발달적 평가에 필수적인 것은 무엇인가? (American Journal of Evaluation, 2016)

What is Essential in Developmental Evaluation? On Integrity, Fidelity, Adultery, Abstinence, Impotence, Long-Term Commitment, Integrity, and Sensitivity in Implementing Evaluation Models

Michael Quinn Patton1

Bob Williams는 시스템 접근 방식을 평가하는 데 기여한 누적 공로로 2014 AEA Lazarsfeld Theory Award를 수상했습니다. 밥은 덴버에서 열린 어워즈 런천에서 400명 이상의 평가자들이 참석한 가운데 단어 시스템의 기원에 대해 설명했다.

Bob Williams was awarded the 2014 AEA Lazarsfeld Theory Award for his cumulative contributions bringing systems approaches into evaluation. In accepting at the Awards Luncheon in Denver, attended by more than 400 evaluators, Bob explained the origin of the word system.

'시스템'이라는 단어는 '함께 서다'라는 뜻의 그리스어 synhistonai 에서 유래했다. 그래서 모든 분이 잠시 서 계셨으면 합니다.

The word ‘system’ comes fromthe Greek word synhistonai (a verb incidentally, not a noun) meaning ‘to stand together’. So I’d like to invite all that can do so to stand for a moment.

이제 몇 분 앉으시라고 하겠습니다. 저는 평가 관행에 어떤 형태나 형태, 더 크든 덜 크든 시스템과 복잡성 아이디어를 적용했다고 생각하는 모든 분은 그대로 서 계십시오.

I’m now going to ask some of you to sit down. I’d like to remain standing anyone who to some extent feels that you have applied systems and complexity ideas—of whatever shape or formand to a greater or lesser extent—in your evaluation practice.

평가에서 시스템 사고의 적용에 대한 질문은 거의 모든 접근법에 적용될 수 있습니다. 이 글에서는 뚜렷한 평가 접근 방식을 구현함에 있어 충실도 과제의 범위를 제시하고, 구체적인 사례를 제시하며, 개발 평가(DE)를 사용하여 충실도에 대한 새로운 사고 방식과 대처 방식을 도입할 것입니다.

The questions about application of systems thinking in evaluation could be applied to almost any approach. This article will lay out the scope of the fidelity challenge in implementing distinct evaluation approaches, illustrate the challenge with specific examples, and use developmental evaluation (DE) to introduce a newway of thinking about and dealing with fidelity.

차별화된 평가 접근 방식을 구현하는 데 있어서의 충실도 과제

The Fidelity Challenge in Implementing Distinct Evaluation Approaches

경험이 많은 DE 실무자가 최근 제게 '발달평가DE를 하고 있다고 말하는 경우가 많지만, 실제로는 그렇지 않다'고 말했습니다.

An experienced DE practitioner recently told me: ‘‘More often than not, I find, people say they are doing Developmental Evaluation, but they are not.’’

[충실도fidelity 과제]는 [특정 평가를 지정된 명칭으로 부르는 것을 정당화하기 위해, 전반적인 접근법의 핵심 특성을 충분히 포함하는 정도]에 관한 것이다. [충실도]가 [효과적인 프로그램을 새로운 장소 복제하려는 노력의 중심 문제]인 것처럼(복제품은 기초가 되는 오리지널 모델에 충실한가?), 특정 모델을 따르는 평가자가 해당 모델의 모든 핵심 단계, 원칙 및 프로세스를 이행하는 데 충실한지 여부를 평가한다.

The fidelity challenge concerns the extent to which a specific evaluation sufficiently incorporates the core characteristics of the overall approach to justify labeling that evaluation by its designated name. Just as fidelity is a central issue in efforts to replicate effective programs to new localities (are the replications faithful to the original model on which they are based?), evaluation fidelity concerns whether an evaluator following a particular model is faithful in implementing all the core steps, principles, and processes of that model.

형성적-총괄적 구별에 대한 충실도

Fidelity to the Formative–Summative Distinction

충실성의 과제를 설명하기 위해 가장 오래되고, 가장 기본적이며, 가장 신성불가침적인 구분인 형성적, 총괄적 특성을 고려하십시오. [형성적-총괄적 구분]은 철학자이자 평가자인 Michael Scriven(1967)에 의해 학교 커리큘럼 평가를 위해 처음 개념화되었다. 그는 총괄 평가의 광범위한 채택, 정상급 결정 또는 효과의 요약에 대한 승인을 얻고 보급해야 하는지를 결정하기 위한 커리큘럼의 평가를 촉구했다.

To illustrate the challenge of fidelity, consider our oldest, most basic, and most sacrosanct distinctions: formative and summative. The formative–summative distinction was first conceptualized for school curriculumevaluation by philosopher and evaluator extraordinaire Michael Scriven (1967). He called evaluating a curriculum to determine whether it should be approved and disseminated for widespread adoption of a summative evaluation, evoking a summit-like decision or a summing-up of effectiveness.

원래의 [총괄평가]는 purpose에 대한 용어였다. 즉, 교육과정, 프로그램, 제품, 개입의 미래 결정(중단, 축소, 지속 등)에 inform하기 위한 목적을 위해, 이들의 [장점, 가치, 중요성에 대한 주요 결정]을 내리는 것으로 시작되었다. 그러나 총괄평가라는 용어는 빠른 속도로 [프로그램이나 프로젝트가 끝날 때 실시되는 평가]를 지칭하는 방식으로 확장되었습니다.

Summative evaluation began as a purpose designation, the purpose being to inform a major decision about the merit, worth, and significance of a curriculum, program, product, or other intervention to determine its future (kill it, cut it back, continue as is, enlarge it, and take it to scale). But the term summative evaluation quickly expanded to designate any evaluation conducted at the end of a program or project.

(총괄평가의 정의에서) [뚜렷하고 중요한 목적]이 [프로그램 종료라는 타이밍] 지정designation으로 변형되었습니다. 이것은 아이러니할 뿐만 아니라 왜곡적이다. 왜냐하면 대부분의 [총괄적 결정]은 최종 총괄평가 보고서가 제출되기 훨씬 전에, 즉 [실제 프로그램이 종료되기 몇 달 전에 미리 이루어져야 하기 때문]입니다. 나는 매년 "총괄적"이라는 라벨이 붙은 수십 개의 보고서를 검토하는데, 그 중 거의 어떤 보고서도 식별 가능한 [총괄적 의사결정자들]에 의한 [실제 총괄 결정]에 inform하는 방식으로 작성되거나 기록되지 않는다. 내가 보기에, "총괄"의 원래 의미에 대한 충실성은 이미 많이 상실되었다.

