영국 기본의학교육에서 핵심 의사소통 커리큘럼의 합의문(Patient Educ Couns. 2018)

Consensus statement on an updated core communication curriculum for UK undergraduate medical education

Lorraine M. Noblea,*, Wesley Scott-Smithb, Bernadette O’Neillc, Helen Salisburyd, On behalf of the UK Council of Clinical Communication in Undergraduate Medical Education

1. 소개

1. Introduction

임상 커뮤니케이션은 1990년대에 학부 의학 커리큘럼에 도입되었고, 영국, 그리고 전 세계적으로 모든 의학 과정의 표준 구성요소가 되었다. 2008년, 모든 33개 영국 의과대학의 대표성을 포함하는 반복적인 협의 과정에 의해 도출된 합의문은 학부 의학 교육을 위한 임상적 의사소통을 위한 핵심 커리큘럼을 결정지었다[1].

Clinical communication was introduced into the undergraduate medical curriculum in the 1990s and has become a standard component in all medical courses in the UK, and increasingly, across the world. In 2008 a consensus statement, reached by an iterative consultative process involving representation fromall 33 UK medical schools, crystallised the core curriculum for clinical communication for undergraduate medical education [1].

의사소통의 가르침이 변해야 할 것 같지는 않다; 유전 과학의 최첨단에 있는 우리의 동료들과는 달리, 우리는 10년만에는 크게 달라질 수 없는 인간의 상호 작용에 대한 영원한 진리를 다루고 있다고 느낄지도 모른다. 아무리 의료가 바뀌어도 의료에 대한 기대는 달라지고, 의사 소통은 필연적으로 뒤따라야 한다.

It may seem unlikely that communication teaching should change; unlike our colleagues at the cutting edge of genetic science, we may feel we are dealing with eternal verities about human interactions which surely cannot vary much in a decade. However medical care does change, expectations of medical care alter and doctors’ communication must inevitably follow suit.

임상 커뮤니케이션 커리큘럼에 영향을 미치는 변화의 동인은 다음과 같이 분류할 수 있다.

The drivers of change affecting the clinical communication curriculum can be categorised as:

- 관계적

- 상황적

- 테크놀로지컬

- Relational

- Contextual

- Technological

의사와 환자의 관계는 항상 환자 중심의 치료와 환자 자율성 지원에 중점을 두고 임상 커뮤니케이션 교육의 초점이 되어 왔다. 지난 합의문 이후 광범위한 문헌을 통해 구체화된 shared decision making의 개념은 최근 대법원 판결에서 비롯된 법적 선례에 의해 표면화됐다. 이것은 당뇨병을 앓고 있는 임산부에게 출생 선택권과 그들의 가능한 이익과 위험에 관한 정보를 제공하였다[4]. 환자를 위해 결정된 판결의 결과로서, [동의]는 [합리적인 의사가 말하고 싶어하는 것]이 아니라 [합리적인 환자가 알고 싶어하는 것]에 기초하여 판단된다 [5]. 이것은 의사-환자-다이아드의 어떤 구성원이 의사소통이 효과적인지에 대한 최종 결정권자인지에 대한 오랜 믿음을 뒤집었다.

The relationship between the doctor and patient has alwaysbeen a focus of clinical communication teaching, with an emphasison patient-centred care and supporting patient autonomy. The concept of shared decision making, which has been elaborated inan extensive literature since the last consensus statement, was recently brought to the fore by a legal precedent arising from a Supreme Court ruling. This concerned the information given to apregnant patient with diabetes about birth options and their likelybenefits and risks [4]. As a consequence of the ruling, which was decided in favour of the patient, consent is now judged on the basis of what a reasonable patient wants to know, not what a reasonable doctor wants to say [5]. This has overturned long-held beliefs aboutwhich member of the doctor-patient dyad is the final arbiter ofwhether communication has been effective.

의사의 역할은 [의료 서비스를 제공할 수 있는 기술과 지식을 가진 사람들에 대한 사회적 기대를 반영하므로] 끊임없이 발전하고 있습니다 [6]. 의사와 환자가 모두 자신의 경험 분야에서 전문가라는 이전의 급진적인 생각[7]은 의료 의사결정이 이러한 의사 결정의 결과를 감수해야 하는 사람들과 함께 가장 잘 협력적으로 이루어진다는 것을 이해하는 길을 열었다.

The doctor’s role reflects societal expectations of those with the skills and knowledge to provide medical care and thus isconstantly evolving [6]. The previously radical idea that thedoctor and the patient are both experts in their own areas of experience [7] has paved the way for an understanding that healthcare decisions are best made collaboratively with the people who have to live with the consequences of those decisions

이는 2010년 영국 정부의 백서에 반영되었는데, 그는 의료에서 공유 의사 결정이 표준이 될 것이며 환자들이 '나 없이는 나에 대한 결정이 없을 것'을 기대할 수 있다고 강조하였다[8].

This was reflected in the UK Government’s White Paper in 2010, which emphasised that shared decision making would become the normin medical care and that patients could expect ‘no decision about me without me’ [8].

의사의 역할이 [환자가 내릴 결정의 근거가 될 '정보에 입각한 선호'를 개발하는 데 있어 환자를 지원하는 것]이라는 개념은 [9] 의사가 [환자가 단순히 '준수comply'할 것으로 예상되는 조언을 제공]한다는 관례를 점차 대체하고 있다. 자신의 의료에 대한 의사 결정에 있어 환자의 중심적 역할은 영국 국가 지침[10]에서 계속 강조되고 있다 [11]. 의사-환자 관계가 시간이 지남에 따라 어떻게 계속 변화하고 있는지에 대한 인식은 학생들을 돕기 위해 필수적이다.

The notion that the doctor’s role is to supportthe patient in developing an informed preference on which to base their decision [9] is gradually replacing the convention that the doctor provides advice with which patient is simply expected to ‘comply’. The central role of patients in making decisions about their own healthcare continues to be emphasised in UK national guidance [10] albeit sometimes as a consequence of litigation [11]. An awareness of howthe doctor-patient relationship continues to change over time is essential to help students

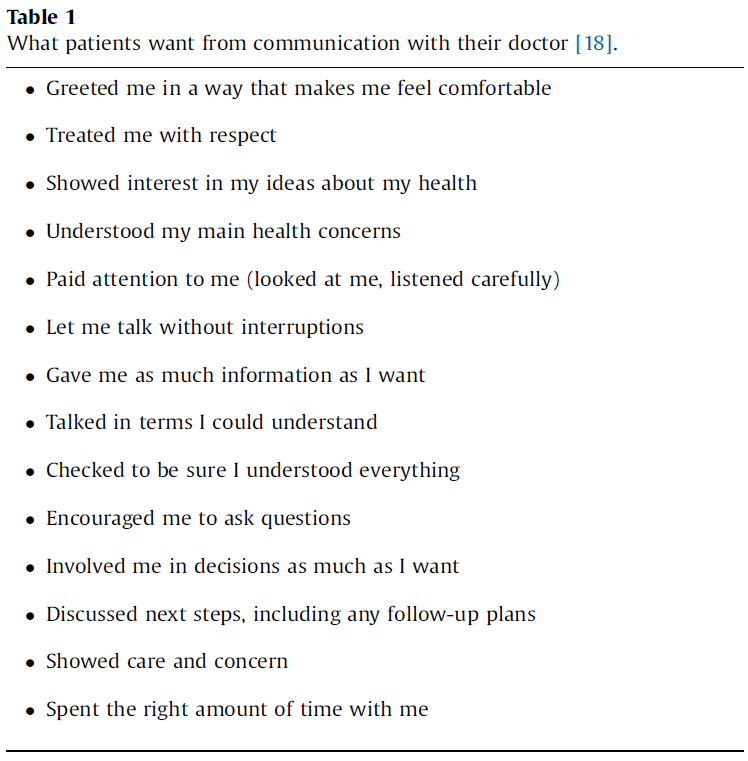

이러한 문제의 원인은 많고 다양할 수 있지만, 의료에서 사람들이 기대하는 것과 그들이 받는 것 사이의 근본적인 불일치는 의료 전문가들이 환자들처럼 진지하게 의사 소통을 해야 한다는 것을 의미한다. 모든 커뮤니케이션 커리큘럼은 환자가 원하는 것을 고려해야 합니다(표 1) [18].

