기본의학교육에 성공적인 보건기스템과학의 통합과 유지를 위한 우선순위 영역과 잠재적 해결책(Acad Med, 2017)

Priority Areas and Potential Solutions for Successful Integration and Sustainment of Health Systems Science in Undergraduate Medical Education

Jed D. Gonzalo, MD, MSc, Elizabeth Baxley, MD, Jeffrey Borkan, MD, PhD, Michael Dekhtyar, Richard Hawkins, MD, Luan Lawson, MD, MAEd, Stephanie R. Starr, MD, and Susan Skochelak, MD, MPH

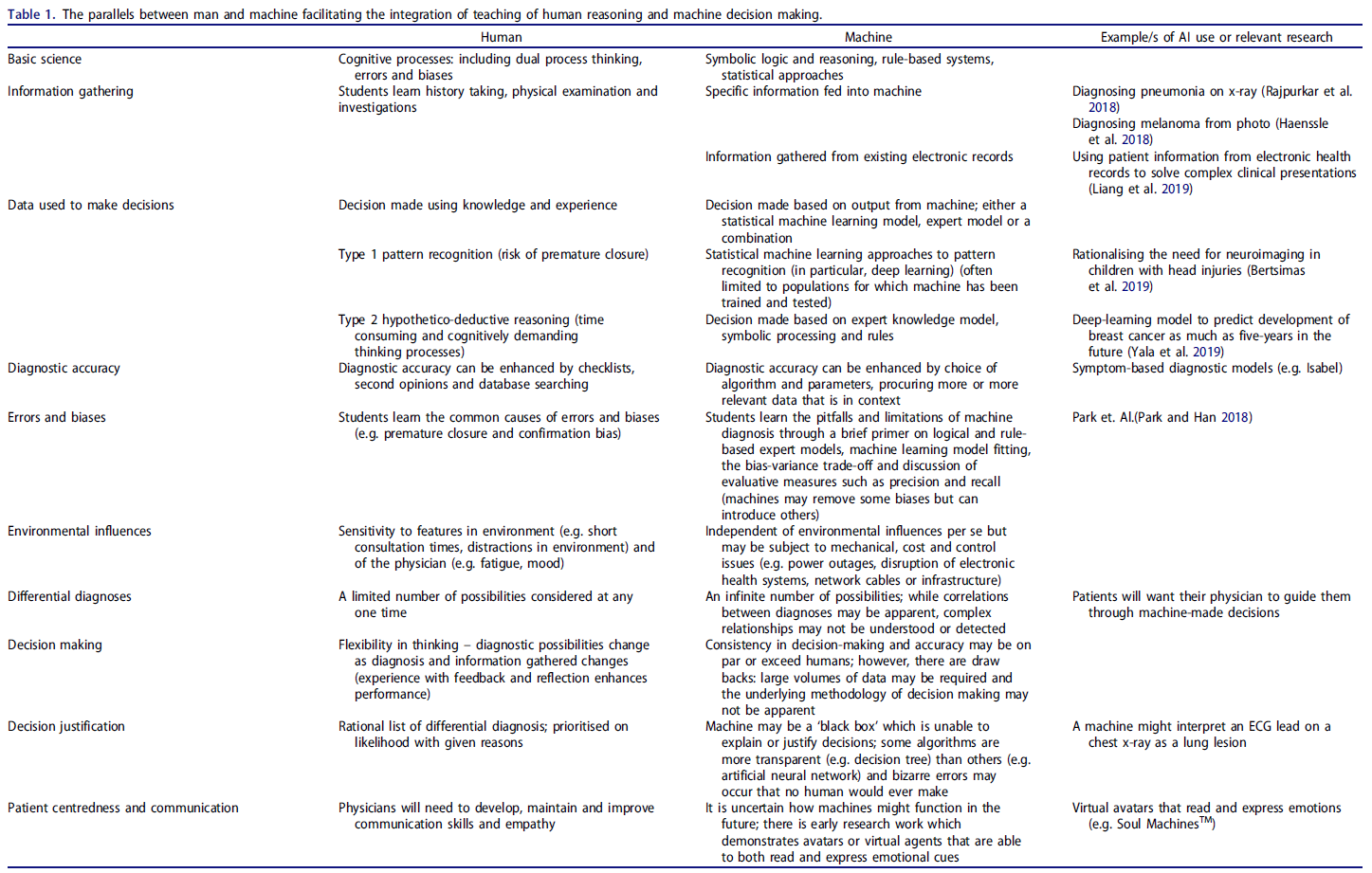

교육자, 정책 입안자 및 보건 시스템 지도자들은 의료 시스템의 진화하는 요구에 부응하기 위해 학부 의학 교육(UME)과 대학원 의학 교육(GME) 프로그램의 중요한 개혁을 요구하고 있다. 권고되는 개혁의 중요한 요소 중 하나는 의사 교육에 가치 기반 관리, 보건 시스템 개선, 임상 정보학, 인구 및 공공 보건과 같은 주제를 포함하는 보건 시스템 과학(HSS)을 담는 것이다.

Educators, policy makers, and health systems leaders are calling for significant reform of undergraduate medical education (UME) and graduate medical education (GME) programs to meet the evolving needs of the health care system.1–3 One critical component of recommended reforms is physician education in health systems science (HSS), which includes topics such as value-based care, health system improvement, clinical informatics, and population and public health.4,5

기존의 기초과학과 임상과학이 통합된 "제3의 과학"으로 간주되는 HSS는 [환자와 환자 모집단에 대한 의료 전달의 품질, 결과 및 비용을 개선하는 방법과 원칙]으로 볼 수 있다. HSS의 교육은 환자와 사회의 요구를 충족시키기 위해 의료 시스템을 더 잘 이끌 수 있는 보다 광범위하게 준비된 의사 인력을 개발할 수 있는 잠재력을 가지고 있다.

Considered the “third science” that integrates with the traditional basic and clinic sciences, HSS can be viewed as the methods and principles of improving quality, outcomes, and costs of health care delivery for patients and populations of patients. Education in HSS has the potential to develop a more broadly prepared physician workforce that is better able to lead the health care system to meet the needs of patients and society.5

의료 교육에서 HSS의 중요성에 대한 인식이 높아졌음에도 불구하고, 대부분의 의과대학은 HSS 관련 역량을 커리큘럼에 실질적으로 통합하지 못하였으며, 그 결과 의료 교육과 진화하는 의료 시스템의 필요성과 이 시스템 내에서 care를 받는 환자 사이의 불일치를 초래했다. 전국적으로 여러 의과대학이 교실과 근무지 학습 환경 모두에서 HSS 관련 혁신 커리큘럼을 시작했고, 최근 연구는 HSS 커리큘럼의 프레임워크를 만들었다. 그러나 UME 내 통합의 비교적 초기 단계를 고려할 때, 의과대학 전체에 걸친 HSS 커리큘럼의 성공적인 대규모 구현은 커리큘럼 설계, 평가, 문화 및 인증의 문제로 인해 어려움을 겪고 있다.

Despite increasing awareness about the importance of HSS in medical education, most medical schools have not substantially integrated HSS-related competencies into their curricula, resulting in a mismatch between medical education and the needs of the evolving health care system and the patients cared for within this system.2,3,6,7 Nationally, several medical schools have initiated HSS-related innovative curricula in both classroom and workplace learning environments, and recent work has created a framework for HSS curricula.5,8–10 However, given the relatively nascent stage of integration within UME, the successful large-scale implementation of HSS curricula across medical schools is challenged by issues of curriculum design, assessment, culture, and accreditation, among others.

2013년과 2015년 사이에 미국 의학 협회(AMA)의 11개 의과대학(ACE) 컨소시엄은 UME의 이 영역에서 진전을 진전시키기 위해 HSS 커리큘럼 구현의 과제를 구체적으로 해결하기로 결정했다.

Between 2013 and 2015, the American Medical Association’s (AMA’s) Accelerating Change in Medical Education (ACE) consortium of 11 U.S. medical schools (see below) chose to specifically address the challenges of implementing an HSS curriculum to advance progress in this area of UME.

ACE 컨소시엄 작업

ACE Consortium Work

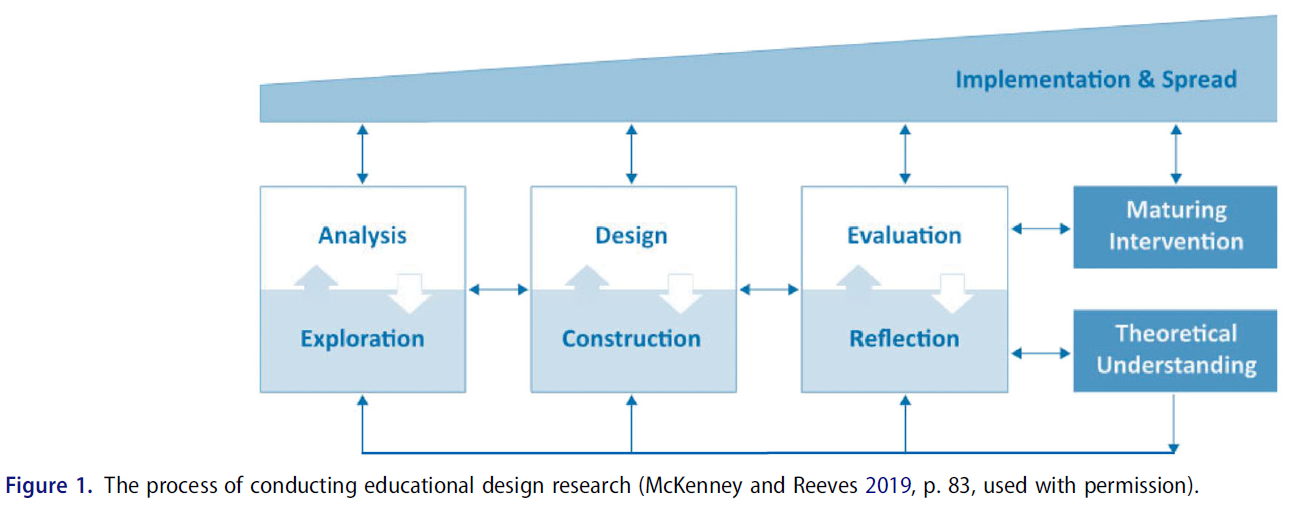

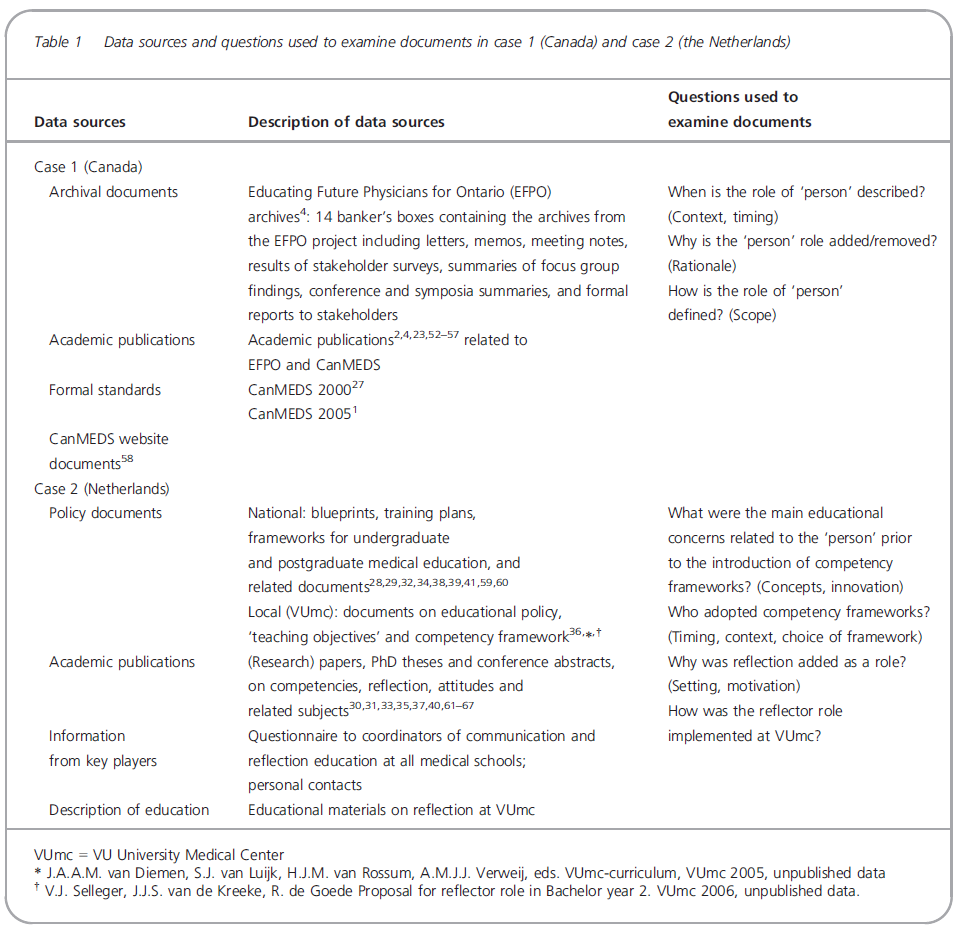

2013년, 11개의 미국 의과대학으로 구성된 ACE 컨소시엄은 HSS 훈련을 위한 포괄적인 프레임워크를 식별하기 위해 광범위한 조사에 착수했다. 조사는 개별 학습자부터 의과대학별 프로그램, 협력적 국가 노력에 이르기까지 여러 단계에 걸쳐 이루어졌다.

