의학교육연구의 근거이론(AMEE Guide No. 70) (Med Teach, 2012)

Grounded theory in medical education research: AMEE Guide No. 70

Christopher J. Watling &Lorelei Lingard

소개 Introduction

지난 몇 년 동안 의학 교육 연구에서 질적인 조사 방법의 사용과 수용이 점진적으로 증가해왔다. 이러한 경향은 이 분야에서 가장 시급하고, 목적적합하며, 중요한 질문 중 일부는 전통적으로 생물 의학 영역을 지배해온 실험 및 정량적 연구 방법을 사용하여 만족스럽게 탐색할 수 없다는 인식이 증가하고 있음을 반영한다. 연구자가 이용할 수 있는 많은 정성적 방법 중, 근거이론은 생물의학과 사회과학 영역 모두에서 가장 자주 사용되어 왔다(Harris 2003).

The last several years have witnessed a gradual increase in the use and acceptance of qualitative methods of inquiry in medical education research. This trend reflects a growing recognition that some of the most pressing, relevant, and important questions in the field cannot be satisfactorily explored using the experimental and quantitative research methods that have traditionally dominated the biomedical domain. Among the multitude of qualitative methods available to the researcher, grounded theory has been the approach most frequently used in both the biomedical and social science realms (Harris 2003).

역사적 관점

An historical perspective

근거이론은 사회학자 창시자인 바니 글레이저와 앤셀름 스트라우스와 불가분의 관계를 유지하고 있는데, 그는 1967년 저서 "근거이론의 발견"에서 경험적 데이터로부터 이론을 생성하는 방법을 설명했다. 그들은 이 방법을 정성적 데이터와 정량적 데이터에 모두 적용할 수 있다고 언급했지만, 이론 생성에 관한 한 두 가지 유형의 데이터 간의 구분이 무의미하다는 것을 암시하기까지 했지만, 그들 자신의 연구는 정성적이었다. 근거이론의 비평가들조차 그들의 선구적인 연구가 사회과학의 질적 연구 방법의 정당화에 중요한 영향을 끼쳤다는 것을 인정한다(Thomas & James 2006).

Grounded theory remains inextricably linked with its sociologist founders, Barney Glaser and Anselm Strauss, who described, in their 1967 book The Discovery of Grounded Theory, a method for generating theory from empirical data (Glaser & Strauss 1967). Although they noted that the method could be applied to both qualitative and quantitative data, even suggesting that the distinction between the two types of data was meaningless as far as theory generation was concerned, their own research was qualitative. Even critics of grounded theory acknowledge that their pioneering work was a key influence on the legitimization of qualitative research methods within the social sciences (Thomas & James 2006).

[근거이론이 개발된 시대]의 맥락에 대한 관점이 유용하다. 글레이저와 스트라우스는 지난 수십 년 동안 사회과학 내에서 이론 검증에 대한 강한 경향을 한탄했고, 기존 이론을 시험하고 검증하기 위한 연구만을 이용하기보다는 자료로부터 이론의 생성을 촉진하고 싶었다(글레이저 & 스트라우스 1967). 또한, 질적 연구가 이전에는 잘 알려져 있었지만, 1960년대에 이르러 양적 학자들은 질적 연구를 종속적인 지위로 격하시켰다. (덴진 & 링컨 2005) Glaser와 Strauss는 데이터 분석을 위한 절차와 관행을 명확히 하고 코딩함으로써 정량적 접근법에 의해 점점 더 지배되는 분야에서 질적 연구를 정당화하는 것을 목표로 했다. 요컨대, 그들은 질적 연구가 잘 수용된 정량적 조사 방법과 나란히 설 수 있도록 하는 엄격함의 수준을 달성할 수 있다는 것을 증명함으로써 사회과학 연구의 발전뿐만 아니라 정치적 의제의 발전에도 관심이 있었다. (Bryant 2002)

A perspective on the context of the times in which grounded theory was developed is useful. Glaser and Strauss lamented the strong trend toward theory verification within the social sciences over the preceding decades, and wanted to promote the generation of theory from data rather than the use of research exclusively to test and verify existing theories (Glaser & Strauss 1967). In addition, although qualitative research had previously been well-regarded, by the 1960s, quantitative scholars had relegated qualitative research to subordinate status (Denzin & Lincoln 2005). Glaser and Strauss aimed to legitimize qualitative research in a field increasingly dominated by quantitative approaches by clarifying and codifying their procedures and practices for data analysis. In short, they were interested not only in advancing social science research but also in advancing a political agenda by demonstrating that qualitative research could attain levels of rigour that would allow it to stand alongside well-accepted quantitative methods of inquiry (Bryant 2002).

글레이저와 스트라우스의 "이론"과 그 발견에 대한 아이디어에 대한 고찰은 계몽적이다. 이론이 경험적 데이터로부터 나오고, 따라서 데이터에 "근거"되어 있다는 그들의 핵심 개념은, 심지어 출현에 대한 개념이 논쟁되고 비판되었음에도 불구하고 오늘날 많은 근거이론작업을 안내하는 중요한 원리로 남아 있다. (Bryant 2002, 2003; Kelle 2005) 그들은

- 특정 영역 내의 경험적 조사 영역에 기초한 실질적 이론substantive theory과

- 특정 설정과 사회 구조의 시간과 장소와는 별개로 존재하며, 개념적conceptual인 형식적 이론formal theory을 구별했다.

An examination of Glaser and Strauss's ideas about “theory” and its discovery is enlightening. Their key notion that theory emerges from empirical data, and is thus “grounded” in data, remains an important principle guiding much grounded theory work today, even as the idea of emergence has been disputed and critiqued (Bryant 2002, 2003; Kelle 2005). They distinguished between

- substantive theories, based on empirical areas of inquiry within a particular domain, and

- formal theories, which were conceptual, distinct from the time and place of specific settings and social structures.

그들은 실질적인 이론substantive theory이 연구자 자신의 데이터로부터 생성될 수 있고 생성되어야 한다고 주장했다. 그들은 ("논리적인 추론 이론가들의 방식을 빌리기" 보다는) 데이터의 공식적 이론formal theory조차 근거가 있어야 한다고 주장했지만(Glaser & Strauss 1967, p.91) 그들은 공식적 이론formal theory이 다양한 실질적인 분야에서 연구되지 않는 한 [연구자 자신의 데이터에서 쉽게 도출될 수 없다는 것]을 인정했다.

Substantive theories, they argued, could and should be generated from the researcher's own data (Glaser & Strauss 1967). While they called for grounding of even formal theories in data rather than “borrowing the ways of logico-deductive theorists” (Glaser & Strauss 1967, p.91), they acknowledged that formal theory could not easily be derived from the researcher's own data, unless a large number of studies in a variety of substantive areas had been done.

실증주의Positivism

원래의 형태에서, 근거이론은 객관적이고 실증주의적 가정에 뿌리를 두고 있었다. 실증주의 패러다임은 객관적이고 초연한 연구자가 이해할 수 있는 진정한 현실을 가정한다(Guba & Lincoln 2005). 글레이저와 스트라우스의 원작은 사실 포스트 포지티브 패러다임이 출현하고 있던 시기에 일어났다(Guba & Lincoln 2005, p.193). 이 패러다임에서는 현실을 "불완전하고 확률적으로만 이해가능한apprehendable" 것으로, 보다 비판적으로 보았다. 그러나 사실 실증주의와 후기실증주의가 연구질문의 접근법에 미치는 영향은 미미하다. 실증주의적 사고는 근거이론 방법의 원래 설명에서 "발견"이라는 단어의 두드러진 사용에서 명백하다. 그 의미는 진리가 연구자에 의해 "발견"되기를 기다리고 있다는 것이다.

In its original form, grounded theory was rooted in objectivist and positivist assumptions. The positivist paradigm assumes a true reality that is apprehendable by a detached, objective researcher (Guba & Lincoln 2005). Glaser and Strauss's original work, in fact, occurred at a time when a post-positivist paradigm was emerging, in which reality is viewed more critically as “only imperfectly and probabilistically apprehendable” (Guba & Lincoln 2005, p.193), but in fact the differences between positivism and post-positivism in terms of their influences on the approach to research questions are minor. The positivist thinking is apparent in the prominent use of the word “discovery” in the original description of the grounded theory method; the implication is that truth is waiting to be “discovered” by the researcher.

새로운 패러다임

New paradigms

근거이론의 원래 서술 이후 수십 년 동안, 구성주의를 포함한 새로운 패러다임의 출현과 연구의 기초가 되는 실증주의적 가정에 대한 광범위한 비판을 목격했다. 구성주의 패러다임은 지식을 인간의 상호작용과 관계의 산물로서 능동적으로 구성되고 공동 창조된 것으로 본다.

- 따라서 데이터와 분석은 "참가자 및 기타 데이터 출처와의 공유된 경험 및 관계"에서 작성된다(Charmaz 2006, 페이지 130).

- 구성주의 패러다임 내에서 연구 목표는 진리를 발견한다는 실증주의 목표에서, 특정 목적의 이해와 적절한 모델의 개발로 전환된다(Bryant 2002).

- 구성주의자들은 이론 생성의 해석적 성격을 인정한다. 그들은 이러한 해석을 만드는 데 있어 연구자의 역할에 대해 반사적으로 반응하고 열정 분석가로서의 연구자의 실증주의적 개념을 거부한다(Charmaz 2005).

- 연구 과정은 연구자가 자신의 배경과 가정을 분석 과정에 가져오는 적극적인 참여의 하나로 간주된다.

The decades that followed the original description of grounded theory witnessed extensive critiques of the positivist assumptions underlying research and the emergence of new paradigms, including constructivism. The constructivist paradigm views knowledge as actively constructed and co-created as the product of human interactions and relationships. Data and analysis are therefore created from “shared experiences and relationships with participants and other sources of data” (Charmaz 2006, p. 130). Within the constructivist paradigm, the goals of research shift from the positivist goal of discovering truth toward the development of understanding and adequate models for specific, situated purposes (Bryant 2002). Constructivists acknowledge the interpretive nature of theory generation. They are reflexive about the role of the researcher in creating these interpretations and reject positivist notions of the researcher as dispassionate analyst (Charmaz 2005). The research process is viewed as one of active engagement, where the researcher brings his or her own background and assumptions to the analytic process.

지식 생산의 포스트모던 개념의 영향은 근거이론 방법을 업데이트해야 하는 추가적인 요구로 이어졌다.

- 단순하고 일반화될 수 있는 기본적인 사회 과정을 밝혀내려는 실증주의적인 목표와 달리, 포스트모더니즘은 복잡성, 불안정성 및 이질성을 인정하고 강조한다(Clarke 2003).

- 클라크는 포스트모더니즘이 요구하는 복잡성에 대한 반사성과 명시적 인정 없이는 근거이론과 다른 질적 접근법이 더 이상 받아들여질 수 없다고 주장한다. 그녀는 포스트모던 감성과 더 잘 호환되는 상황 매핑situational mapping과 같은 새로운 접근법의 통합을 통해 근거이론 방법의 보다 전면적인 정비를 주장해왔다(Clarke 2003).

The influence of postmodern notions of knowledge production has led to further calls to updating the grounded theory method. In stark contrast to positivism, with its goal of uncovering basic social processes that are simple and generalizable, postmodernism acknowledges and emphasizes complexity, instability, and heterogeneity (Clarke 2003). Clarke contends that grounded theory and other qualitative approaches are no longer acceptable without the reflexivity and explicit acknowledgment of complexity that postmodernism demands. She has advocated for a more sweeping overhaul of the grounded theory method through the incorporation of newer approaches, such as situational mapping, that are more compatible with postmodern sensibilities (Clarke 2003).

근거이론조사: 원칙 및 절차

Doing grounded theory research: Principles and procedures

근거이론의 기저 가정에 대한 이 비판적인 질문의 결과로 근거이론이 진화했지만, 근거이론 연구를 정의하는 많은 근본적인 방법론적 전략이 남아 있다.

Although grounded theory has evolved as a result of this critical questioning of its underlying assumptions, there remain a number of fundamental methodologic strategies that define grounded theory studies.

우리는 의사 학습에 대한 중요한 영향을 탐구한 최근 근거이론 연구('영향 경험 연구')를 참고하여 이러한 원칙과 절차를 설명할 것이다(Watling et al. 2012). 그러나 우리는 모든 연구가 시작되어야 하는 곳에서 강력한 연구 질문으로 시작할 것입니다.

We will illustrate these principles and procedures, where useful, by making reference to a recent grounded theory study of our own (the “influential experiences study”) in which we explored the important influences on physicians’ learning (Watling et al. 2012). We will start, however, where every piece of research should start – with a strong research question.

