주요 교육과정 개편 기저의 사회적 메커니즘 탐색을 위한 보르도의 개념을 적용한 질적 연구(Med Teach, 2022)

A qualitative study applying Bourdieu’s concept of field to uncover social mechanisms underlying major curriculum reform

Anne Franz , Miriam Alexander, Asja Maaz and Harm Peters

서론

Introduction

의대의 주요 커리큘럼 개편은 기관과 관련자 모두에게 복잡하고 도전적인 과정이다. 기획 위원회Planning committees는 새로운 커리큘럼에 대해 구상되는 주요 변화, 즉 형태, 내용 및 전달의 변화를 설계하는 데 핵심적인 역할을 한다. 그러한 위원회의 구성원들은 종종 [업무의 본질적인 복잡성]과 [프로세스의 역동성]에 압도당하고, 위원회 구성원과 그룹 간의 [상충되는 상호작용과 교묘한 계책manoeuvring]으로 특징지어지기 때문에 [계획 영역을 탐색하는 데 어려움]을 겪는다. 이러한 상호작용과 역학의 사회적 특성, 관련 메커니즘 및 주요 교육과정 개혁의 청사진에 대한 잠재적 영향에 대해 지금까지 거의 관심이 없었다. 본 정성적 연구의 목적은 [사회이론], 즉 [부르디외의 장개념concept of field]에서 도출된 잘 확립된 개념렌즈를 통해 우리 기관의 주요 교육과정 변화 계획과정에 대한 위원회 구성원들의 인식과 경험을 분석하고 해석하는 것이다.

Major curriculum reform at medical schools is a complex, challenging process, both for the institution and for the people involved (Bland et al. 2000; Hawick et al. 2017; Gonzalo et al. 2018; Maaz et al. 2018; Reis 2018; Velthuis et al. 2018). Planning committees play a key role in blueprinting the major changes envisaged for the new curriculum: changes to its form, content, and delivery (Hendricson et al. 1993; Whalen 1993). Members of such committees often feel overwhelmed by the inherent complexity of the task and the dynamics of the process, and they struggle with navigating the planning arena, as it is characterized by conflictful interactions and manoeuvring between the committee members and groups (Bland et al. 2000; Velthuis et al. 2018). Little attention has been paid so far to the social nature of these interactions and dynamics, the mechanisms involved and their potential impact on the blueprint for major curriculum reform. The purpose of this qualitative study is to analyse and interpret the perceptions and experiences of committee members with respect to the planning processes of a major curriculum change at our institution through a well-established conceptual lens derived from social theory, namely, Bourdieu’s concept of field.

주요 교육과정의 변화를 가져오는 복잡성은 [이미 복잡한 하나의 시스템(교육과정)]을 [다른 복잡한 시스템(기관)] 내에서 변경하려는 시도에 부분적으로 뿌리를 두고 있으며, 이 둘은 밀접하게 얽혀 있다. 주요 교육과정 개혁은 중앙 교육과정 관리, 교육위원회, 교수진과 학생 단체의 대표, 그리고 기관의 연구 활동과 환자 치료와 더 연결된 많은 수의 기관과 임상 부서와 같은 기관의 여러 조직 구조에 영향을 미친다.

The complexity of bringing about major curriculum change is rooted in part in the attempt to change one already complex system (the curriculum) within another complex system (the institution), both being closely interwoven (Maaz et al. 2018). Major curriculum reform affects multiple organizational structures in an institution, such as central curriculum management, educational committees, representation of the faculty and student body, and a large number of institutes and clinical departments that are further linked to the research activities and patient care of the institution.

의료 교육과정 개혁을 제정하기 위해, 기관들은 교육과정 계획 위원회를 설치했다. 이들은 규모는 다양하지만 일반적으로 기초과학 및 임상 교수진 및 교사, 학생, 교육과정 개발 인력 및 관리 인력과 같은 다양한 이해관계자와 전문가를 통합하는 것을 목표로 한다. 그래야만 [관련 조직의 복잡성을 해결]하고, 개혁을 위해 기관 단체로부터 [필요한 지지와 참여를 얻는 것]이 가능하기 때문이다. 위원회 구성원들은 다양한 수준의 [전문적인 사회화와 문화]를 가지고 있으며, 커리큘럼 변화에 대한 [다양한 기대]를 가지고 있는 매우 다양한 그룹을 대표한다.

To enact medical curriculum reform, institutions have put in place curriculum planning committees (Bland et al. 2000; Borkan et al. 2018; Nousiainen et al. 2018). These vary in size but generally aim to incorporate various stakeholders and experts, for instance, basic science and clinical faculty and teachers, students, curriculum development staff, and management personnel, to tackle the organizational complexity involved as well as gain the support and buy-in needed from institutional groups for the reform. Committee members represent a very diverse group with different levels of professional socialization and cultures and with divergent expectations of the curricular changes (Harden 1986; Nordquist and Grigsby 2011; Borkan et al. 2018; Velthuis et al. 2018).

위원회 구성원과 기관은 두 개의 문헌을 활용하여 의과대학의 주요 커리큘럼 개혁을 제정할 수 있습니다.

- (1) 결과 기반 프로그램 설계 및 공유 경험과 같은 커리큘럼 개발

- (2) 리더십을 포함하여 변화를 촉진하는 데 사용되는 조직 변경 관리 접근 방식 및 도구.

우리 기관은 최근 이처럼 대대적인 교육과정 개편 과정을 거쳤다. 이 두 개의 주요 기둥 위에 세워지는 동안, 우리는 [갈등, 저항, 자아 투쟁, 개인과 집단에 의한 전술적 묘책]과 같은 [다양한 사회 현상]이 모든 과정에 드리워졌다는 것을 경험했다. 이러한 경험은 문헌에 반영되어 있지만, 기존 연구는 그것의 본질과 잠재적인 근본적인 메커니즘을 잘 보여주지 못하고 있다. 따라서 본 논문에서는 사회 이론의 개념이 커리큘럼 계획 위원회에서 발생하는 프로세스를 설명, 분석 및 해석하는 보완 렌즈 역할을 할 수 있다는 생각을 진전시킨다.

Committee members and institutions can draw on two bodies of literature to enact major curriculum reform at medical schools:

- (1) curriculum development, i.e. outcome-based programme design and shared experiences (Mennin and Krackov 1998; Bland et al. 2000; Muller et al. 2008; Yengo-Kahn et al. 2017; Marz 2018; Reis 2018), and

- (2) organizational change management approaches and tools used to facilitate change, including leadership (Loeser et al. 2007; Arja et al. 2018; Maaz et al. 2018; McKimm and Jones 2018; Velthuis et al. 2018; Banerjee et al. 2019).

Our institution recently went through such a major curriculum reform process (Maaz et al. 2018). While building on these two major pillars, we experienced that the whole process was overshadowed by a range of social phenomena, such as conflicts, resistance, ego struggles, and tactical manoeuvring by individuals and groups. This experience is echoed in the literature (Mennin and Krackov 1998; Bland et al. 2000; Hawick et al. 2017; Reis 2018; Velthuis et al. 2018), but the existing research does not well illuminate it´s nature and the potential underlying mechanisms. In the present article, we therefore advance the idea that concepts from social theory may serve as a complementary lens to describe, analyse, and interpret the processes occurring in a curriculum-planning committee.

잘 확립된 [사회 실천 이론]은 [피에르 부르디외]에서 유래하며, 그의 [분야field] 개념은 교육과정 계획 위원회에서 일어나는 사회 실천에 적용될 수 있다. 이 이론은 커리큘럼 변화를 사회 구조, 관계 네트워크, 역사적 맥락에 의해 형성되는 사회 현상으로 프레임화한다. Bourdieu의 이론은 [실무자에게는 '보이지 않는invisible' 커리큘럼을 형성하는 구조적인 힘]을 발견하는 것을 돕는다.

부르디외에게 필드는 각 개인이 자원(자본)에 따라 위치를 차지하는 구조화된 사회 공간이다. 자본은 경제적, 문화적, 사회적 성격을 가질 수 있다.

- [경제적 자본]은 재정적, 물질적, 시간적 자원을 포함한다.

- [문화적 자본]은 교육을 통해 발생하는 자원을 설명한다. 내재화 된 것(지식, 기술 및 경험)과 제도화 된 것(자격증, 직함)이 모두 가능하다.

- [사회적 자본]은 관계망(개인적 인맥 또는 집단 내 구성원 자격)에서 나오는 자원이다.

A well-established theory of social practice derives from Pierre Bourdieu and his concept of field (Bourdieu 1975) could apply to the social practices that take place in curriculum planning committees. The theory frames curriculum change as a social phenomenon that is shaped by social structures, networks of relationships and historical contexts. Bourdieu’s theory helps medical schools to uncover ‘the structural forces shaping their curriculum—that may be 'invisible' to practitioners’ (Albert and Reeves 2010). For Bourdieu, a field is any structured social space, in which each individual occupies a position depending on his/her resources (capital) (Bourdieu 1986). Capital can be of an economic, cultural or social nature.

- Economic capital includes financial, material and time resources.

- Cultural capital describes resources that arise through education. It can be incorporated (knowledge, skills and experiences) and institutionalized (certificates, titles).

- Social capital is resources that come from relationship networks (personal connections or membership in a group) (Bourdieu 1986).

모든 분야는 [자체적인 규칙과 관행]을 개발하고, [사회적 공간] 내에서 [가치 있는 것]으로 인식되는 [자원에 대한 경쟁]에 의해 [개인이나 집단의 상호작용]이 형성되는 [권력 투쟁의 장]을 나타낸다. [에이전트]들은 그 분야에서 그들의 사회적 지위를 유지하거나 높이기 위해 자본을 놓고 경쟁한다. [사회적 지위]는 각각의 자본의 양에 따라 설정되며, 지배적(높은 가치의 자본) 또는 지배적(낮은 가치의 자본)이며 분야 내에서 권력의 분배를 결정한다.

