비판적 '보기'를 향하여: 비판적 페다고지의 영향에 대한 베이지안 분석(Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2022)

Toward ‘seeing’ critically: a Bayesian analysis of the impacts of a critical pedagogy

Stella L. Ng1,2,8 · Jeff Crukley2,3 · Ryan Brydges4,6,8 · Victoria Boyd5,8 · Adam Gavarkovs5,8 · Emilia Kangasjarvi6 · Sarah Wright7,8 · Kulamakan Kulasegaram7,8 · Farah Friesen1 · Nicole N. Woods7,8

서론

Introduction

이 논문은 비판적 페다고지의 실행enactment의 결과를 비판적 성찰적 실천을 위한 렌즈인 비판적 성찰에 대한 교육 접근법으로 분석한다. [비판적 성찰적 실천]은 [존재함과 바라봄의 한 가지 방법으로서, 가정, 권력 관계 및 구조에 대해 의문을 제기하고 도움이 되지 않을 때 이를 변경하는 방법]이다. 이 기사는 교육(비판적 교육학)과 실천(비판적 성찰적 실천)에 대한 이러한 접근 방식이 보건 전문가 교육의 중요한 과제를 해결할 수 있는 방법을 제공할 수 있기 때문에 중요하다.

This paper analyzes the outcomes of one enactment of critical pedagogy, as an approach to teaching for critical reflection, which is a lens for critically reflective practice: a way of being and seeing in practice that orients the practitioner to question assumptions, power relations, and structures, and to change these when they are unhelpful (Ng et al., 2019a, b). This article is important because these approaches to teaching (critical pedagogy) and to practice (critically reflective practice) may offer a way to address an important challenge in health professions education.

치료의 사회적 역할을 최적으로 수행할 전문가를 어떻게 준비할 수 있는가? (Mykhalovsky & Farrell, 2005; Verma et al., 2005; Kumagai, 2014; Ng et al., 2020). 이러한 역할에는 건강 옹호자, 의사 전달자, 협력자, 전문직 종사자 및 시스템 기반 실무자가 포함된다. 이들은 총체적으로 인문학적, 본질적, 사회적 역할로 다양하게 언급되어 왔다(다인 외, 2002; 프랭크 & 다노프, 2007; 셰르비노 외, 2011; 화이트헤드 외, 2014). 현재, 이러한 사회적 역할에 대한 실무자를 준비하기 위한 주요 접근 방식에는 건강(SDoH)의 사회적 결정 요소와 문화적 역량을 가르치고, 포트폴리오 또는 이와 유사한 '성찰적' 문서를 사용하는 것이 포함된다. 이들 각각의 접근방식은 상당한 비판을 받았다(Driessen et al., 2005; Kumagai & Lipson, 2009; Metzl & Hansen, 2014; Kuper et al., 2017; Ng et al., 2015a; Sharma et al., 2018).

How can we prepare professionals to optimally perform the social roles of care? (Mykhalovskiy & Farrell, 2005; Verma et al., 2005; Kumagai, 2014; Ng et al., 2020. These roles include the health advocate, communicator, collaborator, professional, and systems-based practitioner; collectively, they have been variably referred to as humanistic, intrinsic, or social roles (Dyne et al., 2002; Frank & Danoff, 2007; Sherbino et al., 2011; Whitehead et al., 2014). Currently, dominant approaches to prepare practitioners for these social roles include teaching social determinants of health (SDoH) and cultural competence, and using portfolios or similar ‘reflective’ documents. Each of these approaches have encountered considerable critique (Driessen et al., 2005; Kumagai & Lypson, 2009; Metzl & Hansen, 2014; Kuper et al., 2017; Ng et al., 2015a; Sharma et al., 2018).

예를 들어,

[SDoH 접근법]이 [어떻게 인종주의가 아니라 인종, 업압이 아니라 빈곤, 동성애혐오가 아니라 동성애에 초점을 두게 만드는가]에 대해서 Sharma 등이 비판한 고찰이 있다. 본질적으로 샤르마 등은 SDoH를 [사회와 시스템의 결과]보다는 [개인의 측면]으로 포지셔닝하고, 따라서 [시스템을 변경]하는 대신, [개인/환자의 변화에 초점]을 맞추기 때문에, 이것이 SDoH 접근법이 해결하고자 하는 [불평등을 바꾸는] 대신, 영구화될 위험이 있다고 주장한다.

[문화적 역량]에 대한 접근법은 마찬가지로, 복잡한 문화적 경험과 정체성을 평가절하하고, [환원주의적 체크박스 접근법]을 전파할 위험이 있다. 개성, 복잡성 및 뉘앙스의 지나치게 단순화하고 지나치게 일반화하면, [가정된supposed 문화적 역량의 기계적인 수행]으로 이어질 수 있고, 이는 잠재적으로 환자에게 해를 끼칠 수 있다(Kumagai & Lypson, 2009).

[자기반성 포트폴리오와 자기성찰 과제]는 사회적 역할의 개발을 고무inspire, 문서화 및 평가하는 것을 목표로 하지만, 오히려 학생들이 [자신이 진실하지 않게 수행해야 하고 감시당하고 있다]고 느끼게 할 수 있다(Nelson & Purkis, 2004; Hodges, 2015; Ng et al., 2015a, b; de la Croix & Veen, 2018).

- Critiques include, for example, Sharma et al.’s (2018) discussion of how a SDoH approach can focus learners on race but not racism, poverty but not oppression, homosexuality but not homophobia. In essence, Sharma et al. contend that this focus risks perpetuating rather than transforming the inequities that a SDoH approach espouses to remedy, because it positions SDoH as aspects of individuals rather than consequences of society and systems, and thereby diverts focus onto changing individuals/patients instead of changing systems (Sharma et al., 2018).

- Approaches to cultural competence similarly risk discounting complex cultural experiences and identities and propagating a reductionist checkbox approach. This oversimplification and overgeneralization of individuality, complexities, and nuances can lead to rote performance of supposed cultural competence that can potentially do harm to patients (Kumagai & Lypson, 2009).

- Self-reflective portfolios and related self-reflective assignments, which aim to inspire, document, and assess the development of social roles, can instead lead students to feel they must perform inauthentically and are being surveilled (Nelson & Purkis, 2004; Hodges, 2015; Ng et al., 2015a, b; de la Croix & Veen, 2018).

우리는 [비판적 성찰]이 [대안적 프레임]을 제공하고, 위에서 강조된 과제에 대처할 수 있다고 제안한다. 이 틀과 관련된 교육 접근법, 비판적 교육학은 하버마스의 비판적 학문에 뿌리를 두고 있으며, 브룩필드, 켐미스, 킨첼로와 같은 현대 교육학자들과 킨셀라, 쿠마가이, 웨어와 같은 보건직 교육 사상가들을 후크한다. [성찰]의 개념(=지식 주장과 그 출처에 대한 적극적이고, 지속적이며, 신중한 질문)에서 구축된 [비판적 성찰]은, 자신self에 초점을 덜 맞추는 대신, [개인적, 사회적 가정]과 [도움이 되지 않는 권력 관계]로 시선을 돌려서, 선택한 직업을 어떻게 실천하는지를 향상시키는 것을 목표로 한다.

We propose that critical reflection can offer an alternative frame and rise to the challenges highlighted above. This frame and its associated teaching approach, critical pedagogy, are rooted in the critical scholarship of Habermas, Freire, hooks, contemporary education scholars such as Brookfield, Kemmis, and Kincheloe, and health professions education thinkers like Kinsella, Kumagai, and Wear (Habermas, 1971; Brookfield, 2000; Freire, 2000; Kemmis, 2005; Kinsella, 2006; Kumagai & Lypson, 2009; Kumagai, 2014; Hooks, 2015; Ng et al., 2019a, b). Building from the concept of reflection—the active, persistent, and careful questioning of knowledge claims and their sources (Dewey, 1910)—critical reflection focuses less on self and instead turns its gaze to personal and societal assumptions and unhelpful power relations, with the goal of improving how one practices one’s chosen profession (Brookfield, 2000; Freire, 2000).

[비판적으로 성찰하는 전문가]는 [바라봄과 존재함에 대해 비판적으로 성찰하는 방식]을 채택하여, 윤리 및 정의에 대한 헌신을 가지고 실천하도록 유도한다. 예를 들어, [비판적으로 성찰하는 시각을 가진 전문가]는 [장애]를 이해할 뿐만 아니라, 재활 계획에 내재된 미묘한 차이를 알아차리고 바꿀 수도 있다. 그들은 [사회경제적 지위]가 어떻게 의료 접근에 영향을 미치는지 이해할 뿐만 아니라, [의료 시스템에 내재된 계급주의]를 인식하고 완화하는 것을 목표로 할 수도 있다. 과거의 연구는 [비판적 성찰]이 보다 온정적이고 (Rowland & Kuper, 2018), 협력적이며 (Ng et al., 2020), 공평한 (Mykhalovsky & Farrell, 2005) 실천을 지원하므로, 학습자가 의료의 사회적 역할을 준비할 수 있는 기회를 제공한다는 것을 입증했다.

A critically reflective professional adopts a critically reflective way of seeing and being that orients them to practice with a commitment to ethics and justice (Freire, 2000; Kumagai & Lypson, 2009; Ng et al., 2015a, b). For example, professionals with a critically reflective way of seeing may not only understand disability but also notice and change subtle ableism embedded in a rehabilitation plan. They may not only understand how socioeconomic status influences health access but also recognize and aim to mitigate classism embedded in healthcare systems. Past research has demonstrated that critical reflection supports practice that is more compassionate (Rowland & Kuper, 2018), collaborative (Ng et al., 2020), and equitable (Mykhalovskiy & Farrell, 2005), thus providing an opportunity to prepare learners for the social roles of health care.

그러나, 과거의 연구는 또한 전문가들이 주로 [개인적인 경험과 관계]를 통해 [비판적으로 성찰하는 능력을 배운다]는 것을 보여주었다(Mykhalovsky & Farrell, 2005; Rowland & Kuper, 2018; Ng et al., 2020). 예를 들어, 롤랜드와 쿠퍼(2018)는 의사가 환자의 역할을 직접 경험한 후 더 비판적으로 반사적이고 따라서 동정심이 생긴다는 것을 발견했다. Ng 외 연구진(2020)은 전문가와 환자 보호자가 자신의 비판적 성찰적 관점을 [정규 교육]의 덕분이 아닌, [개인적 관계, 과거의 경력 및 우연에 의해 발생한 경험 탓]으로 돌린다는 것을 발견했다. 이러한 형태의 개인 및 경험적 학습은 경험과 참여를 통한 학습을 강조하는 비판적 교육학의 원리와 일치하며, 이야기의 공유를 통해 다른 사람의 공통 인간성과 연결된다(Kumagai et al., 2009; Halman et al., 2017; Baker et al., 2019, 2020). 그럼에도 불구하고, 문제는 여전히 남아 있다: 어떻게 하면 보다 공식적인 보건 전문가 교육 커리큘럼에서 비판적 성찰과 비판적 페다고지를 적절하게 통합할 수 있는가 하는 것이다.

