학부의학교육 변화의 복잡성 탐색하기: 변화 선도자의 관점(Acad Med, 2018)

Navigating the Complexities of Undergraduate Medical Curriculum Change: Change Leaders’ Perspectives

Floor Velthuis, MSc, Lara Varpio, PhD, Esther Helmich, MD, PhD, Hanke Dekker, PhD, and A. Debbie C. Jaarsma, DVM, PhD

학부 의학 커리큘럼을 갱신하는 것은 전 세계의 의과대학에서 정기적으로 반복되는 과정이다. 커리큘럼 변경을 제정하는 것은 여러 조직 구조(예: 대학 및 부속 병원)와 각 부서, 다양한 직원, 교수진 및 의사가 교육에 참여하는 복잡한 노력이다. 따라서 커리큘럼 변화는 (새로운 커리큘럼에 대해 나름의 기득권을 가진) 많은 이해당사자들을 포함한다. 이러한 복잡한 과정을 성공적으로 이끌기 위해서는 강력한 리더십 기술이 필요하다. 의학 교육에서 리더십 역할을 연구하는 문헌이 있지만, 커리큘럼 변경 과정에서 이러한 리더의 역할에 초점을 맞춘 연구는 거의 없다. 기관 지도자들이 학부 의료 교육과정 변화 과정을 어떻게 집행enact하고 지시direct하는지에 대한 학문적 관심은 거의 없었다. 이 리더십 작업은 커리큘럼 개혁이 상당한 인적, 재정적 자원을 필요로 하는 큰 과제이기 때문에 훨씬 더 많은 연구 관심을 필요로 한다. 커리큘럼 변경 리더는 불가피하게 직면하게 될 도전을 극복할 수 있는 충분한 준비가 되어 있어야 한다. 만약 우리가 리더들이 이러한 도전을 극복하기 위해 사용한 과정과 기술에 대해 더 잘 안다면, 우리는 미래의 리더들이 성공적으로 커리큘럼 변화를 가져올 수 있도록 더 잘 지원할 수 있을 것이다.

Renewing an undergraduate medical curriculum is a regularly recurring process at medical schools around the world. Enacting curriculum change is a complex endeavor1 involving multiple organizational structures (e.g., university and affiliated hospital[s]), each housing multiple departments and a variety of staff, faculty members, and doctors in training.1 Curriculum change thus involves many stakeholders, all with a uniquely vested interest in the new curriculum.2 Successfully spearheading such a complex process requires strong leadership skills. Although there is a body of literature studying leadership roles in medical education, little research has focused on these leaders’ roles in curriculum change processes.3,4 Little scholarly attention has been paid to how institutional leaders enact and direct undergraduate medical curriculum change processes. This leadership work requires much more research attention because curriculum reform is a high-stakes undertaking, requiring significant human and financial resources. Curriculum change leaders must be adequately prepared to overcome the challenges they will inevitably face. If we knew more about the processes and the techniques that leaders employed to overcome these challenges, we could better support future leaders to successfully bring about curriculum change.

의대 교육과정 변화와 관련된 과제에 대한 조사를 뒷받침할 수 있는 세 가지 문헌에는 다음이 있다.

- 복잡성 이론(변화가 발생하는 과정과 맥락의 다면적 특성을 이해하기 위한 것)이다.

- 조직 변화 문헌(변경을 제정하는 데 사용되는 도구를 조사하기 위해) 그리고

- 이 조직 변화 문헌 중에서도 변화 리더십에 대한 문헌(변화 프로세스를 이끌고 관리하는 개인의 역할을 이해하기 위해)

세 과목 모두 커리큘럼 변화에 대한 연구에 정보를 줄 수 있지만, 우리는 리더의 관점에서 의료 커리큘럼 변화의 복잡성을 더 잘 이해하고, 개인이 이러한 복잡한 맥락을 어떻게 탐색하고 변화와 관련된 과제를 해결하는지에 관심이 있다. 따라서, 우리는 [변화 리더십 문헌]을 기반으로 합니다.

Three bodies of literature that can underpin investigations of the challenges related to medical school curriculum change are

- complexity theory (to understand the multifaceted nature of the processes and contexts in which change occurs)5–7;

- organizational change literature (to investigate the tools used to enact change)8; and within this organizational change literature,

- the literature on change leadership (to understand the role of the individual who is leading and managing the change process).9–14

Although all three subjects can inform research into curriculum change, we are interested in better understanding the complexity of medical curriculum change from the leader’s perspective, exploring how that individual navigates this complex context and deals with change-related challenges. Thus, we build on the change leadership literature.

이 연구분야에서는 [조직 변화를 가져오는 데 있어 변화 리더의 역할]을 강조한다. 우리는 [변화 리더]를 [학부 의료 커리큘럼을 갱신하거나 크게 변경할 책임이 있는 개인]으로 정의합니다. 변화 지도자를 연구하기 위한 제한된 양의 의학 교육 연구가 이용 가능하다. Bland 등은 의료 커리큘럼 변경의 리더가 "성공에 필수적인 거의 모든 다른 특징들을 통제하거나 실질적으로 영향을 미치기" 때문에 중요한 역할을 수행한다고 말한다. 그들은 중요한 변화 리더십 행동에 "주장적인 참여적, 문화적/가치적 영향을 미치는 행동들, '유연성'을 가지고, 다양한 인식적 프레임워크로 조직을 보고, 다른 사람들을 동원하여 변화 모멘텀을 유지하는 것"이 포함된다고 본다.

This literature emphasizes the role of change leaders in bringing about organizational change.9–14 We define a change leader as the individual primarily responsible for renewing or significantly changing an undergraduate medical curriculum. A limited amount of medical education research directed specifically at studying change leaders is available. Bland et al9 state that leaders of medical curriculum change fulfill a critical role because they “control or substantially influence nearly all the other features essential for success.”(p592) They identify important change leadership behaviors as including “assertive participative and cultural/value-influencing behaviors, to be ‘flexible,’ to view the organization through a variety of perceptual frames and to mobilize others to maintain the change momentum.”9(p580)

의학 교육의 변화 리더에 대한 최근의 경험적 연구는 주로 단일 의과대학에서 수행되었고, 주요 학부 프로그램 개정에 초점을 맞추지 않았다. 여러 기관의 리더가 직면한 과제를 더 잘 이해하기 위해, 본 연구는 여러 의과대학의 커리큘럼 변경 리더의 통찰력에 초점을 맞추고 있다. 우리는 커리큘럼 변경 리더들이 변화를 제정하는 과정을 어떻게 생각하는지, 그리고 그들이 그들의 노력에 성공하기 위해 의존하는 전략을 알고 싶었다.

Recent empirical studies about change leaders in medical education have predominantly been conducted at single medical schools3,4,15,16 and were not focused on major undergraduate program revisions. To gain a better understanding of the challenges faced by leaders across different institutions, our study focuses on insights from curriculum change leaders at multiple medical schools. We wanted to know how curriculum change leaders conceive of the process of enacting change, and the strategies they relied on to succeed in their efforts.

