성찰적 그리고 비성찰적 학생을 위한 성찰적 공간 만들기: 대그룹 글쓰기 세션에서 결정적 순간 탐색(Acad Med, 2020)

Creating Reflective Space for Reflective and “Unreflective” Medical Students: Exploring Seminal Moments in a Large-Group Writing Session

Bruce H. Campbell, MD, Robert Treat, PhD, Benjamin Johnson, MD, and Arthur R. Derse, MD, JD

문제

Problem

자신을 "반성적이지 않다"고 묘사하는 바쁜 의대생들은 그들의 초기 임상적 만남의 실존적 스트레스, 모호한 감정, 죽음과의 붓, 도덕적 딜레마를 자발적이고 창의적으로 숙고할 것 같지 않다. 그러나, 매우 반성적인 학생들은 의도적으로 저널링을 하거나, 글을 쓰거나, 창의적인 표현을 위한 다른 배출구를 찾으면서 독립적으로 이러한 사건들에 집중하기 위해 잠시 멈출 수 있다. 의학 교육자들은 성찰을 모든 의사들에게 중요하고 필요한 기술로 보고 있으며, 대부분의 미국 의대들은 성찰 활동을 임상 전 교육과 임상 교육의 필수 구성요소로 지정하고 있다. 이러한 커리큘럼 요소들은 종종 성찰 능력과 성숙도의 증거를 위해 수집되고 평가되지만, 학생들은 빈번하고 조정되지 않은 성찰 활동이 "성찰 피로"를 초래할 수 있다는 점에 주목한다. 결과적으로, 빠르게 적응하는 학생들은 적절한 응답을 만들고 제출하는 것을 배울 수 있는데, 이는 진정한 성찰적 노력에서 비롯되지 않을 수 있다.

Busy medical students who describe themselves as being “unreflective” are unlikely to spontaneously and creatively contemplate the existential stress, ambiguous emotions, brushes with mortality, and moral dilemmas of their initial clinical encounters. However, highly reflective students might independently pause to focus on these events, intentionally journaling, writing, or finding other outlets for creative expression. Medical educators see reflection as a critical and necessary skill for all physicians,1 and most U.S. medical schools assign reflective activities as required components of preclinical and clinical education. These curricular elements are often collected and assessed for evidence of reflective capacity and maturity, but students note that frequent, uncoordinated reflective activities can lead to “reflection fatigue.”2 Consequently, students who adapt quickly can learn to create and submit appropriate responses, which may not result from actual reflective effort.3

우리는 위스콘신 의과대학(MCW)의 모든 학생들, 특히 초기 임상 경험이 있는 학생들에게 성찰적이고 서사-기반 기술 개발 활동을 제공할 기회를 찾고 있었다. 그 때 우리는 ERAS에 대한 personal statement을 작성하는 것에 대한 전체 3학년 수업을 위한 워크숍을 만들고 운영하라는 요청을 받았다. 우리는 성찰적인 활동을 워크숍과 연계할 것을 제안했다. 우리는 성찰적 글쓰기가 매우 개인적이어야 한다는 것을 인정했지만, 우리는 또한 학생들이 그들의 동료들과 함께 일하는 것에 이점이 있다는 것을 느꼈다.

We were seeking opportunities to provide reflective and narrative-based skill-building activities for all students at the Medical College of Wisconsin (MCW)—particularly those having their initial clinical encounters—when we were asked to create and run a workshop for the entire third-year class on creating a personal statement for the Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS). We proposed linking a reflective activity to the workshop. We acknowledged that reflective writing should be intensely personal, yet we also felt that there were advantages for the students in working with their peers.

이에 학생들이 [3학년]의 중요한 순간을 파악하고 성찰적 글쓰기 연습을 통해 탐색하는 세션을 기획한 후 또래 집단 내에서 [메타 성찰(반사 과정에 대한 성찰)]을 진행하였다. 우리는 학생들의 글쓰기, 성찰, 서술 연습에 대한 인식, 특히 이번 세션에 대한 인식을 더 잘 이해할 수 있도록 수업 전후에 설문지 자료를 수집했다.

Therefore, we designed a session in which students identify the seminal moments of their third year and explore them through a reflective writing exercise followed by meta-reflection (reflection on the reflective process) within a group of peers. We gathered questionnaire data before and after the session to help us better understand students’ perceptions of writing, reflective, and narrative exercises in general and of this session in particular.

접근

Approach

2014년부터 MCW는 의과대학 교육과정 전반에 걸쳐 지속적인 전문직업성 개발의 일환으로 3학년에 2주의 필수 intersession를 추가했다. [1주일간의 intersession 프로그램]은 1월(학사 중간)에, 6월(3학년에서 4학년으로 전환)에 진행된다. 중간고사 주간은 학생들이 수업으로 다시 연결하고 나쁜 소식, 관심의 충돌, 다양성과 포용성, 생명윤리, 말기 관리, 개인 건강, 전공의 준비와 같은 주제에 대한 토론에 참여하도록 장려한다.

Beginning in 2014, MCW added 2 required intersession weeks to the third year as part of continuous professional development interspersed throughout the medical school curriculum. The first week-long intersession program is held in January (the midpoint of the academic year) and the second in June (as students transition from the third to the fourth year). The intersession weeks encourage students to reconnect as a class and to engage in discussions on topics such as breaking bad news, conflicts of interest, diversity and inclusion, bioethics, end-of-life care, personal wellness, and residency preparedness.

