자기주도학습에는 "자기" 이상의 것이 있어요: 학부생의 자기주도학습(SDL) 탐색 (Med Teach, 2021)

There is more than ‘I’ in self-directed learning: An exploration of self-directed learning in teams of undergraduate students

Tamara E. T. van Woezika , Jur Jan-Jurjen Koksmab , Rob P. B. Reuzela , Debbie C. Jaarsmac and Gert Jan van der Wilta

서론

Introduction

평생학습은 특히 의학과 같은 복잡한 직업의 훈련에서 고등교육의 중요한 목표가 되었다. 의료 커리큘럼은 종종 매우 역동적인 분야의 자기 주도적인 전문가들에게 필요한 비판적이고 성찰적인 태도의 개발을 포함한다. 자기 주도 학습은 진정한authentic 학습 상황에서 가장 잘 촉진되는데, 이는 학습 상황이 전문적인 실천을 반영한다는 것을 의미합니다. 진정한 의학 학습은 무엇보다도 학생들이 팀을 이루어 일하는 것을 의미하는데, 이것은 전문가들이 자주 접하게 되는 환경이다. 사회환경에서의 학습이 토론과 성찰을 자극하기 때문에 자기주도학습은 아마도 이 환경에서 육성될 것이다(Bolhuis 2003). 팀 내에서 자기 주도 학습이 어떻게 발전하는지를 이해하면, 협업 환경에서 교육을 설계하는 데 도움이 될 수 있습니다. 이 연구의 목적에 대해 자세히 설명하기 전에 자기주도학습과 진정한 학습의 개념에 대해 좀 더 자세히 설명하겠습니다.

Lifelong learning has become an important aim for higher education, especially in training for complex professions such as medicine (Mahan and Clinchot 2014; Delany et al. 2016). The medical curriculum often includes the development of a critical and reflective attitude that is needed for self-directed professionals in their highly dynamic field (Miflin et al. 2000; Murad et al. 2010; Chitkara et al. 2016). Self-directed learning is best promoted in authentic learning situations, meaning that the learning situation reflects professional practice (Jennings 2007; Goldman et al. 2009; Taylor and Hamdy 2013). Authentic learning in medicine means, among other things, that students work together in teams, a setting that professionals will often encounter. Self-directed learning is probably fostered in this setting, because learning in a social environment will stimulate discussion and reflection (Bolhuis 2003). Understanding more about how self-directed learning develops in teams could help designing for education in a collaborative setting. Before we elaborate on this aim of our study, the concepts of self-directed learning and authentic learning will be explained in more detail.

자기주도학습(SDL)은 일반적으로 학생들이 자신의 학습목표를 개발하고 추구하며 학습과정과 결과를 평가하는 (1)능력과 (2)태도로 정의된다.

Self-directed learning (SDL) is commonly defined as the (1) ability and (2) attitude of students to develop and pursue their own learning objectives and to evaluate their learning process and results (Knowles 1975; Candy 1991; Taylor and Hamdy 2013).

- 첫째, [인지능력] 측면에서 SDL은 학습자가 보통 특정 코스에 대해 설정된 미리 정의된 학습 목표를 달성하는 데 도움이 되는 학습 방법인 SRL(Self-Regulated Learning)과 밀접하게 관련되어 있습니다. SRL은 SDL처럼 비판적 사고, 정교화, 학습 과정의 모니터링과 같은 학습 전략을 포함한다.

- SRL과 SDL이 차이가 있는 것은, SDL은 코스 전체에 걸쳐 보다 장기적인 프로세스를 수반하기 때문에 [학습에 대한 태도]로 해석translate됩니다.

- SDL에는 목표 설정 및 학습 프로세스의 평가와 조정을 위한 자기 모니터링 기능이 있습니다.

- 또한 SDL은 몇 가지 학습 전략을 수반할 수 있지만 비판적 사고와 메타 인지적 자기 규제가 없는 경우에는 결함이 있는 것으로 간주됩니다(Candy 1991).

- First, in terms of cognitive ability, SDL is closely related to self-regulated learning (SRL), which is a way of learning that helps learners to complete predefined learning goals that are usually set for a certain course. SRL involves learning strategies such as critical thinking and elaboration, and monitoring the learning process, as does SDL.

- SRL and SDL differ in the sense that SDL involves more long-term processes often overarching a course, and therefore translates to an attitude towards learning (Sandars and Walsh 2016).

- SDL includes goal setting, and self-monitoring to evaluate and steer the learning process (Lloyd-Jones and Hak 2004).

- Moreover, SDL may entail several learning strategies, but is considered flawed when critical thinking and meta-cognitive self-regulation are absent (Candy 1991).

- 둘째, [SDL에 대한 태도]라고 불리는 것은 학습자 개개인의 SDL 개발에 있어 중요한 몇 가지 특징과 행동으로 구성됩니다. 우리는 이러한 태도를 감정, 개방성 및 동기 부여의 관점에서 정의합니다.

- Affect는 자신의 감정과 접촉touch하거나 감정과 관련된 행동을 보여주는 것을 의미합니다. 관심이나 흥분을 수반하는 경우, 영향은 SDL에 긍정적인 영향을 미칠 수 있으며, 불안 등 부정적인 감정의 경우 부정적인 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다.

- 둘째, SDL(Mercer 2011)에 필요한 비판적 사고와 자기 평가를 촉진하기 위해서는, 경험에 대한 개방성, 성장 마인드, 창의성이 중요하다는 것을 알 수 있습니다.

- 마지막으로 학습목표를 설정하기 위해서는 내적 동기부여가 중요합니다.이러한 목표는 SDL의 열쇠가 됩니다.

- Second, what is referred to as the attitude for SDL consists of some characteristics and behaviour that seem important for the development of SDL in the individual learner (Guglielmino 1978; Fisher and King 2010). We define this attitude in terms of affect, openness and motivation.

- Affect means to be in touch with your emotion or to show behaviour that is connected to emotions. Affect can have a positive influence on SDL when it involves interest or excitement, as well as negative influence in case of negative feelings such as anxiety (Brookfield 1995; Meyer and Turner 2002; Redwood et al. 2010).

- Second, openness in terms of being open to experience, having a growth mindset, and being creative is shown to be important to stimulate critical thinking and self-evaluation which are needed for SDL (Mercer 2011).

- Lastly, motivation in terms of intrinsic motivation is important for setting learning goals, which, as mentioned above, is key for SDL (Abd-El-Fattah 2010; Stockdale and Brockett 2011).

[진정한 맥락에서의 학습]과 [사회적 맥락에서의 학습]은 밀접하게 관련되어 있다. 첫째, SDL은 진정한 학습 환경을 통해 추진됩니다. 이러한 상황에는 팀으로 함께 일하는 상황이 포함되는 경우가 많습니다. 프로젝트, 시뮬레이션, 문제 기반 학습 등 SDL 강화를 목적으로 하는 교육 형식에는 모두 사회적 요소가 포함되어 있습니다. 진정한 학습 상황에서 SDL에게 중요한 것은 개인의 영향과 동기 부여에 대한 영향을 통해 사회적 상호작용이 학습을 결정한다는 것입니다(Johnson 및 Johnson 2009). 둘째, 모든 학습은 사회적이라고 주장할 수 있다. 따라서 SDL은 세계에 관한 지식을 구축하면서 세계를 이해하는 수단이라고 생각할 수 있다(Li 등 2010). 중요한 의미는 SDL의 개발이 컨텍스트를 구성하고 있다는 것입니다. 즉, 자기 주도적인 학습자는 조직 구조와 그룹에 포함되어 있습니다.

The ideas of learning in an authentic context and social context are closely related (Yardley et al. 2012). First, SDL is promoted by means of authentic learning situations, which often include working together in teams. Educational formats aimed at strengthening SDL such as projects, simulations or problem-based learning all involve a social component. Important to SDL in authentic learning situations is that social interaction determines learning because of the influence on individuals’ affect and motivation (Johnson and Johnson 2009). Second, one could argue that all leaning is social (Thoutenhoofd and Pirrie 2015). Hence, SDL may be conceived as a means to come to an understanding of the world, while constructing knowledge in relation to this world (Li et al. 2010). An important implication is that context constitutes the development of SDL. That is, the self-directed learner is embedded in organizational structures and groups.

