의학교육에 환자와 공공의 참여를 향하여 (Med Educ, 2016)

Towards a pedagogy for patient and public involvement in medical education

Sam Regan de Bere & Suzanne Nunn

소개

Introduction

환자는 다양한 단계, 다양한 맥락, 다양한 목적을 가진 의학교육의 중심입니다. 하지만 현재 의대생과 의사 교육에 환자와 대중이 실제로 얼마나, 얼마나 효과적으로 참여하고 있으며, 앞으로는 어떻게 발전해야 할까요? 환자 및 대중 참여(PPI)가 임상의가 경력을 쌓는 동안 학습하는 방식에 실질적인 영향을 미친다는 것을 어떻게 알 수 있으며, 어떤 증거를 바탕으로 해야 할까요? 이러한 질문은 새로운 것이 아닙니다. 10여 년 전부터 교육자들은 임상 교육에 환자의 참여를 늘려야 한다고 요구해 왔습니다.1-3 이러한 요구는 2010년 Medical Education 학술지에서 강조되었는데, Towle 외.4는 보건의료 전문가 교육에서 PPI와 관련된 학술 문헌을 체계적으로 검토하여 다양한 현지화된 이니셔티브의 존재를 자세히 설명하고 '참여의 사다리'를 통해 참여를 이해하는 개념적 틀을 제공했습니다. 이 연구는 향후 이니셔티브를 구축하기 위한 명확한 이론, 스키마, 적용 또는 평가가 부족하다는 점을 강조했습니다.4 이듬해에는 보건의료 전문가 교육에서 지속 가능한 PPI 개발의 개념적, 이론적, 경험적 측면에 대한 주요 보고서5가 발간되어 보다 엄격한 연구와 실행을 위한 명확하고 설득력 있는 사례를 제시했습니다.

Patients are central to medical education at different stages, in different contexts and for different purposes. But how far and how effectively are patients and the public now actually involved in training medical students and doctors, and how should this be developed in the future? How do we know that patient and public involvement (PPI) has any real impact on the way in which clinicians learn throughout their careers, and what evidence do we have to draw upon? These questions are not new: over 10 years ago, educators were calling for increased patient involvement in clinical education.1-3 The imperative was highlighted in Medical Education in 2010, when Towle et al.4 reported a systemic review of the academic literature pertaining to PPI in health care professionals’ education, detailing the existence of various localised initiatives and providing a conceptual framework for understanding engagement via the ‘ladder of involvement’. This work highlighted a disconcerting lack of definitive theory, schema, application or evaluation upon which to build future initiatives.4 In the following year, a major report on the conceptual, theoretical and empirical aspects of developing sustainable PPI in health care professionals’ education5 was published, stating a clear and persuasive case for more rigorous research and implementation.

그러나 5년이 지난 지금, 의학교육 전반에 걸쳐 PPI를 개발하고 평가하기 위한 명확한 전략은 여전히 부족합니다. 학술 문헌은 다양한 전문 분야 또는 커리큘럼 주제에서 다양한 수준의 환자 또는 학생에 대한 인식을 바탕으로 한 설명적인 보고서와 PPI 이니셔티브에 대한 이질적인 스냅샷이 주를 이루고 있습니다. 이론, 실무 및 결과 사이의 연관성에 대한 증거는 거의 없으며, 국제적으로 비교할 수 있는 범위도 아직 미미합니다.

Five years later, however, a clear strategy for developing and evaluating PPI across the continuum of medical education remains lacking. The academic literature is dominated by descriptive reports and disparate snapshots of PPI initiatives, based on perceptions of patients or students involved at various levels in various specialties or curriculum topics. There remains little evidence of connection between theory, practice and outcomes, and less still any scope for international comparison.

개별적인 노력으로 '참여의 사다리'에 대한 검토를 포함하여 PPI 분류체계를 개선하고 평가를 강화하라는 Towle 등의 요구에 부응하기 위해 노력했지만,6 이 분야는 여전히 환자, 대중 및 일반인이 평생 의료 학습자의 반성적 전문적 실천에 대한 멘토링, 평가 및 지원에서 가질 수 있는 체계적이고 진보적인 역할에 대한 강력한 증거를 필요로 하고 있습니다. 이는 의대 선발부터 의과대학, 성공적인 졸업, 지속적인 전문성 개발, 규제, 그리고 잠재적으로 교정에 이르기까지 의학교육의 연속성을 거치면서 의료 전문가에 대한 경험과 지원의 일관성에 대한 의문을 제기합니다. 지적 측면과 실용적 측면 모두에서 의학교육 분야는 서로 다른 것처럼 보이는 영역 간의 경계를 넘나들며 모든 의료 전문가를 위한 공식 교육과 교육을 통한 규제를 모두 포함하는 일관되고 상황에 맞는 접근 방식을 개발함으로써 많은 것을 얻을 수 있을 것입니다.

Although individual endeavours have sought to answer Towle et al.'s call to improve PPI taxonomies and strengthen evaluation, including a review of their ‘ladder of involvement’,6 the field is still in need of robust evidence of the systematic and progressive role patients, the public and lay representatives may have in the mentoring, assessment and support of reflexive professional practice of life-long medical learners. This raises questions over the consistency of experience and support for medical professionals as they progress through the continuum of medical education, from selection to medical school, through to successful graduation, continuing professional development, regulation and, potentially, remediation. In both intellectual and practical terms, the field of medical education could have much to gain from crossing the boundaries between those seemingly different spheres and developing a cogent, context-specific approach to embedding PPI as both formal education and education-through-regulation for all medical professionals.

이 백서는 의학교육의 전체 연속체에서 미래 PPI 전략의 개발을 진전시키기 위한 논거를 제시합니다. 특히 교육 과정 및 결과(공식적이든 그렇지 않든), 환자 중심 학습에 대한 요구를 해결할 수 있는 역량, 공유된 의사 결정 의제와 관련된 환자 참여에 대한 접근 방식으로 통합된 다양한 출처를 활용합니다. PPI에 대한 자체 연구를 참조하여, 우리는 의학교육자를 위한 3가지 핵심 우선순위를 확인했습니다.

- (i) 통합된 문헌 코퍼스를 통해 의학교육과 관련된 PPI에 대한 증거의 통합,

- (ii) 의학교육에서 PPI에 대한 공유된 정의를 통한 개념적 명확성,

- (iii) 복잡성 관리 및 PPI 이니셔티브 평가에 대한 학문적으로 엄격한 접근 등

이러한 과제에 대한 대응책으로 활동 모델링을 분석적 휴리스틱으로 사용하여 역동적인 교육 맥락에서 상호 작용하는 여러 PPI 시스템에 대한 이해를 제공하는 방법을 설명하고, 이를 미래로 나아가는 데 있어 환자와의 파트너십 접근 방식을 촉구합니다.

This paper presents an argument for advancing the development of future PPI strategies across the full continuum of medical education. It draws on a range of sources unified by their approach to engagement with patients that relates specifically to educational processes and outcomes (formal or otherwise), the capacity to address demands for patient-centred learning, and shared decision-making agendas. Referring to our own research into PPI, we identify three key priorities for medical educators, including:

- (i) the integration of evidence on PPI relevant to medical education, via a unifying corpus of literature;

- (ii) conceptual clarity through shared definitions of PPI in medical education, and

- (iii) an academically rigorous approach to managing complexity and the evaluation of PPI initiatives.

As a response to these challenges, we outline how activity modelling may be used as an analytical heuristic to provide an understanding of a number of PPI systems that interact within dynamic educational contexts, and call for a partnership approach with patients in taking this forward to the future.

PPI의 문제점은 무엇인가요? 점점 더 시급해지는 의학교육 의제 해결

What is the problem with PPI? Addressing an increasingly pressing agenda for medical education

의학교육에서 [PPI의 교육적 이점]은 오랫동안 논의되어 왔으며, 특히 학습의 관련성 입증, 공감 능력 배양, 의사소통을 포함한 주요 전문 기술 개발 장려를 통해 학생에게 동기를 부여하는 능력 측면에서 논의되어 왔습니다.7-10 의학교육에서 [환자의 역할]은 '의학과 외과를 전공하는 후배 학생에게는 환자를 텍스트로 하지 않는 교육은 하지 않는 것이 안전한 규칙이며, 가장 좋은 가르침은 환자가 직접 가르치는 것'이라는 오슬러의 주장이 자주 인용된 이후 극적으로 발전해 왔습니다. 11 [광범위한 사회적 및 전문적 담론], [의료기관 현대화를 위한 정치적 동인], [거버넌스 구조에 대한 대중의 참여를 통한 독립적인 '목소리'의 강조]에 힘입어, [전통적인 '가부장적' 의료 모델]에서 보다 ['환자 중심'의 의료 설계, 제공 및 실천 모델]로 상당한 전환이 이루어지고 있습니다.12-14 현재의 정치적 환경에서 이 모델에 대한 높은 가치는 이제 잘 확립되어 있으며, PPI는 종종 그 목표의 핵심으로 간주됩니다. 의료 서비스 연구 분야에서도 PPI는 한동안 의제로 다뤄져 왔습니다. 예를 들어, 영국에서는 국립보건연구원(NIHR)의 지원을 받아 국가 자문 그룹(INVOLVE)을 구성하여 NHS, 공중보건 및 사회복지 연구에 대한 대중의 참여를 지원하고 있습니다. 물론 이는 보건 서비스 연구에 PPI를 포함시켜야 할 필요성에 대한 대응입니다. 그러나 이후 이 의제는 교육 정책과 실천으로까지 이어졌습니다.15

The educational benefits of PPI in medical education have long been debated, notably in terms of its capacity for motivating students by: demonstrating the relevance of learning; fostering empathy; and encouraging the development of key professional skills, including communication.7-10 The role of the patient in medical education has developed dramatically since Osler's oft quoted assertion that ‘for the junior student in medicine and surgery, it is a safe rule to have no teaching without a patient for a text, and the best teaching is that taught by the patient himself’.11 Informed by wider social and professional discourses, political drivers for modernising medical institutions, and an increasing emphasis on the independent ‘voice’ via public involvement in governance structures, there has been a significant shift away from the traditional ‘paternal’ medical model towards a more ‘patient-centred’ model of health care design, provision and practice.12-14 In current political climates, the high value placed on this model is now well established, and PPI is often regarded as being central to its aims. In the field of health services research, PPI has been on the agenda for some while. For example, in the UK, a national advisory group (INVOLVE) is funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) to support public involvement in NHS, public health and social care research. This is, of course, a response to the need to embed PPI in health services research. However the agenda has since filtered through to education policy and practice.15

[영국의 정책 계보]가 대표적인 사례입니다.

- 2003년, Tomorrows Doctor's12 는 영국의 학부 의학교육에 대한 요건을 제시하면서, 대학의 진료 의무와 관련하여 환자를 언급하고 학생과 환자의 상호 작용이 환자를 존중하고 관계를 발전시켜야 한다고 명시했습니다.

