대만 의과대학생의 문화간 전문직업성 딜레마 내러티브: 서양의학과 대만문화의 긴장(Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2017)

Taiwanese medical students’ narratives of intercultural professionalism dilemmas: exploring tensions between Western medicine and Taiwanese culture

Ming-Jung Ho1 • Katherine Gosselin1 • Madawa Chandratilake2 • Lynn V. Monrouxe3 • Charlotte E. Rees4

서론

Introduction

세계화 시대에 의료 종사자들은 다양한 문화적 배경을 가진 사람들을 치료하고, 일하고, 소통해야 합니다. [문화적 역량]은 양질의 의료 서비스를 제공하는 데 필수적인 것으로 널리 인정되어 왔습니다. 그러나 문화적 역량훈련은 서양 의학 커리큘럼에 포함되었지만, 유사한 훈련은 서양 이외의 의학 교육 맥락에서 아직 관심을 끌지 못하고 있다. 동시에, 세계적인 이주와 그에 수반되는 문화의 흐름에 매료된 기존 의학 교육 문헌은 서양의 맥락에서 '기타' 또는 소수 문화에 초점을 맞추는 경향이 있다. 현재의 문헌은 대만과 같은 비서양 국가에서 서양 의학을 배우는 비서양 학생들이 겪는 도전을 대부분 무시하고 있다.

In an era of globalization, healthcare practitioners must treat, work and communicate with people from diverse cultural backgrounds. Cultural competence has been widely acknowledged as essential to the provision of quality healthcare (Anderson et al. 2003; Betancourt 2006). However, while cultural competence training has been incorporated in Western medical curricula (Betancourt 2003; Brach and Fraser 2000), similar training has yet to gain traction in non-Western medical education contexts. At the same time, enamored with global migration and its attendant flows of culture, existing medical education literature has tended to focus on ‘other’ or minority cultures within Western contexts. Current literature largely ignores the challenges experienced by non-Western students learning Western medicine in non-Western countries, such as Taiwan.

대만의 문화간 전문직업성 딜레마

Intercultural professionalism dilemmas in Taiwan

대만에서는 의대생들이 환자 진료에서 직면하는 문화적 문제를 다룰 준비가 잘 되어 있지 않다는 연구 결과가 나왔다. 비록 짧은 교육 개입이 학생들의 문화-간cross-cultural 커뮤니케이션 기술을 향상시켰지만, 장기간의 유지는 걱정거리이다. 게다가 서구의 틀에 근거한 문화적 역량에 대한 일부 정량적 평가는 대만 문맥에서 유효하지 않거나 신뢰할 수 없는 것으로 판명되어 그 적용성에 의문이 제기되어 왔다. 여전히, 현재 대만에서 문화적 역량에 대한 관념은 [대만 문화에서 서양 의학의 도전]을 간과하고, 소수민족이나 '외국foreign' 문화와의 만남에 초점을 맞추는 경향이 있다. 대만과 같이 서양 이외의 맥락에서 서양 의학을 훈련받은 의대생들에게는 문화 간 딜레마가 더 뚜렷할 수 있다.

In Taiwan, research suggests that medical students are not well prepared to deal with cultural issues encountered in patient care (Lu et al. 2014). Although brief educational interventions have improved students’ cross-cultural communications skills, long-term retention is of concern (Ho et al. 2008, 2010). Moreover, some quantitative assessments of cultural competence based on Western frameworks have been found invalid or unreliable in the Taiwanese context, which has raised the question of their applicability (Ho and Lee 2007). Still, existing notions of cultural competence in Taiwan tend to focus on encounters with minority or ‘foreign’ cultures (Kleinman and Benson 2006), overlooking the challenges of Western medicine in Taiwanese culture. For medical students trained in Western medicine in non-Western contexts, as in Taiwan, intercultural dilemmas may be more pronounced.

문화 및 문화 역량

Culture and cultural competence

- [문화]는 가치, 규범, 실천, 역할 및 관계에서 나타나는 믿음과 행동의 패턴을 나타내기 위해 사용되는 광범위한 용어입니다.

- [각 개인]은, 단일 집단의 정체성을 보여주기보다는, 단순한 인종, 민족, 종교를 넘어 문화적 영향을 미치는 독특한 [키메라]입니다(베탕쿠르 2003).

- 이것을 확장하면, [문화적 역량]은 다양한 문화적 관행과 신념으로 특징지어지는 대인관계와 맥락에서 효과적으로 작동할 수 있는 능력을 의미한다(베탕쿠르 2006). 이 능력은 또한 '문화 상대주의', '문화 간 효과', '문화적 겸손', 그리고 '초국가적 능력'으로 언급되어 왔다.

Culture is a broad term used to signify patterns of belief and behavior, as manifest in values, norms, practices, roles and relationships (Anderson et al. 2003; Betancourt 2003). Far from denoting a singular group identity, each individual is a unique chimera of cultural influences beyond simply race, ethnicity or religion (Betancourt 2003). By extension, cultural competence implies the ability to operate effectively in interpersonal interactions and contexts characterized by diverse cultural practices and beliefs (Betancourt 2006). This ability has also been referred to as ‘cultural relativism’ (Sobo and Loustaunau 2010), ‘cross-cultural efficacy’ (Núñez 2000), ‘cultural humility’ (Tervalon and Murray-García 1998) and ‘transnational competence’ (Koehn and Swick 2006).

문화적 역량에 대한 이전의 움직임은 학생들에게 문화 간 지식과 기술을 전수하는 것을 추구했는데, 이때 주로 [문화적 고정관념]과 [과도하게 단순화된 문화 간 및 문화 내 이질성]에 의존해왔다. 그러나 문화적 역량에 대한 최근의 접근은 환자를 위한 공감적이고 개인화된 치료를 제공하기 위하여 [문화적 배경을 통합하는 것]으로 옮겨가고 있습니다.

Earlier movements towards cultural competence sought to impart students with cross-cultural knowledge and skills (Kripalani et al. 2006; Altshuler et al. 2003) relying on cultural stereotypes and oversimplifying inter- and intra-cultural heterogeneity (Koehn and Swick 2006; Dreher and Macnaughton 2002). Recent approaches to cultural competence, however, have shifted towards the integration of cultural background in the provision of empathic, individualized care for patients (Tervalon and Murray-García 1998; Koehn and Swick 2006; Dreher and Macnaughton 2002).

문화 간 역량에 대한 이론적 관점

Theoretical perspectives on intercultural competence

많은 학자들이 교육, 학습 및 의료 분야에서 [문화 간 역량intercultural competence]을 탐구해 왔지만, 우리는 특히 관리 연구로부터 문화 간 커뮤니케이션에 이르기까지 프리드먼과 베르토인 안탈의 공헌을 바탕으로 하고 있습니다. 우리가 이 이론을 선택한 것은 행동과학 및 정체성 기반 갈등의 개념을 바탕으로 한, [문화 간 역량]에 대한 [행동지향적 접근법] 때문이다(Friedman and Bertoin Antal 2005). 이 작가들은 [문화적 역량]은 [문화 간 역량]과 다르다고 정의한다. 그들의 관점에 따르면,

- [문화적 역량]은 문화-간 상호작용에서 미성찰적 행동을 의미한다. 즉, 학습된 [기술, 지식 또는 '다른' 문화에 대한 가정]에 의존하는 것이다.

- [문화 간 역량]은 '현실 협상negotiating reality'을 수반한다. 이는 높은 옹호와 높은 탐구의 신중한 조합을 통해 상호 문화적 인식과 반성을 창출하는 과정이다. [옹호]란 자신의 문화를 표현하고 대변하는 것이다. [탐구]란 자신과 타인의 문화를 탐구하고 성찰하는 것이다.

While many scholars have explored intercultural competence in teaching and learning and healthcare contexts (Byram 1997; Leininger 1996; Srivastava 2007), we draw specifically on Friedman and Berthoin Antal’s contributions from management studies to cross-cultural communication (Berthoin Antal and Friedman 2008; Friedman and Berthoin Antal 2005, 2006). We chose this theory because of its action-orientated approach to intercultural competence, drawing on concepts of action science and identity-based conflict (Friedman and Berthoin Antal 2005). These authors define cultural competence as differing from intercultural competence (Berthoin Antal and Friedman 2008; Friedman and Berthoin Antal 2005, 2006).

- In their view, cultural competence denotes non-reflective action in cross-cultural interactions; reliance on a set of learned skills, knowledge or assumptions about ‘other’ cultures.

- Intercultural competence, on the other hand, involves ‘negotiating reality’: a process of generating mutual cultural awareness and reflection through a careful combination of high advocacy and high inquiry (Berthoin Antal and Friedman 2008), where advocacy involves expressing and championing one’s own culture and inquiry means exploring and reflecting upon one’s own and others’ cultures (Friedman and Berthoin Antal 2005).

