교육과 보건을 변혁할 의과대학생을 위한 밸류-추가 임상시스템 학습 역할: 의과대학과 보건시스템 사이의 파트너십 빌딩을 위한 가이드(Acad Med, 2017)

Value-Added Clinical Systems Learning Roles for Medical Students That Transform Education and Health: A Guide for Building Partnerships Between Medical Schools and Health Systems

Jed D. Gonzalo, MD, MSc, Catherine Lucey, MD, Terry Wolpaw, MD, MHPE, and Anna Chang, MD

미국의 의료 서비스가 결과 개선을 위해 빠르게 변화함에 따라, 의료 시스템과 의료 교육은 의사에게 21세기 과제를 해결할 수 있는 기술을 제공하기 위해 진화하고 있다. 매년 27,000명의 의사가 졸업함에 따라, 의과대학은 오늘날의 개인 및 모집단 건강 결과를 개선하기 위해 의료 시스템을 변화시키는 데 있어 의사의 실천 준비와 리더십을 향상시킬 수 있는 중요한 개혁이 필요하다. 이 과제를 해결하기 위해, 학부 의학 교육을 위한 새로운 [3개 기둥 프레임워크]는 인구 건강, 의료 정책 및 전문가 간 팀워크를 포함하는 [의료 시스템 과학]과 생의학과 임상과학을 통합한다. 임상 기술에 대한 이러한 광범위한 정의는 오늘날 직무를 위하여 [시스템 스킬과 환자 기술(예: 이력 촬영, 신체 검사)]을 모두 갖춰야 하는 의사에게 반향resonate을 일으킨다.

As U.S. health care changes rapidly to improve outcomes, health systems and medical education are evolving to provide physicians with skills to address 21st-century challenges.1–4 With 27,000 physicians graduating each year, medical schools need significant reform to advance physician readiness for practice and leadership in changing health systems to improve today’s individual and population health outcomes.5,6 To address this challenge, an emerging three-pillar framework for undergraduate medical education integrates the biomedical and clinical sciences with health systems science, which includes population health, health care policy, and interprofessional teamwork.7,8 This broader definition of clinical skills resonates with physicians whose work today includes both systems and patient skills (e.g., history taking, physical examination).7,9,10

그러나 오늘날 흔히 볼 수 있는 의대와 보건 시스템 간의 파트너십은, 프리셉터십 모델을 바탕으로, 여전히 보건의료 시스템을 학습의 substrate로 사용할 때 [일대일 임상의-환자 만남]이라는 방식을 고수한다. 이러한 현재의 파트너십은 종종 건강 증진을 위한 의학교육의 잠재력을 활용하지 못하며 임상 생산성과 효율성을 저하시킬 수 있다. 따라서 오늘날의 의료 교육 노력은 건강 결과health outcome에 대한 보다 강력한robust 초점을 포함하도록 진화될 수 있다.

However, the partnerships between medical schools and health systems that are commonplace today, which include preceptorship models, still use health systems as a substrate for learning through one-on-one clinician–patient encounters. These current partnerships frequently do not leverage medical education’s potential for improving health and may decrease clinical productivity and efficiency.11,12 Thus, today’s medical education efforts could evolve to include a more robust focus on health outcomes.

마찬가지로, 보건 시스템 리더들은, [의대생이 환자 관리와 시스템 개선에 가치를 더할 수 있다]라는 새로운 관점을 아직 받아들이지 않고 있다. 의대생들에게 진정한 직장 역할을 제공하는 새로운 파트너십은 의료 교육을 부담에서 인식되지 않는 자산으로 전환하는 동시에 의료 시스템에 가치를 더할 수 있다.

Likewise, health system leaders have yet to embrace the novel perspective of medical students as a value added to patient care and systems improvement. New partnerships that provide authentic workplace roles for medical students could add value to health systems while transitioning medical education from a burden to an unrecognized asset.11–14

맥락 Context

2013년, 펜실베이니아 주립 의과대학(PSCOM)과 캘리포니아 대학교, 샌프란시스코 의과대학(UCSFSOM)은 모든 의대 1학년 학생들(약 150명)을 위한 교실과 직장에서 요구되는 새로운 종방향적이고 진정한 건강 시스템 과학 커리큘럼을 개발하기 위한 대규모 노력을 시작했다.

In 2013, the Penn State College of Medicine (PSCOM) and University of California, San Francisco School of Medicine (UCSF SOM) began large-scale efforts to develop novel required longitudinal, authentic health systems science curricula in classrooms and workplaces for all first-year medical students (n ≈ 150).8,15

두 학교 모두 여러 보건 시스템(예: 대학 병원, 안전망 병원, 보훈 의료 센터 및 지역사회 기반 초등 진료소)에 소속된 공립 학교이다. 독립적인 설계, 이질적인 지리, 그리고 시차적 일정에도 불구하고, 두 학교는 유사한 접근법을 적용했고, 단일 기관의 경험을 넘어 내적 타당성을 보여준다.

Both are state schools affiliated with multiple health systems (e.g., university hospitals, safety net hospitals, Veterans Affairs medical centers, and community-based primary care clinics). Despite independent design, disparate geography, and staggered timelines, both schools applied similar approaches, lending internal validity beyond single-institution experiences.

새로운 의대-보건 시스템 파트너십을 설계할 때, 우리는 두 가지 모델을 교차하는 방식으로 결합했다.