방법

Method

참가자

Participants

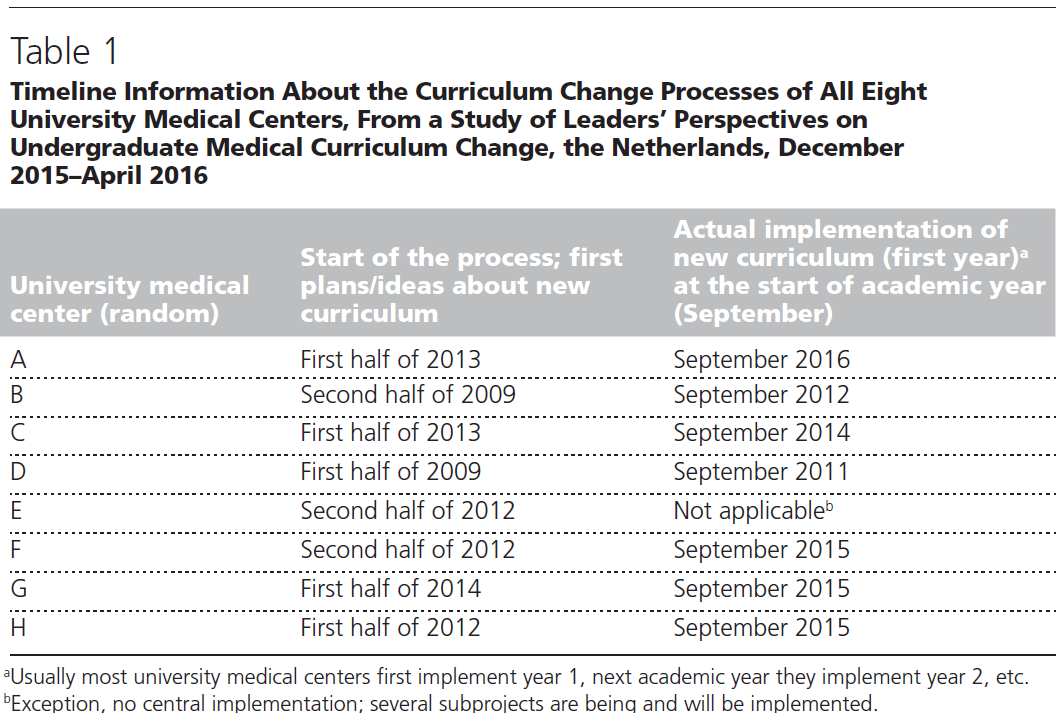

연구 참여자는 현재 네덜란드의 8개 대학 의료 센터(UMC) 중 하나에서 주요 학부 의료 커리큘럼 변경 프로세스를 주도하거나 최근에 주도했던 개인이었다. (이들은 알파벳 순서로 AMC [암스테르담], Erasmus MC [로터담], LUMC [라이덴], Maastrich UMC+ [마스트리히트 UMC], Radumbudnci [니즈메겐], UMCG [그로닝언], UMCU [위트레흐트] 및 VUMC [암스테르담]이다. 각 학교는 연간 평균 400명의 학생을 받아들인다.) 우리는 "주요 커리큘럼 변경"을 과정 수준에서 연간 정기적 조정에 관한 것이 아니라, [전체 커리큘럼]과 [커리큘럼에 관련된 조직]에 영향을 미치는 [중앙에서 조직되고 의도적으로 시작된 변경 프로젝트]로 정의한다. 7개의 UMC에서는 한 명이 이 위치에 있다고 보고했고, 1명의 UMC에서는 두 명이 이 선두 위치에 있다고 보고했다. 따라서, 우리의 연구는 8개의 UMC 모두를 대표하는 9명의 참가자의 데이터를 기반으로 한다. 변경 프로세스에 대한 일정은 그림 1 및 표 1을 참조하십시오.

Study participants were individuals who were currently leading or had recently led a major undergraduate medical curriculum change process in one of the eight university medical centers (UMCs) in the Netherlands. (These are, in alphabetic order: AMC [Amsterdam], Erasmus MC [Rotterdam], LUMC [Leiden], Maastricht UMC+ [Maastricht], Radboudumc [Nijmegen], UMCG [Groningen], UMCU [Utrecht], and VUmc [Amsterdam]. Each school accepts an average amount of ~400 students annually.) We define “major curriculum change” as changes that were not about the yearly, regular adjustments at course level, but were centrally organized, intentionally initiated change projects that affected the entire curriculum and organization involved in the curriculum. Seven UMCs reported having one individual in this position, and one UMC reported having two individuals in this lead position. Thus, our study is based on data from nine participants, representing all eight UMCs. For timelines of the change processes, see Figure 1 and Table 1.

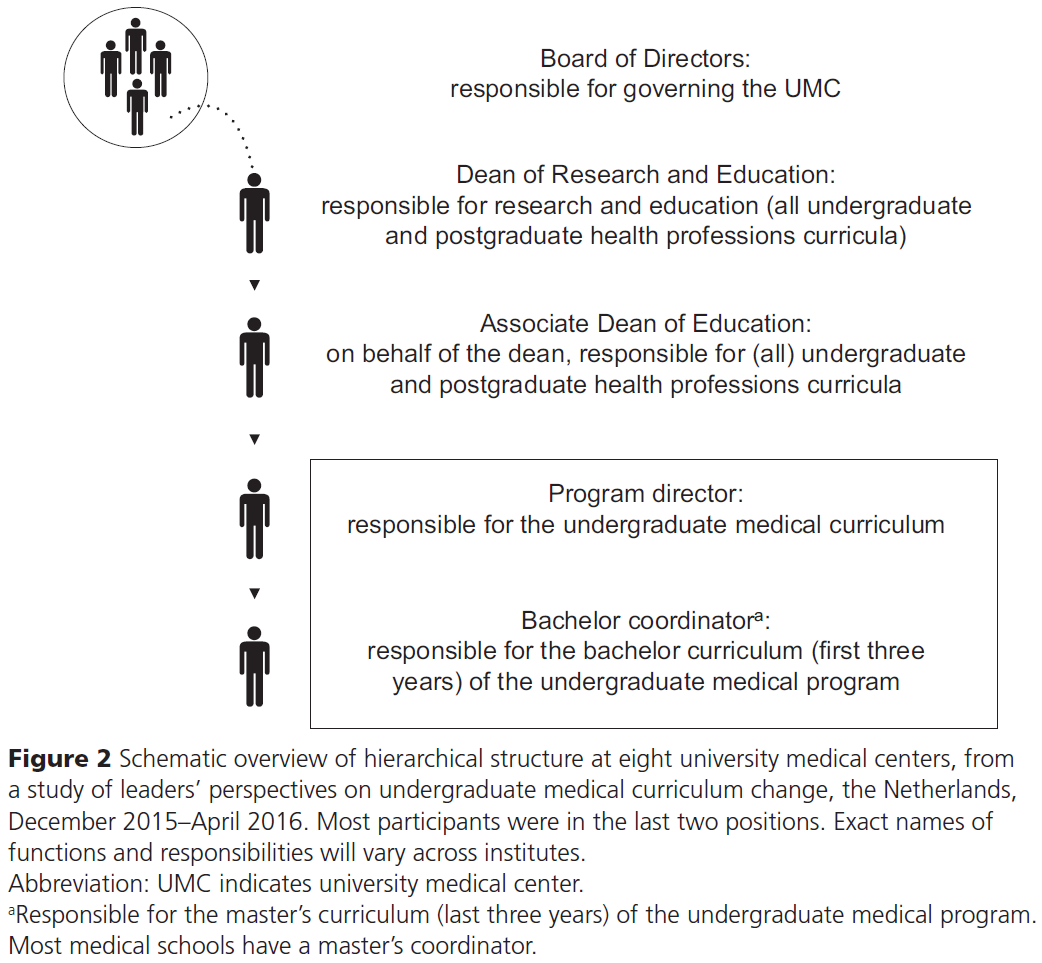

네덜란드의 각 기관 내에는 서로 다른 조직 구조와 유사하거나 유사한 위치에 있는 사람들에 대한 서로 다른 이름과 책임이 있으며, 이는 그림 2에 요약되어 있다.

Within each institute in the Netherlands there are different organizational structures and different names and responsibilities for people in similar or comparable positions, which are summarized in Figure 2.

네덜란드의 각 UMC는 이사회에 의해 관리된다. 이사회에서 학장은 연구 및 학부 및 대학원 보건 전문가 커리큘럼을 담당합니다. 학장 아래 계층적으로 위치한 대부분의 기관에서 부교육장은 보건 전문 교육과정을 전체적으로 감독할 책임이 있다. 학장을 대신하여 대부분의 학원은 학부 의료 교육과정을 추가로 실행하고 감독할 책임을 지는 프로그램 책임자를 두고 있다. 이 직책 아래에는 일반적으로 의료 커리큘럼의 두 부분 중 한 부분의 내용, 품질 보증 및 일관성을 책임지는 두 명의 조정자가 있다.

- 학사 코디네이터(처음 3년 전 임상 의학 학부 과정),

석사 코디네이터(마지막 임상 3년 동안 학부 의학 프로그램)

Each UMC in the Netherlands is governed by a board of directors. On the board, the dean is responsible for research and the undergraduate and postgraduate health professions curricula. At most institutes, hierarchically positioned under the dean, the associate dean of education is responsible for overseeing the health professions curricula as a whole. On behalf of the dean, most institutes have a program director being responsible for further executing and overseeing the undergraduate medical curriculum. Below this position, there are—at a more daily, executive level—usually two coordinators who are responsible for the content, quality assurance, and coherence of one of two parts of the medical curriculum;

- the bachelor’s coordinator (first three preclinical years undergraduate medical program), and

- master’s coordinator (last three clinical years undergraduate medical program).

4명의 참여자는 프로그램 감독직 내에서 또는 프로그램 감독직과 더불어 변화를 선도하는 역할을 수행했으며, 3명은 학사 코디네이터로 활동했습니다. 나머지 참여자 2명은 위에서 약술한 바와 같이 정식 직책을 다하지 못하였으나 교육과정 변화를 주도하도록 요청받은 의학교육교육과정 교수였다. 모든 경우에 참여자들은 학장 또는 부교육장이 임명하여 학교의 교육과정 변경 과정을 이끌었고, 따라서 학장 또는 부학장에 대한 책임이 있었다. 모든 참가자(남성 8명, 여성 1명)는 의학교육과 의과대학에서 다양한 직책에서 상당한 경험을 했고, 여전히 전임상, 임상 또는 연구 부서의 선도적 직책에 있었다.

Four participants fulfilled the change-leading role within or in addition to their job as program director, and three as bachelor’s coordinator. The remaining two participants were professors in the medical education curriculum who did not fulfill a formal position as outlined above but were asked to lead the curriculum change. In all cases, participants were appointed by the dean or the associate dean of education to lead the school’s curriculum change process, and so were accountable to the dean or associate dean. All participants (eight males, one female) had substantial experience—in various positions—within medical education and the medical school, and were still or had been in leading positions in preclinical, clinical, or research departments.

