교육혁신을 구축-측정-학습으로 빠르게 평가하기: 린 스타트업을 보건의료전문직 교육에 적용하기 (Med Teach, 2022)

Evaluating education innovations rapidly with build-measure-learn: Applying lean startup to health professions education

David A. Cook, Abhishek Bikkani & M. Jeannie Poterucha Carter

서론

Introduction

교육자는 항상 혁신합니다. 교육 혁신의 예로는

- 기존 과정의 새로운 교육 활동(예: 온라인 모듈, 그룹 토론, 수업 전 비디오 또는 인공지능 적응형 학습 인터페이스),

- 평가에 대한 새로운 접근 방식(예: 학생이 절차적 과제에 대한 성과를 직접 기록),

- 커리큘럼 내에서의 새로운 과정 또는 관리 절차 (예: 로테이션 성적 제출 또는 데이터 웨어하우스의 개발 및 사용을 위한 온라인 도구) 또는

- 완전히 새로운 커리큘럼 내의 요소.

물론, 어떤 아이디어들은 다른 아이디어들보다 더 잘 작동한다. 유지할 혁신과 중단할 혁신을 선택하는 것은 유익성, 비용 및 단점과 관련된 경험적 증거를 이상적으로 기반으로 한다. 그러나 전통적인 연구 방법의 답은 종종 혁신 평가를 시기적절하고 의미 있는 방식으로 안내하기에는 너무 늦고 너무 드물게 나타난다. 예를 들어, e-러닝 및 시뮬레이션과 같은 교육 기술을 사용하는 혁신은 현재 특히 흔하지만, 이러한 기술은 매우 빠르게 발전하여 일반적인 교육 연구 연구를 수행하는 데 걸리는 시간(12~18개월) 동안 현대 스마트폰은 두 가지 디자인 '세대'를 거치게 될 수 있다. 혁신자들은 어떻게 따라갈 수 있을까?

Educators innovate all the time. Examples of educational innovations include

- new instructional activities in an existing course (e.g. an online module, group discussion, pre-class video, or artificial intelligence adaptive learning interface),

- novel approaches to assessment (e.g. students self-recording their performance on a procedural task),

- new courses or administrative procedures within a curriculum (e.g. an online tool for submitting rotation grades, or development and use of a data warehouse), or

- an entirely new curriculum.

Of course, some ideas work better than others. Choosing which innovations to sustain and which to stop is ideally based on empiric evidence regarding benefits, costs, and disadvantages. Yet the answers from traditional research methods often come too late and too infrequently to guide innovation evaluations in a timely and meaningful way. For example, innovations using educational technologies such as e-learning and simulation are particularly common at present, yet these technologies evolve so rapidly that in the time it takes to conduct a typical education research study (12–18 months), a modern smartphone might go through two design ‘generations.’ How can innovators keep up?

혁신 평가에 대한 '린 스타트업' 접근법은 전통적인 연구에 대한 유용한 대안을 제공한다. 이 접근법은 첨단 소프트웨어 시장에서 혁신의 개발과 생존에 기원을 두고 있지만, 그 이후 산업과 군대를 포함한 인터넷 기반 사업과 '전통적' 사업 모두에 널리 적용되어 왔다. 창안자(기업가)는 (적어도 서류상 또는 이사회에서) [좋게 들리는 아이디어]에서 [수익성 있는 비즈니스 모델]로 빠르게 전환하도록 촉진하기 위해 이 프로세스를 만들었습니다. 기업가들과 그들의 자금 제공자들은 제한된 시간과 자원을 고객의 요구를 충족시키는 데 효과적이고, 실행 가능하고, 지속 가능한(수익성) 아이디어에 사용할 강력한 인센티브를 가지고 있다. 그리고 그렇지 않은 아이디어들을 가능한 한 빨리 버려야 한다. [린 스타트업 접근 방식]은 짧은 평가 및 수정 주기를 사용하여 중요한 가정을 테스트하고 효과가 있는 모델에 빠르게 수렴하고 실행 불가능한 아이디어를 버린다. 신제품 제작 도구(예: 게시, 웹 사이트 제작, 게임 디자인 및 3D 인쇄용 도구)가 널리 보급되어 있다는 점을 감안할 때, 현대의 초점은 제품을 효율적으로 [구축하는 것building]이 아니라 고객이 원하고, 사용하고, 실제로 지불할 제품에 대해 [배우는 데learning] 있습니다. 실제로 '학습 속도가 새로운 불공평한 장점'이다(Maurya 2022).

The ‘Lean Startup’ approach to innovation evaluation offers a useful alternative to traditional research. This approach has its origins in the development and survival of innovations in the fiercely-competitive market of high-tech software, although it has since been widely applied to both Internet-based and ‘traditional’ businesses including industry and the military. The originators—business entrepreneurs—created this process to promote rapid transition from ideas that sound good (at least on paper, or in the board room) into profitable business models. Entrepreneurs and their funders have strong incentives to channel limited time and resources to ideas that are effective in meeting customer needs, practicable, and sustainable (profitable); and abandon as quickly as possible ideas that are not. The Lean Startup approach uses short cycles of evaluation and revision to test critical assumptions and rapidly converge on a model that works, and discard nonviable ideas. Given widespread availability of tools to build new products (e.g. tools for publishing, website creation, game design, and 3D printing), the contemporary focus is not on efficiently building a product but on learning about the product that customers want, use, and will actually pay for. Indeed, ‘Speed of learning is the new unfair advantage’ (Maurya 2022).

교육 혁신은 기업가적인 벤처이며, 상업적인 비즈니스 스타트업은 유망한 아이디어를 신속하게 식별하고 다듬는 린 스타트업 방법의 혜택을 받을 것이다. 그러나 린 스타트업 접근법은 교육에서 거의 주목을 받지 못했다. '린 스타트업'에 대한 PubMed 검색 결과, 혁신 보고서의 일환으로 린 스타트업 방법론을 간략하게 설명한 교육 중심 기사(Kaylan et al. 2021)가 1건만 공개됐다. 구글이 'Lean Startup Education'을 검색한 결과 다수의 블로그 게시물, 한 가지 방법 중심 기사(LeMahieu et al. 2017b), 박사 논문(Tran 2015)이 나타났다.

Education innovations are entrepreneurial ventures, and like a commercial business startup would benefit from Lean Startup methods to rapidly identify and refine promising ideas. Yet the Lean Startup approach has received little attention in education. A PubMed search for ‘Lean Startup’ revealed only one education-focused article (Kaylan et al. 2021) that briefly outlined the Lean Startup methodology as part of an innovation report. A Google search for ‘Lean Startup Education’ revealed a number of blog posts, one method-focused article (LeMahieu et al. 2017b), and a doctoral thesis (Tran 2015).

이 글의 목적은 린 스타트업의 역사와 주요 원칙을 개괄하고, 이를 보건 전문직 교육에 적용하고, 우리의 개인적인 경험을 활용하여 설명하는 것이다. 주요 청중은 보건 전문 교사들이다. 교육 관리자, 연구자 및 기업가들은 또한 이 접근법이 유용하다는 것을 알게 될 것이다.

The purpose of this article is to outline the history and key principles of Lean Startup, apply these to health professions education, and illustrate these using our personal experience. The primary audience is health professions teachers. Education administrators, researchers, and business entrepreneurs will also find this approach useful.

교육자는 기업가이고, 혁신 팀은 스타트업입니다.

Educators are entrepreneurs, innovation teams are startups

[기업가]의 한 가지 정의는 '대개 상당한 진취성과 위험을 지닌 모든 기업을 조직하고 관리하는 사람'이다. 대부분의 교육 혁신가들은 스스로를 조직자이자 창시자로 인식하겠지만, 그들은 정말 위험을 감수하는 사람들일까? 교육 혁신의 위험은 벤처 캐피털 투자를 수반하지 않을 수 있지만, 그럼에도 불구하고 위험은 사소하지 않다.

- 첫째로, 혁신의 개발과 구현은 혁신자와 그 팀의 시간과 자원의 헌신을 요구한다.

- 둘째, 기술혁신을 사용하는 것은 사용자(학습자 또는 기타 교육자)에 의한 투자도 포함한다:

- 시간과 자원의 투자(예: 기회 비용)와

- 기술혁신이 실제로 의도한 대로 작동하는 신뢰의 투자(예: 이러닝 모듈이 그들을 임상실습을 위해 적절하게 준비할 것이다).

- 셋째, 일부 혁신은 학교나 프로그램의 인증 상태에 영향을 미칠 것이다.

- 마지막으로, 혁신자의 명성은 위태롭습니다. 실패한 혁신은 이력서에 좋지 않을 수 있습니다.

One definition of entrepreneur (www.dictionary.com) is ‘a person who organizes and manages any enterprise, usually with considerable initiative and risk.’ Most education innovators will recognize themselves as organizers and initiators, but are they really risk-takers? Risk in education innovation may not involve a venture capital investment, but risks are nonetheless non-trivial.

- First, the innovation’s development and implementation requires a commitment of time and resources by the innovator and their team.

- Second, using the innovation involves investments by users (learners or other educators) as well:

- investments of time and resources (i.e. opportunity costs), and

- investment of trust that that the innovation actually works as intended (for example, that an e-learning module will adequately prepare them for clinical practice).

- Third, some innovations will impact a school or program’s accreditation status.

- Finally, the innovator’s reputation is on the line: a failed innovation might not look good on one’s curriculum vitae.

[스타트업]은 '극도의 불확실성 조건 하에서 새로운 제품과 서비스를 창출하도록 설계된 인간 기관'으로 정의되어 왔다(Ries 2011). 이러한 기준을 충족할 수 있는 다양한 기관 중에는 혁신자와 협력하여 아이디어를 실현하는 교육 혁신 팀이 있습니다. 교육 혁신은 확실히 '불확실성이 있는 조건'이다. 예를 들어, 전공의 정오 회의를 재설계하려면 다음과 같은 수많은 우선 순위를 균형 있게 조정해야 한다.

