학부의학교육에서 AI: 스코핑 리뷰(Acad Med, 2021)

Artificial Intelligence in Undergraduate Medical Education: A Scoping Review

Juehea Lee, Annie Siyu Wu, David Li, and Kulamakan (Mahan) Kulasegaram, PhD

지난 10년 동안, 인공지능(AI)은 끊임없이 증가하는 데이터와 컴퓨팅 능력으로 인해 빠르게 발전했다. AI는 이미지 인식, 음성 인식, 자막 생성과 같은 인지 작업을 모방하는 기계의 능력이다. 간단히 말해서, AI 모델은 다양한 작업에 대해 매우 정확한 예측을 하기 위해 대량의 데이터에서 패턴을 찾는 데 사용될 수 있다.

Over the past decade, artificial intelligence (AI) has advanced rapidly due to an ever-increasing amount of data and computing power. 1 AI is the capability of a machine to imitate cognitive tasks such as image recognition, speech recognition, and caption generation. 2 Simply put, AI models can be used to find patterns in large quantities of data to make highly accurate predictions for various tasks. 3

의료 분야에서 AI는 의료 서비스 제공 방식, 의료 전문가들이 사용하는 도구, 환자와 의료 전문가의 전통적인 역할을 변화시킬 대규모 변화를 일으키는 시점에 임박해 있다. 기계 학습 알고리듬의 정확도는 수많은 작업에서 전문 의사의 정확도에 도달했거나 초과했다. 예를 들어 AI 시스템은 유방암 예측에서 인간 방사선사를 앞질렀고 평균 방사선사를 11.5%나 앞질렀다. 또 다른 AI 시스템은 피부과 의사 및 간호사보다 성능이 우수하고 피부과 의사와 비교하여 1차 진료에서 보이는 사례의 80%를 대표하는 26개의 공통 피부 상태를 식별할 수 있다.

In medicine, AI is on the precipice of instigating large-scale changes that will transform how health care is delivered, the tools used by health care professionals, and the traditional roles of patients and health care professionals. 4,5 The accuracy of machine learning algorithms has reached or exceeded that of expert physicians on numerous tasks. For example, an AI system surpassed human radiologists in breast cancer prediction and outperformed the average radiologist by an absolute margin of 11.5%. 6 Another AI system could identify 26 common skin conditions representing 80% of cases seen in primary care with performance noninferior compared with dermatologists and superior to primary care physicians and nurse practitioners. 7

새로운 기술은 의학의 미래와 인간 의사의 역할에 대한 수많은 의문을 제기한다. 새로운 기술에 대한 관심이 증가하고 있음에도 불구하고, 의학 교육은 AI에서 만들어진 놀라운 돌파구를 따라가지 못했다. 그동안 여러 차례 실천요구가 있었지만 체계적인 증거가 부족했기 때문인지, 학부 의료교육(UME)에 AI 교육을 도입하는 데는 한계가 있었다. 의료 분야에서 AI의 채택이 계속 증가함에 따라, UME의 통합은 UME가 경력 초기에 가장 큰 의료 훈련생 그룹에 도달할 수 있기 때문에 향후 실무에 상당한 혜택을 제공할 것이다. AI가 어떻게 가르쳐지고 UME 커리큘럼에 통합되어야 하는지에 대한 이해는 가능한 가장 좋은 학술적 증거에 의해 인도되어야 한다. AI는 아직 의학 교육에서 비교적 새로운 개념이기 때문에, 증거가 어디에 있고 어떤 차이가 남아 있는지 판단하기 위해 문헌의 합성이 필요하다.

New emerging technologies raise numerous questions about the future of medicine and the role of human physicians. Despite increasing interest in new technology, medical education has not kept pace with the remarkable breakthroughs made in AI. There have been several calls to action, 8–10 but adoption of AI training into undergraduate medical education (UME) has been limited, perhaps due to the lack of systematic evidence. 11 As adoption of AI continues to grow in health care, integration in UME will offer substantial benefits for future practice since UME can reach the largest group of medical trainees early in their careers. An understanding of how AI should be taught and integrated into UME curricula should be guided by the best available scholarly evidence. Since AI is still a relatively new concept in medical education, a synthesis of the literature is required to determine where the evidence is and what gaps remain.

이와 같이, 본 범위 검토의 목적은 AI 시대에 임상실습을 위해 학부생들을 훈련시키고 준비시키는 최선의 방법에 대한 주요 주제를 매핑하고 사용 가능한 문헌의 격차를 확인하는 것이었다. 본 연구의 결과는 의료교육계의 현재 관행을 알리고 향후 학문분야를 조명할 것이다.

As such, the objective of this scoping review was to map key themes and identify gaps in the available literature on how best to train and prepare undergraduate students for clinical practice in the age of AI. The results of this study will inform current practices and highlight future areas of scholarship for the medical education community.

방법

Method

범위 검토는 문헌의 포괄적인 검토를 통해 광범위하거나 탐구적인 연구 문제를 해결하는 것을 목표로 한다. 본 범위 지정 검토는 UME의 AI 교육 주제에 초점을 맞추고 있으며, 이 주제는 복잡하고 이전에 종합적으로 검토되지 않았기 때문에 범위 지정 검토를 사용하기로 결정했다. 우리의 방법이 신뢰할 수 있고 쉽게 복제될 수 있도록 하기 위해, 우리는 Arcsey와 O'Malley, Levac과 동료들이 제안한 방법론적 프레임워크를 따랐다.

Scoping reviews aim to address a broad or exploratory research question through a comprehensive review of the literature. 12,13 This scoping review focuses on the topic of AI training in UME. We chose to use a scoping review as this topic is complex and has not been reviewed comprehensively before. 14 To ensure that our methods were reliable and could be easily replicated, we followed the methodological framework proposed by Arksey and O’Malley and Levac and colleagues. 12,13

연구 질문 식별

Identifying the research question

본 범위 검토의 주요 연구 질문은 "UME의 AI 훈련에 관한 기존 문헌에서 어떤 핵심 주제와 간극을 확인할 수 있는가?"였다. 구체적으로 본 범위 검토의 목적은 현재 문헌에서 UME의 AI 훈련에 관한 주요 주제를 요약하고 보급하는 것은 물론 잠재적인 연구와 학문을 파악하는 데 있었다.이 목표를 달성하기 위해 기계 학습, 딥 러닝, 자연어 처리와 같은 AI의 하위 도메인을 포함하여 AI를 광범위하게 정의하여 이용 가능한 문헌을 광범위하게 검색하였다. 이와는 대조적으로, 우리는 이 검토의 범위를 오직 UME로 제한했다. 우리는 대학원 또는 대학원 수준의 AI 교육이 전문성에 특화되어 모든 의학 학습자에게 적용되지 않는 개념이나 응용에 초점을 맞출 수 있을 것으로 기대했다. UME에 초점을 맞추어 모든 의학 학습자의 토대를 마련할 수 있는 의료 AI 교육에 대한 개념을 파악하고자 하였다.

The primary research question of this scoping review was: “What key themes and gaps can be identified in the existing literature on AI training in UME?” Specifically, the purpose of this scoping review was to summarize and disseminate key themes regarding AI training in UME in the current literature as well as identify potential research and scholarly priorities to advance AI curricular development in UME. 13 To meet this objective, we defined AI broadly, including subdomains of AI such as machine learning, deep learning, and natural language processing, to expansively search the available literature. In contrast, we restricted the scope of this review to UME only. We anticipated that AI training at the graduate or postgraduate level may be specialty-specific and focus on concepts or applications that are not applicable to all medical learners. By focusing on UME, we sought to identify concepts on medical AI education that could lay the groundwork for all medical learners.

관련 연구 확인

Identifying relevant studies

의료 사서의 도움을 받아 만들어진 우리의 검색 전략은 의료 주제 제목, 키워드 및 AI와 그 하위 도메인(예: 기계 학습) 및 UME(예: 임상 사무원, 의학 학생, 의학 학습자)와 관련된 텍스트 단어로 구성되었다. 초기 검색은 2019년 11월 25일 메들린, 엠베이스, 펍메드, 스코푸스, 에릭, 메드 에드 포털, 코크레인 라이브러리를 포함한 7개의 전자 데이터베이스에서 수행되었다. 검색은 2020년 7월 21일에 업데이트되었다. 검색은 2000년 1월 1일부터 영어 출판물로 제한되었다. 우리는 AI의 빠르게 진화하는 특성과 번역 서비스 접근 제한 때문에 각각 출판일과 언어별로 검색을 제한하기로 했다. 검색은 포함된 기사의 참조 목록을 손으로 검색함으로써 보완되었다.

