보건전문직 교수개발에서 어떻게 문화가 이해되는가: 스코핑 리뷰(Acad Med, 2020)

How Culture Is Understood in Faculty Development in the Health Professions: A Scoping Review

Lerona Dana Lewis, PhD, and Yvonne Steinert, PhD

교수 개발(FD)은 보건직업 교육의 필수적인 부분이며 정부 자원이 종종 할당되는 보건 서비스 개선에 중요한 공헌자이다. FD는 보건 전문가들이 교사 및 교육자, 지도자와 관리자, 연구자와 학자로서 지식, 기술 및 행동을 향상시키기 위해 추구하는 활동을 말한다. FD 활동들은 그들이 펼쳐지는 기관의 규범, 가치, 신념, 관행뿐만 아니라 설정과 자원의 영향을 받습니다. 다른 교육활동과 마찬가지로 FD도 가치중립적이지 않다—문화를 형성하고, 문화에 의해 형성된다.

Faculty development (FD) is an integral part of health professions education and a significant contributor to the improvement of health services for which government resources are often allocated.2–4 FD refers to those activities that health professionals pursue to improve their knowledge, skills, and behaviors as teachers and educators, leaders and managers, and researchers and scholars.5 These activities are influenced by setting and resources as well as by the norms, values, beliefs, and practices of the institutions in which they unfold. Like any other type of educational activity, FD is not value free—it shapes and is shaped by culture.

문화는 의료 전문가들이 공유할 수 있는 "학습된 신념과 행동의 통합된 패턴"으로 정의되었습니다; 그것은 "생각, 의사소통 스타일, 상호작용 방법, 역할과 관계의 관점, 가치, 관행, 그리고 관습"을 포함합니다. 6 FD는 국제적으로 성장하고 있으며, 종종 서로 다른 나라에서 기관 파트너에 의해 수행되고 있습니다. 블랫과 동료7은 "세계화가 증가하는 이 시대에 의료교육의 문화 간 공유 추세는 증가하고 있다"고 말했다. 그러나 FD의 설계, 전달 및 효과가 문화의 영향을 받는 방법에 대해서는 거의 알려져 있지 않다. 우리는 또한 FD가 문화의 개념을 어떻게 직접적으로 다루는지 모른다. 문화를 중요한 요소로 식별하는 FD 모델이 몇 가지 있지만, 8-10과 많은 저자들은 FD에서 문화를 고려해야 한다고 주장하지만, 11-13 저자들이 "문화를 고려해야 한다"고 말할 때 저자들이 무엇을 의미하는지 여전히 불분명하다.

Culture has been defined as “an integrated pattern of learned beliefs and behaviors” that can be shared by health care professionals; it includes “thoughts, communication styles, ways of interacting, views of roles and relationships, values, practices, and customs.”6 FD is growing internationally, and it is often undertaken by institutional partners in different countries. As Blatt and colleagues7 said, “In this age of increasing globalization, cross-cultural sharing of medical education represents a growing trend.” However, little is known about how the design, delivery, and effectiveness of FD are influenced by culture. We also do not know how FD addresses notions of culture directly. While there are several models of FD that identify culture as a critical component,8–10 and a number of authors argue that culture should be considered in FD,11–13 it often remains unclear what authors mean when they say that we should “take culture into account.”

더욱이, 세계화가 증가하고, 국가 문화 전반에 걸친 자원의 공유로, 4,7,14,15 문화가 FD에 미치는 영향에 대한 인식이 매우 중요해졌다.

Moreover, with increasing globalization and the sharing of resources across national cultures,4,7,14,15 an awareness of the influence of culture on FD becomes critically important.

[범위 검토scopring review]는 증거를 요약하거나 매핑하거나, 필드의 폭과 깊이를 전달하거나, 복잡한 개념을 명확히 하는 데 사용될 수 있다.17 범위 검토는 특히 문화와 FD의 개념을 탐구하는 데 유용하다.

Scoping reviews can be used to summarize or map evidence, convey the breadth and depth of a field, or clarify a complex concept.17 In our opinion, a scoping review is particularly useful for exploring the notion of culture and FD.

방법 Method

Arcsey와 O'Malley, 17명은 5단계로 구성된 공통 분석 프레임워크 및 검토 프로세스를 옹호합니다.

Arksey and O’Malley,17 advocate for a common analytic framework and review process consisting of 5 stages.

1단계: 연구 질문 식별

Stage 1: Identifying the research question

우리의 중요한 검토 질문은 다음과 같았다. 보건 분야에서 문화와 FD에 대해 알려진 것은?

Our overarching review question was: What is known about culture and FD in the health professions?