- 변화 관리를 위한 Kotter의 8단계 16

- 컨의 교육과정 개발을 위한 6단계. 17

In designing new medical school–health system partnerships, we combined two models in an intersecting manner:

이 새로운 통합 프레임워크에 매핑된(그림 1) 교육 및 임상 기업 간의 상호 유익한 파트너십을 구축하기 위한 전략을 권장한다. 이러한 8가지 전략(및 해당 원리)을 순차적으로 제시하지만, 두 모델(Kotter 및 Kern)의 단계는 동시에, 반복적으로 또는 번갈아 발생할 수 있다.

Mapped to this new integrated framework (Figure 1), we recommend strategies for building mutually beneficial partnerships between education and clinical enterprises. Although we present these eight strategies (and corresponding principles) sequentially, the steps from the two models (Kotter and Kern) may occur concurrently, iteratively, or in an alternating order.

의과대학과 보건의료 시스템 파트너십을 구축하기 위한 전략

Strategies for Building Medical School–Health System Partnerships

초기 단계: 비전 및 계획

Initial phase: Vision and planning

전략 1: 긴급성(Kotter)을 설정하고 문제(Kern)를 식별합니다.

Strategy 1: Establish a sense of urgency (Kotter) and identify the problem (Kern).

생산성 요구와 품질 기대치가 높아짐에 따라, 의료 교육 및 보건 시스템은 상호성과 유사한 목표를 지향할 필요가 있다. 의학교육의 관점에서, 학생들을 위한 적절한 수의 임상 학습 사이트를 유지하기 위해서는 변화가 필요하다. 일부 교실classroom에는 보건 시스템 주제가 존재하지만, 학생의 건강 관리 경험을 살려줄 수 있는 [경험적 학습 기회]가 거의 없다. 학생들이 신체 검사와 환자 의사소통의 기술을 다듬는 데 도움이 되는 [핸즈온 임상 기술 학습 경험]과 마찬가지로, 이제 모든 학생들을 위한 새로운 [시스템 활동]이 필요하다.

As productivity demands and quality expectations rise, medical education and health systems need to align toward similar goals with reciprocity. From the medical education perspective, change is necessary to sustain an adequate number of clinical learning sites for students. Although health systems topics exist in some classrooms, there are few to no experiential learning opportunities that can bring a patient’s health care experience to life for students.8,18–22 Akin to hands-on clinical skills learning experiences that help students refine techniques in physical examination and patient communication, novel systems activities for all students are now needed.21,23

교육과정 시간을 [종단적이고 의미 있는 임상 시스템]을 학습하는 역할과 과제(아래 예시)에 배정한다면, 의대생이 건강, 질병 및 전문직 간 진료 전달 시스템에 대한 환자의 경험에 대한 더 넓은 시야를 얻을 수 있게 할 것이다.

- 예: 환자 네비게이터, 건강 코치, 패널 매니저, 초기 의약품 조정, "방문 후 요약" 초안, 병원 퇴원 후 후속 전화 통화 및 품질 개선 프로젝트의 데이터 수집

Curricular time for longitudinal, meaningful clinical systems learning roles and tasks would allow medical students to gain a broader perspective of patients’ experiences of health, illness, and the interprofessional care delivery system.13,24,25

- (e.g., patient navigator, health coach, panel manager, initial round of medication reconciliation, first draft of “after visit” summaries, follow-up phone calls after hospital discharges, and data collection in quality improvement projects)

[제한된 경험적 학습 기회]에는 현재 [선택적인 커뮤니티 서비스]나, (전부가 아니라) 일부 학생들을 위한 [무료 진료소]가 포함되어 있다.

Limited experiential learning opportunities currently include optional community service or student-run free clinics for some, but not all, students.26–28

현재 의료 교육자들은 학생들이 오늘날의 환자의 건강을 개선하는 데 도움이 되는 [시스템 역할]을 직장에서 포함시키기 위한 [핵심 임상 기술 커리큘럼]을 요구하고 있다. 또한, 의학교육은 전공의와 전임의 의사들의 인력으로 일하는 동안에도 의사가 [인구 기반의 환자 중심 환경]에서 기능할 수 있도록 "시스템적 준비systems ready"가 되도록 준비할 기회를 제공한다. [레지던트 매치의 수치적 성공에 기초하여 긴급함을 인식하지 못하는 교육자]에게는 의사로서 오늘날의 practice에 필요한 포괄적인 기술을 포함하는 역량 기반 교육 프레임워크를 수용하도록 권장될 수 있다.

Medical educators are now calling for core clinical skills curricula to include systems roles in the workplace for students to help improve the health of today’s patients.23,29–33 Additionally, medical education has an opportunity to prepare physicians to be “systems ready” to function in a population-based, patient-centered environment even while serving as a workforce of residents and fellow physicians.6,7,13 Educators who perceive less urgency on the basis of the numeric success of residency matches can be encouraged to embrace a competency-based education framework that encompasses the comprehensive skills required for today’s practice as a physician.