Whilst the causes of these problems are likely to be many and varied, the underlying discrepancy between what people expect from medical care and what they receive points to a need for healthcare professionals to take communication as seriously as patients do. Any communication curriculum must take into account what patients want (Table 1) [18].

심지어 지난 10년 사이에도 의사-환자 관계를 묘사하는 데 사용되는 언어가 바뀌었다. 많은 출판물은 의료 서비스를 이용하거나 장기간 의료 상태를 유지하고 있는 사람을 설명할 때 더 이상 '환자'라는 단어를 사용하지 않는다[12–14]. '환자 중심'이라는 용어가 널리 이해되고 있는 것처럼, '사람 중심'이라는 용어에 자리를 내주고 있다. 의대 교사들은 더 이상 학생들에게 '감정적인 환자를 상대한다'거나 '환자가 말할 수 있게 (허락)한다'는 전략을 권하지 않고 '환자의 감정에 반응한다'거나 '환자의 공헌을 가능케 한다'는 말을 할 것이다. 마찬가지로 환자를 라벨링하는 것(예: '어려운 환자' 또는 '답답한heartsink')는 당연히 무례하게 여겨지며, 의사들이 힘들다고 생각하는 상황에서 효과적으로 의사 소통을 하도록 장려하지 못한다. 언어의 사용은 건강관리를 받는 사람들이 '질병된 신체diseaed body'나 문제의 근원이 아닌 [존중과 인간으로서 대우받는다는 기대]를 보여준다. 이것은 전통적인 '수동적인 환자' 담론의 적절성에 문제를 제기하는데, '수동적 환자 담론'은 [흔히 사용되는 용어]에서 여전히 드러난다. 예를 들어 '병력 청취', '환자 동의', '치료에 순응'과 같은 말이다.

Even within the last decade, the language used to describe the doctor-patient relationship has changed. Many publications no longer use the word ‘patient’ when describing a person who uses healthcare services or lives witha long-term medical condition[12– 14]. Just as the term ‘patient-centred’ is becoming more widely understood, it is giving way to the term ‘person-centred’. Medical teachers no longer recommend strategies for students to ‘deal with emotional patients’ or suggest ‘allowing the patient to talk’ but will refer to ‘responding to the patient’s emotions’ or ‘enabling the patient’s contribution’. Similarly the labelling of patients (e.g. as ‘difficult’ or ‘heartsink’) is rightly viewedas disrespectful andfails to encourage doctors to take responsibility for communicating effectively in situations they find challenging. The use of language demonstrates the expectation that people receiving healthcare are treated with respect and as people rather than as ‘diseased bodies’ or a source of problems. This challenges the appropriateness of the traditional discourse of a ‘passive patient’, which is represented by terms still commonly used, such as ‘taking a history’, ‘consenting a patient’ and ‘compliance with treatment’.

의사는 다음과 같은 경우 보고서가 계속 나타납니다.

reports continue to appear where doctors:

- 나쁜 소식을 전달할 때 자신을 소개하거나 환자를 보는 데 실패 [15]

- 환자가 마치 없는 것처럼 이야기하다[16]

- 의사소통이 원활하지 않고 존경심이 부족하다[17].

- fail to introduce themselves or to look at the patient when delivering bad news [15]

- talk about patients as if they were not there [16]

- communicate poorly and show lack of respect [17].

환자 중심의 관리가 영국의 의료 관행을 뒷받침하는 철학이지만, 학생들은 현실에서 의사-환자 관계의 다양한 모델에 노출되어 있다.

Whilst patient-centred care is the philosophy underpinning medical practice in the UK, in reality students are exposed to a variety of models of the doctor-patient relationship

이는 또한 의료 과실에 의해 영향을 받는 환자와 가족에게 효과적으로 대응하는 데 초점을 맞추는 것이 증가하여 솔직함candour이라는 새로운 법적 의무가 생기게 했다. [전문적 행동]의 개념은 대인 관계 기술, 작업 그룹 규범 및 조직 문화의 요소를 통합하여 의료 교육에서 점점 더 채택되고 있다[22].

This also prompted an increased focus on responding effectively to patients and families affected by medical error, resulting in a new statutory duty of candour [21]. The concept of professional behaviour as a taught subject is being increasingly adopted in medical education, incorporating elements of interpersonal skills, working group norms and organisational culture [22].

이와 동시에, 일부 의과대학에서 임상적 의사소통 외에도 임상적 추론의 명시적 교육에 대한 집중력이 증대되었다[25–27]. 부적절한 정보 수집 및 처리로 인해 많은 진단 오류가 발생한 것으로 확인되었습니다 [28,29]. 환자의 문제를 효과적으로 평가하는 데 있어 [임상 지식, 추론 및 커뮤니케이션 간의 상호 작용]은 많은 커리큘럼에서 강조되고 있다.

In parallel, there has been an increased focus on the explicitteaching of clinical reasoning in addition to clinical communication in some medical schools [25–27]. Inadequate gathering and processing of information have been found to be responsible for many diagnostic errors [28,29]. The interplay between clinical knowledge, reasoning and communication in effectively assessing a patient’s problems is being emphasised in many curricula.

전문성, 환자 안전 및 임상 추론에 대한 이러한 새로운 강조는 임상 커뮤니케이션 교육에 시사하는 바가 있다. 시뮬레이션 기반 훈련의 급증은 환자 및 친척과의 커뮤니케이션뿐만 아니라 동료로의 인계 등 환자 안전과 관련된 주요 이벤트를 포함하여 명백하게 나타났다 [30,31].

These new emphases on professionalism, patient safety and clinical reasoning have implications for clinical communication teaching. An upsurge in simulation-based training has been evident, focusing not only on communication with patients and relatives, but including key events relating to patient safety, suchas handover to colleagues [30,31].