2단계: 관련 연구 식별

Stage 2: Identifying relevant studies

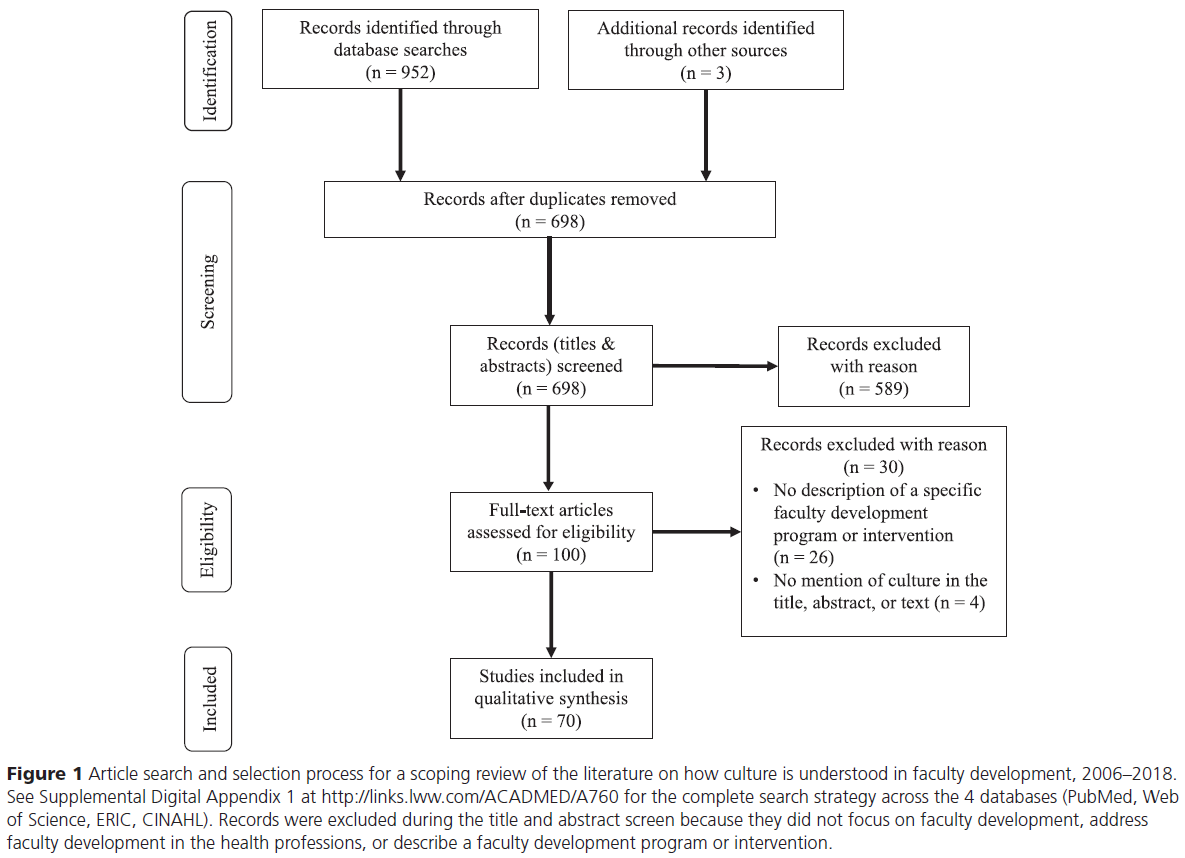

3단계: 스터디 선택

Stage 3: Study selection

4단계: 데이터 차트 작성

Stage 4: Charting the data

5단계: 결과 수집, 요약 및 보고

Stage 5: Collating, summarizing, and reporting results

우리는 서술적 주제 분석과 정성적 주제 분석을 모두 사용하여 차트화한 데이터를 요약했다.17,18 기술 분석은 설명된 위치, FD 주제 및 접근 방식, 건강 직업 및 평가 방법에 대해 보고되었다. 정성적 주제 분석을 위해, 19 우리는 저자들이 FD 프로그램 또는 개입에서 문화를 다루는 방법을 탐구했다.

We summarized the data we charted using both a descriptive and a qualitative thematic analysis.17,18 The descriptive analysis reported on the location, FD topic and approach, health profession, and evaluation methods described. For the qualitative thematic analysis,19 we explored how the authors addressed culture in their FD program or intervention.

결과

Results

기술분석

Descriptive analysis

위치.

Location.

우리는 20개국에서 온 연구들을 포함했습니다. 미국이 가장 많은 연구(n = 37, 53%)를 가지고 있었다. 그 외에도, 중국에서 온 3개의 기사가 있었다; 캐나다, 인도, 사우디아라비아, 스웨덴, 베트남, 그리고 보츠와나, 덴마크, 아이티, 이란, 일본, 몽골, 네덜란드, 카타르, 러시아, 한국, 남아프리카 공화국, 영국, 짐바브웨에서 각각 1개씩. 지역 그룹도 FD 프로그램에 대해 보고했습니다.—남아시아 5개국이 포함된 지역 그룹 4개국이, 사하라 이남 아프리카 11개국이 포함된 두 번째 그룹. 20 우리는 여러 국가의 참가자가 참여하는 FD를 "국제"로 분류했습니다.15,21–24

We included articles from 20 different countries. The United States had the most articles (n = 37, 53%). In addition, there were 3 articles from China; 2 from Canada, India, Saudi Arabia, Sweden, and Vietnam; and 1 each from Botswana, Denmark, Haiti, Iran, Japan, Mongolia, the Netherlands, Qatar, Russia, South Korea, South Africa, the United Kingdom, and Zimbabwe. Regional groups also reported on FD programs—One regional group included 5 South Asian countries4 and a second included 11 sub-Saharan African countries.20 We categorized FD involving participants from multiple countries as “international.”15,21–24

FD 주제 및 접근 방식.

FD topic and approach.

우리는 각 기사의 주요 초점을 결정하고 이러한 주제를 6개의 주요 FD 범주로 나누었다. 이 프로세스는 FD 내용 영역의 공통 분류를 통해 알려졌습니다.5 주요 콘텐츠 분야는

- 교수 및 학습(n = 30, 43%),

- 문화 역량(n = 13, 19%),

- 경력 개발(n = 13, 19%),

- 리더십(n = 5, 7%),

- 연구 및 장학(n = 6, 9%),

- 전문성과 윤리(n = 3, 4%)였다.

We determined each article’s primary focus and divided those topics into 6 major FD categories. This process was informed by a common classification of FD content areas.5 The major content areas were

- teaching and learning (n = 30, 43%),

- cultural competence (n = 13, 19%),

- career development (n = 13, 19%),

- leadership (n = 5, 7%),

- research and scholarship (n = 6, 9%), and

- professionalism and ethics (n = 3, 4%).