PSCOM과 UCSF SOM의 새로운 교육 담당자들은 [시스템 역할]과 [향상된 파트너십]의 gap을 해결하기 위해, 여러 개의 광범위한 이해 관계자 회의를 열어 의사 시스템 기술을 향상시키기 위한 임상 및 교육 임무의 통합을 촉구했습니다. 양쪽의 학장은 의사가 효과적으로 기능하고 미래 진료 전달 모델을 주도할 수 있도록 준비하기 위한 의학교육의 공유 동기를 기술했다. 임상 리더가 [의료 시스템, 조직 및 재정 개혁]에 초점을 맞추게 되면, [환자 만족도, 의료 품질, 환자 안전 및 진료 접근성을 개선할 준비가 된 여러 영역에서 즉시 기술을 사용하여 효과적으로 작업을 시작할 수 있는 잘 훈련된 미래 의사]로부터 혜택을 누릴 수 있다. 현재의 의료 교육 시스템이 [숙련된 임상의사]를 배출하지만, 정책 및 시스템 리더는 여전히 [의사가 미래의 의료 실습을 위해 필요한 새로운 시스템 기술을 적절하게 준비하지 못하고 있다]고 우려하고 있다.

To address the gap in both systems roles and enhanced partnerships, new education deans at the PSCOM and UCSF SOM held multiple broad-based stakeholder meetings to urge integration of the clinical and education missions to advance physicians’ systems skills. Both deans described the shared motivation for medical education to prepare physicians to effectively function and lead in future care delivery models. As clinical leaders focus on health system, organizational, and financing reform, they can appreciate the benefit of well-trained future physicians who can immediately begin working effectively with skills in multiple domains, ready to improve patient satisfaction, quality of care, patient safety, and access to care. Although the current medical education system produces skilled clinicians, policy and system leaders remain concerned that physicians are not being adequately prepared with the new systems skills needed for future medical practice.6,34

요컨대, 긴박감은 [교육education과 돌봄 전달care delivery이 계속 병렬적으로 진행되는 것이, 상호관련된 실체로서 이 둘을 고립시킨다]는 문제 진술에 의해 이미 설명되고 있다. 학문적 사명을 위한 자금 모델의 진화에 비추어, 이제는 지속 가능한 전략이 필요하다. 게다가, 현재의 임상 노동력은 압도되고 있다. 따라서, [상호 이익이 되는 협력 관계]는 오늘날 임상적 목적을 advance시키는 데 의대생들의 창의성을 끌어 들일 수 있다. 그리고 우리는 이것이 의과대학 1학년때부터 실현 가능하다고 생각한다.

In short, the sense of urgency is already described by the problem statement that education and care delivery continuing to progress in parallel isolates these two interrelated entities. Sustainable strategies are needed now, in light of evolving funding models for academic missions. Furthermore, the current clinical workforce is overwhelmed. Thus, a mutually beneficial partnership could engage the creativity of medical students in advancing clinical aims today—a goal that we believe is feasible starting in the first year of medical school.

전략 2: 안내 연합(Kotter)을 만들고 니즈 평가(Kern)를 수행합니다.

Strategy 2: Create the guiding coalition (Kotter) and conduct a needs assessment (Kern).

두 번째 전략은 [교육계 리더]와 [보건계 리더] 사이의 초기 관계를 확립하는 것을 포함한다. 이러한 링크는 과거에는 강력하지 않았을 수 있습니다. 이러한 리더는 신뢰성을 제공하고, 추진력을 창출하며, 새로운 비전을 구현하는 데 있어 책임감을 제공하기 위해 새로운 파트너와 중요한 대화를 시작하는 데 도움을 줄 수 있습니다.

The second strategy involves establishing initial relationships between education and health system leaders, including community partners new to academic affiliations. These links may not have been robust in the past. These leaders can assist with initiating critical conversations with new partners to offer credibility, create momentum, and provide accountability in implementing a new vision.

[보건 시스템]의 경우, 그러한 리더는 학장, 최고 경영자, 최고 품질 관리자 또는 최고 운영 책임자가 될 수 있으며, [의과 대학]의 경우 교육 학장 또는 교육과정 학장이 될 수 있다. 보건 시스템 리더를 효과적으로 참여시키기 위해 PSCOM 및 UCSFSOM에서 다양한 실무 현장 및 전문 분야로 구성된 자문 위원회가 작성되었습니다.

For health systems, such leaders may be the dean, chief executive officer, chief quality officer, or chief operating officer, and for medical schools, they may be the education dean or curriculum dean. To effectively engage health system leaders, an advisory board was created at the PSCOM and UCSF SOM, consisting of members from diverse practice sites and specialties.

이러한 유형의 지도 연합guiding coalition을 통해, 임상 리더는 의료 시스템 내에서 교육 프로그램의 설계에 inform하는 consultation partner가 됩니다. 이 강력한 연합은 긴박감 확립 및 문제 파악(전략 1)에서 시스템의 니즈를 설명하는(전략 2)으로 이동하며, 팀 구성원들이 공유 비전(전략 3)에 대한 목표를 가져오면서 파트너십을 강화합니다.

With this type of guiding coalition, clinical leaders become consultative partners who inform the design of education programs based within health systems. This powerful coalition moves from establishing a sense of urgency and identifying the problem (strategy 1) to describing the systems’ needs (strategy 2), strengthening the partnership as team members bring goals for a shared vision (strategy 3).

전략 3: 공유된 비전 및 전략을 개발하고 학습 목표와 목표를 식별합니다(Kern).

Strategy 3: Develop a shared vision and strategy (Kotter) and identify learning goals and objectives (Kern).

보건 시스템과 효과적으로 협력하기 위해 교육 리더는 의료 교육에서 시스템 학습에 대한 비전, 전략 및 목표를 명확히 설명해야 합니다. PSCOM과 UCSFSOM의 시스템 커리큘럼의 비전과 설계는 네 가지 시너지 원칙에 기초했다(표 1).