데이터 수집

Data collection

2015년 12월부터 2016년 4월까지 한 연구원이 개별 대면 인터뷰를 진행했다. 인터뷰 프로토콜을 세분화하기 위해 다른 건강 전문직 교육과정 변경 참가자(즉, 목표 모집단 외부의 개인)와 세 번의 파일럿 인터뷰가 이루어졌다. 그 의정서는 네 부분으로 구성되었다. 인터뷰는 두 가지 시각화 프롬프트로 시작되었습니다.

- 첫 번째는 리더가 커리큘럼 변화를 어떻게 시각화했는지에 대한 짧은 그리기 연습이었습니다.

- 둘째, 참가자들에게 52개의 "브리핑 카드" 중에서 자신의 교육과정 변화 경험에 대한 감정이 공명하는 1개의 포토카드를 선택하도록 하였다. 이러한 시각적 기법은 참가자들이 커리큘럼 변경과 함께 전문적이고 개인적인 경험을 상기하도록 격려했다.

- 인터뷰의 세 번째 부분은 변화 과정과 맥락에 대한 참가자의 인식(예: 이해관계자 참여, 경험된 과제, 가속기 및 감속기)과 커리큘럼 변화 노력의 리더로서 리더의 경험(예: 준비, 개인적 원동력, 지원, 학습 내용)을 탐구하는 반구조화된 인터뷰 프로토콜을 따랐다..

- 인터뷰의 네 번째 부분에서, 참가자들은 교육과정 변화의 이야기를 그린 다른 포토카드를 선택하도록 요청받았다.

이것은 인터뷰를 마무리하는 데 사용되었다.

인터뷰는 1시간 반에서 2시간 동안 진행되었다. 모든 인터뷰는 녹음되었고 녹음 과정에서 익명으로 처리되었다. 시각적(즉, 도면과 선택된 카드)은 촬영되었지만 본 연구를 위한 분석에 통합되지 않았다. 그것들은 단순히 추가적인 연구 자료라기보다는 대화를 촉구하기 위한 것이었다. 선택한 사진의 유형과 그에 따른 설명을 독자에게 이해시키려면 보충 디지털 부록 1을 참조하십시오.

Working from a constructivist orientation,17 one researcher (F.V.) conducted individual face-to-face interviews between December 2015 and April 2016. Three pilot interviews took place with other health professions curriculum change participants (i.e., individuals outside our target population) to refine the interview protocol. The protocol consisted of four parts. The interviews started with two visualizing prompts.

- The first was a short drawing exercise about how leaders visualized the curriculum change.

- Second, participants were asked to choose 1 photo card from 52 “briefing cards”18 that resonated with their feelings about their curriculum change experience. These visual techniques encouraged participants to recall professional and personal experiences with curriculum change.

- The third part of the interview followed a semistructured interview protocol exploring participants’ perceptions of the change process and context (e.g., involvement of stakeholders, challenges experienced, accelerators and decelerators of the process) and the leaders’ experiences as leader of the curriculum change effort (e.g., preparation, personal drives, support, lessons learned).

- In the fourth part of the interview, participants were asked to select another photo card that depicted the story of curriculum change; this was used to wrap up the interview.

Interviews lasted 1.5 to 2 hours. All interviews were audio-recorded and rendered anonymous in the transcription process. The visuals (i.e., drawings and selected cards) were photographed but were not incorporated into the analysis for this study. They were simply meant as a prompt for the conversation rather than additional research material. To give readers an impression of the type of pictures chosen and the accompanying explanations, see Supplemental Digital Appendix 1, available at https://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A528.

데이터 분석

Data analysis

우리는 질적 내용 분석을 사용했는데, 이는 "데이터의 정보 내용을 요약하는 데 중점을 둔 역동적 분석(…)"으로 설명되었다. 데이터 분석은 데이터 수집과 동시에 이루어졌으며, 테마는 데이터로부터 귀납적으로 구성되었으며, 결과적으로 교육과정 변경 과정에 대한 참가자들의 개념과 그 변경을 성공적으로 수행하기 위한 전략에 대한 상세한 서술적 요약이 이루어졌다.

We employed qualitative content analysis, which has been described as a “dynamic form of analysis (…) oriented towards summarizing the informational contents of that data.”19(p338) Data analysis occurred concurrently with data collection, with themes being constructed inductively from the data, resulting in a detailed descriptive summary19 of participants’ conceptions of the process of curriculum change and their strategies for successfully carrying out that change.

인터뷰가 끝난 뒤 우리 연구팀 3명(F.V., H.D., A.J.)이 각 녹취록를 논의하는 것으로 데이터 분석이 시작됐다. 모든 데이터가 수집되면 4명의 연구자(F.V., L.V., H.D., A.J.)가 여러 팀 토론에 참여하여 초기 데이터 테마를 구성하였으며, Atlas.ti 소프트웨어 버전 7(Atlas.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin)에서 데이터를 코딩하기 위한 출발점으로 사용되었다. 한 팀 구성원(F.V.)이 코딩 프로세스를 주도하고 데이터 샘플을 검토하였으며, 또한 주제와 상호 관계를 개선하는 데 기여한 두 명의 다른 구성원(H.D. 및 A.J.)과 함께 코딩 구조에 대한 진화하는 아이디어와 변화에 대해 정기적으로 논의했습니다. 이 회의들은 정확성을 보장하고 합의에 도달하기 위한 체계적인 점검이었다. 인터뷰가 네덜란드어로 진행되었기 때문에 우리 중 한 명(L.V.)은 원시 데이터의 코딩에 참여할 수 없었습니다. 팀 전체와 합의에 도달하기 위해, 우리는 정기적인 팀 회의를 열어 그 과정과 우리의 진화하는 해석에 대해 논의했습니다. 우리는 특히 개별 코드를 주요 주요 테마로 연결하기 위해 L.V.의 입력(예: 코드 정의와 포함 범위에 대한 질문, 코드 간 가능한 연결에 대한 질문 등)에 의존했다. 전체 과정 동안, 수석 연구원(F.V.)은 성찰 및 분석 메모의 개발에 주목했습니다. 이러한 노트는 팀 토론 중에 검토되고 검토되었습니다. 한 연구자(E.H.)가 이 후반 단계에서 팀에 합류하여 코딩 프로세스와 분석을 검토했다. 우리의 해석의 신뢰성을 높이기 위해, E.H.는 대본을 읽고 코드와 주요 주제를 다듬는 것을 도왔다.

Data analysis began with three members of our research team (F.V., H.D., and A.J.) discussing each transcript after the interview. Once all data were collected, four researchers (F.V., L.V., H.D., and A.J.) participated in several team discussions and constructed an initial set of data themes, which were used as a starting point for coding the data in Atlas.ti software, version 7 (ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin). One team member (F.V.) led the coding process and regularly discussed the evolving ideas and changes to the coding structure with two others (H.D. and A.J.), who also reviewed data samples and contributed to refining themes and interrelations. These meetings were systematic checks to ensure accuracy and to reach agreement. Because the interviews were conducted in Dutch, one of us (L.V.) was not able to participate in the coding of the raw data. To reach agreement with the whole team, we held regular team meetings to discuss the process and our evolving interpretations. We especially relied on L.V.’s input (e.g., asking questions about the code definitions and their scope of inclusion; about possible connections between codes, etc.) to link individual codes into major, overarching themes. Throughout the entire process, the lead researcher (F.V.) noted developing reflections and analysis memos. These notes were reviewed and vetted during team discussions. One researcher (E.H.) joined the team at this later stage and reviewed the coding processes and analyses. To enhance the trustworthiness of our interpretations, E.H. read the transcripts and helped refine the codes and overarching themes.

팀구성

Team composition

연구팀은 의학교육 분야(L.V., E.H., H.D., A.J.)의 선임 연구원 4명과 후배 1명(F.V.)으로 구성됐다. 원(F.V.)은 사회심리학에 대한 배경을 가지고 있으며, L.V.에 의해 연구면접을 수행하는 기술과 과정에 대한 교육을 받았다. One(L.V.)은 보건 전문 교육 분야의 부교수이자 경험 많은 질적 연구자입니다. 원(E.H.)은 질적 연구에 전문지식을 가진 노인 요양 의사이자 의료 교육자이다. 한 명(H.D.)은 주요 커리큘럼 변경 과정에서 교육 혁신 태스크 그룹을 주재하는 선임 교육자이고, 한 명(A.J.)은 보건 전문 교육 교수입니다.

The research team consisted of one junior (F.V.) and four senior researchers in medical education (L.V., E.H., H.D., A.J.). One (F.V.) has a background in social psychology and was trained by L.V. in the techniques and processes of conducting research interviews. One (L.V.) is an associate professor and an experienced qualitative researcher in the health professions education domain. One (E.H.) is an elderly care physician and medical educator with expertise in qualitative research. One (H.D.) is a senior educationalist chairing a task group on education innovation during a major curriculum change process, and one (A.J.) is a professor in health professions education.