Any field develops its own rules and practices and represents an arena of struggle over power in which the interactions of individuals or groups are shaped by competition over resources recognized as valuable within that social space (Bourdieu 1975, 1990). Agents compete over capital to maintain or elevate their social position within the field. Social positions are established by the respective amount of capital and are either dominating (highly valued capital) or dominated (lowly valued capital) and determine the distribution of power within the field (Bourdieu 1975).

지금까지 몇몇 연구는 의학 교육에서 사회 현상에 대한 우리의 이해를 높이기 위해 부르디외의 사회 실천 개념을 사용했다. Brosnan(2011)은 영국의 의료 교육이 일부 학교는 생물의학을 지향하고 다른 학교는 임상 실습을 지향하는 등 다양한 형태의 자본을 위한 학교 간 경쟁에 의해 형성되었음을 나타낸다. 발머 외 연구진(2015)은 의대생들이 학부 의학교육에서 전환을 탐색하는 방법을 설명하기 위해 분야, 자본 및 습관에 대한 부르디외의 개념을 사용했다.

To date, a few studies have used social practice concepts from Bourdieu to enhance our understanding of social phenomena in medical education. Brosnan (2011) indicates that medical education in the United Kingdom was shaped by competition among schools for different forms of capital, such that some schools oriented towards biomedical sciences and others oriented towards clinical practice. Balmer et al. (2015) employed Bourdieu’s concepts of field, capital, and habitus to explain how medical students navigate transitions in undergraduate medical education.

이 경험적이고 질적인 인터뷰 연구의 목적은 [주요 교육과정 개편을 계획할 때 우리 기관의 위원회에서 발생한 복잡한 사회적 과정]을 질적으로 조명하고 분석하기 위해 개념 렌즈로서의 부르디외의 현장 개념을 적용하는 것이다. 우리는 교육과정 개발과 변화관리에서 도출된 관점을 확대하고, 다른 보완적 관점을 도입하고자 한다. 관련된 사회 메커니즘을 이해하는 것은 기관과 위원회 구성원들이 주요 교육과정 개혁의 본질적인 과제를 더 잘 탐색하는 데 도움이 될 수 있다.

The aim of this empirical, qualitative interview study is to apply Bourdieu’s concept of field as a conceptual lens to qualitatively illuminate and analyse the complex social processes that occurred in a committee at our institution when planning a major curriculum reform. We want to expand perspectives derived from curriculum development and change management and to introduce a different, complementary perspective. Understanding the social mechanism involved may help institutions and committee members to better navigate the inherent challenges of major curriculum reform.

방법들

Methods

설정

Setting

본 연구는 독일 베를린(Charité)의 Charité – Universitätsmediz에서 수행되었다. 학부 의학 프로그램(MCM(Modular Curriculum of Medicine)은 6년간 진행되며, 매년 약 320명의 신입생이 2회 등록한다. 교육은 100개 이상의 이론 및 임상 부서에서 이루어지며 2,000명 이상의 교수진이 참여한다.

This study was conducted at the Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin (Charité), Germany. Its undergraduate medical programme (Modular Curriculum of Medicine (MCM)) spans six years, and approximately 320 new students are enrolled twice each year. Teaching occurs across more than 100 theoretical and clinical departments and involves more than 2,000 teaching faculty members.

학부 의학 교육과정의 주요 개혁

Major reform of the undergraduate medical curriculum

2010년부터, 전통적인 분야 기반 프로그램은 교수진 전체의 계획 및 실행 과정을 통해 완전히 통합된 역량 기반 커리큘럼으로 학기별로 대체되었다. 개혁 과정과 결과는 최근 ASPIRE에서 커리큘럼 개발 및 학생 참여 부문 우수상을 수상했습니다. 개혁의 필요성은 주로 1980년대 베를린에서 시작된 학생 시위와 장기적인 참여에 의해 주도되었다. 새로운 커리큘럼은 문제 기반 학습(PBL), 의사소통 훈련, 강의 감소와 같은 [소그룹 학습의 상당한 증가]를 포함했다. 개혁은 전체 의료 프로그램과 새로운 교육 형식의 설계 및 전달에 대한 중앙 집중적인 책임과 함께 커리큘럼 관리 관련 직원의 도입과 성장을 수반했다. 새 교육과정의 청사진은 새 교육과정이 시행되기 1년 전에 설립된 학장 주도의 기획위원회에 의해 개발되었다.

Starting in 2010, the traditional, discipline-based programme was replaced term-by-term with a fully integrated, competency-based curriculum through a faculty-wide planning and implementation process (Maaz et al. 2018). The reform process and outcome were recently recognized by an ASPIRE to Excellence Award in Curriculum Development and Student Engagement (www.aspire-to-excellence.org). The need for reform was largely driven by student protests and a long-term engagement that started in the 1980s in Berlin (Maaz et al. 2018). The new curriculum involved substantial increases in small-group learning, such as problem-based learning (PBL); communication training; and a reduction in lectures. The reform was accompanied by the introduction and growth of curriculum management-related staff, with centralized responsibility for the design and delivery of the whole medical programme and the new teaching formats. The blueprint for the new curriculum had been developed by a dean-led planning committee that was established the year before the new curriculum began to be implemented.

주요 교육과정 개편의 대대적인 개혁 필요성

Need for a major reform of the major curriculum reform

5학기까지 MCM을 기획하고 시행하던 2013년 초, 주요 교육과정 개편에 대한 대대적인 개혁이 필요하다는 점이 분명해졌다. 이는 새로운 교육과정에 따른 교수 및 연구에 있어 조직적, 로지스틱적 타당성 문제뿐만 아니라 독일의 학부 의학교육과 관련된 법적, 재정적 규정의 최근의 명확화를 준수할 필요성에 근거를 두었다.

In early 2013, when the MCM had been planned and implemented until the fifth semester, it became clear that a major reform of the major curriculum reform was necessary. This was grounded in the need to comply with recent clarification in the legal and financial regulations related to undergraduate medical education in Germany as well as organizational and logistic feasibility issues in teaching and studying under the new curriculum.

주요 개혁 청사진을 위한 기획위원회 설치

Installing a planning committee for blueprinting the major reform

2013년 10월, 현재 진행 중인 주요 개혁의 청사진을 개발하기 위한 기획 위원회가 구성되었다. 위원은 MCM 연구위원회가 광범위한 이해관계를 대표하는 '유엔 접근법'에 따라 임명하였다(Harden 1986). 모든 위원회 구성원(n = 18)은 2010년에 시작된 첫 번째 주요 개혁 과정에 참여했다. 위원회는 학과 대표자(n = 8, DR), 학생 대표자(n = 4, SR), 교육과정 관리 직원 대표자(n = 6, CR)의 3개 주요 그룹으로 구성되었다. 많은 사람들이 MCM 커리큘럼과 관련된 다른 위원회(교수 위원회, MCM 연구 위원회, MCM 평가 위원회)에서 병행했다.

In October 2013, a planning committee was formed to develop a blueprint for the major reform of the ongoing major reform. Committee members were appointed by the MCM study committee according to the ‘United Nations Approach,’ in which a wide range of interests is represented (Harden 1986). All committee members (n = 18) had been involved in the first major reform process that started in 2010. The committee consisted of three main groups: department representatives (n = 8, DR), student representatives (n = 4, SR), and curriculum management staff representatives (n = 6, CR). Many served in parallel on other committees related to the MCM curriculum (faculty council, MCM study committee, and MCM assessment board).

이 청사진 위원회의 임무는 2010년에 시작된 새로운 통합 역량 기반 교육과정의 의도와 원칙을 가능한 한 많이 유지하는 것이었다. 조직 및 물류 문제를 해결하는 것 외에도, 이번 개혁은 교직원의 부서별 재정 예산을 약 10% 절감해야 했다. 위원회 과정에서 강의(+49%), 침대 옆 강의(+41%), 실험실 실습(+6%)이 증가했고, PBL(-36%), 커뮤니케이션 교육(-29%), 비대학 초등 돌봄 배치(-84%)가 감소했다. 샤리테에서, 부서의 교직원들의 자금 조달은 실제로 완료된 수업 시간 수에 직접 기초하며 형식 수정 요소를 포함한다. 예를 들어, 교정계수는 강의의 경우 1, PBL의 경우 0.5이므로, 1시간 강의는 PBL 촉진의 2배의 비율로 보상된다.

Task of this blueprinting committee was to retain as much as possible of the intentions and principles of the newly integrated, competency-based curriculum as launched in 2010. In addition to addressing organizational and logistical matters, this reform of the reform had to reduce the budget for departmental financing of the teaching staff by approximately 10%. The committee process resulted in increases in lectures (+49%), bedside teaching (+41%, requested by regulations), and lab practicums (+6%) and decreases in PBL (–36%), communication training (–29%), and placements in non-university primary care (–84%). At the Charité, the financing of the department’s teaching staff is directly based on the number of teaching hours actually completed and includes a format correction factor. For instance, the correction factor is 1 for lectures and 0.5 for PBL; thus, 1 hour of lecturing is compensated at twice the rate as 1 hour of PBL facilitation.

위원들은 2주에 한 번씩 3~4시간 동안 만났다. 이 과정은 2014년 5월 설계도가 MCM 연구위원회에 넘겨지기까지 7개월이 걸렸다. 설계도는 2014년 8월에 승인되었고 그 후 MCM의 연구 규정으로 이관되었다.

The committee members met every two weeks for three to four hours. The process took seven months until the blueprint was handed over to the MCM study committee in May 2014. The blueprint was approved in August 2014 and subsequently transferred into the study regulations for the MCM.

리서치 디자인.

Research design

질적 접근을 통해 주요 교육과정 개편의 주요 청사진을 마련하기 위한 담당 교육과정기획위원들의 인식과 경험을 일련의 개별 면접에서 도출하였다. 그 녹취록들은 그 후에 내용 분석을 받았다. 연구 프로토콜은 Charité 데이터 보호 사무소(No. 628-15)와 Charité Ethics Board(No. EA4/096/15)의 승인을 받았다.