Our search strategy, created with the help of a medical librarian, consisted of medical subject headings, keywords, and text words related to AI and its subdomains (e.g., machine learning) as well as to UME (e.g., clinical clerkship, medical student, medical learner). The initial search was conducted on November 25, 2019, in 7 electronic databases, including Medline, Embase, PubMed, Scopus, ERIC, MedEdPortal, and Cochrane Library. The search was updated on July 21, 2020. The search was limited to English publications from January 1, 2000, and onward. We chose to restrict the search by publication date and language due to the rapidly evolving nature of AI and limited access to translational services, respectively. The search was supplemented by hand-searching reference lists of included articles. The full version of the search strategy can be found in Supplemental Digital Appendix 1 at https://links.lww.com/ACADMED/B156.

스터디 선택

Study selection

모든 인용문은 코비던스 온라인 소프트웨어(호주 멜버른, 베리타스 헬스 이노베이션)를 사용하여 수입 및 관리되었다. 스터디 선택은 3단계로 수행되었습니다.

- 첫째, 3명의 검토자가 연구 적격성을 결정하기 위해 독립적으로 제목과 초록을 선별하였다. UME에서 AI 훈련을 논의한 모든 연구가 포함됐다.

- 둘째, 초기 제목과 추상적 심사에 이어 사후적으로 포함 및 제외 기준을 논의하고 개선했다.

- 셋째, 포함 및 제외 기준을 사용하여 전체 텍스트 심사를 수행하였다. 갈등은 각 단계별로 논의와 합의를 통해 해결됐다.

All citations were imported and managed using the Covidence online software (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia). Study selection was performed in 3 steps.

- First, 3 reviewers (J.L., A.S.W., D.L.) independently screened titles and abstracts to determine study eligibility. All studies that discussed AI training in UME were included.

- Second, following initial title and abstract screening, we discussed and refined the inclusion and exclusion criteria post hoc.

- Third, we performed full-text screening using the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Conflicts were resolved through discussion and consensus at each stage.

전반적으로 UME에서 AI 교육을 폭넓게 논의하면 검토 대상에 포함됐고, 다음 중 하나에 해당하면 제외됐다.

Overall, articles were included in the review if they broadly discussed AI training in UME. Articles were excluded if they:

- 대학원 또는 지속적인 의학교육에서 AI를 가르치는 것에만 집중한다.

- 골병리학 또는 제휴 의료 전문가에 대한 AI 교육에만 집중합니다.

- 의료 교육 커리큘럼의 주제와 반대로 의료 교육을 위한 도구로서 AI의 사용을 탐구했다.

- 회의 요약이 있거나 전체 텍스트 원고를 사용할 수 없는 경우. 출판 유형이나 방법론에 대한 다른 제한은 구현되지 않았다.

- Focused exclusively on the teaching of AI in postgraduate or continuing medical education;

- Focused exclusively on the teaching of AI in osteopathic medicine or for allied health professionals;

- Explored the use of AI as a tool for medical education as opposed to a topic within medical education curricula; or

- Were a conference abstract or where a full-text manuscript was not available. No other restrictions were implemented for publication type or methodology.

데이터 차트 작성

Charting the data

반복 프로세스를 통해 데이터 추출이 발생했습니다. 첫째, 데이터 차트의 '구조'양식을 사용하여 실시되었다. (J.L., A.S.W., DL)3비평가들 모든 full-text 기사가 데이터 형태 차트를 사용하는 데이터 뽑아 냈다. 그리고 우리는 그 반대가 결의 형태의 문헌에 증가한 친근감을 바탕으로 정제 형태의 일관성을 확보하기 위해 만났다. 토론에 따라서, 우리는 좀 더 다음 범주로 결과를 추출 칼럼 갈라지기:로 결정했다.

- 왜(예:왜 AI의대생들을 준비하지 않도록 가르쳐야 한다? 학습목표는 무엇인가?)

- 무엇(예:의대생들에게 AI에 대해 무엇을 가르쳐야 한다?),.

- 누가(예를 들어, 강사들 누가 있을까?),.

- 어떻게(예를 들어, 어떻게 인공 지능을 교과 과정 의대생들에게 보내야 하는가?),.

- 어디(예:무엇을 정하는 인공 지능 교육 과정을 보내야 하는가?).

- 얼마나 잘(예:어떤 방법 AI교육 과정의 효율성을 판단하는 데 취해 진?).

Data extraction occurred through an iterative process. First, data charting was performed using a structured form (see Supplemental Digital Appendix 2 at https://links.lww.com/ACADMED/B156). Three reviewers (J.L., A.S.W., D.L.) extracted data from all full-text articles using the data charting form. We then met to ensure consistency between forms, resolve disagreements, and refine the form based on increased familiarity with the literature. Upon discussion, we decided to further divide the results extraction column into the following categories:

- why (e.g., Why should AI be taught to undergraduate medical students? What are the learning objectives?),

- what (e.g., What should be taught to medical students about AI?),

- who (e.g., Who would the instructors be?),

- how (e.g., How should an AI curriculum be delivered to medical students?),

- where (e.g., In what setting should an AI curriculum be delivered?), and

- how well (e.g., What steps were taken to determine the effectiveness of AI curriculum?).

이들 범주들의 분배 지침에 의해 보고Evidence-based 연습 교육적 간섭과를 가르치는 것은(GREET),은 검증된 체크 리스트 교육적 도구의 증거를 연습하러 보고를 데이터 추출을 구성하는데 도움이 되기 위해 개발된 소식을 들었다. 업데이트된 데이터 추출 형태를 사용하여 3비평가들과 추출한 모든full-text 기사로부터 데이터 re-reviewed. 까지 합의에 도달했다 이 과정 반복되었다.

The division of these categories was informed by the Guideline for Reporting Evidence-based practice Educational interventions and Teaching (GREET), 15 a validated checklist developed for the reporting of educational interventions for evidence-based practice, to help organize data extraction. Using the updated data extraction form, 3 reviewers (J.L., A.S.W., D.L.) re-reviewed and extracted data from all full-text articles. This process was repeated until consensus was reached.

요약하고 그 결과를 보고 Collating.

