걸출한 교육자 되기: 성공에 대하여 뭐라고 말하는가? (Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract, 2020)

Becoming outstanding educators: What do they say contributed to success?

Larissa R. Thomas1 · Justin Roesch2 · Lawrence Haber1 · Patrick Rendón2 · Anna Chang3 · Craig Timm2 · Summers Kalishman4 · Patricia O’Sullivan5

도입

Introduction

의료교육 경력에서 성공하는 길은 초기 경력 교수진과 특히 지도를 하는 부서장, 부서장, 선배 멘토에게 수수께끼처럼 보일 수 있지만, 그들 자신의 경험이 종종 기초 과학자 또는 임상 조사원으로서이다. 연구 커리어에서 교수진(예: 보조금 및 논문 수)이 경력 진행을 위한 단계와 메트릭을 정의한 것과 달리, 의학 교육에서 주니어 교수가 성공적인 경력 궤적을 위한 유사한 로드맵 개요 벤치마크가 부족하다(Sanfey 및 Gantt 2012). 또한 멘토가 있을 수 있지만, 공식적인 멘토 관계와 멘토링 전략에 대한 지침은 덜 일반적이다(Feldman et al., 2010). 교수개발 프로그램은 이러한 가이드를 제공할 수 있는 하나의 장소이지만, 현재 의학교육의 교수진 개발 프로그램은 종종 명시적으로 커리어 개발에 초점을 맞추기보다는, 교수기술 강화에 초점을 맞추고 있다(Irby and O'Sullivan 2018).

The pathway to success in medical education careers can appear enigmatic to early-career faculty and especially to department chairs, division chiefs, and senior mentors who provide guidance, but whose own experiences often are as basic scientist or clinical investigators. In contrast to faculty in research pathways, who have defined steps and metrics for career progression (such as numbers of grants and articles), junior faculty lack a similar roadmap outlining benchmarks for a successful career trajectory in medical education (Sanfey and Gantt 2012). Furthermore, while mentors may be available, formal mentoring relationships and guidance on mentorship strategies are less common (Feldman et al. 2010). Although faculty development programs are one venue that could provide such guidance, current faculty development programs in medical education often focus primarily on technical skill-building rather than explicitly on career advancement (Irby and O’Sullivan 2018).

연구자들은 직업 궤도에 대한 영향을 이해하기 위한 개념적 프레임워크로서 사회 인지 직업 이론(SCCT)(Lent et al. 1994)을 자주 그린다. SCCT는 사회 인지 학습 이론(Bandura 1986)의 기초 위에서 확장하여 개별 요인(배경, 성별, 민족 등)과 상황적 요인(환경 및 동료와의 상호작용 등) 사이의 상호작용이 어떻게 자기 효율성과 결과 기대치를 이끌어 내 직업 관심사, 목표 및 성과에 영향을 미치는지를 설명한다. 경력개발과 관련된 적응적 과정adaptive process을 더 잘 다루기 위해, SCCT 이론가들은 경력개발을 고려함에 있어서 프로세스 차원process dimension을 포함시킬 것을 제안했다. 이러한 프로세스 차원에는 다음이 있다.

- 커리어 도전과 일상적인 경력 결정,

- 커리어 전환 협상,

- 커리어 내 개인적 목표 통합 및 추구,

- 다양한 역할의 관리 및 경력 지연 검토(Lent and Brown 2013)

Researchers frequently draw on the social cognitive career theory (SCCT) (Lent et al. 1994) as a conceptual framework to understand influences on career trajectory. SCCT expands on the foundation of social cognitive learning theory (Bandura 1986) to describe how the interaction between individual factors (such as background, gender, ethnicity), and contextual factors (such as environment and interactions with peers) drives self-efficacy and outcome expectations to influence career interests, goals and performance. To better address the adaptive processes associated with career development, SCCT theorists proposed including process dimensions in considering career development. Some of these process dimensions include

- examining career challenges and routine career decisions,

- negotiation of career transitions,

- integration and pursuit of personal goals within one’s career,

- management of multiple roles and examination of career setbacks (Lent and Brown 2013).

이번 연구는 의학교육자의 경력을 연구하는 데 SCCT를 포함한 다양한 프레임워크를 사용했다. 여러 연구가 SCCT의 렌즈를 이용한 의료 교육자 경력과 관련 이론을 조사했으며, 주로 초기 경력 교수진의 경험을 살펴보았다

Researchers have used various frameworks, including SCCT, in studying the careers of medical educators. Several studies have examined medical educator careers using the lens of SCCT and related theories, primarily looking at experiences of early-career faculty.

변화 변화를 연구하고 의료 교육 교직원의 형성을 식별한 다른 연구자들은 의료 교육에서 다양한 직업 단계와 관련된 긴장 및 다면적인 차원을 해석하기 위해 실무 커뮤니티의 중요한 이론적 프레임워크를 식별했다(Sethi et al., 2017). 경력 개발에 대한 연구는 또한 Schlossberg의 4S(자기, 상황, 지원 및 전략)를 사용하여 전환 이론transition theory에서 끌어낸 Browne 외(2018)가 포착한 정체성 형성과 중복된다.

Other researchers studying transformational change and identify formation of medical education faculty identified an overarching theoretical framework of communities of practice to interpret the tensions and the multi-faceted dimensions associated with various stages of careers in medical education (Sethi et al. 2017). Studies on career development also overlap with identify formation as captured by Browne et al. (2018), who drew from transition theory using Schlossberg’s 4 Ss (self, situation, support and strategy).

방법

Methods

이 연구는 연구자와 연구자 간의 상호 작용이 의미를 발생시킨다는 것을 인식하면서 건설주의적 패러다임에 뿌리를 두고 있다(Ng 등. 2019). SCCT가 지도한 이전 연구에서 확립된 우수 교육자의 관점을 더 탐구할 수 있는 기회를 확인했기 때문에, 본 연구는 SCCT를 참조 프레임워크로 채택하여 주제분석 접근 방식을 사용했다.

This research is rooted in a constructivist paradigm, recognizing that the interaction between researchers and those whom they study produces meaning (Ng et al. 2019). Because prior work guided by SCCT identified opportunities for further exploration of perspectives of established outstanding educators, this study used the approach of thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke 2006), employing SCCT as a reference framework.

이번 연구에는 두 개의 사이트가 포함되었는데, 두 개의 서로 다른 학문의 환경을 대표한다는 목표로 편의 표본으로 선정되었다. 둘 다 공립 대학이다. 캘리포니아 대학교 샌프란시스코(University of California San Francisco, UCSF)는 학부 및 대학원 교육을 위한 의료 센터와 프로그램을 갖춘 종합 대학이다. UNM의 의료캠퍼스는 UCSF에 비해 규모가 작고 오랜 기간 동안 의료 교육 인프라가 구축되지 않았다.

The study included two sites, which were selected as a convenience sample with the goal of representing two different academic environments. Both are public universities. The University of California San Francisco (UCSF) is an academic medical center and the University of New Mexico (UNM) is a comprehensive university with both a medical center and programs for undergraduate and graduate education. UNM’s medical campus is smaller compared to UCSF and has had less longstanding medical education infrastructure.