근거이론 연구의 연구 질문

Research questions in grounded theory studies

생물 의학 분야를 지배하는 연구에 대한 실험적 접근법과 달리, 근거이론 연구는 시험 가설에 관한 것이 아니다. 오히려, 근거이론 연구는 관심 대상 현상의 근간을 이루는 [핵심 사회적] 또는 [사회 심리적 과정]을 이해하고자 하는 탐구적인 것이다. 근거이론은 연구자가 "어떤 상황이나 특정한 사건을 둘러싸고, 무엇이 일어나고 있거나 무슨 일이 일어나고 있는지 설명할 수 있게 해준다." (Morse 2009, 페이지 14) 이러한 목표는 근거이론 연구에서 질문해야 하는 연구 질문의 유형을 결정한다.

Unlike the experimental approach to research that dominates biomedical disciplines, grounded theory research is not about testing hypotheses. Rather, grounded theory research is exploratory, seeking to understand the core social or social psychological processes underlying phenomena of interest. Grounded theory allows the researcher “to explicate what is going on or what is happening … within a setting or around a particular event.” (Morse 2009, p.14) These aims determine the types of research questions that should be asked in a grounded theory study.

질문은 연구자가 완전히 집중되지 않은 상태에서 주제를 깊이 탐구할 수 있을 정도로 충분히 광범위해야 한다(Corbin & Strauss 2008). 초기 연구 질문은 연구의 범위를 정의하고 데이터 수집을 안내하는 동시에, 연구자가 데이터를 검토할 때 때때로 발생하는 예기치 않은 방향을 유연하게 따를 수 있도록 해야 한다. 예를 들어, 우리의 "영향력 있는 경험 연구"에서, 우리는 의사의 학습에 의미 있는 영향을 미치는 임상 경험의 qualities을 탐구하는 데 관심이 있었다1. 데이터 수집을 위해 진행한 인터뷰에서, 우리는 의사들이 학습에 가장 영향력 있다고 생각하는 유형의 경험과 이러한 경험이 그들에게 반향을 일으킬 수 있는 것이 무엇인지 물었다(Watling et al. 2012). 이러한 질문은 임상 학습 경험을 심층적으로 설명하는 데이터를 수집할 수 있을 정도로 충분히 광범위하면서도 관심 있는 맥락과 개인을 정의할 수 있도록 허용했다.

The questions should be broad enough to allow the researcher the freedom to explore a topic in depth, while not being entirely unfocused (Corbin & Strauss 2008). The initial research questions should define the scope of the study and guide the collection of data, while allowing flexibility for the researcher to follow the sometimes unexpected turns that arise as data is examined. For example, in our “influential experiences study”, we were interested in exploring the qualities of those clinical experiences that meaningfully influenced physicians’ learning1. In the interviews we employed for data collection, we asked what kinds of experiences physicians considered most influential in their learning, and what allowed these experiences to resonate with them (Watling et al. 2012). These questions were sufficiently broad to allow us to collect data that elucidated the experience of clinical learning in some depth, while still allowing us to define the contexts and individuals of interest.

방법론적 적합성 보장

Ensuring methodologic fit

연구자는 이 단계에서 근거이론 방법이 당면한 연구 질문을 탐구하는 데 적합한지 확인하기 위해 일시 중지하는 것pausing에서 이익을 얻을 수 있다.

The researcher may benefit, at this stage, from pausing to ensure that the grounded theory method is an appropriate fit for exploring the research questions at hand.

질적 탐구에 대한 다양한 접근법들 사이에 약간의 중복이 있을 수 있지만, 그들의 핵심에는 분명히 다른 목표를 가지고 있으며, 결과적으로 그들은 분명히 다른 제품으로 이어진다.

- 민족학 연구는 데이터를 해석하는 렌즈로서의 문화 개념을 사용한다(Goodson & Vassar 2011). 민족학자는 사회 조직을 내부에서 이해하는 것을 목표로 하며, 일반적으로 사회적 환경에서 지속적인 몰입적 참여를 통해 얻어지는 데이터 출처로서의 관찰에 크게 의존한다(앳킨슨 & 퍼글리 2005). 민족학 연구의 산물인 민족학은 연구된 집단의 "전체주의적 문화적 초상화"를 제공한다. (크레스웰 2007, 페이지 72)

- 이와는 대조적으로, 현상학은 경험된 개념이나 현상의 의미를 설명하는 데 초점을 맞추고 있다. 연구는 관심 있는 현상으로 시작하여 그 현상에 대한 여러 개인의 경험을 연구하여 그 본질로 축소한다(Cresswell 2007). 현상학의 중심은 연구자가 데이터 해석에 영향을 미칠 수 있는 선입견, 가정 및 편견을 식별한 다음 이러한 편견을 의도적으로 배제하려고 시도하는 괄호치기 관행이다(Dornan et al. 2005).

- 사례 연구 접근법에서, 연구원은 경계를 쉽게 정의할 수 있는 사례 또는 소수의 사례를 연구하기로 선택한다(Stake 2005). 사례 연구 연구는 연구 방법보다는 연구된 것에 의해 정의되며, 일반적으로 여러 출처로부터 정보를 수집하고 분석하는 것을 포함한다. 그것의 목표는 이론의 도출이나 일반화할 수 있는 원칙의 정교함이 아닌 개별 사례의 복잡성에 대한 심층적인 이해이다(Cresswell 2007).

Although there may be some overlap between the various approaches to qualitative inquiry, they have, at their core, distinctly different goals, and as a result they lead to distinctly different products.

- Ethnographic research uses the concept of culture as a lens through which to interpret data (Goodson & Vassar 2011). The ethnographer aims to understand a social organization from within, and typically relies heavily on observations as a data source, often obtained through sustained immersive engagement in a social milieu (Atkinson & Pugsley 2005). The product of ethnographic research, an ethnography, provides a “holistic cultural portrait” of the studied group. (Cresswell 2007, p. 72).

- Phenomenology, in contrast, focuses on describing the meaning of an experienced concept or phenomenon. The research starts with a phenomenon of interest, then studies several individuals’ experiences of that phenomenon to reduce it to its essence (Cresswell 2007). Central to phenomenology is the practice of bracketing, in which the researcher identifies preconceptions, suppositions, and biases that may influence data interpretation, then attempts to deliberately set these biases aside (Dornan et al. 2005).

- In the case study approach, the researcher chooses to study a case or a small number of cases whose boundaries can be readily defined (Stake 2005). Case study research is defined by what is studied rather than by how it is studied, and typically involves the collection and analysis of information from multiple sources. Its goal is an in-depth understanding of the complexity of an individual case, rather than the derivation of theory or the elaboration of generalizable principles (Cresswell 2007).

우리는 연구자들이 가장 관련성이 높은 방법론적 선택권과 연구과정의 이 단계를 진지하게 받아들이도록 권장할 것이다. 특정한 연구 문제를 해결하기 위해 상대적인 강점과 약점을 따져보는 것.

we would encourage researchers to take seriously this step of the research process by informing themselves of the most relevant methodological options and weighing their relative strengths and weaknesses for grappling with a particular research question.

다음은 근거이론연구의 수행을 정의하는 절차적 요소

the procedural elements that define the conduct of a grounded theory study, which we describe below.

반복공정

Iterative process

The Discovery of Ground Theory에서 Glaser와 Strauss는 데이터의 수집, 코딩 및 분석이 "연속적이어야 하며, (경계가) 흐리고 얽혀야 한다"고 언급하면서, 근거이론방법의 반복적 성격을 강조했다(Glaser & Strauss 1967, 페이지 43) 데이터 수집이 신중하게 제어되고 의도적으로 새로운 결과에 영향을 받지 않는 대부분의 실험적이고 가설 중심적인 정량적 연구와 대조적으로, 근거이론연구는 데이터 수집과 데이터 분석을 동시에 수행하며, 서로에게 정보를 제공한다. 예를 들어, 인터뷰 연구에서, 반복 프로세스는 스크립트가 완료될 때 스크립트를 읽고 초기 분석 통찰력과 개념 아이디어가 후속 데이터 수집을 형성할 수 있도록 하는 것을 의미한다. 예상치 못했거나 추가 탐구를 위한 설득력 있는 영역을 나타낼 수 있는 연구 결과는 유도 조사와의 후속 인터뷰에서 후속적으로 추적된다. 결과적으로, 조사를 신흥 지역emerging area으로 유도함으로써 얻은 추가 정보는 진행 중인 분석을 형성한다.

In The Discovery of Grounded Theory, Glaser and Strauss highlighted the iterative nature of the grounded theory method, noting that collection, coding, and analysis of data should “blur and intertwine continually” (Glaser & Strauss 1967, p.43). In contrast to most experimental, hypothesis-driven quantitative research, in which data collection is carefully controlled and deliberately not influenced by emerging results, grounded theory research involves performing data collection and data analysis simultaneously, with each informing the other. In an interview study, for example, an iterative process means reading transcripts as they are completed and allowing early analytic insights and conceptual ideas to shape subsequent data collection. Findings that were unanticipated or that may represent a compelling area for further exploration are followed up in subsequent interviews with directed probes. In turn, the additional information gained by directing the inquiry toward emerging areas shapes the ongoing analysis.

부호화

Coding

코딩은 근거이론 연구에서 분석 전략의 핵심 부분이다. 코딩과정에서 데이터를 핵심 개념 영역이나 테마를 중심으로 정리한다. 결과적으로, 잘 처리한 코딩은 단순히 데이터의 내용을 기술하거나 요약하는 것 이상을 필요로 한다. 오히려 코딩은 연구자가 데이터를 이해하기 위해 데이터와 상호작용해야 한다. 그러므로 코딩은 이론 구축 과정의 본질적이고 필수적인 부분이다.

Coding is a key part of the analytic strategy in grounded theory studies. Through coding, data are organized around key conceptual areas or themes. As a result, coding done well requires more than merely describing or summarizing the contents of the data. Rather, coding requires the researcher to interact with their data in order to make sense of it. Coding is therefore an intrinsic and essential part of the process of theory building.

다른 곳에서 자세히 설명한 코딩 데이터에 대한 여러 가지 접근법이 있다(Charmaz 2006; Corbin & Strauss 2008). [초기 코딩] 중에는 연구자가 가능한 많은 개념적 및 이론적 방향에 열려 있는 것이 중요하다(Charmaz 2006). 스크립트 내의 개별 줄이나 문장과 같은 작은 분석 단위에 초기 코딩 단계를 집중하면 가장 두드러진 아이디어가 식별되고 적절한 주의를 기울이도록 보장한다. 이 초기 상세 데이터 마이닝으로부터 개념적으로 관련된 많은 아이디어를 포함할 수 있는 더 넓은 범주가 개발되는 두 번째 코딩 단계가 온다. 종종, 코딩 체계는 추가 데이터가 수집됨에 따라 진화할 것이다. 특정 범주는 데이터가 특정 통합 기능에 의해 관련된다는 것이 분명해짐에 따라 다른 범주는 흡수될 것이며, 다른 범주는 새로운 데이터를 조사하는 과정에서 뚜렷한 하위 개념이 등장함에 따라 분할될 것이다.

There are multiple approaches to coding data that have been described in detail elsewhere (Charmaz 2006; Corbin & Strauss 2008). During initial coding, it is important that the researcher remains open to many possible conceptual and theoretical directions (Charmaz 2006). Focusing the initial coding phase on small units of analysis, such as individual lines or sentences within transcripts, ensures that the most salient ideas are identified and given appropriate attention. From this initial detailed mining of data comes a second coding phase where broader categories are developed that may encompass a number of conceptually related ideas. Frequently, the coding scheme will evolve as further data are collected. Certain categories will be absorbed by others as it becomes clear that their data are related by particular unifying features, while other categories will split as distinct sub-concepts emerge in the process of examining fresh data.