그럼에도 불구하고 SDL에 대한 연구는 오랫동안 [개별 학습자]에 초점을 맞추고 있습니다. SDL에 대한 이러한 개인주의적 접근방식은 학습자가 개별적으로 작업하거나 행동하지 않는다는 점에서 [몇 가지 문제]를 일으킨다(Schmidt 2000). SDL에 관한 지금까지의 조사에서는, 사회적 환경이 SDL의 개발에 관여하는 것을 알 수 있었습니다. 일반적으로 학습의 경우, 사회적 메커니즘이 심리적 안전에 미치는 영향을 통해 학습 과정과 결과에 영향을 미친다는 것을 알 수 있다. 예를 들어, 팀 활동의 결과는 사회적 역학에 의해 영향을 받습니다. 왜냐하면 이러한 역학은 동기 부여와 토론의 깊이를 방해하거나 증가시킬 수 있기 때문입니다(Dolmans and Schmidt 2006). 게다가 팀워크에 대한 연구는 개방성에 영향을 미치는 사회적 과정이 전문직 경력 전반에 걸쳐 남아있다는 것을 보여준다. 따라서 개별 학습자의 SDL은 그룹 학습 과정과 교육 결과에 쉽게 일반화되지 않을 수 있다(Hommes 등 2014).

In spite of this, studies of SDL have long focused on the individual learner (Merriam 2001). This individualistic approach to SDL poses some problems, given that a learner does not work nor act individually (Schmidt 2000). Previous studies on SDL show that the social environment could play a role in SDL development (Levett-Jones 2005; Lee et al. 2010). For learning in general, we see that social mechanisms influence learning processes and outcomes through their impact on psychological safety (Beachboard et al. 2011; Hommes et al. 2014). For instance, outcomes of team activities are influenced by social dynamics because these can deter or increase motivation and depth of discussions (Dolmans and Schmidt 2006). Moreover, research on working in teams shows that social processes influencing openness remain throughout a professional career (de Groot et al. 2014). Therefore, SDL of the individual learner may not be easily generalized to the group learning process and outcomes in education (Hommes et al. 2014).

장래의 의료진이 팀워크를 실시할 때 SDL을 확실히 사용하고 싶은 경우는, 우선 의학교육에서 SDL을 사용하는 것을 추천합니다. 나아가야 할 방향은, 팀 내에서 학습이 어떻게 발전하는지를 더 이해하는 것입니다. 학생들이 자기 주도적인 학습자가 되기를 원한다면, 우리는 공부 시간 및 일정과 같은 [공식적인 메커니즘]과 팀 내에서의 그룹 결속 및 심리적 안전과 같은 [사회적 메커니즘]을 모두 고려해야 한다(Hommes et al. 2014). 개인의 SDL 행동이 그룹의 역동성에 의해 어떻게 영향을 받는지를 이해하면 교사와 교육자가 학생에게 팀 내 학습 방향을 올바르게 안내하는 데 도움이 됩니다. 따라서, 이 탐색적 연구 프로젝트에서는, [소그룹 학습]에서 SDL이 어떻게 발전하는지를 조사했습니다.

If we want to make sure that future medical professionals do use SDL when they work in teams, we should start with that in medical education. A way forward is to understand more about how learning develops within teams. If we want our students to be self-directed learners, we need to take into account both formal mechanisms such as study time and schedules, as well as social mechanisms such as group cohesion and psychological safety in teams (Hommes et al. 2014). Understanding how SDL behaviour of individuals is influenced by group dynamics will help teachers and educators to properly guide students towards learning in a team. In this exploratory research project, we, therefore, explored how SDL develops in students learning in small groups.

연구 프로젝트의 목적

Aim of the research project

우리는 두 가지 목표를 추구했다.

- 우선, 학생의 SDL을 [의학 교육의 관점]에서 소그룹 학습으로 설명하고 싶다고 생각하고 있습니다.

- 둘째, [그룹 역학]이 소규모 그룹 학습에서 SDL 행동을 어떻게 방해하거나 촉진하는지 알아보는 것을 목표로 했습니다.

We pursued two aims.

- First, we wanted to describe students’ SDL in small group learning, in the context of medical education.

- Second, we aimed to explore how group dynamics impedes or promotes SDL behaviour in small group learning.

방법

Method

맥락

Context

본 연구에서는 네덜란드 Nijmegen의 Radboudumc에서 [의학 및 생물의학 전공 1학년 학생들이 8개월 동안 팀을 이루어 건강(관리) 문제를 식별하고 정의하며 이를 위한 혁신적인 솔루션을 개발]하는 이른바 '혁신 프로젝트'의 맥락에서 SDL을 조사하기로 선택했습니다. 그러기 위해서는 혁신 프로젝트가 실제 상황과 매우 유사하도록 하는 분야(의사, 환자, 업계, 의료 관리 등)의 이해관계자와 협력해야 합니다. 중요한 것은 프로젝트 과제가 사전에 정의된 세부 가이드라인 없이 제공된다는 것입니다. 학생은 자신의 프로젝트를 관리하고 학습 프로세스를 지시합니다. 이 설정은 그룹 작업, 목표 설정, 감시가 장기간에 걸쳐 필요하기 때문에 그룹별로 SDL에 대한 조사에 적합합니다.

In this study, we choose to investigate SDL in the context of the so-called ‘Innovation project’, where first year students of medicine and biomedical sciences of the Radboudumc, Nijmegen, the Netherlands, over an 8-month period work in teams to identify and define a health(care) problem, and develop an innovative solution to it. To be able to do so, they need to engage with stakeholders in the field (physicians, patients, industry, healthcare management, etcetera), which ensures that the Innovation project closely resemble an authentic situation. Importantly, the project assignment comes without detailed predefined guidelines; students manage their own projects and hence direct their own learning processes. This setting is suitable for our research on SDL in groups, because it requires group work, goal setting and monitoring over a long period of time.

팀은 4~6명의 학생으로 구성되며, 팀의 45%는 의대생과 생물의대생이 혼합된 팀입니다. 팀은 일반적으로 자신의 이상과 아이디어를 바탕으로 혁신 주제를 자유롭게 선택하거나 친척이나 친구의 건강 문제에 직면할 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, 한 그룹의 학생들이 아이들이 천식 약을 기억하도록 돕는 게임을 고안했다. 또 다른 팀은 안약을 필요로 하는 환자들이 디스펜서를 더 잘 배치하고 복용량을 조절할 수 있도록 도와주는 장치를 고안했다. 이들은 실제 파트너와 협업하고 이해관계자 인터뷰를 기반으로 컨텍스트 분석을 수행하며 혁신적인 아이디어의 일부를 실현하려고 합니다. 학생들은 SDL 전략을 사용할 필요가 있습니다. 자신의 경험과 효과를 반영하고 이를 바탕으로 프로젝트 전체의 장기적인 목표와 관련된 미팅의 학습 목표를 특정해야 한다. 결국, 각 팀은 프로토타입 또는 모델의 형태로 혁신을 제공합니다. 또한, 그들은 자신의 혁신을 설명하는 그룹 보고서를 작성하고, 자신의 학습 과정과 그룹 과정에 대한 성찰 에세이를 개별적으로 작성합니다. 프로젝트의 최종 성적은 보고서와 에세이 결과에 기초한다.

Teams consist of 4–6 students and 45% of the teams are mixed teams with both medical and biomedical students. Teams are free to choose a topic for innovation, which is commonly based on their own ideals and ideas, or encounters with health(care) problems of relatives or friends. For example, a group of students designed a game to help children remember their asthma medication. Another team designed a device to help patients who need eye medication to better position the dispenser and control the dosage. They collaborate with real-world partners, perform a context analysis based on stakeholder interviews and try to realize part of their innovative idea. Students need to use SDL strategies: they reflect on their experiences and effectiveness, and on this basis they identify learning goals for the meetings that relate to their long-term goals for the entire project. In the end, each team delivers an innovation in the form of a prototype or model. In addition, they write a group report explaining their innovation, and they individually write a reflection essay about their own learning process and the group process. The final grade for the project is based on the results of both the report and the essay.

학생들은 자신들의 주제에 대해 어느 정도 전문 지식을 가진 교수자, 소위 '혁신-전문가'로부터 지도를 받을 수 있습니다. 또한 최종 프로젝트와 그룹 프로세스를 코스 마지막에 채점합니다. 그 다음, 학생들은 현실 세계에서 '고객'을 찾습니다. 즉, 혁신 분야의 기업 또는 개인 이해관계자이기 때문에 학생들에게 혁신 개발을 알리거나 도울 수 있습니다. 프로젝트 기간 동안 학생들을 지도하기 위해 과정 내내 한 달에 한 번 워크샵에 참여할 수 있습니다. 워크숍 내용은 다음과 같습니다. 팀워크(Belbin 2014), 이해관계자 분석, 인터뷰 스킬 및 프로젝트 관리에 있어 역할을 이해하는 데 도움이 되는 Belbin 역할.

