapted and implemented in: MEDLINE (Ovid), PsycInfo (Ovid), Scopus, EMBASE (Ovid), and ERIC (EBSCO). We limited the search to studies published between 2000 to November 16, 2020 (search first executed June 17, 2017 and updated in 2020). We chose to anchor to 2000 as this represented a shift in the literature towards discussing the educational value of assessment in health professions education (Frank et al., 2010). More specifically, this represented a turning point towards reforms in medical education focused on outcomes (i.e., competency) of learning and assessment (Frank et al., 2010).

3단계: 스터디 선택

Step three: Study selection

포함된 논문: (1) 의학 학습자를 초점 모집단으로 두고, (2) 프로그램이나 환자가 아닌 개별 학습자에 대한 평가를 포함하고, (3) 평가 또는 평가-생성 피드백과 관련하여 신뢰성을 논의했으며, (4) 주요 연구 연구였으며, (5) 영어 또는 프랑스어(연구팀의 언어 역량)였다.

Included papers: (1) had medical learners as the focal population, (2) contained assessment of individual learners (rather than programs or patients), (3) discussed credibility as related to assessment or assessment-generated feedback, (4) were primary research studies, and (5) were in English or French (linguistic competencies of the research team).

두 명의 저자(SL, MY)는 웹 기반 선별 애플리케이션 Rayyan을 사용하여 모든 제목과 추상(Peters 등, 2015)을 독립적으로 심사했다. 의견이 일치하지 않는 경우, 세 번째 검토자(CSO)는 불일치를 해결했다. 원시 백분율 합의는 평가자 간 신뢰도의 척도로 사용되었다(Kastner 등, 2012). 전체 텍스트 검토를 위해 포함된 문서는 EndNote X8.0.2로 내보내졌다(EndNote Team, 2013). SL은 모든 전체 텍스트 기사를 독립적으로 심사했으며, MY는 포함을 위해 전체 텍스트 문서의 10%를 검증했다.

Two authors (SL, MY) independently screened all titles and abstracts (Peters et al., 2015) using the web-based screening application Rayyan (http://rayyan.qcri.org) (Ouzzani et al., 2016). In cases of a disagreement, a third reviewer (CSO) resolved discrepancies. Raw percent agreement was used as a measure of inter-rater reliability (Kastner et al., 2012). Articles included for full-text review were exported to EndNote X8.0.2 (The EndNote Team, 2013). SL independently screened all full-text articles, with MY verifying 10% of full-text articles for inclusion.

4단계: 데이터 차트 작성

Step four: Charting the data

추출된 데이터: 저널, 발행 연도, 대륙, 연구 설계, 방법론, 인구 특성, 평가 유형, 평가 제공자, 제공된 피드백 유형, "타당성"이 사용되지 않은 경우, "타당성"이라는 용어는 구조를 지칭하는 데 사용되었다., 신뢰성의 정의 , 신뢰도에 영향을 미치는 요인.

Data extracted: journal; year of publication; continent; study design; methodology; study population characteristics; types of assessment; who provided the assessment; type of feedback provided; use of term “credibility”, if “credibility” was not used which term was used to refer to the construct; definition of credibility; factors that affect credibility.

평가 유형, 평가 제공자, 피드백 유형은 원본 기사에 사용된 정확한 언어에 따라 코딩되었습니다.

Assessment type, provider of assessment, and feedback type were coded relying on the exact language used in the original articles.

5단계: 결과 수집, 요약 및 보고

Step five: Collating, summarizing, and reporting the results

데이터 합성은 서지학적 설명과 주제 분석에 초점을 맞췄다. 우리는 PRISMA-ScR에 따라 결과를 보고했다.

The data synthesis focused on bibliometric description and thematic analysis. We reported our results according to the PRISMA extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) (Peters et al., 2020; Tricco et al., 2018).

데이터 분석

Data analysis

정량분석

Quantitative analysis

연구의 특성 및 분포(예: 연구 설계, 출판 연도, 연구 인구)를 설명하기 위해 서지학 특성에 대한 기술 분석이 사용되었다.

Descriptive analyses of bibliometric characteristics were used to describe the nature and distribution of the studies (e.g., study design, year of publication, study population).

정성적 주제 분석

Qualitative thematic analysis

우리는 토마스와 하든(2008)이 설명한 주제 분석을 위한 방법론적 프레임워크를 적용했다.

We applied the methodological framework for thematic analysis described by Thomas and Harden (2008).

결과Results

검색 결과 Search results

80개의 문헌이 포함 기준을 충족하여 합성에 포함되었다(그림 1 "보완 디지털 부록 2" 참조).

Eighty articles met the inclusion criteria and were included in the synthesis (Fig. 1, see "Supplemental Digital Appendix 2" for a list of all included articles).

Fig. 1

포함된 문서의 특성

Characteristics of included articles

포함된 연구는 2000년 1월 1일부터 2020년 11월 16일 사이에 발표되었으며, 시간 경과에 따른 출판물 수가 분명히 증가했다(보완 디지털 부록 3).

- 연구는 48개 저널에 걸쳐 발표되었다.

- 다양한 지리적 지역에서 수집되었지만, 대다수는 유럽(n=38, 38.8%)과 북미(n=31, 31.6%)였다.

- 참여자는 의대생(n = 60, 61%), 레지던트(n = 17%, 17%), 펠로우(n = 2, 2.0%), 전문 교육생(n = 17%, 17%), 전공의(n = 2, 2.0%) 등이다.

- 대부분의 평가는 감독관 또는 심사원(n=43%, 38%)이 실시했으며, 평가-생성 피드백은 주로 점수 또는 등급(n=32, 23%)으로 제시되었으며, 주로 서면(n=29,20%) 또는 구두(n=29,21%) 형식으로 제공되었다.

- 포함된 논문은 광범위한 연구 접근법에서 나왔으며, 반구조화 인터뷰(n = 20%, 10%), 포커스 그룹(n = 31, 23%), 설문지(n = 37, 28%), 설문조사(n = 18, 13%), 설문지 또는 설문지의 자유 텍스트 논평(n = 13, 9.7%)에서 생성된 데이터에 의존했다. (n = 14, 10%).

Studies included were published between January 1, 2000 and November 16, 2020, with an apparent increase in the number of publications across time (Supplemental Digital Appendix 3).

- Studies were published across 48 journals.

- Literature was drawn from a variety of geographic regions, but the majority were from Europe (n = 38, 38.8%) and North America (n = 31, 31.6%).

- Participants included: medical students (n = 60, 61%), residents (n = 17, 17%), fellows (n = 2, 2.0%), specialist trainees (n = 17, 17%), and registrars (n = 2, 2.0%).

- Most assessments were provided by a supervisor or an assessor (n = 43, 38%), and assessment-generated feedback was primarily presented as scores or ratings (n = 32, 23%), usually provided in written (n = 29, 20%) or verbal form (n = 29, 21%).

- Included papers were from a breadth of research approaches, relying on data generated from semi-structured interviews (n = 20, 10%), focus groups (n = 31, 23%), questionnaires (n = 37, 28%), surveys (n = 18, 13%), free-text comments from surveys or questionnaires (n = 13, 9.7%), a pile-sorting activity, and psychometric analysis of assessment data (n = 14, 10%).

표 1 본 검토에 포함된 간행물의 서지학적 세부 정보

Table 1 Bibliometric details of publications included in this review

신뢰성의 개념화

Conceptualization of credibility

80개 출판물 중 34개 논문만이 '신뢰성credibility'이라는 특정 용어를 사용했으며, 명시적인 정의를 제공한 것은 없었다. 동일한 현상(즉, 평가 또는 평가-생성 피드백의 인식된 신뢰성)을 반영하는 것으로 간주되는 27개의 다른 용어를 식별했다. 가장 자주 사용되는 용어는 유용한(n = 23), 공정한(n = 17), 가치있는(n = 10)이었다("보완 디지털 부록 5"에서 식별된 전체 용어 목록).

Of the 80 publications included in the synthesis, only 34 articles used the specific term ‘credibility’, and none provided an explicit definition. We identified 27 other terms that were considered to reflect the same phenomenon (i.e., perceived credibility of assessment or assessment-generated feedback). The most frequently used terms were useful (n = 23), fair (n = 17), and valuable (n = 10) (full list of terms identified in "Supplemental Digital Appendix 5").

평가의 교육적 가치

Educational value of assessment

여러 논문(Malau-Aduli 등, 2019; Ricci 등, 2018; Ryan 등, 2017; Yielder 등, 2017)은 평가의 교육적 가치와 관련된 결과를 명시적으로 설명하고 포함시켰다. 교육적으로 가치 있는 것으로 인식되는 평가는 (Rici 등, 2018)에서 인용한 "우리가 남은 경력 동안 사용할 지식을 최대로 유지할 수 있는 황금 같은 기회"(참여자 73, 페이지 358)로 간주되었다. 교육적으로 가치 있는 평가로부터 기대되는 긍정적 결과는 [학습자가 자신의 약점을 성찰할 수 있도록 한다는 것]이었다. "…내가 잘하지 못하는 분야를 식별하게 한 것은 질문 그 자체였다." (참가자 14CP, 페이지 967)는 (라이언 외, 2017)에서 인용했다.