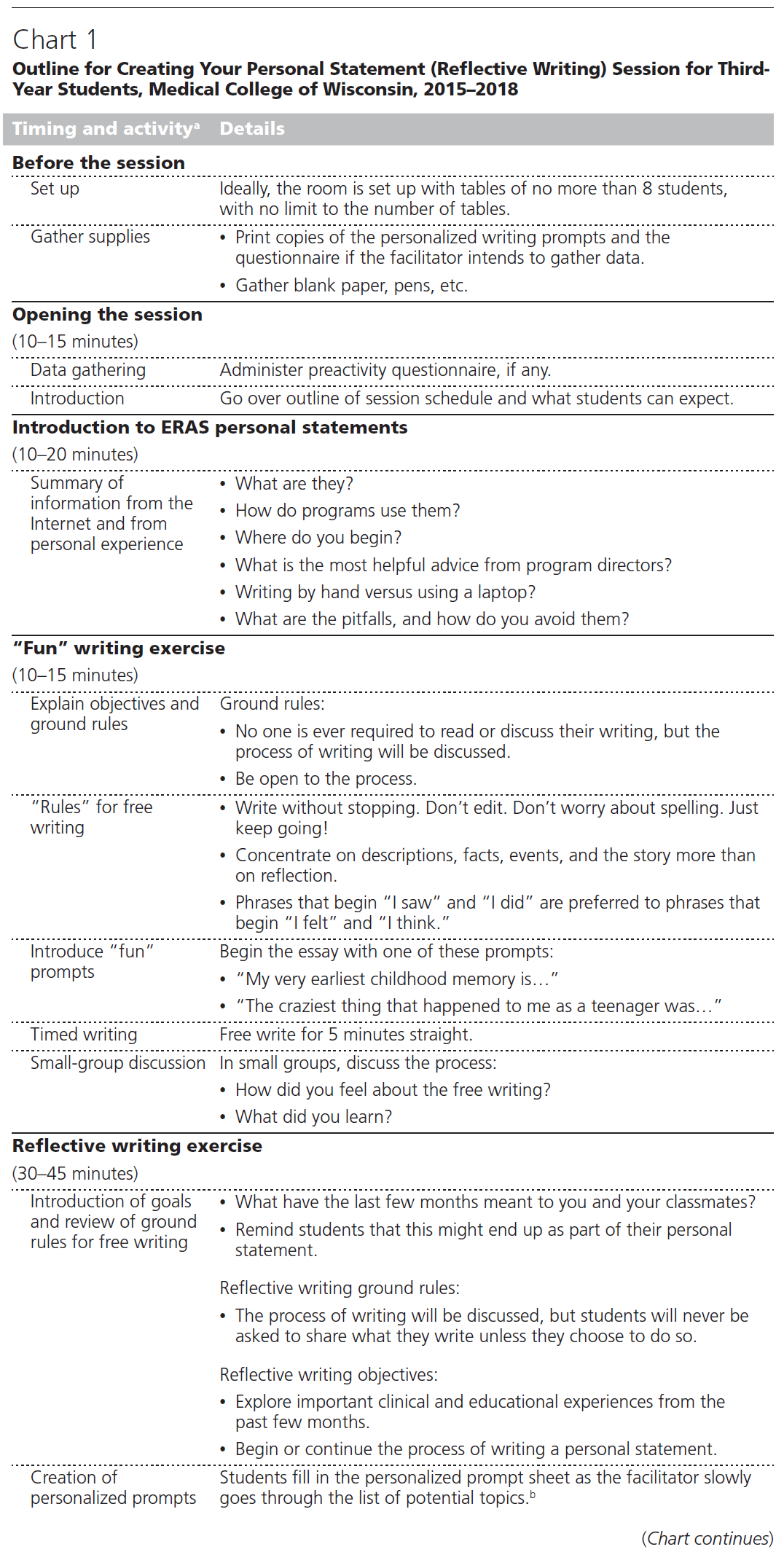

우리는 [4학년을 위한 레지던트 애플리케이션 개인 진술 작성 워크숍]을 진행하는 것을 바탕으로 [자기만의 개인 진술 써보기 세션]을 진행하도록 초대받았습니다. 2015년에 처음 제공되고 각 중간고사 프로그램의 일환으로 모든 3학년 학생들에게 요구되는 이 새로운 [1.5~2시간 세션]은 아래에 자세히 설명되어 있으며 차트 1에 요약되어 있습니다. 모든 학생들이 글쓰기 활동에 참여할 것으로 기대하지만, 세션 전후에 우리가 요구하는 익명의 연구 질문은 선택 사항이며, 세션이 끝날 때 그들이 쓴 글을 소리내어 읽거나 제출할 것이라는 기대는 전혀 없다는 것을 명시적으로 듣는다.

We were invited to facilitate a Creating Your Personal Statement session based on our ongoing voluntary fourth-year Residency Application Personal Statement Writers Workshops.4 This new 1.5- to 2-hour session—first offered in 2015 and required for all third-year students as part of each intersession program—is detailed below and outlined in Chart 1. Although all students are expected to participate in the writing activities, they are explicitly told that the anonymous research questions we ask them to complete before and after the session are optional and that there is no expectation that they will either read their writing aloud or submit it at the end of the session.

이 프로젝트의 연구 부분은 MCW 제도 검토 위원회의 승인을 받았고, 학술 문제를 위한 수석 부학장의 승인을 받았다.

The research portion of the project was approved by the MCW Institutional Review Board and endorsed by the senior associate dean for academic affairs.

