내과의 종단적 코칭 프로그램에서 목표의 공동구성 및 대화(Med Educ, 2022)

Goal co-construction and dialogue in an internal medicine longitudinal coaching programme

Laura Farrell1 | Cary Cuncic1 | Wendy Hartford2 | Rose Hatala1 | Rola Ajjawi3

1 소개

1 INTRODUCTION

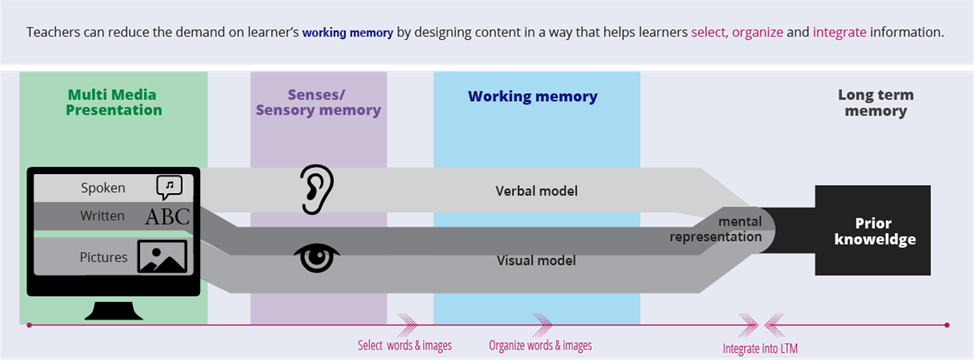

코칭은 특히 역량 기반 의학교육(CBME)의 도입과 함께 대학원 의학교육에서 각광을 받고 있습니다. 북미 지역에서는 레지던트 프로그램에서 '학습자가 잠재력을 최대한 발휘할 수 있도록' 종단적 학업 코치 역할을 할 교수진을 배정하기 시작했습니다.1 캐나다 왕립 의사 및 외과의사 대학(RCPSC)은 이러한 '시간 경과에 따른 코칭'2,3 이 임상 환경 밖에서 이루어지며, 여러 프리셉터와 짧고 단편적인 로테이션으로 인해 평가가 수집되지만 반드시 의미 있는 방식으로 집계되지 않는 문제를 해결하기 위해 필요하다고 설명했습니다.4, 5 레지던트와 코치는 평가 데이터를 협력적이고 성찰적으로 검토하여 역량 발전을 돕고, 이상적으로는 레지던트의 자기조절학습(SRL) 기술을 개발합니다.6-9 많은 프로그램이 이러한 종단적 코칭 모델을 채택하고 있지만, 프로그램에서 시행하는 코칭은 일반적으로 보다 지시적인 상호작용인 조언 및 멘토링과 같은 다른 역할과 모호해질 위험이 있습니다.10 종단적 코치는 학습자 목표와 프로그램 요구사항에 모두 초점을 맞추도록 해야 합니다.2

Coaching has gained prominence in postgraduate medical education, particularly with the introduction of Competency-Based Medical Education (CBME). Within North America, residency programmes have begun to assign faculty to act as longitudinal academic coaches, ‘to facilitate learners achieving their full potential’.1 The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada (RCPSC) has described this ‘coaching over time’2, 3 as occurring outside the clinical environment to address the challenges of short, fragmented rotations with different preceptors, where assessments are collected but not necessarily collated in a meaningful way.4, 5 Residents and coaches collaboratively and reflectively review assessment data to aid in progression of competence, ideally developing residents' self-regulated learning (SRL) skills.6-9 Despite many programmes adopting this longitudinal coaching model, coaching that is implemented by the programme risks blurring with other roles such as advising and mentoring, which are generally more directive interactions.10 Longitudinal coaches are challenged to ensure a focus both on learner goals and on programme requirements.2

스포츠, 음악 및 비즈니스에서 배운 것을 모델로 한 다양한 종단 코칭 프로그램의 개발이 설명되었습니다.4, 11, 12 학업 코치는 대부분 프로그램에서 의도적으로 전공의와 짝을 이루어 그들의 전문성을 활용하여 관련 평가 정보를 논의하고, 전공의가 앞으로 나아가는 데 도움이 되는 달성 가능한 목표를 공동 구성하고, 목표 도달 여부를 평가합니다.2, 4, 11 이상적으로는 레지던트가 취약점을 공유하고 이를 통해 지속적인 SRL(목표 설정, 성과 모니터링, 학습 계획 반영 및 조정)에 필요한 기술을 개발할 수 있는 기회가 있습니다.5 코치는 코치가 레지던트 네트워크의 일부가 되어 공동 목표 설정, 성과 모니터링 및 반영에 참여하면서 학습을 공동 조정할 수 있습니다.13 성과 목표 개발에 피드백을 통합하는 것을 명확하게 강조하는 코칭 논의에 대한 다양한 접근법이 제공되었습니다.4, 7, 9, 12 예를 들어, R2C2(관계, 반응, 내용 및 코칭) 모델은 달성 가능한 목표를 설정하고 피드백을 중심으로 학습 변화 계획을 개발하는 코칭의 중요성을 강조합니다.7, 9

The development of various longitudinal coaching programmes, modelled from what has been learned from sport, music and business, have been described.4, 11, 12 Academic coaches are most often intentionally paired with residents by the programme and draw on their expertise to discuss relevant assessment information, co-construct achievable goals that aid the resident to move forward and assess whether goals have been reached.2, 4, 11 Ideally, there is opportunity for the resident to share vulnerabilities and in doing so develop skills needed for ongoing SRL (goal setting, monitoring performance, reflecting and adapting a learning plan).5 Coaches may co-regulate learning as the coach becomes part of the resident network, engaging the resident in collaborative goal setting, performance monitoring and reflection.13 Various approaches to coaching discussions have been provided that place clear emphasis on the incorporation of feedback into developing performance goals.4, 7, 9, 12 For example, the R2C2 (relationship, reaction, content and coaching) model emphasises the importance of coaching where achievable goals are set and a learning change plan developed around feedback.7, 9

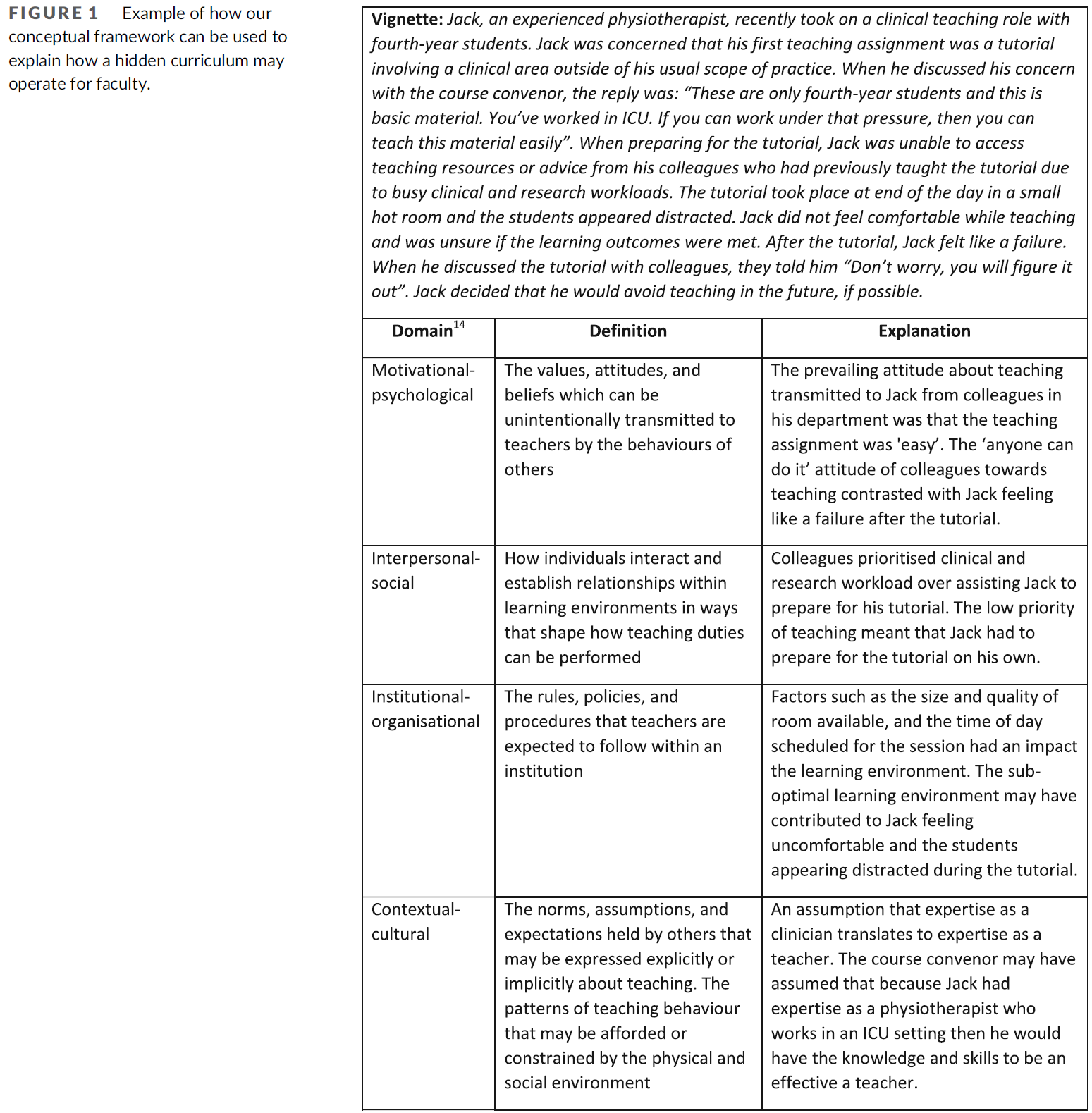

목표 개발에 대한 의도적인 강조에도 불구하고, 현재 종단적 코칭 대화에서 목표가 어떻게 논의되고 목표 공동 구성이 어떻게 진행되는지에 대한 설명은 거의 없습니다. 또한 이러한 대화에서 논의되는 내용이 전공의의 성장을 어떻게 지원할 수 있는지에 대해서는 추가적인 연구가 필요합니다. 따라서 임상 교육에서 피드백 대화에서 목표에 대한 의도적인 대화에 대해 이해한 내용을 바탕으로 코칭 환경에서 목표를 성공적으로 공동 구성하는 데 필요한 요소를 밝히는 것이 유용할 수 있습니다. 피드백 문헌에 따르면, 프리셉터가 목표의 필요성을 역할 모델링하고 학생을 목표에 대한 대화에 참여시키는 초기 목표 설정 및 목표 논의에 중점을 둡니다.14, 15 목표 불일치는 프리셉터와 학습자 간에 단순히 어떤 목표를 우선순위에 둘 것인지뿐만 아니라 학습자가 인지한 필요와 프리셉터의 기대를 모두 충족하는 새로운 목표를 생성하기 위해 협상됩니다. 목표 공동 구성의 원칙을 통합하면 코치와 레지던트가 종단적 코칭에서 목표를 식별하고 우선순위를 정하는 데 도움이 될 수 있습니다.15 그러나 피드백 대화에서 목표 설정과 관련된 문제는 종단적 코칭 관계에서 다르게 나타날 수 있습니다.

Despite an intentional emphasis on goal development, currently, there is little description of how goals are discussed and how goal co-construction plays out in longitudinal coaching conversations. In addition, how the content of the discussions during these conversations might support residents' growth needs further study. It may, therefore, be useful to draw on what is understood around intentional dialogue of goals in feedback conversations in clinical teaching to shed light on the elements needed to successfully co-construct goals in the coaching setting. From the feedback literature, there is a focus on initial goal setting and discussion of goals, where the preceptor role models the need for goals and engages students in dialogue around their goals.14, 15 Goal mismatches are negotiated between preceptor and learner not merely around which or whose goals to prioritise but also to generate new goals that address both learners' perceived needs and preceptors' expectations. Incorporating tenets of goal co-construction may help coaches and residents identify and prioritise goals in longitudinal coaching.15 However, challenges around goal setting in feedback conversations may manifest differently in the longitudinal coaching relationship.

이 연구에서는 내과 종단 코칭 프로그램에서 코치와 레지던트 간의 실제 코칭 대화를 분석했습니다. 이 연구는 목표 공동 구성을 민감화 개념으로 사용하여 코칭 관계와 공동 피드백에 대한 대화를 탐색함으로써 종단 코칭에 대해 현재 이해되고 있는 내용을 기반으로 합니다. 레지던트의 목표와 그 진화에 대한 분석을 통해 종단적 코칭이 수련 중인 레지던트에게 미칠 수 있는 과정과 효과에 대해 조명합니다. 요약하면, 이 연구는 다음과 같은 질문을 던집니다: 레지던트 의학 교육에서 종단적 코칭 관계에서 목표 공동 구성은 어떻게 전개될까요?

In this study, we analysed the actual coaching conversations between coach and resident in an internal medicine longitudinal coaching programme. Our research builds on what is currently understood about longitudinal coaching by exploring coaching relationships and dialogue around collated feedback using goal co-construction as a sensitising concept. Through analysis of residents' goals and their evolution, we shed light on the processes and effects longitudinal coaching may have on residents in training. In summary, this research asks: How does goal co-construction unfold in longitudinal coaching relationships in resident medical education?