A distinct and important purpose morphed into a timing designation: end of a program. Which is ironic—and distorting—since most summative decisions must be made months before the actual end of a program, long before evaluation final summative reports are submitted. I review scores of reports labeled ‘‘summative’’ every year, virtually none of which are written or timed in such a way as to informan actual summative decision by identifiable summative decision-makers. Fidelity to the original meaning of summative has been largely lost from my perspective.

그럼 형성 평가는 어떠한가? 스크리븐은 커리큘럼을 총괄 평가하기 전에, [엄격한 총괄평가를 할 수 있으려면], [개정과 개선의 기간을 거쳐야 하며, 버그와 문제를 해결하고, 빈틈을 메우고, 학생의 반응을 얻어야 한다]고 지혜롭게 주장했다. 즉, 형성 평가의 목적은 모델을 [form, shape, standardize, and finalize]하여 종합 평가를 위한 준비를 갖추는 것이었다. 그러나 총괄평가가 그러했듯, 프로그램 개선을 위한 평가라면 어떤 것이든 형성평가라는 레이블을 적용하면서, 형성평가는 본래 목적에서 탈피하게 되었다.

And what of formative evaluation? Scriven argued wisely that before a curriculum was summatively evaluated, it should go through a period of revision and improvement, working out bugs and problems, filling in gaps, and getting student reactions, to ensure that the curriculum was ready for rigorous summative testing. The purpose of formative evaluation was to form, shape, standardize, and finalize a model so that it was ready for summative evaluation. But, as happened with summative evaluation, the idea of formative evaluation morphed from its original purpose as the label came to be applied to any evaluation that improves a program.

비록 형성적 designation과 총괄적 designatino이 (원래는) 함께 개념화되었지만, 형성적 지정의 목적은 총괄적 준비를 위한 것이지만, 그러한 기대는 종종 달성되지 않는다. [명확한 목적]에서 [시점(프로그램 종료)의 문제]로 총괄평가가 변형된 것처럼, 이제는 단순히 [자금 지원 주기의 중간]에 평가가 이루어진다는 이유만으로 '형성(평가)'라는 이름으로 불리는 중간평가(midterm evaluation)가 매우 많다. 이러한 '형성적' 평가는 종종 프로그램이 [구현 규격]을 준수하고 있고, [이정표 성과 척도]를 충족하고 있는지를 결정하는, 중간시점의 책무성 연습(midterm accountability exercise)에 불과하다. 내가 보기에, [형성평가]의 원래 의미에 대한 충실도는 크게 떨어졌습니다. 예를 들어, 교수 평가 워크숍에서 나는 [형성 평가]와 [과정process 평가], [총괄 평가]와 [결과outcome 평가]를 동일시하는 참가자를 정기적으로 보곤 한다. 하지만 이들은 서로 다르다.

Though formative and summative designations were conceptualized hand in glove, the purpose of formative being to get ready for summative, that expectation often goes unfulfilled. Just as summative morphed froma clear purpose to a matter of timing (end of program), I now see a great many midterm evaluations designated as ‘‘formative’’ simply because the evaluation takes place in the middle of a funding cycle. These supposedly ‘‘formative’’ evaluations are often midterm accountability exercises determining whether the program is adhering to implementation specifications and meeting milestone performance measures. From my perspective, fidelity to the original meaning of formative has been largely lost. For example, in teaching evaluation workshops, I regularly find participants equating formative evaluation with process evaluation and summative evaluation with outcomes evaluation. Not so.

다시 한 번 말씀드리겠습니다. Scriven은 [평가의 목적]은 [모델을 점검하고 판단하는 것]이라는 가정 하에 형성적-총괄적 평가라는 구별을 만들었다.

- 원래의 형성 평가는 [모델을 개선하기 위한 것]이었습니다.

- 원래의 총괄 평가는 [모델을 테스트]하고 [모델이 원하는 성과를 생성하는지 여부에 근거하여 장점, 가치, 중요성을 판단]하기 위한 것이었으며, 그러한 성과는 프로그램에 귀속될be attributed to수 있다.

Let me reiterate. Scriven originated the formative–summative distinction under the assumption that the purpose of evaluation is to test and judge a model.

- Formative evaluations were meant to improve the model.

- Summative evaluations were meant to test the model and judge its merit, worth, and significance based on whether it produces the desired outcomes and those outcomes can be attributed to the program.

[형식적]이라는 용어와 [총괄적]이라는 용어가, 평가 내에서 그리고 자금을 조달하고 사용하는 사람들 사이에서 지배적이 되었습니다. 그러나 평가 실무자들은 무엇이 실제로 형성적 또는 종합적 평가를 구성하는지와 둘 사이의 연관성에 대해 허술해졌다.

The terms formative and summative have become dominant both within evaluation and among those who fund and use it. But evaluation practitioners have become sloppy about what actually constitutes a formative or summative evaluation and the connection between the two.

DE의 출현

Emergence of DE

DE는 [형성 평가]와 [총괄 평가]의 충실성을 존중하겠다는 나의 약속에서 나왔습니다. 저는 자선 재단의 리더십 프로그램을 평가하기 위해 5년 계약을 맺었고, 2.5년은 형성적이고, 모델을 안정시키고 표준화하며, 2.5년은 모델의 효과를 테스트하고 판단하기 위한 계약을 맺었습니다. [형성 기간] 동안, 선임 프로그램 직원들과 재단 지도부는 자신들이 [표준화된 모델]을 만들고 싶지 않다는 것을 깨닫게 되었습니다. 대신, 그들은 세상이 변함에 따라 [리더십 프로그램을 지속적으로 적응할 필요가 있다는 것]을 깨달았습니다. 리더십 개발 프로그램을 적절하고 의미 있게 유지하려면 시간이 지남에 따라 다음의 것들을 지속적으로 업데이트하고 적응해야 한다는 결론을 내렸습니다.

- 그들이 한 일;

- 누가 어떻게 사람들을 프로그램에 모집했는지,

- 신기술 사용

- 공공 정책, 경제 변화, 인구학적 전환 및 사회 문화적 변화에 주의를 기울이고 이를 통합합니다.

DE emerged from my commitment to respect the fidelity of formative and summative evaluation. I had a 5-year contract to evaluate a philanthropic foundation leadership program, and 2.5 years were to be formative, to stabilize and standardize the model, followed by 2.5 years to test and judge the model’s effectiveness. During the formative period, the senior program staff and foundation leadership came to realize that they didn’t want to create a standardized model. Instead, they realized that they would need to be continuously adapting the leadership programas the world changed. To keep a leadership development program relevant and meaningful, they concluded, they would need, over time, to continuously update and adapt

- what they did;

- who and how they recruited people into the program;

- use of new technologies; and

- being attentive to and incorporating developments in public policy, economic changes, demographic transitions, and social–cultural shifts.

