글로벌 평정척도가 체크리스트보다 전문성의 상승단계 측정에 더 나은가? (Med Teach, 2019)

Are rating scales really better than checklists for measuring increasing levels of expertise?

Timothy J. Wooda and Debra Pughb

도입

Introduction

객관적 구조화 임상검사(OSCE)에서 성과를 평가할 때 평정 척도rating scale는 학습자의 전문성 증가에 민감하지만, 체크리스트는 그렇지 않다는 것이 원칙이 되었다. 이에 대한 일반적인 설명은, 초보자들이 익숙하지 않은 문제에 직면했을 때 상세한 접근법을 사용할 가능성이 높은 반면, 더 경험이 많은 임상의들은 진단에 도달하기 위해 지름길을 사용할 수 있기 때문에 체크리스트를 사용하여 평가할 때 실제로 낮은 점수를 받을 수 있다는 주장과 관련된다(Regehr et al. 1998; Hawkins and Bullet 2008). 이와 같이, 체크리스트(조치 수행 여부를 평가하는 것)는 [철저성과 데이터 수집 능력을 보상한다]는 비판을 자주 받는 반면, 평정 척도rating scale(평가자가 조치가 얼마나 잘 수행되었는지 판단할 수 있게 하는 것)는 임상적 추론과 같이 전문가에게 보이는 고차적 기술을 평가하는 데 더 낫다는 평을 받는다.

It has become a doctrine that, when assessing performance in an objective structured clinical examination (OSCE), rating scales are sensitive to the increasing expertise of learners, whereas checklists are not. A common explanation for this relates to the assertion that novices are likely to use a detailed approach when encountering an unfamiliar problem while more experienced clinicians are able to use shortcuts to arrive at a diagnosis and, thus, may actually get lower scores when assessed using a checklist (Regehr et al. 1998; Hawkins and Boulet 2008). As such, checklists (which assess whether or not an action was performed) are often criticized for rewarding thoroughness and data-gathering ability, while rating scales (which allow raters to judge how well an action was performed) are touted as being better for assessing the higher-order skills seen in experts, such as clinical reasoning (Hodges and McIlroy 2003; Yudkowsky 2009).

이론적인 관점에서 볼 때, 증가하는 전문성을 포착하는 데 있어서 등급 척도가 체크리스트보다 낫다는 주장이 타당하다. 이중 프로세스 이론은 문제에 직면했을 때 자동, 비분석 프로세스(유형 1) 또는 노력이 드는, 분석적 프로세스(유형 2)를 사용할 수 있다고 제안합니다. 따라서 OSCE 환경에서,

- 전문 임상의가 사례에 접근할 때 무의식적(유형 1) 프로세스를 더 강조하여 실제로 일부 체크리스트 항목을 누락할 것으로 예상할 수 있다.

- 반대로, 같은 경우에 접근하는 초보자는 보다 체계적(유형 2) 접근법에 더 큰 중점을 둘 수 있으며, 결과적으로 체크리스트 과제를 더 많이 수행하기 때문에 더 높은 점수로 보상받을 수 있다.

From a theoretical perspective, the assertion that rating scales are better than checklists at capturing increasing levels of expertise makes sense. Dual-process theory suggests that when faced with a problem we may use automatic, non-analytic processes (i.e. Type 1) or effortful, analytic processes (i.e. Type 2) (Evans 2008, 2018; Kahneman 2011).

- In an OSCE setting, therefore, one might expect an expert clinician to place greater emphasis on unconscious (i.e. Type 1) processes when approaching a case and therefore actually miss some checklist items.

- In contrast, a novice approaching the same case may place greater emphasis on a more systematic (i.e. Type 2) approach and, consequently be rewarded with a higher score because they perform more of the checklist tasks.

연구 결과를 설명할 수 있는 또 다른 접근방식은, 전문가가 될수록 전문가는 다른 개발 단계를 거쳐 발전한다는 것이다(Dreyfus and Dreyfus 1986). [초보 단계]는 대량의 데이터 수집을 강조하는 반면, [전문가]들은 집중된 데이터를 보다 효율적으로 수집할 수 있으며 주어진 문제를 해결하도록 이끈 모든 단계를 파악하기 위해 어려움을 겪을 수 있습니다. 마찬가지로, 전문가들은 임상 데이터를 신속하게 해석할 수 있는 질병 스크립트를 개발하여 초보자가 수행할 수 있는 모든 단계를 따르지 않고도 문제를 해결할 수 있도록 할 수 있다(Schmidt et al. 1990).