Guidance is available from teachers with some expertise on the student’s topic, the so-called ‘Innovation-experts’, whom students can approach for support. This person also grades their final project and the group process at the end of the course. Next to that, the students find a ‘Customer’ in the real world: a company or individual stakeholder in the area of the innovation and thus can inform or help the students with the development of their innovation. To guide the students during the project, they can participate in workshops once a month throughout the course. Workshops include: Belbin roles to help understand roles in teamwork (Belbin 2014), stakeholder analysis, interviewing skills, and project management.

참가자 선정 및 모집

Selection and recruitment of participants

2016년 11월 이노베이션 프로젝트 과정의 첫 번째 워크숍에서 우리는 모든 학생을 이 연구에 참여시키고 8개월 프로젝트 기간 동안 팀 미팅에서 관찰하도록 초대하였습니다. 학생 그룹을 집중적으로 추적하고 싶었기 때문에 연구자가 대부분의 학생 팀 회의에 참석할 수 있도록 최소 3개 팀, 최대 7개 팀을 포함시키는 것을 목표로 했습니다. 학생들은 그룹 전체가 연구에 참여하기로 동의해야만 모집되었다. 그들은 사전동의서를 작성했고 첫 번째 작성자의 연락처를 받았다. 그 후 학생들은 이메일이나 WhatsApp을 통해 첫 번째 작가에게 연락하여 그들의 약속에 대한 최신 정보를 계속 전달했습니다. 첫 번째 저자가 한 달 넘게 학생들로부터 소식을 듣지 못하자, 그들이 여전히 연구 프로젝트에 참여하고 싶은지에 대한 질문과 함께 독촉장이 보내졌다. 학생들의 그룹 미팅에서, 첫 번째 작가는 대화를 녹음하고 짧은 메모를 했다. 그룹 회의의 녹화 허가를 미리 요청하고 각 녹화 시작은 항상 학생들에게 명시적으로 언급되었습니다. 이 연구의 프로토콜은 네덜란드 의학 교육 협회(NVMO)의 윤리 검토 위원회(파일 번호 677)에 의해 승인되었다.

During the first workshop of the Innovation project course in November 2016, we invited all students to participate in this study and be observed during team meetings throughout the 8-month project. We wanted to intensively follow the groups of students, so to make sure a researcher would be able to attend most meetings of the student teams, we aimed to include at least three teams and a maximum of seven teams. Students were only recruited if the entire group agreed to participate in the study. They filled out an informed consent form and received contact information of the first author. Students then approached the first author via e-mail or WhatsApp, to keep her updated about their appointments. When the first author did not hear from the students for more than a month, a reminder was sent along with the question whether they still wanted to participate in the research project. During the group meetings of the students, the first author made audio recordings of the conversation and kept short notes. Permission to make recordings of the group meetings was asked beforehand and the start of each recording was always explicitly mentioned to the students. The protocol for this study was approved by the ethical review board of the Netherlands Association for Medical Education (NVMO), file number 677.

데이터 수집

Data collection

이 연구는 오디오 녹음에 기초한 정성적 연구로 설정되었다. 이 연구는 Giacomini와 Cook(2000)의 질적 연구에 대한 지침을 따랐다. 이전 연구에 따라 대부분의 학습 행동이 명시적으로 발생할 것으로 예상하였다(Chi 2009). 그룹 프로세스의 일부 측면은 의견 불일치를 나타내는 눈살을 찌푸리거나 반성을 위해 잠시 멈출 시간을 나타내는 웅얼거림처럼 구두로 나타나지 않을 수 있기 때문에 첫 번째 저자는 추가적인 관찰을 하기 위해 항상 동석했다. 오디오 녹음은 분석 전에 녹음되었습니다(단절과 망설임 포함). 학생 이름이 숫자 식별자로 대체되었습니다. 학생들의 목소리는 녹취록 전반에 걸쳐 각각의 학생들이 동일한 식별자를 가지고 있는지 확인하기 위해 추적되었다. 이렇게 하면 그룹뿐만 아니라 그룹 내 개별 학생도 시간이 지남에 따라 그룹 역학에서 패턴을 볼 수 있고 학생들이 역할을 수행하거나 역할을 바꾸는 것을 볼 수 있습니다.

This research was set up as a qualitative study, based on audio recordings. This study followed the guidelines for qualitative research of Giacomini and Cook (2000). Following previous research, we expected most of the learning behaviour to occur explicitly (Chi 2009). Since some aspects of the group process may not manifest themselves verbally, such as a frown indicating disagreement or a hum indicating a moment to pause for reflection, the first author was always present to make additional observations. The audio recordings were transcribed before analysis, including breaks and hesitations. Student names were replaced by numeric identifiers. The students’ voices were traced to make sure each student had the same identifier throughout the transcripts. This way, we could follow not only the group, but also the individual student in the group over time, to see patterns in group dynamics and students taking on roles or changing roles.

학생 팀은 평균 2주에 한 번 만났고, 특히 프로젝트 시작과 종료에 한 주에 두 번 만난 팀도 있었습니다. 회의 중에 학생들은 프로젝트의 진행 상황에 대해 토론하고, 정보를 공유하고, 계획을 세우고, 약속을 정하고, 아이디어를 실험하고, 보고서를 쓰고, 서로를 알아가는 데 시간을 보내고, 불평하고, 어려움을 공유하는 등 여러 활동을 할 수 있다. 우리는 총 39회의 학생회의를 기록했고, 이는 기록된 시간의 23시간 이상에 달했다. 학생들은 몇 번 더 회의를 가졌지만 연구원이 참석하지 못하거나 다른 그룹의 회의가 겹치는 시간이었습니다. 간섭을 최소화하기 위하여, 우리는 첫 번째 저자(TW)만 관찰을 하도록 결정했다.

The student teams met once every 2 weeks on average, with short peak moments when some of the teams met two times in 1 week, especially in the beginning and at the end of the project. During the meetings, students could have several activities: they may discuss the progress of the project, share information, make plans, set appointments, experiment with ideas, write on their report, spend time getting to know each other, complain, share hardship, etc. We recorded 39 meetings of the students in total, which amounted to over 23 h of recorded time. The students had some more meetings, but those were on times when the researcher could not be present or the meeting of different groups was overlapping. For reasons of being minimally intrusive, we decided to let only the first author (TW) make the observations.

데이터 분석 및 템플릿 개발

Data analysis and template development

템플릿 분석을 사용하여 데이터를 코드화하고 구조화함으로써 보충 부록에 표시된 템플릿으로 이어졌습니다. 템플릿 분석은 다른 인식론 및 온톨로지에 적용할 수 있는 방법입니다. [사회적 구성주의 패러다임]이 결과를 체계화하기 위해 사용되었습니다. 이러한 관점에서 SDL은 세계를 이해하기 위한 수단으로서 개념화되어 있으며, 세계에 관한 지식을 구축하고 있습니다(Li et al. 2010). 이 인식론과 우리의 연구 목적에 부합하는 주요 관심사는 사회적 맥락이 SDL의 발전을 어떻게 구성하느냐이다. 이는 개별 학습 행동 대신 대화에서 학생과 에피소드 간의 상호작용에 초점을 맞췄다는 것을 의미한다. 참가자가 대화할 때 데이터가 수집되었기 때문에 코드는 이러한 상호작용을 반영합니다. 예를 들어, '정서적 가이드'는 누군가의 감정 표현에 대한 반응을 반영하는 코드이며, '계획과 실행'은 개인이 아닌 그룹 토론에서 이루어졌다.

We used template analysis to code and structure the data (Waring and Wainwright 2008; Brooks and King 2012), which led to the template displayed in Supplementary Appendix. Template analysis is a method that can be adapted to different epistemology and ontology (Braun and Clarke 2006; Brooks et al. 2015). A social constructivism paradigm was employed to frame the results. From this point of view, SDL is conceptualized as a means to come to an understanding of the world, while constructing knowledge in relation to this world (Li et al. 2010). Given this epistemology and in line with our research aims, a major concern is how the social context constitutes the development of SDL (Thoutenhoofd and Pirrie 2015). This means that the focus was on interactions between students and episodes in their conversation, instead of individual learning behaviour. Since data were collected when the participants were in a conversation, the codes reflect this interaction. For instance, ‘Emotional guidance’ is a code reflecting a reaction on someone’s expression of emotion, and ‘Planning and implementation’ took place in group discussions, not individually.