Several papers (Malau-Aduli et al., 2019; Ricci et al., 2018; Ryan et al., 2017; Yielder et al., 2017) explicitly described and included findings pertaining to the educational value of assessment. Assessments perceived as educationally valuable were viewed as “…golden opportunit[ies] to stay on top of the knowledge we will be using for the rest of our careers” (Participant 73, p. 358) quoted from (Ricci et al., 2018). A promising outcome of educationally valuable assessment was that it allowed learners to reflect on their weaknesses: “…what made me identify the areas I wasn’t good at was the questions themselves” (Participant 14CP, p. 967) quoted from (Ryan et al., 2017).

인식된 신뢰도에 영향을 미치는 요인

Factors that affect perceived credibility

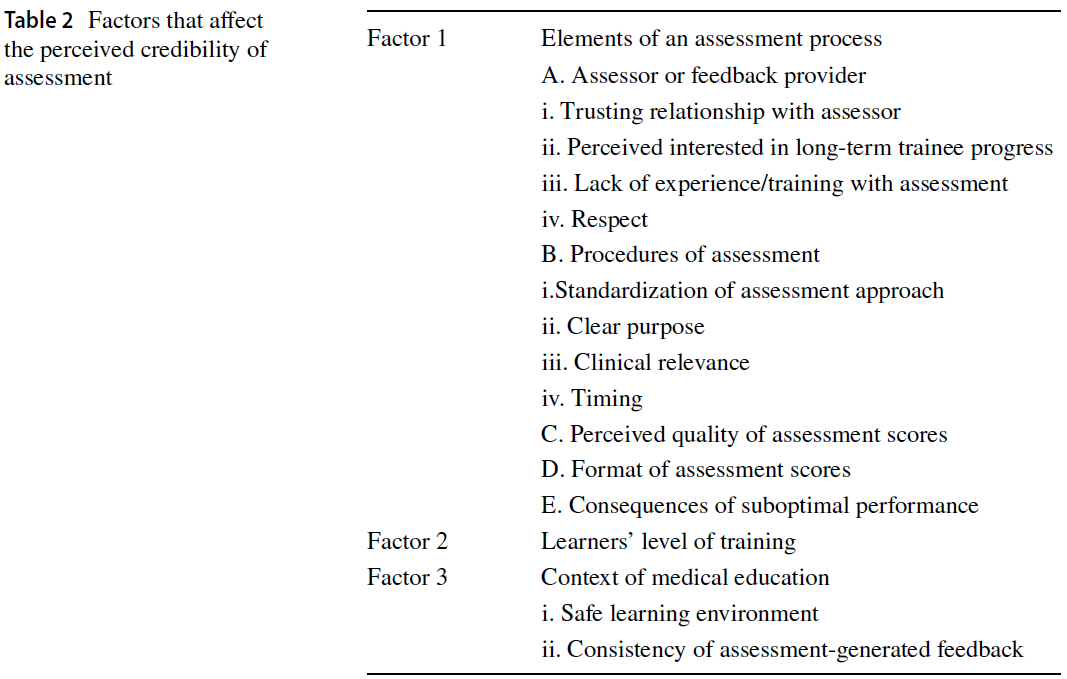

학습자의 평가 및 평가-생성 피드백에 대한 인식 신뢰도에 영향을 미치는 세 가지 요소를 확인했습니다.

We identified three sets of factors that affect learners’ perceived credibility of assessment and assessment-generated feedback:

- (i) 평가 프로세스의 요소

- (ii) 학습자의 교육 수준 및

- (iii) 의학교육의 맥락

- (i) elements of the assessment process,

- (ii) learners’ level of training, and

- (iii) context of medical education

(모든 테마와 하위 테마의 개요는 표 2를 참조하고, 각 테마를 지원하는 예시 인용문은 "보완 디지털 부록 6"을 참조한다.)

(see Table 2 for an overview of all themes and subthemes; and "Supplemental Digital Appendix 6" for exemplary quotes supporting each theme).

표 2 평가의 인식된 신뢰도에 영향을 미치는 요소

Table 2 Factors that affect the perceived credibility of assessment

요인 1: 평가 프로세스의 요소

Factor 1: Elements of an assessment process

우리는 학습자의 신뢰도에 대한 인식에 영향을 미치는 평가 프로세스의 다섯 가지 요소를 확인했습니다.

We identified five elements of the assessment process that influenced learners’ perceptions of credibility:

- (A) 평가자 또는 피드백 제공자,

- (B) 평가 절차,

- (C) 인식된 평가 점수의 품질

- (D) 평가점수의 형식 및

- (E) Suboptimal performance에 따르는 결과.

- (A) assessor or feedback provider,

- (B) procedures of assessment,

- (C) perceived quality of assessment scores,

- (D) format of assessment scores, and

- (E) consequences of suboptimal performance.

A.평가자 또는 피드백 제공자

A.Assessor or feedback provider

여기에는 다음이 포함된다.

which included:

- (i) 평가자와의 신뢰 관계 (i) trusting relationship with assessor,

- (ii) 장기 훈련생 진행 상황에 대한 관심 인식 (ii) perceived interest in long-term trainee progress,

- (iii) 평가에 대한 경험/훈련 부족, (iii) lack of experience/training with assessment, and

- (iv) 존경 (iv) respect.

(i)평가자와의 신뢰관계

(i)Trusting relationship with assessor

대부분의 학습자는 피드백을 제공한 개인(동료를 포함)과 강력하고 신뢰할 수 있는 관계가 있는 경우 평가 및 평가-생성 피드백을 신뢰할 수 있는 것으로 인식했다. 이 결과는 모든 평가 형태에 걸쳐 일관되었으며, 자신의 성과를 평가하는 개인과 신뢰 관계가 있다면 긍정적이든 부정적이든 의학 학습자들이 평가에서 생성된 피드백을 수용하고 반응한다는 것을 나타낸다.

Most learners perceived an assessment and assessment-generated feedback as credible if they had a strong and trusting relationship with the individual who provided it (Bogetz et al., 2018; Bowen et al., 2017; Duijn et al., 2017; Feller & Berendonk, 2020; LaDonna et al., 2017; Lefroy et al., 2015; MacNeil et al., 2020; Mukhtar et al., 2018; Ramani et al., 2020; Watling et al., 2008), including peers (Rees et al., 2002). This finding was consistent across forms of assessment and indicates that medical learners were accepting and responsive to assessment-generated feedback, be it positive or negative, if there was a trusting relationship with the individual assessing their performance:

"그녀는 저를 잘 알고 있기 때문에 그 피드백은 믿을 만하다고 생각합니다. 당신을 잘 알고 좋아하는 사람에게서 끔찍한 말을 듣기는 힘들 것 같아요. 하지만, 이것이 당신이 더 잘할 수 있는 것이라고 말하고 실행 가능한 조언을 주는 것에 있어서, 저는 당신이 많은 것을 하는 것을 보고 당신이 어떻게 일을 잘하는지 아는 사람에게서 오는 것이 좋다고 생각합니다." (R6, 페이지 1076) (라마니 외, 2020)에서 인용했습니다.

“She knows me well, so I think the feedback is reliable. I think it might be hard to get something horrible coming from someone who knows you well and who you like. But, in terms of saying this is what you could do better, and giving actionable pointers, I think that it’s nice coming from someone who’s seen you do a lot of stuff and knows how you work very well.” (R6, p. 1076) quoted from (Ramani et al., 2020).

그 반대도 사실이었다. 즉, 학습자는 꾸준히 자신이나 자신의 기술에 덜 익숙한 개인의 피드백을 무시하고 평가절하했다.

The inverse was also true, learners regularly ignored and discounted feedback from individuals who were less familiar with them or their skills (Beaulieu et al., 2019; Bogetz et al., 2018; Cho et al., 2014; Duijn et al., 2017; Levine et al., 2015; McKavanagh et al., 2012).

(ii)연수생 장기진도에 대한 관심도 인식

(ii)Perceived interest in trainee long-term progress

학습자를 적극적으로 관찰하지 않거나 불충분한 관찰을 바탕으로 수행에 대한 판단을 내린 평가자에 의해 완료된 평가는 신뢰할 수 있는 것으로 인식되지 않았다. 평가-생성 피드백을 개인화하고, 구체적이고, 행동가능하게 주기 위하여 시간과 공간을 제공한 평가자를 가치있게 여겼다.

Assessments completed by assessors who did not actively observe their learners or made judgments about performance based on insufficient observations were not perceived as credible (Areemit et al., 2020; Bowen et al., 2017; Cho et al., 2014; Duijn et al., 2017; Eady & Moreau, 2018; Ingram et al., 2013; MacNeil et al., 2020; McKavanagh et al., 2012; Ramani et al., 2020). Assessors who provided time and space for

- personalized (Bleasel et al., 2016; Bowen et al., 2017; Duijn et al., 2017; Harrison et al., 2015),

- specific (Beaulieu et al., 2019; Brown et al., 2014; Duijn et al., 2017; Green et al., 2007; Gulbas et al., 2016; Harrison et al., 2015; Ramani et al., 2020), and

- actionable assessment-generated feedback (Areemit et al., 2020; Bleasel et al., 2016; MacNeil et al., 2020; Murdoch-Eaton & Sargeant, 2012; Perron et al., 2016; Ramani et al., 2020) were valued:

(iii)평가에 대한 경험/훈련 부족

(iii)Lack of experience/training with assessment

평가자가 교육 및 평가 프로세스에 대한 경험이 부족한 경우, 학습자는 평가 또는 평가에서 생성된 피드백을 신뢰할 수 있는 것으로 인식할 가능성이 적습니다. 평가자가 다음과 같은 경우 믿을 만한 것으로 보이지 않았다.

