사회적 책무성 프레임워크와 그것이 의학교육과 프로그램 평가에 갖는 함의: 내러티브 리뷰(Acad Med, 2020)

Social Accountability Frameworks and Their Implications for Medical Education and Program Evaluation: A Narrative Review

Cassandra Barber, MA, Cees van der Vleuten, PhD, Jimmie Leppink, PhD, and Saad Chahine, PhD

의과대학이 봉사하고자 하는 인구에 대한 사회적 책무성을 다해야 한다는 국제적인 요구가 계속 제기되어 왔습니다. 사회적 책무성은 많은 교육기관이 추구하는 이상이지만, 이를 측정하는 것은 전 세계적인 과제로 남아 있습니다. 투명성과 책임성에 대한 사회적 요구가 증가함에 따라 의과대학은 사회적 책무성에 대한 더 강력한 증거를 제시해야 한다는 압박에 직면해 있습니다.1,2

There have been repeated international calls for medical schools to be socially accountable to the populations they intend to serve. While social accountability is an ideal that many institutions strive toward, measuring it remains a global challenge. With increasing societal demands for greater transparency and accountability, medical schools face growing pressures to produce stronger evidence of their social accountability.1,2

1995년 세계보건기구(WHO)는 사회적 책무성을 다음과 같이 정의했습니다:

In 1995, the World Health Organization (WHO) defined social accountability as:

[의과대학은 교육, 연구 및 봉사 활동을 그들이 봉사해야 하는 지역사회, 지역 및 국가의 우선적인 건강 문제를 해결하는 방향으로 이끌어야 할 의무가 있습니다. 우선적 건강 요구는 정부, 의료 기관, 의료 전문가 및 대중이 공동으로 파악해야 합니다.3

[T]he obligation of medical schools to direct their education, research and service activities towards addressing the priority health concerns of the community, region, and/or the nation they have a mandate to serve. The priority health needs are to be identified jointly by governments, healthcare organizations, health professionals and the public.3

그 이후로 사회적 책무성에 관한 문헌이 확대되고 이니셔티브의 수가 증가했습니다.4,5 많은 의과대학이 사명 선언문, 프로그램 목표 및 전략 계획에 사회적 책무성 정책을 포함시켰으며 일부 조직은 공식 인증 절차에 포함시켰습니다.5 그러나 증가하는 관심에도 불구하고 사회적 책무성이 측정 가능한 속성으로 운영되는 방법은 여전히 불분명하여 사회적 책무성을 객관적으로 평가하기 어렵습니다.6

Since then, the literature surrounding social accountability has expanded and the number of initiatives has multiplied.4,5 Many medical schools have embedded social accountability policies in their mission statements, program objectives, and strategic plans, and some organizations have included them in formal accreditation processes.5 Yet despite the growing interest, how social accountability is operationalized into measurable attributes remains elusive, making social accountability difficult to evaluate objectively.6

의과대학의 사회적 책무성 평가를 지원하기 위해 다양한 정책과 프레임워크가 마련되었지만, 사회적 책무성 원칙, 지표 및 매개변수에 대한 설명은 주로 개념적인 수준에 머물러 있습니다. 위의 WHO의 사회적 책무성 정의는 의학교육의 세 가지 영역(교육, 연구, 봉사 활동)을 포괄하며, 이 검토에서는 교육 영역에 대해 다룹니다. 이 검토의 목적은 프로그램 평가 모델을 조직적 프레임워크로 사용하여 대규모 사회적 책무성 프레임워크 전반에서 공통 주제와 지표를 식별하고 문서화하는 것입니다. 이는 의학교육의 사회적 책무성을 평가하는 데 필요한 초기 운영 구조의 개발을 촉진하기 위한 것입니다.

Although various policies and frameworks have been established to assist medical schools in the evaluation of social accountability, their descriptions of socially accountable principles, indicators, and parameters remain predominately conceptual in nature. The WHO’s social accountability definition, above, encompasses the 3 domains of medical education (education, research, and service activities), and this review addresses the educational domain. The purpose of this review is to identify and document common themes and indicators across large-scale social accountability frameworks, using a program evaluation model as an organizational framework. It is intended to facilitate the development of initial operational constructs needed to evaluate social accountability in medical education.

배경

Background

설명하다(account)라는 동사에서 파생된 책무성은 가장 단순한 형태의 답변성, 즉 자신의 행동에 대해 설명하고 책임을 져야 하는 의무를 의미합니다.7,8 교육에서 책무성은 기관의 효과성(즉, 기관이 목표를 얼마나 잘 달성했는지)을 평가하는 시스템으로 기능하여 기관이 결과에 대한 책임을 지고 교육 개선을 촉진합니다.9-12 이 시스템은 교육 기관이 자신의 행동에 대해 사회에 답변해야 하는 책임감, 투명성 및 공공 신뢰를 의미합니다.13,14 다양한 형태의 책임성은 존재하지만 모두 다음의 근본적인 질문을 다루고 있습니다:

- 누가, 무엇에 대해, 누구에게, 어떤 수단을 통해 책임을 져야 하는가?7,10,15

Derived from the verb account, accountability in its simplest form means answerability, the obligation to provide an account and be held responsible for one’s actions.7,8 In education, accountability functions as a system to evaluate institutional effectiveness (i.e., how well institutions meet their goals), holding institutions responsible for results and promoting educational improvement.9–12 This system implies a sense of responsibility, transparency, and public trust, whereby educational institutions are obligated to answer to society for their actions.13,14 While many forms of accountability exist, they all address the following fundamental questions:

모든 의과대학은 이러한 의무를 인정하거나 해결하기로 선택했는지 여부에 관계없이 대중에 대해 책임을 집니다.3 보건의료 전문직 교육 프로그램과 미래의 보건의료 인력을 준비하는 모든 교육기관은 다음에 대해 책임을 집니다.

- 의료계,

- 대중(환자, 가족, 지역사회, 사회),

- 교육 결과물(졸업생, 봉사 활동, 연구 활동),

- 미래의 보건의료 수요

책임의 한 형태인 사회적 책무성은 의과대학이 지역사회의 변화하는 공공 의료 수요에 대응할 준비가 된 유능한 졸업생을 배출해야 한다는 점에서 암묵적, 명시적, 예상되는 것입니다.16-20

All medical schools are accountable to the public, regardless of whether they choose to acknowledge or address this obligation.3 Health professions education programs and any educational institutions responsible for preparing the future health care workforce are accountable to

- the medical profession;

- the public (patients, families, communities, and society);

- their educational products (graduates, service activities, and research activities); and

- future health care needs.

As a form of accountability, social accountability is implicit, explicit, and anticipated, in that medical schools must produce competent graduates prepared to respond to the changing public health care needs within their local communities.16–20

의료계는 사회로부터 일정한 책임과 특권을 부여받았습니다. 의과대학은 법률, 규제 및 인가를 통해 사회의 요구를 충족할 준비가 된 유능한 의사를 배출하도록 위임받았습니다.21,22 이러한 사회적 역할은 의사와 사회 간의 본질적인 사회적 계약을 의미하는 큰 책임을 수반합니다.23 이러한 사회적 계약은 특히 의학교육이 정부 자금으로 지원되는 국가에서 더욱 강화됩니다. 그 결과, 의과대학은 긍정적인 사회적 환원에 대한 증거를 제공해야 한다는 사회적 압력에 직면해 있습니다.3,16 사회적 책무성은 의학과 사회 사이에 존재하는 전방위적인 사회적 계약을 나타냅니다.24-31

The medical profession has been granted certain responsibilities and privileges by society. Through legislation, regulation, and accreditation, medical schools are entrusted to produce competent physicians who are prepared to meet the needs of society.21,22 This social role carries great responsibilities, signifying the intrinsic social contract between physicians and society.23 This social contract is specifically amplified in countries where medical education is government funded. As a result, medical schools face increasing societal pressures to provide evidence of a positive social return.3,16 Social accountability represents an omnipresent social contract that exists between medicine and society.24–31

일반적으로 사회적 책무성이란 기업이 자신의 행동, 행위 및 성과에 대해 봉사하고자 하는 사회에 대한 헌신을 의미합니다.32 WHO의 사회적 책무성에 대한 정의는 국제적으로 가장 널리 받아들여지고 있습니다. 2010년에 의과대학의 사회적 책무성에 대한 글로벌 컨센서스는 이 정의를 재확인하면서 사회적 책무성이 측정 가능한 활동임을 강조했습니다:

Broadly, social accountability implies an entity’s commitment to the society it is intended to serve for its actions, conduct, and performance.32 The WHO’s definition of social accountability remains the most widely accepted internationally. In 2010, the Global Consensus for Social Accountability of Medical Schools reaffirmed this definition, emphasizing that social accountability is a measurable activity:

주요 이해관계자, 정책 입안자, 의료기관, 의료보험 제공자, 의료 전문가 및 시민사회와 협력하면서 사회의 현재 및 미래 건강 요구와 도전에 대응하기 위한 행동입니다.19

[A]n action to respond to current and future health needs and challenges in society while working collaboratively with key stakeholders; policy-makers; healthcare organizations; health-insurance providers, health professionals and civil society.19

광범위한 책임성 문헌에서 책임성이라는 용어는 종종 개념적 우산13,33,34 으로 불리며 신뢰, 신뢰성 또는 투명성의 이미지를 묘사하기 위해 책임성, 답변 가능성 또는 효과성과 상호 교환적으로 사용됩니다. 그러나 의학교육 문헌에서 책임성, 책임감, 응답성이라는 용어는 동일하지 않습니다. 이들 간의 차이점은 Boelen과 Woollard의 사회적 의무 척도에 명확하게 정의되어 있습니다.32 이 분류법은 사회적 책무성을 달성하기 위한 선형적 진행을 나타냅니다:

- 책임성이란 "사회의 요구에 부응해야 할 의무를 인식하는 상태"를 의미합니다;

- 반응성은 "사회의 요구에 반응하는 행동 과정"을 의미합니다.

- 책무성은 프로그램이 공중 보건에 긍정적인 영향을 미치기 위해 주요 이해관계자들과 협력하면서 사회의 우선적인 보건의료 요구를 선제적으로 충족한다는 증거를 제공하는 "측정 가능한 활동"을 의미합니다.32

Within the broader accountability literature, the term accountability is often referred to as a conceptual umbrella13,33,34 and used interchangeably with responsibility, answerability, or effectiveness to portray an image of trust, trustworthiness, or transparency. However, in the medical education literature, the terms accountable, responsible, and responsive are not equivalent. Differences between them are clearly defined within Boelen and Woollard’s social obligation scale.32 Their taxonomy represents a linear progression toward achieving social accountability:

- responsibility refers to a “state of awareness of duties to respond to society’s needs”;

- responsiveness refers to “a course of action addressing society’s needs”; and

- accountability represents a “measurable activity” to provide evidence that programs proactively meet the priority health care needs of society while working alongside key stakeholders to positively impact public health.32

방법

Method

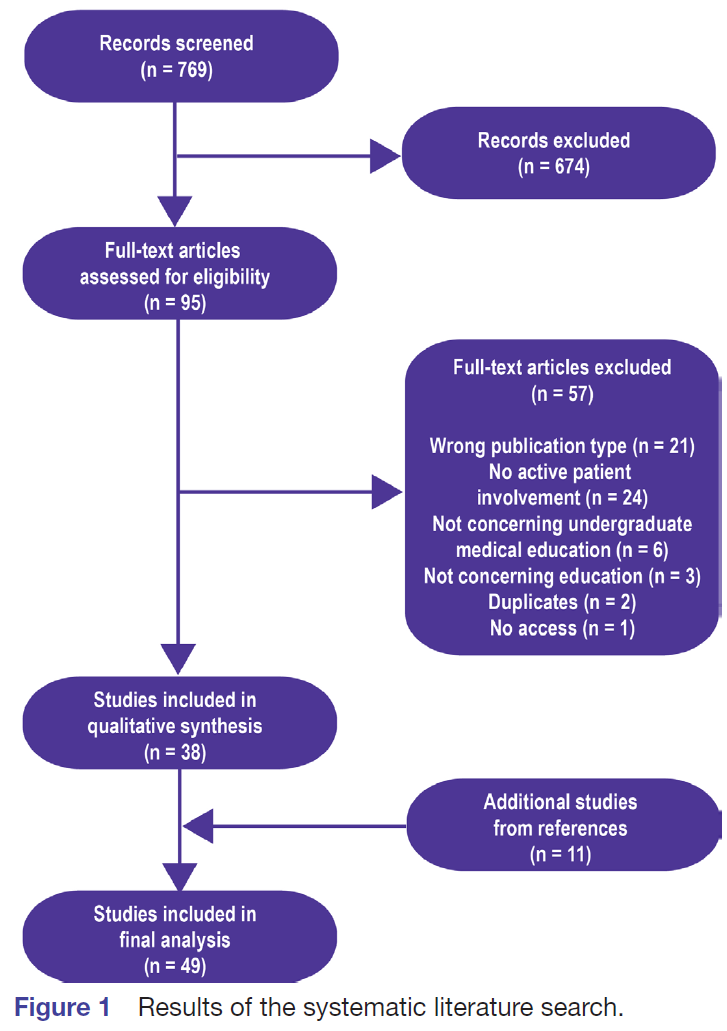

프로그램 평가 모델은 사회 정책, 프로그램 및 개입에 대한 포괄적인 평가를 제공하기 위해 여러 분야에서 널리 사용됩니다.35-39 우리는 프로그램 평가 모델을 조직적 프레임워크와 체계화된 프로세스로 사용하여 대규모 사회적 책무성 프레임워크와 저널 논문 및 의학교육 문헌의 기타 문서를 검토하는 내러티브 검토40를 수행했습니다. 그런 다음 질적 접근법을 사용하여 핵심 개념을 종합했습니다.

Program evaluation models are widely used in multiple fields to provide comprehensive evaluations of social policies, programs, and interventions.35–39 We conducted a narrative review40 using a program evaluation model as an organizational framework and a systematized process to review large-scale social accountability frameworks as well as journal articles and other documents from the medical education literature. We then synthesized key concepts using a qualitative approach.