지난 10년간 기술 변화로는 [원격의료의 성장과 화상회의]와 같은 전자적 방법으로 안전하고 효과적으로 상담하는 데 필요한 기술이 있다. 영국에서는 임상 실습과 커뮤니케이션 교육에서 대부분의 상호작용이 대면적이어서 많은 졸업생들이 다른 매체를 통해 치료를 제공할 준비가 되어 있지 않다. 기술은 또한 전통적인 상담에서도 문제를 제기합니다. 일부 의사들은 10년 이상 전자 건강 기록을 사용해 왔지만, 이 3자(환자-의사-컴퓨터) 상담에 필요한 상호 작용 기술은 거의 주목을 받지 못했다[32]. 1차, 2차 및 3차 진료 범위에 걸친 서비스가 모든 환자 상담에서 전자 건강 기록의 사용으로 전환됨에 따라 이것이 우선순위가 되고 있다. '디지털 원주민'인 학습자가 단순히 기술을 자신의 실무에 원활하게 통합할 것으로 예상될 수 있지만, 증거에 따르면 (디지털 원주민) 학생들도 전자 건강 기록의 사용에 대한 지침과 역할 모델링이 필요하다는 것을 시사한다[32,33]. 학생 스스로도 기술이 환자와의 상호 작용 품질에 미치는 영향을 알고 있습니다 [33].

Technological changes over the past decade include the growth of telemedicine and skills needed to consult safely and effectively by electronic means, such as video-conferencing. In the UK, most interactions in clinical practice and communica tion teaching are face-to-face, which leaves many graduates ill prepared to provide care via other media. Technology also presents challenges in traditional consultations. Although some doctors have been using electronic health records for over a decade, the interactional skills needed for this triadic (patient doctor-computer) consultation have received little attention [32]. This is becoming a priority, as services across the spectrum of primary, secondary and tertiary care switch to the use of electronic health records in every patient consultation. Whilst it might be expected that learners who are ‘digital natives’ will simply incorporate technology seamlessly into their practice, evidence suggests that students need guidance and role modelling in the use of electronic health records [32,33]. Students themselves are aware of the impact of technology on the quality of their interactions with patients [33].

기술적 진보가 환자의 생리학적 데이터의 원격 모니터링을 용이하게 함에 따라(예를 들어 장기 조건 관리에서) 의사와 환자 간의 상호 작용의 성격과 빈도가 변화하고 있다. 이는 다학문 팀의 확대, 다른 학문 출신 팀 구성원과의 환자 접촉 증가, 시간에 따른 의사-환자 관계의 연속성 감소[34]로 인해 증폭된다. [개별 환자의 유전자 구성, 건강, 라이프스타일 및 환경에 따라 표적형 치료를 제공하는 것을 목표로 하는] 정밀 의료와 같은 진보는 환자 데이터의 수집 및 사용뿐만 아니라 의사와 환자 간 상담에서 논의된 주제에 영향을 미친다[35].

As technological advances facilitate remote monitoring of patients’ physiological data (for example, in the management of long term conditions) the nature and frequency of interactions between doctors and patients is changing. This is amplified by the expansion of multi disciplinary teams, the increase inpatient contacts with team members from other disciplinary backgrounds and a reduction in continuity of the doctor-patient relationship over time [34]. Advances such as precision medicine, which aims to provide targeted care based on the individual patient’s genetic make-up, health, lifestyle and environment, have implications for topics discussed in the doctor-patient consultation, as well as the collection and use of patient data [35].

이러한 관계적, 상황적, 기술적 변화의 복합적 영향은 지난 10년 동안 의사-환자 간 의사 소통에 지대한 영향을 끼쳐 커리큘럼의 개정을 촉진했다.

The combined impact of these relational, contextual and technological changes has had a profound effect on doctor-patient communication in practice over the past decade, prompting a revision of the curriculum

2. 방법

2. Methods

3. 결과

3. Results

3.1. 교육과정 바퀴

3.1. The curriculum wheel

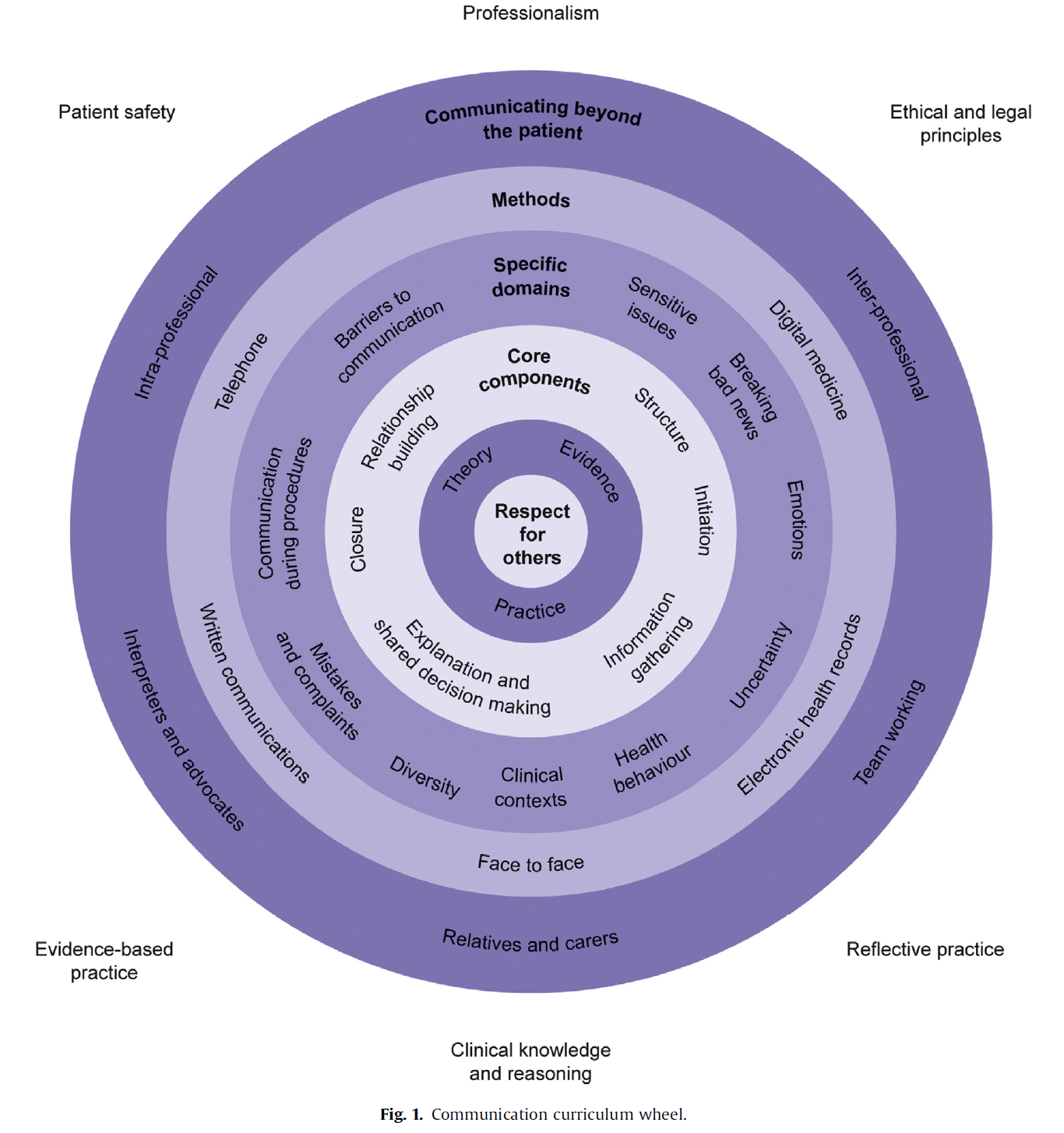

원래의 커리큘럼은 쉽게 접근할 수 없는 형태로 전체 커리큘럼을 제시하는 것을 목표로 하는 '휠'로 표현되었다. 원래 교육과정을 이용한 사람들의 경험과 신입 회원들의 관점을 바탕으로 한 이번 상담에서 얻은 공감대는 이 도식표현이 도움이 됐다는 데 있었다. 특정 요소를 업데이트하면서 형식을 유지하기로 합의하였다(그림 1).