- 전공의의 실제 학습 요구 충족(이전보다 더 효과적으로 개선됨),

- 현상 유지를 원하는 교직원의 기분을 상하게 하지 않고,

- 지원 직원을 압도하지 않으며,

- 인증 요구 사항을 충족하며,

- 관리자들을 행복하게 하고,

- 제한된 시간과 리소스로 이를 달성합니다.

어떻게 이런 일이 일어날 수 있을까요? 그것은 불확실합니다!

A startup has been defined as, ‘A human institution designed to create new products and services under conditions of extreme uncertainty’ (Ries 2011). Among the various institutions that might meet these criteria is the education innovation team—those working with the innovator to bring their ideas to fruition. An educational innovation certainly represents a ‘condition of uncertainty.’ For example, a redesign of resident noon conferences would require balancing numerous priorities:

- meeting residents’ real learning needs (hopefully more effectively than before),

- avoiding offending faculty members who want to maintain the status quo,

- not overwhelming the support staff,

- meeting accreditation requirements,

- keeping administrators happy, and

- accomplishing this with limited time and resources.

How can this happen? It is uncertain!

우리의 목적을 위해, 우리는 '제품'이라는 용어를 매우 폭넓게 정의하며, 기본적으로 [모든 교육 활동이나 혁신]을 포함합니다.

For our purposes, we define the term ‘product’ very broadly—encompassing essentially any educational activity or innovation.

또한 우리는 '고객'이라는 용어를 혁신자가 해결하려고 하는 문제를 실제로 물건을 구매하는지 여부에 관계없이 폭넓게 정의합니다. 교육 고객은 일반적으로 학습자이지만 다른 이해관계자(교사, 관리자, 환자, 연구원)도 포함될 수 있다. 일반적인 사업에서 고객은 제품과 공급업체 중에서 선택한 후 제품을 구매합니다. 때때로 이것은 학생이 대학, 선택 과정, 지속적인 교육 활동, 교과서 또는 온라인 자원 구독을 선택할 때 교육에서도 마찬가지이다. 또는 관리자가 온라인 학습 관리 시스템 또는 표준화된 테스트를 선택할 때에도 그렇다. 그러나 일반적으로 교육 고객은 의식적으로 특정 제품을 선택하거나 구입하지 않습니다. 일단 레지던트 프로그램에 연결되면 대학원 의사는 훈련과 환자 치료 활동을 거의 통제할 수 없습니다.

일단 과정에 등록하면, 학생들은 일반적으로 교육이 매일 어떻게 진행되는지 선택하지 않는다. 그럼에도 불구하고 학습자와 기타 이해관계자를 고객으로 보는 것은 비금전적 투자(시간, 정신적 에너지)와 암묵적 옵션(지시적 격차, 필요, 욕구, 우선순위, 혁신, 솔루션, 개입 및 다른 상황에서 선택을 제시할 수 있는 대안)에 주의를 집중한다면 도움이 될 수 있다.

We also define the term ‘customer’ broadly, as anyone whose problem the innovator is trying to solve—regardless of whether anyone actually buys anything. The customer in education is usually the learner, but could also include other stakeholders (teachers, administrators, patients, researchers). In a typical business a customer purchases a product after choosing among products and suppliers. Sometimes this is also true in education, as when a student chooses a university, an elective course, a continuing education activity, a textbook, or an online resource subscription; or when an administrator chooses an online learning management system or standardized test. Commonly, however, education customers don’t consciously choose or purchase a specific product: once attached to a residency program, postgraduate physicians have little control over training and patient care activities; once enrolled in a course, students don’t typically choose how instruction proceeds day by day. Nonetheless, viewing learners and other stakeholders as customers can be helpful if it focuses attention on non-monetary investments (time, mental energy) and implicit options (instructional gaps, needs, wants, priorities, innovations, solutions, interventions, and alternatives that could present a choice under other circumstances).

린 스타트업 접근 방식

The lean startup approach

내역 및 개요

History and overview

에릭 리스는 2000년대 후반에 소프트웨어 회사를 공동 설립하면서 '린 스타트업'의 아이디어를 개발했으며, 자신의 경험을 앞서 설명한 두 가지 개념과 결합했다(Ries 2011).

- 컨셉 1은 도요타의 '린 제조'(Womack et al. 2007)로, [제조 공정에서 낭비를 전략적으로 제거하는 데 중점]을 두고 있다. 그리고 제품이 사전에 완전히 명시되지 않고 짧고 반복적인 주기로 개발되고 정제되는 소프트웨어 산업의 '애자일 개발'의 보완적 개념(Beck et al. 2001).

- 컨셉 2는 Steve Blank의 '고객 개발' 아이디어입니다(Blank 2013, 2020). —[고객의 니즈를 이해하고 대응하는 것]이 엔지니어링 및 제품 개발보다 더 중요하다는 것을 의미합니다.

Eric Ries developed the idea of the ‘Lean Startup’ while co-founding a software company in the late 2000s, merging his own experiences with two previously-described concepts (Ries 2011).

- Concept 1 is Toyota’s ‘lean manufacturing’ (Womack et al. 2007), which focuses on strategically eliminating waste in a manufacturing process; and the complementary concept of ‘agile development’ (Beck et al. 2001) from the software industry in which products are developed and refined in short, repeated cycles rather than being fully specified up-front.

- Concept 2 is Steve Blank’s idea of ‘customer development’ (Blank 2013, 2020)—that understanding and responding to customer needs (sources of ‘pain’) are more important than engineering and product development.

[린 스타트업의 핵심 전제]는 다음과 같다.

- 모든 새로운 벤처(우리의 경우 교육 혁신을 포함)가 성공하는 방법을 배워야 한다.

- 학습은 경험적 데이터에 기반해야 한다,

- 이러한 데이터는 '사무실 밖으로 나가기'와 고객과의 상호작용을 통해 가장 잘 얻어낸다.

The central premises of the Lean Startup are

- that any new venture (including, in our case, education innovations) must learn how to be successful,

- that learning must be based on empiric data, and

- that these data are best obtained by ‘getting out of the office’ (Blank 2020) and interacting with customers.

린 스타트업 접근 방식은 혁신가들이 아이디어를 기능성 제품으로 전환하고, 고객이 어떻게 반응하는지 측정하고, 이러한 결과로부터 학습하여 제품을 개선한 다음, 이 사이클을 반복하도록 지원합니다(이상적으로 여러 번, 그리고 빠르게). 중요한 것은 초기 제품이 잘 개발되어서는 안 된다는 것입니다. 오히려, 아이디어를 미리 완성하려는 모든 노력은 시간과 자원의 낭비이기 때문에 거의 기능적이지 않아야 합니다('최소한의 실행 가능한 제품'). 핵심은

- 가능한 한 빠르고 빈번하게 주기를 반복하여

- 고객의 요구를 더 잘 이해하고 응답하도록 제품을 반복적으로 수정하고,

- 이로서 제품 아이디어를 고객이 실제로 사용할 수 있는 것으로 신속하게 다듬는 것입니다(이는 혁신자가 처음에 구상한 것과 상당히 다를 수 있음).

The Lean Startup approach helps innovators turn their idea into a functional product, measure how customers respond, learn from these results to refine the product, and then repeat this cycle (ideally multiple times, and rapidly). Importantly, the initial product need not—in fact, should not—be well-developed. Rather, it should be barely functional (a ‘minimal viable product’), because any efforts to perfect the idea up-front are a waste of time and resources. The key is

- to repeat the cycle as quickly and as frequently as possible,

- iteratively revising the product to better understand and respond to customer needs, and

- thus rapidly refine the product idea into something that customers will actually use (which may be quite different from what the innovator initially envisioned).

린 스타트업은 실제로 [특정 영역에 초점을 둔 과학적 방법의 응용]일 뿐이며, 실용적인 시간에 민감한 문제로 용도 변경되었다(Ries 2011).

Lean Startup is really just a focused application of the scientific method, repurposed to a practical time-sensitive problem (Ries 2011).

5대 원칙

Five key principles

Ries(2011)는 린 스타트업의 5가지 핵심 원칙을 개략적으로 설명합니다. 첫째, 기업가들은 어디에나 있다. 위에서 언급했듯이, 교육 혁신가들은 기업가이고, 그들의 팀은 스타트업이다.

Ries (2011) outlines five core principles of the Lean Startup. First, entrepreneurs are everywhere. As noted above, education innovators are entrepreneurs, and their teams are startups.

둘째, 기업가정신은 경영이다. 스타트업은 '단순한 상품이 아니라 기관'이며 효과적인 관리가 필요하다. 핵심 혁신자인 팀 리더는 벤처 기업을 관리하고 팀에 책임을 물을 준비가 되어 있어야 합니다.

Second, entrepreneurship is management. A startup ‘is an institution, not just a product’ and requires effective management. The team leader—the key innovator—must be prepared to manage the venture and hold the team accountable.

셋째, 스타트업은 고객에 대해 학습한 것을 검증할 필요가 있다. 스타트업(즉, 혁신 팀)의 목적은 [학습하는 것]이지 반드시 제품을 구축하거나 고객의 요구를 충족하기 위한 것은 아닙니다. Ries는 혁신자들이 효과적이고 지속 가능한 제품과 사업을 구축하는 방법(즉, 무엇을 구축해야 하는지)을 배울 필요가 있다고 주장한다. 만약 그들이 배움learning 대신 스스로의 구축building하는 데 초점을 맞춘다면 그들은 결국 실패할 것이다. 학습은 혁신자들이 그들의 기본 가정과 비전을 경험적으로 시험할 수 있게 하는 실험을 필요로 한다.—비즈니스 모델을 'de-risk'하는 것이다. 교육 환경에서, 이는 새로운 과정 아이디어를 도입하기보다는, 혁신 팀이 [변화가 정말로 필요한지 여부를 결정하는 데 집중]하도록 장려한다는 것을 의미합니다. 그리고 변화의 필요가 당연하자면warranted, 코스 개발에 [반복적인 '지속적인 품질 개선' 접근법]을 채택해야 한다. 학습자가 정말로 필요로 하는 것(현재 어떤 gap이 존재하는가, 학습자가 무엇을 실제로 사용할 것인가, 무엇이 학습 결과를 실제로 최적화할 것인가)을 파악하는 데 초점을 맞춥니다. 마우리아가 말했듯이, '인생은 아무도 원하지 않는 것을 만들기에는 너무 짧다'(Maurya 2012). 혁신의 [지속가능성]과 [확장성] 또한 테스트되어야 합니다. 새로운 고객들(예: 내년 또는 다른 기관의 학생)이 그것을 사용할 수 있을까?

