여자지원자가 남자지원자보다 MMI 점수가 더 높은가? 캘거리 대학 결과(Acad Med, 2017)

Are Female Applicants Rated Higher Than Males on the Multiple Mini-Interview? Findings From the University of Calgary

Marshall Ross, MD, Ian Walker, MD, Lara Cooke, MD, MSc, Maitreyi Raman, MD, MSc, Pietro Ravani, MD, PhD, Sylvain Coderre, MD, MSc, and Kevin McLaughlin, MBChB, PhD

의대에 입학하는 학생의 약 95%가 궁극적으로 졸업하기 때문에, 의대 입학 과정은 많은 사람들에게 의대 진로를 위한 "이상적인" 지원자를 선택할 수 있는 최선의 (그리고 아마도 유일한) 기회로 여겨진다.1,2 지원자들에게 면접 과정은 삶의 결정적 순간일 수 있으며, 이는 주어진 지원자가 동료들보다 CanMED-proficient한 의사로 성숙할 가능성이 더 높은지 예측하는 것이기 때문에 선발 과정에 참여하는 우리 중 누구에게나 큰 부담이 될 수 있습니다. 그러한 예측은 어렵고 부정확하기로 악명 높지만, 사회가 의사를 필요로 하기 때문에 (또한 의과대학에 지원한 지원자가 채용 가능한 숫자보다 훨씬 많기에) 우리는 의사 선발 과정이 필요하며 가능한 한 신뢰할 수 있고 타당하며 "공정"하게 만들기 위해 노력해야 합니다.

Since approximately 95% of students entering medical school will ultimately graduate, the medical school admissions process is considered by many as our best (and perhaps only) opportunity to select the “ideal” candidates for a career in medicine.1,2 For applicants, the interview process may be a life-defining moment, a fact that weighs heavily on those of us involved in the selection process as we try to predict whether a given applicant is more likely to mature into a CanMEDS- proficient physician than his or her peers.3 Such predictions are notoriously difficult and inaccurate,4,5 but because society needs physicians—and there are many more applicants to medical school than positions available—we need a selection process and must strive to make this as reliable, valid, and “fair” as possible.

대부분의 의과대학은 이전의 학업성취도 및 비학업적 특성의 지표를 평가하는 shor-listing 과정 외에도, 미래의 의사와 관련이 있을 수 있는 다른 속성을 평가하기 위한 형태의 인터뷰도 사용한다. 과거에는, 각 후보자에 대해 단일 인터뷰를 실시하는 선정 위원회가 필요했으며, 그 구체적인 방법(위원회의 구성, 논의되는 내용, 인터뷰의 구조화 정도, 최종 합격자를 뽑는 과정)에는 여러 기관 내 및 여러 기관 간 상당한 차이가 있었습니다. 그리고 이러한 접근방식은 편리했지만, 단일 면접의 제한된 범위와 면접관에 기인하는 점수차이의 비율을 고려할 때 이 과정의 [공정성에 대한 우려]가 제기되었다.

In addition to a short-listing process that rates indicators of prior academic performance and nonacademic attributes, most medical schools also use some form of interview to assess other attributes that may be relevant for future physicians. Historically, this involved a selection committee conducting a single interview of each candidate, and there was often significant variation—both within and between centers—in the makeup of committees, the content discussed, the degree of structure of the interviews, and the process of selecting the best candidates.6,7 And, although this approach was convenient, concerns arose about the fairness of this process given the limited scope of a single interview and the proportion of variance in scores attributable to the interviewers.8,9

의대 입학 과정에 MMI를 포함함으로써 지원자들은 기존의 면접 형식보다 더 신뢰성이 높고, 더 수용 가능하며, 덜 의존적이며, 미래 성과를 더 예측하는 것으로 보이는 선발 과정이 이루어졌다. MMI의 타당성과 차원성에 대한 지속적인 우려에도 불구하고, 이러한 인상적인 연구 결과는 북미, 유럽 및 호주의 많은 의과대학에서 MMI를 선발 과정에 포함시키는 것을 촉진했습니다. 그러나 모든 변화는 [의료계의 인구학적 특성을 바꾸는 것]과 같은 의도하지 않은 결과의 가능성을 수반한다.

The inclusion of the MMI to the medical school admissions process has resulted in a selection process that appears to be more reliable,10,14–16 more acceptable to applicants,13,14 less rater dependent,10 and more predictive of future performance than the traditional interview format.14,15,17,18 Despite ongoing concerns regarding the validity and dimensionality of the MMI,14,19 these impressive findings have fomented the incorporation of the MMI into the selection process in many medical schools in North America, Europe, and Australia.11–13 Yet every change carries the possibility of unintended outcomes, such as changing the demographic characteristics of the medical profession.