In 2013, the ACE consortium of 11 U.S. medical schools undertook a broad-based investigation to identify a comprehensive framework for HSS training. The investigation spanned multiple levels from the individual learner, to medical-school-specific programs, to collaborative national efforts.

The 11 ACE consortium schools were

- the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University;

- Brody School of Medicine at East Carolina University;

- University of California, San Francisco, School of Medicine;

- University of California, Davis, School of Medicine;

- Indiana University School of Medicine;

- Mayo Medical School;

- University of Michigan Medical School;

- New York University School of Medicine;

- Oregon Health & Science University School of Medicine;

- Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine; and

- Vanderbilt University School of Medicine.11

HSS 작업 그룹

HSS workgroup

ACE 컨소시엄 회의

ACE consortium meeting

데이터 분석

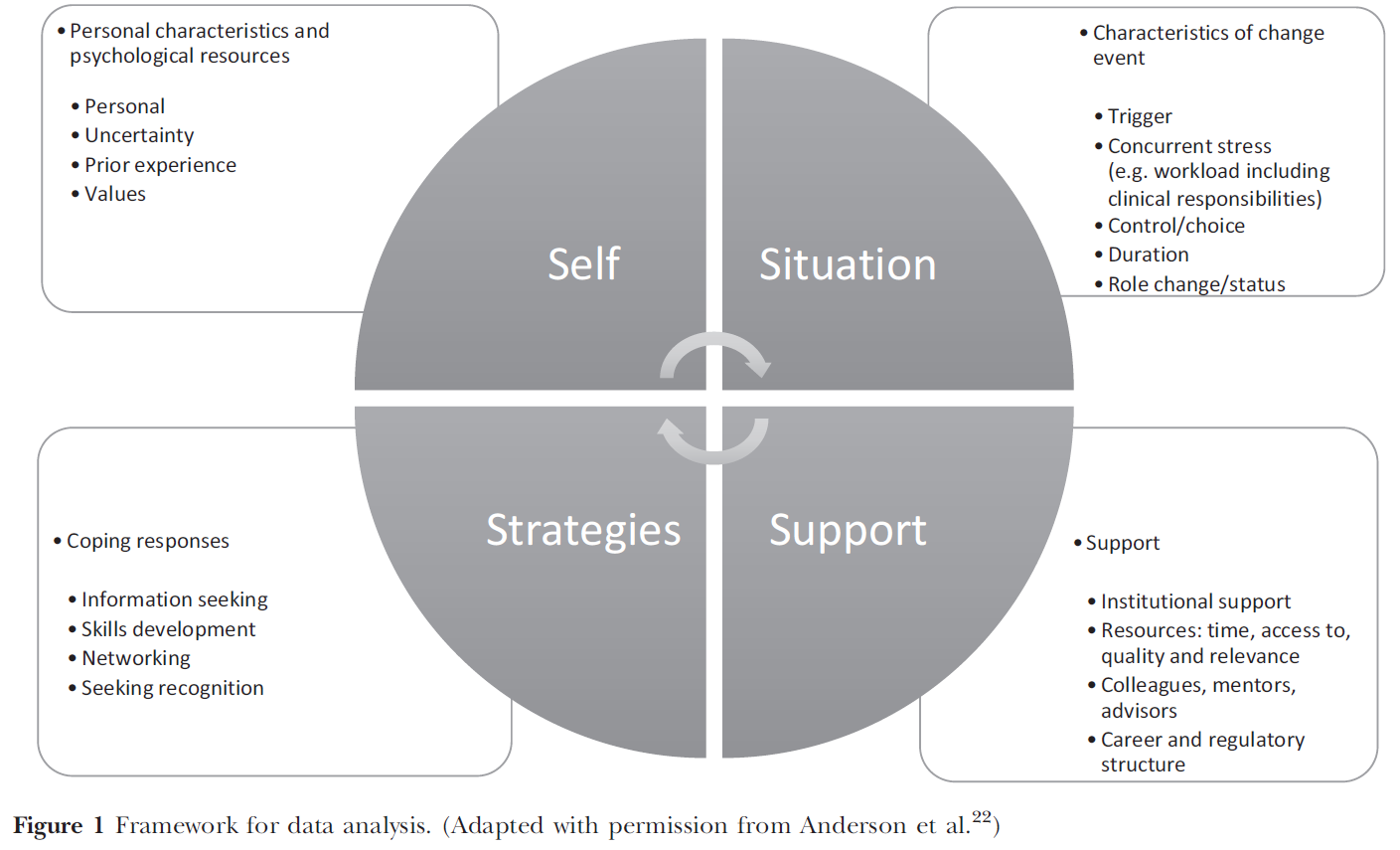

