학부 의학에서 해부학을 배울 때 카데바가 정말 필요한가? (Med Teach, 2018)

Do we really need cadavers anymore to learn anatomy in undergraduate medicine?

P. G. McMenamina , J. McLachlanb, A. Wilsonc , J. M. McBrided, J. Pickeringe , D. J. R. Evansf and A. Winkelmanng

서론

Introduction

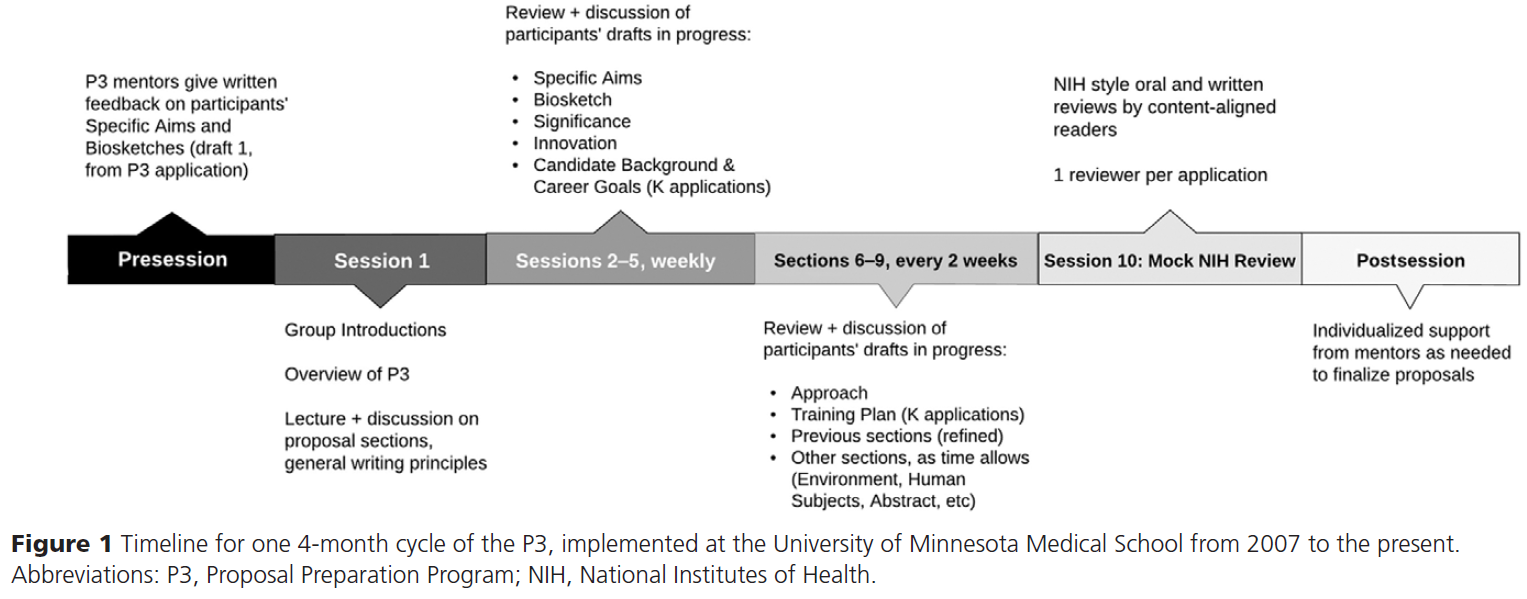

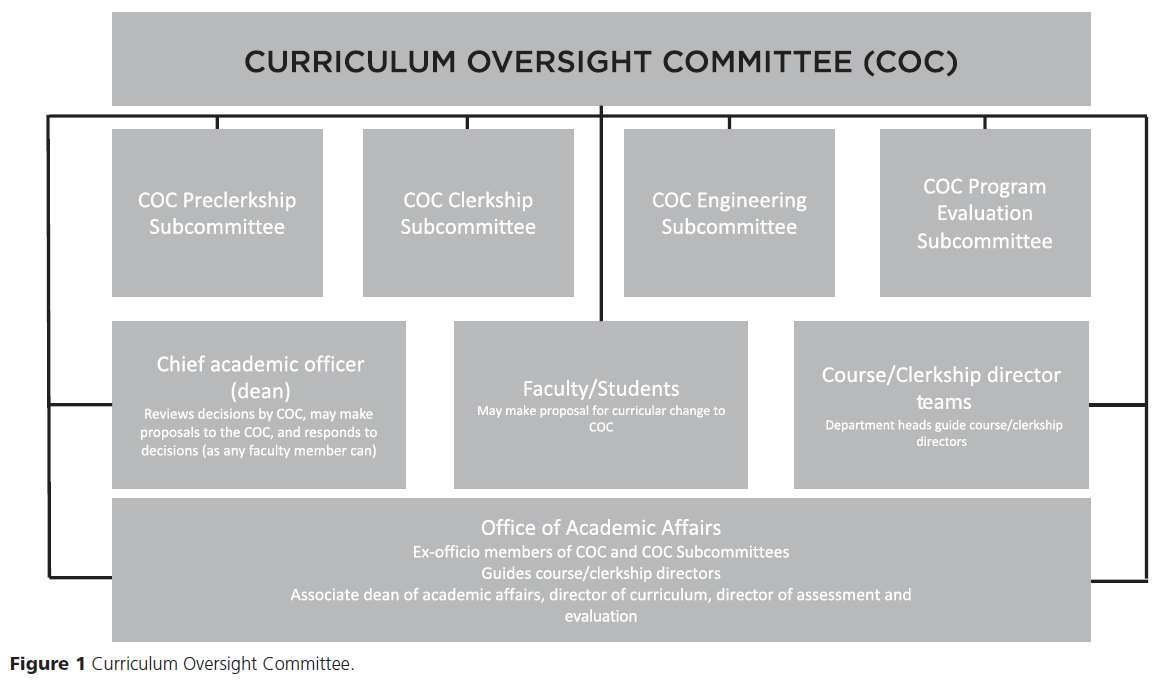

이 심포지엄은 거의 35년 동안 해부학을 가르쳐온 그의 분야에서 인정받는 지도자인 폴 맥메나미나 교수가 의장을 맡았다. 해부학 교수법의 다양하고, 효율적이고, 참신한 방법을 탐구하는 것이 그의 주된 열정 중 하나였다. 맥메나민 교수는 론 하든 교수에 의해 이 토론의 촉진자 역할을 하도록 초대되었다. "프레젠테이션만"하는 일반적인 방법보다는 청중 참여 토론이 더 유익할 것이라는 의견이 제시되었다. 따라서 대화를 자극하기 위해 제안된 제목은 다음과 같습니다.

The symposium was chaired by Prof Paul McMenamin a recognized leader in his field who has been teaching anatomy for nearly 35 years. Exploring different, efficient, and novel methods of anatomy teaching has been one of his main passions. Professor McMenamin was invited by Professor Ron Harden to act as facilitator for this debate. Rather than the usual method of “presentations only”, it was suggested that an audience participated debate would be more informative. Therefore to stimulate the conversation the suggested title of:

"대학 의학부에서 해부학을 배우기 위해 카데바가 더 이상 필요할까요?"

“Do we really need cadavers anymore to learn anatomy in undergraduate medicine?”

청중에게 제안되었습니다. 청중들은 이것을 주의 깊게 읽고 그들 자신의 반응을 되새겨보라는 요청을 받았다. 찬성파와 반대파의 제안을 지지하는 두 팀은 위의 구체적인 토론 논점에 근거해 자신들의 주장을 할 것을 요청받았다.

was proposed to the audience. The audience were asked to read this carefully and reflect on their own individual response. The two teams, those supporting the proposition in the affirmative and the opposing house, were requested to base their argument on the specific debating point above.

맥메나민 교수는 자신을 소개했고, 진행자로서 토론 주제에 대해 개인적인 견해를 밝히지 않았지만, 각각의 발표자들이 그들의 자격증과 함께 청중들에게 개별적으로 소개될 것이라고 설명했다. 그리고 나서 연설자들은 개인적으로 그들의 토론 주장을 발표할 약 15분의 시간을 가졌다. 맥메나민 교수는 토론 이면의 논거를 설명하면서 옥스퍼드 전통에 따라 반대론자들이 '아니오 우리는 하지 않습니다'와 '네 우리는 합니다'라는 두 개의 집단이 존재할 것이라고 말했다. 전통과 마찬가지로, 화자들은 반드시 그들이 토론하도록 요청받았던 견해를 가지고 있지는 않을지 모르지만, 토론 기술의 힘을 이용하여, 그들은 그들의 메시지를 전달하기 위해 약간의 지적인 충돌과 약간의 유머를 섞어서 희망적으로 몇몇 심각한 논쟁을 제공할 수 있었다. 어떤 토론에서도 그렇듯이, 양원이 청중 참여를 허용해야 할 것으로 기대되었다.

Professor McMenamin introduced himself and as facilitator gave no personal views on the topic to be debated, but explained that each speaker would be individually introduced to the audience along with their credentials. The speakers then had approximately 15 minutes to present their debating argument personally. Professor McMenamin explained the reasoning behind the debate and that it would be based on the Oxford tradition where there would be two groups of opposing speakers, the “No we do not” house and the “Yes we do” house. As with tradition, the speakers may not necessarily hold the views that they had been asked to debate on, but using the power of debating techniques they were free to provide some serious arguments hopefully with some intellectual jostling and a bit of humor interspersed, to convey their message. As in any debate, it was hoped that both houses should allow for the inclusion of audience participation.

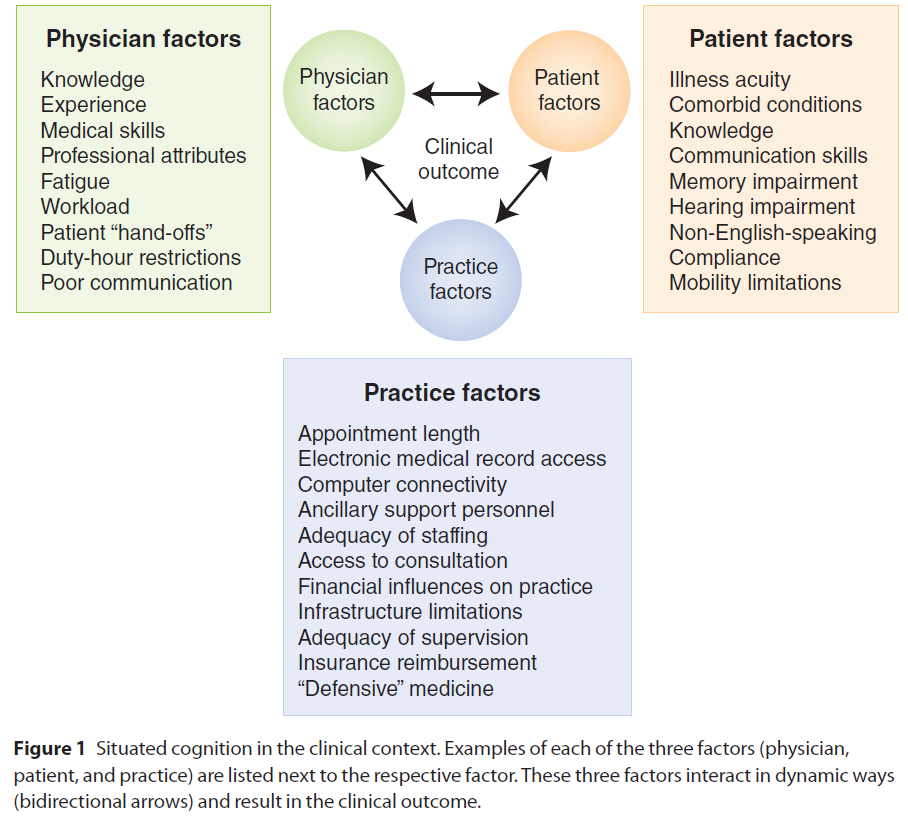

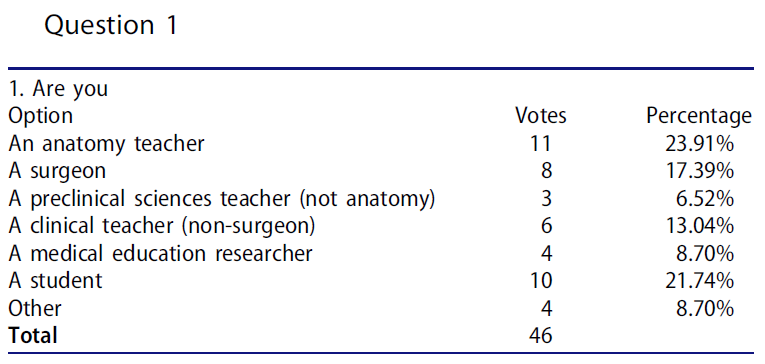

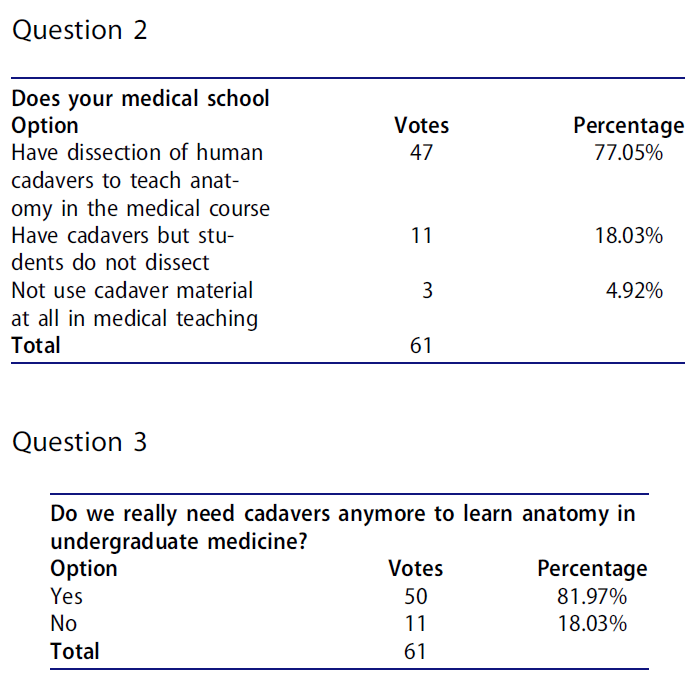

맥메나민 교수는 청중들의 프로필을 기록하고 시작에 앞서 객관식 질문을 던지며 청중들에게 답변을 등록하기 전에 질문의 표현을 신중하게 생각하라고 지시했습니다.

Noting the audience profile and prior to commencement Professor McMenamin posed a series of multiple choice questions and instructed the audience to think carefully about the wording of the questions before registering their answer.

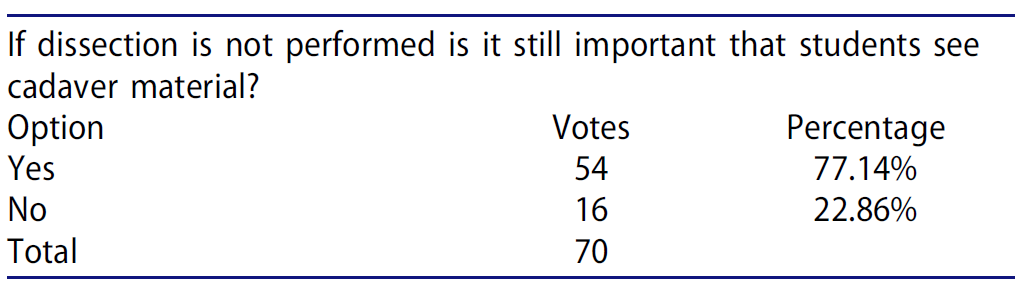

그 결과는 실제로 해부하는 과정과 해부하지는 않지만 해부하지 않는 과정으로 상당히 긍정적인 경향을 보여주었고 82%의 대다수는 우리가 학부 의학에서 시체들이 필요하다고 믿었다. 토론이 시작되었고 McMenamin 교수는 그들의 자격증과 함께 연사들을 소개했다.

The results indicated quite a strong positive leaning towards courses that actually do dissect cadavers and those that use cadavers but do not dissect and an 82% majority believing we do need cadavers in undergraduate medicine. The debate commenced and Professor McMenamin introduced the speakers along with their credentials.

존 맥래클런 교수는 "아니, 우리는 그렇지 않다"라는 집안의 토론을 시작했다.

Professor John McLachlan opened the debate for the “No, we do not,” house.

반대측

“No we do not” house

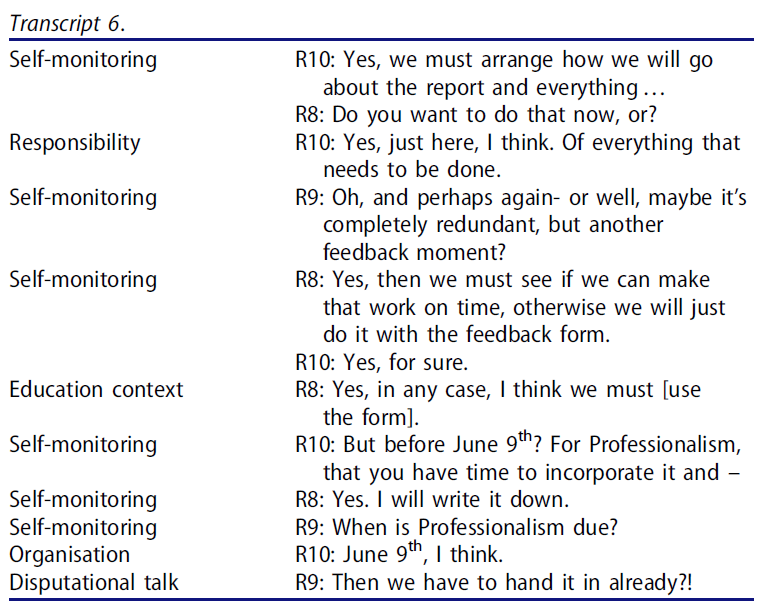

편집된 스크립트 Edited transcript

존 맥라클란 교수 Prof John McLachlan

이 "카다베릭" 해부학 교사들과 외과의사들은 우리가 문제가 있다고 제안합니다!

This audience of “cadaveric” anatomy teachers and surgeons suggest we have a challenge!

먼저, 저는 사람들이 왜 시체들을 사용하는지 추측할 것입니다. 그리고 나서 왜 제가 시체 없이 해부학을 가르치는 것을 장려했는지에 대해 추측할 것입니다. 그리고 나서 어떻게 우리가 시체 없이 해부학을 가르치는지 그리고 의사로서 학생들에게 미치는 영향에 대해 설명하겠습니다. 왜냐하면 이것이 해부학자를 배출하는 것이 아니라 우리의 목표이기 때문입니다. 마지막으로 외과 교육에 대해 설명하겠습니다.

First, I will speculate on why people use cadavers; then why I have promoted teaching anatomy without cadavers. Then I will describe how we teach anatomy without cadavers, and describe the impact on students as doctors, because this is our aim, rather than producing anatomists. Finally, I will comment on surgical training.

왜 해부학은 전통적으로 시체에게 가르쳐지는가? 이 문화적 현상은 르네상스 시대부터 시작되었다. 유럽의 의학은 점성술, 교감마술, 민속학, 한방학을 포함했다. 이 세상에 비살리우스의 훌륭한 작품이 나왔는데, 그는 이곳 저곳으로 일관되는 무언가를 묘사했고, 이것은 분명 큰 영향을 미쳤을 것이다. 그러나 파라셀수스는 "해부학자를 가르치는 것은 살아있는 몸이다. 그러므로 당신은 살아있는 해부학을 필요로 한다."라고 말했다. 그 논평은 우리의 목표의 중심이다.

