N을 어떻게 할까? 포커스그룹 연구에서 샘플 사이즈 보고에 관한 방법론적 연구(BMC Med Res Methodol, 2011)

What about N? A methodological study of sample-size reporting in focus group studies

Benedicte Carlsen1*, Claire Glenton2,3

배경 Background

포커스 그룹 또는 포커스 인터뷰는 일반적으로 연구자가 결정한 주제에 대한 참가자의 인식과 경험에 기초하여 moderated 그룹 토론을 통해 연구 데이터를 수집하는 방법으로 정의된다[1-6]. 초점 그룹은 진행자나 연구자와 참가자 사이의 상호작용보다는 [참가자 간의 상호작용에 중점]을 둔다는 점에서 그룹 인터뷰와 다르다[4]. 최근 몇 년 동안, 포커스 그룹은 건강 과학 연구에서 점점 더 인기를 얻고 있다; 1999년 메디라인 검색에서 투하이와 퍼트남[7]은 1985년 이전에는 포커스 그룹 연구가 없었지만 1985년과 1999년 사이에 1000개 이상의 연구를 발견했다. 포커스 그룹은 사람들의 주관적인 경험과 태도를 탐구하는 데 매우 적합하며, 보건 연구원들은 반복적으로 포커스 그룹을 사용하여 보건 서비스를 평가하거나, 주요 이해관계자 또는 의사결정자의 견해를 도출하거나, 우편 설문 조사나 정보에 반응하지 않는 소외 그룹의 견해를 탐구하도록 권장된다.기존 인터뷰 상황에 겁을 먹을 수 있습니다 [2, 5, 7, 8]. 설문 조사 또는 시험 연구의 데이터를 준비하거나 해석하기 위해 사전 또는 사후 스터디로 포커스 그룹 인터뷰도 권장된다.

A focus group or focus interview is commonly defined as a method of collecting research data through moderated group discussion based on the participants' perceptions and experience of a topic decided by the researcher [1–6]. Focus groups differ from group interviews in that the emphasis is on the interaction between the participants rather than between the moderator or researcher and the participants [4]. In recent years, focus groups have become increasingly popular within health science research; in a Medline search in 1999, Twohig and Putnam [7] found no focus group studies before 1985 but more than 1000 studies between 1985 and 1999. Focus groups are well suited to explore people's subjective experiences and attitudes, and health researchers are repeatedly encouraged to use focus groups to evaluate health services, to elicit the views of key stakeholders or decision makers or to explore the views of marginalised groups that typically would not respond to a postal survey or would be intimidated by a conventional interview situation [2, 5, 7, 8]. Focus group interviews are also recommended as a pre- or post-study to prepare or interpret data from surveys or trial studies.

1980년대 이후 보건 과학 저널의 포커스 그룹 연구가 급격하게 증가했음에도 불구하고, 이 방법이 어떻게 사용되고 왜 사용되는지에 대한 지식은 의외로 적다 [1, 9, 10]. 1993년, 포커스 그룹 연구 방법론의 "founding father" 중 한 명인 리차드 크루거는 이 분야가 "설계가 부실하고 보고가 부실하다"고 불평했다[11]. 1996년 이 분야를 검토한 후, 모건은 "현재 포커스 그룹 절차의 보고는 기껏해야 haphazard한 수준"이라고 결론지었다. 1990년대에 수행된 포커스 그룹 연구에 대한 두 개의 상위 및 Putnam의 검토[7]는 그 방법이 어떻게 사용되었는지에 대한 "어마어마한 차이tremendous variation"를 보여주었고 보고가 종종 부적절하다고 결론지었다. 우리는 10년 후 낙관론에 대한 더 많은 이유가 있는지 알아내는 데 관심이 있었다.

Despite this apparent sharp increase in focus group studies in health sciences journals since the 1980 s, there is surprisingly little knowledge about how this method is used and why [1, 9, 10]. In 1993, one of the "founding fathers" of focus group research methodology, Richard Krueger, complained that the field is burdened with "poor design and shoddy reporting" [11]. After reviewing the field in 1996, Morgan concluded that "At present the reporting of focus group procedures is a haphazard affair at best." Twohig and Putnam's review [7] of focus group studies carried out in the 1990 s showed a "tremendous variation" in how the method was used and concluded that reporting is often inadequate. We were interested in discovering whether there is more reason for optimism a decade later.

수행할 그룹의 수를 결정하는 방법에 대한 조언은 방법의 다른 측면에 대한 조언과 비교하여 종종 미묘하다. 실제로, 일부 교재들은 그룹 수를 결정하는 기존의 지침이 없다고 주장한다 [13, 16, 18].

Within this literature, advice on how to decide on the number of groups to conduct is often meagre compared to advice on other aspects of the method. In fact, some teaching books claim that there are no existing guidelines for deciding number of groups [13, 16, 18].

지침의 대부분은 포커스 그룹이 포커스 그룹 연구의 분석 단위여야 한다고 권고한다. 이에 따라 표본 크기는 연구의 총 참여자 수가 아니라 그룹 수를 참조해야 합니다. 그러나 표본 크기에 대한 이 두 가지 측면 사이에는 당연히 본질적인 관계가 있다. 따라서, 일부 저자들은 연구의 참가자 수가 적을 경우, 그룹의 크기를 줄임으로써 그룹의 수를 증가시킬 수 있다고 제안한다 [4]. 그룹 크기에 대한 지침은 일반적이며 그룹당 최소 4명 이상 최대 12명의 참가자를 초과하지 않는다 [2, 5, 6, 13]. 여기서 Fern의 실험 연구는 [4명의 참가자로 구성된 두 그룹 및 8명의 참가자로 구성된 한 그룹을 수행함으로써 더 많은 정보를 얻을 수 있다]는 것을 나타냈다는 것을 주목하는 것이 흥미롭다[19].

Most of this guidance recommends that the focus group should be the unit of analysis in focus group-studies. In line with this, sample size should refer to number of groups and not the total number of participants in a study. However, there is of course an intrinsic relationship between these two aspects of sample size. Thus, some authors suggest that if the number of participants in a study is small, it is possible to increase the number of groups by reducing the size of the groups [4]. Guidance on group size is common and seldom goes beyond a minimum of 4 and a maximum of 12 participants per group [2, 5, 6, 13]. Here, it is interesting to note that Fern's experimental study indicated that more information is obtained by conducting two groups of four participants then one group of eight participants [19].

질적 방법의 강점은 현상의 깊이와 복잡성을 탐구하는 능력이다. 따라서 Sandelowski는 정성적 연구에서 표본 크기에 대한 그녀의 논의에서 너무 적은 그룹이나 너무 많은 그룹 모두 포커스 그룹 연구의 품질을 낮출 수 있다고 강조한다[20]. 양은 질과 균형을 이루어야 하며, 녹음된 자료의 테이프 인터뷰나 페이지가 많을수록 저자가 자료에서 추출할 수 있는 깊이와 풍부함이 줄어듭니다 [21]. 이러한 지식은 최적의 포커스 그룹 수를 달성하는 방법에 관한 조언을 직접적으로 제공하지는 않지만, 작성자가 그룹 수를 결정할 때 알아야 할 문제를 강조합니다.

The strength of qualitative methods is their ability to explore the depth and complexity of phenomena. Thus, Sandelowski, in her discussion of sample size in qualitative research, emphasizes that both too few and too many groups can lower the quality of focus group studies [20]. Quantity must be balanced against quality, and the more hours of taped interviews or pages of transcribed material, the less depth and richness the authors will be able to extract from the material [21]. While this knowledge does not directly offer advice regarding how to achieve the optimal number of focus groups, it does highlight an issue that authors should be aware of when determining number of groups.