가장 일반적인 FD 접근 방식은 다양한 기간(2일에서 5일 교육 프로그램 및 1년 과정 등)으로 구성된 워크숍이었다. 많은 다년간의 펠로우쉽도 보고되었으며, 많은 FAIMER(국제 의료 교육 및 연구 선진화 재단) 프로그램의 일부로 보고되었다.20,21 대부분의 이니셔티브는 경험적 학습, 코칭 및 멘토링, 성찰적 실천과 같은 다양한 형식을 포함했다.

The most common FD approaches were workshops of varying duration, 2to 5-day training programs, and year-long courses. A number of multiple-year fellowships were also reported, many as part of the Foundation for Advancement of International Medical Education and Research (FAIMER) program.20,21 Most initiatives included multiple formats, such as experiential learning, coaching and mentoring, and reflective practice.

보건전문직

Health profession.

검토한 기사 중 53%(n = 37)가 다학제 보건 전문가 그룹을 위해 설계되었다. 또한 간호 분야에서는 17%(n = 12), 의학 분야에서는 16%(n = 11), 치과 분야에서는 7%(n = 5)로 나타났다.

Of the articles we reviewed, 53% (n = 37) were designed for multidisciplinary groups of health professionals. In addition, 17% (n = 12) took place in nursing, 16% (n = 11) in medicine, and 7% (n = 5) in dentistry.

평가 방법.

Evaluation methods.

62개(89%)의 기사가 평가 계획을 기술했다. 다른 개념적 모델들이 평가 과정을 안내했으며, 커크패트릭의 모델 8개 기사(11%)에 사용되었다. Chen의 프로그램 평가 모델은 1개 논문에서, Guskey의 평가 모델 다른 논문에서 기술되었다.85

Sixty-two (89%) articles described an evaluation plan. Different conceptual models guided the evaluation process, with Kirkpatrick’s model86 being used in 8 articles (11%). Chen’s program evaluation model87 was described in 1 article77 and Guskey’s evaluation model88 was described in another.85

참여자들의 문화에 대한 이해의 변화는 다문화 평가 설문지 89와 의료 전문가들 사이의 문화적 역량의 과정을 평가하기 위한 재고와 같은 심리학적 특성을 입증하는 도구를 사용하여 여러 연구에서 평가되었다.40

Changes in participants’ understanding of culture were assessed in several studies using instruments that demonstrated psychometric properties, such as the Multicultural Assessment Questionnaire89 and the Inventory for Assessing the Process of Cultural Competence among Health Care Professionals.40

정성적 주제 분석

Qualitative thematic analysis

세 가지 주요 테마가 나타났다:

- (1) 문화는 자주 언급되었지만 설명되지 않음,

- (2) 다양성 문제를 중심으로 한 문화,

- (3) 문화적 고려는 국제 FD에서 일상적으로 설명되지 않았다.

Three main themes emerged:

- (1) culture was frequently mentioned but not explicated;

- (2) culture centered on issues of diversity, aiming to promote institutional change; and

- (3) cultural consideration was not routinely described in international FD.

문화는 자주 언급되었지만 설명되지는 않았다.

Culture was frequently mentioned but not explicated.

전체 데이터 세트에 3개 기사만 문화를 정의했습니다. 전체 데이터 세트에 3개 기사만 문화를 정의했습니다. 한 기사는 문화를 "한 세대에서 다음 세대로 배우고 전승한 한 무리의 사람들이 공유하는 의미 체계이며, 문화에는 신념, 전통, 가치관, 관습, 의사소통 방식, 행동, 관행, 그리고 제도가 포함"된다고 정의했다. 이러한 문화의 개념은 게르츠의 연구에 바탕을 두고 있었다. 나머지 2개 기사도 가치관, 신념, 규범, 실천이 문화의 정의에 필수적이라고 강조했다.

Only 3 articles in the entire dataset defined culture. One article defined culture as “a system of meanings shared by a group of people learned and passed on from one generation to the next. Culture includes beliefs, traditions, values, customs, communication styles, behaviors, practices, and institutions.”38 This conception of culture was based on Geertz’s work.91 The other 2 articles9,40 also underscored that values, beliefs, norms, and practices were integral to the definition of culture.

동시에, 문화라는 용어는 종종 다른 단어들과 함께 사용되었다. 예를 들어 '문화간호', '문화간호', '문화간호', '문화적 패권', '문화간호', '문화간호', '문화간호', '문화적 패권', '문화적 인식' 등의 문구가 흔했다. 다른 일반적인 문구들은 "학문의 문화," "학습의 문화," 그리고 "의학의 문화"였다.

At the same time, the term culture was often used in conjunction with other words. For instance, phrases such as “institutional culture,” “organizational culture,” “physician culture,” “college culture,” “teaching culture,” and “research culture” were common, as were “cross-cultural care,” “sociocultural competence,” “cultural diversity,” “cultural hegemony,” and “cultural awareness.” Other common phrases were “culture of scholarship,” “culture of learning,” and “culture of medicine.”

다른 방식으로, 문화라는 용어는 [저자와 독자 사이에 공유된 의미를 가정한 개념]의 "잡동사니grab bag"을 나타내는 것처럼 보였다. 예를 들어, Behar Horenstein과 동료 75의 글에서 "대학 문화"의 의미를 비판적으로 추궁하는 것은 가정된 공유된 의미의 문제성을 드러낸다.

In different ways, the term culture appeared to represent a “grab bag” of concepts for which a shared meaning was assumed between authors and readers. For example, critically interrogating the meaning of “college culture” in an article by BeharHorenstein and colleagues75 revealed the problematic nature of assumed shared meanings.

문화는 제도적 변화를 촉진하는 것을 목표로 다양성 문제에 초점을 맞췄다.

Culture centered on issues of diversity, aiming to promote institutional change.