조직 프레임워크

Organizational framework

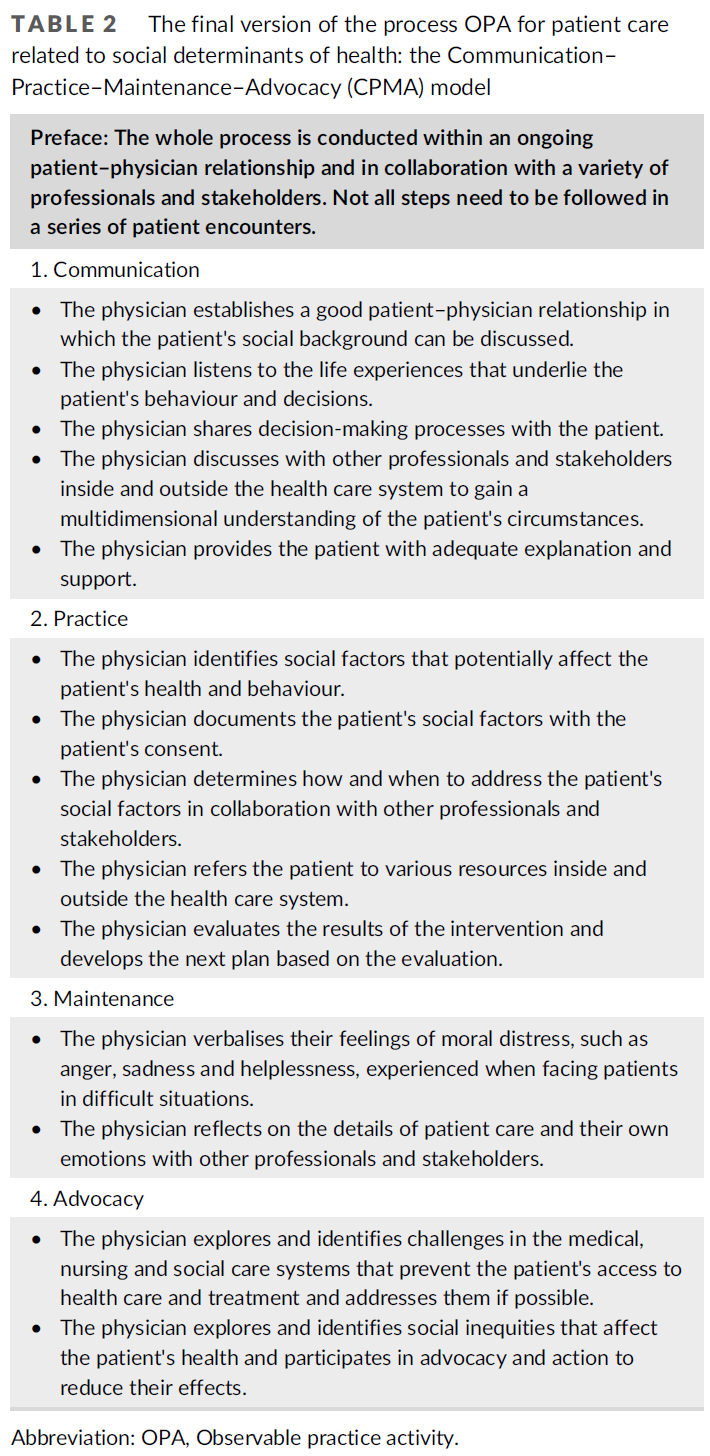

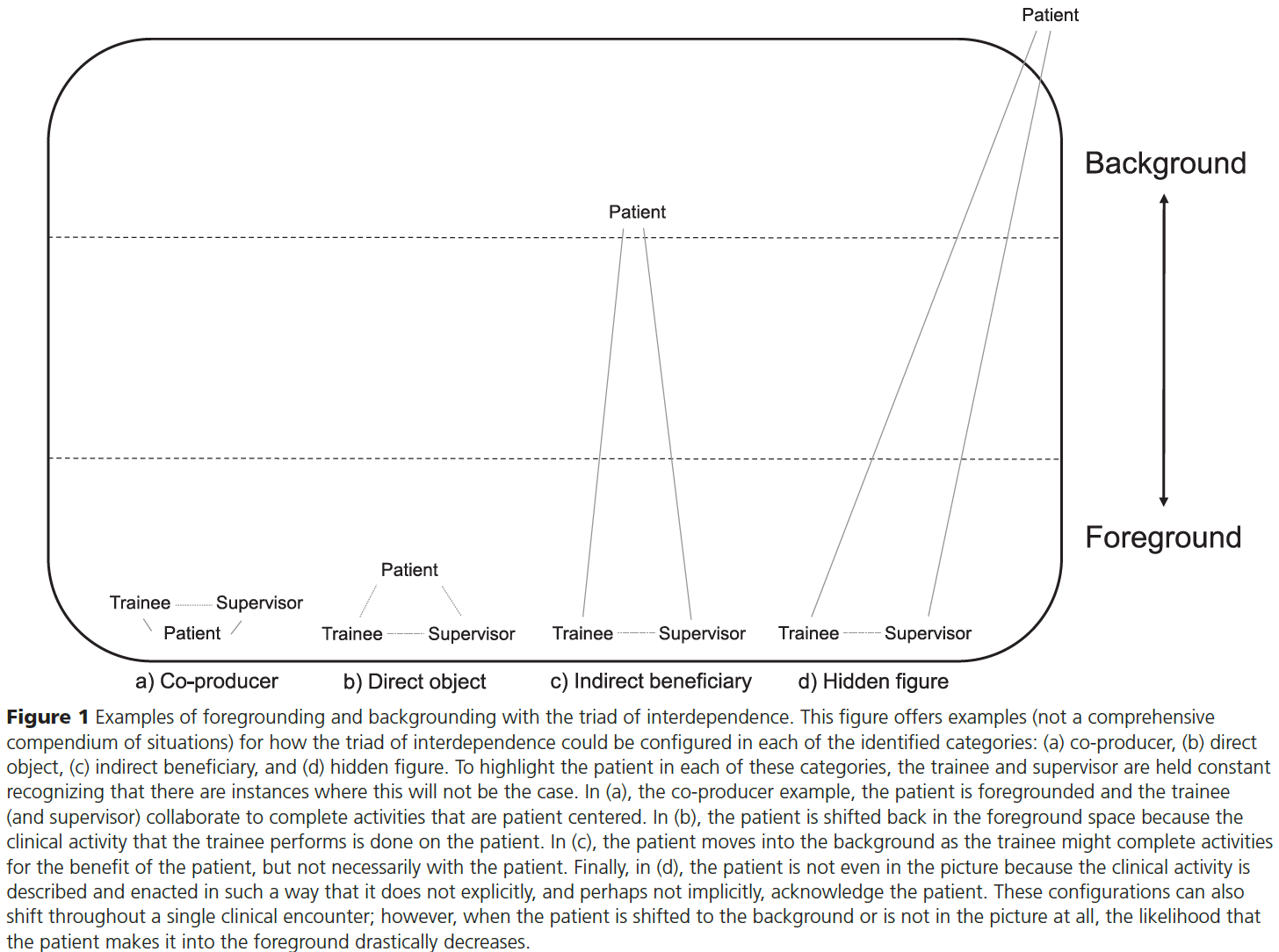

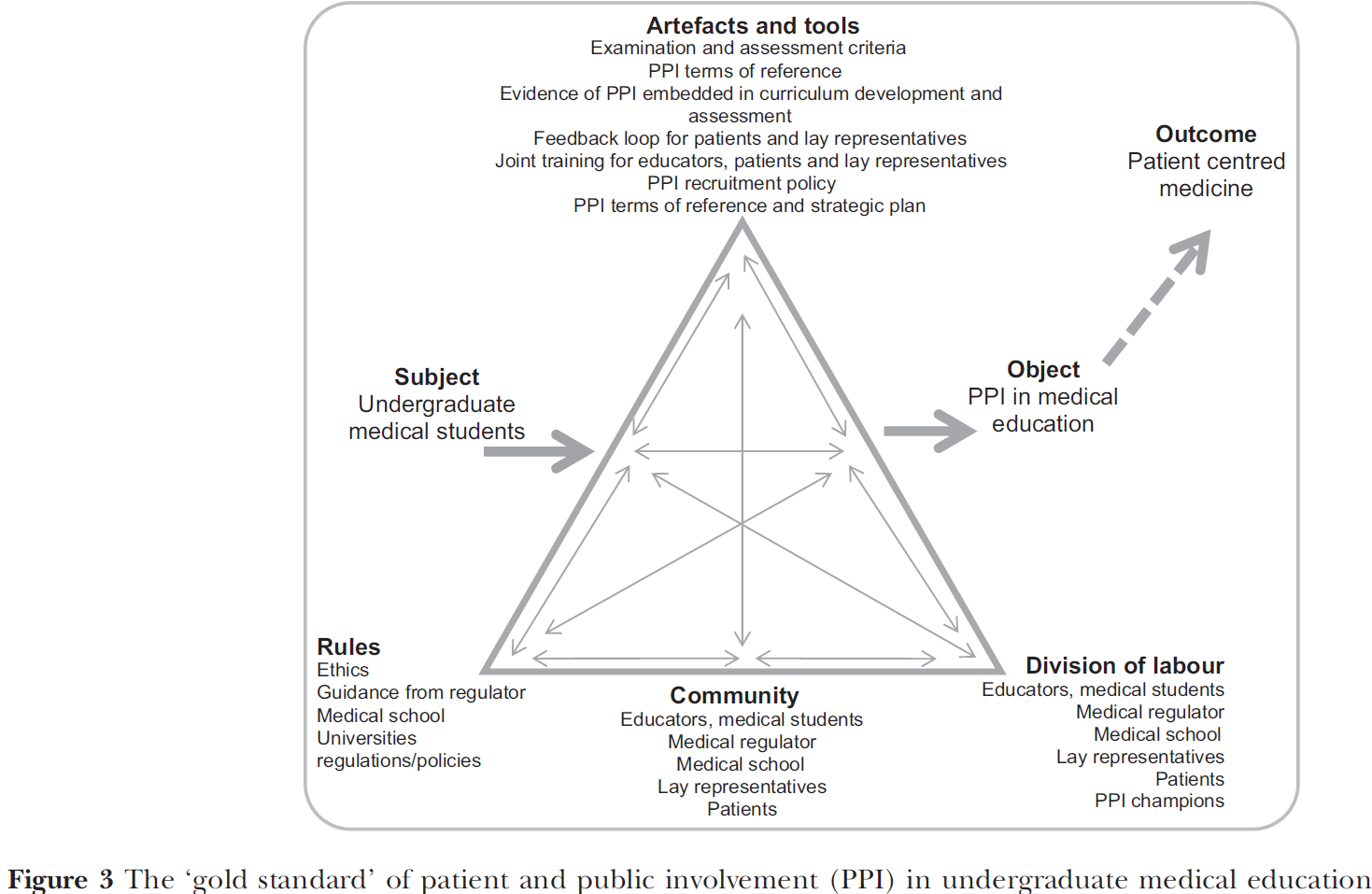

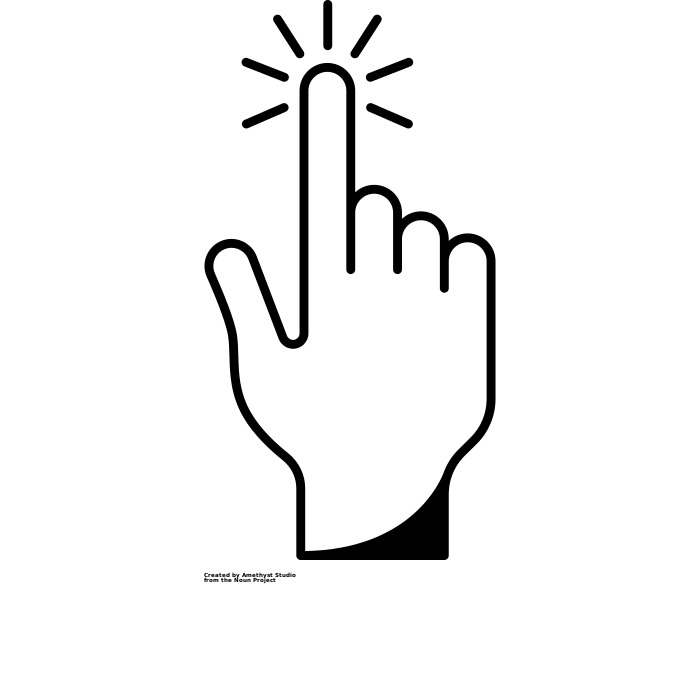

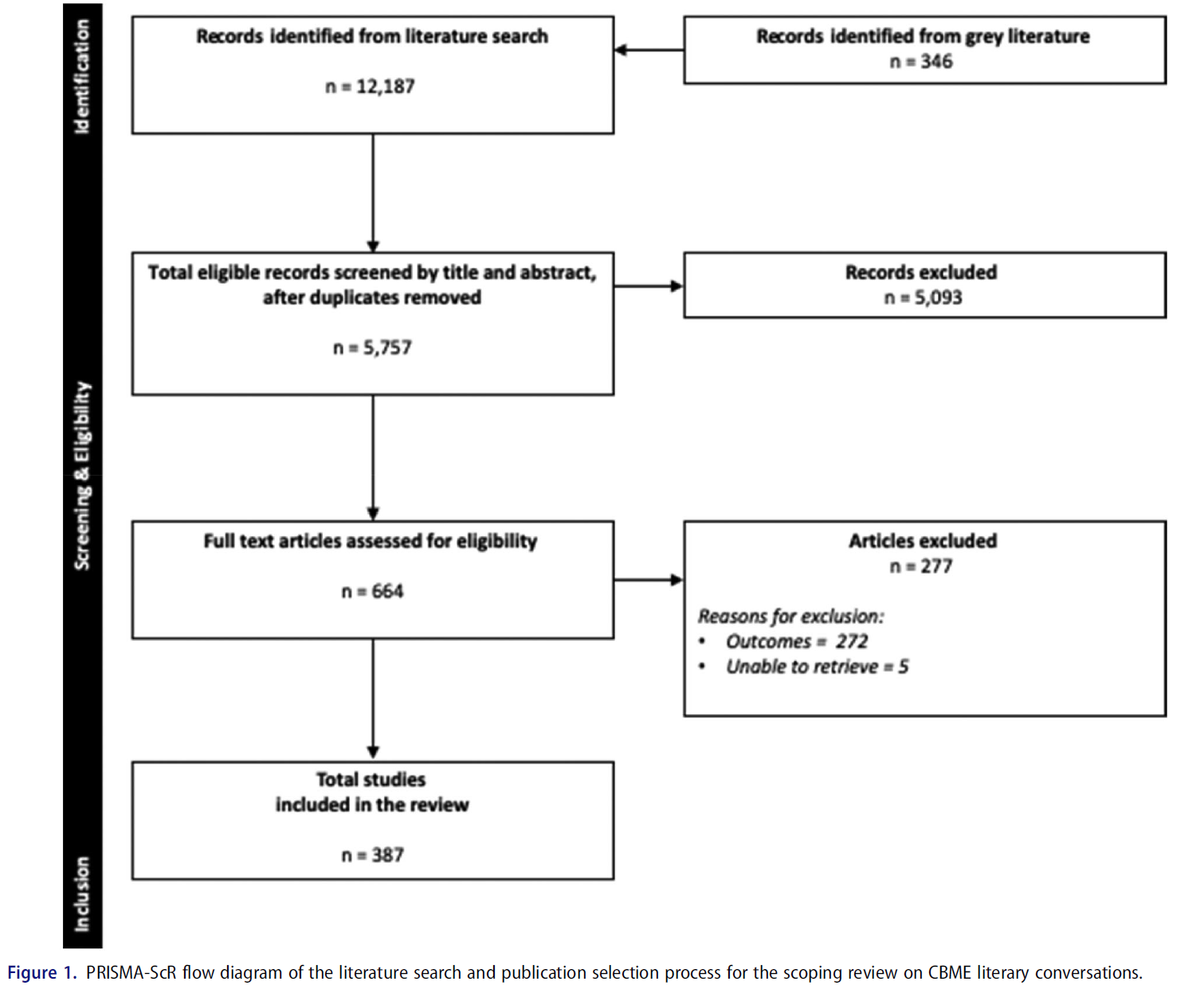

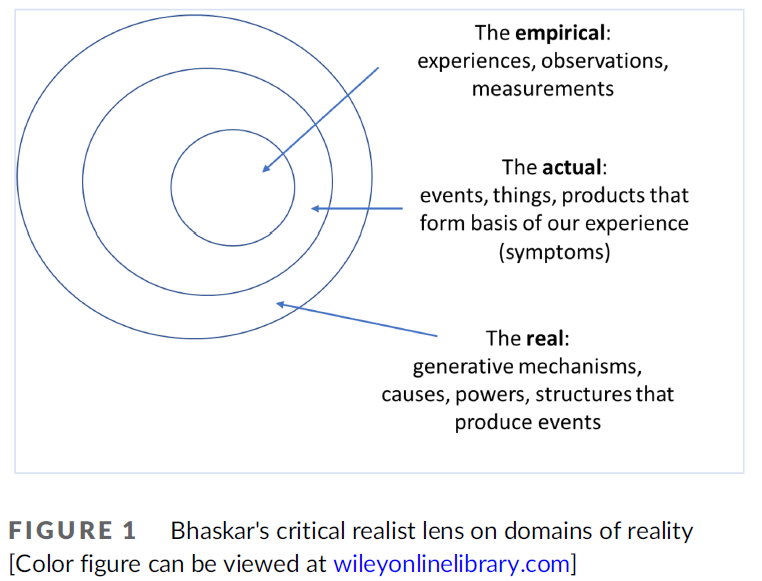

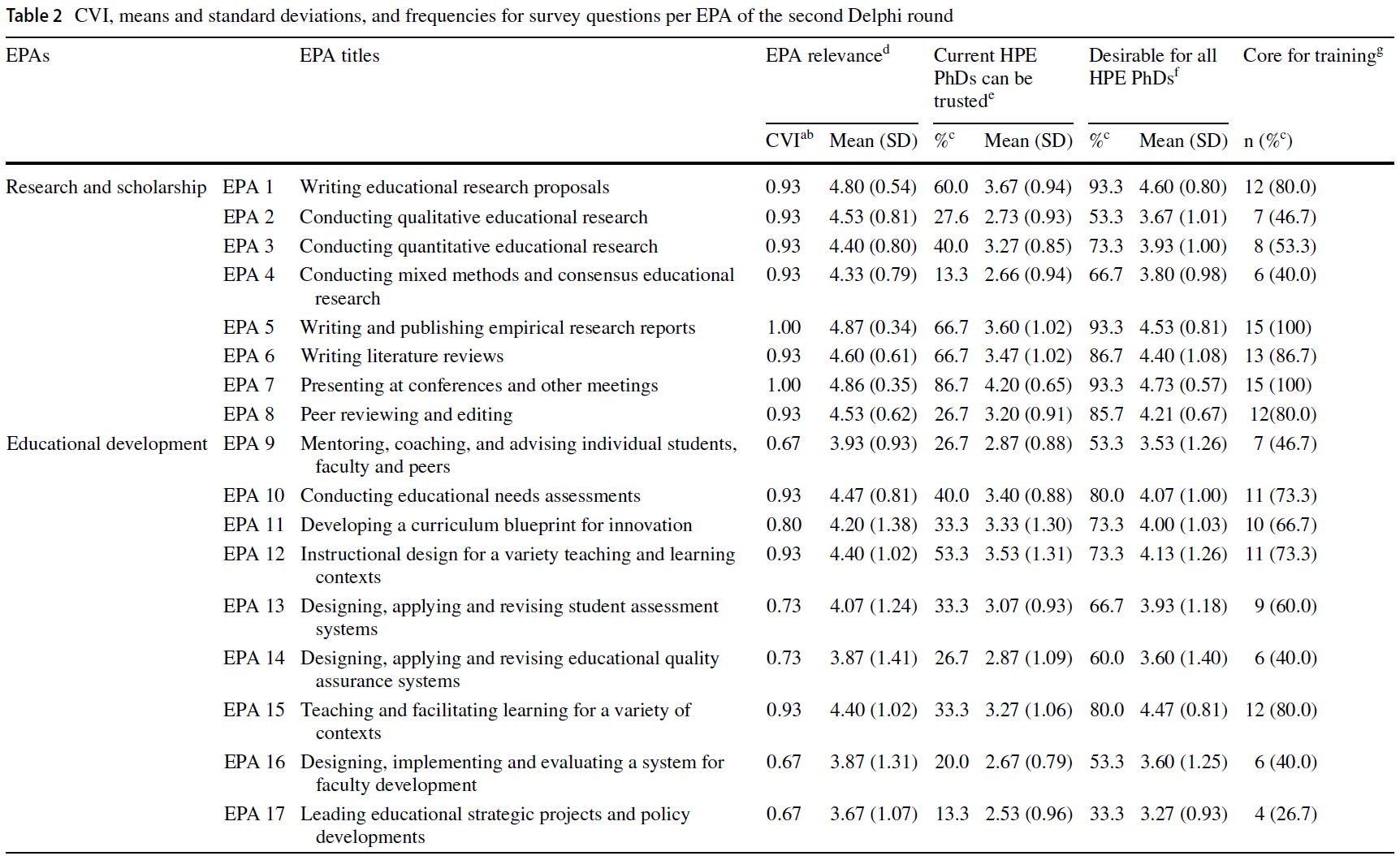

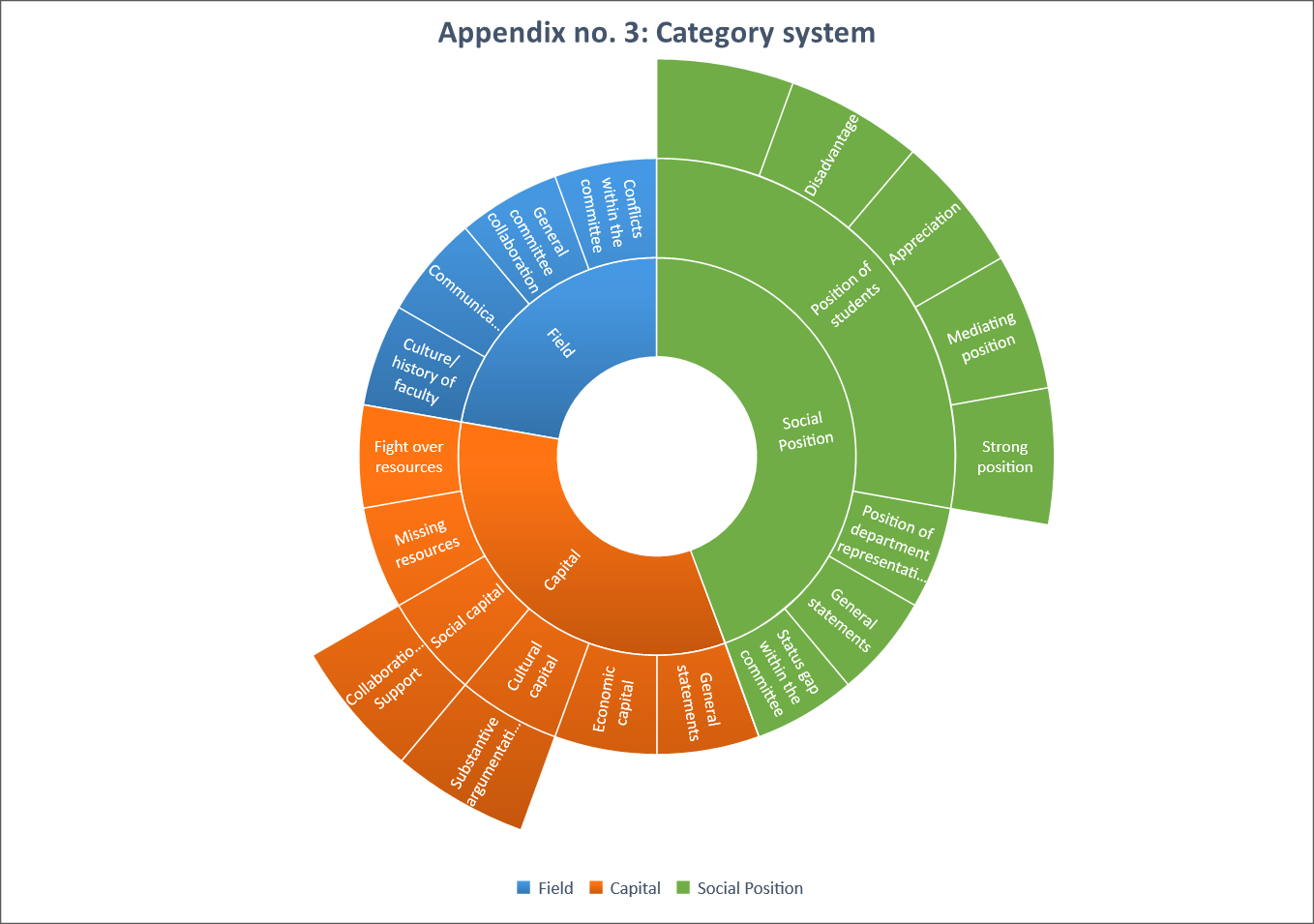

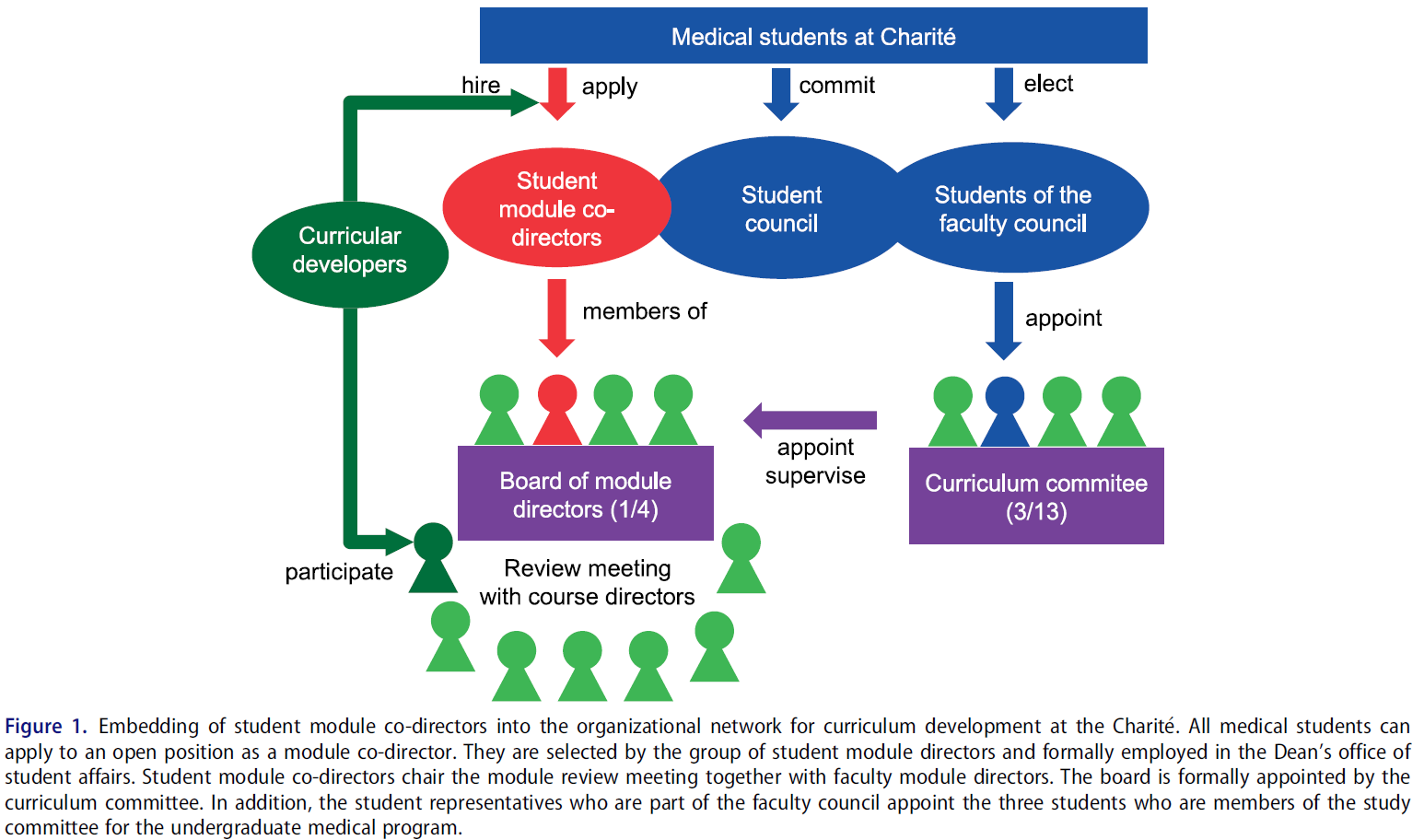

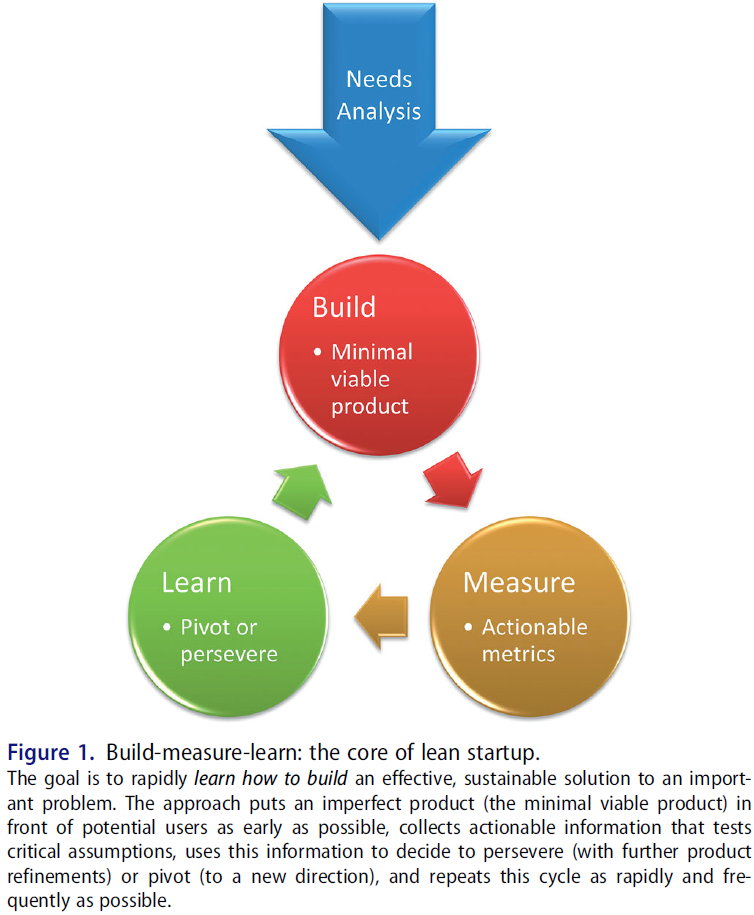

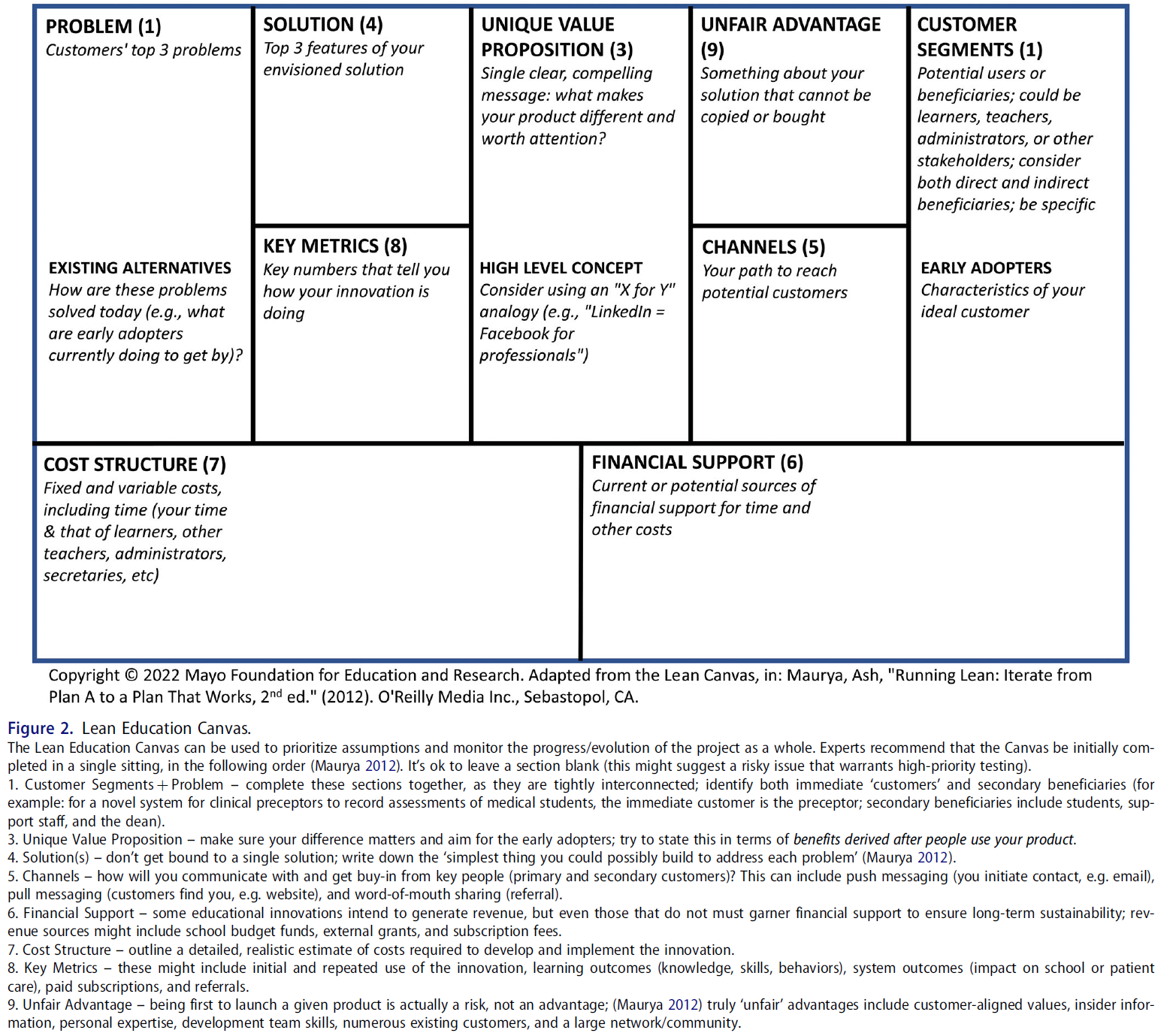

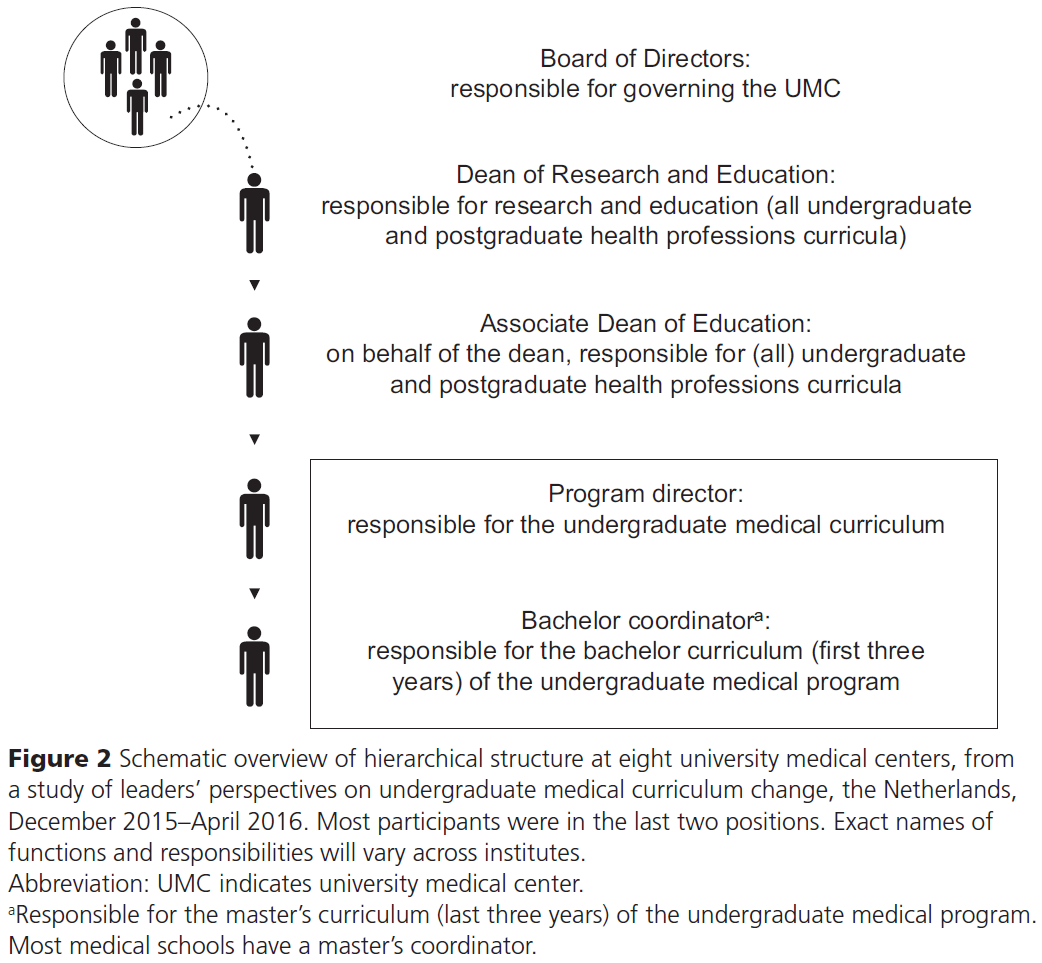

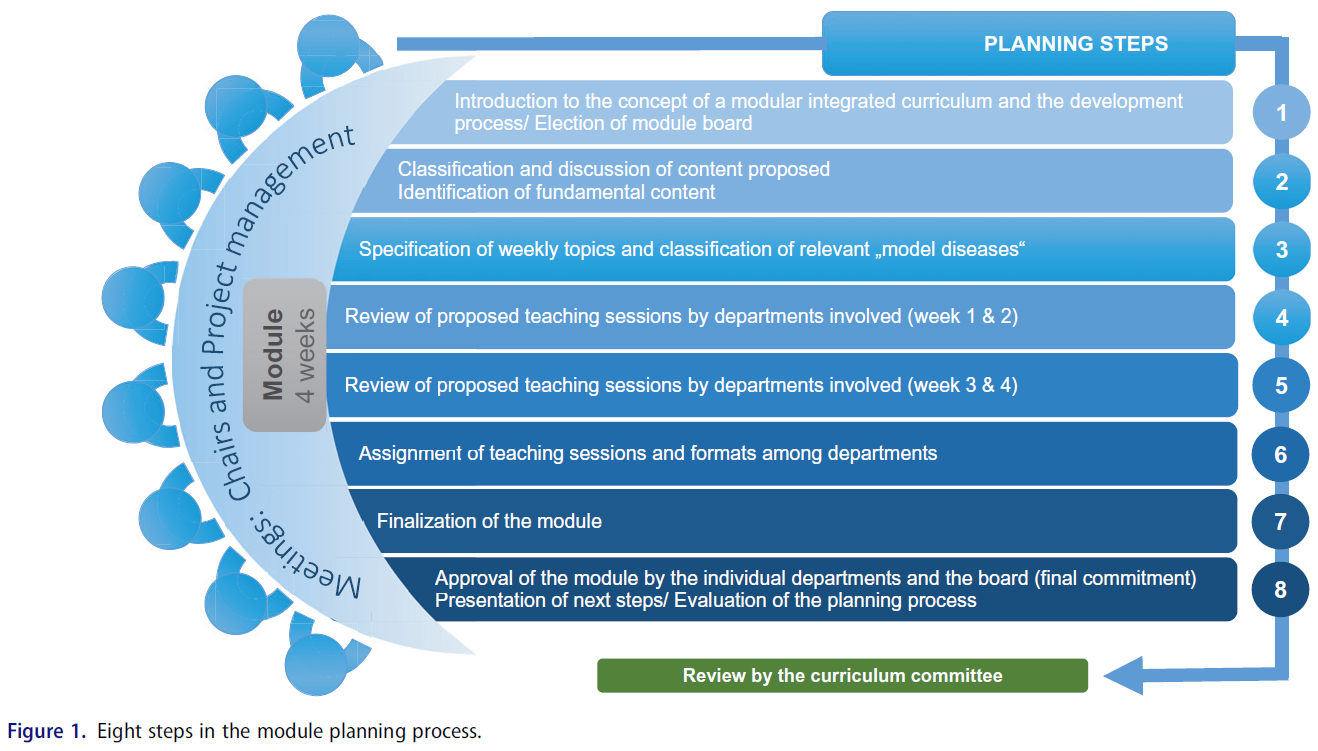

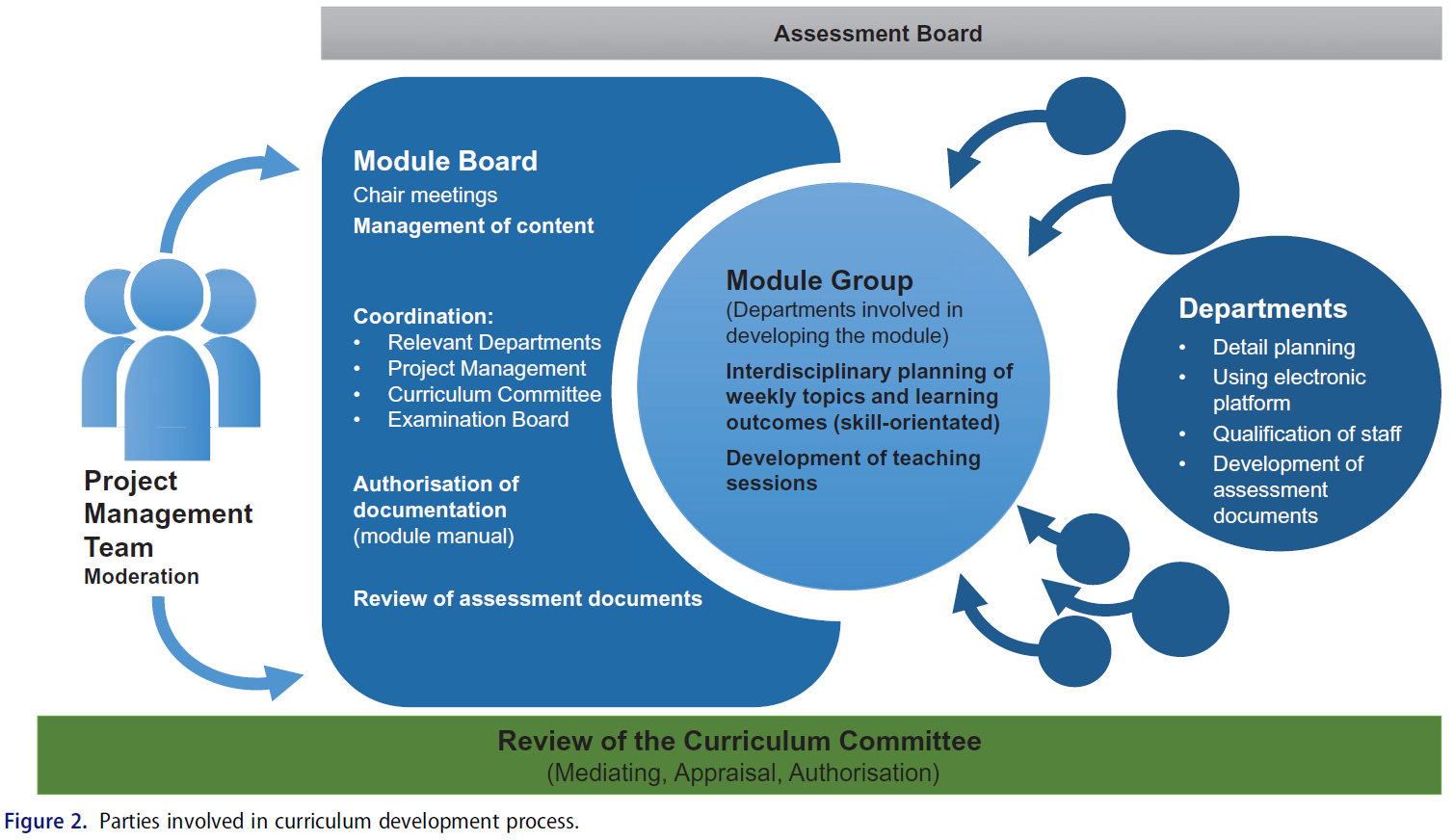

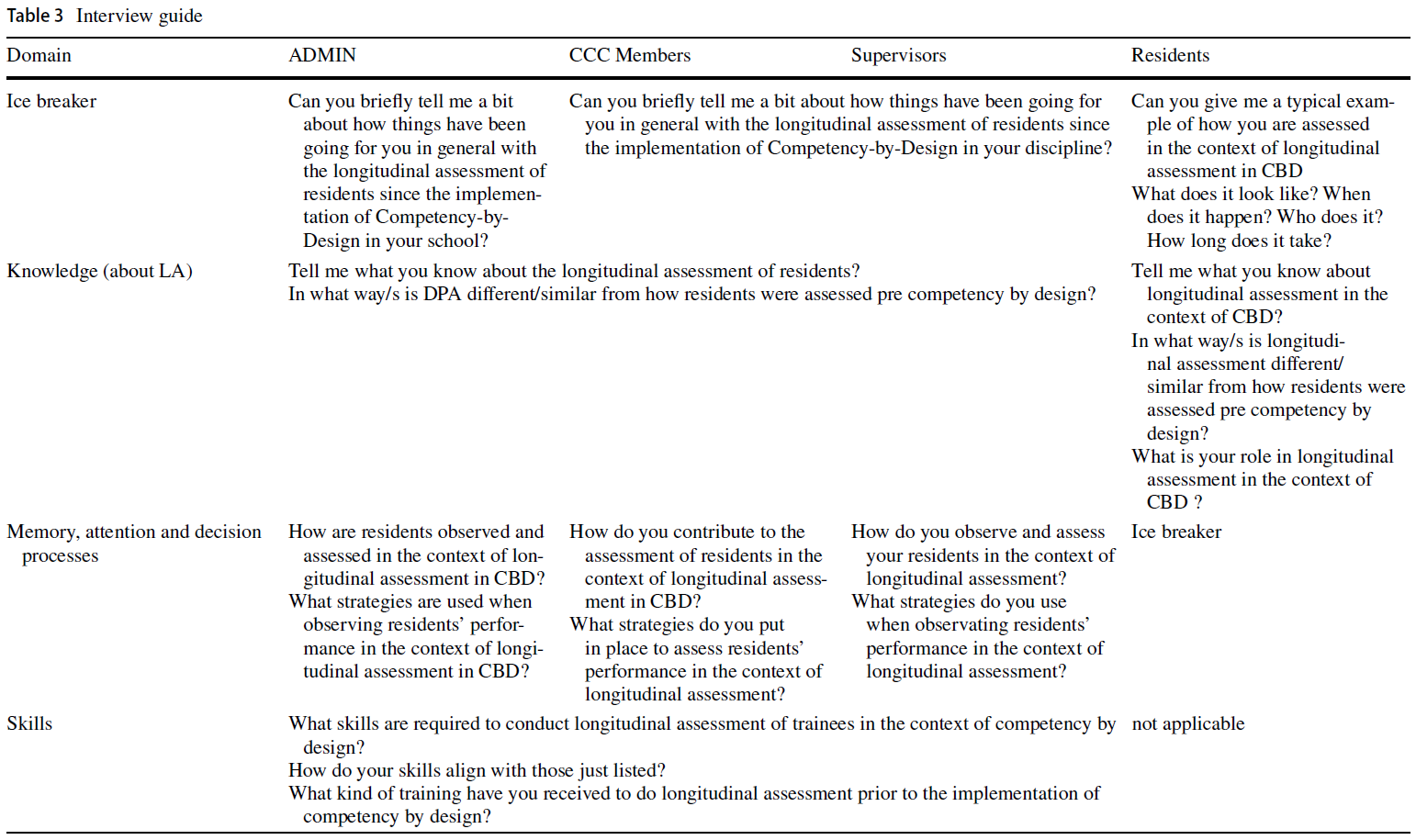

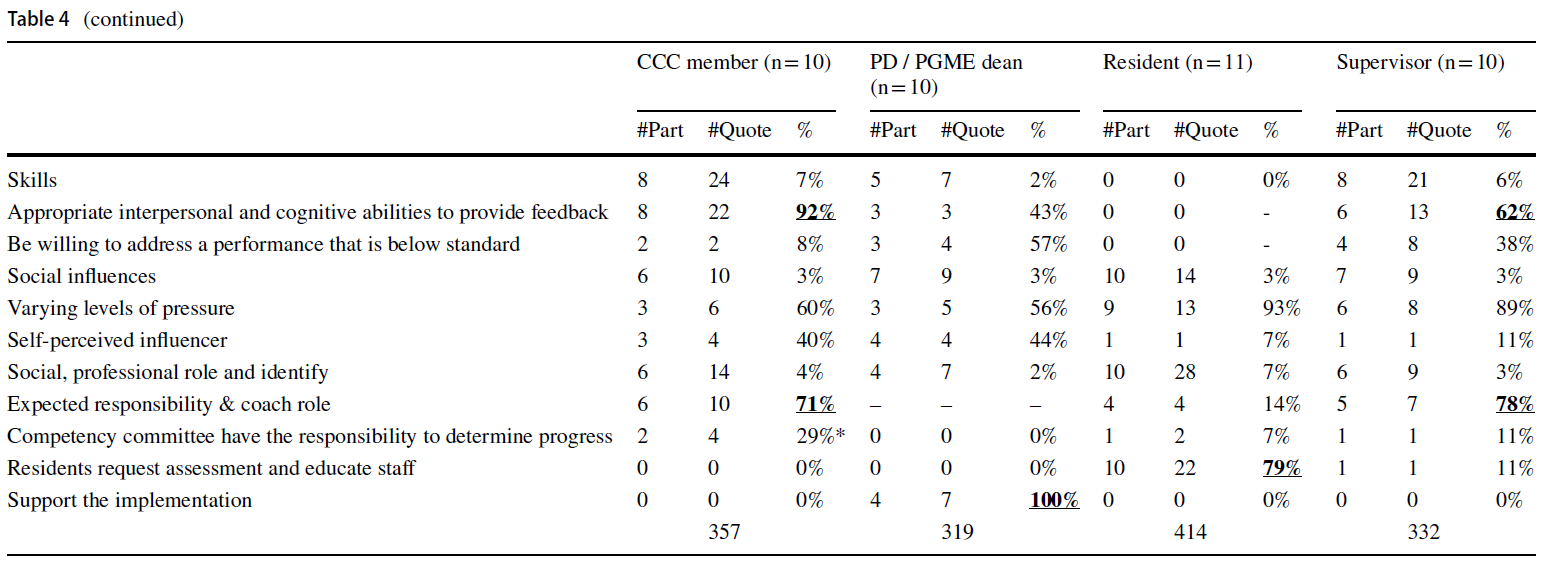

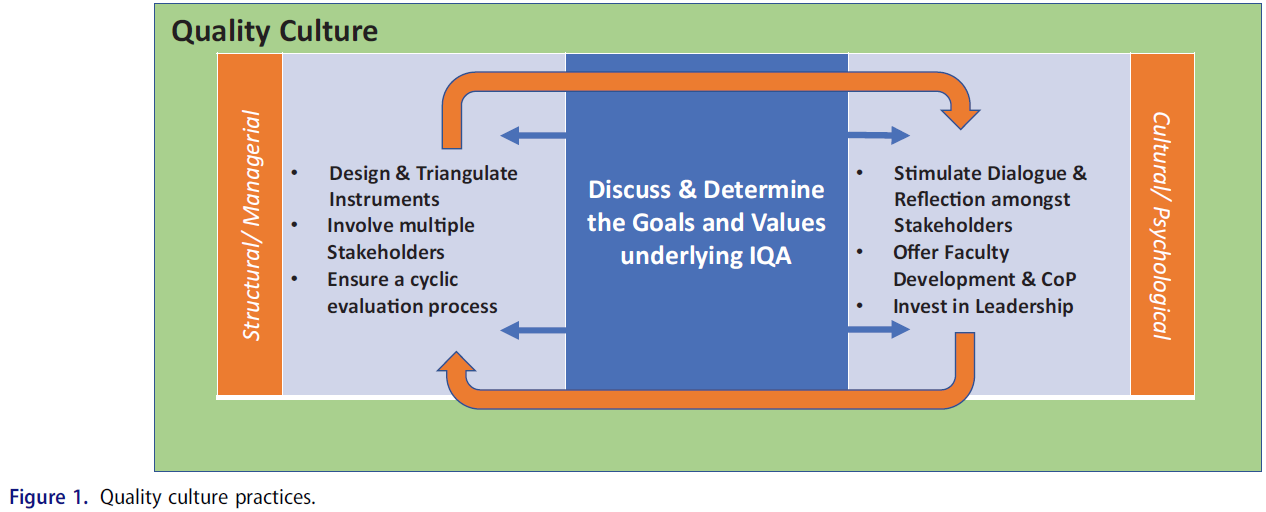

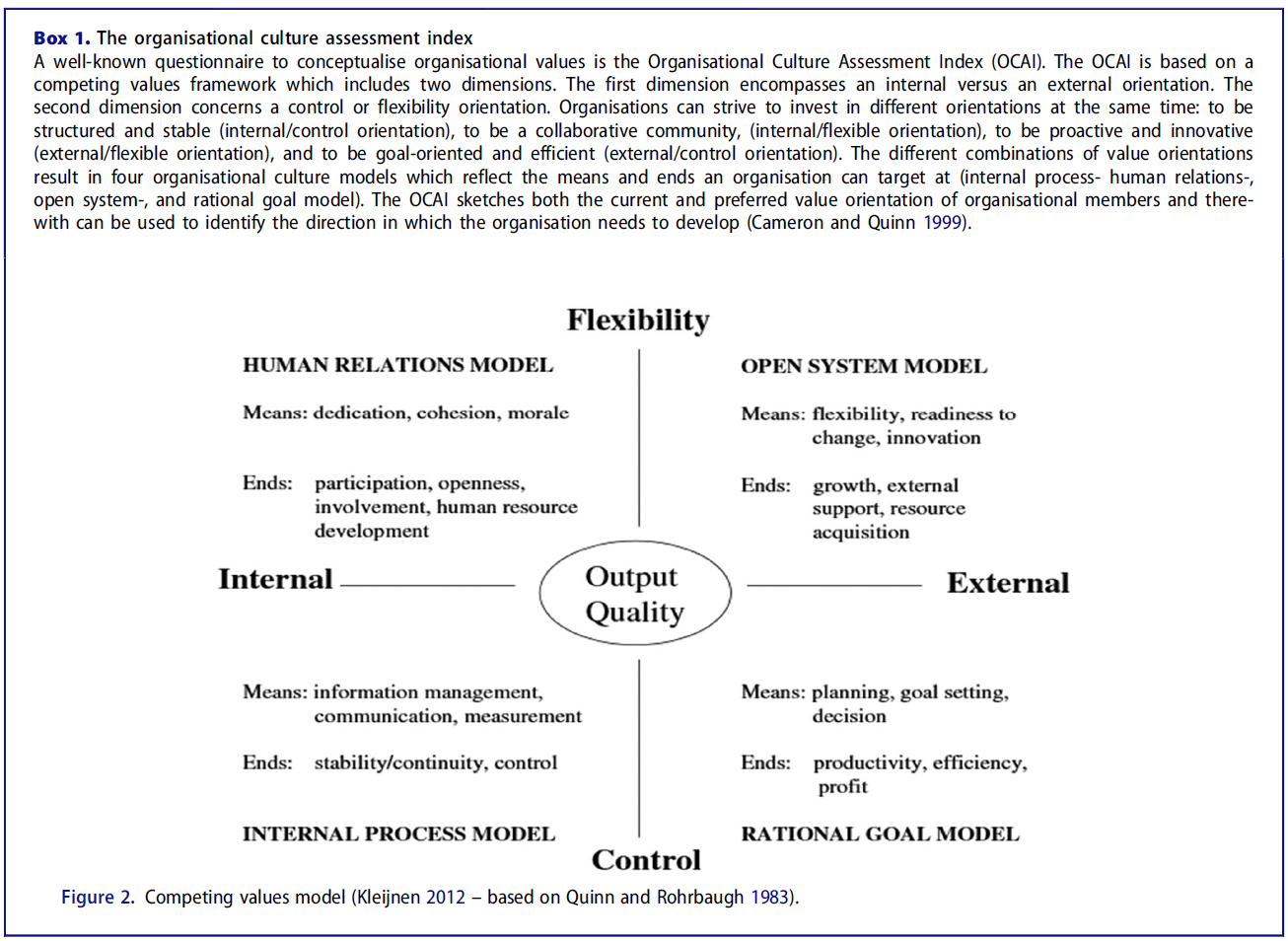

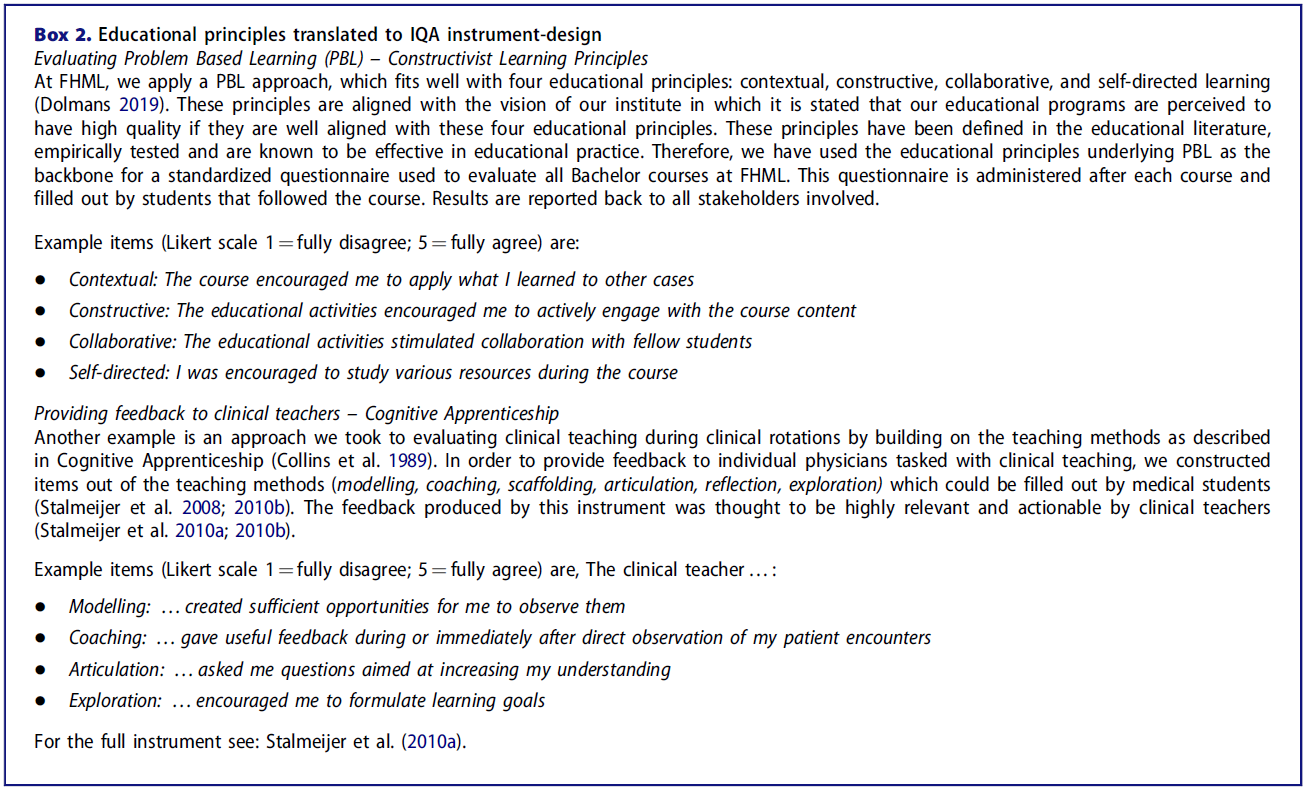

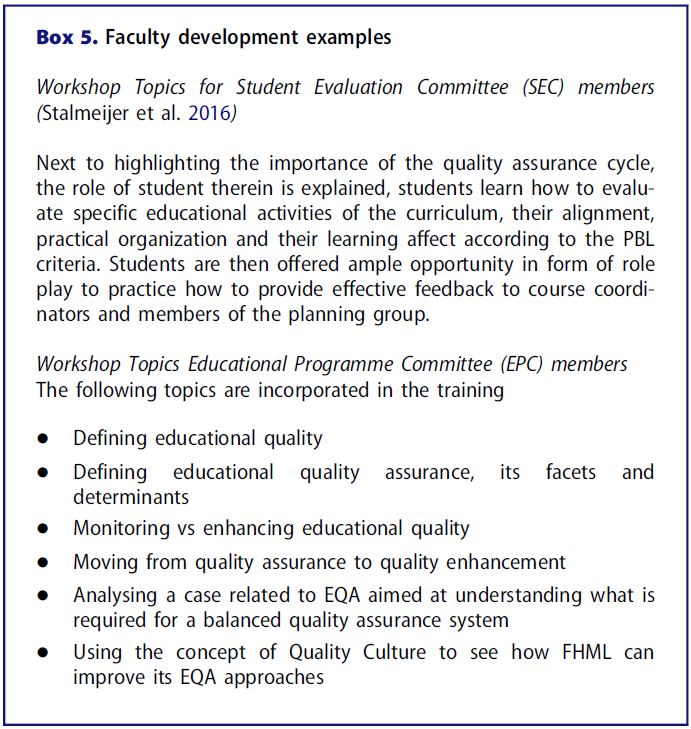

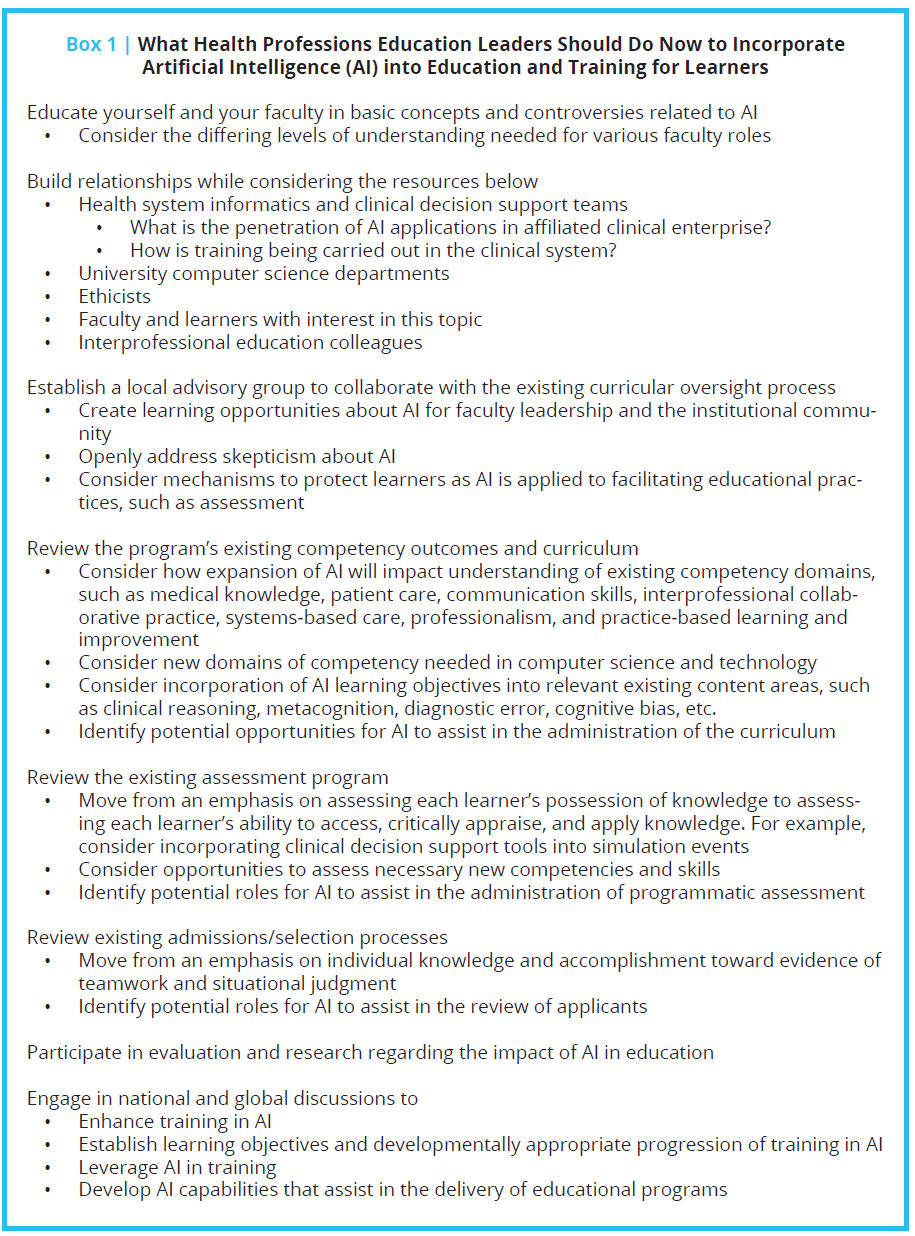

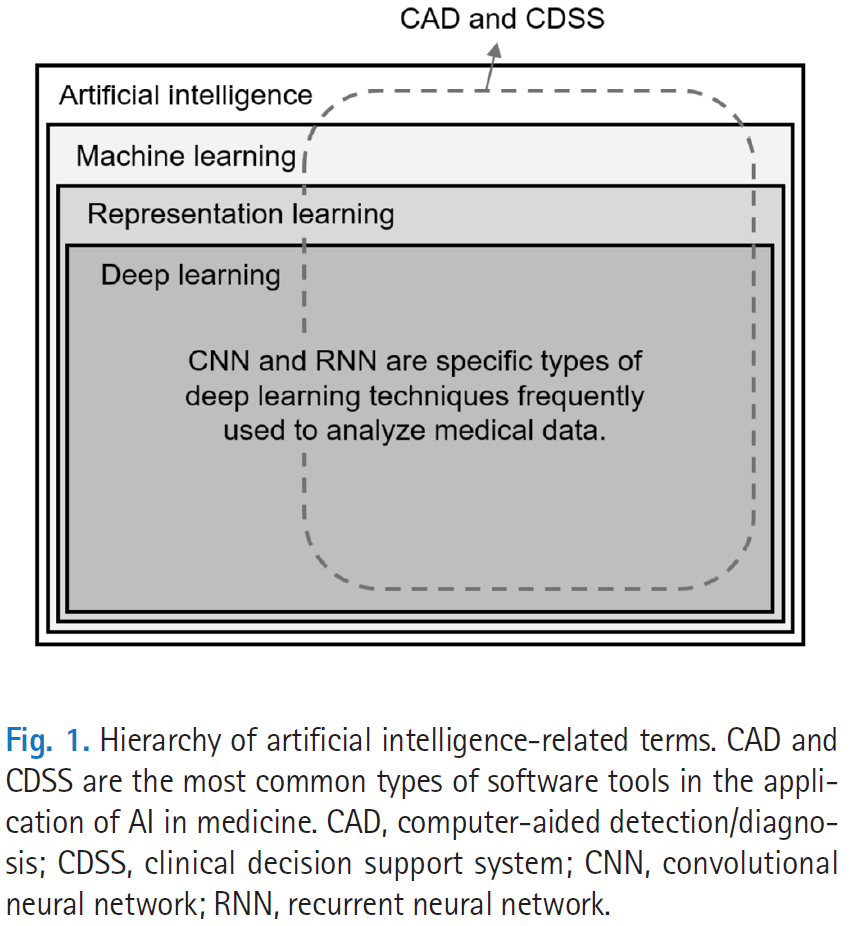

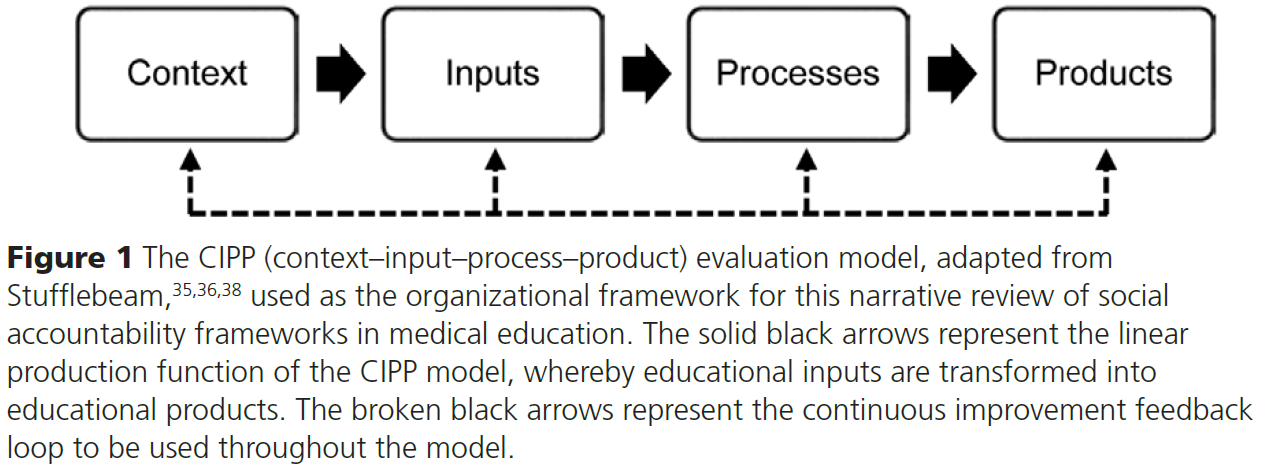

우리는 사회적 책무성의 복잡한 요구, 지표, 결과를 체계적으로 파악하기 위한 평가 도구로 스터플빔의 맥락-입력-과정-산출물(CIPP) 모델을 선택했습니다.35 교육의 책무성을 높이기 위해 1960년대에 처음 개념화된 이 프로그램 평가 모델은 국제적으로 사용되는 책무성 모델이며 의학 교육에서 널리 수용되고 있습니다.35-37 그림 1에 표시된 대로 CIPP 모델은 프로그램 개선 및 책무성을 위한 방법으로 평가를 사용합니다. 이 모델은 상호 관련된 4개의 구성요소로 구성되어 있으며 평가 모델 전체에서 사용되는 지속적인 질 개선 피드백 루프를 통합합니다.35,36,38

We selected Stufflebeam’s context–input–process–product (CIPP) model as the assessment tool to systematically identify social accountability complex needs, indicators, and outcomes.35 First conceptualized in the 1960s to provide greater accountability in education, this program evaluation model is an internationally used accountability model and widely accepted in medical education.35–37 As depicted in Figure 1, the CIPP model uses evaluation as a method for program improvement and accountability. It consists of 4 interrelated components and incorporates continuous quality improvement feedback loops to be used throughout the evaluation model.35,36,38

CIPP 모델에서35-37

- 맥락은 배경을 의미하며, 교육 기관의 요구, 목표 및 기회를 파악하는 데 사용되는 요구 평가이다.

- 투입은 교육기관이 효과적으로 기능하는 데 필요한 물적 및 인적 자원을 의미합니다. 투입은 프로그램 목표와 목적을 달성하는 데 필요한 적절한 행동 방침을 결정하는 데 사용됩니다.

- 프로세스는 프로그램 실행을 가이드하는 데 사용됩니다.

- 산출은 학생 학습의 질과 개인 및 사회에 대한 유용성을 나타냅니다. 산출은 결과를 측정하는 데 사용됩니다. 이후 CIPP 모델에서는 프로그램의 영향력, 효과성, 지속가능성, 전달성을 평가하기 위해 산출 구성요소를 4개의 하위 구성요소로 나누었습니다.36,38

CIPP 모델은 역동적이며 교육을 생산 기능으로 간주하여 교육 투입물이 교육 산출물로 전환되는 방식으로 접근합니다. 각 구성 요소는 독립적으로 평가할 수 있지만, 어떤 지표도 프로그램 성과를 절대적으로 나타내는 것은 아닙니다.36,38

In the CIPP model,35–37