- 평가 프로세스를 구현하는 방법에 익숙하지 않은 경우,

- 역량을 적절하게 평가하는 방법에 대해 확신이 없는 경우

- "절차를 따르지 않는 것"

When an assessor lacked training and/or experience with the assessment process, learners were less likely to perceive the assessment or assessment-generated feedback as credible (Brits et al., 2020; Gaunt et al., 2017; Mohanaruban et al., 2018). If an assessor was

- unfamiliar with how to implement the assessment process (Bleasel et al., 2016; Mukhtar et al., 2018),

- unsure about how to properly evaluate competence (Johnson et al., 2008), or

- “w[as] not buying into the process” (p. 592) quoted from (Braund et al., 2019), it was not seen as credible.

이는 수행능력-중심 평가, 직장-기반 평가 및 포트폴리오에서 가장 두드러졌다.

This was most apparent in performance-based assessment (Green et al., 2007), workplace-based assessment (Brown et al., 2014; Gaunt et al., 2017; Johnson et al., 2008; McKavanagh et al., 2012; Ringsted et al., 2004; Weller et al., 2009), and portfolios (Johnson et al., 2008; Kalet et al., 2007; Sabey & Harris, 2011).

(iv)존중

(iv)Respect

학습자는 자신이 존경하는 의사의 평가 피드백을 가치있게 여기고, 선호한다고 보고했다. 그리고 그러한 존경은 의사의 임상 기술과 교육 능력 모두에서 생성되었다.

Learners reported valuing and preferring assessment-generated feedback from physicians they respected– where respect arose from both the physician’s clinical skills (Bello et al., 2018; Bleasel et al., 2016; Feller & Berendonk, 2020; Ramani et al., 2020) and teaching abilities (Bowen et al., 2017; Dijksterhuis et al., 2013; Sharma et al., 2015):

"내가 정말 존경하는 사람으로부터 긍정적인 피드백을 받으니 내 일에 대한 자신감이 높아지고 목적의식이 높아졌다.". 학습자들은 또한 자신의 교수 능력을 향상시키길 원하는 지도자들의 중요성을 강조했다(Dijksterhuis 등, 2013; 샤르마 등, 2015).

“Getting positive feedback from someone I really admired boosted my confidence and increased my sense of purpose in my work.” (Unspecified resident, p. 509) quoted from (Beaulieu et al., 2019). Learners also stressed the importance of supervisors who wanted to improve their own teaching skills (Dijksterhuis et al., 2013; Sharma et al., 2015).

요약하자면, 이러한 발견들은 아래와 같은 특징을 보이는 평가자 또는 슈퍼바이저와 신뢰할 수 있는 관계에 있을 때, 평가 또는 평가에서 생성된 피드백도 신뢰할 수 있는 것으로 인식될 가능성이 더 높다는 것을 시사한다.

- 주어진 평가에 대한 경험이 있다.

- 학습자의 장기적 성공에 대한 관심을 보여준다.

- 자신의 교육 능력을 향상시키길 원하는 사람으로 인식된다.

- 믿을 만 하다.

In summary, these findings suggest that an assessment or assessment-generated feedback is more likely to be perceived as credible if there is a trusting relationship with an assessor or supervisor who

- has experience with a given assessment,

- shows an interest in the long-term success of a learner,

- is perceived as someone who wants to improve their teaching skills, and

- is seen as trustworthy.

B.평가 절차

B.Procedures of an assessment

평가 절차의 신뢰성에 대한 교육생의 인식에 영향을 미친 주요 요인은 다음과 같다.

The major factors that affected trainee perceptions of the credibility of the procedures of an assessment were:

- (i) 평가 접근법의 표준화, (i) standardization of assessment approach

- (ii) 명확한 목적 (ii) clear purpose

- (iii) 임상 관련성, (iii) clinical relevance

- (iv) 타이밍 (iv) timing.

(i)평가 접근법의 표준화

(i)Standardization of assessment approach

학습자는 [표준화된 평가와 평가-생성 피드백]을 [비표준화된 양식]보다 더 신뢰할 수 있는 것으로 인식했다(Harrison et al., 2016). 학습자들은 직장 기반 평가(Khairy, 2004) 또는 성과 기반 평가(Jawaid et al., 2014)와 같은 평가 방법의 표준화 및 구조 부족에 대해 우려를 제기했다. 예를 들어, 학습자는 일관된 방식으로 평가(제프리 외, 2011; 프레스턴 외, 2020)되고 성과를 명시적 표준에 대해 평가하는 것이 중요하다고 강조했다(벨로 외, 2018; 해리슨 외, 2016; 리스 외, 2002; 샤르마 외, 2015; 수호요 외, 2017; 웰러). 학습자는 비구조화된 평가가 불공정하고(Nesbitt 등, 2013) 자신의 수행 정도를 덜 대표한다고 느꼈다(Brits 등, 2020).

Learners perceived standardized assessment and assessment-generated feedback as more credible than non-standardized forms (Harrison et al., 2016). Learners raised concerns regarding the lack of standardization and structure of assessment methods such as workplace-based assessments (Khairy, 2004) or performance-based assessments (Jawaid et al., 2014). For instance, learners stressed the importance of being assessed in a uniform manner (Jefferies et al., 2011; Preston et al., 2020) and having their performance evaluated against explicit standards (Bello et al., 2018; Harrison et al., 2016; Rees et al., 2002; Sharma et al., 2015; Suhoyo et al., 2017; Weller et al., 2009). Learners felt that unstructured assessments were unfair (Nesbitt et al., 2013) and less representative of their performance (Brits et al., 2020).

(ii)명확한 목적

(ii)Clear purpose

학습자는 그 목적을 이해했을 때 평가가 더 의미 있다고 인식했으며(Gaunt 등, 2017년; Given 등, 2016년; Green 등, 2007년; LaDonna 등, 2017년; MacNeil 등, 2020년) 평가 프로세스에 더 많이 참여하도록 이끌었다(Eenman 등, 2015년). 그러나 학습자가 평가의 목적에 대해 혼란스럽거나 불분명할 때 평가의 가치를 무시하는 경향이 있었다(Cho 등, 2014).

Learners perceived assessments to be more meaningful when they understood its purpose (Gaunt et al., 2017; Given et al., 2016; Green et al., 2007; Kalet et al., 2007; LaDonna et al., 2017; MacNeil et al., 2020), which lead them to engage more with the assessment process (Heeneman et al., 2015). However, when learners were confused or unclear about the purpose of an assessment, they tended to dismiss its value (Cho et al., 2014):

(iii)임상 관련성

(iii)Clinical relevance

학습자는 실제 시나리오에서 임상 기술을 실습할 기회를 제공하는 것으로 보이는 것과 같이 [실제 임상진료를 복제replicated한, 임상적으로 관련이 있다고 인식한 평가]를 가치 있게 평가했다. 이러한 평가는 임상 역량을 입증할 수 있는 기회로 간주되었다.

Learners valued assessments they perceived as clinically relevant because they were seen to provide opportunities for practicing clinical skills in authentic scenarios (Barsoumian & Yun, 2018; Bogetz et al., 2018; Foley et al., 2018; Hagiwara et al., 2017; Jawaid et al., 2014; Khorashad et al., 2014; Malau-Aduli et al., 2019; Olsson et al., 2018; Pierre et al., 2004; Preston et al., 2020; Shafi et al., 2010; Yielder et al., 2017) that replicated real-life clinical care (Bleasel et al., 2016; Craig et al., 2010; McLay et al., 2002; Moreau et al., 2019). These assessments were viewed as opportunities to demonstrate clinical competence.

(iv)평가 타이밍

(iv)Timing of assessment

마지막으로, [평가의 타이밍]은 교육생이 평가의 신뢰성을 인식하는 방식, 특히 훈련 중에 평가를 해야 하는 시점에 영향을 미쳤다. 평가가 커리큘럼과 수련 단계에 적합하고 적절하다고 판단될 때 평가에 대한 인식의 신뢰도가 증가하였다. Kalet 등은 [학습자들이 아직 노출되지 않은 역량에 대해 평가하는 것]은 시간 활용이란 점에서 부적절하다고 느꼈다고 보고했다. 또한 학습 잠재력을 최적화하고 개선할 영역을 식별하기 위해 훈련 초기에 특정 성과 기반 평가(예: OSCE, 시뮬레이션 임상 검사)가 요청되었다.

Lastly, the timing of an assessment also affected how a trainee perceived its credibility, specifically at which point during training an assessment should be given. Perceived credibility of assessment increased when the assessment was believed to be relevant and appropriate to the curriculum (Brits et al., 2020; Labaf et al., 2014; McLaughlin et al., 2005; Papinczak et al., 2007; Pierre et al., 2004; Vishwakarma et al., 2016) and level of training (Kalet et al., 2007; Pierre et al., 2004; Wiener-Ogilvie & Begg, 2012). Kalet et al. (2007) reported that learners felt it was a poor use of time to be assessed on competencies to which they had not yet been exposed. In addition, certain performance-based assessments (e.g., OSCE, simulated clinical examination) (Wiener-Ogilvie & Begg, 2012) were requested earlier in training to optimize learning potential and identify areas for improvement.

요약하면, 우리의 연구 결과는 학습자가 평가 또는 평가에서 생성된 피드백은 그것이 [표준화된 경우], [명확하게 전달되는 목적이 있고], [임상적 관련성을 보유]하고 있으며, [교육 중에 적절한 시점에 제공받는 경우]에 신뢰할 수 있는 것으로 인식할 가능성이 더 높다는 것을 보여준다.