프리드먼과 베르토인 안탈에 따르면,

- [높은 옹호/낮은 탐구] 접근법에는 타인의 가치를 고려하지 않고 자신의 가치를 장려하는 것이 포함됩니다. 의료 환경에서 드물지 않다. '의료 중심medicocentric' 의료인을 만난다거나, 위계적 의사-환자 관계이다.

- [낮은 옹호/높은 탐구] 접근법은 자신의 견해를 공유하지 않고, 타인의 견해와 가치를 탐색하는 것을 포함하며, 이는 환자 치료에 잠재적인 해를 끼친다.

- [낮은 옹호/낮은 탐구] 접근법은 다른 문화와의 만남에서 철수하거나 이탈하는 것으로 해석될 수 있다.

- [높은 옹호/높은 탐구]은 가장 바람직한 접근법이다. 탐구, 토론 및 상호 이해 정신으로 열린 의견 교환이다.

A high advocacy/low inquiry approach involves exhorting one’s own values without considering those of others—not uncommon in healthcare settings, where one might encounter ‘medicocentric’ practitioners (Campinha-Bacota and Munoz 2001; Pfifferling 1981) and hierarchical provider-patient relationships (Chandratilake et al. 2012).

On the other hand, a low advocacy/high inquiry approach involves exploring the views and values of others without sharing one’s own views, with potential detriment to patient care.

A low advocacy/low inquiry approach can be interpreted as withdrawal or disengagement from a cross-cultural encounter.

The most desirable approach, according to Friedman and Berthoin Antal, is high advocacy/high inquiry: an open exchange of views in the spirit of exploration, discussion and mutual understanding (Berthoin Antal and Friedman 2008; Friedman and Berthoin Antal 2005).

서구의 [크로스 컬쳐 프레임워크]가 대만에 적용될 수 있는지는 의문이지만, 기존의 독자적인 이론 프레임워크가 없기 때문에, 높은 옹호/높은 탐구가 최선이라는 결론을 정해두지는 않되, 프리드먼과 베르토인 안탈의 모델을 휴리스틱 장치로서 사용하였다. [서양의 이론 체계를 사용하지 않는 것]의 대안은 [이론 체계를 전혀 사용하지 않는 것]이었다. 그러나 우리는 [이론이 질적 분석 과정에 엄격함을 가져올 것]이라고 생각했기 때문에, 무-이론 접근법theory-free approach를 따르지 않기로 결정했다(Rees and Monrouxe 2010).

Although the applicability of Western cross-cultural frameworks is questionable in the context of Taiwan, due to a lack of existing indigenous theoretical frameworks, we adopt Friedman and Berthoin Antal’s model as a heuristic device to analyze our data without commiting to their conclusion that high advocacy/high inquiry is ncessarily the best. The alternative to not using a Western theoretical framework was to not use a theoretical framework at all. However, we decided against this theory-free approach as we felt that theory would bring rigour to the qualitative analytic process (Rees and Monrouxe 2010).

근거 및 조사 질문

Rationale and research questions

비서양적 맥락에서의 의학 교육이 점점 서구화됨에 따라, 서양의학과 비서양 문화 사이의 단절을 다룰 필요가 있다. 대만에서는 의과대학의 정식 커리큘럼이 서양의 표준(서양의 프로페셔널 코드와 환자의 자율성, 기밀성, 정보에 근거한 동의를 나타내는 커뮤니케이션 모델 등)을 따르고 있지만, 임상 실무의 비공식 및 숨겨진 커리큘럼은 현지 문화에 영향을 받는다. 예를 들어, [가족]은 [환자의 자율성을 훼손할 정도]로 의료 의사결정에 중요한 역할을 한다.

As medical education in non-Western contexts becomes increasingly Westernised, there is a need to address any disconnects between Western medicine and non-Western cultures. In Taiwan, while the formal curriculum in medical schools follows Western standards, including formal teaching and assessment of Western professional codes and communication models articulating patient autonomy, confidentiality and informed consent, the informal and hidden curriculum in clinical practice is affected by local culture. For example, families play important roles in medical decision-making, to the degree of compromising patient autonomy (Ho et al. 2012).

환자 중심의 돌봄, 상호 이해 및 공동 의사결정을 장려하는 기존 문화역량 모델(베탕쿠르 2006)에 따라 대만 학생들의 문화 간 딜레마 내러티브 분석에 '문화 간 역량intercultural competence'이라는 개념을 채택했다. 이 이야기들은 학생들의 [전문직업성 딜레마]에 대한 탐구를 통해 도출되었다: 그들이 목격했거나 참여한 상황들, 그들 자신의 문화적 관점에서 볼 때 부도덕하거나 부적절하거나 프로답지 않다고 생각하는 상황들(Christakis and Pondtner 1993). 의대생들은 문화적 차이를 수반하는 전문성 딜레마에 자주 직면하기 때문에, 문화적 역량을 키우는 것이 학생들의 전문성 학습과 실천에 핵심이다. 따라서 이 백서에서는 다음 두 가지 조사 질문에 대해 설명합니다.

- (1) 학생들의 문화 간 전문성 딜레마 이야기에서 대만 문화의 어떤 측면이 강조됩니까?

- (2) 이러한 딜레마에 대응하여 대만 의대생들은 어떤 옹호와 질문을 조합하여 이야기합니까?

In line with existing models of cultural competence that encourage patient-centered care, mutual understanding and joint decision-making (Betancourt 2006), we employed the concept of ‘intercultural competence’ (Friedman and Berthoin Antal 2005) in our analysis of Taiwanese students’ intercultural dilemma narratives. These narratives were elicited through an exploration of students’ professionalism dilemmas: situations that they witnessed or participated in, which they believe to be immoral, improper or unprofessional from their own cultural perspective (Christakis and Feudtner 1993). Since medical students frequently encounter professionalism dilemmas involving cultural differences, developing cultural competence is key to students’ learning and practice of professionalism (Ho et al. 2008; Monrouxe and Rees 2012). This paper, therefore, addresses two research questions:

- (1) Which aspects of Taiwanese culture are highlighted in students’ intercultural professionalism dilemma narratives?

- (2) Which combinations of advocacy and inquiry do Taiwanese medical students narrate in response to these dilemmas?

방법들

Methods

연구 설계

Study design

이 연구는 대만 의대생들의 전문직업성 딜레마에 대한 이야기를 조사하는 대규모 연구 프로젝트의 일부입니다. 질적 내러티브 인터뷰를 사용하였으며, [지식을 '사회적 상호 작용을 통해 협상되는 것'으로 개념화]하고, [다중적 현실의 존재를 인정]하는 [사회적 구성주의social constructionism]에 의해 뒷받침된다(Crotty 2003). 따라서 우리는 데이터에서 몇 가지 기본적인 정량적 패턴을 확인했음에도 불구하고 이 연구에서 정성적 해석적 접근법을 취한다.

This study is part of a larger research project investigating Taiwanese medical students’ narratives of professionalism dilemmas. It employs qualitative narrative interviewing (Monrouxe and Rees 2012; Monrouxe et al. 2014) and is underpinned by social constructionism, which conceptualizes knowledge as negotiated through social interaction and acknowledges the existence of multiple realities (Crotty 2003). We therefore take a qualitative interpretive approach in this study, despite identifying some basic quantitative patterns in our data (Maxwell 2010).

맥락

Context

대만의 의학교육은 서양의학과 전통 의학을 어느 정도 수용하는 문화적 배경에도 불구하고 서양의학 교육에 기반을 두고 있다. 대만의 의학 학위는 보통 7년이며, 본 학교에서는

- 4학년 학생들이 일주일에 하루 오후를 신체 검사와 환자력 검사를 배우는 데 소비합니다.

- 5학년과 6학년 학생은 다양한 임상 부서에서 임상실습을 하며 관찰하고, 환자 진료에 대한 제한된 책임을 맡습니다.

- 7학년 학생들은 환자 진료에서 직접적이지만 감독된 책임을 지는 인턴으로 활동합니다.

Taiwanese medical education is based on Western medical education (Ho et al. in press), despite the cultural backdrop embracing both Western and traditional medicine to varying degrees (Huang et al. 2014). Taiwanese medical degrees are typically seven years, and in the participating school,

- year 4 students spend one afternoon per week learning to do physical examinations and take patient histories.

- Year 5 and 6 students undertake clerkships in different clinical departments, observing and taking on limited responsibilities in patient care. Finally,

- year 7 students act as interns with direct but supervised responsibilities in patient care.

참가자 모집

Participant recruitment

윤리적 승인에 따라, 우리는 참가자를 모집하기 위해 전자 게시판과 학생회 대표들의 도움을 이용했습니다. 2013-2014년에 대만 의과대학 14개 초점 그룹이 64명의 학생을 대상으로(20~33세, 평균 연령 = 24.5세) 4-7년차에 실시되었다. 초점 그룹에는 4학년 학생 10명(여자 4명, 남자 6명), 5학년 학생 15명(여자 3명, 남자 12명), 6학년 학생 16명(여자 3명, 남자 13명), 7학년 학생 23명(여자 4명, 남자 19명)이 포함됐다.