연구 참여자는 직접 교육, 커리큘럼 개발, 평가, 멘토링/자문 및 리더십/관리 분야에서 의료 교육 내에서 중요한 역할 또는 인정을 받은 전임 의사 또는 부교수 수준의 교수였다. 8명으로 구성된 조사팀에는 2개의 현장 기반 팀이 포함되어 있으며, 각 팀에는 2명의 주니어 및 2명의 수석 의료진, 2명의 선임 교수진에는 모두 임상의, 2명의 임상의와 2명의 의사가 준비된 교육자가 포함되어 있다.

Study participants were full-time physician faculty at the full or associate professor level with prominent roles or recognition within medical education in the areas of direct teaching, curriculum development, assessment, mentoring/advising and leadership/management. The eight-member investigator team included two site-based teams, each with two junior and two senior medical education faculty; the junior faculty were all clinicians, and the senior faculty included two clinicians and two doctorally-prepared educators.

그런 다음 각 현장 기반 팀은 2006년 AAMC 컨센서스 콘퍼런스(Simpson et al. 2007)에서 제정된 기준에 따라 의료 교육에 대한 기여의 주요 분야로 후보자를 하나 이상 분류했다. 직접 교육, 커리큘럼 개발, 평가, 조언 및 멘토링, 교육 리더십/행정. 이러한 범주 중 하나 이상에 대한 중요성(보급 및 평판 증명)은 참여 자격을 갖추기 위한 요건이었다.

Each site-based team then categorized each candidate by one or more primary areas of contribution to medical education according to criteria established in the 2006 AAMC consensus conference (Simpson et al. 2007): direct teaching, curriculum development, assessment, advising and mentoring, and educational leadership/administration. Prominence (as demonstrated though dissemination and reputation) in one or more of these categories was a requirement to be eligible for participation.

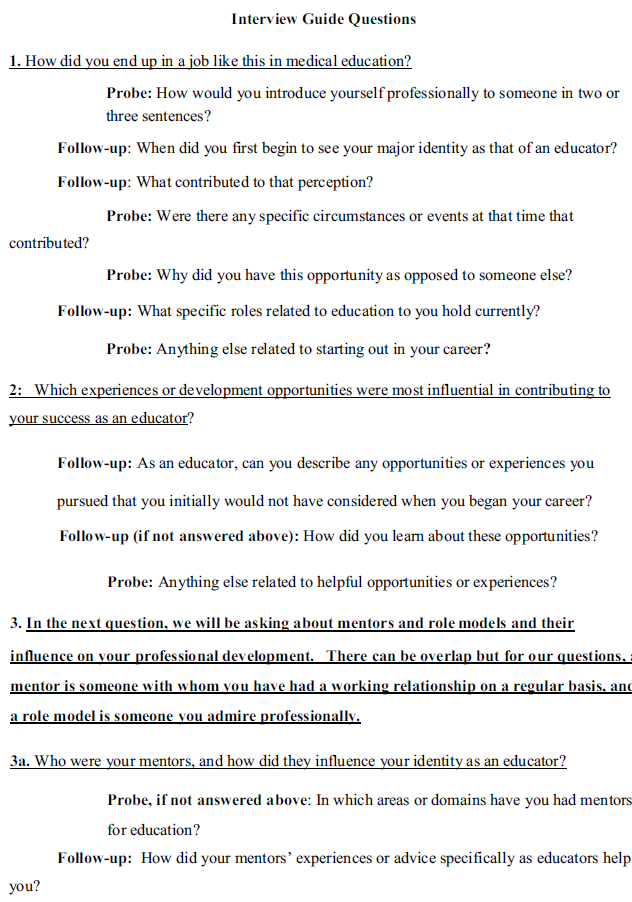

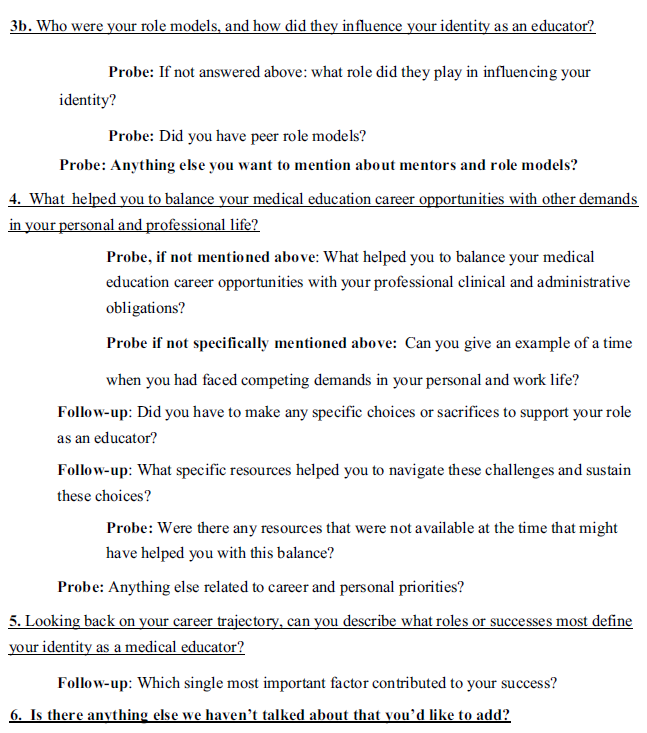

연구팀은 SCCT로부터 informed된 인터뷰 가이드를 개발했으며, 각 현장에서 연구 샘플에 포함되지 않은 1–2명의 교수진을 대상으로 시범 실시한 후 가이드를 세분화하여 6개의 주요 질문을 프로브와 함께 작성했다("부록 1" 참조). 면접관은 소급 재검사에서 발생할 수 있는 리콜 편향을 방지하기 위해 참가자의 경험과 관련된 추가 특이성, 상세성, 컨텍스트 및 이벤트를 장려하기 위해 조사를 사용했다.

The team developed an interview guide informed by SCCT, which was piloted at each site with 1–2 faculty not included in the study sample, then refined the guide, resulting in 6 main questions with probes (See “Appendix 1”). Interviewers used probes to encourage additional specificity, detail, context, and events related to the participant’s experiences, in order to guard against recall bias that could emerge from a retrospective recounting.

팀 전체가 추가 조사를 위해 초기 인터뷰를 검토했다. 연구팀은 SCCT의 세 가지 광범위한 주제인 자기효능주의 신념, 결과 기대치, 개인적 목표를 사용하여 두 개의 대본을 검토함으로써 초기 코드북을 개발했다. 이러한 테마는 교육자의 경력 관점을 분류하는 출발점이 되었고, 이를 확장하여 추가 코드를 포함시켰다. 코드북은 광범위한 논의와 추가적인 대본 검토와 재검토를 통해 다듬어지고 최종 마무리되었다. 그 후 두 명의 수사관에 의해 각각의 녹취록은 독립적으로 코딩되었다. 즉, 인터뷰 대상자와 같은 사이트의 선임 수사관이 다른 사이트의 하위 수사관과 함께 작업했다. 각 쌍은 코딩의 차이를 판단하기 위해 만났고, 선임 조사관은 필요한 경우 면접 대상 기관에 대한 상황 정보를 명확히 했다. 이 조사관은 최종 합의 코드를 Dedoose (CA, Hermosa Beach)에 입력했다. 각 인터뷰 대상자가 식별된 주제와의 정렬을 검토하기 위한 경력 궤적을 설명하는 요약서를 개발하는 등 데이터의 신뢰성을 보장하기 위한 많은 단계가 수행되었다(Shenton 2004). 인터뷰는 정보 충분성에 도달할 때까지 계속되었으며, 이후 인터뷰에서도 유사한 주제가 나타났다(Malterud et al., 2016).