However, past research has also shown that professionals predominantly learn their critically reflective capabilities through their personal experiences and relationships (Mykhalovskiy & Farrell, 2005; Rowland & Kuper, 2018; Ng et al., 2020). For example, Rowland and Kuper (2018) found that physicians became more critically reflexive, and thus compassionate, after experiencing the patient role firsthand. Ng et al. (2020) found that professionals and patient caregivers attributed their own critically reflective views to personal relationships, past careers, and experiences occurring by happenstance, not to formal education. These forms of personal and experiential learning align with the principles of critical pedagogy, which emphasize learning through experience and engaged participation, and connecting with others’ common humanity through sharing of stories (Kumagai et al., 2009; Halman et al., 2017; Baker et al., 2019, 2020). Nonetheless, the question remains: how to appropriately integrate critical reflection and pedagogy in more formal health professions education curricula.

[사회적 구성주의 패러다임]에서 일하는 [비판적 성찰 학자]들은 [비판적 교육학]을 통해 이러한 시각을 가르치는 방법에 대해 썼고, 그들의 동시대인들은 정성적 연구 설계를 사용하여 이러한 접근법의 적용을 평가했다(Tillle et al., 2018; Kumagai & Lipson, 2009). 그러나 전통적으로 생물의학 모델과 실험주의 전통이 지배하는 학제 간 분야인 보건직 교육에서 [비판적 성찰과 비판적 교육학의 지지자]들은 종종 [효과성에 대한 질문]에 직면한다. 특히, 교육자와 연구원들은 종종 교육 개입에 대한 측정 가능한 결과를 보기를 기대한다. 그러나 [비판적 성찰을 가르치는 목적]이 [사전 결정된 방식으로 콘텐츠 지식의 습득이나 기술의 성과를 향상시키는 것]이 아니기 때문에, 전통적인 필기(예: 객관식 문제) 및 성과 기반(예: 방송국 기반 시험) 측정에 의해 그 효과가 누락되거나 잘못 전달될 수 있다. 대신, 우리는 [비판적 성찰을 가르치는 것]이 학생들이 실천의 불확정 영역(즉, 불확실하고, 고유하며, 가치가 상충하고, 역동적인 실천의 측면들)을 경험하면서, [실천-기반 학습과 비판적 성찰적 실천에 대한 견해와 능력에 영향을 미친다]고 주장한다(Schön, 1983; Cheng et al., 2017).

Critical reflection scholars, working from social constructionist paradigms, have written about how to teach this way of seeing through critical pedagogy, and their contemporaries have evaluated applications of these approaches using qualitative research designs (Thille et al., 2018; Kumagai & Lypson, 2009). However, in health professions education, an interdisciplinary field traditionally dominated by the biomedical model and experimentalist traditions, proponents of critical reflection and critical pedagogy often face questions of effectiveness. In particular, educators and researchers often expect to see measurable outcomes for educational interventions. However, the purpose of teaching critical reflection is not to enhance the acquisition of content knowledge or the performance of skills in a pre-determined manner; thus, its effects could be missed or misrepresented by traditional written (e.g. multiple-choice questions) and performance-based (e.g. station-based exams) measurements. Instead, we argue that teaching critical reflection influences students’ views about, and capabilities for, practice-based learning and critically reflective practice when they experience indeterminate zones of practice—that is, uncertain, unique, value-conflicted, and dynamic aspects of practice (Schön, 1983; Cheng et al., 2017).

따라서 비판적 성찰의 교육을 실험적으로 연구하려면 [비판적 성찰의 기원]에 따라 [패러다임 호환성]을 유지하기 위해, [성과 측정에 대한 대안적 접근법]이 필요한 동시에, [건강 전문가 교육의 실험적인 모델에 의해 제기되는 질문을 해결할 것]을 제안한다. 우리는 이 격차를 메우는 것을 목표로 삼았다: 비판적 반성을 능력으로 가르치는 것이 향후 경험에서 보건 전문가의 시각 방식을 바꿀 수 있다는 이론적 주장을 실험적으로 탐구하기 위해서였다. 우리는 질문을 해결하기 위해 실험을 수행했다: 비판적 성찰을 가르치는 것이 학습자가 후속 학습 세션과 결과 발표 중에 말하는 것(즉, 토론 주제)과 말하는 방식(즉, 비판적 성찰 방식으로 말하는지 여부)에 영향을 미치는가? 시간의 경과가 성과에 영향을 미칠 수 있다는 것을 인정하여, 초기 교육 후 1주일 후에 변경된 효과가 있는지 살펴보았다.

Thus, we propose that studying the teaching of critical reflection experimentally requires alternative approaches to measuring outcomes, in order to maintain paradigmatic compatibility (Tavares et al., 2020) with the origins of critical reflection, while also addressing questions posed by experimentalist models of health professions education. We aimed to fill this gap: to explore, experimentally, the theoretical assertion that teaching critical reflection as a capability can shift health professionals’ ways of seeing in subsequent experiences. We conducted an experiment to address the questions: does teaching critical reflection influence what learners talk about (i.e. topic of discussion) and how they talk (i.e. whether they talk in critically reflective ways) during a subsequent learning session and debrief? Acknowledging that the passage of time can impact performance, we explored whether any effects changed one week after initial training.

우리는 학습자들이 [비판적으로 성찰하는 대화 수업 후에 말하는 방식]을 우리의 [바라봄의 방법way of seeing에 대한 실험적인 대용물proxy]로 사용했다. 대화/텍스트를 분석하여 보는 방법을 추론하는 이러한 접근 방식은 학자들이 전문적 정체성과 같은 다른 가치 있는 구성을 어떻게 다루었는지와 일치한다(Kalet et al., 2018). 중요한 것은, 우리는 성찰의 질을 판단한 것이 아니라, [그들의 대화]가 [비판적 교육학적 접근법 교육에서 목표로 하는 비판적 성찰의 정의]와 일치하는지 여부를 판단했다는 것이다. 우리는 [비판적 성찰]이 [컨텐츠에 덜 초점을 맞추고 프레임에 더 집중하기에(예: 연령뿐만 아니라 연령 차별 주의)], 비판적 성찰을 위한 교육은 [학습자의 발표 내용]에는 영향을 미치지 않을 것으로 예상했고, 그보다는 학습자가 같은 내용에 대해서 [어떻게 바라보고 이야기하는지]에 영향을 미칠 것으로 예상했습니다.

(예: 연령 차별 언어를 채택하기보다는 반격).

—.

We used the way learners talked following a critically reflective dialogic teaching session as our experimental proxy for ways of seeing. This approach to analyzing talk/text to infer a way of seeing is aligned with how scholars have handled other value-laden constructs, such as professional identity (Kalet et al., 2018). Importantly, we did not judge the quality of the reflection but rather whether or not their talk was consistent with a definition of critical reflection that a critical pedagogical approach aimed to teach. We expected that teaching for critical reflection would not have an effect on the what of learners’ talk—given critical reflection is less focused on content and more on framing (e.g. noticing not just age but ageism)—and expected it would impact how they see and thus talk about the same content (e.g. countering rather than adopting ageist language).

방법들

Methods

연구 설계 개요

Overview of study design

이 연구는 토론토 대학 연구 윤리 사무소에 의해 승인되었고, 캐나다 토론토에서 수행되었다. 우리는 비판적 성찰, 반사성 및 비판적 교육학의 이론과 첫 번째 저자와 동료의 교재 및 장학금에 기초하여 단일 교수 및 학습 세션을 개발했다(Kinsella et al., 2012; Ng, 2012; Ng et al., 2015a, b; Pelan & Ng, 2015; Halman et al., 2017; Baker et al., 2018; Ng, 2018; 2018; 2018; Et. 2020). 그 효과를 시험하기 위해, 우리는 그림 1과 같이 단순히 즉각적인 지식 습득과 보존을 시험하는 것이 아니라, [후속/미래 경험으로의 학습 전이]를 시험하기 위한 확립된 교육 연구 설계를 채택했다.

The study was approved by and complied with the University of Toronto Office of Research Ethics and took place in Toronto, Canada. We developed a single teaching and learning session based on theories of critical reflection, reflexivity, and critical pedagogy, and on the teaching materials and scholarship of the first author and colleagues (Kinsella et al., 2012; Ng, 2012; Ng et al., 2015a, b; Phelan & Ng, 2015; Halman et al., 2017; Baker et al., 2018, 2020; Ng et al., 2018, 2020). To test its effectiveness, we employed an established education research design meant to test the transfer of learning to subsequent/future experiences, rather than simply test immediate knowledge acquisition and retention, as outlined in Fig. 1.

이 설계는 참가자들이 [비판적 페다고지 학습 경험]에 대한 교육적 노출 후, [새로운 학습 경험에 참여하거나 보는 방법을 가시화]하도록 의도했다. 제어 및 개입 조건의 참가자들은 SDoH에 대한 온라인 모듈을 완성하고, 이어서 비판적으로 반사되는 대화 또는 추가적인 SDoH 토론과 같은 다양한 지침 노출이 뒤따랐다. 그런 다음, 두 조건의 참가자들은 우리의 결과 평가 역할을 하는 두 개의 공통 학습 세션을 경험했다. 하나는 [교육 노출 직후]이고, 다른 하나는 [초기 교육 후 일주일 뒤]이다. 이 두 가지 공통 경험은 관심의 결과를 측정할 수 있게 했다.

This design intended to make visible how participants engage with, or see, a new learning experience following their instructional exposure to the critical pedagogical learning experience. Participants in the control and intervention conditions completed an online module about SDoH, followed by different instructional exposures: either a critically reflective dialogue or further SDoH discussion. Then, participants in both conditions experienced two common learning sessions that served as our outcome assessment, one immediately after the instructional exposure and another one-week after the initial training. These two common experiences enabled measurement of the outcomes of interest.

교재

Teaching materials

본 연구에 사용된 교재는 표 1에 요약되어 있다. 여기에는 SDoH에 대한 [온라인 모듈(통제 및 개입 조건 모두)]과 [후속 SDoH 토론(통제) 및 비판적 반영 대화(개입)]를 위한 가이드가 포함되었다. 온라인 홈케어 커리큘럼과 홈케어 커리큘럼을 따르기 위한 보고 가이드가 결과 측정치를 생성하는 공통 학습 리소스 역할을 했습니다.

The teaching materials used in this study are summarized in Table 1. They included an online module on SDoH (for both control and intervention conditions) and guides for the follow-up SDoH discussion (control) and for the critically reflective dialogue (intervention). An online homecare curriculum and a debriefing guide to follow the homecare curriculum served as the common learning resources that generated the outcome measures.

참가자

Participants

토론토 대학 MD 프로그램의 첫 2년(n = 31), 혼합 학위 배경의 학생들이 있는 4년 학부 사전 교육 서비스 학습 과정(n = 18), 석사 수준의 직업 치료의 첫 해(n = 6), 물리 치료(n = 6) 및 sp에서 전문 간 학생 그룹(n = 75)을 모집했다.e-언어 병리학(n = 10), 치과, 약학, 물리치료 보조 및 방사선 치료 프로그램 학생(n = 4). 우리는 그들이 가질 수 있는 공식적인 보건직 교육 및 임상 실습 노출의 양을 최소화하기 위해 임상 전 및 초학년 학생들을 선택했다.

An interprofessional group of students (n = 75) were recruited from: the first two years of the University of Toronto MD program (n = 31), a fourth-year undergraduate pre-clinical service-learning course with students of mixed degree backgrounds (n = 18), the first year of master’s level occupational therapy (n = 6), physical therapy (n = 6) and speech-language pathology (n = 10), and one student from dentistry, pharmacy, physiotherapy assistant, and radiation therapy programs (n = 4). We chose pre-clinical and early year students to minimize the amount of formal health professions education and clinical practice exposure they would have had.