2 방법

2 METHODS

우리는 내과 종단 코칭 프로그램을 조사하기 위해 구성주의적 탐구 지향에 부합하는 질적 연구 접근 방식인 해석적 기술법16 을 사용했습니다. 간호과학에서 비롯된 해석적 기술법의 인식론적 뿌리는 연구자가 통합된 지식을 식별하고 적용하는 과정을 포함하는 유연한 질적 접근법을 사용하여 이론을 넘어 실천으로 나아갈 수 있도록 합니다.16 해석적 기술법은 개인의 경험과 데이터 전반의 공통 패턴에 주목하고 실천에 적용할 수 있는 지식을 생성하고자 하는 매우 실용적인 접근법입니다.16

We used interpretive description,16 a qualitative research approach aligned with a constructivist orientation to inquiry, to examine an internal medicine longitudinal coaching programme. Interpretive description's epistemological roots, stemming from nursing science, allow the researcher to move beyond theory into practice using a flexible qualitative approach that includes processes for identifying and applying aggregated knowledge.16 It is a highly pragmatic approach that attends to individual experiences and common patterns across the data and seeks to generate applied knowledge for practice.16

2.1 설정 및 모집

2.1 Setting and recruitment

브리티시 컬럼비아 대학교(UBC)의 내과 레지던트 프로그램은 매년 약 50명의 레지던트를 수용하는 3년 과정의 프로그램입니다. 연구 당시에는 1년차 레지던트만 프로그램에서 학업 코치와 짝을 이루었습니다. 코치는 일반적으로 레지던트에 대한 평가나 평가에 관여하지 않았습니다. 2019년 7월에 수련을 시작한 모든 1년차 레지던트(N = 47명)와 그들의 코치(N = 30명)가 1년 동안 이 연구에 참여하도록 초대되었습니다. 코치와 레지던트는 본질적으로 취약할 수 있는 토론을 녹음하도록 요청받았기 때문에 편의 표본 추출을 사용했습니다. 코치 6명과 레지던트 8명(코치 2명은 레지던트 2명과 각각 짝을 이루었습니다)을 포함한 8쌍의 부부가 참여에 동의하고 사전 동의를 제공했습니다. 코치와 레지던트 모두 1년 동안 4번의 미팅을 오디오 테이프로 녹음하고 개별적으로 오디오 녹음된 퇴소 인터뷰에 참여하도록 요청받았습니다.

The University of British Columbia's (UBC) internal medicine residency programme is a 3-year programme accepting approximately 50 residents per year. At the time of the study, only first-year residents were being paired by the programme with an academic coach. The coach was not typically involved in assessment or evaluation of the resident. All first-year residents (N = 47) starting training in July 2019 and their coaches (N = 30) were invited to participate in this study for the duration of 1 year. We used convenience sampling as coaches and residents were asked to record discussions that could be inherently vulnerable. Eight dyads including six coaches and eight residents (two coaches were paired with two residents each) agreed to participate and provided informed consent. Both coach and resident were asked to audiotape their four meetings over a 1-year period and participate in individual audiotaped exit interviews.

2.2 코치 교육/레지던트 교육

2.2 Coach training/resident training

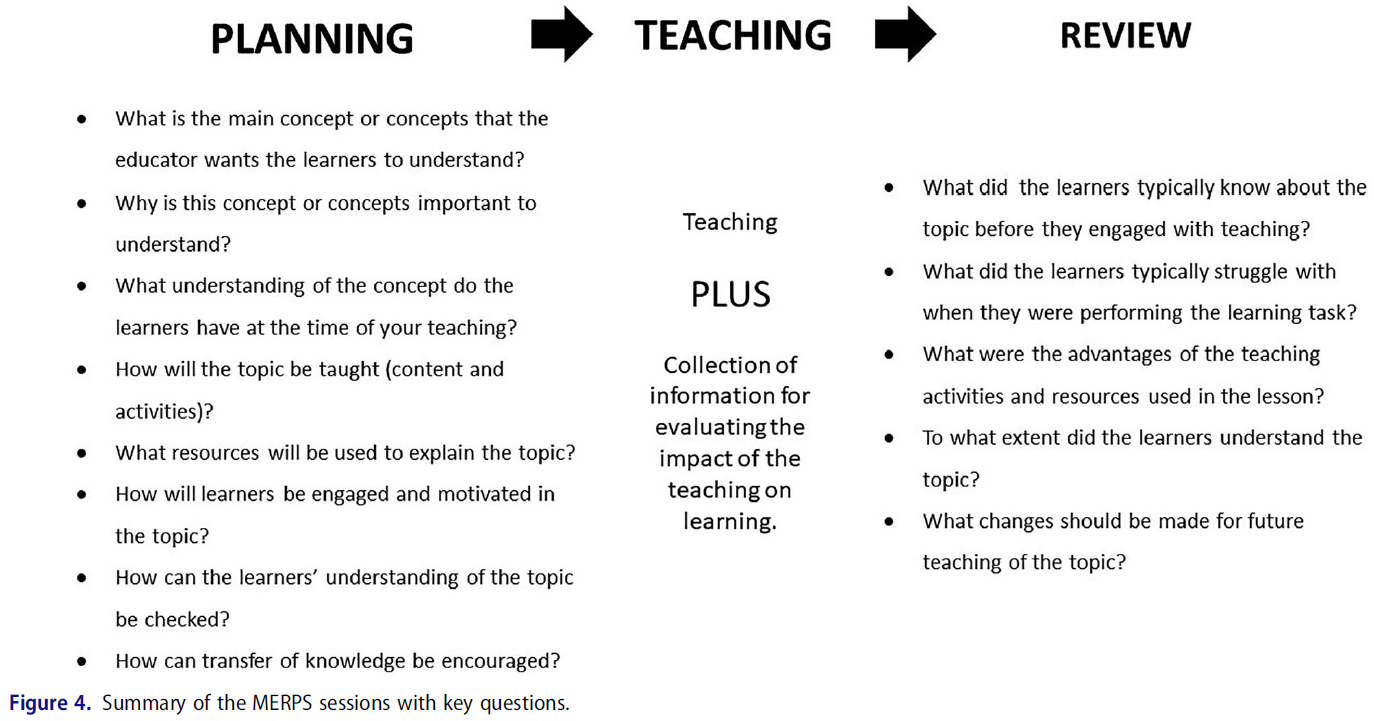

모든 코치와 레지던트는 레지던트 프로그램 디렉터, 역량 위원회 위원장 및 연구팀 구성원인 RH, LF, CC가 제공하는 별도의 교육을 받았습니다. 교육은 위에서 설명한 바와 같이, 레지던트가 역량을 발전시키고 평생 학습 기술을 구축할 수 있도록 협력적이고 성찰적으로 코칭하는 '시간에 따른 코칭'에 대한 RCPSC 접근 방식을 기반으로 이루어졌습니다.2 코칭의 틀을 제공하기 위해 R2C2 모델이 도입되었습니다.7, 9 R2C2 모델에 따라 코치는 레지던트와 관계를 구축하고, 평가에 대한 레지던트의 반응을 탐색하고, 평가의 내용을 탐색하고 변화를 위해 코치하도록 권장되었습니다.7, 9 또한 고려해야 할 성찰 프롬프트 등 R2C2에 대한 요약 팜플릿을 제공받았습니다. 이들에게는 위에 명시된 코칭 프로그램의 목적과 코치와 임상 수퍼바이저 또는 멘토의 차이점에 대한 교육이 제공되었습니다. 레지던트들은 코치에게 역량 위원회에 소감을 제출하도록 요청받지만 레지던트 진급에 관한 결정에는 직접 관여하지 않는다는 사실을 들었습니다. 변화를 위한 코칭의 일환으로 코치와 레지던트 모두와 함께 목표 공동 구성의 원칙을 검토했습니다.15

All coaches and residents underwent separate training delivered by residency programme directors, competency committee chairs and members of the research team, RH, LF and CC. Training was based on the RCPSC approach to ‘coaching over time’ as described above: to collaboratively and reflectively coach residents towards progression of competency and build lifelong learning skills.2 To provide a framework for coaching, the R2C2 model was introduced.7, 9 As per the R2C2 model, coaches were encouraged to build relationships with their residents, explore residents' reactions to the assessments, explore the content of the assessments and coach for change.7, 9 Residents were also provided with a pamphlet outlining R2C2 including reflection prompts to consider. They were educated on the above stated purpose of the coaching programme and the differences between a coach and clinical supervisor or mentor. Residents were told that their coach would be asked to provide an impression to the competency committee but would not be involved directly in the decisions regarding resident promotion. As part of coaching for change, the tenets of goal co-construction were reviewed with both coaches and residents.15

2.3 코치-전공의 회의

2.3 Coach–resident meetings

모든 레지던트는 회의 전에 자신의 최근 평가를 검토하고 강점/약점 및 학습 목표에 대해 언급하는 자기 성찰 양식을 작성하여 제출해야 했습니다. 이 문서는 레지던트의 모든 평가(필기 시험, 관찰된 구조화된 임상 시험 및 직장 기반 평가)와 더불어 코치가 회의 전에 검토하거나 회의 중에 논의했습니다. 코치는 레지던트 1년차에 세 번, 2년차 초에 한 번, 총 세 차례에 걸쳐 1시간 동안 개별 레지던트와 만났습니다.

All residents were required to complete and submit a self-reflection form involving reviewing their recent assessments and commenting on strengths/weaknesses and learning goals prior to each meeting. This document, in addition to all of the resident's evaluations (written examinations, observed structured clinical exams and workplace-based assessments), was reviewed by the coach before the meeting and/or discussed during the meeting. The coach met with their individual residents for 1 hour three times during their first year and one time during the start of their second year.

2.4 데이터 수집

2.4 Data collection

코치들은 전공의와의 미팅을 오디오 테이프로 녹음하여 연구팀에 제출하도록 요청받았습니다. 모든 코치와 8명의 전공의 중 7명이 반구조화된 퇴사 인터뷰에 참여했으며, 이 인터뷰는 WH에서 Zoom을 통해 오디오 테이프로 진행했습니다. 코칭 세션에서는 논의되는 목표의 유형, 이러한 목표가 어떻게 협상되는지, 시간이 지남에 따라 어떻게 진행되는지에 대한 데이터를 제공했습니다. 인터뷰 데이터는 코칭에 대한 참가자들의 경험을 조사했습니다. 코치에 대한 인터뷰 질문은 코칭 역할에 대한 인식, 레지던트와의 관계, 코칭 세션 중 목표 공동 구성 등을 고려했습니다(부록 S1). 레지던트를 대상으로 한 인터뷰 질문에는 목표 공동 구성 및 관계에 대한 인식 외에도 사전 성찰의 이점과 코칭의 인지된 효과도 고려되었습니다(부록 S2). 코칭 세션과 인터뷰의 오디오 테이프는 필사하고 비식별화했습니다. 8쌍의 부부 중 6쌍만 오디오테이프를 제출했으며(2쌍은 녹음에 기술적 어려움이 있었음), 총 18개의 녹취록을 제출했습니다. 3명의 dyads는 4번의 코칭 세션을 모두 제출했고, 1명은 3번, 1명은 2번, 1명은 1번의 세션만 제출했습니다. 모든 녹음 데이터는 총 894분 분량의 코칭 데이터(세션은 약 30~60분 길이로 다양함)와 총 367분 분량의 출구 인터뷰 데이터(24~34분 범위)로 분석되었습니다.

Coaches were asked to audiotape meetings with residents and submit these to the research team. All coaches and seven of the eight residents engaged in semi-structured exit interviews, which were conducted by WH via Zoom and audiotaped. The coaching sessions provided data on the types of goals being discussed, how those goals are negotiated and how they progress over time. The interview data sought participants' experiences of coaching. Interview questions for coaches considered their perceptions of the coaching role, their relationship with the resident and goal co-construction during the coaching session (Appendix S1). In addition to perceptions of goal co-construction and relationships, interview questions for residents considered the benefits of pre-reflection and perceived effects of coaching (Appendix S2). Audiotapes of the coaching sessions and interviews were transcribed and de-identified. Of the eight dyads, only six submitted audiotapes (two dyads had technical difficulties with recordings) for a total of 18 recordings. Three dyads submitted all four coaching sessions, one submitted three sessions, one submitted two sessions and one submitted only one session. All recordings were analysed for a total of 894 minutes of coaching data (sessions varied from approximately 30–60 minutes in length) and a total of 367 minutes (range 24–34 minutes) of exit interview data.