With a qualitative approach, the perceptions and experiences of the curriculum-planning committee members in charge for blueprinting the major reform of the major curriculum reform were elicited in a series of individual interviews. The transcripts were subsequently subjected to content analysis. The study protocol received approval from the Charité data protection office (No. 628-15) and Charité Ethics Board (No. EA4/096/15).

스터디 참가자 및 인터뷰 절차

Study participants and interview procedure

우리는 교육과정 기획위원회의 모든 위원들에게 대면 면접에 참여할 것을 요청하는 이메일을 보냈다. 한 동료가 2015년 12월부터 2016년 6월까지 인터뷰를 진행하고 녹음했습니다. 인터뷰는 우리가 그룹(AM, HP)에서 상세히 설명하고 논의한 부르디외의 이론(부록 1번)에 기초한 반구조적 인터뷰 가이드를 따랐다. 인터뷰는 45분에서 120분, 중간값은 66분이었다. 우리는 음성 기록을 익명화된 방식으로 정확하게 전사했다.

We sent emails to all members of the curriculum planning committee inviting them to take part in a face-to-face interview. One colleague conducted and audio-recorded the interviews between December 2015 and June 2016. The interviews followed a semi-structured interview guide based on Bourdieu’s theory (Supplementary Appendix no. 1), which we elaborated and discussed in a group (AM, HP). Interviews lasted from 45 to 120 minutes with a median of 66 minutes. We transcribed the audio records verbatim in an anonymized manner.

데이터 분석

Data analysis

Mayring(2014)에 따라 구조화 콘텐츠 분석과 결합된 요약을 포함하는 체계적인 귀납적-귀납적 범주 할당 접근 방식을 통해 전사를 분석했다. 이 접근법은 해석과 구성(유도)의 과정을 통해 데이터에서 범주가 나타날 수 있고, 부르디외의 분야 개념과 관련된 범주가 분석 과정(추출)에도 통합될 수 있는 가능성을 허용했다. 두 명의 연구원(AF, MA)이 모든 데이터 자료를 코드화했습니다. 두 연구원은 합의가 도출될 때까지 서로의 코딩에 대해 지속적으로 질문하고 토론하는 등 전 과정을 분석하면서 협업했다. 연구팀은 해석(AF, MA, AM, HP)에 대해 논의했다.

We analysed the transcriptions through a systematic, inductive–deductive category assignment approach involving summarizing combined with structuring content analysis, following Mayring (2014). The approach allowed for the possibility that categories could emerge from the data through a process of interpretation and construction (induction) and that categories related to Bourdieu’s concept of field could be integrated into the analytic process (deduction) as well. Two researchers (AF, MA) coded all of the data material. Both researchers collaborated while analysing the entire process by constantly questioning and discussing each other’s codings until an agreement was reached. The research team discussed interpretations (AF, MA, AM, HP).

[프로세스의 첫 번째 부분]에서는 데이터 자료에서 [하위 범주를 생성]하기 위해 귀납적 접근 방식으로 요약 내용 분석을 사용하여 모든 전사를 설명적으로 분석했다. 여기에는 Mayring(2014)에서 채택된 다음 단계가 포함되었다.

In the first part of the process, we analysed all transcriptions descriptively using summarizing content analysis with an inductive approach to generate subcategories from the data material. This involved the following steps adapted from Mayring (2014).

- 문구의 핵심 의미를 필터링하기 위해 본문을 줄이고 장식적이거나 필러적인 단어를 생략하여 언어학적으로 일관된 수준으로 패러프레이징하는 행위

Paraphrasing on a linguistically consistent level by reducing the text and leaving out decorative or filler words to filter the core meaning of the phrases; - 보다 일반적이고 추상적이며 상위적인 의미를 갖는 데이터의 패러프레이즈를 생성하여 일반화하는 것

Generalizing by creating paraphrases of the data with more general, abstract, and superordinate meanings; - 동의어, 중요하지 않은, 비어 있는 패러프레이즈를 삭제하여 첫 번째 축소를 수행한다.

Performing a first reduction by crossing out synonymous, insignificant, and empty paraphrases; and - 동일하거나 유사한 여러 개의 파라프레이즈를 하나의 파라프레이즈로 결합하고, 초기 하위 카테고리를 생성하여 두 번째 감소를 수행한다.

Performing a second reduction by combining multiple identical or similar paraphrases into one paraphrase and generating initial subcategories.

두 번째 부분에서는 구조화된 내용 분석과 연역적 절차를 통해 프로세스의 첫 번째 부분의 결과를 분석적으로 해석적으로 분석했다. 여기에는 Mayring(2014)에서 채택된 다음 단계가 포함되었습니다.

In the second part, we analytically-interpretatively analysed the results of the first part of the process via structuring content analysis and a deductive procedure. This involved the following subsequent steps adapted from Mayring (2014):

- 부르디외의 분야개념에 기초한 범주체계를 개발하고 정의하여, 이론적에 기반한 차원의 결정

Determining theoretically based dimensions by developing and defining a category system based on Bourdieu’s concept of field; - 범주에 대한 정의를 수립하고 앵커 샘플을 검색하여 코딩 지침을 개발하고,

텍스트 구절을 특정 범주의 전형적인 예로 인용하고 코딩 규칙을 정의한다.

Developing a coding guideline by establishing definitions for the categories and searching for anchor samples,

citing text passages as typical examples of the particular category and defining coding rules; - 기존에 귀납적으로 개발된 하위범주를 부르디외의 이론에 따라 연역적으로 정의된 주요범주와 일치시키는 것. 필요하다면 코딩규칙을 지속적으로 확인하고 수정하는 것이다.

Matching the previously inductively developed subcategories to the deductively defined main categories according to Bourdieu’s theory by constantly checking and revising the coding rules when necessary. - 요약 및 구조 분석의 주요 범주와 하위 범주를 하나의 범주 시스템으로 병합하여 프로세스를 완료합니다. 부록 2번은 Mayring에 따른 분석 과정의 예를 보여준다.

Completing the process by merging both the main categories and subcategories of the summarizing and structuring analysis into one category system. Supplementary Appendix no. 2 shows an example of the analysis process according to Mayring.

마지막으로, 관련 텍스트 구절은 원어민이 영어로 번역하고 두 명의 연구원(AF, HP)이 교차 점검했다. 모든 인용구는 익명화되었고 성별을 중립적으로 만들었다. 따옴표는 주 위원회 그룹(DR, SR 또는 CR)을 나타내기 위해 표시됩니다. 서로 다른 사람의 진술을 구별하기 위해 추가 번호가 부여되었다. 예를 들어 DR1은 부서 대표 1을 가리킨다.

Finally, the relevant text passages were translated into English by a native speaker and cross-checked by two researchers (AF, HP). All quotes were anonymized and made gender neutral. Quotes are marked to indicate the main committee group (DR, SR, or CR). An additional number was given to distinguish the statements of different persons: for example, DR1 refers to department representative 1.

결과.