- Context refers to background—a needs assessment used to help identify needs, objectives, and/or opportunities of an educational institution.

- Inputs refer to material and human resources needed for effective functioning of an educational institution. Inputs are used to determine the appropriate course of action(s) required to achieve program goals and objectives.

- Processes are used to guide the implementation of a program.

- Products refer to the quality of student learning and its usefulness for the individual and for society. Products are used to measure outcomes. In later iterations of the CIPP model, the product component was divided into 4 subcomponents to assess a program’s impact, effectiveness, sustainability, and transportability.36,38

The CIPP model is dynamic and views education as a production function, whereby educational inputs are transformed to educational outputs. While each component can be evaluated independently, no indicator independently represents an absolute measure of program performance.36,38

선택 및 검색 기준

Selection and search criteria

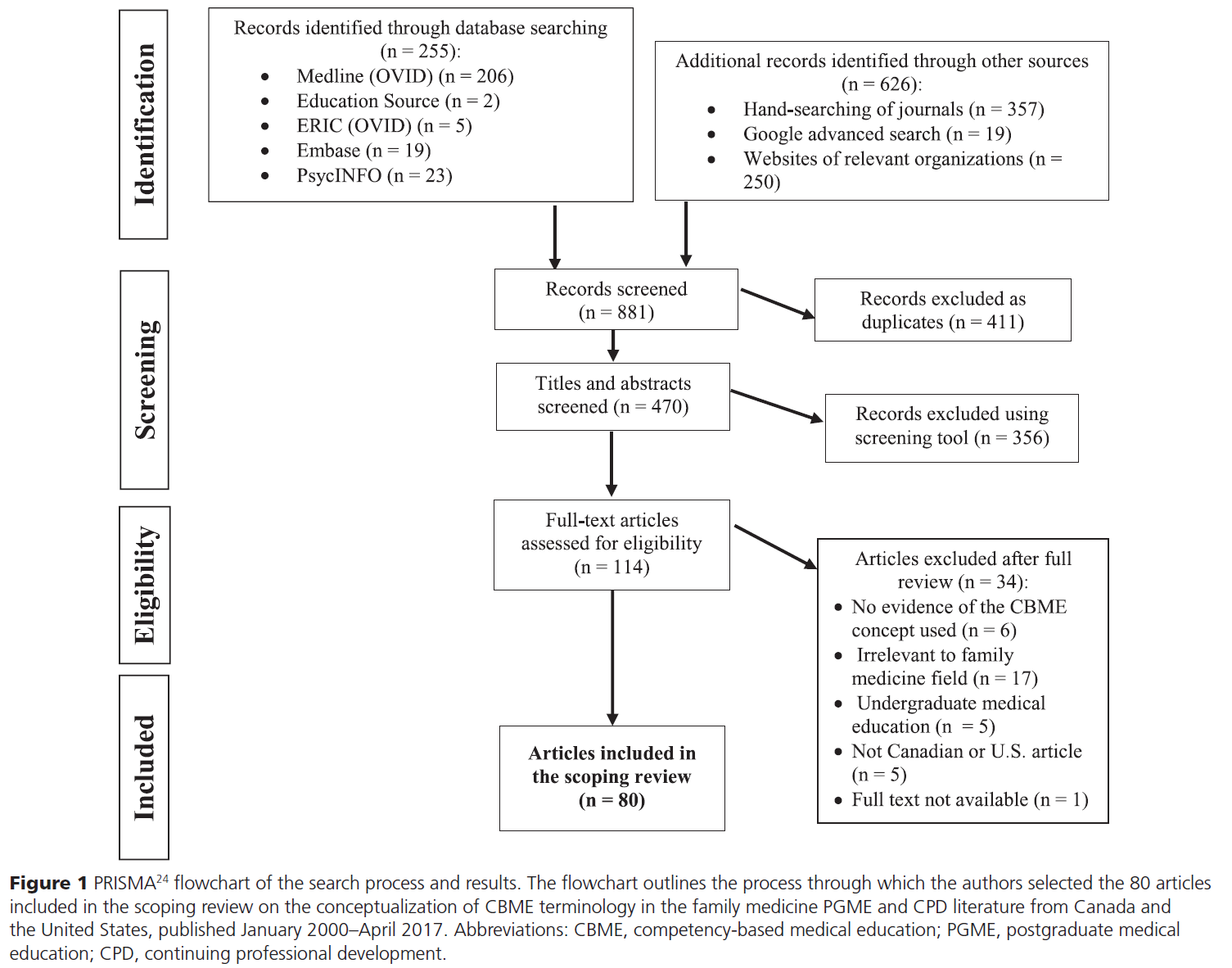

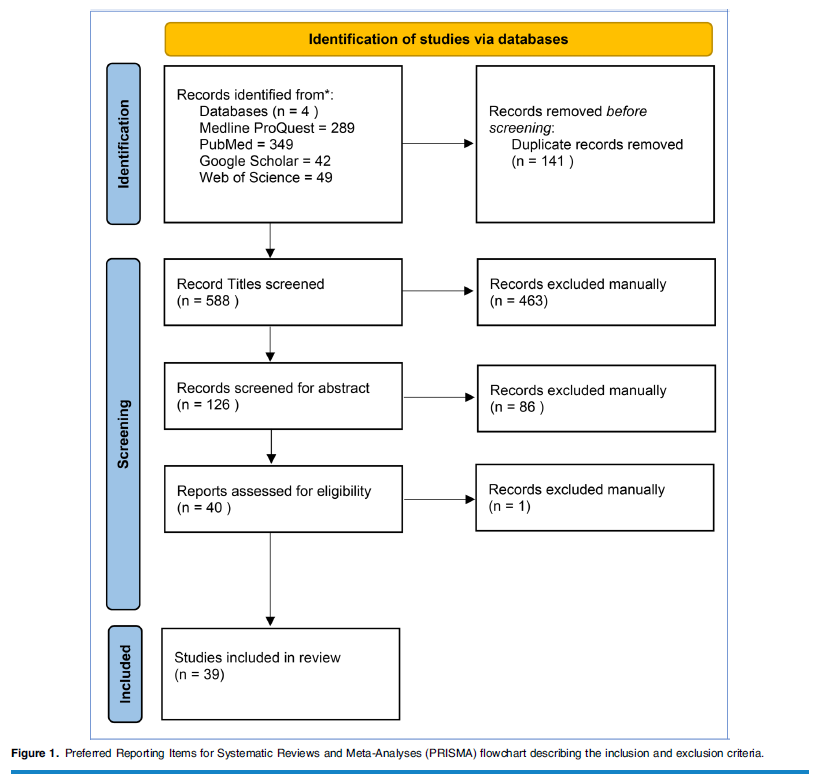

반복적인 프로세스를 사용하여 5개의 전자 서지 데이터베이스 및 플랫폼(PubMed, Embase, ERIC, Web of Science, Google Scholar)과 광범위한 월드 와이드 웹(Google 사용)에서 의학교육에 적용 가능한 사회적 책무성 프레임워크와 동료 평가 저널 논문 및 문서를 검색했습니다. 이러한 검색은 영어 문서로 제한되었습니다. 검색은 2018년 10월에 처음 수행된 후 2019년 3월 31일에 최신 문서를 포함하기 위해 반복되었습니다. 검색 전략에 사용된 키워드에는 사회적 책무성 또는 책임, 사회적 책무성 또는 책임, 사회 정책 등이 포함되었습니다. 이러한 단어는 의학교육, 의과대학, 의료 수련 프로그램, 보건 전문직 교육 주제 제목 용어와 함께 검색되었습니다. 데이터베이스 검색 전략 샘플은 부록 디지털 부록 1에 제공됩니다.

Using an iterative process, we searched 5 electronic bibliographic databases and platforms (PubMed, Embase, ERIC, Web of Science, and Google Scholar) as well as the broader World Wide Web (using Google) for social accountability frameworks and peer-reviewed journal articles and documents applicable to medical education. These searches were limited to English-language documents. The searches were first conducted in October 2018 and then repeated on March 31, 2019, to include any more recent documents. Keywords used in the search strategies included social accountability OR responsibility, socially accountable OR responsible, and social policies. These words were searched in combination with medical education, medical schools, medical training programs, and health professions education subject heading terms. A sample database search strategy is provided in Supplemental Digital Appendix 1 at https://links.lww.com/ACADMED/B24.