In sum, our findings show that learners are more likely to perceive assessments or assessment-generated feedback as credible if they are standardized, have a clearly communicated purpose, hold clinical relevance, and are given at an appropriate time during their training.

C.평가점수의 인정된 품질

C.Perceived quality of assessment scores

학습자는 [점수의 퀄리티가 높다고 인식했을 경우]에 가장 호의적으로 반응했고, 이는 (점수가) 자신의 수행능력을 가장 잘 대표한다고 믿었을 때를 의미한다. 동등한 점수의 부족은 [수행능력-기반 평가]나 [직장 기반 평가]에서 주로 제기되었다. 그러나 한 연구는 [서면 시험(훈련 중 검사)]에 대해서도 유사한 우려를 식별했다(Kim 등, 2016; Ryan 등, 2017). 성과 기반 및 직장 기반 평가의 경우, 이러한 우려는 학습자가 자신의 평가자를 선택함으로써 도입된 인식 편향과 강하게 연결되었다(Brown et al., 2014; Curran et al., 2018; Feller & Berendonk, 2020).

Learners responded most favourably to scores they perceived to be of high quality, as they were believed to be most representative of their performance (Brits et al., 2020; Jawaid et al., 2014; Pierre et al., 2004). Lack of comparable scoring was an issue primarily raised with performance-based (Jawaid et al., 2014; Pierre et al., 2004) and workplace-based assessments (Kim et al., 2016; Nesbitt et al., 2013; Weller et al., 2009). One study, however, identified similar concerns on a written assessment (in-training examination) (Kim et al., 2016; Ryan et al., 2017). For performance-based and workplace-based assessments, this concern was strongly linked to perceived bias introduced by learners selecting their own assessors (Brown et al., 2014; Curran et al., 2018; Feller & Berendonk, 2020).

D.평가 점수 형식

D.Format of assessment scores

[평가 점수의 형식]은 훈련생이 그 신뢰도를 인식하는 방식에도 영향을 미쳤다. 학습자는 수행 평가 척도(Braund et al., 2019; Castonguay et al., 2018) 또는 양식(Curran et al., 2018)과 같은 [특정한 수행능력 채점 방법]은 "다양한 수준의 훈련과 실제 기술의 뉘앙스를 파악할 수 없었다"며 "학습 목표를 해석하고 해석하는데 어려움을 겪었다"고 느꼈음을 밝혔다. 이들은 평점이 '의미를 상실했다'고 느꼈고, 주어진 항목에서 '좋은 것good에서 우수한 것excellent으로' 나아가는 데 필요한 구체적인 기술을 찾아내기 위해 고군분투했다.

The format of assessment scores also affected how a trainee perceived its credibility. Learners felt certain assessment scoring methods such as performance rating scales (Braund et al., 2019; Castonguay et al., 2019) or forms (Curran et al., 2018) were unable to “catch the nuances of different levels of training and actual skills.” (Unspecified SR resident, p. 1500) quoted from (Bello et al., 2018) and were “difficult to interpret and translate into learning goals. They felt ratings ‘lacked meaning’ and struggled to identify specific skills to improve on to ‘move from good to excellent’ on a given item.” (Results, p. 178) quoted from (Bogetz et al., 2018).

E.최적이 아닌 성능의 결과

E.Consequences of suboptimal performance

평가자의 인식된 신뢰성이 [평가자 및 피드백 제공자], [평가 절차], [표준화된 채점], [평가 점수 형식] 및 [부족한 성과에 따르는 결과]를 포함한 [평가 프로세스의 여러 요소]에 의해 영향을 받는다는 것을 시사한다.

Our results suggest that the perceived credibility of an assessment is influenced by multiple elements of the assessment process including the assessor and feedback provider, procedures of an assessment, standardized scoring, format of assessment scores, and consequences of suboptimal performance.

평가는 부족한 성과에 따른 결과가 명확할 때 더 신뢰할 수 있는 것으로 인식되었다(Arnold 등, 2005). 즉 "과정 중은 물론 심지어 졸업에서도 동료의 성적에 영향을 미쳐야 한다"라는 생각과 같다.

- 일부 학습자는 감독자 기반 평가와 동료 평가를 모두 포함하여, [수반되는 결과가 없는 평가]는 학습에 미치는 영향이 제한적이라고 느꼈다(Arnold 등, 2005).

- 그러나 일부 학습자는 반대로 특정 평가(예: 지식 테스트 또는 수행 기반 평가)의 결과는 "그런 테스트가 실제로 가져야 할 결과보다 훨씬 더 크다"고 느꼈다.

Assessments were perceived to be more credible when there were clear consequences of suboptimal performance, i.e., “it should affect the peer’s grades in courses and even in graduation” (p. 821) (Arnold et al., 2005). Some learners felt assessments with no consequences limited potential for learning (Dijksterhuis et al., 2013; Schut et al., 2018)—including both supervisor-based and peer assessment (Arnold et al., 2005). However, some learners felt the consequences of certain assessments e.g., knowledge tests or performance-based assessment were “much bigger than the consequences such a test should actually have.” (Participant B1, p. 660) quoted from (Schut et al., 2018).

요인 2: 학습자의 교육 수준

Factor 2: Learners’ level of training

[학습자의 수련 단계]는 평가에 대한 인식된 신뢰성과 평가-생성 피드백에 대한 후속 수용성에 영향을 미쳤다(Bello 등, 2018; Bowen 등, 2017; Murdoch-Eaton & Sargeant, 2012; Wade 등, 2012). 학습자가 주니어 학습자에서 시니어 학습자로 발전함에 따라 수동적인 피드백 수신(예: 평가자가 기준을 충족하는지 알려 주기를 기대함)에서 성과 향상을 위한 학습 전략을 조정하기 위한 보다 적극적인 피드백 탐색으로 발전적 전환이 일어날 수 있습니다(Dijsterhuis 등, 2013; Murdoch-Eaton & Sargeant)., 2012).

- 주니어 학습자는 자신의 성과를 긍정하기 위해 긍정적인 피드백을 원했고, 부정적인 피드백으로 인해 사기가 저하되었습니다(Murdoch-Eaton & Sargeant, 2012).

- 반대로 상급 학습자는 성과 향상에 사용될 수 있기 때문에 부정적인 피드백에서 더 큰 가치를 보았다(Bleasel et al., 2016; Chaffinch et al., 2016; Murdoch-Eaton & Sargeant, 2012; Sabey & Harris, 2011). 상급 학습자들은 긍정적인 피드백이 "자신을 현실에 안주하게 할 수 있다"(Trainee A3a, 페이지 718)는 것과 항상 실천 가능한 개선 단계를 제공하는 것은 아니기 때문에 의미가 적다고 느꼈습니다(Harrison et al., 2016).

A learner’s level of training influenced their perceived credibility of an assessment and their subsequent receptivity to assessment-generated feedback (Bello et al., 2018; Bowen et al., 2017; Murdoch-Eaton & Sargeant, 2012; Wade et al., 2012). As learners progressed from being junior to senior learners, a developmental shift may occur from passive reception of feedback (e.g., expecting assessors to inform them if they are meeting standards) to more active seeking of feedback in order to adapt learning strategies to improve performance (Dijksterhuis et al., 2013; Murdoch-Eaton & Sargeant, 2012).

- Junior learners wanted positive feedback to affirm their performance and were demoralized by negative feedback (Murdoch-Eaton & Sargeant, 2012).

- On the contrary, senior learners saw greater value in negative feedback as it could be used to improve performance (Bleasel et al., 2016; Chaffinch et al., 2016; Murdoch-Eaton & Sargeant, 2012; Sabey & Harris, 2011). Senior learners felt that positive feedback was less meaningful because it “can make you complacent” (Trainee A3a, p. 718) quoted from (Murdoch-Eaton & Sargeant, 2012) and it did not always provide actionable steps for improvement (Harrison et al., 2016).

주니어 학습자는 동료의 피드백이 관리자의 피드백보다 신뢰성이 떨어진다고 느꼈습니다. (Burgess & Mellis, 2015)에서 인용한 "[학술]들이 준 피드백은 반 친구의 피드백이라기보다는 내가 가져간 것이다." (의대생 12, 페이지 205) 또한, 주니어 학습자들은 동료들이 자신의 기술을 평가할 때 객관적으로 생각하는 데 어려움을 겪을 수 있다고 느꼈다(Murdoch-Eaton & Sargeant, 2012).

Junior learners felt peer feedback was less reliable than feedback from a supervisor: “…the feedback they [academic] gave was what I took away rather than my class mate’s” (Medical student 12, p. 205) as quoted from (Burgess & Mellis, 2015). Additionally, junior learners felt their peers may have difficulty being truly objective when evaluating their skills (Murdoch-Eaton & Sargeant, 2012).

그러나 상급 학습자는 도움이 되는 것으로 인식되어 동료 평가에서 더 자주 가치를 발견했다(McKavanagh 등, 2012; Lees 등, 2002). 상급 학습자들은 또한 동료 평가의 신속성과 심도 있는 토론으로 후속 조치를 취할 수 있는 능력에 대해 높이 평가했다(Murdoch-Eaton & Sargeant, 2012).

Senior learners, however, more often found value in peer assessment as it was perceived to be helpful (McKavanagh et al., 2012; Rees et al., 2002). Senior learners also appreciated peer assessment for its immediacy and the ability to follow-up with in-depth discussion (Murdoch-Eaton & Sargeant, 2012).

간단히 말해서, 우리의 연구 결과는 주니어 학습자와 시니어 학습자가 피드백의 제공자와 극성에 따라 피드백의 효용성에 대해 서로 다른 관점을 가지고 있음을 시사한다.