The original curriculum was represented by a ‘wheel’, which aimed to present the entire curriculuminan easilyaccessible form. The consensus fromthe consultation, based on the experiences of those who had used the original curriculumand the perspective of newer members, was that this diagrammatic representation was helpful. It was agreed that the format would be retained, whilst updating certain elements (Fig. 1).

의사소통의 핵심 구성 요소는 휠의 내부 원으로 표시됩니다. 외부 링은 환자 이외의 링과의 통신, 통신 방법 및 통신에서 특정 문제를 나타냅니다. 커리큘럼은 바퀴를 둘러싼 맥락으로 제시되는 모든 의료 행위를 지배하는 일련의 원칙들에 의해 뒷받침된다.

Core components of communication are represented by the inner circles of the wheel. Outer rings represent specific issues in communication, methods of communication and communication with those other than the patient. The curriculumis underpinned by a set of principles which govern all medical practice, presented as the context surrounding the wheel.

이 바퀴는 링이 독립적으로 회전할 수 있도록 설계되어 있어 커리큘럼에 다이얼을 돌린다. 예를 들어, 교육과정 계획자는 전화로 통역사를 통해 영어를 거의 하지 않는 환자와 정보수집을 연습하거나 상대적인 면전에서 의료 오류를 설명하는 연습을 할 수 있는 세션을 설계할 수 있다.

The wheel is designed such that the rings can be rotated independently, in order to ‘dial a curriculum’. For instance, a curriculum planner may design a session for students to practise gathering information with a patient who speaks little English via an interpreter over the phone or a session to practise explaining a medical error to a relative face-to-face.

3.2. 임상 커뮤니케이션 교육을 뒷받침하는 핵심 원칙

3.2. Key principles underpinning clinical communication teaching

[타인에 대한 존중]이라는 핵심 가치는 여전히 커리큘럼의 중심에 있다. 존중은 환자, 친척, 동료 및 환자 치료에 관여하는 다른 사람들과의 모든 상호 작용의 핵심이다. 효과적인 파트너십을 개발하기 위한 첫 번째 구성 요소이며, 환자 자신의 의료에서 환자의 역할을 지원하고 활성화하는 데 필수적입니다.

The core value of respect for others remains at the centre of the curriculum. Respect is key to all interactions with patients, relatives, colleagues and others involved in patient care. It is the first building block for developing effective partnerships and is essential in supporting and enabling the patient’s role in their own healthcare.

추가로, 학생들은 임상 의사소통을 위한 핵심 지식 기반, 즉 개념적 프레임워크 및 연구 증거의 파악이 필요하며, 여기에는 다음이 포함된다.

In addition, students need a core knowledge base for clinical communication: an appreciation of conceptual frame works and research evidence, which includes:

– 효과적인 의사-환자 간 커뮤니케이션과 환자 만족도, 리콜 및 의료 결과 간의 관계에 대한 근거[36,37]

– 돌봄에 대한 개념적 프레임워크 및 철학(예: 환자 중심)

– 의사-환자 관계 및 상담 모델

– 다양한 치료 단계에서의 환자 지원에 대한 접근 방식[38]

– evidence about effective doctor-patient communication and the relationship between communication and patient satisfaction, recall and healthcare outcomes [36,37]

– conceptual frameworks and philosophies of care (such as patient-centredness)

– models of the doctor-patient relationship and the consultation

– approaches to supporting patients at different stages of care[38].

기본 원칙에 새롭게 추가된 것은 [임상 커뮤니케이션에 대한 개인의 이해와 기술의 개발]에 있어 [연습practice의 명확한 역할]이다. 연습은 다음을 가리킨다.

A new addition to the underpinning principles is the explicit role of practice in the development of an individual’s understanding of, and skills in, clinical communication. Practice refers to:

– 학생들이 자신의 임상적 상호작용에 개념을 통합하는 방법 (예: '존중' 또는 '환자 중심 진료' 등)

– 반복을 통한 기술 향상[39]

– the way in which students integrate concepts (such as ‘respect’ or ‘patient-centred care’) into their clinical interactions

– the refinement of skills through repetition [39].

3.3. 임상 커뮤니케이션의 핵심 구성 요소

3.3. Core components of clinical communication

영국의 의과대학에서 널리 사용되는 캘거리-캠브리지 인터뷰 가이드[36]는 원래 커리큘럼의 핵심 구성 요소에 대해 알려주었다. 이 프레임워크는 네 가지 순차적 단계로 협의의 기본 구성 요소를 설정합니다.

The Calgary-Cambridge Guide to the Medical Interview [36], which is widely used in UK medical schools, informed the core components in the original curriculum. This framework sets out the fundamental building blocks of the consultation in four sequential stages:

– 상담 개시

– 정보 수집

– 설명 및 계획

– 상담 종료

– Initiating the consultation

– Gathering information

– Explanation and planning

– Closing the consultation

이러한 작업은 상담 중에 두 가지 병렬 작업으로 지원됩니다.

These are supported by two parallel tasks throughout the consultation:

– 관계 구축

– 구조 제공

– Building the relationship

– Providing structure

환자면담에서 '설명explanation' 과제에 공유 의사결정shared decision making이 추가되었다. 2008년에 '설명 및 계획'의 과제는 다음과 같다.

Shared decision making has been added to the ‘explanation’ task of the consultation. In 2008, the task of ‘explanation and planning’ included:

– 다루어야 할 내용: 예: 관련 진단 설명, 계획 및 협상

– 프로세스 기술: 환자의 시작점 결정, '정보 확인' 및 이해도 확인 등

– the content to be addressed: e.g. explaining relevant diagnoses, planning and negotiating

– process skills: such as determining the patient’s starting point, ‘chunking’ information and checking understanding

공유 의사 결정 프로세스는 환자가 자신의 의료에 이해 당사자로서 적극적으로 참여합니다. 여기에는 다음과 같은 여러 추가 요소가 포함된다. [40–42]

The process of shared decision making actively involves the patient as a stakeholder in their own healthcare. This includes a number of additional elements [40–42], such as:

– 치료 목표 명확화

– 사용 가능한 치료 옵션에 대한 정보 공유(치료 불가 옵션 포함)

– 불확실성을 포함한 치료 옵션의 잠재적 편익과 해악에 대한 정보 논의

– 선호 결과 논의

– 환자의 가치(환자에게 가장 중요한 것)를 명확히 함

– 환자의 숙고 지원

– 환자의 선택 사항 문서화 및 구현

– clarifying goals for treatment

– sharing information about available treatment options, including the option of taking no treatment

– discussing information about the potential benefits and harms of the treatment options, including any uncertainties

– discussing preferred outcomes

– clarifying the patient’s values (what matters most to the patient)

– supporting the patient in deliberating

– documenting and implementing the patient’s choice

3.4. 특정 통신 영역

3.4. Specific domains of communication

핵심 구성 요소는 의사가 상담을 구축할 수 있는 안전한 플랫폼을 제공합니다. 이들 외에도 의사들에게 어려운 것으로 알려져 있으며, 가르침에 대한 특별한 주의를 필요로하는 커뮤니케이션 영역이 있다. 이러한 영역 중 일부는 더 어려운 상황에서 동정적이고 효과적인 대화를 나누기 위해 학생들이 필요로 하는 기술과 접근 방식에 초점을 맞춘다. 여기에는 다음이 포함됩니다.