- 2009년 개정판인 Tomorrow's Doctors13에서는 이를 확장하여 커리큘럼의 모든 측면에 PPI를 명시적으로 포함시켰으며, 이를 '파트너십'이라는 용어로 설명했습니다.

- 이제 이 정책의 세 번째 반복을 앞두고 있는 이 자문 문서는 [의과대학의 질 보증 및 거버넌스] 외에도 [교육뿐만 아니라 평가, 학생 성과에 대한 피드백 및 코스 설계]에 환자가 적극적으로 참여할 수 있는 문화를 옹호하고 있습니다.

- 동시에 데이비드 그린어웨이 교수가 주도한 영국의 의사 교육에 대한 독립적인 검토인 The Shape of Training에서는 다음과 같이 권고했습니다:

- '적절한 조직은 의사 교육 및 훈련에 환자를 참여시킬 수 있는 더 많은 방법을 찾아야 한다'고 권고했습니다.

- 이 리뷰는 다음과 같이 대담하게 말합니다:

- '환자와 보호자로부터 배우는 것은 실행하기 어렵다는 것을 알고 있지만, 수련 중인 의사가 환자 중심 치료에 대한 경험을 쌓을 수 있는 가장 좋은 방법입니다. 이는 대학원 커리큘럼과 평가 시스템에 명시적으로 포함되어야 하며, 커리큘럼 검토의 일부가 되어야 합니다'라고 말합니다.14

The genealogy of policy in the UK is a case in point.

- In 2003, Tomorrows Doctor's12 set out the requirements for undergraduate medical education in the UK, referring to the patient in relation to the universities’ duties of care and the students’ interactions with patients being respectful and developing relationships with them.

- The revised edition of Tomorrow's Doctors in 200913 expanded on this to explicitly include PPI in all aspects of the curriculum, describing it in terms of a ‘partnership’.

- Now on the cusp of the third reiteration of the policy, its consultation document advocates, in addition to the quality assurance and governance of medical schools, a culture that enables active involvement of patients not only in teaching but also in assessments, feedback on student performance and course design.

- At the same time, The Shape of Training, an independent review of doctors’ training in the UK led by Professor David Greenaway, recommended that:

- ‘Appropriate organisations should identify more ways of involving patients in educating and training doctors’.

- The review states boldly that:

- ‘We recognise that learning from patients and carers is difficult to implement, but it is the best way for doctors in training to gain experience in patient-centred care. It must be an explicit part of postgraduate curricula and assessment systems, and should be part of a review of curricula’.14

환자 참여 확대를 위한 변화는 영국에만 국한된 것이 아닙니다. 이러한 논의는 영국에서 특히 활발하게 이루어지고 있지만, 국제 문헌, 특히 영국, 캐나다, 미국, 호주의 학자들이 참여한 연구를 통해 동일한 이슈가 분명하게 드러납니다.5, 16 이러한 변화는 의료계 안팎, 다른 보건 전문직의 교육 전략(뒤에서 살펴볼), 보건과학과 같은 관련 학문의 전략에서 모두 나타납니다.17 환자가 다양한 수준에서 의료를 제공하는 사람들의 교육에 참여하기를 원한다는 것을 시사하는 분명한 증거가 있습니다. 환자들은 PPI 포럼이나 기타 참조 그룹을 통해 다음을 원합니다.18-20

- 아이디어를 공유하고 '새로운 교육 이니셔티브 및 문서에 대해 의견을 제시하고,

- 혁신을 권고하며,

- 관련 학생 피드백을 살펴보고 중요한 사건에 대해 논의함으로써 환자 중심주의를 향한 진전을 모니터링

Shifts towards greater patient involvement are not limited to the UK. The debate is particularly lively in the UK, but the same issues are evident in the international literature, notably through work involving academics from the UK, Canada, the USA and Australia.5, 16 They are represented both within and outside of the profession, in the educational strategies of other health professions (to which we turn later), and in those of cognate disciplines such as health sciences.17 There is clear evidence to suggest that patients wish to be involved in the education of those who provide health care at various levels. They are keen to:

- share their ideas and ‘comment on new teaching initiatives and documents;

- recommend innovations; and

- monitor progress towards patient centeredness by looking at relevant student feedback and discussing significant events’, potentially through PPI forums or other reference groups.18-20

그러나 비평가들은 학생들이 [일반적으로 다른 의사들로부터 환자 중심주의에 대해 계속 배우기 때문에], 현대의 교육 관행이 여전히 부족하다고 주장합니다.21, 22 Bleakley & Bligh가 주장하듯이, 현재의 분위기는 '의대생과 환자가 진료실, 교실 및 병동에서 실제로 마주치는 방식에 관해서는 다소 침묵합니다'(189페이지).23 여기서 문제는 [의사가 설계한 교육과정]과 [환자의 경험을 통해 확인된 요구] 사이의 [상당한 차이를 해결해야 한다]는 것입니다:

- '기존의 커리큘럼 설계는 환자에게 중요한 핵심 영역을 놓칠 수 있습니다'.24

However, critics argue that contemporary educational practice remains wanting, as students typically continue to learn about patient-centredness from other doctors.21, 22 As Bleakley & Bligh argue, the current climate ‘falls rather silent when it comes to the ways in which medical students and patients actually encounter each other in the clinic, classroom and on the wards’ (p.189).23 The challenge here is to address the significant divergence between doctor-designed curricula and the needs identified through patients’ experiences, where:

- ‘conventional curriculum design may miss key areas that are important to patients’.24

환자 참여에 대한 이러한 ['전문가 중심'의 접근 방식]은 앞서 언급한 환자 중심 의제에 대한 대응으로서 PPI 개념에 이념적 걸림돌을 제공합니다. 따라서 의학교육의 학문 분야에서는 [현재 PPI의 개념]에 대해 그 [기원]뿐만 아니라 의료계에서 [실제로 나타나는 모습]에 대해서도 비판적으로 분석할 필요가 있습니다. 의학 문헌에서는 비판이 잘 드러나지 않지만, 사회 과학자들은 [의료 헤게모니]라는 까다로운 문제를 제기하며, PPI에 대한 많은 접근 방식이 '하향식'으로 진행되며, 환자는 의대생(수련의와 개업 의사 모두)이 [학습의 직접적인 파트너]가 아니라, [그저 정보를 얻을 수 있는 대상으로 위치]한다고 제안합니다. 이러한 비판은 PPI가 [의료 헤게모니의 요구에 복무]하고 있으며, [참여가 그들에 의해 의무화]되고, [전통적으로 가부장적 의학교육에 대한 도전을 무력화시키는 방식]으로 조직되어 있다는 점을 지적합니다.

This ‘profession-centred’ approach to engagement with patients provides an ideological stumbling block to the notion of PPI as a response to the aforementioned patient-centred agenda. Thus, within the academic field of medical education there is a need for critical analysis of current notions of PPI, not only in terms of their origins, but also as they actually manifest in the medical world. Although critique is less evident in the medical literature, social scientists raise the thorny issue of medical hegemony, suggesting that many approaches to PPI are directed ‘from the top down’, with patients positioned as objects from which medical students (trainees and practising physicians alike) can draw information, as opposed to being direct partners in learning. Such critiques point to PPI servicing the needs of the medical hierarchy, as involvement is mandated by them and organised in such a way as to negate any significant challenge to a more conventionally paternalistic medical education.

이는 [정체성 정치]와 [대표성]이라는 또 다른 정치적 문제를 제기합니다.

- [의학적 시선]으로 문제를 바라보는 경향25은 의학교육자가 [정확히 누가 참여받고 이으며, 그들은 어떻게 선택되었는지 대해 의문을 제기하지 않았다]는 것을 의미합니다.

- 더 중요한 것은, 의학교육 연구는 [참여받지 못한 환자와 대중]에게 더 많은 주의를 기울이고, 그들이 [선택되지 않는 이유]를 파악하는 데 도움이 될 수 있다는 것입니다.

현재 교육 PPI 활동에서 일어나지 않는 것을 고려해야 한다는 요구사항은 나중에 다시 다루겠지만, 여기서 중요한 것은 [PPI 자체가 문제가 있는 개념]이라는 점입니다. 그렇다고 해서 교육학으로 발전하는 것이 불가능하다는 것이 아니라, 이러한 모순을 인식하고 이를 교육학에 대한 이해의 폭을 넓히는 데 통합할 필요가 있다는 것입니다.

This in turn raises a further political issue: that of identity politics and representation.

- A tendency to view matters through a medical gaze25 means that medical educators have yet to question who, precisely, is involved, and how they are selected.

- Perhaps more importantly, research in medical education could benefit from paying more attention to the patients and public who are not involved and identifying why they are not selected.

The requirement to consider what is not occurring in current educational PPI activity is something we return to later, but the point here is to note that PPI is a problematic concept in itself. This is not to render it impossible to develop into pedagogy; rather, it is necessary to recognise and incorporate these inconsistencies into our growing understanding of it.

따라서 환자와 대중을 의학교육에 참여시킴으로써 얻을 수 있는 잠재적 이점에 대한 이해를 발전시키기 위해 문헌을 연구할 수는 있지만, 현재 PPI에 대한 종합적이고 체계적인 비평은 없습니다. 다양한 맥락에서 실제로 어떤 모습인지, 얼마나 바람직한지(실행 가능성은 말할 것도 없고), 커리큘럼이나 '주최' 기관에서 참여의 다양성과 평등이 어떻게 구조화되고 지원되어야 하는지에 대한 비판적 탐구는 거의 이루어지지 않고 있습니다. 미래의 PPI가 지속 가능하고 목적에 부합하도록 맞춤형 또는 일반적 교육법을 개발하는 데 있어 연구의 역할, 또는 실제로 그 목적이 무엇인지 정의하는 것을 포함하여 의학교육의 연속체 전반에 걸쳐 그 역할에 대한 수많은 질문에 대한 해답이 아직 제시되지 않았습니다.

So, although we can study the literature in order to develop an understanding of the potential benefits that can be brought about by involving patients and the public in medical education, there is currently no comprehensive or systematic critique of PPI. There remains little critical exploration of what it actually looks like in its different contexts, how much is desirable (let alone practicable), and how diversity and equality in involvement should be structured and supported, either in curricula or by ‘hosting’ organisations. Numerous questions about its role across the continuum of medical education remain unanswered, including the role of research in developing either bespoke or generic pedagogies to ensure that PPI for the future is sustainable and fit for purpose – or indeed defining what that purpose might be.

이 백서에서는 이러한 문제를 차례로 다룹니다. 먼저, 우리는 출판의 이질적이고 단절된 특성을 살펴보고 그 함의를 고려합니다. 우리는 의학교육자들이 관련 지식의 전담 기관을 개발하고, 교육 및 평가 방법론에 정보를 제공하며, 연구자들이 자신의 연구 결과를 보고하고 새로운 교육학에 대해 토론할 수 있는 장을 제공하도록 도전합니다.