In brief, our findings suggest that junior and senior learners have different perspectives on the utility of feedback which depend on the provider and polarity of the feedback.

요소 3: 의료 교육의 맥락

Factor 3: Context of medical education

우리는 의료 교육의 맥락과 관련된 평가-생성 피드백의 인식 신뢰성에 영향을 미치는 두 가지 요인을 식별했다.

We identified two factors that influence the perceived credibility of assessment-generated feedback related to the context of medical education:

- (i) 안전한 학습 환경 및

- (ii) 평가-생성 피드백의 일관성.

- (i) safe learning environment and

- (ii) consistency of assessment-generated feedback.

이러한 요소들은 프로그램이나 기관의 수준에서 문제를 반영하기 때문에 이전에 확인된 요소들과 다릅니다. 따라서 이러한 요소들은 [이전 섹션에서 논의한 평가의 과정이나 실천과 관련된 요소에 비해 평가-생성 피드백의 인지된 신뢰성을 지원하도록] 수정 또는 조정하기가 더 어려울 수 있다.

These factors differ from those previously identified because they reflect issues at the level of the program or institution. These factors may therefore be more difficult to amend, adapt, or adjust to support the perceived credibility of assessment-generated feedback compared to factors related to the process or practice of assessment discussed in previous sections.

(1)안전한 학습환경

(1)Safe learning environment

학습자는 [안전한 학습 환경에서 발생하는 평가]가 학습(Duijn et al., 2017; Sargeant et al., 2011), 자기 성찰(Nikendei et al., 2007)을 촉진하고 평가 및 평가-생성 피드백에 대한 참여를 촉진했기 때문에 신뢰할 수 있는 것으로 인식했다. 그러나 "[f]필수 순환과 더 짧은 배치가 있는 임상 학습 환경은 의미 있는 교육 관계를 개발하기 위해 사용 가능한 시간에 영향을 미쳤다." (결과, 페이지 1306) (Bowen 등, 2017) 안전한 학습 환경은 학습자가 도움을 구하고, 지식 격차를 인정하며, 실수를 공개적으로 토론하는 학습 풍토라고 설명하였다(상사 등, 2011).

Learners perceived assessment occurring in a safe learning environment as credible as it fostered learning (Duijn et al., 2017; Sargeant et al., 2011), self-reflection (Nikendei et al., 2007), and facilitated engagement with assessment and assessment-generated feedback. However, clinical learning environments with “[f]requent rotations and shorter placements affected time available to develop meaningful educational relationships.” (Results, p. 1306) (Bowen et al., 2017). A safe learning environment was described as a learning climate in which learners felt comfortable to seek help, admit knowledge gaps, and openly discuss mistakes (Sargeant et al., 2011).

(2)평가 결과 피드백의 일관성

(2)Consistency of assessment-generated feedback

일부 학습자는 [간헐적인 피드백이 신뢰도에 대한 인식을 저하시켰다]고 보고했다(Brits et al., 2020; Korszun et al., 2005; Murdoch-Eaton & Sargeant, 2012; Perera et al., 2008; Weller et al., 2009). "전반적으로 의료 훈련에서 완전히 부족한 것은 피드백이며, 동료들과 당신이 어디에 있는지, 그리고 당신의 전문가가 실제로 어떻게 생각하는지 아는 것이다." (미확인 훈련생, 페이지 527). 제공된 산발적인 피드백 중 대부분은 지나치게 일반적이고(MacNeil 등, 2020; Mohanaruban 등, 2018; Moreau 등, 2019; Preston 등, 2020), 일방적으로 지시적인 것(Dijksterhuis 등, 2013)으로 보여 도움이 되지 않는 것으로 판단되었다. 반면 어떤 학습자들은 피드백 내용과 제공이 개선되어 보다 구체적인 초과 근무 및 임상적 집중이 되고 있다고 느꼈다(Murdoch-Eaton & Sargeant, 2012). 이러한 일관되지 않은 연구 결과는 각 기관이 임상 교육 사이트마다 어느 정도 차이가 있지만, 학습자의 평가-생성 피드백 제공과 후속 수용성에 영향을 미치는 [고유한 문화]를 가지고 있을 수 있음을 시사한다(Craig 등, 2010). 평가에서 생성된 피드백은 교육 과정, 순환, 연도별로 차이가 있어 향후 교육에는 해당되지 않을 수 있으므로 추가 개발에 통합 및 활용하기 어렵다. 이러한 피드백 불일치는 학습자가 의료 교육 내에서 제한된 피드백 문화를 나타내는 것으로 확인되었다(Weller 등, 2009).

Some learners reported infrequent feedback decreased perceived credibility (Brits et al., 2020; Korszun et al., 2005; Murdoch-Eaton & Sargeant, 2012; Perera et al., 2008; Weller et al., 2009): “[o]ne thing that’s totally lacking in medical training across the board is feedback, and knowing where you are in relation to your colleagues and also what your specialist actually really [thinks]” (Unidentified trainee, p. 527) quoted from (Weller et al., 2009). Of the sporadic feedback provided, most was judged as unhelpful as it was seen as overly general (MacNeil et al., 2020; Mohanaruban et al., 2018; Moreau et al., 2019; Preston et al., 2020) and primarily directive (Dijksterhuis et al., 2013). Other learners felt feedback content and provision was improving, becoming more specific overtime and clinically focused (Murdoch-Eaton & Sargeant, 2012). These inconsistent findings suggest that each institution may have its own culture that influences the provision of assessment-generated feedback and subsequent receptivity by learners, with some variability across clinical education sites (Craig et al., 2010). Assessment-generated feedback appears to vary by course, rotation, and year of training, making it difficult to integrate and use for further development as it may not be applicable in future training. These feedback inconsistencies have been identified by learners as indicative of a limited feedback culture within medical education (Weller et al., 2009).

요약하자면, 우리의 검토는 [안전한 학습 환경]에서 이루어지고 [일관된 피드백을 제공]하는 평가가 신뢰할 수 있는 것으로 인식될 가능성이 더 높다는 것을 시사한다.

In summary, our review suggests that assessments that take place in a safe learning environment and provide consistent feedback are more likely to be perceived as credible.

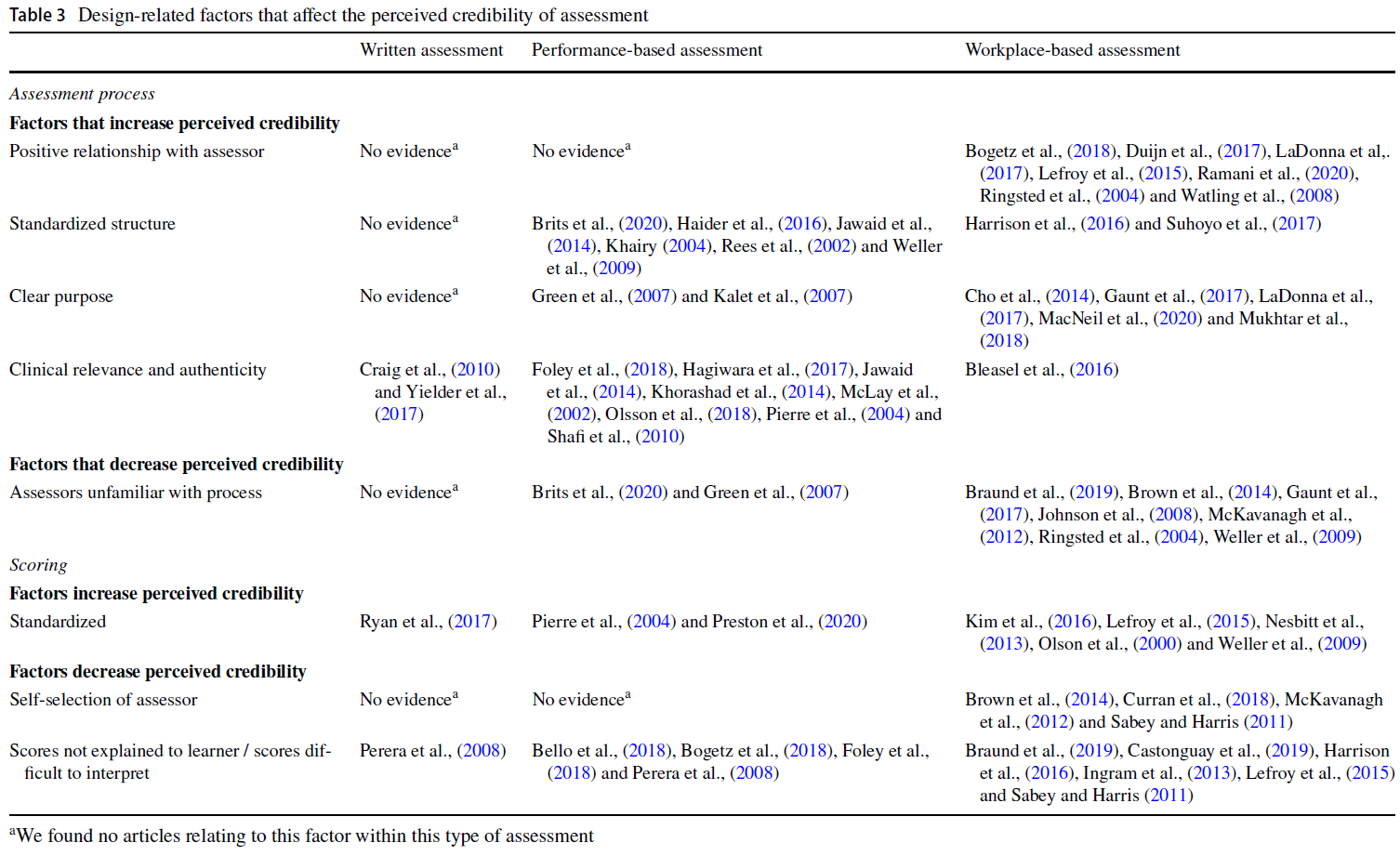

여러 평가 유형에 걸쳐 평가의 인식된 신뢰성에 영향을 미치는 요인

Factors that influence the perceived credibility of assessment across assessment types

위에 보고된 평가 및 평가-생성 피드백의 인식 신뢰성에 영향을 미치는 요소는 학생의 훈련 수준을 통해 주어진 평가를 받은 평가자의 경험에서 학습 환경에 이르기까지 다양하다. 표 3에 포함된 요소를 고려하면 평가에 대한 인식 신뢰도와 평가-생성 피드백 및 학습에 대한 지원 평가가 증가해야 한다.