Results

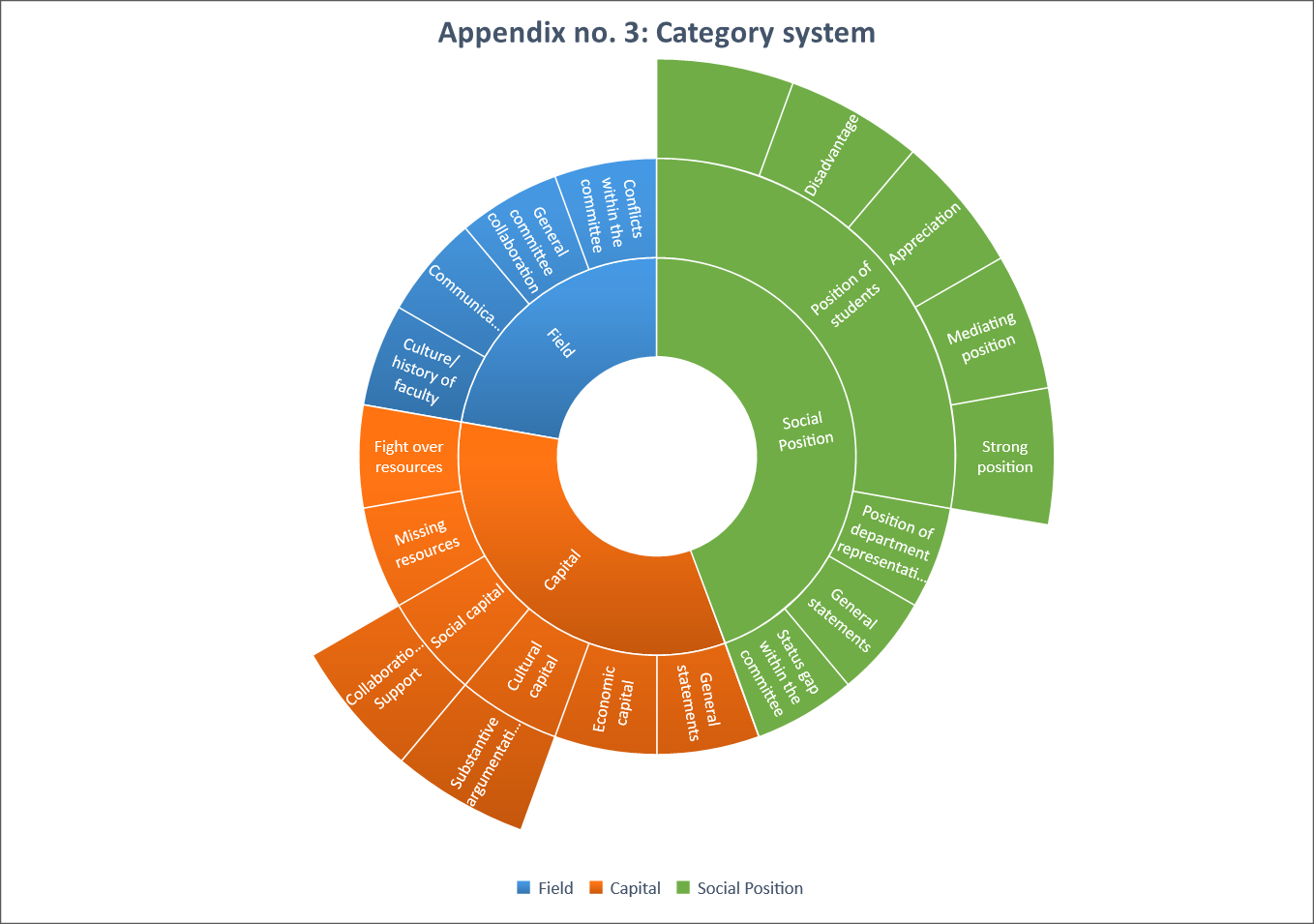

13명의 구성원(5 f/8 m)이 이 연구에 참여했다(기초 및 임상 과학에서 4개의 DR, 4개의 SR, 5개의 CR). 그 결과는 183 DIN A4 페이지의 녹취록을 분석하여 도출되었다. 우리의 내용 분석은 부르디외의 이론에 기초한 3개의 주요 범주와 21개의 하위 범주(부록 3번)를 가진 체계를 도출하였다. 선택한 인용문의 전문은 부록 번호 4에 수록되어 있다.

Thirteen members (5 f/8 m) participated in this study (4 DRs from the basic and clinical sciences, 4 SRs, and 5 CRs). The results were derived by analysing 183 DIN A4 pages of transcripts. Our content analysis resulted in a system with 3 main categories based on Bourdieu’s theory and 21 subcategories (Supplementary Appendix no. 3). The full text of the selected quotes is given in Supplementary Appendix no. 4.

교육과정계획위원회 – 갈등과 경쟁이 치열한 사회 분야

The curriculum planning committee – A social field of intense conflict and competition

위원들은 이 작업을 기획위원회와 '개인적으로 매우 무력감을 느낀 순간'(Q2-DR2)으로 경험했는데, 이는 치열한 갈등과 경쟁이 특징이기 때문이다.

Committee members experienced the work in the planning committee and ‘the whole discussion [as] just very gruelling’ (Q1-CR1) with ‘moments where one personally felt very helpless’ (Q2-DR2), as it was characterized by intensive conflicts and competition.

갈등의 유형과 성격에 대해 한 위원은 '매우 공격적인 논의가 매우 빠르게 전개되었다'(Q3-CR1)와 '일부 교직원들이 개인적인 차원에서도 서로 강하게 공격했다'(…)고 보고했고, 다른 교직원들의 역량을 부정했다'(Q4-SR2)고 보고했다. 다른 위원회 위원은 '모든 사람이 상호 존중과 공정성의 규칙을 준수한다면, 이것은 실제로 문제가 되지 않지만 불행히도 이것은 이상적인 세계에서만 발생한다; 실제로는 항상 그렇지는 않다'고 반성했다(Q5-DR1). '[I]일부는 사실 수준과 개인 수준을 분리할 수 없었다.'(Q3-CM1) 이는 '대부분 소수의 갈등이지만 전체적으로 쉽게 분위기에 부담을 줄 수 있다'(Q3-CR1)는 것이었다. 일부 갈등은 '그런 과정에서 많은 오해'에서 비롯된 것으로 보였고, '소문 공장이 만연하고 불신이 많이 발생했기 때문에'(Q6-CR2) '모든 사람이 같은 수준의 지식에 있었던 것은 아니다'(Q6-CR2). 기존의 갈등이 '다시 불거졌다'(Q2-DR2). '[T]이미 이전에도 다툼이 있었다', '교수진 모두가 서로를 잘 신뢰하고 이해하지 못한다는 것은 비밀이 아니다'(Q4-SR2).

Regarding the type and nature of the conflicts, one committee member reported that ‘very offensive discussions very rapidly developed’ (Q3-CR1) and ‘[s]ome faculty members strongly attacked each other (…) partly also on a personal level, and denied the others’ competencies’ and ‘act[ed] out their animosities’ (Q4-SR2). Another committee member reflected, ‘[i]f everyone adheres to the rules of mutual respect and fairness, then this is actually not a problem, but unfortunately this only happens in an ideal world; in reality, this is not always the case’ (Q5-DR1). ‘[I]t happened that some could not separate the factual level and personal level’ (Q3-CM1). These were ‘mostly conflicts between a few, but those could easily burden the mood overall’ (Q3-CR1). Some conflicts appeared to result from ‘many misunderstandings in such a process,’ and ‘[n]ot everybody was on the same level of knowledge’ (Q6-CR2), as there ‘were rumour mills prevailing and a lot of mistrust that arose’ (Q7-SR2). Pre-existing conflicts ‘erupted again’ (Q2-DR2). ‘[T]here have already been quarrels previously,’ and ‘[i]t’s no secret that not everybody in the faculty trusts and understands each other very well’ (Q4-SR2).

경쟁과 관련하여, 위원회 위원들은 위원회의 작업을 '힘든 싸움'(Q8-DR2), '너무 많은 리소스를 손실하지 않고 그로 인해 어려움을 겪어야 한다'(Q5-DR1)고 설명했습니다. 어떤 이들은 '밤샘 계산'(Q9-CR2)을 했고, 다른 이들은 '특정 마감일에 준비해야 했다; (…) 많은 것들이 일주일 내에 할 수 없었기 때문에 주말로 옮겨야 했다.'(Q10-DR2)를 언급했다. 위원회 내에서 경쟁하는 것을 넘어, 위원들은 '임상 의사들은 시간이 없다; 그들은 환자가 있다'(Q11-SR2)라는 논쟁에서 경쟁하는 사회 분야의 압력을 가했다. 한 임상의는 '나는 지금 나의 진료소로 돌아가야 한다; 내 환자들 중 몇몇은 암으로 고통 받고 있다. 암 진단을 전달해야 하는 세 가지 상담이 앞에 있습니다. 이를 수행할 시간이 없습니다(Q11-SR2).

Regarding competition, the committee members described the work in the committee as a ‘tough fight’ (Q8-DR2); ‘you have to make sure (…) that you don’t lose too many resources and go under with it’ (Q5-DR1). Some did ‘night-long calculations’ (Q9-CR2); others stated, ‘things had to be ready at certain deadlines; (…) many things had to be shifted to the weekend because they were not doable within the week, and they expanded into my spare time’ (Q10-DR2). Beyond competing within the committee, committee members applied pressure from competing social fields in argumentation: ‘Clinicians don’t have time; they have patients’ (Q11-SR2). One clinician said, ‘I have to go back to my clinic now; several of my patients are suffering from cancer. I have three consultations ahead of me where I have to convey to them their cancer diagnoses – I don’t have time for this’ (Q11-SR2).

위원회에서의 논의는 두 층으로 이루어진 토론으로 경험되었다. "앞에서는 사실적인 수준에 대한 많은 논의가 있지만, 그 이면에는 다른 것들이 있다."(Q12-CR1). "나는 그 과정에서, [야망]이 서로 마찰하면서, 아마도 더 잘 인식되고 분명해지며, 특정 시점에서, 사람들은 그 이면에 정말로 무엇이 있는지 깨닫게 될 것이라고 생각한다."(Q13-SR1). "어느 순간, (…) 명확해졌다: 네, 그것은 단지 사실에 관한 것이 아닙니다; 그것은 한 그룹의 정치적 로비에 관한 것입니다. (…) (Q14-SR3). "어떤 토론은 단순히 다른 그룹이 어느 수준에서 주장하는지 모르기 때문에 실패합니다." (Q15-CR1). 그것은 내용이나 관련 수준과 관련하여 사실적인 차원에서 논의되었지만, 사실 그것은 직업에 관한 것이다. 그러나 이것은 말하지 않았다. 그리고 그것은 우리가 내내 행동했던 이 두 계층일 뿐이다'(Q1-CR1).

The discussion in the committee was experienced as a debate on a basis with two layers. ‘There are lots of discussions on the factual level in the foreground, but there are other things behind it’ (Q12-CR1). ‘I think, in the course of the process, the [ambitions] perhaps become more perceptible and evident, as they rub against each other, and at a certain point, one realizes what's really behind it’ (Q13-SR1). ‘At some point, (…) it became clear: ok, it’s not just about the facts; it's about the political lobbying of one group (…)’ (Q14-SR3). ‘Some discussions simply fail because (…) they do not know on which level the other one argues’ (Q15-CR1). It was ‘discussed on a factual level with regards to content or a pertinent level, but in fact it is actually about the jobs. But this has not been said (…). And that is just (…) these two layers on which we acted the whole time’ (Q1-CR1).

커리큘럼 계획 위원회 – 다양한 종류의 자본을 위한 투쟁

Curriculum planning committee – a struggle for and with different kinds of capital

세 그룹은 서로 다른 형태의 자본을 중요시하고 노력했다.

The three groups valued and strove for different forms of capital.

부서 대표자

Department representatives

그들의 행동은 '일자리를 잃는 기관 내의 공공연하거나 숨겨진 두려움'(Q16-CR1)에 의해 결정되었다. 그들은 경제 자본을 우선시했다. "글쎄요, 모든 사람들이 그/그녀의 규율을 위해 로비를 합니다. 물론, 그것은 때때로 매우 논쟁적이고, 물론 어떻게든 자신의 사건을 극복하고 살아남기 위해 노력합니다."(Q17-DR2). "이 교수진 내에서, 여러분은 피해를 방지하고 자신의 직원 자금 조달을 보호할 수 있습니다."(Q18-DR1). 또 다른 사람은 '연구소장으로서 직원들에게도 일종의 복지 의무가 있다. (…) 교육 내용을 전달해야 하는 [연구소] 또한 필요한 직원들을 돌봐야 한다.'(Q19-DR1)고 말했다. 이러한 인식은 이해 관계자들이 다양한 교육 형식을 저울질하는 데에도 반영되었습니다. '(…) 세미나 시간이나 다른 것을 잃게 될 것이기 때문에 제가 잠재적으로 제 기관을 손상시킬 수 있을까요? 그리고 잠재적으로 일자리를 잃을까?' (Q16-CR1).