Third, startups need validated learning about customers. The purpose of a startup (i.e. the innovation team) is to learn, not necessarily to build a product or meet customer needs. Ries maintains that innovators need to learn how to build an effective and sustainable product and business (i.e. what to build). If they focus on building itself instead of learning they will ultimately fail. Learning requires experiments that allow innovators to empirically test their fundamental assumptions and vision—to ‘de-risk’ their business model. In an education setting, this means that rather than jumping in and implementing a new course idea, Lean Startup encourages the innovation team to focus on determining whether a change is really needed; and if change is warranted then to adopt an iterative ‘continuous quality improvement’ approach to course development. The focus is on identifying what learners really need (what gaps currently exist, what they will actually use, and what will really optimize learning outcomes). As Maurya stated, ‘Life’s too short to build something nobody wants’ (Maurya 2012). The sustainability and scalability of the innovation should also be tested: will new customers (e.g. students next year or from other institutions) be able to use it?

넷째, 검증된 학습을 달성하기 위해 스타트업(혁신 팀)은 빌드-측정-학습 사이클(그림 1 및 아래 설명)을 빠르고 자주 거쳐야 합니다. 성공적인 팀은 주요 질문(가정)에 계속 집중하면서 이 프로세스를 가속화할 수 있습니다.

Fourth, to accomplish validated learning, startups (innovation teams) need to go through the Build-Measure-Learn cycle (Figure 1, and described below) quickly and frequently. Successful teams can accelerate this process while continuing to focus on key questions (assumptions).

다섯째, 스타트업(혁신팀)은 혁신회계에 집중해야 한다. 여기에는 의미 있는 메트릭스 식별, 구체적인 목표 설정, 결과 측정, 데이터에 대응하고 목표를 달성하기 위한 작업의 우선 순위가 포함됩니다. 이러한 초점은 혁신자들이 장기적으로 원하는 결과를 달성할 책임을 지게 한다.

Fifth, startups (innovation teams) must focus on innovation accounting. This involves identifying meaningful metrics, setting specific goals, measuring results, and prioritizing work to respond to data and meet objectives. Such focus holds innovators accountable to achieving the long-term desired outcomes.

검증된 학습 및 빌드-측정-학습 주기

Validated learning and the build-measure-learn cycle

성공 정의: 비즈니스 모델 명확화

Define success: Articulate the business model

그것은 '성공'이 어떻게 생겼는지 명확하게 정의하는데 도움이 된다. 비즈니스 벤처의 경우, 성공은 보통 고객에게 지불하고 순이익에서 측정된다. 교육 혁신의 경우 성공은 [신규 사용자, 완료율, 학습자 지식 또는 개발 또는 지속적인 비용(교사 시간 포함)]에서 측정될 수 있다.

It helps to clearly define what ‘success’ would look like. For a business venture, success is usually measured in paying customers and net profits. For an educational innovation, success might be measured in new users, completion rates, learner knowledge, or development or ongoing costs (including teacher time).

이러한 성공의 비전을 '비즈니스 모델'('조직이 가치를 창출, 제공 및 포착하는 방법'에 대한 설명)에서 포착하면 훨씬 더 도움이 됩니다. Maurya(2012)는 혁신의 본질(및 수반되는 비즈니스 모델)을 한 페이지로 증류하기 위해 [린 캔버스]를 개발했다. 린 캔버스를 제작하면 팀은 깊이 있고 명확하게 생각할 수 있으며, 가정을 우선시하고, 다른 모델을 대조하며(예: 다른 고객, 문제, 솔루션 또는 비용 구조로 여러 캔버스 생성) 효과적으로 의사 소통할 수 있습니다. 우리는 이 템플릿을 새로운 린 교육 캔버스를 만들기 위해 적용했습니다(그림 2).

Capturing this vision of success in a ‘business model’ (a description of ‘how an organization creates, delivers, and captures value’ [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Business_model]) helps even more. Maurya (2012) developed the Lean Canvas to distill the essence of an innovation (and the accompanying business model) onto a single page. Creating a Lean Canvas forces the team to think deeply and clearly, and helps to prioritize assumptions, contrast different models (e.g. generating several Canvases with different customers, problems, solutions, or cost structures), and communicate effectively. We have adapted this template to create a novel Lean Education Canvas (Figure 2).

린 교육 캔버스를 사용하여 가정의 우선순위를 정하고 프로젝트 전체의 진행 상황/진화를 모니터링할 수 있습니다. 전문가들은 캔버스의 초기 완성을 다음과 같은 순서로 권장합니다(Maurya 2012). 섹션을 공백으로 두어도 괜찮습니다(이는 높은 우선순위 테스트를 수행할 수 있는 위험한 문제가 될 수 있습니다).

The Lean Education Canvas can be used to prioritize assumptions and monitor the progress/evolution of the project as a whole. Experts recommend that the Canvas be initially completed in a single sitting, in the following order (Maurya 2012). It’s ok to leave a section blank (this might suggest a risky issue that warrants high-priority testing).

1. 고객 부문 + 문제 – 이러한 섹션은 긴밀하게 연결되어 있으므로 함께 작성합니다. 즉, '고객'과 2차 수혜자를 모두 식별합니다(예: 의대생에 대한 평가를 기록하는 임상 강사의 새로운 시스템의 경우, 1차 수혜자는 강사, 2차 수혜자는 학생, 지원 직원 및 학장).

1. Customer Segments + Problem – complete these sections together, as they are tightly interconnected; identify both immediate ‘customers’ and secondary beneficiaries (for example: for a novel system for clinical preceptors to record assessments of medical students, the immediate customer is the preceptor; secondary beneficiaries include students, support staff, and the dean).

3. 고유한 가치 제안 – 차이가 중요한지 확인하고 얼리 어답터를 목표로 삼으십시오. [사람들이 제품을 사용한 후 얻을 수 있는 혜택]의 관점에서 이를 설명하도록 하십시오.

3. Unique Value Proposition – make sure your difference matters and aim for the early adopters; try to state this in terms of benefits derived after people use your product.

4. 솔루션 – 단일 솔루션에 얽매이지 말고 '각 문제를 해결하기 위해 구축할 수 있는 가장 간단한 것'을 적습니다(Maurya 2012).

4. Solution(s) – don’t get bound to a single solution; write down the ‘simplest thing you could possibly build to address each problem’ (Maurya 2012).

5. 채널 – 주요 인력(기본 및 보조 고객)과 어떻게 소통하고 참여를 이끌어낼 것인가? 여기에는 푸시 메시징(예: 이메일), 풀 메시징(예: 고객이 웹 사이트) 및 입소문 공유(리퍼링)가 포함될 수 있습니다.

5. Channels – how will you communicate with and get buy-in from key people (primary and secondary customers)? This can include push messaging (you initiate contact, e.g. email), pull messaging (customers find you, e.g. website), and word-of-mouth sharing (referral).

6. 재정 지원 – 일부 교육 혁신은 수익을 창출하기 위한 것이지만, 장기적인 지속 가능성을 보장하기 위해 재정적 지원을 받지 않아도 됩니다. 수익 출처에는 학교 예산 기금, 외부 보조금 및 등록금이 포함될 수 있습니다.

6. Financial Support – some educational innovations intend to generate revenue, but even those that do not must garner financial support to ensure long-term sustainability; revenue sources might include school budget funds, external grants, and subscription fees.

7. 비용 구조 – 혁신을 개발하고 구현하는 데 필요한 비용에 대한 상세하고 현실적인 추정치를 개략적으로 설명합니다.

7. Cost Structure – outline a detailed, realistic estimate of costs required to develop and implement the innovation.

8. 주요 지표 – 여기에는 혁신의 초기 및 반복 사용, 학습 결과(지식, 기술, 행동), 시스템 결과(학교 또는 환자 치료에 미치는 영향), 유료 구독 및 추천이 포함될 수 있습니다.

8. Key Metrics – these might include initial and repeated use of the innovation, learning outcomes (knowledge, skills, behaviors), system outcomes (impact on school or patient care), paid subscriptions, and referrals.

9. 불공평한 이점 – 주어진 제품을 처음 출시하는 것은, 이점이 아니라, 실제로 위험입니다. (Maurya 2012) 진정한 '불공정한' 이점에는 고객과의 연계 가치, 내부자 정보, 개인 전문 지식, 개발 팀 기술, 수많은 기존 고객 및 대규모 네트워크/커뮤니티가 포함됩니다.

9. Unfair Advantage – being first to launch a given product is actually a risk, not an advantage; (Maurya 2012) truly ‘unfair’ advantages include customer-aligned values, insider information, personal expertise, development team skills, numerous existing customers, and a large network/community.

원래의 비즈니스 모델은 경험적 테스트에서 거의 살아남지 못할 것이다(Blank 2020). 당연하다. 실제로 비즈니스 모델을 변경하거나 성공의 비전을 재정의할 수 있는 증거(검증된 학습!)를 제공하는 것이 린 스타트업의 핵심 목적입니다.

The original business model will almost never survive empiric testing (Blank 2020). That’s expected. Indeed, providing evidence (validated learning!) to change the business model or redefine the vision of success is the central purpose of the Lean Startup.