In this paper we address these issues in turn. First, we look to the disparate and disjointed nature of publication and consider the implications. We challenge medical educators to develop a dedicated body of relevant knowledge, to inform teaching and evaluation methodologies and to provide an arena in which researchers can report their own findings and debate emerging pedagogies.

PPI에 대해 무엇을 알고 있나요?

의학교육과 관련된 PPI에 대한 통합된 문헌 코퍼스 개발

What do we know about PPI?

Developing a unifying corpus of literature on PPI relevant to medical education

'의학 커리큘럼'이라는 용어는 표면적으로는 광범위하지만 일반적으로 학부 교육을 지칭하는 데 사용됩니다. 대학원 교육과 지속적인 전문성 개발은 교육의 연속체에서 구성 요소로 취급되기보다는 별도의 독립체로 취급되는 경우가 많습니다. Sklar가 지적한 것처럼

- (i) 의학교육에 대한 통일된 비전을 제시하지 못하고 있으며,

- (ii) 교육 부문 간 전환이 거칠다'26

이는 PPI에 시사하는 바가 있습니다. PPI가 적극적인 목표로 간주된다면, 아마도 선발 시점부터 학부 교육, 졸업, 등록 및 실습을 거쳐 은퇴에 이르기까지 전문직 경력의 [연속체 전반에 걸쳐 지속적이고 점진적인 교육적 역할을 수행해야 할 것]입니다.

The term ‘medical curriculum’, though ostensibly broad, is typically used to refer to undergraduate education. Postgraduate training and continued professional development are frequently treated as separate entities, rather than as component parts of the continuum of education. As Sklar points out:

- (i) there is a failure to create a unifying vision for medical education, and

- (ii) the transitions between the segments of education are rough’.26

This has implications for PPI. If it is considered to be an active goal, it should presumably play a continuous and progressive educative role across the continuum of a professional career; from the point of selection through undergraduate training, graduation, registration and practice until retirement.

향후에는 [환자와 대중]이 교육 연속체를 통해 점점 더 [원활한 전환을 촉진하기 위해 통합된 초점 역할]을 할 수 있다고 제안합니다. 그러나 이를 달성하려는 정치적 의지는 보다 포괄적이고 이론적으로 발전된 문헌을 활용하여 연속체 전반에 걸쳐 정책과 실무에 정보를 제공하는 신뢰할 수 있고 체계적인 PPI 교육학에 달려 있을 것입니다. 우리는 의학교육 커뮤니티가 한 걸음 더 나아가 이 과제를 해결해야 한다고 주장합니다. PPI를 실무와 교육학 모두에서 변화의 압력에 따라 좌우되는 복잡한 활동으로 보려면 교육 실무의 모든 영역에 걸쳐 수많은 다른 영향을 고려해야 합니다. 의미 있는 정책을 수립하고 연속체 전반에 걸쳐 적절하고 효과적인 실천을 구현하려면 의학교육에서 [PPI의 다양한 역할과 현실에 대한 이론적 근거]와 [경험에 기반한 이해]가 필요합니다. 하지만 안타깝게도 의학교육의 여러 영역에서 PPI에 대한 다양한 연구를 수행하려면 맥락을 파악하기 위해 개별적이고 매우 독특한 문헌 검토가 필요했습니다.

We suggest that, in the future, patients and the public could serve as a unifying focus to facilitate an increasingly seamless transition through the educational continuum. The political will to achieve this, however, is likely to depend on a credible and systematic pedagogy of PPI that draws on a more inclusive and theoretically developed corpus of literature to inform policy and practice across the continuum. We would argue that it is the job of the medical education community to step forward and pick up this particular gauntlet. Viewing PPI as a complex activity that is contingent on the pressure of changes in both practice and pedagogy requires us to consider a plethora of other influences throughout all spheres of educational practice. Formulation of meaningful policy and implementation of relevant and efficacious practice across the continuum will be dependent on a theoretically grounded and empirically based understanding of the multiple roles and realities of PPI in medical education. Frustratingly, though, our various research studies of PPI in different areas of medical education have required separate and quite distinctive literature reviews for context.

규제 관련 문헌에서 PPI를 서술적으로 종합한 결과27 정책 입안자(회색 문헌), 의료 교육자(학술) 대상, 환자 및 일반인(일반인 지식)을 위한 글 사이에 존재하는 분열이 드러났습니다. 인용의 매핑을 통해 [의료 및 학술 언론]에 지식이 집중되고 유통되는 것을 확인할 수 있었으며, 이는 전문 의료 이해관계자 웹사이트의 위탁 보고서 및 기타 문서로 보완되었습니다. 이러한 자료는 PPI에 대한 지식 코퍼스를 형성했지만, 그 자체의 영역에 머물렀고 그 너머로 전파되지는 않았습니다. 따라서 이 글을 쓰는 시점에서 [환자와 대중은 자신과 관련된 공식 담론과 지식으로부터 고립되어 있으며], 이는 앞서 언급한 환자 중심적 수사에도 불구하고 가부장적 태도가 지속되고 있음을 반증하는 것이라고 주장할 수 있습니다.

Our narrative synthesis of PPI in regulation-related literatures27 revealed a schism that existed between writings for policy-makers (the grey literature), medical-educator (academic) audiences, and patients and the public (lay knowledge). Mapping citations highlighted a concentration and circulation of knowledge in the medical and academic press, which was supplemented by commissioned reports and other documents from professional medical stakeholder websites. These formed a corpus of knowledge about PPI, but one that remained in its own sphere and was not disseminated beyond it. At the time of writing, patients and the public therefore remain isolated from official discourses and knowledge about their own involvement, which we could argue testifies to a continuing paternalistic attitude in spite of the patient-centred rhetoric referred to earlier.

이러한 [분열은 의학교육 문헌에도 반영]되어 있는데, PPI에 대한 이론적, 정치적 논쟁과는 분리된 상태로, 현지화된 이니셔티브에 대한 [피어 리뷰 보고서]가 강조되고 있습니다. [회색 문헌]과 [피어 리뷰 문헌] 사이의 분리는 여기에서도 명백하며, 이전 문헌과 학술 연구 및 프로그램 평가 보고서의 유용한(그러나 종종 출판되지 않고 찾기 어려운) 기여도 사이에는 고려해야 할 추가 구분이 있습니다. 또한, 많은 기본 원칙과 목적이 의학의 원칙과 일치한다는 개념에도 불구하고 관련 전문직 교육에서 PPI를 사용하는 것에 대한 가교가 거의 없습니다. 예를 들어, 간호 및 조산 교육 문헌에서는 현재 커리큘럼에서 환자 참여 그룹(PPG)의 역할에 대한 활발한 논의가 이루어지고 있으며,6 정신건강 및 지역사회사업 논문집에서는 앞서 언급한 '가부장주의'와 '의료적 시선'에 대한 의학교육자의 이론적 이해를 돕는 참여 문제에 대한 논의28를 제시하고 있습니다.

The schism is reflected in the medical education literature, where there is an emphasis on peer-reviewed reports of localised initiatives, disjointed from more theoretical and political debates around PPI. Divisions between grey and peer-reviewed literature are evident here also, and there is a further divide to be considered, between those former literatures and the useful (but often unpublished and difficult to locate) contributions of scholarly work and programme evaluation reports. Moreover, there is little bridging of the use of PPI in the education of related professions, despite the notion that many of the underlying principles, and perhaps the purposes, coincide with those of medicine. The nursing and midwifery education literatures, for example, currently host a lively conversation about the role of patient participation groups (PPGs) in curricula,6 while the corpus of mental health and community work papers presents a discussion of issues of participation28 that might well help medical educators to address more theoretical understanding of the aforementioned ‘paternalism’ and ‘medical gaze’.

[전문적이고 학제적인 '사일로 문화'] 외에도 [지식 생산의 문화적 관습]은 PPI가 점유하는 다양한 영역을 가로지르는 것을 어렵게 하며, 이는 의심할 여지없이 이 주제에 대한 포괄적이고 엄격한 이해를 발전시키는 데 어려움을 초래할 것입니다. 따라서 환자와 대중의 참여에 직접적으로 초점을 맞춘 새로운 동료 심사 저널(예: 새로운 연구 참여 및 참여29)의 개발은 환영할 만한 이니셔티브가 될 것입니다. 특히 이러한 움직임은 [지식 생산에 대한 가부장적 접근 방식]에서 벗어나 [파트너십 지향적 접근 방식]을 촉진할 수 있습니다. 우리 연구 분야는 환자와 대중의 기여를 포용하는 학문적으로 신뢰할 수 있는 '허브'가 PPI 관련 연구에 전념한다면 큰 도움이 될 수 있습니다. [가부장적인 의학교육 문화]에서는 [학자나 임상 학자]가 다른 기관을 대신해 일을 하는 경우가 많지만, [학자 및 환자와 협력하고 파트너십]을 맺는다면 [사일로 출판 상황]을 극복하는 데 도움이 될 수 있으며, 무엇보다도 [PPI 교육학의 실제 창시]에서 [더 많은 PPI의 방향]으로 우리를 이끌 수 있을 것입니다.

In addition to professional and disciplinary ‘silo-cultures’, the cultural mores of knowledge production make it difficult to traverse the different realms occupied by PPI, and this will undoubtedly represent a challenge to the development of an inclusive and rigorous understanding of the subject. The development of new peer-reviewed journals (e.g. the new Research Involvement and Engagement29), which focus directly on patient and public involvement, would therefore represent a welcome initiative. In particular, such moves could facilitate less paternalistic and more partnership-orientated approaches to knowledge production. Our field of enquiry could well benefit from the provision of academically credible ‘hubs’ dedicated specifically to PPI-related work that embrace the contributions of patients and the public. Although a paternalist medical education culture often involves academics or clinical academics doing things on behalf of other agencies, working in collaboration and partnership with academics and patients might help overcome the silo-publishing situation and, perhaps most importantly, lead us in the direction of more PPI in the actual genesis of PPI pedagogy.

이러한 논쟁을 염두에 두고, 우리는 [일관되고 포괄적이며 진보적인 말뭉치의 개발이 교육학 말뭉치 개발의 중심]이 되어야 하며, [이질적인 문헌과 집단을 통합]하여 보다 체계적인 스키마 내에서 관행을 이해할 수 있도록 해야 한다고 주장합니다. 이러한 스키마는 규범적prescriptive이어서는 안 되며, PPI의 역동적인 특성을 제약하기보다는 촉진해야 합니다. Towle 등4 의 연구로부터 5년이 지난 지금, 우리는 의학교육자들이 다음과 같이 노력해야 한다고 제안합니다:

Mindful of these contentions, we argue that the development of a cogent, inclusive and progressive corpus must be central to the development of a pedagogic corpus, and that disparate literatures and populations should be consolidated so practices can be understood within a more systematic schema. These schemas should not be prescriptive: they should facilitate, rather than constrain, the dynamic nature of PPI. Five years on from Towle et al.4 then, we suggest that medical educators should endeavour to:

- 학술적, 학술적, '회색' 문헌의 지식을 통합합니다;

- 의학 학습의 연속체 전반에 걸친 연구를 통합합니다;

- 이론적 기여를 경험적 연구와 종합합니다;

- 다른, 특히 건강 관련 전문직 및 관련 분야의 토론과 혁신에 참여합니다.