다양성에 초점을 맞춘 기사에서, FD 프로그램이나 활동의 명시된 목표는

- (1) 환자의 다양성에 초점을 맞춤으로써 의료 관행을 변화시키는 것이었다. (보통 문화적 역량의 중추 아래),

- (2) 과소대표된 교직원과 함께 작업함으로서 교수진의 구성을 변화시키는 것이었다. FD).

In articles focusing on diversity, the stated objectives of the FD program or activity were to change

- (1) health care practices by focusing on patient diversity (usually under the rubric of cultural competence) or

- (2) the composition of the faculty by working with underrepresented faculty members (often under the rubric of under represented minority FD).

13개 기사에서 [문화 역량에 초점을 맞춘 FD 이니셔티브]를 기술했는데, 문화적 역량은 "임상치료의 문화적 구성요소에 참여하기 위해 필요한 지식, 기술 및 인식"으로 정의할 수 있다.38 이들 프로그램의 대부분은 교직원들에게 교양간 환경에서 학습자들이 효과적으로 일할 수 있도록 지식과 기술을 제공하는 것을 목표로 했다. 또한 여러 기사들은 FD 프로그램에서 종종 명시적으로 다루지 않았던 과정인 [개인적 가정, 편견 및 사회적 불평등의 성찰과 조사]라고 기술된 [비판적 의식critical consciousness]의 중요성을 강조했다.

Thirteen articles described FD initiatives focusing on cultural competence, which can be defined as the “knowledge, skills, and awareness required for attending to cultural components of clinical care.”38 The majority of these programs aimed to give faculty members the knowledge and skills to help learners work effectively in cross-cultural settings.15,38–47,49 Several articles also highlighted the importance of critical consciousness, described as reflection and examination of personal assumptions, biases, and social inequalities,43 a process that was often not addressed explicitly in FD programs.46,47

문화적 역량을 위한 FD는 보통 그 자체로 독립적stand-alone 프로그램으로 제공되었다. 그러나, 3개의 기사에서 기술된 FD 활동은 특정 과정과 연결되어 있었다. 41, 46, 47개의 여러 연구는 소규모 집단 사례 연구와 반사적 연습을 포함한 문화적 민감성을 촉진하기 위한 특정 [교육 및 학습 전략]을 강조했다. 38,43 흥미롭게도, 이 기사들 중 한 가지를 제외한 모든 것이 북미에서 왔다.

FD for cultural competence was usually offered as a stand-alone program. However, in 3 articles, the FD activities described were linked to specific courses.41,46,47 Several studies45–47 highlighted specific teaching and learning strategies to promote cultural sensitivity, including small group case studies and reflective exercises.38,43 Interestingly, all but one of these articles came from North America.

[진로개발]에 초점을 맞춘 13개 기사 중 7개 기사는 교직원의 다양성을 높이고 저평가된 교직원의 학업성취도를 보장하기 위한 시책을 기술하였다.

Seven of the 13 articles focusing on career development described initiatives to increase the diversity of faculty members and ensure the academic success of underrepresented faculty members.9,28,30,31,33,34,37

전반적으로, 교수진의 다양성을 증가시키기 위한 FD 프로그램은 성공적인 것으로 간주되었지만, 미국 밖에서는 그러한 프로그램이 보고되지 않았다.

Overall, FD programs to increase faculty diversity were considered successful, though no such programs were reported outside the United States.

문화적 고려는 국제 FD에서 일상적으로 설명되지 않았다.

Cultural consideration was not routinely described in international FD.

24개의 기사는 국제 FD 프로그램에 대해 기술했다.

- 일부는 한 국가(예: 미국)에서 다른 국가(예: 중국, 러시아 또는 스웨덴)로 FD 프로그램 또는 활동을 옮겼으며,

- 다른 일부는 내용 또는 프로세스를 구체적으로 변경하여, 기존의 FD 프로그램을 채택했으며,

- 일부는 "파트너십"으로 설명되었다.20, 21,61

Twentyfour articles described international FD programs.

- Some transferred an FD program or activity from one country (e.g., the United States) to another (e.g., China, Russia, or Sweden)62,69,71;

- others adapted known FD programs50,68,70 by making specific changes to the content or process; and

- some were described as “partnerships.”20,21,61

또한 이러한 기사 중 약 50%에서 [국가적 맥락 또는 문화적 규범과 신념의 중요성]을 인정하였다. 그러나 단지 14(20%)에서만 [문화적 차이를 수용하기 위해 만들어진 특정 변화나 적응]을 기술했으며, 그 중 오직 하나의 프로그램만이 [문화적 관련성을 평가]하였다.50

Moreover, although close to 50% of these articles acknowledged the importance of national contexts or cultural norms and beliefs, only 14 (20%) described specific changes or adaptations made to accommodate cultural differences, of which only 1 program evaluated for cultural relevance.50

몇 가지 프로그램이 미국에서 다른 나라(예: 스탠포드 FD 모델)로 옮겨졌으며, 이 때 프로그램이 특별한 수정이나 적응 없이 진행되었다. 한 예로, Wong과 Fang62는 미국에서 중국으로 FD 프로그램을 이전하는 것이 성공적이었으며, 이는 미국과 중국의 의과대학 제도 사이의 유사성 때문에 문화적 적응이 불필요하게 되었다고 주장했다. 또 다른 시책에서 왕과 아기셰바69는 "의료교사에게 존재하는 교육적 도전은 제도적, 문화적 경계를 모두 초월했다"며 문화적 수용cultural accommodation이 불필요하다고 봤다. 스웨덴에서는 [스웨덴과 미국의 의과대학 시스템 사이의 "근접성closeness"]이 FD 프로그램의 성공적인 이전을 가능하게 하는 것으로 간주되었다.71

Several programs were transferred from the United States to another country (e.g., the Stanford FD model),71 without specific modifications or adaptations. In one instance, Wong and Fang62 argued that the transfer of an FD program from the United States to China was successful because of similarities between the medical school system in the United States and China, which rendered cultural adaptations unnecessary. In another initiative, Wong and Agisheva69 observed that “the educational challenges that exist for medical teachers transcended both institutional and cultural boundaries” and that cultural accommodation was unnecessary. In Sweden, the “closeness” between the Swedish and U.S. medical school systems was viewed as enabling the successful transfer of an FD program.71

FD 프로그램에 대한 적응이 이루어졌을 때, 그들은 지역적 상황에 대응하기 위한 많은 방법과 전략을 포함했다.