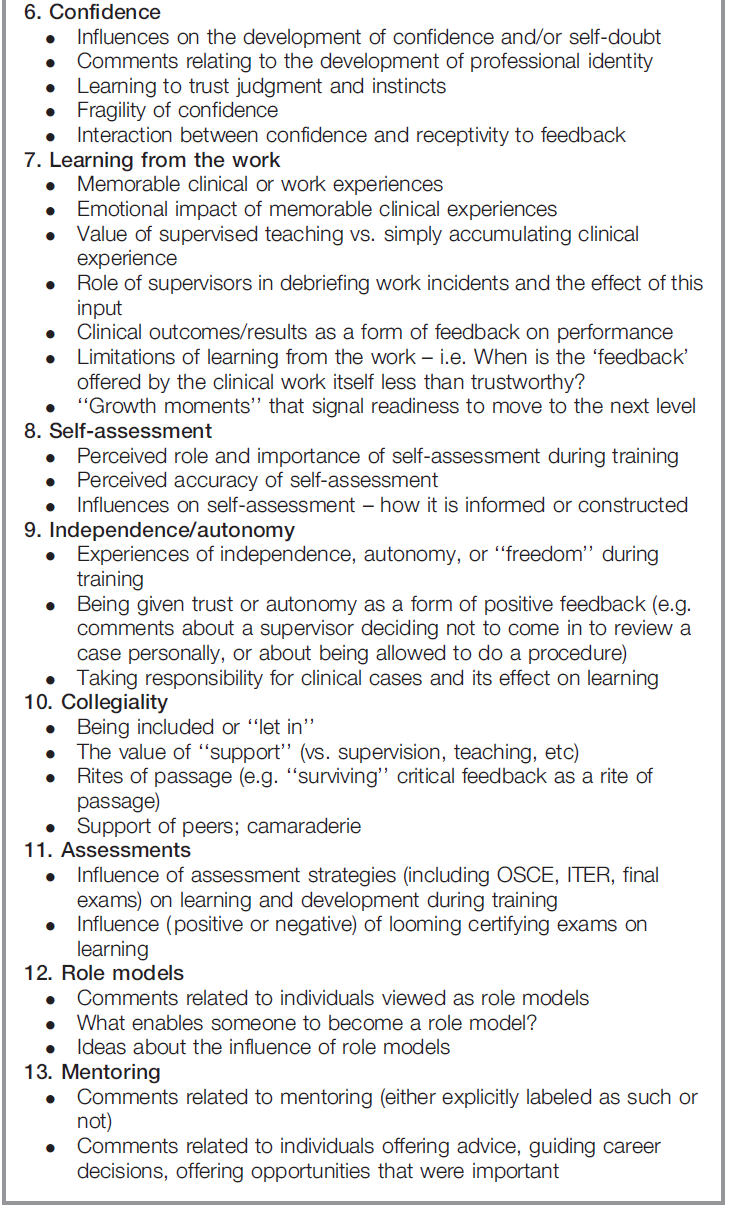

이 단계에서는 보다 상세한 코딩 예제가 도움이 될 수 있다. 상자 1에서, 우리는 "영향력 있는 경험 연구"에서 인터뷰 데이터가 분석됨에 따라 진화한 초기 코딩 체계를 보여준다. 상자 1에 표시된 코딩 방법은 궁극적으로 22개의 인터뷰 대본이 될 첫 15개를 읽고 다시 읽은 후에 개발되었다. 제안된 각 코드는 그 특성과 한계를 정의하는 일련의 [설명자]가 뒤따른다. 이 전략은 데이터 분류 작업에 접근함에 따라 연구자에게 중요한 지침을 제공한다.

A more detailed coding example may be instructive at this stage. In Box 1, we show an early coding scheme that evolved as interview data were analyzed in our “influential experiences study”. The coding scheme shown in Box 1 was developed after reading and re-reading the first 15 of what would ultimately turn out to be 22 interview transcripts. Note that each proposed code is followed by a series of descriptors that define its characteristics and its limits. This strategy provides important guidance to the researcher as the task of categorizing data is approached.

Box 1 "유입 경험 연구"를 위한 코딩 방법

Box 1 Coding scheme for “Influential Experiences Study”

지속적 비교

Constant comparison

코딩이 진행됨에 따라, 제정된 분석 프로세스는 지속적인 비교 중 하나입니다. 데이터를 조사examine함에 따라, incidents는 다른 incidents와 비교되고 범주의 새로운 특성 및 특성(Glaser & Strauss 1967; Corbin & Strauss 2008)과 비교된다. 비교 프로세스는 각 범주의 폭과 특성을 정의하고, 새로운 개념을 설명하는 사고가 발생할 때 새로운 범주의 출현을 촉진한다. 반례(반대 사례 – 마주치는 "부정적 사례")는 지속적인 비교 과정 내에서 특히 중요하다. 실제로, 그러한 특이치는 이론 개발에 기여하는 중요한 분석 통찰력을 열 수 있다. 이러한 사고를 범주의 기존 속성과 비교함에 있어, 연구원은 마주치는 데이터의 전체 범위를 설명할 수 있는 프로세스 개념 원칙을 드러내며, 이와 같은 간단한 분류를 넘어 생각할 수밖에 없다.

As coding proceeds, the analytic process enacted is one of constant comparison. As the data are examined, incidents are compared with other incidents and with the emerging characteristics and properties of the category (Glaser & Strauss 1967; Corbin & Strauss 2008). The comparative process defines the breadth and characteristics of each category, and facilitates the emergence of new categories when incidents are encountered that illustrate new concepts. Counter-examples – the “negative cases” that are encountered – are particularly important within the constant comparative process. Indeed, such outliers can unlock vital analytic insights that contribute to theory development. In comparing these incidents with the existing properties of the category, the researcher is forced to think beyond simple categorizations of like with like, revealing in the process conceptual principles that can account for the full range of data that is encountered.

코드에서 개념으로

From codes to concepts

코딩은 그 자체로 끝이 아니다; 오히려, 그것은 이론 개발을 용이하게 하는 전략이다. 전략은 힘을 이용할 때만 성공하며, 그렇게 하려면 연구자가 주제 분류만으로 만족하지 않아도 된다. 이론을 생성하기 위해서는 범주categorical에서 개념conceptual으로 분석이 제기되어야 한다. [개념 수준]에서 분석하려면 데이터에 대해 다음과 같은 질문을 해야 합니다.

- 여기서 무슨 일이 일어나고 있나요?

- 이 사건은 어떤 예입니까?

- 왜 참가자들은 이런 식으로 반응하는가?

Coding is not an end in itself; rather, it is a strategy to facilitate theory development. The strategy only succeeds when its power is harnessed, and doing so requires that the researcher not be satisfied with mere thematic classification. The analysis must be raised from the categorical to the conceptual in order to generate theory. Analysis at the conceptual level requires asking questions of the data:

- What is happening here?

- What is this incident an example of?

- Why are participants reacting this way?

데이터 내에서 기본 스토리를 정의하려는 이러한 노력은 보다 풍부한 분석 제품으로 보상됩니다. 더 깊고 개념적인 분석에 대한 한 가지 접근 방식은 코딩 프로세스에서 발생하는 주요 범주categories 간의 관계를 탐구하는 것을 포함한다. 범주를 연결하는 아이디어는 이론 개발을 지원하는 개념적 발판을 제공할 수 있습니다.

Such efforts to define the underlying story within the data are rewarded with a richer analytic product. One approach to deeper, conceptual analysis involves exploring the relationships among the major categories that emerge from the coding process. The ideas that link categories can provide the conceptual scaffold to support theory development.

우리의 예제로 돌아가면, 코드 체계는 더 많은 데이터가 분석되고 범주 간의 연결이 탐색되고, 말해진 것what was said뿐만 아니라 의미하는 것what was meant이 무엇인지 질문함에 따라 발전되고 다듬어졌다. 이 연구를 위한 코딩 범주의 최종 목록은 [단순히 데이터를 분류하기보다는 개념화하려는 움직임]을 반영한다(박스 2). 예를 들어, 이전의 범주인 "학습자 태도"와 "독립성/자율성"은 "학습 조건"의 요소로 개념화되었고, "측정", "형식 평가", "역할 모델"은 "학습 신호"의 요소로 개념화되었다. "피드백"도 학습 신호였지만, 우리는 이 범주가 매우 중요하다고 느꼈기 때문에 분석에서 풍부함이 손실되지 않도록 구별하는 것을 선택했다.

Returning to our example, the coding scheme evolved and was refined as further data were analyzed, as the links between categories were explored, and as we asked not only what was said but what was meant. The final list of coding categories for this study reflects a move toward conceptualizing our data rather than simply categorizing it (Box 2). For example, the previous categories of “learner attitude” and “independence/autonomy” were conceptualized as elements of “learning conditions”, while “measuring up”, “formal assessments”, and “role models” were conceptualized as elements of “learning cues”. Although “feedback” was also a learning cue, we felt this category was so significant that we opted to keep it distinct to ensure that its richness was not lost in the analysis.

상자 2 "유입 경험 연구"를 위한 최종 코딩 방법

Box 2 Final coding scheme for “Influential Experiences Study”

메모 및 다이어그램을 사용하여 분석 촉진

Facilitating analysis with memos and diagrams

메모는 분석의 기록이다(Charmaz 2006; Corbin & Strauss 2008). 근거이론 연구자는 자료를 수집하고 분석할 때 정기적으로 메모를 작성해야 한다. 메모 쓰기는 자료 수집과 출판 원고 초안 작성 사이의 중간 단계 역할을 할 수 있지만, 과정은 자유롭고 비공식적이어야 한다. 연구자들은 축적된 데이터를 탐색하는 과정을 거치면서 발생하는 아이디어를 기록해야 한다. 메모 쓰기는 새로운 통찰력의 출현과 범주 간의 관계의 정교화를 촉진하여 분석 과정을 진전시킨다. 메모를 작성하는 행위는 연구자가 코드화된 데이터를 검토하고 그 의미를 개념적 수준에서 해석하도록 강요force한다. 메모 모음에는 근거이론의 개발을 게시하여 프로세스가 논리적이고 체계적이며 데이터에 기반을 두고 있는지 확인합니다.

Memos are a written record of analysis (Charmaz 2006; Corbin & Strauss 2008). Grounded theory researchers should write memos regularly as they collect and analyze their data. Although memo writing can serve as an intermediate step between collecting data and drafting a manuscript for publication, the process should be free and informal. Researchers should record the ideas that occur to them as they move through the process of exploring their accumulating data. Memo-writing facilitates the emergence of new insights and the elaboration of relationships among categories, propelling the analytic process forward. The act of writing a memo forces the researcher to examine coded data and to interpret its meaning at a conceptual level. A collection of memos signposts the development of a grounded theory, ensuring that the process is logical, systematic, and grounded in the data.

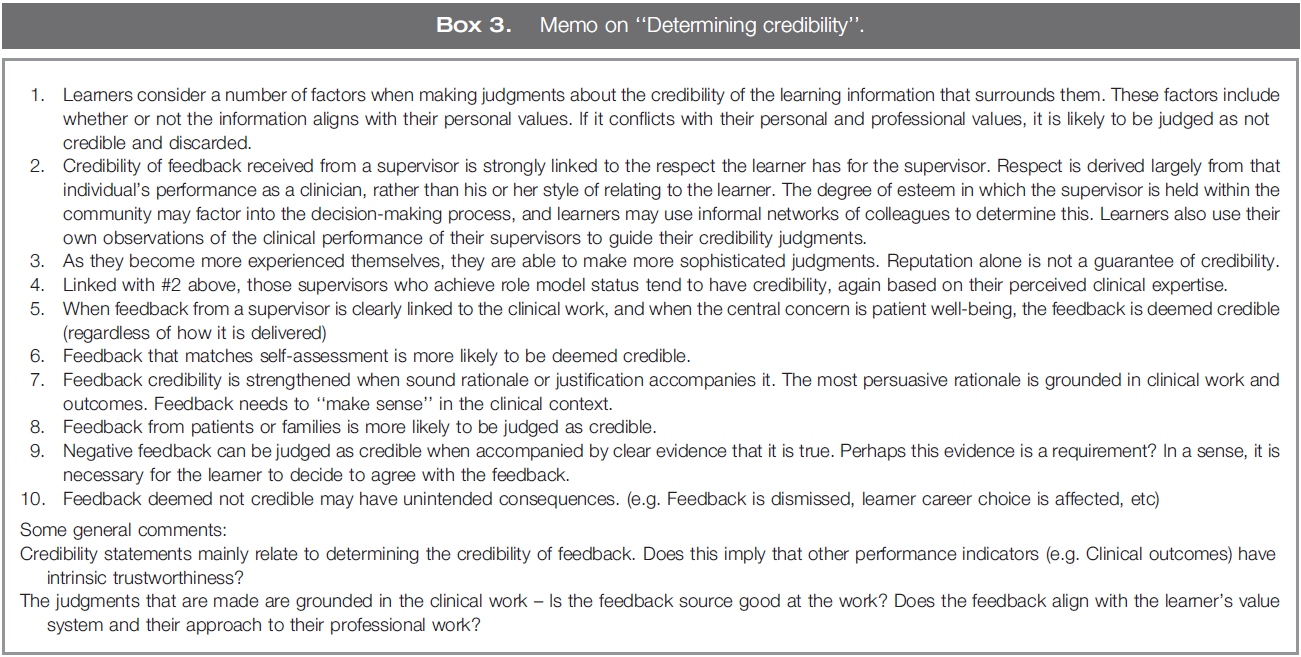

상자 3은 "영향 경험 연구" 예제를 위해 수집된 데이터의 분석 중에 작성된 메모의 추출물을 포함한다. 데이터를 검사하면서, 우리는 학습자가 자신의 성과와 관련하여 이용할 수 있는 정보의 신뢰성에 대한 반복적인 언급을 주목했고, 학습자가 특히 감독자로부터 받은 피드백과 관련하여 어떤 정보가 신뢰할 수 있고 없는지를 어떻게 결정했는지에 관심을 갖게 되었다. 상자 2에 표시된 최종 코딩 체계의 "신뢰도를 결정하는" 범주에 포함된 데이터를 면밀하게 검토한 후 작성된 이 메모에는 이 문제에 대한 데이터에서 나오는 핵심 통찰력이 요약되어 있다. 글쓰기가 자유롭고 스타일리스트적으로 조잡하다는 것에 주목하라; 관심은 문법과 구문보다는 아이디어 자체에 집중된다. 분석 과정에서 제기되는 질문들은 더 많은 생각과 주의를 요하는 잠재적으로 중요한 아이디어에 신호를 보내기 위해 메모에 명시되어 있다.