The entire team reviewed initial interviews to refine additional probes. The team developed an initial codebook by reviewing two transcripts using three broad themes from SCCT: self-efficacy beliefs, outcome expectations, and personal goals. These themes served as a starting point for categorizing educators’ perspectives of their careers and they were expanded upon and additional codes included. The codebook was refined and finalized through extensive discussion and further transcript review and re-review. Each transcript was then independently coded by hand by two investigators: a senior investigator from same site as the interviewee worked with a junior investigator from the other site. Each pair met to adjudicate differences in coding, with the senior investigator clarifying contextual information about the interviewee’s institution where necessary. The junior investigator entered the final consensus codes into Dedoose (Hermosa Beach, CA). Many steps were taken to ensure trustworthiness of the data, including developing a summary for each interviewee to describe their career trajectory to examine for alignment with the identified themes (Shenton 2004). Interviews were continued until information sufficiency was reached, with similar themes appearing in subsequent interviews (Malterud et al. 2016).

코딩에 이어, 팀은 코드 보고서를 검토하고 테마를 합성하고 궤적 스토리와 정렬을 결정하는 반복적인 프로세스를 시작했다. 이 과정은 1년 동안 여러 팀 회의를 통해 수행되었습니다. 테마는 SCCT의 요소를 유지하였고, 유도적으로 개발된 코드와 토론은 최종 테마를 도출한 경력 개발에 대한 세부 사항으로 이어졌다. 각 테마는 참가자 번호로 식별된 지지 인용문과 함께 설명됩니다.

Following coding, the team began an iterative process of reviewing the code reports, synthesizing themes and determining alignment with trajectory stories. This process was done over the course of a year with a number of whole team meetings. The themes sustained elements from the SCCT, and the inductively developed codes and discussions led to elaborations about career development that resulted in the final themes. Each theme is described with supporting quotes identified by a participant number.

성찰성

Reflexivity

[팀의 폭넓은 경험]은 특정한 편견에서 생길 수 있는 해석에 도전하는데 도움이 되었다. 즉, 선배들은 대부분 교수진 개발에 투자를 했고, 후배들은 커리어 가이드guidance를 구했다. 건설주의 패러다임에서 우리는 후배 교수팀원들이 면접을 진행하고 면접지도자의 발전을 이끌도록 의도적으로 선택했는데, 이들이 진로지도에 대한 자신의 관점을 대변했기 때문이다. 이 결정이 면접 조사 선택과 데이터 해석에 영향을 줄 수 있었지만, 이 잠재적 성찰성은 인터뷰 가이드 작성 및 분석 중에 빈번한 회의와 연구팀의 고위 구성원(기관 내 및 기관 간 모두)과 짝을 이루어 균형을 이루었다. 그 견해는 최종 테마를 설명하는 과정에서 서로 균형을 이루었다.

The team’s breadth of experience was helpful to challenge interpretations that could arise from particular biases: senior members largely had an investment in faculty development, and the junior members sought career guidance. From a constructivist paradigm, we intentionally chose to have junior faculty team members conduct interviews and lead the development of the interview guide, since they represented the perspective of those who were themselves seeking career guidance. Although this decision could have influenced choice of interview probes and interpretation of data, this potential reflexivity was balanced by frequent meetings and pairing with the senior members of the study team (both within and across institutions) during interview guide creation and analysis. The views balanced each other in the elucidation of the final themes.

결과

Results

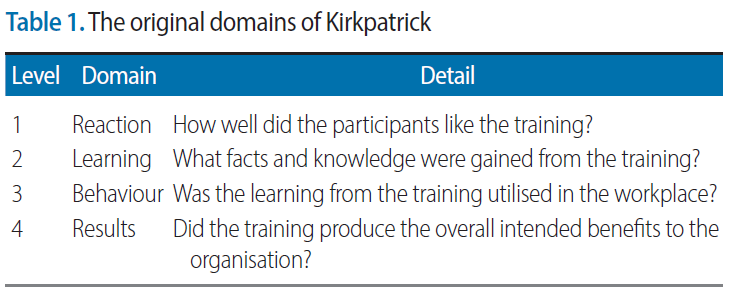

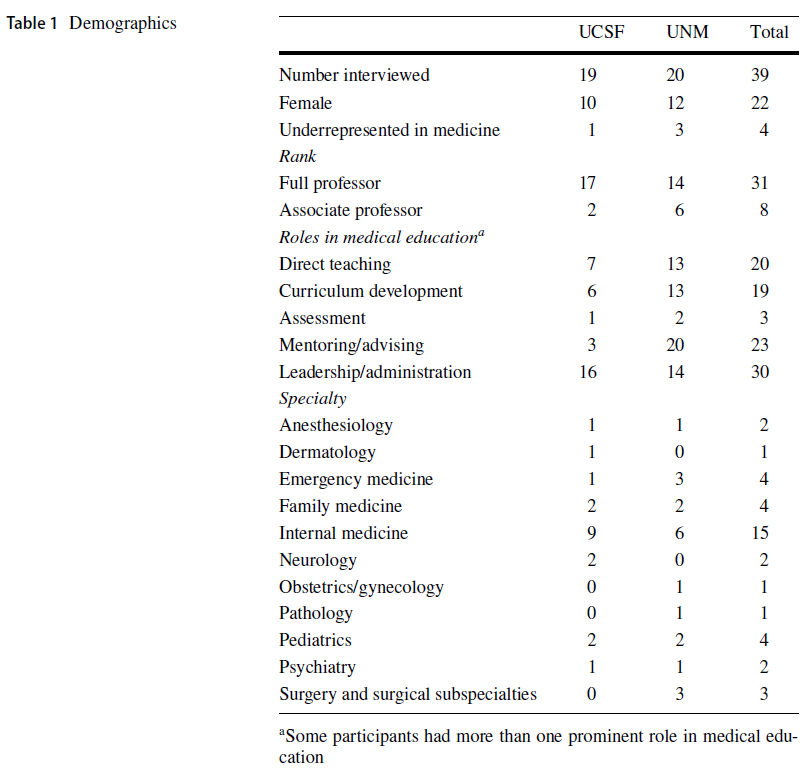

표 1은 참가자를 설명합니다(표 1 참조).

Table 1 describes the participants (see Table 1).