Data analysis

HSS 진전을 위한 우선순위 영역

Priority Areas for Advancing HSS

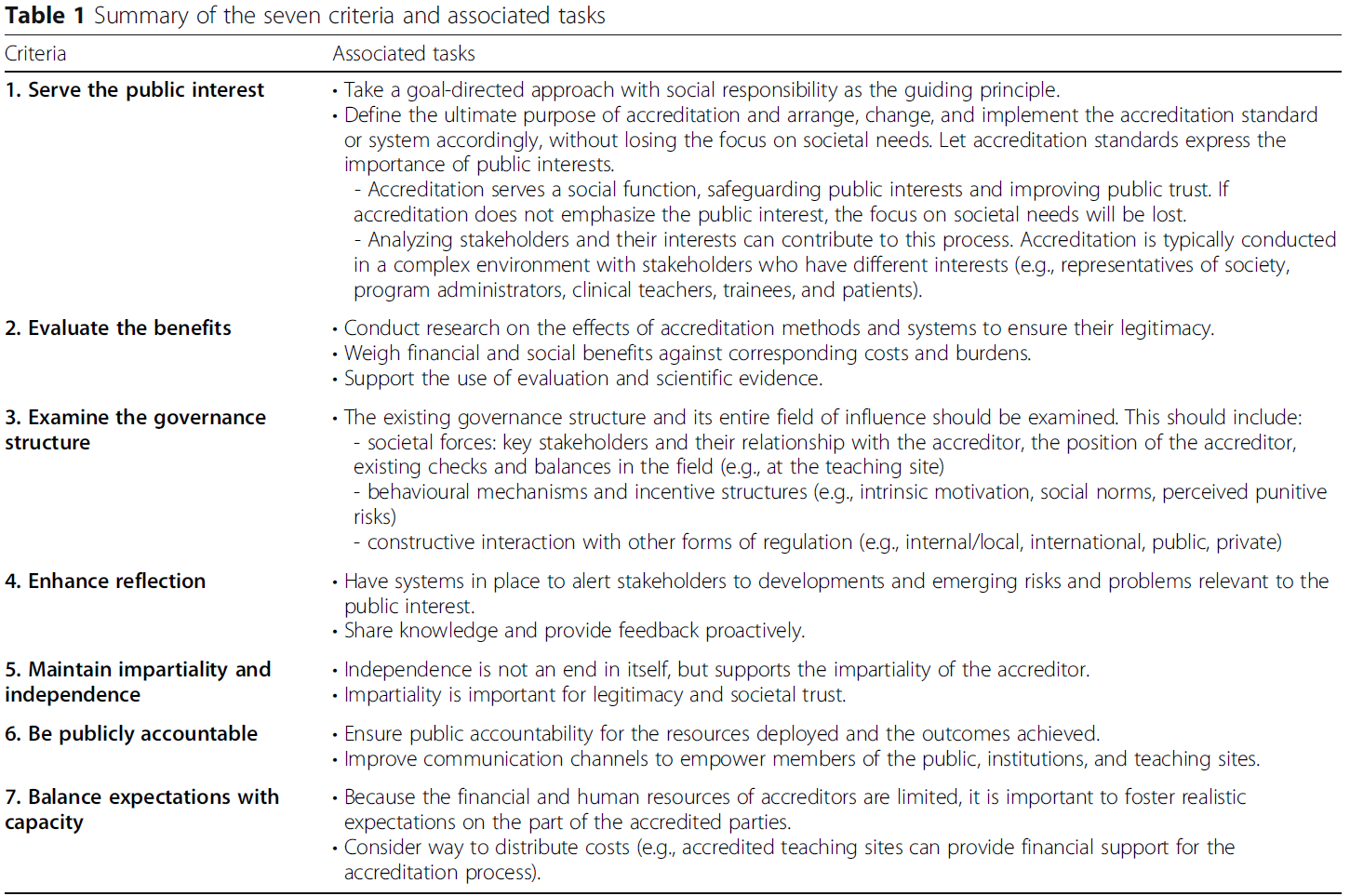

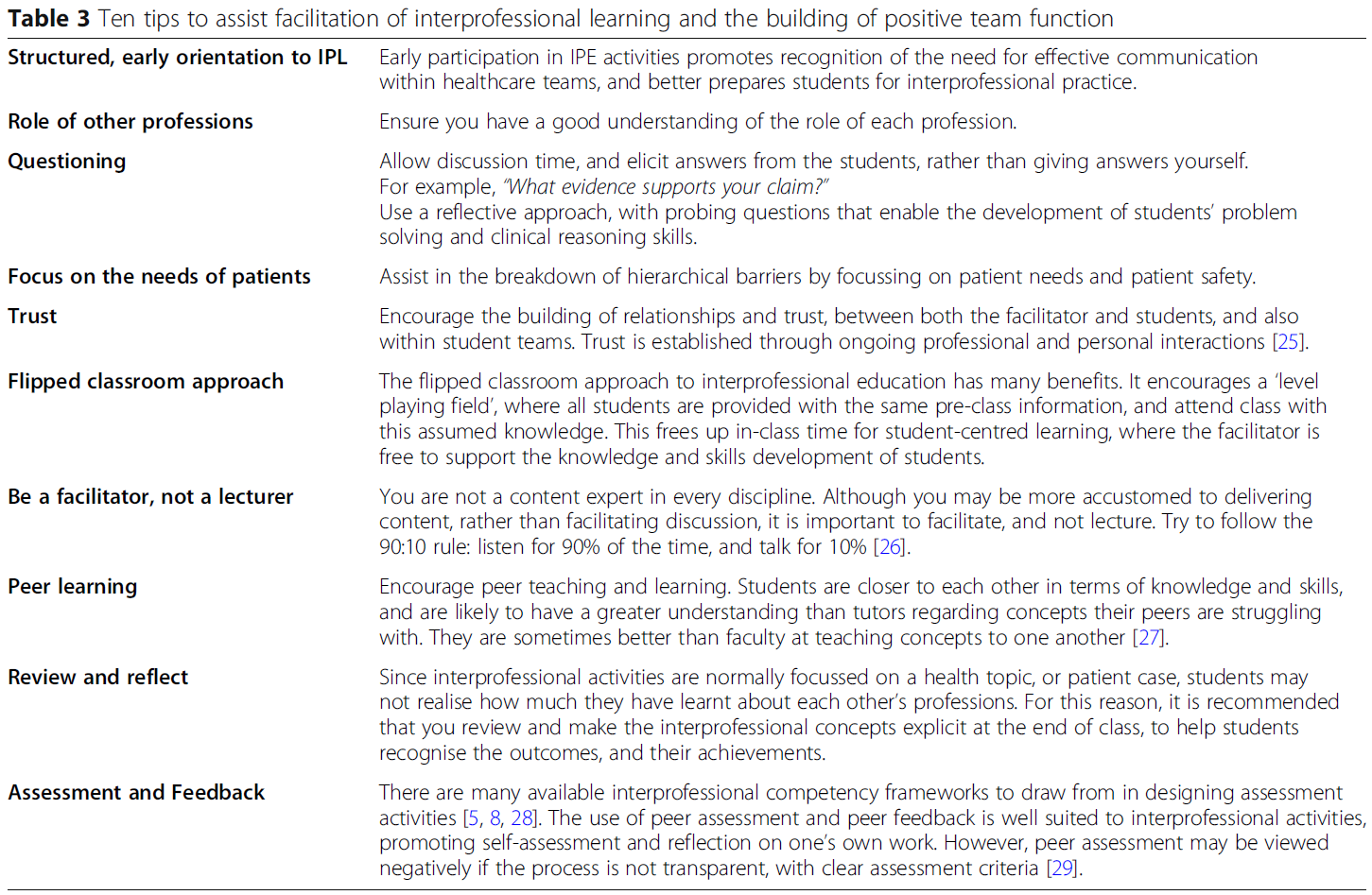

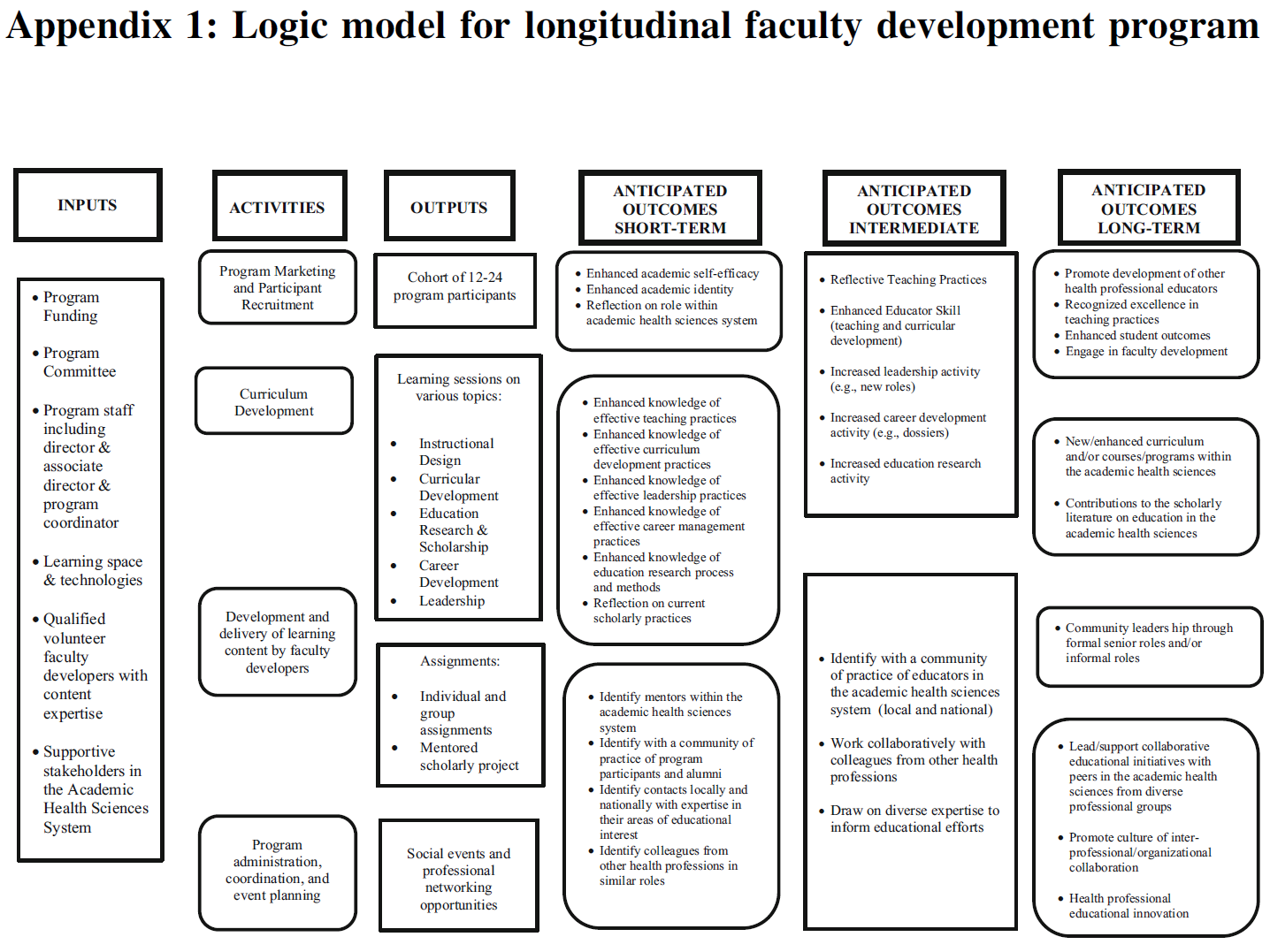

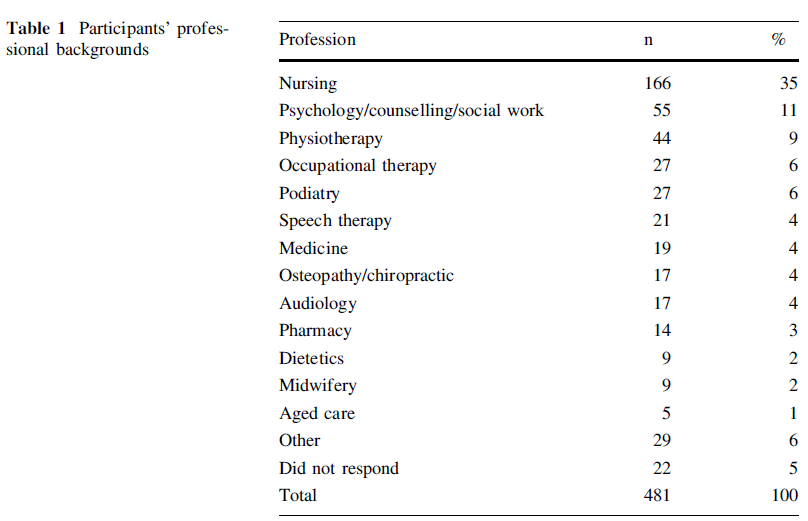

분석은 일곱 가지 우선순위 영역을 식별하였다.

- (1) 면허, 인증 및 인증 기관과 협력,

- (2) 종합, 표준화 및 통합 커리큘럼 개발,

- (3) 평가의 개발, 표준화 및 조정,

- (4) UME에서 GME로의 이행 개선,

- (5) 교사의 지식과 기술 향상, 교사 인센티브 강화,

- (6) 보건시스템에 더해진 가치(value added)를 입증

- (7) 숨겨진 커리큘럼을 다룸

The analysis identified seven priority areas:

- (1) partner with licensing, certifying, and accrediting bodies;

- (2) develop comprehensive, standardized, and integrated curricula;

- (3) develop, standardize, and align assessments;

- (4) improve the UME to GME transition;

- (5) enhance teachers’ knowledge and skills, and incentives for teachers;

- (6) demonstrate value added to the health system; and

- (7) address the hidden curriculum.

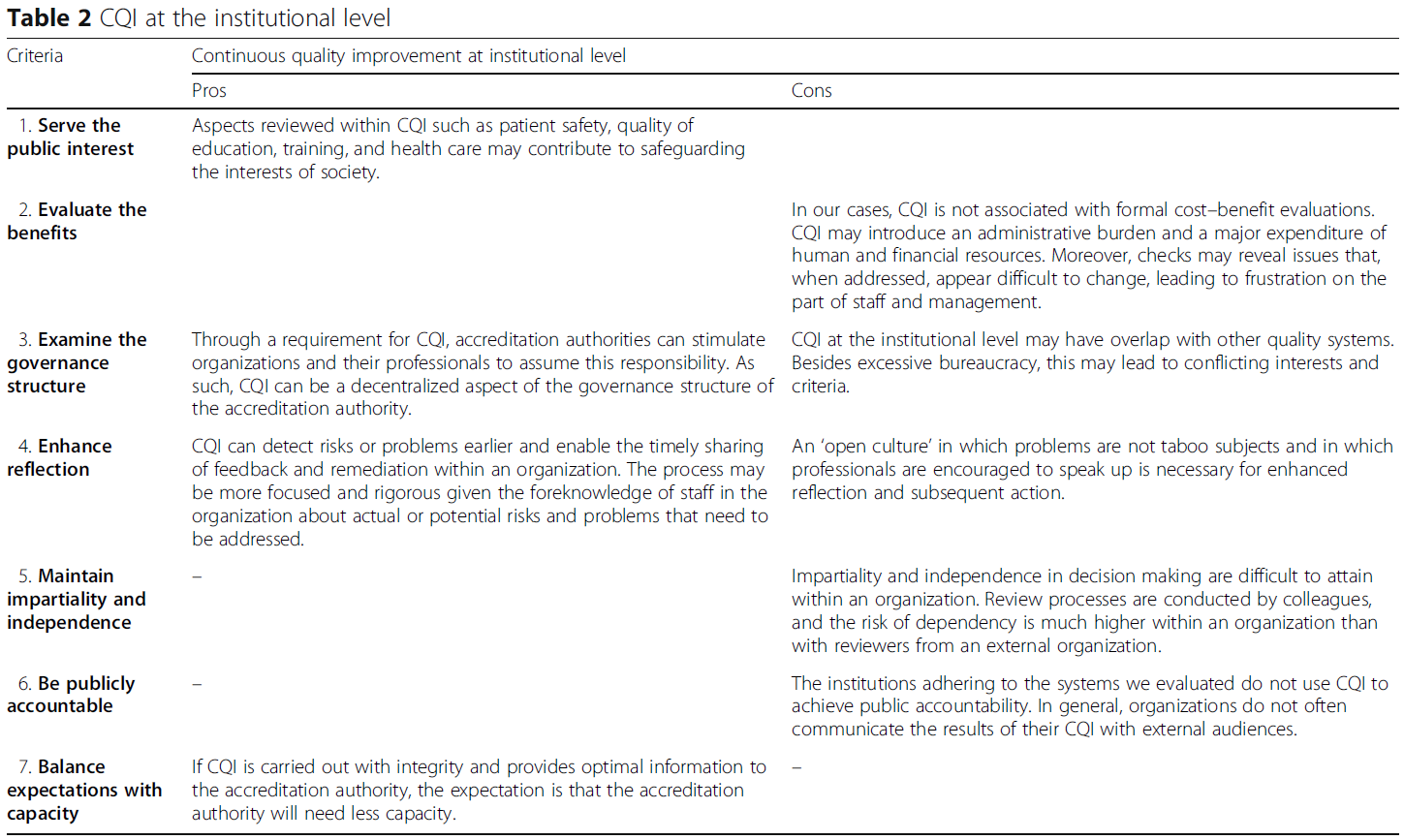

확인된 각각의 우선순위 영역에 대해, 두 가지 구성요소가 고려되었다.