- 이러한 노력에 환자 및 대중과 함께 참여합니다(이에 대해서는 나중에 다시 설명합니다).

- consolidate knowledge from academic, scholarly and ‘grey’ literatures;

- bring together work from across the continuum of medical learning;

- synthesise theoretical contributions with empirical work;

- engage with debates and innovation in other, particularly health-related, professions and cognate disciplines; and

- engage with patients and the public in this endeavour (we return to this later).

PPI는 무엇을 의미하나요? 의학교육의 개요 파악하기

What do we mean by PPI? Gaining the overview in medical education

의료 전문직 전반에 걸쳐 환자의 적극적인 참여를 조사한 Towle 등의 연구4는 환자와 대중이 교육 활동 전반에 걸쳐 다양한 수준에서 통합될 수 있는 [참여 시스템으로서 PPI]를 이해하는 데 매우 유용했습니다. 앞서 언급한 '사다리'를 통해 이해한 [내장성embeddedness의 유형학]에서 저자들은 PPI 수준 간의 명확한 차이를 모델링했습니다.

- 교육 전략 및 커리큘럼 개발(드문 경우),

- 직접 교육 및 학습(약간 더 분명한 경우),

- 연구 대상 또는 연구 목적으로서의 교육 활동 참여(대부분의 연구에서 나타나는 경우)

Towle et al.'s4 review examining the active engagement of patients across the health professions, was invaluable to understanding PPI as a system of engagement within which patients and the public may be integrated at a range of levels across educational activities. In their resulting typology of embeddedness, understood via the aforementioned ‘ladder’, the authors modelled clear differences between levels of PPI in

- educational strategy and curriculum development (which they found to be a rare occurrence),

- direct teaching and learning (which was marginally more evident), and

- participation in teaching activities as a subject or object of study (which was the case in the majority of studies).

Towle 등의 연구는 PPI의 실행 및 평가를 다루는 다른 기관에서 채택한 개념적 틀을 제공했습니다. 특히 영국의 보건의료과학위원회는 '관여 없음'에서부터 '제한적', '증가', '협력', '파트너십'에 이르는 5가지 범주 체계를 채택했습니다.17

Towle et al.'s work provided a conceptual framework that has been picked up by other agencies dealing with the implementation and evaluation of PPI. Notably, the Council of Healthcare Sciences in the UK has adopted a 5-category system, ranging from ‘no involvement’, through ‘limited’ and ‘growing’ involvement, to ‘collaboration’ and ‘partnership’.17

Towle 등이 교육에서 다양한 수준의 PPI 활동에 대한 이해를 개발하는 것과 동시에, PPI를 연구하는 국제 팀은 [PPI의 성격과 목적에 따라 추가적인 구분]을 제시했습니다. 스펜서 등5은 [환자, 일반인, 일반인 대표 역할]의 몇 가지 범주를 설명하면서 의과대학이 현지의 필요를 충족하고 가용한 전문성을 활용하기 위해 유연한 체계를 채택해야 한다고 제안했습니다. 저희는 자체 연구를 통해 의사가 국가 규제 기관인 일반의학회(GMC)에 면허를 갱신하기 위해 진료 적합성에 대한 증거를 제출해야 하는 규제 프로세스인 영국의 의료 재검증에서 PPI의 목적과 실제를 살펴봤습니다. 여기에는 제도적 차원에서는 조직에 대한 대중의 참여가, 전문적 평가 및 지속적인 개발 차원에서는 환자의 피드백이 반영의 원동력이 되었습니다.30 규제 및 교육적 장치로서 PPI의 성격, 목적 및 부가 가치 측면에서 우리 자신의 관찰 결과는 Towle 및 Spencer 연구 결과와 직접적으로 일치했습니다.1, 4 앞서 언급한 PPI의 유형에 대한 논쟁과 마찬가지로, 우리는 [환자, 일반인 및 대중]이 PPI에 적극적으로 참여하는 사람들조차 계속해서 [혼용되는 용어]라는 것을 발견했습니다.

Concurrent with Towle et al.'s development of an understanding about differential levels of PPI activity in education, an international team working on PPI provided a further set of distinctions based on the character and purpose of PPI. Spencer et al.5 outlined several categories of patient, public and lay representative roles, suggesting that medical schools should adopt flexible schemes to meet local needs and make use of available expertise. In our own research, we explored the purpose and practice of PPI in medical revalidation in the UK: the regulatory process by which doctors must now provide evidence of their fitness to practise in order to renew their licence with the national regulator, the General Medical Council (GMC). This involved, at the institutional level, public engagement in organisations and, at the level of professional appraisal and ongoing development, patient feedback as a driver for reflection.30 In terms of the character, purpose and value added by PPI as both a regulatory and educative device, our own observations were directly translatable to the findings of the Towle and Spencer studies.1, 4 In common with the aforementioned debates about typologies of PPI, we found that patients, lay persons and the public are terms that continue to be used interchangeably, even by those actively engaged in PPI themselves.

물론 이러한 역할은 [존재론적]으로 구별되며, 따라서 PPI의 본질과 목적을 이해하는 [인식론적 논쟁]에 영향을 미치기 때문에 이 점이 중요합니다. 개념적 측면에서 보면, PPI의 용어와 언어가 '대중'과 '환자'를 동화시킴으로써 고유한 존재론적 경계를 모호하게 만드는 역할을 합니다. 예를 들어,

- '환자'라는 용어는 개인과 의사 또는 소규모 의료 또는 교육 팀 간의 소규모 지역 관계를 지칭하는 반면,

- '공공'은 이해관계자 그룹으로서의 환자 집단을 포괄합니다.

- 일반인 대표성은 일반인을 의료기관의 조직적 수준과 연관시키는 거버넌스와 더 관련이 있습니다.

우리는 서로 다른 주체로서 이러한 역할은 모든 PPI 모델 내에서 서로 다른 수준의 분석의 대상이 되어야 한다고 주장합니다.

This is important because these roles are, of course, ontologically distinct, and therefore they have implications for epistemological debate about understanding the nature and purpose of PPI. In conceptual terms, as the terminology and language of PPI assimilates ‘public’ and ‘patients’, it serves to blur the inherent ontological boundaries. For example,

- the term ‘patient’ refers to the small local relationship between individuals and their doctors or small medical or educational teams,

- whereas the ‘public’ encapsulates the collective of patients as a stakeholder group.

- Lay representation is more concerned with governance, relating lay persons to the organisational level of medical institutions.

We argue that, as different entities, these roles should be subject to different levels of analysis within any model of PPI.

이러한 경계 모호함 또는 존재론적 혼동은 널리 퍼져 있는 것으로 보입니다. 문헌에 대한 여러 주요 기여를 통해 다양한 역할이 명시되었지만,4,31 일반적으로 용어가 일관되지 않아 명확성이 결여되어 있습니다. 놀랍지 않게도, 우리의 연구27,30는 이 문제가 순전히 철학적 논쟁을 초월한다는 사실을 입증했습니다. 이는 비용 및 운영 효율성뿐만 아니라 실제로 PPI를 적용할 때 목적 적합성에 영향을 미칩니다. 이러한 범주는 [필연적으로 광범위한 범주]이며 교육과 같은 역동적인 시스템에서 볼 때 상황에 따라 달라질 수 있다는 점을 인식하고, 적절하게 맞춤화된 교육법을 개발하기 위해 다음과 같은 구분이 필수적이라는 점에 주목합니다.

This boundary blurring or ontological muddling appears to be widespread: although various roles have been articulated by several key contributions to the literature,4, 31 there is a general terminological inconsistency that sustains a frustrating lack of clarity. Perhaps unsurprisingly, our research27, 30 has demonstrated that this matter transcends purely philosophical debates. It has implications for the fitness for purpose in any application of PPI in practice, as well as for cost and operational effectiveness. Recognising that these are necessarily broad categories, and that they are subject to contextual variations when viewed in a dynamic system such as education, we note the following distinctions as imperative for the development of appropriately tailored pedagogies.

환자

Patient

[환자]는 [의사와 의료 전문가와 즉각적이고 개인적인 관계]를 맺고 있기 때문에 교육에서 고유한 역할을 담당합니다. 환자는 이를 가능하게 하는 도구가 필요하지만 특정한 기술이 필요하지 않습니다. [환자의 목소리]가 도구가 되고 [건강, 질병 및 개별화된 치료를 받은 경험]이 기술이 됩니다. '환자'라는 실체와 관련하여, 우리 모두가 언젠가는 환자일 가능성이 높지만 그렇다고 해서 우리 모두가 항상 환자라는 의미는 아니라는 점을 기억하는 것이 중요합니다.

Patients have a unique role in education, because they have an immediate and personal engagement with doctors and the health profession. Patients require tools to enable them to do this but do not need a specific skill set: their voices are their tools and their experiences of health, illness and individualised receipt of care are their skills. In regard to ‘the patient’ as an entity, it is important to remember that, although in all likelihood we are all patients at some point, that does not mean that we are all always patients.

대중

Public

[대중]은 [집단적인 '환자의 목소리' 역할]을 하며 [어떤 식으로든 모든 환자를 대표]합니다. '대중'은 개별적으로 인식되는 '공익'을 대변하는 개인으로 구성될 수도 있고, 모든 의료 서비스 소비자를 위해 행동하고 의제를 공유하는 다른 보건 네트워크와 협력하는 국제환자단체연합과 같은 조직을 통해 대변될 수도 있습니다. 대중은 지역, 국가 및 국제 수준에서, 그리고 즉각적인 맥락과 보다 장기적인 맥락 모두에서 유용한 것으로 간주됩니다.

The public acts as the collective ‘patient voice’ and is representative of all patients in some way. The ‘public’ may comprise individuals speaking on behalf of the individually perceived ‘public interest’, or they may be represented through organisations, such as those represented by the International Alliance of Patient Organizations https://iapo.org.uk/, who act for all consumers of health care services and work collaboratively with other health networks with shared agendas. The public is viewed as useful at local, national and international levels, and in both immediate and more longitudinal contexts.