예를 들어, 이 기술을 신뢰성 있게 평가할 수 있는 순간, 일반적으로 여성이 남성보다 높은 평가를 받기 때문에, 의사소통이 수반되는 업무에 대한 지원자의 성과를 평가할 때마다 여성이 남성보다 더 높은 성과를 낼 것이라고 예측할 수 있다. McMaster에서 MMI를 처음 시험했을 때 이 초기 연구의 표본 크기가 상대적으로 작았지만(n = 117) 신청자 성별과 MMI 등급 사이에는 유의한 연관성이 없었다. 후속 연구에서도 여성 지원자와 남성 지원자의 등급 차이는 없다고 보고했지만, 다시 한 번 이러한 연구의 표본 크기는 작았고, 남성 지원자도 30명 미만인 경우가 많았다.

For example, because females are typically rated higher than males in communication as soon as this skill can be reliably assessed,20 one might predict that females would outperform males whenever we assess the performance of applicants on tasks that involve communication.21,22 When the MMI was first piloted at McMaster there was no significant association between applicant gender and MMI ratings, although the sample size in this initial study was relatively small (n = 117).10 Subsequent studies also reported no difference in ratings of female and male applicants,23–26 although, once again, the sample size in these studies was small, with studies often including fewer than 30 male applicants.24–26

캘거리 커밍 의과대학에서 MMI를 소개할 때, 브라우넬과 동료는 지원자와 면접관 모두의 의견으로 MMI가 "성 편견이 없었다"고 보고했고, 이후 연구에서도 이러한 결론이 도출되었다. 흥미롭게도 스코틀랜드의 한 센터에서 실시한 보다 최근의 연구에서 10개 스테이션 MMI가 신뢰할 수 있는 것으로 보고되었으며, 이 과정은 "모든 당사자가 수용할 수 있다" (후보와 평가자의 90% 이상이 공정성 진술에 동의하거나 강력하게 동의)고 하였다.

When introducing the MMI at the University of Calgary Cumming School of Medicine, Brownell and colleagues11 reported that, in the opinion of both applicants and interviewers, “the MMI was free of gender bias,” and this conclusion was also drawn in subsequent studies.15,16,25 Interestingly, in a more recent study from a single center in Scotland, a 10-station MMI was reported as reliable, and the process was “acceptable to all parties” (more than 90% of candidates and raters agreed or strongly agreed with a fairness statement).13

여기서는 여성 및 남성 지원자의 MMI 등급을 의과대학과 비교하고 MMI 등급이 지원자 순위에 미치는 영향을 탐색한 두 가지 연구를 설명합니다.

Here we describe two studies in which we compared MMI ratings for female and male applicants to our medical school, and explored the impact of MMI ratings on the ranking of applicants.

연구 1 Study 1

방법 Method

참여자 Participants.

재료 Materials.

절차 Procedures.

통계뿐석 Statistical analysis.

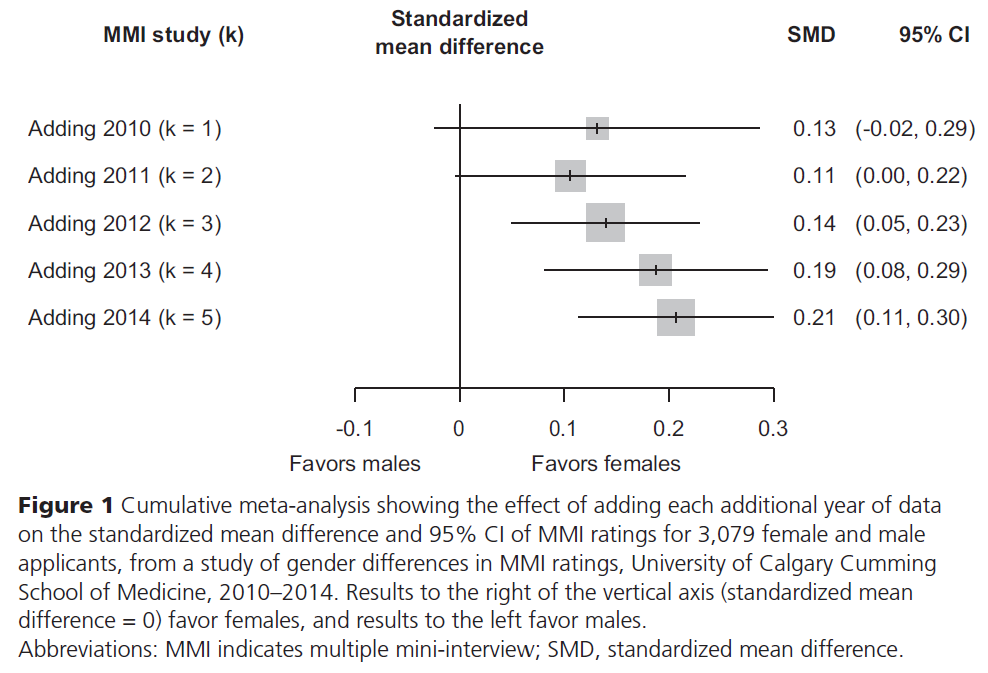

우리는 평균과 SD를 표준화된 평균 차이로 변환하고 효과 크기 계산을 위해 Hedges g를 사용했습니다.28 그런 다음 STATA 버전 11 통계 소프트웨어(STATA Corporation, College Station, 텍사스)를 사용하여 랜덤 효과 모델을 사용한 누적 메타 분석을 수행했다.