2.5 데이터 분석

2.5 Data analysis

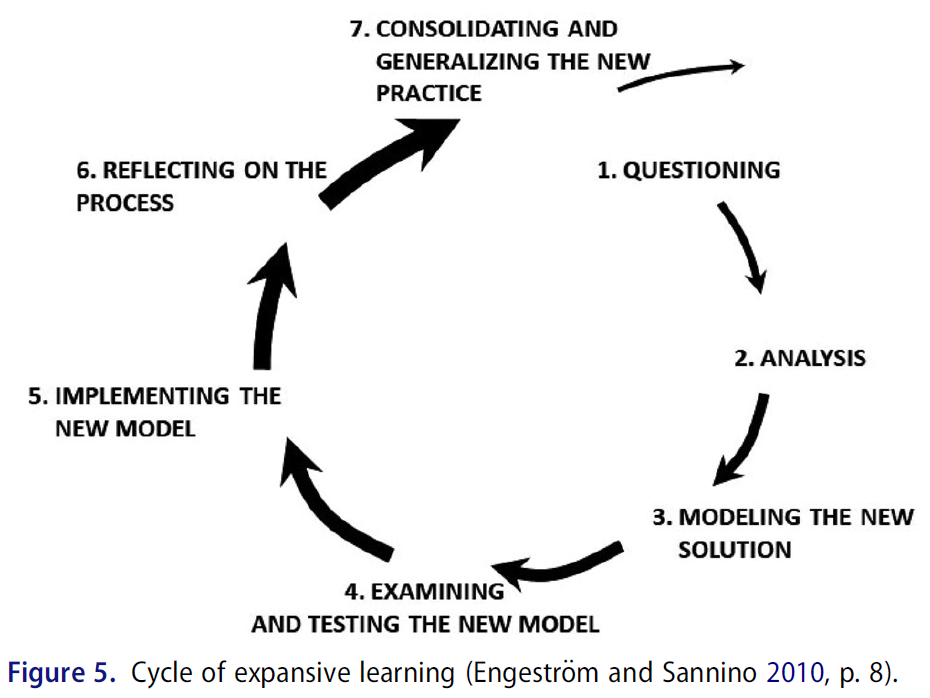

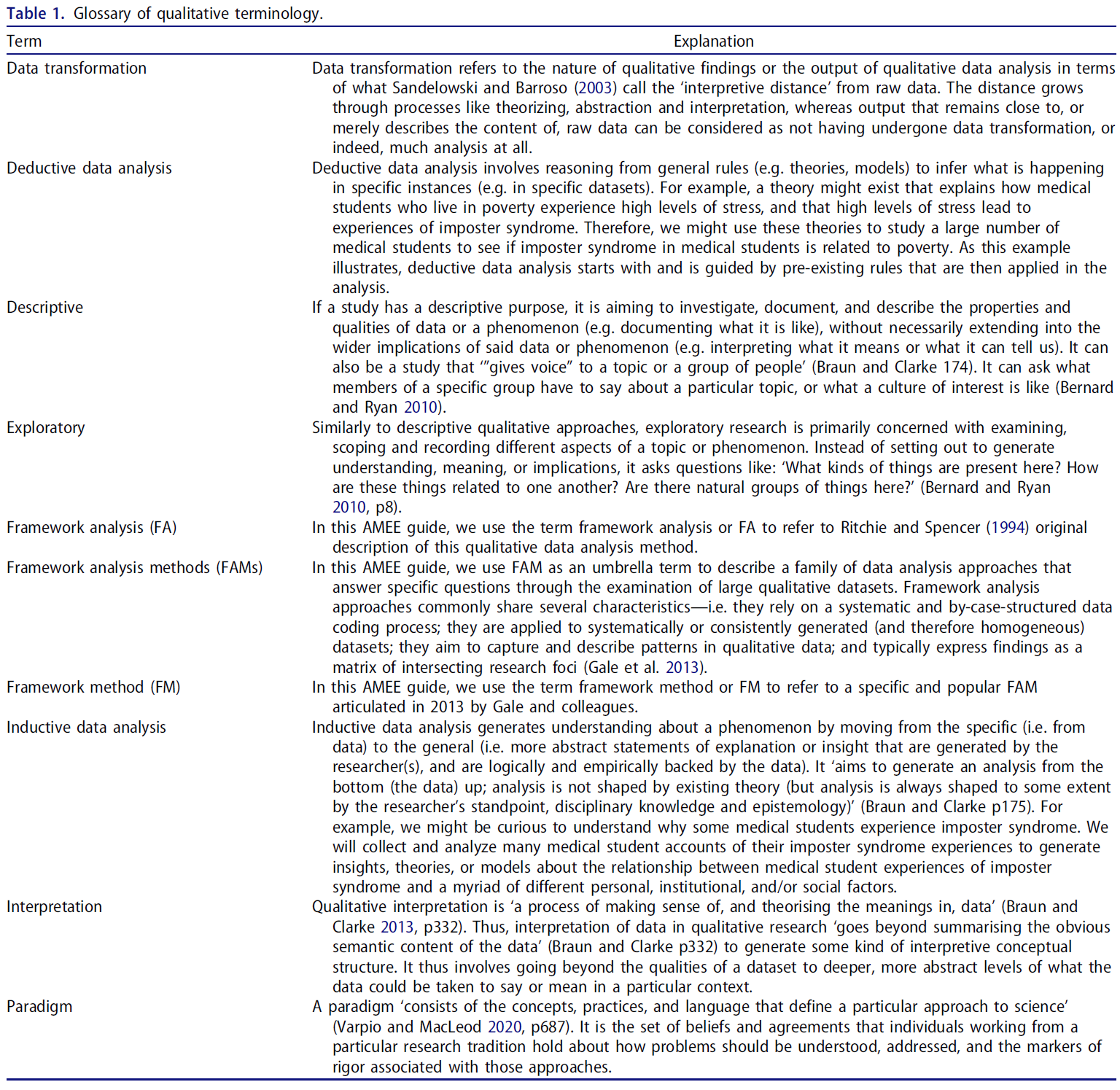

해석적 설명 Interpretive description은 연구자가 연구의 도구로서 연구자를 포용합니다.16 분석 전반에 걸쳐 우리는 문헌, 우리 자신의 해석과 경험, 경험적 데이터를 바탕으로 주제를 개발하는 분석 프레임워크를 개발하려고 노력했습니다.

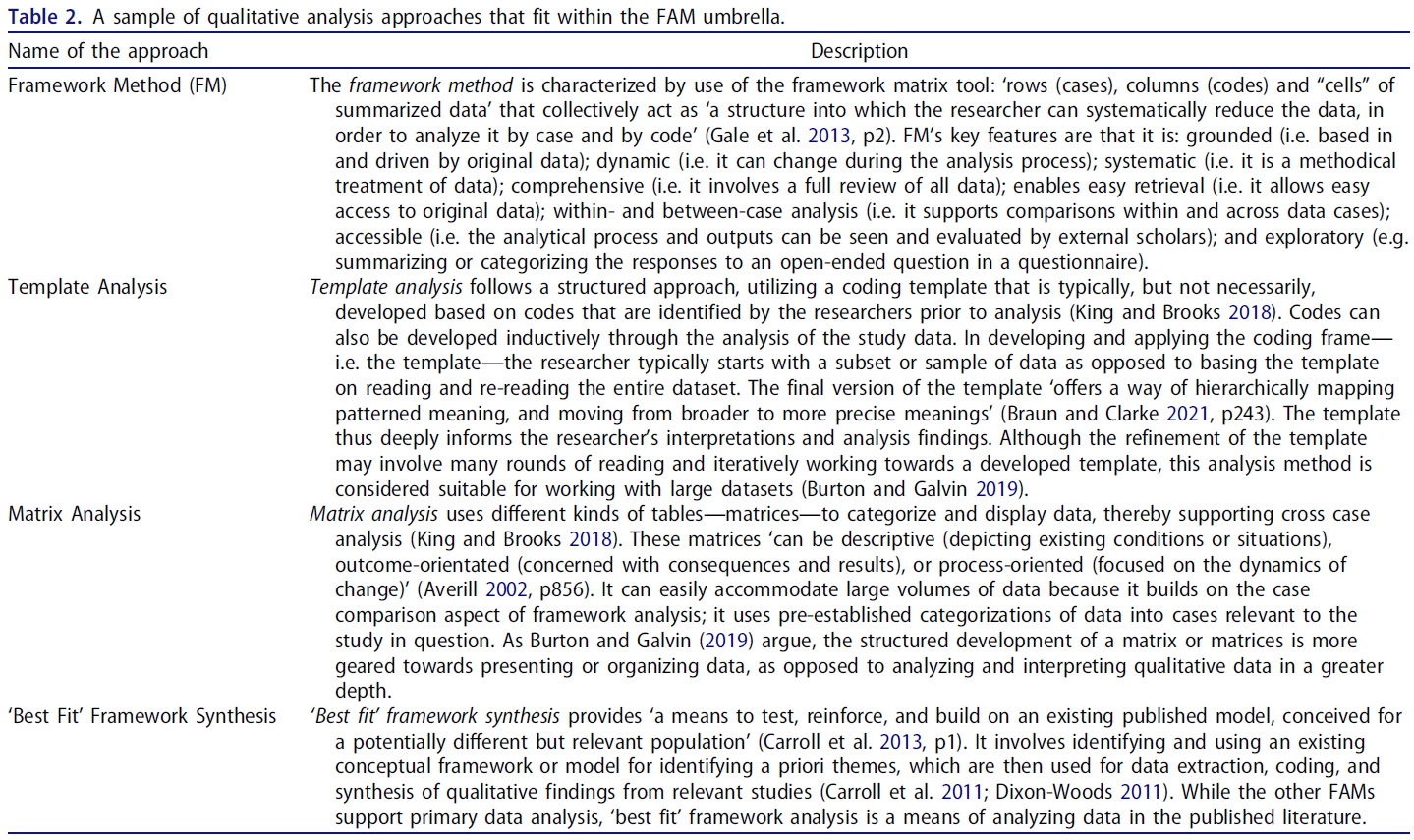

- 연구팀의 두 팀원(LF와 WH)은 모든 녹취록을 읽고 처음에는 연역적 코딩 접근법을 사용하여 코칭 데이터를 분류하고 설명하기 시작했습니다.

- 이는 R2C2 개념에 대한 코딩으로 시작하여 목표 공동 구성의 원칙(역할 모델링 목표, 목표 관련 대화, 목표 협상 및 프로그램 표준 보장)을 민감화 렌즈로 코딩했습니다.7, 9

- 또한 목표 공동 구성의 증거, 목표의 진화 및 목표 달성 계획을 포함하여 회의가 진행되는 동안 표를 사용하여 목표 유형을 귀납적으로 코딩하고 추적했습니다.

- 예비 아이디어와 주제는 데이터 샘플을 읽은 연구팀과 함께 논의하고 다듬었습니다.

- 이 단계에서는 어떤 목표가 논의되었는지, 누가(코치 또는 레지던트) 목표를 확인했는지, 목표가 어떻게 구성되었는지, 목표를 달성하기 위한 계획과 시간이 지남에 따라 목표가 어떻게 진화했는지에 특히 주의를 기울였습니다.

- 이 수준의 코딩은 '의미를 미리 결정하는 데 사용되는 것이 아니라, 식별된 주제에 대한 부분을 한곳에 모아 해석 과정을 완료하는 데 사용됩니다."(14쪽)

- 그런 다음 모든 연구자는 목표 공동 구성을 염두에 두고 출구 인터뷰와 관련하여 코치-레지던트 간 다이애드 대화를 귀납적으로 분석했습니다. 이 단계에서는 다이애드 경험의 해석(유사점과 차이점)과 코칭의 효과에 초점을 맞춰 데이터 간 연결고리를 찾았습니다.

- 팀은 정기적으로 만나 코드를 더욱 세분화하고 의미를 도출하여 참가자 경험에 대한 일관된 그림을 형성하고 데이터에서 누락될 수 있는 부분에 대해 논의했습니다. 두 가지 데이터 수집 방법과 두 참가자 그룹을 통해 강화된 데이터는 연구 질문에 답하기 위한 충분한 이해를 제공한다고 판단했습니다(Dey의 이론적 충분성 개념에서 도출).17

Interpretive description embraces the researchers as instrumental to the research.16 Throughout the analysis, we sought to develop an analytical framework that draws from the literature, our own interpretations and experiences, and the empirical data to develop themes.

- Two members of the research team (LF and WH) read all of the transcripts and initially employed a deductive coding approach to begin to categorise and describe the coaching data.

- In addition, types of goals were inductively coded and tracked using tables over the course of the meetings including evidence of goal co-construction, evolution of goals and plans to meet goals.

- Preliminary ideas and themes were discussed and refined with the research team who read a sample of the data.

- At this level, we paid particular attention to what goals were discussed, who (coach or resident) identified goals, how goals were constructed, plans to meet goals and how they evolved over time.

- Coding at this level is not used to ‘predetermine meaning, but to allow for segments about an identified topic to be assembled in one place to complete the interpretative process’.14, p. 340

- All researchers then inductively analysed one coach–resident dyad conversation in relation to the exit interviews with goal co-construction in mind. At this level, we focused on interpretations of dyad experiences (similarities and differences) and the effects of coaching making connections between the data.

- The team met regularly to further refine the codes and derive meaning and form a cohesive picture of participant experiences, as well as to discuss what might be missing in the data. We judged the data offered a sufficient understanding (drawn from Dey's notion of theoretical sufficiency) for answering the research question, strengthened by the two methods of data collection and the two participant groups.17

연구팀에는 내과 레지던트들과 임상적으로 함께 일하는 의학교육 연구 경력이 있는 세 명의 일반 내과 의사(LF, CC, RH)가 참여했습니다. LF, CC, RH는 모두 코치들을 위한 초기 교수진 개발 세션을 진행했으며 반복적인 코치 회의에 참여했습니다. LF와 CC는 현재 학술 코치이기도 하며, 코치로서의 경험이 분석에 영향을 미쳤습니다. RH는 역량 위원회 위원장을 맡고 있습니다. WH는 재활 과학 프로그램의 박사 과정 학생이며 이 연구의 연구 조교였습니다. RA는 경험이 풍부한 의학교육 연구자(피드백 대화 포함)이자 맥락과 전문 분야에 대한 외부인으로, 프로그램 내에서 당연하게 여겨지는 코칭의 가정에 대한 대화를 유도했습니다.

Members of the research team included three general internists with backgrounds in medical education research (LF, CC and RH) who all work clinically with internal medicine residents. LF, CC and RH all facilitated the initial faculty development session to coaches and participated in the iterative coach meetings. LF and CC are also current academic coaches, and their experiences as coaches influenced analysis. RH is chair of the competency committee. WH is a doctoral student in the Rehabilitation Science Program and was the research assistant for the study. RA is an experienced medical education researcher (including feedback dialogues) and outsider to the context and specialty, who prompted conversations about the taken for granted assumptions of coaching within the programme.

2.6 윤리

2.6 Ethics

이 연구는 UBC 윤리 심의 위원회(H19-00634)의 승인을 받았습니다.

This study was approved by UBC Ethics Review Board (H19-00634).

3 결과

3 RESULTS

우리는 두 가지 주제를 개발했습니다:

- (i) 목표의 내용은 레지던트가 되는 방법에 초점을 맞추었으며, 코칭 상호작용은 임상 진료 환경의 문제를 해결하는 방법에 대한 내용은 드물고, 대신 레지던트 과정에서 발생하는 많은 비환자 대면 문제에 초점을 맞추었고,

- (ii) 공동 구성은 주로 목표의 우선순위를 정하거나 새로운 목표를 식별하는 것이 아니라, 목표를 달성하는 방법에 대해 발생했습니다.