일반인 대표

Lay representation

[일반인]은 비임상 또는 비전문가의 참여를 지칭하는 일반적인 용어로 사용되지만, 우리 연구에 따르면 일반인 대표는 은퇴한 임상의인 경우가 많습니다.30 일반인 대표는 환자 지위보다는 관련 기술과 속성을 보유하고 적용하는 데 더 중점을 둡니다. 우리의 연구에 따르면 일반인 대표들은 전문적인 배경을 가짐으로써 스스로 혜택을 받는다고 생각합니다.30 일반인의 의견은 [거버넌스 논의 및 의사 결정에 대한 일반인의 참여와 관련]이 있으므로, 자문보다는 [적극적인 참여자]로 분류하는 것이 대중의 참여에 더 공감을 불러일으킬 수 있습니다. 따라서 [외부의 '독립적인' 목소리를 제공]한다는 점에서 일반인과 조직 모두의 관점에서 매우 가치 있는 것으로 간주됩니다.

Lay is used as a general term of reference for the involvement of persons who are non-clinical or non-specialists, although our research highlighted that lay representatives are often retired clinicians.30 Lay representation is less about patient status and more about possessing and applying relevant skills and attributes. Our research indicates that lay representatives feel they themselves benefit from having a professional background.30 Lay input is concerned with the participation of lay persons in governance discussions and decision-making, hence our categorisation of active participant rather than consultant, which may resonate more with public involvement. As such, it is deemed to be extremely valuable from both lay and organisational perspectives as it provides an external and ‘independent’ voice.

액면 그대로 받아들이면, 이 광범위한 유형론은 매우 복잡한 주제를 단순하게 구분하는 것처럼 보일 수 있습니다. 하지만 [의사, 기타 전문가, 대중, 환자]는 모두 각기 다른 정체성을 가지고 있으며, 환자 또는 대중 그룹마다 매우 다른 의제와 관점을 가지고 있으며, 이러한 관점은 끊임없이 변화하고 광범위한 개인적, 사회적, 문화적, 정치적, 경제적 압력에 영향을 받는 역동적인 시스템 속에서 형성되고 발전한다는 점을 인정합니다. 이는 일반인 대표의 정의에서 잘 드러납니다.

- 우리의 연구는 일반인 대표들이 전문적인 배경을 필요로 하기 때문에 운영에 익숙하고 따라서 '독립적인' 목소리를 낼 수 있는 특별한 특성이 있으며, 이 모든 것이 [일반인 대표]들이 인구학적 구성 측면에서 상당히 일반적인 사회적 정체성을 공유하게 한다는 점을 강조했습니다.27

- 또한 일반인들은 참여 시간이나 수준이 증가하거나 서비스에 대한 보수를 받을 경우 ['일반인'라는 정체성을 덜 갖게 될 수 있다]는 주장도 제기되고 있습니다.

- 따라서 일반인 대표를 체계화하거나 거버넌스 구조에 다양한 그룹의 참여를 확대하려는 모든 노력은 [가변성과 맥락적 요인]에 주의를 기울여야 합니다.

Taken at face value, this admittedly broad typology may appear to offer a simplistic demarcation of a very complex topic. We do acknowledge that doctors, other professionals, the public and patients all have different identities at different times; that different patient or public groupings have very different agendas and viewpoints, and that these are shaped and nurtured in dynamic systems that are ever-changing and subject to broader individual, social, cultural, political and economic pressures. This is exemplified in our definition of lay representation:

- our research highlighted how lay representatives require professional backgrounds so there is operational familiarity and therefore a particular quality to their ‘independent’ voice, all of which leads lay representatives to share a fairly common social identity in terms of their demographic make-up.27

- Moreover, lay people arguably become less characterised by their ‘lay’ identity as their time or level of involvement increases, or if they are remunerated for their services. Any endeavour to systematise lay representation, or to widen the participation of diverse groups in governance structures, therefore requires attention to variability and contextual factors.

그러나 우리는 이러한 문제를 단순화하려는 시도보다는 [PPI의 모호성과 복잡성]이 바로 의학교육이 PPI 학문과 연구에서 [존재론적, 인식론적 문제를 더 많이 고려해야 하는 이유]라고 주장하고 싶습니다. 이것이 강력한 분석 프레임워크를 개발하는 가장 중요한 동인 중 하나라고 제안합니다. 존재론적, 인식론적 구분은 PPI를 실행하는 사람들이 PPI와 (종종 추측적으로) 연관된 다양한 결과를 이해하는 데 도움이 되는 개념적 발판을 제공합니다. 물론 이 점은 단순히 의미론의 문제로 볼 수도 있지만, 그 자체로 이론과 실제에서 PPI의 다양한 측면을 이해하는 데 또 다른 차원을 추가합니다. 그러나 '사다리' 또는 [내재성 원칙]과 함께 보면 복잡성을 포착할 수 있는 범위가 더 넓어집니다.

Rather than attempting to simplify these matters, however, we would argue that ambiguity and complexity in PPI is precisely why medical education should demand more consideration of ontological and epistemological matters in PPI scholarship and research. We suggest that this is one of the most important drivers for developing a robust analytical framework. Ontological and epistemological distinctions offer a conceptual scaffold to help those implementing PPI to appreciate the many different outcomes with which it has been (often speculatively) associated. This point may of course be viewed as merely a matter of semantics, which, on its own, adds another dimension to understanding the many faces of PPI in theory and practice. Viewed in combination with the ‘ladder’ or embeddedness principle, however, it offers greater scope for capturing complexity.

따라서 우리는 이 두 가지 유형을 통해 [참여의 양적 측정]과 [참여의 본질에 대한 보다 질적인 탐구]를 통합함으로써 교육 과정으로서의 PPI에 대한 학문적 이해를 강화할 수 있을 것이라고 제안합니다. 의학교육 커뮤니티에 중요한 것은, 이는 보다 복잡한 이론적 발전의 토대가 될 수 있으며, 사회 및 학습 이론을 현장의 PPI 현실에 적용할 수 있는 기회를 제공할 수 있다는 점입니다. 이는 결국 의학교육의 모든 측면에서 보다 프로그램적인 접근 방식으로 이러한 다양한 수준과 유형을 가장 잘 구현할 수 있는 방법을 이해하는 데 도움이 될 수 있습니다. 따라서 [다양한 형태의 참여]와 [다양한 수준의 참여] 중 어떤 것이 의학교육에서 PPI를 구성할 수 있는지에 대한 명확하고 공유된 개념을 개발하는 것뿐만 아니라, 이러한 모든 형태의 PPI의 복잡성을 수용할 수 있는 휴리스틱이 필요합니다.

We therefore suggest that integrating quantitative measures of participation with more qualitative exploration of the nature of engagement, via these two typologies, will strengthen our academic grasp on PPI as an educational process. Importantly for the medical education community, this could provide a basis for more complex theoretical development, and an opportunity to apply social and learning theories to the reality of PPI on the ground. This could in turn help us to understand how we might best implement these different levels and types in a more programmatic approach across all aspects of medical education. As well as developing a clear and shared concept of which of the various forms and levels of engagement might constitute PPI in medical education, we are therefore in need of a heuristic that can accommodate the complexity of PPI in all these forms.

PPI는 어떻게 작동하나요?

복잡하고 역동적인 교육 시스템으로서의 PPI 이해

How does PPI work?

Understanding PPI as complex and dynamic educational systems

PPI에 대해 발표된 연구들은 일반적으로 현지 프로젝트의 장점을 설명하는 데 그쳤으며, PPI가 실제로 어떻게 '작동'하는지에 대한 정교한 개념적 이해를 바탕으로 한 경우는 드뭅니다. 최근의 이니셔티브는 이러한 필요성을 해결하기 위해 노력했습니다. 예를 들어, 이 글을 쓰는 시점에 고등 교육 기관(HEI)에 일반적인 프레임워크를 제공하기 위해 마련된 보건의료과학위원회(Council of Healthcare Sciences)는 지침에서 다음과 같은 잠재적 평가 질문을 식별합니다.17

Published studies of PPI have typically outlined the merits of local projects, and have rarely been framed by any sophisticated conceptual understanding of how PPI actually ‘works’. More recent initiatives have sought to address this need. The Council of Healthcare Sciences, for example, which at the time of writing is set to provide a generic framework for higher education institutions (HEIs), identifies the following potential evaluation questions in its guidance:17

PPI는 HEI의 구조와 문화에 어느 정도 정착되어 있는가?

이전에는 참여가 어떠했는가?

참여 과정이 서비스 제공 및 결과 개선으로 이어졌는가?

이를 입증하기 위해 어떤 종류의 증거를 사용할 수 있는가?

참여자가 더 넓은 커뮤니티를 대표했나요?

이것이 참여 활동의 성공에 중요한 요소로 고려되었나요?

활동이 교직원, 학생, 참가자 간의 관계에 어떤 영향을 미쳤나요?

활동이 직원과 학생의 이해/지식 또는 태도를 변화시켰나요?

활동이 프로그램 제공에 영향을 미쳤나요?

활동이 HEI의 정책과 전략에 영향을 미쳤나요?

참가자, 교직원 및 학생이 어떤 활동에 참여해야 하는지 명확하게 이해했는가?

참가자들이 적절하게 지원받았나요?

참가자들이 활동을 얼마나 즐겼나요?

HEI는 참여의 지속 가능성을 지원하기 위해 평가 결과에 어떻게 대응해야 할까요?

How far has PPI been embedded into the structure and culture of the HEI?

What was involvement like before?

Will the process of involvement lead to improved service provision and outcomes?

What sort of evidence could be used to demonstrate this idea?

Were participants representative of a wider community?

Was this considered important to the success of the involvement activity?

What impact has the activity had on relationships between staff, students and participants?

Did the activity change staff and student's understanding/knowledge or attitudes?

Has the activity impacted on programme delivery?

Has the activity impacted on policy and strategy at the HEI?

Were participants, staff and students clear about what they were being asked to get involved in?

Were participants supported appropriately?

How much did participants enjoy the activity?

How should HEIs respond to the findings of an evaluation to support the sustainability of involvement?