- (1) 의료 교육에서 HSS를 구현하고 유지하기 위한 구체적인 과제(또는 과제),

- (2) 분야 발전을 위한 잠재적 해결책 또는 개입.

For each of the identified priority areas, two components were considered:

- (1) the specific challenge (or challenges) to implementing and sustaining HSS in medical education; and

- (2) the potential solutions, or interventions, to advance the field.

라이센스, 인증 및 인증 기관과 파트너

Partner with licensing, certifying, and accrediting bodies

과제들 Challenges.

의료 교육을 위한 국가 표준과 커리큘럼 내용에 대한 합의가 교육 커뮤니티에서 나타나고, 널리 수용이 이루어졌을 때, 이러한 표준은 LCME와 ACGME와 같은 인증 기관에 의해 성문화된다. 안전하고 효과적인 의사 진료와 관련된 커리큘럼 내용은 미국 의료 면허 시험 단계 시험 또는 전공의 훈련 시험과 같은 국가단위 평가 절차에 통합된다. 새로운 커리큘럼 콘텐츠의 광범위한 개발 및 채택과 새로운 국가 표준의 최종 발표를 포함한 새로운 합의를 위한 프로세스에는 긴 주기(보통 10년 이상)가 필요할 수 있다. (다양한 단계에서 의료 교육에 대한 전국적 합의가) 인증 및 평가 기관이 채택된 예시로는 문화적 역량(예: 문화적 역량 훈련을 위한 도구), 행동 과학의 통합, 학생 성과를 추적하기 위한 위탁 가능한 직업 활동(EPA)의 사용 등이 있다.21 이 기준 프로세스 및 관련 지연은 빠르게 진화하는 의료 환경에 적응하고자 하는 새롭고 혁신적인 교육 프로그램에 대한 특정 과제를 야기할 수 있다.

Consensus on national standards and curricular content for medical education emerges from the education community, and when widespread acceptance has occurred, these standards become codified by accrediting bodies, such as the Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME). Curriculum content that is relevant to safe and effective physician practice is then incorporated into national assessment procedures, such as the United States Medical Licensing Examination Step exams or resident training exams. The process for emerging consensus, including the widespread development and adoption of new curricular content and eventual promulgation of new national standards, can require a lengthy cycle time (often a decade or longer). Recent examples of national consensus in medical education, in various stages of adoption by accrediting and assessment agencies, include cultural competence (e.g., the Tool for Assessing Cultural Competence Training),19 integration of behavioral science,20 and use of entrustable professional activities (EPAs) to track student performance.21 This process and the associated delays can create particular challenges for new and innovative educational programs seeking to be adaptive with the rapidly evolving health care landscape.

잠재적 해결책 Potential solutions.

혁신적인 교육 프로그램 도입에 대한 장벽과 도전을 완화하기 위해 커리큘럼 변화의 리더는 지속 가능한 개혁을 구현하기 위해 관련된 모든 이해관계자의 권고와 지침을 구해야 한다. 이해관계자에는 UME, GME, CME에 이르는 국가 라이선스 및 인증 기관 및 인증 기관이 포함된다. 면허, 인증 및 인증 기관은 가이드라인, 역량, 시험을 align하여 HSS 관련 콘텐츠의 학습을 필요로 하는 협업 프로세스를 촉진할 수 있다. 커리큘럼 개혁이 구현되고 평가되면, 기회는 임상 교수진과 실무practicing 의사가 정의된 HSS 지식과 기술에 대한 역량을 개발할 수 있도록 해야 한다. 이러한 변화는 현재 의사와 미래의 의사 모두에 대한 의사 면허, 인증 및 인증 요건 유지에 있어 개혁을 가져올 수 있다. 인증 기관의 이러한 시스템 수준의 변화 없이는, HSS 통합의 장기적인 성공은 한계가 있을 것이다.

To mitigate the barriers and challenges to introducing innovative educational programs, curriculum change leaders should seek the recommendations and guidance of all stakeholders involved to implement sustainable reform. These stakeholders include national licensing and certifying bodies and accrediting organizations across the continuum from UME, to GME, to continuing medical education (CME). Licensing, certifying, and accrediting agencies could catalyze the collaborative processes that would align guidelines, competencies, and exams to necessitate the learning of HSS-related content. Once curricular reforms have been implemented and evaluated, opportunities should enable clinical faculty and practicing physicians to develop competence in the defined HSS knowledge and skills. These changes may lead to reforms in physician licensure, certification, and maintenance of certification requirements for both current and incoming physicians. Without such systemic change from accrediting organizations, the long-term success of HSS integration will be limited.

종합적이고 표준화된 통합 커리큘럼 개발

Develop comprehensive, standardized, and integrated curricula

과제 Challenges.

HSS에서 적절한 교육을 보장하려면, 학생의 발달 궤도에서 [적절한 시기에 기초 및 임상 과학과 통합된 포괄적인 콘텐츠 프레임워크]가 필요하다. 이를 충족시키기 위해서는 의과대학들 간의, 특히 졸업생들이 전공의 수련단계와 그 이후에 전국적으로 분산되는 것을 고려할 때, 어느 정도의 표준화가 이상적일 것이다. 불행하게도, 종합 HSS 커리큘럼을 가진 의과대학은 거의 없고, 심지어 더 적은 수의 커리큘럼이 통합되고, 많은 학교들은 HSS 콘텐츠를 가르칠 수 있는 능력을 가진 교수진들이 부족하다.

Ensuring appropriate education in HSS requires a compre hensive content framework that is integrated with the basic and clinical sciences at the appropriate time in students’ developmental trajectory. To meet this end, some level of standardization between medical schools, particularly given the dispersion of graduates across the country as they transition to residencies and practice, would be ideal. Unfortunately, few medical schools have comprehensive HSS curricula, even fewer of these curricula are integrated, and many schools lack faculty members with the ability to teach HSS content.

또한 현재는 각 의과대학이 커리큘럼에 포함되어야 하는 HSS 영역(위 참조)에 대해 합의할 수 있는 표준이나 메커니즘이 없다. 의료 교육계는 의료 훈련 및 규제 부문(LCME, ACGME, USMLE 등)을 담당하는 조직과 함께 이 문제에 대한 조정된 접근 방식을 아직 개발하지 않았다. 의과대학이 HSS 콘텐츠를 교육과정에 추가했음에도 불구하고, 이렇게 추가된 것은 여러 UME 프로그램 사이에 거의 협업되지 않은 채로, 주로 지역적 니즈와 커리큘럼을 위해 개발되고 맞춤화되었다. 마찬가지로, HSS에 대한 의료 교육 문헌은 파편화되어 있으며, 의료 훈련 전체에 걸쳐 효과적인 HSS 커리큘럼을 개발하고 실행하기 위한 포괄적인 전략을 제공하려는 시도는 알려져 있지 않다.

Additionally, there are currently no standards or mechanisms allowing schools to reach agreement on which of the HSS domains (see above) should be included in the curriculum. The medical education community, along with the organizations responsible for segments of medical training and regulation (such as the LCME, ACGME, and United States Medical Licensing Examination), has not yet developed a coordinated approach to this issue. Although medical schools have added HSS content to their curricula, these additions have largely been developed for and tailored to local needs and curricula, with few collaborations across UME programs.20,22 Likewise, the medical education literature on HSS has been fragmented, with no known attempts to provide a comprehensive strategy for developing and executing effective HSS curricula across the whole of medical training.22

잠재적 해결책 Potential solutions.

종합적이고 표준화된 통합 HSS 커리큘럼을 위한 중요한 첫 단계는 [보건의료전문직 교육기관]이 이러한 역량 확대의 중요성과 필요성을 인식하는 것이다. HSS를 전담하는 [지역 및 국가 토론 포럼]은 이러한 필요성에 대한 인식을 높이고 이러한 커리큘럼에 포함될 핵심 내용과 개념에 대한 담론을 촉진할 수 있다. CME 인증 기관과 전문 위원회뿐만 아니라 allopathic and osteopathic UME 및 GME 프로그램 모두를 포함하면 이 작업에 가장 적합할 수 있으며 의료 교육 연속체를 처음부터 끝까지 다룰 수 있다.

A critical first step toward comprehensive, standardized, and integrated HSS curricula will be for health professions schools to recognize the importance and necessity of expanding these competencies. Local and national discussion forums dedicated to HSS can raise awareness of this need and promote discourse around the core content and concepts to be included in such curricula.12 Inclusion of both allopathic and osteopathic UME and GME programs, as well as CME accrediting bodies and specialty boards, would best inform this work and allow the medical education continuum to be addressed from beginning to end.

[표준화]를 달성하기 위한 노력은 [모든 trainee가 HSS 영역에서 역량을 확보하도록 충분히 엄격]해야 하지만, [의료 현실이 변화함에 따라 혁신이나 지속적인 평가를 저해할 정도로 경직되지 않아야] 한다. 이 분야의 리더십은 의료 교육 기관, 의료 기관 또는 훈련생으로부터 얻을 수 있으며, 모든 이해 관계자들 간의 협업 벤처가 가장 성공할 가능성이 크다.

Efforts to achieve standardization will need to be sufficiently rigorous to ensure that all trainees gain competencies in HSS domains, but not so inflexible that they discourage innovation or the ongoing evaluation of topics as health care realities change. Leadership in this area may come from medical education organizations, health care organizations, or trainees, with collaborative ventures among all stakeholders having the greatest chance of success.