가정 식별 후 테스트

Identify assumptions, then test

스타트업(혁신팀)의 목적은 고객에 대해 최대한 많이 배우는 것입니다. 팀은 일반적으로 고객이 무엇을 원하거나 필요로 하는지 아이디어로 시작하지만, 실제로는 단순한 가정일 뿐이며 가정을 테스트해야 합니다. 가정을 식별하는 것은 직관적이거나 쉽지 않다. 표 1은 다음 두 가지 접근 방식을 설명합니다.

- 스스로에게 일련의 탐색적 질문을 던지고

- 린 교육 캔버스의 각 진술을 체계적으로 잠재적인 가정으로 봅니다.

The purpose of a startup (innovation team) is to learn as much as they can about their customers. The team usually starts with an idea of what the customer wants or needs, but in reality this is merely an assumption—and assumptions need to be tested. Identifying assumptions is not intuitive or easy. Table 1 describes two approaches:

- asking oneself a series of probing questions, and

- systematically viewing each statement in the Lean Education Canvas as a potential assumption.

일단 식별되면, 가정은 프로젝트 실패의 위험에 기초한 시험을 위해 [우선 순위]를 매겨야 한다: [불확실성]이 높고, 잠재적으로 [임팩트]가 큰 가정이 우선 순위가 된다. [테스트하기 쉬운 가정]도 종종 조기에 테스트됩니다.

Once identified, assumptions should be prioritized for testing based on risk of project failure: assumptions with high uncertainty and potentially high impact get first priority. Assumptions that are easy to test are often tested early as well.

사무실에서 나가십시오. 고객과의 대화

Get out of the office: Talk with customers

가정을 식별하고 테스트하기 위해 혁신자들은 [사무실에서 나와 잠재 고객과 소통]해야 합니다(Blank 2020). 만트라는 다음과 같다. '당신의 건물 안에는 사실이 없으니 밖으로 나가세요'(Blank 2012). 고객 중심 학습('고객 개발')은 '깨달음으로 가는 길'(Blank 2020)으로 분류되었습니다.

To both identify and test assumptions, innovators need to get out of the office (Blank 2020) and interact with potential customers (Constable 2014). The mantra is: ‘There are no facts inside your building, so get outside’ (Blank 2012). Customer-focused learning (‘customer development’) has been labeled the ‘path to epiphany’ (Blank 2020).

'문제점'(고객 발견)에 대한 초기 이해는 일반적으로 고객과의 대화(질적 데이터)를 수반합니다. 전문가들은 포커스 그룹(그룹 사고를 유발함)이나 서면 질문지(팀이 이미 올바른 질문과 잠재적 답을 알고 있다고 가정함)보다는 일대일 인터뷰를 권고한다(Maurya 2012; Constable 2014). 이러한 인터뷰에 대한 자세한 지침을 이용할 수 있다(Constable 2014). 정량적 테스트는 이후 단계에서 인터뷰를 보완한다(Constable 2018; Blank 2020).

Initial understanding of ‘pain points’ (customer discovery) typically involves talking with customers (qualitative data). Experts recommend 1-on-1 interviews rather than focus groups (which promote group-think) or written questionnaires (which presume the team already knows the right questions and potential answers) (Maurya 2012; Constable 2014); detailed guidance on such interviews is available (Constable 2014). Quantitative testing complements interviews at later stages (Constable 2018; Blank 2020).

빌드: 실행 가능한 최소 제품

Build: The minimal viable product

불행히도, 고객들은 자신이 진정으로 원하는 것이 무엇인지, 무엇이 가장 효과적으로 작동할 것인지 모르는 경우가 많습니다. 그들의 의견과 믿음은 시험되어야 할 추가적인 가정이다. 따라서 고객(학습자, 교사 등)과 상호 작용할 수 있는 '최소 실행 가능한 제품'(MVP)이라는 가시적인 것을 매우 조기에 구축하는 것이 중요합니다. MVP는 가정을 경험적으로 테스트할 수 있게 한다.

- 고객은 정말 그 제품을 사용하나요?

- 고객은 그것을 예상한 대로 사용하나요?

- 원하는 (학습) 결과를 쉽게 얻을 수 있습니까?

- 어떤 장애물에 부딪히고, 이를 해결하기 위해 제품을 재설계할 수 있는 방법은 무엇입니까?

- 이러한 변화가 초기 비전과 의도된 기능에 어떤 영향을 미칩니까?

이러한 모든 질문 및 기타 질문에 대한 답변은 빌드-측정-학습 주기(그림 1)에 따라 이루어집니다.

Unfortunately, customers often don’t know what they really want or what will work most effectively; their opinions and beliefs are further assumptions that need to be tested. Thus, it is critical to build something tangible very early—a ‘minimal viable product’ (MVP) with which customers (learners, teachers, etc) can interact. The MVP enables assumptions to be empirically tested:

- Do customers really use the product?

- Do they use it as envisioned?

- Does it facilitate the desired (learning) outcomes?

- What stumbling blocks do they encounter, and how can the product be redesigned to resolve these?

- How do these changes affect the initial vision and intended functionality?

All of these questions, and more, will be answered in cycles of Build-Measure-Learn (Figure 1).

혁신자들은 일반적으로 그들의 제품이 거의 완벽하기를 원하지만, 린 스타트업은 정반대의 것을 장려한다. 첫 번째 제품은 '최소한의 노력(시간과 비용 포함)으로 검증된 학습을 최대한 수집할 수 있는 신제품 버전'이어야 합니다(Ries 2009). 이것은 보통 MVP가 의도적으로 저렴하고 불완전하다는 것을 의미한다. [스타트업의 초점]은 제품을 만들거나 고객을 기쁘게 하는 것이 아니라 [문제에 대한 실행 가능하고 지속 가능한 솔루션을 구축하는 방법을 배우는 것]입니다. 따라서 MVP에는 [하나 이상의 중요한 가정(가설)을 테스트하는 데 필요한 최소한의 기능]만 포함되어야 한다. 종종 이것은 [계획된 최종 제품과 표면적으로 거의 유사하지 않은 구현]을 포함한다. 그러나 MVP는 기능성의 [더 깊은 수준에서 강한 오버랩]을 가져야 한다. 기능 보존 단축키의 구체적인 예로는 주문을 처리하기 위해 컴퓨터 프로그램을 작성하는 대신 손으로 주문을 처리하는 것, 소셜 네트워크를 사용하는 대신 혁신 팀이 사용자의 질문에 답하도록 하는 것, 화면상의 아바타가 화면을 돌아다니는 것보다 한 곳에 서도록 하는 것 등이 있다. 표 2에는 추가적인 미니멀리즘 대안이 나열되어 있다.

Innovators typically want their product to be near-perfect, but Lean Startup encourages precisely the opposite: the first product should be a ‘version of a new product which allows a team to collect the maximum amount of validated learning with the least effort’ (Ries 2009) (including time and money). This usually means the MVP is deliberately inexpensive and incomplete. Remember that the focus of the startup is not to build products or please customers, but to learn how to build practicable, sustainable solutions to a problem. Thus, the MVP should contain only the minimal features required to test one or more critical assumptions (hypotheses). Often this involves an implementation that bears little superficial resemblance to the envisioned final product. However, the MVP should have strong overlap at deeper levels of functionality. Specific examples of function-preserving shortcuts include processing orders by hand instead of writing a computer program to process orders; having the innovation team answer users’ questions instead of employing a social network; and making on-screen avatars stand in one place rather than walk around the screen. Table 2 lists additional minimalistic alternatives.

MVP 출범이 늦어진다는 것은 학습의 지연을 의미한다. 혁신자들은 종종 열등하거나 불완전한 제품을 출시하는 것에 대해 우려를 표하며, 고객을 소외시킬 것을 두려워한다. 이러한 두려움은 고객이 누구인지, 고객이 진정으로 원하는 기능이 무엇인지 알고 있으며, 고객은 누락된 기능에 대해 충분히 신경 써서 불쾌감을 느낀다고 가정합니다. 이 모든 가설은 시험할 수 있고, 종종 시험할 때 거짓으로 판명된다. 실제로 가장 중요한 질문 중 하나는 항상 이것이다. 고객은 품질을 어떻게 정의합니까? 즉, 고객이 진정으로 관심을 갖는 기능은 무엇입니까? 중요한 것은, MVP가 '실패'하더라도 학습이 이루어지면(특히 실패가 예상한 방식으로 발생하지 않는 경우가 많기 때문에) 그 경험이 큰 성공을 거둘 수 있다는 것이다.

Any delay in launching the MVP means a delay in learning. Innovators often express concerns about releasing an inferior or incomplete product, fearing to alienate customers. This fear assumes that they know who their customer is, they know what features their customer truly wants, and the customers will care enough about missing features that they will be offended. All of these are hypotheses that can (and should) be tested; and often, when tested, they prove false. Indeed, one of the most important questions is always: How does the customer define quality, i.e. what features do they really care about? Importantly, even if the MVP ‘fails’ the experience can be a great success if learning is gained (especially since failure often does not occur in the expected way).

다시 강조하자면, MVP의 목적이 꼭 고객을 기쁘게 하기 위한 것이어야 할 필요는 없으며, 전반적인 혁신에 대한 가정(가설)을 테스트하여 학습하는 것입니다.

To again emphasize: the purpose of the MVP is not (necessarily) to please customers, but to test assumptions (hypotheses) about the overall innovation and thereby to learn.

측정

Measure

MVP를 테스트하려면 [의미 있고 실행 가능한 결과]의 측정이 필요합니다. '의미 있음'은 테스트 중인 가설(가정)과의 관계를 나타냅니다. 이상적으로, 결과는 강력한 원인-효과 추론(즉, MVP에 대한 학습)을 지원할 것이다. 웹사이트 조회수 또는 환자 체류 기간과 같은 결과를 측정하는 것은 이러한 결과가 MVP의 특정 특징에 기인할 수 없거나 핵심 가정을 다루지 않는 경우 검증된 학습을 제공하지 않는다.