Why is anatomy traditionally taught with cadavers? This cultural phenomenon dates from the Renaissance (McLachlan and Patten 2006). European medicine then included astrology, sympathetic magic, folklore and herbal medicine. Into this world came the wonderful work of Vesalius, who described something that was consistent from place to place, and this must have had huge impact. But Paracelsus commented, “It is the living body that teaches the anatomist, you therefore require a living anatomy”. That comment is central to our goals.

페닌슐라에서 새로운 의대를 설립할 때, 우리는 백지 한 장을 가지고 있었다. 우리의 핵심 질문은 무엇을 가르칠 것인가 뿐만 아니라 왜 어떻게 가르칠 것인가 하는 것이었다. GMC에 의해 명시된 우리의 목표는 비전문의 후배 의사들을 양성하는 것이었다. 우리의 직업 분석 결과, 하위 의사들은 주로 살아있는 해부학과 의학 이미지를 통해 해부학을 보는 것으로 나타났다. 이것이 우리가 초점을 맞춘 것입니다. 우리는 또한 그들의 사회적 역할을 고려했는데, 우리는 그들의 경험에 중심적으로 만들고 싶었다.

In setting up a new medical school at Peninsula, we had a blank sheet of paper. Our key questions were not just what to teach, but also why and how. Our aim, specified by the GMC, was to train non-specialist junior doctors. Our job analysis showed that junior doctors see anatomy primarily through living anatomy and medical imaging. So this is what we focused on. We also considered their social role, which we wanted to make central to their experience.

그렇다면, 시체 없이 어떻게 해부학을 가르칠 수 있을까요? 중요한 측면은 임상 기술과의 통합이다. 우리는 또한 살아있는 해부학, 동료 검사, 살아있는 모델 또는 임상 기술 파트너의 사용, 그리고 바디 페인팅을 강조한다. 의료 영상 촬영에 중점을 두고 있다. 의학 방사선 전문의와 방사선사는 해부학 강의의 4분의 1을 담당했다. 우리는 안전하고 비침습적인 휴대용 초음파 기술에 열광했습니다. 적절한 안내가 있으면 학생들이 서로 사용할 수 있어 신체 내부의 실시간 생활 구조를 놀라울 정도로 자세하게 볼 수 있다. 휴대용 초음파는 중앙 정맥 라인의 배치와 같은 향후 일상적인 임상 용도로 사용될 것이기 때문에 이것은 중요하다.

How, then, do we teach anatomy without cadavers? A key aspect is integration with clinical skills. We also emphasize living anatomy, peer examination, use of living models or clinical skills partners, and body painting (McLachlan and Regan 2004; McLachlan 2004). Heavy emphasis is placed on medical imaging. Medical radiologists and radiographers delivered a quarter of the anatomy teaching at Peninsula. We were enthusiastic about portable ultrasound, a safe, noninvasive, technique. With appropriate guidance, students can use it on each other, allowing them to see real-time living structures inside the body, in remarkable detail. This is important, because portable ultrasound will be in routine clinical use in the future, such as during the placement of central venous lines.

살아있는 해부학과 관련하여, 우리는 학생들이 종종 인체에 대해 당황한다는 것을 발견했다. 우리는 그 당혹감을 없애고, 서로를 검사함으로써, 검사받는 것이 어떤 느낌인지 이해하고 싶었습니다. 많은 학교들이 살아있는 해부학을 사용하지만, 우리에게는, 이미징과 함께, 해부학 학습의 중심이었습니다. 학생들은 서로의 동의(핵심 학습 포인트)를 얻었고, 주저하거나 당황하지 않고 표면 랜드마크를 유창하게 식별하는 법을 배웠다. 이것은 이후의 임상 환경에 대한 그들의 자신감을 증가시켰다. 물론 우리가 연구로 개발한 학생들로부터의 참여에는 개인적, 문화적 차이가 있었다.

With regard to living anatomy, we discovered that students are often embarrassed about the human body. We wanted to remove that embarrassment, and through examining each other, understand what it felt like to be examined. Many schools use some living anatomy, but for us it was, with imaging, central to anatomy learning. Students obtained consent from each other (a key learning point), and learnt to identify surface landmarks fluently, without hesitation or embarrassment. This increased their confidence in later clinical settings. There were of course personal and cultural variations in engagement from the students, which we developed as research (Rees et al. 2005).

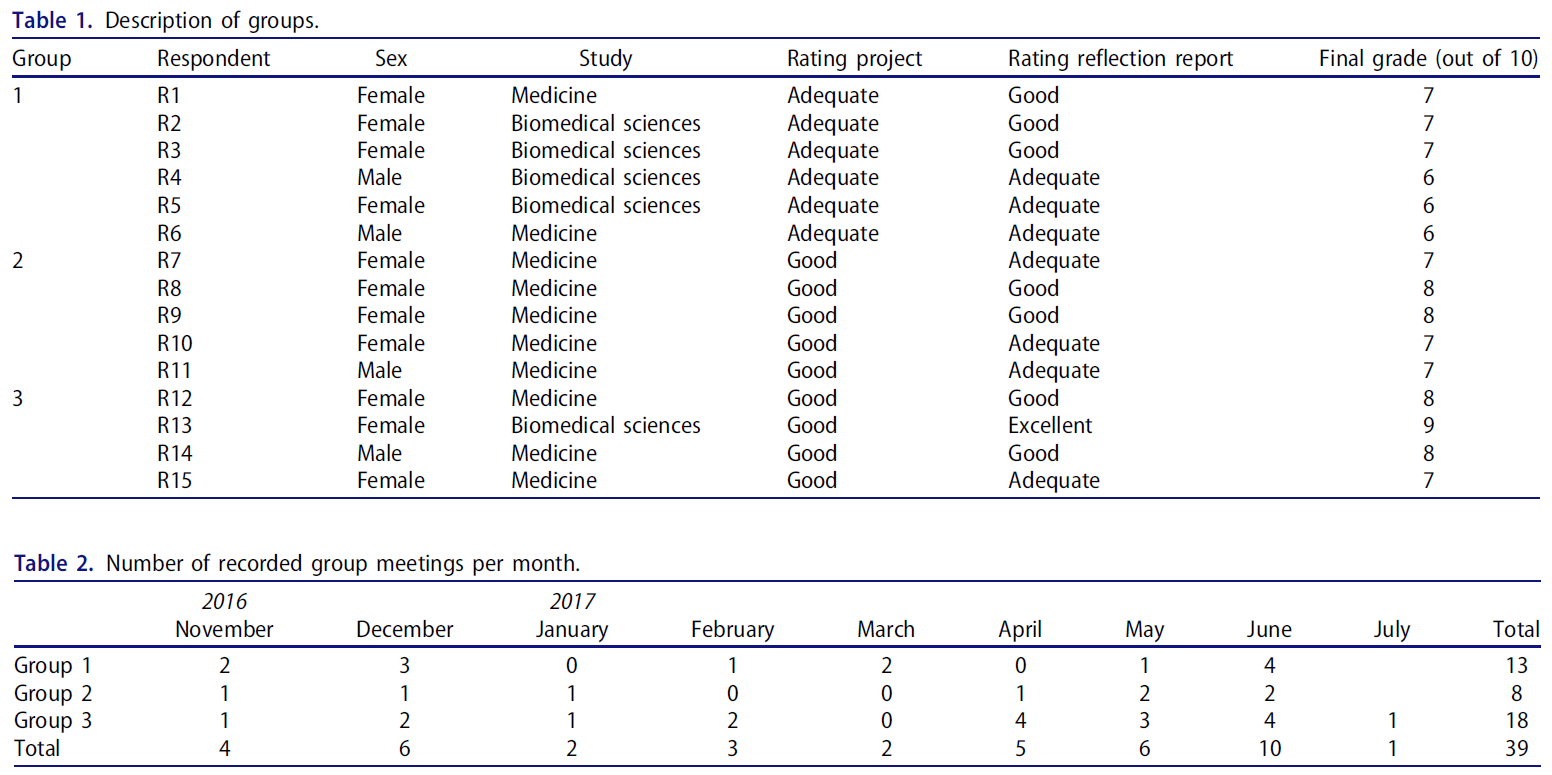

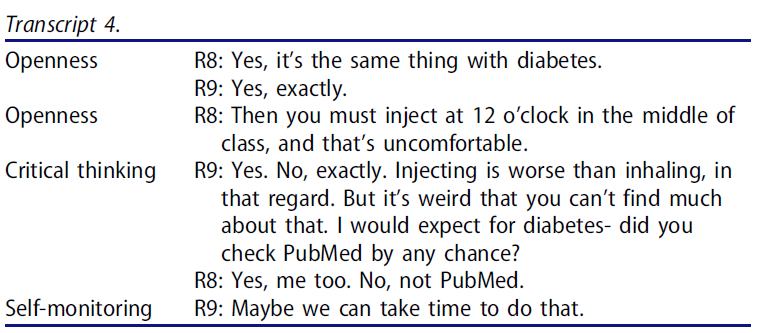

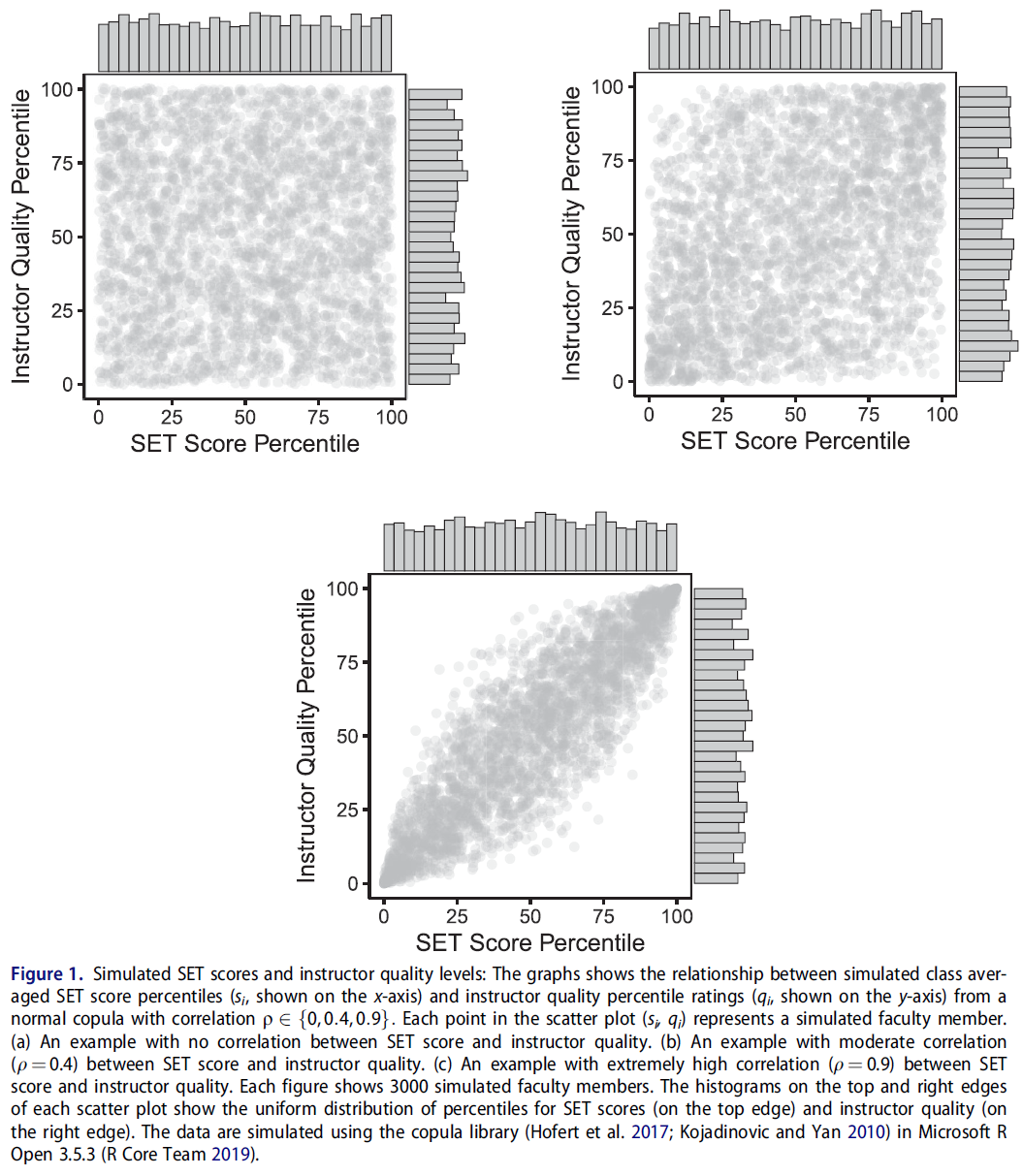

우리는 보디페인팅이 동료 시험에서 학생들이 느낄 수 있는 당혹감을 해소하는 데 실질적인 도움이 된다는 것을 발견했다(그림 1(A)). 또한 그것은 매우 기억에 남으며 매우 인기가 있다. 특히 시각 학습자에게 적합하며 임상 검사와 잘 통합됩니다. 우리는 학생들이 서로 연습할 수 없는 유방 검사 및 기타 임상 기술을 위해 임상 기술 파트너(CSP)를 사용한다. 학생들이 진짜 유방 검사를 본 적이 없고, 하물며, 심전도 검사를 받은 적이 없으며, 여성에게도 심전도 검사를 한 적이 없다는 것을 알게 된 것은 매우 실망스러운 일이었습니다. 이것은 해부학 교육의 문화적 구성과 함께 오는 사회적 당혹감의 일부이다. CSP는 상대적으로 젊고 마른 경향이 있는 우리 학생들보다 더 넓은 범위의 신체 형태를 가지고 있었다. CSP는 또한 학생 경험에 추가된 방식으로 자발적으로 그들의 인생 경험을 공유했다. 그들은 "손이 시리다" "화장실 다녀왔느냐고 묻지 않으면 누르지 말라"는 말을 서슴지 않았다. 그들은 환자가 아니기 때문에 권한을 박탈당하지 않는다.

We found body painting to be a real help in defuzing the embarrassment students may feel in peer examination (Figure 1(A)) (Finn and McLachlan 2010). It is also highly memorable and very popular. It particularly suits visual learners, and integrates well with clinical examination. We use clinical skills partners (CSPs) for breast examination and other clinical skills, which students cannot practice on each other (Collett et al. 2009). It had been deeply dismaying for me to discover that students were graduating without ever having seen a real breast examination, far less done one, and had never placed ECG leads on a female. This is part of the social embarrassment that comes with the cultural construction of anatomy teaching. The CSPs had a wider range of body morphologies than our students, who tend to be relatively young and lean. CSPs also shared their life experiences spontaneously in ways that added to the student experience. They did not hesitate to say, “Your hands are cold,” or, “Don’t press me there unless you’ve asked if I’ve been to the toilet”. They are not patients, and are therefore not disempowered.

또한 전자 본체(예: VH 디섹터)를 사용하고 학생들에게 이미지를 투사하여 가치를 더했습니다(그림 1(B)). 자원봉사자를 회전시키면서 내부 구조도 회전시킬 수 있다. DR의 시체조차도 이러한 유연성을 제공하지 않습니다. 이 접근법은 특히 임상적으로 관련 있는 횡단 뷰를 나타내는 데 뛰어나다.

We also used electronic bodies (e.g. VH Dissector), and add value by projecting images onto students (Figure 1(B)). One can rotate a volunteer while also rotating their internal structures. Even the cadaver in the DR does not offer this flexibility. This approach is particularly good at indicating clinically relevant transverse views.

특히 흥미로운 것은 3D 인쇄를 사용하는 것입니다. 예를 들어, 인쇄된 '팔로의 지형학'을 학급의 모든 학생들에게 배포하여 처리하고 회전시킬 수 있으며, 병리학적 표본으로도 허용되지 않는 이해를 얻을 수 있습니다.

Particularly exciting is the use of 3D printing, for instance, a printed ‘Tetralogy of Fallot’ can be circulated to all the students in the class, to handle and rotate it, gaining understanding that even a pathological specimen wouldn’t allow.

우리는 학생들이 신체의 모든 측면을 이해하기를 원했고, 그래서 우리는 학생들이 인간적인 맥락에서 신체에 대해 생각하도록 격려하기 위해 인생 그림, 조각, 그리고 시 수업을 통해 예술과 인문학을 포함했습니다. 이것은 웰컴 트러스트로부터 자금을 끌어모았다. 한 프로젝트("Flex + Ply")에는 직물 관련 작업이 포함되었으며, 그림 1(C) (Fleming et al. 2010)에 표시된 피부색 청바지를 특징으로 했습니다. "이거 입으면 내 S3가 커 보이나?"라는 제목이 학생들에게서 나왔다. '절개 가운'은 수술과 생검의 주요 장소를 표시했다.

We wanted students to understand all aspects of the body, so we included arts and humanities via life drawing, sculpting, and poetry classes, to encourage students to think about the body in a human context (Collett and McLachlan 2005; Collett and McLachlan 2006). This attracted funding from the Wellcome Trust. One project (“Flex + Ply”) included work with textiles, and featured the dermatome jeans shown in Figure 1(C) (Fleming et al. 2010). The title, “Does my S3 look big in this?” came from the students. The ‘Incision Gown’ marked the major sites of operations and biopsies.

이러한 새로운 접근 방식에 맞게 평가를 조정하는 것이 중요합니다. 임상적 맥락이 있는 질문은 더 잘 수행되었고 더 인기가 있었다(Ikah et al. 2015).

It is important to adjust assessment to match these new approaches. Questions with clinical context performed better and were more popular (Ikah et al. 2015).

학생들이 시체들을 사용하지 않음으로써 중요한 것을 놓치나요? 아닐 거예요. 죽음은 호스피스 치료와 같은 현실 세계에서 가장 잘 보인다. 비슷하게, 손재주와 팀워크를 훈련시키는 많은 방법들이 있다. 시체가 "첫 번째 환자"라는 생각은 실망스럽다. 우리는 학생들이 그들의 첫 번째 환자를 분해하기를 원합니까? 오히려, 우리는 학생들이 그들을 살아있는 사람으로 보기를 원한다. 예를 들어, 우리는 1학년 학생들을 임신 중인 산모에게 소개하는데, 산모는 임신 기간 내내 따라다닌다. 우리는 이것이 훨씬 더 나은 "첫 번째 환자"라고 느낍니다. 그리고 그것은 일부 학생들이 시체들과 함께 일하는 것에 대해 느끼는 고통을 피한다.

Do students miss out on anything important by not using cadavers? We believe not. Death is best seen in a real world context, such as in hospice care. Similarly, there are many ways to train for dexterity and team work. The idea of the cadaver as “the first patient” is dismaying: do we want students to disassemble their first patient? Rather, we want students to see them as living people. For instance, we introduce first year students to a pregnant mother, who they follow through her pregnancy, including imaging sessions. We feel this is a much better “first patient”. And it avoids the distress that some students feel with regard to working with cadavers.

이러한 접근법의 학생들에게 미치는 영향은 무엇인가? 우리는 그들이 다른 과목들과 같은 속도로 해부학을 배운다는 것을 보여주었고, 반대편 "팀"의 일원인 아담 윌슨의 메타 분석은 해부학을 가르치기 위해 어떤 양식을 사용하는지를 나타내지 않는다는 것을 보여주었다. 의사로서 학생들에게 미치는 영향은 무엇인가? 우리는 그것이 그들을 더 편안하게 하고 연습에 대비하게 한다는 것을 발견했다(Chinna et al., 2011).

What is the impact on the students of these approaches? We have shown that they learn anatomy at the same rate as other subjects, and a meta-analysis by Adam Wilson, a member of the opposite “team”, has shown that it does not signify which modality you use to teach anatomy (Wilson et al. 2017). What is the impact on students as doctors? We have found that it makes them more relaxed and prepared for practise (Chinnah et al. 2011).