포커스 그룹 연구에서 샘플 크기에 대한 대부분의 조언은 "포화점" 또는 "이론적 포화점"을 가리키며, "이론적 포화점"이라는 용어는 1967년 글레이저와 스트라우스[22]에 의해 "근거 이론"의 개요로 도입되었으며, 그 이후로 비록 단순화된 버전이지만 대부분의 질적 연구 환경으로 확산되었다. 일반적으로 "데이터 포화"라고 합니다. 이 접근법에서, 인터뷰는 이론이나 가설을 지속적으로 구성하고 다듬기 위해 "이론적 표본 추출"에 따라 다른 범주의 informants들과 함께 수행되어야 한다. 이 방법은 데이터 수집(즉 모집, 인터뷰 및 분석)이 각 인터뷰가 진행되는 동안 반복적 프로세스로 수행되어야 하므로, 표본 크기를 연속적으로 계산하고 수집된 모든 데이터를 분석하는 기존의 정량적 설계와는 상당히 다른 접근 방식을 나타낸다[23, 24].

Most advice about sample size in focus group studies refers to "point of saturation" or "theoretical saturation", The term "theoretical saturation" was introduced by Glaser and Strauss [22] in 1967 in their outline of "grounded theory" and has since spread to most qualitative research environments, albeit in a simplified version, usually referred to as "data saturation". In this approach, interviews should be conducted with different categories of informants following a line of "theoretical sampling" to continuously construct and refine theory or hypotheses. The method requires that data collection, i.e. recruiting, interviewing and analysis, is conducted as an iterative process for each interview, thus representing quite a different approach from the traditional quantitative design of successively calculating sample size beforehand and analysing all data collected [23, 24].

포화점 개념은 운용하기에 너무 모호하다는 비판을 받아왔다 [25].

- 글레이저와 스트라우스는 "각 범주의 이론적인 포화도에 도달할 때까지 표본 추출"을 해야 한다고 제안하고,

- 스트라우스와 코빈은 "범주에 관한 새로운 또는 관련 데이터가 나타나지 않을 때까지 데이터를 수집해야 한다"고 말한다. [15] (1990:188)

그러나 저자들은 "새로운 데이터 또는 관련 데이터"에 대한 정의를 제시하지 않았으며, 연구자가 포화 상태에 이르렀음을 합리적으로 확인할 수 있기 전에 새로운 정보가 필요하지 않은 인터뷰 횟수에 관한 조언을 하지 않았다.

The concept of point of saturation has been criticised for being too vague to operationalise [25].

- Glaser and Strauss suggest that researchers should: "sample until theoretical saturation of each category is reached" [22](1967:61-62, 11-112) while

- Strauss and Corbin state that researchers should collect data until "no new or relevant data seem to emerge regarding a category." [15] (1990:188).

However, the authors present no definition of "new or relevant data", and give no advice regarding the number of interviews with no new information that is required before the researcher can be reasonably certain that saturation has been reached.

포커스 그룹 방법론에 대한 보다 실용적인 권위자들은 많은 연구자들이 assignment에 대해 연구하고 있으며 funder들은 그룹 수를 사전 연구로 결정하도록 요구할 수 있다[2, 4, 12]. 그룹 수와 관련된 일반적인 사항에 대한 권장 사항 및 참조는 이러한 텍스트북 내에서 다양합니다. 일반적으로 참가자 범주당 2-5개의 그룹을 추천한다. 그러나 저자는 대개 이러한 것들이 rule of thumb일 뿐이며, 포커스 그룹의 수는 연구 질문의 복잡성과 그룹의 구성에 달려 있다고 강조한다. 종종, 주어진 조언은 rule of thumb을 따르되 약간 더 높은 숫자가 "안전한 쪽에" 있도록 제안하는 것이다. 일부 저자들은 연구자들이 필요한 최종 그룹의 수를 결정하면서 포화점을 사용할 것을 제안한다 [2, 4].

More pragmatic authorities on focus group methodology recognise that many researchers work on assignment and their funders may require that the number of groups are decided pre-study [2, 4, 12]. The recommendations and references to what is common regarding number of groups vary within these text books. In general they recommend from two to five groups per category of participants. However, the authors usually underline that these are only rules of thumb and that the number of focus groups depends on the complexity of the research question and the composition of the groups. Often, the advice given is to follow the rules of thumb but to suggest a slightly higher number to be "on the safe side". Some authors suggest that the researchers then use point of saturation as they go along to decide the final number of groups needed [2, 4].

이 교과서들 중 일부는 여전히 글레이저와 스트라우스를 언급하지만, 다른 책들은 그렇지 않다. 이러한 경우에 이론적 표본 추출과 이론적 포화의 개념과 그 이면의 이론은 ["목적 표본 추출"과 "데이터 포화" 또는 단순히 "포화"라는 less theoretically sustained한 용어로 대체된 것]처럼 보인다. 다만 새로운 필수 정보가 발견되지 않을 때까지 지속적인 데이터 분석과 새로운 데이터 획득 과정을 통해 제보자를 선정하고 그룹 수를 결정하는 기본 절차가 남아 있다.

While some of these text books still refer to Glaser and Strauss, others do not. In these cases the concept of theoretical sampling and theoretical saturation and the theory behind it seem to have been lost on the way and replaced with the less theoretically sustained terms of "purposive sampling" and "data saturation" or merely "saturation". However, the basic procedure of selecting informants and deciding on the number of groups through a constant process of analysing data and obtaining new data until no new essential information is found, remains.

정성적 방법론 분야의 비평가들에 의해 포화 개념이 연구 보고서에서 종종 잘못 사용되고 있다고 주장되어 왔다 [23, 26]. Charmaz [25] (2005:528)는 "연구자들이 종종 작은 표본 - 얇은 데이터를 가진 매우 작은 표본을 정당화하기 위해 포화 기준을 호출한다"고 주장한다. 실제로 이러한 작은 표본 크기는 [시간 부족 또는 자금 부족의 결과]일 수 있습니다. 따라서 '포화'가 차르마즈가 암시하듯 포커스 그룹 보고서에서 잘못된 디자인을 가리는 마법 단어가 되었는지는 아직 조사되지 않았다.

It has been claimed by critics within the field of qualitative methodology that the concept of saturation is often misused in research reports [23, 26]. Charmaz [25] (2005:528) claims that "Often, researchers invoke the criterion of saturation to justify small samples - very small samples with thin data." In reality, these small sample sizes may, in fact, be a result of lack of time or lack of funds. Whether "saturation" has thus become the magic word which obscures faulty designs in focus group reports, as Charmaz insinuates, has yet to be investigated.

일반적으로 포커스 그룹 방법이 어떻게 사용되고 작업이 이루어지는지에 대한 경험적 연구는 부족하다.

In general, empirical research into how focus group methods are used and work is scarce.

목표 Objectives

방법 Methods

자격기준 Eligibility criteria

언급한 바와 같이, 포커스 그룹 인터뷰의 정의는 일반적으로 주어진 주제에 대한 토론을 용이하게 할 목적으로 연구자가 시작한 소규모 그룹의 모임을 가리킨다. [1, 4–6] 그러나, 우리는 작성자 자신이 데이터 수집 방법을 참조하기 위해 "초점 그룹"이라는 용어를 사용한 모든 연구를 포함했다. 포커스 그룹만을 사용한 연구와 혼합 방법을 사용한 연구를 포함했다. 우리는 2009년 리뷰 작업을 시작하고 그 분야의 최신 기술을 검토하고 싶어 2008년에 발표된 연구를 선택했습니다. 게다가 우리는 2003년과 1998년, 즉 5년과 10년 전에 그 분야의 확장에 대한 조잡한 견제로 같은 조사를 반복했다.