We converted means and SDs into standardized mean differences and used Hedges g for our effect size calculation.28 We then performed cumulative meta-analysis using the random-effect model, using STATA version 11 statistical software (STATA Corporation, College Station, Texas).

연구결과 Results of Study 1

고찰 Discussion of Study 1

우리의 연구 결과는 MMI에서 여성이 남성보다 높은 평가를 받고 있음을 시사한다. 시간이 지남에 따라 [표준화된 평균 차이]가 변한다는 것은 2012년에 이러한 결론을 도출하기에 충분한 데이터가 있었다는 것을 의미하며 후속 데이터를 추가하면 이러한 결과를 더 정확하게 확인할 수 있다는 것을 의미한다.

Our findings suggest that at our medical school, females are rated higher than males on the MMI. The change in the standardized mean difference over time implies that there were sufficient data to draw this conclusion in 2012 and that the addition of subsequent data simply confirms this finding with greater precision.

연구 2 Study 2

방법 Method

참여자 Participants.

재료 Materials.

본 연구에 사용된 데이터는 본 의과대학의 입학 전형 과정의 일환으로 전진적으로 수집되었습니다. 이러한 데이터에는 지원자 파일의 등급과 후속 MMI 등급이 포함되었습니다. 지원자의 파일 데이터에는 이력서, 학력(학부 성적 평균[GPA]), 적성 시험 성적(MCAT]), 추천서 등이 포함되어 있었다. 또한 지원자의 성별과 나이를 기록했으며, 각 MMI 방송국별로 면접관의 성별과, 면접관이 수습생인지 여부를 기록했습니다. MMI의 12개 스테이션 각각에 대해 우리가 평가하고자 하는 단일 속성이 있었으며, 대상 속성의 전체 목록은 다음과 같았다.

- 갈등 관리/통신

- 학습에 대한 태도

- 피드백에 대한 반응성.

- 의사결정 능력/데이터 해석

- 연구 윤리

- 의사소통 기술,

- 문화적 역량

- 공감;

- 시각적 관찰 및 창의적 사고

- 자원 관리/프로젝트 계획;

- 정직과 진실,

- 오류 공개

The data used for this study were collected prospectively as part of our admissions selection process. These data included ratings of applicants’ files and subsequent MMI ratings. Applicants’ file data included their curriculum vitae, academic record (undergraduate grade point average [GPA]), performance on an aptitude test (Medical College Admission Test [MCAT]), and letters of reference. We also noted the gender and age of applicants, and for each MMI station we noted the gender of the interviewer and whether the interviewer was a trainee. For each of the 12 stations on the MMI there was a single attribute that we intended to assess, and the complete list of target attributes was as follows:

- conflict management/communication;

- attitude towards learning;

- responsiveness to feedback;

- decision-making ability/data interpretation;

- research ethics;

- communication skills;

- cultural competency;

- empathy;

- visual observation and creative thinking;

- resource management/project planning;

- honesty and integrity; and

- disclosure of error.

MMI에 대한 성과는 체크리스트와 전지구적인 평가 척도를 조합하여 평가되었으며, 이는 주어진 관측소에 대한 최종 평가에도 동일하게 기여하였다.

Performance on the MMI was rated using a combination of a checklist and a global rating scale, which then contributed equally to the final rating for a given station.

절차 Procedures.

각 지원자의 파일은 7개 CanMED 역량을 나타내려는 7개 영역에 대해 주관적인 점수를 제공한 60명의 패널로부터 4명의 독립 검토자에 의해 검토되었다.3 예를 들어, 학업 성적은 전문가 역할의 일부로 평가되었고, 관리자 역할을 평가할 때 리더십 경험이 고려되었습니다. 그런 다음, 파일 검토 점수는 다음과 같은 가중치를 사용하여 작성되었다: 7개의 CanMED 역량을 나타내는 각 도메인에 대해 10%, GPA에 대해 20%, MCAT의 구두 추론 구성요소에 대해 10%이다. 평균 파일 검토 점수를 기준으로 지원자의 순위를 매기고 상위 526명의 지원자를 MMI에 초대했습니다. MMI 스테이션은 7분이며 단일 면접관이 평가했습니다.