ERAS 개인 정보 소개

Introduction to ERAS personal statements

학생들은 3학년 전체 수업(약 200명)을 수용할 수 있도록 설계된 방의 테이블에서 최대 8명의 학생들이 스스로 선택한 그룹으로 앉습니다. 이 세션은 인터넷, 문헌, 그리고 우리의 개인적인 경험으로부터 얻은 정보를 요약하는 개인 진술에 대한 소개로 시작한다. 리소스는 전자적으로뿐만 아니라 하드카피 형식으로도 공유됩니다.

Students sit in self-selected groups of up to 8 at tables in a room that is designed to hold the entire third-year class (approximately 200 students). The session begins with an introduction to personal statements, which summarizes information from the Internet, the literature, and our personal experience. Resources are shared in hard-copy format as well as electronically.

워밍업 글쓰기: "재미있는" 글쓰기 연습

Warm-up writing: “Fun” writing exercise

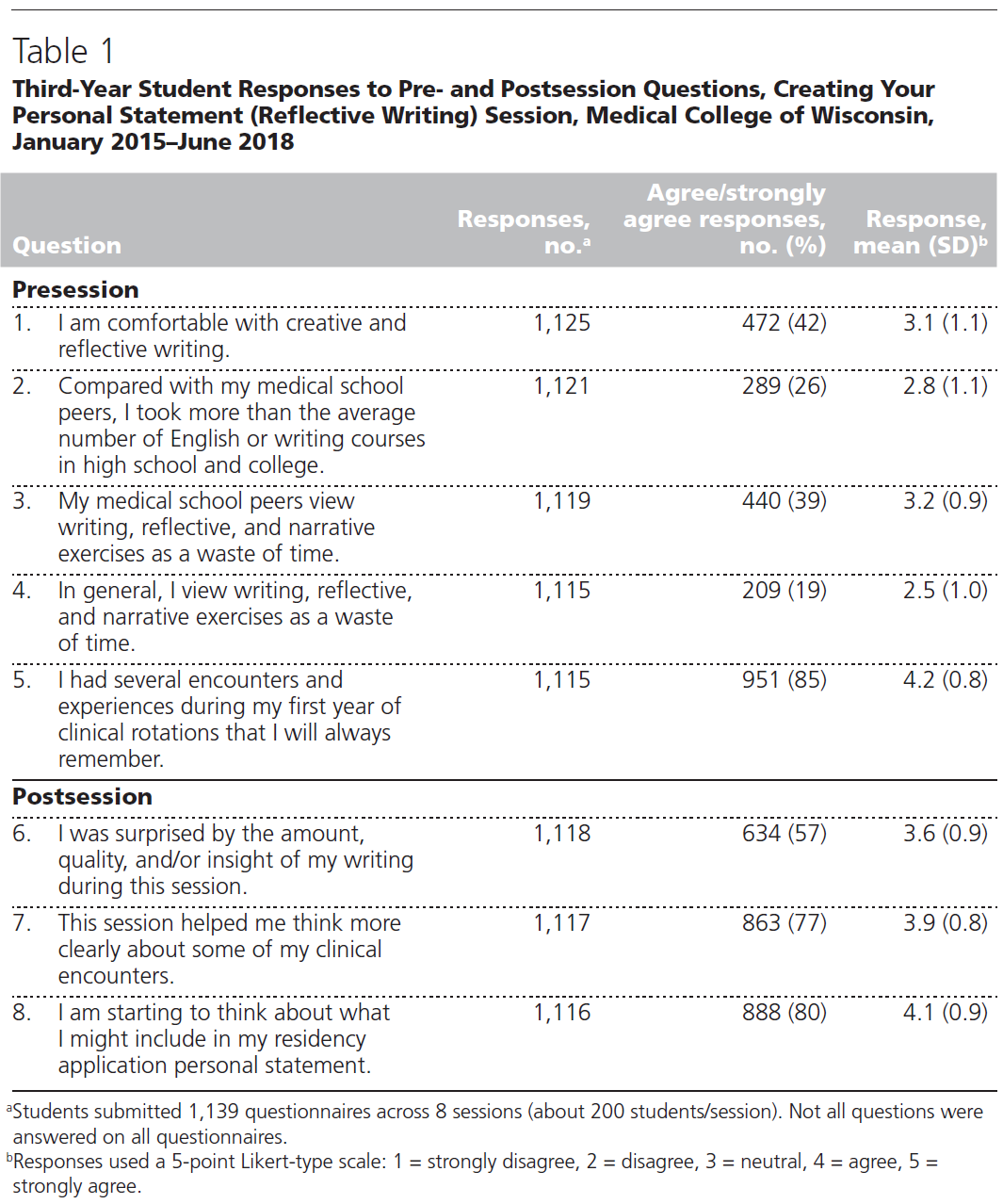

소개가 끝난 후 학생들은 세션 설문지의 처음 5개 질문에 5점 척도(1 = 5에 강하게 반대 = 강하게 동의함, 표 1)를 사용하여 답변하고 세션이 끝날 때 완료되도록 설문지를 따로 준비해야 합니다. 그런 다음 [간단하고 재미있는 주제의 "자유롭게 쓰기"]를 해보게 된다 (이 글쓰기는 편집, 수정, 다시 읽지 않고 지속적으로 글을 쓰고, "내가 봤다"와 "내가 했다"를 "느꼈다"와 "생각한다"보다 더 많이 묘사하는 데 초점을 맞춘다.). 종이가 제공되고 학생들은 손으로 글을 쓰도록 권장되지만, 많은 학생들은 대신 노트북으로 작업하는 것을 선택한다. 일단 학생들이 그들의 프롬프트를 선택하면, 그들은 [5분 동안 중단 없이 글을 쓴다]. 그리고 나서 그들은 그들의 테이블 동료들과 그 [과정에 대해 토론]하도록 초대된다. 이들은 자신이 쓴 글의 내용을 마음에 들면 공유할 수 있게 돼 있지만, 글 자체보다는 글을 쓰는 과정에 대해 이야기하는 것이 권장된다.