Collating, summarizing, and reporting the results

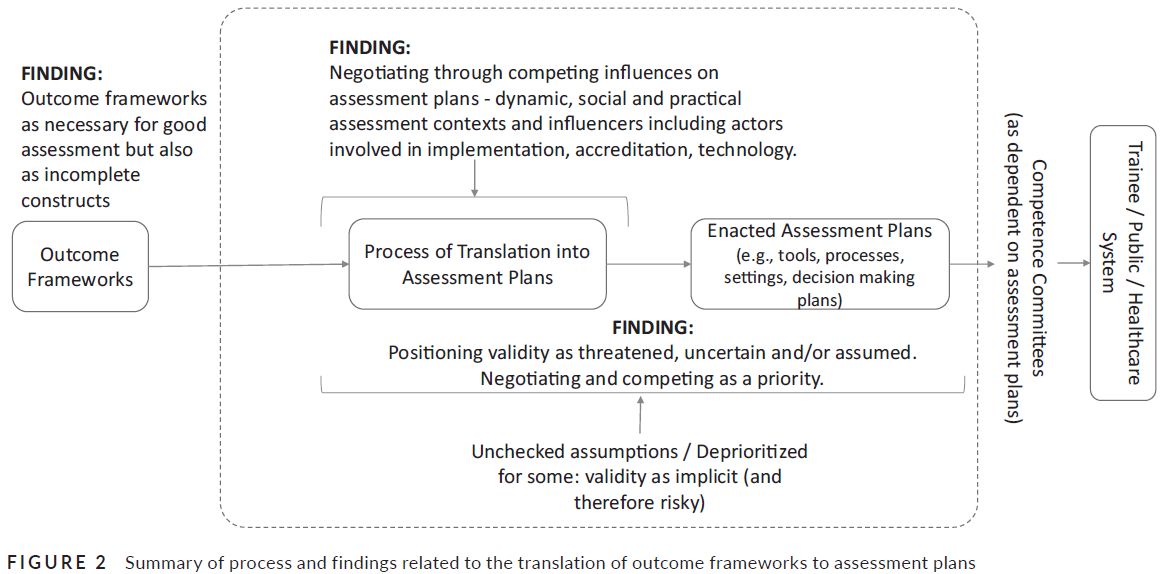

연구 인구 통계 기술 통계를 사용하여 요약되었다. 추출된 질적 데이터는 Miles와 Huberman의 방법론에 의해 다음과 같이 주제분석을 이용하여 신흥주제로 묶었다. 먼저 각 전체 텍스트 기사 내에서 패턴과 공통 주제를 식별하기 위해 설명 코드를 할당했다. 우리는 여러 개의 설명 코드를 더 적은 수의 범주 또는 테마로 그룹화하는 패턴 코드를 생성하기 위해 코딩의 두 번째 주기를 수행했다. 그 다음, 우리는 매트릭스는 범주는 이전 단계에서 식별되는 각 기사 요약을 만들었다. 그 매트릭슨 다음 공통점과 기사들 사이의 차이고 노트 시각화 한장의 표로 줄었다. 우리는 마침내 범주를 커리큘럼 권장 사항으로 재구성하여 UME에서 AI에 대한 교육 개혁을 알리는 데 도움을 주었다.

Study demographics were summarized using descriptive statistics. Qualitative data from the extraction form were grouped into emerging themes using thematic analysis, informed by Miles and Huberman’s methodology, as follows. 16 First, we assigned descriptive codes to identify patterns and common topics within each full-text article. We performed a second cycle of coding to generate pattern codes that grouped multiple descriptive codes into a smaller number of categories or themes. Next, we created matrices summarizing each article according to the categories identified in the previous step. The matrices were then reduced into a single table, where commonalities and differences between articles were visualized and noted. We finally reframed the categories into curricular recommendations to help inform educational reform for AI in UME (see Figure 1).

결과.

Results

연구 특성

Study characteristics

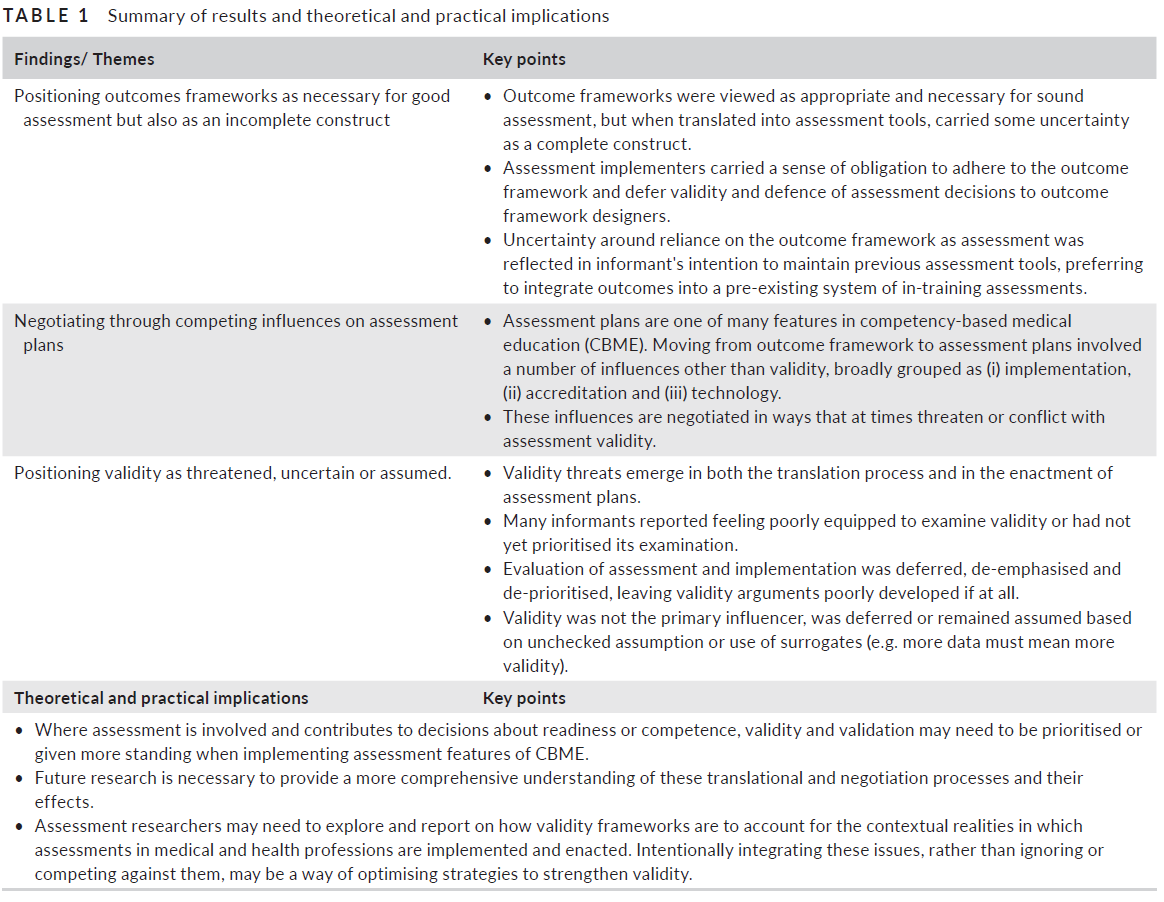

우리의 검색의 22full-text 물품은 우리 최종 분석에 포함되었다 4,299 독특한 제목으로 확인했다. 이들 논문의 대부분은 원근법 논문(n = 18, 81.8%)이었으며, 같은 저자인 스티븐 A가 3편의 논문을 작성하거나 공동 집필했다. Wartman(표 1을 보). 다른 연구 설계(n=2, 9.1%)와 리뷰 케이스 스터디(nx1, 4.5%)고 기조 연설(nx1, 4.5%)이 포함되어 있다. 많은 기사가 미국에서 유래된(nx9일 전체 학생의 40.9%), 연구 설정 다양한 표현, 캐나다(nx4, 18.2%), 한국(n=2, 9.1%)프랑스(nx1, 4.5%), 인도(nx1, 4.5%), 네덜란드(nx1, 4.5%), 뉴질랜드(nx1, 4.5%), 오만(nx1, 4.5%), 파키스탄(nx1, 4.5%), 그리고 스페인(nx1,4를 포함했다.5%)(표 1을 보). 여기 우리는 중요 요점들 우리scoping 검토에서 파생된를 보여 준다.

Our search identified 4,299 unique titles, of which 22 full-text articles were included in our final analysis. 8–11,17–34 The majority of these articles were perspective pieces (n = 18, 81.8%), with 3 papers authored or coauthored by the same author, Steven A. Wartman (see Table 1). Other study designs include reviews (n = 2, 9.1%), a case study (n = 1, 4.5%), and a keynote speech (n = 1, 4.5%). While many articles originated from the United States (n = 9, 40.9%), there was a diverse representation of study settings, including Canada (n = 4, 18.2%), South Korea (n = 2, 9.1%), France (n = 1, 4.5%), India (n = 1, 4.5%), the Netherlands (n = 1, 4.5%), New Zealand (n = 1, 4.5%), Oman (n = 1, 4.5%), Pakistan (n = 1, 4.5%), and Spain (n = 1, 4.5%) (see Table 1). Here we present the key themes derived from our scoping review.

왜 의료 학생들 가르쳐야 한다? 어떻게 AI의학의 실제 영향을 줄까?

Why should medical students be taught it? How will AI affect the practice of medicine?

22개 연구 모두 [AI가 의료에 미치는 불가피한 영향]과 [AI의 적응과 통합]을 위한 의료교육의 필요성을 확인했다.