참가자는 5명씩 16개 그룹에 배정되어 각 그룹별로 다원화된 학생 수를 확보하여 전문 간 학습을 가능하게 하였다. 8개 그룹은 통제 조건에 랜덤하게 할당되었고 8개 그룹은 개입 조건에 랜덤하게 할당되었습니다. 우리는 80명의 참가자를 대상으로 연구를 시작했지만, 5명의 참가자(제어 조건의 2명, 개입 조건의 3명)는 연구 외부 요인(예: 날씨 조건)으로 인해 참여 전에 중단되었다.

Participants were assigned to sixteen groups of five, ensuring a multiprofessional complement of students per group to enable interprofessional learning. Eight groups were randomly assigned to the control condition and eight to the intervention condition. We began the study with 80 participants but five participants—2 from the control condition and 3 from the intervention condition—dropped out prior to participation due to factors external to the study (e.g. weather conditions).

절차들

Procedures

연구 조정자는 학생들에게 동의하고 데이터 수집 세션의 관리 요소를 관리했습니다. 통제 및 개입 참가자 모두 짧은 SDoH 커리큘럼 온라인 모듈을 완료했습니다. 5명의 참가자로 구성된 각 그룹은 컴퓨터 실험실에서 각자의 속도로 이 SDoH 온라인 모듈을 완료했으며, 각 그룹은 개인 정보 보호를 위해 헤드폰을 사용했으며, 방해 요소가 없도록 하기 위해 연구 조정자가 참석했습니다.

A research coordinator consented students and managed administrative elements of the data collection sessions. Both control and intervention participants completed a short SDoH curriculum online module. Each group of five participants completed this SDoH online module in a computer lab, each at their own pace using headphones for privacy, with a research coordinator present to ensure no distractions.

5명으로 구성된 동일한 그룹들에 대해, 학습은 참가자들이 [SDoH 토론(통제)] 또는 [비판적 성찰적 대화(개입)]로 진행됨에 따라 분산되었다. 모든 세션은 작은 학생 라운지에서 진행되었으며, 의자를 원형으로 배치하고, 토론/대화 진행자가 참가자들과 함께 앉았습니다. 이러한 디테일은 교사-학습자 계층 구조를 최소화하고 공개적으로 도전하는 가정에 도움이 되는 학습 환경을 강조하는 비판적 교육학 접근 방식과 일치한다. [SDoH 세션]은 반구조화 촉진 가이드("부록 1")를 사용했다. [비판적 성찰 세션]에만 텔레비전 화면을 노트북에 연결하여 서포트 슬라이드를 보여주었다(부록 2). 참가자들은 이 세션 동안 음식과 음료가 제공되었습니다. 통제와 개입 조건은 모두 1시간 동안 지속되었다. 세션은 음성으로 녹음되었고 나중에 문자로 기록되었다. 진행자들은 둘 다 석사 학위를 가지고 있었고 첫 번째 저자에 의해 세션을 운영하도록 훈련 받았습니다. 개별 촉진 스타일의 교란 변수/요인을 최소화하기 위해 [SDoH 토론 세션]과 [비판적 성찰 대화 세션]의 퍼실리테이터는 데이터 수집의 중간 지점에서 역할을 교환했다. 또한 잠재적인 영향을 설명하기 위해 퍼실리테이터를 분석에 포함시켰습니다.

In their same groups of five, learning then diverged as participants proceeded to either a SDoH discussion (control) or critically reflective dialogue session (intervention). All sessions were completed in a small student lounge, with chairs set up in a circle, with the discussion/dialogue facilitator seated along with participants. These details align with a critical pedagogy approach in which the teacher-learner hierarchy is minimized and a learning climate conducive to openly challenging assumptions is emphasized. The SDoH session used a semi-structured facilitation guide (“Appendix 1”). A television screen was connected to a laptop to project supporting slides for the critical reflection session only (“Appendix 2”). Participants were provided with food and beverage during these sessions. Both the control and intervention conditions were one-hour in duration. Sessions were audio-recorded and later transcribed verbatim. The facilitators both held master’s degrees and were trained to run their sessions by the first author. To minimize the confounding variable/factor of individual facilitation styles, the facilitators for the SDoH discussion and critically reflective dialogue session switched roles at the halfway point of data collection. We also included facilitator as a factor in the analysis to account for any potential effects.

SDoH 토론 또는 비판적으로 반성하는 대화를 마친 후, 참가자들은 작은 회의실에서 같은 그룹 내에서 다시 모이기 전에 10분간의 짧은 휴식 시간을 가졌다. 이 설정에는 참가자와 진행자를 위한 테이블과 학습 리소스인 CACE 홈케어 커리큘럼을 표시하는 텔레비전 화면이 포함되었습니다. 세 번째 진행자가 홈케어 커리큘럼과 결과를 운영했습니다. 우리의 목표는 참가자들이 홈케어에 대해 배웠는지 또는 SDoH를 홈케어 환경에 적용했는지 여부를 결정하는 것이 아니었다. 대신, 우리의 목표는 홈케어 커리큘럼에 이어진 디브리핑을, (SDoH 토론 참여자에 비해) [비판적 성찰 대화 세션이 참가자]들이 커리큘럼과 디브리핑 중에 [어떤 주제에 대해 이야기했는지]와 [이 때 그들이 어떻게 이야기했는지(비판적 성찰적 방식인지 또는 그렇지 않은지)]를 밝혀내기 위해 이용했다. 참가자들은 환자 사례 모듈에 직접 관여하는 것처럼 행동하도록 지시 받았습니다. 각 그룹은 진행자의 안내에 따라 커리큘럼에서 "아미타"(치매 중시) 또는 "안네"(델리륨 중시)를 35분짜리 모듈로 완성했다. 그 세션은 음성녹음되고 문자 그대로 녹음되었다.

After completing the SDoH discussion or critically reflective dialogue sessions, participants were given a brief 10-min break before reconvening within the same groups in a small conference room. The setup included a table for participants and facilitator, and television screen to display the learning resource, the CACE Homecare Curriculum (http://www.capelearning.ca). A third facilitator ran the homecare curriculum and debriefs. Our aim was not to determine whether the participants learned about homecare or applied SDoH to the homecare context. Instead, we used the homecare curriculum followed by a debrief to uncover whether the critically reflective dialogue session, relative to the SDoH discussion, influenced what topics participants talked about during the curriculum and debrief, as well as how they talked during these experiences (in a critically reflective manner, or not). Participants were instructed to act as though they were directly involved in the patient case module. Each group completed one 35-min module from the curriculum—either “Amrita” (dementia-focused) or “Anne” (delirium-focused)—with the facilitator’s guidance. The sessions were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

그런 다음 진행자는 홈케어 커리큘럼을 완료하는 즉시, 그룹 내에서 참가자들과 함께 30분 동안 디브리핑을 가이드했다. 촉진자는 시뮬레이션에 관한 우수성 증진 및 성찰적 학습(PEARLS)에서 얻어진 디브리핑 스크립트를 사용하도록 교육받았다(「부록 3」 참조). 이 보고에서 참가자들은 홈케어 커리큘럼에 대한 경험, 고령자의 상황과 필요성에 대한 생각, 학습한 주요 교훈에 대해 논의하였다. 그 보고 내용은 음성으로 녹음되어 그대로 녹음되었다. 홈케어/브리프 진행자 또한 석사 학위를 가지고 있었고, 첫 번째 저자에 의해 교육을 받았고, 각 그룹의 조건 할당에 눈이 멀었다.

The facilitator then guided a 30-min debriefing with participants, within their groups, immediately after completing the homecare curriculum. The facilitator was trained to use the Promoting Excellence and Reflective Learning in Simulation (PEARLS)-informed (Eppich & Cheng, 2015) debriefing script (see "Appendix 3"). The debrief prompted participants to discuss their experience of the homecare curriculum, thoughts on the older adults’ situations and needs, and key lessons learned. The debriefing was audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. The homecare/debrief facilitator also held a master’s degree, was trained by the first author, and remained blinded to each group’s condition assignment.

1주일 후, 참가자들은 그룹별로 후속 홈케어 커리큘럼 모듈을 완료하고, 이전 세션에서 확인된 효과가 지속되거나 변경되었는지 확인하기 위한 보고를 완료하도록 했다. 모든 참가자가 다른 환자 사례 모듈(암리타 모듈을 받은 경우 이제 앤을 받았고, 그 반대도 마찬가지)을 완료한 후 유사한 구조화된 결과 보고(부록 3")를 작성했다. 세션과 브리핑은 녹음되고 녹음되었다.

One week later, participants were brought back in their groups to complete the follow-up homecare curriculum module plus debrief to determine if any effects identified in the previous session persisted or changed. All participants completed another patient case module (if they received the Amrita module, they now received Anne, and vice versa) followed by a similarly structured debrief (“Appendix 3”). The sessions and debriefs were audio-recorded and transcribed.

코딩

Coding

통제(SDoH 토론) 및 개입(비판적 반영 대화) 세션에서 5명의 전문가 간 학습자의 각 그룹 및 가정 관리 커리큘럼 세션과 교육 후 즉시 디브리핑에 대한 분석이 수행되었다.

Analysis was performed on each group of five interprofessional learners’ transcripts from the control (SDoH discussion) and intervention (critically reflective dialogue) sessions, as well as the homecare curriculum sessions and debriefs immediately post-instruction and at follow-up.

코딩 전, [의미 단위]를 생성하여, 이후에 어떤 코드를 어떻게 적용했는지와 두 코더가 동일한 텍스트 세그먼트를 코딩했는지에 대한 텍스트 양과 유형의 일관성을 보장하였다. [의미 단위]는 다음과 같이 생성되었습니다. 각 필사본 내에서, [참가자에 의한 모든 고유한 발화(유일한 발화의 경계가 화자의 변화에 의해 결정됨)]는 그것이 특정 배제 기준(퍼실리테이터의 발언, 중립적 긍정)을 충족하지 않는 한 의미 단위로 라벨링되었다. 내용에 대한 추가 설명이 없는 모듈(예: "이 모듈은 재미있다", 참가자의 프로그램/연도에 대한 질문에 대한 응답 또는 명확한 질문(진행자가 질문을 하고 참가자가 설명을 요구하며 아무런 의미도 추가하지 않은 진술) 모든 의미 단위는 적어도 하나의 what code와 하나의 how code로 코딩될 준비가 되었다.

Before coding, meaning units were created, to ensure consistency in the amount and type of text to which what and how codes were subsequently applied, and that our two coders coded the same segments of text. Meaning units were created as follows. Within each transcript, every unique utterance by a participant (the boundaries of a unique utterance were determined by change in speaker) was labelled as a meaning unit, unless it met the exclusion criteria of: facilitator comments, neutral affirmations (mhmm, etc.), responses to homecare module quiz questions, responses about the quality of the module with no additional comment about content (e.g. “This module is fun”), responses to questions about participants’ program/year, or clarifying questions (facilitator asks a question and participant asks for clarification, and statements that added no meaning). Every meaning unit was then ready to be coded with at least one what code and one how code.

[what 코딩 프레임워크]를 만들기 위해 두 명의 연구원 VB(공동 저자)와 첫 번째 저자는 처음에 8개의 설명 코드와 "no code" 코드와 각 코드에 대한 관련 설명으로 합의된 집합에 도달하기 위해 전사들을 유도적으로 코딩했다. 그들은 더 이상의 변경 없이, 의미 단위의 주제에 이름을 붙이기 위해 엄격하게 적용될 수 있을 때까지 반복적으로 코드를 정의했다. 코딩 프로세스를 지원하기 위해 사용된 하위 코드가 있었지만, 통계 분석에는 상위 레벨 코드만 사용되었습니다.