Following ethical approval, we used electronic bulletin boards and assistance from student association representatives to recruit participants. In total, 14 focus groups at one Taiwanese medical school were conducted with 64 students in 2013–2014 (15 females and 49 males, reflective of the school’s gender ratio) in Years 4–7 (age ranged from 20 to 33, mean age = 24.5). The focus groups included 10 students from Year 4 (4 females, 6 males), 15 students from Year 5 (3 females, 12 males), 16 students from Year 6 (3 females, 13 males), and 23 students from Year 7 (4 females, 19 males).

데이터 수집

Data collection

그룹 전체에서 인터뷰의 일관성을 확보하기 위해 두 명의 저자가 실시한 이전의 연구에 근거한 토론 가이드를 채용했다. 그룹 참가자 집중, 소개 및 기본 규칙 토론에 대한 전반적인 환영을 받은 후, 우리는 오리엔테이션 질문으로 각 그룹 토론을 시작했습니다. [O학년 의대생으로서, 전문직업성에 대해 어떻게 알고 계십니까?] 그런 다음, 참가자들은 그들의 전문성에 대한 정의에 대한 논의를 바탕으로 전문직업성 딜레마에 대해 공유하도록 요구받았다. 문헌에서 [전문직업성 딜레마]는 비윤리적, 비전문가적, 비도덕적 또는 잘못된 사건을 목격하거나 참여하는 학생들의 일상적인 경험으로 정의된다. 전문직업성 딜레마에는 윤리적 딜레마가 포함되지만 이에 국한되지는 않습니다. 학생들의 전문직업성 딜레마가 소진된 후, 우리는 인터뷰를 끝내고, 토론에 중요한 기여를 한 참가자들에게 감사를 표하고, 떠나기 전에 설문지를 작성하도록 요청했습니다. 여기에는 기본 인구통계(예: 연령, 성별)와 교육 관련 세부사항(예: 연구 연도)이 포함되어 표본과 각 하위 그룹의 특성을 정의할 수 있었다.

We employed a discussion guide based on previous studies conducted by two of the authors (Monrouxe and Rees 2012; Monrouxe et al. 2014) in order to ensure consistency in interviewing across the groups. After a general welcome to focus group participants, introductions and a discussion of ground rules, we started each group discussion with an orienting question: “what is your understanding of professionalism as a [state year] medical student?”. Then, participants were asked to share their professionalism dilemmas based on their discussion of their definitions of professionalism. In the literature, professionalism dilemmas are defined as day-to-day experiences of students in which they witness or participate in an event that they find unethical, unprofessional, immoral or wrong (Christakis and Feudtner 1993). Professionalism dilemmas include, but are not limited to, ethical dilemmas. Once students’ professionalism dilemmas were exhausted, we closed the interviews, thanking participants for their important contributions to the discussions and asking them to complete a questionnaire before they left. This included basic demographic (e.g. age, gender) and education-related details (e.g. year of study) so that we could define the characteristics of our sample and each sub-group.

데이터 분석

Data analysis

그룹 토론은 오디오 녹음, 문자 변환, 익명화 및 ATLAS.ti 버전 7.5.2에 입력되었습니다. 첫째, 일반화된 대화가 아닌 코딩의 주요 단위로 개인적인 사고 기록(특정 사건의 이야기)을 식별했다. (예: "항상 있는 일입니다…"). 총 233건의 개인적 사건 내러티브가 확인되었다. 이 데이터의 1차 주제 분석은 [프레임워크 분석]의 5단계를 사용하여 수행되었다.

Group discussions were audio-recorded, transcribed, anonymized and entered into ATLAS.ti Version 7.5.2 (Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany). First, we identified personal incident narratives (i.e. stories of specific events) as the primary unit for coding, rather than generalized talk (e.g. “it happens all the time…”). In total, 233 personal incident narratives were identified. A primary thematic analysis of this data was undertaken using the five stages of framework analysis (Ritchie and Spencer 1994):

- 1. 모든 저자는 주제와 하위 주제를 식별하기 위해 독립적으로(각각 최소 6개의 대본) 데이터를 숙지했다. 5명의 저자 중 2명은 영국과 호주에서 전문직업성을 위해 이전에 개발된 코딩 프레임워크에 대한 지식을 바탕으로 [연역적인 방식]으로 이를 수행했다. 다른 세 명의 저자는 이 과정을 [귀납적인 방식]으로 수행했다.

1. All authors familiarised themselves with the data independently (at least 6 transcripts each) in order to identify themes and sub-themes. Note that two of five authors did this in a deductive manner based on their knowledge of a previously developed coding framework for professionalism from the UK and Australia (Monrouxe and Rees 2012; Monrouxe et al. 2014). The other three authors engaged in this process in an inductive fashion. - 2. 우리는 서로의 통찰력을 공유하고 상호 합의된 코딩 프레임워크를 개발하기 위해 함께 모였습니다. 학생의 내러티브에서 식별되는 가장 일반적인 주제 중 하나가 [문화간 딜레마]였고, 문화간 딜레마 내러티브의 2차 분석을 실시하기로 결정하였으며, 이 논문의 초점이 되었다. 그런 다음, 우리는 문화간 전문직업성 딜레마에 대한 추가적인 코딩 프레임워크를 개발했고(예를 들어, 학생들은 어떤 유형의 문화 간 딜레마를 경험했는가) 데이터를 코드화하기 위해 프리드먼과 베르토인 안탈(2005)의 옹호와 질문 조합을 사용했다.

2. We came together to share our insights and to develop a mutually-agreed coding framework. As intercultural dilemmas were among the most common themes identified in students’ narratives, we decided at this point to undertake a secondary analysis of intercultural professionalism dilemma narratives, which became the focus of this paper. We then developed an additional coding framework for intercultural professionalism dilemmas (for example, what types of intercultural dilemmas did students experience?) and employed Friedman and Berthoin Antal’s (2005) combinations of advocacy and inquiry, to code the data. - 3. 두 번째 저자는 모든 문화 간 전문지업성 딜레마 내러티브를 코드화하고, 연구 보조자는 코드화를 재확인했다(승인 참조). 이견은 제1저자와의 논의를 통해 해결되었다.

3. The second author coded all intercultural professionalism dilemma narratives and a research assistant double-checked the coding (see acknowledgements). Disagreements were resolved through discussion with the first author. - 4. 데이터를 차트화했다(즉, 주제 내에서 패턴을 탐색했다).

4. The data were charted (i.e., patterns were explored within the themes). - 5. 이 주제들은 프리드먼과 베르토인 안탈(2005)의 이론 체계와 기존 문헌에 비추어 해석되었다.

5. These themes were interpreted in light of Friedman and Berthoin Antal’s (2005) theoretical framework and existing literature.

결과.

Results

우리는 109개의 문화 간 딜레마를 확인했는데, 그 중 98개(90%)는 대만 문화 문제를, 10개(9%)는 국제 문화 문제를, 그리고 1개(1%)는 둘 다와 관련된 이야기(Monrouxe와 Rees 2017)를 확인했다.

We identified 109 intercultural dilemmas, 98 (90%) of which referred to one or more Taiwanese cultural issues and 10 (9%) to international cultural issues, as well as one narrative (1%) referring to both (Monrouxe and Rees 2017).

학생들의 문화 간 딜레마에서 대만 문화의 어떤 측면이 인용되는가?

Which aspects of Taiwanese culture are cited in students’ intercultural dilemmas?