표준을 높이고 일관성을 보장하기 위한 이러한 유형의 이니셔티브는 우리가 이미 설명한 과제를 고려할 때 이 분야에 환영할 만한 기여를 제공합니다. 이제 필요한 것은 PPI의 개념적, 이론적 측면을 모두 운영화하여 평가 목적에 맞게 분석 프레임워크 내에 수용하는 것입니다. 다시 말해, PPI를 [능동적인 프로세스]로 이해하려면 PPI 이니셔티브를 [구성 요소로 분해]하고 [상호 작용의 고유하고 '실제적인' 복잡성]에 초점을 맞춘 분석이 필요합니다. 우리는 인간의 활동을 특정 맥락에서 활동을 통해 학습과 변화가 일어나는 시스템으로 개념화하는 활동 이론(AT)이 이러한 전제를 충족한다는 것을 발견했습니다.32

This type of initiative to drive up standards and ensure consistency provides a welcome contribution to the field given the challenges we have already outlined. What is now required is operationalisation of both the conceptual and theoretical aspects of PPI, and their accommodation within an analytical framework for evaluation purposes. In other words, understanding PPI as an active process requires some deconstruction of PPI initiatives into their component parts, with analysis focused on the inherent and ‘real life’ complexities of their interactions. We have found that activity theory (AT) fulfils this premise,32 in conceptualising human activity as a system whereby learning and change happen through activity in a specific context.33

[AT 원칙]의 역사적 발전에 대한 논의는 이 백서의 범위를 벗어나지만, 1970년대 러시아의 문화사적, 심리적 연구 전통에서 비롯되었으며, [사고와 구체적인 사회적 실천 사이의 관계]에 대한 근본적인 질문에 뿌리를 두고 있다는 점에 주목하는 것이 유용할 것입니다.34 AT는 그 개념이 정립된 이후 Engeström35 등의 연구를 통해 다양한 연구 분야에서 복잡한 활동 시스템을 모델링하는 데 사용되어 왔으며, 점차 '교육 연구 및 실천을 위한 통합 로드맵'을 제시할 수 있다는 점이 인정받게 되었습니다.36 또한, 의학 분야를 포함한 직장 및 조직 이론가37 에 의해 자주 채택되었으며,32, 35, 38 직장 환경에서의 활동에 대한 풍부한 구조적 설명을 제공합니다.37, 39

Discussion of the historical development of the principles of AT is beyond the scope of this paper, but it is perhaps useful to note that it originated from a Russian cultural-historical and psychological research tradition in the 1970s and is rooted in fundamental questions about the relationship between thinking and concrete social practices.34 Since its conception, and through the work of Engeström35 and others, AT has been used to model complex activity systems in various fields of research, and it has gradually become accepted that it can present ‘an integrated road map for educational research and practice’.36 Moreover, it has been frequently adopted by workplace and organisational theorists,37 including those in medicine,32, 35, 38 in providing a richly structured account of activity in workplace settings.37, 39

중요한 것은, AT가 PPI에 적용될 때 모든 활동 시스템의 구조를 ['복잡성을 '노이즈'로 치부하기보다는, 이해를 높이기 위해 이러한 복잡성을 중시'하는 방식]으로 복잡성을 조직화하는 원칙으로 취급한다는 점에서 다양성과 모호성을 수용하는 데 대한 우리의 우려를 해결한다는 점입니다. 40 엥게스트룀의 행동 개념에서,35 [인간 활동]은 분리할 수 없고 상호 구성적인 여섯 가지 요소의 상호 작용입니다:

- 주체(활동을 바라보는 관점을 가진 개인 또는 공동체);

- 대상(활동이 지향하는 도전);

- 도구 및 인공물(주체와 대상을 매개하고 대상을 특정 결과로 형성하거나 변형하는 체계적 문화의 일부인 기호 또는 공유된 상징);

- 규칙(활동 시스템 내에서 행동과 상호작용을 제약하는 명시적 및 암묵적 규정, 규범, 관습),

- 커뮤니티(동일한 일반 대상general object을 공유하는 다수의 개인 또는 하위 그룹으로 구성),

- 분업(커뮤니티 구성원 간의 수평적 업무 분담과 수직적 권력 및 지위 분담을 모두 의미함).

Importantly, for its application to PPI, AT addresses our concerns about accommodating variety and ambiguity, in that it treats the structure of any activity system as an organising principle for complexity in a way that ‘values this complexity to increase understanding, rather than to dismiss it as ‘noise’.40 In Engeström's conception of action,35 human activity is the interaction of six inseparable and mutually constitutive elements:

- the subject (those individuals or communities from whose perspective the activity is being viewed);

- the object (the challenge towards which the activity is directed);

- the tools and artefacts (signs or shared symbols that are part of a systemic culture, which mediate between the subject and the object and shape or transform the object into specific outcomes);

- the rules (the explicit and implicit regulations, norms and conventions that constrain actions and interactions within the activity system);

- the community (comprising the multiple individuals or subgroups who share the same general object), and finally

- the division of labour (which refers to both the horizontal division of tasks between the members of the community and the vertical division of power and status).

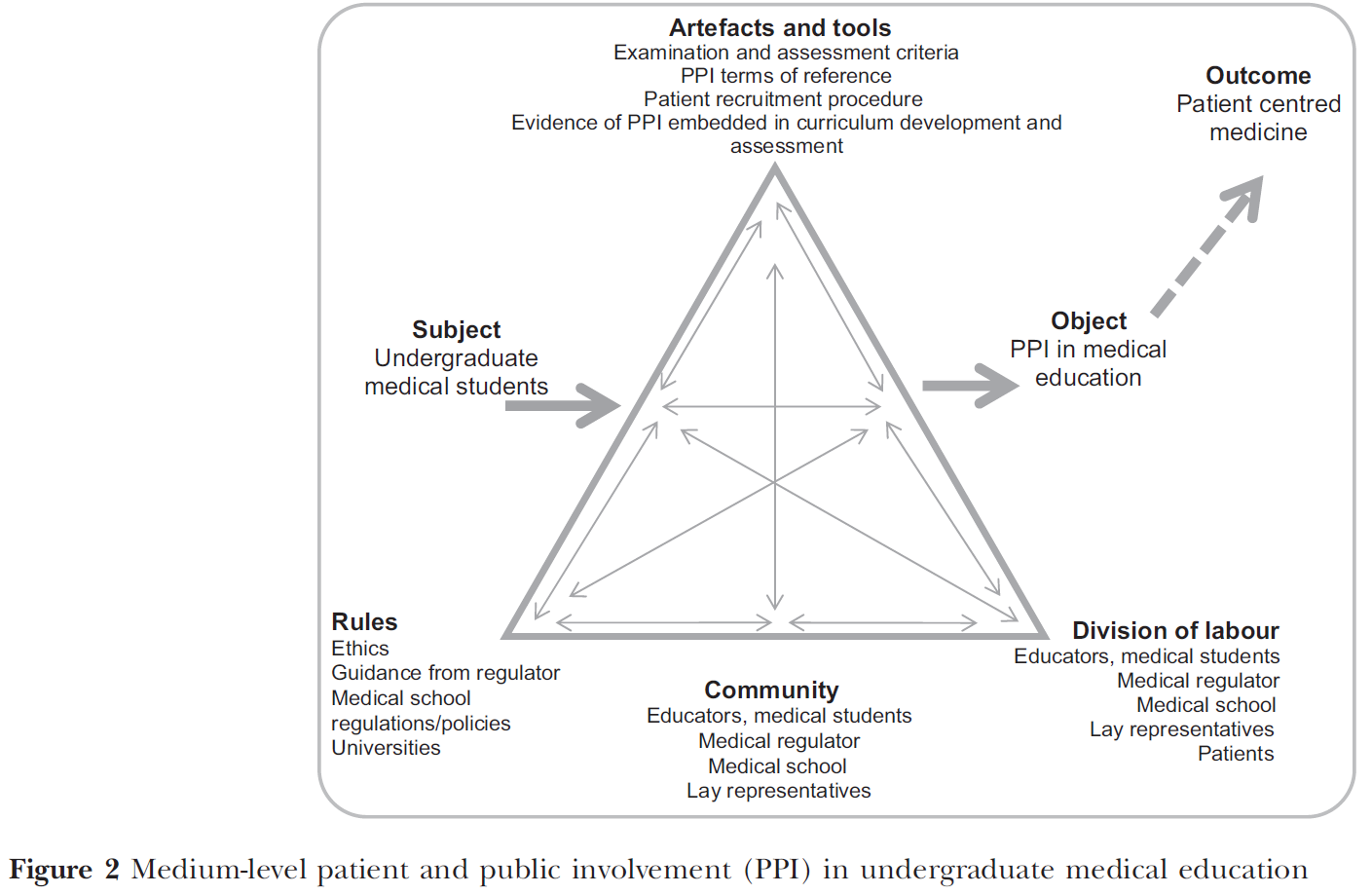

이러한 다양한 구성 요소와 잠재적인 상호 작용을 설명하기 위해 그림 1-3에서는 고수준, 중수준, 저수준 PPI 모델, 잠재적으로 인정된 브론즈, 실버, 골드 표준으로 개념화했습니다.

To illustrate, these different constitutive elements and their potential interactions are conceptualised in Figs 1-3 as high, medium and low-level PPI models, potentially a recognised bronze, silver and gold standard.

AT를 사용하면 시스템의 여러 요소(1차 모순)와 요소 간(2차 모순) '모순'을 체계적으로 탐색할 수 있습니다. 이를 통해 이러한 요소들이 [어떻게 함께 작용하여 활동의 성격을 형성하는지 이해]하고 [잠재적인 장벽과 기회]를 파악할 수 있습니다. 예를 들어,

- 환자는 [분업]에 포함되지만 환자는 동질적인 집단이 아니며 현재 환자, 전문가 환자, 표준화 또는 시뮬레이션 환자 사이에는 미묘하게 다른 입력이 있으며,

- 환자 기록이든 객관적인 구조화된 임상 시험의 평가 역할이든 적절한 인공물이 생성되도록 [도구]에서 고려해야 할 미묘하게 다른 입력이 있습니다.

AT allows us systematically to explore ‘contradictions’ within the different elements of the system (the primary contradictions) and between them (the secondary contradictions). This helps us to understand how they work together to shape the nature of the activity, and allows us to identify potential barriers and opportunities. For example,

- patients are included in the division of labour, but patients are not a homogenous group and there are further distinctions between current patients, expert patients and standardised or simulated patients,

- each with subtly different input that will need to be accounted for by the tools to ensure that appropriate artefacts are produced, be that patient notes or an assessment role in an objective structured clinical examination.

- 또한 커뮤니티 내에서 '목소리'에 따라 권위의 등급이 다르며, 이는 문화마다 맥락에 따라 달라질 수 있음을 인정해야 합니다.

- 그림 1-3의 화살표를 따라가다 보면 모든 구성 요소 간의 상호 연결성을 확인할 수 있습니다. 예를 들어 부적절한 도구를 사용하는 경우, 이는 환자 또는 학생이 활동에 참여하는 데 있어 평등과 다양성(즉, 규칙) 측면에 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다. 그러면 대상물이 위험에 처할 수 있습니다.

- 예를 들어, 영국의 내일의 의사13,31에서 환자가 평가에 참여하게 될 것이라는 구체적인 기대와 함께, 향후 실행에 도움이 되는 교육법을 개발하기 위해 새로운 도구를 개발하고 평가해야 할 것입니다.

- We must also acknowledge that different ‘voices’ within the community will have different grades of authority, and this will vary in the contexts of different cultures.

- Following the arrows around Figs 1-3 testifies to the interconnection between all component elements. If, for example, inappropriate tools are used, this may impact on the equality and diversity (that is the rules) aspects of patient or student involvement in the activity. The object may then be jeopardised.