평가 개발, 표준화 및 조정

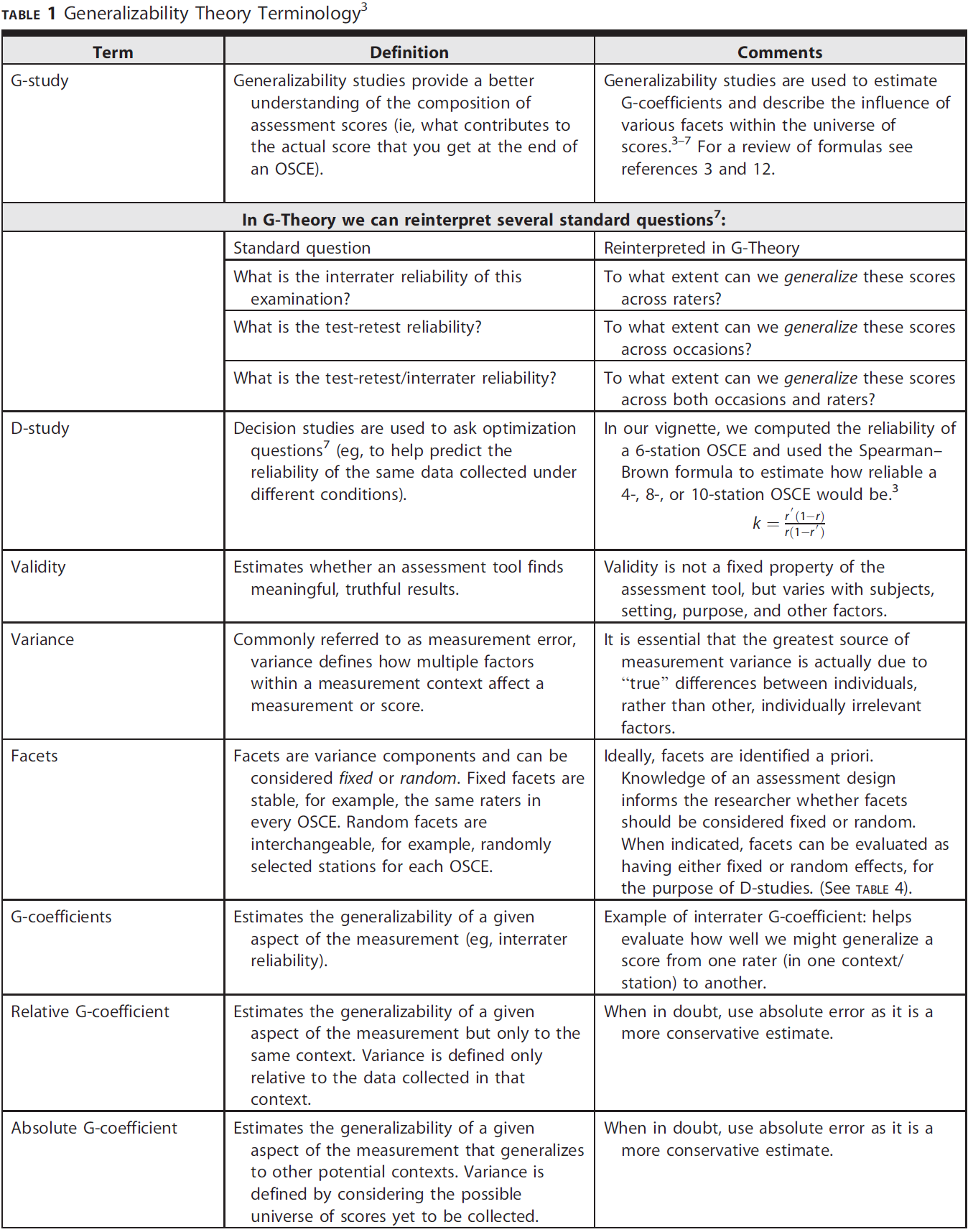

Develop, standardize, and align assessments

과제 Challenges.

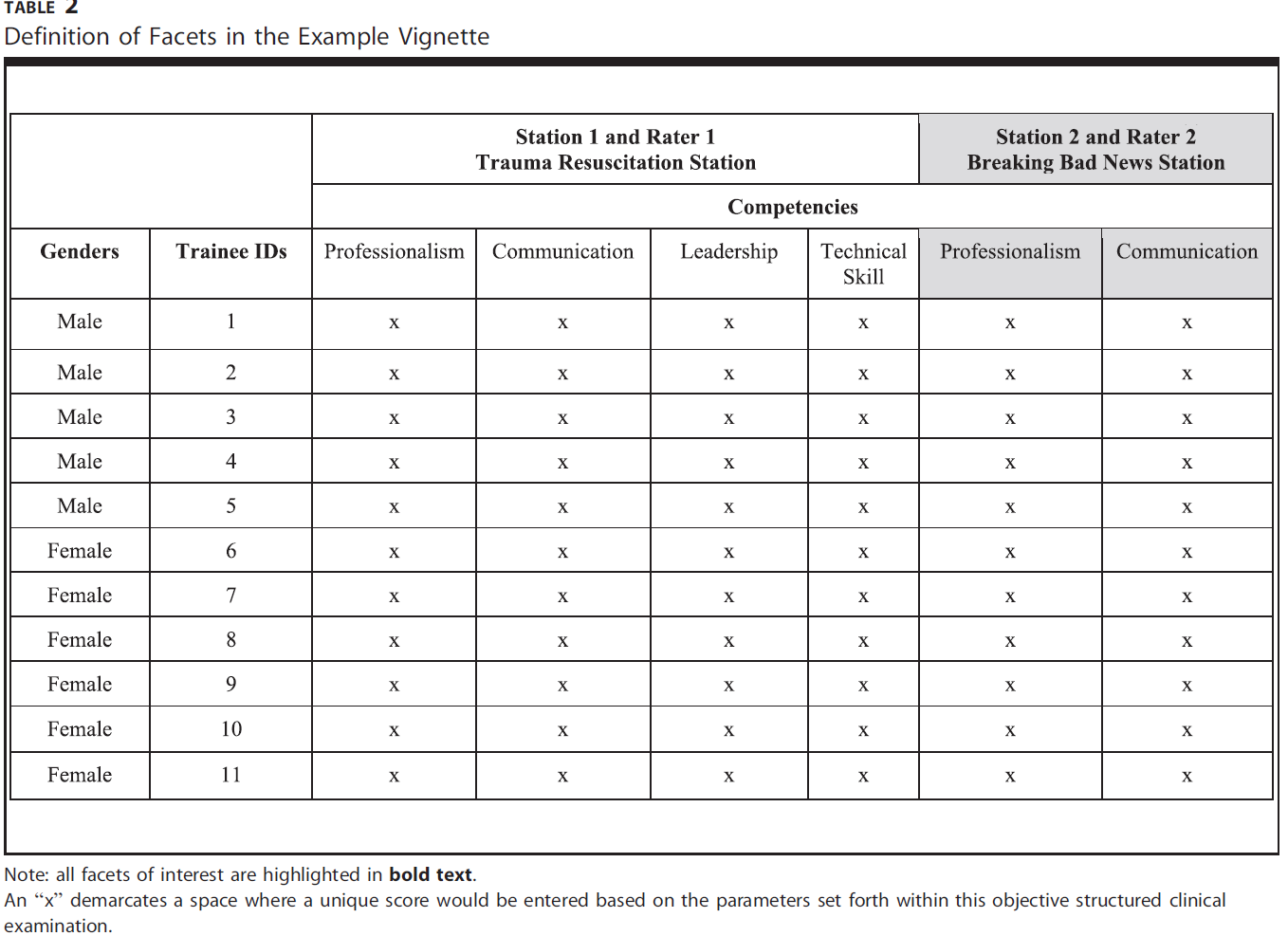

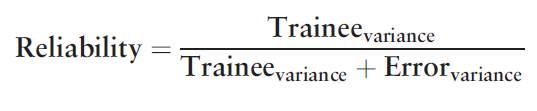

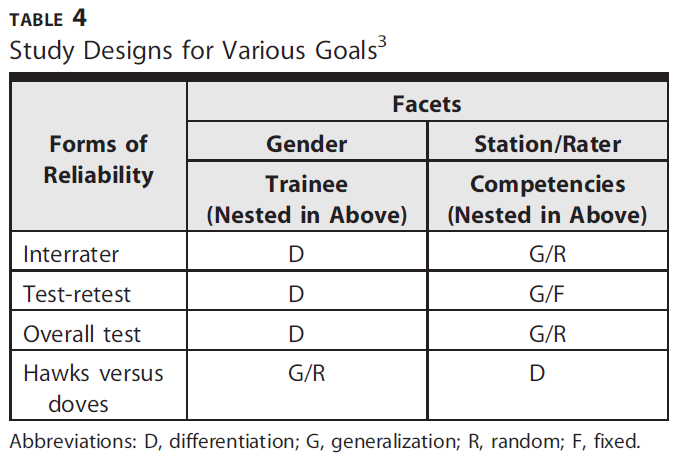

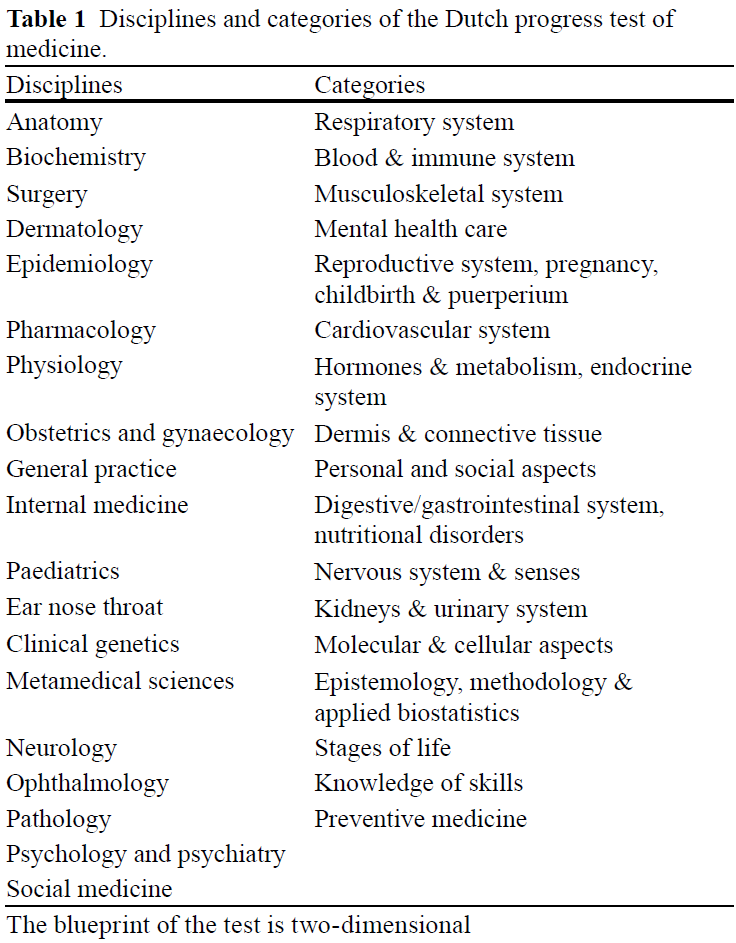

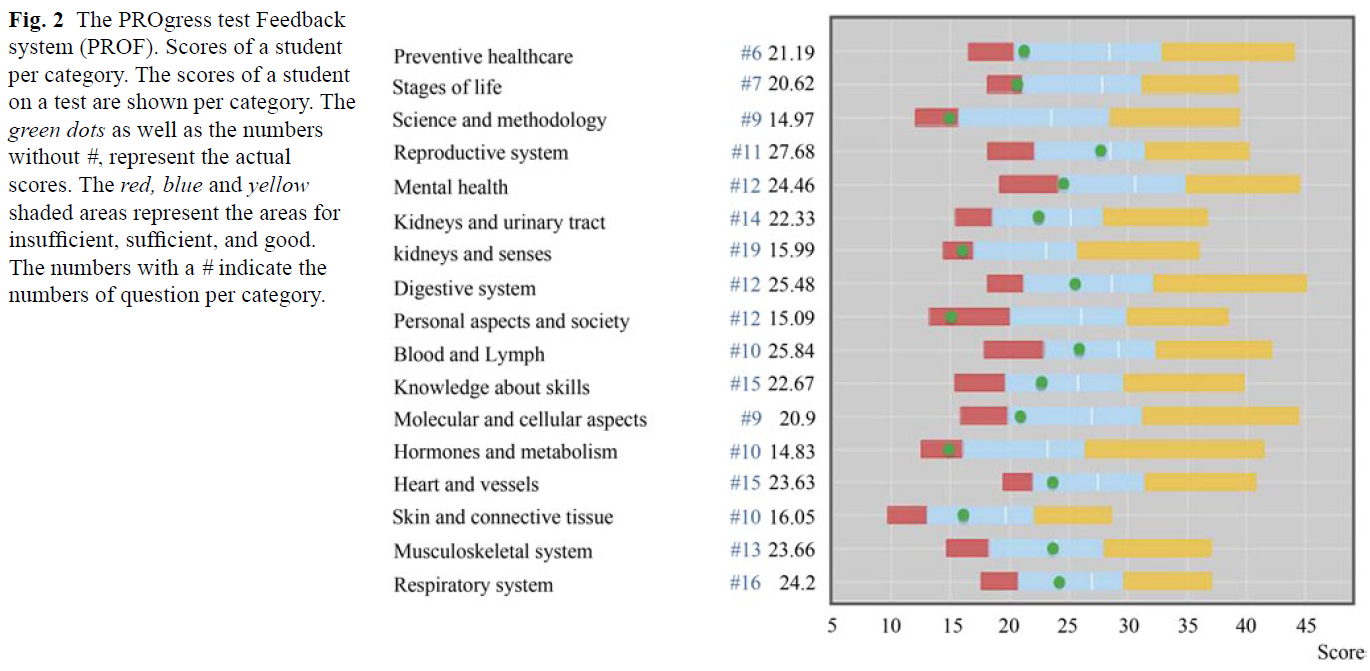

HSS 역량 달성에 있어 학습자의 진전을 보장하기 위해서는 고품질 평가 방법이 필수적이다. 또한 평가는 학생들의 학습을 촉진하고, 직장 기반 환경에서 기술 개발을 촉진합니다. 예를 들어, HSS 도메인을 대상으로 하는 검증된 평가 방법이 상대적으로 부족하다. HSS는 강력한 마일스톤, 역량, EPA 프레임워크를 가지고 있지 않다. UME에서 HSS 평가 방법을 개발하고 구현하는 한 가지 과제는 이러한 도메인에 대한 숙달에 대한 명확한 개발 패러다임이 없다는 것이다.