수술의 경우, 외과적 훈련은 보존된 시체들의 연구와 해부를 필요로 할 수 있지만, 그것은 대학원 이후의 활동이어야 한다.

As for surgery, surgical training may well require the study and dissection of preserved cadavers, but that should be a post-graduate activity.

그래서 제가 마지막으로 추천하는 것은, 죽은 자보다 산 자를 선택하는 것입니다.

So my final recommendation is, choose the living over the dead.

찬성 측

“Yes we do” house

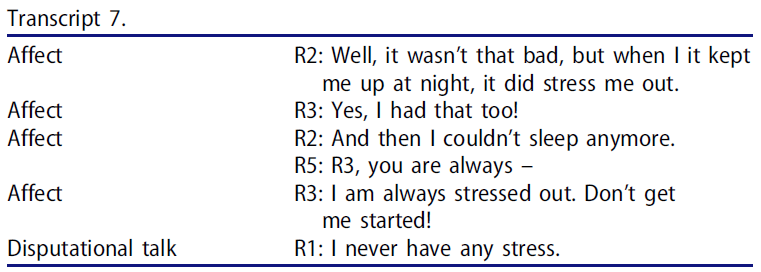

애덤 윌슨 박사

Dr Adam Wilson

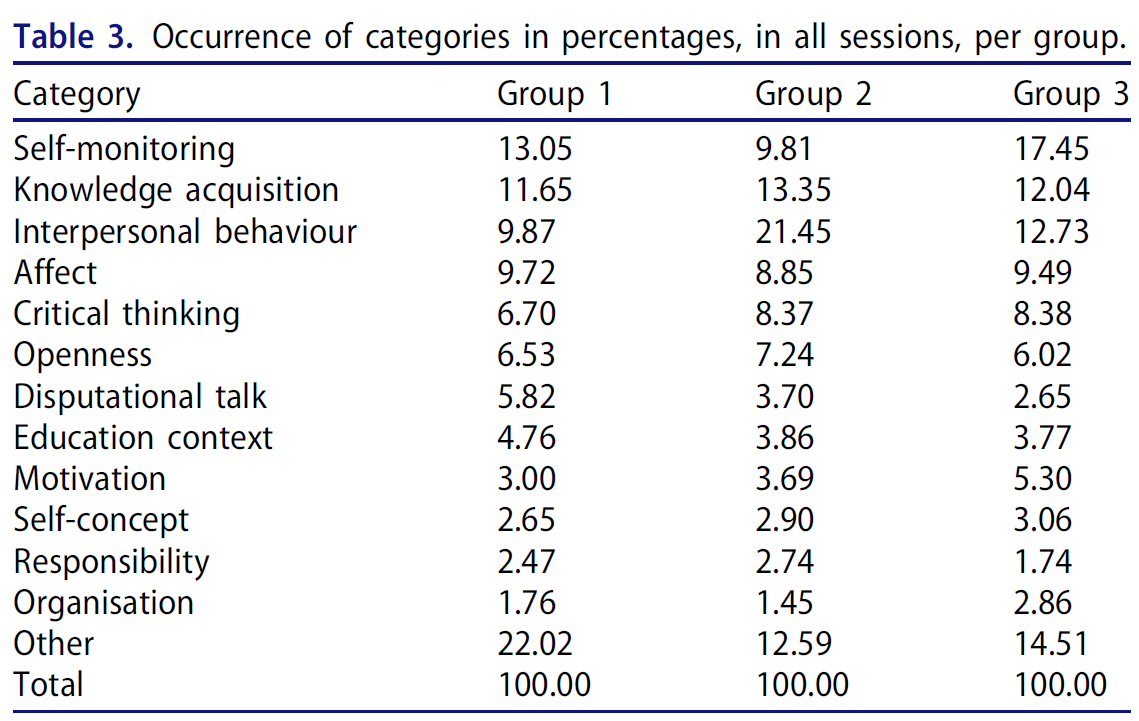

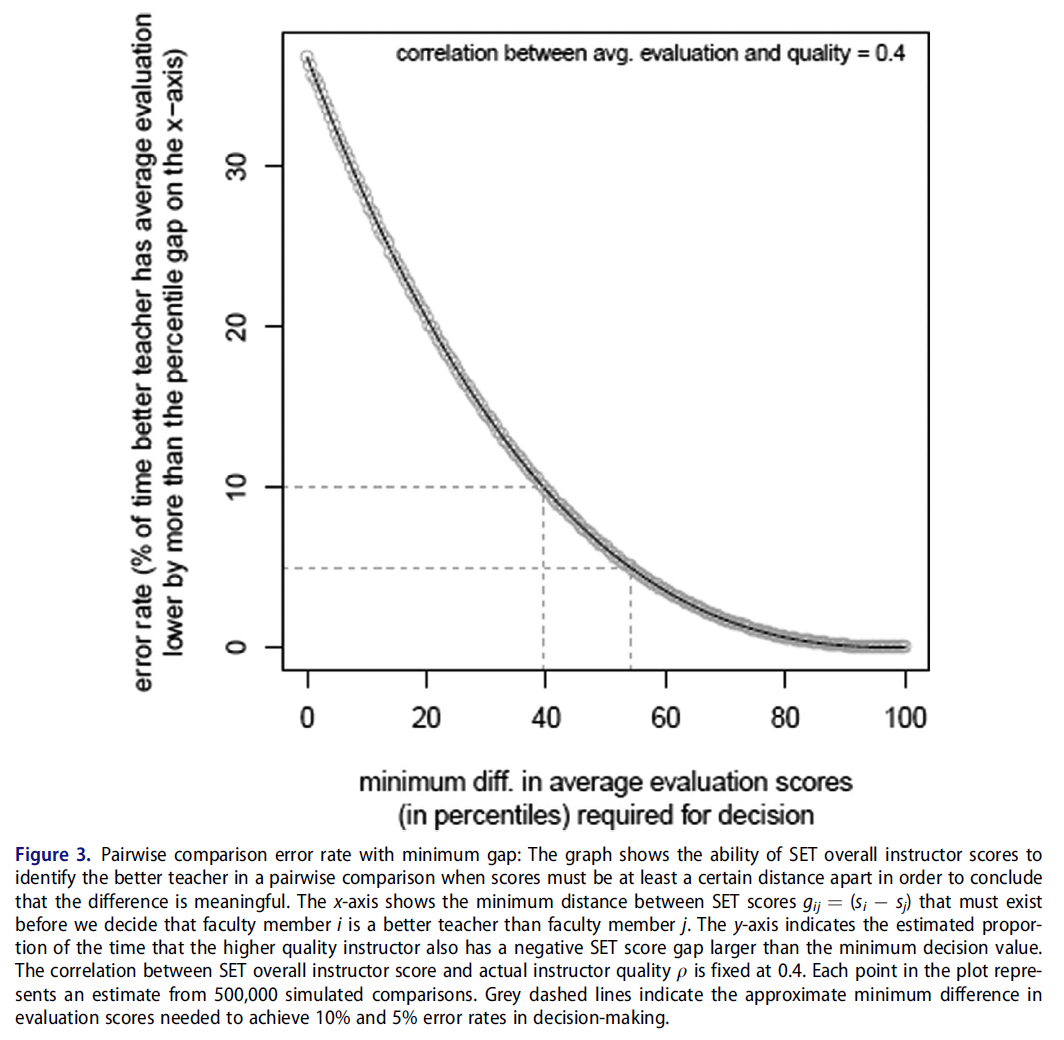

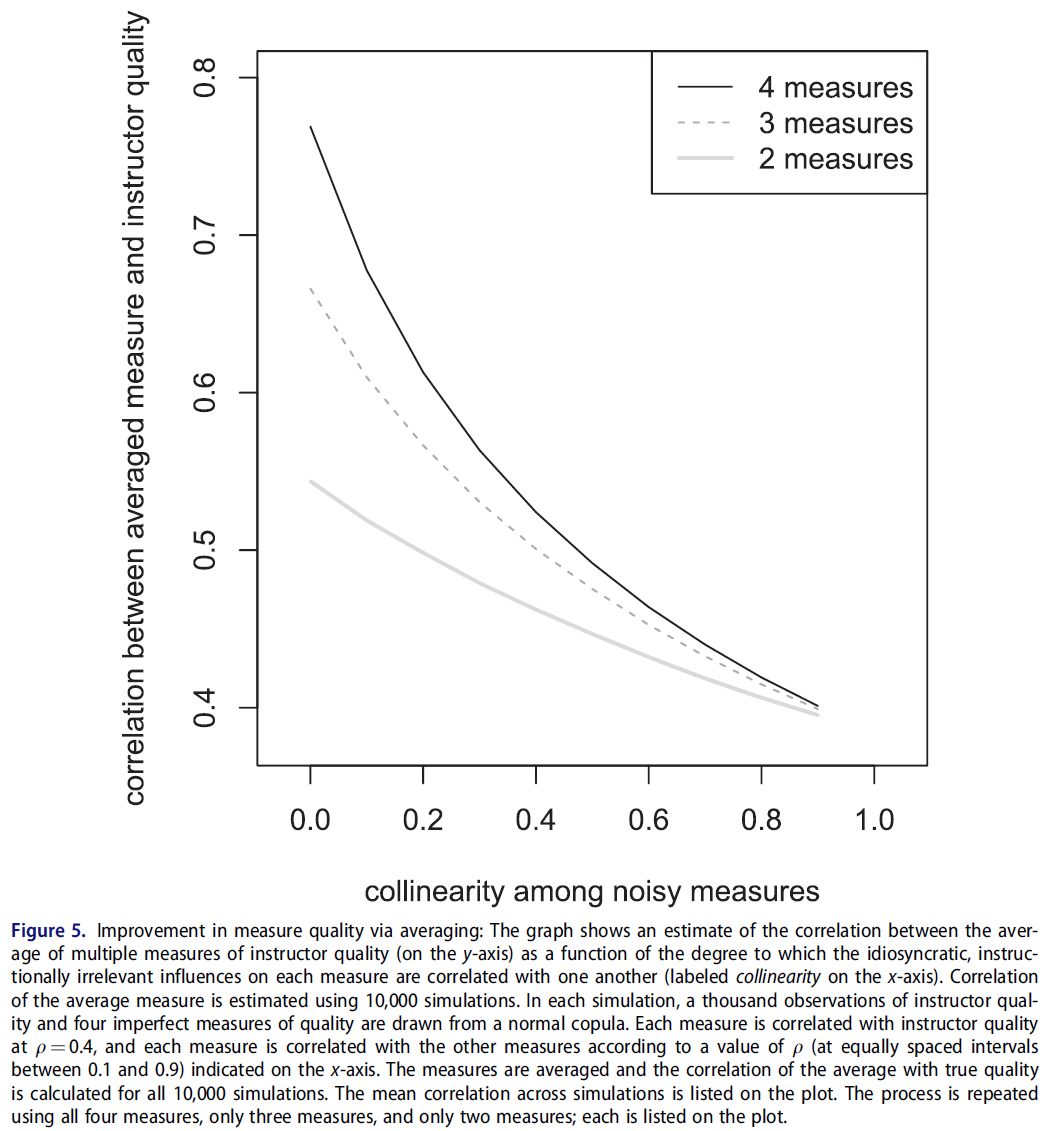

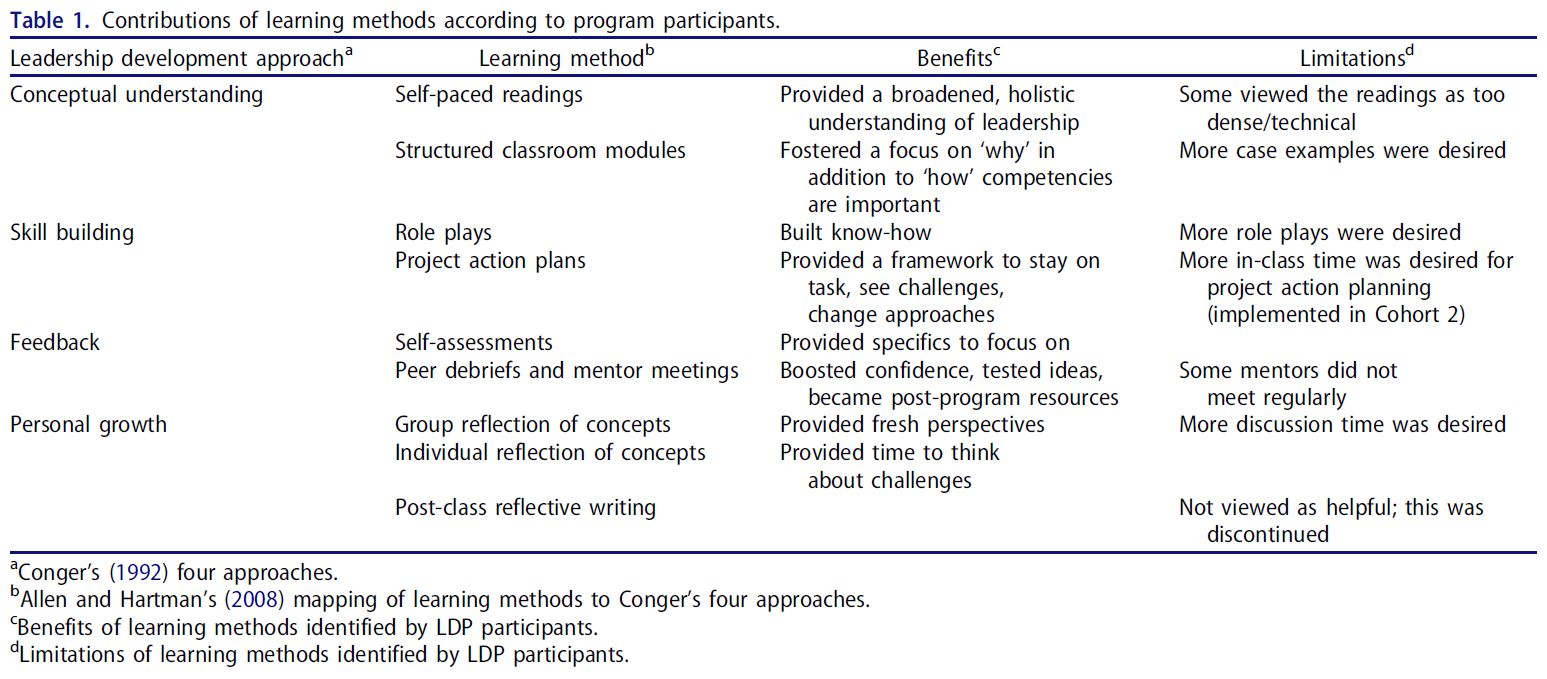

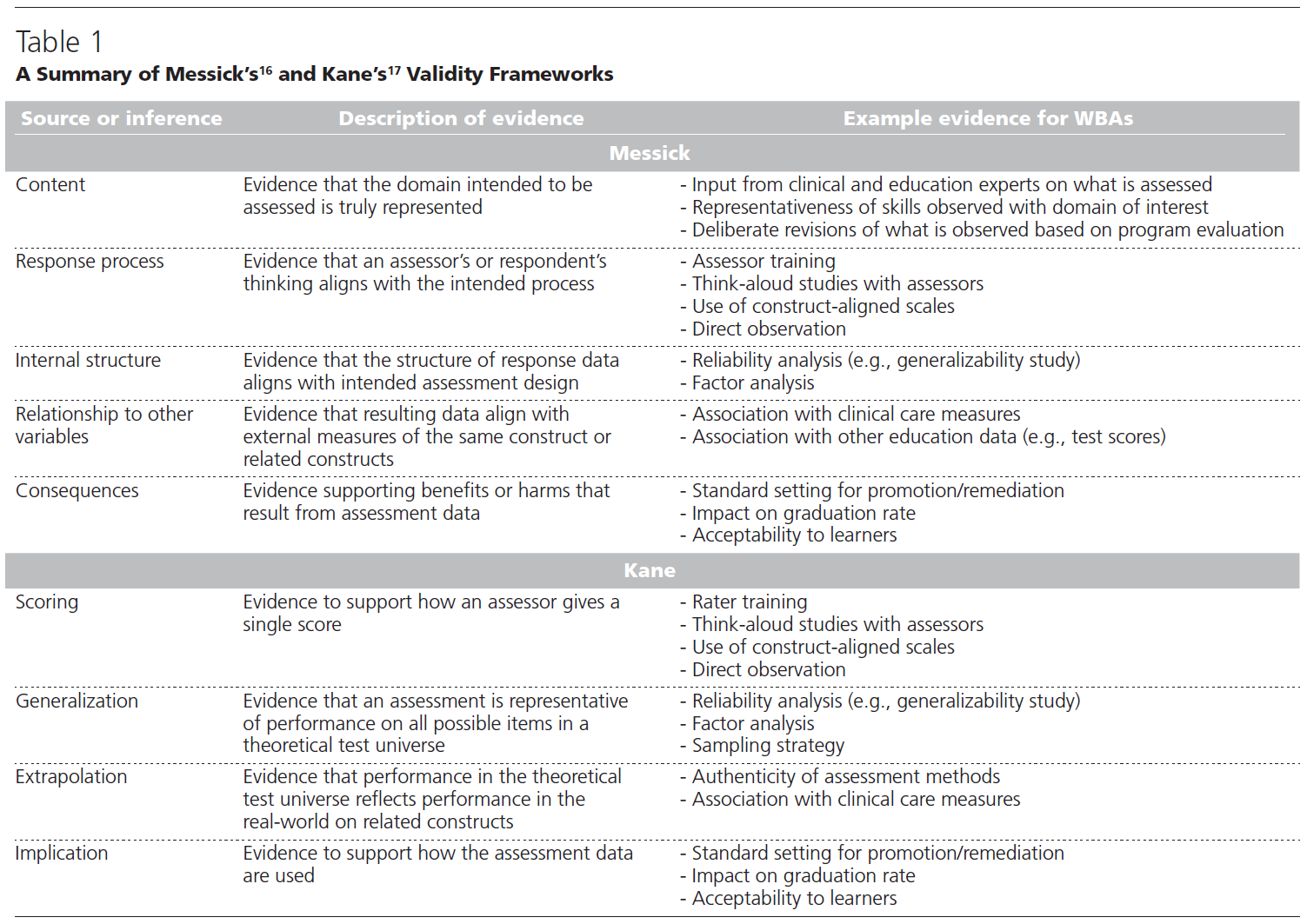

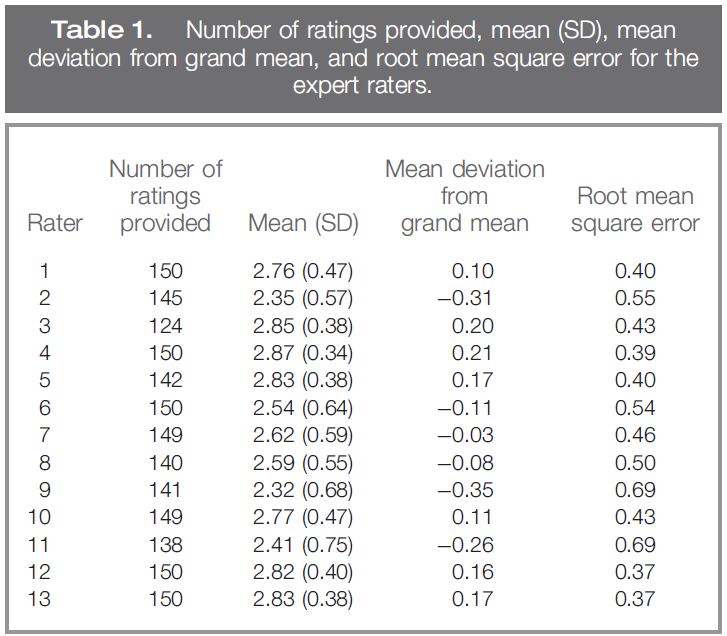

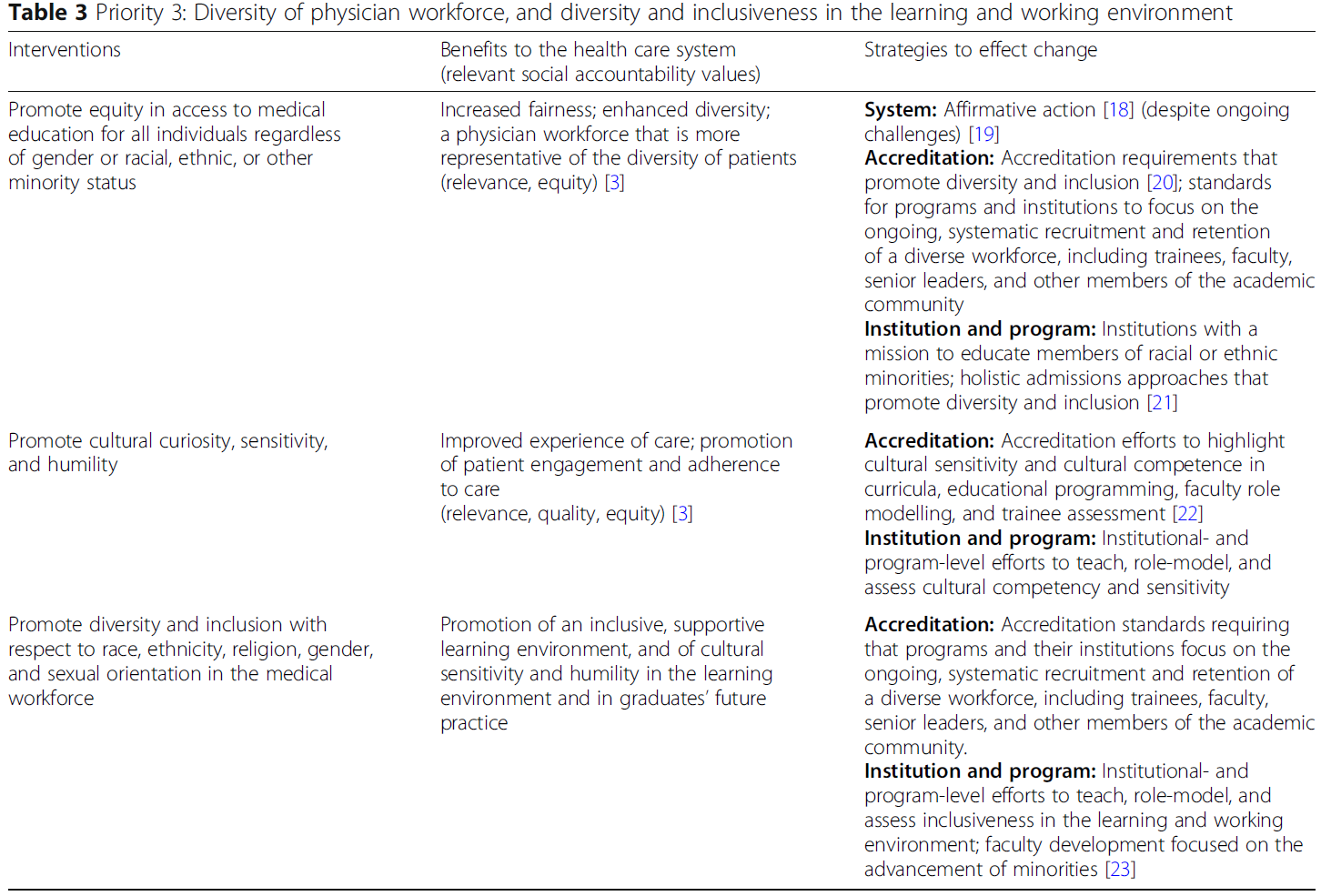

최근 발표된 해부학 실험실 교육학에 대한 메타 분석은 핵심 증거 기반 연구로, 많은 주장이 따를 수 있는 토대를 마련한다. 요약하면, 메타 분석은 해부 대 해부, 해부 대 모델/모델링, 해부 대 디지털 미디어, 해부 대 하이브리드 접근법을 조사하는 4가지 하위 분석을 수행했다. 이 연구의 전반적인 목표는 이러한 다른 접근법에 비해 해부의 효과를 이해하는 것이었다. 3000개가 넘는 기록을 검토한 결과, 총 27개의 연구가 최종 분석에 포함되었다. 7,000명 이상의 참가자를 포함한 27개 연구에서 메타 분석은 학습자의 성과에 영향을 미치지 않았다. 다시 말해서, 해부학에서 학생들의 단기적인 지식 증가는 [해부용 시체들에 노출되거나 그렇지 않은 것과 상관없이 동등]했다.

Our recently published meta-analysis on anatomy laboratory pedagogies (Wilson et al. 2018) is a key evidence-based study, which lays the groundwork for many of the arguments to follow. In summary, the meta-analysis conducted 4 sub-analyses that investigated dissection vs prosection, dissection vs. models/modeling, dissection vs digital media, and dissection vs hybrid approaches. The overall goal of this study was to understand the effectiveness of dissection compared to these other approaches. Upon reviewing over 3000 records, a total of 27 studies were included in the final analysis. Across those 27 studies (which included over 7000 participants), the meta-analysis detected no effect on learner performance. In other words, students’ short-term knowledge gains in anatomy were equivalent regardless of being exposed to dissecting cadavers or not.

액면 그대로 말하자면, 대학 의학 교육에서 시체들은 더 이상 필요하지 않은 것처럼 보인다. 그러나 나는 개인들에게 이 연구를 지나치게 해석하지 말라고 경고한다. 이러한 결과는 학생들의 [단기적인 지식 향상]에만 초점을 맞춘다. 많은 사람들은 시체들과 해부가 해부학적 지식의 보존에 더 큰 영향을 미친다고 주장할 것 같다. 구조물은 학습자들이 진짜 해부학을 경험할 때 장기적으로 학습자들의 마음에 더 잘 각인됩니다. 우리가 교육 문헌을 볼 때, 커스터(2010)는 [장기적인 지식 보존]의 가장 중요한 결정 요인은 학습 중인 콘텐츠와의 장기적인 접촉이라고 알려준다. 이 논리에 따르면, 시체 해부의 시간 강도 과정은 해부학적 지식을 더 잘 장기적으로 보존하는 것으로 해석될 가능성이 높다. 하지만, 완전한 투명성에서는, 이 주제에 대한 문헌이 거의 없기 때문에, 시체들이 지식 보존에 미치는 진정한 영향을 확실히 아는 것은 어렵습니다. 이 점은 좀 더 엄밀한 조사가 필요하다

At face value, it appears that cadavers are no longer needed in undergraduate medical education. However, I caution individuals not to over-interpret this study. These results focus only on students’ short-term knowledge gains. Many are likely to argue that cadavers and dissection have a greater impact on the retention of anatomical knowledge. Structures are better imprinted in the minds of learners, for the long-term, when they experience authentic anatomy. When we look at the educational literature, Custer (2010) informs us that the most important determinant of long-term knowledge retention is prolonged contact with the content under study. Following this logic, the time intensiveness process of cadaveric dissection likely translates to better long-term retention of anatomical knowledge. However, in full transparency, the literature on this topic is scant, so it’s hard to know for certain the true impact of cadavers on knowledge retention. This point deserves more rigorous investigation.

흥미롭게도, 지난 10여 년 동안 적어도 5개의 미국 의과대학과 일부 호주와 뉴질랜드 의과대학이 시신 유기 및 해부 실험을 했다. 이 학교들은 몇 년 후에 시신 해부를 다시 시작한다는 것을 알게 되었다. 다음은 면과 관련하여 이러한 현상이 발생한 이유에 대한 두 가지 설명입니다.

Interestingly, over the past decade or so, at least 5 US medical schools and some Australian and New Zealand medical schools have experimented with abandoning cadavers and dissection. These same schools found themselves reinstating cadaveric dissection a few years later (Rizzolo and Stewart 2006; Craig et al. 2010). Here are two explanations for why this about face may have occurred:

- 한 연구는 임상실습 책임자들이 일화적으로 학생들의 임상실습 수행 능력이 부족하다고 느낀다고 언급했다(리졸로와 스튜어트 2006). 그들은 해부를 포기하는 것과 같은 커리큘럼의 변화에 성과적 부족을 돌렸다. 이것은 해부학적 지식의 보존에 기여하는 시체들의 잠재적인 역할로 돌아간다.

- One study cited that clerkship directors anecdotally felt the performance of their students on clerkship was lacking (Rizzolo and Stewart 2006). They attributed performance deficits to curricular changes, such as abandoning dissection. This circles back to the potential role of cadavers in contributing to the retention of anatomical knowledge.

- 학교들이 시체 기반 해부로 복귀한 이유에 대한 두 번째 설명은 대다수의 학생들이 교과 과정에 시체 해부를 하는 것을 선호하는 경향이 있다는 것이다. 해부학 실험실 교육학의 동일한 메타 분석에서, 17개의 연구에서 시체들에 대한 선호도와 시체들에 대한 선호도가 집계되었다. 평균적으로 응답자의 57%가 시체 기반 학습을 선호하거나 가치를 발견했다. 이 발견은 고등학생, 대학생, 보건 직업 학생, 의대생을 포함한 매우 다양한 학습자 집단에서 파생되었다. 57%의 이 추정치는 (아마도 다른 어떤 그룹보다) 자신의 해부학적 지식을 임상 환경에서 적용하도록 강요받는 의대생들 사이에서 더 높을 것이다.

- A second explanation for why schools returned to cadaver-based dissection is that the majority of students tend to favor having cadavers and dissection in their curricula (Wilson 2017). In the same meta-analysis of anatomy laboratory pedagogies, preferences for and against cadavers were tallied across 17 studies. On average, 57% of respondents favored or found value in cadaver-based learning. This finding was derived from a very diverse population of learners, which included, high school students, college students, health professions students, and medical students. This estimate of 57% is likely to be higher among medical students who (more so than perhaps any other group) are forced to apply their anatomical knowledge in clinical settings.

- 그렇긴 하지만, 왜 학생들은 시체들을 선호할까? 한 가지 잠재적인 대답은 시신 기반 해부학이 인간의 변이, 죽음에 대한 노출 및 수술 기술을 수반하고 조직 질감과 공간 관계의 고유성을 통해 구조의 차등 식별을 포함하는 [진정한 해부학authentic anatomy]을 가르친다는 것이다. 어떤 사람들은 또한 시체 기반 학습이 학생들이 나중에 임상 환경에서 해부학적 지식을 증명하도록 요구될 때 학생들의 자신감 수준을 높이는 데 도움이 된다고 주장할 수 있다.

- That being said, why do students prefer cadavers? One potential answer is that cadaver-based anatomy teaches authentic anatomy which entails human variation, exposure to death and surgical skills, and involves the differential identification of structures through the uniqueness of tissue textures and spatial relationships. Some may also contend that cadaver-based learning helps to boost students’ confidence levels when they are later called upon to demonstrate their anatomical knowledge in clinical settings.