The core components provide a secure platform upon which doctors can build their consultations. Beyond these, there are specific areas of communication which are known to be challenging for doctors, and which warrant particular attention in teaching. Some of these domains focus on the skills and approaches that students need in order to have compassionate and effective conversations undermore challenging circumstances. These include:

– 민감한 이슈들에 대한 논의: 어렵고 창피하거나, 낙인적인 주제. 사망, 죽어감, 사별, 섹스, 정신질환, 낙태, 중독, 가정폭력, 아동학대 등

– 감정에 반응하기: 고통, 두려움, 분노 등. 환자와 가족에게 미치는 질병의 정서적 영향을 이해하고 이에 대응합니다.

– 불확실성에 대한 대응: 진단, 예후 및 환자의 요구 사항을 충족하는 '정확한' 치료 옵션 설정에 대한 내용

– 실수와 불만사항 논의: 환자와 가족에게 의료오류(의사 개인 또는 팀원에 의해 발생)를 공개하고, 진료에 대해 불만을 제기하고자 하는 사람에게 대응

– Discussing sensitive issues, e.g. difficult, embarrassing and stigmatised topics, suchas death, dying, bereavement, sex, mentalillness, abortion, addiction, domestic violence and child abuse.

– Responding to emotions, e.g. distress, fear and anger, as well as understanding and responding to the emotional impact of illness on the patient and their family.

– Responding to uncertainty: about diagnosis, prognosis andestablishing the ‘correct’ treatment option for the patient to meet their needs.

– Discussing mistakes and complaints: disclosing medical error(caused by the doctor personally or a teammember) to patients and families; responding to those who wish to complain about their care.

이러한 영역은 이전 커리큘럼에 포함되었지만, 언어는 변경되었다(이전에는 '감정 처리', '실수와 불만 처리', '불확실성 처리').

Whilst these domains were included the previous curriculum, the language has changed (previously ‘handling emotions’, ‘handling mistakes and complaints’ and ‘dealing with uncertainty’).

변경된 특정 도메인은 다음과 같습니다.

Specific domains which have changed are:

– 나쁜 소식전하기. 원래 '민감한 문제'의 영역 아래에 포함되었지만, 이것은 개정된 커리큘럼의 바퀴에 명시적으로 추가되었다. 여기에는 어려운 소식을 공유하고 환자 및 가까운 사람들과 토론하는 것이 포함됩니다.

– Breaking bad news. Originally included under the domain of‘sensitive issues’, this has been explicitly added to the wheel inthe revised curriculum. This includes sharing difficult news anddiscussing with patients and those close to them:

– 진단 및 예후(예: 상태가 심각하거나, 장기적이며, 수명이 변화하거나, 수명이 변화할 때)

– 치료(예: 효과적인 치료법이 없는 경우, 심각한 부작용의 위험이 있는 경우, 치료는 더 이상 효과적이지 않은 경우, 완화의료로의 전환, DNAR 결정

- – diagnosis and prognosis, e.g. when the condition is serious, long-term, life-changing or life-limiting

- – treatment, e.g. there are no effective treatments, there is a riskof serious adverse effects, treatment is no longer effective, transfer to palliative care, ‘do not attempt resuscitation’ decisions

또한 특정 영역은 환자의 [개별 상황에 따라 모든 환자의 요구를 충족시키는 공평한 치료를 제공해야 하는 의사의 의무]를 포함한다. 여기에는 다음이 포함됩니다.

The specific domains also encompass the duty of doctors to provide equitable care which meets every patient’s needs according to their individual circumstances. This includes:

– 커뮤니케이션의 다양성. 다양성(diversity)이란 용어는 연령, 국적, 신체적 능력 또는 장애, 민족적 또는 문화적 배경, 성적 지향, 종교적 신념, 학습 능력 또는 어려움, 사회 경제적 지위, 교육, 의사소통 능력, 가족적 배경 등으로 인해 사람들 사이의 개별적인 차이를 가리킨다. 이는 이전 교육과정의 두 영역('나이별'과 '문화적·사회적 다양성')을 병합하는 동시에 학생들이 배경, 개인적 특성, 세계관과 관계없이 모든 환자와 효과적으로 소통할 수 있을 것이라는 기대감으로 소관을 확대한다.

– 의사소통의 장벽. 여기에는 언어, 인지 또는 청각 장애 또는 신체 또는 학습 장애로 인해 발생할 수 있는 특정한 의사소통의 장벽 탐색이 포함된다[43].

– Diversity in communication. The term diversity refers to individual differences among people: due to age, nationality,physical ability or impairment, ethnic or cultural background,sexual orientation, religious beliefs, learning ability or difficul ties, socio-economic status, education, communicative abilityand family background. This merges two domains from theprevious curriculum (‘age-specific’ and ‘cultural and social diversity’) whilst expanding the remit to include the expectationthat students will be able to communicate effectively with allpatients, regardless of background, personal characteristics or world view.

– Barriers to communication. This includes navigating specific communication barriers, which may be due to language, cognitive or hearing impairments, or physical or learning disabilities [43].

도메인에는 [다양한 유형의 상담]도 포함됩니다.

The domains also include communication in different types of consultations:

– 구체적인 임상 상황: 예를 들어, 응급의학의 긴급성은 신속한 진단, 다중 작업, 조정 및 팀워크 또는 공격에 대응하는 기술을 강조할 수 있다. 알코올 및 약물 오용과 같은 특정 임상 주제는 임상 환경에 따라 다르게 협의하여 다룰 수 있다(예: 일반 진료, 응급 진료부, 약물 오용 클리닉).

– Specific clinical contexts. For example, the exigencies of emergency medicine may emphasise the skills of rapid diagno sis, multi-tasking, co-ordination and teamwork, or responding to aggression. Particular clinical topics, such as alcohol and substance misuse, may be addressedina consultation differently depending on the clinical setting (e.g. general practice, emergency department, substance misuse clinic).

– 건강 행동 변화: 여기에는 행동 변화를 지원하고 사람들이 장기 상태를 관리할 수 있도록 하는 데 필요한 기술이 포함됩니다. 이것은 이전 커리큘럼의 도메인('설명의 구체적인 적용')을 대체합니다.

– Health behaviour change. This includes the skills required to support behavioural change and enable people to manage their long-term conditions. This replaces a domain (‘specific application of explanation’) from the previous curriculum.

– 프로시져 중 의사소통. 새롭게 추가된 것으로, 환자가 시술/수술을 받는 상황에서 다음과 같은 커뮤니케이션 절차를 포함합니다.