All 22 studies identified the inevitable impact of AI on health care and the need for medical education to adapt and integrate AI. 8–11,17–34

대부분의 연구는 의료 영상 해석에서 의사보다 뛰어난 AI 시스템을 인용하면서 진단 및 예측 AI 도구가 의사 의사 의사 결정 과정에 미치는 임박한 영향에 대해 논의했다. 또한, 저자들은 현재의 AI 시스템이 매우 구체적인 패턴 기반 작업만 수행할 수 있지만, AI가 곧 의사의 의사 결정 과정에 더 광범위하게 영향을 미치도록 확장될 것이라는 데 동의했다. 예를 들어, 일부는 AI 시스템이 의사들의 최신 증거 기반 의약품을 제공하는 데 도움을 주기 위해 많은 양의 데이터를 통합하고 처리함으로써 의사들의 의사 결정 과정을 보완할 것이라고 가정했다. 대조적으로, 다른 사람들은 AI 시스템에 의한 의사들의 (거의) 완전한 교체를 가정하면서 AI의 파괴적인 잠재력을 주장했다. 19,29

Most studies discussed the imminent impact of diagnostic and predictive AI tools on physicians’ decision-making processes, 18,20,21,24,28,29,33 citing AI systems that outperform physicians in interpreting medical images. 17,19–21,24,25,31,32 Furthermore, authors agreed that while current AI systems can only perform highly specific, pattern-based tasks, 17,19–21,24 AI would soon expand to impact physician’s decision-making processes more broadly. For example, some posited that AI systems will complement physicians’ decision-making processes by amalgamating and processing large amounts of data 22,23,26,28,31–33 to aid physicians in providing the most up-to-date evidence-based medicine. 19,20,29 In contrast, others argued for AI’s disruptive potential, postulating the (almost) complete replacement of physicians by AI systems. 19,29

그 정도에 관계없이, 연구는 데이터 처리에 대한 도움을 받지 않는 의사의 어려움을 겪을 거라는 것에 동의했다. 한 가지 이유는 [지속적으로 증가하는 의학 지식] 때문이며, 다른 이유는 의사의 역할이 "정보를 가진" 사람에서 "정보를 관리하는" 사람으로 이동하기 때문이다.

Regardless of the extent, studies agreed on the difficulty of unaided physicians to data process given the ever-increasing medical knowledge 8–10,17,28–31,33 and the shift in physicians’ role as those who “have information” to those who “manage information.” 8–10,29

의학에서 AI의 통합이 임박하고 의료에 미치는 영향을 고려할 때, 저자는 의료 전문가들이 AI의 사용자이며 AI가 안전하고 적절하게 실제로 통합될 수 있도록 [AI 도구를 운전, 감독 및 평가drive, oversee, and evaluate]할 필요가 있다고 강조했다. 이에 따라, 저자들은 의과대학이 미래의 임상의에게 [AI와 함께 일하고, 관리하고, 상호작용하는 데 필요한 기술]을 가르칠 것을 주장했다. 나아가 맥코이 외 연구진과 콜라찰라마와 가그는 의과대학이 AI에 대한 학생들의 학문적 관심을 육성할 추가적인 책임이 있다고 주장했다.

Given the imminent integration of AI in medicine and its impacts on health care, authors highlighted the need for medical professionals to be users of AI and also drive, oversee, and evaluate AI tools to ensure safe and appropriate integration of AI into practice. 11,17,19,20,29,31,34 Accordingly, authors advocated for medical schools to teach future clinicians the skills needed to work with, manage, and interact with AI. 8–11,17–29,33,34 Furthermore, McCoy et al 27 and Kolachalama and Garg 11 argued that medical schools have an additional responsibility to nurture students’ academic interests in AI.

의대생들이 AI 시스템과 함께 일하기 위해 알아야 할 것은 무엇인가?

What will medical students need to know to work alongside AI systems?

많은 연구들이 학생들에게 임상 실습에서 AI에 대한 개념적 이해를 제공하는 임상 중심 커리큘럼인 UME에서 AI의 전반적인 학습 목표를 논의했다. 그러나 제한된 연구는 특정 AI 학습 목표와 커리큘럼 권장 사항을 다루었다. 마찬가지로, 미국 의학 협회와 같은 통치 기관들은 UME에 AI를 통합하라고 요구했지만, 그들은 구체적인 커리큘럼 권고안을 제공하지 않았다. 그럼에도 불구하고, 우리는 여러 논문에서 공통적인 5가지 핵심 AI 학습 목표를 제시한다(표 2 참조).

Numerous studies discussed the overall learning goals of AI in UME—a clinically focused curriculum providing students with a conceptual understanding of AI in clinical practice. 11,27–30 However, limited studies addressed specific AI learning objectives and curricular recommendations. Similarly, while governing organizations such as the American Medical Association made calls to integrate AI in UME, 35 they did not provide specific curricular recommendations. Nevertheless, we present 5 key AI learning objectives common to several papers (see Table 2).

AI 시스템 관련 작업 및 관리

Working with and managing AI systems.

대부분의 연구는 임상 실습에서 AI와 협력하고 관리하는 데 필요한 기술을 학생들에게 가르치기 위한 UME 커리큘럼의 필요성을 논의했습니다. 이것은 학생들의 육성을 포함했다.

- (1) AI 접근 방식을 이해하는 데 중요한 기초 통계 개념의 이해

- (2) 기계 학습 및 자연어 처리와 같은 개념을 포함한 인공지능의 기본을 이해한

- (3) AI 시스템의 응용, 유익성, 한계 및 위험에 대한 감사appreciation

- (4) AI 시스템 운영 능력. 즉, AI 시스템이 데이터를 캡처, 처리 및 알고리즘에 적용할 수 있도록 AI에 의미 있는 인풋을 제공하는 능력

- (5) 임상 추론에 대한 AI의 영향에 대한 감사appreciation

- (6) AI 결과(종종 확률)를 환자에게 의미 있게 전달하는 능력.

Most studies discussed the need for UME curricula to teach students skills needed to work with and manage AI in clinical practice. This included fostering students’

- (1) understanding of foundational statistical concepts critical to comprehending AI approaches 9,10,19,23,24,26,28,31,34;

- (2) understanding AI fundamentals, 11,17–21,23,27,32–34 including concepts like machine learning and natural language processing;

- (3) appreciation for the application, benefit, limitations, and risks of AI systems 8–11,18,19,21–23,27–30,34;

- (4) ability to operate AI systems, that is, the ability to provide meaningful input to AI so that AI systems can capture, process, and apply the data to its algorithms 11,19,20,22,27,33;

- (5) appreciation for the impact of AI on clinical reasoning 10,11,20–22,24,27; and

- (6) ability to meaningfully communicate AI results (often probabilities) to patients. 8,9,27–29,34

[블랙박스 AI(우리가 이해하지 못하는 AI 시스템)]를 막기 위해서는, [ AI와 협력하고 관리하는 데 필요한 기술]이 필요했기 때문에 이는 많은 저자들에게 가치 있는 학습 목표였다. 블랙박스 AI는 두 가지 수준에서 다루어져야 한다.

- 1) 개발 중에, 투명한 AI 도구를 만들어냄으로써, 그리고

- 2) 구현 중, AI 시스템을 사용하는 의사가 AI의 의사 결정 프로세스를 이해하도록 보장한다.

의사들은 그들이 이해하지 못하는 시스템에 의존해서 임상적 결정을 내릴 수 없다.

This was a valuable learning objective for many authors as the skills needed to work with and manage AI were necessary to prevent black box AI20,23—an AI system we do not understand. Black box AIs must be addressed at 2 levels:

- (1) during development, by creating AI tools that are transparent, and

- (2) during implementation, ensuring that physicians using AI systems understand AI’s decision-making processes.

Physicians cannot rely on and make clinical decisions based on a system that they don’t understand. 20,23

AI 시스템의 윤리적 및 법적 영향.

Ethical and legal implications of AI systems.

10명의 저자는 [AI 시스템의 윤리적 및 법적 함의 이해]와 관련된 구체적인 학습 목표를 논의했다. 이것은 인공지능 시스템의 안전하고 정보에 입각한 사용을 보장하는 데 필수적인 것으로 여겨졌다. 구체적인 학습 목표는 다음과 같다.

- (1) 학생들에게 인공지능 윤리에 접근할 수 있는 틀을 제공한다.

- (2) 책임 및 데이터 개인 정보 보호와 같은 중요한 AI 윤리 주제에 대한 논의를 촉진합니다.

Ten authors discussed specific learning objectives related to understanding AI systems’ ethical and legal implications. 11,18,19,23,27,28,30,31,33,34 This was considered essential in ensuring safe and informed use of AI systems. Specific learning objectives include

- (1) providing students with frameworks to approach AI ethics 27,28 and

- (2) facilitating discussions of important AI ethics topics like liability and data privacy. 23,28,30,31,34

AI 시스템에 대한 비판적 평가.