Each applicant’s file was reviewed by 4 independent reviewers, from a panel of 60, who provided subjective scores for seven domains that were intended to represent the seven CanMEDS competencies.3 For example, academic record was rated as part of the Expert Role, and leadership experience was considered when rating the Manager Role. The file review scores were then compiled using the following weighting: 10% for each of the domains representing the seven CanMEDS competencies, 20% for GPA, and 10% for the verbal reasoning component of the MCAT. We ranked applicants based on mean file review scores and invited the top 526 applicants to attend our MMI. Our MMI stations were seven minutes long and were rated by a single interviewer.

통계 분석

Statistical analysis.

여성 및 남성 지원자에 대한 MMI 등급을 비교하기 위해 Cohen d와 함께 독립 표본 t 검정을 효과 크기 측정값으로 사용했습니다. 다른 잠재적 설명 변수에 대한 조정 후 신청자 성별과 MMI 등급 간의 연관성을 연구하기 위해 다중 선형 회귀 분석을 수행했다.

- 지원자의 나이,

- 내신,

- MCAT 점수(언어 추론, 물리, 생물)

- 면접관의 성별, 그리고

- 면접관이 훈련생(의대생 또는 레지던트)이었는지 여부.

To compare MMI ratings for female and male applicants, we used an independent-sample t test with Cohen d as our measure of effect size. We performed multiple linear regression to study the association between applicant gender and MMI ratings after adjustment for other potential explanatory variables:

- applicant’s age,

- GPA,

- MCAT score (for verbal reasoning, physical sciences, and biological sciences),

- interviewer’s gender, and

- whether the interviewer was a trainee (medical student or resident).

우리는 회귀 모형에 지원자와 면접관 변수 간의 교호작용을 포함시키고 교호작용 항부터 시작하여 유의하지 않은 설명 변수를 제거하기 위해 후진 제거를 수행했습니다.

We included interactions between applicant and interviewer variables in our regression model and performed backward elimination to remove nonsignificant explanatory variables, beginning with interaction terms.

MMI 등급에 부여된 가중치가 의과대학원 직책을 제안받을 확률에 미치는 영향을 조사하기 위해, 각 지원자에 대한 파일 검토 점수와 MMI 등급을 결합한 민감도 분석을 수행했다.

To explore the impact of the weighting given to the MMI rating on the odds of female applicants being offered a medical school position, we performed a sensitivity analysis where we combined file review scores and MMI ratings for each applicant.

결과 Results of Study 2

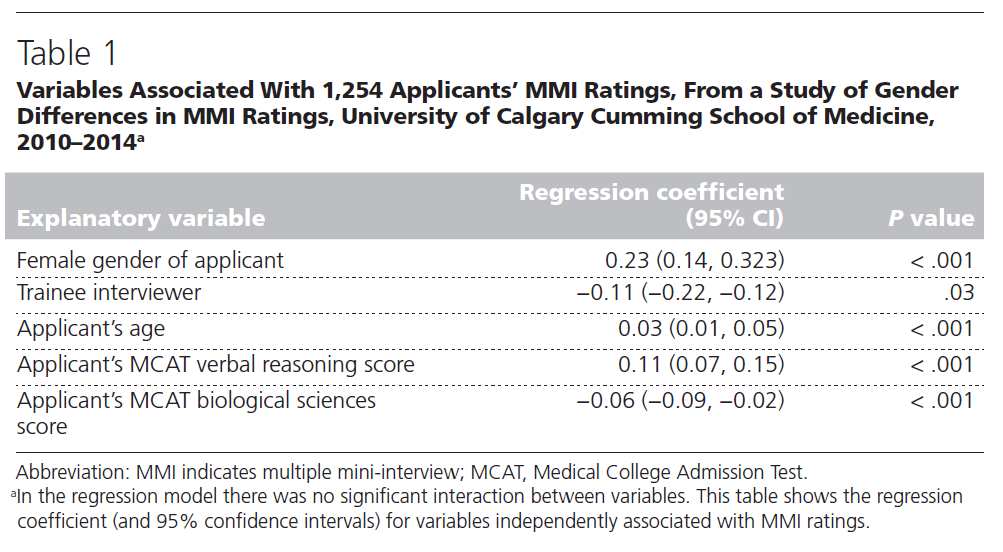

여성 신청자와 남성 신청자에 대한 평균 MMI 등급은 각각 6.60 (SD 1.75)과 6.34 (SD 1.88)이었다 (P = 0.01, d = 0.14). 지원자와 면접관의 성별(P =.94) 간의 상호작용을 포함하여 우리의 회귀 모델에서 상호작용은 없었지만, 지원자의 성별, 지원자의 나이, 면접관의 지위(연수생 대 비훈련생), 언어 추론 및 생물 과학에 대한 MCAT 점수는 MMI 등급과 관련이 있었다. 다른 변수에 대해 조정한 후에도 여성 신청자와 MMI 등급 사이에는 유의한 양의 연관성이 있었습니다(회귀 계수 0.23, 95% CI [0.14, 0.33, P < 0.001]). 이러한 데이터는 표 1에 나와 있습니다.