Testing the MVP requires measurement of meaningful, actionable outcomes. ‘Meaningful’ indicates a relationship with the hypothesis (assumption) being tested: ideally, outcomes will support a strong cause-effect inference (i.e. learning about the MVP). Measuring outcomes such as Website hits or patient length of stay does not provide validated learning if these outcomes cannot be attributed to a specific feature of the MVP or do not address a key assumption.

정성적 데이터(인터뷰)는 모든 단계에서 필수적이지만, 프로젝트가 진행됨에 따라 정량적 데이터(수치)의 중요성이 점점 커지고 있습니다. 유료 고객을 유치하는 데 의존하는 기업에게 '해적 지표'(McClure 2007)는 의미가 있다('AARR'이라는 머리글자가 해적처럼 들리기 때문에 일명). 이러한 지표는 다음에 초점을 맞춥니다.

- 고객 획득(신규 방문자 수),

- 활성화(진행 상황을 저장하거나 계정을 활성화하여 재방문을 계획할 수 있을 만큼 충분한 경험을 누리는 고객),

- 유지(실제 재방문),

- 추천(동료에 대한 추천),

- 수익(어떤 것에 대한 지불)

이들은 많은 교육 환경에 적응할 수 있다(예: 온라인 모듈은 새로운 사용자, 모듈 완료, 지속적인 사용 및 추천을 추적할 수 있다). 교육의 다른 성과로는 환자 결과 및 재정적 비용뿐만 아니라 학습자 만족도, 동기 부여, 태도, 지식, 기술 및 침대 머리맡에서의 행동이 포함될 수 있다. '최고의' 결과는 문제의 가정을 직접적으로 알려주는 것이다. 잠재적 결과 측정의 비용, 타당성, 타당성 및 임상/교육 관련성 또한 중요한 고려사항이다.

Qualitative data (interviews) are vital at all stages, but quantitative data (numbers) become increasingly important as a project progresses. For a business dependent on attracting customers who pay, the ‘pirate metrics’ (McClure 2007) (so-called because the acronym ‘AARRR’ sounds like a pirate) are meaningful. These metrics focus on customer

- Acquisition (number of new visitors),

- Activation (customers who enjoy the experience enough to plan a return visit by saving progress or activating an account),

- Retention (actual return visits),

- Referral (recommendations to colleagues), and

- Revenue (payment for something);

these could be adapted to many education settings (e.g. an online module might track new users, module completion, ongoing use, and referrals). Other outcomes in education might include learner satisfaction, motivation, attitudes, knowledge, skills, and behaviors at the bedside, as well as patient outcomes and financial cost. The ‘best’ outcome is one that directly informs the assumption in question. Cost, feasibility, validity, and clinical/educational relevance of potential outcome measures are also important considerations.

정량적 데이터는 시간 경과에 따른 비교(설계 변경과 이상적으로 연계), '경쟁사'와의 비교(또는 전통적인 접근 방식) 또는 동시 통제군과의 비교 등이 있다. 강력한 원인 효과 결정을 용이하게 하는 한 가지 방법은 'A-B 테스트'를 포함하며, 이는 기본적으로 두 가지 버전의 MVP(버전 A, 버전 B)가 생성되는 제어 실험이며, 중요할 것으로 의심되는 특징에서만 다르다. 사용자의 절반은 버전 A를 제공하고 절반은 버전 B를 제공하며 결과는 비교된다. 대면 교육에서는 종종 어렵지만, A-B 비교는 컴퓨터 보조 교육에서는 비교적 간단하며 소프트웨어 개발에서는 일반적이다. 실제로 구글과 아마존 같은 거대 기술기업들은 제품 디자인을 다듬기 위해 지속적으로 A-B 테스트를 사용한다. 한 전문가(McLure 2007)는 무엇을 해야 할지 모르면 '대단히 추측해 보고 A-B 테스트를 해보십시오.'라고 제안합니다.

Quantitative data can be compared over time (ideally linked with design changes), with a ‘competitor’ (or traditional approach), or with a concurrent control. One way to facilitate robust cause-effect determinations involves ‘A-B testing,’ which is basically a controlled experiment in which two versions of the MVP (version A, version B) are created, differing only in a feature suspected to be important. Half the users are offered version A, half are offered version B, and outcomes are compared. While often difficult in face-to-face instruction, A-B comparisons are relatively straightforward for computer-assisted instruction, and are commonplace in software development. In fact, technology giants such as Google and Amazon use A-B testing continuously to refine their product design. One expert (McClure 2007) suggests that if you don’t know what to do, ‘Just guess and then A-B test—a lot!’

학습: 피벗 또는 지속성

Learn: Pivot or persevere

측정이 수집되고 분석되면 학습(데이터 해석)과 의사결정이 필요한 시점이다. 근본적인 결정은 [인내]할 것인지(초기 아이디어를 계속 다듬을 것인지) 아니면 [피벗]할 것인지(초기 아이디어를 포기하거나 근본적으로 변경하여 다른 고객, 기능 세트 또는 제품에 초점을 맞출 것인지)입니다. 핵심은 각 결정이 검증된 학습을 기반으로 한 정보에 정통하다는 것입니다. 다시 말하지만 스타트업(혁신팀)의 초점은 제품을 만들거나 고객(학습자)에게 서비스를 제공하는 것이 아니라 효과적이고 실용적이며 지속 가능한 솔루션(비즈니스 모델)을 구축하는 방법을 배우는 데 있습니다.

Once measurements have been collected and analyzed, it is time for learning (data interpretation) and decisions. The fundamental decision is whether to persevere (continuing to refine the initial idea) or to pivot (abandoning or radically changing the initial idea to focus on a different customer, feature set, or product). The key is that each decision is well-informed—based on validated learning. Again, the focus of a startup (innovation team) is not so much to build a product or serve customers (learners) but rather to learn how to build an effective, practicable, sustainable solution (business model).

반복하다…빠르게

Repeat … rapidly

그런 다음 또 다른 핵심 가정(가설)의 우선 순위를 정하고, 그 가설, 측정 및 결정을 테스트할 MVP를 만드는 것으로 다시 순환이 시작됩니다. 가설과 측정값이 더 우수하고 각 사이클이 더 빨리 완료될수록 혁신 팀은 더 잘 배우고 더 많은 경쟁 우위를 확보할 수 있습니다.

And then the cycle begins again—with prioritization of another key assumption (hypothesis), creation of an MVP to test that hypothesis, measurement, and decision. The better the hypotheses and measurements, and the faster each cycle can be completed, the better and more the innovation team will learn and the greater their competitive advantage.

전체적으로, Maurya(2012)는 [고객과 관련성을 유지하고, 솔루션이 아닌 문제를 사랑하며, 전체 혁신(효과와 지속 가능성 포함)의 위험을 체계적으로 제거]할 필요성을 강조한다. 린(교육) 캔버스(그림 2)는 모델의 만족도, 실행 가능성 및 실현 가능성을 포함하여 모델을 체계적으로 '스트레스 테스트'하는 데 도움이 됩니다.

Throughout, Maurya (2012) emphasizes the need to stay relevant to customers, love the problem not the solution, and systematically de-risk the entire innovation (including effectiveness and sustainability). The Lean (Education) Canvas (Figure 2) is helpful in systematically ‘stress testing’ the model, including its desirability, viability, and feasibility.

물론, 실제 교육 설정은 전형적으로 과정 빈도(예: 매년 1회)와 사이클 빈도를 제한하는 잠재적 '고객'(예: 연간 25명)에 의해 제약을 받는다. 그러나 초점은 [제품 테스트]보다는 [검증된 학습]에 있다. 관련 가정을 테스트할 수 있다면 구체적인 과정, 주제, 참여자는 중요하지 않습니다. 따라서, 많은 빌드-측정-학습 주기는 의도된 과정과 학습자의 외부에 초점을 맞출 수 있습니다(제안 내용은 표 2 참조).

Of course, real-life education settings are typically constrained by the course frequency (e.g. once each year) and potential ‘customers’ (e.g. 25 students per year), which limit the cycle frequency. However, the focus on validated learning rather than product testing is liberating: the specific course, topic, and participants don’t matter if relevant assumptions can be tested. Thus, many Build-Measure-Learn cycles could focus outside the intended course and learners (see Table 2 for suggestions).

교육은 복잡하고 완전히 이해되지 않는 활동이다. 교육 관련 문제에 대한 혁신적인 해결책도 마찬가지로 복잡하며 '효과가 있었는가'라는 단순한 예/아니오 질문으로 좀처럼 줄어들지 않는다. Build-Measure-Learn의 반복적 특성은 각 사이클이 점진적으로 미묘한 질문을 다루면서 자연스럽게 이 상황에 적합하다(이게 중요한 문제인가). 이 혁신은 실행 가능한 해결책입니까? 그것이 얼마나 학습을 촉진하는가? 비용 효율적이고 지속 가능한 제품입니까?)

Education is a complex and incompletely understood activity. Innovative solutions to education-related problems are likewise complex and rarely reduce to simple yes/no questions of ‘Did it work?’ The iterative nature of Build-Measure-Learn lends itself naturally to this situation, with each cycle addressing progressively nuanced questions (

- Is this an important problem?

- Is this innovation a viable solution?

- How well does it promote learning?

- Is it cost-effective and sustainable?).