After the introduction, students are asked to answer the first 5 questions on the session questionnaire using a 5-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree; Table 1) and to set the questionnaire aside to complete at the end of the session. They are then guided through a “free write” of a simple, fun topic (writing continuously without editing, correcting, or rereading, and focusing on describing what “I saw” and “I did” more than what “I felt” and “I think”). Paper is provided and students are encouraged to write by hand, but many choose to work on their laptops instead. Once students choose their prompt, they write for 5 uninterrupted minutes. They are then invited to discuss the process with their tablemates. They are allowed to share the content of what they wrote if they choose, but they are encouraged to talk about the process of writing rather than the writing itself.

성찰적 글쓰기 연습

Reflective writing exercise

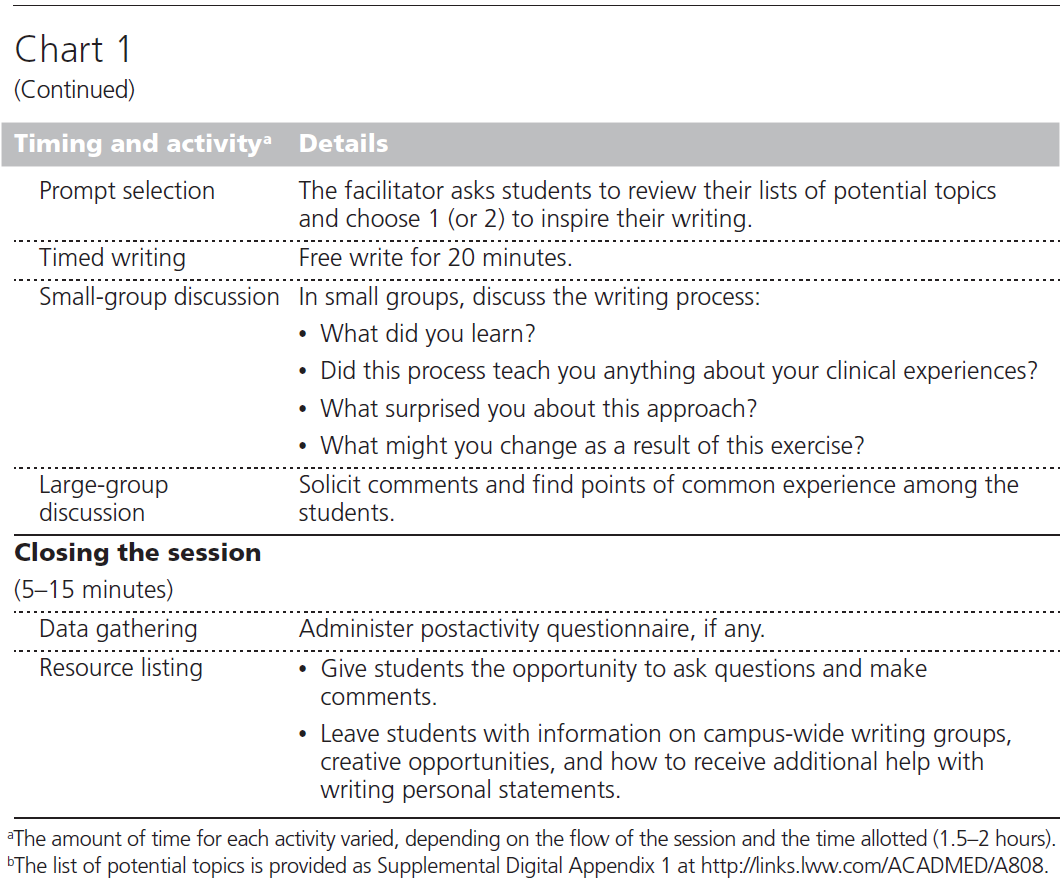

다음으로, 주요 [성찰적 글쓰기 연습의 목표]가 설명되고(차트 1), 학생들은 자신이 쓴 것을 동료나 교수진과 공유하라는 요청을 결코 받지 않을 것임을 상기시킨다. 학생들은 보충 디지털 부록 1에 나열된 각 시나리오에 대해 1~2개의 단어를 적음으로써 이전 몇 달 동안의 임상 및 비임상 경험을 바탕으로 일련의 잠재적인 글쓰기 프롬프트를 작성하도록 안내받는다.

Next, the goals of the main reflective writing exercise are described (Chart 1) and students are reminded that they will never be asked to share what they have written with their peers or the faculty. The students are guided to create a series of potential writing prompts based on their clinical and nonclinical experiences over the prior months by jotting down 1 or 2 words in response to each of the scenarios listed in Supplemental Digital Appendix 1 (available at https://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A808).

학생들이 시나리오 목록을 작성한 후 '보여줘, 말하지마'에 초점을 맞춰 [20분간 자유롭게 글을 쓸 수 있는 기준이 될 경험 중 1~2개를 선택]한다. 시간이 되면, 그들은 그들의 [글을 검토하고 소그룹 토론]에 참여한다. 그들은 글쓰기 과정에서 발생한 통찰력과 놀라움에 초점을 맞추도록 요청받는다. 그런 다음 소규모 그룹은 이러한 [통찰력을 전체 클래스와 공유]합니다.