템플릿의 첫 번째 버전은 1년 전에 동일한 코스의 별도의 파일럿 연구에서 처음 개발되었으며, 이는 현재 연구와 유사하며 혁신 프로젝트의 맥락에서 수행되었습니다. 이 템플릿은 처음에 3개의 트랜스크립트의 오픈 코딩에 의해 작성되었습니다. 그런 다음 다양한 설문지(MSLQ, SDL-SRS, SDLRS, PRO-SDL; 문학: Brookfield (1995), de Groot et al. (2014), Lloyd-Jones 및 Turner (2004)에서 SDL 및 관련 학습 행동의 정의를 인용하여 문헌에 맞게 조정했다. 그 결과 43개의 코드로 구성된 초기 코드북이 생성되었습니다.

A first version of the template was initially developed in a separate pilot study in the same course 1 year earlier, which was similar to the present study and conducted in the context of the Innovation project as well. This template was initially constructed through open coding of three transcripts. These codes were then aligned to literature by taking the definitions of SDL and related learning behaviour from different questionnaires: MSLQ (Pintrich et al. 1993), SDL-SRS (Fisher and King 2010), SDLRS (Guglielmino 1978), PRO-SDL (Stockdale and Brockett 2011); and literature: Brookfield (1995), de Groot et al. (2014), Lloyd-Jones and Hak (2004), Meyer and Turner (2002), Redwood (2010). This resulted in an initial codebook of 43 codes.

다음 단계에서는 현재 프로젝트의 대본을 읽고 성찰성 노트를 보관했습니다. 데이터에 익숙해진 후, 두 명의 연구자(TW와 동료는 학력이 있지만 프로젝트에 공식적으로 참여하지 않은 사람)가 템플릿을 사용하여 4개의 트랜스크립트를 코드화했다. 동기 부여 또는 목표 설정 행동과 관련된 인용문에 대해 차이가 발생했다. 예를 들어, 이러한 차이에 대한 논의는 학생들이 프로젝트나 다른 학습 목표를 완수할 수 있을지 고민한다는 것을 인정하는 '자기 개념' 코드를 추가하는 결과를 낳았다. 다른 예로는 일부 코드의 삭제 또는 조정이 있습니다. 예를 들어, 우리는 '배움의 사랑'을 사용하기로 하고, 밀접하게 연관된 '배움의 욕구'를 없앴다. 다음으로 템플릿은 TW, JK 및 GW에 의해 3개의 추가 트랜스크립트에 사용되었습니다. 코딩의 나머지 차이점을 논의하여 해결하였다(TW, JK, RR, GW). 이를 통해 템플릿의 최종 버전이 생성되었습니다. 그룹 회의의 39개의 모든 대화록은 이 템플릿을 사용하여 코드화되었습니다.

In the next step, the transcripts of the current project were read, and reflexivity notes were kept. After becoming familiar with the data, two researchers (TW and a colleague with an educational background but no formal affiliation to the project) coded four transcripts by use of the template. Differences occurred for quotes relating to motivation or goal-setting behaviour. Discussion about these differences resulted in, for instance, adding a code ‘Self-concept’ to acknowledge that students contemplated whether they would be able to complete the project or other learning goals. Another example is removal or adjustments of some codes: We decided, for instance, to use ‘Love of learning’ and removed the closely related ‘Desire for learning’. Next, the template was used by TW, JK and GW for three additional transcripts. Remaining differences in coding were discussed and settled (TW, JK, RR, GW). This led to the final version of the template. All 39 transcripts of group meetings were coded using this template.

Atlas.ti® 소프트웨어 버전 8을 사용하여 스크립트를 코드화하고 분석했습니다. Atlas.ti에서 프로세스를 보다 잘 이해하기 위해 시퀀싱 분석을 실시하였습니다. 이 방법은 여러 코드 간의 가장 중요한 관계를 이해하는 데 도움이 됩니다. 이 그룹의 프로젝트 보고서 최종 성적, 반영 보고서 및 과정의 최종 성적도 고려되었습니다.

We used Atlas.ti® software version 8 to code and analyse the transcripts. To understand more about the processes, we conducted a sequencing analysis in Atlas.ti. This method helps to understand what the most prominent relations between the different codes are. The group’s final grades for the project report, the reflection report and final grade for the course were also taken into account.

성찰성

Reflexivity

저자인 JK, RR, GW, TW는 모두 교사로서 이노베이션 프로젝트에서 적극적인 역할을 했으며, 코스의 이념에 공감했습니다. JK, RR 및 GW에게 이노베이션 프로젝트는 프로젝트가 (바이오) 의학 커리큘럼의 필수적인 부분이 되기 전에 소규모 환경에서 시범적으로 시행한 아이디어였습니다. 학생 전체로 확대하는 것은 고객이 설정한 과제에서 벗어나는 등 일부 타협을 수반했지만, 그들의 약속에는 영향을 미치지 않았습니다. AJ는 연구원으로서 이노베이션 프로젝트에 관여하지 않았지만, 더 큰 규모의 연구 프로젝트에 관여했습니다. 사회적 구성주의적 패러다임은 의미 형성 과정에서 우리를 인도했다. 여기에는 대화록의 상호 작용과 대화록에 부여되는 의미가 모두 함께 만들어졌다고 생각하는 것도 포함됩니다. 환경과 학습자는 서로 영향을 미치지만, 연구자와 그 환경 또한 서로 영향을 끼친다. 이 의미가 어떻게 구성되는지에 대한 이해를 돕기 위해, 우리는 대화록의 일부를 보여주고 어떻게 해석했는지 설명하는 것이 중요하다고 생각합니다.

The authors JK, RR, GW and TW all had an active role in the Innovation project as teachers and sympathized with the ideology of the course. For JK, RR and GW, the Innovation project was an idea that they had piloted in a smaller setting, before the project became an integral part of the (bio)medical curricula. Scaling up to the entire student population did involve some compromises, such as departing from assignments set by clients, but that did not influence their commitment. AJ as researcher was not involved in the Innovation project but affiliated with the larger research project. A social constructivist paradigm guided us in the process of meaning-making. This includes that we think that both the interactions in the transcripts, as well as the meaning we give to the transcripts, is co-created. The environment and learner influence each other, but also the researcher and his/her environment influence each other. To give insight into how this meaning is constructed, we think it is important to show parts of the transcripts and explain how we interpreted this.

결과.