Their actions were determined by ‘an overt or hidden fear within the institutions of losing jobs’ (Q16-CR1). They prioritized economic capital. ‘Well, everyone lobbies for his/her discipline; of course, it is sometimes very contentious, and of course one tries somehow to get through one’s cases and to survive’ (Q17-DR2). ‘Within this faculty, you can avert damage and safeguard your own staff financing’ (Q18-DR1). Another stated, ‘As the institute director, you also have kind of a welfare duty to your staff. (…) Those [institutes] who have to convey the teaching content also have to take care of the necessary staff’ (Q19-DR1). This perception was also echoed in the stakeholders’ weighing of the different teaching formats: ‘(…) will I potentially damage my institution, as we will lose seminar hours or something else? And potentially lose jobs?’ (Q16-CR1).

[경제적 자본]은 [문화적 자본]을 대표하는 특정한 교육 내용을 전달하는 것보다 우선시되었다. 결국, 그것은 여전히 돈에 관한 것이지 항상 내용에 관한 것은 아니다. (…) 중요한 주제가 누락되었다고 말해야 한다.(Q20-DR2) 흥미롭게도, 부서 대표들은 문화 자본의 한 형태로 학과 내용을 가르치는 데 있어 그들의 전문 지식을 알고 있었다: '물론, 나는 내 학과에 대한 구체적인 개념을 가지고 있었다. 나는 또한 이에 관한 교과서를 여러 권 썼는데, 누구나 나의 개념이 무엇이고 그것들을 어떻게 전달해야 하는지 읽을 수 있다'(Q21-DR1). 그러나 그들은 이 전략을 무기로 사용하지 않았다. 또한 사회적 자본의 전략적 활성화는 거의 없었다: '교수들은 각자 자신의 이익을 위해 노력하고 있었기 때문에 서로를 지지한 적이 없었다'(Q22-CR4).

Economic capital was prioritized over conveying certain teaching content, representing cultural capital. ‘After all, it is still about the money and not always about the content (…) you have to say that important topics are missing’ (Q20-DR2). Interestingly, department representatives were aware of their expertise in teaching the discipline content as a form of cultural capital: ‘Of course, I had specific conceptions about my discipline (…). I have also written several textbooks on this, and anyone can read what my conceptions are and how to convey them’ (Q21-DR1). However, they did not use this strategy as a weapon. Furthermore, there was little strategic activation of social capital: ‘The professors never supported each other, as each of them was looking out for his/her own interest’ (Q22-CR4).

궁극적으로, 한 부서 대표가 말했듯이, '문제의 핵심은 결국, 그것은 당신이 인정하고 싶어하는 것보다 훨씬 더 많은 돈에 관한 것이다. 나에게, 그것은 사실 의학과 개혁의 모듈식 커리큘럼의 주요 문제이다.'(Q20-DR2) 이 견해는 한 교육과정 직원 대표가 공유했다: '이것은 항상 전체 이야기에 중첩되는 것이다'(Q16-CR1).

Ultimately, as one department representative stated, ‘The whole crux of the matter is that, in the end, it is much more about the money than you want to admit. For me, that is actually the main problem of the Modular Curriculum of Medicine and the reform’ (Q20-DR2). This view was shared by a curriculum staff representative: ‘This is what is always superimposed on the whole story’ (Q16-CR1).

학생 대표

Student representatives

학생들의 주요 목표는 '이 개혁을 통해 가능한 한 의학의 모듈식 커리큘럼을 구조하는 것'과 '가능한 많은 훌륭한 개념들을 보존하는 것'(Q23-SR1)으로, 이 새로운 의학 학위 프로그램을 통해 지금까지 습득한 문화 자본을 언급했다. 그들은 따라서 '심지어 일종의 데미지 억제라는 의미에서, 불리한 입장에 놓일 수 있는 모든 것을 제한하기를 바랐다'(Q23-SR1).

The students’ main goal was to ‘rescue the Modular Curriculum of Medicine as well as possible over this reform’ and ‘to save as many of the great concepts as possible (…)’ (Q23-SR1), referring to cultural capital they had acquired so far through this new medical degree programme. They hoped thereby ‘to limit everything that would get the short end of the stick, in the sense of maybe even a kind of damage containment’ (Q23-SR1).

교육과정 개혁을 둘러싼 투쟁에서, 학생들은 그들의 문화적, 사회적 자본을 활성화하는 데 초점을 맞춘 전략을 사용했다. 그들은 유지하거나 노력할 교육과정과 관련된 경제적 자본이 없었다(Q19-DR1). 문화자본에 대해서는 '우리 모두는 그것을 위해 믿을 수 없을 정도로 자기희생 의지가 있었다(…) 적어도 그런 종류의 것을 위해 새벽 5시에 일하는 사람은 아무도 없었다.(…) 이것은 비교적 독특한 종류의 열정을 필요로 한다'(Q24-SR3)는 높은 동기를 보였다. 그들은 또한 높은 수준의 헌신을 공유했습니다. '결국, 우리는 많은 노력과 프로젝트 작업, 워크숍 등을 통해 학생 쪽에서 매우 집중적으로 일했고(…), 이는 확실히 우리의 입장을 촉진했습니다'(Q25-SR2). 게다가, 그들은 계산을 하고 무엇이 가능하고 무엇이 가능하지 않은지, 무엇이 가능하지 않은지, 무엇이 시사하는 바가 무엇인지를 보여주고 있었다. 그들은 다른 사람들이 아닌 그들에게 특별한 관심이 있는 모델들을 계산하고 있었다. 그 결과, (…) 그들은 또한 공정을 잘 조정할 수 있었습니다' (Q26-CR4).

In the struggle over curriculum reform, the students used strategies focused on activating their cultural and social capital. They had no economic capital related to the curriculum to be maintained or to strive for (Q19-DR1). Regarding cultural capital, they showed high motivation: ‘We all had an unbelievable willingness to self-sacrifice for it (…) there was no one else who worked at five o'clock in the morning, at least for that sort of thing. (…) This requires a kind of passion that is relatively unique’ (Q24-SR3). They also shared a high level of commitment: ‘After all, we accomplished it through a lot of labour, also through project work and workshops, etc., working on the student side so intensively (…) and this certainly facilitated our position’ (Q25-SR2). In addition, they ‘were doing the calculations and showing what is possible and what is not possible and what the implications are. They were calculating those models that were of particular interest to them and not others. As a result, (…) they were also able to steer the process well’ (Q26-CR4).

사회적 자본의 활성화와 관련하여, 학생들은 다양한 전략을 사용했다. 여기에는 팀으로 일하는 것이 포함되었습니다. '학생들은 단순히 더 나은 정보를 얻고, 모든 경우에 더 잘 준비했습니다. 그들은 그룹 내에서 어떻게 논쟁하고 서로를 지지하는지 조정했습니다.' (Q22-CR4). 게다가, 그들은 동맹을 결성했다: '물론, 우리는 적어도 그들을 조직하기 위해 미리 다수와 지지자들을 조직하려고 노력했다, 그래서 사람들이 '네, 우리는 이것에 동의하지만, 우리는 그것을 공개적으로 지지하지는 않을 것이다'라고 말할 수 있다.' (Q27-SR1. '일부 더 큰 기업들이 우리를 지지했다면, 우리의 제안이 잘 될 가능성이 훨씬 높았을 것이다.'(Q28-SR3) '[A]그리고 그들[학생들]은 보통 사건을 끝까지 밀고 나간다'(Q29-CR4). 학생들은 또한 학생 단체의 지원을 받았다: '우리는 학생으로서 배경에 팀을 두는 사치를 누렸고, 반복적으로 다른 학생들의 지원을 받을 수 있었다.' (Q30-SR2) 학생들은 '학생 단체 전체의 지지를 반복적으로 찾고 있었다; 그들은 천 명 이상의 학생들이 참여한 모듈식 의학 커리큘럼의 장단점에 대해 훌륭한 설문 조사를 했다'(Q31-CR2).

Regarding the activation of social capital, the students employed a number of strategies. This involved working as a team: ‘The students were simply better informed, better prepared in all cases; they coordinated in their group how to argue and supported each other’ (Q22-CR4). In addition, they formed alliances: ‘Of course, we tried to organize majorities and supporters in advance, at least to organize them, so that people say, ‘yes, we agree to this, although we will not support it overtly’’ (Q27-SR1). ‘[I]f some of the bigger ones supported us, we had a much higher chance that our proposal would work out well’ (Q28-SR3). ‘[A]nd they [students] usually push their cases through’ (Q29-CR4). Students were also supported by the student body: ‘We, as the students, had the luxury of having a team in the background and repeatedly could gain support from other students’ (Q30-SR2). Students were ‘repeatedly seeking backing from the entire student body; they did a great survey about the pros and cons of the Modular Curriculum of Medicine, where more than a thousand students took part’ (Q31-CR2).

교육과정 담당자

Curriculum staff representatives

그들은 학생들과 교육과정을 가능한 한 잘 유지해야 한다는 목표를 공유했다. "물론, 커리큘럼을 유지하는 것이 우리 자신에게 가장 이익이 되었습니다. 계획되었기 때문에, 거의 완료되었습니다." (Q32-CR5).5). 그들이 세운 문화적 자본을 유지하기 위해, 그들은 '모든 PBL 시간, 모든 의사소통 훈련 시간'(Q32-CR5)을 위해 싸웠고, 이는 이러한 교육 형식의 관리자로서의 그들의 위치와 연결되어 그들의 경제적, 문화적 자본과 연결되었다. 같은 정도로, 그들은 학생들과의 동맹에 참여했다.