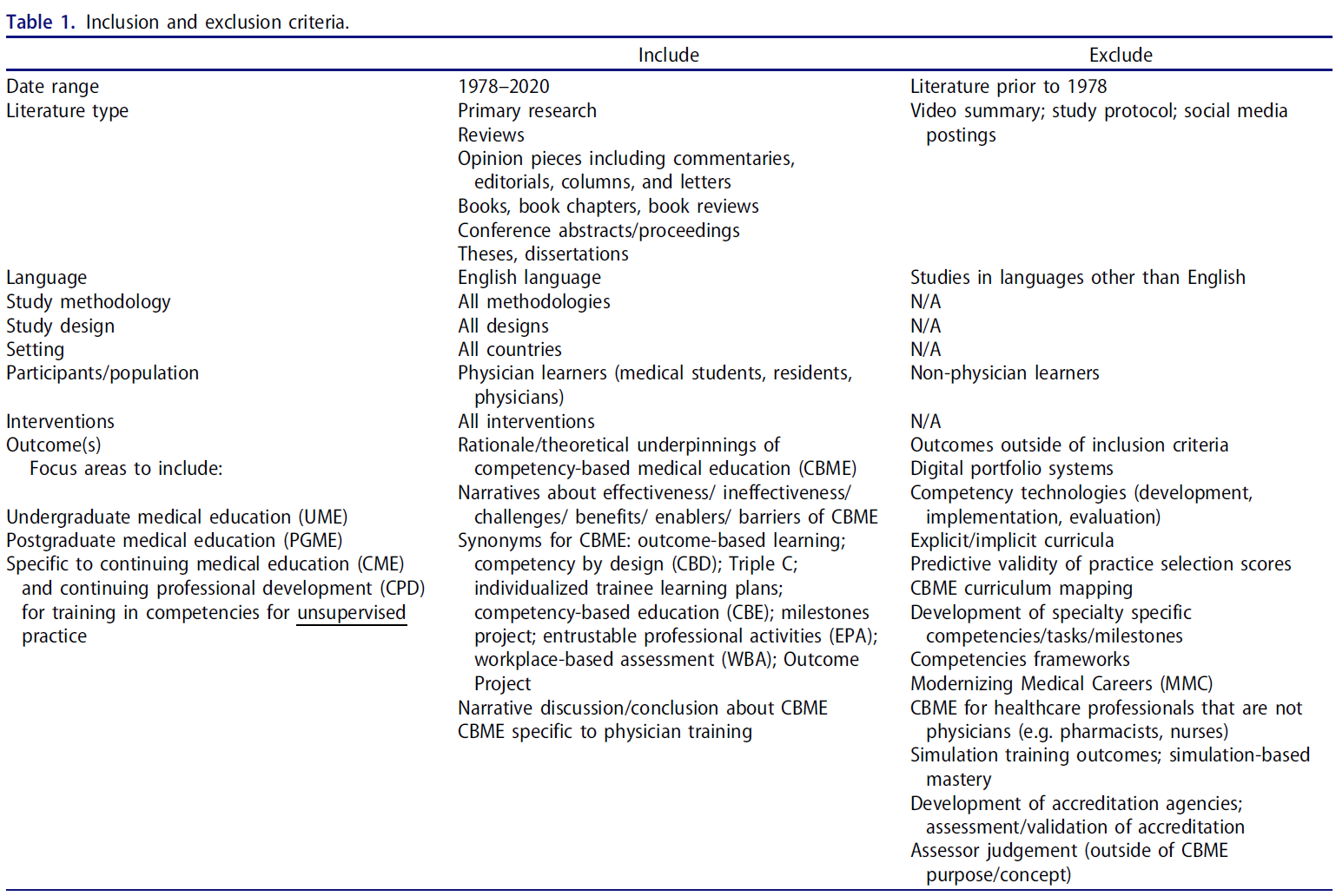

포함 및 제외 기준

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

저희는 의과대학의 사회적 책무성에 초점을 맞추었습니다. 1990년(사회적 책무성이라는 용어가 의학교육 문헌에 명시적으로 등장한 시기)부터 2019년 3월까지 출판된 주요 영어 정책 프레임워크와 동료 검토 문서가 포함 대상에 포함되었습니다. 사회적 책무성 프레임워크에 대해 논의하지 않은 문서는 제외되었습니다. 검색에서 확인된 모든 문서는 연구팀의 포함 여부 검토 과정을 거쳤습니다. 저자 중 두 명(C.B., S.C.)이 검색에서 확인된 모든 문서를 선별했습니다. 전체 연구팀은 수시로 만나 문서를 검토하고 자격 요건에 관한 합의를 도출했습니다. 의과대학이 사회적 책무를 다하기 위해 노력할 수 있는 기본 가치, 원칙 및/또는 매개변수를 나타내고 사회적 책무를 개념화하기 위해 후속 논문에서 사용된 주요 출처의 사회적 책무 프레임워크가 검토에 포함되었습니다. 하위 프레임워크 및/또는 프로그램 또는 기관별 문서는 이전에 확립된 프레임워크를 기반으로 구축되어 일반화 가능성이 부족할 수 있으므로 제외되었습니다.

Our focus was social accountability in medical schools. Key English-language policy frameworks and peer-reviewed documents published from 1990 (when the term social accountability explicitly emerged within the medical education literature) through March 2019 were eligible for inclusion. Documents that did not discuss social accountability frameworks were excluded. All documents identified in the searches underwent an inclusion review process by the research team. Two of the authors (C.B. and S.C.) screened all documents identified in the searches. The full research team met frequently to review the documents and come to consensus regarding eligibility requirements. Primary source social accountability frameworks which represented the foundational values, principles, and/or parameters of the attributes medical schools can strive toward to fulfill their social mandate and which were used in subsequent papers to conceptualize social accountability were included in the review. Subframeworks and/or program- or institution-specific documents were excluded as these built upon previously established frameworks and could lack generalizability.

분석

Analysis

주제별 종합41-44은 포함된 사회적 책무성 프레임워크 전반에 걸쳐 공통 요소와 고유 요소를 설명하는 데 사용되었습니다. 주제 종합은 귀납적 접근법을 사용하여 텍스트를 체계적으로 코딩하여 주제를 생성하는 것입니다.43,44 3단계 분석 프로세스는

- 텍스트의 줄별 코딩으로 시작하여,

- CIPP 모델의 4가지 차원을 조직적 프레임워크로 사용하여 특성화한 설명적 주제를 개발한 다음

- 분석적 주제를 생성하는 것으로 이어집니다.

저자 중 두 명(C.B. 및 S.C.)이 포함된 문서를 독립적으로 코딩했습니다. 결과물은 두 명의 코더가 검토하고 코딩의 정확성과 포괄성을 보장하기 위해 합의에 도달할 때까지 연구팀 내에서 논의했습니다.

Thematic synthesis41–44 was used to describe common and unique elements across the included social accountability frameworks. Thematic synthesis involves the systematic coding of text using an inductive approach to generate themes.43,44 The 3-stage analytical process starts with

- line-by-line coding of text;

- followed by the development of descriptive themes, which we characterized using the 4 dimensions of the CIPP model as an organizational framework; and

- then the generation of analytical themes.

Two of the authors (C.B. and S.C.) coded the included documents independently. Resulting themes were reviewed by the 2 coders and discussed within the research team until consensus was reached to ensure coding accuracy and inclusivity.