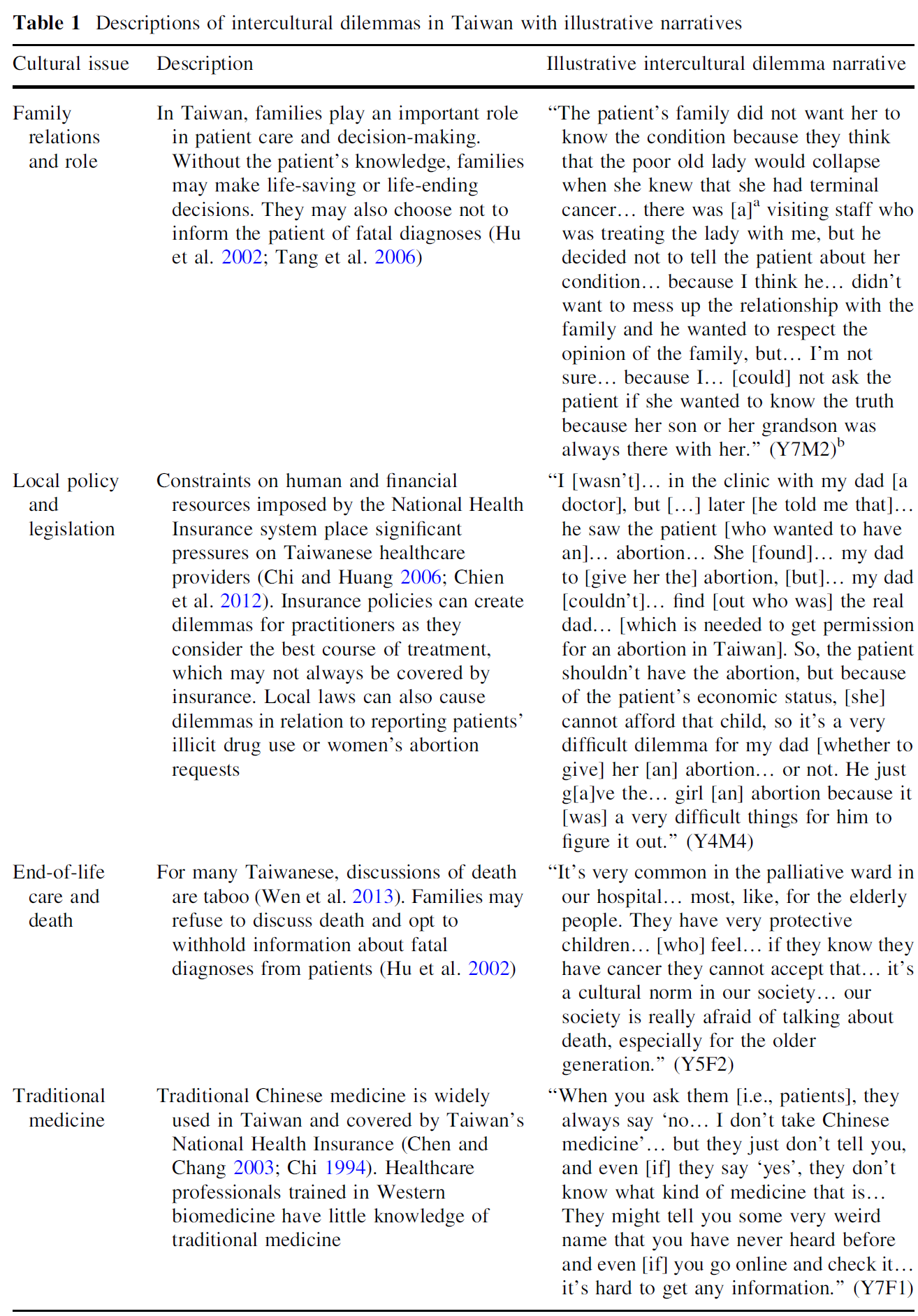

다음과 같은 대만 문화 주제가 확인되었으며, 여러 주제와 관련된 서술이 일부 확인되었다.

- (1) 가족 관계 및 역할(n = 37),

- (2) 지방 정책(n = 33),

- (3) 말기 의료(n = 15),

- (4) 한의학(n = 15),

- (5) 젠더 관계(n = 11)

- (6) 대만어

- (7) 기타 문화적 이슈

각 주제와 설명에 대한 설명은 표 1을 참조하십시오.

The following Taiwanese cultural themes were identified, with some narratives involving multiple themes:

- (1) Family relations and role (n = 37);

- (2) Local policy (n = 33);

- (3) End-of-life care (n = 15);

- (4) Chinese medicine (n = 15);

- (5) Gender relations (n = 11);

- (6) Taiwanese language (n = 7); and

- (7) Other cultural issues (n = 8).

See Table 1 for a description of each theme and illustrative narratives.

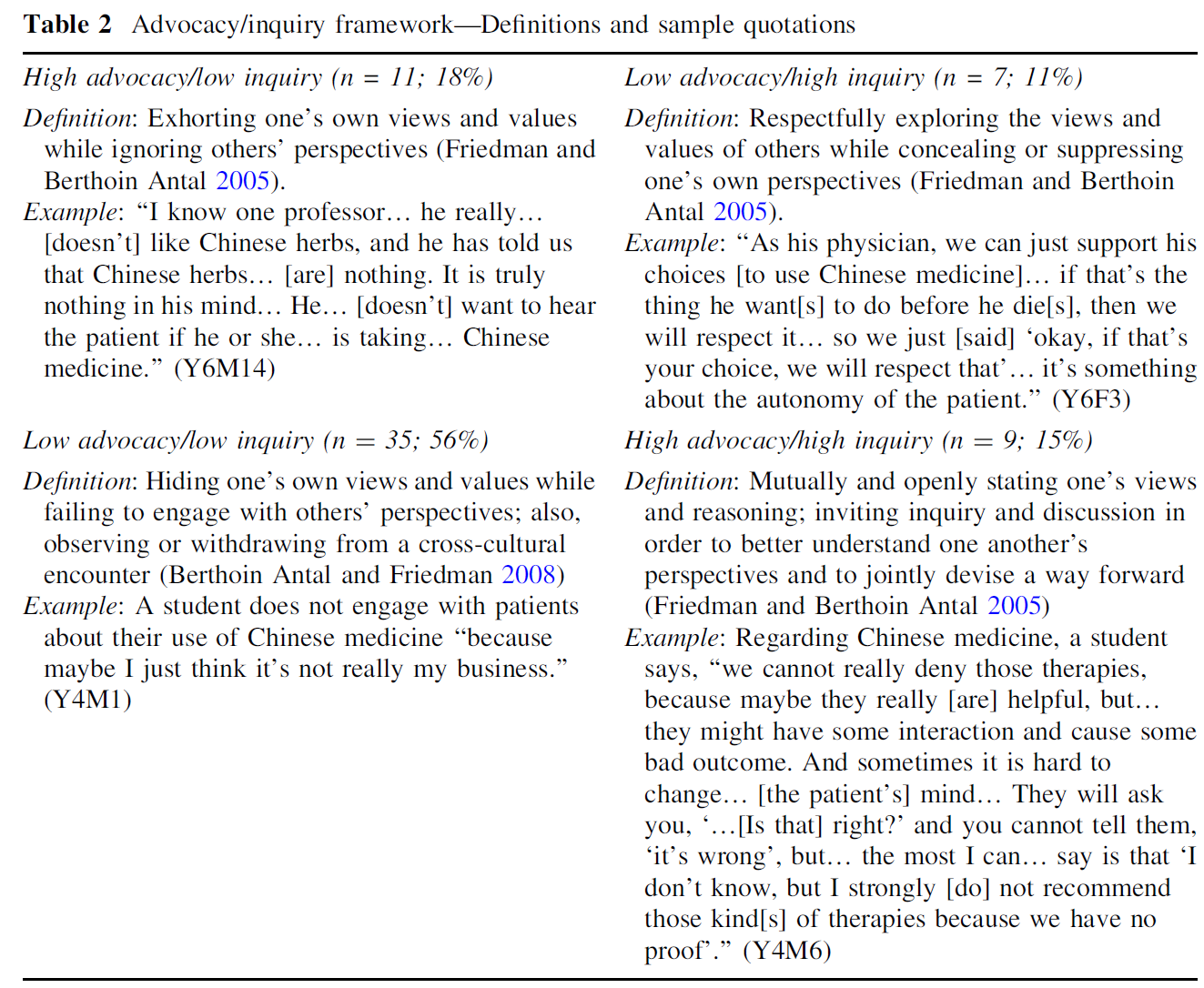

대만 학생들은 어떤 옹호와 탐구를 조합하여 이야기합니까?

Which combinations of advocacy and inquiry do Taiwanese students narrate?

109개의 문화 간 딜레마 내러티브 중 62개는 옹호/탐구 프레임워크를 적용하기에 대인관계에 대한 충분한 세부사항을 제공했다(정의와 예는 표 2 참조). 이하에, 특정된 옹호와 탐구의 조합의 예를 나타냅니다.

Of the 109 intercultural dilemma narratives, 62 provided sufficient detail about interpersonal interactions to apply the advocacy/inquiry framework (see Table 2 for definitions and examples). Below, we provide examples of the combinations of advocacy and inquiry identified.

낮은 옹호/낮은 탐구

Low advocacy/low inquiry

대부분의 학생들의 내러티브는 대만의 문화적 딜레마에 관여하는 것을 꺼리는 것을 반영했다. 흥미롭게도, 학생들은 종종 그러한 경우에 불확실하거나 실망감을 표현했다. 한 7학년 학생은 자기 친적 이야기를 했다. 친척은 폐색전증으로 혈액을 희석하면서 한약을 사용하기 시작했다. 이 학생은 양약과 한약의 조합이 친척의 사망으로 이어졌다고 의심했다.