As mentioned, definitions of focus group interviews usually refer to researcher-initiated gathering of a small group of people with the aim of facilitating discussion about a given topic [1, 4–6]. However, we included any study where the authors themselves used the term "focus group" to refer to their method of data collection. We included studies using focus groups only and studies using mixed methods. We chose studies published in 2008 as we started working with the review in 2009 and wanted to review the state of the art in the field. In addition we repeated the same search for 2003 and 1998, i.e. five and ten years earlier as a crude check on the expansion of the field.

Search methods for identification of studies

Data selection, extraction and analysis

We extracted data about the following aspects as numerical data:

- Number of focus groups in each study

- Maximum and minimum number of participants in the focus groups in each study

- Total number of participants

- Whether any explanation for number of groups was given

- Whether this explanation was tied to:

- Practical issues (such as convenience when recruiting or limited resources to conduct interviews)

- Recommendations in the literature (pragmatic guidelines to number of focus groups)

- Saturation

- Capacity when analyzing, i.e. balancing between depth and breadth of data

결과 Results

포커스 그룹 스터디의 샘플 크기 현재 상태

The current status of sample size in focus group studies

전자 데이터베이스 검색을 통해 우리는 2008년에 발표된 240개의 논문을 확인했다. 이에 비해, 1998년과 2003년에 대한 우리의 연구는 각각 23건과 62건의 연구를 낳았다.

Through our electronic database search we identified 240 papers published in 2008. In comparison, our search for 1998 and 2003 resulted in 23 and 62 studies respectively.

우리는 검토에 포함시키기 위해 2008년부터 240편의 논문 각각에 대한 전체 텍스트 버전을 고려했다. 본문 전문을 읽고 20편의 논문이 제외되었다 이 중 6건은 기획연구여서 제외됐고, 4건은 인터넷 기반이라 제외됐고, 3건은 1차 연구가 아니어서 제외됐으며, 7건은 추상화에도 '초점집단'이라는 용어가 등장했는데도 실제로는 보고하지 않아 제외됐다. (이들 중 일부는 보고된 연구에서 평가된 개입의 일부로 포커스 그룹을 언급했습니다.)

We considered the full text version of each of the 240 papers from 2008 for inclusion in the review. Twenty papers were excluded after reading the full text version. Of these, six were excluded because they were planned studies, four were excluded because the focus groups were Internet-based, three were excluded because they were not primary studies and seven were excluded because they did not, in fact, report the results of focus group studies even though the term "focus groups" appeared in their abstracts. (Some of these referred to focus groups as part of an intervention that was evaluated in the reported study).

220개의 논문이 우리의 포함 기준에 부합했다. (포함된 스터디 목록은 추가 파일 1을 참조하십시오.) 이것들은 117개의 다른 학술지에 발표되었습니다. 61%는 혼합 데이터 수집 방법을 사용한 반면 39%는 포커스 그룹만 사용한 적이 있다.

Two hundred and twenty papers met our inclusion criteria. (See Additional file 1 for a list of included studies.) These were published in 117 different journals. Sixty-one percent had used mixed methods of data collection, while 39% had used focus groups only.

220개의 논문 중 많은 논문들이 표본 크기에 대한 불충분한 보고로 특징지어졌다.

- 22(10%)가 포커스 그룹 수를 보고하지 않음

- 42명(19%)은 총 참여자 수를 보고하지 않았다.

- 102명(46%)이 포커스 그룹의 최소 및 최대 참가자 수를 보고하지 않았다.

Many of the 220 papers were characterised by an insufficient reporting of sample size:

- 22 (10%) did not report number of focus groups

- 42 (19%) did not report total number of participants

- 102 (46%) did not report minimum and maximum number of participants in the focus groups

또한, 이 정보가 때때로 논문의 다른 섹션에 보고되었기 때문에 포커스 그룹과 참가자 번호를 찾기가 때때로 어려웠다(예: [28, 29 참조). 혼합 방법 연구의 경우, 다른 데이터 수집 방법에 대한 표본 크기 정보를 구분하기가 어려운 경우가 있었다(예: [30] 참조).

In addition, it was sometimes difficult for us to find focus group and participant numbers as this information was sometimes reported in different sections of the papers (See for example [28, 29]. For mixed method studies, it was sometimes difficult to separate between sample size information for different data collection methods (See for example [30]).

그룹 및 참가자 수를 보고한 논문은 이 숫자에 큰 범위를 보였지만 데이터 분포는 오른쪽으로 꼬리가 길었다. 즉, 포커스 그룹 숫자가 적은 연구가 많았고, 포커스 그룹 숫자가 많은 연구는 거의 없었다(표 1).

Those papers that did report numbers of groups and participants showed a great range in these numbers, but data distribution was positively skewed, i.e. there were many studies with a few focus groups and few studies with high numbers of focus groups (Table 1).