To partner effectively with health systems, education leaders need to articulate vision, strategy, and objectives for systems learning in medical education. The vision and design of systems curricula at the PSCOM and UCSF SOM were based on four synergistic principles (Table 1).15,35

이러한 원칙은 처음에는 문헌 검토, 지역 요구 평가 및 규제 요건에 기초했으며, 지역 및 국가의료 교육 리더와의 논의에서 주제별로 세분화되었다. 일단 비전과 원칙이 수립되면, 구현 전략이 구체화되기 시작할 수 있습니다. PSCOM 및 UCSFSOM의 초기 구현 단계는 현장 방문 및 계획 대화를 시작하기 위한 [모바일 사이트 개발 작업 그룹(의사 교육자, 커리큘럼 조정자 및/또는 프로그램 관리자로 구성)]의 지정이었다.

These principles were initially based on a literature review, local needs assessments, and regulatory requirements, and were refined thematically in discussions with local and national medical education leaders. Once a vision and principles have been established, an implementation strategy can begin to take shape. An early implementation step at the PSCOM and UCSF SOM was the designation of a mobile site development work group (consisting of physician educators, curriculum coordinators, and/or program managers) to begin site visits and planning conversations.

- 이 작업 그룹은 각 임상 현장과의 관계를 설정하고, 교육 비전을 공유하며, 관련 임상 결과를 듣고, 각 현장의 파트너십 준비 상태를 평가합니다. 여러 임상 사이트에서 [구현 계획을 개별화하는 데 따른 복잡성을 예상]하며, [새로운 학습 커뮤니티의 챔피언] 역할을 한다. PSCOM과 UCSF SOM 모두 임상 사이트의 접점point of contact이 될 수 있는 새로운 위치가 생성되었다.

This work group establishes a relationship with each clinical site, shares the education vision, hears relevant clinical outcomes, and assesses each site’s readiness for partnership. It anticipates the complexity of individualizing implementation plans with multiple clinical sites (e.g., Department of Health tuberculosis clinic, family/community medicine patient-centered medical home clinic, surgical weight loss program, Veterans Affairs Medical Center inpatient medicine service, safety net hospital rheumatology clinic, and academic medical center surgery clinic) and serves as a champion for the new learning communities. At both the PSCOM and UCSF SOM, new positions were created to be the point of contact for clinical sites.

- 이 작업 그룹은 [현장 방문 및 진행 상황에 대한 업데이트를 보고]하고, 교육 리더와의 정기 회의에서 [새로운 시스템 역할 및 파트너십]을 도입하는 장벽을 식별하고, 전략을 브레인스토밍 한다. 그런 다음 교육 리더들은 [학생들을 위한 학습 목표]를 파악하고, 작업 그룹은 이를 사용하여 임상 파트너와 협력하여 학생들을 위한 새로운 시스템 역할을 설계합니다.

The work group reports updates on site visits and progress, and identifies barriers to and brainstorms strategies for new systems roles and partnerships in regular meetings with education leaders. Education leaders then identify learning goals for students, and the group uses these to design new systems roles for students in collaboration with clinical partners.

이러한 방식으로 파트너십은 문제 식별(전략 1)에서 니즈 평가(전략 2)로, 공유된 비전과 전략 개발로, 그리고 목표와 목표(전략 3)로 진전됩니다.

In this manner, the partnership advances from problem identification (strategy 1), to needs assessment (strategy 2), to the development of a shared vision and strategy, as well as goals and objectives (strategy 3).

유지보수 단계: 지속성장

Maintenance phase: Sustaining and growing

전략 4: 조직 및 교육 전략(Kern)과 변화 비전(Kotter)을 소통합니다.

Strategy 4: Communicate the change vision (Kotter) with organizational and educational strategies (Kern).

임상 현장과의 초기 회의는 조정, 실현 가능성 및 공유 목표의 이해를 위한 경청하는 데 초점을 맞추어야 한다. 시스템 역할의 학생 개념은 교육자와 임상의 모두에게 새로운 것일 수 있습니다. 한 번의 만남 후에 최종 파트너십 모델이 등장하지는 않는다. PSCOM과 UCSF SOM의 경우, 일련의 회의를 통해 양자가 함께 새로운 모델을 구축할 수 있게 되었다. 여기에는 구현을 위한 세부 사항에는 협업 개발collaborative development이 필요하다는 것을 인정하는 것도 포함되었습니다. 문제가 발생할 때 문제를 해결하기 위해 효과적인 피드백 루프를 지원하는 인프라가 매우 중요했습니다. 바쁜 임상팀에게 교육 업무는 장벽이 될 수 있다.

Initial meetings with clinical sites should focus on respectful listening for alignment, feasibility, and understanding of shared goals. The concept of students in systems roles is likely new for both educators and clinicians. A final partnership model is unlikely to emerge after one meeting. In the case of the PSCOM and UCSF SOM, a series of meetings began to allow both parties to build a new model together. This included an acknowledgment that implementation details were awaiting collaborative development. An infrastructure to support effective feedback loops to address issues as they arose was critical. For busy clinical teams, the workload of education could become a barrier.