Most of the students’ narratives reflected their reluctance to engage with Taiwanese cultural dilemmas, though a few observed superiors taking the same approach. Interestingly, students often expressed uncertainty or disappointment in such cases. In a narrative combining end-of-life care, the role of the family and Chinese medicine, a Year 7 student shared that her own relative, while taking blood thinner for a pulmonary embolism, began to use Chinese medicine. The student suspected that the combination of Western and Chinese medicines led to her relative’s death:

대학에서 전통의학 동아리에 가입했는데... 그래서 배웠어요. 인삼과 동콰이 항응고 효과에 대한 연구가 있어요. (Y7F2)

I participated in a traditional medicine club in the university… So I learned… that there… [is] some research about… ginseng and… dong-quai hav[ing an] anticoagulation effect. (Y7F2)

하지만 친척이 죽었다는 소식을 듣고 그녀는 관여하지 않기로 결정했다.

Yet, upon hearing of her relative’s death, she chose not to get involved:

가족에게는 설명하지 않았다… 왜냐하면 그 환자의 딸이 아버지가 전통 의학을 찾아야 한다고 제안했기 때문이다… 그들은 전통 의학이 항응고 효과도 있다는 것을 알지 못한다. (Y7F2)

I didn’t explain that to the family… because I think it’s the patient’s daughter that suggest[ed] that… [her] father should seek… traditional medicine… They… don’t know that traditional medicine also include[s] some anticoagulation effect. (Y7F2)

그러나 이 학생의 한의학 지식은 흔치 않았다. 서양 생물의학 교육을 받은 대부분의 학생들은 전통의학을 배우는 데 거의 관심을 보이지 않았다. 한 학생은 환자가 한의학을 언급했을 때 더 이상 묻지 않고 이 점을 공유했다.

This student’s familiarity with Chinese medicine was, however, uncommon. Most students, having been trained in Western biomedicine, expressed little interest in learning about traditional medicine. One student shared that, instead of inquiring further when a patient mentioned Chinese medicine:

그냥 적어두지만 독소가 아닌 한 아무도 신경 쓰지 않을 겁니다. (Y5M4)

I just write [it down], but I think nobody cares about that as long as it is not some kind of toxin. (Y5M4)

대만에서는 죽음을 둘러싼 문화적 금기사항 때문에 위독한 환자나 노환자의 가족은 종종 환자와 상의하지 않고 중요한 임종 결정을 내린다. 한 7학년 학생은 가족이 환자에게 자신의 상태를 말하는 대신 혼수상태에 빠질 때까지 기다려 DNR오더를 내린 암 환자의 이야기를 들려주었다. 이 학생은 이러한 방식에 불편함을 표시하며 다음과 같이 말했다.

Due to cultural taboos surrounding death in Taiwan, the families of critically ill and elderly patients often make important end-of-life decisions without consulting patients. A Year 7 student shared the story of a patient with cancer whose family, rather than telling the patient about his condition, waited until he was in a coma to sign a ‘do not resuscitate’ order. The student expressed discomfort with this practice, saying:

하지만 그건 말이 안 돼요. 환자가 소생하지 않는다는 것을 알려야 하는데... 대만 문화, 이런 상황은 정말 흔해요. (Y7M5)

but that doesn’t make sense, because we should let the patient know that he will [not be resuscitated]… but I think in… Taiwanese culture, this situation is really common. (Y7M5)

이 학생은 다음과 같은 딜레마에 직면한 의대생들 사이에서 낮은 지지/낮은 질의 응답이 일반적이라고 관찰했다.

The student observed that a low advocacy/low inquiry response is common among medical students faced with this type of dilemma:

몇몇 의대생들은 그런 이상한 상황을 마주하고 싶지 않기 때문에 그냥 물러설 것이다. (Y7M5)

some of the medical students will just withdraw… because they d[o]n’t want to face that strange situation. (Y7M5)

높은 옹호/낮은 탐구

High advocacy/low inquiry

일부 학생들은 높은 옹호/낮은 탐구 방식을 사용하여 자신의 경험을 공유했지만, 대부분은 이 방식을 사용한 상관에 대해 비판적이었다. 예를 들어, 한 5년차 학생은 환자 치료에 가족이 관여하는 사건에 대한 치프 레지던트의 높은 옹호/낮은 탐구 접근법의 비효율성에 주목했다. 환자의 며느리는 [의대생들이 시어머니를 방문하는 것]에 대해 불만을 표시했다.

While some students shared their own experiences using a high advocacy/low inquiry approach, most were critical of their superiors who used this approach. For example, a Year 5 student noted the ineffectiveness of a chief resident’s high advocacy/low inquiry approach in an incident concerning family involvement in patient care. When a patient’s daughter-in-law expressed frustration with the medical students visiting her mother-in-law:

치프 레지던트도 조금 화가 나서 '여기는 교육병원이니 학생들을 거절하면 안 된다'고 말했다. (Y5F3)

the chief resident was also a little bit angry and [told] her, ‘this is the teaching hospital, so you should not decline the students’. (Y5F3)

그러나 이 학생은 치프 레지던트가 종종 대만 가족의 비난을 받는 [며느리에 대한 시댁의 압박]에 대해 알아보기 위해 노력하지 않았다는 것을 인정했다.

The student recognized, however, that the chief resident made no effort to inquire about family pressures on the daughter-in-law, who often bears the brunt of a Taiwanese family’s blame:

우리는 다른 전공의와 다른 치프 레지던트로부터 그녀가 환자의 유일한 간병인이라는 이야기를 들었습니다만, 다른 가족들은 그녀에게 '어머니를 잘 돌봤나요?'라고 질문할 수도 있습니다. 우리 할머니 잘 보살펴드렸니?' 가족들로부터 엄청난 압박감을 받고 있는 것 같아요. 거기엔 그녀 한 명밖에 없어요. (Y5F3)

We’ve heard from other residents and [another] chief resident that she’s the only caregiver of the patient, but the other [family members] may… question her, ‘Did you take good care of my mother? Did you take good care of my grandmother?’ So maybe she’s under great pressure [from] the family, and there’s only one of her. (Y5F3)

한 6학년 학생은 표 2와 같이 한약을 사용하는 환자와의 상호작용에서 '의학중심주의'가 뚜렷한 한 교수를 관찰하였다. 한 5학년 학생은 이 관찰을 반복하면서 다음과 같은 의사를 묘사했다.

A Year 6 student observed a professor whose ‘medicocentrism’ was evident in interactions with patients who used Chinese medicine, as indicated in Table 2. A Year 5 student echoed this observation, describing a doctor who:

한약을 가지고 귀찮게 만들고 싶지 않다. 그래서 그는 그냥 '오, 제발 이 약을 드세요, 한약은 먹지 마세요.'라고 말한다.(Y5M3)

doesn’t want to bother himself [with]… Chinese medicine, so he just say[s], ‘oh come on… please just take this drug, don’t take Chinese medicine’. (Y5M3)

학생은 이 접근방식이 다음과 같이 환자에게 해를 끼칠 수 있다고 인식했다.

This approach, the student recognized, may harm the patient, as it:

의사가 처방하는 약의 성질을 설명하지 않기 때문에 환자의 순응도가 좋지 않다. (Y5M3)

results in… bad compliance… because the doctor just simply doesn’t explain what kind[s] of characteristics the drug that he prescribe[s has]. (Y5M3)

높은 옹후/높은 탐구

High advocacy/high inquiry

학생들은 종종 선배의사가 취한 [높은 옹호/높은 탐구 접근법]에 감탄하고, 다른 학생들은 이 접근방식을 성공적으로 사용하는 것을 자랑스럽게 여겼다. 예를 들어 표 1에서 설명한 바와 같이, 이제 많은 대만인들이 만다린어를 구사하여 더 이상 대만어로 의사소통을 할 수 없게 되었다. 일반적으로 짧은 환자와의 만남에서는 언어 능력을 배울 수 없지만, 한 5학년 학생은 자신이 어떻게 대만어를 하는 환자들과 더 잘 소통하고 배울 수 있었는지에 대해 이야기했습니다.

Students often admired the high advocacy/high inquiry approaches taken by their superiors, with others being proud to share their own successful use of this approach. For example, as explained in Table 1, many Taiwanese people speak Mandarin and are no longer able to communicate in Taiwanese. Although language skills cannot typically be learned during brief patient encounters, a Year 5 student related how she was better able to communicate with and learn from Taiwanese-speaking patients:

저는 대만어로 할 수 있는 단어를 제한적으로 사용하려고 합니다. 또한 그들이 자신의 방식으로 이해한 것을 알려주면 더 많은 대만어를 배울 수 있기 때문에 단어를 더 잘 설명할 수 있습니다. 좋아지고 있어요. (Y5F3)

I try to use the limited words I can speak in Taiwanese and when they tell us what they understand in their own way, I can learn more Taiwanese word[s]… so I can use the words [t]o explain better to them so… I’m improving. (Y5F3)

환자에게 더 물어봄으로써 그녀는 다음과 같이 할 수 있었다.