린 스타트업의 실제 적용: 사례 시리즈

Application of lean startup in practice: A case series

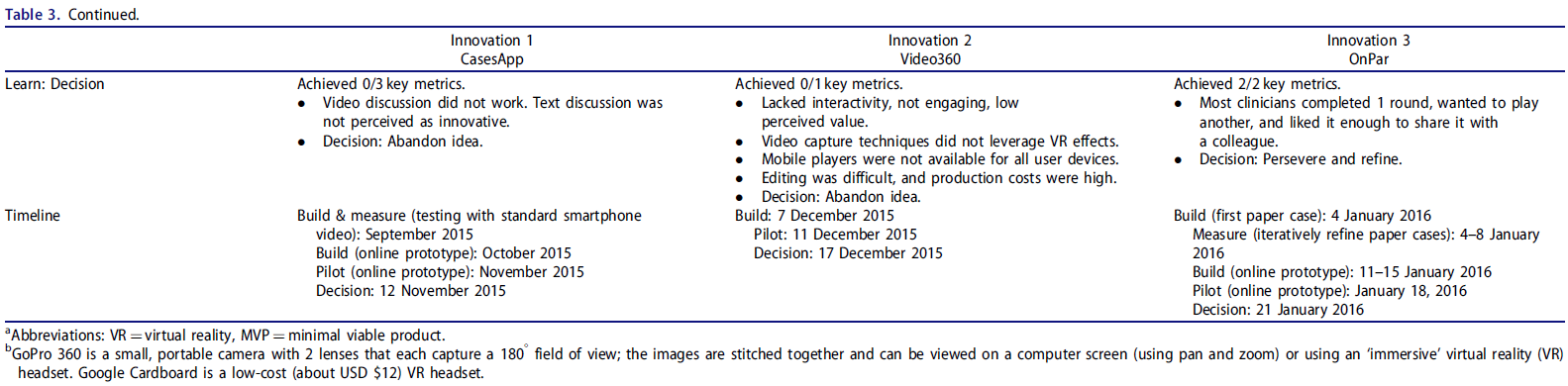

2015년 9월부터 2016년 1월까지 린 스타트업(Lean Startup) 방법에 대한 경험이 있는 외부 컨설팅 업체와 제휴하여 보건전문가를 위한 온라인 학습에 적극적으로 혁신을 꾀했습니다. 이 기간 동안 우리는 고객 개발 인터뷰와 시장 조사를 실시했으며, 이 정보를 사용하여 세 가지 개별 교육 혁신을 식별하고 테스트했습니다(표 3 참조). 이 중 두 개는 실패했다. 세 번째는 상당한 가능성을 보였지만 불행히도 지속적인 개발을 우선시할 자금을 확보하지 못했다. 이러한 프로젝트 중 어느 것도 규모에 맞게 구현된 적은 없지만, 교육 활동을 분류하고 개발하는 린 스타트업의 속도와 유연성을 보여줍니다. 예를 들어, 우리는 다른 가정들이 더 높은 우선순위로 판단되었기 때문에 이러한 혁신들 중 어떤 것이 실제로 학습을 얼마나 잘 촉진시키는지 시험하지 않았다(예: 혁신의 학습 효과는 사람들이 그것을 사용하지 않거나 재정적으로 실행 불가능한지는 중요하지 않다).

From September 2015 to January 2016 we partnered with an external consulting firm with experience in Lean Startup methods to actively innovate in online learning for health professionals. During this period we conducted customer development interviews and market research, and using this information we identified and tested three separate educational innovations (see Table 3). Two of these failed. The third showed substantial promise, but unfortunately has not secured funding to prioritize continued development. While none of these projects was ever implemented at-scale, they illustrate the speed and flexibility of Lean Startup in triaging and developing educational activities. For example, we did not test how well any of these innovations actually promoted learning because other assumptions were judged as higher priority (e.g. an innovation’s learning effectiveness doesn’t matter if people don’t use it or if it is financially infeasible).

초기 고객 발굴 및 아이디어 발굴

Initial customer discovery and ideation

지역 리더와의 대화를 바탕으로 중간 수준의 제공자(간호사 실무자 및 의사 보조자)가 지속적인 교육을 위해 혁신적인 지원이 잠재적으로 필요한 것으로 파악했다. 13개 중간 수준의 제공자와의 인터뷰는 사례 기반 학습(서면, 시뮬레이션 및 실제 환자와의 학습), 동료와 사례를 논의할 기회, 매우 짧은 기간 동안의 활동을 포함한 몇 가지 '페인 포인트'을 확인했다.

Based on conversations with local leaders, we identified midlevel providers (nurse practitioners and physician assistants) as potentially needing innovative support for continuing education. Interviews with 13 midlevel providers identified several ‘pain points’ including a desire for more case-based learning (written, simulated, and with real patients), opportunities to discuss cases with colleagues, and activities of very short duration.

후속 팀 브레인스토밍 세션은 세부 사항, 관련성, 혁신 및 실현 가능성에 있어 큰 차이를 나타내는 30개 이상의 고유한 아이디어를 식별했습니다. 비록 많은 아이디어가 모호하거나 실현 불가능했지만, 이 활동은 팀을 단결시키고 후속 활동을 위한 토대를 제공했다. 시간이 지남에 따라, 우리의 목표 고객 그룹은 (인터뷰에서) 사례 기반 학습의 인지된 가치를 확인한 실무 의사와 거주자를 포함하도록 다양화되었습니다.

A subsequent team brainstorming session identified over 30 unique ideas representing large variation in detail, relevance, innovation, and feasibility. Although many ideas were vague or infeasible, the activity united the team and provided a foundation for subsequent activities. Over time, our target customer group diversified to include practicing physicians and residents, who affirmed (in interviews) the perceived value of case-based learning.

혁신 1. '케이스 앱'

Innovation 1. ‘CasesApp’

고객 발굴, 아이디어 제시 및 가정

Customer discovery, ideation, and assumptions

우리의 초기 고객 개발은 임상의가 진정한 임상 사례에 대한 접근과 논의를 중요시할 것을 제안했다. 임상의들은 또한 우리에게 학습 시간이 매우 제한적이라고 말했고, 모바일 장치가 이 장벽을 극복하는 데 도움이 될 수 있다고 제안했다. 따라서 신뢰할 수 있는 동료와 실제 환자 사례를 공유하고, 보고, 비동기적으로 논의하는 것을 지원하는 모바일 앱이 중요한 요구를 충족할 것이라고 가정했다. 바쁜 임상의들이 서면 사례를 입력할 시간이 없을 수 있다는 것을 인지하고, 모바일 장치 카메라로 캡처한 비디오를 사용하여 사례를 만들고 논의하는 것이 더 빠르고 쉬울 것이라는 가설을 세웠다.

Our initial customer development suggested that clinicians would value access to, and discussion of, authentic clinical cases. Clinicians also told us that time for learning was very limited, and proposed that mobile devices might help overcome this barrier. Consequently, we hypothesized that a mobile app to support sharing, viewing, and asynchronously discussing real patient cases with trusted colleagues would fill a critical need. Recognizing that busy clinicians might not have time to type out a written case, we further hypothesized that creating and discussing cases would be faster and easier using video captured with mobile device cameras.

우리는 기존 제품을 탐색하는 시장 조사를 실시했습니다. 여러 제품이 의사 사례 기반 학습을 지원했지만 모바일 장치를 사용한 제품은 거의 없었고 신뢰할 수 있는 그룹 내에서 사례 토론을 지원하지 않았습니다.

We conducted market research exploring existing products. Several products supported physician case-based learning, but few used mobile devices and none supported case discussions within trusted groups.

우리는 몇 시간 동안 브레인스토밍을 하고 사실이 아닐 경우 실패로 이어질 수 있다는 가정에 우선순위를 매겼다(표 3 참조). 그런 다음 가장 위험한 가정을 테스트하기 시작했습니다.

We spent several hours brainstorming and prioritizing the assumptions that, if untrue, could lead to failure (see Table 3). We then set out to test the riskiest assumptions.

초기 가정 테스트: 빌드-측정-학습

Testing initial assumptions: Build-measure-learn

한 가지 중요한 가정은 임상의가 짧은 사례를 구두로 제시하고 모바일 기기를 사용하여 기록하는 것이 편하다는 것이었다. 이번 테스트에서 MVP는 단순히 표준 비디오 녹화 기능을 갖춘 스마트폰이었다. 주요 지표는 사례를 다른 사람과 공유하고자 하는 임상의의 수와 2분 이내에 사례를 생각해 낼 수 있으며 스마트폰을 사용하여 구술 발표를 편안하게 비디오로 녹화하는 것이었다. 우리는 질문한 임상의의 80%가 하나의 사례를 기록할 의향이 있고 기록할 수 있을 것이라는 가설을 세웠다. 우리는 스마트폰을 손에 들고 복도를 뛰었고, 한 시간 내에 6명의 의료 전문가(의사 5명, 중간급 의료진 1명)에게 접근했다. 6명 모두 2분 이내에 사례를 기록했고, 4명은 최소한의 도움만 필요했으며, 5명은 다른 임상의와 사례를 기꺼이 공유했습니다. 이것은 우리의 가정을 확인했고, 우리는 다음 단계로 진행하기로 결정했다.

One key assumption was that clinicians were comfortable orally presenting a short case and recording it using a mobile device. The MVP for this test was simply a smartphone with standard video recording capability. Key metrics were the number of clinicians willing to share a case with others, able to come up with a case in two minutes or less, and comfortable video-recording their oral presentation using our smartphone. We hypothesized that 80% of clinicians asked would be willing and able to record one case. We hit the hallways with smartphones in hand, and within an hour had approached six health professionals (five physicians and one midlevel provider). All six recorded a case in under two minutes, four required only minimal help, and five were willing to share their case with other clinicians. This affirmed our assumption, and we decided to proceed with the next step.

빌드

Build

다음 가정은 임상의가 다른 임상의의 비디오 클립 사례와 관련이 있다는 것이었습니다. 이 가정을 테스트하려면 표준 스마트폰 소프트웨어보다 더 많은 것이 필요했습니다. 양방향 상호 작용을 용이하게 하는 프로토타입이 필요했습니다. 따라서 우리는 임상의가 환자 사례를 비디오로 녹화하여 스스로 선택한 동료 그룹과 공유할 수 있는 매우 간단한 스마트폰 앱을 개발했다. 그런 다음 동료들은 비디오로 녹화하고 사건에 대한 의견을 공유할 수 있었다. 우리는 6명의 임상의사를 고용하여 각각의 사례를 기록하고 이 사례를 논의하기 위해 동료 그룹을 초대했다.