Results

참가자 및 수집된 데이터

Participants and gathered data

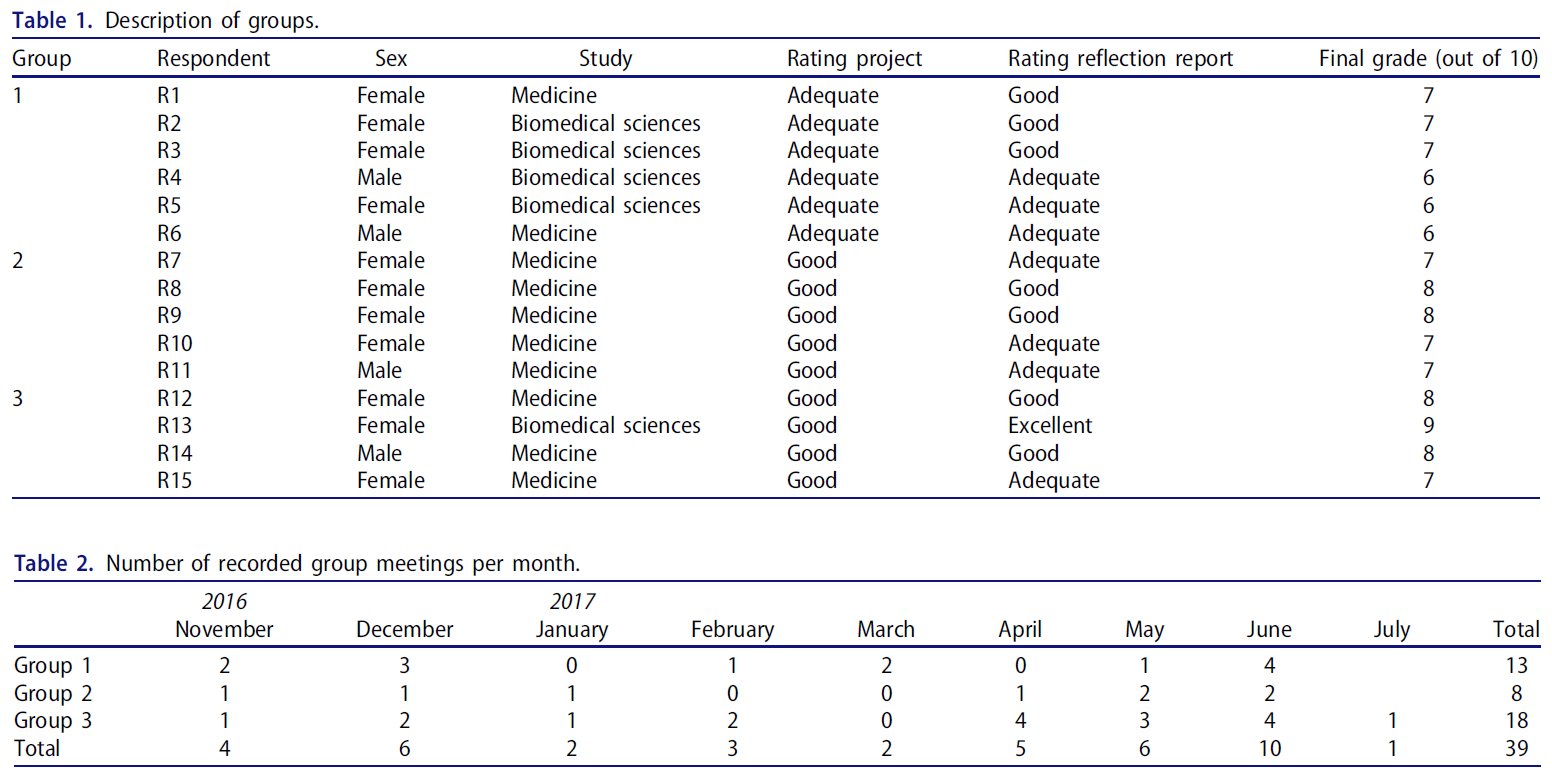

세 그룹의 학생들이 이 프로젝트에 참여하기로 합의했다. 그들은 회의를 할 때 연구원에게 연락했다. 그룹에 대한 설명은 표 1에서 찾을 수 있습니다. 이들 3개 그룹 중 2개 그룹은 생물의학과 의대생 모두 혼성팀이었다. 한 팀은 의대생으로만 구성되었다. 남학생 비율(26%)과 의대생 비율(66.6%)은 남학생 30%, 의대생 65%로 학생 수가 많은 것과 비슷했다.

Three groups of students agreed to be part of this project. They contacted the researcher when they had a meeting. A description of the groups can be found in Table 1. Two out of the three groups were mixed teams with both students from biomedical sciences and medicine. One team consisted of only medicine students. The percentage of males (26%) and the percentage of medicine students (66,6%) was comparable to the larger student population with 30% males and 65% students of medicine.

총 39개의 스크립트를 코드화하여 템플릿으로 텍스트의 약 34.19%를 코드화할 수 있었습니다. 텍스트의 다른 부분은 전날 학생들과 있었던 일 또는 다음날 일어날 일 등 잡담을 포함하고 있었다. 그들이 이야기할 주제는 음식, 친구, 대중교통 문제, 또는 프로젝트, 팀, 그리고 학습과 관련이 없는 것으로 보이는 다른 주제들이다. 학습과 관련된 토론(예: 다른 과정이나 바쁜 일정에 대한 토론)은 코드화되었습니다. 표 2는 그룹이 얼마나 자주 관찰되었는지를 요약한 것이다.

We coded 39 transcripts in total and could code about 34.19% of the text with our template. The other parts of the text involved small talk: things that happened with the students the day before or what would happen the next day(s). Topics they would talk about were food, friends, problems with public transport, or other topics that evidently were not related to the project, the team, and learning in general. Discussions that did relate to learning, e.g., about other courses or their busy schedule, were coded. Table 2 summarizes how often the groups were observed.

게다가, 많은 녹음물이 소셜 토크나 가십을 포함하고 있기 때문에, 학생들은 자유롭게 대화하는 것처럼 보였는데, 녹음물이나 연구원의 존재에 대해 학생들이 매우 경각심을 가졌다면 아마 일어나지 않았을 것이다. 그들은 종종 연구나 연구자의 상태에 대해 묻곤 했지만, 보통 그들의 대화에 연구자를 끌어들이지 않았다. 성적표 1에서 볼 수 있듯이, 학생들은 서로 녹음에 대해 상기시켰습니다.

Furthermore, students appeared to have talked freely as many recordings involved social talk or gossip, which would probably not occur had the students been highly alert about the recordings or the presence of the researcher. They usually did not engage the researcher in their conversations, although sometimes they would ask about the research or how the researcher was doing. At some points students reminded one another or themselves about the recordings, as can be seen in Transcript 1.

소규모 그룹 학습에서의 SDL 설명

Description of SDL in small group learning

첫 번째 연구의 목적은 소규모 그룹 학습의 맥락에서 SDL이 어느 정도 발생하는지를 이해하는 것이었습니다. 템플릿 내 코드의 개요를 표 3에 나타냅니다. 또한 이 표는 코드가 다른 그룹에서 인식된 정도를 나타내며, 각 그룹의 모든 인용에 대한 백분율로 나타냅니다. 템플릿에 대한 자세한 개요는 부록을 참조하십시오. 자기 모니터링, 지식 습득 및 대인 관계가 가장 자주 코드화되었습니다.

The first research aim was to understand the degree to which SDL occurs in the context of small group learning. An overview of the codes in the template is displayed in Table 3. This table also shows the degree to which the codes have been recognized in the different groups, expressed as a percentage of all quotations of each group. A more detailed overview of the template can be found in Supplementary Appendix. Self-monitoring, knowledge acquisition and interpersonal behaviour were coded most often.

그룹 다이내믹스와 SDL

Group dynamics and SDL

두 번째 연구 목표는 소규모 그룹에서 그룹 역학이 SDL을 촉진하거나 방해하는 방법을 이해하는 것이었다. Atlas.ti의 시퀀스 분석에서는 자기 모니터링(예를 들어 무엇을 알아야 합니까?)과 비판적 사고(예를 들어, 그러한 가정이 유효한가요?)가 지식 습득을 유도하는 것으로 자주 나타나지만(예를 들어, 다른 정보 소스를 사용하여 학습하는 등), 책임감에 대해서도 마찬가지다(예를 들어 학생이 뭔가 해야 한다고 느낌). 이러한 관계는 단방향적이지 않다: 학생들은 다른 종류의 행동들 사이를 왔다 갔다 할 수 있다. 예를 들어, 스트레스(감정)의 느낌을 표현하는 것이 그룹 내 학생들이 이에 대해 토론하고 서로 지지하도록 만들어줄 수 있는 반면(대인 행동), 그룹 프로세스에 대한 피드백에 대한 직접적인 질문(대인 행동)은 스트레스나 좌절감(감정)을 공유하는 것으로 이어질 수 있다. SDL의 메카니즘을 특정하기 위한 본 연구의 목적을 고려하여 자기 감시, 지식 습득, 비판적 사고 하에 파악된 그룹 역학이 이러한 학습에 영향을 미치는 관계에 초점을 맞추고 있습니다. 또, SDL에 관해서 개인이 팀에 영향을 주는 메카니즘도 포함했습니다.이 메카니즘에 근거해, 다음의 3개의 메카니즘은 다음과 같습니다.

The second research aim was to understand more about the way group dynamics promote or impede SDL in small groups. The sequencing analysis in Atlas.ti shows many relations, for instance self-monitoring (e.g., what do we need to know?) and critical thinking (e.g., is that assumption valid?) are often seen to induce knowledge acquisition (e.g., using different sources of information to learn), but this is also the case for responsibility (e.g., a student feeling he or she needs to do something). These relations are not unidirectional: students can go back and forth between the different kinds of behaviour. For example, expressing feelings of stress (affect) may lead the students in a group to discuss this and support one another (interpersonal behaviour), whereas direct questions for feedback about the group processes (interpersonal behaviour) may lead to sharing feelings of stress or frustration (affect). In view of the aim of our study to identify mechanisms of SDL, we have focused on relations where group dynamics influenced this kind of learning as captured under self-monitoring, knowledge acquisition, and critical thinking. We also included mechanisms by which the individual had an influence on the team in terms of SDL. On this basis, we have identified three main mechanisms, where:

- [감정]은 [자기 모니터링 또는 책임]으로 이어지는 대인 행동을 유도한다.

- [개방성]이 [비판적 사고]를 유지시킨다.

- [논쟁적 대화]는 [배움을 좌절]시킨다.

- Affect induces interpersonal behaviour leading to self-monitoring or responsibility

- Openness sustains critical thinking

- Disputational talk frustrates learning.

이러한 메카니즘에 대해서는, 이하에 자세하게 설명합니다.

We explain these mechanisms in greater detail below.