시체들의 사용에 반대하는 또 다른 일반적인 주장은, 예를 들어, 유전학과 같은 다른 성장하는 분야들에 대해 배우는 데 더 나은 시간을 보낼 수 있다는 것이다. 반박하자면, 의학 연구는 항상 진화할 것이다. 그것은 당연해요! 그러나, 의학의 기초는 인체와 그 기계적인 과정에 대한 복잡한 이해이며, 그것은 결코 변하지 않을 것이다. 해부학은 역사적으로 의학의 초석으로 불리며, 임상 지식과 통찰력이 구축되는 중요한 기본 구성 요소로서 지속되어 왔다. 찰스 프로버(스탠포드 의학교육 학장)는 해부학을 '상록수' 학문이라고 불렀는데, 이는 해부학이 항상 관련성이 있다는 것을 의미한다. 어떤 이들은, 심지어 시체 기반 교육이 가장 엄격한 교육학적 적합성 시험인 [시간의 검증test of time]에서도 살아남았다고 말할 것이다. 마치 모래 대신 바위 위에 집을 지은 현명한 사람처럼, 의학 커리큘럼도 진짜 시체 기반 해부학의 견고한 토대 위에 세워져야 한다고 생각합니다.

Another common argument against the use of cadavers is that the time spent learning detailed anatomy could be better spent learning about other growing disciplines like genetics, for example. In rebuttal, the study of medicine will always be evolving. That’s a given. However, the foundational basis upon which medicine is build is an intricate understanding of the human body and its mechanistic processes—and that will never change. Anatomy has historically been called the cornerstone of medicine, and it continues to persist as an important basic building block upon which clinical knowledge and acumen are built. Charles Prober (a medical education dean at Stanford) along with the founder of the Kahn academy have called anatomy an ‘evergreen’ discipline, meaning it will always be relevant (Prober and Khan 2013). Some would even say that cadaver-based instruction has survived the most rigorous test of pedagogical fitness—the test of time. Like the wise man who built his house upon the rock, instead of the sand, so too should medical curricula be built on the solid foundations of authentic cadaver-based anatomy, in my opinion.

여기 고려해야 할 마지막 요점이 있다. 쿠퍼와 데온(2011)은 논문에서 역사적으로 의료 커리큘럼은 사회적, 정치적, 경제적 힘에 의해 외부적으로 영향을 받았다고 밝혔다. 그들은 커리큘럼이 종종 "문화적으로 기반하고 사회적으로 조정된다"고 주장한다. 의과대학이 학생들이 환자를 보기 전에 해부학에서 의사들을 훈련시키기 위해서만 가상현실을 사용한다고 홍보하는 것을 상상해보라. 사회는 이것에 어떻게 반응할까? 훈련 기관의 명성을 더럽힐 수 있는 대중의 불만이나 불만이 있을 수 있는가? 아마도요. 본질적으로, 우리는 여론의 법정을 과소평가할 필요가 없다. 이 같은 이념은 예비 학생들의 인식, 기대, 요구에도 적용된다.

Here is one final point to consider. In their paper, Kuper and D’Eon (2011) articulated that, historically, medical curricula have been externally influenced by social, political, and economic forces. They argue that curricula are often “culturally based and socially mediated”. Imagine a medical school publicizing that its students only use virtual reality to train their doctors in anatomy before they begin to see patients. How might society respond to this? Might there be some level of public dissatisfaction or discontent that could potentially tarnish the reputation of the training institution? Perhaps. In essence, we need not underestimate the court of public opinion. This same ideology also applies to the perceptions, expectations, and demands of prospective students.

전반적으로, 시체 기반 학습에 유리한 이 논평은 네 가지 핵심 포인트를 통해 요약될 수 있다.

Overall, this commentary in favor of cadaver-based learning can be summarized through four key points:

- 구조물은 학생들이 진짜 해부학을 볼 때 더 잘 각인된다. 이것은 장기적인 지식 보존을 향상시킬 가능성이 있다.

- 학생들은 시체로부터 배우는 것을 선호하고 그것은 아마도 교과목에 대한 그들의 신뢰 수준을 증가시킨다.

- 시체들과 함께 가르치는 것은 시간의 시련을 견뎌냈고 시체 해부를 포기한 학교들은 다시 그 시대로 돌아왔다.

- 커리큘럼 결정을 내리는 데 있어서 대중의 인식의 역할을 과소평가해서는 안 된다.

- Structures are better imprinted in students’ minds when they see authentic anatomy—which is likely to enhance long-term knowledge retention.

- Students prefer learning from cadavers and it likely increases their confidence levels in the subject matter.

- Teaching with cadavers has withstood the test of time and schools that have abandoned cadaveric dissection have returned to it.

- The role of public perception in making curricular decisions must not be underestimated.

반대측

“No we do not “house

제임스 피커링 부교수

Assoc Prof James Pickering

해부학을 가르치는데 시체들이 필요할까요? 그것이 우리가 토론하고 있는 질문이고 나는 커리큘럼 디자인의 프리즘을 통해 그 질문에 대답하기를 희망한다. 맥라클란 박사에 의해 탐구된 주제를 계속하기 위해, 우리는 누구를 원합니까? 현재 대학생들이 의과대학에 합격하면 우리는 누가 의학을 전공하고 싶은가? 우리는 효율적이고 효과적인 의사나 효율적이고 효과적인 해부학자를 원하는가? 나는 우리 모두가 전자에 동의할 것이라고 생각한다. 그렇다면, 우리의 직업은 무엇일까요? 의학 교육자로서, 해부학자로서 우리의 일은 효과적이고 효율적인 의사의 개발을 지원하는 것이다. 우리는 해부학자를 훈련시키기 위해 여기에 있는 것이 아니다. 저희는 대학원 연수 과정에 들어갈 의사들을 양성하기 위해 이곳에 왔습니다. 정신과, 수술, 일반 진료와 같은 다양한 전공분야를 전문으로 하고 있습니다.

Do we need cadavers to teach anatomy? That is the question we are debating and through the prism of curriculum design I hope to answer that question. To continue the theme that has been explored by Dr McLachlan, who do we want? Who do we want to be practicing medicine once our current undergraduate students have passed through medical school? Do we want efficient and effective doctors or efficient and effective anatomists? I think we’d all probably agree with the former. Therefore, what is our job? Our job as medical educators, as anatomists, is to support the development of effective and efficient doctors—we are not here to train anatomists. We are here to train doctors that are going to enter postgraduate training and specialize in a whole range of different specialties such as psychiatry, surgery and general practice.

그렇다면, 우리는 어떻게 이러한 효율적이고 효과적인 의사로서의 발달을 지원할 수 있을까요? 우리는 어떻게 그들의 졸업과 동시에 효율적이고 효과적인 의사들을 낳는 커리큘럼을 설계할까요? 그 질문에 답하기 위해 우리는 오늘날의 의사들의 역할을 이해할 필요가 있다. 무슨 일을 하시는데요? 오늘날 또는 미래의 의사들은 점점 더 다양해지는 문화, 다른 약, 그리고 현재 이용 가능한 획기적인 치료 방안과 함께 환자의 신체적, 심리적, 사회적 측면을 이해할 필요가 있다. 게다가, 현재의 의사들은 어떻게 이러한 다양한 측면을 환자 치료에 통합하는가? 더 이상 외과의사만 어떤 문제를 해결하는 것이 아니다; 복잡한 현대 문제를 해결하기 위해 함께 모이는 것은 다학제 전문가들로 구성된 팀이다. 임상의는 더 이상 고립된 상태로 일하지 않는다. 그들은 한 팀으로 함께 일한다. 이런 맥락에서 저는 우리가 이러한 [현대의 복잡한 문제]들을 해결할 수 있도록 우리의 학생들과 미래의 의사들을 지원하는 커리큘럼을 개발하고, 구성하고, 설계해야 한다고 믿습니다.

So, how do we support the development of these efficient and effective doctors? How do we design curricula that results in efficient and effective doctors upon their graduation? To answer that question we need to understand the role of today’s doctors. What do they do? Today’s or indeed tomorrow’s doctors need to understand the physical, psychological and social aspect of the patient, alongside the increasingly varied cultures, differing medicines and breakthrough treatment options that are now available. Moreover, how do current doctors then integrate all of these varying aspects to patient care? It is no longer the surgeon that seeks to solve a certain problem; it is a multidisciplinary team of specialists who come together to solve complex modern-day problems. Clinicians no longer work in isolation. They work together as a team. It is in this context I believe we need to develop, construct and design curricula that support our students, our future doctors, in being able to solve these modern day complex problems.