Box 3 contains an extract of a memo written during the analysis of data collected for the “influential experiences study” example. As the data was examined, we noted recurring references to the credibility of information that was available to learners related to their own performance, and we became interested in how learners determined what information was credible and what was not, particularly as it related to feedback received from their supervisors. In this memo, written after careful examination of the data contained in the “determining credibility” category of the final coding scheme shown in Box 2, key insights emerging from the data on this issue are outlined. Note that the writing is free and stylistically crude; the attention is on the ideas themselves rather than on grammar and syntax. Questions raised in the analytic process are articulated in the memo to signal potentially important ideas requiring further thought and attention.

3번 상자 "신뢰도 결정" 메모

Box 3 Memo on “Determining credibility”

궁극적으로, 우리는 피드백의 신뢰성에 대한 학습자의 판단과 그들의 성과에 대한 다른 정보가 임상 학습에 중추적인 역할을 한다는 것을 인식했다. 이와 같은 메모는 우리가 이 아이디어의 풍부함과 중심성을 인식하는 데 도움이 되었다. 메모가 반복적으로 처리될 경우 분석이 강화되며, 데이터 수집 및 분석이 진행됨에 따라 이를 재검토하고 수정해야 한다. 상자 3에 표시된 메모의 길이가 더 긴 원본 버전에서, 각 나열된 포인트는 데이터에서 직접 추출한 2-3개의 인용구로 지원된다는 점에 주목할 필요가 있다. 메모에 직접 인용문이 등장할 필요는 없지만, 신뢰도 결정에 관한 원래 메모에 삽입하는 연습은 통찰력이 데이터에 기반을 두게 할 뿐만 아니라 나중에 원고를 쉽게 쓸 수 있도록 하는 데 도움이 되었다.

Ultimately, we recognized that learners’ judgments about the credibility of feedback and other information about their performance played a pivotal role in their clinical learning. Memos such as this one facilitated our recognition of the richness and centrality of this idea. Analysis is strengthened when memos are treated iteratively; they should be revisited and revised as data collection and analysis proceeds. It is worth noting that in the original, lengthier version the memo shown in Box 3, each listed point was supported by 2-3 quotations directly drawn from the data. Although direct quotations need not appear in memos, the exercise of inserting them into the original memo on determining credibility served not only to ensure that the insights were grounded in the data but also to facilitate the writing of the manuscript later.

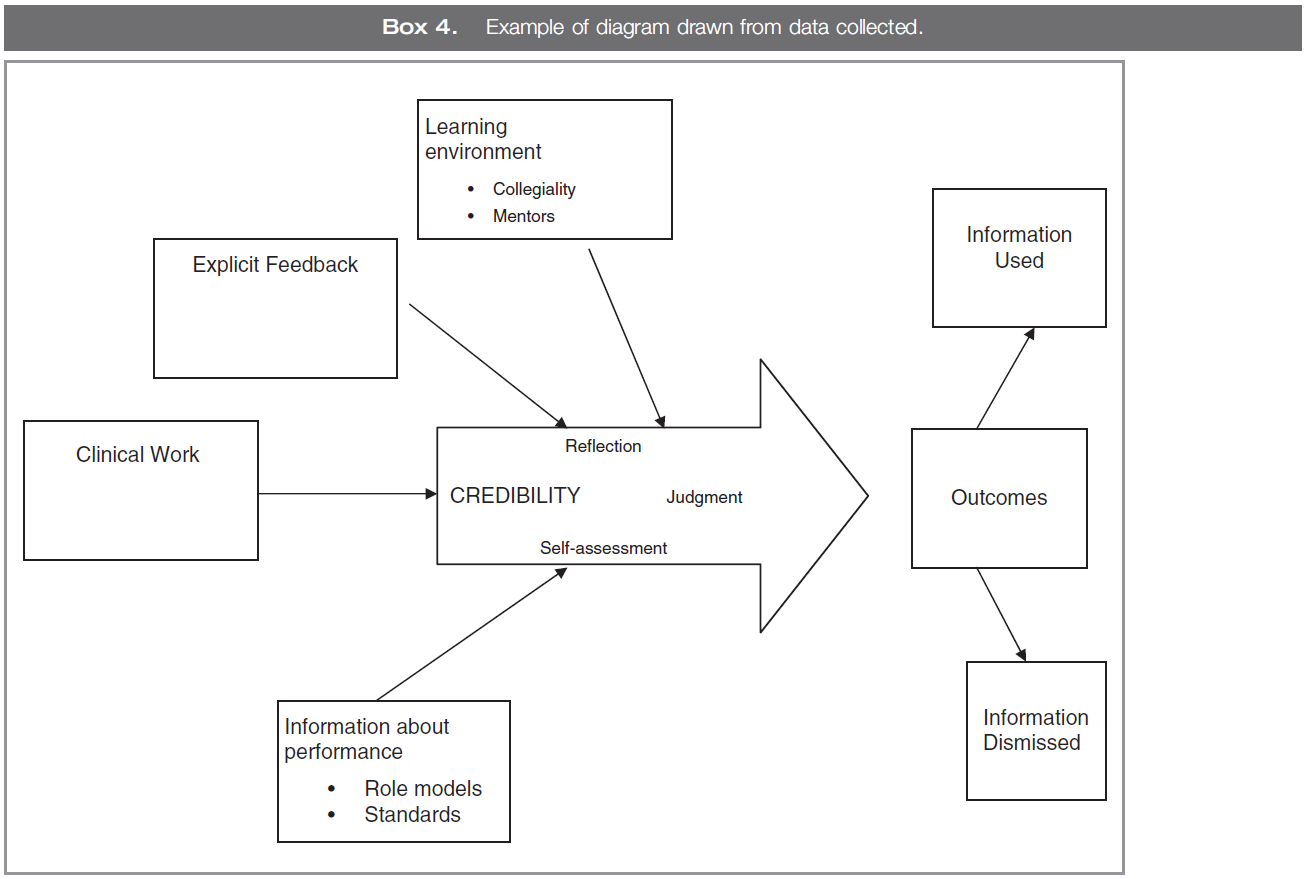

다이어그램은 기본 이론 작업에서 메모와 유사한 목적으로 사용될 수 있습니다. 다이어그램은 나타나는 개념 간의 관계를 시각적으로 표현한 것입니다. 다이어그램을 작성하려면 연구자가 데이터에 대한 생각을 범주 수준에서 개념 수준으로 끌어올려 분석에 가치를 더해야 합니다(Corbin & Strauss 2008). 개념 구성, 개념 간의 관계 이해 및 데이터의 본질적 축소를 촉진한다(Corbin & Strauss 2008).

Diagrams can serve a similar purpose to memos in grounded theory work. Diagrams are visual representations of the relationships between concepts that emerge. The creation of a diagram requires the researcher to raise their thinking about the data from the level of categories to the level of concepts, adding value to the analysis (Corbin & Strauss 2008). They promote organization of concepts, understanding of relationships among concepts, and reduction of data to its essence (Corbin & Strauss 2008).

상자 4는 그러한 다이어그램의 예를 보여준다. 관심 있는 독자들은 이 초기 다이어그램을 우리의 출판된 원고에 포함된 최종 버전과 비교하기를 원할 수 있다(Watling et al. 2012).

Box 4 shows an example of one such diagram; interested readers may wish to compare this early diagram with the final version that was included in our published manuscript (Watling et al. 2012).

상자 4 수집된 데이터에서 그린 다이어그램의 예

Box 4 Example of diagram drawn from data collected

영감과 창의력

Inspiration and creativity

근거이론은 수집된 데이터에서 발생하는 프로세스와 관련된 요소와 범주를 주의 깊게 조사함으로써 프로세스에 대한 개념적 이해를 도출하려고 한다. 범주가 어떻게 개념이 되고 설명이 어떻게 이해되는가 하는 것만으로 신비롭고 이해하기 어려울 수 있다. 창의적 사고는 근거이론 연구의 피할 수 없는 요소로, 단순한 서술보다는 해석이 필요하다. 그러나 해석적 영감은 우연이 아니다.

Grounded theory seeks to derive conceptual understanding of a process by carefully examining the elements and categories related to that process emerging from the data collected. Just how categories become concepts and description becomes understanding can seem mysterious and difficult to grasp. Creative thinking is an inescapable element of grounded theory research, which requires interpretation rather than mere description. Interpretive inspiration, however, is not accidental.

연구자는 의미 있는 해석적 통찰의 출현을 촉진할 조건을 의도적으로 만들어야 한다.

- 데이터에 반응하는 유연한 코딩 시스템을 유지하고,

- 정기적인 메모 작성에 관여하며,

- 아이디어를 일관성 있는 스토리로 모을 수 있도록 도표를 사용하는 것은 모두 해석 과정을 촉진하기 위한 의도적인 전략이다.

The researcher must deliberately create the conditions that will facilitate the emergence of meaningful interpretive insights.

- Maintaining a flexible coding system that is responsive to the data,

- engaging in regular memo writing, and

- using diagrams to help bring ideas together into a coherent story are all deliberate strategies for facilitating the interpretive process.

그러나 궁극적으로 해석의 주요 촉진자는 데이터에 대한 철저한 지식입니다. 데이터를 자세히 검토하고 다시 검토해야만 연구자가 분석 과정을 안내할 패턴과 반복 테마를 인식할 수 있다.

Ultimately, however, the key facilitator of interpretation is a thorough knowledge of the data. Only by examining and re-examining data in detail will the researcher be able to recognize the patterns and recurring themes that will guide the analytic process.

이론 표본 추출

Theoretical sampling

근거이론 연구의 표본 추출 전략은 목적적이며 이론적 고려에 의해 유도된다. [초기 표본 추출]은 연구 질문에 의해 유도된다. 연구원은 이러한 질문과 관련된 풍부한 정보를 제공할 가능성이 있는 것으로 간주되는 데이터의 출처를 의도적으로 선택한다. 차르마즈가 지적한 바와 같이, 이 초기 샘플링은 "출발 지점"만 제공한다(Charmaz 2006, 페이지 100). 후속 이론적 샘플링은 이 초기 데이터 수집에서 나온 범주와 개념에 의해 안내된다.

The sampling strategy in grounded theory research is purposive and guided by theoretical considerations. Initial sampling is guided by the research question. The researcher purposefully selects sources of data that are considered likely to provide rich information relevant to these questions. As Charmaz points out, this initial sampling provides only “a point of departure” (Charmaz 2006, p.100); subsequent theoretical sampling is guided by the categories and concepts that emerge from this initial data collection.

[이론적 표본 추출]은 "사람, 장소 및 사건으로부터 데이터 수집을 수반하며, 이들의 특성과 치수의 측면에서 개념을 개발하고, 변화를 발견하며, 개념 간의 관계를 식별하는 기회를 최대화한다."(Strauss & Corbin 2008, 페이지 143).

Theoretical sampling entails the collection of data “from people, places, and events that will maximize opportunities to develop concepts in terms of their properties and dimensions, uncover variations, and identify relationships between concepts” (Strauss & Corbin 2008, p.143).

가설 중심 실험 연구에 사용되는 표본 추출 전략과 달리, [이론적 표본 추출]은 연구가 시작되기 전에 확립된 것이 아니라 데이터에 반응적responsive이다(Strauss & Corbin 2008). 따라서 이론적 샘플링은 데이터 분석이 데이터 수집과 동시에 발생할 뿐만 아니라 실제로 데이터 수집을 추진하는 반복 프로세스의 맥락에서만 발생할 수 있다. 연구원은 이론적 구조를 개발하고 다듬는 것을 촉진하는 새로운 데이터 소스를 명시적으로 찾는다. 이론적 표본 추출의 목적은 표본이 모집단을 대표하는지 확인하거나 결과의 통계적 일반화 가능성을 허용하는 것이 아니라, 범주와 개념을 정교하고 다듬기 위한 전략적이고 구체적인 표본 추출을 통해 풍부하고 완전한 이론적 개발을 보장하는 것이다(Charmaz 2006). 이론적인 표본 추출은 연구자가 개발 아이디어를 확인하고, 반박하고, 확장하고, 다듬을 수 있게 한다.