영향 및 대인관계 행동

Affect and interpersonal behaviour

학생 집단에서 [감정]은 [스트레스나 분노]의 감정을 표현하는 방식으로 나타나는 경향이 있다. 학생들은 그들이 경험하는 스트레스, 프로젝트의 결과에 대한 두려움, 또는 때때로 어떻게 동기를 잃는지에 대해 이야기함으로써 그룹 내에서 그들의 감정을 드러낸다. 이러한 발언에 대한 반응은 학생 그룹마다 다르며 다양하다. 어떤 그룹에서는, 그 반응은 대부분 개인적인 것이고 누군가의 기분을 좋게 만드는 것을 목표로 한다. 다른 그룹에서는 대부분 학습 과정으로 반응이 향합니다. 통상적으로, [감정]은 SDL 프로세스의 시작을 나타냅니다. 두 가지 방식의 반응은 모두 최종적으로 SDL 동작으로 이어집니다.

Affect tends to show in the groups of students by expressing emotions of stress or anger. Students show their emotions in the group by talking about the stress they experience, their fears about the outcomes of the project, or how they sometimes lose motivation. The reaction to these remarks differs and varies between the groups of students. In some groups, the reaction is mostly personal and targeted at making someone feel better. In other groups, the reaction is mostly directed towards the learning process. Usually affect marks the start of a SDL process, with both kinds of reaction leading to SDL behaviour in the end.

예를 들어, 한 그룹에서 한 학생이 프로젝트에 대한 동기를 유지하는 데 어려움을 겪고 있다고 말합니다. 그녀는 이 프로젝트를 즐기지 않는 반면, 그녀의 동료들은 그것에 열광하기 때문에 이것에 대해 화가 나 있다. 게다가, 그 그룹은 저녁을 함께 먹고 대학 밖에서 만나는 등 꽤 친해졌다. 학생이 자신의 문제에 대해 목소리를 높이면, 그 그룹은 정확히 무슨 일이 일어나고 있는지 탐색함으로써 그 문제를 추적합니다. 그리고 나서 그들은 어떻게 그들이 학생을 도울 수 있는지에 대한 결론에 도달한다. 이렇게 하면 Transcript 2에서 볼 수 있듯이 그룹이 공동 책임을 집니다.

For instance, in one group a student tells that she has trouble staying motivated for the project. She is upset about this, because she does not enjoy the project, whereas her peers are enthusiastic about it. Moreover, the group has become quite close, having dinner together and meeting up outside university. When the student speaks up about her problem, the group follows up on that by exploring what is going on exactly. They then come to a conclusion about how they can help the student. This way the group assumes a shared responsibility, as seen in Transcript 2.

또 다른 예에서, 한 학생은 또한 동기 상실을 언급하고, 마감시한에 의한 압박도 느끼지 않음을 암시한다. 그녀는 또한 의욕이 없는 것에 대해 화가 나 있다. 그녀의 코멘트에도 불구하고, 그녀는 그녀의 어조로 압박감을 전달한다. 그 그룹은 감정을 모방하고 다양한 해결책을 제시함으로써 반응한다. 그런 다음 프로젝트에서 수행할 다음 단계를 결정합니다. 이 경우 동료들의 반응은 개인적인 문제보다는 학습 과정에 초점이 맞춰집니다. 대화 내용은 Transcript 3에 나와 있습니다.

In another example, a student also mentions a loss of motivation, and implies that she misses the pressure from a deadline. She is also upset about not being motivated. Despite her comment, she does convey feelings of pressure in her tone of voice. The group reacts by mimicking the feelings and offering a variety of solutions. They then go on to decide on the next steps to take in the project. In this case, the reaction of the peers is focused on the learning process rather than the personal problem. The conversation is shown in Transcript 3.

개방성이 비판적 사고를 유지하다

Openness sustains critical thinking

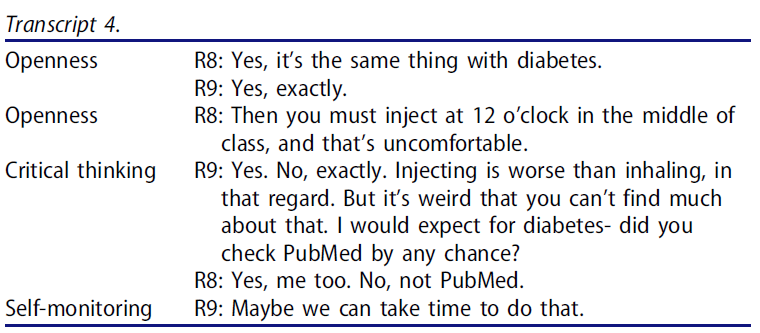

두 번째 메커니즘은 [개방성]과 [비판적 사고]를 포함한다. Transcript 4에서 한 학생이 문학 검색 결과를 자신의 주제에 대한 생각과 연관지어 질문하고 정보를 놓치지 않도록 합니다(비판적 사고). 또한 학생들은 그것이 어떨지 상상하고 그것에 대한 몇 가지 생각을 실험하기 위해 개방성과 관련된 발언들을 포함한다. 따라서, 이 대본은 개방성과 비판적 사고가 서로를 어떻게 강화시키는지 보여준다.

The second mechanism involves openness and critical thinking. In Transcript 4, one of the students is questioning the results of their literature search by relating it to her own idea about the topic and trying to make sure they have not missed out on information (critical thinking). It also involves some remarks that relate to openness, as students try to imagine what it would be like and experiment with some thoughts on that. Thus, the transcript shows how openness and critical thinking reinforce each other.

정보의 공유와 다양한 지식의 원천의 결합은 Transcript 5에 나타나 있다. 이것은 [지식 습득과 비판적 사고의 관계]를 예시하고 있으며, [개방성]도 이에 한몫하고 있다. Transcript 5는 비판적 사고를 표현하는 학생을 보여준다. 다른 그룹 구성원의 반응은 지식 습득에서 시작해 개방성으로 변한다.

Sharing information and combining different sources of knowledge is seen in Transcript 5. This exemplifies the relation between knowledge acquisition and critical thinking, and that openness plays a role in this as well. Transcript 5 shows a student expressing critical thinking. The reaction of the other group members starts with knowledge acquisition and turns into openness.

논쟁적 대화는 배움을 좌절시킨다.

Disputational talk frustrates learning

세 번째 메커니즘은 [논쟁적 대화]에 관한 것입니다. 이것은 학습 과정에서 [생각의 선을 멈추는 상호작용]입니다. 학생들은 종종 [교육조직의 문제]를 인식한다. 예를 들어 디지털 학습 환경에 파일을 업로드할 수 없거나, 회의를 준비하려고 할 때 팀원 개개인의 스케줄로는 업로드할 기회가 없습니다. 이는 좌절감을 야기하고 결국 눈앞의 일에 더 이상 집중할 수 없게 될 수 있습니다. 다음 대본은 대화가 계획에서 논쟁적인 대화로 어떻게 흘러가는지를 보여준다. 이 경우 학생들은 해야 할 일의 양에 압도감을 느끼고 시간에 쫓긴다. 학생들은 최종 보고서를 위한 계획을 세우지 않고 피드백 시간을 계획하지도 않습니다.

The third mechanism concerns disputational talk, which is an interaction that stops the line of thinking, in this case, in a learning process. Students often perceive problems with the organization of education. For instance, when they cannot upload a file to the digital learning environment, or when they try to arrange a meeting, but the schedules of the individual team members leave no opportunity to do that. This may result in feelings of frustration and ultimately escalate in not being able to focus on the task at hand anymore. The next transcript illustrates how the conversation goes from planning to disputational talk. In this case, the students feel overwhelmed by the amount of work they need to do and feel time pressure. The students do not come back to planning for the final report, nor to scheduling a feedback moment.

학생들이 좌절감이나 다른 부정적인 감정들에 어떻게 대처할 수 있는가는 또한 그룹에 달려있다. 어떤 학생들은 부정적인 감정을 공유하는 데 유능하고 그 이후에 나아갈 수 있다. 다른 그룹에서는, 개인 차원이나 그룹 차원 중 하나에서 더 깊은 감정이나 사회적 문제가 있을 때, 그들은 상세한 설명을 삼가는 경향이 있다. 학생들은 동료들로부터 통합을 받기도 하지만, 아래 설명과 같이 항상 원인이나 해결책에 대해 논의하지는 않습니다. 이 그룹에서는 스트레스를 받은 학생들이 다른 학생들이 충분히 열심히 공부하지 않거나 프로젝트에 대한 동기부여가 되지 않는다는 생각을 가지고 있었기 때문에 결국 더 심해졌다. 이것은 좌절과 오해로 이어졌다.