By further inquiring of the patient, she could:

그들이 이해하고 있는 것을 확인하고 더 잘 이해할 수 있도록 한다. (Y5F3)

make sure [of] what they understand… and make [a] better understanding. (Y5F3)

표 2에서 강조된 바와 같이, 4학년 학생은 가족이나 친구와 한의학에 대해 이야기할 때 공감과 정직으로 응답하면서 높은 지지와 높은 관심을 보였다.

As highlighted in Table 2, a Year 4 student exercised high advocacy/high inquiry when talking about Chinese medicine with family and friends, responding with empathy and honesty.

낮은 옹호/높은 탐구

Low advocacy/high inquiry

소수의 학생들은 낮은 옹후/높은 탐구의 접근법에 대한 경험과 관찰을 공유했는데, 그 중 많은 수가 환자에게 치명적인 진단에 대해 알리는 것을 가족이 거절하는 것에 관한 것이었다. 6학년 학생은 환자의 자율성에 대한 신념과 합법성에 대한 우려를 억누르면서 가족의 관점을 존중하는 방법을 공유했습니다.

A few students shared experiences and observations of low advocacy/high inquiry approaches, many of which concerned families’ refusals to inform patients about fatal diagnoses. A Year 6 student shared how he respected a family’s point of view while suppressing his belief in patient autonomy and concerns about legality:

그 가족은 의사에게 아버지에게 아버지의 건강에 대해 말하지 말라고 설득했다. 그들은 그가 행복하게 살기를 원했고 어떤 치료도 거부했다. 하지만 사실 환자의 자율성을 존중하기 위해 환자의 몸에서 무슨 일이 일어나고 있는지 환자에게 알려야 합니다. 하지만 대만에서는 사회적 또는 전통적 가치나 규범 때문에 가족이 결정하는 것을 존중하는 경향이 있습니다. 하지만 그건... 법에 있어요. 말기 환자라도 치료 계획이나 선택지에 대해 말해줘야 하지만 실제로는 쉽지 않다. (Y6M8)

the family sort of lie[d], persuade[d] the doctors… not [to] tell… their father about… his health. They wanted [him] to live happily and… refuse[d] any medical treatment. But actually, in order to respect the patient’s autonomy, we’re supposed to tell the patient about what’s going on in his body. But in Taiwan… perhaps due to… social or traditional value[s] or norms… we tend to… respect what [the] family decide[s]. But it’s… in the law. It sa[ys] even the terminal[ly] ill patient, you have to tell him about the treatment plan or his options… but in practice… [it’s] usually not easy to. (Y6M8)

한편, 표 2에서 강조된 바와 같이, 6학년 학생은 자신의 신념에 관계없이, 말기 치료 시 한약 사용을 존중하는 이유로 환자의 자율성을 들었다. 비슷한 상황에서, 한 7학년 학생은 방문진들이 침과 피를 흘리기 위해 한의사를 방문하는 것을 반대하지 않는 것을 관찰했다.

On the other hand, as highlighted in Table 2, a Year 6 student cited patient autonomy as a reason to respect the use of Chinese medicine during end-of-life care, regardless of her own beliefs. In a similar situation, a Year 7 student observed how a visiting staff did not oppose a visit from a Chinese medicine doctor to administer acupuncture and blood-letting.

논의

Discussion

이 연구에서 우리는 대만의 의대생들이 공유하는 [전문직업성 딜레마의 거의 절반]과 [문화간 딜레마의 거의 대부분]이 서양의학과 대만 문화의 긴장을 우려하는 것임을 관찰했다.

- 첫 번째 조사 질문에서는 대만 문화 간 전문성 딜레마에 대해 가족관계와 역할, 지방정책과 입법, 종말관리와 죽음, 전통의학, 성관계와 규범, 대만어 및 기타 문화적 신념과 실천 등 7가지 주제를 특정했다.

- 두 번째 연구 질문에 대해,

- 대부분 낮은 옹호/낮은 탐구 접근법을 언급하였고, 이는 학생들이 대체로 문화 간 딜레마에 빠져나가는 쪽을 선택했다는 것을 시사한다.

- 흥미롭게도, 학생들은 종종 높은 탐구/높은 옹호로 분류된 경험에 대해 긍정적으로 말하면서,

- 높은 옹호/낮은 탐구로 분류된 내러티브에서는 종종 윗사람을 비판했습니다.

- 낮은 옹후/낮은 탐구의 경우, 그들은 종종 불확실성이나 실망감을 표현했다.

In this study we observed that, nearly half of the professionalism dilemmas shared by Taiwanese medical students related to culture and nearly all were intercultural dilemmas, in that they concerned tensions between Western medicine and Taiwanese culture.

- In terms of our first research question, we identified seven themes for Taiwanese intercultural professionalism dilemmas: family relations and role, local policy and legislation, end-of-life care and death, traditional medicine, gender relations and norms, Taiwanese language and other cultural beliefs and practices.

- With respect to our second research question, we found that

- a low advocacy/low inquiry approach was narrated the majority of the time, suggesting that students typically opted out of engagement with intercultural dilemmas.

- Interestingly, students frequently spoke positively about experiences classified as high inquiry/high advocacy,

- while they often criticized superiors in narratives categorized as high advocacy/low inquiry.

- In cases of low advocacy/low inquiry, they often expressed uncertainty or disappointment.

조사결과와 기존 문헌과의 비교

Comparison of findings with existing literature

우리는 영국과 호주에서 학생들의 내러티브를 수집하는 데 사용된 것과 동일한 포커스 그룹 방법론과 내러티브 인터뷰를 사용했다. 이전 연구는 아마도 서양의학을 배우는 서양 맥락의 학생들이 포함되었기 때문에 문화 간 딜레마를 발견하지 못했는데, 이는 학생들이 이러한 문화 간 긴장을 경험할 기회가 적다는 것을 의미했다. 대만 의대생들의 문화 간 딜레마는 부분적으로 [서양적 방식의 의학과 대만적 방식의 수련]으로 설명될 수 있다. 이러한 서구화된 의료 문화는 대만 학생들을 대만의 특정 가치관, 관행, 신념과 충돌시킬 수 있다. 비록 서양의학과 비서양의 문화 사이의 갈등이 비서양의 환경에서 더 뚜렷하게 나타날 수 있지만, 비슷한 도전은 서양의 맥락에서 존재하는 것으로 밝혀졌다.

We employed the same focus group methodology with narrative interviewing as was used to collect student narratives in the UK and Australia (Monrouxe and Rees 2012). However, the previous study did not find intercultural dilemmas, probably because it involved students in a Western context learning Western medicine, which meant fewer opportunities for students to experience such intercultural tensions. The intercultural dilemmas expressed by our Taiwanese medical students may, in part, be explained by the Western style of medicine and medical training in Taiwan. Such Westernised medical culture can set Taiwanese students at odds with certain Taiwanese values, practices and beliefs (Dreher and Macnaughton 2002). Although the conflict between Western medicine and non-Western cultures may be more pronounced in non-Western settings, similar challenges have been found to exist in Western contexts (Westerhaus et al. 2015).

대만에서 대부분의 학생들이 낮은 옹호/낮은 탐구 방식을 통해 [문화 간 딜레마에 관여하지 않기로 선택했다는 것]은, [문화적 지식]만 가지고 있는 것은 부족하다는 것을 보여준다. 학생들의 낮은 지지/낮은 질문 접근법에 대한 의존은 그들의 권위와 경험 부족으로 설명될 수 있으며, 이는 학생들이 민감한 상황에서 결정을 내리는 것을 방해한다. 사실, 대만과 같은 [중등도 위계 사회]에서, 학생의 목소리를 듣고자 하지 않기 때문에, 문화적 갈등과 같은 복잡한 문제를 다루는 것은 보통 윗사람에게 맡겨질 수 있다. 문화 간 역량은 공감 및 개인화된 환자 관리와 관련이 있기 때문에, 아시아 학생들 사이에서 이전에 보고된 낮은 공감 수준이 이탈에 기여했을 수 있다. 또한, 감정적으로 충전된 시나리오(예: 수명 만료 관리)에서는 자신의 감정을 조절하기 위하여 withdraw했을 수도 있다. 대만의 이전 연구에 따르면 완화의료 종사자들은 [환자를 개종하려 들지 말고, 교육하고, 지원하며, 환자 가족과 공공연하게 소통해야 한다는 것]을 인식하고 있습니다. '체면'이 중요한 대만에서는 낮은 옹호/낮은 탐구 접근법이 선호될 수 있으며, 이는 환자가 [부정적인 체면(즉, 원하는 대로 행동할 자유)]을 유지하면서 학생들이 자신과 환자의 [긍정적인 체면(즉, 자기 이미지)]을 유지할 수 있게 해준다.