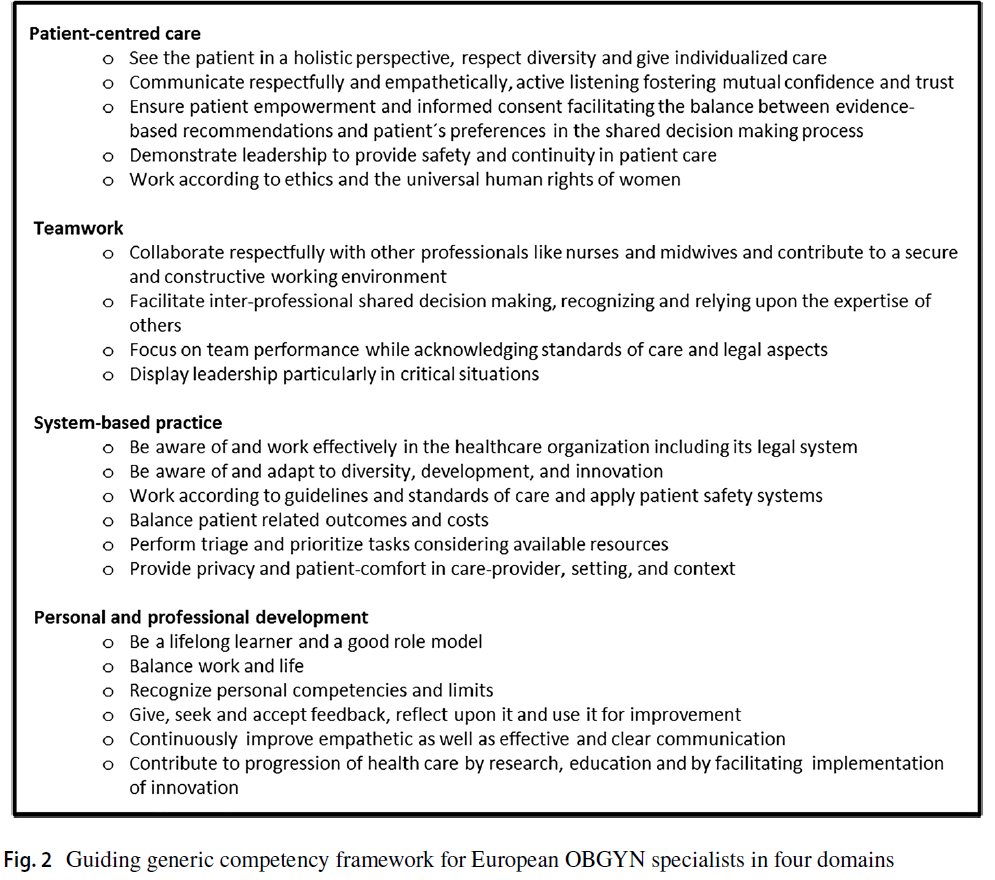

We developed two themes:

- (i) The content of the goals focused on how to be a resident, in that coaching interactions were infrequently about how to address challenges in the clinical care environment, but instead focused on many of the non-patient-facing issues that come up in residency, and

- (ii) the co-construction mainly occurred in how to meet goals, rather than in prioritising goals or identifying new goals.