Unlike sampling strategies used in hypothesis-driven experimental research, theoretical sampling is responsive to the data rather than established before the research begins (Strauss & Corbin 2008). Theoretical sampling can therefore only occur in the context of an iterative process in which data analysis not only occurs concurrent with data collection, but actually drives data collection. The researcher explicitly seeks out new sources of data that facilitate developing and refining theoretical constructs. The goal of theoretical sampling is not to ensure that the sample is representative of a population nor to allow statistical generalizability of the results; rather, the aim is to ensure rich and full theoretical development through strategic and specific sampling to elaborate and refine categories and concepts (Charmaz 2006). Theoretical sampling allows the researcher to confirm, refute, expand, and refine developing ideas.

포화

Saturation

연구자는 충분한 데이터가 수집되었을 때 어떻게 알 수 있는가? 포화 상태에 도달할 때까지 표본 추출을 계속하는 것이 지침 원칙이지만, 포화도는 단순히 새로운 데이터가 출현하지 않는 상태 이상more than을 가리킨다. 포화도는 분석 프로세스와 밀접하게 연관되어 있으며, 데이터 수집 및 데이터 분석의 반복 프로세스 내에서만 결정할 수 있습니다. 포화도는 데이터 수준이 아닌 [개념적 및 이론적 수준]에서 보아야 합니다. 포화도를 결정할 때 질문해야 할 중요한 질문은 연구자가 출현한 개념과 테마의 차원과 특성에 대해 충분한 이해를 할 수 있도록 충분한 데이터가 수집되었는지와 관련이 있다.

How does the researcher know when enough data has been collected? The guiding principle is to continue sampling until saturation has been reached, but saturation refers to more than a state where no new data are emerging. Saturation is intimately linked with the analytic process, and can only be determined within an iterative process of data collection and data analysis. Saturation must be viewed at a conceptual and theoretical level, rather than at a data level. The important questions to ask in determining saturation relate to whether sufficient data has been collected for the researcher to have gained an adequate understanding of the dimensions and properties of the concepts and themes that have emerged.

포화라는 개념은 연구자의 판단과 경험에 달려 있기 때문에 도전적challenging이다. 생물 의학 연구에 익숙한 정량적 방법과는 달리, 근거이론 연구자들이 연구 문제를 적절히 해결하기 위해 필요한 표본 크기를 추정하기 위한 지침이나 공식은 없다. 결과적으로, 질적 연구의 일반적인 표본 크기는 초보 연구자와 기관 검토 위원회 및 허가 기관, 특히 양적, 실험적인 연구 접근법이 지배적인 분야의 연구 기관 모두에게 어려운 문제가 될 수 있다.

The notion of saturation is challenging because the determination that it has been reached rests on the judgment and experience of the researcher. Unlike in the quantitative methods familiar in biomedical research, there are no guidelines or formulae available to grounded theory researchers for estimating the sample size that will be required to adequately address the research question. As a result, sample size in qualitative research in general can be a thorny issue for both novice researchers and for institutional review boards and granting agencies, particularly those from fields where the quantitative, experimental approach to research is dominant.

모스(1995)는 포화 문제를 해결하기 위한 많은 유용한 지침을 제공했다. 아마도 가장 중요한 것은, [포화가 편의성 또는 무작위 샘플링보다 이론적 샘플링에서 더 쉽게 발생할 것이라는 점에 주목]하면서, 샘플의 사려 깊고 이론적 정당성을 요구한다. 또한 데이터 양에 대한 데이터의 풍부성과 변동을 강조합니다. 위에서 강조했듯이, 드물게 발생하는 특이치와 부정적인 사례에 대한 세심한 주의는 개념 설명, 개념 연결 및 이론 개발을 용이하게 할 수 있는 이러한 드문 사례에 대한 검토이기 때문에 많은 유사한 사례를 수집하는 것보다 포화를 달성하는 데 훨씬 더 생산적일 수 있다. 간단히 말해서, [데이터 수집]은 [논리의 격차gaps나 비약leaps 없이, 데이터에 대한 그럴듯한 설명을 제공하는, 완전하고 설득력 있는 이론이 개발되었을 때 중단]될 수 있다(Morse 1995).

Morse (1995) has offered a number of useful guidelines for addressing problem of saturation. Perhaps most important, she calls for thoughtful and theoretical justification of the sample, noting that saturation will occur more readily with theoretical sampling than with convenience or random sampling. She also emphasizes data richness and variation over data quantity. As we have emphasized above, careful attention given to the infrequently occurring outliers and negative cases may be much more productive in achieving saturation than collecting a large number of like cases, as it is the examination of these infrequent cases that can facilitate delineation of concepts, linking of concepts, and development of theory. In short, data collection can stop when a complete and convincing theory has been developed that provides a plausible account of the data without gaps or leaps of logic (Morse 1995).

근거 이론의 비판

Critiques of grounded theory

그 근거이론 방법은 여러 면에서 비판을 받아왔다. 몇 가지 핵심 비판에 대한 간략한 개요는 방법을 사용하는 연구자와 근거이론 연구의 독자 모두에게 관련된다.

The grounded theory method has been criticized on a number of fronts. A brief overview of some of the key critiques is relevant both for researchers using the method and for readers of grounded theory studies.

해석학자들의 비판

Critiques from the interpretivists

근거이론의 가장 강력한 비판은 [그것의 실증주의적 기원]을 떨쳐 버리고 지식과 그것의 세대에 대한 새로운 사고방식이 등장함에 따라 그 자체를 재상상상하고 재정렬하는 데 실패하는 것을 목표로 한다. (Bryant 2002) 구성주의적 패러다임을 수용하는 사람들에게, 데이터로부터 이론의 "등장"이라는 개념은 특히 문제가 있다. 어떻게 이론이, 사실, 데이터로부터 나올까요?

The strongest critiques of grounded theory target its failure to shake off its positivist origins and to reimagine and realign itself as new ways of thinking about knowledge and its generation have emerged (Bryant 2002). To those who embrace the constructivist paradigm, the notion of “emergence” of theory from data is especially problematic. How does theory, in fact, emerge from data?

[고전적인 근거이론가]들은 연구자가 "추상적인 놀라움"(Glaser 1992, 페이지 22)으로 그 분야에 진입enter하고, 연구자의 "정보적인 분리informed detachment"를 강조할 것을 요구한다(Glaser & Strauss 1967) 그러면 연구자는 사전 지식이나 개인적인 관점의 족쇄에서 벗어나 데이터 내에서 진실을 "발견"할 수 있습니다.

Classic grounded theorists call for the researcher to enter the field with “abstract wonderment” (Glaser 1992, p. 22), and emphasize the “informed detachment” of the researcher (Glaser & Strauss 1967). The researcher, freed from the shackles of prior knowledge or personal perspectives, can then “discover” the truth within their data.

[구성주의자]들은 위와 같은 데이터에 대한 연구자의 수동적 입장과 이론의 출현에 대한 이러한 생각들이 포스트모던 패러다임에서는 도저히 옹호될 수 없다고 주장한다. (Bryant 2002) Fish(1994)는 근거이론 연구를 하기 위한 목적으로 [개인적인 믿음과 관점을 제쳐두는 것의 얼빠짐zaniness]에 대해 다채롭게 언급헸다. 이 논평은 근거이론에 대한 주요 구성주의적 비판을 반영한다: 참여자 및 데이터와의 상호작용을 통해 지식을 구축하고 창출하는 데 있어 연구자의 주요 역할을 인식하지 못한다는 것이다.

Constructivists argue that these ideas about the passive stance of the researcher toward their data and the emergence of theory are simply not tenable within postmodern paradigms (Bryant 2002). Fish (1994) speaks colourfully about the zaniness of putting aside personal beliefs and perspectives for purposes of doing grounded theory research, and this comment reflects a key constructivist critique of grounded theory: that it fails to acknowledge the researcher's key role in constructing and creating knowledge through interaction with the participants and with the data.

일부 근거이론가들은 분석 과정에서 연구자의 [반사성의 중요성]을 강조함으로써 이러한 비판에 대응했다. 의도적 성찰deliberate reflection은 연구자가 연구과정에 미치는 영향에 대한 관점을 제공하여 지식의 구축에 대한 연구자 자신의 공헌을 더욱 명확하게 한다. 연구자가 성찰로 얻은 통찰력으로 무엇을 해야 하는지가 토론의 주제다. 예를 들어, 코빈과 스트라우스(Corbin & Strauss 2008)는 근거이론 프로세스에 필수적인 반사성을 포함시키는 데 있어 구성주의의 힌트를 보여주지만, 반사성의 가치는 부분적으로 분석에 대한 개인적 편견이 침입하는 것에 대한 안전성을 제공하는 것이라는 것을 암시한다.

Some grounded theorists have responded to these critiques by emphasizing the importance of researcher reflexivity in the analytic process. Deliberate reflection provides perspective on the researcher's influence on the research process, making clearer his or her own contribution to the construction of knowledge. What the researcher should do with the insights gained from reflection is the subject of debate. Corbin and Strauss, for example, display hints of constructivism in enshrining reflexivity as essential to the grounded theory process, but imply that the value of reflexivity is, in part, in providing a safeguard against the intrusion of personal bias into the analysis (Corbin & Strauss 2008).

[이론수립]이라는 과제에 접근하면서, [연구자가 자신의 관점을 인식하고 고의적으로 절제해야 한다는 이 관념]은 여전히 [실증주의적 전통을 강하게 반영]하고 있다는 지적을 받아 왔는데, 이는 연구자가 어떻게든 그 밖에 남아 있어야만 밝혀낼 수 있는 진실이 데이터 안에 존재한다는 것을 시사하기 때문이다.

This notion that the researcher must recognize and then deliberately temper his or her perspective as they approach the task of theory-building has been criticized as still firmly reflective of a positivist tradition, as it suggests that there is a truth within the data that can only be revealed if the researcher remains somehow outside of it.

보다 확고하게 [구성주의자]나 [해석주의자]의 입장에서 말하는 사람들은 왜 이런 종류의 해석적 거리가 유용한지에 의문을 제기한다.

- [구성주의 근거이론]은 데이터 분석과 개념화에 대한 반복적 접근법에 중점을 두지만, "해석적 이해와 위치적 지식"을 목표로 하는 궁극적인 이론-구축 목표를 재정의한다(Charmaz 2008, 페이지 133).

- [구성주의 근거이론]은 반사성을 강조하지만, 이는 연구자의 역할, 연구 참여자의 역할, 지식 구조에서의 연구 상황과 과정을 인정하는 것이다(Charmaz 2008).

- [구성주의 근거이론]의 기초가 되는 지식 창출에 대한 근본적인 가정의 변화를 고려할 때, 일부 해석학자들은 '근거 이론'이라는 용어가 왜 구성주의 패러다임에서 질적 연구를 수행하는 사람들에 의해 전혀 유지되는지 의문을 제기하였다(Thomas & James 2006).

Those speaking from a more firmly constructivist or interpretivist position ask why this kind of interpretive distance is useful.

- Constructivist grounded theory retains the emphasis on an iterative approach to analyzing and conceptualizing data, but redefines the ultimate theory-construction goal to aim for “interpretive understanding and situated knowledge” (Charmaz 2008, p.133).

- Constructivist grounded theory stresses reflexivity, acknowledging the roles of the researcher, the research participants, and the research situation and process in knowledge construction (Charmaz 2008).

- Given the shift in fundamental assumptions about knowledge creation that underlie constructivist grounded theory, some interpretivists have questioned why the term ‘grounded theory’ is retained at all by those who undertake qualitative research in the constructivist paradigm (Thomas & James 2006).

고전주의자들의 비판

Critiques from the classicists

바니 글레이저가 이끄는 [고전적 근거 이론의 지지자]들은, 그 방법을 정의하는 몇몇 중요한 원리들을 유지하지 못한 것에 대해, 근거 이론의 구성주의적 수정을 비판해 왔다.

- 특히 연구자 편향 문제는 데이터를 개념적 수준으로 끌어올리는 것을 확실히 하고, 일부 연구 참여자의 경험과 유사할 경우 연구자 자신의 경험을 다른 데이터와 비교해야 할 데이터로 처리함으로써 해결할 수 있는 문제로 제시된다.

- 글레이저는 차마즈 및 다른 구성주의자들의 연구가 합법적인 정성적 데이터 분석을 나타내지만, 정당한legitimate 근거 이론이 아니라고 주장한다(글레이저 2002).

- 그는 근거이론에서 정당성legitimacy은 지속적인 비교 접근법에 대한 신뢰와 고수에서 성장한다고 주장한다.

- 만약 연구자가 동일한 현상의 여러 사례를 주의 깊게 본다면, 연구자의 편향이 없어지고 데이터가 객관적으로 만들어질 것이라고 그는 주장한다.