- – 시술/수술의 절차를 설명

- – 계속하기 전에 환자가 절차에 동의했는지 확인

- – 환자의 질문, 우려 및 감정에 효과적으로 대응

- – 적절한 해설(코멘터리)을 제공

– Communication during procedures. A new addition, this includes communication procedures to: whilst the patient is undergoing practical

- – explain the proposed procedure

- – ensure that the patient has agreed to the procedure before proceeding

- – respond effectively to patient questions, concerns and emotions

- – provide an appropriate commentary

3.5. 의사소통 방법

3.5. Methods of communicating

교육에서 일반적으로 사용되는 방법에는 대면, 전화 및 서면 통신이 포함되지만, 업데이트된 커리큘럼에는 디지털 의학과 전자 건강 기록이 구체적으로 언급된다. 여기에는 다음과 같은 기술이 포함됩니다.

Whilst commonly used methods addressed in teaching include face-to-face, telephone and written communication, the updated curriculum specifically mentions digital medicine and the electronic health record. These include skills in:

– '제3자'로서 존재하는 컴퓨터를 관리하면서 효과적인 상담 수행

– 다양한 전자적 통신 방법(전자 메일, 화상 회의, 데이터 원격 전송 등)을 사용하여 환자 진료를 조정, 전달 및 문서화

– 디지털 시대의 변화하는 관리 방법이 환자, 친척 및 동료와의 의사소통에 미치는 영향 평가

– conducting an effective consultation whilst managing the ‘third party’ presence of the computer

– using a variety of electronic methods of communication (including email, video conferencing and remote transmission of data) to co-ordinate, deliver and document patient care

– evaluating the impact of changing methods of care in the digital age on communication with patients, relatives and colleagues

3.6. 환자 이상의 커뮤니케이션

3.6. Communication beyond the patient

이 커리큘럼은 또한 환자들에 대한 커뮤니케이션을 포함하는데, 이것은 친인척, 통역자, 옹호자, 그리고 보호자와 함께 효과적으로 일하는 것뿐만 아니라 의학 내/외부 동료들을 포함한다. 여기에는 다음과 같은 기술이 포함됩니다.

The curriculum also includes communication about patients, which encompasses working effectively with relatives, inter preters, advocates andcarers, as well as colleagues bothwithinand outside medicine. This includes skills in:

– '삼자' 상담(예: 환자-친인척-의사)

– 환자와 가까운 사람들이 참여하는 의사 결정 상담

– 일반 및 전문 통역사와 함께 작업

– 다양한 미디어를 통한 동료와의 커뮤니케이션

– conducting a ‘triadic’ consultation (e.g. patient-relative-doctor)

– decision making consultations involving those close to thepatient

– working with lay and professional interpreters

– communication with colleagues through a variety of media

업데이트된 커리큘럼에는 다음과 같은 기술이 포함된 '팀워크'도 추가되었습니다.

In the updated curriculum, ‘team-working’ has also beenadded, which includes skills in:

– 다학제 팀 내에서 작업하고 다학제 팀을 이끌기

– 환자 사례 및 인계 시 체계적인 접근 방식 사용

– 우려concern 제기raising

– working within and leading multi-disciplinary teams

– using structured approaches to presenting patient cases and handover

– raising concerns

3.7. 지지 원칙

3.7. Supporting principles

전체 커뮤니케이션 커리큘럼은 전문성, 윤리적, 법률적 원칙, 증거 기반 관행, 성찰적 실천 등 [의료적 실천의 모든 분야를 관장하는 일련의 원칙]의 맥락 속에 자리 잡고 있다. 환자 안전과 임상 지식 및 추론이라는 두 가지 영역이 추가되었다. 이는 학생들이 다음과 같은 점을 높이 평가하게 될 것이라는 기대를 강조합니다.

The entire communication curriculum is sited in a context of a set of principles which govern all areas of medical practice: professionalism, ethical and legal principles, evidence-based practice and reflective practice. Two further domains have been added: patient safety and clinical knowledge and reasoning. This highlights the expectation that students will have an appreciation of:

– 의료 과실의 위험을 증가 또는 감소시키는 데 있어 의사 소통의 역할

– 환자 안전을 촉진하기 위한 커뮤니케이션 전략 및 도구(예: 세계 보건 기구 수술 안전 점검표)

– 진단 오류를 유발하는 상담에 영향을 미치는 임상적 추론의 편향

– the role of communication in increasing or decreasing the risk of medical error

– communication strategies and tools to promote patient safety (e.g. the World Health Organisation Surgical Safety Checklist)

– biases in clinical reasoning affecting the consultation which lead to diagnostic errors

4. 토론과 결론

4. Discussion and conclusion

4.1. 토론

4.1. Discussion

핵심 가치로서 존중respect은 최근의 여러 보고서와 정책 이니셔티브[20,44] 및 환자에게 중요한 커뮤니케이션 요소를 조사하는 연구에 의해 강조되었다. 존중은 의사들이 환자의 나이, 사회적, 문화적, 인종적 배경, 장애 또는 언어에 관계없이 효과적이고 민감하게 의사소통할 것이라는 기대를 뒷받침한다. 그럼에도 불구하고, 의사 소통 불량과 존중 부족은 여전히 의사들에 대한 불만에서 매우 널리 퍼져 있는 것으로 나타났다[17]. 이는 의료 교육에서 존중하는respectful 의사소통에 대한 요구사항을 계속 명시적으로 다룰 필요가 있음을 나타낸다.

The core value of respect has been highlightedby recent reports and policy initiatives [20,44] as well as by research examining what elements of communication are important to patients. It underpins the expectation that doctors will communicate effec tivelyand sensitively regardless of the patient’s age, social, cultural or ethnic background, disabilities or language[45,46]. Nonetheless, poor communication and lack of respect are still consistently found to be highly prevalent in complaints against doctors [17]. This signals a need to continue to explicitly address the requirement for respectful communication in medical teaching.

효과적인 커뮤니케이션에는 가치, 지식 및 행동 기술의 조합이 포함됩니다. 학습 모델은 시간이 지남에 따라 복잡한 학습을 포함시키는 데 있어 연습의 역할을 점점 더 인식하고 있다[47,48]. [기술]과 [접근법]의 레퍼토리를 배우는 것뿐만 아니라, 학생들은 [반복 연습]을 통해 서로 다른 상황에서 무엇이 요구되는지, 그리고 진정한genuine 대화를 통해서 계획을 어떻게 집행enact하는지를 배운다. 예를 들어, '환자 중심 진료'에 대한 학습자의 이해는 이러한 치료를 제공한 경험이 없으면 완전하지 않습니다.

Effective communication involves a combination of values, knowledge and behavioural skills. Learning models increasingly recognise the role of practice in embedding complex learning over time [47,48]. As well as learning a repertoire of skills and approaches, students learn, through repeated practice, how to make decisions about what is required in different situations and how to enact their plans as part of a genuine dialogue. A learner’s understanding of ‘patient-centred care’, for example, is not complete without the experience of delivering this care.

면담consultation의 많은 필수 업무(예: 의제에 합의하고, 파트너십을 구축하고, 정보를 교환하고, 시간을 효율적으로 사용하고, 계획에 합의하는 것)는 지난 10년 동안 바뀌지 않았다. 그러나 환자 자율성에 대한 집중도가 높아지면서 공유 의사 결정SDM 작업을 명시적으로 서명하는 것이 중요해졌다. 의과대학은 [8,10,40]의 학생이 치료에 대한 결정에 효과적으로 참여할 수 있도록 준비하여 졸업생이 법적 선례[4]의 기준에 맞는 치료를 제공할 수 있도록 보장해야 한다.