3.1 목표의 내용: 레지던트가 되는 방법

3.1 Content of goals: How to be a resident

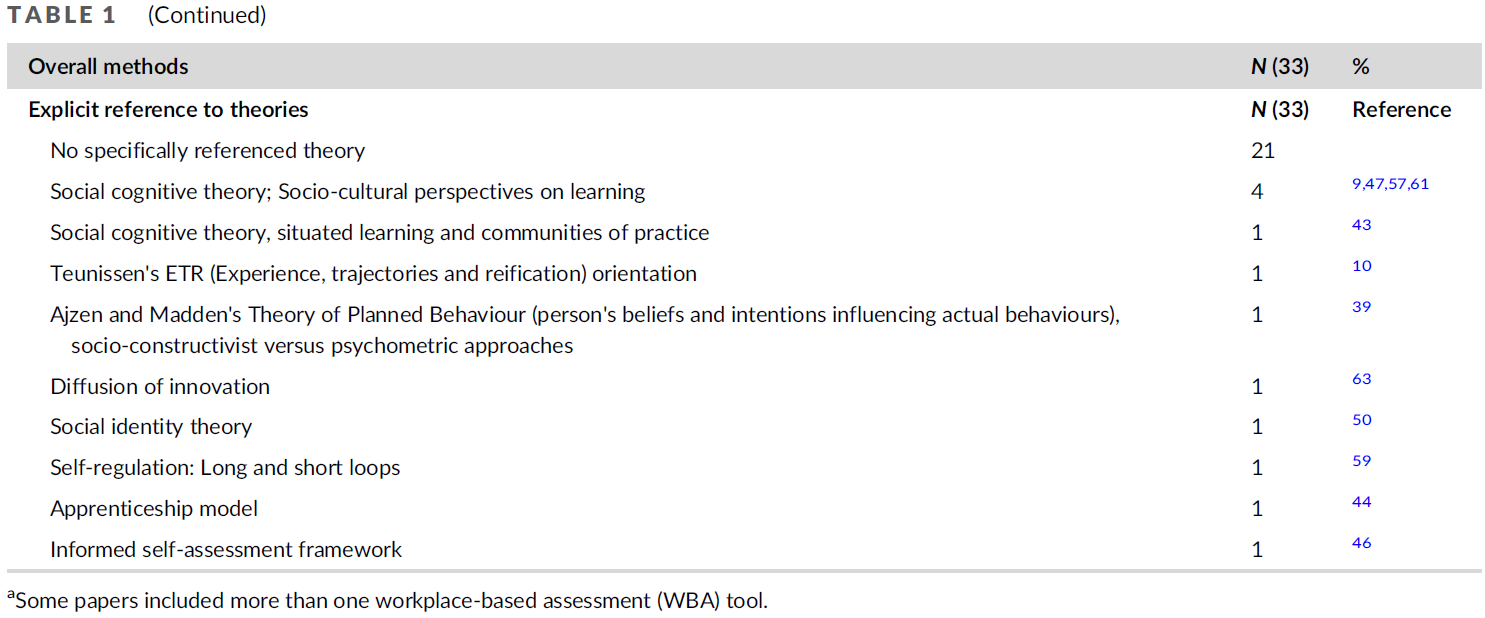

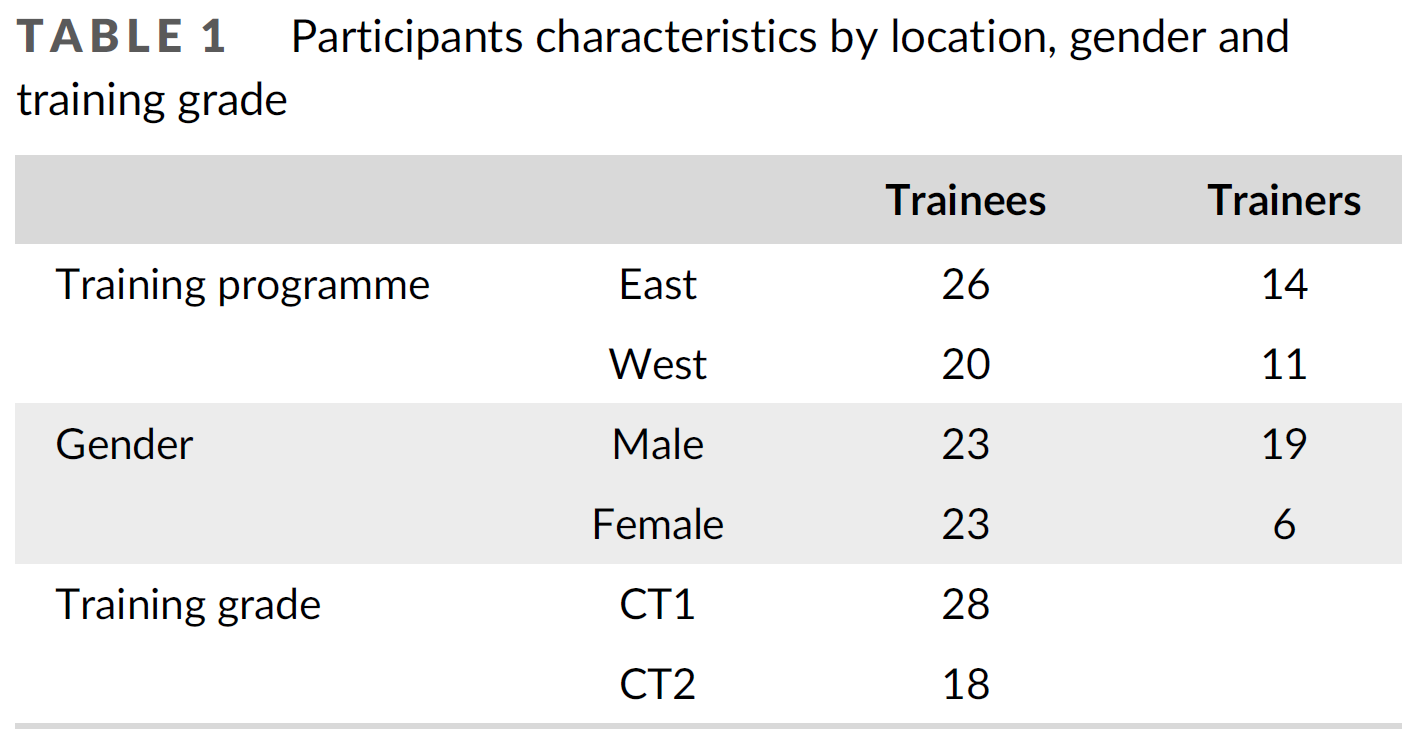

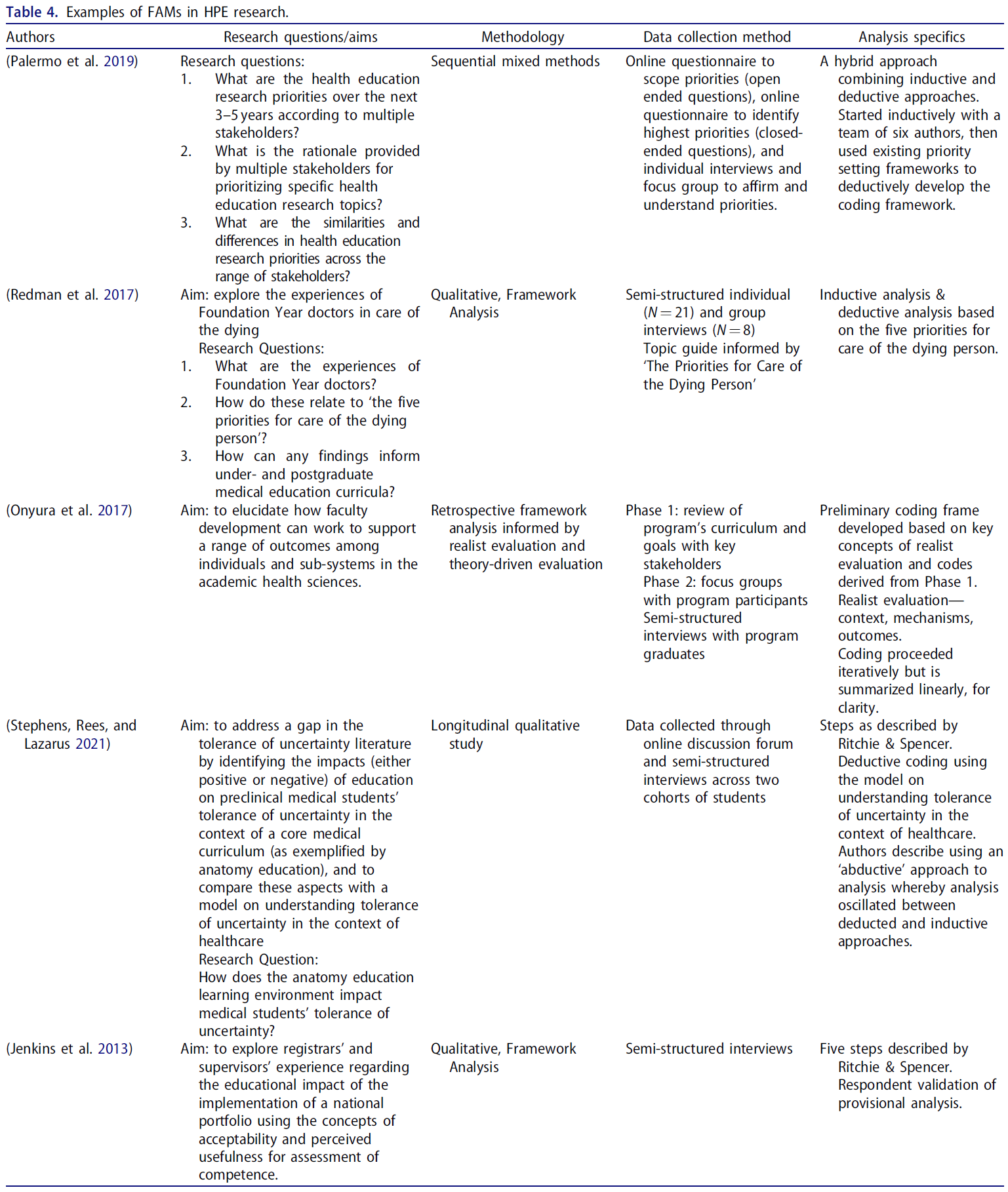

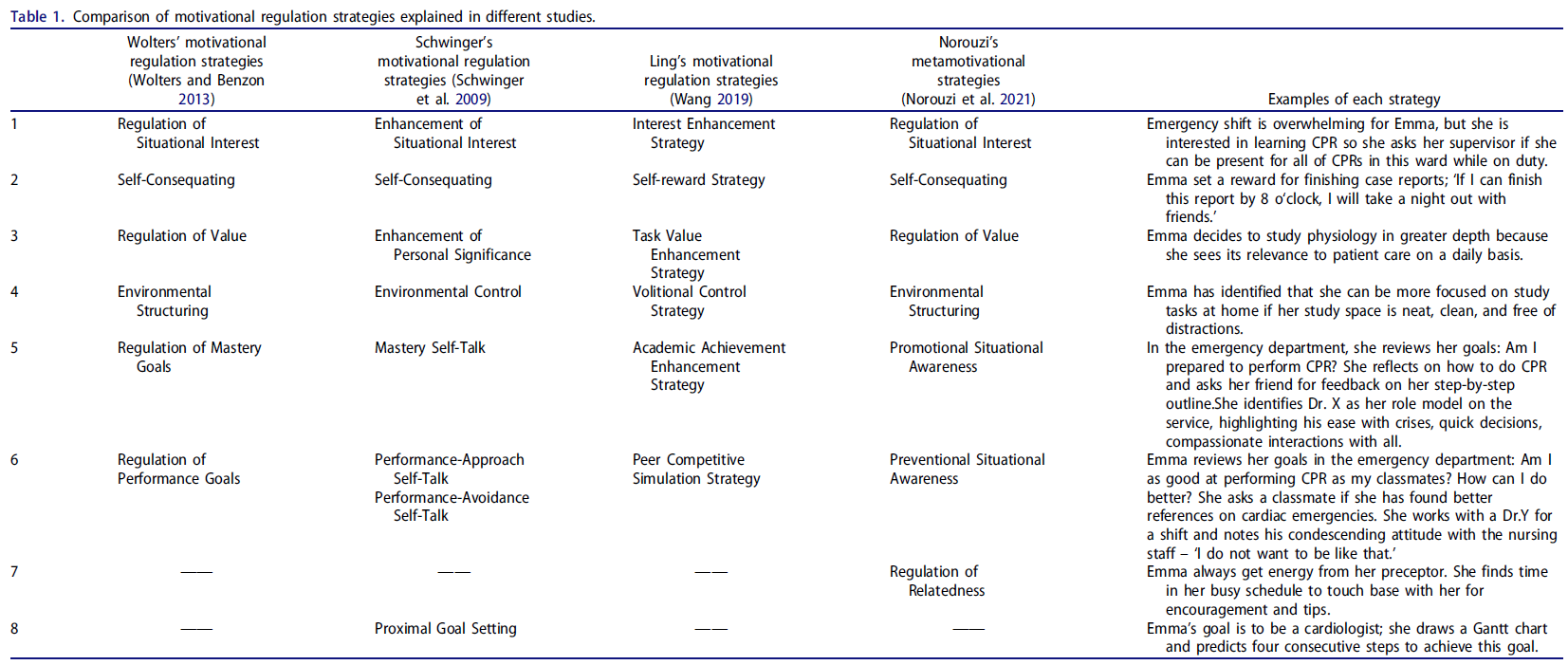

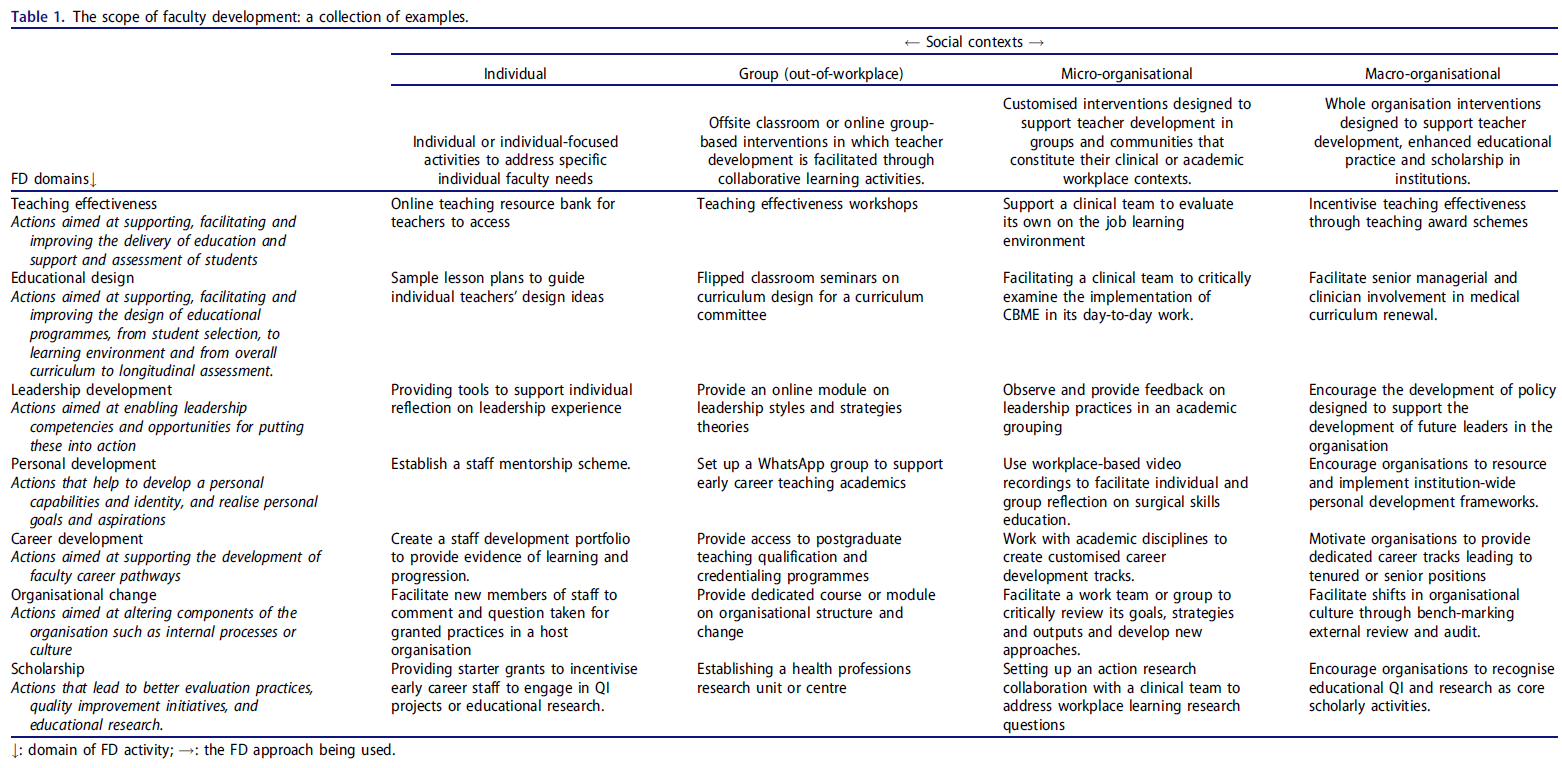

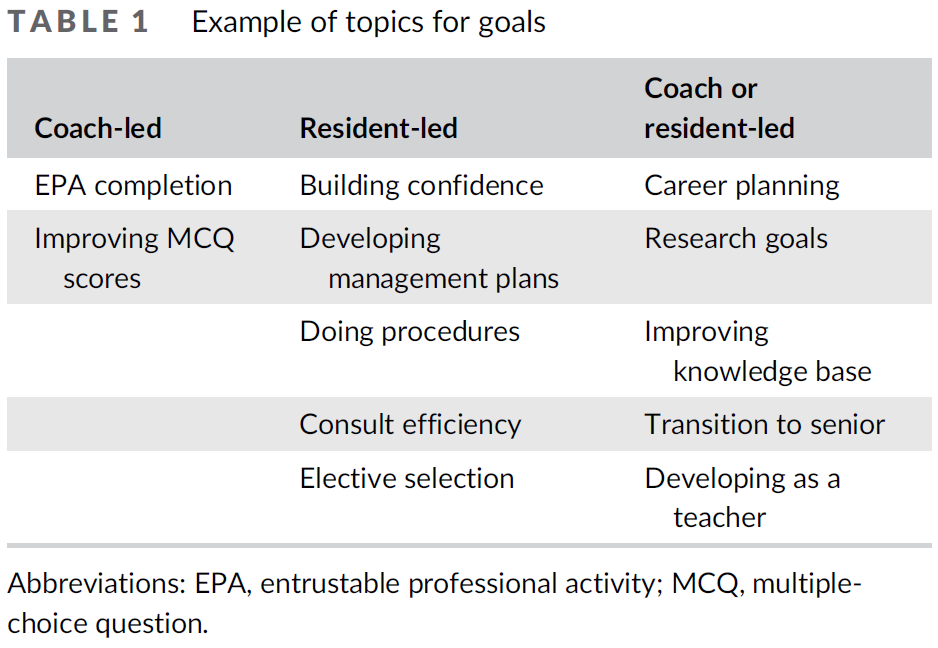

초기 레지던트 목표는 주로 내과 1년차 레지던트의 역할에서 배우고 발전하는 것에 관한 것이었습니다(표 1). 여기에는 코치와 레지던트 모두가 시작한 목표가 포함되었습니다. 프로그램에서 코치에게 평가 데이터가 완전하고 검토되었는지 확인하도록 요청했기 때문에 코치는 레지던트가 이 주제와 관련된 목표를 개발하도록 했습니다. 코칭 관계 초기에 레지던트의 목표에는 지식 기반, 효율성 및 절차적 기술 향상과 자신감 개발이 포함되었습니다.

Initial resident goals were mainly about learning and developing in the role of a first-year internal medicine resident (Table 1). These included goals initiated by both coaches and residents. As the programme had asked coaches to confirm assessment data were complete and reviewed, the coach ensured the resident developed goals related to this topic. Early in the coaching relationship, resident goals included improving knowledge base, efficiency and procedural skills and developing confidence.

... 관리 계획과 절차에 대해 더 자신감을 갖는 것. 더 많은 것을 찾고 시도해 보려고 하지만 어떤 모습일지 모르겠습니다. (레지던트 H, 미팅 1)

… being more confident with my management plan and then the procedures: to try to seek and attempt more but I don't know what it looks like. (Resident H, Meeting 1)

첫해 중반에 접어들면서 더 많은 전공의들이 시니어 레지던트 역할로의 전환 준비, 교육 기술 향상, 경력 계획에 도움이 되는 일렉티브 선택에 대해 논의했습니다. 경력 계획과 연구 목표(예: 프로젝트 선정 및 원고 완성)는 모두 일 년 내내 개발되고 발전했습니다.

Towards the middle of the first year, more dyads discussed preparing for the transition to the senior resident role, improving teaching skills as well as elective selection to help with career planning. Both career planning and research goals (e.g. project selection and manuscript completion) were developed and evolved throughout the year.

레지던트들은 한 해 동안 자신의 목표가 발전했음을 인정했지만, 직접적인 임상 환자 치료의 문제 해결과 관련된 목표는 여전히 거의 없었습니다:

Residents acknowledged that their goals evolved over the year, though there were still very few goals around addressing challenges in direct clinical patient care:

신입 레지던트로서 기본을 배우려고 노력하는 것 같았지만, 해가 지날수록 팀을 어떻게 이끌어야 할까? 팀을 어떻게 관리해야 할까요? 직원들은 집에 가고 나 혼자 당직인데 어떻게 하룻밤 사이에 이 모든 일을 처리할 수 있을까요? 그래서 제가 달성하려고 했던 목표의 성격이 바뀐 것 같아요... 기본기를 배우는 것에서 회진에 대한 자신감을 키우고 학생들을 가르치는 것으로 바뀌었죠. (레지던트 C, 퇴사 인터뷰)

As a new resident, I just felt I was trying to learn the basics … but as the year went on it became more about how do I lead a team? How do I manage a team? How do I do all this stuff overnight when it's just me … and my staff has gone home and I'm on call … dealing with all the stuff that I don't know about? And so I think the nature of the goals I was trying to achieve changed … it went from learning about fundamentals to developing more confidence when it comes to … rounds, and teaching students. (Resident C, exit interview)

어려운 케이스나 어려운 상호작용에 대한 레지던트의 의견을 코치가 조사할 기회가 여러 번 있었습니다. 그러나 대화는 필수 근무지 기반 평가 완료와 같은 레지던트 교육에 초점을 맞춘 주제로 돌아갔습니다. 환자 치료에 대한 제한적인 논의는 대개 특정 환자의 관리에 대해 설명하거나 어려운 케이스에서 큰 그림을 볼 필요성에 대해 논의하는 등 개별적인 사건에 관한 것이었으며, 목표가 개발되지 않는 경우가 많았습니다.

On several occasions, there was opportunity for a coach to probe a comment made by the resident about a difficult case or challenging interaction. However, often the conversation turned back to topics focused on resident training such as completing the required workplace-based assessments. The limited patient care discussions were usually about isolated incidents (e.g. describing the management of a specific patient or discussing needing to see the big picture in a difficult case), and often no goals were developed.

세션의 종적 측면이 이러한 과제를 논의할 공간을 제공했기 때문에 코칭 토론은 레지던트가 되는 방법(예: 공부하는 방법, 연구 계획, 위탁 전문 활동[EPA] 완료 및 경력 계획)에 더 집중되었을 수 있습니다. 실제로 한 레지던트는 레지던트 학습에 대한 논의가 환자 치료 문제가 주요 초점이 되어야 하는 임상 환경에서는 잘 이루어지지 않는다고 말했습니다:

Coaching discussions may have been focused more on the logistics of how to be a resident (e.g. how to study, research planning, completing entrustable professional activities [EPAs] and career planning) because the longitudinal aspect of sessions provided the space to discuss these challenges. In fact, one resident stated that discussions about resident learning were less available in the clinical setting where patient care issues need to be a primary focus:

... [임상에서는] 나보다는 환자에 대해 더 많은 시간을 이야기하는 반면, 코칭 미팅에서는 나 자신, 내가 학습을 어떻게 하고 있는지, 무엇을 더 발전시켜야 하는지에 대해 더 많은 시간을 보냈습니다. (레지던트 H, 퇴사 인터뷰)

… [clinically] we spend time talking more about the patient than me, whereas the coaching meetings were more driven about myself, how I'm doing with my learning, what I need to get up [to] more. (Resident H, exit interview)

또 다른 레지던트는 임상 환경에서 일상적으로 발생하지 않는 문제에 대해 논의할 수 있다는 점을 장점으로 꼽았습니다:

Another resident brought forward the benefit of discussing issues that do not come up on a day-to-day basis in the clinical setting:

코칭 세션은 일상적으로 필요하지 않은 기술에 대해 정말 유용했다고 생각합니다. 그리고 임상적인 것 외에도 연구와 같은 다른 측면의 중요성에 대해 이야기하는 것도 도움이 된 것 같아요. (레지던트 E, 퇴사 인터뷰)

I think [the coaching sessions were] really useful for those skills that aren't necessarily as required day to day. And then I think outside of clinical things it was just helpful to talk about the importance of other aspects like research or things like that. (Resident E, exit interview)

첫 회의에서 여러 전공의가 중요한 임상 환자 치료 목표(예: 환자가 안전하고 필요한 치료를 받을 수 있도록 하는 것)에 대해 논의했지만, 레지던트가 수련을 진행하면서 이러한 중요한 목표는 재검토되지 않았습니다. 흥미롭게도 한 레지던트는 첫 번째 코치-레지던트 미팅에서 수련 첫 해에 예상되는 목표의 진화를 요약했는데, 이 요약은 모든 레지던트가 한 해 동안 발전하는 모습을 반영했습니다:

Although several dyads discussed overarching clinical patient care goals in the first meeting (such as making sure patients are safe and get the care they need), these overarching goals were not revisited as the resident progressed in training. Interestingly, one resident summarised their expected evolution of goals over the first year of training in their initial coach–resident meeting, and this summary mirrored what we saw develop over the course of the year for all residents:

따라서 처음에는 레지던트들이 일반적인 지식과 사물에 대한 접근 방식을 개선하는 등 효율성을 높이려고 노력했습니다. 그리고 시간이 지남에 따라 의대생들을 가르치는 역할, 멘토링 역할, 그리고 조직적인 역할을 더 많이 개발하여 선임 레지던트가 될 수 있습니다. 이것이 첫해의 매우 일반적인 목표에 대한 저의 이해입니다. (레지던트 E, 미팅 1)

So initially we are [residents] just kind of trying to get more efficient—improve our general knowledge, our approach to things. And then as we go along, develop more of a teaching role, a mentorship role for medical students and then an organizational role, where we would be more of a senior level resident. That's kind of my understanding of the very general overarching goals of the first year. (Resident E, Meeting 1)

3.2 각 회의에서 주로 목표 달성을 위한 계획에 초점을 맞춘 공동 구성

3.2 Co-construction in each meeting mainly focused on plans to meet goals

대부분의 경우, 목표가 정해지면 그 목표를 달성하기 위한 계획이 논의되었습니다. 각 세션에서 우선순위를 정할 목표에 대한 논의는 거의 없었습니다. 코치와 레지던트 모두 목표를 제시할 수 있었고, 피드백을 검토하면서 회의 중에 다른 목표가 확인되었습니다. 이렇게 설정된 목표에 따라 목표 달성을 위한 계획에 대한 공동 구성 또는 협상이 자주 이루어졌습니다.