번역

Translations

각 기록의 일부는 우리 팀 중 한 명이 영어로 번역했다. 두 명의 연구자(E.H.와 A.J.)가 이를 확인하기 위해 번역을 검토했습니다. 의심이 들 경우, 2개 국어를 할 수 있는 동료와 상담했다. 보고서에 사용된 인용문으로 작업할 때, 한 팀 구성원(L.V. 원어민)이 원고를 여러 번 편집하여 인용문을 포함한 텍스트의 변경 사항을 확인하고 제안했습니다. 우리 중 한 명(F.V.)은 새로운 문구가 네덜란드어 필사본 원본을 정확하게 반영하도록 하기 위해 항상 이러한 변경 사항을 확인했습니다.

Portions of each transcription were translated to English by one of our team (F.V.). Two researchers (E.H. and A.J.) reviewed the translations to confirm these. In case of doubt, a bilingual colleague was consulted. When working with quotes used in the report, one team member (L.V., a native English speaker) edited the manuscript several times, checking and offering suggested changes to the text including the quotes. One of us (F.V.) always verified these changes to ensure that the new phrasings accurately reflected the original Dutch transcripts.

The Dutch Association for Medical Education ethical review board approved this study (number 592).

결과.

Results

익명성을 지원하기 위해, 모든 참가자는 남성 성별로 언급된다. 예시적인 견적은 응답자 번호로 귀속됩니다.

To support anonymity, all participants are referred to in the masculine gender. Illustrative quotations are attributed by respondent number.

참가자들은 커리큘럼 변화를 많은 상호 작용 요소를 포함하는 동적이고 복잡한 과정이라고 설명했습니다. 한 참가자는 철도 건널목의 그림을 묘사하면서 "이 카드는 과정의 복잡성을 보여줍니다. 어떤 것으로 이어지기 위해 매우 많은 것들이 수렴되어야 합니다." (R5) 참가자들은 변화를 시행한 경험이 도전적이었다고 보고했습니다. 참가자들은 [많은 정보를 처리하고 여러 수준에서 다양한 채널을 통해 결정을 내려야 하는 협업 연습]으로 커리큘럼 변화를 경험했다.

Participants described curriculum change as a dynamic, complex process involving many interacting factors. As one participant stated when describing the picture he chose of a railroad crossing: “[This card] shows the complexity of the process; very many things need to converge to lead to something” (R5) (see Supplemental Digital Appendix 1, at https://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A528). Participants reported that the experience of enacting change was challenging. Participants experienced curriculum change as a collaborative exercise in which a lot of information had to be processed and decisions had to be made at many levels and via various channels.

우리는 모든 참가자가 직면한 세 가지 핵심 과제와 해결을 위한 몇 가지 관련 전략을 식별했다. [중심 과제]는 크고 다양한 이해 관계자들을 다루는 것이었습니다. 다른 두 가지 과제는 [이해당사자들의 저항을 다투는 것]과 [변화 과정을 이끄는 것]이었습니다. 참가자들은 다른 과제를 언급했지만 이러한 과제를 해결하기 위한 전략을 설명하지 않았다. 따라서 이러한 다른 과제는 이 보고서에 설명되지 않습니다.

We identified three core challenges faced by all participants, and several associated strategies for resolution. The central challenge was dealing with a large and diverse group of stakeholders. The other two challenges were contending with stakeholders’ resistance and steering the change process. Participants mentioned other challenges but did not describe strategies for addressing those challenges. Therefore, these other challenges are not described in this report.

과제 1: 다양한 이해 관계자의 대규모 그룹 대처

Challenge 1: Dealing with a large group of diverse stakeholders

참가자들은 커리큘럼 변화를 협업 연습으로 설명했습니다. 그러나 크고 다양한 이해관계자 그룹(예: 행정 직원, 교육자, 학생, 교사, 부서장, 내부 위원회, 이사)을 다루는 것은 어려웠다. 이 이해관계자들은 각기 다른 배경을 가지고 있었고 조직의 다른 부분을 대표했으며, 각각 다른 시기에 프로세스에 대한 이해관계를 가지고 있었다. 의료교육과정과 변화 제정 과정에 대한 이해관계자들의 시각은 달랐다. 이러한 [관점을 결합하는 것]은 리더가 직면해야 할 과제였습니다.

Participants described curriculum change as a collaborative exercise; however, dealing with the large and diverse groups of stakeholders (e.g., administrative staff, educationalists, students, teachers, department heads, internal committees, board members) was challenging. These stakeholders had different backgrounds and represented different parts of the organization, each having a stake in the process at different times. Stakeholders had different perspectives regarding the medical curriculum and the process of enacting change. Interweaving these perspectives was a challenge the leaders needed to face:

커리큘럼 변경은 많은 사람들이 자신의 특정 전문지식을 바탕으로 생각하는 힘입니다. 물론 그것은 매우 좋습니다. 그러나 어느 시점에서 결정이 내려져야 하고 당신은 그것을 엮어야 합니다. 원하는 모든 것이 가능한 것은 아니다. 도전은 다양한 배경을 가진 사람들을 하나로 모으고, 그들이 하나의 공동 제품을 만들도록 동기를 부여하려고 노력하는 것이다. (R4)

Curriculum change is a power play in which many people … think from their own specific expertise. Of course that is very good; however, at some point decisions have to be made and you have to interweave that; not everything one wants is possible.… The challenge is trying to bring people from various backgrounds together, trying to motivate them to make one, joint product. (R4)

참가자들은 변화에 대한 비전을 가진 이해 관계자들을 참여시키기 위해 다양한 전략을 사용했습니다. 예를 들어, 그들의 제안에 대해 [부학장, 학장 및/또는 이사회의 명확한 지지를 얻는 것]은 일부 참가자들에게 커리큘럼 변경에 필요한 전제 조건이었다.

Participants employed different strategies to get stakeholders on board with their vision for change. For instance, gaining explicit support of the associate dean, dean, and/or board for their proposals was, for some participants, a necessary precondition for curriculum change:

언제나 그렇듯이 이사회는 입장을 취해야 합니다. 그렇지 않으면 아무 일도 일어나지 않습니다. 조직을 이끄는 것은 이사회에서 시작됩니다. 그들은 그것을 전적으로 지지해야 한다. 그렇지 않으면 당신은 정말로 그것을 잊을 수 있다. 이들은 (a) 이러한 일이 발생하는 것이 중요하다고 생각하며 (b) 설계도*가 준비되었다면 자신의 설계도임을 전적으로 지지한다는 점을 전체 조직에 분명히 말해야 합니다. 그리고 내 청사진은 아니야. (R5)

As always … the board of directors needs to take a stance, otherwise nothing happens.… Getting the organization with you starts with the board of directors. They have to fully support it, otherwise you can really forget it. They have to speak out loud … to the entire organization that (a) they think that it is important that this happens, and (b) if the blueprint* is ready, that they fully support that this is their blueprint. And not my blueprint. (R5)

참가자들은 교육과정 변경 계획과 함께 최대 이해관계자 그룹인 교직원이 탑승해야 한다고 강조했다. 일부에서는 핵심 교직원들만 이미 100명에서 200명 정도라고 말했다. 참가자들은 이러한 이해 관계자들에게 변경 아이디어와 진행 상황에 대해 알려줌으로써 변경 일정의 초기 단계에서 교육 인력(병원 기반 임상 교사 또는 기초 과학 교사)을 포함하기 위한 전략을 개발했습니다.

Participants emphasized needing the teaching staff, the largest stakeholder group, on board with the curriculum change plans. Some stated that only the core group of teaching staff already numbered 100 to 200 people. Participants developed strategies for including the teaching staff (either hospital-based clinical teachers or basic science teachers) at an early stage in the change timeline, by informing these stakeholders about change ideas and progress:

저는 그것이 중요하다고 생각했습니다. 왜냐하면 당신은 그것을 병원에 폭탄처럼 떨어뜨리고 싶지 않기 때문입니다. 왜냐하면 그것은 잘 착륙하지 않을 것이기 때문입니다. 모두와 이야기를 나눠야 합니다. 사람들에게 지속적으로 알리고, 모든 것이 여전히 괜찮은지 확인합니다. 그것이 가장 중요하다고 생각합니다. (R6)

I thought that was important to do, because you don’t want to drop it like a bomb in the hospital, because then it will not land very well. You have to talk with everybody.… Continuously informing people, checking whether everything is still okay. I think that is the most important. (R6)

참가자들은 이해관계자들에게 계속 정보를 제공하기 위한 노력으로 회의를 조직하고, 웹사이트를 만들고, 뉴스레터를 썼다. 일부는 맞춤형 접근법으로 개별 이해관계자 집단을 의도적으로 다루는 것을 강조했다.