- 아시아의 문화적 감수성을 높이기 위한 교육 설계 원칙 통합4

- 대한민국에서 근무일수 단축에 대한 현지 기대치를 수용하기 위한 프로그램 기간 단축70

- 사우디 아라비아의 종교적 차이를 수용하기 위해 전문성 강화53;

- 사우디아라비아, 53개 보츠와나, 52개 카타르, 68개 중국, 7개 및 남아프리카 공화국의 현지 문화를 반영하기 위한 맞춤형 사례 및 역할극 시나리오 50;

- 중국 및 러시아에서 과정 자료 및 전체 프레젠테이션 번역, 7,69 및

- 남아프리카에서 이메일 사용과 아이티에서 온라인 설문 조사의 사용에 영향을 미친 열악한 통신 네트워크에 적응하는 것.

When adaptations to FD programs were made, they included a number of methods and strategies to respond to the local context:

- incorporating educational design principles to enhance cultural sensitivity in Asia4;

- shortening the length of a program to accommodate local expectations of shorter work days in South Korea70;

- reframing professionalism to accommodate religious differences in Saudi Arabia53;

- tailoring case vignettes and role-playing scenarios to reflect local cultures in Saudi Arabia,53 Botswana,52 Qatar,68 China,7 and South Africa50;

- translating course materials and plenary presentations in China and Russia7,69; and

- adapting to poor telecommunications networks, which affected the use of email in South Africa50 and the use of online surveys in Haiti.63

또한 국제 교육자들이 지역적 맥락에 대한 준비되지 않은 느낌을 설명하면서 문화의 영향을 인정하였다. 예를 들어

- 베트남의 FD 프로그램 운영자들은 현지 참가자들이 질병과 치료를 이해하는 방식, 간호사와 의사 간의 계층적 관계, 간호사가 수행하는 업무의 차이, 종교적 신념, 환자의 기대 등에 대해 준비되지 않았다고 보고했다.84

- 다른 이니셔티브에서 중국에서는 가족 권리가 개별 환자 권리보다 더 중요하게 여겨졌으며, 그 결과 서구의 촉진자들은 의사와 환자의 의사소통에 초점을 맞춘 역할극에서 비롯되는 논의를 정확하게 예상하지 못했다.7

The impact of culture was also acknowledged when international educators described feeling unprepared for local contexts. For example,

- facilitators of an FD program in Vietnam reported that they were unprepared for the ways in which the local participants understood illness and treatment, the hierarchical relationship between nurses and doctors, the difference in tasks performed by nurses, religious beliefs, and the expectations of patients.84

- In another initiative in China, it was noted that family rights were considered more important than individual patient rights, and, as a result, facilitators from the West did not accurately anticipate the discussions that resulted during a role-play which focused on doctor–patient communication.7

언어는 분명히 국제 FD에서 또 다른 중요한 고려사항이다. 그러나, 단지 몇몇 기사만이 언어의 차이가 어떻게 해결되었는지를 기술하였다. 7,62,69 FD는 지역 언어가 다른 경우에도 영어로 수행되었다. 그러나 참가자들의 영어 능력은 다양하여 일부 FD 프로그램의 성공에 영향을 미쳤다. 4,70 게다가 FD 문서와 자원 자료의 번역은 표준 관행이 아니었다.

Language is clearly another important consideration in international FD; however, only a few articles described how language differences were addressed.7,62,69 FD was most often conducted in English, even when the local language was different. However, participants’ fluency in English varied, affecting the success of some FD programs.4,70 In addition, the translation of FD documents and resource materials was not a standard practice.

더욱이, 문서가 번역되었을 때에도, 언어는 때때로 한계나 장벽으로 간주되었다. 4,62,70 일부의 경우, 동일한 단어가 로컬 언어에는 존재하지 않았다. 또한, 일부 워크숍에서는 번역의 충실도가 문제였으며, 1개의 경우 참가자와 진행자 간의 "소통 단절"으로 이어졌다.84

Moreover, even when documents were translated, language was sometimes considered a limitation or barrier.4,62,70 In some instances, equivalent words did not exist in the local language. As well, during some workshops, the fidelity of the translation was an issue and, in 1 case, led to a “breakdown in communication” between participants and facilitators.84

하지만,

- "큰 그림 번역"(즉, 청중에게 주기적인 요약을 제공하는 번역가) 및

- 속삭임 번역(즉, 번역가가 발표자에게 속삭인다).

등은 프로그램에서 참가자 사이의 용기와 상호작용을 번역하는 효과적인 수단임이 입증되었고 다른 프로그램에서 평가를 용이하게 했다. 실로, [문화 통역사의 사용]은 FD 프로그램의 성공에 기여하는 것으로 보고되었다. 왜냐하면 언어와 문화적인 맥락을 모두 해석했기 때문이다.63 However, “big picture translation” (i.e., a translator providing periodic summaries to the audience) and whisper translation (i.e., a translator whispering back to the presenter) proved to be effective means of translating plenaries and interactions among participants in one program7 and facilitated evaluation in another.63 In fact, the use of cultural interpreters was reported to contribute to the success of FD programs because these individuals interpreted both the language and cultural contexts.63

예를 들어, 사하라 이남 아프리카의 프로그램 참가자들은 자국의 "학술적 문화"가 열악함에 대해 말했고, 그들의 FAIMER 경험이 그들이 국내에서 학술활동 개발을 촉진하는 문화를 구축하는 데 도움이 되었다고 언급했다.