For the most part, if goals were identified, plans to meet those goals were discussed. Within each session, there was little negotiation around which goals to prioritise. Both the coach and resident were able to bring goals forward, and other goals were identified during the meeting as feedback was reviewed. With these established goals, co-construction or negotiation frequently occurred around the plans to meet them.

일부 목표는 한 번만 제시되었지만(예: 다가오는 로테이션에 대한 목표), 다른 목표는 각 세션에서 레지던트가 1년 동안 목표를 달성하기 위해 계획을 발전시킨 증거와 함께 논의되었습니다.

- 예를 들어, 한 다이애드의 경우, 코치가 첫 번째 회의에서 콘텐츠 지식 향상이라는 목표를 제시하고, 이후 회의에서 다시 언급하고, 레지던트가 최종적으로 목표를 구체화했습니다.

- 미팅 1에서 레지던트는 향후 3개월 동안 100개가 넘는 핵심 내과 주제 중 절반에 대한 접근법을 배우겠다고 말했습니다.

- 미팅 2에서 이 계획은 달성할 수 없다는 것이 분명해졌고 코치는 계획을 수정할 것을 권유합니다. 두 사람은 레지던트가 매주 1~2개의 주제를 학습해야 한다는 데 동의합니다.

- 마지막 세션에서 레지던트는 코치에게 시니어 레지던트 역할로 전환하면서 학습의 초점을 서비스에서 확인된 지식 격차에 맞춰 변경해야 한다고 전달합니다.

코치는 초기에 계획에 대해 상당한 조언을 제공했지만, 마지막 세션에 이르러 레지던트는 코치의 조언 없이도 계획을 조정할 수 있었습니다:

Though some goals only came up once (e.g. goals for upcoming rotations), other goals were discussed at each session with evidence of evolution of the resident's plan to meet the goal across the year.

- For example, in one dyad, the goal of improving content knowledge was brought up in the first meeting by the coach, returned to in the subsequent meetings and ultimately refined by the resident.

- In Meeting 1, the resident states that they will try to learn an approach to half the over 100 core internal medicine topics in the following three months.

- In Meeting 2, it is clear that this plan was not achievable, and the coach recommends revising the plan. Together, they agree that the resident should attempt to learn one to two topics per week.

- By the last session, the resident relays to the coach that they needed to change the focus of their studies as they transitioned to the senior resident role, to the knowledge gaps identified on service.

The coach provided significant input on the plan early on, but by the last session, the resident was able to adjust their plan without input from the coach:

공부 습관이 작년부터 조금씩 적응하고 바뀌어야 한다는 것을 깨달았습니다... 임상적인 질문을 중심으로 하루에 15분씩 매일 하는 루틴 같은 것이 추상적인 내용이나 접근 방식에 대해 읽는 것보다 실제로 더 도움이 된다는 것을 알게 되었습니다. (레지던트 G, 미팅 4)

I realize that my study habits need to adapt and change a little bit from last year … I found that like a daily kind of routine with just 15 minutes a day kind of thing, based around a clinical question, is actually more helpful than reading about like abstract things or even an approach. (Resident G, Meeting 4)

목표를 달성하기 위한 계획을 함께 세우는 데 도움을 주기 위해 코치들은 광범위한 목표(예: 지식 기반 개선)에 대한 대화에 참여하여 그 목표를 어떻게 달성할 수 있는지에 초점을 맞춥니다. 이러한 토론에서 코치들은 스터디 그룹을 구성하거나 의도적인 학습 습관을 개발하는 것의 이점을 공유하는 등 레지던트로서의 전략을 공유했습니다. 이러한 계획은 종종 종단적으로 재검토되었습니다:

To help co-construct plans to meet goals, coaches would engage in a dialogue about a broad goal (e.g. improve knowledge base), focusing on how that goal might be met. In these discussions, coaches shared their strategies as residents, including sharing benefits of forming study groups or of developing intentional study habits. These plans were often revisited longitudinally:

그리고 [이전 목표]가 다루어지지 않은 경우, 저는 다시 돌아가서 이것이 여러분의 이전 목표라고 말하고 이것이 방금 논의한 내용과 여러분이 작업하기로 선택한 것과 어떤 관련이 있는지 살펴봅시다. 그리고 X, Y, Z를 하겠다는 계획은 어떻게 진행되었으며 실제로 그 계획이 도움이 되었나요? (코치 6, 종료 인터뷰)

And then you know if [a previous goal] has not been covered, I would circle back and say well these are your previous goals and let us see how that relates to what you have just discussed and what you have chosen to work on. And how did it go with your plan of doing X, Y, Z and was that the plan that actually served you? (Coach 6, exit interview)

코치들은 EPA와 같은 직장 기반 평가를 완료하는 등 프로그램에서 요구하는 목표를 달성하는 데 도움이 되었습니다. 많은 Dyad들이 EPA를 완료하는 데 장애가 되는 요소(예: 질문을 잊어버리는 것, 프리셉터가 완료하는 것을 잊어버리는 것, 기술 문제)에 대해 논의했습니다. 여러 코치들은 이러한 장벽을 극복하는 방법에 대해 논의했으며, 몇몇 코치는 시스템 솔루션을 포함한 프로그램 개선을 옹호하겠다고 밝혔습니다. 예를 들어

Coaches were helpful in troubleshooting goals required by the programme, for example, completing workplace-based assessments, such as EPAs. There was discussion in many of the dyads around the barriers to completing EPAs (e.g. forgetting to ask, preceptor forgetting to complete and technology issues). The dyad would discuss how to overcome these barriers, with several coaches indicating that they would advocate for programme improvements, including systems solutions. For instance:

제가 생각한 가장 좋은 방법은 아마도 다음에 하위 전문 서비스에 전화해야 할 때 선배에게 전화 통화를 들어달라고 요청하면 '그 컨설팅을 요청할 때 더 잘할 수 있었던 점은 다음과 같습니다'라고 말할 것입니다. 또는 컨설턴트를 지나가다가 만나서 환자에 대해 이야기하는 것도 좋습니다. 선배를 끌어들이면 컨설턴트도 함께 작성할 수 있을 거예요. (코치 1, 미팅 2)

I was going to say for [foundational EPA], the best way that I've thought of as far as getting [foundational EPA] is probably, the next time you need to call a subspecialty service, ask your senior to just listen to the phone call and they'll say, ‘Here's what you could have done better in asking for that consult’. Or if you meet the consultant in passing and talk about the patient or something like that. Just try to rope your senior into being there with you and they'll be able to fill it out. (Coach 1, Meeting 2)

드물게 코치는 레지던트에게 (시니어 레지던트의 환자 분류 기술과 같이) 수련 후반기에 더 적합한 목표를 다시 검토해 보라고 권유했습니다. 수련 첫 3개월 차의 주니어 레지던트가 의대생 교육에 대해 우려하며 공식적으로 교육 자료를 준비해야 하는지 논의했을 때 코치는 다음과 같은 통찰력을 제공했습니다:

Rarely, the coach recommended to a resident that they revisit a goal more suited to later in training, such as senior resident triage skills. When a junior resident in their first 3 months of training was concerned about teaching medical students and discussed whether they should formally prepare teaching material, the coach offered this insight:

... 우리는 확실히 새로운 주니어들이 적극적으로 가르칠 것이라고 기대하지 않습니다. 그러니 여러분이 기여할 수 있는 모든 것, 그리고 여러분이 한 모든 것이 대단하지 않나요? ... 지금 이 시점에서는 여러분이 먼저 산소 마스크를 쓰고 제자리를 찾았으면 좋겠어요. (코치 6, 미팅 1)

… we're certainly not expecting new juniors to be actively teaching. So I just think anything that you were able to contribute and anything you did, isn't that great? … at this point in time, we're wanting you to put your own oxygen mask on first and find your feet. (Coach 6, Meeting 1)

4 토론

4 DISCUSSION

본 연구는 목표 공동 구성에 의도적으로 초점을 맞추어 내과 레지던트 수련 프로그램 첫 해의 종단 코칭에서 발생하는 목표 개발에 대해 조명합니다. 이 연구에서 종단 코칭은 코치와 레지던트가 함께 협력하여 레지던트의 요구, 고유한 피드백, 평가 및 경험에 맞는 계획을 맞춤화할 수 있었기 때문에 레지던트가 레지던트 생활의 일부 실제 기술과 관련된 목표를 논의하고 달성할 수 있는 공간을 만들었습니다.

Through an intentional focus on goal co-construction, our study sheds light on the goal development that occurs in longitudinal coaching in a first year of an internal medicine resident training programme. Longitudinal coaching in this study created a space for residents to discuss and achieve goals related to some of the practical skills of being a resident, as coaches and residents were able to work together to tailor plans specific to the residents' needs, unique feedback, assessments and experiences.