After students work through the list of scenarios, they select 1 or 2 of the experiences to serve as the basis for a 20-minute free write, focusing on “show, don’t tell.” When the time is up, they review their writing and engage in small-group discussions. They are asked to focus on the insights and surprises that occurred during the writing process. The small groups then share these insights with the entire class.

마무리

Wrap-up

실습을 마치면 학생들은 이 세션의 목적이 [자신의 임상 로테이션과 환자 치료 경험을 되돌아볼 수 있는 기회]를 제공하기 위한 것이었음을 상기하게 된다. 우리는 그들이 쓴 것이 그들의 개인적인 진술의 일부로 끝날 수 있다고 제안한다. 학생들은 교내 창의적 기회를 요약하고 검토한 후, 세션 시작 시 주어진 설문지의 마지막 3개 항목(표 1)을 완료해야 합니다. 서면 의견을 제시해 주십시오. 학생들은 설문지를 두고 가지만, 그들의 글을 가지고 간다. 추가적인 도움을 원하는 학생들은 세션을 진행하는 교수진과 직접 대화할 수 있다. 이 경험으로 인해 트라우마를 느끼는 학생은 누구나 교직원과 대화하거나 학생 정신 건강 서비스를 받을 수 있다.

At the end of the exercise, the students are reminded that the purpose of the session was to offer them an opportunity to reflect on their clinical rotations and patient care experiences. We suggest that what they wrote could end up as part of their personal statement. After a summary and a review of on-campus creative opportunities, the students are asked to complete the last 3 items on the questionnaire they were given at the beginning of the session (Table 1). Written comments are encouraged. The students leave their questionnaires behind but take their writing with them. Students who want extra help can speak directly with the faculty facilitating the session. Any student who feels traumatized by the experience is encouraged to talk to a faculty member or is directed to student mental health services.

데이터 분석

Data analysis

첫 번째 8개 세션(2015년 1월 ~ 2018년 6월)의 설문지 데이터는 마이크로소프트 엑셀 for Office 365 데이터베이스(워싱턴주 레드먼드 소재 마이크로소프트 Corporation)에 입력되었다. 데이터는 IBM SPSS Statistics 24.0(IBM, Armonk, New York)을 사용하여 Spearmanrho 상관관계, 분산 분석 및 Mann-Whitney U-tests를 계산하였다. 자유응답 댓글은 긍정적, 부정적 또는 제안으로 분류되었다.

The data from the questionnaires from the first 8 sessions (January 2015–June 2018) were entered into a Microsoft Excel for Office 365 database (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, Washington). The data were analyzed with IBM SPSS Statistics 24.0 (IBM, Armonk, New York) to calculate Spearman rho correlations, analysis of variance, and Mann–Whitney U-tests. Free-response comments were classified as being positive, negative, or suggestions.

결과

Outcomes

2015년 1월부터 2018년 6월까지 진행된 8회 개인 진술 작성 세션에 참여한 MCW 3학년 학생들은 약 71%에 해당하는 1,139개의 익명 설문지를 반환했다(각 MCW 반에는 약 200명의 학생이 있으며, 각 학생은 두 번 참여하도록 배정되어 총 가능한 1,600개의 설문지 중에서. 설문지를 작성하지 않고 참석했거나 참석하지 않아 참석하지 못한 학생이 몇 명인지 파악할 수 없었습니다.) 제출된 1,139개의 설문지에서 유효한 응답은 질문당 1,115개에서 1,125개까지 다양했다(표 1). 설문지의 338개(30%)에도 최소 1개의 추가 서면 의견이 포함됐다.

MCW third-year students participating in the 8 Creating Your Personal Statement sessions held between January 2015 and June 2018 returned 1,139 anonymous questionnaires, representing a questionnaire completion rate of about 71%. (Each MCW class had approximately 200 students, and each student was assigned to participate twice, for a possible total of 1,600 questionnaires. We were unable to determine how many students either attended without completing a questionnaire or failed to attend as attendance was not taken.) On the 1,139 questionnaires that were turned in, valid responses varied from 1,115 to 1,125 per question (Table 1). Three hundred and thirty-eight (30%) of the questionnaires also included at least one additional written comment.

이 자료는 학생들이 동료들이 성찰적인 활동을 어떻게 보는지 잘못 인식했다는 것을 보여주었다. 또래 학생들이 글쓰기, 성찰, 서술형 연습이 자신들보다 시간 낭비라고 느낀다는 데 동의하거나 강하게 동의하는 학생(이하 동의)이 2배 더 많았다(440/1119[39%] 대 209/1115[19%]).

The data demonstrated that students misperceived how their peers viewed reflective activities. Twice as many students agreed or strongly agreed (hereafter agreed) that their peers felt writing, reflective, and narrative exercises were a waste of time as they themselves did (440/1,119 [39%] vs 209/1,115 [19%]).

학생들은 또한 그들이 예상했던 것보다 더 많은 운동으로부터 이익을 얻는 것으로 보였다. 472/1,125명(42%)만이 창의적 글쓰기에 익숙하다는 데 동의했지만, 세션이 끝난 후 634/1,118명(57%)은 세션 중 자신의 글쓰기 양, 품질 및/또는 통찰력에 놀랐다는 데 동의했고 863/1,117명(77%)은 세션이 일부 수업에 대해 더 명확하게 생각하는 데 도움이 되었다는 데 동의했습니다초면의 만남. 대부분의 학생들(951/1,115[85%])은 그들이 임상 회전의 첫 달 동안 항상 기억할 수 있는 여러 번의 만남과 경험을 가졌다고 믿었다.