우리는 이 장벽을 해결하기 위해 이 모델과 전통적인 임상 교훈 모델(표 2) 사이의 차이를 설명할 뿐만 아니라 value added와 learning을 둘 다 반복할 것을 권고한다. 예를 들어, 학생은 장애물을 예측하고, 입원 및 외래 환경에서 환자와 제공자 간의 의사소통을 촉진하며, 안전한 퇴원 시 환자 교육을 강화하기 위해 병원의 전환 프로그램에 통합될 수 있다. 이러한 학생 역할에 대한 모델 구축은, 가장 필요한 환자부터 시작하여, value-added nature를 다른 환자 그룹으로 확대할 수 있다. 초기에는 리소스와 창의성이 필요하지만, 시간이 지남에 따라 수익returns이 증가해야 합니다.

We recommend reiterating both the value added and learning, as well as describing differences between this model and the traditional clinical preceptorship model (Table 2), to address this barrier. For example, students can be integrated into a hospital’s transitions program to anticipate barriers, facilitate communication between patients and providers in inpatient and outpatient settings, and reinforce patient education for safe discharges. Model building for these student roles can begin with those patients most in need, followed by broadening the value-added nature to other patient groups. Although resources and creativity are required at initiation, returns should increase with time.

Strategy 5: 광범위한 기반 조치를 강화하고 구현 시 장벽(Kern)을 극복합니다(Kotter)

Strategy 5: Empower broad-based action and overcome barriers (Kotter) in implementation (Kern).

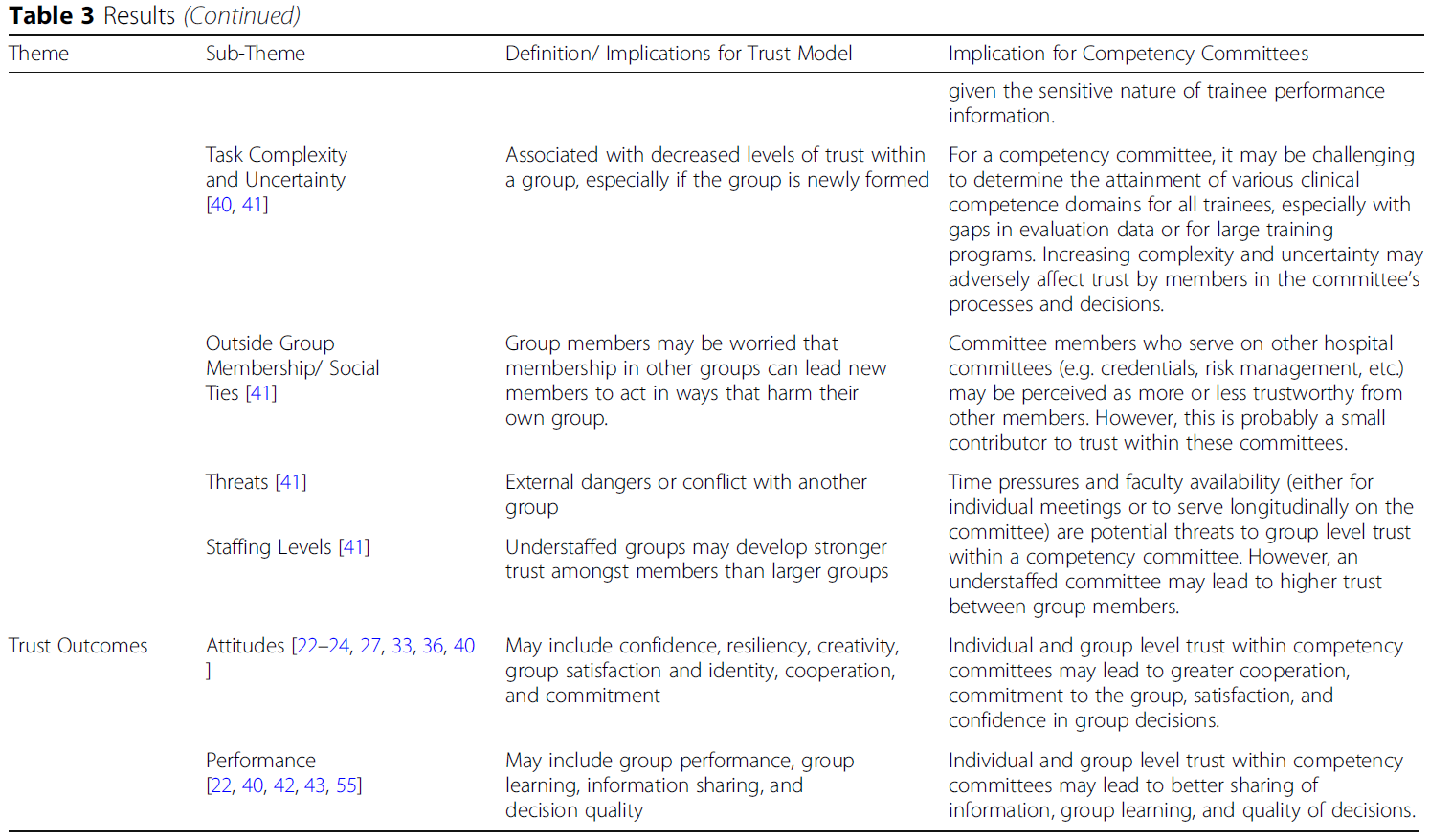

PSCOM 및 UCSFSOM에서 [대규모 커리큘럼 개편]을 이루기 위해 [설계 원칙]을 적용하여 임상 사이트와의 종적 협력 기준을 식별하였다(표 3).