High-quality assessment methods are essential to ensure learner progress in achieving HSS competencies. In addition, assessment drives student learning, and facilitates skill development in workplace-based settings.23 There is a relative paucity of validated assessment methods targeting HSS domains; for example, HSS does not have a robust framework of milestones, competencies, and/or EPAs. One challenge to developing and implementing HSS assessment methods in UME is the lack of a clear developmental paradigm for mastery in these domains.

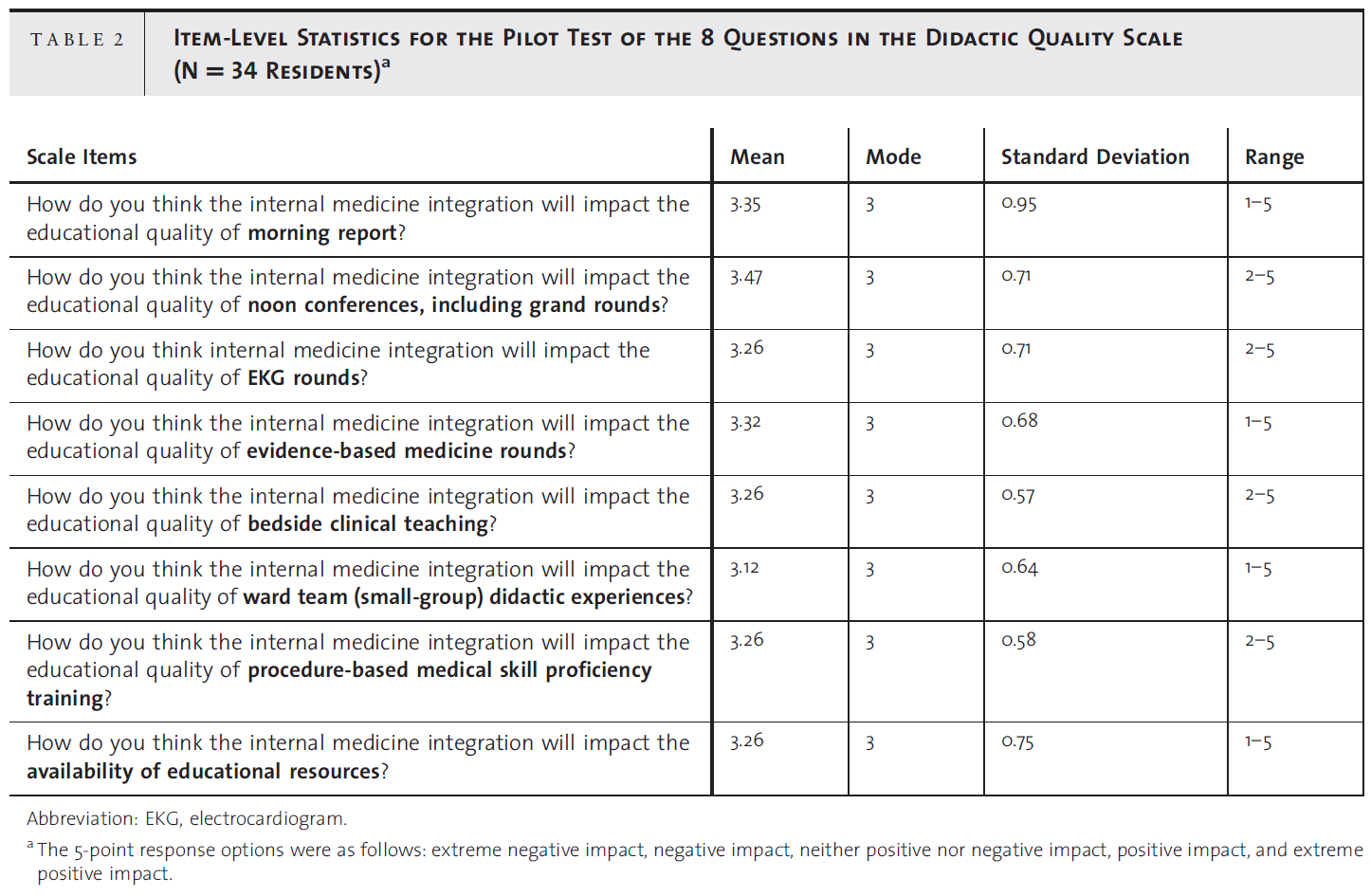

현재 기초적인 HSS 지식은 어느 정도 정의되었으나, 학생들이 HSS 도메인에서 입증해야 할 잠재적인 역할과 기대 수준의 성과는 아직 설명되지 않았다. 또한, 합성적synthetic HSS 커리큘럼 프레임워크가 있든 없든, 주요 HSS 도메인의 지식을 평가하기 위해 고품질의 MCQ를 구성하기는 어려울 것이다(이전 우선순위 영역 참조). HSS에 대한 보다 현실적인 평가를 위하여 작업장에서 관찰 방법을 개발하고 구현해야 하며, 이 분야에서 평가 결과의 품질, 신뢰성, 타당성을 보장하기 위한 접근법이 진화하고 있다.

Foundational HSS knowledge is currently being defined, and the potential roles and expected level of performance that students should demonstrate in HSS domains have not yet been elucidated. Furthermore, it would be difficult to construct high-quality multiple-choice items to assess knowledge in key HSS domains with or without a synthetic HSS curricular framework (see previous priority area). Assessments of more practical aspects of HSS will require the development and implementation of observational methods in the workplace, where approaches to ensuring high-quality, reliable, and valid assessment outcomes are evolving.24,25

잠재적 해결책 Potential solutions.

HSS에서 핵심 커리큘럼, 목표 및 내용을 정의하기 위한 지속적인 작업은 필요한 새로운 평가 방법의 유형을 이해하는 데 있어 중요한 단계이다. 면허, 증명, 인증 기관과의 협력은 교육의 연속성을 따라 HSS 지식과 기술에 대한 포괄적인 평가를 개발하는 데 필수적이다. 핵심 지식, 기술 및 역량이 정의되면 검증된 평가를 요약한 매트릭스를 개발하고 HSS 도메인과 연계해야 한다.

Ongoing work to define the core curriculum, objectives, and content in HSS is a critical step in understanding the types of new assessment methods that are needed.12 Collaboration with licensing, certifying, and accrediting bodies is essential for developing a comprehensive assessment of HSS knowledge and skills along the continuum of education.26 As core knowledge, skills, and competencies are defined, a matrix outlining validated assessments should be developed and aligned with the HSS domains.

다행히 이 매트릭스 내에서 기존 평가 방법을 사용할 수 있으며 초기 교육 도구 키트를 제공할 수 있다. 예를 들어 팀워크, 품질, 안전성 및 증거 기반 실무와 관련된 평가 방법에는 객관식 시험, 지식 응용 시험, 작업 결과물 평가work product rating, 시뮬레이션 기반 도구, 간접 관찰 방법(예: 동료 평가, 다중 소스 피드백) 및 임상 활동의 직접 관찰이 포함된다.

Fortunately, existing assessment methods could be used within this matrix and provide an initial educator tool kit. For example, assessment methods related to teamwork, quality, safety, and evidence-based practice include multiple-choice exams, knowledge application tests, work product ratings, simulation-based tools, indirect observation methods (e.g., peer assessment, multisource feedback), and direct observation of clinical activities.27–41

불행히도 대부분의 평가 방법은 [국지적으로locally 개발된 도구]이거나, [심리측정 특성이 안정적이지 않은, 소규모 샘플만을 사용한 기존의 도구를 수정한 것] 정도이다. 이는 도구 사용에 inform하기 위한 기존 타당성 데이터를 사용하는 것을 금지하고, 연구 간의 비교를 방지하며, 새로운 도구의 엄격한 분석을 방해한다. 향후 연구는 평가 매트릭스가 각 도구의 품질과 효과적인 사용을 위한 권고사항에 관한 신뢰할 수 있는 정보를 포함하도록 하기 위해 기존 및 아직 개발되지 않은 검증된 도구를 사용한 협업 연구를 장려해야 한다.

Unfortunately, most assessment methods involve locally developed tools or modifications to existing national tools using small samples of students with variable psychometric characteristics. This forbids the use of existing validity data in informing the use of the tool, prevents comparisons across studies, and hinders rigorous analysis of new tools.42,43 Future work should encourage collaborative research using existing and yet-to-be-developed validated tools to ensure that the assessment matrix contains trustworthy information regarding each tool’s quality and recommendations for effective use.

UME에서 GME로의 전환 개선

Improve the UME to GME transition

과제 Challenges.

학습자가 UME에서 GME로 원활하게 이행할 수 있도록 보장하는 것은 HSS만의 과제가 아닙니다. GME가 ACGME Next Accreditation System의 일부로 마일스톤을 사용하고 있고 미국 의학 대학 협회(American Medical College Association)가 졸업하는 의대생을 위한 결과 목표로 EPA를 제공했지만, LCME는 어느 하나에 대한 선호도를 규정하지 않았다. EPA와 마일스톤(많은 학교에서 작성)은 서로 보완적으로 사용할 수 있지만, 교육적 핸드오프를 이상적으로 한다는 측면에서는 일관된 '평가 언어'가 없는 것이 문제가 된다.

Ensuring learners’ smooth transition from UME to GME and beyond is not a challenge unique to HSS.2,3,7,44 While GME is using the language of milestones as part of the ACGME Next Accreditation System and the Association of American Medical Colleges has offered EPAs as outcome goals for graduating medical students, the LCME does not stipulate a preference for either.21,45,46 Although EPAs and milestones (being written by many schools) can be used in a complementary manner, ideal educational handoffs are hindered by the lack of a consistent assessment language.47

ACGME 임상 학습 환경 검토 프로그램과 임상 실습과 교육의 reimagined integration을 통해 care를 개선하려는 임무는 HSS에서 UME에서 GME로의 전환의 중요성을 강화한다. 마지막으로, HSS에서 의대생 역량 졸업에 대한 GME 프로그램의 기대와 전공의 선발 과정에서 이러한 도메인의 평가 및 우선 순위 간의 차이는 UME에서 GME로의 전환의 격차를 더욱 강화한다.

The ACGME Clinical Learning Environment Review Program and its mission to improve care via a reimagined integration of clinical practice and education strengthens the importance of the UME to GME transition in HSS.48 Lastly, variation across GME programs’ expectations of graduating medical student competence in HSS and their assessment and prioritization of these domains in the residency selection process further reinforce gaps in the UME to GME transition.

잠재적 해결책 Potential solutions.