포커스 그룹 수에 대한 작성자 설명

Authors' explanations for number of focus groups

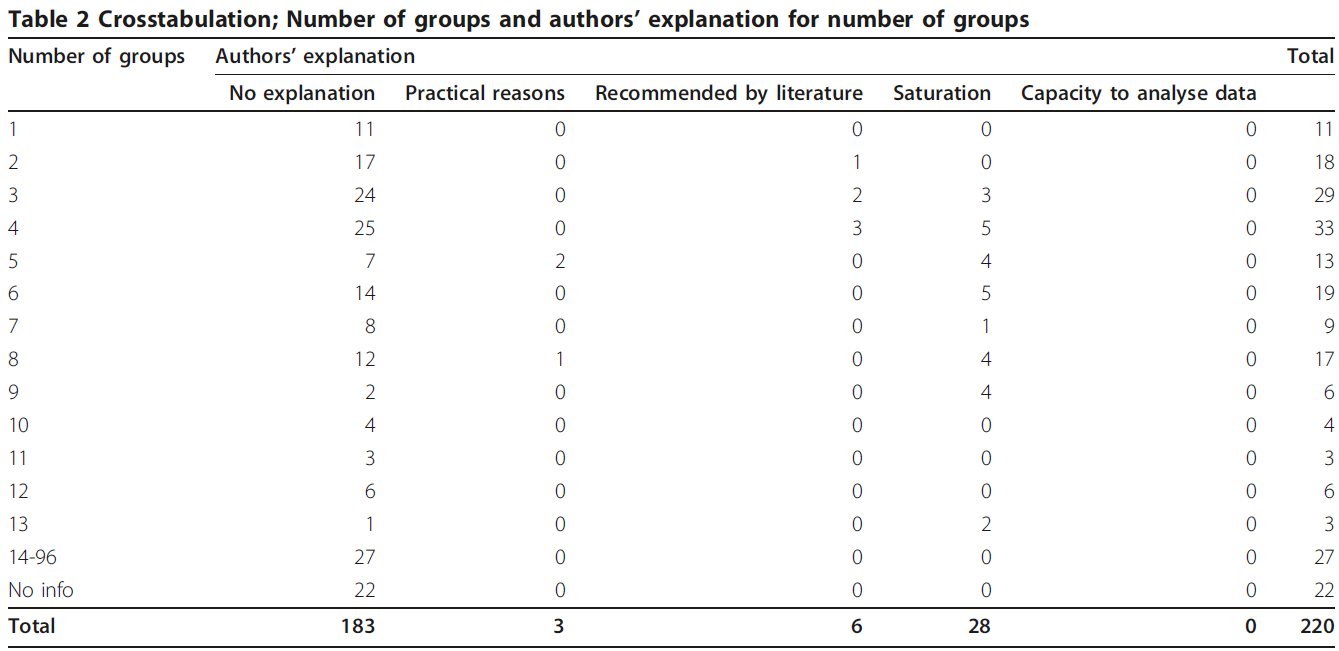

수행된 포커스 그룹의 수를 결정하거나 결정하게 된 방법에 대한 저자들의 설명은 다양했지만, 명확하지 않거나 완전히 결여된 경우가 많았다(예: [31, 32]. (표 2 참조) 저자들이 혼합 방법을 사용할 때, 연구의 정량적 부분에 대한 표본 크기에 대한 설명은 종종 꼼꼼한 반면, 포커스 인터뷰의 표본 크기는 종종 불분명하고 피상적이었다.

Authors' explanations of how they had decided on or ended up with the number of focus groups carried out varied, but were often unclear or completely lacking (e.g. [31, 32]). (See Table 2.) When authors used mixed methods, explanations of sample size for the quantitative part of the study were often meticulous, while the sample size of the focus interviews in contrast was often unclear and superficial, as in this example:

- 필요한 숫자에 도달할 때까지 객관적인 샘플링이 수행되었다[33].

- purposive sampling was undertaken till the necessary number was attained [33].

포함된 220개의 연구 중 183개(83,2%)는 포커스 그룹의 수에 대해 아무런 설명도 하지 않았다(즉, 37개는 어떤 종류의 설명을 하지 않았다). 종종 저자들은 포커스 그룹의 수보다는 참가자의 수를 설명했다 [34, 35]. 이러한 경우에 대표적인 것은 임상 개입 연구와 함께 포커스 그룹 연구가 수행되고 저자가 포커스 그룹 인터뷰에 참여하도록 개입 연구의 모든 참가자를 초대한 상황이었다 [34, 36]. 이 경우 포커스 그룹의 수보다 참여자의 수를 설명하므로, 이는 "설명 없음"으로 분류되었다.

Of the 220 studies included, 183 (83,2%) gave no explanation for number of focus groups (i.e. 37 did give some type of explanation). Often, authors explained the number of participants rather than the number of focus groups [34, 35]. Typical for these cases were situations where focus group studies were carried out alongside clinical intervention studies and where the authors had invited all participants from the intervention study to participate in the focus group interviews [34, 36]. As these accounts explain the number of participants rather than the number of focus groups, this was categorised as "no explanation".

표 2에서 우리는 데이터 품질과 수량(데이터를 분석할 수 있는 용량)의 균형을 유지해야 한다는 점을 언급하여 그룹 수를 정당화하는 연구는 없다는 것을 알 수 있다. 이 표에는 또한 표본 크기에 대한 모든 설명이 포커스 그룹이 두 개에서 13개 사이인 연구에서 발견되었음을 보여줍니다. 포커스 그룹의 수와 수행된 그룹 수(Pearson 상관 관계)에 대한 설명의 존재 사이에 상관 관계가 있는지 테스트했다. 선형 관계를 찾을 수 없습니다. 11개의 단일 그룹 연구 중 어느 것도 한 그룹이 충분한 이유를 정당화하려고 시도하지 않았다. 이러한 연구는 모두 [혼합된 방법]을 사용했으며, [설문지 등을 개발하기 위해 일반적으로 포커스 그룹 연구를 파일럿으로 사용]했다.

From Table 2 we also see that no study justified the number of groups by referring to the need to balance data quality and quantity (capacity to analyse data). The table also shows that all the explanations for sample size were found in studies that had between two and 13 focus groups. We tested if there was any correlation between the presence of an explanation for number of focus groups and the number of groups conducted (Pearson correlation). We found no linear relationship. None of the eleven single-group studies attempted to justify why one group was sufficient. These studies all use mixed methods and the qualitative assessment showed that they typically used the focus group study as a pilot for developing questionnaires etc.

지적한 바와 같이, 13개 이상의 그룹을 포함하는 연구 중 표본 크기에 대한 설명을 제공하는 것은 없으며 정성적 평가에서 높은 수의 그룹을 연구 한계로 지칭하는 연구도 없었다. 반대로, 저자가 표본 크기가 상대적으로 높다고 판단했을 때, 이는 다음과 같은 이점이 있었다.

As noted, none of the studies that included more than 13 groups gave any explanations for sample size and the qualitative assessment showed that none of the studies referred to a high number of groups as a study limitation. On the contrary, when authors considered their sample size to be relatively high, this was seen as advantageous:

시설 직원의 상당한 단면도로 다수의 포커스 그룹을 수행함으로써, 코딩 중 단일 포커스 그룹 또는 방법론적 선택에 의해 결과가 크게 영향을 받을 가능성을 줄였다[37].

By conducting a large number of focus groups with a significant cross-section of the facility's employees, we reduced the possibility that results would be dramatically affected by a single focus group or methodological choice during coding [37].

한편, 저자들이 소수의 포커스 그룹만을 포함했을 때, 그들은 종종 이것을 한계로 묘사했다. 그러나 이러한 여러 연구에서 저자들은 포커스 그룹의 수가 데이터 포화에 의해 결정되었다고 주장하였다. 이것은 이론적으로 포커스 그룹의 수가 사실 적절했다는 것을 암시해야 한다. (예: [38–43]을 참조하십시오.) 그러나 저자들은 종종 적은 수의 포커스 그룹을 약점으로 설명했지만, 여러 연구는 포커스 그룹이 심층적으로 다루고 문제에 대한 두꺼운 설명을 제공하기 위해 제공한 가능성을 참고하여 그들의 방법 선택을 정당화했다.

On the other hand, when authors had included only a small number of focus groups, they frequently described this as a limitation. However, in several of these studies, authors also claimed the number of focus groups had been determined by data saturation. This should, in theory, imply that the number of focus groups was, in fact, appropriate. (See for example [38–43]). But while authors often described a small number of focus groups as a weakness, several studies justified their choice of method with reference to the possibilities that focus groups gave to go in depth and provide a thick description of the issue.

포화 Saturation

포커스 그룹의 수에 대한 설명을 한 37개 연구 중 28개는 포화 상태에 이르면 중단했다고 주장했다. 그러나 이러한 설명의 절반 이상(28개 중 15개)은 포화 상태로 끝난 데이터 수집 및 분석을 포함하는 반복 프로세스가 발생했다는 것을 확신하게 보고하지 않았다. 그 이유는 주로 방법론적 절차에 대한 설명의 불일치가 주된 원인이었다. 한 가지 일반적인 예는 포화점에 대한 레퍼런스에도 불구하고, 포커스 그룹의 수가 미리 결정되었다는 것이다([44, 45] 참조).

Among the 37 studies that did give an explanation for the number of focus groups, 28 claimed that they had stopped once they had reached a point of saturation. However, more than half of these explanations (15 of 28) did not report convincingly that an iterative process, involving data collection and analysis that ended with saturation, had taken place. The reason for this was mainly inconsistencies in the description of the methodological procedures. One common example was that, despite their reference to point of saturation, their number of focus groups was pre-determined, as the extraction below shows (See also [44, 45]):

특정 커뮤니티의 주민과 함께 세 개의 포커스 그룹이 수행되었다. 그것은 작은 공동체였고, 세 개의 포커스 그룹 후에 그들의 장벽과 제안된 해결책에 대한 포화점이 있을 것이라고 결정되었다[46].