Another approach that could account for the findings is that professionals progress through different developmental stages as they become experts (Dreyfus and Dreyfus 1986). The novice stage isc haracterized by an emphasis on the gathering of large amounts of data, while experts are able to gather focused data more efficiently and may struggle to identify all the steps that led them to solve a given problem. Similarly,experts may capitalize on their experience to develop illness scripts that allow them to quickly interpret clinical data, allowing them to solve problems without following all the steps that a novice might (Schmidt et al. 1990).

이러한 세 가지 이론을 고려할 때, 전문성이 높은 수험생을 평가할 때 평가 척도가 체크리스트보다 더 나은 도구가 될 것으로 예상할 수 있다.

Given these three theories, one would expect rating scales to be a better tool than checklists when assessing examinees with increasing levels of expertise.

그러나, 이러한 등급 척도 우위에 대한 주장은 정당한가? 가장 자주 인용되는 연구에서 가정의사는 글로벌 등급 점수(5점 만점 기준)에서 전공의나 임상실습생보다 높은 점수를 받았지만, 2개 스테이션 정신의학 OSCE(Hodges et al. 1999)에 대한 체크리스트로 평가했을 때 두 그룹보다 더 나쁜 점수를 받았다.

But, is this claim of rating scale superiority warranted? In the most frequently cited study, family physicians scored higher than residents and clinical clerks on a global rating score (derived from five 5-point rating scales), but worse than both groups when assessed with a checklist on a two-station psychiatry OSCE (Hodges et al. 1999).

호지스 외 연구진(1998)은 8개 스테이션의 정신의학 OSCE에서 전공의와 임상실습생을 비교했다. 전공의들은 임상실습생보다 Rating scale 등급이 높았지만 체크리스트 점수는 비슷했다. 더 많은 스테이션이 있음에도 불구하고, 이러한 결과 패턴이 서로 다른 도메인을 평가하는 OSCE로 일반화 될지는 완전히 명확하지 않다. 저자들이 지적하듯이, 정신의학은 중요한 면에서 다른 학문과 다를 수 있다.

study by Hodges et al. (1998) compared residents and clerks on an 8-station psychiatry OSCE. Residents had higher global ratings than clerks but similar checklist scores. Despite having more stations, it is not entirely clear if this pattern of results would generalize to OSCEs assessing different domains. As the authors point out, psychiatry may differ fromother disciplines in important ways.

체크리스트의 한계에도 불구하고, 성과 평가 시 많은 장점을 제공한다. 즉, 체크리스트는 비교적 사용하기 직관적이고, 균일한 등급 기준을 제공하고, 높은 신뢰성을 가질 수 있으며, 취약 영역에 대한 특정 피드백을 제공할 수 있다(Harden et al. 2016; Norcini 2016). 실제로 잘 구성된 체크리스트와 등급 척도가 종종 다른 교육 수준을 구별하는 유사한 결과를 낳는다는 것을 보여주는 문헌 기구가 증가하고 있다. 예를 들어, 최근의 체계적인 검토(Ilgen et al. 2015)는 시뮬레이션 기반 평가에서 체크리스트와 등급 척도의 사용에 대한 타당성 증거를 탐색했다. 그 중 7개는 등급 척도 사용을 선호했고, 2개는 체크리스트 사용을 선호했으며, 대다수는 도구에서 차이를 발견하지 못했다. 그러나 이 체계적인 검토는 시뮬레이션 기반simulation-based 평가에만 초점이 맞춰져 있다는 점에 유의해야 한다. 시뮬레이션과 직접 관련되지 않은 수행능력 기반performance-based 평가에 대한 점검 목록과 등급 척도의 비교에는 제한된 증거만 있을 뿐이다.

Despite the purported limitations of checklists, they offer many advantages when assessing performance, namely: checklists are relatively intuitive to use; provide uniform rating criteria; can have high reliability; and allow for the provision of specific feedback on areas of weakness to residents (Harden et al. 2016; Norcini 2016). In fact, there is a growing body of literature demonstrating that wellconstructed checklists and rating scales often produce similar results in discriminating between different levels of training. For example, a recent systematic review (Ilgen et al. 2015) explored validity evidence for the use of checklists and rating scales in simulation-based assessment. Of those, seven favored the use of rating scales, two favored the use of checklists, and the vast majority (n¼25) found no difference in the tools. However, it is important to note that this systematic review focused only on simulation-based assessments. There is only limited evidence in the comparison of checklists and rating scales for performance-based assessments not directly related to simulation.