- 한 예에서 의대생은 수술 전 진료소, 가정, 수술실 및 수술 후 환자 설정에 이르기까지 지속적인 관리를 제공합니다. 학생들은 고위험 수술 전에 기능과 영양을 최적화하고 심각한 질병 중에 연결이 끊길 수 있는 의료 환경에 대한 환자의 경험을 개선하기 위해 취약 환자에게 전문 의료 계획을 사용하도록 지도한다.

- 또 다른 예로, 의대생들은 국가가 운영하는 결핵 클리닉에서 환자와 매칭되어 수개월에 걸친 잠복결핵 치료 동안 adherence barrier을 식별한다. 학생들은 진료소 방문, 정기적인 전화 통화, 정기적인 가정 방문을 통해 환자와 제공자 간의 커뮤니케이션을 촉진하고 환자 경험을 개선하기 위한 전략을 파악한다.

Applying our design principles to create large-scale curricular reform at the PSCOM and UCSF SOM, we identified criteria for longitudinal partnerships with clinical sites (Table 3).

- In one example, medical students provide continuity of care from the preoperative clinic, to the home, to the operating room, and to the postoperative inpatient setting. Students coach vulnerable patients to use interprofessional care plans to optimize function and nutrition prior to high-risk surgery and to improve the patients’ experiences of health care settings that would otherwise be disconnected during a serious illness.

- In another example, medical students are matched with patients in a state-operated tuberculosis clinic to identify adherence barriers during the months-long treatment for latent tuberculosis. Through clinic visits, regular phone calls, and periodic home visits, students facilitate communication between patients and providers and identify strategies to improve the patient experience.

시스템 역할의 효과적인 구현을 위해 몇 가지 잠재적 장벽을 해결해야 한다.

For effective implementation of systems roles, several potential barriers should be addressed.

- 첫째, 학생 역할이 의미 있는 기여를 하기 위해서는 종방향 노출이 필요하다.36 PSCOM 및 UCSF SOM에서, 전임상실습 의과대학생에게는, [systems workplace learning]을 위한 전용 커리큘럼 시간이 한 달에 2번~4번의 반일half-days가 있다. 교육과정에 공간을 마련하기 위해서는, 공유된 비전을 검토하고, 기존의 중복성 또는 시대에 뒤떨어진 콘텐츠를 제거할 기회를 식별하기 위해 모든 교육 이해당사자와의 공개 대화가 필요했다.

First, longitudinal exposure is necessary for student roles to result in meaningful contributions.36 At the PSCOM and UCSF SOM, dedicated curricular time for systems workplace learning ranges from two to four half-days per month for preclerkship medical students. Creating space in the curriculum required an open dialogue with all education stakeholders to review the shared vision and identify opportunities to remove existing redundancy or outdated content.

- 둘째, 학생 활동을 조정하려면 각 임상 현장에서 챔피언이 필요합니다. 리더들이 소개를 할 수도 있지만, 일선 의료진이 매일 학생들을 지도한다. [현장의 챔피언site champion]은 학생 활동에 대한 주인의식을 가지고 있다. 치료 코디네이터, 환자 탐색기 또는 간호사가 될 수 있으며, 의사가 챔피언이 될 수 있지만 반드시 그럴 필요는 없다. 챔피언은 학생들이 교육 목표를 달성하고 의료 시스템 목표에 기여하는 동시에 직원과 환자의 만족도를 유지하도록 돕는다.

Second, coordinating student activities requires a champion at each clinical site. Although leaders may make the introductions, frontline clinical staff guide students daily. A site champion has a sense of ownership for student activities. This can be a care coordinator, patient navigator, or nurse practitioner; the champion can, but need not be, a physician. The champion helps students achieve educational objectives and contribute to health system goals, while maintaining staff and patient satisfaction.

- 마지막으로, [의대생 전체 학급]에 대해 [다양한 특성을 가진 여러 임상 사이트를 사용하는 것]은 variability을 가져온다. PSCOM과 UCSF SOM의 대규모 네트워크에는 단일 목표(예: 높은 활용도) 또는 환자 인구(예: 유방암 생존자)가 아닌 광범위한 임상 초점 영역이 있는 사이트가 포함된다. 이는 [서로 다른 현장의 수많은 시스템 활동]이 [동일한 학습 목표]에 매핑될 수 있음을 의미한다.

Finally, using multiple clinical sites with a diversity of characteristics for a whole class of medical students brings variability. The large-scale networks of the PSCOM and UCSF SOM include sites with broad clinical focus areas rather than a system with a single goal (e.g., high utilization) or patient population (e.g., breast cancer survivors). This means that a number of systems activities at different sites can map to a single learning objective;

예를 들어, [가정의학 클리닉]은 [수술 체중 감소 클리닉]과 다르지만, 둘 다 학생들이 환자 경험과 질병 결과를 측정하고 개선하기 위해 전문 의료 팀에 포함될 기회를 포함한다. 이러한 포괄적인 접근 방식은 authentic work를 통해 학생 교육을 촉진할 수 있는 다수의, 다양한 사이트를 가능하게 한다. 의료 제공 시스템이 만성 치료와 높은 활용도에 계속 최적화됨에 따라, 기존의 의과대학-보건 시스템 제휴는 혁신적인 치료 모델 내에서 새로운 교육 기회를 공동 창출할 준비가 될 것이다.

for example, a surgical weight loss clinic is different from a family medicine clinic, but both include opportunities for students to be embedded within interprofessional care teams to measure and improve patient experience and disease outcomes. Such an inclusive approach allows for a number and variety of sites that can all facilitate student education through authentic work. As care delivery systems continue to be optimized for chronic care and high utilization, existing medical school–health system partnerships would stand ready to co-create new educational opportunities within innovative care models.