To create the what coding framework, two researchers VB (co-author) and the first author, initially coded transcripts inductively to arrive at an agreed upon set of eight descriptive codes plus a “no code” code and associated descriptions for each code. They iteratively defined codes until they could be applied strictly to name the topic of meaning units, without further changes. While there were sub-codes used to assist the coding process, only the higher-level codes were used in our statistical analyses.

[how 코딩 프레임워크]의 경우, 다음 정의를 사용하여 데이터를 [비판적으로 성찰하거나 비판적으로 성찰하지 않는 방식]으로 코딩했다.

For the how coding framework, the following definition was used to code data as critically reflective, or not.

[비판적 성찰]로 코드화된 의미 단위는 다음과 같다.

- 지배적인 담론을 넘어서는 경우(예: 장애의 의학적 모델과 반대되는 사회적 모델에 대해 논의)

- 개인 또는 사회적 가정/문제에 의문을 제기한다.(예: 장애아를 위해 학교가 하는 일에 대한 권한이 있다는 임상의의 믿음)

- 더 광범위한 시스템과 그 위치에 대한 인식을 보여준다(예: 개인 지원 종사자가 규제 보건 전문가와 관련된 자원과 교육 기회가 부족할 수 있음을 인지한다).

- 구조에 질문 하거나 도전한다 (예: 홈케어에 대한 현재 자금조달 접근방식이 가능한 관행을 제한하는지 여부 질문) 및

- 유해한 실천에 저항한다(예: 관련 사항을 알아차린 경우 크게 말함). (Ng et al., 2019a, b)

[비판적 성찰이 아닌 것]으로 코드화된 의미 단위는 다음과 같다.

- 중립적인 설명,

- 좁은 시야(예: 낙인찍는 언어를 통해 설명됨),

- 절차 또는 단계를 무조건 따르거나 묘사함

- 환자/간병인/보건 종사자를 비난하거나 비호하는 행위

Meaning units coded as critically reflective were statements that:

- move beyond a dominant discourse (e.g. discuss a social model as opposed to medical model of disability),

- question individual or societal assumptions/beliefs (e.g. a clinician’s belief that they have authority over what a school does for a child with disability),

- demonstrate awareness of the broader system and how one is situated (e.g. recognize that personal support workers may lack resources and training opportunities relative to a regulated health professionals),

- question or challenge structures (e.g. question whether current funding approaches for homecare are limiting possible practices), and

- resist harmful practices (e.g. speak up if noticing something concerning) (Ng et al., 2019a, b).

Meaning units coded as not critically reflective were:

- neutral descriptions,

- narrow views (e.g. illustrated through stigmatizing language),

- rote following/description of procedures or steps,

- blaming or patronizing the patient/caregiver/health worker.

두 개의 블라인드 코드(VB, 공동 작성자 및 LN, 인정됨)는 이러한 코드를 스크립트에 적용하도록 훈련되었다. 우리는 코더가 코드를 일관되게 적용하도록 보장하기 위해 8개의 필사본에 대한 평가자 간 합의를 계산했다. what 코드의 경우 원시raw 평가자 합의가 95.9%, how 코드의 경우 82.1%였다. 우리는 이것이 두 개의 코더가 독립적으로 진행하기에 충분하다고 판단했고, 후속 스크립트는 각각 하나의 코더로만 코딩되었다.

Two blinded coders (VB, co-author and LN, acknowledged) were trained to apply these codes to the transcripts. We calculated the inter-rater agreement on eight transcripts to ensure the coders applied the codes consistently. For what codes, raw rater agreement was 95.9%; for how codes it was 82.1%. We determined that this was sufficient to allow the two coders to proceed independently, and subsequent transcripts were only coded by one coder each.

통계분석

Statistical analysis

우리는 이 연구의 목표에 따라 분석을 수행했다. 즉, 비판적 성찰을 위한 가르침이 미래의 학습 경험 동안 학생들이 말하는 것과 그것에 대해 어떻게 말하는지에 영향을 미쳤는지 조사하기 위해서였다. 따라서, 우리는 두 개의 [회귀 모델]을 구성했는데, 하나는 각 의미 단위에서 [what 코드의 존재를 모델링]하는 것이고, 하나는 각 의미 단위에서 [how 코드의 존재를 모델링]하는 것이다.

We conducted our analysis in accordance with the aims of this study: to investigate whether teaching for critical reflection influenced what students talked about during a future learning experience and how they talked about it. Thus, we constructed two regression models, one to model the presence of a what code in each meaning unit and one to model the presence of a how code in each meaning unit.

패러다임적으로 정렬된 측정과 분석이 이 연구에 결정적이었다. 우리는 베이지안 프레임워크에서 모델을 구성, 테스트 및 선택하였다. 다음은 우리의 정당성입니다. [빈도주의 추론]은 효과가 없을 경우 관측된 데이터의 집합이 얼마나 확률적일지에 대한 질문을 다룬다. 우리는, 본질적으로 [베이지안 질문]인, 우리의 개입의 결과로 코드가 의미 단위에 존재할 가능성이 얼마나 높은지에 대한 질문을 다루는 데 특히 관심이 있었다. [베이지안 추론]은 불확실성을 직접 정량화한다. 모수 추정치의 확률, 차이, 그리고 그러한 추정치의 불확실성에 대한 추정치를 제공하고, 따라서 도출된 결론을 제공한다. [베이지안 추론]은 수집된 데이터를 '고정fixed'으로 취급하고 [모델과 매개 변수]는 관찰된('고정') 데이터를 설명하려는 '변화' 시도로서 취급하는 동시에 모델과 매개 변수 불확실성을 정량화한다. 의학 교육의 일부 사람들은 사전 지식에 의해 정보를 얻은 분석을 통해 데이터의 이야기를 표현하기 위한 불완전한 최상의 시도로 모델을 포지셔닝하는 방법에 대해 베이지안 통계를 구성주의 기반 이론과 비교했다(Young et al., 2020). 베이지안 통계에 대한 세부 정보, 특히 사후 분포에 대한 세부 정보를 보려면 McElreath(2020)를 권장한다. 모든 모델은 R 통계 컴퓨팅 소프트웨어(R Core Team, 2019)의 rstan(Stan Development Team, 2020) 및 brms(Burkner, 2017, 2018) 패키지를 통해 Stan 프로그래밍 언어(Carpenter et al., 2017)를 사용하여 구성되었다.

Paradigmatically aligned measurement and analyses were crucial to this study. We constructed, tested, and selected our models under a Bayesian framework. The following are our justifications. Frequentist inference addresses the question of how probable a set of observed data would be if there were no effect. We were specifically interested in addressing the question of how likely a code would be present in a meaning unit as a result of our intervention, which is an inherently Bayesian question. Bayesian inference directly quantifies uncertainty. It provides estimates of the probability of parameter estimates, their differences, and the uncertainty in those estimates and thus any conclusions drawn. Bayesian inference treats the gathered data as ‘fixed’ and models and their parameters as ‘varying’ attempts to explain the observed (‘fixed’) data, while quantifying the model and parameter uncertainty. Some in medical education have compared Bayesian statistics to constructivist grounded theory for the way in which it positions models as imperfect best attempts at representing the story of the data, with analyses informed by prior knowledge (Young et al., 2020). For details on Bayesian statistics, particularly details on the posterior distribution, we recommend McElreath (2020). All models were constructed using the Stan programming language (Carpenter et al., 2017) through the rstan (Stan Development Team, 2020) and brms (Burkner, 2017, 2018) packages in R statistical computing software (R Core Team, 2019).

우리는 [계층적 다항식 회귀 모델]을 사용하여 what 코드에 대한 예측 확률을 모델링했다. 의미 단위는 우리의 귀납적 코딩 프레임워크에 기초하여 9개의 코드 중 하나 또는 전부를 포함하는 것으로 분류되었다. 사전 지식, CanMED 역할, 보호자, 전문적 전문 지식, 환자, 환자-심리 사회, 실천에 대한 권고 사항, 건강의 사회적 결정 요소 또는 (8개의 주요 코드 중 어느 것과도 관련성이 결여되어 있어서) 코드화 가능한 집합에 남아 있는 의미 단위에 대한 코드가 없다. 이러한 코드의 정의는 부록 4의 코드북에 포함되어 있다. 이 모델의 인구 수준 효과에는 조건(제어 또는 개입), 세션(초기 지침, 초기 홈케어, 초기 보고, 후속 홈케어, 후속 홈케어, 후속 보고), 촉진자(조정자 1 또는 조정자 2)가 포함되었다. 또한 code*condition, code*session, condition*session 및 Facilitator*session에 대한 상호 작용 항도 포함했습니다. SDoH 토론 그룹(대조군 참여자용) 또는 비판적 반영 대화 그룹(개입 참여자용)은 각 5인 그룹 내 의미 단위의 군집화를 조정하기 위한 다양한 효과로 입력되었다. [통제 조건의 교육 세션에서 진행자 1이 한 것]이 "코드 없음"이 reference 케이스로 사용되었습니다. 우리는 회귀 계수에 대해 αi ~ N(0,1), βi ~ N(0,1), βi ~ 코시(0,e1)라는 다소 유익한 이전 사항을 사용했다.

We modelled predictive probabilities of what codes with a hierarchical multinomial regression model. Meaning units were categorized as containing any or all of nine codes, based on our inductive coding framework: Building on prior knowledge, CanMEDS roles, caregiver, professional expertise, patient, patient-psychosocial, recommendations for practice, social determinants of health, or no code for meaning units that remained in the codable set despite lacking relevance to any of the eight main codes. The definitions of these codes are included in the codebook within "Appendix 4". Population-level effects in this model included condition (control or intervention), session (initial instruction, initial homecare, initial debrief, follow-up homecare, follow-up debrief), and facilitator (Facilitator 1 or Facilitator 2). We also included interaction terms for: code*condition, code*session, condition*session, and facilitator*session. SDoH discussion group (for control participants) or critically reflective dialogue group (for intervention participants) was entered as a varying effect to adjust for clustering of meaning units within each five-member group. The presence of “no code,” at the Instruction Session, in the Control Condition, with Facilitator One was used as the reference case. We used mildly informative priors on the regression coefficients: αi ~ N(0,1), βi ~ N(0,1), σi ~ cauchy(0, e1).

우리는 파레토 평활화 중요도 샘플링 Leave-one-out 교차 검증(PSIS-LOO)(Vetari et al., 2016)을 사용하여 전체(계층적 모델)를 "빈"(절단 전용) 모델과 (같은 모집단 수준 효과를 가진) 비계층적 모델의 적합성을 평가하고 비교했다. 우리는 우리의 전체 모델이 (i) PSIS-LOO 예상 로그 예측 밀도(ELPD)가 1599.8(표준 오차 42.2)이고 (ii) ELPD가 93.9(표준 오차 13.3)인 비계층적 모델 모두에서 데이터에 상당히 더 적합하다는 것을 발견했다.