How students can cope with frustration or other negative emotions also depends on the group. Some students are competent at sharing negative emotions and can move on after that. In other groups, when it comes to deeper emotional or social problems on either an individual level or group level, they tend to refrain from elaborating. Although students receive some consolidation from their peers, they do not always discuss the causes or solutions, as shown in the transcript below. In this group, it ultimately escalated, because the students that felt stressed had the idea that the other students did not work hard enough or were not motivated for the project. This led to frustration and misunderstanding.

논의

Discussion

학생들이 그룹 작업에서 SDL을 어떻게 사용하는지에 대한 질문에 답하기 위해 1학년 동안 3개의 프로젝트 그룹을 추적했습니다. 모든 그룹은 어느 정도 SDL을 보였지만, [자기 모니터링]와 [대인 행동] 면에서 차이가 있었다. SDL 개발에서 그룹을 지도하려면 이러한 차이를 이해해야 합니다.

따라서 두 번째 연구 질문의 초점은 그룹 역학으로, SDL이 표면화되거나 표면화되지 않는 이유를 설명할 수 있는 행동 패턴을 식별하려고 했다. 본 연구의 결과는 [감정(정동)을 공유 및 토론하는 능력과 개방성]이 [자기 모니터링]과 [비판적 사고] 측면에서 SDL에 긍정적인 영향을 미치는 반면, [논쟁적인 대화]는 이 과정을 저해하는 것으로 보일 수 있음을 시사합니다.

To answer the question how students employ SDL in group work, we followed three project groups of students throughout one academic year. All groups showed SDL to some extent, but there were differences in terms of self-monitoring and interpersonal behaviour. If we want to guide groups in SDL development, we need to understand these differences.

Therefore, the focus of the second research question was on group dynamics, trying to identify patterns of behaviour that could explain why SDL does or does not surface. The results of the present study suggest that a capability to share and discuss emotions (affect) and openness influence SDL positively in terms of self-monitoring and critical thinking, whereas disputational talk sometimes appears to inhibit this process.

메커니즘

Mechanisms

첫 번째 메커니즘은 [감정]과 [대인관계 기술]이 SDL 행동을 향한 프로세스에서 중요한 역할을 한다는 것을 나타냅니다. 학생들이 해결해야 할 문제의 지표로서 감정을 인식하는 것은 중요하다. 이것은 학습의 중요한 출발점이 되는 이전의 발견과 일치합니다. 현재의 연구는 [감정]이 [자기 모니터링]와 [비판적 사고]의 관점에서 시간을 효과적으로 사용할 수 있다는 것을 보여준다. 이것은 감정과 감정 조절이 자기 조절에 중요하다는 것을 발견함으로써 입증된다. 감정은 또한 내재적 동기 부여와 학습에 필요한 의미를 지닌 사건을 나타낼 수 있다(Boyd 2002; Redwood 등 2010). 하지만 학생 그룹은 이 문제에 대해 다른 방식으로 대처한다는 것을 알게 되었습니다. 일부 그룹은 감정의 신호 전달 기능을 무시했고, 자기조절이나 비판적 사고를 강화하는 측면에서 이득을 얻지 못하였다.

The first mechanism indicates that affect and interpersonal skills play a key role in the process towards SDL behaviour. It is important for students to acknowledge emotions as an indicator of a problem that needs to be solved. This is in line with previous findings that affect is an important starting point for learning (van Woezik et al. 2019). The present study shows that affect can then lead to effective use of the time in terms of self-monitoring and critical thinking. This corroborates with the finding that emotion and emotion regulation are important for self-regulation (Lajoie et al. 2019). Affect may also indicate events that have meaning, which are necessary for intrinsic motivation and learning (Boyd 2002; Redwood et al. 2010). We did find however, that groups of students deal with this in different ways. Some groups may in fact disregard this signalling function of affect and not benefit from in terms of enhancing self-regulation or critical thinking.

우리는 [개방성]이 비판적 사고를 유지하는 데 중요한 역할을 한다는 것을 발견했다. 새로운 관점에서 문제를 비판적으로 성찰하고 가능한 해결책으로 이어질 수 있는 새로운 사고와 정교함을 장려합니다. 게다가, 개방성은 학생들이 집단 사고에 도전할 수 있게 하는데, 이는 비판적 사고에 대한 이전의 연구와 일치한다. 이러한 개방성의 특징은 성장형 마음가짐과 일치하며, 이는 학습이 실수가 문제가 되지 않는 과정으로 짜여진다는 것을 의미합니다. 본 연구에서는 [대인관계 행동]이 이러한 성장 마인드를 확립하는 데 중요할 뿐만 아니라, 그룹 내에서 [개방성과 비판적 사고]를 유지하는 데 중요하다는 것을 발견했다. 이러한 연구결과는 전문적인 팀워크로 확대되며, 이 팀워크에서는 고품질 상호작용이 잘 발달된 커뮤니티에서 보다 비판적으로 성찰적인 대화가 이루어지며(de Groot 등 2014), 팀은 긍정적인 정서적 학습 환경에서 보다 효과적으로 일한다(Jansen 등 2019).

We found that openness plays a role in sustaining critical thinking. It encourages thinking out of the box and elaboration which may lead to new perspectives helping to critically reflect on problems as well as possible solutions. Moreover, openness enables students to challenge groupthink, which is in line with previous studies on critical thinking (de Groot et al. 2014; Koksma et al. 2017). These features of openness are in line with a growth mindset, meaning that learning is framed as a process where mistakes are not problematic (Dweck and Master 2008). In this study, we found that interpersonal behaviour is important for establishing such a growth mindset as well as sustaining openness and critical thinking in groups. These findings extend to professional teamwork, where more critically reflective dialogues take place in well-developed communities with high quality interaction (de Groot et al. 2014), and teams work more effectively with a positive affective learning climate (Jansen et al. 2019).

이 연구에서, [대인관계 행동]은 그룹마다 다른 것처럼 보였다.

- 우리가 관찰한 두 그룹에서는 스트레스나 다른 부정적인 감정에 대한 대화가 질문이나 문제 해결 행동으로 이어졌다.

- 다른 그룹에서는 감정만 피상적으로 논의되었다. 우리는 이 마지막 그룹이 논쟁적인 대화로 더 자주 후퇴하는 것을 보았다.

여기서 [그룹 응집력group cohesion]은 중요한 것으로 보인다: 서로 개인적으로 접근하고 대학 밖에서 만나는 학생들은 감정을 공유하고 피드백을 주고 받으며 비판적인 사고를 할 수 있는 안전한 환경을 구축한다. 이전 연구들은 그룹 응집력이 학습 성과에 중요한 영향을 미친다는 것을 보여주었다. 실제로 비치보드 외 연구진(2011)은 동료와 교사와의 관계성relatedness이 비판적 사고에 긍정적인 영향을 미친다는 것을 보여주고 있다. 따라서 본 연구를 바탕으로 교사들에게 그룹의 관계성relatedness이나 결속을 촉진하는 데 투자할 것을 제안한다. 우리는 다른 연구를 통해 선생님들이 프로젝트의 내용뿐만 아니라 그룹 프로세스 레벨에 대한 성찰을 자극함으로써 그렇게 할 수 있다는 것을 알고 있습니다.

In this study, interpersonal behaviour seemed to vary between the groups.

- In two of the groups we observed, conversations about stress or other negative emotions led to asking questions and problem-solving behaviour.

- In the other group, the emotions were only discussed superficially. We saw that this last group fell back to disputational talk more often.

Group cohesion appears to be key here: students who approach one another more personally and meet outside university establish a safe environment with room for sharing emotions, giving and receiving feedback, and critical thinking. Previous studies have shown that group cohesion indeed has an important influence on learning outcomes (Beachboard et al. 2011; Hommes et al. 2014). In fact, Beachboard et al. (2011) show that relatedness to both peers and teachers has a positive influence on critical thinking. Based on the present study, we therefore suggest that teachers invest in stimulating relatedness or cohesion in the groups. We know from other research that teachers could do so by stimulating (guided) reflection on the group process level as well as on the contents of the project (Jansen et al. 2019).

[대인관계 행동]의 또 다른 긍정적인 효과는 커리큘럼에서 [조직 문제에 대한 논쟁적인 대화]에 대항하는 데 도움이 될 수 있다는 것이다. 우리는 학생들이 이러한 조직적인 문제에 대해 이야기하는 데 얼마나 많은 시간을 할애하고 있고, 이러한 문제들이 그들의 학습을 방해하는 방식을 보고 놀랐다. 조직 문제로 인해 스트레스가 더 높은 상황에서, 학생들은 더 산만하거나 부정적인 상호작용을 보일 가능성이 더 높은 것으로 보인다. 이것에 의해, SDL 의 동작이 억제되어 이전의 조사와 일치합니다(Magno 2010). 그러나 한 그룹은 감정 공유와 반사성을 기반으로 학습 행동에 대한 잠재적 위협을 완화하는 데 성공했습니다. 다른 그룹은 더 적은 범위로 그렇게 했다. 이러한 효과는 [적극적으로 경청하고 판단을 보류하는 것]이 팀의 문제를 가장 효과적으로 해결하는 데 도움이 된다고 주장하는 샤인의 대화 이론theory on dialogue과 일치한다(Schein 2003).