그들은 자신들의 열망이 [모델을 개선]하거나 [테스트]하거나 [모델을 배포]하는 것에 있지 않다는 것을 깨닫게 되었습니다. 대신, 그들은 프로그램을 계속 개발하고 적응하기를 원했다. 이들은 무엇을 변경, 확장, 종료 또는 더 발전시킬 것인지에 대한 [지속적인 적응과 시기적절한 결정을 지원하는 접근 방식]을 원했습니다. 이것은 형성평가와는 달랐다. 그리고 그들은 총괄적으로 평가될 수 있는 표준화된 모델이 없기 때문에 절대 종합 평가를 의뢰하지 않을 것이라고 결론지었다. 그들이 원하고 필요로 하는 것이 무엇인지에 대한 우리의 논의는, [지속적인 적응과 개발]을 중심으로 응집되었으며, 이를 DE 접근법이라고 불렀다.

They came to understand that they didn’t want to improve a model or test a model or promulgate a model. Instead, they wanted to keep developing and adapting the program. They wanted an approach that would support ongoing adaptation and timely decisions about what to change, expand, close out, or further develop. This was different from formative evaluation. And they concluded that they would never commission a summative evaluation because they wouldn’t have a standardized model that could be summatively evaluated. Our discussions about what they wanted and needed kept coalescing around ongoing adaptation and development so we called the approach DE. (For more details about this designation and how the DE terminology emerged, see Patton, 2011, pp. 2–4.)

DE의 틈새 및 목적

The Niche and Purpose of DE

DE는 복잡한 역동적 환경에서 적응적 발달을 알리기 위해 사회 혁신가에게 평가 정보와 피드백을 제공합니다. DE는 평가 질문을 하고, 평가 논리를 적용하고, 프로젝트, 프로그램, 이니셔티브, 제품 및/또는 조직 개발을 지원하기 위해 평가 데이터를 수집하고 보고하는 프로세스를 혁신과 적응에 도입합니다.

DE provides evaluative information and feedback to social innovators to inform adaptive development in complex dynamic environments. DE brings to innovation and adaptation the processes of asking evaluative questions, applying evaluation logic, and gathering and reporting evaluative data to support project, program, initiative, product, and/or organizational development with timely feedback.

DE niche는 복잡하고 역동적인 환경의 혁신을 평가하는 데 초점을 맞춥니다. 왜냐하면 그 영역이야말로 사회 혁신가들이 활동하고 있는 영역이기 때문입니다. 이들은 주요한 방식major way으로 사물의 방식을 바꾸고자 하는 사람들이다. 여기서 사용되는 혁신은 다루기 어려운 문제에 대한 새로운 접근법, 변화된 조건에 대한 지속적인 프로그램 적응, 새로운 맥락에 대한 효과적인 원칙 적응(스케일링), 시스템 변경 및 위기 상황에서의 신속한 대응 적응을 포함하는 광범위한 틀입니다. 사회 혁신은 복잡한 문제에 대한 모든 종류의 긴급/창의/적응적 개입을 단축하는 것입니다.

The DE niche focuses on evaluating innovations in complex dynamic environments because that’s the arena in which social innovators are working. These are people who want to change the way things are in major ways. Innovation as used here is a broad framing that includes creating new approaches to intractable problems, ongoing program adaptation to changed conditions, adapting effective principles to new contexts (scaling), systems change, and rapid response adaptation under crisis conditions. Social innovation is shorthand for any kind of emergent/creative/adaptive interventions for complex problems.

필수 원칙을 민감화 개념으로 취급

Treating Essential Principles as Sensitizing Concepts

DE의 필수 원칙을 열거하기 전에, DE를 식별하는 데 사용되는 개발 접근법에 대해 설명하겠습니다. DE 실무자의 핵심 그룹은 대화형, 명확화 및 개발 프로세스에서 아이디어와 반응을 공유했습니다. 우리는 DE에 대해서 (핵심 개념과 척도의 조작화에 기반한) 레시피 또는 체크리스트 접근 방식을 피하고 싶었습니다. 대신, 우리는 이러한 필수 원칙을 DE에서 명시적으로 다루어야 하는 민감한 개념으로 보지만, 이 원칙을 다루는 방법과 원칙 활용의 정도는 상황과 맥락에 따라 달라진다.

Before listing the essential principles of DE, let me describe the developmental approach used to identify them. A core group of DE practitioners shared ideas and reactions in an interactive, clarifying, and developmental process1. We wanted to avoid a recipe-like or checklist approach to DE based on operationalizing key concepts and dimensions. Instead, we view these essential principles as sensitizing concepts that must be explicitly addressed in DE, but how and the extent to which they are addressed depends on situation and context.

이는 "충실성"에 대한 일반적인 접근 방식에서 크게 벗어난 것이다. "충실성"은 전통적으로 매번 정확히 동일한 방식으로 접근 방식을 구현하는 것을 의미했다. 충실도는 레시피를 고수하는 것이며, 매우 규범적인 단계와 절차를 준수하는 것을 의미했다. 이와는 대조적으로 DE의 필수 원칙은 상황별로 해석되고 적용되어야 하는 지침을 제공한다. 그러나 평가가 진실하고 완전히 발전적인 것으로 간주되려면 어느 정도 그리고 어느 정도 적용되어야 한다.

This is a critical departure fromthe usual approach to ‘‘fidelity,’’ which has traditionally meant to implement an approach operationally in exactly the same way each time. Fidelity has meant adherence to a recipe or highly prescriptive set of steps and procedures. The essential principles of DE, in contrast, provide guidance that must be interpreted and applied contextually—but must be applied in some way and to some extent if the evaluation is to be considered genuinely and fully developmental.

[DE 충실도 준거]를 조작화하는 대신, 저는 이 접근법, 즉 [명시적 민감도 정도]를 평가하는 것을 지정designating하려고 한다. 충실함 대신, 나는 [접근법의 진실성integrity를 검사하는 것]을 선호한다. DE가 integrity을 가지려면 필수 DE 원칙이 프로세스와 결과, 그리고 결과 설계와 결과 사용 모두에서 명백하고 맥락적으로 명시되어야 한다. 따라서 DE 보고서를 읽거나, DE 관련자들과 대화를 나누거나, 학회에서 DE 프레젠테이션을 들을 때, DE의 필수 원칙이 어떻게 수행되고 어떤 결과를 초래하는지/감지/이해할 수 있어야 합니다.