We used Pareto smoothed importance sampling leave-one-out cross-validation (PSIS-LOO) (Vehtari et al., 2016) to evaluate and compare the fit of our full (hierarchical model) to an “empty” (intercept-only) model, and a non-hierarchical model (with the same population-level effects) to the data. We found our full model to be a significantly better fit to the data relative to both

- (i) the intercept-only model, with a favorable difference in PSIS-LOO expected log predictive density (ELPD) of 1599.8 (with a standard error of 42.2), and

- (ii) the non-hierarchical model with an ELPD of 93.9 (with a standard error of 13.3).

[how 코드의 예측 확률]을 모델링하기 위해 계층적 이진 로지스틱 회귀 모델을 구성했다. 의미 단위는 이항적으로 임계 반사의 유무로 분류되었다. 이 모델의 모집단 수준 효과에는 조건(제어 또는 개입), 세션(지시, 초기 홈케어, 초기 홈케어, 후속 홈케어, 후속 홈케어, 후속 브리핑), 촉진자(조정자 1 또는 조정자 2)가 포함되었다. 또한 조건*세션 및 촉진자*세션에 대한 상호 작용 항도 포함했습니다. 어떤 모델과 마찬가지로 SDoH 토론 그룹(대조군 참여자용) 또는 비판적 반영 대화 그룹(개입 참여자용)은 5인 그룹 내 의미 단위의 클러스터링을 조정하기 위한 다양한 효과로 입력되었다. 제어 조건의 진행자 1과 함께 지침 세션이 참조 사례로 사용되었습니다. 우리는 회귀 계수에 대해 αi ~ N(0,1), βi ~ N(0,1), βi ~ 코시(0,e1)라는 다소 유익한 이전 사항을 사용했다.

To model the predictive probabilities of the how codes, we constructed a hierarchical binary logistic regression model. Meaning units were categorized binomially as either present or absent of critical reflection. Population-level effects in this model included condition (control or intervention), session (instruction, initial homecare, initial debrief, follow-up homecare, follow-up debrief), and facilitator (Facilitator 1 or Facilitator 2). We also included interaction terms for: condition*session and facilitator*session. As in the what model, SDoH discussion group (for control participants) or critically reflective dialogue group (for intervention participants) was entered as a varying effect to adjust for clustering of meaning units within five-member groups. The Instruction Session, in the Control condition, with Facilitator One, was used as the reference case. We used mildly informative priors on the regression coefficients: αi ~ N(0,1), βi ~ N(0,1), σi ~ cauchy(0, e1).

What 모델로 수행했듯이, PSIS-LOO를 사용하여 데이터에 대한 전체(계층적 모델)와 "빈"(절편 전용) 모델 및 (같은 모집단 수준 효과를 가진) 비계층적 모델의 적합성을 평가하고 비교했다. 우리는 우리의 전체 모델이

- (i) 172.6(표준 오차 15.5)의 PSIS-LOO ELPD의 유리한 차이를 가진 절편 전용 모델과

- (ii) ELPD 18.0(표준 오차 6.1)의 비계층적 모델 모두에 비해 데이터에 상당히 더 적합하다는 것을 발견했다.

As conducted with our what model, we used PSIS-LOO to evaluate and compare the fit of our full (hierarchical model) to an “empty” (intercept-only) model, and a non-hierarchical model (with the same population-level effects) to the data. We found our full model to be a significantly better fit to the data relative to both

- (i) the intercept-only model with a favorable difference in PSIS-LOO ELPD of 172.6 (with a standard error of 15.5), and

- (ii) the nonhierarchical model with an ELPD of 18.0 (with a standard error of 6.1).

개입의 효과를 평가하기 위해, 우리는 각 세션 유형에 존재하는 코드의 사후 예측 확률 차이의 분포를 계산한 다음, 이러한 예측 차이 분포의 89% 최고 밀도 신뢰 구간이 0을 포함하는지 여부, 즉 0을 표시로 삼았다. 조건 간에 차이가 없습니다.

- Credible interval 은 관심 모수의 지정된 비율(즉, 사후 예측 확률의 차이)을 포함하는 후방 분포의 범위로 다음과 같이 말할 수 있다.: "관측된 데이터를 고려할 때 효과가 이 범위에 포함될 확률은 89%입니다."

- 이와 반대로, 빈도주의 Confidence interval은 덜 직관적이며, 다음과 같이 해석될 수 있다. "이러한 종류의 데이터에서 신뢰 구간을 계산할 때 효과가 이 범위에 속할 확률은 89%입니다."

To evaluate the effect of our intervention, we calculated the distribution of differences in posterior predicted probabilities of codes being present in each Session Type and then determined if the 89% highest density credible intervals of these predicted difference distributions included zero where the inclusion of zero was taken as an indication of no difference between Conditions.

- The credible interval is the range of the posterior distribution containing the specified proportion (i.e. 89%) of the parameters of interest (i.e., the differences in posterior predicted probabilities) such that one could say: “given the observed data, the effect has an 89% chance of falling in this range”

- as opposed to a less intuitive frequentist confidence interval, which would be interpretable as “there is an 89% probability that when computing a confidence interval from data of this sort, the effect falls within this range” (Makowski et al., 2019).

89% 신뢰 구간은 95% 구간과 비교하여 계산 안정성에 대해 다수의 베이지안 통계 사상가들에 의해 권장된다(Kruschke, 2014). 90% 또한 이러한 이유로 제안되었지만, McElreath(2014, 2020)는 89%가 "이미 불안정한 95% 임계치를 초과하지 않는 가장 높은 소수"이기 때문에 89%가 잠재적으로 더 의미가 있다고 제안했다.(Makowski 외, 2019a, b). 베이지안 분석은 관측된 데이터에서 직접 계산된 모수 값(예: 회귀 계수)의 확률 분포를 산출하기 때문에 p 값 또는 관련 신뢰 구간을 계산할 필요가 없다. 오히려 불확실성은 모수의 계산된 확률 분포에서 직접 정량화된다(Kruschke & Liddell, 2018).

The 89% credible interval is recommended by a number of leading Bayesian statistics thinkers for its computational stability relative to 95% intervals (Kruschke, 2014). While 90% was also proposed for this same reason, McElreath (2014, 2020) suggested that 89% makes potentially more sense because 89 is “the highest prime number that does not exceed the already unstable 95% threshold.”(Makowski et al., 2019a, b). Because Bayesian analyses yield probability distributions of parameter values (e.g., regression coefficients) calculated directly from observed data, they do not require calculation of p values or their associated confidence intervals. Rather, uncertainty is quantified directly from the calculated probability distributions of parameters (Kruschke & Liddell, 2018).

결과.

Results

학습자가 이야기한 내용

What learners talked about

그림 2에 제시된 what 코드에 대한 최종 계층 모델의 요약과 "Empty"(절편 전용) 모델, 비계층 모델 및 "부록 5"에 포함된 코드에 대한 최종 계층 모델의 회귀 요약 표.

A summary of our final hierarchical model for what codes is presented in Fig. 2 and a regression summary table of our “empty” (intercept-only) model, a non-hierarchical model, and our final hierarchical model for what codes is included in "Appendix 5".

SDoH 교육 세션(0.17[0.11, 0.23])보다 비판적 성찰 대화 세션에서 파생된 단위를 위해 "CanMeds"가 코딩될 확률이 높고, SDoH 교육 세션에서 "사전 지식을 기반으로 구축" 및 "SDoH"가 코딩될 확률(0,033)이 더 높다.비판적 성찰 대화 지침 세션(각각 0.1[0.06, 0.15] 및 0.07[0.03, 0.11])보다 0.35[0.24, 0.46]가 더 높다. 그렇지 않으면, 코드가 의미 단위에 적용될 확률은 사실상 우리의 what codes에 대한 조건들 사이에 동일했다.

We see a higher probability of “CanMeds” being coded for meaning units deriving from the critically reflective dialogue instruction sessions (0.64 [0.57, 0.71]) than the SDoH instruction sessions (0.17 [0.11, 0.23]), and a higher probability of “building on prior knowledge” and “SDoH” being coded during the SDoH instruction sessions (0.33 [0.24, 0.44] and 0.35 [0.24, 0.46], respectively) than in the critically reflective dialogue instruction sessions (0.1 [0.06, 0.15] and 0.07 [0.03, 0.11], respectively). Otherwise, the probabilities of codes being applied to a meaning unit were virtually equivalent between conditions for our what codes.

그림 3은 SDoH와 비판적 성찰 대화 그룹 사이의 각 세션 유형의 각 코드에 대한 사후 예측 차이 분포를 보여준다. 점은 평균 확률 차이를 나타내며, 막대는 평균을 둘러싼 89%의 가장 높은 밀도 신뢰 구간을 나타내며, 음영 영역은 사후 확률 차이의 분포를 나타내며, 점선은 0을 표시합니다.

Figure 3 depicts the posterior predictive difference distributions for each code in each Session Type between SDoH and critically reflective dialogue groups. Points represent mean probability differences; bars represent the 89% highest density credible interval surrounding the means; shaded regions indicate the distribution of posterior probability differences, and the dashed lined marks zero.

그림 3에 나타낸 것과 같이, "사전 지식을 기반으로 구축"과 "SDoH"가 코딩될 확률은 비판적으로 반사되는 대화 세션보다 SDoH 명령 세션에서 더 높았다(각각의 차이 0.24[0.31, 0.16]와 0.26[0.33, 0.2]. "CanMeds"가 코딩될 확률은 SDoH 명령 세션보다 비판적 성찰 대화 세션에서 더 높았다(차이 0.49[0.43, 0.55].

As depicted in Fig. 3, the probability of “building on prior knowledge” and “SDoH” being coded were more likely for the SDoH instruction sessions than in the critically reflective dialogue instruction sessions (differences 0.24 [0.31, 0.16] and 0.26 [0.33, 0.2], respectively). The probability of “CanMeds” being coded was more likely in the critically reflective dialogue instruction sessions than in the SDoH instruction sessions (difference of 0.49 [0.43, 0.55]).

전반적으로, 이러한 결과는 결과 평가로 사용되는 공통 학습 조건(즉, 초기 및 후속 조치 모두) 동안 개입 대 제어 조건에서 파생되는 의미 단위에서 어떤 what 코드도 더 많거나 더 적을 가능성이 없다는 것을 보여준다.

Overall, these results show that during the common learning conditions (i.e. both initial and follow-up) serving as our outcome assessment, no what codes were more, or less, probable among meaning units deriving from the intervention versus control conditions.