The factors that influence the perceived credibility of assessment and assessment-generated feedback reported above span from assessor experience with a given assessment through student’s level of training to the learning environment. In Table 3, we summarize the evidence regarding design-related factors (i.e., assessment process and scoring) that influence the perceived credibility of assessment in order to better support the development of credible assessment practices. We organized the evidence according to three common assessment approaches (written assessment, performance-based assessment, workplace-based assessment) whether these factors increase or decrease perceived credibility and provide supportive evidence. Consideration of the factors included in Table 3 should increase perceived credibility of assessments and assessment-generated feedback and support assessment for learning.

표 3 평가의 인식 신뢰도에 영향을 미치는 설계 관련 요인

Table 3 Design-related factors that affect the perceived credibility of assessment

고찰 Discussion

이 범위 지정 검토는 의료 교육 문헌에서 평가 및 평가-생성 피드백의 인식된 신뢰성의 개념에 초점을 맞췄다. 1차 문헌에서 추출한 우리의 연구 결과는 의료 학습자가 평가의 신뢰성과 관련 평가에서 생성된 피드백을 인식하는 방법에 영향을 미칠 수 있는 요인의 집합이 있음을 시사한다. 점점 더 관련성이 있는 개념임에도 불구하고, 검토에 포함된 매우 적은 수의 연구만이 '신뢰성credibility'이라는 용어를 정확히 사용했으며, 명시적 정의를 포함하는 연구는 없었다. 용어 사용 빈도가 낮음에도 불구하고, 신뢰성credibility의 개념은 문헌에서 공정성, 타당성, 유용성, 가치성 등의 측면에서 반영되었다. 하나의 개념을 설명하는 데 여러 용어가 사용되고 명시적인 정의가 없기 때문에, 우리의 연구 결과는 인식된 신뢰성이 다음과 밀접하게 관련된 새로운 개념임을 시사한다.

- 방어 가능(Norcini 등, 2011),

- 교육적으로 가치 있는(Holmboe 등, 2010) 및

- 학생 지향 평가 실천 (Epsein 등, 2011)

This scoping review focused on the concept of perceived credibility of assessment and assessment-generated feedback in the medical education literature. Drawn from primary literature, our findings suggest there is a constellation of factors that can influence how medical learners perceive the credibility of assessment and associated assessment-generated feedback. Despite being an increasingly relevant concept, very few studies included in our review used the exact term ‘credibility’, and none included an explicit definition. Despite the low frequency of the term, the concept of credibility was present in the literature—reflected in terms such as fair, valid, helpful, useful, and valuable. With several terms being used to describe one concept, and no explicit definitions, our finding suggests that perceived credibility is an emerging concept tightly related to

- defensible (Norcini et al., 2011),

- educationally-valuable (Holmboe et al., 2010), and

- student-oriented assessment practices (Epstein, 2007; Norcini et al., 2011).

검토 과정을 통해 신뢰성과 타당성credibility and validity 이 평가 품질 보장을 위한 유사한 고려사항을 반영할 수 있다는 것이 분명해졌다. 현대의 타당성 개념화는 합격/실패 결정 또는 역량의 판단(일반적으로 평가 관리자의 책임) 측면에서 점수의 해석을 뒷받침하는 증거를 고려한다(Messick, 1995). 관리자는 주어진 점수 해석을 뒷받침하는 타당성 근거에 무게를 두고 해당 점수 해석이 타당한지 여부를 판단한 후 평가 결과를 교육기록부에 입력한다. 평가의 교육적 가치를 고려할 때, [점수 해석의 '책임감'은 학습자 개인의 몫]입니다. 각 학습자는 자신의 점수나 평가 결과를 자신의 성과나 순위를 나타내는 지표로 해석하고, 추가 학습이나 성과 개선 영역을 식별하기 위해 이러한 해석을 바탕으로 할 책임이 있습니다.

Through the review process, it became apparent that the terms credibility and validity may reflect similar considerations for ensuring assessment quality. Modern conceptualizations of validity consider the evidence supporting the interpretation of scores in terms of pass/fail decisions or judgments of competence—typically the responsibility of assessment administrators (Messick, 1995). An administrator weights the validity evidence supporting a given score interpretation, decides whether or not that score interpretation is sound, and then the results of the assessment are entered into an educational record. When considering the educational value of assessment, the ‘responsibility’ of score interpretation rests in the hands of individual learners. Each learner is responsible for interpreting their scores or assessment results as indicators of their own performance or standing, and to build on those interpretations in order to identify areas of further study or performance improvement.

[점수 해석을 지지하는 데 사용할 수 있는 타당성 증거를 평가하는 관리자]와 병행하여 [학습자는 성과 개선을 위해 피드백에 의존해야 하는지 결정하기 위해, 평가 또는 평가-생성 피드백의 신뢰성에 대한 증거를 평가]하는 것으로 보입니다. 이 두 명의 서로 다른 교육 이해 당사자들은(즉 교육 관리자 및 학습자), 공식적인 교육 평가를 위해서든 또는 비공식 수행 능력 향상을 위해서든, 점수 해석의 적절성에 대한 결정에 참여하고 평가 데이터의 정당한 사용(또는 비사용)을 결정한다.

In parallel to an administrator weighing validity evidence available in support of a score interpretation, learners appear to weigh evidence of the credibility of an assessment or assessment-generated feedback to determine whether to rely on the feedback for performance improvement. These two different educational stakeholders—assessment administrators and learners—both engage in decisions about the appropriateness of a score interpretation and decide on the legitimate use (or not) of the assessment data, either for formal educational assessment or informal performance improvement.

생성한 평가 데이터에 대한 [학습자의 참여와 해석]은 [평가의 교육적 가치]를 뒷받침한다. 이 검토의 결과는 학습자가 평가 점수에 어떻게 참여하는지engage with는, 최소한 부분적으로 [해당 점수에 대한 신뢰도]에 달려 있음을 시사한다.

- 평가 또는 평가에서 생성된 피드백이 신뢰할 수 있는 것으로 인식되면 학습자는 향후 성과를 개선할 수 있는 기회로 해당 피드백에 참여할 가능성이 높아집니다(Watling et al., 2012).

- 신뢰할 수 없는 것으로 인식되면 무시, 무시 또는 기각됩니다.

This engagement with, and interpretation of, assessment-generated data by a learner underpins the educational value of assessment. The findings of this review suggest that how learners engage with assessment scores is at least partially dependent on how credible those scores are perceived to be. When an assessment or assessment-generated feedback is perceived as credible, learners are more likely to engage with it as an opportunity to improve future performance (Watling et al., 2012). When it is not perceived as credible, it is discounted, ignored, or dismissed.

어떤 면에서 평가 데이터에 참석할지 또는 무시할지 결정할 때, 학습자는 평가 또는 평가-생성 피드백의 타당성 또는 신뢰성에 의문을 제기하는 것으로 보인다. 학습자가 평가 설계, 구현 및 채점을 신뢰할 수 있는 것으로 인식하지 않을 경우 평가 과정이 평가의 교육적 가치를 훼손할 가능성이 있기 때문에, [평가 과정에서 학생을 행위자actor 또는 이해관계자]로 고려해야 한다.(Harrison 등, 2016; Ricci 등, 2018). 이러한 관점은 평가 데이터가 향후 개선에 기여할 수 있도록 학생 중심의 평가 실천을 지원하고, 평가에 대한 잠재적인 방법을 개별 학습자의 요구와 관심사에 더 잘 맞출 것을 제안한다(Looney, 2009).

In a way, learners appear to be questioning the validity (Ricci et al., 2018), or credibility of assessments or assessment-generated feedback when deciding whether to attend to, or ignore, assessment data. These findings contribute to a consideration of students as actors or stakeholders in the assessment process (Harrison et al., 2016; Ricci et al., 2018) because if learners do not perceive the assessment design, implementation and scoring as credible, the assessment process will likely undermine the educational value of assessment. This perspective supports more student-centred assessment practices to ensure assessment data can contribute to later improvement, and suggests potential avenues for assessments to be more tailored to individual learner's needs and interests (Looney, 2009).

평가 또는 평가-생성 피드백이 신뢰할 수 있는 것으로 인식될 가능성을 높이는 몇 가지 요인을 식별했다.