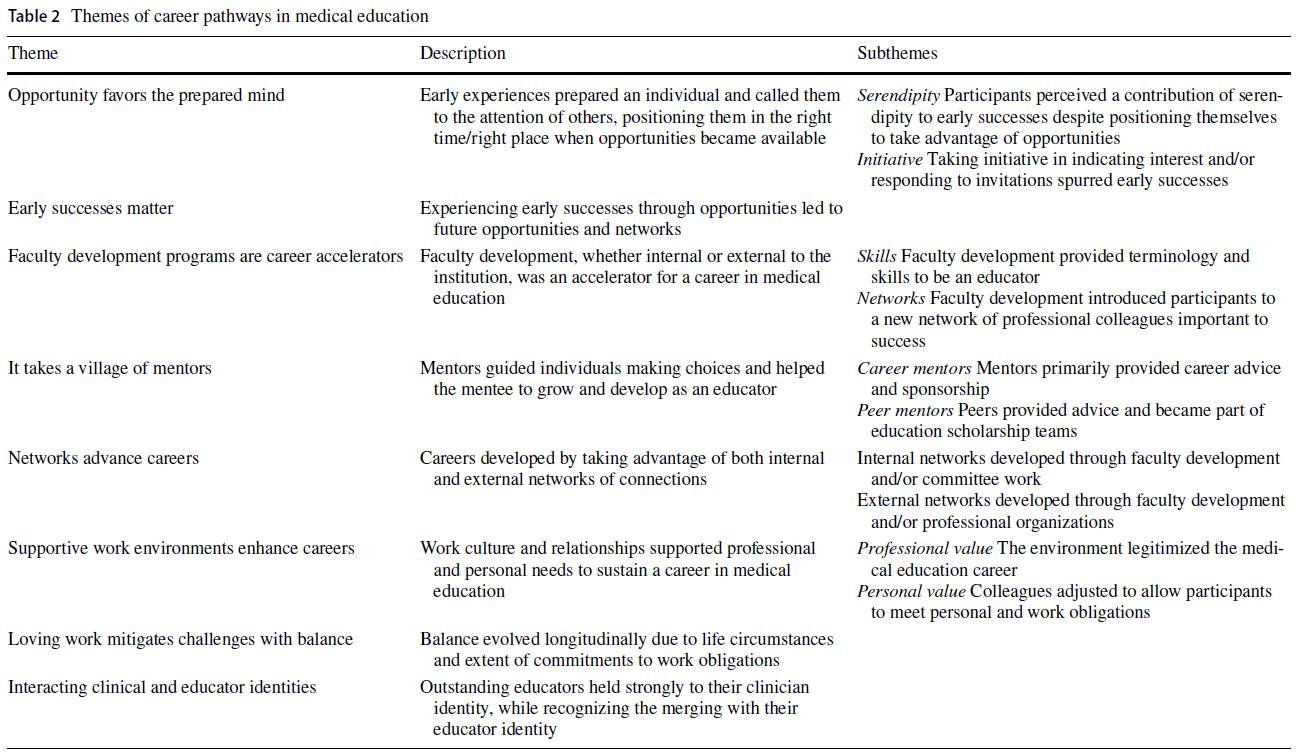

테마 1: 기회는 준비된 마음을 선호한다.

Theme 1: opportunity favors the prepared mind

참가자들은 역할에 대한 준비를 하고 의료교육의 초기 성공을 이끈 초기 경험을 떠올리는 경우가 많았다. 이러한 경험은 종종 보호되는 시간 없이 관심 영역에서 자원봉사를 하는 것과 관련이 있다. 개인은 자신의 관심분야를 다른 사람들에게 분명하게 전달했고, 그랬기에 발생하는 기회를 이용할 준비가 되어 있었다.

Participants often recalled early experiences that prepared them for roles and led to initial successes in medical education. These experiences frequently involved volunteering in an area of interest without protected time. Individuals communicated their interests explicitly to others and were therefore poised to take advantage of opportunities that occurred.

하위 테마: 첫 번째 기회로 이어지는 우연성에 대한 인식

Sub theme: perception of serendipity leading to first opportunities

기회가 생겼을 때, 연구 참가자들은 종종 이러한 성공을 우연한 감각이나 (우연히) '적절한 시기에 알맞은 장소'에 있기 때문이라고 했다. 그러나 많은 경우(예: 직책 개설을 유도하는 교직원의 퇴직)에 기회 또는 타이밍 요소가 존재했지만, 사전 작업 및 준비는 일반적으로 고려 대상이 되었다.

When opportunities arose, study participants frequently attributed these successes to a sense of serendipity or being in the “right place at the right time.” However, while some element of chance or timing did exist in many cases (for example, retirement of a faculty member leading to a position opening), prior work and preparation had usually positioned them for consideration.

하위 테마: 솔선수범하고 "예"라고 말함

Subtheme: taking initiative and saying “yes”

또 다른 하위 주제는 자발적으로 기회를 요청하는 것의 중요성과 자신의 초기 경력에서 생겨난 기회들에 대해 정기적으로 "예"라고 말하는 것이었다. 이러한 활동은 많은 참가자들에게 새로운 역할과 기회로 직결되었다.

Another sub-theme was the importance of taking initiative to ask for opportunities, as well as regularly saying “yes” to opportunities that arose in one’s early career. This proactivityled directly to new roles and opportunities for many participants.

테마 2: 초기의 성공이 중요하다.

Theme 2: early successes matter

초기 성공은 종종 새로운 기회로 이어졌으며, 종종 리더십 위치 또는 역할의 형태로 가시성, 네트워킹 기회 및 추가 책임으로 이어졌다.

Early successes often led to new opportunities, frequently in the form of leadership posi-tions or roles that led to increased visibility, networking opportunities, and additional responsibility.

게다가, 이러한 초기의 성공은 자신감을 키우는 것이었고, 의료 교육자로서의 진로를 재확인했다.

Additionally, these early successes were confidence-building and reaffirmed the career path of being a medical educator.

Theme 3: 교수진 개발 프로그램은 직업 가속기

Theme 3: faculty development programs are career accelerators

거의 모든 참가자들이 공식적인 (교수)개발 프로그램을 마쳤습니다. 교수진 개발은 기술을 개발하고, 네트워크를 개선하고, 추가 개발에 대한 관심을 촉진함으로써 직업 가속기 역할을 했습니다. 역량 습득 측면에서 교수개발 프로그램은 기존에 생소했던 교육원리, 교육이론, 전략 등을 명확히 하고, 의료교육에 대한 관심을 더욱 증폭시켰다.

Nearly all participants had completed a formal development program. Faculty development served as a career accelerator by developing skills, enhancing a network, and spurring an interest in further development. In terms of skills acquisition, faculty development programs clarified pedagogical principles, educational theory, and strategies that were previously unfamiliar, and fueled their further interest in medical education.

참가자들은 또한 동료 교육자 네트워크에 연결함으로써 얻을 수 있는 예상치 못한 이점을 설명했는데, 이는 참가자들을 부서 밖의 새로운 아이디어에 노출시킬 뿐만 아니라 향후 작업에 대한 협업과 지원을 위한 자원으로도 작용했다.

Participants also described unanticipated benefits of connection to a network of fellow educators, which not only exposed participants to new ideas outside of their departments, but also served as a resource for collaboration and support for future work.

테마 4: 멘토들의 마을이 필요하다.