학습자가 말하는 방식

How learners talked

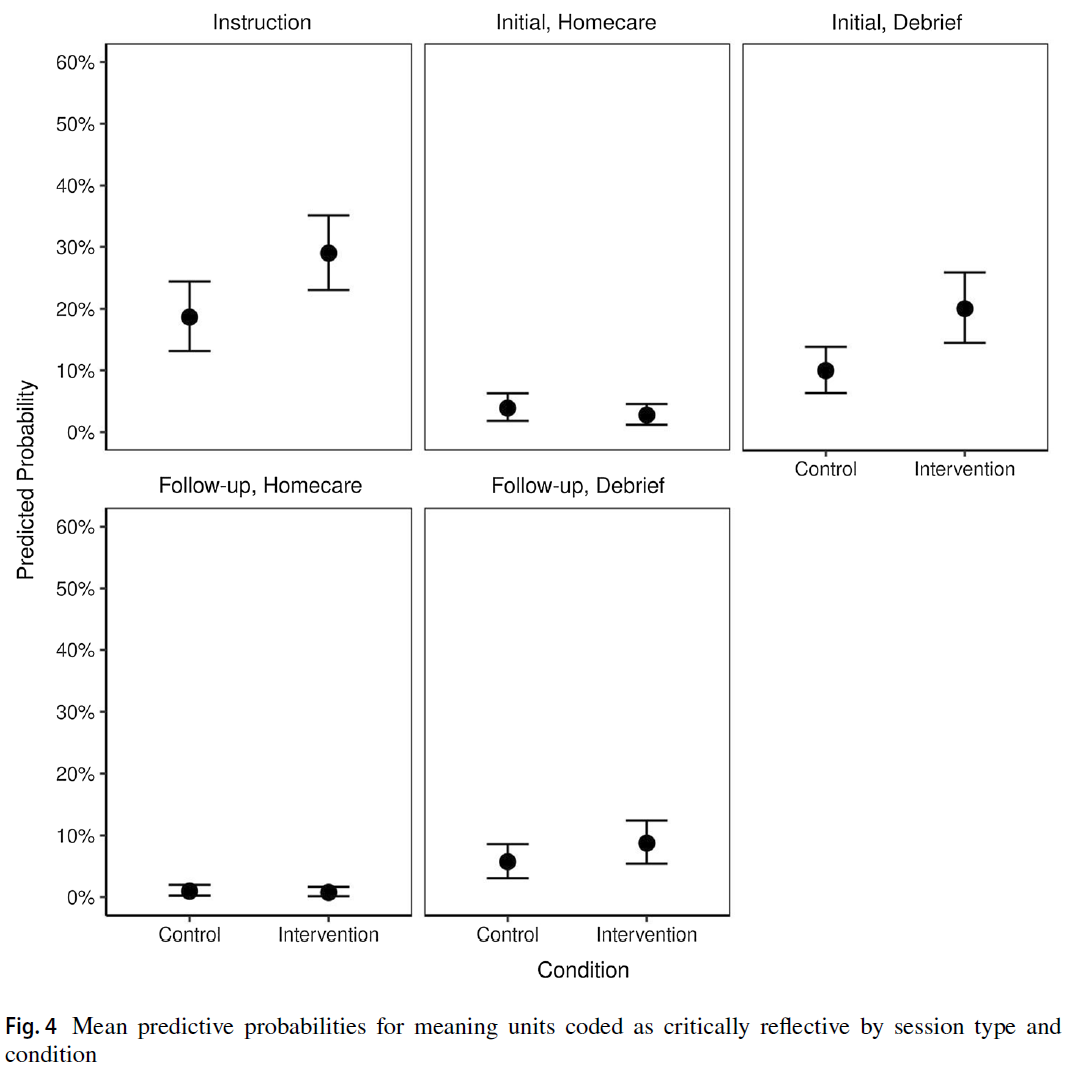

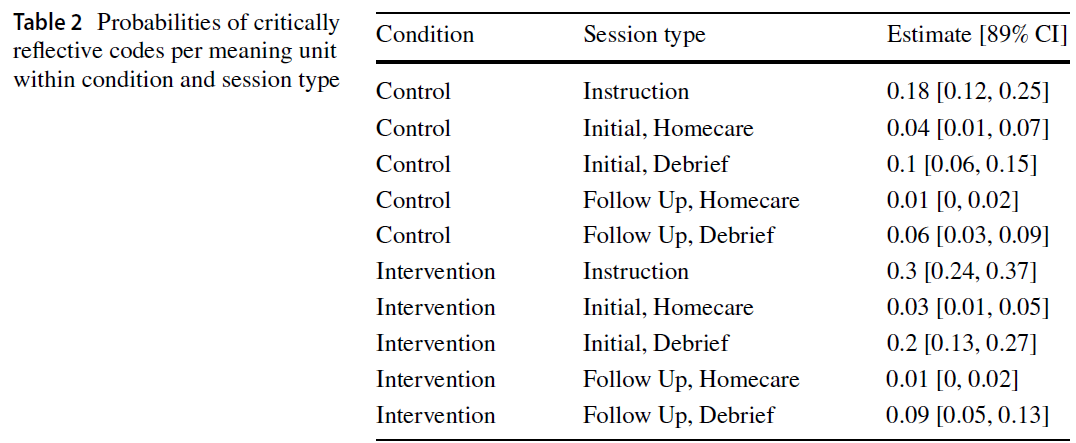

참가자들이 [어떻게how 말하는지]에 대한 최종 모델의 요약은 그림 4에 제시되어 있다. "빈"(절편 전용) 모델, 비계층적 모델 및 코드가 "부록 5"에 포함되는 방법에 대한 최종 계층적 모델의 회귀 요약 표입니다.A summary of the final model for how participants spoke (critically reflective or not) is presented in Fig. 4. The regression summary table of our “empty” (intercept-only) model, a non-hierarchical model, and our final hierarchical model for how codes is included in "Appendix 5".

모든 세션(지시, 초기 및 후속 홈케어 및 보고)에서 의미 단위가 "비판적 성찰"으로 코딩될 확률은 모든 세션에서 낮았지만, 초기 디브리핑에서 통제와 개입 조건 사이에 의미 단위가 "비판적 성찰"으로 코딩될 확률은 10% 차이가 있었다(표 2).

Overall, there was a 10% difference between the probability of a meaning unit being coded as “critically reflective” between control and intervention conditions at initial debrief, though the probability of any meaning unit being coded as such was low across all sessions (instruction, initial and followup homecare and debrief) (Table 2).

그림 5는 SDoH와 비판적 반사 대화 그룹 사이의 각 세션 유형에서 비판적으로 반사되는 것으로 코딩된 의미 단위에 대한 사후 예측 차이 분포를 나타낸다. 점은 평균 확률 차이를 나타내며, 막대는 평균을 둘러싼 89%의 가장 높은 밀도 신뢰 구간을 나타내며, 음영 영역은 사후 확률 차이의 분포를 나타내며, 점선은 0을 표시합니다.

Figure 5 depicts the posterior predictive difference distributions for meaning units being coded as critically reflective in each Session Type between SDoH and critically reflective dialogue groups. Points represent mean probability differences; bars represent the 89% highest density credible interval surrounding the means; shaded regions indicate the distribution of posterior probability differences, and the dashed lined marks zero.

의미 단위가 "비판적 성찰적"으로 코딩될 확률은 개입 조건의 지침(0.112[0.05, 0.17])과 초기 디브리핑(0.096[0.04, 0.15])에서 더 높았다.

The probability of a meaning unit being coded as “critically reflective” was higher for the intervention condition at instruction (0.112 [0.05, 0.17]) and initial debrief (0.096 [0.04, 0.15]).

논의

Discussion

우리는 [비판적 성찰적 대화 세션]이 학습자가 말하는 내용과 말하는 방식에 영향을 미치는지 물었다. 실험적으로 이 질문에 답하는 것은 의료의 사회적 측면을 위한 교육에 관한 대화에 중요하다.

- 예상대로, 교육 조건은 서로 다른 내용에 초점을 맞췄지만, 홈케어 및 보고 결과 측정 중에 특정 내용이 논의될 확률은 개입 대 통제 조건에 노출된 참가자 간에 유사했다.

- 대조적으로, 그리고 가설대로, 우리는 참가자들이 그들의 후속 학습 경험에서 비판적으로 더 비판적으로 반성하는 방식으로 말하는 경향이 있는 비판적인 반사 대화 세션에 노출된 참가자들의 말투에 영향을 관찰했다.

We asked whether a critically reflective dialogue session would impact what learners talked about and how they talked. Answering this question, experimentally, is important to conversations about teaching for the social aspects of healthcare.

- As anticipated, while the instructional conditions focused on different content, the probability of specific content being discussed during the homecare and debrief outcome measurement was similar between participants exposed to the intervention versus control condition.

- By contrast, and as hypothesized, we did observe an impact on how participants spoke, with those exposed to the critically reflective dialogue sessions tending to speak in more critically reflective ways in their subsequent learning experience.

이러한 영향은 학습자가 미래의 학습 활동을 위해 새로운 맥락/내용 영역으로 이동했음(소아적 맥락에서 노인적 맥락으로)에도 불구하고 나타났다. 첫 번째 공통 학습 세션 동안 이러한 영향은 시간이 지남에 따라 잘 지속되지 않았는데, 1주간의 후속 세션에서 확률의 차이가 현저하게 감소했기 때문이다. 전반적으로, 이 연구는 조건 간의 관측된 확률 차이는 작았지만, 학습자의 새로운 분석 방법과 패러다임적으로 일치하는 분석 방법을 활용하는 방법에 대한 비판적 반성을 위한 교육의 영향을 입증할 수 있음을 보여주었다.

This impact was seen even though learners moved to a novel context/content area for the future learning activity (from a pediatric context to an older adult context). This impact during the initial common learning session did not persist well over time, as the difference in probability was markedly reduced at the one-week follow up session. Overall, this study showed that we could demonstrate the impact of teaching for critical reflection on learners’ subsequent ways of seeing, utilizing novel and paradigmatically congruent analysis methods; albeit the observed probability differences between conditions were small.

결과 및 결과 해석

Interpreting the results and outcomes

학습자들이 '무엇'을 이야기했는지 보면, [통제 교육 세션]이 SDoH에 대한 더 많은 이야기를 하고 [개입 교육 세션]에서 CanMED에 대한 더 많은 이야기를 하게 된 것이 일리가 있다. SDoH 세션은 학습자들에게 SDoH에 대해 성찰할 것을 특별히 요청했습니다. 비판적 성찰 세션은 명시적으로 CanMED에 초점을 맞추지 않았다. 그러나 비판적 성찰은 이러한 역할에 초점을 맞춘다. [비판적 성찰 세션]에서 대화를 촉발하는 데 사용된 사례들은 협업, 옹호 및 전문직업성에 대한 접근 방식에 대한 숙고(contemplation)를 불러일으킬 수 있는 문제에 초점을 맞췄다. 그러나, 초기 교육을 넘어서, 학습자가 미래의 홈케어 커리큘럼 또는 결과 발표 중에 이야기한 '무엇what'에서 조건의 영향은 없었다. 이 발견은 우리가 사용한 [대화형 방식으로 비판적 성찰을 가르치는 것]이 학습자가 학습에서 전진할 때 주제 내용 초점을 추가하거나 저하시키지 않는다는 것을 시사한다.

In terms of what learners talked about, it makes sense that the control instruction session led to more talk about SDoH and the intervention instruction session to more talk about CanMEDS. The SDoH session specifically asked learners to reflect on SDoH. The critical reflection sessions did not explicitly focus on CanMEDS; however, critical reflection affords a focus on these roles. The cases used to spark dialogue during the critical reflection sessions focused on issues that would invoke contemplation about approaches to collaboration, advocacy, and professionalism. Beyond initial instruction, however, there was no effect of condition on what learners talked about during their future homecare curriculum or debrief. This finding suggests that teaching critical reflection in the dialogic manner we used neither adds to nor detracts from learners’ topical content focus as they move forward in their learning.