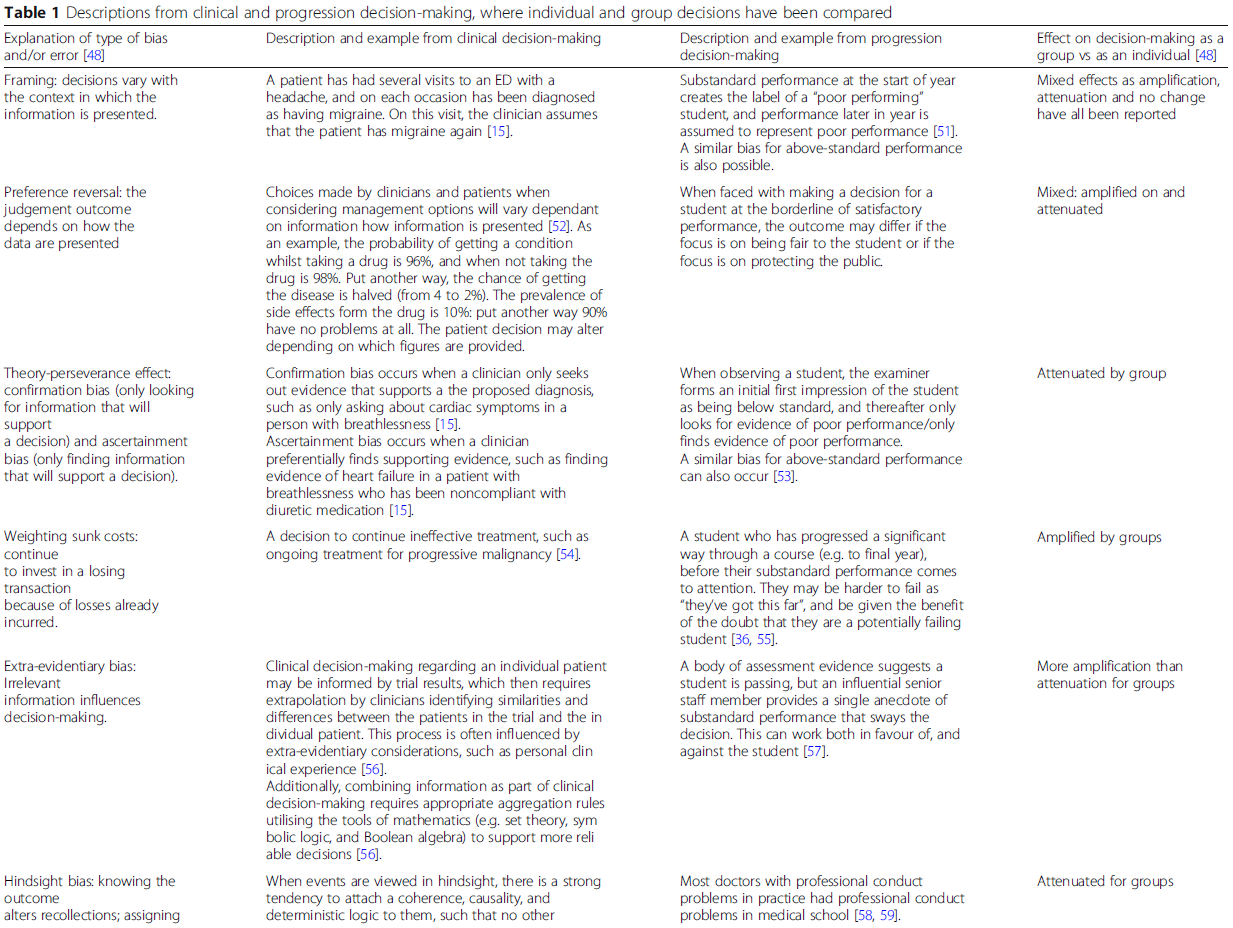

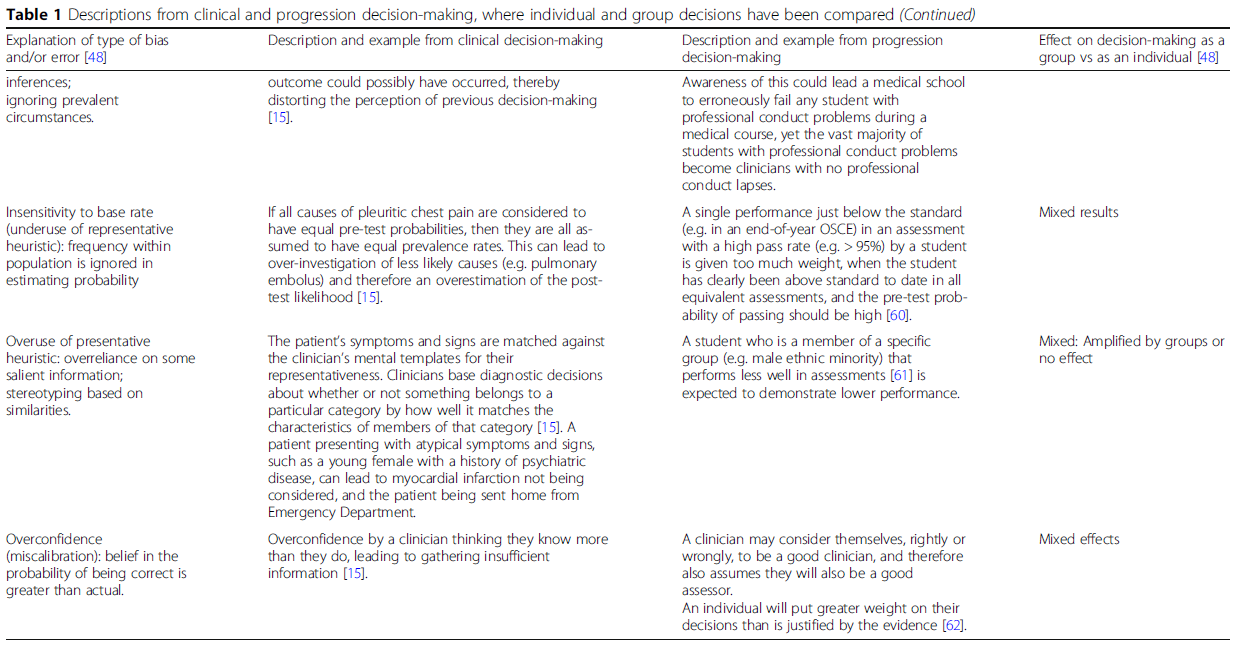

연구 결과에 따르면 코칭 논의는 주로 1년차 레지던트로서 기능하는 것과 관련된 목표(예: 학습 기술, 조직 기술, 교육, 연구, 건강, 경력 계획 및 시니어 레지던트로의 전환)에 초점을 맞추었으며, 직접적인 환자 진료 환경과 관련된 임상 역량 개발에는 덜 중점을 두었습니다. 이러한 비환자 진료 관련 영역에 대한 코칭이 학습자의 특정 수련 단계(이 경우 레지던트 1년차)와 관련된 전문직 정체성 개발을 향상시키는 데 핵심이 될 수 있습니다.18 다양한 수련 단계에서 이루어져야 하는 전문직 정체성 개발에 대한 지원은 의사의 전반적인 전문직 정체성 형성의 중요한 측면이지만 연구가 잘 이루어지지 않았습니다.18, 19 레지던트 전환과 같은 전환 시점에 레지던트를 지원하는 것이 중요한 것으로 나타났습니다.20-23 본 연구는 내과 전공의의 수련 전환 단계 이후에도 코칭 관계를 지속하는 것이 유익하다는 것을 보여줍니다. 이를 통해 레지던트들은 1년차 레지던트로서 수련의 기초부터 선임 레지던트로서 수련의 핵심, 그리고 최종적으로 진료 전환에 이르기까지 역량을 발전시키는 동안 전문가로서의 정체성을 개발할 수 있도록 지속적으로 지원받을 수 있습니다.24

Our study reveals that coaching discussions mainly focused on goals related to functioning as a first-year resident (e.g. study skills, organisational skills, teaching, research, wellness, career planning and transitioning to senior residency), with less emphasis on developing clinical competencies related to direct patient care settings. It is possible that coaching around these non-patient care-related areas may be key to enhancing the professional identity development related to a particular stage of training of a learner, in this case, that of a first-year resident.18 Support for the professional identity development that needs to occur at various stages of training is an important aspect of overall professional identity formation of a physician, though it has been less well studied.18, 19 Supporting residents during transition points such as transitioning to residency has been shown to be important.20-23 Our study demonstrates the benefit for continuing coaching relationships beyond the transition to discipline stage of an internal medicine resident. This ensures that residents continue to be supported as they develop their professional identity during their progression of competencies, from foundations of discipline as a first-year resident, to core of discipline as a senior resident, and eventually to transition to practice.24

레지던트가 되는 방법을 의도적으로 지원하는 공간을 갖는 것은 종단 코칭의 중요한 측면일 가능성이 높으며, 레지던트들이 종단 코칭 관계를 보편적으로 높이 평가하는 이유일 수 있습니다.4, 11, 12 그러나 종단 코칭 환경에서 직접적인 임상 진료 관련 역량에 대한 논의가 현저히 부족하다는 점은 더 고려해야 할 사항입니다. 본 연구에 따르면 종단 코칭은 (바쁜 임상 환경에는 적합하지 않은 대화 유형인) '레지던트가 되기 위한 탐색'에 대해 논의할 수 있는 공간을 제공한다고 합니다. 환자 치료 역량에 대한 논의(예: 환자 상태 변화 인식 및 치료 목표 수립 필요성)는 임상 환경에서 자주 발생하므로 본질적으로 다른 곳에서 다루어질 수 있습니다.25 또는 우리 프로그램의 종단 코치는 임상 환경에서 레지던트를 직접 관찰하는 경우가 거의 없거나 전혀 없었기 때문에, 환자 치료 상호 작용을 공유하는 데 직접 참여하지 않아 논의하기가 더 어려웠을 수 있습니다. 자기 성찰 양식의 사전 제출로 인해 보다 가시적인 주제에 초점을 맞추게 되어 덜 구체적인 주제에 대한 논의에 대한 단서를 놓치거나, 전공의 간 목표의 동질성, 예를 들어 배려심 있고 지식이 풍부한 의사로 성장하는 것과 같은 중요한 목표에 집중하지 못했을 가능성이 있습니다. 마지막으로, 코치들이 레지던트 평가 데이터에 의도적으로 초점을 맞추다 보니 기회를 놓쳤을 수도 있습니다. 이는 자연스럽게 환자 진료 중 레지던트를 직접 관찰하는 즉각성에서 벗어난 코치로서 시간과 다양한 평가 과제에 걸쳐 성과 및 피드백 정보의 의미 결정을 지원하는 것이 얼마나 쉽고 자연스러운 일인지에 대한 의문을 제기합니다.

Having a space that intentionally supports how to be a resident is likely an important aspect of longitudinal coaching and may be why residents universally appreciate longitudinal coaching relationships.4, 11, 12 However, the notable lack of discussion around direct clinical care-specific competencies in the longitudinal coaching setting deserves more consideration. Our study suggests that longitudinal coaching provides the space to discuss navigating being a resident: a type of conversation that does not fit into a busy clinical environment. It may be that discussions around patient care competencies (e.g. recognising changes in patient status and the need to establish goals of care) occur frequently in the clinical setting and so are essentially dealt with elsewhere.25 Alternatively, longitudinal coaches in our programme rarely or never directly observed their residents in clinical settings and, therefore, were not directly part of any shared patient care interactions making it more difficult to discuss. It is possible that the pre-submission of a self-reflection form resulted in targeting topics that were more tangible, perhaps leading to missed cues for the discussion of less concrete topics, homogeneity of goals across dyads and the loss of focus on an overarching goal of, for example, developing into a caring, knowledgeable physician. Finally, there may have been missed opportunities due to the intentional focus of coaches on resident assessment data. This naturally begs the question of how easy or natural is it to support meaning-making of performance and feedback information across time and different assessment tasks, as a coach who is once removed from the immediacy of direct observation of the resident during patient care?

종단 코칭에서는 코치가 직접 관찰에 관여하지 않을 수 있으므로, 평가 '데이터'는 특정 루브릭과 역량 라벨에 맞추기 위해 환자 경험의 세부 사항이 제거된 채 탈맥락화됩니다. 데이터 학자들은 데이터는 표현적인 것이 아니라(즉, 데이터는 맥락과 무관하게 고정된 의미를 갖지 않음) 관계적이고 맥락적이라고 말합니다.26 따라서 코치와 레지던트는 데이터를 재맥락화해야 하며, 코치는 다양한 데이터가 특정 주장을 어느 정도 뒷받침하는지 반복적으로 이해해야 합니다. 코치는 코칭 토론에서 목표 공동 구성을 지원하기 위해 의미 있게 사용하기 위해 레지던트의 주장 및 해석과 관련하여 그렇게 해야 합니다. 코치와 학습자를 위한 특정 임상 성과/피드백 토론을 위해 평가 데이터를 재맥락화하는 것은 어려울 수 있지만, 성과에 대한 토론을 장려하기 위해 종단적 코칭에 직접 관찰 기회를 포함하면 코칭 관계와 대화의 성격이 달라질 수 있습니다.

In longitudinal coaching, coaches may not be involved in direct observation, so the assessment ‘data’ is decontextualised, stripped of the specifics of the patient encounter, to fit within certain rubrics and labels of competence. Data scholars suggest that data are not representational (i.e. data do not have a fixed meaning independent of context) but, instead, relational and contextual.26 Therefore, the coach and resident were required to recontextualise the data, with the coach repeatedly needing to understand the extent to which various data support particular claims. The coach must do so in relation to the resident's claims and interpretations in order to use them meaningfully to support goal co-construction within a coaching discussion. Although recontextualising assessment data for specific clinical performance/feedback discussions for coach and learners might be a challenge, including direct observation opportunities for longitudinal coaching to encourage discussion around performance would alter the nature of the coaching relationship and dialogue.

4.1 제한 사항

4.1 Limitations

본 연구는 수련 첫 해 동안 피드백을 논의하고 성과 목표를 개발하기 위해 반복적인 코치-레지던트 미팅을 포함하는 종단적 코칭에 대한 단일 레지던트 프로그램의 접근 방식을 연구한 것이므로 연구 결과의 적용 가능성은 제한적입니다. CBME 내에서 종단적 코칭을 시행하는 방식은 시간이 지남에 따라 코칭이 진행되는 방식에 영향을 미칠 수 있으며 코치와 레지던트 간의 논의가 달라질 수 있습니다. 저희 교수진 개발에서는 R2C2와 목표 공동 구성을 강조했는데, 이러한 접근 방식이 코치-레지던트 간 토론에 영향을 미쳐 목표와 관련하여 두 집단 간에 유사성을 보이는 결과를 낳았을 수 있습니다. 이 연구는 코치와 레지던트 간의 실제 토론을 실시간으로 포함함으로써 이점을 얻었지만, 더 큰 데이터 세트를 사용했다면 기록된 대화 유형에서 더 다양한 유형을 발견했을 가능성이 있습니다.

The transferability of our findings is limited as this was a study of a single residency programme's approach to longitudinal coaching involving iterative coach–resident meetings to discuss feedback and develop performance goals over their first year of training. Within CBME, variations in the implementation of longitudinal coaching may impact how coaching plays out over time and may lead to different coach–resident discussions. Our faculty development emphasised R2C2 and goal co-construction, and this approach may have impacted coach–resident discussions and resulted in the similarities we see across dyads with respect to goals. Though the study benefited from including actual discussions between coach and resident as they occurred in real time, it is possible that with a larger data set, we would have found a greater variety in the types of conversations recorded.

5 시사점

5 IMPLICATIONS

우리는 종단 코칭 프로그램이 1년차 레지던트에게 프로그램 요건을 탐색하는 과정에서 1년차 레지던트가 되는 방법에 대해 이야기할 수 있는 공간과 시간을 제공함으로써 직접적인 환자 진료 외에 레지던트의 직업적 정체성 형성에 도움이 되는 역할을 한다는 것을 보여주었습니다. 또한 레지던트들은 비슷한 수준의 수련 과정에서 비슷한 목표를 가질 수 있지만, 개인마다 이러한 목표를 달성하는 방법은 다릅니다. 코치는 목표 달성을 위한 계획과 관련하여 레지던트별 문제를 해결하는 데 중요한 역할을 할 수 있습니다. 이를 염두에 두고 코치는 레지던트 목표에 대한 코칭이 레지던트의 전문적 정체성 형성에 어떤 영향을 미칠 수 있는지에 대한 추가적인 교수진 개발을 통해 이점을 얻을 수 있습니다.

We have shown that our longitudinal coaching programme provides first-year residents a space and time to talk about how to be a first-year resident as they navigate the programme requirements, thus demonstrating a role in helping to develop professional identity formation of residents outside of direct patient care. What's more, though residents may have similar goals at similar levels of training, how an individual can meet these goals differs. The coach can play an important role in troubleshooting resident-specific challenges around plans to meet goals. With this in mind, coaches may benefit from further faculty development around how coaching around resident goals can impact professional identity formation of a resident.

향후 연구에서는 데이터 과학 렌즈를 통해 종단적 코칭 논의에서 환자 치료 과제가 어떻게 그리고 왜 두드러지게 나타나지 않는지 탐구하는 것을 고려할 수 있습니다. 물론, 특정 임상 성과/피드백 논의를 위해 평가 데이터를 재맥락화하는 문제는 특히 종단 코칭이 학습자가 진정한 환자 치료에 대한 책임이 증가함에 따라 자신의 진척도를 측정하는 종단 통합 수련과는 대조적으로 더 고려할 가치가 있습니다.27 교수진 개발을 고려할 때 코치에게 환자 치료와 관련된 문제를 논의하도록 유도할 수 있는 단서에 특히 주의를 기울이도록 요청하면 논의되는 목표 유형이 더 넓어질 수 있습니다. 즉, 코칭을 위한 스캐폴딩 구조와 개방형 코칭 회의 사이에 균형이 있다고 생각합니다. 종단적 코칭 요건에 더 많은 방향과 지원을 계속 추가하면 다양한 수련 단계에서 레지던트의 정체성 형성을 지원하는 기능이 저하될 위험이 있습니다. 더 많은 교수진 개발이 더 나은 것은 아닐 수도 있습니다. 종단적 코칭 대화가 역량과 전문적 정체성 형성 모두에 대한 공동 규제와 성찰을 개선하는 데 가장 잘 기여할 수 있는 방법에 대한 이해를 높이는 데 집중하는 것이 핵심일 수 있습니다.