방법

Methods

참여자 Participants

Internal Medicine 진행률 검사 OSCE(IM-OSCE)는 Ottawa University(PGY1–PGY4)의 모든 Internal Medicine 레지던트에게 필수적이지만 형식적인 연례 검사로 시행됩니다.

The Internal Medicine progress test OSCE, or IM-OSCE, is administered as a mandatory, but formative, annual examination for all Internal Medicine residents at the University of Ottawa (PGY1–PGY4).

설계 Design

IM-OSCE는 지식, 임상 의사 결정, 신체 검사 기술 및 커뮤니케이션 기술을 평가하도록 설계된 9개 스테이션으로 구성되었습니다. 시험의 각 행정의 청사진은 캐나다 왕립의과대학 외과의가 정한 내과 교육 목표(RCPSC 2011)에 기초했다. 각 행정부마다 다양한 신체 시스템과 분야를 대표하는 사례가 선정되었습니다. 각 IM-OSCE의 내용은 사례 반복 없이 매년 달랐다.

The IM-OSCE consisted of nine stations that were designed to assess knowledge, clinical decision making, physical examination skills, and communication skills. The blueprint for each administration of the exam was based on the Objectives of Training for Internal Medicine set by the Surgeons of Royal College of Physicians and Canada (RCPSC 2011). For each administration, cases were selected to represent a variety of different body systems and disciplines. The content on each IM-OSCE was different every year, with no repetition of cases.

내과 전문의들은 각 스테이션마다 고유한 평가자 한 명씩을 두고 각 역마다 전공의들의 성과를 평가했다. 그러나 IM-OSCE의 설계 때문에 평가자는 분석에 포함되지 않았다. 각 IM-OSCE는 하나의 관리에서 두 개의 좌석이 있었고 각 좌석에 여러 개의 트랙이 있었습니다. 이 설계는 평가자와 표준화된 환자가 교락 요인이 되고 트랙과 좌석에 내포된다는 것을 의미합니다. 전공의는 이러한 선로에 무작위로 할당되고 PGY 레벨에 의해 체계적으로 할당되지 않았기 때문에 설계가 더욱 복잡했으며, 따라서 정격자 또는 선로와 같은 요소를 포함하면 상당한 데이터 누락과 전력 상실로 이어질 수 있었다. 따라서 우리는 스테이션 수준에서 데이터를 분석하기로 결정했으며, 분석에 트랙이나 레이터를 포함하지 않았습니다.

Internal Medicine specialists assessed the residents’ performance on each station with a single, unique examiner at each station. Raters were not included in the analysis, however, because of the design of the IM-OSCE. Each IM-OSCE had two sittings in one administration and multiple tracks within each sitting. This design would mean that raters and standardized patients would be confounded factors and would be nested within track and sitting. The design was further complicated because residents were randomly allocated to these tracks and not systematically assigned by PGY level, therefore including factors like rater or track would have led to considerable missing data and a loss of power. We decided therefore to analyze data at the station level and did not include track or rater in the analysis.

Pugh 외 연구진(2014)에 기술된 바와 같이, 전공의들은 스테이션-특이적 체크리스트와 작업-특이적 평정 척도(MeanGR)를 조합하여 평가받았다. 또한 표준 설정에 사용되는 단일 글로벌 등급 척도(GRS)를 사용하여 평가했으며, 응시자의 성과를 의대생 수준 또는 PGY 1~4의 연수생 수준으로 평가하기 위해 개발된 교육 수준 평가 척도traning level rating scale도 사용했다. 이 시험의 경우, 스테이션 점수는 표준 설정의 수정된 경계선 방법(McKinley 및 Norcini 2014)을 적용하는 데 사용되는 GRS와 체크리스트와 MeanGR(위원회가 결정한 각 가중치)의 조합을 사용하여 도출되었다. PGY1-4 척도는 피드백용으로만 사용되었으며 스테이션 점수에 반영되지 않았습니다. 각 스테이션별 점수를 합산해 총점을 만들어 수험생에게 보고했다.