- 그의 견해에 따르면, [정당한 근거 이론은 개념화에 관한 것]이고, 반면에 [구성주의적 수정은 그것의 연구 주체의 목소리와 서술에 초점을 맞추고 있어서, 더 이상 근거 이론이 아니다]. (Glaser 2002)

Led by Barney Glaser, adherents to classical grounded theory have criticized the constructivist modification of grounded theory for its failure to maintain some of the important principles that define the method. In particular, the issue of researcher bias is presented as a problem that can be resolved by ensuring that the data is raised to a conceptual level, and by treating the researcher's own experiences, if they are similar to those of some of the research participants, as data to be compared with other data. Glaser contends that the work of Charmaz and other constructivists represents legitimate qualitative data analysis, but not legitimate grounded theory (Glaser 2002). He maintains that legitimacy, in grounded theory, grows out of trust in and adherence to the constant comparative approach. If, he contends, the researcher looks carefully at multiple cases of the same phenomenon, researcher bias will be eliminated and the data will be made objective. Legitimate grounded theory, in his view, is about conceptualization, while the constructivist modification is so focused on description and on representing the voice of its research subjects that it ceases to be grounded theory (Glaser 2002).

위치 지정

Positioning ourselves

우리는 이러한 스펙트럼의 양쪽 끝에서 나온 비판을 근거이론 연구에 적합하고 활력을 주는 것으로 본다. 근거이론에 대한 구성주의적 접근법에 내재된 반사성의 정신에서, 우리는 구성주의적 질적 연구자로서 우리 자신의 위치를 인정한다. 목적적합성을 유지하기 위해 우리는 근거이론이 지식 창출에 대한 구성주의적 개념을 통합하도록 진화해야 한다고 믿는다. [연구자가 연구분야에 진입함에 있어 자신의 배경지식, 경험, 이론적인 성향 등을 한 쪽으로 밀쳐둔 채], [수동적이고 객관적인 관찰자 역할을 할 수 있다는 생각]은 시대에 뒤떨어지고 믿을 수 없는 것으로 보인다.

We view these critiques from both ends of the spectrum as healthy and invigorating for grounded theory research. In the spirit of reflexivity that is inherent in the constructivist approach to grounded theory, we acknowledge our own position as constructivist qualitative researchers. In order to remain relevant we believe that grounded theory must evolve to incorporate constructivist notions of knowledge creation. To us, the idea that the researcher can set aside his or her own background knowledge, experience, and theoretical leanings on entering the research field and play the role of passive, objective observer seems outdated and implausible.

반면에, 우리는 근거이론이 탐구적이고 질적인 연구에 접근하기 위해 제공하는 원칙에는 많은 가치가 있다고 믿는다. 지식과 그것의 정교함에서 연구자의 역할에 대한 근본적인 가정에 대한 재고에 기초한 방법론적 진화는 이러한 유용한 원칙들을 포기해야 한다는 것을 의미하지는 않는다. Babchuk(1997)이 언급했듯이, 근거이론은 다양한 문헌에 걸쳐 질적 데이터 분석에 대한 다양한 스타일과 접근 방식을 포괄하는 우산umbrella 용어로 사용되어 왔다. 이같은 "뭐든 가능하다anything goes" 접근 방식은 근거이론 연구의 신뢰성과 관련성에 확실히 해롭다.

On the other hand, we believe there is much value in the principles grounded theory provides for approaching exploratory, qualitative research. Methodologic evolution based on reconsideration of underlying assumptions about knowledge and the role of the researcher in its elaboration does not mean that these useful principles should be abandoned. As Babchuk (1997) has noted, grounded theory has been used as an umbrella term for a wide variety of styles and approaches to qualitative data analysis across a range of literatures; this “anything goes” approach is surely harmful to the credibility and relevance of grounded theory research.

따라서 우리는 GT의 infromed use를 지지한다. 다만, 이 때 GT의 핵심 교리tenets을 유지함으로써 달성되는 rigor를 존중하되, GT가 처음 형성된 실증주의적 가정에 대해서는 지식 형성의 구성주의적 개념의 관점에서 다시 생각해 볼 필요가 있음을 인정해야 한다.

We therefore advocate for

an informed use of grounded theory,

combining respect for the rigour provided by maintaining its core tenets

with recognition that the positivist assumptions on which the method was built require rethinking in view of constructivist conceptions of knowledge creation.

근거이론 연구자는 패러다임의 충실성, 배경, 데이터 수집에서의 역할, 주제 또는 연구 분야와의 관계에 대해 명시함으로써 독자들이 그들의 작품을 정보에 입각한 방식으로 사용할 수 있도록 도울 수 있다.

Grounded theory researchers can help readers to use their work in an informed way by being explicit about their paradigmatic allegiances, their background, their role in data collection, and their relationship to their subjects or to their field of study.

근거이론연구의 함정

Pitfalls in grounded theory research

해석 프로세스를 충분히 수행하지 않음

Not taking the interpretive process far enough

모든 근거이론 연구가 대담하고 계몽적인 새로운 이론을 만들어 낼 수 있는 것은 아니다. 그러나 일부 연구는 데이터의 "큰 그림"을 렌더링하기보다는 테마나 개념의 목록에 맞춰 시도하지 않는 것으로 만족한다(Kennedy & Lingard 2006). 다른 형태의 질적 조사와 비교했을 때, 근거이론은 연구자들이 그들의 노력을 지도할 수 있는 더 명확한 로드맵을 제공하는 것으로 보인다. 그러나 이러한 구조는 완전히 실현되지 않은 분석을 촉진할 수 있다. 데이터를 분류하고 분류할 수 있는 과정을 기술하는 것은 비교적 쉽지만, 해석적 기술과 창의성을 요구하는 이러한 범주에서 이론을 개발하는 후속 창조적 요소를 기술하는 것은 전혀 간단하지 않다.

Not all grounded theory studies can generate bold, enlightening new theories. However, some studies seem content not to try, settling instead for lists of themes or concepts, rather than a “big picture” rendering of their data (Kennedy & Lingard 2006). Compared with other forms of qualitative inquiry, grounded theory seems on the surface to provide a clearer roadmap for researchers to guide their efforts. This very structure, however, might promote an analysis that is not fully realized. It is relatively easy to describe a process by which data can be classified and categorized, but not at all straightforward to describe the subsequent creative element of developing theory from these categorizations, which calls for interpretive skill and creativity.

GT에서 연구자는 겉으로 보여지는 규범적인 코딩 절차의 늪에 빠져 더 큰 목표를 놓치기 쉽다. 근거 이론 방법의 기술과 절차를 상당히 상세하게 설명한 줄리엣 코빈은 "분석 과정이 가장 우선적이고 최우선적으로 사고 과정"이라고 상기시키며, 이는 특정 절차를 따를 필요보다는 데이터와의 상호작용을 통해 얻어진 통찰에 의해 추진되어야 한다. (Corbin 2009, 페이지 41) 차르마즈는 연구자들이 연구 결과의 경계를 넓히고 '그래서 어쩌지so what?'라는 질문에 답할 것을 강력히 촉구한다.

It is easy for the researcher to become bogged down in the apparently prescriptive coding procedures and to lose sight of the larger goal. Juliet Corbin, who has described the techniques and procedures of the grounded theory method in considerable detail, reminds us that “the analytic process is first and foremost a thinking process” (Corbin 2009, p.41) that should be driven by the insights gained through interaction with data rather than by a need to follow specific procedures. Charmaz helpfully urges researchers to push the boundaries of their findings and answer the ‘So what?’ questions (Charmaz 2006, p.107).

설명할 수 없는 주장을 하는 것

Making unsupportable claims of explanation

근거이론 연구의 산물이 정말로 "이론"인지 여부에 대한 정당한 의문이 제기되었다. (토마스 & 제임스 2006) 토머스는 근거이론이 너무 많은 것을 약속한다고 비판해 왔다; 그의 주장에 따르면, 그 제품이 기술이나 이해가 아닌 "이론"이라는 주장은, 거의 존재하지 않는다고 설명하고 예측하는 힘을 시사한다. (토머스 & 제임스 2006) 사실, 근거이론가들은 그들의 분석으로부터 지지할 수 없는 주장을 하는 것을 경계해야 한다. 그러나 토마스나 제임스와는 달리, 우리는 이론 생성의 목표가 버려져야 한다고 생각하지 않는다. 왜냐하면 이것은 근거이론 작업과 다른 형태의 질적 연구를 구별하는 바로 이 목표이기 때문이다.

Legitimate questions have been raised about whether the product of grounded theory studies is really “theory” at all (Thomas & James 2006). Thomas has criticized grounded theory for promising too much; its insistence that its product is “theory” rather than description or understanding suggests a power to explain and predict that, he argues, is rarely present (Thomas & James 2006). Indeed, grounded theorists must guard against making unsupportable claims from their analyses. Unlike Thomas and James, however, we do not believe that the goal of theory generation should be abandoned, as it is this very goal that distinguishes grounded theory work from other forms of qualitative research.

차마즈(2006)는 근거이론 연구자들에게 설명explanation이라기보다는, "상상적 이해imaginative understanding"를 강조하는 이론의 해석적 정의를 추구할 것을 제안함으로써 이 문제를 해결한다. 마찬가지로 브라이언트(2002)는 설명하고 예측하는 힘으로 진실을 발견하거나 일반화할 수 있는 이론을 수립하는 [실증주의적 목표]보다는 특정 맥락과 목적에 대해 적절한 이해를 달성하려는 [구성주의적 목표]를 목표로 삼을 것을 제안한다.

Charmaz (2006) resolves this issue by suggesting that grounded theory researchers look to interpretive definitions of theory that emphasize “imaginative understanding” (p. 126) rather than explanation. Similarly, Bryant (2002) suggests targeting a constructivist goal of achieving adequate understanding for specified contexts and purposes, rather than a positivist goal of discovering truth or establishing generalizable theories with the power to explain and predict.

그러므로 GT 연구자들은 그들의 연구의 목표와 그들의 새로운 이론의 설명력의 한계에 대해 곰곰이 생각해 보아야 한다. 연구 결과의 일반화에 대한 과감한 주장은 의심으로 보아야 한다. 근거이론은 예를 들어, 개인이나 그룹이 직면하는 관련 관계, 프로세스에 대한 주요 영향 또는 도전을 식별할 수 있지만, 이러한 관계, 영향 또는 도전의 크기를 결정할 수는 있다. 이러한 결정을 내리려면 통계 샘플링과 관련된 완전히 다른 연구 접근법이 필요하며, 이는 뚜렷한 목표를 가지고 있다. 따라서 근거이론은 [(정량적 실험 방법을 포함한 다른 방법을 사용하여) 시험될 수 있는 가설을 생성]할 수 있지만, 근거이론은 그러한 [가설을 시험하기 위한 수단이 아니다].

Researchers should therefore reflect thoughtfully on the goals of their work and the limits of their emerging theory's explanatory power. Bold claims of generalizability of findings should be viewed with suspicion. Grounded theory might identify relevant relationships, key influences on a process, or challenges facing individuals or groups, for example, but cannot determine the magnitude of these relationships, influences, or challenges. Making such determinations would require an entirely different research approach, involving statistical sampling, with a distinctly different goal. Grounded theory might therefore generate hypotheses that could be tested using other methods, including quantitative, experimental methods, but grounded theory is not the vehicle for testing those hypotheses.

근거이론연구논란

Controversies in grounded theory research

문학고찰에 관한 논란

The literature review

연구자들이 가변적이고 종종 상충되는 조언을 접할 수 있는 한 영역은 근거이론 연구에서 문헌 검토의 장소이다. Dunne(2011)은 문헌 검토를 수행하는 것이 근거이론의 스펙트럼을 따라 모든 점에서 연구자들에 의해 적절하다고 생각한다는 점에 주목한다. 문헌고찰에 관한 논란은 문헌 검토의 시기에 있다.

- 예를 들어, 글레이저와 다른 사람들은 조기적이고 포괄적인 문헌 검토가 연구자의 분석 능력이 돌이킬 수 없을 정도로 약화될 선입견과 이론적 짐을 너무 부담한다는 이유로 데이터 수집 및 분석에 앞서 유의한 문헌 검토에 반대한다(글레이저 1992, 나타니).2006년).

- 다른 사람들은 사전 문헌 검토를 자제하는 것의 비효율성을 미리 언급했고, 문헌 검토가 초점을 날카롭게 하고 연구 질문을 개선함으로써 연구를 풍부하게 할 수 있는 가능성에 대해 언급하였다(Dunne 2011). 한 연구가 선행하는 연구로부터 논리적으로 따르는 프로그램적 연구에서는 연구자가 연구 분야에서 관련 문헌에 대한 친숙함을 증가시키는 것은 피할 수 없으며 사실상 프로그램을 진전시키는 새로운 연구 질문의 생성을 촉진할 것이다.