이 목표를 달성하기 위해서는 전이transfer가 필요하다고 생각합니다. 현대 의학의 기초인 종합 해부학, 조직학, 병리학, 살아있는 해부학 및 방사선학에 대한 기본 지식을 현대 의학에서 복잡한 문제를 해결하는 데 도움이 될 수 있는 솔루션을 찾는 데 전이할 수 있도록 지원합니다. 해부학자나 해부학 교육자로서, 우리는 인체의 신체적 기초를 이해하기 위해 미래의 의사들을 지원하고 발전시키는 데 있어, 전면적이고 중심적인 역할을 할 수 있는 운이 좋은 위치에 있다. 그러나, 이것은 [육안gross 해부학을 이해하는 것] 이상이다; 예를 들어, 다양한 근육의 부착 부위나 맹장의 위치를 이해하기 위해 시신으로 학습하는 것이 아니다. 이러한 영역들이 핵심 지식의 중요한 영역이지만, 우리는 학생들에게 단지 "육안gross" 또는 지형적 해부학 이상을 가르쳐야 할 책임이 있다. 우리는 그들에게 이런 것들을 가르친다.

- 발달 해부학, 배아학; 임상 기술을 뒷받침할 수 있는 표면 및 살아있는 해부학; 현미경 또는 조직학; 기능적 해부학 및 생리학; 비정상적인 해부학 또는 병리학; 그리고 마지막으로 영상 해부학 방사선학을 우리의 코스에 통합합니다.

후자는 해부학 커리큘럼의 필수적인 요소인데, 대부분의 의사들이 인체를 이미지 형태로 조사examine할 것이기 때문이다.

To achieve this goal, I believe the requirement is transfer. Supporting our students to transfer the basic knowledge of gross anatomy, histology, pathology, living anatomy, and radiology—the bedrock of modern medicine—into finding solutions that can help solve modern day complex problems. As anatomists, or as anatomy educators, we are in the fortunate position to have a front and central role in supporting and developing the future doctors to understand the physical basis of the human body. However, this is more than understanding gross anatomy; it is not just about working with cadavers, for example, to understand the attachment sites of various muscles or the location of an appendix. Whilst these are important areas of core knowledge, we are charged with teaching our students more than just “gross” or topographical anatomy. We teach them

- developmental anatomy, embryology; surface and living anatomy to support their clinical skills; micro-anatomy or histology; functional anatomy and physiology; abnormal anatomy or pathology; and finally we integrate imaging anatomy radiology into our courses.

The latter is an essential element of any anatomy curriculum, as the vast majority of doctors will examine the human body in image form.

그래서 영국 리즈에서 우리의 커리큘럼의 초점은 무엇인가? 시체들을 해부하고 이것을 신경표와 추천된 교과서에 있는 부착물과 연결시키는데 시간을 보내기 위해서? 앞에서 언급한 다른 영역보다 본 코스의 이러한 측면이 더 중요합니까, 아니면 덜 중요합니까? 거시 해부학macro-anatomy이 중요하지 않다고 주장하는 것은 어리석은 일일 것이다. 하지만 그것은 학생들이 알아야 할 다른 것이다. 저는 우리가 이 [모든 개별적인 요소들을 통합]하는데 우리의 커리큘럼을 집중할 필요가 있다고 생각합니다. 그렇지 않으면, 우리는 커리큘럼을 "원자화"하고, 개별 요소를 우리가 왜 이 내용을 가르치는지에 대한 중요한 근거는 없는, 상당히 상세한 체크리스트로 환원시킬 위험이 있다. 교과 과정의 해부학적 내용을 자세히 이해하는 것은 문제될 것이 없다. 사실 세부적으로 이해하는 것만이 복잡한 문제를 해결할 수 있다. 다양한 "핵심" 해부학 강의 요강은 커리큘럼을 개발하는 데 유용하다고 알려져 왔다. 하지만 원래의 질문으로 돌아가자면, 여러분은 이 논문에서 제시된 해부학을 이해하기 위해 시체 한 구가 필요할까요? 물론, 여러분은 그것을 하기 위해 시체를 사용할 수 있지만, 아마도 다른 방법들도 있을 것이고, 그것은 똑같이 효과적일 것입니다. 해부학자로서, 해부학 커리큘럼을 설계하는 학자로서, 우리는 이것보다 더 잘할 수 있습니다.

So what is the focus of our curriculum at Leeds in the UK? To spend time dissecting cadavers and linking this to tables of nerves and attachments from the recommended textbook? Is this aspect of our course more or less important than the other areas mentioned previously? It would be folly to argue that macro-anatomy is not important, but it is just something else the students need to know. I believe we need to focus our curricula on integrating all of these individual elements together. If not, we risk “atomising” our curricula and reducing the individual elements into quite detailed checklists absent of an overarching rationale for why we are teaching this content. There is nothing wrong with a detailed understanding of the anatomy content of the curriculum, in fact, only by having a detailed understanding can complex problems be solved. Various “core” anatomy syllabi have been said to be useful in developing curricula (Tubbs et al. 2014; Moxham et al. 2015; Smith et al. 2016). But to return to the original question: do you need a cadaver to understand the anatomy presented in these papers? You could use a cadaver to do it, of course, but there are probably other ways to do it, which are just as effective. I think as anatomists, as academics who are designing anatomy curricular, we can do better than this.

학생들은 교과 과정의 해부학 내용을 알아야 하지만, 복잡한 문제를 풀기 위해 이 내용을 어떻게 사용하는지도 알아야 합니다. 예를 들어, 폐암은 복잡한 문제이다. 영국에서 가장 흔하고 심각한 유형의 암 중 하나로, 연간 45,000건의 진단이 있다. 만약 누군가가 폐암에 걸렸다고 의심한다면, 그들은 어떻게 해야 할까요? 그들은 의사에게 간다. 그들의 의사는 무엇을 하는가? 그들을 검사하고, 그들의 가슴을 듣고, 청진하고, 촉진하고, 타진한다. 이는 [생체 해부학]이다. 그들은 잠재적으로 그들을 CT 스캔과 흉부 엑스레이 촬영을 위해 보내고, 그리고 나서 이 발견들을 해석할 것이다. 이것은 [방사선 해부학]이다. 그들은 용량을 계산하기 위해 폐 부피 테스트를 할 수 있다. 이것은 [기능적 해부학]이다. 그들은 조직검사를 받고 조직학(미소해부학)을 검사한 다음 병리를 평가할 수 있다. 이는 [이상 해부학]이다. 일단 환자가 이 순서를 거치면 그들은 거시 해부학을 검사하기 위해 수술을 받을 수 있다. 이는 [육안 해부학]이다.

The students need to know the anatomy content of their course, but they also need to know how to use this content to solve complex problems. For example, lung cancer is a complex problem. It is one of the most common and serious types of cancer in the United Kingdom, with 45,000 diagnoses per year. If someone suspects they have lung cancer, what do they do? They go to the doctor. What does their doctor do? Examine them, listen to their chest, auscultate, palpate, percuss - living anatomy. They will potentially send them for a CT scan, a chest x-ray and then interpret these findings—radiological anatomy. They may do a lung volume test to calculate capacity—functional anatomy. They may go for a biopsy and examine the histology—microanatomy—and then assess for pathology—abnormal anatomy. Only once the patient has gone through this sequence may they go and have surgery to examine the macro-anatomy—gross anatomy.

교육 과정을 [전달 방법]보다는 [내용에 집중]하기 위해서는, 보다 [전체적인 설계]가 필요하다. 원자화된 접근 방식에서 보다 전체적인 접근 방식으로 전환함으로써, 영역의 통합이 발생할 수 있습니다. 그러나 학생들이 이러한 복잡한 생각을 배우기 위해서는 복잡한 가르침이 필요하며 해부학의 각 영역에 대해 어떤 면이 정말로 시체 한 구를 필요로 하는가? 생체, 방사선, 미시, 거시, 비정상적인 해부학은 현재 이용 가능한 광범위한 대체 자원을 사용하여 모두 가르칠 수 있다. 보디페인팅에서 가상현실 소프트웨어 및 시뮬레이션, 3D 프린팅에서 플라스틱에 이르기까지 단순하고 복잡한 형태를 만들 수 있습니다. 만약 이 자원들이 대안들만큼 효과적이라는 것을 보여줄 수 있다면, 왜 시체들은 해부학 커리큘럼을 전달하기 위해 어디에나 있는 접근법이 필요할까요? 난 그렇게 생각하지 않습니다.

A more holistic design is necessary to focus our curricula on the content rather than the delivery method. By moving away from the atomized approach to a more holistic approach, integration of areas can occur. However, for the students to learn these complex ideas you need complex teaching and for each area of anatomy which aspect really needs a cadaver? Living, radiological, micro, macro, abnormal anatomy can all be taught by using the wide range of alternative resources currently available. Form the simple to the complex, from body painting to virtual reality software and simulation, from 3D printing to plastination. If these resources can be shown to be as efficacious as the alternatives (Pickering 2017; Clunie et al. 2018; Wilson et al. 2018), then why do cadavers need to be the ubiquitous approach to delivering our anatomy curricula? I don’t think they do.

찬성측

“Yes we do” house

제니퍼 맥브라이드 부교수

Assoc Prof Jennifer McBride

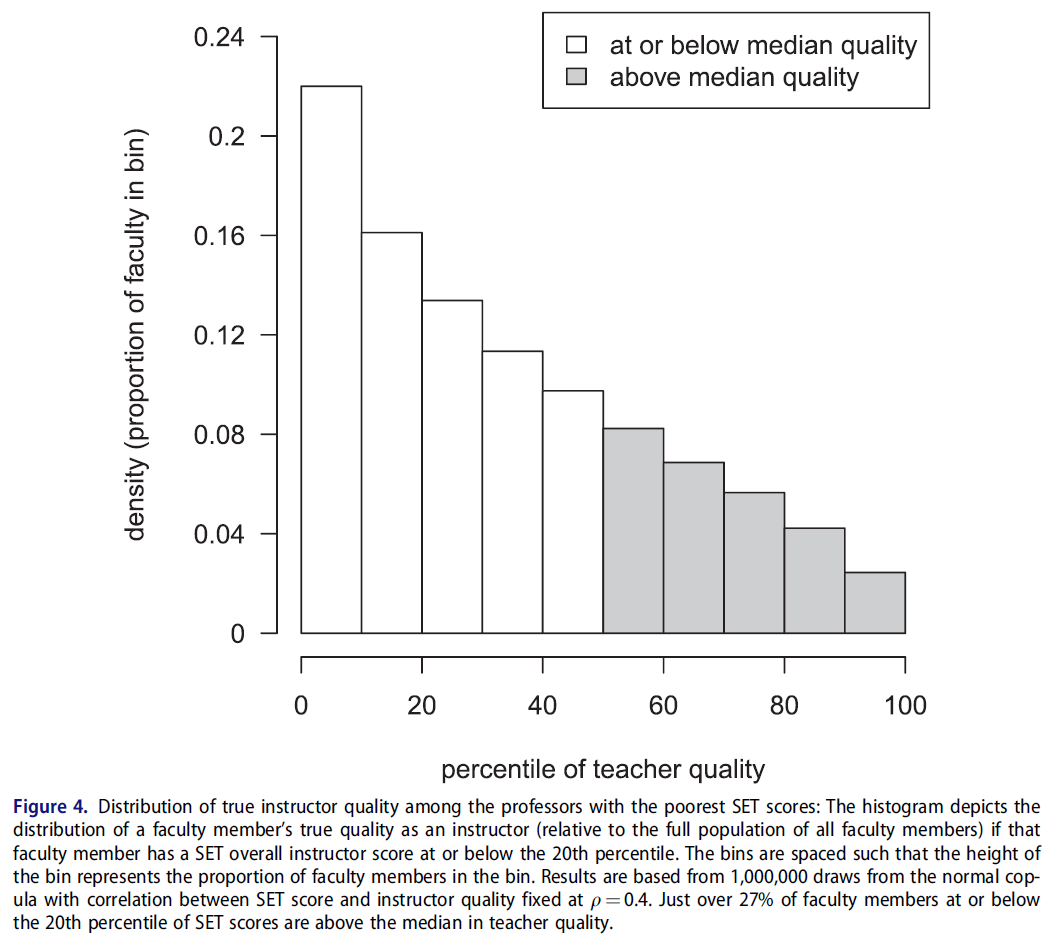

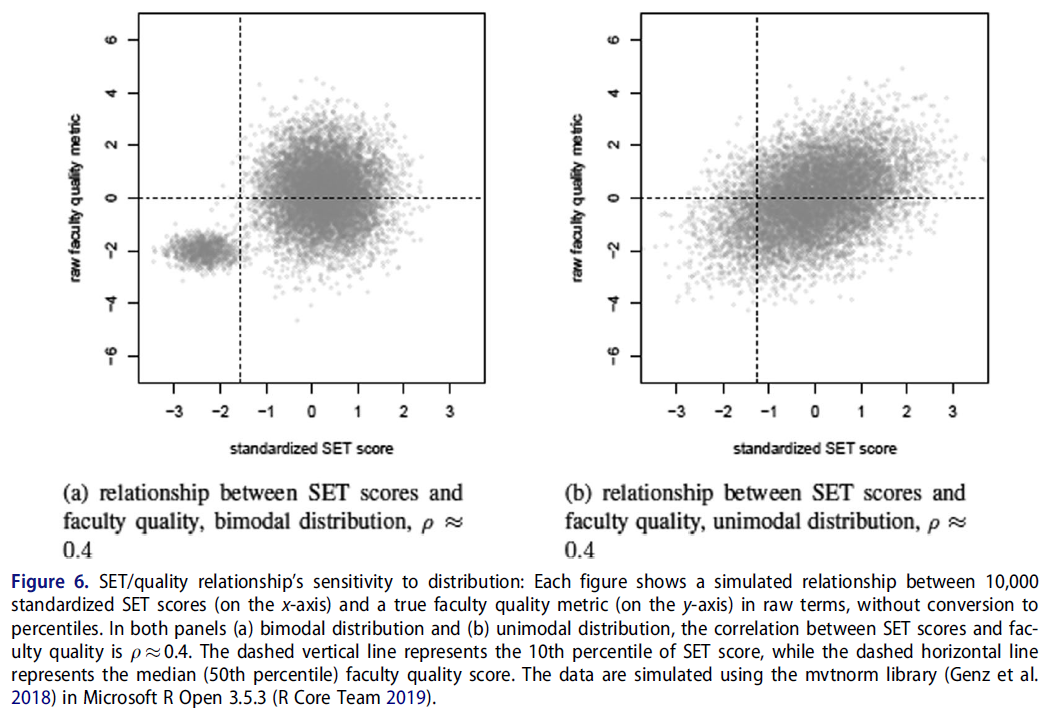

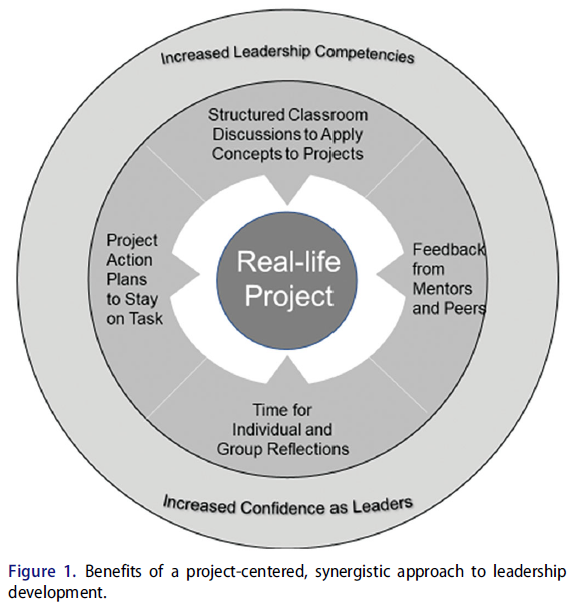

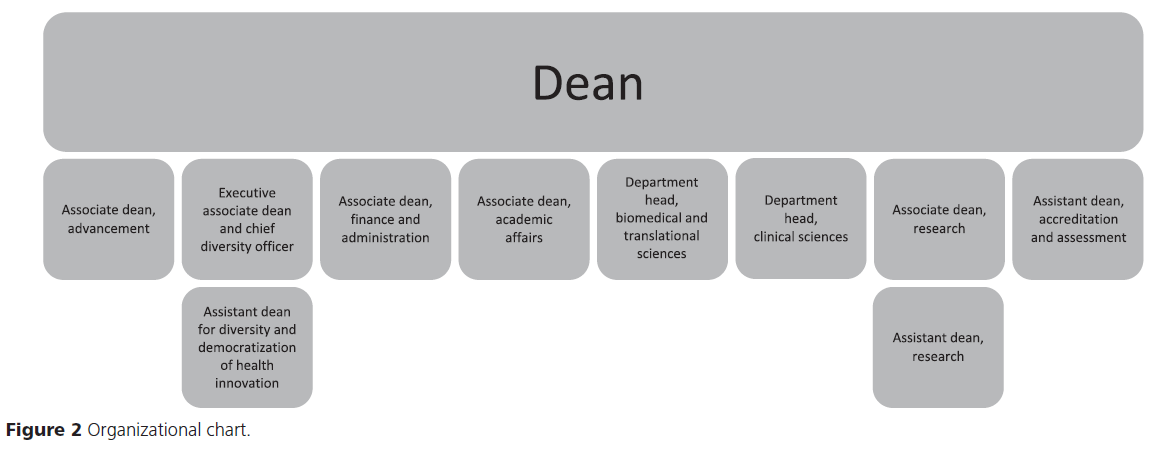

해부학 교육자들은 계속해서 변화에 관여해 왔다. 우리가 가르치는 환경에 변화가 일어났습니다. 크고 희미한 해부를 하는 극장에서부터, 스테인리스 스틸, 조명이 좋은 해부를 하는 실험실에 이르기까지요. 우리는 또한 학생들에게 해부학적 구조와 서로간의 관계에 대해 가르치는 것을 돕기 위해 수년간 [도구 모음]을 수집해 왔다. 우리의 도구상자에 있는 더 성숙한 도구들 중 일부는 다른 영상 양식을 가진 관절 골격, 해부학적 구조의 도면 및 신체의 지역적 뷰를 포함한다. 수년간 우리는 플라스틱 모형과 플라스틱 견본과 같은 도구를 추가해 왔다. 우리는 심지어 해부학 기반의 컬러링 북, 바디 페인팅, 점토 모델링과 같은 더 창의적인 도구들을 우리 컬렉션에 추가했습니다. 최신 도구 중 일부는 컴퓨터 보조 학습 시스템, e-러닝, 그리고 가장 최근에는 3D 증강 및 가상 현실 장치이다.

Educators of the anatomical sciences have continually been involved in change. Changes have occurred in the environment in which we teach; from large, dimly lit dissection theaters, to stainless steel, well-lit dissection laboratories. We have also amassed a collection of tools over the years to assist in teaching students about anatomical structures and their relationships to one another. Some of the more mature tools in our toolbox include disarticulated skeletons, drawings of anatomical structures and regional views of the body with different imaging modalities. Over the years we’ve added additional tools such as plastic models and plastinated specimens. We’ve even added more creative tools to our collection, such as anatomy based coloring books, body painting and clay modeling. Some of the newest tools are computer assisted learning systems, e-learning, and most recently, 3D augmented and virtual reality devices.