Theme 4: it takes a village of mentors

오늘날 존재하는 등 공식적인 멘토링 프로그램을 접하지 못한 참가자가 많았지만, 모든 참가자가 멘토를 확인했다. 멘토는 주로 진로·동료 멘토로 참여자들이 다음 단계의 우선순위를 정할 수 있도록 돕고, 새로운 기회에 대해 알리고, 직책·발전기회 지원을 독려하는 데 중요한 역할을 했다.

Though many participants did not have access to formal mentoring programs such as exist today, all participants identified mentors. Mentors were primarily career and peer mentors, and played an important role in helping participants prioritize next steps, alerting them to new opportunities, and encouraging them to apply for positions and development opportunities.

참가자들은 특히 [학문적 일을 추진하는 데 있어 원동력이 되는] 동료 멘토에 대해 종종 말했다.

Participants often spoke about peer mentors who seemed to be driving forces, particularly in the pursuit of scholarly work

Theme 5: 네트워크는 경력을 발전시킵니다.

Theme 5: networks advance careers

내부/국내/외부/국내 네트워크 모두 경력 발전을 촉진했고, 전문 학회와 같은 공식 네트워크 및 동료 커뮤니티와 같은 비공식 네트워크를 포함했다. 참가자들은 주로 멘토, 의료교육 역할 참여, 교수 개발 프로그램을 통해 이들 네트워크에 진입했으며, 의료교육 공동체의 문화와 정치에 대한 이해를 돕는 네트워크의 가치를 강조했다.

Both internal/local and external/national networks facilitated career advancement, and included formal networks such as professional societies, as well as informal networks such as peer communities. Participants usually entered these networks through a mentor, involvement in a medical education role, or a faculty development program, and highlighted the value of networks for helping them to understand the culture and politics of the medical education community.

또한 네트워크는 참가자들에게 특정 기회(예: 연설 또는 위원회 의장 역할)와 향후 프로젝트를 위한 협력자들에게 모두 소개했습니다.

Networks also introduced participants both to specific opportunities (such as speaking or committee chair roles) and to collaborators for future projects.

Theme 6: 지원 작업 환경, 경력 향상

Theme 6: supportive work environments enhance careers

많은 참가자들이 자신의 진로를 검증하기 위한 [지지적 업무 환경]의 중요성을 설명했습니다. 이러한 환경에는 감독자 및 동료와의 [지지적 업무 관계]와 [공유된 가치]가 결합되어 있습니다.

Many participants described the importance of a supportive work environment for validating their career paths. This environment included a combination of supportive work relationships with supervisors and colleagues and shared values.

참가자들은 또한 균형을 촉진하는 데 도움이 되는 자원으로서 임상적 서포트를 제공하는 동료의 중요성에 대해 언급했다. 유연성과 임상 백업을 지원하기 위해 작업 커뮤니티work community에 의존할 수 있었던 참가자들은 업무관련 및 업무비관련 책임 충족을 위해 더 많은 지원을 받는다고 설명했습니다.

Participants also commented on the importance of colleagues providing clinical support as a resource to help promote balance. Participants who were able to rely on a work community to support flexibility and clinical backup described feeling more supported in their efforts to meet work and non-work responsibilities.

Theme 7: 애정 어린 작업이 균형 있게 과제를 만들고 완화합니다.

Theme 7: loving work creates and mitigates challenges with balance

많은 교수진들은 그들의 진로를 통해 직장 밖의 삶이나 일과 관련하여 균형이나 안정을 달성하는 데 장애물을 설명했다. 참가자들은 "그렇다"고 말하는 충동적 성향이 경력 초기에는 종종 기회로 이어졌지만, 중년이후에는 경력의 불균형에 기여했고, 사생활에 미친 (안 좋은) 대한 결과도 있었다고 설명했다.

Many faculty members described barriers to achieving balance or stability with respect to work or life outside of work over the course of their careers. Participants described that the same impulse to “say yes,” which had often led to opportunities early in their career, contributed to lack of balance, especially in mid-career, with consequences on personal life.

일부 참가자들은 새로운 책임을 지는데 있어 보다 까다로워지고 명확한 경계를 세울 수 있었기 때문에 그들의 경력에 걸쳐 종래에 걸쳐 더 큰 균형을 이루었다.

Some participants achieved greater balance longitudinally over the course of their careers as they were able to become more selective in assuming new responsibilities and established clearer boundaries.

거절하는 게 정말 중요한 것 같아. 모든 것을 다 할 수는 없고, 할 일을 골라야 잘 할 수 있다. 그 중 일부는 당신의 직업에서 당신의 방향이 무엇인지 이해하는 것이다. (D10)

I think it’s really important to say no to some things. You can’t do everything, and you have to pick and choose the things that you’re going to do so you can do them well. Part of that is understanding what your direction is in your career. (D10)

다른 교수진들은 그들의 학업이 자부심과 자생력의 원천이었기 때문에 전통적인 근무 주 이외의 교육자의 책임 침해를 부정적으로 보지 않았다.

Other faculty did not view encroachment of educator responsibilities beyond the traditional work-week negatively, as their academic work was a source of pride and self-sustaining.

나는 [균형]이라는 단어가 싫다. 도저히 충족시킬 수 없는 기대를 만들어 낸 것 같아요. 삶의 균형을 맞출 수 있는 방법은 없습니다. 그것은 불가능한 것을 암시하고 있다. 제가 믿는 것은 이렇습니다. 저는 여러분이 하는 일을 사랑한다면, 저절로 해결된다고 믿습니다. (D6)

I hate that word [balance]. I think it’s created expectations that are impossible to meet. There’s no way you can balance your life…That implies something that’s impossible… o here’s what I believe: I believe that if you love what you do, it works itself out. (D6)

보다 균형 잡힌 지원자에는 지원 커뮤니티, 가족, [업무 외 개인적 의무에 대한 보호 시간]을 관리schedule할 수 있는 능력이 포함되었습니다.

Enablers of greater balance included a supportive community, family, and the ability to schedule protected time for personal obligations outside of work.

테마 8: 임상 및 교육자 신분 상호 작용

Theme 8: interacting clinical and educator identities

뛰어난 교육자로서의 외부 인식에도 불구하고, 많은 참여자들은 임상업무가 전체업무에서 차지하는 비율이 낮더라도 주요 임상의사 정체성을 계속 옹호했다. 이러한 정체성은 때때로 단절된 것처럼 느껴졌지만, 경험이 풍부한 교육자들은 서로를 지탱하고 풍요롭게 하는 경향이 있는 임상적 정체성과 교육적 정체성의 중복을 인식했습니다.

Despite external recognition as outstanding educators, many participants continued to espouse a primary clinician identity, even if clinical work became a low percentage of their total effort. While these identities at times felt disconnected, experienced educators recognized overlap of their clinical and educator identities, which tended to sustain and enrich each other.