That most students opted out of engagement with Taiwanese intercultural dilemmas through low advocacy/low inquiry approaches highlights that cultural knowledge alone is insufficient. Students’ reliance on a low advocacy/low inquiry approach might be explained by their lack of authority and experience, which precluded them from taking decisions in sensitive situations. Indeed, students in a moderately hierarchical society like Taiwan (Hofstede n. d.) may leave their superordinates to deal with complex issues like cultural conflicts, as their voices might not be heard (Sidanius and Pratto 1999). As intercultural competence is related to empathy and individualised patient care, the low empathy levels previously reported among Asian students may have contributed to disengagement (Berg et al. 2015). Also, in emotionally charged scenarios (e.g., end-of-life care), students might withdraw in an effort to regulate their own emotions (Gross 1998; Gross and Thompson 2007). Previous research in Taiwan indicates that palliative care workers recognize that they should not proselytize, but educate, support and openly communicate with patients’ families (Hu et al. 2002). In Taiwan, where ‘face’ is important, a low advocacy/low inquiry approach might be preferred, permitting students to maintain their own and the patients’ positive face (i.e., self image) while allowing patients to maintain their negative face (i.e., freedom to act as they wish: Goffman 1967; Johnson et al. 2004).

[높은 옹호/높은 탐구 접근법]은 의미가 명시적이고 직접적으로 표현되는 저맥락 커뮤니케이션 스타일(일반적으로 서양 맥락)에 가장 적합해 보일 수 있지만, 우리의 조사 결과(학생들이 높은 옹호/높은 탐구 내러티브에 대해 긍정적으로 말한 것)는 문화간 역량은 고맥락 의사소통 맥락(일반적으로 아시아 맥락)의 경우에도 효과가 있을 수 있음을 시사한다. 의사와 환자는 고맥락의 커뮤니케이션 환경에서 덜 명확하게 의사소통을 할 수 있지만, 다른 관점을 표현하고 상호 이해를 위해 노력할 수 있는 문화적으로 적절한 방법을 찾을 수 있다.

Although a high advocacy/high inquiry approach might seem best-suited to low context communication styles (typically found in Western contexts), where meanings are expressed explicitly and directly, our findings (that students spoke about high inquiry/high advocacy narratives positively) suggest that intercultural competence might also work in high context communication settings (typically in Asian contexts). Physicians and patients may communicate less explicitly in high context communications settings, but could still find culturally appropriate ways to express differing perspectives and work towards mutual understanding (Gudykunst et al. 1996; Nishimura et al. 2008).

방법론상의 과제와 강점

Methodological challenges and strengths

우리의 연구와 관련하여 많은 방법론적 문제가 있다.

- 첫째, 포커스 그룹은 단일 대만 의과대학에서 실시되었으며 다른 기관 학생들의 경험과 관찰을 반영하지 않을 수 있다. 예를 들어, 대만의 몇몇 의과대학 학생들은 중국과 서양 의학을 공부한다. 서양의학과 한의학을 포함한 프로그램을 선택하는 학생들은 이문화간의 전문성 딜레마를 다르게 생각할 수 있다.

- 둘째, 이 연구는 대만의 문화 간 딜레마를 검토하기 위한 것이 아니라 지역 문화를 이차 분석의 테마로 파악했다. 즉, 우리는 학생들에게 그들의 내러티브의 문화적 측면에 대한 논리와 반응을 묻지 않았다.

- 마지막으로, 프리드먼과 베르토인 안탈이 개발한 프레임워크는 높은 옹호/높은 탐구 접근법을 지지하지만, 이 프레임워크 기저의 가정이 [비서구 문화 환경]에서는 완전히 적용되지 않을 수 있다. 예를 들어, Friedman과 Bertoin Antal은 다국적 기업 구성원 간의 권력 관계가 본 연구에서 설명한 의사-환자 및 교사-학생 상호 작용과 다른 국제 비즈니스 맥락에서 프레임워크를 개발했습니다. 본 연구의 맥락에서, 옹호는 존중이 없는 것으로, 탐구는 무례한 것으로 해석될 수 있는 상황이 있습니다. 따라서 다른 문화적 맥락과 시나리오에서 높은 옹호/높은 질의 접근방식을 신중하게 적용해야 할 수 있다.

There are a number of methodological challenges concerning our study.

- First, focus groups were conducted at a single Taiwanese medical school and may not reflect the experiences and observations of students at other institutions. For example, students at some medical schools in Taiwan study both Chinese and Western medicine. Students who opt for programs including Western and Chinese medicine might conceptualize intercultural professionalism dilemmas differently.

- Second, this study did not set out to examine Taiwanese intercultural dilemmas, but instead identified local culture as a theme for secondary analysis, meaning that we did not ask students for their reasoning of and reactions towards the cultural aspects of their narratives.

- Finally, although Friedman and Berthoin Antal’s Western-developed framework advocates for a high advocacy/high inquiry approach, the assumptions underpinning this framework might not be wholly applicable in non-Western cultural settings. For example, Friedman and Berthoin Antal developed their framework in the context of international business, in which the power relationships among members of multinational corporations differ from the doctor-patient and teacher-student interactions outlined in our study. In the context of our study, there are circumstances in which advocacy might be interpreted as disrespectful, and inquiry as rude. Thus, high advocacy/high inquiry approaches may need to be applied thoughtfully in different cultural contexts and scenarios.

이러한 도전에도 불구하고, 본 논문은 많은 방법론적 강점을 가지고 있다.

- 우선, 우리가 아는 한, 우리의 연구는 대만 학생들의 문화 간 딜레마와 이러한 딜레마에 직면한 옹호와 질문의 조합을 고려한 첫 번째 연구이다. 대만 문화는 표면적으로는 환자, 학생 및 의료 전문가를 포괄하지만, 우리는 '외국' 또는 '소수민족' 문화뿐만 아니라, 어떤 맥락에서든 ['내부home' 문화 또한 학생의 학습과 환자 치료에 어떤 challenge가 될 수 있음]을 강조한다.

- 둘째, 본 연구는 경영 문헌에서 의학 교육 분야에 이르기까지 유용한 프레임워크인 문화 간 역량을 소개합니다. 상기 경고에도 불구하고, 우리는 문화 간 역량 프레임워크가 문화 간 전문성 딜레마에 접근하는 데 유용한 기초가 될 수 있다고 믿는다.

- 마지막으로, 우리는 비서양의 의학 교육 맥락에서 문화적 역량에 대한 기존 연구의 제한된 부분을 추가하지만, 대만의 경험 측면은 문화적 환경 전반에 걸쳐 의학 교육자들에게 공감을 줄 수 있다.

Despite these challenges, our paper has a number of methodological strengths.

- First, to our knowledge, our study is the first to consider Taiwanese students’ intercultural dilemmas and the combinations of advocacy and inquiry employed in the face of these dilemmas. Though Taiwanese culture ostensibly encompasses patients, students and healthcare professionals, we highlight how ‘home’ cultures—not just ‘foreign’ or minority cultures—can pose challenges to student learning and patient care in any context.

- Second, our study introduces a useful framework—intercultural competence—from the management literature to the field of medical education. Despite the caveats mentioned above, we believe the intercultural competence framework can serve as a useful basis from which to approach intercultural professionalism dilemmas.

- Finally, we add to the limited body of existing research on cultural competence in non-Western medical education contexts (Ho et al. 2008; Lu et al. 2014), though aspects of the Taiwanese experience may resonate with medical educators across cultural settings.

교육 실무에 미치는 영향

Implications for education practice

대만 학생이 주로 [낮은 옹호/낮은 탐구] 방식을 채택한다는 것은, 이들이 [문화 간 딜레마에 휘말릴 때 직면하는 어려움]이 무엇인지 보여주며, 학생들의 [문화 간 역량 향상]에 더 관심을 기울일 필요가 있음을 시사한다. 이는 이전의 연구가 한편으로는 문화적 차이를 다루지 못하면 불만족스러운 환자, 오진 및 최적의 건강 결과를 초래할 수 있다는 점을 시사하는 것을 고려할 때 매우 중요하다. 한편, 강력한 의사-환자 간 커뮤니케이션은 환자 만족도와 순응도를 향상시키고, 환자 중심의 커뮤니케이션 모델은 환자의 건강을 향상시킵니다. 우리의 연구는 의료 종사자들이 어떤 맥락에서든 문화적 격차를 효과적으로 메울 수 있도록 이해, 교육 및 실천의 전환이 필요하다는 것을 시사합니다.

Taiwanese students’ frequent adoption of a low advocacy/low inquiry approach highlights the challenges faced in engaging with intercultural dilemmas and suggests that attention needs to be paid to developing students’ practices of intercultural competence. This is crucial given that previous research suggests, on the one hand, that failure to address cultural differences can result in dissatisfied patients, misdiagnoses and less optimal health outcomes (Barker 1992; Lavizzo-Mourey and Mackenzie 1996); and, on the other hand, that strong physician-patient communication improves patient satisfaction and compliance (Beckman and Frankel 1984; Betancourt et al. 1999) and patient-centered models of communication can improve patient health (Epstein and Street 2007; Mead and Bower 2002). Our study suggests the potential need for a shift in understanding, teaching and practice towards intercultural competence, so that healthcare practitioners can effectively bridge cultural gaps in any context.