Future studies may consider exploring how and why patient care challenges might not feature prominently in longitudinal coaching discussions, perhaps through a data science lens. Certainly, the challenge of recontextualising assessment data for specific clinical performance/feedback discussions merits further consideration, especially as longitudinal coaching is in contrast longitudinal integrated clerkships, where learners gage their progress by their increased responsibility for authentic patient care.27 In considering faculty development, it is possible that asking coaches to pay particular attention to cues that may lead to discussing issues related to patient care will broaden types of goals discussed. That said, we suspect there is a balance between scaffolding structure for coaching and open-ended coaching meetings. There is a risk of continuing to add more direction and supports to the longitudinal coaching requirements, as this may detract from its ability to support residents in their identity formation at various stages of training. It may be that more faculty development is not better. Focusing on improving our understanding of how longitudinal coaching conversations can best contribute to improving co-regulation and reflection on both competencies and professional identity formation may be the key.

Goal co-construction and dialogue in an internal medicine longitudinal coaching programme

PMID: 36181337

DOI: 10.1111/medu.14942

Abstract

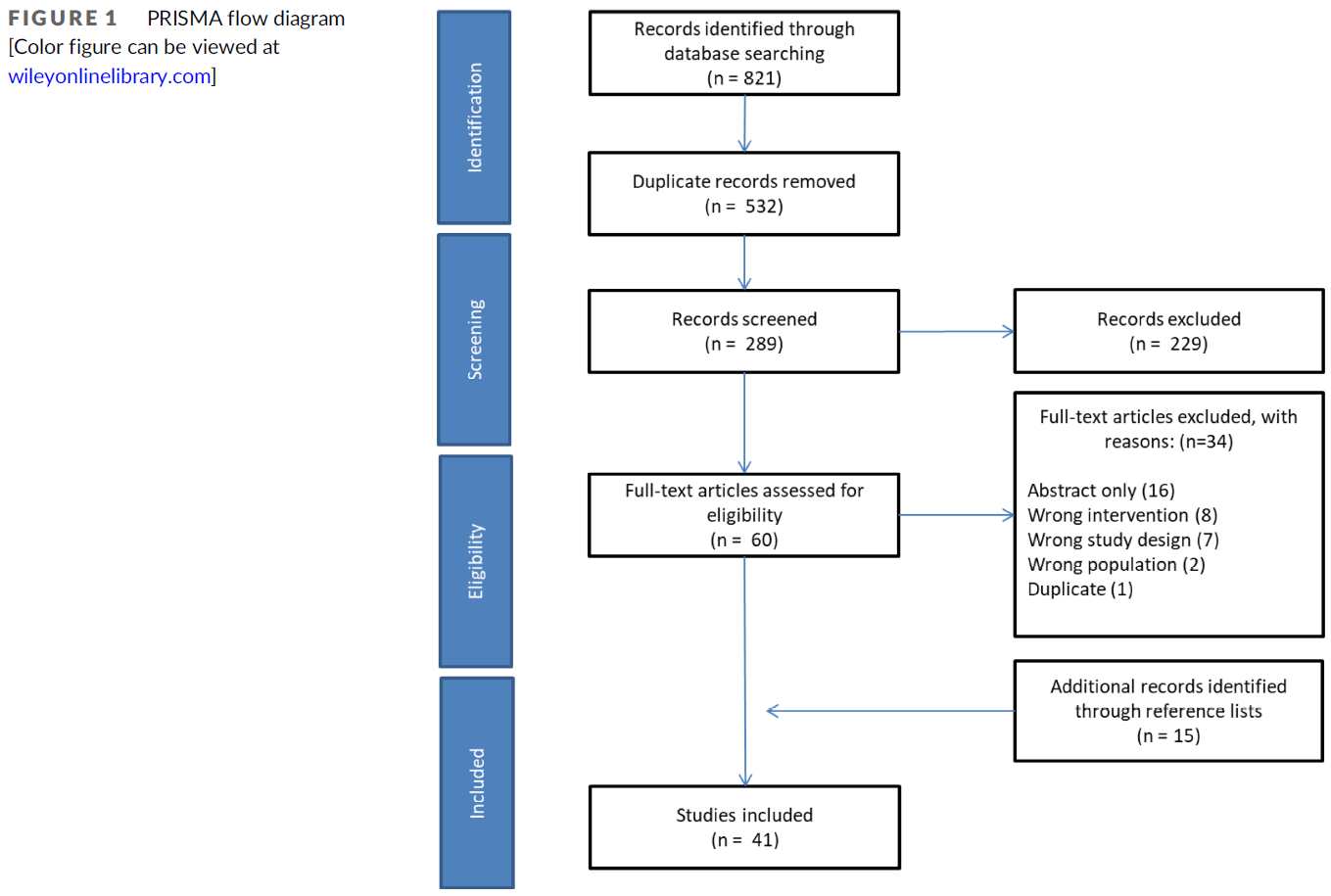

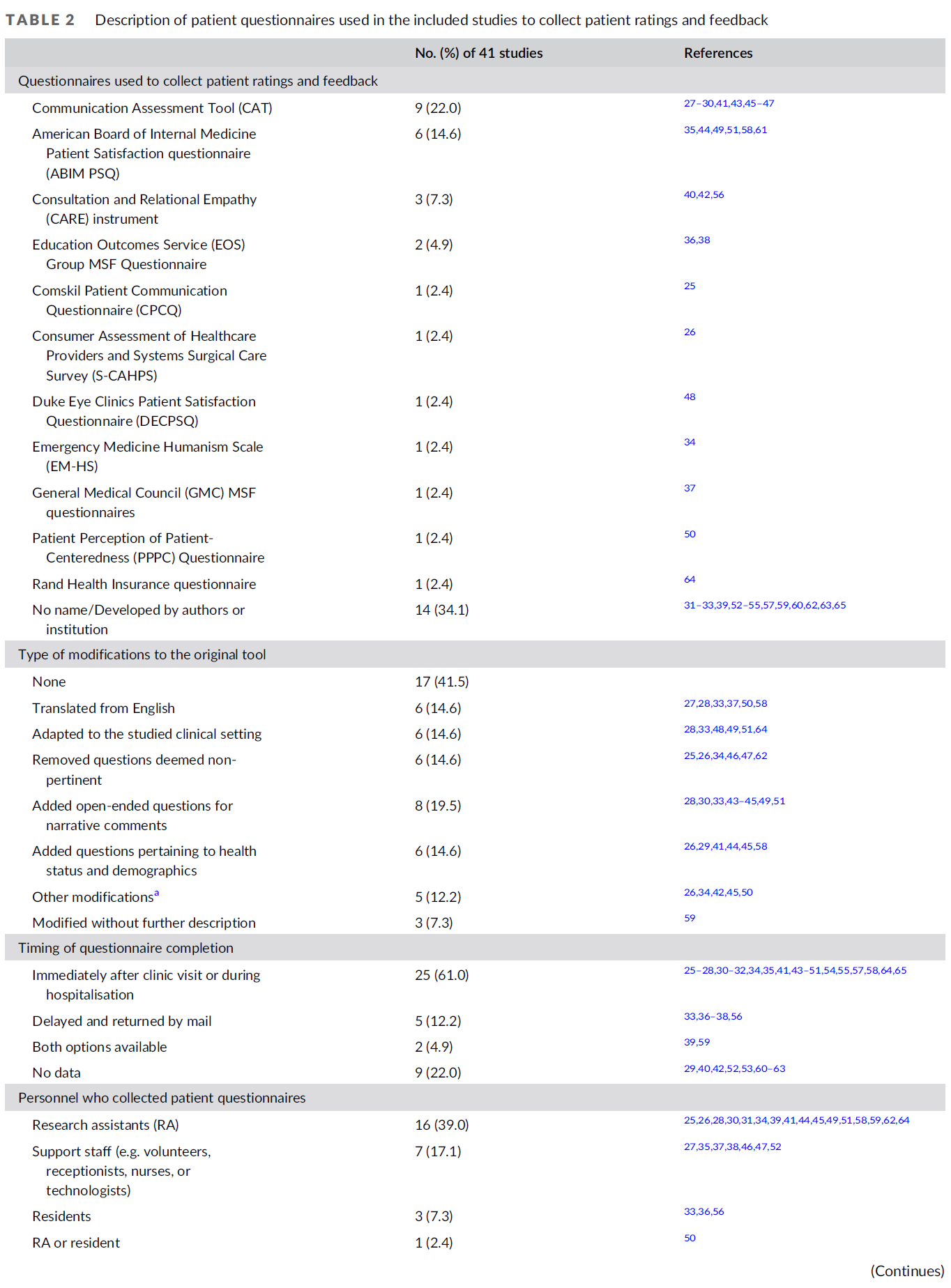

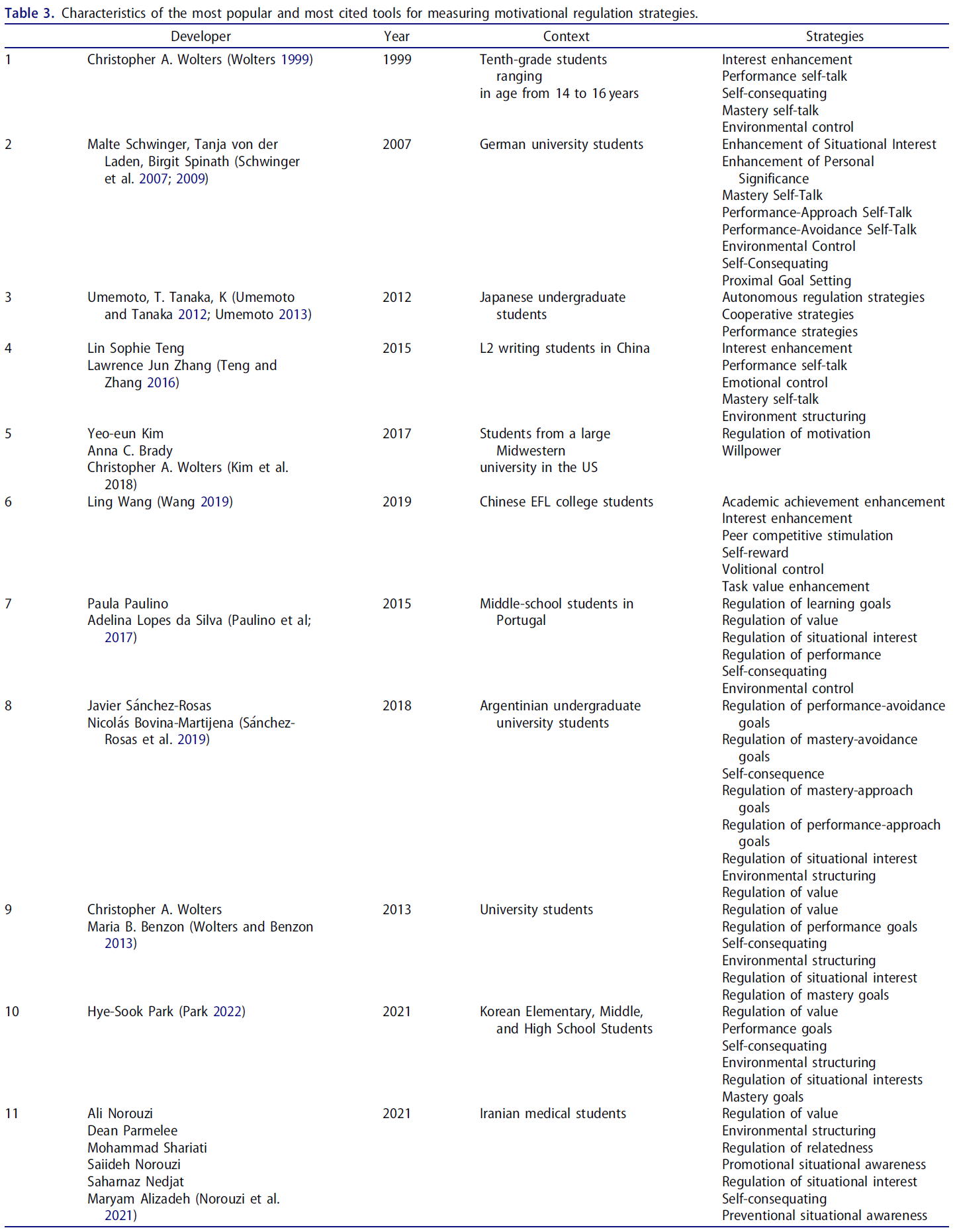

Background: Longitudinal coaching in residency programmes is becoming commonplace and requires iterative and collaborative discussions between coach and resident, with the shared development of goals. However, little is known about how goal development unfolds within coaching conversations over time and the effects these conversations have. We therefore built on current coaching theory by analysing goal development dialogues within resident and faculty coaching relationships.

Methods: This was a qualitative study using interpretive description methodology. Eight internal medicine coach-resident dyads consented to audiotaping coaching meetings over a 1-year period. Transcripts from meetings and individual exit interviews were analysed thematically using goal co-construction as a sensitising concept.

Results: Two themes were developed: (i) The content of goals discussed in coaching meetings focused on how to be a resident, with little discussion around challenges in direct patient care, and (ii) co-construction mainly occurred in how to meet goals, rather than in prioritising goals or co-constructing new goals.

Conclusions: In analysing goal development in the coach-resident relationships, conversations focused mainly around how to manage as a resident rather than how to improve direct patient care. This may be because academic coaching provides space separate from clinical work to focus on the stage-specific professional identity development of a resident. Going forward, focus should be on how to optimise longitudinal coaching conversations to ensure co-regulation and reflection on both clinical competencies and professional identity formation.

© 2022 Association for the Study of Medical Education and John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 임상교육(Clerkship & Residency)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 복잡성 보기: 공유의사결정의 렌즈로서 문화-역사적 활동이론(CHAT) (Acad Med, 2021) (0) | 2024.01.02 |

|---|---|

| 공유의사결정을 가르치는 열두가지 팁(Med Teach, 2023) (0) | 2024.01.02 |

| 보건의료 업무를 통한 학습: 전제, 기여, 실천(Med Educ, 2016) (0) | 2023.11.12 |

| 어떻게 근무현장-기반 평가가 졸업후교육에서 학습을 가이드하는가: 스코핑 리뷰 (Med Educ, 2023) (0) | 2023.11.10 |

| 임상환경에서 문화가 학습, 실천, 정체성 발달에 영향을 주는 방식에 대한 시야 넓히기(Med Educ, 2021) (0) | 2023.09.14 |