The next assumption was that clinicians would engage with video clip cases from other clinicians. Testing this assumption required more than standard smartphone software; we needed a prototype that would facilitate bi-directional interaction. Thus, we developed a very simple smartphone app that allowed clinicians to video-record themselves presenting a patient case and share this with a group of self-selected peers. The peers could then video-record and share comments on the case. We recruited six clinicians to each record a case and invite a group of peers to discuss this case.

재다

Measure

우리는 세 가지 주요 메트릭스를 제안했습니다. 예를 들어 사례를 본 응답자의 30%는 질문이나 코멘트로 응답하고, 40%는 두 번째 사례를 보고, 40%는 동료에게 사례 앱을 추천합니다. 테스트에서 초청된 72개 공급자 중 24개(33%)가 실제로 시제품을 사용해 보았다. 이 중 5명(21%)이 댓글 달기에 성공했고, 2명(10%)은 두 번째 사례를 봤으며, 2명(10%)은 동료에게 케이스앱을 추천하겠다고 답했다.

We proposed three key metrics: 30% of those who viewed a case would respond with a question or comment, 40% would view a second case, and 40% would recommend CasesApp to a colleague. In testing, 24 of 72 (33%) invited providers actually tried the prototype. Of these, 5 (21%) successfully added a comment, 2 (10%) viewed a second case, and 2 (10%) indicated they would recommend CasesApp to a colleague.

배우다.

Learn

목표 메트릭을 충족하지 못했습니다. 임상의들이 사례 기반 논의에 관심을 표명했지만, 실제로는 이러한 비디오 녹화 사례에 관여하지 않았다. 그래서 우리는 이 생각을 버렸습니다.

We failed to meet any target metrics. Although clinicians expressed interest in case-based discussions, in actuality they did not engage with these video-recorded cases. So, we abandoned this idea.

혁신 2. '''비디오 360'''

Innovation 2. ‘Video360’

고객 발굴, 아이디어 제시 및 가정

Customer discovery, ideation, and assumptions

11월 중순에 첫 번째 혁신을 포기한 후 연말(4주) 전에 두 번째 제품을 구상, 개발 및 테스트하자고 제안했습니다. 깨끗한 슬레이트로부터 시작하여 고객 개발 대화를 재분석하고 광범위하게 브레인스토밍했으며, 마지막으로 시뮬레이션된 환자 만남의 몰입형 온라인 가상 현실(VR) 비디오가 실제 환자와의 더 많고 다양한 경험에 대한 명시된 욕구를 대체할 수 있는 아이디어(가설)를 선택했다. 우리는 이것이 학습 결과에 어떻게 긍정적인 영향을 미칠지에 대한 명확한 기대를 가지고 있지 않았지만, 이 고위험 고수익 아이디어를 테스트하는 것은 타당해 보였다. 결국, 린 스타트업 접근 방식을 사용하면 우리는 노력해도 크게 손해 볼 것이 없다.

After abandoning our first innovation in mid-November, we proposed to ideate, develop, and test a second product before year-end (4 weeks). Starting with a clean slate we re-analyzed our customer development conversations and brainstormed broadly, finally choosing the idea (hypothesis) that immersive online virtual reality (VR) videos of simulated patient encounters might substitute for the stated desire for more, varied experiences with real patients. We didn’t have a clear expectation for how this would favorably impact learning outcomes, but it seemed reasonable to test this high-risk, high-payoff idea. After all, using the Lean Startup approach we would not lose much for trying.

다시 한 번 우리는 관련 임상 주제 범위를 중심으로 한 중요한 가정(표 3)을 우선시했다(이것이 틈새에서만 작동할 것인가). 아니면 우리는 이것을 임상 훈련의 범위에 걸쳐 사용할 수 있습니까?)

Once again we prioritized critical assumptions (Table 3), which revolved around the range of relevant clinical topics (Would this work only in a niche? Or could we use this across the spectrum of clinical training?).

제작 및 측정

Build and measure

제안된 혁신은 360° 카메라(비용 $400)를 사용하여 시뮬레이션 또는 실제 환자 만남을 기록하고, 저렴한 VR 헤드셋(각 $10)을 사용하여 후속 재생을 수행하는 것이었다. 다양한 주제에 대한 우리의 가정을 테스트하기 위해, 우리는 상담, 신체 검사 및 외상 소생이라는 세 가지 다른 임상 활동의 시뮬레이션을 비디오로 녹화했다. 우리는 이 비디오들을 진행하기 위해 유튜브를 이용했다. 우리는 공식적인 '사용자 경험' 실험을 통해 이러한 시나리오를 평가할 계획이었지만, 임상의, 교육자 및 전문 혁신자로 구성된 우리 팀은 이 단계 이전에도 심각한 문제를 확인했다.

- 우선 영상이 다소 흐릿하고 편집이 예상보다 번거로웠다.

- 둘째, 신체 검사와 의사소통 만남은 360° 기능의 혜택을 받지 못했고, 어떤 면에서는 실제로 더 나빴다.

- 셋째, 소생 시나리오의 증분적 이점은 최소였고, 여러 카메라의 비디오와 더 광범위하고 비용이 많이 드는 편집이 필요했을 것이다.

The proposed innovation involved recording simulated or real patient encounters using a 360° camera (cost USD $400) and subsequent playback using inexpensive VR headsets ($10 each). To test our assumption regarding range of topics, we video-recorded simulations of three distinct clinical activities: counseling, physical exam, and trauma resuscitation. We used YouTube to host these videos. We planned to evaluate these scenarios through formal ‘user experience’ experiments, but our team of clinicians, educators, and professional innovators identified serious problems even before this step. First, the video was somewhat blurry and the editing more cumbersome than anticipated. Second, the physical exam and communication encounters did not benefit from the 360° feature, and in some ways were actually worse. Third, the incremental benefit for the resuscitation scenario was minimal, and would have required video from multiple cameras and more extensive (and costly) editing.

배우다.

Learn

이러한 발견은 360° 비디오가 광범위한 주제에 걸쳐 가치를 더할 것이라는 우리의 희망을 반증했다. 따라서 우리는 정량적 데이터 수집이나 최종 사용자 테스트를 진행하지 않았습니다. 대신, 우리는 이 아이디어가 만들어진 지 2주 만에 포기했다.

These findings disproved our hope that 360° video would add value across a broad spectrum of topics. As such, we never proceeded with quantitative data collection or end-user tests. Instead, we abandoned this idea only two weeks after its genesis.

혁신 3. '온 파'

Innovation 3. ‘OnPar’

아이디어와 첫 번째 MVP

Ideation and first MVP

우리의 세 번째 혁신은 다시 사례 기반 학습과 연결되었습니다. 그러나 이 아이디어는 공식적인 브레인스토밍에서 나오는 것이 아니라 비디오360 프로젝트를 중단한 후 팀이 압축을 풀기 위해 카드 게임을 하는 동안 발생했다. 누군가가 카드 게임이 임상 사례 관리를 시뮬레이션할 수 있다고 제안했고, 우리는 그 아이디어를 Solitaire와 유사한 게임으로 정교하게 만들었다. 다음 근무일에, 우리는 의사에게 최근의 흥미로운 사례에 대해 설명하도록 요청하고 주요 결과(이력, 시험, 테스트 결과)를 종이 색인 카드에 기록했습니다. 각 카드의 반대편에 우리는 발견을 이끌어낼 임상 질문을 작성했다('가슴 엑스레이에서 무엇을 나타냈습니까?'). 간단한 규칙을 만들었습니다. 플레이어는 각 카드의 질문을 검토하고 사건 해결을 위해 결과가 필요한지 여부를 결정했다. 만약 그렇다면, 그들은 카드를 넘기고, 그렇지 않다면 그들은 카드를 버렸습니다. 가장 적은 카드를 내면서 올바른 진단을 내리는 것이 목표였다.

Our third innovation again connected to case-based learning. However, rather than emerging from formal brainstorming, this idea occurred while the team was playing cards to decompress after dropping the Video360 project. Someone suggested that a card game might simulate management of clinical cases, and we elaborated the idea into a game similar to Solitaire. The following workday, we asked a physician to describe a recent interesting case and recorded key findings (history, exam, test results) on paper index cards. On the opposite side of each card we wrote a clinical question that would elicit that finding (‘What did chest x-ray show?’). We created simple rules: The player reviewed each card’s question and decided whether the result was needed to solve the case. If yes, they turned the card over; if not they discarded the card. The goal was to make the right diagnosis while playing the fewest cards.

우리는 여러 명의 임상의와 함께 그 게임을 테스트했다. 모두가 게임을 즐겼고, 이 개념을 열렬히 지지했으며, 이는 일상적인 임상 실습에서 시간과 비용 효율에 대한 실질적인 요구를 모방했음을 시사했다. 한 임상의 교육자는 이것이 비분석적 임상 추론 과정을 장려한다고 추가로 제안했다.

We tested the game with several clinicians. All enjoyed the game and enthusiastically endorsed the concept, suggesting that it emulated the practical demands for time and cost efficiencies in their daily clinical practice. One clinician educator further suggested that this encouraged nonanalytical clinical reasoning processes.

빌드-측정-학습: 2세대 MVP

Build-measure-learn: Second-generation MVP

이 MVP에 대한 호의적인 반응이 우리를 앞으로 나아가게 했다. 가장 위험한 가정(표 3)은 임상의가 게임을 원하는지 여부(구체적으로 2차 게임을 원하는지 여부)와 임상의가 게임 라이브러리를 강화하기 위해 새로운(실제) 사례를 공유하는지 여부에 초점을 맞췄다. 2세대 MVP는 인덱스 카드로 다시 구성되었는데, 이번에는 진단 관련 심전도와 교과서에서 복사한 흉부 X-ray의 접착 이미지를 사용하여 더욱 세심하게 제작되었다.

The favorable reception to this MVP prompted us to move forward. The riskiest assumptions (Table 3) focused on whether clinicians would want to play the game (specifically, that they would play a second round), and whether clinicians would share new (real) cases to augment our game library. The second-generation MVP again consisted of index cards, this time more carefully constructed (but still hand-written) and using glued-on images of diagnosis-relevant electrocardiograms and chest x-rays copied from textbooks.