Three focus groups were conducted with residents of a specific community. It was a small community, and it was determined that after three focus groups, there would be a saturation point regarding their barriers and suggested solutions [46].

포화도 주장이 근거 없는 것으로 보이는 다른 일반적인 예로는 (목적적 또는 이론적 표본 추출 대신) 편의 표본 추출을 사용한 경우, 또는 참여를 자원한 모든 사람이 포함된 연구였으며, 분석 전에 모든 데이터가 수집된 것으로 보였다(예: [41, 42, 47–49].

Other common examples where claims of saturation appeared unsubstantiated were studies that used convenience sampling, and included everyone who volunteered to participate, instead of purposive or theoretical sampling, and where, in addition all data seemed to have been gathered before the analysis (See for example [41, 42, 47–49]).

또한 포화 상태에 도달했다고 판단되기 전에 새로운 관련 정보가 없이 수행된 포커스 그룹의 수를 보고하거나 논의한 저자는 없다는 점에 주목했다. 반대로, 작가들은 대개 포화 상태에 도달하는 과정에 대해 피상적이고 막연한 언급을 했는데, 그들 중 많은 사람들은 이 시점에 도달했다는 "느낌"을 언급한다.

We also noted that no author reported or discussed the number of focus groups that had been conducted with no new relevant information before it was decided that a point of saturation had been reached. On the contrary, authors normally gave superficial and vague references to the process of reaching point of saturation, many of them referring to a "feeling" of having reached this point:

포커스 그룹은 "포화"(새로운 테마가 확인되지 않음)에 도달해다고 느낄 때까지 수행되었다. [41]

Focus groups were [...] conducted until we felt "saturation" (no new themes identified) was reached [41].

다섯 번째 포커스 그룹이 끝날 때, 우리는 주제의 포화가 충족되었다고 느꼈고, 그래서 우리는 모집을 중단했다. [50]

At the end of the fifth focus group, we felt that theme saturation had been met, so we stopped recruitment... [50]

우리는 또한 포화점에 관한 적절한 보고의 몇 가지 예를 발견했다.

- 예를 들어 바리마니 외 연구진[51]은 근거 이론의 사용을 설명하고 이론적 포화도가 충족될 때까지 경험적 소견과 이론 간의 끊임없는 비교가 샘플링 절차를 어떻게 안내했는지를 설명했다. 그러나 이 논문은 이례적으로 9000단어 정도 길었다.

- 또 다른 예는 슈발 외[52]이다. 저자들은 약 3000단어의 논문에서 "포화"라는 용어를 구체적으로 언급하지 않았지만 표본 추출 절차와 포화가 어떻게 충족되었는지에 대한 명확한 설명을 제공했다.

We also found some examples of adequate reporting regarding point of saturation.

- For example Barimani et al [51] explained their use of grounded theory and described how a constant comparison between empirical findings and theory had guided their sampling procedure until theoretical saturation was met. This paper was, however, unusually long, around 9000 words.

- Another example is Shuval et al [52]. In their paper of around 3000 words, the authors have not specifically referred to the term "saturation" but have offered a clear description of the sampling procedure and how saturation was met:

우리는 주요 정보 제공자를 선정하고(연구자의 지인에 기초하여), 그룹 상호 작용을 촉진하고 참가자의 다양한 특성(즉, 성별, 연령, 거주 환경, 민족/종교 및 자체 보고 소득)을 포착하기 위해 [패튼 1990 참조] 목적적 샘플링을 사용했다. 우리가 접근한 모든 학생들은 포커스 그룹에 참여하기로 동의했습니다.

We used purposeful sampling [with reference to Patton 1990] to select key informants (on the basis of researchers' acquaintance), promote group interaction, and capture the diverse characteristics of participants (i.e., sex, age, living environment, ethnicity/religion, and self-reported income). All students whom we approached agreed to participate in focus groups.

새로운 테마가 나타나지 않을 때까지 포커스 그룹을 개최하였다(9). [...] 연구자들은 각 세션을 검토하기 전에 각 세션을 반영하여 후속 세션에서 새롭게 식별된 개념을 검토할 수 있게 되었다. [52]

Focus groups were held until no new themes emerged (9). [...] Researchers reviewed the transcripts to reflect on each session before conducting the next, thereby enabling newly identified concepts to be examined in subsequent sessions [52].

문헌상의 권고사항

Recommendations in the literature

포커스 그룹의 수에 대해 명시적인 설명을 한 37개의 연구 중 6개는 문헌에서 rule of thumb을 언급했다. 이들은 대부분 포화 상태에 도달하기 위해 필요한 그룹 수에 대한 실용적인 지침을 참조했다(예: [53]). 아래 예에서 알 수 있듯이, 저자들은 필드에 일관된 지침이 없다고 보고했습니다.

Six of the 37 studies that gave an explicit explanation for the number of focus groups referred to rules of thumb in the literature. These were mostly references to pragmatic guidelines of how many groups are necessary to reach a point of saturation (e.g. [53]). As the example below illustrates, authors reported that the field lacks consistent guidelines.

포커스 그룹 수와 표본 크기에 대한 권장 사항은 서로 다릅니다. 권장 세션 수는 연구 설계의 복잡성과 목표 표본의 구별 수준에 따라 달라집니다 [18–21]. 스튜어트 외 연구진. (2007) 사회과학에서 수행되는 3-4개 이상의 포커스 그룹이 드물다는 것을 관찰했다. 우리는 각 사이트의 두 그룹이 단일 그룹 또는 사이트에서 볼 수 있는 편견을 제한하고 그룹 간에 공통되는 테마를 검토할 수 있다고 느꼈다 [54].

Recommendations for both the number of focus groups and sample size vary. The number of recommended sessions depends on the complexity of the study design and the target sample's level of distinctiveness [18–21]. Stewart et al. (2007) observed that rarely are more than 3-4 focus groups conducted in the social sciences. We felt that two groups at each site would limit bias that might be seen in a single group or site and allow us to examine themes common across groups [54].

그러나 확인해본 바, 레퍼런스가 항상 정확한 것은 아니었다. 예를 들어, Gouterling 등의 경우 세 개의 포커스 그룹을 수행하고 숫자를 다음과 같이 설명합니다.

However, when we checked with the literature, referrals to recommendations were not always accurate. For example Gutterling et al, conducted three focus groups and explain the number thus:

좋은 결과를 얻기 위해서는 데이터가 포화 상태가 되고 처음 몇 개의 그룹 이후에 새로운 정보가 거의 나타나지 않기 때문에 소수의 포커스 그룹만으로도 충분합니다 [Morgan 96] [55].

For good results, just a few focus groups are sufficient, as data become saturated and little new information emerges after the first few groups [Morgan 96] [55].

Morgan[1]을 찾아보면, 대부분의 연구에서 4~6개의 그룹이 포화 상태에 도달하기 때문에 사용된다고 주장하지만, 참가자의 범주가 더 많고 질문의 표준화가 덜 될수록 포커스 그룹의 수가 더 많다는 점도 강조합니다.

Looking up Morgan [1], we found that he claims that most studies use four to six groups because they then reach saturation, but he also underlines that the more categories of participants and less standardisation of questions, the higher number of focus groups.