For example, program participants in sub-Saharan Africa spoke of a poorly developed “culture of scholarship” in their own countries and noted that their FAIMER experiences helped them to build a culture that would promote the development of scholarship at home.

국제 FD 이니셔티브의 형식은 종종 1~2일에서 2주까지 또는 종단적 성격을 갖는 것으로 기술되었다. 50,67,84 국제 의료 교육자 교환은 다른 나라에 있는 5개 의과대학 중 1개 학교에서 몇 주를 보낸 독특한 형식이었다.24

The format of international FD initiatives was often described as workshop based, ranging from 1 or 2 days to 2 weeks, or as longitudinal in nature.50,67,84 The International Medical Educators Exchange was a unique format in which medical educators spent several weeks in 1 of 5 medical schools in another country.24

고찰

Discussion

1924년, "문화가 교육과 무슨 관계가 있는가?"라는 그의 질문에 대한 대답으로. 러시모어는 이렇게 썼다.

"문화는 해석과 의미와 가치, 다른 것들과 지식의 다른 분야와의 관계를 암시한다."

In 1924, in response to his own question “What has culture to do with education?” Rushmore wrote that

“culture implies interpretation and significance and values; relation to other things and to other branches of knowledge.”1

이 범위 지정 검토는 Rushmore의 질문의 관련성을 강조했으며 문화와 FD에 대한 이해에서 핵심 개념, 결과 및 차이를 식별하는 데 도움이 되었습니다. 특히, 우리는 2006년 이후 이 주제에 명시적으로 초점을 맞춘 문헌은 소수에 불과하다는 것을 발견했다. 우리는 또한 대부분의 기사가 문화를 정의하지 않는다는 것을 발견했다.

This scoping review highlighted the relevance of Rushmore’s question and helped us to identify key concepts, findings, and gaps in our understanding of culture and FD. In particular, we found that only a small body of literature has focused on this topic explicitly since 2006. We also discovered that the majority of articles do not define culture;

문화를 정의하기

Defining culture

"내가 말할 때…"라는 제목의 흥미로운 기사에서."문화"라고 Pratt과 Schrewe92는 [의학에서 문화는 모든 것과 아무것도 아닌 것을 동시에 의미하는 "모호한 참조"가 되었다]고 지적했다. 우리의 범위 검토는 문화라는 용어가 거의 명확하게 정의되지 않는다는 개념을 뒷받침한다. 단지 3개의 기사만이 문화를 정의했고, 다른 기사에서는 문화가 "문화 인식" 또는 "학문의 문화"와 같은 다른 용어와 관련이 있는 경우, 이 용어들은 보통 설명되지 않았다. 이러한 발견은 문화의 개념과 그에 관련된 용어가 국내외 교육자들에게 동일한 의미를 전달하는지 의문을 제기한다. 그들은 또한 공동체로서, 우리는 문화라는 의미와 그 관련 용어(예: 문화 인식, 대학 문화)를 더 잘 정의하고 FD의 설계와 전달에서 문화의 어떤 측면이 중요한지 식별해야 한다고 제안한다.

In an interesting article, titled “When I Say…Culture,” Pratt and Schrewe92 noted that, in medicine, culture has come to be a “vague referent” meaning everything and nothing at the same time. Our scoping review supports the notion that the term culture is rarely defined clearly. Only 3 articles defined culture; in other articles, where culture was associated with another term such as “cultural awareness” or the “culture of scholarship,” these terms were not usually explained. These findings raise the question as to whether the notion of culture and its associated terms convey the same meaning to educators nationally and internationally. They also suggest that, as a community, we need to better define what we mean by culture and its associated terms (e.g., cultural awareness, college culture) and to identify which aspects of culture are important in the design and delivery of FD.

문화적 다양성

Cultural diversity

우리의 주제 분석에서 나타난 한 가지 주제는 나이, 민족, 인종과 같은 사회적 위치의 차이와 연계된 문화에 대한 이해였는데, 이 모든 것들은 문화적 역량을 위한 FD와 과소대표된 교수진을 위한 FD로 다루어졌다.

One theme that emerged from our thematic analysis was an understanding of culture that was linked to differences in social location, such as age, ethnicity, and race, all of which were addressed in FD for cultural competence and for underrepresented faculty members.

미국 밖의 FD는 이 imperative가 반영되지 않았다.

FD outside the United States did not reflect this imperative.

환자 모집단의 다양성을 다루는 것을 목표로 한 개입의 주된 초점은 교직원들이 학습자의 "문화적 역량"을 향상시키는 것이었다. 보건 전문가들 사이의 문화적 역량을 개선하기 위한 교육적 개입이 환자 치료 개선과 관련이 있는지를 비판적으로 평가한 체계적인 검토 결과, 문화적 역량과 개선된 환자 결과 사이에 긍정적인 관계의 증거가 제한적이라는 것을 발견했다.94 우리의 연구 결과는 [문화 역량에 대한 교수진의 이해]와 [이 내용을 그들의 교육에 통합하는 인식된 능력의 변화]를 보고하면서 문화적 역량에 대한 FD가 종종 성공적인 것으로 인식되었음을 시사한다. 그러나 학생 행동 및 환자 관리의 변화와 관련된 문화적 역량에 대한 FD의 효과에 대한 보다 엄격하고 장기적인 평가의 필요성이 여전히 중요하다.95