교육자는 (모든 단계에서) 의사가 [복잡하고 진화하는 팀 기반 치료 모델에 의미 있게 참여할 준비가 되어 있는지] 확인하기 위해, 특히 [HSS를 위한 학습과 평가를 guide하는 공통 언어]가 필요하다. 의과대학은 HSS와 관련된 AAMC의 EPA와 지역적으로 작성된 마일스톤(기존 GME 이정표에 근거)를 시험해야 한다. 전공의 프로그램은 HSS 도메인의 폭과 깊이가 만족스러운지 또는 시간이 지남에 따라 이러한 영역이 진화해야 하는지 여부를 검토해야 한다.

Educators at all levels need a common language to guide learning and assessment, specifically for HSS, to reliably ensure that physicians are prepared to meaningfully participate in complex, evolving, team-based care models. Medical schools should pilot the Association of American Medical Colleges’ EPAs and locally written milestones (grounded in existing GME milestones) that pertain to HSS. Residency programs should examine whether the breadth and depth of the HSS domains are satisfactory or whether these need to evolve over time.

여러 discipline에 걸쳐, UME 및 GME 교육자 파트너십을 이룬다면, 이상적인 교육적 핸드오프의 특징을 정의하고 UME-GME 연속체에 걸쳐 사용할 수 있는 평가 도구를 구현할 수 있다.

Together, UME and GME educator partnerships across disciplines can define identifying features of ideal educational handoffs and implement assessment tools that can be used across the UME-GME continuum.

교사의 지식과 기술, 교사에 대한 인센티브 향상

Enhance teachers’ knowledge and skills, and incentives for teachers

과제 Challenges.

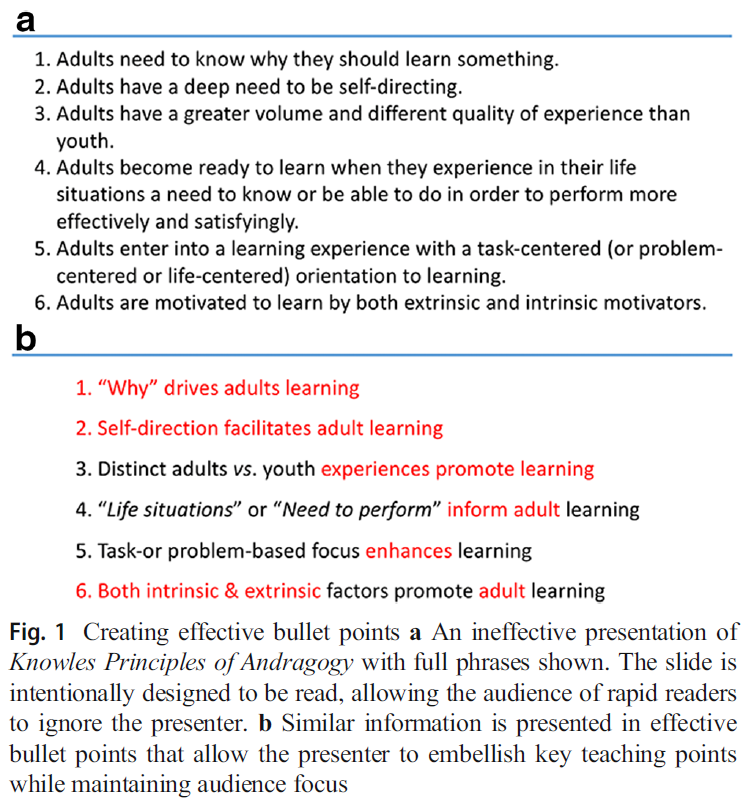

HSS 콘텐츠를 이해하고, 연습하고, 효과적으로 가르치는 교수진을 식별하는 것이 HSS를 기존 커리큘럼에 통합하는 핵심이다. 일반적으로 [전통적으로 훈련된 임상 교수진]은 HSS 전문성을 강화해야 한다.2.7 이는 임상 교사가 (지속적으로 변화하는 환경에서) HSS를 배워가면서 동시에 가르쳐야 한다는 것을 의미한다.49 한정된 시간을 두고 여러 우선순위들이 경쟁하며, 자원 배분이 부적절하고, 점차 임상 생산성을 강조하는 상황은, 교수진이 집중적인 훈련을 수행하거나 새로 개발된 기술을 임상 실습 및 교육에 통합하는 것을 어렵게 한다.

Identifying faculty who understand, practice, and effectively teach HSS content is key to integrating HSS into existing curricula. Traditionally trained clinical faculty typically need to enhance their own HSS expertise.2,7 This means that clinical teachers are challenged to teach HSS while they are learning it and simultaneously working in a continuously changing environment.49 Competing priorities for time and inadequate resource allocation, coupled with increased emphasis on clinical productivity, make it difficult for faculty to undertake intensive training or integrate newly developed skills into clinical practice and teaching.

교수진을 교육할 수 있는 대학 내 전문지식과 제도적 인프라가 없다면, 이러한 공백을 메우기 위해 외부 프로그램을 사용하는 경우도 있다. 그러나 이러한 프로그램은 비용이 많이 들고 교수들이 일상 업무 환경의 맥락에서 내용을 이해할 수 있는 기회를 제공하지 않는다. 보건 전문가 부문 전반에 걸친 협업 노력은 새로 학습한 개념을 연습에 일관성 있게 통합하고, 결과를 개선하고, 교육생과 동료에게 새로운 역량을 롤모델링하기 위해 필요하다.

Without in-house expertise and institutional infrastructure to educate faculty, external programs are sometimes used to fill this gap. However, these programs are costly and do not provide an opportunity for faculty to understand the content within the context of the daily work environment. Collaborative efforts across health professions’ disciplines are required to consistently integrate newly learned concepts into practice, improve outcomes, and role model new competencies to trainees and colleagues.

잠재적 해결책 Potential solutions.

의료 개선, 교육 혁신 및 HSS 학술활동 보급에 대한 교수 능력의 훈련 및 지원은 지속 가능한 임상 학습 환경을 조성한다. 또한 의료 시스템과의 협업을 통해 새로운 개념과 관행을 일상 업무 환경에 통합하는 데 필요한 실습 학습 기회를 제공합니다. [교육 모듈 및 자료의 공유 저장소]에 의해 서포트되는 온라인, 대면 및 체험 학습의 혼합물mixture를 사용한다면 기관 교수진 개발 프로그램과 학습 커뮤니티를 만들 수 있다.

Training and support of faculty capabilities in care improvement, educational innovation, and dissemination of HSS scholarship facilitates a sustainable clinical learning environment, and collaboration with the health care system provides the hands-on learning opportunities required to integrate new concepts and practices into the daily work environment. Institutional faculty development programs and learning communities can be created using a mixture of online, face-to-face, and experiential learning that is supported by a shared repository of educational modules and materials.

전문직업적 발달을 명예롭게 인정하고, 인증 유지 및 CME의 구조적 지원, 질 향상 개입을 촉진하기 위한 [간소화된 기관 검토 위원회 프로세스], 학습 및 교사의 진척을 위한 [보호된 시간], 임상 및 교육 환경에서의 [리더십 및 관련 경력 기회], 학술적 생산성에 대한 지원, [승진 가이드라인에 HSS 학술활동 포함] 등을 통해 교수진을 지원할 수 있다. [국가 자격증 프로그램]은 기관들이 지속적인 학습과 개선을 위해 지역 통합과 교수진 지원에 집중할 수 있도록 하는 동시에 광범위한 의료 교육자에게 정보의 보급을 촉진할 수 있다.

Institutions can support faculty by facilitating honorific recognition of professional development, structural support for maintenance of certification and CME, streamlined institutional review board processes to encourage quality improvement interventions, protected time to advance learning and teaching, leadership and career opportunities in related clinical and educational environments, assistance with scholarly productivity, and inclusion of HSS scholarship in promotion guidelines. A national certificate program could promote the dissemination of information to a broad base of medical educators while allowing institutions to focus on local integration and faculty support for continued learning and improvement.

보건시스템에 value added를 보여주는 것

Demonstrate value added to the health system

과제 Challenges.

전통적으로, UME는 미래에 환자를 돌보는 것을 목표로 기초 및 임상 과학에서 학생들의 지식과 기술의 개발에 주로 초점을 맞추었다. 그리고 임상 훈련 경험은 임상 치료 임무 동안 학생들을 전공의 및 주치의와 직접 연결시킨다. 50 이 견습 모델은 학생들을 지도하고 교육하는 시간을 필요로 하는데, 이는 종종 효율성을 떨어뜨리고 의사 생산성과 보건 시스템의 수익성에 부정적인 영향을 미친다.51-55 비용을 최소화하면서 효율성과 품질을 최적화하기 위한 의사 및 의료 제공 모델의 증가하는 필요성과 이 견습 모델에서의 의대생 멘토링 작업의 추가 작업을 재검토할 필요가 있다. 교수진과 학교들은 전통적으로 [학생들이 학생인 동안에는 환자 치료에 가치를 더할 수 없다]고 추정해왔다. 그러나, 학생들이 배우는 동안 건강 시스템에 가치를 더할 수 있도록 의과대학과 학생 활동을 학문적 보건 센터와 지역사회 건강 프로그램과 더욱 통합하기 위한 교육과 연구를 늘리기 위한 권고안이 만들어졌다.

Traditionally, UME has focused primarily on the development of students’ knowledge and skills in the basic and clinical sciences, with the goal of caring for patients in the future. And clinical training experiences continue to link students directly with resident and attending physicians during clinical care duties.50 This apprenticeship model requires time to mentor and educate students, which often decreases efficiency and negatively impacts physician productivity and the profitability of the health system.51–55 The increasing need for physicians and care delivery models to optimize efficiency and quality while minimizing cost, and the added work of mentoring medical students in this apprenticeship model, needs to be reexamined. Faculty and schools have traditionally presumed that students cannot add value to patient care while they are students. However, recommendations have been made for increased education and research into further integrating medical schools and student activities with academic health centers and community health programs so that students could add value to the health system while they learn.56,57

잠재적 해결책 Potential solutions.

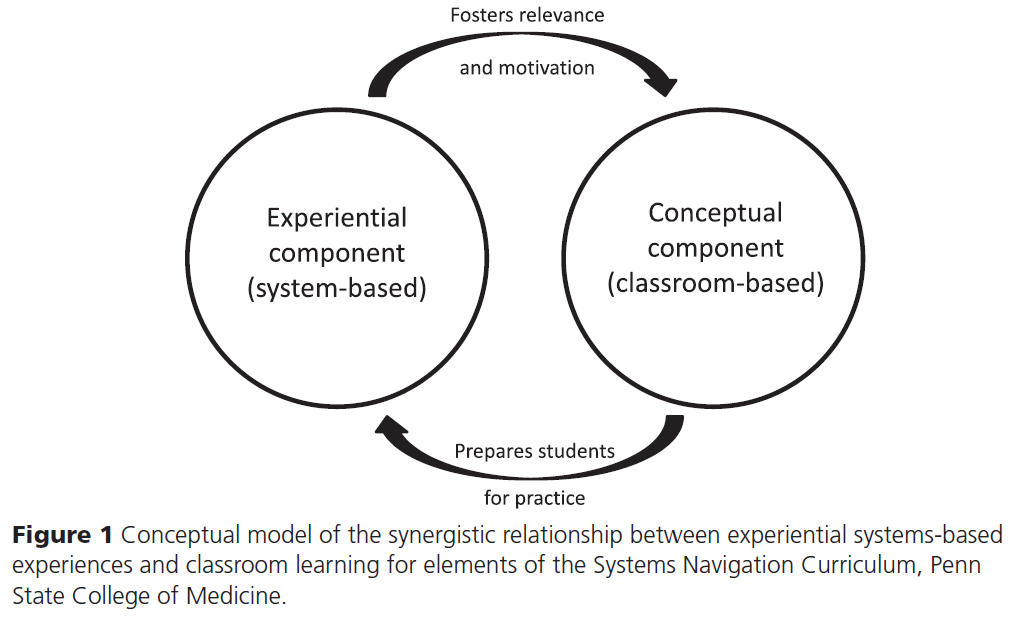

교육자들은 의료 학생들이 의료 서비스 전달의 "진료"를 "공유share the care"할 수 있는 부가 가치 역할을 식별하고 제공하는 데 초점을 맞출 것을 권고했다. 의료 시스템 내의 경험적 역할에서 HSS를 적용하는 것은 종종 [기존의 생의학적 결정(예: 약 처방 오더)]에 비해 [저부담 단계(예: 건강 코칭)]가 될 수 있다. 이러한 주요 차이는 HSS를 학습하는 동시에 가치를 추가하고 환자 결과를 개선할 수 있는 진정한 시스템 기반 작업을 수행함으로써 의대 학생들이 보건 시스템에 참여할 수 있는 몇 가지 기회를 열어준다.