현실적 이유

Practical reasons

37건의 연구 중 3건은 수행된 포커스 그룹의 수에 대한 현실적 이유를 보고했다. 예를 들어, 이 설명에서는 다음과 같이 채용 제약 조건에 대해 제공된 정보가 불완전합니다.

Three of the 37 studies reported practical reasons for the number of focus groups conducted. The information offered regarding recruitment constraints was incomplete as, for example, in this explanation:

이용 가능한 참가자 수는 제한되었고 따라서 포커스 그룹의 수는 적었다 [56].

The number of available participants was limited and the number of focus groups was therefore few [56].

두 가지 설명은 참가자를 추가 그룹으로 모집하는 어려움과 관련이 있는 것으로 보였고 [56, 57], 한 명은 제한된 자원("예산 및 인력 제약")을 언급했다. 이런 이유로 연구자는 사전 연구를 통해 5개 포커스그룹을 결정하게 되었다[38]. 이 마지막 연구에서도 포화 상태에 이르렀다고 주장했습니다(그룹 수 결정 절차로 명시하지 않음).

Two of the explanations appeared to be tied to difficulties in recruiting participants to additional groups [56, 57], while one mentioned limited resources ("budgetary and staffing constraints") which led the researchers to decide pre-study to conduct five focus groups [38]. This last study also claimed to have reached saturation (without stating this as the procedure for deciding number of groups):

그러나 데이터 분석에 따르면 모든 테마가 포화 상태에 이르렀으며, 이는 추가 참가자가 상위 응답의 깊이 또는 폭을 추가하지 않았을 가능성이 크다는 것을 의미한다[38].

However, data analysis indicates that all themes reached saturation, meaning additional participants would likely not have added to the depth or breadth of parent responses [38]

추가 8개 연구에서도 모집 한도에 대해 기술했지만, 참가자가 몇 개의 그룹으로 나뉘었는지에 대한 설명이 아닌 전체 참여자 수에 대한 설명으로만 기술했다. 이들 연구에서는 교과서 추천으로 그룹 규모가 사전에 결정된 것으로 보여 그룹별 참여자 수를 이미 모집한 총인원으로 나눈 그룹 수를 정했다.

An additional eight studies also described recruitment limitations, but only as an explanation for the total number of participants, not for how many groups the participants were divided into. In these studies, the size of the groups seems to have been decided beforehand, due to text book recommendations, and thus the number of groups was given by the total number of already recruited participants divided by the number of participants per group.

고찰 Discussion

1998년, 2003년 및 2008년의 검색 결과는 지난 10년 동안 포커스 그룹 연구가 증가했다는 주장을 뒷받침한다. 2008년에 포커스 그룹 연구를 발행하는 건강 저널의 광범위한 범위는 이 방법이 현재 널리 받아들여지고 있음을 나타낸다. 동시에, 많은 저널이 일년에 한두 개의 포커스 그룹 연구를 발표한다는 사실 또한 포커스 그룹 연구를 평가하기 위한 편집자와 검토자 사이의 방법론적 역량이 부족함을 의미할 수 있다.

The results from our searches from 1998, 2003 and 2008 support the claims that there has been an increase in focus group studies over the last ten years. The wide range of health journals publishing focus group studies in 2008 indicates that this method is now widely accepted. At the same time, the fact that many journals publish only one or two focus group studies a year could also mean that the methodological competence among editors and reviewers to assess focus group studies is lacking.

우리가 등록한 포커스 그룹의 수에서 큰 variation는 놀랍고, 교재나 교과서의 저자들이 추측하는 것보다 더 넓었다wider. 예를 들어 Stewart 외 연구진[13](2007:58)은 "대부분의 포커스 그룹 애플리케이션은 한 개 이상의 그룹을 포함하지만 세 개 또는 네 개 이상의 그룹을 포함하는 경우는 거의 없다"고 주장한다. 또한 Two high 및 Putnam은 1차 치료 연구에서 포커스 그룹 연구의 검토에서 훨씬 더 좁은 변동을 발견했으며, 연구당 2 - 8 그룹의 범위를 가지고 있다[7].

The great variation in the number of focus groups that we registered was surprising, and was wider than authors of teaching materials and text books assume. For example Stewart et al [13] (2007:58) claim: "Most focus group applications involve more than one group, but seldom more than three or four groups." Twohig and Putnam also found a much narrower variation in their review of focus group studies in primary care research, with a range of two to eight groups per study [7].

전반적으로, 표본 크기에 대한 보고와 이 크기에 대한 설명은 부실했습니다. 설명이 제공된 경우, 주로 데이터 포화의 개념의 지배적인 역할을 확인했다.

Overall, reporting of sample size and explanations for this size was poor. Where such explanations were given, our study confirms the dominant role of the concept of data saturation.

우리는 또한 모든 설명이 두 개에서 13개 그룹의 연구에서 발견되었다는 것을 발견했다. 이러한 연구의 일부는 이 지침에서 권장되는 범주당 2-5개의 포커스 그룹이 연구에서 총 2-5개의 그룹이 된 것처럼 보이지만, 그들의 수를 정당화하기 위해 기존의 실용적인 지침을 참조한다. 어쩌면 [rule of thumb에 어긋나는 숫자인 하나의 포커스 그룹]만 사용하는 연구는 정당화하기가 너무 어렵고, 따라서 설명이 회피된다고 추측할 수 있다.

We also discovered that all explanations were found in studies of between two and 13 groups. Some of these studies refer to existing pragmatic guidelines to justify their numbers, although the two to five focus groups per category recommended in these guidelines sometimes appear to have become two to five groups in total in the studies. We could speculate that studies using only one focus group, a number that goes against the rules of thumb offered by these guidelines, is simply too hard to justify and explanations are therefore evaded.

또한 모든 단일 그룹 연구는 혼합 방법 연구였으며, 포커스 그룹은 일반적으로 연구의 조사 부분에 대한 설문지를 개발하거나 테스트하기 위해 파일럿으로 사용되었다. 이러한 예에서 포커스 그룹이 연구의 주요 부분보다 덜 주의를 기울인다는 것은 이해할 수 있다. 척도의 다른 쪽 끝에서, 표본 크기가 두 자리 숫자에 도달하면, 큰 N이 양의 자산으로 간주되어 정당화하기에 덜 중요한 "양적 연구의 논리"가 시작된다고 가정할 수도 있다.

Also, all the single group studies were mixed methods studies, where the focus group typically was used as a pilot to develop or test a questionnaire for the survey part of the study. In these examples, it is understandable that the focus group is offered less attention than the main part of the study. At the other end of the scale, one could also speculate that when the sample size reaches two-digit numbers, a "quantitative study logic" kicks in where a big N is seen as a positive asset and therefore less important to justify.

데이터 포화를 포커스 그룹의 수에 대한 설명으로 언급한 연구의 약 절반은 접근법의 사용에 일관성이 없는 것으로 보였다. 이러한 결과는 해당 분야의 초기 검토와도 부합한다.

- 투하이(Twohigh)와 푸트남(Putnam)[7]도 포커스 그룹 연구의 절차와 보고의 variation에 놀랐고,

- 간호 연구에서 포커스 그룹 연구를 검토한 웹과 케번[58]은 저자들이 "근거 이론"과 같은 용어를 non-rigorous한 방식으로 사용했다는 것을 발견했다.

- 또한 연구자들이 전체적으로 동시적 데이터 생성 및 분석, 또는 "반복적 프로세스"와 같은 포화 상태에 도달하기 위한 기본적인 전제를 따르지 않았다고 결론짓는다[15].