They shared the goal of maintaining the curriculum as well as possible with the students. ‘Of course, it was in our own very best interest to maintain the curriculum; since it had been planned, it was almost finished’ (Q32-CR5). To maintain the cultural capital they had established, they ‘fought for every PBL hour, for every communication training hour’ (Q32-CR5), which was linked to their positions as managers of these teaching formats and thus to their economic and cultural capital. To the same degree, they were involved in alliances with the students.

교육과정 관리자들은 교육과정 개혁을 둘러싼 경쟁에서 기반이 될 교육적, 문화적 자본이 부족했다. '만약 의료 교육 센터가 20년 된 기관이었다면, 우리는 (…) 국내 및 국제 교육 개발에 대한 20년의 경험을 토대로 구축할 수 있었을 것이고, 이는 변화를 만들었을 것입니다. 그러나 우리는 그것을 가지고 있지 않았다." (Q33-CR3). "좋은 가르침은 정의하기 어렵다는 것이 갈등이었다. (…) 어디선가 책을 펴서 그것이 무엇인지 찾을 수 없다." (Q34-CR3).CR3. 당연히, 계획 위원회에서 교육적 관점에 대해 논의할 시간이 없었습니다. 'PBL을 마지막까지 자르는 것에 관해서, 우리는 생각했습니다: PBL 개념이 무엇인가? 그게 무슨 뜻인가요? (…) 그 때는 시간이 없었어요.' (Q35-CR2)

The curriculum managers lacked educational and cultural capital to build on in the competition over curriculum reform. ‘If the Center for Medical Education had been a 20-year-old institution, (…) we would have been able to build on 20 years of experience with national and international teaching development, which would have made a difference. But we didn't have that’ (Q33-CR3). ‘The conflict was that good teaching is difficult to define. (…) one can’t open a book somewhere and look up what it is’ (Q34-CR3). Unsurprisingly, there was no time to discuss educational perspectives in the planning committee: ‘When it came to cutting PBL until the end, we thought: what is a PBL concept? What does that mean? (…) We didn't have time at that moment’ (Q35-CR2).

교육과정계획위원회 – 사회적 지위를 위한 투쟁

Curriculum planning committee – a struggle for social position

교육과정계획위원회에서, 에이전트 그룹마다 서로 다른 사회적 입장을 가지고 있었다. 일반적으로 교육과정 담당자는 '우리는 우리의 계층을 가지고 있다'(Q36-CR5)고 지적했다.

The field of the curriculum planning committee held different social positions for its group of agents. In general, a curriculum staff representative pointed out, ‘we do have our hierarchies’ (Q36-CR5).

부서 대표들, 특히 부서장들은 그들의 이전 사회적 지위에 대해 질문을 받았다: '한 번은, 다른 진료소의 의사가 왔는데, 그 의사는 [주임 의사]와 동등한 기준으로 참여하려고 했지만, '교수님'이라고 말하지 않았다.' 그리고 나서 그것은 분명해졌다: 그는 '교수 의사'이며, 그는 경청받고 존중받기를 원한다'(Q36-CR5). '계획'은 거의 중요하지 않은 과정입니다. 내용이 어디에서 결정되는지, 수석 의사가 있든, 아니면 매우 헌신적인 교육 코디네이터(…)가 있든 간에 말입니다(Q36-CR5). 그럼에도 불구하고, 학생들은 '그룹에 속한 다른 사람들은 샤리테의 명사들, 즉 가르침에 역할을 한 사람들'이라는 것을 잘 알고 있었다(Q37-SR3).

The department representatives, especially the department heads, were questioned about their former social positions: ‘Once, a physician from another clinic came along, who then tried to engage on an equal basis with [the head physician] but did not say, ‘Professor Doctor.’ And then it was made clear: He is a ‘Professor Doctor’, and he wants to be listened to and to be respected’ (Q36-CR5). The ‘planning is a process, where this almost doesn’t matter – where the content rules – whether there is a head physician or the very dedicated teaching coordinator (…)’ (Q36-CR5). Nevertheless, the students were well aware that ‘other people who were in the group were the luminaries of the Charité, (…) those who played a role in teaching’ (Q37-SR3).

반면 학생 대표들은 '우리는 계층의 맨 아래에 있었다'(Q38-SR3)고 말하면서도 사회적 지위가 상승하는 것을 경험했다.'(Q38-SR3)' '학생으로서 그런 집단에 처음 가입할 때, 이 집단에 가입하는 교수님과 같은 존경을 받기 전에 (…) 더 많은 노력을 기울여야 한다고 생각한다. 그리고 처음부터 그것을 얻는다. 그럼에도 불구하고, 확실히 나는 우리에 대한 존중이 낮지 않았다고 생각한다; 나는 우리가 그곳에서 잘 존경받았다고 생각한다'(Q39-SR2). 이에 대한 역사적 이유, 특히 개혁된 연구 프로그램과 관련된 역사적인 이유는 교수진이 존중하는 상호작용에서도 특정한 개방성을 가지고 우리를 만났다는 역사적인 항의로 이어졌다(Q40-SR2). 인식된 계층 격차에 접근하기 위한 학생들의 전략 중 하나는 다음과 같다: '[W]우리는 그룹 내에서 우리의 권위를 통해서는 절대로 그렇게 할 수 없고, 좋은 주장만 가지고는 그렇게 할 수 없다. 궁극적으로, 이것은 우리가 통과하기를 원하는 모든 사례에 대해 좋은 주장을 내놓도록 강요했다.' (Q41-SR3)

The student representatives, on the other hand, experienced an elevation in their social position, despite stating, ‘We were standing at the very bottom of the hierarchy’ (Q38-SR3). ‘I think as a student, when you first join such a workgroup, you need to make more effort (…) before you earn such respect as a professor has, who joins this workgroup and gets it in the first place. Nevertheless, I think the respect was certainly not lower for us; I think we were well respected there’ (Q39-SR2). There were also ‘historical reasons for this, especially related to the reformed study programme, related to the historical protests that had led to this [reform] (…) that the faculty met us with a certain openness, also in respectful interactions’ (Q40-SR2). One of the students’ strategies for approaching the perceived hierarchy gap was as follows: ‘[W]e could never do that through our authority in the group, but with good arguments only. Ultimately, this forced us to come up with good arguments for every case we wanted to get through’ (Q41-SR3).

한 학생 대표는 '최종적인 결정, 즉 어떤 위치에 있는 사람이 어떤 역할을 했는지에 관한 것'(Q42-SR3)을 주목했습니다. 교육과정 관리자들의 눈에는 '그들[학생들]은 교육과정을 경험했기 때문에 상당히 동등한 위치에 있었다; (…) 그들은 이 교육과정을 공부한 유일한 사람들이었다. 그들은 매우 심각하게 받아들여졌다.' (Q43-CR2) '여기 베를린에서는 학생들이 그렇게 강한 입장을 가지고 있어서 학생들에게 불리한 결정을 내릴 수 없는 경우가 많다는 것이 약간 문제였다.'(Q44-CR1) 한 부서 담당자는 '사실 그들 중 일부는 너무 많은 영향력을 가지고 있다는 인상을 받았다'고 말했다(Q45-DR2). 한 교육과정 담당자는 자신들의 입장을 강조하며 '그 당시 학생들은 많은 것을 했다. 10명의 학생들로 구성된 그룹이 이 과정을 상당히 진전시켰다.' (Q46-CR2)

One student representative noticed that ‘concerning the ultimate decisions, (…) who was in what position played a role’ (Q42-SR3). In the eyes of the curriculum managers, ‘they [the students] had a fairly equal position by virtue of having experienced the curriculum; (…) they were the only ones who had studied this curriculum. They were taken very seriously’ (Q43-CR2). ‘Here in Berlin, it was a bit of a problem that the students have such a strong position, so many cases cannot be decided against the students’ (Q44-CR1). A department representative stated, ‘I actually had the impression that some of them partly had too much influence’ (Q45-DR2). Emphasizing their position, a curriculum manager pointed out, ‘[T]he students did a lot at that time. There was a group of ten students who significantly drove the process forward’ (Q46-CR2).

모든 자료에는 교육과정위원회에서 교육과정관리자의 잠재적인 사회적 지위에 대한 언급이 없었다.

In all the material, there was no mention of the potential social position of the curriculum manager in the curriculum committee.

논의

Discussion

본 연구에서는 주요 교육과정 개혁을 입안하기 위한 위원회의 구성원들의 관행을 설명하고 분석하고 더 잘 이해하기 위해 부르디외의 장field 개념을 적용했다. 이 이론적 틀을 이용하여, 이 정성적이고 경험적인 연구에서, 우리는 위원회 구성원들의 경험적 현실(Albert and 리브스 2010)의 표면 아래로 파고들 수 있었고 주요 교육과정 개혁에서 작동하는 것으로 보이는 사회적 메커니즘을 발견할 수 있었다. 본 연구의 주요 결과는, [주요 교육과정의 블루프린팅]은 설계와 전달에 관련된 [다양한 형태의 자본과 사회적 입장]을 놓고 [위원회 구성원들의 권력투쟁]에 의해 실질적으로 형성된다는 것이다.

In this study, we applied the Bourdieuan concept of field to describe, analyse, and better understand the practices of members of a committee for blueprinting a major curriculum reform. Using this theoretical framework, in this qualitative, empirical study, we were able to dive beneath the surface of the experienced realities (Albert and Reeves 2010) of the committee members and uncover social mechanisms that appear to operate in major curriculum reform. Among this study’s main findings are that blueprinting a major curriculum is substantially shaped by the power struggles of the committee members over various forms of capital and social positions related to the design and delivery of the future curriculum.