우리가 학생들을 가르치기 위해 선택하는 도구의 정도에 대해 교사로서 우리에게 알려주는 많은 것들은 학습자와 우리가 가르치려고 하는 특정한 개념에 바탕을 두고 있다. 많은 학생들이 [육안 해부학]에 대한 통달성을 위해 엄청난 노력을 기울이는 것처럼 느끼지만, 지식 보유라는 장기적 목표를 가지고 그들의 지식을 적용하고 스스로 평가할 수 있는 기회를 제공함으로써 이러한 노력을 완화하는 것이 우리의 과제이다. 해부학자인 우리가 학생들과 함께 이것을 접근한 몇 가지 다른 방법이 있습니다.

Much of what informs us as teachers about the extent to which tools we choose to teach our students is based on the learner and the particular concept we are trying to teach. While many students feel as though they put forth an enormous effort to achieve mastery in gross anatomy, it is our task to ease this effort by providing the basic units of knowledge followed by opportunities to apply and self-assess their knowledge, with the long term goal of knowledge retention. There are several different ways in which we as anatomists have approached this with our students.

물론, 대부분의 사람들에게 떠오르는 첫 번째 방법은 시신을 사용하는 것이다. 의학교육에서 시체사용의 다양한 측면에 대한 많은 출판물들이 있는데, 나는 몇 가지를 간단히 언급할 것이다. 1990년 연구에서, Nnodim은 하지의 전체 해부학을 연구하는 첫 번째 임상 전 의대생들의 두 그룹을 다른 방법으로 매치시켰다(한 그룹은 직접 해부했고, 다른 그룹은 프로섹션을 리뷰했다). Nnodim은 학생들이 해부한 시체보다 절제된 시체로부터 하지 해부학을 더 잘 배운다는 것을 발견했다. 이 연구에서, Nnodim은 Prosection이 인간의 총체적 해부학을 배우는 효과적인 방법이라고 제안했다. 실제로, 그것은 단축된 수업 시간에 대해 싸워야 하는 부서들에게 고려할 가치가 있는 방법일 수 있다. 몇 년 후인 1996년, 예거는 몇몇 학생들이 해부를 완료하고 다른 학생들이 미리 해부된 표본들을 연구함으로써 배우도록 함으로써 전체 해부학에서 동료 교수법을 탐구했다. 두 그룹 간의 객관식 테스트의 성능은 통계적으로 유의하지 않았다. 그러므로 [Prosected 시신]에서 해부학적 구조를 학습함으로써 시간적 이점이 있을 수 있지만, 두 방법 모두 대등한 것으로 보인다.

Of course, the first way that comes to most people’s minds is with the use of cadaveric material. There are a number of publications on various aspects of cadaveric use in medical education, I will briefly mention a few. In a 1990 study, Nnodim matched two groups of first-year preclinical medical students studying the gross anatomy of the lower limb by different methods (one group dissected one group reviewed prosections). Nnodim discovered that students learned lower limb anatomy better from prosected cadavers than dissected cadavers (Nnodim 1990). From this work, Nnodim suggested that prosections are an effective way of learning human gross anatomy. Indeed it may be a worthy method to consider for departments who have to contend with curtailed teaching time. A few years later, in 1996, Yeager explored peer teaching in gross anatomy by having some students learn by completing dissections while other students learned from studying the predissected (prosected) specimens (Yeager 1996). The performances on multiple-choice tests between the two groups were not statistically significant. So while there may be a time advantage from learning anatomical structures on a prosected cadaver, both methods seem comparable.

시신 기반 과정의 사용에 대한 또 다른 견해는 이전 작업을 기반으로 하며, 해부 기반dissection-based 과정이 학생들이 전문적인 역량을 개발하는 데 도움이 된다는 것을 암시한다. 2010년, Böckers 등은 학생들이 "중요한" 과정으로서 총 해부학에 두는 가치를 이해하기 위해 정량적인 세로 질문지를 개발하여 총 해부학 과정의 124명의 의학 학생들에게 제시했다. 이 과정에 대해 긍정적이거나 부정적인 의견을 가진 학생들의 하위 그룹은 이 과정의 전문적인 역량을 전달하는 능력에 대한 학생들의 의견과 상관관계가 있었다. 학생들은 해부과정에 참여함으로써 해부학 지식뿐만 아니라 팀워크, 스트레스 대처, 시간 관리 등과 관련된 기술을 습득할 수 있다고 느꼈다(Böckers et al., 2010).

Another take on the use of cadaver-based courses builds on previous work, which suggests that dissection-based courses help students develop professional competencies. In 2010, Böckers et al. developed a quantitative longitudinal questionnaire and presented it to 124 medical students in a gross anatomy course, to understand the value students place on gross anatomy as an “important” course. Subgroups of students with positive or negative opinions of the course were correlated with student opinions about the course’s ability to convey professional competencies. Students felt that participation in the course facilitated their acquisition of anatomy knowledge as well as skills related to teamwork, coping with stress, and, to a lesser extent, time management (Böckers et al. 2010).

마지막으로, [cadaver-based dissection 과정]에서의 학생 성과와 통합과목에서 [prosection-based 과정]의 학생 성과를 비교한 한 연구를 언급하고자 합니다. 한 학기 내내 다양한 평가에서 해부를 기반으로 한 강좌의 학생들이 약간 더 좋은 성적을 거둔 반면, 통합 강좌 세션에 참여한 학생들은 이러한 활동을 좋아할 뿐만 아니라 이러한 경험들이 학습에 도움이 된다고 느꼈다고 보고했다. 많은 의과대학 커리큘럼이 보다 통합된 구조로 향하고 있기 때문에 이것은 흥미로운 발견이다.

Finally, I would like to mention one study, which compared student performance in a cadaver-based dissection course versus student performance in a prosection-based course where students also attended integrated course sessions. While students in the dissection based course performed slightly better during the various assessments throughout the semester, students who participated in the integrated course sessions reported that they not only liked these activities but felt that these experiences enhanced their learning (Eppler et al. 2018). This is an interesting finding as many medical school curriculum are heading towards a more integrated structure.

우리 공구함에 있는 다른 도구에 대한 증거는 어떻게 되나요? 컴퓨터 보조 교육(CAI)은 지난 수십 년 동안 많은 관심을 받아왔다. McNulty 등은 CAI의 효과와 개별 사용 수준에 영향을 미치는 요인을 조사하는 총 해부학 강좌에서 다년간의 연구를 완료했습니다. 그들은 성별, 성격 선호도 및 학습 스타일에 따라 활용 수준이 상당히 다양하지만 컴퓨터 사용능력은 그렇지 않다는 것을 발견했다. 흥미롭게도, 자원에 가장 자주 접속한 학생들은 자원에 접속한 적이 없는 학생들보다 시험에서 상당히 높은 점수를 받았습니다. Khot 등은 지식 습득에서 CAI 효과에 대한 이 문제를 더 자세히 조사했습니다. 본 연구에서는 학습 해부학 (1) VR 컴퓨터 기반 모델 (2) 주요 뷰를 가진 정적 컴퓨터 기반 모듈 및 (3) 플라스틱 모델의 세 가지 형식의 효과를 조사했다. 그들은 [컴퓨터 기반 학습 자원]이 명목 해부학을 학습하는 데 있어 [전통적인 표본]에 비해 상당한 단점을 가지고 있는 것으로 보인다는 것을 발견했다. 이전 연구와 일관되게, 이러한 발견은 가상 현실이 주요 관점key view의 정적 표현static presentation에 비해 이점이 없다는 것을 보여주었다. 살타렐리 외 연구진은 멀티미디어 학습 시스템을 전통적인 학부 인간 시체 실험실과 비교한 결과 비슷한 결론을 얻었다. 그들은 인간 시체 실험실이 신원 확인 및 설명 지식의 시체 기반 측정에 대한 멀티미디어 시뮬레이션 프로그램보다 상당한 이점을 제공한다는 것을 발견했다.

What about evidence for the other tools in our toolbox? Computer-aided instruction (CAI) has received a lot of attention in the past few decades. McNulty et al. completed a multi-year study in a gross anatomy course investigating the effectiveness of CAI and the factors affecting level of individual use. They found considerable variability in level of utilization based on gender, personality preferences and learning style, but not with computer literacy. Interestingly, students who accessed the resources most frequently scored significantly higher on exams than those who had never accessed the resources (McNulty et al. 2009). Khot et al. explored this question of CAI effectiveness in knowledge acquisition further. In this study, they examined effectiveness of three formats of learning anatomy (1) VR computer based model (2) static computer-based module with key views and (3) plastic model. They found that computer based learning resources appeared to have significant disadvantages compared to traditional specimens in learning nominal anatomy (Khot et al. 2013). Consistent with previous research, these findings indicated that virtual reality has no advantage over static presentation of key views. Saltarelli et al. had a similar conclusion after comparing a multimedia learning system with a traditional undergraduate human cadaver laboratory. They found, that the human cadaver lab offered a significant advantage over the multimedia simulation program on cadaver-based measures of identification and explanatory knowledge (Saltarelli et al. 2014).

우리가 최근에 소개한 도구 중 일부는 플라스틱 샘플, 3D 인쇄를 통해 만들어진 모델, 가상 또는 증강 현실 리소스이다. 플라스티드 표본은 매우 상세한 해부를 시간 내에 포착할 수 있는 기회를 제공하지만, 촉각적 특성과 표본 다양성의 부족은 학생들의 경험을 제한하는 것으로 보고되었다. 3D 프린팅 모델의 사용과 관련하여, 한 보고서는 3D 프린팅 모델이 교훈적인 2D 이미지 기반 교육 방법에 비해 지식을 크게 증가시켰다는 것을 발견했습니다. 이러한 결과는 앞서 언급한 결과와 유사합니다.

Some of the more recent tools we have been introduced to are plastinated specimens, models created via 3D printing, and virtual or augmented reality resources. While plastinated specimens offer an opportunity to capture a very detailed dissection in time, the lack of haptic qualities and specimen diversity have been reported to limit the student experience (Fruhstorfer et al. 2011). Regarding the use of 3D printed models, one report found that 3D printed models significantly increased knowledge compared to didactic 2D image based teaching methods (Smith et al. 2018). These findings are similar to findings mentioned previously (Khot et al. 2013).

요약하자면, [툴 박스에 있는 툴을 제거할지 여부]에 대한 질문을 하기보다는, [이러한 툴의 사용방식을 어떻게 수정할 수 있는지] 대한 질문으로 바뀌어야 합니다. 교육자로서, 우리는

- (1) 학생 중심의 학습 환경을 조성하고,

- (2) 가능한 경우 콘텐츠를 통합하고,

- (3) 임상적으로 적용할 수 있는 상관관계를 포함하고,

- (4) 학생의 진행 상황을 관찰하고 분석하며,

- (5) 새로운 교육 개입의 결과를 반영하고, 그 결과를 문헌에 보고해야 한다.

In summary, the question of whether or not to remove any tool in our tool box should be changed to a question of how we can revise the way we have been using these tools. As educators, we need to:

- (1) create a student-centered learning environment,

- (2) integrate content where possible,

- (3) include clinically applicable correlates,

- (4) observe and analyze student progress, and

- (5) reflect on the outcomes of new educational interventions and report the findings in the literature.

토론은 마지막 두 명의 연사가 자신들의 주장을 발표하고 주장을 요약하기 위해 초대되는 것으로 끝났다.

The debate concluded with the last two speakers being invited to present their case and summarize the arguments.

반대측

“No we do not” house

대럴 에반스 교수

Prof Darrell Evans

13년 전, 저는 에든버러에서 열린 AMEE 연차총회에서 존 맥라클란의 강연을 들었습니다. "해부학은 삶입니다. 해부학은 죽음이 아니다." 해부를 통한 가르침의 열렬한 지지자로서 나는 확실히 이야기의 추진에 동의하지 않았고 방 뒤에서 야유했다. 그렇다면 제가 왜 이제 대학 의학부에서 해부학을 가르치기 위해 시체들을 더 이상 필요로 하지 않는다고 말할까요? 뭐가 달라진거죠? 첫째, 우리가 이용할 수 있는 더 많은 대안이 있고 둘째, 해부학 교수법에 대한 다른 접근방식을 뒷받침하는 교육학의 효과에 대한 우리의 이해가 발전했다. 이것은 저널에 발표된 수많은 활발한 연구를 통해 촉진되었습니다. 그 중 일부는 에든버러에서 열린 AMEE 회의 당시에는 없었습니다. 이전에 견고하고 질 높은 연구가 부족했던 것은 우리가 학생 학습에 정말로 차이를 만드는 것이 무엇이고 해부학 교육에 대한 이러한 새로운 접근법이 시체 기반 가르침에 비해 어떤 영향을 미치는지를 정의하는 데 초점을 맞추지 않았다는 것을 의미했다. 동시에, 의학 커리큘럼은 [해부학을 단독으로 배우는 것]에서 벗어나, [좋은 의사가 되는 것을 배우기 위해 해부학에 대한 근본적인 이해를 사용하는 것]으로 옮겨가고 있다.

Thirteen years ago, I sat in a session at the AMEE annual meeting in Edinburgh listening to a talk by John McLachlan entitled “Anatomy is life. Anatomy is not death”. As an ardent supporter of teaching through dissection I was certainly not in agreement with the thrust of the talk and heckled from the back of the room. So why would I now be saying we don’t really need cadavers anymore to teach anatomy in undergraduate medicine. What’s changed? Firstly there are many more alternatives available to us and secondly our understanding of the effects of the pedagogy that underpins different approaches to anatomy teaching has developed. This has been promoted through a plethora of active research published in journals, some of which weren’t around at the time of the AMEE meeting in Edinburgh (Pawlina and Drake 2010). The previous lack of robust and high quality research meant that we didn’t focus on defining what was really making a difference in student learning and what effect these new approaches to anatomy teaching were having in comparison to cadaveric based-teaching. At the same time medical curricula have refocused, moving away from learning anatomy in isolation to using a foundational appreciation of anatomy for learning to be a good doctor.

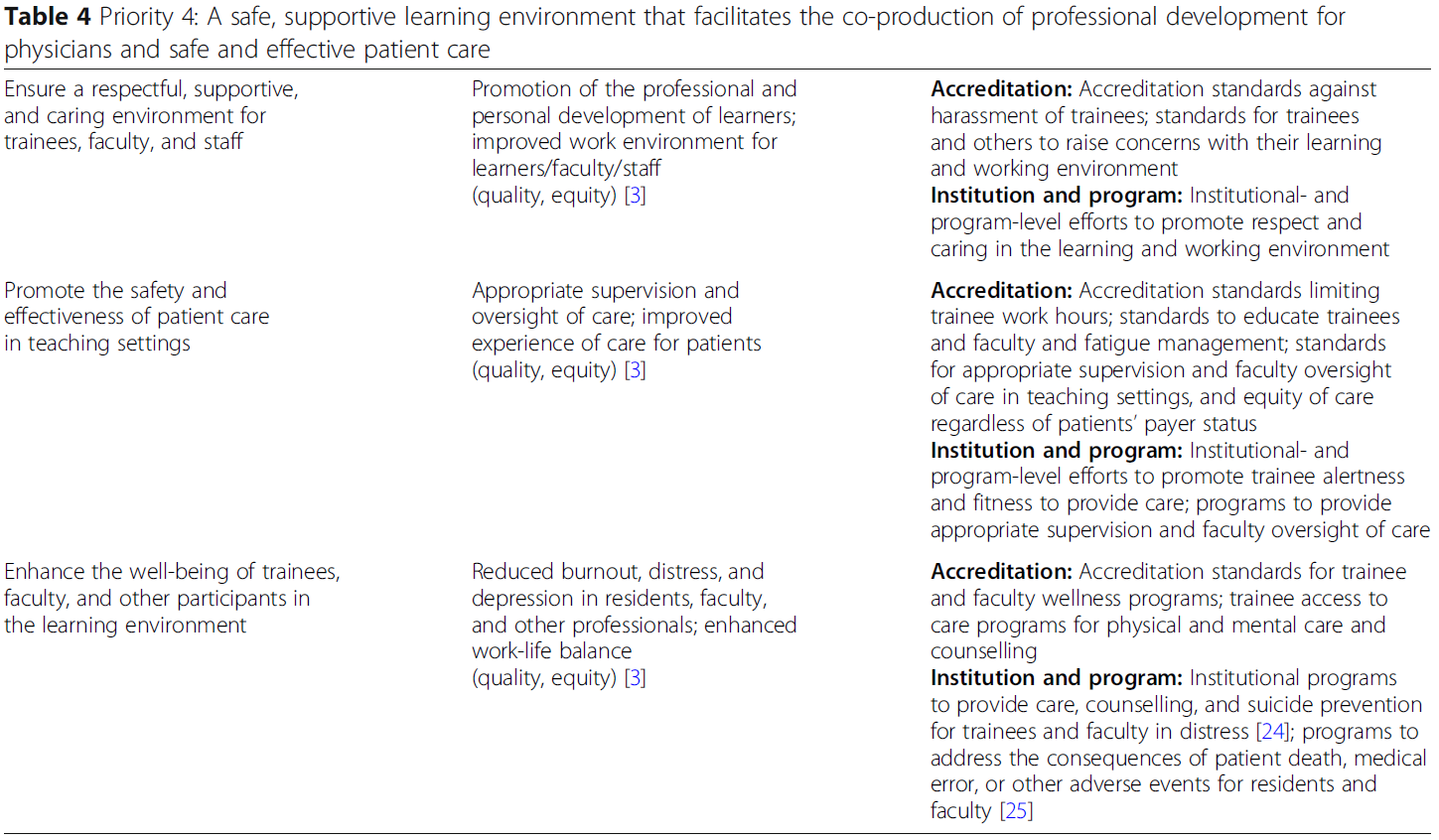

시신들은 확실히 졸업후 의학훈련과 해부학 관련 분야와 전문 분야의 지속적인 전문적 발전을 특징으로 해야 한다. 시신들은 또한 증강현실 프로그램, 3D 모델 등을 포함한 많은 기술 기반 해부학적 도구들을 개발하기 위한 기초를 형성한다. 도전은 또한 어떤 해부학을 배워야 하는지, 어떤 깊이에서 배워야 하는지, 왜 여러분이 해부학의 특정한 요소나 개념을 배우는지에 대한 것이 아닙니다. 그건 다른 논쟁이고, 지금은 우리가 어떻게 우리의 [학부 의대생]을 가르치는지에 대한 논의가 필요하다. 그리고 우리가 여기에 시신이 [진정으로 필요한지]에 대한 것입니다. 그 점을 염두에 두고 나는 우리가 "진짜 필요really needed"와 "학부 의학undergraduate medicine"이라는 단어에 계속 집중하기를 바란다.

Cadavers should certainly feature within postgraduate medical training and ongoing professional development in anatomically related disciplines and specialties. Cadavers also form the basis for developing many of the technology-based anatomical tools including augmented reality programs, 3D models etc. The challenge is also not about what anatomy should be learned, in what depth that anatomy should be learned and why you're learning a particular fact or concept of anatomy. That’s a different debate and instead this is about how we teach our undergraduate medical students and whether we really need cadavers for this. With that in mind I want us to keep focused on the words “really needed” and “undergraduate medicine”.

이 문제는 커리큘럼 디자인으로 귀결됩니다. 그렇다면 어떻게 하면 학생들이 필요로 하는 기초 지식을 발견할 수 있도록 좋은 커리큘럼 설계를 통해 학생들을 도울 수 있을까요? 학습 과정에 포함시키고 기능적으로나 임상적으로나 관련이 있는지 어떻게 확인할 수 있을까요? 우리는 학생들이 해부학을 배우고 이해할 수 있는 다양한 기회를 가질 수 있도록 해부학을 배우는 다면적인 접근 방식을 가져야 한다. 그래서 학생들은 해부학을 다른 관점에서 그리고 다른 맥락에서 볼 수 있다(Evans and Watt 2005). [통합 커리큘럼 내에 해부학을 배치하는 것]은 학생들이 기초 및 임상 지식, 이해 및 추론을 연결할 수 있도록 하는 데 필요한 [표지게시signposting 및 관련성]을 제공한다. 학생들이 제대로 된 학습을 쌓을 수 있도록 표지판signposting이 핵심이다.