Many of the essential tasks of the consultation (for example, to agree an agenda, build a partnership, exchange information, use time efficiently and agree a plan) have not changed in the past decade. However, the increased focus on patient autonomy has highlighted the importance of explicitly signalling the task of shared decision making. Medical schools must prepare students to enable effective patient participation in decisions about care [8,10,40] to ensure that graduates can deliver care that meets the standard set by legal precedent [4].

의료가 발전함에 따라, 환자 자신의 건강과 치료에 대한 논의에 환자가 적극적으로 참여하는 것은 증폭될 것이다. 예를 들어 정밀 의학에서 개입은 개별 유전학, 환경 및 필요에 대한 개별 환자의 고유한 목표치를 목표로 한다. 이는 정보 제공, 위험 커뮤니케이션, 환자 선택 지원 및 불확실성 대처에 새로운 영향을 미치며, 이는 가르침이 다루어야 한다.

The active participation of the patient in discussions about their own health and treatment is set to be amplified by advances in medical care. In precision medicine, for example, interventions are uniquely targeted towards the individual patient’s uniquely targeted towards the individual genetics, circumstances and needs. This has new implications for information provision, risk communication, supporting patient choice and coping with uncertainty, which teaching must address.

의사들은 항상 환자와 가까운 사람들과 어려운 주제에 대해 민감하고 동정적인 대화를 나눌 수 있어야 할 것이다. 여기에는 질병이 가족에게 미치는 정서적 영향을 평가하고, '최고의' 행동방법이 명확하지 않을 때 의료보험 결정을 탐색하며, 일이 잘못될 때 정직하고 존경스러운 관계를 유지하는 것이 포함된다. 최근의 정책 변화는 이러한 상황에서 환자와 가족의 권리를 강조하는 데 기여하고 있으며 [21]은 의사소통 교육에 반드시 반영되어야 한다. 특히, 나쁜 소식 전하기는 업데이트된 커리큘럼에서 새로운 명성을 얻었다. 최근의 증거는 의사들이 다양한 상황에서 환자나 친척들과 나쁜 소식을 논의하는 데 계속 고군분투하고 있다는 것을 보여준다.

Doctors will always need to be able to conduct sensitive and compassionate conversations with patients and those close to them about difficult subjects. This includes appreciating the emotional impact of illness on families, navigating healthcare decisions when the ‘best’ course of action is not clear, and maintaining honest and respectful relationships when things go wrong. Recent policy changes have served to emphasise the rights of patients and relatives in these situations [21], which must be reflected in communication teaching. Specifically, breaking bad news has been given newprominence in the updated curriculum. Recent evidence shows that doctors continue to struggle with discussing bad news with patients and relatives, across a range of situations

개정된 커리큘럼의 다른 특정 영역은 의료 커뮤니케이션에서 평등, 다양성 및 포함의 역할이 점점 더 인식됨에 따라 [공정한equitable 치료care]를 제공해야 하는 의사의 의무를 명시적으로 강조한다[52]. 학생과 교수진이 환자뿐 아니라 그들 자신의 문화적 신념과 관행을 탐구하는 개방적 태도openness를 취하도록 장려하는 교육 프로그램이 제안되었다 [53]. 학생들은 또한 법에 따라 (통신 지원 부족을 포함하여) 어떤 형태의 장애가 있는 환자도 불이익을 받지 않도록 하기 위해 특정한 통신 장벽을 탐색할 수 있는 장비를 갖추어야 한다[54].

Other specific domains in the revised curriculum explicitly emphasise the duty of doctors to provide equitable care, as the role of equality, diversity and inclusion in healthcare communication has been increasingly recognised [52]. Educational programmes that encourage students and faculty to adopt an openness to exploring their own cultural beliefs and practices, as well as those of patients have been proposed [53]. Students also need to be equipped to navigate specific communication barriers, to ensure that patients with any form of disability are not disadvantaged (including through a lack of communication support), in accor dance with the law [54].

환자의 상황setting, 임상 시나리오 및 특정 요구를 고려해야 하는 필요성은 커뮤니케이션 커리큘럼에 항상 존재해왔다. 학생들에게 행동 변화를 지원하고 사람들이 그들의 장기적인 상태를 관리할 수 있도록 하는 데 더욱 강조되었다 [55]. 이는 개인 의료 만남에서 제공되는 기회를 사용하여 인구 건강을 개선하는 것을 목표로 건강 증진 및 예방 의학을 의료 상담의 일상적인 구성요소로 포함하려는 추세를 반영한다[56]. 자기관리를 필요로 하는 장기적이고 복잡한 조건의 환자가 계속 증가함에 따라, 졸업생들은 이러한 필요를 가진 환자들을 지원하기 위한 효과적인 상담 기술을 필요로 할 것이다[34].

The need to take account of the setting, clinical scenario and specific needs of the patient has always been present in the communication curriculum. Increased emphasis has been given to equipping students to support behavioural change and enable people to manage their long-term conditions [55]. This reflects the trend to include health promotion and preventive medicine as a routine component of health care consultations [56], with the aim of using the opportunity afforded in individual healthcare encounters to improve population health. As the number of patients with long-term, complex conditions requir ing self-management continues to increase, graduates will need effective consultation skills to support patients with these needs[34].

우리의 모델에 [시술/수술에 관한 커뮤니케이션]을 추가하는 것은 현재 학부 수준에서 실용적 기술과 커뮤니케이션 기술의 통합에 관심을 기울이고 있는 분명한 관심을 나타냅니다 [57]. 또한 이것은 잠재적인 [이론-실천 격차]를 극복하기 위해, 진정한authentic 임상 환경 내에서 의사 소통 기술을 가르치는 관행이 증가하는 것을 반영한다[58].

The addition of communicating during procedures to our model signals the explicit attention now being paid to the integration of practical and communication skills at undergraduate level [57]. It also reflects the increasing practice of siting communication skills teaching within an authentic clinical environment to overcome the potential theory/practice gap [58].

의료에서 전자적 통신 방법의 급속한 확장으로 인해 장기적 관리의 맥락에서는 전자 템플릿이 환자 서술보다 우선할 수 있다는 우려가 제기되었다[59,60]. 이는 컴퓨터의 추가적인 '제3자' 존재와의 협의의 상호작용 프로세스를 관리하는 방법에 대한 도전과 함께 [61]의 지속적인 커리큘럼 개발의 핵심이다[32,34].

The rapid expansion of electronic methods of communication in healthcare has raised concerns that electronic templates may override the patient narrative in the context of long-term condition management [59,60]. This, along with the challenge of how to manage the interactional process of the consultation with the additional ‘third party’ presence of the computer [61], are key inthe ongoingdevelopmentof curricula[32,34].

광범위한 맥락에서, [치료의 파괴적인 실패와 알려진 오류 출처에서 얻은 교훈]은 안전하고 효과적인 실천을 위한 [임상 추론]과 [팀 작업 역량]의 역할을 강조했다[20,28,29,62].

In the broader context, lessons learned from devastating failures of care and known sources of error have emphasised the role of clinical reasoning and team-working competencies in safe and effective practice [20,28,29,62].