Students also appeared to benefit from the exercise more than they anticipated. Only 472/1,125 (42%) came into the session agreeing that they were comfortable with creative writing, yet after the session, 634/1,118 (57%) agreed that they were surprised by the amount, quality, and/or insight of their writing during the session and 863/1,117 (77%) agreed that the session had helped them think more clearly about some of their clinical encounters. Most students (951/1,115 [85%]) believed that they had several encounters and experiences during their first months of clinical rotations that they would always remember.

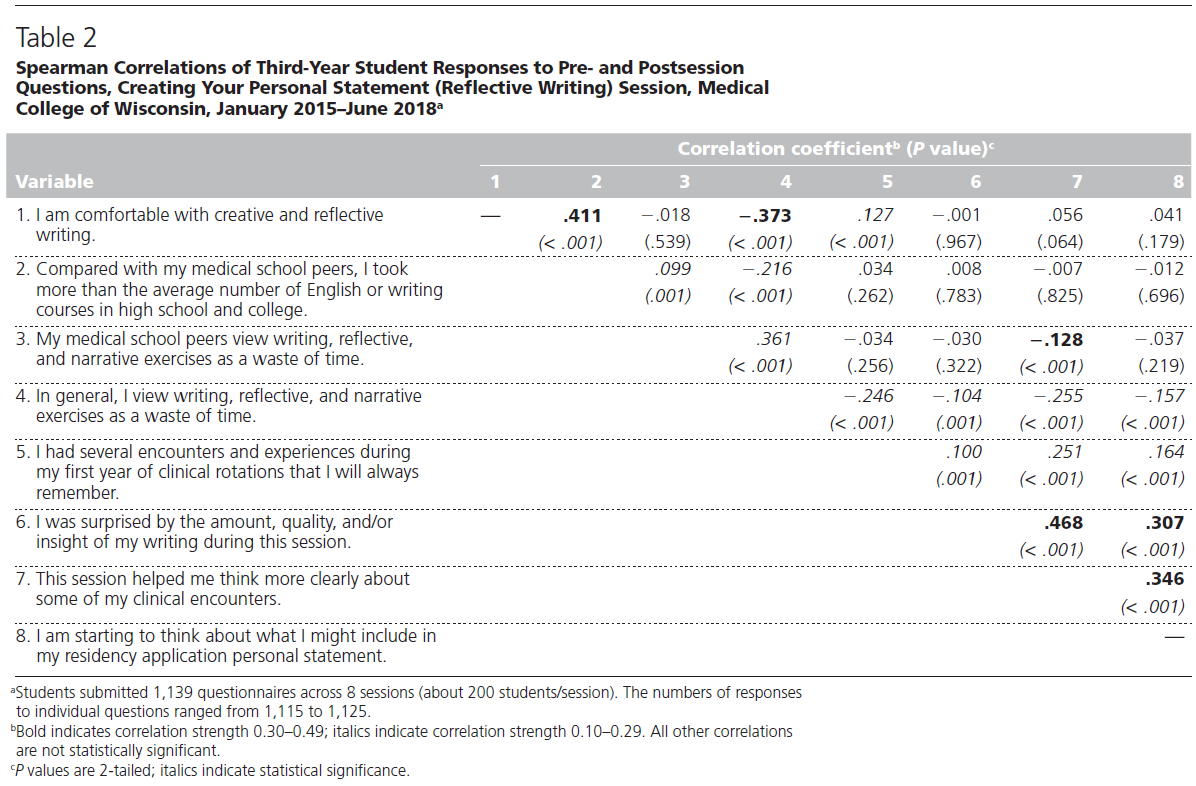

Spearman 상관관계(표 2)를 사용하여 우리가 발견한 가장 강력한 관계 중 하나는 [고등학교와 대학에서 더 많은 영어 또는 쓰기 수업을 듣는 것으로 보고된 학생]들이 쓰기, 성찰, 서술 연습을 [시간 낭비로 볼 가능성이 적다]는 것이다. 또한 이 학생들은 창의적이고 성찰적 글쓰기에 더 익숙했다. 이 세션이 임상적 만남에 대해 명확하게 생각하는 데 도움이 되었다고 보고한 학생들은 그들의 글의 양, 질, 그리고/또는 통찰력에 대해 동료들보다 더 많이 놀라고 있었다. 다가올 personal statements에 대해 생각하고 있다고 보고한 학생들은 [그들의 글쓰기의 질에 놀랐고, 그 세션이 그들의 임상적인 만남 중 일부에 대해 더 명확하게 생각하는 데 도움을 주었다]는 특성을 동료들보다 더 많이 보였다.

Using Spearman correlations (Table 2), one of the strongest relationships we found was that students who reported taking more English or writing classes in high school and college than their peers were less likely to view writing, reflective, and narrative exercises as a waste of time; these students were also more comfortable with creative and reflective writing. Students who reported that the session helped them think clearly about clinical encounters were more likely than their peers to be surprised by the amount, quality, and/or insight of their writing. Students who reported that they were thinking about their upcoming personal statements were more likely than their peers to be surprised by the quality of their writing and to indicate that the session helped them think more clearly about some of their clinical encounters.