The mean MMI rating for female and male applicants was 6.60 (SD 1.75) and 6.34 (SD 1.88), respectively (P < .01, d = 0.14). There were no interactions in our regression model, including no interaction between gender of applicant and interviewer (P = .94), but applicant’s gender, applicant’s age, interviewer’s status (trainee vs. nontrainee), and MCAT scores for verbal reasoning and biological science were associated with MMI rating. After adjusting for other variables, there was still a significant positive association between being a female applicant and MMI rating (regression coefficient 0.23, 95% CI [0.14, 0.33], P < .001). These data are shown in Table 1.

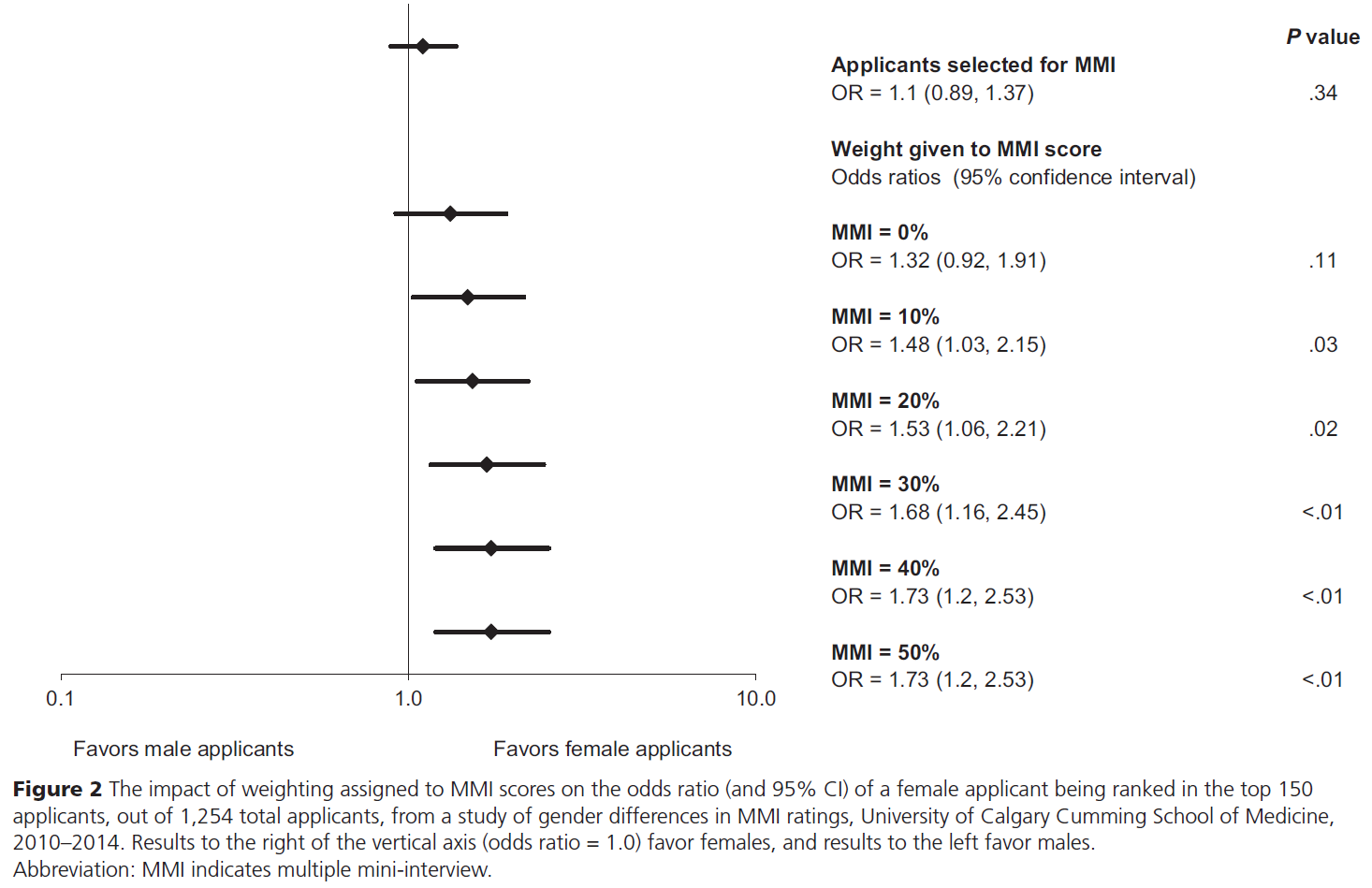

민감도 분석에서, 서류점수 검토만을 기반으로 한 상위 150명의 지원자의 성별 구분(즉, MMI 등급이 전체 지원자 점수에 기여하지 않은 경우)이 원래 지원자 코호트의 성별 구분과 크게 다르지 않다는 것을 발견했다. (지원자가 여성이었던 비율 1.32; 95% CI[0.92, 1.91] P =.11) MMI 등급에 부여된 가중치를 변화시킬 때, MMI 등급이 전체 점수의 10% 이상을 기여할 때마다, 여성 지원자가 남성 지원자보다 상위 150명 안에 들 확률이 상당히 높았다. 이러한 데이터는 그림 2에 나와 있습니다.

In our sensitivity analysis, we found that the gender breakdown of the top 150 applicants based solely on file review scores (i.e., when MMI rating did not contribute to overall applicant score) was not significantly different from that of the original application cohort (odds ratio of an applicant being female was 1.32; 95% CI [0.92, 1.91], P = .11). When varying the weight given to MMI rating, we found that whenever the MMI rating contributed 10% or more of the overall score, the odds of a female applicant being ranked in the top 150 students were significantly higher than for male applicants. These data are shown in Figure 2.

고찰 Discussion of Studies 1 and 2