따라서 우리는 교육자가 지역 커뮤니케이션 스타일에 맞게 문화 간 역량에 대한 가르침을 조정하고 문화 간 역량을 언제 사용해야 하는지에 대한 이해를 높일 수 있다고 믿는다. 실제로, [문화간 역량]에 대해서 어떻게 학생들을 교육시킬지를 고려할 때, 우리의 연구결과는 [의료계의 문화]와 [역할모델]이 학생들의 학습과 실천에 중요하다는 것을 보여준다. 일부 학생은 상급자가 모델링한 [높은 옹호/낮은 탐구 접근법]의 부정적인 의미를 인식했으며, 다른 학생들은 'negotiating reality'에 있어 상급자의 능숙함에 감탄했다. 의학 교육자들이 일부 학생들에 의해 부정적인 롤모델로 인식되었다는 사실은 교수개발이 필요함을 보여준다. 공식 커리큘럼은 또한 [지역의 요구]를 반영하기 위해 다시 초점을 맞출 수 있다. 대만의 경우, 일반적으로 접하는 문화 간 딜레마(예를 들어 대만어, 한의학)와 관련된 특정 지식 및 기술(예: 대만어)이 커리큘럼에 포함될 수 있다.

We believe, therefore, that educators could adapt their teaching of intercultural competence to suit local communication styles and foster understanding of when to use intercultural competence. Indeed, in considering how we might educate students for intercultural competence, our findings indicate the importance of medical culture and role modeling to students’ learning and practice. Some students recognized the negative implications of high advocacy/low inquiry approaches role modeled by their superiors, while others expressed admiration for superiors’ adeptness in ‘negotiating reality’. The finding that medical educators were recognized by some students as negative role models warrants further faculty development. Formal curricula could also be refocused to reflect local needs. In the Taiwanese case, certain knowledge and skills related to commonly encountered intercultural dilemmas (e.g., Taiwanese language, Chinese medicine) could be incorporated into the curriculum.

문화 간 역량 육성은 공식 및 숨은 커리큘럼에서 장기적이고 통합된 교육을 필요로 하는 복잡한 노력이 될 것입니다. 학생들이 경험을 쌓을수록, 그들은 프로네시스(즉, 실용적인 지혜)를 실천하고 옹호와 질문의 다른 조합이 특정 환경에 더 적합하다는 것을 발견할 수 있다.

Fostering intercultural competence will be a complex endeavor, requiring long-term and integrated teaching in formal and hidden curricula (Berthoin Antal and Friedman 2008). As students gain experience, they may practice phronesis (i.e. practical wisdom) and find that different combinations of advocacy and inquiry are better suited to particular circumstances (Dowie 2000; Hofmann 2002).

추가 연구에 대한 시사점

Implications for further research

본 연구는 대만 학생들의 문화 간 딜레마의 표면만을 긁어낼 뿐이지만, 다른 비서양의 의과대학에서의 문화 간 및 문화 간 역량 이니셔티브를 조사하고 서양의학과 전통 의학을 배우는 사람들의 견해를 이끌어내기 위해 더 많은 연구가 필요하다. 추가적인 종단적 연구는 학생들이 임상 경험이 쌓이면, [사용하는 옹호/탐구 조합]이 달라지는지 여부를 탐구해야 한다. 추가적인 연구는 또한 프로페셔널리즘 내러티브의 문화적 측면에 대한 학생들의 논리와 반응을 탐구할 수 있다. 그것은 학생들이 이러한 문화적 딜레마를 서술하면서 교차하는 개인과 직업적 정체성을 어떻게 구성하는지 탐구하기 위해 교차성 이론에 기초한 서술적 조사를 사용할 수 있다. 마지막으로, 학생, 교사 및 의료 전문가들이 특정 옹호/문의 접근법을 채택하는 이유와 방법을 이해하기 위해 문화 관련 경험과 관찰에 초점을 맞출 수 있습니다.

While our study only scratches the surface of intercultural dilemmas for Taiwanese students, further research is now needed to investigate cultural and intercultural competence initiatives at other non-Western medical schools and elicit views from those learning both Western and traditional medicine. Additional longitudinal research should explore whether students employ different combinations of advocacy and inquiry as they gain clinical experience. Further research could also explore students’ reasoning of and reactions towards the cultural aspects of professionalism narratives. It could employ narrative inquiry, drawing on intersectionality theory (Tsouroufli et al. 2011; Monrouxe 2015), to explore how students construct their intersecting personal and professional identities while narrating these cultural dilemmas. Finally, additional research could focus explicitly on the culture-related experiences and observations of students, teachers and healthcare professionals, with the aim of understanding why and how they adopt certain advocacy/inquiry approaches.

결론들

Conclusions

우리의 연구결과는 대만의 의대생들 사이에서 문화 간 역량 향상의 필요성을 강조하고 자신의 교육적 맥락에서 문화 간 역량을 육성하고자 하는 의학 교육자들에게 통찰력을 제공한다. 의료 종사자는 다수의 문화적 문제와 일상적으로 마주치는 문제를 협상할 수 있는 기술과 도구를 갖추어야 할 뿐만 아니라 문화적 배경에 관계없이 모든 환자에게 고품질의 개인화된 치료를 제공할 준비가 되어 있어야 합니다. 서양의학과 비서양문화 사이의 유사한 단절을 목격한 글로벌 의학 교육자는 이 연구를 자신의 의료 환경에서 문화 및 문화 간 역량의 교육과 실천을 재고하기 위한 기초로 사용할 수 있다.

Our findings highlight the potential need for improved intercultural competence among Taiwanese medical students and offer insights for medical educators seeking to foster intercultural competence in their own educational contexts. Not only should healthcare practitioners be equipped with the skills and tools to negotiate everyday encounters with majority cultural issues, but they must be prepared to provide high quality, individualized care to any patient, regardless of cultural background. Global medical educators witnessing a similar disconnect between Western medicine and non-Western cultures may use this study as a basis from which to reconsider the teaching and practice of cultural and intercultural competence in their own healthcare settings.

doi: 10.1007/s10459-016-9738-x. Epub 2016 Nov 26.

Taiwanese medical students' narratives of intercultural professionalism dilemmas: exploring tensions between Western medicine and Taiwanese culture

PMID: 27888427

Abstract

In an era of globalization, cultural competence is necessary for the provision of quality healthcare. Although this topic has been well explored in non-Western cultures within Western contexts, the authors explore how Taiwanese medical students trained in Western medicine address intercultural professionalism dilemmas related to tensions between Western medicine and Taiwanese culture. A narrative interview method was employed with 64 Taiwanese medical students to collect narratives of professionalism dilemmas. Noting the prominence of culture in students' narratives, we explored this theme further using secondary analysis, identifying tensions between Western medicine and Taiwanese culture and categorizing students' intercultural professionalism dilemmas according to Friedman and Berthoin Antal's 'intercultural competence' framework: involving combinations of advocacy (i.e., championing one's own culture) and inquiry (i.e., exploring one's own and others' cultures). One or more intercultural dilemmas were identified in nearly half of students' professionalism dilemma narratives. Qualitative themes included: family relations, local policy, end-of-life care, traditional medicine, gender relations and Taiwanese language. Of the 62 narratives with sufficient detail for further analysis, the majority demonstrated the 'suboptimal' low advocacy/low inquiry approach (i.e., withdrawal or inaction), while very few demonstrated the 'ideal' high advocacy/high inquiry approach (i.e., generating mutual understanding, so 'intercultural competence'). Though nearly half of students' professionalism narratives concerned intercultural dilemmas, most narratives represented disengagement from intercultural dilemmas, highlighting a possible need for more attention on intercultural competence training in Taiwan. The advocacy/inquiry framework may help educators to address similar disconnects between Western medicine and non-Western cultures in other contexts.

Keywords: Cultural competence; Culture; Intercultural competence; Intercultural professionalism dilemmas; Professionalism.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 전문직업성(Professionalism)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| '그들'에서 '우리'로: 그룹 경계를 팀 포함성으로 연결하기 (Med Educ, 2019) (0) | 2022.04.11 |

|---|---|

| 비-서구 문화권에서 의료 전문직업성 프레임워크: 내러티브 개괄(Med Teach, 2016) (0) | 2022.03.24 |

| 보건의료전문직 학생이 경험하는 전문직업성 딜레마: 단면 연구(J Interprof Care. 2020) (0) | 2022.03.24 |

| 성격은 무엇인가? 두 개의 미신과 하나의 정의(New Ideas in Psychology, 2020) (1) | 2022.03.21 |

| 복잡성 해결하려고 노력하기: 전문직정체성 발달의 창으로서 의과대학생의 환자 조우 성찰적 글쓰기(Med Teach, 2018) (0) | 2022.03.16 |