결과

Results

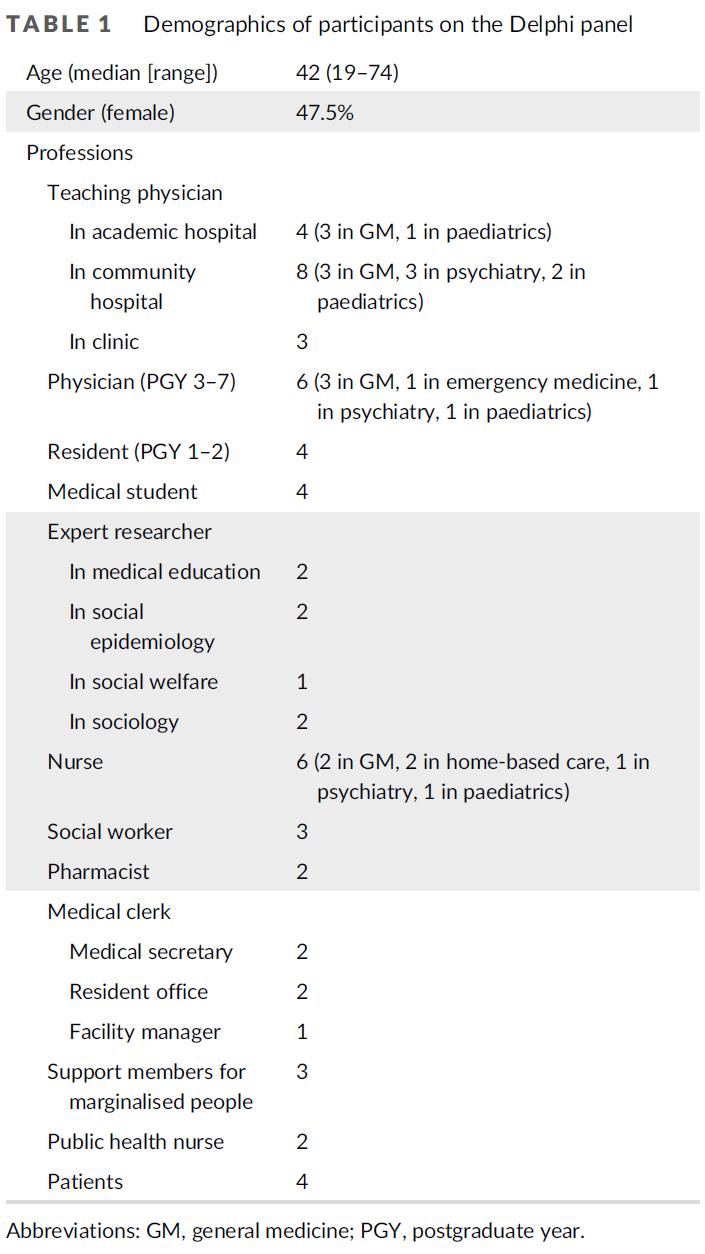

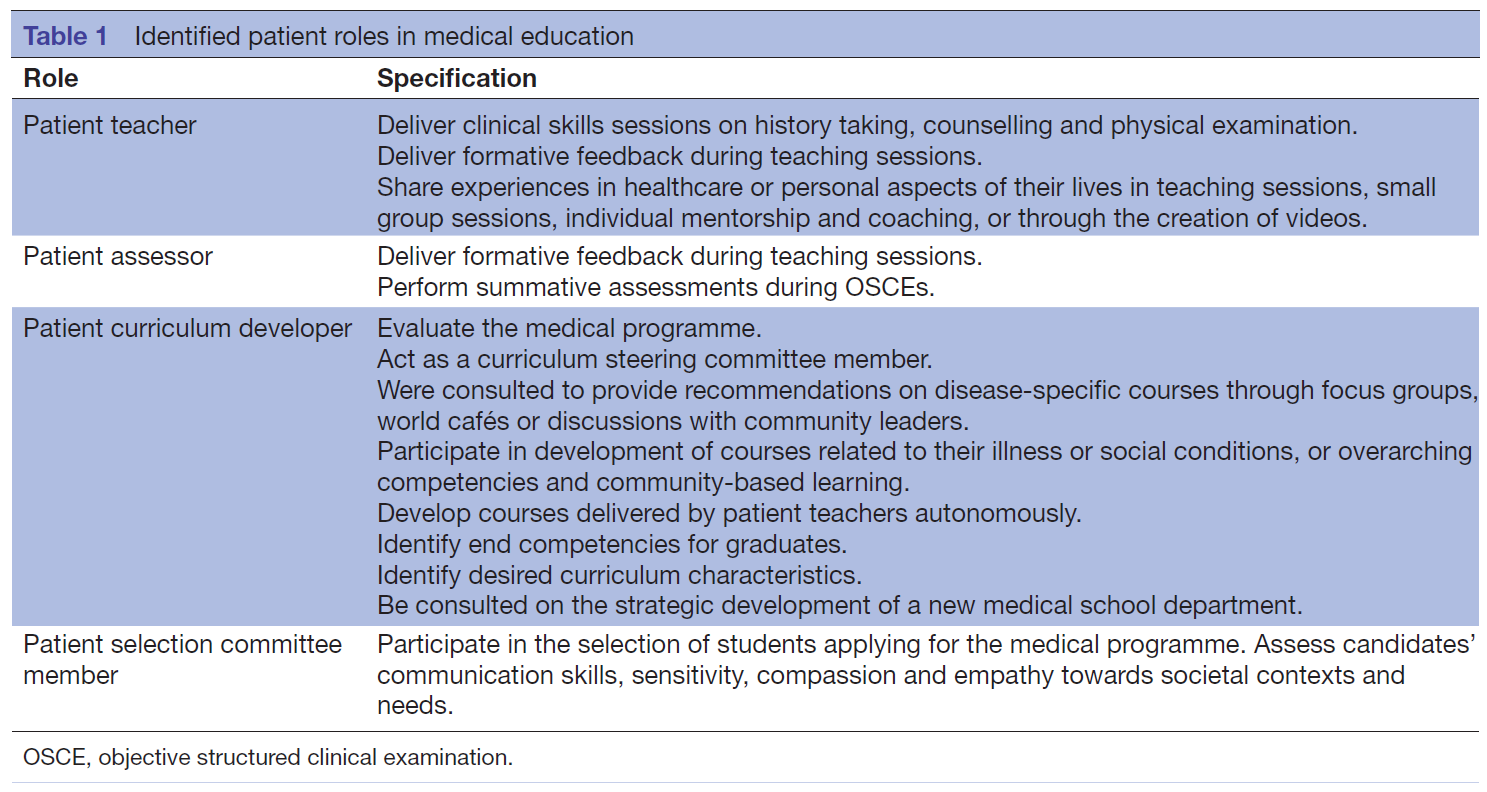

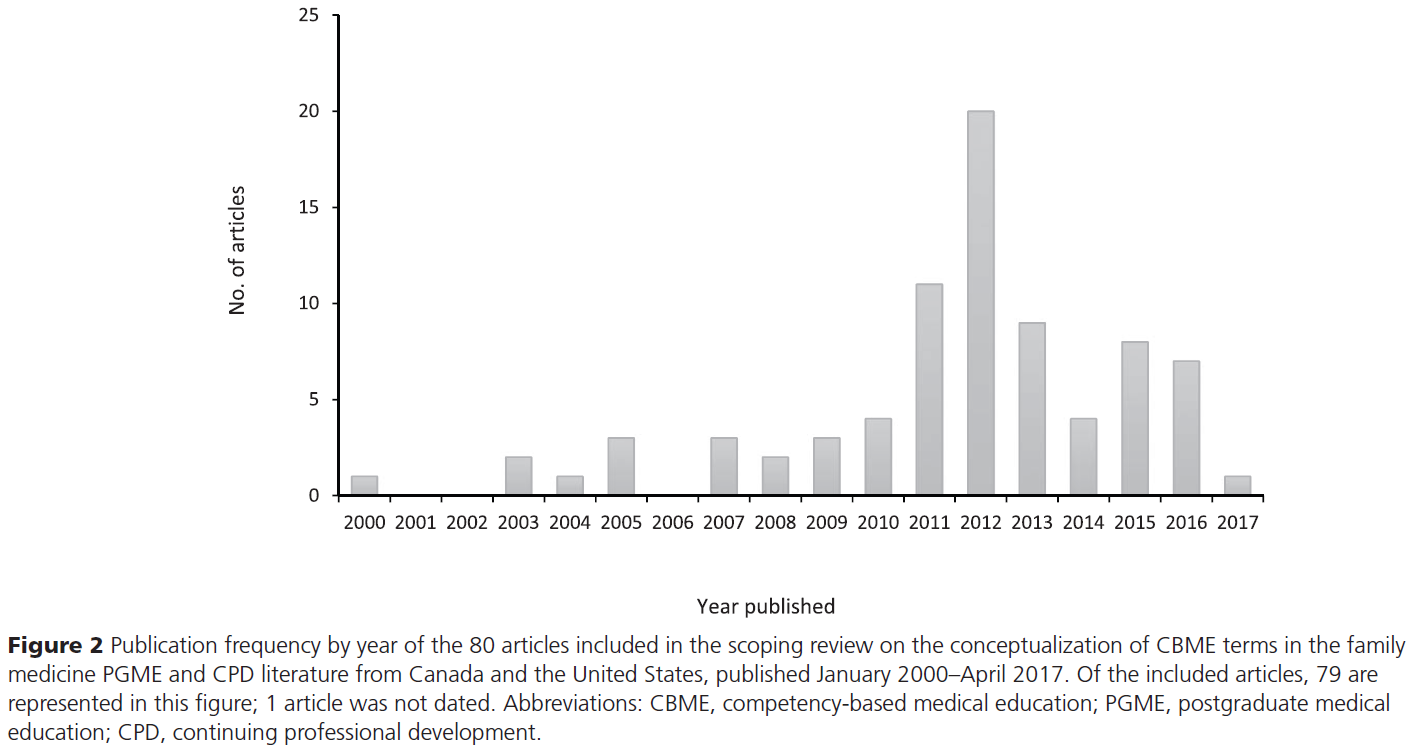

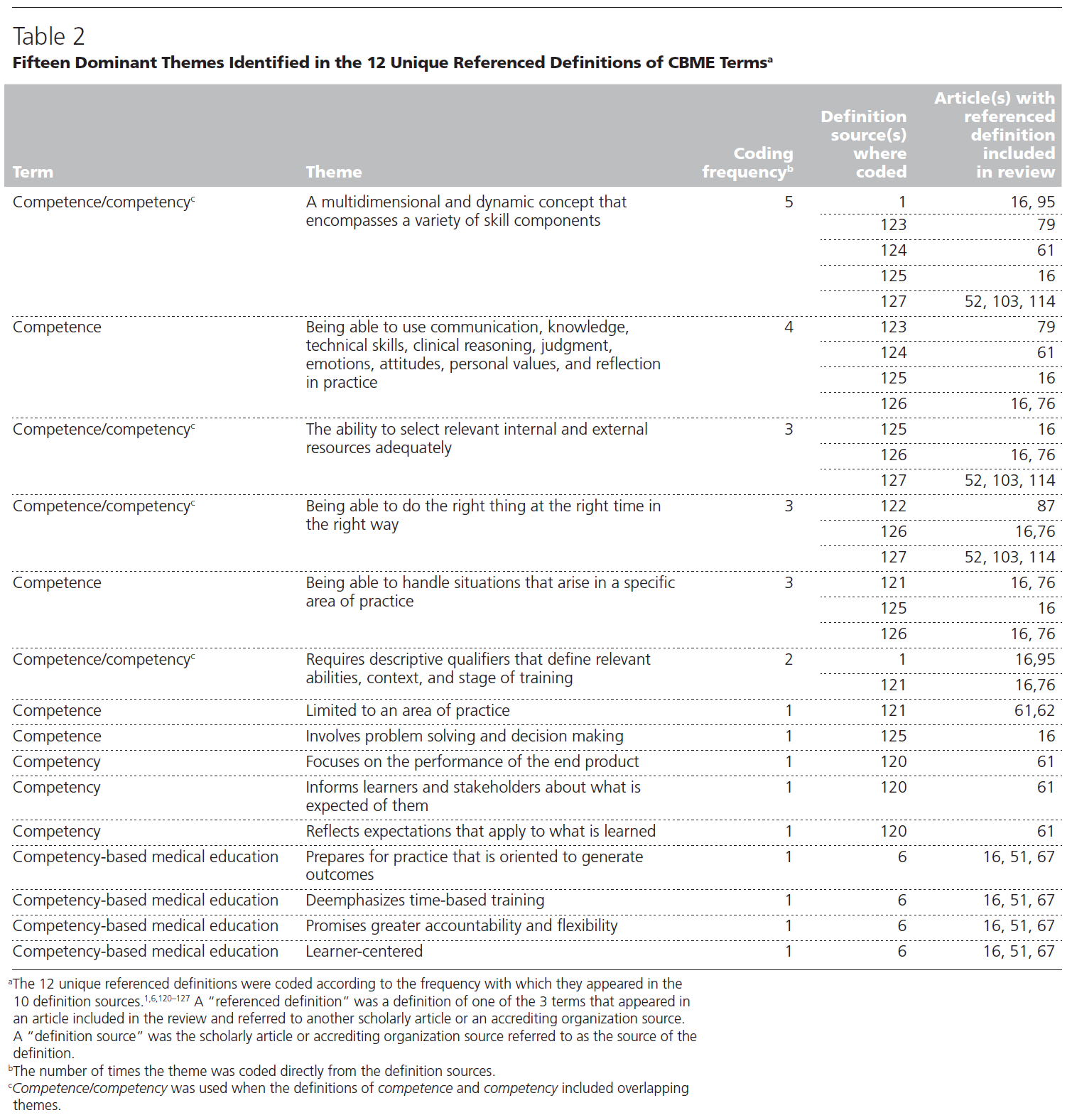

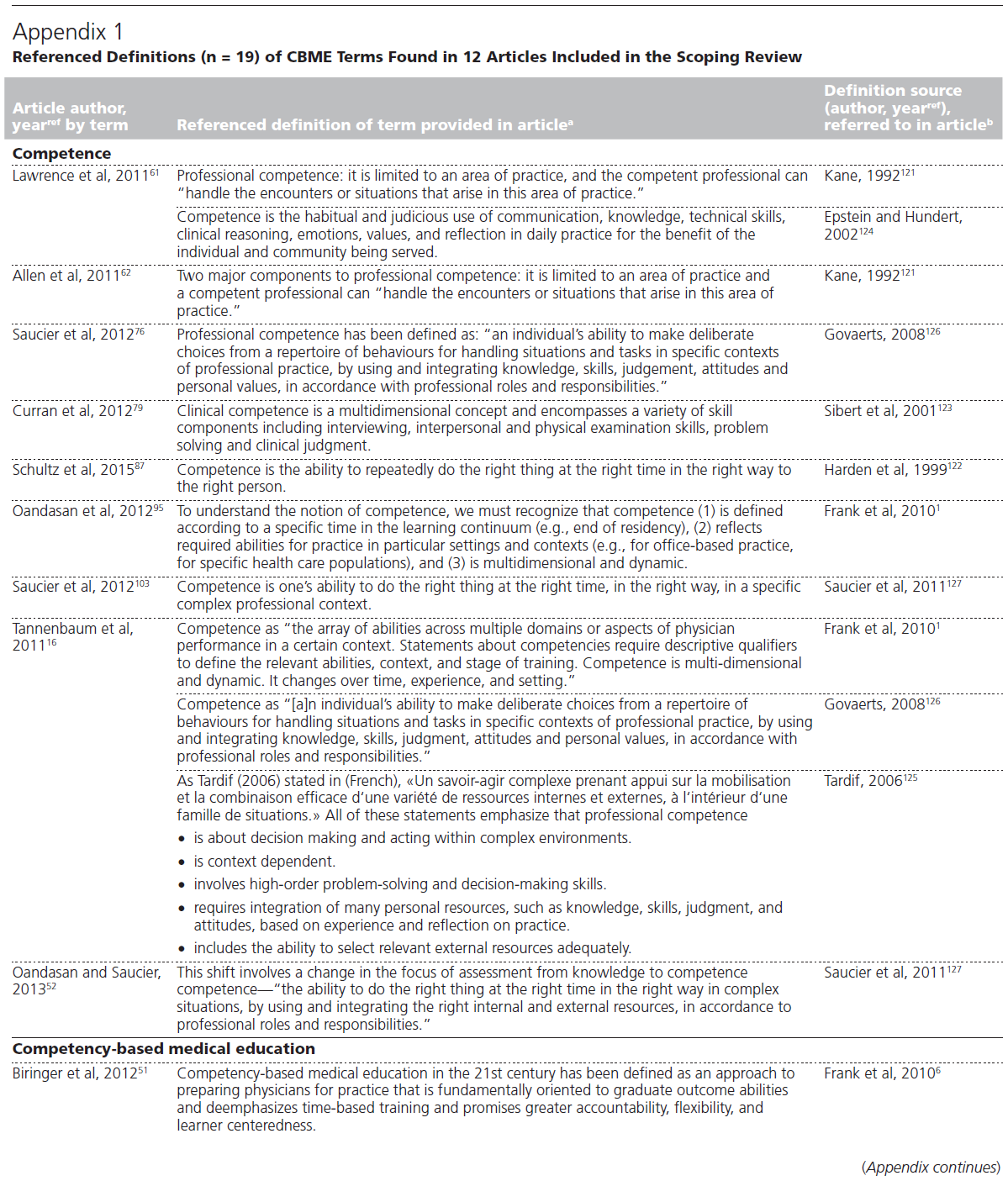

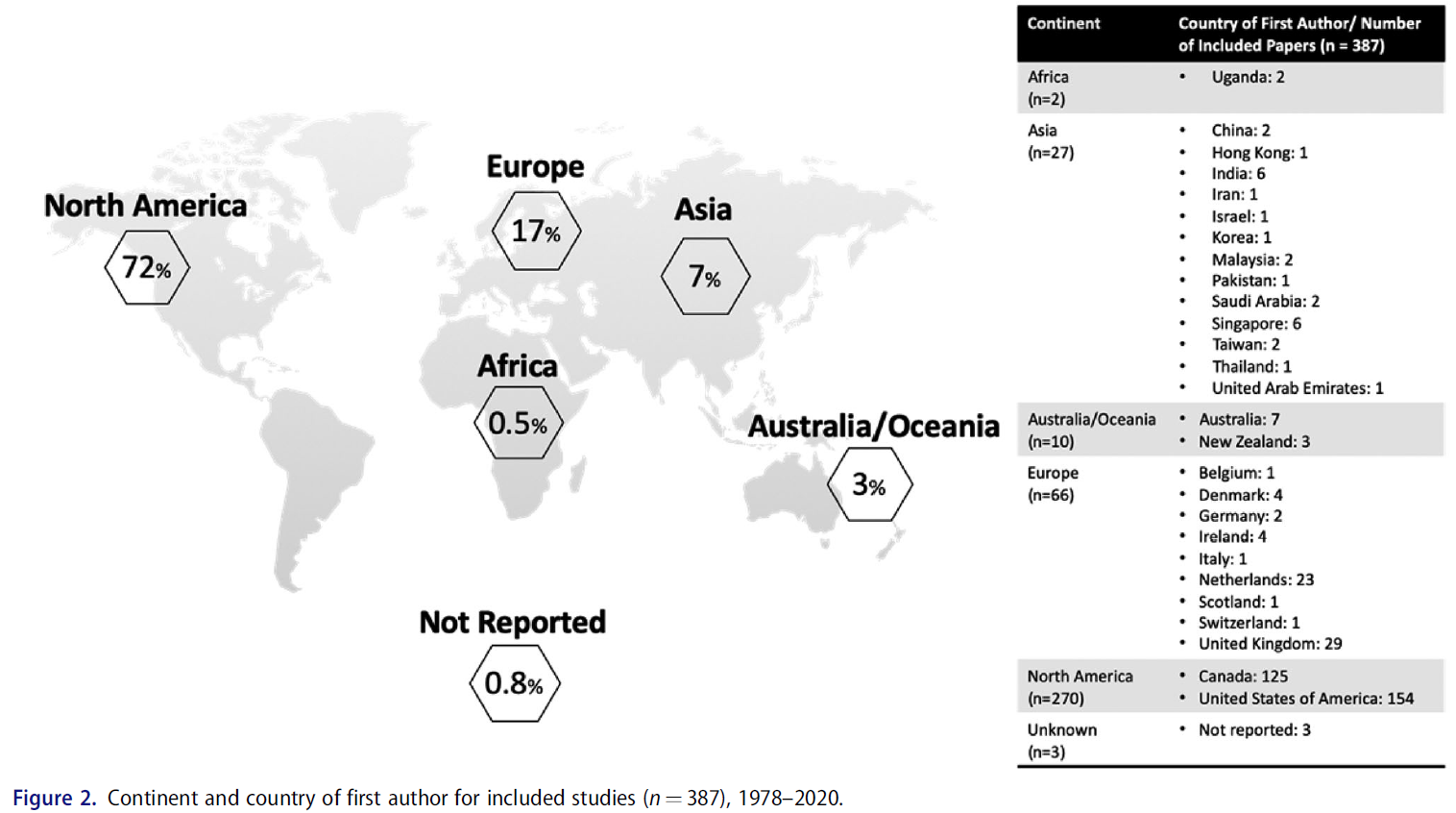

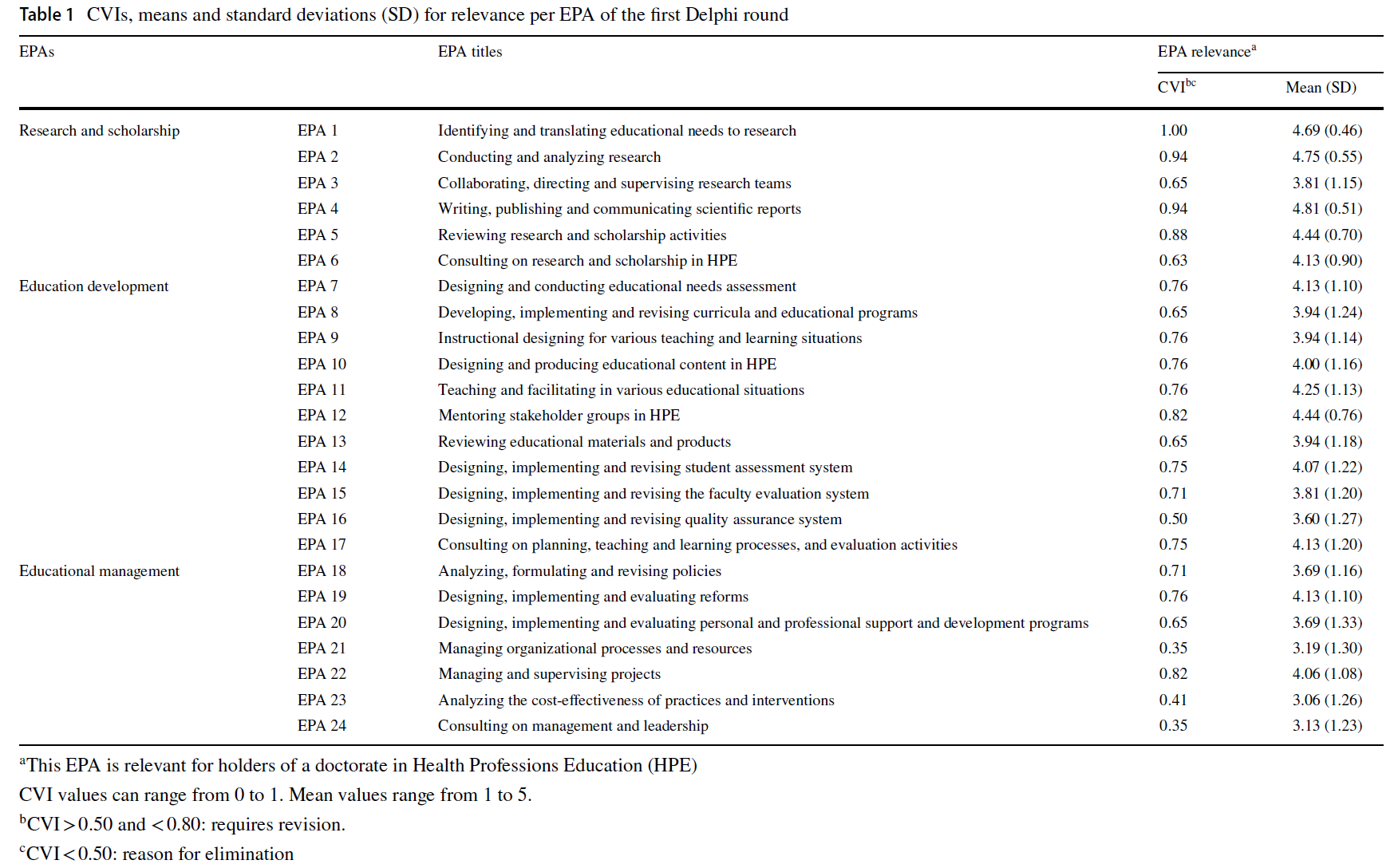

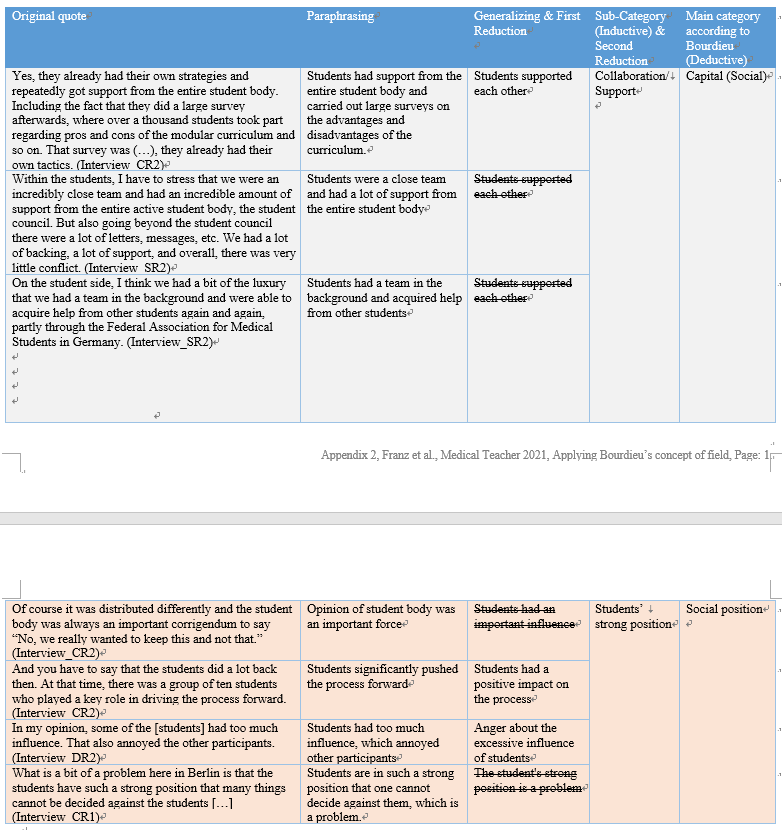

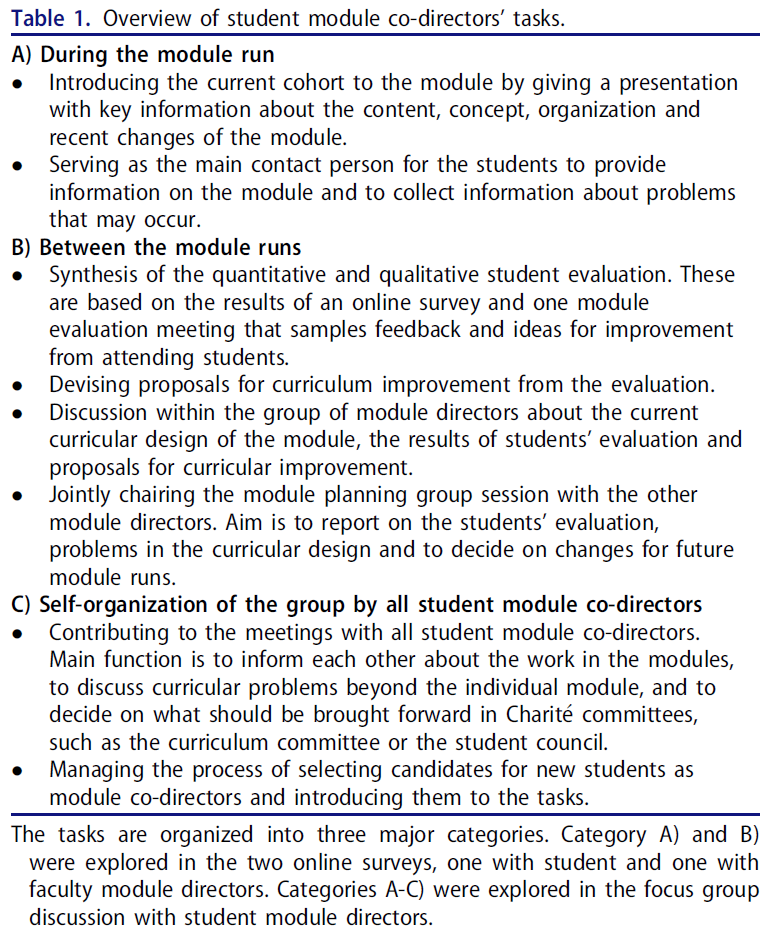

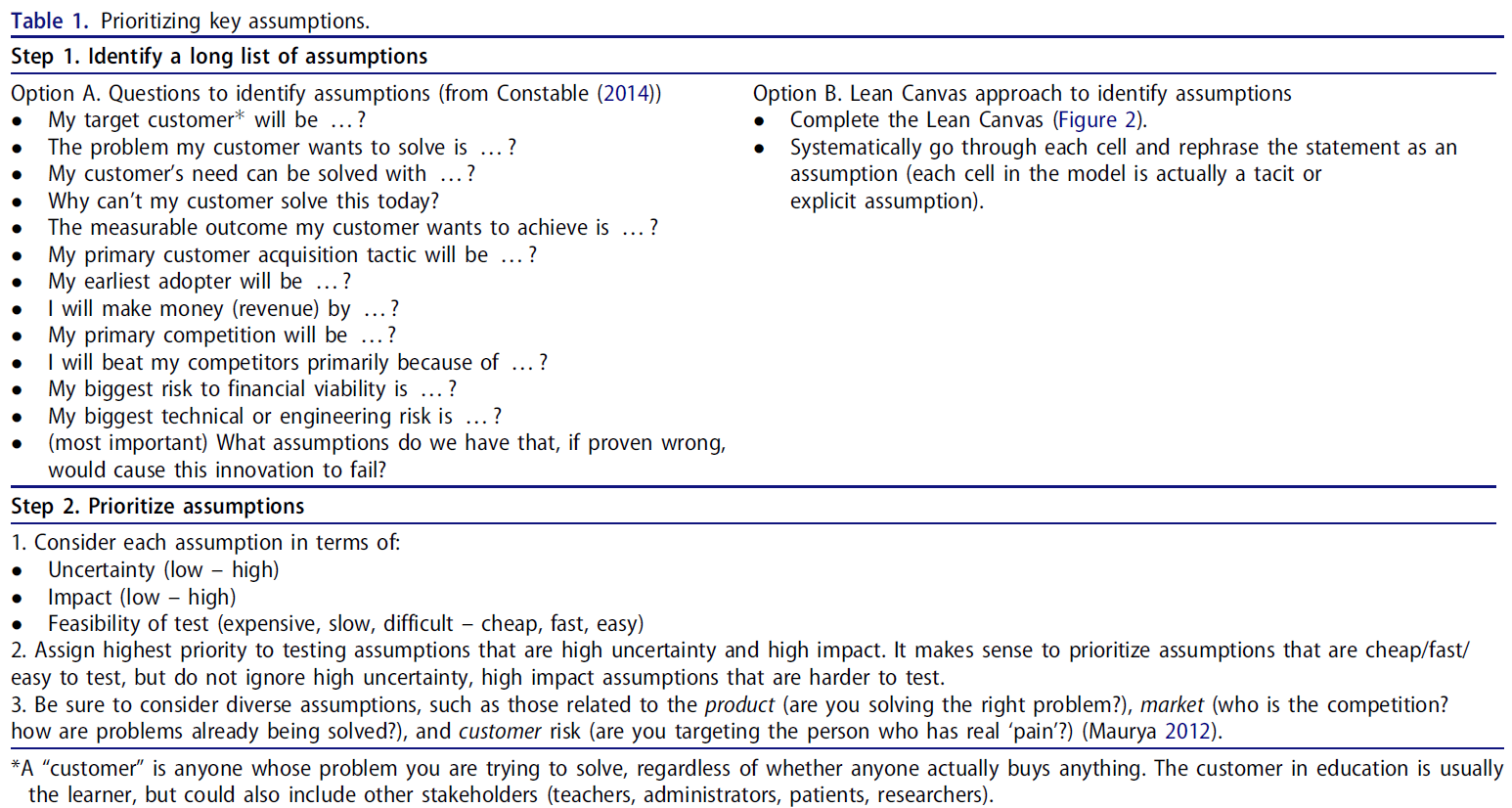

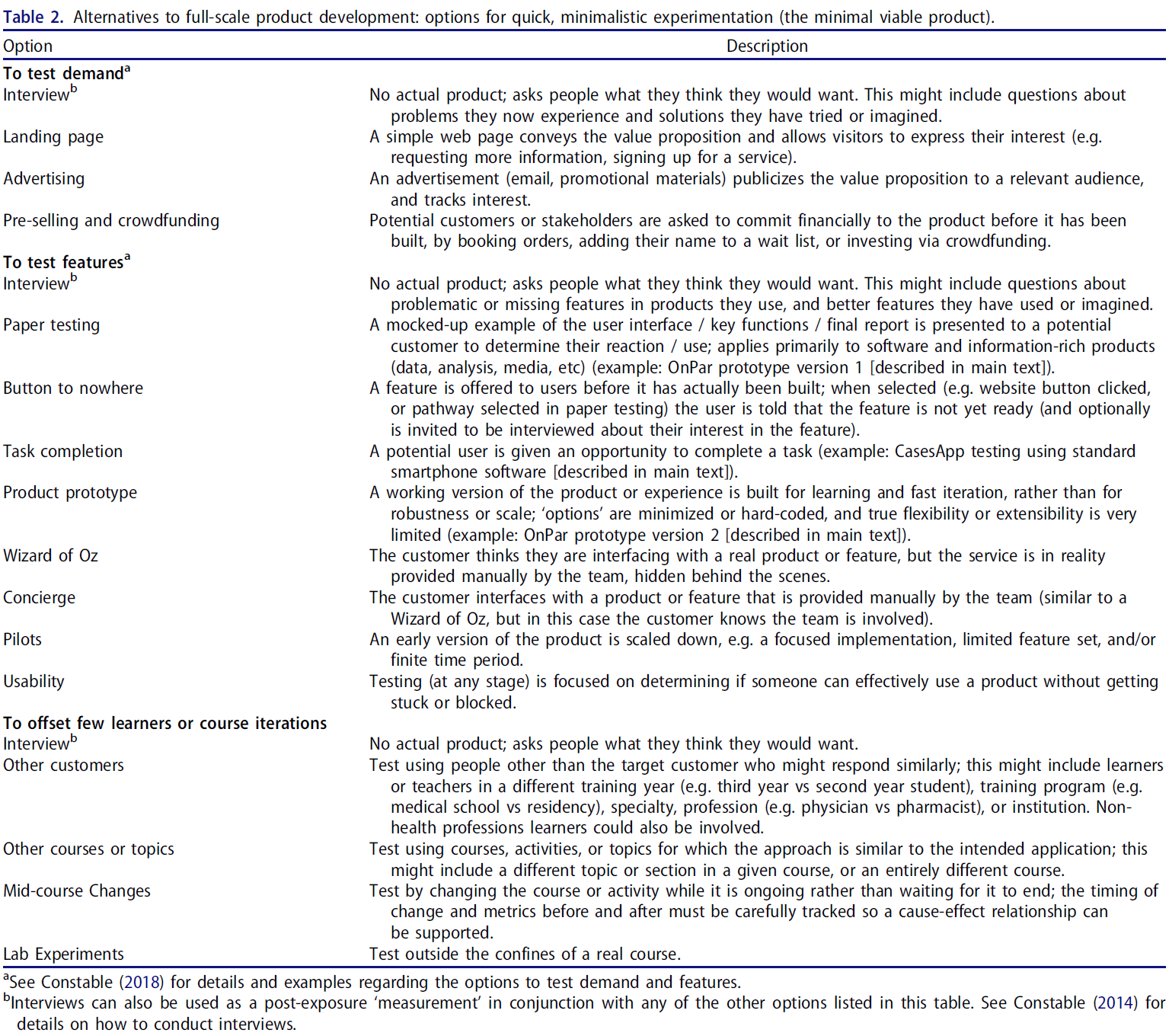

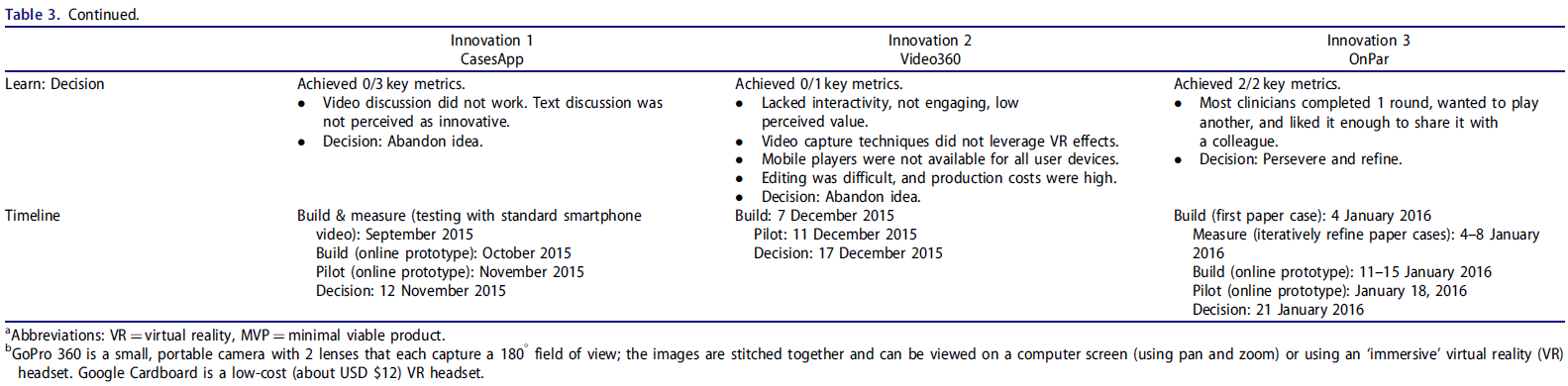

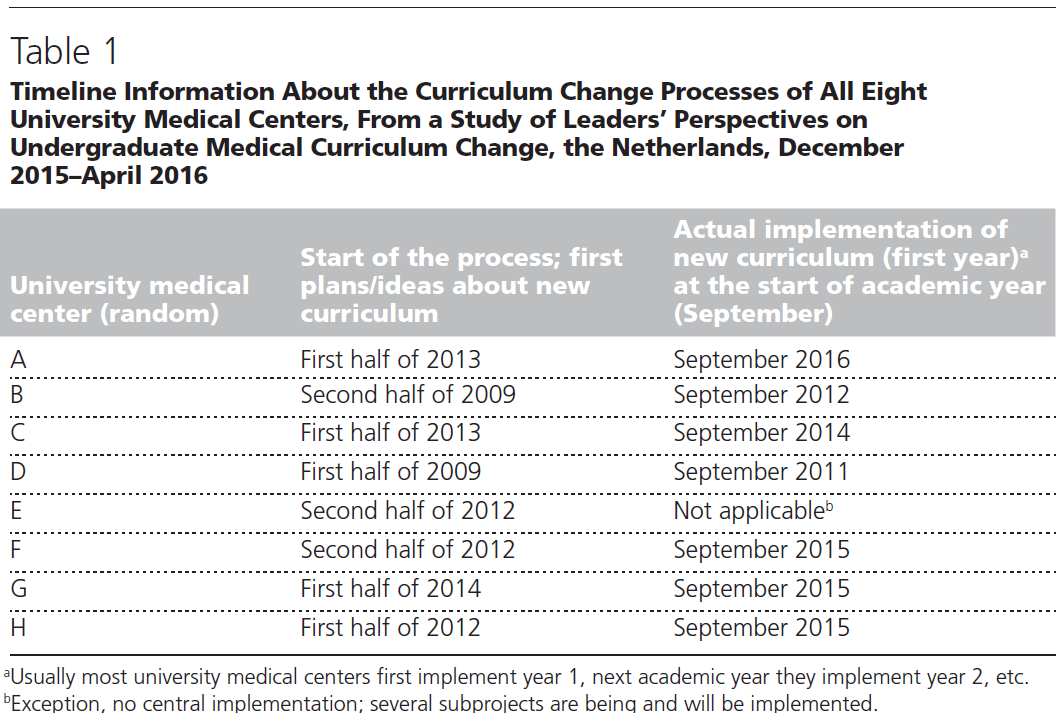

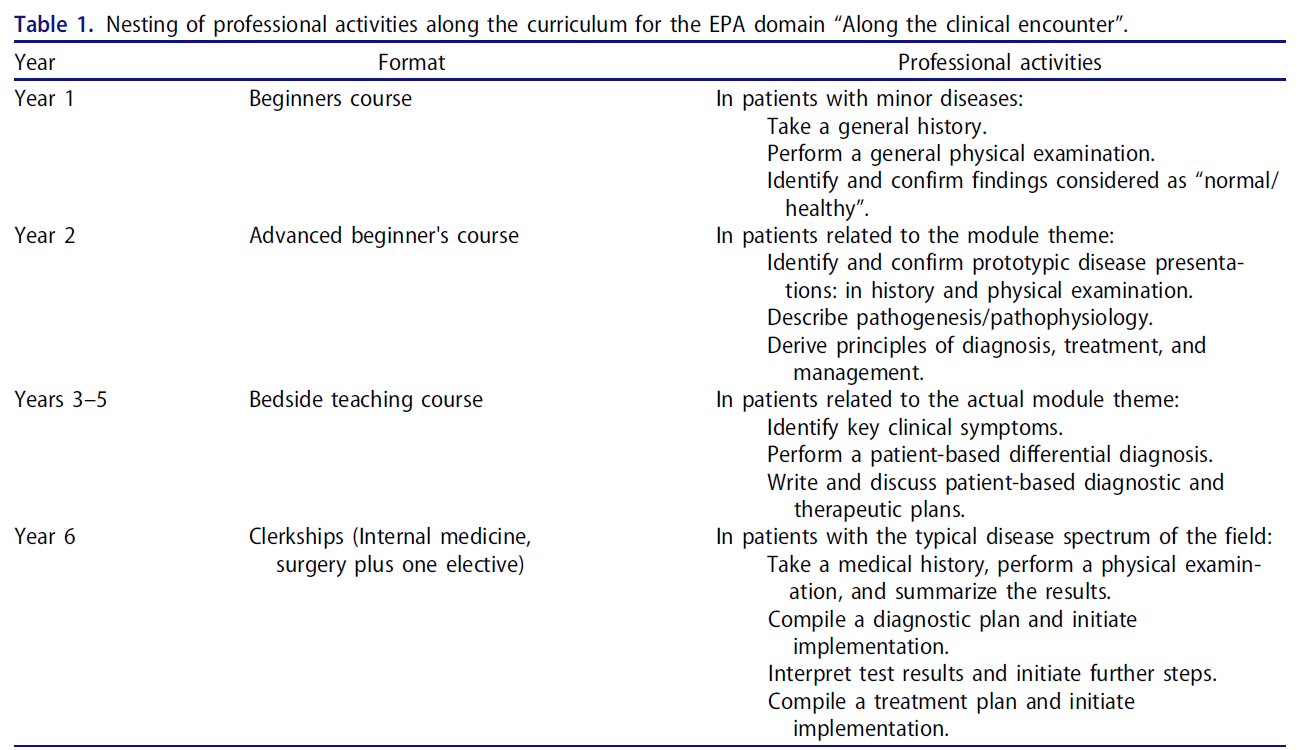

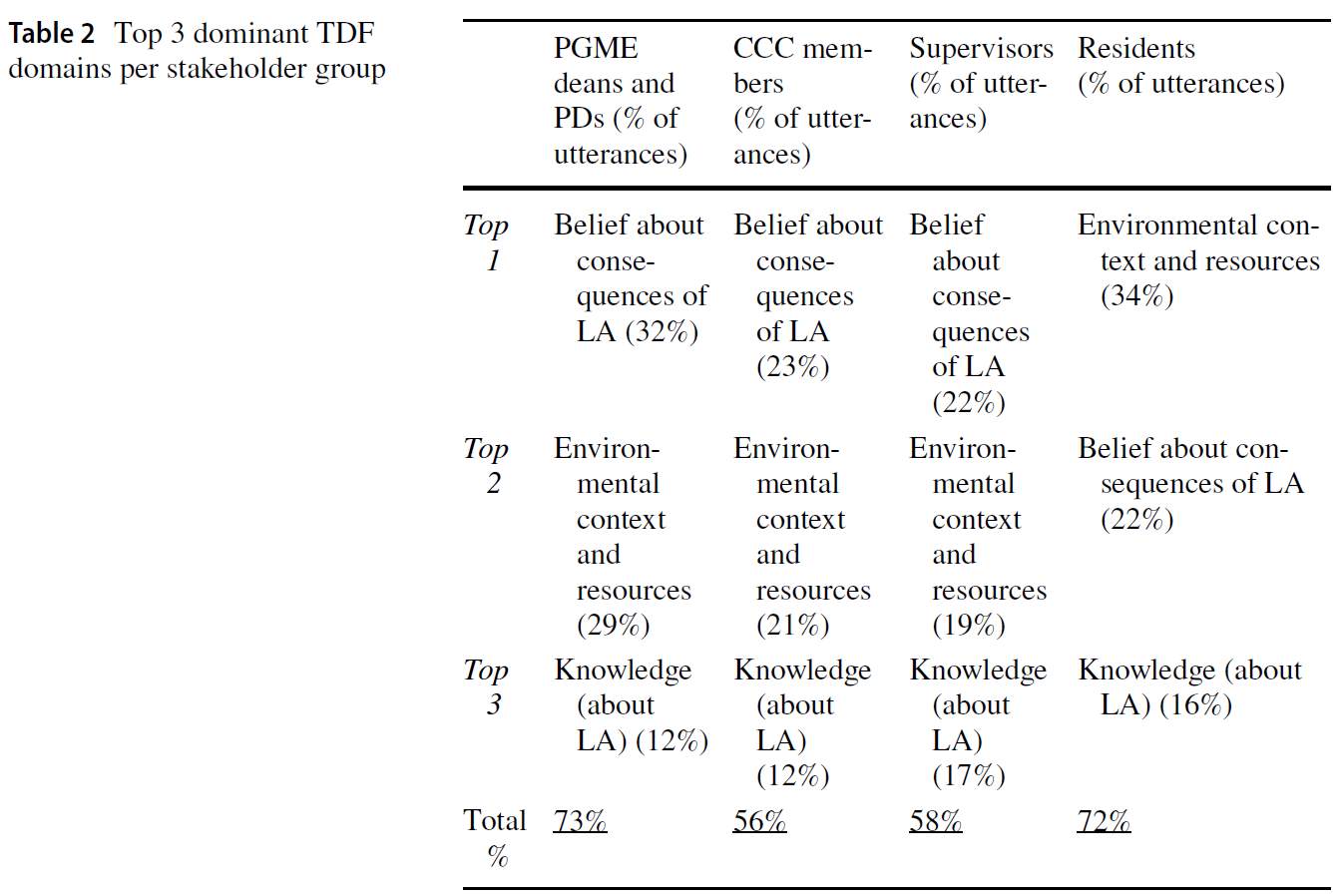

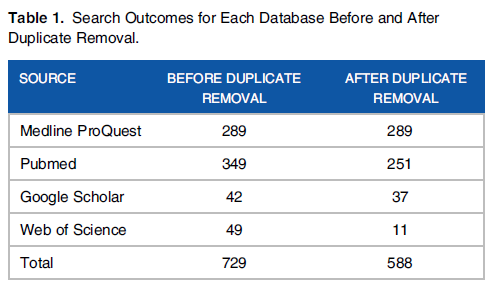

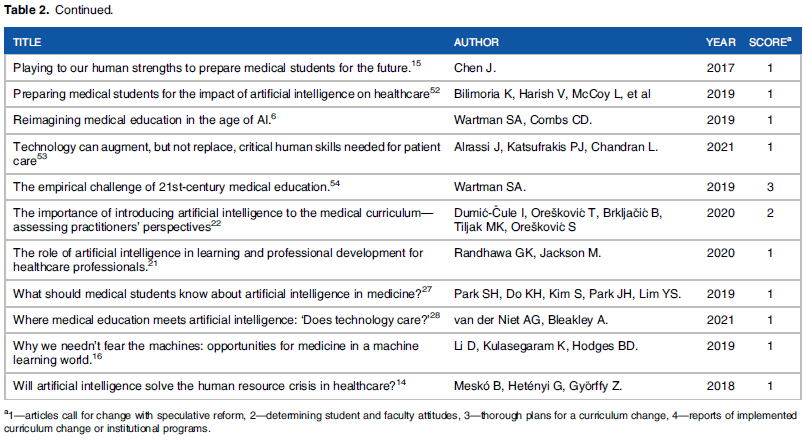

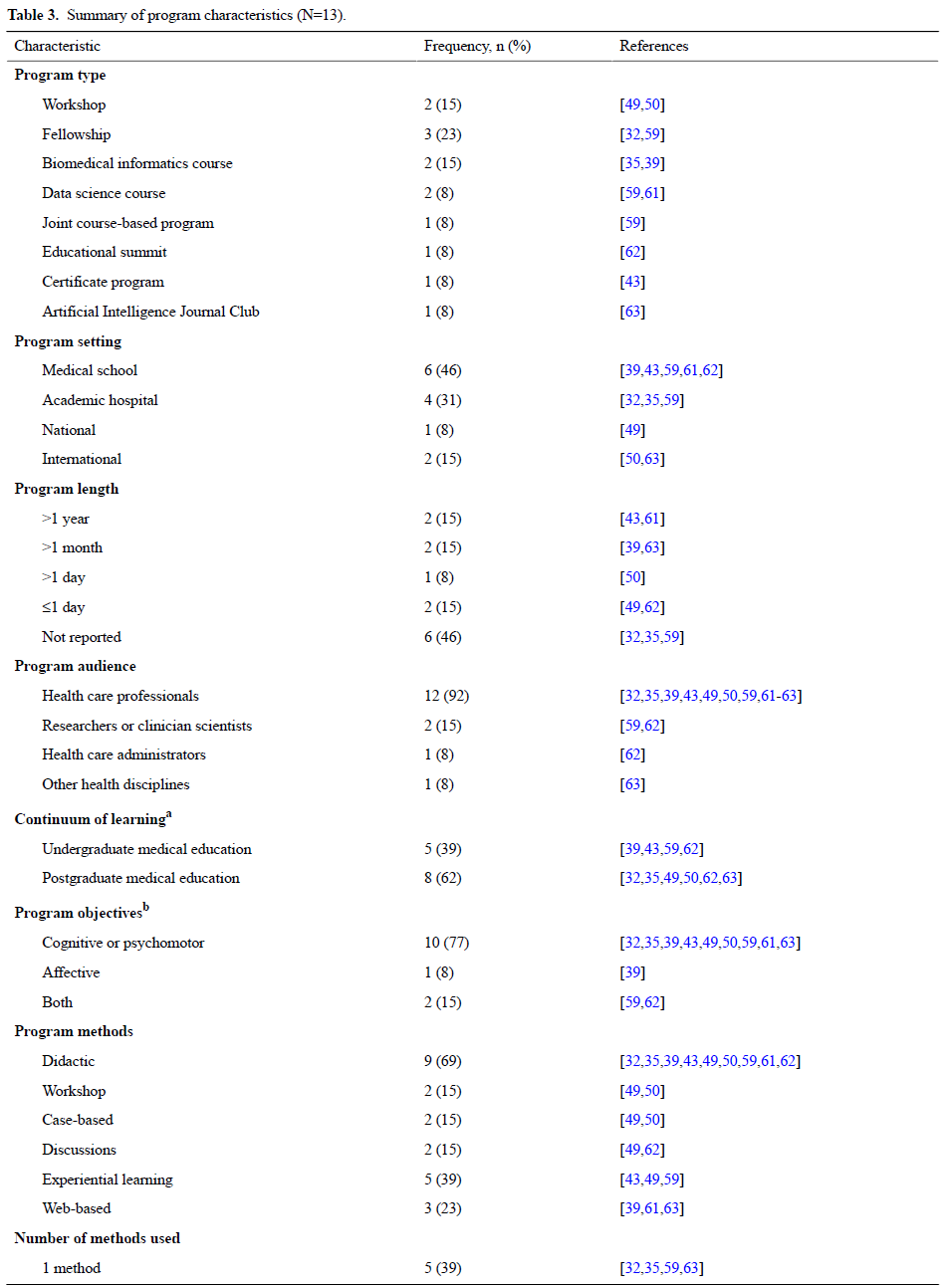

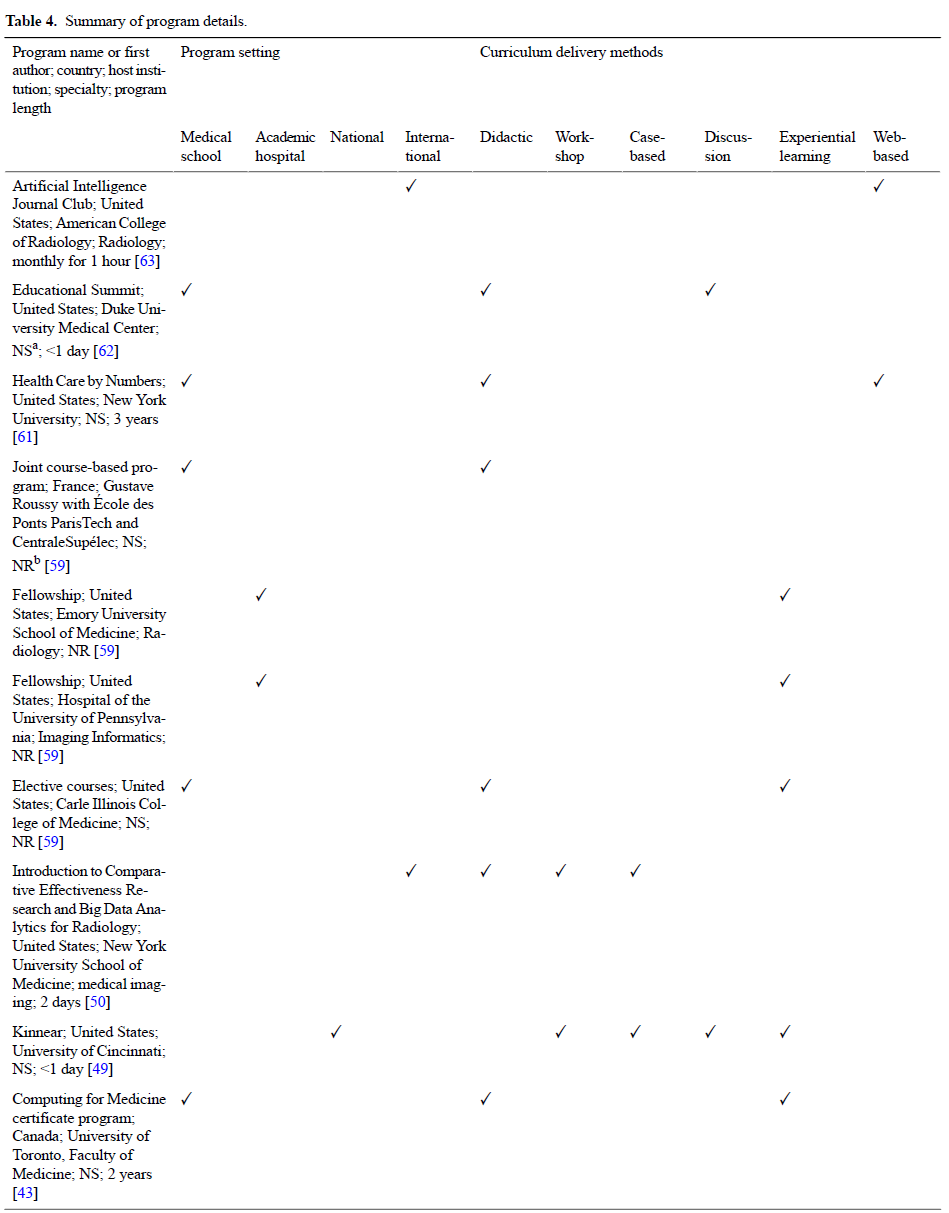

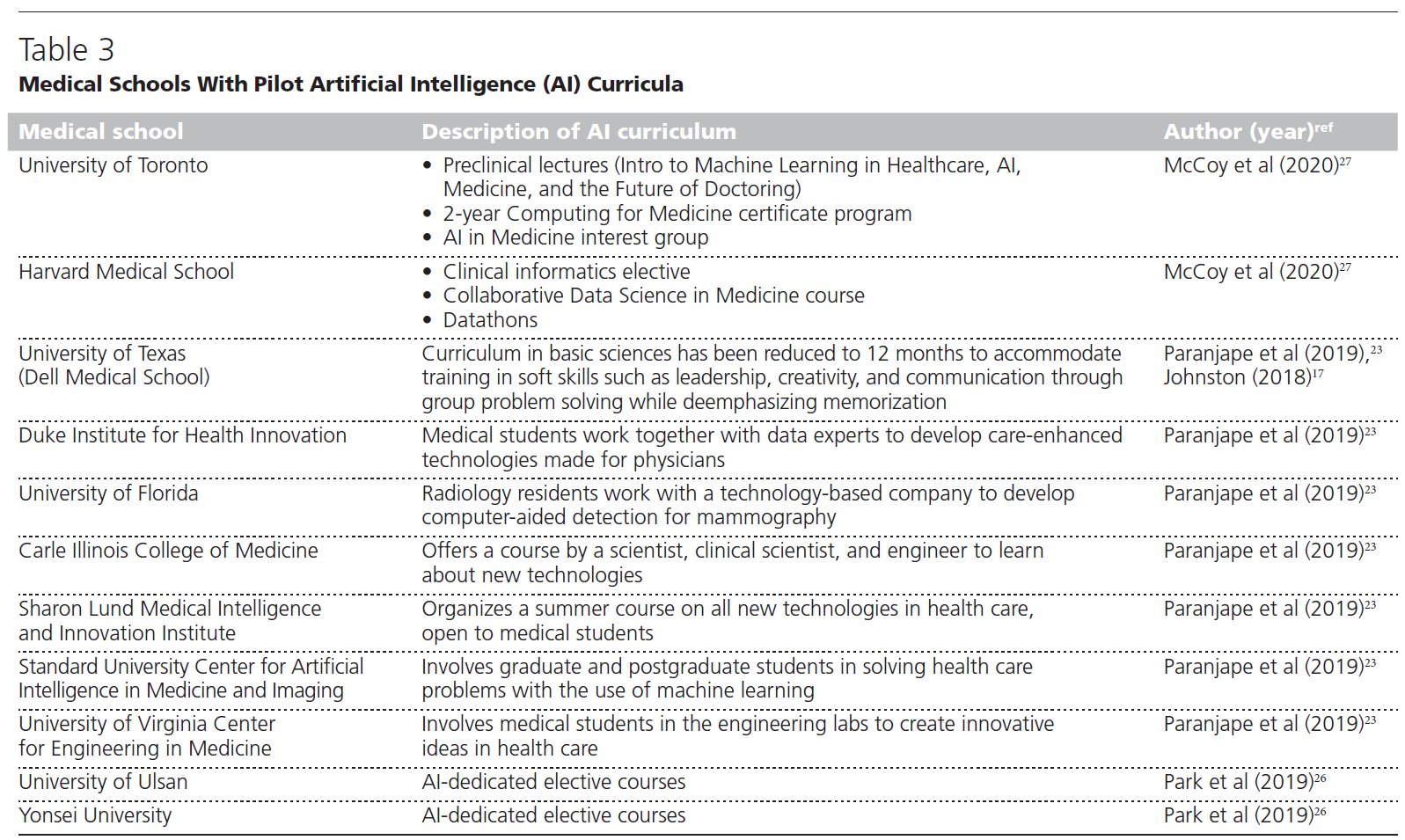

33개의 초기 샘플 문서3,16,18-20,23,44-70에서 4개의 주요 대규모 사회적 책무성 정책 프레임워크3,16,18,19를 선정하여 검토에 포함시켰습니다(선정된 프레임워크의 개요는 표 1 참조). 이 4개의 주요 출처 문서는 의학교육에서 사회적 책무성의 기본 가치, 원칙 또는 매개변수를 나타냅니다. 또한 이 문서들은 모두 사회적 책무성을 개념화하기 위한 후속 논문에서 많이 인용되고 사용되었습니다. 또한 건강 형평성을 위한 교육 네트워크 평가 프레임워크47 및 다양한 기관별 교육, 연구, 서비스 활동의 정보로도 사용되었습니다.