As described in Pugh et al. (2014), residents were scored using a combination of station-specific checklists and task-specific rating scales (MeanGR). They were also assessed using a single global rating scale (GRS) used for standard setting, as well as a training level rating scale developed to rate candidate performance as being at the level of a medical students or at the level of a trainee in PGYs 1 to 4. For this examination, station scores were derived using a combination of the checklist and the MeanGR (weightings for each determined by a committee) with the GRS used to apply the modified borderline method of standard setting (McKinley and Norcini 2014). The PGY1–4 scale was used only for feedback and did not factor into the station score. A total score was created by summing the scores on each station and were reported to examinees.

분석 Analysis

시험 연도 내의 각 스테이션에 대해 체크리스트와 MeanGR 점수를 먼저 z-점수로 변환하여 두 측정치의 점수와 등급이 동일한지 확인했습니다. 음수를 제거하기 위해 각 측도의 z-점수는 평균 100, 표준 편차는 10으로 표준화되었습니다.

For each station within an exam year, the Checklist and MeanGR scores were first converted to z-scores to ensure scores and ratings on both measures were on the same scale. To remove the negative numbers, the z-scores for each measure were standardized to have a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 10.

시험 연도별 각 스테이션마다 주 요인subject factor으로 취급되는 전공의의 PGY 수준(PGY1–4)과 반복 측정 요인repeated measure factor으로 취급되는 측정(즉, 체크리스트 및 평균GR 점수)을 사용하여 혼합 분산 분석을 수행하였다. 주된 관심은 다음과 같다.

- (1) PGY 수준의 주요 효과가 있었던 비교: 훈련 증가의 함수에 따라 점수가 변경되었음을 나타낼 수 있기 때문

- (2) PGY 수준과 두 측정값 사이에 교호작용 비교: 이는 한 측정값에서 점수가 다른 측정값과 다르게 증가했음을 나타내기 때문

For each station by exam year, a mixed ANOVA was conducted with PGY level of the resident (PGY1–4) treated as a between subject factor and the measure (i.e. Checklist and MeanGR scores) treated as a repeated measures factor. Of most interest were:

- (1) comparisons in which there was a main effect of PGY level, because this would indicate that scores changed as a function of increases in training; and

- (2) comparisons producing an interaction between PGY level and the two measures, because this would indicate that scores increased differently for one measure compared to the other.

스테이션에서 교호작용이 발견되면 교호작용의 근원을 탐색하기 위해 후속 분석이 수행되었습니다. 해당 스테이션에 대한 각 측도에 대해 PGY 수준을 과목 간 인자로 처리한 상태에서 과목 간 분산 분석을 별도로 수행했습니다.

If an interaction was found on a station, a subsequent analysis was conducted to explore the source of the interaction. For each measure on that station, a separate between subjects ANOVA was conducted with PGY level treated as a between subject factor.