부르디외의 분야 개념을 적용해보면, 교육과정위원회 위원들이 치열한 갈등과 경쟁에 가려져 그들의 업무를 경험한 것은 놀라운 일이 아니었다. 우리의 분석에 따르면, 부르디외의 분야 개념은 교육과정 개혁의 이면을 들여다볼 수 있는 눈을 뜨게 했다. 다른 사회 분야와 마찬가지로, 교육과정 위원회는 배우들이 권력을 획득하기 위해 고군분투하고 경쟁하는 장으로 등장했다(Bourdieu 1980). 분명히, 주요 교육과정 개편은 [기존의 구조와 계층, 즉 현재의 자본과 사회적 지위의 배분]을 무너뜨리고, 교육 프로그램과 주최 기관 모두에서 [미래의 권력 분배]에 큰 변화를 동반한다. 각 커리큘럼 위원회는 다른 사회 분야와 마찬가지로 [개별적이고 지역적인 맥락]에 포함embed되어 있습니다. 즉, 자체적인 조직 구조, 전통, 규칙 및 실습 옵션을 가지고 있습니다(Bourdieu 1977). 이러한 독특한 특성에도 불구하고, 부르디외의 분야 개념은 교육과정 위원회에서의 실습이 다른 분야와 동일한 사회적 역학을 나타낼 가능성을 허용한다. 즉, 위원회 구성원들은 [권력]과 [사회적 지위]를 유지하거나 획득하기 위한 자원을 놓고 경쟁할 것이다.

When applying Bourdieu’s concept of field, it turned out not surprising that the committee members experienced their work in the curriculum committee as overshadowed by intense conflicts and competition. In our analysis, Bourdieu’s concept of field became as an eye-opener that provided a look behind the scenes of the curriculum reform. Like any other social field, the curriculum committee emerged as an arena in which actors struggle and compete to acquire power (Bourdieu 1980). Evidently, major curriculum reform breaks up existing structures and hierarchies, i.e. the current allocation of capital and social positions, and is accompanied by major shifts in the future distribution of power in both the educational programme and the host institution. Each curriculum committee, like other social fields, is embedded in individual, local contexts, i.e. has its own organizational structures, traditions, rules and practice options (Bourdieu 1977). Despite these unique characteristics, Bourdieu’s concept of field allows the likelihood that the practice in a curriculum committee exhibits the same social dynamics as other fields; in other words, committee members will compete over resources to maintain or acquire power and social position.

부르디외에게, [의료 교육과정 분야의 권력]은 [합법적으로 좋은 의료 교육으로 간주되는 것을 정의할 수 있는 권한과 역량]에 해당하는 것으로 볼 수 있다. 우리의 주요 교육과정 개혁의 경우, 예를 들어, 프로그램이 좋은 교육이 무엇인지 [합법적으로 정의]하는 데 있어 [교수의 지배적인 역할]과 함께 [전통적인 학부 의학 훈련에 대한 고전적 가정]에 의문이 제기되었다. 우리의 경우, 개혁의 주요 동인인 의대생들은 교수와 학습에 대한 새로운 접근법을 도입했는데, 예를 들어 프로그램이 [통합적이고 학생 중심이며 실습 중심이어야 한다]고 제안함으로써 [좋은 의학 교육에 대한 새로운 정의]를 도입했다.

For Bourdieu, power in the field of medical curricula can be seen as being equivalent to the authority and capacity to define what is considered legitimately good medical education. In our case of major curriculum reform, classical assumptions of traditional undergraduate medical training were questioned, for instance, that the programme should be discipline-based, teacher-centred, and theory-focused, along with the dominant role of professors in legitimately defining what good teaching is. Medical students, in our case, the main drivers of the reform, brought in new approaches to teaching and learning, for instance, proposing that the programme be integrative, student-centred, and practice-focused, thereby introducing a new definition of good medical education.

부르디외의 현장 개념을 사용한다면, 교육과정위원회에서의 투쟁이 다소 의식적으로 실존적인 것으로 인식되었던 싸움인 거칠고 치열한 싸움으로 경험되었다는 것도 놀라운 일이 아닌 듯하다. 위원들이 개별적으로 또는 단체로 주요 교육과정 설계과정의 결과에 직접적인 영향을 받는 것은 분명하다. 이는, 이미 보고된 것처럼, 열띤 작업 분위기와 위원들이 모든 과정을 투덜대는 것으로 인식한 점을 설명한다. 주요 교육과정 개혁은 승자와 패자를 낳는다. 부르디외의 분야 개념은, 한 집단이 [지배력을 얻거나 잃는 자본의 유형과 양]에 직접 연결될 수 있기 때문에, [승패가 무엇을 의미하는지]에 대한 [유형적이고 점진적인tangible and gradual 조작화]를 가능하게 한다.

If Bourdieu’s concept of field is used, it also seems not surprising that the struggle in the curriculum committee was experienced as a tough and intense fight, a fight that was perceived more or less consciously as being existential. Obviously, the committee members, individually or as groups, are directly affected by the outcome of the major curriculum blueprinting process. This explains the reportedly heated working atmosphere and the fact that the committee members perceived the whole process as gruelling. Major curriculum reform generates winners and losers. Bourdieu’s concept of field allows a tangible and gradual operationalization of what winning and losing means, as it can be directly linked to the type and amount of capital one group gains or loses control over.

우리의 분석은 커리큘럼 계획 위원회의 작업이 다른 종류의 자본을 위한 투쟁에 의해 주도된다는 점에서 부르디외의 분야 개념과 일치한다. 더 일반적인 관점에서, 자원의 유형과 양은 그 분야에서 널리 가치가 있고 추구된다면 관련된 자본의 형태로서 자격을 얻을 수 있다. 교육과정계획위원회의 경우, 위원회가 권력 또는 사회적 지위를 얻기 위해 경쟁하거나 사용한 자본의 구체적인 형태를 확인했다. 한 가지 높은 가치를 지닌 형태는 [경제적 자본]이었다. 향후 교육과정에서 [할당된 교수시간을 통해 한 부서가 얻을 수 있는 교수진 직위의 수]로 조작화되었다. 가중점수(Multiplication factor)가 높은 강의나 세미나와 같은 교수형식은 가중점수가 절반에 불과한 PBL이나 의사소통훈련과 비교하여 경쟁률이 높았다. 또한 전통적인 강의와 세미나를 선호하는 것은 부서들이 그 분야-특이적인 [문화적 자본]을 유지할 수 있게 해주었다. 즉, 과목 전문가로서, 그들은 이러한 형식으로 교육 내용을 결정할 수 있었다. 결과적으로, [PBL] 또는 [환자 의사소통]과 같은 분야 독립적인 교육 형식은 부서 대표자들에 의해 평가절하되었다. 따라서, 부서 대표들은 전통적인 수업 형식의 분배를 놓고 서로 경쟁했고, 동시에 새로운 형식의 수업 시간을 줄이는 것을 선호했다.

Our analysis is in line with Bourdieu’s concept of field in that the work in a curriculum-planning committee is driven by a struggle for and with different kinds of capital. From a more general perspective, any type and amount of a resource can qualify as a relevant form of capital if it is widely valued and sought after within the field (Varpio and Albert 2013). In the case of the curriculum planning committee, we identified the specific forms of capital the committee competed over or used to gain power and/or social standing. One highly valued form was economic capital. It was operationalized as the number of teaching staff positions a department could obtain through the number of teaching hours allotted in the future curriculum. Teaching formats, such as lectures and seminars, with a high multiplication factor were competed over more than those such as PBL or communication training that had a multiplication level that was half as high. In addition, favouring traditional lectures and seminars allowed departments to maintain their discipline-specific cultural capital; in other words, as subject experts, they could determine the teaching content in these formats. In turn, discipline-independent teaching formats such as PBL or patient communication were less valued by the departmental representatives. Thus, departmental representatives competed with each other over the distribution of the traditional teaching formats and at the same time favoured reducing the number of teaching hours in the new formats.

학생들은 [사회적 자본](상호지원적인 팀에서 활동하고, 다른 위원회 구성원이나 그룹과 동맹을 맺고, 전체 학생들의 목소리를 이끌어냄)을 활성화함으로써 학과의 강력한 힘에 대항하고자 했다. 그들의 전략은 또한 그들이 권력을 가진 경제 자본(시간)의 활성화(밤샘 계산을 통해, 그들은 항상 준비되어 있었다)과 문화 자본(실행 중인 새로운 교육과정에 대한 지식, 복잡한 계산을 하는 특정 기술, 새로운 개념)에 기반을 두었다. 학생들은 PBL, 기술, 의사소통 훈련과 같은 새로운 교수법을 지지했다. 이는 그들의 문화적 자본에 긍정적인 영향을 미칠 것이고 따라서 의사로서 미래에 효과적으로 일할 수 있는 그들의 능력이다. 교육과정 관리자 대표들은 소수의 경제자본(직급 관련)에만 의존할 수 있었고, 문화자본(교육 및 교육과정 전문성)은 위원회 논의에서 큰 역할을 하지 못했다.

Students sought to counter-balance the strong power of the departments by activating their social capital (working in a mutually supportive team, building alliances with other committee members or groups, eliciting the voice of the whole student body). Their strategies were also built on the activation of the economic capital (time) over which they had power (through night-long calculations, they were always prepared) and of cultural capital (knowledge about the new curriculum in action, specific skills in doing complex calculations, new concepts). The students advocated for the new teaching formats, such as PBL, skills and communication training, that would have a positive impact on their cultural capital and therefore their ability to work effectively in the future as physicians. The curriculum manager representatives could rely on only minor amounts of economic capital (related to their positions), and their cultural capital (didactic and curriculum expertise) did not play a major role in the committee discussions.