From the initial sample of 33 documents,3,16,18–20,23,44–70 we selected 4 key large-scale social accountability policy frameworks3,16,18,19 for inclusion in the review (see Table 1 for an overview of the selected frameworks). These 4 primary source documents represent the foundational values, principles, and/or parameters of social accountability in medical education. Additionally, these documents have all been highly cited and used in subsequent papers to conceptualize social accountability. They were also used to inform the Training for Health Equity Network evaluation framework47 as well as various institution-specific education, research, and service activities.

이러한 프레임워크에는 지역, 국가 및 국제 수준에서 사회적 책무성에 대한 정책, 정의, 적용 및 평가가 포함됩니다.71 이러한 프레임워크는 조금씩 다르지만 모두 [사회적 책무성을 입증하는 데 사용할 수 있는 특성]을 설명합니다. 공통점으로는

- 지역 공중보건 수요에 대응하고,

- 주요 이해관계자와 협력하여 기존 및 향후 사회적 공중보건 수요를 파악하고,

- 주변 지역사회에 봉사하고,

- 의사 부족 문제를 해결하고,

- 지역 인구통계와 지리를 반영하여 입학 과정 내 다양성을 높이고,

- 유능한 의료 전문가를 배출하고,

- 교육과정에 우선적 보건 수요를 반영하는 것 등이 있습니다.3,16,18,19

These frameworks include policy, definition, application, and evaluation of social accountability at the local, national, and international levels.71 Although these frameworks differ slightly, they all describe characteristics that can be used toward demonstrating social accountability. Commonalities include

- responding to local public health needs;

- working alongside key stakeholders in identifying existing and forthcoming societal public health needs;

- servicing surrounding communities;

- addressing physician shortages;

- increasing diversity within the admissions process to reflect local demographics and geography;