만약 MMI에서 여성이 남성보다 높은 평가를 받는다면, 우리는 그 이유를 이해하려고 노력해야 한다. 우리는 MMI의 타당성에 대해 서로 다른 의미를 갖는 두 가지 가능한 설명을 제안할 것이다. 첫 번째는 MMI가 포착하려는 속성을 여성들이 더 잘 보여줄 가능성이 높다는 것이다. 일반적으로, 남성과 비교했을 때, 여성이 더 나은 의사소통 기술을 보일 때, 20-22는 비판적 사고의 특정 측면(예: 열린 마음, 성숙도)에서 더 높은 평가를 받고, 18,29 그리고 더 많은 윤리적 결정을 내린다.30,31

If females are rated higher than males on the MMI, then we should try to understand why. We would propose two possible explanations that have divergent implications for the validity of the MMI. The first is that females are more likely to demonstrate the attributes that the MMI is intended to capture. In general, when compared with males, females typically demonstrate better communication skills,20–22 are rated higher on certain aspects of critical thinking (such as open-mindedness and maturity),18,29 and make more ethical decisions.30,31

이러한 업무에서 여성이 남성보다 높은 성과를 낼 것으로 예상하기 때문에, MMI에서 여성이 남성보다 높은 등급을 받는다는 사실이 [MMI의 타당성 원천]이라고 주장할 수 있다. 그러나 또 다른 설명으로 가능한 것은 여성이 의사소통, 비판적 사고, 윤리적인 모습을 [더 잘할 것으로 기대하기 때문에] MMI에서 더 높은 평가를 받는다는 것이다. 만약에 후자의 경우라면, 여성은 MMI 점수의 타당성을 감소시키는 편견의 일종인 [관찰자 기대]의 결과로 더 높은 등급을 받은 것이다.

Because we expect females to outperform males on these tasks, one could argue that the fact that females are rated higher than males on the MMI is a source of validity for the MMI.32 However, the alternative explanation is that females are rated higher on the MMI because we expect them to be better at communication, critical thinking, and ethical decision making. In this scenario, females are rated higher as a result of observer expectancy, a type of bias that would reduce the validity of MMI ratings.

[관찰자 기대] 또는 [확증 편향(또는 "자기 충족 예언"33)]은 기존의 신념이 이러한 기존 신념을 뒷받침하는 방식으로 데이터의 해석에 무의식적으로 영향을 미치는 과정을 말하며, 심리학 문헌에는 관찰자 기대 편향의 예가 많다.36

- 예를 들어, 근지구력 과제에서 남성과 여성의 성과를 평가해 달라고 요청했을 때, 남녀 대학생 모두 남성의 성과를 과대평가하고 여성의 성과를 과소평가하는 경향이 있었다.

- 동영상에서 남성과 여성의 웃는 정도를 평가해 달라는 질문에 심리학과 학생들은 남성에 비해 여성의 웃는 모습을 과대평가했다.