We identified several factors that increase the likelihood of an assessment or assessment-generated feedback being perceived as credible

첫째, 평가의 인식된 신뢰성과 관련 피드백은 [평가자나 피드백 제공자]에 대한 훈련생의 인식에 크게 영향을 받았다. 예를 들어, 학습자는 다음과 같은 경우 평가를 신뢰할 수 있는 것으로 인식할 가능성이 더 높다.

First, perceived credibility of an assessment and its associated feedback was greatly influenced by a trainee’s perception of their assessor or feedback provider. For instance, a learner was more likely to perceive an assessment as credible if they

- 평가자와 신뢰관계가 있었다

- 존경했다.

- 장기적 발달에 관심이 있는 것으로 인식되었다

- had a trusting relationship with their assessor (Bogetz et al., 2018; Bowen et al., 2017; Duijn et al., 2017; Feller & Berendonk, 2020; LaDonna et al., 2017; Lefroy et al., 2015; MacNeil et al., 2020; Mukhtar et al., 2018; Ramani et al., 2020; Watling et al., 2008),

- respected them (Beaulieu et al., 2019; Bello et al., 2018; Bleasel et al., 2016; Bowen et al., 2017; Dijksterhuis et al., 2013; Feller & Berendonk, 2020; Ramani et al., 2020; Sharma et al., 2015), and

- perceived them to be interested in their long-term progress (Areemit et al., 2020; Bleasel et al., 2016; Bowen et al., 2017; Duijn et al., 2017; Eady & Moreau, 2018; Harrison et al., 2015; MacNeil et al., 2020; Ramani et al., 2020).

둘째, [평가 자체]의 몇 가지 측면은 신뢰성의 인식 가능성으로 이어졌으며, 이러한 요소들은 다음을 포함한다.

Second, several aspects of an assessment itself led to greater likelihood of perceived credibility, these factors included

- 표준화된 접근방식

- 명확한 목적

- 임상 관련성 및 진정성

- 훈련 중 적절한 시간에 평가를 제공한다

- standardized approach (Harrison et al., 2016; Jawaid et al., 2014; Jefferies et al., 2011; Khairy, 2004; Nesbitt et al., 2013; Rees et al., 2002; Sharma et al., 2015; Suhoyo et al., 2017; Weller et al., 2009),

- clear purpose (Cho et al., 2014; Green et al., 2007; Heeneman et al., 2015; Kalet et al., 2007),

- clinical relevance and authenticity (Bleasel et al., 2016; Craig et al., 2010; Given et al., 2016; Jawaid et al., 2014; Khorashad et al., 2014; McLay et al., 2002; Pierre et al., 2004; Shafi et al., 2010), and

- provision of the assessment at an appropriate time during their training (Curran et al., 2007; Kalet et al., 2007; Labaf et al., 2014; McLaughlin et al., 2005; Papinczak et al., 2007; Pierre et al., 2004; Vishwakarma et al., 2016; Wiener-Ogilvie & Begg, 2012).

셋째, [평가점수의 품질]에 대한 인식은 신뢰도 인식에 필수적이었다(Brown 등, 2014년; Jawaid 등, 2014년; Kim 등, 2016년; Nesbitt 등, 2013년; Pierre 등, 2004년; Weller 등, 2009년). 학습자가 점수가 임의적이라고 느낄 때 신뢰도에 대한 인식이 감소했다.

Third, perceived quality of assessment scoring was imperative to perceived credibility (Brown et al., 2014; Jawaid et al., 2014; Kim et al., 2016; Nesbitt et al., 2013; Pierre et al., 2004; Weller et al., 2009), when learners felt scoring was arbitrary, perceptions of credibility decreased.

마지막으로 학습자는 평가 중 [부적절한 성과에 대한 명확한 후속결과]를 원했으며(Arnold et al., 2005; Dijksterhuis et al., 2013) 평가 없이는 평가가 학습을 진척시킬 수 없다고 느꼈기 때문에 신뢰할 수 없었다.

Lastly, learners wanted clear consequences for suboptimal performance during an assessment (Arnold et al., 2005; Dijksterhuis et al., 2013), without it, learners felt the assessment could not drive learning forward and thus was not as credible.

우리의 연구 결과는 [학습자가 평가의 많은 상황적, 과정적, 형식적(평가자, 평가 자체, 그리고 평가에서 생성된 피드백) 측면을 기반으로, 평가의 신뢰성에 대해 판단하여, 무시할 정보와 향후 성과 개선을 위해 통합하고 사용할 정보를 결정한다]는 결론을 뒷받침한다. 따라서 향후 학습을 지원할 목적으로 평가를 설계할 때는 평가 절차, 학습자와 평가자 간 신뢰 관계, 적절한 채점 접근법 등을 고려해야 한다.

Our findings support the conclusion that medical learners make judgments about the credibility of assessment based on many contextual, process, and format aspects of assessment – including assessors, the assessment itself, and the assessment-generated feedback – to determine what information they will dismiss and what they will integrate and use for future performance improvement. Therefore, when designing an assessment with the intention to support future learning, considerations of assessment procedures, trusting relationships between learners and assessors, and appropriate scoring approaches should be made.

또한 평가의 인식된 신뢰성을 훼손하는 몇 가지 요인을 확인했으며, 따라서 아래의 것들은 평가 또는 평가 프로그램을 설계할 때 피해야 한다. 일부는 평가자와 관련이 있다.

- 평가 프로세스에 익숙하지 않은 평가자

- 평가자를 스스로 선택할 수 있는 권한

- 평가자에 의해 점수가 학습자에 대해 설명되거나 상황에 맞게 조정되지 않은 경우

We also identified several factors that undermined the perceived credibility of assessment; and therefore, should be avoided when designing an assessment or assessment program. Some are related to the assessor;

- assessors who are unfamiliar with assessment process (Bleasel et al., 2016; Brown et al., 2014; Green et al., 2007; Johnson et al., 2008; Kalet et al., 2007; McKavanagh et al., 2012; Ringsted et al., 2004; Sabey & Harris, 2011; Weller et al., 2009),

- the ability to self-select an assessor (Brown et al., 2014), and

- when scores are not explained or contextualized for the learner by the assessor (Bello et al., 2018; Bogetz et al., 2018; Braund et al., 2019; Castonguay et al., 2019; Curran et al., 2018).

예를 들어, 학습자가 평가 과정에 익숙하지 않고 훈련이 부족한 평가자를 만났을 때, 그 평가는 신뢰할 만한 것으로 인식될 가능성이 낮았다. 또한 학습자는 [자신의 점수를 이해하는 것]의 중요성과 [점수를 향상시킬 수 있는 방법]을 강조했습니다. 이러한 요소가 없다면, 학습자는 평가에서 생성된 피드백을 신뢰할 수 있는 것으로 인식하지 못할 가능성이 더 높습니다. 이러한 결과는 평가에서 생성된 피드백이 향후 학습을 지원할 수 있는 가능성을 높이는 데 평가자의 중요성을 강조한다. 평가 자체의 질과 상관없이, 평가자가 신뢰할 수 있는 것으로 인식되지 않는 경우, 학습자는 평가를 배움의 기회가 아닌 "후프 투 스쳐 지나가기"로 볼 수 있습니다. 학습자가 자신의 평가를 이러한 관점에서 인식하면 결과 점수 해석의 타당성이 훼손됩니다. 좀 더 구체적으로 말하면, 학습자는 이 평가에 교육의 기회로 참여하지 않을 것이며, 따라서 평가가 좋은 데이터의 수집으로 이어지지는 않을 것이다. 이 때, 이 평가에 근거한 학습자의 성과에 대한 판단은 타당하지 않을 수 있습니다.

For instance, when learners encountered an assessor who was unfamiliar and lacked training with the assessment process, the assessment was less likely to be perceived as credible. Additionally, learners highlighted the importance of understanding their scores and how they could improve them, without this piece, they were more likely to not perceive the assessment-generated feedback as credible. These findings highlight the importance of the assessor in increasing the likelihood that assessment-generated feedback can support future learning. Regardless of the quality of the assessment itself, if an assessor is not perceived as credible, learners may view the assessment as a “hoop to jump through” rather than an opportunity for learning. When learners perceive their assessments in this light, the validity of resulting score interpretations are undermined. More specifically, the learner will not engage with this assessment as an educational opportunity, and thus, the assessment will not lead to the collection of good data. When this occurs, any judgments made regarding the learner’s performance based on this assessment may not be valid.

마지막으로, 우리는 평가 또는 평가-생성 피드백의 인식된 신뢰성에 부정적인 영향을 미치는 [평가 문화를 둘러싼 상황적 요인(즉, 안전한 학습 환경, 피드백 불일치)]을 식별했다. 평가와 피드백 문화를 바꾸기는 어려운 반면, 식별된 많은 요소들은 관련 설계, 구현 및 피드백 관행을 신중하게 고려하여 수정할 수 있다. 역량 기반 의료 교육의 맥락에서 훈련생 성과 평가는 학습자의 발달 궤적을 지원하는 종적 및 프로그램적 평가에 의존한다(Frank et al., 2010). 본 리뷰에 포함된 문헌에 따르면, 주니어 학습자와 시니어 학습자가 원하는 피드백 유형의 차이를 문서화하였다. 상급 학습자가 비판적 피드백을 선호하는 경향이 있는 경우, 이는 향후 성과를 개선하는 데 더 유용한 것으로 인식된다. 반면 하급 학습자들은 사기를 꺾는다고 느꼈습니다.