Critical appraisal of AI systems.

8개의 연구는 학생들에게 [인공지능 시스템을 비판적으로 평가할 수 있는 기술]을 갖추는 것에 대해 논의했다. 여기에는 AI 도구와 주장의 과대광고 대 현실을 판단하고 평가하기 위한 비판적 평가와 증거 기반 의약에 대한 학생들의 이해를 함양하는 내용이 포함됐다.

Eight studies discussed equipping students with skills to critically appraise AI systems. 18,19,23,26–28,30,33 This included fostering students’ understanding of critical appraisal and evidence-based medicine to evaluate and assess the hype versus reality of AI tools and their claims.

질병에 대한 생물의학 지식과 병태생리학에 대한 지속적인 강조.

Continued emphasis on biomedical knowledge and pathophysiology of disease.

네 명의 저자들은 학생들의 [생물의학 지식을 계속 강조]할 필요성을 언급했지만, 세 명의 저자들은 다르게 주장했다. 린 20은 이를 적어도 새로운 AI 도구가 만들어지고 구현되는 향후 수십 년 동안 필수적인 학습 목표로 설명했다. 의사는 새로운 AI 도구가 주장하는 바를 평가하는 데 중요한 역할을 할 것이며, 이러한 새롭게 개발된 AI 시스템을 평가하기 위해서는 질병에 대한 생물의학 지식이 필수적이다.

Four authors addressed the need to continue emphasizing students’ biomedical knowledge, 20,22,25,26 in contrast to 3 authors who argued otherwise. 8,17,24 Lynn 20 explained this as an essential learning objective, at least in the next few decades where novel AI tools are created and implemented. Physicians will play a critical role in evaluating the claims made by novel AI tools, and biomedical knowledge of diseases is essential to appraise these newly developed AI systems.

전자 건강 기록으로 작업합니다.

Working with electronic health records.

전자 건강 기록(EHR)은 AI 시스템을 위한 데이터 수집의 주요 모드이다. 따라서 4명의 저자는 학생들에게 EHR 설계 원리 및 기술에 대한 지식을 제공하고, [EHR에 편향되지 않은 인풋]을 제공하기 위한 의료 커리큘럼의 필요성을 주장했다.

Electronic health records (EHRs) are the primary mode of data collection for AI systems. Thus, 4 authors 11,19,23,31 argued the need for medical curricula to provide students with knowledge of EHR design principles and skills to communicate and provide unbiased input to EHR (which will then be used by AI systems to inform its algorithms).

의대생과 미래의 임상의는 새로운 인공지능 기술에 의해 주도되는 관행 패러다임 변화로 인해 만들어진 새로운 역할을 충족시키기 위해 무엇을 알아야 할까?

What will medical students and future clinicians need to know to meet new roles created by changing practice paradigms as driven by emerging AI technologies?

22건의 연구 중 13건이 AI 기반 의료 변화에 대응해 의사가 육성해야 하는 [비 AI 역량]에 대해 논의했다. 이는 AI에 대응한 의사 역할의 자연스러운 진화이자 AI로 대체되는 것을 피하기 위한 필수 단계로 간주되었다. 구체적으로, 연구는 "독특한 인간 기술", 즉 다음과 같은 [AI 시스템으로 대체할 수 없는 기술]의 중요성을 논의했습니다.

- (1) 자기반성과

- (2) 배려의 기술과 동정심, 의사소통, 그리고 공감과 같은 그것의 구성 요소들.

Thirteen out of 22 studies discussed additional non-AI competencies physicians must foster in response to the AI-driven health care changes. 8–10,17,19,21–25,29,30,33 This was regarded as a natural evolution of physicians’ roles in response to AI and a necessary step to avoid being replaced by AI. Specifically, studies discussed the importance of “uniquely human skills,” that is, skills that cannot be replaced by AI systems such as

- (1) self-reflection 25,30 and

- (2) skills of caring and its components like compassion, communication, and empathy. 8–10,17,19,21–25,29,30,33

대부분의 연구는 자기반성과 보살핌의 기술에는 다음과 같은 특성이 있기 때문에 이것을 환영하는 변화로 간주했다.

- (1) 가르칠 수 있고 측정할 수 있고

- (2) 근거 기반이 있다(환자 결과 및 의사 직무 만족도를 개선하는 데 효과가 있음을 입증하는 연구)

Most studies regarded this as a welcome change as self-reflection and skills of caring are

- (1) teachable and measurable and

- (2) evidence based—with studies demonstrating their effectiveness in improving patient outcomes and physician job satisfaction. 17

독특하게도 마스터스와 피녹 등은 AI 시스템이 이를 대체할 수 있기 때문에 공감조차도 의사의 유일한 역할이 아닐 수 있다는 점에 대해 논의했다. 그럼에도 불구하고, 두 저자들은 의사들에게 환자와 보다 효과적이고 공감적으로 소통할 수 있도록 향상된 의사소통과 상담 기술을 가르칠 필요가 있다고 강조했다.

Uniquely, Masters 19 and Pinnock et al 21 discussed how even empathy may not be the sole role of physicians, as AI systems could replace it. Nevertheless, both authors emphasized the need for physicians to be taught improved communication and counseling skills to communicate more effectively and empathically with patients. 19,21

AI 커리큘럼은 어떻게 전달되어야 하는가?

How should an AI curriculum be delivered?

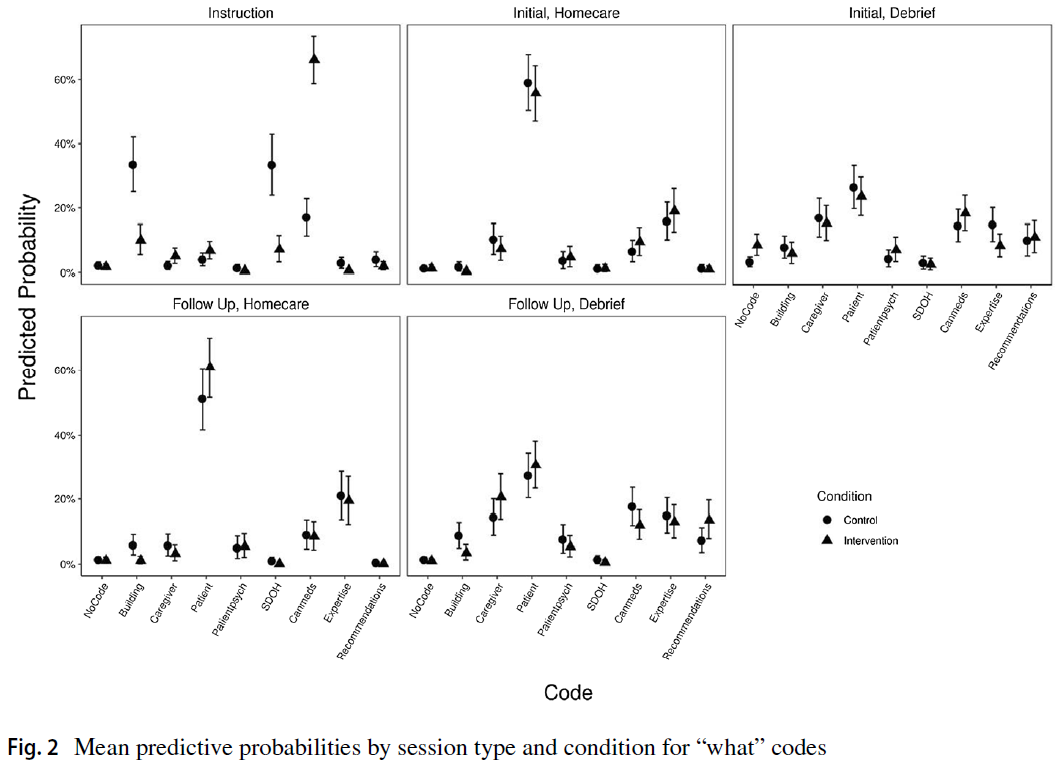

세 가지 연구가 AI 커리큘럼의 전달에 대해 논의했습니다. 그러나, UME에서 AI 커리큘럼을 가장 잘 제공하는 방법에 대한 명확한 합의가 없었다. 제공 권장 사항은 광범위하고(즉, 학습 목표에 특정하지 않고(Mcoy 등을 제외) 특정 교육 이론에 기초하지 않았다. 표 3에는 AI 시범 교육과정이 있는 의과대학 목록이 포함되어 있다.