지난 10년 동안 언어 사용에 있어 미묘하지만 중요한 변화가 있었다. 언어는 의사-환자 관계의 틀을 짜는 데 중요한 역할을 하며, 환자가 상담의 동등한 파트너이자 이해관계자라는 것을 학생들에게 알리는 데 중요한 역할을 한다. 언어는 물론 계속 발전하고 있다; 아마도 커리큘럼이 다시 업데이트될 때쯤에는 '환자'가 '사람'으로 대체될 것이다.

In the past ten years, there have been subtle but important changes in the use of language. Language plays a key role in the framing of the doctor-patient relationship and signalling to students that the patient is an equal partner and stakeholder in the consultation. Language of course continues to evolve; perhaps by the time the curriculum is updated again, ‘patient’ will be replaced by ‘person’.

4.2. 결론

4.2. Conclusion

의사 소통의 필수 기준required standard은 [의료에 대한 기대]와 불가분의 관계 이루는데, 이는 사회의 문화적 변화, 진화하는 전문적 지도, 법적 선례, 진료 실패에서 얻은 교훈 등을 반영한다. 많은 면에서, 임상 커뮤니케이션 교육의 초점은 변하지 않았습니다: 학생들은 환자와 자신의 치료에 대한 의사 결정권을 존중하는 방식으로 듣고, 질문하고, 설명하고, 지원을 제공하는 것을 배워야 합니다. 그럼에도 불구하고, 커뮤니케이션 커리큘럼은 임상 통신에 근본적으로 영향을 미칠 수 있는 [상황 변화에 지속적으로 대응]해야 한다. 학생들은 복잡한 결정을 내릴 때 환자를 지원하고, 오류에 대한 솔직한 설명을 제공하며, 디지털 의학의 시대에 효과적으로 상담할 준비가 되어 있어야 한다.

The required standard of doctors’ communication is inextricably linked to expectations of medical care, which reflects cultural changes in society, evolving professional guidance, legal precedent and lessons learned from failures in care. In many ways, the focus of clinical communication teaching has not changed: students must learn to listen, question, explain and offer support in a way which respects patients and their right to make decisions about their owncare. Nonetheless, the communication curriculum must remain responsive to contextual changes which can fundamentally affect clinical communication. Students must be prepared to supportpatients in navigating complex decisions, provide honest explan ations of errors andconsult effectivelyinanage of digital medicine.

의사 소통은 의료의 핵심이며, 결과적으로 학생들은 의료 경력 전반에 걸쳐 환자를 가장 잘 돌보기 위해 종합적인 준비가 필요하다. 업데이트된 임상 커뮤니케이션 커리큘럼은 의과대학이 자신의 가르침을 개발하고 자원을 주장하기 위해 사용할 수 있는 'best practice'의 모델을 제공한다.

Communication is at the heart of medical care, and conse quently students require comprehensive preparation in order to best care for patients throughout their medical careers. The updated clinical communication curriculum provides a model of ‘best practice’ which medical schools can use to develop their teaching and to argue for resources.

4.3. 시사점 실천

4.3. Practice implications

커리큘럼 계획자는 업데이트된 합의를 사용하여 현재 강의 내용을 검토하고, 새로운 세션을 개발하거나, 다른 주제와 커뮤니케이션을 통합한 세션을 고안하거나, 이러한 내용을 조합하여 사용하기를 원할 수 있다. 경험이 풍부한 임상 커뮤니케이션 교육자들은 다음의 경우에 가르침이 가장 효과적이라는 것을 알게 될 것이다 [38,63–67].

- 학생들이 연습하고 성찰할 기회를 가질 때,

- 학생들에게 (일회성이 아닌) 반복될 때

- 의료 과정의 패브릭(및 평가)에 통합될 때,

Curriculum planners may wish to use the updated consensus to review the content of current teaching, develop new sessions, devise sessions integrating communication with other topics, or acombination of these. Experienced clinical communication edu cators will be aware that teaching is most effective when students

- have the opportunity to practise and reflect,

- is repeated (rather than a one-off), and

- is integrated into the fabric (and assessments) of the medical course [38,63–67].

의과대학은 종종 커뮤니케이션 커리큘럼을 이끄는 챔피언(또는 소규모 팀)을 가지고 있지만, 학생들이 효과적인 의사 소통자가 되도록 지원하는 것은 의과대학 전체에 걸쳐 공유되는 책임이다.

Whilst medical schools often have a champion (or even asmall team) leading the communication curriculum, supporting students in becoming effective medical communicators is a responsibility shared across the whole medical school.

[24] General Medical Council and Medical Schools Council, First, Do No Harm. Enhancing Patient Safety Teaching in Undergraduate Medial Education. AJointReport by the General Medical Council and the Medial Schools Council, General Medical Council, Manchester, 2015.

Patient Educ Couns. 2018 Sep;101(9):1712-1719.

doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2018.04.013. Epub 2018 Apr 22.

Consensus statement on an updated core communication curriculum for UK undergraduate medical education

Lorraine M Noble 1, Wesley Scott-Smith 2, Bernadette O'Neill 3, Helen Salisbury 4, UK Council of Clinical Communication in Undergraduate Medical Education

Affiliations collapse

Affiliations

-

1UCL Medical School, University College London, London, UK. Electronic address: lorraine.noble@ucl.ac.uk.

-

2Division of Medical Education, Brighton & Sussex Medical School, Brighton, UK.

-

3School of Medical Education, King's College London, London, UK.

-

4Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK.

-

PMID: 29706382

Abstract

Objectives: Clinical communication is a core component of undergraduate medical training. A consensus statement on the essential elements of the communication curriculum was co-produced in 2008 by the communication leads of UK medical schools. This paper discusses the relational, contextual and technological changes which have affected clinical communication since then and presents an updated curriculum for communication in undergraduate medicine.

Method: The consensus was developed through an iterative consultation process with the communication leads who represent their medical schools on the UK Council of Clinical Communication in Undergraduate Medical Education.

Results: The updated curriculum defines the underpinning values, core components and skills required within the context of contemporary medical care. It incorporates the evolving relational issues associated with the more prominent role of the patient in the consultation, reflected through legal precedent and changing societal expectations. The impact on clinical communication of the increased focus on patient safety, the professional duty of candour and digital medicine are discussed.

Conclusion: Changes in the way medicine is practised should lead rapidly to adjustments to the content of curricula.

Practice implications: The updated curriculum provides a model of best practice to help medical schools develop their teaching and argue for resources.

Keywords: Communication; Curriculum; Undergraduate medical education.

Copyright © 2018 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 교육과정 개발&평가' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 의사를 위한 CME활동에서의 기획 및 평가의 개념 프레임워크(Med Teach, 2018) (0) | 2021.02.05 |

|---|---|

| 위계적이지 않은 선형적 교육 이니셔티브 평가: 7I 프레임워크(J Educ Eval Health Prof, 2015) (0) | 2021.02.05 |

| 학부의학교육에서 의사소통 교육과정의 내용에 대한 합의문(Med Educ, 2008) (0) | 2021.01.30 |

| 실패하는 것이 인간이다: 의학교육의 재교육을 재교육(Perspect Med Educ, 2017) (0) | 2020.12.27 |

| 의학교육에서 수직통합: 포괄적 관점(BMC Med Educ, 2020) (0) | 2020.12.20 |