우리의 연구는 동일한 경향을 보여주며, 의료 연구에서 포커스 그룹의 사용이 증가했다고 보고의 질이 향상되지는 않았음을 시사한다.

Roughly half of the studies that referred to data saturation as an explanation for number of focus groups did not appear to be consistent in their use of approach. These findings support earlier reviews of the field.

- Twohig and Putnam [7], were also startled by the variation in procedures and reporting of focus group studies, and

- Webb and Kevern [58], who reviewed focus group studies in nursing research, found that authors used terms such as "Grounded theory" in non-rigorous ways.

- These authors also conclude that researchers, on the whole, did not follow basic premises for reaching saturation such as concurrent data generation and analysis, or an "iterative process" [15].

Our study shows the same tendencies, and suggests that the increased use of focus groups in health care studies has not led to an improvement in the quality of reporting.

우리는 또한 우리가 찾지 못한 것에 충격을 받았다. 포커스 그룹 연구에 대한 우리의 경험에서, [모집recruitment 문제]는 이 검토가 나타내는 것보다 훨씬 더 흔하다. 또한 제한된 비용과 시간을 포함하여 수행된 포커스 그룹의 수를 제한할 수 있는 여러 가지 현실적인 한계가 발생한다. 자원 제약이 제기된 한 연구를 제외하고, 언급된 유일한 실질적인 제한은 더 많은 참여자를 모집하는 데 어려움이 있었다.

We were also struck by what we did not find. In our own experience with focus group research, recruitment problems are much more common than this review indicates. In addition, a number of practical limitations arise that can limit the number of focus groups conducted, including limited money and time. Excepting one study, where resource constraints were brought up, the only practical limitations mentioned were difficulties in recruiting more participants.

또 다른 'non-finding'은 [많은 수의 포커스 그룹]을 연구의 잠재적 한계로 논의한 연구가 없다는 것이다. 이러한 연구에서 데이터의 풍부함과 깊이를 도출하기 위한 정성적 방법론의 장점에 대한 빈번한 언급을 고려할 때, 저자들이 다수의 포커스 그룹의 데이터를 철저히 분석하기 어렵다는 주장을 전혀 사용하지 않은 이유는 명확하지 않다.

Another non-finding was that none of the studies discussed a large number of focus groups as a potential limitation of the study. Given frequent references in these studies to the advantages of qualitative methodology for eliciting richness and depth of the data, it is not evident why the authors never used the argument that data from a large number of focus groups is difficult to analyse thoroughly.

잘못된 보고는 어떻게 설명할 수 있는가?

How can poor reporting be explained?

연구에 나타난 부적절한 보고는 [대부분의 건강 과학 저널이, 질적 연구자들에게 구체적인 보고 기준을 요구하지 않는다는 사실]을 반영할 수 있다. 그러나, 이러한 저자들 사이의 부실한 보고는 또한 포커스 그룹 기반 데이터 수집을 수행하고자 하는 연구자들에게 적절하게 기술되고 일관된 조언이 부족함을 반영하는 포커스 그룹의 수를 언제 어떻게 결정해야 하는지에 대한 혼란을 나타내는 것 같다.

The inadequate reporting indicated in our study could reflect the fact that most health science journals do not require specific standards of reporting from contributors presenting qualitative research. However, the poor reporting among these authors also seem to indicate confusion about when and how to decide the number of focus groups, which may reflect a lack of properly described, consistent advice to researchers wishing to carry out focus group-based data collection.

teaching material에서 표본 크기에 대한 주의의 부족은 표본 크기가 그러한 연구에서 중요하지 않다는 표시로 쉽게 인식될 수 있다. 게다가, 제공되는 조언은 혼란스럽고 때로는 상충되기도 한다.

- 글레이저와 스트라우스의 이론적 포화 절차는 저자들에게 이론적인 표본 추출을 사용하고 포화 상태가 될 때까지 반복적으로 데이터를 분석하고 수집하도록 지시하지만, 이 접근법을 어떻게 운용할지에 대한 자세한 해석을 제공하지 않는다.

- 한편, 포커스 그룹 방법론에 관한 "how to do" 문헌은 [포화점에 도달하기 전에 연구자들이 수행하기를 기대해야 하는 그룹의 수]에 관한 실용적인 조언을 제공하지만, [실제 포화점을 어떻게 결정할지]는 명확히 하지 않는다. 따라서 이 조언은 연구자들이 그룹 수에 대한 그들의 제안을 따르고, 모든 데이터를 수집한 후에 분석을 하도록 유혹할 수 있다. 그런 다음 데이터가 포화 상태에 이를 것으로 예상함에 따라 포화 상태에 대한 결론을 도출할 때 비판적 감각이 저하될 수 있습니다.

The lack of attention to sample size in the teaching material could easily be perceived as an indication that sample size is unimportant in such studies. In addition, the advice that is offered is confusing and sometimes conflicting.

- While the Glaser and Strauss's procedure of theoretical saturation instructs authors to use theoretical sampling and to analyse and collect data iteratively until saturation is achieved, it does not offer a detailed interpretation of how to operationalise this approach.

- The "how to do" literature on focus group methodology, on the other hand, offers pragmatic advice regarding the number of groups that researchers should expect to conduct before point of saturation is reached, but do not clarify how to decide about point of saturation in practice. This advice may thus tempt researchers to follow their suggestions for number of groups and do the analysis after collecting all data. Then, as they expect data to be saturated, their critical sense could be undermined when drawing conclusions about saturation.

데이터 포화 개념의 실제 적용 문제가 있음에도, '데이터 포화'는 질적 건강 연구에서 무언가 이상적인 것이 된 것 같다. 이는 비록 제대로 운영되지 않았지만, 필요한 정확한 인터뷰 수에 대한 조언을 제공하는 유일한 이론이기 때문일 수 있다. 전통적으로 건강 연구의 긍정적인 영역에서 편집자들은 정확한 수의 그룹에 대한 설명을 선호하는 경향이 있을 것이다. 실무적 한계, 특히 경제적 또는 자원적 한계에 대한 명시적 언급은 허용되지 않을 수 있다.

Despite problems associated with the practical application of the concept of data saturation, it seems to have become something of an ideal in qualitative health research. This could be due to the fact that it is the only theory that offers advice, albeit, poorly operationalised, about the exact number of interviews needed. It is plausible that editors in the traditionally positivistic realm of health research are inclined to prefer explanations for exact number of groups. Practical limitations might not be as acceptable, especially not explicit references to economic or resource limitations.

이러한 연구의 방법론 논의에서 저자들은 종종 질적 연구에서 작은 표본 크기가 합법적이라고 지적한다. 동시에, 그들은 종종 항상 연구 한계로 간주되는 작은 표본 크기를 정당화해야 할 필요성을 느낀다. 이것은 질적 연구가 보건 과학 저널에서 여전히 소수라는 사실의 결과일 수 있다. 실증주의적 관점에서는 "지나치게 많은 그룹"이라는 것이 가능하다는 주장을 어렵게 만든다. 그럼에도 불구하고, 질적연구의 품질은 데이터의 깊이와 풍부성 및 분석에 따라 달라진다. 따라서 [포커스 그룹의 수]와 [설명의 thickness] 사이의 tradeoff에 대한 레퍼런스는 (제한된) 표본 크기에 대해 허용 가능한 설명이어야 한다. 표본 규모에도 윤리적 측면이 있다: 과도한 인터뷰는 추가적인 과학적 가치에 의해 정당화되지 않고, 환자나 의료 종사자들에게 부담을 주는 것을 의미하므로 비윤리적인 것으로 간주될 수 있다.