Participants organized meetings, created websites, and wrote newsletters in their efforts to keep stakeholders informed. Some emphasized deliberately addressing individual stakeholder groups with tailor-made approaches:

학생들에게는 공식적인 시험이나 교육위원회와는 다른 이야기가 있었고, 또 다시 코디네이터와 교사들에게도 또 다른 이야기가 있었다. 아이디어와 함께: 커뮤니케이션은 대상 그룹에 집중되어야 하며, 그렇지 않으면 잘 작동하지 않습니다.(R7)

For students I had a different story compared to the formal exam and educational committees, and again another story for coordinators, as well as for teachers. With the idea: Communication should be focused on the target group; otherwise, it does not work well. (R7)

교육과정 변경 과정에서 [이해관계자가 조기에 참여할 수 있는 기회]를 만드는 것도 리더들이 채택한 전략이었다. 참석자들은 예를 들어 공론화 회의(최대 150명 참석)를 포함하여 초기 계획에 대한 논의를 창출하기 위해 대규모 활동을 조직하는 것에 대해 이야기했다. 초기 포함은 두 가지 목적을 달성하였다. 이해 관계자의 지식을 바탕으로 정보를 수집하고 헌신적 참여buy-in를 장려합니다. 이후 단계에서는 새로운 커리큘럼의 실제 개발 중에 여러 관점에서 입력을 자극하기 위해 의도적으로 여러 사람을 혼합한 작업 그룹과 같은 소규모 참여 노력이 수행되었습니다.

Creating opportunities for stakeholders to participate early on in the curriculum change process was another strategy that leaders employed. Participants talked about organizing large-scale activities to generate discussions about initial plans including, for instance, public discussion meetings (with as many as 150 people in attendance). Early inclusion served two aims: collecting input to build on stakeholder knowledge, and encouraging their committed buy-in. At a later stage, during actual development of the new curriculum, small-scale engagement efforts were implemented, such as working groups with a deliberate mix of people to stimulate input from multiple perspectives:

각 작업 그룹은 실제로 [교육과정]을 처리해야 하는 사람들로 구성되었다.… [A] 코디네이터, 선생님, 그리고 학생들의 혼합. 그리고 필요한 경우, 교육자, 평가 전문가 등 조직의 사람들이 이러한 관점에서 의견을 제시했습니다. 음, 그리고 마침내, 합의가 이루어졌다. (R7)

Each working group consisted of people who really had to deal with [the curriculum] in practice.… [A] mix of coordinators, teachers and students. And if necessary, people from the organization: educationalists, assessment experts … who delivered input from that perspective. Well, and finally, consensus was there. (R7)

최종 전략으로, 일부 리더들은 교육과정 내용 논의를 전문가들에게 맡겨, 이해당사자들의 전문성과 관점을 명시적으로 활용하면서 교육과정 변경 과정의 촉진자 역할을 수행했다. 이 전략은 사람들을 변화 과정에 참여시키는 것 외에도 변화에 대한 저항을 막거나 최소한 줄이는 데 도움이 되었습니다.

As a final strategy, some leaders acted as facilitators of the curriculum change process, explicitly harnessing stakeholders’ expertise and perspectives by leaving curriculum content discussions to the professionals. In addition to engaging people in the change process, this strategy helped prevent, or at least diminish, resistance to change.

과제 2: 저항에 대처하기

Challenge 2: Dealing with resistance

이해관계자를 상대할 때 참가자들은 [저항과 씨름]해야 했다. 새로운 교육과정의 방향이나 변화 과정에 대한 이해당사자들의 우려나 의견 불일치로 인해 저항이 촉발되었다. 보다 구체적으로 이해당사자의 불만은 [교육 일자리에 대한 우려, 새로운 교육과정의 질에 대한 우려, 그리고 그 직업들이 새로운 프로그램에 충분히 반영되었는지에 대한 우려] 등 많은 문제와 관련이 있었다. 참가자들은 저항을 예상함으로써 이러한 반대파를 능동적으로 관리했고, 그 순간에는 저항에 적극적으로 대처했다.

When dealing with stakeholders, participants had to contend with resistance. Resistance was triggered by stakeholders’ concerns or disagreements about the new curriculum’s directions or the change process. More specifically, stakeholder discontent was related to many issues, including concerns about educational jobs, worries about the quality of the new curriculum, and concerns about whether the professions were sufficiently reflected in the new program. Participants managed this opposition proactively by anticipating resistance, and in the moment by actively dealing with resistance.

저항을 예상하기

Anticipating resistance.

참가자들은 이러한 불만이 변화 과정에 미칠 수 있는 부정적 영향을 인식하고 있어 저항을 예상하고자 했다. 일부는 변화 과정의 초기에 "파괴적인 개인들"과 "완전히 보수적인 사람들" 그리고 "반대론자들"을 포함시켰다. 이 전략은 그러한 개인들의 잠재적인 미래 반대를 완화시킬 것으로 기대되었지만 그들의 비판적인 목소리로부터 이익을 얻는 데도 사용되었다.

Participants tried to anticipate resistance as they were cognizant of the negative effects that such discontent could have on the change process. Some described including the “disruptive individuals,” the “utterly conservative people,” and the “naysayers” early on in the change process. This strategy was expected to mitigate potential future opposition from those individuals but was also used to profit from their critical voices:

나는 감히 나에게 도전하는 사람들을 선택한다. 그렇지 않으면, 그것은 나에게 도움이 되지 않는다. (R1)

I choose [to engage] people who dare to challenge me; otherwise, it does not help me. (R1)

저항하는 이해당사자들의 buy-in를 유지하기 위해, 지도자들은 원래 사람들을 참여시키기 위해 의존했던 전략과 유사한 전략을 사용했다. 예를 들어, 저항을 예상하여 참가자들은 커리큘럼 변경 과정의 특정 요소(예: 새로운 커리큘럼의 청사진 또는 새로운 커리큘럼을 형성하는 기본 원칙)에 대한 합의를 모색했다. 변화 리더들은 조기 참여 기회와 이해관계자와의 지속적인 커뮤니케이션을 통해 이를 달성했습니다. [합의 형성]은 buy-in을 늘리는 방법으로 작용하여 미래의 저항을 감소시키는 것처럼 보였다.

To retain the buy-in of resisting stakeholders, leaders used strategies similar to those they relied on to get people on board originally. For instance, in anticipation of resistance, participants sought consensus around specific elements of the curriculum change process (e.g., the new curriculum’s blueprint, or the foundation principles shaping the new curriculum). The change leaders achieved this by creating early engagement opportunities and continuous communication with stakeholders. Consensus building seemed to work as a method to increase buy-in, thus diminishing future resistance.

저항에 대처하기

Addressing resistance.

저항을 예상하려는 노력에도 불구하고, 참가자들은 이해당사자들의 직간접적인 저항에 직면했다고 설명했다. 교육과정 변화 아이디어와 결정에 반대하는 이들이 직접적인 저항을 했다. 이러한 저항을 관리하기 위한 전략에는 [일대일 대화]를 통해 저항자들과의 대화를 모색하고, 저항에 대한 이유를 주의 깊게 듣고, 타협을 위한 협상을 하는 것이 포함되었다.

Despite efforts to anticipate resistance, participants described facing both direct and indirect resistance from stakeholders. Direct resistance came from those who were opposed to curriculum change ideas and decisions. Strategies for managing this resistance involved seeking dialogue with resisters via one-on-one dialogue; listening carefully to their reasons for resistance; and negotiating to a compromise:

더 잘 설명하기 위해 이 사람들에게 말할 것이다. 말하자면, 이것이 그 이면에 있는 생각이다. "이리 와… 생각해봐, 이것이 우리가 할 일이니까. 하지만, 만약 우리가 조금 조정해야 한다면, 우리는 반드시 그렇게 할 것입니다. 저는 현실적인 방법으로 여러분이 필요합니다. 그래서 만약 제가 오른쪽으로 간다면, 그리고 여러분이 정의상 왼쪽으로 가게 된다면, 우리는 해낼 수 없을 것입니다. 그래서 나는 당신이 나와 함께 조금 가줄 것을 요청합니다." 음, 그리고 그것은 대부분 매우 잘 작동됩니다. (R6)

I will talk to these people, to better explain it. To show: This is the idea behind it. “Come … try to think along, because this is what we are going to do. However, if we have to adjust a bit, then we will certainly do that.… I need you in a way that is realistic, so if I go right, and you will, by definition, go to the left, we are not going to make it. So I ask you to come along with me a bit.” Well, and that works very well most of the time. (R6).

일부 지도자들은 또한 [간접적인 저항]에 직면했다. 이 저항은 "숨겨진 역력과 움직이는 저전류"(R3)로 묘사되어 덜 눈에 띄었다. 그런 상황에서 사람들은 직접 변화 리더에게 친절했지만, 그가 없을 때 "내 밑에서 내 발을 즐겁게 때려눕히고 있었다"(R3)고 했다. 이러한 간접적인 저항은 이해당사자들이 리더를 우회하여 그들의 불만을 학장에게 직접 가져갔을 때도 나타났다.

Some leaders also faced indirect resistance. This resistance was less visible, described as “hidden counterforces and a mobilizing undercurrent” (R3). In such situations, people were kind to the change leader in person, but “they were cheerfully knocking my feet out from under me” (R3) when he was not present. This indirect resistance also manifested itself when stakeholders bypassed the leader and took their complaints directly to the dean.