전략 6: 구현(Kern)에서 단기 성공(Kotter)을 창출합니다.

Strategy 6: Generate short-term wins (Kotter) in implementation (Kern).

[초기 성공]에 대한 이야기는 교육 및 보건 시스템 리더가 혁신에 대한 자신감을 얻는 데 도움이 됩니다. 성공적인 파일럿 프로그램에 대한 이야기를 퍼뜨리는 습관은 그 노력을 진전시키고 성취를 축하한다. 임상 사이트 네트워크 활동의 챔피언으로서 태스크포스, 포인트 퍼스널, 또는 관리 인프라가 성공을 위해 중요하다. 또한, 교육기업의 모든 대표들은 의대생들의 구체적인 성공 스토리가 변화를 가져올 수 있도록 도와야 한다. 예를 들어, UCSF SOM 학생들은 전자 건강 기록에 통합된 지속 가능한 프로세스를 설계하는 데 도움을 주어 한 클리닉에서 골절 위험이 높은 환자에 대한 골다공증 검사율을 개선하였다. 학교의 웹사이트와 회의 중에 그러한 성공 사례를 공유하는 것은 다른 사이트들이 학생들을 치료 개선에 참여시키는 기회를 브레인스토밍하는 데 도움이 되었다.

Stories of early successes help both education and health systems leaders gain confidence about innovations. A habit of disseminating stories about successful pilots advances the effort and celebrates accomplishments. A task force, point person, or administrative infrastructure as the champion for clinical site network activities is critical for success. In addition, all representatives of the education enterprise should be facile with concrete success stories of medical students making a difference. For example, at the UCSF SOM students helped design a sustainable process integrated into the electronic health record that led to improved osteoporosis screening rates for patients at high risk of fractures at one clinic. Sharing such success stories on the school’s Web site and during meetings helped other sites brainstorm opportunities for engaging students in improving care.

전략 7: 평가 및 피드백(Kern)을 시작하는 동안 이익(Kotter)을 공고하게consolidate 합니다.

Strategy 7: Consolidate gains (Kotter) while beginning evaluation and feedback (Kern).

의과대학과 보건시스템 간의 제휴는 "단거리 달리기"보다는 "마라톤" 관계를 구축해야 한다. 이 프로세스에는 집단 비전을 구축하고, 아이디어를 창출하고, 문제를 해결하며, 목표를 공유하고, 구현 모델을 식별하기 위한 여러 가지 대화가 포함됩니다. 장기적인 파트너십을 개발하려면 정기적인 직접 미팅과 후속 전화 통화 일정을 수립해야 합니다.

Partnerships between medical schools and health systems require relationship-building “marathons” rather than “sprints.” The process involves multiple conversations to build a collective vision, generate ideas, solve problems, share goals, and identify an implementation model. Developing long-term partnerships involves scheduling periodic in-person meetings and follow-up phone calls.

PSCOM 및 UCSF SOM은, [시간이 지남에 따라 각 임상 사이트에서 발생할 수 있는 예상치 못한 문제를 해결]하기 위해 향후 몇 년 동안 의도적인 성능 개선 주기를 계획하고 있습니다. 직원은 프로그램적 목표를 상기시켜야 할 수 있으며, 학생 시스템 역할은 재협상이 필요할 수 있다. 또한 예상치 못한 직원 이직도 거의 예고 없이 발생할 수 있습니다. 우리의 사이트 기반 구현 팀은 이러한 예상치 못한 변화에 즉각적으로 대응할 수 있도록 학생과 사이트를 적시 지원할 준비가 되어 있습니다. 특정 파트너십이 비효율적인 경우 백업 임상 사이트가 필요할 수 있습니다. 요컨대, 새로운 파트너십에는 과제가 포함되므로 지속적인 개선을 위한 프로세스가 필요합니다.

The PSCOM and UCSF SOM are planning intentional performance improvement cycles in the coming years to address unanticipated issues at each clinical site over time. Staff may need reminders of programmatic goals, and student systems roles may need to be renegotiated. Additionally, unexpected personnel turnover can occur with little notice. Our site-based implementation teams are ready for just-in-time support of students and sites for immediate response to such unanticipated changes. If particular partnerships prove ineffective, backup clinical sites may be necessary. In short, a new partnership will include challenges, and so requires a process for continuous improvement.

전략 8: 평가 및 피드백(Kern)을 계속하면서 문화(Kotter)에 새로운 접근 방식을 정착시킵니다.

Strategy 8: Anchor new approaches in the culture (Kotter) while continuing evaluation and feedback (Kern).

PSCOM과 UCSF SOM, 그리고 점점 더 전국적으로 증가하고 있는 작업 조직에서는 보건 시스템 과학을 교육과 임상 임무의 우선순위 영역으로 확립하는 데 도움을 주고 있다. 우리의 접근 방식은 의학 교육의 떠오르는 "제3의 과학"이라고 일컬어진 것을 통합하기 위한 실용적인 접근 방식입니다.