윤리 Ethics review

결과

Results

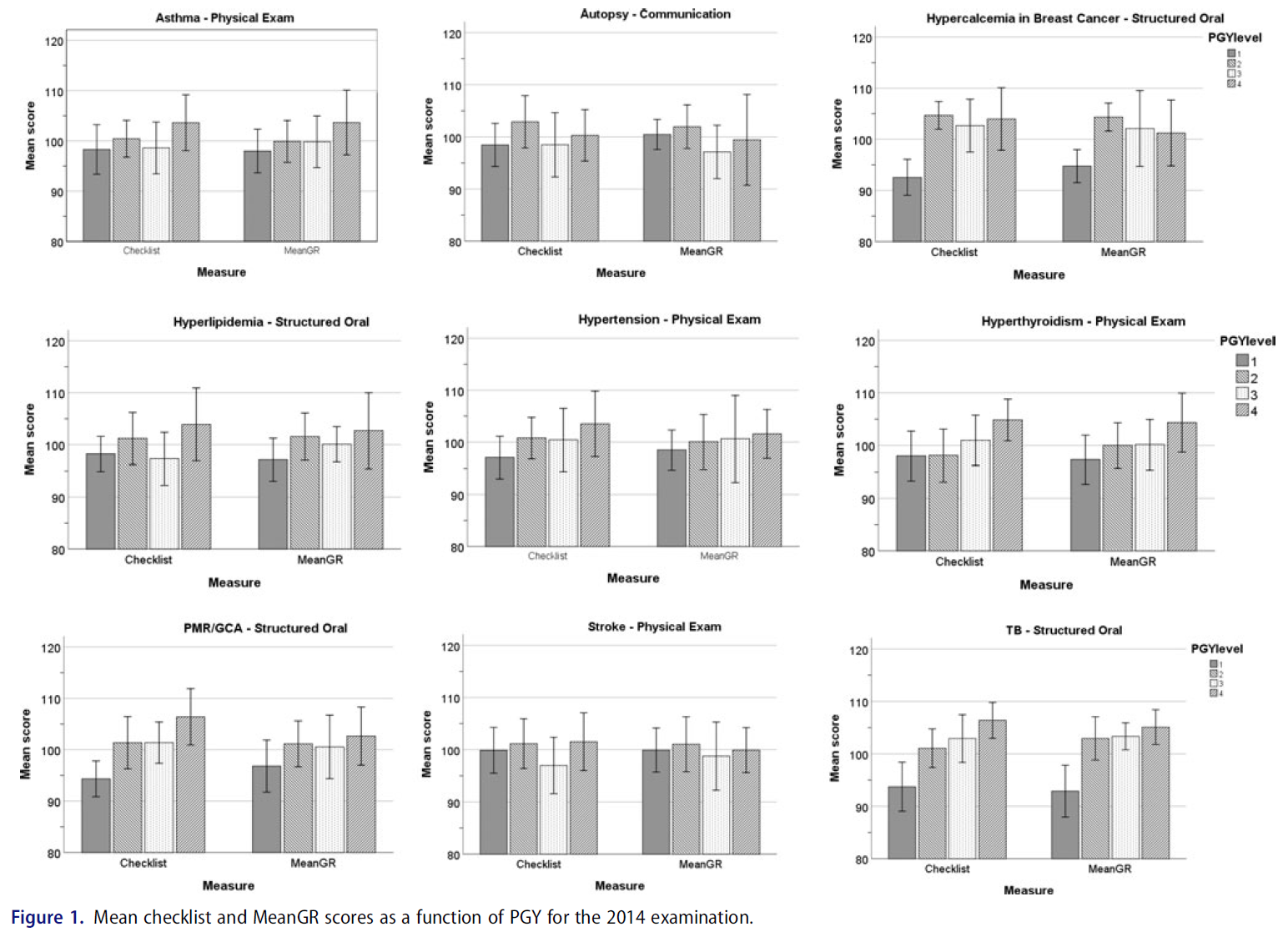

2014년 총 73명, 2015년 85명, 2016년 86명의 전공의가 시험에 응시했다. 그림 1-3은 주어진 관리 연도의 각 스테이션 별 체크리스트와 평균 GR 점수를 나타낸 막대 그래프를 보여준다.

There was a total of 73 residents attempting the examination in 2014, 85 in 2015 and 86 in 2016. Figures 1–3 display bar graphs depicting Checklist and Mean GR scores by PGY for each station in a given administration year.

즉, 27개 스테이션에 걸쳐 총 13개 스테이션에서 체크리스트 점수와 평균 GR 점수에 대해 동등하게 교육 수준 상승 함수로 점수가 증가했음을 입증했으며, 한 스테이션만 체크리스트 점수가 증가하지 않고 등급 척도가 증가했음을 입증했다.

In other words, across 27 stations, a total of 13 stations demonstrated that scores increased as a function of increase in training level equally for both Checklist and Mean GR scores and only one station demonstrated that checklist scores did not increase but rating scale did.

고찰

Discussion

본 연구의 목적은 OSCE 내에서 전문지식의 증가와 채점 도구 사이의 관계를 재검토하여 [평정 척도rating scales]가 [체크리스트]보다 전문지식의 증가에 실제로 더 민감한지를 판단하는 것이었다. 체크리스트는 그렇지 않지만, 평정 척도는 전문지식 수준에 민감하다는 일반적인 견해를 고려할 때, 평정 척도 점수는 PGY 수준의 함수로 증가해야 하는 반면, 점검표 점수는 증가해서는 안 된다고 예상할 수 있다. 우리의 결과는 전문성 증가를 측정할 때 체크리스트에 비해 종종 인용되는 등급 척도 우위에 대한 주장에 반대challenge한다. 우리가 조사한 27개 스테이션 중 rating scale에서만 PGY 수준별 차이가 나타난 것은 1개뿐이었다.