- producing competent medical professionals; and

- ensuring the curriculum reflects priority health needs.3,16,18,19

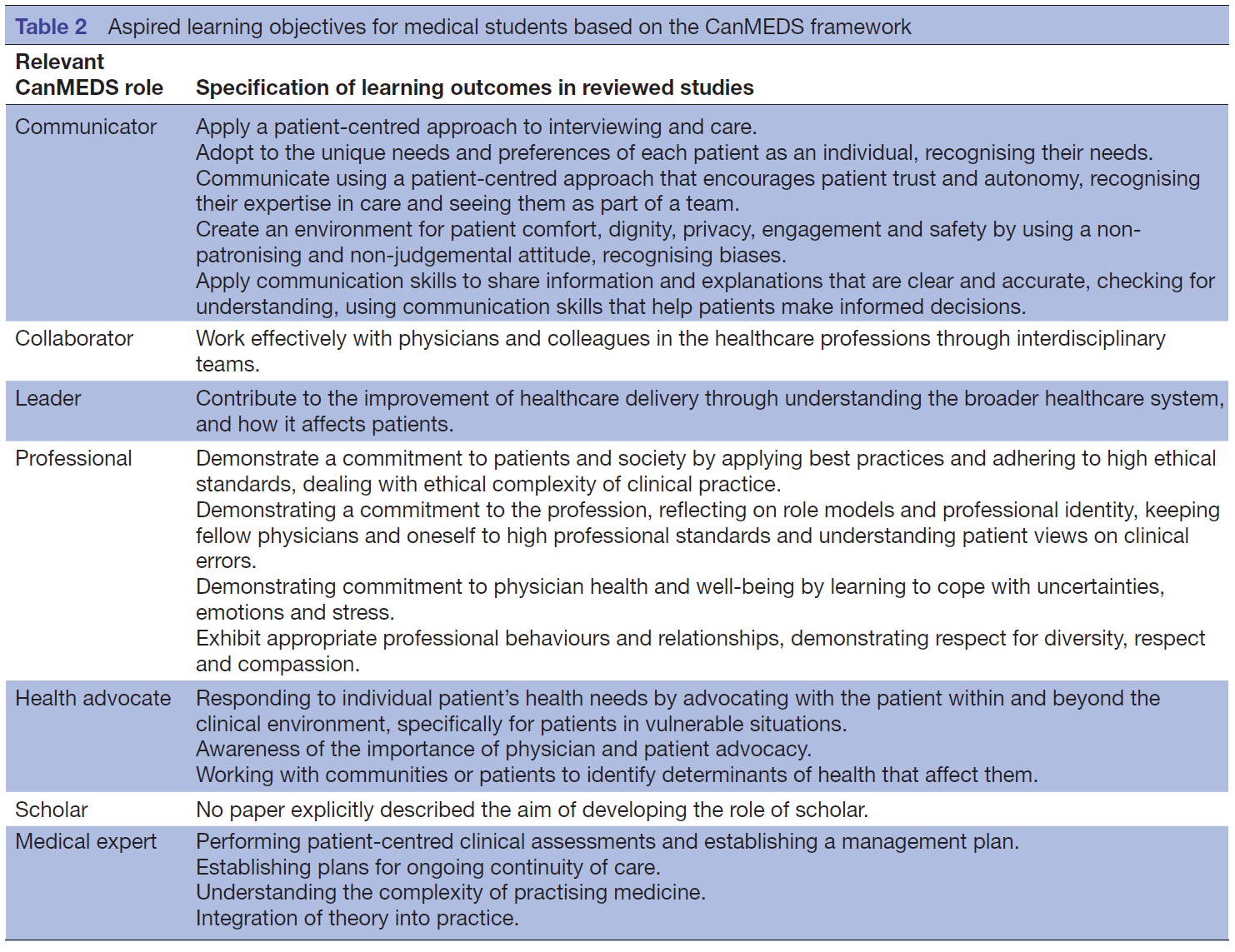

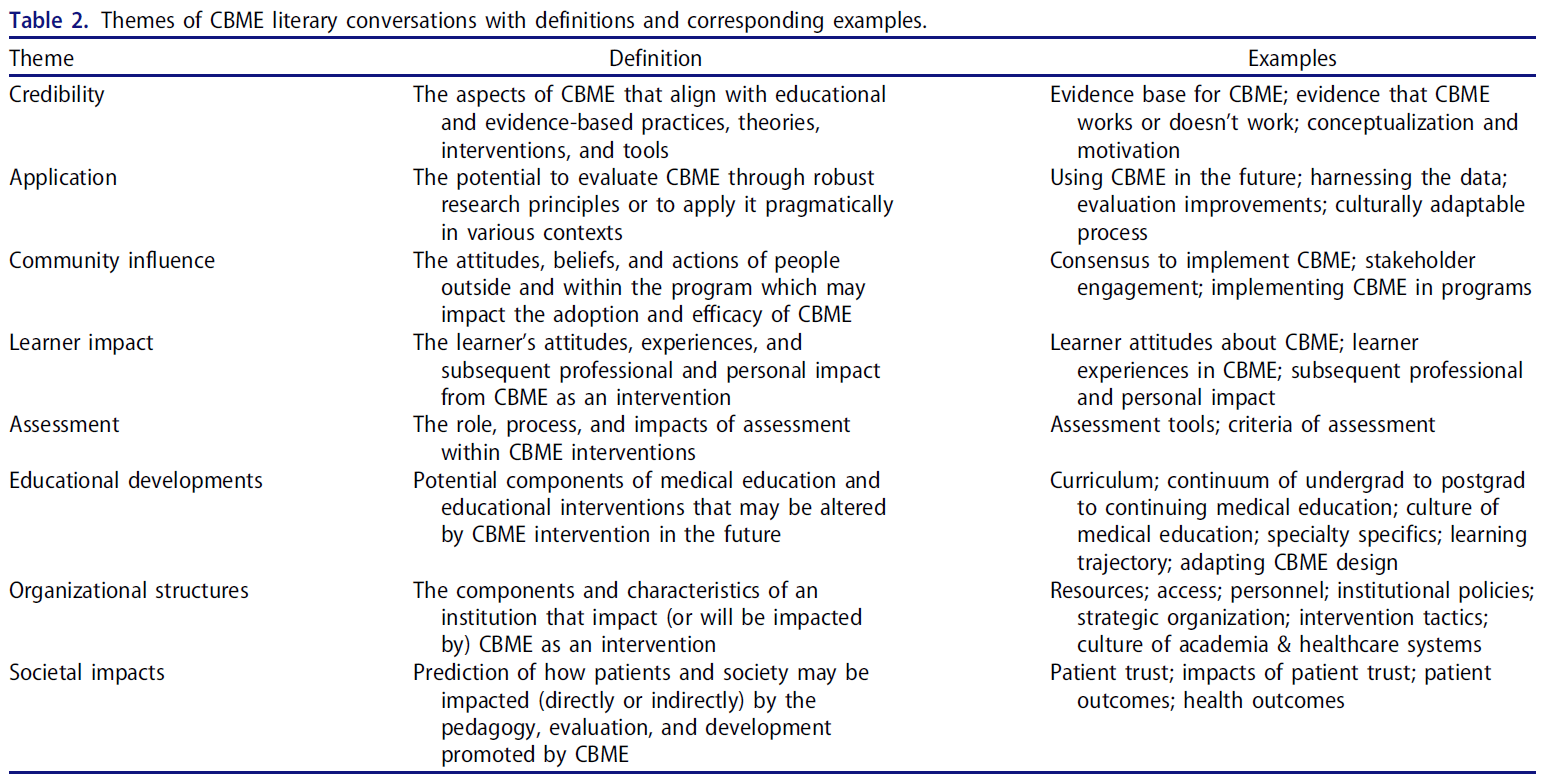

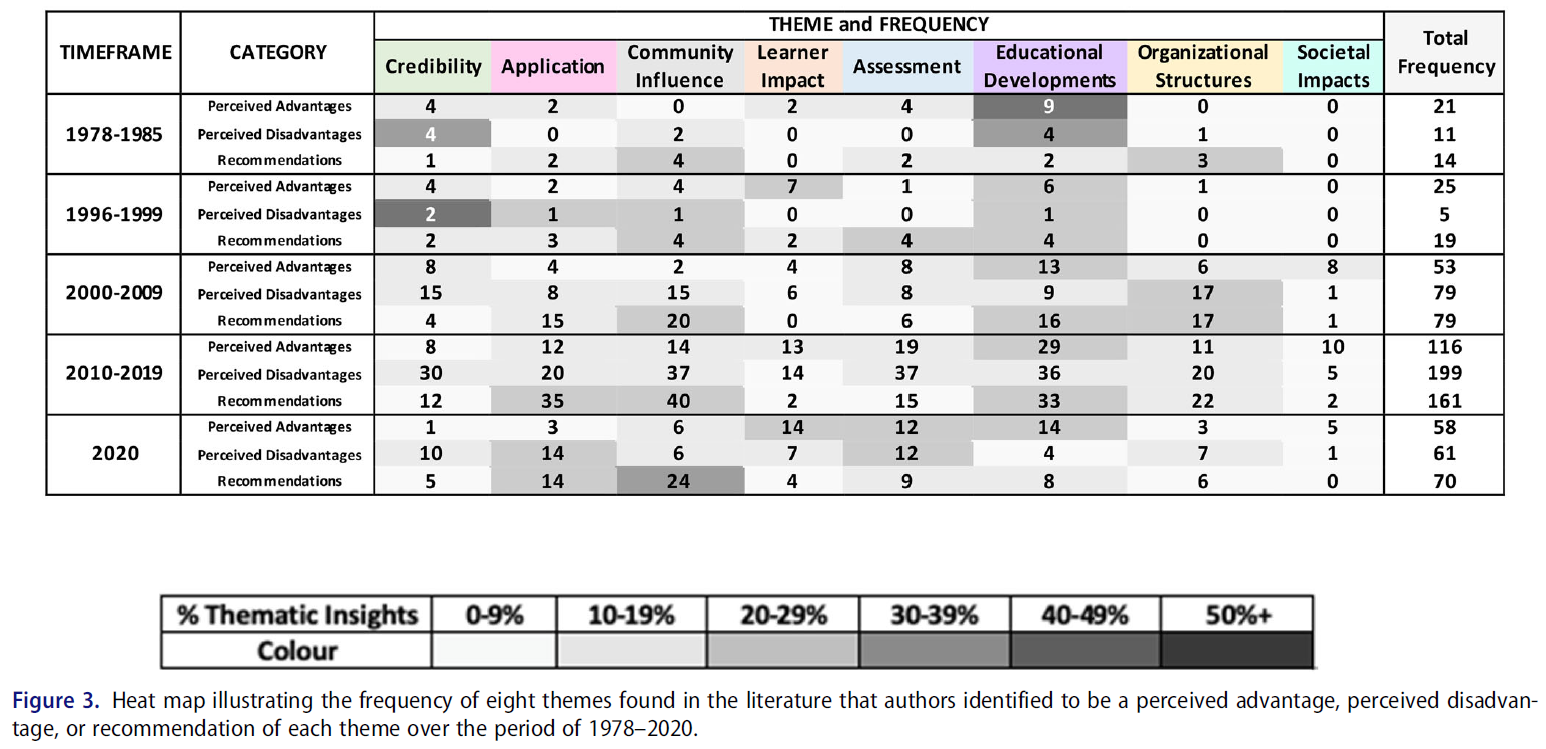

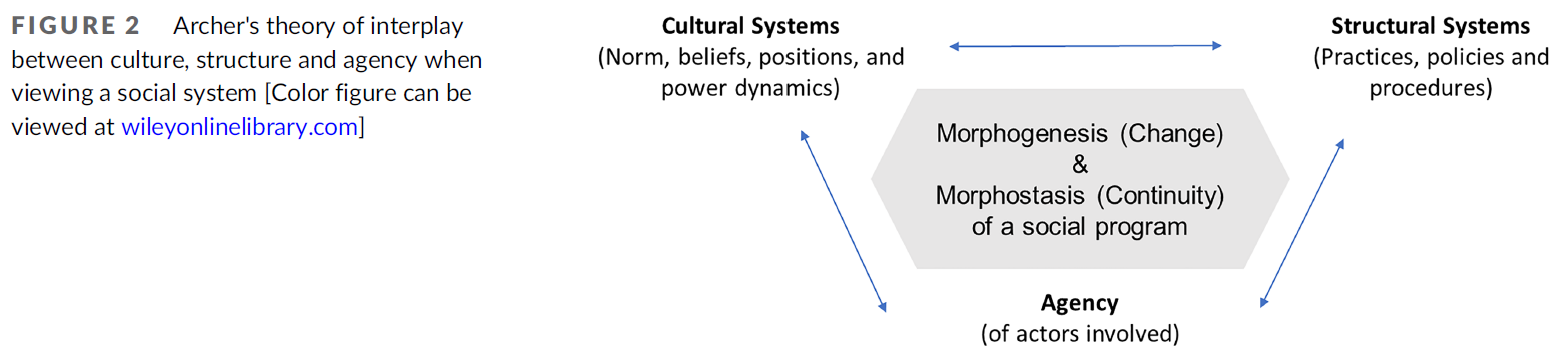

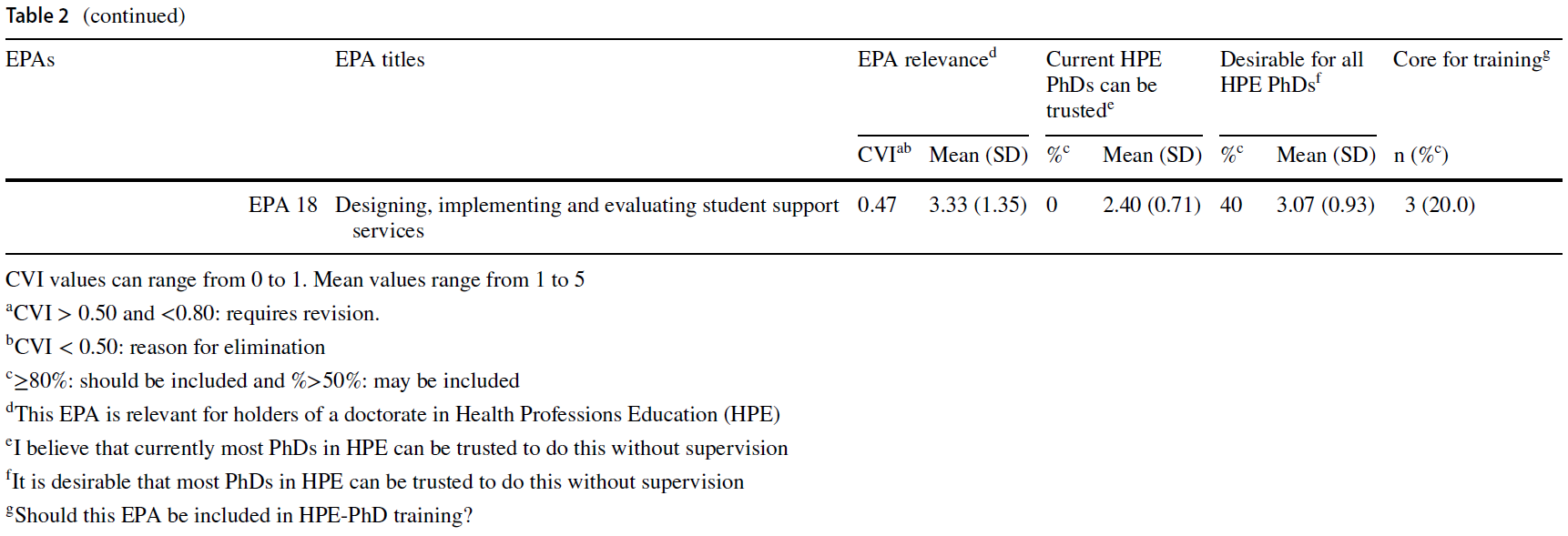

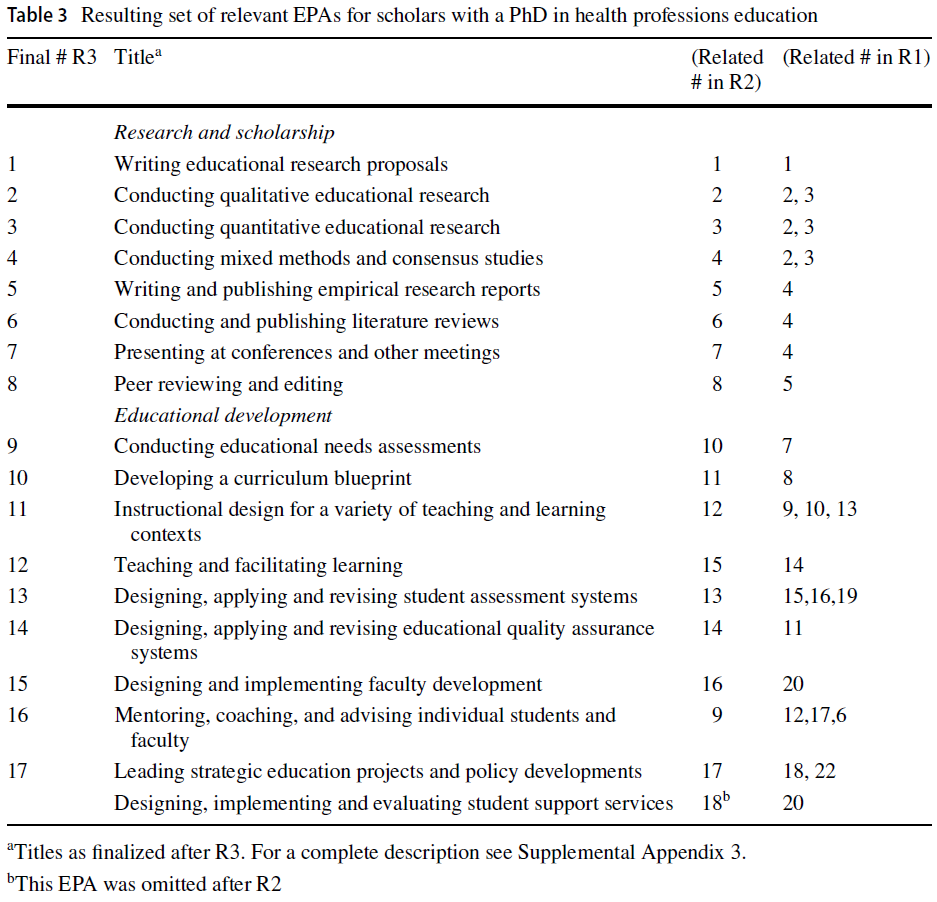

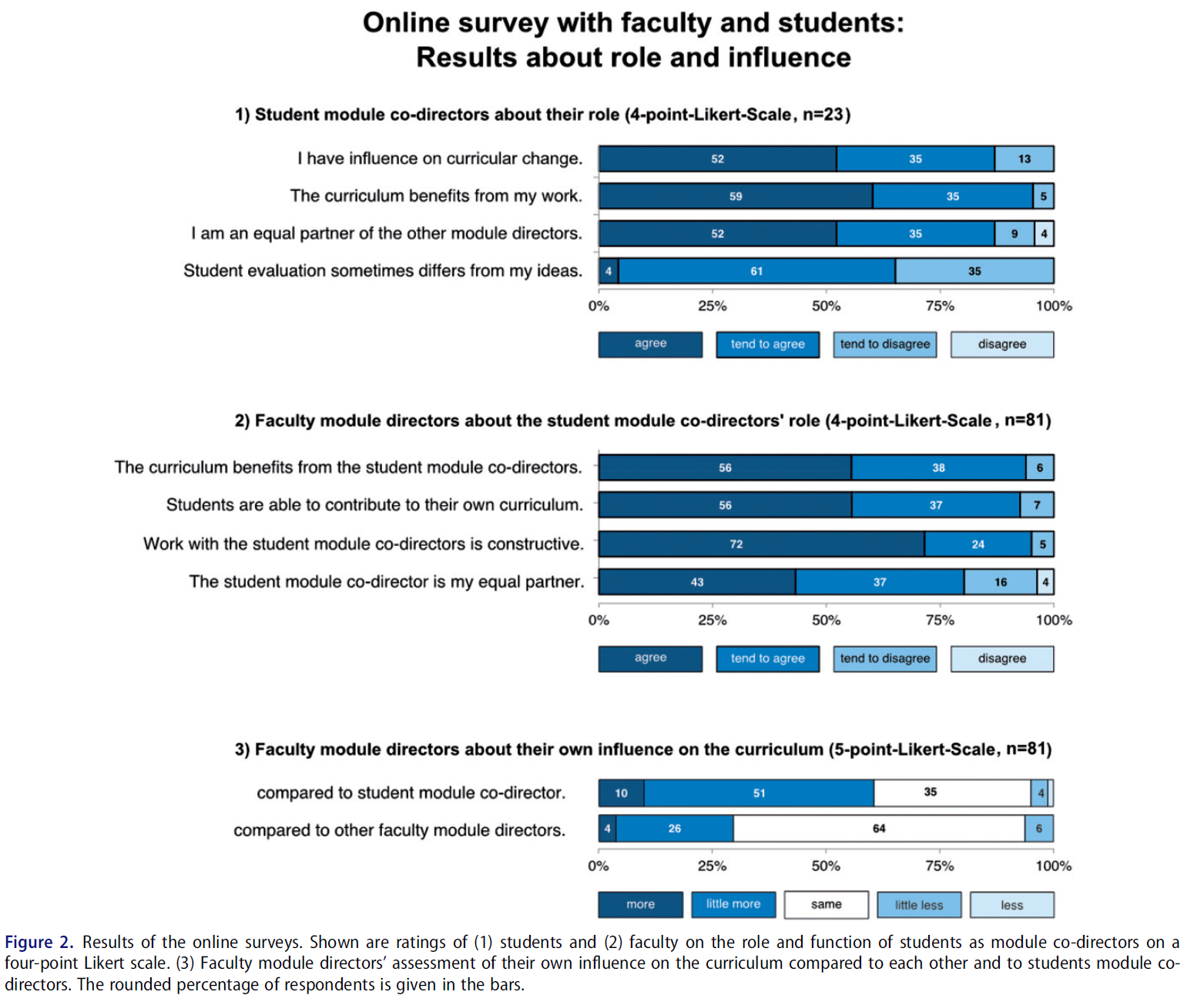

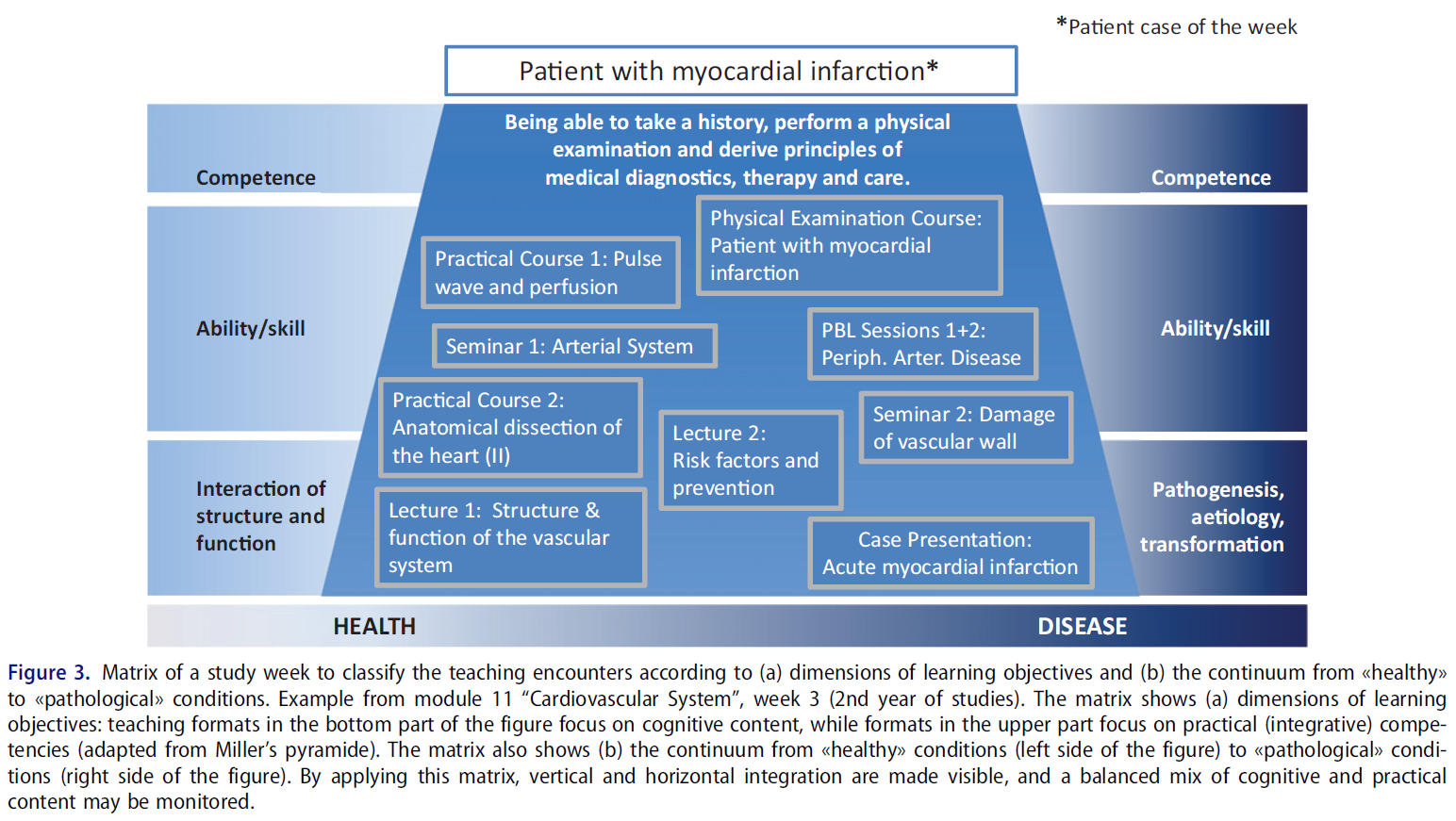

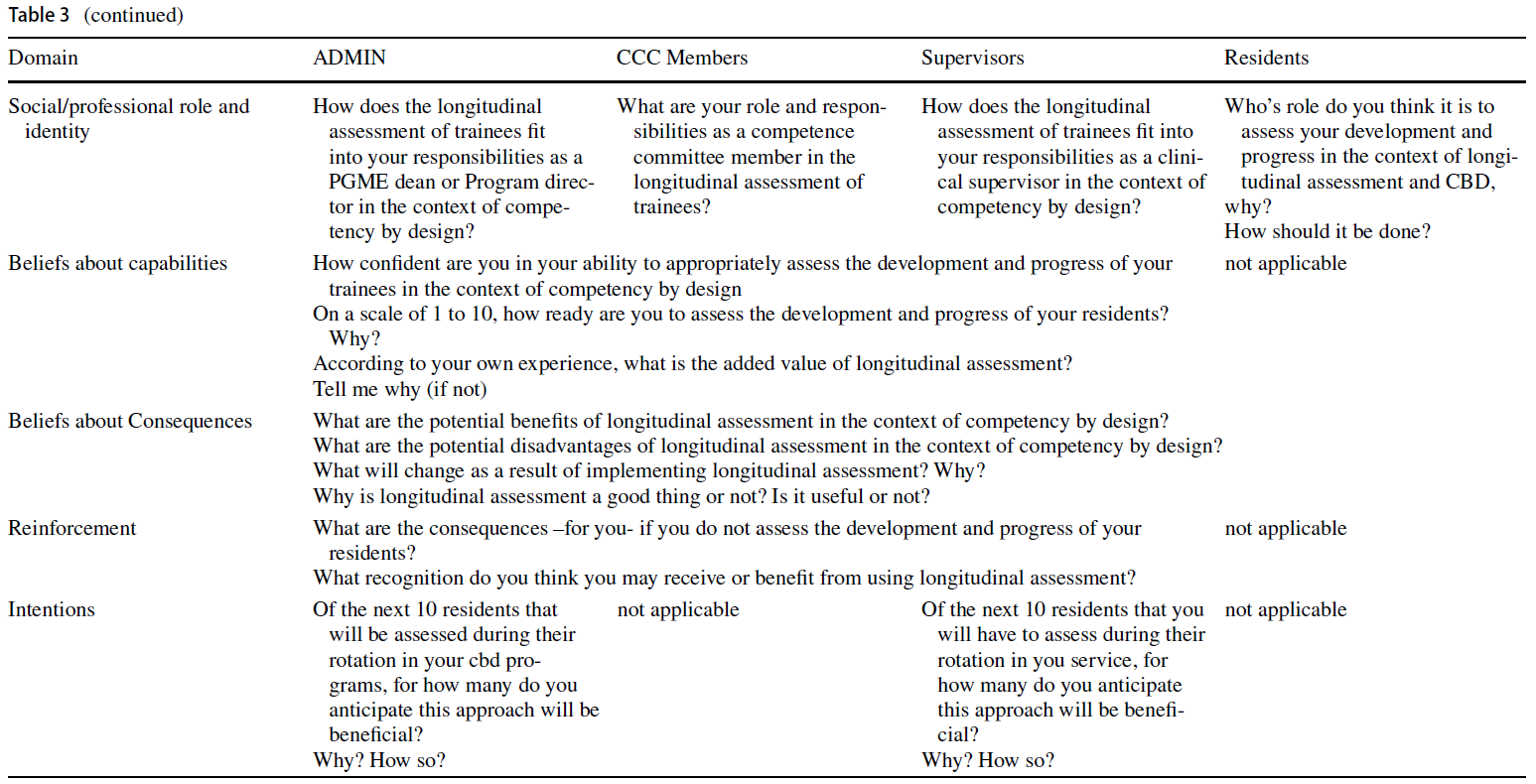

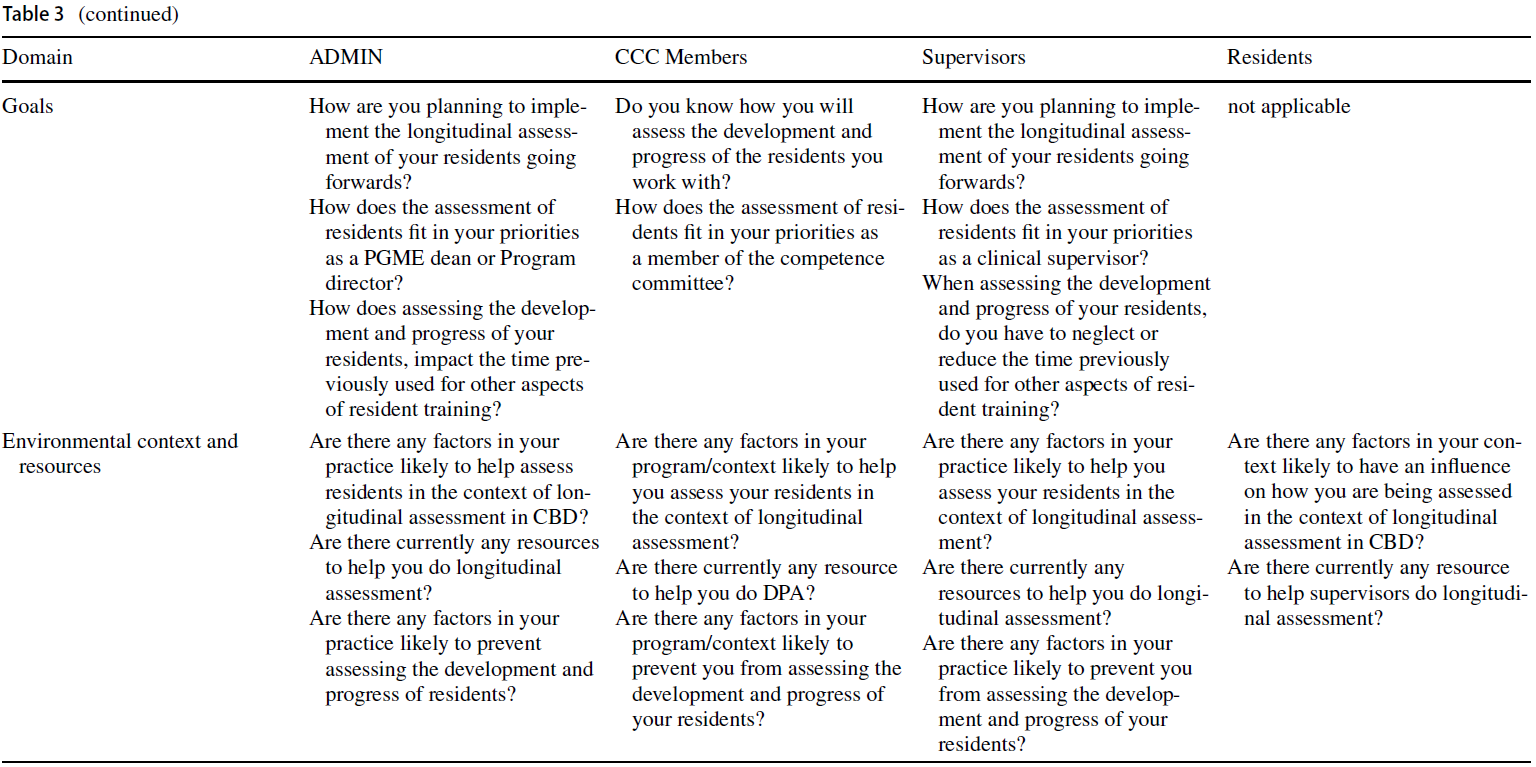

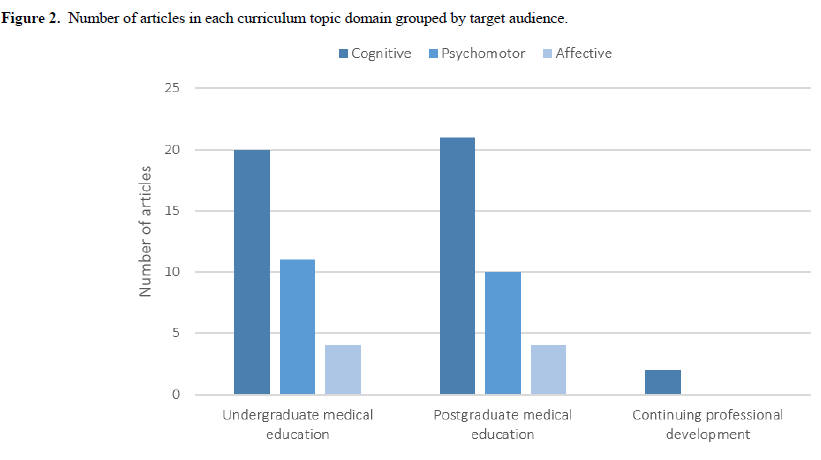

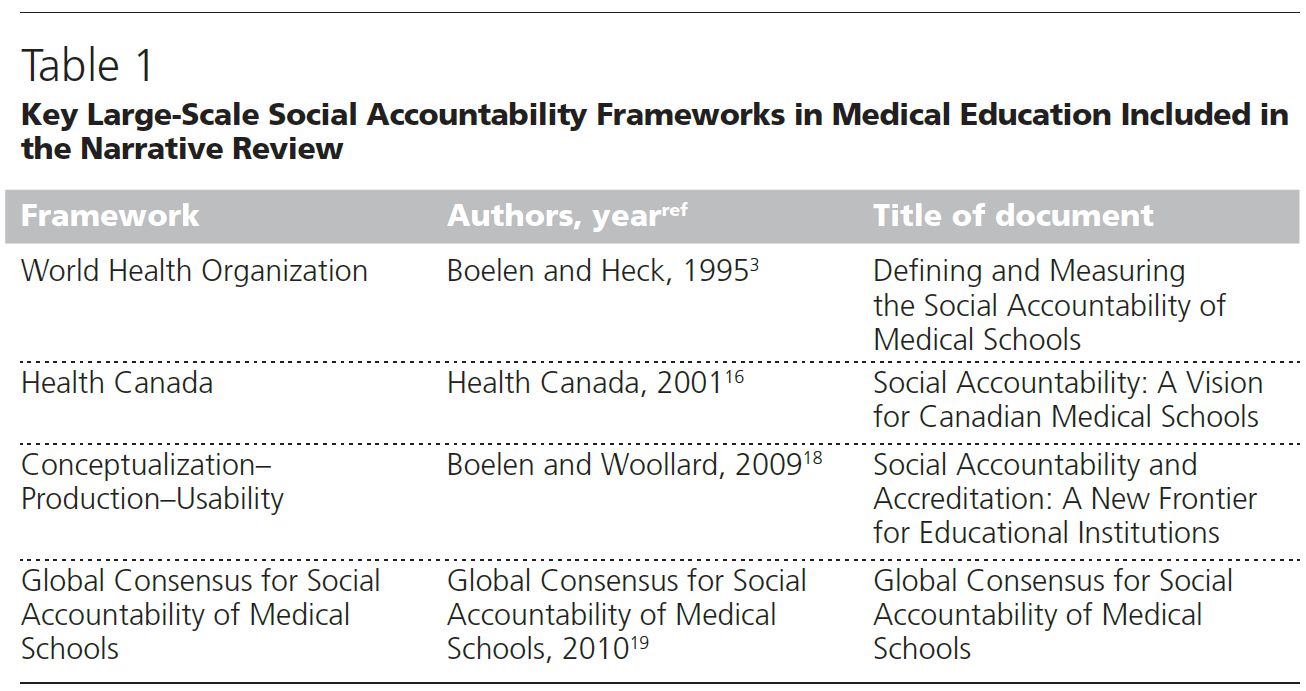

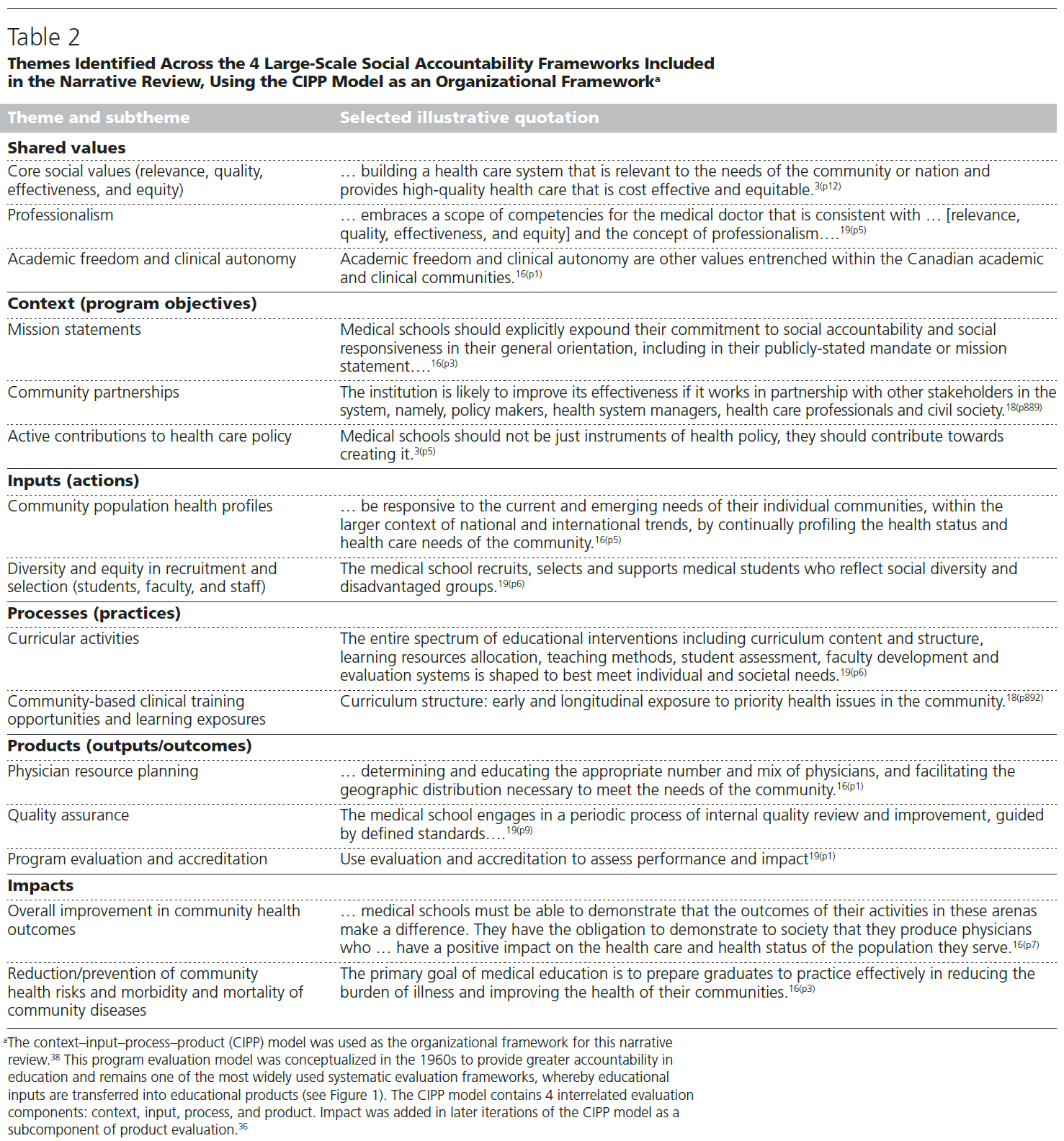

주제별 종합에서는 공유 가치를 포함한 6가지 주제와 CIPP 평가 모델과 관련된 5가지 지표를 확인했습니다.

- 맥락(프로그램 목표),

- 투입물(활동),

- 과정(활동),

- 결과물(기관의 산출물/결과),

- 사회 보건에 미치는 영향

영향 평가는 CIPP 모델에서 제품 평가의 하위 구성 요소이지만, 의학교육의 사회적 책무성이 실무에 미치는 영향과 공중 보건 개선에 중점을 두는 점을 고려하여 분석에서 영향 평가를 별도의 주제로 다루었습니다. 또한 아래 설명과 그림 2에 표시된 것처럼 각 테마 내에서 하위 주제를 식별했습니다. 주제와 하위 주제를 설명하기 위한 인용문은 표 2에 나와 있습니다.

Our thematic synthesis identified 6 themes, including shared values and 5 indicators as they relate to the CIPP evaluation model:

- context (program objectives),

- inputs (actions),

- processes (activities),

- products (institutional outputs/outcomes), and

- impacts on societal health.

While impact evaluation is a subcomponent of product evaluation in the CIPP model, given the emphasis of social accountability in medical education on impact in practice and improvement in public health, we treated impacts as a separate theme in our analysis. Additionally, we identified subthemes within each theme, as described below and depicted in Figure 2. A selection of quotes to illustrate the themes and subthemes is provided in Table 2.

공유 가치

Shared values

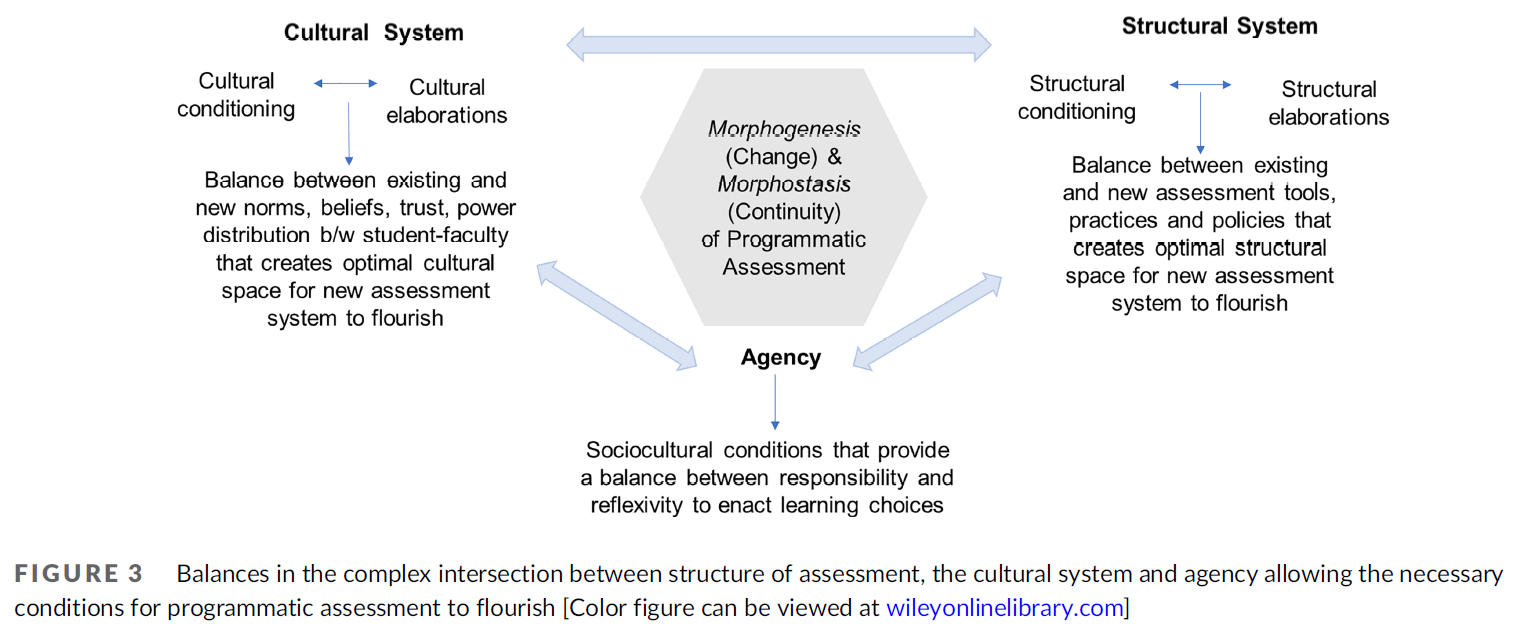

4개의 프레임워크는 모두 4가지 핵심 사회적 가치(관련성, 품질, 효과성, 형평성)를 강조합니다.3,16,18,19 이러한 광범위한 가치는 CIPP 모델의 모든 구성 요소에 걸쳐 있습니다. 일반적으로 핵심 사회적 가치는 맥락(프로그램 목표), 투입물(행동), 프로세스(활동), 결과물(기관의 산출물/결과)에 정보를 제공하기 위한 사회적 책무성의 개념적 이상과 잘 의도된 속성을 나타냅니다. 이는 행동 지향적이며 사회적 요구의 파악에 기반을 두고 있습니다. 이는 교육, 연구 및 서비스 전반에 걸쳐 의학교육 프로그램 활동을 안내하기 위한 것입니다.18

All 4 frameworks emphasized the 4 core social values (relevance, quality, effectiveness, and equity).3,16,18,19 These far-reaching values extend across all components of the CIPP model. Generally, the core social values refer to the conceptual ideals and well-intended attributes of social accountability intended to inform context (program objectives), inputs (actions), processes (activities), and products (institutional outputs/outcomes). They are action oriented and grounded in the identification of societal needs. They are intended to guide medical education program activities in education, research, and service across the training continuum.18

핵심 사회적 가치는 의과대학이 사회적 책무성에 대한 진전을 평가하는 데 도움을 주기 위해 1995년 WHO3 에 의해 처음 개념화되었으며, 이후 후속 프레임워크에서 적용되었습니다.16,18-20,23,44-70

- 관련성은 의학교육 프로그램이 교육, 연구 및 봉사 활동에서 체계적인 접근법을 사용하여 인구, 지역사회 또는 국가의 우선적인 건강 요구 또는 우려를 해결한다는 것을 의미합니다.3,16,18,19

- 질은 근거에 기반하고 포괄적이며 문화적으로 민감한 최상의 진료를 개인에게 제공하는 것을 말합니다.3,16,18,19

- 효과성은 보건의료 자원(비용)을 활용하고, 자원을 최대한 활용하면서 공중보건에 가장 큰 영향을 미치는 것을 말합니다.3,16,18,19

- 형평성은 보편적 접근성을 의미하며 모든 개인이 양질의 보건의료에 접근할 수 있도록 노력하는 것을 말합니다.3,16,18,19

The core social values were originally conceptualized in 1995 by the WHO3 as a means to help medical schools evaluate their progress in addressing social accountability and have since been adapted by subsequent frameworks.16,18–20,23,44–70

- Relevance implies that a medical education program addresses priority health needs or concerns of the population, community, or nation using a systematic approach in education, research, and service activities.3,16,18,19

- Quality refers to providing individuals with the best possible care that is evidence based, comprehensive, and culturally sensitive.3,16,18,19

- Effectiveness refers to the utilization of health care resources (costs) and ensuring that the greatest impact on public health is achieved while making the best use of resources.3,16,18,19

- Equity refers to universal access and striving to ensure that all individuals have access to quality health care.3,16,18,19

이러한 핵심 사회적 가치들 간의 상호관계는 "지역사회 또는 국가의 필요와 관련이 있고, 비용 효율적이며, 공평한 양질의 진료를 제공하는 의료 시스템을 구축"하겠다는 보편적인 사회적 약속을 나타냅니다.3 교육, 연구, 봉사 및 보건 정책에서 의과대학 활동은 이러한 필요를 반영해야 하며, 인구의 우선적인 건강 요구와 관련되고, 이에 대응하며, 예측해야 합니다.3,16,18,19

The interrelationship between these core social values represents a universal social commitment to “building a health care system that is relevant to the needs of the community or nation and provides high-quality care that is cost-effective and equitable.”3 Medical school activities in education, research, and service as well as health policies must be reflective of these needs—they must relate to, respond to, and anticipate priority health needs of the population.3,16,18,19

핵심 사회적 가치에 더하여, 포함된 3개의 프레임워크16,18,19 는 전문직업성의 가치와 윤리, 팀워크, 문화적 역량, 리더십, 의사소통, 평생 학습, 근거 기반 실천 등의 역량을 강조했습니다. 캐나다의 맥락에서는 학문적 자유와 임상 자율성의 가치도 강조되었습니다.16

In addition to the core social values, 3 of the included frameworks16,18,19 emphasized the value of professionalism as well as the following competencies: ethics, teamwork, cultural competence, leadership, communication, lifelong learning, and evidence-based practice. In the Canadian context, the values of academic freedom and clinical autonomy were also highlighted.16

CIPP 모델

CIPP model

맥락.

Context.

맥락은 CIPP 모델의 첫 번째 구성 요소입니다. 프레임워크 전반에 걸쳐 반복적으로 등장하는 하위 주제에는 사명 선언문, 지역사회 파트너십, 보건의료 정책에 대한 적극적인 기여가 포함됩니다.

Context is the first component in the CIPP model. Recurring subthemes that emerged across the frameworks included mission statements, community partnerships, and active contributions to health care policy.

[기관 또는 프로그램 사명 선언문, 의무, 정책, 목적 및 목표]는 사회적 책무성의 핵심 사회적 가치와 사회적 건강 요구 충족에 대한 명시적 약속을 반영해야 합니다.3,16,18,19 이러한 선언문은 공개적으로 게시하고 일반 대중이 쉽게 접근할 수 있도록 해야 합니다.16 또한 의과대학의 사명 선언문과 교육, 연구, 봉사 활동의 내용과 맥락의 특수성은 해당 기관이 서비스를 제공하는 지역사회 및 국가의 현재 및 예상되는 우선적 건강 요구 또는 관심사에 영감을 받고 이에 부합해야 합니다.3,19 이러한 사명 선언문은 요구 평가의 역할을 하며 기관의 교육, 연구, 봉사 활동이 사회에 대한 사회적 의무와 헌신을 입증하도록 안내하기 위한 것입니다.3

Institutional or program mission statements, mandates, policies, objectives, and/or goals must reflect the core social values of social accountability and the explicit commitment to meeting societal health needs.3,16,18,19 These statements should be posted publicly and made easily accessible to the general population.16 Additionally, the content and context specificity of a medical school’s mission statement and activities in education, research, and service should be inspired by and aligned with the current and anticipated priority health needs or concerns of the community and/or nation the institution serves.3,19 These mission statements serve as needs assessments and are intended to guide institutions’ education, research, and service activities to demonstrate their social obligation and commitment to society.3

지역 보건 시스템 및 기타 이해관계자들과 효과적인 지역사회 파트너십을 개발하는 것도 중요합니다.3,16,18,19 의과대학은 다른 이해관계자들과 협력하여 우선순위를 설정하고 현재 및 미래의 보건 요구를 파악하면 그 효과를 개선할 가능성이 더 높습니다.18 지역사회는 모든 의과대학의 주요 이해관계자 역할을 합니다.19 따라서 학교는 보건의료 정책, 계획, 재정을 담당하는 지역 이해관계자들과 협력하여 우선순위 건강 요구와 최적의 환자 치료에 필요한 서비스 및 자원을 파악하는 것이 필수적입니다.3,16,18,19 관련 보건의료 기관, 전문가 그룹, 정부, 소비자, 시민사회와의 파트너십은 보건 계획, 정책 개발, 보건의료 전달 및 평가에 대한 공동 작업을 촉진하고 장려할 수 있습니다.16

Developing effective community partnerships with local health systems as well as other stakeholders is also important.3,16,18,19 Medical schools are more likely to improve their effectiveness if they work collaboratively with other stakeholders to establish priorities and identify current and future health needs.18 The local community serves as the primary stakeholder of all medical schools.19 Therefore, it is imperative that schools work in partnership with local stakeholders responsible for health care policy, planning, and finance to identify priority health needs as well as services and resources required for optimal patient care.3,16,18,19 Partnerships with affiliated health care organizations, professional groups, governments, consumers, and civil society could facilitate and encourage shared work on health planning, policy development, health care delivery, and evaluation.16

의료 교육 프로그램도 보건의료 시스템을 형성하는 데 중요한 역할을 합니다. 지역사회 파트너십은 의과대학이 보건의료 정책에 적극적으로 기여할 수 있는 수단이 될 것입니다.3,16,18,19 의과대학은 변화의 촉매제 역할을 하고 보건의료 계획 및 전달, 정책 개발의 지속 가능성과 평가에 적극적으로 기여해야 합니다.16

Medical education programs also play an important role in shaping the health care system. Community partnerships would serve as a means for medical schools to actively contribute to health care policy.3,16,18,19 Medical schools should act as catalysts of change and actively contribute to the sustainability and evaluation of health care planning and delivery, and policy development.16

입력.

Inputs.

인풋은 목표한 목표를 달성하기 위해 프로그램에서 취하는 조치입니다. 이러한 행동은 기관/프로그램의 의무와 사명 선언문에 의해 동기가 부여되며, 사회적 책무성의 핵심 사회적 가치를 반영합니다. 프레임워크 전반의 하위 주제에는 다음이 포함됩니다.

- 모집 및 선발(학생, 교수진, 교직원)의 다양성 및 형평성,

- 지역사회 인구 건강 프로필

Inputs are actions taken by programs to meet targeted goals. These actions are motivated by institution/program mandates and mission statements, and they reflect the core social values of social accountability. Subthemes across frameworks included

- diversity and equity in recruitment and selection (students, faculty, and staff) and

- community population health profiles.

두 가지 프레임워크는 학생 모집 및 선발에서 다양성과 형평성의 중요성을 강조했습니다.18,19 핵심 사회적 가치와 사명 선언문에 포함된 사회적 약속을 이행하기 위해 의과대학은 모집 및 선발 정책을 조정하여 지원자의 다양성을 높여 소외된 인구와 취약 계층을 포함해야 합니다.18 학생들은 인종 및 민족, 가시적 소수 또는 원주민 신분, 사회경제적 지위, 성별 및 성적 지향, 종교를 포함한 일반 인구의 인구통계를 반영하고 농촌 및 소외된 지역사회 등 기타 취약 계층의 특성을 반영해야 합니다.19 또한 학교는 사회적 약자 지원자에게 동등한 기회를 보장하기 위해 지원 메커니즘(예: 재정 지원, 상담 서비스)뿐만 아니라 소외 계층을 위한 전략적 파이프라인 또는 할당제를 시행해야 합니다.19 의과대학은 또한 의학, 의료 서비스 전달 및 사회과학 부서의 교수진이 커리큘럼과 프로그램 의사 결정에 대표성을 갖고 참여하도록 해야 합니다.18 마지막으로 의과대학은 WHO 보고서에서 권고한 대로 일반의로서 진료할 가능성이 더 높은 학생을 입학시켜야 합니다.3

Two frameworks emphasized the importance of diversity and equity in the recruitment and selection of students.18,19 To meet the social commitments embedded within the core social values and mission statements, medical schools must adapt their recruitment and selection policies to increase the diversity of accepted applicants to include individuals from underrepresented populations and disadvantaged groups.18 Students should reflect the demographics of the general population—including race and ethnicity, visible minority or indigenous status, socioeconomic status, gender and sexual orientation, and religious affiliation—and reflect other disadvantaged groups, such as rural and underserved communities.19 Additionally, schools should implement strategic pipelines and/or quotas for underrepresented groups as well as support mechanisms (e.g., financial aid, counseling services) to ensure equal opportunities for socially disadvantaged applicants.19 Medical schools should also ensure that faculty from medicine, health service delivery, and social science divisions are represented and involved in the curriculum and in programmatic decision making.18 Lastly, medical schools should matriculate students who are more likely to practice as generalists, as recommended by the WHO report.3

세 가지 프레임워크의 또 다른 핵심 주제는 의과대학이 대상 지역사회 또는 국가의 서비스 격차뿐만 아니라 인구 요구를 파악해야 한다는 것입니다.3,18,19 학교는 잘 정의된 인구 건강 연구와 포괄적인 지역사회 인구 건강 프로필 개발을 통해 이러한 요구를 파악하기 시작할 수 있습니다.3,18 이러한 프로필에는 지역사회의 사회 인구학적 및 지정학적 구성과 인구 건강 위험, 건강의 사회적 결정 요인, 서비스 접근 장벽이 반영되어야 합니다.