- 의학교육의 '제3 과학'은 - 기본 및 임상 과학을 보완하고, (전문가 간 팀워크, 인구 건강, 환자 안전 및 품질 향상의 기초가 되는 증거를 포함하여) 다양한 시스템 관련 주제에 대한 과정 연구 및 적용을 포함합니다.

At both the PSCOM and UCSF SOM, and increasingly across the country, a mounting body of work is helping to establish health systems science as a priority area in the education and clinical missions.7 Our approach is a practical one for integrating what some have referred to as an emerging “third science” of medical education—

- which complements the basic and clinical sciences and includes course work and application of various systems-related topics, including the evidence underlying interprofessional teamwork, population health, patient safety, and quality improvement.10

더욱이, [professional-in-training으로서 (시스템에) 기여하는 학생]은 결국 보건 시스템의 환영받는 표준이 될 수 있다. 첫날부터 그들은 오늘날의 의사들의 작업을 시뮬레이션하면서 생물 의학, 임상 및 시스템 주제에 대한 통합된 3가지를 배울 수 있기 때문이다.

Furthermore, with this work, students contributing as professionals-in-training may eventually become a welcome norm for health systems, as from day one, they would learn an integrated triad of biomedical, clinical, and systems topics, simulating the work of physicians today.

학술 기관에 있어 의과대학의 질은 보건 시스템의 성공에 영향을 미치며, 그 반대의 경우도 마찬가지이다. 학생들을 위한 부가가치 임상 시스템 역할은 의료 교육이 건강 시스템의 발전을 도울 수 있도록 하여 장기적인 성공에 시너지를 창출한다.

For academic institutions, the quality of the medical school has implications for the success of the health system, and vice versa. Value-added clinical systems roles for students allow medical education to help advance the health system, creating synergy for long-term success.

결론

Conclusion

의학교육 및 보건 시스템은 전통적으로 사일로에서 운영되어 왔습니다. 의학교육은 지식과 견습성을 강조하는 반면, 임상 시스템은 효율성과 품질을 우선시한다. 이러한 두 가지 서로 다른 정신 모델은 효과적인 협업을 구축하기 위해 변형될 수 있다. 의료 전달과 의학교육이 개혁을 거친다면, 의대생들은 보건 시스템을 배우고 기여할 수 있다.

Medical education and health systems have traditionally operated in silos. Clinical systems prioritize efficiency and quality, while medical education emphasizes knowledge and apprenticeships. These different mental models can be transformed to build effective collaborations. As care delivery and medical education undergo reform, medical students can learn and contribute to health systems.

Acad Med. 2017 May;92(5):602-607.

doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001346.

Value-Added Clinical Systems Learning Roles for Medical Students That Transform Education and Health: A Guide for Building Partnerships Between Medical Schools and Health Systems

Jed D Gonzalo 1, Catherine Lucey, Terry Wolpaw, Anna Chang

Affiliations collapse

Affiliation

- 1J.D. Gonzalo is assistant professor of medicine and public health sciences and associate dean for health systems education, Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey, Pennsylvania. C. Lucey is professor of medicine and vice dean for education, University of California, San Francisco School of Medicine, San Francisco, California. T. Wolpaw is professor of medicine and vice dean for educational affairs, Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey, Pennsylvania. A. Chang is professor of medicine and Gold-headed Cane Endowed Education Chair in Internal Medicine, University of California, San Francisco School of Medicine, San Francisco, California.

- PMID: 27580433

- DOI: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001346Abstract

- To ensure physician readiness for practice and leadership in changing health systems, an emerging three-pillar framework for undergraduate medical education integrates the biomedical and clinical sciences with health systems science, which includes population health, health care policy, and interprofessional teamwork. However, the partnerships between medical schools and health systems that are commonplace today use health systems as a substrate for learning. Educators need to transform the relationship between medical schools and health systems. One opportunity is the design of authentic workplace roles for medical students to add relevance to medical education and patient care. Based on the experiences at two U.S. medical schools, the authors describe principles and strategies for meaningful medical school-health system partnerships to engage students in value-added clinical systems learning roles. In 2013, the schools began large-scale efforts to develop novel required longitudinal, authentic health systems science curricula in classrooms and workplaces for all first-year students. In designing the new medical school-health system partnerships, the authors combined two models in an intersecting manner-Kotter's change management and Kern's curriculum development steps. Mapped to this framework, they recommend strategies for building mutually beneficial medical school-health system partnerships, including developing a shared vision and strategy and identifying learning goals and objectives; empowering broad-based action and overcoming barriers in implementation; and generating short-term wins in implementation. Applying this framework can lead to value-added clinical systems learning roles for students, meaningful medical school-health system partnerships, and a generation of future physicians prepared to lead health systems change.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 임상교육(Clerkship & Residency)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 어떻게 임상감독자는 수련생에 대한 신뢰를 형성하는가: 질적 연구(Med Educ, 2015) (0) | 2021.07.13 |

|---|---|

| 위임결정내리기: 밀러의 피라미드 확장(Acad Med, 2021) (0) | 2021.07.13 |

| 적응적 전문성(When I say...) (Med Educ, 2017) (0) | 2021.05.21 |

| 인간과 기계: 임상추론학습의 공생적 접근을 위하여(Med Teach, 2019) (0) | 2021.03.13 |

| 임상 상황에서 일반역량의 발전정도 탐지의 어려움(Med Educ, 2018) (0) | 2021.03.07 |