The purpose of this study was to reexamine the relationship between increases in expertise and scoring instruments within an OSCE in order to determine if ratings scales are indeed more sensitive to increases in expertise than checklists. Given the prevailing view that rating scales are sensitive to levels of expertise whereas checklists are not, one would expect that rating scale scores should increase as a function of PGY levels whereas checklist scores should not. Our results challenge the oft-cited claim of rating scale superiority over checklists when measuring increases in expertise. Of the 27 stations we examined, there was only one in which rating scales but not checklists demonstrated a difference by PGY level.

우리의 결과는 시뮬레이션과 관련된 여러 논문에서 보고된 결과를 복제하지만(Ilgen et al. 2015) 왜 우리의 연구 결과가 [등급 척도의 우월성]에 대한 일반적인 가정에 도전하는지 의문을 제기한다. 여러 가지 이유가 있을 수 있습니다. 첫째, 체크리스트 설계는 초기 Hodges 등 연구 이후 발전해 왔다. 즉, 체크리스트는 요청되거나 [수행될 수 있는 모든 단계의 전체 목록]을 나타내지 않으며, 사례의 주요 기능key feature에 초점을 맞출 가능성이 더 높아졌습니다(Daniels et al. 2014; Yudkowsky et al. 2014). 확실히, 이것은 본 연구에 포함된 OSCE가 주요 특징key features에 초점을 두고 개발된 사례이다.

Our results replicate findings reported in several papers related to simulation (Ilgen et al. 2015) but raise the question as to why our findings challenge the common assumption of rating scale superiority. A number of reasons might exist. First, the design of checklists has evolved since the initial Hodges et al. study. That is, checklists are now less likely to represent an exhaustive list of all steps that could be asked or done, and more likely to focus on the key features of the case (Daniels et al. 2014; Yudkowsky et al. 2014). Certainly, this is the case with the OSCEs included in the present study which were developed with a focus on key features.

세 번째 가능성은 스테이션들의 난이도와 관련이 있을 수 있다. Hodges 등의 연구에서 스테이션은 임상 실습생 수준으로 설계되었지만 전공의와 수련후 의사를 테스트했다. 본 연구의 관측소는 PGY-4 수준의 성능을 테스트하기 위해 만들어졌기 때문에 상당히 어려웠다.

A third possibility could be related to the difficulty of the stations. The Hodges et al. stations were designed to be at the level of clinical clerks but tested residents and practicing physicians. The stations in this study were considerably more difficult, having been created to test ability at the level of a PGY-4.

연구 대상 27개 스테이션 중 13개 스테이션만only이 사용하는 채점도구와 무관하게 PGY 수준별 차이를 보인 것은 다소 놀라운 일이었다. PGY-4 수준에서 설정된 난이도 시험이지만 모든 수련 연차의 전공의가 시도한 진도 시험임을 감안할 때, 모든 스테이션에 적어도 하나의 도구instrument에서 변화가 있을 것으로 예상할 수 있다. 그러나 이는 적어도 부분적으로는 스테이션 유형의 함수일 수 있습니다. 주목할 점은 의사소통 스테이션 (0/3) 중 단 한 곳도 없었고, 단지 신체검진 스테이션에서 3/12에서만 두 척도 중 하나 이상에서 PGY level에 따른 차이가 나타났다.

It was somewhat surprising that only 13 of the 27 studied stations demonstrated a difference by PGY level regardless of the scoring instrument used. Given that this is a progress test with a difficulty set at a PGY-4 level but attempted by residents of all training years, one would have expected changes with at least one of the instruments in all stations. However, this may be again, at least in part, a function of station type. It is noteworthy that none of the communication stations (0/3) and only 3/12 physical examination stations examined demonstrated a difference by PGY level for either of the measures.

세 번째 신체 검사 스테이션은 상호작용이 있었고, 평정 척도만이 PGY 수준이 증가를 보였다. 신체 검사 스테이션과 관련된 이러한 발견은 많은 신체검사 기술(예: 관절 검사 또는 신경 검사 수행 능력)이 수련 초기에 획득되었을 것으로 예상되고 레지던트 기간 동안 크게 발전하지 않았을 수 있기 때문에 발생했을 수 있습니다. 의사소통 스테이션에 대한 PGY 수준의 차이가 없는 것과 관련하여, 이는 수련기간 증가에 따른 내과 레지던트 의사소통 능력 개발의 진전이 없음을 입증하는 이전에 발표된 연구와 일치한다(Pugh et al. 2016).