The primary focus of interventions that aimed to address diversity in patient populations was helping faculty members enhance the “cultural competence” of learners. A systematic review, that critically assessed whether educational interventions to improve cultural competence among health professionals were associated with improved patient care, found that there was limited evidence of a positive relationship between cultural competence and improved patient outcomes.94 Our findings suggest that FD for cultural competence was often perceived as successful, with reported changes in faculty members’ understanding of cultural competence and their perceived ability to integrate this content into their teaching.38,39,41 However, the need for more rigorous, long-term assessment of the effectiveness of FD for cultural competence that is linked to changes in student behavior and patient care remains important.95

[비판적 의식]은 학생, 환자, 그리고 과소되표된 소수 교수들 사이의 차이와 유사성에 대한 환원주의적 또는 단순한 사고방식과 반대되는 것이다. 왜냐하면 문화적 수사cultural trope를 기반으로 한 범주에 개인을 배치하는 것은 해로운 고정관념의 재확인을 초래할 수 있기 때문이다.

critical consciousness is the antithesis to reductionist or simplistic ways of thinking of the differences and similarities among students, patients, and underrepresented minority faculty, as placing individuals into categories based on cultural tropes can result in the reification of harmful stereotypes.

간문화적 역량intercultural competence은 태도, 지식, 기술에 기초하여 문화 간 상황에서 효과적이고 적절하게 상호작용하는 능력으로 정의되었다.96

- 간문화적 태도는 다른 문화를 가치 있게 여기고, 다른 문화를 이해하려는 호기심과 동기를 부여하며, 민족 중심적인 행동을 인식하는 것을 포함한다.

- 간문화적 기술에는 비판적인 자기반성, 가정에 의문을 제기하는 것, 불확실성을 참는 법을 배우는 것이 포함된다.

이러한 역량에 대한 인식과 획득을 촉진하는 것은 국내외에서 교육자의 전문성을 강화시킬 것이다.14,97

Intercultural competence has been defined as a person’s ability to interact effectively and appropriately in cross-cultural situations based on their attitudes, knowledge, and skills.96

- Intercultural attitudes include valuing other cultures, being curious and motivated to understand other cultures, and being aware of ethnocentric behaviors;

- intercultural skills include critical self-reflection, questioning assumptions, and learning to tolerate uncertainty.

Promoting an awareness and acquisition of these competencies would enrich educators’ expertise both at home and abroad.14,97

국제 FD 프로그램

International FD programs

문화의 개념과 문화의 사용 방법을 신중하게 정의해야 하는 필요성이 세계화 시대에 더욱 중요해지고 있습니다.

The need to carefully define the concept of culture—and how it is being used—becomes even more important in this era of globalization.

분명히, 국가의 차이는 FD 교육자가 자신의 프로그램을 계획, 구현 및 평가하는 방식에 영향을 미칠 수 있다.7 따라서 이 검토의 많은 이니셔티브가 지역적 맥락의 중요성을 인정했지만, 대부분은 프로그램이 지역적 요구를 충족시키는 방법 또는 문화적 영향을 수용하기 위해 어떤 수정이나 개조가 이루어졌는지에 대한 명확한 설명을 제공하지 않았다는 것이 놀랍다. 그들은 또한 프로그램의 문화적 관련성이나 지역적 맥락에 맞게 만들어진 어떤 accommodation도 평가하지 않는 것 같았다.

Clearly, national differences can influence the way that FD educators plan, implement, and evaluate their programs.7 It is surprising, therefore, that although many initiatives in this review acknowledged the importance of local contexts, most did not provide an explicit description of how their programs met local needs or what modifications or adaptations were made to accommodate cultural influences. They also did not seem to evaluate the cultural relevance of the program or any accommodations made to fit the local context.

또한 [문화를 고려하지 않음의 함의를 고려하는 것]과 [국가 문화를 필수화하거나 지나치게 단순화하지 않는 것]을 염두에 두는 것은 가치 있을 것이다. 왜냐하면 언어, 지리, 역사 또는 관행에 영향을 미치는 지역적 관습에서 발생하는 국가 내 지역적 차이가 있을 수 있기 때문이다. 그러므로 우리는 다음을 제안한다.

- 모든 국제 FD 프로그램에 정기적 니즈 평가를 포함시킨다.

- FD 활동 평가에서 문화적 관련성의 개념을 다룬다.

- 교차 문화 FD에서 학습에 대한 언어와 접근 방식의 역할을 고려하라.

It also would be worthwhile to consider the implications of not taking culture into account and to remember to not essentialize, or oversimplify, national cultures as there may be regional differences within a country arising from language, geography, history, or localized customs that influence practices. We would therefore suggest that educators

- include routine needs assessments in all international FD programs,4,50

- address the notion of cultural relevance in the evaluation of their FD activities,50 and

- consider the role of language and approaches to learning in crosscultural FD.7,50,84

이 범위 검토에서 나온 우리의 연구 결과는 채택된 프로그램, 적응된 프로그램 또는 진정한 파트너십의 세 가지 렌즈를 통해 국제 FD 프로그램을 볼 수 있음을 시사한다. 문헌과 문화적 겸손을 증진하는 관점에서 볼 때 FD 활동의 설계와 전달에 동등하게 참여하는 [파트너십 모델]이 선호된다. 그러나, 우리의 연구 결과는 몇 가지 예외를 제외하고, 국제 FD 파트너십이 주로 서구 이외의 국가로 서구 교육 프로그램을 [이전transferred했다는 것]을 강조한다. 나아가 FD 프로그램을 책임지는 교육자들은 문화적 차이에 대한 개방성, 문화적 겸손, 그리고 배운 교훈을 자신의 환경으로 되돌리고자 하는 욕망에서 시작하여 양방향 학습을 촉진하기 위해 노력해야 한다. 많은 면에서, 문화 간 역량 96에 포함된 지식, 태도 및 기술은 이러한 목표를 달성하는 데 도움이 될 수 있습니다.