Another central theme in 3 frameworks was the need for medical schools to identify population needs as well as service gaps of a targeted community and/or nation.3,18,19 Schools can begin to identify these needs through well-defined population health research and the development of a comprehensive community population health profile.3,18 These profiles must reflect the community’s sociodemographic and geopolitical composition as well as population health risks, social determinants of health, and barriers to accessing services.

프로세스.

Processes.

과정에는 교육 활동의 전체 스펙트럼이 포함됩니다.

- 커리큘럼 내용 및 구조,

- 교수법,

- 지역사회 기반 임상 교육 기회 및 지역 인구와 의료 서비스 소외 지역에 대한 학습 노출,

- 학습 평가,

- 지속적인 전문성 개발,

- 평가 시스템 등

Processes include the entire spectrum of educational activities:

- curricular content and structure;

- teaching methods;

- community-based clinical training opportunities and learning exposures to local populations and underserviced areas;

- learning assessments;

- continuing professional development; and

- evaluation systems.

프레임워크 전반에 걸쳐 반복적으로 등장하는 하위 주제에는 다음이 포함되었습니다.

- 커리큘럼 활동과

- 지역사회 기반 임상 교육 기회 및 학습 노출

Recurring subthemes that emerged across frameworks included

- curricular activities as well as

- community-based clinical training opportunities and learning exposures.

의과대학은 우선순위 공중보건 요구를 해결하는 방향으로 교과과정 활동을 진행해야 합니다.3,16,18,19 교과과정 내용과 구조는 학생 중심 패러다임으로 접근해야 하며, 건강의 사회적 결정요인, 공중보건 위험, 인구, 지역사회, 국가의 지정학적, 사회인구학적, 역학적 특수성을 포함해야 합니다.3,19 또한 학교의 교과과정 활동은 강력한 지속적인 전문성 개발 프로그램을 통해 결함 학생, 졸업생, 직원에게 평생 학습 기회를 지원해야 합니다.16,18

Medical schools must direct their curricular activities toward addressing priority public health needs.3,16,18,19 Curricular content and structure should be approached using a student-centered paradigm and must include the social determinants of health; public health risks; and the geopolitical, sociodemographic, and epidemiological specificities of a population, community, and/or nation.3,19 Additionally, schools’ curricular activities should support lifelong learning opportunities for faulty, graduates, and staff through the availability of robust continuing professional development programs.16,18

지역사회 기반 임상 교육 기회와 학습 노출은 인구 접근법을 사용하여 설계되어야 합니다.3,19 의과대학은 일차 진료를 장려하고 일차 진료 실습에 대한 학습 기회와 노출을 제공해야 합니다.3,16,19 또한 학교는 지역사회의 건강 요구와 관련된 종단적 지역사회 기반 학습 경험을 제공해야 합니다.3,19 마지막으로 학교는 농촌 의료 환경에서 학습 기회를 제공하고 불우하고 소외된 그룹에 노출되도록 해야 합니다.3,19

Community-based clinical training opportunities and learning exposures should be designed using a population approach.3,19 Medical schools should promote primary care and provide learning opportunities and exposure to primary care practices.3,16,19 Additionally, schools should provide longitudinal community-based learning experiences that are relevant to the community’s health needs.3,19 Lastly, schools should provide learning opportunities in rural health care settings as well as exposure to disadvantaged and underserved groups.3,19

제품.

Products.

제품 평가는 프로그램 졸업생들의 유용성을 의미합니다. 프레임워크 전반에 걸쳐 반복적으로 등장하는 하위 주제에는 다음이 포함되었습니다.

- 의사 자원 계획,

- 품질 보증,

- 프로그램 평가 및 인증

Product evaluation refers to the usability of a program’s graduates. Recurring subthemes that emerged across frameworks included

- physician resource planning,

- quality assurance, and

- program evaluation and accreditation.

4개의 프레임워크 모두 의사 자원 계획의 중요성을 강조했습니다. 의과대학은 학생의 적절한 구성을 결정하고 교육하며, 사회적 요구를 충족하는 데 필요한 졸업생의 분포, 배치 및 유지를 결정하는 데 적극적으로 참여해야 합니다.3,16,18,19 또한 학교는 일차 진료 의사를 위한 지역 취업 기회를 보장해야 합니다.18,19

All 4 frameworks emphasized the importance of physician resource planning. Medical schools should be actively involved in determining and educating the right composition of students and in determining the distribution, deployment, and retention of graduates necessary to meet social needs.3,16,18,19 Additionally, schools must ensure local employment opportunities for primary care physicians.18,19

또 다른 핵심 주제는 프로그램 평가 및 인증의 중요성이었습니다.3,16,18,19 인증 기준 및 프로세스는 사회적 책무성 원칙을 통합해야 합니다.3,16,18,19 평가 및 인증은 정기적으로 수행되어야 하며,3,19 결과는 공개적으로 이용 가능하고 제도 개선에 사용되어야 합니다.19 또한 평가 및 인증 팀은 정책 입안자, 보건 전문가, 지역사회 구성원을 포함한 이해관계자를 폭넓게 대표할 수 있어야 합니다.3,16,18,19

Another central theme was the importance of program evaluation and accreditation.3,16,18,19 Accreditation standards and processes should incorporate social accountability principles.3,16,18,19 Evaluation and accreditation must be conducted at regular intervals,3,19 and the results should be made publicly available and used for institutional improvement.19 Additionally, evaluation and accreditation teams should be widely representative of stakeholders, including policymakers, health professionals, and community members.19

마지막으로, 교육, 연구 및 서비스 제공에서 지속적인 품질 보증 프로세스를 수용하는 것의 중요성은 모든 프레임워크에서 강조되었습니다.3,16,18,19 이 프로세스는 투명해야 하며, 교육 개선을 촉진하기 위해 잘 정의된 표준을 사용하여 안내해야 합니다.3,19 또한 졸업생 역량을 정기적으로 평가하고, 잘 정의된 교육 기준을 반영하여 치료의 질을 보장하고, 졸업생이 변화하는 공중 보건 요구를 충족하는 데 필요한 기술을 갖추고 실무에 투입되도록 해야 합니다.3,16,18,19

Lastly, the importance of embracing a continuous quality assurance process in education, research, and service delivery was emphasized across all frameworks.3,16,18,19 This process should be transparent and guided using well-defined standards to promote educational improvements.3,19 Additionally, graduate competencies must be assessed regularly and reflect well-defined educational standards to ensure quality of care and that graduates enter practice equipped with the skills required to meet changing public health needs.3,16,18,19

영향.

Impacts.

사회적 책무성의 전제는 의학교육 프로그램의 목적과 실천이 사회적 필요를 파악하는 데서 시작하여 그러한 필요를 충족하는 것으로 마무리될 것을 요구합니다.18 영향 평가는 제품 평가의 일부입니다.

- 프레임워크 전반에서 강조되는 공통 주제는 지역사회 건강 결과의 전반적인 개선입니다.3,16,18,19

- 또 다른 공통 주제는 지역사회 건강 위험과 지역사회 질병의 이환율 및 사망률의 감소 및 예방입니다.16,19

The premise of social accountability requires that the purpose and practices of medical education programs commence in the identification of societal needs and conclude in meeting those needs.18 Impact evaluation is part of product evaluation.

- A common theme highlighted across frameworks was overall improvement in community health outcomes.3,16,18,19

- Another common theme was reduction and prevention of community health risks and morbidity and mortality of community diseases.16,19

사회적 영향을 효과적으로 평가하기 위해 의과대학은 교육 연속체를 포괄하고 졸업생이 실제로 미치는 영향에 초점을 맞춘 표준을 개발해야 합니다.19 졸업생이 질병 부담을 줄이고 그들이 봉사하는 지역 사회의 건강을 개선하는 정도를 평가하는 지표를 개발해야 합니다.16 의과대학은 활동 결과가 지역 사회 건강에 긍정적인 영향을 미친다는 것을 입증할 수 있어야 합니다.3,16,18,19 졸업생이 지역사회 건강 위험과 지역사회 질병의 이환율 및 사망률을 줄여 공중 보건에 긍정적인 사회적 투자 수익을 얻도록 해야 할 의무가 있습니다.16,19

To evaluate societal impacts effectively, medical schools must develop standards that span the educational continuum and focus on impacts of graduates in practice.19 They must develop metrics to assess the extent to which their graduates reduce the burden of illness and improve the health of the communities they serve.16 Medical schools must be able to demonstrate that the outcomes of their activities have positive impacts on community health.3,16,18,19 They have an obligation to ensure their graduates have a positive social return on investment to public health by reducing community health risks and the morbidity and mortality of community diseases.16,19

토론

Discussion

이 검토에서는 CIPP 평가 모델을 사용하여 4개의 대규모 사회적 책무성 정책 프레임워크3,16,18,19 에서 주요 주제와 지표를 확인했습니다.35 의학교육 문헌에서 정책 문서 전반에 걸쳐 사회적 책무성 지표를 식별하는 데 CIPP 모델이 사용된 적은 없지만, 이 검토는 의학교육의 사회적 책무성 평가를 위한 초기 운영 구성 개발에서 그 유용성을 입증합니다. 포함된 프레임워크에서 탐구된 주제는 의학교육의 광범위한 사회적 책무성 문헌과 일치합니다. 그러나 CIPP 모델은 책무성 시스템을 강화하기 위한 의학교육 프로그램의 평가 프레임워크를 제공합니다.35-38 또한, 이 검토에서는 책임에 대한 근본적인 질문도 의도치 않게 다루고 있습니다: 누가, 무엇에 대해, 누구에게, 어떤 수단을 통해 책임을 져야 하는가.7,10,15 이러한 질문은 책무성을 이해하는 데 중요하며, 의과대학의 사회적 책무성을 어떻게, 어떤 방식으로 평가할 수 있도록 사회적 책무성 프레임워크를 운영하는 데 도움이 될 수 있습니다.

This review identified major themes and indicators across 4 large-scale social accountability policy frameworks3,16,18,19 using the CIPP evaluation model.35 The CIPP model has not been used previously in the medical education literature to identify social accountability indicators across policy documents, but this review provides evidence of its utility in the development of initial operational constructs to evaluate social accountability in medical education. The themes explored in the included frameworks are consistent with the broader social accountability literature in medical education. However, the CIPP model provides an evaluation framework for medical education programs to strengthen their accountability systems.35–38 Additionally, this review also inadvertently addresses the fundamental questions of accountability: Who is held to account, for what, to whom, and through what means?7,10,15 These questions are critical to understanding accountability and can be used to help operationalize social accountability frameworks to better evaluate how and in which ways medical schools are socially accountable.

이 검토는 주로 의과대학의 사회적 책무성에 초점을 맞추었지만, 사회적 책무성은 역동적인 과정이라는 점을 인식하는 것이 중요합니다. 이는 시민, 정부, 수련기관, 의료 교육자/공급자 간의 협력 관계를 통해 사회적 건강 요구를 체계적으로 파악하고 우선순위를 정하여 해결하는 과정입니다.3,72 의과대학의 사회적 책무성을 측정하고 체계적으로 평가하려면 개념적, 운영적 복잡성을 포착할 수 있는 강력한 평가 모델을 사용해야 합니다. 인증은 이러한 많은 문제를 해결할 수 있지만, 의과대학이 직장에서 일할 수 있는 유능한 졸업생을 배출하도록 하는 다른 목적도 있습니다. 이 경우 학교는 인증기관에 책임을 집니다. 캐나다와 호주는 인구의 우선적인 건강 문제를 해결하기 위한 의과대학의 노력을 평가하기 위한 수단으로 공식적인 사회적 책무성 기준을 인증 절차에 통합했습니다.19,72,73 이는 긍정적인 발전이지만, 사회적 책무성 결과에 대해 더 폭넓게 생각하고 교육 투입물, 산출물, 영향 간의 의미 있는 관계를 확립해야 합니다.19,73

While this review focused primarily on social accountability of medical schools, it is important to acknowledge that social accountability is a dynamic process. It represents a collaborative relationship between citizens, government, training institutions, and health care educators/providers to systematically identify, prioritize, and address societal health needs.3,72 The measurement and systematic evaluation of social accountability in medical schools requires the use of a robust evaluation model to capture its conceptual and operational complexities. While accreditation may address many of these issues, it often serves a different purpose—ensuring medical schools produce competent graduates for the workplace. In this instance, schools are accountable to the accreditors. Canada and Australia have incorporated formal social accountability standards into their accreditation processes as a means to evaluate a medical school’s commitment to addressing the priority health concerns of the population.19,72,73 While this is a positive advancement, we need to continue to think about social accountability outcomes more broadly and establish meaningful relationships between educational inputs, outputs, and impacts.19,73

그러나 의과대학이 사회적 필요를 충족시킨다는 가정에 대한 연구가 부족합니다. Boelen에 따르면,72 사회적 책무성을 다하는 의과대학은 1%에 불과한 반면, 사회적 대응을 하는 의과대학은 9%, 사회적 책무성을 다하는 의과대학은 90%에 달한다고 합니다. 투명성 및 책임성 이니셔티브가 공공 서비스 개선을 위한 핵심 전략으로 부상했지만, 이러한 이니셔티브와 공중 보건에 미치는 영향 사이의 관계는 거의 알려지지 않았습니다.74 이 문제는 의학교육에만 국한된 것이 아닙니다.75 졸업생들이 실제로 지역사회에 미치는 사회적 영향을 평가 및 입증하고, 이론과 실무 사이의 연결 고리를 구축해야 할 필요성이 있습니다. 이러한 입증은 사회적 책무성에 대한 선한 의도와 헌신을 공개적으로 보여주는 것이 아니라 개념 증명에 가까워지고 있습니다.75 개별 의과대학이 사회적 책무성을 다하기 위한 진전을 확인하고자 하는 문헌이 증가하고 있습니다(체계적인 검토는 Reeve 외76 참조). 의과대학의 노력의 예로는 입학 절차를 통한 접근성 확대,77-82 건강의 사회적 결정 요인을 반영한 커리큘럼 개혁,83-86 지역사회 기반 임상 교육 기회 및 학습 노출,87-90 학습자의 위치 등이 있습니다.91-97

There is, however, an understudied assumption that medical schools meet societal needs. According to Boelen,72 only 1% of medical schools are socially accountable, whereas 9% of medical schools are socially responsive and 90% are socially responsible. While transparency and accountability initiatives have emerged as a key strategy for improving public services, the relationship between these initiatives and their impacts on public health remains largely unknown.74 This issue is not specific to medical education.75 There is a need to evaluate and demonstrate the social impacts graduates have in practice on communities and establish a link between theory and practice. This demonstration becomes less about providing public displays of good intentions and commitment to social accountability and more about proof of concept.75 A growing body of literature seeks to affirm the progress of individual medical schools toward becoming socially accountable (see Reeve et al76 for a systematic review). Some examples of medical schools’ efforts include widening access through admissions processes,77–82 curricular reforms reflecting social determinants of health,83–86 community-based clinical training opportunities and learning exposures,87–90 and location of learners.91–97

일부 의학교육 환경에서 사회적 책무성 평가의 진전이 계속 확대되고 있지만,98 사회적 책무성 이니셔티브가 사회 건강에 미치는 영향은 거의 알려지지 않았습니다.99,100 그러나 소수의 경험적 논문에서 환자 건강 결과를 의사 교육 및 성과와 연관시키고 있으며101,102 일부 논평103-105에서는 의학교육 프로그램이 공중 보건 요구에 미치는 영향을 더 잘 이해하기 위해 국가 임상 데이터 세트를 사용하여 졸업생 결과를 환자 영향과 연결해야 한다는 점을 강조하고 있습니다.

While progress in evaluating social accountability continues to expand in select medical education settings,98 the extent to which social accountability initiatives impact societal health remains largely unknown.99,100 However, a small number of empirical papers associate patient health outcomes with physician training and performance101,102 and some commentaries103–105 emphasize the need to link graduate outcomes with patient impacts using national clinical datasets to better understand the effects medical education programs have on public health needs.

한계점

Limitations

이 검토는 이전 연구를 확장한 것입니다.3,16,18-20,23,44-70 가능한 모든 사회적 책무성 지표의 포괄적인 목록을 제공하지는 않습니다. 여기에 제시된 주제와 지표는 주요 출처의 사회적 책무성 정책 프레임워크에 국한되어 있으며, 품질 평가에 사용되는 지표를 반드시 포함하지는 않습니다. 이 검토에서는 글로벌 건강 격차에 대한 우려가 커지는 등 최근의 글로벌 건강 운동은 다루지 않았습니다. 또한 CIPP 모델은 교육에 대한 하향식 시스템 접근 방식을 가정하여 교육 투입물이 제품으로 전환된다고 가정합니다. 또한 이 검토는 주로 의학교육에 초점을 맞추고 있으며, 사회적 책무성의 다른 상호 연관되고 상호 의존적인 프로그램 활동(예: 연구 및 서비스)은 포함하지 않았습니다. 이러한 관계를 더 자세히 조사하고 의과대학이 지역 보건 요구를 해결하고 이에 대응하는지 여부를 결정하기 위해서는 추가 연구가 필요합니다.

This review extends earlier work.3,16,18–20,23,44–70 It does not provide a comprehensive list of all possible social accountability indicators. The themes and indicators presented here are limited to primary source social accountability policy frameworks and are not necessarily inclusive of metrics used to assess quality. This review does not address more recent global health movements, for instance, the growing concerns regarding global health disparities. Additionally, the CIPP model assumes a top-down systems approach to education, whereby educational inputs are turned into products. This review is also primarily on medical education, not other interrelated and interdependent program activities of social accountability (i.e., research and service). Further research is needed to examine these relationships in more detail and determine whether medical schools address and respond to local health needs.

결론

Conclusion

이 검토는 확립된 프로그램 평가 모델과 4가지 대규모 사회적 책무성 정책 프레임워크의 증거를 연결하여 의학교육 연속체 전반에 걸쳐 지표를 생성할 수 있도록 합니다. 프로그램 평가 모델은 교육기관이 원하는 목표와 목적을 향해 나아가는 과정을 모니터링하기 위한 체계적이고 쉽게 이해할 수 있는 실용적인 가이드를 제공합니다. 그러나 의과대학이 사회적 의무를 다하려고 노력하더라도 이러한 행동이 공중 보건에 긍정적인 영향을 미칠 것이라는 보장은 없습니다.3

This review links an established program evaluation model and evidence from 4 large-scale social accountability policy frameworks, which may lead to the creation of indicators across the medical education continuum. Program evaluation models provide a systematic and easily understood practical guide for monitoring the progress of an institution toward desired goals and objectives. However, even when medical schools attempt to fulfill their social obligations, there is no guarantee that these actions will positively impact public health.3

사회적 책무성을 평가하는 일은 복잡합니다.65 의학교육 프로그램의 질을 평가하는 대부분의 이전 문헌은 주로 투입물과 과정에 초점을 맞추었습니다.72 사회적 책무성이 더욱 강조됨에 따라, 우리 커뮤니티는 [교육 투입물과 과정]에서 [산출물과 영향]에 초점을 전환해야 합니다. 다음의 것들 사이에 의미 있는 관계를 설정할 필요가 있습니다.32,74

- 투입물(누가, 어디서, 어떤 교육을 받았는지),

- 산출물(졸업생이 실제 진료 현장에서, 어떤 의료 전문 분야에서, 어떤 일을 하는지),

- 영향(졸업생의 활동이 인구 건강을 어떻게 개선하는지)

이러한 관계를 설정하기 시작하는 한 가지 방법으로 CIPP 프로그램 평가 모델을 사용할 것을 제안합니다.

The task of evaluating social accountability is complex.65 Most of the previous literature assessing the quality of medical education programs has focused predominantly on inputs and processes.72 As more emphasis is placed on social accountability, it is imperative that we as a community shift our focus from educational inputs and processes to products and impacts. There is a need to establish meaningful relationships between program

- inputs (who is trained and from where),

- products (what graduates do in practice, in what medical specialty, and where), and

- impacts (how graduates’ activities improve population health).32,74

We suggest a way to begin to establish these links is through the use of the CIPP program evaluation model.

Social Accountability Frameworks and Their Implications for Medical Education and Program Evaluation: A Narrative Review

PMID: 32910000

DOI: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003731

Free article

Abstract

Purpose: Medical schools face growing pressures to produce stronger evidence of their social accountability, but measuring social accountability remains a global challenge. This narrative review aimed to identify and document common themes and indicators across large-scale social accountability frameworks to facilitate development of initial operational constructs to evaluate social accountability in medical education.

Method: The authors searched 5 electronic databases and platforms and the World Wide Web to identify social accountability frameworks applicable to medical education, with a focus on medical schools. English-language, peer-reviewed documents published between 1990 and March 2019 were eligible for inclusion. Primary source social accountability frameworks that represented foundational values, principles, and parameters and were cited in subsequent papers to conceptualize social accountability were included in the analysis. Thematic synthesis was used to describe common elements across included frameworks. Descriptive themes were characterized using the context-input-process-product (CIPP) evaluation model as an organizational framework.

Results: From the initial sample of 33 documents, 4 key social accountability frameworks were selected and analyzed. Six themes (with subthemes) emerged across frameworks, including shared values (core social values of relevance, quality, effectiveness, and equity; professionalism; academic freedom and clinical autonomy) and 5 indicators related to the CIPP model: context (mission statements, community partnerships, active contributions to health care policy); inputs (diversity/equity in recruitment/selection, community population health profiles); processes (curricular activities, community-based clinical training opportunities/learning exposures); products (physician resource planning, quality assurance, program evaluation and accreditation); and impacts (overall improvement in community health outcomes, reduction/prevention of health risks, morbidity/mortality of community diseases).

Conclusions: As more emphasis is placed on social accountability of medical schools, it is imperative to shift focus from educational inputs and processes to educational products and impacts. A way to begin to establish links between inputs, products, and impacts is by using the CIPP evaluation model.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 교육과정 개발&평가' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 인공지능이 의학교육에 갖는 함의 (Lancet Digit Health. 2020) (0) | 2023.07.07 |

|---|---|

| 의학교육은 정보시대에서 인공지능시대로 옮겨가야 한다(Acad Med, 2018) (0) | 2023.07.07 |

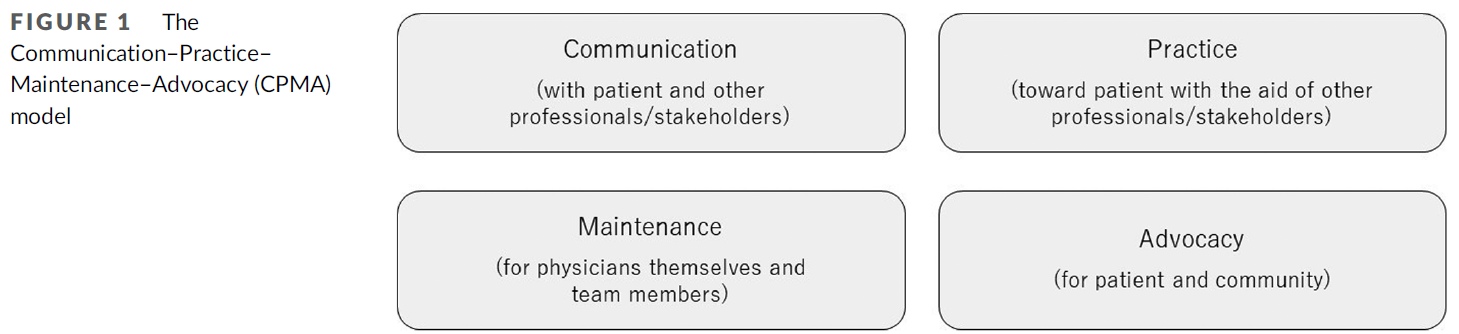

| 건강의 사회적 결정요인과 관련한 환자돌봄의 관찰가능한 프로세스 정의 (Med Educ, 2022) (0) | 2023.05.28 |

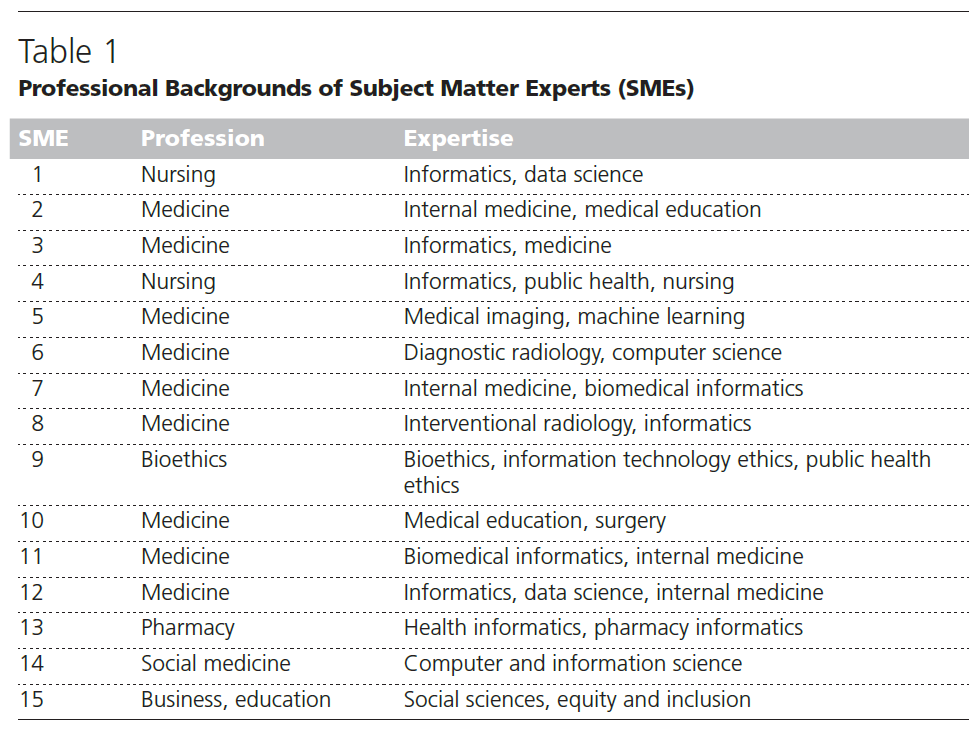

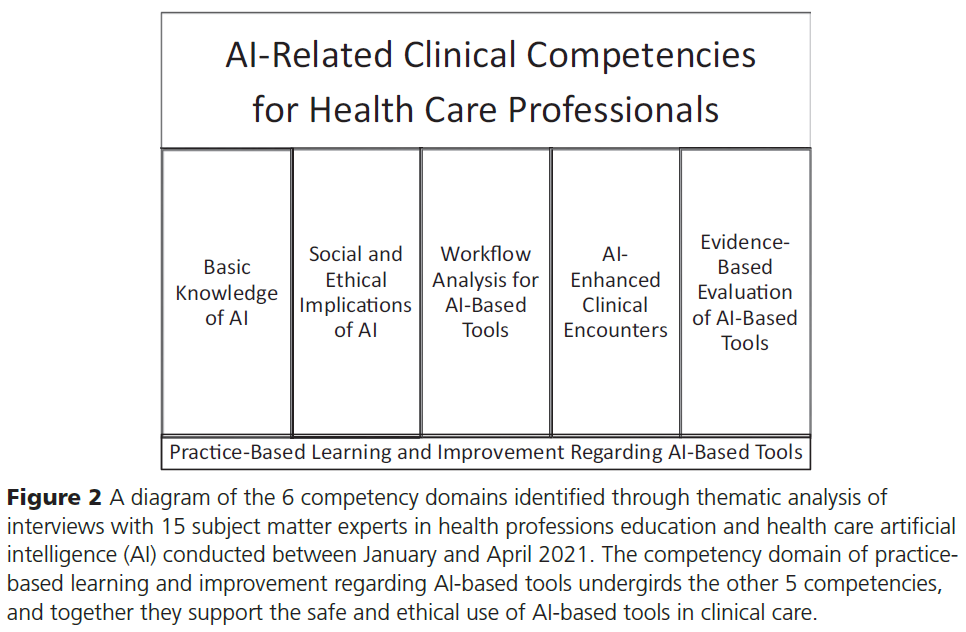

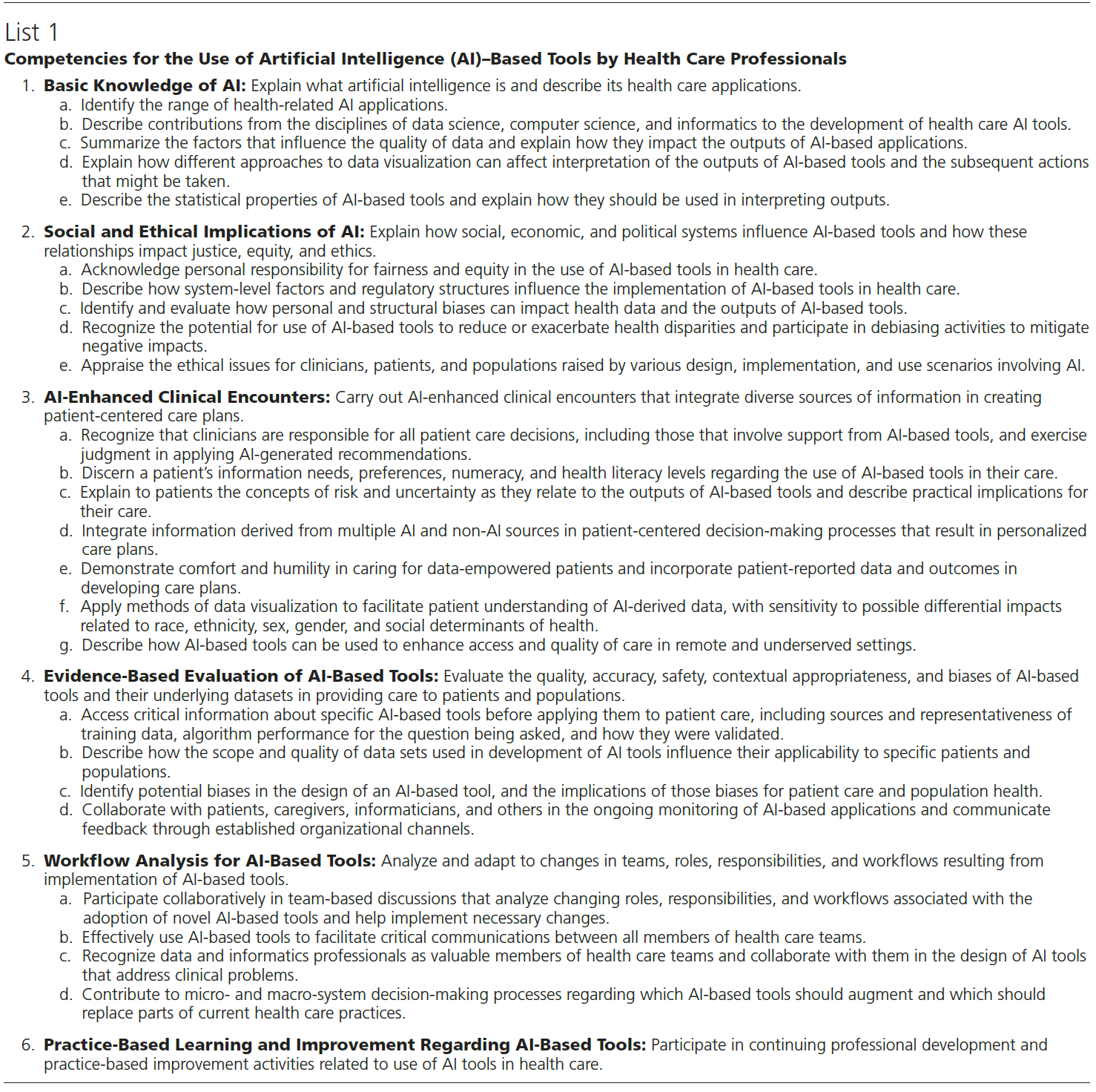

| 보건의료전문직이 인공지능-기반 도구를 사용하기 위한 역량(Acad Med, 2023) (0) | 2023.05.25 |

| 필요하지만 충분하지 않고, 어쩌면 반생산적인 것: 강의평가의 복잡한 문제(Acad Med, 2023) (0) | 2023.05.14 |