대화와 협상이 통하지 않고 저항이 변화의 진보를 진정으로 방해했을 때, 변화 리더는 더 [공격적인 전략]을 사용했다. 한 참가자는 저항하는 개인들이 직면하는 상황을 변화시켜 그 저항자들이 공개적으로 변화의 진행을 방해하지 않도록 함으로써 상황을 전략적으로 재조정하는 것을 묘사했다. 또한, 일부 참가자들은 저항자들을 측면으로 이동시키거나 완전히 변화 과정 밖으로 이동시키는 것에 대해 설명하였다. 또 다른 반복되는 전략은 젊은 교수진과 새로운 교수진을 포함함으로써 그 과정을 부채질하는 것이었다. 한 사람이 말했듯이:

When talking and negotiating did not work and resistance truly hampered the change progress, the change leader employed more aggressive strategies. One participant described strategically realigning a situation to his benefit by shifting the context in which resistant individuals were confronted so that those resisters could not publicly hinder the progress of change. In addition, some participants described moving resisters to the sidelines or out of the change process entirely. Another recurring strategy was to fuel the process by including young and new faculty. As one said:

교육위원회를 포함하여 이 과정을 방해하는 사람들을 몇 번 해고했다. 그들은 그저 미루고 있었을 뿐이었다. 우리는 교육에 대해 다른 관점을 가진 전자의 "밑에 있는" 세대인 새로운 위원회를 설립했습니다. 그리고 그 순간부터 달리기 시작했다. (R7)

A few times I have dismissed people from their position who hindered the process, including an [educational committee],… they were merely delaying.… We established a new committee, a generation “underneath” the former, let’s say, who had a different perspective on education.… And from that moment on, it started running. (R7)

마지막으로, 일부 참가자들은 저항을 극복하기 위해 부학장, 학장 및/또는 이사회의 지원을 요청했습니다. 때때로 이 고위 지도자들은 특정 문제를 해결하는 방법을 생각하기 위한 울림판이나, [저항자들에게 그들의 의지를 강요할 수 있는 권위자 역할]을 했다. 학장이나 부학장의 중요성은 또한 변화 과정에 대한 그의 지지가 참가자들에 의해 도움이 되지 않는다고 인식되거나(예: 저항자들에게 접근하는 방법에 대한 상충되는 믿음) 전혀 존재하지 않을 때 분명했다. 예를 들어, 한 참가자는 조직의 구성원들이 비판을 표명했을 때 부학장이 자신의 계획과 결정을 즉시 훼손했다고 느꼈다.

Finally, some participants sought support from the associate dean, dean, and/or board to overcome resistance. Sometimes these higher-level leaders acted as sounding boards to think through ways of tackling specific problems, or as authorities who could impose their will upon resisters. The importance of the dean or associate dean was also evident when his or her support for the change process was not perceived to be helpful by participants (e.g., conflicting beliefs on how to approach resisters), or was not present at all. For example, one participant felt that the associate dean undermined his plans and decisions immediately when critiques were expressed by members of the organization:

"BOOOO!"라고 외치는 사람은 단 한 명이어야 했고 모든 것이 다시 바뀌어야 했습니다. (R3)

There had to be only one person screaming “BOOOO!” and everything had to change again. (R3)

지원 부족은 해결하기 어려웠지만, 참가자들은 부학장 또는 학장의 참여 여부를 전략적으로 선택함으로써 지지하지 않는 리더십에 대처하는 것을 묘사했다.

Although the lack of support was hard to solve, participants described dealing with unsupportive leadership by strategically choosing whether or not to involve the associate dean or dean.

과제 3: 변경 프로세스 주도

Challenge 3: Steering the change process

참가자들이 직면했던 세 번째 도전은 [변화 과정 운영과 관련된 어려움]과 관련이 있었다. 원하는 커리큘럼으로 가는 경로가 변경되고 변경의 정확한 최종 목표가 커리큘럼 변경 과정에서 종종 진화하고 있었기 때문에 운영 과정이 어려웠다.

The third challenge participants faced had to do with difficulties related to steering the change process. The steering process was difficult because the route to the desired curriculum changed and the precise end goal of the change was often evolving throughout the curriculum change process:

나는 또한 이것이 정확히 어디로 가고 있는지 또는 어떻게 해야 하는지 모른다. 하지만, 제가 염두에 두고 있는 것이 있고, 그 정도는 마진 정도입니다. 그런 다음 탐색을 해야 합니다. 제 말은, 그것은 과정의 일부이고, 미리 정해진 경로가 아니라는 것입니다. 나는 내가 가고 싶은 곳을 대충 알고 있고, 물론 더 구체적으로 말하는 것이다… 내 말은, 지금 나는 그것을 1년 전보다 더 정확하게 알고 있다. 그 불확실성으로 나는 살아갈 수 있어야 한다. (R5)

I also don’t know exactly where this is going or how it has to be done. However, I do have something in mind and that is approximately the margin, and then you have to navigate.… I mean, that is part of the process, it is not a predetermined route.… I know roughly where I want to go to, and [that] is of course getting more concrete … I mean, right now I know that more precisely than a year ago. With that uncertainty I have to be able to live. (R5)

또한 참가자들은 프로세스를 책임지고 있었으므로, [적극적으로 변화 프로세스를 지시]하는 동시에, [이해관계자들에게 변화를 지시할 수 있는 충분한 자유를 제공하고 프로세스의 성공에 투자되었다고 느끼는 것] 사이에서 균형을 찾아야 하는 필요성에 고심했다. 조직의 우수한 프로세스를 보호하는 것이 중요하다고 강조되었습니다.

Additionally, participants struggled with the need to find a balance between being responsible for the process and therefore actively willing to direct the change process, and at the same time providing enough freedom to stakeholders for them to direct change and so feel invested in the success of the process. Safeguarding a good process in the organization was emphasized to be important:

사람들이 저를 너무 과단성 있게 생각하지 않았으면 좋겠어요. 모두에게 충분한 공간을 주셨으니, 제가 그랬기를 바랍니다. 사람들은 듣기에 불충분하다고 느낄 수 있다. 아니었으면 좋겠는데... 사람들이 [충분한 공간]을 경험했더라면 좋았을 텐데. [그것은 중요하다] 왜냐하면 그것은 과정에 도움이 되기 때문이다. 만약 누군가가 아주 좋은 아이디어를 생각해냈을 수도 있지만, 내가 무언가를 밀고 나간다는 생각을 가지고 있다면, 그것은 그 과정에 좋지 않다. (R4)I hope people did not experience me as too decisive.… That you have given enough room to everyone, I hope I did that.… People may feel insufficiently listened to. I hope not … I wish people have experienced [enough room]. [That is important] because that benefits the process. If you have the idea that I push something through, while somebody might have come up with a very good idea, then that is not good for the process. (R4)

커리큘럼 변경 과정을 지시하기 위해 채택된 전략에는 함께 일할 "적절한" 사람을 선택하는 것이 포함되었습니다.

The strategies participants employed for directing the curriculum change process included selecting the “right” people to work together:

여러분이 끊임없이 하고 있는 것은 일을 성사시킬 사람들을 모으는 것입니다. (R1)

What you are constantly doing is bringing those people together that will make things happen. (R1).

예를 들어, "올바른" 사람들은 새로운 교육과정에 대해 같은 열정을 가지고 협력할 수 있는 사람들, 그리고 새롭고 신선한 아이디어를 가진 사람들이었다. 적절한 인재를 모으는 힘에 초점을 맞춘다는 점을 감안할 때, 일부 참가자들은 관계에 상당한 시간을 투자했습니다.

The “right” people were, for example, those who could collaborate with the same enthusiasm for the new curriculum, and those with new and fresh ideas. Given this focus on the power of bringing the right people together, some participants spent considerable time investing in relationships:

나는 나의 선생님들을 알고 있고 나는 의식적으로 젊은 인재를 찾고 있다. 학과장들에게 제안을 하고, 그 다음에 약속 일정을 잡으려는 젊은 직원이나 새로 임명된 교수들의 명단을 받습니다. 그래서 저는 젊은 인재와 응급처치 및 선임 교사들의 명단을 가지고 있습니다. [언제] 새로운 프로그램을 개발해야 합니다. 제가 필요한 사람을 정확히 알고 있습니다. (R1)

I know my teachers and I’m consciously looking for young talent. I ask for suggestions from department heads, then I get a list of names of young staff or newly appointed professors with whom I’m scheduling an appointment. So I just have a list available of young talent, as well as emeriti and senior teachers.… [When] we have to develop the new program I know exactly who I need. (R1)

참가자들이 사용한 또 다른 전략은 [변화 프로세스의 전반적 상황을 확인하는 것]이었습니다.

Another strategy participants used was making sure to have an overview of the change processes:

[과제는] 약속을 만들고, 약속을 유지하며, 프로세스를 모니터링하는 것과 관련이 있습니다. 낡은 교육과정이 변장하고 은밀히 되돌아오는 것이 아니라는 점을 감시해야 한다. 우리는 개발이 실제 의도했던 것에서 벗어나면 신호를 받고 싶다. (R9)

[The challenge is related to] creating commitment, retaining commitment, and monitoring the process.… We have to monitor that the old curriculum is not secretly returning in disguise. We want to get signals if the development drifts away from what was actually intended. (R9)

참가자들은 새로운 커리큘럼 콘텐츠 개발과 조직의 변화하는 과정에 적응하기 위해 노력했습니다. 교육과정 내용과 관련해서는 [리더, 교육과정변경팀원, 다양한 실무그룹 간 정기적인 '정렬 세션'을 구성해 일관성 있는 교육과정]이 이뤄지도록 했다. 조직의 변화하는 프로세스에 대해 최신 정보를 제공하기 위해 리더는 조직의 모든 수준에서 "느낌feelers"을 유지하고, 사람들과 위원회와 정기적으로 대화하며, 문제나 저항의 신호를 주의 깊게 들었습니다.