우리가 가장 관심을 갖는 것은 학습자들이 '어떻게how' 말하는가 하는 것이다. 특히, 학습자들이 가정교육 과정 경험에 대해 보고했을 때, [비판적 성찰 대화]에 노출된 학습자들이 향후 학습 중에 더 비판적으로 성찰하는 의미 단위를 계속해서 만들어냈다는 것이다. 제어 그룹과 개입 그룹 간의 확률 차이는 언뜻 보기에는 낮지만(10%) 이 차이를 의미 있는 것으로 해석한다. 전반적으로, 우리는 두 가지 이유로 가정교육 커리큘럼과 결과 발표 중에 어떤 발언도 비판적으로 반영될 가능성이 낮다고 예상한다. 첫째, 개입 조건에서 비판적 교육학에 대한 노출을 최소화했으며, 둘째, 홈케어 커리큘럼과 디브리핑 과정에 걸쳐 참여자들은 본질적으로 비판적 성찰해야 할 가능성이나 그럴 필요가 낮은 서술적 진술이 많다. 실제로, 개입 조건에서도 의미 단위가 비판적으로 반영될 확률은 20%에 불과했는데, 이는 앞서 언급한 이유 때문에 낮고, 예상된 것이다.

Of most interest to us is how learners talked—specifically, our finding that the learners exposed to critically reflective dialogue went on to produce more critically reflective meaning units during their future learning—when debriefed about their homecare curriculum experience. While the difference in probability between control and intervention groups is low at first glance (10%), we interpret this difference as meaningful. Overall, we would expect the potential for any utterance to be critically reflective, during the homecare curriculum and debrief, to be low for two reasons. First, the intervention produced minimal exposure to critical pedagogy and second, over the course of the homecare curriculum and debrief participants would make many descriptive statements that would by nature have low potential or need to be critically reflective. Indeed, the probability for a meaning unit to be critically reflective even in the intervention condition was only 20%, which is low and expected for the aforementioned reasons.

따라서, 작은 차이는 비판적 반성을 위한 교육의 결과를 탐구하는 이 초기 실험 연구에 의미가 있다. 불확실성 추정의 형태로 신뢰할 수 있는 간격과 신념의 정도는 일반적으로 빈도주의 접근법에 사용되는 포인트 추정과 이진 결정(즉, null을 거부)보다는 베이지안 접근법의 초점이다. 우리의 연구에서, 차이의 중심 경향(중앙 추정치)에 대한 우리의 측정은 거의 모든 [what 코드]에서 narrow credible intervals로, 0에 가까웠다. 우리의 주요 연구 질문인 [how 코드]에 있어서, 0은 개연성이 있는 추정치가 아니었다. 데이터가 사후 분포를 이전 분포에서 멀리 이동시켰기 때문에 우리는 우리의 결론에 확신을 가질 수 있다. 종합하면, 이 정보는 의미 있는 추론을 도출하기에 충분한 데이터를 나타낸다(Kruschke & Liddell, 2018; McElreath, 2020).

Thus, a small difference is meaningful to this initial experimental study that explores the outcomes of teaching for critical reflection. Credible intervals and the degree of belief, in the form of uncertainty estimates, are generally the focus of Bayesian approaches rather than the point estimates and binary decisions (i.e. reject the null) used in frequentist approaches. In our study, our measure of central tendency (median estimates) of differences was close to zero with narrow credible intervals in almost all what codes. Of import to our main research question, for our how codes, zero was not a probable estimate. We can be confident in our conclusions because the models indicated the data moved the posterior distributions away from the priors. Taken together, this information indicates sufficient data from which to draw meaningful inference (Kruschke & Liddell, 2018; McElreath, 2020).

모든 연구와 마찬가지로, 우리의 해석은 우리의 설계와 그것의 한계에 따라 제한되어야 한다. 비록 모두 미래에 의료 전문가로 활동할 의향이 있는 대학생들이었지만, 우리의 표본 크기는 상대적으로 작고 이질적이었다. 패러다임 정렬(Creswell, 2003; Baker et al., 2020; Tavares et al., 2020)을 실험 설계 원칙과 균형을 맞추는 것을 목표로, 우리는 우리의 실험 접근 방식에 몇 가지 제한을 둘 수 있다. 이러한 설계 선택 중 하나는 [그룹 차원에 초점을 두는 것focus]이었습니다. 우리의 학습 조건은 [그룹 단위로 발생]했으며, 우리의 분석은 [개인 수준의 발언]을 코딩하지 않았다. 우리는 학생들로 하여금 자신들이 [비판적 성찰]에 대해서 발언이 코딩될 것이라는 것을 알지 못하는 상태로 전문직간 그룹학습 및 시뮬레이션 연습 상황에서 대화를 이끌어내기를 원했기 때문에 이러한 선택을 정당화했다. 그렇지 않았다면 학생들은 우리가 측정하고자 하는 것에 맞춰서 연기했을 것이다.

As in all studies, our interpretations must be constrained according to our design and its limitations. Our sample size was relatively small and heterogenous, although all were university students intending to practice as health professionals in the future. In aiming to balance paradigmatic alignment (Creswell, 2003; Baker et al., 2020; Tavares et al., 2020) with experimental design principles, we may have imposed some limitations on our experimental approach. One such design choice was our group-level focus. Our learning conditions occurred in groups and our analyses did not code utterances per individual. We justified this because we wanted to elicit conversations in an interprofessional group learning / simulated practice situation, during which students were unaware that we would be coding their talk for critical reflection; we expected this would prevent them from performing to our measure.

[비판적 성찰]을 높이기 위한 대화형 접근 방식을 평가하는 틸 외 연구진(2018)의 연구도 그룹 대화를 분석하여 그룹 역학을 의도적으로 보존했다. 마찬가지로, 그룹별 결과물을 통해 학습자가 그룹 내에서 대화할 때 학습자의 시각에 대한 일치되고 진실된 감각을 얻을 수 있었습니다. 그러나 이러한 선택은 비판적 성찰과 교육학에 대해 패러다임적으로 정당화되었지만, 대화의 단위를 [그룹]에 초점을 맞춘 것은, 개별 학습자가 비판적 성찰적 시각을 일관되게 집행했는지 여부를 볼 수 없다는 것을 의미했다.

A study by Thille et al. (2018) evaluating a dialogic approach to foster critical reflexivity also analyzed group conversations, preserving group dynamics purposefully. Likewise, our group debriefs enabled us to obtain an aligned and authentic sense of learners’ ways of seeing as they talked amongst their groups. However, while these choices were paradigmatically justified for critical reflection and pedagogy, our focus on the group as a dialogic unit meant that we were unable to see whether individual learners consistently enacted critically reflective ways of seeing.

저자 팀의 일부를 포함한 많은 학자들이 [성찰을 평가하는 것이 걱정스럽다]고 주장했지만(Summation & Flet, 1996; Hodges, 2015; Ng et al., 2015a), 이 연구는 두 평가자가 [진술의 비판적 성찰] 여부를 신뢰성 있게 코딩할 수 있다는 것을 입증함으로써 중요한 기여를 한다. 이 연구는 [개인의 평가]가 아니라 [교육의 성과]에 관한 것이었다. 우리는 교육 접근법이 의도된 영향을 미치는지 결정하기 위해 비판적 성찰의 유무를 살펴보았다. 우리는 비판적 성찰의 품질을 평가하지 않았다. 우리는 계속해서 개인의 성찰적 사고의 질을 판단하는 것에 대해 강력히 경고한다. 다른 사람들이 지적하듯이, 그렇게 하는 것은 학습자의 개인적, 정치적 신념을 감시하는 어조를 취할 수 있다(Nelson & Purkis, 2004; Hodges, 2015). 또한, 성찰을 평가하면 진위성이 떨어져 지나치게 규범적일 수 있다(Hodges, 2015; Ng et al., 2015a; de la Croix & Veen, 2018). 의심할 여지 없이, 비판적 성찰은, 비판적 렌즈가 비판 이론의 본체에서 파생되기 때문에, 다른 형태의 성찰보다 더 쉽게 식별할 수 있고 평가할 수 있다(Ng et al., 2019b). 따라서 관찰할 수 있을 것으로 예상되는 지식의 형태는 미리 정의되어 있으며 식별될 수 있다. 그렇긴 하지만, 우리는 여전히, [비판적 성찰의 존재presence]와 반대로 [비판적 성찰의 품질quality]을 평가하는 것이 심리학적 이유와 패러다임적 정렬 오류의 이유 모두에 문제가 될 수 있다고 주장한다(Summation & Flet, 1996; Koole et al., 2011; Moniz et al., 2015; Ng et al., 2015a, b; Grierson et al., 2020).

While many scholars—including some on our author team—have argued that assessing reflection is fraught (Sumsion & Fleet, 1996; Hodges, 2015; Ng et al., 2015a), this study makes an important contribution by demonstrating that two raters can reliably code whether a statement is critically reflective or not. This study was about outcome of teaching, not about assessment of individuals. We looked at presence or absence of critical reflection to determine whether a teaching approach had its intended effect; we did not assess the quality of critical reflection. We continue to caution strongly against judging the quality of an individual’s reflective thought; as others note, doing so can take on a tone of surveilling learners’ personal and political beliefs (Nelson & Purkis, 2004; Hodges, 2015). Further, assessing reflection may take away from its authenticity, making it overly prescriptive (Hodges, 2015; Ng et al., 2015a; de la Croix & Veen, 2018). Arguably, critical reflection is more readily identifiable and assessable than other forms of reflection because the critical lens derives from a body of critical theory (Ng et al., 2019b). Thus, the forms of knowledge one would expect to observe are pre-defined and can be identified. That said, we still argue that assessing the quality of critical reflection as opposed to its presence may be problematic for both psychometric reasons and reasons of paradigmatic misalignment (Sumsion & Fleet, 1996; Koole et al., 2011; Moniz et al., 2015; Ng et al., 2015a, b; Grierson et al., 2020).

교육디자인

Educational design

우리의 주요 발견을 해석할 때, 교육 디자인의 세 가지 주요 요소에 관심을 끄는 것이 중요하다. 첫째, 비판적 성찰 세션에 대한 교육학적 접근법은 [비판적 성찰을 촉진하는 방법에 대한 이론]에 의해 신중하고 깊이 inform되었다(Ng, 2012, Ng et al., 2015a, 2019a). 이러한 세션은 학습자에게 [비판적 성찰에 대한 이론을 가르치기]보다는, [지배적인 가정을 교란]하고, [강의실의 권력 차이]를 다루며, [해결책을 찾는 것보다 질문]을 하고, [현 상태를 넘어서는 방법을 구상하는 것]을 목표로 삼았다. 그들은 과거 실무 기반 연구에서 실제 사례 사례를 경험했다(Ng et al., 2015b; Phelan & Ng, 2015).

When interpreting our main findings, it is important to draw attention to three main elements of educational design. First, our pedagogical approach to the critically reflective session was carefully and deeply informed by theories of how to foster critical reflection (Ng, 2012, Ng et al., 2015a, 2019a). Rather than teaching learners theory about critical reflection, these sessions aimed to equip them to disrupt dominant assumptions, to address the power differentials in the room, to ask questions rather than aim to identify solutions, and to envision ways forward beyond the status quo. They experienced real case examples from past practice-based research (Ng et al., 2015b; Phelan & Ng, 2015).