- For example, with the specific expectation in the UK's Tomorrow's Doctors13, 31 that patients will become involved in assessment, new tools will need to be developed and evaluated, in order to develop a pedagogy to inform future implementation.

자체 PPI 연구에서 AT는 다양한 그룹의 역할을 체계적으로 모델링하고 원하는 결과를 위해 사용된 도구와 산출물에 대한 분석을 통합할 수 있게 해 주었습니다. 영국 규제 시스템과 관련된 작업에서,41 AT는 다음과 같은 정보를 제공함으로써 PPI를 제도에 포함시키기 위한 요건을 파악하는 데 도움을 주었습니다:

- 활동에 대한 매우 상세한 설명, PPI에 대한 커뮤니티 인식의 모순 파악,

- 개별 의사 대 시스템 및 조직에 대한 피드백,

- 전문 표준 유지에 대한 참여 대 전문성 개발에 대한 정보 제공,

- 규제로서의 피드백 대 전문성 개발을 위한 형성 교육에 대한 피드백.

중요한 것은 이러한 접근 방식을 통해 이러한 [커뮤니티 인식]이 참여 규칙(피드백 및 불만 사항) 및 인공물(다양한 피드백 도구 및 의사의 진료에 대한 논평을 제공할 수 있는 기회 등)과 필요한 분업(환자, 의사 및 더 넓은 의료팀 포함)과 [어떻게 상호작용하고 영향을 미치는지]에 대한 통찰력을 얻을 수 있었다는 점입니다.

In our own PPI research, AT has enabled us systematically to model the roles of many different groups that have been involved, and to incorporate analysis of the tools used and artefacts produced for the desired outcome. In our work around the systems of UK regulation,41 AT helped us to identify the requirements for embedding PPI in the system, through the provision of:

- a highly detailed description of its activity, and identification of contradictions in community perceptions of PPI;

- feedback on individual doctors versus systems and organisations;

- involvement in maintaining professional standards versus informing professional development; and

- feedback as regulation versus formative education for professional development.

Importantly, this approach has afforded us insights into how such community perceptions then interact with, and influence, the rules of engagement (feedback and complaints) and the artefacts (such as different feedback tools and opportunities to provide commentary on a doctor's practice), as well as the required division of labour (including patients, doctors and wider health care teams).

또한 불만 제기 [활동 수행 적합성]과 관련된 복잡하고 다양한 데이터를 정리하고,41 다음을 식별하여 PPI 평가를 구성하는 데 도움이 되는 개념적 프레임워크로서 AT를 사용했습니다.

- 환자, 일반인, 공공 역할 사이의 긴장 지점

- 각 역할이 관여할 수 있는 영향력 영역

역할의 혼동을 파악함으로써 프로세스의 여러 단계와 수준에서 여러 그룹의 유형과 잠재적 참여 수준을 구분할 수 있게 되었습니다. 중요한 것은 AT를 사용하여 이러한 복잡한 시스템의 모순을 식별함으로써 효율성을 개선하기 위해 변경할 수 있는 부분을 제안할 수 있었다는 점입니다. 여기에는 다음이 포함되었습니다.30

- 교육이 필요한 부분과 이를 촉진하기 위한 충분하거나 적절한 '도구'의 부재,

- 적절한 경우 보다 명확한 역할 설명과 채용 절차의 필요성,

- 영향력에 대한 엄격한 평가, 가치의 존재 여부 및 부가가치 식별에 대한 조항 등

We have also used AT as a conceptual framework to help us order complex and varied data relating to fitness to practise complaint-making activity,41 as well as to structure an evaluation of PPI, by identifying points of tension between:

- patient, lay and public roles; and

- the spheres of influence in which each can engage.

In teasing out the confusion of roles it became possible to differentiate types and potential levels of involvement by different groups at different stages and levels of the process. Importantly, using AT to identify contradictions in these complex systems made it possible to suggest where changes might be made to improve effectiveness. These included recognising:

- where training was required and the absence of sufficient or appropriate ?tools’ to facilitate this;

- the need for clearer role descriptions and recruitment procedures where appropriate;

- provision for rigorous evaluation of impact, where value is and identification of value added.30

[활동 이론(AT)을 실무 모델working model로 사용]하여 PPI에 대한 이러한 통찰력을 바탕으로, 우리는 AT가 다양한 PPI 활동이 작동하는 미시적 및 거시적 맥락을 모두 이해하고, 연속체 전반에 걸쳐 특정 PPI 교육 프로그램의 목표와 관련하여 그 효과를 평가하기 위한 분석적 휴리스틱으로 더 널리 사용될 수 있다고 제안합니다. 물론 의학이 점점 더 국제화됨에 따라 PPI 교육학의 개발은 의료 시험에 대한 '글로벌 표준'이라는 새로운 담론을 고려해야 할 것입니다. 영국 대학원 의학교육의 한 예로, 전체 응시자 중 85% 이상이 국제 의대 졸업생(IMG)인 국제적으로 인정받는 표준인 왕립 산부인과 의사 회원 시험(MRCOG)의 필기 시험 파트 1과 2가 있습니다.42 MRCOG는 전 세계에 시험 센터를 두고 있으므로 교육과정 개발과 잠재적으로 평가에서 모든 PPI는 국제적 맥락에서 문화적 영향을 고려하는 교육학에 기반해야 할 것입니다.

Drawing on these insights into PPI using Activity Theory (AT) as a working model, we suggest that AT can be used more widely as an analytical heuristic to understand both the micro and macro-contexts within which different PPI activities operate, and to evaluate their effectiveness in relation to the aims of any given educational programme of PPI across the continuum. Of course, as medicine becomes increasingly internationalised, the development of a PPI pedagogy will need to take into account the emergent discourse of ‘global standards’ for medical exams. One example of this, from UK postgraduate medical education, is the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists membership exam (MRCOG), written exam Parts 1 and 2, which is an internationally recognised standard with more than 85% of the total candidates being international medical graduates (IMG).42 The MRCOG has exam centres around the world, and therefore any PPI in curriculum development, and potentially assessment, will need to draw on a pedagogy that considers cultural implications in an international context.

PPI는 사회적, 문화적, 정치적 맥락 속에서 이루어지는 역동적인 과정입니다. 의학교육의 국제화를 고려할 때, 서구 의학교육의 활동 체계에서 개발된 PPI는 반드시 보편적이지 않은 가치를 불러일으킨다는 점을 염두에 두어야 합니다. 다문화 교육 연구자들은 교육 정책과 관행에 대한 문화적 규범의 영향을 인식하고 문화적 문제를 연구할 때 복잡성의 역할을 강조해 왔습니다.43-45 실제로 AT는 글로벌 교육이 학습할 수 있는 통찰력을 제공하기 위해 지역적 차이를 포착하고 매핑할 수 있는 유용한 분석적 '렌즈'로 확인되었습니다.46

PPI is a dynamic process, situated within social, cultural and political contexts. Given the internationalisation of medical education, we must be mindful that PPI developed in the activity system of Western medical education invokes values that are not necessarily universal. Cross-cultural education researchers have recognised the influence of cultural norms on education policies and practices, and highlighted the role of complexity when studying cultural issues.43-45 Indeed, AT has been identified as a useful analytical ‘lens’, through which local variations can be captured and mapped in order to provide insights from which global education can learn.46

PPI가 효과적인지 어떻게 알 수 있을까요?

의학교육 연속체 전반에서 참여도 평가하기

How can we know if PPI is effective?

Evaluating engagement across the medical education continuum

의제 설정과 잠재적 접근 방식에 대한 논의는 아직 초기 단계에 머물러 있지만, 의학교육에서 이론적으로 견고하고 근거에 기반한 PPI를 뒷받침하는 지식은 개발 초기 단계에 있습니다. 우리는 AT가 학부생 교육부터 자격을 갖춘 의사의 계속 교육에 이르기까지 의학교육 연속체 전반에 걸쳐 교육자들이 PPI의 현재 및 잠재적 범위를 모두 이해하고, 아직 개발되지 않은 전용 교육학에 의해 정보를 제공해야 하는 연속체의 지점을 식별하는 데 도움이 되는 개념적 프레임워크를 제공할 수 있다고 제안하고 싶습니다. 이러한 관계는 Engeström35이 개발한 AT 삼각형 모델을 사용하여 표현할 수 있으며, 학부 의학교육에 초점을 맞춘 예시를 통해 설명할 수 있습니다.

Despite its arguably drawn out gestation in terms of setting out the agendas and potential approaches, a body of knowledge supporting theoretically robust and evidence-based PPI is at an early stage of development in medical education. We would suggest that AT can provide a conceptual framework to help educators understand both the current and potential scope of PPI across the medical education continuum, from the teaching of undergraduates to the continuing education of qualified doctors, and to identify points in the continuum that need to be informed by a dedicated pedagogy yet to be developed. We can express this relationship using the AT triangular models developed by Engeström35 and by way of an example we have focused on undergraduate medical education.

그림 1은 환자가 학습의 능동적 파트너가 아닌 수동적 파트너인 [가부장적 PPI 모델]을 보여줍니다. 이 모델에서는 PPI를 촉진하는 데 사용할 수 있는 제한된 도구 세트와 그 과정에 참여하는 다양한 그룹을 식별합니다. 이 모델에는 비전문가의 표현이나 이를 [뒷받침하는 '규칙' 또는 '도구'가 존재하지 않습니다]. 이 모델에서 중요한 점은 커리큘럼 개발이나 평가에서 PPI를 위한 기회가 전혀 없다는 것입니다. 환자는 커뮤니티의 일원으로 참여하지만, 참여 전용 도구와 인공물에 의해 역할이 제한됩니다. 중간 수준의 PPI AT 모델(그림 2)로 시선을 돌리면, 동일한 주체가 다수 존재하지만 [사용 가능한 도구가 더 많기 때문에 역할이 다르다]는 것을 알 수 있습니다. 이 모델에는 환자 외에도 일반인 대표도 포함됩니다.

Figure 1 illustrates a paternalistic model of PPI, in which the patient is a passive rather than active partner in learning. The model identifies only a limited set of tools available to facilitate PPI and the various groups who are involved in the process. There is no lay representation present or any ‘rules’ or ‘tools’ to support it. What is important about this model is the absence of any opportunity for PPI in either curriculum development or assessment. Although patients are present as part of the community, their role is limited by the tools and artefacts dedicated to their participation. If we turn our attention to the medium-level PPI AT model (Fig. 2), we can see that many of the same protagonists are present but that their roles are different because there are more tools available. In addition to patients, lay representatives are also included in this model.