Participants sought to be attuned to the development of new curriculum content and to the organization’s changing processes. In relation to curriculum content, regular “alignment sessions” were organized between the leader, the curriculum change team members, and various working groups to ensure a coherent curriculum. To stay up-to-date about the changing processes in the organization, leaders kept “feelers” out at all levels of the organization, talking regularly with people and committees, listening carefully for signals of problems or resistance:

조직의 신호에 둔감해지는 것이 가장 큰 위험이라고 생각합니다. 왜냐하면 조직을 9월로 이동시키느라 바쁘기 때문입니다. 당신은 항상 주의 깊게 들어야 합니다. 그렇게 하지 않으면 맹목적으로 잘못된 방향으로 갈 것이다. 최종 목표를 염두에 두고 계속 적응할 수 있어야 합니다. (R5)

I think, getting insensitive to signals from the organization is the greatest danger because you are so busy with getting the organization on the move to reach September.… You always have to keep on listening carefully.… If you don’t do that you will go blindly in the wrong direction. You need to be willing to keep on adjusting, while still having the final goal in mind. (R5)

당면 과제 관리 및 전략 구현

Managing challenges and implementing strategies strategically

체인지 리더는 커리큘럼 변화를 가져오기 위해 몇 가지 전략에 의존했습니다. 비록 우리가 그 문제들을 별도로 설명했지만, 실제로는 그들은 다른 여러 새로운 이슈들과 함께 동시에 발생하면서 상호 작용했다.

Change leaders relied on several strategies to bring about curriculum change. Although we described the challenges separately, in reality they interacted, taking place simultaneously, along with multiple other emerging issues.

커리큘럼 변화를 주도하는 복잡하고 지속적으로 발전하는 이 과정을 관리함에 있어, 리더들은 이해 관계자들과 변화 과정에 걸쳐 어떤 일이 일어나고 있는지 계속 알고 있어야 했습니다. 변화하는 상황과 개인의 반응에 대한 이러한 인식을 형성함으로써 리더는 [변화하는 상황에 맞게 전략을 수정]할 수 있었습니다.

In managing this complex and continually evolving process of leading curriculum change, the leaders needed to remain aware of what was going on across stakeholders and the change processes. Creating this awareness of evolving situations and individuals’ reactions enabled leaders to modify their strategies to suit changing circumstances:

만약 여러분이 매우 생각만 한다면 여러분이 생각하는 것보다 훨씬 더 많은 것들이 여러분이 할 수 있는 역할을 할 수 있다는 것을 알아야 합니다. 예를 들어 프로세스 기반과 같이 A에서 B까지 체계적으로 말해 봅시다. 경우에 따라서는 올바른 버튼을 누르지 않았기 때문에 작동하지 않을 수 있습니다. 잘 되지 않으면 "이제 우리는 일을 바로잡을 것입니다."라고 말해야 합니다. 그러나 [상황]은 얼마나 자유를 주어야 하는지, 또는 얼마나 직접 결정을 내려야 하는지를 결정한다.… 이러한 대규모 조직에서는 어떤 경우에도 유연성이 중요합니다. (R2)

You have to be aware that a lot more can be playing a part than you possibly think if you only think very … let’s say systemically from A to B, like process based. Sometimes things … do not work because you apparently did not push the right button.… If it does not go well you have to say, “And now we are going set things right.”… However, the situation determines how much space you have to give freedom or that you have to be more direct [and make decisions].… Flexibility is, in any event, important in this kind of large organization. (R2)

논의

Discussion

본 연구에서는 변화리더들이 교육과정 변화를 제정하는 과정에 대해 어떻게 생각하는지, 그리고 그들이 그들의 노력에 성공하기 위해 의존하는 전략에 대한 이해를 발전시켰다. 이 지도자들은 여러 가지 도전으로 가득 찬 복잡한 과정으로 커리큘럼 변화에 대해 이야기했다. 특히 주목할 만한 세 가지 과제는 다음과 같았다.

- 크고 다양한 이해관계자 그룹을 다루는 것

- 저항과 다투는 것

- 변화 과정을 지휘하는 것

이러한 과제를 관리하기 위해 지도자들은 여러 가지 다른 전략에 의존했습니다. 이러한 전략을 성공적으로 적용하기 위해, 변화 리더들은 진화하는 상황적 상황에 대한 인식을 유지하려고 노력했고, 이에 따라 그들의 전략을 조정하여 커리큘럼 변화를 이끌어냈다.

In this study, we developed an understanding of how change leaders conceive of the process of enacting curriculum change and the strategies they relied on to succeed in their efforts. These leaders talked about curriculum change as a complex process, fraught with several challenges. Three challenges of particular note were

- dealing with the large and diverse groups of stakeholders;

- contending with resistance; and

- steering the change process.

To manage these challenges, leaders relied on several different strategies. To successfully apply these strategies, change leaders tried to remain aware of the evolving contextual situations and adapted their strategies accordingly to bring about curriculum change.

네덜란드의 모든 8개 UMC에 걸쳐 수행된 우리의 경험적 연구는, [커리큘럼 변경 과정이 선형적이고 질서 있고 예측 가능한 과정으로 전개되지 않는다]는 생각을 지지하고 확장한다. 대신 의과대학과 부속병원에서 커리큘럼 변경을 제정하는 것은 새롭고 복잡한 과정이다. 본 연구는 변화 리더가 직면한 주요 도전과 이를 처리하기 위해 활용했던 전략에 대한 보다 상세하고 경험적인 설명을 제공함으로써 의료 커리큘럼 변화로 성공하는 방법에 대한 Bland 등의 작업을 향상시킨다.

Our empirical study—conducted across all eight UMCs in the Netherlands—supports and extends the idea that the process of curriculum change does not unfold as a linear, orderly, and predictable process.8 Instead, enacting curriculum change in a medical school and its affiliated hospitals is an emerging, complex process. Our study enhances the work of Bland et al9 about how to succeed with medical curriculum change by providing a more detailed, empirical description of the main challenges faced by change leaders and the strategies they harnessed to deal with it.

우리는 주요 커리큘럼 변화의 복잡성을 탐색하는 과정의 중심은 [끊임없이 변화하는 상황 상황에 대한 인식을 유지하는 것]이라는 것을 발견했다. 변화 리더들은 무슨 일이 일어나고 있는지 알고, 대응에 어떤 행동을 취해야 하는지, 그리고 그 과정에 누구를 참여시켜야 하는지에 대한 결정을 내리기 위해 다양한 방법을 사용했습니다. 프로세스가 원하는 방향으로 진행되도록 하기 위해, 변화 리더들은 [새로운 상황의 요구를 충족]시키기 위해 전략을 수정했습니다. 이것은 전체 과정이 계획 없이 자발적으로 진화했다는 것을 말하는 것은 아니다. 대신, 우리의 분석은 단순히 커리큘럼 변화를 "계획하고 실행하는" 것이 변화를 실현하는 방법이 아니라는 것을 입증했다. 상황은 지속적으로 변화하며, 변화 리더는 상황 인식을 유지하고 성공을 보장하기 위해 전략을 조정해야 합니다.

We found that central to the process of navigating the complexities of major curriculum change was maintaining awareness of ever-changing contextual situations. Change leaders used a variety of methods to be aware of what was going on, to make decisions about what actions to take in response, and who to involve, at what time, in the process. To make sure the process was going in the desired direction, change leaders adapted their strategies to meet the demands of the emerging situations. This is not to say that the entire process was spontaneous, evolving without thoughtfully created plans. Instead, our analysis demonstrated that simply “planning and executing” curriculum change is not how change is realized. Situations continuously change, requiring the change leader to maintain situational awareness and to adapt strategies to ensure success.

이는 변화 리더십 문헌에 설명된 "성찰 전략"과 일치합니다. Van de Ven과 Sun은 더 선호되는 "행동 전략"보다는 리더에 대한 [성찰 전략]을 옹호합니다. 이들은 조직의 리더들이 변화하는 상황으로 인해 "고장(즉, 현실에서 보이는 것이 기대와 일치하지 않는 상황)"이 발생할 수 있다고 주장한다. 이는 변화 리더들이 [직면한 현실(즉, 새롭게 부상하는 상황)이 여전히 그들이 선택한 전략과 일치하는지 또는 그들이 새로운 현실에 맞추기 위해 전략을 조정할 필요가 있는지를 검토]할 필요가 있음을 의미한다. 이는 변화 지도자들이 [그들의 전략을 바꾸지 않고 대신 현실이나 관련자들을 바꾸려고 하는 "행동 전략"]과 대조적이다. 행동 접근법은 인기가 있지만, 종종 변화의 복잡한 맥락 앞에서 효과적이지 못하다. 변화 리더들의 인식과 [목표 지향적 유연성]은 '상황 인식' 개념에도 반향을 불러일으킨다. 이 개념의 핵심은 끊임없이 변화하는 복잡한 상황에 대처하는 데 있어 지속적인 인식과 유연성이 필요하다는 것입니다.