Observer expectancy or confirmation bias (also referred to as “self-fulfilling prophecy”33) refers to a process where preexisting beliefs subconsciously influence interpretation of data in a way that supports these preexisting beliefs,34,35 and there are many examples of observer expectancy bias in the psychology literature.36

- For example, when asked to rate the performance of males and females on a muscular endurance task, both male and female college students tended to overestimate the performance of males and underestimate the performance of females,37

- whereas when asked to rate the amount of smiling of males and females on video clips, psychology students overestimated smiling of females relative to males.38

이러한 성별 기반 고정관념은 자동으로 생성되며 컴퓨터의 음성 출력이나 가상 인간의 인식된 성별과 같은 미묘한 조작에 의해 유발될 수 있습니다. [관찰자의 기대]는 대체로 잠재의식 수준에 존재하는 것이므로, 감지하기 어렵고 마찬가지로 억제하기도 어려울 수 있습니다. —특히 관측자에게 8분 MMI 관측소와 같이, 노출이 제한된 상황에서, ill-defined 구인에 대한 평정을 해야 하는 경우 그렇다.

These gender-based stereotypes are generated automatically and can be triggered by subtle manipulations, such as altering the voice output of computers or perceived gender of virtual humans.39,40 Being largely subconscious, observer expectancy may be difficult to detect and equally difficult to suppress—especially when observers are asked to rate ill- defined constructs based upon limited exposure, such as an eight-minute MMI station.41–43

MMI(또는 다른 데이터 출처)의 포함이 의대 입학에서 성비 불균형을 야기하는지 우려해야 하는가? 이 질문에 대한 답은 취해진 관점에 따라 달라지며, 우리는 의과대학 입학 과정에 변화가 미치는 영향을 판단할 수 있는 가장 의미 있는 방법으로 [환자 중심의 결과]를 제안할 것이다. 선발 과정의 변화를 통해서 양질의 의료 서비스를 제공하는 인력이 양성된다면, 성별 불균형이 허용될 수 있다. 심지어는 의료 서비스 제공 개선을 위하여 필요할 수도 있습니다.

Should we be concerned if the inclusion of the MMI (or any other source of data) creates a gender imbalance in medical school admissions? The answer to this question depends on the perspective taken, and we would propose patient-centered outcomes as the most meaningful way to judge the impact of any change to the medical school admissions process. If changes to the selection process produce a workforce that delivers higher-quality health care, a gender imbalance may be acceptable— and may even be necessary to improve health care delivery.

그러나 동등하거나 더 나쁜 의료 결과로 성비 불균형을 초래하는 입학 과정은 용납될 수 없다. 이전의 연구들은 여성 의사들이 환자와 상호작용할 때 일반적으로 남성보다 더 큰 공감을 보이고 더 많은 긍정적인 진술을 사용하며, 이러한 유형의 의사소통은 더 나은 과거 데이터를 제공하고, 더 나은 만족도와 정신건강을 보고하고, 덜 사용하는 환자와 관련이 있다고 제안했다. 45–48 그러나 이러한 유형의 데이터는 어떤 유형의 입학 절차를 지원하는 직접적인 증거를 제공하지 않는다.

But an admissions process that creates a gender imbalance with equal or worse health care outcomes is unacceptable. Previous studies have suggested that female physicians typically demonstrate greater empathy and use more positive statements than males when interacting with their patients21,44 and that this type of communication is associated with patients providing better historical data, reporting enhanced satisfaction and psychosocial health, and using less health care resources.45–48 However, these types of data do not provide direct evidence in support of any type of admissions process.

그렇다면 선발 프로세스가 의료 결과에 미치는 영향을 어떻게 입증할 수 있는가? 의료 성과 개선을 목적으로 설계된 인터벤션은 지속적으로 도입되고 있으므로 선택 프로세스의 사전/사후 비교는 다른 개입으로 인하여 confound될 수 있다. 두 가지의 성발 과정을 종단적으로 추적하여 무작위 비교하는 것이 이상적이지만, 이러한 유형의 다중 센터 연구는 많은 의과대학에서 수용되거나 가능하지 않을 수 있다.

So, how can we demonstrate the impact of the selection process on health care outcomes? Interventions designed to improve health care outcomes are being implemented continuously, so a pre/post comparison of selection processes would be confounded by other interventions. A randomized comparison of different selection processes with longitudinal follow-up would be ideal, but this type of multicenter study may not be acceptable or feasible for many medical schools.

분명히 우리는 입학 과정이 측정 가능하고 의미 있는 결과에 미치는 영향을 입증하는 데 있어 중대한 도전에 직면해 있습니다.5 MMI가 보건의료 성과에 미치는 영향을 알지 못하면 MMI 등급의 성별 차이가 허용 가능한지 여부를 말할 수 없다. — 그러나 우리는 의과대학 입학에서 성 불균형의 기원을 MMI의 역사보다 훨씬 더 거슬러 올라갈 수 있다는 것을 알고 있다. 미국에서는 남성이 지속적으로 여성 졸업생 수를 앞섰다.49 1993-1994년(MMI가 나오기 10년 전) 이후, 캐나다에서는 지난 22년 동안 2년을 제외한 모든 기간에서 여학생이 남학생보다 많았다. 그 전 22년동안에는 반대로 여성은 늘 상대적으로 소수였다 50 이러한 성별 불균형의 이유와 의료 제공에 미치는 영향은 알려지지 않았지만, 추가 탐구할 가치가 있다.