Three studies 11,23,27 discussed the delivery of AI curricula. However, there was no clear consensus on how best to deliver an AI curriculum in UME. The delivery recommendations were broad (i.e., not specific to learning objectives—except for McCoy et al 27) and not based on a particular education theory. Table 3 includes a list of medical schools with pilot AI curriculum.

그럼에도 불구하고 3개 연구 모두 체험학습의 중요성을 강조했는데, 즉 학생들이 AI 도구를 이용해 직접 작업할 수 있는 기회를 제공하는 것이다. 22개 연구 중 2개 연구 11,27개는 소그룹 세션과 강의를 AI 기초를 가르치는 수단으로 사용하는 것을 논의했다. 맥코이 외 연구진과 파란제이 외 연구진은 각각 학생들에게 AI 기초를 가르치고 AI 윤리에 대한 이해를 함양하기 위한 e-모듈과 대화형 사례 기반 워크숍의 유용성을 강조했다.

Nevertheless, all 3 studies 11,23,27 highlighted the importance of experiential learning, that is, providing opportunities for students to work directly with AI tools. Two out of 22 studies 11,27 discussed using small-group sessions and lectures as a means to teach AI fundamentals. McCoy et al 27 and Paranjape et al 23 highlighted the utility of e-modules and interactive case-based workshops to teach students AI fundamentals and cultivate their understanding of AI ethics, respectively.

두 연구는 정보기술(예: 증거 기반 의학)에 초점을 맞춘 기존 커리큘럼에 AI 콘텐츠를 포함할 가능성에 대해 논의했고 학제 간 데이터 과학자와 같은 AI 커리큘럼의 잠재적 강사에 대해 논의했다.

Two studies 11,23 discussed the possibility of embedding AI content into preexisting curricula focused on information technology (e.g., evidence-based medicine) and discussed potential instructors for AI curricula, such as interdisciplinary data scientists. 11,23

UME에 AI 커리큘럼을 도입하는 것과 관련된 어려움은 무엇인가?

What are the challenges associated with introducing an AI curriculum into UME?

6개의 연구는 AI 커리큘럼 도입과 관련된 과제를 강조했다. UME에서 AI 커리큘럼을 도입하는 데 장애물로는 [교수진의 저항, AI 인증 및 면허(예: USMLE) 요구 사항 부족, 제한된 커리큘럼 시간]을 논의하였다. 추가 장애에는 AI 핵심 역량의 부족, AI에 대한 교수 전문 지식의 부족, AI가 의료 제공에 어떤 영향을 미칠지에 대한 증거의 부족이 포함된다.

Six studies 8–11,18,23 highlighted the challenges associated with introducing AI curricula. Studies discussed

- faculty resistance,

- lack of AI accreditation and licensing (e.g., USMLE) requirements, and

- limited curricular hours

...as barriers to introducing AI curricula in UME. 8–11,23 Additional barriers include

- lack of AI core competencies, 18

- lack of faculty expertise on AI, 11,23 and

- lack of evidence regarding how AI will impact health care delivery. 23

문헌에 대한 방법론적 논평

Methodological comments on the literature

이번 검토에 포함된 22개 조항은 모두 의대생들이 AI를 의학에 접목할 수 있도록 대비할 필요성을 확인하고 AI 교육과정에 대한 권고안을 제시했다. 공통된 주제가 등장했지만, 권고사항 간의 불일치가 지적되었다. 예를 들어,

- 존스턴, 리 외 연구진, 워트먼과 같은 저자들은 AI가 의료 전문가로서 임상의사를 대체할 것이라고 제안했다. 그런 만큼 의과대학은 기초과학을 강조하고, 늘어난 교육시간을 의사 소통 능력 등 의학의 '비분석적, 인문학적' 측면에 할애해야 한다고 주장했다.

- 대조적으로, de Leon, Lynn, Srivastava 및 Waghmare와 같은 작가와 Park 등은 AI 도구에 대한 적절한 감독을 수행하고 유지하기 위해 기초 과학과 병리 생리학의 지속적인 우선 순위를 주장했습니다.

All 22 articles included in this review identified a need to prepare medical students for the integration of AI into medicine and put forth recommendations for an AI curriculum. While common themes emerged, inconsistencies between recommendations were noted. For example,

- authors such as Johnston, 17 Li et al, 24 and Wartman 8 suggested that AI will replace clinicians as medical experts. As such, they argued that medical schools should deemphasize basic sciences and dedicate increased curricular hours for the “nonanalytical, humanistic” aspects of medicine, such as communication skills.

- In contrast, authors such as de Leon, 25 Lynn, 20 Srivastava and Waghmare, 22 and Park et al 26 argued for continued prioritization of basic sciences and pathophysiology to work with and maintain appropriate oversight of AI tools.

22개 논문이 모두 수많은 교육과정 권고안을 제시한 반면 AI 교육과정 전달에 대한 논의는 22개 논문 중 3개 논문에 그쳤고, 평가방법에 대한 논의는 22개 논문 중 1개 논문에 불과했으며 학습성과에 대한 논의 기사는 없었다.

While all 22 articles presented numerous curricular recommendations, only 3 out of 22 articles discussed delivery of an AI curriculum, 11,23,27 1 out of 22 articles discussed methods of evaluation, 22 and no articles discussed learning outcomes.

마지막으로, 우리는 UME에서 AI 훈련에 대한 사용 가능한 문헌에서 연구 유형의 빈약한 표현에 주목했다. 22개의 기사 중 18개는 perspective였고, 22개의 기사 중 13개는 1~2명의 저자를 가지고 있었다. 22개 기사 중 4개가 서로 다른 의과대학에서 시행되는 AI 시범 교육과정을 설명하거나 참조하고 있지만(표 3 참조), 우리가 아는 한 GREET 체크리스트와 같은 검증된 보고 지침을 사용하여 UME에서 AI에 대한 교육 개입을 시범, 평가 및 보고한 연구는 없다. 마찬가지로, MedEdPortal에서는 UME에서 AI를 위한 완성된 교수 또는 학습 모듈을 찾을 수 없었다.

Finally, we noted a poor representation of study types in the available literature on AI training in UME. Eighteen out of 22 articles were perspective pieces, 8–11,17,19–26,28,29,32–34 and 13 out of 22 articles had 1 to 2 authors. 8–11,17–20,22,25,29,32,33 While 4 out of 22 articles 17,23,26,27 describe or reference pilot AI curricula implemented in different medical schools (see Table 3), to the best of our knowledge, there are no studies that have piloted, evaluated, and reported an educational intervention for AI in UME using validated reporting guidelines such as the GREET checklist. 15 Likewise, no completed teaching or learning modules for AI in UME were found on MedEdPortal.

논의

Discussion

이 범위 검토는 UME에서 AI 훈련과 관련하여 현재 이용 가능한 문헌을 요약하여 주요 주제를 매핑하고 현재 관행과 미래 연구에 정보를 제공할 수 있는 문헌의 격차를 강조한다.

This scoping review summarizes the currently available literature regarding AI training in UME, mapping key themes and highlighting gaps in the literature that can inform current practice and future research.

포함된 모든 기사는 2017~2020년 발간돼 의학 교육계의 AI에 대한 관심이 싹트고 있음을 반영했다. 포함된 모든 연구는 의료 제공에 AI가 미치는 영향을 포함하여 UME에 AI 커리큘럼을 도입하는 근거를 논의했습니다. 마찬가지로 모든 연구에는 AI 커리큘럼 내용에 대한 제안이 포함되었으며, 이를 통해 의학교육자들이 AI 커리큘럼을 개발할 때 고려해야 할 5가지 핵심 AI 테마를 도출하였다(표 2 참조). 그러나 연구 전반에 걸쳐 상당한 이질성이 있었고 학생들이 UME 기간 동안 어떤 AI 기술을 배워야 하는지에 대한 공감대가 부족했다. 각 기사는 AI 학습 영역의 하나 이상의 요소를 강조했으며, 5가지 주제를 모두 논의한 단일 연구는 없었다.