Another positive effect of interpersonal behaviour is that it may help to counteract disputational talk about organizational problems in the curriculum. We were surprised to see how much time students spent on talking about such organizational problems and the way these interfered with their learning. In situations with higher stress due to organizational issues, students appear more likely to be distracted or show negative interactions. This inhibits SDL behaviour, which is in line with earlier research (Magno 2010). However, one group was successful in mitigating potential threats to their learning behaviour based on sharing emotions and reflexivity. Other groups did so to a smaller extent. These effects are in line with the theory on dialogue of Schein who argues that active listening and withholding judgment will help solve problems in teams most effectively (Schein 2003).

성찰

Reflections

본 연구의 한계는 자발적으로 연구에 등록한 소수의 학생만 포함할 수 있다는 것이며, 이는 선택 편향으로 이어질 수 있습니다. 그러나, 우리는 오랜 세월에 걸쳐 학생들을 추적해 왔고, 이로 인해 우리는 그들의 상호작용과 사고에 대한 심오한 이미지를 개발할 수 있었다. 게다가, 그 팀들은 상호작용과 동기부여 면에서 상당히 다르다는 것을 증명했다. 학생들이 프로젝트 자체와 커리큘럼 전반에 대해 공개적으로 비판하는 것은 연구원과 보이스 레코더의 존재가 그들의 행동이나 태도에 영향을 미치지 않았음을 시사한다.

Limitations of this study are that we could include only a small number of students, who voluntary enrolled in the study, which may have led to a selection bias. However, we have followed the students over a long period of time, which has enabled us to develop a profound image of their interactions and thinking. Moreover, the teams proved to be fairly different in terms of interaction and motivation. The fact that students sometimes openly criticized the project in itself and the curriculum as a whole suggests that the presence of a researcher and a voice recorder has not influenced their behaviour or attitude.

우리의 탐색적 연구를 바탕으로 SDL과 관련된 소그룹 학습의 메커니즘에 관한 가설을 세울 수 있었습니다. [사회적 구성주의] 관점의 연구가 학습자, 동료, 교사 및 환경 간의 상호작용을 더 잘 이해하는 데 도움이 될 것이라고 생각합니다. 여기서, 감정의 대처가 강조되어야 하는데, 감정이 학습에 큰 역할을 하기 때문이다. 이것은 [법제주의enactivism] (학습에서 감정과 구현에 더 많은 초점을 두는, 정신 철학에서 비롯된 학습의 새로운 패러다임)과 일치한다. 이 패러다임을 사용하여 그룹 다이내믹스와 SDL 간의 상호작용 모델은 논쟁적 대화의 효과 또는 자기 모니터링, 책임 및 대인 행동 간의 상호작용의 기초가 되는 메커니즘에 대한 질문에 답함으로써 추가 조사를 위한 출발점이 될 수 있습니다.

Based on our explorative study, we have been able to formulate some hypotheses regarding the mechanisms at work in small group learning that relates to SDL. We think more research from a social constructivist viewpoint could help to still better understand the interaction between the learner, peers, teachers, and the environment. Here, coping with emotions should be emphasized, as the present study underlines that it plays a large role in learning. This aligns with enactivism: a new paradigm of learning that stems from philosophy of mind, in which more focus is placed on emotion and embodiment in learning (Picard et al. 2004; Stephan et al. 2014; Maiese 2017). Using this paradigm, our model of interaction between group dynamics and SDL could be a starting point for further investigation, answering questions on mechanisms that underlie the effects of disputational talk, or the interaction between self-monitoring, responsibility and interpersonal behaviour.

결론

Conclusion

SDL을 소그룹으로 나누어 진정한 학습환경에서 조사했습니다. SDL에서는 개인의 능력이나 태도에 초점을 맞추는 것을 넘어 [감정과 개방성]의 중요한 역할을 찾아냈습니다. 긍정적인 환경에서 감정을 내보내는channeling 것은 SDL에 대한 행동을 유도하는 데 도움이 됩니다. 동료나 교사와 관련된 개방성은 이 메커니즘에서 큰 역할을 합니다. 1학년 학생들은 성찰과 대인관계 행동을 자신들에게 유리하게 사용할 수 있다. 교사는 학생들이 이러한 기술을 습득하도록 도와야 하며, 학생들과 좋은 관계를 맺음으로써 그룹 과정을 성찰할 수 있도록 도와야 한다.

In conclusion, we investigated SDL in small groups in an authentic learning environment. We moved beyond a focus on individual ability or attitude in SDL, finding important roles for affect and openness. Channelling affect in a positive environment will help to steer behaviour towards SDL. Openness, with relatedness to peers and teachers, plays a large role in this mechanism. First-year students are able to use reflection and interpersonal behaviour to their benefit. Teachers should help students acquire these skills and help them reflect on the group process by establishing a good relationship with the students.

용어집

Glossary

영향: 감정과 감정의 조합. 이는 긍정적(예: 기쁨)과 부정적(예: 좌절 또는 불안)일 수 있습니다. 두 가지 모두 메타인지적 영향 또는 영향으로 표현되는 학습에 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다. 영향과 학습 사이의 관계는 인지력에 대한 물리적 또는 내재적 접근법에 의해 설명될 수 있다.

Affect: A combination of emotions and feelings. These can be both positive (i.e., joy) and negative (i.e., frustration or insecurity). Both may have an impact on learning, described as metacognitive affect or affect. The relation between affect and learning may be explained by a physical or embodied approach to cognition.

정규 학습 환경: 진정한 학습환경은 실제 세계에 존재하는(또는 존재할 수 있는) 학습환경입니다. 실천에 기초한 학습 이론과 자기주도 학습은 모두 학습을 위해 이러한 유형의 환경에 의존한다. 이러한 환경은 복잡한 상황에서 연습하는 기술과 지식을 제공하여 학습자가 학습 중인 문제의 필요성과 의미를 이해하는 데 도움이 됩니다.

Authentic learning environment: An authentic learning environment is a learning environment which exists (or may exist) in the real world. Both practice-based learning theory and self-directed learning rely on this type of environment for learning. Such an environment affords practicing skills and knowledge in complex circumstances, helping learners to understand the necessity and meaning of the issue they are learning about.

Med Teach. 2021 May;43(5):590-598.

doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2021.1885637. Epub 2021 Feb 22.

There is more than 'I' in self-directed learning: An exploration of self-directed learning in teams of undergraduate students

PMID: 33617387

Abstract

Preparing future professionals for highly dynamic settings require self-directed learning in authentic learning situations. Authentic learning situations imply teamwork. Therefore, designing education for future professionals requires an understanding of how self-directed learning develops in teams. We followed (bio-)medical sciences students (n = 15) during an 8-month period in which they worked on an innovation project in teams of 4-6 students. Template analysis of 39 transcripts of audio-recorded group meetings revealed three mechanisms along which group dynamics influenced self-directed learning behaviour. First, if expressions of emotions were met with an inquisitive response, this resulted in self-monitoring or feelings of responsibility. Second, openness in the group towards creativity or idea exploration stimulated critical thinking. Third, disputational talk frustrated learning, because it adversely affected group cohesion. We conclude that emotions, openness, and relatedness are important drivers of self-directed learning in teams and hence should be given explicit attention in designing collaborative learning for future professionals.

Keywords: Collaborative/peer-to-peer; education environment; study skills; undergraduate.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 자기주도학습, 자기평가' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 의과대학생의 커리어 지향: Q방법론 연구(PLoS One, 2021) (0) | 2022.08.12 |

|---|---|

| 왜 이 학생이 시험을 잘 못 볼까요? 자기조절학습을 활용한 문제 진단 및 해결 (Acad Med, 2018) (0) | 2022.04.02 |

| 맥락 속의 자기조절학습: 자기-, 공동-, 사회적으로 공유된 학습의 조절(Med Educ, 2021) (0) | 2021.12.28 |

| 무엇을 생각하고 있었나요? 의과대학생의 자기조절학습에 대한 메타인지와 인식 (Teach Learn Med, 2021) (0) | 2021.12.28 |

| 자기자신을 넘어: 의과대학생의 자기조절학습에서 공동조절의 역할 (Med Educ, 2020) (0) | 2021.12.28 |