그것은 나의 주된 정체성이었던 적이 없다. 아이러니한 것은 제가 지금 제 시간의 60%를 교육 행정에 쓰고 30%만 임상 의사로 쓰고 있지만, 여전히 제 자신을 1차 진료 의사로 보고 있기 때문입니다. 그렇다고 해서 교육자로서 제 역할을 무시하거나 무시하는 것은 아니지만, 제 자신의 정의에 따르면, 저는 스스로 클리닉 파트타임에서 일하는 교육자가 아니라, 교육을 하는 1차 진료 의사라고 생각합니다. (C2)

It has never been my primary identity. It is ironic because I now spend 60 percent of my time in educational administration and only 30 percent as a clinician, but I still see myself as a primary care physician. That’s not that I discount or ignore my role as an educator, but I still don’t see it…in my own self-definition, I see myself as a primary care physician who teaches, rather than an educator who works in the clinic part-time. (C2)

토론

Discussion

공통 궤적에 대한 네 가지 핵심 관찰은 성공적인 교육자의 경력 개발에 관한 문헌에 추가된다.

- 첫째, 교육자는 종종 성공이 우연의 일치에 기인함에도 불구하고 준비와 사전 준비를 통해 교육의 길을 걷기 시작했다. 이러한 초기 단계들은 초기 기회(리더십 역할 또는 책임)로 이어졌고, 이를 교수진 개발 프로그램을 포함한 네트워크, 멘토, 기회를 소개하는 "런치 포인트" 역할을 했다.

- 둘째, 거의 모든 성공한 교육자들은 여러 명의 멘토가 있었으며, 그들은 종종 후원 역할을 했으며 동료 멘토쉽이 두드러진 역할을 했다. 네트워크 및 교수진 개발 프로그램과 함께 멘토는 추가 멘토, 네트워크 및 교수진 개발을 포함하여 교육자들에게 더 많은 기회를 소개하는 커리어 액셀러레이터 역할을 했습니다.

- 셋째, 일반적으로 의학교육 경로에 대해 지지적supportive인 작업 환경 내에서 상호작용이 이루어졌다.

- 마지막으로, 이 궤적은 직업의 각 지점에서 반복되고 나선형으로 보였으며, 그러한 성공은 새로운 개발 기회, 네트워크 및 멘토를 가능하게 하는 새로운 기회로 이어졌다.

Four key observations about common trajectories add to the literature on career development of successful educators.

- First, an educator began down the path of education through preparation and proactivity, despite often attributing success to serendipity. These early steps led to an initial opportunity (a leadership role or responsibility) that served as a “launch point” to introduce them to networks, mentors, and opportunities, including faculty development programs.

- Second, nearly all successful educators had multiple mentors, who often served in a sponsorship role, and peer mentorship played a prominent role. Along with networks and faculty development programs, mentors served as career accelerators to introduce educators to more opportunities, including additional mentors, networks, and faculty development.

- Third, interactions generally took place within a work environment supportive of medical education pathways.

- Finally, this trajectory appeared to repeat itself and spiral at each point in the career, such that success led to new opportunities that allowed for new development opportunities, networks, and mentors

준비의 역할이 과소평가되어서는 안 된다. 준비가 처음에는 비공식적인 기회를 이용하면서 나타났지만, 교수진 개발 프로그램에 참여함으로써 종종 경력 성장을 가속화했다. 의료 교육의 많은 교수 개발 연구와 리뷰는 참가자들이 무엇을 배우고 직면하는지 강조하였다(Steinert et al. 2006, 2016). 더 최근의 연구는 진로 진행에서 교수 개발 프로그램의 역할을 다룬다(Leslie et al. 2013). 그러나, 이 연구는 교수 개발이 경력에 기여하는 방법에 대한 우리의 통찰력을 더해준다. 즉, [핵심 지식을 보완]하고 [문을 열어opening doors] 참가자들이 대내외적으로 새로운 역할을 맡을 준비가 더 잘 되도록 하는 것이다.

The role of preparation should not be undersold. While preparation initially manifested in taking advantage of informal opportunities, participation in faculty development programs often accelerated the career growth. Many faculty development studies and reviews in medical education have highlighted what participants learn and challenges they face (Steinert et al. 2006, 2016), and more recent studies address the role of faculty development programs in career progression (Leslie et al. 2013). However, this study adds to our insight about ways that faculty development contributes to the career: by supplementing key knowledge and opening doors, so that participants are better prepared to take on new roles, both internally and externally.

우리는 준비로 인한 초기 성공을 "발사점launch point"으로 특징지었습니다. 위에서 언급한 바와 같이, 개별 이니셔티브 및 교수진 개발 기회는 모두 새로운 기회를 시작하는 데 기여하는 데 도움이 됩니다. 그러나, 이 발사는 종종 의대 교육계 내의 가시성visibility과도 관련이 깊었다. 의료 정체성 문헌에 기술된 바와 같이, 이러한 가시성은 [개인의 정체성] 및 [개인이 자신을 보는 방식], [지지받고 있다는 느낌]과 관련이 있을 수 있다(Browne et al. 2018; Cantillon et al. 2018; Jauregi et. 2019; Onyura et. 2017; O'Suliban et al. 2016). 발사점의 중요성에 대한 이러한 관찰은 정체성 개발을 교수 개발 오퍼링에 보다 명시적으로 통합해야 할 필요성을 말해 줄 수 있다(Steinert et al. 2019).

We characterized initial success resulting from preparation as a “launch point.” As noted above, both individual initiative and faculty development opportunities help contribute to the launch into new opportunities. However, the launch was also often highly related to visibility within the medical education community. As described in the medical identity literature, this visibility may be related to identity, and how individuals see themselves and feel supported (Browne et al. 2018; Cantillon et al. 2018; Jauregui et al. 2019; Onyura et al. 2017; O’Sullivan and Irby 2014; O’Sullivan et al. 2016). This observation of the importance of a launch point may speak to the need to incorporate identity development more explicitly into faculty development offerings (Steinert et al. 2019).

우리의 연구는 멘토링이 필수적인 기여자였던 방법을 나타내는 이전 연구의 결과를 향상시킨다(Feldman et al. 2010).

[공식적인 연구 멘토 관계]가 우세한 [연구 커리어]와는 대조적으로, 우리의 참가자들은 주로 그들의 경력에 걸쳐 [다수의 직업 멘토]들을 언급했습니다. 그들은 종종 후원자였고, 참가자들에게 기회와 네트워크를 소개해주었다.

Our study enhances findings from prior studies indicating the ways in which mentorship was an essential contributor (Feldman et al. 2010). In contrast to research pathways, in which formal research mentorship relationships predominate, our participants predominantly described multiple career mentors over the course of their career, who were frequently sponsors, introducing participants to opportunities and networks (Travis et al. 2013; Chopra et al. 2018).

흥미롭게도, [동료 멘토]들은 네트워크를 공유하고 프로젝트에 협력하는 등 많은 참가자들에게 중요한 역할을 하기도 했다. 연구들은 특히 주니어 교수의 동료 멘토링의 효과를 주니어 교수 멘토링으로 뒷받침해 왔다. 동료 멘토의 중요성에 대한 우리의 발견은 [주니어 교수들은 (특히 네트워크를 개발하여) 동료 멘토와 코-멘토를 더 의식적으로 찾음]으로써 이익을 얻을 수 있음을 시사한다.