A third physical examination station had an interaction with only the rating scale producing increases in PGY level. This finding related to physical examination stations may have occurred because many of the skills tested (e.g. ability to perform a joint or neurologic exam) might be expected to have been acquired early in training and may not have evolved much during residency. With regards to the lack of differences seen by PGY-level on the communication stations, this is in keeping with a previously published study which also demonstrated no progression in the development of Internal Medicine residents’ communication skills over time (Pugh et al. 2016).

이론의 여지없이, (수험생이 효율적인 데이터 수집하고, 진단을 내리고, 관리 계획을 수립하는 과정에서 문제에 대한 접근 방식을 입증해야 하는) [구조화된 구술structured oral]은 더 복잡하며, 따라서 주니어 훈련생과 시니어 훈련생 사이의 차이를 입증할 가능성이 더 높을 수 있다. (10/12 structured oral station는 PGY-수준별 차이를 보였다.)

Arguably, structured orals, which require an examinee to demonstrate an approach to a problem that includes efficient data gathering, diagnosis and formulation of a management plan, are more complicated and therefore may be more likely to demonstrate a difference between junior and senior trainees (10/12 structured oral stations demonstrated a difference by PGY-level).

본 연구의 가장 큰 한계는 동일한 평가자가 체크리스트와 평가 척도를 모두 완료했기 때문에 두 측정이 서로 영향을 미쳤을 가능성이 매우 크다는 것이다. 즉, 체크리스트가 역량 증가를 측정할 수 없다는 가정이 얼마나 일반적인지를 고려할 때, 두 측정이 서로 교란되어 있더라도 우리의 결과는 최소한 주의를 시사해야 합니다.

A major limitation to our study is that the same rater completed both the checklist and the rating scales and therefore it is quite possible that the two measures influenced each other. That said, considering how common the assumption is that checklists cannot measure increases in competency, our results should at the least suggest caution even with both measures being confounded with each other.

결론적으로, 우리는 체크리스트가 등급 척도보다 낫거나 나쁘다고 주장하는 것이 아니다 – 둘 다 특정한 상황에서 장점이 있다.

In conclusion, we are not arguing that checklists are better or worse than rating scales – both have merits under particular circumstances.

Med Teach. 2020 Jan;42(1):46-51.

doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2019.1652260. Epub 2019 Aug 20.

Are rating scales really better than checklists for measuring increasing levels of expertise?

Timothy J Wood 1, Debra Pugh 2

Affiliations collapse

Affiliations

- 1Department of Innovation in Medical Education, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada.

- 2Department of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada.

- PMID: 31429366

- DOI: 10.1080/0142159X.2019.1652260Abstract

- Background: It is a doctrine that OSCE checklists are not sensitive to increasing levels of expertise whereas rating scales are. This claim is based primarily on a study that used two psychiatry stations and it is not clear to what degree the finding generalizes to other clinical contexts. The purpose of our study was to reexamine the relationship between increasing training and scoring instruments within an OSCE.Approach: A 9-station OSCE progress test was administered to Internal Medicine residents in post-graduate years (PGY) 1-4. Residents were scored using checklists and rating scales. Standard scores from three administrations (27 stations) were analyzed.Findings: Only one station produced a result in which checklist scores did not increase as a function of training level, but the rating scales did. For 13 stations, scores increased as a function of PGY equally for both checklists and rating scales.Conclusion: Checklist scores were as sensitive to the level of training as rating scales for most stations, suggesting that checklists can capture increasing levels of expertise. The choice of which measure is used should be based on the purpose of the examination and not on a belief that one measure can better capture increases in expertise.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 평가법 (Portfolio 등)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| "일단 척도가 과녁이 되면, 좋은 척도로서는 끝이다" (J Grad Med Educ, 2021) (0) | 2021.08.22 |

|---|---|

| 감정과 평가: 위임의 평가자-기반 판단에서 고려사항(Med Educ, 2018) (0) | 2021.08.22 |

| 친구 다음에 OSCE를 볼 때의 이득: 후향적 연구(Med Teach, 2018) (0) | 2021.08.21 |

| 의학교육에서 기준선 설정: 고부담 평가(Understanding Medical Education Ch 24) (0) | 2021.08.20 |

| 형성적 OSCE가 어떻게 학습을 유도하는가? 전공의 인식 분석 (Med Teach, 2017) (0) | 2021.08.19 |