우리가 발견한 더 약하지만 여전히 중요한 연관성은 [동료들보다 더 많은 영어나 쓰기 수업을 듣는다고 보고한 학생들]이 [동료들이 쓰기, 성찰, 서술 연습을 시간 낭비로 간주한다고 믿는 경향]이 [더 강하다]는 것이다. [글쓰기를 가장 편안하게 생각한 학생들]은 그들이 항상 기억할 것이라고 믿었던 초기 임상적 만남을 여러 번 경험했을 가능성이 더 높았다. 그들의 초기 임상 경험 중 몇 가지를 항상 기억할 것이라고 믿는 학생들은 그들의 글쓰기의 양, 질, 그리고/또는 통찰력에 더 많이 놀라고, 그 세션이 그들의 임상 경험에 대해 더 명확하게 생각하고 그들의 개인적인 진술에 대해 생각하는 데 도움을 주었다고 믿는다.

Weaker but still significant associations we found included that the students who reported taking more English or writing classes than their peers were more likely to believe that their peers viewed writing, reflective, and narrative exercises as a waste of time. The students who were most comfortable with writing were more likely to have had several initial clinical encounters they believed they would always remember. Students who reported believing that they would always remember several of their initial clinical experiences were more likely to be surprised by the amount, quality, and/or insight of their writing, believe that the session helped them think more clearly about their clinical experiences, and be thinking about their personal statements.

반대로 [성찰적 글쓰기를 시간 낭비로 보는 학생들]은 [또래 친구들도 같은 생각을 한다고 믿는 경향]이 더 높았다. 게다가, 그들은 그들의 동료들보다 영어와 글쓰기 수업을 덜 들었다고 믿는 경향이 더 있었다; 자신의 초기 임상적 만남들 중 몇 가지를 항상 기억할 것이라고 믿는 경향이 더 적었고, [자신의 글쓰기의 양, 질, 통찰력에 덜 놀라는 경향]이 있었다. 이들은 이 세션이 임상적인 만남에 대해 명확하게 생각하는 데 유용하다고 생각할 가능성도 낮고, 개인적인 진술에 대해 생각할 가능성도 적었다.

Conversely, students who viewed reflective writing as a waste of time were more likely to believe that their peers felt the same way. In addition, they were more likely to believe that they took fewer English and writing classes than their peers; were less likely to believe they would always remember several of their initial clinical encounters; were less likely to be surprised by the amount, quality, and/or insight of their writing; were less likely to believe that the session was useful in clearly thinking about clinical encounters; and were less likely to be thinking about their personal statements.

1월(중년)과 6월(3학년 말) 세션에서 서로 다른 반응을 이끌어낸 질문은 8번, "전공의 지원 개인 진술에 무엇을 포함시킬지 생각하기 시작했다"는 질문뿐이었다. ERA 마감일이 다가올수록 학생들은 개인 진술에 대해 생각할 가능성이 더 높았다. Mann-Whitney U-testing은 다른 모든 질문에 대한 응답이 세션 간에 안정적이라는 것을 보여주었다.

The only question that elicited different responses between the January (midyear) and June (end-of-third-year) sessions was question 8, “I am starting to think about what I might include in my residency application personal statement,” confirming that students were more likely to be thinking about their personal statements as the ERAS deadline approached. Mann–Whitney U-testing demonstrated that responses to all the other questions were stable between the sessions.

2018년에는 학생들에게 3학년 때 반성적인 활동(쓰기 등)을 한 적이 있는지 묻는 질문을 추가했다. 이 질문에 응답한 280명의 학생 중 105명(38%)이 일부 성찰적이거나 창의적인 활동을 보고했다.

In 2018, we added a question asking students if they had done any reflective activity (writing or otherwise) during the third year. Of the 280 students who responded to this question, 105 (38%) reported some reflective or creative activity.

세션이 끝날 때 모인 익명의 서면 의견은 성찰적인 쓰기 세션을 지속하는 데 도움이 되었습니다. 338건의 댓글 중에서,

275명(81%)이 긍정적이었습니다(예: "대단한 세션!", "생각을 말로 표현하는 멋진 방법"), 18명(5%)은 부정적이었다(예: "글을 쓰기에는 너무 길다. "수갑 터널" "어떻게 이것이 긍정적인 경험이 될 수 있을까?" 그리고 44명(13%)이 제안을 했다(예: "반성적이거나 서술적인 글쓰기에 대해 더 많이 알려주세요" "연초에 이것을 해라.").

Written, anonymous comments gathered at the end of the sessions were supportive of continuing the reflective writing sessions (see Supplemental Digital Appendix 2 at https://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A808). Of the 338 comments received, 275 (81%) were positive (e.g., “Great session!” “Cool way to put thought into words”), 18 (5%) were negative (e.g., “Too long to write. Carpal tunnel.” “How could this be a positive experience?”), and 44 (13%) offered suggestions (e.g., “Say more about reflective or descriptive writing.” “Do this earlier in the year.”).

이 연구의 잠재적 한계는 다음을 포함한다

- (1) 검증되지 않은 설문지를 사용하여 하나의 캠퍼스에서만 수행되었습니다

- (2) 표본 크기가 크면 통계적으로 유의한 연관성 중 일부는 중요하지 않을 수 있습니다.

Potential limitations with this study include that

- (1) it was performed at only one campus using nonvalidated questionnaires, and

- (2) given the large sample size, some of the statistically significant associations might be unimportant.