Interestingly, peer mentors also played an important role for many participants, serving in a co-mentorship role by sharing networks and collaborating on projects. Studies have supported the effectiveness of peer mentoring specifically at junior faculty member to junior faculty member mentoring. (Heinrich and Oberleitner 2012; Johnson et al. 2011). Our finding of the importance of peer mentors suggests that junior faculty may benefit from more consciously seeking out peer mentors and co-mentors, especially by developing networks.

또 다른 두드러진 발견은 의료 교육 및 일과 삶의 균형에서 성공적인 경력을 달성하는 데 있어 업무 환경의 역할이었다. SCCT의 개발자인 Lent and Brown(2013)은 개인 및 전문적 목표에 걸쳐 통합해야 할 필요성을 강조했다. 업무 환경이 지지적이었을 때, 업무 환경은 [임상의]와 [교육자]의 정체성의 합병을 강화하는 데 도움이 되었다. 또한 지적 공동체, 사회적 지원, 그리고 [개인적 목표에 부합하는 전문적 기회를 탐색할 수 있는 자유latitude]를 제공했다.

Another prominent finding was the role of the work environment in achieving successful careers in medical education and work-life balance. Lent and Brown (2013), the developers of SCCT, highlighted the need to integrate across personal and professional goals. When it was supportive, the work environment helped reinforce the merging of clinician and educator identities that we observed, and provided intellectual community, social support, and latitude to explore professional opportunities that aligned with personal goals.

이러한 [임상의사-교육자에 대한 구조적 지원]은 교육자로서의 개발과 다른 전문적 역할 사이의 충돌을 최소화하기 위해 최근에 제안되었다(Elmberger et al., 2018). 지지적 업무 환경이 일부 기관에서는 쉽게 드러나지 않거나 이용할 수 없을 수 있기 때문에, 주니어 교수진은 교수개발 프로그램 및 부서리더와 함께 전문적 개발의 일환으로 이러한 환경을 보다 명시적으로 육성하고자 할 수 있습니다. 참가자들이 "그렇다"고 말하는 경향이 중기경력mid-career의 균형 부족에 기여했다고 자주 설명하였기 때문에, 작업 환경은 또한 [관리 가능한 작업량]을 중심으로 문화적 기대치를 설정하는 잠재적 역할을 할 수 있다(Strong et al., 2013).

Such structural support for clinician-educators has recently been suggested to minimize conflicts between development as an educator and other professional roles (Elmberger et al. 2018). Because a supportive work environment may not be readily apparent or available in some institutions, junior faculty, along with faculty development programs and division or department leaders, may seek to cultivate this climate more explicitly as part of professional development. Given that participants often described that the tendency to “say yes” contributed to lack of balance in mid-career, the work environment could also potentially play a role in setting cultural expectations around manageable workload (Strong et al. 2013).

이전 문헌과 일관되게, 우리는 교육자로서 성공적인 경력을 쌓기 위해서는 초기 성공이 필수적이라는 것을 발견했다(Hu et al. 2015). 그리고 성공에서 우연한 역할이 인식되었음에도 불구하고 의도적인 준비가 종종 이러한 기회로 이어졌다(Bartle and Thistlethwaite 2014; Hu et al. 2015). 자기효능감 문헌과 연계하여, 우리는 특정 속성, 특히 사전 적극성proactivity이 새로운 기회와 성공에 기여했음을 발견했다(Browne et al. 2018; Sethi et al. 2017). 우리의 테마는 주로 SCCT를 사용하여 자기효능감 신념을 자극하는 개인과 상황적 영향 사이의 상호 작용을 이해했다는 점에서 기존 연구와 일치했지만, 우리는 또한 이 주제theme가 [교육자의 경력 성숙 과정에 걸쳐 복잡성과 깊이를 증가시키며 개인에 대해 여러 번 반복재생된다는 것]을 발견했다.

Consistent with prior literature, we found that early successes are essential to launch a successful career as an educator (Hu et al. 2015), and that deliberate preparation often led to these opportunities, despite a perceived role of serendipity in their success (Bartle and Thistlethwaite 2014; Hu et al. 2015). Aligned with self-efficacy literature, we found that certain attributes, specifically proactivity, contributed to new opportunities and successes (Browne et al. 2018; Sethi et al. 2017). Although our themes largely aligned with previous work using SCCT to understand the interaction between individual and contextual influences that spur self-efficacy beliefs, we also found that our themes replayed multiple times for an individual, spiraling with increasing complexity and depth over the course of the educator’s career maturation.

문헌의 격차를 해소하고자 하는 우리의 목표로 돌아가, 우리는 교육자로서 선배 교직원의 발전 관점, 그들의 직업에서 교육자가 수행하는 다양한 역할, 그리고 교육자의 경력에 미치는 교수진 발전의 영향과 관련된 중요한 개념을 확인하였습니다. 설계에 의해 우리의 연구는 선배 교수들이 자신의 경력 개발을 회고적으로 바라볼 때 그들의 관점을 식별했다. 위에서 파악되고 기술된 모든 중요한 주제는 광범위한 경험을 가진 상급 교수진의 관점을 반영하며, 무엇이 상급 의학 교육자로서 성공하게 했는지에 대한 종합적인 시각을 제공한다.

Returning to our goal of addressing gaps in the literature, we have identified important concepts related to perspectives of senior faculty in their development as educators, the diverse roles played by educators in their careers, and the impact of faculty development in educators’ careers. By design our study identified the perspectives of senior faculty as they looked retrospectively at their own career development. All of the important themes identified and described above reflect the view of senior faculty with extensive experience, giving a comprehensive look at what led to their success as senior medical educators.

시니어 교수로서, 참가자들은 그들의 경력에서 다양한 역할들을 설명했습니다. 이러한 역할의 대부분은 의학교육에도 관련되어 있었지만, 의학교육을 직업으로 추구하기로 결정한 것을 알 수 있는 다른 관련 역할도 직접적으로 관련되어 있었다. 성공적인 시니어 교수는 문헌에 대한 이해를 심화시키는 데 중요하게 공헌했던 [자신에 대한 일반적인 행동과 인식]을 기술했다. [준비된 상태]와 [기회의 응하기], [교육자로서의 조기 성공], [많은 동료(멘토, 동료)와 함께 참여하고 배우며], [전문 개발 프로그램]에 전념하고, [전문 네트워크]를 넓히고, [임상의와 교육자의 이중 정체성을 유지]하는 것이 일반적인 주제였다.

As senior faculty, our participants described a variety of diverse roles in their careers. Many of these roles directly involved medical education, as well as other related roles that might have informed their decisions to pursue medical education as a career. Successful senior faculty described common behaviors and perceptions of self that are important contributions to deepening understanding of the literature. Being prepared and saying yes to opportunities, having an early success as an educator, engaging with and learning from many colleagues (mentors, peers), committing to professional development programs, expanding professional networks, and holding the dual identities of clinician and educator were common themes.