Finally, we identified contextual factors surrounding the culture of assessment (i.e., safe learning environment, Duijn et al., 2017; Nikendei et al., 2007; Sargeant et al., 2011), feedback inconsistencies (Craig et al., 2010; Korszun et al., 2005; Murdoch-Eaton & Sargeant, 2012; Perera et al., 2008; Weller et al., 2009)) that negatively impact the perceived credibility of assessment or assessment-generated feedback. While the culture of assessment and feedback remains challenging to influence, many of the factors identified are possible to amend with careful consideration of the associated design, implementation, and feedback practices. In the context of competency-based medical education (Frank et al., 2010), the evaluation of trainee performance is dependent on longitudinal and programmatic assessment which supports the developmental trajectory of learners (Frank et al., 2010). Literature included in this review documented a difference in the type of feedback desired by junior versus senior learners; where senior learners tended to prefer critical feedback as it was perceived as more useful in improving future performance (Chaffinch et al., 2016; Murdoch-Eaton & Sargeant, 2012; Sabey & Harris, 2011), whereas junior learners felt it was demoralizing.

요약하자면, 이 범위 지정 검토는 교육생이 평가의 신뢰성과 그에 관련된 피드백에 참여, 사용 및 지각하는 방법에 영향을 미치는 다양한 요소를 식별했다. 과거의 의료 교육 실천 권고안과는 달리, 우리의 연구 결과는, 학습자 관점에서 유용성과 신뢰성을 개선하기 위해 동원될 수 있는 평가 및 피드백 프로세스의 측면을 강조함으로써, [학습자를 학습 프로세스의 중심에 배치]한다(Spenzer & Jordan, 1999). (체크리스트, 점수, 등급 척도 등) 특정 형태의 평가-생성 피드백은 해석이 어렵고 의미가 부족한 것으로 인식됐다. 성과 또는 직장 기반 피드백과 같은 다른 형태는 교육생들에게 드물고 특정적이지 않으며 도움이 되지 않는 것으로 인식되어 왔다.

In sum, this scoping review has identified a variety of factors that influence how trainees engage, use, and perceive the credibility of an assessment and its associated feedback. Distinct from past medical education practice recommendations (Telio et al., 2015), our findings place the learner at the centre of the learning process (Spencer & Jordan, 1999) by highlighting aspects of the assessment and feedback process that can be mobilized to improve its utility and credibility from the learner perspective. Certain forms of assessment-generated feedback such as checklists, scores, rating scales were perceived as difficult to interpret and lacking meaning. Other forms such as performance- or workplace-based feedback have been perceived by trainees as infrequent, non-specific, and unhelpful.

이러한 결과는 교육생과 평가자 간의 "교육적 동맹"의 중요성을 나타낸다. 이러한 개념 하에서, 평가와 피드백 프로세스는 [일방적인 정보 전송(평가자에서 수습사원으로)]에서 [실제로 피드백을 사용하여, 학문적 목표를 달성하기 위해 협력할 목적을 가지고, 학습 목표, 성과 및 표준에 대한 공유된 이해를 갖고있는, 진정한 교육적 관계]로 재구성되어야 한다. 평가자-학습자 대화 이외의 평가-생성 피드백의 역할을 고려할 경우, 평가와 평가-생성 피드백이 효과적인 학습에 기여하도록 보장하기 위해 학습자와 기관 또는 프로그램 간에 교육적 동맹을 형성하는 방법을 고려하는 것이 가치가 있을 수 있음을 시사한다.

These findings point to the importance of an “educational alliance” between trainees and assessors, whereby the assessment and feedback processes are reframed from one-way information transmission (from assessor to trainee) to an authentic educational relationship with a shared understanding of learning objectives, performance, and standards with the aim of working together to achieve academic goals using feedback in practice (Molloy et al., 2019; Telio et al., 2015). If we consider the role of assessment-generated feedback outside of assessor-learner conversations, it suggests that there may be value in considering how educational alliances can be formed between a learner and an institution or program in order to ensure assessment and assessment-generated feedback contribute to effective learning.

이 범위 지정 연구에는 몇 가지 제한이 있습니다. 문헌에서 신뢰도credibility 라는 용어를 상대적으로 자주 사용하지 않고, 우리의 검색 전략에서 신뢰의 구성이 운영화된 방식 때문에, 일부 관련 문헌이 누락되었을 가능성이 있다. 관련 문헌을 최대한 많이 확인하기 위해 경험이 풍부한 학계 사서를 팀에 포함시키고 검색 전략을 반복적으로 다듬었습니다. 또한 검색 전략을 보완하기 위해 주요 기사의 인용 추적에 의존했다. 연구 중인 개념이 평가 및 의료 교육 문헌 전반에 걸쳐 광범위하게 표현될 가능성이 높기 때문에 이 검토는 수작업을 수행하지 않았다(Young 등, 2018). 우리는 또한 동료 검토 저널에 발표된 주요 문헌으로 검색을 제한하여 평가 및 평가-생성 피드백의 인식 신뢰성에 영향을 미치는 요소를 연구 증거에 의해 뒷받침되었다. 대부분의 확인된 논문들은 유럽과 북미에서 온 것이므로, 우리의 발견이 국제적으로 적용될 수 있는 가능성은 제한적일 수 있다. 국제적인 수준에서 우리의 발견의 일반화 가능성을 향상시키기 위해, 향후 연구는 이러한 발견을 국제적으로 적용하기 위해 더 잘 맥락화하기 위한 주요 국제 전문가와의 논의를 포함할 수 있다.

This scoping study has some limitations. Due to the relatively infrequent use of the term credibility in the literature, and the way in which the construct of credibility was operationalized in our search strategy, it is possible that some relevant literature was missed. To ensure we identified as much relevant literature as possible, we included an experienced academic librarian on our team and iteratively refined our search strategy. We also relied on citation tracking of key articles to supplement our search strategy. This review did not perform handsearching as the concept under study was likely to be broadly represented across the assessment and medical education literature (Young et al., 2018). We also decided to limit our search to primary literature published in peer-reviewed journals to synthesize the factors, supported by research evidence, that influenced the perceived credibility of assessment and assessment-generated feedback. Most identified articles were from Europe and North America; therefore, the international applicability of our findings may be limited. To enhance the generalizability of our findings at the international level, future research could engage discussions with key international experts to better contextualize these findings for international application.

결론 Conclusion

이 검토에 요약된 결과는 [학습을 지원하고 추진하는 수단]으로서의 평가 및 평가-생성 피드백의 가치를 뒷받침하며, 평가 개발자, 평가 관리자 및 의료 교육자가 의료 학습자를 포함하는 [학습자 중심의 평가 접근 방식]을 채택하는 것을 고려하는 것이 의미 있을 수 있다. 그 효용성을 보장하기 위해서 평가 전략이나 도구의 개발에 학습자를 포함할 수 있다.

The findings summarized in this review support the value of assessment and assessment-generated feedback as a means to support and drive learning, and it may be meaningful for assessment developers, assessment administrators, and medical educators to consider adopting a learner-centred assessment approach that includes medical learners in the development of learning assessment strategies and tools for assessment to ensure their utility.

Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2021 Sep 27.

doi: 10.1007/s10459-021-10071-w. Online ahead of print.

Factors affecting perceived credibility of assessment in medical education: A scoping review

Stephanie Long 1, Charo Rodriguez 1, Christina St-Onge 2, Pierre-Paul Tellier 1, Nazi Torabi 3, Meredith Young 4 5

Affiliations expand

- PMID: 34570298

- DOI: 10.1007/s10459-021-10071-wAbstractKeywords: Assessment; Credibility; Feedback; Learner engagement; Medical education.

- Assessment is more educationally effective when learners engage with assessment processes and perceive the feedback received as credible. With the goal of optimizing the educational value of assessment in medical education, we mapped the primary literature to identify factors that may affect a learner's perceptions of the credibility of assessment and assessment-generated feedback (i.e., scores or narrative comments). For this scoping review, search strategies were developed and executed in five databases. Eligible articles were primary research studies with medical learners (i.e., medical students to post-graduate fellows) as the focal population, discussed assessment of individual learners, and reported on perceived credibility in the context of assessment or assessment-generated feedback. We identified 4705 articles published between 2000 and November 16, 2020. Abstracts were screened by two reviewers; disagreements were adjudicated by a third reviewer. Full-text review resulted in 80 articles included in this synthesis. We identified three sets of intertwined factors that affect learners' perceived credibility of assessment and assessment-generated feedback: (i) elements of an assessment process, (ii) learners' level of training, and (iii) context of medical education. Medical learners make judgments regarding the credibility of assessments and assessment-generated feedback, which are influenced by a variety of individual, process, and contextual factors. Judgments of credibility appear to influence what information will or will not be used to improve later performance. For assessment to be educationally valuable, design and use of assessment-generated feedback should consider how learners interpret, use, or discount assessment-generated feedback.

- © 2021. The Author(s), under exclusive licence to Springer Nature B.V.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 평가법 (Portfolio 등)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 암묵적이고 추론되는: 평가 과학에 도움이 되는 철학적 입장에 대하여(Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2021) (0) | 2021.11.03 |

|---|---|

| 호환가능성 원칙: 임상역량 평가의 철학에 관하여(Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2020) (0) | 2021.10.28 |

| "일단 척도가 과녁이 되면, 좋은 척도로서는 끝이다" (J Grad Med Educ, 2021) (0) | 2021.08.22 |

| 감정과 평가: 위임의 평가자-기반 판단에서 고려사항(Med Educ, 2018) (0) | 2021.08.22 |

| 글로벌 평정척도가 체크리스트보다 전문성의 상승단계 측정에 더 나은가? (Med Teach, 2019) (0) | 2021.08.21 |