All included articles were published between 2017 and 2020, reflecting the budding interest in AI among the medical education community. All included studies discussed their rationale for introducing AI curricula in UME, including the impact of AI in health care delivery. Likewise, all studies included suggestions for AI curricular content, 8–11,17–34 and from it, we derived 5 key AI themes that medical educators should consider when developing AI curricula (see Table 2). However, there was considerable heterogeneity across studies and a lack of consensus regarding which AI skills students should learn during UME. Each article emphasized one or more elements of AI learning domains, with no single study discussing all 5 themes.

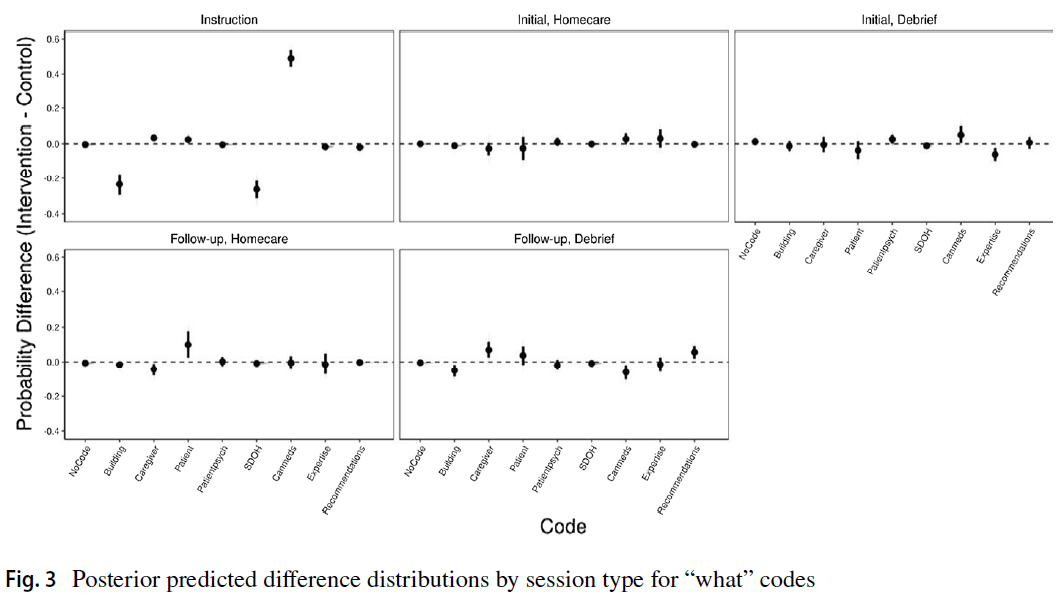

비슷하게, 22개의 연구 중 3개는 AI 커리큘럼 전달에 대해 논의했다. 다양한 AI 기술 세트에 맞춰 강의, e-모듈, 소그룹 학습 등 다양한 교육학적 접근법이 제시됐다. 모든 저자의 추천은 경험적 학습으로, 학생들에게 AI 도구로 직접 작업할 수 있는 기회를 제공했다. 그러나, 그들의 AI 전달 권장 사항을 알려주는 교육 이론이나 프레임워크를 명시적으로 논의한 연구는 없었고, 구현된 프로그램의 사례 연구를 포함하는 논문은 거의 없었다. 시범 프로그램의 몇 안 되는 사례 연구 중, 학생 만족도, 지식 습득 및 기술 이전과 같은 AI 커리큘럼의 결과에 대한 보고는 없었다. 평가의 부족과 AI 커리큘럼 전달 권장 사항 간의 이질성 때문에, 우리는 AI 커리큘럼을 가장 잘 전달하는 방법에 대한 합의를 추론할 수 없었다.

Similarly, 3 out of 22 of studies discussed AI curricula delivery. 11,23,27 Various pedagogical approaches were suggested, including lectures, e-modules, and small-group learning, in line with the diverse AI skill sets. Common to all authors’ recommendations was experiential learning—providing students with the opportunity to work directly with AI tools. However, none of the studies explicitly discussed educational theories or frameworks that informed their AI delivery recommendations, and very few papers included case studies of implemented programs. Among the few case studies of piloted programs, none reported on outcomes of their AI curriculum, such as student satisfaction, knowledge acquisition, and skill transfer. Due to the lack of evaluations and the heterogeneity among AI curriculum delivery recommendations, we could not extrapolate a consensus regarding how best to deliver AI curricula.

AI 커리큘럼 콘텐츠와 전달에 대한 합의 부족에는 여러 가지 요인이 작용했을 수 있다.

- (1) 이 범위 검토에 포함된 연구에서 확인된 장애요인으로 인해 AI 통합 노력이 부족

- (2) AI는 지난 10년 동안 괄목할만한 발전을 이룬 비교적 새로운 분야이다. —의료 교육자들은 AI가 의료 서비스 제공과 그에 따른 의료 교육에 어떤 영향을 미치는지 감사할 시간이 충분하지 않을 수 있습니다.

- (3) AI 커리큘럼 통합의 복잡성 —AI 통합 의료 분야에서 일하는 것은 간호 기술과 같은 비 AI 영역의 개선과 함께 AI 고유의 역량을 포함하는 복잡한 기술 세트를 필요로 한다. (즉, 공감과 소통).

Numerous factors may have contributed to the lack of consensus regarding AI curricular content and delivery:

- (1) lack of AI integration efforts due to the barriers identified from studies included in this scoping review, 8–11,18,23

- (2) AI is a relatively new field with remarkable advances made within the last 10 years—medical educators may not simply had enough time to appreciate how AI will impact health care delivery and thus medical education, and

- (3) the complexity of integrating AI curricula—working in AI-integrated health care requires complex skill sets that include AI-specific competencies along with improvements in non-AI domains such as skills of caring (i.e., empathy and communication).

따라서, 문헌에서 강조된 격차를 고려하여, 우리는 의학 교육자들이 UME에서 AI 커리큘럼을 제공하기 위해 취해야 할 세 가지 다음 단계를 제안한다.

Thus, in light of the highlighted gaps in the literature, we propose 3 next steps that medical educators should take in their efforts to deliver AI curricula in UME.

1. AI 교육을 위한 표준화된 핵심 역량 세트 생성

1. Create a standardized set of core competencies for AI training

[핵심 역량]은 개인이 적절한 표준으로 일련의 작업을 수행할 수 있도록 하는 지식 및 기술과 같은 속성들의 조합입니다. 따라서, 명목 집단 기술 또는 델파이 조사와 같은 합의 그룹 방법을 사용하여 개발된 일련의 역량은 다음과 같은 공유 언어를 제공할 것이다.

- (1) 문학의 모순을 다루고,

- (2) AI 교육 커리큘럼 개발을 위한 프레임워크를 제공합니다.

- (3) 인증 및 면허 요건에 AI 기술을 포함시키기 위해 캐나다 의학 협회와 같은 조직에 옹호 노력을 알린다.

Core competencies are a combination of attributes like knowledge and skills that enable an individual to perform a set of tasks to an appropriate standard. 36,37 Thus, a set of competencies developed using consensus-group methods such as nominal group technique or Delphi surveys 38 will offer a shared language that

- (1) addresses the inconsistency in literature,

- (2) provides a framework for developing AI educational curricula, and

- (3) inform advocacy efforts to organizations such as the Canadian Medical Association for the inclusion of AI skills in accreditation and licensing requirements.

2. 피드백에 대응하여 커리큘럼을 개선하고 개선하기 위해 목적적이고 계획적인 평가를 통해 유연한 증거 및 이론 정보를 가진 AI 커리큘럼을 개발하고 구현합니다.

2. Develop and implement flexible, evidence- and theory-informed AI curriculum with purposeful and planned evaluations to refine and improve the curriculum in response to feedback

이 범위 검토는 UME에서 AI 커리큘럼의 전달에 관한 문헌의 부족을 강조하지만, 모범 사례에 관한 방대한 의학교육 문헌은 증거 및 이론 정보 AI 커리큘럼의 개발을 안내할 수 있다. 한 가지 제안은 스타이너트 등이 알려주는 AI 커리큘럼 전달이다.

- (1) 다양한 인공지능 기술을 가르치기 위한 다양한 교육 방법 (예: AI 윤리에 관한 미묘한 대화를 위한 토론 기반 튜토리얼 대 AI 기초를 가르치는 강의/모듈) 및

- (2) 경험적 학습—학생에게 AI 도구를 사용하여 작업하고 AI 기술에 대한 피드백을 받을 수 있는 기회를 제공합니다.