이 모델에서 환자의 역할은 수동적인 역할에서 [보다 적극적인 역할(예: 평가 및 커리큘럼 개발에 대한 기여)]로 이동합니다. 이 모델에는 [의대생 및 교육자에 대한 환자의 피드백]이 포함됩니다. 환자는 환자 피드백을 통해 개인의 목소리를 낼 수 있지만, 이 모델에서는 [일반인 대표를 통해 집단적인 '공공의 목소리'가 추가]됩니다. 여기서 일반인 대표의 역할은 현재 또는 최근의 환자 신상에 관한 것이 아니라 광범위한 '전문 기술'인 기술과 속성에 관한 것입니다.30 따라서 일반인 대표는 중요한 거버넌스 역할을 수행하지만, 효율성을 보장하기 위해 적절한 규칙과 도구가 포함되어야 합니다.

The role of patients in this model moves from a passive to a more active one (e.g. in relation to contributing to assessment and curriculum development). This model includes patient feedback to medical students and educators. Patients have an individual voice through patient feedback but in this model there is an additional collective ‘public voice’ through lay representatives. Our lay representative roles here are less about current or recent patient identities and more about skills and attributes that are broadly ‘professional skills’.30 Lay representatives therefore have an important governance role, but this requires appropriate rules and tools to be embedded in order to ensure efficacy.

최종 ['골드 스탠다드' 모델(그림 3)]에서 PPI는 의학교육 커리큘럼 전반에 걸쳐 완전히 통합됩니다.

In the final ‘gold standard’ model (Fig. 3), PPI is fully integrated across the medical education curriculum.

이 모델은 낮은 수준의 모델(그림 1)과는 대조적으로 의사, 고용주, 교육자 및 PPI 역량을 갖춘 사람들을 위한 공동 교육을 통해 [진정으로 협력적인 업무 방식]을 보여줍니다. 그림 1의 근간을 이루는 '하향식' 권력 구조가 해결되었으며, PPI는 전략 계획과 정책 문서(공동 제작)를 통해 입증되고 확립된 피드백 루프를 통해 지속적인 평가를 받는 등 커리큘럼 전반에 걸쳐 완전히 통합되어 있습니다. [PPI 챔피언]은 이 모델의 뚜렷한 특징이며, 지속 가능한 커뮤니티를 개발하기 위해 환자와 일반인의 다양성을 위해 노력하는 임무를 맡습니다.

This model, in sharp contrast to the low-level model (Fig. 1), evidences a truly collaborative way of working, with joint training for doctors, employers, educators and those in a PPI capacity. The ‘top-down’ power structure underpinning Fig. 1 has been addressed and PPI is fully integrated across the curriculum: it is evidenced through strategic plans and policy documents (which are coproduced), and is subject to ongoing evaluation via an established feedback-loop. PPI champions are a distinct feature of this model and are tasked to work on patient and lay diversity to develop a sustainable community.

위에서 설명한 것처럼 AT는 실용적인 이론입니다. [개인과 집단 간의 관계]와 이들이 [서로 다른 맥락에서 작동하는 방식을 조사]하기 위한 프레임워크를 제공한다는 장점이 있습니다. 예를 들어, 한 요소가 변경될 때 의도한 결과와 의도하지 않은 결과가 어떻게 뒤따를 수 있는지를 밝혀내는 등 연구자들이 동적 변화의 영향을 탐구할 수 있게 해줍니다. 이러한 모델에서 PPI 참조 조건이 개발되고 PPI 전략이 실행되면 다른 변화가 어떻게 발생할지 예측할 수 있습니다. 그림 4는 PPI를 통해 [학부 교육]과 [대학원 교육] 간의 상호 관계를 관련 활동 시스템으로 보여줍니다. 이 모델의 중요성은 다양한 수준의 의학교육에 걸쳐 PPI를 내장하고 연속성을 제공하는 방법으로 시각화하는 데 있습니다.

As described above, AT is a practical theory. It has the advantage of providing a framework for examining the relationships between individuals and groups and the ways in which they operate in different contexts. It enables researchers to explore the impact of dynamic change; for example, it reveals how, as one element is changed, both intended and unintended consequences can follow. In these models, once PPI terms of reference are developed and a PPI strategy is implemented, we can envisage how other changes might occur. Figure 4 shows the interrelation between undergraduate and postgraduate education as related activity systems through PPI. The importance of this model lies in visualising PPI as both embedded across different levels of medical education, and as a way to provide continuity.

물론 특정 활동 시스템에는 다양한 유형의 PPI가 존재할 수 있으며, 실제로 앞서 언급한 의미론의 문제는 각각 다른 목적을 가진 다양한 유형의 존재에서 비롯됩니다. 다양한 형태를 해체하고 이를 활동 모델에 매핑할 수 있는 능력이 바로 이 모델을 유용하게 만드는 요소이며, 이 모델에 대한 경험을 통해 다양한 교육 및 규제 영역에서 다양한 유형의 PPI를 해체하고 해당 시스템에 개선 사항을 포함하기 위한 응용 연구에 자신감을 갖게 되었습니다. 광범위한 의학교육 커뮤니티의 더 큰 과제는 이러한 해체, 평가 및 보급을 발전시키고 이러한 노력을 통해 보다 포괄적인 교육학 스키마를 개발하는 것입니다.

Of course, various types of PPI may be present in any given activity system; indeed, the aforementioned issue of semantics derives from the existence of a multitude of types, each with different purposes. The ability to deconstruct their different forms and map these onto an activity model is precisely what makes it so useful, and our experience with this model has given us the confidence to deconstruct different types of PPI in different areas of education and regulation, in applied research aimed at embedding improvement in those systems. The bigger challenge, for the broader medical education community, is to take forward such deconstruction, evaluation and dissemination, and develop more encompassing pedagogic schema from these endeavours.

결론

Conclusion

정책의 시급성과 의과대학 및 기관이 목표를 달성해야 한다는 요구 사항을 고려할 때, 의학교육 커리큘럼 전반에 걸쳐 PPI를 실행하는 교육자는 근거 기반이 절실히 필요합니다. 지금까지 의학교육의 PPI 분야에 대한 몇 가지 귀중한 공헌을 강조했지만, 앞으로는 연구자들이 새로운 교육학에 기반한 커리큘럼과 강의 계획서를 설계하고, 개입을 함께 평가하고, 연속체 전반에 걸친 연구를 종합한 의학교육 문헌에 결과를 발표하고, 교육과정의 다양한 측면에서 다양한 활동을 통해 배우고 전반적으로 보다 일관된 참여를 촉진할 수 있는 방법론과 기술을 이해함으로써 향후 실행 및 평가 주기에 정보를 제공하는 데 협력해야 한다는 점을 제안합니다.

Given the prescience of policy and the requirement for medical schools and organisations to meet targets, educators implementing PPI across the medical education curriculum are in desperate need of an evidence base. Although we have highlighted some invaluable contributions to the field of PPI in medical education, moving forward we suggest that researchers should work collaboratively in designing curricula and syllabi based on emerging pedagogy, together evaluating interventions, publishing findings in a comprehensive medical education literature that brings together work across the continuum, and informing further cycles of implementation and evaluation by learning from different activities in various aspects of the curriculum and understanding what methodologies and technologies might facilitate more consistent involvement across the board.

PPI의 교육학이 발전하면 의학교육자들은 '스마트'하고 기회를 극대화하기 위해 정책 입안자 및 전문 기관과 협력할 수 있는 독특한 위치에 놓이게 될 것입니다. 이 외에도 [환자 중심 교육]의 핵심인 [공유 학습의 원칙]은 [전문가 간 교육]을 뒷받침하는 원칙과 유사하며, 환자는 모든 의료 전문직의 통합적인 초점입니다. 따라서 '다른 사람들'이 어떻게 대중의 참여를 전문 교육에 통합하는지에 대한 통찰력은 이 주제에 대한 우리 자신의 성장하는 지식 모음에 매우 귀중한 정보가 될 수 있습니다. 마지막으로, PPI 분야의 의학교육 연구자들은 자신이 설파하는 바를 실천하고, 환자 및 대중과 협력하여 공동 연구를 통해 PPI를 완전히 달성하기 위해 노력해야 합니다. 의과대학 및 평생교육에서 의사의 멘토링, 평가 및 교정을 위한 PPI 전략을 개발할 때 학계, 정책 입안자 및 환자 간의 연속적인 대화가 매우 중요합니다.

A developing pedagogy of PPI will place medical educators in a unique position to work in partnership with policy makers and professional bodies in order to be ‘smart’ and maximise opportunities. In addition to this, the principle of shared learning that is central to patient-centred education is akin to that which underpins interprofessional education, and the patient is the unifying focus of all health professions. Insight into how ‘others’ incorporate public engagement into their professional education could therefore be invaluable to our own growing corpus of knowledge on the subject. Finally, medical education researchers in the field of PPI should practise what they preach, and work in partnership with patients and the public to fully achieve PPI in collaborative inquiry. In developing PPI strategies for the mentoring, assessment and remediation of doctors in medical schools and continuing education, dialogue across the continuum between academics, policy makers and patients, is crucial.

Med Educ. 2016 Jan;50(1):79-92. doi: 10.1111/medu.12880.

Towards a pedagogy for patient and public involvement in medical education

Affiliations collapse

PMID: 26695468

DOI: 10.1111/medu.12880

Abstract

Context: This paper presents a critique of current knowledge on the engagement of patients and the public, referred to here as patient and public involvement (PPI), and calls for the development of robust and theoretically informed strategies across the continuum of medical education.

Methods: The study draws on a range of relevant literatures and presents PPI as a response process in relation to patient-centred learning agendas. Through reference to original research it discusses three key priorities for medical educators developing early PPI pedagogies, including: (i) the integration of evidence on PPI relevant to medical education, via a unifying corpus of literature; (ii) conceptual clarity through shared definitions of PPI in medical education, and (iii) an academically rigorous approach to managing complexity in the evaluation of PPI initiatives.

Results: As a response to these challenges, the authors demonstrate how activity modelling may be used as an analytical heuristic to provide an understanding of a number of PPI systems that may interact within complex and dynamic educational contexts.

Conclusion: The authors highlight the need for a range of patient voices to be evident within such work, from its generation through to dissemination, in order that patients and the public are partners and not merely objects of this endeavour. To this end, this paper has been discussed with and reviewed by our own patient and public research partners throughout the writing process.

© 2015 John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 교육과정 개발&평가' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 학부의학교육에서 적극적 환자 참여의 역할: 체계적 문헌고찰(BMJ Open. 2020) (0) | 2023.04.13 |

|---|---|

| 대표성의 딜레마: 보건전문직교육의 환자참여(Acad Med, 2018) (0) | 2023.04.09 |

| 가정의학 전공의교육 및 CPD에서 역량중심의학교육 용어의 개념화: 스코핑 리뷰(Acad Med, 2020) (1) | 2023.02.28 |

| 역량바탕의학교육 문헌의 대화를 이해하기: 스코핑 리뷰(BEME Guide No. 78) (0) | 2023.02.28 |

| 대규모 의과대학 교육과정에서 프로그램 평가에 대한 학생들의 관점: 비판적 현실주의자 분석(Med Educ, 2022) (0) | 2023.02.18 |