우리는 세 가지 사례를 만들고 여러 전문 분야와 훈련 단계를 대표하는 임상의와 함께 게임을 시험해 보았고, 각 시험 후에 게임 규칙을 반복적으로 개선했다. 각 케이스가 끝난 후 우리는 우리의 가정을 테스트하고, 그들이 두 번째 라운드를 하기를 원하는지 물어보고(가능한 경우 허용) 그들을 초대하여 케이스를 작성하는 데 도움을 주었다. 골프(최소 타수를 노리는 것)와 유사성을 인식해 경기 이름을 '온파'로 지었다.

We created three cases and trialed the game with clinicians representing several specialties and stages of training, iteratively refining the game rules after each trial. After each case we tested our assumptions, asking if they wanted to play a second round (allowing this when possible) and inviting them to help us write a case. Recognizing the similarity to golf (i.e. striving for the fewest strokes), we named the game ‘OnPar.’

빌드-측정-학습: 3세대 MVP

Build-measure-learn: Third-generation MVP

종이 프로토타입에 대한 반응이 매우 좋았기 때문에 우리는 빠른 프로토타이핑 도구를 사용하여 컴퓨터 기반 MVP를 만들 수 있었다. 우리는 개인적으로 약 30명의 임상의들을 초대했고, 그들은 차례로 이메일과 트위터를 통해 동료들을 초대했고, 그 결과 30일 동안 90명이 프로토타입에 액세스했다. 이 중 30%는 계정을 활성화하고 최소 1건의 사례를 완료했다. 예상을 뛰어넘는 성과로 우리는 더 많은 발전을 지속하기로 했다. 불행하게도, 우리 기관은 다른 교육 우선 순위를 추구하기로 결정했고 이 프로그램에 대한 자금 지원은 철회되었다.

The highly-favorable response to paper prototypes led us to create a computer-based MVP using a rapid-prototyping tool. We personally invited about 30 clinicians to play, who in turn invited colleagues by email and Twitter resulting in 90 people accessing the prototype over a 30-day period; of these, 30% activated an account and completed at least 1 case. With outcomes exceeding expectations, we decided to persevere with further development. Unfortunately, our institution opted to pursue other educational priorities and funding for this program was withdrawn.

논의

Discussion

린 스타트업은 지금까지 주로 비즈니스 벤처에 적용되었지만, 우리의 경험은 교육 혁신을 신속하게 테스트, 정제 및 포기하는 데 있어 이 접근 방식의 유용성을 강조합니다. 불과 5개월 만에 고객 니즈를 파악하고, 혁신을 위한 수많은 아이디어를 창출했으며, 공식적으로 3개의 혁신을 테스트했습니다(그 중 2개는 불과 2주 만에 폐기). 우리는 이 접근 방식이 교실 수업 방법, 온라인 모듈 및 게임, 소규모 그룹 형식, 임상 순환 구조, 평가 활동 및 커리큘럼 재설계를 포함한 사실상 모든 교육 혁신에 적용될 수 있다고 예상한다.

Although Lean Startup has thus far been applied primarily to business ventures, our experience highlights the utility of this approach in rapidly testing, refining, and abandoning education innovations. In only five months we identified customer needs, generated numerous ideas for innovation, and formally tested three innovations (abandoning two of them in as little as two weeks). We envision that this approach could apply to virtually any educational innovation, including classroom teaching methods, online modules and games, small group formats, clinical rotation structures, assessment activities, and curriculum redesigns.

우리는 (초기 '지속적 vs 피벗' 결정으로 제한되지 않음) 구현을 위해 선택된 아이디어를 다듬는 데 있어 이 접근 방식의 가치를 강조한다. Build-Measure-Learn은 혁신을 최대 규모(및 전체 투자)로 구축 및 테스트하는 일반적인 접근 방식과 달리 소규모(저비용) 테스트 실행을 기반으로 제품을 정교하게 다듬기 위해 반복되는 빠른 데이터 중심 주기를 강조합니다. 혁신자도 고객도 대개 고객이 진정으로 필요로 하는 것이 무엇인지 알지 못합니다. 린 스타트업은 상상된 니즈가 아닌 실제 니즈를 발견하고 해결할 수 있는 도구를 제공합니다.

We underscore the value of this approach in refining ideas once selected for implementation (not limited to the initial ‘persevere vs pivot’ decision). Build-Measure-Learn emphasizes fast, data-driven cycles that iterate to refine the product based on small-scale (inexpensive) test runs, in contrast to the typical approach of building and then testing an innovation at full scale (and full investment). Neither innovators nor customers usually know what the customer really needs; Lean Startup provides the tools to discover and address real rather than imagined needs.

린 스타트업은 (전통적인) 린 접근법, PDSA(Plan-Do-Study-Act), 식스 시그마, 구현 과학 등의 품질 개선 프레임워크와 대비된다. 이러한 전통적 접근법은 [고객 개발 및 검증된 학습('무엇을 만들 것인가?')]이 아닌, 주어진 제품이나 결과를 최소의 낭비와 오류('어떻게 더 낫게 만들 것인가?')로 제공하는 방법에 초점을 맞추고 있습니다. 린 스타트업은 디자인 사고(고객 중심 아이디어에 초점을 맞춘) 및 민첩성과 같은 다른 혁신 프레임워크를 보완하고 겹칩니다. (고객의 요구를 충족하기 위해 아이디어를 신속하게 점진적으로 세분화합니다.)

Lean Startup contrasts with quality improvement frameworks such as (traditional) Lean approaches (Womack et al. 2007; LeMahieu et al. 2017b), Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) (Cleghorn and Headrick 1996; Berwick 1998; LeMahieu et al. 2017b), Six Sigma (LeMahieu et al. 2017a), and implementation science (Glasgow et al. 1999; Nordstrum et al. 2017). These traditionally focus on how to deliver a given product or outcome with minimum waste and error (‘How to build it better?’) rather than customer development and validated learning (‘What to build?’). Lean Startup complements and overlaps other innovation frameworks such as design thinking (which focuses on customer-focused ideation) and Agile (which quickly incrementally refines ideas to meet customer demands) (Kidd and Johnson 2020).

Build-Measure-Learn은 과학적 방법의 다른 이름일 뿐이며, A-B 테스트는 단순히 집중(잠재적으로 무작위화됨) 제어 시험이다(Constable 2018). 잘 실행된 린 스타트업 프로젝트의 연구 결과는 종종 동료 검토 출판을 보증할 수 있으며, 특히 여러 주기의 연구 결과가 '실제로 작동하는 것'에 대한 일관된 메시지로 통합되는 경우 더욱 그렇다.

Build-Measure-Learn is just another name for the scientific method, and A-B testing is simply a focused (potentially randomized) controlled trial (Constable 2018). Findings from well-executed Lean Startup projects could often warrant peer-reviewed publication, especially if findings from several cycles are amalgamated into a coherent message of ‘what really works.’

우리가 '고객'이나 '비즈니스 모델'과 같은 용어를 사용하는 것은 교육의 시장화에 대한 지지를 의미하는 것이 아니라, 린 스타트업이 그 기원을 두고 있는 분야에서 이러한 용어를 빌렸을 뿐입니다. 교육의 시장화, 경제성, 비용효율은 이 글의 범위를 넘어서는 복잡한 주제이다.

Our use of terms like ‘customer’ and ‘business model’ does not imply endorsement of the marketization of education; we merely borrowed these terms from the field in which Lean Startup had its origin. The marketization, economics, and cost-effectiveness of education are complex topics beyond the scope of this article (Furedi 2011; Cook and Beckman 2015; Maloney et al. 2019).

결론

Conclusion

린 스타트업은 보건 전문 교육 분야에서 빠르고 강력한 혁신과 평가를 위한 엄청난 잠재력을 가지고 있다.

Lean Startup has tremendous potential for rapid, robust innovation and evaluation in health professions education.

Evaluating education innovations rapidly with build-measure-learn: Applying lean startup to health professions education

PMID: 36170876

Abstract

Purpose: The Lean Startup approach allows innovators (including innovative educators) to rapidly identify and refine promising ideas into models that actually work. Our aim is to outline key principles of Lean Startup, apply these to health professions education, and illustrate these using personal experience.

Methods and results: All innovations are grounded in numerous assumptions; these assumptions should be explicitly identified, prioritized, and empirically tested ('validated learning'). To identify and test assumptions, innovators need to get out of the office and interact with customers (learners, teachers, administrators, etc). Assumptions are tested using multiple quick cycles of Build (a 'minimal viable product' [MVP]), Measure (using metrics that relate meaningfully to the assumption), and Learn (interpret data and decide to persevere with further refinements, or pivot to a new direction). The MVP is a product version that allows testing of one or more key assumptions with the least effort. We describe a novel 'Lean Education Canvas' that synopsizes an innovation and its business model on one page, to help identify assumptions and monitor progress. We illustrate these principles using three cases from health professions education.

Conclusions: Lean Startup has tremendous potential for rapid, robust innovation and evaluation in education.[Box: see text].

Keywords: Program evaluation; agile development; empirical research; qualitative research; research design.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 교육과정 개발&평가' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 주요 교육과정 개편 기저의 사회적 메커니즘 탐색을 위한 보르도의 개념을 적용한 질적 연구(Med Teach, 2022) (0) | 2022.11.20 |

|---|---|

| 의학교육의 학생참여: 교육과정 개발에서 모듈 공동책임자로서 학생에 관한 혼합연구(Med Teach, 2019) (0) | 2022.11.17 |

| 보건의료시스템과학 교육과정 도입 과제: 학생 인식의 질적 분석(Med Educ, 2016) (0) | 2022.11.09 |

| 학부의학교육 변화의 복잡성 탐색하기: 변화 선도자의 관점(Acad Med, 2018) (0) | 2022.10.08 |

| 산을 옮기는 일: 대형 유럽 의과대학의 주요 교육과정 개편을 향한 실용적 통찰(Med Teach, 2018) (0) | 2022.10.08 |