둘째, 학습 환경 설정은 목적적이었으며, 비판적 페다고지의 원칙과 일치했다(Greene, 1986; Hooks, 1994; Freire, 2000; Halman et al., 2017;). 퍼실리테이터는 퍼실리테이터-참가자의 권력 차이를 줄이기 위해 참가자들과 원을 그리며 앉았고, 편안함과 격식을 함양하기 위해 음식을 두었으며, 공간과 조명은 대화에 도움이 되는 환경을 구성하기 위해 선택되었다. 이러한 "instruction"의 특징은 학습자와 진행자 사이의 편안함과 연결을 촉진하므로 대화를 촉진하는 데 중요한 것으로 간주됩니다. 이러한 환경적 특징은 통제와 개입 조건 모두에서 동일했다. 향후 연구는 학습에 있어 그러한 요인의 영향을 탐구할 수 있을 것이다. 우리는 [이러한 특징에 주의를 기울이는 것]이 보건의료전문직의 객관성과 확실성의 지배적인 배경에 대한 중요한 교육학 설정의 과제를 극복하는 데 중요하다고 믿었지만, 이러한 믿음은 향후 연구에서 탐구될 필요가 있을 것이다. 이러한 연장선에서, 비판적 성찰 대화 세션을 "instruction"이라고 부르는 것은 객관주의적 패러다임의 지배를 보여주며 비판적 교육학의 원칙과 일치하지 않는다. 특히, 우리는 교육 연구 설계와 일관성을 유지하기 위해 "instruction"를 사용한다. 그러나 비판적 교육학에서는 학습자가 자신의 유효한 경험과 공유 가치가 있는 지식을 테이블로 가져오므로 강사 또는 교육 자체instructor or instruction per se에 대한 강조가 적다(Hooks, 1994; Freire)., 2000; Halman et al., 2017).

Second, the learning environment setup was purposeful and aligned with critical pedagogical principles (Greene, 1986; Hooks, 1994; Freire, 2000; Halman et al., 2017;). Facilitators sat in a circle with participants to reduce the sense of a facilitator-participant power differential, the presence of food was intended to foster comfort and informality, the spaces and lighting were chosen to help construct an environment conducive to dialogue. These features of the “instruction” would be considered important for fostering dialogue as they promote comfort and connection amongst learners and the facilitator. These environmental features were the same for both the control and intervention conditions; future research could explore the influence of such factors in learning. We believed that attending to these features may be important to overcome the challenges in setting up critical pedagogies against a dominant backdrop of objectivity and certainty in the health professions (Kuper et al., 2017; Ng et al., 2019a, b; Whitehead et al., 2011) but this belief would need to be explored in future studies. Along these lines, calling the critically reflective dialogue session “instruction” demonstrates the dominance of objectivist paradigms and is incongruent with principles of critical pedagogy. Notably, we use “instruction” to be consistent with our education research design; however in critical pedagogy, there is less of an emphasis on a single instructor or instruction per se, as learners bring their own valid experiences and knowledge worth sharing, to the table, alongside the facilitator’s experience and knowledge (Hooks, 1994; Freire, 2000; Halman et al., 2017).

셋째, 우리는 비판적 성찰의 학습에 제한된 시간/노출 시간을 할당했다. 이는 연구의 실현가능성을 위해서였고, 보건의료전문직 교육의 현실을 반영한 것이다. 많은 사람들은 대체 전통에서 파생된 일회성, 짧은 교육 경험의 "짜깁기" 또는 "짜내기"을 한탄한다(Ousager & Johannessen, 2010; Diachun et al., 2014; Charise, 2017). 실제로 비판적 교육학의 효과가 시간이 지남에 따라 지속되기 위해서는 교육에 대한 비판적 접근법이 교육 프로그램에 보다 일관되고 포괄적이며 종적으로 포함되어야 할 것이다(Ng et al., 2020). 이러한 강도의 잠재적인 결과는 학습자의 발언이 비판적 성찰될 가능성이 증가하는 것일 수 있다.

Third, we allotted a limited amount of time/exposure to critically reflective learning, for study feasibility and to represent the reality in health professions education. Many lament this “tacking on” or “squeezing in” of one-off, brief educational experiences deriving from alternative traditions (Ousager & Johannessen, 2010; Diachun et al., 2014; Charise, 2017). Indeed to see the effect of critical pedagogy persist over time, critical approaches to education would need to be embedded more consistently, comprehensively, and longitudinally in a training program (Ng et al., 2020). A potential consequence of this increased intensity could be an increased probability of learners’ utterances being critically reflective.

[비판적 교육학]을 [인지주의 교육 패러다임]과 연결하기 위한 한 가지 유망한 접근법은 Cheng의 PEARLS 프레임워크에 기초한 보고 스크립트에 있을 수 있다(Eppich & Cheng, 2015). [홈케어 교육과정 중 학습자가 말하는 방식]에 실험 조건condition의 영향이 없었다는 것 자체가 구조화된 교육과정인 만큼 놀랍지 않았다. 그러나 (보다 개방적이고 비판적인 반성이 제기되어 질문을 유도하는) 디브리핑에서, 개입은 기대했던 효과를 발휘했다. "가족 간병인에 대해 어떻게 생각하느냐"와 같은 질문들은 그 자체로 비판적 성찰을 불러일으킬 수 있다. 예를 들어, 이 질문은 보건 및 사회 복지 시스템이 그러한 간병인을 적절히 지원하는지 여부에 대한 통찰력이나 질문을 촉발할 수 있다. 개입에 노출된 학습자와 그렇지 않은 학습자의 차이는 개입이 학습자가 이러한 보고 프롬프트를 더 많이 활용할 수 있도록 지원한다는 것을 나타냅니다. 디브리핑에서 Pearls 접근법을 사용하는 것은 [지속적 비판적 성찰 교육]의 한 형태일 수 있다. 그러나 1주일의 후속 보고에서 줄어든 영향은 지속적인 보고만으로는 비판적 성찰 교육의 효과를 지속하기에 불충분하다는 것을 시사한다. 향후 연구는 공식적인 의료 전문가 교육 전반에 걸쳐 그리고 그 이상으로 비판적 성찰을 지속하는 가장 효과적인 방법을 더 깊이 연구할 수 있을 것이다.

One promising approach to bridge critical pedagogy with cognitivist education paradigms (which emphasizes knowledge acquisition as opposed to ways of seeing and being [Baker et al., 2020]) may lie in our debriefing script based on Cheng’s PEARLS framework (Eppich & Cheng, 2015). That there was no effect of condition on how learners talked during the homecare curriculum itself was unsurprising as it was a structured curriculum. But during the debrief, in which more open and critical reflection prompting questions were posed, the intervention did have its expected effect. Questions like “what were your thoughts about the family caregiver” could in and of themselves trigger critical reflection. For example, this question may trigger insights or queries about whether the health and social care systems adequately support such caregivers. The difference between learners who were exposed to the intervention versus those who were not suggests that the intervention supports learners to take greater advantage of such debriefing prompts. It is possible that the PEARLS approach to debriefing is a form of continued critical reflection teaching. However, the reduced impact at the one-week follow up debrief suggests that continued debriefing alone is insufficient to sustain the effects of the critical reflection teaching. Future research could delve more deeply into the most effective way to sustain critical reflection throughout and beyond formal health professions training.

궁극적으로, 우리는 이 연구가 비판적 성찰을 촉진하는 것을 목표로 하는 비판적 교육학과 교육 개입 연구에 대한 실험적인 접근 방식 사이에 매우 필요한 다리를 제공한다고 믿는다. 의료 전문직 교육의 학제 간 분야에서 패러다임 다양성은 도전과 기회를 제공한다(Young et al., 2020). 우리는 학제간 팀원들 사이에 많은 대학 논쟁을 야기시킨 차이를 조정하려고 노력했다. 실험론자들은 비판적 성찰을 위한 가르침의 효과에 대한 주장은 실험적인 증거가 부족하기 때문에 충분히 입증되지 않았다고 주장했다. 비판적인 교육자들은 그러한 형태의 증거가 진실하고 구체화된 반사 능력을 진실하지 않고 지나치게 규범적인 캐리커처로 강등시킬 것이라고 주장했다. 학제 간 토론과 대화를 통해, 우리 팀은 두 가지 관점을 모두 만족시키는 비판적 성찰의 가르침에 대한 지식을 발전시키는 접근 방식을 개발했습니다. 현장이 이 다리로 무엇을 할지는 두고 봐야 한다. 우리의 연구가 이 기사에서 보고한 바와 같이, 그리고 그 안에 있는 교육학이 증명한 바와 같이 중요성과 대화에 대한 약속을 진행하는 것이 현명할 수 있다.

Ultimately, we believe this study offers a much-needed bridge between critical pedagogy aiming to foster critical reflection, and experimentalist approaches to studying educational interventions. In the interdisciplinary field of health professions education, paradigmatic diversity offers challenges and opportunities (Young et al., 2020). We sought to reconcile a difference that caused much collegial debate amongst members of our interdisciplinary team. Experimentalists argued that claims about the effects of teaching for critical reflection were under-substantiated given a paucity of experimental evidence. The critical pedagogues argued that such forms of evidence would relegate authentic, embodied reflective capabilities to inauthentic and overly prescriptive caricatures. Through interdisciplinary debate and dialogue, our team developed an approach to advancing knowledge on the teaching of critical reflection that satisfied both perspectives. What the field does with this bridge remains to be seen; it may be prudent to proceed with commitment to criticality and dialogue as both our research reported in this article, and the pedagogy within it, demonstrated.

doi: 10.1007/s10459-021-10087-2. Epub 2022 Jan 1.

Toward 'seeing' critically: a Bayesian analysis of the impacts of a critical pedagogy

PMID: 34973100

PMCID: PMC9117363

DOI: 10.1007/s10459-021-10087-2

Free PMC article

Abstract

Critical reflection supports enactment of the social roles of care, like collaboration and advocacy. We require evidence that links critical teaching approaches to future critically reflective practice. We thus asked: does a theory-informed approach to teaching critical reflection influence what learners talk about (i.e. topics of discussion) and how they talk (i.e. whether they talk in critically reflective ways) during subsequent learning experiences? Pre-clinical students (n = 75) were randomized into control and intervention conditions (8 groups each, of up to 5 interprofessional students). Participants completed an online Social Determinants of Health (SDoH) module, followed by either: a SDoH discussion (control) or critically reflective dialogue (intervention). Participants then experienced a common learning session (homecare curriculum and debrief) as outcome assessment, and another similar session one-week later. Blinded coders coded transcripts for what (topics) was said and how (critically reflective or not). We constructed Bayesian regression models for the probability of meaning units (unique utterances) being coded as particular what codes and as critically reflective or not (how). Groups exposed to the intervention were more likely, in a subsequent learning experience, to talk in a critically reflective manner (how) (0.096 [0.04, 0.15]) about similar content (no meaningful differences in what was said). This difference waned at one-week follow up. We showed experimentally that a particular critical pedagogical approach can make learners' subsequent talk, ways of seeing, more critically reflective even when talking about similar topics. This study offers the field important new options for studying historically challenging-to-evaluate impacts and supports theoretical assertions about the potential of critical pedagogies.

Keywords: Bayesian; Critical pedagogy; Critical reflection; Equity; Social responsibility.

© 2021. The Author(s).

'Articles (Medical Education) > 교육과정 개발&평가' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 환경-정규화: 맥락 속 혁신의 수명을 평가하기 (Acad Med, 2021) (0) | 2022.06.14 |

|---|---|

| 마라톤입니다, 단거리가 아닙니다: CBME 도입의 신속 평가(Acad Med, 2020) (0) | 2022.05.31 |

| 의사소통, 학습, 평가: 디지털 학습 환경의 차원 탐색(Med Teach, 2019) (0) | 2022.03.18 |

| 인식론, 문화, 정의, 권력: 의학 훈련을 위한 비-생물과학적 지식(Med Educ, 2017) (0) | 2022.02.24 |

| 보건의료전문직 교육의 평가 - 성과 측정은 충분한가? (Med Educ, 2022) (0) | 2022.01.14 |