Clearly, we face significant challenges in demonstrating the impact of the admissions process on outcomes that are both measurable and meaningful.5 Without knowing the impact of the MMI on health care outcomes, we cannot say whether gender differences in MMI ratings are acceptable or unacceptable— but we do know that the origins of gender imbalance in medical school admissions can be traced back much further than the history of the MMI. In the United States, males have consistently outnumbered female graduates.49 Since 1993–1994 (10 years before the description of the MMI), in Canada female students have outnumbered males in all but 2 years— after being consistently in the minority in the preceding 22 years.50 The reason for these gender imbalances and their impact on health care delivery are unknown, but are also worthy of further exploration.

결론 Conclusions

우리는 이것이 먼저 확인되고 설명되어야 할 중요한 발견이라고 생각합니다. 특히 MMI에서는 커뮤니케이션, 비판적 사고, 윤리적 의사결정 능력이 향상되어 여성 지원자를 선발하는 것인지, 아니면 추가 설명이 필요한 대안적 설명 때문에 여성 지원자를 더 높게 평가하는 것인지 알 필요가 있다.

We feel that this is an important finding that needs first to be confirmed and then explained. In particular, we need to know if we are selecting female applicants because during the MMI we observe better communication, critical thinking, and ethical decision-making skills, or if we rate female applicants higher because of alternative explanations that need to be further elucidated.

Acad Med. 2017 Jun;92(6):841-846.

doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001466.

Are Female Applicants Rated Higher Than Males on the Multiple Mini-Interview? Findings From the University of Calgary

Marshall Ross 1, Ian Walker, Lara Cooke, Maitreyi Raman, Pietro Ravani, Sylvain Coderre, Kevin McLaughlin

Affiliations collapse

Affiliation

- 1M. Ross is a resident, Department of Emergency Medicine, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada. I. Walker is clinical associate professor, Department of Emergency Medicine, and director of admissions, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada. L. Cooke is associate professor, Department of Clinical Neurosciences, and associate dean of continuing medical education, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada. M. Raman is clinical associate professor, Department of Medicine, and associate director of admissions, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada. P. Ravani is professor, Department of Medicine, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada. S. Coderre is professor, Department of Medicine, and associate dean of undergraduate medical education, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada. K. McLaughlin is professor, Department of Medicine, and assistant dean of undergraduate medical education, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada.

- PMID: 28557950

- DOI: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001466Abstract

- Purpose: The multiple mini-interview (MMI) improves reliability and validity of medical school interviews, and many schools have introduced this in an attempt to select individuals more skilled in communication, critical thinking, and ethical decision making. But every change in the admissions process may produce unintended consequences, such as changing intake demographics. In this article, two studies exploring gender differences in MMI ratings are reported.Results: Females were rated higher than male applicants (standardized mean difference 0.21, 95% CI [0.11, 0.30], P < .001). After adjusting for other explanatory variables, there was a positive association between female applicant and MMI rating (regression coefficient 0.23 [0.14, 0.33], P < .001). Increasing weight assigned to MMI ratings was associated with increased odds of females being ranked in the top 150 applicants.

- Conclusions: In this single-center study, females were rated higher than males on the MMI, and the odds of a female applicant being offered a position increased as more weight was given to MMI ratings. Further studies are needed to confirm and explain gender differences in MMI ratings.

- Method: Cumulative meta-analysis was used to compare MMI ratings for female and male applicants to the University of Calgary Cumming School of Medicine between 2010 and 2014. Multiple linear regression was then performed to explore gender differences in MMI ratings after adjusting for other variables, followed by a sensitivity analysis of the impact of varying the weight given to MMI ratings on the odds of females being ranked in the top 150 applicants for 2014.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 입학, 선발(Admission and Selection)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 보건전문직 교육의 선발 방법에 대한 지원자 인식: 이유와 집단간 차이(Med Educ, 2022) (0) | 2023.05.28 |

|---|---|

| 의학교육 수련생 선발을 위한 추첨 활용의 논리적 근거: 수십년의 네덜란드 경험(J Grad Med Educ. 2021) (0) | 2021.11.16 |

| 성격, 직업, 선발의 미래: 신화와 오해와 측정과 제안(Adv in Health Sci Educ, 2017) (0) | 2020.09.11 |

| 능력(When I say ... ) (Med Educ, 2019) (0) | 2020.09.11 |

| 의학적 능력주의의 문화적 신화를 넘어(Med Educ, 2020) (0) | 2020.08.09 |