In lieu of operationalizing DE fidelity criteria, I am designating this approach: assessing the degree of manifest sensitivity. In lieu of fidelity, I prefer to examine the integrity of an approach. For a DE to have integrity, the essential DE principles should be explicitly and contextually manifest in both processes and outcomes, in both design and use of findings. Thus, when I read a DE report, talk with those involved in a DE, or listen to a DE presentation at a conference, I should be able to see/ detect/understand how these essential principles of DE informed what was done and what resulted.

좀 더 자세히 설명하면 이러하다. [핵심 원칙에 대한 명시적 민감도manifest sensitivity 정도]를 평가함으로써 [접근법의 integrity을 판단]한다는 개념은, [민감화 개념sensitizing concept]에 의해 유도되는 현장작업의 개념에서 비롯된다(Patton, 2015a). [민감화 개념]은 무언가에 대한 의식을 높이고, 그 관련성을 주의하도록 경고하며, 특정 맥락에서 현장 작업 전반에 걸쳐 개념을 참여하도록 상기시킵니다. [DE의 기본 원칙]은 우리로 하여금 [DE 실무에 무엇을 포함해야 하는지]에 민감해지도록 만든다.

Let me elaborate just a bit. The notion of judging the integrity of an approach by assessing the degree of manifest sensitivity to essential principles flows from the notion of fieldwork guided by sensitizing concepts (Patton, 2015a). Asensitizing concept raises consciousness about something, alerts us to watch out for its relevance, and reminds us to engage with the concept throughout our fieldwork within a specific context. Essential principles of DE sensitize us to what to include in DE practice.

[혁신]이라는 개념을 생각해보자. DE는 혁신에 중점을 두고 있으며, 이는 잠시 후 설명할 DE의 필수 원칙 중 하나이다. 다음은 혁신의 개념이 DE 프로세스에서 수행하는 작업입니다. 그것은 사회 혁신가, 즉 큰 변화를 가져오려는 사람들에게 우리의 관심을 집중시킨다.

- 우리는 그들이 무엇을 하는지('혁신') 그들이 무엇을 의미하는지 알아내기 위해 그들의 정의에 기민하다.

- 우리는 그들이 무엇을 하고 있는지 그리고 그들이 무엇을 하고 있는지에 대해 어떻게 말하는지 주목하고 기록한다.

- 현재 진행 중인 상황과 노력의 의미 및 문서화된 결과에 대해 고객과 상호 작용합니다.

- 우리는 전개되고 떠오르는 것에 대한 데이터를 수집합니다.

- 우리는 실제로 일어나고 있는 일이 기대와 희망에 어떻게 부합하는지 관찰하고 피드백을 제공합니다.

- 우리는 관련자들과 협력하여 현재 일어나고 있는 일을 해석하고, 효과가 있는지 없는지 판단하여 적응하고, 배우고, 나아가고 있습니다.

Consider the concept innovation. DE is innovation-focused, one of the essential principles I’ll elaborate in a moment. Here is what the concept of innovation does in a DE process. It focuses our attention on social innovators, that is, people who are trying to bring about major change.

- We are alerted by their definition of what they are doing (‘‘innovation’’) to find out what they mean.

- We pay attention to and document what they are doing and how they talk about what they are doing.

- We interact with them about what is going on and the implications of their efforts and documented results.

- We gather data about what is unfolding and emerging.

- We observe and provide feedback about how what is actually happening matches expectations and hopes.

- We work with those involved to interpret what is happening and judge what is working and not working and thereby adapt, learn, and move forward.

이를 통해 우리는 "혁신"이라는 개념에 대해 그들과 협력하고 그러한 맥락에서 혁신이 의미하는 바에 대한 그들의 이해와 우리의 이해를 심화시키고 있습니다. 혁신의 정의와 의미는 DE inquiry의 일부로 진화, 심화 및 변형될 가능성이 높습니다.

In so doing, we are engaging with them around the notion of ‘‘innovation’’ and deepening both their and our understanding of what is meant by innovation in that context. The definition and meaning of innovation is likely to evolve, deepen, and even morph as part of the DE inquiry.

이 프로세스에서 DE는 변화 프로세스 자체의 일부가 되고 개입의 일부가 됩니다. 이렇게 진행된다. 상황 및 특정 변경 중심 이니셔티브 내에서 혁신의 의미를 조사하고 학습된 내용과 생성된 추가 질문에 대한 피드백을 제공함에 있어 DE는 혁신 프로세스와 결과에 영향을 미치고 변경한다.

In this process, DE becomes part of the change process itself, part of the intervention. It happens like this: In inquiring into the meaning of innovation within a context and particular change-focused initiative, and providing feedback about what is learned as well as further questions generated, DE affects and alters the innovation process and outcomes.

통합 접근 방식으로서의 DE

DE as an Integrated Approach

"DE"라는 라벨에 걸맞은 평가를 위해서는 표 1의 모든 원칙이 어느 정도 그리고 어느 정도 다루어져야 한다. 표 1에서 언급한 바와 같이, 이 목록은 pick-and-choose 목록이 아닙니다. 모두 필수입니다. 이는 DE 과정에서 이러한 필수 원칙이 어떤 의미 있는 방식으로 다루어졌거나 특정한 상황적 이유로 명시적으로 통합되지 않았다는 증거가 있다는 것을 의미한다. 예를 들어, "복잡성"이라는 단어를 싫어하는 사회적 혁신가 및/또는 기금가와의 작업을 상상해보자. 그래서 DE 프로세스는 복잡성 용어를 명시적으로 사용하지 않지만 출현, 적응 및 비선형성을 명시적으로 다룬다. 그러한 협상은 상황 민감도와 적응성의 일부이며 필수적인 DE 학습 프로세스의 일부이므로 보고되어야 한다.

For an evaluation to merit the label ‘‘DE,’’ all of the principles in Table 1 should be addressed to some extent and in some way. As noted in Table 1, this is not a pick-and-choose list. All are essential. This means that there is evidence in the DE process and results that these essential principles have been addressed in some meaningful way or, for specific contextual reasons, not incorporated explicitly. For example, let’s imagine working with a social innovator and/or funder who hates the word ‘‘complexity,’’ thinks it is overused jargon, so the DE process avoids explicitly using the termcomplexity but does explicitly address emergence, adaptation, and nonlinearity. Such negotiations are part of contextual sensitivity and adaptability and part of the essential DE learning process and should be reported.

더욱이, 필수적인 원칙들은 상호 연관되어 있고 상호 보강되어 있다.