궁극적으로, 다른 기초 및 준비 지식 영역과 마찬가지로, AI 훈련은 프로그램, 과정 및 세션 수준에서 효과적인 통합이 필요하다. AI를 임상 추론 및 기타 핵심 활동에 대한 교육과 적절히 통합하면 이러한 교육의 효율성을 높이고 과밀화를 제한하거나 현재 UGME 커리큘럼을 "팽창"시킬 수 있다.

This scoping review highlights the paucity of literature regarding the delivery of AI curriculum in UME. However, the vast medical education literature regarding best practices 39–41 can guide the development of evidence- and theory-informed AI curriculum. One suggestion is an AI curricular delivery informed by Steinert et al, 39 comprising

- (1) diverse education methods to teach diverse AI skills sets (e.g., lecture/modules to teach AI fundamentals versus discussion-based tutorials for nuanced conversations regarding AI ethics) and

- (2) experiential learning—providing students with the opportunity to work with AI tools and receive feedback regarding their AI skills.

Ultimately, like other foundational and preparatory knowledge domains, AI training needs effective integration at the program, course, and session levels. 42 Integration of AI appropriately with teaching on clinical reasoning and other core activities may increase the efficacy of such teaching and limit overcrowding or “bloating” current UGME curricula. 43

게다가, 우리는 AI 커리큘럼을 만드는 핵심이 [완벽한 커리큘럼을 만드는 것]에 있는 것은 아니라고 가정한다. 대신, 학생과 교직원의 피드백에 반응하여 [커리큘럼에 대한 반복적 개선]을 촉진하기 위해 목적적이고 계획된 평가를 가진 유연하고 증거에 근거한 커리큘럼을 개발하는 것이다. AI 교육과정의 평가에는 학생의 태도 변화, AI 지식의 객관적 측정, 향후 훈련에서 새로운 AI 관련 기술 습득과 같은 종단적 결과 등이 포함될 수 있다.

Furthermore, we postulate that the key to creating an AI curriculum is not about creating the perfect curriculum. Instead, it is about developing a flexible and evidence-informed curriculum with purposeful and planned evaluations to facilitate iterative refinements to the curriculum in response to student and faculty feedback. Evaluations of AI curriculum can include self-reported changes in students’ attitudes, objective measures of AI knowledge, and longitudinal outcomes such as acquisition of new AI relevant skills in future training.

3. AI 및 UME에 대한 문헌의 보급, 기여 및 확장을 위해 AI 커리큘럼 콘텐츠 및 전달에 관한 연구 결과를 발표하려는 노력 증가

3. Increased effort to publish findings regarding AI curricular content and delivery to disseminate, contribute to, and extend the literature on AI and UME

우리의 범위 검토는 커리큘럼 내용, 전달, 특히 UME의 AI 훈련 평가에 관한 문헌의 부족을 확인했다. 우리는 의학 교육자들 사이에서 UME의 AI 커리큘럼 개발을 안내하고 발전시키기 위해 사용 가능한 연구 결과를 공유하고 발표하기 위한 연구와 헌신을 강화할 것을 지지한다.

Our scoping review identified a lack of literature regarding curricular content, delivery, and in particular, the evaluation of AI training in UME. We advocate for increased research and commitment among medical educators to share and publish available findings to guide and advance AI curricular development in UME.

제한 사항

Limitations

우리의 발견은 그것의 한계라는 맥락에서 해석되어야 한다. 영어로 작성된 연구만 포함하고 회색문학, 즉 미발표 문학이나 정부 보고서와 같은 비상업적 플랫폼에서 출판된 문학은 조사하지 않았다. 따라서, 우리는 우리의 검토와 관련된 추가 연구를 놓쳤을 수 있다. 또한, 우리의 검토는 UME에만 초점을 맞췄습니다. 따라서 이러한 설정이 AI 훈련을 위한 귀중한 학습 환경을 나타낼 수 있지만, 대학원이나 지속적인 의학 교육에 대해서는 논의할 수 없었습니다. 마지막으로, 우리의 주제 분석에 포함된 많은 기사들이 미국에 기반을 두고 있다는 점에 주목해야 한다. 확인된 주제와 통찰력은 다른 나라의 의료 훈련 프로그램에 적합해야 할 것이다.

Our findings should be interpreted in the context of its limitations. We only included studies written in English and did not examine gray literature, that is, unpublished literature or literature published in noncommercial platforms such as government reports. Thus, we may have missed additional studies relevant to our review. Furthermore, our review only focused on UME. As such, we could not discuss postgraduate or continuing medical education, although these settings may represent valuable learning environments for AI training. Finally, it should be noted that the many articles included in our thematic analysis are based in the United States. Identified themes and insights will need to be adapted for medical training programs in other countries.

결론들

Conclusions

AI는 의학에 중요하고 광범위한 영향을 미칠 수 있는 잠재력을 가지고 있다. 의학 교육은 학습자들이 이러한 잠재적인 변화에 대비해야 한다. UME는 AI 훈련과 의학에서 잠재적으로 독특한 역할을 한다.

- (1) 의료 교육에 AI를 [조기]에 노출하고 통합할 수 있습니다.

- (2) 가장 [광범위]한 의학 학습자 집단에 도달할 수 있는 능력을 가지고 있다.

이 범위 검토는 AI 커리큘럼 내용과 전달에 대한 중요한 고려 사항을 확인했지만, 문헌 내 유의미한 이질성과 낮은 합의도 확인되었다. 이 증거를 평가하고 조정하여 의학 학습자가 다가올 의학에서의 인공지능의 통합에 적절하게 대비하기 위해 추가 연구가 필요할 것이다.

AI has the potential to have significant and wide-sweeping impacts on medicine. Medical education must prepare learners for these potential changes. UME has a potentially unique role in AI training and medicine as it (1) allows for early exposure and integration of AI into medical education and (2) has the capability to reach the broadest medical learner population. While this scoping review identified important considerations for AI curricular content and delivery, significant heterogeneity and poor consensus within the literature was also identified. Further research will be needed to appraise and reconcile this evidence to adequately prepare medical learners for the forthcoming integration of AI in medicine.

Artificial Intelligence in Undergraduate Medical Education: A Scoping Review

PMID: 34348374

Abstract

Purpose: Artificial intelligence (AI) is a rapidly growing phenomenon poised to instigate large-scale changes in medicine. However, medical education has not kept pace with the rapid advancements of AI. Despite several calls to action, the adoption of teaching on AI in undergraduate medical education (UME) has been limited. This scoping review aims to identify gaps and key themes in the peer-reviewed literature on AI training in UME.

Method: The scoping review was informed by Arksey and O'Malley's methodology. Seven electronic databases including MEDLINE and EMBASE were searched for articles discussing the inclusion of AI in UME between January 2000 and July 2020. A total of 4,299 articles were independently screened by 3 co-investigators and 22 full-text articles were included. Data were extracted using a standardized checklist. Themes were identified using iterative thematic analysis.

Results: The literature addressed: (1) a need for an AI curriculum in UME, (2) recommendations for AI curricular content including machine learning literacy and AI ethics, (3) suggestions for curriculum delivery, (4) an emphasis on cultivating "uniquely human skills" such as empathy in response to AI-driven changes, and (5) challenges with introducing an AI curriculum in UME. However, there was considerable heterogeneity and poor consensus across studies regarding AI curricular content and delivery.

Conclusions: Despite the large volume of literature, there is little consensus on what and how to teach AI in UME. Further research is needed to address these discrepancies and create a standardized framework of competencies that can facilitate greater adoption and implementation of a standardized AI curriculum in UME.

Copyright © 2021 by the Association of American Medical Colleges.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 교육과정 개발&평가' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 의과대학생이 AI에 대해서 알아야 하는 것은 무엇인가? (J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2019) (0) | 2022.09.01 |

|---|---|

| 보건의료전문직 교육에서 인공지능: 스코핑 리뷰(JMIR Med Educ. 2021) (0) | 2022.09.01 |

| When I say … 상황 (Med Educ, 2021) (0) | 2022.08.31 |

| 의대생들에게 가르치는 것 가르치기: 내러티브 리뷰와 문헌에 기반한 권고(Acad Med, 2022) (0) | 2022.08.24 |

| 의대생들에게 어떻게 가르치는지를 가르치기: 스코핑 리뷰(Teach Learn Med. 2022) (0) | 2022.08.24 |