또한, 우리의 분석은 교육과정 계획 위원회의 작업이 [사회적 지위를 위한 투쟁]에 의해 주도된다는 점에서 부르디외의 장 개념과 일치하며, 이는 다시 [의료 프로그램과 주최 기관 내의 권력 분배 및 위계]에 영향을 미친다. 우리의 경우, [전통적인 학문 기반 프로그램]을 [통합된 역량 기반 프로그램]으로 개혁하는 것은 [대학 내 권력과 위계]의 큰 변화를 수반한다는 것이 분명했다. 그 부서의 대표들은 지배적인 사회적 위치에서 왔기에, [좋은 의학 교육을 위한 새로운 아이디어]가 [오랜 시간 지속되어온 교육 관행]에 도전할 때 [권력의 상실]을 두려워했다. 그 분야에서 [지위가 높을수록 잃을 염려가 커지고], 비슷한 지위에 있는 사람들과 수평적으로, 그리고 학생들과 같이 낮은 지위에 있는 사람들과 수직적으로 모두 더 많은 갈등과 경쟁이 일어날 수 있다고 추측할 수 있다. 이러한 [두려움]과 [사회적 위계의 변화]는 주요 교육과정 개혁에서 자주 발생하는 변화에 대한 저항에 대한 설명을 제공할 수도 있다.

Furthermore, our analysis is in line with Bourdieu’s concept of field in that the work in the curriculum-planning committee is driven by a struggle for social position, which in turn has an impact on the power distribution and hierarchy within a medical programme and its host institution. In our case, it was evident that the reform of a traditional discipline-based programme into an integrated, competency-based programme was accompanied by a major shift in power and hierarchy within the university. The department representatives came from a dominating social position and feared a loss of power when new ideas for good medical education challenged their old teaching practices. One may speculate, the higher the position in the field is, the greater the fear of losing it and the more conflicts and competition may arise, both horizontally with those in similar high positions and vertically with those in lower positions, such as the students. This fear and change in social hierarchy may also provide some explanation to the resistance to change that frequently occurs in major curriculum reform (Mennin and Krackov 1998; Bland et al. 2000; Hawick et al. 2017; Reis 2018; Velthuis et al. 2018).

이 사례 연구 자체의 발견 외에도, 그 결과는 구성원들이 주요 교육과정 개혁과 관련된 사회적 메커니즘을 설계하기 위한 위원회를 탐색하는 방법에 대한 이해를 풍부하게 함으로써 주요 교육과정 개혁에 대한 문헌에 추가된다. 그들은 우리가 왜 주요 교육과정 개혁을 계획하는 것이 선형적이고 질서 있는 과정으로 전개되지 않는지 더 잘 이해할 수 있도록 도와준다. 연구 결과는 주로 결과 기반 설계와 같은 합리적 '계획 및 실행' 교육과정 개발 접근법을 보완한다. 그들은 이미 어느 정도 인적, 사회적 요인을 고려하고 있는 의료 교육과정 개혁에 적용되는 조직 변화 관리 접근법을 보완한다.

Beyond the findings of this case study itself, its results add to the literature on major curriculum reform by enriching our understanding of how members navigate committees for blueprinting major curriculum reform and the social mechanisms involved. They help us to better understand why planning a major curriculum reform does not unfold as a linear and orderly process (Hawick et al. 2017). The findings primarily complement rational ‘planning and executing’ curriculum development approaches such as outcome-based design. They complement organizational change management approaches applied to medical curriculum reform that already, to some degree, take into account human and social factors (Loeser et al. 2007; Arja et al. 2018; Maaz et al. 2018; McKimm and Jones 2018; Banerjee et al. 2019).

한계

Limitations

우리는 한 대규모 의과대학의 주요 교육과정 개혁위원회를 분석했다. 향후 연구는 우리의 연구 결과가 다른 위원회와 맥락으로 이전될 수 있는 정도를 검토할 필요가 있다. 교육과정 기획위원회가 작아서 우리는 목적적인 샘플링을 사용할 수 없었다. 그럼에도 불구하고 3개 위원회 그룹 모두 비교적 대표적이었고, 각 위원들은 그 과정에서 자신의 경험에 대해 풍부하고 광범위한 통찰력을 제공했다. 본 연구는 분야의 개념과 관련된 습관 개념에 대한 분석은 포함하지 않았다. 우리는 개별 사회적 행위자들의 습성에 대한 분석이 보다 포괄적인 질적 방법론적 접근을 필요로 할 것이며 향후 연구의 주제가 될 수 있다고 생각한다. 마지막으로, 위원회의 청사진 작성 과정과 인터뷰 사이의 간격은 인터뷰 내용을 방해했을 수 있다; 어떤 면은 기억되지 않았을 수 있고, 다른 면은 왜곡되었을 수 있다.

We analysed one major curriculum reform committee at one large medical university. Future studies need to examine the degree of transferability of our findings to other committees and contexts. The curriculum planning committee was small, so we could not employ purposive sampling. Nevertheless, all three committee groups were comparably represented, and each committee member provided rich and extensive insight into his or her experience during the process. This study did not include an analysis of the concept of habitus, which is related to the concept of field. We feel that the analysis of individual social agents’ habitus would require a more comprehensive qualitative methodological approach and could be the subject of future research. Finally, the interval between the committee blueprinting process and the interviews may have interfered with the content of the interviews; some aspects may not have been remembered, while others may have become distorted.

시사점

Implications

이 연구가 제공하는 통찰력은 주요 교육과정 개혁을 위한 제도적 계획을 안내하고 위원회에 있는 개인이 주요 교육과정 개혁을 설계하는 데 도움이 될 수 있다. 그 결과는 주요 교육과정 개혁을 위해 이러한 고위험 기획위원회를 탐색하는 복잡성에 더 잘 대처할 수 있도록 그들의 준비와 훈련의 기초로서 보완적인 역할을 할 수 있다. 근본적인 사회 메커니즘에 부르디외의 렌즈를 가진 개별 위원회 구성원이나 그룹을 귀속시키는 것도 주요 교육과정 변화의 과정과 결과에 유익한 영향을 미칠 수 있다.

The insights offered by this study can help to guide institutional planning for a major curriculum reform and assist individuals being on committees to blueprint a major curriculum reform. The results can serve in a complementary fashion as a foundation for their preparation and training so that they can better cope with the complexities of navigating such high-stakes planning committees for major curriculum reform. Vesting individual committee members or groups with Bourdieu’s lens on the underlying social mechanisms may also have a beneficial impact on the process and outcome of major curriculum change.

결론들

Conclusions

부르디외의 현장개념을 적용함으로써, 교육과정위원회에서 작동하면서, 주요 교육과정 개혁의 과정과 결과에 실질적인 영향을 미치는 [숨겨진 사회적 메커니즘]을 파악하고 발굴할 수 있었다. 경험이 풍부한 현실에서 볼 때, 교육과정 개혁은 좋은 의학교육에 대한 학문적 담론으로 보인다. 이러한 표면 아래에서 [미래 교육과정의 설계와 전달]과 관련된 [다양한 형태의 자본]과 [사회적 입장]을 놓고 위원회 구성원들 사이에 [치열한 권력 투쟁]이 벌어지고 있다. 우리의 연구 결과는 이러한 고위험 사업에 대한 현재의 이해를 보완하고 기관과 위원회 구성원들이 주요 교육과정 개혁의 복잡성을 더 잘 탐색하기 위해 활용할 수 있다.

Applying Bourdieu’s concept of field allowed us to identify and uncover hidden social mechanisms that operate in curriculum committees and have a substantial impact on the process and results of major curriculum reform. On the surface of experienced realities, curriculum reform appears to be an academic discourse about good medical education. Beneath this surface operates an intense power struggle among committee members over various forms of capital and social positions related to the design and delivery of future curriculums. Our findings complement the current understanding of this high-stakes undertaking and may be utilized by institutions and committee members to better navigate the complexity of major curriculum reform.

A qualitative study applying Bourdieu's concept of field to uncover social mechanisms underlying major curriculum reform

PMID: 34802364

Abstract

Purpose: Planning committees play a key role in blueprinting major curriculum reform. In this qualitative study, we apply Bourdieu's sociological concept of field to the perceptions of committee members to identify the social mechanisms operating in major curriculum reform.

Method: A planning committee with 18 members developed a blueprint for major curriculum reform at the Charité Berlin in its transition from a discipline-based programme to a fully integrated undergraduate medical programme. Interviews with 13 members about their experiences were subjected to inductive-deductive content analysis.

Results: Viewed through a Bourdieuan lens, the curriculum committee represents a social field of intense competition and conflicts. Groups of committee members struggled for and with different forms of economic, cultural and social capital to maintain and increase their power and social position in the medical programme. In our case, the major reform was accompanied by loss of power within the teaching department group, while the student group gained power.

Conclusion: Bourdieu's concept of field reveals that a major curriculum reform is substantially shaped by power struggles over various forms of capital and social positions related to the future curriculum. The findings may serve as a complementary guide for those navigating the complexity of major curriculum reform.

Keywords: Curriculum reform; Pierre Bourdieu; curriculum committee; social theory.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 교육과정 개발&평가' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 성찰적 그리고 비성찰적 학생을 위한 성찰적 공간 만들기: 대그룹 글쓰기 세션에서 결정적 순간 탐색(Acad Med, 2020) (0) | 2022.12.15 |

|---|---|

| 학부의학교육과정에 건강의 사회적 결정요인 교육과정 도입: 교수 경험의 질적 분석 (Acad Med, 2022) (0) | 2022.11.20 |

| 의학교육의 학생참여: 교육과정 개발에서 모듈 공동책임자로서 학생에 관한 혼합연구(Med Teach, 2019) (0) | 2022.11.17 |

| 교육혁신을 구축-측정-학습으로 빠르게 평가하기: 린 스타트업을 보건의료전문직 교육에 적용하기 (Med Teach, 2022) (0) | 2022.11.13 |

| 보건의료시스템과학 교육과정 도입 과제: 학생 인식의 질적 분석(Med Educ, 2016) (0) | 2022.11.09 |