Moreover, the essential principles are interrelated and mutually reinforcing.

EE(권한 부여 평가)를 반대 사례로 사용 또는 사용 안 함

Empowerment Evaluation (EE) as a Contrary Example, or Not

라벨 권한 부여를 정당화하기 위해 EE에 포함되어야 하는 것은 무엇입니까? Miller와 Campbell(2006)은 1994년부터 2005년 6월까지 발표된 47건의 "권력 평가"를 체계적으로 검토했다. 10가지 역량 강화 원칙은 (1) 개선, (2) 지역사회 소유, (3) 포함, (4) 민주 참여, (5) 사회 정의, (6) 공동체 지식, (7) 증거 기반 전략, (8) 역량 강화, (9) 조직 학습 및 (10) 책임과 같다.

What must be included in an EE to justify the label empowerment? Miller and Campbell (2006) systematically examined 47 evaluations labeled ‘‘empowerment evaluation’’ published from 1994 through June 2005. The 10 empowerment principles are as follows: (1) improvement, (2) community ownership, (3) inclusion, (4) democratic participation, (5) social justice, (6) community knowledge, (7) evidence-based strategies, (8) capacity building, (9) organizational learning, and (10) accountability.

아, 하지만 그 마지막 삽입구의 해명이 문제의 핵심을 찌릅니다. 필수 파트 말이다. 필수란: ''절대적으로 필요한 것'' (온라인 사전, 2015) 필수적인 것은 절대 언급되지 않는다. 그와는 정반대로, (필수가 아니라) [선택]인 것들이 제공됩니다. 고를 수 있는 것이다. "제스탈트 또는 그것을 작동시키는 전체 포장"이라고 가정되는 것은 결국 본질이 없기 때문에 덧없는 것이다.

Ah, but that last parenthetical clarification gets to the heart of the matter. Essential parts. Essential: ‘‘a thing that is absolutely necessary’’ (Online dictionary, 2015). What is essential is never stated. Quite the contrary, a menu of options is offered. Pick-and-choose. The supposed ‘‘gestalt or whole package that makes it work’’ is ultimately ephemeral because the essence is absent.

내가 느끼는 바는, 포괄적이고, 반응적이고, 융통성 있게 되기 위한 노력의 일환으로, EE 이론가들과 옹호자들은 많은 가능한 재료들로 구성된 [은유적인 과일 샐러드]를 만들어냈다는 것입니다. 그것들 중 필수적인 것은 아니지만, 몇몇 재료들이 과일인 한, 그것은 과일 샐러드라고 불릴 수 있다. 그렇긴 하지만, 페터맨(2005)은 더 많은 권한 부여 원칙을 통합하는 것이 더 적은 것보다 낫다고 언급했습니다.

My sense is that in an effort to be inclusive, responsive, and flexible, EE theorists and advocates have created a metaphorical fruit salad of many possible ingredients, none of which is essential, but as long as some of the ingredients are fruit, it can be called a fruit salad. That said, Fetterman (2005) has stated that incorporation of more empowerment principles is better than fewer.

일반적으로 원칙의 수는 시너지 효과이기 때문에 원칙의 개수에 따라 [권한 강화 평가]의 질이 증가한다. 이상적으로는 각 원칙이 어느 정도 시행되어야 한다. 그러나 각 권한 부여 평가에서 특정 원칙이 다른 원칙보다 더 우세할 것이다. 지배하는 원칙은 평가의 지역적 맥락과 목적과 관련이 있을 것이다. 주어진 시간이나 프로젝트에 대해 모든 원칙이 동일하게 채택되는 것은 아니다(9페이지).

As a general rule, the quality [of an empowerment evaluation] increases as the number of principles are applied, because they are synergistic. Ideally each of the principles should be enforced at some level. However, specific principles will be more dominant than others in each empowerment evaluation. The principles that dominate will be related to the local context and purpose of evaluation. Not all principles will be adopted equally at any given time or for any given project. (p. 9)

DE 무결성 평가 과제에 대한 민감한 개념 접근법의 정교화

Elaboration of a Sensitizing Concept Approach to the Challenge of Evaluating DE Integrity

[개념을 조작화하는 것]은 [그것을 구체적인 척도로 변역하는 것]이다. 이것은 경험적 연구에 대한 잘 확립된 학문적 접근방법이다. 그러나 혁신, 복잡성, 출현 및 적응과 같은 개념은 [정량적 연구]의 전통이 아니라, [정성적 연구]의 조사 전통에서 민감한 개념sensitizing concept으로 가장 잘 취급된다(Patton, 2015a). [민감화sensitizing] 대 [개념 조작화]의 구분은 평가 접근법에서 [충실성과 무결성 문제]에 중요하기 때문에, 이러한 구별과 DE의 필수 원칙을 다루기 위한 의미를 설명하는 것이 유용할 수 있다. (이것은 민감화 개념으로서 프로세스 사용에 대한 나의 이전 논의를 재현한다; Patton, 2007.)

Operationalizing a concept involves translating it into concrete measures. This constitutes a wellestablished, scholarly approach to empirical inquiry. However, concepts like innovation, complexity, emergence, and adaptation are best treated as sensitizing concepts in the tradition of qualitative inquiry, not as operational concepts in the tradition of quantitative research (Patton, 2015a). Since the distinction between sensitizing versus operational concepts is critical to the issue of fidelity and integrity in evaluation approaches, it may be useful to explicate this distinction and its implications for dealing with the essential principles of DE. (This reprises my previous discussion of process use as a sensitizing concept; Patton, 2007.)

세 가지 문제가 조작화를 방해합니다.

Three problems plague operationalization.

- 첫째, "underdetermination"은 "시험 가능한 명제가 이론을 완전히 적용할 수 있는지"을 결정하는 문제이다(Williams, 2004, 페이지 769). 노숙, 자급자족, 탄력성, 소외감 등 사회적 맥락에 따라 다양한 의미를 갖는 개념들이 대표적이다. 예를 들어, "홈리스"가 의미하는 것은 역사적으로나 사회적으로 다릅니다.

- 두 번째 문제는 객관적인 학문적 정의가 어떤 것을 경험하는 사람들의 주관적 정의를 포착하지 못할 수도 있다는 것입니다. 빈곤이 그 예입니다. 한 사람이 가난하다고 여기는 것, 다른 사람은 꽤 괜찮은 삶이라고 볼 수도 있다. '빈곤 완화' 사명을 띠고 있는 노스웨스트 지역 재단은 결과 평가를 위해 빈곤을 운영하기 위해 고군분투하고 있다. 게다가, 그들은 아이오와와 몬태나와 같은 주에서 가난에 대한 모든 공식적인 정의에 맞는 꽤 가난한 많은 사람들이 스스로를 가난하다고 보지도 않고, 더구나 "빈곤"이라고 보지도 않는다는 것을 발견했다.