Our findings from this scoping review suggest that international FD programs could be viewed through 3 lenses:

- adopted programs,

- adapted programs, or

- true partnerships.

Based on the literature, and from the viewpoint of promoting cultural humility,98,99 a partnership model, with equal participation in the design and delivery of the FD activity, is preferred. However, our findings highlight that, with a few exceptions, international FD partnerships mainly transferred Western educational programs to non-Western countries. Moving forward, educators responsible for FD programs should work to promote bidirectional learning,7 starting with an openness to cultural differences, a sense of cultural humility, and a desire to bring lessons learned back to their own setting. In many ways, the knowledge, attitudes, and skills subsumed in intercultural competence96 could help to accomplish this objective.

마지막으로, 우리가 검토한 기사에서 문화의 개념은 종종 "국가적인" 문화를 언급했다는 것을 주목하는 것이 중요하다. 전문적인 문화나 학문적인 문화에 대한 언급은 거의 없었다.

Lastly, it is important to note that the notion of culture in the articles we reviewed often referred to “national” cultures. There was little mention of professional or academic cultures, to name a few.

한계

Limitations

미래 연구

Future research

연구원들은 문화와 FD 사이의 복잡한 상호 작용을 평가하는 데 더 명시적으로 초점을 맞추어야 한다.

핵심 개념의 정의를 식별하고, 다음에 대해 연구를 시작해야한다.

- 문화와 언어가 가르침과 배움에 미치는 영향,

- 특정한 문화적 적응accommodation의 가치, 그리고

- FD 프로그램과 개입에서 문화적 관련성의 평가.

researchers should focus more explicitly on assessing the complex interactions between culture and FD, starting with identifying the definitions of key concepts and moving forward to include studying

- the influence of culture and language on teaching and learning,

- the value of specific cultural accommodations, and

- the evaluation of cultural relevance in FD programs and interventions.

결론

Conclusions

FD에서 문화적 영향을 수용하는 효과(예: 지역적 요구, 가치 및 신념 이해, 교수와 학습의 문화적 차이를 식별하고 인정, 지역 맥락과 문화에 대한 교재 맞춤화, 유연하고 대응력 있는 것)에 대한 더 많은 연구가 필요하다.

More research on the effectiveness of accommodating cultural influences in FD (e.g., understanding local needs, values, and beliefs; identifying and acknowledging cultural differences in teaching and learning; tailoring teaching materials to local contexts and culture; and being flexible and responsive) is needed.

만약 우리가 Rushmore의 질문으로 돌아가서 스스로에게 "문화가 교육과 무슨 관계가 있는가?"라고 묻는다면, 우리는 문화가 1924년처럼, 오늘날에도 관련이 있다고 말할 수 있을 것이다.

If we return to Rushmore’s question and ask ourselves “What has culture to do with education?” we could say that culture is as relevant today as it was in 1924.

Review

Acad Med

. 2020 Feb;95(2):310-319.

doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003024.

How Culture Is Understood in Faculty Development in the Health Professions: A Scoping Review

Lerona Dana Lewis 1, Yvonne Steinert

Affiliations collapse

Affiliation

-

1L.D. Lewis was postdoctoral fellow, Centre for Medical Education, Faculty of Medicine, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, at the time this work was completed. Y. Steinert is professor of family medicine and health sciences education, director of the Institute of Health Sciences Education, and the Richard and Sylvia Cruess Chair in Medical Education, Faculty of Medicine, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

-

PMID: 31599755

Abstract

Purpose: To examine the ways in which culture is conceptualized in faculty development (FD) in the health professions.

Method: The authors searched PubMed, Web of Science, ERIC, and CINAHL, as well as the reference lists of identified publications, for articles on culture and FD published between 2006 and 2018. Based on inclusion criteria developed iteratively, they screened all articles. A total of 955 articles were identified, 100 were included in the full-text screen, and 70 met the inclusion criteria. Descriptive and thematic analyses of data extracted from the included articles were conducted.

Results: The articles emanated from 20 countries; primarily focused on teaching and learning, cultural competence, and career development; and frequently included multidisciplinary groups of health professionals. Only 1 article evaluated the cultural relevance of an FD program. The thematic analysis yielded 3 main themes: culture was frequently mentioned but not explicated; culture centered on issues of diversity, aiming to promote institutional change; and cultural consideration was not routinely described in international FD.

Conclusions: Culture was frequently mentioned but rarely defined in the FD literature. In programs focused on cultural competence and career development, addressing culture was understood as a way of accounting for racial and socioeconomic disparities. In international FD programs, accommodations for cultural differences were infrequently described, despite authors acknowledging the importance of national norms, values, beliefs, and practices. In a time of increasing international collaboration, an awareness of, and sensitivity to, cultural contexts is needed.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 교수개발(Faculty Development)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 임상교사 되기: 맥락 속에서의 정체성 형성(Acad Med, 2019) (0) | 2021.02.10 |

|---|---|

| 교수개발 만다라: 이론기반 평가를 활용한 맥락, 기전, 성과 탐색(Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract, 2017) (0) | 2021.02.07 |

| 임상교육자에서 교육적 학자, 그리고 리더: HPE분야에서 커리어 개발(Clin Teach, 2020) (0) | 2021.02.07 |

| 왜 우리는 교사를 가르쳐야 하는가? 임상감독관의 학습 우선순위 확인(Adv in Health Sci Educ, 2018) (0) | 2021.02.05 |

| 걸출한 교육자 되기: 성공에 대하여 뭐라고 말하는가? (Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract, 2020) (0) | 2021.02.05 |