Educators have recommended an increased focus on identifying and providing value-added roles for medical students to “share the care” of health care delivery.58,59 The application of HSS in experiential roles within the health care system can often be lower-stakes (e.g., health coaching) compared with traditional biomedical decisions (e.g., ordering medications). This key difference opens up several opportunities for medical students to engage with the health system by performing authentic systems-based tasks that can add value and improve patient outcomes, while also learning HSS.5,10,59

학생들은 환자 네비게이터와 건강 코치의 역할을 하고, 효과적인 치료 전환transitino을 촉진하며, 약물 조정과 교육을 지원함으로써 가치를 더할 수 있다. 이러한 역할은 의료 시스템의 임상 치료 요구와 일치하며, 특히 재입원 감소, 진료 transition 개선, 환자 만족도 향상과 같은 결과에 초점을 맞춘다. 이러한 새로운 학생 역할은 시스템과 멘토에 대한 "부담"을 줄이고, HSS의 학생 교육을 강화하며, 잠재적으로 건강 결과를 개선할 수 있다.

Students can add value by serving as patient navigators and health coaches, facilitating effective care transitions, and assisting with medication reconciliation and education. These roles align with the clinical care needs of the health system, specifically focusing on outcomes such as reducing readmissions, improving care transitions, and improving patient satisfaction.60 These new student roles can lessen the “burden” on the system and mentors, enhance student education in HSS, and potentially improve health outcomes.

잠재 커리큘럼 해결

Address the hidden curriculum

과제 Challenges.

잠재 교육과정은 [제도적 구조와 문화가 학습환경에 미치는 영향]으로, 의사 자율성과 권위의 개념을 강화하는 경우가 많고, 이는 trainee가 교수의 행동을 따라model하기 때문에, 환자 가치와 의료팀 구성원의 역할에 대해 갖는 인식에 영향을 준다. 마찬가지로, [정책, 공식적인 커리큘럼, 시험, 그리고 교수진의 전문적 개발]은 제도적인 목표와 가치를 반영하고, 이는 다시 학습 환경에 영향을 미친다.

The hidden curriculum is the influence of institutional structure and culture on the learning environment61 and often reinforces the notions of physician autonomy and authority, influencing trainees’ perceptions of patient worth and the roles of health care team members as they model faculty behaviors.62–64 Similarly, policies, the formal curriculum, exams, and professional development of faculty reflect institutional goals and values, which, in turn, affect the learning environment.65–67

교육생들이 HSS 교육의 격차를 파악했지만, 이 내용은 인허가 및 이사회 시험이나 레지던트 배치 기준에 포함되지 않아 우선순위가 낮은 것으로 배정됐다. 새롭게 떠오르는 근거에 따르면, 자원 사용이 낮은 임상 환경에서 훈련하는 학생들이 향후 유사한 방법으로 practice할 가능성이 더 높으며, 이는 훈련 중의 역할 모델링이 학습자 개발에 매우 중요하다는 것을 시사한다. 역할 모델이 HSS-informed clinical practice를 보여주지 않는 경우, 학습자는 이러한 행동을 자신의 실제에 통합할 가능성이 줄어듭니다.

Although trainees have identified gaps in their HSS education, this content is assigned a lower priority because it is not included in licensing and board exams or residency placement criteria.68–71 Important, emerging evidence suggests that students who train in clinical environments with lower resource use are more likely to practice similar methods in the future, suggesting that role modeling during training is critical to learner development.72,73 If role models do not demonstrate HSS-informed clinical practice, learners will be less likely to incorporate these behaviors into their own practice.

잠재적 해결책 Potential solutions.

HSS 커리큘럼을 도입하기 위한 이니셔티브를 마련하려면 제도적 가치와 문화의 변화가 필요할 것이다. 이와 같이 각 기관의 구체적인 교육과정 변경에 대한 이행과 평가는 나머지 의학교육계에서의 기대가치 변화expected value를 모델링할 필요가 있을 것이다. 기관마다 학습환경에 대한 인식이 다르기 때문에 숨은 교육과정의 효과를 평가하는 노력이 각 특정 로케일specific locale로 향해야 한다.

Creating initiatives to introduce HSS curricula will require a change in institutional values and culture. As such, implementation and evaluation of specific curricular changes at each institution will need to model the expected value changes for the rest of the medical education community. Because perceptions of learning environments vary between institutions, efforts to evaluate the effects of the hidden curriculum must be directed toward each specific locale.74

[교육 변화에 대한 각 공동체의 준비 상태]를 이해하면, 해당 기관이 공식적인 HSS 커리큘럼을 도입할 때의 장벽과 긴장을 이해하는 데 도움이 되며, 이에 따라 교수진(자원 및 홍보를 통해)과 학생(시험을 통해)을 위한 인센티브 구조를 고안할 수 있다. 학생들이 자신의 경력에 HSS의 중요성에 대한 인식을 높이는 것은 학생들이 통합적이고 종적이며 의미 있는 환자 중심적인 경험에 노출시킴으로써 해결할 수 있다.

Understanding each community’s readiness for educational change will assist that institution’s leadership in understanding the barriers and tensions to implementing a formal HSS curriculum and allow them to devise incentive structures for faculty (via resources and promotion) and students (via exams) accordingly. Increasing students’ recognition of the importance of HSS to their careers could be addressed by exposing students to integrated, longitudinal, and meaningful patient-centered experiences.

보건 시스템 개선 노력에 대한 긍정적인 경험과 HSS 교육을 일치시키면, 커리큘럼의 격차를 줄이고 "유동적인fluid" 학습 환경을 조성할 수 있다. [국가 수준에서 HSS 교육에 대한 진화하는 담론]은 의사들의 실천과 교육에 HSS의 개념을 적용할 때 [의사의 책무에 대한 대화]를 포함해야 한다.

Aligning their HSS education with positive experiences in health systems improvement efforts may reduce gaps in the curriculum and create a “fluid” learning environment. Evolving discourse on HSS education at the national level should include conversations about physician accountability in espousing HSS tenets in their practice and teaching.

결론 Conclusions

보건 전문 학교의 커리큘럼 개혁을 요구하는 권고에도 불구하고, 가르치고 측정하는 것과 차세대 의사들에게 필요한 지식과 기술 사이에는 상당한 불일치가 남아 있다. HSS는 교육 개혁의 중추적인 부분으로 의과대학은 관련 분야에 초점을 맞춘 학습 활동을 설계하고 시행하고 있다. 의료 교육 개혁의 다음 물결에서는 HSS가 혁신의 주요 초점이 되어 의료 교육계의 전략적 사고와 행동이 대규모의 지속 가능한 개혁에 긍정적인 영향을 미칠 것을 요구할 것이다. HSS와 관련된 성공의 달성은 [의과대학, 보건 시스템, 면허, 인가 및 규제 기관, 자금 조달 파트너] 간의 새롭고 진화하는 협력 관계를 통해 가장 신속하게 이루어질 것이다.

Despite recommendations calling for curricular reform in health professions schools, there remains a significant mismatch between what is taught and measured and the knowledge and skills that are required for the next generation of physicians. HSS is one pivotal piece in education reform, and medical schools are designing and implementing learning activities focused on related areas. In the next wave of medical education reform, HSS will be a primary focus of innovation, requiring strategic thinking and action by the medical education community to positively influence large-scale, sustainable reform. The achievement of success with regard to HSS will occur most expeditiously through new and evolving collaborative partnerships between medical schools; health systems; licensing, accrediting, and regulatory bodies; and funding partners.

Acad Med. 2017 Jan;92(1):63-69.

doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001249.

Priority Areas and Potential Solutions for Successful Integration and Sustainment of Health Systems Science in Undergraduate Medical Education

Jed D Gonzalo 1, Elizabeth Baxley, Jeffrey Borkan, Michael Dekhtyar, Richard Hawkins, Luan Lawson, Stephanie R Starr, Susan Skochelak

Affiliations collapse

Affiliation

- 1J.D. Gonzalo is assistant professor of medicine and public health sciences and associate dean for health systems education, Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey, Pennsylvania. E. Baxley is senior associate dean of academic affairs, Brody School of Medicine at East Carolina University, Greenville, North Carolina. J. Borkan is chair and professor of family medicine and assistant dean for primary care-population health program planning, Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island. M. Dekhtyar is research associate, Medical Education Outcomes, American Medical Association, Chicago, Illinois. R. Hawkins is vice president, Medical Education Outcomes, American Medical Association, Chicago, Illinois. L. Lawson is assistant dean for curriculum, assessment, and clinical academic affairs and assistant professor of emergency medicine, Brody School of Medicine at East Carolina University, Greenville, North Carolina. S.R. Starr is assistant professor of pediatric and adolescent medicine and director of science of health care delivery education, Mayo Medical School, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, Minnesota. S. Skochelak is group vice president of medical education, American Medical Association, Chicago, Illinois.

- PMID: 27254015

- DOI: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001249Abstract

- Educators, policy makers, and health systems leaders are calling for significant reform of undergraduate medical education (UME) and graduate medical education (GME) programs to meet the evolving needs of the health care system. Nationally, several schools have initiated innovative curricula in both classroom and workplace learning experiences to promote education in health systems science (HSS), which includes topics such as value-based care, health system improvement, and population and public health. However, the successful implementation of HSS curricula across schools is challenged by issues of curriculum design, assessment, culture, and accreditation, among others. In this report of a working conference using thematic analysis of workshop recommendations and experiences from 11 U.S. medical schools, the authors describe seven priority areas for the successful integration and sustainment of HSS in educational programs, and associated challenges and potential solutions. In 2015, following regular HSS workgroup phone calls and an Accelerating Change in Medical Education consortium-wide meeting, the authors identified the priority areas: partner with licensing, certifying, and accrediting bodies; develop comprehensive, standardized, and integrated curricula; develop, standardize, and align assessments; improve the UME to GME transition; enhance teachers' knowledge and skills, and incentives for teachers; demonstrate value added to the health system; and address the hidden curriculum. These priority areas and their potential solutions can be used by individual schools and HSS education collaboratives to further outline and delineate the steps needed to create, deliver, study, and sustain effective HSS curricula with an eye toward integration with the basic and clinical sciences curricula.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 교육과정 개발&평가' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 학술활동을 위한 역량, 마일스톤, EPA의 감독 수준 (Acad Med, 2018) (0) | 2021.07.16 |

|---|---|

| 전문적 실천의 타당한 기술을 전달하기 위한 EPA 구성 접근법 (Teach Learn Med, 2021) (0) | 2021.07.16 |

| 보건시스템과학 과목의 예후: 현재 학생들로부터의 관측(Acad Med, 2018) (0) | 2021.05.31 |

| 의료시스템과학을 의학교육에 통합할 때 우려와 반응(Acad Med, 2018) (0) | 2021.05.28 |

| 보건시스템과학: 기본의학교육의 "브로콜리" (Acad Med, 2019) (0) | 2021.05.28 |