- 세 번째는 핵심 개념을 어떻게 정의하고 운영해야 하는지에 대한 사회과학자들의 의견 불일치 문제입니다. 예를 들어, 지속가능성은 건강한 시스템의 지속 또는 시스템의 적응 능력으로 정의할 수 있습니다.

- First, ‘‘underdetermination’’ is the problem of determining ‘‘if testable propositions fully operationalize a theory’’ (Williams, 2004, p. 769). Examples include concepts such as homelessness, self-sufficiency, resilience, and alienation that have variable meanings according to the social context. For example, what ‘‘homeless’’ means varies historically and sociologically.

- A second problem is that objective scholarly definitions may not capture the subjective definition of those who experience something. Poverty offers an example: What one person considers poverty, another may viewas a pretty decent life. The Northwest Area Foundation, which has as its mission ‘‘poverty alleviation,’’ has struggled trying to operationalize poverty for outcomes evaluation; moreover, they found that many quite poor people in states such as Iowa and Montana, who fit every official definition of being in poverty, do not even see themselves as poor, much less ‘‘in poverty.’’

- Third is the problem of disagreement among social scientists about how to define and operationalize key concepts. Sustainability, for example, can be defined as continuation of a healthy system or the capacity of a system to adapt (Gunderson & Holling, 2002, pp. 27–29; Patton, 2011, p. 199).

두 번째와 세 번째 문제는 한 연구자가 두 번째 문제를 해결하기 위해 국지적이고 상황별적인 정의를 사용할 수 있다는 점에서 관련이 있지만, 이 상황별 정의는 다른 맥락에서 탐구하는 다른 연구자들이 사용하는 정의와 다르고 상충할 가능성이 있다. 조작화 문제를 해결하는 한 가지 방법은 [복잡성과 혁신을 민감한 개념으로 간주]하고 [표준화되고 보편적인 조작화된 정의의 탐색을 포기하는 것]입니다. 이는 모든 특정 DE가 평가의 목적과 목적에 맞는 정의를 생성한다는 것을 의미합니다.

The second and third problems are related in that one researcher may use a local and context-specific definition to solve the second problem, but this context-specific definition is likely to be different from and conflict with the definition used by other researchers inquiring in other contexts. One way to address problems of operationalization is to treat complexity and innovation as sensitizing concepts and abandon the search for a standardized and universal operational definition. This means that any specific DE would generate a definition that fits the specific context for and purpose of the evaluation.

사회학자 허버트 블루머(1954년)는 현장 연구를 지향하기 위해 "sensitizing concept"의 아이디어를 창안한 것으로 인정받고 있다.

- [민감화 개념]에는 피해자, 스트레스, 낙인 및 학습 조직과 같은 개념이 포함되며, 이 개념은 특정 장소 또는 상황에서 어떻게 의미가 부여되는지 질문할 때 연구에 초기 방향을 제공할 수 있습니다(Schwandt, 2001).

- 관찰자는 [민감화 개념]과 [사회 경험의 실제 세계] 사이를 이동하며 개념에 형태와 실체를 부여하고 개념의 다양한 표현으로 개념 체계를 정교하게 만듭니다.

- 이러한 접근방식은 사회적 현상의 구체적인 발현은 시간, 공간, 상황에 따라 다르지만, 민감화 개념은 패턴과 의미를 더 잘 이해하기 위해 이러한 발현을 포착, 보유 및 검사하는 용기라는 것을 인식합니다.

Sociologist Herbert Blumer (1954) is credited with originating the idea of ‘‘sensitizing concept’’ to orient fieldwork.

- Sensitizing concepts include notions like victim, stress, stigma, and learning organization that can provide some initial direction to a study as one inquires into howthe concept is given meaning in a particular place or set of circumstances (Schwandt, 2001).

- The observer moves between the sensitizing concept and the real world of social experience, giving shape and substance to the concept and elaborating the conceptual framework with varied manifestations of the concept.

- Such an approach recognizes that although the specific manifestations of social phenomena vary by time, space, and circumstance, the sensitizing concept is a container for capturing, holding, and examining these manifestations to better understand patterns and implications.

평가자는 일반적으로 [상황에 대한 이해에 inform하기 위해] 민감화 개념을 사용한다. [맥락context]라는 개념을 생각해보세요. 모든 평가는 어떤 맥락에서든 설계되며, 우리는 맥락을 고려하고, 상황에 민감하며, 맥락의 변화에 주의해야 합니다. 하지만 맥락이란 무엇인가? System thinkers에 따르면, 시스템 경계는 본질적으로 자의적이라고 주장하며, 따라서 [평가의 즉각적인 범위 안에 있는 것]과 [그 주변 맥락 안에 있는 것]을 정의하는 것도 자의적임은 불가피하지만, 그 구별은 여전히 유용하다. 실제로 평가의 즉각적인 행동 영역과 포괄적 맥락에 있는 것을 결정하는 데 있어 의도적인 것은 조명하는 연습이 될 수 있으며, 이해관계자들의 관점이 크게 다를 수 있다. 그런 의미에서 '맥락'이라는 개념은 sensitizing concept이다.

Evaluators commonly use sensitizing concepts to inform their understanding of a situation. Consider the notion of context. Any particular evaluation is designed within some context, and we are admonished to take context into account, be sensitive to context, and watch out for changes in context. But what is context? Systems thinkers posit that system boundaries are inherently arbitrary, so defining what is within the immediate scope of an evaluation versus what is within its surrounding context is inevitably arbitrary, but the distinction is still useful. Indeed, being intentional about deciding what is in the immediate realm of action of an evaluation and what is in the enveloping context can be an illuminating exercise—and stakeholders might well differ in their perspectives. In that sense, the idea of context is a sensitizing concept.

고추론 대 저추론 변수 및 개념

High-Inference Versus Low-Inference Variables and Concepts

[원칙]을 민감화 개념으로 생각하고 이해하는 또 다른 방법은 원칙을 "고-추론 개념"으로 처리하는 것이다. 고-추론과 저-추론 변수의 구별은 고등교육의 교사 효과 연구(Rosenshine & Furst, 1971)에서 비롯되었다.2

Another way to think about and understand principles as sensitizing concepts is to treat them as ‘‘high-inference concepts.’’ The distinction between high-inference and low-inference variables originated in studies of teacher effectiveness research in higher education (Rosenshine & Furst, 1971).2

[높은 추론 교사]의 특성은 "명확히 설명"하는 것과 같이 추상적이거나 좋은 관계를 가지고 있다. 반면, [낮은 추론 교사]의 특성은 특이적이고 구체적인 교육행동입니다. 예를 들어 "한 주제에서 다음 주제로의 전환을 설명합니다." '개별 학생 이름 표시' (후자는) 관찰자의 입장에서 추론이나 판단을 거의 하지 않고 기록될 수 있습니다.