In the methodology discussions of these studies, authors often point out that small sample sizes are legitimate in qualitative studies. At the same time, they often feel the need to justify small sample sizes which they invariably see as a study limitation. This may be a consequence of the fact that qualitative studies are still in a minority in health science journals. Here, more positivistic traditions may make it difficult to argue that a qualitative study can have too many groups. Nevertheless, the quality of qualitative studies does depend on the depth and richness of the data and its analysis. Reference to the trade-off between number of focus groups and the thickness of our description should therefore be an acceptable explanation for (a limited) sample size. There is also an ethical side to sample size: an excessive number of interviews means placing a burden on patients or health workers that is not legitimised by added scientific value and can thereby be seen as unethical.

강점 및 제한 사항 연구

Study strengths and limitations

우리의 연구의 한계는 우리의 샘플이 오픈 액세스 저널에서 채취되었다는 것이었다. 이를 통해 관리 가능한 연구 샘플에 쉽고 즉시 액세스할 수 있고 독자가 결과를 쉽게 확인할 수 있지만, 열린 액세스 필터 없이 빠르게 검색하면 2008년에 발표된 모든 포커스 그룹 연구의 20% 미만을 나타내는 샘플이다. 우리는 우리의 샘플이 사용 가능한 연구의 나머지 80%와 어떻게 다를 수 있는지에 대해 상대적으로 거의 알지 못한다. 현재 연구에 따르면 개방형 저널에 게재된 기사는 다른 기사보다 더 자주 인용된다[59]. 따라서 우리가 평가한 논문은 다른 비개방형 기사보다 더 높은 프로파일일 수 있으며 다른 연구자의 예로서 사용될 가능성이 더 높을 수 있다. 우리는 우리의 연구 결과가 주로 개방형 접근 연구에 유효하다는 것을 강조하지만, 따라서 이러한 보고서의 품질을 확보하는 것이 더욱 중요해 보인다.

A limitation of our study was that our sample was taken from open-access journals. While this gave us easy and immediate access to a manageable sample of studies and also allows our readers to easily check our results, a quick search without the open access filter indicates that our sample represents less than 20% of all published focus group studies in 2008. We know relatively little about how our sample might differ from the remaining 80% of available studies. Current research does suggest that articles published in open-access journals are more often cited than other articles [59]. It is therefore possible that the articles we evaluated are of a higher profile than other non-open-access articles and may be more likely to serve as examples for other researchers. While we emphasise that our findings are primarily valid for open access studies, it therefore seems all the more important to secure the quality of these reports.

우리는 포커스 그룹 인터뷰가 종종 주로 정량적 설계의 일부인 혼합 방법 연구도 포함시켰다. 그러한 연구에서 저자들은 질적 연구를 보고하기 위한 표준을 준수하는 것을 목표로 하지 않을 수 있다. 한편, 포커스 그룹을 사용했다고 보고한 연구자들은 그러한 연구에 대한 방법론적 기준을 준수해야 한다고 주장할 수 있다.

We have therefore also included mixed method studies, where the focus group interviews are often part of a predominantly quantitative design. In such studies the authors may not aim to adhere to standards for reporting qualitative studies. On the other hand, it could be argued that researchers who report that they have used focus groups should adhere to the methodological standards for such studies.

결론

Conclusions

연구자들은 사용된 방법에 대해 항상 정확하고 상세한 정보를 제공해야 하지만, 우리의 연구는 포커스 그룹 샘플 크기에 대한 불충분하고 일관되지 않은 보고를 보여준다.

While researchers should always provide correct and detailed information about the methods used, our study shows poor and inconsistent reporting of focus group sample size. Editorial teams should be encouraged to use guidelines for reporting of methods for qualitative studies, such as RATS http://www.biomedcentral.com/info/ifora/rats.

우리의 연구는 또한 잘못된 보고가 최적의 표본 크기를 달성하는 방법에 대한 명확하고 증거 기반 지침의 부족을 반영할 수 있다는 것을 보여준다. 이러한 상황을 수정하기 위해서는, (경험적 연구에 기초한) 교재와 교과서를 포커스 그룹 방법론에 사용해야 하며, 적용 가능하고 정확한 권고사항이 필요하다. 아이러니하게도 [고품질 방법론 연구]의 한 가지 장애물은 현재와 같은 [일차 연구 저자들의 부적절한 보고]이다.

Our study also indicates that poor reporting could reflect a lack of clear, evidence-based guidance about how to achieve optimal sample size. To amend this situation, text books and teaching material based on empirical studies into the use of focus group methodology and applicable and precise recommendations are needed. Ironically, one barrier to high-quality methodological studies is the current lack of proper reporting by authors of primary studies.

BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011 Mar 11;11:26.

doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-26.

What about N? A methodological study of sample-size reporting in focus group studies

Benedicte Carlsen 1, Claire Glenton

Affiliations collapse

Affiliation

- 1Uni Rokkan Centre, Nygårdsgt 5, N-5015 Bergen, Norway. benedicte.carlsen@uni.no

- PMID: 21396104

- PMCID: PMC3061958

Free PMC article

Abstract

Background: Focus group studies are increasingly published in health related journals, but we know little about how researchers use this method, particularly how they determine the number of focus groups to conduct. The methodological literature commonly advises researchers to follow principles of data saturation, although practical advise on how to do this is lacking. Our objectives were firstly, to describe the current status of sample size in focus group studies reported in health journals. Secondly, to assess whether and how researchers explain the number of focus groups they carry out.

Methods: We searched PubMed for studies that had used focus groups and that had been published in open access journals during 2008, and extracted data on the number of focus groups and on any explanation authors gave for this number. We also did a qualitative assessment of the papers with regard to how number of groups was explained and discussed.

Results: We identified 220 papers published in 117 journals. In these papers insufficient reporting of sample sizes was common. The number of focus groups conducted varied greatly (mean 8.4, median 5, range 1 to 96). Thirty seven (17%) studies attempted to explain the number of groups. Six studies referred to rules of thumb in the literature, three stated that they were unable to organize more groups for practical reasons, while 28 studies stated that they had reached a point of saturation. Among those stating that they had reached a point of saturation, several appeared not to have followed principles from grounded theory where data collection and analysis is an iterative process until saturation is reached. Studies with high numbers of focus groups did not offer explanations for number of groups. Too much data as a study weakness was not an issue discussed in any of the reviewed papers.

Conclusions: Based on these findings we suggest that journals adopt more stringent requirements for focus group method reporting. The often poor and inconsistent reporting seen in these studies may also reflect the lack of clear, evidence-based guidance about deciding on sample size. More empirical research is needed to develop focus group methodology.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 의학교육연구(Research)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 일반화가능도 이론 간단히: G-studies를 위한 프라이머(J Grad Med Educ, 2019) (0) | 2021.05.06 |

|---|---|

| 설문 설계의 단계 따라가기: GME 연구 사례(J Grad Med Educ, 2013) (0) | 2021.05.06 |

| 질적 면담 연구에서 샘플 사이즈: 정보력에 의하여 (Qual Health Res, 2016) (0) | 2021.05.06 |

| 교육 디자인연구(EDR) 수행을 위한 열두 가지 팁(Med Teach, 2020) (0) | 2021.05.01 |

| 교육이론을 활용하는 다섯 가지 원칙: HPE 연구를 발전시키기 위한 전략(Acad Med, 2020) (0) | 2021.04.30 |