마지막으로, 우리가 기술한 바와 같이, [교수진 개발 활동과 프로그램]은 [새로운 기술과 지식을 습득하고 다른 교육자들과의 네트워킹 기회를 향상]시킨다는 점에서, 시니어 교육자들은 이를 경력 개발에 중요한 요소로 거의 보편적으로 언급하였다. 이러한 테마는 [자신과 다른 사람 사이의 상호 작용에 대한 미묘한 이해]와 이러한 시니어 임상 교육자의 경력이 위치한 더 큰 컨텍스트를 제공함으로써 문헌의 격차를 해소한다.

Lastly, as we have described, faculty development activities and programs are almost universally identified by successful senior educators as important factors in their career development, both in terms of acquiring new skills and knowledge and enhancing opportunities for networking with other educators. These themes address gaps in the literature by providing nuanced understanding of the interaction between self and others, and the larger context in which these senior clinical educators’ careers are situated.

제한사항

Limitations

흥미롭게도, 우리의 많은 참여자들은 의학교육이 덜 확립된 분야였을 때 그들의 경력을 시작했기 때문에, 그들의 초기 진로는 현재의 주니어 교수진의 그것과는 다를 수 있다. 특히, 샘플의 많은 참여자들이 의료 교육 리더 역할에 임명되었습니다. 더 많은 역할이 경쟁 프로세스를 통한 선택을 포함하기 때문에 이러한 유형의 리더십 역할 진입은 이제 덜 일반적일 수 있습니다. 교육 연구 및 의료 교육의 진로에 대한 정당성이 커짐에 따라 (Irby와 O'Sullivan 2018), 그리고 21세기 학습자의 요구를 충족시키기 위해 의학교육자의 역할도 진화하고 있다(Simpson et al., 2018). 이에 따라 초기 커리어 교수들은 또한 교육적 리더 직위에 지원할 더 많은 기회가 생겼고, [임상 및 기초 과학 멘토와 같은] 뛰어난 교육 연구 멘토에 대한 필요도 더 커질 수 있다.

Interestingly, since our many of our participants began their careers when medical education was a less established field, their early career pathways may differ from those of current junior faculty. Specifically, many participants in our sample were appointed to medical education leadership roles; this type of entry into a leadership role may be less common now as more roles involve selection through a competitive process. As the legitimacy of educational research and medical education as a career pathway grows (Irby and O’Sullivan 2018), and roles of medical educators evolve to meet the needs of twenty-first century learners (Simpson et al. 2018), early career faculty may also have more opportunities to apply for educational leadership positions and a greater need for strong education research mentors akin to clinical and basic science mentors.

Browne, J., Webb, K., & Bullock, A. (2018). Making the leap to medical education: A qualitative study of medical educators’ experiences. Medical Education, 52(2), 216–226.

Cantillon, P., Dornan, T., & De Grave, W. (2018). Becoming a clinical teacher: Identity formation in context. Academic Medicine, 94, 1610–1618.

Chopra, V., Arora, V. M., & Saint, S. (2018). Will you be my mentor? Four archetypes to help mentees succeed in academic medicine. JAMA Internal Medicine, 178(2), 175–176.

Elmberger, A., Björck, E., Liljedahl, M., Nieminen, J., & Bolander Laksov, K. (2018). Contradictions in clinical teachers’ engagement in educational development: An activity theory analysis. Advances in Health Sciences Education: Theory and Practice, 24(1), 124–140.

Irby, D. M., & O’Sullivan, P. S. (2018). Developing and rewarding teachers as educators and scholars: Remarkable progress and daunting challenges. Medical Education, 52(1), 58–67. XXX

Jauregui, J., O’Sullivan, P., Kalishman, S., Nishimura, H., & Robins, L. (2019). Remooring: A qualitative focus group exploration of how educators maintain identity in a sea of competing demands. Academic Medicine, 94(1), 122–128.

Onyura, B., Ng, S. L., Baker, L. R., Lieff, S., Millar, B.-A., & Mori, B. (2017). A mandala of faculty development: Using theory-based evaluation to explore contexts, mechanisms and outcomes. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 22(1), 165–186.

Steinert, Y., O’Sullivan, P. S., & Irby, D. M. (2019). Strengthening teachers’ professional identities through faculty development. Academic Medicine, 94(7), 963–968.

Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract

. 2020 Aug;25(3):655-672.

doi: 10.1007/s10459-019-09949-7. Epub 2020 Jan 15.

Becoming outstanding educators: What do they say contributed to success?

Larissa R Thomas 1, Justin Roesch 2, Lawrence Haber 3, Patrick Rendón 2, Anna Chang 4, Craig Timm 2, Summers Kalishman 5, Patricia O'Sullivan 6

Affiliations collapse

Affiliations

-

1Division of Hospital Medicine at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and Trauma Center and Department of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, 1001 Potrero Ave, 5H, San Francisco, CA, 94110, USA. larissa.thomas@ucsf.edu.

-

2Department of Medicine, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM, USA.

-

3Division of Hospital Medicine at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and Trauma Center and Department of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, 1001 Potrero Ave, 5H, San Francisco, CA, 94110, USA.

-

4Department of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, USA.

-

5Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM, USA.

-

6Departments of Medicine and Surgery, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, USA.

-

PMID: 31940102

Abstract

Aspiring medical educators and their advisors often lack clarity about career paths. To provide guidance to faculty pursuing careers as educators, we sought to explore perceived factors that contributed to the career development of outstanding medical educators. Using a thematic analysis, investigators at two institutions interviewed 39 full or associate professor physician faculty with prominent roles as medical educators in 2016. The social cognitive career theory (SCCT) informed the interview guide. Investigators developed the codebook and performed iterative analysis using qualitative methods. Extensive team discussion generated the final themes. Eight themes emerged related to preparation, early successes, mentors, networks, faculty development, balance, work environment, and multiple identities. Preparation led to early successes, which served as "launch points," while mentors, networks, and faculty development programs served as career accelerators to open more opportunities, and a supportive work environment was an additional enabler of this pathway. Educators who reported balance between work and outside interests described boundary setting as well as selectively choosing new opportunities to establish boundaries in mid-career. Participants described multiple professional identities, and clinician and educator identities tended to merge and reinforce each other as careers progressed. This study revealed common themes describing trajectories of success among medical educators. These themes aligned with the SCCT, and typically replayed and spiraled over the course of the educators' careers. These findings resonate with other studies, lending credence to an approach to career development that can be shared with junior faculty who are exploring careers in medical education.

Keywords: Career development; Faculty development; Identity development; Medical education; Mentorship.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 교수개발(Faculty Development)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 임상교육자에서 교육적 학자, 그리고 리더: HPE분야에서 커리어 개발(Clin Teach, 2020) (0) | 2021.02.07 |

|---|---|

| 왜 우리는 교사를 가르쳐야 하는가? 임상감독관의 학습 우선순위 확인(Adv in Health Sci Educ, 2018) (0) | 2021.02.05 |

| HPE 교육과 실천에서 앎과 함 단절(Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract, 2020) (0) | 2020.07.16 |

| 교육적 타당도: 다양한 형태의 '좋은' 가르침을 이해하는 핵심(Med Teach, 2019) (0) | 2020.03.20 |

| 보건전문직교육에 초점을 둔 멘토십 평가 도구 개발 및 타당화(Perspect Med Educ, 2019) (0) | 2019.06.21 |