High inference teacher characteristics are global, abstract such as ‘‘explains clearly’’ or has good rapport, while low-inference characteristics are specific, concrete teaching behaviors, such as ‘‘signals the transition fromone topic to the next,’’ and ‘‘addresses individual students by name,’’ that can be recorded with very little inference or judgment on the part of a classroom observer. (Murray, 2007, pp. 146–147).

교사 효율성에 대한 연구의 추진력은 관찰자 측의 상당한 판단이 필요한 [높은 추론 변수]와, 반대로 최소 해석이 필요한 [낮은 추론 변수]를 강조하는 것이었다(Cruickshank & Kennedy, 1986). 반대로 [원칙에 초점을 맞춘 실무]는 필연적으로 [높은 추론]이다. 명시적 민감도 정도를 다루는 것은 특정 평가 접근법을 따르고 있다는 주장을 평가할 때 충실도와 무결성을 평가하는 높은 추론 접근법이다.

The thrust of the research on teacher effectiveness has been to emphasize low-inference variables that require minimuminterpretation as opposed to high-inference variables that require considerable judgment on the part of the observer (Cruickshank & Kennedy, 1986). In contrast, principles-focused practice is necessarily high inference. Addressing degree of manifest sensitivity is a high-inference approach to assessing fidelity and integrity when assessing claims that a particular evaluation approach is being followed.

강체 및 비강체 지정자

Rigid and Nonrigid Designators

언어철학자들은 서로 다른 목적을 위한 언어의 다양한 사용에 상당한 관심을 쏟았다. 한 가지 중요한 구별은 강성 지정자와 비강성 지정자 간이다.

- 경직 지정자는 매우 구체적이고, 맥락에 무관하며, 조작적 정의 또는 규칙에 해당합니다.

- 비경직 지정자는 용어의 해석이 말하는 사람이 의도하는 상황과 목적을 고려해야 하는 의미에 대한 맥락에 의존한다.

Philosophers of language have devoted considerable attention to different uses of language for different purposes. One critical distinction is between rigid and nonrigid designators.

- A rigid designator is highly specific and context free, the equivalent of an operational definition or rule.

- A nonrigid designator depends uponcontext for meaningsuchthat the interpretationof a termmust take intoaccount the situation and the purpose intended by the person speaking.

비강성 지정자는 다음에 적용됩니다. "단어만으로는 얻을 수 없는 의미의 부를 분석하는, 실용주의의 지저분한 사회-사회학적 세계. 그러나 말이 만들어지는 맥락으로부터, 중요한 것은, 연설자의 의도를 포함하여, 연설자는 자신의 마음에서 벗어나 청중들의 마음 속으로 더 나아가게 된다."

Nonrigid designators apply to the ‘‘messy social-psychological world of pragmatics, analyzing the wealth of meaning that must be gleaned not from the words alone but fromthe context inwhichthe words are produced, including, importantly, the speaker’s intentions in uttering them, which furthermore take the speaker outside of his own mind and intothe mind of his audience’’ (Goldstein, 2015, p. 50).

경직성 대 비경직성 지정자 및 절대성 대 실용성(맥락적) 정의와 의미는 시대와 상황 변화에 대한 해석의 문맥적 적응 대 엄격한 헌법 구성주의(원래의 의도에 초점을 맞춘다)의 영역으로 우리를 안내한다.

[Rigid versus nonrigid designators] and [absolute versus pragmatic (contextual) definitions and meanings] take us into the territory of [strict constitutional constructionism (focusing on original intent) versus contextual adaptation of interpretation to changing times and situations].

충실도, 무결성 및 매니페스트 민감도에 대한 위협

Threats to Fidelity, Integrity, and Manifest Sensitivity

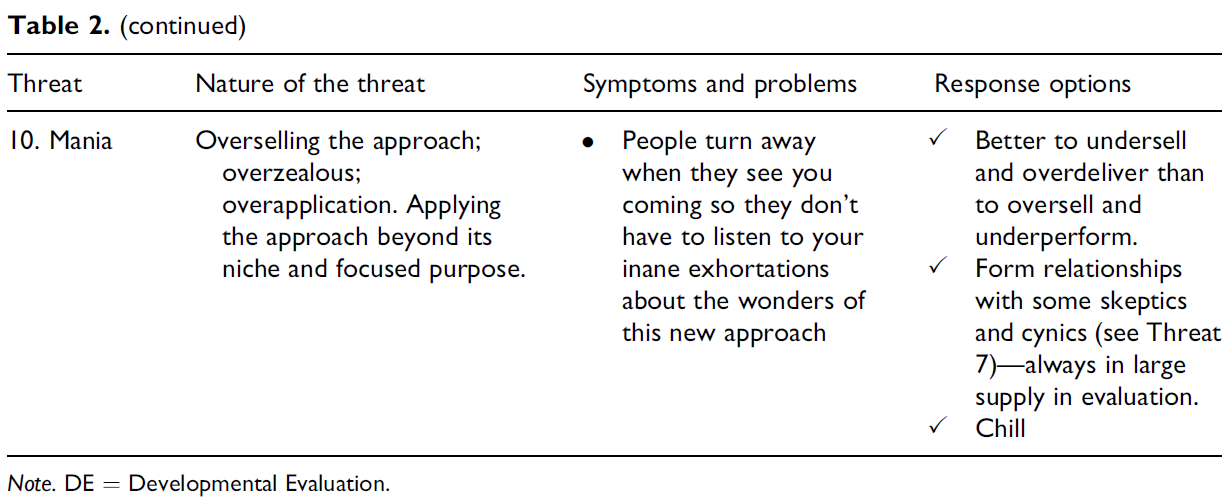

평가 접근법에 대한 충실도를 곰곰이 생각하고 평가를 '발전적developmental'이라고 부르는 데 있어 무엇이 integrity을 구성하는지를 성찰하면서 fidelity와 integrity에 어떤 위협이 나타날 수 있는지 생각하게 되었다. 저는 간통, 금욕, 처녀성, 발기불능, 콤플렉서스 방해, 이혼, 평가 전염병, 실적 부진, 경계 관리 불량, 조증 등 10가지 위협을 확인했습니다. 표 2는 위협을 제시하고 일반적인 증상을 식별합니다. 이것들은 심각한 위협이고, 잠재적으로 구석구석에 숨어있을 수 있습니다. 두려워하라. 매우 두려워하라. 하지만 또한 준비하세요. 표 2는 위협에 대응하기 위한 전략을 제공합니다.