다음 단계

Next Steps

글쓰기를 요청받은 시간에 대한 학생들의 서면 의견을 검토한 결과, 2019년에 우리는 자유 글쓰기 연습을 위한 완벽한 기간을 아직 정하지 못했지만 세션의 [성찰적 글쓰기 부분을 10분으로 단축]했다. 우리는 또한 [워밍업 "재미있는" 글쓰기 연습]을 학생들을 [서사 의학 기술에 노출시키기 위한 독서 연습]으로 대체했다: 우리는 [짧은 한 구절의 소설이나 에세이]를 함께 읽고, 학생들에게 [소그룹 토론에 참여]하도록 한 다음, 학생들에게 [독서의 "영항 속에서" 즉각적인 글을 쓰게] 했다. 나머지 세션은 그대로 유지되었다. 서면 댓글을 바탕으로 한 밀착독서 경험이 호평을 받았다.

Based on our review of the students’ written comments regarding the length of time they were asked to write, in 2019 we shortened the reflective writing portion of the sessions to 10 minutes, although we have yet to settle on the perfect duration for the free-writing exercises. We also replaced the warm-up “fun” writing exercise with a close-reading exercise5,6 to expose students to narrative medicine techniques: We read a short passage of fiction7,8 or an essay9 together, asked the students to engage in small-group discussions, and then had the students write to a prompt “in the shadow” of the reading. The rest of the session remained the same. Based on written comments, the close-reading experience was well received.

ERAS 제출 마감일 몇 주 전에 4학년 학생들에게 동료-편집 레지던트 애플리케이션 개인 진술 작성자 워크숍을 계속 제공하고 있습니다. 이러한 워크샵의 조합은 각 학생들에게 개인적인 진술에 대해 작업할 수 있는 여러 기회를 제공하고, 바라건대, 의미 있는 개인 및 그룹 성찰에 참여할 수 있는 기회를 제공합니다.

We continue to offer our peer-editing Residency Application Personal Statement Writers Workshops to the fourth-year students in the weeks before the ERAS submission deadline. The combination of these workshops offers each student multiple opportunities to work on their personal statements and, hopefully, engage in meaningful individual and group reflection.

우리는 [성찰적 글쓰기와 독서 활동]을 [그룹 환경에 통합]한 3학년 각 세션이 [임상 환경에서 서사적 순간]을 더 잘 이해하면서, 학생들에게 [자신의 경험에 대해 생각하고 쓸 수 있는 사적인 장소]를 제공하기를 바란다. 이 세션은 다음과 같은 두 가지 목표를 달성하려고 시도합니다: [교직원들]은 학생들이 좀더 성찰적이 되기를 바라고, [학생들]은 그들의 개인적인 진술을 시작하고 싶은 욕구가 있다. 학생들은 레지던트 신청서 개인 진술을 곰곰이 생각하면서, 초기의 필수임상실습에 몰입하기 때문에 타이밍으로는 최적이다. 이 접근법이 모든 의대생들(반성적이고 비반성적)이 배려심 있고, 동정심 있고, 유능하고, 통찰력 있는 의사가 되기 위한 여정을 위해 준비한다는 더 큰 목표에 어떻게 부합하는지 알아보기 위해 더 많은 데이터가 필요하다.

We hope that each of our third-year sessions, incorporating reflective writing and close-reading activities in a group setting, offers students a private place to think and write about their experiences while better understanding narrative moments in clinical settings. These sessions attempt to meet twin goals: Faculty hope that the students become more reflective, and the students have a desire to kick-start their personal statements. The timing is optimal since students are immersed in early, required clinical rotations while pondering their residency application personal statements. More data are needed to learn how this approach fits with the larger goal of equipping all medical students—reflective and unreflective, alike—for their journeys toward becoming caring, compassionate, competent, and insightful physicians.

Acad Med. 2020 Jun;95(6):882-887. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003241.

Creating Reflective Space for Reflective and "Unreflective" Medical Students: Exploring Seminal Moments in a Large-Group Writing Session

PMID: 32101930

Abstract

Problem: Reflection is a critical skill for all physicians, but some busy medical students describe themselves as "unreflective." The authors sought to provide all third-year medical students at the Medical College of Wisconsin (MCW) with opportunities to explore seminal clinical and personal moments through reflective writing during workshops on preparing a personal statement for the Electronic Residency Application Service.

Approach: The authors developed and facilitated semiannual 1.5- to 2-hour sessions (January and June) for MCW third-year medical students (about 200 per class), pairing information on personal statements with reflective writing and group reflection activities. Students wrote reflectively but were not required to share their writing with peers or faculty. They discussed insights gleaned during the writing process in small groups and with the class. They completed pre- and postsession questions on an anonymous questionnaire.

Outcomes: Eight all-class sessions were held between January 2015 and June 2018. Students completed 1,139 of 1,600 questionnaires (completion rate of approximately 71%). They misperceived their peers' views of reflective activities. Twice as many students agreed their peers felt writing, reflective, and narrative exercises were a waste of time as they themselves did (39% vs 19%). While 42% entered the session comfortable with creative writing, 57% were surprised by the amount, quality, and/or insight of their writing during the session and 77% agreed the session helped them think more clearly about clinical encounters. Students who believed reflective writing was a waste of time were more likely to believe their peers felt that also, and they were less likely to believe the session helped them reflect on clinical experiences. Most written comments were positive.

Next steps: To expose students to narrative medicine techniques, the authors added a close-reading exercise and shortened the reflective writing activity in 2019, hoping this would better equip all students for their journeys.