One area where researchers will encounter variable and often conflicting advice is the place of the literature review in grounded theory studies. Dunne (2011) notes that performing a literature review is considered appropriate by researchers at all points along the spectrum of grounded theory; the controversy lies in the suggested timing of that review. Glaser and others, for example, argue against a significant literature review in advance of data collection and analysis on the grounds that an early, comprehensive literature review will so burden the researcher with preconceived notions and theoretical baggage that his or her analytic capacity will be irretrievably weakened (Glaser 1992, Nathaniel 2006). Others have noted the inefficiency of abstinence from a literature review in advance, and have commented on the potential for the literature review to enrich the research by sharpening the focus and improving the research questions (Dunne 2011). In programmatic research, where one study follows logically from one that precedes it, the researcher's growing familiarity with relevant literature in the area of research is unavoidable and in fact will facilitate the generation of compelling new research questions that advance the program.

흥미롭게도, 글레이저와 스트라우스조차 연구자들이 관련 데이터를 식별하고 그 데이터에서 중요한 테마를 추출할 수 있는 관점을 필요로 한다는 것을 인정했다. (글레이저 & 스트라우스 1967) 우리의 견해는 문헌 검토가 정확하게 이러한 관점을 제공하고 연구 질문을 형성하는데 필수적이라는 것이다. 그러나, 우리는 연구자들이 데이터와 그것이 포함하는 개념과 아이디어에 의도적으로 개방적인 태도를 유지하기를 경고한다. 근거이론가들의 스펙트럼 전반에 걸쳐, 데이터 분석에 대한 이러한 [초기 개방적인 접근법initial open-minded approach]이 널리 지지된다(Glaser & Strauss 1967; Charmaz 2006).

Interestingly, even Glaser and Strauss acknowledged that researchers require a perspective that allows the identification of relevant data and the abstraction of significant themes from that data (Glaser & Strauss 1967). Our own view is that a literature review is indispensible in providing exactly this perspective and in shaping the research question. We caution researchers, however, to remain deliberately open-minded to the data and the concepts and ideas that it contains: across the spectrum of grounded theorists, this initial open-minded approach to data analysis is widely endorsed (Glaser & Strauss 1967; Charmaz 2006).

기존 이론의 통합에 관한 논란

The integration of existing theory

글레이저와 스트라우스는 연구자들에게 기존의 형식 이론에서 도출된 선입견을 이 분야로 끌어들이지 말라고 경고했지만(글레이저와 스트라우스 1967), 그들은 새로운 근거이론의 생성이 기존 이론과 완전히 분리되어 일어날 필요는 없다는 것을 인정했다. 그들의 목적은 열린 마음을 위한 명시적 노력의 중요성을 강조하는 것이었는데, 우리는 이것이 여전히 근거이론 연구의 중심이라고 믿는다. 열린 마음open-mindedness이 기존의 이론적 관점에 대한 지식과 친숙함과 공존할 수 있는가? 기존 이론이 분석 과정을 "오염"하지 않고 근거이론 연구에 통합될 수 있는가? 우리는 그것이 통합될 수 있고 통합되어야 한다고 믿지만, 기존 이론을 사용하는 접근 방식은 여전히 논쟁의 여지가 있다.

Although Glaser and Strauss cautioned researchers against bringing preconceived notions drawn from existing formal theories into the field (Glaser & Strauss 1967), they acknowledged that the generation of new grounded theory need not occur in complete isolation from existing theory. Their aim was to highlight the importance of explicit efforts at open-mindedness, which we believe remain central to grounded theory research. Can open-mindedness co-exist with knowledge of and familiarity with existing theoretical perspectives? Can existing theory be integrated into grounded theory research without “contaminating” the analytic process? We believe that it can and should be integrated, but the approach to using existing theory remains controversial.

확실히 근거이론이 emerge하고 난 다음에, 기존의 이론적 프레임워크가 어떻게 데이터 해석을 보완하거나 확장하거나 어려운 데이터에 대한 대체 설명을 제공하는지를 고려하는 것이 적절하다. 실제로, 어떤 사람들은 연구자들이, 물론, 기존 이론들로부터 분리되어 행해진 근거이론 작업은, 이론이 축적되지 못할 위험non-cumulative이 있으며, 따라서 지식의 구축을 억제stifles한다는 비판이 있다. 이에 대한 부분적인 대응으로, 기존 이론의 자료에서 도출한 이론에 명백히 "근거ground"해야 한다고 제안했다. (골드컬 & 크론홀름 2003). 심지어 실증주의적인 경향을 가진 연구자들조차도 (근거이론의 개발이 기존의 이론적 틀에 강요되지만 않는다면), 새로운 근거이론과 기존 이론의 연결을 지지하는 경향이 있다.

Certainly after a grounded theory emerges, it is appropriate to consider how existing theoretical frameworks might complement or extend the data interpretation or offer alternate explanations for challenging data. Indeed, some have suggested that researchers should, as a matter of course, explicitly “ground” the theories they derive from data in existing theories, in part as a response to the criticism that grounded theory work done in isolation from existing theories risks non-cumulative theory development and thus stifles the building of knowledge (Goldkuhl & Cronholm 2003). Even those researchers with positivist leanings tend to support the linking of emergent grounded theories with existing theories, provided that the timing of doing so is such that the very development of the grounded theory is not forced into a pre-existing theoretical framework.

그러나, 구성주의자들은 [먼저 기존의 이론적인 제약에서 벗어나 근거이론이 출현하도록 허용하고, 후에 그것을 풍부하게 하기 위해 관련 기존 이론을 통합하는] 이 개념은 인위적이고 비현실적이라고 주장한다. 구성주의자에게 연구자의 훈련 배경과 이론적 관점은 [데이터 내의 가능성과 프로세스에 대해 경각심을 갖게 하며, 관련성 있는 질문을 하도록 안내하는 데 중요한] 민감성 개념sensitizing concept을 제공할 수 있다(Charmaz 2006).

Constructivists would argue, however, that this notion of first allowing the grounded theory to emerge, free of existing theoretical constraints, and then only later integrating relevant existing theories to enrich it is artificial and impractical. To the constructivist, the researcher's disciplinary background and theoretical perspective may provide vital sensitizing concepts that alert them to possibilities and processes within their data and that guide them in asking relevant questions (Charmaz 2006).

기존 이론을 어떻게 언제 근거이론 연구에 통합할 것인가에 대한 논란은 연구자뿐 아니라 자신의 작품을 읽고 검토할 사람들에게도 과제를 안겨준다. 근거이론을 사용하는 연구원들은 출판용으로 제출하는 원고에서 기존 이론의 사용에 기초한 잠재적 비판을 예측하고 해결하는 그들의 연구 방법에 대한 설명을 능숙하게 할 필요가 있다. [연구자가 데이터에 부과impose하는 것이 아니라], [코드와 범주가 데이터에서 나오는emerge] 신중하고 체계적인 코딩 프로세스를 명확하게 설명하면, 독자와 리뷰어는 연구자가 데이터에 대한 초기 접근에서 열린 마음을 가졌다는 것을 안심시킬 수 있다. 더욱이, 연구자들은 기존 이론에 대한 그림을 그리는 논리에 대해 논리를 제시해야 한다. 기존 이론을 사용하는 것은 제시된 데이터 분석의 맥락에서 "이치에 맞아야make sense" 한다.

Controversy around how and when to integrate existing theory in grounded theory research creates challenges not only for researchers but also for those who will read and review their work. Researchers using grounded theory need to be skillful in their descriptions of their research methods in manuscripts they submit for publication, anticipating and addressing potential critiques based on their use of existing theory. A clear description of a careful and methodical coding process in which codes and categories emerge from the data rather than being imposed on the data will reassure readers and reviewers that the researcher has been open-minded in their initial approach to their data. Furthermore, researchers should make the case for the logic of drawing on existing theories; the use of existing theory must “make sense” in the context of the data analysis that is presented.

컴퓨터 지원 데이터 분석

Computer-assisted data analysis

연구자들이 산더미 같은 데이터를 관리해야 하는 어려움에 직면하는 경우가 많기 때문에, 모든 유형의 질적 데이터 분석은 매우 어려울 수 있습니다. 점점 더 많은 컴퓨터 소프트웨어 프로그램들이 데이터 분석 과정을 용이하게 하기 위해 근거이론가들과 다른 질적 연구자들에 의해 사용되고 있다. 이 프로그램들은 연구자에게 많은 잠재적인 이점을 제공한다.

- 소프트웨어 패키지는 데이터를 코딩 카테고리와 하위 카테고리로 구성할 수 있고, 카테고리 간의 연결을 식별할 수 있으며, 카테고리를 메모 및 기타 관련 문서에 연결할 수 있습니다.

- 이 조직 시스템은 쉽게 검색할 수 있으므로 효율적인 데이터 관리가 가능하며 연구자가 분석을 작성하거나 제시할 때 핵심 개념을 지원해야 할 때 데이터 내의 보석을 쉽게 찾을 수 있습니다.

- 또한 데이터 분석 소프트웨어를 사용하면 수행된 분석 단계를 추적하는 감사 추적을 제공할 수 있습니다.

Qualitative data analysis of any type can be daunting, as researchers often face the challenge of managing mountains of data. Increasingly, computer software programs are being used by grounded theorists and other qualitative researchers to facilitate the process of data analysis. These programs offer many potential advantages to the researcher. Software packages can allow organization of data into coding categories and subcategories, can identify links between categories, and can link categories to memos and other relevant documents. This organizational system is readily searchable, allowing efficient data management and ensuring that gems within the data are readily found when the researcher needs to support core concepts as they write up or present their analysis. The use of data analysis software also can provide an audit trail that tracks the analytic steps that were taken.

컴퓨터 보조 데이터 분석은 엄격한 데이터 분석 방법을 대체하는 것이 아니며, "N-Vivo를 사용하여 데이터를 분석했다"와 같은 용어로 기술된 근거이론을 사용하는 것을 지지하는 연구는 의심스럽게 보아야 한다(Jones & Diment 2010). 데이터 분석을 안내하는 원칙을 제공하는 것은 소프트웨어 패키지가 아니라 근거 이론grounded theory입니다. 컴퓨터는 연구자가 분석에 철저하고 효율적일 수 있도록 지원하는 도구일 뿐이다. 연구자는 여전히 데이터를 해석하고, 떠오르는 개념을 인식하고, 개념과 범주가 서로 어떻게 관련되는지 묻고, 분석을 이론 개발을 촉진하는 추상적인 수준으로 밀어넣어야 한다. 이론 개발에 있어 연구자가 요구하는 창의성은 컴퓨터에 의해 제공될 수 없다(Becker 1993). 그러나 소프트웨어 패키지는 연구자가 다양한 방법으로 데이터를 시각적으로 탐색할 수 있는 기회를 제공할 수 있으며, 전략적으로 사용될 경우 창의적인 사고를 촉진하고 분석 프로세스를 향상시키는 통찰력의 출현을 자극할 수 있다(Bringer et al. 2006).

Computer assisted data analysis is not a substitute for a rigorous method of data analysis, and studies purporting to use grounded theory whose methods are described in terms such as “Data were analyzed using N-Vivo” should be viewed with suspicion (Jones & Diment 2010). It is grounded theory, and not the software package, that provides the principles that guide the data analysis. The computer is merely a tool that can support the researcher in being both thorough and efficient in the analysis. The researcher still must interpret the data, recognize emerging concepts, ask how concepts and categories relate to one another, and push the analysis to an abstract level that promotes theory development. The creativity required of the researcher in developing theory cannot be provided by a computer (Becker 1993). However, software packages can provide opportunities for researchers to explore their data visually in a variety of ways, which when used strategically may foster creative thinking and stimulate the emergence of insights that enhance the analytic process (Bringer et al. 2006).

단독 분석 대 협업 분석

Solo analysis versus collaborative analysis

많은 근거이론 작업은 마치 컴퓨터 위에 매달려 있는 단일 연구자에 의해 분석이 완전히 수행되거나 데이터에 대한 어떤 감각이 만들어질 수 있을 때까지 테이블 위의 문서 더미를 살펴보는 것처럼 묘사된다. 실제로, 뛰어난 근거이론 연구는 단독 연구자들에 의해 수행될 수 있다. 방법 그 자체만 본다면, 반드시 연구자들 간의 협업을 필요로 하는 것은 없다. 데이터를 단독으로 작업하는 연구자들은 연구 영역에 대한 위치 및 관점에 대해 특히 반성하고, 그러한 관점이 분석과 이론 구성에 어떤 영향을 미치는지 인식하고 설명해야 한다.