This issue for me comes down to curriculum design. So how do we enable students through good curriculum design to discover the foundational knowledge that they’re going to need? How do we make sure it’s embedded within their learning journey and is functionally and clinically relevant? We need to have a multifaceted approach to learning anatomy (that might include cadavers) so that students have different opportunities to learn and understand the anatomy, see it from different perspectives and in different contexts (Evans and Watt 2005). Placing anatomy within an integrated curriculum provides the signposting and relevance necessary to enable students to connect foundational and clinical knowledge, understanding and reasoning. The signposting is key so that the students can build their learning appropriately.

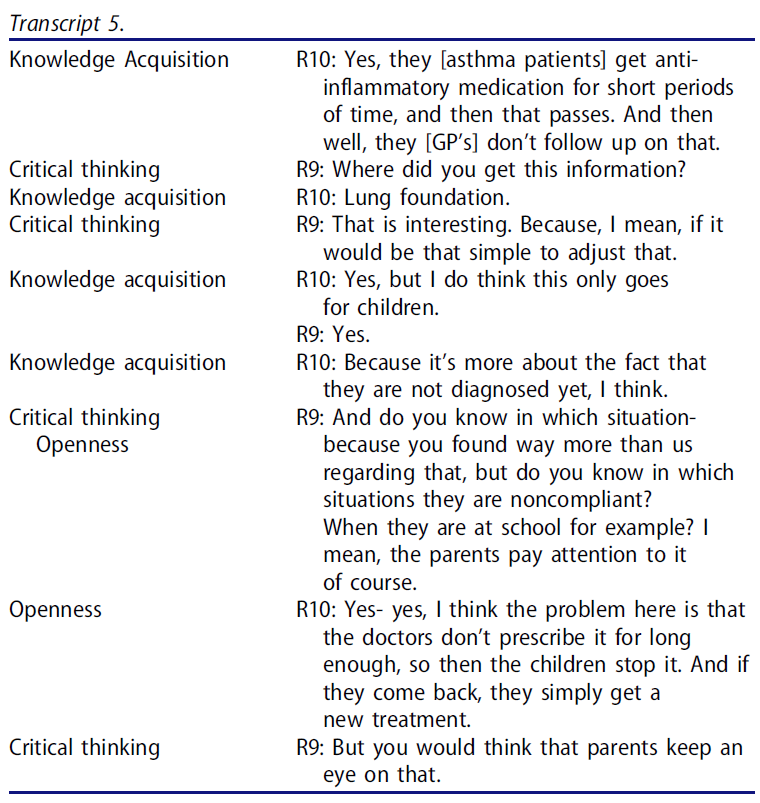

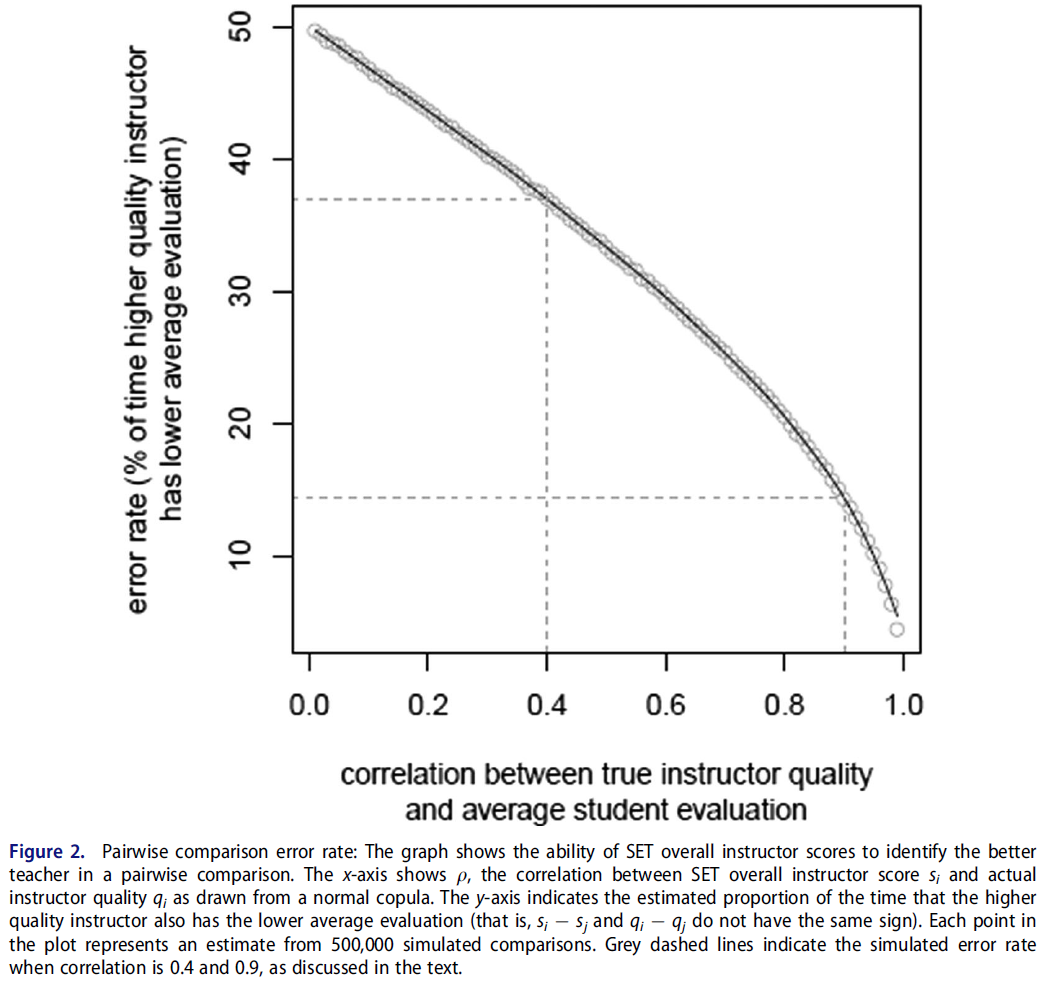

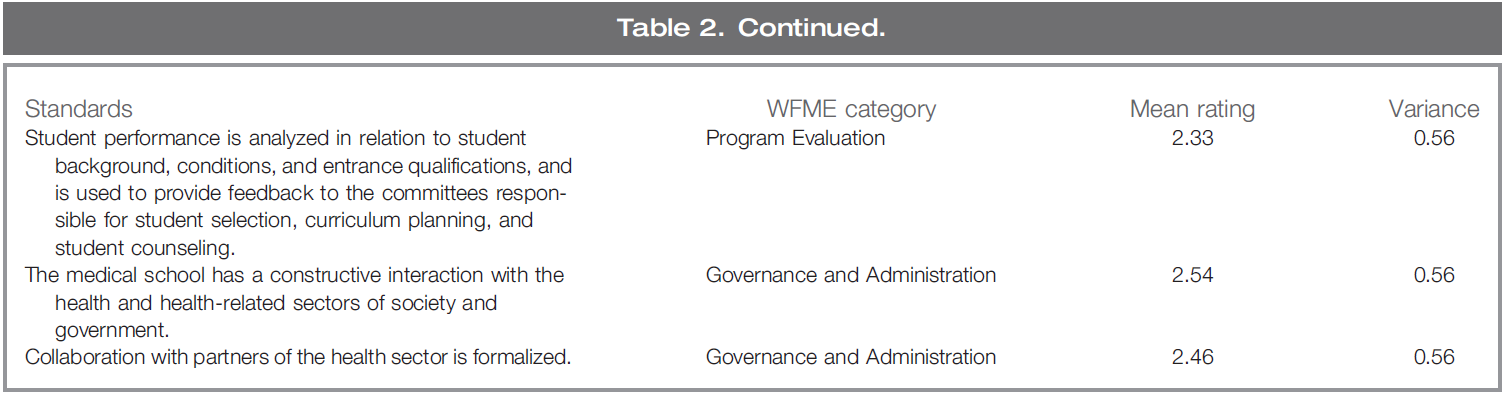

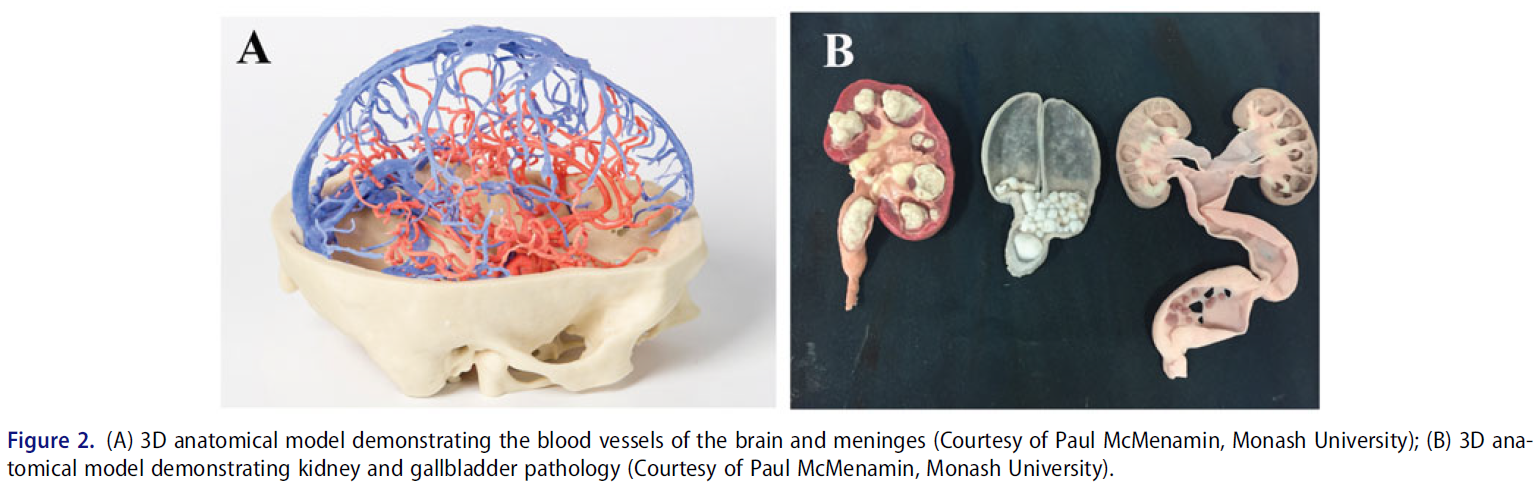

최근의 많은 발전을 통해, 우리는 해부학을 가르치기 위해 테크놀로지를 효과적으로 활용할 수 있다. 우리는 기술을 사용하여 인체 여러 층을 걸어다니면서 해부학의 다른 요소들을 알아낼 수 있습니다. 우리는 컴퓨터 시뮬레이션을 통해 해부할 수 있고, 그리고 나서 우리는 학생들이 어려운 부분에 다시 집중할 수 있도록 해 줄 수 있다. 해부학은 위치 결정과 연관성, 그리고 복잡한 관계를 이해하는 맥락에서 배울 필요가 있다. 3D 모델링의 창조를 통해 학생들은 시체 물질을 사용하지 않고도 이러한 관계를 인식할 수 있습니다. 우리는 다른 수지를 사용하여 생명체와 같은 또는 예시적인 색칠과 느낌을 제공할 수 있습니다. 3D 모델은 시체 내에서 쉽게 해부되거나 명백하지 않은 해부학을 시각화할 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, 시체에서 뇌의 혈관을 해부할 수 있습니까? (그림 2(A)).

Through many recent advances, we can utilize technology effectively to teach anatomy. We can use technology to walk through the various layers of the human body to uncover different elements of that anatomy. We can dissect via computer simulation and then we can put the body back together again (you can’t do that with a cadaver) allowing students to refocus on difficult areas. Anatomy needs to be learned in the context of positioning and association, and understanding intricate relations. The creation of 3D modeling allows students to recognize these relationships without the need for them to use cadaveric material (McMenamin et al. 2014). We can use different resins to provide life-like or illustrative colorings, and feel. 3D models enable visualization of anatomy not easily dissected or apparent within the cadaver—could you dissect the blood vessels of the brain in a cadaver for instance? (Figure 2(A)).

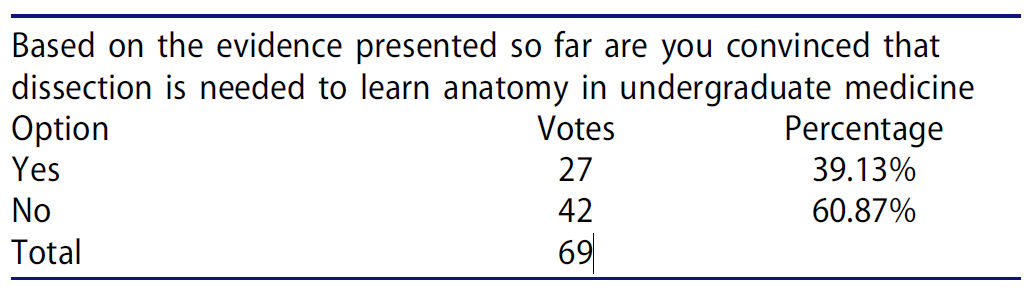

3D 모델은 생산 비용이 저렴하고, 안전 요소가 제거되었으며, 재료에 대한 접근성이 높아 licensed premises를 사용할 필요가 없습니다. 각 학생은 자신의 시간과 심지어 미니어처 규모에서 검토할 수 있도록 특정 정상 또는 병리 해부학 사본(그림 2(B))을 제공할 수 있으며, 높은 수준의 자원을 보유하지 않은 국가는 이러한 자료를 사용할 수 있다. 해부학을 맥락 안에서 시각화하는 이 능력은 더 깊은 학습을 가능하게 한다. 학생들은 전체적인 그림을 그릴 수 있어야 하지만, 시신이나 접근할 수 없는 구조물의 단면을 볼 때 어려웠습니다. 호주 뉴캐슬대 등 전 세계 동료들이 이런 문제를 해결하기 위해 증강현실(Augmented Reality)을 개발하고 있다. 예를 들어, 뇌의 요소들을 시각화할 때, 여러분은 해부 슬라이드에서는 3D 형태의 모든 요소들을 볼 수 없었을 것이고, 다른 요소들을 제거하거나 추가하는 어떤 방향에서도 볼 수 없었을 것이다. 이러한 새로운 접근방식을 사용하면 해부학적 관계를 매우 다른 방식으로 볼 수 있습니다. 그러나 주의가 필요합니다. 이것은 테크놀로지 그 자체를 위한 테크놀로지에 대한 것이 아니며, 테크놀로지의 사용은 학습 성과를 가능하게 하기 위한 교육학적 기반이 필요하다(Release 2016). 이것은 우리가 이전에 결코 할 수 없었던 무언가를 하거나 우리가 할 수 있는 것보다 더 나은 것을 하는 것에 관한 것입니다.

3D models are cheap to produce, the safety elements are removed and the material is highly accessible—you do not need licensed premises to use them. Each student can be provided with copies of particular normal or pathological anatomy (Figure 2(B)) to review in their own time and even in miniature scale and countries who do not have high levels of resources can use such materials (Smith et al. 2018). This ability to visualize anatomy within its context allows for deeper learning. Students need to be able to build up the whole picture and this has been difficult when looking at sections of cadaveric material or inaccessible structures. Colleagues around the world including at University of Newcastle, Australia are developing Augmented Reality to solve such issues (Jain et al. 2017). For instance, when visualizing the elements of the brain, you wouldn’t have been able to see all the elements in the 3D form from dissection slices and the ability to view from any direction and removing or adding different elements. Using these new approaches, you get to see the anatomical relations in a very different way. However caution is required. This is not about technology for technology’s sake and instead the use of technology needs a pedagogical basis linked to enabling the learning outcomes (Trelease 2016). This is about doing something we could never do before or doing something better than we could do before.

시신은 우리가 기대하는 해부학적 변형을 제공하고, 병리학을 보여주는데 아주 좋습니다. 제가 해부학 연구실을 운영했을 때, 저는 어떤 큰 변화나 병리학적 변화가 있기를 바랬습니다. 그리고 몇 년 동안 당신은 성공했고 다른 사람들은 실패했죠. 테크놀로지는 모든 학생들이 볼 수 있는 [공통 및 희귀 변형과 병리학]을 시각화하고, 문제의 해부학적 맥락 안에서 다시 한 번 도움의 손길을 제공하고 있다. 다시 한 번 3D 인쇄를 사용하면 학생들이 검사하고 기능 및 임상 결과(Mahmoud 및 Bennett 2015)와 연계하여 감사할 수 있는 희귀 병리학의 복사본을 제공할 수 있습니다(그림 2(B)).

Cadavers are great for providing the anatomical variation we expect and for showing pathology. When I used to run dissection labs, I used to hope there was going to be some great variation or pathology and some years you were successful and others not. Technology is once again providing a helping hand by providing visualizations of both common and rare variations and pathologies for all students to see and within the context of the anatomy in question. Once again 3D printing can be used to provide copies of rare pathologies for students to examine and to get an appreciation for by linking to function and clinical outcomes (Mahmoud and Bennett 2015) (Figure 2(B)).

그렇다면 우리는 대학 의학에서 해부학을 배우기 위해 더 이상 카데바가 필요할까요? 해부학은 여전히 학부 의학의 기본이다. 그것은 우리가 학생들이 사용할 수 있기를 바라는 언어이며, 복잡한 임상 문제를 해결하는 데 도움이 되는 지식과 이해로 환자에게 최상의 해결책을 제시합니다(Turney 2007). 그렇다면 어떻게 하면 학생들에게 지식과 이해를 가장 잘 할 수 있을까요? 통합 커리큘럼 내에서 다면적인 접근을 통해 이루어질 필요가 있다고 생각합니다. 그리고 시체도 그 일부가 될 수 있을까요? 물론, 그들은 할 수 있지만, 그들이 정말로 학습 결과를 성취하기 위해 필요한가? 저는 가능한 대안들 때문에 그렇게 생각하지 않습니다(그림 2(A,B)). 그래서 오늘 투표하실 때, 토론 질문을 다시 한 번 살펴보도록 하겠습니다. 나는 해부의 팬이지만 우리는 "학부 의학"을 가르치기 위해 "정말로" 카데바가 필요한가? 난 그렇게 생각하지 않습니다.

So do we really need cadavers anymore to learn anatomy in undergraduate medicine? Anatomy is still fundamental to undergraduate medicine. It is the language we want our students to be able to use, the knowledge and understanding that helps solve complex clinical problems resulting in the best solutions for their patients (Turney 2007). So how do we best enable that knowledge and understanding in our students? I certainly think that it needs to happen through a multifaceted approach within an integrated curriculum. And can cadavers be part of that? Yes they can, but are they really needed to achieve the learning outcomes? I don’t think so because of the alternatives available (Figure 2(A,B)). So I’ll just ask you when you vote today, to look at the debate question again. I’m a fan of dissection but do we “really need” cadavers to teach “undergraduate medicine”. I don’t think so.

찬성측

“Yes we do” house

안드레아스 윙켈만 교수

Prof Dr med Andreas Winkelmann

지금까지 이루어진 많은 논점에 [철학적, 혹은 인류학적 논점]을 추가하고 싶다. 나는 순수한purely 카데바 중심의 교육을 주장하는 것이 아니라, 해부학을 가르치는 많은 대등한parallel 방법들 중 하나로 인체를 사용하는 것에 대해 주장할 것이다.