Pondering fidelity to evaluation approaches and reflecting on what constitutes integrity in calling an evaluation ‘‘developmental’’ have led me to consider what threats to fidelity and integrity may emerge. I have identified 10 threats: adultery, abstinence, virginity, impotence, complexus interruptus, divorce, evaluation transmitted disease, poor performance, poor boundary management, and mania. Table 2 presents the threats and identifies common symptoms. These are serious threats, potentially hiding around every corner. Be afraid. Be very afraid. But also be ready. Table 2 provides strategies for countering the threats.

결론

Conclusion

장미는 장미다 장미는 장미다. —Gertrude Stein, Sacred Emily (1913; 페이지 3)

A rose is a rose is a rose is a rose. —Gertrude Stein, Sacred Emily (1913; p. 3)

그리고 DE는 DE이고 DE는 DE입니다. 그랬다면. 하지만, 사실, 상황에 따라 다르다. 이는 8가지 필수 DE 원칙 모두가 명시적이고 효과적으로 다루어진 정도에 따라 달라진다. 그것이 이 글의 요점입니다. 평가에 ''발달적'' 또는 ''활용-중심''과 같은 라벨을 붙이는 것이 평가를 그렇게 만드는 것이 아니다. 접근법의 무결성을 판단하려면 모델의 필수 원칙에 대한 명백한 민감도의 평가가 필요하다. 끝으로, 대장내시경 검사를 예로 들며 경고하는 이야기가 왜 중요한지 설명하겠습니다.

And a DE is a DE is a DE. Would that it were so. But, actually, it depends. It depends on the extent to which all eight of the essential DE principles have been explicitly and effectively addressed. That’s the point of this article. Labeling an evaluation ‘‘developmental’’ or ‘‘utilizationfocused’’ doesn’t make it so. An assessment of manifest sensitivity to a model’s essential principles is necessary to judge the integrity of the approach. In closing, let me illustrate why this matters using colonoscopies as an example and cautionary tale.

대장내시경은 대장내시경이다. 아니면 그러한가? 변형이 있나요? 그 과정이 어떻게 이루어지느냐가 중요한가요? 대장내시경은 대장암을 일으킬 수 있는 용종을 찾아내기 위해 내시경이라고 불리는 유연한 스코프로 대장을 검사하는 것이다. 경험이 풍부한 인증받은 전문의 12명을 민간 진료로 조사한 결과, 그 중 어떤 의사들은 암으로 변할 수 있는 용종인 선종을 발견하는데 다른 사람들보다 10배나 뛰어났다고 한다. 더 효과적인 대장 내시경 검사와 덜 효과적인 대장 내시경 검사를 구분하는 한 가지 요인은 의사가 대장을 검사하는 데 드는 시간(노력 평가 포함)이었다. 속도를 늦추고 시간이 더 걸린 사람들이 용종을 더 많이 발견했다. 5분도 안 되는 시간에 수술을 마친 사람도 있고 20분 이상 걸린 사람도 있었다. 보험사들은 의사들이 얼마나 많은 시간을 보내더라도 똑같이 급여를 지급한다. 하지만 환자에게는 위험 부담이 큽니다. 매년 4백만 명 이상의 미국인들이 대장암으로부터 자신을 보호하고자 대장내시경 검사를 받는다. 매년 약 55,000명의 미국인이 사망하는 이 암은 미국에서 암 사망의 두 번째 주요 원인이다.

A colonoscopy is a colonoscopy is a colonoscopy. Or is it? Are there variations? Does it matter how the process is done? A colonoscopy is an examination of the colon with a flexible scope, called an endoscope, to find and cut out any polyps that might cause colon cancer. A study of 12 highly experienced board-certified gastroenterologists in private practice found that some were 10 times better than others at finding adenomas, the polyps that can turn into cancer. One factor distinguishing the more effective from less effective colonoscopies was the amount of time the physician spent examining the colon (which involves an effort evaluation). Those who slowed down and took more time found more polyps. Some completed the procedure in less than 5 min, and others spent 20 min or more. Insurers pay doctors the same no matter howmuch time they spend. But the stakes are high for patients. More than four million Americans a year have colonoscopies, hoping to protect themselves from colon cancer. The cancer, which kills about 55,000 Americans a year, is the secondleading cause of cancer death in the United States (Kolata, 2006a, 2006b).

What is Essential in Developmental Evaluation? On Integrity, Fidelity, Adultery, Abstinence, Impotence, Long-Term Commitment, Integrity, and Sensitivity in Implementing Evaluation Models

First Published March 22, 2016 Research Article

Abstract

Fidelity concerns the extent to which a specific evaluation sufficiently incorporates the core characteristics of the overall approach to justify labeling that evaluation by its designated name. Fidelity has traditionally meant implementing a model in exactly the same way each time following the prescribed steps and procedures. The essential principles of developmental evaluation (DE), in contrast, provide high-inference sensitizing guidance that must be interpreted and applied contextually. In lieu of operationalizing DE fidelity criteria, I suggest addressing the degree of manifest sensitivity to essential principles. Principles as sensitizing concepts replace operational rules. This means that sensitivity to essential DE principles should be explicitly and contextually manifest in both processes and outcomes, in both design and use of findings. Eight essential principles of DE are identified and explained. Finally, 10 threats to evaluation model fidelity and/or degree of manifest sensitivity are identified with ways to mitigate those threats.

Keywords

developmental evaluation, fidelity, principles, sensitizing concepts

'Articles (Medical Education) > 교육과정 개발&평가' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 역량바탕 졸업후교육: 과거, 현재, 미래 (GMS J Med Educ, 2017) (1) | 2021.11.12 |

|---|---|

| 개인, 팀, 프로그램의 교육성과 평가를 위한 기여와 귀인의 힘(Acad Med, 2020) (0) | 2021.11.07 |

| CBME의 성과 잡아내기: 요구와 도전(Med Teach, 2021) (0) | 2021.07.20 |

| 의과대학생토론포럼에서 드러난 CBME에 대한 인식(Med Educ, 2019) (0) | 2021.07.20 |

| CBME에 관한 가정과 근거의 상태: 비판적 내러티브 리뷰(Acad Med, 2021) (0) | 2021.07.20 |