This aligns with the “reflection strategy” described in change leadership literature. Van de Ven and Sun20 advocate the reflection strategy for leaders to bringing about change in organizations, rather than the more favored “action strategy.” They argue that leaders in organizations are continuously confronted with changing circumstances and situations that could cause “breakdowns” (i.e., situations where what is seen in reality does not align with expectations). This means that change leaders need to examine whether the faced reality (i.e., the emerging situation) still fits with their chosen strategies or whether they need to adapt their strategy to align with the new reality. This stands in contrast to the “action strategy,” where change leaders do not alter their strategies but instead try to change the reality or the people involved. Although the action approach is popular, it often fails to be effective in the face of the complex contexts of change.20 The change leaders’ awareness and goal-directed flexibility also resonates with the concept of “situation awareness.”21,22 Central in this concept is the need for an ongoing awareness and flexibility in responding to ever-changing, complex situations.

이는 변화를 실현하기 위한 몇 가지 조직적 변화 관점과 전략에 대한 인식을 갖는 변화 리더의 중요성을 지적합니다. "어떤 하나의 이론적 관점도 항상 복잡한 현상에 대한 부분적인 설명만을 제공하기 때문에, 조직 생활에 대한 보다 포괄적인 이해를 얻는 데 도움이 되는 것은 서로 다른 관점 간의 상호 작용이다." 복잡한 커리큘럼 변경 과정을 탐색하기 위해서는 새로운 상황에 대한 성찰과 인식이 필수적이다. 의도된 결과에 도달할 확률을 높이기 위해 자신의 광범위한 전략 레퍼토리를 신중하게 적용하는 것은 변화를 실현하는 중요한 접근법이다.

This points toward the importance of change leaders having an awareness of several organizational change perspectives and strategies to enact change: “It is the interplay between different perspectives that helps one gain a more comprehensive understanding of organizational life, because any one theoretical perspective invariably offers only a partial account of a complex phenomenon.”23(p510) To navigate the complex curriculum change processes, reflecting on and being aware of emerging situations is vital. Carefully adapting one’s broad repertoire of strategies to increase the probability that the intended outcomes are reached is an important approach to realize change.

강점과 한계/방법론적 반영

Strengths and limitations/ methodological reflections

단 한 명의 연구원(F.V.)이 모든 참가자 인터뷰를 수행했다. 그녀의 초보적인 지위와 연구에 대표되는 모든 조직 밖의 그녀의 위치는 참가자들이 대화에서 위협받지 않고 솔직하고 열린 대화를 지지할 수 있게 해주었다. 하지만, 그녀는 변화 지도자로서의 개인적인 경험을 가지고 있지 않다. 이는 다른 면접관(예: 변화를 시행한 경험이 더 많은 사람)이 탐구했을 수 있는 범위인 그녀의 조사 범위를 제한했다. 이 논쟁은 질적 연구에 내재되어 있다. 서로 다른 인터뷰어들은 다른 데이터를 수집할 것이다. 본 연구에서는 주요 조직변화를 선도하는 과제에 순진하게 대처하는 면접관을 두면 참여자들의 개인적인 생각, 느낌, 고민을 공유할 수 있는 개방적이고 풍부한 대화를 지원할 수 있을 것으로 느꼈다.

Just one researcher (F.V.) conducted all participant interviews. Her novice status and her position outside all the organizations represented in the study enabled participants to feel unthreatened in the conversation, supporting a frank and open dialogue. However, she does not have personal experiences as a change leader. This limited the scope of her probes, a scope that another interviewer (e.g., one with more experience enacting change) might have explored. This debate is inherent to qualitative research; different interviewers will gather different data. In this study, we felt that having an interviewer who was naïve to the challenges of leading major organizational change would support open and rich conversations in which participants could share their personal thoughts, feelings, and concerns.

또한, 최대 6년 전에 발생한 프로세스에 대한 질문을 받았을 때 사람들에 대한 [리콜 편견]이 있을 것이다. 그러나 장점은 잠시 후 과정을 되돌아보면 무엇이 가장 중요했고 무엇이 그렇지 않았는지에 대한 성찰과 비판적 사고를 할 수 있다는 것이다.

Additionally, there will be a recall bias for people when asked about processes that occurred up to six years ago. An advantage, however, might be that looking back on a process after a while allows for reflection and critical thinking about what was of utmost importance and what was not.

우리는 변화리더의 관점에서 교육과정 변화 제정 과정을 검토하기로 선택했지만, [교육과정 변화의 영향을 받는 사람들(예: 교육자)의 관점]을 탐구함으로써 동등하게 가치 있는 통찰력을 개발할 수 있었다. 다른 이해 관계자들과 함께 변경 과정을 연구하면 커리큘럼 변경의 복잡성에 대한 우리의 이해가 풍부해질 것이며 현재 진행 중인 연구 프로그램의 일부가 될 것이다.

We chose to examine the process of enacting curriculum change from the perspective of the change leader; however, equally valuable insights could be developed by exploring the perspectives of those affected by the curriculum change (e.g., educators). Studying the change processes with other stakeholders would enrich our understanding of the complexities of curriculum change and will be part of our ongoing program of research.

우리 연구의 강점 중 하나가 다원적 접근이지만, 이번 연구 결과가 전 세계 다른 의과대학에 대표적일 것이라고 가정할 수는 없다.

Although one of the strengths of our study is the multi-institutional approach, we cannot assume that the findings will be representative for other medical schools around the world.

시사점

Implications

우리의 연구 결과는 다양한 방법으로 사용될 수 있다. 우리가 개발한 통찰력은 미래의 커리큘럼 변경 리더를 훈련하고 코칭하는 데 도움이 될 수 있습니다. 더 넓은 의미에서, 우리의 연구 결과는 의료 교육(예: 연구, 의료)과 관련된 다른 분야의 변화 지도자들에게 정보를 제공할 수 있다. 우리의 연구를 통해 발전된 통찰력은 미래의 교육과정 변화 리더들이 교육과정 변화 제정과 관련된 도전과제, 이러한 과제를 해결하기 위한 가능한 전략, 그리고 그 과정에서 그들 자신의 성찰과 상황 인식의 중요성을 더 잘 인식하도록 해야 한다.

The results of our study could be used in a variety of ways. The insights we developed could serve as resources for training and coaching future curriculum change leaders. In a broader sense, our findings might inform change leaders in other areas related to medical education (e.g., research, health care24). The insights developed through our research should make future curriculum change leaders more aware of the challenges involved in enacting curriculum change, the possible strategies to address those challenges, and the importance of their own reflections and situational awareness while in the process.

결론

Conclusion

의료 교육과정 변화를 제정하는 과정은 변화 리더들이 여러 가지 도전에 직면하는 복잡한 노력이다. 이러한 복잡한 프로세스를 탐색하기 위해 변화 리더는 몇 가지 전략에 의존합니다. 이러한 전략에 공통되는 중요한 기본 원칙은 [변화의 진보를 촉진하는 결정]을 내리기 위해 [현재와 새롭게 부상하고 있는 상황을 계속 인식하는 것]이었다.

The process of enacting medical curriculum change is a complex endeavor in which change leaders are faced with several challenges. To navigate in this complex process, change leaders rely on several strategies. An important underlying principle common across these strategies was remaining aware of current and newly emerging situations in order to make decisions that further the progress of change.

Navigating the Complexities of Undergraduate Medical Curriculum Change: Change Leaders' Perspectives

PMID: 29419547

Abstract

Purpose: Changing an undergraduate medical curriculum is a recurring, high-stakes undertaking at medical schools. This study aimed to explore how people leading major curriculum changes conceived of the process of enacting change and the strategies they relied on to succeed in their efforts.

Method: The first author individually interviewed nine leaders who were leading or had led the most recent undergraduate curriculum change in one of the eight medical schools in the Netherlands. Interviews were between December 2015 and April 2016, using a semistructured interview format. Data analysis occurred concurrently with data collection, with themes being constructed inductively from the data.

Results: Leaders conceived of curriculum change as a dynamic, complex process. They described three major challenges they had to deal with while navigating this process: the large number of stakeholders championing a multitude of perspectives, dealing with resistance, and steering the change process. Additionally, strategies for addressing these challenges were described. The authors identified an underlying principle informing the work of these leaders: being and remaining aware of emerging situations, and carefully constructing strategies for ensuring that the intended outcomes were reached and contributed to the progress of the change process.

Discussion: This empirical, descriptive study enriches the understanding of how institutional leaders navigate the complexities of major medical curriculum changes. The insights serve as a foundation for training and coaching future change leaders. To broaden the understanding of curriculum change processes, future studies could investigate the processes through alternative stakeholder perspectives.