To the many points that have been made so far, I would like to add a philosophical and/or anthropological one. I will not argue for a purely cadaver-centred teaching, but for using human bodies as one of many parallel approaches to teaching anatomy.

데카르트적 이원론은 오늘날 우리가 실천하고 있는 "서양" 생물의학의 기초이며, "서양"은 이것이 문화적으로 특정한 기반을 둔 의학이라는 사실을 가리킨다. 17세기에 데카르트는 세계를 "res extensa"(확장 물질)와 "res cognitans"(사고 물질)로 나누었다. 매우 넓게 말하면, 이것은 의학이 역사상 처음으로 신체에 대한 진정한 신체적 접근을 개발할 수 있는 기회를 주었습니다. 이 접근법은 생물의학의 많은 성공의 기초가 되어왔지만, 물론 질병의 심리적 사회적 요인을 이해하는 것과 같은 생물의학의 일부 문제에 대해서도 책임이 있다.

Cartesian dualism is at the basis of “Western” biomedicine as we practise it today, with the attribute “Western” pointing to the fact that this is a culturally specific foundation of medicine. In the 17th century, Descartes divided the world as we understand it in “res extensa” (extended matter) and “res cogitans” (thinking matter). Very broadly speaking, this gave medicine, for the first time in history, the opportunity to develop a truly physical approach to the body (Leder 1992). This approach has been the basis of many of the successes of biomedicine—most obviously in surgery or radiology—but is of course also responsible for some of biomedicine’s problems, like the difficulty to understand psychosocial factors of illness.

역사적으로 [해부학적 해부]는 이러한 발전을 뒷받침하는 역할을 해왔고(데카르트 자신은 해부를 관찰함으로써 영향을 받았다), 오늘날의 의학 커리큘럼에서 해부는 이러한 [데카르트적 접근법의 강력한 상징]으로 인식되는 것으로 보인다. 나는 이러한 [상징적인 의미]가 이 교육 도구가 반복적으로 논의되고, 예를 들어 생화학 수업보다 훨씬 더, 학문적인 관심을 끄는 이유 중 하나라고 주장할 것이다. 일부 저자들은 해부 과정이 해부학뿐만 아니라 사람과 그들의 신체에 대한 이원론적 접근을 가르치는 암묵적 또는 암묵적 커리큘럼의 일부라고 주장해왔다. 이것은 적어도 상상할 수 있는 것이다. 학생들은 신체에 대한 데카르트적 관점을 가지고 태어나지 않으며, 만약 신체 생물의학의 핵심이라면, 그들은 교과 과정의 어느 시점에서 신체에 대해 배워야 한다. 이러한 견해는 많은 저자들이 해부 과정을 "의학으로의 시작" 또는 "통과의례"로 보아왔다는 사실에 기여했을 수 있다. [시작 의식initiation ritual]의 오래된 인류학적 개념이 현대 사회에 적용되는지는 논란의 여지가 있을 수 있지만, 해부실은 더 넓은 사회의 금기가 깨지는 폐쇄적인 공간이며, 의료인과 비전문가를 구분하는 이러한 방식은 일부 사람들에게 이것이 '시작initiation'에 해당한다고 제안했다. 한편, 이러한 관점은 해부 과정에 대한 비판을 촉발시켰으며, 이는 학생들이 나중에 환자를 "시신처럼" 다루는 그러한 과정의 암묵적인 결과일 수 있음을 시사한다. (Winkelmann and Guldner 2004).

Historically, anatomical dissection has played a role in supporting this development (Descartes himself was influenced by observing dissections), and it seems that in today's medical curriculum, dissection is perceived as a strong symbol of this Cartesian approach. I would argue that this symbolical meaning is one reason why this educational tool is repeatedly debated and attracts much more scholarly attention than, say, biochemistry classes. Some authors have argued that the dissection course is part of an implicit or tacit curriculum, that does not only teach anatomy but also this dualistic approach to people and their bodies (Reifler 1996). This is at least conceivable—students are not born with a Cartesian view of the body, and if it is at the heart of biomedicine, they have to learn it at some point in the curriculum. This view may have contributed to the fact that so many authors have seen dissection courses as an “initiation into medicine” or “rite of passage". It may be debatable whether older anthropological concepts of initiation rituals (van Gennep, 1909). apply to modern societies, but the dissecting room is a closed space in which taboos of the wider society are broken, and this way of setting apart medical people from nonspecialists has suggested to some that this constitutes an “initiation” (Harper 1993; Shaffer 2004). On the other hand, this perspective has also triggered critique of the dissection course, suggesting that it may be an implicit outcome of such courses that students later treat patients “like cadavers” (cf. Winkelmann and Güldner 2004).

이 비평은, 제 생각에, 교과 과정의 작은 부분의 힘을 과대평가하는 듯 하다. 만약 의사들이 정말로 환자를 사람처럼 대하기 보다는 물질처럼 대한다면, 물론 해부 과정을 비난할 수 있습니다. 왜냐하면 그것의 상징적인 맥락이 이러한 비판에 어울리기 때문입니다. 그러나, 의사들이 해부를 통해서만 그러한 태도를 배웠다고 상상하기는 어렵다. 예를 들어, [번아웃된, 공감없는 임상의사들]과 같은 다른 맥락이나 교사들로부터 (또한) 배우지 않았다고 보기는 어렵다.

This critique, I think, overrates the power of one small part of the curriculum. If doctors in the end really treat a patient like material rather than like a person, you can of course blame the dissection course because its symbolic context lends itself to this criticism. However, it is difficult to imagine that doctors have learnt such an attitude just from dissection and not (also) from other contexts or teachers, like for example from burnt-out non-empathetic clinicians.

비록 역사적으로 해부학이 인체의 객관화에 큰 역할을 했을지라도, 학문으로서의 해부학은 또한 단지 육체적인 접근에 도전하기 위해, 특히 지난 수십 년 동안, 그 자체로도 멀리 왔다. 과거에는 해부학자들이 주로 처형된 범죄자들의 시체, 그 다음에는 가난한 사람들의 시체를 사용했지만, 지금은 적어도 서구 세계와 아시아의 많은 나라들에서 기증자들의 시신을 주로 사용한다. 시체 뒤에 있는 사람을 인정하는 것은 많은 의과대학의 강한 면이다. 예를 들어, 전세계의 해부학자들과 학생들은 또한 이러한 기증자들과 그들의 가족들을 위한 추모식을 조직한다. 또한 시체를 "몸"이나 "시체"라고 부르지 않고 "기부자" 또는 "선생님"이라고 부르는 경향이 증가하고 있다(Bohl et al., 2011). 이러한 모든 변화는 해부실에서 사체의 모호성이 점점 더 인정된다는 것을 의미한다. 사체는 물건인 동시에 죽은 사람이기 때문에 애매하다. 객체object과 주체subject의 모호성은 생물의학의 중심이며, 생물의학에서는 환자를 대상(예: 방사선학 또는 수술)처럼 취급해야 하지만, 그럼에도 불구하고 환자를 사람처럼 취급해야 한다.

Even if historically, anatomy may have played a big role in the objectification of the human body, anatomy as a discipline has also come a long way itself, particularly over the last decades, to challenge a merely physical approach (Dyer and Thorndike 2000). In the past, anatomists mainly used the bodies of executed criminals, then the bodies of the poor, but now they mostly use bodies of donors, at least in the western world and in many countries in Asia (Habicht et al. 2018). Acknowledging the person behind the cadaver is a strong aspect of many medical schools. For example, anatomists and students around the world also organize memorial services for these donors and their families. There is also an increasing tendency not to call the cadaver “body” or “cadaver” but rather “donor” or “teacher” (Bohl et al. 2011). All of these changes have meant that the ambiguity of the dead body in the dissecting room is increasingly acknowledged (Hafferty 1988). The dead body is ambiguous because it is an object and at the same time a deceased person. This ambiguity of object and subject is central to biomedicine, which often has to treat patients like objects (e.g. in radiology or surgery), but should nevertheless also treat them like persons.

그러므로 해부학에서 암묵적인 커리큘럼이 있다면, 사람과 사물의 이런 모호함에 대한 전문적인 관점, 시체나 환자에 대한 전문적인 관점, 이런 모호함에 대한 전문적인 관점을 기를 것이어야 한다고 생각합니다. 해부실 경험은 이러한 모호성을 억누르고 사람을 사물로 생각하는 위험을 수반할 수 있지만, 이 위험은 해부를 완전히 폐지해야 하는 이유가 아니라 이러한 맥락에서 전문적인 관점을 개발하기 위한 선택사항인 도전으로 받아들여져야 한다(Robbins et al., 2008).

Therefore, if there is an implicit curriculum in dissection, I think it should be about this ambiguity of person and object, about developing a professional perspective on this ambiguity, a professional perspective on cadavers and also on patients. The dissecting room experience may carry a risk to repress this ambiguity and to think of people as objects, but this risk should not be the reason to do away with dissection altogether but should be taken as a challenge, an option for developing a professional perspective in this context (Robbins et al. 2008).

저는 다음과 같이 질문하면서 결론짓고 싶습니다: 왜 우리는 카데바처럼 강력한 교육 도구를 없애야 할까요? 그것은 독특한 교육 도구입니다. 그 이유는 첫째, 그것은 (아틀라스, VR 데이터 세트, 3D 프린트처럼) 육체의 표상representation이 아니라, 살아 있는 생명의 "산출product"인, 개인의 운명의 진정한 육체authentic body의 표상representation이기 때문이다. 둘째로, 시체들은 독특하다. 해부는 매우 특별한 학습 경험을 만들어내기 때문이다. 그것은 진정한 멀티모달이고 활동적이다. 그것은 또한 감정적이고 실존적인 학습 경험이며 따라서 지속적인 기억을 만들어낸다. 어떤 사람들은 해부 과정이 그들에게 나쁜 기억을 주었다고 말하지만, 나는 그들이 잘못된 교사나 잘못된 교육 시설을 가지고 있었을지 몰라도, 잘못된 교육 도구를 가지고 있지는 않았다고 제안한다. 마지막으로, 위에서 설명한 바와 같이, 기증자가 해부되는 상황은 기회입니다. 왜냐하면 그것은 학생으로 하여금 인체가 [물체가 아니면서 동시에 물체가 되는 것being an object and not an object]에 도전하기 때문입니다. 그리고 이것이 바로 옛 인류학적 관점에서 통과의례가 실제로 의미하는 것입니다. "초보자나 초심자를 자극하여… 그들의 세계의 요소와 기본 구성 요소에 대해 곰곰이 생각하도록 유도한다." (Turner 1977). 물론, 음악 없이도 노래 텍스트를 배울 수 있는 것처럼, 시체 없이도 해부학을 배울 수 있지만 커리큘럼은 독특한 자원을 잃게 될 것이다.

I would like to conclude by asking: why should we do away with such a powerful teaching tool as a cadaver? It is a unique teaching tool, firstly, because it is not a representation of a body—like figures of an atlas, virtual reality datasets or 3D prints are—but an authentic body, the “product” of a lived life, of an individual fate. Secondly, cadavers are unique because dissection creates a very special learning experience, which is truly multimodal and activating. It is also an emotional and existential learning experience and therefore creates lasting memories. Some people tell me that their dissection course has given them bad memories, but I suggest that they had either the wrong teachers or the wrong teaching facilities but not inevitably the wrong teaching tool. And finally, as outlined above, the situation of a donor being dissected is an opportunity because it challenges the students with the human body being an object and not an object at the same time. And this is what rites of passage are actually about in the good old anthropological sense: “provoking the novices or initiands … into thinking hard about the elements and basic building blocks” of their world (Turner 1977). Of course, you can learn anatomy without cadavers—as you can learn song texts without the music—but the curriculum would lose a unique resource.

토론의 요약 및 결론

Summary and conclusion of debate

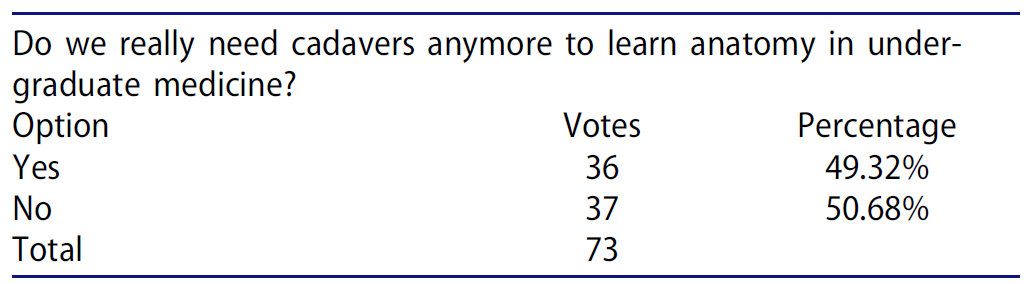

양원 모두 반대 의견을 제시한 후 퇴임했고 청중들은 현재 제기되는 질문에 대한 답을 등록하기 위해 대화형 시스템을 사용하여 다시 제시된 주장을 바탕으로 의견을 검토하도록 요청받았다.

Both houses, having presented their opposing cases, retired and the audience were asked to review their opinions based on the arguments presented by again using the interactive system to register their answers to the question now being posed.

McMenamin 교수는 우리 팀이 실제 시체 해부에 대한 주장을 많이 했다고 요약했는데, 그것은 실제로 논의되고 있는 질문이 아니었다. 하지만, 분명히 대다수의 청중들은 학부 의학 강좌에서 실제 해부가 필요하다는 것을 확신하지 못했다. 다음 질문은 학생들이 사체 물질에 대한 노출이 여전히 학부 의대생들의 경험으로 중요한지를 알아보기 위해 제시되었다.

Prof McMenamin summarized that the yes we do team had made much of their case about actual dissection of a cadaver, which was not in fact the question being debated. However, clearly the majority of the audience were not convinced that actual dissection was needed in an undergraduate medical course. The next question was posed to see if the audience thought whether exposure to cadaver material was still important as an experience for undergraduate medical students.

분명히 대다수의 청중들은 그것이 중요하다고 생각했다. 이어 맥메나민 교수는 토론 중인 실제 질문의 문구를 강조하며 투표할 때 이를 신중히 고려해 줄 것을 청중에게 당부했다. 이것은 토론이 시작될 때 다루어진 질문을 반복하는 마지막 투표였다.

Clearly a majority of the audience thought yes it was important. Professor McMenamin then emphasized the wording of the actual question being debated and called on the audience to consider this carefully when voting. This was the final vote repeating the question addressed at the commencement of the debate.

결과는 현재 논쟁 중인 문제에 대해 균일한 의견의 분열이 있다는 것을 분명히 보여주었고, 학부 의학에서 시체 사용에 대해 원래 80%의 찬성 의견이 있었기 때문에 McMenamin 교수는 토론에서 '아니오 불필요합니다' 측이 승리했다고 선언하고 그들의 발표에 대해 양원을 축하했다.

The results clearly showed that there was now an even split of views on the matter under debate and since there was originally majority of 80% in favor of the use of cadavers in undergraduate medicine Professor McMenamin declared the ‘No we do not’ house to have won the debate and congratulated both houses for their presentations.

Do we really need cadavers anymore to learn anatomy in undergraduate medicine?

PMID: 30265177

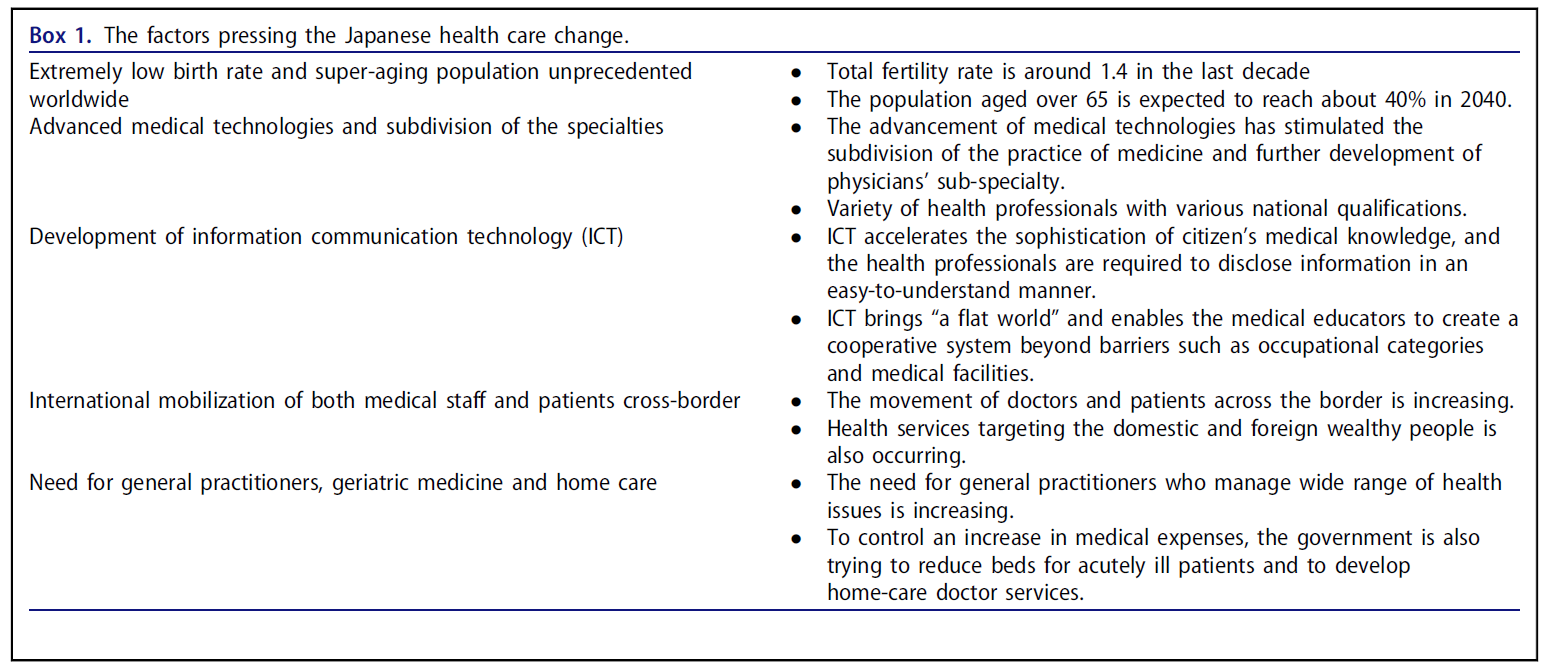

Abstract

With the availability of numerous adjuncts or alternatives to learning anatomy other than cadavers (medical imaging, models, body painting, interactive media, virtual reality) and the costs of maintaining cadaver laboratories, it was considered timely to have a mature debate about the need for cadavers in the teaching of undergraduate medicine. This may be particularly pertinent given the exponential growth in medical knowledge in other disciplines, which gives them valid justification for time in already busy medical curricula. In this symposium, the pros and cons of cadaver use in modern medical curricula were debated and audience participation encouraged.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 교수법 (소그룹, TBL, PBL 등)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 해부학에 대해서 왜 충분히 알지 못하는가? 내러티브 리뷰(Med Teach, 2011) (0) | 2022.04.16 |

|---|---|

| 해부학 교육의 베스트 프랙티스: 비판적 문헌고찰(Ann Anat, 2016) (0) | 2022.04.16 |

| 해부학 지식의 영향: 주장의 종합(Clinical Anatomy, 2014) (0) | 2022.04.16 |

| 의학교육에서 동료지원학습(PAL): 체계적 문헌고찰과 메타분석(Med Educ, 2021) (0) | 2022.03.30 |

| 침묵 또는 질문? 학생-중심 교육에서 토론 행동의 문화간 차이(Studies in Higher Education, 2014) (0) | 2022.03.26 |