Much grounded theory work is described as if the analysis is done entirely by a single researcher, hunched over a computer or sifting through piles of documents on a table until some sense can be made of the data. Indeed, outstanding grounded theory work can be done by solo researchers; there is nothing in the method that requires collaboration among researchers. Researchers working alone with their data must be particularly reflective about their position and perspective relative to the area of study, recognizing and accounting for how that perspective influences their analysis and their theory construction.

우리는 협력적으로 일하는 것이 분석 과정을 크게 향상시킬 수 있다는 것을 발견했다. 전체 과정이 그룹 차원의 노력이 될 필요는 없지만, 공동작업자의 전략적 활용이 고도로 생산적이고 조명적일 수 있는 연구 과정에서 핵심 포인트가 있다.

- 초기 코딩 단계 동안, 두 명 또는 세 명의 연구자가 동일한 데이터를 독립적으로 검사하고 데이터를 코드에서 나오는 것으로 인식하는 테마에 대해 데이터를 코드화하는 것이 도움이 될 수 있다.

- 공동작업자가 만나서 그들이 고안한 데이터와 코드에 대한 초기 인상을 논의함에 따라, 의견 불일치가 방송되고 합의가 이루어짐에 따라 보다 강력한 코딩 체계가 나타날 수 있다.

- 따라서 지속적 비교constant comparison 과정은 데이터뿐만 아니라 데이터에 대한 서로 다른 인식과 reading 간의 비교를 포함하도록 확장된다.

- 또한 공동작업은 초기 코딩이 완료된 후 연구자가 해석 수준을 범주에서 개념으로, 구체적인 것에서 추상적인 것까지 올려야 하는 중요한 단계에서 가치가 있을 수 있다.

- 우리는 종종 이 단계에서 협력자를 불러서 하나 이상의 범주의 요소를 해석적 수준에서 논의한다. 이러한 논의는 항상 분석적 사고를 개념적 수준으로 높이는 데 도움이 됩니다. 데이터 내에서 확인된 프로세스의 이유why, 방법how, 그리고 so what이 서로 다른 관점에서 검토되기 때문입니다.

- 새로운 개념에 대한 협력적 논의는 또한 연구자에게 이러한 개념이 목표 대상자에게 어떻게 반향을 일으킬 수 있는지, 또는 연구의 전체 이야기에서 어떤 개념이 가장 중심적이거나 설득력 있는지에 대한 유용한 관점을 제공할 수 있다.

We have found that working collaboratively can enhance the analytic process significantly. The entire process need not be a group effort, but there are key points in the course of the research where strategic use of collaborators can be highly productive and illuminating. During the phase of initial coding, it can be helpful to have two or three researchers examine the same data independently and code the data for the themes that they perceive as emerging from it. As collaborators meet to discuss their initial impressions of the data and the codes they have devised, a more robust coding scheme can emerge as disagreements are aired and consensus is reached. The process of constant comparison is thus expanded to include comparisons not only among the data but among different perceptions and readings of the data. Collaboration may also be valuable after the initial coding is complete, at the critical stage where the researcher needs to raise the interpretive level from the concrete to the abstract – from categories to concepts. We often bring in collaborators at this stage to discuss the elements of one or more categories at an interpretive level. These discussions invariably assist in raising the analytic thinking to a conceptual level, as the why, how, and so what of the processes identified within the data are examined from different perspectives. Collaborative discussions of emerging concepts can also provide the researcher with a useful perspective on how these concepts might resonate with their target audience, or on which concepts are the most central or compelling in the overall story of the research.

협동은 근거이론가의 반사성을 대체하는 것이 아니다. 그러나 서로 다른 관점을 가진 동료와의 의도적인 협업은 분석 프로세스에서 데이터의 균형 잡힌 렌더링을 보장하는 데 도움이 될 수 있습니다. 다른 배경을 가진 동료들은 연구자가 자신의 학문적 상자displinary box를 넘어서 생각하도록 push할 수도 있고, 또는 그 이론이 주로 자신의 배경과 관점에 의해 형성되도록 하기보다는 데이터에서 그들의 이론 개발을 확고하게 뒷받침할 것을 상기시킬 필요가 있는 연구자를 구속할 수도 있다.

Collaboration is not a substitute for reflexivity for the grounded theorist. However, deliberate collaboration with colleagues with distinctly different perspectives can help to ensure a balanced rendering of the data in the analytic process. Colleagues from different backgrounds can push the researcher to think beyond their own disciplinary box, or rein in the researcher who needs reminding to ground their theory development firmly in the data rather than allowing that theory to be shaped primarily by their own background and perspective.

근거이론 연구의 품질 기준

Quality criteria for grounded theory research

근거이론 연구를 수행하는 절차는 고도로 구조화되어 있지만, 근거이론 연구의 품질을 평가해야 하는 기준은 명확하지 않다. 연구자와 독자 모두가 연구의 품질을 평가하기 위한 명확한 지침을 참조할 수 있는 생물 의학 연구를 지배하는 정량적 연구 전략에 비해, 근거이론 작업을 판단하는 기준은 모호하고 해석하기 어려워 보일 수 있다. 그럼에도 불구하고, 많은 저자들이 근거이론 연구를 평가하기 위한 기준을 제안했고, 이러한 기준 중 일부를 간략하게 검토하는 것이 유용하다.

Although the procedures for carrying out grounded theory research are highly structured, the criteria on which the quality of a grounded theory study should be evaluated are less clear. Relative to the quantitative research strategies that dominate biomedical research, where researchers and readers alike can refer to clear guidelines for appraising the quality of a piece of research, the criteria for judging grounded theory work can seem vague and challenging to interpret. Nonetheless, a number of authors have suggested criteria for evaluating grounded theory studies, and a brief examination of some of these criteria is useful.

글레이저와 스트라우스는, 그들의 기초 이론 방법에 대한 원래 설명에서, 근거이론은 다음을 갖춰야 한다고 제안했다.

- 쉽게 이해할 수 있어야 한다.

- 적용 대상인 실질적인 영역에 "적합"해야 한다.

- 다양한 일상 상황에 적용할 수 있을 만큼 충분히 일반적이어야 한다.

- 사용자가 상황 변화를 가져올 수 있을 만큼 충분한 통제 권한을 제공해야 한다.

Glaser and Strauss, in their original description of the grounded theory method, suggested that a grounded theory needed

to be readily understandable,

to “fit” the substantive area to which it was applied,

to be sufficiently general to be applied to a variety of diverse daily situations, and

to provide the user with sufficient control to bring about change in situations.

그들에게는 근거이론이 연구된 분야에 유용하고 적용 가능해야 했다. (글레이저 & 스트라우스 1967) 코빈과 스트라우스는 또한 "적합fit"의 중요성을 강조했는데, 이는 이 발견이 연구가 의도된 전문가와 연구에 참여한 참가자, 그리고 적용가능성 또는 유용성 모두에게 반향을 불러일으킨다는 것을 암시한다. 그들은 개념의 개발 및 상황화, 논리, 깊이, 변화, 창의성, 민감성, 메모의 증거 등 많은 다른 품질 기준을 추가했다(Corbin & Strauss 2008). 이 마지막 기준(memo)은 글레이저와 스트라우스에 의해 강조된 투명한 과정의 중요성을 말해준다. 연구자는 데이터로부터 어떻게 이론을 도출했는지 입증할 수 있어야 한다. 메모는 분석 과정을 설명하고 "인상주의적impressionistic" 이론 개발의 감각을 경계한다(Glaser & Straus 1967).

Grounded theory, to them, needed to be useful and applicable to the area studied (Glaser & Strauss 1967). Corbin and Strauss also stressed the importance of “fit”, which implies that the findings resonate with both the professionals for whom the research was intended and the participants who took part in the study, as well as applicability or usefulness. They added a number of other quality criteria, including the development and contextualization of concepts, logic, depth, variation, creativity, sensitivity, and evidence of memos (Corbin & Strauss 2008). This last criterion speaks to the importance of a transparent process, also highlighted by Glaser and Strauss. The researcher should be able to demonstrate how they derived theory from data; memos elucidate the process of analysis and guard against the sense of “impressionistic” theory development (Glaser & Strauss 1967).

차르마즈(2006)는 근거이론 연구를 평가하기 위한 4가지 핵심 기준인 신뢰도, 독창성, 공명, 유용성을 제시했다.

- 신뢰성은 데이터 수집의 깊이와 범위가 분석적 주장을 뒷받침하기에 충분하다는 것을 의미한다. 신뢰성은 또한 나타나는 인수가 논리적이고 데이터에 명확하게 연결되도록 보장하는 체계적인 비교 프로세스에 따라 달라집니다.

- 독창성은 연구가 새로운 통찰력, 신선한 개념적 이해를 제공하고 이론적으로나 사회적으로 중요한 분석을 제공한다는 것을 암시한다.

- 공명resonance은 근거이론이 참가자들에게 이치에 맞으며 그들의 경험의 본질과 충만함을 포착한다는 것을 암시한다.

- 유용성은 연구 대상 세계에 거주하는 개인이 일상 상황에서 사용할 수 있는 해석을 의미한다(Charmaz 2005, 2006).

매우 다른 패러다임의 관점에서 근거이론에 접근하는 개인에 의해 개발되었음에도 불구하고, 이러한 기준에서 상당한 중복을 인식할 수 있다. 이러한 기준은 근거이론 작업의 품질을 조사하기 위한 접근법으로 독자와 연구자를 모두 무장시킬 수 있다.

Charmaz (2006) has suggested her own set of four key criteria for evaluating grounded theory studies: credibility, originality, resonance, and usefulness.

- Credibility implies that the depth and range of data collection is sufficient to support the analytic claims made. Credibility also depends on a systematic process of comparisons that ensures that the argument that emerges is logical and linked clearly to the data.

- Originality implies that the research offers new insights, fresh conceptual understandings, and that the analysis is theoretically or socially significant.

- Resonance implies that the grounded theory makes sense to the participants and captures the essence and fullness of their experience.

- Usefulness implies interpretations that can be used in day-to-day situations by individuals who inhabit the world under study (Charmaz 2005, 2006).

One can appreciate considerable overlap in these criteria, even though they were developed by individuals who approach grounded theory from very different paradigmatic perspectives. These criteria can arm readers and researchers alike with an approach to interrogating the quality of grounded theory work.

결론

Conclusion

질적 연구 방법론 중에서, 근거이론은 의학 교육자들이 가장 쉽게 접근할 수 있다. 의학교육자라는 청중에게 근거이론의 매력은 그것의 객관주의적 기원과 관련이 있을 수 있는데, 이것은 실험적인 연구 방법에 익숙한 사람들에게 친숙하고 편안해 보일 수 있다. 근거이론은 그것의 시작 이후 상당한 진화를 거쳤고, 점점 더 구성주의적 패러다임과 더 최근에는 포스트모던 지향성을 통합했다.

Among qualitative research methodologies, grounded theory may be the most accessible to medical educators. The appeal of grounded theory to this audience might relate to its objectivist origins, which may seem familiar and comfortable to those accustomed to experimental research methods. Grounded theory has undergone considerable evolution since its inception, increasingly incorporating constructivist paradigms, and, more recently, postmodern orientations.

Med Teach. 2012;34(10):850-61. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.704439. Epub 2012 Aug 22.

Grounded theory in medical education research: AMEE Guide No. 70

Christopher J Watling 1, Lorelei Lingard

Affiliations expand

- PMID: 22913519

Abstract

Qualitative research in general and the grounded theory approach in particular, have become increasingly prominent in medical education research in recent years. In this Guide, we first provide a historical perspective on the origin and evolution of grounded theory. We then outline the principles underlying the grounded theory approach and the procedures for doing a grounded theory study, illustrating these elements with real examples. Next, we address key critiques of grounded theory, which continue to shape how the method is perceived and used. Finally, pitfalls and controversies in grounded theory research are examined to provide a balanced view of both the potential and the challenges of this approach. This Guide aims to assist researchers new to grounded theory to approach their studies in a disciplined and rigorous fashion, to challenge experienced researchers to reflect on their assumptions, and to arm readers of medical education research with an approach to critically appraising the quality of grounded theory studies.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 의학교육연구(Research)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 교육이론을 활용하는 다섯 가지 원칙: HPE 연구를 발전시키기 위한 전략(Acad Med, 2020) (0) | 2021.04.30 |

|---|---|

| RIME을 앞으로: 교육연구의 과학을 구성하는 것은 무엇인가? (Acad Med, 2020) (0) | 2021.04.30 |

| 질적자료의 주제분석: AMEE Guide No. 131 (Med Teach, 2020) (0) | 2021.02.13 |

| 어떻게 현상학이 다른 사람의 경험으로부터 배울 수 있도록 돕는가 (Perspect Med Educ, 2019) (0) | 2020.12.17 |

| 교육 설계연구: 생산적 학술활동을 계획하고, 수행하고, 강화하는 것(Med Educ, 2020) (0) | 2020.12.17 |